Illustrated by Swenson

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction, January 1947.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Plutonium was an equalizer. Nations learned the art of being polite, just as individuals had learned. To lash out with Plutonium wildly would be inviting national disaster, and to behave in an antisocial manner would get any nation the combined hatred of the rest of the world—equally a national disaster.

This was surface politeness. Beneath, the work went on to find an adequate defense, for now that all nations were equal, the first capable of defending itself was to be winner. Ultimately, atomic death was licked. Nicely licked but only at the expenditure of more power than it took to develop the atomic weapon itself. It was, however, developed. And that nation then lashed out—to find that other nations of less belligerency had also licked the problem.

The war—fizzled. For the wall shield that killed the effectiveness of the atomic bomb found no difficulty in stopping a lesser weapon.

All war—fizzled. And nations looked at one another and formed the Terran Union. Then the Terran Union looked to the stars for a new world to conquer. They found Mars ready and waiting.

The Terran Union colonized Mars and exploited the Red Planet as men have always done with a new frontier. The next hundred years wrought their changes and the Martian Combine fell away from the Terran Union because of the distance, the differences of opinion, and because of slight mutational changes.

There were interplanetary wars. The First was fought to eliminate the fact of governing Mars from Terra, the Second was fought to stop interplanetary piracy and to force both planets to respect the integrity of the other. The Third Interplanetary War was started because of sheer greed.

During the Third Interplanetary War, atomic bombing sprung up, died, and then continued on a very strange nuisance value basis. It became complex, and upon the 1327th Day of the Third Interplanetary War, interplanetary robombing assumed a most dangerous aspect. The swift action of a small group averted disaster, and from that day on, the course of the Third Interplanetary War was assured.—I. A. Seldenov's History of Sol, Vol. IV.

The call bell tinged gently in a code that pierced sleep.

Colonel Ralph Lindsay reached out sleepily and nudged a button at his bedside. Equally sleepily, he donned trousers over his pajamas, slipped his feet into scuffs, and carefully headed for the door. The open door swung a shaft of light across the bed, and Lindsay opened his eyes wide enough to determine whether Jenna was still asleep.

Satisfied, Lindsay went down the corridor of the ship blinking at the ever-present light. He let himself into the scanning room and dropped into his chair. He picked up the phone and said: "Lindsay speaking, answering 3379X."

"General Haynes, Ralph. They got one through."

"How?" asked Lindsay, coming awake.

"Super velocity job. The finders were behind by a quarter radian, at least."

"Jeepers," grunted Lindsay.

"Say it again," returned the general. "We thought we were bad when we let one out of five hundred slip through to you. This, remember, was one out of one. Period. If they use 'em in quantity—and I see no reason why the devils won't—I can see a good record all shot to pieces."

"Where's it headed?"

"According to the course-calc, it should be hitting Mojave most any minute."

"Well, I'd better get on it," said Lindsay. "May I contact you later?"

"Do so, by all means," said the general, signing off. "We can't permit things like this to happen. I won't hang my head in shame at one per cent missed, but when one hundred per cent of a shipment runs through, I'm scared."

Lindsay mumbled an agreement and then clicked the switch to another line. That would be quicker than juggling the hook for communications central. The new line came in immediately and Lindsay dialed a number.

It rang.

Lindsay waited.

And a sleepy voice answered: "Roberts."

"Lindsay, Jim. We've another one. Haynes just called. Heading for Mojave, should be arriving pretty soon."

"Haynes just called and it is due to land?" demanded Roberts. His voice seemed to come awake and alert instantly. "High speed, huh?"

"Yup."

"I'm shucking into clothing and I'll be in the scanning room of your ship in a few minutes."

Roberts hung up, making a remark about finding things in your own backyard. It was true, reflected Lindsay. The spaceport outside of the scanning room greenhouse lay darkly quiet. A few flickers of distant lights were caused by motion of men between them and him, and on the horizon he could see the soldier-like columns of the vertical boundary marker lights piercing the sky. Lindsay fumbled in a pocket, and swore because his cigarettes were in his battle shirt on the chair beside the bed, and he was still dressed in pajama top and trousers over the pajama bottoms. He wondered whether he could steal in and get cigarettes, or whether he'd better wake Jenna anyway, and wondered where she kept them in the ship—somehow he never really knew because there was always a package available when he wanted one. He wondered—

And the door opened and Jenna entered with a bright smile. "Cigarette, darling?" she asked. Over her nightgown she wore Ralph's battle shirt. She was holding the lighter to two of them held simultaneously between her very red lips.

He would have forgiven her anything for that. And the fact that instead of being dull with sleep, Jenna looked fresh and bright gave the woman an added charm. "Ghastly time to be up and around," she observed with a smile. She handed him one of the cigarettes and glanced at the clock. "Oh-two-hundred," she said idly. "Pacific War Time. Thirteen hundred and twenty-seventh day of. What's up, Ralph?"

Lindsay puffed deeply and let the smoke trickle out with his words. "Another one—high-speed job."

Jenna nodded. "Roberts?"

"He's coming right over."

"I've coffee brewing. It hasn't landed yet?"

"Not yet, but we're expecting it any minute."

"We'll have time for coffee."

"We'll take time for coffee," said Ralph. "Roberts will do a better job for a bit of stimulant and something warm."

Jenna yawned and laughed at herself. Ralph turned as blue streamers cast flickerings on the walls. Outside in the dark, ships of Terra's fleet were taking off, trailing their flares into the twinkling sky above them. They were getting out of range of the robomb blast; clearing the vast Mojave Spaceport. The marker lights winked off as the last ship left the port, and the sudden roar of the skytrain crescendoed and then died as the personnel of Mojave left in haste. Only the decontamination ship remained on the port.

Seconds later, a pale actinic glow suffused the area. The walls of the buildings glowed with it as the wall shields hugged the buildings and anchored them to the solid crust of the planet. In the ship a counting-rate meter climbed up the scale and a radiation identifier winked, indicating that it was very hard gamma that triggered the counter. The internal meter showed no danger inside of the ship; it was far enough from the nearest building on the port.

The door opened again and Jim Roberts walked in. "Give it to me," he said crisply, nodding cheerfully at Jenna.

Ralph's wife nodded back and then left to get the coffee. When she returned, Ralph had explained to Captain Roberts fully.

"The devil," muttered Roberts. "Looks rough."

"We've been expecting the high-speed stuff, though," said Jenna, pouring coffee into three cups.

Lindsay opened his mouth to speak. "You've—" he started, but he was interrupted by a ground-shaking rumble. Out of the dark California sky a juggernaut fell, its braking blast lighting up the area. The shrill of its passage came then, a lowering shrill that started up in the ear-splitting register and running down the scale like a dying siren until it was lost in a moan. The earth shook again as the monster hit the sands of the desert. It sent them high in a mighty impact crater, plowed its short furrow, and then at the bottom of its inverted cone it nuzzled into the ground and—started to tick.

Lindsay's jaw closed and he continued: "—been predicting it for a long time, Jenna." Then he laughed shortly and with just a bit of mirth. "I won't even let a Martian robomb interfere with what I intend to say." He became serious again. "No, Jenna, I think you're the only one who has been insisting that there will be a high-speed job coming along."

Roberts nodded. "The boys at the driver labs claimed it couldn't be done."

Jenna smiled. It was an elfin smile that brought out the unearthly beauty of the woman. "That's because I'm Martian," she said simply. "I know how their minds work."

"That you do," assented Roberts, sipping his coffee. "No one but a Martian could have unpacked the Gooney."

Lindsay's face paled slightly. Reference to the first and only fuse that Jenna had ever dissected brought goose pimples to him. Up to that particular time, the Martians had never included killing charges in the fuses themselves. Once the thing was out of the robomb, the fuse could not harm any one. But this diabolical jigsaw puzzle was different. And Jenna had handed the three pellets to Ralph and then fled. Lindsay followed her drawings, and they all knew that no one but a Martian could ever have been able to follow the mechanical labyrinth of that fuse in safety. Yet they all knew that she'd been safe where not one of them would have been, for if she'd not asked, amusedly, for permission, the Gooney would have taken them, one by one. The Gooney had been dissected and the robomb it came with had been fitted with a Terran fuse and shipped back. All hoped it would give Mars as much worry as it had caused Terra.

"I've tried detonating it, and naturally, no dice," said Roberts.

"Better defuse it, then. You've hit it with everything?"

"Everything but another atomic."

"That's asking too much," said Lindsay. "They're packed to the limit with atomics now, and doubling the power—brrrrr."

"Well," said Roberts with a slight smile, "my gear is in the battle buggy. Outside."

"O.K.," said Lindsay. "We'll move back to a clearer area and set the recorders going. It's cold, for Haynes' outfit didn't so much as heat it on the way in. High-speed job for fair, and probably loaded with mercurite."

The ship sat down again far enough from the buildings so that the green actinic light from the force fields did not rise to dangerous levels. The pale glow gave enough light to make the television cameras usable without any other artificial means, though the shapeless blob that was the battle buggy and Jim Roberts was hard to keep from losing with the unaided eye.

Roberts' voice came over the communicator. "O.K.? I'm about to go after that devil."

"Go ahead, Jim," said Lindsay. A few beads of sweat popped out on his forehead.

Jenna frowned. "It must be sheer hell to be like him."

Lindsay nodded, held a finger up to his lips. Jenna nodded, too, having been warned that the recorder was on, and also that Roberts could hear every word.

"I'm within one hundred feet of the crater, Lindsay. My first approach will be with the standard radiation detectors and the initial tools." This was well-known to all, but stated for recording purposes. "I have stopped the battle wagon at this distance. I am picking up my kit. I am stepping to the ground, now, and—"

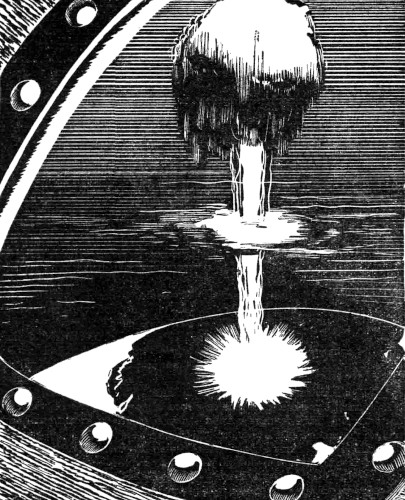

He was interrupted by the ka-plunking sound in the speaker. It was a cross, in sound, between plucking a screen door spring and dropping a boulder into a placid lagoon. A blinding flash of light burst against the dark sky, an expanding ball of flame raced skyward and died in a faintly luminous cloud that boiled upwards to a terrific height. Immediately afterwards, the ground shook madly. The counting-rate meter chattered and screeched as it overloaded and the radiation identifier winked furiously on all pilot lights, indicating all kinds of possible radiation. The pale actinic glow on the walls of the squat buildings flamed bright, wavered, flickered, paled again, and went out for good. The area and the ship was pelted with a fine rain of dirt, pebbles, and fused glass.

The roar of the sound came, then, a thundering tortured blast that tore at the planeted ship, whistling through the minute scratches from previous blasts, and producing a thrumming sound.

Quiet came once more, and only the faint buzz of the counting rate meter audio broke the silence.

Then a slight sob from Jenna.

And Colonel Ralph Lindsay took a deep, indrawn breath that shuddered his large frame.

He shook himself, and turned to his wife. "Get hold of yourself," he said harshly.

Jenna nodded, tossed away two tears, blinked her eyes and sat down weakly. "I'll be all right," she said. "I must."

"They all get it, sooner or later," gritted Lindsay. "That's ... that's—"

"Shut up, Ralph," ordered his wife. "You'll be blubbering next. Save it for when you can. We've got work to do."

Lindsay looked at her, and as he looked, he calmed. "It's rather tough," he said. "There's been several ... many. But few within sight. Well, he's gone and there's nothing we can do to bring him back."

"What makes it particularly tough is that Jim Roberts was the only one in the crew that was halfway stable, mentally," said Jenna. "The only one who was not carrying a mental load."

Lindsay nodded. "A case of having specialized mechanical ability and putting it to use in the best way. But Jenna ... I'm ... you're—?"

Jenna smiled. "We aren't," she agreed. She stood up and leaned against him lightly, and then moved into the circle of his arm. "But remember that neither of us is active in decontamination work. General Haynes needed a stable man to direct the group, one that would correlate the information and keep it. Not one that he'd have to replace every few weeks. Losing Jim is tough. Better it have been one of the others; Lacy, who lost his family and the will to live at the same instant of blast; Grant, who is just a plain thrill-seeker and sportsman; Garrard, who does anything and everything without looking ahead because he is convinced that the Book of Fate has his every minute move printed in letters of fire; Harris, who saw his brother die and who now has a psychopathic hatred against the things but has no great dislike for the Martians who fashioned them. He hates our robombs as much as he hates theirs. Well—"

She was interrupted by the phone. Lindsay answered. It was General Haynes.

"Who?"

"Roberts."

"Bad?"

"As soon as the dust clears away we'll know. The force fields are usually good, and they kept out the radiation from the buildings. As soon as the surface activity dies out, Mojave will be workable again. We're leaving as soon as we can."

"Better mobilize your big men," said Haynes. "The second just hissed past us. Looks like a long siege. That one was mercurite, wasn't it?"

"Nothing else."

"Thought so. We saw the blast from here in space. Know what that means?"

Lindsay nodded and said: "It means they think they have an untouchable fuse. Otherwise they'd not bother sending the high-powered stuff over."

"Right. They'd not make us a present."

"Also, there is something about that fuse. Something, something. Look, sir, robombing is a fine art. There is but one defense against it—and that is for those who want to live to get out of the neighborhood. That's what the skytrains are for. That's why you send us immediate word when you have their course predicted. The secondary defense is not really a defense as it is a preservative measure. The force fields go up to protect man's work, and when the blast comes, it really destroys nothing. Then, after a given time, the people return and go to work in safety because the force fields kept the insides of the building from either destruction or radioactivity.

"Now," continued Lindsay, "that one went off within ten to twenty minutes after it landed. The immobilization period for that area is but a couple of days at best. If not touched, the fuse would tick away for weeks while the area stands idle. But not with this new, high-speed job that is also loaded with mercurite. Something—

"Where was this new job?" he asked, changing the subject abruptly.

"Headed for the Gary steel mills," came Haynes' answer.

"I'm putting in a call for my crew," said Lindsay. "We'll all meet in Chicago-South. There's something—" He shook the thought away with a violent shake of his head. "We'll find out in Gary."

He went to the general call phone and cut a tape, fed the end into the automatic transmitter, and checked to see that the general call was being transmitted. He wondered, briefly, just which of them would get to Gary first.

When the decontamination headquarters ship arrived, it was second. The little private strato-speedster that was Jack Grant's own pride and joy was sitting in the main landing field of the Gary port when Lindsay arrived. Lindsay sort of expected that, for Grant's little high-powered job placed the owner no more than a couple of hours from any place on Terra, most of which was spent in going up and down through the thicker atmosphere near the surface.

They landed, and the air lock clanged open. Moments later Jack Grant entered the scanning room with his usual whirlwind manner.

"What's cooking, Ralph?" he greeted, extending an eager hand. His free arm he swept around Jenna, giving her a vigorous hug and a kiss on the forehead. "Jenna, I swear you're more beautiful by the day. Please?"

"Please what?" she countered, freeing herself and backing off a bit.

"Please poison him and marry me?"

"Nope," she said with finality. "And I won't stand to see him ... ah ... removed, as you indelicately put it."

"Ralph, you wouldn't mind getting bumped off for your wife's happiness, would you?"

Lindsay usually lived through Grant's brash manner; made a mental apology for the man because he himself did not understand the kind of mind that saw little serious in life. And usually Grant's disregard of the serious side of life gave all a moral uplift, a chance to disregard with Grant all of the problems that hack and tear. But Lindsay had just seen Jim Roberts go up in a sun-hot inferno, and he was slightly sick with shock. Now, Grant's blithe manner seemed banal, crude; insufficiently sensitive. If Grant had no feelings, he should at least consider the sensitivity of others. Lindsay tried to cheer himself, and managed at best a weak, sickly grin that was lost on Grant completely. Lindsay might have made some biting remark, but he noted with some wonder that Jenna was not bitterly unhappy in the badinage. Jenna, he knew, could and would clutch hysterically at any light point in a crisis to gain just a bit of stability. Lindsay himself was inclined to cling doggedly to a situation, deviating not one bit, until it was finished satisfactorily. Then he would let down.

So noting Jenna's whimsical smile, he merely said, and it was with an effort: "Think it would make her happy?"

Grant laughed and hugged Jenna quickly and said: "Look, you don't mean she's actually happy—?"

Jenna nodded brightly, made a full turn to unwind Grant's arm from her waist and pirouetted over to her husband. That stopped Grant, and he smiled cheerfully and tried to look downcast.

"Love, unrequited," he sang in an off-tone basso, the opening bars of Gilbert and Sullivan's "'Love unrequited robs me of my rest.'" Then he grinned. "Love unrequited and my boss and his best wife who haul me out of a sound and peaceful sleep to go out and pin a baby-blue ribbon on a Martian robomb. O.K., fellers, I'll pull its teeth and then, Jenna, may we continue where you left me off?"

"Been watching it?" asked Lindsay.

Grant nodded. "I've been here since it started in. The mills are clean, the force fields are up, and the temperature of the thing is low enough to handle by now. I'm ready."

"We're waiting," said Lindsay.

"Waiting?"

"For the rest of the crew, you know. This is serious."

"Well, it is in my district," laughed Grant. "Let the rest assemble. By the time they get here I'll have the fuse out and in one hand. Probably semi-disassembled."

"Jim Roberts was a good man," warned Lindsay.

"He was that."

"You're waiting."

"Why?"

"Because there seems to be more to this than meets the eye."

The door opened in time for the entering men to hear Lindsay's last words. Garrard and Harris came in quietly, sat down, and started to smoke. Garrard puffed his pipe with calm indifference, and Harris smoked furiously on a cigarette that he puffed into a long, hot ember that almost burned his lips. Garrard spoke first.

"More than meets the eye, huh?"

Harris nodded, but his mind seemed elsewhere. "Mutants?" he said, giving the inert robomb out there a personality. Harris was pitting himself against a personality when he went to do his job. He had no real hatred for the Martians who engineered them, but he felt and acted as though he were pitting his brain against a wholly alien, inimical sentience.

Lindsay caught his thought, and though Harris was half solemn, the allegory fitted. For what are engineering improvements but a mechanical mutant?

Garrard smiled, and shrugged. "I say let's find out who is more ingenious," he said. "And let's do it quick. Grant, are the mills running on the servos?"

"Uh-huh, but it isn't good enough. There ought to be a human hand at the place instead of remote controls. I agree, let's get going before something happens to that load of steel out there. Stalling production is the only reason for robombing in the first place. Let's lick that fuse before they find out how much mercurite to put in in order to blast the force fields right out of the planet's crust," said Grant. "Go on with your lecture," he told Lindsay.

"Well, first-off, it's a new, high-speed job. It's also loaded with mercurite. They've, as usual, packed everything into their Sunday Punch. Their cocksuredness makes me certain that they think this fuse unremovable."

Grant turned to Jenna. "Jenna, you're of Martian stock, part way, anyway. Have any ideas?"

"Only to agree with Ralph. They wouldn't pack a robomb with mercurite if they thought for one second that it could be inerted. That would present Terra with a large volume of very valuable material. They have succeeded in one item, they've used a new high velocity drive in it. If they weren't certain of the ability of the high-speed drive to escape all detector-driven gear, they wouldn't use mercurite. Mars is not profligate, Jack. Tossing away a robomb load of mercurite on a space-premature is not economically sensible. When they use mercurite, it must be nearly one hundred percent effective."

"Um ... interesting thought," laughed Grant.

"Like to try it out," said Garrard. "If they feel that certain, I'd like to know which of us is suitable to survive."

Harris blinked. He flipped the cigarette into the receptacle. "Let me at the stinking thing," he said in a flat voice.

"Wait for Lacy," said Lindsay.

"Lacy may be late," said Grant. It was one of the very few times that Jack Grant sounded solemn. He was almost pityingly solemn, and it made Lindsay wish for his return to the thick-skinned attitude, for Grant sounding solemn was strictly out of character. "He may be late," insisted Grant, "because he hates to come here."

"He won't deny a general alarm," said Lindsay.

"No, he will not. But I say let's not hurt the guy more than we have to. I say let's go out and pull that thing's teeth and save Lacy the hurt of seeing you and Jenna together."

Lindsay frowned. He wouldn't say it, but Jenna did. "Jack," she said softly, "is that a soft spot that makes you want to keep Tom Lacy from hurt, or are you just giving arguments to get out there and try your skill against that bomb?"

"A little of both," said Grant cheerfully. "Plus the fact that he makes me uncomfortable, somehow. It always makes me uncomfortable to see any man so tied up in his own past emotions that he cannot see clearly."

"Skip it," said Lindsay firmly. "I admit that he is too bound up in the past, but you, Grant, could stand a little more of his sincerity of emotion just as he could stand less."

Harris had been quite alert, and broke in at this point. "All due respects, Grant, but you run this as though you were playing a game. I know why Lacy is that way. His game was for the reward, yours is for the game's sake. He saw everything he'd spent his life for go up in a flaming volcano. Years of living, of loving, of building; puffed out in a millionth of a second. Puffed out, obliterated, disintegrated beyond all recognition. Grant, have you ever loved anything, deeply?"

Grant nodded. "All right, fellows, I'm sorry. I'm sorry that I don't understand Lacy better. I've loved, but I've never let it be my life. For when I've lost, there has always been something—or someone—else. Make off like my chips weren't in this deal, will you?"

"Still a game, Grant?" laughed Garrard. "A game where every throw of the dice is forecast is no game."

"What am I?" chuckled Jack Grant. "Just the baaaaad boy of the decontamination squadron? Sure it's a game—the whole thing is a game. And whether you're playing your brother for marbles or playing the devil for fame, you play to win."

"I say—" started Garrard.

Grant out-talked him. "I say that I am the master of my fate. And if anybody calls me Invictus Grant I shall cut his throat. Or her throat," he added, turning to Jenna with a grin.

The door opened again and Lacy entered. "Quite a conference," he said. "Well, Ralph, where is it and what's to be done?"

Lindsay brought him up to date. Then they ran off the recording of Jim Roberts' unhappy attempt.

"You may just be overcautious," said Lacy when the recording had finished. "It may have been a circumstance."

"Unlikely. The thing is ... has too many facets. Jenna herself claims that a new item was expectable. Haynes had his statisticians at work, and their findings were that the quantity of late has been diminishing, which from past experience means that something new is due."

Jack Grant looked at Lindsay. "You don't suppose they're after the decontamination squadron?"

"If they were gunning for us," said Harris in a voice that shook with hatred, "they'd do it this way!" Then he settled back again. "But would they waste mercurite on us?"

"As a means of keeping production open, we're worth mercurite," responded Lindsay. "And it might take something more than the ordinary to go out and eliminate men who have made a business of defusing the things. Assassination is almost impossible.

"And," he said reflectively, "we may be barking up the wrong tree. All I know is that we've a brand new type, and as usual I've called the entire group in to get the initial factors all complete. Are we a bunch of persecution-complexes that we think they're after us?"

"No," grinned Jack Grant, "but remind me to tell that idea to Ordnance. Eliminating the decontamination squadron is like poisoning a city by shutting off its sewage system, perhaps, but it is effective!"

"We'll forget the personal angle until we get this one solved," said Ralph Lindsay.

"Well, let's go," said Grant eagerly.

"We'll take this easily," objected Lindsay.

"No gambling instinct?" queried Grant with an amused smile.

"That's why he's boss," said Garrard dryly. "Lindsay has neither an ax to grind nor an ego to build up."

"Huh?" asked Grant.

"Admitted ... and I'm sorry, Tom," said Garrard to Lacy, "that Lacy has his ax to grind. You, Jack, apparently get an egotistical lift out of this 'game.' Lindsay has neither."

"O.K., boss man," smiled Grant. "What do we do?"

"All the radiation meters we can pack into the battle buggy. Also we set up a radiating system near it. Then come back and we'll run through the spectrum to see. Now—"

"It's still in my district," reminded Grant.

"You're overeager," objected Garrard.

"And you're too complacent," objected Harris.

"Trouble with you," said Lacy, "is that you get too deep-set in pitting your skill against a mechanical puzzle and forget to tell us the moves."

Lindsay smiled sourly. "To finish this round robin, may I tell you your faults, Tom? You are inclined to make a false move. Not consciously, but there have been a few times when you came out by the skin of your teeth, having pathologically missed a fine point, and having caught it consciously."

Grant reached in a back pocket and rolled a pair of dice on the floor. "Roll for it?" he asked hopefully.

"Never touch dice," objected Harris.

Grant reached inside his jacket and fanned a deck of cards. "Cut?"

"Games," said Garrard sourly. "Games of chance in a preordained world—Bah!"

Jenna hit the table with her small fist. "Stop it, all of you! A finer collection of neurotics I've never seen collected under one roof before. And not one of you dare suggest that Ralph pick a man. Haynes would be wild if he knew that Ralph had been put into a psychological hole by being forced to send any man into ... into ... into that." Deigning to name the menace was itself a psychic block, but Jenna did not care. Instead of talking further, she reached for the deck of cards. "The thirteenth card," she said, starting to deal them off, "One, two, three," placing them face up before her. "Lacy, hearts; Harris, spades; Grant, diamonds, and Garrard, clubs.—Ten, eleven, twelve, and thirteen!"

The ace of spades.

Harris smiled, got up cheerfully, and went to get his trappings ready. Garrard grunted. "Games of chance," he sneered. "In a—"

Grant jumped up. "Look, Ed," he snarled. "In this completely preordained world of yours, how can an inhabitant know the will of the Gods of No-chance? What criterion would you have used to select Harris, huh? So if nothing else, the laws of chance do that much, to at the very least tell us who the Gods select. And so long as we ourselves do not know the answer, who cares if it is preordained?" Having delivered this, Grant looked at Jenna. "Bright girl," he said. "An instrument, if you admit Ed's plan, of the Gods."

Jenna smiled. "You mean 'whom the Gods—select,'" she corrected blithely.

Grant hauled out a flask, unscrewed a one-ounce cap and poured it full. "Here," he snapped, practically forcing it into her mouth.

Jenna spluttered. "Thanks," she said, calming. "I know how Lindsay feels, and it is not up to him to tell us. But I don't care whether it is predestiny or not, and whether we're all non-gamblers or goody-goody boys. But we'll use this set of cards for any future guesswork. See? And, we'll cut, ourselves. See? We'll not make the mistake of forcing Jenna or Ralph into dealing out a poisoned arrow."

"I wish people would stop worrying about my peace of mind," growled Lindsay. "I admit all that's been said. I am not to undergo any personal emotional strain. But being psychologically packed in cotton and linseed oil isn't good for me either."

"And all over one problematical bomb," smiled Jenna. "Why don't we wait. If the first one was coincidence, certainly the rest, after solution, will make us all feel like overwrought schoolgirls."

Harris returned at this point. "Ready," he said with a smile. His eyes were bright, and he seemed eager. There was an exultation about Harris, a bearing that might have been sheer theatrical effort, yet it seemed as though he were going out to do personal battle with his own personal devil.

Lindsay nodded briefly. "Give us every single smidgin of information. If you scrape your feet, tell us. Understand?"

"I get it. O.K., there's been enough time wasted. S'long."

His voice came clearly, and in the dawning light, the automatic television cameras adjusted the exposure as the dawn came brighter by the moment. The battle wagon headed out across the rough ground where the teeming city of Gary had lived a hundred years ago. A mile or two beyond, the battle wagon entered the parking area, now cleared of its horde of parked 'copters by the fleeing personnel.

The ship lifted and retreated a few miles, finding level enough ground to continue observation, and Harris went on and on.

"I'm stopping," he said, and it was faithfully recorded. "I'm about a hundred feet from the crater, setting up detectors and radiators. Shall I drive back or will you come in and pick me up? Seems to be safe enough. He hasn't gone off yet."

"We'll pick you up but quick. Ready?"

"Ready. Everything's set on the servos."

"O.K."

They met, immediately whisked into the sky and back to more than a safe distance. Then they went to work, searching etheric space and subetheric space for radiations. They hurled megawatt pulses of radio energy and subradio energy at the ticking thing. They thundered at it with audio, covering all known manner of vibration from a few cycles per minute of varying pressure to several megacycles of sheer air-wave. They mixed radio and audio, modulated the radio with the audio and hurled both continuous waves and pulsed waves, and mixed complex combinations of both. Then they modulated the subradio with radio, which was modulated with audio and they bombarded it with that. Rejecting the radiation bands entirely, they went after it, exploring the quasi-optical region just below the infra-red in the same complete manner. They fired at it constantly, climbing up into the heat waves, up into visible light and out into the ultra-violet. They hurled Brentz rays, Roentgen rays, and hard X. They tuned up the betatron and lambasted it with the most brittle of hard X rays. They hurled explosive charges at it, to shock it. Then they sent drone fliers, radio controlled, and waved reflecting masses at it gently and harshly by flying the drones back and forth above it.

After three hours of this—and three more incoming robombs of the same type had been reported, they gave up.

"They're piling up," grunted Lindsay.

"Wish we could move it," said Grant.

"You always wish that. You tell us how to grapple with three hundred tons of glass-slick, super-hard ovoid with a high diamagnetic surface and a built-in radiation shield. Moving them is the easiest answer—and the one initially avoided."

Harris blinked. "Nothing else?"

"There's nothing left but to go out and pull its teeth," said Lindsay. "Nothing we know can detonate the thing."

Harris smiled knowingly. "Naturally," he said. "Their point in life is to immobilize Terra. They must not go off until they are ready. They're willing to wait. They found out we could detonate them and then return to work in a couple of hours with radiation shields. So they now get a fuse that cannot be extracted and cannot be detonated until they want it to. Give 'em one chance to prove one effective, and all Terra will be immobilized by them, and they'll drop everywhere. Also, maintaining the force fields takes a lot of valuable power. And if we shut off the fields, it might go up and then we'd lose the whole place."

"How I wish we could take pictures."

"Photographs?" asked Grant, smiling. "I saw one of them once. A family heirloom. Too bad, of course. But what do you expect when the whole world is living in a sort of bath of neutrons, and silver itself becomes slightly radioactive? After all, photography used to use a silver compound of some sort if my physical history is right."

"Silver bromide," said Lindsay slowly. "Look, Harris," he said, his interest showing where his mind was really working, "go out there and make a few sketches. Then come back without touching the thing. Understand?"

"Right."

"I am approaching the thing," he said from the field of action again. "I'm about two hundred feet from it. Working now with the projection box, sketching on the ground glass. This is a fairly standard model of robomb, of course. They load 'em with anything they think useful after making them at another plant, just as we do. The fuse—too bad they can't bury it inside. But it must be set, or at least available to the makers. If they should improve on it, it would be serious business to de-load these things to get to a buried fuse. Yep, there he is, right up on top as usual. Fuse-making has reached a fine art, fellows. Think of a gadget made to work at will or by preset, and still capable of taking the landing wallop they get. Well, they used to make fuses to stand twenty thousand times gravity for use in artillery. But this ... well, Ralph, I've about got it sketched. Looks standard. Except for a couple of Martian ideographs on it. Jenna, what's a sort of sidewise Omicron; three concentric, squashed circles; and a tick-tack-toe mark?"

"Martian for Mark Six Hundred Fifty, Modification Zero," answered the girl.

"Some language when you can cram that into three characters."

"Well, I'm through. Ralph, so far as I'm concerned, this drawing will serve no purpose. Use that one of the standard model and have Jenna make the right classification marks across the fuse top. That's a better drawing anyway. I'm going on out and defu—"

The flash blinded, even through the almost-black glasses. It was warm, through the leaded glass windows. The eventual roar and the grinding hailstorm of sand and stone and sintered glass tore at the ship. The counters rattled madly and fell behind the driving mechanism with a grinding rattle. A rocketing mushroom of smoke drove toward the stratosphere, cooling down to mere incandescence as it went.

Miles away a production official watched the meters on his servo panel. They were stable. The buildings held. With the lighter radioactinic shields, work could be resumed in twenty-four hours. He started to make plans, calling his men happily. The bomb was no longer a menace, and the mills could get back to work.

"Harris," said Garrard solemnly. "So shall it be! Well, may he rest, now. Hatred such as his—an obsession against an inanimate object. I—"

"Shut up," said Lacy quietly. "You're babbling."

"Well," said Grant in his hard voice, "we can detonate 'em if we can't defuse 'em. Only it's hard on the personnel!"

Lacy looked up and spoke quietly, though his face was bitter. "Jack Grant, you have all the sensitivity and feelings of a pig!"

"Why ... you—"

Lindsay leaped forward, hoping to get between them. Jenna went forward instinctively, putting up a small hand. Garrard looked at them reflectively, half aware of the incident and half convinced that if they were to fight, they would regardless of any act of man.

It was the strident ringing of the telephone that stopped them in their tracks; staying Grant's fist in midswing.

Jenna breathed out in a husky sound.

"Who was that at Gary?" asked General Haynes.

"We lost Harris."

"Same as before?"

Lindsay nodded glumly, forgetting that Haynes couldn't see him. Then he added: "Didn't even get close."

"What in thunder have they got?" asked Haynes. It was an hypothetical question, the general did not expect an answer. He added, after a moment of thought: "You've tried everything?"

"Not everything. So far as I've been able to tell, the things will sit there until we go after 'em. They'll foul up production areas until we go after 'em, and then when we're all gone—what then?"

"Lindsay! Take hold, man. You're ... you're letting it get you."

Lindsay nodded again. "I admit it. Oh, I'll be all right."

"Well, keep it up—trying I mean. We're tinkering with the spotters and predictors and we hope to get 'em up to the point where they'll act on those lightning fast jobs."

"We'll be getting to Old London," said Lindsay. "That's next. Good thing they dispersed cities a century ago, even granting the wall shield."

"Good luck, Lindsay. And when you've covered all the mechanico-electrical angles, look for other things."

He hung up, but Lindsay pondered the last remark. What did he mean?

The ship was on its way to Old London before Lindsay called for a talk-fest.

"We don't know anything about these things excepting that they go off when we approach 'em," said Lindsay. "Has anybody any ideas?"

"Only mine," grunted Jack Grant with a half-smile. "Something triggers 'em off whenever we come close."

"Couple of hundred feet," growled Lacy, "isn't close enough to permit operation of any detector capable of registering the human body without some sort of radiation output."

"Not direct detection," agreed Lindsay, facing Grant again.

Grant nodded. Then Garrard said: "I've an idea. But I'm mentioning it to no one."

"Why?"

"I don't want to tip my hand."

"Thought you weren't a gambler," jeered Grant.

"I'm not. I can't foresee the future, written though it is. I'll play it my way, according to my opinion. The fact that I feel this way about it is obviously because it is written so."

"Oh Brother!" grunted Jack Grant. "With everything all written in the Book of Acts, you still do things as you please because so long as you desire to do things that way it is obvious that the Gods wrote it?"

Garrard flushed. And Lindsay said: "Grant, you're a born trouble-maker."

"Maybe I should go out and take the next one apart. I'm still willing to bet my life against a bunch of Martians." Then he looked at Jenna. "I'm sorry, Jenna."

"Don't be," she said. "I may be Martian, but it's in ancestry only. I gave up my heritage when I set eyes on Ralph, you know." Then she stood up. "I'm definitely NOT running out," she laughed. "I'm going down to put on more coffee. I think this may be a long, cold winter."

She left, and Ed Garrard looked up at Lindsay, sourly.

"Well?" asked Ralph.

"Look, Lindsay, I may be speaking out of turn."

"Only the Gods know," chuckled Grant.

"Shut up, you're banal and out of line again," snapped Lindsay. "Look, Ed, no matter what it is, out with it."

"Lindsay, what do you know about this rumor about Martian mind-reading?"

"Very little. It is a very good possibility for the future, I'd say. It's been said that the ability of certain Martians to mental telepathy is a mutation. After all, the lighter atmosphere of Mars makes bombardment from space more likely to succeed."

"Mutation wouldn't change existing Martians," mused Grant. "The thing, of course, may either be a mutation that is expected—in which case it may occur severally—or an unexpected dominant mutation in which case its spread will occur as the first guy inseminates the race with the seeds of his own being."

"Right."

"You don't know?"

"No," said Lindsay. "I don't know which and furthermore it is unimportant."

"Might be," objected Grant. "How many are there and what is their ability?"

"There are about seventy Martians known to be able to do mental telepathy under ideal circumstances. Of the seventy-odd, all of them are attuned to only one or two of the others. So we have an aggregation of seventy, in groups of three maximum, that are able to do it."

"Is any of Jenna's family—?"

"Not that I know of. And besides, Jenna's loyal."

"They might be reading her mind unwittingly," said Garrard.

"Impossible."

"Know everything?" said Garrard, instantly regretting the implication.

"Only that Jenna's father was a psychoneural surgeon, and I've read plenty of his books on the subject. They're authoritative."

"Were, before the war."

Lindsay nodded. "You're thinking of some sort of amplifier system?"

Garrard nodded.

"I doubt it," said Lindsay.

Lacy looked up and shook his head. "It would have to be gentle," he said. "According to what I've heard, the guy who's doing the transmitting is clearly and actually aware of every transmitted thought that is correctly collected by the receiver. Couple a determined will to transmit with certain knowledge of reception, and then tell me how to read a mind that is one, unwilling; and two, unaware." Lacy snorted. "Seems to me we're getting thick on this." He arose and left, slowly.

Lacy wandered into the galley and spoke to Jenna. "Mind?"

"Not at all," she said brightly.

"I need a bit of relaxation," he said. "We've had too many hours of solid worry over this thing."

She put a hand on his shoulder. "Tom," she said, "you're all to bits. Why don't you quit?"

"Quit?" he said dully. "Look, Jenna, I quit a long time ago. Fact of the matter is, there's not one of us but won't kill ourselves as soon as the need for us is over. Excepting you and Ralph. You—have one another to live for. We—have nothing."

"Grant?"

"Grant will be at loose ends, too. Remember, he has been seeking thrill after thrill, and cutting closer to the line each time. This defusing is the ultimate in nerve thrills to him, pitting himself against a corps of mechanical experts. Going back to rocket-racing and perihelion runs will be too tame. He's through, too."

"You all could get a new interest in life. You shouldn't quit," said Jenna softly.

"That's the worst of it," said Tom Lacy looking down at her. "I quit a long time ago. It's the starting-up that I fear."

"I don't follow."

"I think of Irene—and Little Fellow—and I know that when that area went up, my life ended. I've never had Harris' psychopathic hatred of the things. I've just felt that I'd like death, but want to go out doing my part. I have a life-long training against suicide per se, but I euphemize it by taunting death with the decontamination squadron."

"Yes?" said Jenna. She knew more was to come.

"Alone I'm all right. Then I see you and Ralph. I feel a resentment—not against you, or Ralph, but against Fate or Kismet or whatever Gods there be that they should deny me and give to you freely. It's not right that I feel this way. Life is like that." He quoted bitterly: "'Them as has, gits!'"

"Tom, I swear that if it were mine to do, I'd give you all the things you lost—return them."

He nodded. "Giving me wouldn't do," he said in self-reflection. "I'd want return—and that is impossible."

Jenna knew well enough not to say the trite remark about Time being the Great Healer. "Poor Tom," she said gently. Maternally, she leaned forward and kissed him on the cheek. An inner yearning touched him and opened a brief door of forgetfulness. He tightened his arms about her for a moment and as her face came up, he kissed her with a sudden warmth. In Jenna, mixed feelings, conflicting emotions burned away by his warmth. She responded instinctively and in the brief moment removed some of the torture of the lonely, hating days.

Then as the mixed thoughts cleared, Lacy found himself able to think more clearly. Though still flushed, he loosened his tight hold upon her waist, and as he relaxed, Jenna changed from the yielding softness of her to a woman more remote. Her eyes opened, and her arms came down from about his neck and she stepped back, breathing fully.

"Sorry, Jenna—"

She laughed. It was not a laugh that meant derision; in fact it was a laugh reassuring to him, as she'd intended it to be. "Don't be sorry," she said softly. "You've committed no crime, I understand."

He nodded. "I was, sort of, kind of—"

"Tom," she said seriously, "there's a lot of good therapy in a kiss. So far as I know, you needed some, and I gave it to you, freely and gladly. I'll ... do it again ... when it's needed." Then she looked away, shyly.

A moment later, she looked up again, her face completely composed. "What do you suppose Garrard has on his mind?" she asked.

He told her, completely.

The scanning room was dark when they returned. Out through the viewport the actinic glow of the buildings cast a greenish light over the landscape, creating an eerie impression of the scene. The small buildings, widely scattered, were a far cry from Old London of the nineteen hundreds, with its teeming millions and its houses, cheek by jowl.

"Where's Ed?" asked Jenna, fumbling in the dark scanning room with the coffee tray.

"Gone."

"Gone?" she echoed. "How long ago?"

"Ten minutes or so. He should be there—"

Out, a few miles from them, hidden in the canyons of the buildings, a burst of flame soared up. A gigantic puffball that ricochetted from the actinic-lighted walls of the buildings and then went soaring skyward. A pillar of fire and smoke headed for the stratosphere as the counters clicked. The wall shields started to die out as the force of the explosion was spent.

Lindsay snapped on the lights. He faced them, his face white.

"That," he said harshly, "was Garrard."

Grant nodded. "It wasn't in his Book," he said.

"Neither," snarled Lindsay, "was it in his Book to keep his action secret."

"Meaning?" asked Grant.

"Who was the bright one that mentioned where he'd gone?"

"That should have been obvious," said Grant.

"Obvious or not—he's gone."

"What you're saying is that he's gone because I opened my big trap?"

Lindsay blinked. "Sorry, Jack. But I'm at wit's ends. I do wish that he had his chance, perfect, though." He stared at Lacy.

Tom, remembering that he had been kissing the man's wife less than five minutes before, flushed slightly and flustered. He hoped it wouldn't show—

"Tom, that's a new brand of lipstick you're wearing, isn't it?" gritted Lindsay.

Tom colored.

Jenna faced her husband. "I kissed him," she said simply. "I did it as any mother would kiss a little boy—because he needed kissing. Not because—"

"Forget it," said Ralph. "Did you know what Garrard was thinking?"

"Tom told me."

"Nice reward," sneered Ralph, facing Lacy.

Lacy dropped his eyes, bitterly.

Jack Grant looked up. "Listen, Lindsay, you're off beam so far—"

"You keep out of this," snarled Lindsay, stepping forward.

"I'm not staying out of it. It happens to be some of my business, too. Lacy, this may hurt, but it needs explaining. Lindsay, I'm not a soft-hearted bird. I'm not even soft-headed. But if any man ever needed the affection of a woman, Tom Lacy does, did, and will. And if I had mother, wife, or sister that refused to try to straighten Lacy out, I'd cut her throat! I've made a lot of crude jokes about the fact that she married you because of your money or friends, but they were just crude jokes that I'd not have made if she hadn't been so completely Mrs. Ralph Lindsay that mere mention of anything else was funny. And you can scream or you can laugh about it, but whatever she did down in the galley, I say, makes a better woman of her!" Then Grant smiled queerly and turned to Lacy. "You lucky dog," he grinned. "She never tried to kiss me!"

Ralph Lindsay sat down wearily. "Was that it, Jenna?"

She nodded; unable to speak.

"I'm sorry," said Lindsay.

"Look, Lindsay—" started Tom Lacy.

Lindsay interrupted. "Lacy, I'm the one to be sorry. I mean it. Pity—is hard to take, even to give honestly. You don't want it, yet it is there. Yes," nodded Lindsay, "if there's anything, ever, that we can do to see you straightened out, we'll do it. Now—"

The phone.

Lindsay picked up the phone and said: "Garrard got it! Where's the next one?"

Haynes said: "Take the one in the Ruhr Industrial District. How'd Garrard get it?"

"We don't know. He went out unplanned, wondering if utter secrecy mightn't be the answer."

"Too bad," said Haynes and hung up quickly. The general didn't like the tone of Lindsay's voice.

Lindsay faced them. "What do we know?" he asked. He felt that he'd been asking that question for year upon year, and that there had been no answer save a mystical, omnipotent rumbling that forboded ill—and that threatened dire consequences if asked to repeat.

"Not a lot," said Grant. "They go off when we get within a hundred feet or so of them. That's all we know."

"Garrard went out without running his intercom radio. He made no reports, thinking that maybe they listened in on our short-range jobs and fired them somehow by remote control when they feared we might succeed in inerting the things!" Lindsay growled in his throat.

"Look," said Grant. "This is urgent. It is also knocking out our nerves. It's not much of a run from here to Ruhr Industrial, but I'm going to suggest that we all forget the problem completely for a few minutes. Me, I'm going in to take a shower."

The value of relaxation did not need pressing. Jenna nodded. "None of us have had much of anything but coffee and toast," she said. "I'm going down and build a real, seven-course breakfast. Any takers?"

They all nodded.

"And Ralph, you come and break eggs for me," she laughed. "So far as I know, I'm the only one that's capable of taking your mind off of your troubles momentarily."

Lindsay laughed and stood up.

Lacy said it was a good idea, and then added: "I'm going to write a letter."

The rest all looked at one another. If Tom Lacy were writing a letter, it meant that he'd taken some new interest in life. Wordless understanding passed between the other three and they all left Lacy sitting at the desk.

The autopilot was bringing the ship down toward the ground out of the stratosphere, slanting toward the Ruhr when Jenna snapped the intercom switch. "Breakfast," she called. Her voice rang out through the ship. Grant came immediately and sat down. Lindsay was already seated. Jenna served up a heaping plate of ham, eggs, fried potatoes, and a small pancake on the side. "This," she smiled, "is too late for a real breakfast, but I demand a breakfast even if it's nine o'clock in the evening when I first eat for the day. There's more if you're still hungry."

"We'll see," said Grant. He picked up his knife and fork but stopped with them poised. "Where's Lacy?"

"I'll give another call," said Jenna, repeating her cry.

They fell to, attacking their plates with vigor. But no Lacy. They finished and still no Lacy. "Come on," said Jenna. "Maybe he's still feeling remorse. We'll find him and then we'll feed him if we have to hold him down and stuff him. O.K.?"

"Yeah," drawled Grant. "Feeding does wonders for my mental attitude. It'll do Tom good, too! Let's find him."

They headed for the scanning room, but it was empty. The desk where they'd left him was as though he had not been there, except—

"Letter?" queried Lindsay, puzzled. "Now, what—" his voice trailed away as he slit the envelope and took out the sheet of paper. He cleared his throat and began:

"Dear Folks:

"I put no faith in Garrard's suspicions, but since he was lost without an honest chance to prove them, I am taking this chance.

"I am taking my skeeter when I finish this and I'm going on ahead, alone. Knowing you as I do, I'll have plenty of time to inspect that robomb before you read this. I'm explaining my actions because I feel that you may need explanation.

"I think the world and all of both Jenna and Ralph, and feel that I may have caused suspicion and unhappiness there. Since I'll have time to take a good look at this thing and also make some motions toward defusing it long before you arrive, or even find this, let my success be a certain statement of the fact that knowledge of my actions by any of you—or even suspicion cast at the presence of the Decontamination Squadron Ship by the enemy—is not the contributing cause. No one will know until I'm all fin—"

Light filled the scanning room, and the ship rocked as it was buffeted by the blast. The light and the heat and the sound tore at them, and they clung to the stanchions on the scanning room until the ship stopped rocking and then Grant made a quick dash for the autopilot, which was chattering wildly under the impact of atomic by-products. It stabilized itself, however, and the ship continued on down through the billowing dust to the ground.

"That," growled Lindsay, "loses us Lacy and proves nothing."

"Not entirely," drawled Grant. "It does prove that whatever agency is directing these things does not require the presence of this ship as a tip-off."

"A lot of help that is."

"Well, I'm nominated for the next try. Unanimously. I'm the only one voting any more."

Jenna gasped.

"What's the matter, Jenna?" asked Grant.

"I just realized that you were all that's left. Just like that—and in a few hours. Poor Lacy."

"Lacy?" said Grant. "He—got his release. It's what he's wanted. May we all find what we want as quickly."

"I hate to see any one courting death, though," said Jenna.

"My only regret for Lacy is that we don't know whether he—and Garrard, by the way—went in the same way."

"Meaning?" asked Grant.

"The rest got it as they headed out to defuse the things," said Lindsay. "At about a hundred feet. We can only assume that Garrard and Lacy went in the same way. I'd like better than an assumption."

"Why?"

"A hundred feet is too distant to detect the human body without radiation. It presupposes either a warning of some type or—" Lindsay scowled and stopped. He mumbled something about a conference with General Haynes. He stepped to the autopilot and set it for the next location. Then he left to seek the privacy of his own office from which to call General Haynes. As he left, Jenna lifted a worried face to Jack Grant.

"Jack," Jenna said, "he doesn't trust me any more."

"It does look bad," said Grant. "After all, every one of them came in your presence."

"They came in your presence, and his."

"Admitted. But—"

"I know," she said, with deep feeling. "But I can't help being Martian. My loyalty is with Ralph."

"Jenna," said Grant softly, "we know that. All of us know it. Yet, there's some agency that is tipping them off. There's been robombs at the other sites for hours now, and not one of them has gone off. They're tying up production until we arrive, and they'll continue to tie up the area until we make a false move. Something or someone is giving them the tip-off. I know it isn't me, you know it isn't you, and Ralph knows it isn't him. The areas are completely cleared, but, of course, there may have been watchers. But Garrard would have gone out unlighted, and possibly Lacy would have done the same."

"Jack," she pleaded, "do you suspect me, too?"

"Jenna, you know I do. I rationalize myself, and tell myself that it isn't so. But nevertheless, there is that lingering doubt. Evidence, Jenna. Evidence."

"Jack, a criminal is considered innocent until proven guilty."

"Jenna, that's for the safety of all who may be accused. But considering a man guiltless does not prevent people from making charges. And there have been many occasions where the accused was forced to go through a strenuous period before proving his innocence. What they really mean is that they will not punish a man against whom no true conviction is brought. Until he is convicted, he can not be punished. And it is up to the authorities to prove his guilt. It is also up to him to prove his innocence. But considering him innocent permits his own testimony to be considered as valid as that of any witness instead of marking it off of the books as the word of a guilty man."

"And I?"

"Forgive me, Jenna. I think the world of you, and there is in me a rather violent mental storm. One side—the larger side, insists that you are loyal, and above reproach. The other side, that tells me to beware of the woman in you, that if you were really clever and treacherous, you would hurl these doubts out in the open and cause suspicion to fall upon yourself. And, you are Martian. A sort of racial instinct warns me. It's unfair, and I dislike myself thoroughly for it."

Tears welled in Jenna's deep eyes. "Jack, please. What can I do?"

"I don't know," he told her.

"I ... feel miserable," she sobbed.

"It's a tough load to bear," he said softly, putting a hand on her shoulder.

"It's unfair," she said shakily. "Look, Jack, I know you too well to believe that hard exterior. You put that on because you're excessively soft inside and people can hurt you too easily if you're not careful. I am like that, but I'm not as soft as you are."

Jack laughed a bit. It was a false laugh, designed to lift her out of the doldrums.

It failed.

"For eight long years," she said earnestly, "I've taken from Ralph everything that any woman would find ideal. I've had companionship, tenderness, love and affection. Complete compatibility. He's met my every mood. And not only because it will please me for him to mirror my moods, but because he feels that way too, and his moods change as mine do. He is absolutely happy to follow or lead me into any change of mood and we're never far apart. I've been protected and loved by the man I wanted. That's perfection.

"But for four of those years, I've been unable to reciprocate."

"Now, Jenna, that's not true."

"I love him—even more, now. And I'd do nothing to stand in the way of his happiness. But Jack, remember I'm Martian and he is denied his right to command a battle squadron. Because of me. He's stuck in this noncombat group—because of my heritage. In all that time, he has never shown it, yet he must know. If anything, he has become more tender, more protecting, more affectionate. More tolerant. Yet what can I do to give him release from this? Suicide isn't the proper answer. That would deprive me of what I want, and his desire is not completely to the service. But he cannot have his cake and eat it too."

"That's quite a load, Jenna," said Grant tenderly. "I hadn't realized."

"I ignore it, mostly. But there are times when it creeps up and gets me. I wake at night, thinking deeply. I fret, and go sleepless, wishing there were a way out."

"I think you've well made up for it."

"No," she said with a shake of his head. "He must feel denied of his right to honor by his affiliation—made in the face of public objection to mixed-marriage. I ... am now worse. An enemy alien."

"You are a Terran citizen," stated Grant.

"I have papers to prove it," she said scornfully. "And any doctor that didn't see the papers but examined me perfunctorily would pronounce me Martian. Ours will always be—a sterile marriage. It cannot be otherwise. Yet until this shadow came, we were both happy."

"Poor Jenna," said Grant, putting her head down on his shoulder and patting the back of it. "And now that the first doubt has crept in, the rest of Pandora's Troubles all come roaring in through the initial breach."

"And now this," she sobbed. "Grant, it's worse than torture."

Grant's mind whipped back and forth between several types of torture he'd heard about and wondered what she meant.

"No amount of torture could pry a secret from you, could it?" she asked.

"I like to think I'm that way," he said.

"You think a lot of me," she said. "Would you talk to save me from torture?"

A bead of sweat popped out on Jack's forehead as he thought it over. "That's a double curse," he said grimly. "You'd prefer torture to misloyalty and I'd be torn between the two because it is against all natural instincts for a male to harm a female. That's a forty-thousand-year heritage, Jenna."

"Well," she said, "I'm in that position but I'm without the means to say the word and relieve his torture."

"And he," said Grant, with feeling, "is pretty much in the same boat."

"Before this all happened there was enough to outweigh any doubt. But I'm practically accused of treachery."

Grant smiled tolerantly. "Most of that is in your own mind," he said gently. "You've kept your fears bottled up too long, and they're fermenting into all sorts of questionings and worries."

"Then I'm not really under suspicion?"

Grant laughed. "My dear, if they're reading your mind without your will, that's not treachery. Frankly, I've studied the problem myself, and I know that such is impossible. In no known science has there ever been a situation where a transmitter can be heard without the transmitter aware of its output. By 'transmitter' I mean people talking, men holding radioactives, radio, subradio, light, sound, and fury. Furthermore, since unwitting aid is ruled out, if such aid is given, it is given willingly. And that, Jenna, I refuse to believe."

"Truly?" she pleaded.

"I'll stake my life on it," he said. "All the evidence may be damning but somehow, it's too pat. Coincidence may be a little strained, but far from improbable in any sense. Fact of the matter is, Jenna, there's no sense in going out on the Q-T. I'm going out with all recorders open and working furiously, I'm going to record not only my ideas, but my transient thoughts and my overt acts. I'll show 'em a bold front. And, by showing a bold front, I'll win. And if I do not, you'll all know just what goes on and you'll know how to act on the next one."

Grant laughed and shook the girl gently. He removed a handkerchief from his breast pocket and dabbed her wet eyes with it, and told her to get that elfin chin up again.

"Thanks," she whispered, the tears welling up again. "Thanks, Jack ... for ... faith!"

When the door opened to admit Lindsay, her face was once more composed. She put down her cigarette and said: "Any ideas, Ralph?"

His worried face grew darker. "It seems to get down to the problem of defusing a bomb that explodes when you approach it with that intent."

Grant laughed. "As I said before, we can detonate 'em but it's hard on the personnel."

"Oh, Jack!" cried Jenna.

"Well," he grinned, "it's true. And regardless of whether we lose a few fellows who'd prefer death anyway, we are most definitely keeping the production areas uncontaminated. That's something."

Lindsay scowled. "It's not good enough," he said. "A man's life should be worth more than that."

Grant shook his head. "It's more than mere production, Ralph. Production means many lives. And is one man's life worth more than many men's?"

"To me, my life is."

Grant laughed, taking the sting out of his matter-of-fact statement, "You're selfish."

Lindsay nodded glumly. "I admit it. How're you going to tackle that one out there?"

"Boldly, brashly, and brazenly. Whatever agency is manipulating these things will find me slightly different. I hope I'm confusing enough to make them wonder."

"I wish—" said Lindsay.

"Forget it," said Jack. "I've got to go, and there's little sense in stewing about it. I'll be back, and then we can handle the rest of these things with ease. No chin up, fella. You're in the hot spot of doing a hard job."

"I know," he muttered.

When he looked up, Grant had left.

Lindsay passed his hand over his face with the gesture of a completely baffled and worn-out man. He looked up at his wife. "Jenna," he pleaded, "is there—?"

"Don't you trust me, Ralph?"

"My whole being cries out to trust you, Jenna. But there is still wonder."

"There is nothing I can say that will erase that. Nothing. If I am actress enough to play treachery, I'm also liar enough to swear a false oath."

Lindsay nodded.

"Nothing," she repeated dully.

"You think a lot of Grant," he said flatly.

"I've loved them all," she said.

"Grant more than the rest."

"Jack, despite his hard exterior, is an understanding soul."

"That may save him," muttered Lindsay.

"Ralph!"

The jocular voice of Jack Grant broke in: "I'm taking off in the battle buggy now."

"And then again it may not," said Lindsay harshly.

"I'm not a machine, Ralph. I'm a woman."

"So was Circe!"

"Is that what you think of me?"

The loudspeaker chattered: "This is no road for a human being, folks. They paved it with rubble, I think. My tools are rattling around like mad. If any agency is using anything for detection, they're listening to the rattle of machinery in this battle buggy."

Jenna and Ralph faced the radio panel and both hated it for its flat tones. But they could not turn it off.

"He'll go like Roberts, like Harris," snarled Lindsay. "Like—Lacy."

"No!"

"We'll see," he said tritely.

Silence fell, and then the voice again: "I'm approaching the thing. Y'know, it's fearfully quiet out here with the area evacuated and all machinery stopped. The wall shields make the landscape unreal, like the ghost-sequence in a horror movie. Terra was never intended to be seen under a greenish light. You know how people look under mercury vapor lights? That's how Terra looks, sort of."

"Jenna?"

"Yes Ralph."

"You're not ... you're not—?"

"What can I say?" she pleaded. "I'm only human."

He looked up bitterly. The question was in his eyes. He did not need to voice it. Jenna knew what he was thinking. And he knew that she understood, for the hurt was in her eyes.

"Hey!" came Grant's voice. "I've got us a mascot! C'mere, Ears. Nice fella. 'Tis a woebegone pup, spaniel. Lonely and aching for someone to scratch his tummy. Up, Ears! You're my good luck! The mutt is sitting on the seat like he knew what it was all about. A sharp little rascal. I'll bring him home to you."

Jack drove on, one hand on the wheel and the right hand on the dog's head, stroking gently. Who, he wondered, would leave a pet in a contaminated area? Abandoned to something that no dog could possibly understand.

And he thought, briefly, that he and the dog were in the same boat.

"You can carry my tool bag," he told the pup over the rumble of the battle buggy.

Jenna and Ralph listened to Grant talking to the dog. The man rattled on, speaking lightly, caressingly to the animal, and his words were banal to the tensity in the scanning room.

"I wish I knew," said Lindsay.

"Ralph, stop it!" cried his wife. "Stop playing around the point. If you think I'm guilty, come out and say so!"

"I'm ... not certain."

"Have you no faith in me?"

"Jenna, I—"

"Folks, I'm stopping the buggy, and Ears and I will go over and see that thing right now. So far, there's been no mental disturbances, Jenna. That's the one thing I'm watching for."

Lindsay looked at her.

"I don't feel anything," she said. He wondered, again, and it was in his face.

Her voice went out, and Grant answered. "If either of us feel anything—?"

"I'll let you know," she promised.

"Will you?" muttered her husband.

"I will," she blazed at him.

"Lindsay," snapped Grant, "get off of it! Jenna has no more treachery in her soul than I have, and I know my own heart!"

Ralph Lindsay calmed. Jenna looked at him and knew that the man outside was a sort of safety valve. Her husband was on the verge of breakdown, she guessed, and she was in a nervous state herself. The man out there had been holding the group together for hours, now. What would happen if he went—?

"No!" she pleaded.

But something inside of her knew that he would go, like the rest.

"No!" she said with a half-scream.

"'No' what?" asked Lindsay.

"Grant mustn't!"

Lindsay looked at her. "Isn't that his job?" he said flatly.

"Yes, but—"

"Perhaps you can fix it," said her husband cynically. She looked at him in disbelief. Was this the man she loved?

Then he turned the knife in the wound. "Or," he said vindictively, "is that your job?"

"Lindsay, shut up, you fool!"

Lindsay opened his mouth and then closed it again. "Trouble with you, Lindsay, is that you've a rankle or two in your system which should have been burned out a long time ago. You poor fool, don't you know that every man reaches a crossroad every day? There's not one of us who mustn't give up something to get something else. That's why we have asylums—for people who can't make up their minds, or people who dislike their decisions and try to go back, mentally. The normal man accepts his decision and uses that as experience in making the next one, instead of sitting there, spending his life wondering what if he'd taken the other road. Add up your life, Lindsay, and see whether the credits are better than the debits. You can't have everything!"

Then the tone of his voice changed.

"I'm leaving the battle buggy now, and Ears and I are approaching the thing. I have no fear of it, really. I'm ... curious. What makes these things go off? This, fellers, is a physical phenomenon, developed by human beings—"

"Martians," corrected Lindsay.

"They're classified as human," snapped Grant. "And a lot of them are more human than the pure-white Terran. Spinach, I call it. Anyway, there is a simple explanation for all this and when it is uncovered, all of your rantings and ravings will go to pieces like a bit of charred paper. Call it telepathy if you want—I'm not discounting though I'm skeptical—but I don't feel any warnings yet."

Jenna sat down, closed her eyes, and composed her body into a relaxed pose. She said nothing. Lindsay noted, and said: "Keep it coming, Grant."

"Well," said Grant, "we're at the critical hundred feet, Ears and I. Come here, mutt! That thing is dangerous! Dog doesn't care, folks. Y'know, there's nothing like having a mutt around to teach you faith. Jenna?"

She opened her eyes. "Yes?"

"I'm going in! You're Martian and you're sensitive. Maybe you can catch the backwash if there's any mental shenanigans."

"I'll try."

"Believe it now?" called Lindsay.

"Not entirely. But I'm not missing any bets. Now, I am taking my little hatchet in one hand and I'm going out to ... Jenna! You—!"

The storm burst, the sky flared bright, and the waves of sheer energy beat the ship, stormed in through the windows and the radiation counter shrilled madly. The pillar of fire mounted like a rolling cloud, reaching for the sun.

"Grant," said Lindsay with a dry throat.

Jenna sobbed.

"What did he mean?" demanded Lindsay.

Jenna shook away her tears, swallowed deeply. "I know," she said. "I know."

"You—?"

"I caught it," she said.

"Then it was you," he snapped harshly. "Tell me, Jenna, what kind of enticement did you use to get him going?"

"You fool," she snarled at him. "Blind, stupid fool." She stood up, blazing. "Yes," she said. "I've taken all you gave me, and took it gladly, happily. And I hoped that I could make up to you for ... for ... causing your loss. Yet you've never forgotten that I'm Martian, and that if you'd married a Terran you could have the plaudits and the admiration due any fighting officer. That's rankled in your soul until you hate me!" she screamed. "And what could I do? I'd have made it up to you," she said, her voice quieting, "but I didn't know how. And now you think I'm responsible. Well," she said accusingly, "how do I know but that you are planning revenge on Terra for being blind."

"Jenna, you—"

"Well, I do know. And if you think that I'm—"

"What do you want me to think?" he asked her. "What were Grant's last words?"

"He—"

"Accused you!"

Jenna turned quietly. She stopped at the door. "I solved one fuse because I thought Martian," she said quietly. "I'll solve the next one for you! You've wanted to be free to join the Corps in space. Then follow me close, because when I solve this one there will be no question."

"Jenna—what is it?"

"It is the fuse itself," she said. "A rudimentary brain that reacts upon receiving any thought of removal when that thought originates within a hundred feet or so."

"Utterly fantastic!"

"Is it?" she asked. "Watch!"

Jenna passed through the door and left. Moments later, the whine of a skyplane crescendoed and diminished. Jenna was heading for the next site. Lindsay sat for a long time, his mind whirling.

Jenna was right. He'd been fretting over his denial of the right to command. It hadn't been fair. A group of psychoneurotics—commanded by one. Himself. Not denied the right to command because of his wife, but because of his psychotic nature. For one, any Terran who would enter a mixed-marriage was not possessed of the normal adjustment, and the same true of any Martian. Secondly, were he normal, fighting in combat would produce a psychotic condition since he'd be set against his wife's countrymen.

He leaped up and ran to the driving panel. Harshly he threw the autopilot out of gear and took the controls himself. The ship took off raggedly and hissed through the upper air, racing.

"Jenna!" he called into the radio.

No answer.

"Jenna! Turn on your receiver! Please," he begged.

No answer.

His trembling hands turned up the power and the ship shuddered at the overload drive. The upper air shrilled against rivet head and port sill. The burble point came and the ship shook and rattled terribly. Yet he knew that he had but an even chance. For Jenna was driving a superspeed plane that could race as fast as the big ship—with less danger in atmosphere.

No spacecraft was made to travel horizontally across a planet. But Ralph Lindsay in a frenzy, swore at the sidelong pace, and turned his ship to arrow through the upper air. The burble died, but throughout the ship came the rattle of falling objects, dumped from table and shelf.

He continued to cry into the microphone, and strained his ears for the answer that was not there.

He depressed the nose of the ship and went into a steep, screaming dive.

He—saw her. A minute speck, even through the telescope.

And at the moment he saw her, she stepped from the plane onto the ground, and spoke to him through the radio.

"I've no receiver on, Ralph. But listen—and stay back!"

"Jenna!" he screamed.

"Your duty, remember?" she said quietly. "It is to solve these—things. Your duty, I took away, and now I will return it."

"Jenna!" he pleaded. "I don't want—"

In futility, he gave up. She could not hear. An hypnosis took him, held him in its grip.

"Ralph," she said. "Watch carefully."

He shook himself.

Angrily, he fought the controls. Madly he tried to urge another dyne from the drivers. He would be—too late.

"Jenna! Don't!"

"Ralph, I'm approaching the bomb. I am now seventy feet from it. See?"

Seventy feet?

"I'm seventy feet from it, Ralph, because I've thought only of you. Not once have I thought of defus—"