The Project Gutenberg eBook of Algeria from within, by Ronald Victor Courtenay (R.V.C.) Bodley

Title: Algeria from within

Author: Ronald Victor Courtenay (R.V.C.) Bodley

Photographer: Julian Sampson

Release Date: March 14, 2023 [eBook #70287]

Language: English

Produced by: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive and the HathiTrust Digital Library)

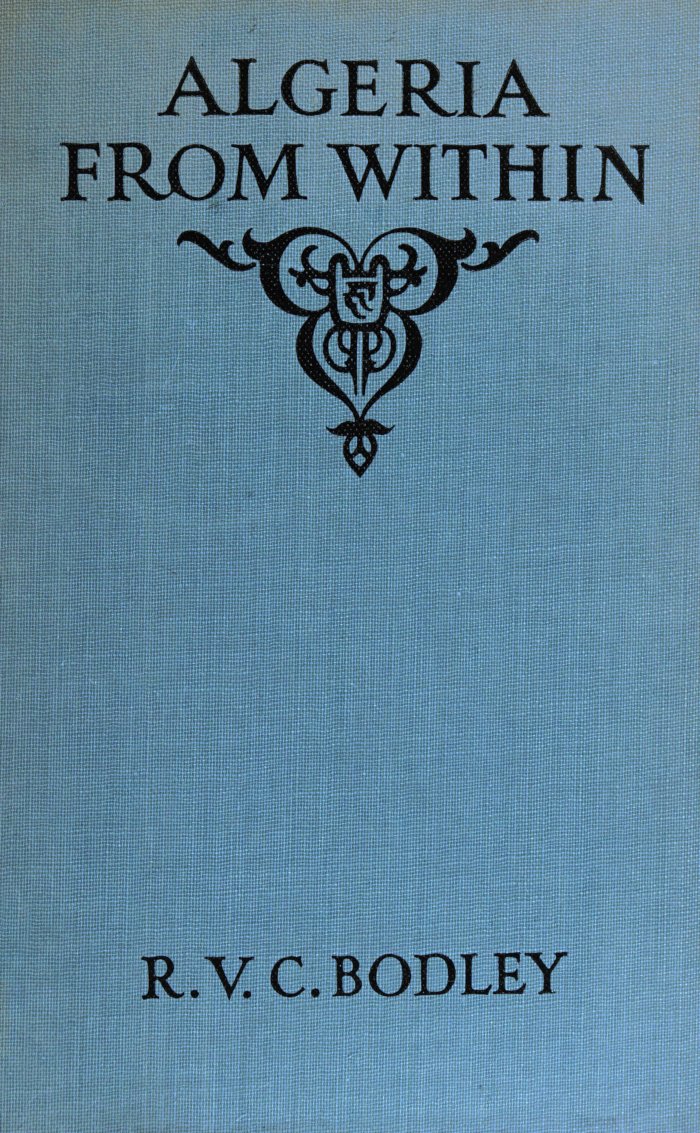

The Author

BY

R. V. C. BODLEY

ILLUSTRATED

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1927,

by The Bobbs-Merrill Company

Printed in the United States of America

PRINTED AND BOUND

BY BRAUNWORTH & CO., INC.

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

To

MY MANY FRIENDS

OF ALL NATIONALITIES WHO

INHABIT ALGERIA

This is not a preface but merely a few words to state that in writing these pages I have in no way tried to criticize the French administration or to discuss the Arab from any point of view but that of a spectator.

I have no political feelings, few ambitions beyond living simply and far away from the world, and if this work exists at all, it is because I have wished that people should know Algeria as it really is.

Once upon a time I had great ideas about worldly position and the sound of long titles; I believed that greatness was to be achieved in the capitals of Europe or on the battle-fields, but I know now that this is not so. Worldly positions and great titles are the weary outcome of much money laboriously reaped, and the heroes of battle-fields pass unnoticed in the street.

Southern Algeria, with all its charm, with all its capricious moods, has, like some lovely woman, taken me in its arms and I am doubtful if it will ever let me go.

Let this book therefore be read in the spirit in which it has been written by one who, having seen life in many parts of the globe, has found peace and solution to all worldly difficulties among the rustling palm-trees and broad expanses of the Sahara.

I must here take the opportunity of thanking certain kind friends who have helped me in my work, notably:

Monsieur Jean Causeret, Secrétaire Général du Gouvernement Général, who has supplied me with maps, Dr. Alfred S. Gubb, the well-known English physician in Algiers, the Rev. Lucius Fry, British Chaplain in Algiers, and Mrs. Clare Sheridan, who have all lent me photos appearing in these pages. My thanks are also due to Mrs. Welthin Winlo, whose untiring secretarial work has helped me to prepare this work, to Miss Una Thomas who has helped me with the proofs, and to Mr. Julian Sampson, who has not only supplied me with photographs, but who has also brought his expert knowledge to bear in the selecting of suitable illustrations.

Laghouat,

November, 1926.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Object of the Book | 13 |

| II | A Little Geography | 17 |

| III | A Little History | 22 |

| IV | The French Conquest of Algeria | 29 |

| V | The Inhabitants To-Day | 35 |

| VI | French Administration of Algeria | 40 |

| VII | Arab Administration | 48 |

| VIII | Marabouts | 57 |

| IX | The Arab Character | 64 |

| X | Life among the Arabs | 72 |

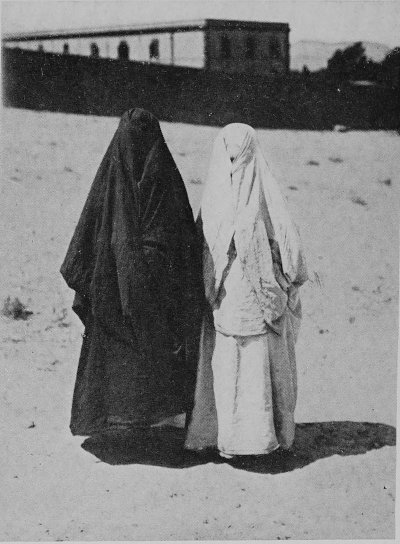

| XI | Arab Women | 80 |

| XII | Arab Love and the Women of the Reserved Quarter | 87 |

| XIII | Arab Music and Dancing | 94 |

| XIV | Religion | 101 |

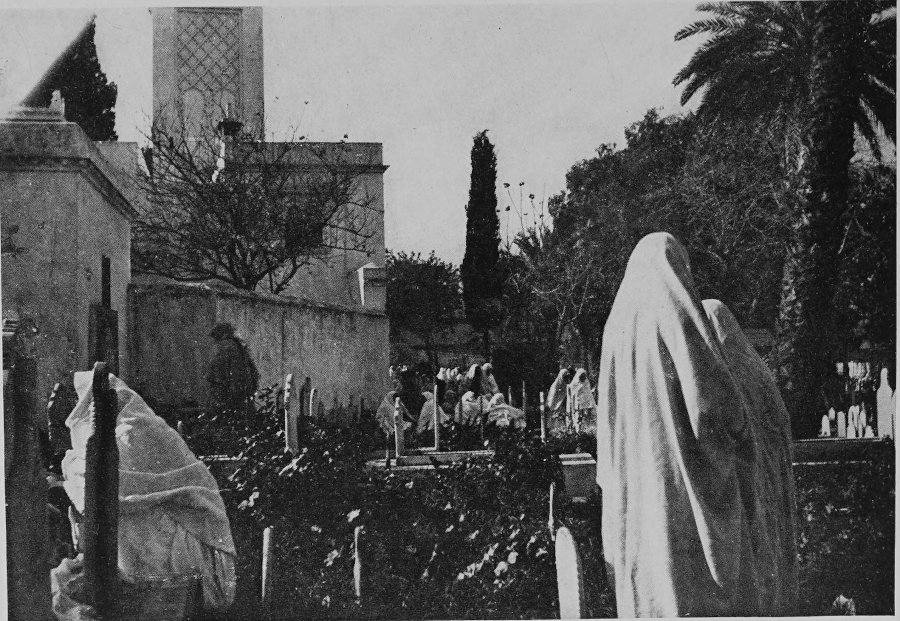

| XV | Religious Observances | 109 |

| XVI | “Mektoub” and Other Superstitions | 116 |

| XVII | Abd-El-Kader | 122 |

| XVIII | Arab Education | 128 |

| XIX | Sport among the Arabs | 133 |

| XX | The Nomads | 140 |

| XXI | Sheep-Breeding | 146 |

| XXII | Other Products | 152 |

| XXIII | Algiers | 158 |

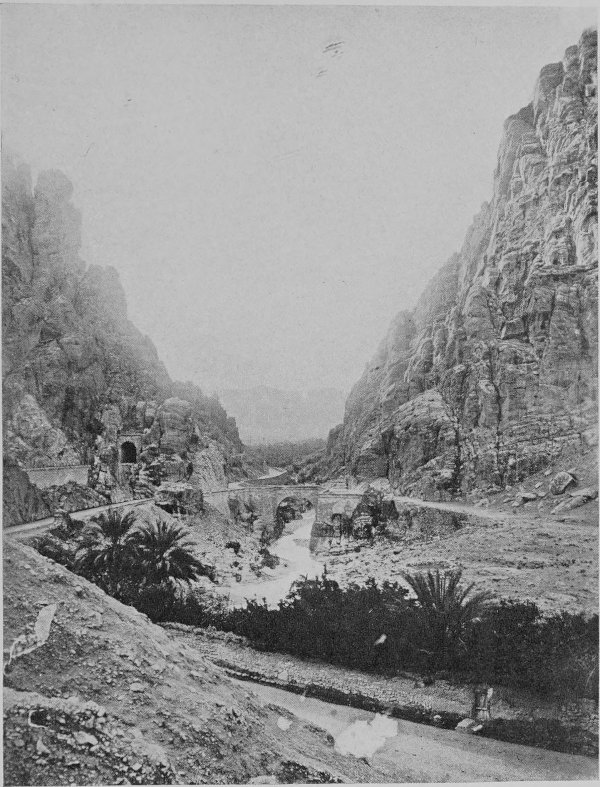

| XXIV | Two Excursions | 164 |

| XXV | Voyage | 170 |

| XXVI | Bou Saada | 176 |

| XXVII | The First Glimpse of the Sahara | 182 |

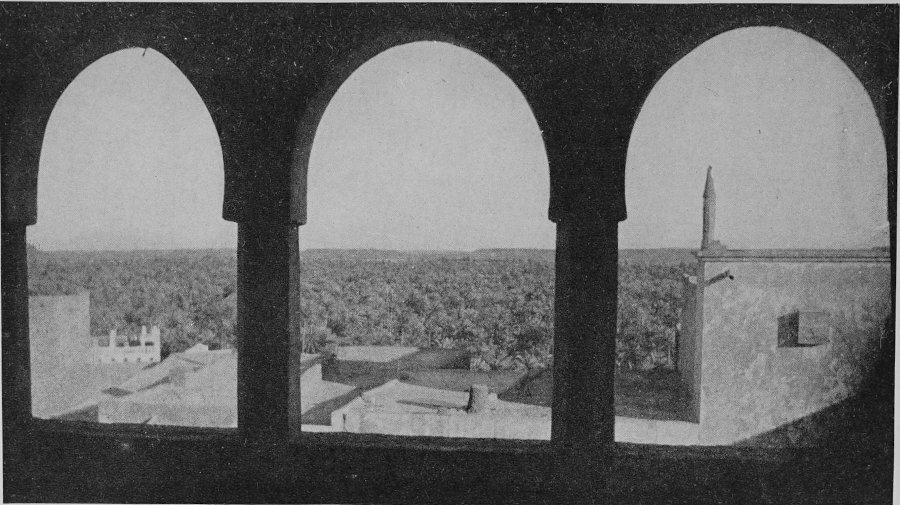

| XXVIII | The Oasis of Laghouat | 187 |

| XXIX | The Mzab | 194 |

| XXX | Ghardaia and Adjoining Towns | 201 |

| XXXI | Guerrera and the Sand Desert | 208 |

| XXXII | Biskra | 213 |

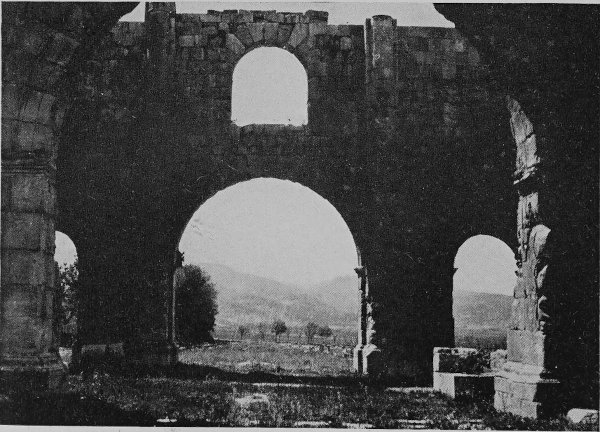

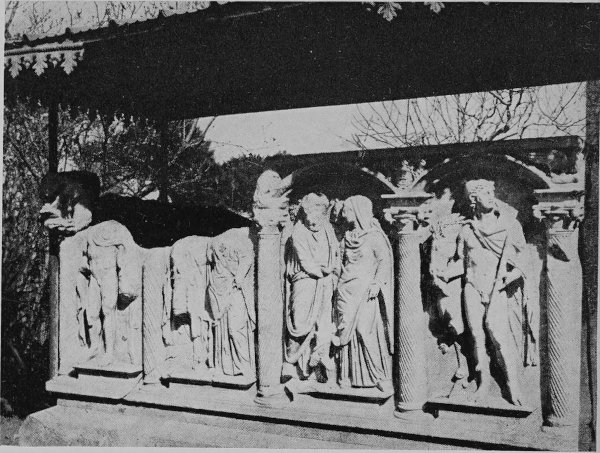

| XXXIII | Timgad | 219 |

| XXXIV | Djemila the Desolate | 226 |

| XXXV | Constantine to the Coast | 232 |

| XXXVI | Kebylie | 239 |

| XXXVII | Traveling Off the Beaten Track | 246 |

| XXXVIII | Few Sketches of Arab Life | 252 |

| XXXIX | A Last Glimpse of the Arab | 295 |

| Index | 303 |

[13]

ALGERIA FROM WITHIN

A writer who sets out to study a foreign country such as Algeria is faced with two difficulties: the first, the natural suspicion of the Mohammedan population; the second, the little information obtainable from the French inhabitants of the country.

It has been possible to overcome the first difficulty by making the Arab realize that there was no intention to interfere with his interior life or to obtain information in order to denounce family secrets. The second difficulty has remained. This is due to two factors. The first is the ignorance of the majority of Frenchmen, whether they be business men or colonists, of the customs and peculiarities of any area not neighboring that in which they actually dwell; the second is the French administrator’s apparent lack of information on anything beyond that which is not already to be found in the official handbooks.

When occasionally one meets some one with a deeper knowledge of the matters which should interest him, it is hard, as a foreigner, to obtain any valuable data. The Frenchman finds it difficult to realize that any one can wish to peer into the inner workings of a foreign country without some ulterior motive. If it is not deliberate spying for a jealous government, it is to steal a march on some business enterprise!

[14]

Comprehensive books on Algeria of to-day are few, and usually contradict one another, according to the point of view of the writers.

The only solution, therefore, to the problem of writing this book has been for the author to settle in the country, living the life of its people, and gleaning what information was possible as a business man in the city of Algiers, as a sheep-breeder on the Sahara, and as a traveler across the great plains and mountains of this sunny land.

The title of the book has perhaps a pretentious sound, suggesting that Algeria is some unexplored country into which the writer has penetrated, bringing back with him revelations of unknown mysteries never yet set before the public. But though this is not the case, it is hoped that the reader, be he a tourist or scholar, will find in these pages information which is new and interesting—Algeria from Within in opposition to the Algeria from “without” as set down by travelers who have passed a few winter months in the country and who, returning home, have compiled an inaccurate volume based on first impressions and on legends served up very hot by the hard-worked guides.

These legends will have to be dispelled at the cost of disillusioning veteran visitors who pass winter after winter in the overheated hotels of Mustapha Supérieur. But, against this, the book will endeavor to explain shortly and accurately what this French colony really is, what its people are doing and thinking, wherein lies its future.

There have been no aspirations to make of it a comprehensive guide-book or survey of the country’s long history, neither has any attempt been made to criticize the French rule, or to compare it with the administration of other colonies. True facts have[15] been set down as seen by one who has lived many years in the country, constantly studying all about him without confining himself to one area nor to one class of people. Living not only in the big cities, but also in the cultivated plains, in the desolation of the desert, and mixing with the French administrators, with business men, with the colonists, and visiting the Arabs in such intimacy that it is possible to tell of their daily life as it is really lived.

It is more a pen-picture of Algeria and the Sahara as it is to-day, drawn in the desire that the reader— be he traveler in all the senses of the word or one who journeys by his fireside on long winter evenings— will close the volume with a feeling that he has peeped for a moment into the intimate life of a country which, with all its youthful future, has a background of history more varied perhaps than any other country in the world. . . .

To the average tourist who leaves the misty London station in search of warmth and sunshine, the country he is about to visit is probably a somewhat uncertain vision of blue skies, palm-trees, and stately Arabs.

The inspired artists of the P. L. M. railway posters have dazzled his eyes with enchanting prospects of palm-green shores and rolling expanses of sand, golden in a perpetual sunset, while the scaleless maps of tourist agencies have graven in his mind the names Algiers, Biskra, Fez and Tunis, leaving him with a vague impression that all these places are in the same country and within easy reach of one another.

His mind is rather in the same state as that of the old lady who asks the officer going to India not to forget to look up her nephew who is stationed in Burmah. He has probably not realized that Algeria[16] differs greatly from Tunisia and Morocco in people and in government, and that it has no connections whatever with either of these two countries which form its eastern and western frontiers.

Even winter residents and regular visitors to Algeria know the country very superficially, and though some have ventured along the beaten tracks as far as the oases of Touggourt and Ghardaia, there are few who have left the main roads and mixed in the private life of the country. And what blame to them? There are few railways, and the motor-transport time-tables are lacking. The guide-books do not dwell upon places off the classical tours, the information at the tourist agencies goes no further, and even if the adventurous traveler pushes into the unfrequented regions, he will find no one to guide him, and unless he knows Arabic he will often be unable to make himself understood. Even when the acquaintance of an Arab chief has been made it takes many months to break through his exterior façade and to obtain a glimpse of his thoughts or his private life.

This book, therefore—which should be read in conjunction with a guide-book—will endeavor to lift a veil on matters which are of the deepest interest to all those who want to learn something about a land which must appeal to the most blasé traveler.

[17]

Algeria is situated some fifteen hundred miles due south of London, and is accessible via Paris and Marseilles in fifty hours, or by sea from Southhampton in four days. The country is bounded on the north by the Mediterranean, on the east by Tunisia, and on the west by Morocco. Its southern boundary is difficult to define, as, though in reality Algeria extends right across the desert to Senegal, Algeria proper does not go farther than the northerly tracts of the Sahara.

Moreover, although considered as a French colony, the country is divided into three departments or counties, having the same status as if in France. From east to west they are Constantine, Alger, Oranie, and there is a further area lying south of these departments known as the Territoires du Sud.

The actual area of the country, again, is uncertain, owing to the great tracts of desert, but, roughly speaking, it can be said that the cultivated and inhabited areas comprising the three departments cover an area of 222,000 square miles—a little smaller than France. Including the Sahara, the country must be reckoned at 1,071,000 square miles.

By natural configuration the land is divided into four distinct belts: the low hills which border the coast protecting the rich cereal and vine lands from the sea winds; the Little Atlas or Mountains of the Tell, which include the lofty peaks of the Kabyle[18] country; the Sersou, forming a kind of broad valley between the hills and the Hauts Plateaux which, as the name implies, is a high tableland, some two thousand feet above sea-level and rolling down to the desert three hundred miles south of the coast; and the Sahara, stretching away to Senegal.

The desert can, again, be divided into different areas. Its northern belts, covered with a kind of scrub, thyme and mint, afford ample nourishment to the flocks of sheep and goats all the winter, while camels can always find plenty to eat there. Beyond this pasture-land, is the rock and the sand desert, the former greatly exceeding the latter in area. It is a desolate and cruel-looking country, except where the oases spring up and form centers unexpectedly rich not only in palms, but also in all kinds of fruit-trees.

Generally speaking, therefore, Algeria is a hilly country, and the Sahara is far from flat; the whole land is very fertile wherever there is water, but subject to great extremes of climate. What surprises the traveler most, after a tour through any of the three departments and down to the desert, is first of all the astonishing variety of scenery through which he passes, and second, the amount of natural products of the land.

The roads along the coast give a wonderful impression of marine scenery—deep red cliffs and a sapphire sea.

To the east of Algiers, forests of cork-trees border the road, olive-yards cover the slopes of the hills, while every now and then one sees extensive tobacco plantations.

Turning inland, the traveler will pass through more forests, then, climbing into the Kabyle Mountains, he will come to the fig-trees clothing the steep hills, till up and up he climbs to a level of some five[19] thousand feet above the sea. Towering mountains are about him, deep in snow for four months of the year and quite unexpectedly cold in this sunny Africa.

Following the coast in a westerly direction, he will traverse miles of all kinds of vegetables, grown by the local farmers for export to France and England. The new potatoes, the salads and tomatoes, associated with exorbitant prices in Paris in winter, will be seen ripening under this southern sun.

If the journey is continued farther west into the confines of Oranie a few cotton plantations will be seen, then the vast plains of cereals—the ancient granary of the Roman Empire—which now that the old system of irrigation has disappeared are sadly dependent on the rainfall.

Turning inland from Algiers, the hills bordering the coast are left behind and the vine-clad plain of the Mitidja is entered. For two hours the car will pass swiftly through vineyard after vineyard, while here and there rich orange-groves will relieve the monotony of the interminable lines of vines. The wine produced in this area is much richer and of higher alcoholic degree than that of France, and in a normal year not only suffices for all the wants of the country, but is exported in large quantities to the mother country, where it is used to cut the Burgundies and Bordeaux, and in some cases to be sold as French vin ordinaire.

Moving still in a southerly direction, the country becomes mountainous as the Atlas range is entered. The slopes are covered with mountain-oak, pine-trees, and now and then cork, but, though this is supposed to be one of the forest-lands of Algeria, the traveler needs to be notified of the fact. There is, however, one very fine cedar forest above Teniet el Haad, but it is rarely visited as it is off the beaten track. The hills are full of tailless monkeys—the[20] Barbary ape—which come down to the roadside, where there are inhabitants and prospects of food.

Beyond the Atlas range, here known as the Tell, where cattle and horses are raised, the country slopes down on to the wide pastures of the Sersou; it is now very flat and desertic in appearance. Soon the tufts of alfa grass are noticed growing in tall bunches right away as far as the eye can reach, and farther, for hundreds of miles to east and west extend these tracts of paper-making grass. Many of the concessions are owned by British concerns, which, having picked the raw material, despatch it to the Lancashire papermills to be manufactured.

Leaving the alfa, the country again becomes mountainous and wooded as the Hauts Plateaux are reached. The trees do not, however, last long, as soon the downward grade is begun, with the rich pasture-lands which run right away into the desert. This is the land of sheep-breeding, and as one travels along one sees countless flocks of sheep and goats.

The beginning of the Sahara is clearly defined by the sudden disappearance of the low, barren hills which have marked the descent from the Hauts Plateaux. The reappearance, too, of the palm-tree, which has not been seen since Algiers, reminds one that one is in the land of the oases, while away, away, stretches the desert, till its grayness merges in the sky like some eternally calm sea.

The pasture continues for a few hundred miles and then gradually disappears, giving place to stones and rocks, desolate and merciless, until in turn these give way to rolling sands, and again to barren wastes of pebbles, broken only by the welcome water-point or the green oasis offering relief to weary wanderers.

In a few words, this is the scenery of Algeria, and after a week’s journeying the traveler is really[21] amazed at the thought that all he has seen is in one country, so varied has been his impression.

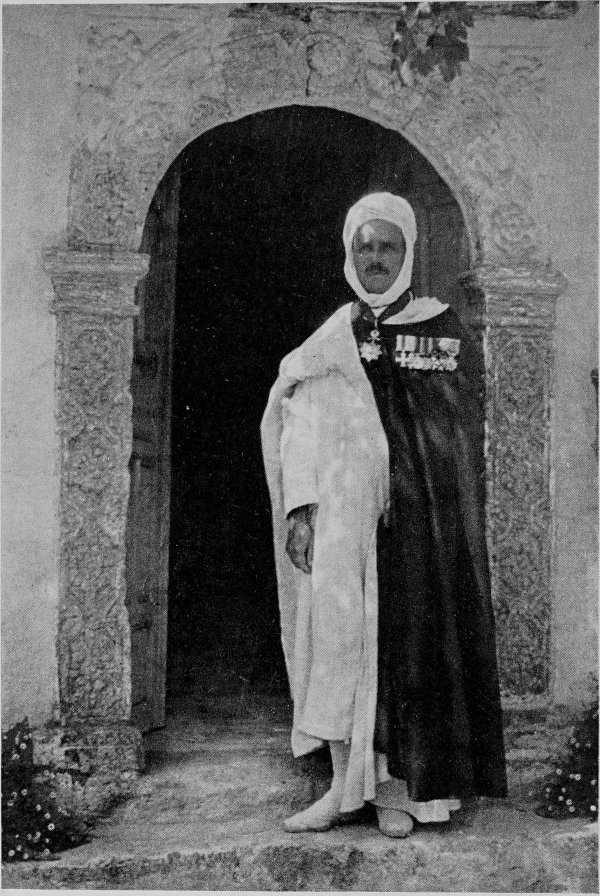

Reproduced by permission of Mr. George Churchill, British Consul General, Algiers

Algiers as It Was before the French Conquest in 1830

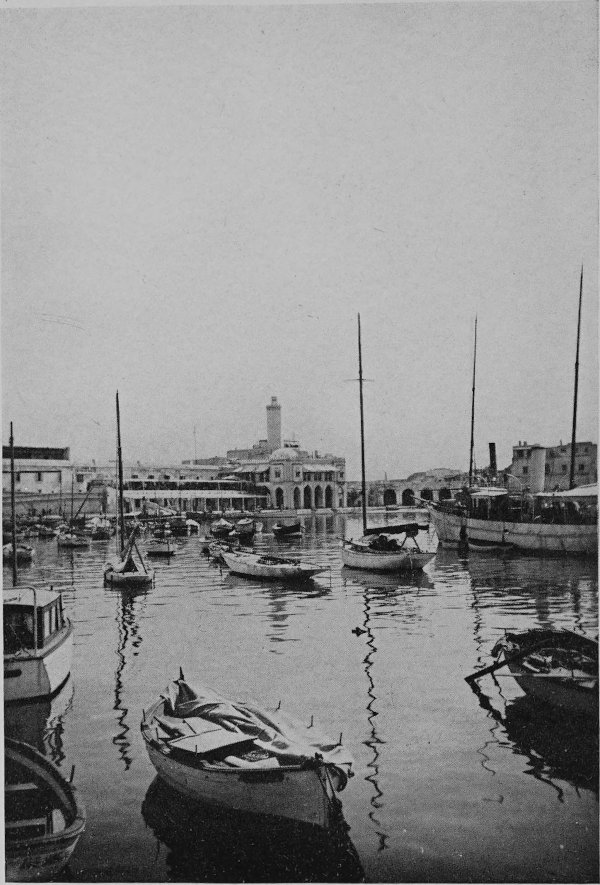

The Old Port of Algiers as it is To-day

Algiers, with its sub-tropical gardens and modern improvements, the sea coast, the broad plains of cereals, the rich vineyards, the orange-groves and olive-yards, the forests of cork and pine, the wild mountains, the silent expanses of alfa, the nomads on the pastures, and the limitless Sahara!

Further, if one remains a year in the country one will realize the difficulties with which the settler is faced owing to the extremes of climate. Generally speaking, it rains too much north of the Sersou during the months of November, December, and January. It never rains too much in the south. The summer and spring are too dry, and, whereas in the winter there is frost as far south as the edge of the Sahara, the summer heat is everywhere excessive. The heat is especially unpleasant in Algiers and along the coast on account of the damp; at midday in the plains it is intolerable, and when the sirocco blows from the desert, life is wretched all over the smitten area.

Irrigation is in its childhood; artificial pasturage is unknown, with the result that a good or a bad year depends entirely on the caprices of the weather. Generally speaking, one can say that in a period of seven years there are two very good years, four average years, and one bad year.

When the year is good it is beyond all imagination, and it is, in fact, said that the two very good years should pay for any losses in the remaining five!

A land of light and shade, of everlasting contrasts, a land which, like a lovely woman, charms one by its unexpectedness, by its tenderness and sudden harshness, by all its capricious moods. A land of the future, but a land also of the past—and this, perforce, brings us to the next chapter.

[22]

The original inhabitants of Algeria were Berbers. The present native inhabitant of Algeria is the Berber, and yet ask any one who the natives are and they will reply “Arabs”; some of the more intelligent will perhaps say “Arabs with a sprinkling of Berbers.”

But this is wrong. When history first threw light on North Africa the Berbers were there, and they have not yet departed. It is true that many invasions and upheavals have passed through Algeria during the past three thousand years, but, though they have left their trace, it is only the Arabs who have really left their mark on the original inhabitants.

The first important landmark in the history of North Africa is the foundation of Carthage about the year 840 B. C. The Phœnicians had already settled on the Tunisian coast for some three hundred years previous to this, but their importance dates from the foundation of their great city, which was to have such an influence on the history of the civilized world for six hundred years.

Since this book, however, is not a history of the country, it will be sufficient to mention the outstanding historical features during those long years during which war and invasion centered round the North African shores. The Carthaginian domination flourished in all its splendor until the year 264 B. C. Up to this period those hardy merchant mariners were masters of the whole of the Mediterranean; they had[23] explored the Atlantic coast as far as Sierra Leone; one expedition had sailed right round the African continent; and they had made it clear to Rome that they would brook no interference. Carthaginian naval power was supreme, and she counted on that alone to ensure her sovereignty of the Mediterranean. In the latter half, therefore, of that century she had defied Rome, and in a few years came into armed conflict with the future masters of the world.

This armed conflict, which was to last for over eighty years, and which was to produce those names famous to every public schoolboy who does not despise classical education—Hanno, Hamilcar, Hannibal, Hasdrubal, Scipio, Fabius Maximus—ended in 146 B. C. with the destruction of Carthage and the foundation of a Roman province consisting of modern Tunisia and part of Tripoli. One hundred years later Numidia, Algeria of to-day, was annexed, and for the next four hundred years the march of empire continued. At first the Romans were not a little embarrassed with their new acquisitions, all the more so on account of the hostile attitude of the Numidian kings at Cirta (modern Constantine). Strifes and minor wars continued for some time. Rome aided first one side and then another, but, finally realizing the futility of her rôle, a strong expedition was despatched and finally succeeded in defeating the Numidian king Jugurtha. It was not, however, until the year 46 B. C. that Cæsar finally routed Juba on the Tunisian coast and in that defeat destroyed the kingdom of Numidia.

The son of Juba, who had been taken to Italy and educated as a Roman, was married to the daughter of Antony and Cleopatra, and was eventually placed on the throne of Numidia, where he ruled in splendor until the year 19 B. C. During his reign the empire had spread and extended over North Africa from the[24] Tunisian coast to the Atlantic, and its military posts guarded the entries of the Sahara. The traces of once-glorious Rome remain in various states of ruin to this day, and will be dealt with in further chapters. It would take too long to enter into details of the administration of the country under the Imperial eagle and of the birth and growth of Christianity in North Africa. The Roman Empire had spread, and it was not until the beginning of its fall that the rule in North Africa tottered.

Ever since the beginning of the fifth century A. D. Roman possessions in Europe were being flooded by the advance of the Vandals. In 428 the terrible Genesric crossed to Africa from Spain, with an army of ninety thousand men, and landed at Ceuta. Like all new invaders, he was welcomed as a savior, and his success was instantaneous. He swept the Roman armies before him, he built a fleet and became the terror of the Mediterranean, and in 455 took Rome.

How far these conquests would have continued it is difficult to say had not Genesric died. With his death his followers, who had drifted into an easy-going state, no longer held together, but became the prey of jealous strifes among chiefs. Their fall was rapid. The Roman Government, now transferred to Constantinople, was awaiting the opportunity to avenge its defeat. A little more than a hundred years after the landing of the Vandals in Africa, Belisarius sailed from Constantinople with six hundred ships, and three months later landed in Tripoli.

The Byzantine invasion had begun, and in three months Belisarius was able to announce to the Emperor Justinian that North Africa was again part of the Roman Empire.

But the Byzantine rule did not last long. The country was rent by wars and revolts; the people[25] were worn out with changes of government; and, though there remain great forts and mightily walled cities as a record of this rule, they are evidence in themselves of the turbulent times which shook the country. When, therefore, the first Arab invasion poured in, there was nothing to quell it, and for one last time Imperial Rome struggled for a moment, staggered and fell.

The first Arab invasion of the seventh century was more a series of raids than anything else. Mohammed had appeared and died, but his teaching had remained, and had inspired those bands of wild nomads to organize themselves. Persia, Syria, Egypt had fallen before the advance, and soon they began moving farther west. The most important of these raids was that led by Sidi Okba, who traversed the whole of Algeria and Morocco, and who, no doubt, would have gone on had he not been arrested by the Atlantic.

He was killed during his return journey by the Berber army under Koceila, and he is buried near Biskra, where his memory is venerated.

Hassan followed him, and finally drove the last Byzantines out of North Africa. Needless to say, the chief object of the invaders had been to convert the people to the new faith, and little by little the Berbers became Mohammedans. It did not take long for them to create dissension in these beliefs, but they remained generally under the law of the Prophet, respecting the principles even more rigidly than their conquerors.

However, the most important point of this conversion is that it created an Arab-Berber alliance for the further march of Mohammedanism into Europe. It is said that it was a Berber named Tarik who first crossed the Straits of Gibraltar, and it was after him that the rock took its name, Djebel el Tarik—the Mountain of Tarik.

[26]

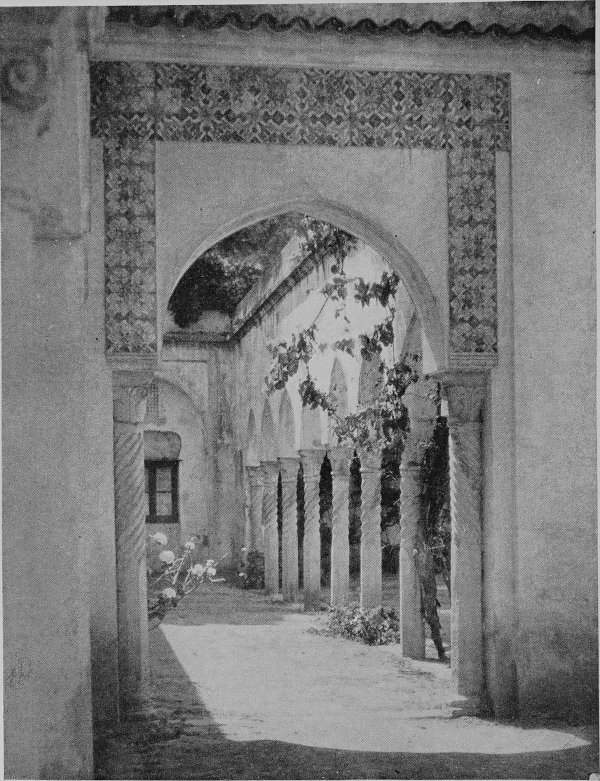

The Arabs and Berbers pressed on through Spain until they were defeated by Charles Martel at Poitiers in 732 and retired into the peninsula. The remains of their grandeur can be seen in the glorious palaces and mosques at Seville, Cordova and Granada. But the Berbers, being of an independent nature, did not readily accept the laws and regulations of the allies. In the tenth century there were a number of insurrections in Algeria, and the Fatimides, or followers of the descendant of Fathma, the daughter of the prophet, succeeded for a period in dominating the country. Unfortunately for them their chief tried to go too far in his independence, and in the twelfth century the Sultan at Cairo launched a punitive expedition composed of the five tribes known as the Hilals.

Unlike the expeditions of the seventh century, these invaders came in hordes, bringing with them their flocks and their belongings, and sweeping mercilessly across the country, leaving devastation behind. Arabs and Berbers united to oppose them, but to no avail. Their armies poured over the land like a cloud of locusts. The little that was left of Roman civilization was destroyed, the cultivation disappeared, and North Africa was the desert of over a thousand years before.

From this period until the end of the fifteenth century North Africa was given over to pillage. With the exception of the cities of Tunis, Tlemçen and Fez, anarchy seems to have reigned everywhere, and there are no records or history of the period. The Arab had shown his worth; the Arab as an administrator had no qualification; he has not yet proved the contrary.

At first it was the Spaniards who took the place as rulers of North Africa. They had gradually driven[27] the Mohammedans out of southern Spain, and during the first ten years of the sixteenth century had occupied the seaports from Oran right down to Bougie, including Algiers. But these conquests did not really interest them as their eyes were turned to the Indies. Moreover, in the meanwhile the brothers Barbarossa were scouring the Mediterranean, and when they were asked to rid Algeria of the Spaniards it did not take them long to do it. But once the deed was accomplished, the Turks refused to leave, and in 1546 took possession of Algiers.

For the next three hundred years the White City became the stronghold of the pirates of the Mediterranean. At first their fleet was nominally a national navy, fighting against Charles Quint, but little by little all form of legitimate warfare disappeared and open piracy became the sole occupation of these wild seamen. Their ships became independent rovers of the sea; built lighter and more handily than the average cargo- or war-vessel of other nations, they fell upon their prey regardless of its flag, captured it, and brought it back to Algiers. Here the cargo was divided: a quarter to the state, and the rest to the owner and crew of the vessel. The sailors or passengers on board the prize were employed as slaves, those who knew trades, to build and beautify the palaces of their masters, the more common to work in the quarries or to row in the galleys. If they were men of importance, they were held to ransom. Among other prisoners who spent a not too pleasant sojourn in Algeria were Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote, and the French poet Regnard.

It was not long, however, before the powers in Europe began to occupy themselves with these acts of open brigandage. In 1541, Charles Quint led an expedition, but partly by reason of adverse weather,[28] and partly by the strength of the Turkish lair, he was entirely defeated, and just escaped with a small portion of his forces.

The squadron sent by Cromwell under Blake in 1655 fared better. Part of the Turkish Fleet was destroyed at Tunis, and the release of the British prisoners was obtained. Louis XIV sent two fleets in 1682 and 1688, under Duquesne and d’Estrès respectively, but, though their bombardments did a good deal of damage to the fortifications, and temporarily hampered the pirates’ activity, the effect did not last long.

About the same time Sir Thomas Allen, and a little later Sir Edward Spragg, inflicted minor defeats on the Turkish fleets, but on the whole little harm was done; and though Lord Exmouth won a decisive victory in 1816 and seriously battered the fortifications, he was unable to land, and it remained for the French in 1830 finally to shake and destroy a rule which had dominated the Mediterranean for three centuries. With their entry on to the scene, the period of anarchy begun by the Vandals finally disappeared, and the task almost completed by the Romans started again on almost as barren a soil as that faced by the great colonists of the Mediterranean a hundred years before Christ.

[29]

It will be easily understood that this undisputed mastery of the Mediterranean basin had given the Turks of Algeria a very great impression of their importance, and had left them with little respect for the European powers. Consideration, therefore, for representatives of those powers was on the same scale, and when one day the French Consul, Deval, paid an official visit to the Dey Hussein to protest about the non-payment of a debt to a French subject, Hussein summarily sent him about his business with a flick over the face with his fan.

This took place in 1827, but it was not until 1830 that the French really decided to have done with the insolence of the dey. An army of thirty-five thousand men was organized under General Bourmont, one of Napoleon’s officers, escorted by a fleet of three hundred ships. Curiously enough the success of the expedition was greatly facilitated by the lack of vigilance of British guards some twenty years before.

In 1808 Napoleon had practically decided to conquer Algeria and Colonel Boutin had been sent on a secret mission to Algiers with orders to reconnoiter the land. During his return journey the ship on which he was traveling was captured by a British man-of-war and the Colonel was imprisoned at Malta.

He, however, succeeded in escaping, and, returning to France, laid his report before the Emperor, who[30] had by that time decided that Egypt was a more interesting goal.

Boutin’s plans were therefore put aside, but when the expedition of 1830 was being prepared they came to light again and were exclusively used in drawing up all the details of the attack.

Wisely avoiding the mistakes of their predecessors who had attempted to take the stronghold itself, the fleet bearing the army sailed to the west of Algiers, and in June, 1830, landed without opposition in the sheltered bay of Sidi Ferruch. The cause of this easy landing has never been clearly established, but it is supposed that Hussein either believed that this invasion would share the same fate as all others, and that by allowing the army to land his victory would be more complete, or else that he did not anticipate an attack from that quarter.

However, the fact remains that the whole of the French army landed without difficulty, and that a few days later they were marching on Algiers. They met the first elements of the Turkish army at Staoueli. The battle was fierce, but the French artillery caused havoc among the ranks of the Moslem troops, which were driven out of their position. The French headquarters were established on the site of the future Trappist monastery, which is now a great wine-cellar.

The advance on Algiers was continued, but there were no roads, and the hills of the Sahel were covered with thick scrub. On June twenty-ninth, however, the army arrived before Algiers. The attack on the fortress where Charles Quint had for a brief moment pitched his tent was immediately commenced. For a time the Turks held out, but, realizing the futility of their task, they set fire to the powder-magazine and blew up the great pile, emblem of their long rule. The French, meeting no longer with any opposition, pushed[31] on, and on July fifth made their triumphal entry into Algiers.

The immediate result of this victory was for the King of France, Charles X, to lose his head. He believed that he was now in a position to exercise absolute power, and he expressed himself by publishing his famous Ordonnances. The consequence was revolution. Charles X was deposed, and Louis Philippe, the son of Philippe Egalité, mounted the throne. General Bourmont was relieved of his post as Commander-in-Chief, giving way to General Clauzel.

As can be imagined, this did not tend to help matters across the Mediterranean. The capture of Algiers had taken barely a month—the subduing of the Arabs was to drag on for over thirty years.

In the first place, the new Government in Paris was very diffident about pushing forward the conquest of the country. At first only the coast was occupied. This was interpreted by the natives of the interior as fear, and it was with little difficulty that the young Emir, Abd-el-Kader, raised the population to a holy war. Until the year 1847 this struggle continued with varying success, and it was not until Bugeaud, an old warrior of the First Empire, took charge of the operations that the unruly chief began to lose ground. The capture of his smala in 1843 at Taguine in the Sersou was the beginning of the end. Four years later he surrendered and was exiled, and he finally died at Damascus. His memory is venerated by all the Arabs of the country.

Once the emir was out of the way, Bugeaud began to penetrate the interior by colonization. His famous motto, “Ense et aratro,” was to prove a veritable success, and little by little the country began transforming itself. In the meanwhile he did not neglect the conquest of the territory still unsubdued. In 1852[32] the Oasis of Laghouat was captured after tedious fighting, and with it the penetration of the Sahara began.

The last strongholds of the Berbers in the Kabyle Mountains fell in 1857. The country seemed turning toward peace. But in 1864 a fierce revolt burst forth in southern Oranie; the French punitive column was massacred, and the rebellion spread all over the department. It took five years to quell it completely.

Hardly was this over than the Franco-Prussian War broke out and Algeria again became a center of agitation. The Kabyles for a short space threatened the peace of the whole country, capturing numbers of French centers and massacring the inhabitants. The French were obliged to send troops back from France at a very awkward moment, but they succeeded in quelling the insurrection. In 1879 the Berbers of the Aurès made an attempt to rise, but were rapidly repressed; the same lot awaited the insurgents of southern Oranie in 1881. I can not pass this point in the history of the conquest without mentioning a name great in the annals of Algeria though sadly forgotten by many historians.

I refer to Cardinal Lavigerie, priest and administrator, founder of the order of the Pères Blancs who did more by his foresight and calm judgment to bring the Arabs under French rule than any governor during these turbulent times. His political activities were only eclipsed by his evangelical work, and his influence in North Africa has ever remained.

Those who are interested in this subject will find some excellent reading in Le Cardinal Lavigerie et Son Action Politique by J. Tournin. This book not only deals with the Cardinal’s long administration in North Africa but also throws much light on all those[33] intrigues which finally led to the disestablishment of the Church in France.

Since then little has occurred to disturb the peace of Algeria, and, in spite of a certain amount of unrest during the Great War, there has been no definite rebellion.

The French conquest took long, but, when one looks at the stupendous difficulties which had to be overcome, one is surprised it was completed so rapidly. Everything was against it: an unstable government, which was overthrown at the outset of the campaign by an equally unstable rule, which itself disappeared a few years later to give place to the adventures of the Second Empire; statesmen who had no definite policy as regards North Africa, and generals who never had sufficient troops nor a free enough hand really to take up the conquest of the country seriously.

Opposing them was an enemy, composed of born fighters, knowing the country as well as their horses, amazingly mobile, capable of concentrating to fight a battle and dispersing again like the sand, and inspired with the spirit of religious war. The country was overgrown with thick brush; there were no roads, great mountains to cross, and, once in the interior, no means of feeding or watering the army, with no towns from which food or cattle could be requisitioned, no wells or springs and a climate of great extremes.

When one traverses the great plains of the Sersou and the Hauts Plateaux leaning back in a comfortable car, or when trekking across the Sahara to some known water-point among a friendly people, one often wonders how it was possible for that small French column in this unknown country to press on after an elusive enemy with lines of communication of such immense length. There is no heroic record of their achievements, and, apart from certain names known[34] to French school-children, no one appears to have been honored or exalted as responsible for this series of campaigns.

Let any trained soldier consider the taking of Laghouat, three hundred miles south of Algiers, in a desert, unpopulated and waterless, and he will wonder how it was done. The conquest of Algeria by the French is one of the greatest pages of military history.

[35]

North Africa has been very aptly described as a melting-pot of the Mediterranean races, and, though all trace of invaders such as the Vandals and the Byzantines have vanished, the other peoples who came and conquered and were in turn defeated have left their mark on the inhabitants of to-day.

The Phœnician, the Roman, the Arab, the Spaniard, the Turk, can be seen in all parts of North Africa, and, though it requires perhaps a little study and experience to place one’s hand on the actual features of the past conquests, they are most striking when one is shown them. The original race of the country is, however, the Berber, and, in spite of these invasions which have devastated, reinstated, and again devastated his country, he has remained in a good many districts as pure as the Celts.

Roughly speaking, it can be said that to-day the pure Berbers are found in all the highest mountains, such as the Aurès above Biskra, the Kabyle country, and that portion of the Tellian Atlas known as the Ouarsenis, strongholds to which they returned during the various invasions, and where they remained unassailable while the tide of war ebbed and flowed beneath them. The people of the Mzab and the Touaregs of the Hoggar are also pure Berbers: in the case of the former because they were determined to remain pure and exiled themselves in the merciless desert, and in the latter because they were too far[36] away to be touched by invasion. In other parts of Algeria intermarriage naturally took place during the various dominations, but, though Roman and Turkish traces remain, these are eclipsed by those of the Arabs.

Roughly speaking, therefore, it can be said that the groups of pure Berbers are located in the high mountains, in the Mzab and in the Hoggar; that the Berber influence is predominant among the people who inhabit the country immediately south of Algiers, as far as the southern slopes of the Atlas, the department of Constantine, and an arm of the southern territories running from Biskra down to Ouargla and the great belt of desert running right across the Sahara from the Atlantic to Tripoli on a latitude just south of El Golea.

The whole of the rest of the country—that is, the department of Oran, the whole of the southern tracts of the department of Alger, and the rest of the southern territories other than the belt named above— is decidedly Arab. The Berber is there, but the influence is almost entirely that of the nomad invader.

If you ask an intelligent native what his nationality is, he will reply that he is an Arab who has been slightly Berberized or else he will say that he is a noble Arab—that is to say, a claimant to direct descent from Mohammed. While on this subject it is interesting to note what the conception of nobility is among these people. Outwardly, before the European, it is the title of bash agha or agha or caïd, but in reality this does not count with the people any more than Lord-Lieutenant of a county in England. To them it is merely a title imposed by the French, which they must respect just as they must respect the Colonel or the Administrateur. Aristocracy to them is the descent from the Prophet, or as one wise old gentleman once said:

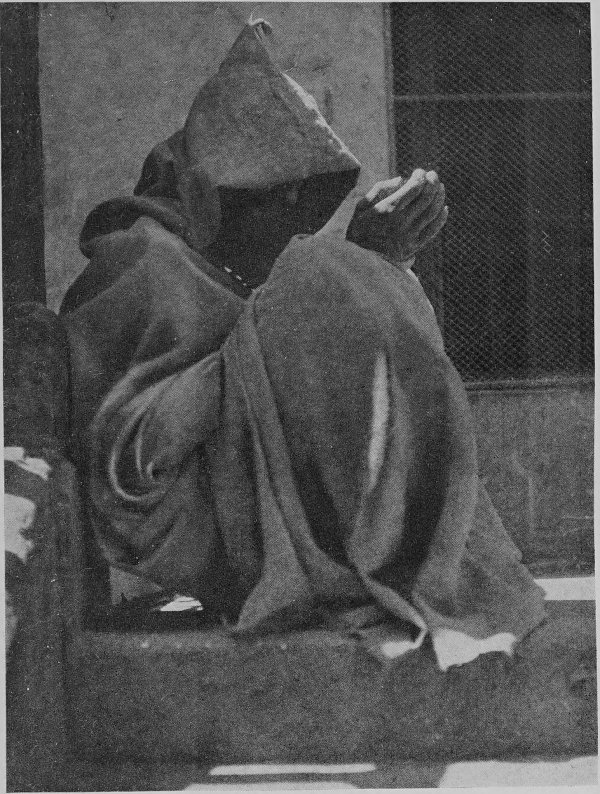

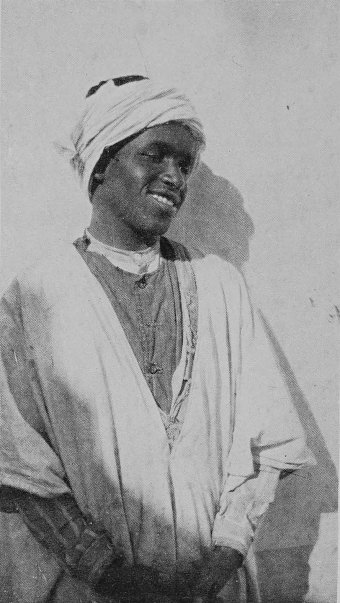

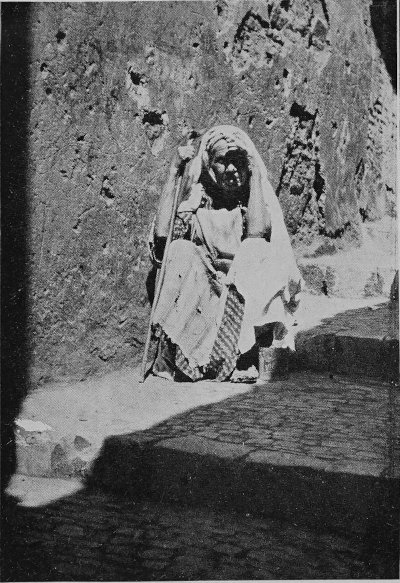

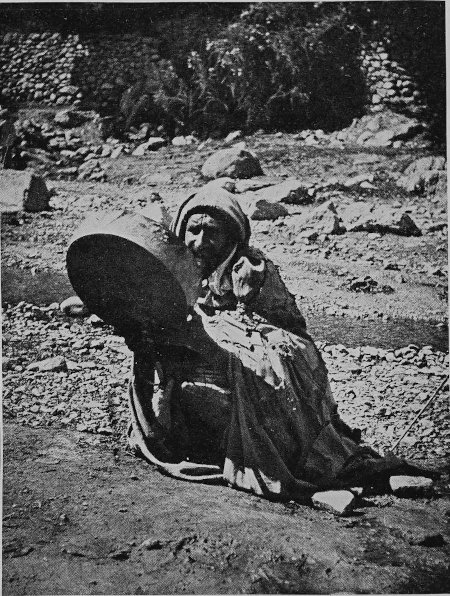

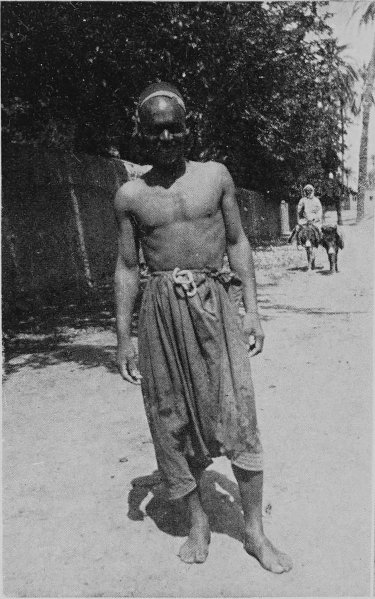

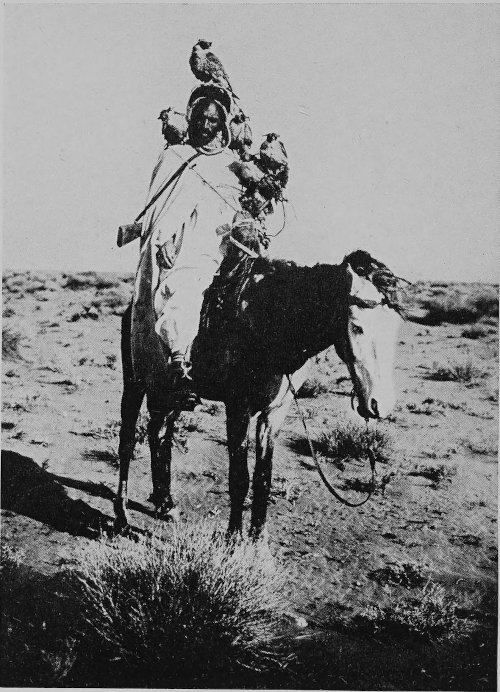

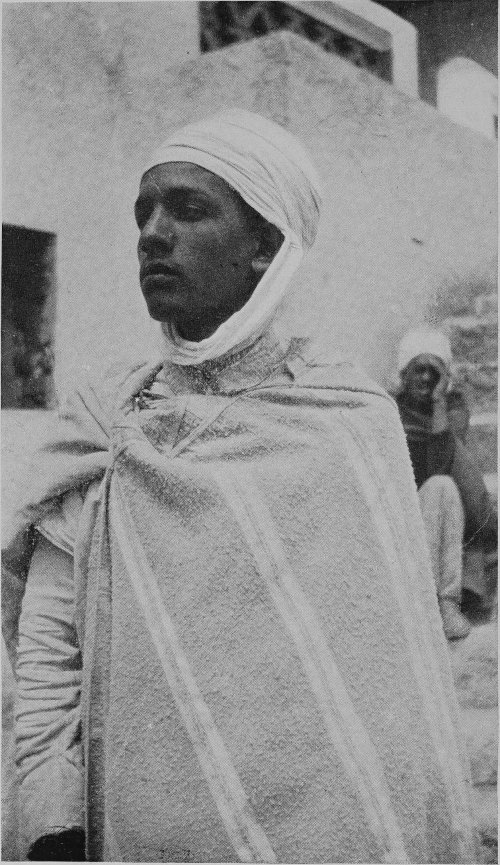

An Arab Beggar

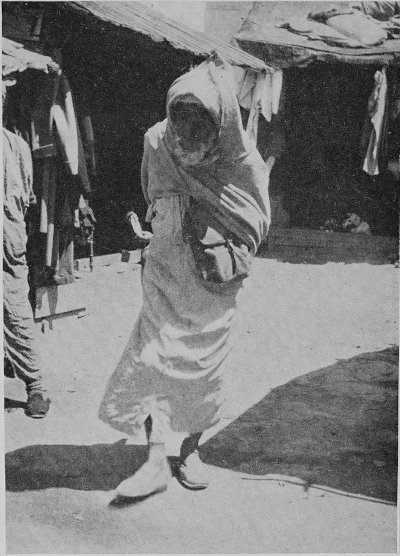

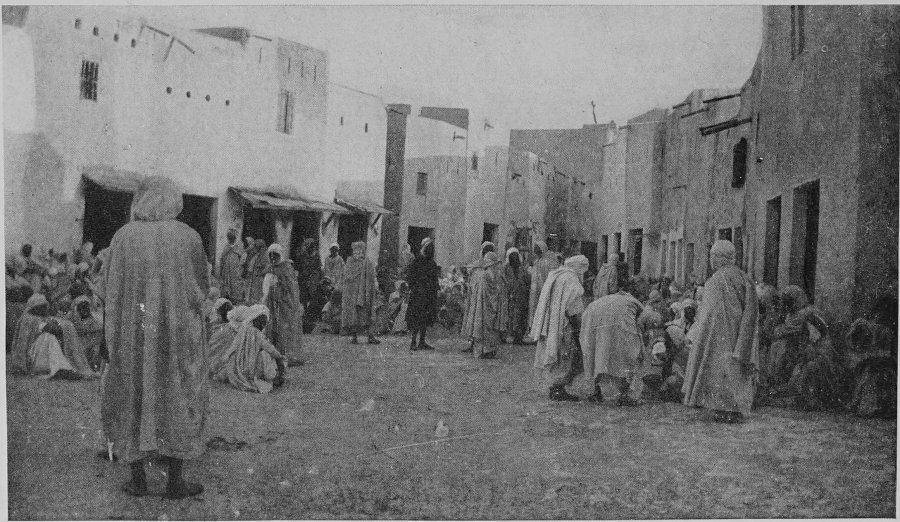

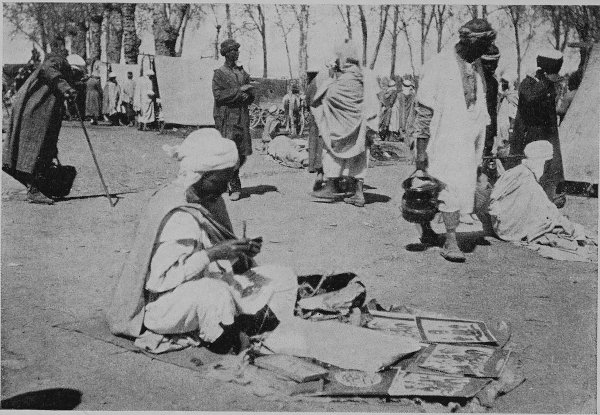

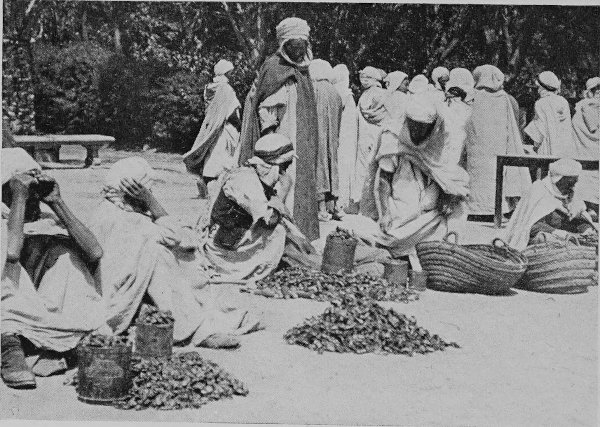

Scene of Arab Life

[37]

“To many of us nobility can be achieved by much learning.”

In other words, the scarlet burnous and the loud-sounding title would carry no weight if it were not enforced by the French authority.

To-day, therefore, the inhabitants of Algeria are Arabs and Berbers of whom fifty per cent. claim almost pure Berber blood, and Frenchmen. There are many Spaniards in the department of Oran, and in the east a fair sprinkling of Italians and Maltese. The Jews, too, form an important section of the community; those who live in the north wear European dress, and in the south most of them wear Arab costume, with a certain little difference in the burnous, and in some districts they have robes peculiar to themselves. Their women, even in some families of the north, keep the dress of their people, the embroidered kerchief about the head and the rather shapeless frock. By a law known as the Décret Crémieux, voted in 1871, to facilitate the conscription of recruits for the Franco-Prussian War, all Jews north of a certain latitude in Algeria automatically became French citizens. It was not very popular at the time, but its consequences now are much appreciated. In spite, however, of this French citizenship and all the wealth acquired in commerce, the Jews of Algeria have kept themselves strangely apart. Even in Algiers all their shops are in a certain quarter; they close without exception on Saturday, and attend the synagogue with the utmost regularity. They never intermarry, and they form as distinct a race as the Arabs. In fact, in many districts—and especially in the south—they are always referred to as Israelites. Sometimes they are persecuted, but this merely knits them closer together. They despise the Arabs, but fear them, and tremble at any sign of force.

[38]

The Arabs equally despise the Jews, but unfortunately they have got themselves rather into their hands through making use of them as money-lenders.

The actual French occupation of the land does not penetrate very far—in fact, in a great many areas the Frenchman is leaving the interior and returning to the coast. Again and again one passes through European villages with a church built to accommodate a thousand people or so, and one sees about twenty European dwellings in the town and the rest of the houses in ruins or inhabited by Arabs. What has caused this? Primarily, the inherent dislike of the Frenchman to expatriate himself. If he comes to Algeria it is with no idea of spending the rest of his days here. His one idea is to make enough money to permit him to return home to France and eke out a pinched existence in his native village, but with the satisfaction of being a rentier. Secondly, the rather ungrateful task of cultivating in a country where all depends on the rainfall. It is all right for the man who has capital and who can bide his time to pay off his losses of the bad year with the profits of the good, but it is heart-breaking work for the small landowner. Of course there are numbers of families who have settled in the cultivated regions and who have become Algerian, but they are the exception; their names can be counted off rapidly.

These men have great fortunes in wine, in cereals and tobacco, and their children have in many cases never seen France; but, generally speaking, the Frenchman is not a colonist, and it is very, very rare to see him away in the Sahara sheep-breeding or alfa-collecting. He has, however, done one rather contradictory thing in imposing his language on practically the whole country. With the exception of the nomads who wander about the Sahara, it is rare to come[39] to any center and not find a French-speaking population.

The Arabs among themselves of course speak their own language; it is a strange dialect based on pure Arabic, but peculiar to North Africa.

Moreover, it differs in accent according to regions. For instance, the language of the south is much deeper and more guttural than that of Algiers, and the talk in Constantine and Oran, again, has many words and intonations not found in other centers.

I think that the correct name for this dialect should be Arabo-Berber. There is, of course, also the pure Berber spoken by the people of the Kabyle and Aurès Mountains, of the Mzab and the Hoggar; and, though Berbers are often found who can not speak anything else, it is almost a general rule to find them bilinguists, while the majority talk French too. It is interesting to note that when the Sultan of Zanzibar came to North Africa the only people with whom he could speak fluently were the Berbers of the Mzab.

The Jews speak both Arab and French fluently; their Arab is often purer than that of the actual natives. A great number speak Hebrew among themselves.

However, to progress comfortably through the country, French is essential, and Arabo-Berber is a great help and inspires confidence among the people. Grammatically, it is a simple language, but the pronunciation is difficult and the number of words which mean the same thing requires one to have command over a large vocabulary. It is a language that can be learned only with a teacher.

These, therefore, are the peoples and the tongues of North Africa, and, armed with this knowledge, we can now penetrate further into the system of administration.

[40]

The administration of any country to a foreigner is always rather incomprehensible, but the manner in which Algeria is administered by the French is more than a surprise.

It is not our duty to criticize the method of government of this country, and let it be said at once that, strange as the method may seem, the results are admirable.

To the uninitiated, Algeria is a colony such as Kenya or the Gold Coast, with a Governor and all the general system of working dominions beyond the seas. But, though the country is administered by a Governor-General, he does not, as might be supposed, depend on the Colonial Office, neither do any of his reports pass through the hands of the Colonial Secretary. His tenure of office is, moreover most uncertain, and he is only appointed for a period of six months at a time, renewable at the end of each period, and this appointment is made by the Home Office (Ministère de l’Intérieur) in Paris, under whose jurisdiction he is.

At first this contradiction of things seems hard to understand, and one is forced to penetrate further into the inner workings of Algeria to understand. In the first place, North Africa—with the exception of Tunisia and Morocco, which are protectorates—is[41] divided into three departments, with practically the same organization as in France. That is to say, each department sends to the Parliament in Paris one senator and two deputies, who are elected by the French inhabitants of the country and by those Arabs who have opted for French nationality.

These departments have their préfets and sous-préfets, as in France, and the towns their mayors, with the municipal council, juges de paix, commissaires de police, etc. Thus up to this point the system of administration in the three departments is identical with that in the mother country.

The first slight difference we come upon is in the case of what are known as communes mixtes. These centers are those where the Arab population is in excess of the French. In this case the mayor is replaced by an administrateur. The area covered by the jurisdiction of this individual is much larger than the commune under the mayor, and comprises numerous douars, or native villages. The administrateur, who wears a vague uniform, something between that of an officer and a lion-tamer, is trained specially for his post. He is assisted in his duties by an administrateur adjoint and by a commission municipale. This commission municipale is composed partly of Frenchmen elected in the area of the commune mixte, and partly of Arabs belonging to the various douars, who are appointed by the Governor-General. The caïds and other Arab chiefs—of whom we will speak later—assist the administrateur as his agents in their respective areas.

The administrateur himself has certain powers of jurisdiction over Arabs, but all those who are French citizens have recourse to the ordinary civil power.

This, therefore, in a few words is the system of administration of Algeria proper, and it would all[42] seem quite simple if we did not suddenly come face to face with the Governor-General. Here, in the midst of all this peaceful organization associated with the Great Revolution, we have Monsieur Le Gouverneur-Général, with his summer palace, his staff, his aides-de-camp, naval and military, flying the tricolor on his motor-car, while the guard turns out and presents arms. What has he to do with all the senators and deputies and préfets?

The answer is simple. For all practical purposes, nothing. He himself may be a French senator with his seat in the upper chamber; at the end of six months he may become a minister or he may be politely dismissed. And how often has the post of Governor-General of Algeria been held by some high functionary not wanted in France, or by one who is merely biding his time to take office again. The Governor-General, therefore, unless he be a man of exceptional value, can not really do very much for or against the welfare of the country, and the most important duties therefore devolve on a permanent official known as the Secrétaire Général du Gouvernement.

This gentleman—though he is usually not a man of great ambition, otherwise he would not be in this thankless post—has a great working knowledge of the country and its people, and it is he who keeps his superior in touch with all that is going on. But even he has nothing to do with the French civil administration, which belongs entirely to France.

On the other hand, there are three assemblies over which the Governor presides and which carry out on their own account a certain amount of the administration of the country. They are the Conseil du Gouvernement, dealing chiefly with the building of new villages, making of roads and railways, and generally[43] opening up the colony; the Délégations Financières, composed of French colonists, French taxpayers, and a certain number of well-to-do Arabs. These financial delegates discuss the budget for Algeria, which incidentally, and contradictorily, is independent of France, as is also the Bank of Algeria, which prints its own banknotes. Finally we have the Conseil Supérieur composed of twenty-two members: the Procureur-Général, the Admiral, the préfets and a few Arabs of importance who meet once a year under the presidency of the Governor-General to vote the budget for Algeria.

But even here the Parliament in Paris is afraid of letting the wretched colony look after itself, and it insists upon ratifying the budget, without knowing anything about it.

Algeria, therefore, is not a colony, but part of France, administered in the same way as any French department, but under the care of the Governor-General appointed by the Home Office, who is all-powerful without having any real authority at all. The communes are French or mixtes; the Arabs have a certain say in the government, but not much; the budget is separate, but under the scrutiny of the Palais Bourbon.

All this seems complicated enough, but the mystery is not over—it deepens as we leave the northern districts of Algeria and move south. We have now seen the rôles of the various functionaries in the three departments of Constantine, Alger and Oranie, and we must turn to the area known as the Territoires du Sud.

The actual boundary between the departments and[44] these southern territories varies somewhat, but it can be said roughly that anywhere two hundred miles from the coast one has passed out of civil control and into military. Thence these territories stretch away across the Sahara until the Niger is reached—great, open spaces with small fertile points where there is water. All this waste land is also under the Governor-General and his permanent staff in Algiers. There is one slight difference. Whereas if he were to make a speech to the townsfolk of some smiling vine center near Algiers he must ask the Secrétaire-Général for the necessary data to address the multitudes, in the south he applies to the Directeur des Territoires du Sud. This functionary, who is often intelligent, has an enviable post, and if he is interested in the Great South, with its strange people, he can make a study under very advantageous circumstances. Here again, however, we have an anomaly, for, though the Directeur des Territoires du Sud is responsible for their order, his administrators are all soldiers and the country south of the civil territory is under the strictest form of martial law. A little explanation on the system of government will perhaps make matters clearer.

The southern areas are divided into what are known as Cercles Militaires, and they may cover an area of one hundred square miles. The Cercle is under a colonel and is subdivided into annexes, each under a captain, who is responsible to the colonel for his area. There are a number of officers attached to these annexes, all specially trained in their duties—in fact, from the colonel down, all the staff have passed through the school of the affaires indigènes and have spent practically all their life in the south. For the future we will refer to the military administration as the Bureau Arabe, the name under which it goes in the[45] south. To all intents and purposes the Bureau Arabe is all-powerful. Fines, fatigues, prison for all persons not having a European status are entirely in its hands. The court-martial convened has the power of life and death over the same category of persons; only Europeans and naturalized Arabs can appeal to the civil courts. The rule is harsh, sometimes unjust—it depends on the staff of the Bureau Arabe. The military in the various oases are commanded by regimental officers who have really nothing to do with the Bureau Arabe; they are just in the garrison as they might be in Algiers or Marseilles. But if the head of the annexe requires them for any administrative or punitive purpose they are at his disposal.

A flock of sheep disappears, the owner complains, and, if he is considered sufficiently important to take notice of, a section of spahis is sent off to trace the flock. Some one has to be ejected from his house—an N.C.O. and four tirailleurs carry out the unpleasant duty.

Unless an Arab carries a great deal of weight he is helpless if the Bureau Arabe decides against him. Apart from this, however, the chief of the annexe has other more peaceful and useful duties. He has all the functions of the mayor to perform, and is surrounded by a municipal council. These worthies— who are partly Arabs, partly French and partly Jews—vote silly laws such as traffic regulations for the non-existent vehicles. They decide whether the main street shall be painted green or gold; they vote money to repair the roof of the colonel’s house. Their most important function is the distribution of water in the oasis. This, as will be explained in a later chapter, is a question of life and death in the long Sahara summer, and it requires infinite care to arrange it all. But, apart from this, the municipal[46] council does little, and, though the Chef d’Annexe occasionally performs a civil marriage, the law and order of the Great South rests in the hands of the military.

I use the word order purposely, as it is through their presence that we can travel safely over those magnificent roads which they also have made across the rolling plains. For, though justice is sometimes miscarried, there is little chance of the bandit escaping if he commits highway robbery or murder on the roads of the Bureau Arabe.

These are, therefore, the pros and cons, and let it be said for these colonels and captains who have spent all the best years of their lives in the Sahara, that they are confronted by great difficulties, and that until the day when the Arab is emancipated and set on the same footing as his conquerors, the only method by which an end can be achieved is severity.

So far it will seem that we have left the realm of complication and entered that of straightforward government. A mere illusion.

Living in the same town and almost next door to the Bureau Arabe, we find the Juge de Paix, the Notaire, and the Commissaire de Police. What the first two can do to justify their existence is beyond the imagination. The Commissaire has functions which he exercises, but which seem quite unnecessary, as in all his actions he is entirely paralyzed by the Bureau Arabe.

For instance, if some petty crime is committed he can investigate it, but he can not condemn without the authority of the Chef d’Annexe. If one requires a gun-license one has to apply to the Commissaire de Police, but he must go to the Bureau Arabe to get it. He is in charge of the few native policemen who wander about the oases in search of crime and bribes,[47] but, though the prison is next door to his office, it is guarded by the military.

It is all the same curious system which causes the Governor-General’s powers—extending across the Sahara, to the verge of Central Africa—to depend on the Home Office in Paris.

Moreover, we have not yet finished with all these different forms of administration, and in the next chapter I shall try to explain how the native functionaries aid in the government of the country.

[48]

It can be said that in the northern districts of Algeria, where civilian rule is supreme, the Arab chief’s position is more honorary than anything else. It is true that he holds the same titles as his brethren in the south and that he is responsible for an area comprising many douars, but his authority is very limited owing to his constant contact with the local administrateurs.

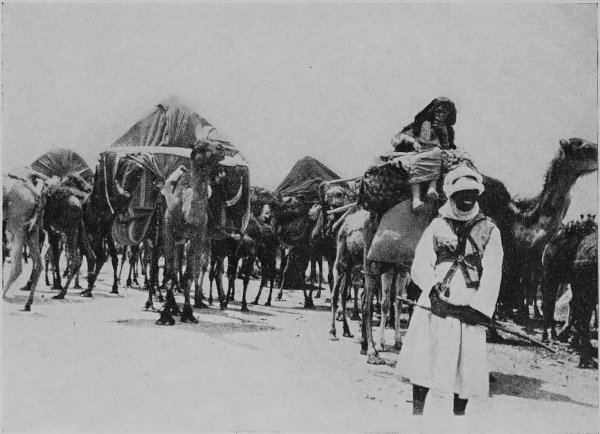

In the south it is very different. Here we are among the nomad tribes, who, though they have certain fixed limits of pasturage, roam over vast areas and great tracts of land, rarely remaining one week in the same place.

It would therefore be materially impossible for any European administration to deal directly with these people always on the move, and who have dialects and pronunciation which only an Arab can understand.

The French Government, therefore, appoints Arab chiefs, who, to all intents and purposes, rule over the nomads, and who are responsible for law and order among the people and for the levying of taxes. The head of the Arab chiefs, who is ruler over the whole tribe or confederation of tribes, is known as the bash agha. He is appointed by the Governor-General, and[49] he is chosen for his authority, for his capacity as an administrator and for the name he bears.

It must be remembered, however, that though the Government tries as far as possible to appoint men of noble lineage, this is not necessarily done, and the Government does not recognize any sort of official succession from father to son. If the eldest son is considered worthy of the post he is probably appointed to take his father’s place, but cases occur where a distant relation, and sometimes an Arab chief of another family is brought in, if the actual ruling house is considered unworthy.

The bash agha has under him one or two aghas whom he recommends to the Bureau Arabe for appointment. One of the aghas is often his eldest son, but here again there is no rule.

The confederation of tribes is divided into subtribes, which, though they each have their own name, all belong to the main clan. These differ in numbers, but the confederation is usually composed of from ten to twenty tribes. These tribes are estimated by the numbers of tents or heads of families they contain. They each represent about two thousand people and have at their head a caïd. It is, moreover, interesting to note that the bash agha and the aghas belong to one of these tribes of which they are honorary chiefs.

The caïd is, as in the case of the agha, recommended by the bash agha to the Bureau Arabe, who, if agreeable to the recommendation, passes it on to the Governor-General for confirmation. Here, again, they try as far as possible to select the caïds from the same family as the bash agha. The appointment of the caïd is most important, as it is he who is in direct touch with the tribe wherever it happens to be. He is assisted in his duties by the khaliphat, who[50] does all the clerical work and who acts in the place of the caïd when he is absent.

The caïd’s tribe is subdivided into four or five “fractions,” each under a sheik. The sheik—about whom so much fantastic literature has been written, and who, though he may be a cultivated man, is usually so by accident—has a small command, and his authority depends on his personality. He can usually neither speak nor write French, and to the casual visitor differs in no way exteriorly from the poorest shepherd in his “fraction.” In fact, with the exception of a few aghas and caïds who are rich and who have come in contact with Europe, the Arab chief, with his silk-decked tent and his smala of glorious beauties, wielding the powers of life and death at a moment’s notice, is a thing of the past. He shambles along on a rickety horse reminding one rather of the bull-ring, and he lives most of his life under a kind of awning which he calls a tent.

Since the war, the Government insists that the chiefs it appoints shall have passed the elementary standard at the local French school, but there are many caïds of pre-war nomination who are completely illiterate and who have never lived anywhere but in a tent. Moreover, the official power of a chief is very limited. He is merely a functionary paid by the Government to assist it in its administrative duties in the south, and with this end in view he has the support of all those in authority.

Officially this is all. Unofficially there is a great deal more power wielded in the background, power used sometimes quite unscrupulously to attain a personal end. For example, the Bureau Arabe only recognizes the bash agha and his subordinates. A crime occurs among the nomads, the caïd of the tribe concerned is notified, and he sets about making his[51] investigations. On his report alone the Bureau Arabe will act. There are, of course, many of these men who are scrupulously honest and who carry out their duties conscientiously, but there are others who do not, and there are certainly frequent miscarriages of justice through personal reasons.

There was a case where the agha had a feud with a sheik of his tribe. The sheik was in the right; the sheik tried to make trouble for the agha, and appealed to the French authority. The French authority gave the sheik his right.

The agha said nothing at the time, but a few weeks later he sent the sheik on a mission, and while he was away he took his wife and kept her till he thought the vengeance sufficient. The sheik was powerless to act, as the agha had committed no crime in the eyes of the French law, and he knew if he made any more fuss that his life would not be safe. It is better for a nomad to keep in with his caïd if he does not want to lose all he has.

Of course these cases are mainly exceptions, and the average caïd does his duty conscientiously. There is one I know well who looks after his people so seriously that he is actually out of pocket when the end of the year comes round. The point to bring out, though, is the danger of giving too much power to people whose idea of justice is very primitive, and who in cases of vengeance are quite unscrupulous. Life and death to an Arab are less important than the evening meal, and it is difficult to say what would happen if ever they were given autonomy. It is a delicate question.

For the moment we must continue our examination of native administration.

[52]

Quite apart from the official chiefs appointed to assist the Bureau Arabe in the enforcement of the law, there are a number of functionaries who have nothing whatever to do with the French civil or military government of the country.

These functionaries exercise their duties in the north as well as in the south, wherever there are believing Mohammedans. They are appointed, of course, with the approval of the Governor-General, but they are chosen chiefly for their knowledge of Moslem laws and rites. In the north, as in the south, they are under the Arab chiefs, but their rulings on purely Arab questions are as final as those of a French civil or military court, and their religious doctrines are based on deep study of the laws of the Prophet.

They are divided into two categories. In the first are those who administer the law, in the second, those whose duties are religious. The young men who qualify for posts in the first category are those whose parents feel that they have a calling for higher things than being shepherds or laborers. While still learning the Koran by heart with the native teacher they are sent to the French school with the definite object of working. Here they are taught all elementary matters in the same way as a European child in a boarding-school, and at the age of sixteen they go up for an examination which, if they pass, gives them an entry into the Medersa.

The Medersa is a college in Algiers where the students study Mohammedan law for a period of six years. Some of those who pass carry their studies further, and go up for the examination for the French bar, but to those who are not so ambitious there are two openings. They can either become Interprètes[53] Judiciaires—that is to say, interpreters in French courts, where Moslem law comes into contact with French law—or else they can definitely take up the Droit Musulman as a profession.

If the student merely passes out unbrilliantly, or even fails to get his diploma, he will probably become a khodja in a Bureau Arabe or in some other French office dealing with Arabs. His duties will be to translate into Arabic all official despatches sent out to the tribes or douars, and likewise to translate into French all incoming Arab documents.

A successful candidate will, however, first of all find himself appointed to the post of adel, a kind of superior clerk in a native lawyer’s office, and from that he can rise to bash adel, or principal clerk. From the bash adels are chosen the kadis. The kadis have many functions, which in England would combine the duties of solicitor, official receiver, registrar, and judge, without the latter’s power of awarding punishment.

All native cases of jurisdiction are first of all brought before the caïds and aghas of the district. If they are crimes or cases with which he can not deal by compromise, he either sends them on to the Bureau Arabe or, if they are not criminal offenses, to the kadi. People who require arbitration can, of course, go direct to the kadi, but the nomad prefers the ruling of his caïd. The most usual cases to come before the kadi are those of inheritance, lawsuits, sales of property, and family quarrels. He also marries and divorces those who wish it.

His decision is final, and even in questions between great chiefs they must either accept the kadi’s ruling or else carry the case before the French tribunals, which is a lengthy and expensive procedure. In fact the kadi is the decisive factor in all native disputes, in[54] all family matters, and in all cases which do not actually incur definite punishment.

The kadis themselves are usually charming people, cultivated, courteous, and full of a quiet sense of humor gathered amidst the comedies and tragedies of daily life which pass before them. Many of them have a great deal of moral influence, and are instrumental in bringing about reconciliations between foolish couples and quarreling families.

There are also learned men, called talebs, in Mohammedan centers. These natives teach the Koran in the schools and counsel others who want advice in legal matters. They have also the important function of writing and translating documents and letters for those illiterate natives who require their services, whether it be in French or in Arabic. On the same plane as the kadi, but without the same official education, are found those of the second category, mentioned above—the religious teachers.

First of all the mufti. The muftis often have had a legal education and are consulted on Mohammedan law before taking cases before the kadi, in the same way as in England one goes to a solicitor, but they are chiefly authorities on religious rites, and they hold official positions at the mosques. Every Friday and on feast days they preach and expound the Koran at the midday and evening prayer. Their power has greatly diminished of late but their knowledge of Mohammedan scripture is profound. In cases where there is no mufti the kadi is regarded as the authority on religious matters.

The priest of the mosque is called the imam. He is in charge of all religious ceremonies, and when the collective prayer is said, the faithful follow him in all the chants and movements. He is sometimes an educated man, but it is not the general rule, and one[55] often finds the imam attending classes held by the taleb to learn how to write and speak literary Arabic. (Literary Arabic in opposition to the bastard tongue spoken in North Africa.)

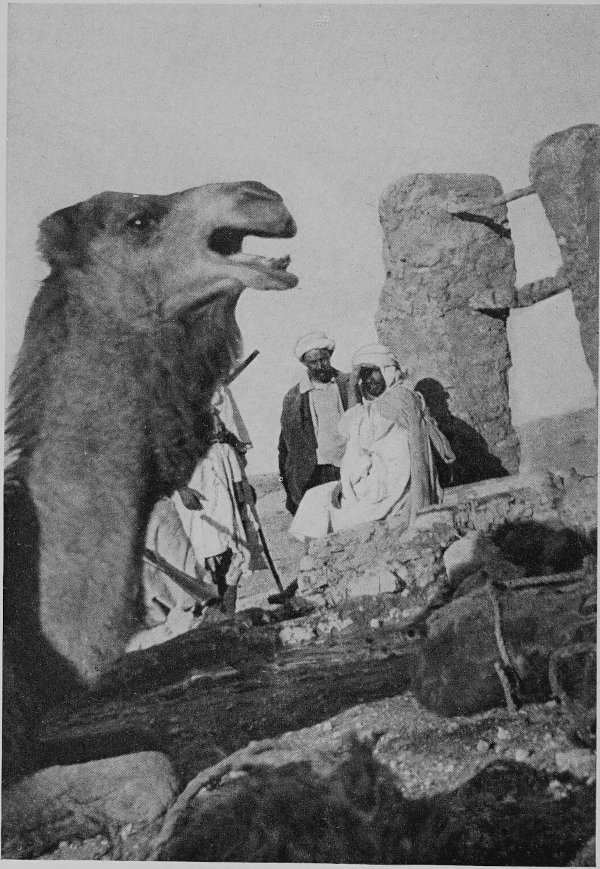

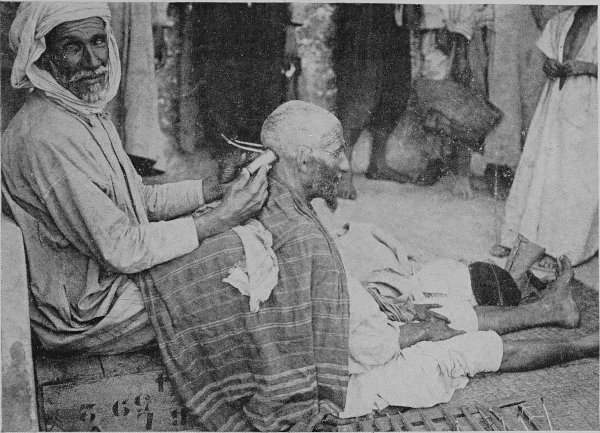

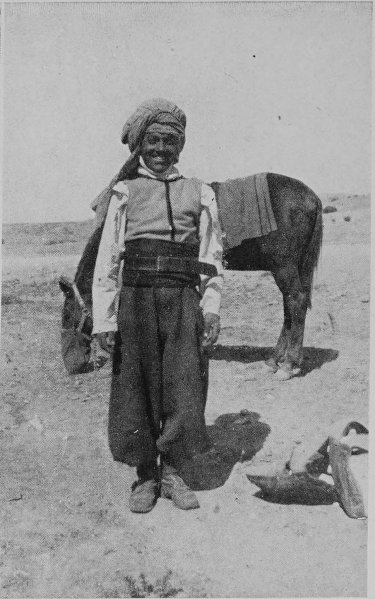

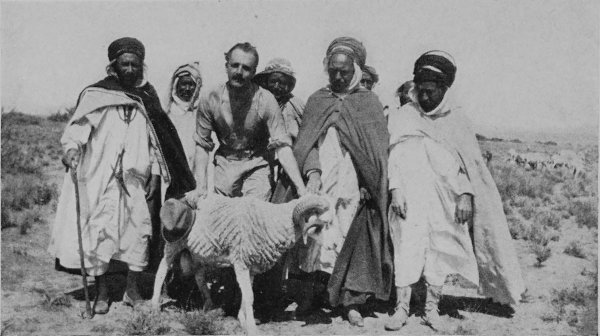

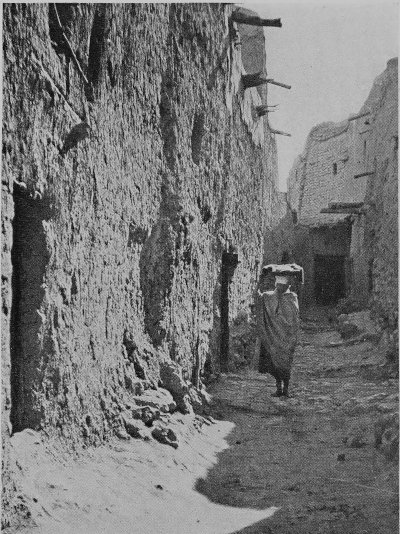

An Arab Barber

Roasting the Lamb Whole

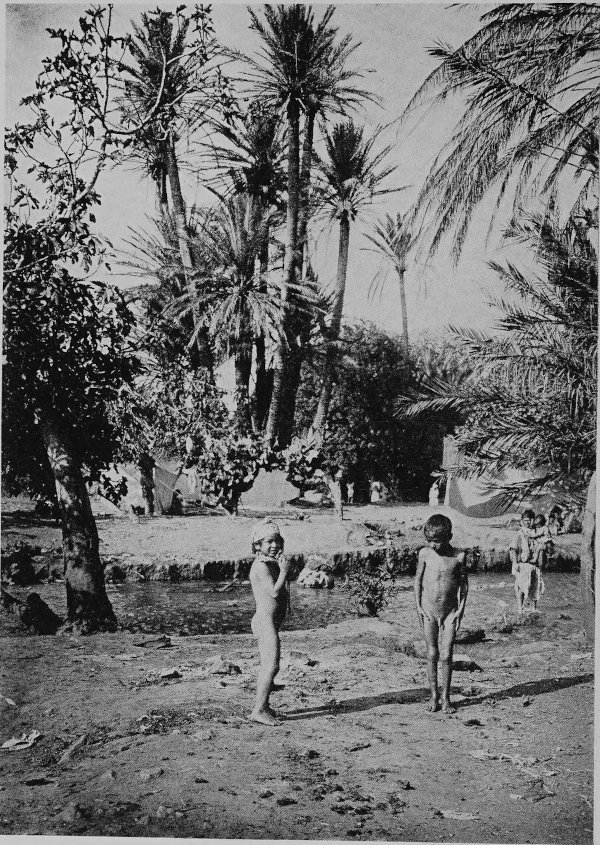

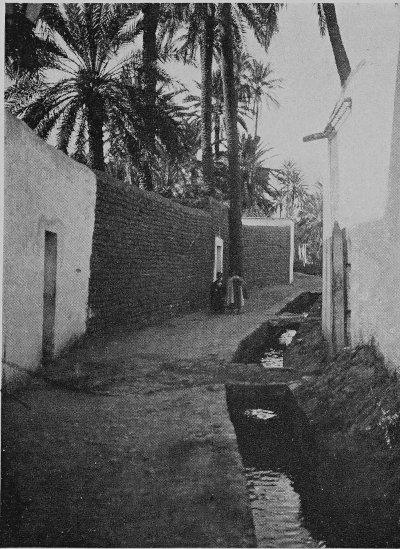

Children Bathing in a Southern Oasis

Then there is the muezzin, who is the verger of the mosque, and whose chief duty is to call the faithful to prayer.

There is no special costume for these different officials, but they usually wear somber or white burnouses, and one can always tell a learned man by the delicacy of his hands.

What strikes one most in all this Mohammedan administration is that it has not altered since the beginning of its creation, and that it has not been in the least degree influenced by contact with laws or customs of other countries.

Even in matters where the application of modern laws would be beneficial, such as in the question of inheritance which causes the greatest muddle imaginable, the old system of twelve hundred years ago is adhered to.

Now previously we noticed the apparent contradiction in the French administration of Algeria, which seemed to be rather overgoverned, and here we have another contradiction in the fact that these native functionaries are allowed to act with complete independence in all matters affecting their own laws. This is one of France’s wisest policies in Algeria, and it is of comparatively recent date.

At first the French did not realize the enormous importance of Islam in North Africa, but now that they have grasped it, they use their knowledge sagaciously.

The French administration of Algeria is complex, but it achieves its end, as the traveler will realize if, on marvelous roads, he traverses this immense country[56] unmolested by the masses of wild men who live there.

I repeat again it is not the duty of a foreigner to criticize the government of another country, but merely to examine it and judge of the results.

[57]

Standing alone and quite apart from the native officials just mentioned are the marabouts. The name is derived from the Arab word marabet, which originally meant one who served as a soldier in a rebat or fortress built on the frontier of Mohammedan countries as defense against the infidel, and which became a base of attack against Christian neighbors.

In the forts the moslem soldiers gave themselves over to acts of piety. When the days of holy war had passed the rebats were converted into religious buildings, and a marabet was, therefore, a holy man, an apostle of Mohammed.

Marabouts in North Africa are now holy men who claim direct descent from Mohammed. There are a few who by that virtue alone become marabouts, and it can be imagined, therefore, that there are a considerable number of these saints in Algeria. Any Arab village which respects itself has a marabout or two buried in the cemetery, and a great many have them living on the premises. They have no official position, and their influence depends entirely on their own personality. In some cases they are great figures wielding an enormous amount of power, which is utilized by the French Government for its own ends, and they are incidentally treated with much consideration.

On the other hand, as practically all the male children of marabouts inherit the title, there are many[58] who are completely insignificant, I will even say unscrupulous and immoral, and who live on what they can make out of the poor and credulous followers of the Prophet. They are not always educated, and though they have probably studied the Koran their knowledge on other matters is very rudimentary. Many of them profess to be doctors, and though their methods are very primitive, wonderful cures have been known at their hands, chiefly owing to the faith of those treated.

They are almost all rich men, owning flocks in the sheep-breeding areas, date-palms in the far south, and extensive properties in the north. This wealth comes from the offerings of the faithful in return for blessings and prayers for their welfare.

This, of course, leads to a great deal of abuse, and there are very many of these holy men who reap in hoards of wealth which they spend on sumptuous living. Moreover, as it is supposed to be an act of grace to be in the following of a marabout their servants are not paid, and are practically slaves whose lives are in the hands of their master. They are beaten or punished at will with no redress, as it is rare that information leaks out officially to the French authorities, who prefer to interfere as little as possible with these holy men, whose religion seems, in their own eyes, to absolve them from all acts of unrighteousness.

They drink alcohol, they rape, they live in the utmost disorder, imposing unscrupulously on the believing faithful. If they find people who oppose them they cast spells on them or curse them into eternity, and the number of credulous folk who believe in this is extraordinary.

Some of them are good at sleight of hand and perform childish conjuring tricks which leave their followers in a state of gibbering astonishment. I[59] remember once confounding a fairly decent type of marabout who conjured before me by explaining the trick. But, though he was rather upset, I saw that the people’s faith was not in the least shaken. Naturally the well-to-do Arabs of good family do not respect these law-breaking saints, and say that though their ancestry must be considered, they can not be regarded as real marabouts, whose lives are examples to all the faithful.

However, against these rogues there are many exceptions: men of great piety who spend a good deal of time and money in relieving the suffering of the poor, and who have devoted a great part of their existence to the study of sacred writings, while in practise they strictly follow the principles of the Koran.

All marabouts, disorderly or otherwise, are at the head of what is known as a zaouia. A zaouia is supposed to be a kind of retreat for men and women, but chiefly women, who are tired of worldly things. They give up all they have, be it one sheep or a large-acred property, to the marabout, and in return are clothed, lodged and fed for the rest of their lives in spiritual beatitude. They also have to work, tilling his land, looking after his horses, weaving carpets and burnouses, etc., the produce of their work being nominally used to raise further money to help the needy.

In the case of the conscientious marabouts this is done, but the practise is also a source of personal revenue to the unscrupulous. However, good and bad alike, they all have that Arab spirit of hospitality and charity, and any person, rich or poor, can always claim lodging and board with the blessing of the holy man.