The Project Gutenberg eBook of Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park, by Jesse Walter Fewkes

Title: Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park

Spruce-tree house

Author: Jesse Walter Fewkes

Release Date: March 24, 2023 [eBook #70366]

Language: English

Produced by: John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

BULLETIN 41

SPRUCE-TREE HOUSE

BY

JESSE WALTER FEWKES

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

1909

Smithsonian Institution,

Bureau of American Ethnology,

Washington, D. C., January 4, 1909.

Sir: I have the honor to submit herewith for publication, with your approval, as Bulletin 41 of this Bureau, the report of Dr. Jesse Walter Fewkes on the work of excavation and repair of Spruce-tree cliff-ruin in the Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. This was undertaken, pursuant to your instructions, under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, and a résumé of the general results accomplished is published in the latter’s annual report for 1907-8. The present paper is more detailed, and deals with the technical archeological results.

It is gratifying to state that Doctor Fewkes was able to complete the work assigned him, and that Spruce-tree House—the largest ruin in Mesa Verde Park with the exception of the Cliff Palace—is now accessible for the first time, in all its features, to those who would view one of the great aboriginal monuments of our country. This is the more important since Spruce-tree House fulfills the requirements of a “type ruin,” and since, owing to its situation, it is the cliff-dwelling from which most tourists obtain their first impressions of structures of this character.

Respectfully, yours, W. H. Holmes, Chief.

The Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D. C.

| Page | |

| Site of the ruin | 1 |

| Recent history | 2 |

| General features | 7 |

| Major antiquities | 8 |

| Plazas and courts | 8 |

| Construction of walls | 9 |

| Secular rooms | 10 |

| Balconies | 15 |

| Fireplaces | 16 |

| Doors and windows | 16 |

| Floors and roofs | 17 |

| Kivas | 17 |

| Kiva A | 20 |

| Kiva B | 21 |

| Kivas C and D | 21 |

| Kiva E | 22 |

| Kiva F | 22 |

| Kiva G | 23 |

| Kiva H | 23 |

| Circular rooms other than kivas | 23 |

| Ceremonial room other than kiva | 24 |

| Mortuary room | 24 |

| Small ledge-houses | 24 |

| Stairways | 25 |

| Refuse-heaps | 25 |

| Minor antiquities | 25 |

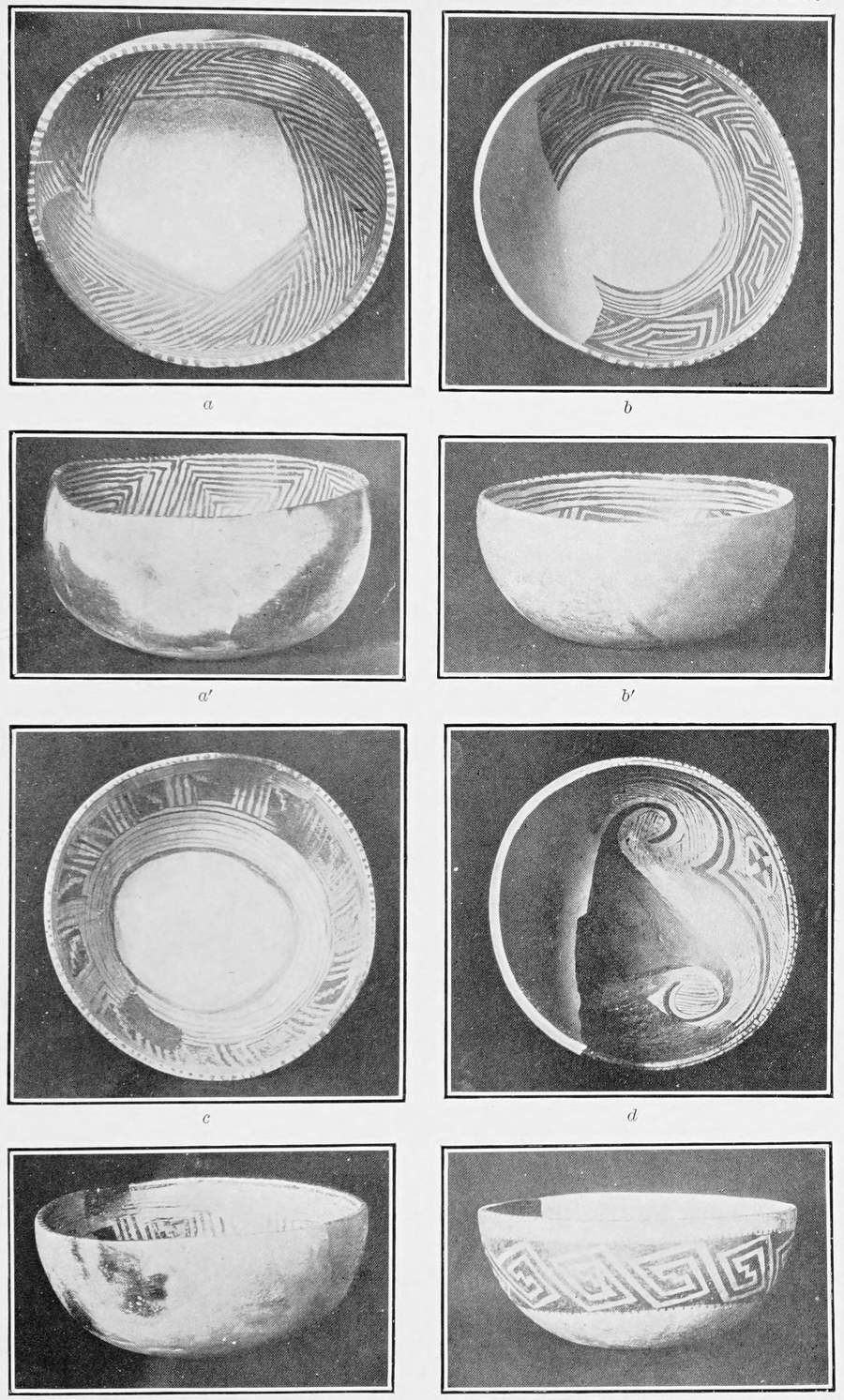

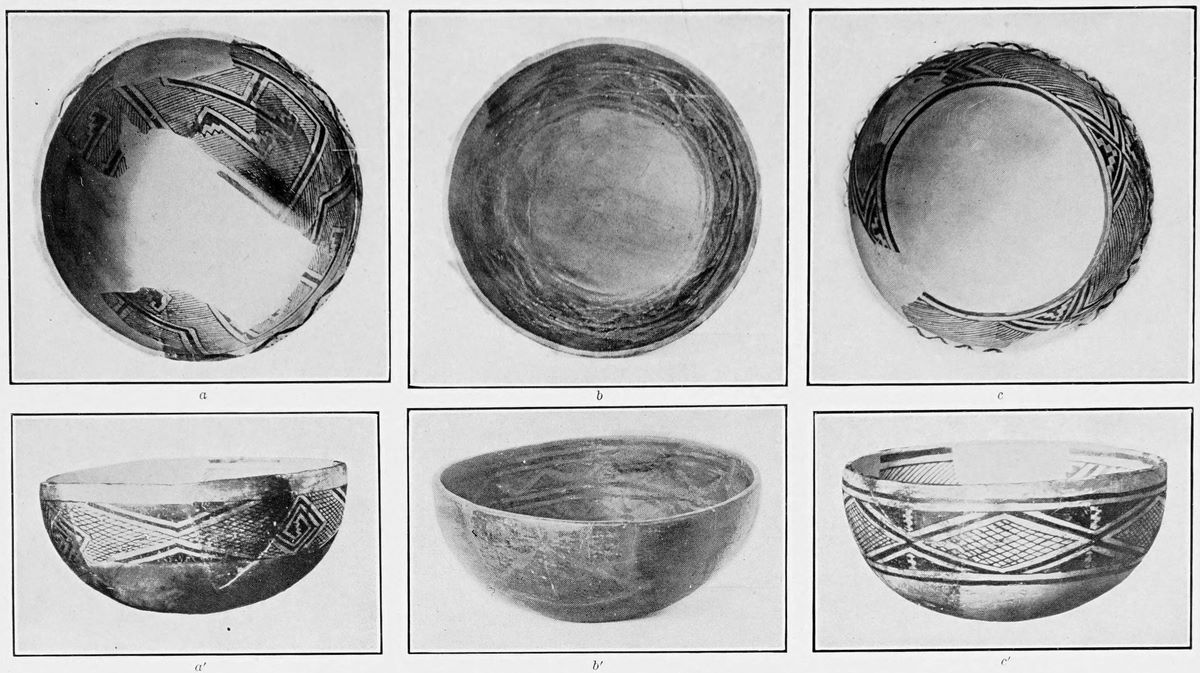

| Pottery | 28 |

| Forms | 29 |

| Structure | 30 |

| Decoration | 32 |

| Ceramic areas | 34 |

| Hopi area | 35 |

| Little Colorado area | 36 |

| Mesa Verde area | 37 |

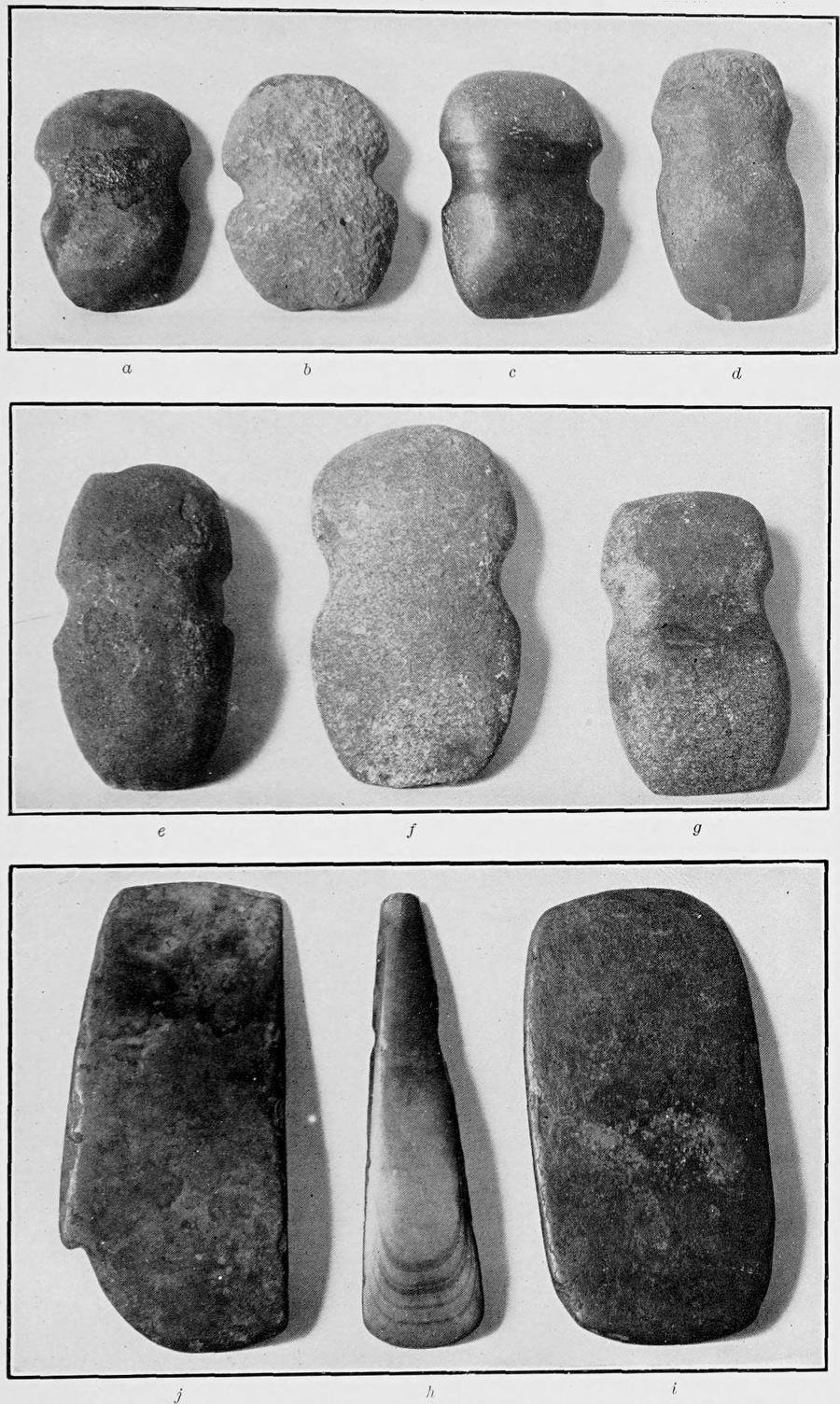

| Stone implements | 38 |

| Axes | 38 |

| Grinding stones | 40 |

| Pounding stones | 41 |

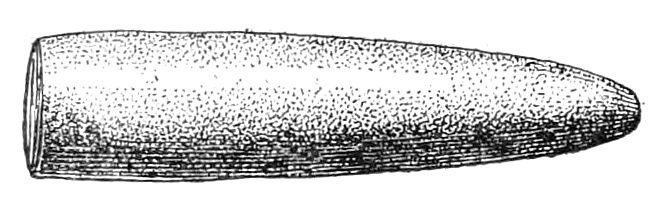

| Cylinder of polished hematite | 41 |

| Basketry | 42 |

| Wooden objects | 42 |

| Sticks tied together | 42 |

| Slabs | 43 |

| Spindles [vi] | 43 |

| Planting-sticks | 44 |

| Miscellaneous objects | 44 |

| Fabrics | 44 |

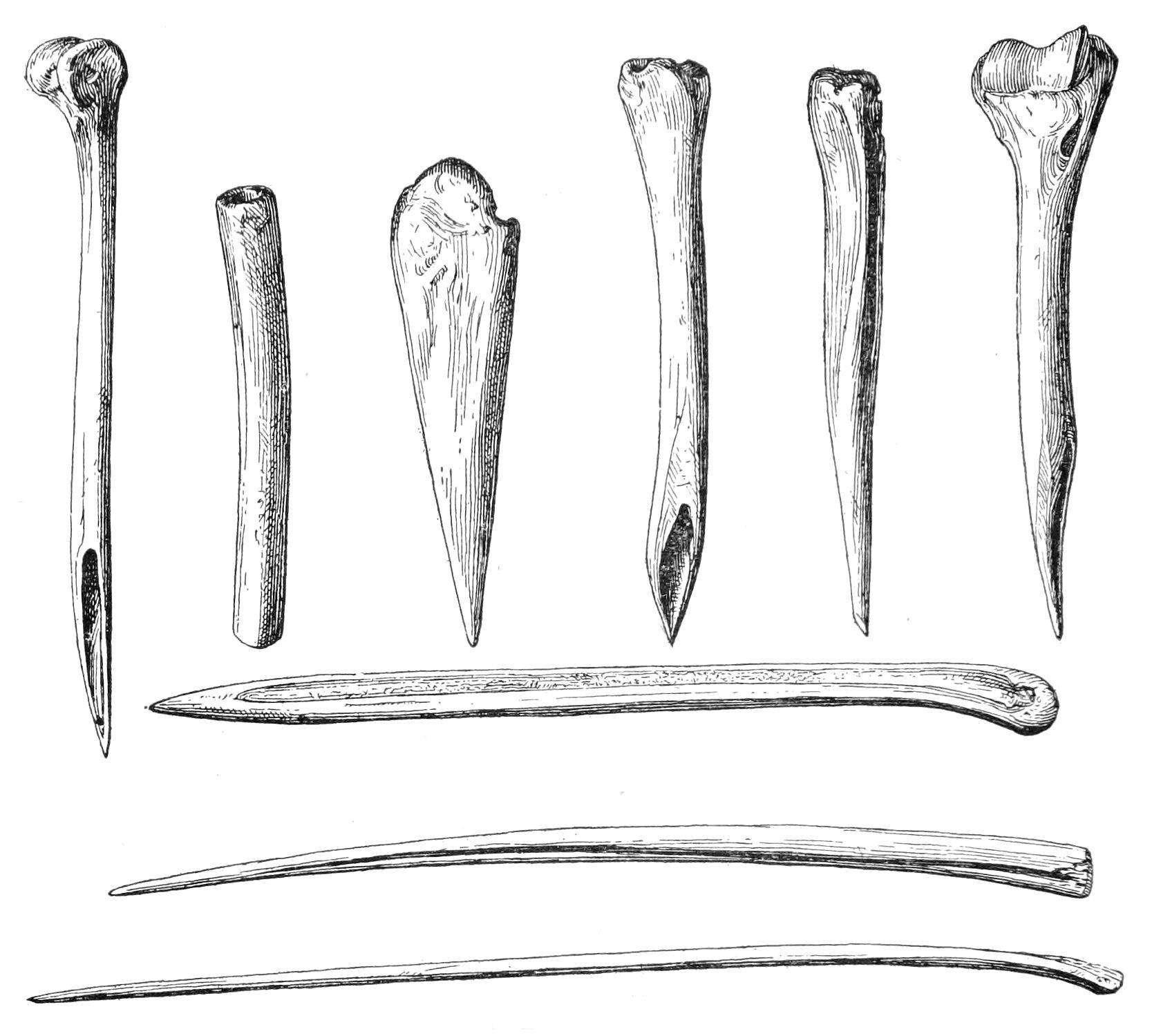

| Bone implements | 48 |

| Fetish | 49 |

| Lignite gorget | 49 |

| Corn, beans, and squash seeds | 50 |

| Hoop-and-pole game | 50 |

| Leather and skin objects | 51 |

| Absence of objects showing European culture | 51 |

| Pictographs | 51 |

| Conclusions | 53 |

| Index | 55 |

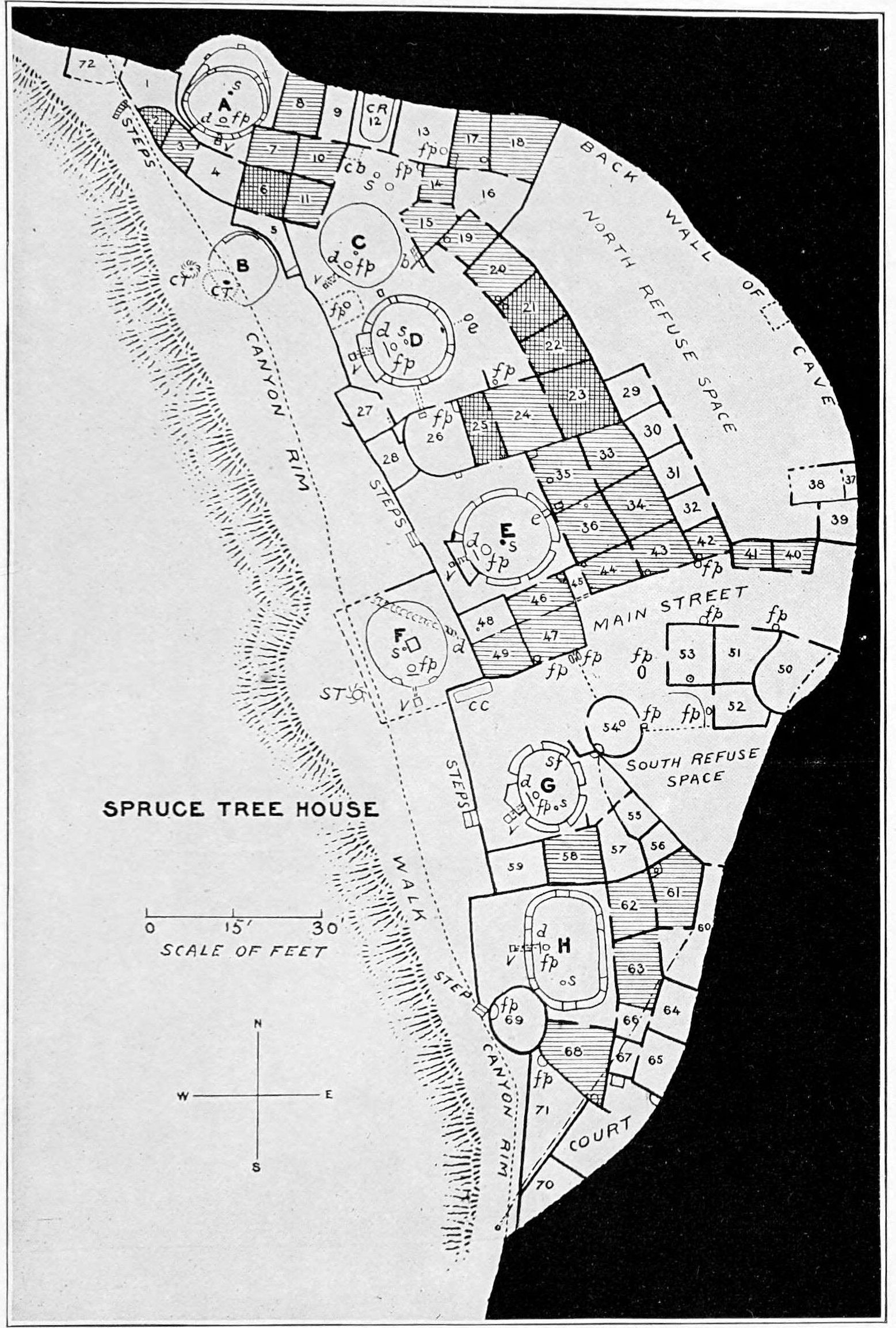

| Plate | 1. Ground-plan of Spruce-tree House. | |

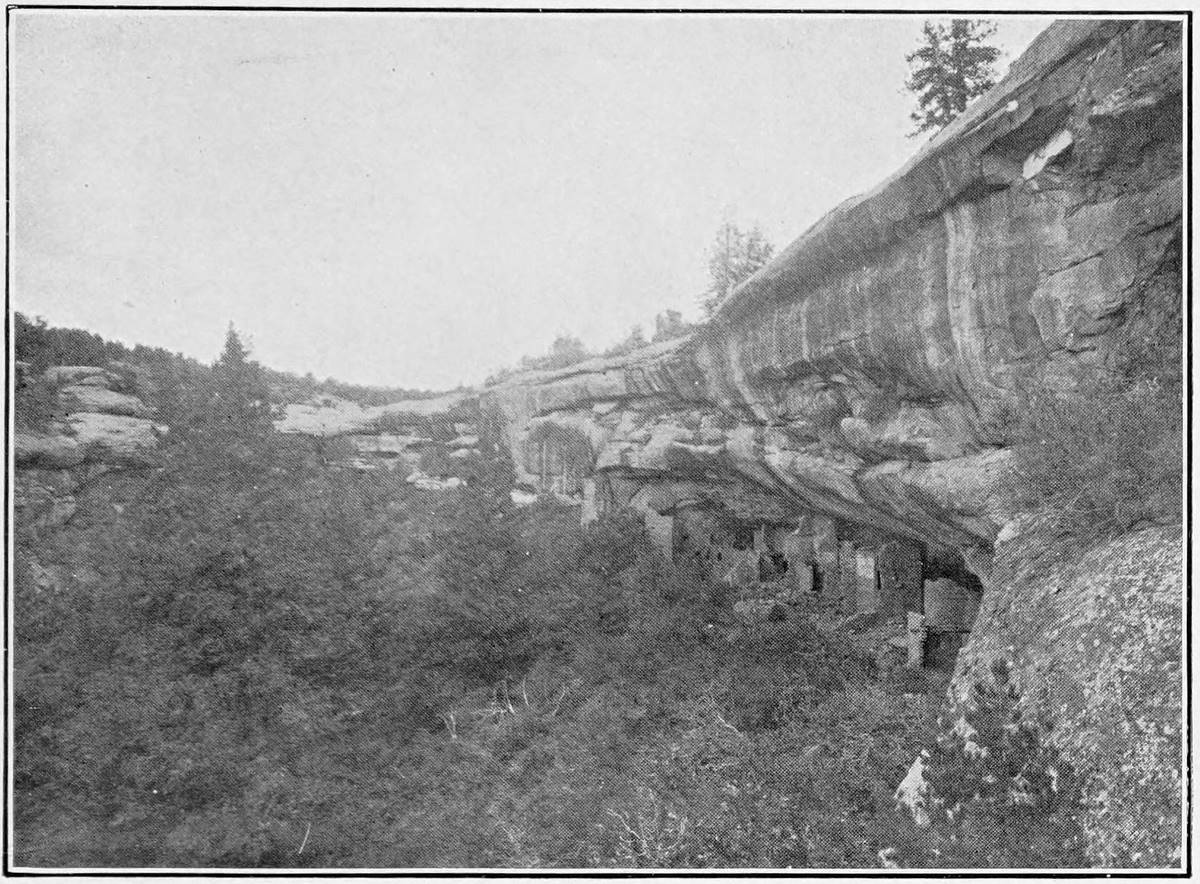

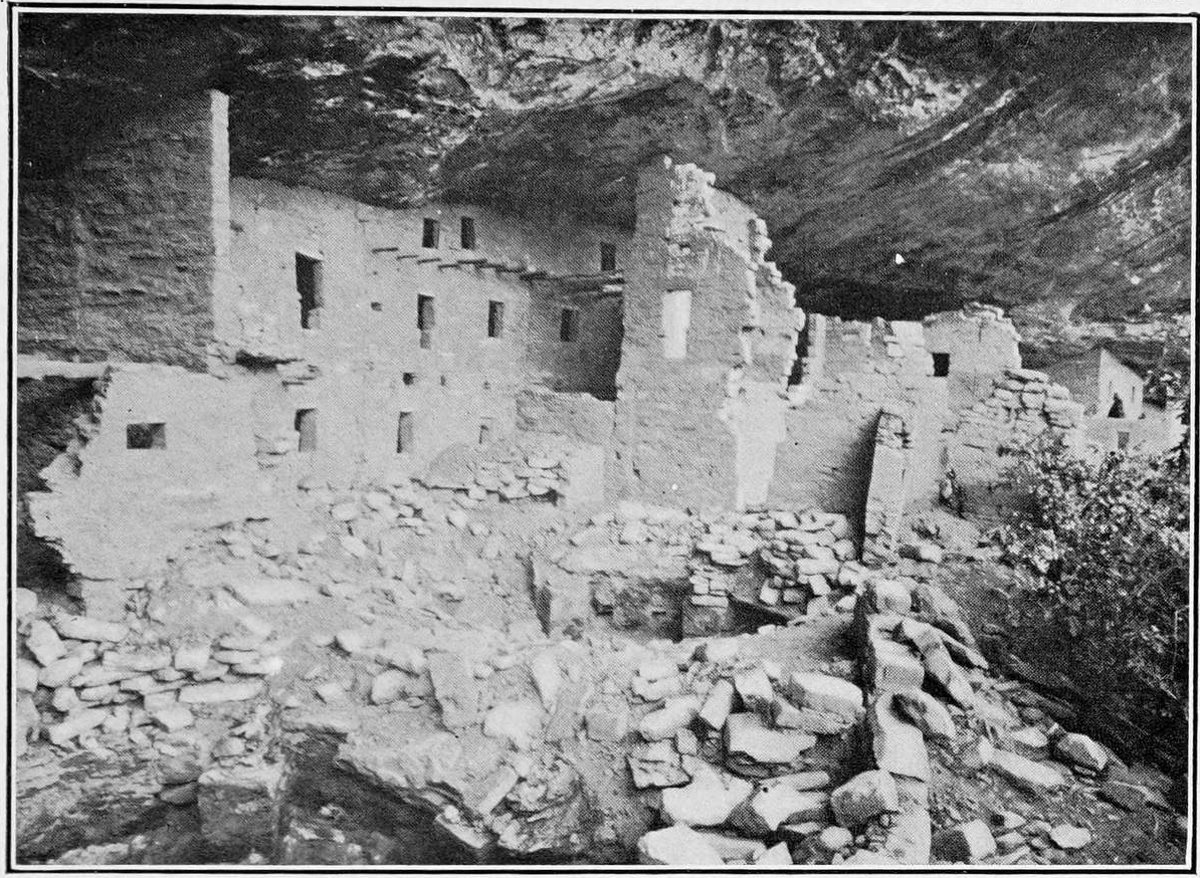

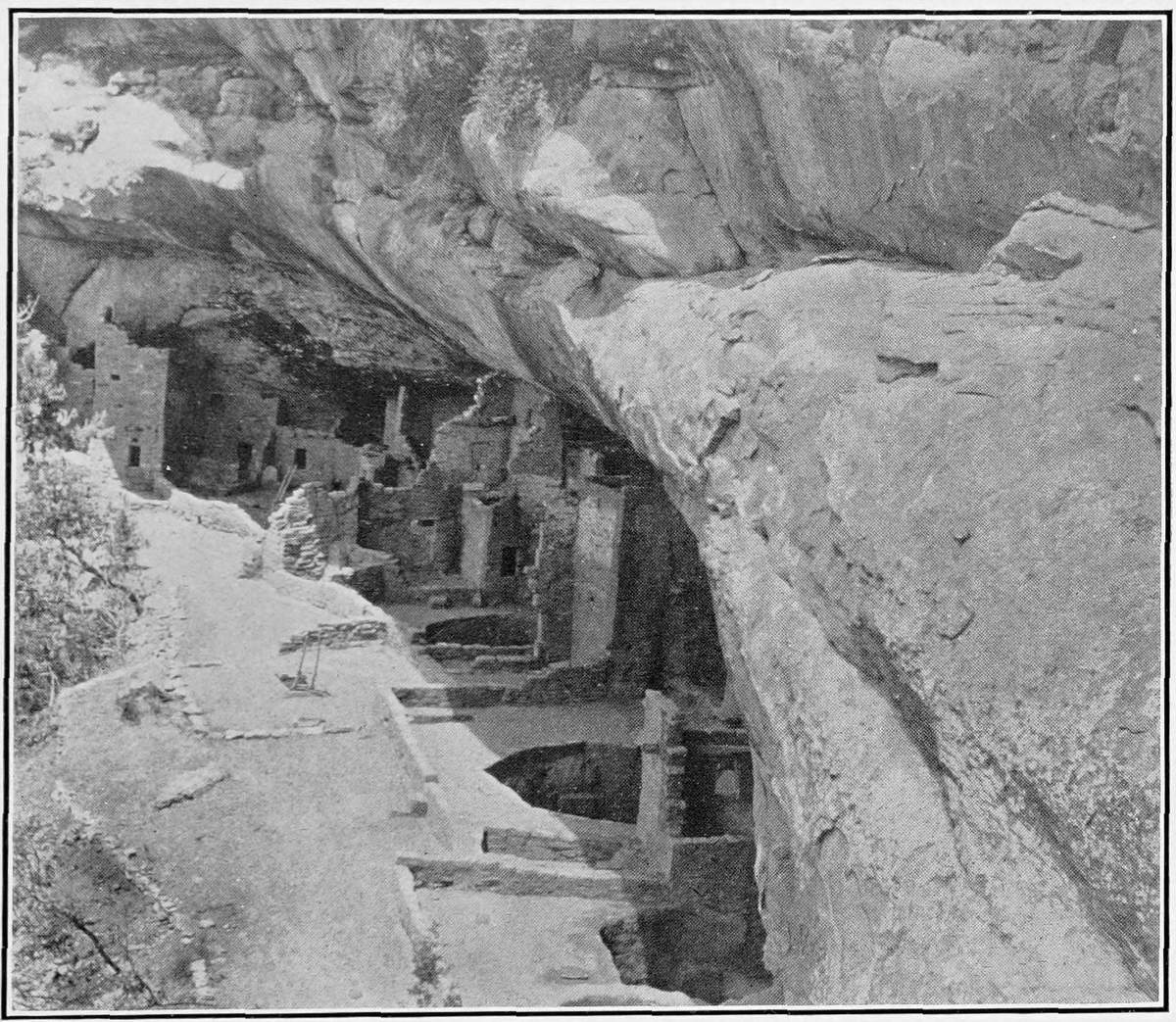

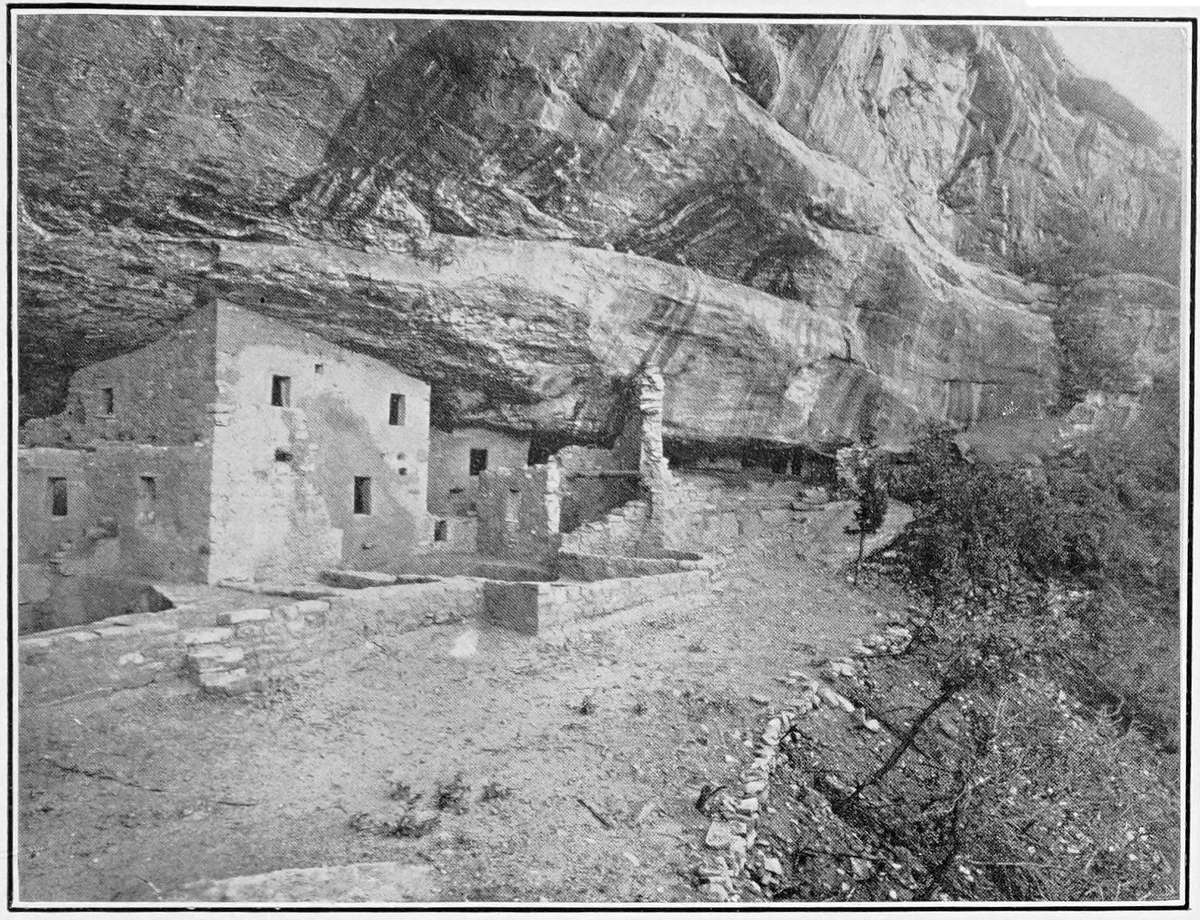

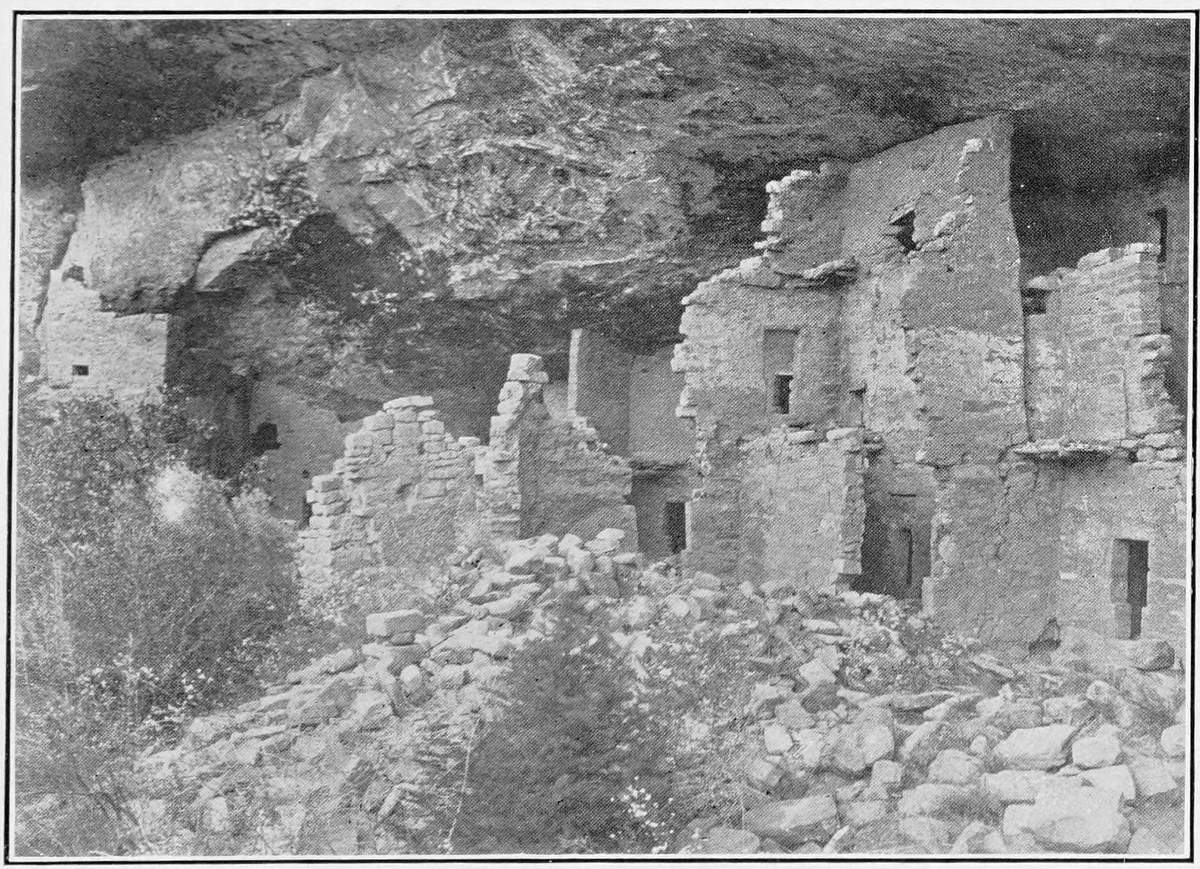

| 2. The ruin, from the northwest and the west. | ||

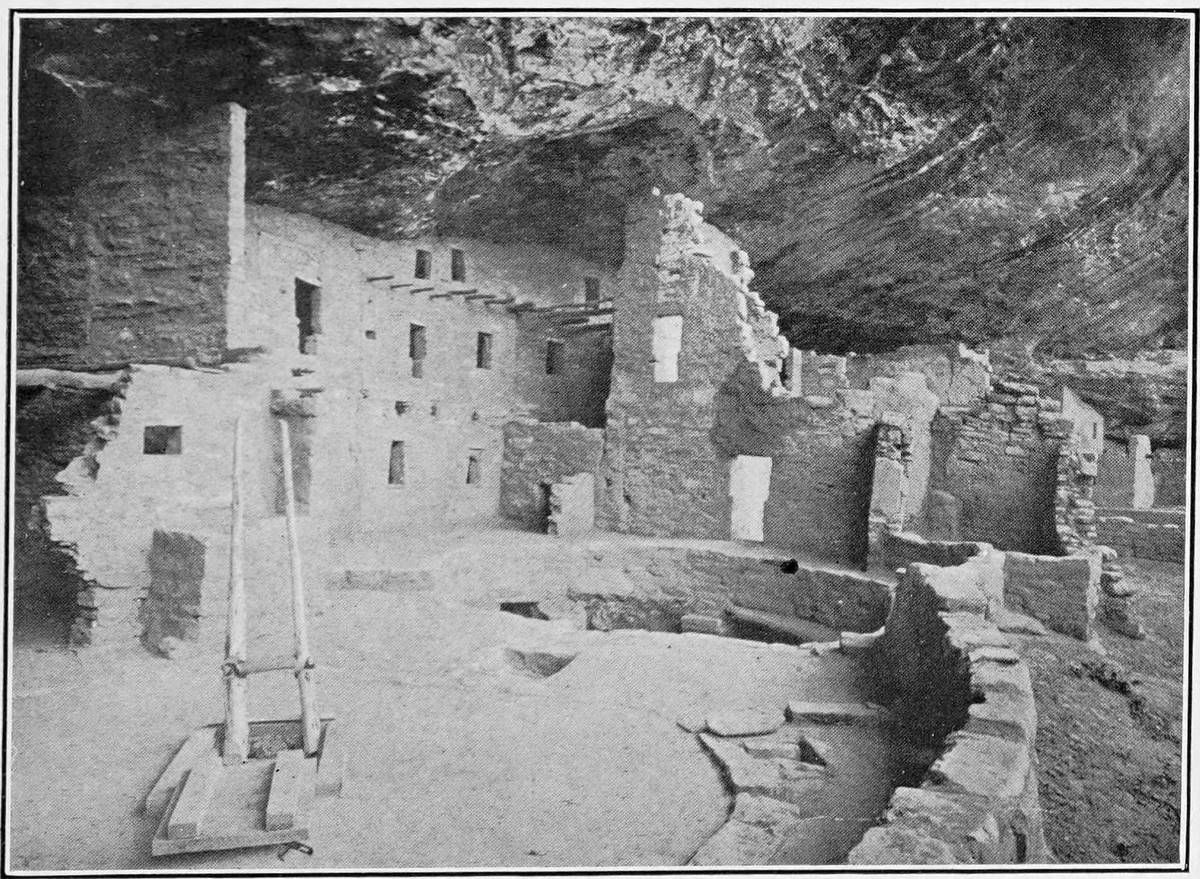

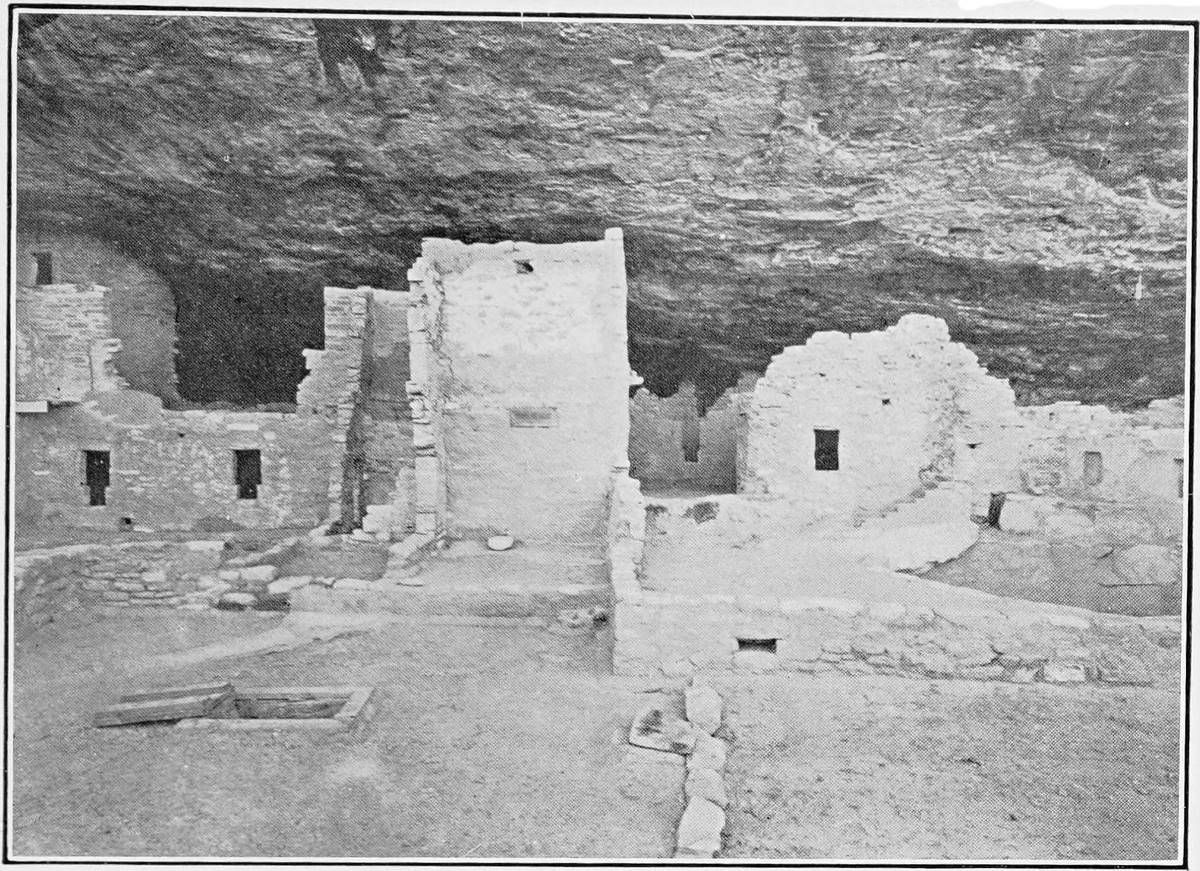

| 3. Plaza D. | ||

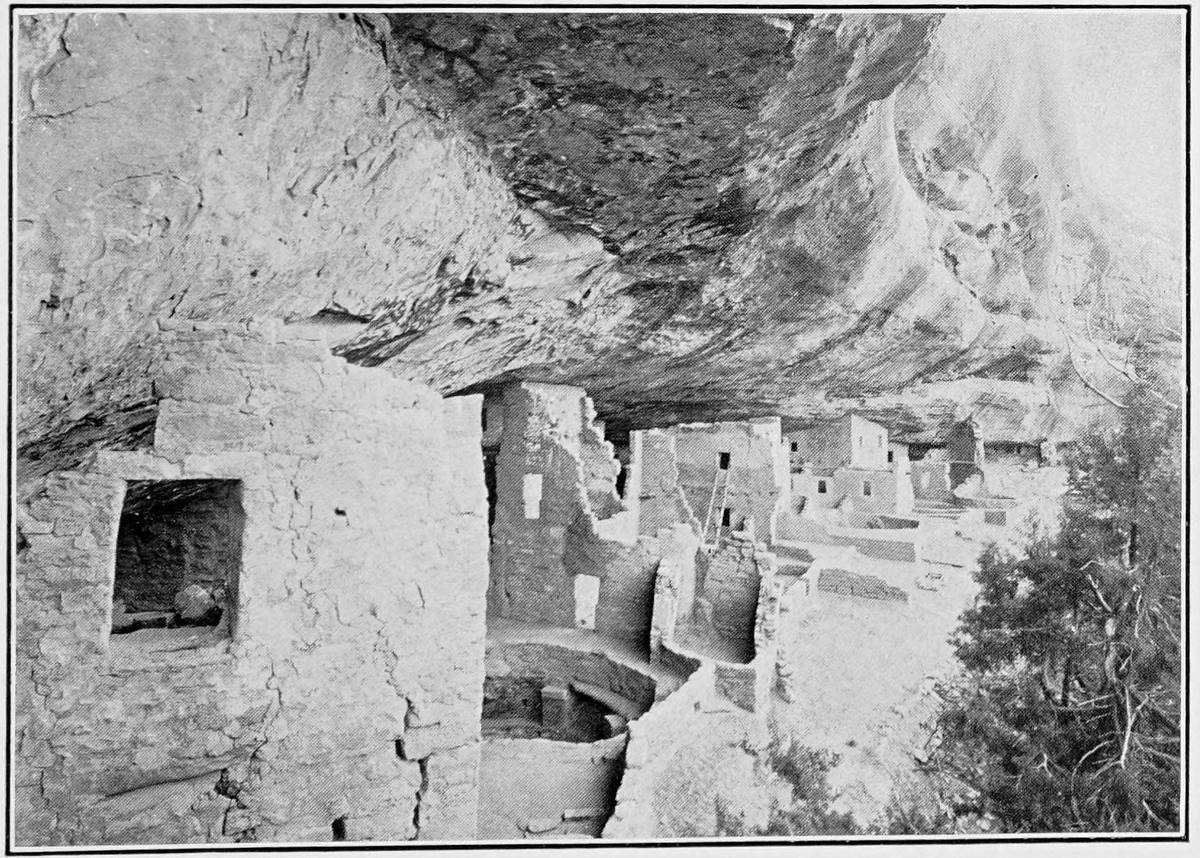

| 4. The ruin, from the south end. | ||

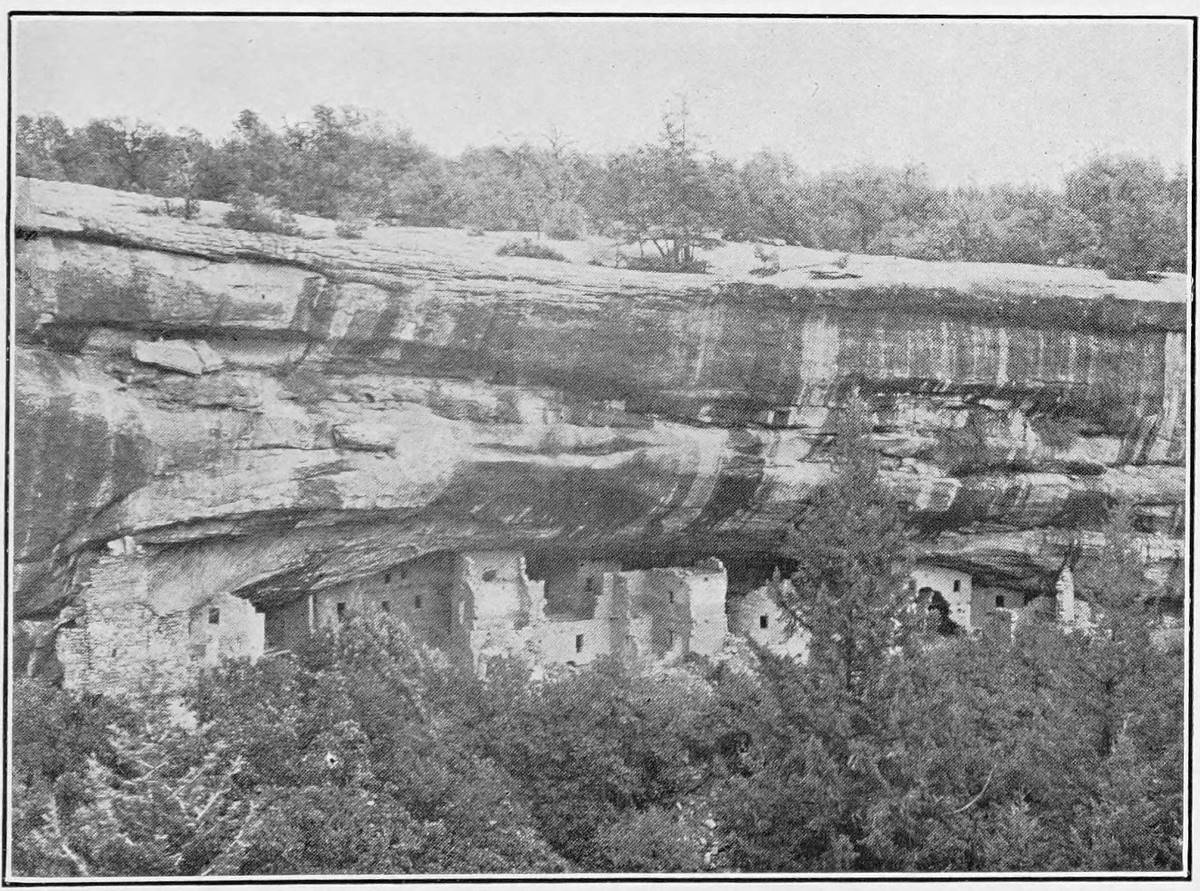

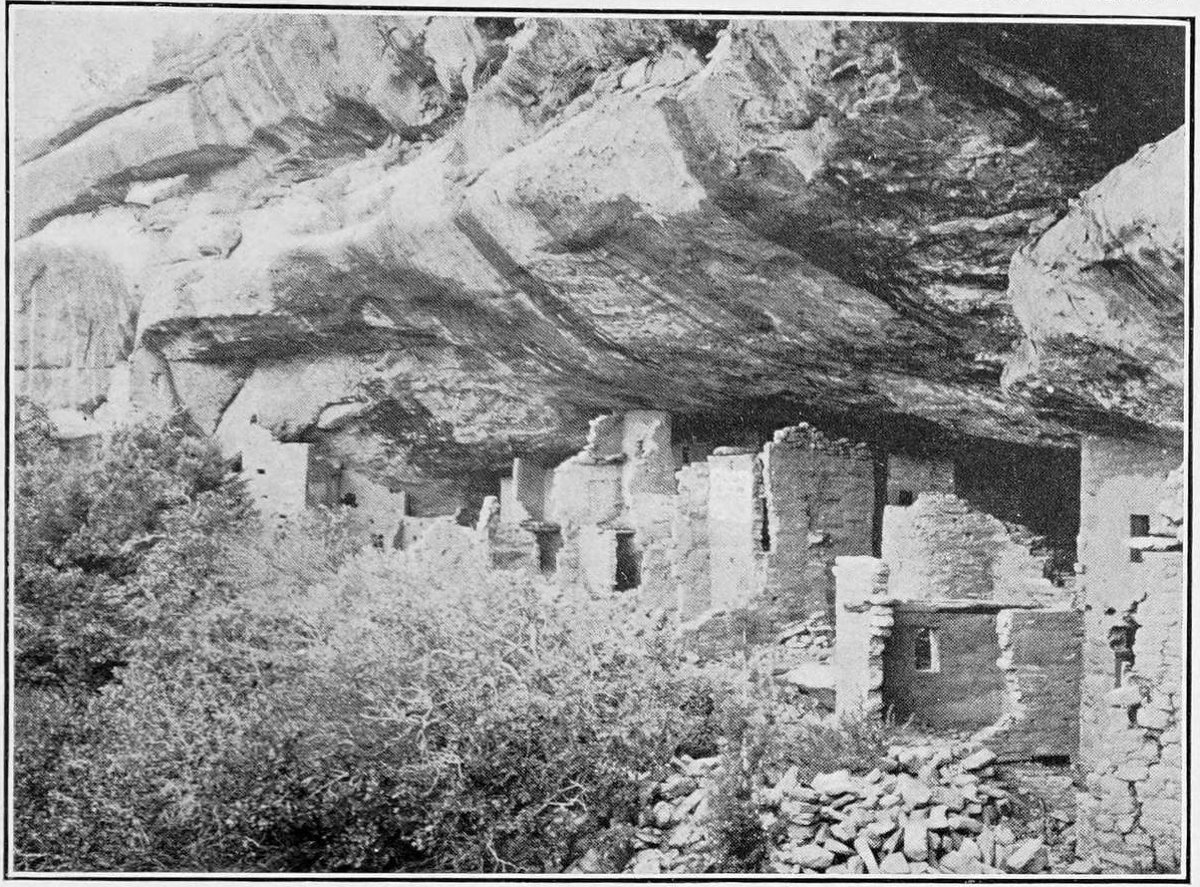

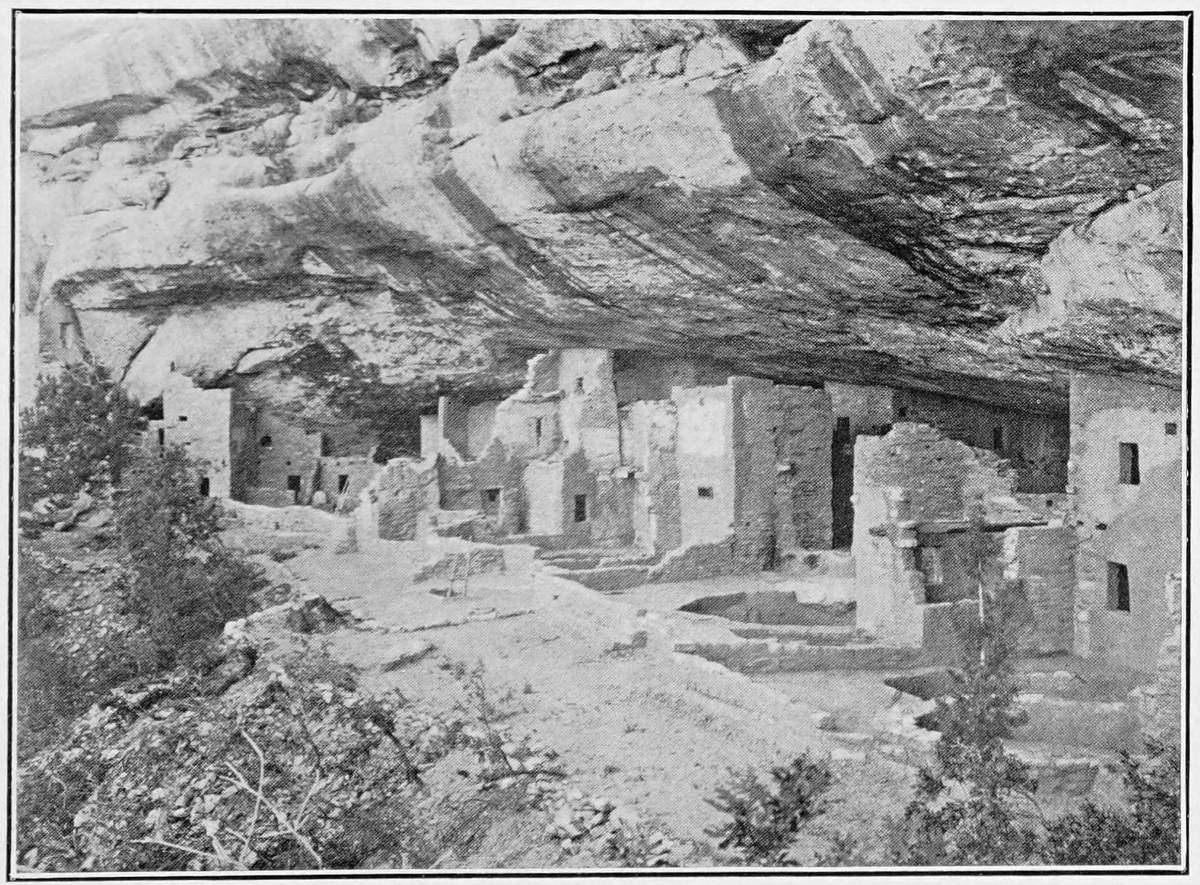

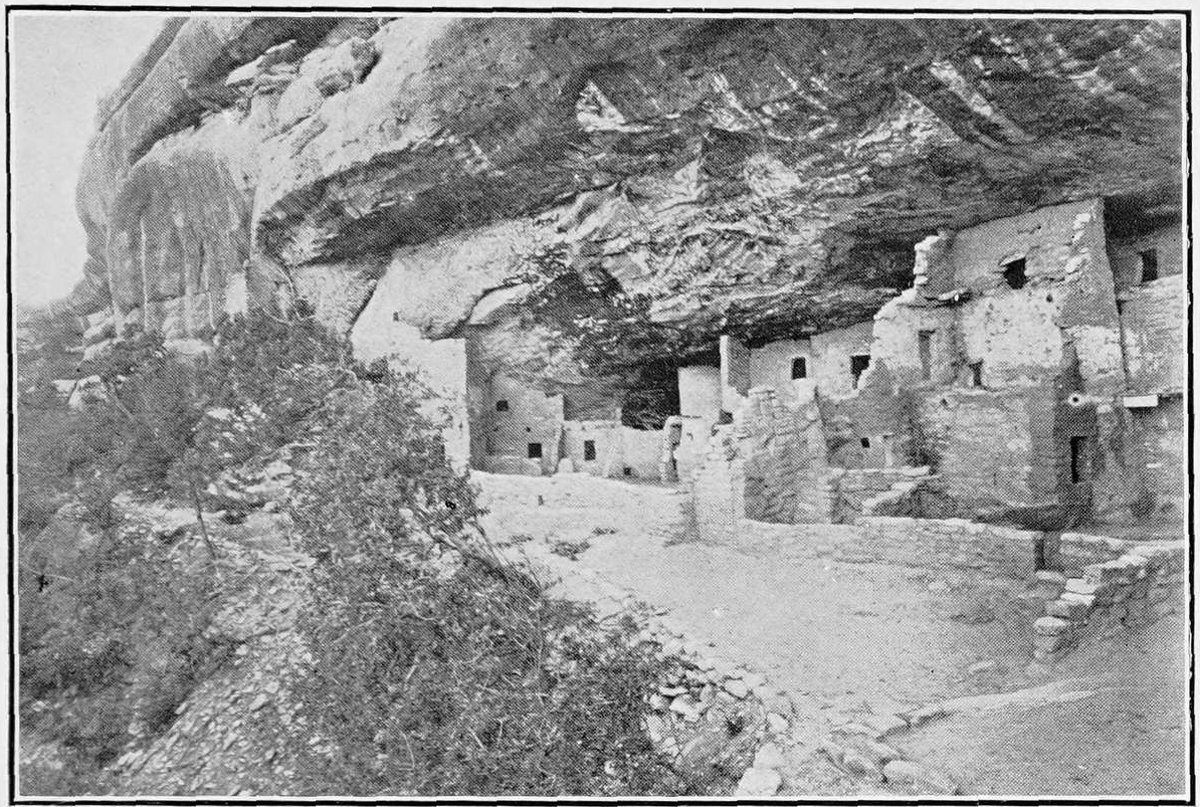

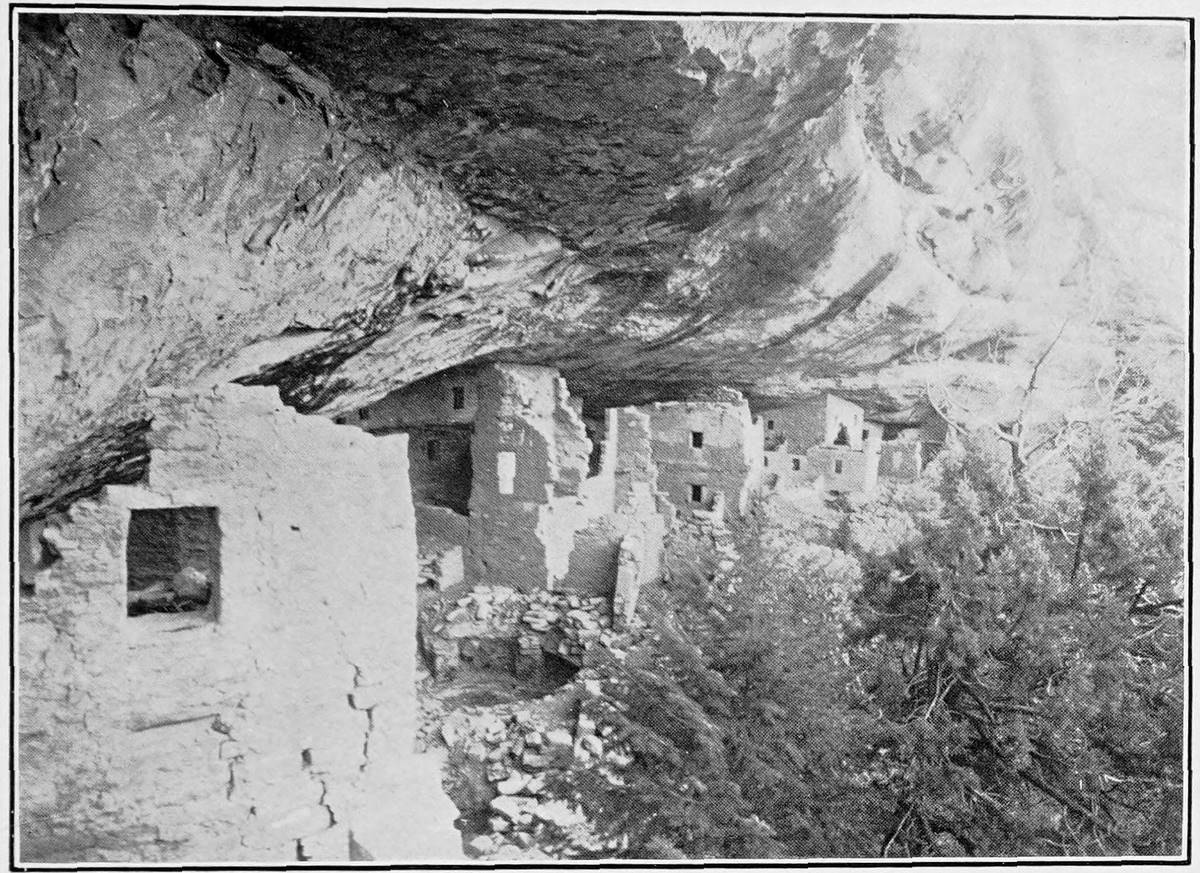

| 5. The ruin, from the south. | ||

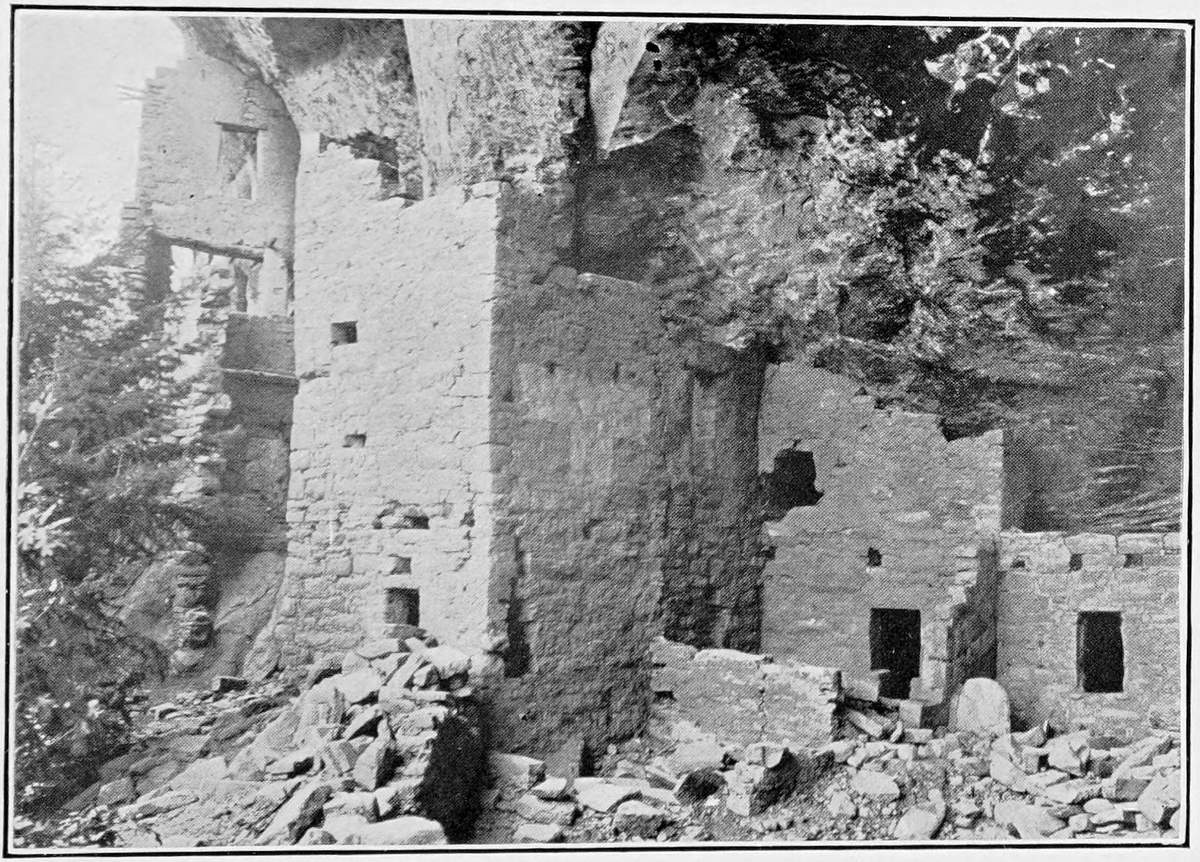

| 6. Rooms 11-24. | ||

| 7. The ruin, from the north end. | ||

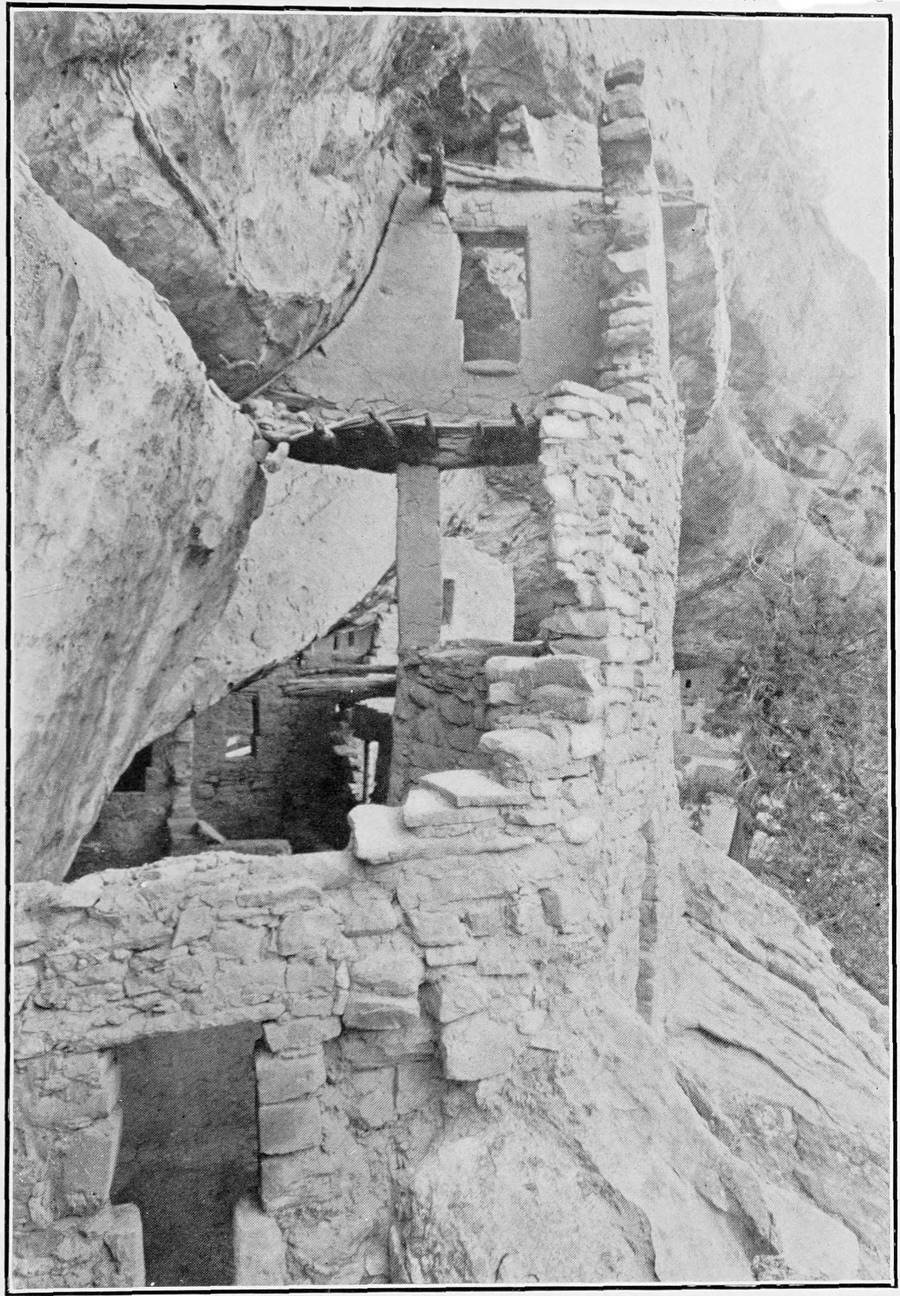

| 8. North end of the ruin, showing masonry pillar. | ||

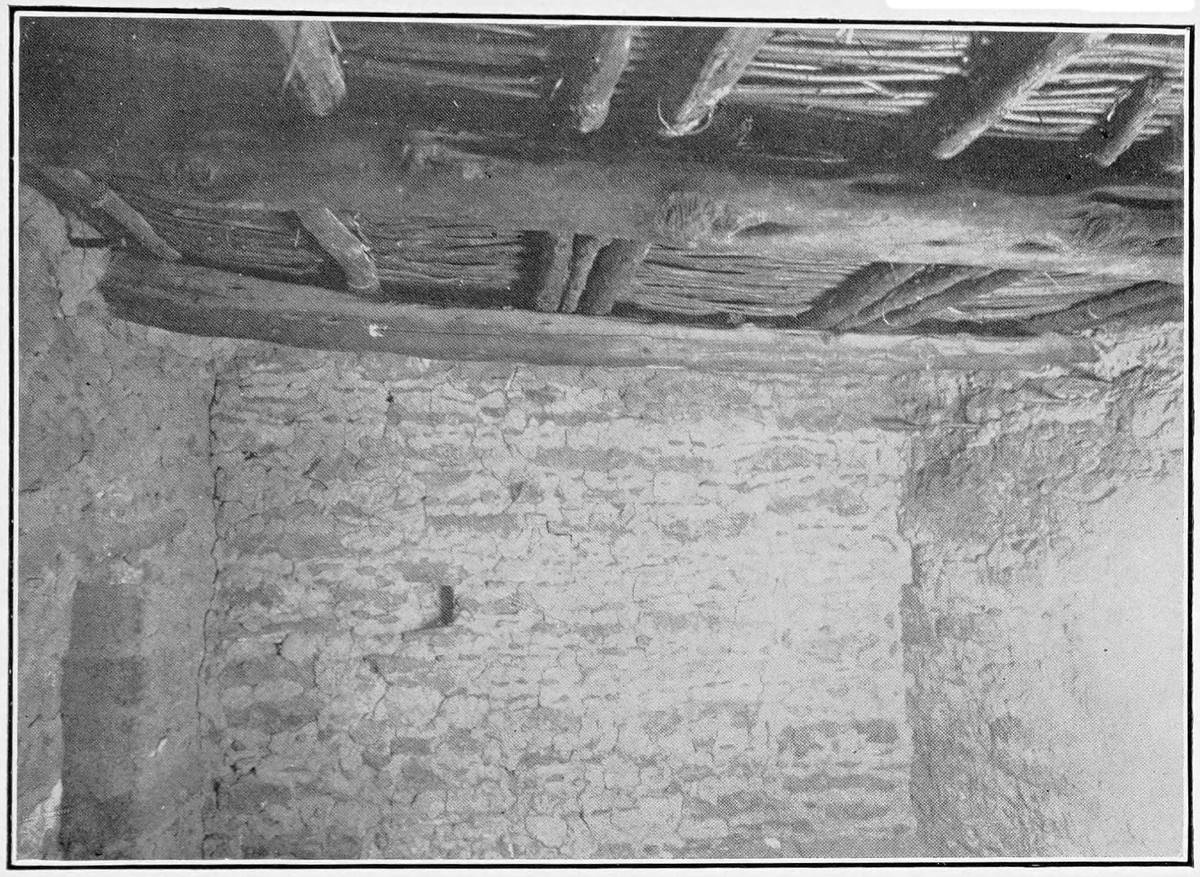

| 9. A roof and a street. | ||

| 10. The ruin from the south end, showing rooms and plaza. | ||

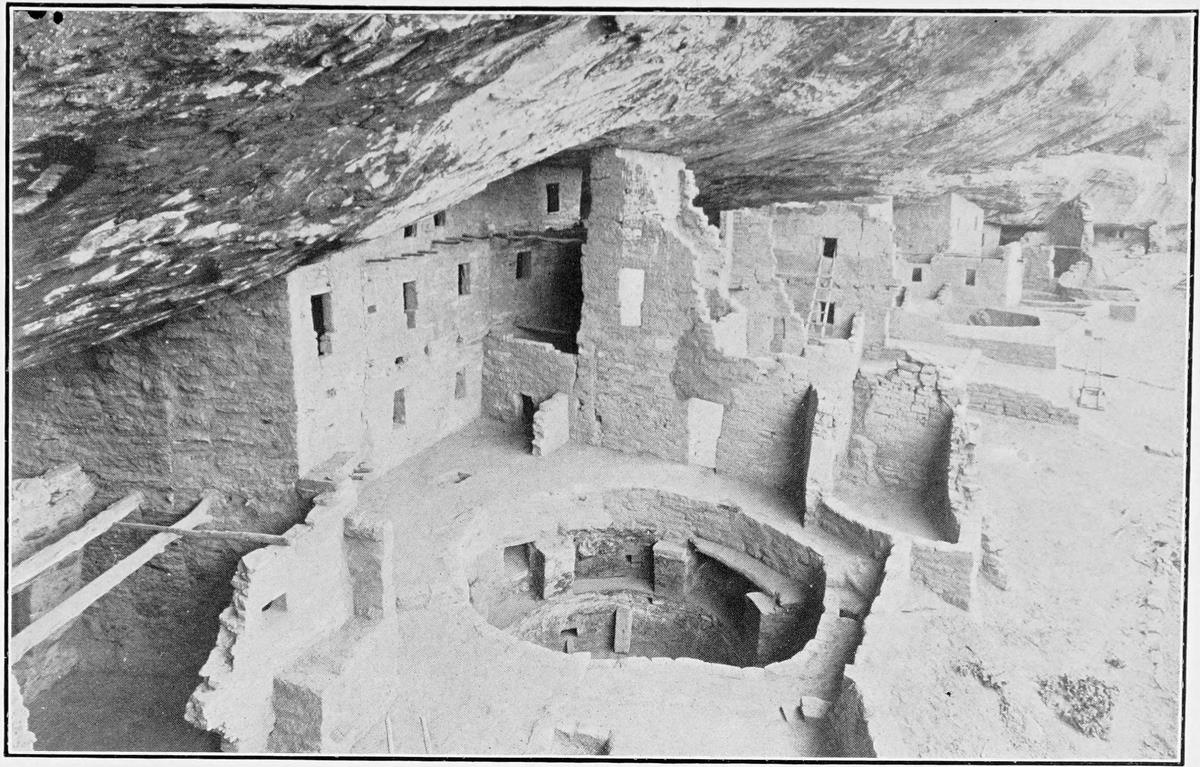

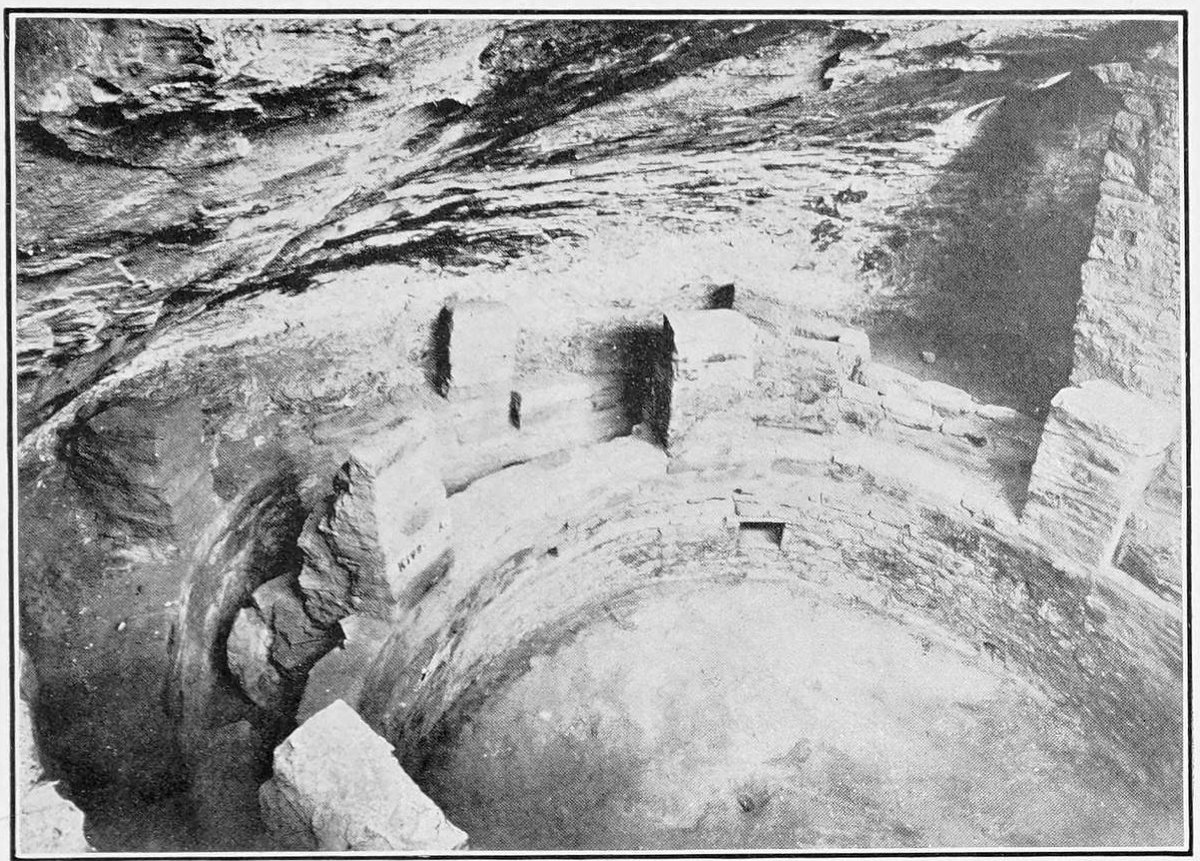

| 11. Kiva D. | ||

| 12. Kiva D, from the north. | ||

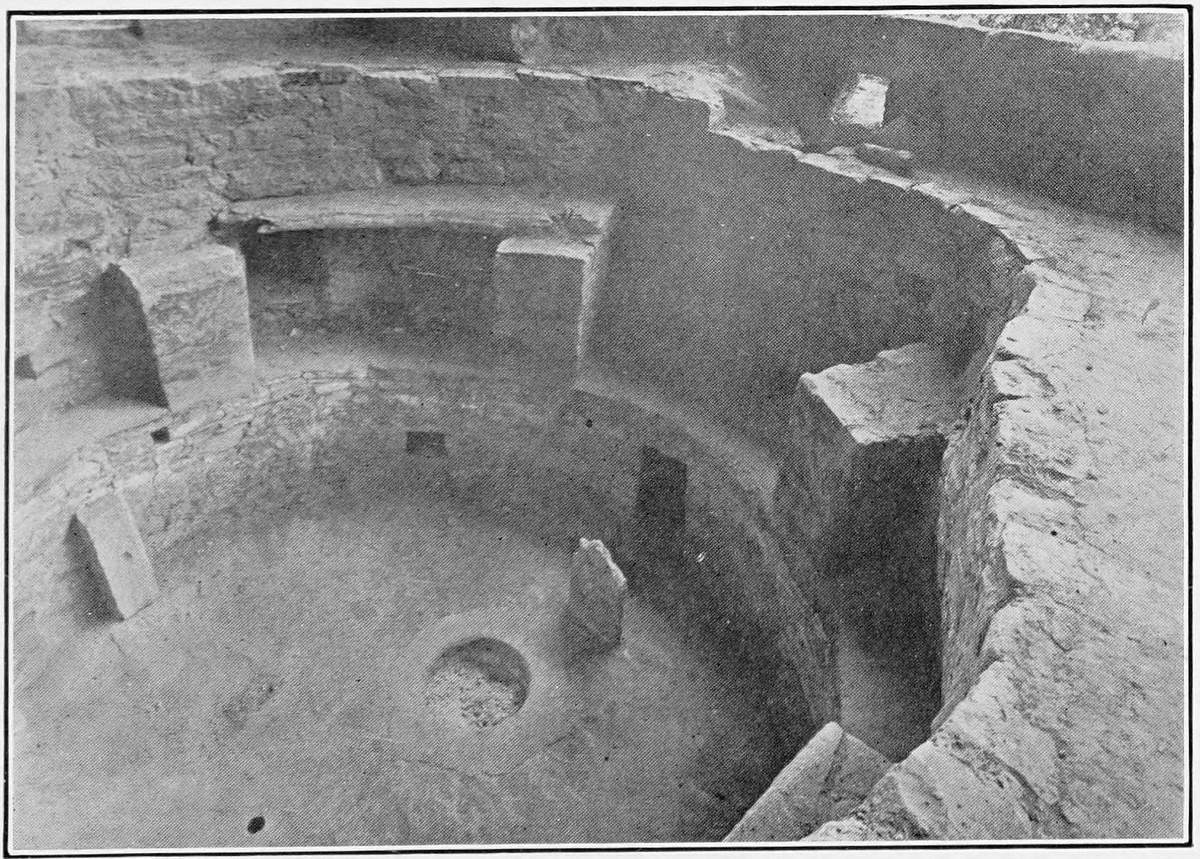

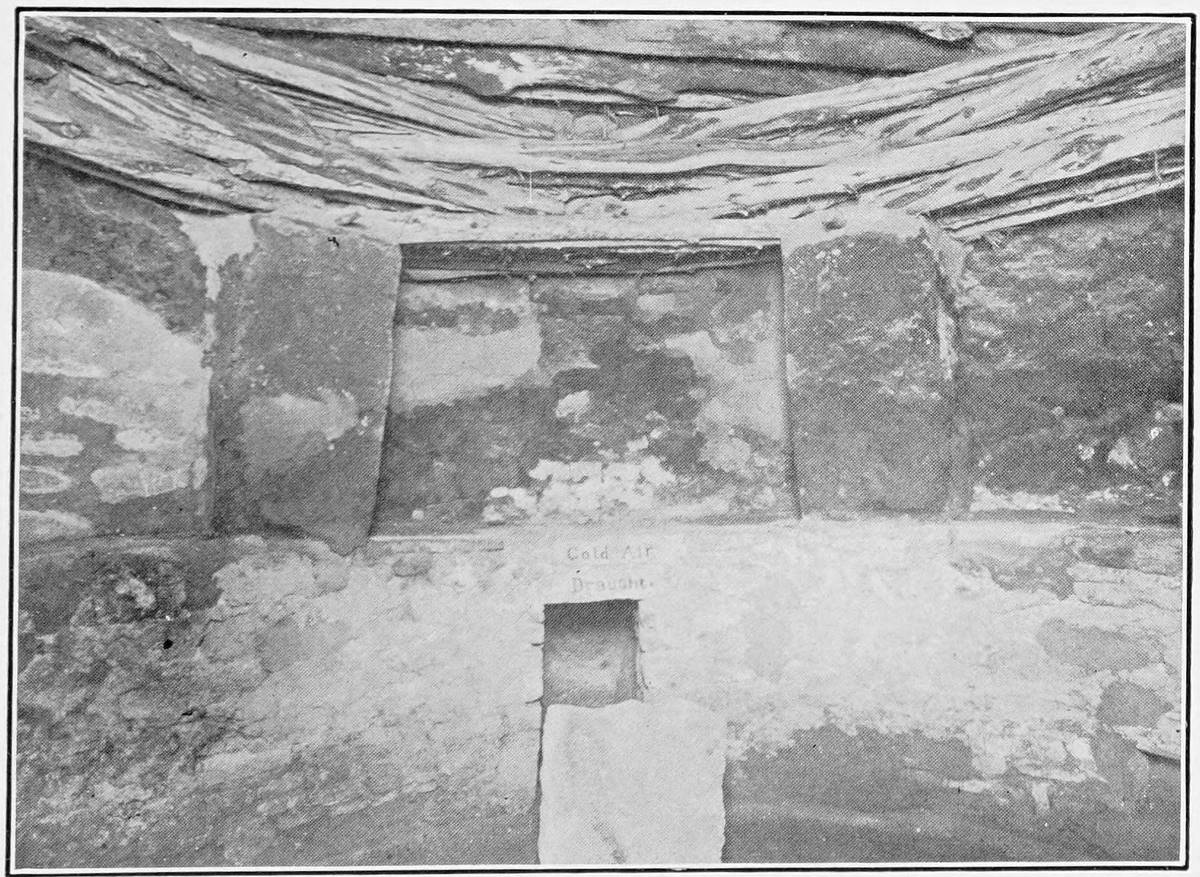

| 13. Interiors of two kivas. | ||

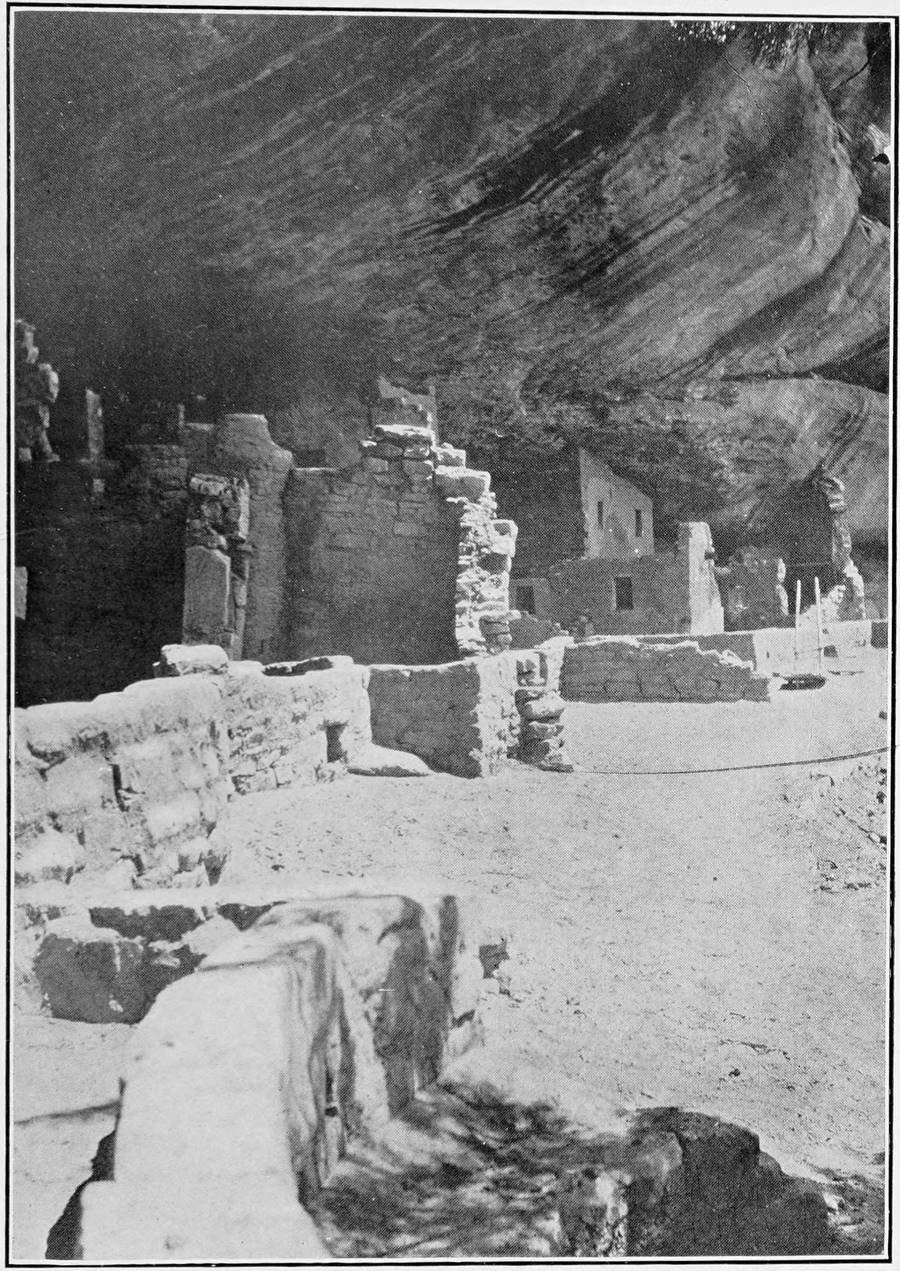

| 14. Central part of ruin, and kiva. | ||

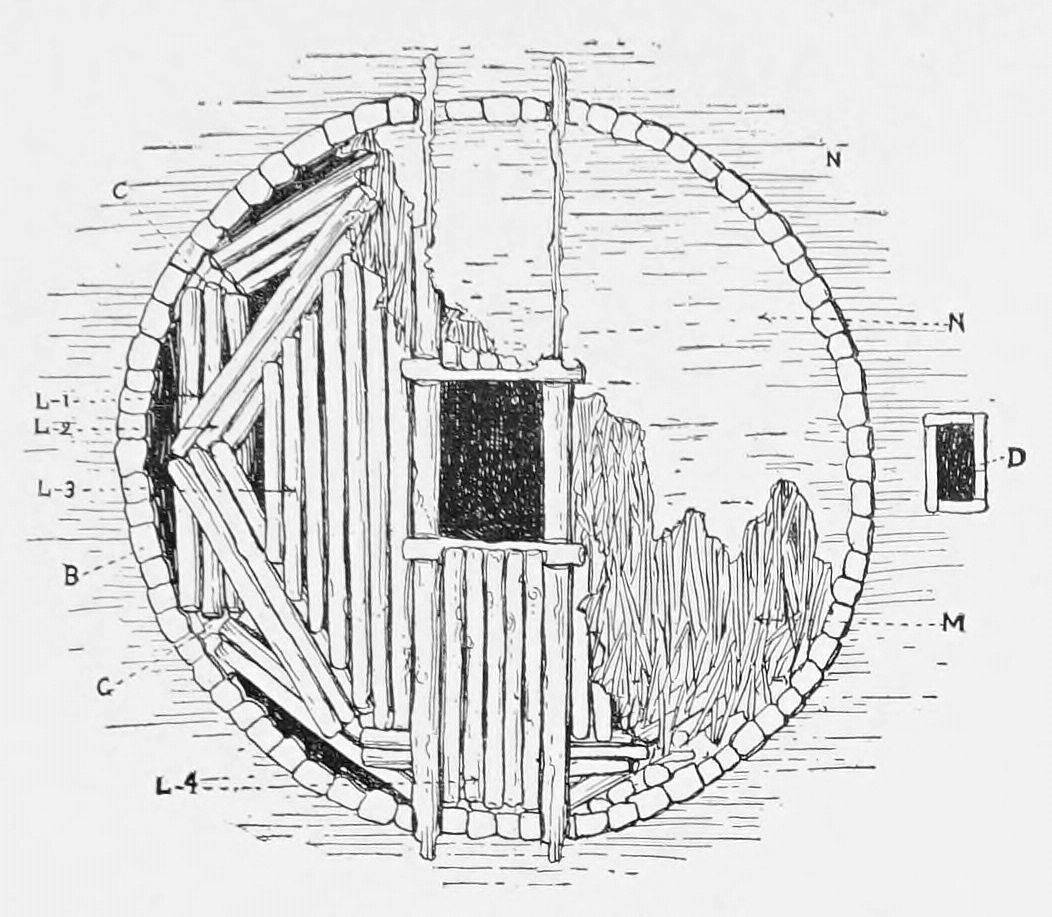

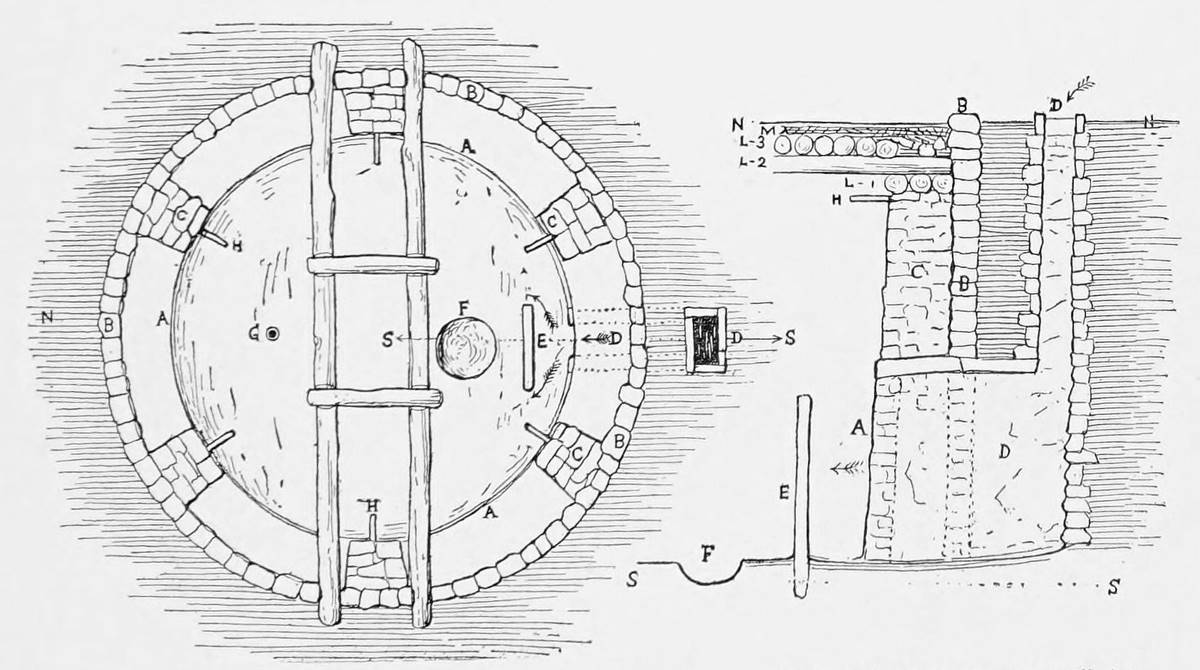

| 15. Diagrams of kiva, showing construction. | ||

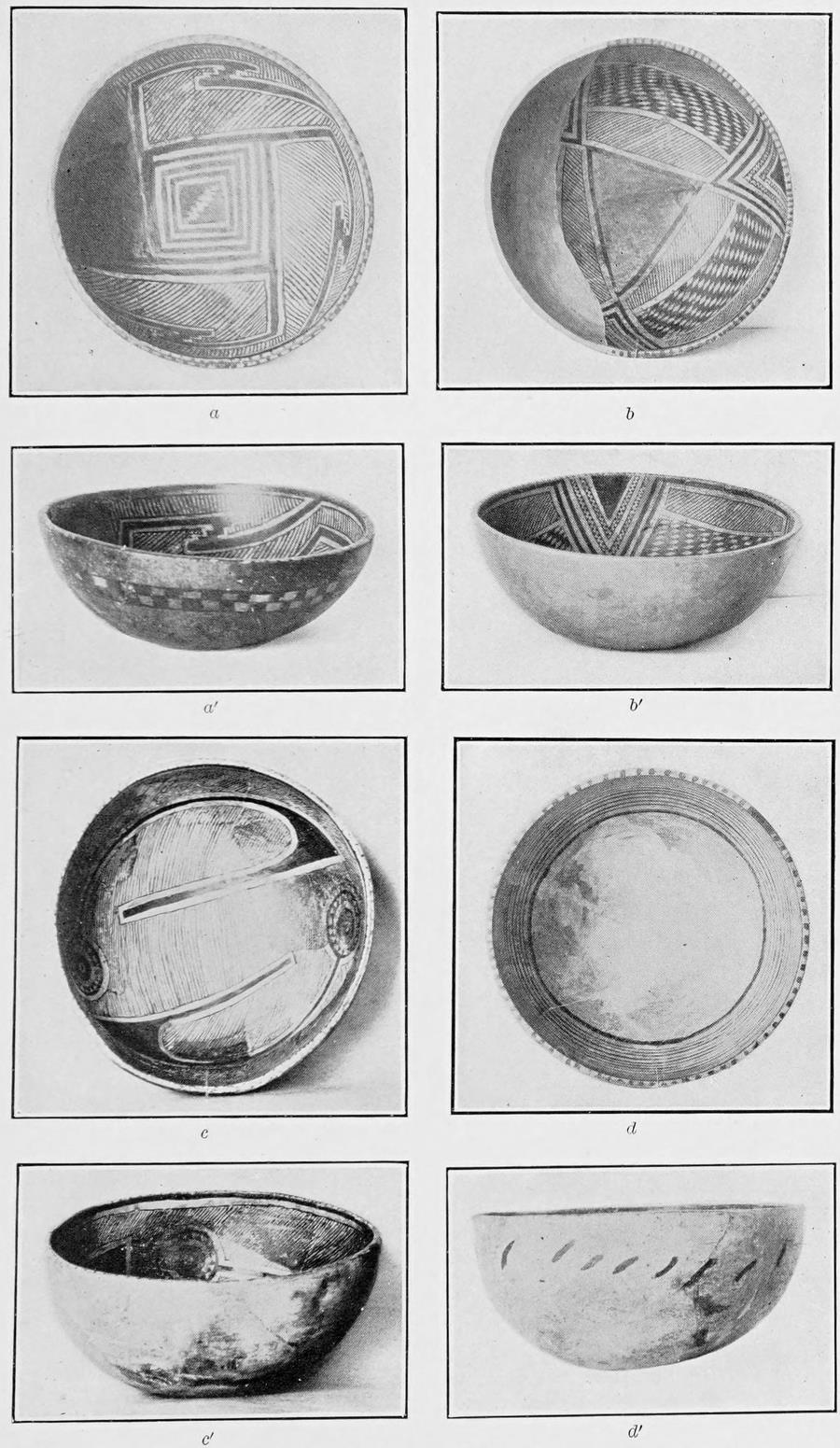

| 16. Decorated food-bowls. | ||

| 17. Decorated food-bowls. | ||

| 18. Decorated food-bowls. | ||

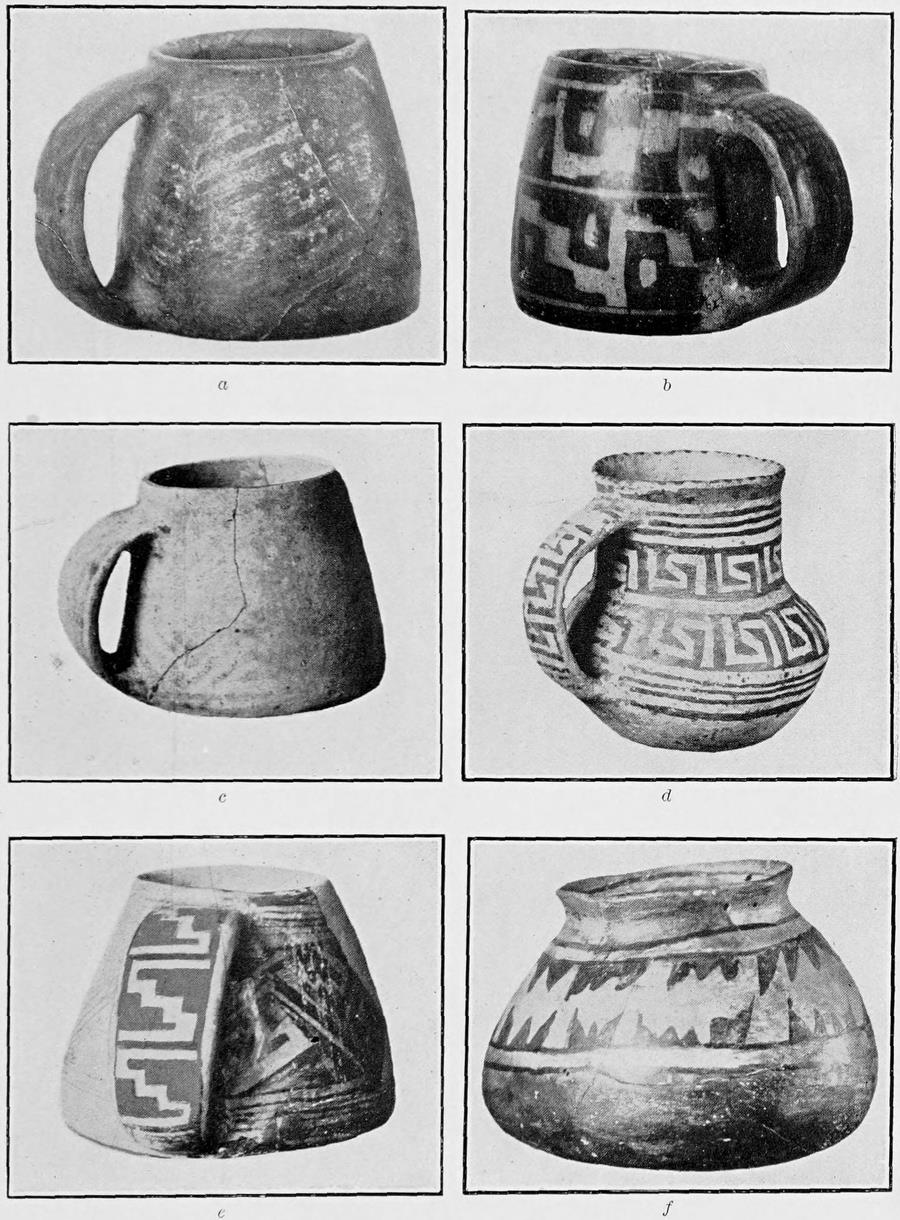

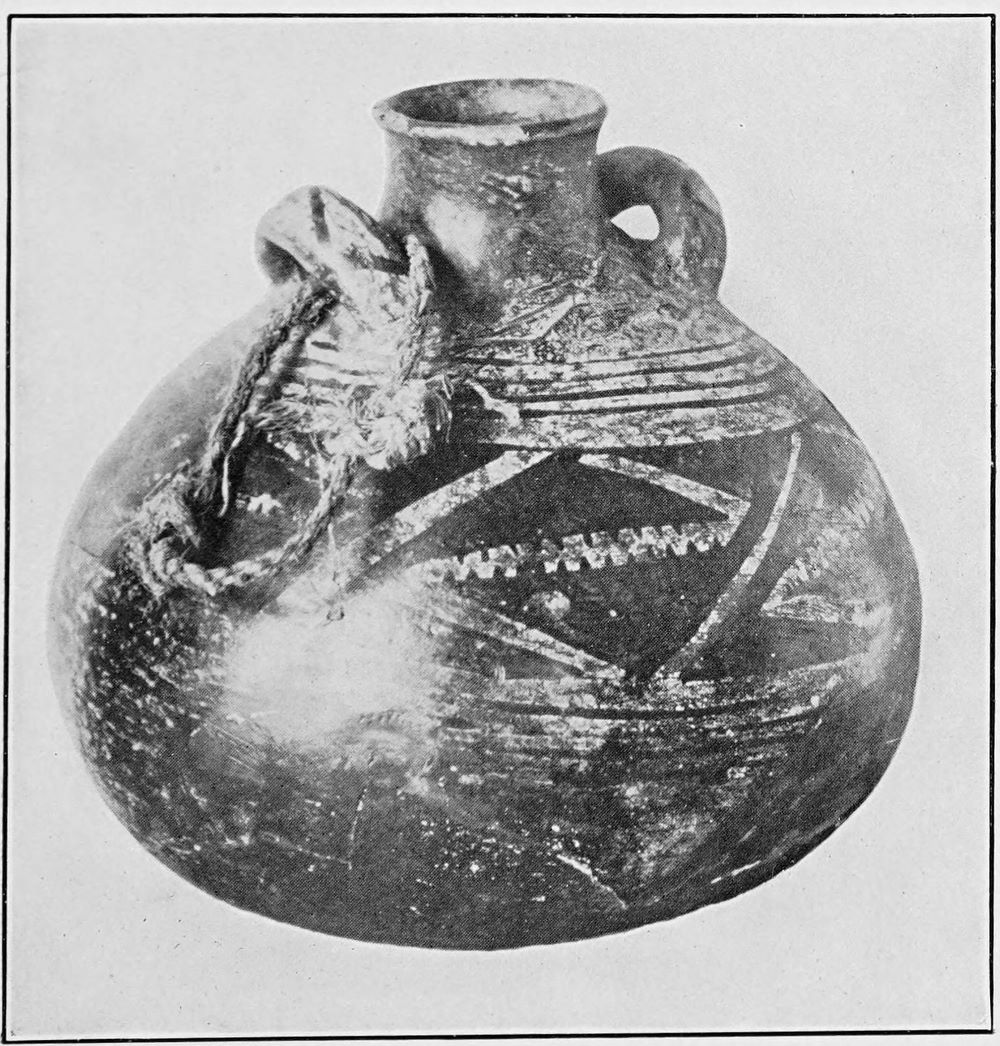

| 19. Decorated vase and mugs. | ||

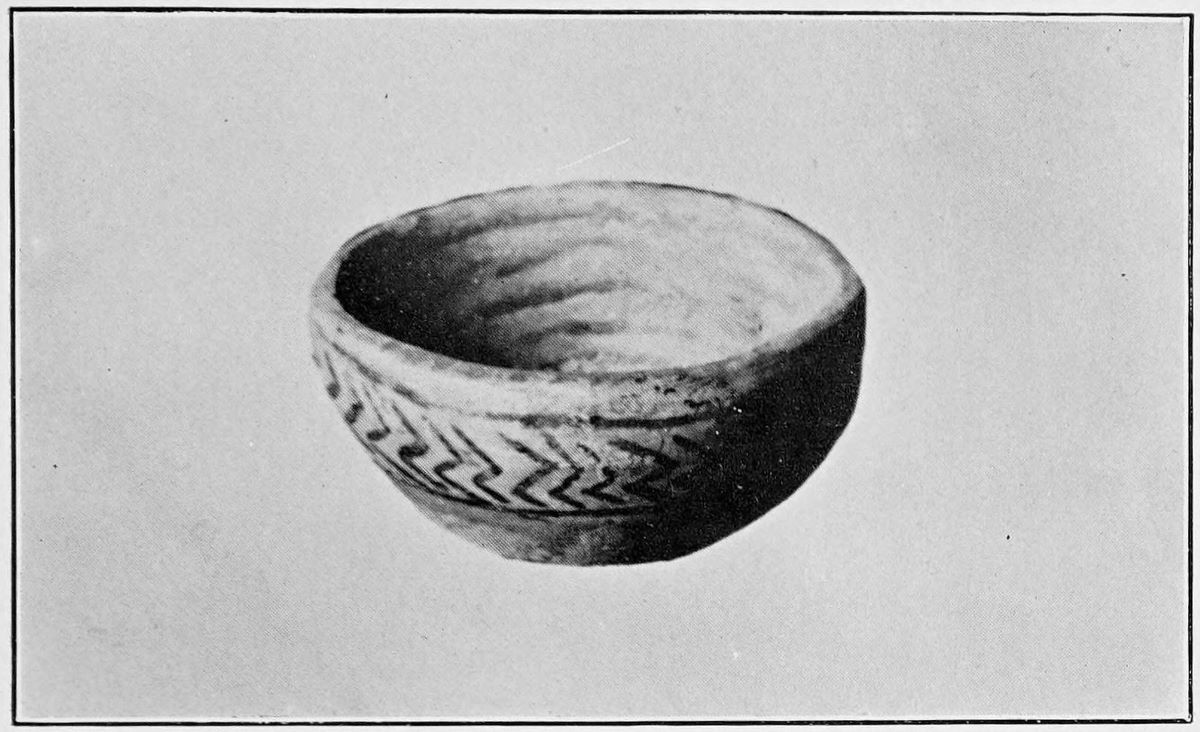

| 20. Decorated bowl and canteen. | ||

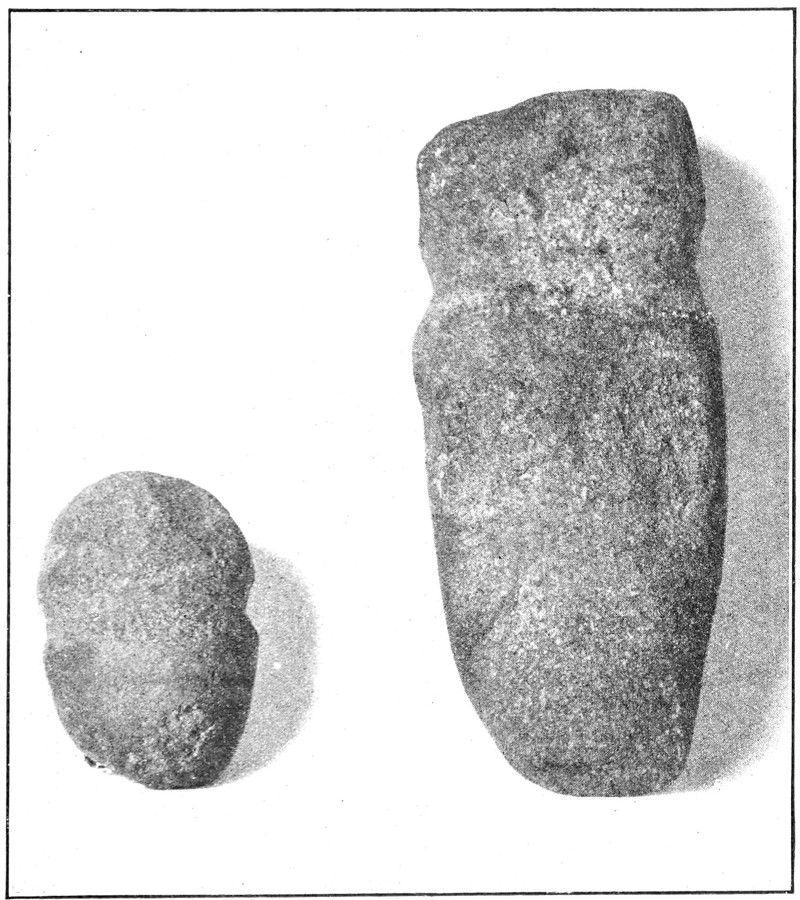

| 21. Stone implements. | ||

| Page | ||

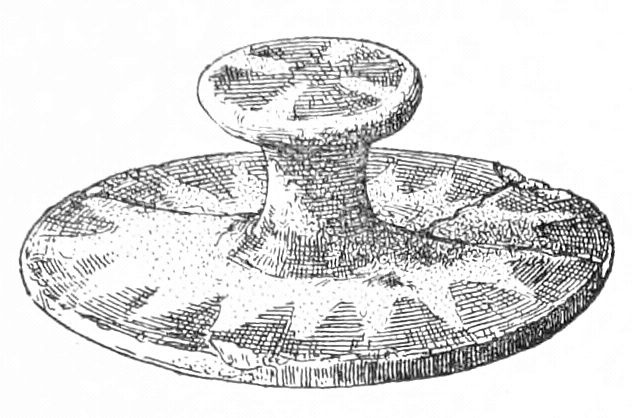

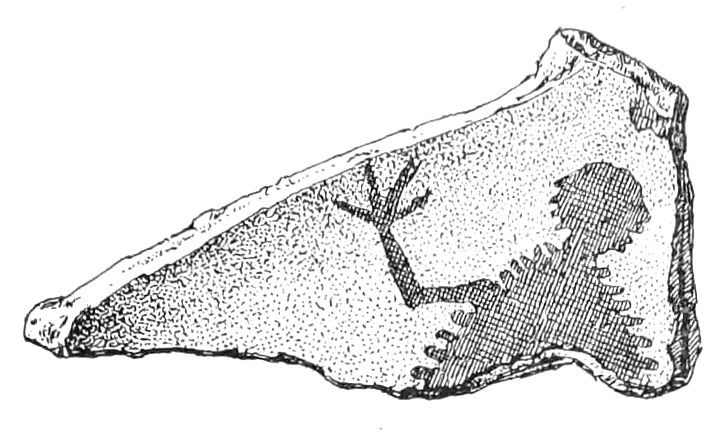

| Figure | 1. Lid of jar | 29 |

| 2. Repaired pottery | 29 | |

| 3. Handle with attached cord | 30 | |

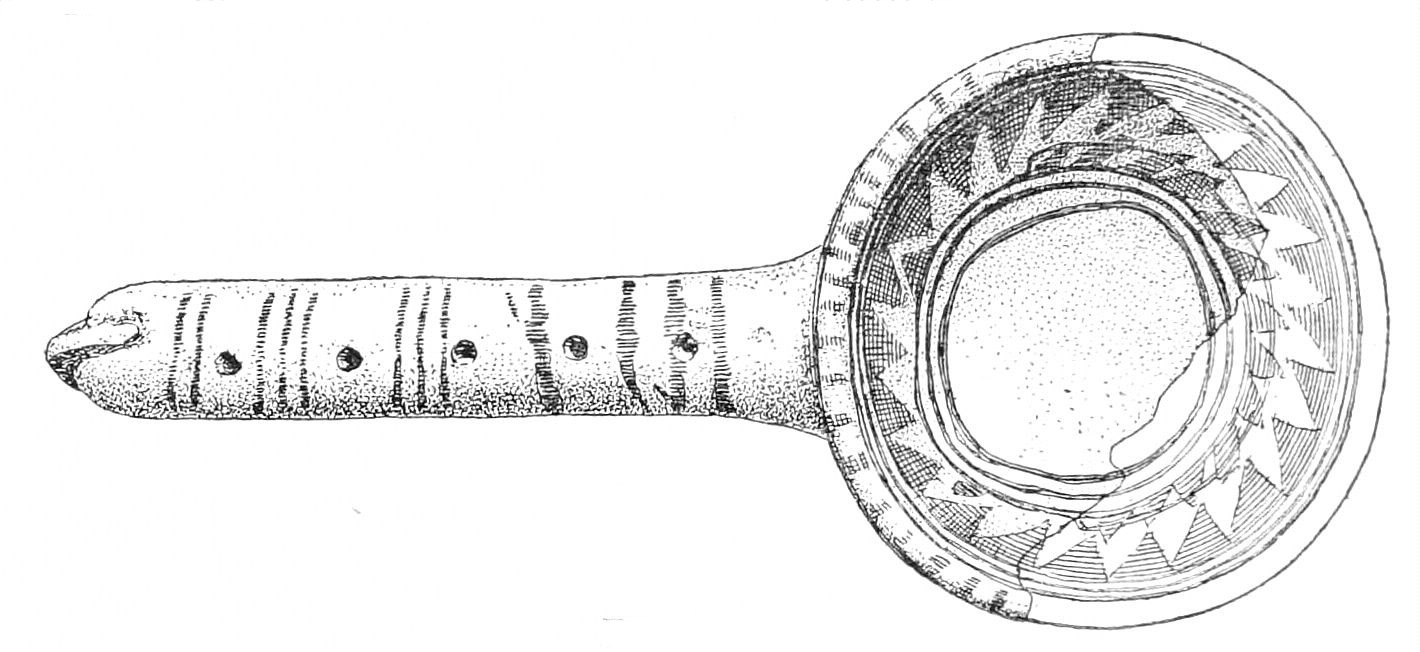

| 4. Ladle | 30 | |

| 5. Handle of mug | 30 | |

| 6. Fragment of pottery | 32 | |

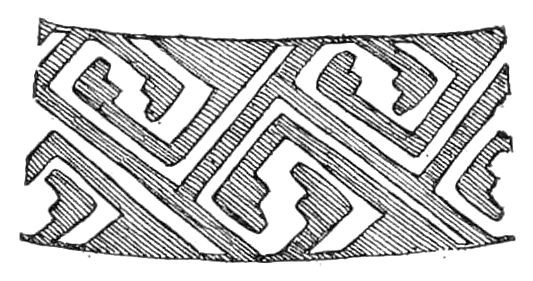

| 7. Zigzag ornament | 32 | |

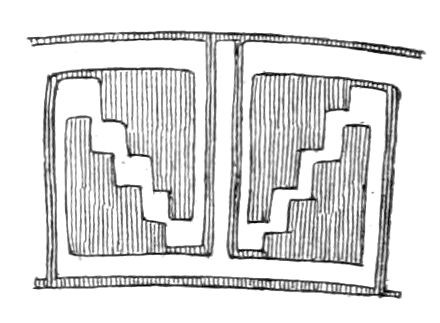

| 8. Sinistral and dextral stepped figures | 32 | |

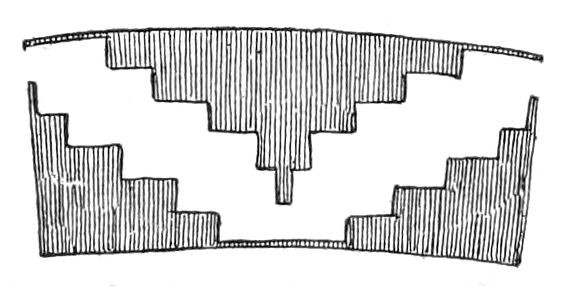

| 9. Triangle ornament | 32 | |

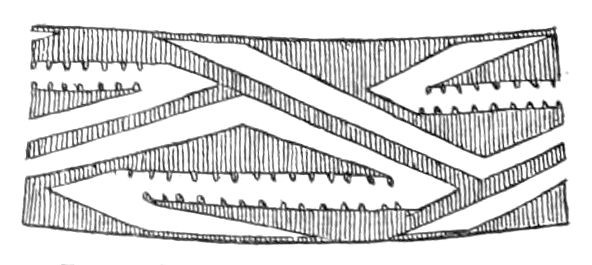

| 10. Meander | 33 | |

| 11. Stone axes | 39 | |

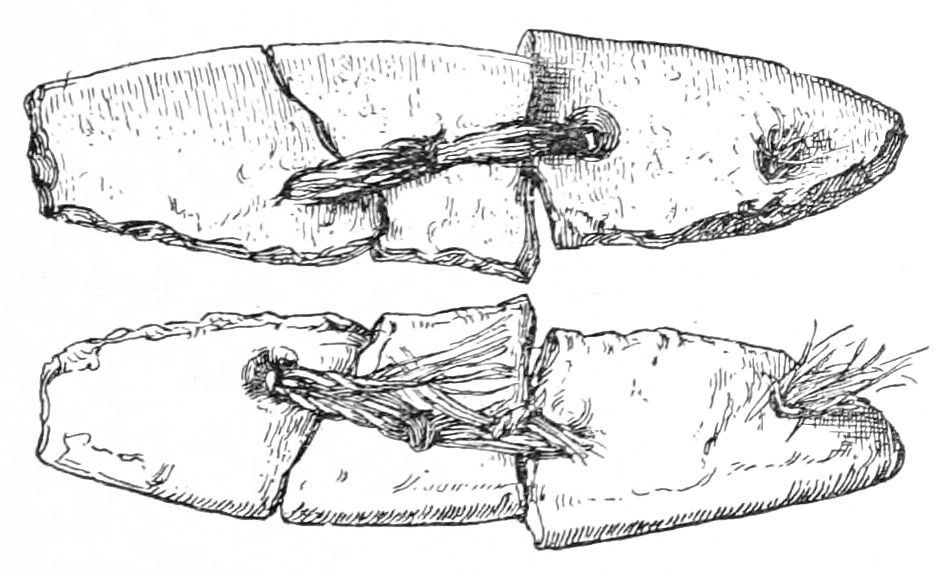

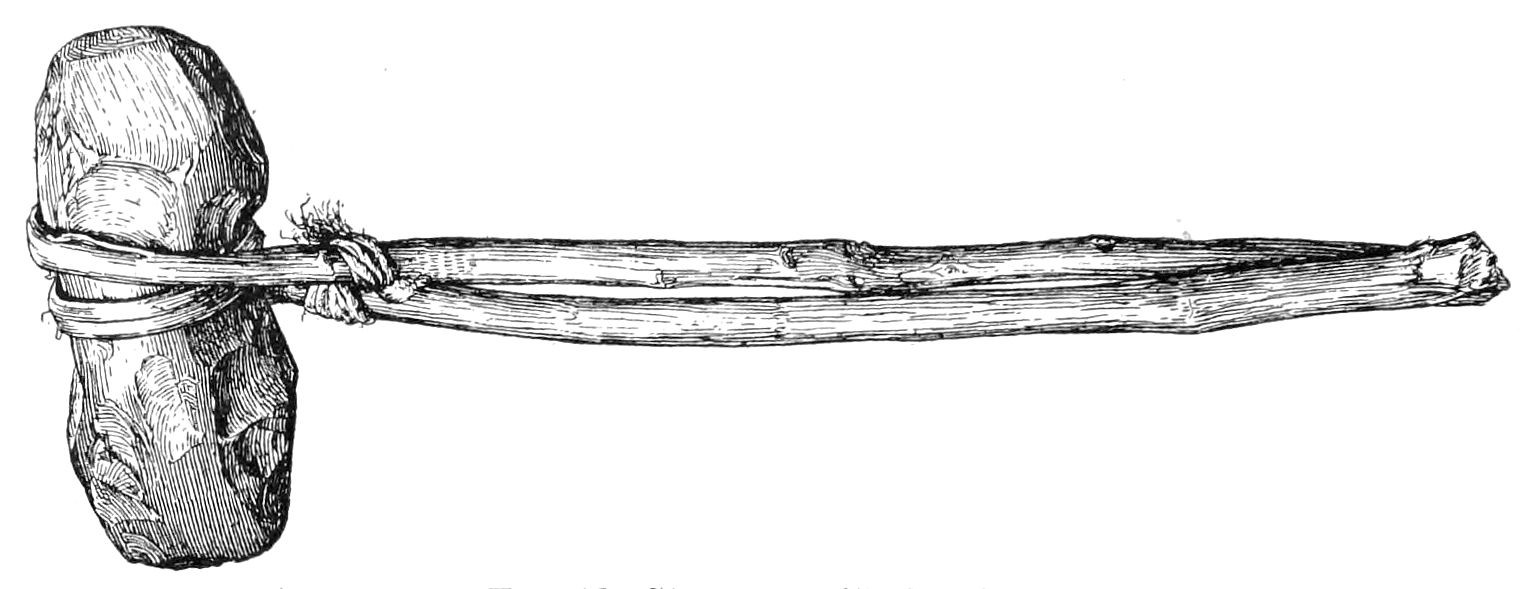

| 12. Stone ax with handle | 40 | |

| 13. Stone pigment-grinder | 41 | |

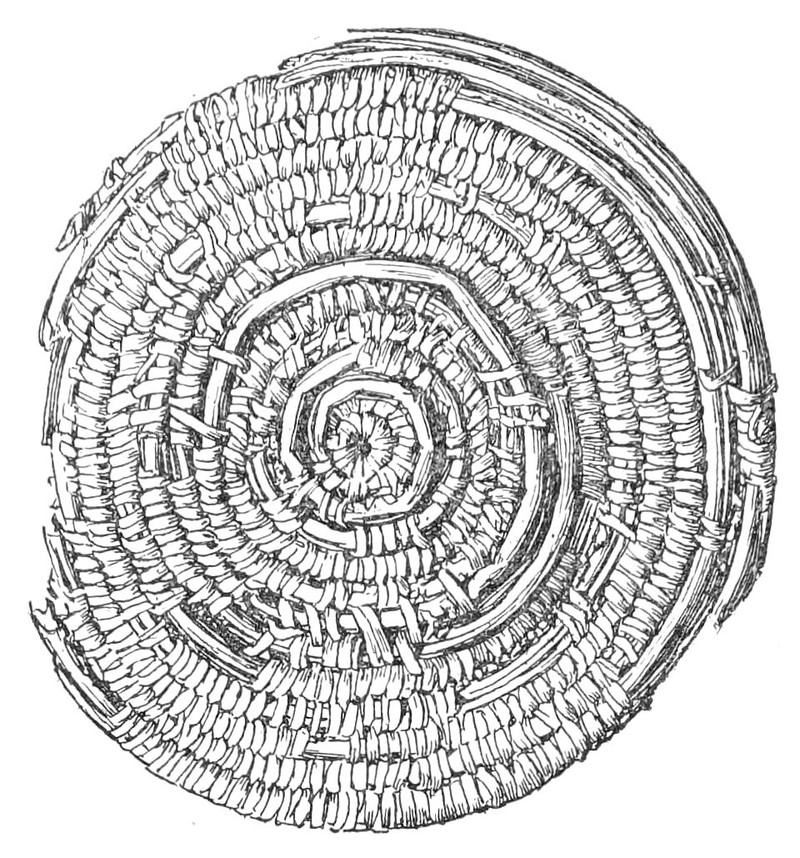

| 14. Fragment of basket | 42 | |

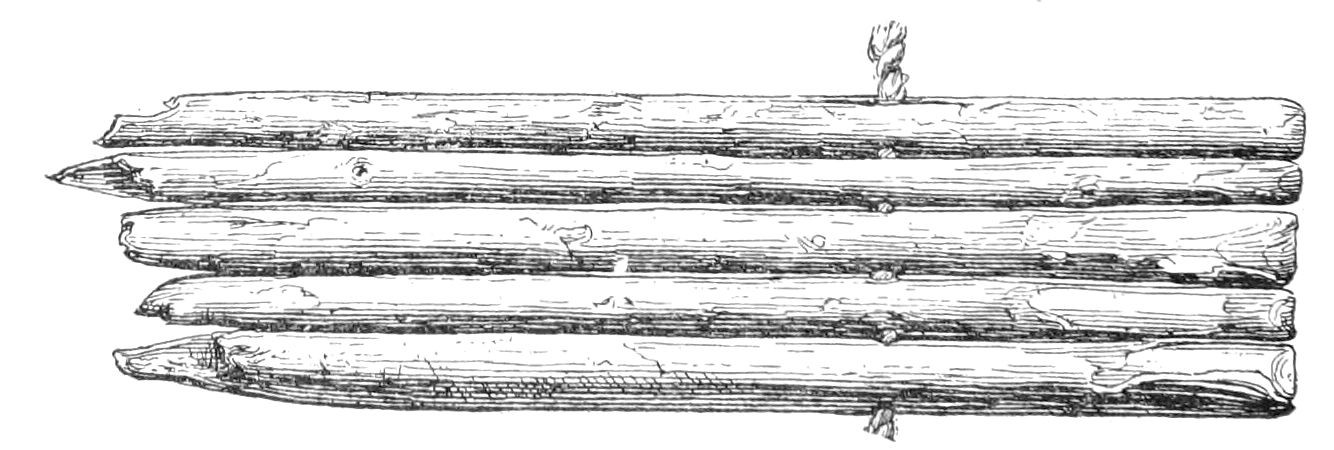

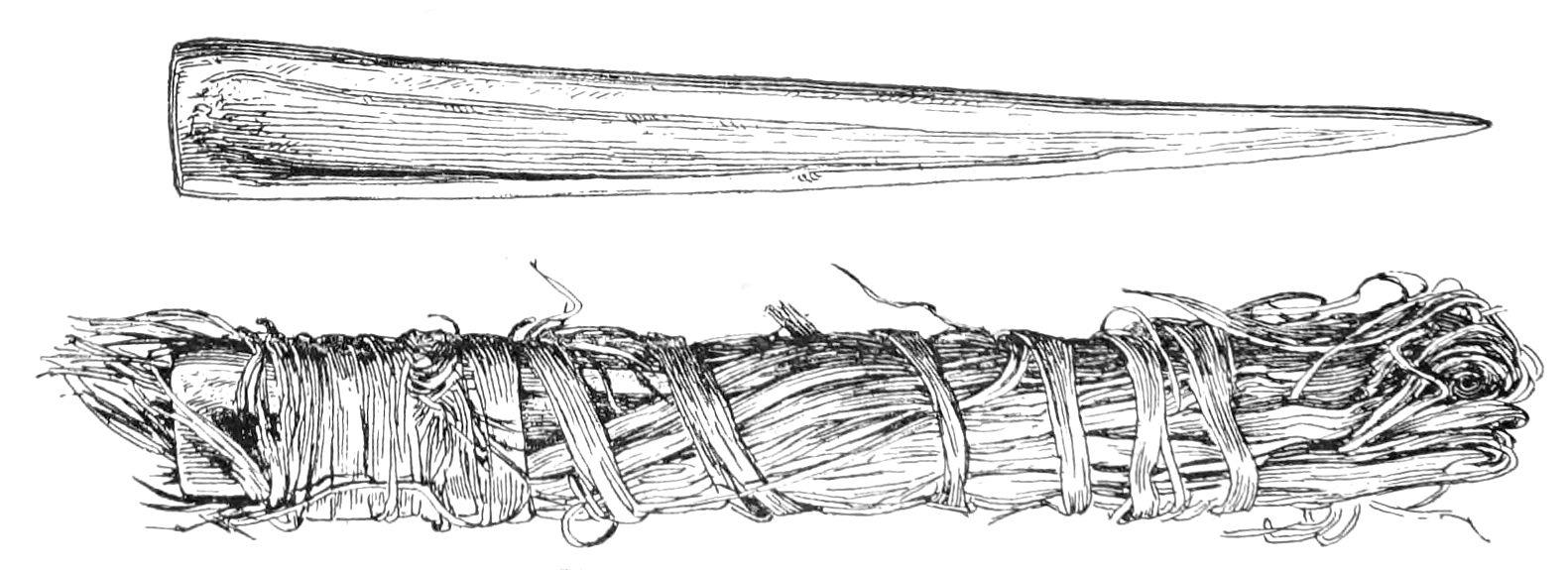

| 15. Sticks tied together | 42 | |

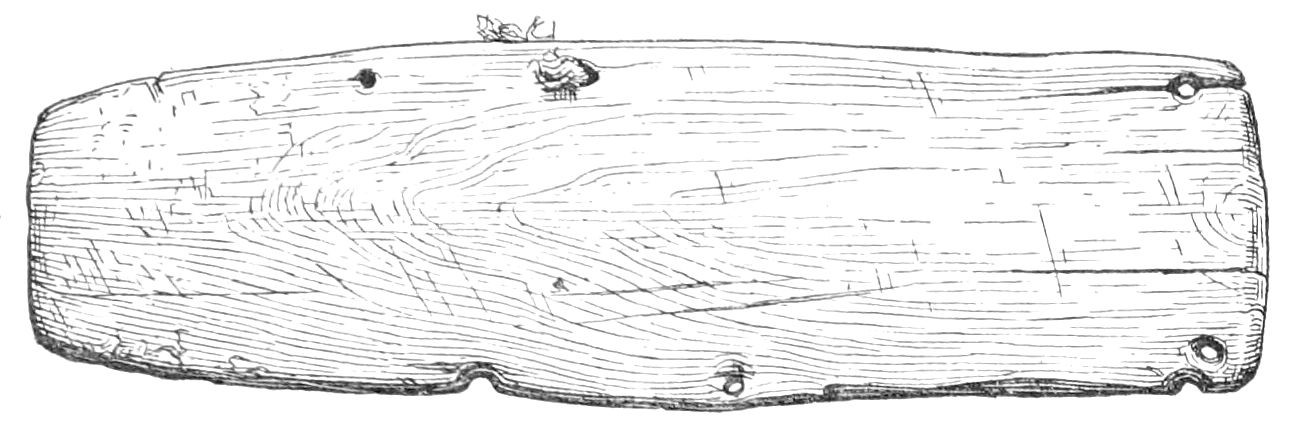

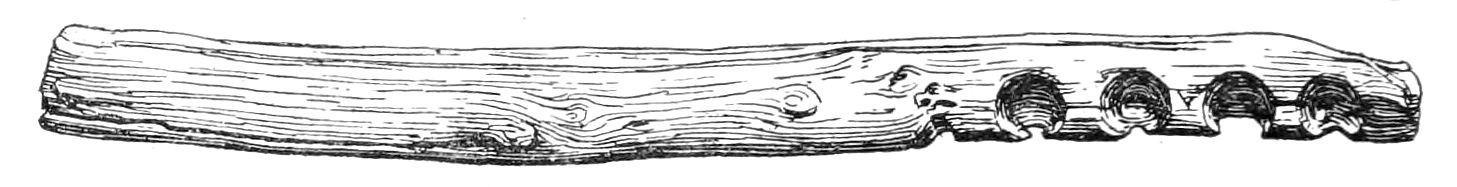

| 16. Wooden slab | 43 | |

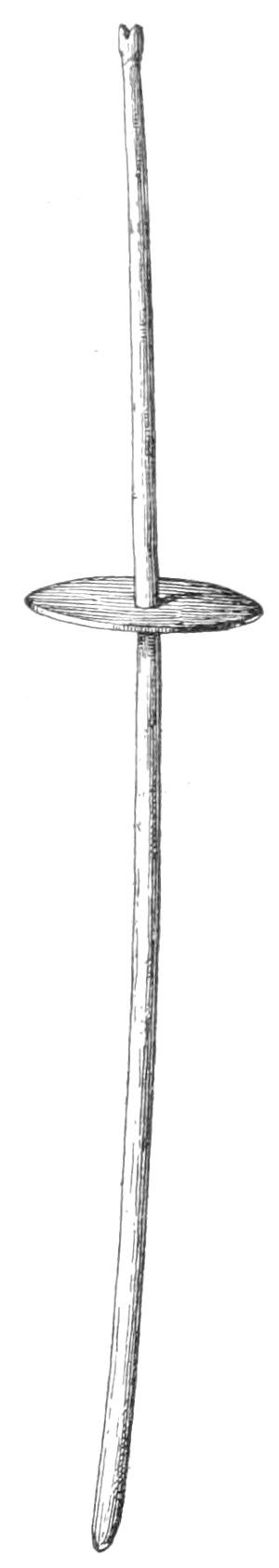

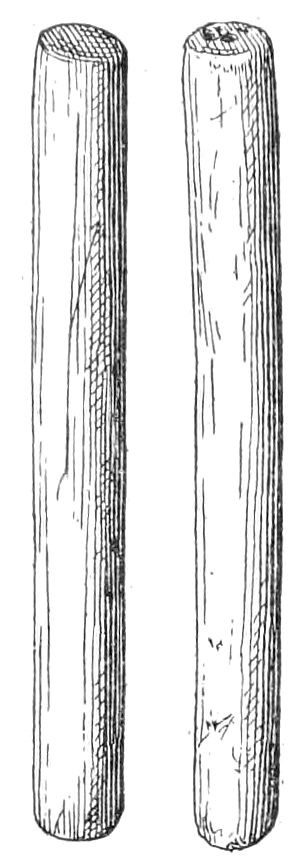

| 17. Spindle and whorl | 43 | |

| 18. Ceremonial sticks | 44 | |

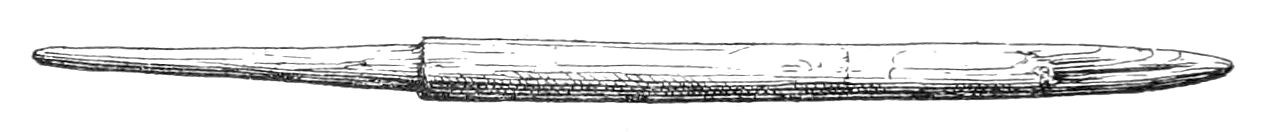

| 19. Primitive fire-stick | 44 | |

| 20. Wooden needle | 44 | |

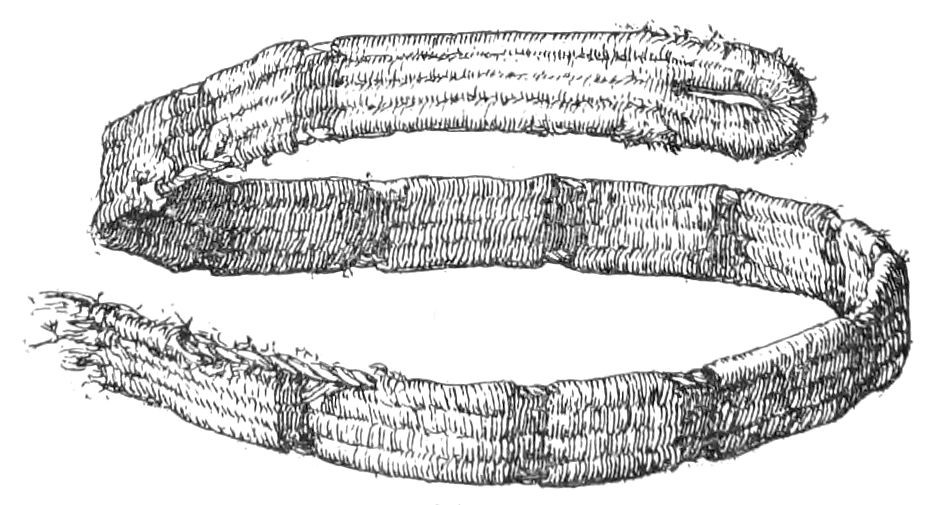

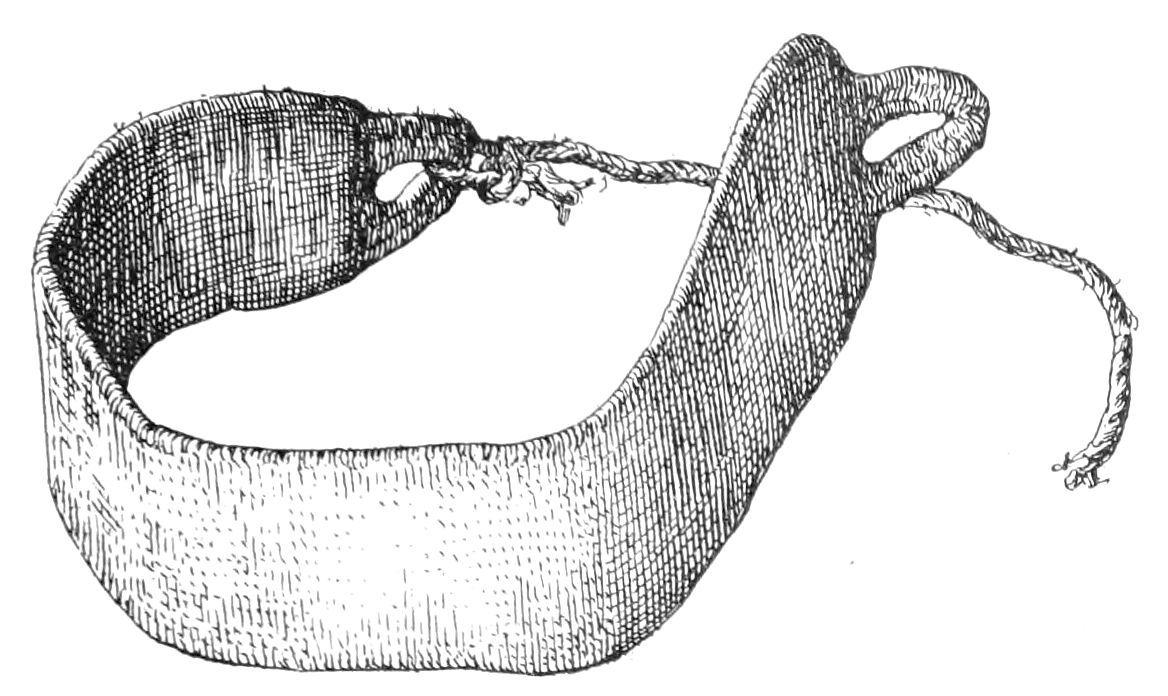

| 21. Belt | 44 | |

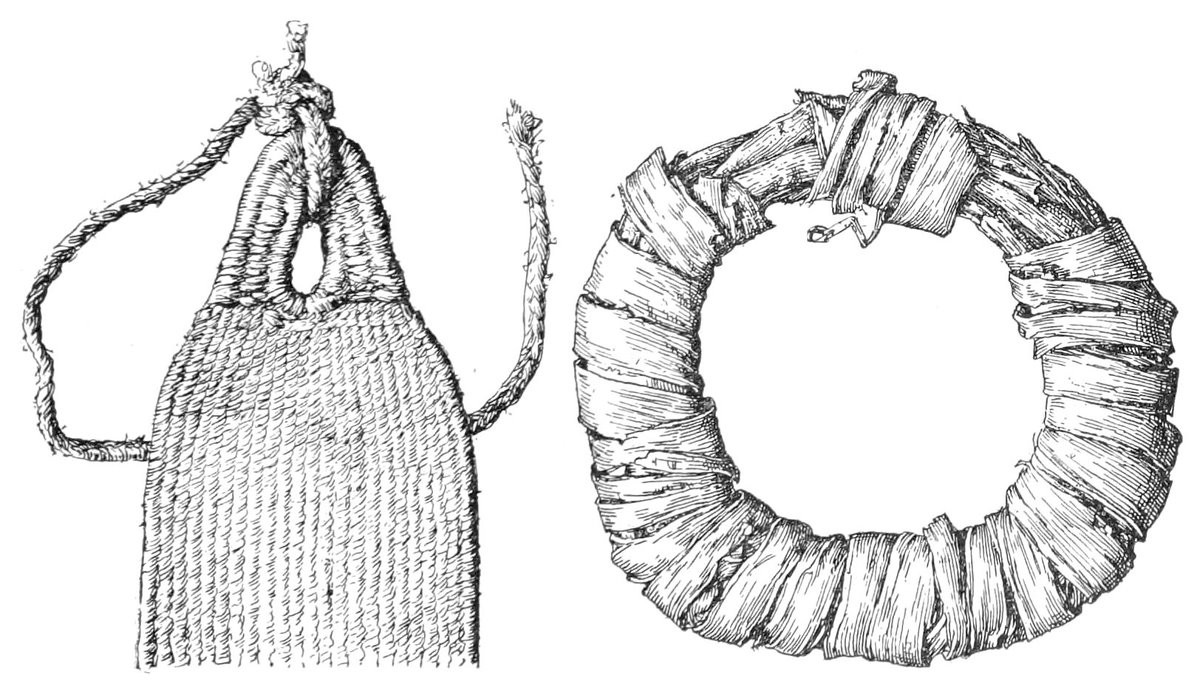

| [viii] | 22. Headband | 45 |

| 23. End of headband | 45 | |

| 24. Head ring | 45 | |

| 25. Yucca-fiber cloth with attached feathers | 46 | |

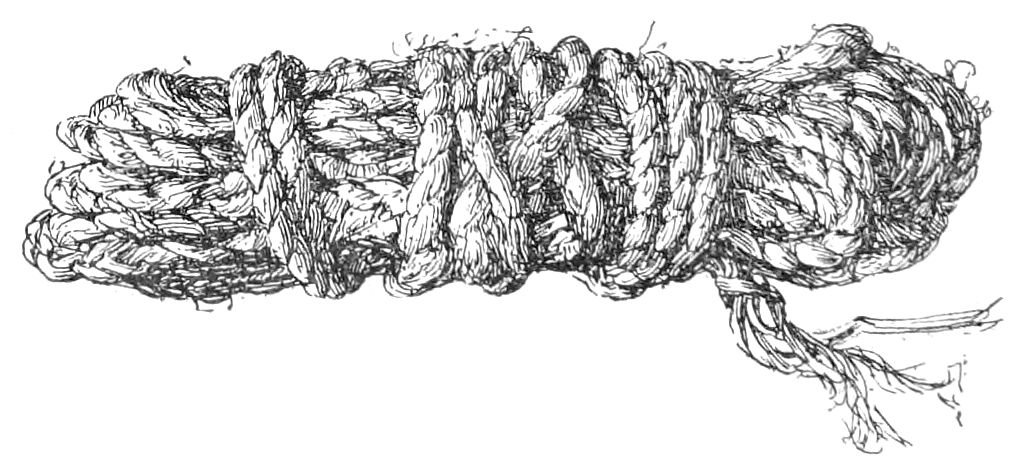

| 26. Woven cord | 46 | |

| 27. Agave fiber tied in loops | 47 | |

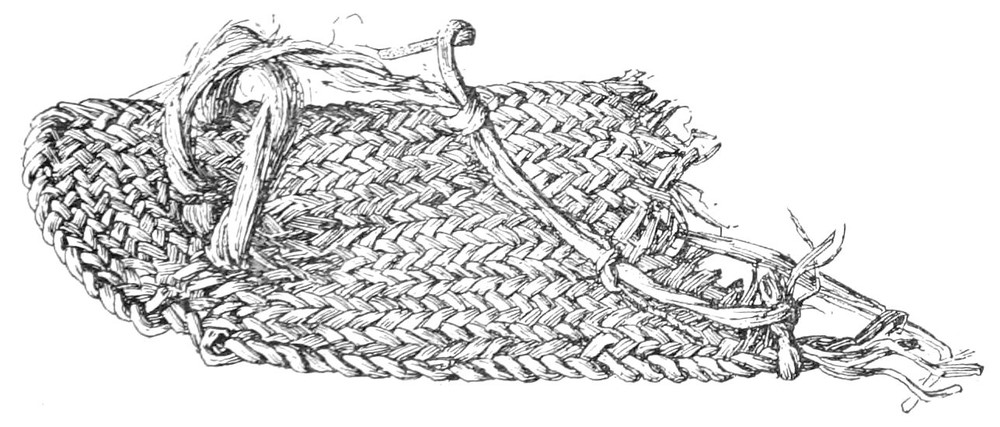

| 28. Woven moccasin | 47 | |

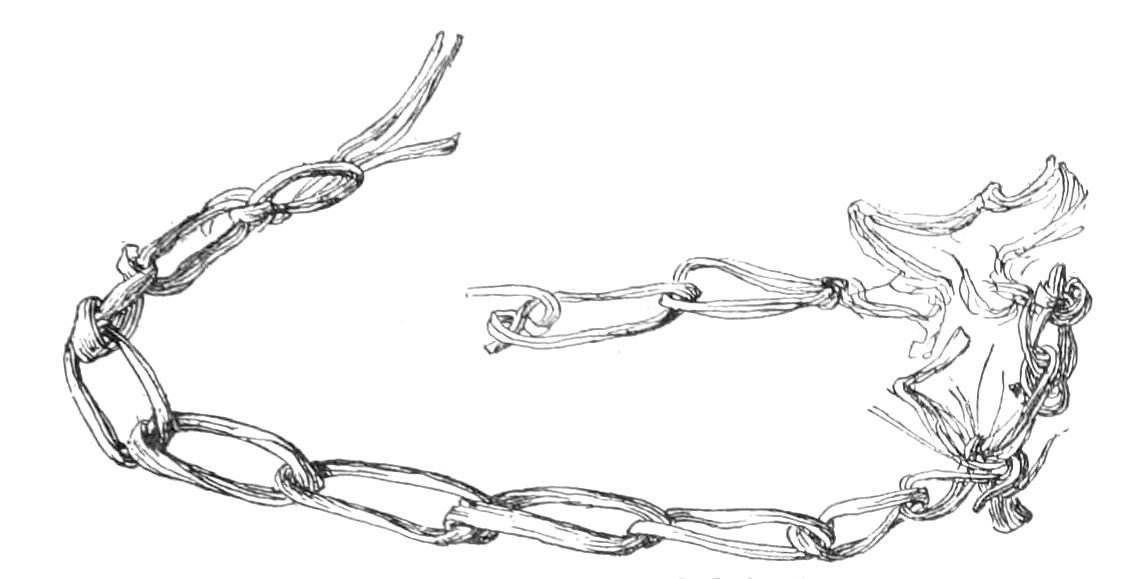

| 29. Fragment of sandal | 47 | |

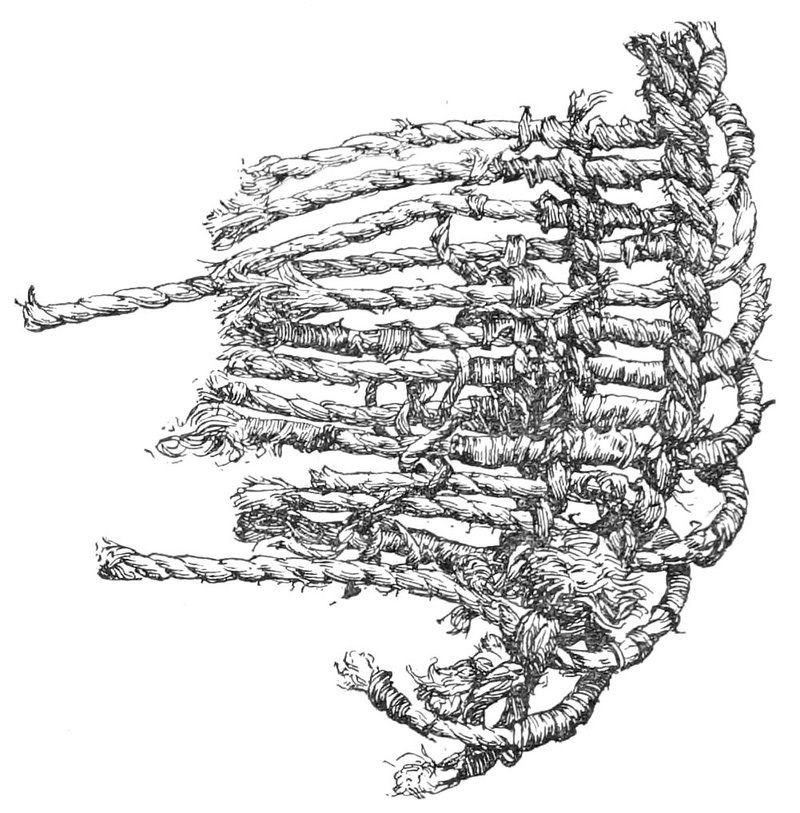

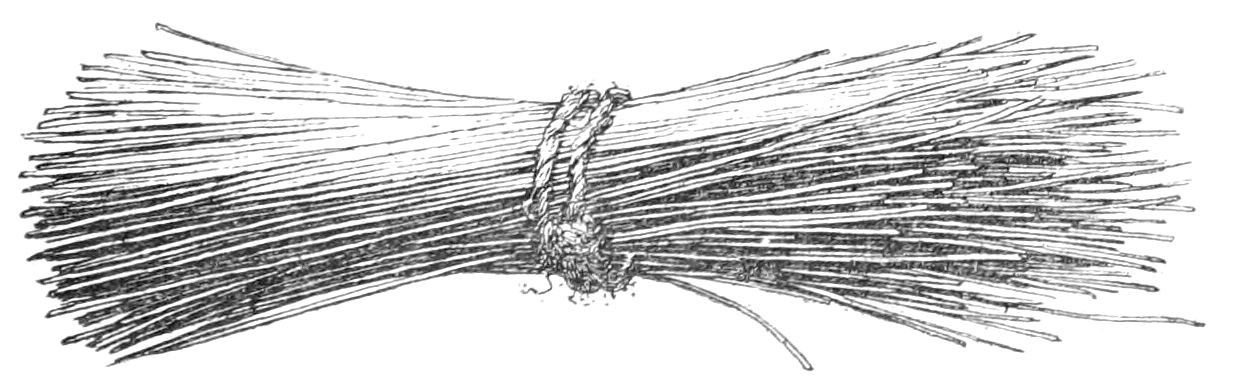

| 30. Hair-brush | 47 | |

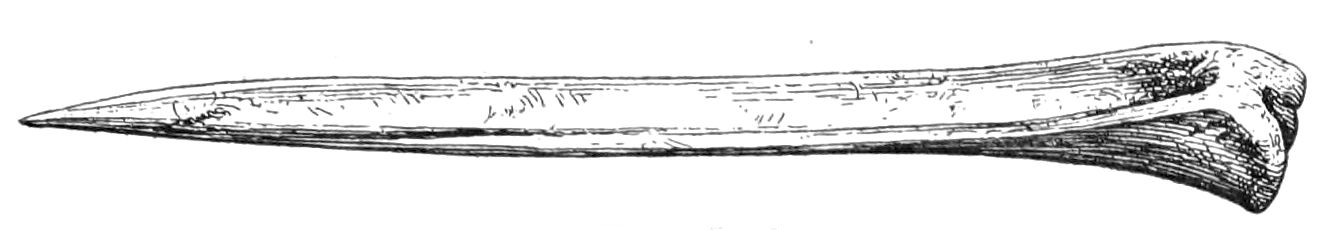

| 31. Bone implements | 48 | |

| 32. Dirk and cedar-bark sheath | 48 | |

| 33. Bone implement | 49 | |

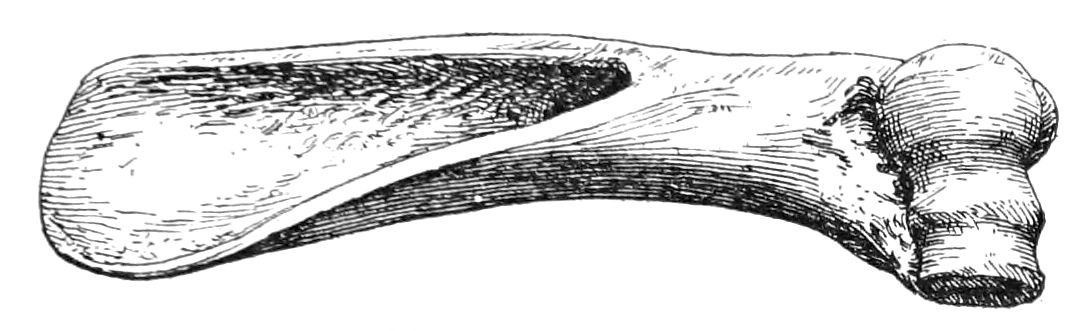

| 34. Bone scraper | 49 | |

| 35. Bone scraper | 49 | |

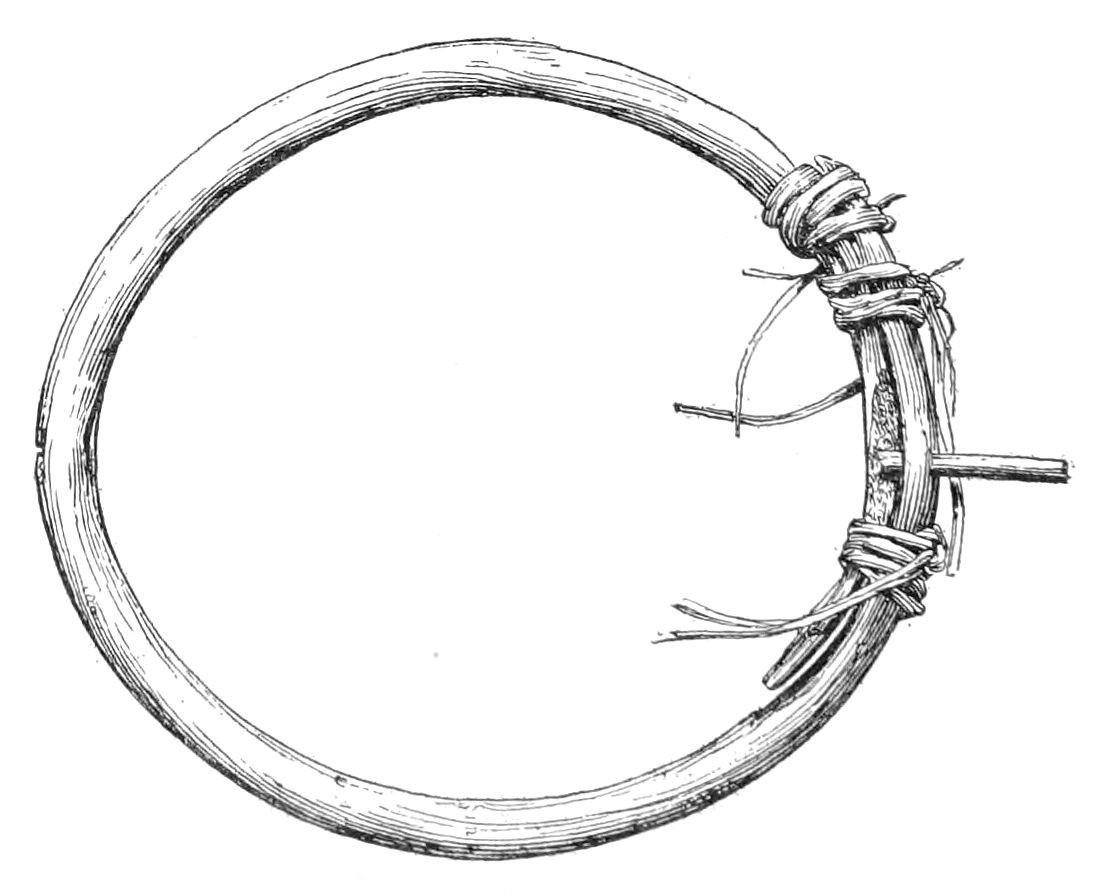

| 36. Hoop used in hoop-and-pole game | 50 | |

| 37. Portion of leather moccasin | 51 |

SPRUCE-TREE HOUSE

By Jesse Walter Fewkes

Spruce-tree House (pls. 1, 2)[1] is situated in the eastern side of Spruce-tree canyon, a spur of Navaho canyon, which at the site of the ruin is about 150 feet deep, with precipitous walls. The canyon ends blindly at the northern extremity, where there is a spring of good water; it is wooded with tall piñons, cedars, and stately spruces, the tops of which in some cases reach from its bed to its rim. The trees predominating on the rim of the canyon are cedars and pines.

The rock out of which the canyon is eroded is sandstone of varying degrees of hardness alternating with layers of coal and shale. The water percolating through this sandstone, on meeting the harder shale, seeps out of the cliffs to the surface. As the water permeates the rock it gradually undermines the harder layers of sandstone, which fall in great blocks, often leaving arches of rock above deep caves. One of these caves is situated at the end of the canyon where the rim rock overhangs the spring, which is filled by water seeping down from above the shale. Another of these caves is that in which Spruce-tree House is situated. Several smaller caves, and ledges of rock harder than that immediately above, serve as sites for small buildings.

The wearing away of the fallen fragments of the cliffs is much hastened by the waterfalls which in time of heavy rains fall over the rim rock, their force being greatly augmented by the height from which the water is precipitated. The fragments continually falling from the roofs of the caves form a talus that extends from the floors of the caves down the side of the cliff. The cliff-dwellings are erected on the top of this talus.

Although there was once an old Spanish trail winding over the mountains by way of Mancos and Dolores from what is now New Mexico to Utah, the early visitors to this part of Colorado seem not to have been impressed with the prehistoric cliff-houses in the Montezuma valley and on the Mesa Verde; at least they left no accounts of them in their writings. It appears that these early Spanish travelers encountered the Ute, possibly the Navaho Indians, along this trail, but the more peaceable people who built and occupied the villages now ruins in the neighborhood of Mancos and Cortez had apparently disappeared even at that early date. Indian legends regarding the inhabitants of the cliff-dwellings of the Mesa Verde are very limited and indistinct. The Ute designate them as the houses of the dead, or moki, the name commonly applied to the Hopi of Arizona. One of the Ute legends mentions the last battle between the ancient house-builders of Montezuma valley and their ancestors, near Battle Rock, in which it is said that the former were defeated and turned into fishes.

The ruins in Mancos canyon were discovered and first explored in 1874 by a Government party under Mr. W. H. Jackson.[2] The walls of ruins situated in the valley have been so long exposed to the weather that they are very much broken down, being practically nothing more than mounds. The few cliff-dwellings in Mancos canyon which were examined by Jackson are for the most part small; these are found on the west side. One of the largest is now known as Jackson ruin.

In the year 1875 Prof. W. H. Holmes, now Chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology, made a trip through Mancos canyon and examined several ruins. He described and figured several cliff-houses overlooked by Jackson and drew attention to the remarkable stone towers which are so characteristic of this region.[3] Professor Holmes secured a small collection of earthenware vessels, generally fragmentary, and also a few objects of shells, bone, and wood, figures and descriptions of which accompany his report. Neither Jackson nor Holmes, however, saw the most magnificent ruins of the Mesa Verde. Had they followed up the side canyon of the Mancos they would have discovered, as stated by Nordenskiöld, “ruins so magnificent that they surpass anything of the kind known in the United States.”

The following story of the discovery of the largest two of these ruins, one of which is the subject of this article, is quoted from Nordenskiöld:[4]

The honour of the discovery of these remarkable ruins belongs to Richard and Alfred Wetherill of Mancos. The family own large herds of cattle, which[3] wander about on the Mesa Verde. The care of these herds often calls for long rides on the mesa and in its labyrinth of cañons. During these long excursions ruins, the one more magnificent than the other, have been discovered. The two largest were found by Richard Wetherill and Charley Mason one December day in 1888, as they were riding together through the piñon wood on the mesa, in search of a stray herd. They had penetrated through the dense scrub to the edge of a deep cañon. In the opposite cliff, sheltered by a huge, massive vault of rock, there lay before their astonished eyes a whole town with towers and walls, rising out of a heap of ruins. This grand monument of bygone ages seemed to them well deserving of the name of the Cliff Palace. Not far from this place, but in a different cañon, they discovered on the same day another very large cliff-dwelling; to this they gave the name of Sprucetree House, from a great spruce that jutted forth from the ruins. During the course of years Richard and Alfred Wetherill have explored the mesa and its cañons in all directions; they have thus gained a more thorough knowledge of its ruins than anyone. Together with their brothers John, Clayton, and Wynn, they have also carried out excavations, during which a number of extremely interesting finds have been made. A considerable collection of these objects, comprising skulls, pottery, implements of stone, bone, and wood, etc., has been sold to “The Historical Society of Colorado.” A still larger collection is in the possession of the Wetherill family. A brief catalogue of this collection forms the first printed notice of the remarkable finds made during the excavations.

Mr. F. H. Chapin visited the Mesa Verde ruins in 1889 and published illustrated accounts[5] of his visit containing much information largely derived from the Wetherills and others. Dr. W. R. Birdsall also published an account of these ruins,[6] illustrated by several figures. Neither Chapin nor Birdsall gives special attention to the ruin now called Spruce-tree House, and while their writings are interesting and valuable in the general history of the archeology of the Mesa Verde, they are of little aid in our studies of this particular ruin. The same may be said of the short and incomplete notices of the Mesa Verde ruins which have appeared in several newspapers. The scientific descriptions of Spruce-tree House as well as of other Mesa Verde ruins begin with the memoir of the talented Swede, Baron Gustav Nordenskiöld, who, in his work, “The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde”, gives the first comprehensive account of the ruins of this mesa. It is not too much to say that he has rendered to American archeology in this work a service which will be more and more appreciated in the future development of that science. In order to make more comprehensive the present author’s report on Spruce-tree House, the following description of this ruin is quoted from Nordenskiöld’s memoir (pp. 50-56):

A few hundred paces to the north along the cliff lead to a large cave, in the shadow of which lie the ruins of a whole village, Sprucetree House. This cave is 70 m. broad and 28 m. in depth. The height is small in comparison[4] with the depth, the interior of the cave thus being rather dark. The ground is fairly even and lies almost on a level, which has considerably facilitated the building operations. A plan of the ruins is given in Pl. IX. A great part of the house, or rather village, is in an excellent state of preservation, both the walls, which at some places are several stories high and rise to the roof of rock, and the floors between the different stories still remaining. The architecture is the same as that described in the ruins on Wetherill’s Mesa. In some parts more care is perhaps displayed in the shape of the blocks and in the joints between them. The walls, here as in other cliff-dwellings, are about 0.3 m. thick, seldom more. A point which immediately strikes the eye in Pl. IX, is that no premeditated design has been followed in the erection of the buildings. It seems as if only a few rooms had first been built, additions having subsequently been made to meet the requirements of the increasing population. This circumstance, which I have already touched upon when describing other ruins, may be observed in most of the cliff-dwellings. There is further evidence to show that the whole village was not erected at the same time. At several places it may be seen that new walls have been added to the old, though the stones of both walls do not fit into each other, as is the case when two adjacent walls have been constructed simultaneously. The arrangement of the rooms has been determined by the surrounding cliff, the walls being generally built either at right angles or parallel to it. At some places the walls of several adjoining apartments of about equal size have been consistently erected in the same direction, some blocks of rooms thus possessing a regularity which is wanting in the cliff-village as a whole. This is perhaps the first stage in the development of the cliff-dwellings to the villages whose ruins are common in the valleys and on the mesa, and which are constructed according to a fixed design.

In the plan (Pl. IX) it may be seen that the cave contains two distinct groups of rooms. At about the middle of the cliff-village a kind of passage (23), uninterrupted by any wall, runs through the whole ruin. We found the remains, however, of a cross wall projecting from an elliptical room (14 in the plan) in the south part of the village. Each of these two divisions of the ruin contains an open space (16 and 28) at the back of the cave, the ground in both these places being covered with bird droppings. It is probable that this was the place where tame turkeys were kept, though it can not have been a very pleasant abode for them, for at least in the north of the ruin this part of the cave is almost pitch dark, the walls of the inner court (28), rising up to the roof of rock. In each of the two divisions of the cliff-village a number of estufas were built, in the north at least five, in the south at least two; while several more are, no doubt, buried in the heaps of ruins. These estufas preserve to the least detail the ordinary type (diam. 4-5 metres) fully described above. They are generally situated in front of the other rooms, with their foundations sunk deeper in the ground, and have never had an upper story. Even their site suggests that they were used for some special purpose, probably as assembly-rooms at religious festivities held by those members of the tribe who lived in the adjacent rooms. In all the estufas without exception the roof has fallen in. It is probable, as I have mentioned before, that the entrance of these rooms, as is still the case among the Pueblo Indians, was constructed in the roof. The other rooms were entered by narrow doorways (breadth 40-55 cm., height 65-80 cm.). These doorways are generally rectangular, often somewhat narrower at the top; the sill consists, as already described, of a long stone slab, the lintel of a few sticks a couple of centimetres in thickness, laid across the opening to support the wall above them. The arch was unknown to the builders of these villages, even in the form common among the ruins of Central America,[5] and constructed by carrying the walls on both sides of the doorway nearer to each other as each course of stones was laid, until they could be joined by a stone slab placed across them. Along both sides of the doorway and under the lintel a narrow frame of thin sticks covered with plaster was built (see fig. 28 to the left). This frame, which leant inwards, served to support the door, a thin, flat, rectangular stone slab of suitable size. Through two loops on the outside of the wall, made of osiers inserted in the chinks between the stones, and placed one on each side of the doorway, a thin stick was passed, thus forming a kind of bolt. Besides this type of door most cliff-villages contain examples of another. Some doorways present the appearance shown in fig. 28 to the right (height 90 cm., breadth at the top, 45 cm., at the bottom 30 cm.) They were not closed with a stone slab. They probably belonged to the rooms most frequented in daily life, and were therefore fashioned so as to admit of more convenient ingress and egress. The other doorways, through which it is by no means easy to enter, probably belonged in general to storerooms or other chambers not so often visited and requiring for some reason or other a door to close them. It should be mentioned that the large, T-shaped doors described above are rare in the ruins on Wetherill’s Mesa which both in architecture and in other respects bear traces of less care and skill on the part of the builders, and are also in a more advanced stage of decay, thus giving the impression of greater age than the ruins treated of in the present chapter, though without showing any essential differences.

The rooms, with the exception of the estufas, are nearly always rectangular, the sides measuring seldom more than two or three metres. North of the passage (23) which divides the ruin into two parts, a whole series of rooms (26, 29-33) still extends outwards from the back of the cave, their walls reaching up to the roof of rock, and the floors between the upper and lower stories being in a perfect state of preservation. The lower rooms are generally entered by small doors opening directly on the “street.” In the interior the darkness is almost complete, especially in room 34, which has no direct communication with the passage. It must be approached either through 35, which is a narrow room with the short side towards the “street” entirely open, or through 33. We used 34 as a dark room for photographic purposes.

The walls and roof of some rooms are thick with soot. The inhabitants must have had no great pretensions as regards light and air. The doorways served also as windows, though at one or two places small, quadrangular loop-holes have been constructed in the walls for the passage of light. Entrance to the upper story is generally gained by a small quadrangular hole in the roof at a corner of the lower room, a foothold being afforded merely by some stones projecting from the walls. This hole was probably covered with a stone slab like the doors. Thick beams of cedar or piñon and across them thin poles, laid close together, form the floors between the stories. In some cases long sticks were laid in pairs across the cedar beams at a distance of some decimeters between the pairs, a layer of twigs and cedar bast was placed over the sticks, and the whole was covered with clay, which was smoothed and dried.

In several other parts of the ruin besides this the walls still reach the roof of the cave. These walls are marked in the plan. In all the estufas and in some of the other rooms, perhaps the apartments of chiefs or families of rank, the walls are covered with a thin coat of yellow plaster. In one instance they are even decorated with a painting, representing two birds, which is reproduced in one of the following chapters. Pl. X: 2 shows a part of the ruin, situated in the north of the cave. The spot from which the photograph was taken, as well as the approximate angle of view, is marked in the plan. The left half of the photograph is occupied by a wall with doorways, rising to a height of[6] three stories and up to the roof of the cave; within the wall lies a series of five rooms on the ground floor; behind these rooms the large open space mentioned above (28) occupies the depths of the cavern. Here the beams are all that remains of the floors of the upper stories, their ends projecting a foot or two beyond the wall between the second and third stories, where support was probably afforded in this manner to a balcony, as an easier means of communication between the rooms of the upper stories. In front of this part of the building, but not visible in the photograph, lie two estufas and outside the latter is a long wall. To judge by the ruins, the roofs of these estufas once lay on a level with the floors of the adjoining rooms, so that over the estufas, which were sunk in the ground, only the roofs being left visible, the inhabitants had an open space, bounded on the outside by the said long wall, which formed a rampart at the edge of the talus. The same method of construction is employed by the Moki Indians in their estufas; but these rooms are rectangular in form.—Farther north lies another estufa. Its site, nearest to the cliff wall, would seem to indicate that it is the oldest. The walls in the north of the ruin still rise to a height of 6 metres.

The south part of the ruin is similar in all respects to the north. Its only singularity is a room of elliptical shape (axes 3.6 and 2.9 m.); from this room a wall runs south, enclosing a small open space (16) where, as at the corresponding place in the north of the ruin, the ground is covered with bird droppings mixed with dust and refuse. At one end there are two semicircular enclosures (17, 18) of loose stones forming low walls. In a pentagonal room (8) south of this open space one corner contains a kind of closet (height 1.2 m., length and breadth O.9 m.) composed of two large upright slabs of stone, with a third slab laid across them in a sloping position and cemented fast (see fig. 29). Of the use to which this “closet” was put, I am ignorant. Farther south some of the rooms are situated on a narrow ledge, along which a wall has been erected, probably for purposes of defense.

Plate X: 1 is a photograph of Sprucetree House from the opposite side of the cañon. The illustrations give a better idea of the ruin’s appearance than any description could do.

Our excavations in Sprucetree House lasted only a few days. This ruin will certainly prove a rich field for future researches.[7] Some handsome baskets and pieces of pottery were the best finds made during the short period of our excavations. In a room (69) belonging to the north part of the ruin we found the skeletons of three children who had been buried there.

A circumstance which deserves mention, and which was undoubtedly of great importance to the inhabitants of Sprucetree House, is the presence at the bottom of the cañon, a few hundred paces from the ruin, of a fairly good spring.

Near Sprucetree House there are a number of very small, isolated rooms, situated on ledges most difficult of access. One of these tiny cliff-dwellings may be seen to the left in fig. 27. It is improbable that these cells, which are sometimes so small that one can hardly turn in them, were really dwelling places; their object is unknown to me, unless it was one of defense, archers being posted there when danger threatened, so that the enemy might have to face a volley of arrows from several points at once. In such a position a few men could defend themselves, even against an enemy of superior force, for an assailant could reach the ledge only by climbing with hands and feet. Another explanation, perhaps better, was suggested to me by Mr. Fewkes. He thinks[7] that these small rooms were shrines where offerings to the gods were deposited. No object has, however, been found to confirm this suggestion.

To the right of fig. 27 a huge spruce may be seen. Its roots lie within the ruins of Sprucetree House, the trunk projecting from the wall of an estufa. In Pl. X: 1 the tree is wanting. I had it cut down in order to ascertain its age. We counted the rings, which were very distinct, twice over, the results being respectively 167 and 169. I had supposed from the thickness of the tree that the number of the rings was much greater.

Like the majority of cliff-dwellings in the Mesa Verde National Park, Spruce-tree House stands in a recess protected above by an overhanging cliff. Its form is crescentic, following that of the cave and extending approximately north and south.

The author has given the number of rooms and their dimensions in his report to the Secretary of the Interior (published in the latter’s report for 1907-8) from which he makes the following quotation:

The total length of Spruce-tree House was found to be 216 feet, its width at the widest part 89 feet. There were counted in the Spruce-tree House 114 rooms, the majority of which were secular, and 8 ceremonial chambers or kivas. Nordenskiöld numbered 80 of the former and 7 of the latter, but in this count he apparently did not differentiate in the former those of the first, second and third stories. Spruce-tree House was in places 3 stories high; the third-story rooms had no artificial roof, but the wall of the cave served that purpose. Several rooms, the walls of which are now two stories high, formerly had a third story above the second, but their walls have now fallen, leaving as the only indication of their former union with the cave lines destitute of smoke on the top of the cavern. Of the 114 rooms, at least 14 were uninhabited, being used as storage and mortuary chambers. If we eliminate these from the total number of rooms we have 100 enclosures which might have been dwellings. Allowing 4 inhabitants for each of these 100 rooms would give about 400 persons as an aboriginal population of Spruce-tree House. But it is probable that this estimate should be reduced, as not all the 100 rooms were inhabited at the same time, there being evidence that several of them had occupants long after others were deserted. Approximately, Spruce-tree House had a population not far from 350 people, or about 100 more than that of Walpi, one of the best-known Hopi pueblos.[8]

In the rear of the houses are two large recesses used for refuse-heaps or for burial of the dead. From the abundance of guano and turkey bones it is supposed that turkeys were kept in these places for ceremonial or other purposes. Here have been found several desiccated human bodies commonly called mummies.

The ruin is divided by a street into two sections, the northern and the southern, the former being the more extensive. Light is prevented from entering the larger of these recesses by rooms which reach the roof of the cave. In front of these rooms are circular subterranean[8] rooms called kivas, which are sunken below the surrounding level places, or plazas, the roofs of these kivas having been formerly level with the plazas.

The front boundary of these plazas is a wall[9] which when the excavations were begun was buried under débris of fallen walls, but which formerly stood several feet above the level of the plazas.

Under this term are included those immovable prehistoric remains which, taken together, constitute a cliff-dwelling. The architectural features—walls of rooms and structures connected with them, as beams, balconies, fireplaces—are embraced in the term “major antiquities.” None of these can be removed from their sites without harm, so they must be protected in the place where they now stand.

In a valuable article on the ruins in valley of the San Juan and its tributaries, Dr. T. Mitchell Prudden[10] recognizes in this region what he designates a “unit type;” that is, a ruin consisting of a kiva backed by a row of rooms generally situated on its north side, with lateral extensions east and west, and a burial place on the opposite, or south, side of the kiva. This form of “unit type,” as he points out, is more apparent in ruins situated in an open country than in those built in cliffs. The same form may be recognized in Spruce-tree House, which is composed of several “unit types” arranged side by side. The simplicity of these “unit types” is somewhat modified, however, in this as in all cliff-dwellings, by the form of the site. The author would amend Prudden’s definition of the “unit type” as applied to cliff-houses by adding to the latter’s description a bounding wall connecting the two lateral extensions of the row of rooms, thus forming the south side of the enclosure of the kiva. For obvious reasons, in this amended description the burial place is absent, as it does not occur in the position assigned to it in the original description.

As before stated, the buildings of Spruce-tree House are divided into a northern and a southern section by a street which penetrates from plaza G to the rear of the cave. (Pl. 1.) The northern section is not only the larger, but there is evidence that it is also the older. It is bounded by some of the best-constructed buildings, situated along the north side of the street. The rooms of the southern section are less numerous, although in some respects more instructive.

There are practically the same number of plazas as of kivas in this ruin. With the exception of C and D, each plaza is occupied by a single kiva, the roof of which constitutes the central part of the floor of the square enclosure (plaza). The plazas commonly contain remnants of small shrines, fireplaces, and corn-grinding bins, and are perforated by mysterious holes evidently used in ceremonies. Their floors are hardened by the tramping of the many feet that passed over them. The best preserved of all the plazas is that which contains kiva G. It can hardly be supposed that the roof of kiva A served as a dance place, which is the ordinary office of a plaza, but it may have been used in ceremonies. The largest plaza of the series, in the rear of which are rooms while the front is inclosed by the bounding wall, is that containing kivas C and D. The appearance of this plaza before and after clearing out and repairing is shown in plate 3; the view was taken from the north end of the ruin.

From the number of fireplaces and similar evidences it may be concluded that the street already mentioned as dividing the village into two sections served many purposes. Most important of these was its use as the open-air dwellings of the villagers. Its hardened clay floor suggests the constant passage of many feet. Its surface slopes gradually downward from the back of the cave, ending at a step near the round room in the rear of kiva G. This step marks also the eastern boundary of the plaza (G) which contains the best preserved of all the ceremonial rooms of Spruce-tree House.

The discovery by excavation of the wall that originally formed the front of the village was important. In this way was revealed a correct ground plan of the ruin (pl. 1) which had never before been traced by archeologists. When the work began, this wall was deeply buried under accumulated débris, its course not being visible to any considerable extent. By removing the fallen stones composing the débris the wall could be readily traced. In the repair work the original stones were replaced in the structure. As in the first instance this wall was probably about as high as the head, it may have been used for protection. The only openings are small rectangular orifices, the presence of one opposite the external opening of the air flue of each kiva suggesting that formerly these flues opened outside the wall. Two kivas, B and F, are situated west of this wall and therefore outside the village. There are evidences of a walk on top of the talus along the front of the pueblo outside the front wall, and of a retaining wall to prevent the edge of the talus from wearing away. (Pls. 4, 5.)

The walls of Spruce-tree House were built of stones generally laid in mortar but sometimes piled on one another, the joints being pointed later. Sections of walls in which no mortar was used occur on the[10] tops of other walls. These dry walls served among other purposes to shield the roofs of adjacent buildings from snow and rain. Whenever mortar was used it appears that a larger quantity was employed than was necessary, the effect being to weaken the wall since the pointing washed out quickly, being less capable than stone of resisting erosion. When the mortar wore away, the wall was left in danger of falling of its own weight. The pointing was generally done with the hands, the superficial impressions of which show in several places. Small flakes of stone or fragments of pottery were sometimes inserted in the joints, serving both as a decoration, and as a protection by preventing the rapid wearing away of the mortar. Little pellets of clay were also used in the joints for the same purpose.

The character of masonry in different rooms varies considerably, in some places showing good, in others poor, workmanship. As a rule the construction of the corners is weak, the stones forming them being rarely bonded or tied. Component stones of the walls seldom break joints; thus a well-known device by means of which walls are strengthened is lacking, and consequently cracks are numerous and the work is unstable. Fully half the stones used in construction were hammered or dressed into desirable shapes, the remainder being laid as they were gathered, with their flat surfaces exposed when possible. (Pls. 6, 7.)

Some of the walls were out of plumb when constructed and the faces of many were never straight. The walls show evidences of having been repeatedly repaired, as indicated by a difference in color of the mortar used.

Plasters of different colors, as red, white, yellow, and brown, were used. The lower half of the wall of a room was generally painted brownish red, the upper half often white. There are evidences of several coats of plastering, especially on the walls of the kivas, some of which are much discolored with smoke.

The replastering of the walls of Hopi kivas is an incident of the Powamû festival, or ceremonial purification of the fields commonly called the “Bean planting,” which occurs every February. On a certain day of this festival girls thoroughly replaster the four walls of the kivas and at the close of the work leave impressions of their hands in white mud on the kiva beams.

The rooms of Spruce-tree House may be considered under two headings: secular rooms, and ceremonial rooms, or kivas. The former are rectangular, the latter circular, in form.

The secular rooms are the more numerous in Spruce-tree House. In order to designate them in future descriptions they were numbered from 1 to 71, in black paint, in conspicuous places on the walls.[11] (Pl. 1.) This enumeration begins at the north end and passes thence to the south end of the ruin, but in one or two instances this order is not followed. The author has given below a brief reference to some of the important secular rooms in the series.

The foundations of room 1 were apparently built on a fallen bowlder, the entrance being reached by means of a series of stone steps built into the side hill. The floor of this room is on the level of the second story of other rooms, being continuous with the top of kiva A. It is probable that when this kiva was constructed it was found impossible to make it subterranean on account of the solid rock. A retaining wall was built outside the kiva and the intervening space was filled with earth in order to impart to the room a subterranean character.

Room 2 has three stories, or tiers, of rooms. The floor of the second story, which is the roof of the first, is well preserved, the sides of the hatchway, or means of passage from one room to the one below it, being almost entire. This room possesses a feature which is unique. The base of its south wall is supported by curved timbers, whose ends rest on walls, while the middle is supported by a pillar of masonry. (Pl. 8.) The T-shaped door in this wall faces south. It is difficult to understand how the aperture could have been of any use as a doorway unless there was a balcony below it, and no sign of such structure is now visible. The west wall of rooms 2 and 3 was built on top of a fallen rock from which it rises precipitously to a considerable height. The floor of room 4, which lies in front of kiva A, is on a level with the roof of the kiva, and somewhat higher than the surface of the neighboring plaza but not higher than the roof of the first story. As the floors of room 1 and room 4 are on the same level, it would appear that both were considerably elevated or so constructed otherwise that the kiva should be subterranean. This endeavor to render the kiva subterranean by building up around it, when conditions made it impossible to excavate in the solid rock, is paralleled in some other Mesa Verde ruins.

The ventilator of kiva A, as will be seen later, does not open through the front wall, as is usually the case, but on one side. This is accounted for by the presence of a room on this side of the kiva. Rooms 2, 3, 4 were constructed after the walls of kiva A were built, hence several modifications were necessary in the prescribed plan of building these rooms.

The foundation of the inclosure, 5, conforms on one side to the outer wall of the village, and on the other to the curvature of kiva B. As this inclosure does not seem ever to have been roofed, it is probable that it was not a house. A fireplace at one end indicates that cooking was formerly done here. It is instructive to note that the front wall of the ruin begins at this place.

Rooms 6, 7, 8, which lie side by side, closely resemble one another, having much in common. They were evidently dwellings, and may have been sleeping-places for families. Rooms 7 and 8 were two stories high, the floor of no. 8 being on a level with the adjoining plaza. Room 9 is so unusual in its construction that it can not be regarded as a living room. It was used as a mortuary chamber, evidences being strong that it was opened from time to time for new interments. Room 12 also was a ceremonial chamber, and, like the preceding, will be considered later at greater length. The walls of the two rooms, 10 and 11, are low, projecting into plaza C, of whose border they form a part. Near them, or in one corner of the same plaza, is a bin, the sides of which are formed of stone slabs set on edge. The use of this bin is problematical.

The front wall of room 15 had been almost wholly destroyed before the repair work began, and was so unstable that it was necessary to erect a buttress to support it. This room, which is one story high, is irregular in shape; its doorways open into rooms 14 and 16. The walls of rooms 16 and 18 extend to the roof of the cave, shutting out the light on one side from the great refuse-place in the rear of the cliff-dwellings. The openings through the walls of these rooms into this darkened area have been much broken by vandals, and the walls greatly damaged. Room 17, like 16 and 18, is somewhat larger than most of the apartments in Spruce-tree House.

Theoretically it may be supposed that when Spruce-tree House was first settled it had one clan occupying a cluster of rooms, 1-11, and one ceremonial room, kiva A. As the place grew three other “unit types” centering about kivas C-H were added, and still later each of these units was enlarged and new kivas were built in each section. Thus A was enlarged by addition of B; C by addition of D; E by addition of F; and G was subordinated to H. In this way the rooms near the kivas grew in numbers. The block of rooms designated 50-53 is not accounted for, however, in this theory.

Rooms numbered 19-22 are instructive. Their walls are well preserved and form the east side of plaza C. These walls extend from the level of the plaza to the top of the cavern, and in places show some of the best masonry in Spruce-tree House. Just in front of room 19, situated on the left-hand side as one enters the doorway, is a covered recess, where probably ceremonial bread was baked or otherwise cooked. This place bears a strong resemblance to recesses found in Hopi villages, especially as in its floor is set a cooking-pot made of earthenware. Rooms 19-21 are two stories high; there are fireplaces in the corners and doorways on the front sides. The upper stories were approached and entered by balconies. The holes in which formerly rested the beams that supported these balconies can be clearly seen.

Rooms 21 and 22 are three stories high, the entrances to the three tiers being seen in the accompanying view (pl. 6). The beams that once supported the balcony of the third story resemble those of the first story; they project from the wall that forms the front of room 29.

The external entrance to room 24 opens directly on the plaza. Some of the rafters of this room still remain, and near the rear door is a projecting wall, in the corner of which is a fireplace. Although room 25 is three stories high, it does not reach to the cave top. None of the roofs of the rooms one over another are intact, and the west side of the second and third stories is very much broken. The plaster of the second-story walls is decorated with mural paintings that will be considered more fully under Pictographs. It is not evident how entrance through the doorway of the second story was made unless we suppose that there was a notched log, or ladder, for that purpose resting on the ground. In order to strengthen the north wall of room 25 it was braced against the walls of outer rooms by constructing masonry above the doorway that leads from plaza D to room 26. This tied all three walls together and imparted corresponding strength to the whole.

The lower-story walls of room 26 are in fairly good condition, having needed but little repair. There is a good fireplace in the floor at the northeast corner. Excavations revealed a passageway from kiva D into room 26, the opening into the upper room being situated near its north wall. The west wall of room 26 is curved. The walls of rooms 27 and 28 are much dilapidated, the portion of the western section that remains being continuous with the front wall of the pueblo. A small mural fragment ending blindly arises from the outside of the west wall of room 27. This is believed to have been part of a small enclosure used for cooking purposes. Much repairing was necessary in the walls of rooms 27 and 28, since they were situated almost directly in the way of torrents of water which in time of rains fall over the rim of the canyon.

The block of rooms numbered 30-44, situated east of kiva E, have the most substantial masonry and are the best constructed of any in Spruce-tree House. (Pl. 9.) As room 45 is only a dark passageway it should be considered more a street than a dwelling. Rooms 30-36 are one story each in height, rectangular in shape, roofless, and of about the same dimensions; of these room 35 is perhaps the best preserved, having well-constructed fireplaces in one corner. Rooms 37, 38, 39 are built deep in the cavern; their walls, especially those of 38, are very much broken down. There would seem to be hardly a possibility that these rooms were inhabited, especially after the construction of the rooms in front of the cave which shut off all light. But they may easily have served as storage places. Their walls were[14] constructed of well-dressed stones and afford an example of good masonry work.

Here and there are indications of other rooms in the darker parts of the cave. In some instances their walls extended to the roof of the cave where their former position is indicated by light bands on the sooty surface.

Rooms 40-47 are among the finest chambers in Spruce-tree House. Rooms 48 and 49 are very much damaged, the walls having fallen, leaving only the foundations above the ground level. Several rooms in this part of the ruin, especially rooms 43 (pl. 9) and 44, still have roofs and floors as well preserved as when they were built, and although dark, owing to lack of windows, they have fireplaces in the corners, the smoke escaping apparently through the diminutive door openings. The thresholds of some of the doorways are too high above the main court to be entered without ladders or notched poles, but projecting stones or depressions for the feet, still visible, apparently assisted the inhabitants, as they do modern visitors, to enter rooms 41 and 42.

Each of the small block of rooms 50-53 is one story and without a roof, but possessing well-preserved ground floors. In room 53 there is a depression in the floor at the bottom of which is a small hole.[11]

In the preceding pages there have been considered the rooms of the north section of Spruce-tree House, embracing dwellings, ceremonial rooms, and other enclosures north of the main court, and the space in the rear called the refuse-heap—in all, six circular ceremonial rooms and a large majority of the living and storage rooms. From all the available facts at the author’s disposal it is supposed that this portion is older than the south section, which contains but two ceremonial rooms and not more than a third the number of secular dwellings.[12]

The cluster of rooms connected with kivas G and H shows signs of having been built by a clan which may have joined Spruce-tree House subsequent to the construction of the north section of the village. The ceremonial rooms in this section differ in form from the others. Here occur two round rooms or towers, duplicates of which have not been found in the north section.

Room 61 in the south section of Spruce-tree House has a closet made of flat stones set on edge and covered with a perforated stone slab slightly inclined from the horizontal.

The inclosures at the extreme south end, which follow a narrow ledge, appear to have been unroofed passages rather than rooms. On[15] ledges somewhat higher there are small granaries each with a hole in the side, probably for the storage of corn.

It will be noticed that the terraced form of buildings, almost universal in modern three-story pueblos and common in pictures of ruins south of the San Juan, does not exist in Spruce-tree House. The front of the three tiers of rooms 22, 23, as shown in plate 3, is vertical, not terraced from foundation to top. Whether the walls of rooms now in ruins were terraced or not can not be determined, for these have been washed out and have fallen to so great an extent that it is almost impossible to tell their original form. Rooms 25-28, for instance, might have been terraced on the front side, but it is more reasonable to suppose they were not;[13] from the arrangement of doors it would seem that there was a lateral entrance on the ground floor rather than through roofs.

Balconies attached to the walls of buildings below rows of doors occurred at several places. On no other hypothesis than the presence of these structures can be explained the elevated situation of entrances opening into the rooms immediately above rooms 20, 21, 22. In fact, there appear to have been two balconies at this place, one above the other, but all now left of them is the projecting floor-beams, and a fragment of a floor on the projections at the north end of the lower one, in front of room 20. These balconies (pl. 3) were apparently constructed in the same way as the structure that gives the name to the ruin called Balcony House; they seem to have been used by the inhabitants as a means of communication between neighboring rooms.

Nordenskiöld writes:[14]

The second story is furnished along the wall just mentioned, with a balcony; the joists between the two stories project a couple of feet, long poles lie across them parallel to the walls, the poles are covered with a layer of cedar bast, and, finally with dried clay.

There are many fireplaces in Spruce-tree House, in rooms, plazas, and courts. From their number it is evident that most of the cooking must have been done by the ancients in the courts and plazas, rather than in the houses. The rooms are so small and so poorly ventilated that it would not be possible for any one to remain in them when fires are burning.

The top of the cave in which Spruce-tree House is built is covered with soot, showing that formerly there were many fires in the courts and other open places of the village. In almost every corner of the buildings in which a fire could be made the effect of smoke on the adjoining walls is discernible, while ashes are found in a depression in the floor. These fireplaces are very simple, consisting simply of square box-like structures bounded by a few flat stones set on edge. In other instances a depression in the floor bordered with a low ridge of adobe served as a fireplace. There remains nothing to indicate that the inhabitants were familiar with chimneys or firehoods as is the case among the modern pueblos. Certain small rooms suggest cook-houses, or places where piki, or paper bread, was fried by the women on slabs of stone over a fire, but none of these slabs were found in place. The fireplaces of the kivas are considered specially in an account of the structure of those rooms (see p. 18).

No evidence that Spruce-tree House people burnt coal was observed, although they were familiar with lignite and seams of coal underlie their mesa.

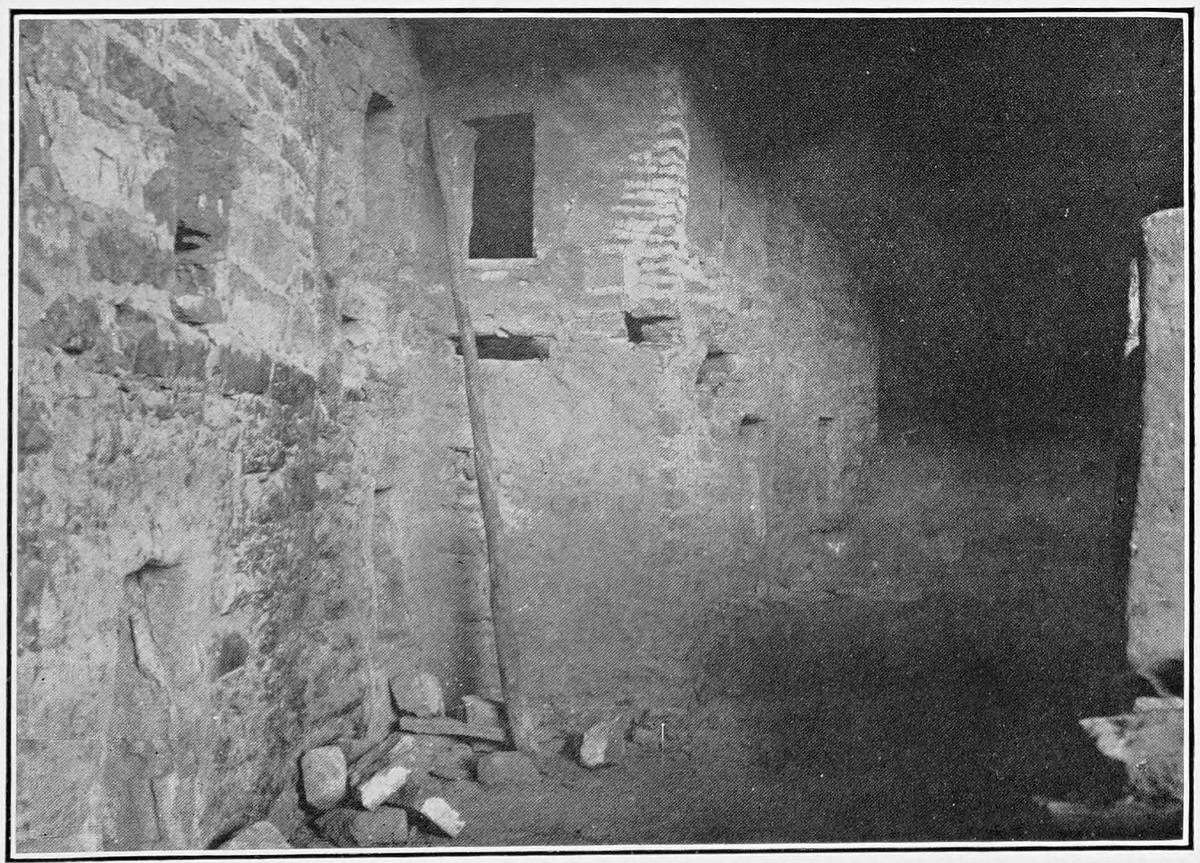

There are both doors and windows in the secular houses of Spruce-tree House, although the two rarely exist together. The windows, most of which are small square peep-holes or round orifices, look obliquely downward, as if their purpose was rather for outlook than for air, the latter being admitted as a rule through the doorway. (Pls. 10, 11.)

The two types of doorways differ more in shape than in any other feature. These types may be called the rectangular and the T-shaped form. Both are found at a high level, but it can not be discovered how they could have been entered without ladders or notched logs. Although these modes of entrance were apparently often used it is remarkable that no traces of the logs have yet been found in the extensive excavations at Spruce-tree House. The T-shaped doorways are often filled in at the lower or narrow part, sometimes with stones rudely placed, oftentimes with good masonry, by which a T-shaped door is converted into one of square type. Doorways of both types are often completely filled in, leaving only their outlines on the sides of the wall.

The floors of the rooms are all smoothly plastered and, although purposely broken through in places by those in search of specimens, are otherwise in fairly good condition. In one of the rooms at the left of the main court is a small round hole at the bottom of a concave depression like a fireplace, the use of which is not known. Many of the floors sound hollow when struck, but this fact is not an indication of the presence of cavities below. In tiers of rooms that rise above the first story the roof of one room forms the floor of the room above it. Wherever roofs still remain they are found to be well constructed (pl. 9) and to resemble those of the old Hopi houses. In Spruce-tree House the roofs are supported by timbers laid from one wall to another; these in turn support crossbeams on which were placed layers of cedar bark covered with a thick coating of mud. In several roofs hatchways are still to be seen, but in most cases entrances are at the sides. One second-story room has a fireplace constructed like those on the ground floor or on the roof. Several fireplaces were found on the roofs of buildings one story high.

The largest slabs of stone used in the construction of the rooms of Spruce-tree House were generally made into lintels and thresholds. The latter surfaces were often worn smooth by those crawling through the opening and in some cases they show grooves for the insertion of the door slabs. Although the sides of the door are often upright slabs of stone these may be replaced by boards set in adobe plaster. Similar split boards often form lintels.

The door was apparently a flat stone set in an adobe casing on the inside of the frame where it was held in position by a stick. Each end of this stick was inserted into an eyelet made of bent osiers firmly set in the wall. Many of these broken eyelets can still be seen in the doorways and one or two are still entire. A slab of stone closing one of the doorways is still in place.

There are eight circular subterranean rooms identified as ceremonial rooms, or kivas, in Spruce-tree House (pls. 12, 13). Beginning on the north these kivas are designated by letters A-H. When excavation began small depressions full of fallen stones, with here and there a stone buttress projecting out of the débris, were the only indications of the sites of these important chambers. The walls of kiva H were the most dilapidated and the most obscured of all, the central portion of the front wall of rooms 62 and 63 having fallen into this chamber; added to the débris were the high walls of the round room, no. 69. Kiva G is the best-preserved kiva and kiva A the most exceptional in construction. Kiva B, never seen by previous[18] investigators, was in poor condition, its walls being almost completely broken down. Part of the wall of kiva A is double (pl. 13), indicating a circular room built inside another room the shape of which inclines to oval, the former utilizing a portion of the wall of the latter. This kiva is also exceptional in being surrounded on three sides by rooms, the fourth side being the wall of the cavern. From several considerations the author regards this as the oldest kiva in Spruce-tree House.

The typical structure of a Spruce-tree House kiva is as follows: Its form is circular or oval; the site is subterranean, the roof being level with the floor of the surrounding plaza. (Pls. 13-15.) Two walls, an outer and an inner, inclose the room, the latter forming the lower part. Upon the top of this lower wall rest six pedestals, which support the roof beams; the outer wall braces these pedestals on one side. The spaces between these pedestals form recesses in which the floors extend a few feet above the floor of the room.

The floor of the kiva is generally plastered, but in some cases is solid rock. The fireplace is a circular depression in the floor, its purpose being indicated by the wood ashes found therein. Its lining is ordinarily made of clay, which in some instances is replaced by stones set on edge.

The other important opening in the floor is one called sipapû, or symbolic opening into the underworld. This is generally situated near the center of the room, opposite the fireplace. This opening into the underworld is barely large enough to admit the human hand and extends only about a foot below the floor surface. It is commonly single, but in one kiva two of these orifices were detected. A similar symbolic opening occurs in modern Hopi kivas, as has been repeatedly described in the author’s accounts of pueblo ceremonials. An important structure of a Spruce-tree House kiva is an upright slab of rock, or a narrow thin wall of masonry, placed between the fireplace and the wall of the kiva. This object, sometimes called an altar, serves as a deflector, its function being to distribute the air which enters the kiva at the floor level through a vertical shaft, or ventilator. Every kiva has at least one such deflector, a single fireplace, and the sipapû, or ceremonial opening mentioned above.

Several small cubby-holes, or receptacles for paint or small ceremonial objects, generally occur in the lower walls of the kiva. In addition to these there exist openings ample in size to admit the human body, which serve different purposes. The first kind communicate directly with passageways through which one can pass from the kiva into a neighboring room or plaza. Such a passageway in kiva E has steps near the opening in the floor of room 35. This entrance is not believed, however, to be the only way by which one could enter or leave this room, but was a private passage, the main[19] entrance being through the roof. Another lateral passageway is found in kiva D, where there is an opening in the south wall communicating with the open air by means of an exit in the floor of room 26; another opening is found in the wall on the east side. Kiva C has a lateral opening communicating with a vertical passageway which opens in the middle of the neighboring plaza. In addition to lateral openings all kivas without exception have others that serve as ventilators, as before mentioned, by which air is introduced on the floor level of the kivas. The opening of this kind communicates through a horizontal passage with a vertical flue which finds its way outside the room on a level with the roof. In cases where the kiva is situated near the front wall these ventilators open through this wall by means of square apertures. All ventilator openings are in the west wall except that of kiva A, which is the only one that has rooms on that side.

The construction of kiva roofs must have been a difficult problem (pls. 14, 15). The beams (L-1 to L-4) are supported by the six pedestals (C) which stand upon the banquettes (A), and in turn are supported by the outer wall (B) of the kiva. On top of each of these pedestals is inserted a short stick (H) that served as a peg on which the inmates hung their ceremonial paraphernalia. The supports of the roof were cedar logs cut in suitable lengths by stone axes. Three logs were laid, connecting adjacent pedestals upon which they rested. These logs, which were large enough to support considerable weight, had been stripped of their bark. Upon these six beams were laid an equal number of beams, spanning the intervals between those first placed, as shown in the illustration (pl. 15). Upon the last-mentioned beams were still other logs extending across the kiva, as also shown in the plate.

The main weight of the roof was supported by two large logs which extended diametrically across the kiva from one wall to the wall opposite; they were placed a short distance apart, parallel with each other. The distance between these logs determines the width of the doorway, two sides of which they form. The other two sides are formed by two beams (L-4) of moderate size, laid across these logs, the space between them and the two beams being filled in with other logs, forming a compact framework. No nails are necessary in a roof constructed in this way.

The smaller interstices between the logs were filled in with small sticks and twigs, thus preventing soil from dropping into the room. Over the supports of the roof was spread a layer of cedar bark (M) covered with mud (N), laid deep enough to bring the top of the roof to the level of the plaza in which the kiva is situated.

No kiva was found in which the plastering of the walls was supported by sticks, as sometimes occurs here, according to Nordenskiöld,[20] and in one or more of the Hopi kivas. The plastering of the walls was placed directly on the masonry.

It is probable that the kiva walls were painted with various devices before their roofs fell in and other mutilation of the walls took place. Among these designs parallel lines in white were common. Similar lines are still made with meal on kiva walls in Hopi ceremonies, as the author has often described. One of the pedestals of kiva A is decorated with a triangular figure on the margin of the dado, to which reference will be made later.

The author has found no conclusive answer to the question why the kivas are built under ground and are circular in form. He believes both conditions to be survivals of ancient “pit-houses,” or subterranean dwellings of an antecedent people. In this explanation the kiva is regarded as the oldest form of building in the cliff-dwellings. We have the authority of observation bearing on this point. Pit-dwellings are recorded from several ruins. In a recent work Dr. Walter Hough figures and describes certain dwellings of subterranean character that are sometimes found in clusters,[15] while the present author has observed subterranean rooms so situated as to leave no doubt of their great antiquity.[16]

The form of the kiva is characteristic and may be used as a basis of classification of pueblo culture. The people whose kivas are circular inhabited villages now ruins in the valley of the San Juan and its tributaries, in Chelly canyon, Chaco canyon, and on the western plateau of the Rio Grande.

The rectangular kiva is a structure altogether different from a round kiva, morphologically, genetically, and geographically. It is peculiar to the southern and western pueblo area, and while of later growth, should not be regarded as an evolution from the circular kiva. Several authors have found in circular kivas survivals of nomadic architectural conditions, while the position of these rooms, in nearly every instance in front of the other rooms of the cliff-dwelling, has led others to accept the theory that they were later additions to the village, which should be ascribed to a different race. It would seem that this hypothesis hardly conforms to facts, as some kivas have secular rooms in front of them which show evidences of later construction. The strongest objection to the theory that kivas are modified houses of nomads is the style of roof construction.

This room (pl. 13), which is the most northerly of all of the ceremonial rooms of Spruce-tree House, is, the author believes, the[21] oldest. In construction this is a remarkable chamber. It is built directly under the cliff, which forms part of its walls. In addition to its site the remarkable features are its double walls, and its floor on the level of the roofs of the other kivas. Although this kiva is not naturally subterranean, the earth and walls built up around it make it to all intents below the surface of the ground.

It appears from the arrangement of walls and banquettes that there is here presented an example of one room constructed inside of another, the inner room utilizing for its wall a portion of the outer. The inner room is more nearly circular than the outer in which it was subsequently built. In this inner room as in other kivas there are six banquettes, and the same number of pedestals to support the roof. Three of these pedestals are common to both rooms. The floor of this room shows nothing peculiar. It has a fire hole, a sipapû, and a deflector, or low wall between the fire hole and the entrance into the horizontal passageway of the ventilator. The ventilator itself opens just outside the west wall through a passageway, the walls of which stand on the wall of a neighboring room. No plaza of any considerable size surrounded the top of this kiva.

In order to get an idea as to how many rectangular rooms naturally accompany a single kiva, the author examined the ground plans of such cliff-dwellings as are known to have but one circular kiva, the majority of these being in the Chelly canyon. While it was not possible to determine the point satisfactorily, it was found that in several instances the circular kiva lies in the middle of several rooms, a fact which would seem to indicate that it was built first and that the square rooms were added later. Several clusters of rooms, each cluster having one kiva, closely resemble kiva A and its surroundings, in both form and structure.

The walls of this subterranean room had escaped all previous observers. They are very much dilapidated, being wholly concealed when work of excavation began. A large old cedar tree growing in the middle of this room led the author to abandon its complete excavation, which promised little return either in enlarging our knowledge of the ground plan of Spruce-tree House or in shedding additional light on the culture of its prehistoric inhabitants.

The two kivas, C and D, the roofs of which form the greater part of plaza C, logically belong together in our consideration. One of these rooms, C, was roofed over by the author, who followed as a model the roofs of the two kivas of the House with the Square Tower (Peabody House); the other shows a few log supports of an original roof—the only Spruce-tree House kiva of which this is true.

Not only was the roof of the kiva restored but its walls were well repaired, so that it now presents all the essential features of an ancient kiva. On one of the banquettes of this room the author found a vase which was evidently a receptacle for pigments or other ceremonial paraphernalia.

Kiva D has a passageway leading into room 26 and a second opening in the west wall on the floor level, besides a ventilator of the type common to all kivas. The top of the opening in the west wall appears covered with a flat stone in one of the photographic views (plate 11).

The wall in front of the village in the neighborhood of kivas C and D was wholly concealed by débris when work was begun on this part of the ruin. Excavation of this débris showed that opposite each kiva there was an opening with which the ventilator is believed formerly to have been connected. There seems to have been a low-storied house, possibly a cooking-place, provided with a roof, in an interval between kivas C and D; in the floor of the plaza at this point a well-made fire hole was uncovered.

Kiva E is one of the finest which was excavated, showing all the typical structures of these characteristic rooms; it almost fills the plaza in which it is situated. The exceptional feature of this room is a passageway through the west wall. Room 35 may have been the house of a chief or of a priest who kept in it his masks or other ceremonial paraphernalia. A similar opening in the wall of one of the Hopi kivas communicates with a dark room in which are kept altars and other ceremonial objects. When such a passageway into a dark chamber is not in use it is closed by a slab of stone.

Kiva F might be designated the Spruce-tree kiva from the large spruce tree that formerly grew near its outer wall. Its stump is now visible, but the tree lies extended in the canyon.

The walls of this kiva were poorly preserved, and only two of the pedestals were in place. The walls were repaired and the roof restored. This room is situated outside the walls, and in that respect recalls kiva B, described above. The ventilator opening of this kiva is situated on the south instead of on the west side of the room, as is the rule in other kivas. The large size of this room would indicate that it was of great importance in the religious ceremonials of the prehistoric inhabitants of Spruce-tree House, but all indications point to its late construction.[17]

Kiva G was so well preserved that its walls were thoroughly restored; it now stands as typical of one of these rooms in which the several characteristic features may be seen. For the guidance of visitors, letters or numbers accompanied by explanatory labels were painted by the author on the walls of the kiva.

Kiva G lies just below and in front of the round tower of Spruce-tree House, which is situated in the neighborhood of the main court, and may therefore be looked on as one of the most important kivas in the cliff-dwelling.[18] The solid stone floor of this room had been cut down about 8 inches.

Kiva H, the largest in Spruce-tree House, contained some of the best specimens excavated by the author. Its shape is oval rather than circular, and it fills the whole space inclosed by walls of rooms on three sides. In the neighborhood of kiva H is a comparatively spacious plaza which is bounded on the front by a low wall, now repaired, and on the other sides are high rooms. The plaza containing this kiva was ample for ceremonial dances which undoubtedly formerly occurred in it. The walls of kiva H formerly had a marked pinkish color, showing no sign of blackening by smoke except in places. Charred roof beams were excavated at one place, however, and charcoal occurred deep under the débris that filled this room.

There are two rooms (nos. 54, 69) of circular shape in Spruce-tree House, one of which resembles the “tower” in the Cliff Palace. This room (no. 54) is situated to the right hand of the main court above referred to, into which it projects without attachment except on one side. Its walls have two small windows or openings which have been called doorways, and are of a single story in height. This tower was apparently ceremonial in character.

It is instructive to mention that remains of a fire hole containing wood ashes occur in the floor on one side of this room, and that the walls are pierced with several small holes opening at an angle. Only foundations remain of the other circular room. It was situated on the south side of the open space containing kiva H and formed a bastion at the north end of the front wall. The floor of this room was wholly covered with fallen débris and its ground plan was wholly concealed when the excavations began; it was only with considerable difficulty that the foundation walls could be traced.

While the circular subterranean rooms above mentioned are believed to be the most common ceremonial chambers, there are others in the cliff-dwellings which were undoubtedly used for similar purposes. One of these, designated room 12, adjoins the mortuary room (11) and opens on the plaza C, D. In some respects the form of this room is similar to an “estufa of singular construction” described and figured in Nordenskiöld’s account of Cliff Palace. Certain distinctive characters of this room separate it on one side from a kiva and on the other from a dwelling. In the first place, it lacks the circular form and subterranean site. The six pedestals which universally support the roofs are likewise absent. In fact they are not needed because in this room the top of the cave serves as the roof. A bank extends around three sides of the room, the fourth side being the perpendicular wall of the cliff. In the southeast corner is an opening, which recalls that in the “estufa of singular construction” described by Nordenskiöld.[19]

Room 9 may be designated a mortuary room from the fact that at least four human skeletons and accompanying offerings have been found in its floor. Three of those, excavated several years ago, were said to have been infants; the skull of one of these was figured and described by Prof. G. Retzius, in Nordenskiöld’s memoir. The skeleton found by the author was that of an adult and was accompanied by mortuary offerings. The skull and some of the larger bones were well preserved.[20] Evidently the doorway of this room had been walled up and there are indications that the burials took place at intervals, the last occurring before the desertion of the village.

The presence of burials in the floors of rooms in Spruce-tree House was to be expected, as the practice of thus disposing of the dead was known from other ruins of the Park, but it has not been pointed out that we have in this region good evidence of several successive interments in the same room. The existence of this intramural burial room in the south end of the ruin is one of the facts that can be adduced pointing to the conclusion that this part of the ruin is very old.

Not far from the Spruce-tree House, situated in the same canyon, there are small one-room houses perched on narrow ledges situated generally a little higher than the cave containing the main ruin.[25] Although it is difficult to enter some of these houses, members of the author’s party visited all of them, and two of the workmen slept in a small ledge-house on the west side of the canyon. Except in rare cases these smaller houses can not be considered dwellings; they may have been used for storage, although it is more than likely that they were resorted to by priests when they wished to pray for rain or to perform certain ceremonies. The ledge-houses form a distinct type of ruin; they are rarely multiple-chambered and therefore are not capacious enough for more than one family.

There are two or three old stairway trails in the neighborhood of Spruce-tree House. These consist of a succession of holes for hands and feet, or of a series of pits cut in the face of the cliff at convenient distances. One of these ancient trails is situated on the west side of the canyon not far from the modern trail to the spring; the other lies on the east side a few feet north of the ruin. Both of these trails were appropriately labeled for the convenience of future visitors. There is still another ancient trail along the east canyon wall south of the ruin. Although all these trails are somewhat obscure, it is hoped that they can be readily found by means of the labels posted near them.

In the rear of the buildings are two large open spaces which, from their positions relative to the main street, may be called the northern and southern refuse-heaps. They merit more than passing consideration. The former, being the larger, has not yet been thoroughly cleared out, although pretty well dug over before the repair work was begun. The author completely cleared out the southern refuse-heap and excavated to its floor.[21]

The southern recess opens directly into the main street and is flooded with light. Its floor is covered with large fragments of rock that have fallen from the cliff above. The spaces between these bowlders were filled with débris and the bowlders themselves were covered with the same accumulations the removal of which was no small task.

The rooms and refuse-heaps of Spruce-tree House had been pretty thoroughly ransacked for specimens by those who preceded the author, so that few minor antiquities were expected to come to light in the excavation and repair work. Notwithstanding this, however, a fair collection,[26] containing some unique specimens and many representative objects, was made, and is now in the National Museum where it will be preserved and be accessible to all students. Considering the fact that most of the specimens previously abstracted from this ruin have been scattered in all directions and are now in many hands, it is doubtful whether a collection of any considerable size from Spruce-tree House exists in any other public museum. In order to render this account more comprehensive, references are made in the following pages to objects from Spruce-tree House elsewhere described, now in other collections. These references, quoted from Nordenskiöld, the only writer on this subject, are as follows:

Plate XVIII: 2. a and b. Strongly flattened cranium of a child. Found in a room in Sprucetree House.

Plate XXXIV: 4. Stone axe of porphyrite. Sprucetree House.

Plate XXXV: 2. Rough-hewn stone axe of quartzite. Sprucetree House.

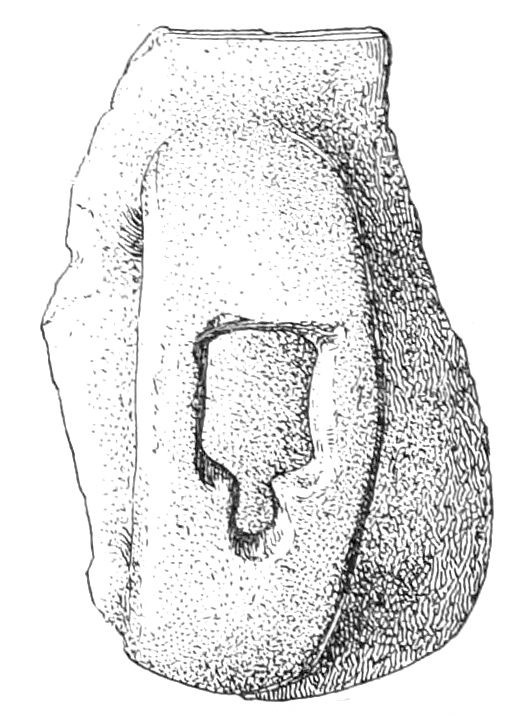

Plate XXXIX: 6. Implement of black slate. Form peculiar (see the text). Found in Sprucetree House.

[In the text the last-mentioned specimen is again referred to, as follows:]

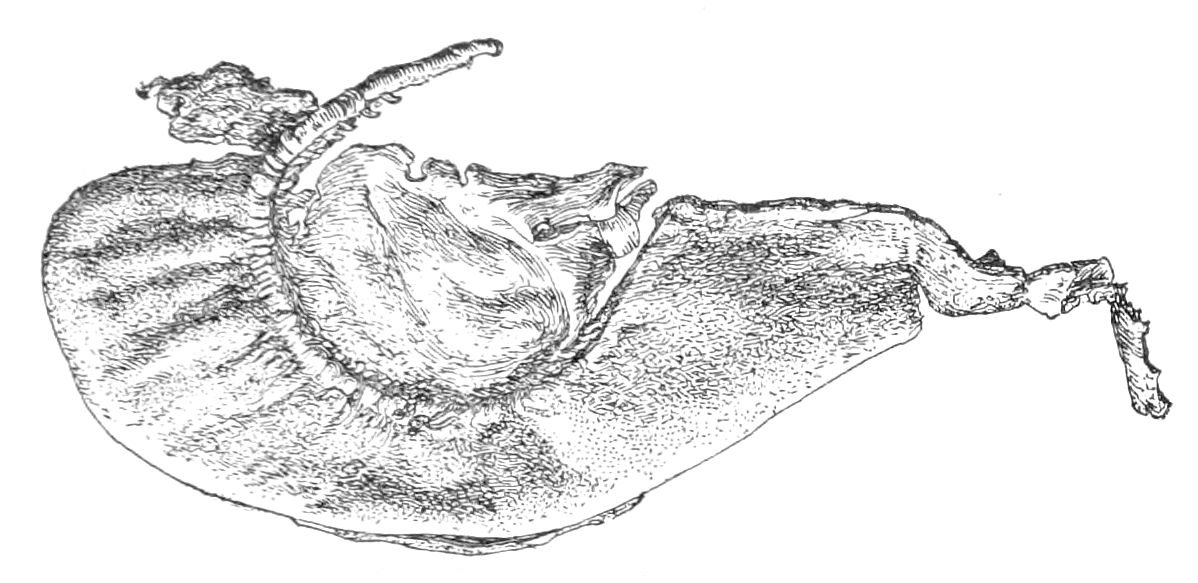

I have still to mention a number of stone implements the use of which is unknown to me, first some large (15-30 cm.), flat, and rather thick stones of irregular shape and much worn at the edges (Pl. XXXIX: 4, 5), second a singular object consisting of a thin slab of black slate, and presenting the appearance shown in Pl. XXXIX: 6. My collection contains only one such implement, but among the objects in Wetherill’s possession I saw several. They are all of exactly the same shape and of almost the same size. I cannot say in what manner this slab of slate was employed. Perhaps it is a last for the plaiting of sandals or the cutting of moccasins. In size it corresponds pretty nearly to the foot of an adult.

Plate XL: 5. Several ulnæ and radii of birds (turkeys) tied on a buckskin string and probably used as an amulet. Found in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLIII: 6. Bundle of 19 sticks of hard wood, probably employed in some kind of knitting or crochet work. The pins are pointed at one end, blunt at the other, and black with wear. They are held together by a narrow band of yucca. Found in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLIV: 2. Similar to the preceding basket, but smaller. Found in Sprucetree House....

[The “preceding basket” is thus described in explanation of the figure (Pl. XLIV: 1):] Basket of woven yucca in two different colors, a neat pattern being thus attained. The strips of yucca running in a vertical direction are of the natural yellowish brown, the others (in horizontal direction) darker....

Plate XLV: 1(95) and 2(663): Small baskets of yucca, of plain colour and of handsomely plaited pattern. Found: 1 in ruin 9, 2 in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLVIII: 4(674). Mat of plaited reeds, originally 1.2 × 1.2 m., but damaged in transportation. Found in Sprucetree House.

It appears from the foregoing that the following specimens have been described and figured by Nordenskiöld, from Spruce-tree House: (1) A child’s skull; (2) 2 stone axes; (3) a slab of black slate; (4) several bird bones used for amulet; (5) bundle of sticks; (6) 2 small baskets; (7) a plaited mat.