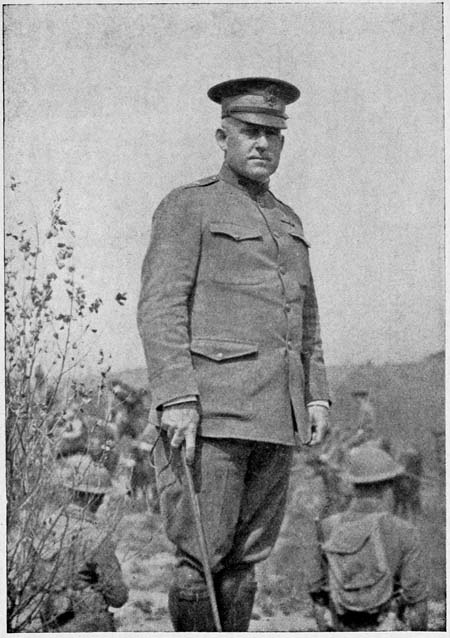

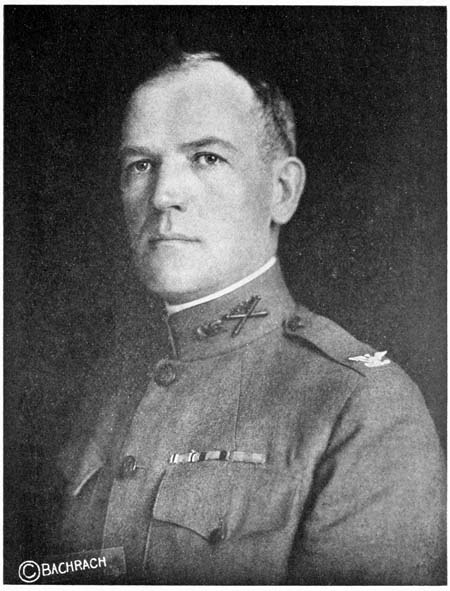

Major-General Wm. S. McNair

THE

151st FIELD ARTILLERY

BRIGADE

BY

RICHARD M. RUSSELL

THE CORNHILL COMPANY

BOSTON

Copyright, 1919, by

The Cornhill Company

If you find in the pages that follow anything to amuse or interest you and yours, thank Mrs. William S. McNair, Major Swift, Captain Converse and Lieutenant Clement, to whom the author is indebted for the information herein contained.

R. M. R.

Boston, April 25, 1919.

THE 151st FIELD ARTILLERY

BRIGADE

The 151st Field Artillery

Brigade

In writing this brief sketch of the Brigade from its inception to its final mustering out of the service, it has not been my aim to account in any way for all the days and nights which have elapsed during that period. Memories fond or hateful to some of us would not be very interesting to the rest. Looking backward from the point of view of the Brigade as a unit, many of those days were so monotonously alike that an attempt to account for all would lead to idle repetition. Well I realize that every one of them stands for something important in the career of some one man; perhaps his first tour of guard duty, or his first ride, a close call, a bawling out, something accomplished, something learnt. But I have not time, space nor knowledge to write these details. If, however, by my generalities I can so picture our life at Devens and after that this little book will recall to its readers those things I have omitted, it will have served its purpose.

THE 151st BRIGADE

In April, 1917, the United States declared war against Germany. It was no surprise, but what did it mean? For it is one thing to declare war and another to wage it. We had no army and no ships and three thousand miles of ocean lay between the Yankee and the Hun. We would of course lend money to our allies. Would we give them our men? The answer, thank God, was the draft law which put into being the greatest democratic institution of our country,—the National Army.

Early in the fall of 1917, men from every walk of life, from every corner of every state, thronged to the huge, ugly, but business-like cantonments which had grown up, like the mushroom over night. These men, scientifically chosen, for their physique, mentality, character and patriotism, were as diversified in their civil life and occupations as men can be, but they had one thing in common: ignorance of the military. This and the single purpose that brought them there, welded them together. If Germany scorned our declaration of war, she must have sung another tune as she watched us prepare to wage it.

Camp Devens, Massachusetts, was the rendez-vous for New England’s Yankees. They were the personnel of the first of the National Army Divisions, the Seventy-Sixth.

[9]The Divisional Artillery was to consist of the 301st, the 302nd, and 303rd regiments, Colonels Brooke, Craig and Conklin respectively commanding. Thus it was that the 151st Field Artillery Brigade was born, and with what promise! Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts furnished the quota, with many a generation of fighting ancestors behind them and traditions of battles won, not only in war but in every field of human endeavor.

Was it strange then that Major-General William S. McNair, then Brigadier-General, shortly after he took command in December of that year said that he felt as proud as the young mother when she sees her first born take its first four steps?

Those early months found us awkward and nearly as helpless as the infant to which the General referred, but men and officers alike were using this time to advantage; both had to adapt themselves to new ways of thinking and living, and even the language of the army was as strange to us then as was French when we finally got to France.

It was perhaps at this time more than any other, that we had cause to be thankful to the General, Colonels and Lieutenant Colonels for their able and generous assistance in getting the younger officers over those first hurdles. Let us here extend our utmost appreciation to Lieutenant Colonels Rehkopf, Danforth and Stopford whose loss to the Brigade we have had many an occasion to regret. But they like many[10] others of our best were called upon to take bigger jobs where they could be of even greater value to the country all were now serving.

In many respects those days were the hardest of all; everything was strange. For a time, standing in line hour after hour was an interesting novelty and gave the ever-present jester an opportunity to exercise his wit; so with the drills. But human beings, particularly the Yankee variety, adapt themselves quickly to their surroundings. Standing in line a couple of hours for a pair of shoes or a cup of soup ceases eventually to be an interesting novelty. And when the soup so acquired is knocked from your hand by an over zealous companion and soils the uniform you must keep clean, you may perhaps forgive him and laugh; but all that is funny therein is almost sure to occur to your fertile mind and keen sense of humor the first time it happens. Repetition is superfluous.

Being herded together, seeing the same man on either side of you every day and all day, having to do what you are told day and night, has but limited charms for the independent citizen of America. Thoughts were turned, first backward, to the days when we had been individuals instead of a mite of a cog in a great machine, and then forward, with the inevitable question: how long was it all to last? We would have been homesick, desperately so, but there was no time. A bugle broke our sleep when it was still dark. Another summoned us to a formation before it was physically[11] possible to get dressed, from which we were marched to breakfast. A whistle, followed by the First Sergeant’s “Fall Out”, arrested the first mouthful and told us we would not have time to wash mess kits before policing. Policing was followed by inspection, where the Captain would bawl us out for the condition of those same wretched mess kits. Inspection was followed by physical exercises; physical exercises by foot drill, foot drill by a hike, the hike by mess. In the afternoon we rehearsed the events of the morning. Supper was followed by school, then taps, then bed, then reveille. To-day is a repetition of yesterday, to-morrow will be a repetition of to-day. But to-day we are not going to be bawled out for dirty mess kits, we wash them and are late for policing; the First Sergeant puts us in the kitchen for a week and we learn the meaning of K. P.[A] We are soon repentant and resolve to be on time to formation. This is the school of the Rookie and this is how he learns the impossible. “Take therefore no thought for the morrow, for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.”

The next quota of men come into camp; we have graduated; they are the rookies; we are the soldiers; we laugh; they look puzzled.

Then came the winter, and what a winter! Arthur Mometer said it was zero hour all the time. Of course[12] he did not know. He was a Rookie, but somehow it didn’t make it any warmer nor the snow less deep. We shovelled snow and froze doing it, we had exercises and we froze doing that, we drilled with the same result. Live horses took the place of those ever-to-be-remembered wooden monstrosities. We groomed them and they bit us. We exercised them and they kicked us. But we got hard and we got health and we became soldiers. Individuality was superseded by discipline.

About this time a touch of war and Hun Hellishness was brought home to us. William S. McNair, Colonel of the 6th Field Artillery was promoted in France and ordered to America to command our Brigade. Accordingly he left France on the U. S. S. “Antilles”. At about 6.45 in the morning of October 17th a German submarine succeeded in torpedoing his boat. She sank immediately with the loss of about 65 lives. The General was in the water for some three quarters of an hour, when he was taken into a life boat. Six hours later one of the convoy, the Morgan yacht “Corsair” returned from trying to find the submarine and took aboard all the survivors. They returned to France and two weeks later the General again sailed for home on the transport “Tenadores”. The “Tenadores” has since been sunk by a mine, but happily for the Brigade it was not on this voyage.

Christmas came and with it the joy of home for a few, but the majority of the men must stay in camp.[13] It was all part of the great task we had undertaken. We accepted it as such. Transportation was not available to move our now vast army to its homes. We made merry, or rather, we did better than that; we pretended to make merry. We sang the songs we had rehearsed for the occasion. It was a holiday. There were no drills. We had time to think. We can be honest now. Our thoughts were not those of the schoolboy on his holiday with his plans for stockings and Christmas tree, dinner and stomach ache. They were far-away thoughts of things, once commonplace and taken for granted, now suddenly and forever dearer than life itself; things which in fact made life worth while. Home, loved, of course, but so much a part of us that we had grown to accept it as a matter of right. But strangely enough our thoughts carried us farther. We found that we were longing for the little individual problems of our daily routine in the past,—problems that had once perplexed and annoyed us we now craved as a hungry man craves food.

Months slipped by, and with them the winter. Spring rumors of France took the place of winter rumors, but the warm weather and a few guns found us ready for the real work of artillerymen. Reveille was an hour earlier and retreat an hour later. But we were up hours before reveille with a call to stables followed by boots and saddles. We hitched the horses to the guns in the darkness, that we might get all the daylight on the range. A runaway was not an unusual[14] diversion. But as we had become fit, so did the horses. Every day saw men and horses in better condition and better trained. Team work and order was taking the place of individual endeavor and chaos. A machine with intelligence was in the making, and results were beginning to assert themselves. Each cog was finding its place and taking hold with a will. A sharp command in the crisp air put the works instantly in motion, where a month before explanations, demonstrations, repeated attempts and failures had only succeeded in getting parts of our engine to function. Now the gears were adjusted, we needed but to limber them up and oil the parts. An occasional “Well Done” would take the place of continuous reprimand. We became proud of ourselves and our organization. A healthy spirit of rivalry stalked abroad. We were the best section in the best battery, and of course our regiment was the best in the Brigade, if not in the army! Officers were proud of their men, and the men were proud of the officers. Each began to know the other, his powers and his limitations. Sympathy took the place of misunderstanding and surliness.

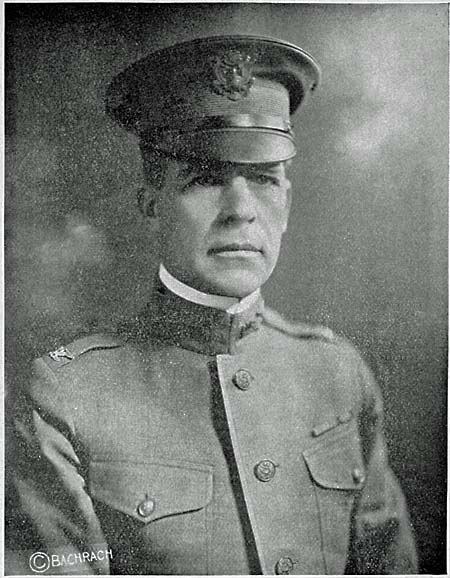

Colonel Geo. M. Brooke

So on the range, the officers acquired the theoretical elements of artillery firing. They learnt to figure their data with accuracy and to convey it to their batteries in terse and comprehensive commands. The men in their turn were seeing the purpose of the monotonous daily drills of the six months past and the value of team work. They acquired an intimate knowledge of[15] the pieces they were serving; the delicacy of the mechanism and the consequent necessity for accurate laying. They responded with alacrity to the orders of their superiors, and the guns responded to the slightest touch of the crews. All were alert, smart, prompt,—officers and men alike, fascinated with the possibilities of the game they were rapidly learning to play. Even the details, after months of labor, became proficient at the wig wag, semaphore, buzzer, map-making and sketching; in short, all of those things which we discovered later, played such an important part in winning the war.

So when the government inspectors began to look us over and rumors flew faster, we were not found wanting. The wheels were oiled and the spirit was there.

But here I am rudely stopped by the adjutant of the 301st who says we can’t leave Devens without a Horse Show. Of course he is right. It can’t be done, although it does seem tough after having oiled the wheels to such perfection. However what must be done shall be done gracefully; so thought Captain Page at the second hurdle where he decided to make the rest of the trip on his ear.

And the horses, too, grasped the spirit. Like many people they enjoyed the show from without the ring better than within it. Some came on the scene with dignity, only to bolt the next minute, not to reappear. Some merely confounded their riders by refusing jumps, while others were unmannered enough to refuse[16] to show. For all that, it was a Horse Show and one of which to be proud.

Since ceremonies are in order, let us not forget the prayer which took place one memorable day on the Parade Ground with the entire Division drawn up for the occasion. Here a horse also figured,—the Division Adjutant’s. As the parson began to pray, the horse started to jump and those who were nearest insisted that the adjutant outdid the parson. I will not say, for I could hear the adjutant and I could not hear the parson. This was the last time the Division was together as a unit.

One day toward the end of June a long train was spotted in the quartermaster yards. Trucks were soon busy carrying officers, men and their baggage in that direction. Of course, nobody knew that an advance party of some hundred officers and three hundred men had been secretly ordered to report to the Commanding General, Port of Embarkation, New York, for transportation overseas. On June 27th they sailed on the British liner “Justicia”, which was sunk on her return trip. But the American soldier is no fool. He has learnt to keep his eyes open and his mouth shut, to believe about half he sees and nothing he hears. He was more sure now that the Division was about to sail for France than if he had read it in every newspaper in the United States.

In another two weeks rumors were forgotten. On July 10th the Division was ordered overseas. This[17] was fact. The air was charged with excitement, which however found its expression in orderly and untiring hustle and bustle. Men, animals and transportation were all worked overtime, but even balky army trucks seemed to go for once with a will. The labors of the last ten months were not to be in vain. We were to have a chance to practise what we had learnt and perhaps to show the Hun a few tricks of his own game.

The Artillery were the last to leave. It was not a difficult task. We were to receive our materiel in France. Individual equipment only was to accompany the troops, for we had nothing else. The few guns we drilled with were out of date and not used abroad. The 302nd, and 303rd regiments were already motorized on paper, so horses were no longer needed for them, but the 301st must have shed bitter tears for the beautiful animals they had spent so much time and energy to condition and train.

Twenty-eight lieutenants of the 302nd left ahead of their regiment and sailed from Boston on the “Katoomba” which touched at Halifax on its way to Liverpool.

Of that last journey from Devens to Boston on July 15th there is nothing to chronicle. We were again for that brief period of time individuals. Thought and not action crowded the hour. And what a curious collection of thoughts they were. Each was absorbed with the things nearest and dearest, soon to be far away. But there were other, exciting thoughts. We were on our way! What boats were to carry us? The sea! What were we going to accomplish? And that far-away France,—what was it like? And war, what was it like? Would we come back?

The train stopped. “Fall out”. There was a scramble for one’s possessions, followed by another for our places on the platform. We were marched on board and to our bunks, where we left our belongings and hastened on deck. All was again hustle and excitement. The gang planks were lowered, the hawsers dropped. The whistles were blowing and we were off for France,—off for the war, July 16th, 1918.

Our boat was the “Winifredian”. Soon we were absorbed in our surroundings. There were twenty-three ships in our convoy, curious in their camouflage, but then all was strange to most of us, who were not used to ocean liners. And the harbor had its fascinations. Comparatively speaking we were men[19] of leisure. Jest once more asserted itself. Our quarters while not altogether to our taste, like most other things in the army would have to do, since there was no alternative. We turned in and strangely enough we slept.

Then sounded that good old familiar bugle with the good old familiar:

Where were we? Oh yes! On our way to France. We dressed hurriedly and got up on deck. The convoy was still there but not all of it. Four ships had disappeared and various theories were propounded. But just as the official dopster had got them well sunk by a submarine and was counting the casualties, it was announced that they had put into Halifax. Apparently the convoy was too large and unwieldy, so four boats had to drop out, one of which was the “Novara” with the 301st on board. However the other two regiments were still in the convoy and we proceeded on our way. We had boat drill and we wore life preservers, and we got rather bored with both. As for guard duty and setting up exercises they bored us eight months before. Seasickness is preferable[20] to either, and there were a good many of us sick.

While we were sailing merrily across the North Atlantic, the 301st had disembarked at Halifax and was playing with the Canadian troops there and thereabouts. But it was only for a week, when they were again on their way, this time on the “Abinsi”.

As the 301st left Canada, the other two regiments landed in England, one at Liverpool, another at Bristol, and Brigade Headquarters at Avonmouth on July 31st.

The next novelty was the English railway carriage or coach, as they call it. It was the latest model limousine with side entrances and compartments. We tried them and landed at Camp Mornhill near Winchester, where we found the twenty-eight officers of the 302nd who had sailed from Boston just ahead of us. A week later the 301st came to Winchester, but they had become somewhat exclusive in Canada and so on August eighth they went to Romsey instead of our camp. Winchester apparently produces a good deal of mud and a lot of rain. At any rate it was not sufficiently alluring to detain us for long. We proceeded to Southampton. “I say does it always rain here?” But before our British friend got around to answering us we were again on the move,—this time to a Channel steamer, and France. So we were really going to France and the war, and not for a tour of the world.

On August 3rd the steamer that took Brigade Headquarters and the 303rd across the English Channel, or[21] La Manche as the French call it, was one of our own,—and hence, a good boat. She used to run between Boston and New York, and her name used to be “The Yale”. Than which there is but one better: “The Harvard”. The 302nd crossed on her the next day.

The 301st was still about a week behind the rest of the Brigade. They sailed from Southampton on August 14th and also landed at Le Havre.

“So this is Frogland! Look at the frogs,—wooden shoes and all! Even the little children speak French here.” But they did not give us time to get acquainted. Again we were off, this time on a French train. They have them like the British, but this one looked like the variety we used to play with as kids, only each car says on the outside “40 Hommes, 8 Chevaux.” We knew not what it meant but the stench was indicative.

Two days got us to Bordeaux. We arrived on August 6th and Brigade Headquarters was established on August 7th at Gradignan in a very attractive villa with beautiful grounds. The 301st also established Headquarters at Gradignan, on August 17th, and billeted their men in the village. You will notice that here they were more than a week behind us. They account for this by an aeroplane attack at Rouen. The 302nd was billeted in two little villages, Ville Nave and Pont de la Maye, a few kilometres from Brigade Headquarters. The 301st Ammunition Train was at[22] Cadaujac.

We seemed doomed to lose a regiment. At Havre the 303rd was ordered to Clermont Ferrand for its training.

While the regiments were en route from the United States to France, the Advance Schools Detachment of the Brigade were wandering over Europe. From Liverpool they went to Southampton and Le Havre, then to Le Valdahon near the Swiss border. There they spent a couple of weeks and saw some American artillery training and a few Hun planes. From Le Valdahon the contingent from the 303rd went to Clermont and those of the other two regiments went to Souge, near Bordeaux.

It was about this time that we were informed that we were no longer a part of the 76th Division, but were to be a Brigade of Corps Artillery. It did not cause many tears as the 76th was already doing duty as a replacement division with no chance of going to the front as a unit. Our tables of organization were changed accordingly and we were rapidly equipped for duty in our new capacity. The 303rd regiment was issued G. P. F.s, the famous French 155 m. m. long rifle with a range of about 17,000 metres. The 301st got the world renowned French 75, the best known gun of the war, and the 302nd got American 4.7 rifles about which nothing was known.

While in Gradignan and vicinity our days consisted largely in getting acquainted with our new guns. We[23] also learnt French and paraded. Some of our number were detailed to join the Advanced Schools Detachment at Camp de Souge, August 14th.

On August 25th the London Evening Mail published the news of General NcNair’s promotion. We were of course glad of the obviously merited reward, but selfishly would rather have had it otherwise, for of course he would cease to be our Brigade commander. However, at the time we consoled ourselves with the thought that he might command the Corps artillery of which we would be a part. That night there was a dinner and celebration at Brigade Headquarters. The scene was picturesque and one to be remembered. The French Mayors of the villages where our troops were billeted were invited and came. The meal was served on the lawn under a huge tree in those beautiful gardens. A hundred yards down the lawn through the trees we could see the 301st band, conducted by Lieutenant Keller. They played as even they had never played before. The villagers, hearing the music, flocked to the gates and the General sent word to the guard that the sentries were to let them in. In they came and went straight to the music. Sitting on the lawn they made a huge circle around the band, and gave our Headquarters a very festive appearance. It was a rare occasion for them. Lovers of music that they were, it was seldom that they had an opportunity to hear it. Their own bands had long been busy nearer the front.

[24]On September 5th and 8th the two regiments, 302nd and 301st respectively, moved to Souge for the final six weeks firing before going to the front. We made the trip, some twenty miles, with our own transportation. Brigade Headquarters was established at the camp on September 8th and the Ammunition Train moved in the same day.

Souge is located in the middle of a sand desert at the end of the world. As far as you can see there is not a landmark to relieve the monotony. It is as flat as a table all the way to the sea, some twenty-five miles distant. As Major Hadley of the 301st remarked: “It is a nice beach but where is the water?” Souge may best be described as follows,—a camp some two miles long of ramshackle, broken down, foul smelling barracks in the middle of the desert which was to be our range. Flies, sand, dust and heat were in abundance, as were dysentery and the “Flu” at times. The flies were like ours except larger, more abundant and infinitely more obnoxious. As one of our men wrote home, he was in the hospital as a result of having been kicked by a fly.

But there we were. We ate the dust, we killed flies and we sweat in the sweltering heat, as we pulled[25] guns, trucks and tractors through that damnable sand.

On September 21st the long dreaded orders for Major-General McNair arrived and with them Secretary of War Baker, General Tasker Bliss and a flock of Major Generals and Brigadiers. That same day he relinquished the command to Brigadier-General Richmond P. Davis and left camp to take command of the Artillery of the First Army.

The finishing touches were applied. We were inspected. We passed our examinations and were ready for the front. When would the orders come? There were already rumors of peace,—were we to miss the party after a year and a half of preparation? The thought was nauseating, but we stuck to our work. We knew our Brigade Commander was a hustler. We could see it, and General McNair had said so. Confidence ran high.

We had an abundance of ammunition and General Davis ordered a problem to cover three days. The guns were to go into position at night and without lights; they did. We established communication by telephone, radio and projector, and maintained it. Conversation was in code and cypher. We were to fire an offensive barrage over the infantry; it was done. The infantry called for a defensive barrage at 11.40 at night; it was layed before the rocket burst.

Altogether in this problem of four regiments the[26] 75s fired about 6,000 rounds and the 4.7s about 600.[B]

In the meantime it rained, or rather poured. The heavens were trying to make good for the past six months of inaction,—they did. Or perhaps it was the 302nd weeping for the now certain loss of Colonel Craig. He had received his promotion and it was only a question of time before his orders would arrive. Loved and respected by all who knew him, he was to leave a vacancy hard to fill. His officers gave him a dinner in Bordeaux on October 7th.

It was while our problem was in progress that General Davis and part of his staff left for the front, October 11th. A few days later, on October 17th, he was followed by the rest of his staff. So the regiments polished and oiled their materiel and entrained at the camp for God-knows-where. One thing was certain and that was we were going forward and not back, for from Bordeaux it takes a boat to go in the latter direction. It was at this time that we knew definitely that the 301st was to leave the Brigade. It was to be army artillery and received different orders, confirming our fears when it was detached by telegraphic order of October 2nd.

Hardly had the General with a few members of his staff arrived at the front when a stray shell killed his aide, Lieutenant W. B. Dixon, Jr., October 19th, 1918. He was buried with military honors where he fell near Bouillonville. He had been with us but a few days, but such was his personality and charm that he had become as closely identified with the Brigade as the oldest member of the staff. His death was a personal loss to every one of us.

Brigade Headquarters was established at St. Mihiel, Meuse, October 19th, 1918, and the entries in the official War Diary begin. I have the diary before me as[28] I write, and I feel that I cannot do better than take the information therein practically word for word as it was recorded each day from October 19th to November 11th.

The famous salient of St. Mihiel had been wiped out a month before. Having held it successfully for four long years, the Germans considered their lines there impenetrable; but it took the Yankees just two short days, September 12th and 13th to reduce that four years’ work to nothing, and on our side of the balance sheet now stood several thousand prisoners and a few hundred guns. It had happened a month before, but the battle fields were still fresh with Hun relics and ruins, and one had but to see to know that Heine and Fritz had lost no time in their departure. Everywhere ammunition dumps and other stores were left untouched by the fleeing foe.

October 19th the 151st Field Artillery Brigade, less one regiment (the 301st) was attached to the 2nd Colonial Corps (French) of the Second Army, A. E. F., as corps artillery, with its rail head at Sorcy and its Refilling Point at Woinville. The zones and mission of the Brigade were assigned. In a general way our sector extended from Bonzee to Vigneulles. The line in this sector ran roughly northwest to southeast, the Germans holding the villages of Ville en Woevre, Pintheville, Riaville, Marcheville, St. Hilaire, Doncourt and Woel.

October 21st was devoted to reconnaissance. The[29] commanding officer, Colonel Conklin of the 303rd F. A. and staff arrived. An air raid by the enemy occurred at 7.00 p. m. They are all alike. This is what happens. Delicate instruments more sensitive than the human ear detect the sound of the aeroplane’s engines at a great distance. These instruments are placed at intervals along the lines at what are known as listening posts or stations. Directly an enemy plane is detected, its whereabouts and direction are telephoned to the areas behind. There, the fact is announced by a bugle call, followed by rattles, sirens and every other variety of music. This is the first you know of the “ships that pass in the night.” There is a scramble for the nearest abri, otherwise known as bomb-proof or dug-out. You stumble and fall down a flight of steps and find yourself from twenty to forty feet below ground. It is dark, and the air is damp and smells vilely. There are from fifty to a hundred other humans in this subterranean tomb, some lie down, prepared to spend the night, others, half-clad, shiver and wait. Then out of the distance you hear a faint humming as of insects in summer. It grows louder. It is the engines of the enemy’s planes. Suddenly Hell is torn loose. The anti-aircraft guns or Archies, as the British call them, have opened fire from the ground. The planes return the compliment with bombs and machine guns. A boiler factory in your head would not be nearly so bad for your ears as the cracking and shrieking that takes place. As suddenly as it[30] started it ceases. All is quiet. We go about our duties or sleep, as the case may be, until the next raid occurs. If it is a clear night and the planes are likely to return, there are many who prefer to stay in the dug-out and make a night of it there rather than spend the time until morning running back and forth.

October 22nd the work of reconnaissance for battery positions and P. C.s[C] continued. More enemy planes were seen over St. Mihiel. But this time it was broad daylight; they reconnoitered and took photographs, but there was no battle royal to disturb the peace. Suddenly little balls of cotton appeared about the plane. They were the bursts of some distant anti-aircraft battery trying to annoy the aviator.

October 23rd the commanding officer (Colonel Platt) of the 302nd F. A. and staff arrived. In the afternoon enemy airplanes made a reconnaissance. The regimental advanced parties arrived.

Reconnaissance was the chief work of the next few days. Lieutenant Colonel McCabe of the 302nd taking the area to the north of Bonzee. The Germans must have had the same idea, for enemy aircraft continued to pass over Headquarters.

On October 28th the 33rd Division relieved the 79th Division in this sector, the 55th Field Artillery Brigade remaining in place, with its Headquarters at Troyon (P. C. Kilbreith).

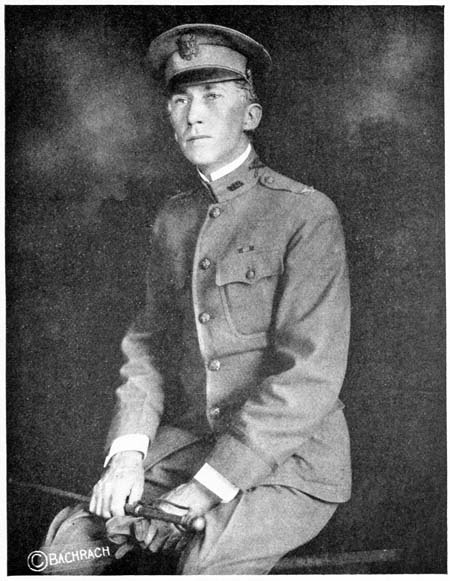

Brigadier-General Daniel F. Craig

[31]By November 1st all the battery positions and P. C.s were located and billets were obtained for the regiments. Colonel Platt of the 302nd F. A. chose some old German shelters near the one-time village of St. Remy for his P. C. His batteries were to be scattered through the Bois des Eparges, mostly to the north. The 3rd Battalion was to be behind the hills to the eastward. The country looked like pictures of the moon sometimes reproduced in scientific magazines because of interest but never on account of beauty. Once there had been woods; now there was hardly a tree standing. All vegetation had been killed by gas and shell,—crater after crater gave mother earth a very diseased appearance. Here we spent our days and nights while the war lasted. Colonel Platt chose Rupt for his billets.

Colonel Conklin in selecting his P. C. showed better taste. He found an old German Headquarters, built like a Swiss chalet in the heart of the woods and far away from harm. Here he settled comfortably, two kilometres to the northeast of Deuxnouds and just South of the Grande Tranchee de Calonne. He had but two battalions. The first he placed to the east of his P. C., the second about four kilometres to the north.

This same day liaison was established with S. R. S. No. 3 American, and on November 2nd with S. R. O. T. Nos. 58 and 67.

November 3rd the Brigade Headquarters detachment[32] arrived and was billeted in St. Mihiel, and information was received that the 302nd F. A. had detrained at Dugny and was moving into Rupt en Woevre.

November 4th information was received that the 303rd F. A. had detrained at Dugny and was moving into Creue. The 3rd Battalion of the 303rd was assigned to the Fourth Army Corps.

November 5th the Second Battalion of the 302nd reported its guns in position and ready to open fire. Hardly was this accomplished when the Huns began to give them a taste of gas, over 3,000 rounds being reported. One gun of Battery B, 303 F. A. was reported to be in position. The Brigade was detached from the 2nd C. A. C. (French), and was put under the command of the 17th C. A. (French).

November 6th one gun of the 303rd F. A. was ready to fire at midnight and the other guns were being moved up as fast as the positions were constructed.

From 10.00 p. m. November 6th to 2.00 p. m. November 7th, about 3,000 gas shells, mostly mustard, fell near B and F Batteries of the 302nd F. A., but though other artillery units nearby had a number of men gassed, the 302nd F. A. had no casualties, thanks to strict and effectual gas discipline.

In the vicinity of P. C. Gross, Second Battalion of the 303d, about two hundred gas and high explosive shells fell, also without casualties.

In the afternoon Field Order No. 1 was issued directing[33] the 302nd to deliver harassing fire during the night on Ville en Woevre and on the roads from that place to Braquis and Hennemont. The 303rd F. A. was to fire on Hennemont, Pareid, Maizeray and Moulotte. At 6.10 the orders were changed by telephone on account of later information, with the result that the 302nd F. A. took under fire two additional targets, which were identified only by their coordinates. The 303rd fired at Pareid and Moulotte and on a battery in the Bois de Harville.

On the night of November 6th and 7th, in a two company infantry raid with artillery support against the Chateau d’Ardnois, one German officer and twenty-two men were captured and from ten to fourteen killed. Our own casualties were slight. There was very little enemy artillery fire during the day. At 9.15 however, on the night of November 7th, the operations officer of the 55th Field Artillery Brigade at P. C. Kilbreith reported heavy shelling by the enemy of Fresnes en Woevre. This village was now strongly held by our troops, and it was thought that the German fire was in retaliation for the raid. Our Sound Ranging Section S. R. S. No. 3 had located the enemy batteries that were executing the fire and we were asked for neutralization at the earliest possible moment. This order was sent to the 303rd F. A. by courier and telephone. At 11.00 a. m. the enemy having ceased his fire, the 303rd F. A. was ordered to discontinue firing. Field Order No. 2 was then[34] issued authorizing the 303rd F. A. to fire at once for neutralization upon any enemy battery reported in action beyond Maizeray. In the meantime Major Hadley’s Battalion of the 302nd F. A. was fired upon by the enemy with gas shells. Captain Lefferts was the only casualty.

On November 8th two strong patrols of our infantry, sent early in the morning to the Bois de Harville and St. Hilaire, brought back three prisoners. The 33rd Division reported considerable harassing fire about Les Eparges and Saulx en Woevre, with some interdiction fire on the villages at the base of the hills. The total was about 3,000 rounds. This was the first day that the air was clear enough for the G. P. F.s to register, and Colonel Conklin registered on Joinville. Shortly after 4.00 o’clock, Balloon No. 22 reported two batteries firing. They were given to the 303rd F. A. for immediate neutralization. In the meantime, orders had been sent out for the night’s firing, the targets assigned to the 303rd F. A. being two batteries of 105 howitzers in the Bois de Harville and the towns Maizeray and Butgneville. The 302nd F. A. was given the Pintheville-Maizeray road, the Pintheville-Pareid road, Maizeray, Butgneville and St. Hilaire, the latter being the most important. The fire was to stop at 3.00 a. m. to permit an infantry raid to go into St. Hilaire and the vicinity. These orders, sent by telephone and courier, were in response to a request for help from the Divisional Artillery.[35] They were followed by a Memorandum to the regiments designating the zones in which, after the start of the infantry raid on November 9th, it would not be safe for them to fire without express authority.

On November 9th a change of organization occurred as a result of the removal of a large part of the French Artillery from the sector. The two batteries which were left,—one of 120 long and one of 155 long,—were taken over by General Davis and assigned to the command of Colonel Platt of the 302nd F. A. in what then became known as the Groupment Platt. General Davis thus became Commander of the Corps Artillery of the sector.

Early in the morning of this same day, a request was received from the infantry through the Operations Officer of the 55th Field Artillery Brigade for help in a raid. It appeared that lack of ammunition for the Divisional artillery threatened to deprive the infantry of much needed artillery assistance. Orders were issued for concentration fire between 2.00 and 5.00 a. m. on Maizeray, Butgneville and St. Hilaire and between 5.00 and 6.45 a. m. on Maizeray and Butgneville. With the approval of Corps Artillery Headquarters the regiments were permitted to use ammunition beyond that authorized for daily expenditure.

The strong reconnoitering patrols sent out by the 33rd Division executed the raid on Marcheville. It was completely successful and resulted in the capture[36] of eighty prisoners including three officers. Patrols near Pintheville and Riaville met strong resistance. At 3.50 p. m. an enemy barrage of about 4,000 shells was laid down between Fresnes and Wadonville, probably in retaliation for the raid of the previous night. Orders were issued that the regiments should fire at once on any batteries reported in action by the Sound Ranging Section (S. R. S. No. 3) and that every clear day should be utilized for registration. During the afternoon the 303rd F. A. was directed to fire on two batteries of 210 howitzers,—one near Labouville and the others northeast of Joinville,—and on a battery of medium calibre, just south of Moulotte.

Late in the afternoon we were informed that an infantry raid would take place at H hour next morning on our front. The Groupment Platt were ordered to fire on Maizeray and on the road between Pintheville and Maizeray. The 303rd was to fire on Maizeray, Harville and the same stretch of road and on batteries reported firing from points back of Maizeray. The fire of both groups was to last for 105 minutes after H hour and at 2.20 in the morning, notification was sent by courier to the commanding officers of the two regiments that H hour would be 5.45 a. m.

At 8.30 in the evening the General ordered a concentration by the 302nd F. A. on Riaville, Pintheville and the road connecting them, to be fired between midnight and 3 a. m. At 8.45, the 303rd F. A. was given[37] counter-battery work in answer to a call from the Divisional Artillery Headquarters.

Upon the change in organization mentioned above, the advanced location for our Brigade P. C. was fixed at Creue. The regiments were ordered to reconnoitre to find locations for at least some of their guns out on the Plain of Woevre where they would be able to reach some of the German long range artillery which had been bothering us, and also follow up the advance of our infantry for a long distance without changing position for a second time.

On November 10th a general advance was ordered to begin at 7.00 a. m. but the order did not reach our Brigade. However, this information was obtained incidentally by the Brigade Commander, and at 10.40 a. m. orders were issued for the regiments to provide advance telephone lines, with a view to establishing forward P. C.s. At the same time the Brigade P. C. was opened at Creue. A series of orders were issued over the telephone with reference to a change of positions by the 302nd F. A. and the 303rd F. A. and at 11.48 we received orders from the corps that the 4.7 regiment must advance as soon as possible. Orders were sent to them to complete all reconnaissance and prepare to move immediately. At 1.25 orders were received from the corps to move two batteries of the 303rd F. A. with 400 rounds of ammunition at the tail of the main body of the 33rd Division in advance. It was thought that this was based on the supposition[38] that the enemy was going to retire, which he had no intention of doing, as later developments showed.

At 4.00 o’clock in the afternoon, word having been received that the country to the north and east of Bonzee was occupied by the enemy, an officer was sent to the 33rd Division occupying our sector and another to the 81st Division on our left to find out the true state of affairs. There proved to be no basis whatever for this report, as the 33rd Division was holding its forward line in great strength with a view to attacking on the morning of the 11th, and the 81st Division was also reinforced for a continuation of their attack, begun on the 10th.

General Bailey, commanding the 81st Division and Colonel Roberts, Chief of Staff, urgently requested artillery help in their attack on Ville en Woevre, Hennemont and other points. The Brigade supported these attacks between 5.00 and 7.00.

The commanding General of the 33rd Division, having received orders to advance, called for support from the Corps Artillery on Pintheville, Harville, Moulotte, Maizeray, Pareid and batteries in the Bois de Harville and elsewhere. This support was given between 9.25 p. m. November 10th and 5.00 a. m. November 11th.

At 7.30 p. m. the 302nd F. A. was ordered to move one battalion into the advanced positions in the Plain of the Woevre and to have another battalion in motion so as to reach its advanced position on the 11th while[39] the guns held in reserve were to continue the firing. One battalion, in accordance with these instructions, took position on the Plain of the Woevre near Tresauvaux, well in advance of the main body of the infantry and of the resistance line. It remained there overnight and until ordered to withdraw on the morning of the 11th, when news was received that the armistice had been signed.

In the meantime, three guns of the 303rd F. A. were successfully moved into similar forward positions from which, if fighting had continued, they might have done highly effective work against some of the distance long range German guns, especially those that had been bothering St. Maurice, Thillot and other towns along the base of the hills. The Brigade fired 736 rounds in the course of the day, against a number of different targets assigned from time to time by Brigade Headquarters, or reported direct to the regiments by the S. R. S.

At about ten o’clock on the night of the 10th the French corps commander under whom we were serving, said he expected important news from the Eiffel Tower wireless station before morning. He asked Brigade Headquarters to notify him should our wireless pick up anything of interest. Taking the daily communiques from the Eiffel Tower had been part of our routine work, so the operators knew her[D] voice[40] intimately. Accordingly they were not unduly surprised when she started her familiar squeak early on that historic morning. Received at 5.45 a. m. November 11th, the message that the armistice had been signed and that hostilities were to cease at 11.00 a. m. was reported at the Brigade P. C., Creue, by telephone from the St. Mihiel Headquarters. To the credit of the Brigade let it be known that it was from our station that the news was given to the entire sector.

The 33rd Division attacked at 5.00 a. m. Strong patrols sent out along the front captured three officers and eighty-three men. Infantry lines were established at the close of hostilities as follows: Chateau d’Aulnois, Riaville, Marcheville, St. Hilaire, south of Butgneville, Bois de Harville thence southward to Ferma d’Hautes Journeux. These towns were taken on the morning of the 11th. It was a glorious piece of work but hardly worth the price in American life it involved. The Germans, pushed to the limit, made a last stubborn resistance and from behind their fortifications and barbed wire delivered a murderous fire on our troops with rear guard machine gun action from hidden nests. The battlefield as I saw it that afternoon, I shall not soon forget. There lay an American sergeant, where he had fallen, and behind him lay his men, not twenty yards from the German machine gun they were attacking. My thoughts were first of sorrow that these men should have made the supreme sacrifice in those last minutes of the great war. In[41] those fine young faces still shone the joy of life, theirs but yesterday, when they had thought of home and all it held in store. But I read another story, that of peace, such as is only experienced after a hard struggle won and as I looked at the scene I felt a thrill of pride. What a sacrifice! but God, how gloriously made!

The plans for the early morning attack contemplated prearranged firing by the Corps Artillery until 7.00 a. m. Information that the Armistice had been signed having arrived at 5.45 a. m., the Heavy Artillery Commander at that hour ordered no more firing, unless urgently called for by some infantry unit which was in need of help or was being effectively shelled. The advance Brigade P. C. at Creue was closed at 11.00 a. m. Ammunition had been brought up during the night and the corps artillery stood ready with some of its guns advanced beyond the main line of resistance, to support fully a further general infantry attack.

At 10.55 on the morning of the Armistice, the 303rd Band at Creue played taps, then the Marseillaise, then the Star Spangled Banner and then Reveille. All that morning the artillery thundered and was still thundering when the music started. When it stopped, all was still.

On the afternoon of November 12th I walked along our front between the lines. The stillness of peace was upon the earth where but yesterday the din of bloody battle reigned. Our lines were held by a series of sentries walking their posts as if on parade. Over[42] yonder the Germans were doing likewise. The sun shone in gladness upon the scene. The air was crisp and the reliefs were gathering wood for their fires. As the shadows grew longer and the sun set in a blaze of glory, the figures of the sentries grew dim, but their positions became identified by the bonfires they had kindled which now alone marked the lines. As I turned to go, rockets once used to call for a barrage or as a warning of gas lit the sky. Thus ended the war.

A resume of the history of the 151st Field Artillery Brigade during its short term at the front shows a great variety of services and connections.

Originally constituting a part of the Artillery of the Second Army, the Brigade was attached on its arrival in the zone of advance to the Second Colonial Corps of the French army in the Troyon sector, where it served under General Blondlat, Corps commander and General Jaquet, Chief of Artillery.

The Second Colonial Corps was relieved by the 17th French Corps, General Hellot commanding, General Walch, Chief of Artillery. On October 29th, the Brigade came under their command.

On November 13th the Brigade was assigned to the Fourth American Corps. When the Fourth Corps moved forward at 5.00 a. m., November 17th, the Brigade passed into the Second Army Reserve. When the regiments first came into the St. Mihiel sector, the infantry holding it were the 79th Division of the American Army, General Joseph E. Kuhn commanding; the 39th French Infantry Division and the 28th French Regiment of Dismounted Cavalry. On the 28th of October, however, the 79th was relieved by the 33rd American Division, General George Bell commanding.

The 39th French Infantry Division and the 28th[44] regiment of Dismounted Cavalry were withdrawn and the sector of the 17th Corps was from Vigneulles to Bonzee.

The Corps Artillery, 151st Brigade and two batteries of French Artillery à Pied, covered the entire front of fifteen kilometres.

This is the story of our few days at the front before the Armistice, and this is what we did in the actual fighting.

I have been obliged for lack of space and knowledge to omit those things most interesting to the individual—little incidentals, perhaps from the point of view of the rest of us, but to him they constituted the war, and always will. For this reason they will remain forever vivid pictures in his memory and are therefore not necessary to chronicle. At the same time it will do no harm to recall a few more facts and feelings that all in one way or another experienced during that momentous although brief period of our lives. Mud is perhaps the foremost to the author. But there were others. At night there was not a light as we stumbled and cursed, feeling our way in those ruined villages; automobiles and trucks travelled similarly without lights in the jet blackness, sometimes on the road but more often off it. And the drivers, let us not forget them and their troubles: the sinking feeling in the region of the stomach as the truck, laden to its limit[45] with ammunition, would itself first sink and then stick in that sea of mud. Tired to the point of exhaustion, they would dig for hours and get out only to be in again a hundred yards down the road. Or perhaps Buddy, with his truck, would try to pull us out with the result that he too got stuck. Then there were the nights spent going into position where the impossible was often accomplished,—that was work such as few outside of the army will experience,—but it was exciting and it was necessary, and that explains how it was done. Following this were the nights spent in serving the guns,—sleepless nights,—but it was fun, and the excitement made it interesting. Last but not least, let us recall for a second, if we can, how it felt to be under fire,—but most of us were too busy and tired to have any feelings. Such as they were they were hardly pleasant.

While most of the Brigade was thus solving its troubles, the 3rd Battalion of the 303rd was having troubles of its own. Detached from the Brigade and assigned to the Fourth Corps on November 4th, they were ordered to take a position a thousand metres in front of the Seventy-fives and about the same distance behind our own front line. The terrain assigned them for their guns was a wooded swamp, perhaps a thousand metres from the road. It was down this road that they brought their guns under practically continuous enemy fire. Nor did the fire stop when they reached their positions. Just as regularly as the half[46] hours came around on the clock so did the Germans go the rounds of these two batteries and Battalion Headquarters with high explosive and gas. There were many narrow escapes but no serious casualties. The dispersion of the German guns and the regularity with which they fired were alone responsible, so say the Third Battalion. But I am inclined to think, in spite of German declarations of “Gott mit Uns”, that the Bon Dieu was on our side; for besides the elements above mentioned, practically every direct hit or what was so close as to amount to a direct hit, proved to be a dud. Of the labors involved in taking this position and the will that delivered the goods we cannot say enough. The job was done and done gloriously.

While the Brigade, minus one regiment, was disporting itself in and about St. Mihiel, that regiment, the 301st F. A. was ordered to another part of the front, November 2nd. Accordingly they went to Neufchateau near Chaumont, where they were to become a part of the Army Artillery for the 1st army. There they were held in reserve and obliged to wait for further orders, which did not come. Finally it was learnt that they were to move forward and take up positions about November 12th, but the Germans also hearing of this, signed the Armistice on the 11th. So it was that our lost regiment did not get into action. We sympathize with them, but we do not feel as they do, for we know the goods were there and given the opportunity, would have been delivered. On November[47] 29th they were ordered to prepare for return to the United States. Many miserable weeks followed at Brest, but finally, one glorious day, the Statue of Liberty appeared before them and January 6th, 1919, they landed in New York from the good ship “Nieuw Amsterdam”. In this the rest of the Brigade fared not so well.

Colonel Arthur Conklin

After the Armistice was signed, the regiments were withdrawn to billets and the materiel was parked. The 302nd returned to Rupt en Woevre, where they got busy on the famous show they produced a few weeks later. The 303rd were not as easily satisfied. They had some troops still in and about the positions,—some more at Creue, a lot more at Savannieres, and the 3rd Battalion which had rejoined the regiment was now at St. Christophe Ferme. Later, the First and Second Battalions moved to Troyon and the Third Battalion to Ambly, while regimental Headquarters was established at St. Mihiel.

While thus in billets there were many rumors, but they were mostly of “occupation” with the Third Army. The fact was, we were kept busy policing the villages and a good part of France. The part we got was not in the very best of order, so we had our hands full. At the same time it was not all work; the 302nd show took us out of the mud and gunk of the busted villages of France and dropped us temporarily in front of the foot-lights of Broadway. There were other bright spots but they were not the weather. Meantime[48] we waited for we knew not what. We got to know our French brothers in arms, and we sympathized with them for all they had lost. But they demanded our admiration even more than our sympathy. In the face of ruined homes and brothers lost, they could say: “C’est la guerre” and could sing with us the Marseillaise and Madelon:

On December 20th the order to prepare arrived. Prepare for what? The United States of America. My God was it possible? Where were they? But it was so, and a better Christmas present would have been hard to find. This was our second Christmas in the army, and apparently it was to be our last. Cheers! The occasion however recalled a remark attributed to General Pershing in August as follows: “Hell, Heaven or Hoboken by Christmas.” He was right, and we got seats at the first show on his list.

On January 3rd 1919, the Brigade was ordered to Bordeaux for transportation to the United States, and on January 8th it entrained at Bannoncourt. It was hoped by all that we would return to our old billets,—but no, they took us back to that Godforsaken Camp de Souge. We arrived January 11th. However it would not be for long and we were on our way home. All were cheerful,—some artificially so. Little did we realize that it was to be a stay of three long months and that we would be allowed to amuse ourselves with skinning mules and guard duty. Looking backwards we can laugh, but I doubt if we could have done so at the time had we known how long it was to be. On February 4th the General and some of his staff sailed from Genecart on the “Matsonia”. This was encouraging;[50] we would follow soon, but we did not. However on March 18th we moved to Pauillac, about twenty-five miles down the river from Bordeaux, where there are docks and delousing plants.

And on April 13th we sailed for Boston on the “Santa Rosa”. And here I must leave, for it is the author’s desire that this little sketch be ready when the brigade lands.

And what has it all amounted to? To many at first thought it has been but a year and a half taken out of their lives. But let us consider for a second. Here was every American energy bent for the first time to the accomplishment of a single purpose. The individual and his every interest was sacrificed for a great cause. We learned that there was something bigger than self and more worth while. We learned to appreciate our vast country as we should have been able to do in no other way.

“NOT WHAT WE DID,

BUT WHAT WE WERE WILLING TO DO.”

FOOTNOTES:

[A] Kitchen Police.

[B] The 346th and 347th regiments were temporarily brigaded with us for administrative purposes.

[C] Poste de Commande

[D] The Eiffel Tower was known among the operators as “Ethel”.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation have been standardized.

Archaic or variant spelling has been retained.