Poetry for

Children

BY

Charles and

Mary Lamb

ILLUSTRATED BY

WINIFRED GREEN

With a prefatory note by

ISRAEL GOLLANCZ

PUBLISHED BY J M DENT & Co

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

BY

Charles and

Mary Lamb

ILLUSTRATED BY

WINIFRED GREEN

With a prefatory note by

ISRAEL GOLLANCZ

PUBLISHED BY J M DENT & Co

As often as I pass a little Blue-coat boy I gaze upon him lovingly: I reverence the quaint vision of a bygone age called up by the long blue gaberdine, the red leathern belt, the yellow stockings—a quaint monkish figure still to be seen in crowded London streets, still adding to their picturesqueness and ever-varying charm.

You, too, dear Reader, have yourself probably asked the meaning of the strange sight, as you have passed one of these English lads so strangely attired. Perhaps you have been shown the famous old school, in the midst of the bustle of London, surrounded by ugly warehouses, offices, and shops; and you have seen the effigy of the Founder, “that godly and royal child, King Edward the Sixth, the flower of the Tudor name—the young flower that was untimely cropped as it began to fill our land with its2 early odours—the boy-patron of boys—the serious and holy child who walked with Cranmer and Ridley.”

Alas, London is no longer to be the home of these boys, and the cloisters of the Old Grey Friars will soon moulder away, when the merry noise of sports and revels cease to awaken them to life.

As I looked through the bars the other day watching the boys at their games, a strange fancy came to me. I thought I saw a pale and studious “Grecian” (as they call the head boys of the school), and walking at his side, with glittering eyes full of wonderment, was a younger lad—a boy with crisply curling black hair, and with ruddy brown complexion, and in his look so much lovableness and trustfulness, that I felt myself envying the elder lad, whose hand rested so affectionately on the shoulder of his friend. I drew near to listen to their talk. The thoughtful Grecian was discoursing learnedly yet so sweetly about some deep matter of philosophy: it seemed somewhat beyond the younger boy, but he listened quietly, rapt in admiration. Suddenly the school-bell sounded. “Hurry on, Charles! ‘’Mid deepest meditation sounds the knell.’ That’s3 how your good old Elizabethans would put it. We’ll have another talk after supper.” “I—I’ve n—not h—h—had o—one t—t—talk y—yet, S ... T ... C,” stammered the other in reply: a painful contrast to the sublime eloquence that flowed from his companion.

The noise of the bell and scampering of the boys soon made me realise that Fancy had led me back a hundred years and more, and had given me a glimpse of the boyhood of two famous Englishmen, who have added glory to their ancient school—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, poet and philosopher, and Charles Lamb, essayist and critic, the best beloved of all the good and great men whose writings are dear to us.

Some day you will read the story of the lives of these two men, and you will love their books,—the weird and fairy poetry of Coleridge, recalling a dreamy youth reared amid the woodlands of Devon—the genial and sweet essays of Lamb, so full of gentle humour, and kindliness, and humanity, so rich in tender thoughts concerning all his fellow-creatures in the great city where he was born and bred, which he loved passionately. To London he had given “his4 heart and his love in childhood and in boyhood,” and throughout his life his heart was filled with “fulness of joy at the multitudinous scenes of life in the crowded streets of ever dear London.”

Charles Lamb’s Essays are among the greatest of our treasures, but even more beautiful than his writings is the record of his noble life—a life of saintly self-sacrifice, cheerfully devoted to the guardianship of a lonely sister, whose girlhood would have been spent in loveless solitude but for her brother’s love. Mary Lamb’s tragic story (too sad to be told here) was illumined by the light of this brotherly love which shone forth when the world was very dark and gloomy.

Mary Lamb had something of her brother’s gift of writing; it was she indeed to whom you owe many of the Tales of Shakespeare you are so fond of. They loved children, and they loved Shakespeare, and their stories from Shakespeare have been and are still read by boys and girls all the world over. They wrote, too, a whole collection of Poetry for Children, and here also Mary’s share was much greater than her brother’s. “Mine,” wrote Charles, “are but one-third in quantity of the whole.” ... “Perhaps5 you will admire the number of subjects, all of children, picked out by an old bachelor and an old maid. Many parents would not have found so many.” This collection of “Poetry for Children” in two small volumes, was so much liked by the children that all the copies were soon bought up, and Charles Lamb himself could not get a copy, when later in life he sought one far and wide. So rare is the book now that only one or two copies are known to exist, and even the British Museum does not possess these precious little volumes. A small selection of the poems are now once again offered to boys and girls: if this prove welcome, more will follow. They are simple little poems such as children should care for, and even grown-up people, for whom they were never intended, cherish every word written by Mary and Charles Lamb, because they know how much goodness and humility dwelt in their souls. If there were any wish to be learned and to explain how they came to write these verses, one would have to tell you something about other writers who were then living and writing, more especially about Lamb’s friend “S. T. C.,”6 who, together with an even greater poet, William Wordsworth, had published ten years before, in 1798, a small volume of simple English poems, which was destined to have the greatest influence on English poetry for long years to come. In that volume Wordsworth first printed the sweet little poem I am sure you know, called We Are Seven, and Coleridge, “the inspired charity boy,” as Charles Lamb called him, gave the world the magical ballad of The Ancient Mariner. One verse from this ballad ought to be printed on the title-page of this little book of poems by Mary and Charles Lamb:—

7

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The First Tooth | 11 |

| II. | The Boy and the Skylark—A Fable | 14 |

| III. | The Rainbow | 18 |

| IV. | Queen Oriana’s Dream | 21 |

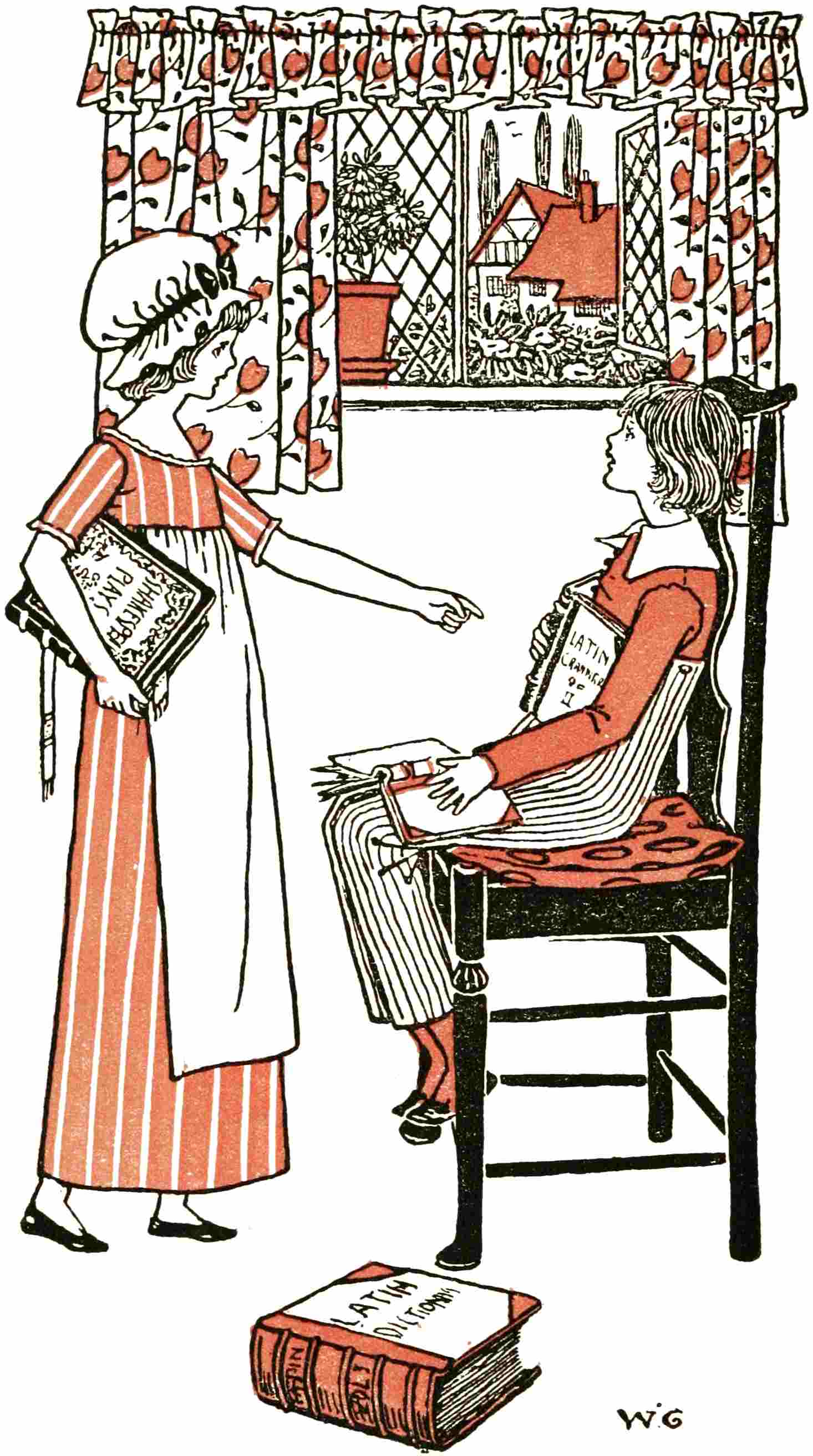

| V. | The Sister’s Expostulation on the Brother’s learning Latin | 23 |

| VI. | The Brother’s Reply | 26 |

| VII. | On the Lord’s Prayer | 29 |

| VIII. | David in the Cave of Adullam | 34 |

| IX. | Cleanliness | 368 |

| X. | To a River in which a Child was drowned | 39 |

| XI. | The Boy and Snake | 40 |

| XII. | The Beasts in the Tower | 43 |

| XIII. | Time spent in Dress | 47 |

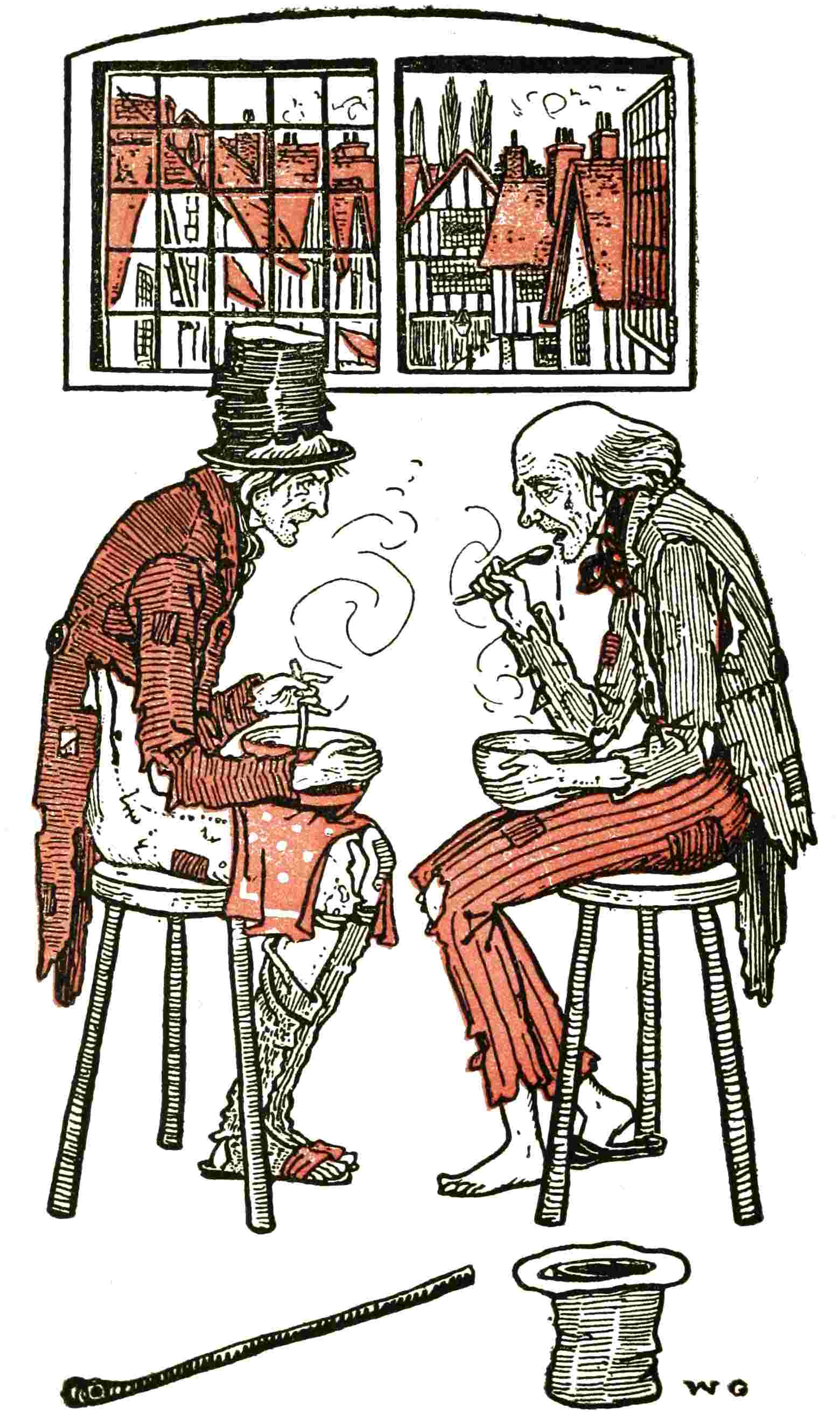

| XIV. | A Ballad: noting the difference of Rich and Poor, in the Ways of a Rich Noble’s Palace and a Poor Workhouse | 50 |

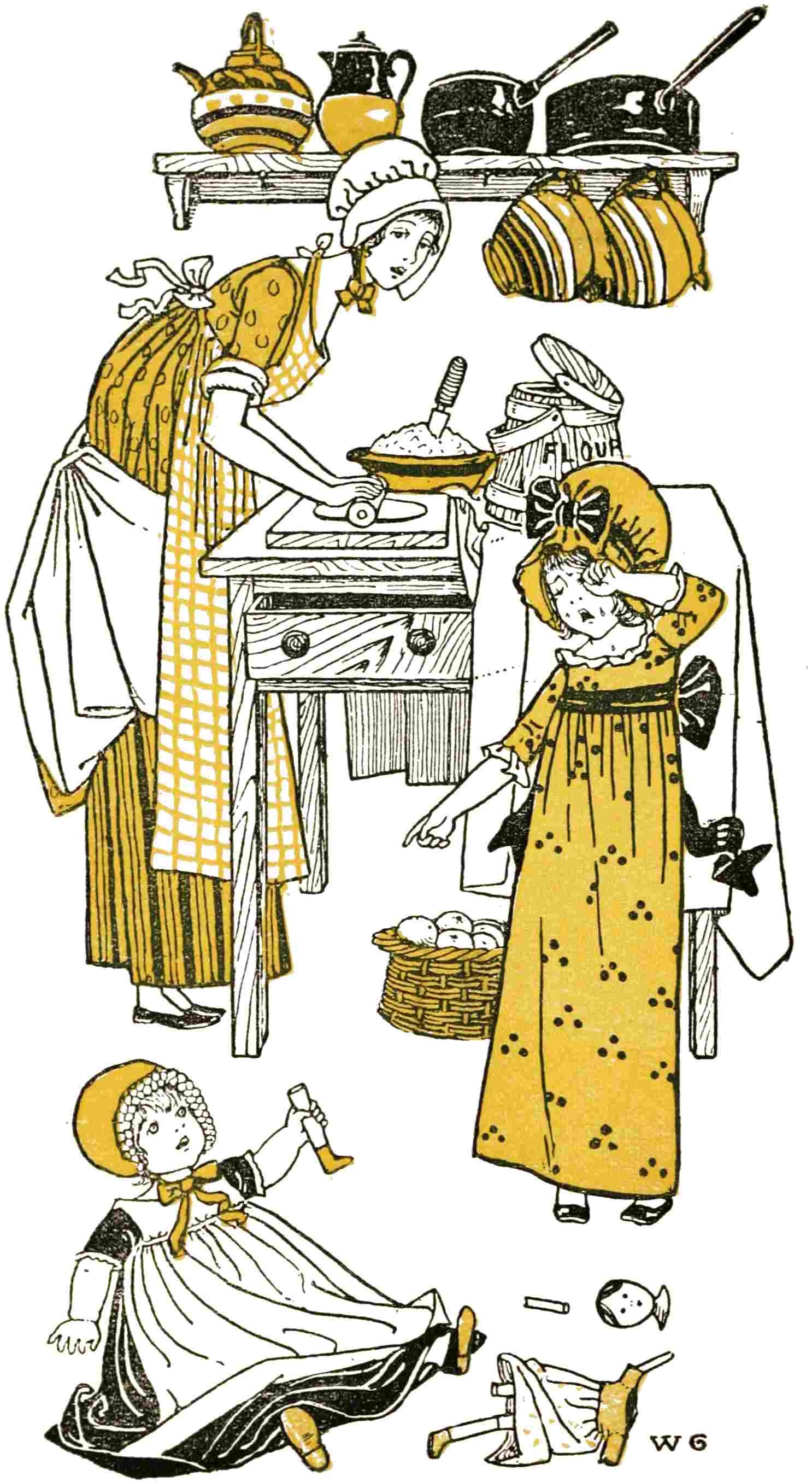

| XV. | The Broken Doll | 55 |

| XVI. | Going into Breeches | 57 |

| XVII. | The Three Friends | 61 |

| XVIII. | Memory | 72 |

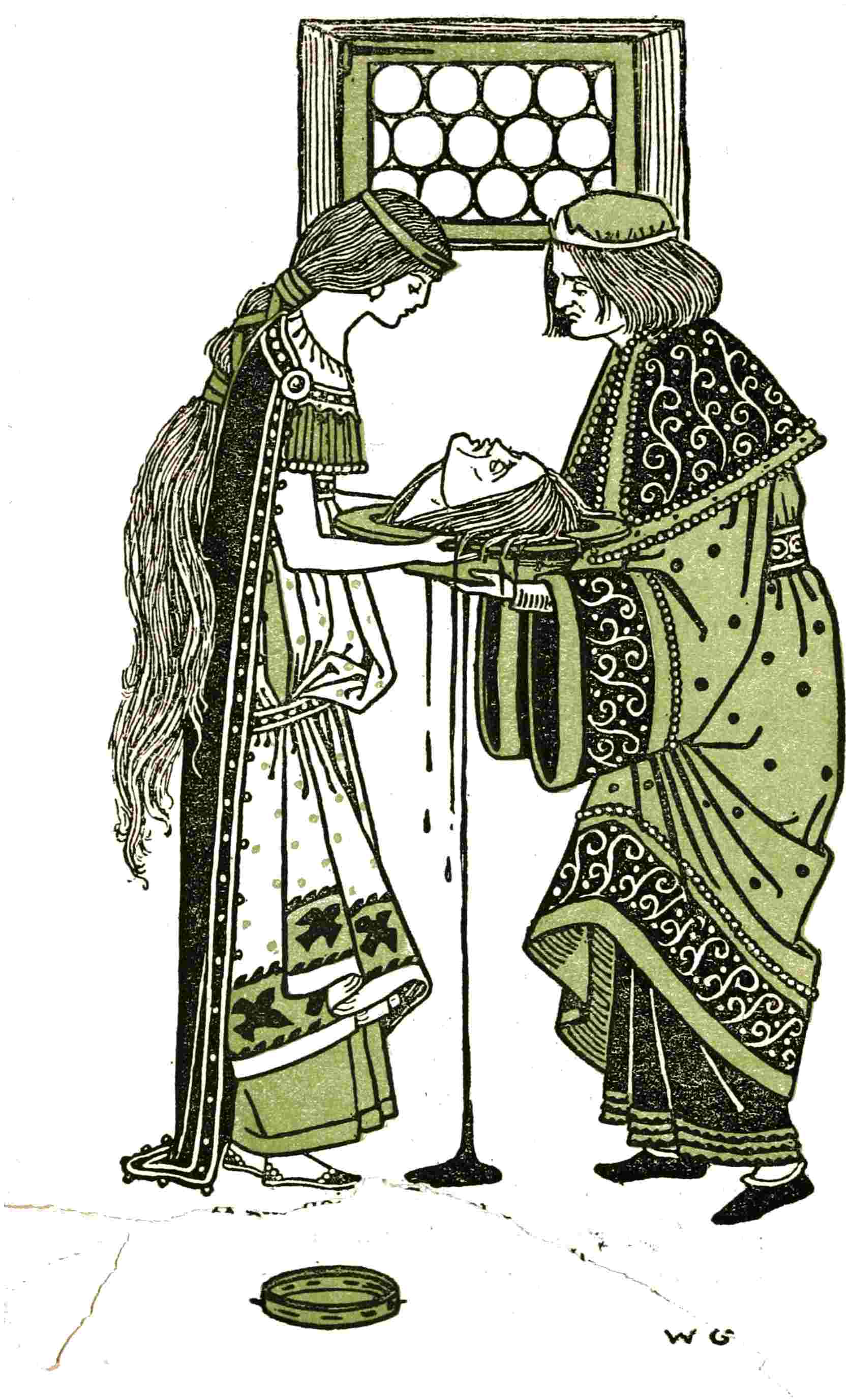

| XIX. | Salome | 74 |

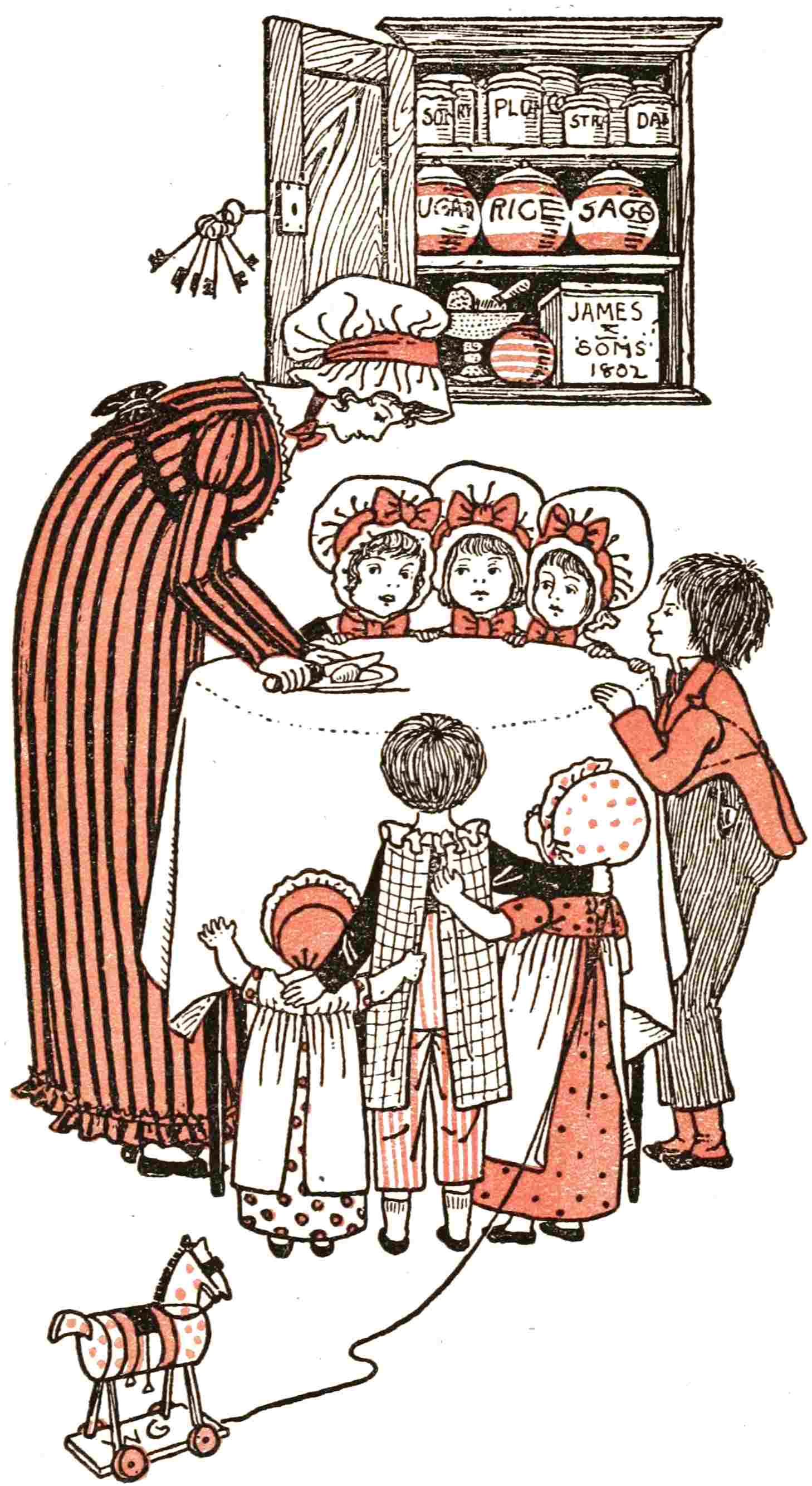

| XX. | The Peach | 78 |

| XXI. | The Magpie’s Nest | 81 |

| XXII. | Nursing | 87 |

| XXIII. | The Rook and the Sparrows | 88 |

| XXIV. | Feigned Courage | 91 |

| XXV. | Hester | 94 |

| XXVI. | Helen | 97 |

| XXVII. | The Beggar Man | 100 |

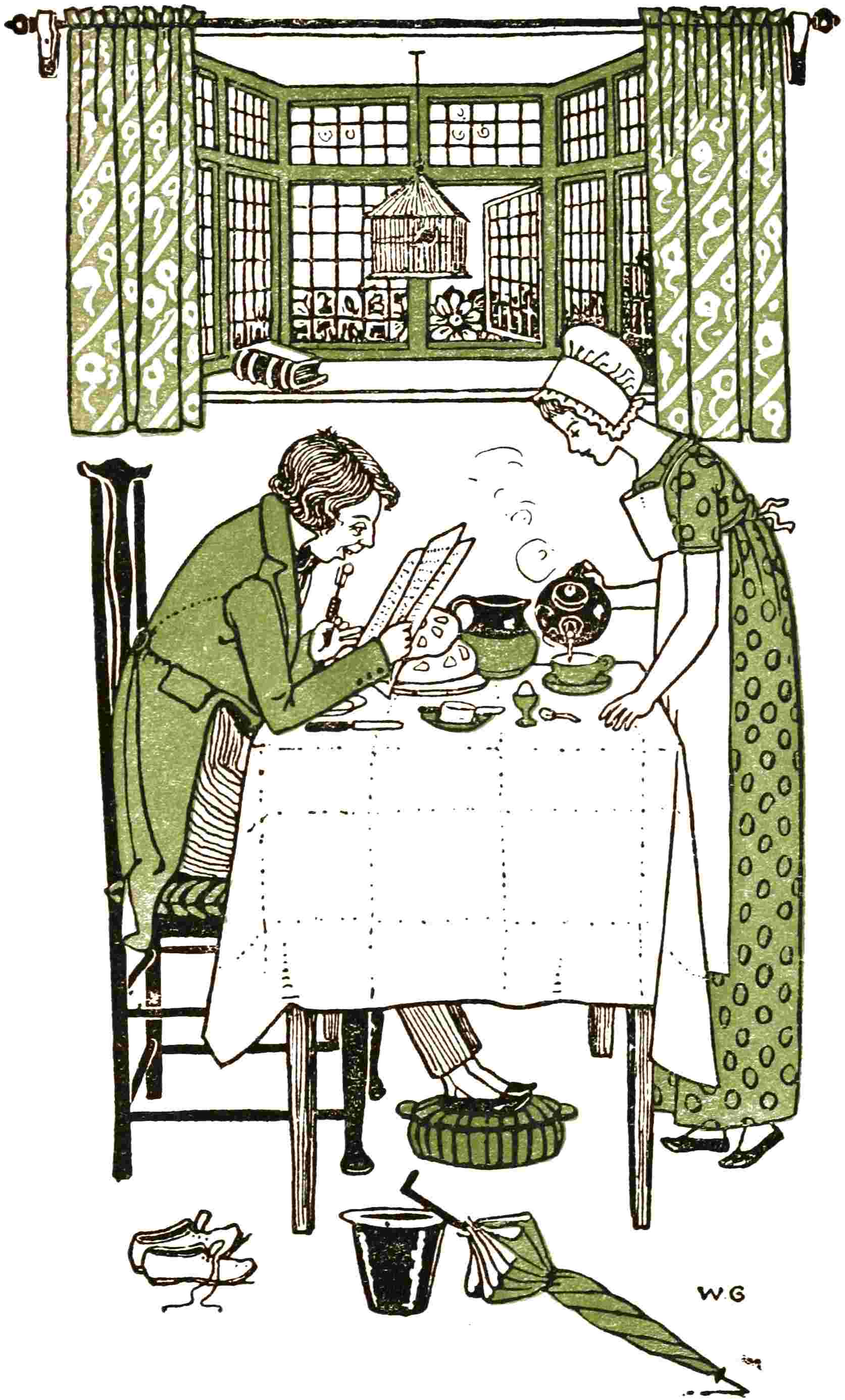

| XXVIII. | Breakfast | 104 |

| XXIX. | The Coffee Slips | 1079 |

| XXX. | Written in the First Leaf of a Child’s Memorandum Book | 110 |

| XXXI. | Envy | 112 |

| XXXII. | Dialogue between Mother and Child | 114 |

| XXXIII. | The First Sight of Green Fields | 116 |

| XXXIV. | Lines suggested by a Picture of two Females by Leonardo da Vinci | 119 |

| XXXV. | Lines on the same Picture being removed to make place for a Portrait of a Lady by Titian | 121 |

| XXXVI. | Lines on the celebrated Picture by Leonardo da Vinci, called The Virgin of the Rocks | 122 |

| XXXVII. | On the same | 123 |

| XXXVIII. | A Vision of Repentance | 124 |

10

11

I

SISTER

BROTHER

12

13

14

II

15

16

18

III

19

20

21

IV

23

V

24

25

26

VI

29

VII

31

32

33

34

VIII

36

IX

37

38

39

X

40

XI

42

43

XII

46

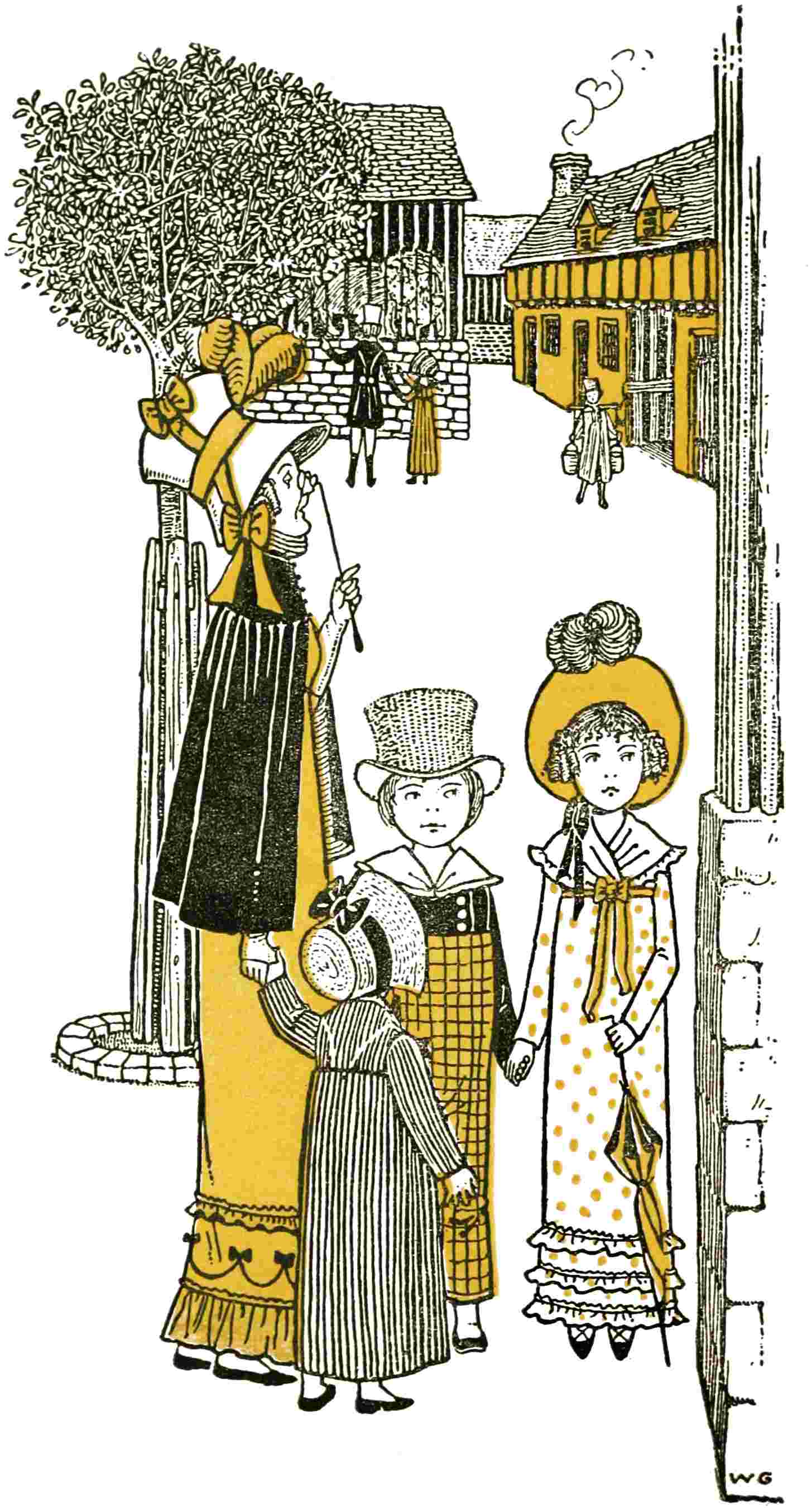

47

XIII

48

49

50

XIV

52

53

54

55

XV

57

XVI

58

59

61

XVII

64

65

67

68

72

XVIII

74

XIX

76

77

78

XX

79

80

81

XXI

82

83

A I beg to inform my young readers that the magpie is the only bird that builds a top to the nest for her young.

86

87

XXII

88

XXIII

89

90

91

XXIV

92

93

94

XXV

95

96

97

XXVI

98

99

100

XXVII

101

102

103

104

XXVIII

105

106

107

XXIX

108

109

B The name of this man was Desclieux, and the story is to be found in the Abbé Raynal’s History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies.

110

XXX

111

112

XXXI

113

114

XXXII

Child.

115

Mother.

Child.

Mother.

Child.

116

XXXIII

117

118

119

XXXIV

121

XXXV

122

XXXVI

XXXVII

124

XXXVIII

London

Engraved & Printed

at

Racquet Court,

by

Edmund Evans

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in the original book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; unbalanced quotation marks were remedied when the change was obvious, and otherwise left unbalanced.

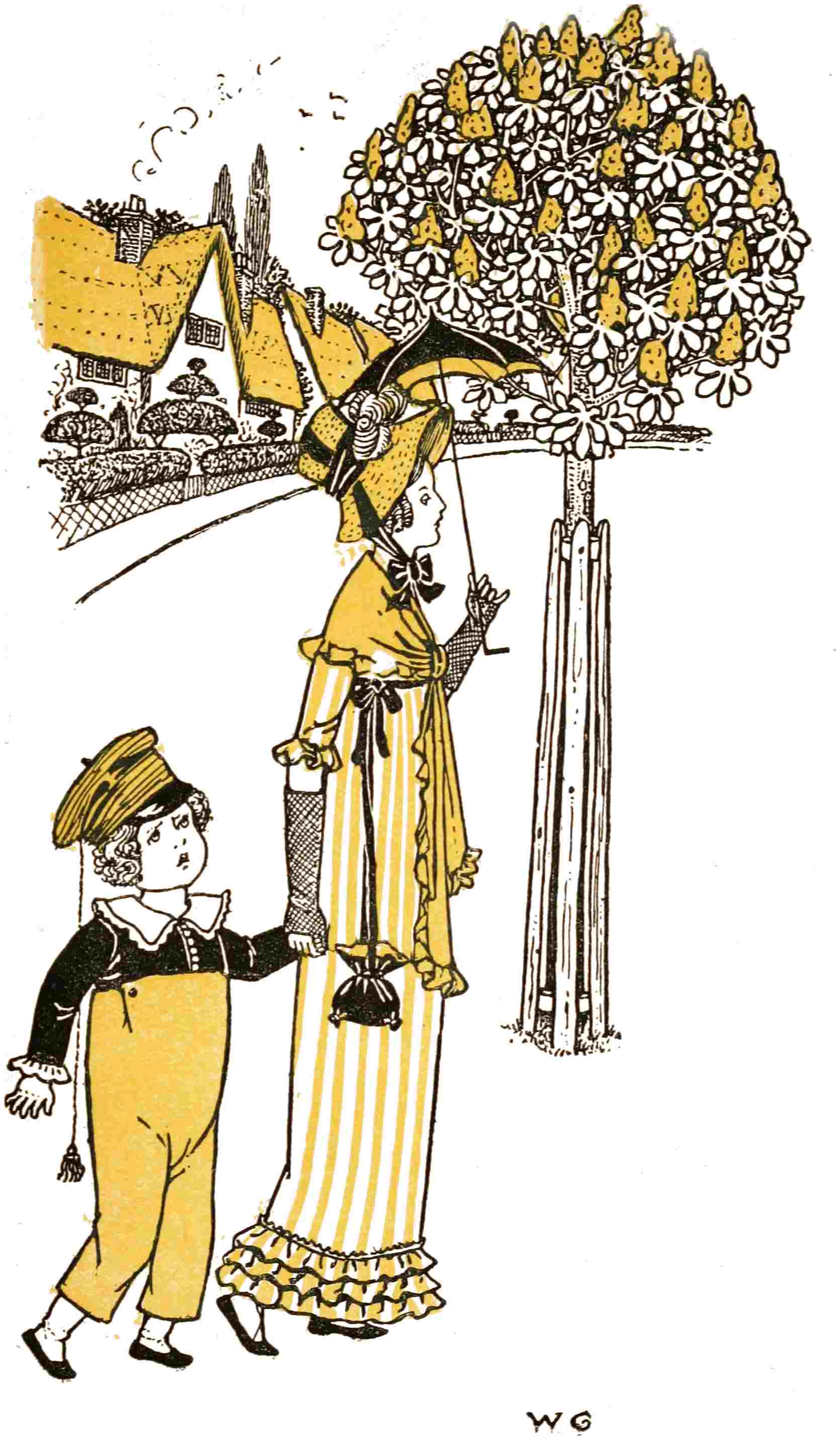

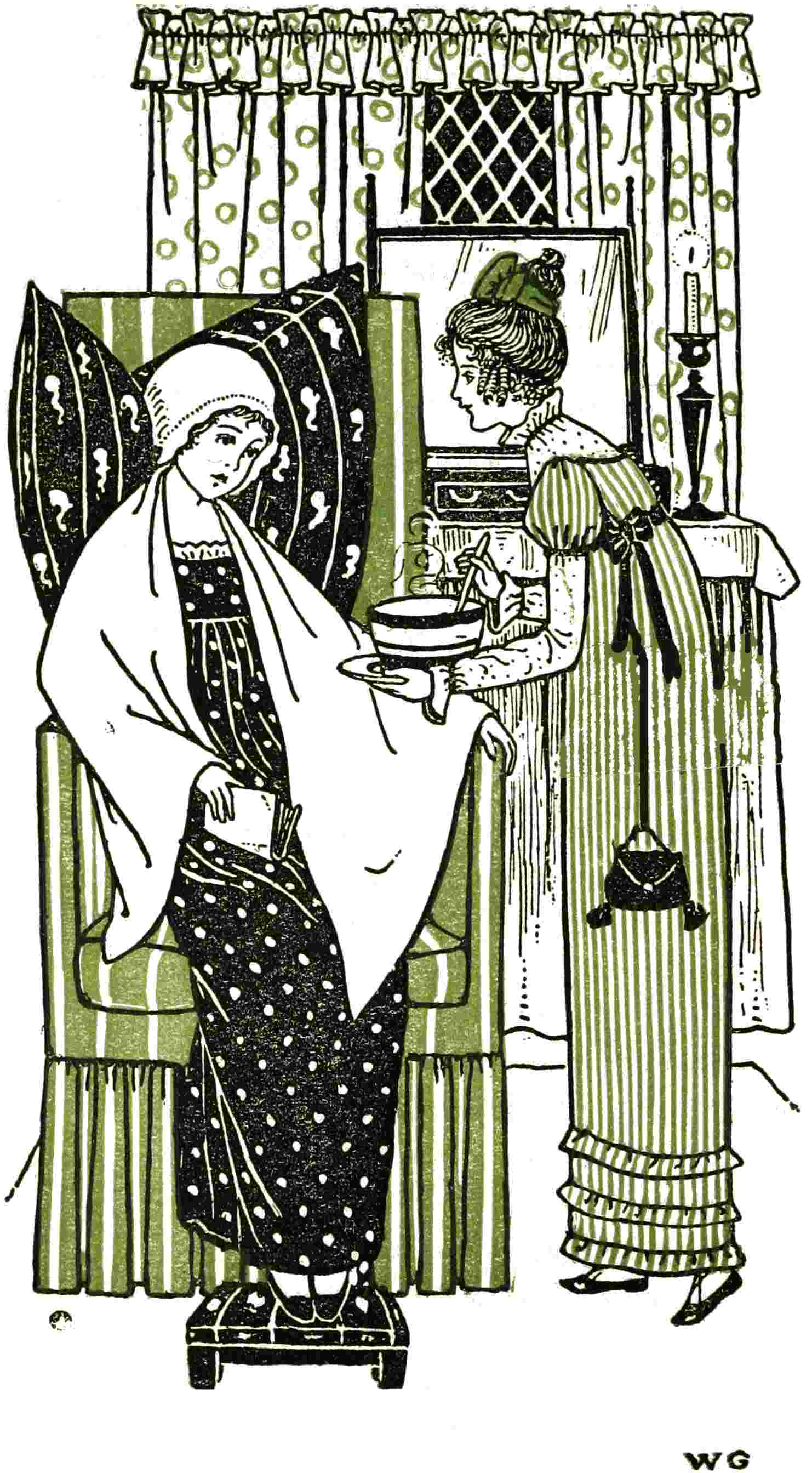

Illustrations in this eBook have been positioned where they occurred in the original book, often within poems. Each poem’s name is enclosed in a decorative floral border and followed by the poem’s Roman Numeral. Many of the other illustrations are full-page with one color, and the ones at the end of many poems are tailpieces or small black-and-white drawings.

The color illustrations bear the artist’s initials, “WG”, but those were not transcribed as captions.

Transcriber restored two defective images and placed the restorations into the Public Domain.