The House on Henry Street

The House on Henry Street

THE HOUSE ON

HENRY STREET

BY

LILLIAN D. WALD

With Illustrations from Etchings and Drawings by

Abraham Phillips and from Photographs

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Copyright, 1915,

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

November, 1938

Printed in U. S. A.

TO

THE COMRADES

WHO HAVE BUILT THE HOUSE

Much of the material contained in this book has been published in a series of six articles that appeared in the Atlantic Monthly from March to August, 1915. And indeed it was due to the kindly insistence on the part of the editors of that magazine that more permanent form should be given to the record of the House on Henry Street that the story was published at all.

During the two decades of the existence of the Settlement there has been a significant awakening on matters of social concern, particularly those affecting the protection of children throughout society in general; and a new sense of responsibility has been aroused among men and women, but perhaps more distinctively among women, since the period coincides with their freer admission to public and professional life. The Settlement is in itself an expression of this sense of responsibility, and under its roof many divergent groups have come together to discuss measures “for the many, mindless, mass that most needs helping,” and often to assert by deed their faith in democracy. Some have found in the Settlement an opportunity for self-realization[vi] that in the more fixed and older institutions has not seemed possible.

I cannot acknowledge by name the many individuals who, by gift of money and through understanding and confidence, through work and thought and sharing of the burdens, have helped to build the House on Henry Street. These colleagues have come all through the years that have followed since the little girl led me to her rear tenement home. Though we are working together as comrades for a common cause, I cannot resist this opportunity to express my profound personal gratitude for the precious gifts that have been so abundantly given. The first friends who gave confidence and support to an unknown and unexperimented venture have remained staunch and loyal builders of the House. And the younger generation with their gifts have developed the plans of the House and have found inspiration while they have given it.

In the making of the book, much help has come from these same friends, and I should be quite overwhelmed with the debt I owe did I not feel that all of us who have worked together have worked not only for each other but for the cause of human progress; that is the beginning and should be the end of the House on Henry Street.

Lillian D. Wald.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The East Side Two Decades Ago | 1 |

| II. | Establishing the Nursing Service | 26 |

| III. | The Nurse and the Community | 44 |

| IV. | Children and Play | 66 |

| V. | Education and the Child | 97 |

| VI. | The Handicapped Child | 117 |

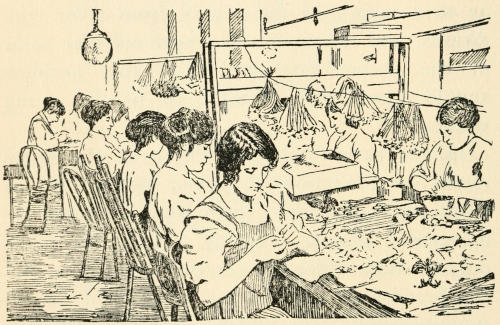

| VII. | Children Who Work | 135 |

| VIII. | The Nation’s Children | 152 |

| IX. | Organizations within the Settlement | 169 |

| X. | Youth | 189 |

| XI. | Youth and Trades Unions | 201 |

| XII. | Weddings and Social Halls | 216 |

| XIII. | Friends of Russian Freedom | 229 |

| XIV. | Social Forces | 249 |

| XV. | Social Forces, Continued | 270 |

| XVI. | New Americans and Our Policies | 286 |

| Index | 313 |

| PAGE | |

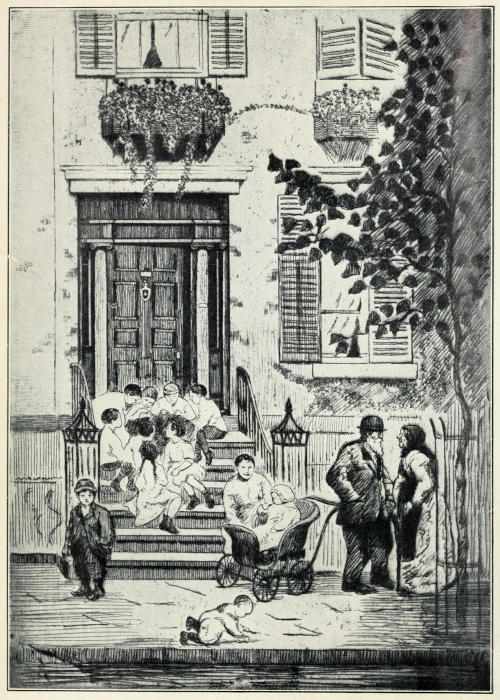

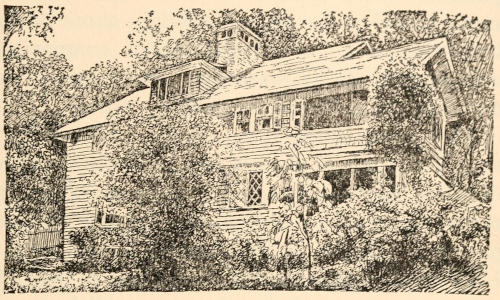

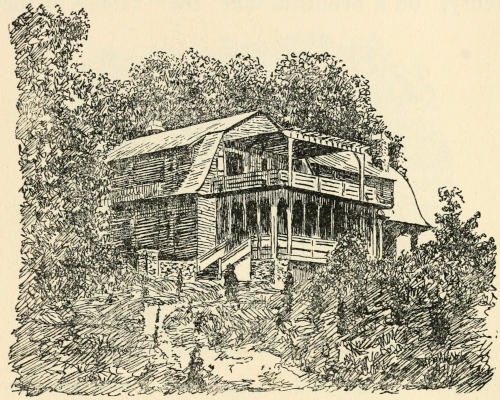

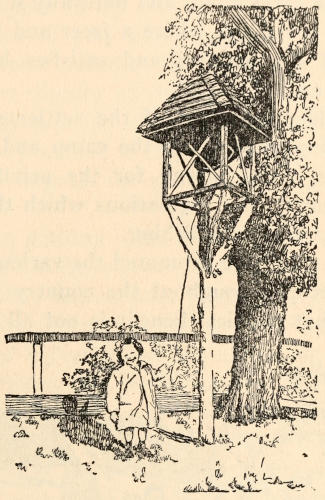

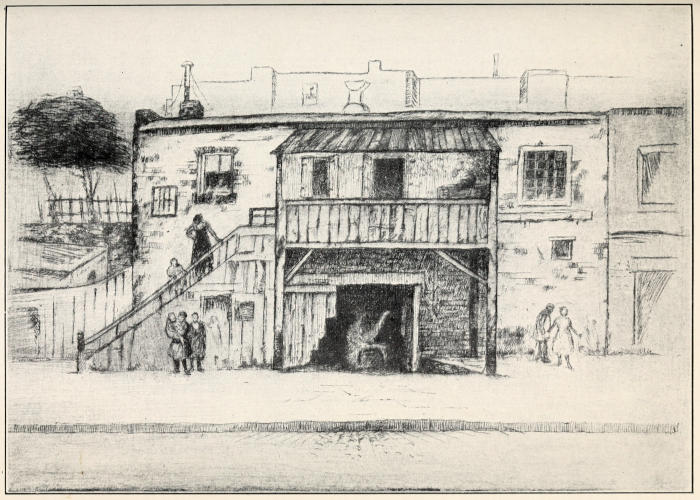

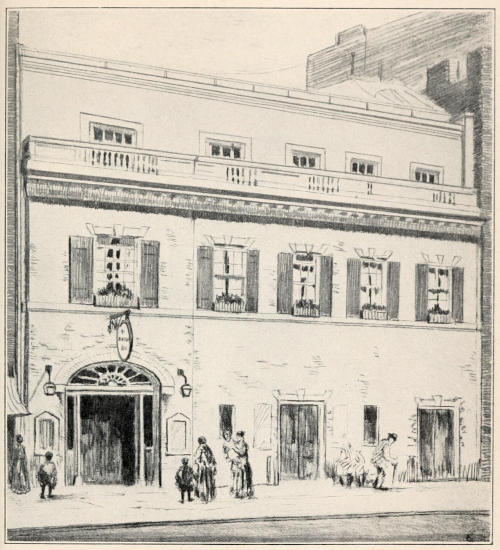

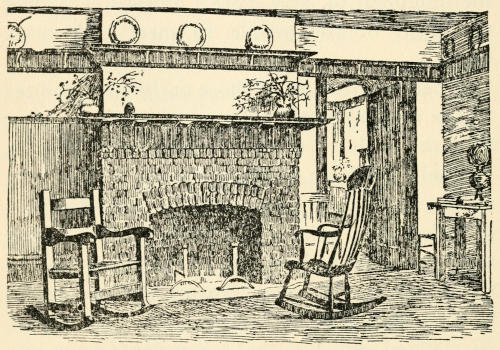

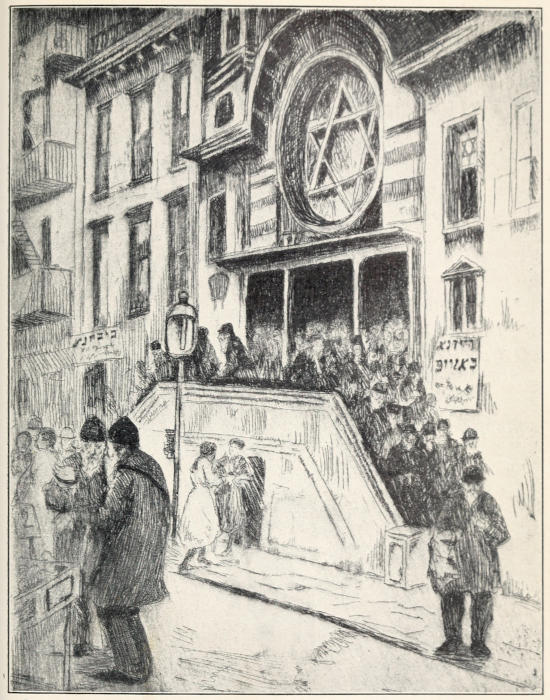

| The House on Henry Street | Frontispiece |

| Etching by Abraham Phillips | |

| Lillian D. Wald and Mary M. Brewster in Hospital Uniform, 1893 | 6 |

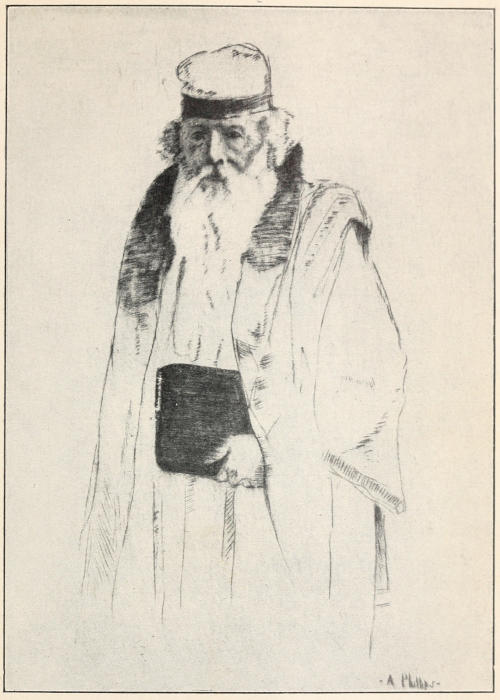

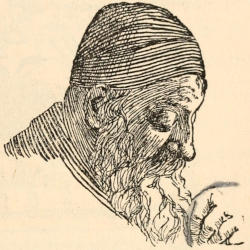

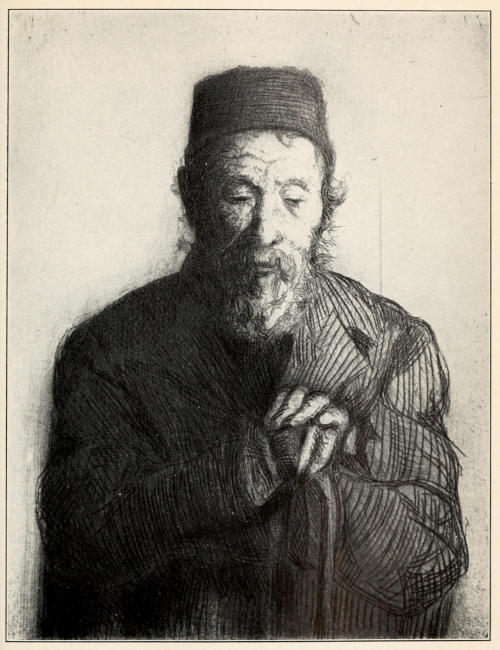

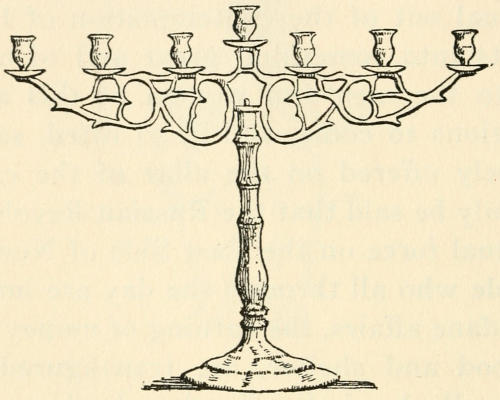

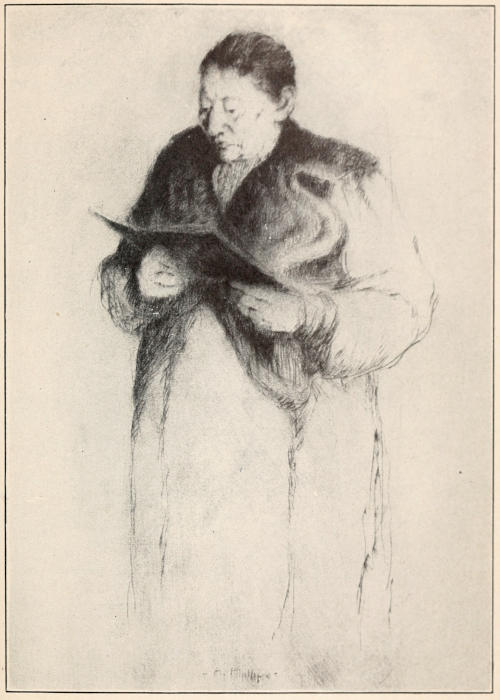

| With Prayer-shawl and Phylactery | 22 |

| Etching by Abraham Phillips | |

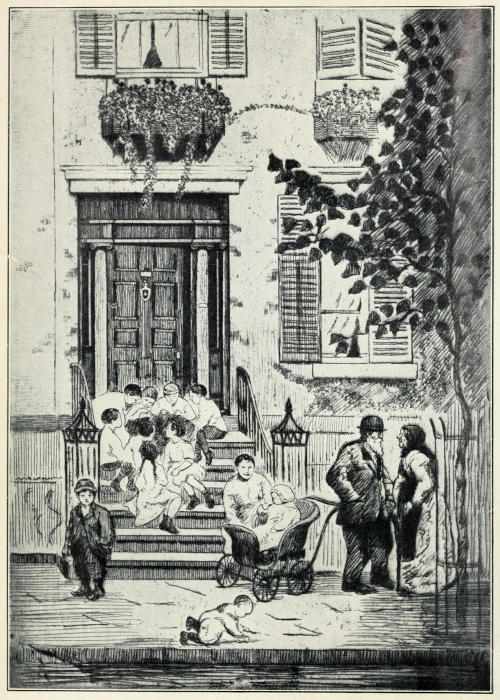

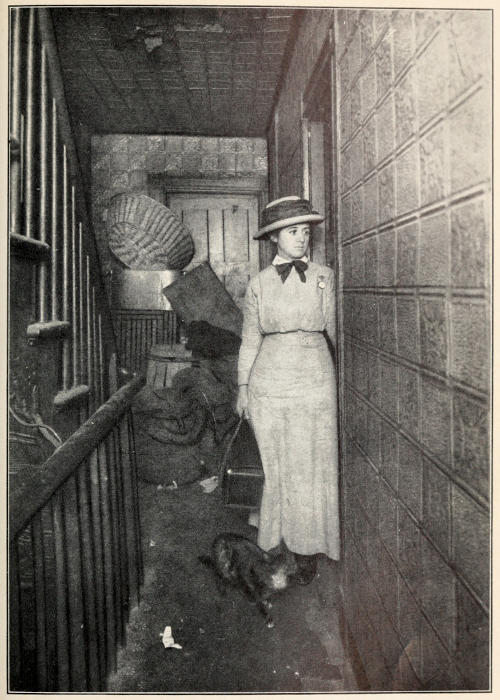

| The Nurse in the Tenement | 28 |

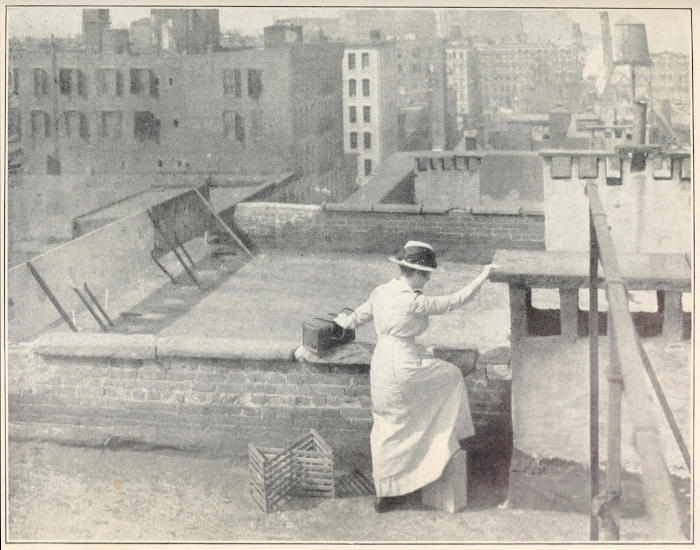

| A Short Cut over the Roofs of the Tenements | 52 |

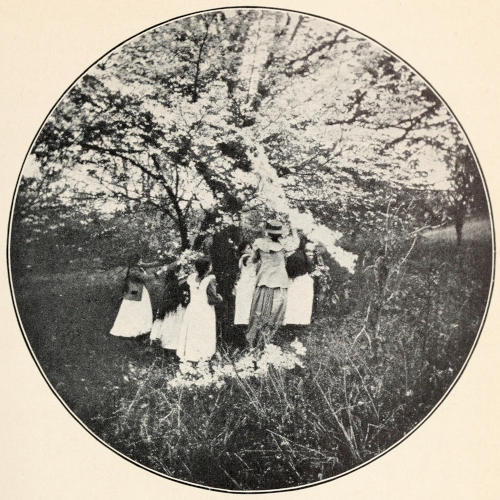

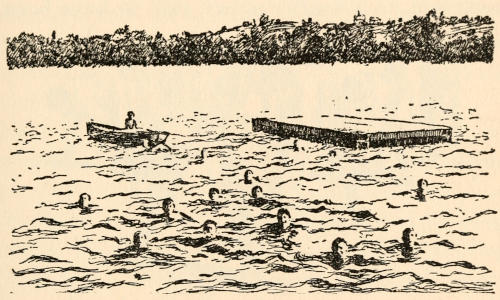

| And their Ecstasy at the Sight of a Wonderful Dogwood Tree | 78 |

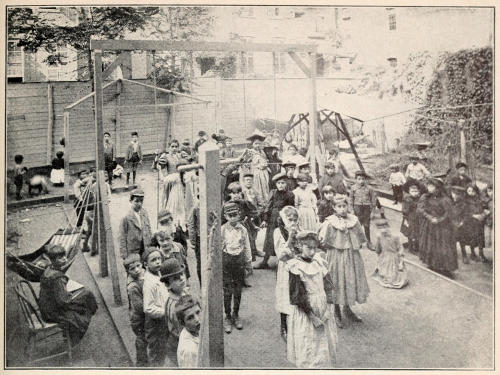

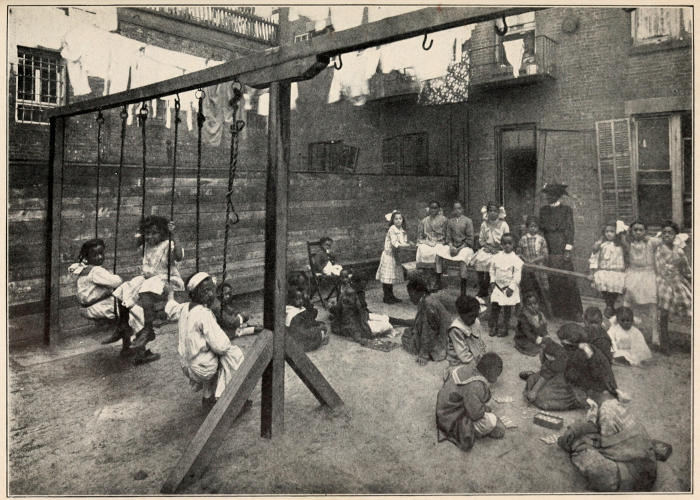

| It Has Been Called the “Bunker Hill” of Playgrounds | 82 |

| The Children Play on Our Roof | 82 |

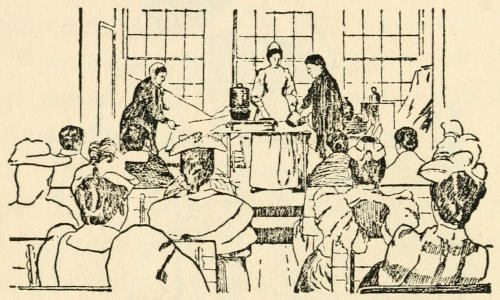

| The Kindergarten Children Learn the Reality of the Things they Sing About | 90 |

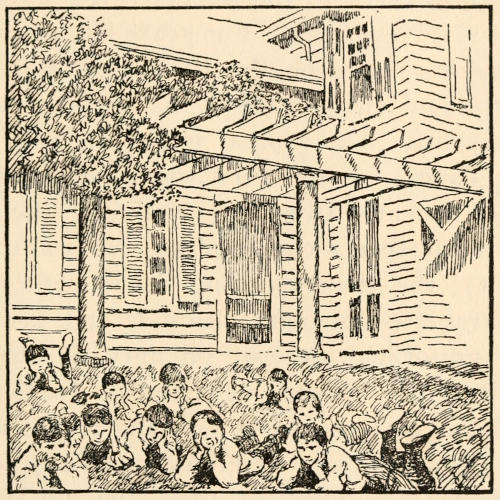

| Uses of the Back Yard in One of the Branches of the Henry Street Settlement | 162 |

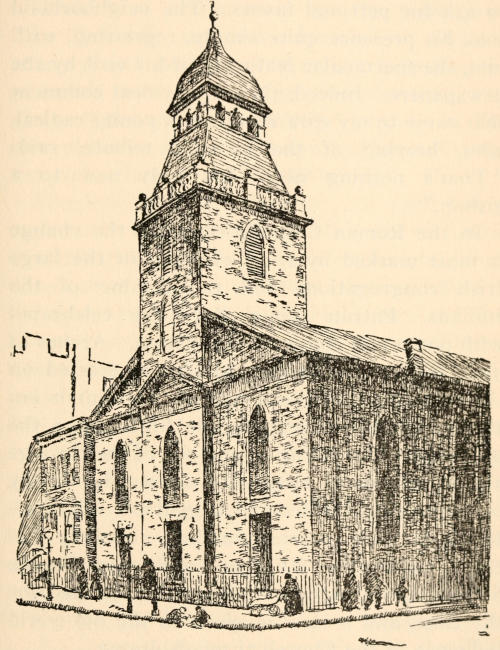

| Here and There Are Still Found Reminders of Old New York | 170 |

| Etching by Abraham Phillips | |

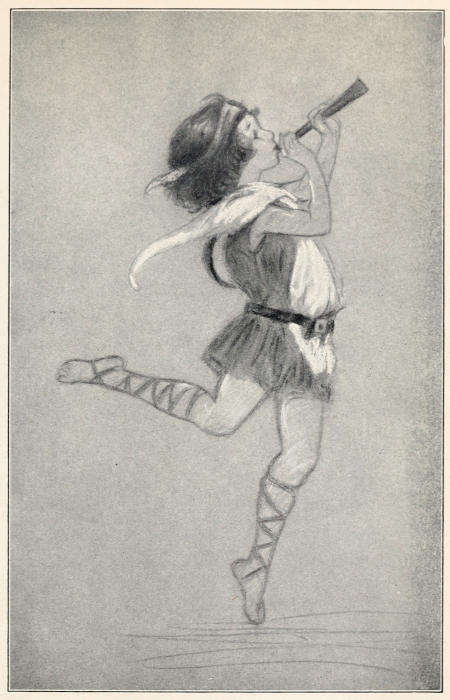

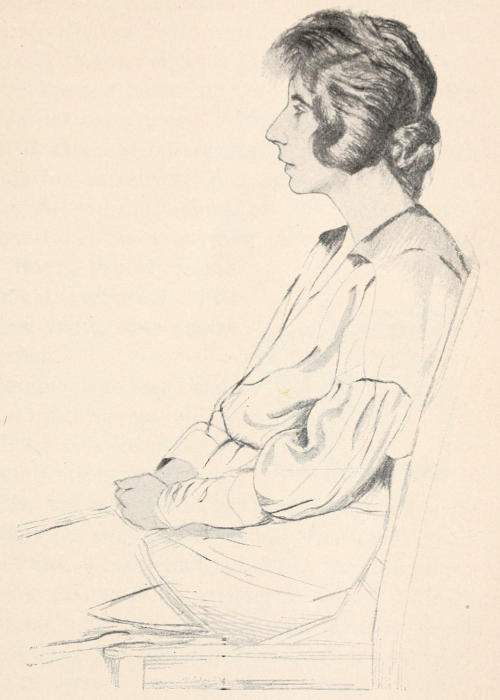

| Esther | 182 |

| Drawing by Esther J. Peck | |

| The Neighborhood Playhouse | 186 |

| Drawing by Abraham Phillips | |

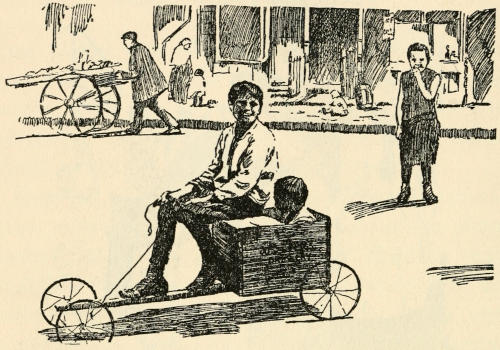

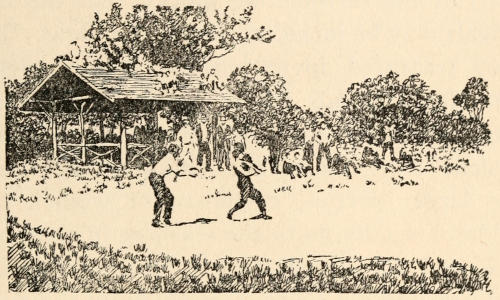

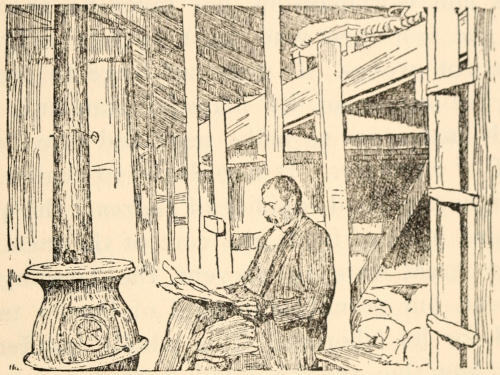

| In a Club-room | 192 |

| Drawing by Abraham Phillips | |

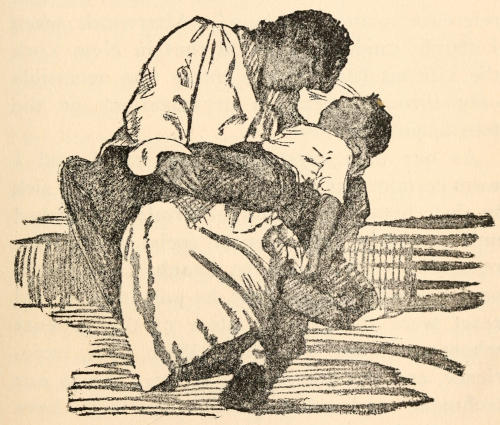

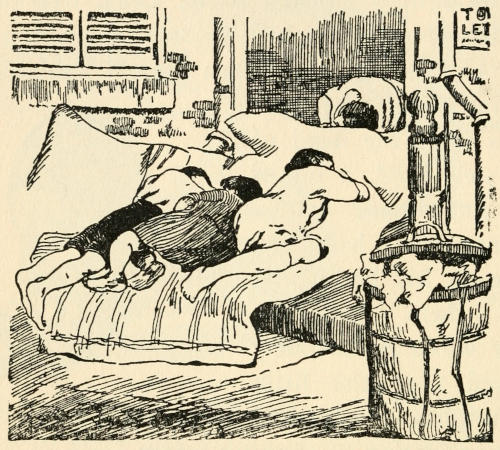

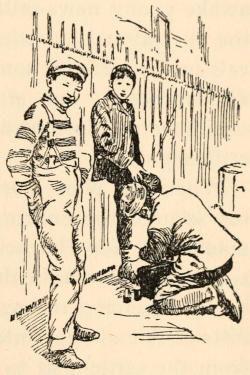

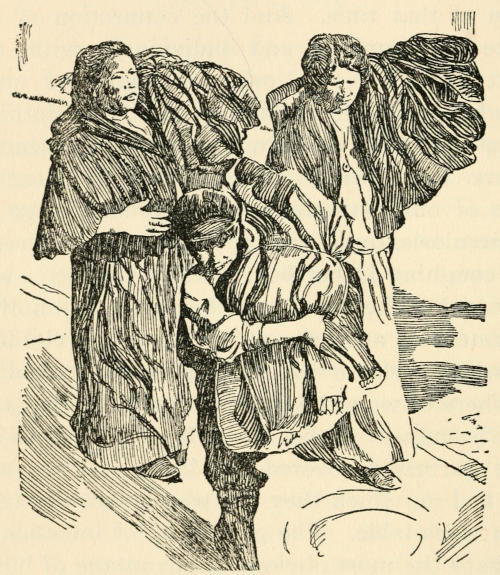

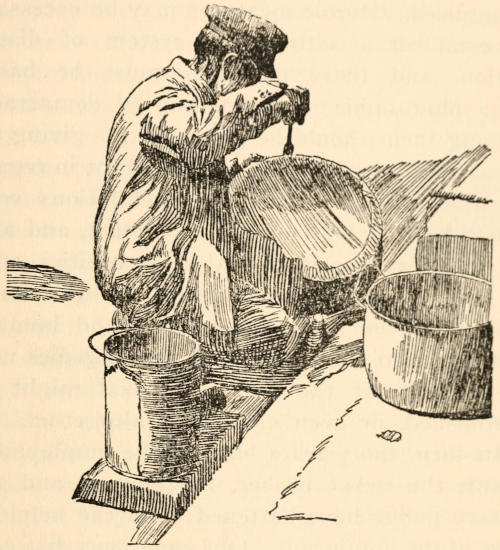

| After the Long Day | 204 |

| Drawing by Abraham Phillips | |

| An Incident in the Historical Pageant on Henry Street, Commemorating the Twentieth Anniversary of the Settlement | 214[xii] |

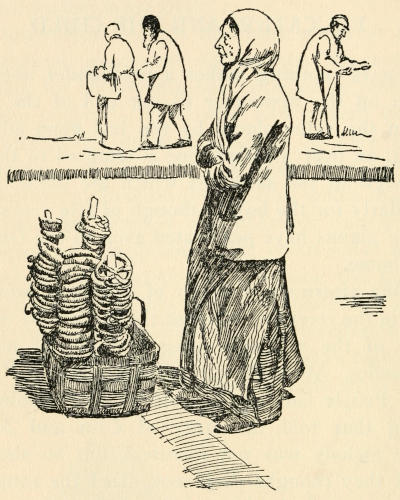

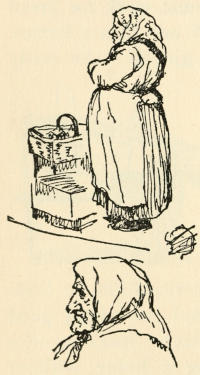

| The Older Generation | 218 |

| Etching by Abraham Phillips | |

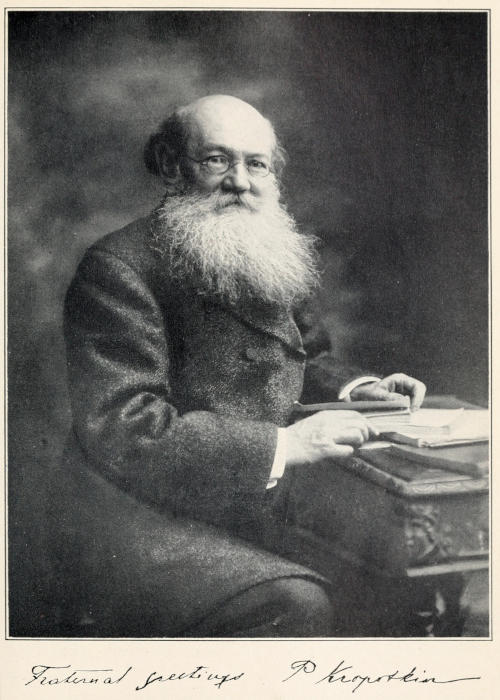

| Prince Kropotkin | 234 |

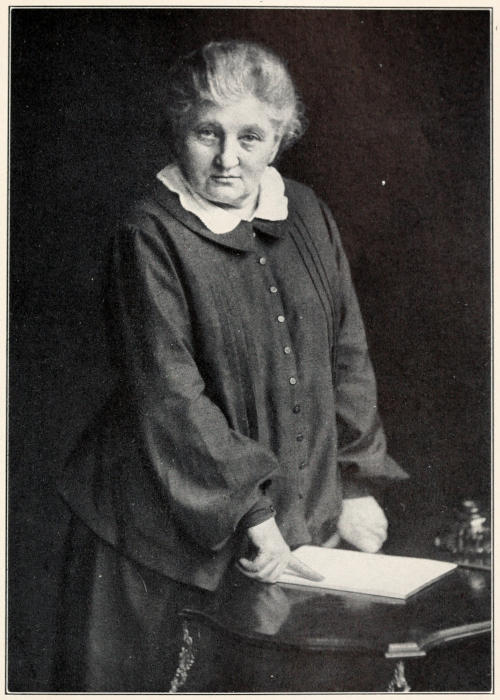

| Babuschka, Little Grandmother | 242 |

| The Synagogues Are Everywhere—Imposing or Shabby-looking Buildings | 254 |

| Etching by Abraham Phillips | |

| A Mother in Israel | 268 |

| Etching by Abraham Phillips | |

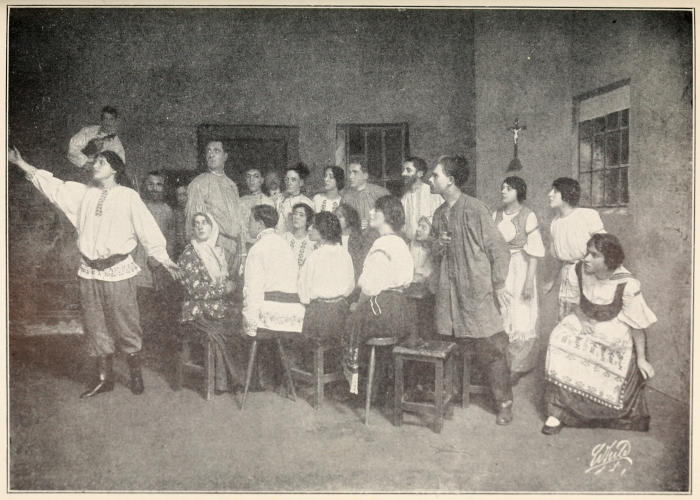

| The Dramatic Club Presented “The Shepherd” | 272 |

| A Region of Overcrowded Homes | 298 |

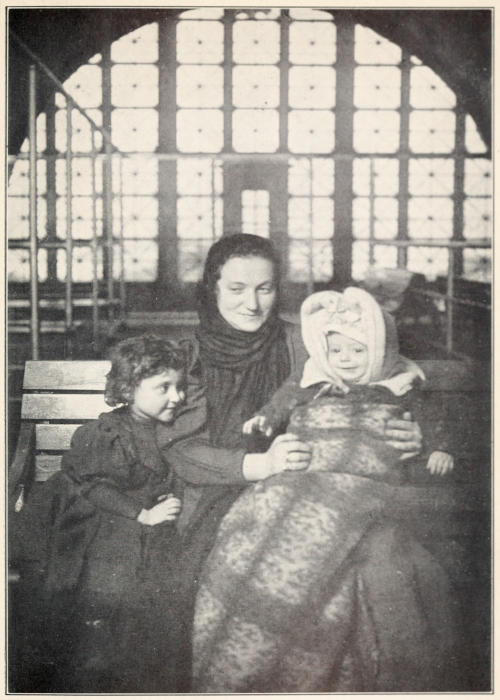

| At Ellis Island There is a Stream of Inflowing Life | 308 |

| Photograph by Louis Hines |

A sick woman in a squalid rear tenement, so wretched and so pitiful that, in all the years since, I have not seen anything more appealing, determined me, within half an hour, to live on the East Side.

I had spent two years in a New York training-school for nurses; strenuous years for an undisciplined, untrained girl, but a wonderful human experience. After graduation, I supplemented the theoretical instruction, which was casual and inconsequential in the hospital classes twenty-five years ago, by a period of study at a medical college. It was while at the college that a great opportunity came to me.

I had little more than an inspiration to be of use in some way or somehow, and going to the hospital seemed the readiest means of realizing my desire. While there, the long hours “on duty” and the exhausting demands[2] of the ward work scarcely admitted freedom for keeping informed as to what was happening in the world outside. The nurses had no time for general reading; visits to and from friends were brief; we were out of the current and saw little of life save as it flowed into the hospital wards. It is not strange, therefore, that I should have been ignorant of the various movements which reflected the awakening of the social conscience at the time, or of the birth of the “settlement,” which twenty-five years ago was giving form to a social protest in England and America. Indeed, it was not until the plan of our work on the East Side was well developed that knowledge came to me of other groups of people who, reacting to a humane or an academic appeal, were adopting this mode of expression and calling it a “settlement.”

Two decades ago the words “East Side” called up a vague and alarming picture of something strange and alien: a vast crowded area, a foreign city within our own, for whose conditions we had no concern. Aside from its exploiters, political and economic, few people had any definite knowledge of it, and its literary “discovery” had but just begun.

The lower East Side then reflected the popular indifference—it almost seemed contempt—for the living conditions of a huge population.[3] And the possibility of improvement seemed, when my inexperience was startled into thought, the more remote because of the dumb acceptance of these conditions by the East Side itself. Like the rest of the world I had known little of it, when friends of a philanthropic institution asked me to do something for that quarter.

Remembering the families who came to visit patients in the wards, I outlined a course of instruction in home nursing adapted to their needs, and gave it in an old building in Henry Street, then used as a technical school and now part of the settlement. Henry Street then as now was the center of a dense industrial population.

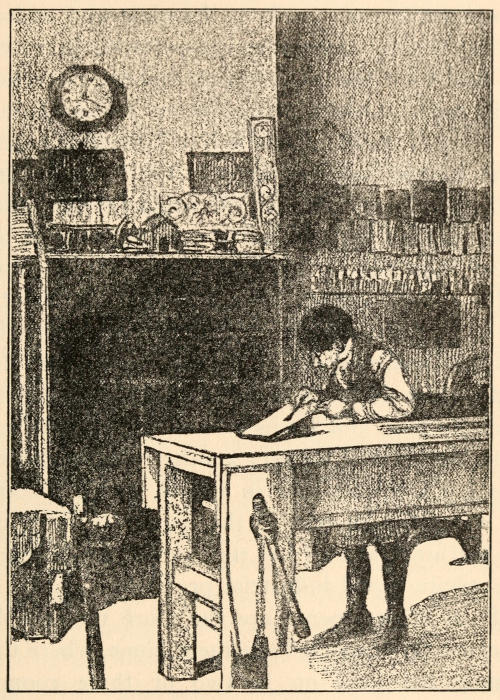

From the schoolroom where I had been giving a lesson in bed-making, a little girl led me one drizzling March morning. She had told me of her sick mother, and gathering from her incoherent account that a child had been born, I caught up the paraphernalia of the bed-making lesson and carried it with me.

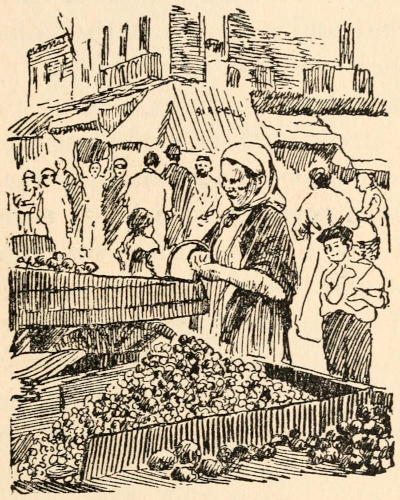

The child led me over broken roadways,—there was no asphalt, although its use was well established in other parts of the city,—over dirty mattresses and heaps of refuse,—it was before Colonel Waring had shown the possibility of clean streets even in that quarter,—between tall, reeking houses whose laden fire-escapes, useless for their appointed purpose, bulged with household goods of every description. The rain added to the dismal appearance of the streets and to the discomfort of the crowds which thronged them, intensifying the odors[5] which assailed me from every side. Through Hester and Division streets we went to the end of Ludlow; past odorous fish-stands, for the streets were a market-place, unregulated, unsupervised, unclean; past evil-smelling, uncovered garbage-cans; and—perhaps worst of all, where so many little children played—past the trucks brought down from more fastidious quarters and stalled on these already overcrowded streets, lending themselves inevitably to many forms of indecency.

The child led me on through a tenement hallway, across a court where open and unscreened closets were promiscuously used by[6] men and women, up into a rear tenement, by slimy steps whose accumulated dirt was augmented that day by the mud of the streets, and finally into the sickroom.

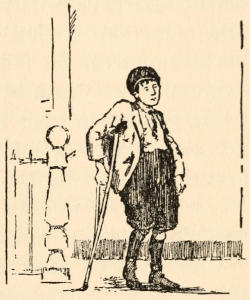

All the maladjustments of our social and economic relations seemed epitomized in this brief journey and what was found at the end of it. The family to which the child led me was neither criminal nor vicious. Although the husband was a cripple, one of those who stand on street corners exhibiting deformities to enlist compassion, and masking the begging of alms by a pretense at selling; although the family of seven shared their two rooms with boarders,—who were literally boarders, since a piece of timber was placed over the floor for them to sleep on,—and although the sick woman lay on a wretched, unclean bed, soiled with a hemorrhage two days old, they were not degraded human beings, judged by any measure of moral values.

Lillian D. Wald Mary M. Brewster

In hospital uniform, 1893

In fact, it was very plain that they were sensitive to their condition, and when, at the end of my ministrations, they kissed my hands (those who have undergone similar experiences will, I am sure, understand), it would have been some solace if by any conviction of the moral unworthiness of the family I could have defended myself as a part of a society which[7] permitted such conditions to exist. Indeed, my subsequent acquaintance with them revealed the fact that, miserable as their state was, they were not without ideals for the family life, and for society, of which they were so unloved and unlovely a part.

That morning’s experience was a baptism of fire. Deserted were the laboratory and the academic work of the college. I never returned to them. On my way from the sickroom to my comfortable student quarters my[8] mind was intent on my own responsibility. To my inexperience it seemed certain that conditions such as these were allowed because people did not know, and for me there was a challenge to know and to tell. When early morning found me still awake, my naïve conviction remained that, if people knew things,—and “things” meant everything implied in the condition of this family,—such horrors would cease to exist, and I rejoiced that I had had a training in the care of the sick that in itself would give me an organic relationship to the neighborhood in which this awakening had come.

To the first sympathetic friend to whom I poured forth my story, I found myself presenting a plan which had been developing almost without conscious mental direction on my part. It was doubtless the accumulation of many reflections inspired by acquaintance with the patients in the hospital wards, and now, with the Ludlow Street experience, resistlessly impelling me to action.

Within a day or two a comrade from the training-school, Mary Brewster, agreed to share in the venture. We were to live in the neighborhood as nurses, identify ourselves with it socially, and, in brief, contribute to it our citizenship.[9] That plan contained in embryo all the extended and diversified social interests of our settlement group to-day.

We set to work immediately to find quarters—no easy task, as we clung to the civilization of a bathroom, and according to a legend current at the time there were only two bathrooms in tenement houses below Fourteenth Street. Chance helped us here. A young woman who for years played an important part in the life of many East Side people, overhearing a conversation of mine with a fellow-student, gave me an introduction to two men who, she said, knew all about the quarter of the city which I wished to enter. I called on them immediately, and their response to my need was as prompt. Without stopping to inquire into my antecedents or motives, or to discourse on the social aspects of the community, of which, I soon learned, they were competent to speak with authority, they set out with me at once, in a pouring rain, to scour the adjacent streets for “To Let” signs. One which seemed to me worth investigating my[10] newly acquired friends discarded with the explanation that it was in the “red light” district and would not do. Later I was to know much of the unfortunate women who inhabited the quarter, but at the time the term meant nothing to me.

After a long tour one of my guides, as if by inspiration, reminded the other that several young women had taken a house on Rivington Street for something like my purpose, and perhaps I had better live there temporarily and take my time in finding satisfactory quarters. Upon that advice I acted, and within a few days Miss Brewster and I found ourselves guests at the luncheon table of the College Settlement on Rivington Street. With ready hospitality they took us in, and, during July and August, we were “residents” in stimulating comradeship with serious women, who were also the fortunate possessors of a saving sense of humor.

Before September of the year 1893 we found a house on Jefferson Street, the only one in which our careful search disclosed the desired bathtub. It had other advantages—the vacant floor at the top (so high that the windows along the entire side wall gave us sun and breeze), and, greatest lure of all, the warm welcome which came to us from the basement,[11] where we found the janitress ready to answer questions as to terms.

Naturally, objections to two young women living alone in New York under these conditions had to be met, and some assurance as to our material comfort was given to anxious, though at heart sympathetic, families by compromising on good furniture, a Baltimore heater for cheer, and simple but adequate household appurtenances. Painted floors with easily removed rugs, windows curtained with spotless but inexpensive scrim, a sitting-room with pictures, books, and restful chairs, a tiny bedroom which we two shared, a small dining-room in which the family mahogany did not look out of place, and a kitchen, constituted our home for two full years.

The much-esteemed bathroom, small and dark, was in the hall, and necessitated early rising if we were to have the use of it; for, as we became known, we had many callers anxious to see us before we started on our sick rounds. The diminutive closet-space was divided to hold the bags and equipment we needed from day to day, and more ample store-closets were given us by the kindly people in the school where I had first given lessons to East Side mothers. Any pride in the sacrifice of material comfort which might have risen[12] within us was effectually inhibited by the constant reminder that we two young persons occupied exactly the same space as the large families on every floor below us, and to one of our basement friends at least we were luxurious beyond the dreams of ordinary folk.

The little lad from the basement was our first invited guest. The simple but appetizing dinner my comrade prepared, while I set the table and placed the flowers. The boy’s mother came up later in the evening to find out what we had given him, for Tommie had rushed down with eyes bulging and had reported that “them ladies live like the Queen of England and eat off of solid gold plates.”

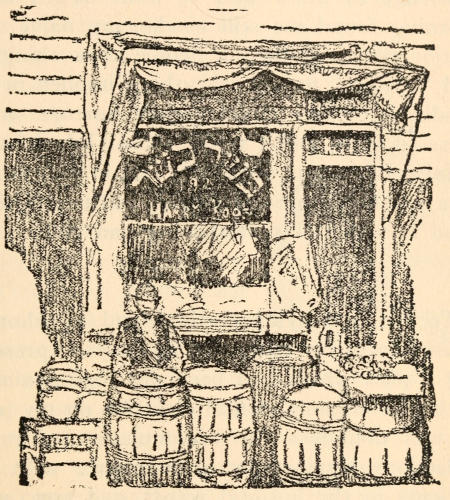

We learned the most efficient use of the fire-escape and felt many times blessed because of our easy access to the roof. We also learned the infinite uses to which stairs can be put. Later we achieved “local color” in our rooms by the addition of interesting pieces of brass and copper purchased from a man on Allen Street whom we and several others had “discovered.”[13] His little dark shop under the elevated railway was fitfully illuminated by the glowing forge. On our first visit the proprietor emerged from a still darker inner room with prayer-shawl and phylactery. He became one of our pleasant acquaintances and lost no occasion of acknowledging what he considered his debt to the appreciative customers who had helped to make him and his wares known to a wider circle than that of the neighborhood.

The mere fact of living in the tenement brought undreamed-of opportunities for widening our knowledge and extending our human relationships. That we were Americans was wonderful to our fellow-tenants. They were all immigrants—Jews from Russia or Roumania. The sole exception was the janitress, Mrs. McRae, who at once dedicated herself and her entire family to the service of the top floor. Dear Mrs. McRae! From her basement home[14] she covered us with her protecting love and was no small influence in holding us to sanity. Humor, astuteness, and sympathy were needed and these she gave in abundance.

It was vouchsafed us to know many fine personalities who influenced and guided us from the first few weeks of residence in the friendly college settlement through the many years that have followed. The two women who stand out with greatest distinction from the first are this pure-souled Scotch-Irish immigrant and Josephine Shaw Lowell. Both, if they were here, would understand the tribute in linking them together.

Occasionally Mrs. McRae would feel impelled to reprove us for “overdoing” ourselves, and from our top story we were hard pushed to save visitors from being sent away when she thought we needed to finish a meal or go to bed. Cautious as we were not to make any distinctions in commenting upon the visitors who came to see us, she made her own deductions. At whatever hour we returned, she would be at the door to welcome us and to[15] report on the happenings during our absence. “So-and-so was here”: shrewd descriptions which often enabled us to identify individuals when names were forgotten. “Lots of visitors to-night,” she would report. “Were messages left, or names?” we would naturally inquire. “No, darlints, nothing at all. I know sure they didn’t bring you anything.”

The key to our apartments, usually left with her, was one day forgotten, and when, upon unlocking the door, we saw a well-known society woman seated in our little living-room, we were naturally puzzled to know how she had arrived there. Mrs. McRae explained that she had taken her up the fire-escape!—no slight venture and exertion for the inexperienced. We suggested that other ways might have been more agreeable and safer. “Whisht,” said Mrs. McRae, with a smile and a wink, “it’s no harm at all. She’ll be havin’ lots of talk for her friends on this.”

When her roving husband died at home, the funeral arrangements were given a last touch by Mrs. McRae, who placed on the casket his tobacco and pipe and ordered the procession to pass his tenement home twice before driving to the cemetery, “So he’d not think we were not for forgivin’ him and hurryin’ him away.”

Her first love went to my comrade, whose[16] beauty and humor and goodness captured her Celtic heart. During our second year in the tenement Miss Brewster was taken seriously ill, and one evening we had at last succeeded in forcing Mrs. McRae to go home and had locked the door. Unknown to us the dear friend remained on the floor outside all through the night, trying to catch the sound of life from the loved one.

Bringing up a large family, with no help from the “old man,” and with stern ideals of conduct and integrity, was not easy. Some of her children, endowed with her character, gave her solace, but she was too astute not to estimate each one properly.

When we moved from the tenement to our first house Mrs. McRae and her family gave up the basement rooms, which were rent free because of her janitor service, in order to be near us, and she spread her warmth over the new abode. When, some years later, she was ill and we knew that the end was near, one close to me in my own family claimed my attention. Torn between the two affections, I was loath to leave the city while Mrs. McRae was so ill. She guessed the cause of my perturbed state and advised me to go. “Darlin’, you ought to go. You go. I promise not to die until you come back.”

Letters kept up this assurance and the promise was fulfilled.

Times were hard that year. In the summer the miseries due to unemployment and rising rents and prices began to be apparent, but the pinch came with the cold weather. Perhaps it was an advantage that we were so early exposed to the extraordinary sufferings and the variety of pain and poverty in that winter of 1893-94, memorable because of extreme economic depression. The impact of strain, physical and emotional, left neither place nor time for self-analysis and consequent self-consciousness, so prone to hinder and to dwarf wholesome instincts, and so likely to have proved an impediment to the simple relationship which we established with our neighbors.

It has become almost trite to speak of the kindness of the poor to each other, yet from the beginning of our tenement-house residence we were much touched by manifestations of it. An errand took me to Michael the Scotch-Irish cobbler as the family were sitting down to the noonday meal. There was a stranger with them, whom Michael introduced, explaining when we were out of hearing that he thought I would be interested to meet a man just out[18] of Sing Sing prison. I expressed some fear of the danger to his own boys in this association. “We must just chance it,” said Michael. “It’s no weather for a man like that to be on the streets, when honest fellows can’t get work.”

When we first met the G⸺ family they were breaking up the furniture to keep from freezing. One of the children had died and had been buried in a public grave. Three times that year did Mrs. G⸺ painfully gather together enough money to have the baby disinterred and fittingly buried in consecrated ground, and each time she gave up her heart’s desire in order to relieve the sufferings of the living children of her neighbors.

Another instance of this unfailing goodness of the poor to each other was told by Nellie, who called on us one morning. She was evidently embarrassed, and with difficulty related that, hearing of things to be given away at a newspaper office, she had gone there hoping to get something that would do for John when he came out of the hospital. She said, “I drew this and I don’t know exactly what it is meant for,” and displayed a wadded black satin “dress-shirt protector,” in very good condition, and possibly contributed because the season was over! Standing outside the circle of clamorous petitioners, Nellie and the woman next her[19] had exchanged tales of woe. When she mentioned her address the new acquaintance suggested that she seek us.

Nellie proved to be a near neighbor. There were two children: a nursing baby “none so well,” and a lad. John, her husband, was “fortunately” in the hospital with a broken leg, for there were “no jobs around loose anyway.” When we called later in the day to see the baby, we found that Nellie was stopping with her cousin, a widower who “held his job down.” There were also his two children, the widow of a friend “who would have done as much by me,” and the wife and two small children of a total stranger who lived in the rear tenement and were invited in to meals because the father had been seen starting every morning on his hunt for work, and “it was plain for anyone with eyes to see that he never did get it.” So this one man, fortunate in having work, was taking care of himself and his children, the widow of his friend, Nellie and her children, and was feeding the strangers. Said Nellie: “Sure he’s doing that, and why not? He’s the only cousin I’ve got outside of Ireland.”

Mrs. S⸺, who called at the settlement a few days ago, reminded me that it was twenty-one years since our first meeting, and brought[20] vividly before me a picture of which she was a part. She was the daughter of a learned rabbi, and her husband, himself a pious man, had great reverence for the traditions of her family. In their extremity they had taken bread from one of the newspaper charities, but it was evidently a painful humiliation, and before we arrived they had hidden the loaf in the ice-box. My visit was due to a desire to ascertain the condition of the families who had applied for this dole. Both house and people were scrupulously clean. It was amazing that under the biting pressure of want and anxiety such standards could be maintained. Yet, though passionately devoted to his family, the husband refused advantageous employment because it necessitated work on the Sabbath. This would have been to them a desecration of something more vital than life itself.

We found that winter, in other instances, that the fangs of the wolf were often decorously hidden. In one family of our acquaintance the father, a cigarmaker, left the house[21] each morning in search of work, only to return at night hungrier and more exhausted by his fruitless exertions. One Sabbath eve I entered his tenement, to find the two rooms scrubbed and cleaned, and the mother and children prepared for the holy night. Over a brisk fire fed by bits of wood picked up by the children two covered pots were set, as if a supper were being prepared. But under the lids it was only water that bubbled. The proud mother could not bear to expose her poverty to the gossip of the neighbors, the humiliation being the greater because she was obliged to violate the sacred custom of preparing a ceremonious meal for the united family on Friday night.

If the formalism of our neighbors in religious matters was constantly brought to our attention, instances of their tolerance were also far from rare. A Jewish woman, exhausted by her long day’s scrubbing of office floors, walked many extra blocks to beg us to get a priest for her Roman Catholic neighbor whose child was dying. An orthodox Jewish father, who had been goaded to bitterness because his daughter had married an “Irisher” and thus “insulted his religion,” felt that the young husband and his mother were equally wronged. This man, when I called on a Sabbath evening, took one of the lights from the table to show the way[22] down the five flights of dark tenement stairs, and to my protest,—knowing, as I did, that he considered it a sin to handle fire on the Sabbath,—he said: “It is no sin for me to handle a light on the Sabbath to show respect to a friend who has helped to keep a family together.”

With Prayer-shawl and Phylactery

There was the story of Mary, eldest daughter, as we supposed, of an orthodox family. When we went to her engagement party we were surprised to see that the young man was not of the family faith. The mother told us that Mary, “such a pretty baby,” had been left on their doorstep in earlier and more prosperous days in Austria. “The Burgomeister had made proclamation,” but no one came to claim her, and the husband and wife, who as yet had no children of their own, decided to keep her. “God rewarded us and answered our prayers,” said Mrs. L⸺, for many children came afterward; but Mary, blonde and blue-eyed, was always the most cherished, the first-comer who had brought the others. When she was quite a young girl she was taken ill—a cold following exposure after her first “grown-up” party, for which her foster-mother had dressed her with pride. It seemed that nothing could save her, and the foster-mother in her distress thought with pity of the woman who had borne[23] this sweet child. Surely she must be dead. No living mother could have abandoned so lovely a baby. And if she were dead and in the Christian heaven, she would look in vain there for her daughter. “So I called the priest and told him,” said Mrs. L⸺, “and he made a prayer over Mary, and said, ‘Now she is a Krist.’ The doctor, we called him too, and he said to get a goat, for the milk would be good for Mary; and she get well, but no so strong, as you see, and that is why she don’t go out to work like her brothers and sisters. We lose our money, that’s why we come to America, and Mary, now she marry a Krist.”

Gradually there came to our knowledge difficulties and conflicts not peculiar to any one set of people, but intensified in the case of our neighbors by poverty, unfamiliarity with laws and customs, the lack of privacy, and the frequent dependence of the elders upon the children. Workers in philanthropy, clergymen, orthodox rabbis, the unemployed, anxious parents, girls in distress, troublesome boys, came as individuals to see us, but no formal organization of our work was effected till we moved into the house on Henry Street, in 1895.

So precious were the intimate relationships with our neighbors in the tenement that we were reluctant to leave it. My companion’s breakdown, the persuasion of friends who had given their support and counsel that there was an obligation upon us to effect some kind of formal organization without further delay, finally prevailed. As usual the neighborhood showed its interest in what we did; and though my comrade and I had carefully selected men from the ranks of the unemployed to move our belongings, when all was accomplished not one of them could be induced to take a penny for the work.

From this first house have since developed the manifold activities in city and country now incorporated as the Henry Street Settlement.

I should like to make it clear that from the beginning we were most profoundly moved by the wretched industrial conditions which were constantly forced upon us. In succeeding chapters I hope to tell of the constructive programmes that the people themselves have evolved out of their own hard lives, of the ameliorative measures, ripened out of sympathetic comprehension, and, finally, of the social legislation that expresses the new compunction of the community.

When I first entered the training-school my outpourings to the superintendent,—a woman touched with a genius for sympathy,—my youthful heroics, and my vow to “nurse the poor” were met with what I deemed vague reference to the “Mission.” Afterwards when I sought guidance I found that in New York the visiting (or district) nurse was accessible only through sectarian organizations or the free dispensary.

As our plan crystallized my friend and I were certain that a system for nursing the sick in their homes could not be firmly established unless certain fundamental social facts were recognized. We tried to imagine how loved ones for whom we might be solicitous would react were they in the place of the patients whom we hoped to serve. With time, experience, and the stimulus of creative minds our technique and administrative methods have naturally improved, but this test gave us vision to establish certain principles, whose soundness[27] has been proved during the growth of the service.

We perceived that it was undesirable to condition the nurse’s service upon the actual or potential connection of the patient with a religious institution or free dispensary, or to have the nurse assigned to the exclusive use of one physician, and we planned to create a service on terms most considerate of the dignity and independence of the patients. We felt that the nursing of the sick in their homes should be undertaken seriously and adequately; that instruction should be incidental and not the primary consideration; that the etiquette, so far as doctor and patient were concerned, should be analogous to the established system of private nursing; that the nurse should be as ready to respond to calls from the people themselves as to calls from physicians; that she should accept calls from all physicians, and with no more red-tape or formality than if she were to remain with one patient continuously.

The new basis of the visiting-nurse service which we thus inaugurated reacted almost immediately upon the relationship of the nurse[28] to the patient, reversing the position the nurse had formerly held. Chagrin at having the neighbors see in her an agent whose presence proclaimed the family’s poverty or its failure to give adequate care to its sick member was changed to the gratifying consciousness that her presence, in conjunction with that of the doctor, “private” or “Lodge,”[1] proclaimed the family’s liberality and anxiety to do everything possible for the sufferer. For the exposure of poverty is a great humiliation to people who are trying to maintain a foothold in society for themselves and their families.

My colleague and I realized that there were large numbers of people who could not, or would not, avail themselves of the hospitals. It was estimated that ninety per cent. of the sick people in cities were sick at home,—an estimate which has been corroborated (1913-14) by the investigation of the Committee of Inquiry into the Departments of Health, Charities, and Bellevue and Allied Hospitals of New York,—and a humanitarian civilization demanded that something of the nursing care given in hospitals should be accorded to sick people in their homes.

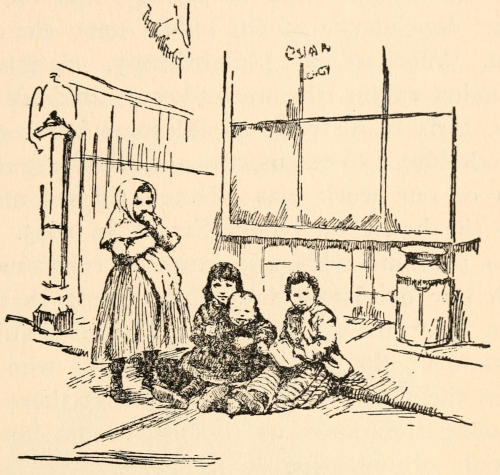

The Nurse in the Tenement

Ninety per cent. of the sick of the city remain at home

We decided that fees should be charged when[29] people could pay. It was interesting to discover that, although nominal in amount compared with the cost of the service, these fees represented a much larger proportion of the wage in the case of the ordinary worker who paid for the hourly service than did the fee paid by a man with a salary of $5,000, who engaged the full time of the nurse. Our plan, we reasoned, was analogous to the custom of “private” hospitals, which give free treatment or charge according to the resources of the ward patients. Both private hospitals and visiting nursing are thereby lifted out of “charity” as comprehended by the people.

We felt that for economic reasons valuable and expensive hospital space should be saved for those for whom the hospital treatment is necessary; and an obvious social consideration was that many people, particularly women, cannot leave their homes without imperiling, or sometimes destroying, the home itself.

Almost immediately we found patients who needed care, and doctors ready to accept our services with probably the least amount of friction[30] possible under the circumstances; for those doctors who had not been internes in the hospitals were unfamiliar with the trained nurse, whose work was little known at that time outside the hospitals and the homes of the well-to-do.

Despite the neighborhood’s friendliness, however, we struggled, not only with poverty and disease, but with the traditional fate of the pioneer: in many cases we encountered the inevitable opposition which the unusual must arouse. It seems almost ungracious to relate some of our first experiences with doctors. No one can give greater tribute than do the nurses of the settlement to the generosity of physicians and surgeons when we recall how often paying patients were set aside for more urgent non-paying ones; the counsel freely given from the highest for the lowliest; the eager readiness to respond. Occasionally sage advice came from a veteran who knew the people well and lamented the economic pressure which at times involved, to their spiritual disaster, doctors as well as patients.

The first day on which we set out to discover the sick who might need a nurse, my comrade found a woman with high temperature in an airless room, more oppressive because of the fetid odor from the bed. Service with one of[31] New York’s skilled specialists had trained the nurse well and she identified the symptoms immediately. “Yes, there was a Lodge doctor.—He had left a prescription.—He might come again.” With fine diplomacy an excuse was made to call upon the doctor and to assume that he would accept the nurse’s aid. My colleague presented her credentials and offered to accompany him to the case immediately, as she was “sure conditions must have changed since his last visit or he would doubtless have ordered” so-and-so,—suggesting the treatment the distinguished specialists were then using. He promised to go, and the nurse waited patiently[32] for hours at the woman’s bedside. When he arrived he pooh-poohed and said, “Nothing doing.” We had ascertained the financial condition of the family from the evidence of the empty push-cart and the fact that the fish-peddler was not in the market with his merchandise. Five dollars was loaned that night to purchase stock next day.

My comrade and I decided to visit the patient early the next morning, to mingle judgments on what action could be taken in this serious illness with due respect to established etiquette. When we arrived, the Lodge doctor and a “Professor” (a consultant) were in the sickroom, and our five dollars, left for fish, was in their possession. Cigarettes in mouths and hats on heads, they were questioning husband and wife, and only Dickens could have done justice to the scene. We were not too timid to allude to the poverty and the source of the fee, and felt free when we were told to “go ahead and do anything you like.” That permission we acted upon instantly and received, over the telephone, authority from the distinguished specialist to get to work. We were prudent enough to report the authority and treatment given, with solemn etiquette, to the physician in attendance, who in turn congratulated us on having helped him to save a life!

Not all our encounters with this class of practitioner were fruitful of benefit to their patients. Heartbreaking was the tragedy of Samuel, the twenty-one-year-old carpenter, and Ida, his bride. They had been boy and girl sweethearts in Poland, and the coming to America, the preparation of the clean two-roomed home, the expectation of the baby, made a pretty story which should have had happy succeeding chapters, the start was so good. Samuel knocked at our door, incoherent in his fright, but we were fast accustoming ourselves to recognize danger-signals, and I at once followed him to the top floor of his tenement.

Plain to see, Ida was dying. The midwife said she had done all she could, but she was obviously frightened. “No one could have done any better,” she insisted, “not any doctor”; but she had called one and he had left the woman lacerated and agonizing because the expected fee had been paid only in part. It was Samuel’s last dollar. The septic woman could only be sent to the city hospital. The ambulance surgeon was persuaded to let the boy husband ride with her, and he remained at the hospital until she and the baby died a few hours later.

Here my comrade and I came against the[34] stone wall of professional etiquette. It seemed as if public sentiment ought to be directed by the doctors themselves against such practices, but although I finally called upon one of the high-minded and distinguished men who had signed the diploma of the offending doctor, I could not get reproof administered, and my ardor for arousing public indignation in the profession was chilled. Later, when I heard protests from employers against insistence by labor organizations on the closed shop, it occurred to me that they failed to recognize analogies in the professional etiquette which conventional society has long accepted.

However, many friendly strong bonds were made and have been sustained with a large majority of the doctors during all the years of our service. We have mutual ties of personal and community interests, and work together as comrades; the practitioners with high standards for themselves and ideals for their sacred profession comprehend our common cause and strengthen our hands. It is rare now, although at first it was very frequent, that the physician who has called in the nurse for his patient demands her withdrawal when he himself has been dismissed. He has come to see that although the nurse exerts her influence to preserve his prestige, for the patient’s[35] sake as well as his own, nevertheless, emotional people, unaccustomed to the settled relation of the family doctor, may and often do change physicians from six to ten times in the course of one illness. The nurse, however, may remain at the bedside throughout all vicissitudes.

The most definite protest against the newer relationship came from a woman active in many public movements, who was a stickler for the orthodox method of procuring a visiting nurse only through the doctor. To illustrate the importance of freedom for the patients, I cited the case of the L⸺ family. A neighbor had called for aid. “Some kind of an awful catching sickness on the same floor I live on, to the right, front,” she whispered. A worn and haggard woman was lifting a heavy boiler filled with “wash” from the stove when I entered; on the floor in the other room three little children lay ill with typhoid fever, one of them with meningitis. The feather pillows, most precious possession, had been pawned to pay the doctor. The father dared not leave the shop, for money was needed, and all that he earned was far from enough. The mother, when questioned as to the delay in sending for nursing help, said that the doctor had frightened her from doing so by telling her that, if a nurse came, the children would surely be[36] sent to the hospital. No disinfectant was found in the house, and the mother declared that no instructions had been given her.

The nurse who took possession of the sickroom refrained from mentioning the hospital; but when the mother saw the skilled ministration, and the tired father, on his return from work, watched the deft feeding of the unconscious child, they awoke to their limitations. The poor, unskilled woman, bent with fatigue, then exclaimed, “O God, is that what I should have been doing for my babies?” When the nurse was about to leave them for the night the parents clung to her and asked her if a hospital would do as much as she had done. “More, much more, I hope,” she said. “I cannot give here what the little ones need.” Late at night three carriages started for the children’s ward of the hospital; the father, the mother, the nurse, each with a patient across the seat of the carriage.

Said the critic when I had finished my story: “I think the nurse should have asked permission of their doctor before she granted the request of the parents.”

All the social agencies combined have not been able to dislodge permanently the quack who preys upon ignorance and superstition. One day a teacher in a nearby school asked us[37] to visit a pupil who was highly excited and uncontrollable. The mother, when questioned, confessed that she had employed the “witch doctor” to exorcise the devil, who, he said, had taken possession of the girl. In our efforts to free the girl from this man’s control I invoked the aid of the parish priest, suggesting that his powers were being usurped. The County Medical Society finally secured conviction of the “doctor” on the charge of practicing without a license.

In the Italian quarter this species still preys upon the superstitious fears of some of the people, and the secrecy involved in his “treatment” makes permanent riddance extremely difficult. The people on the whole, however, give remarkable response to the “American” custom of employing a regular practitioner and the visiting nurse.

In this country, unfortunately, we have little data on morbidity. Statisticians desirous of obtaining figures for study have found interesting material in our files, and it has been possible to make comparison of the results of hospital and home treatment. Those who are familiar with the discussion upon papers presented by children’s specialists in recent[38] conferences on the saving of child life have had their attention drawn to the disadvantage of institutional treatment. Discussion of this subject is recent, and the laity do not always know that certain complications incident to the hospital care of children are obviated by keeping them at home. Among these are cross-infections, while the high mortality among infants in hospitals has long been recognized and deplored as unavoidable.

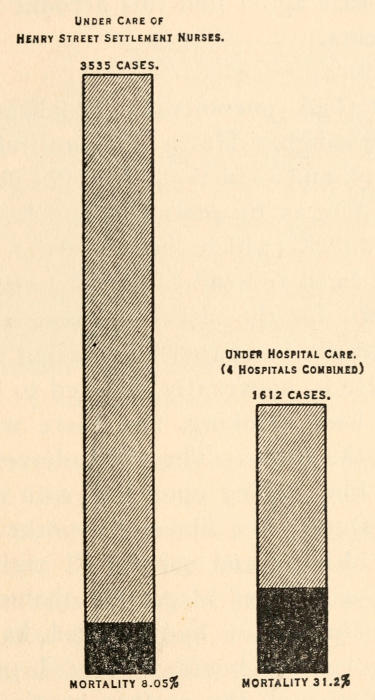

We soon found that children’s diseases, particularly those of brief duration, lent themselves most advantageously to home treatment. Our records show that in 1914 the Henry Street staff cared for 3,535 cases of pneumonia of all ages, with a mortality rate of 8.05 per cent. For purposes of comparison four large New York hospitals gave us their records of pneumonia during the same period. Their combined figures totaled 1,612, with a mortality rate of 31.2 per cent. Among children under two—the age most susceptible to unfortunate termination of this disorder—the mortality rate from pneumonia in one hospital was 51 per cent., and the average of the four was 38 per cent., while among those of a corresponding age cared for by our nurses it was 9.3 per cent.

Doctors and nurses highly trained in hospital routine are apt to be hospital propagandists[39] until they learn by experience that there is justification for the resistance, on the part of mothers, to the removal of their children to institutions, and that even in homes which, at first glance, it seems impossible to organize in accordance with sickroom standards, the little patients’ chances for recovery are better than when sent away. Diseases requiring climatic[40] or operative treatment, or peculiar apparatus, must usually be excluded from home care.

In a letter written to a friend more than twenty years ago I find this account of one of our patients:

“Peter had pneumonia, complicated with whooping-cough. He is a beautiful yellow-haired boy, and even if the hospital could have admitted him, or his mother would have agreed to his removal (which she wouldn’t), I should not have liked to send him. The sense of responsibility for the sick child seemed a force that could not be spared for rousing an erring father. He is, apparently, devoted to the child, but had been drinking, and there was not a dollar in the house. The child, desperately ill, clung to him, calling upon him with endearing names. During the illness he worked all day (he is a driver) and sat up all night, and I think he will never forget his shame and remorse. The doctor had ordered bath treatments every two hours. These I gave until eight o’clock and the mother continued them after my last visit, but when the temperature was highest she was worn out, and active night-nursing seemed imperative. This Miss S⸺ willingly undertook—a service more difficult than appears in the mere telling, for the vermin[41] in these old houses are horribly active at night, and this sweet girl ended her first vigil with neck and face inflamed from bites. Yet the people themselves were clean, and in this were not blameworthy. There is nothing harder to endure than to watch by a night sick-bed in these old, worn houses and see the crawling creatures and the babes so accustomed to them that their sleep is scarcely disturbed. Peter has had a beautiful recovery, rewarding his nurses by a most satisfactory return to a normal state of good health.”

Convalescent Home—“The Rest.”

The staff, which in the beginning consisted of two nurses, my friend and myself, has been increased until it is now large enough to answer[42] calls from the sick anywhere in the boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx, and the calls in the year 1913-14 came from nearly 1,100 more patients than the combined total of those treated during the same period in three of the large hospitals in New York—a comparison valuable chiefly as measuring the growing demand of the sick for the visiting nurse.

The service, though covering so wide a territory, is capable of control and supervision. The division into districts, with separate staffs for contagious and obstetrical cases, may be compared to the hospital division into wards. Like the hospital, it has a system of bedside notes, case records, and an established etiquette between physicians, nurses, and patients. Those that can best be cared for in the hospitals are sent there, the sifting process being accomplished by the doctors and nurses working together. Approximately ten per cent. of our patients are sent to the hospitals.

Serious nurses are gratified that the former casual and almost sentimental attitude of the public toward them and their work has been replaced by a demand for standards of efficiency.

Enthusiasm, health, and uncommon good sense on the part of the nurse are essential, for without the vision of the importance of[43] their task they could not long endure the endless stair-climbing, the weight of the bag, and the pulls upon their emotions.

There has been an extraordinary development of the visiting-nurse service throughout the country since we began our rounds, and the practical arguments for sustaining such work would seem irresistible. It requires imagination, however, to visualize the steady, competent, continuous routine so quietly performed, unseen by the public, and its financial support is the more precarious because there can be no public reminder of its existence by impressive buildings and monuments of marble.

The work begun from the top floor of the tenement comprised, in simple forms, those varied lines of activity which have since been developed into the many highly specialized branches of public health nursing now covering the United States and engaging thousands of nurses.[2]

In trying to forestall every obstacle to the establishment of our nursing service on the East Side, it seemed desirable to have some connection with civic authority. Through a mutual friend I met the President of the Board of Health and, I fear rather presumptuously, asked that we be given some insignia. Desirous of serving his friend and tolerant of my intense earnestness, he sanctioned our wearing a badge which had engraved on its circle, “Visiting Nurse. Under the Auspices of the Board of Health.”

As it transpired, we did not find it necessary[45] or always felicitous to utilize this privilege, but our connection with the Board of Health was not a perfunctory or merely complimentary one. We found from the beginning an inclination on the part of the officials of the department to treat us more or less like comrades. Every night, during the first summer, I wrote to the physician in charge, reporting the sick babies and describing the unsanitary conditions Miss Brewster and I found, and we received many encouraging reminders that what we were doing was considered helpful.

In the new activity for the promotion of public health many campaigns have been waged to popularize the study of social diseases. Education is the watchword, and where emphasis is laid upon the preservation of health rather than upon the treatment of disease, the nurses constitute an important factor. Appreciation of this is recorded by the Commission which drafted the new health law for New York State (1913). “The advent of trained nursing,” says its report, “marks not only a new[46] era in the treatment of the sick, but a new era in public health administration.” This Commission also created the position of Director of the Division of Public Health Nursing in the state department of health.

I had been downtown only a short time when I met Louis. An open door in a rear tenement revealed a woman standing over a washtub, a fretting baby on her left arm, while with her right she rubbed at the butcher’s aprons which she washed for a living.

Louis, she explained, was “bad.” He did not “cure his head,” and what would become of him, for they would not take him into the school because of it? Louis, hanging the offending head, said he had been to the dispensary a good many times. He knew it was awful for a twelve-year-old boy not to know how to read the names of the streets on the lamp-posts, but “every time I go to school Teacher tells me to go home.”

It needed only intelligent application of the dispensary ointments to cure the affected area, and in September I had the joy of securing the boy’s admittance to school for the first time in his life. The next day, at the noon recess, he fairly rushed up our five flights of stairs in the[47] Jefferson Street tenement to spell the elementary words he had acquired that morning.

It had been hard on Louis to be denied the precious years of school, yet one could sympathize with the harassed school teachers. The classes were overcrowded; there were frequently as many as sixty pupils in a single room, and often three children on a seat. It was, perhaps, not unnatural that the eczema on Louis’s head should have been seized upon as a legitimate excuse for not adding him to the number. Perhaps it was not to be expected that the teacher should feel concern for one small boy whom she might never see again, or should realize that his brief time for education was slipping away and that he must go to work fatally handicapped because of his illiteracy.

The predecessor of our present superintendent of schools had apparently given no thought to the social relationship of the school to the pupils. The general public, twenty years ago, had no accurate information concerning the schools, and, indeed, seemed to have little interest in them. We heard of flagrant instances of political influence in the selection and promotion of teachers, and later on we had actual knowledge of their humiliation at being forced to obtain through sordid “pull”[48] the positions to which they had a legitimate claim. I had myself once been obliged to enter the saloon of N⸺, the alderman of our district, to obtain the promise of necessary and long-delayed action on his part for the city’s acceptance of the gift of a street fountain, which I had been indirectly instrumental in securing for the neighborhood. I had been informed by his friends that without this attention he would not be likely to act.

Louis set me thinking and opened my mind to many things. Miss Brewster and I decided to keep memoranda of the children we encountered who had been excluded from school for medical reasons, and later our enlarged staff of nurses became equally interested in obtaining data regarding them. When one of the nurses found a small boy attending school while desquamating from scarlet fever, and, Tom Sawyer-like, pulling off the skin to startle his little classmates, we exhibited him to the President of the Department of Health, and I then learned that the possibility of having physicians inspect the school children was under discussion, and that such evidence of its need as we could produce would be helpful in securing an appropriation for this purpose.

I had come to the conclusion that the nurse would be an essential factor in making effective[49] whatever treatment might be suggested for the pupils, and, following an observation of mine to this effect, the president asked me to take part, as nurse, in the medical supervision in the schools. This offer it did not seem wise to accept. We were embarking upon ventures of our own which would require all our faculties and all our strength. It seemed better to be free from connections which would make demand upon our energies for routine work outside the settlement. Moreover, the time did not seem ripe for advocating the introduction of both the doctor and the nurse. The doctor himself, in this capacity, was an innovation. The appointment of a nurse would have been a radical departure.

In 1897 the Department of Health appointed the first doctors; one hundred and fifty were assigned to the schools for one hour a day at[50] a salary of $30 a month. They were expected to examine for contagious diseases and to send out of the classrooms all those who showed suspicious symptoms. It proved to be a perfunctory service and only superficially touched the needs of the children.

In 1902, when a reform administration came into power, the medical staff was reduced and the salary increased to $100 a month, while three hours a day were demanded from the doctors. The Health Commissioner of that administration, an intelligent friend of children, now ordered an examination of all the public school pupils, and New York was horrified to learn of the prevalence of trachoma. Thousands of children were sent out of the schools because of this infectious eye trouble, and in our neighborhood we watched many of them, after school hours, playing with the children for whose protection they had been excluded from the classrooms. Few received treatment, and it followed that truancy was encouraged, and, where medical inspection was most thorough, the classrooms were depleted.

The President of the Department of Education and the Health Commissioner sought for guidance in this predicament. Examination by physicians with the object of excluding children from the classrooms had proved a doubtful[51] blessing. The time had come when it seemed right to urge the addition of the nurse’s service to that of the doctor. My colleagues and I offered to show that with her assistance few children would lose their valuable school time and that it would be possible to bring under treatment those who needed it. Reluctant lest the democracy of the school should be invaded by even the most socially minded philanthropy, I exacted a promise from several of the city officials that if the experiment were successful they would use their influence to have the nurse, like the doctor, paid from public funds.

Four schools from which there had been the greatest number of exclusions for medical causes were selected, and an experienced nurse, who possessed tact and initiative, was chosen from the settlement staff to make the demonstration. A routine was devised, and the examining physician sent daily to the nurse all the pupils who were found to be in need of attention, using a code of symbols in order that the children might be spared the chagrin of having diseases due to uncleanliness advertised to their associates.

With the equipment of the settlement bag and, in some of the schools, with no more than the ledge of a window or the corner of a room[52] for the nurse’s office, the present system of thorough medical inspection in the schools and of home visiting was inaugurated. Many of the children needed only disinfectant treatment of the eyes, collodion applied to ringworm, or instruction as to cleanliness, and such were returned at once to the class with a minimum loss of precious school time. Where more serious conditions existed the nurse called at the home, explained to the mother what the doctor advised, and, where there was a family physician, urged that the child should be taken to him. In the families of the poor information as to dispensaries was given, and where the mother was at work, and there was no one free to take the child to the dispensary, the nurse herself did this. Where children were sent to the nurse because of uncleanliness, the mother was given tactful instruction and, when necessary, a practical demonstration on the child himself.

A Short Cut over the Roofs of the Tenements

One month’s trial proved that, with the exception of the very small proportion of major contagious and infectious diseases, the addition of the nurse to the staff made it possible to reverse the object of medical inspection from excluding the children from school to keeping the children in the classroom and under treatment. An enlightened Board of Estimate and[53] Apportionment voted $30,000 for the employment of trained nurses, the first municipalized school nurses in the world, now a feature of medical school supervision in many communities in this country and in Europe.

The first nurse was placed on the city payroll in October, 1902, and this marked the beginning of an extraordinary development of the public control of the physical condition of children. Out of this innovation New York City’s Bureau of Child Hygiene has grown.

The Department of Health now employs 650 nurses for its hospital and preventive work. Of this number 374, in the year 1914, were engaged for the Bureau of Child Hygiene.

Poor Louis, who all unconsciously had started the train of incidents that led to this practical reform, has long since moved from his Hester Street home to Kansas, and was able to write us, as he did with enthusiasm, of his identification with the West.

Our first expenditures were for “sputum cups and disinfectants for tuberculosis patients.” The textbooks had said that Jews were practically immune from this disease, and here we found ourselves in a dense colony of the race with signs everywhere of the white plague,[54] which we soon thought it fitting to name “tailors’ disease.”

Long before the great work was started by the municipality to combat its ravages through education and home visitation, we organized for ourselves a system of care and instruction for patients and their families, and wrote to the institutions that were known to care for tuberculosis cases for the addresses of discharged patients, that we might call upon them to leave the cups and disinfectants and instruct the families.

Since 1904 the anti-tuberculosis movement has been greatly accelerated, and although it is pre-eminently a disease of poverty and can never be successfully combated without dealing with its underlying economic causes—bad housing, bad workshops, undernourishment, and so on—the most immediate attack lies in education in personal hygiene. For this the approach to the families through the nurse and her ability to apply scientific truth to the problems of human living have been found to be invaluable.[3]

Infant mortality is also a social disease—“poverty[55] and ignorance, the twin roots from which this evil springs.” There is a large measure of preventable ignorance, and in the efforts for the reduction of infant mortality the intelligent reaction of the tenement-house mother has been remarkably evidenced. In the last analysis babies of the poor are kept alive through the intelligence of the mothers. Pasteurized or modified milk in immaculate containers is of limited value if exposed to pollution in the home, or if it is fed improperly and at irregular periods.

The need of giving the mother training seemed so evident that, in the course of lessons given on the East Side antedating our nursing service, I had demonstrated with a primitive sterilizer a simple method of insuring “safe” milk for babies.

The settlement established a milk station in 1903, when one of its directors began sending milk of high grade from his private dairy. Following our principle of building up the homes wherever possible, the modification of the milk[56] has always been taught there. The nurses report that it is very rare to find a woman who cannot learn the lesson when made to understand its importance to her children.

Children under two years who show the greatest need are given the preference in admission to our clinic. Excellent physicians practicing in the neighborhood have contributed their services as consultants, and conferences are held regularly. In 1914 the number of infants cared for was 518 and the mortality 1.8 per cent. The previous year, with 400 infants, the mortality was one-half of one per cent.

The Health Commissioner of Rochester, N. Y., a pioneer in his specialty, founded municipal milk stations for that city in 1897. He states that the reduction of infant mortality that followed the establishment of the stations was due, not so much to the milk, but to the education that went out with the milk through the nurse and in the press.

In 1911 New York City authorized the municipalization of fifteen milk stations, and so[57] satisfactory was the result that the next year the appropriation permitted more than the trebling of this number. A nurse is attached to each station to follow into the homes and there lay the foundation, through education, for hygienic living. A marked reduction in infant mortality has been brought about and, moreover, a realization, on the part of the city, of the immeasurable social and economic value of keeping the babies alive.

The Federal Children’s Bureau in its first report on the study of infant mortality in the United States showed that, in the city selected for investigation, the infant death rate, in those sections where conditions were worst, was more than five times that in the choice residential sections.

This report constitutes a serious indictment of society, and should goad civic and social conscience to aggressive action. But there are evidences (and, indeed, the existence of the Bureau is one) that the public is beginning to realize the profound importance in our national life of saving the children that are born.

Perhaps nothing indicates more impressively our contempt for alien customs than the general attitude taken toward the midwife. In[58] other lands she holds a place of respect, but in this country there seems to be a general determination on the part of physicians and departments of health to ignore her existence and leave her free to practice without fit preparation, despite the fact that her services are extensively used in humble homes. In New York City the midwife brings into the world over forty per cent. of all the babies born there, and ninety-eight per cent. of those among the Italians.

We had many experiences with them, beginning with poor Ida, the carpenter’s wife, and some that had the salt of humor. Before our first year had passed I wrote to the superintendent of a large relief society operating in our neighborhood, advising that the society discontinue its employment of midwives as a branch of relief, because of their entire lack of standards and their exemption from restraining influence.

To force attention to the harmful effect of leaving the midwife without training in midwifery and asepsis free to attend women in childbirth, the Union Settlement in 1905 financed an investigation under the auspices of a committee of which I was chairman.

A trained nurse was selected to inquire into[59] and report upon the practice of the midwives. The inquiry disclosed the extent to which habit, tradition, and economic necessity made the midwife practically indispensable, and gave ample proof of the neglect, ignorance, and criminality that prevailed; logical consequences of the policy that had been pursued. The Commissioner of Health and eminent obstetricians now co-operated to improve matters, and legislation was secured making it mandatory for the Department of Health to regulate the practice of midwifery. Five years later the first school for midwives in America was established in connection with Bellevue Hospital.

Part of the duty assigned to nurses of the Bureau of Child Hygiene is to inspect the bags[60] of the midwives licensed to practice, and to visit the new-born in the campaign to wipe out ophthalmia neonatorum, that tragically frequent and preventable cause of blindness among the new-born.

These are a few of the manifestations of the new era in the development of the nurse’s work. She is enlisted in the crusade against disease and for the promotion of right living, beginning even before life itself is brought forth, through infancy into school life, on through adolescence, with its appeal to repair the omissions of the past. Her duties take her into factory and workshop, and she has identified herself with the movement against the premature employment of children, and for the protection of men and women who work that they may not risk health and life itself while earning their living. The nurse is being socialized, made part of a community plan for the communal health. Her contribution to human welfare, unified and harmonized with those powers which aim at care and prevention, rather than at police power and punishment, forms part of the great policy of bringing human beings to a higher level.

With the incorporation of the nurse’s service in municipal and state departments for the preservation of health, other agencies, under[61] private and semi-public auspices, have expanded their functions to the sick.

I had felt that the American Red Cross Society held a unique position among its sister societies of other nations, and that in time it might be an agency that could consciously provide valuable “moral equivalents for war.” The whole subject, in these troubled times, is revived in my memory, and I find that in 1908 I began to urge that in a country dedicated to peace it would be fitting for the American Red Cross to consecrate its efforts to the upbuilding of life and the prevention of disaster, rather than to emphasize its identification with the ravages of war.

The concrete recommendation made was that the Red Cross should develop a system of visiting nursing in the vast, neglected country areas. The suggestion has been adopted and an excellent beginning made with a Department of Town and Country Nursing directed by a special committee. A generous gift started an endowment for its administration. Many communities not in the registered area and remote from the centers of active social propaganda will be given stimulus to organize for nursing service, and from this other medical and social measures will inevitably grow. It requires no far reach of the imagination to visualize[62] the time when our country will be districted from the northernmost to the southernmost point, with the trained graduate nurse entering the home wherever there is illness, caring for the patient, preaching the gospel of health, and teaching in simplest form the essentials of hygiene. Such an organization of national scope, its powers directed toward raising the standard in the homes without sacrifice of independence, is bound to promote the social progress of the nation.

In the year 1909 the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company undertook the nursing of its industrial policyholders—an important event in the annals of visiting nursing. I had suggested the practicality of this to one of the officials of the company, a man of broad experience, and he, immediately responsive, provided opportunity for me to present to his colleagues evidence of the reduction of mortality, the hastening of convalescence, and the ability to bring to sick people the resources that the community provides for treatment through the institution of visiting nursing.

The company employed our staff to care for its patients, and the experiment has been extended until a nursing service practically covers[63] its industrial policyholders in Canada and the United States. The company thereby gave an enormous impetus to education and hygiene in the homes and treatment of the sick on the only basis that makes it possible for persons of small means to receive nursing without charity—namely, through insurance.

The demand for the public health nurse coming from all sides was so great that for a time it could not be adequately met. Women of initiative and personality with broad education were needed, for much of the work required pioneering zeal. Instructive inspection, on the nurse’s part, like other educational work, requires suitable and sound preparation, a superstructure of efficiency upon woman’s natural aptitudes.

The Henry Street Settlement and other groups with well-established visiting nursing systems responded to the need by offering opportunities for post-graduate training and experience in the newly opened field of public health nursing, and sought co-ordination with formal educational institutions for instruction in social theories and pedagogy. In 1910 the[64] Department of Nursing and Health was created at Teachers College, Columbia University, embracing in its completed form the Department of Hospital Economics established there in 1899 by the efforts of training-school superintendents. This department is in affiliation with the settlement. At least four important training-schools for nurses are now working under the direction of universities, and other provision has been made to give education supplementary to the hospital training.

Nurses themselves have taken the initiative in securing the means for equipping women in their profession to meet the new requirements. They are providing helpful literature and finding stimulating associations with others enlisted in similar efforts for human welfare. I had the honor to be elected first president of the National Organization for Public Health Nursing. At the conference held in 1913 (less than a year after the formation of the society) an assemblage of women gathered from all parts of the country to seek guidance and inspiration for this work, and something that was very like religious fervor characterized their meetings.

The need of consecration to the sick and the young that has touched generation after generation with new impulse was manifested in[65] their eagerness to serve the community. From the root of the old gospel another branch has grown, a realization that the call to the nurse is not only for the bedside care of the sick, but to help in seeking out the deep-lying basic causes of illness and misery, that in the future there may be less sickness to nurse and to cure.

A pleasant indication that the academic world reached out its fellowship to the nurses in their zeal for public service was given some months later when Mt. Holyoke College, at the commemoration of its seventy-fifth anniversary, honored me by conferring on me the LL.D. degree.

The visitor who sees our neighborhood for the first time at the hour when school is dismissed reacts with joy or dismay to the sight, not paralleled in any part of the world, of thousands of little ones on a single city block.

Out they pour, the little hyphenated Americans, more conscious of their patriotism than perhaps any other large group of children that could be found in our land; unaware that to some of us they carry on their shoulders our hopes of a finer, more democratic America, when the worthy things they bring to us shall be recognized, and the good in their old-world traditions and culture shall be mingled with the best that lies within our new-world ideals. Only through knowledge is one fortified to resist the onslaught of arguments of the superficial observer who, dismayed by the sight, is conscious only of “hordes” and “danger to America” in these little children.

They are irresistible. They open up wide vistas of the many lands from which they[67] come. The multitude passes: swinging walk, lagging step; smiling, serious—just little children, forever appealing, and these, perhaps, more than others, stir the emotions. “Crime, ignorance, dirt, anarchy!” Not theirs the fault if any of these be true, although sometimes perfectly good children are spoiled, as Jacob Riis, that buoyant lover of them, has said. As a nation we must rise or fall as we serve or fail these future citizens.

Their appeal suggests that social exclusions and prejudices separate far more effectively than distance and differing language. They bring a hope that a better relationship—even the great brotherhood—is not impossible, and that through love and understanding we shall come to know the shame of prejudice.

Instinctively the sympathetic observer feels the possibilities of the young life that passes before the settlement doors, and sincerity demands that something shall be known of the conditions, economic, political, religious, or, perchance, of the mere spirit of venture that brought them here. How often have the conventionally educated been driven to the library to obtain that historic perspective of the people[69] who are in our midst, without which they cannot be understood! What fascinating excursions have been made into folklore in the effort to comprehend some strange custom unexpectedly encountered!

When the anxious friends of the dying Italian brought a chicken to be killed over him, the tenement-house bed became the sacrificial altar of long ago; and when the old, rabbinical-looking grandfather took hairs from the head of the sick child, a bit of his finger-nail, and a garment that had been close to his body, and cast them into the river while he devoutly prayed that the little life might be spared, he declared his faith in the purification of running water.

It is necessary to spend a summer in our neighborhood to realize fully the conditions under which many thousands of children are reared. One night during my first month on the East Side, sleepless because of the heat, I leaned out of the window and looked down on Rivington Street. Life was in full course there. Some of the push-cart venders still sold their wares. Sitting on the curb directly under my[70] window, with her feet in the gutter, was a woman, drooping from exhaustion, a baby at her breast. The fire-escapes, considered the most desirable sleeping-places, were crowded with the youngest and the oldest; children were asleep on the sidewalks, on the steps of the houses and in the empty push-carts; some of the more venturesome men and women with mattress or pillow staggered toward the riverfront or the parks. I looked at my watch. It was two o’clock in the morning!

Many times since that summer of 1893 have I seen similar sights, and always I have been impressed with the kindness and patience, sometimes the fortitude, of our neighbors, and I[71] have marveled that out of conditions distressing and nerve-destroying as these so many children have emerged into fine manhood and womanhood, and often, because of their early experiences, have become intelligent factors in promoting measures to guard the next generation against conditions which they know to be destructive.