It was hard to make out the faces.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Remember the 4th!, by Noel Loomis

Title: Remember the 4th!

Author: Noel Loomis

Release Date: March 26, 2023 [eBook #70388]

Language: English

Produced by: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(author of "The Lithium Mountain")

Slim Coleman's brain-finder worked all too well!

If, as has often been contended, the brain contains a complete record of all events the individual has experienced, consciously or otherwise, then a mechanical means of exploring someone's past might be found. It would show the discrepancies between the most reliable memories of events, and actual sense-impressions received at the time, for example. But few people would like such a device, and those few might like it much too much!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Future combined with Science Fiction Stories July 1951.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

This was a warm day in August—a very warm day. Slim Coleman, my partner in detection work, says the sun is ninety million miles away, but this day it must have sneaked up pretty close. You could even see the heat waves coming up off the sidewalk. You can't fry an egg on the pavement in Fort Worth, though, because you can't stay out in the sun that long.

I mopped my brow, slung the water off my fingertips, and went into the lobby of the National Bank Building. The washed air made it cool and nice in there, and I slowed down to enjoy it. But one of the elevators came down, the door slid open, and the first man to get off was Swanberg, the building manager—our landlord—all dressed up in striped trousers and a fancy vest and wearing a high wing collar and a genuine cravat. He looked impeccable, immaculate—and cool.

I wheeled and marched back outside into the sun. Slim and I were three months behind with the rent, and I figured the only reason Swanberg hadn't ordered us out was that he just hadn't gotten around to it. I didn't want to run into him. If we could have paid our rent I wouldn't have been carrying ham sandwiches and a bottle of coffee in my coat-pockets up to Slim Coleman while he worked on the Brain-Finder.

The heat almost smothered me after the coolness of the lobby. Damn that guy Swanberg, anyway. He was always so perfect, so completely unaffected by the weather, so supercilious and so cold, so mechanical. You knew he'd never had any trouble and never would have, because he would never be swayed by anything but cold logic. It's only we humans with sentiments who get in trouble.

It was his untouchableness that griped me. He was so inhumanly perfect he always made me feel rough and uncouth. You know how it is. If I could just get something on him to throw off that complex, I'd be happy even if we did have to vacate. I guess I spent my time day-dreaming about Swanberg—Swanberg wearing an old-fashioned night-cap, Swanberg slurping his coffee, Swanberg sleeping with his socks on—anything human.

What wouldn't I have given to have a picture of him in the roller coaster the way I had been the night of July the Fourth, with a perfectly strange, perfectly gorgeous, slim blonde throwing her arms around his neck the way that one had around mine. I was willing to bet he had a big, hefty wife at home who made him step.

I shivered whenever I thought about that blonde. She was the kind I would have liked to marry, only one like that was way out of my reach. I didn't have much education and I didn't always know what to do around a real high-class female. That's why I had been riding the roller coaster alone.

Well, there was nothing for it now but the coal-chute. A truck was backed up to the sidewalk and two very black-faced men were pushing coal down a steel chute through a manhole in the sidewalk. I ducked into the alley, unrolled the bundle under my arm, and threw out a pair of khaki coveralls. I hated this, but I did it anyway; I had to. We couldn't afford to have my suit cleaned every time I went in through the sidewalk, so I got into the coveralls and zipped them up. I watched around the corner. When the truckers raised the steel bed, I walked up to the open hole in the sidewalk and dropped in casually.

I'm a short man anyway, a little on the chunky side, and that coal-hole was like a furnace. The sweat poured down my back and chest and the coal-dust poured into my nostrils. I got out of there as fast as I could and took the freight elevator to the twenty-second floor. I went through the hall, unlocked the door, got inside, and locked it again.

"That you, Doc?" came Slim Coleman's deep voice.

"Yeah." I held the coveralls out of the window, slapped the coal-dust out of them, took off my damp suit-coat and laid it on top of the desk, got the electric iron out of the desk-drawer and plugged it in. Our sign said Coleman & Hambright, Private Investigators, and we had to maintain appearances, but I wished we could afford a store-bought pressing. I brushed my pants, but they were damp, too, so I took them off and laid them out on the desk-top, over some papers, with the creases pinched tight. I mopped my brow and went into the other room.

Slim Coleman looked up from a work-bench covered with wires, tubes, condensers, and all kinds of electrical gadgets. He had a soldering-iron poised above something that looked like a forty-eight-tube radio. He had deep, deep brown eyes that always looked through everybody, but Slim was a hundred-per-cent. In fact, it was his loyalty that had us behind the eight-ball now. If he had dissolved partnership instead of offering to pay the damages the time I fell from a second-story window and went through a skylight into a whole tableful of expensive orchids—but no, Slim paid it all—twenty-two hundred dollars before he got through, because the cold air ruined a lot more orchids. And I hadn't even gotten the evidence I was after. (No, it was just happenstance that I fell from the bedroom window of a movie star.)

"What luck?" said Slim in his husky voice.

"I served them, but look, Slim, I hope you get that Brain-Finder going pretty quick. Not that I mind crawling under the length of three pullman cars and cutting my ankles on the cinders to serve divorce papers on Tom Ellingbery, who's worth a million. Not that I mind doing all that for a measly five bucks, but when I have to come through the sidewalk in the summertime to duck the landlord—"

Coleman's face lighted up. "The Brain-Finder is ready for a tryout," he said. "Shall I show you yourself the night of July the Fourth?"

Well, partly because I guess I didn't have much real faith in the gadget, I said "Okay," and went to get the four ham sandwiches and the coffee in a milk-bottle out of my coat-pockets. That was why I couldn't take off the coat when I put on the coveralls—for fear of spilling the coffee. Then I groaned and ran for the desk. There was a brown puddle spreading on the desk and soaking up my coat. I very nearly said "Damn!"

"I've got your brain wave-length," Slim was saying. I started mopping up with my handkerchief while I hung the coat up to dry. "Now, all I have to do is—come here, Doc!"

I put the sandwiches on the bench in front of him, but for once Slim didn't even reach. He looked at me and his deep-set eyes were burning. "We are going to be the greatest private investigators in history," he said. "In fact, we'll make history. Doc, we'll be the most important men in America."

I should have been more enthusiastic, but things were going so badly—"I don't care," I told him, "about being a great man, if I can just quit ducking the landlord. I want to walk in under his nose and not be scared of him. If you want to fill my cup to overflowing, just let me use that thing long enough to get something on him."

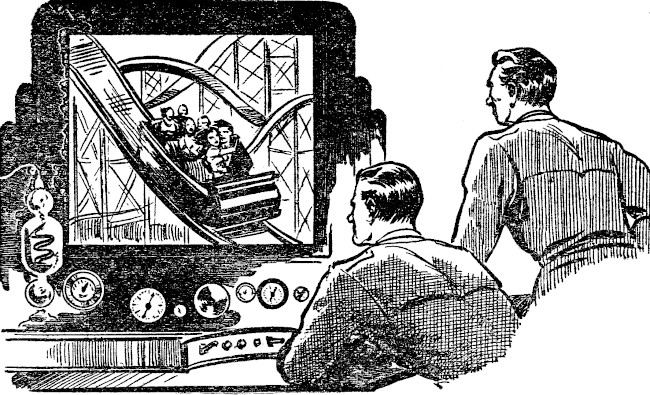

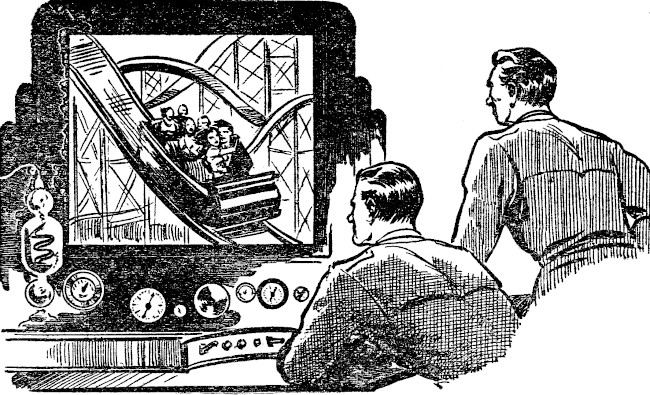

Slim was already turning dials. Tubes were lighting up. The set was humming. Pretty soon he pointed to a screen, and I damn near lost my breath. There on a screen about twelve by eighteen inches, big enough so there wasn't any mistake, I saw myself on the night of July Fourth, just as I bought one ticket for the roller coaster.

I guess my eyes stuck out a foot, for Slim was looking at me with that kind of sad smile. "Roller coasters," he said gently. "Got enough, Doc?"

I gulped. "Plenty. Cut it off, please." In the screen I saw the blonde just behind me, and I didn't want Slim to see her put her arms around me when the roller coaster went over the dip.

It was hard to make out the faces.

Slim smiled and snapped a bunch of switches. The lights in the tubes went out. "Think what this will mean in criminal prosecutions, to be able to follow a man in the past. Present-day testimony will be archaic. The courts won't have to take anybody's word for anything; they can follow a man and watch him in the past."

"Judge Monday wouldn't admit that kind of evidence," I pointed out.

"Naturally not. It will take twenty-five years to get this kind of evidence admitted in court. In the meantime, we'll have to go easy. But we can make millions, just by bluffing. When we know that a man was playing poker in Jones's basement until six o'clock Sunday morning, then we can bluff and put it over. Just so we don't tangle with a real tough guy the first time. For instance—sh! Somebody's at the door."

Slim ran to the door while I ran for my pants. I ducked back into the other room and got them on. I heard the voice. It was a man's voice, and I had heard it before—just recently. I peeked out. Yes, it was Tom Ellingbery. I stayed quiet.

"A pot-bellied little guy just served divorce papers on me," he said harshly. "I got off the train and came here. A friend of mine sent me; I want your services."

"Yes," said Slim.

"Here's a hundred-dollar bill," Tom Ellingbery said. "Start shadowing my wife; get something on her. I'll give you five thousand to get something—ten if it's necessary," he said with a slight leer.

Slim gravely picked up the C note. "We don't do business that way," he said; "but if your wife has been misbehaving we'll find it out."

Ellingbery was a big man with a sharp go-getter look about him. He stared hard at Slim and Slim stared back. Ellingbery's expression didn't show anything; then he left.

Slim locked the door after Ellingbery, and I took off my pants and set up the ironing-board on the desk. Slim went back to adjust the dials on his machine.

"This gadget is a sort of super-sensitive radar," he said as it warmed up. "I can tune it to your brain-waves and pick you up anywhere within forty miles or three months."

A purple indicator began to wink. "It proves I've got brains, anyway," I pointed out.

"Yes, your waves come in at a frequency of approximately 1,832,956,000. That's as close as I can tune it so far, but that's plenty close enough. There are other characteristics, such as power and damping and height of crest and so on, that make it selective enough to pick out any one person in the United States if it could reach that far."

"And then you can see everything I do?"

"No, I can see only what you see with your own eyes."

Then I must have been staring at the blonde. I held my breath when I asked, "Can you tell what I'm thinking?"

"No."

I breathed again.

"I can translate what you say into language, though. Something happens when I throw two hundred and twenty volts into this bank of tubes. As near as I can figure, it creates a 'time-warp'—which doesn't mean much of anything objectively. I don't know how it works; I couldn't even duplicate it. I suppose some high-powered electronics engineer could figure it out, but I don't want anybody but you and me even to know about it. What I'm interested in is what we can do with it."

"What I'm interested in," I said, "is how much money we can make with it."

Slim looked at me with his great burning eyes while the steam rose from under the iron on my pants.

"You're about to find out." The ground-glass screen slowly lighted. A new bank of tubes began to sparkle and then settled down into a greenish glow. Slim turned dials, and there was the figure of a woman on the screen.

"That," said Slim, "is Mrs. Tom Ellingbery."

Well, of course I couldn't see her face. She was playing bridge, apparently. Her hands looked nice. The woman at her left said, "I hear you've filed suit against your husband."

Mrs. Ellingbery reached for a king, but her fingers were nervous. She played a six instead and lost the trick. "Yes," she said quietly, "I have." Her voice was sad.

I waited a minute. Then, "How did you know how to tune in on her?" I asked Slim.

"I got her wave-characteristics when she came up the other day to get us to serve the papers," he said. "I got Tom's today while we were talking. The machine was all set and the recording needles made a permanent record."

I swallowed. "Can you get the landlord's characteristics too?"

Slim held up a sheet of ruled paper. "Got his already. I was just practicing; I got him when he was trying to hammer the door down yesterday."

Suddenly I felt a deep peace. I had the landlord in my power, now, and I didn't have to hurry; I could take my time.

But Slim notched me down. "Get this hundred changed," he said. "Give the landlord fifty and then have the telephone connected again."

I took the hundred.

"Get some more sandwiches, too. We'll be here late tonight."

Well, the landlord wasn't as sarcastic as I had feared. He defrosted slightly when he saw the fifty. Now we owed him only two hundred. I knew he was probably going to put us out on September the first, but I soothed my hurt feelings by imagining him walking around in his shorts. There is nothing else that will so undignify a man. But before long—in fact, as soon as I could get to the Brain-Finder while Slim wasn't watching—I'd get the facts.

We watched Mrs. Ellingbery for four straight nights and days. She went visiting; she played bridge; she shopped. She never did give more than a second glance at any man, and she didn't talk to any man over the phone. We could see her only when she looked at herself in the mirror. That was enough.

We followed her like two blood-hounds, from the time she ate breakfast until she went to bed at night, but Slim turned the machine off when she sat down to remove her stockings. Slim always was a gentleman.

We went back in "time"—fast. Flashes here and there. But Mrs. Ellingbery was like Caesar's wife. On the fifth day Slim called Tom Ellingbery and told him he was dropping the case, that his wife was above suspicion and it wasn't worth while to watch her. I was glad, but Tom Ellingbery swore; anyway, he said he'd send a check for another hundred. Then Slim sat back and looked at me. "Now," he said quietly, "we'll turn this thing where it belongs."

I'd been hoping he'd go out for a sandwich, now that we dared to use the passenger elevators, so that I could sneak a preview of the landlord biting his fingernails in seclusion, but no. Slim fixed his deep eyes on me and said, "We'll see what Tom has been doing recently. Do you realize he hasn't been in the picture but once in five days?"

Tom was it, all right. We trailed him that night to a big apartment house across town. Yes, it was a blonde, only this one had had considerable help from a bottle of peroxide....

Slim made a deal with Mrs. Ellingbery's lawyers. We were to get five triple-o's if Mrs. Ellingbery won. So Slim spent the week-end trailing Tom for the past three months while I wrote it all down like a chronological history of the war. I was tickled over July the Fourth. On July the Fourth, Tom and the bleached blonde started out with a popcorn picnic and wound up—you guess. Riding the roller coaster! I could just imagine what old Judge Monday would say to that; that little scene would be worth half of the property settlement.

We were short on time. Some way or another Tom Ellingbery had rushed the trial, and it was set for August 30. We turned over our notes to Mrs. Ellingbery's lawyers and sat back and waited. Private investigators never go near the courts unless they have to.

At four-thirty that day the telephone rang. Slim listened, then he hung up. "Tom has got a couple of shrewd, tough lawyers," he said. "We have to go to court. Tom isn't admitting anything and he isn't taking any bluffs. He demands proof."

"Well," I said, "for five M notes I'll tell everything."

Slim was worried. He talked to her lawyers, Youngquist and Rubicam, that night. The next morning we were both in court. It was direct examination. Slim identified himself, then he was asked: "You have investigated Tom Ellingbery's activities over the past three months?"

"Yes." Slim was very self-composed.

"Did you, on the night of August 26, observe him going into an apartment house at this address?"

"Yes."

And so on—but never a word of where Slim was when he saw all this. Very clever, I thought, but when I looked at those sharp-eyed young fellows at Tom Ellingbery's table, I knew it'd never get by.

Presently Mr. Youngquist said, "You may inquire." I held my breath. But one of the young fellows looked up and said, "Are you going to put his partner on?"

"Yes," said Mr. Youngquist.

"With that understanding, there are no questions of this witness, your honor."

I jumped as if I had sat down on an electric griddle. It was plain even to me; they figured Slim was pretty sharp, so they'd wait for me, and in the meantime they wouldn't tip me off by asking Slim any questions. I wished I could have held my breath for about three days.

I got along all right with Mr. Youngquist. I was careful not to say anything about where I had stood or sat or walked. I said, "Yes, I followed him," because I did follow him with my eyes. Then Mr. Youngquist turned to the young fellow and said, "You may inquire."

The young fellow got up slowly and looked at me easily and gently, but it was still August. I was sweating. I knew it was coming. I looked at Slim. Slim was sweating too. I looked at Mr. Youngquist. He wiped the perspiration from his forehead.

"You say," the young fellow began softly, "that you and your partner followed Mr. Ellingbery from sometime in June?"

"Yes."

"You testified, I believe, that on the night of July the Fourth, Tom Ellingbery and this girl were at the amusement park?"

"Yes."

"And I believe you have cited some eight or nine dates up to the fifteenth of July."

I looked at Mr. Youngquist and I was astonished to see his face the color of bleached muslin.

"Well, did you or did you not?"

I looked at Slim. He was puzzled, too. Finally I nodded.

"Will you say it for the record, please?"

"Yes."

"That is to say, you are now testifying that you followed Mr. Ellingbery on each of eight or nine occasions prior to July 15, and each time with your partner at your side?"

"Yes."

"And always at Mrs. Ellingbery's request?"

"Yes." That was a nasty question, but it had to be answered yes.

"Were you here in court yesterday?"

"No, sir." I would have said, "No, your majesty," if it would have helped.

"You didn't hear Mrs. Ellingbery testify that her suspicions were first aroused when somebody reported to her that on July the Fourth Tom Ellingbery was riding the roller coaster with another girl?"

I wish I could have jumped into the Brain-Finder and gone back about two weeks. I would have walked through the sidewalk while the coal was being poured.

"No," I said finally.

The young fellow looked triumphantly at Mr. Youngquist, who looked as if he would like to be buried in ashes up to his ears.

"That's all."

Mr. Youngquist rallied and put Slim back on the stand. Then there was a recess. Mr. Youngquist and Mr. Rubicam and Slim and Mrs. Ellingbery and I went into a big huddle out in the hall. "That's what comes of messing around with imbecilic things like this Brain-Finder," Mr. Youngquist moaned. "Why didn't we stick to straight law?"

"Because we couldn't win that way," Mr. Rubicam reminded him. "We didn't have any real evidence."

Well, they decided the only chance to win the case was to have Slim tell about and demonstrate the Brain-Finder. Slim didn't like to do that; but we needed those five G's. That afternoon he told. The next morning we lugged it into court and set it on a table with the screen facing the judge.

There was a crowd in court that morning, thanks to a news story in the morning Herald. Slim groaned; crowds aren't good for private investigators. I pricked up my ears when in marched Mr. Swanberg, our landlord, as austere as striped trousers could possibly make him, but with a beauteous blonde in a pink dress, clinging as if she was afraid he'd get away. That opened my eyes. Maybe the old iceberg was human after all, to rate that kind of devotion. Maybe he did have an occasional moment of abandonment when he would lick the butter from his knife. If we ever got through this mess I was going to find out. "That's Mrs. Swanberg," Youngquist said to Slim.

I looked his wife over in my best professional style. I thought I'd seen her some place, and a detective is supposed to remember faces, but I couldn't quite place her. Anyway, there were now three blondes mixed in with that court-room—and that's a lot of blondes. Mr. and Mrs. Swanberg sat down at one side opposite the jury-box where they could see the screen of the Brain-Finder as well as the judge. I suppose Swanberg had read the story and wanted to see what we were up to in his building. Mrs. Ellingbery sat across the counsel table from me. She was a winner if there ever was one.

Slim went on the stand. He demonstrated the Brain-Finder very feebly—that is, innocuously. It was obvious that Youngquist was scared to death of what might happen.

And again Tom Ellingbery's lawyers passed up cross examination of Slim. I knew they were waiting for me.

They were. "Do you understand this machine?" one asked me scornfully.

"No, sir."

"You know how to work it, don't you?"

"Yes. I think so."

"Do you mean to tell this court that you can adjust the dials and gadgets on this thing and see what I was doing last week or the week before?"

I tried to be cautious. "If it's plugged in."

"Okay, we'll plug it in."

He invited me to step down and turn on the switches. I looked at Slim. He nodded. After all, there was nothing else to do. I went.

Some of the tubes crackled and then settled down to a steady green glow, and one bank showed purple. Then the lawyer said, "Now, do you mean to tell me you can tune this contraption in on a man's brain and find him anywhere in the past?" He sounded completely skeptical.

"Within three months," I said defiantly.

"For instance, you testified that Tom Ellingbery was riding the roller coaster on the night of July the Fourth with the girl who has been named in this case. You saw this on this screen?"

"Yes."

"Can you tune it in again?"

Well, I knew this was all preliminary. It would take something absolutely dynamic to convince Judge Monday that the Brain-Finder was the real thing and not a fake. So I wasn't worrying—yet. "Yes," I said, and set the dials to Tom Ellingbery's brain-waves. I picked up Tom and the bleached blonde just as they stepped into the roller-coaster car, and followed them around the ride. It wasn't very sensational; she screamed and hid her eyes and grabbed Tom around the neck. Standard technique.

Then the lawyer said, "Can you pick up your own brain-wave on this thing?"

"Yes."

"What were you doing on the night of July the Fourth?"

"I was—" I swallowed. "I was riding the roller coaster."

I think somebody snickered.

"Can you show us?"

"Yes," I said cautiously.

I began to adjust the dials. Again the amusement park flickered over the ground glass, as seen through my eyes. I was in line. I put my money on the counter to buy a ticket. I saw a slim white hand reach up to the window from my left and I started to turn. Then it hit me!

That gorgeous blonde! That girl who had thrown her arms around me in the car a minute later. That was Swanberg's wife.

I looked around at them in the court-room. I knew what was happening on the screen. I hadn't looked at her face until she got into the car after me. Mrs. Swanberg was leaning over, now, watching the screen. One arm was slipped through the landlord's elbow and she was surreptitiously but affectionately patting the back of his hand. Swanberg himself looked completely blissful. What had she been out there alone for, that night? Well, no telling. Maybe he'd been out of town and she'd felt like doing something childish. Certainly there was no meanness or deceit in her face. She was in love with him. And he, in spite of all his austerity, was obviously in love with her.

I looked out the window. There was no doubt that the fame of the Brain-Finder by now would be all over town. Within a week we'd be flooded with work—high-priced work. We'd take only the very best cases, the highest priced, the least messy. We'd pay the rent. We'd eat in restaurants instead of carrying sandwiches. In another three months we'd be rolling in money—and almost without work. If we wanted to work hard with the Brain-Finder, we'd make millions. I could maybe find myself the right kind of girl to marry.

I looked back at the screen. I had just settled myself in the seat of the roller-coaster car. A pink dress came into my field of vision on the right. Yes, sir, this demonstration would do it. This, and those to follow. Whatever Judge Monday might say, there would be an appeal, and we'd have to take the thing to the Supreme Court, and how could any judge ignore it if Slim could show the judge himself working on his pet corn the night before? We were about to be what is vulgarly but happily known as "in the bucks."

What would happen to Swanberg? I remembered how I'd always pictured his wife as unattractive, and all of a sudden it made me feel kind of ashamed. He had certainly shown good taste in his choice of a wife.

Well, pretty quick now I could afford to travel in that kind of company.

I wondered what would happen when Swanberg saw his wife throwing her arms around me on the roller coaster. I guessed maybe he wouldn't be cold; he'd be jealous. Well, a man with a young and beautiful wife—somehow it kind of got me. I mean that sort of calf-like happiness. He loved her and he felt secure in the knowledge that she loved him, and—well, you know how it is.

Gosh, how I wanted that money. Here it was within our reach—the thing we'd worked so hard for, the reason I'd crawled under pullman cars and gone through the sidewalk and sneaked in to evade the landlord—all so Slim could keep working on the Brain-Finder. He had it now. Slim didn't know how to duplicate it, but one was all we needed. That one was worth a fortune.

I looked back at the Swanbergs, sitting there so close together. Swanberg hadn't really been tough with us. In fact, he'd been lenient. Three months was a lot to be behind. No, I guess the only thing I hadn't really liked about him was the fact that he was always so perfectly dressed and so cool while I had to go through the sidewalk on a hot day in August and then press the sweat out of my clothes with a flat-iron.

I looked at the girl. She was nice. She hadn't been doing anything out of the way that night. She certainly hadn't made any sort of pass at me. And they were in love.

I guess I had no business being an investigator. I looked at the judge, watching every move with his sharp old eyes. I glanced at Slim Coleman, sitting there, looking a little puzzled, his eyes deep and burning. I tried to ask Slim to forgive me. I looked at the screen. The roller-coaster car was pulling up to the top of the first hump.

I took hold of the Brain-Finder. It was heavy, but I picked it up and held it over my head, then I heaved it onto the floor, and it was nothing but a mass of loose wires and broken glass.

A woman screamed. Youngquist fainted. Slim came running with a question in his deep eyes. Tom Ellingbery's lawyer was triumphant. The judge pounded for order....

This is four days later. Tom Ellingbery and his wife made up. Last night's paper showed them on the roller coaster. He was quoted as saying: "All I wanted was to ride the roller coaster." And she had said: "Boys will be boys."

Slim brings me four ham sandwiches and coffee twice a day. He got acquainted with the blonde that Tom Ellingbery was riding the roller coasters with, and they went out to the park and had five dollars worth of rides the night that Tom Ellingbery paid Slim the five G's. (Tom said it was worth that much to have his wife back.) And do you know whom Slim and the blonde ran into at the Park? Mr. and Mrs. Swanberg. First thing I ever heard of a man in a tail-coat riding the roller coaster.

In fact, everybody's got a blonde but me, and everybody's riding the roller coaster but me. I'm not riding them now. I got thirty days for contempt of court.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.