The Project Gutenberg eBook of Elizabeth Montagu, the queen of the bluestockings, Volumes I and II, by Emily Jane Climenson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Elizabeth Montagu, the queen of the bluestockings, Volumes I and II

Her Correspondence from 1720 to 1761

Authors: Emily Jane Climenson

Elizabeth Montagu

Release Date: April 19, 2023 [eBook #70593]

Language: English

Produced by: Fay Dunn and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ELIZABETH MONTAGU, THE QUEEN OF THE BLUESTOCKINGS, VOLUMES I AND II ***

ELIZABETH MONTAGU

THE QUEEN OF THE BLUE-STOCKINGS

HER CORRESPONDENCE FROM

1720 TO 1761

Transcribers’ Note

The cover image was created by the transcriber, and is placed in the public domain.

It is based on the original cover.

Original cover

Volumes one and two of “Elizabeth Montagu” are also published separately at Project Gutenberg.

This combination of the two volumes consists of: Volume I, Volume II, Index, and the Robinson Pedigree

Please also see the note at the end of this book.

Volume I

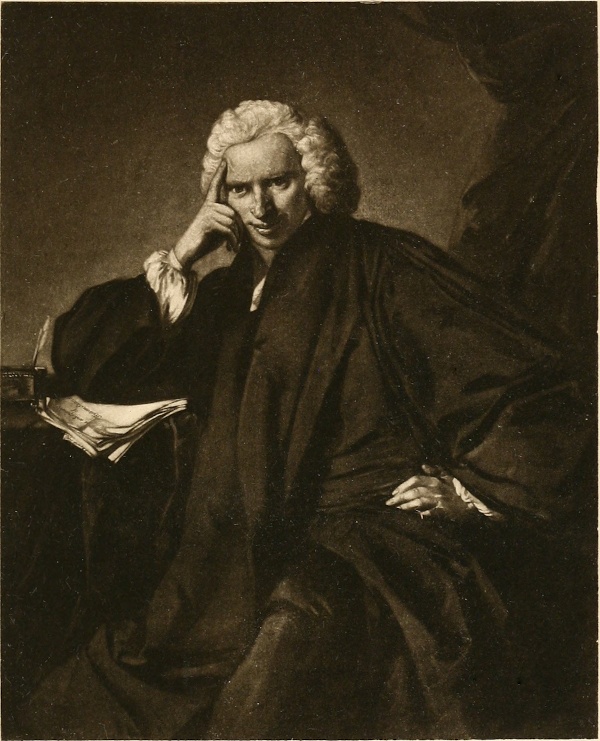

C. F. Zincke. Pinx. Emery Walker Ph. Sc.

Mrs. Montagu

née Elizabeth Robinson

from a miniature in the possession of Miss Montagu

ELIZABETH MONTAGU

THE QUEEN OF THE

BLUE-STOCKINGS

HER CORRESPONDENCE FROM

1720 TO 1761

BY HER GREAT-GREAT-NIECE

EMILY J. CLIMENSON

AUTHORESS OF “HISTORY OF SHIPLAKE,”

“HISTORICAL GUIDE TO HENLEY-ON-THAMES,”

“PASSAGES FROM THE DIARIES OF MRS. P. LYBBE POWYS,” ETC., ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. I

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET

1906

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED

LONDON AND BECCLES

AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

TO

MY COUSINS

MAGDALEN WELLESLEY

AND

ELIZABETH MONTAGU

BY

THE AUTHORESS

[vii]

PREFACE.

From my early youth I heartily desired to know more

of the life of my great-great-aunt, Mrs. Elizabeth

Montagu. Every scrap of information I could pick

up respecting her I accumulated; therefore when my

cousins, Mrs. Wellesley and her sister, Miss Montagu,

in October, 1899, gave me the whole of her manuscripts

contained in 68 cases, holding from 100 to 150 letters

in each, my joy was unbounded!

In 1810 my grandfather, the 4th Baron Rokeby (her

nephew and adopted son), published two volumes

of her letters; these were followed by two more

volumes in 1813. To enable him to perform this

pleasing task he asked all her principal friends to return

her letters to him, beginning with the Dowager

Marchioness of Bath,[1] daughter of the Duchess of

Portland, who gave him back the earliest letters to her

mother, many carefully inserted in a curious grey paper

book by the duchess, who placed the date of reception

on each, and evidently valued them exceedingly. The

Rev. Montagu Pennington returned her letters to his

aunt, Mrs. Elizabeth Carter, the learned translator of

Epictetus; Mrs. Freind those to her husband; and

many other people did the same. From General

Pulteney, at Lord Bath’s death, she had asked for and[viii]

received her correspondence with Lord Bath, which

she carefully preserved. At the death of Lord Lyttelton,

the executors, at her request, returned her her letters;

those to Gilbert West and other correspondents were

returned in the same manner. Meanwhile she kept all

letters of her special friends, as well as notabilities, so

that one may deem the collection quite unique, though

doubtless many letters have disappeared, notably those

of Sir Joshua Reynolds, many of whose letters were

destroyed by an ignorant caretaker of Mrs. Montagu’s

house, Denton Hall, near Newcastle-on-Tyne. There

are none of Horace Walpole’s, from whom she must have

received some; and those from several other celebrities

she knew well are missing.

Owing to the enormous quantity of letters undated,

the sorting has been terribly difficult, and I spent one

entire winter in making up bundles and labelling each

year. My grandfather made a variety of mistakes as to

the dates of the letters. I hope I have atoned for some

of his deficiencies, though a few mistakes are probably

inevitable. He nearly blinded himself by working at

night, and my grandmother[2] had constantly to copy the

letters in a large round hand to enable him to make them

out. After my grandmother’s death he discontinued

arranging them, though they might have been continued

till 1800, the year of Mrs. Montagu’s death.

In the present volumes only her early life is

presented, interwoven with portions of her most intimate

friends’ letters to herself. Were the whole of

this vast correspondence printed, a large bookcase

could be filled with the volumes. In order to consult

the varied tastes of the general reader, I have endeavoured

to pick out the most interesting portions of

her letters, such as relate to customs, fashions in[ix]

dress, price of food, habits, but I have often groaned in

spirit at having to leave out much that was noble in

sentiment, or long comments upon contemporary books

and events. If life should be spared me, I hope to

be able to continue my narrative, for, like the ring

produced by a stone thrown on the water, her circle of

friends and acquaintances increased yearly, and not

only comprised her English friends and every person

of distinction in Great Britain, but also the most distinguished

foreigners of all nations, notably the French.

It has been asserted that Gilbert West was the first

person to influence Mrs. Montagu on religious points.

That his amiable Christianity may have strengthened

her religious opinions I do not deny, but I hope it will

be seen from this book that from her earliest days,

when at the height of her joie de vivre, the religious

sentiment was existent—a religion that prompted her

ever to the kindest actions to all classes, that had nothing

bitter or narrow in it, no dogmatism. Adored by men

of all opinions, and liking their society, she was the

purest of the pure, as is amply proved by the letters

of Lord Lyttelton, Dr. Monsey, and others, but she was

no prude with all this. Her worthy husband adored

her, and no wife could have been more devoted and

obedient than she was. His was a noble character, and

doubtless influenced her much for good. As a wife, a

friend, a camarade in all things, grave or gay, she was

unequalled; as a housewife she was notable, beloved

by her servants, by the poor of her parish, and by her

miners and their wives and children. She planned

feasts and dances and instituted schools for them, and

fed and clothed the destitute.

With Mr. Raikes[3] she was one of the first people[x]

to institute Sunday-schools. She was as interested

in Betty’s rheumatism as she was in the conversation

of a duke or a duchess; a discussion with bishops and

Gilbert West on religion, or with Emerson on mathematics,

or Elizabeth Carter on Epictetus, all came alike

to her gifted nature. She danced with the gay, she

wept with the mourner; her sympathies never lay idle,

even to the very end of life; and in a century which

has been deemed by many to be coarse, uneducated,

and irreligious, her sweet wholesome nature shone like

a star, and attracted all minor lights. Where in the

twentieth century should we find a coterie of men and

women of the highest rank and influence in the world,

either from intellect or position, so content and devoted

to each other, so free from the petty jealousies and

sarcasms of the present fashionable society, so anxious

for each other’s welfare, socially and morally; so free

from cant or prudery, so devoted to each other’s

interest?

A great and terrible break in this book was caused

by the death of my beloved husband in May, 1904,

after a long, lingering illness. I doubt if I should

have taken courage to resume my pen if it had not

been for my friend Mr. A. M. Broadley, whose interest

in my literary work and affectionate solicitude for

myself has been a kindly spur to goad me on to action,

so as to complete the present volumes. To him I

tender my thanks for past and present encouragement,

as well as many other kindnesses.

EMILY J. CLIMENSON.

[xi]

CONTENTS TO VOL. I.

| PAGE |

| Preface |

vii |

| List of Illustrations |

xv |

| CHAPTER I. |

| The Robinson, Sterne, and Morris families — Birth and childhood

of Elizabeth Montagu — Correspondence with Duchess of Portland

(passim) — Dr. Middleton’s second wife — “Fidget” — A

summons — Tunbridge Wells — Mrs. Pendarves — Lady Thanet

— Miss Anstey — Bevis Mount — The Wallingfords — A suit of

“cloathes” — Anne Donnellan |

1–25 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| Correspondence with Duchess of Portland (passim) — Sir Robert

Austin — The goat story — The Freinds — Country beaux — Thomas

Robinson, barrister — Lady Wallingford — Duke of

Portland’s letter — A coach adventure — Influenza — Smallpox — Cottage

life — Bath — Lord Noel Somerset — Dowager Duchess

of Norfolk — Frost Fair on the Thames — The plunge bath — “Long”

Sir Thomas Robinson — Lord Wallingford’s death — The

menagerie at Bullstrode — Lady Mary Wortley Montagu — Princess

Mary of Hesse — Monkey Island — Lydia Botham — Mrs.

Pendarves — Lord Oxford — Admiral Vernon — Anne Donnellan — Charlemagne — Dr.

Young’s Night Thoughts — Duchess of

Kent — Mr. Achard |

26–62 |

| CHAPTER III. |

| Hairdressing — Correspondence with Duchess of Portland (passim)

— Sarah Robinson attacked by smallpox — Hayton Farm — A

country squire — Handel — Dr. Middleton — Laurence Sterne — Duke

of Portland’s letter — A brother’s tribute — Carthagena — The

Westminster election — A South Sea lawsuit — Lord Oxford’s

death — Panacea of bleeding — A one-horse chaise — A Windsor

[xii]hatter — Lord Sandwich’s marriage — Ducal baths — Domestic

service — Cibber’s Life — Peg Woffington — Dowager Duchess

of Marlborough — Revolution in Russia — New Year’s Day — Lord

George Bentinck — Northfleet Fair — Sir R. Walpole — Duchess

of Norfolk’s masquerade — Sir Hans Sloane — A House

of Lords debate — The Opera — Garrick |

63–107 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| Love triumphs — Sir George Lyttelton — Edward Montagu — Anne

Donnellan’s advice — Elizabeth’s engagement and marriage — Correspondence

with Duchess of Portland — “Delia” Dashwood — Odd

honeymoon etiquette — Mr. Robinson’s letter — Dr.

Middleton’s letter — Cally Scott — Mrs. Freind — Père Courayer — Works

of Manor — The Dales — Whig principles — Correspondence

with Edward Montagu — Hanoverian troops — Handel’s

Oratorios — Young’s Night Thoughts — A country beau

and roué — A bolus — The Lord Chancellor — Dr. Sandys — A

cook |

108–140 |

| CHAPTER V. |

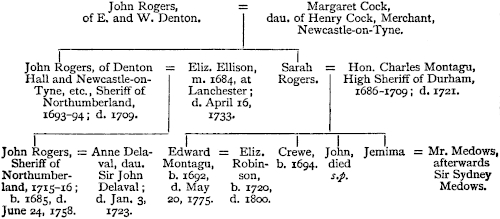

| Journey to London — The floods — A faithful steward — The Rogers’

pedigree — A curious letter — Mr. Montagu’s visit to Newcastle — Birth

of “Punch” — Inoculation — Baby clothes — Sandleford

Priory — A parson and his wife — Countess of Granville — Correspondence

with Duchess of Portland — Courayer — Woman’s

education — Lord Orford’s letter to General Churchill — Preparation

for inoculation — Elizabeth’s letter to her husband — Army

discipline — Physicians’ fees — Pope’s grotto — A highwayman — Dangers

of a post-chaise — “Punch’s” chariot — A Bath ball — “Mathematical

inseration” — Midgham — A footpad — The

Ministry — Pope’s Dunciad — Mrs. Pococke — Sugar tax — The

Pretender — Sir Septimus Robinson — “Hide” Park — Gowns

and fans — The wearing of “Punch” — A wet-nurse — Aprons — Orange

trees — Lord Anson — Clothes and table-linen — Stowe — Thoresby — Death

of “Punch” — Loss of an only child — Submission

to God’s will — Duchess of Marlborough’s death — A

Raree Show — Cattle disease — Mrs. Robinson’s illness |

141–197 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| Correspondence with the Duchess of Portland — Donnington Castle —

Tunbridge Wells — Dr. Young and Colley Cibber — Buxton — Tonbridge

Castle — The 1745 rising in Scotland — George Lewis

[xiii]Scott — National terrors — Wade’s army — County meeting at

York — The Northern gentry — General Cope’s defeat at Preston

Pans — Sussex privateers — Tunbridge ware — Walnut medicine — D.

Stanley’s letter to Duke of Montagu — Cattle murrain — Fears

of invasion — The Law regiment — Romney Marsh — A footman — A

brave gamekeeper |

198–226 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| Correspondence with Duchess of Portland — Death of Mrs. Robinson — Lydia

Botham — The Hill Street house — “Such a Johnny” — Courayer — Mr.

Carter’s death — Denton estate — Elixir of

vitriol and tar-water — Dr. Shaw — Young Edward Wortley

Montagu — General election — Huntingdon Election — Dr. Pococke — Mrs.

Theophilus Cibber — Courayer’s figure — A high

and dry residence — Lady Fane’s grottoes — In search of an axletree —

Winchester Cathedral — Mount Bevis — The New Forest — Wilton

House — Savernake — Courayer’s letter — Matthew Robinson,

M.P. for Canterbury — Lyttelton’s Monody — Thomas

Robinson’s death — Coffee House, Bath — Cambridge — Richardson’s

Clarissa — Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle — Spa — The Hague — James

Montagu’s death — Price of tea |

227–263 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| Ranelagh masquerade — Tunbridge Wells — Duke of Montagu’s

death — Coombe Bank — The feather screen — Hinchinbrook — The

Miss Gunnings — Chinese room in Hill Street — A parson’s

children — Dowager Duchess of Chandos — Lord Pembroke’s

death — The earthquake — Death of Dr. Middleton — Anniversary

of Elizabeth’s wedding day — Mrs. Boscawen — Gilbert West — Barry

and Garrick — Embroidered flounces — “The cousinhood” — West

family — Berenger — Hildersham — Miss Maria Naylor — The

“Pollard Ashe” — Mrs. Percival’s death — Dr. Shaw’s death — The

Dauphin — Dr. Middleton’s works — Anne Donnellan — Nathaniel

Hooke |

264–296 |

[xv]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

VOL. I.

| Mrs. Montagu (née Elizabeth Robinson) |

Frontispiece |

| From a miniature by C. F. Zincke, in the possession of The Hon. Elizabeth

Montagu, Farnham Royal. (Photogravure.) |

|

| TO FACE PAGE |

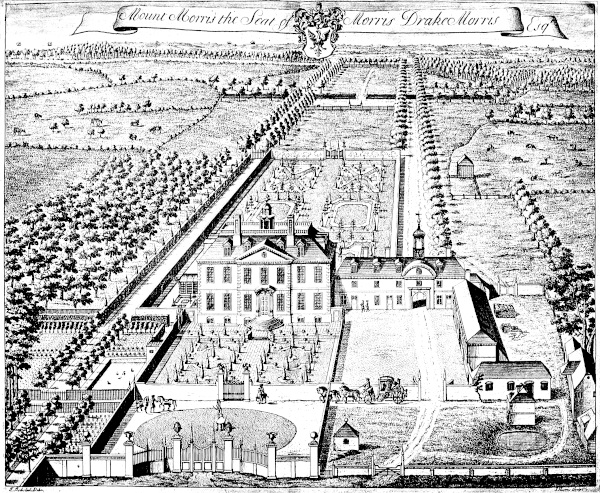

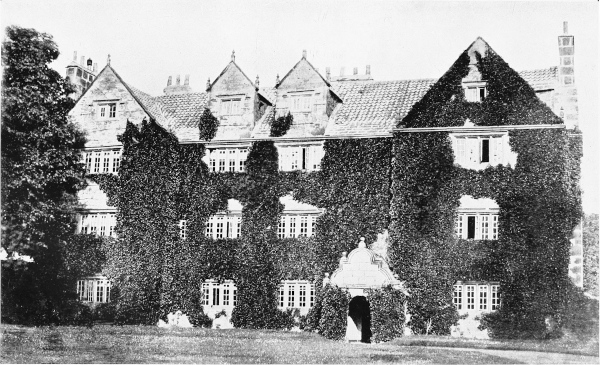

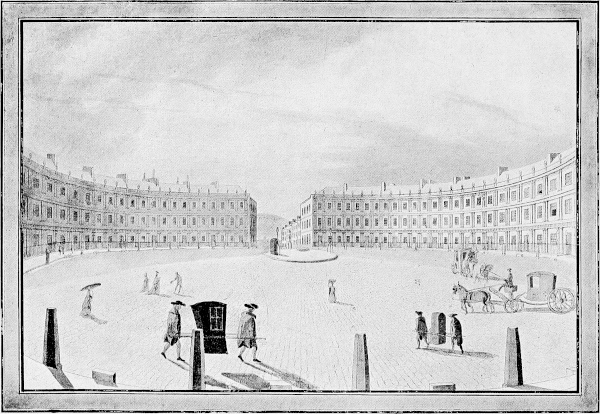

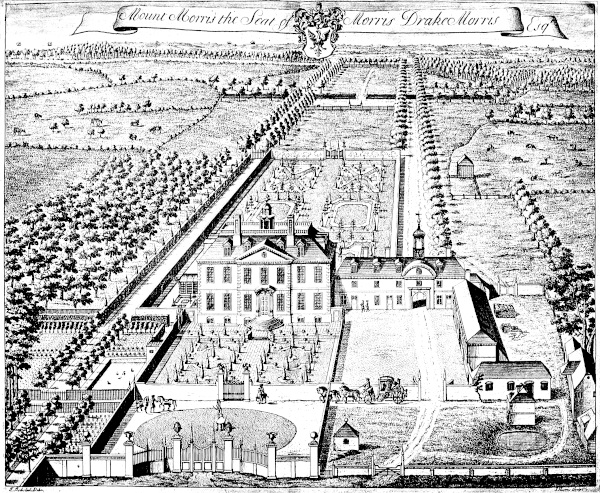

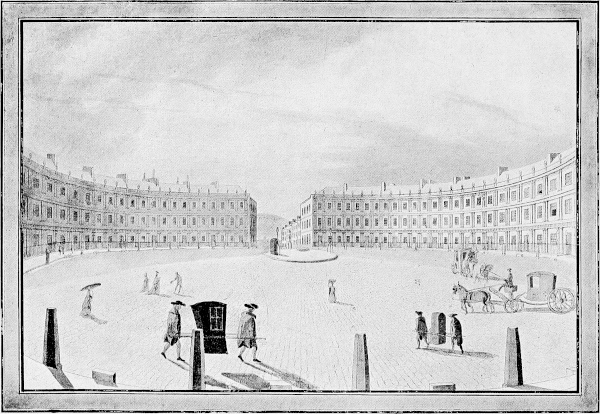

| Mount Morris, near Hythe, Kent |

8 |

| From an old print, 1809. |

|

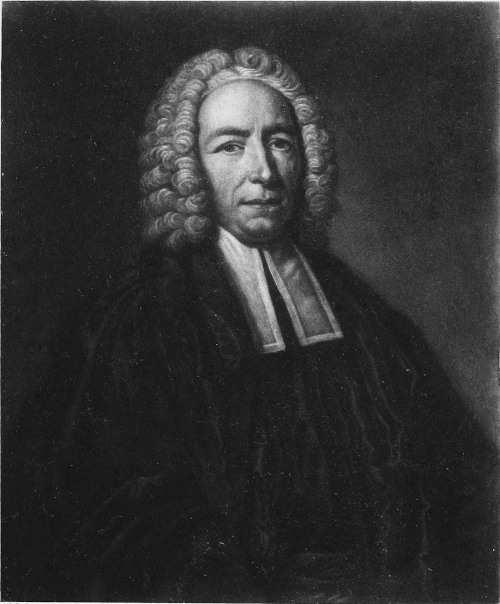

| Miss Morris, Grandmother of Mrs. Montagu |

16 |

| From a picture (artist unknown), in the possession of the Hon. Elizabeth

Montagu. (Photogravure.) |

|

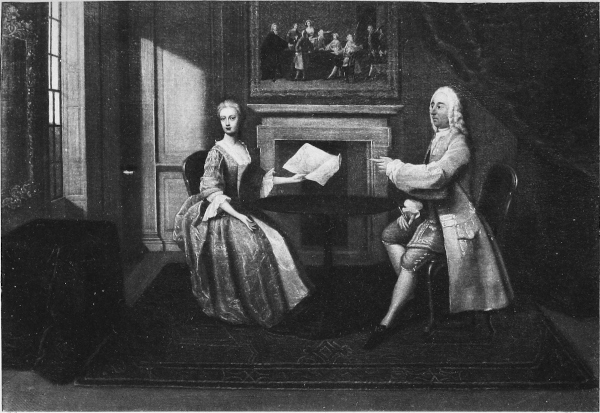

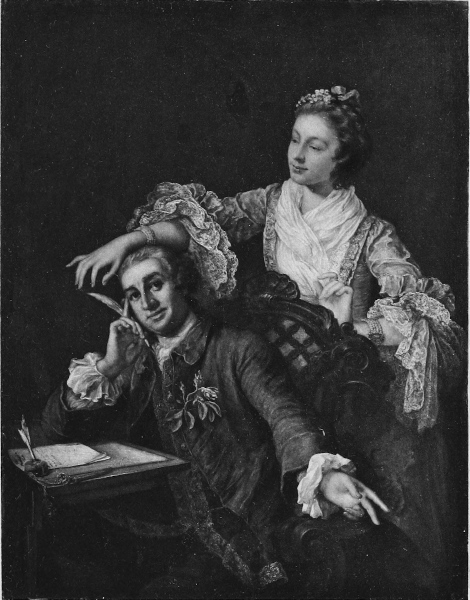

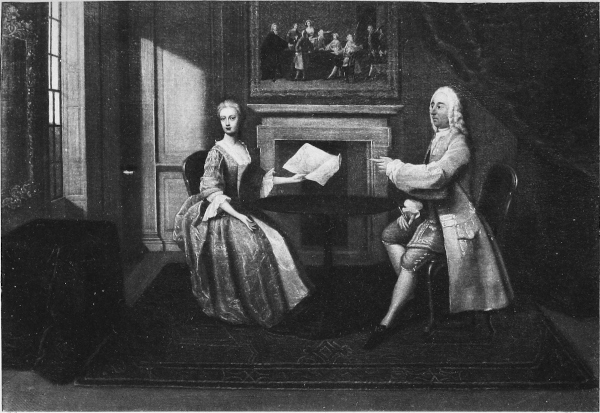

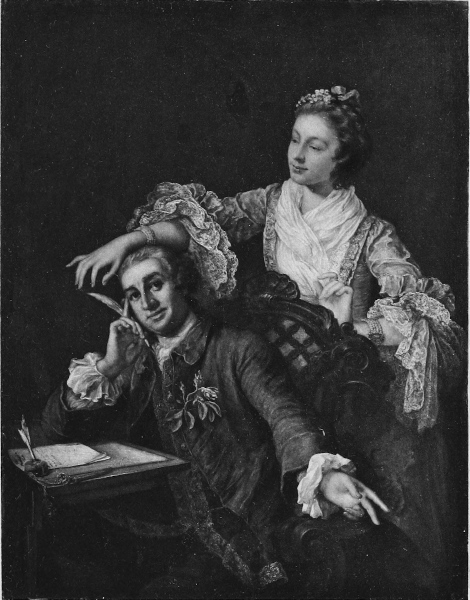

| Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Robinson (Mrs. Montagu’s Father

and Mother) |

32 |

| From a picture by W. Hamilton, in the possession of The Hon. Elizabeth

Montagu, Farnham Royal. (Photogravure.) |

|

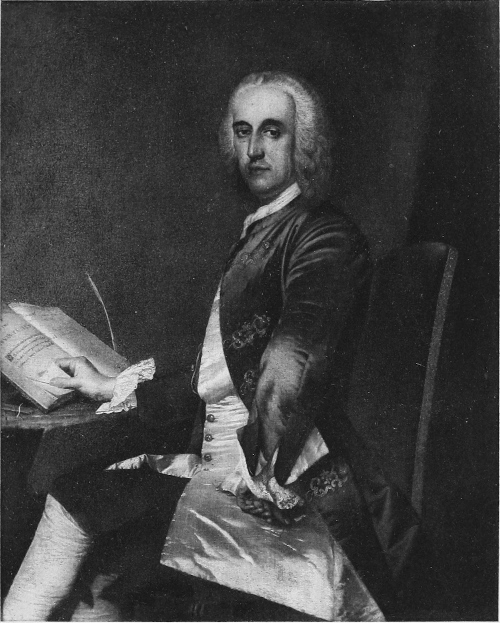

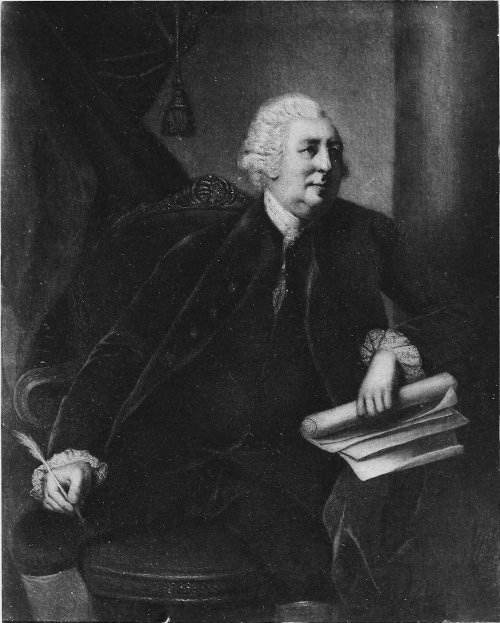

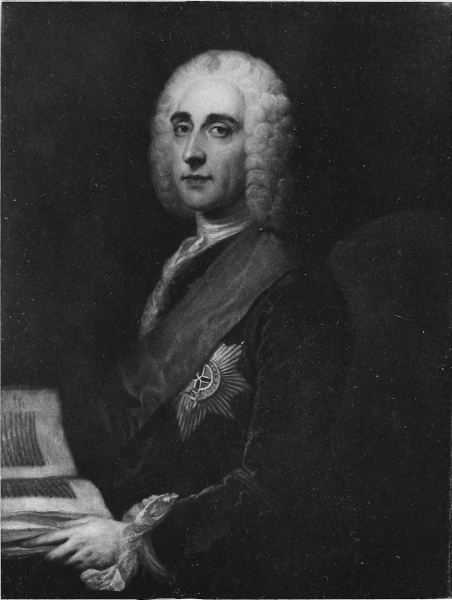

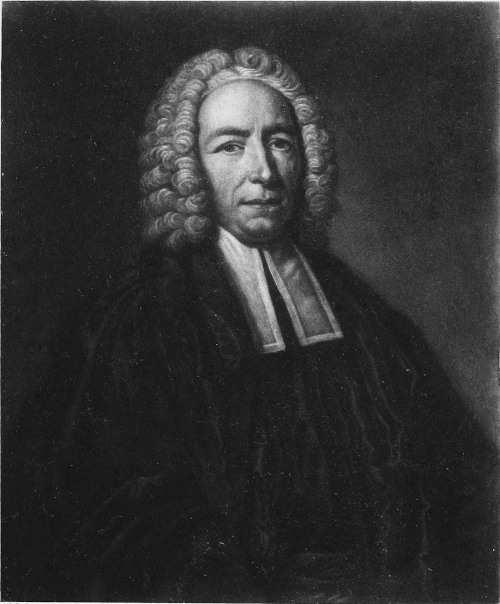

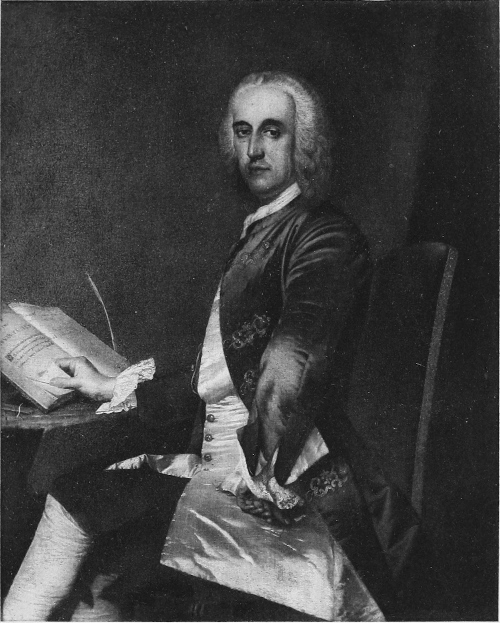

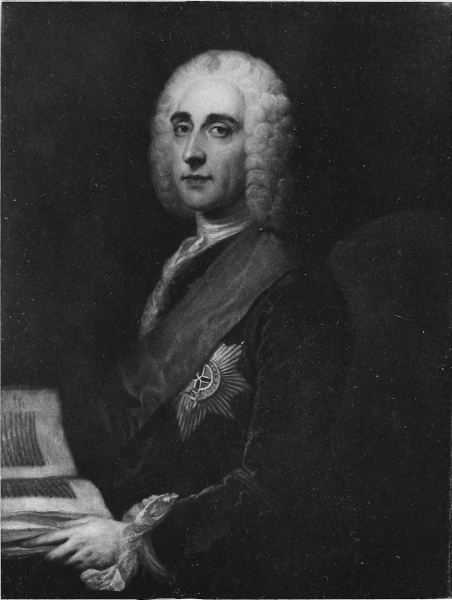

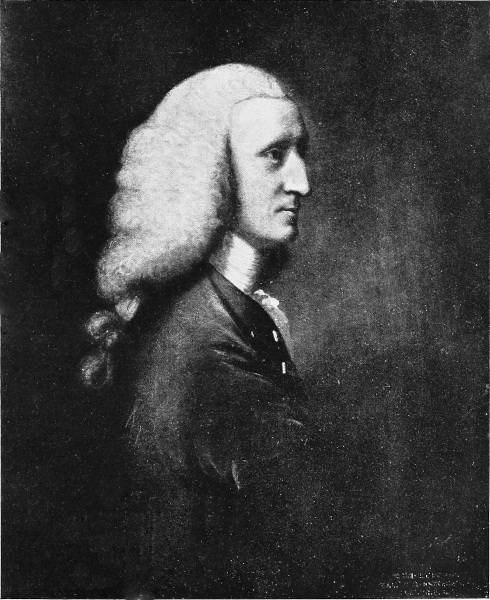

| W. Freind, D.D., Dean of Canterbury |

64 |

| From the picture by T. Worlidge. |

|

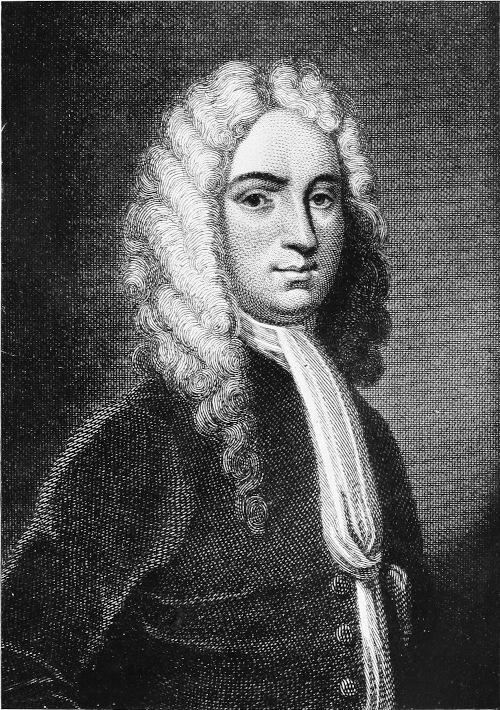

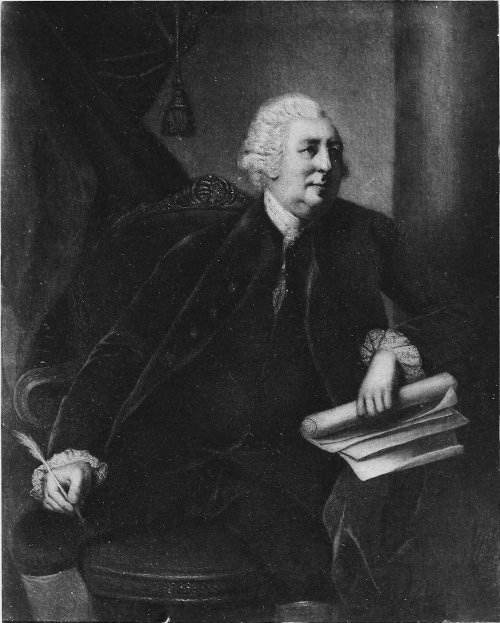

| William, Second Duke of Portland |

76 |

| From the picture by Thomas Hudson, in the possession of the Duke of

Portland. (Photogravure.) |

|

| Lady Mary Wortley Montagu |

80 |

| From a miniature (artist unknown), in the possession of Mrs. Climenson.

(Photogravure.) |

|

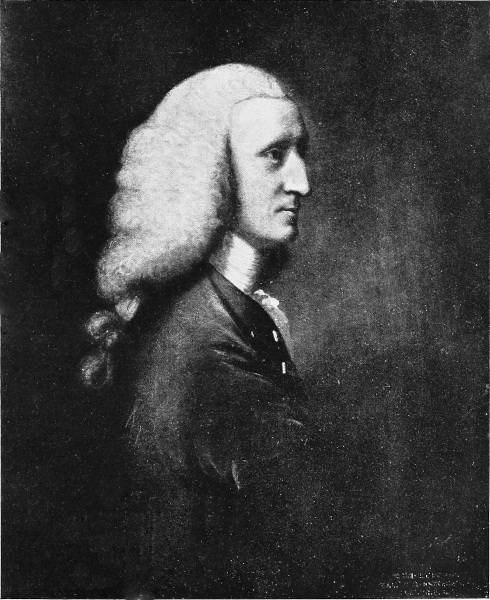

| Sir Thomas Robinson (1st Baron Rokeby) |

100 |

| From a picture (artist unknown), in the possession of The Hon. Elizabeth

Montagu, Farnham Royal. (Photogravure.) |

|

| Morris Robinson |

144[xvi] |

| From the picture by the Rev. M. W. Peters, R.A., in the possession of The

Hon. Elizabeth Montagu, Farnham Royal. (Photogravure.) |

|

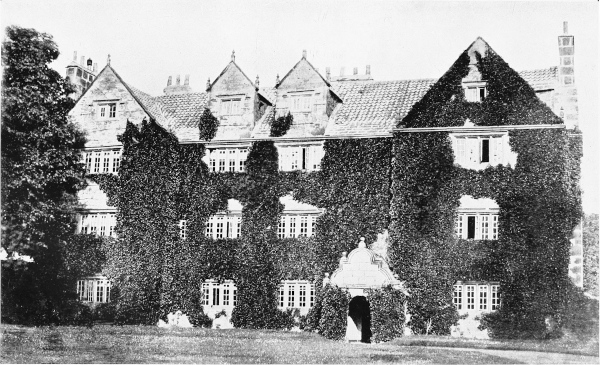

| Sandleford Priory, near Newbury, Berkshire |

152 |

| From a photograph. |

|

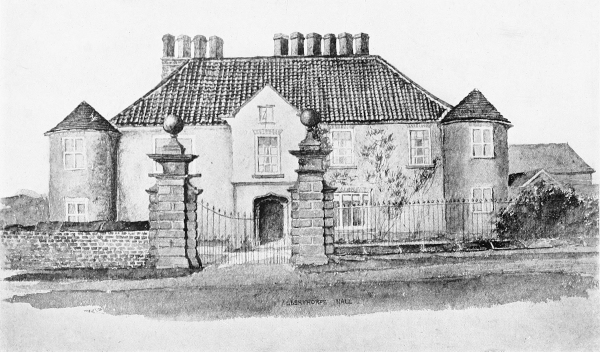

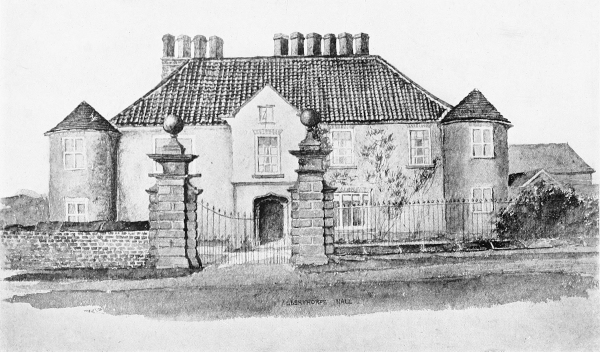

| Denton Hall, Northumberland |

160 |

| Margaret Cavendish Harley, Duchess of Portland |

192 |

| From the picture by Thomas Hudson, in the possession of the Duke of

Portland. (Photogravure.) |

|

| Lady Lechmere (née Howard), Afterwards Lady (Thomas)

Robinson |

208 |

| From a picture (artist unknown), in the possession of The Hon. Elizabeth

Montagu, Farnham Royal. (Photogravure.) |

|

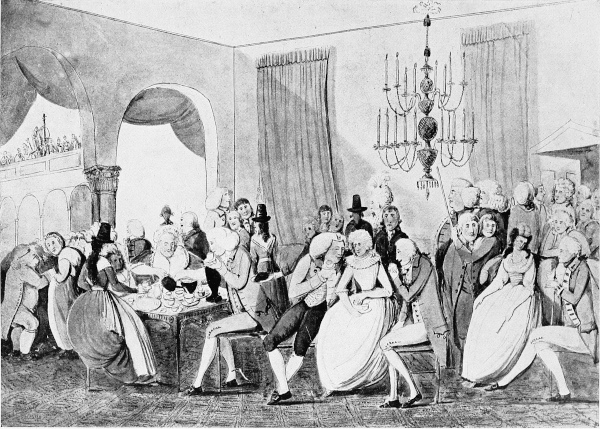

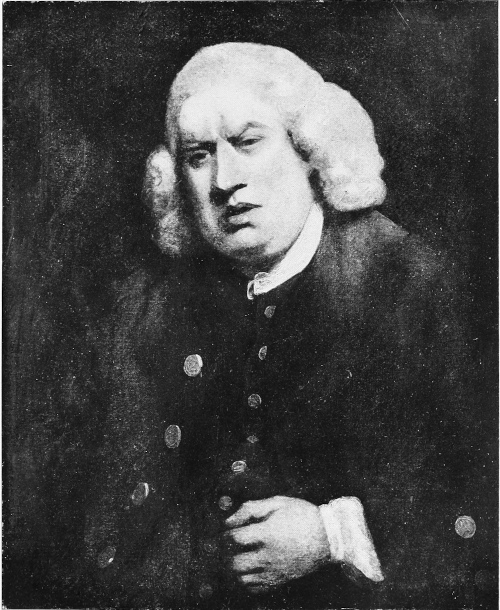

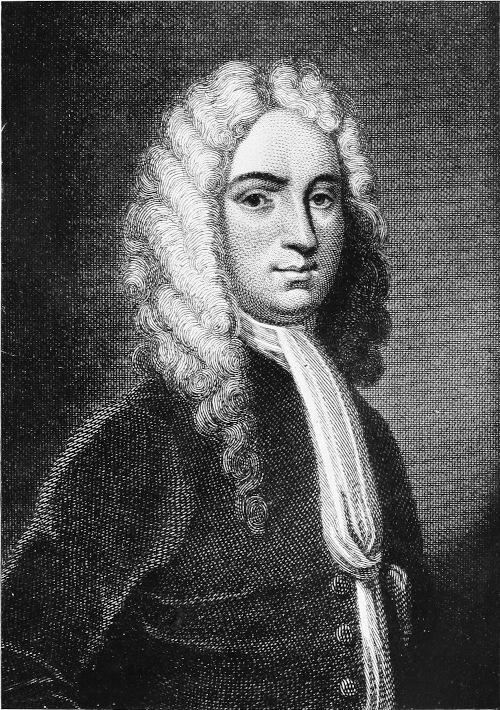

| Gilbert West |

296 |

| From an engraving by E. Smith, after W. Walker. |

|

[1]

ELIZABETH MONTAGU

THE QUEEN OF THE BLUE-STOCKINGS

CHAPTER I.

GIRLHOOD UP TO 1738, AND BEGINNING OF THE CORRESPONDENCE

WITH THE DUCHESS OF PORTLAND.

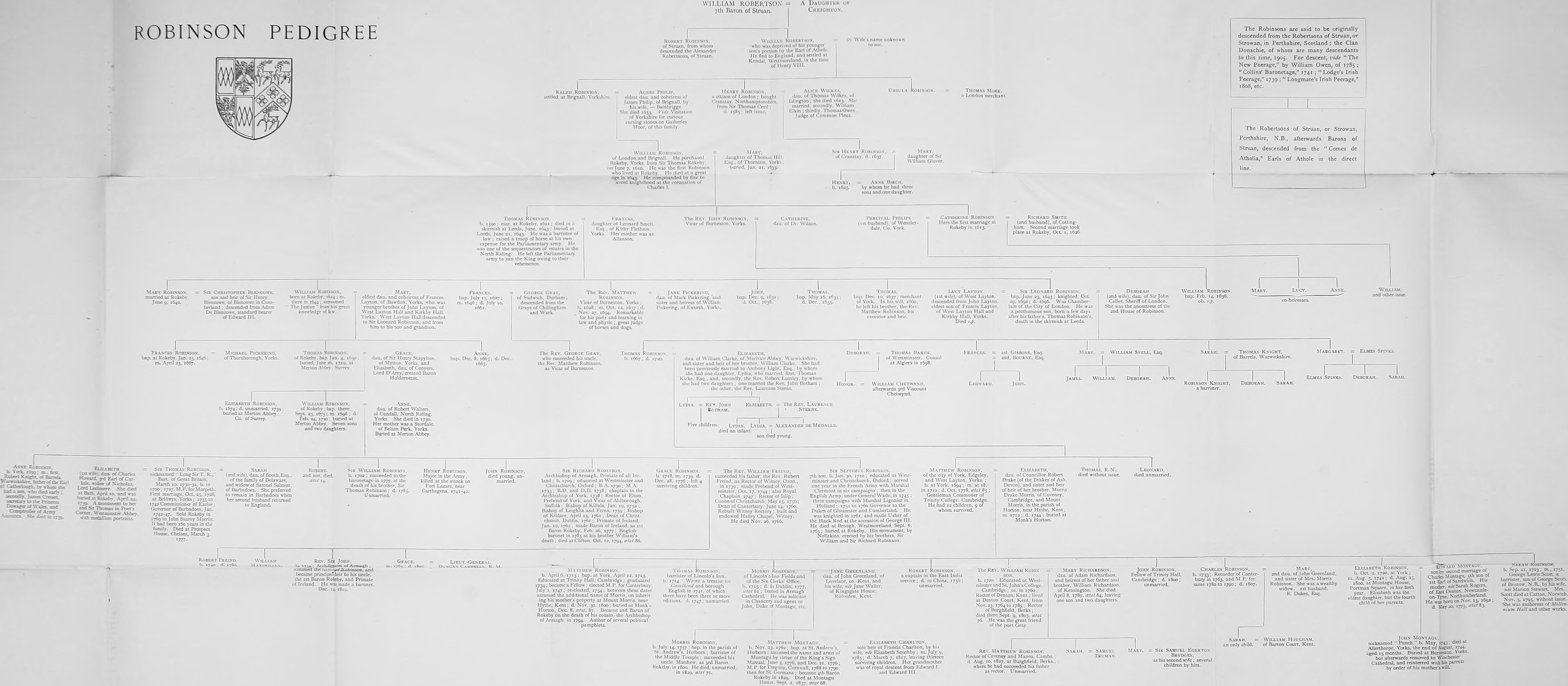

THE ROBINSON FAMILY

Before entering on the life of Elizabeth Robinson,

afterwards Mrs. Edward Montagu, the famous bas bleu,

the focus, as she may be called, of all the cleverest and

most intellectual society of the last half of the eighteenth

century, a few words must be said of the family she

sprang from. The Robinsons are said to have been

originally Robertsons, the name being corrupted into

Robinson. They are in many Peerages[4] said to descend

from the Robertsons of Struan, or Strowan, in Perthshire,

who descended from Duncan de Atholia, Earl of

Athole, hence descendants of Duncan, King of Scotland.

My grandfather, the 4th Baron Rokeby, in an unfinished

pedigree, believed this, but there have been Robinsons

bearing the same[5] coat-of-arms in Yorkshire as early

as the time of copyhold record in Edward III.’s reign.[2]

However, they may have been related. Our narrative

starts from William, said to be younger son of

the 7th Baron Robertson of Strowan, who, being

deprived of his portion of inheritance as younger son

by the Earl of Athole, fled into England, and settled

at Kendal in Westmorland, in the time of Henry VIII.

He had three children, Ralph, Henry, and Ursula.

Ralph married Agnes Philip, by whom he had William,

who succeeded to his father’s estates at Kendal and

Brignal, and who on June 7, 1610, bought the estate

of Rokeby in Yorkshire from Sir Thomas Rokeby,

whose family had been possessed of it before the Conquest.

Rokeby continued to belong to the Robinson

family for 160 years, when “Long Sir Thomas Robinson”

sold it in 1769 to John B. Saurey Morritt, the

friend of Sir Walter Scott. The Robinsons finally

assumed two lines (vide Pedigree), William, the eldest,

remaining master of Rokeby, and his posthumous

brother, Leonard, becoming the direct ancestor of our

heroine. Leonard Robinson was a merchant in London;

he became Chamberlain of the City of London, and was

knighted on October 26, 1692. He married, first, Lucy

Layton, of West Layton, etc., by whom he had no issue.

For his second wife he married Deborah, daughter of

Sir James Collet, Knight and Sheriff of London, by

whom he had six daughters, all of whom married and

had issue, and one son, Thomas, who married a widow,

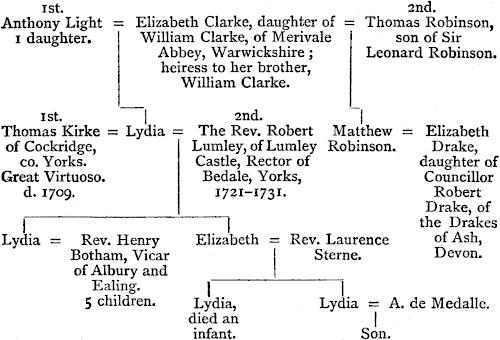

Elizabeth Light. She was daughter of William

Clarke, Esq., of Merivale Abbey, Warwickshire, and

heiress of her brother, William Clarke. By her first

husband, Anthony Light, she had one daughter, Lydia.

By her second marriage with Thomas Robinson she

had three sons. Matthew, the eldest, alone concerns us

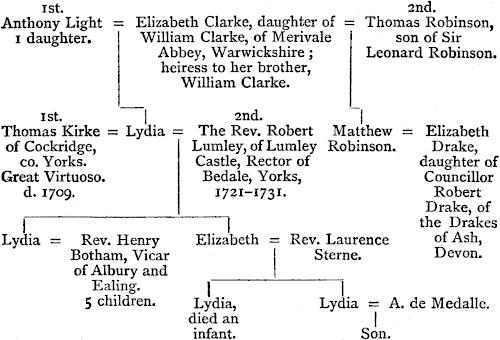

as father of Mrs. Montagu. The following table will

show the connection between the Robinson and Sterne[3]

families: the Rev. Laurence Sterne marrying their

cousin, Elizabeth Lumley:—

PEDIGREE OF THE ROBINSONS AND STERNES

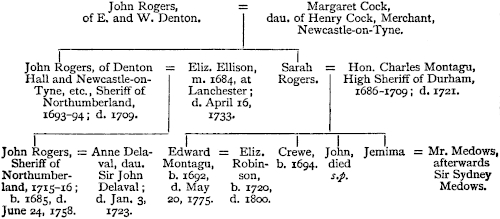

{Skip transcribed table} {See image for table}

1st.

Anthony Light

1 daughter. |

=

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Elizabeth Clarke, daughter of William Clarke, of Merivale Abbey, Warwickshire;

heiress to her brother, William Clarke. |

=

|

|

|

|

|

| |

2nd.

Thomas Robinson, son of Sir Leonard Robinson. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

1st. Thomas Kirke

of Cockridge, co, Yorks. Great Virtuoso. d. 1709 |

= |

Lydia |

=

|

|

|

|

|

| |

2nd. The Rev. Robert Lumley of Lumley Castle, Rector of Bedale, Yorks, 1721–1731. |

Matthew Robinson. |

= |

Elizabeth Drake, daughter of Councillor Robert Drake, of the Drakes of Ash, Devon. |

|

|

| | |

|

| |

|

| Lydia |

= |

Rev. Henry Botham, Vicar of Albury and Ealing.

5 children. |

Elizabeth |

=

|

| |

Rev. Laurence Sterne. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Lydia died an infant. |

|

Lydia |

=

| |

A. de Medalle. |

|

Son. |

1694

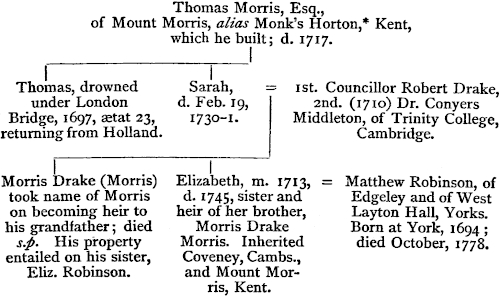

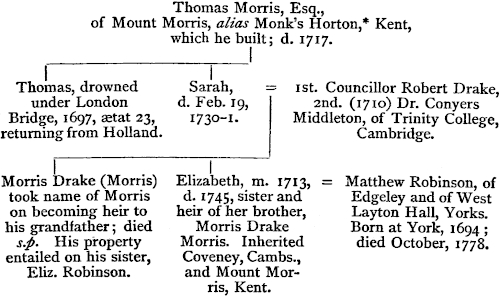

THE MORRIS FAMILY

We now enter on the history of Matthew Robinson,

the eldest surviving son of Thomas, and his wife

Elizabeth. He was born in 1694, therefore was only

six years old when his father died. At an early age he

was entered at Trinity College, Cambridge, and became

a fellow-commoner. He was a person of great intellectual

parts, a conversationalist and wit, the life of

the coffee-houses, which then served, as clubs do nowadays,

as a rendezvous for men of fashion. His talent

for painting was remarkable. His great nephew states,

“He acquired so great a proficiency as to excel most

of the professional artists of his day in landscape.”

At the early age of eighteen, in 1712, he married

[4]Elizabeth Drake, daughter of Councillor Robert Drake,

of Cambridge, descended from the Drakes of Ashe in

Devonshire. Elizabeth’s mother’s name was Sarah

Morris. The Morris family had been seated in Kent

at East Horton since the reign of Elizabeth. Thomas

Morris, father of Sarah, built the mansion of Mount

Morris, sometimes called Monk’s Horton, near Hythe.

He had one son, Thomas, who was drowned under

London Bridge on his return from Holland in 1697,

ætat 23. His sister Sarah had two children by Councillor

Drake, Morris and Elizabeth. Their maternal grandfather

lived to 1717, when he devised his estates to his

grandson, Morris Drake, with the proviso of his assuming

the extra name of Morris, and failing of his issue

with remainder to Elizabeth, his sister, then Mrs.

Matthew Robinson. Her mother, Mrs. Drake, having

become a widow, had remarried the celebrated Dr.

Conyers Middleton, but had no children by him. The

following table will elucidate this:—

{Skip transcribed table} {See image for table}

Thomas Morris, Esq.,

of Mount Morris, alias Monk’s Horton,[6] Kent,

which he built; d. 1717. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| | |

| |

|

| Thomas, drowned under London Bridge, 1697, ætat 23,

returning from Holland. |

Sarah, d. Feb. 19, 1730–1.

|

|

|

| |

= |

1st. Councillor Robert Drake,

2nd. (1710) Dr. Conyers Middleton, of Trinity College, Cambridge. |

|

|

| | |

| |

|

| Morris Drake (Morris) took name of Morris on

becoming heir to his grandfather; died s.p. His property entailed on his sister, Eliz. Robinson. |

Elizabeth, m. 1713, d. 1745, sister and heir of her brother, Morris Drake Morris. Inherited

Coveney, Cambs., and Mount Morris, Kent. |

= |

Matthew Robinson, of Edgeley and of West Layton Hall, Yorks. Born at York, 1694; died October, 1778. |

1712

ELIZABETH ROBINSON

[5]

To return to the Robinsons, they settled at their

property of West Layton Hall, derived from Lucy

Layton, first wife of Sir Leonard Robinson, and Edgeley

in Wensleydale for the summer, and spent the winter

in York; most country families at that period repairing

to London or their nearest county town for convenience

and society during the winter. To this young couple

were born twelve children, of whom seven sons and

two daughters lived to grow up—

1. Matthew, born April 6, 1713; afterwards 2nd

Baron Rokeby. Educated at Trinity Hall, Cambridge;

became a Fellow. Died November 30, 1800,

ætat 87.

2. Thomas, born 1714, died in 1746–7. Barrister-at-law.

3. Morris, born 1715, died 1777; of the Six Clerks’

Office.

4. Elizabeth, born at York, October 2, 1720, died

August 25, 1800.

5. Robert, Captain, E.I.C.S. Died in China, 1756.

6. Sarah, born September 21, 1723, died 1795.

7. William, born 1726, died 1803.

8. John, of Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

9. Charles, born 1733, died 1807.

DR. CONYERS MIDDLETON

Elizabeth, the subject of this book, was about seven

years old when, by the death of her uncle, Morris

Drake Morris, her mother inherited, as his heir, the

important property of East Horton, and Mount Morris

in Kent. The family then left Yorkshire for residence

at Mount Morris. But before and after their inheritance

of the Kentish property much time was spent with the

Conyers Middletons both at Coveney, Cambridgeshire, a

property Mrs. Conyers Middleton had inherited from

her first husband, Councillor Drake; the advowson of

the living being hers, she bestowed it on her second[6]

husband, Dr. Conyers Middleton,[7] whom she had

married in 1710; also at Cambridge, where was their

usual residence, and where several of the little Robinsons

were born in their grandmother’s house, as we

learn from a letter of Dr. Middleton’s. Elizabeth

Robinson was naturally much with her grandmother,

with whom and Conyers Middleton she was a great

favourite. Her nephew and adopted son, in his volumes

of her letters[8] that he published in 1810, states—

“Her uncommon sensibility and acuteness of understanding,

as well as extraordinary beauty as a child,

rendered her an object of great notice in the University,

and Dr. Middleton was in the habit of requiring from

her an account of the learned conversations at which, in

his society, she was frequently present; not admitting

of the excuse of her tender age as a disqualification, but

insisting that although at the present time she could but

imperfectly understand their meaning, she would in

future derive great benefit from the habit of attention

inculcated by this practice.”

Her father was proud of her vivacious wit, and

encouraged her gifts of repartee which she possessed

in as large a measure as himself.

“In her youth her beauty was most admired in the

peculiar animation and expression of her blue eyes,

with high arched eyebrows, and in the contrast of her

brilliant complexion with her dark brown hair. She

was of the middle stature, and stooped a little, which

gave an air of modesty to her countenance, in which the

features were otherwise so strongly marked as to express

an elevation of sentiment befitting the most exalted

condition.”

[7]

1727–28

Her elder brothers, members of Cambridge University,

were all extremely literary, and became, early,

distinguished scholars. We are told—

“Their emulation produced a corresponding zeal in

their sisters, and a diligence of application unusual in

females of that time. Their domestic circle was

accustomed to struggle for the mastery in wit, or in

superiority in argument, and their mother, whose frame

of mind partook rather of the gentle sedateness of good

sense than of the eccentricities of genius, was denominated

by them ‘the Speaker,’ from the frequent mediation

by which she moderated their eagerness for

victory.”

MOUNT MORRIS —

LADY MARGARET CAVENDISH HARLEY

In Harris’s “History of Kent,” published in 1719, on

p. 156, is a picture of Mount Morris, the home of the

Robinsons, a large square house with a cupola surmounted

by a ball and a weathercock, surrounded by

a number of walled gardens laid out in the formal

Dutch manner, an inner Topiary garden, leading to a

steep flight of steps to the front door. Whilst staying

in Cambridgeshire, Elizabeth had several times visited

at Wimpole with her father and mother. Wimpole

was the seat of Edward,[9] second Earl of Oxford and

Mortimer, who had married Henrietta Cavendish, only

daughter and heiress of John Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-on-Tyne.

She was a great heiress, and brought

her husband £500,000; she is said to have been a good

but a very dull woman, very proud, and a rigid worshipper

of etiquette. In the “National Biography” she

is said to have “disliked most of the wits who surrounded

her husband, and hated Pope!”[10] The Earl spent

[8]enormous sums in collecting books, manuscripts, pictures,

medals, and articles of virtu, spending £400,000 of his

wife’s fortune. To him we are indebted for the Harleian

manuscripts, bought from his widow in 1753 for £10,000

by the nation, now in the British Museum. With the

Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley,[11] only child of the

Earl and Countess of Oxford, Elizabeth became on

the most intimate terms, and her first extant letter is

addressed to her when she was only eleven years old,

and the Lady Margaret eighteen. So greatly did Lady

Margaret value Elizabeth’s letters, that for a series of

years she preserved them between the leaves of an old

grey book which I possess. The first letter is endorsed,

“Received, February 24, 1731–2, at Wimpole.” It commences—

“Madam,

“Your ladyship’s commands always give me a

great deal of pleasure, but more especially when you

ordered me to do myself this honour, without which I

durst not have taken that liberty, for it would have been

as great impertinence in me to have attempted it as it is

condescension in your ladyship to order it.”

This alludes evidently to Lady Margaret having

desired her to write to her. It ends—

“My duty to my Lord and Lady Oxford, and

service to Lord Dupplin,[12] and my best respects to

Miss Walton,[13] hope in a little while it may be duty. I

am in great hopes that when your ladyship sees any

impertinent people in London it will put you in mind

of, Madam,

“Your ladyship’s most obliged, humble servant,

MOUNT MORRIS.

[9]

1731–32

The formal terms in this letter were then considered

essential, even when addressing those of lower birth,

all the more so to a person of Lady Margaret’s rank.

Viscount Dupplin, whose name frequently occurs in the

letters, was a cousin of Lady Margaret’s on her father’s

side, his mother being a daughter of Robert Harley,

1st Earl of Oxford. The two young friends now kept

up a lively correspondence, but as many of the letters

have been published by my grandfather in 1810, I shall

for this early period of her life give only a résumé of

them, picking out such facts as point to the manners of

the time, or that strike one as of interest. From Mount

Morris in August, 1732, she writes—

“Since I came here I have been to Canterbury Races,

at which there was not much diversion, as only one

horse ran for the King’s Plate.... We had an assembly

for three nights; the rooms are so small and low that

they were exceedingly hot.”

From this date one perceives that young ladies were

allowed to appear in public early, as Elizabeth was then

not quite twelve years old!

1733

TUNBRIDGE WELLS

In October, 1733, she paid, in company of her parents,

her first visit to Tunbridge Wells, ever afterwards such

a favourite resort of hers. She says—

“It is so pleasant a place I don’t wonder the physicians

prescribe it as a cure for the spleen; a great part of the

company, especially of the gentlemen, are vapoured.

When the wind is not in the east they are very good

company, but they are as afraid of an easterly wind as if

it would bring caterpillars upon our land as it did on the

land of Egypt.... I am very sorry I could not get you

any verses at Tunbridge, of which, at the latter part of

the season, when the garrets grow cheap, that the poets

come down, there is commonly great plenty.”

[10]

Further on she says, “I thank your ladyship for the

verses, and I wish I had any to send you in return for

them, but my poet is turned lawyer, and has forsook

the Muses for ‘Coke upon Littleton.’” This alludes

to her brother Tom, who was then studying law. The

collecting of verses on every sort of circumstance seems

to have been as fashionable then as photograph, autograph,

or stamp-collecting, etc., are now.

“MRS.” PLACE

In the next letter of November, 1733, she alludes

to Dr. Conyers Middleton, who, as stated before, had

married Mrs. Drake, Elizabeth’s grandmother, and who

was now a widower—

“I suppose you have heard Dr. Middleton has

brought his Cousin Place[14] to keep his house. He very

gravely sent us word that his cousin had come to spend

the winter with him, and it was not impossible they

might agree for a longer time; so I fancy he has

brought her with him to see if she likes to play at

quadrille, and sup on sack posset with the grave

doctors, whose company to one of her gay temper must

be delightful. I suspected his designs when he made

so many complaints in London, that it was so very

difficult to find a maid who understood making jellies

and sack posset, which he and a certain doctor used

to have for their suppers. He lost one lady because

she was deaf to him; but I believe that fortune, to

make amends to him, has blinded this. For though

I don’t doubt he always takes care to show her the

side of his face which Mr. Doll says is younger by

ten years than the other, yet that is rather too old to

be a match for twenty-five, which I believe is the age of

Mrs.[15] Place.”

[11]

The next letter she says—

“I have not heard from Dr. Middleton a great while.

I suppose his thoughts are taken up with business and

his pretty cousin in the West. I don’t know whether

she has made a complete conquest of his heart.”

In May, 1733—

“Dr. Middleton now owns his marriage. I wish he

finds the felicity of it answers his resigning a £100 a

year. I am glad, for the sake of any other family, he

has not got another rich widow; if he had, it would have

been her turn to resign.”

This alludes to the fact that on the learned doctor’s

remarriage he had to resign his fellowship.

MR. ROBINSON

Mr. Robinson, Elizabeth’s father, was not fond of the

country, where his wife’s fine estate and his nine children

condemned him to reside the greater part of the year;

and when we consider how young a man he was, then

only thirty-one, and his great love of witty society, one

cannot be surprised at his having attacks of the “hyp”

or “vapours,” as the terms for ennui were then. Elizabeth

writes to Lady Margaret from Mount Morris—

“Though I am tired of the country, to my great

satisfaction I am not so much so as my Pappa; he is a

little vapoured, and last night, after two hours’ silence,

he broke out with a great exclamation against the

country, and concluded in saying that living in the

country was sleeping with one’s eyes open. If he sleeps

all day, I am sure he dreams much of London. What

makes this place more dull is, my brothers are none of

them here; two of them went away about a fortnight

ago, and ever since my Pappa has ordered me to put a

double quantity of saffron[16] in his tea.”

[12]

1734

February 11, 1734, she writes—

“Dr. Middleton sends us word my Pappa’s acquaintance

wonder he has not the spleen, but they would

cease their surprise if they knew he was so much

troubled with it that his physicians cannot prescribe

him any cordial strong enough to keep up his spirits.

We think London would do it effectually, and I believe

he will have recourse to it.”

THE DUCHESS OF PORTLAND

On July 11, 1734, Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley

married William, 2nd Duke of Portland.[17] There

are no letters of Elizabeth’s in my possession on the

occasion of her friend’s marriage; they recommence

October 20 in the same year. Henceforward all the

duchess’s letters were franked by the duke, and many

of Elizabeth’s, often unfortunately undated. At this

period ladies prevailed on such of their friends as

were either Peers or members of Parliament, to sign

sheets of letter-paper with their names at the back, often

of folio size, which they used free of cost as they wanted

them, wrapping their letters in these outer sheets and

sealing them. As a single letter from London to

Edinburgh cost 1s. 1½d., if double 2s. 3d., and if treble

3s. 4½d., the smallest inclosure being treated as an

additional sheet, to send letters unfranked was a costly

luxury. The practice of forging people’s names led to

such intolerable abuse of franking that an Act was

passed in 1764 making it compulsory for the whole

address to be written by the person franking the

letter.

In October, the same year, Elizabeth replies to a

letter from the duchess chiding her for not writing—

“Oct. 3, 1734.—I am surprised that my answer to

[13]your Grace’s letter has never reached your hands. I

sent it immediately to Canterbury by the servant of a

gentleman who dined here, and I suppose he forgot to

put it in the post. I am reconciled to the carelessness

of the fellow, since it has procured to me so particular a

mark of your concern. If my letter were sensible, what

would be the mortification, that instead of having the

honour to kiss your Grace’s hands, it must lie confined

in the footman’s pocket with greasy gloves, rotten

apples, a pack of dirty cards, and the only companion of

its sort, a tender epistle from his sweetheart, ‘tru tell

deth.’ Perhaps by its situation subject to be kicked by

his master every morning, till at last, by ill-usage and

rude company, worn too thin for any other use, it may

make its exit in lighting a tobacco-pipe. I believe the

fellow who lost my letter knew very well how ready I

should be to supply it with another.

“I am, Madam,

“Your Grace’s most obedient servant,

“Elizabeth Robinson.”

“FIDGET”

The duchess’s favourite name for Elizabeth was

“Fidget,” a name adopted by all the Bullstrode[18] circle.

This was due to her vivacity of mind and body. She

was never really a strong person, but her nervous

energy enabled her frail body to perform feats that a

more lethargic person could not have accomplished.

“Why should a table that stands still require so many

legs when I can fidget on two?” she would exclaim.

The duchess returns an answer on October 25, portions

of which I copy—

“Dear Fidget,

“I assure you I am very angry at the fellow’s

not taking care of your letter, for they always give me

infinite pleasure, and I esteem it as a great loss. I am

[14]very sensible of the friendship you have for me, and

hope you never shall find any reason to the contrary.

You have painted extremely well the fate of your letter

was not according to its deserts.... Pray do you hear

anything of Dr. Middleton and his fine wife?[19] I had a

letter not long ago wherein it was said she made the

doctor very sensible she had a tongue, and a very sharp

one too, with the addition of a clear and distinct voice.

If you have any poetry, send it to me; you know it will

be acceptable to her who is

“Dear Fidget’s

“Very humble servant and admirer,

“M. Cavendish Portland.”

DRAWING LESSONS

In Elizabeth’s next letter, November 3, 1734, she

regrets that her father, having recovered his spirits,

had given up going to Bath as projected, and says—

“One common objection to the country, one sees no

faces but those of one’s own family, but my Pappa thinks

he has found a remedy for that by teaching me to draw;

but then he husbands these faces in so cruel a manner

that he brings me sometimes a nose, sometimes an eye

at a time: but on the King’s birthday, as it was a festival,

he brought me out a whole face with its mouth wide

open. Your Grace desired me to send you some verses;

I have not heard so much as a Rhyme lately, and I

believe the Muses have all got agues in this country,

but I have enclosed you the following Summons which

we sent an old bachelor, who is very much our humble

servant, and would die but not dance for us; but being

once in great necessity for partners, we thought him

better than an elbow chair, and compelled him to come

to this Summons, which pleased me extremely, as I

believe it was the first time he ever found the power of

the fair sex.... I am so far from Cambridge, and have

no friend charitable enough to send me any scandal,

[15]I have heard nothing of either of the doctors, but as to

my dear grandmother,[20] I have before heard she was as

famous as a free speaker as he is for a free-thinker.[21]

A SUMMONS

“‘Summons.

“‘Kent, to J. B., Esqre.[22]

“‘Whereas complaint has been made to us Commissioners

of Her Majesties’ Balls, Hopps, Assemblies, &c.,

for the county aforesaid, that several able and expert men,

brought up and instructed in the art or mistery of

Dancing, have and daily do refuse, though often thereunto

requested, to be retained and exercised in the

aforesaid Art or Mistery, to the occasion of great

scarcity of good dancers in these parts, and contrary

to the Laws of Gallantry and good manners, in that

case made and provided: And whereas we are likewise

credibly informed that you J. B., Esqre., though educated

in the said Art by that celebrated Master, Lally, Senior,

are one of the most notorious offenders in this point,

these are therefore in the name of the Fair Sex, to

require you, the said J. B., Esqre., personally to be and

appear before us, at our meeting this day at the sign of

the “Golden Ball,” in the parish of Horton, in the county

aforesaid, between the hours of twelve and one in the

forenoon to answer to such matter as shall be objected

against you, concerning the aforesaid refusal and contempt

of our jurisdiction and authority, and to bring

with you your dancing shoes, laced waistcoat and white

gloves. And hereby fail not under peril of our frowns,

and being henceforth deemed and accounted an Old

Bachelor. Given under our hands and seals this eighth

day of October, 1734, to which we all set our hands.’”

[16]

THE “GOLDEN BALL”

The “Golden Ball” was the ball of the weathercock

on the lantern cupola of the house at Mount Morris.

In the next letter, November 20, she says—

“Out of my filial piety I would persuade my Pappa

to set out for London. I have been preaching to him all

this day, that when Saul had the spleen, David’s musick

did him a great deal of good, and that I am satisfied

Farinelli[23] would do him as much service. He goes

frequently shooting or coursing, and fancies that will

prevent its return, and to answer me with the Scripture,

says, Nimrod the mighty hunter never had the Hyp.

Dr. Middleton designed to bring his Dearee to London,

but if she is so gay it may be as prudent to keep her at

Cambridge ... if it should enter her head that the doctor

is no greater than another, what a mortification it would

be to my good Grand-pappa; if he knows himself and

her, I think he would agree with Arnolfe in L’Ecole des

Femmes[24]—

“‘Que c’est assez pour elle, a vous en bien parler,

De savoir prier Dieu, l’aimer, coudre, et filer.’”

Emery Walker Ph. Sc.

Miss Sarah Morris

Mr. Robinson, who drew and painted in a style

worthy of a professional artist, was anxious Elizabeth

should become a proficient in the same art, but she

writes to the duchess—

“If you design to make any proficiency in that art,

I would advise you not to draw old men’s heads. It was

the rueful head countenance of Socrates or Seneca that

first put me out of conceit of it; had my Pappa given me

the blooming faces of Adonis or Narcissus, I might have

been a more apt scholar; and when I told him I found

those great beards difficult to draw, he gave me St.

[17]John’s head in a charger, so to avoid the speculation of

dismal faces, which by my art I dismalized ten times

more than they were before, I threw away my pencil.”

1735

TUNBRIDGE WELLS

In October, 1735, the duchess’s first child was born,

Elizabeth, eventually wife of the 1st Marquis of Bath.

Elizabeth writes to congratulate her, and states she

heard Dr. Mead (then the great ladies’ doctor) pronounced

it the finest child he ever saw. Elizabeth had

just returned from her first visit to Tunbridge Wells for

her health, suffering much from headaches and weak

eyes. At this period the Dowager Duchess of Portland

died. The letters up to this date were addressed to “To

Her Grace, The junior Duchess of Portland.”

LORD STANHOPE

Elizabeth writes a description of her five weeks at

Tunbridge Wells. After comments on an unhappy

marriage recently made, she says—

“You know some of our Grub Street wits compared

marriage to a country dance, which scheme I

extremely approved, but when I read it, I thought it

should have been set to the tune of ‘Love for ever;’

but they say it never did go to that tune, nor ever

would. I danced twice a week all the time I was at

Tunbridge, and once extraordinary, for Lord Euston[25]

came down to see Lord Augustus Fitzroy,[26] and made a

ball. Lord Euston danced with the Duchess of Norfolk,[27]

but her Grace went home early, and then Lord Euston

danced with Lady Delves. We all left off about one

o’clock. The day after I left the Wells, I went to the

Races (Canterbury), which began on Monday, and ended

on Thursday.... Monday there was an Assembly,

Tuesday a Play, Wednesday an Assembly again, and

Thursday another play, and as soon as that was over,

we had a ball where we had ten couple. I did not go to

[18]bed after our private ball till six o’clock, and rose again

before nine.

“The person who was taken most notice of at Tunbridge

as particular is a young gentleman your Grace

may be perhaps acquainted with, I mean Lord Stanhope.[28]

He is always making mathematical scratches in his

pocket-book, so that one half the people took him for a

conjurer, and the other half for a fool.”

In a letter of October 2 is the first mention of Mrs.

Pendarves,[29] afterwards Mrs. Delany. It runs—

“Your pleasures are always my satisfactions; I

assure you I partake at Mount Morris all the happiness

you tell me you receive at Bullstrode. I am sure Mrs.

Pendarves cannot give you any pleasure in her conversation

that she is not repayed in enjoying yours. I am

glad you have got so agreeable a companion with you;

it is a happiness you have not always enjoyed, though

deserved.”

LADY THANET

Mention is made of the duchess’s desire to obtain

beautiful shells, and Elizabeth desired her sailor brother

Robert, who had just returned from Italy, and was

going in his ship to the East Indies, to bring home what

he can in shells and feathers of all sorts—parrots,

peacocks, etc.—for work the duchess was doing. This

feather work became a rage of both the duchess and

Elizabeth, and was the precursor of the celebrated

feather hangings, immortalized by Cowper’s verses in

Elizabeth’s later years. A humorous description of

Lady Thanet,[30] then the great lady of West Kent, an

amusing character, and great-aunt of the Duchess of

Portland, is given in the same letter—

[19]

“Lord Thanet[31] said when he came to Kent this

summer that Lord Cowper[32] had brought his Countess[33]

to affront all East Kent, and he had brought his Countess

to affront all West Kent. She was a little discomposed

one day at dinner and threw a pheasant and a couple of

partridges off the table in shoving them up to my Lord

to cut up.”

1737

Early in 1737, the second daughter of the duchess’s

was born—Henrietta, afterwards Countess of Stamford

and Warrington. Elizabeth writes to congratulate her

on the event. She and her family were very ill of fever

that summer, thirteen persons down with it in the

house. The smallpox raged at Canterbury, and Mrs.

Robinson would not allow her daughters to attend the

races. In a letter of September mention is made of

Dr. Conyers Middleton’s disappointment at not obtaining

the Mastership of the Charter House, which he most

desired. Another peep at Lady Thanet—

“Lady Thanet came into this part of the country ten

days ago; her French woman rode astride through the

wilds of Kent, and the country people having heard her

Ladyship was something odd, took Mademoiselle for

Lady Thanet.”

The first letter extant between Elizabeth and Miss

Anstey, sister of Christopher Anstey, the author of the

“New Bath Guide,”[34] may be placed here, though undated,

except “Mount Morris, near Hythe, July 15.” This

extract shows her vivacious nature—

“Yesterday I was overturned coming from a neighbour’s.

We got no hurt at all, but were forced to borrow

[20]a coach to bring us the rest of the way, our own being

quite disabled by the fall.... I always think one visits

in the country at the hazard of one’s bones, but fear is

never so powerful with me, as to make me stay at home,

and the next thing to being retired, is to be morose:

contemplation is not made for a woman on the right

side of thirty, it suits prodigiously well with the gout or

the rheumatism: rest and an elbow chair are the comfort

of age, but the pleasures of youth are of a more lively

sort. I have in winter gone eight miles to dance to the

music of a blind fiddler, and returned at two in the

morning, mightily pleased that I had been so well entertained.

I am so fond of dancing that I cannot help

fancying I was at some time bit by a tarantula,[35] and

never got well cured of it. I shall this year lose my

annual dancings at Canterbury Races, for my Papa has

made a resolution (I assure you without my advice) not

to go to them.”

MERSHAM HATCH —

THE PLAY

In the next letter to the duchess, October 15, 1737—

“Lady Thanet made a ball at Hothfield a few days

ago to which she did our family the honour to invite

them, and as we were obeying her commands and got

into the coach with our ball airs and our dancing shoes,

at five miles of our journey we met with a brook so

swelled by the rain it looked like a river, and the water,

we were told, was up to the coach seat, and as I had

never heard of any balls in the Elysian Fields, and don’t

so much as know whether the ghosts of departed beaux

wear pumps, I thought it better to reserve ourselves for

the Riddotto[36] than hazard drowning for this ball, and

so we turned back and went to Sir Wyndham Knatchbull’s,[37]

who were hindered by the same water; for my

part I could think of nothing but the ball, when any one

[21]asked me how I did I cry’d tit for tat, and when they

bid me sit down, I answered ‘Jack of the green.’ A few

days after the ball, Lady Thanet bespoke a play at a

town eight miles from us, and summoned us to it; two

of my brothers, and my sister,[38] and your humble servant

went, and after the play the gentlemen invited all the

women to a supper at a tavern, where we staid till two

o’clock in the morning, and then all set out for their

respective homes. Here I suppose you will think my

diversion ended, but I must tell your Grace it did not;

for before I had gone two miles, I had the pleasure of

being overturned, at which I squalled for joy; and to

complete my felicity I was obliged to stand half an hour

in the most refreshing rain, and the coolest north breeze

I ever felt; for the coach’s braces breaking were the

occasion of our overturn, and there was no moving till

they were mended. You may suppose we did not lose

so favourable an opportunity of catching cold; we all

came croaking down to breakfast the next morning, and

said we had caught no cold, as one always says when

one has been scheming, but I think I have scarce recovered

my treble notes yet. We had seven coaches at

the play; there was Lord Winchilsea,[39] Lady Charlotte

Finch,[40] Lady Betty Fielding,[40] Capt. Fielding,[41] his lady,

and the Miss Palmers.[42] Mr. Fielding and Miss Molly

Palmer caught such colds they sent for a physician the

next day; Lady Knatchbull and Miss Knatchbull have

kept their beds ever since: poor Lady Thanet was overturned

as she went home, and caught a terrible hoarseness,

which was the better for the poor coachman, who

by that means escaped a sharp and shrill reproof; and

indeed it is enough for any poor man to lye under the

terror of her frowns, with a look she can wound, with a

[22]frown she can kill; I think I never saw so formidable a

countenance. I think Lord Thanet’s education of his

son[43] is something particular; he encourages him in

swearing and singing nasty ballads with the servants:

he is a very fine boy, but prodigiously rude; he came

down to breakfast the other day when there was company,

and his maid came with him, who, instead of

carrying a Dutch toy, or a little whirligig for his Lordship

to play with, was lugging a billet for his plaything.

There was a fine supper at the ball, 33 dishes all very

neat. My elder brother got out of the coach and put on

a pair of boots, and rode on to the ball when we turned

back.”

LADY WALLINGFORD

November 21, the duchess writes to condole with

Elizabeth on the loss of the ball, and mentions having

been staying with the Duke at Lady Peterborough’s[44]—

“Bevis Mount[45] is the most delightful place I ever

saw, the house bad and tumbling down, but there is a

summer-house in the garden, such a one! From thence

there is a prospect of the sea, the Isle of Wight, New

Forest, the town of Southampton, the garden laid out

with an elegant taste, and in short everything that is

agreeable, but particularly the Mistress.... Lord and

Lady Wallingford are with us now; they are extremely

agreeable. I fancy you must have seen her in public

places. She is extremely pretty, and in the French dress.”

Lady Wallingford was the daughter of John Law,

the famous financier, by his wife Katherine Knollys,

third daughter of Charles Knollys, titular 3rd Earl of

Banbury. Mary Katherine Law married in 1732 her first

cousin, called Viscount Wallingford.

[23]

THE SUIT OF CLOATHES

At this period, though undated, may be placed Elizabeth’s

request to her father for a handsome suit of

clothes. In a letter to her mother she thanks her “for

your goodness in giving me leave to stay, and making it

convenient to answer the Duchess’s and my wishes to

stay during her confinement. When we came to town

the Duchess reckoned the end of April.” From Bullstrode,

therefore, she accompanied the duchess and her

family to Whitehall, where in a portion of the old palace

was the Portlands’ town residence. Elizabeth was now

in her eighteenth year. In a letter to her father, too

lengthy to insert entirely, worded in the respectful

way children addressed their parents then, with “Sir”

and “Madam,” and concluding with “your most dutiful

daughter,” she says—

“You know this year I am to be introduced by the

Duchess to the best company in the town, and when she

lies in, am both to receive in form with her all her visits

as Lady Bell[46] used to do on that occasion, all the people

of quality of both sexes that are in London, and I must

be in full dress, and shall go about with her all the

winter, therefore a suit of cloathes will be necessary for

me, the value of which I submit entirely to you. I shall

never so much want a handsome suit as upon this occasion

of first appearing with my Lady Duchess; but as

the first consideration is to please you, I would by no

means urge this beyond your pleasure, by duty or inclination,

I shall always be content with what you order,

and hope you will not be displeased with my requests.”

To this appeal her father sent her £20, and she

returns thanks thus:—

“Whitehall, Thursday.

“Sir,

“Wit is seldom accompanied with money, but

your letter came to me with so much of both, that I

can neither send you thanks, nor an answer worthy of

[24]your present epistle. You are very good to gratify my

bosom friend, vanity, which, though it does not abandon

me in a plain gown, takes greater delight in seeing me

in a handsome one, and it has promised me that I shall

appear to advantage in my new suit of cloathes, both

to myself and other people.... The Duchess, with her

advice, will help me to make the best use of your

generosity. I have been to the Mercer’s, but have not

yet pitched upon a silk.... Mr. Pope has wrote an

epitaph upon himself, which is not by far the best

monument of his wit; it is a trifling thing, and seems

wrote for amusement. I would send it you if I could,

but I have not got a copy of it; as soon as I have I will

convey it to Mount Morris, where I imagine you may

want amusements, and our roads are not smooth enough

for Pegasus.”

ROBERT ROBINSON

This epitaph is probably the one commencing “Under

this marble, or under this sill, or under this turf, or e’en

what they will.” At the end of the letter she says of

her sailor brother—

“Now Robert is secure of his commission, his life

is something hazardous, but he holds danger in contempt,

the golden fruit of gain is always guarded

by some dragon which courage or vigilance must

conquer.”

He had just been made captain of the Bedford, a

ship in the merchant service. Evidently Mrs. Robinson

wrote a letter of advice as to the important choice of

“cloathes.” The answer runs—

“Madam,

“I have obeyed your commands as to my cloathes,

and have bought a very handsome Du Cape within the

twenty pounds; a little accident which had happened

to the silk in the Lomb made it a great deal cheaper, and,

I believe, will not be at all the worse when made up; the

colour in some places is a little damaged, but that will

[25]cut for the tail, and the rest is perfectly good. It will

last longer clean than a flowered silk, and I have already

had two since I have been in Mantuas:[47] I saw some of

25s. a yard that I did not think so pretty. Pray, Madam,

let my thanks be repeated to my Pappa, to whose goodness

I owe this suit of cloathes.... Pray send me by

Tom the figured Dimity that was left of my upper coat,

for it is too narrow and too short for my present hoop,

which is of the first magnitude.”

ANNE DONNELLAN

At the end of this letter Anne Donnellan is mentioned

for the first time. She was a friend of Dean Swift’s,

together with her sister, Mrs. Clayton, and her brother,

the Rev. Christopher Donnellan. Anne Donnellan’s pet

name in the Duchess of Portland’s circle was “Don,” as

Mrs. Pendarves (afterwards Mrs. Delany) was “Pen,”

Miss Dashwood “Dash,”[48] and Lady Wallingford “Wall.”

[26]

CHAPTER II.

LIFE IN BATH, LONDON, AND AT BULLSTRODE, 1738–1740

BEGINNING OF CORRESPONDENCE WITH MRS. DONNELLAN.

1738

On April 16, 1738, the Duchess of Portland’s son,

William Henry, afterwards 3rd Duke, was born, after

which Elizabeth returned home with her father. On

June 30 the duchess wrote to apologize for a long

silence—

“I should have answered dear Fidget’s letter before

I left London, but you are sensible what a hurry one

lives in there, and particularly after being confined some

months from public diversions, how much one is engaged

in them, Operas, Park, Assemblies, Vaux Hall—which

I believe you never had the occasion of seeing. You

must get your Papa to stay next year: it is really insufferable

going out of town at the most pleasant time

of the year. I am positive the easterly winds have

much greater effect upon the spirits in the country,

than it is possible they should have in London. I

dare say the chief part of the year your Papa is in town

he don’t know which way the wind is, except when he

goes into a Coffee House and meets with some poor

disbanded Officer who is quarrelling with the times

and consequently with the weather, because he is not a

General in time of peace; or a valetudinarian, that if a

fly settled on his nose, would curse the Easterly wind,

and fancy it had sent it there; these are the only people

that ever thought of East wind in London.”

[27]

At the end of the letter the duchess says, “My

amusements are all of the Rural kind—Working, Spinning,

Knotting, Drawing, Reading, Writing, Walking,

and picking Herbs to put into an Herbal.”

SIR ROBERT AUSTIN

This little peep of her life is most characteristic,

though fond of the pleasures of high society diversions,

and the varieties of London, she took an interest in all

sorts of country and domestic pursuits, and excelled in

them. She turned in wood and ivory; she was familiar

with every kind of needlework; she made shell frames,

adorned grottoes, designed feather work, collected

endless objects in the animal and vegetable kingdom;

was a hearty lover of animals and birds of all kinds.

Her letters are lively and affectionate, but not clever

and witty as her friend Elizabeth Robinson’s. She

complains of her stupidity in letter-writing. Elizabeth

had the witty head, and the duchess the cunning hand,

but both possessed that valuable possession, warm

hearts. To the duchess’s last letter Elizabeth replies—

“I arrived at Mount Morris rather more fond of

society than solitude. I thought it no very agreeable

change of scene from Handel[49] and Cafferelli.[50]... Sir

Francis Dashwood’s sister is going to be married to Sir

Robert Austin, a baronet of our county; if the size of

his estate bore any proportion to the bulk of his carcase,

he would be one of the greatest matches in England ...

a lady may make her lover languish till he is the size

she most likes ... as it is the fashion for men to die for

love, the only thing a woman can do is to bring a man

into a consumption; what triumph then must attend the

lady who reduces Sir Robert Austin ... to asses’ milk.

Omphale made Hercules spin, but greater glory awaits

the lady who makes Sir Robert Austin lean.... I told

[28]my Pappa how much he laid under your Grace’s displeasure

for hurrying out of town: but what is a fine

lady’s anger, or the loss of London, to five and forty?

They are more afraid of an easterly wind than a frown

when at that age.”

VARIOUS RECIPES —

THE GOAT

On December 17 Elizabeth writes to the duchess

in answer to a string of queries the latter had sent

her—

“I must take the liberty to advise what is to be done,

and to avoid confusion will take them in the order of

the letter. Item, for the wet-nurse[51] after the chickenpox,

that she may become new milch again, a handful of

Camomile flowers, a handful of Pennyroyal, boiled in

white wine, and sweetened with treacle, to be taken at

going to rest. For my Lord Titchfield who grows

prodigiously, Daisy roots and milk. For the small

foot and taper ancle of my Lady Duchess, bruised and

strained by a fall, a large shoe and oil Opodeldock.

For the horse whose Christian name I have forgotten,

Friar’s Balsam, and for the death of a dormouse take

four of the fairest Moral and Theological Virtues, with

patience and fortitude, quantum sufficit, and they will

prevent immoderate grieving.... I heard a very ridiculous

story a few days ago: Mr. Page, brother to Sir

Gregory, going to visit Mr. Edward Walpole,[52] a tame

goat which was in the street followed him unperceived

when he got out of the coach into the house. Mr.

Walpole’s servant, thinking the goat came out of Mr.

Page’s coach, carried it into the room to Mr. Walpole,

who thought it a little odd Mr. Page should bring such a

visitor, as Mr. Page no less admired at his choice of so

savoury a companion; but civility, a great disguiser of

sentiments, prevented their declaring their opinions, and

the goat, no respecter of persons or furniture, began to

rub himself against the frame of a chair which was

[29]carved and gilt, and the chair, which was fit for a

Christian, but unable to bear the shock of a beast, fell

almost to pieces. Mr. Walpole thought Mr. Page very

indulgent to his dear crony the goat, and wondering he

took no notice of the damage, said he fancied tame goats

did a great deal of harm, to which the other said he

believed so too: after much free and easy behaviour of

the goat, to the great detriment of the furniture, they

came to an explanation, and Mr. Goat was turned downstairs

with very little ceremony or good manners....

Dr. Middleton has got two nieces whom he is to keep

entirely, for his brother left them quite destitute. They

are very fine children, and my Grannam is very fond of

them. The doctor is soon to bring forth his ‘Cicero,’

everybody says the production will do him credit. Lady

Thanet has set an assembly on foot about eight miles from

hence, where we all meet at the full moon and dance till

12 o’clock, and then take an agreeable journey home.

Our assembly in full glory has ten coaches at it; and

Lady Thanet, to make up a number, is pleased in her

humility to call in all the parsons, apprentices, tradesmen,

apothecaries, and farmers, milliners, mantua-makers,

haberdashers of small wares, and chambermaids. It is

the oddest mixture you can imagine—here sails a reverent

parson, there skips an airy apprentice, here jumps a

farmer, and then every one has an eye to their trade;

the milliner pulls you by the hand till she tears your

glove; the mantua-maker treads upon your petticoat

till she unrips the seams; the shoemaker makes you

foot it till you wear out your shoes; the mercer dirties

your gown; the apothecary opens the window behind

you to make you sick. Most of our neighbours will be

in town by the next moon, so we shall have no more

balls this winter. In town the ladies talk of their stars,

but here, ‘If weak women go astray, the moon is more

in fault than they.’ Will o’ Whisp never led the

bewildered traveller over hedge or ditch as a moon

does us country folk; a squeaking fiddle is an occasion,

and a moonlight night an opportunity, to go ten miles in[30]

bad roads at any time. I must tell your Grace that my

Papa forgets twenty years and nine children, and dances

as nimbly as any of the Quorum, but is now and then

mortified by hearing the ladies cry, ‘Old Mr. Robinson

hay sides, and turn your daughter:’ other ladies who

have a mind to appear young say, ‘Well, there is my

poor Grandpapa; he could no more dance so.’ Then

comes an old bachelor of fifty and shakes him by the

hand, and cries, ‘Why you dance like us young fellows:’

another more injudicious than the rest, says by way of

compliment, ‘Who would think you had six fine children

taller than yourself? I protest if I did not know you

I should take you to be young.’ Then says the most

antiquated Virgin in the company, ‘Mr. Robinson wears

mighty well; my mother says he looks as well as ever

she remembers him; he used often to come to the house

when I was a girl.’ You may suppose he has not the

‘hyp’ at these balls; but indeed it is a distemper so well

bred as never to come but when people are at home and

at leisure.”

1739

WILLIAM AND GRACE FREIND

In April, 1739, Elizabeth’s cousin, Grace Robinson,

sister of “Long” Sir Thomas Robinson,[53] married the

Rev. William Freind,[54] son of the Rev. Dr. Robert

Freind, Head Master of Westminster School. Soon

after the marriage, Elizabeth, who appears to have known

Mr. Freind intimately before he married her cousin,

writes from “Leicester Street, near Leicester Fields,”

to Mr. and Mrs. Freind, “How rare meet now, such

pairs in love and honour joyn’d,” and addresses them as

“my inestimable cousins.” She states that her family

return to Kent shortly, whilst she is going to the

Duchess of Portland in White Hall. Elizabeth writes

[31]to the duchess on July 1, 1739, having just returned

home from her visit—

“I have thought of nothing but the company I was

in on Tuesday since I left town, though a worshipful

Justice with a new leathern belt, scarlet waistcoat and

plush breeches, has been endeavouring this whole afternoon

to put you out of my head. I have been forced to

hear the most elegant encomiums upon the country, and

the most barbarous censures upon the town. First his

Worship talked of Larks and Nightingales, then enlarged

upon the sweetness of bean blossom, roses and honeysuckles,

said the town stunk of cabbages and limekilns,

so that I found as to pleasures he was lead by the nose.”

COUNTRY BEAUX

Further on she says, the Canterbury Races were to

be on July 18, and begs her Grace, if she knows any

dancing shoes which lye idle, to bid them trip to

Canterbury, as there will be many forsaken damsels—

“Our collection of men is very antique, they stand in

my list thus: a man of sense, a little rusty, a beau a

good deal the worse for wearing, a coxcomb extremely

shattered, a pretty gentleman, very insipid, a baronet

very solemn, a squire very fat, a fop much affected, a

barrister learned in ‘Coke upon Lyttelton’ but knows

nothing of ‘long ways for many as will,’ an heir-apparent,

very awkward; which of these will cast a favourable eye

upon me I don’t know.”

THOMAS ROBINSON —

A BONE-SETTER

She was destined not to go after all, for she writes—

“Mount Morris, July 18, 1739.

“Madam,

“The great art of life is to turn our misfortunes

to our advantage, and to make even disappointments

instrumental to our pleasures. To follow which rule I

have taken the day which I should have gone to the

Races to write to your Grace. About ten days ago my

[32]Papa took an hypochondriacal resolution not to go to

the Races, for the Vapours and Love are two things

that seek solitude, but for me, who have neither in my

constitution, a crowd is not disagreeable, and I always

find myself prompted by a natural benevolence and

love of Society to go where two or three are gathered

together.... The theory of dancing is extreamly odd,

tho’ the practice is agreeable; who could by force of

reasoning find out the satisfaction of casting off right

hand and left, and the Hayes; we often laugh at a kitten

turning round in pursuit of its tail, when the creature is

really turning single. I shall have an account of the

Races from my brother Robinson, who is there; as for

the Barrister,[55] he came down to the Sessions, and when

he had sold all his Law, packed up his saleable eloquence

and carried it back to Lincoln’s Inn, there to be left till

called for. Would you think a person so near akin to me

as a brother could run away from a ball? I hear some

Canterbury girls who could aspire no higher than a

younger brother, are very angry, and say they shall never

put their cause into his hands, as he seems so little

willing to defend it.... Next year we must certainly

go to the Races for the good of the county, and dance out

of the spirit of Patriotism. The Election year always

brings company to Canterbury upon this occasion, and

as for me I will dance to either a Whig or a Tory tune,

as it may be, for in any wise I will dance. I am not like

the dancing Monkies who will only cut their capers for

King George, I will dance for any man or Monarch in

Christendom, nay were it even a Mahometan or idolatrous

King; I should not make much scruple about it. I had

the misfortune to be overturned the other day coming

from Sir Wyndham Knatchbull’s,[56] the occasion of it

was one of our wheels coming off. I assure you I but

just avoided the indecency of being topsy turvey, my

head was so much lower than its usual situation, as put

my ideas much out of place, and I think my head has[33]

been in a perfect litter ever since.... I shall begin to

think from my frequent overturns a bone-setter a

necessary part of equipage for country visiting. I am

sure those who visit much, love their neighbours better

than themselves; perhaps you will be as apt to suspect

me as anybody of that extream of charity, but I am so

tender of myself there are few I would hazard even a

gristle or a sinew, but civility is a debt that must be

paid. I hope in all accidents I shall preserve a finger

and thumb, to write myself

“Your Grace’s most obedient and obliged

“Humble servant,

“E. Robinson.

“My humble service to the Duke.”

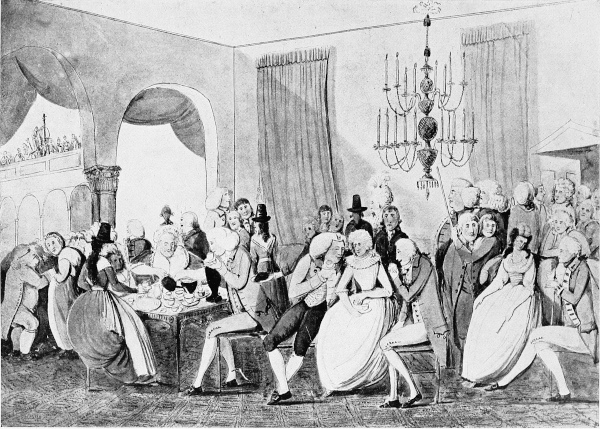

Hamilton, Pinx. Emery Walker Ph. Sc.

Mr. & Mrs. Matthew Robinson

DUKE OF PORTLAND

The duchess was now expecting her confinement,

and Lady Wallingford, who was staying with her,

corresponded with Elizabeth in French. Owing to

the residence of her father in France as Superintendent

of Finances, she was more French than English.

Her letters are well written and expressed, though the

spelling is peculiar. At a later date she writes to

Elizabeth in broken English, and she scolds her for

making her correspond in English instead of French.

Horace Walpole, in a letter to the Earl of Buchan,

states that Lady Wallingford was the image of her

father, and that her mother, Lady Katherine Law, lived

during her husband’s power in France in great state.

On July 26, 1739, another daughter, Lady Margaret, was

born to the duchess. Dr. Sandys was, as usual, the