The Project Gutenberg eBook of Strange stories of the Civil War, by Robert Shackleton

Title: Strange stories of the Civil War

Authors: Robert Shackleton

John Habberton

William J. Henderson

L. E. Chittenden

Howard Patterson

Release Date: August 20, 2022 [eBook #68798]

Language: English

Produced by: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

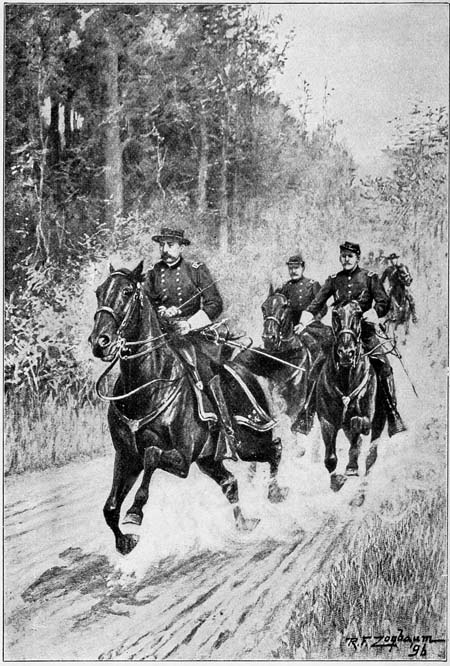

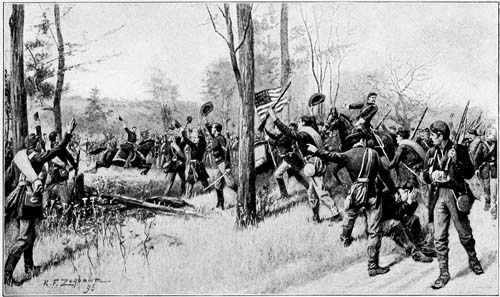

[See page 168

TO THE FRONT FROM WINCHESTER

BY

ROBERT SHACKLETON, JOHN HABBERTON

WILLIAM J. HENDERSON, L. E. CHITTENDEN

CAPT. HOWARD PATTERSON, U.S.N.

GEN. G. A. FORSYTH, U.S.A.

AND OTHERS

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1907, by Harper & Brothers.

Published May, 1907.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

| I |

| A BOY’S IMPRESSIONS OF THE CIVIL WAR |

| By William J. Henderson |

| II |

| THE CAPTAIN OF COMPANY Q |

| The Tale of an Unenlisted Soldier |

| By Robert Shackleton |

| III |

| MIDSHIPMAN JACK, U.S.N. |

| The Action of Appalachicola |

| By William Drysdale |

| IV |

| CAPTAIN BILLY |

| Aid and Comfort to the Enemy |

| By Lucy Lillie |

| V |

| THE BLOCKADE-RUNNER |

| A Dangerous Prize |

| VI |

| TWO DAYS WITH MOSBY |

| An Adventure with Guerillas |

| VII[vi] |

| THE FIRST TIME UNDER FIRE |

| The Experience of a Raw Recruit |

| VIII |

| HOW CUSHING DESTROYED THE “ALBEMARLE” |

| One of the Bravest Deeds in Naval History |

| Captain Howard Patterson, U. S. N. |

| IX |

| PRESIDENT LINCOLN AND THE SLEEPING SENTINEL |

| By L. E. Chittenden |

| X |

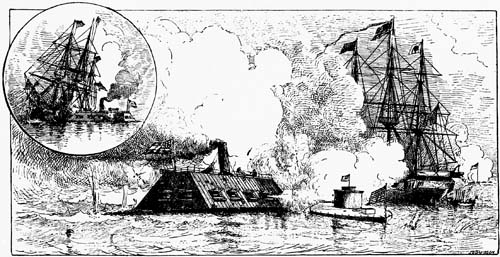

| THE BATTLE BETWEEN THE “MONITOR” AND “MERRIMAC” |

| Told by Captain Worden and Lieutenant Greene of the “Monitor” |

| By L. E. Chittenden |

| XI |

| SHERIDAN’S RIDE |

| Told by his Aide |

| By General G. A. Forsyth, U. S. N. (Retired) |

| XII |

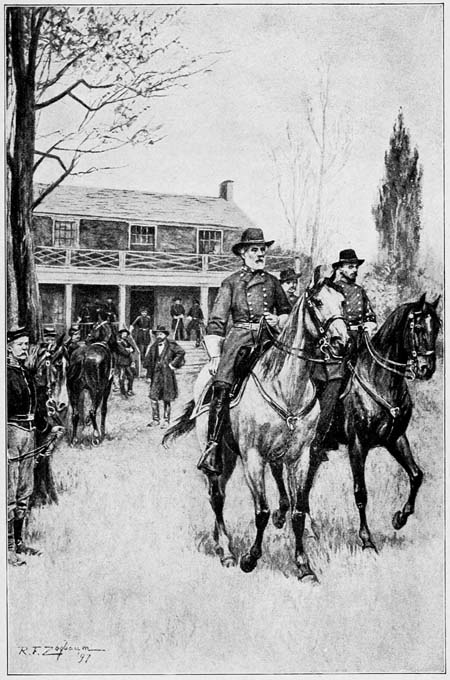

| LEE’S SURRENDER AT APPOMATTOX |

| Told by One Who was Present |

| By General G. A. Forsyth, U. S. N. (Retired) |

| TO THE FRONT FROM WINCHESTER | Frontispiece |

| THEN ZEBEDEE DASHED OUT ACROSS THE PLAIN | Facing p. 20 |

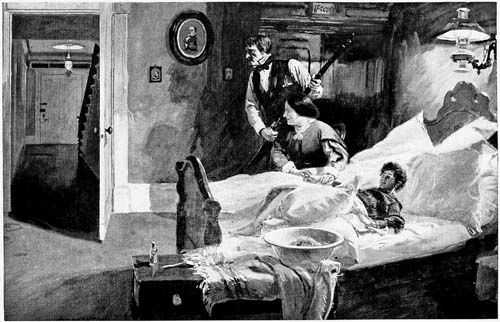

| “COULD THEY COME TO ATTACK US WHEN THEY KNOW WHAT TROUBLE WE ARE IN?” | “ 40 |

| MEAN AS WERE THE SURROUNDINGS IT MADE A TRAGIC SCENE | “ 56 |

| CHASING A BLOCKADE-RUNNER | “ 62 |

| THE BATTLE BETWEEN THE “MONITOR” AND “MERRIMAC” | “ 158 |

| “SHERIDAN! SHERIDAN!” | “ 178 |

| DEPARTURE OF GENERAL LEE AFTER THE SURRENDER | “ 216 |

[viii]

TO the younger readers of the twentieth century the great war of 1861-65, fought to maintain the authority of the national government and to preserve the union of the States, may sometimes seem remote and impersonal. The passage of time has healed the bitterness and animosity which an older generation can remember, and if proof were needed of the real union of our country it was shown when South and North marched side by side under the old flag in the war with Spain. It is well that the passions of war should be laid aside, but the examples of heroism on both sides and the lessons of patriotism are something always to be kept in mind. Grant and Lee, Sherman, Sheridan, “Stonewall” Jackson—figures like these are[x] not to be forgotten—and personal views of some of these leaders will be found in this book.

Of the great campaigns of those terrible four years, when vast armies marched and countermarched and wrestled in battles of giants, there are many accounts, and yet the necessarily limited space allotted in short histories may well be supplemented by narratives alive with human interest. That is the purpose of this book. Mr. Henderson’s recollections, which serve as a prologue, will take the boy of to-day back to these eventful years and make him realize what it was to live in the days when North and South were summoning their sons to arms. Mr. Shackleton’s dramatic story is the first of some imaginative tales of the war which aim to preserve the atmosphere of those thrilling days in the guise of fiction. The stories which follow—“The Blockade Runner” and “Two Days with Mosby,” are believed to be essentially relations of actual experiences; and the balance of the book, including the tales of Lincoln, Worden and the Monitor, Sheridan’s[xi] Ride, and Lee’s surrender, is vivid, first-hand history. One feature of this book is that the latter stories are told by those who took an actual part. This is a book of adventure and of heroic deeds, which are not only of absorbing interest, but they also bring a closer realization of the one country which was welded together in the furnace of the Civil War.

More extended versions of the narratives by L. E. Chittenden and General G. A. Forsyth are presented in the former’s Recollections of Lincoln and the latter’s Thrilling Days of Army Life.

STRANGE STORIES

OF THE CIVIL WAR

STRANGE STORIES

OF THE CIVIL WAR

EVERY time I see the citizen soldiers of the National Guard march down the avenue I have a choking sensation in my throat, and sometimes tears come to my eyes. A young man who stood beside me one day when I could not help making an exhibition of myself, said, “What’s the matter with you?” And my answer was, “They make me think of the men I saw going to the front in war-times.” Then the young man laughed, and said, “What can you remember of[2] the war?” He was about twenty-three or twenty-four years of age, and the Civil War was to him something to be read of in a dusty book. I was five years old when the war began. I could read and write, and was going to school. Many of the things which I saw then made impressions on my mind never to be effaced this side of the grave.

I was living in the city of Pittsburg, at the junction of the Alleghany and Monongahela rivers, whose waters, joined in the Ohio, flowed past many a field that will live in history. Pittsburg was not in the midst of the war, but it was close enough to some scenes of action, especially Gettysburg, and important enough as a point of departure and source of supplies to keep it filled with soldiers, and warmly in touch with all that was going on. What I wish to tell you is something about the way it all appeared to a boy.

My first recollection is of my father reading from a newspaper the announcement that Major Anderson and his garrison at Fort Sumter had been fired upon. That[3] was in April, 1861, and I was in my sixth year; but I remember that I was greatly excited, and wondered what it all meant. It must have been later than that when my father gave me an explanation, which I remember to this day. He said: “My little boy, there is war between the people of the North and those of the South. The people in the South want to have slaves, and the people in the North say they must not have them. So the people of the South say they will not belong to the United States any more, and the people of the North say they must. And so they are fighting, and the fighting will go on till one or the other is beaten.”[1]

All at once Pittsburg became alive with military preparations. Drums were beating in the streets all day and far into the night. Every hour a detachment of soldiers would march along Smithfield Street, and as I lived[4] just above the corner of it on Second Street, now called Second Avenue, I would run to see every squad go by, till it became tiresome, and nothing short of a regiment could interrupt my play. Those must have been the seventy-five thousand volunteers called for by Abraham Lincoln to serve three months and crush the rebellion. Some of those men came back at the end of their three months, but of that I remember little or nothing. The only thing that made a strong impression on me in the early days of the war, after the attack on Sumter, was the killing of Ellsworth. I suppose every boy knows now how the gallant young Colonel of the New York Fire Zouaves took down the Confederate flag that was flying over an inn in Alexandria, and was shot dead by the proprietor of the house, who was immediately killed by Private Brownell.

That incident fired the hearts of all the boys in Pittsburg. We could not understand much of what we heard about the movements of troops, and I have forgotten everything which may have reached my ears at the time.[5] But we could understand the murder of Ellsworth, and to this day I remember how we little fellows burned with indignation, and how we all wished we had been Brownell to shoot down the innkeeper. Somehow the untimely fate of the brave young Zouave commander appealed to us very forcibly, and I think some of us cried about it. It appealed to our mothers too, and suddenly the little boys in Pittsburg began to blossom out in Zouave suits. My mother had one made for me—a light-blue jacket with brass buttons, a red cap, and red trousers. She bought me a little flag, and had my picture taken in my uniform, and she has that picture yet. Next she got me a little tin sword; and then two older boys procured blue army overcoats and caps, and borrowed two muskets from the property-man at the theatre, and I used to drill those boys, and march them proudly all over Pittsburg, to the intense delight of the grown-up people, who cheered us wherever we went.

The next thing which remains indelibly fixed in my memory is the surprise and terror[6] which flashed across the whole North when we heard the news from Bull Run. Of course I do not remember the date of the battle, and I am obliged to refer to my history to find that it took place in July, 1861. But we boys in Pittsburg had been indulging in much loud talk, as boys will, of the way in which our soldiers were going to blow out the rebellion, as one would blow out a candle; and here came the news that these miserable rebels, whom we despised, had thrashed our glorious army terribly, and were thinking about walking into Washington. My impressions at the time were that a lot of Southern slave-drivers, armed with snake whips and wearing slouch-hats, would soon arrive in Pittsburg and make us all stand around and obey orders. My father about this time used to pace the floor in deep thought after reading the newspaper, and used to set off for business with a bowed head. Later in life I learned that in those days he drew his last twenty-five dollars out of the bank, and did not know where more was to come from. But I thought he expected to[7] be killed or made a slave. The boys used to discuss what steps they would take if the rebels came, and it was pretty generally agreed that we would all have to run across the Monongahela River bridge, climb Coal Hill, and hide in the mines.

From the time of Bull Run to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln my boyhood memories, as they come back to me now, present no orderly sequence of events. In a dim way I remember the distress and consternation caused by the dread event at Ball’s Bluff, and in an equally uncertain way I remember how we cheered and danced when the news of a victory arrived. Just across the street from my father’s house stood the Homœopathic Hospital, and next to it was a vacant lot in which pig-iron was stored. There we boys were wont to resort. We sat on the piles of pig metal and gravely discussed the progress of the war, and I well remember that one of my earliest combats arose from my proclaiming my belief that General Burnside was a greater man than George B. McClellan. That was rank treason;[8] but I think Burnside’s whiskers made a conquest of me. I will add that the dispute ended in a triumphant victory for the defender of McClellan’s fame. Thereupon I went home to my mother and “told on” the defender. I got little consolation, for my mother said: “Don’t come to me. If a boy hits you, you must hit back; but don’t come in crying to me.” We were a warlike race in those days.

Gettysburg is a word that conjures up memories for me. We thought we had seen soldiers in Pittsburg before that, but we had simply seen samples. When the Confederates invaded Pennsylvania, we found ourselves in a most unpleasant place; but we had plenty of excitement. From early dawn till late at night drums were beating in the streets and the walls of the houses echoed the tread of many feet. For three weeks I never set my foot inside the Second Ward School in Ross Street, where I was supposed to be, but every morning I stole quietly across the bridge and ascended Coal Hill. Do you know what was going on up there? Soldiers[9] were working like beavers, throwing up earthworks. Similar operations were in progress on every hill around the city, and many an hour I spent carrying water for the boys in the hot sun.

When I descended the hill I always went to the yard at the Birmingham end of the bridge, and watched the workmen who were building Monitors. I do not remember how many Monitors were built there, but I remember very distinctly seeing the launch of the Manayunk. Later she steamed away down the Ohio, and I knew no more of her. The original Monitor, the wonderful little craft that so ably defended the Minnesota in Hampton Roads, was my special object of worship in those days. Little did I dream then that I should live to know the sea as well as I do, or to drill on the deck of the Minnesota. The Monitor’s success in her great duel with the Merrimac filled all of us boys with excitement. We promptly built Monitors with round boxes placed on shingles sharpened at both ends. Then we made Merrimacs of an equally rude type. Next[10] we went down to the river, and in the still water between the big stern-wheelers that lay with their noses against the levee, we had some of the most tremendous naval engagements that ever escaped the eye of history. And the Merrimac was always defeated, whereupon she retreated up the river and promptly blew herself up. Those were good times!

But when the man came with the Great Diorama of the War we learned something new. A diorama is, to be Hibernian, just like a panorama, only it is different. In a panorama you see pictures; in a diorama you see moving figures cut out in profile. After each scene the curtain must be lowered and the stage reset. I remember that this man (I wish I knew his name) began his entertainment with an ordinary series of panoramic views, after which the curtain fell, and we prepared ourselves for the new revelation. When the curtain rose again, we saw a miniature stage set with scenic waters. In the background were two large ships, cut out in profile, and in the distance were two or[11] three more. The next moment we were startled by seeing a flash shoot out from the side of one, followed by a dull boom. Then the other big ship fired, and next the forts, which were at the sides, opened up. We began to tingle with excitement, and could hardly remain in our seats.

Suddenly a long, low craft, looking something like an inverted cake-pan, came gliding out at the front of the stage. Then we knew we were looking at the feared and hated Merrimac. She opened fire on the ships. Then she circled round, and, putting on steam, rushed against one of them with her ram. The poor wooden vessel careened far over on one side. Then the Merrimac drew back, and hurled two shots into her at short range. The big ship began to sink. She went clear away down out of sight—royals, trucks, and all. Next the Merrimac went for the other ship; but just then we saw another queer craft sail on. “It was the immortal cheese-box on a plank”—the Monitor. The Merrimac paused. The two iron-clads seemed to stop and look at each[12] other. Then they rushed together. And how they spit fire and banged and butted! We boys were crazy with excitement. And when suddenly the Merrimac blew up with a loud report, and the Monitor displayed half a dozen American flags, we cheered till we were hoarse. It was not strictly according to history, but it was glorious. And we boys went right home, and began building a Grand Diorama of the War in the cellar of the St. Charles Hotel the next day. That diorama would have been a tremendous success but for one thing. Jim Rial’s brother dropped a match into the powder-bottle, which blew up the diorama and nearly blinded the boy. However, we built another diorama; and the boy got well.

But to return to Gettysburg. When troops were being hurried forward to that point from every direction, thousands of soldiers passed through Pittsburg. Many of them were sent out by the Pittsburg and Connellsville Railroad to Uniontown, and thence to the front. Every afternoon I used to go to the Connellsville station, at the foot[13] of Ross Street, and ride out on the four-o’clock train as far as the historic Braddock’s Field, where, you remember, the British commander Braddock refused to take Washington’s advice in the matter of Indian-fighting, and paid the penalty. This station was just ten miles out, and I could get back in time for supper. Attached to every train out in those days were several flat-cars with planks laid across from side to side for seats, and these cars were loaded with soldiers. I always rode in one of those cars, and listened in breathless awe to the conversation of those real live soldiers who were going out to fight. As I remember them now, they were hearty, good-natured fellows, very kind to the little boy who took so much interest in them. And when I returned to Pittsburg I used to dream about them at night, and wake up very early in the morning to listen for the sound of the guns of the approaching invaders. I was no worse than older people. Many a good woman in Pittsburg went on the roof very often to listen for those same guns.

[14]Another thing which I remember very distinctly is the work we used to do in the public schools in those days. Every afternoon we devoted a part of our time to picking lint. We were told by our teachers that it was to be sent to the front, where it would be used in dressing the wounds of the soldiers. None of us dreamed of the real horrors of war, but I think our hearts were in that work just the same. And we used to get our mothers to make housewives, which we filled with combs, brushes, and soap; and these, too, were sent to the front. We saw soldiers going to war every day with no other baggage than their knapsacks, and we well understood, children as we were, that the housewife would be welcome in every tent.

And finally came the news of Appomattox. Guns were fired, and people cheered, and we boys simply danced war-dances all over the city. Soon the troops began to come home, and then we had our eyes opened a bit. The boys of to-day see the old fellows of the Grand Army of the Republic turn out in their sober blue uniforms, carrying the old[15] battle-flags carefully wrapped up, and the boys think them a monotonous lot, and take little interest in them. But I saw them come back with their bare feet sticking out of their ragged shoes, with the legs of their trousers and the arms of their coats hanging in tatters, with the army blue faded by the sun and washed by the rain to a sickly greenish-gray, with their faces baked and frozen and blown till they looked like sheets of sole-leather, saving the happy smiles they bore. And I saw those old battle-flags come back with their rent and shivered stripes streaming in the wind, while strong men stood looking on with tears in their eyes. And I saw one of my uncles, who had been a prisoner in Andersonville, come to Pittsburg with a gangrened foot, which my mother dressed every day. I shall never forget his condition, nor that of the heroes who marched through Pittsburg day after day when the war was over. I am sorry there had to be a war; but I am unspeakably grateful that I was old enough to get those impressions, which will live as long as I do. They spring[16] to life again whenever I see troops on the march, and they give the old flag a meaning for me which I think it cannot have for those without my memories.

The Tale of an Unenlisted Soldier

ZEBEDEE was the Captain of Company Q. Sheer merit had won him the title. He was the first and the last of his kind. He stood unique. For it was the only Company Q that had ever been captained—Company Q being the stragglers and camp-followers, miscellaneous and heterogeneous, who drift in an army’s wake.

Unique though Zebedee’s position was, it was far from satisfying the ambition that he had once cherished. For he had longed to be a soldier. He had dreamed of doing great deeds; of rising from the ranks, of steadily mounting upward, of winning lofty title and mighty fame.

[18]But the surgeon curtly refused him. It was the heart, he said. And when Zebedee, amazed, bewildered, for he had never suspected himself to be a sick man, stammered a protest, the surgeon said a few cutting words about worthless men trying to get in for pay and pension—which words were to Zebedee as blows. And he yielded with such bleak finality as never again to ask for enlistment.

But although he himself could scarcely explain how it came to pass, he found himself a camp-follower, a drudge, a volunteer servant to the command of a general to whose fame he gave humble and admiring awe. At first the soldiers had tolerated him; gradually there had come a recognition of his willingness, his good-nature, his real cleverness. It somehow came to be believed that it was by some vagrant choice of his own that he was a member of Company Q, and none ever dreamed that he longed with pathetic intensity for his lost chance of being a soldier. On the march he wore a look of exaltation whenever, which was not seldom, two or three of the men would carelessly give him[19] their muskets to carry. In the camp he was happy if he could do some service—he would chop wood, build fires, and cook. And in time of battle he was perforce resigned when the soldiers marched by him into the smoke and the roar, leaving him behind to hold some officer’s horse or look after some tent.

But the innate spirit that, if given the opportunity, would have carried him far upward, made him master of the motley members of Q, and it gradually came to be that his words had the force of law with them.

He never assumed a complete uniform. His very reverence for it and for all that it represented kept him from such a height of undeserved glory. But he tried to satisfy his craving soul with the tattered jacket of an artilleryman, a shabby cavalry cap, and the breeches of infantry; and the sartorial dissimilitude, through the working of some obscure logic, obviated presumption yet kept alive some pride.

How it happened that Zebedee was so often in dangerous places which the other members of Company Q carefully avoided[20] was a puzzle to the soldiers, and it came to be ascribed to a sort of blundering heedlessness—not bravery, of course, for he was only a camp-follower.

And one day, when the command failed in its attack upon a fort, Zebedee found himself with the handful who fled for safety close up against the hostile works. There they were protected from shots from above; and the enemy dared not, on account of a covering fire, come out into the open to attack them; and there they hoped to stay till darkness should permit retreat.

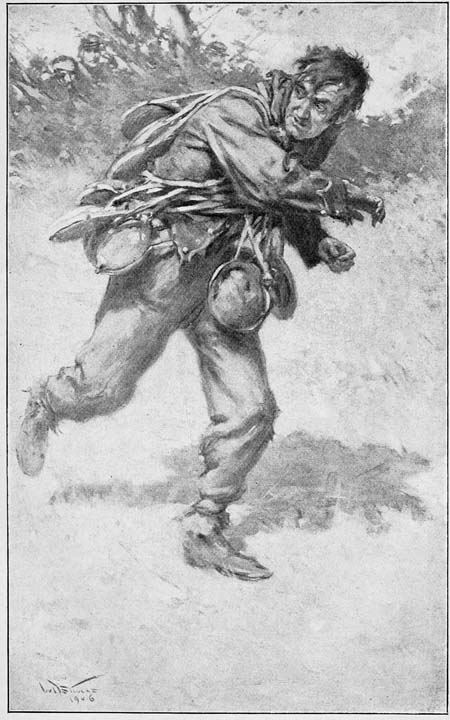

But the day was blisteringly hot, and thirst began to madden them. Then Zebedee slung about him a score of canteens, and dashed out across the plain, and lead rained pitilessly about him as he jingled on, but he was not hit. His canteens were swiftly filled by friendly hands, and he turned to go back across that deadly space.

THEN ZEBEDEE DASHED OUT ACROSS THE PLAIN

He knew that fire would flash along the hostile works; that lead again would rain; but he did not waver. He saw the dark line of his comrades, he knew their misery, he[21] could at least give one life for his country—and the men watched him with awe as, with a curious gravity, he, about to die, saluted them in farewell and ran unhesitatingly out. A sort of glory was upon his countenance. There was a hush. Friend and enemy alike were awed and still. No sound was heard but the rapid patter of his feet. There came no flash and smoke, no splintering sound of musketry. But there arose a mighty shout—friends and enemies alike were cheering him!—and he sank, hysterically sobbing, among his comrades.

This, of course, brought about important recognition. The General heard of it; heard, too, that the Captain of Company Q did not, from some crotchet, some whimsy, wish to be a regular soldier.

“Zebedee,” he said, “you are a brave man.”

Zebedee’s heart beat high with hope, and the look of exaltation shone in his eyes. Not knowing whether or not to use words, or what words to use, he could only stand stiffly at salute—he knew how to salute, although[22] no drill-master had ever paid attention to him; he had eagerly watched and practised, and was perfect at this as at many other things. He stood rigidly at salute—but his eyes were like the eyes of a faithful dog that hungrily watches his master for a bone.

“I am sorry you are not an enlisted man, Zebedee.”

Ah! how high his heart beat now! To be a corporal—perhaps even a sergeant—

The General went on, speaking slowly so that the full sense of his condescension should sink in: “And so, you shall be my own personal servant.”

Zebedee stood rigid as if he were a piece of mechanism, and all expression was swept from his face as marks are swept from a slate.

And having thus conferred honor, the General went out; he, the great warrior so able to discern the hidden movements of an opposing army, to read the secret plans of an enemy, but quite unable to discern the poignant suffering of a brave man.

[23]Zebedee was a sturdy man, not given to running away or to changeableness. In his heart—the heart of which the surgeon had spoken so contemptuously—he had enlisted for the war; he would not be permitted, so it seemed, to fight the good fight, but he must patiently finish the course and keep the faith.

What mattered it now that by observation he had learned many things besides how to salute! With bitter resignation he would watch the coming and going of officers, the forms and ceremonies of war. At dress parade he knew just when the drums were to march slowly down from the right flank; just when there was to be the thrice-repeated, long, brisk roll; just when the drums were to turn back, with quicker step; just how the commanding officer out there in front would keep his hand upon the hilt of his sword; just when the adjutant would take his place at the front of the line; just when was to come the command, “First sergeants to the front and centre!” The roll of drums, and the crash of music, and the tramp of many feet—and[24] the Captain of Company Q would turn away, his eyes filled with tears, as vague visions came of the heights to which he had aspired when he hurried to enlist—before he knew he had a heart. But he knew it now; he knew it, and it hurt.

In the uncommunicative companionship of General and servant he learned much. He learned to know and almost to love the stern, strong man, who held his men in iron discipline and led them into battle with a fierceness that was almost joy.

There came, too, a sort of liking for Zebedee on the part of the grim officer. He trusted him, sometimes let him write orders, treated him with a curt kindliness, and often permitted him to remain within hearing when discussions went on.

And Zebedee, still in touch with Company Q, which stood more in awe of him than ever, and in touch, since his day of glory, with the men, came also to know and to understand the officers. By observation, divination, putting together this and that, he came to know how much depended upon the personality[25] of the General, and how bitter was the rivalry among those next in command; he knew that they would do their utmost under the overmastering influence of their leader’s spirit, but that jealousy and laxity would work disaster should the potent headship be lost.

And with this there came to Zebedee a new sense of responsibility and pride. When so much depended upon the General, surely the importance was great of the servant who saw to it that he should sleep in comfort and properly eat!

He no longer wore the old clothes whose acquisition had been such pride to him. The General had given him some of his own cast-off things, which fitted him measurably well and relieved the shabbiness of effect which would not have consorted with his present dignity.

There had been a day of fighting, a day of doubt. The General, almost overwhelmingly outnumbered, had fought with splendid skill. But as night fell there went shiveringly[26] through the ranks the rumor that he had been desperately hurt.

The General lay unconscious in his tent. Absolute quiet had been ordered. Zebedee must watch him, nurse him, tend him, and the sentinels must keep even the highest officers away. The sentinels’ duty would be well done, for iron discipline had taught each man to hold the General’s tent a thing sacred.

Absolute silence had been ordered. And, as if heeding, the rattle of musketry died away, the sullen cannon stopped from muttering, even there ceased the sound of trampling feet, of rolling wagons, of the swinging tinkle of canteens. Only the chirring hum of frogs and katydids and tree-toads, the multitudinous murmur of a Virginia summer night, was heard. Then from far in the distance came solemnly the strain, “My country, ’tis of thee,” and the soul of Zebedee was thrilled and uplifted as never before in his poor life.

Once in a while the chief surgeon hurried back from the multitude of other cases that[27] the day had given. In piercing anxiety Zebedee watched by the General’s side. “Has there been any change?” “There has been no change.”

Slowly the hours marched towards morning. The chief surgeon again appeared and led Zebedee outside the tent. “There will be an advance and an engagement at daybreak. The General will sleep for hours. I may be unable to come in again for a while. Be sure to let him sleep. I depend upon you, Zebedee.”

Zebedee had held all surgeons to be his enemies, but here was one that roused his humble devotion. And the words crystallized a feeling which had already come over him with almost oppressive weight—the feeling that upon him, Zebedee, there lay a heavy responsibility. He thought of the renewed battle, now so imminent, and as by a flash of inspiration he saw the results of jealousy and half-hearted co-operation; he saw the soldiers, like frightened children, making an ineffectual stand; the impotency of his position came upon him like pain.

[28]He glanced from the tent. A nebulous lustre marked the glow from the enemy’s fires. Through the air came faintly the mysterious light that tells of the coming of morning. A dull slow wind crept laggard by. Statued sentinels stood stiff and still. Two dimly outlined aides conversed in cautious sibilation. Silently he drew back and returned to the General’s side.

The General still slept. To Zebedee’s anxious ears a soft thudding told of soldiers marching through the feeble light. The sound increased. He knew that shadows were passing by. There was the crunch of heavy wheels and he knew that cannon, sulkily tossing their lowered heads from side to side, were being dragged unwillingly towards fight. Faintly audible firing began in the far distance, and the sulky cannon set up a hoarse and excited cry.

The laggard dawn came with a plumping rain. The candle in the bayonet end flamed yellow. The sounds of distant battle grew more loud.

The General opened his eyes. He sighed[29] with a great weariness. He listened to the sounds, and thought himself again a boy, on a farm, hearing the homely noise of breakfast-dishes and milk-cans and wagons. “I can’t get up—I’m tired,” he said, and his voice was as the querulous voice of a boy. His eyes fell upon Zebedee, and the tense look of dread anxiety almost roused him. He sat up; then fell back, smiling quietly. “I have always trusted you, Zebedee,” he said, simply, in such a tone as Zebedee had never before heard; “always—trusted—you.” And with that, he was dead.

Dead, and the battle was on. To Zebedee it meant the end of all things precious. His mind in its agony lost all sense of proportion. The General was dead!—that was the one important fact in all the universe.

A shell flew over the tent. Already the enemy were advancing! Another shell, and another and another. They fascinated him. In their sounds they marked the full range of life and of passion. One shrieked, one groaned, one muttered like a miser counting gold, one whispered like a child, one was[30] petulant, one expostulated, one whispered softly like a maid confessing love. Zebedee shivered. Suddenly the shell sounds turned to taunts. He could have wept from very impotence. He felt choking, smothered. Passionate cannon began a louder uproar.

The General was dead. Yes; that was the one important fact in all the universe. He, only he, knew!—And suddenly there came an awesome thought.

Even from the first frightened contemplation of it he snatched a fearful joy. He steadied himself. He drew himself up to his full height. He drew a deep breath and stretched out his arms as a man preparing for some feat of strength. His face grew strange, and a thousand tiny wrinkles aged him as the thought bewilderingly grew. His breath came in queer respirations.

The sinister droning of another shell—and doubt fell from him like a garment.

The astonished aides saw the General come forth into the rain, with hat drawn over his face and collar turned up high. Something of menacing austerity in his motions repressed[31] all words of sympathy or dissuasion. In an instant he was upon a horse and had set off at headlong gallop for the front.

Panic had already begun. Men were confusedly huddling, firing distractedly and at random. A curious quaking cry was beginning to arise—the cry of frightened men in hysteria; and ranks were beginning to crumble, and soldiers were on the verge of tumultuous retreat.

But now the General was there! Like magic the news spread. His very presence checked the panic and hysteria. He gave a few quick orders, in a voice so tense and strange that the officers scarcely knew it. His wild, stark energy stirred officers and men into invincibleness. It was as if the fate of all the world and all time hung upon what he could accomplish in the few minutes thus permitted him. He dared not stop to think.

Slowly the enemy crumbled. The sun struggled through the clouds and the colors shone in glorified indistinctness in a wet glitter of sunlight.

[32]It was over now. He turned his horse and rode slowly back towards the tent. “Don’t follow me,” he said, curtly. And he rode back, slowly and alone. The cry of the cannon was now triumphant and glad. A shell, whirling above him, spluttered in futile animosity. The wild cheering was music to his ears.

His dream was over now—the dream he had dreamed when he longed to enlist. He flung up his arms and laughed aloud. His dream! To enlist as a private, to win patiently through grades of sergeant and lieutenant, to captain and colonel and general in command!

He wearily dropped from his horse. He went into the tent. The Captain of Company Q looked down upon the General’s peaceful face.

The Action of Appalachicola

“I AM not one of those fellows who ‘can fight and run away, and live to fight some other day,’” one of the bravest Lieutenant-Commanders in the United States navy said one evening to a party of friends, who were making him feel uncomfortable by discussing his brilliant war record. “My bad leg won’t let me run, so I always have to stand and fight it out.”

“Why, Commander,” one of his friends exclaimed, “I did not know that you had a bad leg. You do not limp.”

“No,” he answered, “not ordinarily. But when I tire myself I limp a little, and if I were to undertake to run I should come to grief.”

[34]“Where did you receive your injury?” another asked.

“In action at Appalachicola,” the Commander replied; “the severest action I ever saw.”

There was a twinkle in his eyes as he spoke, and he looked about the table to see what effect the words had upon his friends. Two of them merely muttered their sympathy, and the third asked for the story of the fight; but the fourth man looked up with a comical expression that told the Commander he was understood in one quarter at least.

“You will certainly have to tell us about that,” this fourth man laughed, seeing that the Commander was waiting for a question; “for I have always understood that Appalachicola, being an out-of-the-way place, was one of the few Southern towns that escaped without a scratch in the war. I never heard of any battle there.”

“No, there was no battle there,” the Commander replied, “and you would hardly hear of the action, because there were so few engaged in it. In fact, I was the only one on[35] the Federal side, and there were no Confederates. When I was a boy there I fell out of a pine-tree and broke my thigh; so it was my own action, and one that I still have reason to remember.”

This was the Commander’s modest way of describing an accident that brought out all the manliness he had in him, and made him an officer in the United States navy, and he seldom gives any other account of it; but some of the grown-up boys of Appalachicola tell the story in a very different way—the same “boys,” some of them, who used to set out in parties of three or four and chase young Jack Radway and make life miserable for him.

Jack had a strange habit, when he was between fifteen and sixteen (this is the way they tell the story in Appalachicola), of going down to the wharf and sitting by the half-hour on the end of a spile, looking out over the bay. That was in 1862. His name was not Jack Radway, but that is a fairly good sort of name, and on account of the Commander’s modesty it will have to answer for[36] the present. While he sat in this way it was necessary for him to keep the corner of one eye on the wharf and the adjacent street, watching for enemies. Oddly enough, every white boy in the town was Jack’s enemy, generous as he was, and brave and good-hearted; and when one came alone, or even two, if they were not too big, he was always ready to stay and defend himself. But when three or four came together he was forced to retire to his father’s big brick warehouse, across the street. They would not follow him there, because it was well known that the rifle standing beside the desk was always kept loaded.

This enmity with the other boys, for no fault of his own, was Jack’s great sorrow. A year or two before he had been a favorite with all the boys and girls, and now he was hungry for a single friend of his own age. The reason of it was that his father was the only Union man in Appalachicola. Every white man, woman, and child in the town sympathized with the Confederacy, except John Radway and his wife and their son[37] Jack. The elder Radway had thought it over when the trouble began, and had made up his mind that his allegiance belonged to the old government that his grandfather had fought for.

Near the mouth of the river lay the United States gun-boat Alleghany, guarding the harbor, with the stars and stripes floating bravely at her stern.

“Look at that flag,” Jack’s father told him. “Your great-grandfather fought for it, and I want you always to honor it. It is the grandest flag in the whole world. It is my flag and yours, and you must never desert it.”

By the side of Mr. Radway’s house stood a tall pine-tree, much higher than the top of the house, with no limbs growing out of the trunk except at the very top, after the manner of Southern pines. Jack was a great climber, and nearly every day, when he did not go down-town, he “shinned” up this tall tree to make sure that the gun-boat was still in the harbor. And one day, the day of what the Commander calls “the action at Appalachicola,” he lost his hold in some[38] way, or a limb broke, and he fell from the top to the ground.

For some time he lay there unconscious, and when he came to his senses he could not get up. There was a terrible pain in his left hip, and he called for help, and his mother and some of the colored women ran out and carried him into the house, and when they laid him on a bed he fainted again from the pain.

Mr. Radway was sent for, and after he had examined the leg as well as he could, he looked very solemn, for there was no doubt that the bone was badly broken. Even Jack, young as he was, could tell that; but with all his pain he made no complaint.

“This is serious business,” Mr. Radway said to his wife when they were out of Jack’s hearing. “The bone is badly fractured at the thigh, and there is not a doctor left in Appalachicola to set it. Every one of them is away in the army, and I don’t know of a doctor within a hundred miles.”

“Except on the gun-boat,” Mrs. Radway[39] interrupted; “there must be a surgeon on the gun-boat.”

“I have thought of that,” Mr. Radway answered; “but if he should come ashore he would almost certainly be killed, so I could not ask him to come. And if I should take Jack out to the boat, we would very likely be attacked on the way. I must take time to think.”

Medicines were scarce in Appalachicola in those days, but they gave Jack a few drops of laudanum to ease the pain, and made a cushion of pillows for his leg. For all his terrible suffering, and the doubt about getting the bone set, he did not utter a word of complaint. But he turned white as the pillows, and the great heat of midsummer on the shore of the Gulf added to his misery.

For hours Mr. Radway walked the floor, trying to make up his mind what to do. Jack’s suffering was agony to him, and the uncertainty of getting help increased it. Late in the evening, when all the household were in bed but Mr. and Mrs. Radway, they heard the sound of many feet coming up the[40] walk, then a shuffling of feet on the piazza, and a heavy knock at the front door.

“Have they the heart for that?” Mr. Radway exclaimed. “Could they come to attack us when they know what trouble we are in? Some of them shall pay dearly for it if they have.”

The knock was repeated, louder than before, and Mr. Radway took up a rifle and started for the door. Standing the rifle in the corner of the wall, and with a cocked revolver in one hand, he turned the key and opened the door a crack, keeping one foot well braced against it.

“You don’t need your gun, neighbor,” said the spokesman of the party without; “it’s a peaceable errand we are on this time.”

“What is it?” Mr. Radway asked, still suspicious.

“COULD THEY COME TO ATTACK US WHEN THEY

KNOW WHAT TROUBLE WE ARE IN?”

“We know the trouble you are in,” the man continued, “and we are sorry for you. It’s not John Radway we are down on; it’s his principles; but we want to forget them till we get you out of this scrape. There are twenty of us here, all your neighbors and[41] former friends. We know there is no doctor in Appalachicola, and we have come to say that if you can get the surgeon of the gun-boat to come ashore and mend up the sick lad, he shall have safe-conduct both ways. We will guard him ourselves, and we pledge our word that not a hair of his head shall be touched.”

This friendly act came nearer to breaking down John Radway’s bold front than all the persecutions he had been subjected to. He threw the door wide open, put the revolver in his pocket, and grasped the spokesman’s hand.

“I need not try to thank you,” he said; “you know what I would say if I could. My poor Jack is in great pain, and I shall make up my mind between this and daylight what had better be done.”

The knowledge that he was surrounded by friends instead of enemies made Jack feel better in a few minutes; but the pain was too great to be relieved permanently in such a way, and all night long he lay with his teeth shut tight, determined to make no complaint.

By daylight he was in such a high fever[42] that his father had no further doubts about what to do. He must have medical attendance at once; and the quickest way was to take him out to the gun-boat, rather than risk the delay of getting the surgeon ashore. So a cot-bed was converted into a stretcher by lashing handles to the sides. Colored men were sent for to carry it, and another was sent down to the shore to make Mr. Radway’s little boat ready.

The morning sun was just beginning to gild the smooth water of Appalachicola Bay, when the after-watchman on the gun-boat’s deck, who for some time had been watching a little sail-boat with half a table-cloth flying at the mast-head, called out:

“Small flag-of-truce boat on the port quarter!”

Jack Radway, lying on the stretcher in the bottom of the boat, heard the words repeated in a lower tone, evidently at the door of the Captain’s cabin: “Small flag-of-truce boat on the port quarter, sir.”

An instant later a young officer appeared at the rail with a marine-glass in his hand.

[43]“Ahoy there in the boat!” he called. “Put up your helm! Sheer off!”

The Alleghany lay in an enemy’s waters, and she was not to be caught napping. Nothing was allowed to approach without giving a good reason for it.

Then Jack’s father stood up in the boat. “I have a boy here with a broken thigh,” he said. “I want your surgeon to set it.”

“Who are you?” the officer asked.

“John Radway—a loyal man,” was the answer.

The name was as good as a passport, for the gun-boat people had heard of John Radway.

“Come alongside,” the officer called; and five minutes later a big sailor had Jack in his arms, carrying him up the gangway, and he was taken into the boat’s hospital and laid on another cot. It was an unusual thing on a naval vessel, and when the big bluff surgeon came the Captain was with him, and several more of the officers.

The examination gave Jack more pain than he had had before, but still he kept his teeth clinched, and refused even to moan.

[44]“It is a bad fracture, and should have been attended to sooner,” the surgeon said at length. “There is nothing to be done for it now but to take off the leg.”

“Oh, I hope not!” Mr. Radway exclaimed. “Is there no other way?”

“He knows best, father,” Jack said; “he will do the best he can for me.”

“He is too weak now for an operation,” the surgeon continued; “but you can leave him with me, and I think by to-morrow he will be able to stand it.”

If Jack had made the least fuss at the prospect of having his leg cut off, or had let a single groan escape, there is hardly any doubt that he would be limping through life on one leg. But the brave way that he bore the pain and the doctor’s verdict made him a powerful friend.

The Captain of a naval vessel cannot control his surgeon’s treatment of a case; but the Captain’s wishes naturally go a long way, even with the surgeon. So it was a great point for Jack when the Captain interceded for him.

[45]“There’s the making of an Admiral in that lad in the hospital,” the Captain told the doctor later in the day. “I never saw a boy bear pain better. I wish you would save his leg if you possibly can.”

“He’d be well much quicker to take it off,” the surgeon retorted. “But I’ll give him every chance I can. There is a bare possibility that I may be able to save it.”

There was joy in the Radway family when it became known that there was a chance of saving Jack’s leg; but all that Jack himself would say was, “Leave it all to the doctor; he will do what he can.”

Three weeks afterwards Jack still lay in the Alleghany’s hospital with two legs to his body, but one half hidden in splints and plaster. Mr. and Mrs. Radway visited him every day, and the broken bone was healing so nicely that the doctor thought that in three or four weeks more Jack might be able to hobble about the deck on crutches, when more trouble came. A new gun-boat steamed into the harbor to take the Alleghany’s place, bringing orders for the Alleghany to go at once[46] to the Brooklyn Navy-Yard. This was particularly unfortunate for Jack, for his broken bone was just in that state where the motion of taking him ashore would be likely to displace it. But that unwelcome order from Washington proved to be a long step towards making Jack one of our American naval heroes.

“It would be a great risk to take him ashore,” the surgeon said to Mr. Radway. “The least movement of the leg would set him back to where we began. You had much better let him go North with us. The voyage will do him good; and even if we are not sent back here, he can easily make his way home when he is able to travel.”

Nothing could have suited Jack better than this, for he had become attached to the gun-boat and her officers; so it was soon settled that he was to lie still on his bed and be carried to Brooklyn. For more than a month he lay there without seeing anything of the great city on either side of him; and the Alleghany was already under orders to sail for Key West before he was able to[47] venture on deck with a crutch under each arm. There were delays in getting away, so by the time the gun-boat was steaming down the coast Jack was walking slowly about her deck with a cane, and the color was in his cheeks again and the old sparkle in his eyes. He was in hopes of finding a schooner at Key West that would carry him to Appalachicola; but he was not to see the old town again for many a day.

The Alleghany was a little below Hatteras, when she sighted a Confederate blockade-runner, and she immediately gave chase. But, much to the surprise of the officers, this blockade-runner did not run away, as they generally did. She was much larger than the Alleghany, and well manned and armed, and she preferred to stay and fight. Almost before he knew it Jack was in the midst of a hot naval battle. The two vessels were soon close together, and there was such a thunder of guns and such a smother of smoke that he does not pretend to remember exactly what happened. But after it was all over, and the blockade-runner was a prize, with the[48] stars and stripes flying from her stern, Jack walked as straight as anybody down to the little hospital where he had spent so many weeks.

His mother would hardly have known him as he stepped into the hospital and waited till the surgeon had time to take a big splinter from his left arm.

“Where’s your cane, young man?” the surgeon asked, when Jack’s turn came.

“I don’t know, sir!” Jack replied, surprised to find himself standing without it. “I must have forgotten all about it. I saw one of the gunners fall, and I took his place, and that’s all I remember, sir, except seeing the enemy strike her colors.”

That action made Jack a Midshipman in the United States navy, and gave him a share in the prize-money, and a year later he was an Ensign. For special gallantry in action in Mobile Bay he was made a Lieutenant before the close of the war, and in the long years since then he has risen more slowly to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander.

Aid and Comfort to the Enemy

WHEN the General invited the Fortescue girls and their friends to spend an evening in the house on the Square, it was always understood that part of the entertainment was to be a “war story,” and, on the special evening I refer to, a barrel of apples, sent from the “northern part of the State,” gave the subject.

“Oh yes, Molly,” said the General to the girl, whom the old nurse now called “the eldest Miss Fortescue,” “you can put the apples out; and they’ve just made me remember I never told you about ‘Tobacco Billy,’” and as his eager auditors settled themselves comfortably about the fire, the General, with his peculiar quiet smile, began.

[50]“Just hand me down that old photograph in the little black frame; there you are—poor old Tobacco Billy!”

“Old!” exclaimed Tom Fortescue, in surprise, for the picture was that of a plain-looking, rather gawky lad of only nineteen—a “boy in blue”—with honesty and fearlessness in every line of his homely, gentle face.

“Well, I don’t say in years, perhaps,” said the General, “but in wisdom. Anyway, here’s his story. Give that coal a stir, will you. Now, then, here we are:

“We were in camp, not very far from Charleston, and it was a pretty serious business with us. You see, we hadn’t the least idea what the enemy were up to. My particular friend, Captain Kard, of the Confederate army, and I were talking about it not long ago, and he said he well remembered how, on their side, they were chuckling over our perplexity. Well, I must tell you that at the extreme end of our camp we had a bridge, and it was regularly patrolled by two of the men I picked out for the purpose, and the[51] ‘other side’ had a place beyond similarly patrolled. If any message had to be sent over, the sentries reversed their guns as a signal of truce, and word was exchanged.

“Now although we were pretty badly off for provisions, and even ammunition, it wasn’t a circumstance to the condition of the ‘Johnnies,’ as we called the gentlemen over the way, and, worst of all, the poor chaps hadn’t the comfort of a ‘smoke’ even, which, as all soldiers will tell you, keeps the gnawing feeling of hunger away for a time at least. No, sir! they hadn’t five pounds of tobacco in their camp. But never mind! I’ll tell you what they did have. They had regularly every day a copy of their own Charleston paper, which, of course, was printed for Confederate eyes alone. I was sitting in my tent one night smoking and thinking and wondering how I could lay hands on one or two of those papers. You must know, my dear children, stratagem is always allowed and understood to be used on both sides in war. It is as much a part of the whole unhappy business as loading guns and firing[52] them, and far better if it leads to peace and an end of cruel feeling. Now, if I could only get a copy or two of those papers, do you see, the key to the enemy’s next movements might be in our hands, and I suddenly struck a bright idea. I sent a man to replace Billy Forbes on the bridge, and presently that lad appeared in my doorway. He saluted, and I motioned him to come inside. Then, after warning him of the need of secrecy and caution, I told him my dilemma. Billy rubbed his head, whistled softly, looked up and down anxiously, and finally, after a moment’s star-gazing, ‘Lieutenant,’ says he, in his slow, Connecticut voice, ‘I’ve hit on a way—if you don’t mind.’

“‘Go ahead, Billy,’ I rejoined.

“‘Well, sir, you see those poor devils have scarcely a chew or a smoke of ’baccy among them.’

“‘How do you know?’

“‘Johnny on the other side made signs, sir, and mate and I weren’t slow to understand.’

“‘Well. Go on.’

“‘Now, if I could sneak over a bit from[53] those great packages in the Quartermaster’s department, and make him know what we were after, sure as guns, Lieutenant, you’d have the papers.’

“‘Billy,’ said I, ‘you are a credit to your regiment, to say nothing of your Yankee mother. Come here in an hour, and I’ll see you have the tobacco.’

“Some enterprising dealer in the North had received a contract for that lot of stuff, and we had really, for the time being, an overabundance, so that it was by no means a difficult matter for me to secure two half-pound packets, done up in blue paper, and in about as short a time as it takes to tell the story, Billy Forbes had it tucked away, and went whistling back to his post.

“It was a clear, soft, starlit night. I sat up attending to various duties—listening to the fussy complaints and talk of one of my colleagues in command, who had it on the brain, and felt we were disgraced not knowing how to get in there. Somehow, I relied on my friend Billy to win the day by his fair ‘exchange,’ and he didn’t fail me.

[54]“Towards morning I went down to the bridge, having sent a relief for the lad, who came back simply grinning.

“‘Easy as could be,’ he whispered. ‘Here you are, sir.’

“And from the depths of his trousers he produced the coveted little sheets.

“‘Billy,’ said I, ‘when the war is over you are likely to be a great man.’

“And I turned in to read the news.

“About ten o’clock I received an awful message, in answer to which I started post-haste for the guard-house, meeting my anxious comrade Captain Hubert on the way.

“‘A nice mess your protégé is in, Lieutenant!’ he exclaimed. ‘I’ve had to put him under arrest, and he’s doomed, sir, doomed. Will no doubt be shot, and a good warning to all like him.’

“As the Captain—in temporary command—marched on, I stood rooted to the ground. What had happened! Well, I soon found out. Billy, white to the lips, but with his head well up, told me the story. His companion,[55] cherishing some old grudge, had watched him making the exchange—tobacco for the journals—and had made haste to report him. Billy well knew the penalty. A court-martial had to be held at once.

“Billy, poor lad, for violating the law which forbids absolutely giving aid or comfort to the enemy, must be shot! That was the law, and you must bear in mind that the well-being of a whole nation, especially in time of war, depends upon the strict discipline of the army being maintained. There were important reasons why I could not at that moment say I had, through Billy, procured the papers, and relieve him of the extreme penalty. Yet something must be done, and I must try and think it out, even though in discharging my duty I must sit in the court-martial which would undoubtedly condemn him.

“‘Billy,’ said I, with my hand on the lad’s shoulder, and looking at his white and haggard young face, ‘I’ll do my best. Unless compelled to, don’t mention the papers. That can’t be known just yet.’

[56]“‘God bless you, sir,’ said Billy, with tears rolling down his cheeks. ‘You see, mother’d be proud if I had to die in battle; but shot down, Lieutenant, for treason—’

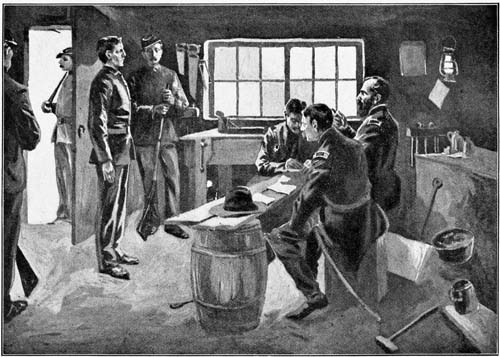

“Well, I can tell you, I couldn’t stand it much longer, and I went dismally enough to the court-martial. You needn’t imagine it was in any fine court-room. Dignified and often tragic as were the cases, the court sat in an old tool-shed; planks on barrels formed the tables, and for seats we had empty provision boxes turned upside down. But there was about it the solemnity of such an occasion—of a death charge, perhaps, and all the grave formality of the promptest law known. When in the paltry place the court-martial began I knew that my colleague, Captain Hubert, was in a great state of excitement, and determined, if possible, to ‘put down’ such recklessness as had been Billy Forbes’s. We had some minor cases first quickly disposed of, and then my poor fellow was led up.

MEAN AS WERE THE SURROUNDINGS IT MADE A TRAGIC SCENE

“Mean as were the surroundings, I assure you it made a tragic scene. And there the[57] Connecticut lad stood—thinking of the mother who could never bear to hear of shame upon her soldier boy, nor care to hear after where they had made his grave.

“The Captain began the formal questioning; and Billy, in a clear, low voice, answered. Asked if he knew what it meant to converse with the enemy, he said:

“‘Yes, sir.’

“‘Had he reversed his gun?’

“‘Yes, sir.’

“‘Had he handed the enemy a package?’

“‘Yes, sir.’

“‘What did it contain?’

“‘Tobacco, sir.’

“Billy whitened again, but he did not lie; and I seemed to read in the depths of his blue eyes a thought of ‘mother.’ There was a brief pause, and then I knew my moment had come. From my coat-pocket I produced a packet of the tobacco sent by our Northern contractor.

“‘Forbes.’

“‘Yes, sir.’

“‘Was the tobacco you gave the enemy[58] like this?’ I spoke, breaking a deathlike stillness.

“Billy’s lips quivered. His look was like Cæsar’s ‘Et tu, Brute!’ But he did not flinch. Honest eye and proudly uplifted head were there when he answered, ‘Yes, sir.’

“‘Captain Hubert,’ I observed, turning to my superior, ‘there is a cart-load of the stuff still unused, for the reason that this tobacco was condemned as unfit, owing to some poisonous substance in the blue paper wrappers. I need scarcely point out to you,’ I continued, ‘that sentence of death could only be passed on Forbes for “carrying aid or comfort to the enemy.” Now, then, Captain, if you will kindly fill your pipe from this package, I feel sure you will decide whether Forbes can be condemned to death for providing the Johnnies with comfort from old Briggs’s consignment.’

“The tension was too great for even a smile, and Captain Hubert’s face flushed scarlet. He put out his hand, then drew it back. ‘This being the case,’ said he, in a stifled[59] voice and rising to his feet, ‘we—we—can consider the case dismissed!’

“I met Billy a moment or two later, standing like a statue near my quarters. He looked at me piteously; but when I held out my hand, did not at once take it.

“‘Lieutenant,’ said he, with the queer smile in his honest eyes I somehow felt he’d learned from his mother, ‘I—I—God bless you, sir; but did you send me with poison to those poor chaps?’ His voice shook, but he held up his head proudly. ‘Killing them in battle, sir, would be fair and square—’

“‘Billy,’ said I, ‘give me your hand, and you’ll get your shoulder-straps before the week is out! No, my boy! I picked out papers that hadn’t a speck of white stain on them. No, you’re not a murderer, my poor Billy; and go to your tent and write to your mother, for we’re near a battle harder than the one you and I fought this morning, thanks to the papers from the enemy.’”

“Oh, General!” exclaimed Molly, “and what happened then?”

“Why, my child, Billy went home on a[60] furlough six months later Captain Forbes, if you please, and at present he owns a fine country grocery, from which the apples you’re eating this minute have just come, as they do every year regularly, and not once but he encloses a big packet of tobacco marked, ‘Not dangerous, General, even to the enemy!’”

A Dangerous Prize

“NOW, Lieutenant, the yarn,” said I, as I settled myself comfortably. A heavy sea was running; night had fallen; we were off watch, and snugly stowed between decks, with our legs under the gun-room table, and—jollier still—Lieutenant Bracetaut had promised a yarn. He looked musingly at the oscillating lantern above our heads, and then made a beginning:

“It was not in these days of iron pots, cheese-boxes, and steam-engines, you must know,” said he; “but on the dear old frigate Florida—requiescat in pace!—without her mate before a stiff breeze, and with more rats in her hold than in a North Sea whaler. We were the flag-ship of the African squadron.[62] Prize-money was scarce, and the days frightfully hot; when just as the day dropped at the close of September, we were overjoyed to hear tidings of—”

“All hands on deck if you want a share in this prize!” bawled the boatswain down the companionway; and we ungraciously tumbled up, snapping Bracetaut’s yarn without compunction.

“Where is she?”

“What is she?”

“I don’t see her.”

“There she is to the sou’west,” said the cockswain, pointing with his spy-glass.

“By Jove, a steamer, too!” cried Bracetaut, delightedly.

“The Great Eastern, stuffed with cotton to her scuppers,” suggested Jerry Bloom, commencing a hornpipe; and every one else had some guess as to the character of the strange craft.

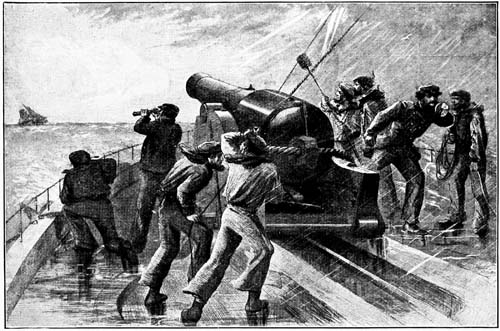

CHASING A BLOCKADE-RUNNER

(From a contemporary picture in Harper’s Weekly)

“Bracetaut is right,” said the Captain of the Petrel, who had been studying her intently with his telescope; “she’s a steamer, and a big ’un. But she’s not coming out;[63] she’s making for the Lights with her best foot foremost.”

We were glad to hear it; for even cotton could be foregone for the sake of English rifles, hospital stores, and army stuffs. We cracked on more steam, unfurled the top-gallants, and made all preparations for a short chase. We had been to Philadelphia for coal, and were still fifty knots from our old blockading station on the North Carolina coast, to which we were returning. There was a heavy sea from the tempest of the day before; but the sky was cloudless and the moon unusually bright, and our craft was the swiftest in the squadron; so that, with so much sea-room, we had little doubt of overhauling the stranger before she could reach the protecting guns of Fort Macon. A mere speck at first, the object of our attention grew rapidly bigger as we sped on under the extra head of steam and the straining top-gallants. She enlarged against the sky until she grew as big as a whale, and in a few moments we distinguished the column of black smoke which her low chimneys trailed[64] against the sky; but she seemed to have little canvas stretched. Indeed, the gale was yet so strong that any extensive spread of sail was imprudent.

“See what you make of her, Bracetaut,” said the Captain, handing his telescope to the weather-worn seaman. “I would be sure that she’s none of our own.”

“Clyde-built all over,” mused the Lieutenant, with his eye to the tube. “No one but a Cockney could have planted her masts; and her jib has the Bristol cut. She sees you and is doing her best. I doubt if you catch her.”

“We’ll see about that,” retorted the skipper. “Let out the studdin’ sails! trim the jib!” he roared through his trumpet. “I’ll spread every rag if we scrape the sky! More head if possible, Jones,” he added; and the engineer went below to see what could be done.

The gale was strong, and her head of steam was already great; but we soon seemed to leap from crest to crest under the stimulus of replenished fires, and the masts fairly bowed[65] beneath their press of canvas. Everybody was agog with excitement, and half the seamen were in the rigging gazing ahead and speculating as to the vessel and her contents.

“Try her with the big bow-chaser, Captain,” suggested the Lieutenant; and the order was immediately given.

Boom! went the huge piece, as we quivered on the summit of a lofty wave, and the rushing bolt flashed a phosphorescent light from a dozen crests ere its course was lost in the distance.

“No, go! it’s a good three miles,” growled Captain Butler, measuring the interval once more with his glass.

“Let me try,” said Bracetaut, quietly taking his stand behind the gun, which was now being charged anew, and carefully adjusting the screws.

Again the sullen thunder spouted from the port, and we marked the ball by its path of fire.

“Gone again,” grumbled the skipper. “We’re paving the floor of the sea with—Ha!”[66] For an instant the messenger had vanished like its predecessor; then, far away to the south, there sprang a fountain of spray—its last dip in the brine—and the mizzen-mast of the stranger snapped short off at the cross-trees, and dragged a cloud of useless canvas down her shrouds.

“Brave shot!” exclaimed the Captain. “Try again, Lieutenant.”

“‘Try, try again,’” sang that limb of a middy, Jerry Bloom, renewing his hornpipe.

But the rigging of the stranger suddenly grew black with men, the broken spars were cleared away as by magic, another sail puffed out broadly from her foretop to make up for the vanished mizzen-mast, and even as we gazed a strain of band-music came floating over the sea, with the “Bonny blue flag” for its burden.

“She’s telling her name,” said Bracetaut, laughing.

“Yes, but she’s going to kick us,” cried Jerry, as a long tongue of flame leaped from the stranger’s stern; and the rolling thunder of her gun came to us almost simultaneously[67] with the ball, which whistled through our tops, letting down a heavy splinter on the cockswain’s head, who dropped like a dead man, but was only stunned.

It was evident that the stranger was plucky, and not to be taken alive. We still worked on her with our bow-gun, seldom doing much damage, but with the best of intentions; while she kicked off the point of our bowsprit with provoking ease, and burned an ugly hole through our maintop-sail.

“By Jingo! she’s growing saucy,” said Captain Butler. “Now let me have a shy;” and grasping the piece with a practised hand, he swiftly adjusted it.

“Huzza! I told you so! Clean through her poop!”

Sure enough, the shot struck her after-bulwarks, and must have played hob with the chandeliers in the cabin.

“Just wait till we can give her a broadside,” added the winger of the bolt, rubbing his hands good-humoredly.

“We mustn’t wait too long, then,” said[68] the cool Lieutenant, “for I see the Lookout lights. In half an hour we shall be under the guns of Fort Macon.”

He pointed over the side as he spoke, far down the western verge, to a faint, lurid glimmering scarcely brighter than the many stars that surrounded it, but with the hazy lustre which there was no mistaking.

“The rebels are reported to have destroyed the lanterns,” said I, suggestively.

“Don’t you believe it, my boy,” replied the old sailor. “They know when to douse them and when to light a British skipper to their nest.”

The chase had now lasted between two and three hours, and the fort at Cape Fear could not be more than twelve miles to our lee. We were still two miles from the stranger, and the chances were momently lessening of overhauling her in time, unless we should succeed in materially disabling her, while our own risk of becoming crippled from her well-directed stern-shots was very great. If the wind had been light the shots in our rigging would have checked our speed but slightly;[69] but the bracing gale that had us in its teeth lent us half our speed, and an unlucky shot in our cross-trees might be irretrievable.

“There! there! we have it now! Was there ever such luck?” cried the Captain, despondently. And our main-sail came down with a rush as he spoke, every one flying from the splinters of the mast, which was severed like a pipe-stem.

We all looked glum enough at this mishap, and began to consider the prize as a might-have-been. But the Captain determined on a last effort, and ordered a broadside volley, though the distance, a mile and a half at least, made success extremely doubtful. The ship rounded to handsomely. The ports were open, twenty cannon were already loaded and manned, and, at the given signal, a long sheet of flame leaped from the side, and the noble frigate roared and quivered to her keelson. Another instant and a wild huzza swelled upward from our crowded deck; for the broadside was a success. The entire rigging of the stranger seemed in ruins; her bowsprit was trailing in the sea; and we could[70] distinguish another ugly smash in her stern, which must have come very near destroying her precious flukes. Of course the prospect was now far better than before, but still by no means certain, as it was questionable whether we were not almost equally disabled in the rigging, and the rapidity with which the damaged tops of the stranger were mended and cleared away seemed miraculous, though she now gave over firing, apparently bent on safety only by sharp sailing.

New spars were already up on our own main-mast, and, with a clew or two on the mizzen-shrouds, and the use of the after-braces, with double duty on the mizzen-top-gallant spars, our main-sail was again aloft, with cheering indications that we were gaining fast. In fifteen minutes we had so sensibly diminished the interval between us and our prey that we ceased firing. But we were over-confident. The lanterns of Cape Lookout were now left far away on our starboard quarter, and every forward furlong we made was so much nearer to the formidable fort. Just then a faint flash,[71] like the horizon glimmer of summer lightning, shone above the waters far beyond the ship we were pursuing, and a hardly heard but ominous boom told us that the old sea-dragon, Fort Macon, was not sleeping in the moonlight. We now renewed our pelting of the stranger with further damage to her tops. Whereupon she veered for Shackleford Shoals, with the evident intention of beaching herself if unable to get under the fort. Another quarter of an hour and we were within long range of the heavy coast-guns of the fortress, which seemed to understand the state of the case perfectly, for shells began to drop around us briskly. And now the great breakers of the sandy coast were plainly discernible on the starboard, tossing their white plumes high above the beach. Here and there a bluff rose from the monotone of sand; and the Devil’s Skillet—a dangerous reef—was boiling white a little lower down.

Shackleford Shoals is a low, narrow sand-bank, about twenty miles in length. Its lower extremity comes within three miles, at[72] a rough guess, of the Borden Banks, or Shoals, on the easternmost point of which the fort is situated. The bank is everywhere treacherous, but especially at this southern point, where the danger of the shoals is hidden by apparently deep water. And now as we neared our expected prey, she made a bold push for this inlet; but as we dashed in between her and the fort, regardless of the latter’s continuous firing, she altered her course, and steered head-on for the fatal breakers.

“She’s bent on suicide!” said Jerry, who then ran below for his pistols, as the Captain ordered the boats to be manned.

“Has she struck?”

“No—yes—there she goes!”

Sure enough, she had grounded and slightly heeled over, but in such deep water that the soft sand of the shoals would not hold her long. Two of our boats were manned, with our beloved Lieutenant as commander of the expedition, and I was in his boat. We pushed off with some difficulty, on account of the heavy sea. As we did so we saw the boats[73] of the blockade-runner also lowered, and pulling inside for the inlet. The rats were leaving the crib.

“You can get her off if you try, Bracetaut. Throw over everything to lighten her,” was the parting injunction of Captain Butler, and as we pulled away he hauled his ship out of range of the fort. It was rather uncomfortable the way the shells ducked and plunged around us, or burst above our heads, but we pulled away for the prize. Our boat was the last to reach the ship—a first-class iron propeller, of great tonnage, and clipper-built. As the crew of the advanced boat climbed up her sides several crashes made us aware that the fort was turning her guns against the vessel, to deprive us of the plunder.

“And hot-shot at that. Listen!” said Bracetaut to me; when the fizzing sound of the plunging hot-shot was plainly distinguishable.

Our boat was within a rod of the prize when we perceived the men who had already boarded her jumping hastily over the bulwarks,[74] dropping into their boat, and pushing off, as if something unusual was to pay. One had been left behind. It was the little middy, Jerry Bloom, who now appeared unconcernedly leaning over the side and coolly awaiting the Lieutenant’s orders.

“What’s her cargo?” bellowed Bracetaut through his trumpet.

“Powder!” sang back the shrill tones of the New World Casabianca, and siz! siz! went the plunging red-hot shot; and crash! crash! they went against the floating magazine with frightful precision.

“Jump for your life!” roared the Lieutenant to Jerry. “Back-water, you lubbers! back, for your lives!”

We saw the midshipman join his palms over his head and leap from the gunwale of the fated ship. Scarcely had his slender figure cut the brine before a number of sharp reports were heard—then a long, deep, volcanic rumbling, that swelled into a terrific thunder, deafened our ears; a dozen columns of blood-red flame shot up to the stars; and we saw the deck and majestic spars of the[75] doomed blockade-runner spring aloft in fragments! A huge black mass descended with a fearful splash a yard from our bows—the long stern-chaser going to the bottom—the sides of the powder-ship yawned wide open an instant, filled with fire, then disappeared, the flames dying out. The sea was ploughed around us by the falling fragments of deck and spar, and the glorious steamer was no more!

An Adventure with Guerillas

I WAS up at reveille. Orders to inspect the camp of dismounted cavalry near Harper’s Ferry had been in my pocket two days, while I awaited an escort through the fifty miles of guerilla-infested country which lay between me and that distant post. This was the day for the regular train, and a thousand wagons were expected to leave Sheridan’s headquarters, on Cedar Creek, at daylight, with a brigade of infantry as guard, and a troop of cavalry as outriders.

An hour’s ride of eight miles along a picketed line across the valley brought me to the famous “Valley Pike,” and near the[77] headquarters of the army. Torbert was there, and I awaited his detailed instructions. Unavoidable delay ensued. Despatches were to be sent, and they were not yet ready. An hour passed, and, meantime the industrious wagon-train was lightly and rapidly rolling away down the pike. The last wagon passed out of sight, and the rear-guard closed up behind it before I was ready to start. No other train was to go for four days. I must overtake this one or give up my journey. At length, accompanied by a single orderly, and my colored servant, George Washington, a contraband, commonly called “Wash,” I started in pursuit of the train.

As I had nearly passed Newtown I overtook a small party apparently from the rear-guard of the train, who were lighting their pipes and buying cakes and apples at a small grocery on the right of the pike. They seemed to be in charge of a non-commissioned officer.

“Good-morning, Sergeant. You had better close up at once. The train is getting well ahead, and this is the favorite beat of Mosby.”

[78]“All right, sir,” he replied with a smile, and nodding to his men, they mounted at once and closed in behind me, while quite to my surprise I noticed in front of me three more of the party whom I had not before seen.

An instinct of danger seized me. I saw nothing to justify it, but I felt a presence of evil which I could not shake off. The men were in Union blue complete, and wore on their caps the well-known Greek cross which distinguishes the gallant Sixth Corps. They were young, intelligent, cleanly, and good-looking soldiers, armed with revolvers and Spencer’s repeating carbine. I noticed the absence of sabres, but the presence of the Spencer, which was a comparatively new arm in our service, reassured me, and I thought it impossible that the enemy could as yet be possessed of them.

We galloped on merrily, and just as I was ready to laugh at my own fears, “Wash,” who had been riding behind me and had heard some remark made by the soldiers, brushed up to my side, and whispered through his teeth, chattering with fear:

[79]“Massa, Secesh, sure! Run like de debbel!”