*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 69403 ***

Transcriber’s Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation, capitalization, and spelling in the original document have

been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

The following inconsistencies were noted and retained:

- Grous and Grouse

- John Bullow and John Bulow

- Ingalls and Ingals

- Lehman and Leehman

- lents and lints

- Magdaleine and Magdeleine Islands

- oppossum and opossum

- waggons and wagons

- Schuylkill and Schuylkil

- arcuato-declinate and arcuate-declinate

- cæca and cœca

- Macculloch and M’Culloch

The following are possible errors, but retained:

- unrol

- “at the height of fifty years or more”

- John Quincey Adams

- Daniel Boon

- “The matin calls”

- Persimons

- pork-rhind

- p. 487 of Vol. II should possibly be page 435 of that volume.

The Errata on page 632 have been corrected in the text.

Links are provided to Volume 1 of this work. The links are designed to work when the book is read on line. If you want to download that volume and use the links, you will need to change the links to point to the file name on your own device.

Download Volume 1 at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/56989.

Download Volume 2 at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/39979.

ORNITHOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY.

ORNITHOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY,

OR AN ACCOUNT OF THE HABITS OF THE

BIRDS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

ACCOMPANIED BY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE OBJECTS REPRESENTED

IN THE WORK ENTITLED

THE BIRDS OF AMERICA,

AND INTERSPERSED WITH DELINEATIONS OF AMERICAN

SCENERY AND MANNERS.

BY JOHN JAMES AUDUBON, F.R.SS.L. & E.

FELLOW OF THE LINNEAN AND ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETIES OF LONDON; MEMBER OF THE LYCEUM

OF NEW YORK, OF THE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY OF PARIS, THE WERNERIAN NATURAL

HISTORY SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH; HONORARY MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF NATURAL

HISTORY OF MANCHESTER, AND OF THE SCOTTISH ACADEMY OF PAINTING, SCULPTURE,

AND ARCHITECTURE; MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, OF THE

ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES AT PHILADELPHIA, OF THE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETIES

OF BOSTON, OF CHARLESTON IN SOUTH CAROLINA, &C. &C.

Vol. III

EDINBURGH:

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK, EDINBURGH;

LONGMAN, REES, BROWN, GREEN & LONGMAN, LONDON; R. HAVELL,

ENGRAVER, 77. OXFORD STREET, LONDON; THOMAS SOWLER,

MANCHESTER; MRS ROBINSON, LEEDS; ALEXANDER HILL, EDINBURGH;

J. HENRY BEILBY, BIRMINGHAM; E. CHARNLEY, NEWCASTLE-UPON-TYNE;

AND GEORGE SMITH, LIVERPOOL.

MDCCCXXXV.

PRINTED BY NEILL & Co.

Old Fishmarket, Edinburgh.

INTRODUCTION.

Ten years have now elapsed since the first number of my

Illustrations of the Birds of America made its appearance. At

that period I calculated that the engravers would take sixteen

years in accomplishing their task; and this I announced in my

prospectus, and talked of to my friends. Of the latter not a

single individual seemed to have the least hope of my success,

and several strongly advised me to abandon my plans, dispose of

my drawings, and return to my country. I listened with attention

to all that was urged on the subject, and often felt deeply

depressed, for I was well aware of many of the difficulties to be

surmounted, and perceived that no small sum of money would

be required to defray the necessary expenses. Yet never did

I seriously think of abandoning the cherished object of my

hopes. When I delivered the first drawings to the engraver, I

had not a single subscriber. Those who knew me best called

me rash; some wrote to me that they did not expect to see a

second fasciculus; and others seemed to anticipate the total

failure of my enterprise. But my heart was nerved, and my

reliance on that Power, on whom all must depend, brought

bright anticipations of success.

vi

Having made arrangements for meeting the first difficulties,

I turned my attention to the improvement of my drawings, and

began to collect from the pages of my journals the scattered notes

which referred to the habits of the birds represented by them.

I worked early and late, and glad I was to perceive that the

more I laboured the more I improved. I was happy, too, to

find, that in general each succeeding plate was better than its

predecessor, and when those who had at first endeavoured to dissuade

me from undertaking so vast an enterprise, complimented

me on my more favourable prospects, I could not but feel happy.

Number after number appeared in regular succession, until at

the end of four years of anxiety, my engraver, Mr Havell,

presented me with the First Volume of the Birds of America.

Convinced, from a careful comparison of the plates, that at

least there had been no falling off in the execution, I looked forward

with confidence to the termination of the next four years’

labour. Time passed on, and I returned from the forests and

wilds of the western world to congratulate my friend Havell,

just when the last plate of the second volume was finished.

About that time, a nobleman called upon me with his family,

and requested me to shew them some of the original drawings,

which I did with the more pleasure that my visitors possessed

a knowledge of Ornithology. In the course of our conversation,

I was asked how long it might be until the work

should be finished. When I mentioned eight years more, the

nobleman shrugged up his shoulders, and sighing, said, “I may

not see it finished, but my children will, and you may please to

add my name to your list of subscribers.” The young people

exhibited a mingled expression of joy and sorrow, and when I

with them strove to dispel the cloud that seemed to hang over

vii

their father’s mind, he smiled, bade me be sure to see that

the whole work should be punctually delivered, and took his

leave. The solemnity of his manner I could not forget for several

days; I often thought that neither might I see the work

completed, but at length I exclaimed “my sons may.” And

now that another volume, both of my Illustrations and of my

Biographies is finished, my trust in Providence is augmented,

and I cannot but hope that myself and my family together may

be permitted to see the completion of my labours.

I have performed no long journey since I last parted from you,

and therefore I have little of personal history to relate to you.

I have spent the greater part of the interval in London and

Edinburgh, in both which cities I have continued to enjoy a

social intercourse with many valued friends. In the former, it

has been my good fortune to add to the list the names of William

Yarrell, Esq., Dr Bell, Dr Boott, Captain James

Clark Ross, R. N., and Dr Richardson. From Mr Yarrell

and the two latter gentlemen, both well known to you as

intrepid and successful travellers, I have received much valuable

information, as well as precious specimens of birds and eggs,

collected in the desolate regions of the extreme north. My

anxiety to compare my specimens with those of the Zoological

Society of London, induced me to request permission to do so,

which the Council freely accorded. For this favour I now present

my warm acknowledgments to the Noble Earl of Derby,

the Members of the Council, their amiable Secretary Mr Bennett,

and to Mr Gould, who had the kindness to select for me

such specimens as I wanted. My friend Professor Jameson of

Edinburgh has been equally kind in allowing me the means of

comparing specimens. From America I have received some

viii

valuable information, and many interesting specimens of birds

and eggs, for which I am indebted to the Rev. John Bachman,

Dr Richard Harlan, Dr George Parkman, Edward

Harris, Esq. and others.

The number of new species described in the present volume

is not great. Among them, however, you will find the largest

true Heron hitherto discovered in the United States. I have

corrected some errors committed by authors, and have added to

our Fauna several species which, although described by European

writers, had not been observed in America. The habits

of many species previously unknown have also been given in

detail.

Having long ago observed, in works on the Birds of the

United States, the omission of the females and the different appearances

produced by the change of season in most water birds,

I have represented the male accompanied by his mate, and, in

as many instances as possible, the young also. The technical

descriptions have been given at greater length than in the former

volumes, with the view of preventing error even in comparing

dried skins with either the figures or the descriptions.

I have also given the average measurement of the eggs, which

I regret I had omitted to do in the other volumes; an error

which I purpose to atone for by presenting you, in the last

number of my Illustrations, with figures of all those which I

have collected.

The figures in the third volume of my Illustrations amount

to one hundred and eighty-two, and are thus much fewer than

those in either of the preceding volumes. This, however,

was rendered necessary by the comparatively large size of the

originals, the aquatic species of Birds greatly exceeding the

ix

terrestrial in this respect. Many of them in fact are so large

that only a single figure could be given, and that not always in

so good an attitude as I could have wished. For this reason I

have sometimes been obliged to give the figure of the young in

a separate plate; and this I shall in a few cases continue to do,

in order to correct the errors of authors respecting certain species,

which I have proved to be merely nominal. Still the number

contained in the three volumes being six hundred and

seventy-four, there are more than two to each species.

The engraving and colouring of the plates of this volume

have generally been considered as much superior even to those

of the second. Indeed, some of my patrons, both in Europe

and America, have voluntarily expressed their conviction of the

superiority of these plates. This is the more gratifying to me,

that it proves the unremitted care and perseverance of Mr

Havell and his assistants, of whom I mention with approbation

Messrs Blake and Edington.

The Ornithology of the United States may be said to have

been commenced by Alexander Wilson, whose premature

death prevented him from completing his labours. It is unnecessary

for me to say how well he performed the task which

he had imposed upon himself; for all naturalists, and many who

do not aspire to the name, acknowledge his great merits. But

although he succeeded in observing and obtaining a very great

number of our birds, he left for others many species which he

was unable to procure. These have been sought for with eagerness,

and not without success, by persons who have engaged in

the pursuit with equal ardour. The Prince of Musignano,

full of enthusiasm, having his judgment matured by long observation,

and his mind stored with useful learning, collected in

x

our woods and prairies, by our great rivers, and along our extended

shores, materials sufficient for four superb volumes, intended

as a continuation of Wilson’s work. Thomas Nuttall,

equally learned and enthusiastic, next entered the field. His

Manual of our Birds contains a mass of useful information, and

is for the most part excellent. Many others have, in various

ways, endeavoured to extend our knowledge on this subject;

but with the exception of Thomas Say, none have published

their discoveries in a connected form. Dr Harlan has given

to the world an excellent account of our Mammalia; various

works on Mollusca have appeared, and at present Dr Horlbeck

of Charleston is engaged in publishing an account of our

Reptiles.

Along our extended frontiers I have striven to observe and

gather whatever had escaped the notice of the different collectors;

and now, kind Reader, to prove to you that if not so fortunate

as I had wished, I yet have done all that was in my

power, I present you with a third volume of Ornithological Biographies,

in which you will find some account of about sixty

species of Water Birds not included in the works of Wilson.

These, at one season or other, are to be met with along the

shores or streams of the United States. Some of them are certainly

very rare, others remarkable in form and habits; but all,

I trust, you will find distinct from each other, and not inaccurately

described.

The difficulties which are to be encountered in studying the

habits of our Water Birds are great. He who follows the feathered

inhabitants of the forests and plains, however rough or

tangled the paths may be, seldom fails to obtain the objects of

his pursuit, provided he be possessed of due enthusiasm and perseverance.

xi

The Land Bird flits from bush to bush, runs before

you, and seldom extends its flight beyond the range of your

vision. It is very different with the Water Bird, which sweeps

afar over the wide ocean, hovers above the surges, or betakes itself

for refuge to the inaccessible rocks on the shore. There,

on the smooth sea-beach, you see the lively and active Sandpiper;

on that rugged promontory the Dusky Cormorant; under

the dark shade of yon cypress the Ibis and Heron; above

you in the still air floats the Pelican or the Swan; while far

over the angry billows scour the Fulmar and the Frigate bird.

If you endeavour to approach these birds in their haunts, they

betake themselves to flight, and speed to places where they are

secure from your intrusion.

But the scarcer the fruit, the more prized it is; and seldom

have I experienced greater pleasures than when on the Florida

Keys, under a burning sun, after pushing my bark for miles over

a soapy flat, I have striven all day long, tormented by myriads

of insects, to procure a heron new to me, and have at length succeeded

in my efforts. And then how amply are the labours of

the naturalist compensated, when, after observing the wildest

and most distrustful birds, in their remote and almost inaccessible

breeding places, he returns from his journeys, and relates

his adventures to an interested and friendly audience.

I look forward to the summer of 1838 with an anxious hope

that I may then be able to present you with the last plate of

my Illustrations, and the concluding volume of my Biographies.

To render these volumes as complete as possible, I intend to undertake

a journey to the southern and western limits of the

Union, with the view of obtaining a more accurate knowledge

of the birds of those remote and scarcely inhabited regions.

xii

On this tour I shall be accompanied by my youngest son, while

the rest of my family will remain in Britain, to direct the progress

of my publication.

In concluding these prefatory remarks, I have to inform

you that one of the tail-pieces in my second volume, entitled

“A Moose Hunt,” was communicated to me by my young friend

Thomas Lincoln of Dennisville in Maine; and that it was

at his particular request, and much against my wishes, that his

name was not mentioned at the time. I have now, however,

judged it proper to make this statement.

JOHN J. AUDUBON.

Edinburgh, 1st December 1835.

xiii

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

|

|

Page |

| The Canada Goose, |

Anser canadensis, |

1 |

| The Red-throated Diver, |

Colymbus septentrionalis, |

20 |

| The Great Red-breasted Rail, or Fresh-water Marsh-Hen, |

Rallus elegans, |

27 |

| The Clapper Rail, or Salt-water Marsh-Hen, |

Rallus crepitans, |

33 |

| The Virginian Rail, |

Rallus virginianus, |

41 |

| The American Sun Perch, |

|

47 |

| The Wood Duck, |

Anas Sponsa, |

52 |

| The Booby Gannet, |

Sula fusca, |

63 |

| The Esquimaux Curlew, |

Numenius borealis, |

69 |

| Wilson’s Plover, |

Charadrius Wilsonius, |

73 |

| The Least Bittern, |

Ardea exilis, |

77 |

| The Eggers of Labrador, |

|

82 |

| The Great Blue Heron, |

Ardea Herodias, |

87 |

| The Common American Gull, |

Larus zonorhynchus, |

98 |

| The Puffin, |

Mormon arcticus, |

105 |

| The Razor-billed Auk, |

Alca Torda, |

112 |

| The Hyperborean Phalarope, |

Phalaropus hyperboreus, |

118 |

| Fishing in the Ohio, |

|

122 |

| The Wood Ibis, |

Tantalus Loculator, |

128 |

| The Louisiana Heron, |

Ardea ludoviciana, |

136 |

| The Foolish Guillemot, |

Uria Troile, |

142 |

| The Black Guillemot, |

Uria Grylle, |

148 |

| The Piping Plover, |

Charadrius melodus, |

154

xiv |

| The Wreckers of Florida, |

|

158 |

| The Mallard, |

Anas Boschas, |

164 |

| The White Ibis, |

Ibis alba, |

173 |

| The American Oyster-Catcher, |

Hæmatopus palliatus, |

181 |

| The Kittiwake Gull, |

Larus tridactylus, |

186 |

| The Kildeer Plover, |

Charadrius vociferus, |

191 |

| The White Perch and its Favourite Bait, |

|

197 |

| The Whooping Crane, |

Grus americana, |

202 |

| The Pintail Duck, |

Anas acuta, |

214 |

| The Green-winged Teal, |

Anas Crecca, |

219 |

| The Scaup Duck, |

Fuligula Marila, |

226 |

| The Sanderling, |

Tringa arenaria, |

231 |

| A Racoon Hunt in Kentucky, |

|

235 |

| The Long-billed Curlew, |

Numenius longirostris, |

240 |

| The Hooded Merganser, |

Mergus cucullatus, |

246 |

| The Sora Rail, |

Rallus carolinus, |

251 |

| The Ring-necked Duck, |

Fuligula rufitorques, |

259 |

| The Sooty Tern, |

Sterna fuliginosa, |

263 |

| A Wild Horse, |

|

270 |

| The Night Heron, |

Ardea Nycticorax, |

275 |

| The Hudsonian Curlew, |

Numenius hudsonicus, |

283 |

| The Great Marbled Godwit, |

Limosa Fedoa, |

287 |

| The American Coot, |

Fulica americana, |

291 |

| The Roseate Tern, |

Sterna Dougallii, |

296 |

| Reminiscences of Thomas Bewick, |

|

300 |

| The Great Black-backed Gull, |

Larus marinus, |

305 |

| The Snowy Heron, |

Ardea candidissima, |

317 |

| The American Snipe, |

Scolopax Wilsonii, |

322 |

| The Common Gallinule, |

Gallinula Chloropus, |

330 |

| The Large-billed Guillemot, |

Uria Brunnichii, |

336 |

| Pitting of Wolves, |

|

338 |

| The Eider Duck, |

Fuligula mollissima, |

342 |

| The Velvet Duck, |

Fuligula fusca, |

354

xv |

| The Pied-billed Dobchick, |

Podiceps carolinensis, |

359 |

| The Tufted Puffin, |

Mormon cirrhatus, |

364 |

| The Arctic Tern, |

Sterna arctica, |

366 |

| A Tough Walk for a Youth, |

|

371 |

| The Brown Pelican, |

Pelecanus fuscus, |

376 |

| The Florida Cormorant, |

Phalacrocorax floridanus, |

387 |

| The Pomarine Jager, |

Lestris pomarinus, |

396 |

| Wilson’s Phalarope, |

Phalaropus Wilsonii, |

400 |

| The Red Phalarope, |

Phalaropus fulicarius, |

404 |

| Breaking up of the Ice, |

|

408 |

| The Reddish Egret, |

Ardea rufescens, |

411 |

| The Double-crested Cormorant, |

Phalacrocorax dilophus, |

420 |

| The Hudsonian Godwit, |

Limosa hudsonica, |

426 |

| The Horned Grebe, |

Podiceps cornutus, |

429 |

| The Forked-tailed Petrel, |

Thalassidroma Leachii, |

434 |

| A Maple-sugar Camp, |

|

438 |

| The Whooping Crane, |

Grus americana, |

441 |

| The Tropic Bird, |

Phaeton æthereus, |

442 |

| The Curlew Sandpiper, |

Tringa subarquata, |

444 |

| The Fulmar Petrel, |

Procellaria glacialis, |

446 |

| The Buff-breasted Sandpiper, |

Tringa rufescens, |

451 |

| The Opossum, |

|

454 |

| The Common Cormorant, |

Phalacrocorax Carbo, |

458 |

| The Arctic Jager, |

Lestris parasiticus, |

470 |

| The American Woodcock, |

Scolopax minor, |

474 |

| The Greenshank, |

Totanus Glottis, |

483 |

| Wilson’s Petrel, |

Thalassidroma Wilsonii, |

486 |

| A Long Calm at Sea, |

|

491 |

| The Frigate Pelican, |

Tachypetes Aquilus, |

495 |

| Richardson’s Jager, |

Lestris Richardsonii, |

503 |

| The Cayenne Tern, |

Sterna cayana, |

505 |

| The Semipalmated Snipe, or Willet, |

Totanus semipalmatus, |

510 |

| The Noddy Tern, |

Sterna stolida, |

516 |

| Still Becalmed, |

|

520

xvi |

| The King Duck, |

Fuligula spectabilis, |

523 |

| Hutchins’s Goose, |

Anser Hutchinsii, |

526 |

| Schinz’s Sandpiper, |

Tringa Schinzii, |

529 |

| The Sandwich Tern, |

Sterna cantiaca, |

531 |

| The Black Tern, |

Sterna nigra, |

535 |

| Natchez in 1820, |

|

539 |

| The Great White Heron, |

Ardea occidentalis, |

542 |

| The White-winged Silvery Gull, |

Larus leucopterus, |

553 |

| The Wandering Shearwater, |

Puffinus cinereus, |

555 |

| The Purple Sandpiper, |

Tringa maritima, |

558 |

| The Forked-tailed Gull, |

Larus Sabini, |

561 |

| The Lost Portfolio, |

|

564 |

| The White-fronted Goose, |

Anser albifrons, |

568 |

| The Ivory Gull, |

Larus eburneus, |

571 |

| The Yellowshank, |

Totanus flavipes, |

573 |

| The Solitary Sandpiper, |

Totanus chloropygius, |

576 |

| The Red-backed Sandpiper, |

Tringa alpina, |

580 |

| Labrador, |

|

584 |

| The Herring Gull, |

Larus argentatus, |

588 |

| The Crested Grebe, |

Podiceps cristatus, |

595 |

| The Large-billed Puffin, |

Mormon glacialis, |

599 |

| The Pectoral Sandpiper, |

Tringa pectoralis, |

601 |

| The Manks Shearwater, |

Puffinus Anglorum, |

604 |

| Great Egg Harbour, |

|

606 |

| The Barnacle Goose, |

Anser leucopsis, |

609 |

| The Harlequin Duck, |

Fuligula histrionica, |

612 |

| The Red-necked Grebe, |

Podiceps rubricollis, |

617 |

| The Dusky Petrel, |

Puffinus obscurus, |

620 |

| The Golden Plover, |

Charadrius pluvialis, |

623 |

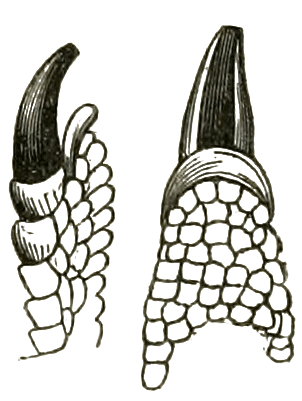

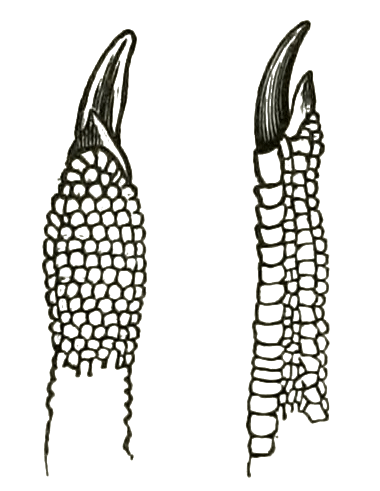

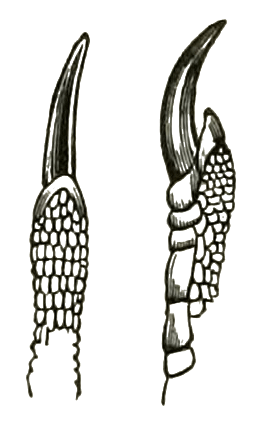

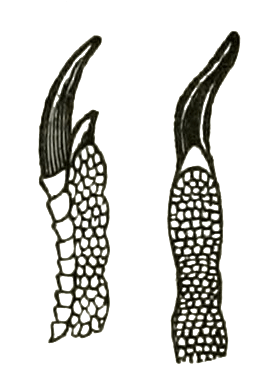

| Remarks on the Form of the Toes of Birds, |

|

629 |

1

ORNITHOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY.

THE CANADA GOOSE.

Anser canadensis, Vieill.

PLATE CCI. Male and Female.

Although the Canada Goose is considered as a northern species, the

number of individuals that remain at all seasons in the milder latitudes,

and in different portions of the United States, fully entitles this bird to

be looked upon as a permanent resident there. It is found to breed sparingly

at the present day, by many of the lakes, lagoons, and large

streams of our Western Districts, on the Missouri, the Mississippi, the

lower parts of the Ohio, on Lake Erie, the lakes farther north, and in several

large pools situated in the interior of the eastern parts of the States

of Massachusetts and Maine. As you advance farther toward the east

and north, you find it breeding more abundantly. While on my way to

Labrador, I found it in the Magdeleine Islands, early in June, sitting on

its eggs. In the Island of Anticosti there is a considerable stream, near

the borders of which great numbers are said to be annually reared; and

in Labrador these birds breed in every suitable marshy plain. The

greater number of those which visit us from still more northern regions,

return in the vernal season, like many other species, to the dismal countries

which gave them birth.

Few if any of these birds spend the winter in Nova Scotia, my friend

Mr Thomas M’Culloch having informed me that he never saw one about

Pictou at that period. In spring, as they proceed northward, thousands

are now and then seen passing high in the air; but in autumn, the flocks

are considerably smaller, and fly much lower. During their spring movements,

the principal places at which they stop to wait for milder days are

2

Bay Chaleur, the Magdeleine Islands, Newfoundland, and Labrador, at

all of which some remain to breed and spend the summer.

The general spring migration of the Canada Goose, may be stated to

commence with the first melting of the snows in our Middle and Western

Districts, or from the 20th of March to the end of April; but the precise

time of its departure is always determined by the advance of the season,

and the vast flocks that winter in the great savannahs or swampy

prairies south-west of the Mississippi, such as exist in Opellousas, on the

borders of the Arkansas River, or in the dismal “Ever Glades” of the

Floridas, are often seen to take their flight, and steer their course northward,

a month earlier than the first of the above mentioned periods. It

is indeed probable that the individuals of a species most remote from the

point at which the greater number ultimately assemble, commence their

flight earlier than those which have passed the winter in stations nearer

to it.

It is my opinion that all the birds of this species, which leave our

States and territories each spring for the distant north, pair before they

depart. This, no doubt, necessarily results from the nature of their place

of summer residence, where the genial season is so short as scarcely to afford

them sufficient time for bringing up their young and renewing their

plumage, before the rigours of advancing winter force them to commence

their flight towards milder countries. This opinion is founded

on the following facts:—I have frequently observed large flocks of

Geese, in ponds, on marshy grounds, or even on dry sand bars, the mated

birds renewing their courtship as early as the month of January, while

the other individuals would be contending or coquetting for hours every

day, until all seemed satisfied with the choice they had made, after which,

although they remained together, any person could easily perceive that

they were careful to keep in pairs. I have observed also that the older

the birds, the shorter were the preliminaries of their courtship, and that

the barren individuals were altogether insensible to the manifestations of

love and mutual affection that were displayed around them. The bachelors

and old maids, whether in regret, or not caring to be disturbed by

the bustle, quietly moved aside, and lay down on the grass or sand at

some distance from the rest; and whenever the flocks rose on wing, or

betook themselves to the water, these forlorn birds always kept behind.

This mode of preparing for the breeding season has appeared to me the

more remarkable, that, on reaching the place appointed for their summer

3

residence, the birds of a flock separate in pairs, which form their nests

and rear their young at a considerable distance from each other.

It is extremely amusing to witness the courtship of the Canada Goose

in all its stages; and let me assure you, reader, that although a Gander

does not strut before his beloved with the pomposity of a Turkey, or the

grace of a Dove, his ways are quite as agreeable to the female of his

choice. I can imagine before me one who has just accomplished the defeat

of another male after a struggle of half an hour or more. He advances

gallantly towards the object of contention, his head scarcely raised

an inch from the ground, his bill open to its full stretch, his fleshy tongue

elevated, his eyes darting fiery glances, and as he moves he hisses loudly,

while the emotion which he experiences, causes his quills to shake, and

his feathers to rustle. Now he is close to her who in his eyes is all loveliness;

his neck bending gracefully in all directions, passes all round her,

and occasionally touches her body; and as she congratulates him on his

victory, and acknowledges his affection, they move their necks in a hundred

curious ways. At this moment fierce jealousy urges the defeated

gander to renew his efforts to obtain his love; he advances apace, his

eye glowing with the fire of rage; he shakes his broad wings, ruffles up

his whole plumage, and as he rushes on the foe, hisses with the intensity

of anger. The whole flock seems to stand amazed, and opening up a

space, the birds gather round to view the combat. The bold bird who

has been caressing his mate, scarcely deigns to take notice of his foe, but

seems to send a scornful glance towards him. He of the mortified feelings,

however, raises his body, half opens his sinewy wings, and with a

powerful blow, sends forth his defiance. The affront cannot be borne in

the presence of so large a company, nor indeed is there much disposition

to bear it in any circumstances; the blow is returned with vigour, the

aggressor reels for a moment, but he soon recovers, and now the combat

rages. Were the weapons more deadly, feats of chivalry would now be

performed; as it is, thrust and blow succeed each other like the strokes

of hammers driven by sturdy forgers. But now, the mated gander has

caught hold of his antagonist’s head with his bill; no bull-dog could cling

faster to his victim; he squeezes him with all the energy of rage, lashes

him with his powerful wings, and at length drives him away, spreads out

his pinions, runs with joy to his mate, and fills the air with cries of exultation.

But now, see yonder, not a couple, but half a dozen of ganders are

4

engaged in battle! Some desperado, it seems, has fallen upon a mated

bird, and several bystanders, as if sensible of the impropriety of such conduct,

rush to the assistance of the wronged one. How they strive and

tug, biting, and striking with their wings! and how their feathers fly

about! Exhausted, abashed, and mortified, the presumptuous intruder

retreats in disgrace;—there he lies almost breathless on the sand!

Such are the conflicts of these ardent lovers, and so full of courage

and of affection towards their females are they, that the approach of a

male invariably ruffles their tempers as well as their feathers. No sooner

has the goose laid her first egg, than her bold mate stands almost erect

by her side, watching even the rustling sound of the breeze. The least

noise brings from him a sound of anger. Should he spy a racoon making

its way among the grass, he walks up to him undauntedly, hurls a vigorous

blow at him, and drives him instantly away. Nay I doubt if man

himself, if unarmed, would come off unscathed in such an encounter.

The brave gander does more; for, if imminent danger excite him, he

urges his mate to fly off, and resolutely remains near the nest until he is

assured of her safety, when he also betakes himself to flight, mocking as

it were by his notes his disappointed enemy.

Suppose all to be peace and quiet around the fond pair, and the female

to be sitting in security upon her eggs. The nest is placed near

the bank of a noble stream or lake; the clear sky is spread over the

scene, the bright beams glitter on the waters, and a thousand odorous

flowers give beauty to the swamp which of late was so dismal. The gander

passes to and fro over the liquid element, moving as if lord of the

waters; now he inclines his head with a graceful curve, now sips to

quench his thirst; and, as noontide has arrived, he paddles his way towards

the shore, to relieve for a while his affectionate and patient consort.

The lisping sounds of their offspring are heard through the shell; their

little bills have formed a breach in the inclosing walls; full of life, and

bedecked with beauty, they come forth, with tottering steps and downy

covering. Toward the water they now follow their careful parent, they

reach the border of the stream, their mother already floats on the loved

element, one after another launches forth, and now the flock glides

gently along. What a beautiful sight! Close by the grassy margin,

the mother slowly leads her innocent younglings; to one she shews the

seed of the floating grass, to another points out the crawling slug. Her

careful eye watches the cruel turtle, the garfish, and the pike, that are

5

lurking for their prey, and, with head inclined, she glances upwards to

the eagle or the gull that are hovering over the water in search of food.

A ferocious bird dashes at her young ones; she instantly plunges beneath

the surface, and, in the twinkling of an eye, her brood disappear after

her; now they are among the thick rushes, with nothing above water but

their little bills. The mother is marching towards the land, having lisped

to her brood in accents so gentle that none but they and her mate can

understand their import, and all are safely lodged under cover until the

disappointed eagle or gull bears away.

More than six weeks have now elapsed. The down of the goslings,

which was at first soft and tufty, has become coarse and hairlike. Their

wings are edged with quills, and their bodies bristled with feathers. They

have increased in size, and, living in the midst of abundance, they have

become fat, so that on shore they make their way with difficulty, and as

they are yet unable to fly, the greatest care is required to save them from

their numerous enemies. They grow apace, and now the burning days

of August are over. They are able to fly with ease from one shore to

another, and as each successive night the hoarfrosts cover the country,

and the streams are closed over by the ice, the family joins that in their

neighbourhood, which is also joined by others. At length they spy the

advance of a snow-storm, when the ganders with one accord sound the

order for their departure.

After many wide circlings, the flock has risen high in the thin air, and

an hour or more is spent in teaching the young the order in which they

are to move. But now, the host has been marshalled, and off it starts,

shewing, as it proceeds, at one time an extended front, at another a single

lengthened file, and now arraying itself in an angular form. The old

males advance in front, the females follow, the young come in succession

according to their strength, the weakest forming the rear. Should one

feel fatigued, his position is changed in the ranks, and he assumes a place

in the wake of another, who cleaves the air before him; perhaps the parent

bird flies for a while by his side to encourage him. Two, three, or

more days elapse before they reach a secure resting place. The fat with

which they were loaded at their departure has rapidly wasted; they are

fatigued, and experience the keen gnawings of hunger; but now they spy

a wide estuary, towards which they direct their course. Alighting on the

water, they swim to the beach, stand, and gaze around them; the young

full of joy, the old full of fear, for well are they aware that many foes

6

have been waiting their arrival. Silent all night remains the flock, but

not inactive; with care they betake themselves to the grassy shores, where

they allay the cravings of appetite, and recruit their wasted strength.

Soon as the early dawn lightens the surface of the deep they rise into the

air, extend their lines, and proceed southward, until arriving in some place

where they think they may be enabled to rest in security, they remain

during the winter. At length, after many annoyances, they joyfully perceive

the return of spring, and prepare to fly away from their greatest

enemy, man.

The Canada Goose often arrives in our Western and Middle Districts

as early as the beginning of September, and does not by any means confine

itself to the seashore. Indeed, my opinion is, that for every hundred

seen during the winter along our large bays and estuaries, as many thousands

may be found in the interior of the country, where they frequent

the large ponds, rivers, and wet savannahs. During my residence in the

State of Kentucky, I never spent a winter without observing immense

flocks of these birds, especially in the neighbourhood of Henderson, where

I have killed many hundreds of them, as well as on the Falls of the Ohio

at Louisville, and in the neighbouring country, which abounds in ponds

overgrown with grasses and various species of Nympheæ, on the seeds of

which they greedily feed. Indeed all the lakes situated within a few miles

of the Missouri and Mississippi, or their tributaries, are still amply supplied

with them from the middle of autumn to the beginning of spring.

In these places, too, I have found them breeding, although sparingly.

It seems to me more than probable, that the species bred abundantly in

the temperate parts of North America before the white population extended

over them. This opinion is founded on the relations of many old

and respectable citizens of our country, and in particular of General

George Clark, one of the first settlers on the banks of the Ohio, who,

at a very advanced age, assured me that, fifty years before the period

when our conversation took place (about seventy-five years from the present

time), wild geese were so plentiful at all seasons of the year, that he

was in the habit of having them shot to feed his soldiers, then garrisoned

near Vincennes, in the present State of Indiana. My father, who travelled

down the Ohio shortly after Bradock’s defeat, related the same to

me; and I, as well as many persons now residing at Louisville in Kentucky,

well remember that, twenty-five or thirty years ago, it was quite

easy to procure young Canada Geese in the ponds around. So late as

7

1819, I have met with the nests, eggs, and young of this species near

Henderson. However, as I have already said, the greater number remove

far north to breed. I have never heard of an instance of their

breeding in the Southern States. Indeed, so uncongenial to their constitution

seems the extreme heat of these parts to be, that the attempts made

to rear them in a state of domestication very rarely succeed.

The Canada Goose, when it remains with us to breed, begins to form

its nest in March, making choice of some retired place not far from the

water, generally among the rankest grass, and not unfrequently under a

bush. It is carefully formed of dry plants of various kinds, and is of a

large size, flat, and raised to the height of several inches. Once only did

I find a nest elevated above the ground. It was placed on the stump of

a large tree, standing in the centre of a small pond, about twenty feet

high, and contained five eggs. As the spot was very secluded, I did not

disturb the birds, anxious as I was to see in what manner they should

convey the young to the water. But in this I was disappointed, for, on

going to the nest, near the time at which I expected the process of incubation

to terminate, I had the mortification to find that a racoon, or some

other animal, had destroyed the whole of the eggs, and that the birds had

abandoned the place. The greatest number of eggs which I have found

in the nest of this species was nine, which I think is more by three than

these birds usually lay in a wild state. In the nests of those which I

have had in a domesticated state, I have sometimes counted as many as

eleven, several of them, however, usually proving unproductive. The

eggs measure, on an average,

3 1/2 inches by

2 1/2, are thick shelled, rather

smooth, and of a very dull yellowish-green colour. The period of incubation

is twenty-eight days. They never have more than one brood in a

season, unless their eggs are removed or broken at an early period.

The young follow their parents to the water a day or two after they

have issued from the egg, but generally return to land to repose in the

sunshine in the evening, and pass the night there under their mother, who

employs all imaginable care to ensure their comfort and safety, as does

her mate, who never leaves her during incubation for a longer time than

is necessary for procuring food, and takes her place at intervals. Both

remain with their brood until the following spring. It is during the

breeding-season that the gander displays his courage and strength to the

greatest advantage. I knew one that appeared larger than usual, and of

which all the lower parts were of a rich cream colour. It returned three

8

years in succession to a large pond a few miles from the mouth of

Green River in Kentucky, and whenever I visited the nest, it seemed to

look upon me with utter contempt. It would stand in a stately attitude,

until I reached within a few yards of the nest, when suddenly lowering

its head, and shaking it as if it were dislocated from the neck, it would

open its wings, and launch into the air, flying directly at me. So daring

was this fine fellow, that in two instances he struck me a blow with one

of his wings on the right arm, which, for an instant, I thought, was

broken. I observed that immediately after such an effort to defend his

nest and mate, he would run swiftly towards them, pass his head and neck

several times over and around the female, and again assume his attitude

of defiance.

Always intent on making experiments, I thought of endeavouring to

conciliate this bold son of the waters. For this purpose I always afterwards

took with me several ears of corn, which I shelled, and threw towards

him. It remained untouched for several days; but I succeeded at last,

and before the end of a week both birds fed freely on the grain even

in my sight! I felt much pleasure on this occasion, and repeating my

visit daily, found, that before the eggs were hatched, they would allow

me to approach within a few feet of them, although they never suffered

me to touch them. Whenever I attempted this the male met my fingers

with his bill, and bit me so severely that I gave it up. The great

beauty and courage of the male rendered me desirous of obtaining possession

of him. I had marked the time at which the young were likely

to appear, and on the preceding day I baited with corn a large coop

made of twine, and waited until he should enter. He walked in, I

drew the string, and he was my prisoner. The next morning the female

was about to lead her offspring to the river, which was distant nearly half

a mile, when I caught the whole of the young birds, and with them the

mother too, who came within reach in attempting to rescue one of her

brood, and had them taken home. There I took a cruel method of preventing

their escape, for with a knife I pinioned each of them on the

same side, and turned them loose in my garden, where I had a small but

convenient artificial pond. For more than a fortnight, both the old birds

appeared completely cowed. Indeed, for some days I felt apprehensive

that they would abandon the care of the young ones. However, with

much attention, I succeeded in rearing the latter by feeding them abundantly

with the larvæ of locusts, which they ate greedily, as well as with

corn-meal moistened with water, and the whole flock, consisting of eleven

9

individuals, went on prosperously. In December the weather became intensely

cold, and I observed that now and then the gander would spread

his wings, and sound a loud note, to which the female first, and then all

the young ones in succession, would respond, when they would all run

as far as the ground allowed them in a southerly direction, and attempt

to fly off. I kept the whole flock three years. The old pair never

bred while in my possession, but two pairs of the young ones did, one

of them raising three, the other seven. They all bore a special enmity

to dogs, and shewed dislike to cats; but they manifested a still greater

animosity towards an old swan and a wild turkey-cock which I had. I

found them useful in clearing the garden of slugs and snails; and although

they now and then nipped the vegetables, I liked their company.

When I left Henderson, my flock of geese was given away, and I have

not since heard how it has fared with them.

On one of my shooting excursions in the same neighbourhood, I chanced

one day to kill a wild Canada Goose, which, on my return, was sent

to the kitchen. The cook, while dressing it, found in it an egg ready

for being laid, and brought it to me. It was placed under a common

hen, and in due time hatched. Two years afterwards the bird thus raised,

mated with a male of the same species, and produced a brood. This

goose was so gentle that she would suffer any person to caress her, and

would readily feed from the hand. She was smaller than usual, but in

every other respect as perfect as any I have ever seen. At the period of

migration she shewed by her movements less desire to fly off than any

other I have known; but her mate, who had once been free, did not participate

in this apathy.

I have not been able to discover why many of those birds which I have

known to have been reared from the egg, or to have been found when very

young and brought up in captivity, were so averse to reproduce, unless

they were naturally sterile. I have seen several that had been kept for more

than eight years, without ever mating during that period, while other individuals

had young the second spring after their birth. I have also observed

that an impatient male would sometimes abandon the females of his species,

and pay his addresses to a common tame goose, by which a brood would

in due time be brought up, and would thrive. That this tardiness is not

the case in the wild state I feel pretty confident, for I have observed having

broods of their own many individuals which, by their size, the dulness

of their plumage, and such other marks as are known to the practical

10

ornithologist, I judged to be not more than fifteen or sixteen months

old. I have therefore thought that in this, as in many other species, a

long series of years is necessary for counteracting the original wild and

free nature which has been given them; and indeed it seems probable

that our attempts to domesticate many species of wild fowls, which would

prove useful to mankind, have often been abandoned in despair, when a

few years more of constant care might have produced the desired effect.

The Canada Goose, although immediately after the full development

of its young it becomes gregarious, does not seem to be fond of the company

of any other species. Thus, whenever the White-fronted Goose,

the Snow Goose, the Brent Goose, or others, alight in the same ponds, it

forces them to keep at a respectful distance; and during its migrations I

have never observed a single bird of any other kind in its ranks.

The flight of this species of Goose is firm, rather rapid, and capable

of being protracted to a great extent. When once high in the air, they

advance with extreme steadiness and regularity of motion. In rising

from the water or from the ground, they usually run a few feet with outspread

wings; but when suddenly surprised and in full plumage, a single

spring on their broad webbed feet is sufficient to enable them to get

on wing. While travelling to some considerable distance, they pass

through the air at the height of about a mile, steadily following a direct

course towards the point to which they are bound. Their notes are distinctly

heard, and the various changes made in the disposition of their

ranks are easily seen. But although on these occasions they move with

the greatest regularity, yet when they are slowly advancing from south

to north at an early period of the season, they fly much lower, alight

more frequently, and are more likely to be bewildered by suddenly formed

banks of fog, or by passing over cities or arms of the sea where much

shipping may be in sight. On such occasions great consternation prevails

among them, they crowd together in a confused manner, wheel irregularly,

and utter a constant cackling resembling the sounds from a disconcerted

mob. Sometimes the flock separates, some individuals leave the rest, proceed

in a direction contrary to that in which they came, and after a while,

as if quite confused, sail towards the ground, once alighted on which they

appear to become almost stupified, so as to suffer themselves to be shot

with ease, or even knocked down with sticks. This I have known to take

place on many occasions, besides those of which I have myself been a witness.

Heavy snow-storms also cause them great distress, and in the midst

11

of them some have been known to fly against beacons and lighthouses,

dashing their heads against the walls in the middle of the day. In the

night they are attracted by the lights of these buildings, and now and then

a whole flock is caught on such occasions. At other times their migrations

northward are suddenly checked by a change of weather, the approach

of which seems to be well known to them, for they will suddenly

wheel and fly back in a southern direction several hundred miles. In

this manner I have known flocks to return to the places which they had

left a fortnight before. Nay even during the winter months, they are

keenly sensible to changes of temperature, flying north or south in search

of feeding-grounds, with so much knowledge of the future state of the

weather, that one may be assured when he sees them proceeding southward

in the evening, that the next morning will be cold, and vice versa.

The Canada Goose is less shy when met with far inland, than when

on the sea-coast, and the smaller the ponds or lakes to which they resort,

the more easy it is to approach them. They usually feed in the manner

of Swans and fresh-water Ducks, that is, by plunging their heads towards

the bottom of shallow ponds or the borders of lakes and rivers, immersing

their fore parts, and frequently exhibiting their legs and feet with the

posterior portion of their body elevated in the air. They never dive on

such occasions. If feeding in the fields or meadows, they nip the blades

of grass sidewise, in the manner of the Domestic Goose, and after rainy

weather, they are frequently seen rapidly patting the earth with both

feet, as if to force the earth-worms from their burrows. If they dabble

at times with their bills in muddy water, in search of food, this action is

by no means so common with them as it is with Ducks, the Mallard for

example. They are extremely fond of alighting in corn-fields covered

with tender blades, where they often remain through the night and commit

great havoc. Wherever you find them, and however remote from

the haunts of man the place may be, they are at all times so vigilant and

suspicious, that it is extremely rare to surprise them. In keenness of

sight and acuteness of hearing, they are perhaps surpassed by no bird

whatever. They act as sentinels towards each other, and during the

hours at which the flock reposes, one or more ganders stand on the watch.

At the sight of cattle, horses, or animals of the deer kind, they are seldom

alarmed, but a bear or a cougar is instantly announced, and if on

such occasions the flock is on the ground near water, the birds immediately

betake themselves in silence to the latter, swim to the middle of

12

the pond or river, and there remain until danger is over. Should their

enemies pursue them in the water, the males utter loud cries, and the

birds arrange themselves in close ranks, rise simultaneously in a few seconds,

and fly off in a compact body, seldom at such times forming lines

or angles, it being in fact only when the distance they have to travel is

great that they dispose themselves in those forms. So acute is their sense

of hearing, that they are able to distinguish the different sounds or footsteps

of their foes with astonishing accuracy. Thus the breaking of a

dry stick by a deer is at once distinguished from the same accident occasioned

by a man. If a dozen of large turtles drop into the water, making

a great noise in their fall, or if the same effect is produced by an alligator,

the Wild Goose pays no regard to it; but however faint and distant may

be the sound of an Indian’s paddle, that may by accident have struck the

side of his canoe, it is at once marked, every individual raises its head

and looks intently towards the place from which the noise has proceeded,

and in silence all watch the movements of their enemy.

These birds are extremely cunning also, and should they conceive

themselves unseen, they silently move into the tall grasses by the margin

of the water, lower their heads, and lie perfectly quiet until the boat has

passed by. I have seen them walk off from a large frozen pond into the

woods, to elude the sight of the hunter, and return as soon as he had

crossed the pond. But should there be snow on the ice or in the woods,

they prefer watching the intruder, and take to wing long before he is

within shooting distance, as if aware of the ease with which they could be

followed by their tracks over the treacherous surface.

The Canada Geese are fond of returning regularly to the place which

they have chosen for resting in, and this they continue to do until they

find themselves greatly molested while there. In parts of the country

where they are little disturbed, they seldom go farther than the nearest

sandbank or the dry shore of the places in which they feed; but in other

parts they retire many miles to spots of greater security, and of such extent

as will enable them to discover danger long before it can reach them.

When such a place is found, and proves secure, many flocks resort to it,

but alight apart in separate groups. Thus, on some of the great sandbars

of the Ohio, the Mississippi, and other large streams, congregated

flocks, often amounting to a thousand individuals, may be seen at the approach

of night, which they spend there, lying on the sand within a few

feet of each other, every flock having its own sentinel. In the dawn of

13

next morning they rise on their feet, arrange and clean their feathers,

perhaps walk to the water to drink, and then depart for their feeding

grounds.

When I first went to the Falls of the Ohio, the rocky shelvings of

which are often bare for fully half a mile, thousands of wild geese of this

species rested there at night. The breadth of the various channels that

separate the rocky islands from either shore, and the rapidity of the currents

which sweep along them, render this place of resort more secure

than most others. The wild geese still betake themselves to these islands

during winter for the same purpose, but their number has become very

small; and so shy are these birds at present in the neighbourhood of

Louisville, that the moment they are disturbed at the ponds where they

go to feed each morning, were it but by the report of a single gun, they

immediately return to their rocky asylums. Even there, however, they

are by no means secure, for it not unfrequently happens that a flock

alights within half gunshot of a person concealed in a pile of drifted wood,

whose aim generally proves too true for their peace. Nay, I knew a gentleman,

who had a large mill opposite Rock Island, and who used to kill

the poor geese at the distance of about a quarter of a mile, by means of

a small cannon heavily charged with rifle bullets; and, if I recollect truly,

Mr Tarascon in this manner not unfrequently obtained a dozen or more

geese at a shot. This was done at dawn, when the birds were busily engaged

in trimming their plumage with the view of flying off in a few minutes

to their feeding grounds. This war of extermination could not last

long: the geese deserted the fatal rock, and the great gun of the mighty

miller was used only for a few weeks.

While on the water, the Canada Goose moves with considerable grace,

and in its general deportment resembles the wild Swan, to which I think

it is nearly allied. If wounded in the wing, they sometimes dive to a

small depth, and make off with astonishing address, always in the direction

of the shore, the moment they reach which, you see them sneaking

through the grass or bushes, their necks extended an inch or so above the

ground, and in this manner proceeding so silently, that, unless closely

watched, they are pretty sure to escape. If shot at and wounded while

on the ice, they immediately walk off in a dignified manner, as if anxious

to make you believe that they have not been injured, emitting a loud note

all the while; but the instant they reach the shore they become silent,

and make off in the manner described. I was much surprised one day,

14

while on the coast of Labrador, to see how cunningly one of these birds,

which, in consequence of the moult, was quite unable to fly, managed for

a while to elude our pursuit. It was first perceived at some distance from

the shore, when the boat was swiftly rowed towards it, and it swam before

us with great speed, making directly towards the land; but when we

came within a few yards of it, it dived, and nothing could be seen of it

for a long time. Every one of the party stood on tiptoe to mark the spot

at which it should rise, but all in vain, when the man at the rudder

accidentally looked down over the stern and there saw the goose, its

body immersed, the point of its bill alone above water, and its feet busily

engaged in propelling it so as to keep pace with the movements of the

boat. The sailor attempted to catch it while within a foot or two of him,

but with the swiftness of thought it shifted from side to side, fore and aft,

until delighted at having witnessed so much sagacity in a goose, I begged

the party to suffer the poor bird to escape.

The crossing of the Canada Goose with the common domestic species

has proved as advantageous as that of the wild with the tame Turkey,

the cross breed being much larger than the original one, more easily raised,

and more speedily fattened. This process is at present carried on to a considerable

extent in our Western and Eastern States, where the hybrids are

regularly offered for sale during autumn and winter, and where they bring

a higher price than either of the species from which they are derived.

The Canada Goose makes its first appearance in the western country,

as well as along our Atlantic coast, from the middle of September to that

of October, arriving in flocks composed of a few families. The young

birds procured at this early season soon get into good order, become tender

and juicy, and therefore afford excellent eating. If a sportsman is

expert and manages to shoot the old birds first, he is pretty sure to capture

the less wily young ones afterwards, as they will be very apt to return

to the same feeding places to which their parents had led them at

their first arrival. To await their coming to a pond where they are known

to feed is generally effectual, but to me this mode of proceeding never

afforded much pleasure, more especially because the appearance of any

other bird which I wished to obtain would at once induce me to go after

it, and thus frighten the game, so that I rarely procured any on such occasions.

But yet, as I have witnessed the killing of many a fine goose, I

hope you will suffer me to relate one or two anecdotes connected with the

shooting of this kind of game.

15

Reader, I am well acquainted with one of the best sportsmen now

living in the whole of the western country, one possessed of strength, activity,

courage, and patience,—qualities of great importance in a gunner.

I have frequently seen him mount a capital horse of speed and bottom at

midnight, when the mercury in the thermometer was about the freezing

point, and the ground was covered with snow and ice, the latter of

which so encased the trees that you might imagine them converted into

glass. Well, off he goes at a round gallop, his steed rough shod, but nobody

knows whither, save myself, who am always by his side. He has a

wallet containing our breakfast, and abundance of ammunition, together

with such implements as are necessary on occasions like the present. The

night is pitch-dark, and dismal enough; but who cares! He knows the

woods as well as any Kentucky hunter, and in this respect I am not much

behind him. A long interval has passed, and now the first glimpse of day

appears in the east. We know quite well where we are, and that we have

travelled just twenty miles. The Barred Owl alone interrupts the melancholy

silence of the hour. Our horses we secure, and on foot we move

cautiously towards a “long pond,” the feeding-place of several flocks of

geese, none of which have yet arrived, although the whole surface of open

water is covered with Mallards, Widgeons, Pintail Ducks, Blue-winged

and Green-winged Teals. My friend’s gun, like mine, is a long and

trusty one, and the opportunity is too tempting. On all fours we cautiously

creep to the very edge of the pond; we now raise ourselves on

our knees, level our pieces, and let fly. The woods resound with repeated

echoes, the air is filled with Ducks of all sorts, our dogs dash

into the half frozen water, and in a few minutes a small heap of game

lies at our feet. Now, we retire, separate, and betake ourselves to different

sides of the pond. If I may judge of my companion’s fingers by

the state of my own, I may feel certain that it would be difficult for

him to fasten a button. There we are shivering, with contracted feet and

chattering teeth; but the geese are coming, and their well known cry,

hauk, hauk, awhawk, awhawk, resounds through the air. They wheel

and wheel for a while, but at length gracefully alight on the water,

and now they play and wash themselves, and begin to look about for

food. There must be at least twenty of them. Twenty more soon arrive,

and in less than half an hour we have before us a flock of a hundred

individuals. My experienced friend has put a snow-white shirt over his

apparel, and although I am greatly intent on observing his motions, I

16

see that it is impossible even for the keen eye of the sentinel goose to follow

them. Bang, bang, quoth his long gun, and the birds in dismay instantly

start, and fly towards the spot where I am. When they approach

I spring up on my feet, the geese shuffle, and instantaneously rise upright;

I touch my triggers singly, and broken-winged and dead two birds come

heavily to the ground at my feet. Oh that we had more guns! But the

business at this pond has been transacted. We collect our game, return

to our horses, fasten the necks of the geese and ducks together, and throwing

them across our saddles, proceed towards another pond. In this

manner we continue to shoot until the number of geese obtained would

seem to you so very large that I shall not specify it.

At another time my friend proceeds alone to the Falls of the Ohio,

and, as usual, reaches the margins of the stream long before day. His

well-trained steed plunges into the whirls of the rapid current, and, with

some difficulty, carries his bold rider to an island, where he lands drenched

and cold. The horse knows what he has to do as well as his master,

and while the former ranges about and nips the frozen herbage, the latter

carefully approaches a well-known pile of drifted wood, and conceals

himself in it. His famous dog Nep is close at his heels. Now the dull

grey dawn gives him a dim view of the geese; he fires, several fall on the

spot, and one severely wounded rises and alights in the Indian Chute.

Neptune dashes after it, but as the current is powerful, the gunner whistles

to his horse, who, with pricked ears, gallops up. He instantly vaults

into the saddle, and now see them plunge into the treacherous stream.

The wounded game is overtaken, the dog is dragged along, and at length

on the Indiana shore the horse and his rider have effected a landing. Any

other man than he of whose exploits I am the faithful recorder, would

have perished long ago. But it is not half so much for the sake of the

plunder that he undergoes all this labour and danger, as for the gratification

it affords his kind heart to distribute the game among his numerous

friends in Louisville.

On our eastern shores matters are differently managed. The gunners

there shoot geese with the prospect of pecuniary gain, and go to work in

another way. Some attract them with wooden geese, others with actual

birds; they lie in ambush for many hours at a time, and destroy an

immense number of them, by using extremely long guns; but as there is

little sport in this sort of shooting, I shall say no more about it. Here

the Canada Goose feeds much on a species of long slender grass, the Zostera

17

marina, along with marine insects, crustacea, and small shell-fish,

all of which have a tendency to destroy the agreeable flavour which their

flesh has when their food consists of fresh-water plants, corn, and grass.

They spend much of their time at some distance from the shores, become

more shy, diminish in bulk, and are much inferior as food to those which

visit the interior of the country. None of these, however, are at all to

be compared with the goslings bred in the inland districts, and procured

in September, when, in my opinion, they far surpass the renowned Canvass-backed

Duck.

A curious mode of shooting the Canada Goose I have practised with

much success. I have sunk in the sand of the bars to which these birds

resort at night, a tight hogshead, to within an inch of its upper edges,

and placing myself within it at the approach of evening, have drawn over

me a quantity of brushwood, placing my gun on the sand, and covering

it in like manner with twigs and leaves. The birds would sometimes

alight very near me, and in this concealment I have killed several at a

shot; but the stratagem answers for only a few nights in the season. During

severe winters these birds are able to keep certain portions of the

deepest parts of a pond quite open and free from ice, by their continued

movements in the water; at all events, such open spaces occasionally occur

in ponds and lakes, and are resorted to by the geese, among which

great havoc is made.

It is alleged in the State of Maine that a distinct species of Canada

Goose resides there, which is said to be much smaller than the one now

under your notice, and is described as resembling it in all other particulars.

Like the true Canada Goose, it builds a large nest, which it lines

with its own down. Sometimes it is placed on the sea-shore, at other

times by the margin of a fresh-water lake or pond. That species is distinguished

there by the name of Flight Goose, and is said to be entirely

migratory, whereas the Canada Goose is resident. But, notwithstanding

all my exertions, I did not succeed in procuring so much as a feather of

this alleged species.

While we were at Newfoundland, on our return from Labrador, on

the 15th August 1833, small flocks of the Canada Goose were already

observed flying southward. In that country their appearance is hailed

with delight, and great numbers of them are shot. They breed rather

abundantly by the lakes of the interior of that interesting country. In

the harbour of Great Macatina in Labrador, I saw a large pile of young

18

Canada Geese, that had been procured a few days before, and were already

salted for winter use. The pile consisted of several hundred individuals,

all of which had been killed before they were able to fly. I was

told there that this species fed much on the leaves of the dwarf firs, and,

on examining their gizzards, found the statement to be correct.

The young dive very expertly, soon after their reaching the water, at

the least appearance of danger. In the Southern and Western States, the

enemies of the Canada Goose are, by water, the Alligator, the Garfish,

and the Turtle; and on land, the Cougar, the Lynx, and the Racoon.

While in the air, they are liable to be attacked by the White-headed

Eagle. It is a very hardy bird, and individuals have been kept in a state

of captivity or domestication for upwards of forty years. Every portion

of it is useful to man, for besides the value of the flesh as an article of

food, the feathers, the quills, and the fat, are held in request. The eggs

also afford very good eating.

Anas canadensis, Linn. Syst. Nat. vol. i. p. 198.—Lath. Ind. Ornith. vol. ii. p. 838.

Anser canadensis, Ch. Bonaparte, Synopsis of Birds of the United States, p. 377.

Canada Goose, Anas canadensis, Wils. Amer. Ornith. vol. viii. p. 52. pl. 67. fig. 4.

Anser canadensis, Canada Goose, Swains. and Richards. Fauna Bor. Amer. p. 468.

Canada Goose, Nuttall, Manual, vol. ii. p. 349.

Adult Male. Plate CCI. Fig. 1.

Bill shorter than the head, rather higher than broad at the base, somewhat

conical, depressed towards the end, rounded at the tip. Upper

mandible with the dorsal line sloping, the ridge broad and flattened, the

sides sloping, the edges soft and obtuse, the oblique marginal lamellæ

short, transverse, about thirty on each side; the unguis obovate, convex,

denticulate on the inner edge. Nasal groove oblong, parallel to the ridge,

filled by the soft membrane of the bill; nostrils medial, lateral, longitudinal,

narrow-elliptical, open, pervious. Lower mandible straight, with

the angle very long, narrow, and rounded, the edges soft and obtuse, with

about thirty oblique lamellæ on a perpendicular plane.

Head small, oblong, compressed. Neck long and slender. Body full,

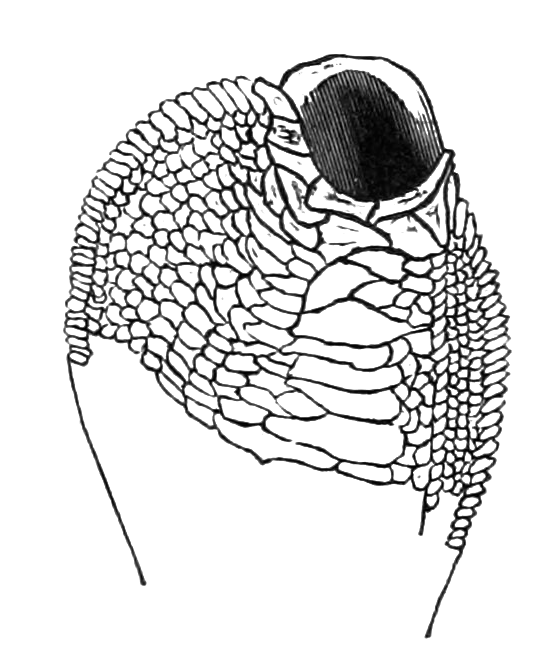

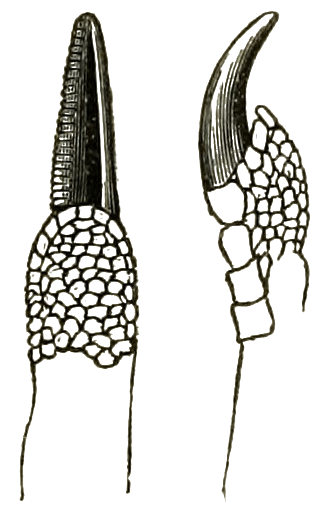

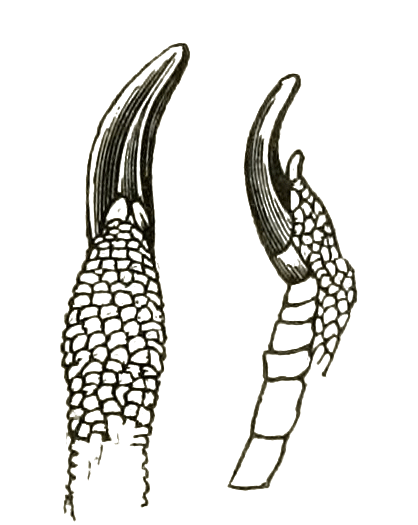

slightly depressed. Feet short, stout, placed behind the centre of the

body; legs bare a little above the tibio-tarsal joint; tarsus short, a little

compressed, covered all round with angular reticulated scales, which

are smaller behind; hind toe very small, with a narrow membrane;

third toe longest, fourth a little shorter, but longer than second; all the

19

toes reticulated above at the base, but with narrow transverse scutella towards

the end; the three anterior connected by a reticulated membrane,

the outer with a thick margin, the inner with the margin extended into a

two-lobed web; claws small, arched, rather compressed, except that of

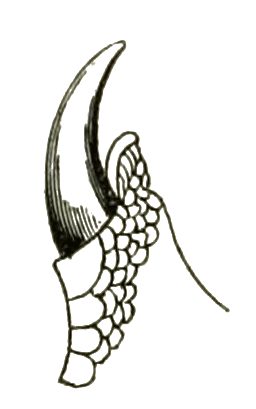

the middle toe, which is bent obliquely outwards and depressed, with a

curved edge. Wings of moderate length, with an obtuse protuberance at

the flexure.

Plumage close, rather short, compact above, blended on the neck and

lower parts of the body. The feathers of the head and neck very narrow,

of the back very broad and abrupt, of the breast and belly broadly rounded.

Wings, when closed, extending to about an inch from the end of the

tail, acute; primaries very strong, curved, the second longest, the third

slightly shorter, the first almost as long as the third, the rest rapidly

graduated; secondaries long, rather narrow, rounded. Tail very short,

rounded, of eighteen stiff, rounded, but acuminate, feathers.

Bill, feet, and claws black. Iris chestnut-brown. Head and two

upper thirds of the neck glossy black; forehead, cheeks, and chin, tinged

with brown; lower eyelid white; a broad band of the same across the

throat to behind the eyes; rump and tail-feathers also black. The general

colour of the rest of the upper parts is greyish-brown, the wing-coverts

shaded into ash-grey; all the feathers terminally edged with very pale

brown; the lower part of the neck passing into greyish-white, which is

the general colour of the lower parts, with the exception of the abdomen,

which is pure white, the sides, which are pale brownish-grey, the feathers

tipped with white, and the lower wing-coverts, which are also pale brownish-grey.

The margins of the rump, and the upper tail-coverts, pure

white.

In very old males, I have found the breast of a fine pale buff.

Length to end of tail 43 inches, extent of wings 65; bill along the

ridge

2 1/2, in depth at the base

1 2/12, in breadth 1; tarsus

3 7/12; middle toe

and claw

4 1/4; wing from flexure 20; tail

7 1/2. Weight 7 lb.

Adult Female. Plate CCI. Fig. 2.

The Female is somewhat less than the male, but similar in colouring,

although the tints are duller. The white of the throat is tinged with

brown; the lower parts are always more grey, and the black of the head,

neck, rump, and tail, is shaded with brown.

Length 41 inches. Weight

5 3/4 lb.

20

THE RED-THROATED DIVER.

Colymbus septentrionalis, Linn.

PLATE CCII. Male in summer, Young Male in winter, Female, and Young

unfledged.

Whilst the icicles are yet hanging from the rocks of our eastern

shores, and the snows are gradually giving way under the influence of

the April rains, the Bluebird is heard to sound the first notes of his love-song,

and the Red-throated Diver is seen to commence his flight. Already

paired, the male and female, side by side, move swiftly through

the air, steering their course, at a great height, towards some far distant

region of the dreary north. Pair after pair advance at intervals during

the whole day, and perhaps continue their journey all night. Their long

necks are extended, their feet stretched out rudder-like beyond the short

tail, and onwards they speed, beating the air with great regularity. Now

they traverse a great arm of the sea, now cross a peninsula; but let what

may intervene, their undeviating course holds straight forwards, as the

needle points to its pole. High as they are, you can perceive the brilliant

white of their lower parts. Onward they speed in silence, and as I stand

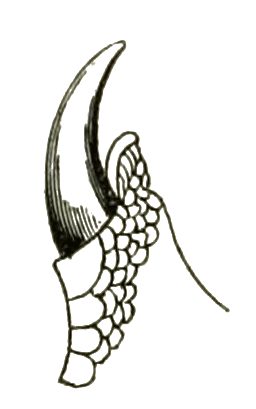

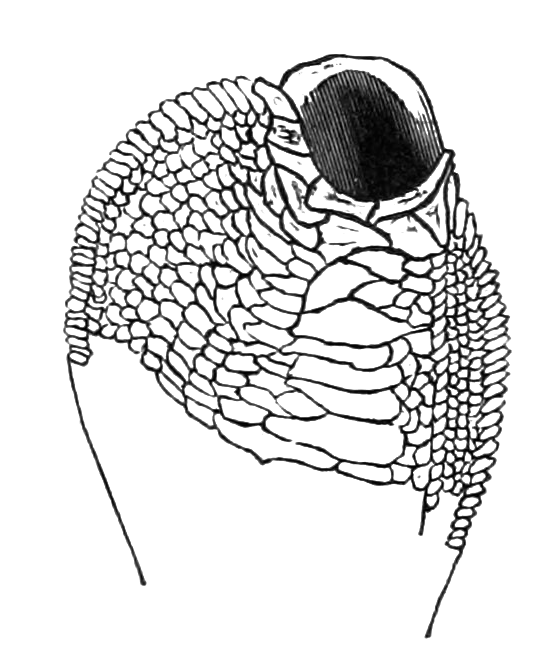

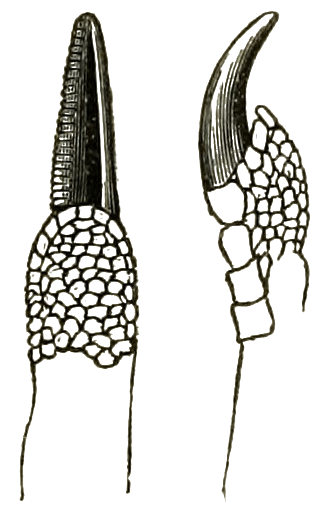

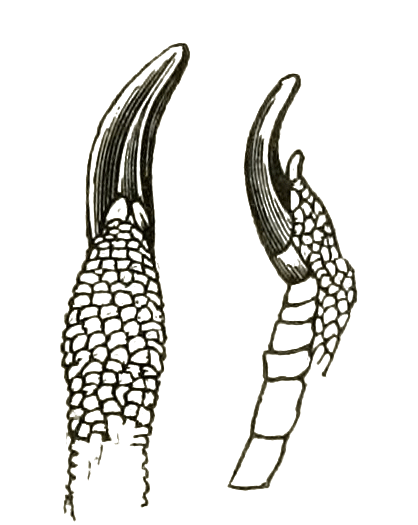

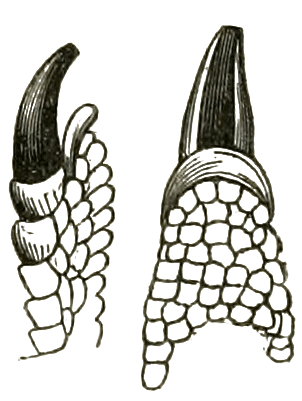

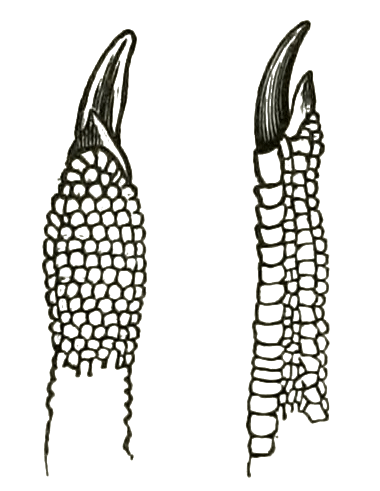

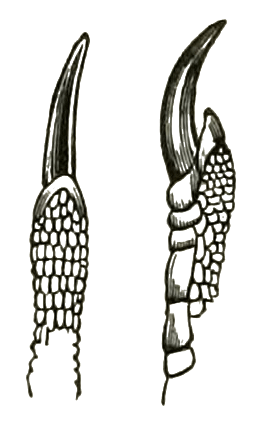

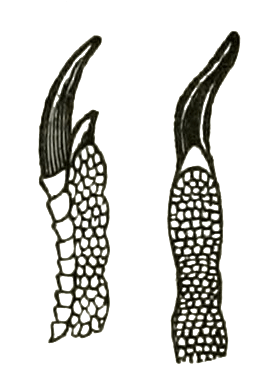

gazing after them, they have already disappeared from my view.