The Project Gutenberg eBook of Parodies of the works of English & American authors, vol VI, by Walter Hamilton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Parodies of the works of English & American authors, vol VI

Compiler: Walter Hamilton

Release Date: April 14, 2023 [eBook #70548]

Language: English

Produced by: Carol Brown, Chris Curnow, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PARODIES OF THE WORKS OF ENGLISH & AMERICAN AUTHORS, VOL VI ***

PARODIES

OF THE WORKS OF

ENGLISH AND AMERICAN AUTHORS,

COLLECTED AND ANNOTATED BY

WALTER HAMILTON,

Fellow of the Royal Geographical and Royal Historical Societies;

Author of “A History of National Anthems and Patriotic Songs,” “A Memoir of George Cruikshank”

“The Poets Laureate of England,” “The Æsthetic Movement in England,” etc.

VOLUME VI.

CONTAINING PARODIES OF

A. C. Swinburne. G. R. Sims. Robert Browning.

F. Locker-Lampson. Austin Dobson. Dante G. Rossetti.

OSCAR WILDE. J. DRYDEN. A. POPE. MARTIN F. TUPPER.

Ballades, Rondeaus, Villanelles, Triolets.

NURSERY RHYMES AND CHILDREN’S SONGS.

PARODIES AND POEMS IN PRAISE OF TOBACCO.

PROSE PARODIES.

SLANG, FLASH, AND CANT SONGS.

RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL PARODIES.

Bibliography of Parody, and Dramatic Burlesques

Some things are very good, pick out the best,

Good wits compiled them, and I wrote the rest;

If thou dost buy it, it will quit the cost,

Read it, and all thy labour is not lost.

John Taylor, the Water Poet.

REEVES & TURNER, 196, STRAND, LONDON, W.C.

1889.

PREFACE.

t is now a little more than six years since this publication was commenced, and

the completion of the Sixth Volume enables me to say that nearly every Parody

of literary merit, or importance, has been mentioned in its pages, whilst some

thousands of the best have been given in full.

t is now a little more than six years since this publication was commenced, and

the completion of the Sixth Volume enables me to say that nearly every Parody

of literary merit, or importance, has been mentioned in its pages, whilst some

thousands of the best have been given in full.

To form such a collection required not only an intimate knowledge of English

Poetical Literature, but involved the reference to many very rare and scarce books,

English, American, and Colonial.

I beg to offer my sincere thanks to the Authors who kindly permitted their

copyright poems to be inserted in this volume, particularly to F. Locker-Lampson, Esq.,

and G. R. Sims, Esq., as well as to the following gentlemen, for copies of Parodies and

other information they have afforded—Messrs. Cuthbert Bede, G. H. Brierley, of Cardiff;

F. W. Crawford, T. F. Dillon Croker, Frank Howell, J. H. Ingram, Walter Parke, F. B.

Perkins, of San Francisco; C. H. Stephenson, C. H. Waring, and Gleeson White.

In nearly every case the permission of the authors has been obtained for the

re-publication of their Parodies; in the few instances where this was not done, it was

owing to the impossibility of finding the author’s address.

During the progress of the work, some further Parodies appeared of Authors already

dealt with, it is proposed to include these in a supplementary volume, which will be

published at some future date.

It is believed that the ample Bibliographical information relating to Parodies and

Burlesques contained in this volume will be specially useful to Librarians, Managers of

Penny Readings, and Professors of Elocution.

Editors of Provincial Papers who offer prizes for Literary compositions should be on

their guard against unscrupulous persons who copy Parodies from this Collection, and

send them in as original compositions.

In much of the compilation, and especially those portions requiring the exercise of

taste, and in the somewhat dreary process of proof reading, I have been greatly assisted by

my wife, whose cheerful co-operation in all my labours adds just the zest which

renders Life worth living.

Whilst bidding my subscribers Farewell, I wish to add that the subject of Parodies

will continue to engage my attention, and that I shall always be grateful for any

information, or examples, that may be sent to me, addressed to the care of Messrs.

Reeves and Turner.

WALTER HAMILTON.

Christmas, 1889.

1

Algernon Charles Swinburne.

r. Swinburne, son of Admiral

Charles Henry Swinburne, and

grandson of Sir John Edward

Swinburne, sixth baronet, was born

in 1838, and educated first at Eton, and

afterwards at Oxford.

r. Swinburne, son of Admiral

Charles Henry Swinburne, and

grandson of Sir John Edward

Swinburne, sixth baronet, was born

in 1838, and educated first at Eton, and

afterwards at Oxford.

Despite his ancient pedigree, his aristocratic

connections, and his university education, the

early writings of Mr. A. C. Swinburne, both in

prose and verse, were coloured by Radical

opinions of the most advanced description.

Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Southey commenced

thus, with results which should have

taught him how unwise it is for a poet, who

wishes to be widely read, to descend into the

heated atmosphere of political strife.

The Undergraduate Papers, published by Mr.

Mansell, Oxford, 1857-8, contained some of

Mr. Swinburne’s earliest poems, these were

followed by “Atalanta in Calydon,” “Chastelard,”

and “Poems and Ballads.”

It will be readily understood that only a few

brief extracts can be given from Mr. Swinburne’s

poems, sufficient merely to strike the

key notes of the Parodies.

THE CREATION OF MAN.

Before the beginning of years

There came to the making of man

Time, with a gift of tears;

Grief, with a glass that ran;

Pleasure, with pain for leaven!

Summer, with flowers that fell;

Remembrance fallen from heaven,

And madness risen from hell;

Strength without hands to smite:

Love that endures for a breath;

Night, the shadow of light,

And life the shadow of death.

And the high gods took in hand

Fire, and the falling of tears,

And a measure of sliding sand

From under the feet of the years:

And froth and drift of the sea;

And dust of the labouring earth;

And bodies of things to be

In the houses of death and of birth;

And wrought with weeping and laughter,

And fashioned with loathing and love.

With life before and after,

And death beneath and above,

For a day and a night and a morrow,

That his strength might endure for a span

With travail and heavy sorrow,

The holy spirit of man.

For the winds of the north and the south

They gathered as into strife;

They breathed upon his mouth,

They filled his body with life;

Eyesight and speech they wrought

For the veils of the soul therein,

A time for labour and thought,

A time to serve and to sin;

They gave him light in his ways,

And love, and a space for delight,

And beauty and length of days,

And night, and sleep in the night.

His speech is a burning fire;

With his lips he travaileth;

In his heart is a blind desire,

In his eyes foreknowledge of death;

He weaves, and is clothed with derision;

Sows, and he shall not reap;

His life is a watch or a vision

Between a sleep and a sleep.

* * * * *

A. C. Swinburne.

American Parody.

Before the beginning of years,

There went to the making of man

Nine tailors with their shears,

A coupe and a tiger and span,

Umbrellas and neckties and canes,

An ulster, a coat, and all that—

But the crowning glory remains,

His last best gift was his hat.

And the mad hatters took in hand

Skins of the beaver, and felt,

And straw from the isthmus land,

And silk and black bear’s pelt:

And wrought with prophetic passion,

Designed on the newest plan,

They made in the height of fashion

The hat for the wearing of man.

A Poet’s Valentine.

Before the beginning of post

There came to the making of love

Rhyme and of follies a host;

Ducks with a dart and a dove;

2

Flow’rs with initials beneath,

Cupid conceal’d in a cell,

Lovers alone on a heath.

A Parson pulling a bell.

Follies all fetched afar,

Mirth for a maid and a man,

Jokes that jingle and jar,

And lines refusing to scan.

And still with the change of things

The annual craze comes back

With knocks and riotous rings

From the post piled up with a pack.

Still letters of love and laughter,

And verse in various time,

With roars that reach to the rafter,

And sheets of scurrilous rhyme.

Of old we counted our money

And played but a note for a kiss,

But now we send hampers of honey

And boxes of boisterous bliss.

Fun. February 15, 1868.

Shilling Dreadfuls.

“A nervous and well red-wigged gentleman, Mr. Allburnon-Charles

Swingbun, ran excitedly to our rescue, and rhapsodically

chaunted the following chorus from his ‘Atlas

in Paddington’:

“Now in the railway years

There come to the making of books

Crime with its gift of fears,

Dream with mesmeric looks,

Nihilist Czar-abhorrence,

Acres of ‘snowy sward,’

Ouida, bottled in Florence,

And Broughton in Oxenforde;

Length, to deserve twelve pence;

Plot, to atone for pith;

Not a shadow of sense,

And boys the shadows of Smith.

And the tourist takes in hand

Paper with creasy back,

And a type he can understand,

As he sways with his rolling rack,

And froth and drift of the French,

And mirth that is meet to sell,

And bodies of things that drench

The diversions of Max O’Rell.

They are wrought with weeping for laughter,

And in fashion for chap and cove,

With Life before and after,

And Truth beneath and above.

For a day, for a night, for a nuisance

That the novice may fling his flukes,

And the publisher reap his usance—

The ‘Shillingsworth’ plague of books.”

Christmas Number of The World. 1885.

A chorus in “Atalanta in Calydon” commences:—

“For winter’s rains and ruins are over,

And all the season of snows and sins;

The days dividing lover and lover,

The light that loses, the night that wins.”

This passage was thus parodied by Mr. Austin Dobson:—

“For Mayfair’s balls and ballets are over,

And all the ‘Season’ of drums and dins;

The maids dividing lover and lover,

The wight that loses, the knight that wins;

And last month’s life is a leaf that’s rotten,

And flasks are filled and game bags gotten,

And from green underwood and cover

Pheasant on Pheasant his flight begins.”

——:o:——

The peculiar metre in which “Dolores” and the Dedication

of the “Poems and Ballads” Volume are written,

although it invites parody, is difficult to imitate successfully.

The ending line of each stanza abruptly cut short is a trick in

composition which few but Mr. Swinburne himself have

thoroughly mastered.

The following stanzas from the Dedication will enable

readers to perceive how closely they have been parodied by

Mr. Pollock.

The sea gives her shells to the shingle,

The earth gives her streams to the sea;

They are many, but my gift is single,

My verses, the first-fruits of me.

Let the wind take the green and the grey leaf,

Cast forth without fruit upon air;

Take rose-leaf and vine-leaf and bay-leaf

Blown loose from the hair.

* * * * *

Though the world of your hands be more gracious

And lovelier in lordship of things,

Clothed round by sweet art with the spacious

Warm heaven of her imminent wings;

Let them enter, unfledged and nigh fainting,

For the love of old loves and lost times,

And receive in your palace of painting

This revel of rhymes.

* * * * *

Though the many lights dwindle to one light,

There is help if the heaven has one;

Though the skies be discrowned of the sunlight,

And the earth dispossessed of the sun,

They have moonlight and sleep for repayment

When refreshed as a bride, and set free,

With stars and sea-winds in her raiment,

Night sinks on the sea.

“Dedication to J. S.”

This parody, dedicated to the notorious “John Stiles,” of

the old law-books, was written by Mr. Pollock, and originally

appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette. It has since been

included in a small volume (published by Macmillan & Co.,

London, 1875) entitled “Leading Cases done into English,”

by an apprentice of Lincoln’s Inn.

When waters are rent with commotion

Of storms, or with sunlight made whole,

The river still pours to the ocean

The stream of its effluent soul;

You, too, from all lips of all living

Of worship disthroned and discrowned,

Shall know by these gifts of my giving

That faith is yet found.

3

By the sight of my song-flight of cases

That bears on wings woven of rhyme

Names set for a sign in high places

By sentence of men of old time;

From all counties they meet and they mingle,

Dead suitors whom Westminster saw;

There are many, but your name is single,

The flower of pure law.

When bounty of grantors was gracious

To enfeoff you in fee and in tail,

The bounds of your land were made spacious

With lordship from Sale unto Dale;

Trusts had you, and services loyal,

Lips sovereign for ending of strife,

And the names of the world’s names most royal

For light of your life.

Ah desire that was urgent to Romeward,

And feet that were swifter than fate’s,

And the noise of the speed of them homeward

For mutation and fall of estates!

Ah the days when your riding to Dover

Was prayed for and precious as gold,

The journeys, the deeds that are over,

The praise of them told.

But the days of your reign are departed,

And our fathers that fed on your looks

Have begotten a folk feeble-hearted,

That seek not your name in their books;

And against you is risen a new foeman,

To storm with strange engines your home,

We wax pale at the name of him Roman,

His coming from Rome.

* * * * *

Yet I pour you this drink of my verses,

Of learning made lovely with lays,

Song bitter and sweet that rehearses

The deeds of your eminent days;

Yea, in these evil days from their reading

Some profit a student shall draw,

Though some points are of obsolete pleading,

And some are not law.

Though the Courts that were manifold dwindle

To divers Divisions of one,

And no fire from your face may rekindle

The light of old learning undone;

We have suitors and briefs for our payment,

While so long as a Court shall hold pleas,

We talk moonshine, with wigs for our raiment,

Not sinking the fees.

This “J. S.” was a mythical person introduced for the

purposes of illustration, and constantly met with in old law

books and reports. His devotion to Rome is shown by his

desperate attempts to get there in three days: “If J. S.

shall go to Rome in three days,” was then a standing

example of an impossible condition, which modern science

has robbed of most of its point.

——:o:——

THE BALLAD OF BURDENS.

This poem will be found on page 144 of Mr. Swinburne’s

Poems and Ballads (first series). It is one of his best known

ballads, and in 1879 it was chosen by the editor of The World

as the model on which to found parodies describing the wet

and gloomy summer of that year.

The successful poems in the competition were printed in

The World, July 16, 1879. The first prize was won by a well

known London Architect, the second by a Dublin gentleman

who has since published several amusing Volumes of light

poems.

First Prize.

A burden of foul weathers. Dim daylight

And summer slain in some sad sloppy way,

And pitiless downpour that comes by night,

And watery gleam that has no heart by day,

And change from gray to black, from black to gray,

And weariness that doth at each repine;

Grief in all work, and pleasure in no play—

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of vain blossoms. This is sore

A burden of false hope in fruit-bearing:

Upon thy strawberry-bed, behold, threescore—

Threescore dead blooms for one that’s ripening;

And if that one to fulness thou dost bring,

Thy shuddering lips the scanty feast decline,

For ’tis a pallid and insipid thing—

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of set phrases. Thou shalt hear

The same drear murmurs breathed from every side:

‘Something is wrong with the Gulf Stream, I fear.’

‘Through cycle wet the decade now doth glide.’

‘The sun is “spot”-less, and ashamed would hide.’

Dull ign’rance with long words did aye combine!

And thou shalt half believe and half deride

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of lost leisure. Thou shalt grieve

By rain-vexed stream, drenched moor, or seashore dead;

And say at night, ‘Would I had had no leave!’

And say at dawn, ‘Would that my leave were sped!’

The water of affliction and the bread

For food and for attire shall then be thine,

Goloshed beneath, umbrellaed overhead,

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of cold hearthstones. Thou shalt see

Pale willow shreds and gold above the green;

And as the willow so thy face shall be,

And no more as the thing before-time seen.

And thou shalt say of sunshine, ‘It hath been,’

And, chilling, watch the chilly light decline;

And shivering-fits shall take thy breath between

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of sad sayings. In that day

Thou shalt tell all thy summers o’er, and tell

Thy joys and thy delights in each, and say

How one was calm and one was changeable,

And sweet were all to hear and sweet to smell;

But now of passing hours scarce one doth shine

Of twenty. In the rest deep gloom doth dwell.

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of mixed seasons. Snow in spring,

Thaw, and then frost, with each its miseries;

No summer, though the days be shortening;

No autumn-promise from the fields and trees;

With sad face turned towards Christmas, that foresees

4

Huge bills for fuel, (and yet for fires doth pine;)

Rheumatics, pleurisy, and lung-disease,

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of umbrellas. In thy sight

Dawn’s gray or vesper’s red may promise much,

Yet shalt thou never venture day nor night

Without that ‘little shadow’ in thy clutch.

Horn of rhinoceros and ebon crutch

Shall unmolested in their stand recline;

Thy trusty Penang shall forget thy touch,

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

The burden of sham gladness. In desire

(The substance lost) for shadows of delight,

Though underfoot the trodden lawn be mire,

Tea, tennis, and Terpsichore invite.

Go, then! and let thy face with smiles be dight,

To hollow joy’s ordeal thyself resign

Till dreary daylight yield to drearier night,

Anno Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

L’ENVOY.

Brave hearts, and ye whom hope yet quickeneth,

Hope on; next summer may perchance be fine.

The life grows short, and soon will come the death

Anni Salutis eighteen seventy-nine.

Ziegelstein. (Goymour Cuthbert.)

Second Prize.

The burden of strange seasons. Rain all night,

Blown-rain and wind co-mingling all the day;

Perchance we say the morrow will be bright;

But lo, the morrow is as yesterday:

With sullen skies and sunsets cold and gray,

With lights reverse, the heavy hours retire;

And so the strange sad season slips away—

I pray thee put fresh coals upon the fire.

The burden of rheumatics. This is sore

Damp, and east wind maketh it past bearing;

When thy life’s span has stretched to threescore,

No rest hast thou at dawn or evening.

The shivering in thy bones, the shivering

In all thy marrows through this season dire,

Makes summer seem a shameful wretched thing—

For God’s love put fresh coals upon the fire.

The burden of dead apples. Lo, their doom,

Decay and blight upon the tender trees,

All fruit made fruitless, blossom bloomless bloom

An eastern wind of many miseries.

Naught has survived save pale-green gooseberries,

The food in fools, of fools, who such desire.

God wot, no lack have we of fooleries—

I prithee put fresh coals upon the fire.

The burden of bad harvests. For the gods,

Who change the springing corn from green to red,

Have scourged us for our sins with many rods,

And left our grain and oil ungarnerèd.

The market-men heap ashes on their head,

And cry aloud and rend their best attire;

The gods are just, prayers are unanswerèd—

I pray thee put fresh coals upon the fire.

The burden of lost peaches. Ah, my sweet,

This year I seek them in the sunny South,

To press them to thy sharp white tooth to eat,

To kiss thy amorous hair and curled-up mouth.

Lust and desire are dust and deadly drouth,

For lust is dust and deadly drouth desire,

And time creeps over all with wingèd feet—

For love’s sake put fresh coals upon the fire.

The burden of dull colours. Thou shalt see

Strange harmonies in brown and olive-green,

In curious costumes fashioned cunningly,

And all unlike the things in summer seen;

And thou shalt say of summer, it hath been.

Or if unconsciously thou wouldst inquire

What these my mournful music-measures mean,

I bid thee heap fresh coals upon the fire.

L’ENVOY.

Tourists and ye whom Cook accomp’nies,

Heed well before from him ye tickets hire—

This season is a mist of miseries;

So once more heap fresh coals upon the fire.

Floreant-Lauri (J. M. Lowry).

This parody was afterwards included in A Book of Jousts,

edited by James M. Lowry. London, Field and Tuer.

Ballade of Cricket.

The burden of long fielding: when the clay

Clings to thy shoon, in sudden shower’s down-pour,

And running still thou stumblest; or the ray

Of fervent suns doth bite and burn thee sore,

And blind thee, till, forgetful of thy lore,

Thou dost most mournfully misjudge a skyer,

And lose a match the gods cannot restore—

This is the end of every man’s desire!

The burden of loose bowling: when the stay

Of all thy team is collared—swift or slower—

When bowlers break not in the wonted way

And “yorkers” come not off as heretofore;

When length-balls shoot no more, ah! never more,

And all deliveries lose their wonted fire,

When bats seem broader than the broad barn-door—

This is the end of every man’s desire!

The burden of free hitting; slog away,

Here shalt thou make a five, and there a four.

And then thy heart unto thy heart shall say

That thou art in for an exceeding score;

Yea, the loud Ring, applauding thee shall roar.

And thou to rival Hornby shalt aspire,

And lo! the Umpire gives thee “leg before.”

This is the end of every man’s desire!

ENVOY.

Alas, yet rather on youth’s hither shore

Would I be some poor player, on scant hire,

Ahan King among the old, who play no more.

This is the end of every man’s desire.

A. L.

St. James’s Gazette. June 27, 1881.

5

Ballade of Cricket.

(To T. W. Lang.)

The burden of hard hitting: slog away!

Here shalt thou make a “five” and there a “four,”

And then upon thy bat shalt lean and say,

That thou art in for an uncommon score.

Yea, the loud ring applauding thee shall roar,

And thou to rival Thornton shalt aspire,

When low, the Umpire gives thee “leg before,”—

“This is the end of every man’s desire!”

The burden of much bowling, when the stay

Of all thy team is “collared,” swift or slower,

When “bailers” break not in their wonted way,

And “yorkers” come not off as heretofore.

When length balls shoot no more, ah never more,

When all deliveries lose their former fire,

When bats seem broader than the broad barn-door—

“This is the end of every man’s desire!”

The burden of long fielding, when the clay

Clings to thy shoon in sudden showers downpour,

And running still thou stumblest, or the ray

Of blazing suns doth bite and burn thee sore,

And blind thee till, forgetful of thy lore,

Thou dost most mournfully misjudge a “skyer”

And lose a match the Fates cannot restore,—

“This is the end of every man’s desire!”

Envoy.

Alas, yet liefer on youth’s hither shore

Would I be some poor Player on scant hire

Than king among the old who play no more,—

“This is the end of every man’s desire!”

Andrew Lang.

This second Ballade of Cricket was included in a collection

of “Ballades and Rondeaus” edited by Mr. Gleeson

White, and published by Walter Scott, London, 1887.

A Ballad of Burdens.

The burden of Old Women. They delight

In bulky bundles, always in the way;

In ’busses close they wedge you tight at night,

In railway trains they jam you up by day.

Plump dames with pulpy cheeks and locks of grey,

In weariness they waddle, puff, perspire.

To banish them for ever one would say,

This must be every busy man’s desire.

* * * * *

The burden of Sad Colours. Thou shalt see

Gold tarnished, ghostly grey, and livid green,

And lank and languorous thy face must be

To harmonise with the lugubrious scene.

And thou shalt say of scarlet, “It have been,”

And sighing of old tints and tones shalt tire.

To bring back brightness and to banish spleen,

This must be every cheerful man’s desire.

The burden of Smart Sayings. In this day

All wish as cynic wits to bear the bell.

Men mock at honour, justice, love, and say

The end of life “good stories” is to tell.

The cad’s coarse jest, the cackle of the swell

Are much alike, things that the most admire.

To patter slang and tell side-splitters well,

This is the end of every fool’s desire.

The burden of Bad Seasons. Rain in Spring,

Chill rain and wind among the budding trees,

A Summer of grey storm-clouds gathering,

Damp Autumn one dull mist of miseries,

With showers that soak, and blasts that bite and freeze;

A drenching Winter with north-easters dire.

To make an end of seasons such as these,

This must be every suffering man’s desire.

The burden of Strange Crazes. Woman’s right

To throng the polls, and join the spouting bands;

Theosophy and astral bodies, sleight

Of cunning jugglers from far foreign lands;

Buddhistic bosh which no one understands,

A thousand fads that ’gainst good sense conspire.

To gag the crotcheteers and tie their hands,

This must be every sober man’s desire.

L’Envoy.

Donkeys, and ye whom frenzy quickeneth,

Heed well this rhyme. Life’s many burdens tire.

To lighten them a little, ere our death,

This must be every kindly man’s desire.

Punch. August 7, 1886.

——:o:——

Parodies of

DOLORES.

Pain and Travel.

Perpetual swaying of steamers,

Oh, terrible tumble of tides—

More dear than the drowsing of dreamers,

Who ramble by rustic road-sides!

Oh, lips that are pale with the anguish,

Let me see you again and again;

They are yours when so seasick they languish,

Our Lady of Pain!

I gloat on the grins and the groaning,

The torments that torture—not kill:

And music to me is the moaning

Of travellers terribly ill.

A rapture I cannot unravel,

Their throes set a-thrill in my brain:

These—these are my pleasures of travel,

Our Lady of Pain!

And on landing I lose not the longing,

That mingles my manhood with mud:

For the merry mosquitos come thronging,

With lips that laugh blithely in blood:

And fleas, with their kisses that burn me,

Bite till cruel red mouths show the stain—

Into poesy passionate turn me,

Our Lady of Pain!

And the donkeys Egyptian and spiteful

Shall share in the shame of my hymns,

For the jolting that brands the delightful

Dark bruises on delicate limbs.

6

And the Alps shall be ranked with the asses

For the fracture, the frostbite, the sprain,

And the mangling of flesh in crevasses,

Our Lady of Pain!

And if—leaving me, though, unshattered—

An accident fell should betide,

And the train that I ride in is scattered

In ruin on every side—

Dislocations and discolourations,

And gush of bright gore, not in vain

Shall awake in me languid sensations,

Our Lady of Pain!

Thus I roam through the universe vasty,

O’er mountain, vale, meadow, and wood;

And I venerate all that is nasty,

And gird against all that is good;

In the mire my delight is to linger,

Although I to the heights might attain:

Aut you don’t catch me scratching my finger,

Our Lady of Pain!

Fun. October 12, 1867.

My Lady Champagne.

Wayward, soft, luscious, and tender,

Lightsome, and spotless from stain,

Graceful of figure and slender,

Decked with a golden crown’s splendour—

Our Lady Champagne.

Brilliantly sparkling and creaming,

Haughty and lovely and vain,

Gay ’midst the froth lightly beaming,

Swift o’er the crystal edge streaming—

Our Lady Champagne.

Bubbling and seething and springing,

Solace and soother of pain,

Joys of an outer world bringing,

Sweets to the air gaily flinging—

Our Lady Champagne.

Proud in the depth of deep scorning,

Haughty and grand with disdain,

Rosy as soft clouds at dawning,

Fresh as the breeze of the morning—

Our Lady Champagne.

Kisses seductive in greeting,

Falling like soft summer rain,

Rapturous bliss of lips meeting,

Sighing a woe at retreating—

Our Lady Champagne.

Frothy, light, bubbly and beady,

Life to the overworked brain;

Beer for the humble and needy,

Wine for the wealthy and greedy—

Our Lady Champagne!

Judy. May 26, 1880.

The Southern Cross.

A Frustration.

Four stars on Night’s brow, or Night’s bosom,

Whichever the reader prefers;

Or Night without either may do some,

Each one to his taste or to hers.

Four stars—to continue inditing,

So long as I feel in the vein—

Hullo! what the deuce is that biting?

Mosquitos again!

Oh glories not gilded but golden,

Oh daughters of Night unexcelled,

By the sons of the North unbeholden,

By our sons (if we have them) beheld;

Oh jewels the midnight enriching,

Oh four which are double of twain!

Oh mystical—bother the itching!

Mosquitos again!

You alone I can anchor my eye on,

Of you and you only I’ll write,

And I now look awry on Orion,

That once was my chiefest delight.

Ye exalt me high over the petty

Conditions of pleasure and pain,

Oh Heaven! Here are these maladetti

Mosquitos again!

The poet should ever be placid.

Oh vex not his soul or his skin!

Shall I stink them with carbolic acid?

It is done and afresh I begin.

Lucid orbs!—that last sting very sore is;

I am fain to leave off, I am fain;

It has given me uncommon dolores—

The Latin for pain.

Not quite what the shape of a cross is—

A little lop-sided, I own—

Confound your infernal proboscis,

Inserted well nigh to the bone!

Queen-lights of the heights of high heaven,

Ensconced in the crystal inane—

Oh me, here are seventy times seven

Mosquitos again.

Oh horns of a mighty trapezium!

Quadrilatoral area, hail!

Oh bright is the light of magnesium!—

Oh hang them all, female and male!

At the end of an hour of their stinging,

What shall rest of me then, what remain?

I shall die as the swan dieth, singing,

Mosquitos again!

Shock keen as the stroke of the leven!

They sting, and I change as a flash

From the peace and the poppies of heaven

To the flame and the firewood of—dash!

Oh Cross of the South, I forgot you!

These demons have addled my brain.

Once more I look upward———Od rot you!

You’re at it again.

There! stick in your pitiless brad-awl,

And do your malevolent worst!

Dine on me and when you have had all,

Let others go in for a burst!

Oh silent and pure constellation,

Can you pardon my fretful refrain?

Forgive, oh forgive my vexation—

They’re at it again!

Oh imps that provoke to mad laughter,

Winged fiends that are fed from my brow,

7

Bite hard! let your neighbours come after,

And sting where you stung me just now!

Red brands on it smitten and bitten,

Round blotches I rub at in vain!

Oh Crux! whatsoever I’ve written,

I’ve written in pain.

Ye chrysolite crystalline creatures,

Wan watchers the fairest afield,

Stars, and garters, are these my own features

In the merciless mirror revealed?

They are mine, even mine and none other,

And my hands how they slacken and strain!

Oh my sister, my spouse, and my mother!

I’m going insane!

From Miscellaneous Poems, by J. Brunton Stephens.

Brandy and Soda.

Mine eyes to mine eyelids cling thickly;

My tongue feels a mouthful and more;

My senses are sluggish and sickly;

To live and to breathe is a bore.

My head weighs a ton and a quarter,

By pains and by pangs ever split,

Which manifold washings with water

Relieve not a bit.

My longings of thirst are unlawful,

And vain to console or control,

The aroma of coffee is awful,

Repulsive the sight of the roll.

I take my matutinal journal,

And strive my dull wits to engage,

But cannot endure the infernal

Sharp crack of its page.

What bad luck my soul had bedevilled,

What demon of spleen and of spite,

That I rashly went forth, and I revelled

In riotous living last night?

Had the fumes of the goblet no odour

That well might repulse or restrain?

O insidious brandy and soda,

Our Lady of Pain.

Thou art golden of gleam as the summer

That smiled o’er a tropical sod,

O daughter of Bacchus, the bummer,

A foamer, a volatile tod!

But thy froth is a serpent that hisses,

And thy gold as a balefire doth shine,

And the lovers who rise from thy kisses

Can’t walk a straight line.

I recall, with a flush and a flutter,

That orgie whose end is unknown;

Did they bear me to bed on a shutter,

Or did I reel home all alone?

Was I frequent in screams and in screeches?

Did I swear with a forcéd affright?

Did I perpetrate numerous speeches?

Did I get in a fight?

Of the secrets I treasure and prize most

Did I empty my bacchanal breast?

Did I button-hole men I despise most,

And frown upon those I like best?

Did I play the low farmer and flunkey

With people I always ignore?

Did I caricole round like a monkey?

Did I sit on the floor?

O longing no research may satiate—

No aim to exhume what is hid!

For falsehood were vain to expatiate

On deeds more depraved than I did;

And though friendly faith I would flout not

On this it were rash to rely,

Since the friends who beheld me, I doubt not,

Were drunker than I.

Thou hast lured me to passionate pastime,

Dread goddess, whose smile is a snare!

Yet I swear thou hast tempted me the last time—

I swear it; I mean what I swear!

And thy beaker shall always forebode a

Disgust ’twere not wise to disdain,

O luxurious brandy-and-soda;

Our Lady of Pain.

Hugh Howard. 1882.

Dolores.

[Miss Dolores Lleonart-y-Casanovas, M.D., has

just, at the age of 19, taken her doctor’s degree at Barcelona.

July, 1886.]

With dark eyes that flash like a jewel,

And red lips that flame like a flower

Capricious, coquettish and cruel,

When flirting in boudoir or bower;

So shine Spanish girls in old stories.

But thou’rt of a different strain,

Oh learned and lucky Dolores,

Our M.D. of Spain.

Thy studies commencing, sweet virgin,

At College when scarce more than seven,

Now past mistress scalpel and purge in

A full-blown Physician! Great Heaven!

Sangrados no more to our sorrow

Our veins shall deplete; the control

Of our hearts goes to girls, whence we borrow

Much hope—on the whole.

It startles us, though, the reflection

That you are not twenty to-day,

Yet our tongues may invite your inspection,

Our pulses your touch may assay.

Thou, a girlish she-Galen, arisest:

In faith thou may’st fairly feel vain,

O young among women yet wisest,

Our M.D. of Spain!

Will you “fee” in the fearless old fashion,

And dose like a horse-drenching Vet.?

Ah! it is not alone the Caucasian

Who’s nearly played out, I regret.

However, unless luck desert you,

Barcelona its fame may regain.

Let us hope Hahnemann mayn’t convert you,

Our M.D. of Spain.

(Five verses omitted.)

Punch. July 31, 1886.

8

Strange beauty, eight-limbed and eight-handed,

Whence camest to dazzle our eyes?

With thy bosom bespangled and branded

With the hues of the seas and the skies;

Is thy home European or Asian,

Oh mystical monster marine?

Part molluscous and partly crustacean,

Betwixt and between.

Wast thou born to the sound of sea trumpets?

Hast thou eaten and drunk to excess

Of the sponges—thy muffins and crumpets,

Of the seaweed—thy mustard and cress?

Wast thou nurtured in caverns of coral,

Remote from reproof or restraint?

Art thou innocent, art thou immoral,

Sinburnian or Saint?

Lithe limbs, curling free, as a creeper

That creeps in a desolate place,

To enrol and envelop the sleeper

In a silent and stealthy embrace;

Cruel beak craning forward to bite us,

Our juices to drain and to drink,

Or to whelm us in waves of Cocytus,

Indelible ink!

Oh breast, that ’twere rapture to writhe on!

Oh arms ’twere delicious to feel

Clinging close with the crush of the Python,

When she maketh her murderous meal;

In thy eight-fold embraces enfolden,

Let our empty existence escape;

Give us death that is glorious and golden,

Crushed all out of shape!

Ah thy red lips, lascivious and luscious,

With death in their amorous kiss!

Cling round us, and clasp us, and crush us,

With bitings of agonised bliss!

We are sick with the poison of pleasure,

Dispense us the potion of pain;

Ope thy mouth to its uttermost measure,

And bite us again!

The Light Green. Cambridge, 1872.

Procuratores.

O vestment of velvet and virtue,

O venomous victors of vice,

Who hurt men who never have hurt you,

Oh, calm, cruel, colder than ice;

Why wilfully wage ye this war? Is

Pure pity purged out of your breast?

O purse-prigging Procuratores,

O pitiless pest!

Do you dream of what was and no more is,

When fresher and freer than air?

Does it pain you, proud Procuratores,

These badges of bondage to bear?

In your youth were you greener than grass is,

And fearful of infinite fines,

Or casual, careless of classes,

Frequenters of wines?

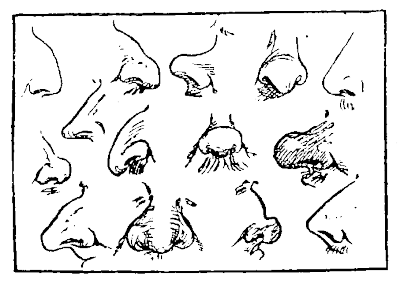

Was it woe for a woman who jilted,

Or dread of your debts or a dun?

Or was it your nose was tip-tilted,

Or a frivolous fancy for fun?

Did duty, dark despot, decide you,

That fame to the dogs must be hurled

Or was it a whim, woe betide you,

To worry the world?

Five shillings ye fine the frail freshmen,

Five shillings, which cads call a crown,

Men caught in your merciless mesh, men

Who care not for cap or for gown.

When ye go grandly garbed in your glories,

With your coarse, callous crew of canines,

O pitiless Procuratores,

Inflictors of fines.

We have smote and made redder than roses,

With juice not of fruit nor of bud,

The truculent town’s-people’s noses,

And bathed brutal butchers in blood;

And we, all aglow with our glories,

Heard you not in the deafening din,

And ye came, O ye Procuratores,

And ran us all in.

I write not as one with no knowledge,

Unaware of your weird, wily ways,

For you’ve often inquired my college,

And fined me on subsequent days.

Oft stopped, I have stuffed you with stories,

When wandering wildly from wines;

Pawned property, Procuratores,

To find you your fines.

E. B. Iwan-Müller.

This parody originally appeared, anonymously, in

“The Shotover Papers, or, Echoes from Oxford.” 1874.

A Song.

Oh, vanished benevolent Bobby!

Ah, beautiful wearisome beats,

Where rascals range, ready to rob ye,

In dim and disconsolate streets!

When I meet with a murderous nature,

And welcome thy bludgeon would be,

Two dirty hens tearing a ’tatur

Are all that I see.

In cosy recesses of kitchens,

Secure from the shrieking of slums;

Where cook’s so uncommon bewitching,

And the infinite tea kettle hums.

Yet art thou misled and mistaken,

Though served with celestial cheer,

Though feasted on liver and bacon,

And beauty and beer.

Oh, leisurely, helmeted Bobby!

Hast never with jealousy shook;

Lest Mercury, Jeames in the lobby,

Should chisel thee out of thy cook?

Ah, mark thou what mischief is hatching,

By love who doth nothing by halves;

What chance hast thou, Bobby, of matching

Those marvellous calves!

9

Oh, there are more perilous places

Than horrible hovering seas!

Come! Radiant the area space is

With the beams of the emerald cheese.

Thou art bold and thy uniform nobby,

But subtle are Syrens, and sweet!

Oh, fiery, melodious Bobby,

Come back to thy beat!

The Figaro. October 11, 1876.

Foam and Fangs.

O, Nymph with the nicest of noses;

And finest and fairest of forms;

Lips ruddy and ripe as the roses

That sway and that surge in the storms;

O, buoyant and blooming Bacchante,

Of fairer than feminine face,

Rush, raging as demon of Dante—

To this, my embrace!

The foam, and the fangs, and the flowers,

The raving and ravenous rage,

Of a poet as pinion’d in powers,

As condor confined in a cage!

My heart in a haystack I’ve hidden,

As loving and longing I lie,

Kiss open thine eyelids unbidden—

I gaze and I die!

I’ve wander’d the wild waste of slaughter,

I’ve sniff’d up the sepulchre’s scent,

I’ve doated on devilry’s daughter,

And murmur’d much more than I meant;

I’ve paused at Penelope’s portal,

So strange are the sights that I’ve seen,

And mighty’s the mind of the mortal,

Who knows what I mean!

From Patter Poems, by Walter Parke,

London,

Vizetelly & Co., 1885.

——:o:——

A MATCH.

One of the cleverest parodies on Swinburne was written

by the late Mr. Tom Hood, the younger, on the above

named poem, and first appeared in Fun, whence it has

frequently been copied without proper acknowledgment.

The parody will be better appreciated after reading a

few stanzas of the original which, as will be observed, is

written in a difficult and very uncommon metre:

If love were what the rose is,

And I were like the leaf,

Our lives would grow together

In sad or singing weather,

Blown fields or flowerful closes,

Green pleasure or gray grief;

If love were what the rose is,

And I were like the leaf.

If I were what the words are,

And love were like the tune,

With double sound and single

Delight our lips would mingle,

With kisses glad as birds are

That get sweet rain at noon;

If I were what the words are,

And love were like the tune.

* * * * *

If you were April’s lady,

And I were lord in May,

We’d throw with leaves for hours

And draw for days with flowers,

Till day like night were shady,

And night were bright like day;

If you were April’s lady,

And I were lord in May.

If you were queen of pleasure,

And I were king of pain,

We’d hunt down love together,

Pluck out his flying-feather,

And teach his feet a measure,

And find his mouth a rein;

If you were queen of pleasure,

And I were king of pain.

A. C. Swinburne.

A Catch.

(By a Mimic of Modern Melody.)

If you were queen of bloaters,

And I were king of soles,

The sea we’d wag our fins in

Nor heed the crooked pins in

The water dropt by boaters,

To catch our heedless joles;

If you were queen of bloaters

And I were king of soles.

If you were Lady Mile-End,

And I were Duke of Bow,

We’d marry and we’d quarrel,

And then, to point the moral

Should Lord Penzance his file lend,

Our chains to overthrow;

If you were Lady Mile-End,

And I were Duke of Bow.

If you were chill November,

And I were sunny June;

I’d not with love pursue you;

For I should be to woo you

(You’re foggy, pray remember)

A most egregious spoon;

If you were chill November,

And I were sunny June.

If you were cook to Venus

And I were J. 19;

When missus was out dining,

Our suppetites combining,

We’d oft contrive between us

To keep the patter clean;

If you were cook to Venus

And I were J. 19.

If you were but a jingle,

And I were but a rhyme;

We’d keep this up for ever,

Nor think it very clever,

10

A grain of sense to mingle

At times with simple chime;

If you were but a jingle

And I were but a rhyme.

Tom Hood, the younger.

Fun. December 30, 1871.

IF!

If life were never bitter,

And love were always sweet,

Then who would care to borrow

A moral from to morrow—

If Thames would always glitter,

And joy would ne’er retreat,

If life were never bitter,

And love were always sweet!

If care were not the waiter

Behind a fellow’s chair,

When easy-going sinners

Sit down to Richmond dinners,

And life’s swift stream flows straighter—

By Jove, it would be rare,

If care were not the waiter

Behind a fellow’s chair.

If wit were always radiant,

And wine were always iced,

And bores were kicked out straightway

Through a convenient gateway;

Then down the year’s long gradient

’Twere sad to be enticed,

If wit were always radiant,

And wine were always iced.

Mortimer Collins.

As a parody this is scarcely inferior to that of Mr. Tom

Hood, but the poet has let the sound run away from the

sense, and has forgotten that a wit who is always a radiant

wit is apt to become tiresome; whilst if “wine were always

iced,” all red wines would greatly suffer, especially Port and

Burgundy.

The University Election.

A Candidates Carol.

If you were an elector,

And I a candidate,

I’d send you round a notice,

And say “I trust your vote is

A thing I may expect, or

Request at any rate.”

If you were an elector,

And I a candidate.

If you were influential,

And I of no renown,

I’d say, “It is a pity

You’re not on my committee,

Your name is consequential

So let me put it down,”

If you were influential,

And I of no renown.

If I were well supported,

And you of little weight,

I’d say, “I hope to rank you

Among my voters—thank you.”

Your promise once extorted,

I’d leave you to your fate;

If I were well supported,

And you of little weight.

If you were at the polling,

And I were in the booth,

And if your vote you gave, or

Recorded in my favour,

I’d find it both consoling,

And powerful to soothe,

If you were at the polling,

And I were in the booth.

If you should vote against me,

And I were standing by,

I might be forced to fell you,

And then should simply tell you

That having so incensed me

You ought to mind your eye;

If you should vote against me,

And I were standing by.

If I were not elected,

And you would keep alive,

You oughtn’t to come nigh me,

But shun, avoid, and fly me,

And go about protected

(For vide stanza 5).

If I were not elected,

And you would keep alive.

If you were not a voter,

Nor I a candidate,

I would not give a penny,

To know your views (if any),

Contingency remoter

I can’t enunciate,

If you were not a voter,

Nor I a candidate.

From Dublin Doggerels, by Edwin Hamilton, M.A.

Dublin. C. Smyth, Dame Street. 1877.

A Matcher.

If you were what your nose is,

And I were like the red,

Then should we glow together,

Sunned in the singing weather,

Blown well as winter closes,

And colds come in the head—

If you were what your nose is,

And I were like the red.

If I were what your words are,

And you H aspirate,

We ne’er should dwell together;

For you would snap your tether,

And leave me where the birds are,

And drop at hailstone rate—

If I were what your words are,

And you H aspirate,

If you were “call to-morrow,”

And I an unpaid bill,

You’d meet me at all seasons,

With plaintive looks and reasons,

And leave me then to sorrow,

And all unsettled still—

If you were “call to-morrow.”

And I an unpaid bill,

11

If you were what’s called “shady,”

And I were quarter-day,

You’d take French leave some hours

Ere I arrived; no powers,

Could make you meet me, Lady,

Nor make me stay away—

If you were what’s termed “shady”

And I were quarter-day.

If you were Queen of Pleasure,

And I were King Champagne,

We’d hunt the bard together,

Pluck out his inked goose-feather,

And leave him “feet” and “measure,”

But muddle his poor brain—

If you were Queen of Pleasure,

And I were King Champagne.

From Lunatic Lyrics, by Alfred Greenland, Junior.

London, Tinsley Brothers. 1882.

A Philistine to an Æsthete.

(By an Oxford Under grad who “makes hay” in

an

Æsthete’s room “while the sun shines.”)

If I were big Nat Langham,

And you the Suffolk Pet,

I’d strike out from the shoulder,

Between your eyes, you’ll bet,

And give you such a drubbing,

As you would not forget;

If I were big Nat Langham,

And you the Suffolk Pet.

If I were Jockey Archer,

And you my racing horse,

I’d give you such a breather

Across a stiff race-course,

That you would think your fortunes

Had altered for the worse;

If I were Jockey Archer,

And you my racing-horse.

* * * * *

If I were a wild Indian,

And you were my canoe,

I’d shoot with you the rapids,

Like the wild Indians do,

And care not if by drowning

Myself I could drown you;

If I were a wild Indian,

And you were my canoe.

Punch. April 1, 1882.

In Pictures at Play, by two Art-Critics, illustrated by

Harry Furniss (Longmans, Green & Co.), a dialogue is

given between a portrait of Mr. Gladstone by Frank

Holl (No. 499), and a bust of the same gentleman by

Albert Toft (No. 1,928). The Bust (supposed to represent

Mr. Gladstone in his younger days) thus addresses the

Portrait:—

I am your Dr. Jekyll

And you’re my Mr. Hyde,

On my head mortals wreak ill,

(I am your Dr. Jekyll)

Of me they often speak ill,

By you left undenied,—

I am your Dr. Jekyll

And you’re my Mr. Hyde!

They say I’ve turned my coat, sir,

’Tis you should bear the blame,

Sold England for a vote, sir,

They say I’ve turned my coat, sir,

Made friends with “Skin the Goat,” sir.

Or Ford, who’s much the same;

They say I’ve turned my coat, sir,

’Tis you should bear the blame.

Be either you or I, sir,

Be Jekyll please, or Hyde,

The Statesman pure and high, sir,

(Be either you or I, sir)

Or cast your virtues by, sir,

And take the darker side,

Be either you or I, sir,

Be Jekyll, please, or Hyde.

——:o:——

In October 1885 the English Illustrated Magazine published

a short poem by Mr. Swinburne, which the Editor of

the Weekly Dispatch shortly afterwards reprinted, in his

competition column, and invited Parodies upon it:—

THE INTERPRETERS.

Days dawn on us that make amends for many

Sometimes,

When heaven and earth seem sweeter even than any

Man’s rhymes,

Light had not all been quenched in France, or quelled

In Greece,

Had Homer sung not, or had Hugo held

His peace,

Had Sappho’s self not left her word thus long

For token,

The sea round Lesbos yet in waves of song

Had spoken.

And yet these days of subtler air and finer

Delight,

When lovelier looks the darkness, and diviner

The light,

The gift they give of all these golden hours,

Whose urn

Pours forth reverberate rays or shadowing showers

In turn,

Clouds, beams, and winds that make the live day’s track

Seem living—

What were they did no spirit give them back

Thanksgiving?

Dead air, dead fire, dead shapes and shadows, telling

Time nought,

Man gives them sense and soul by song, and dwelling

In thought.

In human thought their being endures, their power

Abides:

Else were their life a thing that each light hour

Derides.

The years live, work, sigh, smile, and die, with all

They cherish;

The soul endures, though dreams that fed it fall

And perish.

12

In human thought have all things habitation;

Our days

Laugh, lower, and lighten past, and find no station

That stays.

But thought and faith are mightier things than time

Can wrong,

Made splendid once with speech, or made sublime

By song,

Remembrance, though the tide of change that rolls

Wax hoary,

Gives earth and heaven, for song’s sake and the soul’s

Their glory.

A. C. Swinburne.

Three of the competition poems were printed in the

Weekly Dispatch, October, 18, 1885, the first prize was

awarded to the following:—

Lays dawn on us that have few charms for many,

Sometimes,

Sure heaven and earth were seldom rack’d for any

Worse rhymes.

Light would not all be quench’d were bards compelled

To cease,

Had Tennyson sung not, or Swinburne held

His peace—

Had Algy’s self not writ these lines so long

And broken:

’Tis sad to see our Swinny rave in song

Mad spoken!

And yet few lays or subtler airs give finer

Delight,

Or soar from out the darkness with diviner

A flight,

Than his whose gift, in his most golden hours,

Can earn

Reverberate praise for all his varied powers

In turn;

Grand, grave or gay, that make his verse at times

Seem living,

But where are they who yield him for these rhymes

Thanksgiving?

Dull verse, queer style, dim tropes and rhythm, telling

Us nought;

One looks for sense and shape in song, compelling

Sweet thought!

In this what thought there is all clouded o’er

Abides,

And ev’ry one the more he reads the more

Derides!

The words start, jump and jerk, and rise and fall

So funny,

That one endures, yet deems such stuff is all

For money!

A poet’s thoughts should please in all their stages.

This lay

Seems cobbled up to find a home in pages

That pay.

But thought and rhythm flighty have this time

Gone wrong,

Though splendid once his speech, and oft sublime

His song!

(Remembrance tells the powers of poet-souls

Wax hoary)

This song may give him guineas, but enrols

No glory!

Herbert L. Gould.

Highly commended:—

The Ladies.

Faces we see that make amends for many

Most plain,

When English girls seem sweeter e’en than any

From Spain,

Beauty had not been rare with us, or quelled

In Greece,

Had Tom Moore sung not, or Anacreon held

His peace.

Had Aphrodite never cleft the sea,

In splendour,

Our modern belles would still as winsome be

And tender.

And so these girls of gentle air and manner

Delight:

Who lovelier looks than Hilda, as you scan her?

Sweet sight!

The gleam that shines from every golden tress,

Whose wealth

The sunbeam kisses, or the winds caress

By stealth.

Hair, lips, and eyes, with which our nymphs prepare

For action—

What were they, did no esprit give them rare

Attraction?

Dead lips, dead eyes, dead silken tresses, telling

Men nought;

Wit only gives them life and soul and dwelling

In thought.

In memory must their grace endure, their spell

Abide:

Else were their sway a thing that we might well

Deride.

The “darlings” flirt, sigh, smile, wax old, with none

To cherish;

Their hope endures, though charms fail one by one

And perish.

In faces sweet seek all men consolation;

Our “fair”

Laugh, lisp, and lighten life, and find flirtation

A snare.

But wit and soul are mightier things than Time

Can wrong,

Linked with a silv’ry voice that is sublime

In song.

Dreams of fair girls illume, like stars on pall,

Life’s story;

Give rapture rare, and our soft slumbers all

Their glory.

F. B. Doveton.

Truths take live forms that make a hope for labour,

Though rare,

When life seems sweeter with each bright hope’s neighbour—

Dreams fair.

Progress had not been crushed nor lost its spell

For men,

Had Rousseau never found the tyrant’s knell,

His pen.

Had Gladstone’s self ne’er poured the words that burn

For token,

The voice of Right for myriads who earn

Had spoken.

13

And yet these truths which show to us immortal

To-day,

When swart Injustice sees through its last portal

Decay;

The joy these truths can give to heart and soul,

And pour

Glory on prophets gone who filled the roll

Of yore;

Truths, gifts, and hopes that make our life’s hard track

Worth living—

What were they did no voices thunder back

Thanksgiving?

Mere thoughts, mere hopes, mere dreams, mere visions showing

No form;

The statesman gives their shape in language glowing

Heart-warm.

In deathless speech their life is found, their power

Is seen,

Else were their names the shadows of an hour

That’s been.

Mere theories rise, fall, and fade, though all

May cherish.

The fact endures, free speech forbids its fall

To perish.

In champions’ tongues has truth its full progression:

Bare thought

Dawns, shines, and fades, through finding no expression,

Though sought.

But speech and Press are mightier than all sway

Can bind,

Made potent by wide utterance their way

To find.

Progress and Freedom, though Time’s tide that rolls

Wax hoary,

Give to a nation’s life, both mind’s and soul’s,

Its glory.

A. Pratt.

——:o:——

Lofty Lines.

(By a Swinburnean Lofty Liner.)

Imparadised by my environment,

In rhymes impeccably good,

Let me scribble, as poor proud Byron meant

To have scribbled, if he could!

I’ll strain, as the sinuous cameleopard

Strains after the blossomy bough,

And with faculties that develop hard

Let me write—I can’t say how.

Impish idiom’s idiosyncrasy

Shall my verse festoon with flowers;

In a kingdom of pen-and-inkrasy

I shall wield prosodian powers.

Through innumerous apotheoses

The future my name shall learn,

And like passionate plethoric peonies

My perpetual poems burn.

Let my glory grow as the icicle

Accrues between night and morn;

As the bicyclist rides his bicycle

Let me on my metre be borne.

Flashing thus on verses vehicular,

With Pegasus ’neath my touch,

My method can’t be too particular,

Nor the public see too much.

The critics are all anthropophagous,

And feed on poetic flesh;

My heart nestles in my esophagous,

To think I’ve been in their mesh.

As vessels that sail on the Bosphorus

Catch Constantinople’s beams,

So my soul from prosody’s phosphorus

Still gathers Dædalian gleams.

Funny Folks, May 11, 1878.

The Family Herald (London) for July 28, 1888,

contained an amusing article on Parodies, from

which the following is an extract:

“But we wish to get away from well-trodden tracks, and

we will for once forsake our usual purely didactic groove in

order that we may give our readers an idea of what we regard

as artistic drollery, Take this dreadful imitation of

Mr. Swinburne’s manner. The parodist seems to have

genuinely enjoyed his work; and we have no doubt but that

Mr. Swinburne laughed as heartily as anybody. The poet

is supposed to be attending a wedding of distinguished

persons in Westminster Abbey, and the naughty scoffer represents

him as bursting forth with the following rather

alarming clarion call—

There is glee in the groves of the Galilean—

The groves that were wont to be gray and glum—

And a sound goes forth to the dim Ægean,

To Helen hopeless and Dido dumb—

The sound of a noise of cab or carriage,

A rhythm of rapture, a mode of marriage.

Sing “Hallelujah!” Shout “Io Pæan!”

Hymen—O Hymen, behold, they come!

What shall I sing to them? How shall I speak to them?

Whose is the speech that a groom thinks good?

Oh that a while I might gabble in Greek to them—

Gabble and gush and be understood,

Gush and glow and be understanded,

Apprehended and shaken-handed!

Yea, though a minute should seem a week to them,

I would utter such words as I might or could!

For winter’s coughs and cossets are over,

And all the season of sniffs and snows,

The rheums that ravish lover from lover,

The eyes that water, the nose that blows;

And time forgotten is not remembered,

And cards are wedded and cake dismembered,

And in the Abbey, closed, under cover,

Blooms and blossoms and breaks love’s rose.

A masterpiece! And there is not a touch of malignity in the

lines; the poet’s curious way of writing occasionally in the

Hebraic style, his vagueness, his peculiar mode of procuring

musical effects, are all picked out and shown with a smile.

No one has quite equalled Caldecott, but this anonymous

wit runs him hard.”

Unfortunately the author of the article omits to state the

source from whence he derived the parody he praises so

highly.

Home, Sweet Home.

As Algernon Charles Swinburne might have wrapped

it up in Variations.

(’Mid pleasures and palaces—)

As sea-foam blown of the winds, as blossom of brine that is drifted

14

Hither and yon on the barren breast of the breeze,

Though we wander on gusts of a god’s breast shaken and shifted,

The salt of us stings, and is sore for the sobbing seas.

For home’s sake hungry at heart, we sicken in pillared porches

Of bliss made sick for a life that is barren of bliss,

For the place whereon is a light out of heaven that sears not nor scorches,

Nor elsewhere than this.

(An exile from home, splendour dazzles in vain—)

For here we know shall no gold thing glisten

No bright thing burn, and no sweet thing shine;

Nor Love lower never an ear to listen

To words that work in the heart like wine.

What time we are set from our land apart,

For pain of passion and hunger of heart,

Though we walk with exiles fame faints to christen,

Or sing at the Cytherean’s shrine.

(Variation: An exile from home.)

Whether with him whose head of gods is honorèd

With song made splendent in the sight of men

Whose heart most sweetly stout,

From ravished France cast out,

Bring firstly hers, was hers most wholly then—

Or where on shining seas like wine

The dove’s wings draw the drooping Erycine.

(Give me my lowly thatched cottage—)

For Joy finds Love grow bitter,

And spreads his wings to quit her,

At thoughts of birds that twitter

Beneath the roof-tree’s straw—

Of birds that come for calling,

No fear or fright appalling,

When dews of dusk are falling,

Or day light’s draperies draw.

(Give me them, and the peace of mind.)

Give me these things then back, though the giving

Be at cost of earth’s garner of gold;

There is no life without these worth living,

No treasure where these are not told.

For the heart give the hope that it knows not,

Give the balm for the burn of the breast—

Ior the soul and the mind that repose not,

O, give us a rest!

H. C. Bunner.

This Parody originally appeared in Scribner’s Monthly,

May, 1881, with imitations of Bret Harte, Austin Dobson,

Oliver Goldsmith, and Walt Whitman. They were afterwards

republished in a volume, entitled Airs from Arcady,

by H. C. Bunner. London, Charles Hutt, 1885.

——:o:——

A Swinburnian Interlude.

Short space shall be hereafter

Ere April brings the hour

Of weeping and of laughter,

Of sunshine and of shower,

Of groaning and of gladness,

Of singing and of sadness,

Of melody and madness,

Of all sweet things and sour.

Sweet to the blithe bucolic

Who knows nor cribs nor crams,

Who sees the frisky frolic

Of lanky little lambs:

But sour beyond expression

To one in deep depression

Who sees the closing session,

And imminent exams.

He cannot hear the singing

Of birds upon the bents.

Nor watch the wild-flowers springing.

Nor smell the April scents.

He gathers grief with grinding,

Foul food of sorrow finding

In books of beastly binding

And beastlier contents.

Our hope alone sustains him,

And no more hopes beside,

One only trust restrains him

From shocking suicide:

He will not play nor palter

With hemlock or with halter,

He will not fear nor falter,

Whatever chance betide.

He knows examinations

Like all things else have ends,

And then come vast vacations

And visits to his friends:

And youth with pleasure yoking,

And joyfulness and joking,

And smilingness and smoking,

For grief to make amends.

The University News Sheet. St. Andrews, N. B.

March 31, 1886.

——:o:——

Vaccine.

Written after reading “Faustine.”

Hail! sacred salutary nymph,

Fair freckless queen;

Pure and translucent flows thy lymph,

Potent Vaccine!

“Each shapely silver arm” receives

The lancet keen;

E’en warriors trembling raise their sleeves

For thee, Vaccine.

“Let me go over your good gifts,”

That plain are seen;

Thou sav’st the face from scars and rifts,

Clear-browed Vaccine.

Belovèd maid of many charms,

Calm and serene,

Fondly we take thee in our arms,

Lovely Vaccine!

Virtue of inoculation,

To try we mean;

We’re now a humour-us nation,

You’ll own, Vaccine.

Doctors, like ancient knights again,

With lances keen,

Daily go “pricking o’er the plain,”

With thee, Vaccine.

15

It would have gladdened Jenner’s heart,

Could he have seen

Such thousands suffering from the smart

Of thee, Vaccine.

And Jenner-ations yet to be

Seen on life’s scene,

Shall pæans sing in praise of thee,

Saving Vaccine!

The Day’s Doings. March 4, 1871.

——:o:——

La Belle Dame Sans Merci

(A.D. 1875).

Oh, what can ail thee, seedy swell,

Alone, and idly loitering?

The season’s o’er—at operas

No “stars” now sing.

Oh, what can ail thee, seedy swell,

So moody! in the dumps so down?

Why linger here when all the world

Is “out of town?”

I see black care upon thy brow,

Tell me, are I.O.U.’s now due?

And in thy pouch, I fear thy purse

Is empty, too.

“I met a lady at a ball,

Full beautiful—a fairy bright;

Her hair was golden (dyed, I find!)

Struck by the sight—

“I gazed, and long’d to know her then:

So I entreated the M.C.

To introduce me—and he did!

Sad hour for me.

“We paced the mazy dance, and too,

We talked thro’ that sweet evening long,

And to her—it came to pass,

I breathed Love’s song.

“She promised me her lily hand,

She seemed particularly cool:

No warning voice then whispered low,

‘Thou art a fool!’

“Next day I found I lov’d her not,

And then she wept and sigh’d full sore,

Went to her lawyer, on the spot,

And talked it o’er

“She brought an action, too, for breach

Of promise—’tis the fashion—zounds!

The jury brought in damages

Five thousand pounds!

“And this is why I sojourn here

Alone, and idly loitering,

Tho’ all the season’s through and tho’

No ‘stars’ now sing!”

The Figaro. September 15, 1875.

——:o:——

A Song after Sunset.

The breeze o’er the bridge was a-blowing,

O’er wicked and wan Waterloo,

The busses buzzed, coming and going,

As busses will do.

Amid the cold coigns of the causeway.

I secretly, silently sat,

Aloof, out of laughter’s and law’s way,

Hard-holding my hat.

In crowds that seemed never to cease, men

Heaved, hurtled, home-hurried and howled,

While pestilent prigs of policemen,

Persistently prowled.

From pockets that penniless sounded

Two tickets I’d drearily drawn,

They prated of pledges impounded

In pitiless pawn.

They seemed with a cynical sorrow,

To sing the same sedulous strain:

“Pay up, and redeem us to-morrow,

Your watch and your chain!

We know you of old, sworn tormentor!

You thriver on thriftless and thief!

Spout-spider!—on spoiling intent, or

Rapacious relief!

Avuncular author of anguish,

We damn you with deepest disdain!

We linger, we long, and we languish

For freedom again.”

I smiled on the speakers unheeding,

I grinned at their garrulous games—

When the breeze blew them, splendidly speeding,

Right into the Thames.

They scattered, as seed that is sown, or

The fringe of the fast flowing foam,

And their hungry, hysterical owner

Went hopelessly home.

Judy. June, 16, 1880.

——:o:——

The Mad, Mad Muse.

Out on the margin of moonshine land,

Tickle me, love, in these lonesome ribs,

Out where the whing-whang loves to stand,

Writing his name with his tail on the sand,

And wipes it out with his oogerish hand;

Tickle me, love, in these lonesome ribs.

Is it the gibber of gungs and keeks?

Tickle me, love, in these lonesome ribs,

Or what is the sound the whing-whang seeks,

Crouching low by winding creeks,

And holding his breath for weeks and weeks?

Tickle me, love, in these lonesome ribs.

Anoint him the wealthiest of wealthy things!

Tickle me, love, in these lonesome ribs.

’Tis a fair whing-whangess with phosphor rings,

And bridal jewels of fangs and stings,

And she sits and as sadly and softly sings;

Is the mildewed whir of her own dead wings;

Tickle me, dear; tickle me here;

Tickle me, love, in these lonesome ribs.

Robert J. Burdette.

From S. Thompson’s Collection of Poems. Chicago.

1886.

16

Studies in Exotic Verse.

A Ballade of the Nurserie.

(After Mr. Swinburne’s “Dreamland.”)

She hid herself in the soirée kettle

Out of her Ma’s way, wise wee maid!

Wan was her lip as the lily’s petal,

Sad was the smile that over it played.

Why doth she warble not? Is she afraid

Of the hound that howls, or the moaning mole?

Can it be on an errand she hath delayed?

Hush thee, hush thee, dear little soul!

The nightingale sings to the nodding nettle

In the gloom o’ the gloaming athwart the glade:

The zephyr sighs soft on Popòcatapètl,

And Auster is taking it cool in the shade:

Sing, hey for a gutta serenade!

Not mine to stir up a storied pole,

No noses snip with a bluggy blade—

Hush thee, hush thee, dear little soul?

Shall I bribe with a store of minted metal?

With Everton toffee thee persuade?

That thou in a kettle thyself should’st settle,

When grandly and gaudily all arrayed!

Thy flounces ’ill foul and fangles fade.

Come out, and Algernon Charles ’ill roll

Thee safe and snug in Plutonian plaid—

Hush thee, hush thee, dear little soul.

Envoi.

When nap is none and raiment frayed,

And winter crowns the puddered poll,

A kettle sings ane soote ballade—

Hush thee, hush thee, dear little soul.

John Twig.

——:o:——

On Marriage with a Deceased Wife’s Sister.

O blood-bitten lip all aflame,

O Dolores and also Faustine,

O aunts of the world worried shame,

Lo your hair with its amorous sheen

Meshes man in its tangles of gold;

O aunts of the tremulous thrill,

We are pining—we long to enfold

The Deceased Wife’s Fair Relative Bill.

G. R. Sims.

——:o:——

A Parody.

If it be but a dream or a vision,

The life which is after the grave,

The moil of the metaphysician

Is vain,—but an answer I crave,

Amid bright intellectual flambeaux

I shall find no light clearer than thee,

O sable and sensual Sambo,

The servant of me!

I beheld thee beholding the ballet,

Dumps doleful display’d deep despair,

Thou didst think of thine own land, my valet,

The land in which nought thou didst wear.

* * * * *

O statue, us Philistines loathing,

Of Phœbus!—our tailors we fear,

Come down, and redeem us from clothing,

O nude Belvidere!

We are wise—and we make ourselves hazy,

We are foolish—and, so, go to church;

While Sambo but laughs, and is lazy,