MOZART AS A YOUNG MAN.

(From a print by Schwërer.)

MOZART AS A YOUNG MAN.

(From a print by Schwërer.)

Bell's Miniature Series of Musicians

BY

EBENEZER PROUT, B.A., Mus.D.

PROFESSOR OF MUSIC, DUBLIN UNIVERSITY

LONDON

GEORGE BELL & SONS

1905

First Published, November, 1903.

Reprinted, 1905.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

MOZART AS A YOUNG MAN ... Frontispiece

(From a print by Schwërer.)

MOZART AT THE AGE OF SEVEN

(From a scarce French print.)

MOZART WITH HIS FATHER AND SISTER

(From a rare print.)

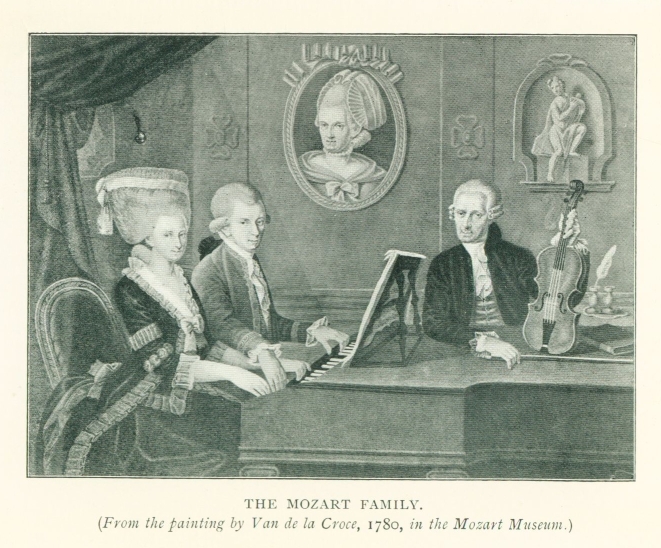

THE MOZART FAMILY

(From the painting by Van de la Croce,

1780, in the Mozart Museum.)

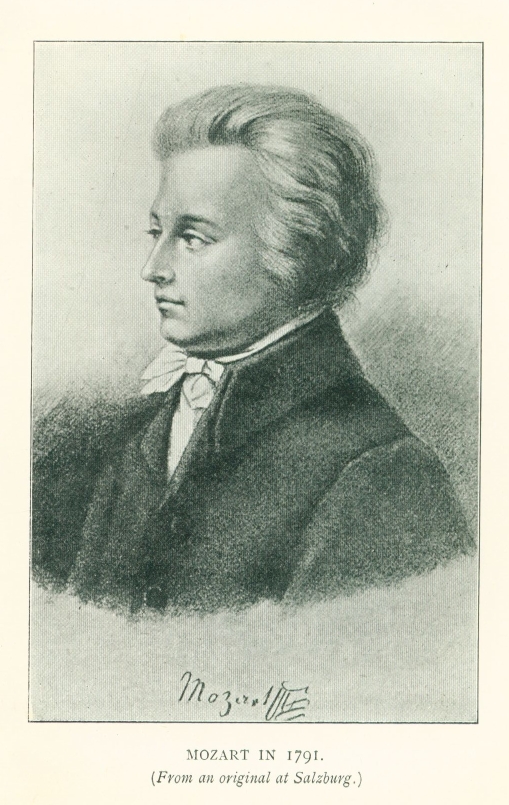

MOZART IN 1791

(From an original at Salzburg.)

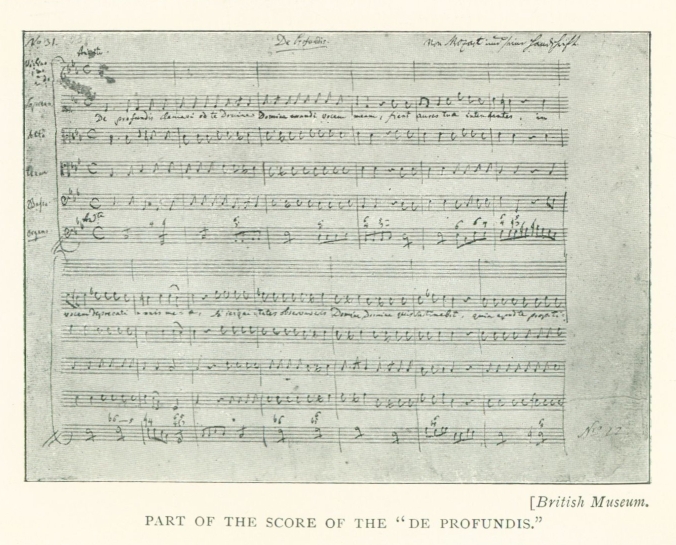

PART OF THE SCORE OF THE "DE PROFUNDIS"

Among the more important biographical and critical works on Mozart are the following:

NISSEN, G. N. VON. "Biographie W. A. Mozart's." Leipzig. 1828.

HOLMES, EDWARD. "Life of Mozart, including

His Correspondence." London. 1845.

Second Edition, edited by the writer of this book. 1878.

JAHN, OTTO. "W. A. Mozart." First Edition,

4 vols. Leipzig. 1856-59. Second Edition,

2 vols. 1867. English translation, 3 vols.

London. 1882.

KÖCHEL, DR. LUDWIG RITTER VON. "Chronologisch-thematisches

Verzeichniss sämmtlicher Tonwerke Wolfgang Amade

Mozart's." Leipzig. 1862.

POHL, C. F. "Mozart und Haydn in London." Vienna. 1867.

NOHL, LUDWIG. "Mozart nach den Schilderungen seiner

Zeitgenossen." Leipzig. 1880.

The article on Mozart by C. F. Pohl in the second volume of Grove's "Dictionary of Music and Musicians" is also well deserving of study, being, in fact, an epitome of Jahn's great work.

LIFE OF MOZART

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born at Salzburg on January 27, 1756. His full name, as given in the church register, was "Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus"; his father used the German equivalent "Gottlieb" of this last name, and the composer himself subsequently adopted the Latinized form "Amadeus."

His family had long been settled in Augsburg, where Wolfgang's father, Leopold Mozart, was born on November 14, 1719. With the object of studying jurisprudence, Leopold entered the university of Salzburg, supporting himself by teaching music and playing the violin. He was a musician of considerable attainments, and in 1743 the Archbishop of Salzburg took him into his service, later appointing him Court composer and leader of the orchestra. He was a voluminous composer, but his works show little inventive power. His fame as a musician rests chiefly on his "School for the Violin," printed in 1756—the year of Wolfgang's birth. This work, from which Otto Jahn in his great monograph on Mozart gives several extracts, was for many years the only work published in Germany on the subject, and was held in great esteem not only for the thoroughness of its instructions, but for the excellence of its style.

In 1747 Leopold Mozart married Anna Maria Pertlin (or Bertlin), by whom he had seven children, only two of whom survived infancy. The elder of these two was a daughter, Maria Anna, born July 30, 1751; the younger was the subject of the present volume.

MOZART AT THE AGE OF SEVEN.

(From a scarce French print.)

Like her illustrious brother, Maria Anna (generally spoken of in the family by the pet name of "Nannerl") very early showed great aptitude for music. At the age of seven her father began to give her lessons on the clavier, on which she made remarkable progress. It was during these lessons that Wolfgang's wonderful musical genius first showed itself. Though the child was then only between three and four years of age, he took the greatest interest in what his sister was doing, and would amuse himself with picking out thirds on the clavier. When he was four his father, more in joke than otherwise, began to teach him little pieces, which he learned with astonishing ease. For a short piece he required only half an hour, for longer pieces an hour, after which he could play them with perfect correctness. What is even more astonishing is that before he was five years of age he began to compose and play little pieces which his father wrote down. Some of these juvenile efforts have been preserved, and show that while the young musician had not at that time acquired any individuality of style, he had an instinctive feeling for clearness of form, while his harmony shows a correctness which is absolutely amazing in so young a child.

J. A. Schachtner, Court trumpeter at Salzburg, an intimate friend of the family, has preserved some reminiscences of the child's early years in a letter which he wrote to the composer's sister soon after Mozart's death. In this letter Schachtner relates how, on returning from church one day with Leopold Mozart, they found little Wolfgang, then four years old, hard at work writing:

"Papa. What are you writing?

"Wolfgang. A piano concerto; the first part is nearly finished.

"Papa. Let me see it.

"Wolfgang. It is not ready yet.

"Papa. Let me see it; it must be something pretty.

"His father took it, and showed me a daub of notes, mostly written over blots that had been wiped out. (N.B.—Little Wolfgang in his ignorance had dipped his pen every time to the bottom of the inkstand, and so made a blot each time he put it on the paper; this he wiped out with his flat hand, and went on writing.) We laughed at first over this apparent nonsense; but the papa then began to notice the principal thing, the composition. He remained motionless for a long while, looking at the page; at last two tears—tears of admiration and joy—fell from his eyes. 'Look, Herr Schachtner,' said he, 'how correctly and regularly it is all arranged, only it cannot be used because it is so extraordinarily difficult that nobody can play it.' Little Wolfgang broke in: 'That is why it is a concerto; it must be practised till one gets it right. Look, this is how it must go!' He played it, but could only just make enough out of it to show us what he meant.'

* * * * *

"Soon after they returned from Vienna, and Wolfgang brought with him a little fiddle that had been presented to him. The late Herr Wentzl, an excellent violinist, who also did a little in composition, brought six trios with him which he had written during your father's absence, and asked his opinion on them. We played the trios, your father taking the bass part on the viola, Wentzl the first violin, and I was to play the second. Wolfgang begged that he might play the second, but his father refused the foolish request, as he had not had the slightest instruction on the violin, and the father thought he was not in the least able to do it. Wolfgang said: 'To play a second violin one need not have learned!' When his father insisted on his going away and not disturbing us any further, he began to cry bitterly, and rushed out of the room with his fiddle. I begged them to let him play with me. At last papa said: 'Well, play with Herr Schachtner; but so quietly that nobody hears you, else you must go.' So Wolfgang played with me. I soon noticed with astonishment that I was quite superfluous. I quietly put down my violin and looked at your father, down whose cheeks tears of admiration and happiness were rolling, and so we played all six trios. When we had finished Wolfgang grew so bold with our applause that he declared he could play the first violin part too. We tried it for a joke, and nearly died of laughing when he played this part also, though with quite incorrect and irregular fingering, yet so that he never stuck fast."

In January, 1762, Leopold Mozart took his children to Munich, where they played before the Elector. Their visit lasted three weeks, and was so successful that in September of the same year they started for Vienna. They travelled leisurely, staying five days at Passau at the request of the Bishop, and giving a concert at Linz under the patronage of the Governor-General of the Province, Count Schlick. The astonishment and delight at the performances of the two children were unbounded. On arriving at Vienna, they received a command to visit the Emperor at Schönbrunn. Both he and the Empress were good musicians, and many incidents are related by Mozart's biographers showing not only the interest taken in the youthful prodigy, but also the tests of ability to which the Emperor submitted him. It was, of course, only natural that the example set by royalty should be followed by members of the Court, and the Mozarts were invited by all the nobility of Vienna. Their visit must have been a source of considerable profit, as many valuable presents were made them. Their success was interrupted for a time, from Wolfgang being attacked by scarlet fever; happily, the attack was not very severe, though sufficient to confine him to the house for a month. The family returned to Salzburg early in January, 1763.

Encouraged by the success of his first venture, Leopold Mozart resolved on a much longer tour, and on June 9, 1763, he, with his wife and the two children, left home for Paris. At Wasserburg their carriage broke down, and a day's delay was caused while it was being repaired. Leopold Mozart writes to his friend Hagenauer:

"The latest thing is that, to amuse ourselves, we went to the organ, and I explained the pedals to Wolferl, whereupon he at once, stante pede, began to try them. Pushing back the stool and standing, he preluded, stepping about on the pedals just as if he had practised for many months. All were amazed; it is a new gift of God, which many only attain after much trouble."

After passing through Munich, Augsburg, Mainz, Frankfort, Cologne, and Brussels, giving many concerts by the way, they reached Paris on November 18, where they were the guests of the Bavarian Ambassador, Count von Eyck, whose wife was the daughter of an official at Salzburg. By means of introductions which he had brought with him, Leopold Mozart soon obtained permission for his children to play at Court, where the King's daughters showed themselves extremely friendly to them. The father in one of his letters tells how they went on New Year's Day to the supper-room of the royal family, and how Wolfgang stood near the Queen, who fed him with sweetmeats and talked to him in German, interpreting his answers to the King, who did not understand the language. Every where the child's performances excited the greatest wonder and admiration. Not only would he play anything set before him at first sight, but he would transpose or accompany from a full score; his improvisations are also spoken of as remarkable, not only for their melodic interest but for their harmony.

MOZART WITH HIS FATHER AND SISTER.

(From a rare print.)

It was while he was in Paris that his father had his first compositions printed for him. These were four sonatas for piano and violin, published in two sets, the first of which was dedicated to the Princess Victoria, the second daughter of the King, and the second to the Comtesse de Tesse, lady-in-waiting to the Dauphiness. It is not too much to say that these four sonatas are the most remarkable examples in existence of precocious musical genius. It is not so much that they show great originality in their subject-matter, though in the slow movements, especially in that of the fourth sonata, foreshadowings of the riper Mozart may be seen; it is the wonderful command of form, the feeling for rhythm and for balance in the different parts of a movement which excite astonishment. The harmony, too, is for the most part absolutely correct, though in one place—in the minuet of the fourth sonata—consecutive fifths are to be seen. Leopold Mozart had corrected them in the proofs, but the correction had not been made before printing, and the father consoled himself with the reflection that they would serve as a proof that the boy had really composed the sonatas himself, which people might otherwise have been not unnaturally inclined to doubt.

In April, 1764, the Mozarts left Paris and came to London. George III. and Queen Charlotte were both extremely fond of music, and the success the children had met with in Paris was even surpassed at the English Court. Wolfgang played at first sight pieces by Wagenseil, Bach, Abel, and Handel, which the King placed before him; he accompanied the Queen in a song and a flutist in a solo; finally, he took a bass part of one of Handel's songs, and extemporized a beautiful melody above it. His father wrote of him at this time: "It surpasses all conception. What he knew when we left Salzburg is a mere shadow to what he knows now. My girl, though only twelve, is one of the cleverest players in Europe; and the mighty Wolfgang, to put it briefly, knows all, in this his eighth year, that one could ask from a man of forty. In short, anyone who does not see and hear it cannot believe it. You all in Salzburg know nothing about it, for the matter is quite different now."

On June 5 Leopold Mozart gave a concert to introduce his children to a London public. The result was a great success, and he, in his own words, "was frightened at taking one hundred guineas in three hours." Subsequently Wolfgang played the piano and organ at a concert given at Ranelagh Gardens for a charitable object. In August Leopold Mozart was attacked by a dangerous inflammation of the throat, which confined him to the house for seven weeks, during which time no music was heard. Wolfgang utilized the occasion by writing his first symphony for orchestra, and his sister afterwards told how, when she was sitting at his side, he said to her: "Remind me to give the horns something good." Like the first sonatas already spoken of, the first symphony, though not remarkable for its themes, shows the wonderful knowledge of instrumental forms that the child had almost intuitively acquired.

After the father's recovery the family were again invited to Court on October 29 for the festivities on the fourth anniversary of the King's coronation. In recognition of the royal favour, Leopold Mozart had six sonatas by Wolfgang for piano and violin engraved at his own expense. They were dedicated to the Queen, who rewarded the composer with a present of fifty guineas. These sonatas, though concise in form and bearing marks of immaturity, already show a perceptible advance on those printed a year earlier in Paris.

It was in London, at the Italian Opera, that the young composer first had the opportunity of hearing great singers. Chief among these were the male soprani, Manzuoli and Tenducci, the former of whom gave him lessons in singing. How he profited by them we learn from his friend Grimm, who, hearing him in Paris on his return there in the following year, writes that he sang with as much feeling as taste. With so impressionable a nature as his, it can scarcely be doubted that these early lessons contributed not a little to the formation of that pure style of vocal writing so characteristic of his music for the theatre and the church.

Finding that, when the novelty had worn off, the performances of his children no longer attracted the same attention as before, the Mozarts left London on July 24, 1765, on a visit to the Hague, as the Princess von Weilburg, sister of the Prince of Orange, was very anxious to see the boy. They were most graciously received, but had not been long at the Hague when Marianne was taken so dangerously ill that her life was despaired of, and extreme unction was administered. Scarcely was she recovered when Wolfgang was seized with a violent fever, which confined him to his bed for several weeks. Even during this illness his ruling passion showed itself. He would have a board laid upon his bed on which he could write, and even when he was weakest it was difficult to restrain him from writing and playing.

In January, 1766, two concerts were given in Amsterdam, the programmes of which consisted entirely of Wolfgang's instrumental compositions. Two months later they returned to the Hague to be present at the festivities of the coming of age of the Prince of Orange. Here Wolfgang, at the desire of the Princess of Weilburg, wrote six more sonatas for piano and violin, besides several smaller pieces for her.

We must pass briefly over the remainder of this long tour. Passing through Mechlin, they returned to Paris, thence by Dijon and Lyons to Switzerland, where they stayed some time. It was not till the end of November, 1766, that, after an absence of nearly three years and a half, the family found themselves once more at home at Salzburg.

It has been advisable to give in considerable detail the particulars of Mozart's earliest years because the precocious development of his genius is absolutely without a parallel in the case of any other composer. The limits of the present volume will render it needful to be somewhat more concise in dealing with the rest of the biography. It is characteristic of the young Wolfgang that his simple nature does not appear to have been in the least spoiled by successes which were enough to have turned the head of an adult. Jahn tells us that he would ride round the room on his father's stick, or jump up from the piano in the middle of his extemporizing to go and play with a favourite cat. Doubtless the judicious training he received from his good and wise father furnishes the explanation of this estimable trait in his character.

For nearly a year the family remained at home, Wolfgang working hard both at playing and composing. The chief works belonging to this period, on none of which it is necessary to dwell, are the first four concertos for the piano, a small sacred cantata, Grabmusik, and the Latin comedy, Apollo et Hyacinthus, written for performance by the students of the Salzburg University. In September, 1767, the whole family left home on a second visit to Vienna, with the intention of being present at the marriage of the Archduchess Maria Josepha with King Ferdinand of Naples, which was shortly to take place. Unfortunately, within a month after their arrival the Archduchess was carried off by small-pox, and Leopold Mozart with all his family fled to Olmütz. His children, nevertheless, did not escape; both were attacked by the complaint, with such severity in the case of Wolfgang that he lay blind for nine days. With the greatest kindness the Dean of Olmütz, Count Podstatsky, who was also a Canon of Salzburg, and therefore knew Mozart, received the whole family into his house, procuring for them the best medical attendance and nursing.

Returning to Vienna in January, 1768, they soon experienced difficulties of all kinds. The Empress Maria Theresa, it is true, as soon as she heard of the dangerous illness of the children whom she had so admired five years before, sent for them; but this visit brought them little profit, for the Emperor was parsimonious, and the nobility followed his example. Even more adverse were the conditions as regards the general public. The Viennese at that time, as Leopold Mozart says in one of his letters, had no desire to see anything serious and sensible, and little or no idea of it; all they cared for was buffoonery, farces, or pantomime. The infant prodigy had been a "draw" in 1762; but they cared little or nothing for the development of the artist a few years later. Added to this was the active opposition of envious musicians. Those who had admired the young child now dreaded the boy of twelve as a dangerous rival. The father says:

"I found that all the clavier players and composers in Vienna opposed our progress, with the single exception of Wagenseil, and he, as he is ill, can do little or nothing for us. The great rule with these people was carefully to avoid all opportunity of seeing us or of examining into Wolfgang's knowledge. And why? So that they, in so many cases when they were asked if they have heard this boy and what they think of him, might always be able to say that they had not heard him, and that it was impossible it could be true; that it was humbug and harlequinade; that matters had been arranged, and that the things given him to play were what he knew already; that it was ridiculous to think he could compose. You see, that is why they avoid us. For anyone who has seen and heard him can no longer say this without the risk of dishonour. I have trapped one of these people. We had arranged with someone to let us know quietly when he would be present. He was to come and bring an extraordinarily difficult concerto. We managed the matter, and he had the opportunity of hearing his concerto played off by Wolfgang as if he knew it by heart. The astonishment of this composer and performer, the expressions which he used in his admiration, gave us all to understand what I have just been pointing out to you. At last he said: 'I can, as an honourable man, say nothing else than that this boy is the greatest man now living in the world; it was impossible to believe.'"

Isolated cases of this kind could do but little to stem the torrent of calumny and depreciation to which the young composer was exposed. But now the Emperor came forward and proposed that Wolfgang should write an opera. The proposal was eagerly accepted; the father saw that a success would not only establish the lad's reputation in Vienna, but would pave the way for further successes in Italy. The text of an opera buffa, La Finta Semplice, was obtained from Coltellini, the poet connected with the theatre, and Wolfgang set to work at once. The score, which contained twenty-five numbers and 558 pages, was soon completed. Jahn, who gives a detailed analysis of the whole opera, concludes his criticism by saying that the work was fully equal to those at that time to be heard on the stage, while in single numbers it surpassed them in nobility and originality of invention and treatment, while it pointed clearly to a greater future. And this, be it remembered, was the composition of a boy of twelve!

In spite of the support of the Emperor, the unscrupulous intrigues of Mozart's enemies, of which his father's letters convey a vivid idea, so influenced the manager of the theatre, Affligio—a scoundrel who, it is satisfactory to learn, ended his days at the galleys—that the opera was never produced. By way of consolation, however, the father had the pleasure of hearing a German operetta by Wolfgang performed. This was Bastien und Bastienne, a piece in one act, which was written for Dr. Messmer, a rich amateur who had built a small theatre in his garden. Wolfgang was also commissioned to compose the music for the dedication of the chapel of an orphan asylum, and to conduct the performance of the same. For this occasion he composed his first Mass (in G major), and an offertorium, Veni sancte Spiritus, of which the latter is the more striking.

On the return of the Mozart family to Salzburg, about the end of 1768, the Archbishop, gratified at the success obtained by a native of the city, had the opera performed by musicians who were in his service. He further appointed Wolfgang concertmeister—that is, leader of the orchestra—and his name appears in this capacity in the Court calendars of 1770.

The greater part of the year 1769 was spent quietly at Salzburg, where Wolfgang, under his father's direction, diligently pursued his studies. In December of that year the father and son set off for Italy, Leopold rightly feeling that such a tour would not only be advantageous to Wolfgang's reputation as a musician, but would enlarge his views and give him wider experience of the world.

The lad was now no longer an infant prodigy, but, it might almost be said, already a mature artist, whose powers were ripening daily, thanks hardly less to his father's judicious training than to his own natural genius. It is noteworthy that he never seems to have been in the least spoiled by his successes; he remained the same natural, affectionate boy that he had always been. The letters that he wrote during his tour to his sister at home are full of charm. While often overflowing with fun, they also show how acute a critic he was of the music which he heard, and how keen an observer of all that passed around him. In this respect they may be compared with the letters written from Italy more than sixty years later by Mendelssohn.

Travelling by way of Innsbruck, Roveredo, and Verona, and meeting everywhere with a most enthusiastic reception, Mozart, with his father, reached Mantua on January 10, 1770. The Philharmonic Society of the city gave a concert on the 16th of the same month, which was in reality a public exhibition of Wolfgang's powers. The programme has fortunately been preserved, and we learn from it that in addition to two of his symphonies, of which he probably directed the performance, he played at first sight a concerto for the harpsichord that was placed before him. He also played at sight a sonata, introducing variations of his own, and afterwards transposed the whole piece into another key. More remarkable still was his improvisation. He extemporized a sonata and a regularly constructed fugue on themes given him at the moment. He also sang and composed extempore a song on words not previously seen, accompanying himself on the harpsichord.

The travellers' next stay was at Milan, where they found a warm friend in Count Firmian, the Governor-General of Lombardy, who interested himself with such success on behalf of Wolfgang that the latter received a commission to compose an opera for the next season, after giving proof of his powers for serious opera by setting three songs from the poems of Metastasio.

Passing through Parma, Bologna (where they made the acquaintance of the celebrated theorist Padre Martini) and Florence, the Mozarts arrived in Rome during Holy Week. It was on this occasion that Wolfgang performed the feat, so often recorded, of writing down from memory Allegri's Miserere after having heard it sung, in the Sistine Chapel. After a visit for a month to Naples, they returned to Rome, where the Pope invested Wolfgang with the order of the Golden Spur.

Revisiting Bologna on his return journey, the lad received the honour of being elected a member of the Philharmonic Society of that city. As a test-piece he composed an antiphon in four parts, Quœrite primum regnum Dei, in the strict contrapuntal style of the old Church music. His father, writing home an account of the affair, says:

"The princeps academiæ and the two censors, who are all old kapellmeisters, put before him in the presence of all the members an antiphon from the Antiphonarium, which he was to set in four parts in an adjoining room, to which he was conducted by the beadle and locked in. When he had finished it, it was examined by the censors and all the kapellmeisters and composers, who then voted upon it with black and white balls. As all the balls were white, he was called in, and all clapped on his entry, and applauded him after the princeps academiæ had announced his reception in the name of the society. He returned thanks, and all was over. I was meantime shut up in the library on the other side of the hall. All were astonished that he had done it so quickly, as many take three hours over an antiphon of three lines. You should know, though, that it is no easy task, for there are many things forbidden in this kind of composition, as he had been previously told. He finished it in exactly half an hour."

While staying at Bologna, Mozart received from Milan the libretto of the opera which he was to write. According to his custom, he wrote the recitatives first, deferring the composition of the airs till he had made acquaintance with the singers, in order that he might suit them the better with their parts. On October 18, Wolfgang and his father returned to Milan, and the boy at once set to work diligently to finish the opera, which was to be produced at Christmas. The subject of the work was Mitridate, Re di Ponto, the libretto being written by a poet of Turin named Cigna-Santi. All the airs were written after consultation with those who were to sing them.

As at Vienna, so at Milan: jealous musicians intrigued to hinder the success of the work, but their efforts were in vain. The principal singers and the members of the orchestra were delighted with the music, and on December 26 it was produced, with so brilliant a result as to silence the detractors. The opera was repeated twenty times to always crowded houses, and with ever-increasing success. At the end of March, 1771, Wolfgang was again in Salzburg.

Two important musical works were the result of the success of Mitridate. The impresario at Milan engaged Wolfgang to write an opera for the season of 1773, while the Empress Maria Theresa commissioned him to compose a theatrical serenata for the marriage of the Archduke Ferdinand, which was to take place at Milan in October, 1771. The work was Ascanio in Alba, which was produced on October 17 with very complete success. The celebrated Hasse, a friend of the Mozarts, and an honourable man, who had always sided with Wolfgang against his detractors, had written an opera, Ruggiero, for the same festivities. Leopold Mozart writes home: "I am sorry that Wolfgang's serenata has so eclipsed Hasse's opera that it is indescribable." Hasse himself was generous enough to acknowledge his defeat, and to say: "This youth will make us all to be forgotten," a prophecy that has been amply fulfilled.

During the greater part of the year 1772 Wolfgang was at home, composing music of almost every kind. An event which took place at this time had an important influence on his future. This was the death of the Archbishop of Salzburg, and the election in his place of Hieronymus, Count of Colloredo, a haughty and surly man, who cared nothing whatever for music. For his installation Mozart composed the one-act allegorical opera, Il Sogno di Scipione—not one of his stronger works. In November of the same year we find him once more in Milan, busy with the new opera that he had been engaged to write. This was Lucio Silla, the words of which were written by a local poet. It was produced on December 26, and repeated more than twenty times to crowded houses. The opera contains some beautiful numbers; but Mozart had not yet emancipated himself from tradition, and it is not till some years later that his dramatic genius shows itself in its full strength. After the production of Lucio Silla, Leopold Mozart, with his son, remained some time in Italy, in the hope of the latter obtaining an appointment in the Court of the Grand Duke Leopold at Florence. This hope was not realized, and in March they returned to Salzburg.

THE MOZART FAMILY.

(From the painting by Van de la Croce, 1780,

in the Mozart Museum.)

With the exception of a two months' visit to Vienna, Mozart remained at home for the rest of the year and for nearly the whole of the following one, composing almost incessantly and in nearly every style. To this period belong two of his best Masses—those in F and D—the fine Litaniœ Lauretanœ in D, four symphonies, six quartetts, concertos for various instruments, serenades, divertimenti, and smaller pieces of all kinds. In the course of the year 1774 Mozart received a commission to write a comic opera for Munich for the Carnival of 1775, and in December of that year he went there with his father. The opera which he had to write was La Finta Giardiniera, the libretto of which had already been set to music by Piccinni in 1770 and Anfossi in 1774. The first performance took place on January 13, 1775, with a success which the composer described the next day in a letter to his mother:

"My opera was produced yesterday, and had, thank God! such success that I cannot possibly describe to mamma the noise and commotion.... At the close of every air there was a terrible noise with clapping and shouting 'Viva maestro!' ... I and my father afterwards went into a room through which the whole Court pass, and where I kissed the hands of the Elector, the Electress, and others of the nobility, who were all very gracious. His Highness the Bishop of Chiemsee sent to me early this morning with congratulations on my success."

Very interesting is the following extract from Schubert's "Teutsche Chronik":

"I have also heard an opera buffa by the wonderful genius Mozart; it is called La Finta Ciardiniera. Flames of genius flashed forth here and there; but it is not yet the quiet fire on the altar which rises to heaven in clouds of incense—a perfume sweet to the gods. If Mozart is not a plant forced in a hot-house, he must become one of the greatest musical composers that has ever lived."

In the music of La Finta Giardiniera a great advance on any of Mozart's previous operas is to be seen. Not only is there a richness of melodic invention worthy to compare with that of his later and greater works, but there is more organic unity in the music as a whole. Though some of the airs now appear unduly spun out, it must be remembered that long solos were the fashion of the day. The orchestra is treated with more independence than hitherto, and the score abounds with beautiful effects of colouring, though in most numbers but few wind instruments are employed. The great duet toward the close of the third act and the elaborate finales which conclude the first and second acts are admirable, and might be inserted into Figaro without producing too strong a feeling of incongruity.

Among those who witnessed the triumph of Mozart's opera was the Archbishop of Salzburg, who was at the time on a visit to the Elector of Bavaria. Though he did not himself hear the work, he was congratulated upon it by the members of the Court, and, as Mozart records, "was so embarrassed as to be unable to make any reply except by shaking his head and shrugging his shoulders."

Returning to Salzburg in March, 1775, Mozart remained there for nearly three years—probably the least happy of his life. The entire want of appreciation showed him by the tyrannical Archbishop rendered his position most irksome. Though the final rupture did not come till later, he was subjected to constant indignities, while the remuneration he received was ridiculously disproportionate to the services that he rendered, both as composer and performer. Yet his activity in production never ceased. The catalogue of the compositions he produced during these years is nearly as astonishing for the large number of masterpieces it contains as for the variety of style that it shows. Nearly a hundred works, including four symphonies, fifteen serenades and divertimenti, ten concertos for various instruments, six sonatas for clavier, six Masses, the grand Litany in E flat, a number of smaller works for the Church, the opera Il Rè Pastore, many songs, some with orchestra, others with piano, bear witness no less to his industry than to the fecundity of his genius. Many of these works were written for performance at the Archbishop's palace, at which concerts were frequently given; but the Archbishop, though fully knowing what a treasure he had in Mozart, not only never paid him for any of his compositions, but insulted him by contemptuous remarks about them, thinking this the best means of keeping the young master from asking for an advance in his salary, which, it should be said, amounted at this time to about £15 sterling per annum! On one occasion, as we learn from a letter written by Leopold to Padre Martini, the Archbishop went so far as to tell Wolfgang that he knew nothing about his art, and that he ought to go to Naples to study. It became more and more evident that there was no prospect of the young man's obtaining an honourable and remunerative post at Salzburg. It was therefore decided that Wolfgang should make another tour, in the hope of obtaining a better appointment. But when he applied for leave of absence that he might earn some money as an addition to his small salary, the Archbishop refused with the ungracious remark that "he could not suffer a man going on begging expeditions." Wolfgang thereupon tendered his resignation, which the Archbishop angrily accepted.

As it was impossible for Leopold to accompany his son on this journey—the Archbishop having refused him leave of absence—Wolfgang's mother went with him. They left Salzburg on September 23, 1777, for Munich, where they stayed till October 11, Wolfgang hoping either to find a post there or to obtain a commission to write an opera. From Munich they went to Augsburg, where Mozart gave a concert which brought him much glory but very little profit.

On October 30 Mozart and his mother arrived at Mannheim. The long stay of between four and five months which they made in this place had in more than one respect an important influence on Mozart's future. The orchestra at Mannheim was considered the finest in Europe, and the young composer writes of it to his father in enthusiastic terms. He was especially struck by the clarinets, which he here for the first time met with in the orchestra. He writes: "Ah, if we only had clarinets! You cannot believe what a splendid effect a symphony makes with flutes, oboes, and clarinets." The Mannheim orchestra included among its members many of the finest performers on their respective instruments then living, and contemporary testimony was to the effect that they were unsurpassed in execution and finish. The first kapellmeister was Christian Cannabich, an excellent violinist, and a very good friend to Mozart; the second was the Abbé Vogler, a clever but eccentric man, of whom Mozart writes: "He is a fool, who fancies that there can exist nothing better or more perfect than himself. He is hated by the whole orchestra. His book will better teach arithmetic than composition." In another letter he gives a criticism of Vogler's music which is so characteristic as to deserve quotation:

"Yesterday was again a gala day. I attended the service, at which was produced a bran new Mass by Vogler, which had been rehearsed only the day before yesterday in the afternoon. I stayed, however, no longer than the end of the 'Kyrie.' Such music I never before heard in my life, for not only is the harmony often wrong, but he goes into keys as if he would pull them in by the hair of the head, not artistically, but plump, and without preparation. Of the treatment of the ideas I will not try to speak; I will only say that it is quite impossible that any Mass by Vogler can satisfy a composer worthy of the name. For though one should discover an idea that is not bad, that idea does not long remain in a negative condition, but soon becomes—beautiful? Heaven save the mark! it becomes bad—extremely bad, and this in two or three different ways. The thought has scarcely had time to appear before something else comes and destroys it, or it does not close so naturally as to remain good, or it is not brought in in the right place, or it is spoiled by the injudicious employment of the accompanying instruments. Such is Vogler's composition."

It is hardly surprising that there should be little sympathy or cordiality between Vogler and Mozart, but there is no ground for the suspicion entertained by Leopold Mozart that the Abbé was plotting against his son.

Mozart was very desirous of obtaining an appointment at Mannheim under the Elector, and this was one of the causes of his long stay there. But, as usual, nothing came of it. The Elector was very complimentary to the composer, but after a delay of nearly two months finally said that he could do nothing. It was therefore the father's wish that they should continue the journey towards Paris. Mozart, however, was in no hurry to leave Mannheim; the society of the members of the orchestra, some of whom—among them Wendling, the flutist, and Ramm, the oboist—were close personal friends, was very congenial. But there was another and more powerful reason: he had for the first time fallen seriously in love. The object of his affection was a young singer, Aloysia Weber, the second daughter of Fridolin von Weber, at that time copyist and prompter in the Mannheim theatre. She was very beautiful, had a fine voice, and sang with great taste and expression. For her Mozart wrote one of the finest of his concert arias, Non so donde viene; he also gave her lessons. His affection would seem to have been returned, but his father was not unnaturally opposed to the youth's fettering himself by such a union. Wolfgang's idea was to make a professional tour in company with the Webers, and to try to procure engagements in Italy for the young lady as a prima donna, and for himself as a composer, Leopold, however, was experienced enough to see clearly that such a scheme was impracticable, and that a young girl who had never appeared on the stage would have no chance of success in an Italian theatre, however well she might sing. He therefore, in order to free his son from the entanglement, wrote a long letter to him, putting the case very plainly and sensibly, and urging him at once to go to Paris to try to make a position there. Like a dutiful son, as he always showed himself, Wolfgang obeyed, and left Mannheim with a heavy heart on March 14, 1778, arriving nine days later at Paris.

The time of his visit was not favourable to his hopes. Musicians in the French capital were busy with the great struggle for supremacy in opera between Gluck and Piccinni, which was then at its height. Besides this, the frivolous Parisian public, who had been so attracted by the infant prodigy, cared little for the mature artist. Mozart obtained an introduction to Le Gros, the director of the Concert Spirituel, who gave him a commission to write some movements of a Miserere, of which, however, only two choruses were performed. Besides this, Mozart composed for the same concerts a Sinfonie Concertante for four wind instruments, with orchestra. But once more the intrigues of enemies pursued him. Two days before the concert was to be given the parts of the new work had not been copied, and when Mozart went to Le Gros to inquire the reason, the latter merely said that he had forgotten it. Mozart suspected, and probably correctly, that Cambini, an Italian composer whom he had unintentionally offended, was at the bottom of it.

For the Duc de Guines, to whom he obtained an introduction through his old friend Grimm, Mozart wrote a double concerto for the unusual combination of flute and harp, to be played by the Duke and his daughter. The two instruments were those which Mozart detested; yet the concerto, though not a great work, is most effectively written for both instruments, and is very pleasing music. Besides this, he gave lessons in composition to the Duke's daughter, who, though a clever performer, seems to have had but little idea of writing. Mozart, in one of his letters to his father, gives a very amusing account of a lesson in which he had tried to make the young lady compose a minuet. He wrote later that she was both stupid and lazy, and he finally gave up the lessons in disgust.

Mozart's great desire, as always, was to write an opera, and, through Noverre, the ballet-master of the Grand Opera, whose acquaintance he had made in Vienna six years before, there seemed to be a fair prospect of the realization of his wish. Noverre set a librettist to work, and the text of the first act of an opera was soon ready. Meanwhile Noverre wanted some ballet music, and Mozart wrote for him the overture and incidental dances for Les Petits Riens. Nothing more, however, came of the opera. The composer, nevertheless, had one musical success during his stay in Paris. This was the production at the Concert Spirituel of his symphony in D, known as the "Parisian." In a letter to his father Mozart tells how warmly it was received, and how the audience were struck with certain passages and began applauding in the middle of the movements. There is no doubt that the symphony was the finest that he had composed up to that time; being written to suit the Parisian taste, it is lighter and more brilliant in style than most of its predecessors, without becoming thereby tawdry or frivolous. This was the first symphony that Mozart had scored for full orchestra, and the rich and varied colouring of the wind instruments shows how he had profited by listening to the fine performances at Mannheim.

Whether the success of his symphony would have led to Mozart's ultimately obtaining a good appointment at Paris cannot be said, for almost immediately after the production of the work a sad event brought about an entire change in his plans. This was the death of his mother, which occurred on July 3, 1778, after a fortnight's illness. His father was anxious, for more than one reason, that he should return home. Not only was there the natural desire for his son's company and support in his bereavement, there was also the apprehension that the young man, now that his mother's restraining influence was removed, might fall into the hands of bad companions.

At this juncture an opening unexpectedly presented itself in Salzburg. The Archbishop had by this time become conscious of the mistake he had made in allowing the young genius to leave him, and was anxious to have him back if possible. The death of the old kapellmeister Lolli, which occurred at this time, gave the Archbishop the opportunity he desired, and, after long negotiations, Lolli's post was offered to Leopold Mozart, and that of second kapellmeister to his son, whose salary was to be 500 florins a year. It was also conceded that he should have leave of absence whenever he wanted to write an opera.

Greatly as Mozart disliked Salzburg—and with good reason, after the Archbishop's treatment of him—he at once yielded to his father's wishes, and accepted the post. There can be no doubt that he did so all the more readily in consequence of one piece of news contained in his father's letter. This was that his beloved Aloysia Weber was engaged to sing at Salzburg, and would be living with the Mozarts. He therefore left Paris on September 26, travelling by way of Strasburg, Mannheim, and Munich, at each of which places he remained for some time. At Munich he visited the Webers, who had removed thither from Mannheim. Here a great disappointment awaited him. His beloved Aloysia had proved faithless, and received him coldly. Mozart thereupon sat down to the piano and sang, "Ich lass das Madel gern, das mich nicht will," (I willingly leave the maid who does not want me). Aloysia subsequently made an unhappy marriage with an actor named Lange, and became a distinguished prima donna. In her later years she confessed that she had failed to realize the genius of Mozart, and saw in him nothing but a little man.

In the middle of January, 1779, Mozart was once more in Salzburg, and for nearly two years he remained in that city, busied with his duties at the Archbishop's palace, and composing works of all kinds. The record of these years is chiefly one of almost ceaseless writing. Many of Mozart's best and ripest works date from this period. Among these are the Mass in C, published as No. 1, though really the composer's fourteenth. This is one of the finest of the series, as well as one of the most popular. The "Agnus Dei," a solo, the chief theme of which foreshadows the "Dove sono" of Figaro, was formerly a favourite air with soprani who valued expression above mere display. Another important work dating from this period is the incidental music to Gebler's drama Thamos, König in Ægypten. This music consists partly of entr'actes and incidental music, but it also contains three magnificent and amply developed choruses, which may justly be described as among the most noble choral pieces that Mozart ever wrote. The play was a failure, but the composer, regretting that the music could not be used, had the choruses adapted to Latin hymns; in this form they have become well-known and popular as the three great motets, Splendente te, Deus, Ne pulvis et cinis, and Deus, tibi laus et honor. To this period also belong the two-act German opera Zaide, two vespers, two symphonies, two great serenades—one being the magnificent one for thirteen wind instruments—the Symphonie Concertante in E flat, for violin and viola, the concerto in the same key for two pianos, and some of his best sonatas for piano solo, besides smaller pieces, vocal and instrumental, too numerous to mention.

In the latter part of the year 1780, Mozart received from the Elector of Bavaria a commission to write an opera for Munich, for the Carnival of 1781. The Archbishop had promised him leave of absence, and on November 6, 1780, he left Salzburg for the Bavarian capital. The libretto was written by the Abbé Varesco, Court chaplain at Salzburg, the subject selected being Idomeneo, and it was founded on a French opera on the same subject that had been composed by Campra, and produced in 1712.

Mozart, on his arrival in Munich, was received with open arms by his many friends in that city, and he worked at the opera with an enthusiasm that may be easily imagined. Though his principal vocalists were not all that he could have desired, he had a splendid orchestra at his disposal, and from the first all the performers were delighted with the music. His letters to his father while writing the opera are full of interesting details. After the first rehearsal, Ramm, the first oboe, an old friend of the composer, assured him that he had never yet heard any music that made so great an effect upon him. Mozart's father, who was most anxious for the complete success of the work, wrote urging his son "to think not only of the musical, but also of the unmusical public. You know, there are a hundred without knowledge to every one connoisseur, so do not forget the so-called 'popular' that tickles even the long ears." Wolfgang replied: "Don't trouble yourself about the so-called 'popular,' for in my opera is music for all kinds of people—only not for the long ears."

Idomeneo was produced on January 29, 1781, with a success that must have satisfied not only the composer, but also his father and sister, who came over from Salzburg to hear it. In this opera we find Mozart in his full maturity. Whether in the flow of his melody, the richness of the harmony, the power of dramatic characterization, or the beauty and variety of the orchestration, this work shows a decided advance on any of its predecessors, and marks a turning-point in the history of dramatic music.

Thanks to the fact that the Archbishop of Salzburg was at this time in Vienna, Mozart was able to prolong his visit to Munich; but in March he was summoned to join his employer, and on March 12 he arrived in Vienna. Here he was treated by the Archbishop with the utmost indignity; not only was he made to take his meals with the servants, but he was refused permission to take any engagements whereby he might add to his meagre income. Insult followed insult, till at length the crisis came, and Mozart resigned the appointment which his self-respect forbade him longer to hold, and determined to seek his fortune in Vienna.

Though now thrown entirely on his own resources, Mozart was very sanguine about the future. At first he earned only a precarious livelihood by playing at fashionable parties and teaching the piano; but he looked forward with great hopes to obtaining an appointment with the Emperor Joseph II. But the monarch, though always affable and even cordial to the composer, preferred Italian music to the more solid style of Mozart, whom he esteemed as a pianist rather than as a composer. "He cares for no one but Salieri," said Mozart of him; and there can be no doubt that the influence of the Italian on the Emperor was very great. Salieri, a musician of talent, though not of genius, saw in Mozart a formidable rival, and, while outwardly polite, secretly intrigued against him.

Joseph II. took great interest in the establishment of a school of German opera, and engaged an excellent company of vocalists, among whom was Mozart's old flame, Aloysia Weber, for the theatre. Mozart, who always delighted in writing for the stage, had brought with him to Vienna his German opera Zaide. He scarcely hoped that it would be produced, as he thought the libretto unsuited to the Viennese public; but Stephanie, the inspector of the opera, was so pleased with the music that he promised to give Mozart a good text to set. The Emperor was quite willing to see what the composer could do in German opera; and in July Mozart, to his great delight, received the libretto of Belmont und Constanze, now known under its second title, Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Owing to various causes, among others the cabals of Mozart's enemies, the production of the opera was much delayed; it was only by the express command of the Emperor that it was at length performed for the first time on July 13, 1782. It was of this opera that the Emperor said to the composer: "Too fine for our ears, and an immense number of notes, my dear Mozart!" which called forth the reply: "Exactly as many notes, your Majesty, as are needful."

The success of the work was immediate and complete. Here Mozart was virtually on new ground. Excepting the operetta Bastien und Bastienne and the Zaide above-mentioned, all Mozart's preceding operas had been written to Italian words; and though in Idomeneo a fusion of Italian and German styles is to be seen, it is not till Die Entführung that we find an important work genuinely German in character. Of Italian influence there is but little trace except in some parts of the music allotted to Constanze. This role was undertaken by Madame Cavalieri, a great bravura singer, but little more; and many of the florid passages in her songs remind one of the popular ornate style of the day. It is difficult to speak too highly of the wealth of melodic invention, the truth of expression, or the skill shown in differentiating the various characters of the drama to be found in this work, while the picturesqueness of the orchestration is perhaps even superior to that of Idomeneo, and certainly far surpasses that of any of the early operas.

At this time Mozart's old friends, the Webers, had removed to Vienna, and the composer had resumed his intercourse with them. A mutual attachment had grown up between him and Constanze, a younger sister of Aloysia, who had jilted him. He wrote to his father asking his consent to his marriage; but Leopold, knowing that his son had no regular appointment, and that his income was precarious, strongly opposed the step, and for some time the course of true love by no means ran smooth.

Through the influence of a patroness of Mozart, the Baroness von Waldstadten, the obstacles were ultimately surmounted, and the marriage was celebrated at the Baroness's house on August 4, 1782. Though the union was, from one point of view, very happy, owing to the true affection that existed between husband and wife, it cannot be doubted that it was, to a great extent, the cause of much of Mozart's later troubles. Constanze, though endowed with many excellent qualities, was a bad housekeeper, while Mozart, besides being generous to a fault, had not the least capacity for business, nor even any idea of economy. No wonder, then, that when to the care and expense of a young family was added a long and severe illness of the wife, they were often in sore pecuniary difficulties. Jahn says that if Mozart had been as good a man of business as his father, he would have done very well in Vienna, for he earned a very good income. As a matter of fact, from this time to the end of his career, his life was one long struggle, and not always a successful one, to keep his head above water.

Mozart's chief source of income at this time seems to have been derived from his playing, for he was in great demand, not only at concerts, but in the houses of the nobility. According to the unanimous verdict of his contemporaries, he was the greatest pianist and (in the best sense of the term) virtuoso of his day. After his death, Joseph Haydn is reported to have said, with tears in his eyes: "I can never forget Mozart's playing; it came from the heart." The Emperor also highly appreciated the composer's genius, and it is probably only owing to the intrigues of the Italian musicians by whom he was surrounded that he did not confer some adequately paid appointment upon Mozart.

In July, 1783, shortly after the birth of his first child, Mozart took his wife to Salzburg to introduce her to his father and sister. He had, before his marriage, made a vow that, if ever Constanze became his wife, he would compose a new Mass for performance at Salzburg. The work was not quite completed, but he supplied the missing numbers from one of his earlier Masses. As the Archbishop of Salzburg refused permission for the Mass to be performed in the cathedral, it was given in St. Peter's Church, Constanze singing the principal soprano part. The Mass, which is in C minor, is laid out on a much larger scale than those which Mozart wrote for Salzburg, the "Gloria" being in seven movements, while two of the choruses are in five and one in eight parts. The work is a curious mixture; many of the choruses are quite elevated in style, and not unworthy of the "Requiem" itself. The solos are much lighter, and of a florid character. Mozart never finished the Mass, but he used the music two years later for his cantata, Davide Penitente.

During his visit to Salzburg Mozart began work on two new buffo operas, L'Oca del Cairo, the libretto by Varesco, who had written the text of Idomeneo, and Lo Sposo Deluso, by an unknown poet. Neither work, however, was completed.

After his return to Vienna in October, 1783, Mozart's time was fully occupied with concerts and composition. The year 1784 saw the birth of many of his finest works, which at this time were exclusively instrumental. Among them are several of his best piano concertos, which he wrote for his own performance at concerts in which he took part. The list also includes the great sonata in C minor for the piano, a work not without influence on Beethoven, and the beautiful sonata in B flat for piano and violin, composed for Mdlle. Strinasacchi, a young violinist for whose benefit concert, Mozart had promised to write a new work. Being pressed for time, Mozart had deferred writing the sonata till the day before the concert, when the young lady, with much trouble, obtained from him the violin part only. She practised it the next morning, and in the evening played it with the composer without any rehearsal. The Emperor was present at the concert, and, looking through his opera-glass, noticed that Mozart had a blank sheet of music-paper before him. After the sonata was finished, the Emperor sent a message that he wished to see the manuscript. The composer brought the blank sheet. "What, Mozart!" said Joseph, "at your tricks again?" "Please your Majesty," was the reply, "there was not a note lost." Only musicians will be able fully to appreciate the wonderful feat of memory which such a performance involved.

In 1785 Leopold Mozart returned his son's visit, and it was at this time that he made the acquaintance of Joseph Haydn, with whom Wolfgang was on intimate terms. Leopold met Haydn for the first time at a party at his son's house, where three of Mozart's recently composed quartetts were played. It was on that occasion that Haydn said to the proud father: "I declare to you before God, and as a man of honour, that your son is the greatest composer that I know; he has taste, and beyond that the most consummate knowledge of the art of composition."

In February, 1786, was produced the music to Der Schauspieldirector, a German comedy in one act, for some festivities given by the Emperor at Schönbrunn. Mozart's share of the work consisted merely of an overture and four vocal numbers. Though the music is extremely melodious, it adds nothing to the composer's fame. Far more interesting and important were the two piano concertos in A major and C minor, both written in March of the same year. But all other compositions of this time sink into insignificance by the side of the opera Le Nozze di Figaro, which was produced in Vienna on May 1, 1786. The libretto was adapted by Lorenzo da Ponte, a theatrical poet who was a favourite with the Emperor, from Beaumarchais' comedy, "Le Mariage de Figaro." The subject was suggested by the composer himself. As on so many previous occasions, there were violent intrigues against the piece; but, thanks probably in a great measure to the support of the Emperor, these were unsuccessful, and the Irish singer, Michael Kelly, who took the part of Basilio at the first performance, says in his "Reminiscences": "Never was anything more complete than the triumph of Mozart and his Nozze di Figaro, to which numerous overflowing audiences bore witness." Almost more enthusiasm was shown at Prague, where the opera was given a few months later. At the invitation of some of his friends, Mozart went to Prague to witness the success of his work. His reception there was overwhelming. Two concerts which he gave in the city realized a profit of 1,000 florins. At the first of these was produced the fine symphony in D known as the "Prague Symphony." At the same concert he extemporized, in his own masterly manner, for half an hour, after which, in reply to a call for "something from Figaro," he improvised variations on "Non più andrai." This visit had an important result. Mozart remarked to Bondini, the manager of the theatre, that, as the people of Prague appreciated him so much, he should like to write an opera for them, whereupon the manager took him at his word, and commissioned an opera from him for the following season.

MOZART IN 1791.

(From an original at Salzburg.)

As the libretto of Figaro had suited him so well, it was only natural that Mozart should again apply to Da Ponte for a book for the new work. The subject chosen was the old legend of Don Giovanni, and in September, 1787, Mozart and his wife went to Prague in order that he might, as was his custom, be near the artists who were to sing in the work. Meanwhile his pen had been by no means idle. From the autograph catalogue of his works, which he began to keep in 1784 and continued till his last illness, we find that between Figaro and Don Giovanni he wrote thirty works, including some of the more important of his compositions in the domain of chamber music. Among these maybe specially named the string quintetts in C major and G minor, the two great pianoforte duet sonatas in F and C, the charming trio in E flat for piano, clarinet, and viola, and the sonata in A for piano and violin.

Arrived in Prague, Mozart first lodged at an inn, but later removed to the house of his friend Duschek, in the suburbs of the city. Here a great part of the opera was written, each number being sent to the singers as soon as it was completed. Visitors to Prague are still shown the summer-house with a stone table in the garden of Duschek's house, at which Mozart used to work at his opera while his friends were playing at bowls. It is said that he would leave his work from time to time to take his part in the game, and then resume it without having lost the thread of his ideas. The story has often been told how, on the night before the production of the opera, the overture was still unwritten. Mozart had parted late in the evening from his friends, and his wife mixed him a glass of punch and sat up with him while he wrote, telling him fairy tales to keep him awake. At last sleep overpowered him, and she persuaded him to lie down for an hour or two. At five she woke him, and when at seven the copyist came for the score the overture was ready. There was barely time to get the parts copied before the evening, and the excellent orchestra played it at sight without rehearsal. Mozart, who was conducting, said to the players near him: "A good many notes fell under the desks, but it went very well."

The first performance of Don Giovanni took place on October 29, 1787, and excited the utmost enthusiasm. Unfortunately, the composer's father was not able to witness his son's triumph, as he had died in the preceding May, after a long illness. Mozart returned to Vienna shortly after the production of his opera, but his success brought about but little improvement in his pecuniary circumstances. True, the Emperor appointed him "kammermusikus" in December, but the salary attached to the post—800 florins—was ridiculously small. His only duty was to write dance music for the masked balls of the Imperial Court; this caused him to make the bitter remark that his salary was too much for what he did, and too little for what he could do.

On May 7, 1788, Don Giovanni was given at Vienna. For this performance the composer had written three additional numbers, two of which were Don Ottavio's air, "Dalla sua pace," and Elvira's "Mi tradi quell' alma ingrata." The work, nevertheless, proved a failure; the style was too novel for the taste of the audience. The Emperor, after hearing it, said: "The opera is divine—perhaps even more beautiful than Figaro—but it is no food for the teeth of my Viennese." When this was repeated to Mozart, he said: "Let us give them time to chew it, then!" and, by his advice, the opera was repeated at short intervals until the public became accustomed to its beauties. The applause increased at each fresh performance.

The most important works composed in the year 1788 were the three great symphonies in E flat, G minor, and C major (generally known as the "Jupiter"), the last of forty-nine which Mozart wrote. In these he rises to a height which in his previous instrumental works he had seldom attained. The symphony in G minor, unquestionably the finest work ever written for a small orchestra, has never been surpassed in its combination of passion and pathos; while the finale of the "Jupiter" symphony, with its elaborate fugal counterpoint, still remains without a rival in its combination of the most consummate learning with the utmost profusion of melodic invention.

It was toward the close of this year that the Baron van Swieten, an enthusiastic lover of Handel's music, commissioned Mozart to arrange Acis and Galatea for performance at some concerts with which the Baron was connected, and of which he superintended the preparation. In Mozart's autograph catalogue, already spoken of, we find that the arrangement was made in November, 1788. In the course of the following year he made a similar arrangement of the Messiah, and, in 1790, of Alexander's Feast and the Ode for St. Cecilia's Day. Space will not allow a detailed criticism of these arrangements; it must suffice to say that, while often extremely beautiful, they are not always in accordance with Handel's spirit or intentions, the probable explanation being that Mozart, as we learn from Otto Jahn, knew but little of Handel's music till introduced to it by Baron van Swieten.

In 1789 Mozart accepted an invitation from his pupil and patron, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, to accompany him on a visit to Berlin. The composer, whose pecuniary position was still very precarious, no doubt hoped that he might find some post in the North of Germany which would be worthy of his acceptance and relieve him from his pressing embarrassments. Leaving Vienna on April 8, he arrived four days later at Dresden, where he played before the Court, receiving for his performance the sum of 100 ducats. Thence he proceeded to Leipzig, where he made the acquaintance of Rochlitz, who, in his "Für Freunde der Tonkunst," has preserved some interesting reminiscences of his visit. It was here also that, through Doles, the cantor of the Thomas-Schule, he learned to know the great motetts of Sebastian Bach, for which he expressed the highest admiration.

On his arrival at Berlin, Mozart was at once conducted by Prince Lichnowsky to Potsdam, to be presented to the King, Frederick William II., who was a great lover of music and a good performer on the violoncello. The King received him very warmly, and took special pleasure in hearing him improvise. Mozart, however, derived but little pecuniary advantage from his visit. The King, it is true, offered him the post of kapellmeister at his Court with a salary of 3,000 thalers, but the composer, with whom worldly considerations had little weight, declined the offer, saying: "Can I leave my good Emperor?" The only profit made by the tour was a present from the King of 100 friedrichs d'or, which was accompanied by a wish that Mozart should write some quartetts for him. Three string quartetts (in D, B flat, and F), in all of which the part for the violoncello is of more than usual prominence, were written for and dedicated to the King.

After his return to Vienna Mozart's embarrassments became more pressing than ever. The ill-health of his wife involved him in constant expense, and his income was at all times precarious. By the advice of his friends he informed the Emperor of the offer that had been made him by the King of Prussia. The Emperor asked if he were really going to leave him, and Mozart replied: "Your Majesty, I throw myself upon your kindness; I remain." No improvement, however, resulted in his position, though it was at the suggestion of the Emperor that he was commissioned to write a new opera for Vienna. This was the two-act opera buffa Cosi fan tutte, the libretto of which was again from the pen of Da Ponte, and which was produced on January 26, 1790. The first performances appear to have been successful; but the death of the Emperor in the following month caused the theatre to be closed for some time; in all it was given ten times, and then fell out of the repertoire. The plot of the opera is weak and improbable, and the indifferent quality of the libretto is without doubt the chief reason why the music is as a whole inferior to that of Don Giovanni and Figaro. Cosi fan tutte, nevertheless, contains some of its composer's best work, especially in the concerted movements, such as the trio "Soave sia il vento," the quintett and sextett in the first act, and the two finales. The orchestral colouring also is almost richer and more varied than in any of Mozart's preceding operas.

The accession of Leopold II. to the throne of Austria brought no improvement in the composer's circumstances, for the new Emperor's tastes differed widely from those of Joseph, and it soon became evident that those who had enjoyed the favour of the latter had but little to hope from his successor. Mozart applied for the post of second kapellmeister, and also asked to be allowed to teach the young Princes; but both requests were refused. Thinking that the coronation of the Emperor at Frankfort might afford him a favourable opportunity for an artistic tour, Mozart, who was obliged to pawn his plate in order to procure the necessary funds, started for that city on September 26, and gave a concert of his own compositions in the Stadt-Theatre on October 14. But neither here nor at Mannheim and Munich, which he visited on his return journey, did he make much profit, and he returned to Vienna with little or no improvement in his circumstances. Here he had the pain of parting with one of his dearest friends, Joseph Haydn, who was just leaving for London with Salomon, who had engaged him for a series of concerts.* Salomon also entered into negotiations with Mozart for a similar series in the following year, but before that time the composer was no more. He and Haydn never met again.

* It was for these concerts that Haydn composed his best-known and finest symphonies—those called in this country the "Salomon Set."

In May, 1791, an old acquaintance of Mozart's, Emanuel Schickaneder, the manager of a small theatre at Vienna, being in embarrassed circumstances, proposed to Mozart to write an opera on a magic subject, of which he, Schickaneder, would prepare the libretto. Mozart, always ready to help a friend, agreed, though with some little hesitation, saying that he had never written a magic opera. The work was Die Zauberflöte, and Mozart began its composition at once. Various causes interfered with its rapid progress. It was while working at it that the first signs of the breaking up of his vital powers showed themselves. He suffered from fainting fits, and in June he was obliged to suspend work on the opera and go to Baden, a suburb of Vienna, to recruit his health.

It was while engaged on the composition of Die Zauberflöte that Mozart received from a mysterious stranger the commission to write a Requiem Mass. He was asked to name his own terms, but was enjoined to make no effort to discover who it was that had ordered the work. Mozart, who had written no church music since his Mass in C minor eight years before, eagerly accepted the commission, and began work at once. It is now ascertained beyond a doubt that the individual who visited Mozart was the steward of a certain Count Walsegg, an amateur musician who desired to be thought a great composer, and who actually copied the score of the Requiem and had it performed as his own work.

Mozart's work on the Zauberflöte and the Requiem were alike interrupted in August by a commission which it was needful to execute at once. This was the composition of an opera for Prague, to be performed there on the occasion of the coronation of the Emperor Leopold II. as King of Bohemia. The libretto selected was Metastasio's La Clemenza di Tito, which had been already set to music by several eminent composers. As the coronation was to take place in the following month, Mozart had but little time for composition; according to Jahn, the opera was completed in eighteen days. Its first performance took place on September 6, and was not a success. Mozart, who was in bad health when he arrived in Prague, and who had become still worse through his arduous exertions in getting the work ready in time for the performance, was greatly depressed at its failure.

Returning to Vienna in September, with health and spirits alike failing him, Mozart resumed work on Die Zauberflöte, which was produced on the 30th of the same month, the composition of the overture and the march which opens the second act having been only completed two days previously. Though the success of the first performance was less than had been anticipated, the public soon began to appreciate its beauties; it was given twenty-four times in the following month and reached its hundredth performance in a little more than a year.

PART OF THE SCORE OF THE "DE PROFUNDIS." (British Museum.)

As soon as the opera was off his mind, Mozart returned to his still incomplete Requiem, a work which now engrossed all his attention and energy. In his enfeebled and depressed state he formed the idea that he was writing the Requiem for himself, and had a firm conviction that he had been poisoned. By the advice of his doctor his wife took away the score from him, and a temporary improvement resulted, which enabled him to write a small cantata for a masonic festival—the last work which he entered in the thematic catalogue already mentioned. At his request his wife returned him the score of the Requiem, but as soon as he resumed work upon it all the unfavourable symptoms returned with increased violence, and partial paralysis set in. In the latter part of November he took to his bed, from which he was never to rise again. By a sad irony of fate, it was during his last illness that fortune smiled upon him for the first time: some of the Hungarian nobility joined to assure him of an annual income of 1,000 florins, while music publishers at Amsterdam gave him commissions for compositions which would have insured him against want for the future. But all came too late for the dying composer, and his last hours were embittered by the thought of leaving his wife and children unprovided for at the very time when he would have been able to support them in comfort. To the last his mind was full of his unfinished Requiem, and on the afternoon before his death, he had the score laid on his bed, and the music sung by his friends, he himself taking the alto part. When they reached the opening bars of the "Lacrymosa," Mozart burst into a violent fit of weeping, and the score was laid aside. In the evening the physician told Mozart's pupil, Süssmayr, in confidence that there was nothing more to be done; but he ordered cold bandages to be applied to the head, which brought on such convulsions that Mozart lost consciousness; he never recovered it, but died at one o'clock on the morning of December 5, 1791. He was buried the next day in the churchyard of St. Marx in so violent a storm that the mourners all turned back before reaching the graveyard, where the great composer was laid, not in a grave of his own, but in that allotted to paupers. When the widow was sufficiently recovered from the first shock to be able to go to the burial-ground to look for the grave, a new sexton was there who knew nothing about the matter, and the exact spot under which Mozart's remains rest has never been identified with certainty.

In surveying Mozart's art work as a whole, one of the first things to strike the student is the comprehensiveness of his genius. There is hardly another of the great composers who has produced so many masterpieces in so many different styles. It may be at once conceded that in certain directions he has been surpassed by one or other of those who have succeeded him. Very few musicians will be found who will place him, either as a symphonist or as a writer for the piano, by the side of Beethoven; but, on the other hand, the latter is far inferior to Mozart in his treatment of the voice. Again, Mozart's songs, taken as a whole, will not compare with those of Schubert, but as an operatic composer Schubert has written nothing to approach, still less to equal, Figaro or Don Giovanni. There is hardly one department of musical composition on which the genius of Mozart has not left its mark. From this point of view, it will be scarcely too much to call him the most wonderful "all-round" musician that the world has ever yet seen.

Without underestimating his remarkable natural gifts, it can hardly be doubted that Mozart's surroundings conduced not a little to the versatility of his genius. Both in Salzburg and in Vienna Italian music was in the ascendant; and in this the vocal element was of far more importance than the instrumental. With his extraordinary power of assimilating all that was best in whatever he heard, and the almost supernatural facility in composition which seems to have come to him instinctively, it is not surprising that his earliest works show strong traces of Italian influence. This was no doubt to some extent modified by the journeys which, as a child, he made with his father to Paris and London, in which cities he learned to know much of both French and German music; but nearly to the end of his life his style, especially in his vocal music, was rather Italian than distinctively German.