The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE LAST ACT OF THE FRENCH MONARCHY

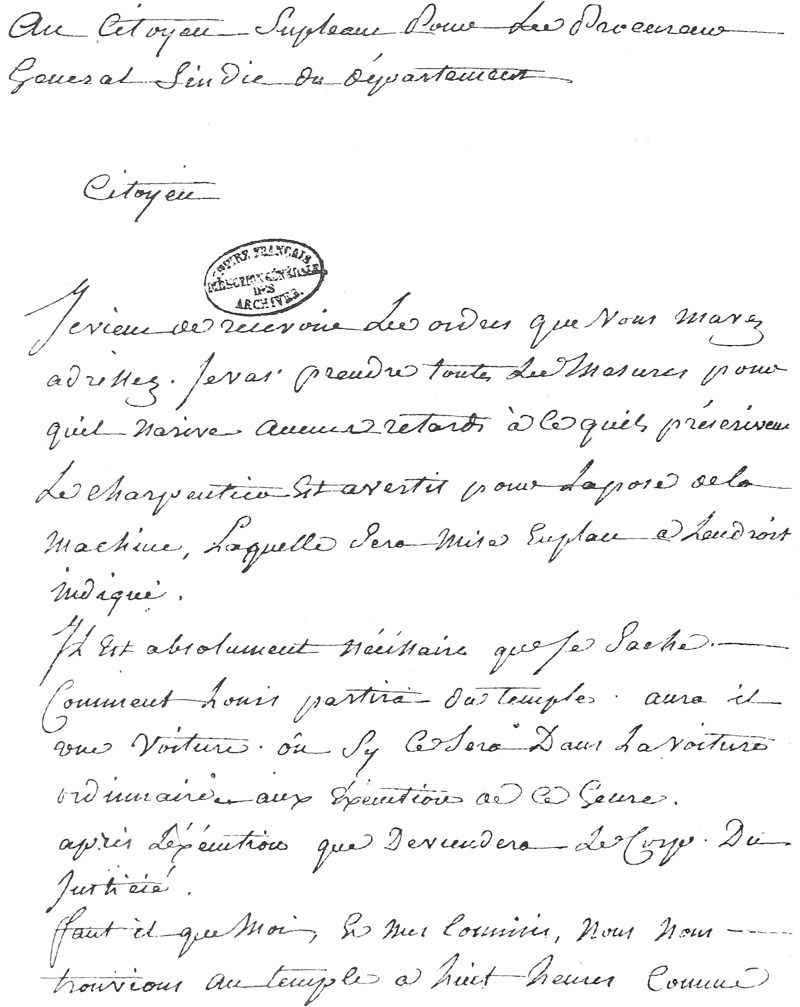

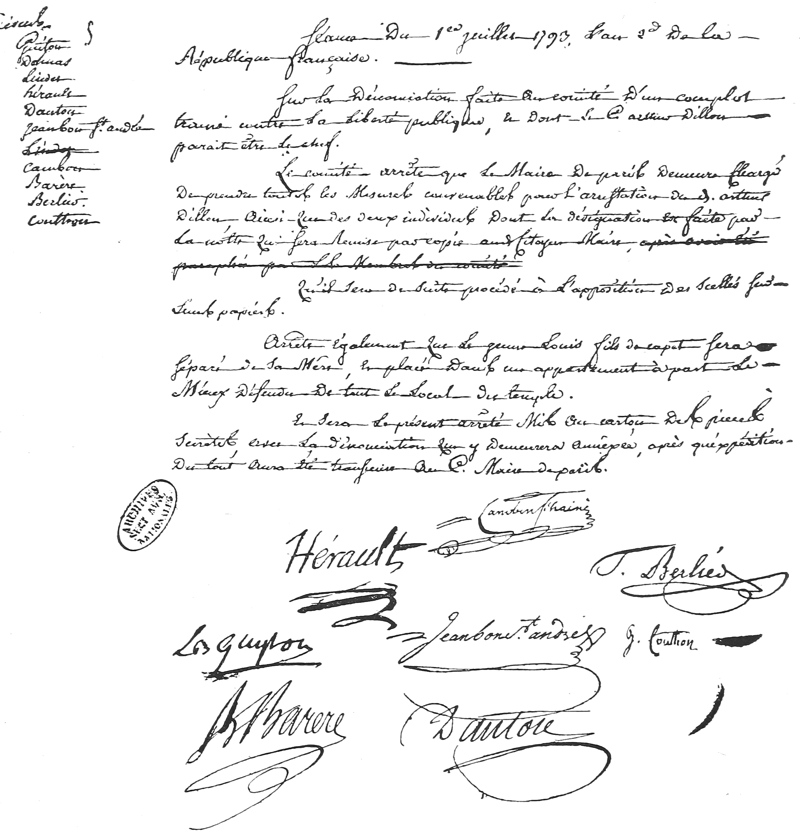

Order given on 10th August, 1792, to the Guard at the Tuileries to Cease Fire and return to Barracks

On the authenticity of this document see Appendix C

THE eighteenth century, which had lost the appetite for tragedy and almost the comprehension of it, was granted, before it closed, the most perfect subject of tragedy which history affords.

The Queen of France whose end is but an episode in the story of the Revolution stands apart in this: that while all around her were achieved the principal miracles of the human will, she alone suffered, by an unique exception, a fixed destiny against which the will seemed powerless. In person she was not considerable, in temperament not exalted; but her fate was enormous.

It is profitable, therefore, to abandon for a moment the contemplation of those great men who recreated in Europe the well-ordered State, and to admire the exact convergence of such accidents as drew around Marie Antoinette an increasing pressure of doom. These accidents united at last: they drove her with a precision that was more than human, right to her predestined end.

In all the extensive record of her actions there is nothing beyond the ordinary kind. She was petulant or gay, impulsive or collected, according to the mood of the moment: acting in everything as a woman of her temper—red-headed, intelligent and arduous—will always do: she was moved by changing circumstance to this or that as many million of her sort had been moved before her. But her chance friendships failed not in mere disappointments but in ruin; her lapses of judgment betrayed her not to stumbling but to an abyss; her small, neglected actions viiimatured unseen and reappeared prodigious in the catastrophe of her life as torturers to drag her to the scaffold. Behind such causes of misfortune as can at least be traced in some appalling order there appear, as we read her history, causes more dreadful because they are mysterious and unreasoned: ill-omened dates, fortunes quite unaccountable, and continually a dark coincidence, reawaken in us that native dread of Destiny which the Faith, after centuries of power, has hardly exorcised.

The business, then, of this book is not to recount from yet another aspect that decisive battle whereby political justice was recovered for us all, nor to print once more in accurate sequence the life of a Queen whose actions have been preserved in the minutest detail, but to show a Lady whose hands—for all the freedom of their gesture—were moved by influences other than her own, and whose feet, though their steps seemed wayward and self-determined, were ordered for her in one path that led inexorably to its certain goal.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | THE DIPLOMATIC REVOLUTION | 1 |

| II. | BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD | 17 |

| III. | THE ESPOUSALS | 32 |

| IV. | THE DU BARRY | 45 |

| V. | THE DAUPHINE | 52 |

| VI. | THE THREE YEARS | 73 |

| VII. | THE CHILDREN | 116 |

| VIII. | FIGARO | 130 |

| IX. | THE DIAMOND NECKLACE | 154 |

| X. | THE NOTABLES | 170 |

| XI. | THE BASTILLE | 193 |

| XII. | OCTOBER | 215 |

| XIII. | MIRABEAU | 240 |

| XIV. | VARENNES | 263 |

| XV. | THE WAR | 292 |

| XVI. | THE FALL OF THE PALACE | 307 |

| XVII. | THE TEMPLE | 324 |

| XVIII. | THE HOSTAGE | 348 |

| XIX. | THE HUNGER OF MAUBEUGE | 365 |

| XX. | WATTIGNIES | 377 |

| APPENDICES | 402 | |

| INDEX | 419 |

| The Last Act of the French Monarchy. Order given on 10th August, 1792, to the Guard at the Tuileries to cease fire and return to Barracks | Frontispiece |

| Maria Theresa - From the tapestry portrait woven for Marie Antoinette and recently restored to Versailles | 13 |

| Madame de Pompadour - From the Portrait by Boucher in the National Gallery, Edinburgh. From a photo by T. R. Annan & Sons | 18 |

| The First Dauphin (the Father of Louis XVI.) | 26 |

| Louis XVI. - From the principal bust at Versailles | 70 |

| The Emperor Joseph II. - From the tapestry portrait woven for Marie Antoinette and recently restored to Versailles | 103 |

| Marie Antoinette - From the principal bust at Versailles | 117 |

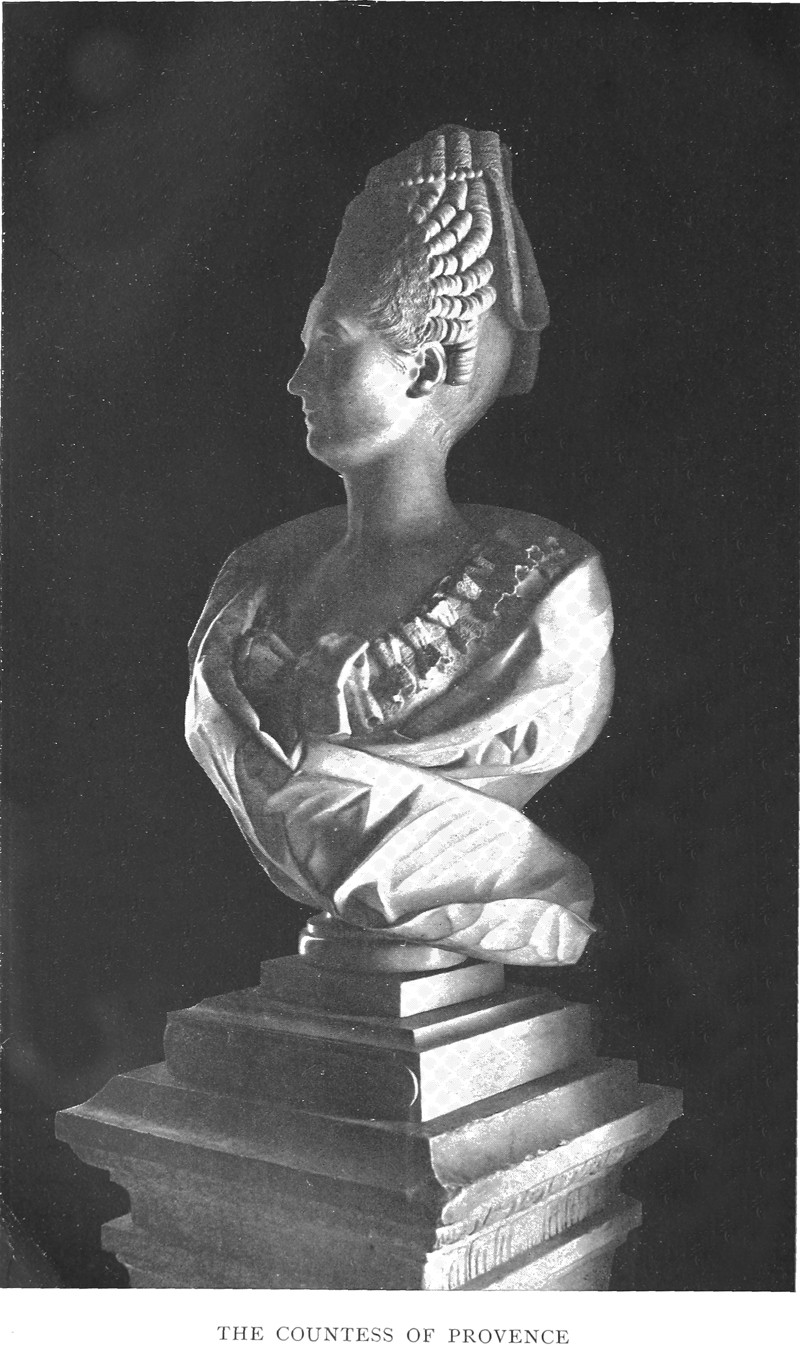

| The Countess of Provence - From the bust at Versailles | 129 |

| Marie Antoinette - After the painting by Madame Vigée Le Brun. From photo kindly lent by Duveen Bros., Old Bond Street | 154 |

| Portrait Bust of the Duke of Normandy, the second Dauphin, Sometimes called Louis XVII., who died in the Temple | 163 |

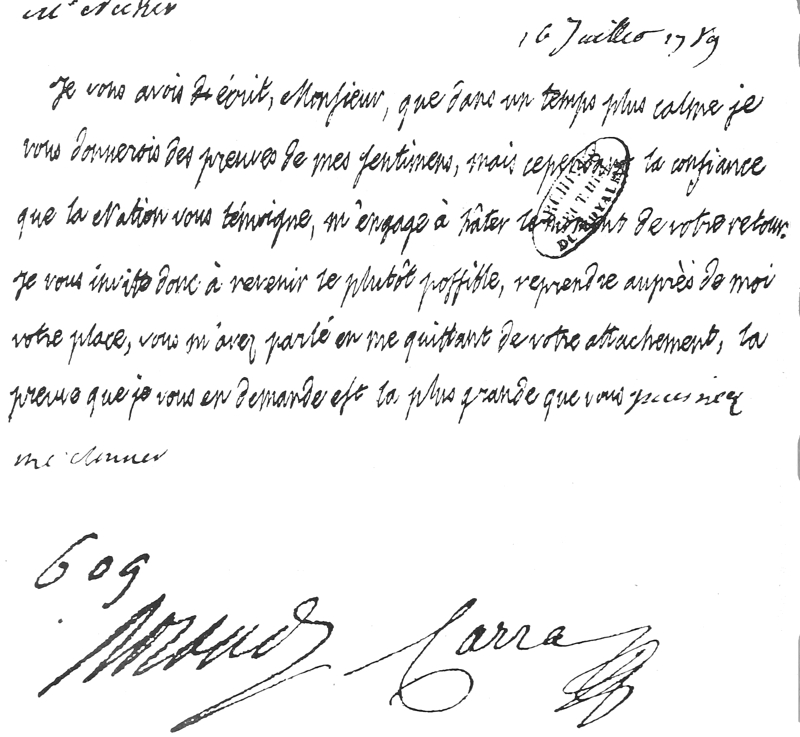

| Autograph Note of Louis XVI. recalling Necker, on the 16th of July, after the Fall of the Bastille | 213 |

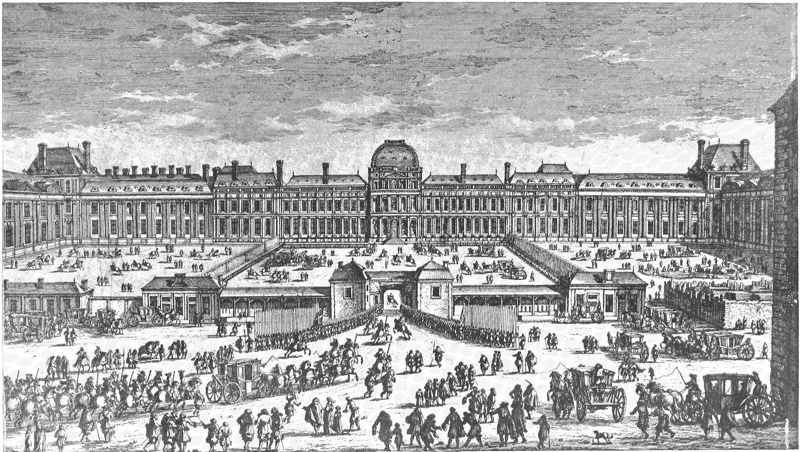

| The Tuileries, from the Garden or West Side, in 1789 | 231 |

| Facsimile of the First Page of the Address to the French People written by Louis XVI. before his Flight | 260 |

| Pétion | 286 |

| Barnave | 289 |

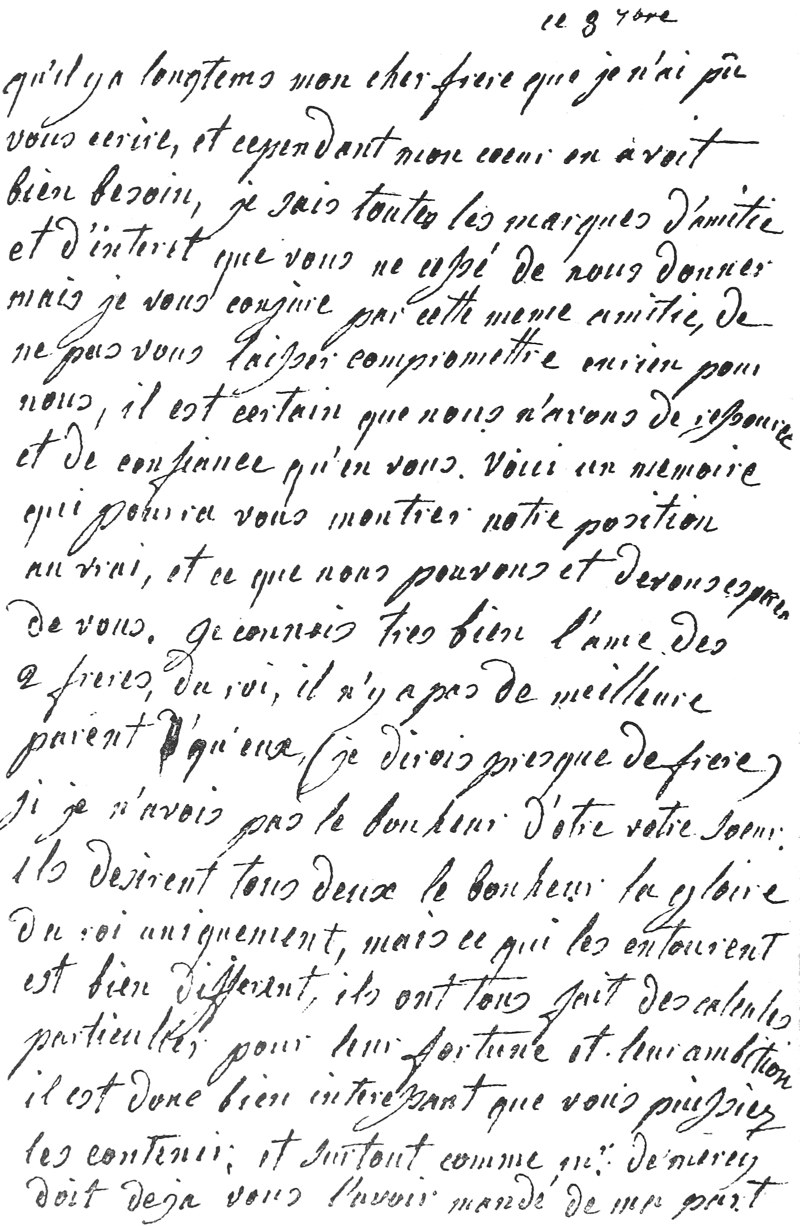

| xiiFacsimile of the First Page of the Letter written on the 3rd September, 1791, by Marie Antoinette to the Emperor, her Brother, proposing Armed Intervention | 297 |

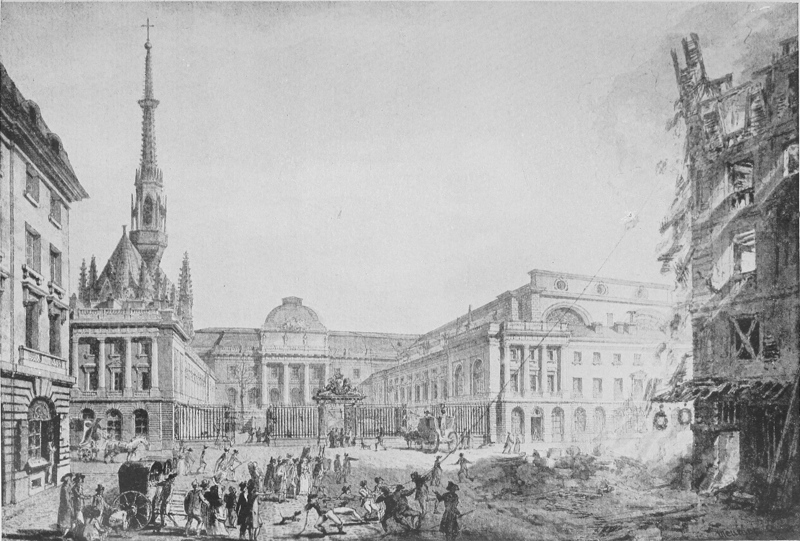

| East Front of the Tuileries (the side Attacked by the Mob) in its last State before the Commune of 1871, after the Clearing away of the Streets and Houses in Front of it | 314 |

| An Early View of the Approach to the Tuileries from the Carrousel, showing the Three Courtyards | 322 |

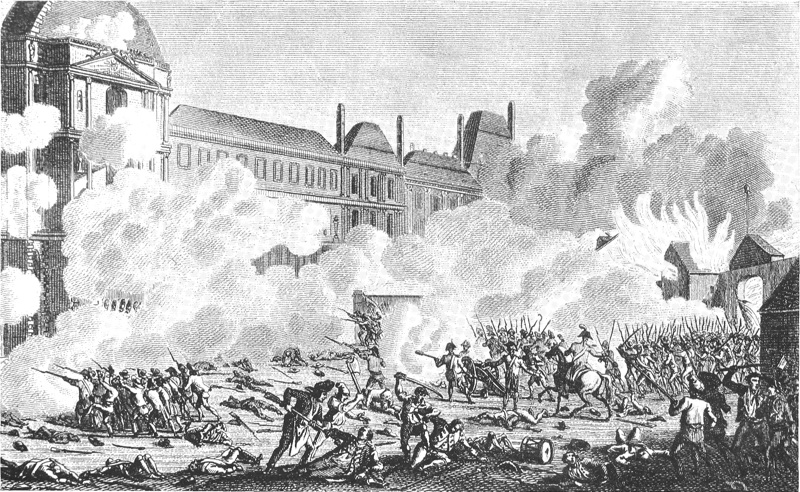

| Contemporary Print of the Fighting in the Courtyard | 327 |

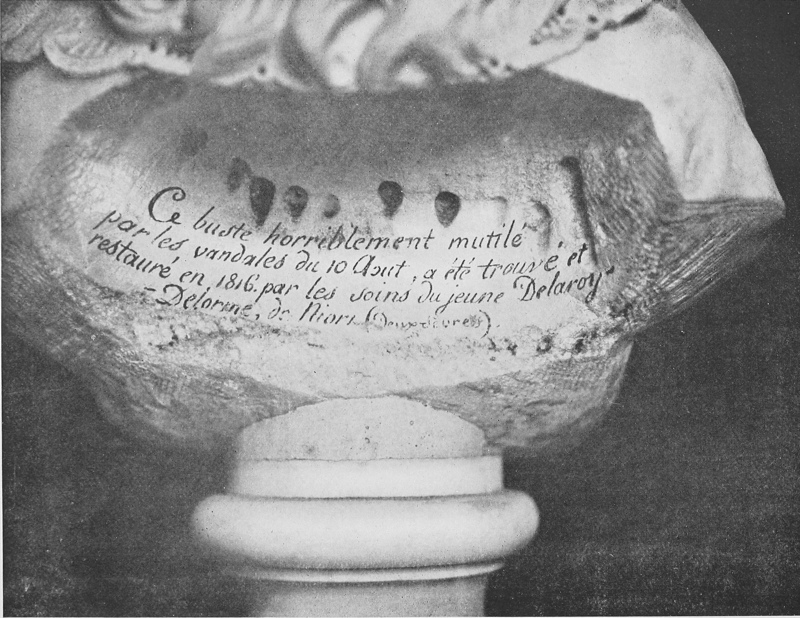

| Inscription on the Broken Bust of the Dauphin. A Relic of the Sack of the Palace | 329 |

| The Tower of the Temple at the Moment of the Royal Family’s Imprisonment | 333 |

| A Rough Miniature of the Princesse de Lamballe Preserved at the Carnavalet | 337 |

| Sanson’s Letter asking the Authorities what Steps he is to take for the Execution of the King | 343 |

| Autograph Demand of Louis XVI. for a Respite of Three Days | 344 |

| Report of the Commissioners that all is duly arranged for the Burial of Louis Capet after his Execution | 346 |

| First Page of Louis XVI.’s Will | 348 |

| Order of the Committee of Public Safety in Cambon’s Handwriting, directing the Dauphin to be separated from his Mother | 356 |

| Last Portrait of Marie Antoinette, by Kocharski Presumably sketched in the Temple, and now at Versailles | 365 |

| Gateway of the Law Courts through which the Queen went to her Death | 380 |

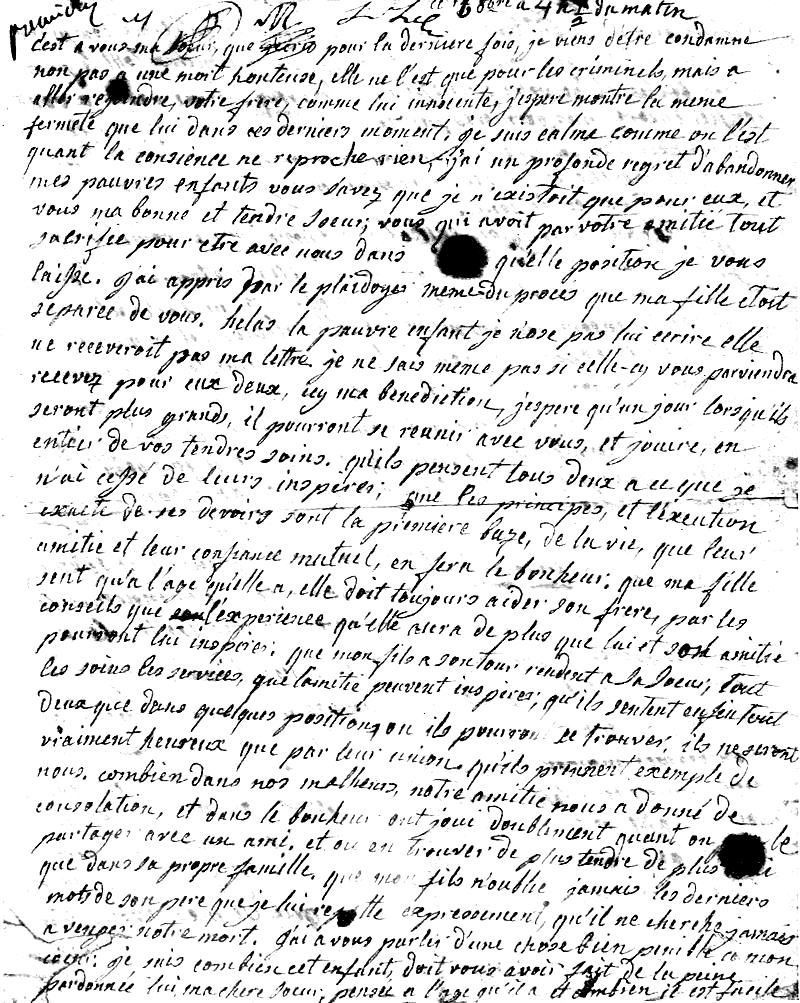

| First Page of Marie Antoinette’s Last Letter | 395 |

| Facsimile of the Death-warrant of Marie Antoinette | 398 |

| Map of the Flight to Varennes and the Return | 263 |

| Sketch Map of the Road from Paris to Varennes, June 21, 1791 | 267 |

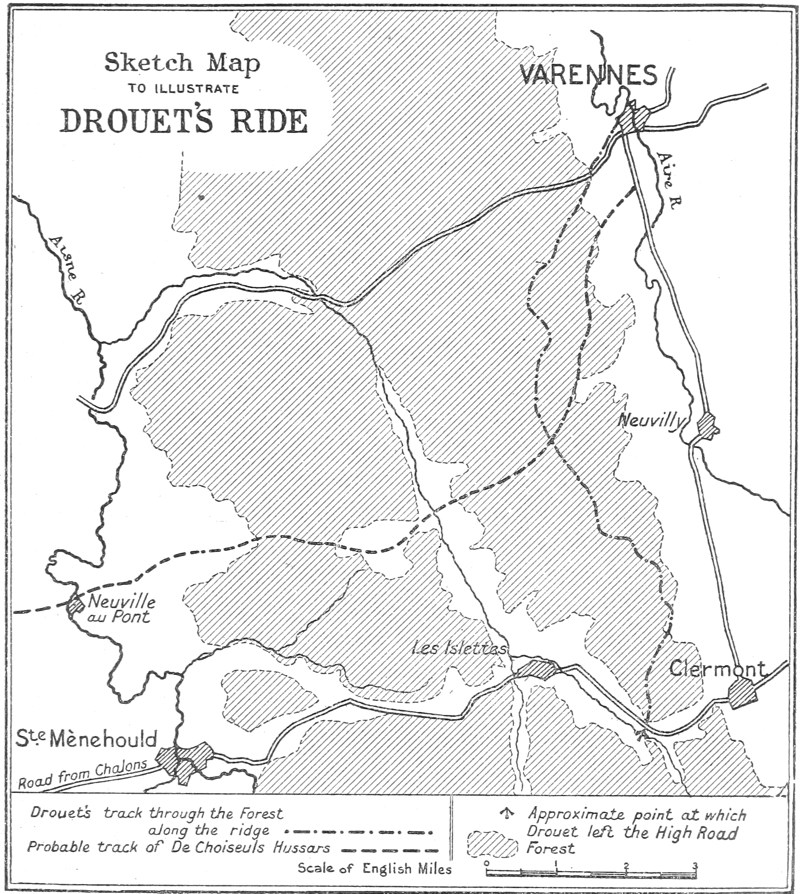

| Sketch Map to Illustrate Drouet’s Ride | 278 |

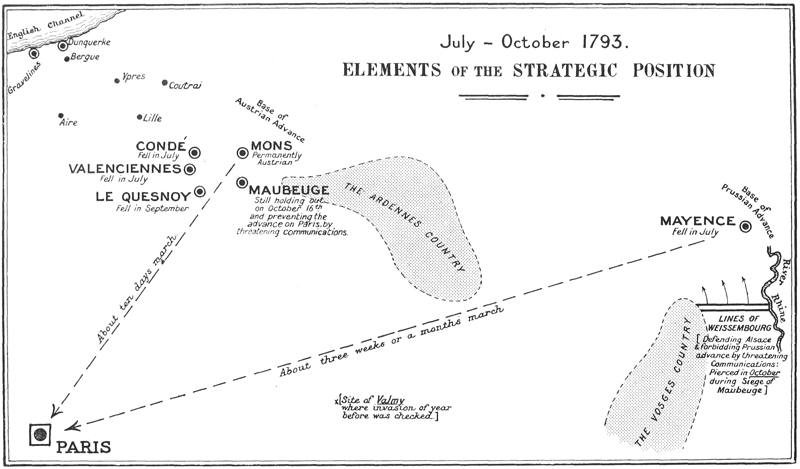

| Elements of the Strategic Position, July-October, 1793 | 359 |

| Battle of Wattignies, Oct. 15 and 16, 1793, and the Relief of Maubeuge | 377 |

EUROPE, which carries the fate of the whole world, lives by a life which is in contrast to that of every other region, because that life, though intense, is inexhaustible. There is present, therefore, in her united history a dual function of maintenance and of change such as can be discovered neither in any one of her component parts nor in civilisations exterior to her own. Europe alone of all human groups is capable of transforming herself ceaselessly, not by the copying of foreign models, but in some creative way from within. She alone has the gift of moderating all this violent energy, of preserving her ancient life, and by an instinct whose action is now abrupt, now imperceptibly slow, of dissolving whatever products of her own energy may not be normal to her being.

These dual forces are not equally conspicuous: the force that preserves us is general, popular, slow, silent, and beneath us all; the force that makes us diversified and full of life shines out in peaks of action.

The agents and the manifestations of the conserving force do not commonly present themselves as the chief personalities and the most remarkable events of our long record. The agents and the manifestations of the force that perpetually transform us are arresting figures, and catastrophic actions. Those who keep us what we are, for the most part will never be known—they are millions. Those, on the other hand, who have brought upon our race its great novelties of mood or of vesture, the battles they have won, the philosophies they have framed and imposed, the polities they have called into existence, they and their works fill history. That power which has forbidden us 2to perish uses servants often impersonal or obscure; it is mostly to be discovered at work in the permanent traditions of the populace, and its effects are but rarely visible until they appear solid and established by a process which is rather that of growth than of construction. That power which keeps the mass moving glitters upon the surface of it and is seen.

There are, nevertheless, in this perennial and hidden task of maintaining Europe certain exceptional events of which the date is clear, the result immediate, and the authors conspicuous. Of early examples the victory of Constantine in the fourth century, the defeat of Abdul Rhaman in the eighth, may be cited. Among the lesser ones of later times is a decision which was taken in the middle of the eighteenth century by the French and Austrian Governments, and to which historians have given the name of the Diplomatic Revolution.

To comprehend or even to follow the career of Marie Antoinette it is essential to seize the nature and the gravity of that rearrangement of national forces, for it determined all her life. To the great alliance between France and Austria by which such a rearrangement was effected she owed every episode of her drama. Her marriage, her eminence, her sufferings, and her death were each directly the consequence of that compact: its conclusion coincided with her birth; from childhood she was dedicated to it as a pledge, a bond, and, at last, a victim. Though, therefore, that treaty can occupy but little place in pages which deal with her vivid life—a life lived after the signing of the document and after its most noisy consequences had disappeared—yet the instrument must be grasped at the outset and must remain permanently in the mind of all who would understand the Queen of France and her disaster; for it was her mother who made the alliance; the statesman who presided over all her fortunes planned and achieved it. It stands throughout her forty years like a fixed horoscope drawn at birth, or a sentence pronounced and sure to be fulfilled.

The Diplomatic Revolution of the eighteenth century sprang, like every other major thing in modern history, from the religious schism of the sixteenth.

If that vast disturbance of the Reformation which threatened so grievously the culture of Europe, which maimed for ever the life of the Renaissance, and which is only now beginning to 3subside, had broken the national tradition of Gaul as it did that of Britain, it may confidently be asserted that European civilisation would have perished. There was not left on the shores of the Mediterranean a sufficient reserve of energy to re-indoctrinate the West. A welter of small States hopelessly separated by the violence and self-sufficience of the new philosophy would each have gone down the roads an individual goes when he forgets or learns to despise traditional rules of living and the corporate sense of mankind. That interaction which is the life of Europe would have disappeared. A short period of intense local activities would have been followed by a general repose. The unity of the Western world would have failed, and the spirit of Rome would have vanished as utterly from her deserted provinces as has that of Assyria from hers.

If, on the other hand, the French had chosen the earliest moment of the Reformation to lead the popular instinct of Europe against the Reformers and to re-establish unity, if as early as the reign of Francis I. (who saw the peril) they had imagined a species of crusade, why, then, the schism would have been healed by the sword, the humanity of the Renaissance would have become a permanent influence in our lives rather than an heroic episode whose vigour we regret but cannot hope to restore, and the discovery of antiquity, the thorough awakening of the mind, would have impelled Europe towards new and glorious fortunes the nature of which we cannot even conjecture, so differently did the course of history turn. For it so happened that the French—whose temperament, whose unbroken Roman legend, and whose geographical position made them the decisive centre of the struggle—the French hesitated for two hundred years.

Their religion indeed they preserved. The attempt to force upon the French doctrines convenient, in France as in England, to the wealthy merchants, the intellectuals and the squires, was met by popular risings; those of the French, as they were the more sanguinary so were also the more successful. The first massacre of St. Bartholomew, when the Catholic leaders were killed in the south, was not forgotten by the north; and after the second massacre of St. Bartholomew in Paris had avenged it, the Reformation could never establish in France that oligarchic polity which it ultimately imposed upon England 4and Holland. In a word, the Catholic reaction in France was sufficiently violent to recover the tradition of the State; but the full consequences of that reaction did not follow, nor did France support the general Catholic instinct of Europe outside the French boundaries, because, allied with the Faith to which the nation was so profoundly attached and had barely preserved, was the political power of the Spanish-Austrian Empire, which the French nation and its leaders detested and feared.

It is difficult for us to-day to comprehend the might of Spain during the century of the Reformation, and still more difficult to grasp that external appearance of overwhelming strength which, as the years proceeded, tended more and more to exceed her actual (and declining) power.

The supremacy of Spain over Europe resided in a dynasty and not in a national idea. It did not take the form of over-riding treaties or of attempting the partition of weaker States, for it was profoundly Christian, and it was military; in twenty ways the position of Spain differed from the hegemony which some modern European State might attempt to exercise over its fellows. But it is possible to arrive at some conception of what that Empire was if we remember that it reposed upon a vast colonial system which Spain alone seemed capable of conducting with success, that it monopolised the production of gold, and that it depended upon a command of the sea which was secured to it by an invincible fleet. To such advantages there must further be added an armed force not only by far the largest and best trained in Europe, but mainly composed of the best fighters as well, and—a circumstance more important than all the rest—an extent of dominion, due to the union of the Austrian and Spanish houses, which gave to Charles V. and his successors the whole background, as it were, upon which the map of Europe was painted: in the sea of that Emperor’s continental possessions, apart from a few insignificant principalities, France alone survived—an intact island with ragged boundaries, menaced upon every side. For the Emperor, then master of the Peninsula, of the Germanies, and of the New World, was everywhere by sea and almost everywhere by land a pressing foe.

However much this Spanish-Austrian power might stand (as it did stand) for European traditions and for the Faith of 5civilisation which France had elected to preserve, it was impossible for the French crown and nation not to be opposed to its political power if that crown and that nation were to survive. The smaller nations of the North—the English, the Low Countries, &c.—were in less peril than the French; for these were now the only considerable exception to, and were soon to be the rivals of, the Spanish-Austrian State. Had the Armada found fair weather, Philip might have been crowned at Westminster; but the English—united, isolated, and already organised as a commercial oligarchy—would have fought their way out from foreign domination as thoroughly as did the Dutch. The duty of the French was other; their independence was not threatened: it was rather their dignity and special soul which were in peril and which had to be preserved from digestion into this all-surrounding influence of Spain. To preserve her soul, France gave—unconsciously, perhaps, as a people, but with acute consciousness as a government—her whole energies during four generations. The defence succeeded. Through a dozen such civil tumults as are native to the French blood, and through a long eclipse of their national power, they treasured and built up their reserves. After a century of peril they emerged, under Louis XIV., not only the masters, but for a moment the very tyrants of Europe.

The French did not achieve this object of theirs without a compromise odious to their clear spirit. In their secular opposition to the Spanish-Austrian power, it was the business of their diplomatists to spare the little Protestant States and to use them as a pack for the worrying of great Austria, whom they dreaded and would break down. The constant policy of Henri IV., of Richelieu, of Mazarin, was to strengthen the Protestant principalities of North Germany, to meet half-way the rising Puritanism of England, and even at home to tolerate an organised opulent and numerous body of Huguenots who formed a State within the State. At a time when it was death to say Mass in England, the wealthy Calvinist just beyond the Channel—at Dieppe, for instance—was protected with all the force of the law from the fanaticism or indignation of his fellow-citizens; he could convene his synods openly, could hold office at law or in municipal affairs, and was even granted a special form of representation and a place in the advisory bodies of the State. All this was done, not to secure internal order—which 6would perhaps have been better affirmed in France, as it was in England, by the vigorous persecution of the minority—but to create a Protestant make-weight to what appeared till nearly the close of the seventeenth century the overwhelming menace of the Spanish and Austrian Houses.

Such was the policy which the French Court wisely pursued during so long a period that it finally acquired the force of a fixed tradition and threatened to last on into an era of new conditions, when it would prove useless or, later, harmful to the State. The general framework of that Anti-Austrian diplomacy did indeed survive from the latter seventeenth till the middle of the eighteenth century; but from the time when Louis XIV. in 1661 began to rule alone, to that final rearrangement of European forces in the Diplomatic Revolution, which it is my business to describe, the Catholic powers tended more and more to be conscious of a common fate and of a common duty. One after another the portions of the old French diplomatic work fell to pieces as the strength of Spain diminished and as the small Protestant States advanced in their cycle of rapid commercial expansion, increasing population and military power; until, a generation after Louis XIV.’s death, Protestant Europe as a whole had formed in line against what was left of Rome.

It would not be germane to my subject were I to enter at any length into the gradual transformation of Europe between 1668 and 1741. That first date is that of the treaty which closed the last clear struggle between France and Spain; the second date is that of the first great battle, Mollwitz, in which Prussia under Frederick the Great appeared as a triumphant and equal opponent against the Catholic forces of the Empire. It is enough to say that during that period the results of the great struggle were solidified. Europe was now hopelessly, and, as it seemed, finally riven asunder; and those who proposed to continue, those who proposed to disperse the stream of European tradition, gravitated into two camps armed for a struggle which is not even yet decided.

The transition may be expressed as the long life of a man—nay, it may be exactly expressed in the life of one man, Fleury, for he stood on the threshold of manhood at its commencement and in sight of death at its close: what such a long life witnessed, between its eighteenth and its ninetieth year, 7was—if the vast confusion of detail be eliminated and the large result be grasped—the confirmation of the great schism and the final decision of France to stand wholly against the North. There appeared at last, fixed and consolidated, a Protestant and a Catholic division in Europe whose opposing philosophies, seen or unseen, denied, ridiculed or ignored, even by those most steeped in either atmosphere, were henceforward to affect inwardly every detail of individual life as outwardly they were to affect every great event in the history of our race, and every general judgment which has been passed upon its actions.

The Spanish Power, based as it had been not on internal resources but on a mere naval and colonial supremacy, could not but rapidly decline; it had long been separated from the German Empire; it was destined to fall into the orbit of France. On the other hand, the England of the early eighteenth century was no longer a small community absorbed in theological discussion; she had become a nation of the first rank, one that was developing its industries, its wealth, and its armed strength. She boasted in Marlborough the chief military genius of the age; she was already the leader in physics; she was about to be the leader in mechanical science (with all the riches such a leadership would bring), and she was upon the eve of acquiring a new colonial empire.

In France the privileges of the Huguenots had been withdrawn as the situation grew precise and clear, and the breach between them and the nation was made final by their active and zealous treason in whatever foreign fleets or armies were attempting the ruin of their country. In England it had been made plain that the oligarchy, and the nation upon which it reposed, would admit neither a strong central government nor the presence of the Catholic Church near any seat of power: the Stuart dynasty had been exiled; its first attempt at a restoration had been crushed.

Meanwhile there was preparing a final argument which should compel men to recognise the clean and fixed division of Europe: that argument was the astonishing rise of Prussia, for with the appearance upon the field of this new and strange force—an own child of the Reform—it was evident that something had changed in the very morals of war.

When Austria was at her weakest, when the French Court, 8bewildered but weakly constant to a now meaningless diplomatic habit, was watching the apparent dissolution of the Empire and was ready to urge its armies against Vienna, when England remained, and that only from opposition to the Bourbons, the only support of the Hapsburgs, there was established within five years the permanent strength of Frederick the Great and the new factor of Prussian Power: a complete contempt for the old rules of honour in negotiation and for the old rules of contract in dynastic relations had been crowned by a complete success.

This advent, when every exception and cross-influence is forgotten, will remain the chief moral and, therefore, the chief political fact of the eighteenth century. By the end of the year 1745, Silesia was finally abandoned by Austria; the Prussian soldier and his atheist theory had compassed the first mere conquest of European territory which had been achieved by any European Power since first Europe had been organised into a family of Christian communities. It had been advanced for the first time that Europe was not one, but that some unit of it might overbear and rule another by arms alone; that there was no common standard nor any unseen avenger upon appeal. That theory had appealed to arms and had conquered.

Within three years the international turmoil, of which this catastrophe was immeasurably the greatest result, was subjected to a sort of settlement. One of those general committees of all Europe with which our own time is so familiar was summoned to Aix-la-Chapelle; representatives of the various Powers confirmed or modified the results of a group of wars, and in the autumn of 1748 affixed their signatures to a complete arrangement which was well known to be unstable, ephemeral, and insincere, but which was yet of tremendous import, for it marked (though in no dramatic manner) the end of an old world.

As the plenipotentiaries left their accomplished work and strolled out of the room which had received them, they were still grouped together by such weak and complex ties as the interests of individual governments might decide. When they met again after the next brief cycle of war, these men were arranged in a true order and sat opposing: for England, Prussia, and experiment of schism on the one side; for the belt of endurance on the other. Since that cleavage these two prime bodies, disguised under a hundred forms and hidden 9and confused by a welter of incidental and secondary forces, have remained opposing, attempting with fluctuating success each to determine the general fortunes of the world. They will so continue balanced and opposing until perhaps—by the action of some power neither of war nor of diplomacy—unity may be re-established and Europe again may live.

Of the men who so strolled out of the room at Aix one only, still young, had grasped in silence the necessity of the great change; he saw that Vienna and Paris must in the next struggle stand together and defend together their common civilisation and their resisting Faith. He not only perceived the advent of this great reversal in the traditions of the chanceries; he designed to aid it himself, to mould it and to determine its character. That he could then perceive of how large a movement his action was to be a part no historian can pretend, for at the time no one could grasp more than the momentary issue, and this man’s very profession made it necessary for him, as for every other diplomat, to see clearly immediate things and to abandon distant speculation. But though his work was greater than himself and far greater than his intention, yet he deserves a very particular attention; for this young man of thirty-six was Kaunitz, and he, for a whole generation, was Austria.

In so determining to effect an alliance between the Hapsburgs and their secular enemy, Kaunitz equally determined, unknown to himself, the whole fortunes of Marie Antoinette; she, years later, when she came to be born to the Imperial house, was, even in childhood, the pledge he needed. It is Kaunitz who stands forever behind the life of Marie Antoinette, like a writer behind the creature in his book. It is he who designs her marriage, who uses her without mercy for the purposes of his policy at Versailles; he is the author of her magnificence and of her intrigue; he is then also indirectly the author of her fall, which, in his obscure and failing old age, he heard of far away, partially comprehended, and just survived.

Kaunitz was the original of our modern diplomatists. In that epoch of governing families not a few nobles were flattered to be called “the Coachmen of Europe”: he alone merited the cant term. He served a sovereign whose armies were constantly defeated; he was the adviser of a mere crown—and that crown worn by a woman; in a time when the divergent races of the 10Danube were first astir, he had at his command or for his support neither a national tradition nor any strong instrument of war, yet, by personal genius, by tenacity, and by a wide lucidity of vision, he discovered and completed a method of “government through foreign relations” which was almost independent of national feeling or of armed strength.

An absence of natural violence, as of all common emotions, was characteristic of Kaunitz. He disdained the vulgar pomp of silence; he talked continually; he knew the strength and secrecy of men who can be at once verbose and deliberate. Nor could his fluency have deceived any careful observer into a suspicion of weakness, for his curved thin nose and prominent peaked chin, his arched eyebrows, his Sclavonic type, ready and courageous, his hard, pale eyes, showed nothing but purpose and execution; and as his tall figure stalked round the billiard tables at evening, his very recreation seemed instinct with plans.

The abounding energy which drove him to success revealed itself in a thousand ways, and chiefly in this, that in the career of diplomacy, where all individuality is regarded with dread, he pushed his personal tastes beyond the eccentric. Thus he had a mania against all gesticulation, and he would present at every conference the singular spectacle of a man chattering and disputing unceasingly and eagerly, yet keeping his hands quite motionless all the while. Again, when he entered the great houses of Europe and dined with men to influence whom was to conduct the world, he did not hesitate to bring with him his own dessert, which when he had eaten he would, to the great disgust of embassies, elaborately wash his teeth at table. In the midst of the hardest toil he was so foppish as to wear various wigs—now brown, now white, now auburn. He was a constant traveller, familiar with every capital in Western Europe, yet he so loathed fresh air that he would not pass from his carriage to a palace door unless his mouth were covered. He was a dandy who, in drawing-rooms loaded with scent and flowers, loudly protested against all perfume; a gentleman who, when cards were the only pastime of the rich, expressed a detestation of all hazard; a courtier who, amidst all the extravagancies of etiquette of the eighteenth century, barely bowed to the greatest sovereigns, and who, on the stroke of eleven, would abruptly leave the Emperor without a word.

11Such marks of an intense initiative, detachment, and pride were tolerated in the earlier part of his life with amusement on account of the affection he could inspire; later they were regarded with ill ease, and at last with a sort of awe, when it was known that his intelligence could entrap no matter what combination of antagonists. This intelligence, and the single devotion by which such natures are invariably compelled, were both laid at the feet of Maria Theresa.

He was older than his Empress by some seven years; there lay between them just that space which makes for equality and comprehension between a man and a woman. The year of her marriage had coincided with that of his own; he had come at twenty-five to the court of this young sovereign of eighteen. She had recognised—with a wisdom that never failed her long and active life—how just and general was his view of Europe, and it was from this moment that her interests and her career were entrusted to his genius. He had already studied in three universities, had refused the clerical profession to which his Canonry of Munster introduced him, and had travelled in the Netherlands, in France, in England, and in Italy, where he was made Aulic Councillor, and enfeoffed, as it were, to the palace.

His abilities had not long to await their opportunity. It was but four years after Maria Theresa’s marriage and his own that she succeeded to the throne and possessions of the Hapsburgs: then it was the sudden advent of Prussia, to which I have alluded, began the great change.

Maria Theresa’s succession was in doubt, not in point of right, but because her sex and the condition in which her father had left his army and his treasury gave an opportunity to the rivals of Austria, and notably to France.

Europe was thus passing through one of those crises of instability during which every chancery discounts and yet dreads a universal war, when the magazine was fired by one who had nothing to lose but honour. Frederick of Prussia was the warmest in acknowledging the title of Maria Theresa; he accepted her claims, guaranteed the integrity of her possessions, and suddenly invaded them.

From the ordering of that march of Frederick’s into Silesia—from the close, that is, of the year 1740—Kaunitz, a man not yet in his thirtieth year, was at work to repair the Empire and 12to restore the equilibrium of Europe. Upon the whole he succeeded; for though the magnitude of the Revolutionary Wars has dwarfed his period, and though the complete modern transformation of society has made such causes seem remote, yet (as it is the thesis of these pages to maintain) Kaunitz unconsciously preserved the unity of Europe.

In the beginning of the struggle he had already saved the interests of Maria Theresa in the petty Italian courts. At Florence, at Rome, at Turin, at Brussels, his mastery continued to increase. In his thirty-sixth year he was ambassador to London—he concluded, as we have seen, the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle; by his fortieth he had been appointed to Paris, and that action by which he will chiefly be remembered had begun. He had seen, as I have said, the necessity for an alliance between the two great Catholic Powers. Within the two years of his residence in Paris he had successfully raised the principle of such a revolution in policy and as successfully maintained its secrecy. A task which would have seemed wholly vain had he communicated it to others, one which would have seemed impossible even to those whom he might have convinced, was achieved. To his lucid and tenacious intellect the matter in hand was but the bringing forth of a tendency already in existence; he saw the Austro-French alliance lying potentially in the circumstances of his time; his business was but to define and realise it.

In such a mood did he take up the Austrian Embassy in Paris. He was well fitted for the work he had conceived. The magnificence which he displayed in his palace in the French capital was calculated indeed to impress rather than to attract the formal court of Versailles; that magnificence was the product of his personal tastes rather than of his power of intrigue, but the details of his over-ostentatious household were well suited to those whom he had designed to capture. The French language was his own; Italian, though he spoke it well, was foreign to him; the German dialects he knew but ill and hardly used at all. His habits were French, to the end of his long life French literature was his only reading, and his clothes, to their least part, must come from the hands of the French.

MARIA THERESA

FROM THE TAPESTRY PORTRAIT WOVEN FOR MARIE ANTOINETTE AND RECENTLY RESTORED

TO VERSAILLES

He moved, therefore, in that world of Paris and Versailles (as did, later, his pupil, Mercy-d’Argenteau) rather as a native than a foreigner. Even if the alliance had been as artificial as 13it was natural, he would have carried his point. As it was, he left Paris in 1753 to assume the Prime Ministry at Vienna with the certitude that, when next Frederick of Prussia had occasion to break his word, the wealth and the arms of the Bourbons would be ranged upon the Austrian side.

Upon that major pivot all the schemes of Vienna must turn at his dictation. Every marriage must be contrived so as to fall in with the projected alliance; every action must be subordinated to the arrangement which would prove, as he trusted, the supreme hope of the dynasty. To this one project he directed every power within him or beneath his hand, and to this he was ready, when the time should come, to sacrifice the fortunes of any member of the Royal House save its sovereign or its heir. To this aspect of Europe, long before the termination of his mission in Paris, he had not so much persuaded as formed the mind of Maria Theresa.

The great and salutary soul of that woman explains in part what were to be the fortunes of her youngest child. Not that Marie Antoinette inherited either the opportunities or the full excellence of her mother, but that there ran through the impatient energy and unfruitful graciousness of the Queen of France a flavour of that which had lent a disciplined power and a conscious dignity to the middle age of Maria Theresa.

The body of the Empress was strong. Its strength enabled her to bear without fatigue the ceaseless work of her office, and in the midst of child-bearing to direct with exactitude the affairs of a troubled State. That strength of hers was evident in her equal temper, her rapid judgment, her fixed choice of men; it was evident also in her firm tread and in her carriage, and even as she sat upon a chair at evening she seemed to be governing from a throne.

A growing but uniform capacity informed her life. She had known the value not only of industry but also of enthusiasm, and had saved her throne in its greatest peril by her sudden and passionate appeal to the Hungarians. It was this instinctive science of hers that had disarmed Kaunitz. If he allowed her to suggest what he had already determined, if he permitted her to be the first to write down the scheme of the Diplomatic Revolution he had conceived, and to send it down to history as her creation rather than his own, it was not the desire to flatter 14her that moved him but a recognition of her due. She it was that sent him to Paris and she that superintended the weaving of the loom he had arranged.

Her dark and pleasing eyes, sparkling and strong, controlled him in so far as he was controlled by any outer influence, for he recognised in them the Cæsarian spirit.

Her largeness pleased him. When she played at cards, she played for fortunes; when she rode, she rode with magnificence; when she sang, her voice, though high, was loud, untrammelled, and full; when she drove abroad, it was with splendour and at a noble turn of speed.

All this was greatly to the humour of Kaunitz, and he continued to serve his Empress with a zeal he would never have given to a mere ambition. In deference to her, all that he could control of his idiosyncrasies he controlled. His great bull-dog, which followed him to every other door, was kept from her palace. His abrupt speech, his failure to reply, his sudden and brief commands—all his manner—were modified in consultation with his Queen. She, on her part, knew what were the limits to which so singular a nature could proceed in the matter of self-denial. She respected half his follies, and her servants often saw her from the courtyard shutting the windows, smiling, as he ran from his carriage, his mouth covered to screen it from the outer air. Her common sense and poise forgave in him alone extravagances she had little inclination to support in others. He respected in her those depths of emotion, of simplicity, and of faith which in others he would have regarded as imbecilities ready for his high intelligence to use at will.

It was neither incomprehensible to him nor displeasing that her temper should be warmer than his intelligence demanded. The increasing strength of her religion, the personal affections and personal distastes which she conceived, above all, the closeness of her devotion to her husband, completed, in the eyes of Kaunitz, a character whose dominions and dynasty he chose to serve and to confirm; for he perceived that what others imagined to be impediments to her policy were but the reflection of her sex and of her health therein.

Kaunitz saw in Frederick of Prussia a player of worthy skill. It was upon the death of that soldier that he gave vent to the one emotional display of his life; yet he permitted Maria 15Theresa to hate her rival with a hatred which was not directed against his campaigning so much as against the narrow intrigue and bitterness of his evil mind.

To Kaunitz, again, Catherine of Russia was nothing but a powerful rival or ally; yet he approved that Maria Theresa should speak of her as one speaks of the women of the streets, despising her not for her ambition but for her licence.

To Kaunitz, Francis of Lorraine, the husband of the Empress, was a thing without weight in the international game; yet he saw with a general understanding, and was glad to see in detail, the security of the imperial marriage.

The singular happiness of Maria Theresa’s wedded life was due to no greatness in Francis of Lorraine, but to his vivacity and good breeding, to his courtesy, to his refinement, and especially to his devotion. It suited her that he should ride and shoot so well. She loved the restrained intonation of his voice and the frankness of his face. She easily forgave his numerous and passing infidelities. The simplicity of his religion was her own, for her goodness was all German as his sincerity was all Western and French; upon these two facets the opposing races touch when the common faith introduces the one to the other. Their household, therefore, was something familiar and domestic. Its language was French, of a sort, because French was the language of Francis; but while he brought the clarity of Lorraine under that good roof, which covered what Goethe called “the chief bourgeois family of Germany,” he brought to it none of the French hardness and precision, nor any of that cold French parade which was later to exasperate his daughter when she reigned at Versailles. He was a man who delighted in visits to his country-side, and who would have his carriage in town wait its turn with others at the opera doors.

Maria Theresa was so wedded, served by such a Minister, in possession of and in authority over such a household during those seven years between the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle and the French Alliance, between 1748 and 1755. These seven years were years of patience and of diplomacy, which were used to retrieve the disasters of her first bewildered struggle against Prussia and the new forces of Europe. They were the seven years of profound, if precarious, international peace, when England was preparing her maritime supremacy, Prussia her full military 16tradition, the French monarchy, in the person of Louis XV., its rapid dissolution through excess and through fatigue. They were the seven years which seemed to the superficial but acute observation of Voltaire to be the happiest of his age: a brief “Antonine” repose in which the arts flourish and ideas might flower and even grow to seeding. They were the seven years in which the voice of Rousseau began to be heard and in which was written the Essay upon Human Inequality.

For the purposes of this story they were in particular the seven years during which Kaunitz, now widowed, working first as ambassador in Paris, then as Prime Minister by the side of Maria Theresa at Vienna, achieved that compact with the Bourbons which was to restore the general traditions of the Continent and the fortunes of the House of Hapsburg.

The period drew to a close: the plans for the alliance were laid, the last discussions were about to be engaged, when it was known, in the early summer of 1755, that the Empress was again with child.

ALL that summer of 1755 the intrigue—and its success—proceeded.

I have said that the design of Kaunitz was not so much to impose upon his time a new plan as to further a climax to which that time was tending. Accidents in Europe, in America, and upon the high seas conspired to mature the alliance.

Fighting broke out between the French and English outposts in the backwoods of the colonies. Two French ships had been engaged in a fog off the banks and captured; later, a sharp panic had led the Cabinet in London to order a general Act of Piracy throughout the Atlantic against French commerce. It was a wild stroke, but it proved the first success of what was to become the one fundamentally successful war in the annals of Great Britain.

In Versailles an isolated and mournful man, fatigued and silent, who was in the last resort the governing power of France, delayed and delayed the inevitable struggle between his forces and the rising power of England. Louis XV. looked upon the world with an eye too experienced and too careless to consider honour. His clear and informed intelligence would contemplate—though it could not remedy—the effects of his own decline and of his failing will. He felt about him in the society he ruled, and within himself also, something moribund. France at this moment gave the impression of a great palace, old and in part ruined. That impression of France had seized not only upon her own central power, but upon foreign observers as well; the English squires had received it, and the new Prussian soldiers. In Vienna it was proposed to use the declining French monarchy as a great prop, and in using it to strengthen and to 18revivify the Austrian Empire until the older order of Europe should be restored. Louis XV., sitting apart and watching the dissolution of the national vigour and of his own, put aside the approach of arms with such a gesture as might use a man of breeding whom in some illness violence had disturbed. Thus as late as August, when his sailors had captured an English ship of the line, he ordered its release. The war was well ablaze, and yet he would consent to no formal declaration of it: Austria watched his necessities.

It was in September that Maria Theresa sent word to her ambassador in Paris—the old and grumbling but pliant Stahremberg—that the match might be set to the train: in a little house under the terrace at Bellevue, a house from whose windows all Paris may be seen far away below, the secret work went on.

It has been asserted that the Empress in her anxiety wrote to the Pompadour and attempted, by descending to so direct a flattery of Louis XV.’s mistress, to hasten that King’s adhesion to her design. The accusation is false, and the document upon which it is based a forgery; but the Austrian ambassador was Maria Theresa’s mouthpiece with that kindly, quiet, and all-powerful woman. It was she who met him day after day in the little house, and when she retired to give place to the Cardinal de Bernis, that Minister found the alliance already fully planned between Stahremberg and the Pompadour. Louis XV. alone was still reluctant. Great change, great action of any sort was harsh to him. He would not believe the growing rumour that Frederick of Prussia was about to desert his alliance and to throw his forces on to the side of the English Power. Louis XV. attempted, not without a sad and patient skill, to obtain equilibrium rather than defence. He would consider an arrangement with Vienna only if it might include a peaceful understanding with Berlin.

MADAME DE POMPADOUR

FROM THE PORTRAIT BY BOUCHER IN THE NATIONAL GALLERY AT EDINBURGH

As, during October, these negotiations matured so slowly in France, in Vienna the Empress awaited through that month the birth of her child. She jested upon it with a Catholic freedom, laid wagers upon its sex (and later won them), discussed what sponsors should be bidden, and decided at last upon the King and Queen of Portugal; to these, in the last days of October, her messengers brought the request, and it was gladly accepted 19in their capital of Lisbon. Under such influences was the child to be born.

The town of Lisbon had risen, in the first colonial efforts of Portugal, to a vast importance. True, the Portuguese did not, as others have done, attach their whole policy to possessions over-sea, nor rely for existence upon the supremacy of their fleet, but the evils necessarily attendant upon a scattered commercial empire decayed their military power, and therefore at last their commerce itself. The capital was no longer, in the Arab phrase, “the city of the Christians”; it was long fallen from its place as the chief port of the Atlantic when, in these last days of October 1755, the messengers of the Empress entered it and were received; but it was still great, overlooking the superb anchorage which brought it into being, and presenting to the traveller perhaps half the population which it had boasted in the height of its prosperity. It was a site famous for shocks of earthquake, which (by a coincidence) had visited it since the decline of its ancient power; but of these no more affair had been made than is common with natural adventures. Its narrow streets and splendid, if not majestic, churches still stood uninjured.

The valley upon which stood the commercial centre of Lisbon is formed of loose clay; the citadel and the portion which to this day recalls the older city, of limestone; and the line which limits the two systems is a sharp one. But though the diversity of such a soil lent to these tremors an added danger, they had passed without serious attention for three or four generations; they had not affected the architecture of the city nor marred its history. In this year, 1755, they had already been repeated, but in so mild a fashion that no heed was taken of them.

By All-Hallow’een the heralds had accomplished their mission, the Court had retired to the palace of Belem, which overlooks the harbour, and the suburbs built high beyond that Roman bridge which has bequeathed to its valley the Moorish name of Alcantara. The city, as the ambassadors of Maria Theresa and the heralds of her daughter’s birth were leaving it, was awaiting under the warm and easy sun of autumn the feast of the morrow.

In the morning of that All Saints, a little after eight, the altars stood prepared; the populace had thronged into the 20churches; the streets also were already noisy with the opening of a holiday; the ships’ crews were ashore; only the quays were deserted. Everywhere High Mass had begun. But just at nine—at the hour when the pressure of the crowds, both within the open doors of the churches and without them, was at its fullest—the earth shook.... The awful business lasted perhaps ten seconds. When its crash was over an immense multitude of the populace and a third of the material city had perished.

The great mass of the survivors ran to the deserted quays, where an open sky and broad spaces seemed to afford safety from the fall of walls. They saw the sea withdrawn from the shore of the wide harbour; they saw next a wave form and rise far out in the land-locked gulf, and immediately it returned in an advancing heap of water straight and high—as high and as straight as the houses of the sea front. It moved with the pace of a gust or of a beam of light towards the shore. The thousands crammed upon the quays had barely begun their confused rush for the heights when this thing was upon them; it swirled into the narrow streets, tearing down the shaken walls and utterly sweeping out the maimed, the dying, and the dead whom the earthquake had left in the city. Then, when it had surged up and broken against the higher land, it dragged back again into the bay, carrying with it the wreck of the town and leaving, strewn on the mud of its retirement, small marbles, carven wood, stuffs, fuel, provisions, and everywhere the drowned corpses of animals and of men. During these moments perhaps twenty, perhaps thirty thousand were destroyed.

Two hours passed: they were occupied in part by pillage, in part by stupefaction, to some extent by repression and organisation. But before noon the accompaniment of such disasters appeared. Fire was discovered, first in one quarter of the city, then in another, till the whole threatened to be consumed. The disorder increased. Pombal, an atheist of rapid and decided thought, dominated the chaos and controlled it. He held the hesitating Court to the ruins of the city; he organised a police; as the early evening fell over the rising conflagration he had gibbets raised at one point after another, and hung upon them scores of those who had begun to loot the ruins and the dead.

The night was filled with the light and the roar of the flames 21until, at the approach of morning, when the fires had partly spent themselves and the cracked and charred walls yet standing could be seen more clearly in the dawn, some in that exhausted crowd remembered that it was the Day of the Dead, and how throughout Catholic Europe the requiems would be singing and the populace of all the cities but this would be crowding to the graves of those whom they remembered.

That same day, which in Lisbon overlooked the clouds of smoke still pouring from broken shells of houses, saw in Vienna, as the black processions returned from their cemeteries, the birth of the child.

Maria Theresa, whose vigour had been constant through so many trials, suffered grievously in this last child-bed of hers. She was in her thirty-seventh year. The anxiety and the plotting of the past months, the fear of an approaching conflict, had worn her. It was six weeks before she could hear Mass in her chapel; and meanwhile, in spite of the official, and especially the popular, rejoicing which followed the birth of the princess, a sort of hesitation hung over the Court. Francis of Lorraine was oppressed by premonitions. With that taint of superstition which his Faith condemned, but which the rich can never wholly escape, he caused the baby’s horoscope to be drawn. The customary banquet was foregone. The dreadful news from Lisbon added to the gloom, and something silent surrounded the palace as the days shortened into winter.

With the New Year a more usual order was re-established. The life of the Court had returned; the first fortnight of January passed in open festivities, beneath the surface of which the steady diplomatic pressure for the French alliance continued. It reached an unexpectedly rapid conclusion. Upon the 16th of January the King of Prussia suddenly admitted to the French ambassador at Berlin that he had broken faith with Louis and that the Prussian Minister in London had signed a treaty with England. For a month a desperate attempt continued to prevent the enormous consequences which must follow the public knowledge of the betrayal. The aversion of Louis to all new action, his mixture of apathy and of judgment, led him, through his ambassador, to forget the insult and to cling to the illusion of peace; but Frederick himself destroyed that illusion. His 22calculation had been the calculation of a soldier in whom the clear appreciation of a strategical moment, the resolution and courage necessary to use it, and an impotence of the chivalric functions combined to make such decisions absolute. It was the second manifestation of that moral perversion which has lent for two hundred years such nervous energy to Prussia, and of which the occupation of Silesia was the first, Bismarck’s forgery at Ems the latest—and probably the final—example: for Europe can always at last expel a poison.

Frederick, I say, was resolved upon war. He met every proposal for reconciliation with German jests somewhat decadent and expressed in imperfect French, which was his daily language. By the end of February 1756 the attempt to keep the peace of Europe had failed, and Louis XV., driven by circumstances and necessity, had at last accepted the design of Maria Theresa and of Kaunitz. The treaty would have been signed in March had not the illness of the French Minister, the Cardinal De Bernis, intervened; as it was, the signatures were affixed to the document on the 1st of May. By summer all Europe was in arms. The little Archduchess, who was later to lay down her life in the chain of consequence which proceeded from that signing, was six months old.

The first seven years of Marie Antoinette’s life were, therefore, those of the Seven Years’ War.

As her mind emerged into consciousness, the rumours she heard around her, magnified by the gossip of the servants to whom she was entrusted, were rumours of sterile victories and of malignant defeats; in the recital of either there mingled perpetually the name of the Empire and the name of Bourbon which she was to bear. She could just walk when the whole of Cumberland’s army broke down before the French advance and accepted terms at Kloster-Seven. Her second birthday cake was hardly eaten before Frederick had neutralised this capitulation by destroying the French at Rosbach. The year which saw the fall of Quebec and the French disasters in India was that with which her earliest memories were associated. She could remember Kunersdorf, the rejoicings and the confident belief that the Protestant aggression was repelled. Her fifth, her sixth, her seventh years—the years, that is, during which the first clear experience of life begins—proved the folly of that 23confidence; her eighth was not far advanced when the whole of this noisy business was concluded by the Peace of Paris and the Treaty of Herbertsburg.

The war appeared indecisive or a failure. The original theft of Silesia was confirmed to Prussia, the conquest of the French colonies to England. In their defensive against the menace to which all European traditions were exposed, the Courts of Vienna and Versailles had succeeded; in their aggressive, which had the object of destroying that menace for ever, they had failed. In failing in their aggressive, as a by-product of that failure, they had permitted the establishment of an English colonial system which at the time seemed of no great moment, but which was destined ultimately to estrange this country from the politics of Europe and to submit it to fantastic changes; to make its population urban and proletariat, to increase immensely the wealth of its oligarchy, and gravely to obscure its military ideals. In the success of their defensive, as by-products of that success, they had achieved two things equally unexpected: they had preserved for ever the South-German spirit, and had thus checked in a remote future the organisation of the whole German race by Prussia and the triumph over it of Prussian materialism; they had preserved to France an intensive domestic energy which was shortly to transform the world.

The period of innocence then and of growth, which succeeds a child’s first approach to the Sacraments, corresponded in the life of Marie Antoinette with the peace that followed these victories and these defeats. The space between her seventh and her fourteenth years might have been filled, in the leisure of the Austrian Court, with every advantage and every grace. By an accident, not unconnected with her general fate, she was allowed to run wild.

That her early childhood should have been neglected is easier to understand. The war occupied all her mother’s energies. She and her elder sister Caroline were the babies whose elder brother Joseph was already admitted to affairs of State. It was natural that no great anxiety upon their education should have been felt in such times. The child had been put out to nurse with the wife of a small lawyer of sorts, one Weber, whose son—the foster-brother of the Queen—has left a pious and inaccurate memorial of her to posterity. Here she first learnt 24the German tongue, which was to be her only idiom during her childhood; here also she first heard her name under the form of “Maria Antonietta,” a form which was to be preserved until her marriage was planned.

Such neglect, or rather such domesticity, would have done her character small hurt if it had ceased with her earliest years and with the conclusion of the peace; it was no better and no worse than that which the children of all the wealthy enjoy in the company of inferiors until their education begins. But the little Archduchess, even when she had reached the age when character forms, was still undisciplined and at large. There was found for her and Caroline a worthy and easy-going governess in the Countess of Brandweiss, an amiable and careless woman, who perhaps could neither teach nor choose teachers and who certainly did not do so.

All the warmer part of the year the children spent at Schoenbrünn; it was only in the depth of winter that they visited the capital. But whether at Court or in the country they were continually remote from the presence and the strong guidance of Maria Theresa.

The Empress saw them formally once a week; a doctor daily reported upon their health; for the rest all control was abandoned. The natural German of Marie Antoinette’s babyhood continued (perhaps in the very accent of her domestics) to be the medium of her speech in her teens, and—what was of more importance for the future—not only of her speech but of her thought also. In womanhood and after a long residence abroad the mechanical part of this habit was forgotten; its spirit remained. What she read—if she read anything—we cannot tell. Her music alone was watched. Her deportment was naturally as graceful as her breeding was good; but the seeds of no culture were sown in her, nor so much as the elements of self-control. Her sprightliness was allowed an indulgence in every whim, especially in a talent for mockery. She acquired, and she desired to acquire, nothing. No healthy child is fitted by nature for application and study; upon all such must continuous habits be enforced—to her they were not so much as suggested. A perpetual instability became part of her, and unhappily this permanent weakness was so veiled by an inherited poise and by a happy heart that her mother, in her rare 25observations, passed it by. Before Marie Antoinette was grown a woman that inner instability had come to colour all her mind; it remained in her till the eve of her disasters.

It is often discovered, when an eager childhood is left too much to its own ruling, that the mind will, of its own energy, turn to the cultivation of some one thing. Thus in Versailles the boyhood of the lonely child, who was later to be her husband, had turned for an interest to maps and had made them a passion. With her it was not so. The whole of her active and over-nourished life lacked the ballast of so much as a hobby. She was precisely of that kind to whom a wide, careful, and a conventional training is most useful; precisely that training was denied her.

The disasters and, what was worse, the unfruitfulness of the war had not daunted Maria Theresa, but her plans were in disarray. The two years that succeeded the peace produced no definite policy. No step was taken to confirm the bond with France or to secure the future, when there fell upon the Empress the blow of her husband’s death; he had fallen under a sudden stroke at Innsbruck, during the wedding feast of his son, leaving to her and to his children not only the memory of his peculiar charm, but also a sort of testament or rule of life which remains a very noble fragment of Christian piety.

Before he set out he remembered his youngest daughter; he asked repeatedly for the child and she was brought to him. He embraced her closely, with some presentiment of evil, and he touched her hair; then as he rode away among his gentlemen he said, with that clear candour which inhabits both the blood and the wine of Lorraine, “Gentlemen, God knows how much I desired to kiss that child!” She had been his favourite; there was a close affinity between them. She was left to her mother, therefore, as a pledge and an inheritance, and Maria Theresa, whose mourning became passionate and remained so, was ready to procure for this daughter the chief advantages of the world.

The loss of her husband, while it filled her with an enduring sorrow, also did something to rouse and to inspire the Empress with the force that comes to such natures when they find themselves suddenly alone. The little girl upon whom her ambitions were already fixed, the French alliance which had been, as it 26were, the greatest part of herself, mixed in her mind. Maria Theresa had long connected in some vague manner the confirmation of the alliance with some Bourbon marriage—in what way precisely or by what plan we cannot tell; her ambassador has credited her with many plans. It is probable that none were developed when, a few weeks after the Emperor’s death, there happened something to decide her. The son of Louis XV., the Dauphin, was taken ill and died before the end of the year 1765. He left heir to the first throne in Europe his son, a lanky, silent, nervous lad of eleven, and that lad was heir to a man nearer sixty than fifty, worn with pleasures of a fastidious kind, and with the despair that accompanies the satisfaction of the flesh. A great eagerness was apparent at Versailles to plan at once a future marriage for this boy and to secure succession. Maria Theresa determined that this succession should reside in children of her own blood.

Nationality was a conception somewhat foreign to her, and as yet of no great strength in her mixed and varied dominions. How powerful it had ever been in France, what a menace it provided for the future of the French Monarchy, she could not perceive. Of the silent boy himself, the new heir, she knew only what her ambassador told her, and she cared little what he might be; but she saw clearly the Bourbons, a family as the Hapsburgs were a family, a bond in Catholic Europe with this boy the heir to their headship. She saw Versailles as the pinnacle still of whatever was regal (and therefore serious) in Europe. She determined to complete by a marriage the alliance already effected between that Court and her own.

THE FIRST DAUPHIN: (THE FATHER OF LOUIS XVI)

She knew the material with which she had to deal: Louis XV., clear sighted, a great gentleman, sensual, almost lethargic, loyal. She had understood the old nonentity of a Queen keeping her little place apart; the King’s spinster-daughters struggling against the influence of mistresses. She understood the power of the Prime Minister Choiseul, with whose active policy the King had so long allowed his power to be merged; she knew how and why he was Austrian in policy, and she forgave him his attack upon the Church. Though Choiseul had not made the alliance he so used it, and above all so maintained it after the doubtful peace, that he almost seemed its author, as later he seemed—though he took so little 27action—the author of her daughter’s marriage. She did not grudge the French Minister such honours. She weighed the historic grandeur of the royal house, and what she believed to be its certain future. She sketched in her mind, with Kaunitz at her side, the marriage of the two children as, years before, she had sketched the alliance.

It was certain that Versailles would yield, because Versailles was a man who, for all his lucidity and high training, never now stood long to one effort of the will; but just because Louis XV. had grown into a nature of that kind, it needed as active, as tenacious, and as subtle a mind as Maria Theresa’s to bring him to write or to speak. Writing or speaking in so grave a matter meant direct action and consequence; he feared such responsibilities as others fear disaster.

It is in the spirit of comedy to see this dignified and ample woman—perhaps the only worthy sovereign of her sex whom modern Europe has known—piloting through so critical a pass the long-determined fortunes of her daughter. There is the mother in all of it. That daughter had imperilled her life. The child was the last of nine which she had borne to a husband whose light infidelities she now the more forgave, whose clear gentility had charmed her life, whose religion was her own, and in respect to whose memory she was rapidly passing from a devotion to an adoration. The day was not far distant when she would brood in the vault beside his grave.

The old man Stahremberg was yielding his place (with some grumbling) to Mercy. He was still the Austrian ambassador at Paris; but his term was ending. Maria Theresa would perhaps in other times have spared his pride, and would not have given him a task upon which he must labour but which his successor would enjoy; but in the matter of her little Archduchess she would spare no one. She had hinted her business to Stahremberg before the Dauphin’s death; the spring had hardly broken before she was pressing him to conclude it. Up to his very departure her importunity pursued him. When Mercy was on the point of entering his office (in the May of 1766), Stahremberg, in the last letter sent to the Empress from Paris before his return, told her that her ship was launched. “She might,” he wrote, “accept her project as assured, from the tone in which the King had spoken of it.”

28Maria Theresa had too firm and too smiling and too luminous an acquaintance with the world to build upon such vague assurance. The dignity of the French throne was too great a thing to be grasped at. It must be achieved. When old Mme. Geoffrin passed through Vienna in that year, Maria Antonietta was kept in the background off the stage—but France was cultivated. The baby, who was Louis XV.’s great-grand-daughter, Theresa, Leopold’s daughter, was presented to that old and wonderful bourgeoise and made much of. They joked about taking her to France; another baby, after all not much older, only eight years older, was going to that place in her time.

And, meanwhile, the common arts by which women of birth perfect their plans for their family were practised in the habitual round. The little girl’s personality, all gilded and framed, was put in the window of the Hapsburgs. She was wild perhaps, but so good-hearted! In the cold winter you heard of (all winters are cold in Vienna) she came up in the drawing-room, where the family sat together, and begged her mother to accept of all her savings for the poor—fifty-five ducats.

Little Mozart had come in to play one night; he had slipped upon the unaccustomed polish of the floor. The little Archduchess, when all others smiled, had alone pitied and lifted him! Maria Theresa met the French ambassador and told him in the most indifferent way how her youngest, when she was asked whom (among so many nations) she would like to rule, had said, “The French, for they had Henri IV. the Good and Louis XIV. the Great.” Weary though he was of such conventionalities, the ambassador was bound by the honour of his place to repeat them.

There still stood, however, in this summer of 1766, between the Empress’s plan and its fruition a power as feminine, as perspicuous, and as exact in calculation as her own. The widow of the Dauphin, the mother of the new heir at Versailles, opposed the match.

She would not retire, as the Queen, her mother-in-law, had done, into dignity and nothingness, nor would she admit—so tenacious of the past are crowns—that the Bourbons and the Hapsburgs had all the negotiations between them. She was of the Saxon House, and though it was but small—a northern bastion, as it were, of the Catholic Houses—yet she had inherited the tradition 29of monarchy, and she might, but for her husband’s sudden death, have inherited Versailles itself. She was still young, vigorous, and German. She had determined not only that her son, the new heir, should marry into her house—should marry his own cousin, her niece—but that he should marry as she his mother chose, and not as the Hapsburgs chose. He was at that moment (in 1766) not quite twelve; the bride whom she would disappoint not quite eleven years old! But her plan was active and tenacious, her readiness alive, when in the beginning of the following year, in March 1767, she in her turn died, and with her death that obstacle to the fate of the little Archduchess also failed.

With every date, as you mark each, it will be the more apparent that the barriers which opposed Marie Antoinette’s approach to the French throne failed each in turn at the climax of its resistance, and that her way to such eminence and such an end was opened by a number of peculiar chances, all adjutants of doom.

The House of Hapsburg was never a crowned nationality; it was and is a crowned family and nothing more. Its states were and are attached to it by no common bond. There is no such thing as Austria: the Hapsburgs are the reality of that Empire. The French Bourbons were, upon the contrary, the chiefs of a nation peculiarly conscious of its unity and jealous of its past. Their greatness lay only in the greatness of the compact quadrilateral they governed and of the finished language of their subjects, and in the achievements of the national temper. Such conditions favoured to the utmost the scheme of Maria Theresa, not only in the detail of this marriage, but in all that successful management of the French alliance which survived her own death and was the chief business of her reign. She could be direct in every plan, unhampered, considering only the fortunes of her House; Louis XV. and his Ministers, as later his grandson, were trammelled by the complexity of a national life of which they were themselves a part.

Versailles had not declared itself: Vienna pressed. It was in March that active opposition within the Court had died with the mother of the heir. Within a month the French ambassador at Vienna wrote home that “the marriage was in the air”: but the King had not spoken.

30In that summer, as though sure of her final success, the Empress threw a sort of prescience of France and of high fortunes over the nursery at Schoenbrünn. The amiable Brandweiss disappeared; the severe and unhealthy Lorchenfeld replaced her.

The French (and baptismal form) of the child’s name, “Antoinette,” was ordered to be used: still Versailles remained dumb.

In the autumn the parallels of the siege were so far advanced that a direct assault could be made on poor Dufort, the advanced work of the Bourbons, their ambassador at Vienna.

Dufort had been told very strictly to keep silent. He suffered a persecution. Thus he was standing one evening by the card-tables talking to his Spanish colleague, when the Empress came up and said to this last boldly: “You see my daughter, sir? I trust her marriage will go well; we can talk of it the more freely that the French ambassador here does not open his lips.”

The child’s new governess was next turned on to the embarrassed man to pester him with the recital of her charge’s virtues. The approaching marriage of her elder sister Caroline with the Bourbons of Naples was dangled before Dufort.

The play continued for a year. Louis XV. bade his ambassador get the girl’s portrait, but “not show himself too eager.” He is reprimanded even for his courtesies, and all the while Dufort must stand the fire of the Court of Vienna and its exaggerated deference to him and its occasional reproaches! Choiseul was anxious to see the business ended. Dufort was as ready (and as weary) as could have been the Empress herself, but the slow balance of Louis XV. stood between them all and their goal.

In the summer of the next year, 1768, the Empress’s eldest son, Joseph, now associated with her upon the throne, determined to press home and conclude. It was the first time that this man’s narrow energy pressed the Bourbons to determine and to act; it was not to be the last. He was destined so to initiate action in the future upon two critical occasions and largely to determine the fortunes of his sister’s married life and final tragedy.

He wrote to Louis XV. a rambling letter, chiefly upon the marriage of yet another sister with the Duke of Parma. It 31wandered to the Bourbon marriage of Caroline; he mentioned his own child, the great-granddaughter of the King. It was a letter demanding and attracting a familiar answer. It drew its quarry. Louis, answering with his own hand and without emphasis, in a manner equally domestic and familiar, threw in a chance phrase: “... These marriages, your sister’s with the Infante, that of the Dauphin....” In these casual four words a document had passed and the last obstacle was removed.

The Empress turned from her major preoccupation to a minor one. This child of hers was to rule in France; she was now assured of the throne; she was near her thirteenth birthday—and she had been taught nothing.

THE fortnightly despatches from France customarily arrived at Vienna together in one bag and in the charge of one courier. The Empress would receive at once the letters of Mercy, the official correspondence, perhaps the note of a friend, and the very rare communications of royalty. In this same batch which brought that decisive letter of Louis XV. to her son, on the same day, therefore, in which she was first secure in her daughter’s future, there also arrived the usual secret report from Mercy. This document contained a phrase too insignificant to detain her attention; it mentioned the rumour of a new intrigue: the King showed attachment to a woman of low origin about him; it was an attachment that might be permanent. This news was immediately forgotten by Maria Theresa; it was a detail that passed from her mind. She perhaps remembered the name, which was “Du Barry.”

The Court of Vienna, permeated (as was then every wealthy society) with French culture, was yet wholly German in character. The insufficiency which had marked the training of the imperial children—especially of the youngest—was easily accepted by those to whom a happy domestic spirit made up for every other lack in the family. Of those who surrounded the little Archduchess two alone, perhaps, understood the grave difference of standard between such education as Maria Antonietta had as yet received and the conversation of Versailles; but these two were Kaunitz and Maria Theresa, and short as was the time before them, they did determine to fit the child, in superficial things at least, for the world she was to enter and in a few years to govern. They failed.

Mercy, the ambassador, was instructed to find in France a tutor who should come to Vienna and could accomplish the task. He applied to Choiseul. Choiseul in turn referred the 33matter to the best critic of such things, an expert in the things of this world, the Archbishop of Toulouse. That prelate, Loménie de Brienne, whose unscrupulous strength had judged men rightly upon so many occasions and had exactly chosen them for political tasks, had in this case no personal appetite to gratify and was free to choose. A post was offered. His first thought was to obtain it for one who was bound to him, a protégé and a dependant. He at once recommended a priest for whom he had already procured the Librarianship of the Mazarin Collection, one Vermond. The choice was not questioned, and Vermond left to assume functions which he could hardly fulfil.