The Project Gutenberg eBook of A note on the position and extent of the great temple enclosure of Tenochtitlan,, by Alfred P. Maudslay

Title: A note on the position and extent of the great temple enclosure of Tenochtitlan,

and the position, structure and orientation of the Teocolli of Huitzilopochtli.

Author: Alfred P. Maudslay

Release Date: July 11, 2022 [eBook #68502]

Language: English

Produced by: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Extracts from the works of the earliest authorities referring to the Great Temple Enclosure of Tenochtitlan and its surroundings are printed at the end of this note, and the following particulars concerning the authors will enable the reader to form some judgment of the comparative value of their evidence.

The Anonymous Conqueror.—The identity of this writer is unknown. That he was a companion of Cortés during the Conquest is undoubted. His account is confined to the dress, arms, customs, buildings, &c. of the Mexicans. The original document has never been found, and what we now possess was recovered from an Italian translation.

Motolinia.—Fray Toribio de Benavento, a Franciscan monk, known best by his assumed name of Motolinia, left Spain in January 1524 and arrived in the City of Mexico in the month of June of the same year. From that date until his death in August 1569 he lived an active missionary life among the Indians in many parts of Mexico and Guatemala.

He was in fullest sympathy with the Indians, and used his utmost efforts to defend them from the oppression of their conquerors.

Motolinia appears in the books of the Cabildo in June 1525 as “Fray Toribio, guardian del Monesterio de Sor. San Francisco”; so he probably resided in the City at that date, and must have been familiar with what remained of the ancient City.

2Sahagun, Fr. Bernadino de, was born at Sahagun in Northern Spain about the last year of the 15th Century. He was educated at the University of Salamanca, and became a monk of the Order of Saint Francis, and went to Mexico in 1529. He remained in that country, until his death in 1590, as a missionary and teacher.

No one devoted so much time and study to the language and culture of the Mexicans as did Padre Sahagun throughout his long life. His writings, both in Spanish, Nahua, and Latin, were numerous and of the greatest value. Some of them have been published and are well known, but it is with the keenest interest and with the anticipation of enlightenment on many obscure questions that all engaged in the study of ancient America look forward to the publication of a complete edition of his great work, ‘Historia de las Cosas de Nueva España,’ with facsimiles of all the original coloured illustrations under the able editorship of Don Francisco del Paso y Troncoso. Señor Troncoso’s qualifications for the task are too well known to all Americanists to need any comment, but all those interested in the subject will join in hearty congratulations to the most distinguished of Nahua scholars and rejoice to hear that his long and laborious task is almost completed and that a great part of the work has already gone to press.

Torquemada, Fr. Juan de.—Little is known about the life of Torquemada beyond the bare facts that he came to Mexico as a child, became a Franciscan monk in 1583 when he was eighteen or twenty years old, and that he died in the year 1624. He probably finished the ‘Monarquia Indiana’ in 1612, and it was published in Seville in 1615. Torquemada knew Padre Sahagun personally and had access to his manuscripts.

Duran, Fr. Diego.—Very little is known about Padre Duran. He was probably a half-caste, born in Mexico about 1538. He became a monk of the Order of St. Dominic about 1578 and died in 1588.

His work entitled ‘Historia de las Indias de Nueva Espana y Islas de Tierra Firme’ exists in MS. in the National Library in Madrid. The MS. is illustrated by a number of illuminated drawings which Don José Ramíres, who published the text in Mexico in 1867, reproduced as a separate atlas without colour. Señor Ramíres expresses the opinion that the work “is a history essentially Mexican, with a Spanish physiognomy. Padre Duran took as the foundation and plan of his work an ancient historical summary which had evidently been originally written by a Mexican Indian.”

Tezozomoc, Don Hernando Alvaro.—Hardly anything is known about Tezozomoc. He is believed to have been of Royal Mexican descent, and he wrote the ‘Cronica Mexicana’ at the end of the 16th Century, probably about 1598.

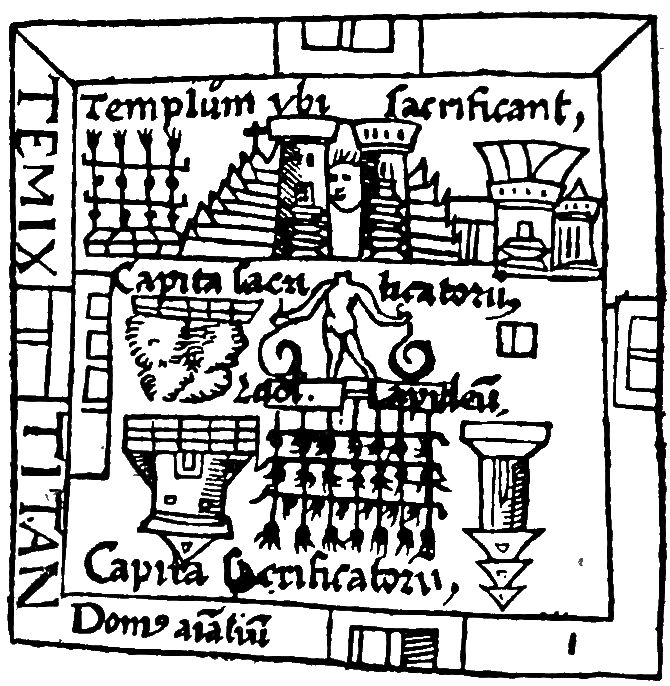

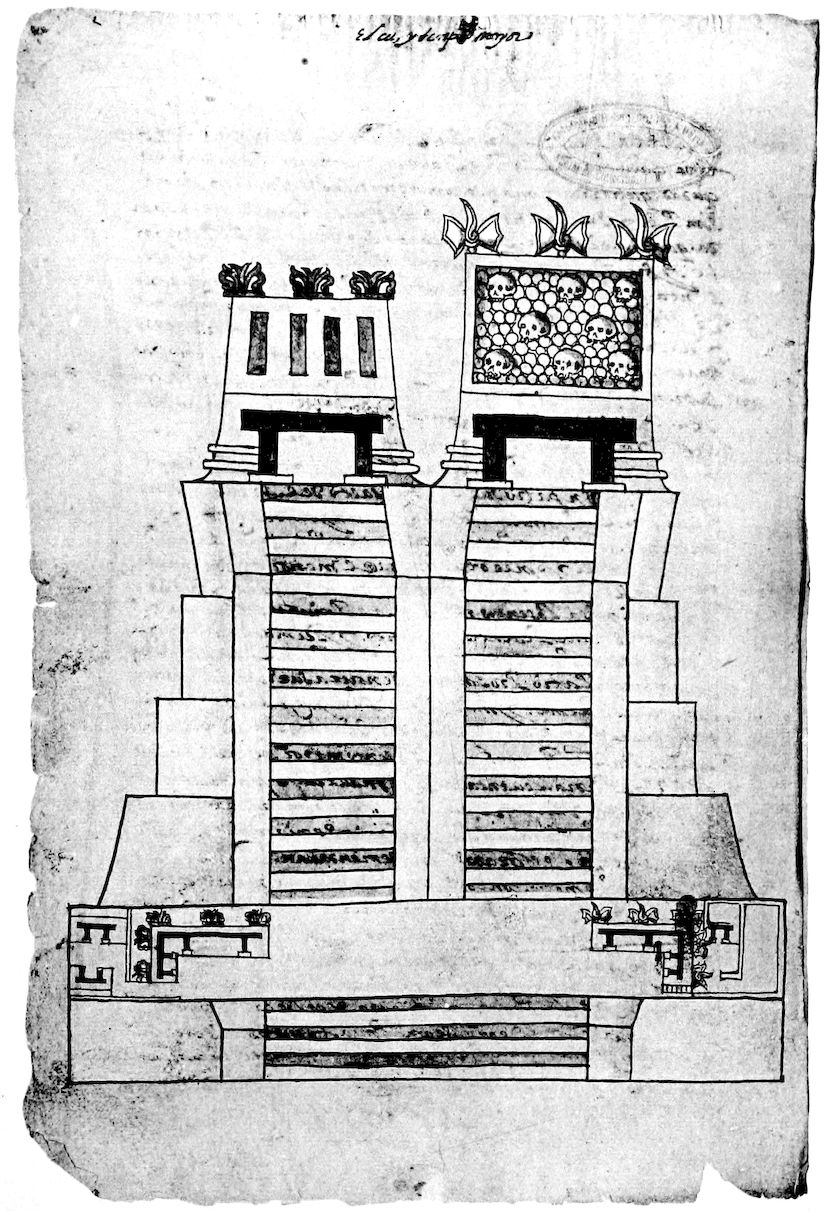

3Ixtlilxochitl.—A fragment of a Codex, known as the ‘Codice Goupil,’ is published in the ‘Catalogo Boban,’ ii. 35, containing a picture of the great Teocalli with a description written in Spanish. The handwriting is said by Leon y Gama to be that of Ixtlilxochitl.

Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl was born in 1568 and was descended from the royal families of Texcoco and Tenochtitlan. He was educated in the College of Sta. Cruz and was the author of the history of the Chichamecs. He died in 1648 or 1649.

The ‘Codice Goupil’ was probably a translation into Spanish of an earlier Aztec text.

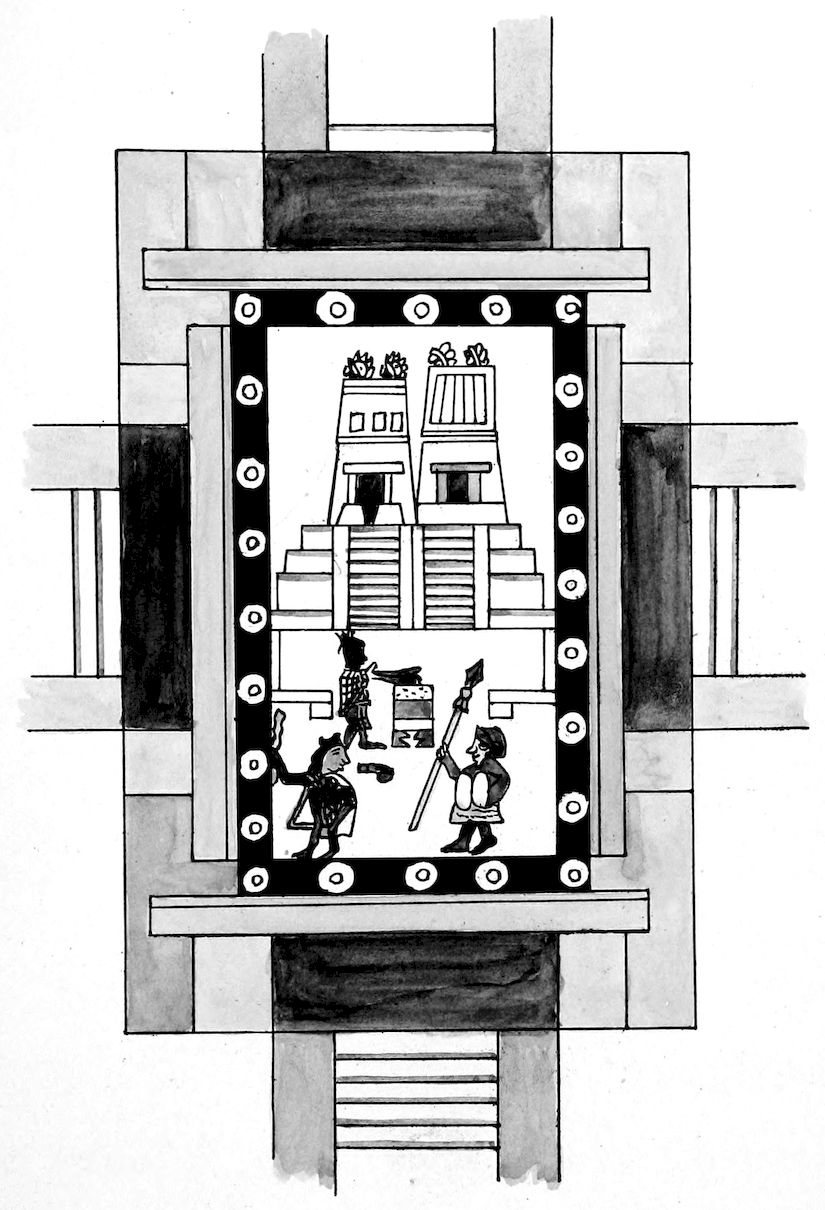

The picture of the great Teocalli is given on Plate D.

The positions of the Palace of Montezuma, the Palace of Tlillancalqui, the Cuicacalli or Dance House, and the old Palace of Montezuma have been defined by various writers and are now generally accepted.

The principal difficulty arises in defining the area of the Temple Enclosure and the position and orientation of the Teocalli of Huitzilopochtli.

The Temple Enclosure was surrounded by a high masonry wall (Anon., Torq., Moto.) known as the Coatenamitl or Serpent Wall, which some say was embattled (Torq. quoting Sahagun, Moto.). There were four principal openings (Anon., Torq., Moto., Duran) facing the principal streets or causeways (Torq., Moto., Duran). (Tezozomoc alone says there were only three openings—east, west and south—and three only are shown on Sahagun’s plan.) “It was about 200 brazas square” (Sahagun), i. e. about 1013 English feet square. However, Sahagun’s plan (Plate C) shows an oblong.

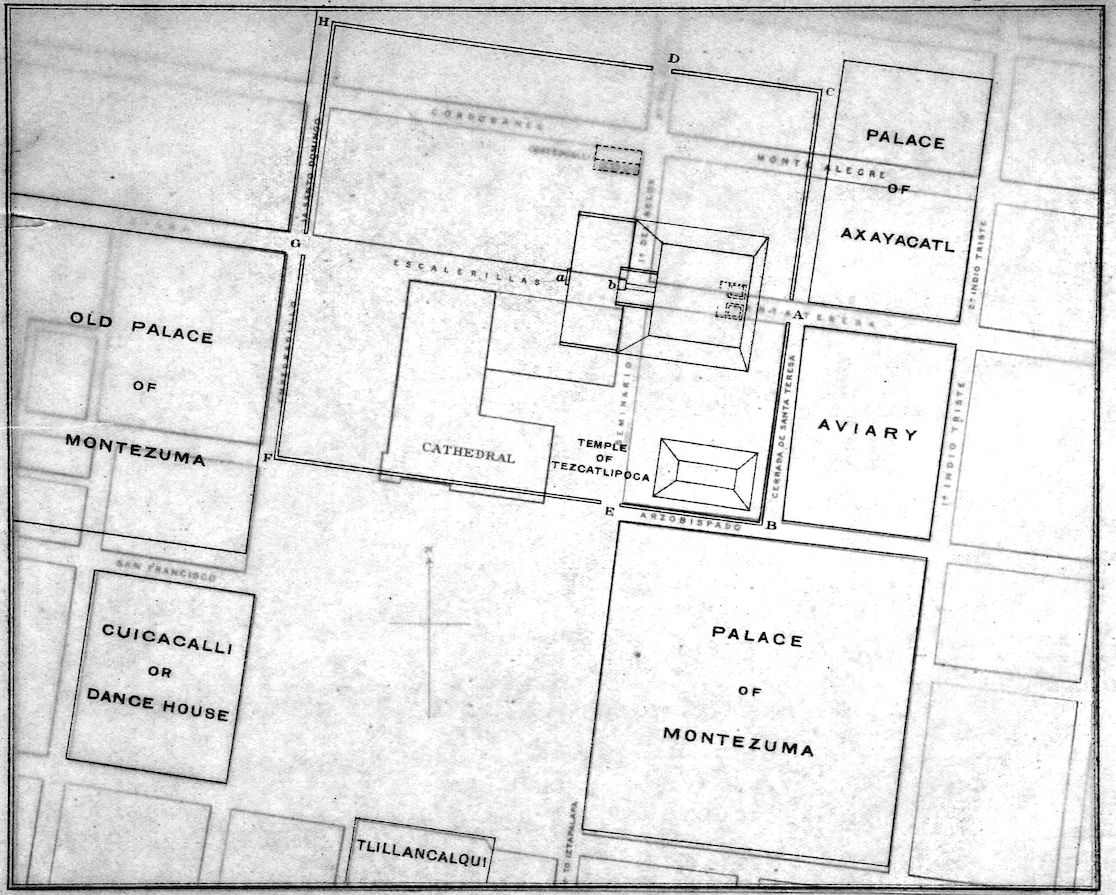

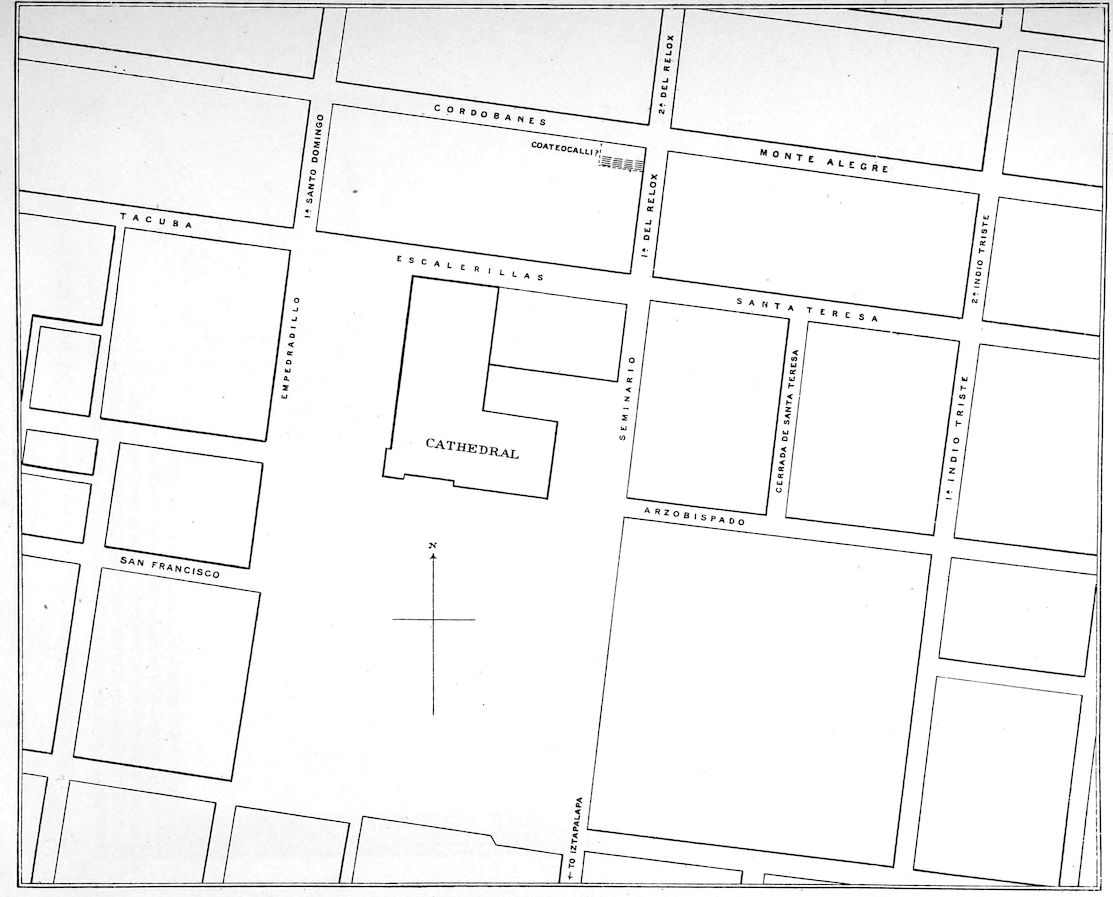

As the four openings faced the principal streets or causeways, the prolongation of the line of the causeways of Tacuba and Iztapalapa must have intersected within the Temple Enclosure. This intersection coincides with junction of the modern streets of Escalerillas, Relox, Sta. Teresa, and Seminario (see Plate A).

We have now to consider the boundaries of the Temple Enclosure, and this can best be done by establishing the positions of the Temple of Tezcatlipoca and the Palace of Axayacatl.

(Duran, ch. lxxxiii.)

“This Temple was built on the site (afterwards) occupied by the Archbishop’s Palace, and if anyone who enters it will take careful notice he will see that it is all built on a terrace without any lower windows, but the ground floor (primer suelo) all solid.”

This building is also mentioned in the 2nd Dialogue of Cervantes Salazar[1], where, in reply to a question, Zuazo says:—“It is the Archbishop’s Palace, and you must admire that first story (primer piso) adorned with iron railings which, standing at such a height above the ground, rests until reaching the windows on a firm and solid foundation.” To this Alfaro replies:—“It could not be demolished by Mines.”

The Arzobispado, which still occupies the same site in the street of that name, must therefore have been originally built on the solid foundation formed by the base of the Teocalli of Tezcatlipoca.

(‘Descripción de las dos Piedras, etc.,’ 1790, by Don Antonio de Leon y Gama. Bustamante, Edition ii. p. 35.)

“In these houses of the family property of the family called Mota[2], in the street of the Indio Triste.... These houses were built in the 16th century on a part of the site occupied by the great Palace of the King Axayacatl, where the Spaniards were lodged when first they entered Mexico, which was contiguous (estaba inmediato) with the wall that enclosed the great Temple.”

Don Carlos M. de Bustamante adds in a footnote to this passage:—“Fronting these same buildings, behind the convent of Santa Teresa la Antigua, an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was worshipped, which was placed in that position to perpetuate the memory that here mass was first celebrated in Mexico, in the block (cuadra) where stood the gate of the quarters of the Spaniards.... This fact was often related to me by my deceased friend, Don Francisco Sedano, one of the best antiquarians Mexico has known.”

(García Icazbalceta, note to 2nd Dialogue of Cervantes Salazar, p. 185.)

“The Palace of Axayacatl, which served as a lodging or quarters for the Spaniards, stood in the Calle de Sta. Teresa and the 2a Calle del Indio Triste.”

5So far as I can ascertain, no eye-witness or early historian describes the position of the Palace of Axayacatl, but tradition and a consensus of later writers place it outside the Temple Enclosure to the north of the Calle de Sta. Teresa and to the west of the 2a Calle del Indio Triste. No northern boundary is given.

Taking the point A in the line of the Calle de Tacuba as the hypothetical site of the middle of the entrance in the Eastern wall of the Temple Enclosure and drawing a line A-B to the Eastern end of the C. de Arzobispado, we get a distance of about 450 feet; extend this line in a northerly direction for 450 feet to the point C, and the line B-C may be taken as the Eastern limit of the Temple Enclosure.

The Northern and Southern entrance to the Enclosure must have been at D and E, that is in the line of the Calle de Iztapalapa.

Extending the line B-E twice its own length in a westerly direction brings us to the South end of the Empedradillo at the point F.

Completing the Enclosure we find the Western entrance at G in the line of the Calle de Tacuba and the north-west corner at H.

This delimitation of the Temple Enclosure gives a parallelogram measuring roughly 900′ × 1050′, not at all too large to hold the buildings it is said to have contained, and not far from Sahagun’s doscientos brazas en cuadro (1012′ × 1012′).

It divides the Enclosure longitudinally into two equal halves, which is on the side of probability.

It leaves two-thirds of the Enclosure to the West and one-third to the East of the line of the Calle de Iztapalapa[3].

It includes the site of the Temple of Tezcatlipoca.

It agrees with the generally accepted position of the Palace of Axayacatl and of the Aviary.

It includes the site of the Teocalli, the base of which was discovered at No. 8, 1ra Calle de Relox y Cordobanes.

It will now be seen how closely this agrees with the description given by Don Lucas Alaman, one of the best modern authorities on the topography of the City.

(Disertaciones, by Don Lucas Alaman, 1844. Octava Disertacion, vol. ii. p. 246.)

“We must now fix the site occupied by the famous Temple of Huichilopochtli[4]. As I have stated above, on the Southern side it formed the continuation of the line from the side walk (acera) of the Arzobispado towards the Alcaiceria touching the front of the present Cathedral. On the West it ran fronting the old Palace of Montezuma, with the street now called the Calle del Empedradillo (and formerly called the Plazuela del Marques del Valle) between them, but on the East and North it extended far beyond the square formed by the Cathedral and Seminario, and in the 6first of these directions reached the Calle Cerrada de Sta. Teresa, and followed the direction of this last until it met that of the Ensenanza now the Calle Cordobanes and the Montealegre.”

The general description of the ancient City by eye-witnesses does not enable us to locate the position of the great Teocalli with exactness, but further information can be gained by examining the allotment of Solares or City lots to the Conquerors who took up their residence in Mexico and to religious establishments; these allotments can in some instances be traced through the recorded Acts of the Municipality.

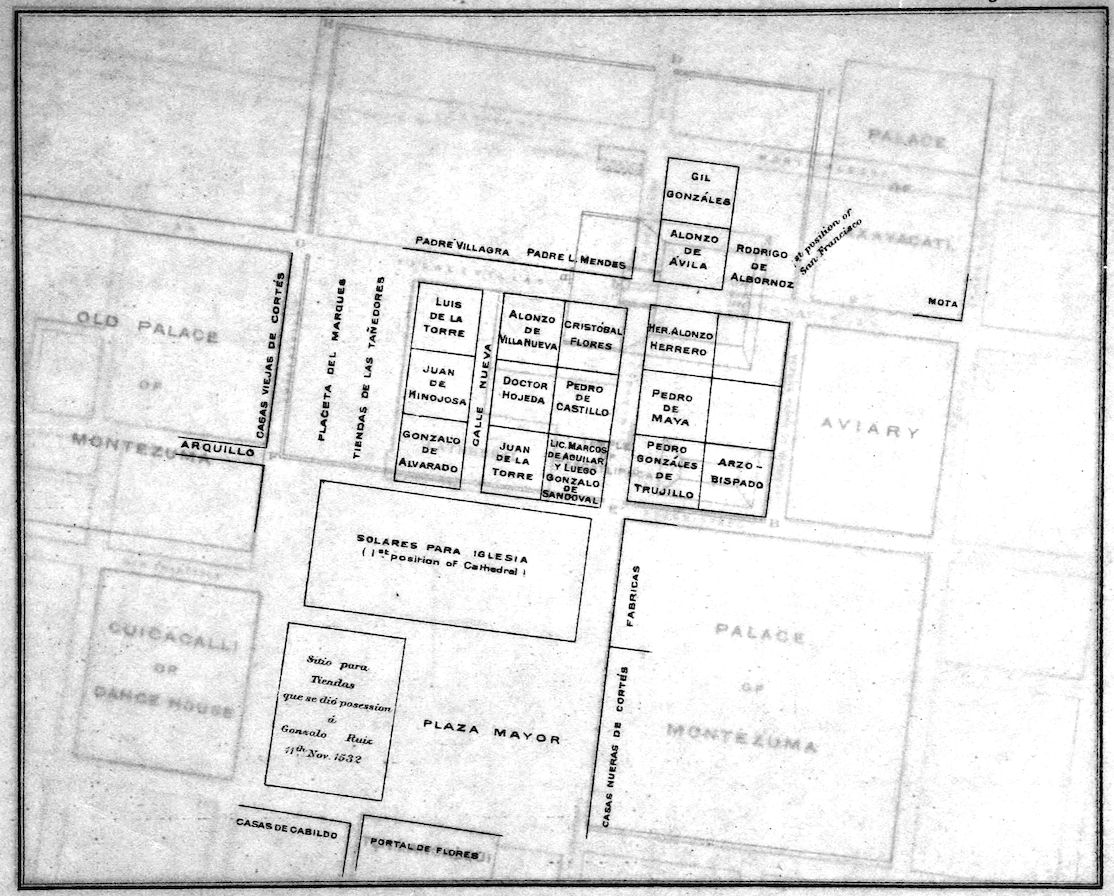

(7th Disertacion, p. 140. Don Lucas Alaman.) (Tracing A1.)

“From the indisputable testimony of the Acts of the Municipality and much other corroborative evidence one can see that the site of the original foundation (the Monastery) of San Francisco was in the Calle de Sta. Teresa on the side walk which faces South.

“At the meeting of the Municipality of 2nd May, 1525, there was granted to Alonzo de Ávila a portion of the Solar between his house and the Monastery of San Francisco in this City. This house of Alonzo de Ávila stood in the Calle de Relox at the corner of the Calle de Sta. Teresa (where now stands the druggist’s shop of Cervantes and Co.), and this is certain as it is the same house which was ordered to be demolished and [the site] sown with salt, as a mark of infamy, when the sons of Alonzo de Ávila were condemned to death for complicity in the conspiracy attributed to D. Martin Cortés. By the decree of the 1st June, 1574, addressed to the Viceroy, Don Martin Enríquez, he was permitted to found schools on this same site, with a command that the pillar and inscription relating to the Ávilas which was within the same plot, should be placed outside ‘in a place where it could be more open and exposed.’ As the schools were not built on this site, the University sold it on a quit rent (which it still enjoys) to the Convent of Sta. Isabel, to which the two houses Nos. 1 and 2 of the 1st Calle de Relox belong, which are the said druggist’s shop and the house adjoining it, which occupy the site where the house of Alonzo de Ávila stood.

“In addition to this, by the titles of a house in the Calle de Montealegre belonging to the convent of San Jeronimo which the Padre Pichardo examined, it is certain that Bernadino de Albornoz, doubtless the son of the Accountant Rodrigo de Albornoz, was the owner of the houses which followed the house of Alonzo de Ávila in the Calle de Sta. Teresa; and by the act of the Cabildo of the 31st Jan., 1529, it results that this house of Albornoz was built on the land where stood the old San Francisco, which the Municipality considered itself authorised to dispose of as waste land.”

7(Duran, vol. ii. ch. lxxx.)

“The Idol Huitzilopochtli which we are describing ... had its site in the houses of Alonzo de Ávila, which is now a rubbish heap.”

(Alaman, Octava Disertacion, p. 246.)

“One can cite what is recorded in the books of the Acts of the Municipality in the Session of 22nd February, 1527, on which day, on the petition of Gil González de Benavides, the said Señores (the Licenciate Marcos de Aguilar, who at that time ruled it, and the members who were present at the meeting) granted him one solar [city lot] situated in this city bordering on the solar and houses of his brother Alonzo de Ávila, which is (en la tercia parte donde estaba el Huichilobos) in the third portion where Huichilobos[5] stood. It was shown in the 7th Dissertation that these houses of Alonzo de Ávila were the two first in the Ira Calle de Relox, turning the corner of the Calle de Sta. Teresa, and consequently that the solar that was given to Gil González de Benavides was the next one in the Calle de Relox, for the next house in the Calle de Sta. Teresa was that of the Accountant Albornoz. This opinion agrees with that of Padre Pichardo, who made such a lengthy study of the subject, and who was able to examine the ancient titles of many properties.”

In a note to the 2nd Dialogue of Cervantes Salazar, Don J. Garcia Icazbalceta discusses the position of the original Cathedral and quotes a decree of the Cabildo, dated 8th Feb., 1527, allotting certain sites as follows:—

“The said Señores [here follow the names of those present] declare that inasmuch as in time past when the Factor and Veedor were called Governors of New Spain they allotted certain Solares within this City, which Solares are facing Huichilobos (son frontero del Huichilobos), which Solares (because the Lord Governor on his arrival together with the Municipality reclaimed them, and allotted them to no one for distribution) are vacant and are [suitable] for building and enclosure; and inasmuch as the aforesaid is prejudicial to the ennoblement of this city, and because their occupation would add to its dignity, they make a grant of the said space of Solares, allotting in the first place ten Solares for the church and churchyard, and for outbuildings in the following manner:—Firstly they say that they constitute as a plaza (in addition to the plaza in front of the new houses of the Lord Governor), the site and space which is unoccupied in front of the corridors of the other houses of the Governor where they are used to tilt with reeds, to remain the same size that it is at present.

8“At the petition of Cristóbal Flores, Alcalde, the said Señores grant to him in this situation the Solar which is at the corner, fronting the houses of Hernando Alonzo Herrero and the high roads, which (Solar) they state it is their pleasure to grant to him.

“To Alonzo de Villanueva another Solar contiguous to that of the said Cristóbal Flores, in front of the Solar of the Padre Luis Méndez, the high road between them, etc.”

(Here follow the other grants.)

“Then the said Señores ... assign as a street for the exit and service of the said Solares ... a space of 14 feet, which street must pass between the Solar of Alonzo de Villanueva and that of Luis de la Torre and pass through to the site of the Church, on one side being the Solar of Juan de la Torre, and on the other the Solar of Gonzalo de Alvarado.”

In the same note Icazbalceta discusses the measurements of the Solares, which appear to have varied between 141 × 141 Spanish feet (= 130 ¾′ × 130¾′ English) and 150 × 150 Spanish feet (= 139′ × 139′ English), which latter measurement was established by an Act of the Cabildo in Feb. 1537. He also printed with the note a plan of what he considered to be the position of the Solares dealt with in this Act of Cabildo. This plan is incorporated in Tracing A1.

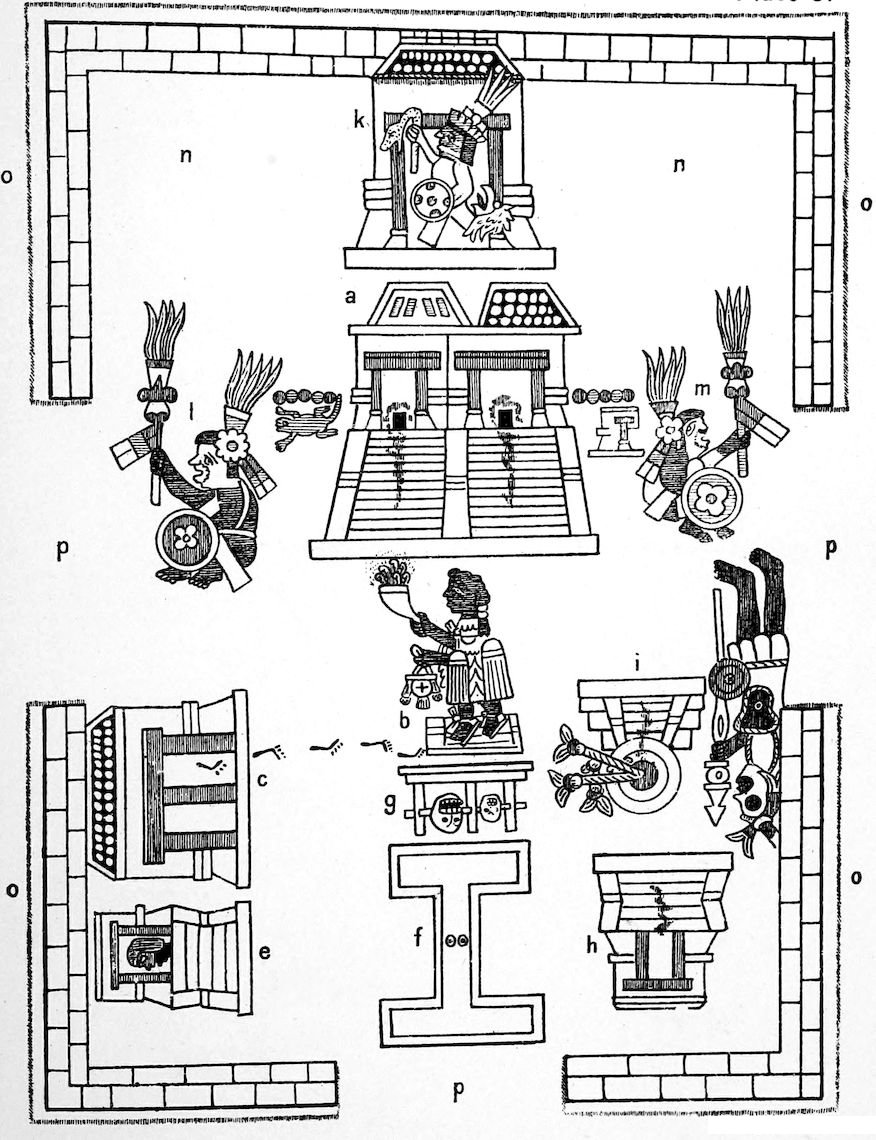

Plate C is a copy of a plan of the Temple Enclosure found with a Sahagun MS., preserved in the Library of the Royal Palace at Madrid and published by Dr. E. Seler in his pamphlet entitled ‘Die Ausgrabungen am Orte des Haupttempels in Mexico’ (1904).

We know from Cortés’s own account, confirmed by Gomara, that the Great Teocalli was so close to the quarters of the Spaniards that the Mexicans were able to discharge missiles from the Teocalli into the Spanish quarters, and according to Sahagun’s account the Mexicans hauled two stout beams to the top of the Teocalli in order to hurl them against the Palace of Axayacatl so as to force an entrance. It was on this account Cortés made such a determined attack on the Teocalli and cleared it of the enemy.

We also know from the Acts of the Cabildo that the group of Solares beginning with that of Cristóbal Flores (Nos. 1–9) are described as “frontero del Huichilobos,” i. e. opposite (the Teocalli of) Huichilobos, and we also learn that the Solar of Alonzo de Avila was “en la tercia parte donde estaba el Huichilobos,” i. e. in the third part or portion where (the Teocalli of) Huichilobos stood. Alaman confesses that he cannot understand this last expression, but I venture to suggest that as the Temple Enclosure was divided unevenly by the line of the Calle de Iztapalapa, two-thirds lying to the West of that line and one-third to the East of it, the expression implies 9that the Teocalli was situated in the Eastern third of the Enclosure. This would bring it sufficiently near to the Palace of Axayacatl for the Mexicans to have been able to discharge missiles into the quarters of the Spaniards. It would also occupy the site of the Solar de Alonzo de Avila, and might be considered to face the Solar of Cristóbal Flores and his neighbours, and we should naturally expect to find it in line with the Calle de Tacuba. Sahagun’s plan is not marked with the points of the compass, but if we should give it the same orientation as Tracing A2, the Great Teocalli falls fairly into its place.

Measurements of the Great Teocalli.

There were two values to the Braza or Fathom in old Spanish measures, one was the equivalent of 65·749 English inches, and the other and more ancient was the equivalent of 66·768 English inches. In computing the following measurements I have used the latter scale:—

| Spanish. | English. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 foot | = 11·128 inches. | ||

| 3 feet = | 1 vara | = 33·384 „ | = 2·782 feet. |

| 2 varas = | 1 Braza | = 66·768 „ | = 5·564 „ |

The Pace is reckoned as equal to 2·5 English feet and the Ell mentioned by Tezozomoc as the Flemish Ell = 27·97 English inches or 2·33 English feet.

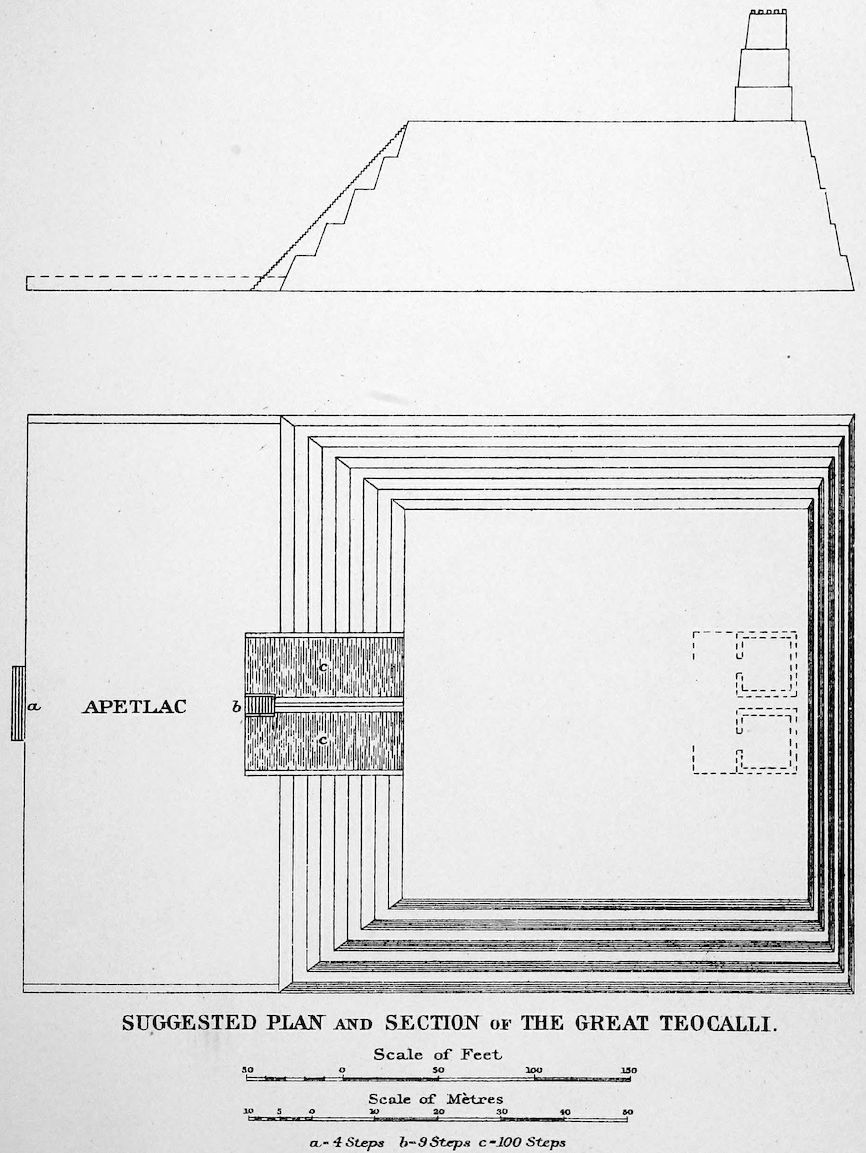

There is a general agreement that the Teocalli was a solid quadrangular edifice in the form of a truncated step pyramid.

The dimensions of the Ground plan are given as follows:—

| Spanish Measure. | English feet. |

|---|---|

| Anonimo 150 × 120 paces | = 375 × 300 |

| Torquemada 360 × 360 feet | = 333·84 × 333·84 |

| Gomara 50 × 50 Brazas | = 278·2 × 278·2 |

| Tezozomoc 125 Ells (one side) | = 291·248 |

| Bernal Díaz = six large Solares measuring 150 × 150 feet each, which would give a square of about | = 341 × 341 |

| Ixlilxochitl 80 Brazas | = 445[6] |

| Motolinea says the Teocalli at Tenayoca measured 40 × 40 Brazas | =222·56 × 222·56 |

The measurements are rather vague. The Anonymous Conqueror’s measurements may refer to the Teocalli at Tlatelolco and the length may have included the Apetlac or forecourt. Torquemada may be suspected of exaggeration. Tezozomoc was not an eye-witness and Bernal Díaz’s estimate of six large Solares is only an approximation.

In Tracing A2 I have taken 300 × 300 English feet as the measurement of the base of the Teocalli.

| Sahagun | Facing the West. |

| Torquemada | Its back to the East, “which is the practice the large Temples ought to follow.” |

| Motolinea | The ascent and steps are on the West side. |

| Tezozomoc | The principal face looked South. |

| Ixtlilxochitl | Facing the West. |

I think the evidence of Sahagun, Torquemada, Motolinia, and Ixtlilxochitl must be accepted as outweighing that of Tezozomoc, who also says that the pyramidal foundation was ascended by steps on three sides, a statement that is not supported by any other authority and which received no confirmation from the description of the attack on the Teocalli as given by Cortés and Bernal Díaz.

Torquemada says that the steps were each one foot high, and Duran describes the difficulty of raising the image and litter of the God from the ground to the platform on the top of the Teocalli owing to the steepness of the steps and the narrowness of the tread.

Both the pictures show four ledges.

The Anonymous Conqueror gives the width of the ledges as two paces.

The height of the wall between each ledge is given as follows:—

| Cortés—the height of three men | = say 16′. |

| Anonimo—the height of two men | = say 10′ 8″. |

| Motolinia—1½ to 2 Brazas | = say 11′. |

11The size of the platform on the top of the Teocalli cannot be decided from the written records. Torquemada says that there was ample room for the Priests of the Idols to carry out their functions unimpeded and thoroughly, yet in an earlier paragraph he appears to limit the width to a little more than seventy feet. Possibly this measurement of seventy feet is meant to apply to a forecourt of the two sanctuaries.

Motolinia gives the measurement of the base of the Teocalli at Tenayoca as 222½′ × 222½′ (English), and the summit platform as about 192′ × 192′ (English). Applying the same proportion to a Teocalli measuring 300′ × 300′ at the base, the summit platform would measure about 259′ × 259′.

Duran says “in front of the two chambers where these Gods (Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc) stood there was a Patio forty feet square cemented over and very smooth, in the middle of which and fronting the two chambers was a somewhat sharp pointed green stone about waist high, of such a height that when a man was thrown on his back on the top of it his body would bend back over it. On this stone they sacrificed men in the way we shall see in another place.”

Ixtlilxochitl gives a similar description but, says the sacrificial stone was on one side towards (hacia) the doorway of the larger chamber of Huitzilopochtli.

Motolinia, Torquemada, Ixtlilxochitl, and Gomara agree in placing the two oratories or shrines on the extreme eastern edge of the platform, so that there was only just room for a man to pass round them on the east side. The two oratories were separate one from the other, each being enclosed within its own walls with a doorway towards the west. The oratory of Huitzilopochtli was the larger of the two and stood to the south. The oratory of Tlaloc stood to the north. No measurements are given of the area covered by these two oratories, but there is no suggestion that they were large buildings[7] except in height. The roof and probably the upper stages were made of wood (Torquemada), and we know that they were burnt during the siege.

Height:—

Ixtlilxochitl gives the height of the great Teocalli as over twenty-seven brazas (150′). If this means the height from the ground to the top of the Oratory of Huitzilopochtli it would very nearly agree with the height given on the hypothetical section on Plate B.

12In the description of the map of the city published in 1524 [see ‘Conquest of New Spain,’ vol. iii. (Hakluyt Society)] I called attention to the “full human face probably representing the Sun” between the Oratories of the Teocalli of Huitzilopochtli. The map is, I believe, in error in placing the Teocalli on the west side of the Temple Enclosure, but that the full human face is intended to represent the sun is confirmed by the following passage from Motolinia[8]:—

“Tlacaxipenalistli.—This festival takes place when the sun stood in the middle of Huichilobos, which was at the Equinox, and because it was a little out of the straight[9] Montezuma wished to pull it down and set it right.”

The map of 1524 was probably drawn from a description given by one of the Conquistadores, and if we turn to the pages of Gomara, an author who was never in Mexico and who wrote only from hearsay, it is easy to see how such a mistake in orientation arose.

Gomara, Historia General de las Indias—Conquista de Mejico. (El Templo de Mejico.)

“This temple occupies a square, from corner to corner the length of a crossbow shot. The stone wall has four gateways corresponding to the four principal streets.... In the middle of this space is an edifice of earth and massive stone four square like the court, and of the breadth of fifty fathoms from corner to corner. On the west side there are no terraces but 113 or 114 steps leading 13up to the top. All the people of the city[10] look and pray towards the sunrise and on this account they build their large temples in this manner.... In addition to this tower with its chapels placed on the top of the pyramid, there were forty or more other towers great and small on other smaller Teocallis standing in the same enclosure (circuito) as this great one, and although they were of the same form, they did not look to the east but to other parts of the heaven, to differentiate them from the Great Temple. Some were larger than others, and each one (dedicated) to a different god.”

The confusion of thought between a temple that faced the east and a temple where the worshippers faced the east is evident.

There can be little doubt that the steps of the Great Teocalli were on the west side, that the Oratories of Huitzilopochtli and Taloc were on the east side of the summit platform, and that their doorways faced the west. The priest and worshippers faced the east to watch the sunrise at the equinox in the narrow space between the two oratories, and because the alignment was not quite correct Montezuma wished to pull down the oratories and rebuild them.

Following from this, it appears to me that Duran was probably not far from correct in placing the great green sacrificial stone “fronting the two chambers,” but that Ixtlilxochitl was still more accurate in placing it towards (hacia) the doorway of the sanctuary of Huitzilopochtli. The heart of the human victim would be torn out and held up to the rising sun from the spot where the priest stood to observe the sunrise.

It will at once be urged against this solution of the difficulties attending the orientation of the Great Teocalli that the plan and tracings locate the Teocalli eight degrees from the east and west line, and that, therefore, my explanation fails. To this I can only reply that I plotted the measurements, taking the east and west line of the Calle de Tacuba from the modern map as a datum, and this may vary slightly from the ancient line of the street. Then I have observed in Maya temples that sometimes the shrines stand slightly askew from the base: this is clearly noticeable at Chichén Itzá. If the error of 8° were divided between the lines of the Temple enclosure, the base of the Teocalli, and the sides of the oratories, the difference would not easily be perceptible.

Moreover, we cannot now ascertain the exact spot from which the observation was made nor the distance between the two sanctuaries. If, as Ixtlilxochitl states, it was towards the doorway of the sanctuary of Huitzilopochtli and not between the two sanctuaries as is stated by Duran, then the error would be reduced.

We have now to consider the position of the Great Teocalli in relation to the excavations made in the Calle de las Escallerillas when pipes were being laid for the drainage of the city in the year 1900. These excavations were watched on behalf of the Government by Señor Don Leopoldo Batres, Inspector General of Archæological Monuments, who published an account of his researches in 1902, with a plan showing the position and depth below the surface at which objects of archæological interest were discovered. Unfortunately Señor Batres was already fully convinced that the Great Teocalli faced the south and occupied more or less the position of the present Cathedral.

At a spot marked a, in Tracing A2, 38 metres from the east end of the Escalerillas, Señor Batres discovered a stairway of four masonry steps which he states measured each 29 cm. in the rise and 22 cm. in the tread, but unfortunately beyond this statement he gives no information whatever regarding them. However, I presume that the steps followed the same direction as a stairway of nine steps which he had previously described and which will be alluded to immediately. These three steps I have taken to be the central stairway leading to the forecourt or apetlac of the Great Teocalli.

Señor Batres had already noted a stairway of nine steps, marked b in Tracing A2, each measuring 22 cm. in rise and 26 cm. in tread. This stairway was 2 metres wide and faced the west. The stairway was apparently joined at one or both sides to a sloping wall[11]. Embedded in the débris which covered these steps was found an idol of green stone measuring 75 cms. in height and 61 cms. in diameter. The idol is now preserved in the National Museum.

I take the foot of this stairway of nine steps to have been in line with the great stairway of the Teocalli, and it may have been part of the great stairway itself; however, a stairway only two metres wide is not likely to be the beginning of what must have been the principal approach to the Teocalli, and I can only suggest that it may have been a stairway leading to a niche which held the idol of green stone and that the great stairways passed on either side of it. An idol in a somewhat similar position can be seen on the Hieroglyphic Stairway at Copan.

15The Anonymous Conqueror. A Description written by a Companion of Hernando Cortés.

They build a square tower one hundred and fifty paces, or rather more, in length, and one hundred and fifteen or one hundred in breadth. The foundation of this building is solid; when it reaches the height of two men, a passage is left two paces wide on three sides, and on one of the long sides steps are made until the height of two more men is reached, and the edifice is throughout solidly built of masonry. Here, again, on three sides they leave the passage two paces wide, and on the other side they build the steps, and in this way it rises to such a height that the steps total one hundred and twenty or one hundred and thirty.

There is a fair-sized plaza on the top and from the middle [of it] arise two other towers which reach the height of ten or twelve men’s bodies and these have windows above. Within these tall towers stand the Idols in regular order and well adorned, and the whole house highly decorated. No one but their high priest was allowed to enter where the principal God was kept, and this god had distinct names in different provinces; for in the great city of Mexico he was called Horchilobos (Huitzilopochtli), and in another city named Chuennila (Cholula) he was called Quecadquaal (Quetzalcoatl), and so on in the others.

Whenever they celebrated the festivals of their Idols, they sacrificed many men and women, boys and girls; and when they suffered some privation, such as drought or excess of rain, or found themselves hard pressed by their enemies, or suffered any other calamity, then they made these sacrifices in the following manner....

They have in this great city very great mosques or temples in which they worship and offer sacrifices to their Idols; but the Chief Mosque was a marvellous thing to behold, it was as large as a city. It was surrounded by a high masonry wall and had four principal doorways.

Fray Toribio Benavente or Motolinia, Historia de los Indios de Nueva España, Treatise No. I. Ch. XII.

There have never been seen or heard of before such temples as those of this land of Anahuac or New Spain, neither for size and design nor for anything else; and as they rise to a great height they must needs have strong foundations; and there was an 16endless number of such temples and altars in this country, about which a note is here made so that those who may come to this country from now onwards may know about them, for the memory of them all has already almost perished.

These temples are called Teocallis, and throughout the land we find that in the principal part of the town a great rectangular court is constructed; in the large towns they measured from corner to corner the length of a crossbow shot, in the lesser towns the courts are smaller.

This courtyard they surround with a wall and many of the walls are embattled; their gateways dominate the principal streets and roads, for they are all made to converge towards the court; and so as to give greater honour to their temples they lay out the roads very straight with rope line for a distance of one or two leagues, and it is a thing worth seeing from the top of the principal temple, how straight all the roads come from all the lesser towns and suburbs and converge towards the Court of the Teocallis.

In the most conspicuous place in this court would stand a great rectangular block (cepa). So as to write this description I measured one in a moderate-sized town named Tenanyocan [Tenayoca] and found that it measured forty fathoms from corner to corner all built up with a solid wall, on the outside the wall was of stone, and the inside was filled up with stone only or with clay and adobe; others were built of earth well tamped.

As the structure rose it contracted towards the centre and at the height of a fathom and a half or two fathoms there were some ledges going inwards, for they did not build it in a straight line, and the thick foundation was always worked towards the centre so as to give it strength and as the wall rose it got narrower; so that when it got to the top of the Teocalli it had narrowed and contracted itself seven or eight fathoms on each side, both by the ledges and the wall leaving the foundation [mound] on the top thirty-four or thirty-five fathoms.

On the west side were the steps and ascent, and above on the top they constructed two great altars, placing them towards the east side, so that there was no more space left behind them than was sufficient to enable one to walk round them. One altar was to the right and the other to the left. Each one stood by itself with its own walls and hood-like roof. In the great Teocallis there were two altars, in the others only one, and each one of these altars[12] had upper stories; the great ones had three stories above the altars, all terraced and of considerable height, and the building (cepa) itself was very lofty, so that it could be seen from afar off.

One could walk round each of these chapels and each had its separate walls. In front of these altars a large space was left where they made their sacrifices, and the building (cepa) itself had the height of a great tower, without [counting] the stories that covered the altars.

17According to what some people who saw it have told me, the Teocalli of Mexico had more than a hundred steps; I have seen them myself and have counted them more than once, but I do not remember [the number]. The Teocalli of Texcoco had five or six steps more than that of Mexico. If one were to ascend to the top of the chapel of San Francisco in Mexico, which has an arched roof and is of considerable height, and look over Mexico, the temple of the devil would have a great advantage in height, and it was a wonderful sight to view from it the whole of Mexico and the towns in the neighbourhood.

In similar courts in the principal towns there were twelve or fifteen other Teocallis of considerable size, some larger than others, but far from as large as the principal Teocalli.

Some of them had their fronts and steps towards others[13], others to the East, again others to the South, but none of them had more than one altar with its chapel, and each one had its halls and apartments where the Tlamacazques or Ministers dwelt, who were numerous, and those who were employed to bring water and firewood, for in front of each altar there were braziers which burnt all night long, and in the halls also there were fires. All these Teocallis were very white, burnished and clean, and in some of them [the temple enclosures] were small gardens with trees and flowers.

There was in almost all these large courts another temple, which, after its square foundation had been raised and the altar built, was enclosed with a high circular wall and covered with its dome. This was [the temple] of the God of the Air, who was said to have his principal seat in Cholula, and in all this province there were many of them.

This God of the Air they called in their language Quetzalcoatl, and they said that he was the son of that God of the great statue and a native of Tollan [Tula], and thence he had gone out to instruct certain provinces whence he disappeared, and they still hoped that he would return. When the ships of the Marqués del Valle, Don Hernando Cortés (who conquered this New Spain), appeared, when they saw them approaching from afar off under sail, they said that at last their God was coming, and on account of the tall white sails they said that he was bringing Teocallis across the sea. However, when they [the Spaniards] afterwards disembarked, they said it was not their God, but that they were many Gods.

The Devil was not contented with the Teocallis already described, but in every town and in each suburb, at a quarter of a league apart, they had other small courts where there were three or four small Teocallis, in some of them more, and in others only one, and on every rock or hillock one or two, and along the roads and among the maize fields there were many other small ones, and all of them were covered with plaster and white, so that they showed up and bulked large, and in the thickly peopled country it 18appeared as though it was all full of houses, especially of the Courts of the Devil, which were wonderful to behold, and there was much to be seen when one entered into them, and the most important, above all others, were those of Texcoco and Mexico.

Sahagun, Fr. Bernadino de (Bustmamante Edition), p. 194. Report of the Mexicans about their God Vitzilopuchtli. [Huitzilopochtli, Huichilobos.]

The Mexicans celebrate three festivals to Vitzilopuchtli every year, the first of them in the month named Panquetzaliztli. During this festival [dedicated] to him and others, named Tlacavepancuexcotzin, they ascend to the top of the Cue, and they make life-size images out of tzoalli: when these are completed, all the youths of Telpuchcalli carry them on their hands to the top of the Cue. They make a statue of Vitzilopuchtli in the district [barrio] named Itepeioc[A]. The statue of Tlacavepancuexcotzin was made in that of Vitznaoao[14]. They first prepare the dough and afterwards pass all the night in making the statues of it.

After making the images of the dough, they worshipped them as soon as it was dawn and made offerings to them during the greater part of the day, and towards evening they began ceremonies and dances with which they carried them to the Cue, and at sunset they ascended to the top of it.

After the images were placed in position, they all came down again at once, except the guardians [named] Yiopuch.

As soon as dawn came the God named Paynal, who was the Vicar of Vitzilopuchtli, came down from the lofty Cu, and one of the priests, clad in the rich vestments of Quetzalcoatl, carried this God (Vitzilopuchtli) in his hands, as in a procession, and the image of Paynal (which was carved in wood and, as has already been stated, was richly adorned) was also brought down.

In this latter festival there went in front of [the image] a mace-bearer, who carried on his shoulder a sceptre in the shape of a huge snake, covered all over with a mosaic of turquoise.

When the Chieftain arrived with the image at a place named Teutlachco, which is the game of Ball [that is at the Tlachtli court], which is inside the Temple courtyard, they killed two slaves in front of him, who were the images [representatives] of the 19Gods named Amapantzitzin, and many other captives. There the procession started and went direct to Tlaltelulco.

Many Chieftains and people came out to receive it, and they burned incense to them [the images] and decapitated many quails before them.

Thence they went directly to a place named Popotla, which is near to Tacuba, where now the church of S. Esteban stands, and they gave it another reception like that mentioned above. They carried in front of the procession all the way a banner made of paper like a fly-whisk, all full of holes, and in the holes bunches of feathers, in the same way as a cross is carried in front of a procession. Thence they came direct to the Cu of Vitzilopuchtli, and with the banner they performed another ceremony as above stated in this festival.

The court of this Temple was very large, almost two hundred fathoms square; it was all paved, and had within it many buildings and towers. Some of these were more lofty than others, and each one of them was dedicated to a God.

The principal tower of all was in the middle and was higher than the others, and was dedicated to the God Vitzilopuchtli Tlacavepancuexcotzin.

This tower was divided in the upper part, so that it looked like two, and had two chapels or altars on the top, each one covered by its dome (chapitel) and each one of them had on the summit its particular badges or devices. In the principal one of them was the statue of Vitzilopuchtli, also called Ilhuicatlxoxouhqui, and in the other the image of the God Tlaloc. Before each one of these was a round stone like a chopping-block, which they call Texcatl, where they killed those whom they sacrificed in honour of that God, and from the stone towards the ground below was a pool of blood from those killed on it; and so it was on all the other towers; these faced the West, and one ascended by very narrow straight steps to all these towers.

(Sahagun mentions seventy-eight edifices in connection with the Great Temple, but it is almost certain that these were not all within the Temple enclosure.)

Sahagun, Hist. de la Conquista, Book 12, Ch. XXII.

They [the Mexicans] ascended a Cu, the one that was nearest to the royal houses [i. e. of Axayacatl], and they carried up there two stout beams so as to hurl them from that place on to the royal houses and beat them down so as to force an entry. When the Spaniards observed this they promptly ascended the Cu in regular formation, carrying their muskets and crossbows, and they began the ascent very slowly, and 20shot with their crossbows and muskets at those above them, a musketeer accompanying each file and then a soldier with sword and shield, and then a halberdier: in this order they continued to ascend the Cu, and those above hurled the timbers down the steps, but they did no damage to the Spaniards, who reached the summit of the Cu and began to wound and kill those who were stationed on the top, and many of them flung themselves down from the Cu: finally, all those [Mexicans] who had ascended the Cu perished.

Hernando Cortés, 2nd Letter. (The attack on the Great Teocalli.)

We fought from morning until noon, when we returned with the utmost sadness to our fortress. On account of this they [the enemy] gained such courage that they came almost up to the doors, and they took possession of the great Mosque[15], and about five hundred Indians, who appeared to me to be persons of distinction, ascended the principal and most lofty tower, and took up there a great store of bread and water and other things to eat, and nearly all of them had very long lances with flint heads, broader than ours and no less sharp.

From that position they did much damage to the people in the fort, for it was very close to it. The Spaniards attacked this said tower two or three times and endeavoured to ascend it, but it was very lofty, and the ascent was steep, for it had more than one hundred steps, and as those on the top were well supplied with stones and other arms, and were protected because we were unable to occupy the other terraces, every time the Spaniards began the ascent they were rolled back again and many were wounded. When those of the enemy who held other positions saw this, they were so greatly encouraged they came after us up to the fort without any fear.

Then I (seeing that if they could continue to hold the tower, in addition to the great damage they could do us from it, that it would encourage them to attack us) set out from the fort, although maimed in my left hand by a wound that was given me on the first day, and lashing the shield to my arm, I went to the tower accompanied by some Spaniards and had the base of it surrounded, for this was easily done, although those surrounding it had no easy time, for on all sides they were fighting with the enemy who came in great numbers to the assistance of their comrades. I then began to ascend the stairway of the said tower with some Spaniards supporting me, and although the enemy resisted our ascent very stubbornly, so much so that they flung down three or four Spaniards, with the aid of God and his Glorious Mother (for whose habitation that tower had been chosen and her image placed in it), we ascended the said tower and reaching the summit we fought them so resolutely that 21they were forced to jump down to some terraces about a pace in width which ran round the tower. Of these the said tower had three or four, thrice a man’s height from one [terrace] to the other.

Some fell down the whole distance [to the ground], and in addition to the hurt they received from the fall, the Spaniards below who surrounded the tower put them to death. Those who remained on the terraces fought thence very stoutly, and it took us more than three hours to kill them all, so that all died and none escaped ... and I set fire to the tower and to the others which there were in the Mosque.

Juan de Torquemada, Monarchia Indiana, Vol. II. Book 8, Ch. XI. p. 144. [Giving a description of the Great Temple.]

This Temple was rebuilt and added to a second time; and was so large and of such great extent, that it was more than a crossbow-shot square.

It was all enclosed in masonry of well squared stone.

There were in the square four gateways which opened to the four principal streets, three of them by which the city was approached along the causeways from the land, [the fourth] on the east in the direction of the lake whence the City was entered by water.

In the middle of this enormous square was the Temple which was like a quadrangular tower (as we have already stated) built of masonry, large and massive.

This Temple (not counting the square within which it was built) measured three hundred and sixty feet from corner to corner, and was pyramidal in form and make, for the higher one ascended the narrower became the edifice, the contractions being made at intervals so as to embellish it.

On the top, where there was a pavement and small plaza rather more than seventy feet wide, two very large altars had been built, one apart from the other, set almost at the edge or border of the tower on the east side, so that there was only just sufficient ground and space for a man to walk [on the east side] without danger of falling down from the building.

These altars were five palms in height with their walls inlaid with stone, all painted with figures according to the whim and taste of him who ordered the painting to be done. Above the altars were the chapels roofed with very well dressed and carved wood.

Each of these chapels had three stories one above the other, and each story or stage was of great height, so that each one of them [of the chapels] if set on the ground (not on that tower, but on the ground level whence the edifice sprang) would have made a very lofty and sumptuous building, and for this reason the whole fabric of the Temple was so lofty that its height compelled admiration. To behold, from the 22summit of this temple, the city and its surroundings, with the lakes and all the towns and cities that were built in it and on its banks, was a matter of great pleasure and contentment.

On the West side this building had no stages [contractions], but steps by which one ascended to the level of the chapels, and the said steps had a rise of one foot or more. The steps, or stairs, of this famous temple numbered one hundred and thirteen, and all were of very well dressed stone.

From the last step at the summit of this Temple to the Altars and entrance to the Chapels was a considerable space of ground, so that the priests and ministers of the Idols could carry out their functions unimpeded and thoroughly.

On each of the two altars stood an Idol of great bulk, each one representing the greatest God they possessed, which was Huitzilupuchtli or by his other name Mexitli.

Near and around this Great Temple there were more than forty lesser ones, each one of them dedicated and erected to a God, and its tower and shape narrowed up to the floor on which the Chapel and altar began to arise, and it was not as large as the Great Temple, nor did it approach it by far in size, and all these lesser Temples and towers were associated with the Great Temple and tower which there was in this City.

The difference between the Great Temple and the lesser ones was not in the form and structure, for all were the same, but they differed in site and position [orientation], for the Great Temple had its back to the East, which is the practice the large temples ought to follow, as we have noticed that the ancients assert, and their steps and entrance to the West (as we are accustomed to place many of our Christian Churches), so that they paid reverence in the direction of the sun as it rose, the smaller temples looked in the other direction towards the East and to other parts of the heaven [that is to] the North and South.

In order that my readers may not think that I speak heedlessly, and without a limit to my figures, I wish to quote here the words of Padre Fray Bernadino de Sahagun, a friar of my Order and one of those who joined very early in the discovery of this New Spain in the year twenty-nine [1529], who saw this and the other temples.... He says these words:—“This Temple was enclosed on all sides by stone walls half as high again as a man, all embattled and whitened. The ground of this Temple was all paved, with very smooth flag stones (not dressed but natural) as smooth and slippery as ice. There was much to be seen in the buildings of this Temple; I made a picture of it in this City of Mexico, and they took it to Spain for me, as a thing well worth beholding, and I could not regain possession of it, nor paint it again, and although in the painting it looks so fine, it was in reality much more so, and the building was more beautiful. The principal shrine or chapel which it possessed was dedicated to the God Huitzilupuchtli, and to another God his companion named Tlacahuepancuezcotzin, and to another, of less importance than the two, called Paynalton....”

23And he adds more, saying “the square was of such great circumference that it included and contained within its area all the ground where the Cathedral, the houses of the Marques del Valle[A], the Royal houses[16] and the houses of the Archbishop have now been built, and a great part of what is now the market place,” which seems incredible, so great is the said area and space of ground.

I remember to have seen, thirty-five years ago, a part of these buildings in the Plaza, on the side of the Cathedral, which looked to me like hills of stone and earth, which were being used up in the foundations of God’s house and Cathedral which is being built now with great splendour.

Padre Fray Diego Duran, Historia de los Indias de Nueva Espana, Vol. II. Ch. LXXX. p. 82.

Having heard what has been said about the decoration of the Idol, let us hear what there is notable about the beauty of the Temples. I do not wish to begin by relating the accounts given me by the Indians, but that obtained by a monk who was among the first of the Conquerors who entered the country, named Fray Francisco de Aguilar, a very venerable person and one of great authority in the order of our Glorious Father Santo Domingo, and from other conquerors of strict veracity and authority who assured me that on the day when they entered the City of Mexico and beheld the height and beauty of the Temples they believed them to be turreted fortresses for the defence and ornament of the City, or that they were palaces and royal houses with many towers and galleries, such was their beauty and height which could be seen from afar off.

It should be known that of the eight or nine temples which there were in the City all stood close to one another within a great enclosure, inside of which enclosure each one adjoined the other, but each had its own steps and separate patio[17], as well as living rooms and sleeping places for the Ministers of the temples, all of which occupied considerable amount of space and ground. It was indeed a most beautiful sight, for some were more lofty than the others, and some more ornamental than others, some with an entrance to the East others to the West, others to the North and others to the South, all plastered and sculptured, and turreted with various kinds of battlements, painted with animals and figures and fortified with huge and wide buttresses of stone, and it beautified the city so greatly and gave it such an appearance of splendour that one could do nothing but stare at it.

However, as regards the Temple, especially [dedicated to] the Idol [Huitzilopochtli] with which we are dealing, as it was that of the principal God, it was the most sumptuous magnificent of them all.

24It had a very large wall round its special court, all built of great stones carved to look like snakes, one holding on to the other, and anyone who wishes to see these stones, let him go to the principal Church of Mexico and there he will see them used as pedestals and bases of the pillars. These stones which are now used there as pedestals formed the wall of the Temple of Huitzilopochtli, and they called this wall Coatepantli, which means wall of snakes. There was on the top of the halls or oratories where the Idol stood a very elegant breastwork covered with small black stones like jet, arranged with much order and regularity, all the groundwork being of white and red plaster, which shone wonderfully [when looked at] from below—on the top of this breastwork were some very ornamental merlons carved in the shape of shells.

At the end of the abutments, which arose like steps a fathom high, there were two seated Indians, in stone, with two torch-holders in their hands, from which torch-holders emerged things like the arms of a cross, ending in rich green and yellow feathers and long borders of the same.

Inside this [the] court there were many chambers and lodgings for the monks and nuns, as well as others on the summit for the priests and ministers who performed the service of the Idol.

This Court was so large that on the occasion of a festival eight or ten thousand men assembled in it; and to show that this is not impossible, I wish to relate an event that is true, related by one who with his own hands killed many Indians within it....

This Court had four doors or entrances, one towards the East, another towards the West, another towards the South, and one on the North side. From these commenced four Causeways, one towards Tlacopan, which we now call the street of Tacuba, another towards Guadelupe, another towards Coyoacan, and the other led to the lake and the landing place of the canoes.

The four principal Temples also have their portals towards the said four directions, and the four Gods which stand in them also have their fronts turned in the same directions.

Opposite the principal gateway of this Temple of Huitzilopochtli there were thirty long steps thirty fathoms long; a street separated them from the wall of the patio[18]. On the top of them [the steps] was a terrace, 30 feet wide and as long as the steps, which was all coated with plaster, and the steps very well made.

Lengthwise along the middle of this broad and long platform was a very well made palisade as high as a tall tree, all planted in a straight line, so that the poles were a fathom apart. These thick poles were all pierced with small holes, and these holes 25were so close together that there was not half a yard between them, and these holes were continued to the top of the thick and high poles. From pole to pole through the holes came some slender cross-bars on which many human skulls were strung through the forehead. Each cross-bar held thirty heads, and these rows of skulls reached to the top of the timbers and were full from end to end ... all were skulls of the persons who had been sacrificed.

After describing a procession in which the God was carried to Chapultapec and thence to Coyoacan, the author continues:—

When they arrived at the foot of the steps of the Temple they placed the litter [on which the image of the God was carried] there, and promptly taking some thick ropes they tied them to the handles of the litter, and, with great circumspection and reverence, some making efforts from above and others helping from below, they raised the litter with the Idol to the top of the Temple, with much sounding of trumpets and flutes, and clamour of conch-shells and drums; they raised it up in this manner because the steps of the Temple were very steep and narrow [in the tread] and the stairway was long and they could not ascend with it on their shoulders without falling, and so they took that means to raise it up.

Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, Cronica Mexicana, Ch. XXX, p. 319, writing of the Temple of Huitzilipochtli, says:—

It could be ascended on three sides and would have as many steps as there are days in the year, for at that time the year consisted of eighteen months, and each month contained twenty days, which amounts to three hundred and sixty days, five days less than our Catholic religion counts. Others count thirteen months to the year. At all events the steps were arranged on three sides of the ascent.

The principal ascent faced the south, the second the east, and the third the west, and on the north side were three walls like a chamber open to the south. It had a great court and Mexican plaza all surrounded by a stone wall, massive and strong, [of which] the foundations were more than a fathom and the height [of the wall] was that of four men’s stature. It had three gateways, two of them small, one facing the east and the other the west; the gateway in the middle was larger, and that one faced the south, and in that direction was the great market place and Tianguiz[19], so that it stood in front of the great palace of Montezuma and the Great Cu. The height of it [the Great Cu or Temple] was so great that, from below, persons [on its summit], however tall they might be, appeared to be of the size of children eight years old or less.

26Ixtlilxochitl (‘Codice Goupil’).

The Temple and principal Cu of this City, indeed of all New Spain, was built in the middle of the city, four square and massive as a mound (terrapleno) of stone and clay, merely and only the surface [built] of masonry. Each side was eighty fathoms long (445 Eng. ft.) and the height was over twenty-seven fathoms (150 Eng. ft.). On the side by which it was ascended were one hundred and sixty steps which faced the west. The edifice was of such a shape that from its foundation it diminished in size and became narrower as it rose in the shape of a pyramid, and at certain distances as it rose it had landing places like benches all around it. In the middle of the steps from the ground and foundation there rose a wall up to the summit and top of the steps, which was like a division that went between the two ascents as far as the patio which was on the top, where there were two great chambers, one larger than the other—the larger one to the south, and there stood the Idol Huitzilopochtli; the other, which was smaller, was to the north and contained the Idol Tlaloc, which (Idol) and Huitzilopochtli and the chambers looked to the west. These chambers were built at the eastern edge and border of the said patio, and thus in front of them the patio extended to the north and south with a [floor of] cement three palms and more in thickness, highly polished, and so capacious that it would hold five hundred men, and at one side of it towards the door of the larger chamber of Huitzilopochtli was a stone rising a yard in height, of the shape and design of an arched coffer, which was called Techcatl (Texcatl) where the Indians were sacrificed. Each of these chambers had upper stories, which were reached from within, the one from the other by movable wooden ladders, and were full of stores of every sort of arms, especially macanas, shields, bows, arrows, lances, slings and pebbles, and every sort of clothing and bows for war. The face and front of the larger chamber was ornamented with stone in the shape and form of death’s heads whitened with lime, which were placed all over the front, and above, for merlons, there were carved stones in the shape of great shells, which and the other with the rest of the Cu is painted on the following page. * * * * [see Plate D].

Tracing A1

after J. GARCÍA ICAZBALCETA

Tracing A2

PART of the CITY of MEXICO from a MODERN MAP

SUGGESTED SITE of the GREAT TEOCALLI and ENCLOSURE

Plate A.

PART of the CITY of MEXICO from a MODERN MAP

Plate B.

Plate C.

PLAN by PADRE SAHAGUN after DR. E. SELER

a = Great Teocalli

b = Eagle Vase

c = Priest’s House

d = Outer Altar

e = Eagle Warrior’s House

f = Tlachtli Court

g = Skull Scaffold

h = Yopic Teocalli

i = Wheel Stone

k = Collaiacan Teocalli

l = 5 Lizard (date)

m = 5 House „

n = Dancing Places

o = Snake Wall

p = Temple Entrances

Plate D.

THE GREAT TEOCALLI.

Codice Goupil—IXLILXOCHITL.

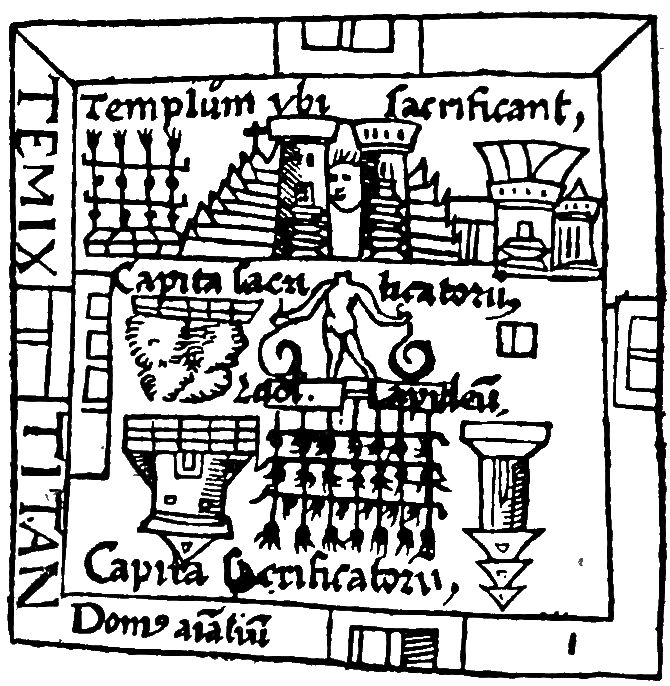

Plate E.

THE GREAT TEOCALLI,

from The Chronicle of Mexico, 1576.

Manuscript,—British Museum, No. 31219. Additional.

1. ‘Mexico en 1554. Tres Dialogos Latinos que Francisco Cervantes Salazar escribio y imprimio en Mexico en dicho año.’ A reprint with Spanish translation and notes by Joaquim García Icazbalceta. Mexico, 1875.

2. Dr. Seler states that the house of Mota still retains its name.

4. I. e. the Enclosure of the Great Temple.

5. A note by Don Lucas Alaman says: “I do not know what was the origin of this division of the Temple into three parts, which this expression appears to indicate.”

6. This would agree fairly well with Tracing A2, if the Apetlac or forecourt were included.

7. Bernal Díaz speaks of them as Torrezillas.

8. Memoriales de Fray Toribio de Motolinia. Manuscrito de la coleccion del Señor Don Jonquin García Icazbalceta, publicalo por primera vez su hijo Luis García Pimentel. Paris: A. Donnamette, 30 Rue de Saints Pères, 1903. This is probably the original manuscript from which the ‘Historia de los Indios de Nueva Hispaña’ was taken.

9. Un poco tuerto.

10. Todo el Pueblo.

11. “Donde parecia terminar la escalinata se descubrió un muro en talud siguiendo la misma dirección de la escalera.”

12. This must refer not to the altars themselves but the temples containing the altars.

13. Or towards the rear.

14. Sahagun specifies 78 edifices in connection with the great Temple, among these are “No. 72, named Itepeioc, a house where the Chieftains make the image of Vitzilopuchtli out of dough [masa],” and “No. 73, the building named Vitznoacealpulli, which is the house where they make the image of the other God, the companion of Vitzilopuchtli, named Tlacavepancuexcozin.” It thus appears that the two “barrios” or districts mentioned were sections of the Temple enclosure.

15. Cortés evidently uses the term Mosque (Mesquita) for the whole group of Temples within the Enclosure.

16. This is evidently an exaggeration, the houses of the Marques del Valle and the Mexican royal houses were not included in the area of the Temple Enclosure.

17. The apetlac?

18. The apetlac?

19. Tianguiz is the Mexican word for Market.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.