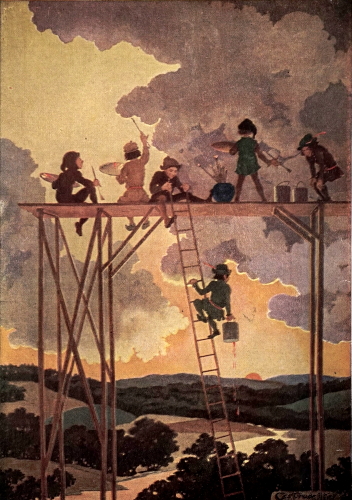

Getting ready for autumn.

Author of "The Grateful Fairy"

NEW YORK

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1923,

By Barse & Hopkins

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

| The Sociable Sand Witch |

| The Fountain of Riches |

| Obstinate Town |

| Toobad the Tailor |

| The Snooping-Bug |

| The Wrong Jack |

| The Second Story Brothers |

| The Imaginary Island |

| The Dancing Pearl |

| The Inherited Princess |

Of all the witches that may be found in all the fairy tales ever told there is none more delightfully sociable than the Sand Witch. This Witch, who lives underneath the heaps of sand at the ocean's edge, where, in the summertime, you dig with your shovel, is not at all like other witches. She never rides on a broomstick, and she never goes down chimneys. In the first place there are no broomsticks or chimneys on the beach at the sea-shore, and in the second place she would not know how to ride on a broomstick or climb down a chimney, if there were. All the Sand Witch knows how to do is to sink into the sand when anything scares her, and to come up through the sand when she sees a chance to get acquainted with a person she never was acquainted with before. So now you know what a Sand Witch is. And if Junior Jenks, seven years old, and dreadfully sunburnt, had known what you know, he would have been much better prepared to face the one that came up right under his nose all of a sudden one hot July morning.

Junior was supposed to be in bathing. His mother, and his father, and his sister were in among the breakers having a fine time, but Junior, although he was wearing a bathing suit just like they were, preferred the good old sandy, sunny beach where foam-crested waves could not tumble you over and over, and fill your mouth with salt water when you yelled. He had tried bathing once, and no amount of coaxing could induce him to try it again, so his folks left him to play by himself while they took their dip.

The first Junior knew about the Sand Witch was when the tip end of a steeple hat began to come up through the sand in front of him. Up, up it came until the whole hat was showing; then followed a long nose, two big, black eyes, a big mouth, and a sharp pointed chin; after that the rest of the Sand Witch followed very quickly, until at last she stood before him as cool as a cucumber.

"Well," she said, not paying the slightest attention to the way Junior's hair was standing up, "here I am. I've heard you digging for some days. I suppose you thought you'd never find me."

"Find you?" said Junior, staring with all his might. "I wasn't trying to find you. I never knew there was such a person. I wasn't trying to find anything."

"You weren't?" said the Sand Witch. "Then what in the name of peace were you digging for?"

"Why," said Junior, "I—I—I was just digging for fun."

"Well," said the Witch, "did you find any fun?"

"Find any fun? Of course not! You don't find fun, you—you just have it."

The Sand Witch pushed her hat on one side and scratched her head in perplexity. "I don't think I understand. You said you were digging for fun, didn't you? And when I asked if you found any fun you say you don't find fun, you just have it. Well, if you have it, what do you dig for? Tell me that?"

But though she waited very politely for Junior to tell her, he made no answer. He just looked at her with his mouth open, and wiggled his bare toes deeper into the sand.

"My goodness," said the Witch, at last, "are you deaf? I asked you a question."

"I—I know," said the boy, "but—but I can't tell you. I—I don't know how."

"Suffering sea serpents!" exclaimed the newcomer. "You certainly are the queerest I ever met!"

"No queerer than you are," responded Junior, indignantly. "You're the queerest person I ever met! Coming up through the sand in such a way!"

"Humph!" retorted the Witch. "How else could I come up? There's nothing else here but sand to come up through. You can't blame that on me."

"Oh, I'm not blaming you," said Junior. "I'm only telling you. I don't suppose it is your fault that all this sand is here. It only seemed so strange for a person to be underneath it. You don't live there, do you?"

"I certainly do!" replied the other; "and all my family, too."

"Underneath the sand? Why, I never heard of such a thing! I—I can't believe it!"

"Now look here," said the Sand Witch. "I won't let anybody talk that way to me. If you don't believe I live underneath the sand come on down and see for yourself. Just hold your nose tight with the fingers of your right hand, put your left hand above your head, draw in a deep breath; and down you go, like this."

Thrusting a hand above her head, and grasping her nose, she took a deep breath, and zip—she sank through the sand like a flash, just the way Junior's father always sank into the ocean when he was bathing. Then bing—the next moment she popped up again, smiling cheerfully. "See how easy it is? Come on, now you try it!"

"No, thank you," said Junior. "I'd rather stay on top of the sand."

"Oh, pshaw!" exclaimed the Sand Witch, "I never saw such a 'fraid cat! You're not only afraid to take a sea bath, but you don't even dare to take a sand bath. I'd be ashamed!"

"Well, be ashamed, if you want!" said Junior, hotly. "I don't care! I don't like baths of any kind; in the ocean, or in the sand; or even in the bathtub. What's the use of them, anyway?"

And with that he started digging again. And then it was that the Sand Witch showed what a thoroughly sociable nature she had, for although the boy had turned his back to her and was paying no attention, she wasn't in the least discouraged. "Did you ever see a crab wait on the table?" she asked.

"Why, no," said Junior, whirling about and looking very much interested. "I thought all a crab could do was to pinch you."

"Not at all! They wait on the table fine if you let 'em. And I've got a shooting starfish, too, that can't be beat. You come on down underneath the sand, and I'll show you. Oh, I've got dozens of delightful things down there. Why, the sand pies I make are the most delicious things you ever tasted. And I know you'll laugh when you see the clams skip rope."

Well, you may be sure all this sounded very, very good to Junior. He had often heard of starfish, but never of shooting starfish. A crab waiting on the table was bound to be interesting; and a clam skipping rope, even more so. As for sand pies, he had often made them himself, but never so they could be eaten. If there was a way to do the trick, he'd like to know it. In fact, it was like being promised a free ticket to the circus. So throwing his bucket and shovel aside he got to his feet without further parley.

"Very well," he said, "I'll go with you. But I've got to be back in a half hour. My father is going to take me sailing as soon as he is through with his bath."

"That's all right," said the Sand Witch. "When you're ready to go back, you just go back. And now do just as I do."

So Junior held his nose tight, put his other hand above his head, took a deep breath, and then bing—he and the Sand Witch sank through the sand in a jiffy, and the next moment came out underneath it.

"Oh!" cried the boy.

All about was a beautiful, white, glistening, sandy city; houses, fences, streets, all of sand. The place where they were standing seemed to be a sort of park with cute, little, carved, sandy benches amid the sand grass, and several tall fountains spouting sand in a fine spray.

"Well, how do you like it?" asked the Witch.

"Fine!" said Junior; "but where are the clams and the—"

"My goodness," said the Witch, "but you are in a hurry. I've got to find my children, first. You don't expect me to neglect my children that way, do you?"

"Oh, no," replied the boy, "of course not. But—but I didn't come here to see your children, you know. I can see children anywhere."

"Not children like mine," said the Sand Witch, proudly. "If there is a more beautiful child than little Lettuce Sand Witch I'd like to see it. And as for dear little Ham Sand Witch, he is the cutest thing."

"Ham Sand Witch! Lettuce Sand Witch!" exclaimed Junior. "Are those the names of your children? Why—why, it sounds like things to eat!"

"Well," said Mrs. Sand Witch, "why not? Both of them are certainly sweet enough to eat."

With that she opened her mouth and gave a piercing yell. "Children!" she shrieked. "Come to mother, quick! I've got a little boy for you to play with!"

And presently, racing across the park toward them came the two little Sand Witches, one a girl and the other a boy. But though their mother thought them sweet enough to eat, Junior did not. Both had long, pointed noses and chins; big, black eyes and dreadfully wide mouths, just like Mrs. Sand Witch. When they saw Junior they just stood and stared, and gnashed their teeth.

"Hello!" said Ham Sand Witch, after a moment. "Who are you?"

"Yes," said his sister, Lettuce Sand Witch, walking about and examining Junior from all sides, "who are you, and where did you come from?"

"I'm Junior Jenks," replied Junior, "and I came from the beach up above to see the clams skip rope."

"Pooh!" said Ham Sand Witch. "That's no fun! We're not going to play with them any more. They want you to turn the rope all the time. If you don't, they nip you."

"Well," said Junior, "if I can't see the clams skip rope, let me see the starfish shoot."

"All right," said Lettuce Sand Witch, "we don't mind. But you'll have to pay his fare if you want to see him shoot."

"Pay his fare?" responded Junior. "I don't know what you mean."

"Ahem!" put in Mrs. Sand Witch. "Perhaps you thought he shot with a gun. Well, he doesn't. He chutes with a chute! And you know as well as I do, you've got to pay your fare when you chute with a chute."

"Oh," cried Junior, in dismay, "I see. But—but I haven't any money."

"Then," said Mrs. Sand Witch, "if you want to see him chute, we'll have to charge it to your father. How about it?"

"Well," said the boy, "I guess he won't mind, as long as I never saw a fish chute before."

So Mrs. Sand Witch took the children to the chute the chutes on the other side of the park, and told the proprietor, a very shaky old jellyfish, that Junior would pay the starfish's fare, and to kindly coax him out of the ocean to take a ride.

So the jellyfish went to the ocean, which was just back of the chute the chutes, and yelled for the starfish to hurry up if he wanted a free ride. And the starfish, highly flattered at the invitation, lost no time in making his appearance.

"I'm awfully obliged to you," he said to Junior, as he whirled about in the sand to dry himself. "And to show I am I'll let you sit with me."

So Junior and the starfish, and Ham Sand Witch, and Lettuce Sand Witch, climbed into the car and went shooting around the chute the chutes.

"Isn't it great?" shrieked the starfish, as they scooted down the inclines. "It makes your insides turn somersaults! It beats swimming all hollow, I think. If ever I get rich I'm going to build one of these things in the ocean."

And when at last the ride came to an end he insisted on Junior shaking hands with every one of his five points. "Any time you fall overboard when you're out sailing," he said, "stop in and see me. My place is the third clump of coral just beyond the bathing grounds. Good-by!"

"Now," said Mrs. Sand Witch, who had waited while the children and the starfish took their ride, "I've got to go home and get dinner. You children amuse yourselves, and after dinner maybe I'll take you to see the mermaids."

So Junior, and Ham Sand Witch, and Lettuce Sand Witch, wandered about the park hand in hand. Although the little Sand Witches were so ugly, Junior was beginning to like them right well, now that he was getting used to them; and they seemed to like him, too.

"Why don't you stay all summer?" said Ham Sand Witch. "We could have lots of fun."

"I'd like to," said Junior, "if my father and mother and sister were here."

"Well, why not ask 'em to come down?" suggested Lettuce Sand Witch.

"Oh, they wouldn't do it," said the boy. "I know they wouldn't. They like it better on the boardwalk and at the hotel. And now let's see if we can't find those clams that skip rope."

"All right," said Ham Sand Witch, "but if we do, they'll make you turn for 'em just so. They're awfully snappish."

And sure enough when presently they came upon the clams sitting on a bench near one of the fountains, and Junior asked if they would skip rope for him, they said they would if he turned for them just so.

"I don't know what you mean by 'just so,'" said Junior, "but I'll do my best."

And he certainly did do the best he could. While Ham Sand Witch held one end of the rope he turned it very, very carefully as the two big, white clams solemnly skipped. They were slow enough until they got warmed up.

"Now give us butter and eggs," said one of the clams, suddenly.

"Butter and eggs?" said Junior. "You mean pepper and salt, don't you?"

"I certainly do not," said the clam who had spoken. "I mean butter and eggs. Pepper and salt is fast, but butter and eggs is lightning; and see that you do it right."

But though Junior turned the rope with all his might and main he simply could not turn it fast enough to suit the clams. And presently with a scream of rage they rushed at him snapping their shells angrily.

"Run! Run!" shrieked Lettuce Sand Witch, "or they'll nip you!"

"Run! Run!" yelled Ham Sand Witch. "They pinch awful."

And maybe Junior did not run. And maybe the clams did not run after him. But luckily, just as they were about to grab him, one of them tripped and fell and cracked its shell, and wept so when it did, that the other clam stopped to help it. So Junior, and Ham Sand Witch, and Lettuce Sand Witch finally reached Mrs. Sand Witch's house and were soon safe indoors.

"Sakes alive!" exclaimed Mrs. Sand Witch, as the children stood before her, panting. "What has happened?"

And after they had told her she said they were never even to speak to those clams again. "I never did care for clams, anyhow," she said. "They're always disagreeing with people."

Then she told them that dinner was almost ready and that she knew they would enjoy it. "We've got the most delicious sandpaper garnished with seaweed," she added; "to say nothing of sand pies for dessert."

And when she said that both the little Sand Witches jumped up and down with glee, and cheered and cheered. "Oh, goody!" they cried. And Junior, being a very polite little boy, cheered also, although he felt quite sure that while he might like the sand pies, he never, never would care for sandpaper garnished with seaweed.

And then as he sat in the parlor waiting for dinner to be served, he heard a clatter of dishes in the next room, and peeping in, gave a gasp of astonishment, for there was a big, green-backed crab putting the dinner on the table, singing cheerfully to itself as it did so. And this is what it sang:

And as the crab sang a funny feeling came over Junior. Only a week or so before he had been out with his father in a boat, and his father had caught a crab on his fishing line, and pulled it into the boat. And Junior, being in his bare feet, had been awfully scared for fear the crab would pinch him, and then, sure enough, before he could get his feet up on the seat, it did, right on the heel; and in trying to kick it loose, he kicked it overboard. He wondered if this could possibly be the same crab.

So when they all went in to dinner he looked at the crab carefully to see if he could recognize it, but as one crab looks like another, he couldn't be sure. But the minute the crab saw him, it was very different.

"Oh!" gasped the creature he had been observing, staggering backward and almost dropping the dish of sandpaper and seaweed it was carrying. Then, putting the dish carefully on the table, it bent over and looked Junior in the face.

"'Tis he!" it shrieked, with a dramatic gesture. "'Tis he! my rescuer!" And if Junior had not leaped from his seat it would have thrown its claws about his neck.

"'Tis he?" exclaimed Mrs. Sand Witch, frowning at her amphibian servant. "What do you mean by ''tis he'? What are you talking about? This is a nice way to behave before company."

But after the creature had explained matters, Mrs. Sand Witch and the little Sand Witches were even more excited than the crab was.

"My, my, how romantic!" said Mrs. Sand Witch; "and how lucky it is, Bertha, that you're a lady crab. Now you can marry him!"

"Oh!" exclaimed Bertha, the crab, trembling violently. "I never thought of that! I'd just love to, if only to show my gratitude. But—but maybe he wouldn't care to marry me. Would you?" she asked, turning to Junior, who had once more resumed his seat.

"Marry you?" said the boy, wishing he hadn't sat down again. "Why—why, of course not. Why—why—I—I—why, I'm only a boy. I—I, my mother wouldn't let me get married. I know she wouldn't."

"Oh, bother your mother!" retorted the crab, crossly. "She'll never know anything about it. We'll get married and settle down here, and she'll never know where you are. And now, when shall it be?"

"Never!" shouted Junior, springing up once more. "I'll never do it. Boys never marry crabs. Boys never marry anybody!"

"Never marry anybody?" put in Mrs. Sand Witch. "Dear me, then how do they ever get married?"

"They don't get married," said Junior. "They—they just play."

"Well," responded the crab, "you can play. I won't mind. You needn't stop playing just because you're married to me. No, sir-ee!"

But Junior shook his head. "I'm very sorry," he said, "but I can't do it." And though the crab kept on coaxing and coaxing, he wouldn't give in.

"Now look here," said Mrs. Sand Witch, "if we keep this up the dinner will be cold. So run along, Bertha, and maybe after Junior has had a good dinner he will change his mind."

"No, I won't," said Junior. "And what is more I want to go back to the beach right off. I told you I was going sailing with my father in a half hour."

"But," replied Mrs. Sand Witch, as she smacked her lips over the last of her sandpaper, "that was before you were engaged to be married."

"I'm not engaged to be married," stormed the boy; "and if I had known you were this kind of a person I'd never have come down here."

"Now, now," said Mrs. Sand Witch, "I'm every bit as old as your mother, and I know what is best for you. You wouldn't like me to spank you, would you?"

And when she said that, Junior decided he might as well give himself up for lost. Soon as a person began to say she knew what was best for you, you might as well make up your mind, you are done for. "Good gracious!" he said to himself, "whatever shall I do?"

And when dinner was over, and he went into the park again with the little Sand Witches, he was so depressed he wouldn't play or do anything; and finally, Ham Sand Witch got tired trying to cheer him up and went off to play with some other sand witches, leaving Junior and Lettuce Sand Witch sitting on a bench side by side.

Lettuce Sand Witch, swinging her legs violently, was looking at him. Then she slid along the bench and snuggled up close. "I'm awfully sorry," she said. "And I think it's dreadfully mean to make you marry Bertha. She's not pretty like I am, is she? Wouldn't you rather marry me?"

And the minute she said that, Junior had a bright idea. He didn't want to marry Lettuce Sand Witch any more than he wanted to marry the grateful Bertha, one was as ugly as the other; but maybe if he let on he wanted to, she might tell him how to get back to the beach. So he snuggled up to her when she snuggled up to him.

"Maybe I would," he said, smiling at her. "But I couldn't possibly do it until I asked my mother. You tell me how to get back to the beach, and if my mother says I can marry you, I'll come right back and do it."

"Oh, will you, really?" cried Lettuce Sand Witch, springing to her feet and clapping her hands. "Then I'll tell you how to get to the beach, or at least the way my mother gets there. She stands up straight like this; holds her nose with her left hand and puts her right hand above her head; then she blows out her breath instead of drawing it in; and up she goes. And now, you won't forget to come back?"

"No, indeed," said Junior, "I'll do just as I promised. If my mother tells me to come back and marry you, I'll do it. And now, good-by, and thank you very, very much."

The next instant he stood up as straight as he could, grasped his nose with his left hand, put his right hand above his head, blew out his breath, and bing—he shot up through the sand, and found himself right alongside of his bucket and shovel.

He looked about. Everything was just the same. The sun was shining, people were still in bathing, but nowhere among them could he see his father, or mother, or sister. And then, presently they came tearing over the sand toward him.

"You bad boy!" scolded Mrs. Jenks. "Where have you been? We've been terribly worried! How dare you go off by yourself? Where were you, I say?"

"Why—why—" began Junior.

Then he stopped. What was the use? He knew they wouldn't believe him. And if he asked his mother if he could go back and marry Lettuce Sand Witch as he promised he would ask her, she would say he was sick or something, and make him go to bed. So he just dug his toes into the sand and said nothing.

And that is why poor little Lettuce Sand Witch is still waiting underneath the sand for Junior Jenks to come marry her. And that is why Junior Jenks keeps looking about so queerly when he plays on the beach by himself. He is taking no chances of another sociable sand witch popping up in his neighborhood.

No matter what other mistakes you may make in your lifetime, never make the mistake of renting a cottage from an ogre. If you do, the chances are you will bitterly regret it, as did Hak, the aged woodcutter.

Hak, was an old, old man who lived in a forest with his little grandson, Omo, whose father and mother were dead; and who earned his living by cutting down trees and chopping them into firewood. The cottage that Hak and his grandson lived in belonged to an ogre, and the rent the old man paid for it was not very much; and as long as he kept his health and strength, he got along very nicely. But one day, while cutting down a tree he tripped and fell, and before he could get out of the way the falling tree struck him and broke his leg. And after Omo had dragged him back into the cottage all he could do was to lie on his bed and groan, and wait for the leg to get well.

"Goodness gracious!" he said to the boy, "What shall we do? I won't be able to work for days and days, and there will be the rent to pay, to say nothing of the doctor's bill."

"Well," said Omo, "the rent and the doctor's bill will have to wait. So don't worry."

"I have to worry," replied the old man. "The doctor may wait for his bill, but the person who owns this cottage will not wait for his rent; no sir-ee."

Then he told Omo that the cottage belonged to an ogre. "He let me have it very cheap, but only for a certain reason. What do you think that reason was?"

"I don't know," replied Omo. "What was it?"

"That he should be allowed to make you into a dumpling for dessert if I did not pay the rent every month without fail."

"Oh," said Omo, his eyes very big. "I don't wonder you are worried. It—it makes me feel worried, too! Why did you ever make such a bargain?"

"Well," said his grandfather, groaning worse than ever, "I never thought for a minute that I would ever have my leg broken, and I was so very, very poor I simply had to have a cottage cheap. But now, I'll not only lose the cottage, but you also. I guess I might as well die."

"Don't you do it!" responded Omo. "I haven't been made into a dumpling yet, and I'm not going to be, if I can help it. I'll go into the city and get the doctor, and while I'm there I'll try to earn enough money to pay the rent."

But Omo's grandfather only shook his head. "You're a plucky boy, Omo," he said, "but you'll never be able to do it. How can a boy of seven earn anything?"

"Well, I can try, can't I?" said Omo. "You can't do anything if you don't try."

So pulling his cap down over his curls, and tucking some bread and cheese into his pocket, he set off for town. But when he arrived at the doctor's office he found that the waiting room was crowded with people, and that he would have to wait his turn.

"Oh, dear," he sighed, as he sat down next to a little old lady with a frilled bonnet on her head, "this is most unfortunate. My grandfather ought to be attended to right away."

"Well, he won't get attended to right away," said the old lady, "I can tell you that! This doctor charges by the length of time you wait in his office, so he never hurries. I've been here three months."

"Three months!" cried the boy. "Oh, I couldn't possibly wait three months, or even three days. I'm in a hurry! I've got to earn enough money to pay the rent of our cottage, or the ogre who owns it will turn me into a dumpling and eat me."

And when he said that everybody in the waiting room twisted about and looked at him. "He seems to have a fever," they said.

"See here," said the old lady, "are you sure you're not sick instead of your grandfather?"

"I'm perfectly well!" exclaimed Omo, indignantly.

"Then you must be joking," responded the other.

"No, I'm not," said Omo. "I mean every word I said. I'm in great trouble."

"H'm," said the old lady. She got to her feet. "Come on, let's go outside! We'll save money by it anyway!"

Then as they walked along the street Omo told her all about his grandfather's accident, and how important it was that the rent should be paid.

"Ha!" exclaimed the old lady. "I know that ogre! His name is Gub and he lives on the hill on the other side of the city. I often used to help people out of his clutches. I'm a retired fairy godmother—haven't been in business for years and years—but your story interests me. I've a good mind to help you!"

"Oh, if you only would!" said Omo, "I'd be awfully obliged. You see, it's not very pleasant to be made into a dumpling, and have my grandfather put out of his cottage when he has a broken leg. Please, please, help me!"

"Well," said the old lady, as she led the way into a little house with a peaked roof, "I only help people who help themselves. Can you help yourself?"

"Certainly!" said Omo. "Just offer me something and watch me help myself."

"Very well then, I will," responded the fairy godmother. Going to a golden desk in a corner she took from it a silver key. "This is the key that turns on the Fountain of Riches in the City of Ootch. All you have to do is to put the key in the keyhole at the base of the fountain, give three turns to the right, three turns to the left, and one turn in the middle, and instantly the fountain will commence to spout gold pieces enough to bury you. But you must promise me this, be sure and turn the fountain off as soon as you get enough gold pieces to fill your cap; and be sure and bring the key back to me, for I wouldn't want that key to be left in Ootch, or that fountain to be left spouting, for anything."

"Why not?" asked Omo. "What's the use of a fountain if it doesn't spout?"

"Well, you see I presented that fountain to the city of Ootch because they named the city after my great aunt's trained cockatoo, but after the fountain started spouting gold pieces everybody had so much money they all stopped working, and it almost ruined them. The butcher stopped selling meat, and the baker stopped baking bread, and the tailor stopped making clothes. Everybody stopped doing everything, and pretty soon, although everybody had plenty of money, you couldn't buy anything because nobody would take the trouble to keep store when they could get money from the fountain. So I locked the fountain up and took the key with me. And after the people of Ootch had spent some of the money they had, and lost the rest, and could not get any more without working for it, everything got all right again. And that's the reason I don't want the fountain to keep on spouting again, or want you to leave the key behind you."

"I should think not," said Omo. "It seems as bad to be too rich as it is to be too poor. I'll be very careful about shutting the fountain off, and I won't forget to bring back the key. And now how do I get to the city of Ootch?"

"Just open my back door," said the fairy godmother, handing him the key, "step out on the step, and then step off. And I do hope you won't find it raining, for when it rains in Ootch, it rains cats and dogs."

So Omo opened the fairy godmother's back door and stepped out on the step, and as he stood there all he saw before him was a pretty little garden. Then, he stepped off the step, and bing—he was in a queer looking city, and the garden and the back step, and the cottage, and the fairy godmother, had all disappeared. And in addition it was raining cats and dogs; regular, real cats and dogs.

"Ouch!" cried Omo, as a fat maltese fell ker-plunk on his head, yowling like anything. "Whee!" he yelled, as a fox terrier dropped with a thud on his shoulder and barked in his ear. And then, as black, white, brown, yellow cats of every color, and dogs, big, little and medium, began pouring on him and around him, all howling, and barking, and spitting at the same time, he made a rush for a small building, open at the sides but with a dome like roof of metal, where a man was standing.

"Quite a shower, isn't it?" said the man, as Omo reached the shelter.

"A shower," gasped Omo, "why—why, I think it's much more than a shower. And—and look what's coming down—cats and dogs!"

"Well," said the other, "why not? That's what always comes down, isn't it? That is why we build these cat and dog proof pavilions for use on rainy days. Now if it rained elephants, that would be an inconvenience."

"I should say so," replied the boy. "But does it always rain like this?"

"Oh, sometimes it's a great deal worse. I remember about two years ago I was caught in a storm and eight cats, all in one lump, and fighting as hard as they could, fell right on top of me as I crossed the street, and I assure you, sir, I almost lost my temper."

"Well," said Omo, "it's lucky they melt as soon as they reach the ground or you'd have more cats and dogs than you knew what to do with."

"Quite true," responded the stranger, "and even as it is, it is quite a nuisance when a storm comes up."

He was an odd looking fellow with a curly beard, a scimitar in his sash, and a spotted turban on his head. As he finished speaking he began twisting at his ear with his finger as though he were winding a clock.

"What's the matter," asked Omo, "is your ear sore?"

"Certainly not! You know as well as I do I'm only winding myself up so I can start home as soon as the storm passes."

"Oh," cried Omo, "is that it? Well, I don't have to wind myself up when I want to go anywhere. I'm always wound up."

"You are!" exclaimed the stranger. "Why, I can hardly believe it! I never heard of anyone being that way! You can't have lived here very long."

"Oh, no," said the boy, "I haven't lived here a half hour. I only just came."

Then he asked his companion if this was the city of Ootch, where the famous Fountain of Riches was located.

"Oh, yes," said the stranger, "this is the city of Ootch all right. And the Fountain of Riches is here, too, but it's turned off; been turned off for years. Gee whiz, don't I remember the good old days when it was turned on. Everybody got so rich we nearly starved to death because nobody would work to provide things for us to live on. And then all of a sudden the fountain stopped, and I had to go to work again. I'm a night watchman. Not that there is much use of watching the night, because no one ever tries to steal it, but that's the trade my father taught me, so I'm it. And now, maybe you'll tell me why you ask about the Fountain of Riches?"

"Well," said Omo, cautiously, "I've heard so much about it I just thought I'd like to see it while I was here." He didn't think it wise to tell anything about the fairy godmother giving him the key to the fountain for fear some one might try to take the key from him.

"Quite so," said the other, "then you'd better come with me. The shower is over now, and if you want to see the fountain you've got to get a permit from the Doodab."

"The Doodab! What's a Doodab?" asked Omo.

"A Doodab," exclaimed the Night Watchman, "is the next swellest person to a Gumshu. Ootch isn't important enough to be governed by a Gumshu so they put a Doodab over us, and he's a right decent chap, and very fond of music. Why I've seen him sit by the hour and push a slate pencil across a slate and go into ecstasies because it made his blood run cold. You'll probably like him if you don't hate him. So come along and see for yourself."

Now the Doodab of Ootch was a very, very fat, and a very, very lazy gentleman. He hated to be bothered about anything at any time. He wore rings on his fingers and bells on his toes, and he had a big hoop of pearls through the end of his nose. And he especially hated to be bothered when he was singing, which is what he was doing as Omo and the Night Watchman entered his apartment. And this is what he was singing in a very quivery voice as he accompanied himself on a slate with an awfully squeaky slate pencil:

"Well," exclaimed the Doodab, fretfully, "what do you want? It seems strange I can't embark on a sea of melody without being dragged ashore like this. What do you want?"

"This boy wants to get a permit to look at the Fountain of Riches," said the Night Watchman.

"He wants—What does he want that for?"

"Oh, I just want to see what it looks like," said Omo. "I never saw a Fountain of Riches before."

"Hum!" said the Doodab of Ootch. "That remark has a very jarring note in it. And what are you going to do after you've seen the Fountain of Riches?"

"Why," said Omo, "just—just look at it, of—of course."

"And what are you going to do after that?"

"Why—why, just—just keep on looking at it, I guess," responded the boy, hardly knowing what to say.

"Nonsense!" said the Doodab, "it won't do any good to keep on looking at it forever. And besides if you look at it too long the permit will run out. It only lasts three minutes."

"Three minutes!" exclaimed Omo. "Oh, I couldn't turn the fountain on and off, and gather up the gold pieces in three minutes." And then he clapped his hand to his mouth in dismay when he realized what he had said.

"Ah, ha!" said the Doodab of Ootch, rattling the bells on his toes. "So you're going to turn it on, eh?"

"Oh, ho!" said the Night Watchman. "And how in the world did you find out how to turn it on?"

"Oh, I found out!" replied the boy.

"Well," said the Doodab, "I'm mighty glad to hear it, for I'm dreadfully hard up. My purse is just about empty."

Then he clapped his hands and when his servants entered the room, he told them to get several large sacks and some shovels, and follow him. Then having twisted his ear and wound himself up, while the Night Watchman did the same, he took Omo by one hand and the Night Watchman by the other, and led the way to the Fountain of Riches.

"See here," said Omo, as they hurried through the streets, "you two needn't think you're going to have piles of gold pieces again, for you're not. I'm only going to turn that fountain on long enough to get my hat full; and then I'm going to turn it off."

"What!" shrieked the Doodab of Ootch, "you're going to turn it off before I get my sacks full?"

"Can I believe my ears?" said the Night Watchman. "You can't mean to turn it off before I get my pockets full? Why—why if it hadn't been for me you never would have seen the Doodab, or found out where the fountain was. You must be spoofing!"

"No, I'm not," said Omo. "I'm very sorry, but I promised to turn the fountain off the minute I got my hat full."

"The minute you get your hat full, eh?" said the Doodab, looking at Omo slyly. Then he whispered in the Night Watchman's ear, after which they both laughed merrily.

"What are you laughing at?" asked Omo.

"We're laughing," said the Night Watchman, "to think how you're going to turn the fountain off after you get your hat full."

By this time they had reached the Fountain of Riches which was in the center of the public square of the city.

"Are you still determined to turn it off as soon as you get your hat full?" asked the Night Watchman.

"I have to," said Omo. "I promised."

"Well," said the Doodab, snappishly, "if you want to shut it off you've got to turn it on first, haven't you? So go ahead!"

So Omo took out the silver key, fitted it into the keyhole at the base of the fountain, and turned three times to the right, then three times to the left, and then three times in the middle, and bing—with a clink and a chink, and a tinkle, the fountain of riches began to spout. And the minute it did that, the Night Watchman grabbed Omo's cap from his head, and the Doodab snatched the key from his hand.

"There," said the Doodab of Ootch, hurling the key as far as he could, "I guess you won't turn off the fountain until you find that key."

"Yes," said the Night Watchman, hurling Omo's cap as far as he could, "and I guess you won't fill your cap until you find your cap either. And by the time you do I'll have my pockets full of gold pieces."

"And," put in the Doodab, "I'll have my sacks full also."

Well, you may be sure Omo was very angry at the trick played on him, and started after the cap and key as quickly as he could. It did not take him long to find his cap, but he simply could not find the key.

"See here," he cried, running back to where the Doodab was tying up the necks of his sacks, which were now filled to bursting, "you've got to help me find that key. I promised to turn this fountain off and I'm going to do it."

"All right," said the Doodab, "I'll help you. I've got gold enough here to last me the rest of my life so I don't care how soon you turn it off."

"Nor I," said the Night Watchman. "I've got all my pockets full, and my stockings full besides, so stop the old thing whenever you want."

But Omo, and the Doodab, and the Night Watchman, although they searched and searched, could not find the key anywhere, and all the while the fountain was spouting gold pieces in a stream a hundred feet high, and so thick it looked like smoke.

"My sakes!" said the Doodab of Ootch, "I don't know how you'll ever stop it! I'm sorry I threw the key away now! But, anyhow, the worst that can happen if the fountain keeps on spouting, is to give the town a spell of nervous prosperity."

But alas, the Doodab of Ootch did not know what he was talking about, for the fountain kept on spouting and spouting, faster and faster; and presently the streets were knee deep in gold pieces. It was awful.

"Say," said the Night Watchman to Omo, "are you sure you turned the fountain on all right? It never spouted like this before. We've always been able to pick up the gold pieces as fast as they came out."

"Of course I turned it on right," said the boy. "I turned the key three times to the right and three times to the left, and then once in the middle."

"No such thing!" shrieked the Doodab. "No such thing! You turned it three times in the middle! I watched you!"

"Oh," cried Omo, in a horrified tone, "did I? Then—then that's why the gold is coming out so fast. And it's getting deeper all the time."

"It'll soon be up to our necks!" cried the Night Watchman.

"We are lost!" roared the Doodab. He glared at Omo angrily. "How dared you turn it on wrong?"

"Well, what did you throw the key away for?" retorted the boy. "If you hadn't done that, I could turn it off."

And there they stood quarreling, and all the time the gold was getting deeper and deeper about them. And when at last they decided they had better go back to the Doodab's palace before they were buried alive, they found it was too late. The gold pieces were so deep they could not walk.

"Mercy me!" groaned Omo. "I'll never get back to my grandfather now. I wish I had never come here!"

"So do I!" snapped the Doodab of Ootch. "Until you came I was perfectly poor and happy, and now I'm horribly rich and wretched. Oh, what shall we do?"

And then all of a sudden Omo remembered a whistle the fairy godmother had given him when she gave him the key. "If you really need me for anything," she had said, "just blow this whistle; but not unless you really need me." So Omo put the whistle to his lips and blew as hard as he could, for he thought if he ever really needed a fairy godmother he needed one now.

And the minute he blew the whistle there was a flutter and a whirr, and the fairy godmother, frilled bonnet and all, stood before them.

"Well," she said, "you are in a nice mess, aren't you?"

"It isn't my fault," said the boy. And then he told her how he had tried to obey her instructions, but could not because the Doodab of Ootch had thrown the key away. "I did make a mistake turning the fountain on," he said, "but I could have turned it off all right if the key had not been taken from me."

"I see!" said the fairy godmother.

Then she told Omo to fill his cap as well as his pockets with gold pieces. And after he had done it, she gave three clucks like a chicken does, snapped her finger twice; and bing—all the gold pieces in the streets of Ootch, all the gold in the Doodab's money bags, all the gold in the pockets and stockings of the Night Watchman; all the gold everywhere except that which Omo had, disappeared, and the Fountain of Riches also.

"There," she said, "that's the best way to settle the matter. And now, come on, Omo, and get the doctor for your grandfather and pay the ogre his rent."

"But," howled the Doodab of Ootch and the Night Watchman, "what do we do? We haven't a cent!"

"You don't deserve any," replied the fairy godmother, sternly. "And as long as you're howling so about it, I'll just make you and the whole city disappear as well."

And she did, with three clucks and a snap of her fingers; and the next moment Omo found himself in the fairy godmother's cottage.

Well, you can easily guess how after thanking his benefactress for what she had done, he hurried off to the doctor's office. And when the doctor saw Omo's cap and pockets full of gold, he went with him at once; and became so interested in Omo's grandfather's case he took ten years to cure him.

But neither Omo nor his grandfather cared if he did, for they had plenty of money. And when the ogre came stamping in to collect his rent, thinking he would not get it and would then make Omo into a dumpling, Omo just laughed and bought the place from him. And not only that, but he added another wing to the cottage and laid out a pretty garden as well, as much like the fairy godmother's as he could make it. And when he did that the fairy godmother was so pleased she came and kept house for them.

And now if you want to see a really happy family, just stop and make a visit at Omo's place in the middle of the forest where his grandfather used to cut down the trees to make a living, but which he does not have to do any more, thanks to the Fountain of Riches.

Of course you know what a postage stamp is: a little, square, gummed stamp with a picture of George Washington on it. But a magic postage stamp is a very different stamp indeed. The George Washington kind you can buy in the drug stores, but the other sort you cannot buy. They are given to you free of charge, if you don't look out.

In the autumn, when the leaves are falling, the Poppykoks come to town. There may be a hundred leaves falling and not one leaf have a Poppykok on it, and then all of a sudden, another leaf falls on your shoulder and a Poppykok is sitting on it, and then—bing—the moment he lands on your shoulder he jumps off the leaf and pastes a magic postage stamp on your cheek, and then—off you start for Obstinate Town by special delivery, that is, you do if you happen to be a boy that always wants his own way. But if you are not that kind of a boy, you need not worry.

However, the boy this story is about was one of the kind who wanted his own way. No matter what he was told to do he wanted to do something else. Otherwise, he was a very nice little chap, and his name was Prince Zep, the only son of a wealthy and powerful king. Of course being a prince he was allowed to have his own way much more than was good for him, and was so used to it, he never thought anything about how unpleasant it might make things for other people.

And so, it is not surprising that one afternoon late in the Fall he was caught, and sent off to Obstinate Town by special delivery.

Now Zep never guessed, any more than you have, that there was such a place as Obstinate Town, or such things as Poppykoks or magic postage stamps. And so, as he strolled through the Royal Park that afternoon scudding his feet through the dried leaves that covered the way, he had not the slightest idea that anything was going to happen to him, until quite unexpectedly, a big, red maple leaf fell on his shoulder, and from it stepped a Poppykok in his bright scarlet coat and breeches, and with his magic postage stamp neatly curled up in a roll in his hand. And before Zep could even gasp, the Poppykok had pasted the stamp on his cheek, leaped from his shoulder to the ground, and stood before him, smiling cheerfully.

"There you are," said the Poppykok, "a good job, well done. Bon voyage!"

"Bon what?" began Zep, "I—I—"

"That's all right," responded the Poppykok, "you don't know where you're going, but you're going. Good-by! I'll see you later!"

And then Zep felt himself leap into the air and start off with a whiz. And the more he whizzed, the more he whizzed, until it seemed as though he would never stop whizzing.

"My gracious," he thought, as well as he could as he hurried along, "what on earth has happened to me, and where, oh where, am I going? This is really dreadful!"

And indeed it was for a little while. But presently he began to get used to the whizzing, and finally found himself descending in a graceful curve before a large and ornate building that looked very much like a palace. And sure enough that is exactly what it was, and sitting on the steps of the palace waiting for him was the very same Poppykok that had started him off on his journey.

"Welcome!" said the Poppykok, rising and coming forward as the Prince reached the ground with a bump, "you're right on time. I hope you had a pleasant trip?"

"No," said Zep, crossly, "I certainly did not. I had a horrid trip. How dare you treat me this way?"

"Pooh! Pooh!" responded the other, snapping his fingers, "everybody says that when they first arrive. You'll be crazy about the place in a little while. And now let's go inside and report to the Emperor."

Pushing open the front door of the palace the Poppykok led the way into the grand entrance hall, and as he did so a short, fat man with a crown on his bald head, and bristling whiskers all about his face, came tumbling down the stairway head over heels, and landed in a heap at their feet.

"Ouch!" he exclaimed, sitting up and rubbing his nose. After which he rubbed his shins and said "ouch" once more; and "oh my" and "good gracious." And after that he bawled up the stairs as loud as he could: "Don't try to tell me to be careful and not fall downstairs, for I'll do as I want."

Then he swung himself about. "The idea," he said, glaring at the Prince and the Poppykok, "of any one trying to keep me from falling downstairs. Huh! Can't I fall down my own stairs? Can't I? Tell me!"

"Certainly you can, your majesty," responded the Poppykok. "You can fall up 'em, too, if you want."

"I should think so," retorted the Emperor, "and yet the Queen tells me to look out and not fall down 'em, because it worries her. Well, let her worry. I want her to worry."

But if the Queen was worried she did not act that way, for as she came tripping down she was laughing so heartily that she nearly fell herself, and finally had to sit on the bottom step to get her breath.

"What—what—" spluttered the Emperor, "what do you mean by not worrying? You ought to be ashamed of yourself. Look at my nose, to say nothing of the bump on my shins. My, oh, my, isn't anybody worried about me?"

"I am, your majesty," put in Zep, "and I think the Queen ought to be, too."

"She ought not," snapped the monarch, scrambling to his feet. "If I wanted her to be glad she would be worried, but as I want her to be worried, she is not. You must be a stranger here."

"He is," said the Poppykok. "He just arrived. I only caught him a little while ago."

Then he told the Emperor who Zep was. "This boy," he said, "is a Prince, and has his own way more than anybody else in his father's kingdom. In fact, he is one of the most delightfully stubborn young persons I have ever met, and never will do what any one wants him to if he can possibly help it."

"My," said the Emperor, grasping Zep's hand and shaking it warmly, "if that isn't the finest record I ever heard of. I couldn't be more pig-headed myself. How did you get so? Did you learn it at school or just teach yourself?"

"Oh," said Zep, feeling rather proud, "I just picked it up, I guess."

"Well," said the monarch, "there is nothing like it to my mind. Perhaps you've read my famous poem on the subject? Have you?"

"No," said Zep, "I never heard of it."

"Humph!" said the Emperor, looking rather disappointed. "You're not very literary, are you? However, there is no reason why you should not hear it now. Listen."

"You can see," said the Emperor, when he had finished, "what a splendid place you have come to. And as the years pass, I hope you may find it even more delightful."

"As the years pass," repeated Zep. "Why—why, I can't stay here for years. What would my folks say?"

"If you ask me," put in the Poppykok, "I should say they'd say: 'thank goodness, he's gone at last.'"

"Yes," said the Emperor, "it's only in Obstinate Town that people like boys like you. Everywhere else they think you're a nuisance. Didn't you know that?"

"Why—why, no," said Zep. "I—I thought everybody liked me."

"Ho, ho, ho!" roared the Poppykok, shaking with merriment.

"Hee, hee, hee!" cackled the Emperor, "my word, that's good! You ought to send that to a comic paper. He thought everybody liked him."

"Well," said Zep, sulkily, "they always acted as though they did. I—I like people to like me. But as long as they don't I'll never go back."

"That's the stuff," said the Emperor. "Don't you do it. You stay here with me and enjoy yourself. Do as you please. Be as cranky as you like. Why, I wouldn't be surprised if you'd be a popular idol some day if you go on the way you've begun."

So Zep settled down in Obstinate Town determined to enjoy himself with all his might. And because he was a prince, the Emperor let him live in the palace and eat his meals at the royal table.

However, he did not care much for the meals. You never could get what you wanted. When you asked the royal butler for cold chicken, he would always tell you he would rather you took cold ham. And if you wanted stewed kidneys, the butler right away said he preferred to give you broiled oysters. No matter what you asked for, the stubborn old butler always insisted on giving you something else, whether you liked it or not. And such an arrangement made Zep awfully cross.

"I don't see why you have such a butler," he said to the Emperor. "When I ask our butler at home for anything, he gives it to me quick. He wouldn't dare give me anything else. If he did my father would hang him."

"Humph!" responded the Emperor, "it seems to me your father must be a very cruel person. The idea of hanging any one for wanting his own way."

"But," said Zep, "it's so—so inconvenient. If they have their own way how can you have yours?"

"Well," said the Emperor, "you can't, with a butler, unless you go to the pantry and help yourself. And yet, why shouldn't he have his way as well as you? Why shouldn't he?"

And the Prince did not know what to say to that. But nevertheless it was tough to have every one else having their own way as well as you. When you got in a trolley car and told the conductor to let you off at a certain street, he would stop the car at another street, and unless you were stronger than he, would put you off there no matter how much you struggled and yelled. And one day, when the Emperor and Zep were put off six blocks from their destination, the monarch was dreadfully angry.

"I know I told you I thought other people ought to have their own way the same as you and I," he said to Zep, "but when a conductor not only puts me off his car before I want to get off, but kicks me into the bargain, it's too much."

"That's what I think," said Zep, "and if I were you I'd issue a royal decree saying that only the upper classes can have their own way always, and that the lower classes can only have their own way, when it suits the upper classes."

"A good idea," said the Emperor, "I'll do it."

And despite the fact that it made the lower classes fairly purple with indignation, the decree was issued at once, and Zep, and the Emperor, and the rest of the upper classes, did as they liked whenever they wanted to, and had a fine time doing it.

"I tell you what," said the Emperor to the Prince one morning after breakfast as he finished reading the paper, "that was a grand idea of yours, Zep, about letting the lower classes have their own way only when it suited us. Life has been much sweeter ever since."

"I think so, too," said Zep, "except that if nobody else could have their own way, it would be sweeter still."

"Hum," said the monarch, "I never thought of that. And the more I think of it, the more I think you're right. I know what I'll do. I'll issue another decree putting all the upper classes into the lower classes, except myself. Then I can do whatever I want, no matter what anybody says."

"But," said Zep, "you wouldn't put me in the lower classes, would you?"

"Why not," replied the Emperor. "Suppose I wanted my own way about something at the same time that you wanted your own way about it, the only way it could be managed without a fight, would be for you to be in the lower classes where you couldn't have your own way unless it suited me. See?"

"Yes," said Zep, sulkily, "I see, but I don't think it's fair. Why not put yourself in the lower classes and let me stay in the upper class?"

"Impossible," said the Emperor, "for if any one ever belonged to the upper classes an Emperor does."

"So does a prince," said Zep.

"Not necessarily," replied the monarch. "I had a dog named Prince once, but you never heard of a dog named Emperor, did you?"

And as Zep could think of nothing to say to that, the Emperor issued his decree, and Zep and all the rest of the upper classes were put in the lower classes, and the monarch enjoyed himself more than ever.

But if the Emperor enjoyed himself, Zep and the rest of the upper classes did not. For if they wanted to do something the Emperor always wanted them to do something different. And if he did not want that, he wanted them to do something nobody could do. And as Zep lived in the palace he had it worse than anybody else.

He was told to hold his breath for an hour; to stand on his ear for half an hour, and not wink for fifteen minutes. And when he did not do what he was told because he could not, the Emperor stuck pins in him and dared him to yell.

"See here," said Zep to the monarch, "I used to like you but I don't a bit any more. I'm going back home right off."

"Very well," said the Emperor, "go ahead. I'm tired of you anyway. The idea of a strong, healthy boy not being able to stand on his ear, and making such a fuss, too, because a few pins are stuck in him. Go on, go back home."

"But," said Zep, "how will I get there? I—I don't know the way."

"Of course you don't," replied the monarch, "nobody does. There isn't any way."

"Isn't any way?" repeated the Prince in a tone of horror. "Why—why, have I got to stay here with you always?"

The Emperor nodded. "Sure thing, unless a Kokkipop sends you back. The Poppykoks bring you here and the Kokkipops send you back. But as no one ever wants to go back it's mighty hard to find a Kokkipop, so I guess I'll be sticking pins in you for some time yet. Ho, ho, ho!"

Well, you can be sure when the Emperor said that and laughed about it, too, Zep felt about as gloomy as he ever had in his life.

"Oh, dear," he said, "what on earth shall I do? If only I can get away from this nasty old place I'll never want my own way again. I'll be a different boy. I never—"

"Here, here," put in the Emperor, sternly, "stop that talk. You mustn't say such things as that. No one ever talks about not wanting their own way in Obstinate Town. It's downright treason. Do you want to go to prison? But anyhow, I don't suppose you meant it."

"Indeed, I did," said Zep, "I meant every word I said. I'm tired of having my own way—it's silly. Look at the mess it's got me into. I'm going to be different—"

"Stop!" shrieked the Emperor, at the top of his lungs, "stop, I say! You'll have a Kokkipop here in another moment, and oh, how I hate 'em. I hate 'em worse than—than spiders. And—and, my goodness gracious sakes alive, you've brought one—you've brought one. Run, run, or the Kokkipop will get you!"

And with that the Emperor dived under his throne, while the Prince, looking about with a startled air, did not know whether to flee or not. And then, as he hesitated, a very brisk old gentleman, dressed in bright yellow, came into the room.

"Did you call?" he asked Zep.

"Call," said the boy, "why—why, no. What do you mean?"

"Did you call for a Kokkipop?" repeated the other testily. "And for mercy's sake don't say you didn't, for I've been waiting for a call all my life. I was a young man when I joined the Kokkipops, and in all that time I have never been called until now. So I hope you did call. Did you?"

"Well," said Zep, "I said I wanted to go home, if that's what you mean."

"And you said you didn't want your own way any more, didn't you?" inquired the Kokkipop, eagerly.

"Yes," replied the Prince, "I did. And I don't."

"He does, too," put in the Emperor, sticking his head out from under his throne. "He doesn't mean what he says. He's just mad at me for sticking pins in him."

"I don't believe it," said the Kokkipop, scowling at the Emperor, "you're just trying to keep me out of a job." Then he turned to the Prince. "You did mean what you said, didn't you?"

"I certainly did," said Zep, "and—"

"Whoopee!" yelled the Kokkipop, joyfully, "then I have got a job at last."

Whereupon he took off his coat, rolled up his sleeves, and began to paste magic postage stamps all over the Prince. "There," he said, standing off to admire his work, "I guess that will take you back all right."

"Take him back," sneered the Emperor, crawling from under his throne, "why it'll take him twice over. You've put excess postage on him. Shows what a Kokkipop knows about his business."

"Is that so," retorted the Kokkipop, "well, I know enough to send this boy where you won't stick pins in him any more, and where he won't want his own way any more." He turned to Zep. "Isn't that so?"

"Yes, indeed," said the Prince.

"Then," responded the Kokkipop, "here's to a quick and comfortable trip. Good-by, I'll see you later."

"No—wait!" shouted the Emperor, running toward Zep, "don't go. I'll put you in the upper classes again. I'll—"

But it was no use. Once again Zep felt himself leap into the air, and whiz, and whiz, and whiz, even faster than he had before. And then just as he was beginning to get used to the whizzing and rather enjoy it, he commenced to descend in a graceful curve, and presently landed with a bump in the gardens adjoining his father's palace. And there, sitting on the grass, was the Kokkipop waiting for him.

"Greeting," said the Kokkipop, "did you have a nice trip?"

"Fine," said Zep, "but of course I'm glad it's over and that I'm safe home again. And of course I'm awfully obliged to you for getting me out of such a scrape."

"Oh, that's all right," said the Kokkipop, as he peeled off the magic postage stamps, "it's been a pleasure to help you. And who knows but you may try to have your own way again and be taken back to Obstinate Town. And if you do, don't forget I'm always glad to get a job."

"All right," said Zep, "I won't, but I never expect to visit Obstinate Town again if I can help it."

And sure enough Zep never did. From that moment he was a changed boy, so much so that it really worried his father, the king.

"I don't understand it," said the King to his Prime Minister. "He does just what I tell him and never whines; and when he takes a walk he jumps about a foot if a leaf falls on him. I don't understand it."

But if the King did not, Zep did, and was determined no Poppykok should get another chance at him.

Once there lived in the city of Vex a tailor named Toobad, which was a very good name for him, for he really was too bad for anything, in fact, he was downright wicked. And not only was he wicked but he was also deceitful, because he was really not a tailor at all but an enchanter or conjuror, and only practiced a tailor's trade to fool the fathers, and grandfathers, and uncles, and big brothers of the little boys of Vex, and make them pay him money. And this is the way he did it:

He put a sign in his window and offered to make clothes for gentlemen very, very cheap out of the very, very best materials that would never wear out, and of course when he offered to do that all the fathers, and grandfathers, and uncles, and big brothers went and ordered their suits from him as quick as they could. But after the clothes were made and the fathers, and grandfathers, and uncles, and big brothers had put them on, then they found out, when it was too late, what sort of a person Toobad was, for they had to keep on paying, and paying, and paying for the clothes forever and forever. If they did not the suits they were wearing got tighter and tighter until their breath was almost squeezed out of them.

It was no use to try to get the clothes off because they simply would not come off. So you can imagine how cross and miserable all the fathers, and grandfathers, and uncles, and big brothers in Vex were.

Now there were lots of little boys in Vex, but the most interesting one was a bright little fellow named Winn, because in his family there happened to be a father, and a grandfather, and an uncle, and a big brother all wearing suits made by Toobad the Tailor, whereas the other boys only had a father, or a grandfather, or an uncle, or a big brother. None of them had all four together, and therefore did not have as much cause to dislike Toobad as Winn had.

Of course when Winn's father, and grandfather, and his uncle and his big brother, had paid for their suits once and Toobad had told them they must keep right on paying every week, they said they would not. But after the suits had squeezed them once or twice, and after they had tried to get the clothes off and found they could not, they changed their minds. And every Saturday night as soon as they got their salaries they rushed right down to Toobad's shop and paid him, so they would have a comfortable Sunday, which did not please Winn's mother at all because it left very little to buy food with.

"Good gracious," she used to say to Winn's father, and grandfather, and uncle, and big brother, "if you keep on giving that tailor half your money, I don't know how I'll get along."

"Indeed," said Winn's father, who was very fat, "and if I don't pay it I don't know how I'll get along. I've got to breathe, haven't I?"

"Yes," said Winn's grandfather, and his uncle, and his big brother, who were all as fat as his father, "we would much rather breathe than eat."

"All right, then," said Winn's mother, "go ahead and breathe but don't blame me if you starve also, for food is so high, I can buy very little with the money you give me."

And when she said that Winn's father, and his grandfather, and his uncle, and his big brother would groan awfully, which made Winn and his mother as blue as indigo, for they knew if Toobad was not paid, the clothes Winn's father, and grandfather, and uncle and big brother wore would squeeze them tighter and tighter so they could not work at all, and yet if he was paid there would not be enough money left to keep the wolf from the door.

So finally Winn determined to go and see Toobad and try and coax him not to be so hard on his folks. "Maybe if I offer to be his errand boy," he said, "he'll agree to let us stop paying for a while until we catch up with our grocery bills."

But when he got to the tailor's shop he had a very hard time to coax Toobad into having an errand boy. "No, no," said the enchanter, testily, "I don't need an errand boy, and even if I did need one I need the money your family pays me much more."

"But think how stylish it is for a tailor to have an errand boy," said Winn. "All fashionable tailors send clothes home to their customers. They never ask customers to come after their clothes. I should think you'd be ashamed not to have an errand boy."

So, finally, after talking and talking, Toobad agreed to hire Winn as his errand boy, and instead of giving him wages to let his family stop paying for their clothes for a few weeks.

"But remember this," said the tailor, "you are not to tell any one about the arrangement, because if you do all my customers will want to stop paying until they get caught up on their grocery bills."

So Winn promised to keep the matter secret and the next morning started in on his duties.

Now it happened that one of the first persons he delivered clothes to was a second cousin of his mother's aunt. This second cousin had not heard of the trouble in Winn's family because Winn's father, and grandfather, and uncle, and big brother had been afraid to tell any one what Toobad had done to them for fear their clothes would squeeze them worse than ever. So when Winn delivered his mother's aunt's second cousin's clothes he did not know whether to warn him about putting them on or not. And while he was trying to make up his mind about it, his mother's aunt's second cousin went into another room to get the money to pay for the clothes, and when he came out he had the clothes on.

"Gee whiz," he said proudly, "don't they fit me grand?"

"Maybe they do," said Winn, "but I was just going to tell you not to put them on, because now you can't get them off, and you've got to keep on paying for them forever and forever."

"What!" yelled his mother's aunt's second cousin.

And then with another yell he began tearing at the clothes with all his might, trying to get them off, but of course it was no use for although he almost turned himself inside out, they stuck to him like sticking plaster.

"You're a nice one!" he shouted, shaking his finger under Winn's nose. "You ought to be arrested. How dared you sit there and let me put these awful things on? I just hope your father, and your grandfather, and your uncle, and your big brother get stuck the same way. I certainly do!"

"They are stuck," said Winn. "They've been stuck for some time. That is why I am working for Toobad. And I'm very sorry I did not warn you about the clothes in time."

And then he told his mother's aunt's second cousin what a fix his folks were in and how if you did not pay for the clothes every week they squeezed you until you did.

"Sakes alive!" groaned his mother's aunt's second cousin, "isn't it dreadful the trouble some people have? Here I am all dressed up fine but I can't enjoy it a bit after what you've told me."

Then he escorted Winn to the door and said he never wanted to see his face again. "I'm sorry to have to say it," he continued, "but until you came a little while ago my life was full of sunshine and now it is nothing but a mud puddle. But I forgive you. Good-by!"

Well, you may be sure Winn felt terribly gloomy as he went back to Toobad's shop. When he hired out as the tailor's errand boy in order to help his family, he had not thought how he would be bringing distress into other families by delivering Toobad's enchanted clothes. But he could see now, after the scene with his mother's aunt's second cousin, how selfish and wicked it was for him to help Toobad get other people into trouble in order to make things easier for his own folks. So he determined that he would give up his job right away.

"I've decided not to be your errand boy any longer," he said to the enchanter, as he handed him the money he had received from his mother's aunt's second cousin. "I find you are too wicked to work for."

"Humph!" said the tailor, "and why am I any wickeder now than I was this morning? You were glad to work for me then."

"I know," said Winn, "but I have just seen my mother's aunt's second cousin turn from a carefree, happy person into a miserable wretch, and all because I delivered him one of your enchanted suits of clothes. And I cannot help you in your crimes any longer even if my family do suffer. Good afternoon!"

"Good afternoon nothing!" shouted Toobad. "Come back here at once. Yesterday when I did not want an errand boy you talked me into having one, and now that I've gotten used to having one you want me to do without one. Well, I shan't do it. You'll work for me whether you want to or not."

And with that he stretched out his hand toward Winn and then drew it back and when he drew it back something mysterious drew Winn back also, and though he tried to get to the door he could not move.

"Now," said Toobad, "will you work for me or not?"

"No," said Winn, firmly, "I will never work for you if I can help it."

"Very well, then," said the enchanter, "you shall work for me because you cannot help it."

And with that he repeated the alphabet backward like lightning, wiggling his fingers at the same time, and in a flash Winn was transformed into a tailor's dummy, after which Toobad placed him on the sidewalk outside his shop with one of the enchanted suits on him and with a sign on his breast which read:

TAKE ME HOME FOR $3.75

so people could see what fine, cheap clothes were sold inside.

And maybe Winn did not feel bad as he stood there day after day not even able to roll his eyes or move or speak. And on Saturday night he felt particularly bad because his father, and his grandfather, and his uncle, and his big brother came by the shop arm in arm, all whistling merrily because they did not have to pay Toobad any money that week and were going to a movie instead.

"My, my!" they exclaimed, when they saw Winn by the door, "doesn't that image look exactly like our Winn, but of course it cannot be because it's made of wax." And then the next moment they went on their way as happy as larks.

"Oh, dear!" said Winn to himself, miserably, "whatever am I going to do? How am I ever going to escape from this terrible tailor? If only I could think of some way."

And later when Toobad had brought him indoors and shut the shop, and gone off to bed and left him standing in a dark corner, he thought and thought with all his might, for he felt if he did not find some way to break the enchantment he might as well die.

And then as he was still puzzling over the problem he heard a stealthy step, and into the room came Toobad in his nightgown, holding a lighted candle in his hand, and Winn saw that he was walking in his sleep. And not only was he walking in his sleep but he was talking in his sleep also, and this is what he was saying:

And when Winn heard what he was saying he knew right away that if he could only escape he could easily get his father, and grandfather, and uncle, and big brother out of the power of Toobad the tailor, for he only had to tell them to pull down their vests and they would be rid forever of the hateful clothing they were wearing. But alas, it was one thing to want to get home, and another to get there, for while he was transformed into a tailor's dummy he was utterly helpless and could only stand and watch Toobad as he wandered about the shop with his eyes shut and the lighted candle in his hand.

And then all of a sudden something happened that transformed him from a tailor's dummy into a very real boy, for Toobad, not seeing where he was going, bumped right into him and the flame of the candle came right against Winn's nose—only for a moment—but it was long enough to scorch it and to make Winn yell—ouch! at the top of his lungs, and to joggle all the enchantment out of him. And if you did not believe an enchanted person can be cured by scorching his nose, just get yourself enchanted and scorch your nose and see if it does not work.

Anyway, it cured Winn, and not only that but it woke Toobad up. And when the tailor found himself in his shop with his nightgown on, and found Winn changed from a dummy into a regular boy again, he was furious.

"Zounds!" he shrieked, dancing up and down, "how the—what the—where did I come from and how did you get all right again?"

And when Winn told him he was more furious than ever. "Well," he said, "I'll soon fix you anyway." And thereupon he began to say the alphabet backward the same as he had done before, but by the time he had said three letters and before the enchantment had had time to work, Winn rushed at him and knocked the candle to the floor. And then while the shop was in darkness he unhooked the door and ran home as fast as he could. When he got there it was past midnight and of course every one was asleep, but by and by his mother heard him knocking and let him in.

And you may be sure it did not take his father, or his grandfather, or his uncle, or his big brother long to hop out of bed where they had been sleeping with their clothes on because they could not get them off. And maybe they were not surprised when they learned that Winn had really been the tailor's dummy they had seen outside the shop. And maybe they were not delighted when they found that Winn knew of a way for them to get rid of the enchanted clothes. And maybe they did not pull down their vests in a hurry as soon as Winn had finished telling them about it.

"My gracious," said Winn's grandfather, as he peeled the last of the hated garments from him, "I feel twenty years younger. And I can hardly wait until morning to get my hands on that villainous tailor."

"Nor I," said Winn's father.

"Me, too," said Winn's uncle.

"I daren't tell you what I'll do to him," said Winn's big brother.

And the first thing after breakfast they all went around to Toobad's shop dressed in their old clothes, and each one of them kept his word so well that Toobad was laid up in the hospital for a week. And every time he got well and came out again a fresh batch of victims was waiting to send him back again, for Winn had gone all about the city telling everybody who had bought the enchanted clothes, how to pull down their vests and get rid of them. And, of course, one of the first persons he told after his immediate family was his mother's aunt's second cousin. But as his mother's aunt's second cousin had forgotten to put on his vest when he donned his enchanted suit, he could not pull his vest down. And so the only thing to do was to give him chloroform and skin the clothes off him a little strip at a time. After which they sent him to the hospital also, where he lay in bed right alongside of Toobad the tailor.

And perhaps that is the reason Toobad is still in the hospital, for after Winn's mother's aunt's second cousin got well, he refused to go home, but sat down on the hospital steps to wait for Toobad. And neither Winn's father, nor his grandfather, nor his uncle, nor his big brother, were able to coax him away.

But as for Winn, he did not try to coax him, indeed he soon forgot all about his mother's aunt's second cousin, for all the persons in Vex who had been wearing Toobad's enchanted clothes, began sending Winn presents to show their gratitude, and when you have sixteen gold watches, and a couple of ponies, and skates, and air guns, and pretty much every sort of a thing that a boy likes, you cannot think of much else.

The best you can do is just to enjoy yourself, and if you think Winn is not doing that, take a trip to Vex some day and you will soon find out.

Once there was a Snooping Bug that lived in a glass jar on a shelf in the cottage of a Fairy Godmother. Now fairy godmothers are always nice, but this Fairy Godmother was very nice, and the reason she kept the Snooping Bug a prisoner in a jar on her shelf was because she was afraid he would go about and get folks into trouble. And another thing that showed she was unusually nice was that every week-end she always invited a little prince or princess to be her guest. And this story opens just as Prince Pranc, the only son of the king of a nearby city, had arrived to spend several days with his Fairy Godmother.

"Now, Pranc," said the Fairy Godmother, "I want you to have the happiest kind of a time, and you'll have it without doubt if you don't get into mischief."

"Oh, that's all right," replied the Prince, as he watched the Fairy Godmother unpack his trunk, "if I get into mischief you just send me home again."

"Yes," said the Fairy Godmother, "but suppose you are not here to send home again; suppose you have disappeared. Don't forget this is an enchanted house and that strange things can happen in an enchanted house."

"Phew!" said Pranc, "I almost wish I hadn't come."

"Not at all," replied the Fairy Godmother, "there is nothing to be alarmed about. You could sit on a keg of gunpowder and be perfectly safe if you didn't explode the powder. But in case you should get into trouble, put this ring on your finger and turn it around and around when danger threatens."