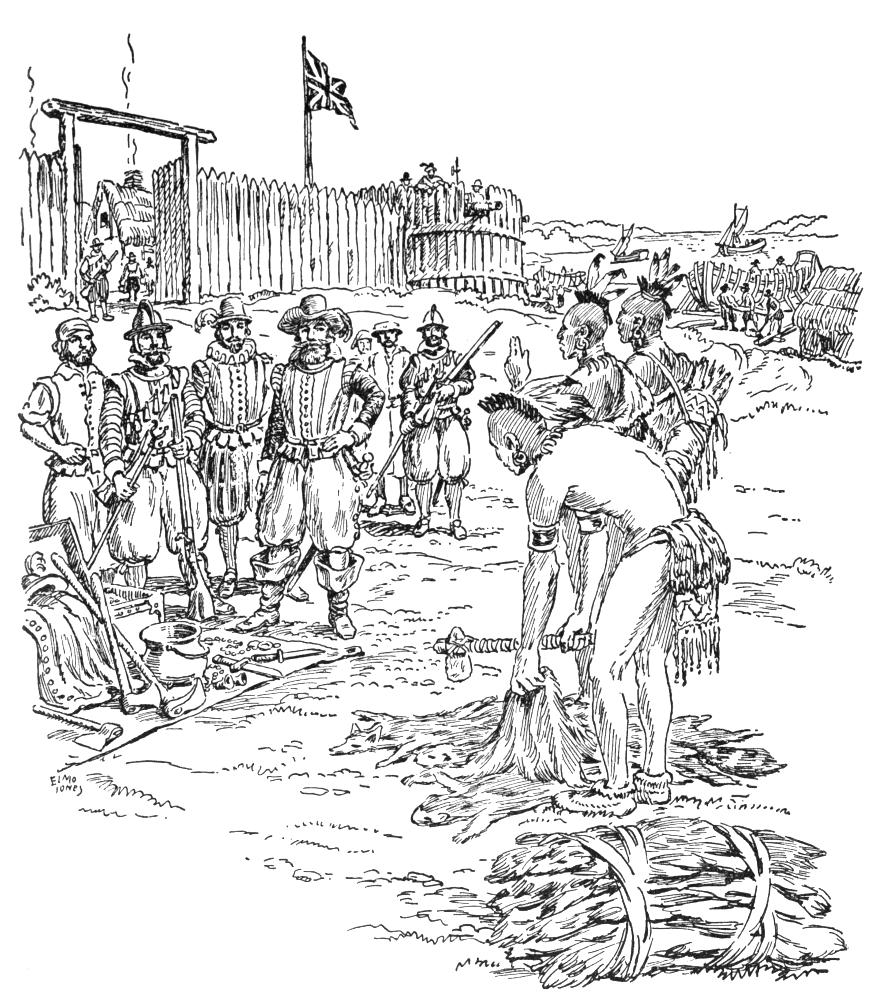

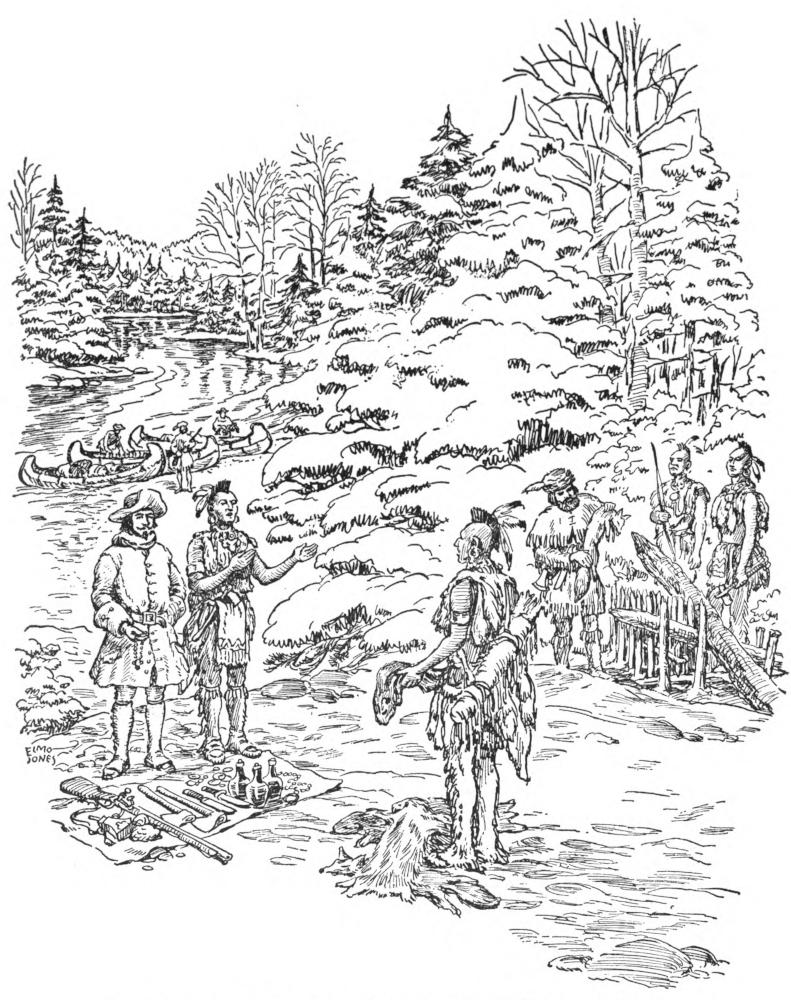

THE FUR TRADE FURNISHED THE MEANS OF CONTACT BETWEEN

WIDELY DIVERGENT CULTURES.

Nathaniel C. Hale graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1925. After serving in the Army, he resigned his commission to enter business, but joined the Army again on the outbreak of World War II. He was Commandant of an Officers Training School prior to overseas duty with the Signal Corps. Since the war, Colonel Hale has become well known as an author and historian. In 1952 he received the annual award of the Society of Colonial Wars in New York for his book, VIRGINIA VENTURER, which was cited as the outstanding contribution of the year in the field of American colonial history. Colonel Hale and his wife, both of Southern birth, make their home in the Rittenhouse Square section of Philadelphia and spend part of their summers at their cottage in Cape May, New Jersey.

A Biography of William Claiborne

1600-1677

THE FUR TRADE FURNISHED THE MEANS OF CONTACT BETWEEN

WIDELY DIVERGENT CULTURES.

THE STORY OF FUR

and the

Rivalry for Pelts in Early America

By

Nathaniel C. Hale

RICHMOND, VA.

THE DIETZ PRESS, INCORPORATED

Copyright by

NATHANIEL C. HALE

© 1959

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

[Pg vii]

To My Grandchildren

The story of fur is as old as the story of man. Some brief account of ancient man’s quest for fur is included in the beginning of this book. However, the main narrative is concerned with the rivalry for pelts in early America.

The discoverers of our country came here looking for gold. They found it in fur. After that the fur trade formed the pattern of exploration, trade and settlement. It sustained the colonies along the Atlantic seaboard until they could be rooted in agriculture and it was a controlling factor in the westward movement of our population.

In the seventeenth century there was a seemingly insatiable demand in Europe for beaver pelts, inflated in no small degree by early laws prohibiting the use of cheaper furs in hat making. Since there was an apparently inexhaustible supply of these pelts in America, the fur trade quickly became the economic lifeblood of the colonies. On it was laid the cornerstone of American commerce.

On it, too, was laid the cornerstone of European imperialism on this continent, the prosecution of which was largely motivated by the energies of the mercantile classes of the nations involved. The merchants, their factors, and the fur traders, shaped colonial policies. The statesmen only signed the implementing documents.

It was the trader in quest of beaver who first met and conducted diplomatic relations with the Indians and who first challenged the claims of competing nations. Indeed, it was this fur trader in the wilderness, making allies and building palisaded trading posts, or forts, who determined colonial borders and who largely influenced the outcome of the imperialistic struggle for the continent.

That struggle culminated in the French and Indian War and that is the event which ends the story in this book. Pelts and Palisades does not pretend to be a comprehensive study of the[Pg viii] early American fur trade. Its only intent is to illustrate in narrative form the significant effect of that trade on the genesis of America and the westward movement of its people.

Included in the narrative are frank accounts of merchants and traders among our founding fathers who built their fortunes or their reputations on fur. As all the men who were prominent in this activity could not be named, only meaningful case histories that point up the pattern of the early fur trade have been cited. Fortunately, there are local histories, county and state, that do name most of these truly pioneer Americans and credit them with their individual accomplishments.

The era of the early fur trade, typified by the white trader and the Indian hunter, began drawing to a close after the French and Indian War. The white trader then became the trapper and a whole new conception of the fur trade in America developed as the frontier rolled across the plains and on to the Rocky Mountains. Today we may be on the threshold of still another era, that of the fur farmer.

In any case the fur industry continues to be big business in this country, total activity at all levels—raw furs, dressing and dyeing, and retail sales—being estimated at about one billion dollars. After exporting some twenty million dollars worth of domestic pelts, the United States annually consumes around two hundred million dollars worth of raw furs altogether—this, according to a recent bulletin of the Department of Commerce. About fifty percent of this consumption is imported.

Our imports are chiefly Persian lamb and caracul, mink, rabbit and squirrel. While the fur farms of this country produce great quantities of mink, fox, chinchilla and nutria, our principal domestic production of wild furs consists of muskrat, opossum, raccoon and mink. All other wild furs including “King Beaver” of colonial times run far behind this field.

Curiously enough, the lowly, unwanted muskrat of the seventeenth century is now the “King” of the wild furs. Its main domicile is the State of Louisiana. Because of the muskrat’s residence there Louisiana produces many more pelts, all fur-bearing animals included, than any other state in the union. Southern[Pg ix] Louisiana is in fact one of the most important fur producing areas on our continent. In that section alone there are approximately twenty thousand local trappers of muskrat, mink, otter and raccoon.

Altogether there are two million full or part-time trappers in the United States, bringing in about twenty million pelts a year. There are also some twenty thousand or more fur farms contributing several million pelts annually, although fur farming had its inception in this country not much more than thirty-five years ago. Additionally, there are the raw fur imports. To transform all these pelts into dressed and dyed furs and retail them to milady calls for the services of thousands of additional people at manufacturing, jobbing and dealer levels.

Even as in ancient times such a great outpouring of commercial energy and money for fur is mainly decreed by fashion. The arbiters of fashion are fickle of course, but at a recent showing of designer collections for women in New York it was said that fur and fur trimmings were everywhere, with mink currently in most popular favor. As one newspaper correspondent reported, hats were made of fur or trimmed with it; coats were collared, cuffed, bordered or lined with it; suits wore wide fur collars and revers; and evening gowns had deep hemline borders of fur. And not so long ago in the New York Times appeared a full page advertisement for a chair upholstered in fur, “the world’s most sumptuous hostess chair ... lavished with the enchanting elegance of genuine mink!”

The author wishes to acknowledge the many kindnesses of those who have been helpful to him. He is much indebted to the staffs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. He is also indebted to members of the General Society of Colonial Wars, the Netherlands Society, the Colonial Society of Pennsylvania and the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia who have assisted him in many ways. From papers he has delivered before these groups has come much of the material used in this book. The author is also very grateful to Professor Arthur Adams of Boston, Massachusetts for his criticism and advice.

[Pg x]

A bibliography of the works consulted in the preparation of the manuscript is appended, special acknowledgement being due to Doctor Amandus Johnson of Philadelphia for his published documentations of the Swedish fur trade in the Delaware valley.

And, to his wife, Eliska, the writer of this book is very thankful for her patient understanding during the many week ends that he spent on the manuscript.

Nathaniel C. Hale

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1959.

[Pg xi]

Friend, once ’twas Fame that led thee forth

To brave the Tropic Heat, the Frozen North;

Late it was Gold, then Beauty was the Spur;

But now our gallants venture but for Fur.

John Dryden, 1672.

[Pg 1]

It might be said that man’s first true possession was the fur skin of an animal.

Prehistoric mankind prowled the earth seeking food, shelter and mates—only those needs intended by nature to preserve him and to perpetuate his species. He had no accumulated wealth. Even his first crude weapons, rocks and sticks, were expendable. He had nothing material to treasure until he began to acquire coverings for his body.

Body coverings must have become useful to primitive man in the last glacial period, during the very evolution of human society. His earliest needs were doubtless served by the pelts of such cold-climate animals as the reindeer and the bear. Once Homo sapiens, stretched out on the floor of a chilly cave, experienced the warmth of fur skins accumulated from these animals that he had eaten, it could have been but a short step to using pelts as clothing. All the world was not cold however.

In the middle latitudes early man knew little of thickly furred animals, and had less need for warm garments. He used foliage, grasses and eventually goat and sheep skins as skirts to hide his uncleanness. It was probably no more than modesty, a primal sense of shame, that first prompted him to cover himself. Later, as he learned to shape and weave and to appreciate his art, he fashioned his clothing for adornment.

Then it was that pelts stripped from bowed chiefs of the colder countries came to be prized as rarities of beauty and usefulness, as kingly trophies. Conquerors adopted them as ornaments and symbols of victory and power. Fur became prime loot. For many generations of man, while contacts between peoples remained essentially war-like, prize pelts from the farthest corners of the known world were brought home by warriors as evidence of their prowess and as tribute to their rulers.

[Pg 2]

Some rulers among the rising civilizations of the ancient world made extravagant use of fur skins, especially the brightly hued pelts of the big cats.

Tradition has it that the voluptuous Assyrian queen, Semiramis, acquired eight thousand tiger skins during a plundering campaign in India. Presumably, much of this loot was used to decorate the palace and hanging gardens of sinful Babylon which this storied enchantress is supposed to have founded.

Pharaohs and high priests of ancient Egypt used quantities of lion, leopard and panther skins as ornamental and ceremonial pieces. Men of high position draped these colorful pelts over their shoulders, tying the paws in the back with ribbons. The tail of the lion was appended animal-fashion by pharaohs to impart the beast’s qualities to the wearer, and warriors stretched their frame-wood shields with leopard skins. Extant today is a wall painting on a tomb of the eighteenth dynasty which shows tax-paying Ethiopians bearing their tribute of pelts to an Egyptian king.

And, when barter finally joined hands with a war as a better means of contact between peoples, it was fur that helped bring it about. Evidence of such military commerce emerges from the mists of Greek antiquity. The legend of Jason and his quest for the Golden Fleece is in all likelihood the fanciful story of a fur trading expedition in the thirteenth or fourteenth century B.C.

Some students of Greek mythology interpret the Golden Fleece as symbolism of one kind or another. However, it is specifically identified in the legend as the pelt of a golden ram and ornamental pelts are shown in archaic bas-reliefs to have been an integral part of Greek culture.

The perils encountered by Jason and his adventurers, as first related by them, were probably intended to point up the difficulties of their achievement and to help guard the secrets of their trade-route discoveries. No doubt Greek hero worship contributed to the subsequent embellishment of the legend. But, if like most other folk tradition this epic of the Argonauts had its origin in some simple fact now obscured by the telling, that fact must lie in the Golden Fleece itself. Certainly, without its existence in some form, as the object of the voyage, there would be no motivation—no story.

[Pg 3]

But of course there is a story, and a good one, even after eliminating the delightful folk-tale embroidery.

For recognition of his right to the throne Prince Jason of Greece bargained with his crafty uncle, King Pelias, to go on a dangerous voyage to the Euxine Sea in search of the Golden Fleece. Jason planned well. All the gods and great heroes of Greece came to his assistance. With Juno’s help a ship called the Argo was built for the expedition. According to the legend it was capable of holding over fifty men, but the building of a ship to accommodate half that number would have been a gigantic accomplishment for those days. After manning the Argo with heroes selected for their particular talents in sailing, fighting and overcoming special dangers of the voyage, Jason set out on his quest.

The Argonauts were involved in many perilous adventures after they left Greece. Nevertheless, they negotiated the treacherous straits at the entrance to the Euxine Sea and followed its shore until at great length they came to the country of Colchis. There they bargained and fought against tremendous odds for the Golden Fleece, much the same as fur trading adventurers who crossed another unknown sea to a New World some three thousand years or more later.

But, when Jason returned with the treasure and placed it at the feet of Pelias, the king became very wrathful. It seems the fleece was no longer golden.

This is entirely believable, whether it was lambskin or something else. Assuredly, prime lambskin, even a mutated sort, could have had no more lustre than royal baum marten, ermine, sealskin or other fine pelts available to Jason in the region he had visited.

In any event Pelias thought he had a good excuse not to keep his end of the bargain with Jason, a common enough denouement in itself, one that has been acted out untold times in both history and fiction.

That is the plot of the legend, as related only to the probable fact of the fleece’s existence. How the fleece came into being, that is, how the golden ram descended from the heavens first into Greece and then betook himself to the far off country of Colchis to be slaughtered for his radiant coat, all would seem to lie in the realm of pure myth. So would many other imaginative[Pg 4] passages of the legend as recited variously by bards who have embroidered on the tale. And, of course, the episodic adventures of the Argonauts have little or no bearing on the plot.

The story in its origin does appear to have been simply that of a Greek expedition bent on military commerce in the Black Sea, the first organized fur trading voyage in recorded history.

From the ancient Greeks, too, comes the English word which describes the fur skin of an animal. Pelt, a contraction of peltry from the old Anglo-French pelterie, is derived from the Greek pelta. A pelta was a half shield made of the skin of an animal. It was carried by the warriors of Greece and later by the Romans. A foot soldier armed with a pelta and a short spear or javelin was called a peltast. Hence also the verb pelt, used to indicate repeated blows by striking or hurling missiles, as against a pelta.

Although the Greeks had competition on occasion from the Persians and others, they drove a great trade in the Black Sea for over a thousand years. At the Bosphorus they founded Byzantium, one of the world’s best known emporiums. Great quantities of fur trimmings for the tall bonnets and robes of the Mesopotamians were traded there. The felting used so extensively by the Scythians, as well as the valuable pelts which the Israelites used as temple decorations and as offerings to the deity, all passed through this famous fur market. And of course from Byzantium came the pelts which the Greeks themselves used so extravagantly as house decorations and body raiment, especially battle dress.

After the Romans took over Greece’s trade, they in turn carried on a brisk commerce in pelts through Byzantium where lambskin, marten, sable and ermine were exacted in vast quantities as tribute.

The market for pelts expanded tremendously under Rome’s driving demand for luxuries. From the Slavic steppes and forests and from the shores of the Black and Caspian Seas came all manner of pelts. Furs of the finest quality—pure white ermine, black fox and silvery sable—along with silks and gems, came by trade caravan from Mongolia and Cathay, across the Asian wastes. Down the Nile from deep in Africa travelled Ethiopians bearing their lion and leopard skins. Arabian traders, having[Pg 5] learned the law of the monsoon winds, crossed the Indian Ocean to bring prime pelts as well as spices and other riches from Hindustan and the Malay Archipelago to the Mediterranean.

Italy was the main center of the world’s commerce in pelts, with the Romans reaching out not only for the far eastern trade in precious fur such as sable and ermine but into northern Europe, to Flanders and even into Scandinavia for beaver, otter and bear—and for more ermine. For ermine was becoming the garment of state wherever royalty held court, pure white ermine being held in highest esteem. Demand for this regal fur far exceeded the means of supply. Not until the Germanic hordes cycloned down from the north did the impetus of this Italian trade in fine pelts abate.

Then all trade, culture, and even most western knowledge of the world, shrank almost into oblivion. The Dark Ages settled down upon civilized Europe.

It took the impact of Mohammed’s vicious attack on Christendom and Islam’s subsequent conquests in the Mediterranean to stir the western world from its lethargy. The resulting Holy Crusades awakened curiosity about Moslem luxuries and better ways of living. Western trade was restimulated; merchants again began bidding up fine furs.

There was a new, stepped-up demand for ermine pelts by dignitaries of the Church and other nobility. Fashion came to require quantities of mantles and robes of the royal white, as whole systems of protocol on the use of ermine were established. To indicate rank on state occasions the lustrous white robes of the nobility were often decorated with the ermine’s black tail tips or the paws of the black lamb. Decrees were issued permitting peers to wear trimmings of the white fur on their scarlet gowns. And, king and judge having originated as one, it was but natural that the judiciary came to be permitted the use of white ermine as the badge of high legal dignity, of purity.

The ermine, a slim little animal of the weasel family which produces a semi-durable pelt of soft, glossy fur, is thought to have gotten its name from Armenia, a fur center in ancient times. Medieval writers often referred to the ermine as the Armenian[Pg 6] rat. However it was the breed inhabiting the northern latitudes of Asia that was most sought after because of its snow-white fur.

In winter the live ermine’s coat ranges from creamy white in northern Europe to pure white in parts of Siberia; the tip of its tail is always black. During the summer the white fur usually darkens in varying degrees to a yellowish brown except for the underparts of the animal’s body. Medieval nobility’s choicest ermine pelts were those which were all pure white, except of course for the black tail tips. Because these came from Siberia they could be obtained only through eastern trade channels.

To make terminal contacts with these eastern channels eager Italian merchants risked their fortunes and their very lives. Eventually, like most frontier traders, they won through by individual enterprise. Commerce with the Moslems was a hazardous business however, even after two rising emporiums of Italy, Genoa and Venice, built armed navies to support it. But bartering and warring, sometimes between themselves, the Genoese and the Venetians extended their trade and their navies gained complete control of the Mediterranean, to make it once more the main western highway of Eurasian commerce.

These encounters, with the Arabs and the ancient cultures they had preserved, eventually reawakened a long dead interest in the far east too. In the thirteenth century the Venetian traveler, Marco Polo, penetrated beyond the Moslem barrier to the East, visited the Great Kublai Khan in Cathay and returned to write a wondrous tale about what he had seen in the Orient.

There was gold plate, and there were sapphires, rubies, emeralds and pearls to be had in the far eastern countries, just as the ancients had said. For proof, road-weary Marco Polo brought home with him samples of these jewels sewed in the linings of his tattered clothing. Also, in plenteous variety in the East he had found spices for seasoning and deodorizing, commodities for which all Europe yearned desperately during the middle ages.

And, Polo reported glowingly, there were silks, and priceless furs!

The clothes of the wealthy Tartars in the far east were for the most part of gold and silk stuffs, lined with costly furs, such[Pg 7] as sable and ermine and black fox, in the richest manner. Robes of vair were much to be seen also. These consisted of hundreds of tiny Siberian squirrel pelts, the grey backs and white bellies of which were joined together checker fashion. In winter the Tartars wore two gowns of pelts, one with the soft, comforting fur inward next to their skin, and the other with the fur outward to defend them against wind and snow.

Sable was esteemed the queen of furs in Mongolia. The dark, silver-tipped fur of the Siberian sable was thick and silky, the leather thin. According to Polo prime sable pelts, scarcely sufficient to line a mantle, were often worth two thousand besants of gold.

However, ermine appears to have been preferred in India where Ibn-Batootah, a famous Moorish traveller of the fourteenth century, reported an ermine pelisse was worth a thousand dinars, or rupees, whereas a pelisse of sable was worth only four hundred at the time.

In any case these two aristocrats of the weasel family, sable and ermine, depending on the quality of their pelts, vied for favor among the lords of the east, as did to some extent the rare black fox of the icy regions in the far north.

Polo said that when the Grand Khan of the Tartar Empire quit his palace for the chase he took ten thousand retainers with him, including his sons, the nobles of his court, his ladies, falconers and life guards. For this entourage great tents were provided, appointed luxuriously and stretched with silken ropes. The Khan’s sleeping tents and audience pavilions were covered on the outside with the skins of lions, streaked white, black and red, and so well joined together that no wind or rain could penetrate. On the inside they were lined with the costly pelts of ermines and sables. The Venetian marvelled at the skill and taste with which the inlaying of the pelts was accomplished.

When this intrepid adventurer travelled into northern Mongolia he found the country alive with traders and merchants. “The Merchants to buy their Furres, for fourteene dayes journey thorow the Desart, have set up for each day a house of Wood, where they abide and barter; and in Winter they use Sleds without wheeles, and plaine in the bottome, rising with a semi-circle[Pg 8] at the top or end, drawne easily on the Ice by beasts like great Dogs six yoked by couples, the Sledman only with his Merchant and Furres sitting therein.”

These fur traders showed the Venetian huge pelts, “twentie palms long,” taken from the white bear in the far north. That was the Region of Darkness, so-called because for “the most part of the Winter moneths the Sun appeares not, and the Ayre is thick and darkish.” There, Polo was told, the natives were pale, had no prince and lived like beasts. But in the polar summer when there was continuous daylight they caught multitudes of large black foxes, ermines, martens and sables.

Ibn-Batootah, who later travelled this country, told how the traders bartered with the mysterious inhabitants of the far north.

After encamping near the borders of the Region of Darkness the traders would deposit their bartering goods in a likely spot and return to their quarters. The next day on returning to the same place they might find beside their goods the skins of sable, ermine and other valuable furs. If a trader was satisfied with what he found, he took it; if not, he left it there. In the latter case the inhabitants of the Region of Darkness might then on another visit increase the amount of their deposit, or as often happened, they might pick up their furs and leave the goods of the foreign merchant untouched.

So far as the traders were concerned these people of the far north with whom they bartered might as well have been ghosts. The traders never saw them.

The pelts of all the polar animals were lusher and finer and consequently much more valuable than those found in the districts inhabited by the Tartars. Because of this the Tartars were often induced to undertake plundering expeditions in the Region of Darkness for furs, as well as for domesticated animals kept by the natives there. Invariably, it appears, the inhabitants simply sought safety in flight from the raiders, putting up no fight and never showing themselves.

Marco Polo said that lest the Tartar raiders lose their way during the long winter night, “they ride on Mares which have Colts sucking which they leave with a Guard at the entrance of that Countrey, where the Light beginneth to faile, and when they[Pg 9] have taken their prey give reynes to the Mares, which hasten to their Colts.” Continuing, he said that from this northern region came “many of the finest Furres of which I have heard some are brought into Russia.”

About the mysteries of Russia, Polo learned little. But he was certain that it was of vast extent, bordering in the north on the Region of Darkness and reaching to the “Ocean Sea.” Although there were many fine and valuable furs there, such as sable, it was not a land of trade he reported.

How wrong he was about that!

German merchants were long since firmly established with fur factories in Russia, and Norse sea-rovers had first tapped the trade of that land hundreds of years earlier.

During the dark centuries when western Europe was sinking in despair fierce Vikings in their horned helmets were traversing the Slavic lands, plundering as they went and dropping Arabian, Byzantine and Anglo-Saxon coins which later marked their routes. By way of the Volga and the Dvina the Norsemen brought back far-eastern spices and pearls obtained on the shores of the Caspian Sea in exchange for amber and tin. But chiefly they transported skins. They bartered Baltic furs for lustrous Oriental pelts and frequently used both slaves and coinage as media of exchange. By way of the Dneiper and other rivers they even traded on the Black Sea, and at Byzantium, portaging their dragon boats from stream to stream with marvelous facility.

In the ninth century the Norsemen established a truly great trading city of their own at Novgorod. It was located on a table-land where four main waterways of Russia converged to form trade routes to the Caspian, Black and Baltic Seas. Here the Vikings, inter-marrying with the natives, settled down and prospered in the riches of their commerce with the farthest corners of the world. Furs and other oriental luxuries, cloths, honey, spices, metals, and the wax consumed in such quantities by the Christians, all passed through their hands.

Rurik, the Norse leader of these Russified Scandinavians, or Varangians, built a castle and a fort at Novgorod in 862 to[Pg 10] protect the independence of the surrounding province, and thus was laid the foundation of Russia.

An ancient chronicler tells also of the wicked, fabulous trading city of Julin at the mouth of the Oder River on the Baltic Sea. The Saxons called it Winetha (Venice). It was inhabited mainly by pagan Slavs. But there were Norsemen there too, and in fact anyone could live and trade in this emporium of the north so long as he didn’t declare himself a Christian. Julin disappeared at an unknown date beneath the water due to the encroachments of the sea. Trusting in the wealth of its trade and despising God, it went the way of Sodom and Gomorrha according to Christian bards.

In the eleventh century whatever did remain of Julin belonged to the Christian Germans. German merchants, crossing the Elbe from the west, colonized the Oder valley and other Slavic lands on the shores of the Baltic. At Thorn in Poland they exchanged cloth and other goods for ermine, sable, fox and calabar (grey squirrel). They even penetrated Russia deeply for trade. At Novgorod they had a fur trading settlement active enough to prompt expressive protestations from the pious Canon Adam of Bremen.

“Pelts are plentiful as dung” in Russia, he wrote, but they are “for our damnation, as I believe, for per fas et nefas we strive as hard to come into the possession of a marten skin as if it were everlasting salvation.” According to him it was from this evil source in Russia “that the deadly sin of luxurious pride” had overspread the west.

Indeed, by comparison with the self-mortifying Christian standards of the time, luxury in dress was very pronounced among the rising German merchants and their wives. It was even more so among the men than among the women. The most conservative patricians and councillors wore cloth hoods ostentatiously trimmed with beaver and other fine fur, and long fur cloaks of exquisite quality. So proud were they of their finery that the Councillors of Bremen once forged a document pretending to prove that Godfrey of Bouillon during the First Crusade had vested them with the right to wear fur and gold chains.

[Pg 11]

The Church frowned upon the use of fur by the laity or any except the highest ecclesiastics. In fact, since early in medieval times the wearing of fur by the common man had been regulated by severe laws. But even among the Christians a man’s wealth and standing permitted its use in some degree. As always in the past, fur was a symbol of power and prestige. And, these German merchants were becoming a real power as they gained a monopoly of the Baltic trade.

They formed a strong federation of the towns they had founded at the river mouths along the south shore of their sea. Their luggers plied the North Sea and the Thames in Britain. At Wisby on the important Isle of Gothland they early established an emporium. From the first Christian centuries barbarian Gothland had been the most active center of Baltic trade. Now it was under the control of this Hanseatic League of German cities which dominated the Baltic Sea and was soon permitting no carrying bottoms there other than its own.

In the thirteenth century the enterprising Hansa towns had monopolistic trade factories established not only in England and Scandinavia, and at Novgorod in Russia, but at Pleskow and perhaps even at Moscow. Their fur traders penetrated to the White Sea. Within another century they had extended their operations beyond the Urals into Siberia as far as Tobolsk and the River Taz. By then their bold assurance had gained them factories or the protection of trade-guild concessions in Flanders, France and Portugal. They were granted concessions even in Venice, their great Italian rival, whose own trading galleys were in turn annually invading England and Flanders.

But cruelty and haughtiness were born of the Hansa’s strength and pride, and lasting enmities resulted.

German arrogance met its first tests at Novgorod. There the Hansa traders incurred the everlasting resentment of the Russians, who in an effort to cope with mounting indignities resorted to cheating the Germans at every opportunity. Buying furs was risky business except in well-lighted places where it was easy to test quality. Resentments often flared into conflict, and the factory in Novgorod became a kind of hostile encampment.

In spite of reduced returns, however, the Hansa merchants[Pg 12] clung tenaciously to their trading privileges in Russia for some time. Not until Ivan the Terrible crushed the independent provinces and consolidated the Russian Empire were the Germans finally driven out—in the sixteenth century.

Then the Scandinavian powers revolted against the Hansa monopolies and the cruelties of the Germans within their borders. During the wars that followed the power of the Hanseatic League declined rapidly. With feudalism breaking up on the continent in western Europe, men had been freed for competitive commerce. It was the time of the Renaissance and trading impulses were quickening everywhere. New maritime states, sensing opportunity, had already risen to challenge the monopoly in the Baltic. Danes, Dutch and even the commercially-retarded English had been competing for the prize.

In England as early as 1404 a group of merchant adventurers organized a company to carry trade to Baltic cities. But as it turned out the agricultural English were not ready, for, although their sailors and traders fought savagely during piratical encounters in the Baltic, at home they were still hindered by their feudal system, a system against which the Germans had early rebelled as being incompatible with commercial enterprise. The absence of a large middle class, of sufficient urban community life in England, forestalled any real commerce.

The backward Englishmen didn’t have anything but lead, tin and cheap skins to export, and they had to buy back some of that, reworked, at a premium. On the continent at the time there was a saying: “We buy fox skins from the English for a groat, and re-sell them the foxes’ tails for a guilder.”

The Danes, situated strategically to cut the Baltic trade lane, fared much better than the English. But in the end it was the Dutch who succeeded the Hansa in carrying trade. The main lane of traffic from Bruges in Flanders, over the North Sea, around the Danish peninsular, and through the Baltic to Russia belonged eventually to Holland. So did the remnants of the Hansa’s former fur trade at Novgorod.

Dutch requirements for skins mounted rapidly with the coming of the Renaissance. Even a brisk market for worn, discarded[Pg 13] and inferior pelts was maintained in Holland. The pinch for pelts came about as a result of a tremendously stepped-up demand for fur in manufacture—in the felting of hats!

In Holland, as in other countries crawling out of the Dark Ages, beaver skin had been permitted as headgear to almost all who could afford it. Beginning with the time that the wearing of hats became fashionable in Europe this costly fur was used extensively for that purpose by people of means. It would appear, in fact, that in England from the time of Chaucer the word beaver was practically synonymous with hat.

Now, felt hats, which had brims and other advantages over those fashioned from pelts, were being pressed out in quantity by the trade-conscious Dutch for world commerce. Dutch beavers, they were called, and they came in a variety of shapes and quality.

Due to the peculiar matting quality of fur filaments, felting had been a profitable manufacturing art for centuries. The Greeks had practiced it. The Mongolians of Kublai Khan’s time used felt matting for tents; rich Tartars sometimes furred their robes with pelluce or silk shag. The Normans who wore felted articles of dress brought the art to England.

Fur is made up of short, barbed hairs that are downy and inclined to curl. Matting or felting, which would expose a live animal to cold and storm, is prevented in most animal coats by relatively stiffer guard hairs lying alongside the fur filaments and keeping them separated. But, the ancients had learned that by first plucking the coarser guard hairs from a pelt, the downy fur that remained could easily be removed from the hide, processed, pressed into felt mats and blocked into any shape.

Although many other furs were used in the manufacture of hats, the best felts were of beaver. For one thing they were practically indestructible. Discarded beaver hats could be worked over and made like new. Then, a new method of combing out the fur filaments of the beaver pelt was developed, to better utilize the skins. This left the pelts with the guard hairs to be worked into stoles for clerics and officials, and the combed-out fur fibers of course for the manufacture of hats.

Dutch beavers for both men and women found their way to England, to Baltic countries, to France, Portugal and into the[Pg 14] Mediterranean. These, as well as other products of the north, were eagerly sought in trade-hungry Venice, until recently the mistress of a thriving Mediterranean carrying trade.

Venice had reached this position of trade eminence in the Mediterranean after a bitter, hundred years’ war to eliminate Genoa as her rival. The most savage of the battles between the fine navies of these two medieval states had been fought over the Black Sea fur trade. But then the Turks, taking Constantinople in 1453, erected a toll-gate at this ancient Eurasian cross-roads, and the bite they took as middlemen all but stagnated world trade through the Mediterranean.

To make matters worse, the Portuguese, who had been exploring the south Atlantic, rounded the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa in 1488. An alternative route to India and Malaya had been discovered!

But, although Italy’s hold on the fur trade and other oriental traffic was broken, her own need for fine pelts and luxuries had not diminished. Italian coffers were overflowing with the riches of past commercial glory, while a golden age of elegance was blossoming in Europe for those who could afford it.

One of the keynotes of the Renaissance, as illustrated in the art and literature of the time, was an increasing appreciation of beautiful furs. Throughout the western world wealthy women took to adorning themselves with expensive pelts. If, as was said at the time, the ermined luxury of a Queen of France was cast into the shade by the furred splendor of a matron of Bruges, much more could have been claimed for the oft-wed daughter of Pope Alexander in Italy.

When this young lady, Lucretia Borgia, was married to her fourth husband, Alfonso de Ferrara, furs competed with jewels in dazzling array. Although the marriage was celebrated by proxy, the twenty-two-year-old bride wore a diadem of diamonds, thirty strings of splendid pearls, a gown of ruby velvet edged with sable, and a cloth-of-gold train lined with ermine. According to Sanuto, the Venetian diarist, it took ten mules to carry the boxes containing the furs of her trousseau, there being no less than forty-five robes trimmed and lined with sable, ermine, rabbit, wolf and marten.

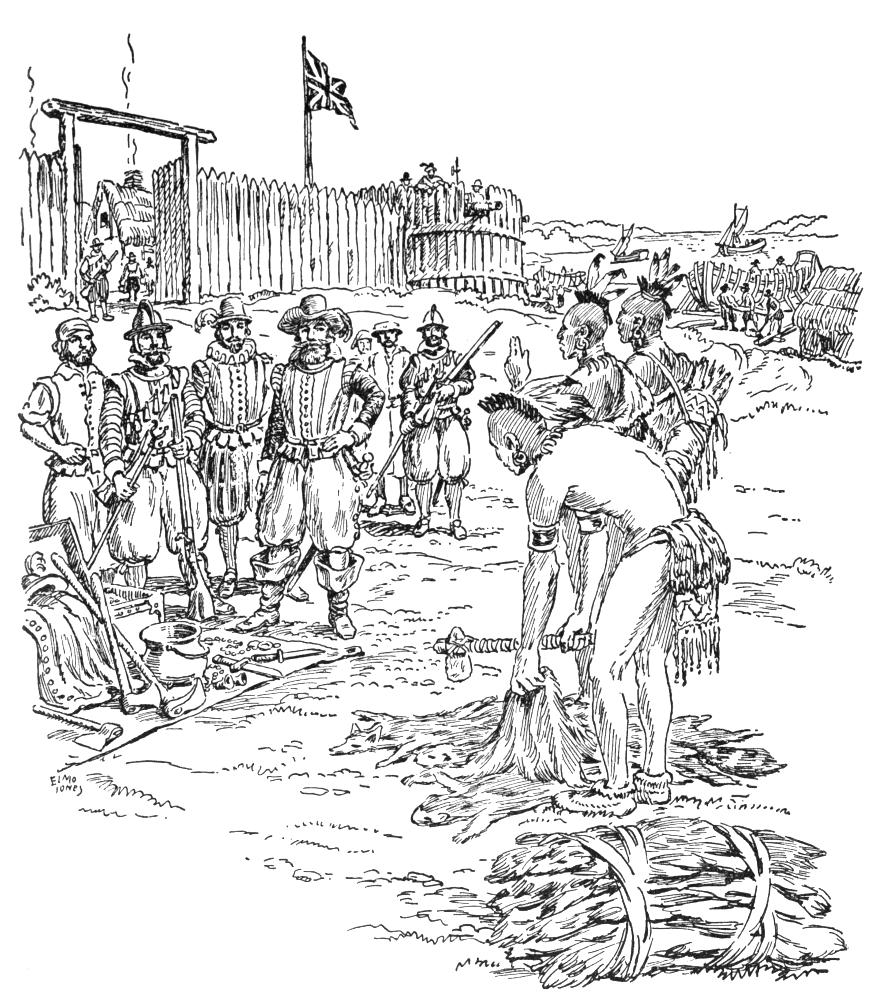

IN EUROPE THERE WAS A TREMENDOUS DEMAND FOR BEAVER FUR

IN THE MANUFACTURE OF FELT HATS.

[Pg 15]

With the need for such elegance, it is small wonder that the cooped-up western world, alive and vigorous by then, hailed the Portuguese discovery of a new spice route to the East Indies and began casting about in every direction for passages to the even greater riches of Cathay.

[Pg 16]

By the closing years of the fifteenth century, not only were the mercantile classes of western Europe thoroughly awake to the possibilities of world trade, but a good number of other people were beginning to think for themselves about the world around them.

If one could cross by land to China, which itself faced on the sea, there must be ways to reach that fabulous country by skirting the land masses of the world. In that manner the Portuguese had discovered an all-water route to India and Malaya. Or, was there the possibility of an even more direct passage to both China and the Indies by sailing straight west across the ocean?

The ancients had said the world was a globe. Hundreds of years before Christ, Greek philosophers were sure the world was round. One of them, Eratosthenes, calculated the earth’s circumference to be 40,000 kilometers (amazingly enough today, within 9 kilometers of the meridional figure!) And Strabo, a geographer who lived in the first century, recorded that if it were not for lack of sailing equipment to negotiate the immensity of the Atlantic Ocean one could travel from Spain to India by keeping to the same parallel.

Of course this did not agree with the teachings of the scriptures which spoke of the “four corners of the earth.” All during the dark ages ignorant clerics of the Church preferred to think of the world as a flat platter and pretended to forbid a contrary conception because it did not conform with the Bible. The low level of western culture had blindly accepted the thesis that the inner edges of this platter-like world were inhabited by monstrous creatures, and beyond the edges—a bottomless gulf!

On such grounds most people of the western world still resisted any notion that the world was round. But there was a question in the minds of many.

[Pg 17]

The Phoenicians, the Greeks and the Arabs had navigated the waters of the Atlantic—so had the Irish and the Vikings who long since discovered and colonized “islands” across the western sea—all without falling off the edges of the world. The Arabs, even now, were making the globes they had made for centuries for their sailors and traders. Many learned men in the west, geographers and scientists, were confident that the world was round; only recently at scholarly Nuremberg a fine globe had been completed showing Asia right across from Spain.

If there were “islands” they could be skirted, large though some of them might be according to the legends and the sagas of ancient mariners. Christopher Columbus, the Genoese sailor, must have heard about these western islands at Iceland when he visited that old Irish-Norse settlement in 1477. Certainly he must have heard much about Greenland.

Greenland, a continent-like island in the west, had been colonized by several thousand Norsemen in the tenth century under the leadership of a red-headed, murderous Icelander named Eric Thorvaldson. From there two of his sons, Leif and Thorvald, an illegitimate daughter named Freydis, and a former daughter-in-law, Gudrid, with her new husband Thorfinn Karlsefni, set out on even more daring trading and colonizing expeditions to other great islands—“the western lands of the world.”

First, Leif, whose conversion to Christianity against his pagan father’s will may have had something to do with his wish to get away, made landings in America in 1003. To Leif it was “White Man’s Land” or “Great Ireland,” for he knew that Christian Irish had preceded him there. There is in fact some evidence today that Celtic missionaries in staunch, hide-covered coracles, and others too, had been crossing the sea and making settlements in America for five hundred years before Leif Ericson sailed west from Greenland. But Leif’s visit is recorded with much more credibleness.

In the tradition of his Viking ancestors Leif and his crew of thirty-five men visited Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, and appear to have made their camp for the winter on Cape Cod where they built a good house. There they leisurely cut timber and gathered vines for cargo back to treeless Greenland. Some of the[Pg 18] crew shaped a new mast from a tall tree for their dragon ship. Others collected peltries. All marvelled at the mildness of the new country’s climate.

Leif called the land surrounding his camp site “Vinland,” probably because of the abundance of the greenbrier vines which grew there. These made strong, flexible rope material when stripped of their thorns and stranded together. On the other hand the name “Vinland” may have been derived from the grape-vines and wineberries discovered there by Leif’s family retainer, a “southerner” called Tyrker. If this slave came originally from the Mediterranean area as his name might indicate he may well have been the first to recognize grapes and demonstrate their usefulness.

One thing is certain however; the addition of wine to Leif’s already valuable cargo, when he embarked for Greenland the following year, made his expedition most exciting—one to be emulated!

Ambitious Thorvald Ericson, for one, did not feel that the western lands had been sufficiently explored by his brother. He set out in 1004 and spent two years in Vinland investigating the coasts and rivers. In his Viking ship, the same one that Leif had used, the sagas seem to say that he ranged north of Cape Cod along the Maine coast and south through Long Island Sound.

The natives Thorvald met on his voyage were surprised whenever possible and liquidated without quarter. Skraelings, he called them, meaning shriekers or war-whoopers. No doubt the rough treatment afforded the wild Skraelings was an approved medieval means of taking possession of their fur skins with the least bother. In any case it ended in Thorvald’s own death. One day hundreds of Skraelings in their canoes suddenly attacked the Viking ship. Although the Norsemen drove them off with much slaughter Thorvald was mortally wounded in his armpit by an arrow. He was buried ashore that same day. His men returned to Greenland the following year, in 1007.

It has been claimed that the encounter in which Thorvald was slain took place at Mount Desert Island on the Maine coast. Somes Sound does seem to fit the site of the battle as related in the saga. Certainly, great numbers of natives could have been in the habit of congregating there with their canoes during fur[Pg 19] trapping season, for Mount Desert Island was a favorite haunt of beavers and other fur bearers in past centuries.

In 1010 wealthy Thorfinn Karlsefni and his wife Gudrid, who had urged the project upon him, took something over 160 colonists from Greenland to establish a permanent Norse trading settlement in the western land. They went in dragon ships and round-bottomed cargo vessels loaded with “all kinds of livestock,” including a bull. The men had headgear adorned with horns, antlers or ravens’ wings. They wore short breeches and were clad with leather armor. Pelts were wrapped about their legs. The women wore girdled tunics. Heavy fur coats and lambskin hoods lined with cat fur protected the voyagers, men and women alike, when the seas were icy and the winds biting. Most of them survived to reach Vinland, where Gudrid bore her husband a son, Snorri, the first autumn they spent at Leif’s old house.

Snorri, who was to become the ancestor of a number of distinguished men including three Icelandic bishops, appears to have been the first European of record born in America.

At Vinland the Skraelings came with “packs wherein were grey furs, sables, and all kind of peltries.” The bull having greatly frightened them, it was some time before they loosened their bundles and offered their pelts in trade. They wanted to exchange them for Norse weapons. Karlsefni rejected this proposition. But the saga relates that he gave them some milk, whereupon the red men wanted nothing else and barter forthwith got under way.

In such manner was the first fur trade of record joined in America, although one cannot resist wondering if the milk was spirituous. Experienced Thorfinn Karlsefni, who had gained his fortune in other parts of the world as a seafaring trader, may well have been the first white man to practice this ancient trick of the trade on the naïve native Americans.

Very soon after this first successful barter the aborigines came back in much greater number than before with bundles of pelts and stood outside the palisades which the Norsemen had been foresighted enough to erect around their house in the meantime. Karlsefni, sensing the making of another good bargain, instructed the women to offer more milk. The Skraelings took it thirstily,[Pg 20] pitching their bundles of furs over the palisades. But then one of them tried to steal a Norse weapon and a battle ensued during which many of the Skraelings were slain.

Evidently Karlsefni thought it was too dangerous at Vinland. It would appear that he moved his colony the second year to a site probably on the Hudson River. In the meantime according to some students he had explored the country from its northernmost parts, where he mentioned seeing “many artic foxes,” to the Chesapeake Bay, no doubt entering many rivers, the St. Lawrence, the Hudson, the Delaware, possibly the James, and identifying correctly the extent of the Appalachian mountain range. There is reason to believe that he built shelters and maintained a separate camp somewhere in the Chesapeake tidewater.

It may have been there, as the Norsemen told it, that swarthy, ill-looking men with broad cheeks and ugly hair on their heads, came in canoes and stared at them in amazement. Later, these same men came back with “fur-skins and all-grey skins” wanting swords and spears in trade. Evidently there was no milk in this camp, wherever it was, but fortunately the natives finally agreed to take red cloth in exchange for their pelts.

“In return for unblemished skins, the savages would accept a span length of red cloth and bind it around their heads. Thus the trading continued. When Karlsefni’s people began to run short of cloth, they ripped it into pieces so narrow that none was broader than a finger, but the savages even then gave as much for it as before, or more.”

And, so the trading continued, according to a version of the saga in Hauk’s Book, until it ended in a battle as usual. Once more many of the natives were killed. So were two of the Norsemen.

After three years Karlsefni abandoned the idea of a permanent settlement. The Skraelings were too hostile. The Norse, with their superior boats and shields, could cope with them on water. But on land the red men were too numerous and had the advantage of surprise. They couldn’t be held at bay—the Norsemen didn’t have the terrifying firearms available to later colonists coming to America.

[Pg 21]

All of which may reasonably account for the dearth of Viking artifacts on the eastern seaboard of America. The Norsemen kept close to the shore-line, whether on the seacoast or on a tidewater river, building their huts near the safety of their shielded dragon ships. Today, the sites of those early camps may well be under water as the level of the sea has risen at least five or six feet in the intervening time due to glacial meltings.

A translation of the Flatey Book saga relates that when Karlsefni’s people returned to Greenland they “carried away with them much booty in vines and grapes and peltries,” and that after this “there was much new talk in Greenland about voyaging to Vinland, for this enterprise was now considered both profitable and honorable.”

Not to be outdone in the matter of profit Freydis, the illegitimate daughter of Eric the Red and with a heart as murderous as that of her father, led an expedition to Vinland a few years later. Honor appears to have had no part in her plans.

Freydis had a husband, but she made the plans. Before leaving Greenland, she arranged with Leif for the loan of his house in Vinland and induced two unsuspecting brothers of another family who had a particularly fine ship to become her partners in the venture. These two men were pledged to take only thirty warriors and their women. Freydis had agreed to take a like number, but somehow she contrived to conceal five extra men in her smaller ship.

After they arrived in Vinland, Freydis managed to keep the two groups apart by fomenting antagonism. The brothers were forced to build a separate house for their men and women. This house, together with too much wine and heavy sleep, proved to be the means of their undoing—all according to the Viking lady’s plan it appears. And what a red-handed proceeding it was!

Freydis, with her husband’s grudging cooperation, succeeded in murdering the two brothers in their house one night after shackling their company. She had all of their men put to death and personally wielded the axe that killed their five women when no one else would do it. Then, taking her deceased partners’ fine trading ship, she returned to Greenland with a rich cargo of furs, wine and lumber.

[Pg 22]

One shudders to think how she went about extracting the furs from the Skraelings!

For two or three hundred years the Greenland republic maintained an active trade between America and Norway, and with other countries, in walrus hides, seal and fur skins, dried fish and whale fat. Norwegian port records, as well as the sagas, testify to trade with “Markland,” the name which had been given to Nova Scotia by Leif Ericson. There are old church records which show that quantities of the pelts of animals not indigenous to Greenland were exported from that country to Norway, pelts that could have come only from the mainland of America. The bills of lading listing church taxes which had been collected in natura include elk, black bear, beaver, otter, ermine, sable, lynx, glutton and wolf.

But, in 1261, the Greenland parliament renounced its independence and swore allegiance to Norway. Independent traffic with other countries was promptly curtailed. Subsequently the dominance of the Hanseatic League through its monopolistic factory at Bergen, which took no interest in Greenland, brought about a withering of all commerce between Greenland and the continent.

Deterioration of the Greenlanders themselves came about through malnutrition and intermarriage with the Eskimos who descended on their settlements. Some who voyaged to America probably remained there and were eventually absorbed by the natives. There is evidence that as late as 1362 an expedition of Swedes and Norwegians, exploring westward in the Hudson Bay, left their ship at the mouth of the Nelson River and in their afterboats penetrated through Lake Winnipeg up the Red River into Minnesota. An inscription on a rhune-stone, ostensibly left by them as a marker, says they were being cut off by the savages at the time. But, whether authentic or not, the storied voyage appears to be of little commercial significance; the era of Viking trade in America was ended.

Among most scholars during the dark ages little notice had been taken of the Norse discoveries, if indeed very much was known about them. True, the chronicler Adam of Bremen had recorded the discovery of a large island in the western sea, called “Vinland,” but then everyone knew there were “islands” in the[Pg 23] sea. Knowledge of any far-western lands, even of Greenland itself, faded with the withering of trade.

Then Christopher Columbus, sailing for Spain, plowed the ocean straight west in 1492 and returned to assert that as he had predicted the east coast of Asia was six thousand miles nearer to Europe than most of the world’s best geographers had estimated it to be.

A new, short route west to Asia! The news was electrifying to a now thoroughly trade-conscious world. Spain, England, Portugal, France—all took to the western sea.

[Pg 24]

Christopher Columbus probably thought that “the western lands of the world” explored by the Norsemen were island-like masses, similar to Greenland, off the northern coast of Asia. From what he was able to learn, especially on his visit to Iceland, he no doubt concluded that these lands stretched far away to the southeast. He had a mariner’s instinct for such things. Certainly he calculated his landfall in 1492 with amazing accuracy.

Columbus came among islands that he confidently took to be the Moluccas off Asia. The continent lay just beyond.

But it was the wrong continent!

Although Christopher Columbus made four voyages, reaching the mainland of South America in 1498, he never knew that he hadn’t really come upon Asia—that the natives he encountered were not wild, borderland East Indians.

In the meantime, a Genoese-born Venetian navigator sailing for an English king landed on the North American coast in 1497 and claimed the country for England. John Cabot was his English name. Cabot made the North Atlantic crossing in a small bark called the Matthew with eighteen men, following the route of the Vikings, and landed first somewhere near Cape Breton. After sailing northern coasts for a week he decided the country was Siberia. Like Christopher Columbus, he returned quickly to report that he had discovered a route to Asia.

Like Columbus too, John Cabot was given a fleet of trading ships and was sent back the next year by an excited monarch and hopeful Bristol merchants to collect the spoils of his discovery. His ships were “fraught with sleight and grosse merchandizes, as course cloth, Caps, laces, points, and other trifles.”

This time Cabot cruised the coast south, possibly as far as Cape Fear, for signs of Cathay or India before he returned to[Pg 25] England. He carried back a few mangy furs taken in trade with the Indians—for the surprised Indians could think of nothing much to give the white god other than the clothes off their backs—but no gold, pearls, silks or spices.

It was hard to believe that this was the Asia about which Marco Polo had written.

It took another decade for Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine astronomer who had gone along on several Spanish and Portuguese voyages to the western lands, to declare that they were in reality a new world. A German savant named Waldseemuller who greatly admired Vespucci revised the map of the earth. He drew in a new continental land mass between Europe and Asia, and he honored Vespucci by calling it Amerigo’s Land—in Latin, Terra America.

Meanwhile, Spain’s only world rival had not been neglecting the west. Portuguese caravels reached Brazil as early as 1500 and explorers from Portugal visited Labrador and Newfoundland in 1501. Within a few years after John Cabot’s crewmen first told Bristol fishermen that the waters off Newfoundland boiled with codfish, Portuguese fishing boats led the way to those American waters.

Armed and battling, rival fishing fleets of the other European countries followed them across the North Atlantic. Soon, almost a hundred sail yearly were frequenting the fabulous Newfoundland banks where fish could literally be hauled in by basket.

These fishermen, Normans, Bretons, Basques, Bristolmen, fell to bartering with the natives when they went ashore to dry their catches. In sailorly tradition they no doubt had a handy reserve of appealing gew-gaws for any chance meetings with the opposite sex. One thing leading to another, it was not long before looking-glasses, beads, tin bells and other trinkets were being exchanged for the fur skins that the natives wore. And the aborigines in turn were then lured into trapping and curing prime skins for this trade.

So, along with their nets, the fishermen from Europe brought over more substantial trade goods, such as knives, axes, fishhooks, combs and colored cloth. Codfish Land, as they called it, began yielding up tidy extra profits from a trade in sealskins, red and[Pg 26] blue fox, otter, beaver and marten. The bulk was small on the return trip; the merchants at home paid well.

The first pelts of the American pine marten taken by the sailors caused much excitement. They were mistaken for sable. At the time Siberian sable was the most expensive of all furs traded in the great international fur center at Leipzig. In Russia it was reserved for the use of royalty only; in England noble women eagerly sought the precious pelts as neckpieces. A sack, as the Russian traders called a robe of Siberian sable, was worth more thousands of rubles than most western royalty could afford.

But, although the pine marten did eventually become known as American sable, the pelt of this little animal was never so precious as that of his glistening, thick-coated Siberian cousin. For one thing the guard hairs of his fur did not have the beautiful silver tips.

However, there was another marten, otter-like in its aquatic habits, that turned out to have a much finer coat than its European and Asian cousins. This one the fishermen learned to call mink. It was the name already given in Finland to this scrappy little member of the weasel family, for whose fur there was a premium market in western European countries. The American wild mink with its thicker, silkier under fur and its glossier guard hair was definitely more desirable, bringing a better price.

Although Portuguese sailors had led the way to Codfish Land, Portugal followed up her early advantages in America only half-heartedly. She agreed to a Papal-sponsored division of the earth that left the new world pretty much to Spain. The Portuguese suspected there was no short route west to Asia. Anyway, they were doing very well in their own sphere with their route to the east around Africa.

In the end the Pope’s line of demarcation was all right with the Spaniards, too. By the time they were sure there was no centrally located strait through America, they had turned up enough gold, silver and other rich loot to keep them well occupied.

With medieval single-mindedness they were plundering, enslaving and killing. It was the only way the criminal conquistadors knew to reward themselves. Because the natives were accounted to be bloodthirsty cannibals their enslavement or[Pg 27] liquidation was looked upon with favor by Spanish authorities. It also greatly simplified the acquisition of aboriginal treasures and mines. Cruelties, so artfully practiced at home, became sheer brutality when transferred to a frontier where the number of victims seemed inexhaustible. Roasting alive, tearing by hounds, dismembering, were all part of the customary Spanish pattern at the time; it was just that these atrocities were committed with higher frequency in America. Wholesale annihilation was the order of the day.

Spain was not so absorbed however that she did not make threatening gestures against those who would intrude on her new possessions. England, following up Cabot’s discoveries, made a prideful attempt to launch a colonizing venture. But it died in birth. The Spaniards warned against any encroachments in their American sphere and the English admiralty was in no position to contest the point.

Not so, the French!

Loot from the Aztec Empire proved too tempting to French captains of swift, handy ships which had been commissioned as privateers. Armed with official “letters of mark” to challenge Spanish depredations on the high seas they found clever ways to exceed their authority when they overhauled cumbersome, treasure-laden galleons from America.

It wasn’t too long before it was difficult to distinguish between a French privateer and a plain pirate. And Francis I, winking broadly, said he knew of no clause in Father Adam’s will which left all the new world and its riches to his cousin Charles of Spain. Whereupon the French monarch went further. He sent out a capable Florentine pilot, Giovanni da Verrazano, to discover and claim lands in America, and if possible to locate a passage to the Indian Ocean.

Verrazano, with a crew of fifty Normans in La Dauphine, made his landfall in 1524 just above Spanish Florida. He coasted northward past the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. It appears that he glimpsed the bay and identified it as the great ocean of the East reaching to China; then he sailed on to the Hudson River.

[Pg 28]

The natives encountered by the Frenchmen along the way were gentle and playful. It was spring and Verrazano’s mariners succumbed to the beauty of the Indian women who braided their hair and modestly covered their loins with soft furs. Otherwise they were quite naked. The sailors gave the aborigines toy bells, bits of paper and colored beads, and found them in turn “very liberal, for they give away what they have.”

La Dauphine left the Hudson River and continued on north, beyond Cape Cod, to lands where the natives were found to wear Arctic bear and seal skins. They were rude and truculent too, possibly as a result of having encountered white men before. These wild men exchanged their furs warily. They wanted only fishhooks, metal cutting tools and other valuable trade goods.

When Verrazano returned home all he could show, of any tangible value, were the furs he had taken in trade along the coast of America. But no one in France was more than passingly interested in pelts; there was the more immediate prospect of finding gold or reaching China.

While the French were preparing to follow up Verrazano’s coastal discoveries with an inland venture the Spaniards looked on with a jealous eye. They themselves explored northward in Verrazano’s track to make sure there was no gold or a northwest passage to Cathay there. They took furs and Indian slaves from the St. Lawrence Gulf. And they actually tried a gigantic colonizing venture in the Chesapeake Bay area. There was the chance that another Aztec Empire lay deep in the interior of those parts!

This country to the north of Tierra Florida, the Spaniards called Tierra D’Ayllon. For it was Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, a justice of Santo Domingo, who had reconnoitered it and traded there for bison hides, beaver, otter and muskrat.

In 1526 Ayllon made a settlement of several hundred men, women and children at San Miquel, possibly on the James River, in the Bay of Santa Maria as the Spaniards called the Chesapeake. He brought priests, armored soldiers, black slaves and the usual instruments of torture to the Chesapeake. But probably he didn’t erect protecting palisades about his town. San Miquel was abandoned after the first winter, its captain having perished. The benighted natives had not taken well to killings. These were of a[Pg 29] prouder race than the West Indian savages, and those colonists who did not die at their hands or from disease were happy to get back to sunny Santo Domingo.

There seemed to be no hope of finding gold or silver in Tierra D’Ayllon anyway. From this time all the closely guarded, secret maps of the Spaniards said so. Except for some further trade in the Potomac for bison hides and pelts, and a fatal missionary effort on the peninsula between the James and York Rivers by a band of brave Jesuit priests, the Spaniards ceased active interest in the Chesapeake area for many years. They were being kept much too busy in Florida and South America. Newly discovered mines, interlopers in the Caribbean, and especially French corsairs lying in wait along their rich trade routes—all demanded attention.

The Frenchmen, however annoying their “privateers” were to the Spaniards, were really only biding their time.

Francis I, as always, had a great many problems. But the most pressing one was his need for gold—much more than his privateers and pirates could safely plunder from Spanish galleons. He had his mind on America itself as a solution.

Jacques Cartier, a stout Breton mariner of St. Malo who knew the fishermen’s route to Codfish Land, was sent out by the French king in 1534, and again in 1535, to explore inland in America. He was to find gold, or the elusive passage to the treasures of Cathay at least. Maybe in the northwest, beyond Spanish claims, the new-found land was joined to Tartary as some of the geographers said. By striking inland Cartier might reach it.

On his first voyage of discovery Cartier explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence and claimed the country, calling it New France. He found the first Indians he met anxious to trade. They followed the French ships, in their birch-bark canoes and along the shores, dancing and singing to prove their friendliness, and holding up pelts on sticks. But the pelts turned out to be “such skinnes as they cloth themselves withall, which are of small value,” Cartier remarked.

However, he gave the aborigines ironware and other things, while they danced about him, rubbed his chest and arms, and cast sea water over their heads in ceremonies of joy. “They gave[Pg 30] us whatsoever they had, not keeping anything, so that they were constrained to go backe againe naked, and made us signes that the next day they would come againe, and bring more skinnes with them.”

Along the shores of the gulf wherever he went Cartier made friends with the natives, giving to the women and children, little tin bells and beads—to the men: hatchets, knives, frying pans. But he found no gold; he located no passage to Cathay. When he embarked for his return to France he took two wild men of “Canada” with him, inveigling them into making the voyage by clothing them in shirts, colored coats and red caps, and putting a copper chain about each of their necks.

These two, in France, assured the French king that far up the deep river of Canada (the St. Lawrence) and beyond, there were walled cities where people lived in houses—Hochelaga, and even more distant Saguenay. Frontier towns of Tartary! They could be. When Captain Cartier left with three ships in 1535 on his second voyage of discovery he was instructed to “go west as far as possible.”

With the two Indians as guides, Cartier’s ships anchored finally in the quiet waters below present-day Quebec. Close by was the village of Donnacona, Indian “Lord of Canada,” who welcomed the white men even more than the safe return of his two subjects. He wanted to trade. But the French captain wasn’t much interested in Donnacona’s personal wardrobe or any other pelts.

He made only a brief note of the great store of fur-bearing animals in Canada—the martens, foxes, otters, beavers, weasels and badgers. Then he pushed on. His was a more glittering objective. Up the swift, narrowing river he toiled with a small party, part way in a little pinnace and then in two long boats, until at length he reached Hochelaga.

The walled city turned out to be a well-palisaded Indian village, near the present site of Montreal, where some of the highly organized Iroquois lived in their traditional long houses. That was all—except that the Indians, noting the silver chain of Cartier’s whistle and a French dagger handle of yellowish copper gilt, said that such metals came from Saguenay. It was much farther inland, several moons travel.

[Pg 31]

But there were difficult rapids and the French captain couldn’t make it. He was already a thousand miles inland. Winter was coming on. In the end he returned downstream to the safety of his ships and the fort his men had built on the river in Canada.

Plagued by scurvy and freezing with cold that winter, Jacques Cartier had another failure on his hands. It was going to be difficult to explain things at home. He treated with Donnacona for food and medicine, for furs with which to protect his men from the cold, and for information about the country to the west. The “Lord of Canada” was anxious to please the white men, that is, in return for their skillets and axes and their bright colored clothes. He provided the things they wanted—and he talked too much.

Donnacona boasted that he had been to Saguenay. Truly, he swore, he had seen there many of the things the Frenchmen valued so much—red rubies, gold, silver—and the people were white men who went about clothed in woolen cloths. Cartier brightened in the face of his troubles. Here, he perceived, was eye-witness testimony on a royal level to the existence of Saguenay and its treasures. When spring came he captured Donnacona by a stratagem and “persuaded” the Indian king to go with him to France for a visit.

Whether or not Donnacona really believed his own story about Saguenay, he played the game effectively all the way for Jacques Cartier when he was presented to the French monarch. No doubt he wanted to make sure that he created the means of getting back to his native land. In any event, he had been canny enough to bring along with him several bundles of his best trade goods, consisting mostly of “Beavers, and Sea Woolves skinnes.” Maybe, among other things, he had French squaws in mind for his holiday abroad, as one old scribbler has suggested.

It was some time before King Francis was able to get around to doing much about the Indian king’s stories. In the meantime Donnacona died. But Francis wanted to make the imagined treasures secure for the French. The only way to do that was to colonize and fortify the approaches through New France, to take possession of the land by occupying it.

[Pg 32]

Realistic French merchants, like Jean Ango, were more interested in the furs that had been finding their way back across the sea. However colonization was an end they sought, too, if it provided a base for their traders. It was a long way, across a dangerous ocean, to New France.

With the support of both the king and the merchants, therefore, Jacques Cartier went back to New France in 1541. The Sieur de Roberval followed him in 1542. In their well-supplied fleets they transported several hundred colonists, including many farmers, also soldiers, miners and traders. Roberval’s expedition included some women. They planted near Quebec, building forts there; both tried desperately to reach mythical Saguenay. Each remained through only one Canadian winter among the now hostile Indians.

Both leaders were more interested in finding quick treasure than in any such prosaic business as fur trading. Cartier took back fool’s gold and false diamonds found on the river’s bank near the forts. Rescue ships had to be sent over from France with enough supplies to evacuate the scurvy-ridden remnant of Roberval’s contingent.

It would be another sixty years before a permanent colony was planted in these parts. But New France was held, nevertheless, for France. And, curiously enough, by the very fur trade that had been so much ignored.

The fishing barques from St. Malo, from Dieppe, Rouen, La Rochelle and Havre, kept coming to America’s northern coasts every summer, hundreds of them. They fished for cod on the banks, hunted walrus in the great gulf, and caught whales in the lower parts of the St. Lawrence River. Always, wherever they were, the mariners drove an ever increasing trade with the Indians for valuable pelts. Over the sides of their ships and on shore they bartered for marten, otter, fox and beaver.

Commerce flourished to such an extent through this individual enterprise that ships’ captains frequently found it profitable to turn all hands to bartering for pelts. It was a French vessel in 1569 at Cape Breton whose master drove a “trade with the people of divers sortes of fine furs” that picked up the Englishmen,[Pg 33] David Ingram and his two companions, Richard Browne and Richard Twide. Along with a large number of others these three had been abandoned ashore following the defeat of their famous leader, John Hawkins, the slaver, in a piratical engagement in the Caribbean with the Spaniards. Ingram and his two friends, however, struck out into the Florida wilderness, “crossed the River May,” and for twelve months beat their hazardous way northward through lands never before trod by white men, until they reached Cape Breton. They reported seeing “plentie of fine furres” along the way.

Gradually the traffic in furs moved inland via the St. Lawrence as occasional traders, adopting the native mode of travel by canoe, braved the wilderness for choicer pelts. There being no soldiers or forts to fall back on, these traders, born of the fishing fleets, found it expedient to treat the Indians well. The Montagnais and the Algonkins, who had been hostile since Cartier’s last visit, reciprocated in kind. So did the Hurons, eventually. They were all hopeful of allies with fire guns to help them against their powerful enemies, the recently formed league of the Five Nations of the Iroquois, who inhabited parts of the St. Lawrence valley in the west and the country to the south.

In 1581 a French bark, sent out exclusively for fur by the merchants of St. Malo, pushed into the upper St. Lawrence. The profits of this venture were so spectacular that organized bulk traffic got under way immediately between France and the St. Lawrence valley.

Within three years Richard Hakluyt, the English geographer, was writing, “And nowe our neighboures, the men of St. Maloe in Brytaine, in the begynnyinge of Auguste laste paste, of this yere 1584 are come home with five shippes from Canada and the contries upp the Bay of St. Lawrence, and have broughte twoo of the people of the contrie home, and have founde suche swete in the newe trade that they are preparinge tenne shippes to returne thither in January nexte....”

Almost overnight New France became noted for its valuable export of pelts, especially beaver. Hakluyt, writing from Paris about this time, said that in one man’s house he had seen Canadian otter and beaver to the value of five thousand crowns.

[Pg 34]

The French merchants mostly kept to the St. Lawrence valley, for Canada and the valley region in the hinterland teemed with fur-bearing animals. Furthermore, communication with the natives in the valley was relatively easy because of their earlier contact with Frenchmen.

Of course dialects differed, but limited palaver in a language similar to that of the Algonkin tribe was possible with all the Indians in these parts except the Iroquois. Theirs was a different tongue. The Algonkin tribe of Canada, however, was part of a great linguistic family which came to be known as Algonquin and which stretched irregularly over most of the northern woodland and as far south as Cape Hatteras on the Atlantic seaboard.

Intrepid French traders often spent the winter in the wilderness with the different tribes, to learn about their habits and dialects. If they were to know what was really in the minds of the unpredictable savages with whom they dealt, it was best to know as much as possible about them and especially the exact meaning of their words. A good knowledge of the dialect of a particular tribe might mean an advantage over a competitor, a better profit, or even the difference between life and death.

The lonely fur trader in his canoe with his Indian guides soon symbolized the occupation of New France. The deeper he penetrated into the country the farther the fame of his conquest spread abroad. New France was more than a claim; without colonization it was becoming a recognized French possession. Geographers so indicated it on their maps.