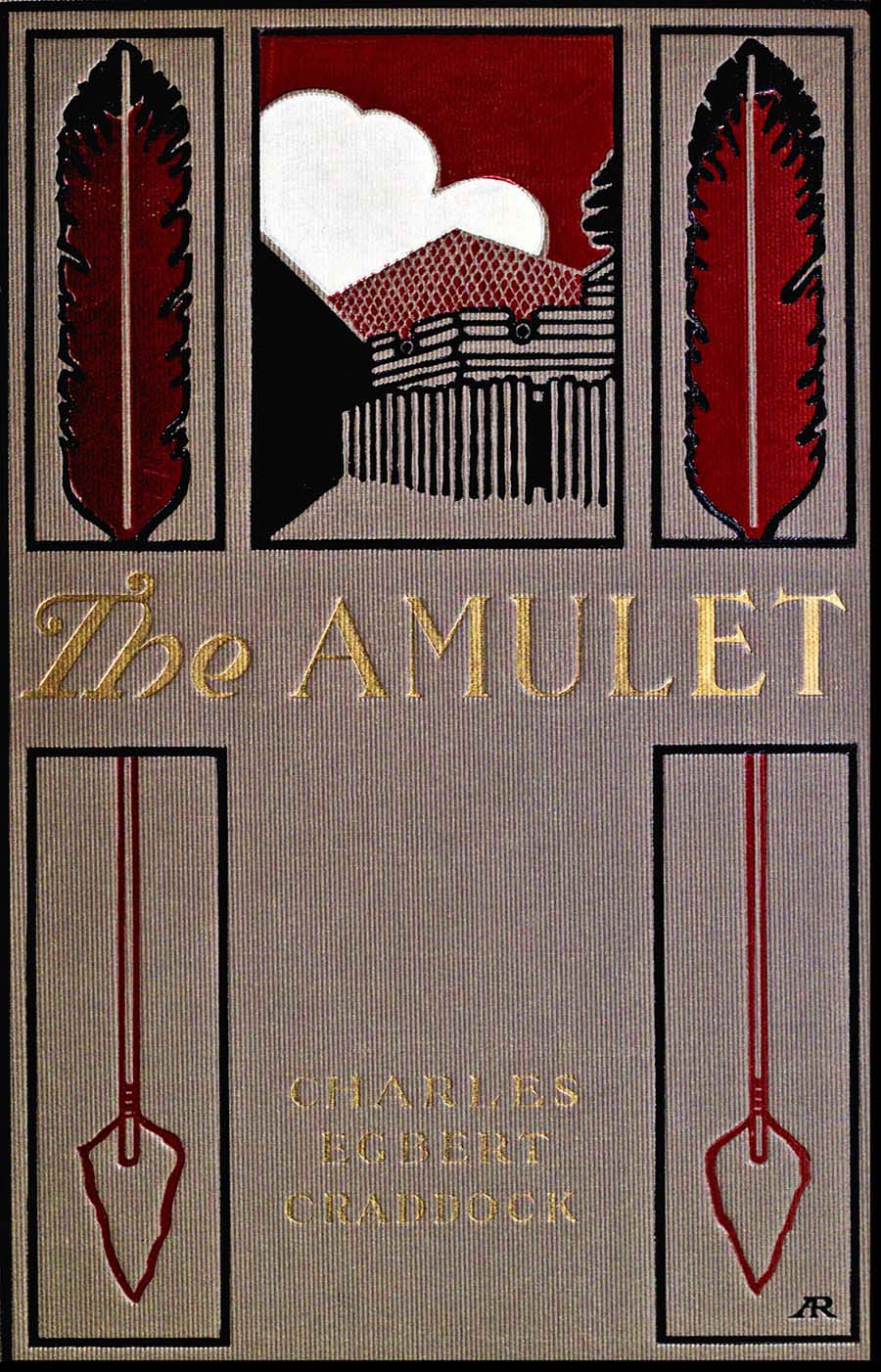

THE AMULET

A Novel

BY

CHARLES EGBERT CRADDOCK

AUTHOR OF

“THE STORM CENTRE,” “THE STORY OF OLD FORT

LOUDON,” “A SPECTRE OF POWER,” “THE

FRONTIERSMEN,” “THE PROPHET OF THE

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS,” ETC., ETC.

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1906

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1906,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1906.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

THE AMULET

THE AMULET

The aspect of the lonely moon in this bleak night sky exerted a strange fascination upon the English girl. She often paused to draw the improvised red curtain at the tiny window of the log house that served as the commandant’s quarters and gaze upon the translucent sphere as it swung westering above the spurs of the Great Smoky Mountains, which towered in the icy air on the horizon. Beneath it the forests gleamed fitfully with frost; the long snowy vistas of the shadowy valleys showed variant tones of white in its pearly lustre. So dominant was the sense of isolation, of the infinite loneliness of the wilderness, that to her the moon was like this nowhere else. A suspended consciousness seemed to characterize it, almost an abeyance of animation, yet this still serene splendor did not suggest death. She had long ago been taught, indeed, that it was an extinct and burnt-out world. But in this strange new existence old theories were blunted and she was ready for fresh impressions. This majestic tranquillity seemed as of deep and dreamless slumber, and the picturesque fancy of the Indians that the moon is but the sun[2] asleep took strong hold on her imagination. She first heard the superstition one evening at dusk, as she stood at the window with one end of the curtain in her hand, and asked her father what was the word for “moon” in the Cherokee language.

“Don’t know! The moon in English is bright enough for me!” exclaimed Captain Howard, as he sat in his easy-chair before the fire with his glass of wine. A decanter was on the table beside him, and with venison and wild-fowl for the solid business of dinner, earlier in the afternoon, and chocolate-and-cocoanut custard, concocted by his daughter, for the “trifle,” he had fared well enough.

Very joyous he was in these days. The Seven Years’ War was fairly over, the treaty of peace concluded, and the surrender of the French forts on the American frontier already imminent, even thus early in the spring of 1763. His own difficult tour of service, here at Fort Prince George, the British stronghold on the eastern edge of the Cherokee country, was nearing its close. He, himself, was to be transferred to a post of ease and comfort at Charlestown, where he would enjoy the benignities of social courtesies and metropolitan association, and where his family, who had come out from England for the purpose, could join him for a time. Indeed, on his recent return from South Carolina, where he had spent a short leave of absence, he had brought thence with him his eldest daughter, an intelligent girl of eighteen years, who was opening great eyes at the wonders of this new world, and who had specially[3] besought the privilege of a peep into the wilderness, now that the frontier was quiet and safe.

George Mervyn, a captain-lieutenant of the garrison, a youth whom her father greatly approved,—the grandson of his nearest neighbor at home in Kent, Sir George Mervyn,—was inclined to pose as a picturesque incident himself of the frontier, the soldier who had fought its battles and at last pacified it. Now he suddenly developed unsuspected linguistic accomplishments. He was tall, blond, and bland, conventional of address, the model of decorous youth. He seemed quiet, steady, trustworthy. His was evidently the material of a valuable future. He rose and joined her at the window.

“There is no more moon,” he said with a somewhat affected but gentlemanly drawl. “You must realize that, Miss Howard. This is ‘the sleeping sun,’ You must not expect to see the moon on the frontier.”

“Only a stray moonling, now and then,” another subaltern struck in with a laugh.

There was something distinctly sub-acid in the quick clear-clipped tones, and Captain Howard lifted his head with a slightly corrugated brow. He looked fixedly into his glass as if he discerned dregs of bitterness lurking therein. He was experiencing a sentiment of surprise and annoyance that had earlier harassed him, to be dismissed as absurd; but now, recurring, it seemed to have gathered force. These two young men were friends of the Damon-and-Pythias type. Their one-ness of heart and unanimity of thought had been of infinite service[4] to him in the many difficult details of his command at Fort Prince George,—a flimsy earth-work with a block-house or two, garrisoned by a mere handful of troops, in a remote wilderness surrounded by a strong and savage foe. These officers had been zealous to smooth each other’s way; they had vied to undertake onerous duties, to encounter danger, to palliate short-comings. They were always companions when off duty; they hunted and fished together; they were on terms of intimate confidence, even privileged to read each other’s letters. They were sworn comrades, and yet to-day (Captain Howard did not know how to account for it—he was growing old, surely) neither had addressed a kindly word to the other; nay, Ensign Raymond was sharply and apparently intentionally sarcastic.

Captain Howard wondered that Arabella did not notice it, but there she stood by the window, the curtain in her hand, the light of the great flaring fire on the hair, a little paler than gold, which she had inherited from her Scotch mother, and the large, sincere, hazel English eyes which were like Captain Howard’s own. The delicate rose tint of her cheek did not even fluctuate; she looked calmly at the young men as they glared furiously at each other. But for her presence Captain Howard would have ordered them to their respective quarters to avoid a collision. Fort Prince George was not usually the scene of internecine strife. He resented the suggestion as an indignity to himself. It impaired the flavor of the dinner he had enjoyed, and jeopardized[5] digestion. It was a disrespect to the formality with which he had complimented the occasion of his daughter’s arrival, inviting his old neighbor’s grandson, with his especial friend, and wearing his powdered wig, his punctilious dress uniform, pumps, and silk hose. It had been long since his table was graced by a woman arrayed ceremoniously for dinner, and the sight of his daughter in her rose-hued tabby gown, with shining arms and shoulders and a string of pearls around her throat, was a pleasant reminder to him, in this bleak exile, of the customs of old times, soon to be renewed, the more appreciated for compulsory disuse. Captain Howard, watching the group as the young men glowered at each other, was amazed to think that she looked as if she enjoyed it, the image of demure placidity.

“The Cherokees call the moon Neusse anantoge, ‘the sleeping sun,’” said the captain-lieutenant, making no rejoinder to Raymond.

“La! How well you speak their language, Mr. Mervyn, to be sure. Oh-h, how musical! As lovely as Italian! Oh-h-h—how I wish I could learn it before I go back to England! Sure, ’twould be monstrous genteel to know Cherokee in London. Neusse anantoge. I’ll remember that. ‘The sleeping sun.’ I’ll say that again. Neusse anantoge. Neusse anantoge.”

“Neusse anantoge!” cried Raymond, with a fleering laugh. “Gad, Mervyn, you are moon-struck.”

His bright dark eyes were angry, although laughing. They seemed to hold a light like coals of fire, sometimes[6] all a-smoulder, and again vivid with caloric or choler. With his florid complexion and dark hair and eyes the powder had a decorative emphasis which the appearance of neither of the other men attained. The lace cravat about his throat was of fine texture and delicately adjusted, but it was frayed along the edge in more than one place and the lapels of his red coat hardly concealed this. Woman-like she was quick to discern the insignia of genteel poverty, and she pitied him with a sympathy which she would not have felt for a rent of the skin or a broken bone. These were but the natural incidents of a soldier’s life; blows and bruises must needs be cogeners. She divined that his education and his commission were all of value at his command,—the younger son of a good family, but poor and proud,—and it was hard to live in a world of lace and powder on so slender an endowment. She began to hate the precise and priggish George Mervyn who roused him so, although the provocation came from Raymond, and she was already wondering at her father that this dashing man, who had a thousand appeals to a poetic imagination, stood no higher in favor. She did not realize that a long command at Fort Prince George was no promoter of a poetic imagination.

As Raymond spoke Miss Howard turned eagerly toward him, the dark red curtain still in her hand, showing a section of the bleak, moonlit, wintry scene in the distance, and in the foreground the stockaded ramparts, the guard-house, its open door emitting an orange-tinted flare of fire, the blue-and-black shadows[7] lurking about the block-house and the hard-trodden snow of the deserted parade.

“What do you say it should be, then?” she demanded peremptorily, as if she were determined not to be brought to confusion by venturing incorrect Cherokee in London,—as if there a slip of the tongue would be easily detected!

“How much Cherokee does he know?” interposed Mervyn, satirically. “We keep an interpreter in constant employ,—expressly for him.”

Raymond was spurred on to assert himself.

“Neusse anantoge!” he jeered. “Then what do you make of Nu-da-su-na-ye-hi? That is ‘the sun sleeping in the night.’ And see here, Nu-da-ige-hi. That is ‘the sun living in the day.’”

“That?—why, that is the Lower town dialect.”

“Oh, the Lower town dialect!” Raymond, in derision, whirled about on the heels of his pumps, for he too was displaying all the glory of silk hose. “The Lower town dialect,—save the mark! It is Overhill Cherokee.”

“Oh,—oh,—are there two dialects of the Cherokee language?” cried Arabella. “How wonderful! And of the different towns! Oh-h—which are the lower towns? and oh,—Mr. Raymond, how prodigiously clever to know both the dialects!”

Captain Howard lifted his head with a brusque challenge in his eye. He tolerated none but national quarrels. He did not understand the interests in conflict. But he thought to end them summarily. The words “moonling,” “moon-struck,” and the tone[8] of the whole conversation were not conducive to the conservation of the peace. Raymond had conducted himself in a very surly and nettling manner all through the day toward his quondam friend, who, so far as Captain Howard could see, had given him no cause of offence.

He was obviously about to strike into the conversation, and all three faces turned toward him, alert, expectant. The suave inscrutable countenance of the young lady merely intimated attention, but it was difficult for the two young men to doff readily their half scoffing expressions of anger and defiance and assume the facial indicia of respect and deference and bland subservience due to their host, their senior, and their superior officer.

His sister, however, quickly forestalled his acrid comments. Mrs. Annandale ostensibly played the part of duenna to her niece and of acquiescent chorus to her brother’s dictatorial opinions. But in her secret heart she controverted his every prelection, and she countermarched his intentions with an unsuspected skill that was the very climax of strategy, for she brought him to the conviction that they were his own plans she had furthered and his own orders she had executed. Her outer aspect aided her designs—it was marvellously incongruous with the character of tactician. She had a scanty little visage, pale and wrinkled, with small pursed-up lips, closely drawn in meek assent, and small bright eyes that twinkled timorously out from gray lashes. A modish head-dress surmounted and concealed her thin[9] gray locks, and an elaborately embroidered kerchief, crossed over the bosom of her puce-colored satin gown, conforming in the décolleté cut to the universal fashion of the day, hid the bones of her wasted little figure. She was very prim, and mild, and upright, as she sat in the primitive arm-chair, wrought by the post-carpenter and covered with a buffalo-skin. In a word she turned the trend of the discourse.

“M—m—m,” she hesitated. “Sure, ’twould seem one dialect might express all the ideas of the Indians—they have a monstrous talent for silence.”

She looked directly at Raymond from out her weak, blinking little eyes.

“They talk more among themselves, madam, and when at home,” responded Raymond, turning away from the young people at the window, and leaning against the high mantel-piece, one hand on the shelf as he stood on the opposite side of the fire from Mrs. Annandale. “They are ill at ease here at the fort,—the presence of the soldiers abashes and depresses them; they are much embittered by their late defeat.”

Mrs. Annandale shuddered. She was afraid of wind and lightning; of waters and ghosts; of signs and omens; of savages and mice; of the dark and of the woods; of gun-powder and a sword-blade.

“And are you not frightened of them, Mr. Raymond?” she quavered.

He stared in amazement, and Captain Howard, restored to good temper, cocked up his eyes humorously[10] at the young soldier. The vivid red and white of Raymond’s complexion, his powdered side-curls, and his bold, bright hazel eyes, were heightened by the delicacy of his lace cravat, and his red uniform was brought out in fine effect by the flaring light of the deep chimney-place, but Mrs. Annandale’s heart was obdurate to all such appeals, even vicariously. A side glance had shown her that the young people at the window had drawn closer together and a low-toned and earnest conversation was in progress there,—the captain-lieutenant was talking fast and eagerly, while the girl, holding the curtain, looked out at the dreary wintry aspect of the sheeted wilderness, the frontier fort, and the “sleeping sun” resting softly in the pale azure sky, high, high above the Great Smoky Mountains. The duenna pressed her lips together in serene satisfaction.

“M—m—m. I should imagine you would be so frightened of the Indians, Mr. Raymond,” she said.

“Ha—ha—ha—!” laughed Captain Howard, outright.

Mrs. Annandale claimed no sense of humor, but she was a very efficient mirth-maker, nevertheless.

“I am beholden to you, madam,” said the young soldier, out of countenance. He could not vaunt his courage in the presence of his commander, nor would he admit fear even in fun. He was at a loss for a moment.

“It is contrary to the rules of the service to be afraid of the Indians,” he said after a pause; “Captain Howard does not permit it.”

[11]“Oh,—but how can anyone help it!—and they are so monstrous ugly!”

“They are considered very fine men, physically,” said Raymond.

“But they will never make soldiers,” interpolated Captain Howard. The English government had done its utmost with the American Indians, as with other subdued peoples of its dependencies, both earlier and later, to incorporate their martial strength into the British armies, but the aborigines seemed incapable of being moulded by the discipline of the drill and the regulations of the camp, and deserted as readily as they were enlisted, rewards and penalties alike of no effect.

“Oh, Mr. Raymond, no one could think them handsome!—they are—greasy!”

“The grease is to afford a surface for their paint, you must understand. But it is a horribly unclean and savage custom.”

He never could account for a shade of offence on the lady’s expressionless, limited face and a flush other than that of the rouge on her delicate, little flabby cheek. How should he know that that embellishment was laid on a gentle coating of pomade after the decrees of fashion. He was not versed in the methods of cosmetics. He had been on the frontier for the last three years—since his boyhood, in fact, and that grace and gentlemanliness which so commended his address were rather the results of early training and tradition than the influence of association with cultured circles of society. He knew that[12] he had said something much amiss and he chafed at the realization.

“I am fitter for an atmosphere of gun-powder than attar of roses,” he said to himself with a half glance over his shoulder at the window, the pale moonlight making the face of the girl poetic, ethereal, and shimmering on her golden hair.

The next moment, however, Mrs. Annandale claimed his attention, annulling the idea that there had been aught displeasing in his remark.

“But sure, Mr. Raymond, there were never towns, called towns, such as theirs—la!—what a disappointment, to be sure!”

“Ha! ha! ha!” exclaimed Captain Howard, mightily amused. “So you are looking for the like of Bond Street and Charing Cross and the Strand—eh!—in Estatoe, and Kulsage, and Seneca,—ha! ha! ha!”

Raymond winced a trifle lest the fragile little lady should find this soldier-like pleasantry too bluff for a sensitive nature, but she laughed with a subdued, deprecating suggestion of merriment. He could not imagine, as she lent herself to this ridicule, that she construed it as humoring the folly of the commandant, of whom indeed she always spoke behind his back in a commiserating way as “poor dear Brother.” She had so often outwitted the tough old soldier that she looked upon his prowess as a vain thing, his fierce encounters with the national foe mere figments of war compared with those subtle campaigns in which she so invariably worsted him. She laughed at herself. She could afford it.

[13]“Dear Brother,” she said, “Charlestown is not London, to be sure, but we found it vastly genteel for its size. There is everything a person of taste requires for life—on a scale, to be sure—on a minute scale. But there is a theatre, and a library of books, so learning is not neglected, and a race-course, and a society of tone. Lord, sir, strangers, well introduced, have nothing to complain of. I’m sure Arabella and I were taken about till we could have dropped with fatigue, Mr. Raymond—what with Whisk and Piquet for me and a minuet for her, night after night, everywhere we went, we might well have thought ourselves in London. And Lord, sir, the British officers there are so content they seem to think they have achieved Paradise.”

“I’ll warrant ’em,” and Captain Howard wagged his head scoffingly, meditating on the contrast with his past hardships in the frontier service.

“And being mightily charmed with what I had seen of the province I was struck with a cold chill by the time I’d crossed Ashley Ferry—the woods half dark by day and a cavern by night; and such howlings of owls, and lions, and tigers, I presume—”

“Oh, ho—ho—ho!” exclaimed Captain Howard. “I’ll detail you, Ensign Raymond, to drill the awkward squad in natural history.”

Raymond, responsive to the spirit of the jest, stood at attention and saluted, as if receiving a serious assignment to duty.

He was not of a wily nature, nor especially suspicious. He had keen perceptions, however, and his[14] own straightforward candor aided them in detecting a circuitous divergence from the facts; when Mrs. Annandale declared herself so terrified that she had begged and prayed her niece and her brother to turn back, he realized dimly that this was not the case, that it was by her own free will the party had kept on, and that Arabella would never have had the cruelty to persist in the undertaking against her aunt’s desire, nor had she the authority to compass this decision. But why had the little woman mustered the determination, he marvelled, for this long and arduous journey. He looked at her with the sort of doubtful and pitying yet fearful repulsion with which a scientist might study a new and very eccentric species of insect. He could realize that she had suffered all the fright and fatigue she described. Her puny little physique was indeed inadequate to sustain so severe a strain, bodily and mentally. Her fastidious distaste to the sight and customs of the Indians was itself a species of pain. Why had she come?

“Before we reached Ninety-Six I saw the first of the savages. Oh,—Mr. Raymond,—it seems a sort of indecency in the government to make war on people who wear so few clothes. They ought to be allowed to peacefully retire to the woods.”

“Oh—ho—ho—ho!—that’s the first time I ever heard the propriety of the government called in question,” said Captain Howard. He glanced over his shoulder to make sure that Arabella had not overheard this jest of doubtful grace.

[15]“She’s busy,” Mrs. Annandale reassured him with a sort of smirk of satisfaction, which impressed Raymond singularly unpleasantly. He too glanced over his shoulder. The tall, fair, graceful young officer could hardly appear to greater advantage than Mervyn did at this moment, in the blended light of the fire and the moon, for the candles on the table scarcely sent their beams so far. The rich dress of the girl was accented and embellished by the simplicity of the surroundings. Her head was turned aside—only the straight and perfect lines of her profile showed against the lustrous square of the window. She still held the curtain and, while he talked, she silently listened and gazed dreamily at the moon. There was a moment of embarrassment in the group at the fireside, as they relinquished their covert scrutiny, and Raymond’s ready tact sought the rescue of the situation.

“It has been urged that we armed the Indians against ourselves through the trade in peace,” he suggested.

“And now Mrs. Annandale thinks they ought to be put in the pink of the fashion before being shot at—ha—ha—ha!” returned Captain Howard.

“Then their towns,—a-lack-a-day,—to call them towns! A cluster of huts and wigwams, and a mound, and a rotunda, and a play-yard. They frightened me into fits with their proffers of hospitality. The women—dressed in some vastly fine furs and with their hair plaited with feathers—came up to our horses and offered us bread and fruit; oh, and a[16] kind of boiled meal and water; and Arabella partook and said it was nice and clean but I pressed my hands to my stomach and rolled up my eyes to intimate that I was ill; and indeed I was at the very sight of them,” Mrs. Annandale protested.

Once more she glanced over her shoulder, thinking her niece might hear her name; again that smirk of satisfaction to note the mutual absorption of the two, then, lest the pause seem an interruption, she went on:

“And have these wretches two sets of such towns? lower and upper—filthy abominations!”

“No, no, Claudia,” said the captain, shaking his head, “they are clean, they are clean—clean as floods of pure water can make them. Every town is on a rock-bound water-course, finest, freshest, freest streams in the world, and every Indian, big and little, goes under as a religious duty every day. No, they are clean.”

“Dear heart!” exclaimed the lady, without either contention or acquiescence.

“And they wear ample clothes, too. The buck-skin hunting-shirt and leggings of our frontiersmen are copied from the attire of the Indians. If you saw savages who were scantily clothed they must have been very poor, or on the war-path against other Indians—for they wear clothes, as they construe them, on ordinary occasions.”

“How nice of them,” commented Mrs. Annandale. “Shows their goodness of heart.”

Once more Raymond bent the gaze of an inquiring scrutiny upon the lady—simple as she was, he had[17] not yet classified her. She had begun to exert a sort of morbid fascination upon him. He did not understand her, and the enigma held him relentlessly.

He had not observed a motion which Arabella had made once or twice to quit the tête-à-tête beside the window, and he was taken by surprise when she suddenly approached the fire. Standing, tall and slender and smiling, between him and her father, with her hand on the commandant’s chair, she addressed the coterie at large:—

“What a jovial time you seem to be having!”

Raymond’s heart plunged, and Mervyn reddened slightly with an annoyance otherwise sedulously repressed. She spoke with a naïve suggestion as of an enforced exclusion from the fun. “What is all this talk about?”

“Mr. Raymond has been admiring the Indians’ taste in dress,” said Mrs. Annandale, titteringly,—“he says they wear the hides of beasts,—their own hides.”

Captain Howard frowned. It did not enter into his scheme of things to question the discretion of a professed duenna. He was confused for a moment, and it seemed to him that the fault lay in Raymond’s bad taste in the remark rather than in its repetition. It did not occur to him that it was made for the first time.

Raymond, realizing that for some reason Mrs. Annandale sought to place him at a disadvantage, was on the point of gasping out a denial, but the gaucherie of contradicting a lady, and she the sister of his host, deterred him.

[18]Though the young girl was convent-bred with great seclusion and care, she had emerged into an atmosphere of such sophistication that she was able to seem to have apprehended naught amiss. She bent her eyes with quiet attention on her aunt’s face when Mrs. Annandale said abruptly:—

“Tell George Mervyn how oddly those gypsies were dressed—gypsies, or Hindoos, or whatever they were—that camped down on the edge of the copse close to his grandfather’s park gates last fall, and told your fortune!”

“Was it on our side of the ha-ha, or your side?” asked Mervyn, eagerly. For as Raymond understood the property of the two families adjoined, large and manorial possessions on the part of the Mervyns, and with their neighbors a very modest holding—a good old house but with little land.

“Oh, to think of the copse!” cried Mervyn with a gush of homesick feeling,—“to think of the beck! I could almost die to be a boy again for one hour, bird-nesting there once more!”

“Even if I made you put the eggs back?” Arabella smiled.

“Though they would never hatch after being touched,” he corroborated.

“But tell the story, Arabella. Tell what the gypsy said,” urged Mrs. Annandale, significantly.

The young lady still stood, her hand resting on her father’s chair. She looked down into the fire with inscrutable hazel eyes. Her face seemed to glow and pale, as the flames flared and fell and sent[19] pulsations of shoaling light along the glistening waves of her pink tabby gown.

“I don’t care what the gypsy said,” she returned.

“But you cared then—enough to cross her hand with silver!” cried Mrs. Annandale. “And, George, your grandfather, Sir George, came riding by—I think that gray cob is a rather free goer for the old gentleman—and he reined up by the hedge and looked over. And he said, ‘Make it gold, young lady, if you want it rich and true. Buy your luck—that’s the way to get it!’”

Captain Howard stirred uneasily. “Sir George is right—the gypsy hussy is bought; she gives a shilling fortune for a shilling and a crown of luck for a crown. I have no faith in the practice.”

“You will when you hear this, dear Brother. Tell what the gypsy said, Arabella!” Mrs. Annandale leaned forward with her small mouth tightly closed and her small eyes twinkling with expectation.

“Oh, I have clean forgot,” declared Arabella, her eyes still on the coals and standing in the rich illumination of the flare.

“I have not forgot. I heard every word!” exclaimed the wily tactician.

Now Arabella lifted her long dark lashes, and it seemed to Raymond that she sent a glance of pleading expostulation, of sensitive appeal to meet the microscopic glitter in the pinched and wizened pale face. Mervyn waited in a quiver of expectation, of suspense; and Raymond, wounded, excluded, set at naught, as he had felt, was sensible of a quickening[20] of his pulses. But why did the old woman persist?

“There is nothing in such prophecies,” said Captain Howard, uneasily.

“She said you had a lover over seas,—didn’t she, my own?”

The girl, looking again at the red fire, nodded her golden head casually, as if in renewing memory.

“One who loved you, and whom you loved!”

Mervyn caught his breath. The blood had flared into his face. He held himself tense and erect by a sheer effort of will, but any moment he might collapse into a nervous tremor.

“She said—oh, she said—” exclaimed Mrs. Annandale, prolonging the suspense of the moment and clasping her mittened hands about her knees, leaning forward and looking into the fire, “she said he was handsome, and tall, and blond. And you—you didn’t know in the least who he was; though you gave her another crown from pure good will!” And Mrs. Annandale tittered teasingly and archly, as she glanced at Mervyn.

“Oh, yes, I did know who he was,”—the girl electrified the circle by declaring. “That is why I gave her more money.”

Her eyes were wide and bright. She tossed her head with a knowing air. Her cheeks were scarlet, and the breath came fast over her parted red lips.

Mrs. Annandale sat in motionless consternation. She had lost the helm of the conversation and it seemed driving at random through a turmoil of chopping[21] chances. Mervyn looked hardly less frightened,—as if he might faint,—for he felt that his name was trembling on Arabella’s lips. It was like the chaos of some wild unexplained dream when she suddenly resumed:—

“The gypsy meant Monsieur Delorme, my drawing-master at Dijon—all the pupils were in love with him—I, more than all—handsome and adorable!”

Raymond’s eyes suddenly met Mervyn’s stony stare of amazement. He did not laugh, but that gay, bantering, comprehending look of joyful relish had as nettling a sting as a roar of bravos.

Captain Howard was but just rescued from a dilemma that had bidden fair to whelm all his faculties, but his disgust recovered him.

“Oh, fie!”—he said rancorously. “The drawing-master! Fudge!”

Mrs. Annandale had the rare merit of knowing when she was defeated. She had caused her brother to invite Raymond merely that the invitation to Mervyn might not seem too particular. But having this point secure she had given him not one thought and not a word save to engage his attention and permit Mervyn’s tête-à-tête with her niece. Since her little scheme of bantering the two lovers, as she desired to consider them, or rather to have them consider each other, had gone so much awry, she addressed herself to obliterate the impression it had made. She now sought to ply Raymond with her fascinations, and with such effect that Mervyn, who had been occupied with plans to get himself away so that he[22] might consider in quiet the meaning of her demonstration and the girl’s unexpected rejoinder, was amazed and dismayed. Mrs. Annandale was of stancher stuff than he thought, and though afterward she much condemned the result of her inquiries touching family relations and mutual acquaintance in England, this seemed to be the only live topic between a young man and an elderly woman such as she, specially shaken as she had been by the downfall of all her plans in the manipulation of the treacherous Arabella. She had not, indeed, intended to elicit the fact that Raymond was nearly connected with some of the best people in the kingdom, that his family was so old and of so high a repute that a modern baronetcy was really a thing of tinsel and mean pretence in comparison. Among them there was no wealth of note, but deeds of distinction decorated almost every branch of the family tree. When at last she could bear no more and rose, admonishing her niece to accompany her, terminating the entertainment, as being themselves guests, Arabella, sitting listening by the side of the fire, thrown back in the depths of the arm-chair among the furs that covered it, exclaimed naively: “What! So early!”

When Mrs. Annandale and her niece repaired to the quarters assigned them, the young lady passed through the room of the elder to the inner apartment, as if she feared that her contumacy might be upbraided. But if Mrs. Annandale felt her armor a burden and was a-wearied with the untoward result of the evening’s campaign she made no sign, but gallantly persevered, realizing the truism that more skill is requisite in conducting a retreat than in leading the most spirited assault. She followed her niece and seated herself by the fire while Arabella at the dressing-table let down her mass of golden hair and began to ply the brush, looking meanwhile at a very disaffected face in the mirror. The youthful maid who officiated for both ladies, monopolized chiefly by Mrs. Annandale, was busied with some duties touching a warming-pan in the outer room, and thus the opportunity for confidential conversation was ample.

“These soldiers talk so much about their hard case,” said the elder lady, looking about her with an appraising eye. “Many folks at home might call this luxury.”

For Captain Howard had exerted his capacity and knowledge to the utmost to compass comfort for his[24] sister and daughter, with the result that he was held to complain without a grievance. A great fire roared in a deep chimney-place—there were no andirons, it is true, but two large dornicks served as well. The log walls were white-washed and glittered with a vaunt of cleanliness. The bed-curtains were pink, and fluttered in a draught from the fire. Rose-tinted curtains veiled the meagre sashes of the glazed windows. The chairs, of the clumsy post manufacture, were big and covered with dressed furs. Buffalo rugs lay before the wide hearth and on the floor. A candle flickered unneeded on the white-draped dressing-table, and there was the glitter of silver and glass and of such bijouterie as dressing-case and jewel-box could send forth. The young girl, now in a pink robe de chambre, seemed in accord with the rude harmony of the place.

“They line their nests right well, these tough soldiers,” said the elder woman. “If it were not for the Indians, and the marching, and the guns, and the noisy powder, and the wild-cats, and the wilderness, one might marry a soldier with a fair prospect. George Mervyn is a handsome young man, Bella.”

“He looks like a sheep,” said Arabella, petulantly. “That long, thin, mild face of his, pale as the powder on his hair, without a spark of spirit, and those stiff side-curls on each side of his head, exactly like a ram’s horns! He looks like a sheep, and he is a sheep.”

With all her unrevealed and secret purposes it was difficult to hold both temper and patience after the[25] strain of the mishaps of the evening. But Mrs. Annandale merely yawned and replied, “I think he is a handsome young man, and much like Sir George.”

“Ba-a-a!—Ba-a-a!”—said the dutiful niece.

The weary little woman still held stanchly on. “I believe you’d rather marry the grandfather.”

“I would—but I don’t choose to marry either.”

Mrs. Annandale had a sudden inspiration. “No, my poor love,” she said with a downward inflection, “a girl like you, with beauty, and brains, and good birth, and fine breeding,—but no money, too often doesn’t choose to marry anybody, for anybody that is anybody doesn’t want her.”

There was dead silence in front of the mirror. A troublous shade settled on the fair face reflected therein. The brush was motionless. An obvious dismay was expressed in the pause. Self-pity is a poignant pain.

“Lord! Lord!—how unevenly the good things of this world are divided,” sighed the philosopher. “The daughter of a poor soldier, and it makes no difference how lovely, how accomplished!—while if you were the bride of Sir George Mervyn’s grandson—bless me, girl, your charms would be on every tongue. You’d be the toast of all England!”

There was a momentary silence while the light flashed from the lengths of golden hair as the brush went back and forth with strong, quick strokes. The head, intently poised, betokened a sedulous attention.

“Out upon the injustice of it!” cried Mrs. Annandale,[26] with unaffected fervor. “To be beautiful, and well-bred, and well-born, and well-taught, and faultless, and capable of gracing the very highest station in the land, and to be driven by poverty to take a poor, meagre, contemned portion in life, simply and solely because those whom you are fit for, and who are fit for you, will not condescend to think of you.”

“I am not so sure of that!” cried Arabella, suddenly, with a tense note of elation. The mirror showed the vivid flush rising in her cheeks, the spirit in her eyes, the pride in the pose of her head. “And, Aunt, mark you now,—no man can condescend to me!”

“Lord! you poor child, how little you know of the ways of the world. But they were not in the convent course, I warrant you. Wealth marries wealth. Station climbs to higher station. Gallantry, admiration, all that is very well in a way, to pass the time. But men’s wounded hearts are easily patched with title-deeds and long rent-rolls. Don’t let your pride make you think that your bright eyes can shine like the Golightly diamonds. Bless my soul, Miss Eva had them all on at the county ball last year. Ha! ha! ha! I remember Sir George Mervyn said she looked a walking pawn-shop,—they were so prodigiously various. You know the Mervyns always showed very chaste taste in the matter of jewellery—the family jewels are few, but monstrous fine; every stone is a small fortune. But he was vastly polite to her at supper. I thought I[27] would warn you, sweet, don’t bother to be civil to young George, for old Sir George is determined on that match. Though the money was made in trade ’twas a long time ago, and there’s a mort of it. The girl has a dashing way with her, too, and sets up for a beauty when you are out of the county.”

“Lord, ma’am, Eva Golightly?” questioned Arabella, in scornful amaze.

“Sure, she has fine dark eyes, and she can make them flash and play equal to the diamonds in her hair. Maybe I’m as dazzled as the men, but she fairly looked like a princess to me. Heigho! has that besom ever finished fixing my bed? Good night—good night—my poor precious—and—say your prayers, child, say your prayers!”

The face in the mirror—the brush was still again—showed a depression of spirit, but the set teeth and an intimation of determination squared its delicate chin till Arabella looked like Captain Howard in the moment of ordering a desperate assault on the enemy’s position. There was, nevertheless, a sort of flinching, as of a wound received, sensitive in a thousand keen appreciations of pain. The word “condescend” had opened her eyes to new interpretations of life. Her father might realize that a captain, however valorous, did not outrank a major-general, but in the splendor of her young beauty, and cultured intelligence, and indomitable spirit, she had felt a regal preëminence, and the world accorded her homage. That it was a mere façon de parler had never before occurred to her—a sort of cheap indulgence[28] to a pretension without solid foundation. Her pride was cut to the quick. She was considered, forsooth, very pretty, and vastly accomplished, and almost learned with her linguistic acquirements and the mastery of heavy tomes of dull convent lore, yet of no sort of account because her people were not rich and she had no dowry, and unless she should be smitten by some stroke of good fortune, as uncontrollable as a bolt of lightning, she was destined to mate with some starveling curate or led captain, when as so humbly placed a dame she would lack the welcome in the circles that had once flattered her beauty and her transient belleship. The candle on the dressing-table was guttering in its socket when its fitful flaring roused her to contemplate the pallid reflection, all out of countenance, the fire dwindling to embers, and the shadows that had crept into the retired spaces of the bed, between the rose-tinted curtains, with a simulacrum of dull thoughts for the pillow and dreary dreams.

The interval had not passed so quietly within the precincts of Mrs. Annandale’s chamber. The connecting door was closed, and Arabella did not notice the clamor, as the maid was constrained to try the latches of the outer door and adjust and readjust the bars, and finally to push by main force and a tremendous clatter one of the great chairs against it, lest some discerning and fastidious marauder should select out of all Fort Prince George, Mrs. Annandale’s precious personality to capture, or “captivate,” to use the incongruous and archaic phrase of the day.[29] Now that the outer door was barricaded beyond all possibility of being carried by storm or of surreptitious entrance, Mrs. Annandale was beset with anxiety as to egress on an emergency.

“But look, you hussy,” she exclaimed, as she stood holding the candle aloft to light the tusslings and tuggings of the maid with the furniture and the bar, “suppose the place should take fire. How am I to get out! You have shut me in here to perish like a rat in a trap, you heartless jade!”

“Oh, sure, mem, the fort will never take fire—the captain is that careful—the foine man he is!” said the girl, turning up her fresh, rosy, Irish face.

“I know the ‘foine man’ better than you do,” snapped her mistress. The victory of the evening had been so long deferred, so hardly won at last, that the conqueror was in little better case than the defeated; she was fit to fall with fatigue, and her patience was in tatters. The War Office intrusted Captain Howard with the lives of its stanch soldiers and the value of many pounds sterling in munitions of war. But his sister belittled the enemy she had so often worsted, and who never even knew that he was beaten. “And those zanies of soldiers—smoking their vile tobacco like Indians!”

“Lord, mem,” said the girl, still on her knees, vigorously chunking and jobbing at the door, “the sojers are in barracks, in bed and asleep these three hours agone.”

“Look at that guard-house, flaring like the gates of hell! What do you mean by lying, girl!” Mrs.[30] Annandale glanced out of the white curtained window, showing a spark of light in the darkness.

“Sure, ma’am, it’s the watch they be kapin’ so kindly all night, like the stars, or the blissed saints in heaven!”

“Mightily like the ‘blissed saints in heaven,’ I’ll wager,” said the old lady, sourly.

“I was fair afeard o’ Injuns and wild-cats till I seen the gyard turn out, mem,” said the maid, relishing a bit of gossip.

Mrs. Annandale gave a sudden little yowl, not unlike a feline utterance.

“You Jezebel,” she cried in wrath, “what did you remind me of them for—look behind the curtains—under the valance of the bed—yow!—there is no telling who is hid there—robbers, murderers!”

Norah, young, plump, neat, and docile to the last degree, sprang up from her knees and rushed at these white dimity fabrics, tossing their fringed edges, with a speed and spirit that might have implied a courage equal to the encounter with concealed braves or beasts. But too often had she had this experience, finding nothing to warrant a fear. It was a mere form of search in her estimation, and her ardor was assumed to give her mistress assurance of her efficiency and protection. Therefore, when on her knees by the bedside she sprang back with a sudden cry of genuine alarm, her unexpected terror out-mastered her, and she fled whimpering to the other side of the room behind the little lady, who, dropping the candle in amazement and a convulsive[31] tremor, might have achieved the conflagration she had prefigured without the aid of the zanies of the barracks, but that the flame failed in falling.

“Boots!—Boots!—” cried the girl, her teeth chattering.

Mrs. Annandale’s courage seemed destined to unnumbered strains. It was not her will to exert it. She preferred panic as her prerogative. She glanced at the door, barred by her own precautions against all possibility of a speedy summons for help. Even to hail the guard-house through the window was futile at the distance; to escape by way of the casement was impossible, the rooms being situated in the second story of the large square building; a moment of listening told her that her niece was all unaware of the crisis, asleep, perhaps, silent, still. There was nothing for it but her own prowess.

“I have a blunderbuss here, man,” she said, seizing the curling-iron from her dressing-table and marking with satisfaction the long and formidable shadow it cast in the firelight on the white wall. “Bring those boots out or I’ll shoot them off you!”

There was dead silence. She heard the fire crackle, the ash stir, even, she fancied, the tread of a sentry in the tower above the gate.

“It’s a Injun—a Injun—he don’t understand the spache, mem!” said Norah, wondering that the unknown had the temerity to disregard this august summons.

“Norah,” said Mrs. Annandale, autocratically, and as she flourished the curling-tongs Norah cowered[32] and winced as from a veritable blunderbuss, so did the little lady dominate by her asseverations the mind of her dependent—and indeed stancher mental endowments than poor little Norah’s—“fetch me out those boots.”

“Oh, mem—what am I to do with the man that’s in ’em?” quavered the Abigail, dolorously.

“Fetch him, too, if he’s there. Give him a tug, I say, girl.”

The doubt that this mandate expressed, nerved the timorous maid to approach the silent white-draped bed. That she had nevertheless expected both resistance and weight was manifest in the degree of strength she exerted. She fell back, overthrown by the sheer force of the recoil, with a large empty boot in her hand, nor would she believe that the miscreant had not craftily slipped off the footgear till the other came as empty, and a timorous peep ascertained that there were no feet to match within view.

“Some officer’s boots!” soliloquized Mrs. Annandale. “He must have left them here when he was turned out of these snug quarters to make room for us. I wonder when that floor was swept.”

“Sure, mem, they’re not dusty,” said Norah, all blithe and rosy once more. “I’m rej’iced that he wasn’t in ’em.”

“Who—the officer?” with a withering stare.

“No’m, the Injun I was looking for”—with a quaver.

“Or the wild-cat you was talking about! Nasty things! Never mention them again.”

[33]Mrs. Annandale was a good deal shaken by the experience and tottered slightly as she paused at the dressing-table and laid down the curling-tongs that had masqueraded as a blunderbuss. The maid, all smiling alacrity to make amends, bustled cheerily about in the preparations for the retirement of her employer. “Sure, mem, yez would love to see ’em dead.”

“You’ve got a tongue now, but some day it will be cut out,” the old woman remarked, acridly.

“I’m maning to say, mem, they have the beautifulest fur—them wild-cats, not the Injuns. There’s a robe or blanket av ’em in the orderly room—beautiful, mem, sure, like the cats may have in heaven.”

As Mrs. Annandale sat in her great chair she seemed to be falling to pieces, so much of her identity came off as her hand-maiden removed her effects. She was severally divested of her embroidered cape, the full folds of her puce-colored satin gown, her slippers and clocked stockings; and when at last in her night-rail and white night-cap, she looked like a curious antique infant, with a malignant and coercive stare. Norah handled her with a fearful tenderness, as if she might break in two, such a wisp of a woman she was! Little like a conquering hero she seemed as she sat there before the fire, now girding at the offices of her attendant, now whimpering weakly, like a spoiled child, her white-capped head nodding and her white-clad figure fairly lost in the great chair, but she was the most[34] puissant force that had ever invested Fort Prince George, though it had sustained both French military strategy and Indian savage wiles. And the days to come were to bear testimony to her courage, her address, and her dominant rage for power. When her little fateful presence was eclipsed at last by the ample white bed-curtains and Norah was free to draw forth her pallet and lay herself down on the floor before the fire, the girl could not refrain a long-drawn sigh, half of fatigue and half self-commiseration. It seemed a hard lot with her exacting and freakish employer. But the cold bitter wind came surging around the corner of the house, and she remembered the bleak morasses across the wild Atlantic, the little smoky hovel she called home, the many to fend from frost and famine, the close and crowded quarters, the straw bed where she had lain, neighboring the pig. She thought of her august room-mate in comparison.

“But faix!—how much perliter was the crayther to be sure!”

It was one of the peculiarities of the officers of the Fort Prince George garrison that they were subject to fits of invisibility, Mrs. Annandale declared. She had been taciturn, even inattentive, over her dish of chocolate at early breakfast. More than once she turned, with a frostily fascinating smile, beamingly expectant, as the door opened. But when the dishes were removed, and the breakfast-room resumed its aspect as parlor, and her niece sat down to her embroidery-frame as if she had been at home in a country house in Kent, and the captain rose and began to get into his outdoor gear, Mrs. Annandale’s sugared and expectant pose gave way to blunt disappointment.

“Where are those villains we wasted our good cheer upon overnight?” she brusquely demanded. “I vow I expected to find them bowing their morning compliments on the door-step!”

“You must make allowances for our rude frontier soldiers,”—the commandant began.

“Were they caught up into the sky or swallowed up by the earth?”

The commandant explained that the tours of service recurred with unwelcome frequency in a garrison so scantily officered as Fort Prince George, and that Mervyn and Raymond were both on duty.

[36]“You should have excused them, dear Brother, since they are our acquaintances, and let some of those rowdy fellows in the mess-hall march, or goose-step, or deploy, or what not, in their stead.”

“Shoot me—no—no!” said the commandant, wagging his head, for this touched his official conscience, and the citadel in which it was ensconced not even this wily strategist could reach. “No, no, each man performs his own duty as it falls to him. I would not exchange or permit an exchange to—to, no, not to be quit forever of Fort Prince George.”

“Poor Arabella—she looks pale.”

“For neither of them,” the niece spoke up, tartly.

“Now that’s hearty,” said her father, approvingly.

“I shall be glad to be quiet a bit, and rest from the journey,” Arabella declared. “I don’t need to be amused to-day.”

“Lord—Lord! I pray I may survive it,” her aunt plained.

Mrs. Annandale was so definitely disconsolate and indignant that the captain held a parley. Lieutenant Bolt, the fort-adjutant, was a man of good station, he said, and also a younger lieutenant and two ensigns; should he not bespeak their company for a game of Quadrille in his quarters this evening?

Truly “dear Brother” was too tediously dense. “A murrain on them all!” she exclaimed angrily. “What are they in comparison with young Mervyn?”

“As good men every way. Trained, tried, valuable officers—worth their weight in gold,” he retorted, aglow with esprit de corps.

[37]She caught herself up sharply, fearing that she was too outspoken; and, realizing that “dear Brother” was an uncontrollable roadster when once he took the bit between his teeth, she qualified hastily. “An old woman loves gossip, Brother. What are these strangers to me? George Mervyn and I will put our heads together and canvass every scandal in the county for the last five years. Lord, he knows every stock and stone of the whole country-side, and all the folks, gentle and simple, from castle to cottage. I looked for some clavers such as old neighbors love.”

“Plenty of time—plenty of time,”—said the commandant. “George Mervyn will last till to-morrow morning.”

“To-morrow—is he in your clutches till to-morrow morning?” the schemer shrieked in dismay.

“He is officer of the day, Claudia, and his tour of duty began at guard-mounting this morning, and will not be concluded till guard-mounting to-morrow morning,” the captain said severely. Then in self-justification, for he was a lenient man, except in his official capacity, he added gravely: “You must reflect, Sister, that though we are a small force in a little mud fort on the far frontier, we cannot afford to be triflers at soldiering. A better fort than ours was compelled to surrender and a better garrison was massacred not one hundred and fifty miles from here. Our duties are insistent and our mutual responsibility is great. We are intrusted with the lives of each other.”

He desired these words to be of a permanent and[38] serious impression. He said no more and went out, leaving Mrs. Annandale fallen back in her chair, holding up her hands to heaven as a testimony against him.

“Oh, the ruffian!” she gasped. “Oh—to remind me of the Indians—the greasy, gawky red-sticks! Oh, the blood-thirsty, truculent brother!”

Arabella was of a pensive pose, with her head bent to her embroidery-frame, her trailing garment, called a sacque, of dark murrey-colored wool, catching higher wine-tinted lights from the fire as the folds opened over a bodice and petticoat of flowered stuff of acanthus leaves on a faint blue ground. She seemed ill at ease under this rodomontade against her father, and roused herself to protest.

“Why, you can’t have forgotten the Indians! You were talking about them every step of the way from Charlestown. And if you have seen one you have seen one hundred.”

“Out of sight out of mind—and me—so timid! Oh—and that hideous Fort Loudon massacre! Oh, scorch the tongue that says the word! Oh—the Indians! And me—so timid!”

“Lord, Aunt—” Arabella laid the embroidery-frame on her knees and gazed at her relative with stern, upbraiding eyes, “you know you lamented to discover that we were not to pass Fort Loudon on our journey, for you said it would be ‘a sight to remember, frightful but improving, like a man hung in chains.’”

Mrs. Annandale softly beat her hands together.

[39]“To talk of guarding life with his monkey soldiers against those red painted demons who drink blood and eat people—oh!—and me, so timid!”

She desisted suddenly as a light tap fell on the door and the mess-sergeant entered the room. She set her cap to rights with both her white, delicate, wrinkled, trembling hands, and stared with wild half-comprehending eyes as the man presented the compliments of Lieutenants Bolt and Jerrold, and Ensigns Lawrence and Innis, who felt themselves vastly honored by her invitation to a game of Quadrille, and would have the pleasure of waiting upon her this evening at the hour Captain Howard had named.

She made an appropriate rejoinder, and she waited until the door had closed upon the messenger, for she rarely “capered,” as her maid called her angry antics, in the presence of outsiders. Then she said with low-toned virulence to her niece:—

“The scheming meddler! That father of yours! That father of yours! Talk of treachery! Wilier than any Indian! Quadrille! Invite them! Smite them! Quadrille! Why, Mervyn is not complimented at all. The same grace extended to each and every!”

“And why should he be complimented, Aunt Claudia?”

“No reason in the world, Miss, as far as you are concerned,” retorted her aunt. “Our compliments won’t move such as George Mervyn!” Then recovering her temper,—“I thought a little special distinction as a dear old friend and a lifelong neighbor[40] might be fitting. Poor dear Brother must equalize the whole garrison!”

It seemed to Captain Howard as if with the advent of his feminine guests had entered elements of doubt and difficulty of which he had lately experienced a pleasant surcease. The joy which he had felt as a fond parent in embracing a good and lovely child, after a long absence, was too keen to continue in the intensity of its first moments and was softened to a gentle and tender content, a habitude of the heart, even more pleasurable. He was fond, too, in a way, of his queer sister, and grateful for her fostering care of his motherless children; he had great consideration for her whims and not the most remote appreciation of her peculiar abilities. The abatement of the joy of reunion was manifest in the fact that her whims now seemed to dominate her whole personality and tempered the fervor of his gratitude. He was already ashamed that he had not invited to the dinner of welcome the four other gentlemen who seemed altogether fit for that festivity and made the occasion one of general rejoicing among his brother officers and fellow-exiles, rather than a nettlesome point of exclusion. He was realizing, too, the disproportionate importance such trifles as the opportunity for transient pleasures possess in the estimation of the young, although they have all the years before them, with the continual recurrence of conventional incidents. Perhaps the long interval, debarred from all society of their sphere, rendered the exclusion a positive deprivation. He regretted that[41] he had submitted to Mrs. Annandale’s arrogation of the privilege of choosing the company invited to celebrate the arrival of the commandant’s daughter at the frontier fort. He seized upon the first moment when the rousing of his official conscience freed him, for the time, to repair the omission. The projected card-party would seem a device for introducing the officers in detail, as if this were deemed less awkward than entertaining them in a body, especially as there were only two ladies to represent the fair sex in the company.

To his satisfaction this implied theory of the appropriate seemed readily adopted. Lieutenant Jerrold was a man of a conventional, assured address, his conversation always strictly in good form and strictly limited. He was little disposed to take offence where the ground of quarrel seemed untenable or, on the other hand, to thrust himself forward where his presence was not warmly encouraged. He welcomed the invitation as enabling him to pay his respects to the ladies, which, indeed, seemed incumbent in the situation, but he had been a trifle nettled by the postponement of the opportunity. He had dark hair and eyes; he was tall, pale, and slender, with a narrow face and a flash of white teeth when he smiled. He was in many respects a contrast to the two ensigns—Innis, blue-eyed, blond, and square visaged, his complexion burned a uniform red by his frontier campaigns, and Lawrence, who had suffered much freckling as the penalty of the extreme fairness of his skin, and who always wore his hair[42] heavily powdered, to disguise in part the red hue, which was greatly out of favor in his day. Bolt, the fort-adjutant, was not likely to add much to the mirth of nations, or even of the garrison—a heavily-built, sedate, taciturn man, who would eat his supper with appreciation and discrimination, and play his cards most judiciously.

Captain Howard left the mess-hall where the recipients of his courtesy discussed its intendment over the remainder of breakfast, and took his way, his square head wagging now and then with an appreciation of its own obstinacy, across the snowy parade.

The gigantic purple slopes of the encompassing mountains showed here and there where the heavy masses of the drifts had slipped down by their own weight, and again the dark foliage of pine and holly and laurel gloomed amongst the snow-laden boughs of the bare deciduous trees. The contour, however, of the great dome-like “balds” was distinct, of an unbroken whiteness against the dark slate-tinted sky, uniform of tone from pole to pole.

Many feet had trampled the snow hard on the parade, and there was as yet no sign of thaw. Feathery tufts hung between the points of the high stockade surmounting the ramparts and choked the wheels of the four small cannon that were mounted on each of the four bastions. The cheeks of the deep embrasures out of which their black muzzles pointed were blockaded with drifts, and the scarp and counterscarp were smooth, and white, and untrodden.[43] The roofs of the block-houses were covered, and all along the northern side of the structures was a thin coating of snow clinging to the logs, save where the protuberant upper story overhung and sheltered the walls beneath. Close about the chimney of the building wherein was situated the mess-hall, the heat of the great fire below had melted the drifts, and a cordon of icicles clung from the stone cap, whence the dark column of smoke rushed up and, with a vigorous swirl through the air, made off into invisibility without casting a shadow in this gray day. He could see the great conical “state-house” on a high mound of the Indian settlement of Old Keowee Town, across the river; it was as smooth and white as a marble rotunda. The huddled dwellings were on a lower level and invisible from his position on the parade. As he glanced toward the main gate he paused suddenly. Before the guard-house the guard had been turned out, a glittering line of scarlet across the snow. The little tower above the gate was built in somewhat the style of a belfry, and through the open window the warder, like the clapper of a bell, stood drooping forward, gazing down at a group of blanketed and feather-crested figures, evidently Indians, desiring admission and now in conference with the officer of the guard. Captain Howard quickened his steps toward the party, and Raymond, perceiving his approach, advanced to meet him. There was a hasty, low-toned colloquy. Then “Damn all the Indians!” cried Captain Howard, angrily. “Damn them all!”

[44]“The parson says ‘No’!” Raymond submitted, with a glance of raillery.

“This is no occasion for your malapert wit, sir,” the captain retorted acridly.

Ordinarily Captain Howard was accessible to a pleasantry and himself encouraged a jovial insouciance as far as it might promote the general cheerfulness, but this incident threatened a renewal of a long strain of perplexity and dubious diplomacy and doubtful menace. It was impossible to weigh events. A trifle of causeless discontent among the Indians might herald downright murder. A real and aggravated grievance often dragged itself out and died of inanition in long correspondence with the colonial authorities, or the despatch of large and expensive delegations to Charlestown for those diplomatic conferences with the governor of South Carolina which the Indians loved and which flattered the importance of the head-men.

He strove visibly for his wonted self-balanced poise, and noticing that the young officer flushed, albeit silent, as needs must, he felt that he had taken unchivalrous advantage of the military etiquette which prevented a retort. He went on with a grim smile:—

“Where is this missionary now, who won’t give the devil his due.”

“The emissaries don’t tell, sir. Somewhere on the Tugaloo River, they give me to understand.”

“And what the fiend does he there?”

“Converts the Indians to Christianity, sir, if he can.”

[45]“And they resist conversion?”

“They say he plagues them with many words.”

Captain Howard nodded feelingly.

“They say he unsettles the minds of the people, who grow slack in the observance of their ‘old beloved’ worship. He reviles their religion, and offends ‘the Ancient White Fire.’”

“There is no rancor like religious rancor, no deviltry like pious strife,” said Captain Howard, in genuine dismay. “Nothing could so easily rouse the Indians anew.”

He paused in frowning anxiety. “Stop me, sir, this man is monstrous short of a Christian, himself, to jeopardize the peace and put the whole frontier into danger for his zeal—just now when the tribe is fairly pacified. This threatens Fort Prince George first of all.”

He set his square jaw as he thought of his daughter and his sister.

Raymond instinctively knew what was passing in his mind, and forgetful of his sharp criticism volunteered reassurance.

“The delegation speak, sir, as if only the missionary were in danger.”

“Why don’t they burn him, then, sir—kindle the fire with his own prayer-book!” cried Captain Howard, furiously. Danger from the Indians—now! with Arabella and Claudia at Fort Prince George! He could not tolerate the idea. Even in their defeated and disconsolate estate the Cherokees could bring two thousand warriors to the field—and[46] the garrison of Fort Prince George numbered scant one hundred, rank and file.

“It might be the beginning of trouble,” suggested Raymond, generously disregarding the acerbity with which his unsought remarks had been received. “You know how one burning kindles the fires of others—how one murder begins a massacre.”

“Lord—Lord—yes!” exclaimed Captain Howard. “What ails the wretch?—are there no sinners at Fort Prince George that he must go hammering at the gates of heaven for the vile red fiends? And what a murrain would they do there! I can see Moy Toy having a ‘straight talk’ with Saint Peter, and that one-eyed murderer, Rolloweh, quiring to a gilded harp! Is there no way of getting at the man? Will they not let him come back now?”

“They have asked him to leave the country.”

“And what said he?” demanded Captain Howard.

“The delegation declare that he said, ‘Woe!’”

“Whoa!” echoed Captain Howard, in blank amaze.

“Yes, sir,—that was his answer to them in conclave in their beloved square. ‘Woe!’”

“Whoa!” repeated Captain Howard, stuck fast in misapprehension. “I think he means, Get-up-and-go-’long!”

Raymond had a half-hysteric impulse to laugh, and yet it was independent of any real amusement.

“I fancy he meant, ‘Woe is unto him if he preach not the gospel,’” he said. “The Indians remember one word only—‘Woe!’”

[47]“He shall preach the gospel hereafter at Fort Prince George! Is there no way to quiet the man?”

“You know the Indians’ methods, sir. I think they have some demand to make of you, but they will not enter on it for twenty-four hours. They want accommodations and a conference to-morrow.”

“Zounds!” exclaimed Captain Howard, in the extremity of impatience. In this irregular frontier warfare he had known many a long-drawn, lingering agony of suspense—but he felt as if he could not endure the ordeal with all he now had at stake, his daughter, his sister, as hostages to the fortunes of war. He had an impulse to take the crisis as it were in the grasp of his hand and crush it in the moment. He could not wait—yet wait he must.

“They only vouchsafed as much as I have told you in order to secure the conference,” said Raymond. “I gave them to understand that the time of our ‘beloved man’ was precious and not to be expended on trifles. But they held back the nature of the demand on you and the whereabouts of the parson.”

“I pray God, they have not harmed the poor old man!” exclaimed Captain Howard fervently, with a sudden revulsion of sentiment.

They both glanced toward the gate where the deputation stood under the archway. The sun was shining faintly and the wan light streamed through the portal. The shadows duplicated the number and the attitudes of the blanketed and feather-crested figures, all erect, and stark, and motionless, looking[48] in blank silence at the conference of the two officers. The shadows had a meditative pose, a sort of pondering attention, and when suddenly the sun darkened and the shadows vanished, the effect was as if some dimly visible councillors had whispered to the Indians and were mysteriously resolved into the medium of the air.

They received Raymond on his return with their characteristic expressionless stolidity, and when the quarter-master appeared, hard on Captain Howard’s withdrawal, with the order for their lodgement in a cluster of huts just without the works, reserved for such occasions and such guests, they repaired thither without a word, and Raymond, looking after them from the gate, soon beheld the smoke ascending from their fires and the purveying out of the good cheer of the hospitality of Fort Prince George. He noticed a trail of blood on the snow, where the quarter-master’s men had laid down for a moment a quarter of beef, and in this he recognized a special compliment, for beef was a rarity with the Indians—venison and wild-fowl being their daily fare.

As the day waxed and waned he often cast his eye thither noting their movements. They came out in a body in the afternoon and repaired together to the trading-house, situated near the bank of the river, and occupied as a home as well as a store by the Scotch trader and his corps of assistants. That fire-water would be in circulation Raymond did not doubt, for to refuse it would work more disturbance than to set it forth in moderation. There were many regulations[49] in hindrance of its sale, but rarely enforced, and he doubted if the trader would forego his profit even at the risk of the displeasure of the commandant. Some difficulty they evidently encountered, however, in procuring it. They all came back immediately and disappeared in their huts, and there was no sign of life in all the bleak landscape, save the vague smoke from the Indian town across the river and the dark wreaths from the fires of the delegation. The woods stood sheeted and white at the extremity of the space beyond the glacis, cleared to prevent too close an approach of an enemy and the firing into the fort from the branches of trees within range. The river was like rippled steel, its motion undiscerned on its surface, and its flow was silent. The sky was still gray and sombre; at one side of the fort the prongs and boughs of the abattis thrust darkly up through the snow that lodged among them.

Somewhat after the noon hour he noticed a party of Indians, vagrant-like, kindling a fire in a sheltered space in the lee of a rock and feeding on the carcass of a deer lately killed. The feast was long, but when it was ended they sat motionless, fully gorged, all in a row, squatting, huddled in their blankets and eying the fort, seemingly aimless as the time passed and the fire dwindled and died, neither sleeping nor making any sign. When the Indians of the delegation accommodated in the huts issued again and once more hopefully took their way to the trading-house, they must have seen, coming or going, this row of singular objects, like roosting birds, dark against the snow,[50] silently contemplating with unknown, unknowable, savage thoughts the little fort. There was no suggestion of recognition or communication. Each band was for the other as if it did not exist. The delegation wended its way to the trading-house, and presently returned, and once more sought the emporium, and again repaired to the temporary quarters. The snow between the two points began to show a heavily trampled path.

That these migrations were not altogether without result became evident when one of the Indians, zig-zagging unsteadily in the rear, wandered from the beaten track, stumbled over the stump of a tree concealed by a drift, floundered unnoticed for a time, unable to rise, and at last lay there so still and so long that Raymond began to think he might freeze should he remain after the chill of the nightfall. But as the skies darkened two of the Indians came forth and dragged him into one of their huts, which were beginning to show as dull red sparks of light in the gathering dusk. And still beyond the abattis that semblance of birds of ill-omen was discernible against the expanse of white snow, as with their curious, racial, unimagined whim the vagrant savages sat in the cold and watched the fort. They did not stir when the sunset gun sounded and the flag fluttered gently down from the staff. The beat of drums shook the thick air, and the yearning sweetness of the bugle’s tone, as it sounded for retreat, found a responsive vibration even in the snow-muffled rocks. Again and again it was lovingly reiterated, and a[51] tender resonance thrilled vaguely a long time down the dim cold reaches of the river.

Lights had sprung up in the windows. A great yellow flare gushed out from the open door of the mess-hall, and the leaping flames of the gigantic fireplace could be seen across the parade. The barracks were loud with jovial voices. Servants bearing trays of dishes were passing back and forth from the kitchen to the commandant’s quarters. The vigorous tramp of the march of soldiers made itself heard even in the snow as the corporal of the guard went out with the relief. A star showed in the dull gray sky that betokened in the higher atmosphere motion and shifting of clouds. A faint, irresolute, roseate tint lay above the purple slope to the west with a hesitant promise of a fair morrow. The light faded, the night slipped down, and the sentries began to challenge.

It was the fashion of the time and place to be zealous in flattering the Indian’s sense of importance, and the hospitality of the fort was constantly asserted in plying the delegation with small presents. Shortly after nightfall the quarter-master-sergeant went out to the Indian huts with some tobacco and pipes, and tafia, and the compliments of the commandant. He returned with the somewhat significant information that they needed no tafia. A few, he stated, were sober, but saturnine and grave. Others were blind drunk. The most troublesome had reached the jovial stage. From where they lay recumbent they had caught the soldier by one leg and then by the other, tumbled him on the floor, and tripped him again and again as he sought to rise; finally, he made his way by scrambling on all fours out into the snow, and running for the gate with two or three of the staggering braves at his heels.

“Faix, if the commandant has any more complimints to waste on thim Injun gossoons,” he remarked, as he stood, panting and puffing, under the archway while the guard clustered at gaze in the big door of the guard-house, “by the howly poker, he may pursint them in person! For the divil be in[53] ivery fut I’ve got if I go a-nigh them cu’rus bogies agin! They ain’t human. Wait, me b’ye, till I git me breath, an’ I’ll give ye the countersign, if I haven’t forgot ut. I’m constructively on the outside yit, seein’ ye cannot let me in till I gives ye the countersign.”

There was a low-toned murmur.

“Pass, friend,” said the sentinel.

“Thankin’ ye fur nothin’,” the quarter-master-sergeant rejoined as he paused under the archway to gaze back over the snow.

“If Robin Dorn ain’t a frog or a tadpole to grow a new laig if one is pulled off,” he remarked, “he’ll hardly make the fort to-night.”

The sentinel, left alone at the gate, peered out into the bleak dark waste. All suggestion of light had faded from the sky, and that the ground was white showed only where the yellow gleams from the doors and windows of the fort fell upon the limited space of the snowy parade. Soon these dwindled to a lantern in front of the silent barracks and a vague glimmer from the officers’ mess-hall, where the great fire was left all solitary to burn itself out. A light still shone through the windows of the commandant’s quarters, where he was entertaining company at cards. But otherwise the fort was lapsing to quiescence and slumber.

A wind began to stir in the woods. More than once the sentinel heard the dull thud of falling masses of snow and the clashing together of bare boughs. Then the direction of the current of the[54] air changed; it wavered and gradually its force failed, a deep stillness ensued and absolute darkness prevailed. The sound of crunching, as wolves or dogs gnawed, snarling, the bones of the deer that the vagrant savages had killed beyond the abattis, was distinct to his ear. It was a cold night and a dreary. The vigilance of watching with naught in expectation is a strain upon the attention which a definite menace does not exert. There was now no thought of danger from the Indians, who were fast declining from the character of warriors and marauders to that of mendicants and aimless intruders and harmless pests. The soldier knew his duty and was prepared to do it, but to maintain a close guard in these circumstances was a vexatious necessity. He paced briskly up and down to keep his blood astir.

A break in the dull monotony can never be so welcome as to a dreary night-watch. He experienced a sense of absolute pleasure in the regulation appearance of the officer of the day, crossing the parade and challenged by the sentinel before the guard-house door. The brisk turning out of the guard was like a reassurance of the continued value and cheer of life. The flare from the guard-house door showed the lines of red uniforms, the glitter of the bayonets, the muskets carried at “shoulder arms!” the officer of the guard, Raymond, at his post, and the sergeant advancing to the stationary figure, waiting in the snow. He watched the familiar scene, on which in the day-time he would not have bestowed a glance, as if it had some new and eager significance—so[55] do trifles of scant interest fill the void of mental inactivity.

The crisp young voices were musical to his ear as they rang out in the night with the stereotyped phrases. “Advance, officer of the day, and give the countersign!” cried the sergeant. Then as Mervyn advanced and a whispered colloquy ensued, the dapper sergeant whirled briskly, smartly saluting the officer of the guard with the cry—as of discovery—“The countersign is right!”

“Advance officer of the day,” said Raymond.

The two officers approached each other and the sentinel, losing interest in their unheard, whispered conference as Mervyn gave the parole, turned his eyes to the wild waste without. He was startled to see vaguely, dubiously, in some vagrant, far glimmer of the flare from the guard-house door or the swinging flicker of the lantern carried by one of the two men who, with a non-commissioned officer, was preparing to accompany the officer of the day on his rounds, a strange illusion, as close as the parapet of the covered way. There were dark figures against the snow, crouching dog-like or wolf-like—and yet he knew them to be Indians. They were gazing at the illuminated military manœuvre set in the flare of yellow light in the midst of the dark night. The sentinel could not be sure of their number, their distance. He cried out harshly—“Who goes there! The guard! The guard!”