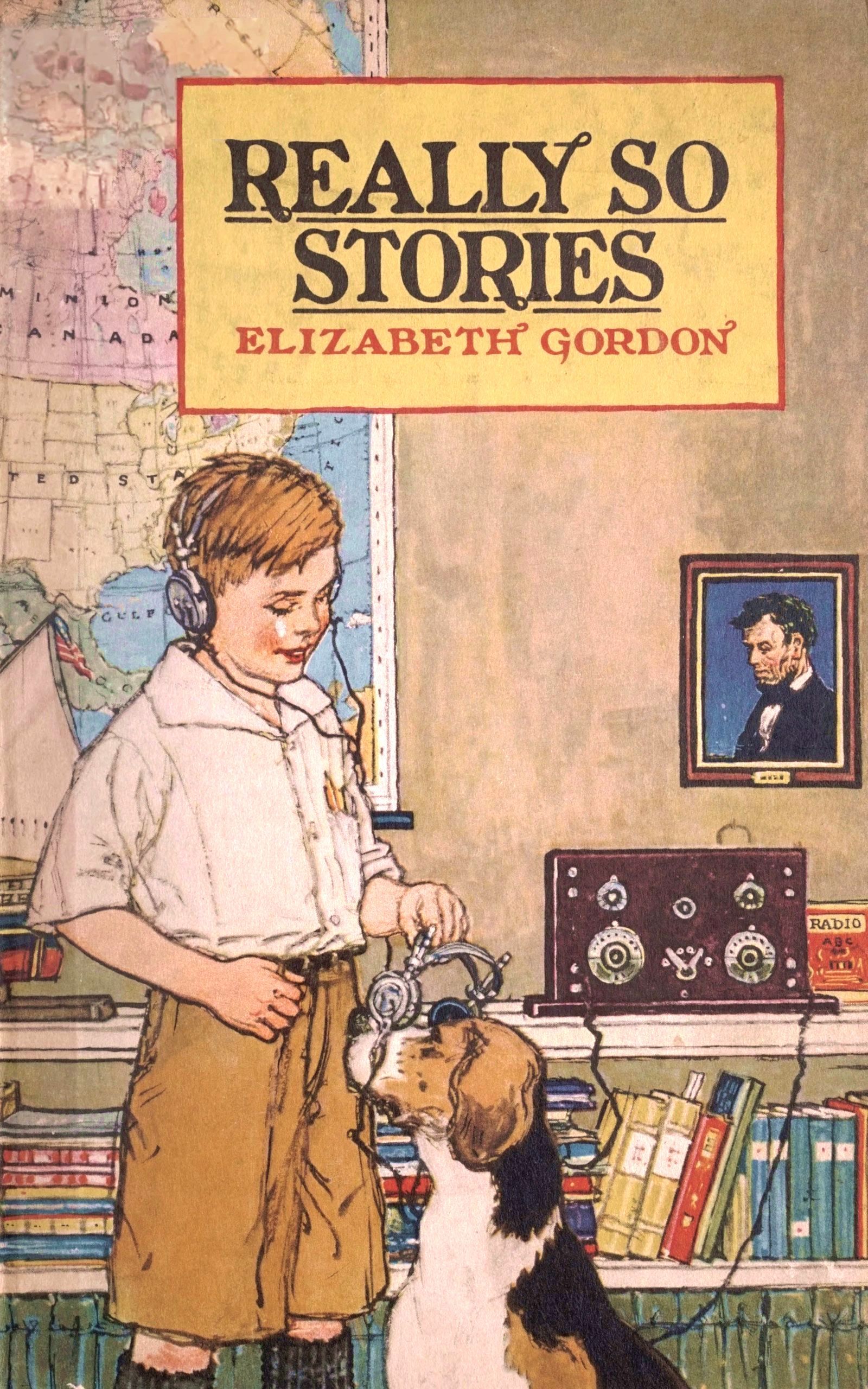

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Really so stories, by Elizabeth Gordon

Title: Really so stories

Author: Elizabeth Gordon

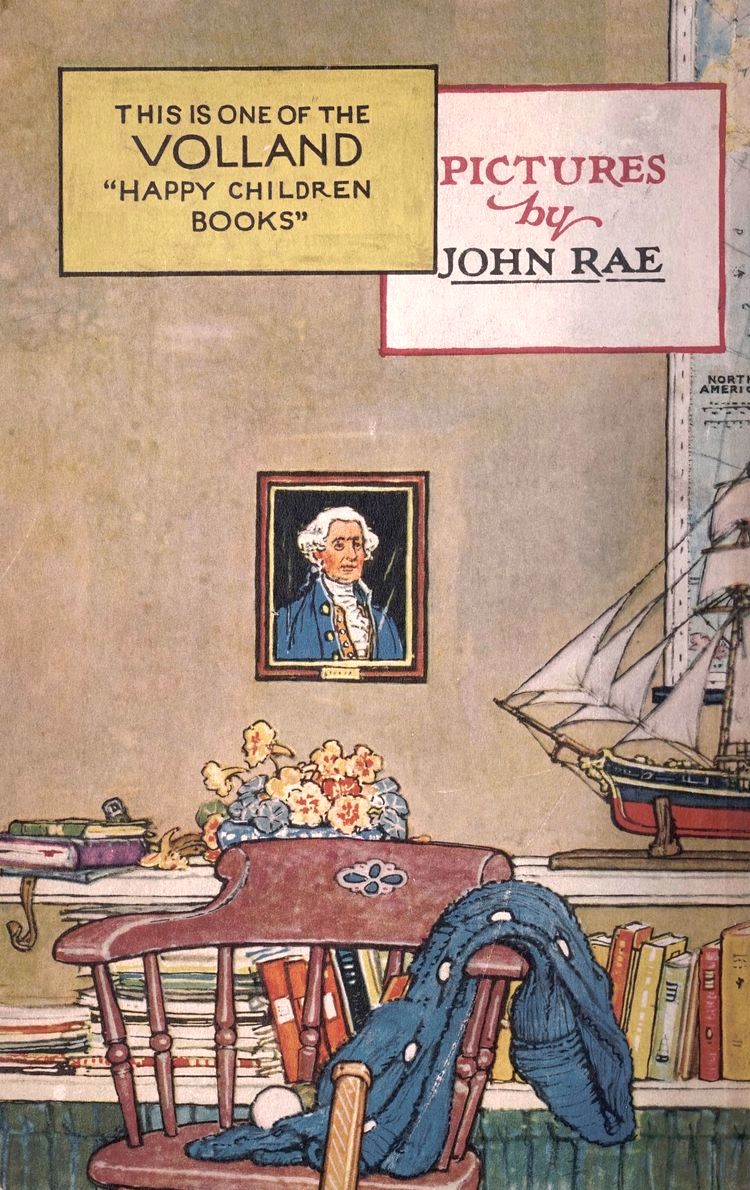

Illustrator: John Rae

Release Date: September 4, 2022 [eBook #68902]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

by

Elizabeth Gordon

Pictures

by

John Rae

Published by

P.F. Volland Company

Chicago

New York Boston Toronto

Copyright 1924

P.F. Volland Company

Chicago, U.S.A.

(All rights reserved)

Copyright, Great Britain, 1924

Printed in U.S.A.

| Page | |

| How the New Year Knows When to Come | 9 |

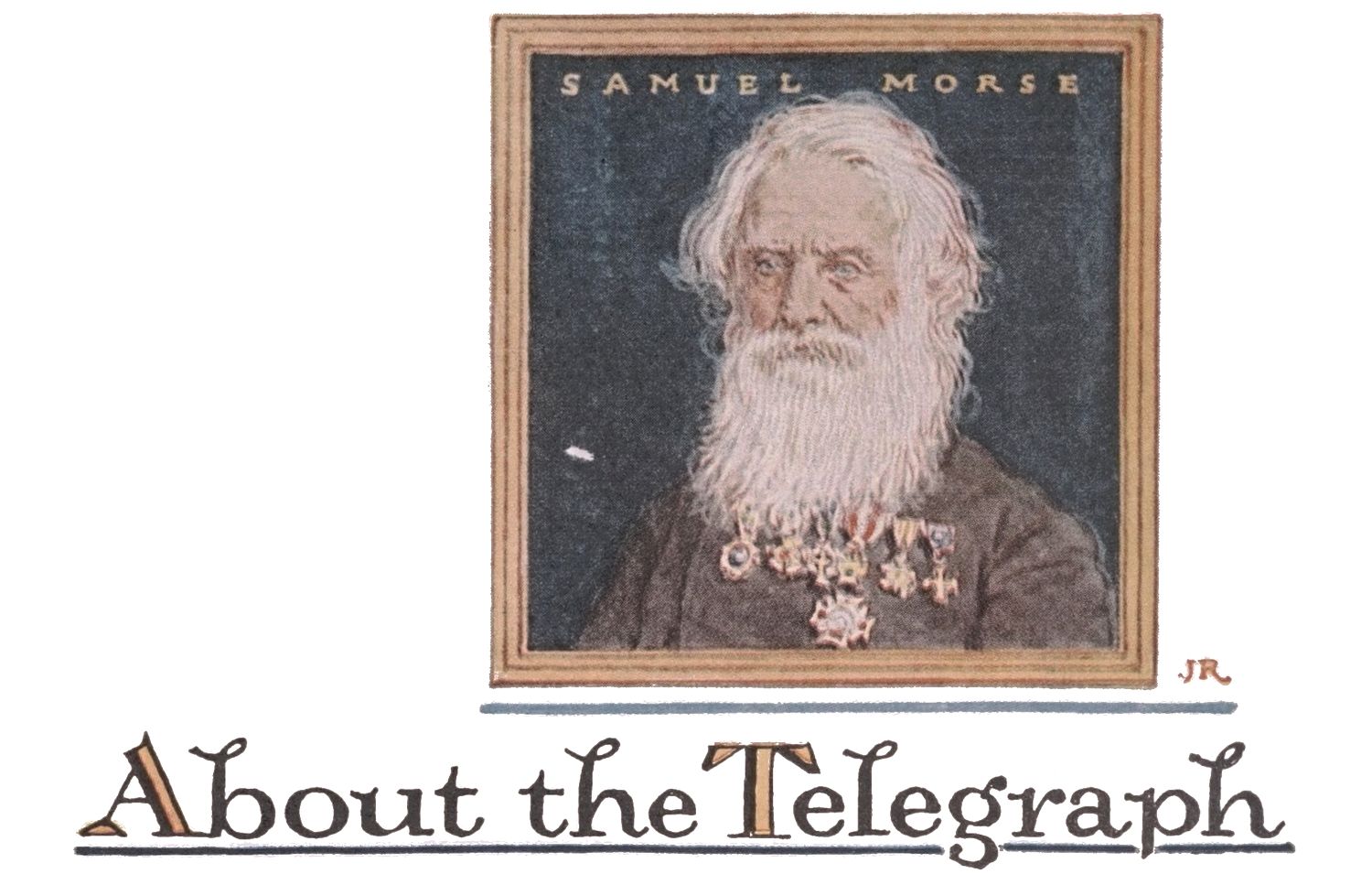

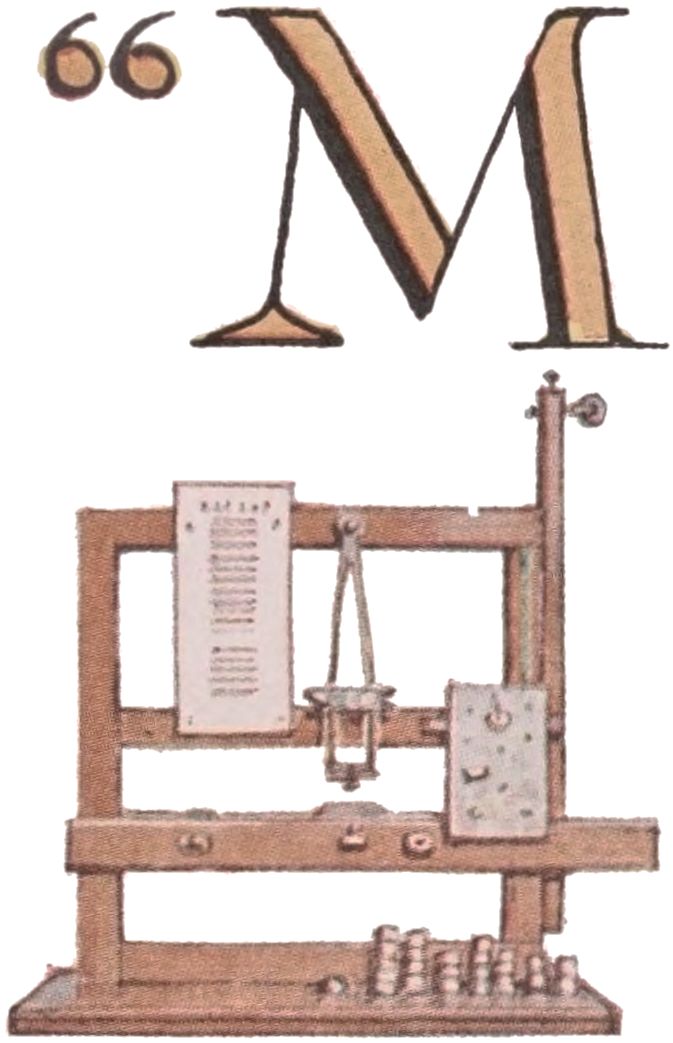

| About the Telegraph | 12 |

| How the Military Salute Came | 14 |

| Candlemas Day | 16 |

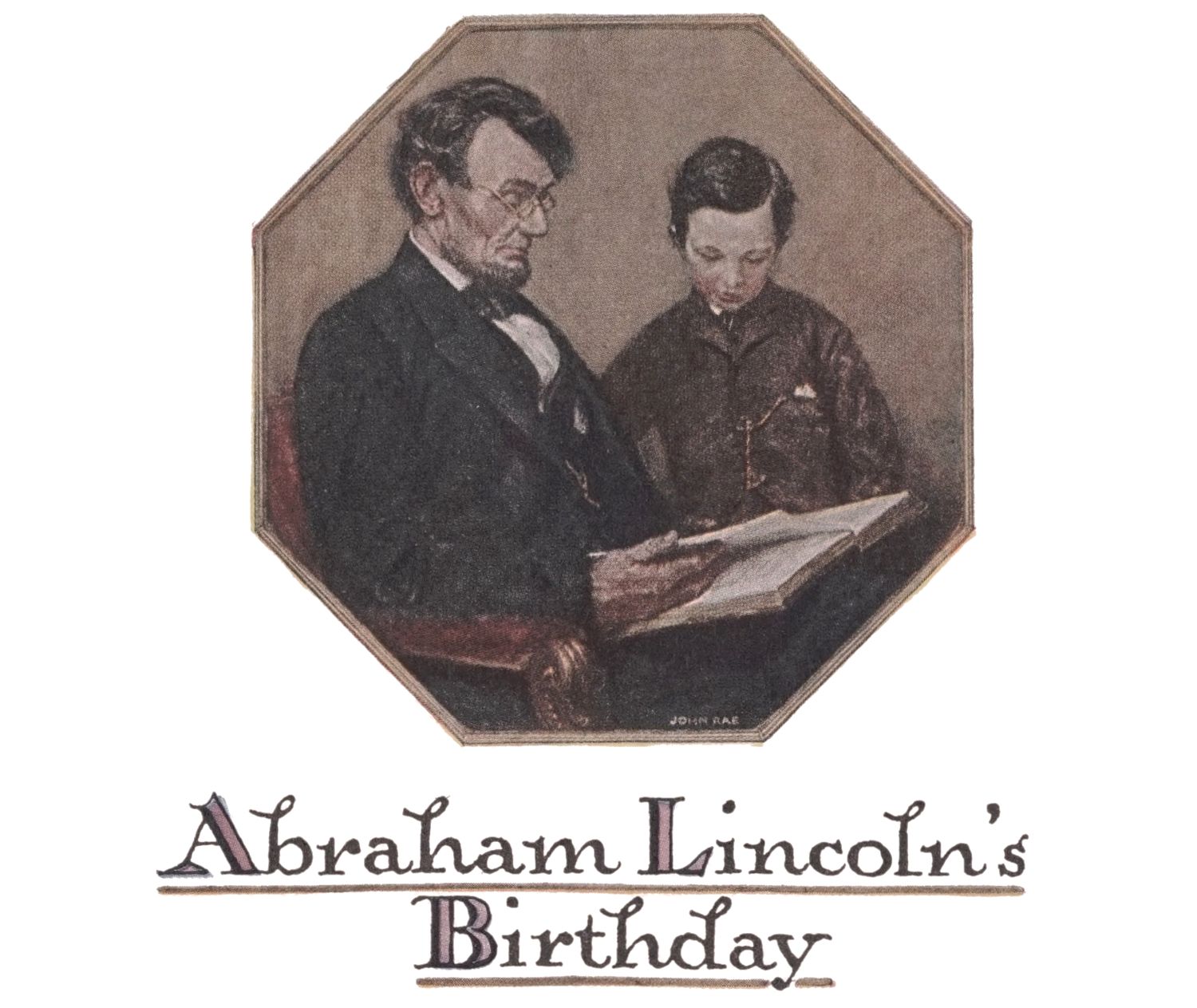

| Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday | 18 |

| About Valentines | 21 |

| Why We Celebrate George Washington’s Birthday | 24 |

| About Boy Scouts | 26 |

| St. Patrick’s Day | 28 |

| Lent | 31 |

| Palm Sunday | 32 |

| The Story of the Bible | 33 |

| Good Friday | 35 |

| About Easter | 37 |

| Trailing Arbutus or Mayflower | 39 |

| About Pearls | 42 |

| About Mr. and Mrs. Pelican | 44 |

| Indian Day | 47 |

| About Hats | 49 |

| Mother’s Day | 51 |

| About Forks | 53 |

| About Silk | 54 |

| All We Know About Strawberries | 57 |

| Children’s Day | 59 |

| About Carrier Pigeons | 60 |

| About Coal | 62 |

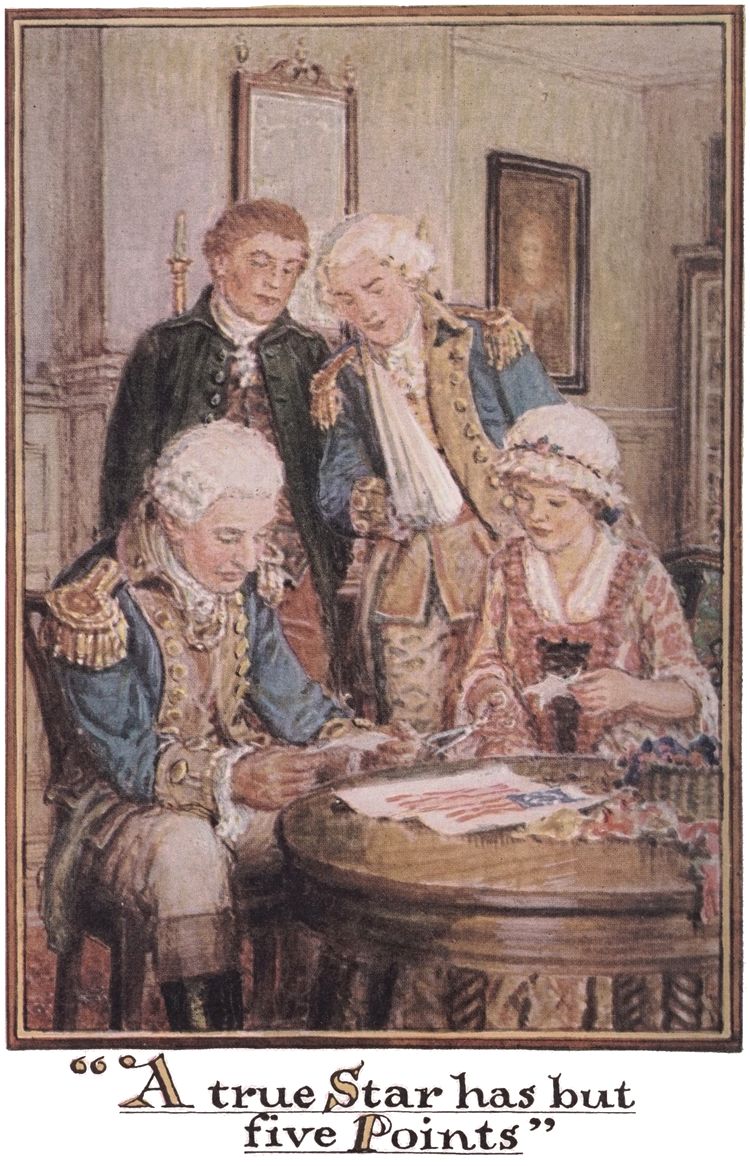

| Flag Day | 65 |

| The Sea-gull Monument | 67 |

| Fourth of July | 69 |

| Mr. Irish Potato | 72 |

| Old Abe, the Wisconsin War-eagle | 75 |

| About Clocks | 77 |

| About Cotton | 80 |

| About Coral | 82 |

| The Star-Spangled Banner | 84 |

| About Umbrellas | 87 |

| Hallowe’en | 88 |

| About Wolves | 89 |

| How Thanksgiving Came | 91 |

| Christmas | 93 |

THERE was once a boy named Billy, who spent a summer in the woods with Somebody.

Somebody had expected to have a wonderful time telling him stories; but it turned out that the boy named Billy did not care for made up stories. He would listen, if they were sufficiently exciting, but even stories of wolves and bears and tigers were not very much worth while unless they were really so.

He wanted to know about the beginning of things, and what certain days meant, and who started customs, and ever and ever so many things that you’d never suppose a small boy would be interested in.

So, I’ve been wondering if there are not many boys like Billy who, also, like to know about things that are really so.

And so, I’ve written down a good many of the things Somebody and the boy named Billy talked about after the lights were out and the fireflies came, during that wonderful summer in the north woods.

Your very own,

THE boy named Billy had begged to be allowed to stay up to greet the New Year. He had something he wanted to ask him if he could only see him, but he presently got so sleepy that his eyes wouldn’t stay open and so off he went to bed and to sleep.

But all at once there was a great tooting of whistles and ringing of bells, and a skyrocket went “whiz” right past his window. The boy named Billy sat up straight in bed.

“Oh,” said he, rubbing his eyes, “the New Year has come and I didn’t even see him.”

“Happy New Year, Billy,” said a jolly little voice. The boy named Billy rubbed his eyes to make sure—yes—he really did believe that there was a roly-poly little person sitting on the edge of the clock shelf swinging his bare pink feet and smiling happily.

“Why,” gasped Billy, “who are you?”

“Whom did you expect?” asked the little fellow. “I’m Father Time’s youngest year, to be sure. Haven’t got my license, or my number yet; I’m waiting until this racket stops. Were you looking for me for any special reason?”

“What I want to know,” said the boy named Billy, “is, how does the world know where one year ends and a new one begins?”

[10]“That’s some question, youngster,” said the jolly New Year, laughing merrily, “and it took the funny old world some time to settle it. You see the year cannot be divided evenly into months and days, because the time actually required for the earth’s journey around the sun is 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 46 seconds. You call that the solar year, because the word ‘solar’ means concerning the sun.

“The old Romans tried having the New Year come on March first, but they had no real system, and were always in trouble. So Julius Caesar, the king, told the world that it was most important to have a calendar that could be depended upon to take care of all the time, because there wasn’t any too much, anyhow. So with the help of some very wise men he took the twelve new moons of the year and built a calendar around them. This was called the Julian calendar, and every fourth year figured this way was made a ‘leap year,’ and was given an extra day, making it 366 days long.

“But putting in a whole day every four years was too much, and after this calendar had been used over 1,500 years it was found that the calendar year was about ten days behind the solar year which wouldn’t do at all.

“So Pope Gregory XIII directed that ten days be dropped from the calendar that year and that the day after October 4, 1582, should be October 15. Then he rearranged the calendar so the New Year would begin January 1 and the calendar year and the solar year kept together. The Gregorian or New Style calendar as this one was called is the one we are using today.

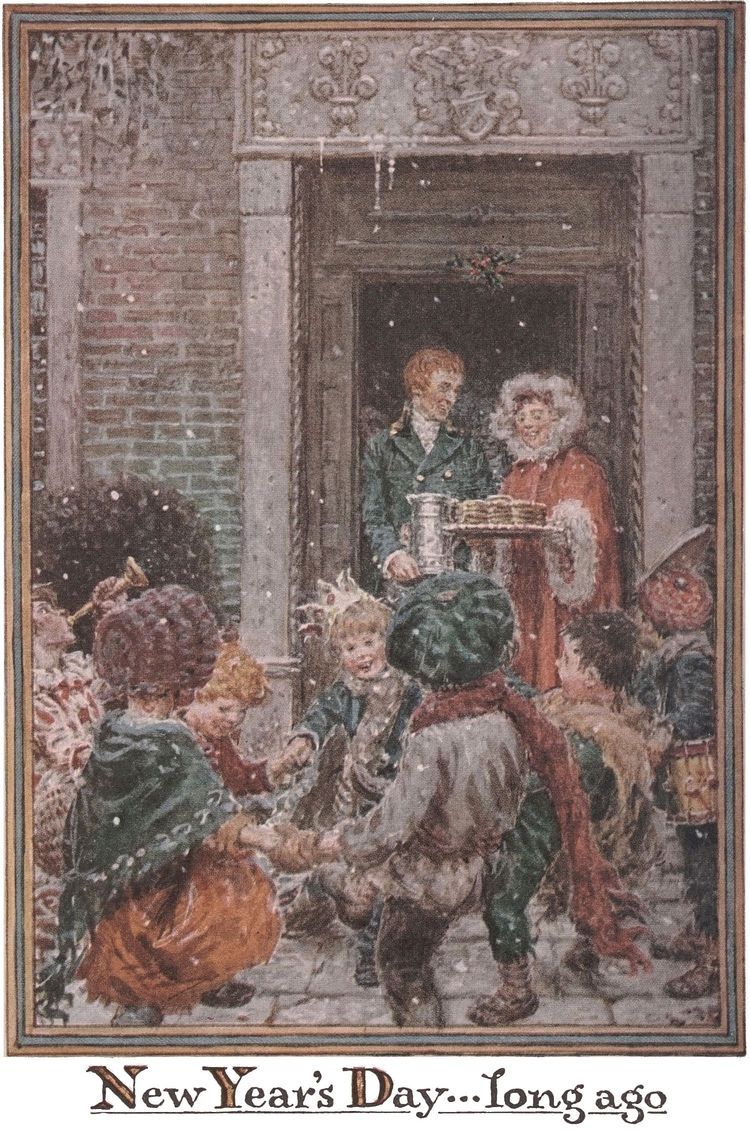

“New Year’s Day has been celebrated in various ways since the dawn of civilization, and if today we could travel around the world on a magic carpet what a wonderfully interesting sight we would see!

“If you were in China you might think the Chinese saved their holidays to celebrate all at once. They close their shops for several days while they make merry with feasts and fireworks and general exchange of gifts and good wishes. In preparation every debt must have been paid, every house swept and cleaned, and each person furnished with holiday clothes and a supply of preserved fruits, candies, and ornamental packages of tea to give to his acquaintances.

[11]“In some European nations, especially France and Scotland, New Year’s Day is a more important holiday than Christmas. If you were a French peasant child you might put a wooden shoe on the hearth for a gift at Christmas, but grownups in France exchange gifts at the New Year festival, at which time there are family parties, with much merrymaking.

“In America the observance of New Year’s Day is varied. New Year’s Eve there are ‘watch night’ services in the churches—gay street revelers—dancing and theater parties; and New Year’s Day is a time for general entertaining and visiting. However, the old custom of keeping open house and making New Year’s calls has practically disappeared.

“People are always glad to see the New Year and always welcome us in some glad and cheery way,” went on the New Year. “And it has always been the custom among all people to exchange gifts and greetings in the name of Happiness on New Year’s day. The Old Year is supposed to take away all sorrow and sadness, and the little New Year is supposed to bring nothing but happiness into the world, so it depends upon each person to see that he gets his share of the happiness.”

“How?” asked the boy named Billy.

“Easily,” answered the little New Year. “By living straight, playing fair, being kind and honest and helping those not so fortunate as you are. That’s all there is to it, little friend. And there goes the last whistle and now for three hundred and sixty-five days of real living. Happy New Year, Billy.”

“Now I wonder,” murmured Billy sleepily, “if that was really so, or did I dream it. I’m going to read up on that calendar thing the very first thing I do, and I’m going to play I saw the New Year anyway; and I’m going to try to do just as I think he would want me to ’cause I want my share in making this year a very, very happy one.”

“MOTHER has just had a telegram from Grandmother that she’s on her way to visit us,” said the boy named Billy. “I’m strong for Grandmother and I’m going to train to meet her.”

“We’re all fond of Grandmother,” corrected Big Sister, “and we’re all going to the train to meet her. Who brought the telegram?”

“Nobody brought it,” said the boy named Billy. “When it got to town it just hopped off the telegraph wires and hopped on the telephone wire and came right out here. That’s got magic beaten a mile I’ll say. Whoever invented the telegraph system anyhow?”

“Oh, you with your ‘who inventeds’!” said Big Sister. “Why don’t you study up such things yourself?”

“I can read it afterwards,” said the boy named Billy, “but when Somebody tells it to me that makes a story of it. Please, who did invent the Telegraph?”

[13]

“Samuel F. B. Morse did,” said Somebody. “He was born at Charlestown, Massachusetts, April 27th, 1791, and lived until April 2nd, 1872. He was a portrait painter, and student of chemistry, and went to London to study painting under Benjamin West, where he made such progress that when he returned to America he was given a commission to paint a full length portrait of LaFayette.”

“LaFayette was some hero and worth painting,” said the boy named Billy, “but when do we come to the telegraph?”

“Right now,” smiled Somebody. “The idea of electricity had been talked of for a long time, and while Mr. Morse was away on one of his trips to England it was found by some experimenting that electricity could be conveyed by means of wire over distances.

“A gentleman whom Mr. Morse met on ship board told him of these experiments and it brought to his mind the old belief held by Benjamin Franklin that intelligence some time would be conveyed by electricity, a belief which he had always shared. He went to work to perfect an instrument and a code for the system which he had in mind, with the result that when the boat landed his idea was ready to present.”

“He struck before the iron was hot, didn’t he?”

“In a manner of speaking, yes,” said Somebody, “but it was two long years after that before the system was completed and in working order. And it took quite some persuasion also to get other people to believe in it, but finally Congress voted him thirty thousand dollars to help him along with his project and so he won out.

“Where, before, it had taken months and years to get word from or to distant places, it could now be done almost instantly. Samuel Morse’s life was one long record of courage, integrity, patience and faith.”

“Bob White and I are fixing up a wireless on the roof of our garage,” said the boy named Billy. “It’s two hours before Grandmother’s train pulls in. Don’t forget to call me, and many thanks, Somebody!”

“I CAN’T seem to get the real snap into the salute that Sergeant Jim does,” said the boy named Billy. “He drills me on it every time I see him. But try as I may I can’t seem to get the style into it, and I’ve just got to learn it before I go into Scout camp; want to spring it on the fellows.”

“Sergeant Jim didn’t learn it in a lesson or two, either,” said Somebody. “He had it literally drilled into him. So don’t get discouraged, Billy.”

“I’m not discouraged; I’m going to get it,” said the boy named Billy. “Sergeant Jim says that when he first went into the service he just hated the salute. But after a while when he began to know what it meant, he didn’t mind it. What does it mean? Why should a soldier salute an officer? An officer’s no better than a soldier, is he?”

“Depends on how you look at it,” said Somebody quietly. “The officer occupies a higher position and the salute is a matter of courtesy—like saying ‘Good morning,’ to your mother, or the boy next door.”

“It is also a matter of discipline, isn’t it?” asked Big Sister.

[15]“It has grown to be that, of course,” answered Somebody. “But it first came into being because the soldiers who were called the ‘Free Men of Europe’ were allowed to carry arms, while the slaves or serfs and poorer classes were not. When one military man met another it was customary for him to raise his arm to show that he had no weapon in it, and that the meeting was friendly. The slaves and serfs, not being allowed to carry weapons, passed without salute. But so imitative are we all that it was not long before everybody was saluting everybody else, which did not suit the aristocratic army men, who then resolved to make their salute so hard to learn that it could not be imitated without real military service, so that an outsider using it would brand himself as a commoner by his incorrect manner of saluting.”

“And so that’s how it became,” said the boy named Billy. “Well, I may not be a soldier, but I am going to get it if Sergeant Jim’s patience holds out.”

“You may not be a soldier, but you are a soldier’s grandson,” said Somebody. “And all of your people have been soldiers when there was any need to fight for the Stars and Stripes.”

“I’ll be right there when the Grand Old Flag needs me,” said the boy named Billy. “And when I’m needed, I’m going to be a captain, so I’ve just got to get this salute right.”

“You’ll have to watch your step in more ways than one,” said Big Sister; “to be an officer in Uncle Sam’s Army means that you must be very well educated, a real gentleman, able to train your men, keep discipline, and make yourself popular with them.

“You should see them drill at West Point, Billy. They know, these fine, clean young men, that some day they will be officers in Uncle Sam’s army so they are earnest—quick to learn and accept the teaching of experienced instructors. Strict mental and physical discipline is necessary to make first rate officers.”

“Leave it to me,” said the boy named Billy, drawing himself up and putting real snap into the salute. “I’m going to be what Sergeant Jim calls a ‘regular.’”

“BOB WHITE’S Grandfather says that we’re going to have six weeks more good hard winter,” said the boy named Billy on one bright Candlemas day, “because it’s been so sunshiny all day that the old ground-hog couldn’t help seeing his shadow when he came out.”

“Well, I certainly hope he proves to be a false prophet this time,” said Big Sister. “I’ve had all the winter I want right now.”

“Oh, Sis, what do you mean you’ve had enough winter!” exclaimed the boy named Billy, reproachfully, “winter’s the jolliest time there is—with all the coasting and the tobogganning and skating. I’m hoping it will stay cold so we can have another carnival. Wasn’t the last one a peach! Bob White’s father said he had never seen better fancy skating or more exciting races. He told us to be a fancy skater you have to have good balance, a sense of rhythm, and no little athletic ability. I’m going to practice so I can do stunts at the carnival next year. Say, Somebody, is there anything to that ground-hog story?”

“Probably not,” said Somebody, “Mr. and Mrs. Arctomis Monax, more familiarly known as Brother and Sister Woodchuck, are pretty wise little people, and are more than likely sleeping the sleep of the just at this time; yet I have heard of them being lured from their dens by unusually bright weather long before the vegetation upon which they feed had started and that they paid for their foolishness with their lives, which is too bad, because they are really nice little folk.”

[17]“Why do they hibernate?” asked the boy named Billy.

“They belong to the family who do such things,” said Somebody. “They, and the bears, and some other animals, find it more convenient to store up fats in their little round bodies in the summer time, and to curl up and sleep through the winter months, when there is nothing to eat that they really like. Saves a lot of trouble.”

“Where did that old yarn come from about them coming out on this day?” asked the boy named Billy.

“The myth is very likely of Indian origin,” said Somebody, “but there is also an old Scottish rhyme to the effect that ‘if Candlemas day be fine and clear there’ll be twa winters in the year.’”

“Do you know why the 2nd of February is called Candlemas day?” asked the boy named Billy.

“It is another of those old made over Pagan Festivals,” said Somebody. “The early Romans always used to burn candles on that day to the goddess Februa, who was the Mother of Mars, making a very beautiful and impressive occasion of it.

“Pope Sergius, after the way of those old priests, wished to do away with all the old pagan rites but did not dare to openly raise the question, so he gave orders for candles to be burned on that day to the Mother of Christ hoping that in the new festival the old one would be lost sight of, which proved to be true. The occasion is still celebrated in some churches, and consecrated candles are supposed to be burned for protection from all evil influences for the balance of the year.”

“But there are so many of those old saints days that are so entirely forgotten,” said Big Sister, “I wonder why Candlemas is so universally remembered?”

“I think our friends, the Woodchucks, are responsible for that,” said Somebody, with a smile.

“IT’S Lincoln’s birthday tomorrow, and we do not have school,” said the boy named Billy. “But I’ve got to tell the class this afternoon why I think Lincoln was the greatest American.”

“Suppose you tell us what you do know about him,” suggested Somebody.

“Well,” said the boy named Billy, “I know he was born in Hardin County, Kentucky, in a poor little old log cabin, on February 12th, 1809. That he lived there until he was seven years old, when he went with his family to Indiana, where they were even poorer than before.

“His mother was never very strong, poor lady, and the rough way in which they had to live was very hard for her, and she died when Abraham was only nine years old. But she taught him to be good, honest and true, and ‘learn all he could and be of some account in the world.’

[19]“After while, his father brought him another mother who was very good to him and as he said later, ‘Moved heaven and earth to give him an education.’ His school years were few, but he was determined to know things, so he studied every minute and often walked ten miles to borrow a book. When he was twenty-one he owned six books, the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress, the Arabian Nights, Statutes of Indiana, Weems’ ‘Life of Washington,’ and ‘Aesop’s Fables.’ He used to read after his work was done by the light of the fire on the family hearth. He almost memorized the Bible.

“He was very kindhearted and once when he went to New Orleans with a flat boat full of lumber to sell, he saw some slaves being sold. It affected him so strongly that he said if he ever got a chance he was going to ‘hit that thing hard!’ He was never idle, and he was absolutely honest, and to be depended upon.

“When he was 21 he went with his parents to a wilderness farm in Illinois, which state almost lost him, because if there had not been a flood making travel impossible he, with his family, would have gone on to Wisconsin where they had started for.

“After studying law, and practicing it for a good many years, and being sent to Congress he was elected to be the president of the United States in 1860, being the 16th president of the land. He was in the presidential chair all through the civil war and when he was shot, soon after his second election, the whole country mourned for the man who had ‘hit that thing hard’ and abolished slavery.”

“Do you know his most famous address?” asked Sister.

[20]“Lincoln’s Gettysburg speech!” exclaimed Billy. “Well, I should say—‘Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in the great Civil War, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our power to add or detract. The world will little know nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us, that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.’”

“You seem to know a good many things about Lincoln after all,” said Somebody, smiling proudly.

“Yes, but I do not know why he was the ‘greatest American’,” said Billy.

“He was the ‘greatest American’,” said Somebody, “because he loved the Union and determined that it must at all costs be preserved. Because he knew that ‘united we should stand, but that divided we must fall.’ Because his own life counted for nothing where the Union was concerned. Because it is due to him and to him only that we are not broken up into small independent states, but are gathered together under the best flag that the sun ever shone upon. Never has the world seen a greater example of wisdom, patience, patriotism and moral courage than animated his every act. Abraham Lincoln is our greatest American because he stood for honesty, loyalty, affection, willing service, and striving after every kind of good.”

“I’ve got it now,” said the boy named Billy.

“WILL you mail these Valentines for me please, Billy?” asked Big Sister.

“Sure,” said Billy. “Gee, that reminds me, we’re going to have a Valentine box at school and I better get some to give Bob White, and Pete and Jack—what a bunch of them you’re sending—do you send Valentines to all the people you know?”

“No, indeed,” said Big Sister, “only to those whom I know best and care most about.”

“It’s a funny custom,” said Billy, “who ever started it any how?”

“I think it’s a splendid custom—a friendly, cheerful way to say ‘Hello, I’m thinking about you,’” said Big Sister, “and I’m much obliged to old St. Valentine for beginning it.”

“Did he start it?” asked the boy named Billy in surprise, “you wouldn’t think a saint would be bothering his head about such things as Valentines.”

“As a matter of fact,” said Somebody, “St. Valentine had nothing to do with it. He was a most pious man who went about his business with no thought of any thing frivolous I’m sure. He very likely did not know that he had been chosen as the patron saint of the day.

[22]

“It was the custom in ancient Rome to celebrate the feasts of Lupercalia through the month of February in honor of Pan and Juno and these feasts were very gay, indeed. There was a custom of the young Pagans by means of which they chose their dancing partners for the day, of writing the name of a young man and a young woman and having a drawing. The young man keeping the young lady whose name he had drawn, as his partner for the day.

“The Christian Pastors of the churches objected to this fun making and so they put the names of Priests in the boxes to be drawn in place of the young women, and St. Valentine’s name came out as the guardian or saint of the day.

“He was accepted as such, but the young people went on celebrating the day in the way to which they were accustomed and out of that grew the idea of Valentine’s day.”

“That was a jolly way for it to start, wasn’t it?” exclaimed the boy named Billy.

“When did people begin sending Valentine messages to each other?” asked Big Sister.

“In early times in England and very likely also in other parts of the world,” said Somebody, “it was the custom to send a gift to the one who had been chosen as a young man’s Valentine. This custom grew more popular year by year, until, as the gifts must be worth while, it very likely grew burdensome, and the sending of gifts was in a manner discontinued. Then some bright person hit upon the plan of sending dainty creations made of lace paper with bright and witty verses written on them. Even that custom was about worn out when some one in England sent a lacy affair to Miss Esther Howland of Worcester, Massachusetts, who saw in it a way to make some money; so she started making Valentines for sale, and succeeded so well that the making of them and the sale of them has grown to be a very great and important industry.”

“So poor old St. Valentine just had the day wished on him,” said the boy named Billy. “What ever did become of him?”

“He offended someone,” said Somebody, “and was beheaded.”

“Playful, weren’t they?” said the boy named Billy, as he gathered up the Valentines.

THE BOY named Billy came into the room to say goodbye to Somebody before going to the celebration of George Washington’s birthday at the schoolhouse.

“Your face has some black streaks on it, Billy,” said Somebody. “Better go and remove them and come back and tell me about it.”

“I don’t like to talk about it,” said the boy named Billy, as he came back from the wash room. “Mom scolded me.”

“What was it all about?” asked Somebody.

“I left my cap on the living room table again. Mom found it there and she held it up for me to see and said, ‘William!’”

Somebody tried not to smile. “That was severe! But George Washington was often reproved by his mother.”

“George Washington,” said the boy named Billy, in astonishment. “Did anyone ever scold George Washington?”

“Indeed, yes,” said Somebody, “and in a very unique way, too. Mary Ball Washington was a wonderful woman, with quantities of good sense and a remarkable idea of truth and justice. It is said of her that when her children disobeyed, or were in need of being reprimanded that she did not trust herself to do it in her own language, but that she always used the words of the Bible.”

[25]“That was a queer way to scold,” said Billy.

“It worked judging from what we know of George and his boyhood,” remarked Somebody. “When he was fourteen he wished to go to sea, but as his mother thought it best that he should not, he abandoned the idea and was given two additional years of schooling, chiefly in mathematics, and so prepared himself for the profession of a surveyor.”

“Sixteen, and finishing school!” exclaimed the boy named Billy.

“School was rather a different affair in George Washington’s day,” said Somebody. “He was born in the country, at a small place named Bridges Creek, Virginia, on the twenty second of February, 1732, and at that time the country was very small and had few schools.”

“It must have been fun being a surveyor,” said Billy.

“It was not much fun, Billy Boy,” Somebody told him. “It was a severe test of character and capacity, but George Washington always accomplished every task given him with success, and reported on it with brevity and modesty.

“The traits of steadfastness of character which he had displayed in school and among his playmates now came out prominently. He excelled in running, wrestling, and horseback riding in his youth and in later years, because of his wisdom, patience, tolerance, courage and consecration to the righteous cause of liberty became the father of his country.”

“My but his mother must have been proud of him,” said Billy.

Somebody nodded. “It was to his mother, a woman of strong and devoted character, that George Washington owed his moral and religious training. Even when her son had risen to the height of human greatness, she would only say, ‘George has been a good boy, and I’m sure he will do his duty.’”

“Guess I better tell Mom I’m sorry about leaving my hat on the living room table,” said the boy named Billy.

“I would if I were you,” said Somebody.

“GET MY new Scout suit,” said the boy named Billy, coming in with himself all in khaki. “Look at the buttons, ’n the leggins ’n all!”

“It’s very Scouty looking,” said Big Sister. “I hope you’ll keep it that way.”

“Have to,” said the boy named Billy, “or get a demerit. Going for drill now over on the parade ground in front of the armory. Got just long enough for Somebody to tell me when and where the Boy Scout movement started.”

“The Boy Scout movement,” said Somebody, “started in England in 1908 being launched by Sir Robert S. S. Baden Powell.”

“Oh say!” exclaimed the boy named Billy, “why did we have to let England beat us to it?”

“We didn’t—exactly,” said Somebody, smiling at the zeal of the young patriot, “because at that very time we had two organizations which had the same purpose in view. One was called the Wood-Craft Indians founded by Ernest Seton Thompson, and another called the Sons of Daniel Boone founded by Dan Beard. Both men were popular writers of out of door stories, and greatly interested in boys and their sports and activities.

“Scouting gives a boy something to do, something he likes to do, something worth doing. It has succeeded in doing what no other plan of education has done—made the boy want to learn. It organizes the gang spirit into group loyalty.

[27]

“In 1910 both these organizations were combined under the title of the Boy Scouts of America, and as you of course know, Billy Boy, before a boy can become a Scout he must take the Scout oath of office.”

“Yes, indeed,” said the boy named Billy. “Wait, ’til I see if I’m up on that. ‘On my honor I will do my best—To do my duty to God and my country, and to obey the scout law; to help other people at all times; to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.’

“A scout is required to know the Scout oath and law and subscribe to both. But his obligation does not end here. He is expected not only not to forget his oath and law, but to live up to them in letter and spirit from first to last.”

“Fine!” said Somebody. “That sounds like a perfectly good working rule. Now what are some of your ideals as Scouts?”

“Well,” said Billy, “we’re divided into three classes. Tenderfoot, that’s what Bob White and I are as yet, but we’ll grow—second class Scouts and first class. According to Scout law one must have honor, loyalty, unselfishness, friendliness, hatred of snobbishness, must be courteous, be really kind to animals, and always obedient to fathers and mothers ’n Somebodys, be gentle, fair minded, save money, look out for fires and clean up after oneself.”

“On account of that last item, thanks be that you joined the Scouts, Billy,” said Big Sister, “and just to help you along, suppose you run up and wash the bowl where you just washed your hands.”

“Oh, excuse me, Sis!” said the boy named Billy, “I guess I forgot, but I won’t after this.

“I’m going to have a lesson on first aid this morning, so if you ever get a sprained ankle or anything I can hold the lines until the doctor gets here. S’long.”

“All of which means that I scrub up after the youngster myself,” said Big Sister, “but Billy’s a pretty good scout at that.”

“BOB WHITE’S going to march in the St. Patrick’s day parade,” said the boy named Billy, “and that leaves me without a thing to do, unless Somebody will tell me who St. Patrick was and why all Irish people think so much of him.”

“Strange as it may seem,” said Somebody, “St. Patrick was not an Irishman at all, but was by birth a Scotchman, having been born in Scotland about 372. When he was sixteen or seventeen years old he was stolen by Pirates and taken to Ireland and made to work at herding swine. He was a very studious boy and in the seven years that he remained a swineherd he learned the Irish language and the customs of the people.

“He then made up his mind that swineherding was not the right sort of occupation for a bright-minded youth like himself, so he escaped to the Continent, where after more years of study he was ordained by Pope Celestine and sent back to Ireland to preach Christianity to the people.

“But the old priests did not like him. He was very likely too bright for them, and they persecuted him, and made things very uncomfortable for him. Finally he was obliged to leave there, but before he went he cursed the lands of the other priests so that they would not bear crops, just to even up things.

“He was none too comfortable himself, but he did not mind small discomforts because one cold and snowy morning when they were on the top of a mountain with no fire to cook their breakfast St. Patrick told his followers to gather a great pile of snowballs, and when that had been done he breathed upon them and immediately there was a great glowing fire, and they got breakfast very nicely. This and other miracles made him very popular, and so when the scourge of snakes came he was sent for and begged to disperse the reptiles.

“‘Easy,’ said St. Patrick, ‘bring me a drum.’ When the drum came he began beating it with such vim and vigor that he broke its head, and it looked for a time as though the trick would fail. But just then an angel came and mended the drum and the snakes were forever banished. Just to prove it they kept the drum for many centuries.

“These and other marvels were performed by St. Patrick, who lived to be 121 years old, dying on his birthday, March 17th, 492.

“Historians have relegated many stories about Saint Patrick to the realm of myth, but the shamrock remains the emblem of Ireland, proudly worn by Irishmen the world over on Saint Patrick’s Day, March seventeenth. The true shamrock (in Irish seamrog, meaning “three-leaved”) is the hop clover, which much resembles our common white clover, except that the flower is yellow instead of blue-green. Large shipments of shamrocks are brought to the United States for Saint Patrick’s Day.”

“So the shamrock is the National emblem of Irish people,” said Billy.

“Yes,” said Somebody. “And it is said that no snake can live where it grows.

“Perhaps if one will take the trouble to think it out, one may find in that belief the idea of faith and loyalty and love of country for which the Irish people are noted, and that emblematically it means that no traitor to Ireland can live near the Shamrock.”

“I see,” said the boy named Billy, “they feel as we do about our Eagle, don’t they?”

“WISH I had somebody to go skating with,” said Billy one winter afternoon.

“Where’s Bob White?” asked Big Sister looking up from her book.

“It’s Ash-Wednesday, and his folks are Catholics,” said the boy named Billy, “and they have after school services. What is Ash-Wednesday and what does it mean, any way?”

“Ash-Wednesday,” said Somebody, “is the beginning of Lent, which lasts forty days and ends with the Saturday before Easter Sunday. It is supposed to commemorate the forty days fasting Christ did before His Crucifixion.”

“My,” said the boy named Billy, “I never could fast forty hours let alone forty days! How is it supposed to help a person to go without food for so long?”

“Fasting,” said Somebody, “is to teach the lesson of self restraint, and self control, and to help us endure discomforts without complaining, how to refrain from all unkind thoughts of others, to control our tempers and make us better people generally.

“It’s a very good idea for each one of us to give up something during Lent; something that we like very much indeed, and to give the money that it would have cost to some one who really needs food and comforts.”

“Do you do that?” asked the boy named Billy.

“I try to,” said Somebody.

“Oh, I see!” said the boy named Billy.

“TOMORROW is Palm Sunday,” said the boy named Billy. “Why do some churches give the people palm branches to carry?”

“On the Sunday preceding the crucifixion Christ made his triumphal entrance into Jerusalem. All the people came out to meet him, strewing palm branches in his path to do him honor, just as you school children all cheer when the president, or some great hero comes to town.”

“Jerusalem is a warm country and must have many beautiful flowers,” said the boy named Billy. “Why didn’t they bring flowers instead of stiff, rusty palm branches?”

“Because they wished to show him all honor,” said Somebody. “And the palm was their emblem of joy and peace and victory. His goodness and power were beginning to have their effect on the minds of the people. They were beginning to believe that Jesus was really the Christ whom their forefathers had promised would come and bring them comfort, peace and general good tidings.”

The boy named Billy looked puzzled. “So they hailed him on Palm Sunday and crucified him the following Friday!”

Somebody nodded. “Human praise and opinion is like that—it is always a variable thing full of chance and change—unstable—but Jesus wasn’t moved for a moment by the praise and flattery of the people, because he knew what was in store for him in Jerusalem. He knew that Judas Iscariot, one of his own disciples, would betray him to the chief priests and magistrates who hated him, because they were afraid he would convert the people and uncover their own wickedness. Christ Jesus knew that he must suffer violence at the hands of those who hated goodness so that he might prove beyond shadow of doubt, by his resurrection, that love is greater than hate—that love is always victorious, because God is Love.”

“I think this is the best really-so story of all!” said Billy.

“BILLY,” called Big Sister one Saturday evening, “want to go to the movies?”

“Can’t, thank you, Sis,” called back the boy named Billy. “Got to study my Sunday School lesson.”

After a half hour of deep study the boy named Billy put the book on the table and said, “That’s great stuff, that story of David and Goliath. Who wrote the Bible, please? It was written by someone, was it not?”

“There were many sacred books written by many different men at many different periods of the world’s history,” said Somebody, “which were accepted as the inspired Word of God.

“At first these were put out as separate volumes, but after a long time they were gathered together and bound into one volume.

“The books of the Old Testament were originally written in Hebrew and those of the New Testament in Greek. Think of the labor of love it must have been to make copies of the Bible. In those days it all had to be done by hand as printing was not invented until a thousand years after the new Testament was written.”

“Some undertaking,” said the boy named Billy. “Were all other books made the same way?”

“Yes, indeed,” said Somebody, “a book was a priceless possession in those days, and there’s not much wonder that there were very few scholars—only priests and physicians had the leisure to become learned, even if they could have obtained the books from which to study.”

“The Bible we have is then a translation,” said the boy named Billy.

[34]“The Bible was translated into various languages,” said Somebody, “but the first English version was translated from the Latin by a priest named John Wycliffe, of Lutterworth, England. He believed that the Bible belonged to everybody and should be put into such form that everyone could read it. But instead of being thanked and made much of for the very great service he was doing he was put out of the church and called a heretic for daring to meddle with the word of God—which did not stop his work at all, because he finished it. After his death no one did any more about it for a hundred years or so until Johan Guttenberg discovered the art of printing, and when in 1454 the use of movable type was found possible many copies of the Bible were printed and everyone could have his own.

“In 1516 Erasmus, a learned Greek scholar, published the New Testament, which was translated by William Tyndale, who was so persecuted by those who did not want it published that he was obliged to go to Germany to finish his work; even there he was so hampered that it was not until 1525 that the New Testament was finally printed.

“Merely as literature, it has made a deeper impression upon the human mind than has any other book, and the extent to which it has helped shape the world’s ideas cannot be estimated. No matter how much you know of poetry or prose, you cannot consider yourself well read unless you are thoroughly acquainted with the Bible.”

“It is wonderful that the language has been kept so beautiful after all those translations and copyings,” said the boy named Billy.

“Very likely it was changed a good bit,” said Somebody, “but its wonderful message of Truth has not been changed.”

“I don’t know where there’s another story like that of David,” said Billy, “and the one about Joseph’s coat has any one of the six best sellers beaten a mile.”

“Perhaps you’ll like to know,” said Somebody, “that the Bible, year in and year out is THE best seller.”

“I don’t wonder,” said the boy named Billy.

“TOMORROW will be Good Friday,” said the boy named Billy. “That is the day on which Christ Jesus was crucified, wasn’t it, Somebody?”

“Yes,” said Somebody, “and is why it is remembered by us all in one way or another—by church services, or in our thoughts.”

“Of course I know the story,” said the boy named Billy, “but won’t you please tell it over again?”

“Early in the morning Christ Jesus prayed to God, his Father, saying that his mission had been accomplished (you’ll find this beautiful prayer in the seventeenth chapter of St. John’s gospel, Billy boy). Then he went into the Garden of Gethsemane with his disciples. Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Jesus, knew the place where he would be and went there with a band of men and officers from the chief priests and Pharisees. (The Pharisees were narrow minded people who paid excessive regard to empty tradition and dead ceremonies. They observed the form, but neglected the spirit of religion.)

“Jesus was arrested, and brought before the Sanhedrin, the Jewish council of priests and elders. After a hasty trial they pronounced him guilty of death for blasphemy. They said ‘we have a law, and by our law he ought to die, because he made himself the Son of God.’ St. John 19:7. And He was the Son of God, sent by the loving Father to bring understanding to the people so they might obey and love God and know the blessing of trusting Him always.

[36]“Then the council of priests and elders delivered Jesus to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor. Pilate didn’t sympathize with the wishes of the people. He said, “I find in him no fault at all.” But the people insisted that he give him up to be crucified, so he washed his hands to show them that he took no responsibility in the affair whatsoever. And they took Jesus away—put a crown of thorns on his head, and followed him with taunts and abuse of every kind as he, bearing his cross, led the way to Golgotha, the place of his execution.

“There on that never to be forgotten Calvary, Christ Jesus was crucified with a criminal on either side.

“Jesus’ body was taken from the cross and placed in a tomb by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus. Three days later, on the first day of the week, when some of the women came with spices to embalm the body, they found the tomb empty. An angel who kept watch told them that Christ had risen from the dead. The risen Christ appeared first to Mary Magdalene, the once sinful woman from whom Jesus had cast out seven devils, and who had become one of the most devoted of his followers; and then to others who were close to him. He spent forty days on earth after his resurrection, and then from the midst of his disciples he was taken up to heaven. He left no writings and no organized church. But from recollections of his teachings his followers later put together the record of his ministry, as we have it in the New Testament, and with it there slowly took shape also the organized Christian church, which more and more has ruled men’s lives.”

“I wish I had been there,” said the boy named Billy, “I could have helped some way, I know.”

“You can help every day, Billy Boy,” said Somebody, “by being kind to everybody, and doing unto others just the thoughtful, loving things you want others to do unto you.”

“AREN’T my hands a sight!” laughed the boy named Billy. “Wish Somebody would tell me how to get these colors off.”

“I should say they are a sight,” said Somebody; “all the colors of the rainbow and several more besides. What’s on them?”

“Easter egg dyes,” said Billy; “they splashed, but we got some beauties.”

“Try some salt and vinegar and a nail brush and soap,” said Somebody. “You’ll find some on my wash stand.”

The boy named Billy scrubbed with right good will. “It’s coming off,” he said. “Say, Somebody, please tell me why Easter doesn’t stand still, like Christmas and New Year’s Day. What makes it come in March one year, and likely as not in April the next? A day is a day, isn’t it? Then why do we never know when to look for it? Last year we gathered pussy willows, and this year it’s cold enough to skate.”

“It is puzzling until you understand about it,” said Somebody, as Billy came back with his hands as clean as could be expected. “Let’s talk about it. There seems to be no authentic record of the actual date of Christ’s death and burial and resurrection. We know that the Crucifixion was on Friday, and the Resurrection was on Sunday, but the date has never been accounted for, although Easter has been celebrated as a church festival since the early days of the Christian church.

[38]“To settle all such disputes it was finally decided by the Council of Nicaea in 325 A. D. that the celebration of the festival commemorating the Resurrection should fall on the first Sunday after March 21st and the full moon.”

“And why was the festival called Easter?” asked the boy named Billy.

“It is a sort of made-over festival,” said Somebody. “The early Christians called it the Paschal festival, and it was so called until the Christian religion was introduced among the Saxons, who had a Spring festival themselves of which they were very fond, held in honor of their Spring goddess Eostre. They seemed inclined to like the new religion, but refused to give up their goddess, so the Christians decided to keep the festival and the name, but to use it in commemoration of the resurrection of Christ.”

“Who was this lady named Eostre?” asked the boy named Billy. “She must have been pretty important.”

“Eostre, meaning ‘from the East, or Venus, the goddess of beauty,’ was supposed to have been hatched by doves from an immense egg which descended from heaven and rested on the Euphrates. Out of it came the goddess of Spring and of beauty to bring warmth and sunshine into the world,” said Somebody.

“That must be where the idea of the Easter egg comes from,” said the boy named Billy. “I was wondering about that. It’s interesting; tell me some more.”

“There are many beautiful legends concerning Easter,” said Somebody. “One which was quite generally believed in Ireland was that on Easter morning the sun dances. But of course we take that with a grain of salt.”

“Just as we take our Easter eggs,” laughed the boy named Billy. “Thank you so much, Somebody; and now I’ll run and get some flowers for Mother. I’m going to get her a beautiful Easter lily.”

“SEE what I’ve got for Mom,” said the boy named Billy bursting into Somebody’s room one bright morning in the latter part of April. “May Flowers! Beauties! Found them away over in the pine woods just peeping out from under a snow bank.”

“Beauties indeed,” agreed Somebody, “I’m glad you cut them so carefully. Most children do not understand the importance of cutting wild flowers instead of tearing them up by the roots.”

“I ought to understand it unless I’m a dunce,” laughed Billy, “you and Mom tell me about it often enough. But why is it called Mayflower when it always comes in April? Of course I know its real name is Trailing Arbutus.”

“The Mayflower,” said Somebody, “is spring’s first messenger wherever it will grow, and its appearance is governed by the length of the winter, and not by the calendar. I’ve heard of it in the Rocky Mountains in August. It seems not to be able to live in very warm places, but loves to snuggle its blossom children under the snows of winter, who, when they awake push aside the blankets and creep out to tell the world that spring has come.

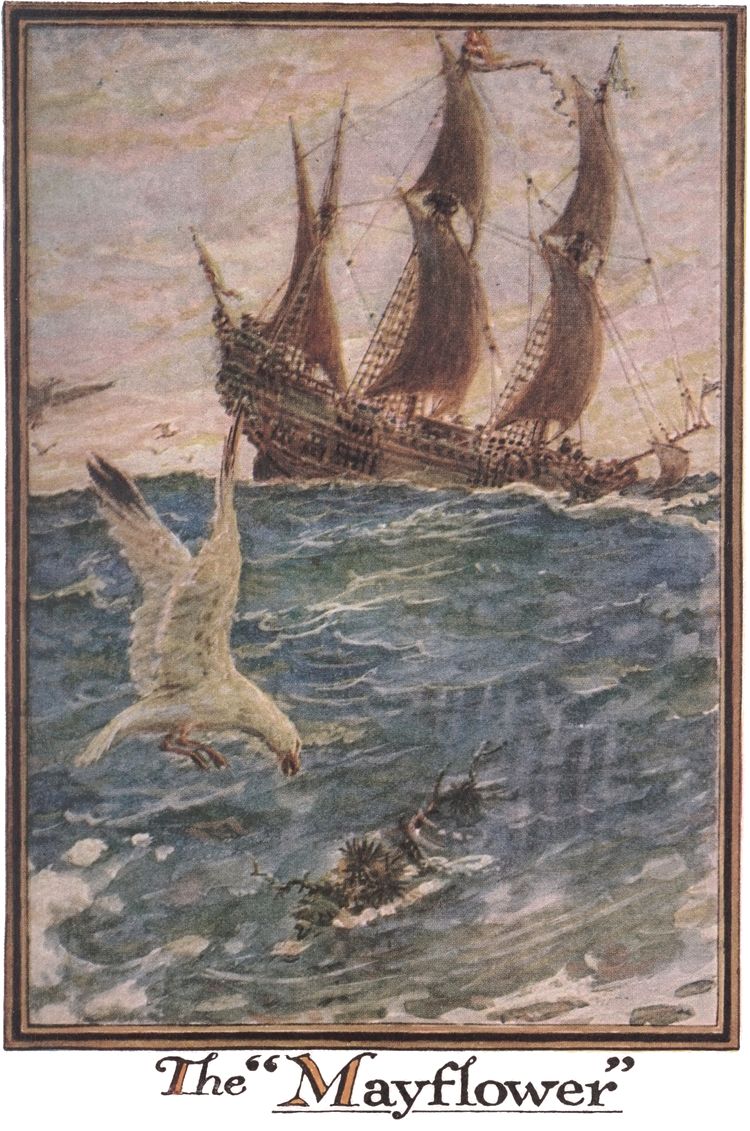

“And small as it is,” went on Somebody, “the dear little pink flower has made history for itself. It was the first flower to welcome the Pilgrim Fathers and Mothers to the new world and as spring, on the bleak coast of Massachusetts, is a late comer, it probably appeared in May, and was christened Mayflower by the pioneers who knew no other name for it. Anyway it was very welcome to those poor people who had come through so many hardships, with its glorious message that the long and cruel winter was over.”

[40]“Was the boat named after the flower or the other way around?” asked the boy named Billy.

“I think it must have been that the flower was named after the boat,” answered Somebody, “as the Mayflower was the boat they came over in—a little sailing vessel of one hundred and eighty tons. Yet no other ship’s arrival has had such significance as that of this little vessel, which brought the Pilgrim Fathers to America in 1620. The sailing of the Mayflower meant a great deal to the future of mankind, because the Pilgrim Fathers formed the compact that established the government of the people, by the people, and for the people. It is well known that they loved the little posie, the first thing that welcomed them with a smile of hopefulness.”

“Why do we not try to cultivate it in our gardens?”

“It starves in gardens,” said Somebody, “very likely because its needs are not studied. Science has found that it has upon its roots a friendly fungus which nourishes it. And this friend refuses to live in the soil of the ordinary garden. Experiments have been made with soils, and seed from the Mayflower fruit has been planted and has made some progress, so I’ve heard.”

“I did not know that the flower had a fruit,” said the boy named Billy.

“I have seen only a few,” said Somebody. “It is a small fruit which tastes not unlike a strawberry. Mrs. Ant knows all about it, and it is very likely due to her that you find the flower in places where it never has been found before.”

“So,” said the boy named Billy, “when one tries to provide a new home for Lady Trailing Arbutus, one must not only please her very dainty tastes but those of her friends.”

“You’ll never get very far with flowers or friends, Billy Boy,” said Somebody, “unless you study them very carefully and try with all your heart to understand them.”

Billy grinned. “What time do you look for Mayflower fruit?” said he.

“Along about wild strawberry time,” said Somebody.

[41]

“MY,” said the boy named Billy. “I nearly broke my tooth on the bone of this oyster. Isn’t it funny? It’s as round as a shot and just as hard.”

Everybody laughed, but Somebody said, “That isn’t a bone, Billy; old Mr. Oyster has no bones. That’s a pearl. Too bad you didn’t find it before it was cooked, because then you might have had it set in a pin to wear in your scarf. Now that it has been cooked, it is worthless.”

“I’m in luck, anyhow,” said Billy, “because I didn’t break my tooth. But how did a pearl ever get inside an oyster?”

“It makes its home there,” said Somebody. “Lives snugly year after year inside Mr. Oyster’s shell and pays no rent at all.”

“Tell me about it,” demanded the boy named Billy. “I always supposed that pearls grew at the bottom of the sea.”

“So they do,” said Somebody, “about fifteen fathoms deep is where the pearl bearing oyster lives. He is rather particular about his home and selects a place where there is a swift current of water. There he and his family lie on the hard bed of the ocean and wait for the current to bring their food. Sometimes they prefer to attach themselves to an overhanging ledge, where they live closely huddled together. The ancient peoples had all sorts of beliefs and ideas about the origin of the pearl. One of the most poetical was that it was made from a drop of dew which the oyster came up to the top of the ocean to get. Another was that pearls were the tears of angels who wept over the sorrows of the world.”

[43]“But what are they really?” asked the boy named Billy, his eyes big with interest.

“Science has discovered,” said Somebody, “that Mr. Oyster accidentally gets a grain of sand, or a small insect inside his shell, which becomes uncomfortable; but as the oyster has no way of opening his door and putting an unwelcome guest outside, it remains. Very likely the unwelcome guest hurts. So Mr. Oyster says, ‘All right, then stay if you want to. But you can’t go on hurting me if I know myself.’ And so he builds a wall of the stuff that the inside of his shell is made of between himself and the cause of the trouble. After about four years the oyster is likely to be caught by pearl fishers, the pearl found, and the shell used for inlaid work on boxes, knife handles and other things.

“The finest pearls are gathered in the East, the most valuable, worth tens of thousands of dollars, coming from the oysters of the Persian Gulf. The largest pearl fishery in America is that of lower California, from which come the largest and the finest black pearls on the market.

“Carl von Linné, the great Swedish naturalist and botanist, discovered that pearls could be grown by opening the shell of the oyster and slipping a small bead of lead or wax inside the shell and then putting the oyster back in his bed for three or four years. Acting upon that idea, the Chinese and Japanese people have established great pearl raising industries and turn out a large amount of pearls every year. They are very pretty, and of good color, but being flat on one side they cannot be made into necklaces. In several of our states the fresh water clams are pearl bearers; the Mississippi River industry being the one of most value. The shells are used for pearl buttons and the flesh of the mussels are fed to the pigs.”

“Makes you think of that verse in the Bible about casting your pearls before swine, doesn’t it?” laughed Billy.

“SAID Pelican quite pleasantly,

‘Come little fish and play with me’;

Said little fishie in a fright,

‘I’ve heard about your appetite,’”

read the boy named Billy from little Sister’s Bird Children book. “Wise little fishie wasn’t he youngster?” said he. “Why is a Pelican anyway—he isn’t good to be eaten and his feathers aren’t worth anything, and he doesn’t do anything except to eat fish in great quantities, at least that is all I’ve ever heard about.”

“Long ago,” said Somebody, “when the first expeditions went across the Colorado desert which had been, until the Colorado River cut it off, a part of the Gulf of California, some one remarked that if the desert could be watered it could be made to raise food enough for a nation. There was the Colorado River going to waste, of course, but how to harness it up and make it provide water for the desert which it had made was a question which no one could answer.

“But along in 1904 it was decided to make the attempt to turn a part of the river back into its old bed and make it work. The river wasn’t quite ready to go back and when she did she meant to go in her own sweet way—but if they wanted her to back into that old bed, why back she would go—and, taking things in her own mighty hands, back she did go with a rush. There was that old Salton Sea Sink—she would first fill that up, and from there it would be easy to give the people all the water they wanted on the desert.

[45]“This was serious! There was a railroad in her track—but what did that matter—people wanted water and water she would give them. It was a Nation’s work to stop that runaway river, but at last it was done, and lo and behold—there was that lovely little sea shining like a jewel in the middle of the desert. They eventually made the Colorado give them water enough besides to water the desert which is now called the Imperial Valley where rice and fruit and cotton and many other things are raised.”

“That is interesting,” said the boy named Billy. “But where does Mr. Pelican fit in?”

“Right here,” said Somebody. “For along about this time very probably along came Mr. and Mrs. Brown Pelican looking for a home. And here was a lovely sea with lots of dear little islands in it just big enough for two. But after they had started their nest they discovered that their private sea had no fish in it. Very probably Brown Pelican said they would move back to the coast, but that Mrs. Pelican wouldn’t listen to him but said, ‘Here we have a whole ocean all to ourselves; let’s raise our own fish—we’ll go right now and bring back our pockets full of mullets and plant them.’ So they did with the result that the Salton Sea is now one of the most important fisheries in the state of California.”

“That’s some story,” said the boy named Billy. “But is it a Really So one?”

“According to scientists it is,” said Somebody. “The Pelican has long been known to be the best friend of the game warden, which is why he is protected. He is supposed to carry fish to inland streams and ponds which otherwise would not have them.”

“Well, he should advertise,” said the boy named Billy, “nobody knows how useful he is.”

“Perhaps he is too modest,” said Somebody.

[46]

“TOMORROW is Indian Day,” said the boy named Billy, “and there isn’t going to be any school; we’re all going out to see their games and get acquainted; anybody seen my scout suit? It isn’t in my closet.”

“It has gone to the cleaner’s,” said Mother. “I knew you’d want it tomorrow and so I sent it out; it will be back this afternoon.”

“Thanks, Mom,” said Billy, “you always do think of everything. Why are the Indians called Indian? Did they name themselves that the way other people do?”

“No,” said Somebody. “That was the name Columbus gave to the natives when he reached the islands and mainland of our country under the impression that he had arrived at the coast of Asia, which he had set out to find.”

“How did those people ever come to be here?”

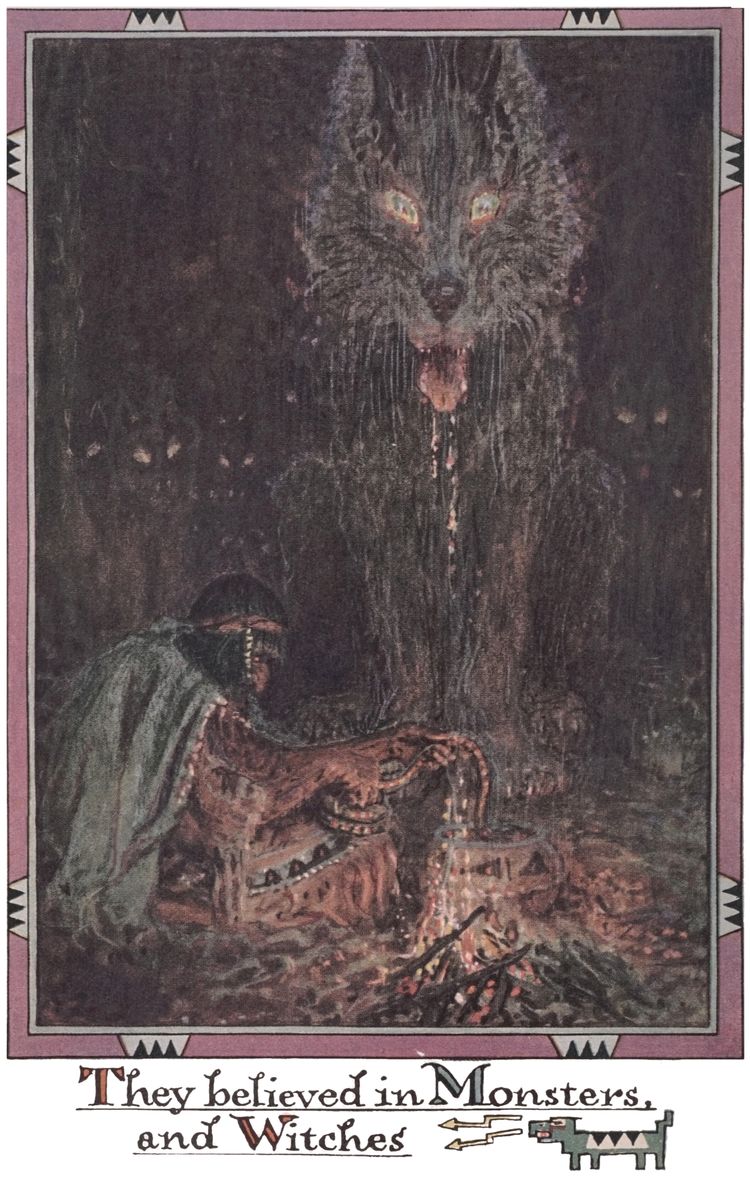

“It is supposed,” said Somebody, “that they had crossed from Asia to Alaska, and were cut off in some way from returning and so drifted inland and started colonies which prospered until it spread across the whole continent. Some may have come from China, and there is even a tradition that some were from the lost tribes of Israel, but no one really knows. All we know is that if they were not really natives of this land that they must have come from somewhere and that they had degenerated into savages or had never been lifted above it.

[48]“But take it all in all they were pretty good savages until they were aroused by the whites; they had laws of their own, and a religion, and real languages distinguishing the different tribes; they had kings and principalities, and the Great Spirit was very real to them. To the Indian everything in Nature had a real personality and was inhabited by a spirit either good or bad.

“They believed in monsters, and fairies and witches. The women were the only ones who could declare war, and when prisoners were brought in they had the right to adopt them into the tribe, or if they did not like them to send them to death.”

“Sweet and gentle ladies, weren’t they?” said the boy named Billy. “I’m glad that they’re just folks nowadays.”

“I’m glad also,” said Somebody, “and this move to have a day set aside for the purpose of getting better acquainted is a move in the right direction.”

“I wonder who thought of doing that,” asked the boy named Billy.

“The idea of having a day set apart for the celebration of the deeds of the red race belongs to Mr. A. C. Parker, State Archaeologist of New York, who launched it at the National Conference at Denver; but no date being set at that time it was later taken up at the Lawrence Kansas conference, when President Coolidge of the Society of American Indians moved to have May 13th appointed as Indian Day, which was done. The different states, in addition to this, have nearly all set apart days of their own as Indian days. That of Illinois being September 4th.”

“We folks in America do get around to doing our duty in time, if you give us time enough,” said the boy named Billy.

“It was high time in this case,” said Somebody.

“Sure was,” said Billy. “I’m going to get acquainted with some Indian about my own age and get some pointers about how to use that bow and arrow Uncle Ned brought me from out west!”

“IN THAT direction,” the cat said, waving his right paw, “lives the hatter. And in that direction,” waving the other paw around, “lives a March hare. Visit either you like—they’re both mad!”

The boy named Billy was reading aloud from Alice in Wonderland, and when he had finished this sentence he looked up, keeping his place with his finger shut in the book, and said, “I know what a March hare would be; it would mean any old hare in the month of March, very likely, but what’s a hatter? Is it a real animal, or a madeup creature, like the Unicorn or the Dodo Bird, or is it just a man who sells hats, as a grocer does groceries?”

“You’ve come very close to the real meaning of it,” said Somebody, “for a hatter, as I see it, is one who makes hats.”

“Why, of course,” said the boy named Billy, “if I’d taken time to think a little about it I’d have known. When did people begin to wear hats, anyway, and what made them do it? They’re a great bother—always blowing off when one is out-of-doors and having to be hung up when one is indoors—they’re no good except to keep one’s head warm and hair would do that if we gave it a chance.”

[50]“Up to a certain point, Billy,” laughed Somebody, “if hair would only stay on as well as hats do even, I’m sure everybody would agree with you, but hair does not stay put in a good many cases, and hats are far better and much less trouble than it would be to wear wigs. No, I think the hat is a very useful invention.

“In fact, it is said that the earliest form of hat was a sort of hood which was tied on over the head to keep the hair from blowing ‘every which way,’ as it was common for both men and women to wear the hair long and to allow it to hang loosely.”

“When did the kind of hats that we wear begin to be stylish?”

“About the time men began to cut their hair short, I suppose,” said Somebody. “The chimney-pot hat, from which all the other shapes grew, is only a little more than a hundred years old.”

“What are hats made of?” asked Billy. “I don’t mean ladies’ hats, of course, they are made of everything, but the kind we men wear.”

Somebody smiled. “The kind you men wear are made of various things. The very fine ones are made from Beaver fur and Coney fur, and Molly Cotton Tail furnishes material for a great many with her long hair which is chopped very fine, and some are made entirely of wool. The braid for the straw hats comes almost entirely from Italy, China and Japan, but is sewed and blocked in this country.”

“Do we make many hats here?” asked Billy.

“Yes, indeed,” said Somebody, “making hats was one of our earliest and most profitable industries. In 1675 laws were passed prohibiting the sale of Raccoon fur outside the provinces, because they were so valuable to the hatters, and it has grown into one of our greatest industries.”

“Well,” said the boy named Billy, “I know now what a hatter is, but I still do not know what he was mad about?”

“That was just a figure of speech,” said Somebody, “meaning that he was not quite right in his head!”

“Oh!” said the boy named Billy, going on with the story.

“I WISH Somebody would help me with this greeting for Mother’s Day,” said the boy named Billy. “I can’t think of anything; and we get marked on it in school, too.”

“Upon whose work do you usually get marks?” asked Big Sister.

“Why, my own, of course,” flashed Billy, “but this is different.”

“It will be easy,” said Somebody, “if you will just think about Mother and write what you would like to say to her.”

“Mom’s the best thing in the world,” said Billy, “but these are to be read aloud and the other fellows would call me sissy!”

“When President Garfield was inaugurated,” said Somebody quietly, “the very first thing he did after taking the oath of office was to kiss his mother.”

“With everybody looking on?” asked Billy.

“Yes, with everybody looking on,” said Somebody. “That was his big and splendid way of telling everybody just what he thought of his mother and of thanking her for all the things she had done for him.”

“Being his mother was enough,” said the boy named Billy, “what more did she do for him?”

[52]“His father died when he was just three years old,” said Somebody, “leaving his mother nothing in the world except a stony farm in the wilderness. She had to work the farm with the help of her eldest son, who was fourteen years old, and also do all the work of the house. Indeed, there was one summer when she lived on one scanty meal a day so that the children might have enough. This made a great impression on James, who resolved that when he grew up he would take great care of her.

“Washington said he owed his success in life to his mother, who gave him his strict sense of honesty and fairness.

“Napoleon said of his mother, ‘She watched over us with devotion, and allowed nothing but what was good and elevating to take root in our understanding.’

“Abraham Lincoln’s mother died when Abraham was ten years old, but she had taught him all she knew of reading, writing, and arithmetic, and also to take pains with everything he did, and to love God and fear no man.

“Although Lincoln never forgot his own dear mother, it was to his father’s second wife that he often said he owed his success, as she almost moved heaven and earth to give him an education.”

“Have we always had Mother’s Day?” asked Billy.

“No, indeed,” said Somebody. “It’s quite recent. Miss Anna Jarvis of Philadelphia, who lost her own dear mother in 1906, presented the world with the idea of setting aside a day for the honoring and remembering of all mothers. The world was ready for the idea, and gladly took it up, and so we have this beautiful custom, which is yearly growing stronger, of remembering our mothers in some special way, sending a flower or a greeting, and wearing a white carnation to show our love and devotion to our own particular mother.”

“Well,” said the boy named Billy, “Mom’s the best thing in the world any way.”

“Then say so,” said Somebody, “right out in meeting.”

“I will!” said Billy.

“WHY so sad and solemncholy?” asked Somebody of the boy named Billy.

“Mother sent me away from the table ’cause I took my pie up in my fingers,” said Billy. “Grandfather said that fingers were made before forks, but Mother said perhaps they were, but that didn’t excuse me for forgetting my table manners. Who made forks, anyhow? I wish they hadn’t.”

“Well, Son,” said Somebody, “had you been born before the year 1600 it would have been quite correct for you to have eaten your meat from your fingers. But it was terribly messy and there had to be a servant called a ewer-bearer whose duty it was to pass around a basin of water and a napkin with which to wash away the stains of the food. But at last some bright Italian person hit upon the idea of copying the large meat forks with which the roast was handled, and making them small enough to be used individually. Visitors to Italy were much interested in the fork.

“Many people thought it a useless invention and it was the middle of the 17th century before the people of England consented to use it. Queen Elizabeth was the first lady in England to own a fork, and hers could not have been much good as a table implement, as it was made of crystal, inlaid with gold and set with sparks of garnets.

“The first forks were very small and narrow, with two prongs, but after people got used to the idea they were made larger. Silver knives and forks were first used in England in 1814 and could only be afforded by the very wealthy.”

“That’s interesting,” said the boy named Billy. “I’m glad I didn’t have to learn to eat peas with those funny little two-tined forks. I guess I’ll go and beg mother’s pardon.”

“THIS is a piece of Sister’s new silk dress,” said the boy named Billy. “It looks as though the fairies had woven it out of cobwebs.”

“It was made by something more wonderful than fairies, if that is possible,” said Somebody. “It was spun by a queer little worm who needed it for his own slumber robe, and had no idea in the world of giving it to sister for a party dress.”

“You mean the silk-worm’s cocoon, of course,” said the boy named Billy.

“About 4,500 years ago there was a Chinese Empress whose name was Si-Ling-Shi, who used to spend a great deal of time in her garden, and as she loved Nature very much she became interested in the worms who lived on her mulberry trees. There were so many of them, and the thread they spun was so strong and beautiful that she thought if it could be unrolled without being tangled or broken it could undoubtedly be spun into a web.

“She knew if the chrysalis were left alive to emerge the thread would be broken and spoiled, so she had some of the cocoons devitalized and experiments proved her theories correct.

[55]“The rest of the world tried hard to induce China to give their secret of silk-making but to no avail, so the Emperor Justinian sent some young monks to China to study and to get the secret. After some years they went back to Constantinople with enough eggs of the silk-worm butterfly in their hollow pilgrim staffs to begin raising them.

“But even after they had the eggs it was not easy to raise them as the children of Mr. and Mrs. Bombyx Mori can only be raised where the mulberry tree will grow.”

“After they get the cocoons how do they get the silk unwound?” asked the boy named Billy.

“That’s interesting,” said Somebody. “I had a chance to see the process at the Panama Pacific Fair. When the worm is ready to spin, and has shed his coat four times, he is about three weeks old. Then he hangs himself on the limb of the tree which has nourished him, and begins to spin. He moves his head around for three whole days, spinning two threads at the same time, until he is completely covered, when he stops spinning and starts to transform. He has spun about 1,200 yards of double-threaded silk. Of course he must not live to emerge so after three or four days he is put in a gently heated oven until he is dead. Then he is immersed in hot water and stirred with a long-handled brush until the ends of the threads are loosened, when he is put into another pan of hot water with several other cocoons and the ends of the threads are passed through an eyelet to keep them from tangling and are wound upon spools or reels into pale golden skeins of what is called raw silk. Afterward it is bleached and colored and woven into webs,” said Somebody.

“That’s got any fairy story beaten a mile,” said Billy. “I’d really like to try out that process with Lady Luna’s cocoon, but she is such a beauty after she comes out that it would be too bad to destroy her.”

“Indeed it would,” said Somebody, “and we’ve got to have beauty as well as utility in this world, Billy.”

“Sure,” said Billy grinning, but he understood.

[56]

“STRAWBERRIES and cream for supper,” sang out the boy named Billy, “wild ones. Got ’em over in the clearing in the woods where the fire ran through last year. Whoppers! I wonder how they ever got there, and why do we call them strawberries? They are far from being the color of straw. Just look at my hands.”

“Look at your face, too, Billy,” laughed Somebody. “You surely did splash.”

“Guess I did,” said Billy, as he repaired the damage. “I couldn’t resist those strawberries. Where did they get the name from?”

“Nobody knows—at least nobody whom I have been able to trace,” said Somebody. “I’ve always been interested in that question myself, and I’ve consulted many authorities and have found out just exactly as much as the two people found out from each other in the early English rhyme, which goes:

“Ye manne of ye wildernesse asked me,

How many strauberies growe in ye sea?

I answer maybe as I thought goode

As manie red herring as growe in ye woode.”

“That sounds as though they didn’t find out a blessed thing,” said the boy named Billy.

[58]“Exactly,” laughed Somebody. “Izaak Walton’s tribute to the strawberry in the ‘Compleat Angler’ is very well known. He said, ‘Doubtless God could have made a better berry, but doubtless God never did.’ The only information I have been able to gather is that ‘the strawberry is a perennial herb of the genus fragaria, order of rosacea,’—that it ‘appears to have been a native of Eastern North America where it appears as a common wild strawberry.’ The strawberry seems to have been grown in gardens less than six hundred years, for though knowledge of it goes back to the time of Virgil, and perhaps earlier, it was not cultivated by the people.

“The Germans have some beautiful legends concerning it. It is said that the Goddess Frigga was very fond of the fruit and that it was supposed to be her task to go with the children to gather them on St. John’s day; and that on that day no mother who had lost a little child would taste a strawberry because if she did, the little one in Paradise could have none; because the mother on earth had already had the share belonging to it.

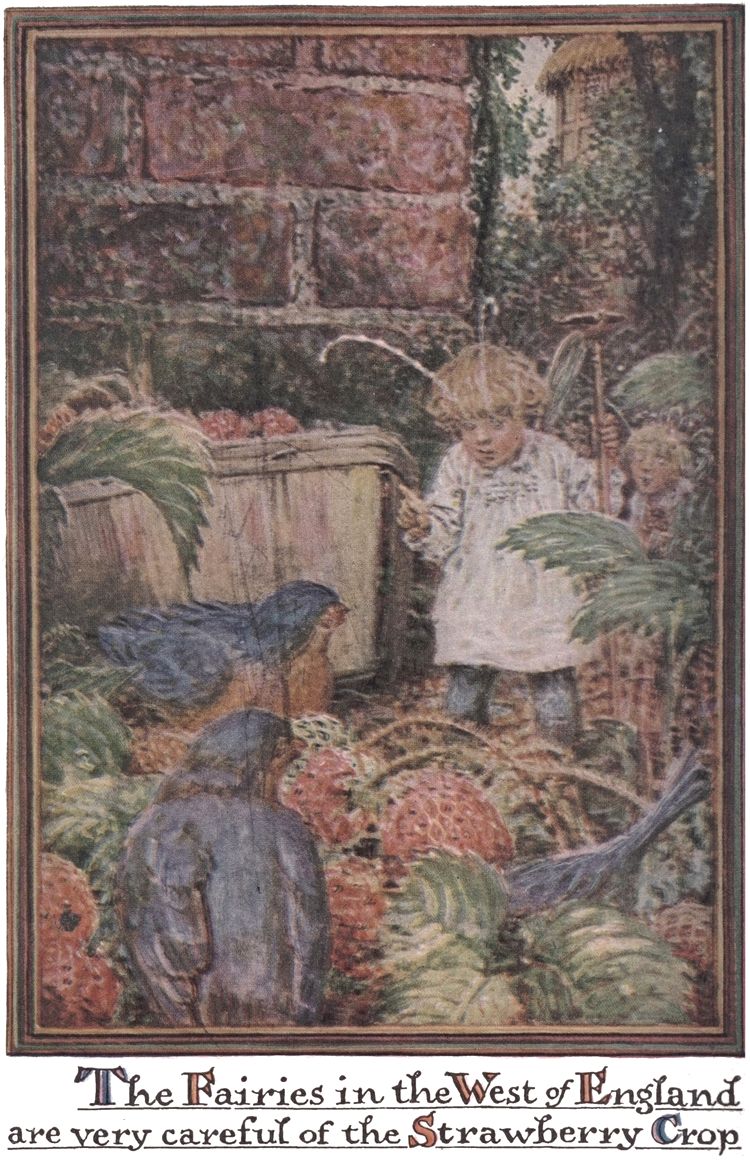

“The fairies in the West of England are very careful of the strawberry crop and woe betide the one who picks the blooms or the unripe fruit. The farmers are always careful not to displease the fairies and always leave a great many ripe berries for them, as they are known to be very fond of them. The Bavarian farmer, knowing the capricious disposition of the elves, is said to tie a basket of the ripe berries between the horns of his cow so that they may sit and enjoy them in comfort and also be more friendly toward the cow.”

“That’s all right interesting,” said the boy named Billy, “but it doesn’t explain why there are berries in the clearing in the wood now, where there never were any before, nor tell us why they are called strawberries.”

“I fancy the birds and the winds could tell you how the strawberry seeds came to the clearing in the wood,” said Somebody; “and as for the other, let us keep our minds and our ears open and perhaps we shall hear more about it in some way or other.”

“I can hear something right now that satisfies me,” said the boy named Billy; “that’s the dinner gong. Me for wild strawberries and Jersey cream!”

“WHAT have you been doing all day that I have not had even a glimpse of you?” asked Somebody, as the boy named Billy came in, looking rather hot and dusty, one Saturday afternoon in June. “Better go bathe your face at my wash-stand and then come and tell me what’s been so interesting—baseball or fishing.”

“Neither baseball nor fishing,” said the boy named Billy, “but it’s been lots of fun just the same. I’ve been helping the ladies over at the church put up the flags and bunting for decorations and to fix up the pulpit with palms and potted plants; Bob White’s been helping, too; we’re the tallest boys in Sunday School. Tomorrow is Children’s Day, you know. What’s the meaning of Children’s Day and do they always have it? I don’t seem to remember anything about it before this year.”

“That is because you are older now and able to help,” said Somebody. “It used to be the custom for each church to have Children’s Day at any time in the year that was most convenient for them, but back in 1883 the Presbyterian Church said, ‘This scattering Children’s Day all over the year is not right and must stop—let’s all get together and agree upon one particular day and keep that and celebrate it!’ And all the other Churches saw the sense of that so they agreed on June—the second Sunday in June, as being warm and sunny weather with flowers blooming and everyone able to get out.”

“But where did the idea of Children’s Day come from?” asked the boy named Billy.

“It probably grew out of that wonderful saying of Our Savior: ‘Suffer little children to come unto me and forbid them not, for of such is the kingdom of heaven,’” said Somebody.

“BOB WHITE’S carrier pigeon has lost its mate,” said the boy named Billy. “He won’t eat or take any notice of anything—just sits humped up making queer little sounds as if he were grieving. Do you suppose that he realizes what has happened to the little mate?”

“Perhaps not, in so many words,” said Somebody, “but he misses her and realizes that things are different. It’s a well-known fact that carrier pigeons never replace a lost mate, which reminds me of a story I heard about pigeons, out in Washington State, which might interest you.”

“Is it a really-so story?” asked Billy.

“Yes indeed,” said Somebody, “a really, truly-so story. It was this way. There was a pigeon fancier in Seattle, who, during the great war, raised carriers for the government, and in order to train the young birds for use in the battle-fields, he used to take them on the engine of the Shasta Limited train, which is the fastest one going south out of Seattle, down as far as Centralia, a small town on the line, where no stop is made by the limited, and then to liberate them and let them make their way back home.

[61]“One particularly beautiful and promising pair of black and white birds had been in training for some time in this way, when, in returning to the loft the little lady bird was lost.”

“Some spy had shot her very likely,” said Billy.