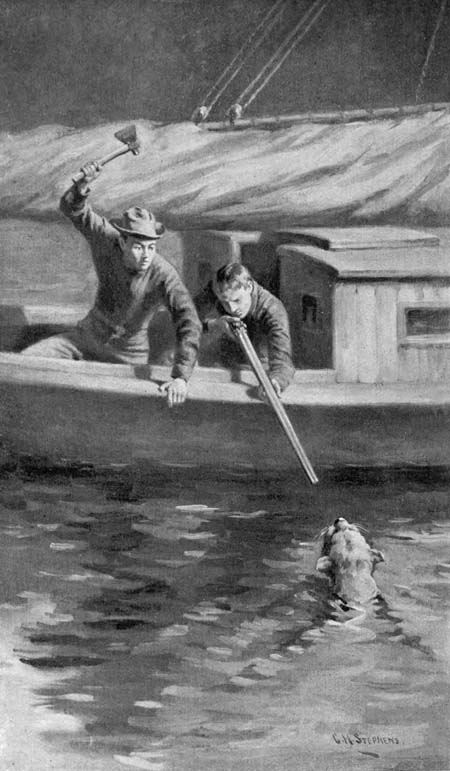

The panther was now within four or five feet of the boat.

Page 196.

OR

The Rolling Stones

BY

Frank R. Stockton

Author of “Rudder Grange,” “A Jolly Fellowship,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

CHARLES H. STEPHENS

PHILADELPHIA

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1897

Copyright, 1882, by James Elverson.

Copyright, 1896, by J. B. Lippincott Company.

Electrotyped and Printed by J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | “The Best Thing You ever heard of” | 7 |

| II.— | A Sea Voyage | 16 |

| III.— | “A Continent before Us” | 27 |

| IV.— | With Hook and Line | 38 |

| V.— | Chap’s Alligator | 50 |

| VI.— | The Rolling Stone | 65 |

| VII.— | The Two Orphans | 73 |

| VIII.— | “Captain of Himself” | 83 |

| IX.— | Friends and Enemies | 92 |

| X.— | Phil’s Uncle and Chap’s Sister | 101 |

| XI.— | Two Expeditions | 111 |

| XII.— | Chap leads the Indians | 119 |

| XIII.— | Adam leads his Party | 127 |

| XIV.— | Chap’s Ambassador | 140 |

| XV.— | The Forces meet | 145 |

| XVI.— | Mary Brown sends a Message | 154 |

| XVII.— | The Channel-Bass | 163 |

| XVIII.— | Chap boards the Maggie | 172 |

| XIX.— | Waiting for a Visitor | 182 |

| XX.— | The Visitor arrives | 190 |

| XXI.— | The Metropolis of the Indian River | 197 |

| XXII.— | The Colonel | 204 |

| XXIII.— | A New Expedition planned | 211 |

| XXIV.— | Coot Brewer takes the Helm | 219[4] |

| XXV.— | Among the Alligators | 224 |

| XXVI.— | The Maggie comes to Town | 234 |

| XXVII.— | The Race through the Woods | 243 |

| XXVIII.— | A Plot against Chap | 251 |

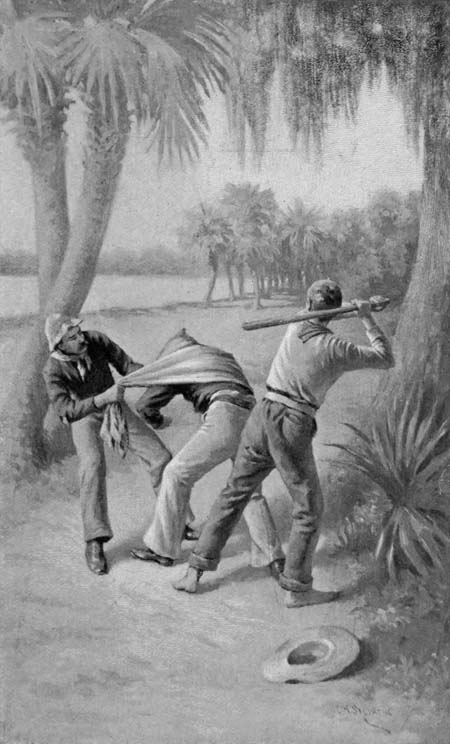

| XXIX.— | How Adam was bagged | 259 |

| XXX.— | The Countess | 267 |

| XXXI.— | A Point of Honor | 273 |

| XXXII.— | Chap is down upon Aristocracy | 282 |

| XXXIII.— | Which finishes the Story | 289 |

| PAGE | |

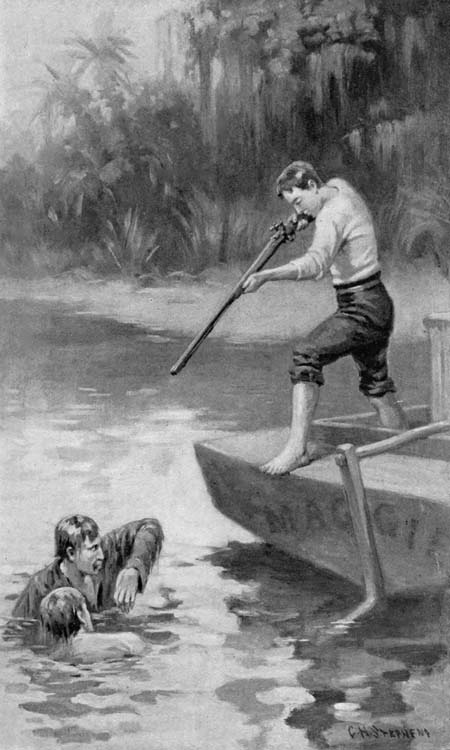

| The panther was now within four or five feet of the boat | Frontispiece. |

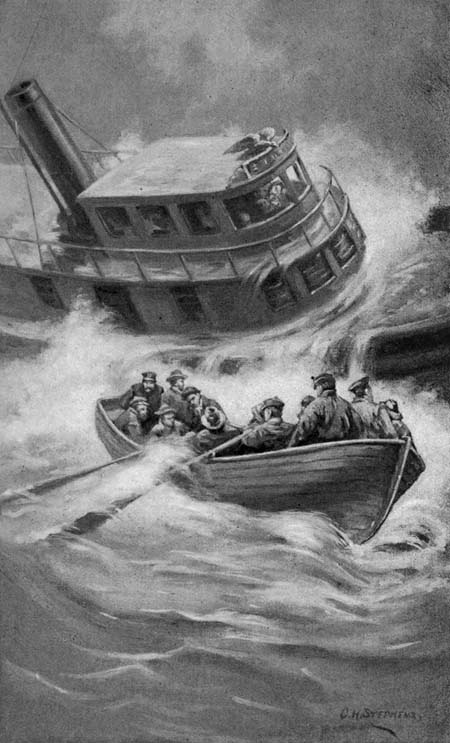

| The rescue | 21 |

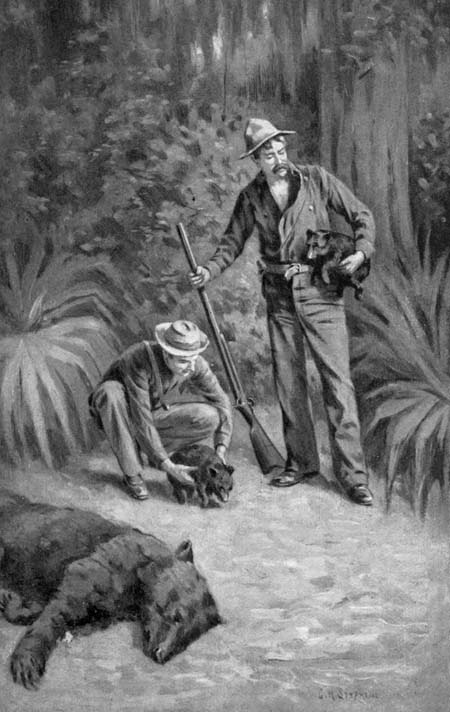

| Adam tucking the other under his left arm | 81 |

| “Crouch down there, you varlets!” | 177 |

| “Don’t fire!” screamed Coot | 226 |

| “Now we’ll give it to him” | 261 |

[6]

CAPTAIN CHAP

It was the month of October, and yet for the boys who belonged to the school of Mr. Wallace, in Boontown, the summer vacation was not yet over. Mr. Wallace had been taken sick, and although he was now recovering, it was not expected that he would be able to resume the labors of his school until about the middle of November.

Everybody liked Mr. Wallace, and very few of his patrons wished to enter their boys at another school when it was expected he would certainly re-open his establishment in the course of the fall. Most of his scholars, therefore, were pursuing their studies at home, according to methods which he[8] recommended, and this plan was generally considered far more satisfactory than for the boys to go for a short time to other schools, where the systems of study were probably very different from those of Mr. Wallace.

It is true that some of the boys did not study very much during this extension of the vacation, but then it must be remembered that those who expect boys to do always everything that is right are very apt to be disappointed.

Philip Berkeley, who lived with his uncle, Mr. Godfrey Berkeley, at Hyson Hall, on the banks of one of Pennsylvania’s most beautiful rivers, had studied a good deal since the time when his vacation should have ended, for he was a boy naturally inclined to that sort of thing, and he had, besides, the example of his uncle—who was hard at work studying law—continually before his eyes. But his two most particular friends, Chapman Webster and Phineas Poole, did not subject their school-books to any great amount of wear and tear.

Chap Webster was a lively, energetic boy, always ready to engage in some enterprise of work or play; and Phineas, generally called Phœnix by his companions, was such a useful fellow on his father’s farm that he was usually kept pretty busy at one thing or another whenever he was at home.

[9]At the time our story begins, Chap Webster had, for a week, been living in what he considered the most delightful kind of clover. He was a great lover of the water, although he had no particular desire for a mariner’s life, in the ordinary sense of the term.

Accustomed since a child to the broad waters of the river, he had a great fancy for what might be called the inland marine service, and his highest ambition was to be captain of a tug-boat.

To course up and down the river in one of these swift and powerful little vessels, and to make fast to a great ship ever and ever so much larger than the “tug,” and to tow her along against wind and tide, appeared to Chap a most delightful thing to do. There was a sense of power in it which pleased him.

He was now paying a visit to a relative in the city, who was one of the officers of a tug-boat company, and this gave Chap an opportunity to take frequent trips on his favorite vessels. He enjoyed all this so much that I fear he was in no hurry for his school to begin.

It was on a Monday afternoon that Philip and Phœnix were at the railroad station in Boontown. Each had come to town on an errand for his family, and they were now waiting for the three o’clock train from the city to come in.

The first person who jumped from the cars was[10] Chap Webster, and his feet had scarcely touched the platform before he spied his two friends.

“Hello, boys!” he cried, striding toward them. “I’m glad I found you here. I want to tell you the best thing you ever heard of! I’m going down to the Breakwater to-morrow on a tug-boat, and you two can go along if your folks will let you. I’ve fixed the whole thing up right. We’ll be gone two days and a night. And I tell you what it is, boys, it will be more than glorious! We’re going down after a big steamer, that’s broken her propeller-blades and has to be towed up to the city. I came up to tell you fellows, and see what my people said about it. But I know they’ll agree, and I don’t want you to let your folks put in any objections. It’ll be just as safe as staying at home, and there’s entirely too much fun in it for any of us to miss it.”

Neither Phil nor Phœnix hesitated for an instant in agreeing that Chap’s idea was a splendid one.

Mr. Berkeley, Phil’s uncle, when the subject was laid before him about an hour afterward, gave a hearty approval to the plan, for he was very glad that Phil should have an opportunity to enjoy an excursion of the kind.

His summer vacation had been filled up much more with work and responsibility than with recreation, and his uncle considered that a trip of some kind was certainly his due.

[11]But the matter did not appear in the same light in the eyes of Mr. Poole. Now that Phœnix was not going to school, he thought it the boy’s duty to make himself useful about the house and farm, and there were a great many things he wanted him to do.

When Phœnix came over to Hyson Hall early the next morning, and told Phil he didn’t believe his father intended to let him go on this jolly old trip, Mr. Berkeley ordered his horse, Jouncer, to be saddled, and rode over to the Poole farm.

When he came back, he found Chap Webster with the other boys, and a noisy indignation meeting going on. He put a speedy stop to the proceedings, by informing the members of the small assemblage that Mr. Poole had consented to let Phœnix join the tug-boat party.

This news was received with a unanimous shout, and the boys separated to get ready as quickly as possible for the expedition, for they were to start for the city on the noon train.

“Take your heavy overcoats with you,” said Mr. Berkeley, as Chap and Phœnix were bidding him a hasty good-by; “for it may be cold on the water at night, and you had better each take a change of linen with you, and some underclothes.”

“What!” cried Phil; “for a little trip like this?”

[12]“Yes,” said Mr. Berkeley. “I am an old traveller, and I know that a great many things happen on these little trips. One of you may tumble overboard, and need a dry shirt, and at any rate you ought to feel that you may rough it as much as you please, and yet look clean and decent when you are coming home.”

Hyson Hall was appointed for the rendezvous of the boys, and, after a slight luncheon, Joel drove them over to Boontown. But before they started Mr. Berkeley gave each of them a long, stout fishing-line, suitable for salt-water fishing.

“You may have a chance to use these,” he said, “and I don’t believe any of your own lines are strong enough for deep-water work.”

He gave Phil a pocket lantern and a tin box of matches, with a paper of extra fish-hooks and various other little articles, which might be of use.

“If I’d been going by myself,” said Chap, “I’d have just clapped on my hat, and started for town.”

“Yes,” said Phœnix, “and then, when you got a chance to fish, you’d have growled because you hadn’t a line. I tell you what it is, Phil, your uncle knows what he is about. I wish I knew what he said to father.”

“Some magic words,” said Chap; “but you needn’t think anybody is ever going to tell them to you. You’d go round slinging spells over your[13] whole family, and having everything your own way. I rather think you’d have an easy time of it.”

“Yes,” said Phœnix, “you’re about right, and when any work turned up that I wanted to do, I’d chuck a spell over a long-legged fellow named Chap Webster, and make him come and help.”

“Joel,” said Chap, “hadn’t you better touch up the noble beast? We don’t want to be late, you know.”

“We’ll get there soon enough,” said Joel. “I drive on time, and I never miss trains.”

“If you hurry up people that way, Chap,” said Phil, “you’ll have this trip over sooner than you want it to be.”

“You needn’t worry your mind about that,” said Chap. “When we get on the real trip, I’m the fellow to help stretch it out as far as it will go.”

The trip down the river and bay was quite as enjoyable as the boys had expected it to be. The little tug was not very commodious, and not very clean, but there was a small after-deck, on which they could lounge quite comfortably.

The boys had never been far below the city, and the scenery was novel and interesting to them. Chap would have been glad to have the tug stop occasionally, so that they could have a chance to fish; but he had sense enough not to propose anything of the kind to the captain.

[14]They reached their destination the next day, and it was then found that the steamer with the broken propeller was not quite ready to be towed up; and it was decided not to start with her on her trip up the river until the following morning.

In the course of the afternoon, however, some work appeared for the captain of the tug-boat. Far out to sea a schooner was perceived, with her foremast and part of her bowsprit gone, and endeavoring, against a head-wind, to make her way to the refuge of the Breakwater.

There was a strong wind blowing from the north, with a chance of its getting farther to the east before long, and it was considered doubtful whether the disabled schooner would be able to get in before a storm came on.

“Boys,” said the captain, coming aft to where our friends were sitting, “I’ve made up my mind to go out and offer to tow that schooner in. I might as well be making some money for the company as to lie here doing nothing. But I think it’s going to be pretty rough, and, if you fellows don’t care to go along, I’ll put you ashore.”

The boys, who had been so much interested in everything around them that they had not even taken out their fishing-lines, cried out at once that they would not think of going ashore. Nothing would please them more than a trip out to sea.

[15]“The rougher the better!” cried Chap. “I just want to feel what it is like to be tossed on the ocean wave.”

“All right!” said the captain, with a grin. “We’ll toss you.”

It was not long after this little conversation that the tug-boat was bravely puffing out to sea. The wind was strong and the waves ran pretty high, but the boat made her way over the rough water without difficulty.

The boys were delighted with the motion of the vessel as it plunged over the waves, and none of them felt in the least degree sick.

Chap wished to go out on the bow, where he could stand and see the boat “breast the billows;” but he was not allowed to do this, for every now and then a shower of spray came over the bows, and he would have been drenched to the skin in ten minutes. Even where they sat in the stern, the boys were frequently treated to a shower of spray; but this, as they wore their overcoats, they did not mind in the least.

[17]It took them longer to near the schooner than they had supposed it would, for she was making very slow headway against the wind, and in some of her long tacks she seemed to the boys as if she were trying to keep out of their way.

At last, however, they reached her, and the tug steamed close enough to her side to allow the people on board to be hailed. But, to the disgust of the captain of the tug-boat, his offers to tow the disabled vessel into shelter were declined.

Her captain believed that he could work her in without any help, and he did not wish to incur the expense of being towed.

“All right, then!” said the captain of the tug-boat to the boys, who stood near him. “She can run in by herself, and perhaps she’ll make the Breakwater in a week or two. We have lost nothing but some of our owners’ coal, and you fellows have had a sea trip. And now we will run back again.”

The captain made two mistakes that day. One was when he thought he was going to make some money by towing a schooner and the other was when he thought he was going to run in again.

The tug-boat had not gone ten minutes on her returning course, when suddenly her machinery stopped, and in a few moments the boat turned about and began to roll in the trough of the sea.

There was now a good deal of confusion in the[18] engine-room, and there the boys made their way, not without difficulty, for the rolling motion of the boat made it very hard for them to keep their feet.

In the engine-room they found the captain, the engineer, and one or two others of the small crew. Something had broken, the boys knew not what, for no one seemed to have time to explain the matter to them.

Efforts were being made to repair the injury. There was a great deal of hammering and banging and loud talking, and presently the engine let off the steam from the boiler, which made such a noise it was almost impossible to hear anything that was not shouted into one’s ear.

Perceiving that they were in the way, and could find out nothing, and were to be told nothing, the boys prudently retired into the inner cabin. Here Phil and Chap became quite sick. They could stand the pitching and tossing of the boat as she rose over and plunged down the waves, but this rolling motion was too much for them.

The two unfortunates crawled into the little bunks in which they had slept the night before, while Phœnix, with an air of brave resignation, braced himself against the cabin-door, and waited to see what would happen next.

Nothing seemed to happen next. After awhile the noise of the escaping steam grew less, and then[19] it stopped. The hammering and banging had also ceased, and thinking that everything was all right now, Phœnix went forward to see how things were going on.

It was not easy to see much, for the engine-room was lighted only by a hanging lantern, but he met the captain, who informed him that they were in a bad way. One of the connecting-rods had been broken, and as the engine was not stopped soon enough, some other parts of the machinery had been damaged.

“We have tried to patch her up,” said the captain, “but it is no go. All we can do is to make everything tight, and lie here until some vessel comes along to give us a tow in. This has been a pretty bad day for us, for we’re not going to take any steamer up the river to-morrow.”

“How long do you think you’ll have to stay here?” asked Phœnix.

“Don’t know,” answered the captain. “Something may come along pretty soon, and we may not be towed in till morning. But you needn’t be afraid. We’ll make everything tight, and though we may roll and pitch, we won’t take in any water.”

“I suppose that vessel with a broken mast couldn’t help us?” said Phœnix.

“No,” said the captain, “it is more than she can do to take care of herself, and she is out of[20] sight now, although she isn’t any nearer the Breakwater than we are.”

“Perhaps some steamboat will come out after us when they find we don’t come back,” suggested Phœnix.

“That may be,” said the captain, willing to give his young passengers as much encouragement as possible. “But you fellows had better get something to eat, and turn in. You’ll be more comfortable in your bunks while we are rolling about in this way.”

But Chap and Phil did not want anything to eat. The very idea was horrible to them. And so Phœnix ate his hard biscuit and some cold meat, for there seemed to be no intention of even boiling a pot of coffee, and then he crawled into his little bunk.

“Boys,” groaned Chap, “I don’t care for a tug-boat as much as I used to.”

“Care for it!” said Phil, in a weak voice. “I hope I may never——”

And here his remark ended; he was too sick to say what he hoped.

The night was a horrible one. Occasionally the boys slept; but as they found, whenever they dropped into a doze, they were very apt to roll out of their bunks, they were obliged to keep awake most of the time. As soon as daylight appeared, they were all anxious to go outside, feeling[21] that a breath of fresh air would be better than anything else in the world. This the captain, who seemed to have been up all night, would not allow.

The rescue.

“You’d be washed overboard,” he said, “and things are bad enough as they are, without any of you getting drowned. There’s a regular gale off shore, and we haven’t sighted an inward-bound steamer yet.”

In the course of an hour or two, it was evident that a vessel ought to be sighted very soon, for the tug, which was not built for such rough work as this, had, in spite of the efforts of the crew to make everything tight on the decks, shipped a good deal of water, and it was necessary to work the pumps. But this did not help matters, for it was found that a leak had sprung somewhere, and the water came in faster than it could be pumped out.

The tug was now far from the land, and in the path of coastwise steamers; and before noon the welcome sight of a line of smoke appeared on the horizon. It was a steamer which was approaching them, but, unfortunately, it was going southward, and not northward.

“She’s a Savannah steamer,” said the captain, “but we’ve got to git on board of her, no matter where she is going; for this old boat can’t stand this sort of thing much longer. We’ve been blowing[22] out from shore all night, and there’s no time for anything to come out after us now.”

The boys looked aghast.

“Savannah!” they cried. “We don’t want to go to Savannah!”

“It’s a good sight better place than the bottom of the ocean,” said the captain.

It was a bad bargain for the boys, but they had to make the best of it.

“What are you going to do in Savannah?” asked Phœnix, in a tone of dismay.

“It can’t take us more than a couple of days to get there,” said Phil, “and then we can telegraph home. As soon as our folks know where we are, I shall feel that everything is all right.”

“I shan’t feel that anything is all right until we know where we are ourselves,” said Chap, looking out of one of the little windows of the cabin. “Did you ever see such a pokey old steamer as that is? I believe we shall sink before she gets to us.”

But this unfortunate event did not happen, although the tug was very deep in the water and rolling heavily when the steamer lay to, with her bow to the wind, a few hundred yards away from them.

A large boat was speedily lowered and rowed to the tug. In less than half an hour the unfortunate occupants of the sinking tug-boat had been taken on the steamer.

[23]A few articles were brought away from the tug, and the boys were allowed to carry with them their valises.

As soon as the boat-load of people was on the steamer, and the boat hauled up to its davits, the vessel put about, and proceeded on her way.

As the boys looked back, they saw the little tug, with her smoke-stack very much on one side, and but little of her hull visible, tossing and pitching on the waves.

“She isn’t good for another half-hour,” said the engineer, who stood by.

The party rescued from the sinking tug-boat was very kindly received on board the steamer, but it was quite evident, even to the hopeful and enthusiastic Chap, that there was no intention of putting back for the Breakwater.

The boys had never been on an ocean steamer before, and would have been greatly delighted with their present experience had it not been for the feeling that every movement of the ponderous engine beneath them was taking them farther and farther from their homes.

It would be impossible for their friends to hear from them for at least two days, and the news that the tug-boat had gone out to sea, and never returned, would probably reach Boontown very soon.

All three were very much dejected when they[24] thought of the misery and grief which the intelligence would cause in their families, and Phœnix seemed more downcast than either of the others.

“If father believes I’m drowned,” he said, “it’ll be just his way to go about grieving that he worked me too hard. I know I made him think that, but I didn’t do so much after all.”

“If my folks look at the thing in that light,” said Chap, “they’ll grieve that they didn’t get more out of me before I was drowned.”

“I don’t believe there’ll be as much mourning as you think,” said Phil. “Uncle will be on hand, and he’s been in so many scrapes, and pulled through them all, that he knows just about how things will turn up. I bet it won’t be half an hour after he hears the news before he thinks out the whole thing, and has made all your people see that it’s as clear as daylight that we’ve been carried out to sea, and picked up by some steamer, and that we’ll be heard from soon after she gets to her port. He’ll know that there wasn’t storm enough to wreck a good, stout tug-boat, and that something must have got out of order, so that she was carried out to sea.”

“If that one-masted schooner ever got in,” said Phœnix, “she’d let them know there was something wrong with us, for she must have seen or heard us blowing off steam.”

“I don’t know about that,” said Chap, “for[25] before I turned into my sick-bed, the vessel was pretty well out of sight. We were going in opposite directions, as well as I could make out.”

“That was because she was sailing against the wind, and had to make long tacks,” said Phœnix.

“Do you suppose I didn’t know that?” asked Chap, drawing himself up in such an erect position that a great lurch of the vessel nearly threw him off his feet.

“We might as well make the best of it,” said Phil, “and have a good time. In a couple of days we will be in Savannah, and when we have telegraphed home, everybody’ll be all serene, if they are not now.”

“Your head’s level, Phil,” said Chap. “Let’s go and explore the ship.”

On the breezy deck of the steamer, none of the boys felt in the least degree sea-sick, and they went about in high spirits. The purser, a good-natured man, took them in charge, and showed them the engine-room and various parts of the vessel, but it was not long before he gave them a piece of information which nearly took their breath away.

In answer to an inquiry in regard to the time at which they might expect to reach Savannah, the purser told them that the vessel could not stop at that port at all. The captain of the tug-boat had been right in saying that this was a Savannah steamer, but she had been temporarily withdrawn[26] from that line, and was now bound for Nassau, in the Bahamas.

“When will we get there?” asked Chap. “Can we telegraph from Nassau?”

“We shall reach Nassau in about four days,” said the purser, “but there is no cable from those islands. You will have to carry the news of your safety yourselves when we bring you back to New York.”

“Can’t we send a letter?” asked Phil.

“Not any sooner than you can come yourselves,” said the purser, “for we shall bring back the mail from Nassau to the United States.”

“And how long will it be before you get back to New York?” asked Phil.

“I don’t know just how long we shall lie at Nassau,” said the good-natured purser; “but I think it will be ten or twelve days before we are in New York again.”

“Won’t we meet some ship that will take us back or carry a letter?” asked Phœnix.

“I can’t say,” replied the purser. “The captain will do what he can for you, but I don’t know that he will have a chance of putting you on board a northern-bound steamer, or of sending news of you to your friends.”

[27]

It was very hard for the boys to get their spirits up after the news they had just heard.

“Ten days before our folks hear from us!” ejaculated Phœnix. “That’s simply dreadful! They’ll give us up long before that time.”

“We will find them all in black when we get back,” said Chap, with a doleful face.

But even this gloomy prospect could not long depress the spirits of our young friends.

By the next morning they were going about cheerfully, hoping and believing that something would soon turn up by which they could speedily get back to their friends, or, at least, send news of their safety.

The weather was now fine, although it was so cool that they were obliged to wear their overcoats whenever they were on deck, and they could not help enjoying this unexpected sea voyage.

[28]They did not see much of the tug-boat people. These men lived forward with the crew of the steamer, while the boys ate and slept with the passengers.

On the morning of the third day of their steamer trip, they met one of the tug-boat crew,—a man named Adam Guy. This man had been the only person on board the tug-boat to whom the boys had taken any particular fancy. He had been a sailor, had visited many parts of the world, and had a great deal to tell of his various experiences on the sea and land. He was a strong and wiry, but not very large, man; and, like many sailors, he wore little gold rings in his ears. His hair was thin and sandy, and hung in short curls at the back of his head. He had a pleasant smile, and appeared to be an easy-going, good-tempered fellow.

“Young men,” said Adam, “I’ve been a-wantin’ to see you and have a little talk with you. Do you know there’s no chance of our meetin’ any vessels, or of your bein’ sent home or gettin’ any word back, either?”

“How is that?” asked the boy.

“Why, it’s just this. We’re out of the way now of all craft bound north. I did think we might a’ met a coast steamer yesterday or the day before; but if we did, we passed them in the night, for I didn’t see any. We are now off the coast of[29] Florida, and as we are sailin’ south, we keep pretty well in shore, so as to be out of the way of the Gulf Stream, which runs northward, you know; and, as you’ve lived on a big river, you understand what it is to sail agin a strong tide. But, of course, every vessel bound north tries to keep in the current of the Gulf Stream, so’s to be helped along. So, just about here, where the Gulf Stream is near our coast, you find all vessels, goin’ south, keepin’ pretty near shore, and them bound north, far out. It won’t be long before we’re near enough to the coast for you to see the trees. And we’ll run down till we git about opposite Jupiter light, and then we’ll sail across the stream and make straight for the Bahamas. I know all about these waters, for I’ve sailed in them often. Now, as for me, I don’t want to go to Nassau, and I don’t believe you want to, either. The captain of our tug and the rest of our men are all willin’ to go, and ship on this steamer for their home trip. They’ll be short o’ hands then, for some of the crew are to be discharged at Nassau, but I don’t want to go to that old English town. I’ve been there, and I’ve had enough of it.”

“But what are we going to do?” asked Phil. “We can’t jump overboard and swim ashore.”

“No,” said Adam, “we can’t do that, but I’ve a plan in my head. Before we git to Jupiter light, the water is so deep near the coast that steamers[30] often run in very close. Now, if the captain would lie-to there and send you fellers and me ashore in a boat, it would be the best thing he could do for us.”

“What would we do when we got there?” asked the boys.

“Do?” said Adam. “Why we’d all go North, and lose no time about it, instead of goin’ over to the Bahamas and stayin’ there, I don’t know how long, and then takin’ a week for the home trip. Just back of the coast-line, down there, is the Indian River, and sometimes it’s not much more’n a stone’s throw from the beach. If we could be landed, we could easily git over to that, and there we’d find a craft to take us up to Titusville, and from that place we’d easy git over to the St. John’s River, and then you boys could telegraph home. I’ve travelled all through that part of Florida, and I could take you along as straight as a bee-line. There are settlements here and there on the Indian River, and you needn’t be afraid but we’ll be taken good care of till we git to Titusville. After that it’ll be all plain sailin’.”

“I’d like that plan first-rate,” said Chap.

“And so would I!” cried both of the other boys.

“But do you think the captain would stop,” asked Phil, “and put us off?”

“That’s what’s got to be found out,” said Adam.[31] “If I was you fellers I’d just go to him and ask about it. Lay the p’ints before him strong, and let him know how much you want to send word to your friends where you are, and then to git along home as quick as possible. Tell him I’ll go along with you and pilot you through all straight.”

The boys agreed that this plan was a capital one, and, after a little consultation, they decided to go and talk to the captain about it, and make Phil the spokesman.

At first, the captain did not take very kindly to the proposition. He did not wish to lose time, nor to incur the trouble and risk of sending a boat on shore. He also knew that a great part of the coast of Florida was nothing but a barren waste, and he did not think it would be any great kindness to the persons he had saved from drowning to put them on shore to suffer from exposure and privation. But, on the other hand, if the boys were landed in Florida, they would be at least in their own country, and ought to be able to communicate with their friends much sooner than if he took them along with him to the foreign islands to which he was bound.

“You would need money,” he said, “after you get ashore, for you couldn’t expect the people there to take care of you, and carry you about free of charge; and, although I am willing to give you a[32] berth here, I can’t supply you with cash for a land trip.”

“I have some money,” said Phil, “though not very much.”

“And I’ve got——” said Chap, thrusting his hands into his pocket.

“Oh, there’s plenty of money,” interrupted Phœnix. “There need be no trouble about that.”

“Well, then,” said the captain, who was beginning to see some sense in the proposition of the boys, “one difficulty is removed. Suppose you go forward and send that man you spoke of to me.”

The captain had a long conversation with Adam, and convinced himself that that individual knew what he was talking about when he proposed his plan. The captain of the tug-boat was called in, and Adam’s trustworthiness seemed well established.

After consultation with some of the other officers, it was decided to put the boys and Adam Guy ashore when a suitable place should be reached. The news created considerable excitement among the passengers, and great interest was taken in the proposed landing of the boys.

The air in these semi-tropical waters was warm and balmy, and the sea was smooth. Everything seemed favorable for going on shore. About four[33] o’clock in the afternoon the ship lay to about half a mile from a broad, sandy beach. This locality Adam declared he knew very well.

The Indian River, he said, lay but a short distance back, behind a narrow forest of palmettos; and at the distance of a mile or two there was a house on the river bank, where shelter could be obtained until they could get transportation up the river.

The captain, however, took care that the little party should not suffer in case they did not reach shelter as soon as they expected. He provided them with provisions suitable for two days, put up in four convenient packages. Each carried a canteen of fresh water, and Adam took charge of a large tarpaulin, rolled up into a compact bundle, which could be used as a protection in case of rain. The weather was so mild that their overcoats would be sufficient to keep them warm at night.

While the men were preparing to lower a boat, Phil took Phœnix aside, and asked him what he meant by saying there was plenty of money.

“Chap has only three dollars,” he said, “and I haven’t that much.”

“I have fifty dollars,” said Phœnix, “and I guess that will take us along till we can telegraph for more.”

“How did you come to have that much?” asked Phil, with surprise.

[34]“Why, you see, our folks haven’t settled what is to be done with some money I got for helping to run the ‘Thomas Wistar’ ashore, and father is taking care of it. But I made up my mind that I was going to keep hold of some of it myself. A fellow likes to feel that he has got something of his own that he can lay hands on, no matter what is done with the general pile. So I locked up fifty dollars in my room, and when we started off, I didn’t want to leave it behind, for I didn’t know but the house might burn down. So I put it in an old money-belt father used to wear, and it’s strapped around me now.”

“You’re a gay old fellow!” said Chap, who had come up and heard this. “You are always turning up at the right time.”

“And right side up,” said Phil.

A few minutes after this, a large boat, pulled by four men, and containing Adam Guy and our three friends, was leaving the side of the steamer, followed by the cheers of the passengers, who had assembled on the decks to bid the little party farewell.

The sea was quiet, with the exception of a long and gentle swell, and the first part of the little trip seemed like rowing on a river. But when they neared the shore and saw the long lines of surf rolling in front of them, the boys began to feel a little uneasy. This was something entirely novel[35] to them, and, although they were not exactly afraid, they could not say that they felt altogether comfortable at the idea of going through these roaring breakers.

But the surf at this point was not really very high, and the boat was a metallic one, with air compartments at each end, and the men rowed steadily on, appearing to have no more fears of the breakers than of the open sea.

As the boat reached the first line of surf and was lifted up and carried swiftly forward on its great back, and then dropped into a watery hollow, to be raised again by another wave and carried still farther on, our boys held tightly to the sides of the boat as if they felt they must stick to that craft, whatever happened. But the men pulled steadily on, keeping the boat’s head straight for the shore.

The breakers came rolling on behind as if they would sweep over the boat and cover her up with their dark green water, but another wave seemed always underneath to carry her on beyond the reach of the one which followed, and it was not long before, by the aid of oars and the incoming surf, they gained the beach.

Before the wave which had carried them in began to recede, Adam and another man jumped into the water and pulled the boat well up on the sands.

[36]Then the whole party disembarked, Chap jumping into water ankle-deep, and giving a shout that might have been heard on the steamer.

As soon as the boys’ valises and the other traps had been put ashore, the boat was turned about, and, with Adam’s help, was launched into the surf.

The pull back through the breakers was harder than the coming in, but the four men knew their business, and the stanch life-boat easily breasted every line of surf.

In five minutes they were out in smooth water and pulling hard for the steamer. As soon as they reached it the boat was hauled up, the vessel was put about, and with a farewell blast from her steam-whistle, she proceeded on her way.

“Hurrah!” cried Chap, waving his cap over his head. “Now I feel that we are really our own masters, and that we’re going to have the rarest old time we’ve ever known. Boys, the whole continent is before us!”

“That’s the trouble of it,” said Phil. “If there wasn’t quite so much continent before us we might expect to get home sooner.”

“Trouble? Home?” cried Chap. “Don’t let anybody mention such things to me. I’m gayer than the larkiest lark that ever flapped himself aloft!”

And, with these words, he ran to the top of a[37] little sand hillock to see as much of the continent as he could.

“If I were you fellers,” said Adam, “I’d make that young man captain. You’ll never be able to manage him if you don’t let him go ahead.”

“Good!” said Phil; “let’s make him captain, and you, Phœnix, ought to be treasurer, for you carry the funds.”

“And what’ll you be?” asked Phœnix.

“You’re mixin’ up your officers,” said Adam; “but as a party of this kind is a little out of the general run, I guess it won’t matter. As this is a land expedition,” he said to Phil, “you might be quartermaster, and I’ll be private.”

“All right!” cried the boys.

And when Chap came running down from the sand-hill he was informed of the high position to which he had been chosen.

“My friends,” cried Chap, drawing himself up and clapping his breast with his hand, “you do me honor, and I’ll lead you—I’ll lead you——”

“Into no end of scrapes,” suggested Phil.

“Perhaps you’re right. That may be so. But you’re bound to follow,” said Captain Chap.

“He’ll lead you sure enough,” laughed Adam. And then he added to himself, forgetting that this was a land, and not a nautical expedition, “I’ll keep my hand upon the tiller.”

[38]

After standing for a few moments to take a last look at the steamer, which was now rapidly making her way southward, our party prepared to take up the shortest line of march for the Indian River.

The boys slung their overcoats and valises over their shoulders, and these, with their water-canteens and provisions, made for each of them a pretty good load. But Adam had a still heavier burden, for he carried the roll of tarpaulin in addition to his other traps.

“I am not captain,” said Adam, addressing Chap, “but I’ll go ahead, for I’ll be able to find my way over to the river better than you will.”

“All right,” said Chap. “Adam was the first man, and you can take the lead. But I am captain, for all that, and I expect to be obeyed.”

[39]“Expect away,” said Phil; “it’ll keep your mind busy, and stop you from making plans for blowing us all up North in one bang.”

“Silence!” cried Chap. “Forward, march!”

The way from the beach back to the river was a very hard one, and a good deal longer than Adam had expected it to be.

For a time they walked over loose, soft sand, which was piled into little hills by the wind, then they came to a thick growth of palmetto-trees, the ground being covered with underbrush of the most disagreeable kind, consisting mainly of a low bush, called the “saw-palmetto,” which was made up of leaves three or four feet long, with sharp teeth at each edge.

A variety of tangled vines, concealing rotten palmetto stumps, of all sizes, helped to make the walking exceedingly difficult. But some man or animal had been that way before, and through the almost undistinguishable path, which Adam seemed to scent out, rather than to see, the party slowly made its way.

When at last they reached the river, the boys gave a great shout, but Adam merely grinned, and looked anxiously up and down.

The broad, smooth waters of the Indian River spread before the delighted eyes of our young friends. Large birds were flying through the air. At a little distance hundreds of ducks were swimming[40] on the water. The low shores were green and beautiful. But what Adam looked for was not there.

As far as the eye could reach—and as the river here bent away from them on either hand, they could see the bank on which they stood for a long distance up and down—not a house, or clearing, or sign of human habitation, could be seen, and on the river there was not a sail or boat.

“I haven’t struck just the place I want to get to,” said Adam, “for the house I’m after is just above this bend where the river turns due north agen; but then it couldn’t be expected I’d pick out the very place I wanted when I was on board a steamer nearly a mile from shore. If I could ’a’ seen the river, I’d been all right, but beaches is pretty much alike.”

“I think you did very well,” said Phil, “to get so near the place. The end of that bend can’t be so very far away.”

“It wouldn’t be much of a walk,” said Adam, “if there was a good beach at the side of the river. There’s a sandy shore on the other side, as you can see, but that’s no good to us. Along here, for pretty much the whole bend, you see the trees and underbrush grow right down to the water, and it would be wadin’ and sloppin’, as well as scratchin’.”

[41]“We might keep farther in shore,” said Chap, “where we could find dry walking.”

“It would be dry enough, but it would be mighty slow,” said Adam. “The best and quickest thing we can do is to get right back to the beach. There we’ll find good, hard walkin’, and we can tramp along lively till we calkilate we’re about opposite John Brewer’s place, and then we can push through agen to the river.”

“I guess that’s about the best thing to do,” said Phil, “for it will give us less of this horrid jungle-scratching than trying to push right straight along through the woods.”

“All right!” cried Chap. “Backward! March!”

And again, with Adam at the head, the party pushed through the strip of woods which separated the river from the ocean-beach. The march along the sand was easy enough, but it seemed very long.

“Why, I thought,” cried Chap, “that it was only a little way to the end of that bend!”

“It’s further than it looks,” said Adam. “I’ve got a pretty good notion how fur we ought to walk before we strike across; but it won’t be long before we try the woods agen.”

In about ten minutes, Adam turned, and led the way toward the river. The strip of land was much narrower here than where they had crossed it before, and after a short season of scrambling and[42] scratching and pushing over ground where it seemed as if no one had ever passed before, the river was reached. Here was a broad strip of clean sand lying between the woods and the water’s edge, but there was no house in sight.

“Isn’t this the end of the bend?” asked Phœnix.

“Yes, it’s the end of the bend,” said Adam, looking about him; “but it’s the wrong bend. I know the place now just as well as if I’d been born here. You see the river makes another bend up there, don’t you? It’s a good while since I’ve been here, and I never came to the place by the way of the sea. The house we’re after is up there. There’s no mistake this time.”

“But that must be ever so far away!” said Phil, dolefully. “The beginning of that bend is more than a mile off, I should say.”

“Yes, it’s a good piece off,” said Adam, “and I don’t believe we’d better try to make it to-night. The best thing we can do is to camp just here.”

At this the boys gave a cheer.

“That’s splendid!” said Chap. “I’d rather camp out than go to fifty houses!”

And, casting his traps on the ground, he called on all hands to go and put up the tent.

“You needn’t be in such a hurry about the tent,” said Adam. “That’s the easiest thing we have to do. After awhile me and one of you will[43] fix up the tarpaulin between a couple of trees back here, and as it isn’t likely to rain, that’ll be all the shelter we’ll want. But the first thing to do is to get supper. Have any of you got fishin’-lines?”

Each of the boys declared he had one, and started to get it out of his valise.

“Two’ll be enough,” said Adam. “One of you might stay and help me with the fire and things, while the other two go and fish.”

Phœnix agreed to stay and help Adam, while Phil and Chap got out their lines.

“I was afraid your hooks wouldn’t be big enough,” said Adam, taking up their lines; “but this is a regular deep-sea tackle.”

“Yes; my uncle gave us the lines,” said Phil. “He thought we might get some fishing down at the Breakwater.”

“Well, all you got to do,” said Adam, “is to go down to the beach and throw out your lines as fur as they will go. We’ll have to bait at first with a little piece of meat from the rations the captain gave us. Of course, you needn’t fish if you don’t want to. We’ve got enough to eat, but I thought it would seem more to you like real campin’ out if we had a mess of nice hot fish for supper.”

“That’s so!” cried Chap; “we wouldn’t think of eating that dry stuff while there’s fish in the river.”

[44]“That is, if we can coax any of the fish out of the river,” remarked Phil.

“Oh, we’ll do that easy enough,” said Chap. “Get your bait, and come along.”

The two boys proceeded a short distance from their proposed camping-ground, and having baited their hooks with some fat and rather gristly beef, they proceeded to throw out their lines; but as they were not used to this kind of fishing, neither of them succeeded in getting his line out into deep water.

Adam had been watching them, and seeing that they were making out badly, he came down to give them what he called “a start.” He unwound the whole of each line, and carefully laid it in coils on the sand. Holding the shore end of the line firmly in his left hand, he swung the hook and heavy lead several times above his head, and let it go. The long line flew out its full length, and the lead and bait plunged into deep water. When each of the lines had been thus put out, he went back to his own work.

It was not long before the boys began to have bites, and in a few minutes Chap commenced hauling in his line like a house a-fire. Hand-over-hand he grasped and jerked the cord, throwing it wildly to each side of him as he violently pulled it in. In a moment he drew a fish out of the water, and threw it up high on the sand.[45] Rushing to it, he picked it up, and held it in the air.

“Look at that!” he cried to Phil. “A splendid fellow! It must be nearly a foot long.”

Phœnix and Phil were both interested in the first fish caught in Florida waters, and they ran to look at it. Adam, also, who was picking up driftwood near by, came to see Chap’s prize.

“It will do for bait,” he said, as he took the fish from the hook.

“Bait!” cried Chap, in amazement. “A big, fat fish like that for bait!”

Adam laughed.

“A fish like that isn’t called a big one in these parts, though I s’pose in your waters it would be a pretty good ketch. It’s a mullet, and good enough eatin’, though it isn’t big enough for a meal for us, and I only want to cook one fish.”

“All right!” said Chap. “If there are fish big enough for you in this river, I’ll catch them.”

The mullet was killed, and both lines baited with a large piece of its flesh; for it was food much more attractive to the big fish they wanted, Adam said, than the cold meat they had used before. Phil went farther down the river, and both boys put out their own lines this time, succeeding, after several attempts, in throwing them a considerable distance from the shore.

[46]In less than two minutes Chap felt a tug at his line. He gave a pull, and his first impression was that his hook had caught in something at the bottom, but the jerking of his line soon let him know that there was a fish at the other end of it. Then he began to haul in; but this hauling in was very different from anything he had been accustomed to.

It took all his strength to pull in the line hand-over-hand, and although he was greatly excited, and worked as fast as he could, it came in but slowly. Sometimes the fish pulled back so hard that Chap thought he would be dragged into the water himself; but, digging his heels into the sand, he tugged away manfully.

The line was a stout one, but it cut his hands, and his arms began to ache from the unaccustomed exercise. But he kept bravely on until the head and back of a great fish appeared above the surface of the water.

Wildly excited, he gave a few mad pulls, and then rushing backward, he hauled high up in the sand a flapping, floundering fish, nearly three feet long. It was a handsome creature, dark on the back, but bright yellow beneath.

For a moment Chap gazed on his prize with triumphant delight, and then he gave a shout, which brought Phœnix, and soon after, Adam.

Phœnix was almost as delighted as Chap himself.[47] This was something like fishing. He had never seen a fish like this in his life.

“Now, then,” cried Chap to Adam, “what do you say to that? Is that fellow big enough for you?”

“Yes,” said Adam, “it’s big enough, and it’s too big. That’s a cavalio, and people eat them when they can’t get anything else; but its flesh is pretty coarse, and I couldn’t manage to cook a fish that size the way I’m goin’ to do it.”

“You ought to mention the exact size of fish you want,” said Chap, in a disappointed tone, “and then, perhaps, a fellow could catch them for you.”

“It is a pity you didn’t get something between the two,” said Adam; “but you can’t expect to hit anything right square the first time. But, hello! here comes the quartermaster, and I believe he’s got a blue-fish.”

Phil now came running up, carrying a fish nearly as long as his arm. As he came near, he raised the flapping fish, whose tail had been dragging in the sand, and gave a shout; but when he saw the magnificent creature, which was still plunging and rolling at the end of the line which Chap held firmly in his hand, his countenance fell.

“What a whopper!” he cried. “Why, mine is nothing to it!”

“No,” said Adam, “but yours is a blue-fish,[48] and we’ll have him for supper. Don’t be cast down, captain; you’ll have plenty of chances yet for blue-fish, bass, and lots of other good fellers. I’ll take the hook out of this young elephant of your’n, as he might snap your fingers, and then we’ll shove him into the water. He looks lively enough to come to all right when he gets into salt water agen, and there’s no use in lettin’ fish die here if you ain’t goin’ to use ’em.”

“All right!” said Chap. “I’m captain, and it was my duty to catch the biggest fish, and I’ve done it. And now the quicker we cook this little fellow for supper, the better, for I’m dreadfully hungry.”

The “little fellow,” a fish nearly two feet long, was taken in charge by Adam, and carried to the camp-ground, where a large fire was already blazing.

“It was havin’ this paper along,” said Adam, “that put it into my head to try baked fish for supper.”

Having dressed the fish, Adam rolled it in the brown paper, and pushing away a portion of the fire, he scooped out a place in the warm sand and ashes, and covered up the fish therein. Then the fire was built up again, and was allowed to blaze away until Adam thought his fish was done.

When the brown paper was removed, the skin of the blue-fish came off with it, leaving the white flesh perfectly baked and temptingly hot.

[49]There was salt and pepper among their rations, and with the fish and the bread and butter and biscuits, the boys and Adam made a splendid meal, although they had nothing to drink with it but the water from their canteens.

“The way to make a tip-top meal off of fish,” said Chap, “is to catch it yourself—or else let some other fellow do it.”

[50]

The preparations for the night were very simple. Adam, whose previous experience in camping and rough life had made him think, before leaving the steamer, of a good many little things that might be useful on a journey such as the one proposed, had brought with him a long, thin rope, something like a clothes-line.

“There’s nothin’ like havin’ plenty of line along,” he said, as he fastened one end of this to a low branch of a tree. “It always comes in useful. I’m goin’ to hang the tarpaulin on this, and make a tent of it.”

“The rope is long enough,” said Phœnix.

“Yes,” said Adam; “but you can’t have a rope too long. The nearest tree that ’twould do to tie it to might be a hundred feet away, don’t you see?”

[51]There was a suitable tree, however, not a dozen feet from the one just mentioned, and to a low branch of this Adam made his line fast, tying it in a slip-knot, and coiling the slack rope on the ground. This proceeding was made the text of another sermon from the prudent sailor.

“Never cut a line, if you can help it,” he said. “Use what you want, and coil away the slack. The time will come when you’ll want the longest line you can get.”

The tarpaulin was thrown over the low rope, and its edges held out by cords and pegs, which Adam had prepared while the supper was being cooked.

“It’ll be pretty close quarters,” he said, looking into the little tent, “but you fellers can squeeze into it, and I can sleep outside as well as not. The sand is as dry as a chip, and if you put on your overcoats, and take your carpet-bags for pillows, you’ll be just as comfortable as if you was at home in your feather beds.”

“A good deal more so, I should think,” said Phil, “in mild weather like this.”

The boys would not allow Adam to sleep outside. As the tarpaulin was arranged, if there was room enough for three, there was room enough for four. The tent was open at both ends, and they lay in pairs, with their feet inside and their heads near the open ends, so as to get plenty of air.

Adam was soon asleep, but the boys did not[52] close their eyes for some time. The novelty of the situation as they thus lay on the soft dry sand, with the tropical foliage all around them, the broad river rippling but a short distance away, and the darkness of this night in an almost foreign land, relieved only by the flashes of the dying camp-fire and the bright stars in the clear sky, kept them awake.

Far off in the river they heard, every now and then, a dull pounding noise, as if some one were thumping at the door of a house. This, Adam told them before he went to sleep, was caused by the drum-fish, who make these loud sounds as they swim near the bottom of the river.

Now and then they heard a distant snort or roar, but from what sort of animal it came they did not know. They were aware that in the woods of Florida there were panthers, bears, and wild-cats; but Adam had told them that in this part of the country these animals were very shy and seldom disturbed any one if not disturbed themselves.

After a time Phil and Phœnix fell asleep, but Chap did not close his eyes. He was an excitable fellow, and he was thinking what he should do if a wild beast should invade their camp. There were no firearms in the party, but he thought of several ways in which four active persons could seize a wild-cat, for instance, and hold it so that it could harm no one of them.

[53]After a time the moon rose, and then Chap, lying with his face turned toward the river, was fascinated by the strange beauty of the scene.

While gazing thus, he saw two small animals slowly creeping across the sand and approaching the tent. The sight of them startled him, and he was about to give an alarm, when he suddenly checked himself. These could not be wild-cats, he thought; they were too little and their movements too slow.

As they came nearer and turned their heads toward him, he saw by the now bright rays of the moon that they had light triangular faces, gray bodies, and rat-like tails, and that they were opossums. He had seen these animals in the North, and laughed quietly when he thought they had frightened him. They were evidently after some pieces of fish which lay near the dead ashes of the camp-fire, and were soon making a comfortable meal.

“I never saw such tame creatures,” thought Chap. “They must know there are people about.”

Then he gave a low, soft whistle. The opossums looked up, but did not move. There was a piece of stick within reach of his hand, and picking it up, he whirled it toward them. They looked up again, but still did not move.

Slowly drawing himself out of the tent so as not to disturb the others, Chap rose to his feet and approached the opossums. One of them turned and[54] ambled slowly to a short distance, but the other stood still.

Chap walked close up to him, but the creature merely arched its back and looked at him.

Picking up a stick which was lying near the ashes, Chap gave the stupid creature a little punch. The opossum merely twisted itself up a little and opened its mouth.

“Upon my word!” said Chap; “if you are not the tamest wild beasts in the world! I don’t believe either of you ever saw a man before, and don’t know that you ought to be afraid of him. But I’m not going to hurt a non-resistant. You can go ahead and eat your supper, for all I care.”

And so he slipped quietly back into the tent, and left the opossums to continue their meal.

It might have been supposed that when Chap did close his eyes, he would sleep longer than the others, but this was not the case. Either because he did not rest well in a new place, or because his mind was disturbed by his responsibilities as captain of the party, he awoke before any of the others. It was broad daylight, and again he slipped out of the tent without disturbing any of his companions.

The opossums were gone, and Chap walked along the water’s edge, looking at the hosts of birds which were flying above him. There were gulls and many others which he did not know, and near the[55] other side of the river was a small flock of very large birds, which he supposed must be pelicans.

As he walked round the little clump of trees, under which the tent was pitched, he saw upon the sand, near the water’s edge, something which made his heart jump.

It was an alligator, the first Chap had ever seen out of a menagerie. It was about eight feet long, and was lying in the sunshine, with its head toward the water.

Chap stood and gazed at it with mingled amazement and delight. He never thought of fear, for he knew an alligator would not come after him.

Slowly and gradually he came nearer and nearer the strange creature. It did not move. Was it dead? or asleep? He felt sure it was the latter, for it did not look dead. What a splendid thing it was to be so near a live alligator on its native sands! If there were only some way of catching it! That was almost too glorious to think of. If he had a rifle he might shoot it; but that would be nothing. But to catch it alive! The idea fired his soul. He would give anything to capture this fellow, but how could he do it?

He remembered the account that had so pleased him, when he was a boy, of the English captain—Waterton, he thought his name was—who sprang astride of an alligator, and seizing its forepaws, twisted them over its back so that the creature[56] could not walk, nor reach its captor with its jaws or tail.

At first Chap thought that he might possibly do this, but he saw it would be a risky business. The alligator’s paws looked very strong, and he might not be able to hold them above its back. Even if it got one paw loose, it might turn round and make things lively.

“If I could only get a rope round the end of his tail,” thought Chap, “I could tie him to a tree. That would be simply splendid!”

This plan really looked more feasible than any other. The alligator was lying with his tail turned a little to the left, and the end of it raised slightly from the sand. It might be possible to slip a rope around this without waking the creature; but where was the rope? Chap racked his brain for an instant. Had they a rope?

Then he remembered the line that supported the tent. There was ever so much of it coiled on the sand, it was already fastened to a tree. If the loose length would reach the alligator, and if he could get the end of it around his tail, and the line was strong enough to hold him, he would have him sure.

Wouldn’t it be glorious to wake up the other fellows and show them the captive alligator which he had caught all by himself while they were fast asleep?

[57]Slipping off his shoes, he stole softly around to the foot of the tree by the tent where the coil of rope lay. Taking the loose end in his hand, he turned, and slowly crept toward the alligator.

The creature was asleep, and Chap made so little noise as he gradually came near it, that its repose was not disturbed. To his great joy, Chap found that the rope was long enough. When he was almost near enough to touch the tip and of the alligator’s tail, he kneeled on one knee, ready to spring up in an instant if the creature should awake, and hesitated for a moment before proceeding to attach the rope.

If he tried to tie it on, the alligator might move before he had time to make a good knot. It would be better to prepare a slip-noose, and put that over the end of his tail. Then when he moved or jerked, he would pull the rope tight.

Chap made a slip-knot and a noose, and, with quickly-beating heart, he leaned forward, and with both hands he gently put the open noose around the alligator’s tail.

He did this so cautiously and carefully that the rope did not touch the creature until it was seven or eight inches above the tip of the tail. Then he gently pulled it so as to tighten it.

Almost at the first moment that the rope touched the alligator it gave its tail a little twitch. Chap sprang to his feet and ran backward[58] several yards. Then the alligator raised its head, looked back, and saw him.

Without a moment’s hesitation the creature lifted itself on its short legs and made for the river. Chap trembled with the excitement of the moment. Would the noose slip off? Would the rope hold?

The noose did not slip off, it tightened; and in a moment the rope was stretched to its utmost length.

Chap was about to give a shout of triumph, when the alligator, feeling a tug on his tail, became panic-stricken and bolted wildly for the water.

The rope, though not heavy, was a strong one, and it did not break, but the slip-knot around the nearest tree to which it was tied was pulled loose in an instant, and down came the tent on the sleepers beneath it.

Then there was a tremendous jerk on the branch to which the extreme end was tied, and in an instant it was torn from the trunk of the tree.

This branch caught in the end of the tarpaulin, the pegs were jerked out of the sand, and the whole tent was hauled roughly and swiftly over the recumbent Adam and the two boys. The branch got under Phil’s head and jerked him into a sitting position almost before it woke him up.

[59]Phœnix thought an earthquake had occurred. In an instant he was enveloped in darkness; then there seemed to be a land slide over his head, and flying bits of wood banged about his ears.

Adam made a grab at the tarpaulin as it swept over him, and held fast to one corner of it. He was instantly jerked about three yards along the sand, and then the branch, to which the end of the rope was tied, slipped under the tarpaulin, and Adam and the tent were left lying together on the ground.

Chap made a wild rush after the branch, but it was pulled into the water before he could reach it. He could see it floating rapidly along the top of the water, as the alligator swam away, and he stood sadly on the bank, watching the disappearance of that branch and his hopes.

Adam, with the two boys, now appeared, half awake and utterly astounded, and anxiously demanded to know what had happened. Never had they been awakened in such a startling style. When Chap explained the state of affairs, Phil and Phœnix burst into a laugh, but Adam looked rather glum.

“You don’t mean to say,” he exclaimed, “that that ’gator has gone off with all my rope?”

“He’s got it all,” said Chap; “and I’m sorry now it didn’t break, so some of it might have been[60] left. But I tell you what we could do, if we could only get a boat; we could run after that branch—it won’t sink, you know—and when we got hold of the rope we might haul the alligator in.”

“Haul him in!” cried Adam; “I’d like to see myself hauling a live alligator into a boat, even if we could do it, and had a boat. No, that line is gone for good. He’s turned round and chawed it off his tail by this time.”

“What did you expect to do with your alligator,” asked Phil, “after you had fastened him to a tree? We haven’t anything to kill him with, and he would have raged around at the end of his line like a mad bull.”

“Perhaps Chap thought he could tame it, and take it along with us,” said Phœnix.

“Look here, boys,” said Chap, “I don’t want any criticisms on this alligator business. If I’d been acting as your captain, and leading you in an alligator hunt, you might say what you pleased when the beast got away; but I was doing this thing in my private capacity, and not as commander of the party, and you fellows have nothing to do with it.”

“Haven’t we?” cried Phil. “When my head was nearly jerked off, and three or four yards of tent hauled over my face?”

“And I was scared worse than if I had been pulled out of bed with a rake?” said Phœnix.

[61]“Nothin’ to do with it!” exclaimed Adam. “When my rope was jerked out of sight and hearin’ in a minute, and the tarpaulin would ’a’ gone with it, if I hadn’t grabbed it? I should think we had something to do with it.”

“Perhaps you had,” said Chap, as he sat down on the sand to put on his shoes. “But I tell you what it is, fellows,” he added, with sparkling eyes, “if we could have tied a live alligator to a tree, it would have been a splendid thing to tell when we got home.”

“There is people,” said Adam, dryly, “who’d tell a story like that without tyin’ a ’gator to a tree.”

“But we are not that kind,” promptly answered Captain Chap.

“But I guess we won’t cry over spilt milk, or lost ropes, either,” said Adam; “and the best thing we kin do is to get along to John Brewer’s house and see about some breakfast.”

“We might catch some more fish,” said Chap, “and have breakfast before we started.”

“If you kin ketch some coffee,” said Adam, “I’ll be willin’ to talk about breakfast here; but I don’t want to make another meal off fish and warm water, if I can help it. John Brewer’s house is just the other side of that bend, and we’ll be there in half an hour.”

The tarpaulin was rolled up, each of the party[62] picked up his individual traps, and, headed by Chap, they were soon walking along the shore of the river.

When they turned the bend above, they were delighted to see that Adam was right, and that John Brewer’s house was really there. It was not much of a house, for it was a frame building, one story high, and containing three or four rooms; but it had an air of human habitation about it which was very welcome to the wanderers. It stood in a small clearing, and John Brewer, a little man, with long, brown hair, which looked as if the wind had been blowing it in several directions during the night, came out of his front door to meet them. Two of his children followed him, and the three others and his wife looked out of a half-opened window.

Mr. Brewer was mildly surprised to see his old acquaintance, Adam, and the three boys, and when he had heard their story, he took a kind but languid interest in the matter, and went into the house to see about getting breakfast.

It was not long before our friends were sitting down to a plentiful meal of coffee, corn-bread, and very tough bacon, Mr. Brewer and his family standing at the end of the table and gazing at them as they ate. Some of them would have joined the breakfast-party had there been plates and cups enough.

[63]About half an hour after breakfast, as our friends, with Mr. Brewer and four of the children, were sitting in the shade in front of the house, and Mrs. Brewer and the other child were looking at them behind a half-opened window-shutter, Adam remarked,—

“What I want to know is what chance we have of gettin’ up the river to Titusville?”

“How did you expect to get up?” asked Mr. Brewer.

“Well,” said Adam, “I thought we might get passage in a mail-boat, if one happened to come along at the right time; and if it didn’t, I thought there’d be some boat or other goin’ up the river to-day that would take us.”

“Well, if them’s your kalkerlations,” said Mr. Brewer, gently rubbing his knees and looking out over the water, “I don’t think you’re going to get up at all.”

“Not get up at all!” cried the boys; and Adam looked puzzled.

“Well, not for a week or so, anyway,” said Mr. Brewer, his eyes still fixed upon the rippling waters. “To be sure, the mail-boat will be along to-day, and she’ll stop if she’s hailed, but she can’t carry you all, and as for other boats, the long and short of it is, there ain’t none gone down, and there can’t none come up. There was a boat went up yesterday with vegetables from Lake Worth, but[64] she won’t be back for a week, and then it’ll be a good while before she goes up again. Every boat that’s been down the river this month has gone up, and they tell me there ain’t nothin’ at Jupiter but the little sloop that belongs to the light-house keeper, and she’s hauled up to have a new mast put in her.”

“Then what are we to do?” asked Phil, anxiously.

“Dunno,” said Mr. Brewer.

The announcement so placidly made by Mr. John Brewer that it was impossible for our friends to get up the river until some of the sail-boats or small sloops—the only craft which then navigated that stream—should come down and go up again, gave rather a doleful hue to the state of affairs.

Mr. Brewer stated that when a boat came down that far, she generally went all the way to Jupiter Inlet before she returned, and some of the big ones, when they got down there, went outside, and made a trip to Lake Worth, and they would, of course, be still longer coming back.

The spirits of the boys were a good deal depressed, but Adam did not give up his hope that they might get passage on the mail-boat.

“We can stow ourselves somewhere,” he said, “and when we get to Fort Capron, we’re likely[66] to find a boat that’ll take us the rest of the way.”

But when, an hour after, the mail-boat came in sight, even Adam’s hopes were crushed. It was not larger than a row-boat, with a small sail, and a cabin not three feet high, and besides the young man who sailed her, she already contained two passengers,—a sportsman who was returning north and a negro boy. There was no room for the latter to sit in the after-part of the vessel, and he had to make himself as comfortable as he could on the little bit of deck in front of the mast.

It was so obviously plain that four additional passengers could not get on board that little boat that the subject was not even broached, Adam confining himself to inquiries in regard to the possibilities of there being other boats down the river of which Mr. Brewer had not heard. But the mail-carrier assured him that there were no boats down there that could come up inside of a week, and the sportsman declared that he never would have squeezed himself inside this little tub if there had been any other chance of his getting up the river.

There was only one relief afforded by the mail-boat. The boys, anticipating that they might not be able to go on themselves, had each written a letter to his family, telling where he was, and giving a brief history of the state of affairs. Each letter, written on rumpled stationery supplied by[67] Mr. Brewer, contained assurances of the perfect safety of the writer, and a request for money to be forwarded to Jacksonville, Florida, which point they hoped to reach in good time.

These, with money for the postage, were given to the carrier, who promised to have them properly mailed at the first post-office on the river.

A telegram was also written and given to the sporting gentleman, who promised to forward it as soon as he reached Sanford, on the St. John’s River, this being the nearest point from which telegrams could be sent.

“There, now,” said Chap, when the little boat had sailed away, “I feel more comfortable. The folks will know all about us just as soon as if we had gone on ourselves, and that’s the main thing; for, as far as I’m concerned, I’m in no particular hurry to get home.”

“You don’t want to stay here, do you?” asked Phœnix.

“No,” said Chap; “but we can tramp along and camp out for a while, till a boat comes by and takes us on. I don’t want any better fun than that.”

“We can’t tramp much farther on this beach,” said Phil. “It only reaches about a mile above us, Mr. Brewer says, and tramping and camping for a week or two, with no paths to walk in and nothing to eat, would be pretty tough work.”

[68]“We could push back to the sea-shore,” said Chap, “and walk along there.”

“That might do as far as the walking is concerned,” said Phœnix; “but how about the victuals?”

“I’m not quartermaster,” said Chap, “I’m captain; and I’ll lead you fellows anywhere you want to go.”

“That’s the way to talk,” said Phil; “but it won’t do to lead us to any place so far from this house that we can’t hear them call at mealtime. We can’t live straight along on fish, you know.”

A few minutes after this conversation, Adam Guy walked up to Mr. Brewer, who was leaning on the fence of his little garden.

“Look here, John Brewer!” he cried; “what did you mean by sayin’ that we couldn’t get a boat to go up the river in? In that little creek back there, there’s a boat plenty big enough for us. Don’t she belong to you?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Brewer, “she’s mine, but her mast’s unshipped, and her main-sail’s in the house to be mended.”

“Can’t we ship the mast and mend the sail?” asked Adam.

“Yes, you might do that,” answered Mr. Brewer.

“Well, then,” cried Adam, “we’re all right![69] She doesn’t leak, does she? And you’ll hire her to us, won’t you?”

“Her hull’s all right,” said Mr. John Brewer, “and I reckon I’d hire her to you.”

“And why didn’t you tell us about her before?” exclaimed Adam.

“You didn’t say anything about my hirin’ you a boat,” said the other. “If you’d ’a’ asked me, I’d ’a’ said you could have her.”

Adam’s shouts soon brought the boys together, and a bargain was speedily concluded with Mr. Brewer, who agreed to hire his boat to our party for a dollar a day.

“That is, till we reach Titusville,” said Adam; “but how are we goin’ to get her back?”

“Well,” said Mr. Brewer, “my brother went up to Enterprise last week, and he’ll be comin’ back afore long, and it’ll suit him fust-rate if you’ll leave the boat at Titusville, and then he can come down in her and save payin’ his passage on the mail-boat.”

“That’s a pretty good arrangement for you and your brother,” said Chap. “I wonder you didn’t think of it before!”

“I didn’t want to bother anybody to take a boat up the river jist for my brother,” said Mr. Brewer.

Everybody now went gayly to work, Adam mending the sail with true sailor-like skill, and[70] the boys, under Mr. Brewer’s direction, and with some of his assistance, getting the mast properly shipped and the boat cleaned out and made ready for her voyage.

She was a well-built little craft, about twenty feet long, and with a small cabin, which would comfortably accommodate four persons. She carried a main-sail and a jib, and was, altogether, very suitable for the purposes of our friends.

By night the boat was ready for the trip, but it was decided to postpone starting until the next morning. All the provisions which Mr. Brewer could spare were purchased, and, although he could not let them have enough to last the three or four days which it would require to reach Titusville, there were places along the river where they could replenish their stores.

Mr. Brewer knew Adam for a good sailor, and had no hesitancy in trusting the boat to his care.

The boys were perfectly delighted at the prospect before them. To sail up the river in a boat which was entirely their own during the voyage was a piece of good fortune they had not dreamed of.

“What is the name of your boat?” asked Chap of Mr. Brewer, as they all sat together after supper.

“Just now she ain’t got no name. She used to be called the Jane P., after my first wife; but[71] when she died I painted the name out, and this Mrs. Brewer don’t want the boat named after her, because she’s afraid she might die too; so, you see, she ain’t got no name.”

“Well, then,” cried Chap, “we can name her ourselves—can’t we?”

“Oh, yes,” said Mr. Brewer, “you can call her what you please, so long as you don’t name her after Mrs. Brewer.”

The boys heartily agreed to this restriction, and a variety of names was now proposed; but after a time, the boys concluded that a title suggested by Phœnix was the jolliest and most suitable name for their boat, and they agreed to call her “The Rolling Stone.”

“That’s a mighty queer name for a boat,” said Mr. Brewer. “It seems like it would sink her.”

“But you needn’t keep it after we’ve done with her,” said Phil.

“I don’t think I will,” said Mr. Brewer.

And Adam, who had declared the name decidedly un-nautical and with something of an unlucky sound about it, said that after all he reckoned it didn’t matter much what the boat’s name was, provided they had a good wind.