Day & Son, lithrs to the Queen.

MAGIC WORDS;

A Tale for Christmas Time.

BY

EMILIE MACERONI.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS BY E. H. WEHNERT.

LONDON:

CUNDALL & ADDEY, 21 OLD BOND STREET.

M.DCCC.LI.

LONDON:

Printed by G. Barclay, Castle St. Leicester Sq.

TO

MRS. AUSTIN

This Little Volume

IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED.

| MARION AND HER FATHER | (Frontispiece) |

| LITTLE MARY AND HER FRIEND TROY | 11 |

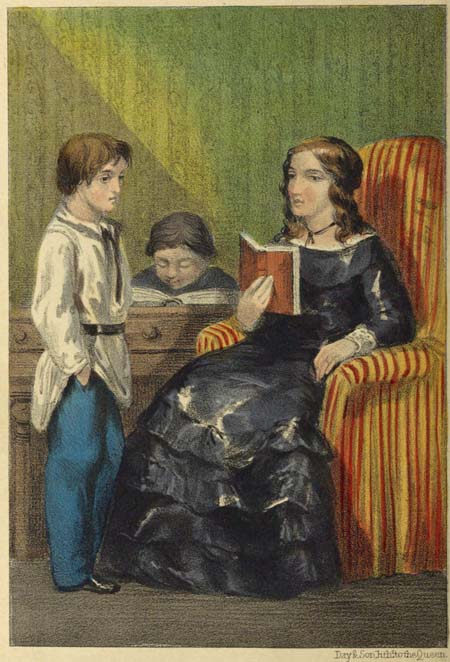

| MARION TEACHING LATIN | 25 |

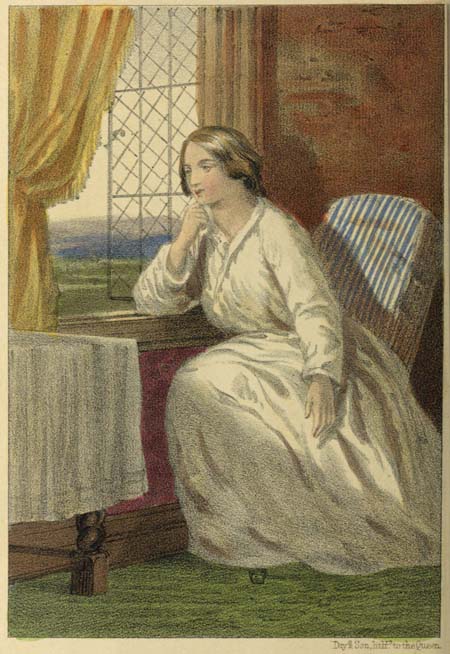

| EDITH WATCHING THE DAWN | 39 |

From Drawings by E. H. Wehnert.

MAGIC WORDS.

It was the evening of Christmas Day. The hymn of “Peace upon earth, good-will towards men,” had been chanted by thousands of voices throughout the land, from the grand cathedral-choir to the simple singers of the village church. Charity had extended her munificent hand to the poor and needy, lighting up smiles on many a care-worn face. Hospitality welcomed the good, the beautiful, and the great to the lordly mansions of the rich. Love and Peace sat enthroned in many a happy home. Poverty, shivering at the present, was consoled by the glowing figure of Hope, pointing with[2] radiant eyes to the future. Memory and Sorrow lingered around the grave of many a departed one; but of all mourners they were the saddest who were estranged from those they still loved. Yes, amid the pain, the sorrow, the suffering of life, their hearts were the heaviest; for (to use the oft-quoted words of the poet) “to be wroth with those we love, doth work like madness in the brain;” and this hallowed season speaks strongest to our kindest feelings, and to the tenderness of our better nature.

A train had stopped at a rough little village station about thirty miles from town, and a few country people, on their way home, leaned over the bridge above to admire the enormous red eyes of the monster as it moved slowly on through a deep cutting crowned with dark firs. They lingered yet a moment longer, to mark whom it had borne from the great city to their quiet village. A beautiful girl of fifteen, glowing with health and exercise, accompanied by two fine, rough-looking dogs, rushed[3] down to meet her playfellows and friends. She was breathless with joy, and with her race over the heath; but her merry laugh and warm greeting sounded pleasantly enough as the noise of the train died away in the distance.

A lady, wrapped in a warm plaid, who had been anxiously waiting for some time, took the arm of her husband, with a few low words of delighted welcome, and they walked briskly away. The dogs of the younger party barked with glee—were patted and caressed. One look at the dear heath and at the hills beyond, with a thrill of delight at the thoughts of a long ramble over them on the morrow, and the ponies were mounted, the dogs whistled to, and away flew the happy trio to the home-welcome, to the dear old hall, to all the joy of a Christmas meeting.

Only two other passengers appeared, winding up the pathway—a gentleman of tall and commanding aspect, and a buxom, brisk-footed countrywoman, wrapped in her scarlet cloak, who passed him with a low curtsey and cheerful good night. She was thinking of the[4] bright fireside, of the dear little faces round it anxiously awaiting her return, and of the enormous amount of joy contained in that wicker basket. An event of great marvel and wonderment is a poor woman’s visit to her friends in town, and she is ever in a tearful state of ecstasy and excitement on reaching home again; all of which becomes a matter of grave family history in the lowly household, and is recounted on many an occasion to eager and attentive hearers.

She quickly disappeared up a winding path cut through the furze and heather, evidently leading to a low-roofed cottage on the skirts of a fir-wood. Lights twinkled in the casement, and joyful voices were soon heard approaching to meet and welcome her. The road was now perfectly solitary. A few deep-red clouds still hung over the west, and here and there a large bright star shone silently through the sharp, pure air. Dogs bayed in the distance; the sound came very pleasantly over the heather through the rough old pines.

The gentleman walked briskly on, and lights[5] began to appear in the valley beneath. He stopped as the merry notes of a flageolet struck his ear, proceeding from a cottage by the road-side. The blaze of a wood fire within illumined the little rustic porch and neat garden. Bright branches of glistening holly shone in the tiny casement. The tune ceased, and was followed by a light-hearted laugh and the sound of young voices.

“How happy they seem!” said he. “It is such scenes as these which make the country so delightful, so cheering to sense and spirit!”

And yet he sighed heavily as he walked on; and passing through an avenue of fir and larch leading to one of the prettiest and most picturesque cottages in the world, he paused when he reached the garden-gate. It seemed, too, a dear, quiet, sweet-smelling home. Lights shone from more than one of the windows; and more than one bright young face might be seen, by the gleam of its golden hair, flitting about in the uncertain light. A sweet young voice singing as sweet a tune ceased, as all young voices do, suddenly, when the bell[6] rang out its summons, and a brisk, rosy little maid appeared, lantern and key in hand, to admit the traveller, and guide him through the long shadow of the firs to the house. A favourite dog bounded to meet and gambol round him with unrepressed joy. The children clustered into the porch to say, timidly, “How do you do?” and hold out their little hands to shake; while their mother, advancing with a kindly greeting, expressed her pleasure at his return. Even the maid looked pleased and happy to see him. But yet it was not his home.

After a few minutes’ conversation, the traveller was seated in his own room, his dog, his sole companion, looking at him with glistening eyes, as his master fondly stroked his magnificent head. He was a man of twenty-eight or thirty years of age, with a sad and thoughtful cast of countenance, yet one that all who looked upon it must instantly love and respect; it was at once so engaging and so noble. He looked round his little room at his sketches and his gun with evident pleasure, placed some books[7] and papers which he had brought on a little table before him, and drawing his arm-chair close to the blazing pine-logs, sat watching the golden cones as they crumbled away, one by one, at the height of their brilliancy. But every reverie must have its end; and his was brought to a close by the appearance of coffee, borne by a bright-eyed country maid, smirking and smiling with pleasure, as country servants are wont to do at every fresh arrival.

It would seem that the reverie by the bright fireside was not an idle one, but that among many revolving thoughts, some, at least, were considered worthy of preservation; for the coffee was soon despatched, the table covered with books and papers, and the stranger intently occupied with his pen.

So absorbed did he become with it, that after one or two long, wistful glances, the fine hound lay down reproachfully on his comfortable rug, as if despairing of any further notice that night.

The wind moaned heavily in the pine-branches round the cottage. Presently the[8] writer paused and listened to the sound, so like the rushing of distant waters. He walked slowly to the window, and gazed long and earnestly into the night. It was moonlight, yet stormy; and large, glittering stars, looked down through the dark branches, when the hurrying white clouds had drifted over them. The distant clock of the old village church, slowly striking the hour, sounded mournfully over the river; and the lonely man at that little window thought of years that were gone, of the bright firesides in many a happy home that night, and turned and put away his papers with a sigh. He thought how differently he used to work years ago, when, with all the ardour of his nature and the energy of hope, and yet with intense fear and anxiety, he strove to render himself worthy of one idolized, one long-sighed-for object! He thought, too, of the bitterness, the agony of disappointment; and how long years of his young life would have been thrown away, had he not struggled hard to save himself from becoming a useless, melancholy being, given up to the indulgence of[9] selfish regrets. He had succeeded,—there was some comfort in that reflection. He knew of what he was capable, and dared not throw away the power he had acquired, because it no longer availed the idol Self. So he still worked on. He had become distinguished for his literary labours, and for his contributions to the improvement and well-being of his fellow-creatures; but to fame and to the praises of the great he was now equally indifferent. His happiest hours were passed in his favourite village, where he was greatly beloved, although he dared not wholly give himself up to the quiet of a country life.

He had had the old Gothic church restored, with all possible observance of its antique ornaments and its fine clustering ivy; and took a kind of Sir Roger de Coverley delight in seeing the country people, bettered and improved in every way, flocking to it on Sundays to hear his good tutor’s sermons, to which he used to listen with so much reverence in his boyish days. He had learned to believe that the word “happiness” signifies, the being reconciled to bear,[10] still having courage to do, and gratitude to enjoy that which remains. Thus, he was usually cheerful in his various occupations; but this was Christmas time: a time when the lonely heart feels most desolate—a time when many a tender word spoken by the absent is remembered with sorrow—when all anger is forgotten in the feeling of peace and love which steals over the heart. And his head lay buried in his hands, his whole soul given up to an overwhelming agony of regret.

[11]

Day & Son, lithrs to the Queen.

“This day last year,” he muttered, “who could have believed the change? Oh, Edith!” he continued, taking up a miniature that lay beside him, “who could have thought then that we should now be as strangers to each other? Who could have thought that that bright face, those many noble qualities, could have wrought so much misery?” Again he looked at the lovely countenance, smiling on him a thousand of the tenderest remembrances, and a still gentler expression, a kindlier spirit, came over him. “Those eyes,” he said, “how softly they have looked on me! Perhaps even now a thought——but what folly! In the pride of beauty and prosperity, what is there to remind her of me?”

A low tap at the door interrupted his meditations. For an instant he could not say, “Come in!” his heart was so very full; but quickly recovering himself, he turned with a smile to welcome a little village child, who timidly advanced to place both her tiny hands in his.

She looked into his face with eyes beaming with love and gratitude; but the joyful, sparkling expression soon faded away, for she saw that he was sadder than usual; and with the quick sympathy and natural grace of childhood she sat down quietly on the rug, and taking the stately head of the hound on her lap, pensively stroked his long, shaggy coat. Presently she ventured to break the silence in her gentle way—“I am so glad you are come back, sir; I have missed you so!”

Her companion’s countenance brightened, and he said with animation—“Have you, though, my poor little Mary? I thought you[12] had forgotten me, being so long away.” And he stroked her bright brown hair.

“You should not have thought that,” said the child, earnestly; “I always remember you, for you taught me all I know. I was longing to come yesterday, and all day to-day,” she continued, “to hear if you had arrived. To-day has been so happy that I could not stay away any longer, and so here I am,” she added, with her merry laugh, which sounded pleasantly in that usually silent room. These simple words, that mute caress, had restored the confidence of the two friends. Mary was herself again, full of fun and prattle. Seated on the extreme edge of a huge Gothic chair, she balanced her little feet on the back of her friend Troy, who, far from resenting the liberty, fixed his dark eyes lovingly on her sweet young face, while she talked on, full of the details of her simple life. How she had gathered pine-cones for several evenings, because she knew he loved their cheerful blaze and sweet smell. How poor Turpin, who was always in trouble, had hunted a rabbit, and[13] been caught in a trap; of her mad race over the hills for help; how she nursed the poor, poor foot afterwards; and how the faithful patient cried because he could not accompany her that night; the relation of all which very much affected his kind little mistress. Presently she produced with great glee her “Christmas present,”—several little bundles of bark, peeled with great care, from the silver birch-trees, cut into slips, and tied with red worsted. “I burnt a little bit the other day,” said she, “and the smell was so nice I thought you would like it, so I got some to light your taper with—do try it;” and the little creature soon held a blazing piece in her hand.

“It is delicious, Mary; and how good of you to collect it for me!”

“I was very happy getting it,” said the child; “but I wish you had not thought I had forgotten you. I could not forget you!” she continued, after a pause; “you, who have been so good to me, and taught me so much! I never looked at a book before you came. Oh, I was sadly wild! Mother said I made[14] more noise than the boys!” And she laughed heartily.

The tutor laughed too, and told the often repeated story, which he knew she loved to hear, of how, in his walks, he had frequently listened to her little voice singing in a cornfield, while “minding” birds; how he had been surprised at her sudden disappearance on his nearer approach, and on making a voyage of discovery, had found her ensconced in the body of a broken-down post-chaise, that, singularly enough, lay between two old fir-trees at the foot of the wood! He did not describe to her how, in imagination, he had pictured the different and exciting scenes in which the once gay equipage might have borne its part; but went on to say how he had peeped in unobserved, and had seen her perched on one of the dilapidated seats, with a little piece of board on her lap, intently occupied in carving a morsel of meat into divers small pieces, which she divided, with impartial care, among three ragged starlings perched on the opposite beam, who watched her with[15] glistening eyes! How merrily she talked to them, and how perfectly they seemed to love and understand each other! He reminded her of her surprise on being discovered, and her frank invitation to the intruder to “look in” on the wonders of the unique aviary, with its valuable illustrations of the “History of Red Riding Hood,” its bright jay’s feathers, and other childish treasures!

Heartily the little Mary laughed; and so the Christmas evening passed on.

“I must go now,” she said; “I promised to read mother the pretty story you gave me, ‘Simple Susan,’ and they will all sit up for it! Good bye! You will promise not to be so sad when I am gone as you were when I came in. You have been thinking of that pretty lady again!” she said, with a face of anxious love—pointing to the miniature—“that makes you so, I know! Why don’t you go to her?”

“Because she does not love me, Mary,” was the faltering reply; “and you know we are not happy with those who do not love us.”

“Are you sure of that?” said the child,[16] earnestly. “People often hide their kindest thoughts—and perhaps she hides hers from you; you must look for them, as I look for violets, in their thick leaves. Oh, I was so unhappy once!” she continued, tears starting into her eyes at the remembrance: “I quarrelled with my brother, and we did not speak all day—both were so proud: but do you know” (and the sweet little face sparkled) “that when I put my arms round his neck and kissed him, and said, ‘Good night, Harry!’ he kissed me, and cried too; and said how unhappy he had been all the time. I had thought he would never, never love me again! Oh! if my brother had died, as baby did, before we kissed each other that night!”

Poor little Mary paused, her heart quite full at the bare idea of such a thing; but she turned again, with admiring eyes, to the miniature. “She looks very kind and good, and so beautiful! Did you speak gently, and ask her to love you again: or were you proud?”

[17]The child did not notice the agitation of her companion, and little did she imagine that, long after her head lay softly on her happy pillow, the simple eloquence of those Magic Words was working powerfully in his heart!

Over many a mile of hard, frosty road, by snow-clad fields and hills and woods, by many an ice-bound stream, must we lead the imagination of our reader on the evening of the same Christmas Day, and peep into another home, far from that we have just quitted.

Undrawing the warm crimson curtains of a charming little room—half drawing-room, half library—the light of a lamp falls brightly on the figure of a lady reading to her husband. It is manuscript, and he puts the pages by for her as she goes on.

She often pauses, to look up with a delighted smile at his praises, and he thinks that she never looked so beautiful before! She is very like Correggio’s Magdalen, and has the same lovely countenance and waving hair.

[19]Presently she came to the last page, and the praise was repeated.

“I had no idea I could translate so well,” said she, “and am glad you like it, for that will give me spirits to go on: I may, in time, become quite useful to you.”

“When are you not everything to me?” was the reply. “But, Marion, you must not work so hard; I cannot afford to see you look one bit less bright. Besides, it is a kind of reproach to me your working so much; indeed you must not!”

“Nonsense!” said Marion, laughing; “you can’t think how happy I am when helping you, for I am sure you are often very weary! Poor Edward! what anxiety I have caused you! Now for a volley of protestations!” said she, laughing again. “But to be serious: I was thinking, to-day, how much we have to be thankful for; and that with all its anxieties how happy this year has been—how infinitely happier, working and striving on together, than droning through an insipid life of ease, as some do. I don’t know what would become[20] of me if you were ever to be rich,” she continued; “to be sure, one might always find some useful employment, some good to be done; but no one knows, except those who have experienced it, the delight of overcoming difficulties, and earning home comforts by one’s own exertions.”

“True, dear Marion! I never knew, until I knew you, how little is necessary for happiness!”

“I knew what life was—I had an anxious one at home, even from a little child,” said Marion, “and adversity taught me to know what is best worth knowing; what flowers to gather in this great garden, that many neglect, or do not perceive. How sweet are the uses of adversity! I love to linger on those words; and if ever I venture to write an essay,” said she, smiling, “it shall be on that subject. What does it not teach us?—the practice of almost every virtue.”

“Nay, not quite so far, enthusiast,” said her husband, smiling; “remember the effect of almost constant sun on flowers; how splendid[21] they become—how fully their beauty is developed!”

“Yes; but they cannot bear the storm that may, that must come. The stout old thistle, reared in cold and sleet, is much better off—much more useful, and protects many a little plant under its vigorous leaves. Now, only think what adversity really does for us. To begin with my early life:—my father and mother treated me as their friend in all their troubles; I was accustomed to watch their anxious care-worn faces, to try to cheer them, and to rejoice when they brightened: this bound us together in the closest affection; I believe no child, no parents, were ever so dear to each other. No little home was ever so loved as mine; and I was quite broken-hearted when away from all its cares, even for a short time, although in the midst of what people called enjoyment. These were very different feelings from those of children nursed in the lap of affluence, who are frequently selfish, and often but little attached to those around them. I knew what it was to be deprived of many[22] comforts, which made me grateful for those I had, and taught me to feel for the sufferings of others infinitely worse off than myself. Naturally impetuous, I grew up patient; for, as you know, my father was a man of eccentric genius, who failed in all his efforts to place us in the brilliant position he dreamed of. I felt and shared in his disappointments, until disappointment itself became powerless! Sympathy with those I loved roused me to exertion—taught me the value of time—the dignity of usefulness! But, above all, the frowns of the world, the sweet uses of adversity, made me feel the dear necessity of clinging to and loving one another, and of living in that ‘peace which passeth all understanding!’”

Marion paused, and looked with inexpressible tenderness on her husband.

“I do not believe we should have loved each other half so well if we had not borne so much anxiety together,” she presently continued, “although it would be a dangerous experiment for those to try, who never knew what care was! We very coolly stepped into its troubled[23] waters. What straits we have been in! There is really some amusement, though, in looking back to a hundred comical little difficulties, mingled with graver trials; in peeping into the crowded picture-gallery of one’s own life—grave and gay! Do you remember when we were so very poor, and your father’s friends, the Saviles, condescended to drive over to luncheon with us?”

“Oh, yes,” said Edward, laughing; “when poor old Jock behaved so inconsiderately!”

“Inconsiderately, indeed,” said Marion, laughing too. “I shall never forget seeing him swallow the delicacies which I had prepared with so much care, in the coolest manner possible, looking me hard in the face all the time. I was in an agony to see the ham sandwiches disappear one after another down his huge throat (knowing there were no more in the house, too), while the capricious fine lady who took a fancy to feed him, drawled out, ‘the d-e-a-r d-o-g! how he li-kes them!’ I should think he did, indeed, with his appetite! I do believe, though, Mr. Edward, that,[24] like all men, you rather enjoyed the scene than otherwise; for you never offered to put the cruel old dog out of the room.”

“How could I tear him from the flattering attentions of his Patroness? But let me see; how did you manage it, Marion? I dare say very ingeniously and gracefully. I remember how proud I felt of you that day.”

“Oh, I appeared to enter into the amusement and drollery of his enormous appetite, but suggested, in the most affectionate manner possible, that he should bow his thanks to the fair lady before tasting another morsel! Poor Jock, who had not the slightest acquaintance with any feat or accomplishment of the kind, was all amazement at my gestures and commands, and only stared hard for more; whereupon he was gently ‘fie-fied,’ and put out of the room for his obstinacy and ingratitude!”

[25]

Day & Son, lithrs to the Queen.

They both laughed heartily at the remembrance of Jock’s delinquency and its punishment; and Marion being in a very merry humour, recounted with much mirth many other similar incidents, which they could laugh at now. “We never deceived each other but once,” said she; “the time when you were so ill, you know, from over-work, and I used to steal slily into the village to give your Latin lessons to those stupid boys you were ‘preparing!’ I often wonder how I took courage to ask their mother to let me take your place: yet I am glad I did, for I don’t know what we should have done without the money; and I studied the lessons so well myself, that I did no injustice to your pupils. But then the dénouement! I shall never forget your walking into that dingy library, pale as death, and your extreme surprise on finding me seated in the great chair, conjugating a tremendous Latin verb, while the poor little mamma looked on with amazement at my proficiency! I was startled too, fully believing you to be quietly resting on the sofa, while I took my walk!”

“We both looked very guilty for an instant.”

“Yes, we did indeed; and I thought I never should cease laughing on our way home, especially as you were half inclined to be angry![26] But my mirth soon vanished when I saw how faint you were, and you rested your head on my shoulder as we sat on the stile. A terrible fear came over me,” continued Marion, shuddering, and drawing closer to her husband—“I never felt pain like that before!”

Both were silent for some time; and Edward tenderly stroked the beautiful head bent down beside him. “Nay, look up, Marion,” he said; “I am quite well now, love, and you must not be so sad.”

“I am not sad,” said Marion, raising her large eyes, and smiling gently. “I was thinking how grateful I am that you are better, and how happy this Christmas would be if you were but reconciled to your father.”

“Every house has its spectre, Marion, and this haunts ours. I believe one always feels any kind of estrangement from those near to us most powerfully on days like these. They seem to have a strange mysterious power of calling up old recollections and early affections!”

“Only those which ought never to be broken come at this holy time,” said Marion; “the[27] gentle thoughts it brings with it seem to me like the soft warning of angel voices,—to be at peace ere it is too late! I wish you would read them so, and write to your mother again: she is of a gentler nature; but they must—yes, they both must, long to see you again!—Oh, if I could but persuade you!” she continued, with emotion: “we know not what a day may bring forth—even to the youngest and strongest among us; and Mrs. Hope says they both seem to ‘age’ very much. How deeply you would grieve through life if——”

“Oh, Marion, say no more!” exclaimed her husband in an agitated voice, “it is that thought which so constantly haunts me. For myself, I could forget all; but their unkindness to you—to you, of whom they ought to have been so proud; I cannot forget that!”

“Do not think of it,” said Marion, in a soothing tone; “we must not quarrel with people because they are unable to see things in the same light as ourselves. They knew very little of me, and thought, I dare say, that I prevented your being much happier with a[28] wealthier bride: besides, they may love me yet when you have made your peace, as I know you will,” said she, smiling. “Remember, it is to your parents that you bend, and I never can feel happy while you are as a stranger to them. I suppose it would be my turn next,” said she, with her musical laugh, “if I were to venture to oppose your wishes, or to say a few angry words.”

“Marion!” said her husband reproachfully.

“Well, what security have I,” was the playful retort, “over one who could be contented under such circumstances? You owe to them infinitely more than you do to me—they loved you for years and years before I did. Oh, Edward! your own heart must tell you more than I could ever speak.”

“We will not discuss the subject any further, dear Marion,” said he, and his voice faltered. “Sing to me, will you? The evening never seems perfect without a song from you.”

Marion sang the following lines in a rich and lovely voice:—

[29]

Marion’s beautiful voice trembled with emotion, and her eyes were filled with tears as she approached her husband. He leaned his head thoughtfully on his hand.

Those Magic Words were thrilling in his heart.

With the exception of the young and thoughtless, who only look forward to a season of festivity and enjoyment, and of the callous and indifferent, who seldom think of such matters at all, the varied feelings which hail the approach of Christmas may be compared to those occasioned by the contemplation of advancing age—of age so different in its aspects, whether we behold our fellow-mortals sinking down into the vale of years alone, neglected and unloved; alienated from kindred and friends, and still retaining the unholy animosities of earlier years; unsubdued by religion, unsupported by the contemplation of a useful and virtuous life; or, on the contrary, surrounded by loved and loving hearts, looking back with gratitude and pleasure to[32] the past, and with hope and resignation to the future, in peace, and love, and charity with all! Many a family in embarrassed circumstances, many a poor widow with a “limited income,” looks on the increased expenses of this season of the year, on its bills and various claims, with the same feelings which anticipate the infirmities of declining years and sharp attacks of rheumatism and gout. Many look forward to increased domestic comfort, and brighter firesides. Many a mother smiles with delight on her children, all assembled round her once more. Many a father rejoices in their joyous laughter, or in the affection and reverence of maturer age. Many an old friend is welcomed to the social board. But, alas! there are many, too, who look back with a dreary regret to the years that are gone, and think, how different Christmas Day seems now to what it was!

Such melancholy thoughts were revolving in the mind of a man of dignified and venerable aspect, pacing gloomily up and down the splendid library of a fine old mansion. It was almost dark, and the glare of the fire played over the[33] rich volumes, and on the antique carving of the furniture. He looked with a sigh at the hearth, once crowded with happy faces. One only remained, and ah! how changed from the blooming figure of earlier days, which rose before him! How feebly that once beautiful head lay on the rich velvet cushion of her chair! How much suffering and sorrow might be traced on that furrowed brow! He felt that her reverie was as sad as his own; and truly too, for she was thinking of many a fair child that had gone down to the tomb in all the promise of early youth!—of the pride and joy of seeing them assembled at Christmas, well and happy!—of the joyous holiday-makings and merry meetings!—of the tearful partings, and the agony of those final ones, when the thin, small hand, pressed in its tiny grasp the last life greeting!

Still she could think of the departed with the softened and resigned feelings which religion and time never fail to produce. But that which fell most heavily on her heart and darkened her declining years, was, that the last and only surviving[34] one—the boy whom she had loved best—whom she had watched over with such intense fear and anxiety—was still a stranger from his father’s home. Month after month passed, and still both, in their pride, hung back from any attempt at a reconciliation. She felt that many more might not elapse before she would be far beyond the reach of mediation, and with a mother’s and a wife’s love she longed to see them united again ere she departed. Presently she walked to the window, and laid her thin white hand on the arm of her husband.

“I see you still love to watch the rooks going to rest in the old elm-trees.”

“Yes,” said Sir John, hastily; “it is amusing to watch their odd flights, and to imagine you can distinguish the croak of a particular bird.” He would not say that it was Edward’s favourite pastime when a boy, but his companion knew well that he thought of the time when both used to stand there together. “But who is this coming up the avenue?” he said at length, as if willing to shake off the chain of thought. “Mrs. Hope,[35] I fancy, by her black dress. I suppose she is come to tell us all about the dinner, as she promised.”

No door ever opened on a better, or kinder, or more zealous village schoolmistress, than did this stately one on the spare, timid little body who now advanced. No one ever looked more placidly happy, and no one more pleased and grateful, when she was kindly placed in the most comfortable of chairs by Sir John, and welcomed with a cordial smile by his lady.

“I came up to tell you, sir, that everything was done as you desired. The children were so happy, it quite did one’s heart good to see them. They all came in the morning with evergreens and holly, and we made some beautiful wreaths to set off the room. Their new dresses look very nice, and they are truly thankful to you for your kindness. The coals and blankets, and other things, are all sent home too, and many say they shall thank Sir John for a happy Christmas; which they wish in return, with all their hearts, I am sure,”[36] continued the good little woman, with emotion; “for, thank God, very few among them are ungrateful.”

Sir John’s benevolent countenance brightened with pleasure as he listened to the kind schoolmistress’s further recital of the village festivities, to which he had contributed so largely; and his wife marvelled how the heart of so good a man could be so unrelenting as she knew it was.

Perhaps similar thoughts were passing in the mind of Mrs. Hope; for after she had told all she ostensibly had to tell, and felt that it was time for her to depart, she still lingered, and yet hesitated to speak.

“Is there anything you wish to say to us, Mrs. Hope?” said the lady, kindly; “pray do not be afraid to mention anything in which we can be of service to you. Is your son——”

“I thank your ladyship, I was not thinking of him then, but of some one very different. I thought you might like to know, and yet was not sure—but Mr. Edward and his lady came over to the school-house to-day,”[37] said she, as if from a desperate resolution, “and my heart was quite full to see them come and go away again like strangers—just at Christmas time, too!” Poor little Mrs. Hope trembled, for she saw that Sir John’s brow darkened, and he drew back in his chair in an agitated manner; but an encouraging look from the lady re-assured her. “It was very pleasant to see him again,” she continued, “in the little parlour where he often used to sit years ago, and give the prizes out to the children, and speak encouragingly to them. I thought he had forgotten the old place, and all he was so good to; but he told me he had been longing to see it, and never could feel so happy anywhere else.”

“Poor Edward!” said the lady, with emotion. “How does he look?”

“Very pale and delicate, ma’am; but just the same as ever—just the same noble look,” said Mrs. Hope, fast gathering courage, “although not quite so joyful like as it used to be. He made particular inquiries as to how his father and mother looked, and seemed terribly cast[38] down when I told him how poorly you had both been.”

“Did he, indeed!” exclaimed Sir. John, starting from his seat, and pacing up and down; “why did you not let me know he was with you?”

“I feared you did not wish to know it,” was the reply. “But oh, Sir John! in my humble way I did think it strange that, in an erring world like this, your heart should be turned from two such children!”

Tears were running fast down the face of the good little schoolmistress. She hurried away; but her Magic Words were not spoken in vain.

[39]

Day & Son, lithrs to the Queen.

Beautifully dawned the last morning of the old year. How lovely are some few winter sunrisings! A cold, grey sky, and dim, glimmering light, scarcely reveals surrounding objects. Presently a delicate blush appears, gently stealing over the east. It deepens to a ruddy glow; and then bright, golden clouds, tinged with many a varied hue, overspread the sky, lighting up in the strongest relief every leafless tree, even to the most fibre-like branches.

Everything is very still. Edith sits silently at the window of her dressing-room, watching that lovely dawn. Presently a few starlings appear on the frosty slopes, with their quick, impatient gestures and rapid movements, seeking a breakfast. A pair of beautiful blackbirds droop their jetty wings, and seem[40] numbed with cold. A robin, cheerful even in adversity, trills a few grateful notes on a shrub near the window, and Edith thinks that no new-year’s serenade could be half as touching as that low, sweet song. She thinks, too, what a lesson it teaches; for her melancholy eye had been straying mournfully over the broad lands stretching far and wide before her, and—“’tis an old tale, and often told,”—she had almost envied the humblest cottager in those her lordly possessions. “Farewell, old year!” she exclaimed; “none other will ever dawn upon me as you did. May the new bear happiness and joy to many! Oh, Marion! you little thought how desolate I am, when you prophesied that there was yet much in store for me.”

Marion’s picturesque cottage could be plainly seen in the distance, shut in by the blue range of hills above, and sheltered with sweeping larches. The morning sun now shone brightly upon it, and Edith pictured to herself the beaming, happy countenance of her friend.

“May God bless you, Marion!” she continued with emotion; “for to the example of[41] your gentle goodness I owe all that is now left me,—the knowledge of that usefulness, that patient love and forbearance, which makes you so dear to others, so happy in yourself, and without which all that the world calls beauty and talent is hollow and heartless indeed! You taught me the value of true affection—the folly and littleness of the false pride I rejoiced in; and yet so sweetly, that I was only humbled to myself—not to you. Would that it had been but a few short months before! Oh, Percy! how willingly would I now confess myself in the wrong! But now I am forgotten! In your benevolent plans, in your honourable successes, there is no thought of me; or I am only remembered as a wilful, imperious woman, whom you once foolishly loved. I shall never see you again—mine the sorrow, mine the fault! But I am earning the right to self-esteem; I am doing all that I believe you would approve of, did you care for me now.”

Her heart was very full as she descended to the breakfast-room. No one was there; but on the table lay a simple nosegay. “From[42] Marion,” was written on a slip of paper. Edith mentally thanked her friend for the love which she knew was expressed in the fragrant gift; but tears sprang into her eyes as she looked on it; for a few lovely roses, the little blue periwinkle, with its shining green leaves and “sweet remembrances,” and a few early primroses and violets, were arranged almost exactly as she had received them from a still more beloved hand the year before. She started as her mother entered the room, and turned hastily to conceal her emotion; but touched by the look of anxious love which she caught fixed on herself, exclaimed, while she suffered the large tears to fall down her face, “Oh, my mother, I will not be proud to you—Heaven knows there would be little merit in that! I was thinking”—and her beautiful head lay on her mother’s gentle bosom—“of the happiness which I have thrown away—of one who has forgotten me.”

“Ah, my dear child!” said her mother, as she tenderly pressed her hand on the throbbing brow, “in the doubtfulness of our nature[43] we often accuse those of forgetfulness whose hearts may be breaking for our sake.”

Edith looked up, a sudden expression of joy beaming over her countenance. As she bent again over the flowers, the sweetest gleam of hope stole over her, and she felt the magic influence of those words.

Happy are they who in their own interests, joys, and sorrows, forget not the welfare of others! Edith looked forward with pleasure to the events of the day; for in the morning the school which she had built was to be opened, with an appropriate address from the good rector; and in the evening, young and old, rich and poor, were to be assembled in her splendid home. She had gaily declared to the gentry her wish to receive, as lady of the manor, “all good comers,” that New-Year’s Eve; and to sup in the old hall of her ancestors, after the manner of feudal times, with the peasantry of her estate “below the salt.” They, of course, looked forward to the event with unmixed pleasure and delight. Not so all those of gentler birth; for she had lived but little[44] among them until of late, and was understood still less. Many thought it a capricious whim of the spoiled beauty, and many wondered what strange thing she would do next. “It was not that she cared more than the rest of them that the poor should enjoy themselves, but that she loved to do as no one else did. What a pity her uncle’s fine estate was left in such hands!”

So charitably reasoned some of the invited guests; but, happily, there were others who knew Edith better, and welcomed with delight her kind and benevolent plan for a happy new-year’s eve to them all.

The important evening at last arrived. The village children could not have existed much longer. Wide were the park-gates flung open, and never had the old avenue rung with the sound of so many merry voices before. Many a little belle startled a sleeping bird by stopping under his resting-place to admire, by the light of the lantern she carried, her bran new shoes and pretty frock, wondering if any of the great ladies would look half as nice, and feel half as happy as she did. Some timid[45] little creatures clung to their mothers’ skirts, and looked with mingled feelings of awe and admiration on the stately mansion, blazing with light in the midst of the dark cedars, half afraid of entering it until re-assured by the promise of seeing the kind lady whom they all loved. But when they arrived there, and were welcomed by that sweet lady herself, who shook hands with all, and wished them a happy new-year; and when they saw the fine old hall with its bright armour, and many magnificent rooms all beautifully lighted up and decorated, and were shown the pictures and other wonderful things, their delight knew no bounds. But, perhaps, that which charmed them most was a deep recess at the lower end of the hall, completely filled with rare and luxuriant plants, in the midst of which stood a beautiful figure of Peace, joining the hands of Anger and Contention, who were regarding with a mingled expression of surprise and admiration the heavenly beauty which they had not perceived when occupied with their unholy strife.

The children whispered softly here; for the[46] light was very dim, but a lovely glow irradiated the beaming countenance of Peace, and here and there flowers glistened in the dark leaves around them.

And now tea and cake, such as they had never tasted before, awaited them in a pretty room, gay with laurel and holly, where our friend Mrs. Hope presided, half beside herself with joy, yet preserving the most perfect order and decorum. Then the amusements of the evening began, which comprised the merriest and oddest of all styles of dancing to the music of the village band, the wonders of a magic lantern, and many a childish game beside; but above all, the crowning delight was the new-year’s gift to each of a pretty little volume, with the name of each written in it by Edith’s own hand.

The hours flew too swiftly by—so thought these delighted little people, as ten o’clock was announced, and Edith wished them all good night as kindly as she had welcomed them; but in few words, for carriages were arriving, and she had to receive her guests: they thanked[47] her in their simple way for the pleasure which she had given them, and the homely sincerity of their gratitude lighted her sweet face with happy smiles.

The spacious picture-gallery, which had been converted into a ball-room for the occasion, was gay with many a shining wreath. The old family portraits seemed to look down with pleasure, and to beam a welcome on all assembled there; so thought several of the wandering villagers, grouped here and there amid the more brilliant throng, watching the mazes of the dance with interest and amazement, and listening with equal surprise to the magnificent band, to the music of which many a fairy foot was flying. Most, however, thought it very inferior to the performance of their own village musicians, and wondered how people could dance to such spiritless tunes on a new-year’s eve like this.

Edith had anticipated their predilection, their shyness, and their love of country-dances and hornpipes; so they were soon marshalled by their gentle chamberlain, Mrs. Hope, into another room, where they could[48] enjoy all these to their hearts’ content, and yet feel themselves privileged to look in on the grandees whenever they pleased. Perhaps this room, with its unrestrained mirth and merry laughter, was happier than the more splendid one; for though many there were thoroughly enjoying the beauty and gaiety of the scene, still there were heart-burnings. In that large assemblage several met, who, though once friends, had not spoken for years, and who felt startled and uneasy at being brought into such close proximity. But scarcely a shadow could be cast where the beautiful hostess moved and spoke—

“Thought in each glance, and mind in every smile.”

There was so much frankness in every kind and earnest word she said, joined to the charm of her gentle and courtly manners, that the coldest, the most obtuse, the most reserved, felt moved and interested beyond themselves, and more cordially inclined to all the world beside.

And Marion was there, whose flowers were the only ornament on Edith’s snowy dress; but she, usually so gay, was thoughtful almost[49] to sadness, and looked anxiously into her husband’s face as they stood for a few moments apart—“I believed that of late years my father never mixed in such scenes as these,” said he. “Edith could not have thought he would come when she invited us.”

“I knew how it was to be,” said Marion; “there are many here to-night whom she hopes to bring together again; rich and poor. See, she is looking towards us now, while speaking to him! Oh, Edward, go up to them at once, I entreat you!” exclaimed she earnestly.

“Not before so many people,” said her husband with emotion. “Suppose he were to refuse my hand?”

Marion sighed: but her hopeful nature whispered that the New-Year’s Eve was not yet ended. And now a clock of silvery tone chimed and struck the hour of midnight. The guests were conducted to supper: unseen harps, and sweet voices, gave a slow farewell to the old year, as they were seating themselves at the upper end of the hall, and then burst forth into a joyful welcome to the new, as the[50] villagers entered and took their places at the lower range of tables; this again died away, and a sweet strain arose, of the softest prayer, for peace and happiness to all! Marion looked round with emotion.

It was a lovely scene, that huge banquet-hall, with its gay wreaths of holly and flowers. The bright assemblage of guests; the happy faces of the villagers below; the beautiful hostess, seated in an antique chair at the upper end, with the banners of her ancient race, trophies of ages long gone by, waving behind her; the lovely figure of Peace below, almost shrouded in the dark leaves, and forming a striking contrast to those warlike emblems: all these afforded a sight which, once beheld, would not be easily forgotten.

After each guest had paid sufficient homage to the choice viands before them, Edith took up a cup of curious workmanship; her face was radiant with kindness and love as she looked on those around her.

“This cup has been possessed, for many a century, by my ancestors,” she said; “preserved[51] for ages as a venerated relic: doubtless many a toast has been pledged in it—many a friendly welcome expressed; but I believe no more cordial and sincere one than that with which I greet you all this night. I would fain express the usual wish of a new-year of all imaginable happiness and prosperity, but as such have never visited this earth, we know it would be vain; and I therefore wish you the greatest of all blessings—that which cheers and supports us in the sorrows of life, and heightens beyond measure its pleasures and enjoyments,—love and harmony in your hearts and homes! There may be some among us estranged from friends and kindred, grieving over the fault, (for few, let us hope, in a Christian land, can live unmoved in enmity one with another,) and yet hanging back, in mistaken pride or want of moral courage, from the few conciliatory words which would, in most cases, suffice for a perfect reconciliation. The old year is now passing away—may it bear with it all anger, all animosity! May those few healing words be spoken,—and[52] Peace, and Love, and Charity be with us all!”

Edith’s voice trembled with emotion, but she did not perceive the agitation of many of her guests, for her eyes were fixed, as if in a dream, on the lower end of the hall. There was a movement of surprise among those seated there: she made her way, she knew not how, through them all. Yes, it was Percy!—One look, expressing a thousand emotions, and their hands were clasped in each other! For an instant her lovely head was bowed before him, while a few large, heavy tears, fell on the flowers at her feet! But she soon mastered her emotion, and, with a face radiant with joy, led him through the crowd of sympathising faces to her mother’s side. In the short silence which ensued, the bells of the village church were plainly heard ringing-in the new-born year! When had they ever sounded so sweetly before?

And now a joyous strain again burst forth, and all returned to the ball-room. Again the young, the beautiful, the gay, joined in the[53] dance; and never feet flew more lightly than theirs. But there were those who felt a deeper joy; the serene, the heavenly one of Reconciliation!

And Percy and Edith once more stood side by side,—united, happy! And Marion told her wondering friend how Percy (who was an old college friend of her husband’s) had come to see them that morning, and in their quiet home had confessed that he was drawn to them by the desire of obtaining news of her, round whom his deep true love still lingered with so much regret. She had tried to persuade him to accompany them that night, but still he doubted—still feared. Yet he now confessed to Edith how, when they were gone, he had longed to see her face again, how he had concealed himself in the crowd, and how he had been moved, by what she had just said, to rush forward from the recess where he stood unobserved, that he might be the first to own the gentle Magic of those words!

And many others had felt them too! Marion was leaning on her father’s arm—her[54] eyes cast down and tearful in their joyfulness, as he spoke to her in a low tone of the invalid whom she must see on the morrow.

And all hearts were touched and softened, and rich and poor felt drawn closer together! And they thought of the voice that had said,—“Love one another as I have loved you,”—and of the divine lessons of peacefulness and long-suffering which some had forgotten! And many blessed to the end of their days the Magic Words spoken by the Peacemaker[A] on that New-year’s Night.

London:—Printed by G. Barclay, Castle St. Leicester Sq.

FOOTNOTE:

[A] Edith, in the Anglo-Saxon language, signifies Peacemaker.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation have been standardized.

Archaic or variant spelling has been retained.