TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The ‘Mayflower Compact’ was in the middle of a paragraph in the original book (on pages 28 and 29). It has been moved to the end of this ebook.

All misspellings in the text, and inconsistent or archaic usage, have been left unchanged.

Being the Story of

THE EDWARD WINSLOW HOUSE · THE MAYFLOWER SOCIETY

· THE PILGRIMS ·

By

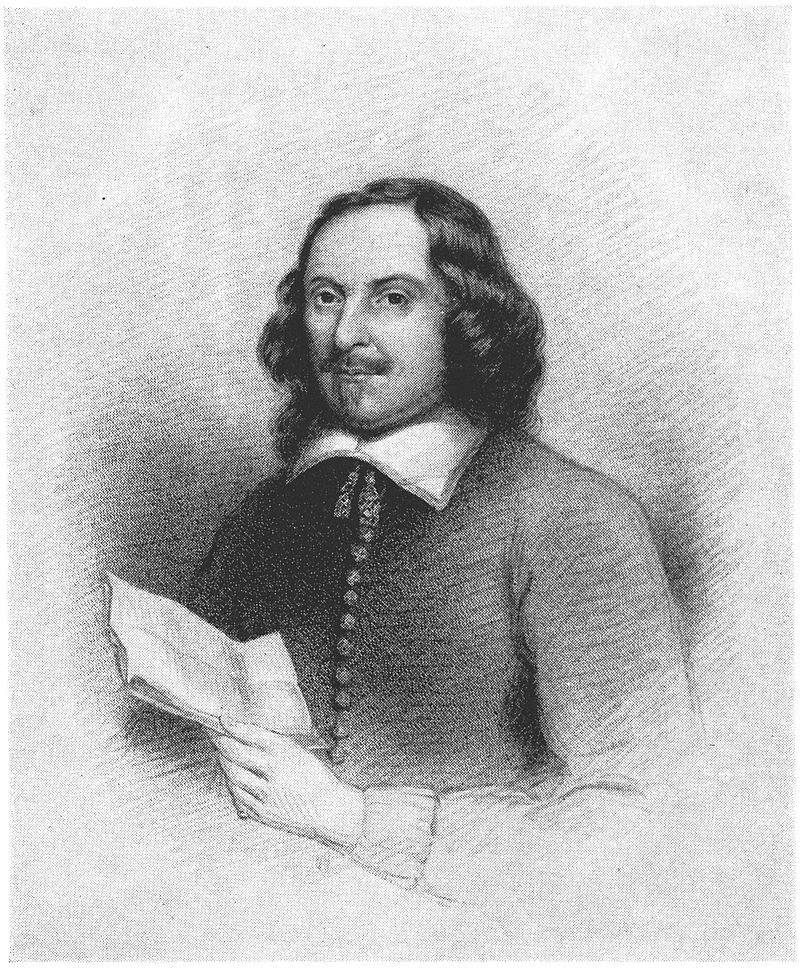

WALTER MERRIAM PRATT

Governor-General of the

GENERAL SOCIETY OF MAYFLOWER DESCENDANTS

SECOND EDITION

Privately Printed

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

1950

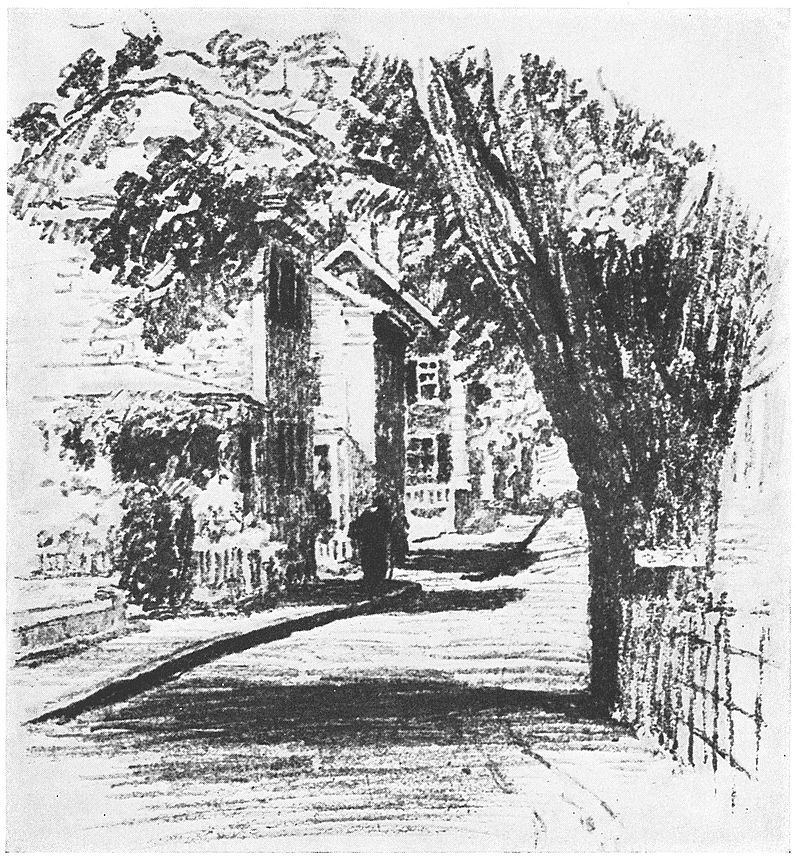

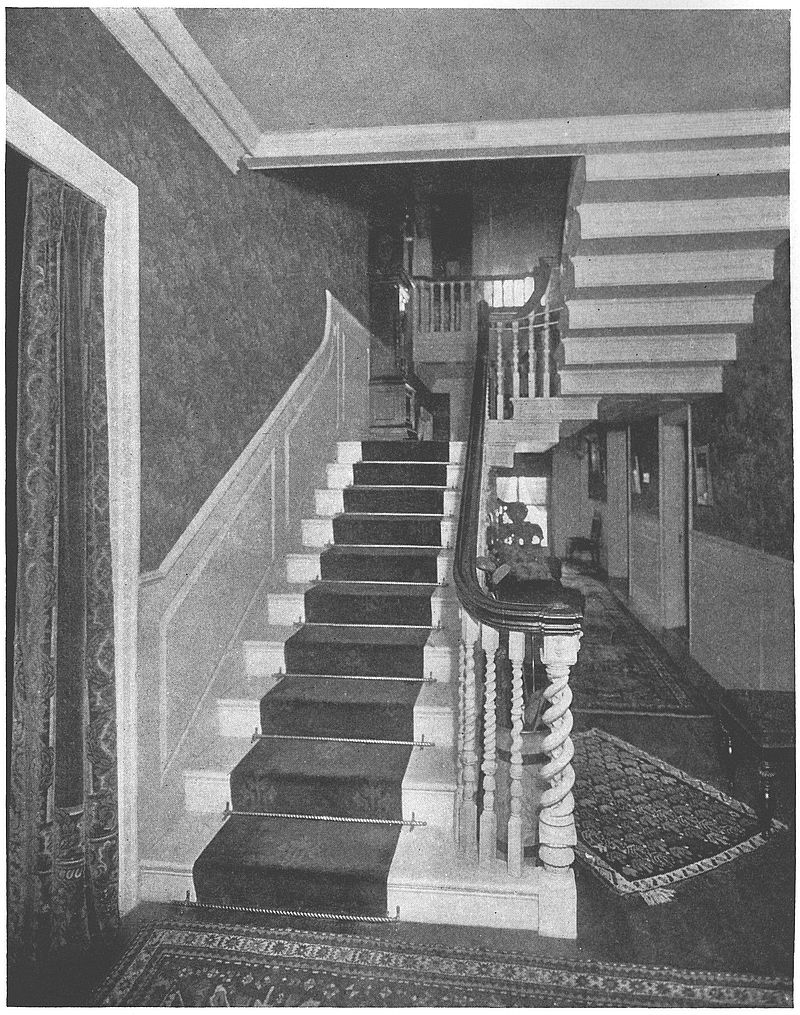

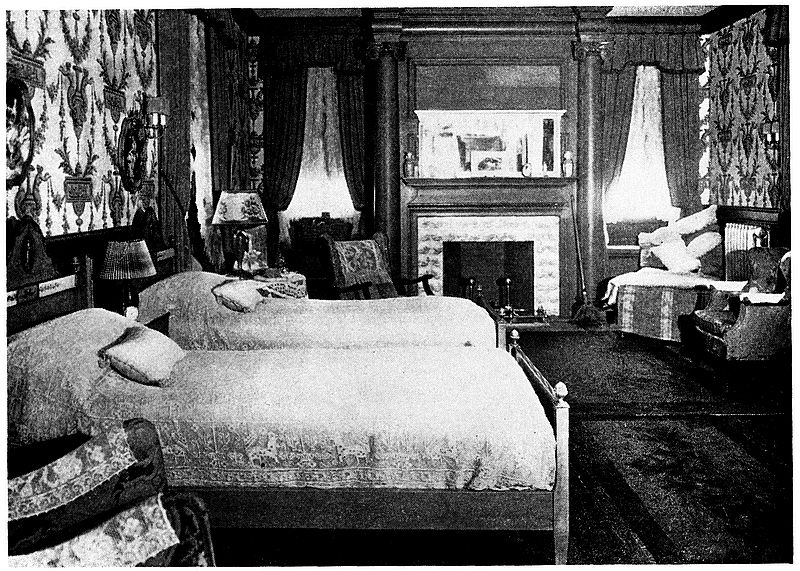

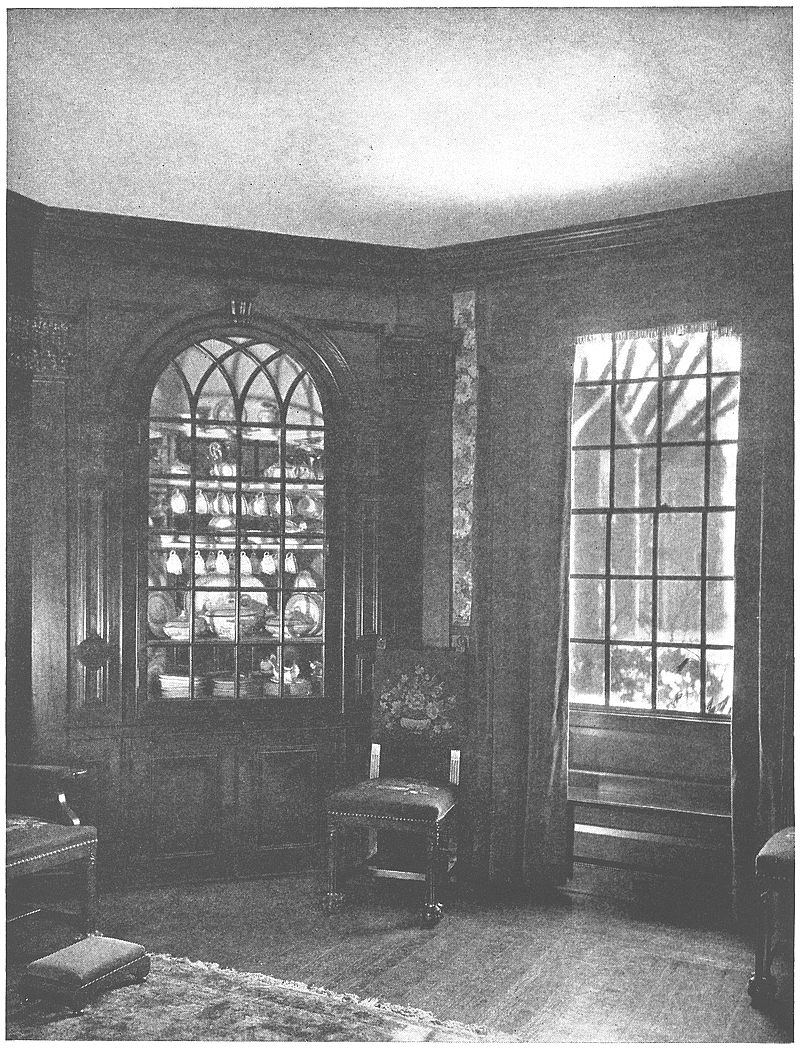

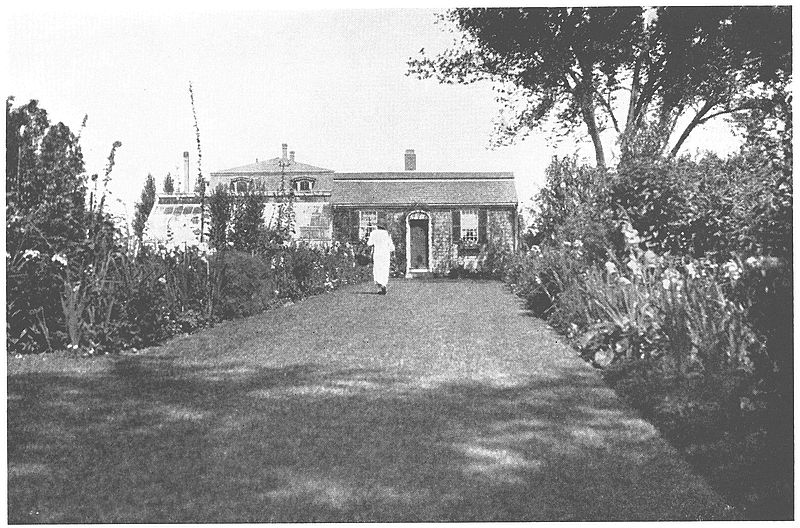

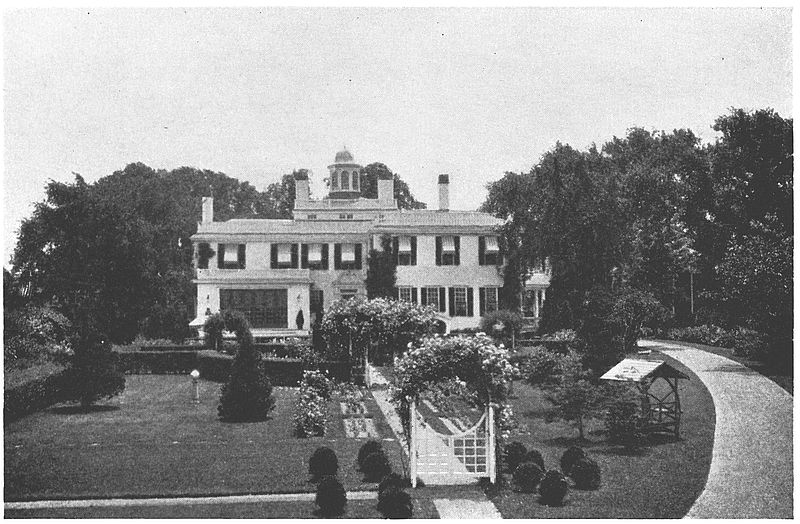

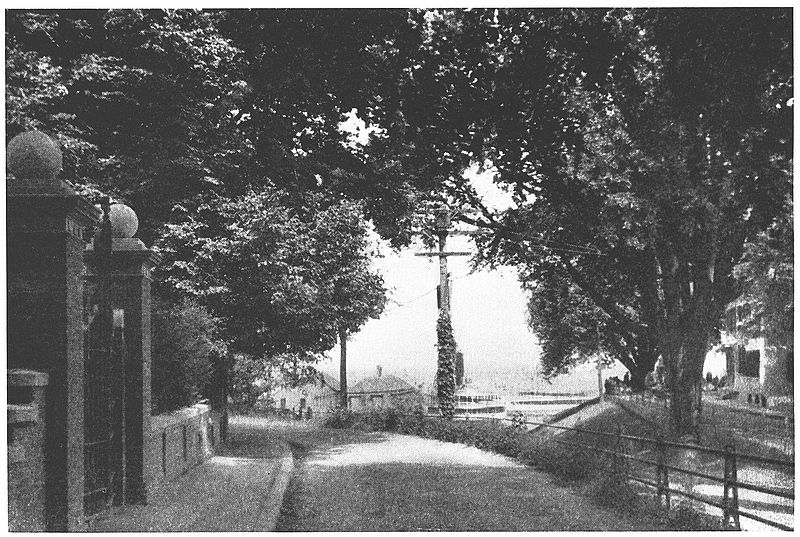

A NOTABLE accomplishment of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants was the purchase in 1941 of the Edward Winslow House in Plymouth, Massachusetts, a house of great beauty and dignity, with history and atmosphere, perfectly located on North Street, one of the five streets laid out by the Pilgrims, overlooking Plymouth Rock and Cole’s Hill, where lie the bones of many of the Pilgrims.

North Street was laid out before 1633. It was first named New Street, later Queen Street, and for some years was called Howland Street, presumably because Joseph Howland, son of John Howland, the Pilgrim, owned land on the north side. His son Thomas inherited it, and in turn it descended to the latter’s son, Consider Howland, who sold it to Edward Winslow, the great-grandson of Edward Winslow, third Governor of the Colony. The younger Winslow attended Harvard College and then settled in Plymouth. He became Clerk of the Court, Registrar of Probate, and Collector of the Port. He married in 1741, the widow, Hannah Howland Dyer, a sister of Consider Howland, and in 1754 built the house.

Winslow was a Royalist and an outspoken supporter of the King. Although a popular man, the townspeople became infuriated at his lack of patriotism, which eventually cost him his town offices and[6] revenue. His son joined the King’s forces, and he frequently entertained the British officers at his home. After the evacuation of Boston by the British, Winslow moved his family to New York, and was granted a pension by Sir Henry Clinton.

Later the family went to Halifax, as did thousands of other Tories, where Winslow died the following year, at the age of seventy-two. He was buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard, mourned by all the dignitaries of the city. At this time Canada was actively hostile to the United States.

In order to support his family after losing his offices, Winslow had pledged his house as security for loans of money made him by Thomas Davis, William Thomas, Oakes Angier, and John Rowe. When he left Plymouth the house was sold on an “execution” at a sacrifice to satisfy the creditors, much to Winslow’s indignation. It is often mistakenly stated that his property was confiscated. The house at this time was half its present size and, as was customary in those days, sat close to the ground, as well as to the street. The frame of the house and some of the paneling are said to have been brought from England, although American craftsmen could and did construct similar houses and paneling.

From Winslow’s creditors the house passed into the hands of Thomas Jackson who occupied it as a residence until 1813, when he moved to the so-called Cotton Farm. The house then passed by an execution from Mr. Jackson to his cousin Charles Jackson, who died in it in 1818 and whose son, Charles Thomas Jackson, born 21 June 1805, played an interesting part in the civil history of this country. He had a keen mind, was a student of electricity and magnetism, but medicine was his main study. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1827, finishing his studies abroad. He returned to America on the sailing vessel with Samuel F. B.[7] Morse, and their meeting may have helped Morse perfect his telegraphic instrument. It is known that Jackson made and displayed a model of a telegraphic instrument a year before Morse patented the one that made him famous.

Jackson was greatly interested in geology and was the State Geologist of Maine in 1836, Rhode Island in 1839, and New Hampshire in 1840, but his greatest claim to fame is his share in discovering etherization and his association with Dr. W. T. G. Morton, a dental surgeon, fourteen years his junior, who studied medicine in his office. Jackson is believed to have made his first personal experiments with the inhalation of ether in the house at Plymouth, and the chair in which he sat is displayed in Pilgrim Hall. Morton patented the process of anesthesia by ether in 1846 and he sued Jackson for claiming the discovery of the anesthetic effects of inhalation of ether back in the winter of 1841-42. The French Government investigated the matter and decreed Jackson a 2500 franc prize as the discoverer, and a similar prize to Morton for being the first to apply it to surgical operations.

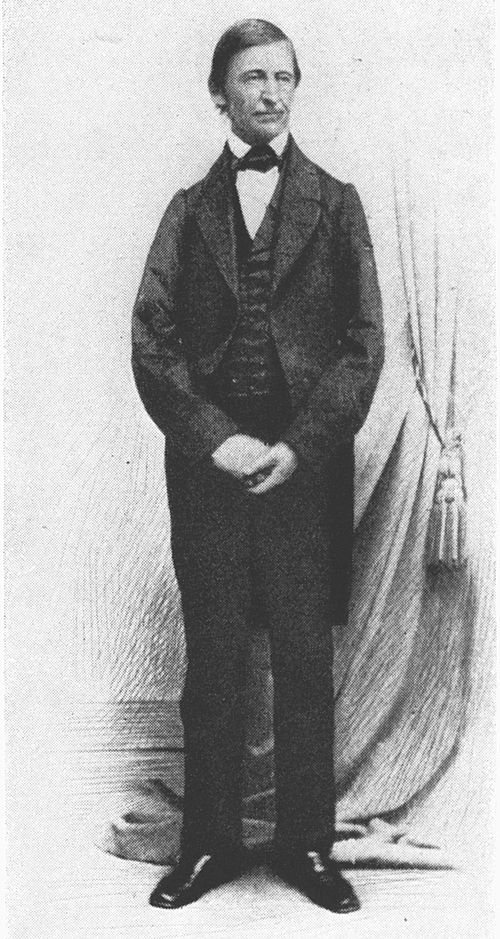

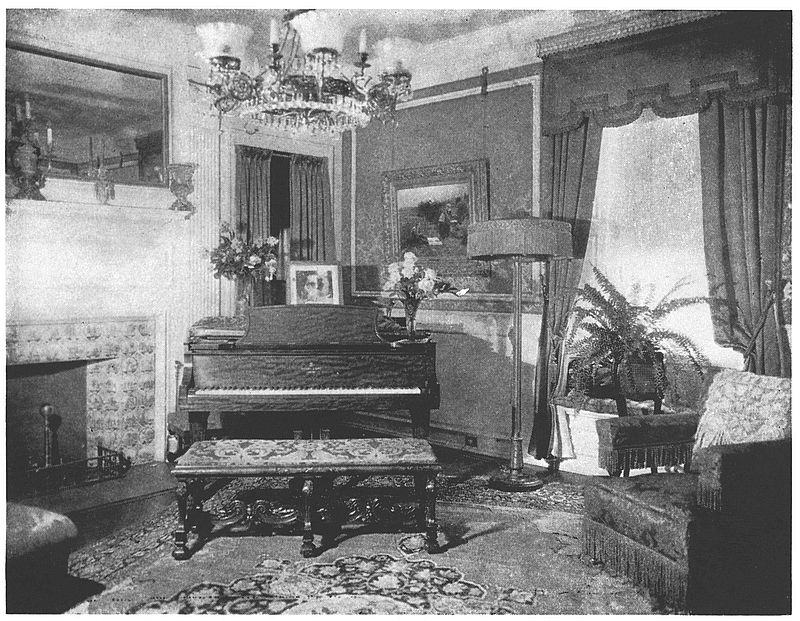

Jackson’s slightly older sister Lydia, sometimes called Lidian, became the second wife of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American poet and philosopher. Their marriage took place in 1835 in the east parlor, later known as the music room.

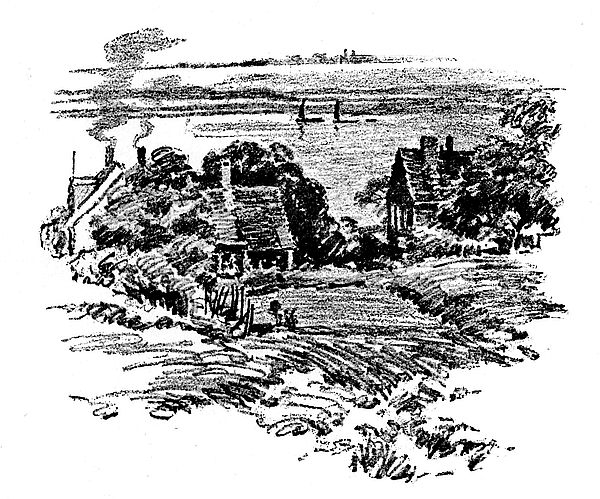

The house was sold by the Charles Jackson heirs in 1872 to Lucia J. Briggs, the wife of the Rev. George W. Briggs, who occupied it as a summer residence until 1898, when it was purchased by Charles L. Willoughby, of Chicago, for a summer home. Gardens were planned and planted. Joseph Everett Chandler, authority on the restoration of New England houses and author of books on the subject, was retained to supervise the work, and it is he we have to thank that so much was saved when it was converted into a gentleman’s estate. He it was who saw to it that the new windows, inner shutters, paneling, and many details, are in keeping with the original structure. He even saw to it that the Tory chimney, with its coping painted black, was saved and that the two lovely linden trees, said to have been planted by Edward Winslow’s daughter Penelope, were protected during the alteration. In tearing off the ell on the north side, a board was uncovered on which was painted “Built by William Drew 1820,” which indicates additions were made that year. The house was moved back thirty feet, raised five, porches were built, side doors, new rooms, and a cupola or, as some erroneously call it, a Widow’s Walk, were added.

To own an old house is a great privilege, but it is also a great responsibility. No amount of money could have made the Winslow house so interesting as its association with events of history and famous people has made it.

Improvements were continued after Mr. Willoughby’s death. Adjoining houses were purchased and razed, improving the view of the Rock and the ocean, and the land they were on was added to the already extensive garden.

A five-car garage was built to the far side of the garden, arranged so that it would be possible to use it as a charity theatre, with quarters overhead for the gardener and his family. As protection against the elements and the public, a six foot red brick wall of Colonial design was erected on the south and east sides of the estate.

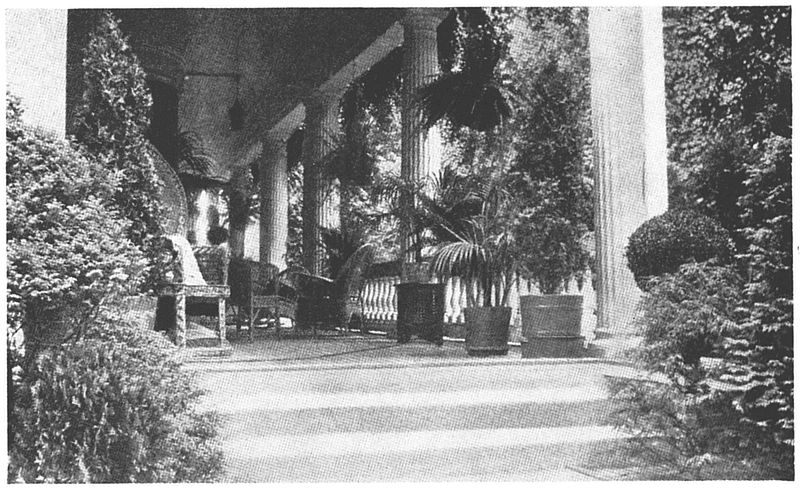

REAR GARDEN TEA HOUSE AND CONSERVATORY FROM THE SOLARIUM

After Mrs. Willoughby’s death, her daughter offered the property for sale. It is fortunate that it passed into the hands of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants (31 December 1941). It might have become a Tea Room, a Road House, or something worse. The Society immediately took up the work of restoration and preservation where Mr. Chandler had left off, but before work could even be started, World War II broke out and the entire Winslow House was turned over to the Plymouth Chapter of the American Red Cross for the duration without charge of any kind. Due to confusion, especially of legal nature, likely to arise, and which in fact had arisen, by the existence of a Winslow House in nearby Marshfield, it was decided at the Seventeenth Congress of the General Society held in Plymouth September 1946, and so voted, to change the name of the Edward Winslow House to the Mayflower Society House.

The house today is far different from the one Edward Winslow built in 1754, but, as the headquarters of a large society, it is better adapted. The interior is being brought back to something of its original appearance with paint and replicas of old wall paper and by gifts and purchases of furniture of the 18th Century period. Members of the Mayflower Society and any interested in preserving the best of the 18th century are asked to contribute items of furniture, wearing apparel, books or other items of the period. All gifts and loans, before being accepted, are passed on by a competent committee. To have an item accepted and exhibited in the Mayflower Society House will some day be a distinction.

SIMILAR VIEW TO THE FRONTISPIECE BUT SHOWING SOLARIUM

The Mayflower Society House is not only a show place of Plymouth, but of the entire country. This lovely and famous house is owned, free and clear of indebtedness, by the General Society of Mayflower Descendants. To insure its perpetual care through generations to come, an endowment is sought to which the public is asked to and should contribute.

NOT until 1894 did descendants of the passengers of the Mayflower organize to perpetuate the ideals and commemorate the memory of their ancestors. The first Society was formed 22 December 1894 in New York, followed by societies in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania within 18 months. These societies founded the General Society 12 January 1897. The General Society now consists of 40 State Societies, with a membership of over 7600 men and women.

19 February 1923 the General Society was incorporated under the laws of Massachusetts. Among those signing the petition to the Great and General Court were Major General Leonard Wood,[18] William Howard Taft, and Henry Cabot Lodge. The Mayflower Society is not interested in the wealth of its members, or their social standing, or their politics, although two Presidents of the United States have been members. Two others were eligible but passed on before its organization. It is proud, however, of the notable achievements of many of its members.

Some of the patriotic Societies were in early days largely social in character. Many joined solely of pride in their ancestry. Democracy was not then under attack and needed no defenders. The country’s growth since the turn of the century has brought to the United States a tremendous number of persons fleeing from Old World conditions. Our melting pot did well for a time; of recent years our freedom has been attacked. The Society now has a mission—that of spreading the wisdom and ideals of our ancestors to the masses who have come to our shores.

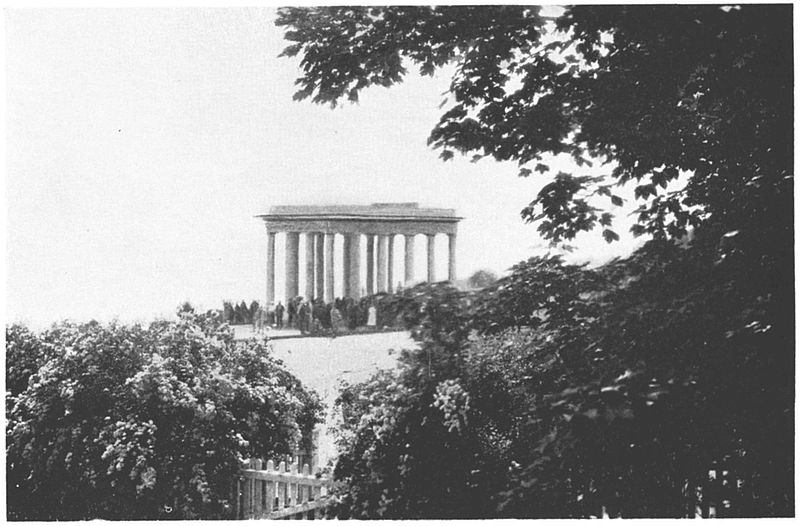

The Society has accomplished much in its effort to discover and publish matter relating to the Pilgrims. It has aided in establishing memorials and has contributed over $100,000.00 toward the Bradford Memorial Tablet, the Provincetown Monument, the Monument to the Pilgrims at Southampton, England, the Sarcophagus on Cole’s Hill, Plymouth, the Aptuxet Trading Post, at Bourne, the Mayflower Index, and to lesser memorials throughout the country. One of the most important things accomplished is the purchase and restoration of the Mayflower Society House. This is more than a National Headquarters. It is propaganda for Americanism. It is a landmark that will inspire those who visit Plymouth to increase their knowledge of the Pilgrims and thus help make better citizens of them, and it is a contribution to patriotism. Plymouth welcomes another museum house, particularly an 18th century one, where visitors may learn more of Colonial life and customs. The important[19] thing is that visitors to the Mayflower Society House, who number thousands each year, coming from every state in the Union, find there exists an organization to perpetuate the memory and carry forward the ideals of the Pilgrims.

When the General Society of Mayflower Descendants was organized, it adopted a declaration of purpose, the most important part of which is to commemorate and honor the Pilgrims, to defend the principle of civil and religious liberty, as set forth in the Mayflower Compact, to discover and publish original matter pertaining to the Pilgrims, and to authenticate, preserve, and mark spots of Pilgrim association.

These things the historian, orator, and poet have helped do. In our libraries are carefully prepared writings on the subject by Fiske, Dexter, John Quincy Adams and Daniel Webster, Choate, Everett and Sumner, and so on down to Henry Cabot Lodge, Calvin Coolidge, and the third Governor Bradford. So diligent have writers and speakers been, it is difficult to find and add new facts.

There are those who say, “It’s not what my ancestors did, it’s what I’ve done. I live in the present, not the past.” One must make good, but statistics prove those most successful are the first to preserve the best of the past.

It is fitting and proper that the descendants of the Pilgrims should gather in Plymouth from time to time and give expression to the respect, gratitude and admiration they feel for the Pilgrims. To express sympathy for them for the terrible months they spent crossing the stormy Atlantic, and the added months on shipboard while shelters were being erected on shore for the first winter in a foreign land, when nearly half the company died of scurvy and ship fever, in spite of which not one member gave up and returned to England when the Mayflower sailed.

The Pilgrims believed in the equality of all men before God; they, therefore, made all men equal before the Law. On the Sarcophagus, which contains the remains of some of the Pilgrims, is this inscription:

“This monument marks the first burying-ground in Plymouth of the Passengers of the Mayflower. Here, under cover of darkness, the fast dwindling Company laid their dead; levelling the earth above them lest the Indians should learn how many were the graves. READER, History records no nobler venture for Faith and Freedom than that of this Pilgrim band. In weariness and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and cold they laid the foundations of a State wherein every man, through countless ages, should have liberty to worship God in his own way. May their example inspire thee to do thy part in perpetuating and spreading throughout the World the lofty Ideals of our Republic.”

We must admire the Pilgrims for their courage and piety, for their attachment to civil rights and religious liberty in exile, under unhappy conditions.

There was a famine the first year, but no actual starvation as there were wild fowl, shellfish, and berries in abundance, but there was cold and snow, and there were Indians and sickness to cope with.

A great disaster befell the community the second year which seldom seems to be mentioned, but which would have discouraged less resolute souls. The ship Fortune carrying their entire year’s yield of furs and products to England to be sold, was captured by the French as a prize.

The gist of the preface of a book entitled “The Pilgrim Fathers,” by W. H. Bartlett, published in London, England, in 1853, is—

“Of the many heroic emigrations from our island, which have covered the face of the earth, no one is more singular than the band of sectaries driven forth in the reign of James I. In an age when toleration was unknown, they were thrust forth from their native land, thus the harshness of the rulers became the instrument which planted on American shores a mighty republic, the proudest and most powerful offshoot of the mother country, whose institutions, as thus founded, are not without a powerful reaction upon her own.

“The details of the story are unknown to the mass of English readers, while across the Atlantic they are known to almost every child, and numerous are the works published about them and many are the Americans who visit Boston, Scrooby and Leyden, but these publications and researchers are all unknown in England and therefore this continuous narrative.”

WHO and what were the Pilgrims and in what way did they differ from the Puritans? They both were English and both lived in the same generation. The Pilgrims were a small band of staunch men, women and children who came to America for religious freedom. They were a part of a great movement. The Protestant Reformation, set on foot in England during the reign of Henry VIII, was finally accomplished in 1588 by the defeat of the Spanish Armada. It did not secure freedom of action or worship, however. There was no country then where such liberty was allowed; in fact, such a thing had never been thought of. The Reformation made the Sovereign, instead of the Pope, the head of the church in England, and there were changes in doctrine and ceremonials, but everyone was required to attend church whether he wished to or not and was also taxed to support it. The Bible had just been translated from Latin into English, and for the first time it was being generally circulated (1557-60).

Among the Protestant reformers there were many who were not satisfied with the doctrines and ritual of the English church. They wished to simplify the government of the church and drop some of the ceremonies. This they considered purifying the church, which gave them the name of Puritans. Most of them had no thought or intention of leaving the Established Church. They wished to stay and be a part of it, but to change it according to their ideas.

Early in 1567 a number of ministers, despairing of getting the desired changes, made up their minds to separate from the church and hold religious services of their own. Robert Brown was one of them and went about the country advocating this policy of separation. Those who adopted it became known as Separatists or Brownists. They did not believe in having bishops rule over them. Some denied that the queen was head of the church. This was called treason. These were the people who became Pilgrims. The Puritans[23] also questioned the spiritual authority of the bishops and claimed the right to worship as they saw fit, but they did nothing in particular about it.

The Separatists, or better, Independents, which describes them accurately, established a little church in the hamlet of Scrooby, near Lincoln, where a congregation listened to the eloquent preaching of John Robinson. English laws provided imprisonment for those who refused to attend the Established Church, or were present at unlawful assemblies, with the further penalties, that the convicted must conform within three months or leave the country. If he refused, he should be deemed a felon and put to death without the benefit of clergy. The little church at Scrooby could not continue under these conditions. Some of the Separatists had given their lives, some were in prison, and others were in exile. Brown had fled the country, and so its members determined to cross to Holland. Under existing laws a family could not migrate without a license, and they were denied one. It was as dangerous to remain as it was to attempt to leave secretly. Meetings were held, and Separatists from Scrooby, Bristol, Exeter, Boston, and sundry other places planned to flee.

In October 1607 they made their first attempt to leave from Boston in a chartered ship. They were seized, searched, and imprisoned. After a month all but seven of the principal men were released.

The next year they arranged with a Dutch ship to meet them at a port near Grimsby at the mouth of the Humber, but the cautious skipper got scared and after taking a few of the women and children aboard, cast off, leaving the husbands and a majority to be seized by the sheriff and his men. Following this, there was no mass effort to cross to Holland, but, with much difficulty and by departing[24] one or two at a time, all got over. After a short stay in Amsterdam they made their way to Leyden. Here they were joined by other refugees from England, until there were more than a thousand. The Pilgrims remained in Leyden for eleven years (1609 to 1620). Brewster became a printer, Robinson entered the University, and all found work in different occupations. They labored hard and continuously. They found in Holland peace and the religious freedom they had left their English homes for, but there were other factors which made them, after a decade, seriously consider leaving Holland. They wished the protection of the English flag; they were losing the English language, and their children were marrying among the Dutch. After careful consideration they decided that the Virginia Colony, extending from Florida to New York, offered the best opportunity. Because of their separation from the Established Church, the King would not guarantee them protection, but agreed not to molest them, and under this agreement they obtained a patent from the London Company to settle on the New Jersey Coast.

It was necessary to secure financial aid, and this they obtained from a group of London merchants, known as the Adventurers. The contract was an oppressive one and became more so as the colonists built their houses; but it cannot be called unfair, considering the financial risk involved. It provided that for seven years the income of the colony should go into a common fund and from this the colonists would get their living. At the end of the period the investment and profits, real and personal, should be equally divided between the Adventurers and the Planters in accordance with the number of shares each held. Its effect was to establish a community life which, long before the seven years were up, resulted in embarrassment and open disaffection, and a compromise between[25] the parties was effected by which the Adventurers were to be paid the sum of eighteen hundred pounds sterling 26 November 1626. Here was Communism pure and simple, and it was a monumental failure and was given up after three years. If Communism cannot succeed under these conditions, with the type of people the Pilgrims were, speaking the same language, governed by the same laws, with common history, tradition, and memories, how could Communism possibly prove a success under far less favorable circumstances today?

The conditions upon which the Pilgrims secured their transportation to America indicate the exhausted state of their finances, and they probably never would have given their assent to the conditions imposed, if not absolutely forced to do so. The famous Captain John Smith wrote in 1624 that the Adventurers who raised the money to begin and supply the Plymouth plantation were about seventy in number, some merchants, some handicraftsmen, some risking great sums, some small, as their affection served. They dwelt mostly about London, knit together by a voluntary combination in a society, without constraint or penalty, aiming to do good and plant religion. The sad intelligence conveyed by the Mayflower on her return to London of the sufferings, sickness, and death, produced a disheartening effect in the most zealous friends, and the necessary supplies required by the infant colony were refused, though they had been promised.

After the Pilgrims had secured financial aid the little band (July 1620) left Leyden and sailed from Delfts-haven in Holland in the Speedwell, which they had bought for the purpose, to Southampton where the Mayflower was awaiting them with friends. Two weeks later the Mayflower and the Speedwell left Southampton for America. The Mayflower of one hundred and eighty tons burden (the Queen[26] Mary of today is over eighty-three thousand tons) had been chartered to transport a part of the Leyden congregation to America.

Before they were out of the English Channel the Speedwell began leaking badly and they ran into Dartmouth for repairs. 2 September they made a second start, but trouble developed and they returned this time to Plymouth. Here they reorganized the expedition. The Speedwell was left behind, some of her passengers were taken on the Mayflower and the others left in England. On 16 September 1620 the Mayflower sailed again and ten weeks later, after a voyage filled with hardships and peril, having been driven far off her course, came to anchor in Cape Cod Harbor. When the Cape was sighted it was decided to sail south for a permanent home, but before the day was over they found themselves in dangerous shoals and roaring breakers and turned back to settle beyond the limits of their patent.

Only about one half of the passengers on the Mayflower were members of the Leyden congregation. Other motives, without thought of religious dissent or separation from the Established Church of England, had added many strangers to the company, and there arose mutterings of discontent among them.

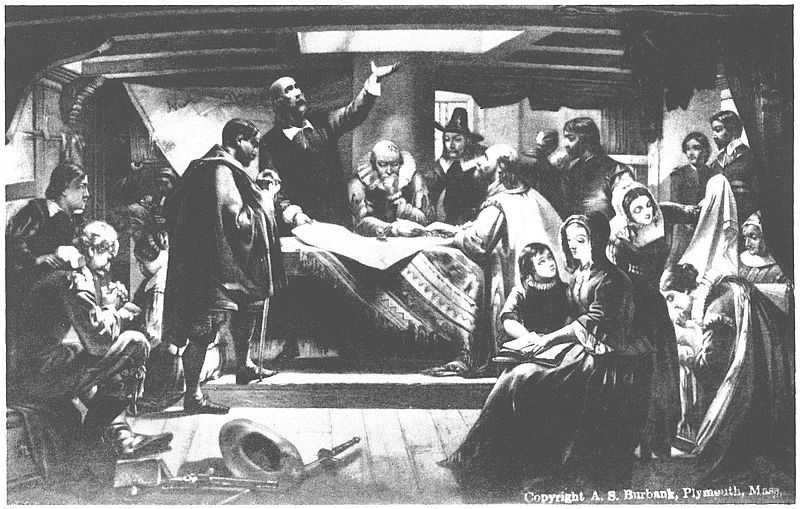

It became evident, therefore, that some means should be devised to maintain law and order as they were out of the jurisdiction of their patent. To accomplish this the members of the Pilgrim Company met in the cabin of the Mayflower off the shores of Cape Cod on 21 November 1620 and banded themselves together by the now famous document known as the Mayflower Compact.

The Mayflower Compact is a great contribution to civil liberty and democracy; it ranks with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. Our democracy was based on it from the landing of the Pilgrims. The Pilgrims established what they planned. The Plymouth settlement was the start of religious[27] freedom. We owe them a great debt of gratitude. They were unimportant people, and their departure attracted little or no attention. Some were educated, others were not; some had means, most little or nothing, but all had character and courage. We call them ordinary people, but their accomplishment made history. When they wrote and signed the Compact they gave the world a new political idea for government by the people, and when, under the Compact, they organized the government of Plymouth, they laid the foundation of political liberty for this nation.

Students of governmental history the world over, as well as statesmen, now know of the Mayflower Compact and discuss it. It cannot receive too much publicity, and there is no better place to reprint it than here in this story of the “House of Edward Winslow” where it can be easily and frequently perused.

In no part of the world up to then did there exist a government of just and equal laws. It is the first incident where a government was formed by the governed, by their consent in writing at one time. One hundred and fifty years later its principles really framed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States, and our laws today are interwoven with the ideals of this band of Pilgrims.

One month after the signing of the Compact, the exploring party of eighteen men in the ship’s shallop that had left the ship 16 December, landed at Plymouth. Plymouth was not just what they wanted, but as Brewster said, it was the best they had seen. They returned to the ship and on 26 December 1620 the Mayflower and her passengers reached Plymouth. It was 31 March that the last of them went ashore for good.

On 15 April 1621 the Mayflower sailed on her return trip, leaving every one of the survivors of the Pilgrim Company behind. It was a more striking picture than her departure from England. A situation[30] more discouraging for the Pilgrims could hardly be conceived.

Some interesting occurrences which happened on board the Mayflower during the trip, are taken from the manuscript of “Prince’s Annals,” in his handwriting. Prince had drawn his pen diagonally across the passages, and they do not appear in his published work. They were first printed in the April number 1847 the New England Historical and Genealogical Register. It reads:

“In a mighty storme a lustie yonge man called John Howland came upon some occasion above ye gratings, was with a seele of ye ship throwne into ye sea; but it pleased God yt he caught hould of ye top saile halliards, which hung overboard and rane out at length; yet he held his hould (though he was sundrie fadomes under water) till he was hald up by ye same rope to ye brink of ye water and then with a boat hook and other means got into ye shipe again, and his life saved, and though he was somewhat ill with it, yet he lived many years after, and became a profitable member both of church and comonwelth.”

And the manuscript goes on to tell of a proud, very profane young man, one of the seamen of husky and able body, which made him the more haughty, who was always annoying the poor people in their sickness by cursing them daily and telling them he hoped to help cast half of them overboard before they came to their journey’s end and if he ever, by any was gently reproved, he would curse and swear most bitterly. But it pleased God to smite this young man with a grievous disease, of which he died in a desperate manner and so was himself the first to be thrown overboard.

John Carver, who had been chosen Governor, died the first winter, and William Bradford succeeded him. The Colony grew slowly. By 1630 it had but 300 persons in it, but it had paid the London merchants. There is little question that the contract was burdensome and oppressive. But as proof that the Pilgrims harbored no[31] resentment is this laudable act: the Plymouth Colony General Court in 1660 ordered that twenty pounds should be sent to a Mr. Ling, one of the Merchant Adventurers, “who had fallen to decay and had felt great extremity of poverty, the same twenty pounds being bestowed on him towards his relief and if it was not given voluntarily that the amount that fell short ‘bee’ made up out of the ‘Countrey stocke’ by the Treasurer.”

The Colony made a treaty with Massasoit, Chief of the Wampanoag Indians, which lasted until broken by his son in 1675. By 1640 the population had increased to over 3000.

As for the Puritans, they became powerful in England and comprised many men of wealth and culture and social standing. Little bodies of them, encouraged by the example of the Pilgrims, began to settle upon the shores of Massachusetts. In 1628 John Endicott and a shipload took command of the place the Indians called Naumkeag and gave it the Bible name of Salem, or Peace. When they arrived they found Roger Conant and his followers, who were, after several years of struggling, happily settled. Endicott practically kicked them out. Within a few years all of Conant’s followers had moved across the river and established new homes in what became Beverly.

In 1629 a number of leading Puritans in England bought of the Plymouth Company a large tract of land, bounded by the Charles and Merrimac Rivers and stretching inland indefinitely. They got a charter from Charles I and incorporated as the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay. Under John Winthrop, a wise and able man, they came over to Salem, bringing 1000 persons, with horses and cattle, and during that year Charlestown, Chelsea, and a small hilly peninsular, called by the Indians Shawmut and by the English Trimountain, or Tremont, and soon changed to Boston, from[32] which the leading settlers had come, were settled. By 1634 nearly 4000 settlers had arrived from England, coming usually in congregations, led by their minister and settled together in parishes or townships until there were about twenty.

In 1636 it was voted to establish a college three miles from Boston at a place called New Town, now Cambridge. A young clergyman, John Harvard, bequeathed his books and half his estate and the new college was called by his name.

The colonization of New England was a complicated affair. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was the largest. South of it was the Plymouth Colony, the oldest. Then there was Rhode Island and Providence Plantation and the Connecticut Colony. In 1643 these four Colonies formed a confederation for defense called the United Colonies of New England. In 1692 King William arranged things to his liking; he annexed the Plymouth Colony to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but let Connecticut and Rhode Island keep their beloved charters, and so the Plymouth Colony forever after remained a part of Massachusetts.

The establishment of the New England Confederacy, the division of the ancient church, the annexation to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the loss of wealth and population, marked the end of Plymouth as an independent Colony, but not of the great influence which the Plymouth Colony and the Pilgrims have exerted, and, we hope, will continue to exert with increasing force, in perpetuating, as it originally established, our democratic form of government.

Signed in the Cabin of the “Mayflower,” Nov. 11th, Old Style, Nov. 21st, New Style, 1620

“In the name of God, amen, we whose names are underwritten, the loyall subjects of our dread soveraigne Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britaine, Franc and Ireland king, defender of the faith, &c., haveing undertaken, for the glorie of God, and advancemente of the Christian faith, and honor of our king and countrie, a voyage to plant the first colonie in the northerne parts of Virginia, doe by these presents solemnly and mutualy in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civill body politick, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherence of the ends aforesaid; and by vertue hereof to enacte, constitute and frame such just and equall laws, ordenances, acts, constitutions and[29] offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meete and convenient for the general good of the colonie, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cap-Codd the 11 of November, in the year of the raigne of our soveraigne lord, King James of England, Franc and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, ANo Dom 1620.”

| ‡ | John Carver | ‡†* | Edward Fuller |

| ‡* | William Bradford | ‡† | John Turner |

| ‡* | Edward Winslow | ‡* | Francis Eaton |

| ‡* | William Brewster | ‡†* | James Chilton |

| ‡* | Isaac Allerton | ‡ | John Crackston |

| ‡* | Myles Standish | ‡* | John Billington |

| * | John Alden | † | Moses Fletcher |

| * | Samuel Fuller | † | John Goodman |

| ‡† | Christopher Martin | †* | Degory Priest |

| ‡†* | William Mullins | † | Thomas Williams |

| ‡†* | William White | Gilbert Winslow | |

| * | Richard Warren | † | Edmond Margeson |

| * | John Howland | * | Peter Brown |

| ‡* | Stephen Hopkins | † | Richard Britteridge |

| ‡† | Edward Tilly | * | George Soule |

| ‡†* | John Tilly | † | Richard Clarke |

| * | Francis Cooke | Richard Gardiner | |

| †* | Thomas Rogers | † | John Allerton |

| ‡† | Thomas Tinker | † | Thomas English |

| ‡† | John Rigdale | * | Edward Doty |

| Edward Leister | |||

(Note: November 21st of our Calendar is the same as November 11th

of the Old Style Calendar.)

* Has descendants now living.

‡ Brought wife.

† Died first winter.