PERSONAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF WELL-KNOWN AMERICAN WRITERS

EDITED BY

J. L. & J. B. GILDER

NEW YORK

A. WESSELS COMPANY

1902

Copyright, 1889,

BY

O. M. DUNHAM.

Copyright, 1902,

BY

A. WESSELS COMPANY.

The sketches of authors at home in this book have as their special value the fact that the writer of each article was selected for the purpose by the author himself. The sketches appeared from time to time in The Critic, where they attracted particular attention by virtue of their authenticity, as well as for the names of the subjects and the writers.

The Canadian border has been crossed in the article on Prof. Goldwin Smith; but with this exception the series treats only of native American writers who make their home on this side of the Atlantic. Since these sketches were written, some of the most distinguished of the authors in the list have died, all of them meeting natural deaths, with one exception, Mr. Paul Leicester Ford.

J. L. G.

New York, June, 1902.

[Pg 1]

[Pg 3]

THOMAS BAILEY ALDRICH

Beacon Hill is the great pyramid, or horn of dominion, as it were, of Boston’s most solid respectability of the older sort. Half-way up Beacon Hill, Aldrich is to be met with at the office of The Atlantic Monthly, of which he has been the editor since 1881. The publishers of this magazine have established its headquarters, together with their general business, in the old Quincy mansion, at No. 4 Park Street, which they have had pleasantly remodeled for their purposes. Close by, on the steep slope, is the Union Club; across the street the long, shaded stretch of Boston Common; and above it is the State House, presiding over the quarter, with its imposing golden dome half hidden amid the greenery. The editor’s office is secluded, small, neat, and looks down into a quiet old graveyard, like those of St. Paul’s and Trinity in New York. It seems a place strictly adapted to business, and is cut off from the outer world even by so much of a means of communication as a speaking-tube. There was formerly a speaking-tube, but an importunate visitor had his[Pg 4] ear to it, and received a somewhat hasty message intended only in confidence for the call-boy, and it was abolished. “Imagine the feelings of a sensitive man—my feelings, of course—on such an occasion,” says the editor with characteristic drollery. “I flew at the tube, plugged it up with a cork, and drove that in with a poker!” Among the few small objects that can be called ornament scattered about is remarked a photograph of a severely classic doorway, which might have belonged to some famous monument of antiquity. It has a funereal look, to tell the truth, but it proves to be nothing less than the doorway of the residence of Thomas Bailey Aldrich himself, in Mt. Vernon Street. Like one of his own paradoxes, it has a very different aspect when put amid its proper surroundings.

Mt. Vernon Street crosses the topmost height of Beacon Hill. Parallel to the famed thoroughfare of Beacon Street, it is like a more retired military line that has the compensation for its retirement of being spared the active brunt of service. A very few minutes’ climb from the office of The Atlantic Monthly suffices to reach it. Precisely at that portion of it where the pretty grass-plots begin, to the houses on the upper side, is the attractive, stately mansion of an elder generation, in which Aldrich has taken up his abode. He bought it, some years[Pg 5] ago, of Dr. Bigelow, a well-known name in Boston, and made it his own. It is one of a block, and is of red brick, four windows (and perhaps thirty feet) wide, and four tall stories in height, with a story of dormers above that. The classic doorway of white marble, solidly built, after the honest fashion of its time, is but a small detail after all in such an amplitude of façade, and melts easily into place as part of a genial whole. The quarter, its sidewalks and all, is chiefly of old red brick, tempered with the green of grass-plots, shrubs, and climbing vines. It has a pervading air of antiquity, and it quaintly suggests a bit of Chester or Coventry. The neighbors are, on the one hand, Charles Francis Adams; on the other, Bancroft, son of the historian; while, diagonally across the way, is a lady who is, by popular rumor, the richest woman in New England. The rooms of the house take a pleasing irregularity from the partial curvature of the walls, front and rear. They are all spacious, above-stairs as well as below. The “hall bedroom,” of modern progress, was hardly invented in its time. A platform and steps at one side of the hall, on entering (they clear a small alley to the rear) have a sort of altar-like aspect. The owner or his books might some time be apotheosized there, at need, amid candles and flowers. Aldrich has been fortunate in his marriage as in so many other ways. His family[Pg 6] consists of a congenial and accomplished wife, and “the twins,” not unknown to literature. The most pervading trait of the interior is a sense of a discriminating judgment and ardor in household decoration. Both husband and wife share this taste, and together they have filled this abode and their two country houses with ample evidence of it, and with rare and taking objects brought from a wide circle of travel and research. Tribute should be paid to the quietness of tone, the air of comfort, in the whole. The collections are not made an end in themselves, but are parts of a harmonious interior. Several stories are carpeted alike, in a soft, low-toned hue. In days of professional decorators who throw together all the hues of the kaleidoscope, and none in a patch larger than your hand, and held upon these, brass, ebony, stamped leather, marquetry, enamels and bottle-glass, in a kind of chaotic pudding—in these days such an exceptional reserve as is here manifest seems little less than a matter of notable personal daring. The furniture is of the Colonial time, with a touch of the First Empire, and each piece has its own history. There is a collection of curious old mirrors. In a variety of old glazed closets and pantries in the dining-room (behind a fine reception-room, on the entrance floor), Mrs. Aldrich shows a rare collection of lovely china, both for use and ornament.

[Pg 7]

This is a dining-room that has entertained many a distinguished guest; and the little dinners, to which invitations are rarely refused by the favored ones, are said to be almost as easy to give as enjoyable to take part in. The agreeable host, who has always allied himself much with artists, has on occasion dined the New York Tile Club. Again, his occupation as editor of The Atlantic makes it often his duty or privilege to bring home strangers of note who drop down upon him from afar. The unexpected is, indeed, one of the things consistently to be looked for in Aldrich. On the evenings of the week when he is not entertaining, he is very apt to be dining out himself. He is a social genius, and understands the arts of good fellowship. Good things abound even more, if possible, in his talk than in his writings. Every acquaintance of his will give you a list of happy scintillations of his wit and humor. There is nothing of the recluse by nature in Aldrich; nothing, either, of the conventional cut of poet or sage in his aspect. His looks might somewhat astonish those—as the guileless are so often astonished in this way—who had preconceived ideas of him from the delicate refinement, the exquisite perfection of finish, of his verse. As I saw him come in the other day from Lynn in a heavy, serviceable reefing-jacket, adapted to the variable summer climate of that[Pg 8] point, he had much more the air of athlete than poet. I shall not enter upon the abstruse calculation of what age a man may now have who was born in 1837, but in looks, manners, habits, Aldrich distinctly belongs to the school of the younger men. He is now somewhat thickset; he is blond, and of middle height. He has features that lend themselves easily to the humorous play of his fancy. The ends of his mustache, pointed somewhat in the French manner, seem to accentuate with a certain fitness and chic the quips and cranks which so often issue from beneath it. Mentally, Aldrich seems Yankee, crossed with the Frenchman. In the matter of literary finish, he is refined by fastidiousness of taste to the last degree. He is a man of strong likes and dislikes; it would sometimes seem fair almost to call them prejudices. In his work he has scarcely any morbid side. He is the celebrator of every thing bright and charming, of things opalescent and rainbow-hued, of pretty women, roses, jewels, humming-bird and oriole, of the blue sky and sea and the daintiest romance of the daintiest spots of foreign climes. If man invented the arts to please,—as can hardly be denied,—few can be called more truly in the vein of art than Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

From the rear window of the dining-room one looks out into a little court-yard, more like a bit[Pg 9] of Chester than ever. The building lot runs quite through to Pinckney Street, and is closed in on the further side by an odd little house of red brick, which is rented as a bachelor apartment. It was formerly a petty shop, until Aldrich bethought him both to transform it thus into a desirable adjunct, and to make it pay a considerable part of the taxes. It is like a dwelling out of a pantomime. One would hardly be surprised to see Humpty Dumpty dive into or out of it at any moment. Pinckney Street might have a chapter to itself. Narrower, modester, and at a further remove still from the front than Mt. Vernon Street, it begins to be invaded now by quiet lodging-houses, but still retains its quaintness and a high order of respectability. A bright glimpse of the sea is had at the end of its contracted down-hill perspective, over Charles Street. Aldrich formerly lived in Pinckney Street, then in Charles Street, and thence removed to his present abode. But, if it be a question of view, we must ascend rather the high, winding staircase to the large cupola, with railed-in platform, set upon the steep roof. The ground falls away hence on every side and all of undulating, much-varied Boston is visible. Mark Twain has pronounced the prospect from here at night, with the electric lights glimmering in the leafy Common and the myriad of others round about, as one of the most[Pg 10] impressive within his wide experience. The golden dome of the State House rears its bulk aloft, close at hand. Up one flight from the entrance are the two principal drawing-rooms of the house, large and handsome. The most conspicuous objects on the walls of these are a few unknown old masters after the style of Fra Angelico—trophies of travel. There are also a remarkable pair of figures in Venetian wood-carving, nearly life-size. The pictures are, for the rest, chiefly original sketches done for illustration of the author’s books by the talented younger American artists.

On the same floor is the library, a modest-sized room, made to seem smaller than it is through being compactly filled from floor to ceiling with a collection of three thousand books. The specialties chiefly observed in its composition are Americana and first editions. Aldrich would disclaim any very ambitious design, but there are volumes here which might tempt the cupidity of the most finished book-fancier, and of a kind that bring liberal sums in market. Something artistic in the form has generally guided the choice, as for instance Voltaire’s “La Pucelle,” and the “Contes Moraux” of Marmontel, containing all the quaint early plates. You take down from the shelves examples of Aldrich’s own works done into several languages. Here is his “Queen of Sheba” in[Pg 11] Spanish, Valencia, 1879. Here is the treasure which perhaps he would hardly exchange against any other—the autograph letter of Hawthorne warmly praising his early poems,—saying, among other things, that some of them seem almost too delicate even to be breathed upon. Never did a young writer receive more intelligent and sympathetic recognition from a greater source. Among the curiosities of the shelves in yet another way is a gift copy of the early poems of Fitz-Greene Halleck to Catherine Sedgwick. On the title-page is found a patronizing line of memorandum from that minor celebrity in American letters, reading “Mr. Halleck, the author of this book, is a resident of New York.” Aldrich has never been subjected to the severe pecuniary straits which befall so many literary men. He has undergone in his time, however, sufficient pressure to acquaint him with that side of life at least as an experience, to give him a proper appreciation no doubt of his ample worldly comfort, and also to furnish the stimulus for the development of his early powers. He had prepared, in his native town of Portsmouth, to enter Harvard College, but, his father dying, he became a clerk instead in the commission house of a rich uncle in New York. He had his own way to make in the literary world; he began at the very foot of the ladder, with fugitive contributions, and by degrees identified himself[Pg 12] with the newspapers and magazines of the day. He even saw something of Bohemian life, a knowledge of which is no undesirable element in one who is to be a man of the world. He dined at Pfaff’s, and was one of a coterie which circled around The Saturday Press and the brilliant, erratic Henry D. Clapp. I recollect passing with him the office of this defunct journal in Frankfort Street, on the occasion when he had come to New York to be the recipient of a complimentary breakfast at Delmonico’s in honor of his induction into the editorship of The Atlantic Monthly. He looked with interest at the dingy quarters commemorating so very different a phase of his life, and repeated to me the valedictory address of the paper: “This paper is discontinued for want of funds, which, by a coincidence, is precisely the reason for which it was started.”

I have described Aldrich’s town house. He passes much of his time at Ponkapog, twelve miles away behind the Blue Hills, and at Lynn, on the sea-coast. “After its black bass and wild duck and teal,” says our author in one of his charming essays, “solitude is the chief staple of Ponkapog.... The nearest railway station (Heaven be praised!) is two miles distant, and the seclusion is without a flaw. Ponkapog has one mail a day; two mails a day would render the place uninhabitable.” He took a large old farmhouse[Pg 13] in the secluded place, remodeled it, arranged for himself an attractive working study, and, used to men and cities though he was, for a period made this exclusively his home. His leading motive was the health of his boys, who needed an out-of-door life. Ponkapog owes him a debt of gratitude for spreading its name abroad. Until the publication of his entertaining book of travel sketches, “From Ponkapog to Pesth,” it must have been wholly unheard of, and even then I, for one, can recollect feeling that the appellation was so ingenious as to be probably fictitious. With a continuity that speaks strongly in its favor, Aldrich has passed the summers at Lynn for seventeen years. From these must be excepted, however, the summers of his jaunts to Europe, which are rather frequent. The latest of these took him to the Russian fair at Nijni Novgorod. In another, perhaps unlike any other traveler, he passed a “day [and a day only] in Africa.” At Lynn, he has lived, in different villas, all along the breezy Ocean Road. This is a street worthy of its name, and it has a certain flavor of Newport, being a little remote from the central bustle of the great shoe-manufacturing mart to which it belongs. Others will quote a list of varied advantages for the site; Aldrich will be apt to tell you he likes it for its nearness to the railway station. The present house, of which he has taken a long lease, is a[Pg 14] large square wooden villa, painted red. It stands just in the edge of a little indentation known as Deer Cove. “After me, probably—who knows?” says the humorous host, who is not at all afraid of a bit of the common vernacular. Nahant, Little Nahant and minor resorts are in the view in front; Swampscott is three-quarters of a mile away, at the left, and Marblehead at no great distance beyond that. The feature of the water view is the bold little reef of Egg Rock, with three white dots of habitations on its back. “Egg Rock is exactly opposite everywhere. I recollect once trying to find some place to which it was not opposite, just as in childhood I tried once to walk around to the other side of the moon. In this latter case I suppose I must have walked fully two miles.” So my host describes his peculiar experience with it.

The main tide of fashion sets rather towards Beverly Farms and Manchester than in this direction. The family lead, gladly, a quiet life, little disturbed by a bustle of visits. They depend chiefly for society upon the guests they bring down with them. They find plenty of occupation and interest, too, in caring for their boys. These are twins, as I have said, and so much twins as to be with difficulty distinguished apart. I was interested to know if they began to develop the literary faculty. ‘Heaven forbid!’ said their[Pg 15] father in comic horror. Aldrich’s study at Lynn is a modest upper room, in a wing, with a plain gray cartridge-paper on the walls, no pictures, and nothing to conspire with a flagging attention in its wanderings. One’s first impulse, on looking up from the little writing-table in the center of the floor, would be to cast his eyes out of the single window, where Egg Rock, in a bit of blue sea, is again visible. This window should be an inspiring influence, letting in its illumination upon the fabrics of the heated brain; and not in the gentler mood alone, for tragedy is often abroad there. The fog shrouds Egg Rock, then rolls in and envelopes the universe under its stealthy domination; again, the gale spatters the brine upon the window-panes, and beats and roars about the house as it might on the light at Montauk.

As an editor, Aldrich is methodical. He goes early in the day to the office of The Atlantic Monthly, and there writes his letters, examines his manuscripts, and sees (or does not see) his visitors upon a regular system. As to his personal habit of writing his literature, he has none—at least no times and seasons. He waits for the mood, and defends this practice as the best, or, at least for him, almost the only one possible. This has to do, no doubt, with the small volume of his writings, smaller comparatively than that of most of his contemporaries. This result is[Pg 16] perhaps contributed to also by the easy circumstances of his life, and yet more by his devotion to extreme literary finish. Experienced though he is, and successful though he is, no manuscript leaves his hands to be printed till he has made at least three distinct and amended drafts of it. He could never have been a newspaper man; the merest paragraph would have received the same care, and in the newspaper such painstaking is ruinous. His was a talent that had to succeed in the front rank or not at all. He has produced little of late, far too little to meet the demands of the audience of eager admirers he has created. So delightful a pen, so droll and original a fancy, so charming a muse, we can ill afford to spare. Yet that mysterious genius that goes about collecting material for the archives of permanent fame can have but little to dismiss from a total so small and a performance so choice.

William Henry Bishop.

[After ten years as editor of The Atlantic Monthly, Mr. Aldrich resigned his position, and has since that time been living in Boston. In 1893 he published “An Old Town by the Sea,” and two years later “Unguarded Gates, and Other Poems.”—Editors.]

[Pg 17]

[Pg 19]

GEORGE BANCROFT

Mr. Bancroft, the historian, was “at home” beneath every roof-tree, beside every fireside, where books are household gods. Mr. Bancroft, the octogenarian, who came into the world hand in hand with the Nineteenth Century, was especially at home at the capital of the country whose history was to him a labor of love and the absorbing occupation of a lifetime. For although his career was one of active participation in public affairs, his pursuits ran parallel with his literary work. He was contributing to the making of one period of a United States history while his pen was engaged in writing of other periods. If self-gratulation is ever permitted to authors, Mr. Bancroft must have more than once exclaimed, “The lines have fallen to me in pleasant places!” as he availed himself of opportunities which only an ambassador could secure and a scholar improve.

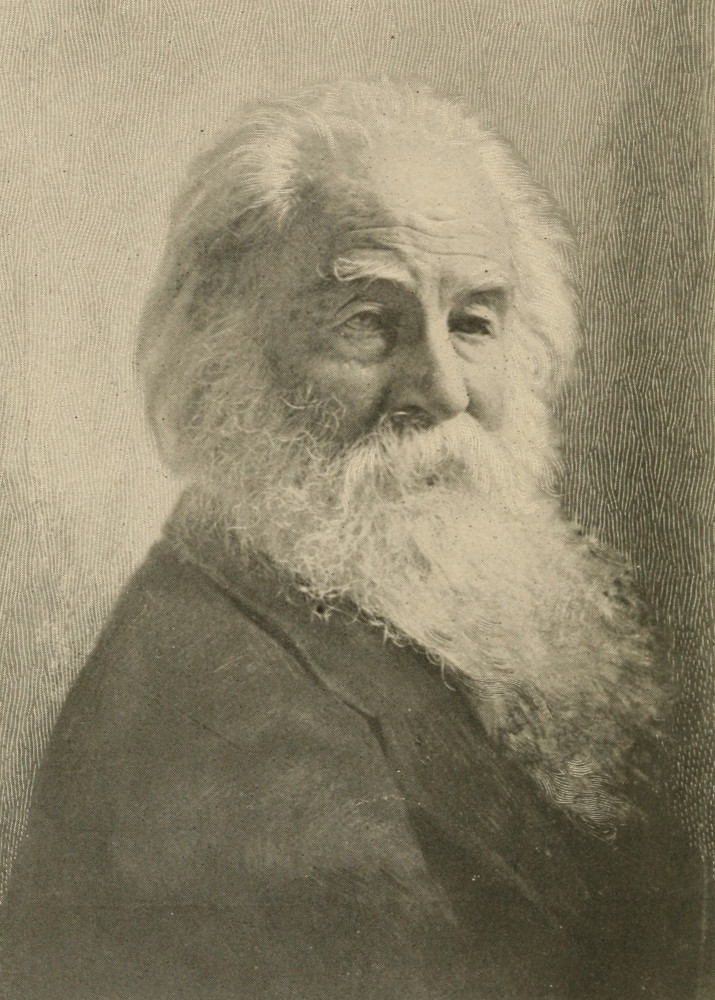

It is the prose-Homer of our Republic whom it is my privilege to present to the readers of this sketch. Picture to yourself a venerable man, of[Pg 20] medium height, slender figure, erect bearing; with lofty brow thinned, but not stripped, of its silvery locks; a full, snowy beard adding to his patriarchal appearance; bluish gray eyes, which neither use nor time has deprived of brightness; a large nose of Roman type, such as I have somewhere read or heard that the first Napoleon regarded as the sign of latent force; “small white hands,” which Ali Pasha assured Byron were the marks by which he recognized the poet to be “a man of birth”;—let your imagination combine these details, and you have a sketch for the historian’s portrait. The frame is a medium-sized room of good, high pitch. In the center is a rectangular table covered with books, pamphlets and other indications of a literary life. Shelving reaches to the ceiling, and every fraction of space is occupied by volumes of all sizes, from folio to duodecimo; a door on the left opens into a room which is also full to overflowing with the valuable collections of a lifetime; and further on is yet another apartment equally crowded with the historian’s dumb servants, companions, and friends; while rooms and nooks elsewhere have yielded to Literature’s rights of squatter sovereignty. In the Republic of Letters, all books are citizens, and one is as good as another in the eyes of the maid-servant who kindles the breakfast-room fire, save perhaps the vellum Plautus or[Pg 21] illuminated missal. But men are known not only by the society they keep, but by the books which surround them. Just as there are “books which are no books,” so are there libraries which are no libraries. But a library selected by a scholar who was a book-hunter in European fields, who spared neither time, money, labor, nor any available agency in his collection, must be rich in literary treasures, particularly those bearing upon his specialty; and such was Mr. Bancroft’s library. The facilities which personal popularity, the fraternal spirit of literary men, and the courtesy of official relations afford, were employed by Mr. Bancroft when ambassador in procuring authentic copies of invaluable writings and state-papers bearing immediately or remotely on the history of the American Colonies and Republic. To these facilities, and his own indefatigable industry and perseverance, is due the priceless collection of manuscripts which, copied in a large and legible handwriting, well-bound and systematically classified, adorned his shelves. Of the printed volumes, not the least precious was a copy of “Don Juan,” presented to him with the author’s compliments, sixty-six years ago.

Mr. Bancroft’s home was a commodious double house, with brown-stone front, plain and solid-looking, which was, before the War, the winter residence of a wealthy Maryland family. Diagonally[Pg 22] opposite, at the corner of the intersecting streets, is the “Decatur House,” whither the gallant sailor was borne after his duel with Commodore Barron, and where he died after lingering in agony. Within a stone’s throw is the White House; and I would say that the historian lived in the centre of Washington’s Belgravia, had not the British Minister’s residence, with an attraction stronger than centripetal, drawn around it a social colony whose claims must be at least debated before judgment is pronounced. In front of Mr. Bancroft’s house is a small courtyard in which, in spring-time, beds of hyacinths blooming in sweet and close communion show his love of flowers. When conversing with the historian, it was impossible to ignore the retrospect of a life so full of interest, for imagination persists in picturing the boyish graduate of Harvard; the ambitious student at Gottingen and Berlin; the inquisitive and ever-acquiring traveler; the pupil returned to the bosom of his Alma Mater and promoted to a Fellowship with her Faculty—preacher, teacher, poet and translator, before his calling and election as his country’s historian was sure; his entrance into the arena of politics and rapid advance to the line of leadership; his membership in Mr. Polk’s Cabinet; his subsequent Mission to England; his much later Mission to Berlin, where he succeeded in obtaining from[Pg 23] Bismarck a recognition of the “American doctrine” that naturalization is expatriation, and negotiated a treaty which endeared him to the German-American heart, since the Fatherland may now be visited without the risk of compulsory service in the army.

When he first went abroad, an American was an object of curiosity to Europeans, and we may compare his reception among German scholars to that of Burns by the metaphysicians, philosophers and social leaders of Edinburgh—first surprise, and then fraternal welcome. Two years were spent at Gottingen, and half a year at Berlin. During this period he was the pupil and companion of the great philologist Wolf, of whom Ticknor’s delightful Memoirs contain such an entertaining account; he studied under Schlosser, who so frequently appears in the pages of Crabb Robinson’s Memoirs; he was a favorite with Heeren, whose endorsement of his history was the imprimatur of a literary Pope. In his subsequent wanderings through France, Switzerland, and over the Alps into Italy, he experienced the friendly offices of men distinguished in literature, famous in history, and foremost in politics. Some time was spent in Paris. With Lafayette intimate relations were established; so much so, that the champion of republican principles enlisted the young and sympathetic American in his too sanguine[Pg 24] schemes. Manuscript addresses were entrusted to Mr. Bancroft to be published and disseminated at certain places along his Italian journey. But the youthful lieutenant saw soon the impracticability of the veteran’s hopes and plans.

It was a novel sensation to converse with one who survived so many famous men of many lands with whom he came in contact; one who discussed Byron with Goethe at Weimar, and Goethe with Byron at Monte Nero; who, seventy years ago, went to Washington and dined at the White House with the younger Adams; who since mingled with the successive generations of American statesmen; witnessed the death of one great political party, and the birth of another, but himself clung with conservative consistency to the principles he espoused in early manhood. Yet neither his years nor his tastes exiled him from the enjoyment of a congenial element of society at the capital. But his circle rarely touched the circumference which surrounds the gay and ultra-fashionable coteries of a Washington season.

Mr. Bancroft had a warm sympathy for youth and childhood, and took pleasure in the occasions that brought them around him. His habits were those of one who early appreciated the fact that time is the most reliable and available tool of the worker. It was for years his custom to rise to his[Pg 25] labors at five o’clock. After a noon-luncheon, he took the exercise which contributed so much to his physical and intellectual activity. He covered considerable distances daily on foot or horseback, for he was both pedestrian and rider of the English type; or, if the weather did not favor these methods of laying in a supply of oxygen, he might have been seen reclining in a roomy two-horse phaeton.

Two generations intervened between the youthful visitor at the capital and the venerable statesman and historian, who in his last days, beneath his own vine and fig-tree, “crowned a youth of labor with an age of ease.” Yet the preacher, teacher, poet, essayist, translator, philologist, linguist, statesman, diplomat, historian, pursued with tempered ardor his literary avocations. Readers of The North American Review had the pleasure of perusing, some years ago, his valuable paper on Holmes’s “Emerson.” He published more recently (in 1886) a brochure on the Legal Tender Acts and Decisions; but nothing was ever allowed to interfere with the revision of his opus major, the History of the United States, the sixth and last volume of the new edition of which was issued by the Appletons in February, 1885.

As an octogenarian is not, strictly speaking, a contemporary, I venture to enter the realm of[Pg 26] biography, and refer to what renders Mr. Bancroft the most interesting of American authors. His translation from the path of pedagogy, from the dream-land of poetry, from the atmosphere of theology, and the arena of party strife and the novelty of official life, was a transition from extreme to extreme. Yet he brought with him into his new fields the best fruits of his experience in the old. He did not inflame the passions of the masses at the hustings, but instructed their judgment. When he assumed the office of Collector of the Port of Boston, he exhibited a capacity for business which would have silenced the modern Senator who not only characterized scholars as “them literary fellers,” but prefixed an adjective which may not be repeated to ears polite. How many Cabinet officers are remembered for any permanent reform or progressive movement they have accomplished or initiated? But to Mr. Bancroft the country owes the establishment of the Naval School at Annapolis; and science is indebted to his fostering care for the contributory usefulness of the National Observatory, which languished until he took the Naval portfolio. When at the Court of St. James he negotiated America’s first postal treaty with Great Britain; while allusion has been made to the important service rendered at the German capital. In politics Mr. Bancroft was[Pg 27] always a Democrat. He was one of those who angered fanatics by their love for the Constitution, and enraged secessionists by their devotion to the Union,—who labored to avert the War, but whom the first gun fired at Fort Sumter rallied to the support of Mr. Lincoln. And when the last great eulogy of the martyred President was to be pronounced, Mr. Bancroft was chosen to deliver it.

On the approach of summer, Mr. Bancroft led the exodus which leaves the capital a deserted village. July found him domiciled at Newport, in an old, roomy house, which faces Bellevue Avenue and is surrounded by venerable trees, beneath whose wide-spreading shade the visitor drives to the historian’s summer home. The view of the ocean is one of the accidental charms of the spot, but the historian’s own hand dedicated an extensive plot to a garden of roses—the flower which was nearest to his heart. At Newport he led a life similar to that in Washington. He rose early and saw the sun rise above the sea; he devoted a portion of his time to literary pursuits, and entered into the social life of the place, without taking part in its gayeties. In October he struck his tent, and returned to his other home in time to enjoy the beauties of our Indian summer.

B. G. Lovejoy.

[Pg 28]

[Pg 29]

GEORGE H. BOKER

[Pg 31]

Like Washington Irving, Bancroft, Hawthorne, Lowell, Motley, Bayard Taylor, and Bret Harte, George H. Boker may be counted among those American authors who have been called upon to serve their country in an official capacity abroad. But the greater part of his life was spent in Philadelphia, where he was born in 1823. The house stands in Walnut Street; a building of good height, with a facing of conventional brown-stone, and set in the heart of the distinctively aristocratic quarter. For Mr. Boker was born to the inheritance of wealth and a strong social position, and it is natural that the place and the face of his house should testify to this circumstance. In fact, he was so closely connected with the society which enjoys a reputed leisure, that when as a young man he declared his purpose of making authorship and literature his life-work, his circle regarded him as hopelessly erratic. Philadelphians, in those days, could respect imported poets, and no doubt partially appreciated poetry[Pg 32] in books, as an ornamental adjunct of life. But poetry in an actual, breathing, male American creature of their own “set,” was a different matter. The infant industry of the native Muse was one that they never thought of fostering.

It was soon after graduating at Nassau Hall, Princeton, that Boker made known his intention of becoming an author. From what I have heard, I infer that his resolve caused his neighbors to look upon him with somewhat the same feeling as if he had suddenly been deposited on their decorous doorsteps in the character of a foundling. Nevertheless, he persisted quietly; and he succeeded in maintaining his position as a poet of high rank and an accomplished man of the world, who also took an active part in public affairs. He takes place with Motley on our roll of well-known authors, as a rich young man giving himself to letters; and it is even more remarkable that he should have cultivated poetry in Philadelphia, where the conditions were unfavorable, than that Motley should have taken up history in Boston, where the conditions were wholly propitious. Boker’s house bears the impress of his various and comprehensive tastes. To this extent it becomes an illustration of his character, and the illustration is worth considering.

The first floor, as one enters from the hallway,[Pg 33] contains the dining-room at the back, and a long, stately drawing-room fitted up with old-time richness and imbued with an atmosphere of courtly reception. But the library or study is above, on the second floor. It has two windows looking out southward over the garden in the rear of the house, and the whole effect of the room is that of luxurious comfort mingled with an opulence of books. The walls are hung with brown and gilded paper, and the visitor’s feet press upon a heavy Turkish carpet, brought by the poet himself from Constantinople, suggesting the quietude of Tennyson’s “hushed seraglios.” The chairs and the lounges are covered with yellow morocco. On the wall between the two windows hangs a copy of the Chandos portrait of Shakspeare; and below this there is a large writing-table, provided with drawers and cupboards, where Mr. Boker kept his manuscripts. His work, however, was not done at this desk, for in the centre of the room there was a round table under the chandelier, with a large arm-chair drawn up beside it. In this chair, and at this round table, Mr. Boker wrote nearly all his works; but, unlike most authors, he did not do his writing on the table. A portfolio held in front of him, while he sat in the chair, served his purpose; and it may also be worth while to note the fact that his plays[Pg 34] and his poems, composed in this spot, were first set down in pencil.

The surroundings are delightful. On all sides the walls are filled with book-cases reaching almost to the ceiling; the windows are hung with heavy curtains decorated with Arabic designs; and in winter a fire of soft coal burns in the large grate at one side of the apartment. The books that glisten from the shelves are cased in bindings and covers of the finest sort, made by the best artists of England and France. As to their contents, the strength lies in a collection of old English drama and poetry and a complete set of the Latin classics. It must be said here, however, that Mr. Boker’s books are by no means confined to the library. The presence of books is visible all through the house, and one can trace at various points the fact that the owner of these books has always aimed to collect the best editions. In later days Mr. Boker has, in a measure, been exiled from the companionship of the choicest books in his study; because, in order to obtain uninterrupted quiet, he has been obliged to retire to a small room on the floor above his library, where he is more secure from disturbance.

The dining-room is a noteworthy apartment, not only because many distinguished persons have been entertained in it, but also because it is[Pg 35] beautifully finished with a ceiling and walls of black oak, framing scarlet panels, that set off the buffets and side-cases full of silver services. If any one fancies, however, that the appointments of the dining-room and the library indicate a too Sybaritic taste, he should ascend to the top floor of the house, where Mr. Boker had a workshop containing a complete outfit for a turner in metals. Mr. Boker always had a taste for working at what he called his “trade” of producing various articles in metal, on his turning-lathe. In younger days it used to be his boast that he could go into the shop of any machinist, take off his coat, and earn his living as a skilled workman. He still practiced at the bench in his own workshop, at the age of sixty-five. It seems to me that he was unique among American authors, in uniting with the grace and fire of a genuine poet the diversions of a rich society man, the functions of a public official, and a capacity for practical work as a mechanic.

We must bear in mind, also, that this skilled laborer, this man of social leisure and amusement, and this poet, was also a man of intense action in the time of the Civil War, when he organized the Union League of Philadelphia, which consolidated loyal sentiment in the chief city of Pennsylvania, at the time when that city was wavering. All the Union Leagues of the country were patterned[Pg 36] after this organization in Philadelphia. Moreover, when Mr. Boker undertook and carried on this work, his whole fortune was in danger of loss, from a maliciously inspired law-suit. With the risk of complete financial ruin impending, he devoted himself wholly to the cause of patriotism, and poured out poem after poem that became the battle-cry of loyalists throughout the North. His character and services won the friendship of General Grant; and after the War, he was appointed United States Minister to Turkey; from which post he was promoted to St. Petersburg. The impression he made at that capital was so deep that, when he was recalled, Gortschakoff received his successor with these words: “I cannot say I am glad to see you. In fact, I’m not sure that I see you at all, for the tears that are in my eyes on account of the departure of our friend Boker.” In both of these places he rendered important services. Among the dramas which were the fruit of his youth, “Calaynos” and “Francesca da Rimini” achieved a great success, both in England and in this country. The revival of “Francesca da Rimini” at the hands of Lawrence Barrett, and its run of two or three seasons, thirty years after its production, is one of the most remarkable events in the history of the American stage. Nor should it be forgotten that Daniel Webster valued one of Boker’s[Pg 37] sonnets so much, that he kept it in memory to recite; and that Leigh Hunt selected Boker as one of the best exponents of mastery in the perfect sonnet.

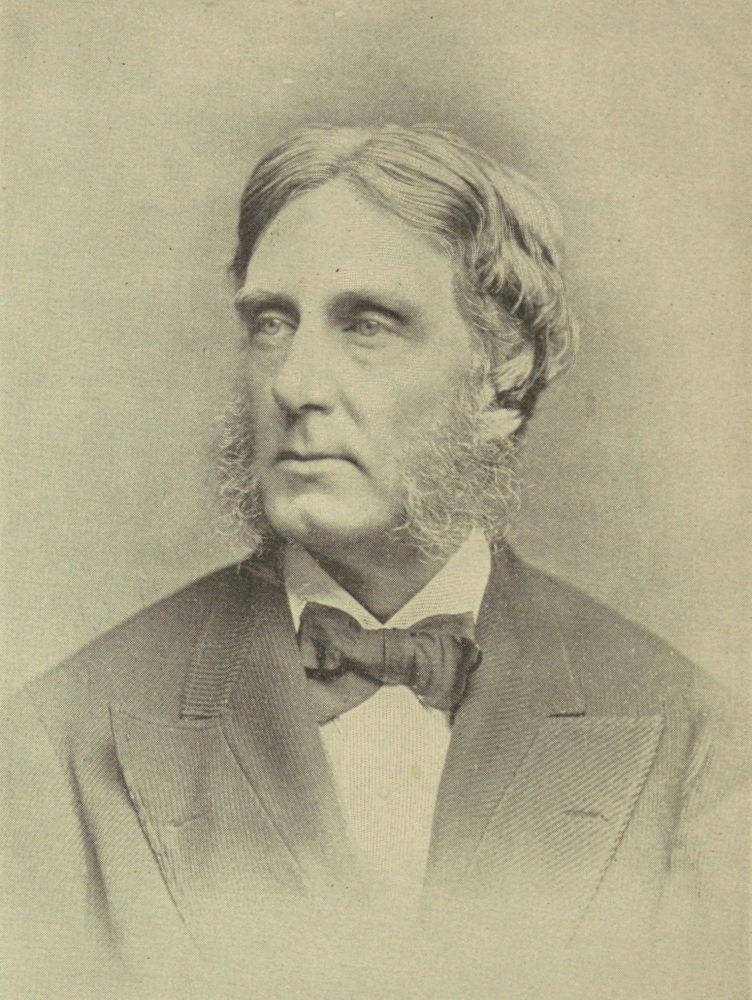

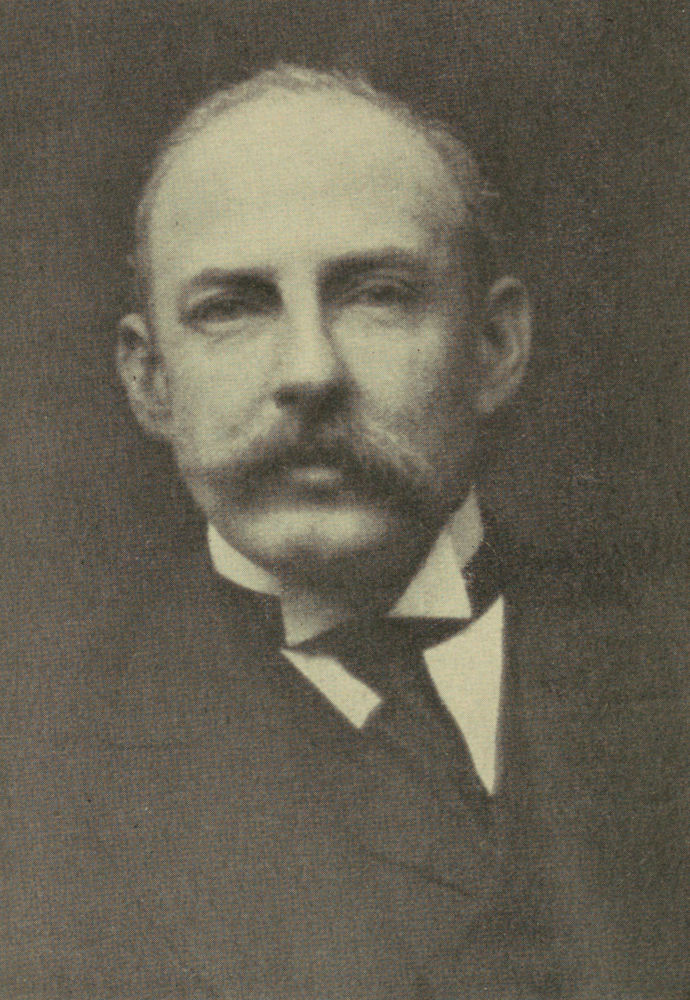

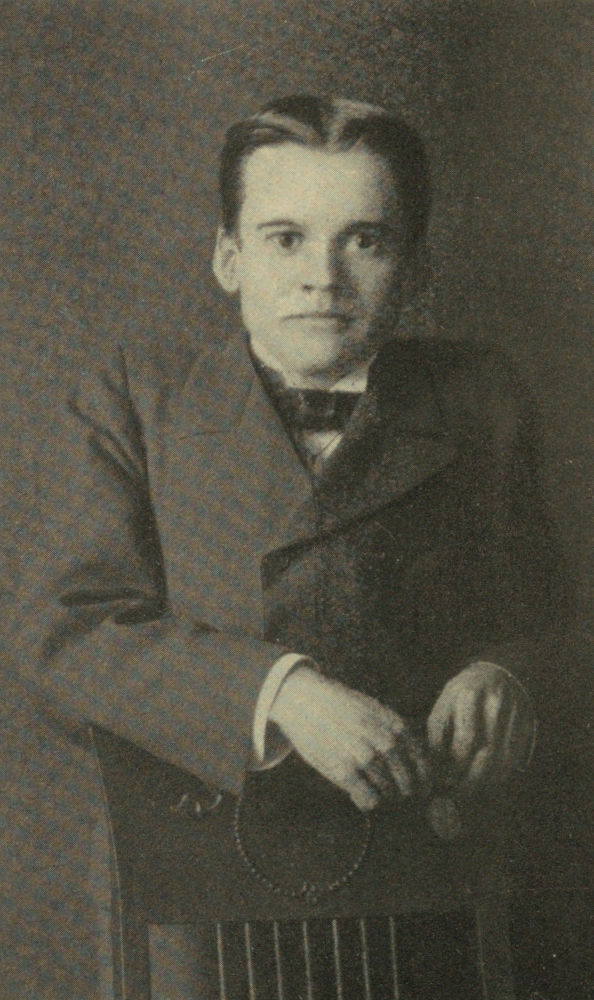

An early portrait of Mr. Boker bears strong resemblance to Nathaniel Hawthorne in his manly prime. But passing decades, while they did not bend the tall, erect figure, whitened the thick, military-looking moustache and short curling hair that contrasted strikingly with a firm, ruddy complexion. His commanding presence and distinguished appearance were as well known in Philadelphia as his sturdy personality and polished manners were. For many years he continued to act as President both of the Union League and of the old, aristocratic, yet hospitable, Philadelphia Club. These two clubs, his home occupations and his numerous social engagements occupied much of his leisure during the winter; and his summers were usually spent at some fashionable resort of the quieter order. How he contrived to find time for reading and composition it is hard to guess; but his pencil was not altogether idle even in his last years. When a man had so consistently held his course and fixed his place as a poet, a dramatist, a brilliant member of society, an active patriot and a diplomatist, it seems to me quite worth our while to recognize that he did this under circumstances of inherited wealth which usually lead to[Pg 38] inertness. It is worth our while to observe that a rich American devoted his life to literature, and did so much to make us feel that he deserved to be one of the few American authors who enjoyed a luxurious home.

George Parsons Lathrop.

[Pg 39]

[Pg 41]

JOHN BURROUGHS

When the author of “Winter Sunshine” comes to town, it is over the most perfectly graded track and through the finest scenery about New York. Returning he is carried past Weehawken and the Palisades, through the Jersey Meadows, in and out among the West Shore Highlands, under West Point, and past Newburg factories and Marlborough berry farms. He leaves the train at West Park, mounts a hill through a peach-orchard, crosses a grassy field, and the high-road when he reaches the top, opens a rustic gate, and is at home. From the road, you look down upon the roofs and dormers and chimneys of the house, about half covered with the red and purple foliage of the Virginia creeper. The ground slopes quite steeply, so that the house is two stories high on the side next the road and three on the side toward the river, which winds away between high, wooded banks to the Catskills, twenty miles to the north, and to the Highlands, thirty miles to the south. The slope, in the rear of the house, to the river, is laid out in a grapery and an orchard of[Pg 42] apple and peach trees. Between the house and the road the steep hillside is tufted with evergreens and other ornamental trees. At the foot of the hill, the gray roofs of a big ice-house are seen. Squirrels, that have their nests in the sawdust packing, clamber around the walls. Near the house, to the left, there is a substantial store-house, and a carriage-shed and stable. There are two other dwellings on the farm. The country immediately about is all very much alike, nearly half of it in ornamental plantations surrounding neat country houses; the other half, where it is not occupied by rocks, being covered with fruit, or corn, or grass. The opposite shore of the Hudson is of the same character, varied with clumps of timber, villas and farm-houses of the style that was in vogue before the introduction of the so-called Queen Anne mode of building; a few cultivated fields and many wild meadows and out-cropping ridges of slate rock intervening. But the interior country, on the hither-side, back of the railroad which cuts through the slate hills like a hay-knife, is a perfect wilderness—rugged, barren, and uninhabited. A number of little lakes lie behind the first range of hills, the highest of which has been named by Mr. Burroughs Mount Hymettus, because it is a famous place for wild bees and sumac honey. From one of these ponds, an exemplary mountain stream—model[Pg 43] of all that a mountain stream should be—makes its way by a series of cascades into the valley, where it forms deep pools, peopled by silvery chub and black bass, brawls over ledges, sparkles in the sun, and sleeps in the shadow, and performs all the recognized and traditional brook “business” to perfection. Its specialty is its bed of black stones and dark green moss, which has gained it its name of Black Creek. At one spot, where it passes under a high bank overhung by hemlocks, it has communicated its dark color to the very frogs that jump into it, and to the dragonflies that rid it of mosquitoes.

The road between West Park and Esopus crosses this brook near a ruined mill, whose charred rafters lie in the cellar, and whose wheel-buckets are filled with corn-shucks. The ruby berries of the nightshade hang in over its window-sills. This is the most varied two miles of road that I can bring to mind. Starting with a fine view up and down the river, it soon dips into the valley, between walls of slate and rows of tall locusts. The locusts are succeeded by the firs and pines of a carefully kept estate. Then comes the stream, spanned by a rustic bridge; the ruined mill, and the new rise of ground which, beyond the railroad, reaches up into summits covered with red oaks and flaming orange maples. A tree by the roadside, now torn in two by a storm, is[Pg 44] pointed out by Mr. Burroughs as the former home of an old friend of his—a brown owl who, in the course of a ten years’ acquaintanceship, as if dreading the contempt that familiarity breeds, never showed an entire and unhesitating confidence in him. The bird would slink out of sight as he approached—slowly and by imperceptible degrees; wisely effacing himself rather than that it should be said he was too intimate with a mere human. Esopus contains a tavern, a post-office, a bank, a blacksmith-shop, and one or two houses; and yet—like an awkward contingency—one never suspects its existence until he has got fairly into it. From the railroad station it is invisible; it cannot be seen from the river; and the road, which runs through it, knows nothing of it before or after.

Mr. Burroughs’s portrait must be drawn out of doors. He is of a medium height, but being well-built and having a fine head, he gives the impression of being by no means a middling sort of a man, physically. His skin is well tanned by exposure to all sorts of weather. He has grisly hair and beard. The eyes and mouth have a somewhat feminine character; the eyes are humid, rather large, and they are half closed when he is pleased; the lips are full, the line between them never hard, and the corners of the mouth are blunt. The nose would be Roman, if it were a[Pg 45] trifle longer. I make no apology for giving so short a description of a man whom it would be well worth while to paint. It is unnecessary to sketch his mental features, for he has unconsciously placed them on record, himself, in the delightful series of essays which he has added to the treasures of the English language.

His walks, his naturalistic rambles, his longer boating or shooting excursions, are the subjects of some of his most entertaining chapters; but a not impertinent curiosity may be gratified by some account of his everyday life when at home and at work. His literary labors are at a standstill throughout the summer. He does not take notes. Even when he has returned from camping out, or canoeing, or from his summer vacation of whatever form, he does not rush at once to pen and paper. He waits till the spirit moves him, which it usually begins to do a little after the first frosts. He rises early—between five and six o’clock; breakfasts, reads the newspapers or employs himself about the house and farm until nine or ten; then writes for three or four hours, seldom more. He has always refused to do literary work to order, although he has had some tempting offers. He will write only what he pleases, and when he pleases, and so much as he pleases. And he observes no method in preparing, any more than in doing, his work. He exacts[Pg 46] from himself no account of his time. He does not feel himself bound in conscience to improve every incident that has occurred, every observation he has made during the year. He simply lets the material which he has absorbed distill over into essays long or short, few or many, as providence directs. He does not belong to the class of methodical laborers who make a business of writing, and who would feel conscience-stricken if, at the close of their working-day, they had not blackened a certain number of sheets of white paper. But he acknowledges that good work is done in that way, and he thinks it is all a matter of habit.

His neighbors see to it that his leisure does not degenerate into idleness. They have made a bank examiner of him, and a superintendent of roads, and, latterly, a postmaster. The first-mentioned position is the only one that has any emoluments attached to it; but, as he likes to drive, he thinks it for his interest to see after the roads, and he hopes, now that his post-office at West Farms is in working order, to get his mails in good time.

Most of his books—“Wake Robin,” “Birds and Poets,” “Winter Sunshine,” etc.—were written in the library of his house, a small room, fitted with book-shelves both glazed and open, and enjoying a splendid view of the Hudson to and beyond[Pg 47] Poughkeepsie. But he has lately built himself a study, several hundred yards from the house and more directly overlooking the river. Here he has pretty complete immunity from noise and from interruptions of all sorts. It is a little, square building, the walls rough-cast within and faced with long strips of bark without. Papers, magazines, books, photographs, lithographs lie scattered over the table, the window-sills and the floor, and fill some shelves let into a little recess in the wall. A student’s lamp on the table shows that the owner sometimes reads here at night. His room-mates at present are some wasps hatched out of a nest taken last winter and suspended to the chimney. This primitive erection is further ornamented with a lot of pictures of men and birds, the men mostly poets—Carlyle being the only exception—and the birds all songsters. Two steps from the study is a summer-house of hemlock branches, with gnarled vine-stocks twisted in among them, where one may sit of an afternoon and read the New York morning papers, or watch the boats or the trains on the opposite bank, or the antics of a squirrel among the branches of the apple-tree overhead, or the struggles of a honey-bee backing out of a flower of yellow-rattle.

Mr. Burroughs has been his own architect; and I know many people who might wish that he had been theirs too. He planned and superintended[Pg 48] the erection of his house, which is a four-gabled structure, with a porch in front and a broad balcony in the rear. Most of the timber for the upper story is oak from his old Delaware County farm. The stone of which the two lower stories are built was obtained on the spot, and is a dark slate plentifully veined with quartz. Great pains were taken in the building to turn the handsomest samples of quartz to the fore, and to put them where they would do the most good, artistically. Over the lintel of the door, for example, is a row of three fine specimens; and a big chunk, with mosses lying between its crystals, protrudes from the wall near the porch. The variety of color so obtained, with the drab woodwork of the upper story and the red Virginia vine, keeps the house, at all seasons, in harmony with its surroundings. It is no less so within; for doors, wainscots, window-frames, joists, sills, skirting-boards, floor and rafters are all of native woods, left of their natural colors, and skillfully contrasted with one another; one door being of Georgia pine with oak panels, another of chestnut and curled maple, a third of butternut and cherry, and so on. Grayish, or brownish, or russet wall-papers, and carpets to match, give the house very much of the appearance of a nest, into the composition of which nothing enters that is not of soft textures and low and harmonious color.

Roger Riordan.

[Pg 49]

[Pg 51]

GEORGE W. CABLE

Far up in the “garden district” of New Orleans stands a pretty cottage, painted in soft tones of olive and red. A strip of lawn bordered with flowers lies in front of it, and two immense orange trees, beautiful at all seasons of the year, form an arch above the steps that lead up to the piazza. Here Mr. Cable made his home for some years, and here were written “The Grandissimes,” “Madame Delphine” and “Dr. Sevier.” Those who were fortunate enough to pass beyond its portals found the interior cosy and tasteful, without any attempt at display. The study was a room of many doors and windows with low bookcases lining the walls, and adorned with pictures in oil and water-colors by G. H. Clements, and in black and white by Joseph Pennell. The desk, around which hovered so many memories of Bras-Coupé and Madame Delphine, and gentle Mary, was a square, old-fashioned piece of furniture, severely plain, but very roomy.

Neither was comfort neglected; for a hammock swung in the study, in which the author could rest,[Pg 52] from time to time, from his labors. Mr. Cable’s plan of work is unusually methodical, for his counting-room training has stood him in good stead. All his notes and references are carefully indexed and journaled, and so systematized that he can turn, without a moment’s delay, to any authority he wishes to consult. In this respect, as in many others, he has not, perhaps, his equal among living authors. In making his notes, it is his usual custom to write in pencil on scraps of paper. These notes are next put into shape, still in pencil, and the third copy, intended for the press, is written in ink on note-paper—the chirography exceedingly neat, delicate and legible. He is always exact, and is untiring in his researches. The charge of anachronism has several times been laid at his door; but this is an accusation it would be difficult to prove. Before attempting to write upon any historical point, he gathers together all available data without reckoning time or trouble; and, under such conditions, nothing is more unlikely than that he should be guilty of error. Mr. Cable has a great capacity for work, and his earlier stories were written under the stress of unremitting toil. Later, when he was able to emerge from business life and follow the profession of literature exclusively, he continued his labors in the church, and never allowed any engagement to interfere with his Sunday-school[Pg 53] and Bible-classes. In his books, religion has the same place that it takes in a good man’s life. Nothing is said or done for effect; neither is he ashamed to confess his faith before the world.

It is perhaps strange that Mr. Cable should have the true artistic, as well as the religious, temperament, since these two do not invariably go hand in hand. Music, painting, and sculpture are full of charms for him, and he is an intuitive judge of what is best in art. His knowledge of music is far above the ordinary, and he has made a unique study of the usually elusive and baffling strains of different song-birds. He is such a many-sided man that he should never find a moment of the day hanging heavily upon his hands. The study of botany was a source of great pleasure to him, at one time; and he had, also, an aviary in which he took a deep interest.

Seemingly sedate, Mr. Cable is full of fun; and charming as he is in general society, a compliment may be paid him that cannot often be spoken truthfully of men of genius—namely, that he appears to the best advantage in his own home. His children are a merry little band of five girls and one boy, each evincing, young as they are, some distinctive talent. It is amusing to note their appreciation of ‘father’s fun,’ and his playful speeches always give the signal for[Pg 54] bursts of laughter. This spirit of humor, so potent “to witch the heart out of things evil,” is either hereditary or contagious, for all of these little folks are ready of tongue. The friends whom Mr. Cable left behind him, in New Orleans, remember with regretful pleasure the delightful little receptions which have now become a thing of the past. Sometimes, at these gatherings, he would sing an old Scotch ballad, in his clear, sweet tenor voice, or one of those quaint Creole songs that he has since made famous on the lecture platform; or, again, he would read a selection from “Dukesborough Tales”—one of his favorite humorous works. Nothing was stereotyped or conventional, for Mr. Cable is, in every aspect of life, a dangerous enemy of the common-place. But the pleasant dwelling-place has passed into other hands; other voices echo through the rooms; and Mr. Cable has found a new home in a more invigorating climate.

The highway leading from the town of Northampton, Mass., which one must follow in order to find Mr. Cable’s house, has the aspect of a quiet country road, but is, in reality, one of the streets of the city, with underlying gas and water-pipes. It is studded with handsome dwellings, some of brick and stone, others of simple frame-work—each with velvet lawn shaded with[Pg 55] spreading elms, and here and there a birch or pine. The romancer’s house is the last at the edge of the town, on what is fitly named the Paradise Road. It is a red brick building of two stories and a half, with a vine-covered piazza; and the smooth-cut lawn slopes gently down to the street, separated only from the sidewalk by a stone coping. Above all things, one is conscious, on entering here, of a sense of comfort and home happiness. The furniture is simple but exceedingly tasteful, of light woods with little upholstery; and the visitor finds an abundance of easy-chairs and settees of willow. The study is a delightful nook, opening by sliding doors from the parlor on one side and the hall on another. A handsome table of polished cherry, usually strewn with books and papers, occupies the center of the room, and, as in the old home, the walls are lined with book-shelves. A large easy-chair, upon which the thoughtful wife insisted, when the room was being fitted up, affords a welcome resting-place to the weary author. Sometimes she lends her gentle presence to the spot, and sits there, with her quiet needlework, while the story or lecture is in the course of preparation. One of the charms of this sanctum is the view from the two windows that extend nearly to the floor. From one may be descried the blue and hazy line of the Hampshire hills, while from the other[Pg 56] one sees Mt. Holyoke and Mt. Tom uprearing their stately heads to the sky. Sloping down from the carriage-drive which passes it lies Paradise—a stretch of woods bordering Mill River. No more appropriate name could be given it, for if magnificent trees, beautiful flowers, green-clad hill and dell, and winding waters, and above all, the perfect peace of nature, broken only by bird-notes, can make a paradise, it is found in this corner of Northampton, itself the loveliest of New England towns. Mr. Cable confesses that this scene of enchantment is almost too distracting to the mind, and that, when deeply engaged in composition, he finds it necessary to draw the curtains.

If the days in Mr. Cable’s home are delightful, the evenings are not less charming. After the merry tea and the constitutional walk have been taken, the family gather in the sitting-room. Usually, two or three friends drop in; but if none come, the children are happy to draw closely around their father, while he plays old-time songs or Creole dances on his guitar. As he sings, one after another joins in, and finally the day is ended with a hymn and the evening worship. The hour is early, for the hard-working brain must have its full portion of rest. It is one of Mr. Cable’s firm-rooted principles that the mind can not do its best unless the body is well[Pg 57] treated; and he gives careful attention to all rules of health. Apart from the brilliant fact of his genius, this is the secret of the evenness of his work. There is no feverish energy weakening into feverish lassitude; it moves on without haste, without rest. Mr. Cable well advised a young writer never to publish anything but his best; and it is this principle, doubtless, that has prevented him from thinking it necessary, as many English and American authors seem to fancy, to turn out a certain amount of printed matter every year. In addition to his literary labors, Mr. Cable is frequently absent from home on reading and lecture engagements, and great is the rejoicing of his family when they have him once more among them. Mr. Cable’s place in literature is as unique as that of Hawthorne. He is distinctively and above all things an American. He has not found it necessary to cross the water in search of inspiration; and he is the only American author of any prominence whose turn of mind has never been influenced by the foreign classics.

What Bret Harte has done for the stern angularity of Western life, Mr. Cable has wrought, in infinitely finer and subtler lines, for his soft-featured and passionate native land. Those who come after him in delineation of Creole character can only be followers in his footsteps, for to him[Pg 58] alone belongs the credit of striking this new vein, so rich in promise and fulfillment. An alien coming among them would be as one who speaks a different language. He would be impressed only by superficial peculiarities, and would chronicle them from this standpoint. But Mr. Cable knows these people to their heart’s core; he is saturated with their individuality and traditions; to him their very inflection of voice, turn of the head, motion of the hands, is eloquent with meaning. His work will endure because it is entirely wholesome, and full of that “sanity of mind” which speaks with such a strenuous voice to the mass of mankind. The writer who appeals from a diseased imagination to an audience full of diseased and morbid tastes, must necessarily have a small clientèle; for there are comparatively few people, as balanced against the vast hordes of workers, who are so satiated with the good things of this life that they must always seek for some new sensation strong enough to blister their jaded palates. The men and women who labor and endure desire after their day of toil something that will cheer and refresh; and this will remain so as long as health predominates over disease.

The engraving in The Century of February, 1882, has made the reading public familiar with Mr. Cable’s features; but there is lacking the[Pg 59] lurking sparkle in the dark hazel eyes, and the curving of the lips into a peculiarly winning smile. In person, Mr. Cable is small and slight, with chestnut hair, beard and moustache; and there is a marked development of the forehead above the eyebrows, supposed, by believers in phrenology, to indicate unusual musical talent. On paper, it is hard to express the charm of his individuality, or the pleasure of listening to his sunny talk, with its quaint turns of thought and the felicitous phrases that spring spontaneously to his lips. Those who have been impressed by the deep humanity that made it possible for him to write such a book as “Dr. Sevier,” will find the man and the author one and indivisible. Nothing is forced, or uttered for the sake of making an impression; and the listener may be sure that Mr. Cable is saying what he thinks. The conscientiousness that enabled him to be a brave soldier and an untiring business man, runs through his whole life; and he has none of that moral cowardice which staves off an expression of opinion with a falsely pleasant word.

J. K. Wetherill.

[Eight years ago Mr. Cable left the house in Paradise Road for a new Colonial house on “Dryad’s Green,” against a background of pines,—“Tarryawhile,” with a cottage workshop of two rooms near by.—Editors.]

[Pg 61]

[Pg 63]

S. L. CLEMENS (MARK TWAIN)

The story of Mark Twain’s life has been told so often that it has lost its novelty to many readers, though its romance has the quality of permanence. But people to-day are more interested in the author than they are in the printer, the pilot, the miner, or the reporter, of twenty or thirty years ago. The editor of one of the most popular American magazines once alluded to him as “the most widely read person who writes in the English language.” More than half a million copies of his books have been sold in this country. England and the English colonies all over the world have taken at least half as many in addition. His sketches and shorter articles have been published in every language which is printed, and the larger books have been translated into German, French, Italian, Norwegian, Danish, etc. He is one of the few living men with a truly world-wide reputation. Unless the excellent gentlemen who have been engaged in revising the Scriptures should claim the authorship of their work, there is no other living writer[Pg 64] whose books are now so widely read as Mark Twain’s; and it may not be out of the way to add that in more than one pious household the “Innocents Abroad” is laid beside the family Bible, and referred to as a hand-book of Holy Land description and narrative.

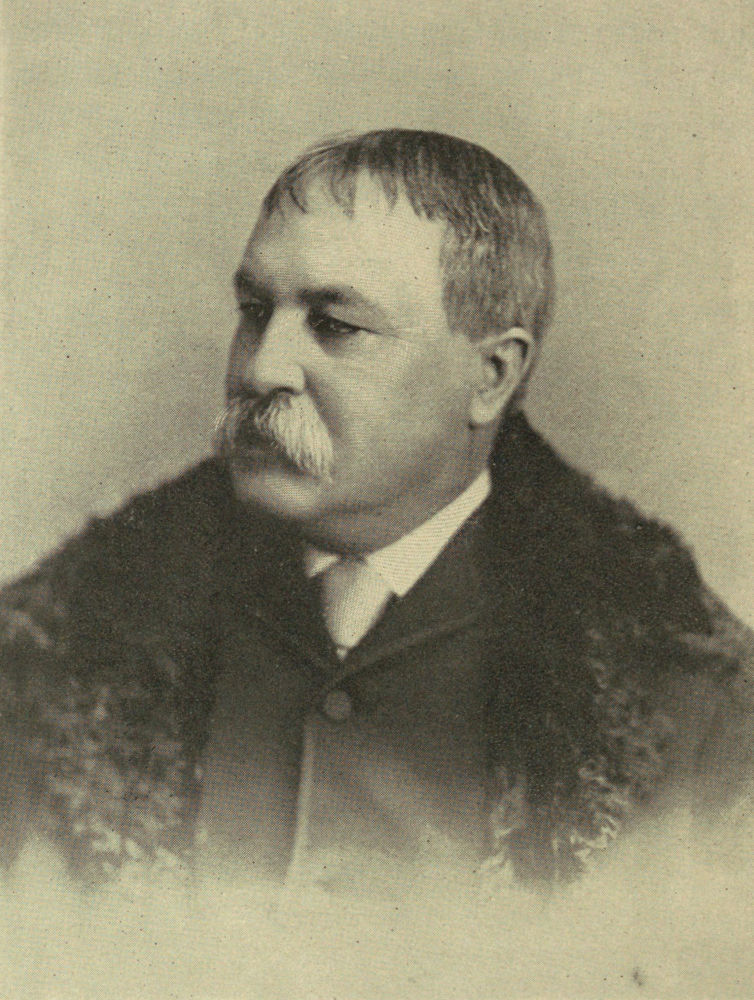

Off the platform and out of his books, Mark Twain is Samuel L. Clemens—a man who was born November 30, 1835. He is of a very noticeable personal appearance, with his slender figure, his finely shaped head, his thick, curling, very gray hair, his heavy arched eyebrows, over dark gray eyes, and his sharply, but delicately, cut features. Nobody is going to mistake him for any one else, and his attempts to conceal his identity at various times have been comical failures. In 1871 Mr. Clemens made his home in Hartford, and in some parts of the world Hartford to-day is best known because it is his home. He built a large and unique house in Nook Farm, on Farmington Avenue, about a mile and a quarter from the old centre of the city. It was the fancy of its designer to show what could be done with bricks in building, and what effect of variety could be got by changing their color, or the color of the mortar, or the angle at which they were set. The result has been that a good many of the later houses built in Hartford reflect in one way or another the influence[Pg 65] of this one. In their travels in Europe, Mr. and Mrs. Clemens have found various rich antique pieces of household furniture, including a great wooden mantel and chimney-piece, now in their library, taken from an English baronial hall, and carved Venetian tables, bedsteads, and other pieces. These add their peculiar charm to the interior of the house. The situation of the building makes it very bright and cheerful. On the top floor is Mr. Clemens’s own working-room. In one corner is his writing-table, covered usually with books, manuscripts, letters, and other literary litter; and in the middle of the room stands the billiard-table, upon which a large part of the work of the place is expended. By strict attention to this business, Mr. Clemens has become an expert in the game; and it is part of his life in Hartford to get a number of friends together every Friday for an evening of billiards. He even plans his necessary trips away from home so as to get back in time to observe this established custom.

Mr. Clemens divides his year into two parts, which are not exactly for work and play respectively, but which differ very much in the nature of their occupations. From the first of June to the middle of September, the whole family, consisting of Mr. and Mrs. Clemens and their three little girls, are at Elmira, N. Y. They live there[Pg 66] with Mr. T. W. Crane, whose wife is a sister of Mrs. Clemens. A summer-house has been built for Mr. Clemens within the Crane grounds, on a high peak, which stands six hundred feet above the valley that lies spread out before it. The house is built almost entirely of glass, and is modeled exactly on the plan of a Mississippi steamboat’s pilot-house. Here, shut off from all outside communication, Mr. Clemens does the hard work of the year, or rather the confining and engrossing work of writing, which demands continuous application, day after day. The lofty work-room is some distance from the house. He goes to it every morning about half-past eight and stays there until called to dinner by the blowing of a horn about five o’clock. He takes no lunch or noon meal of any sort, and works without eating, while the rules are imperative not to disturb him during this working period. His only recreation is his cigar. He is an inveterate smoker, and smokes constantly while at his work, and, indeed, all the time, from half-past eight in the morning to half-past ten at night, stopping only when at his meals. A cigar lasts him about forty minutes, now that he has reduced to an exact science the art of reducing the weed to ashes. So he smokes from fifteen to twenty cigars every day. Some time ago he was persuaded to stop the practice, and actually went a year and more[Pg 67] without tobacco; but he found himself unable to carry along important work which he undertook, and it was not until he resumed smoking that he could do it. Since then his faith in his cigar has not wavered. Like other American smokers, Mr. Clemens is unceasing in his search for the really satisfactory cigar at a really satisfactory price, and, first and last, has gathered a good deal of experience in the pursuit. It is related that, having entertained a party of gentlemen one winter evening in Hartford, he gave to each, just before they left the house, one of a new sort of cigar that he was trying to believe was the object of his search. He made each guest light it before starting. The next morning he found all that he had given away lying on the snow beside the pathway across his lawn. Each smoker had been polite enough to smoke until he got out of the house, but every one, on gaining his liberty, had yielded to the instinct of self-preservation and tossed the cigar away, forgetting that it would be found there by daylight. The testimony of the next morning was overwhelming, and the verdict against the new brand was accepted.

At Elmira, Mr. Clemens works hard. He puts together there whatever may have been in his thoughts and recorded in his note-books during the rest of the year. It is his time of completing work begun, and of putting into definite shape[Pg 68] what have been suggestions and possibilities. It is not his literary habit, however, to carry one line of work through from beginning to end before taking up the next. Instead of that, he has always a number of schemes and projects going along at the same time, and he follows first one and then another, according as his mood inclines him. Nor do his productions come before the public always as soon as they are completed. He has been known to keep a book on hand for five years, after it was finished. But while the life at Elmira is in the main seclusive and systematically industrious, that at Hartford, to which he returns in September, is full of variety and entertainment. His time is then less restricted, and he gives himself freely to the enjoyment of social life. He entertains many friends, and his hospitable house, seldom without a guest, is one of the literary centers of the city. Mr. Howells is a frequent visitor, as Bayard Taylor used to be. Cable, Aldrich, Henry Irving, Stanley, and many others of wide reputation, have been entertained there. The next house to Mr. Clemens’s on the south is Charles Dudley Warner’s home, and the next on the east is Mrs. Stowe’s, so that the most famous three writers in Hartford live within a stone’s throw of each other.

At Hartford Mr. Clemens’s hours of occupation are less systematized, but he is no idler there.[Pg 69] At some times he shuts himself in his working-room and declines to be interrupted on any account, though there are not wanting some among his expert billiard-playing friends to insist that this seclusion is merely to practice uninterruptedly while they are otherwise engaged. Certainly he is a skillful player. He keeps a pair of horses, and rides more or less in his carriage, but does not drive, or ride on horseback. He is, however, an adept upon the bicycle. He has made its conquest a study, and has taken, and also experienced, great pains with the work. On his bicycle he travels a great deal, and he is also an indefatigable pedestrian, taking long walks across country, frequently in the company of his friend the Rev. Joseph H. Twichell, at whose church (Congregational) he is a pew-holder and regular attendant. For years past he has been an industrious and extensive reader and student in the broad field of general culture. He has a large library and a real familiarity with it, extending beyond our own language into the literatures of Germany and France. He seems to have been fully conscious of the obligations which the successful opening of his literary career laid upon him, and to have lived up to its opportunities by a conscientious and continuous course of reading and study which supplements the large knowledge of human nature that the vicissitudes of his[Pg 70] early life brought with them. His resources are not of the exhaustible sort. He is a member of (among other social organizations) the Monday Evening Club of Hartford, that was founded nearly twenty years ago by the Rev. Dr. Bushnell, Dr. Henry, and Dr. J. Hammond Trumbull, and others, with a membership limited to twenty. The club meets on alternate Monday evenings from October to May in the houses of the members. One person reads a paper and the others then discuss it; and Mr. Clemens’s talks there, as well as his daily conversation among friends, amply demonstrate the spontaneity and naturalness of his irrepressible humor.

His inventions are not to be overlooked in any attempt to outline his life and its activities. “Mark Twain’s Scrap-Book” must be pretty well known by this time, for something like 100,000 copies of it have been sold yearly for ten years or more. As he wanted a scrap-book, and could not find what he wanted, he made one himself, which naturally proved to be just what other people wanted. Similarly, he invented a note-book. It is his habit to record at the moment they occur to him such scenes and ideas as he wishes to preserve. All note-books that he could buy had the vicious habit of opening at the wrong place and distracting attention in that way. So, by a simple contrivance, he arranged one that always opens at the right place; that is, of course, at the page[Pg 71] last written upon. Other simple inventions by Mark Twain include a vest which enables the wearer to dispense with suspenders; a shirt, with collars and cuffs attached, which requires neither buttons nor studs; a perpetual-calendar watch-charm, which gives the day of the week and of the month; and a game whereby people may play historical dates and events upon a board, somewhat after the manner of cribbage, being a game whose office is twofold—to furnish the dates and events, and to impress them permanently upon the memory.

In 1885 Mark Twain and George W. Cable made a general tour of the country, each giving readings from his own works: and they had crowded houses and most cordial receptions. It was not a new sort of occupation for Mark Twain. Back in the early days, before his first book appeared, he delivered lectures in the Pacific States. His powers of elocution are remarkable, and he has long been considered by his friends one of the most satisfactory and enjoyable readers of their acquaintance. His parlor-reading of Shakspeare and Browning is described as a masterly performance. He has hitherto refused to undertake any general course of public reading, though very strong inducements have been offered to him to go to the distant English colonies, even as far as Australia.

Charles Hopkins Clark.

[Pg 72]

[After the failure of the firm of Charles L. Webster & Co., of which he was a member, Mr. Clemens accomplished the Herculean task of discharging debts not legally his, by a lecture tour in this country and in Australia. On his return home, he was met in England by the sad news of the sudden death of his eldest daughter. After four more years in Europe, for the most part in Vienna, he came back to this country. The Hartford home was left unoccupied, partly on account of sad associations, and the family spent the winter in New York. They then leased a house at Riverdale on the Hudson, from where they will move to the new home at Tarrytown which Mr. Clemens has recently bought.—Editors.]

[Pg 73]

[Pg 75]

GEORGE WILLIAM CURTIS

It is not noticed that the most determined fighters, both in battle and on the field of public affairs, are often the gentlest, most peaceable men in private converse and at home. The public was for a long time accustomed to regard Mr. Curtis as a combatant; but many who know of him in that character would have been surprised could they have met him in the quiet study on Staten Island, where his work was done.

A calm, solid figure, of fine height and impressive carriage, a moderately ruddy complexion, with snowy side-whiskers, and gray hair parted at the crown, gave him somewhat the appearance that we conventionally ascribe to English country gentlemen. There was an air of repose about the surroundings and the occupant of the room where he worked. Over the door hung a mellowed and rarely excellent copy of the Stratford portrait of Shakspeare; shelves filled with books—the dumb yet resistless artillery of literature—were placed in all the spaces between the three windows; and[Pg 76] other books and pamphlets—the small arms and equipments—covered a part of the ample table. A soft-coal fire in the grate threw out intermittently its broad, genial flame, as if inspired to illumination by the gaze of Emerson, or Daniel Webster, or the presence of blind Homer, whose busts were in an opposite corner. Altogether, the spot seemed very remote from all loud conflicts of the time. There was none of that confusion, that tempestuous disarray of newspapers, common in the workshops of editors. Yet an examination of the new books and documents which lay before him would show that Mr. Curtis established here a sluice-way through which was drawn a current of our chief literature and politics; and some of the lines in his massive lower face indicated the resoluteness which underlay his natural urbanity and kindness. Although his father came from Massachusetts and he himself was born in Providence, Mr. Curtis was identified with New York. In 1839, at the age of fifteen, he moved with his father to this city. Three years later he enlisted with the Brook Farm enthusiasts, but in 1844 withdrew to Concord, as Hawthorne had done. There, with his brother, he worked at farming, and continued to study until 1846, when he came back to New York, still bent upon preparing himself for a literary life, though he chose not to go to college. He went, instead, to Europe, remaining there and in the East for[Pg 77] four years, six months of which he spent as a student at the University of Berlin.