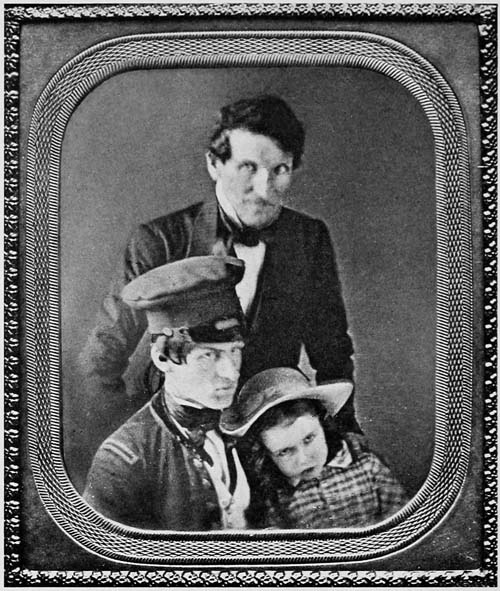

(From a daguerreotype taken in 1846, just before leaving for the front)

Lieut. McClellan, His Father and His Brother Arthur.

EDITED BY

WILLIAM STARR MYERS, Ph.D.,

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AND POLITICS

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON

LONDON: HUMPHREY MILFORD

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

1917

Copyright, 1917, by

Princeton University Press

Published April, 1917

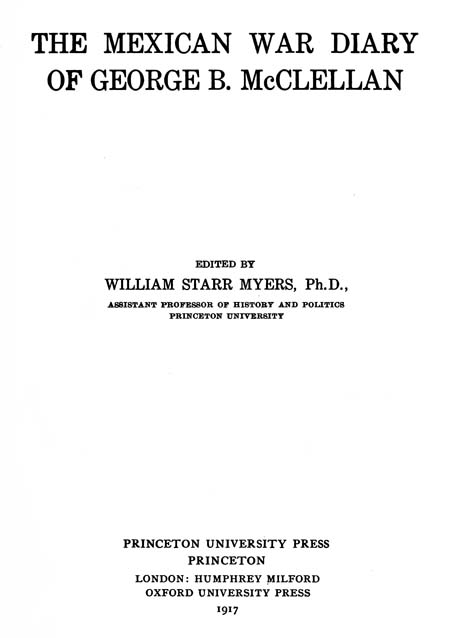

During the past four or five years I have been preparing a life of General McClellan in which I plan especially to stress the political influences behind the military operations of the first two years of the Civil War. The main source for my study has been the large collection of “McClellan Papers” in the Library of Congress at Washington, most of which hitherto never has been published. In this collection is the manuscript Mexican War diary and by the courteous permission and kind cooperation of General McClellan’s son, Professor George B. McClellan of Princeton University, I have been able to make the following copy. I desire to thank Professor McClellan for other valuable help, including the use of the daguerreotype from which the accompanying frontispiece was made. My thanks also are due Professor Dana C. Munro for his timely advice and valued assistance in the preparation of the manuscript for the press. The map is reproduced from the “Life and Letters of General George Gordon Meade,” with the kind permission of the publishers, Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[iv]It has seemed to me that this diary should prove to be of special value at the present time, for it throws additional light upon the failure of our time honored “volunteer system” and forecasts its utter futility as an adequate defense in a time of national crisis or danger.

Wm. Starr Myers.

Princeton, N. J.

January 3, 1917.

| Lieut. McClellan, His Father and His Brother Arthur From a daguerreotype taken in 1846, just before leaving for the front | Frontispiece |

| War Map | opp. p. 6 |

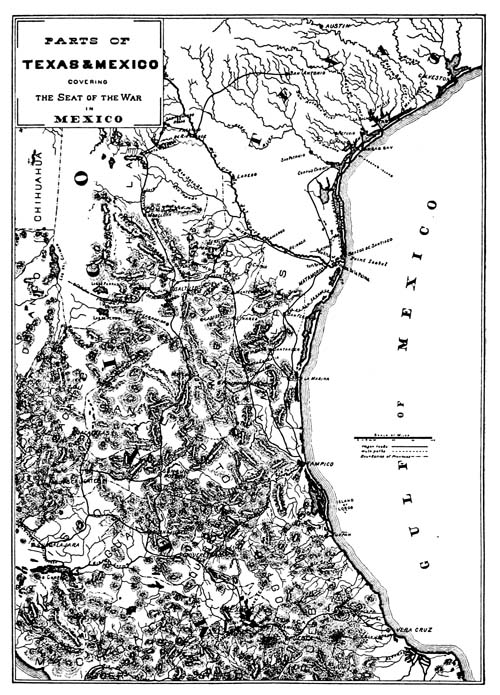

| First Page of the Mexican War Diary in an Old Blankbook Facsimile reproduction of McClellan’s manuscript | opp. p. 40 |

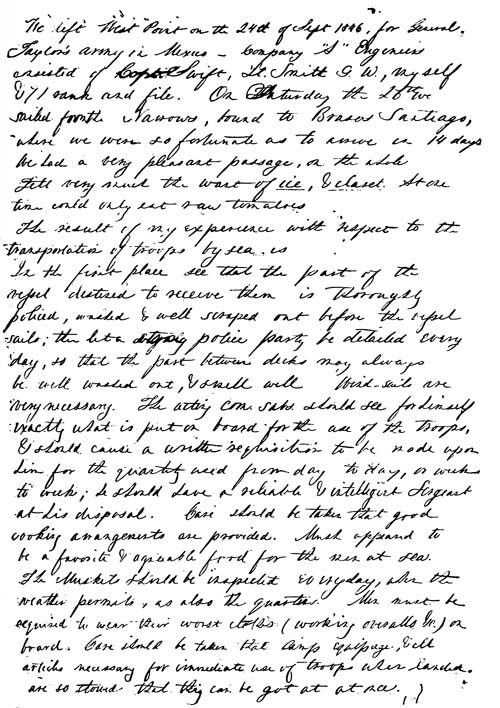

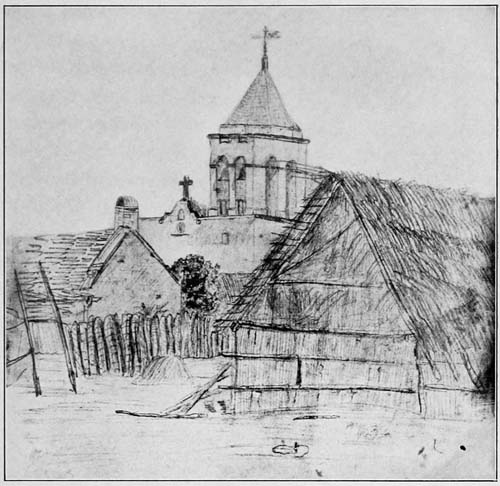

| Church at Camargo, Seen from the Palace Facsimile reproduction of a sketch by McClellan | opp. p. 70 |

George Brinton McClellan was born in Philadelphia, Pa., on December 3, 1826. He died in Orange, N. J., on October 29, 1885. His life covered barely fifty-nine years, his services of national prominence only eighteen months, but during this time he experienced such extremes of good and ill fortune, of success and of failure, as seldom have fallen to the lot of one man.

While still a small boy McClellan entered a school in Philadelphia which was conducted by Mr. Sears Cook Walker, a graduate of Harvard, and remained there for four years. He later was a pupil in the preparatory school of the University of Pennsylvania, under the charge of Dr. Samuel Crawford. McClellan at the same time received private tuition in Greek and Latin from a German teacher named Scheffer and entered the University itself in 1840. He remained there as a student for only two years, for in 1842 he received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.

McClellan graduated from West Point second in his class in the summer of 1846 and was commissioned[2] a brevet second lieutenant of engineers. On July 9 Colonel Joseph G. Totten, Chief of Engineers, ordered McClellan to “repair to West Point” for duty with the company of engineers then being organized by Captain A. J. Swift and Lieutenant Gustavus W. Smith. The Mexican War had begun during the preceding May and the young graduate of West Point was filled with delight at the new opportunity for winning reputation and rank in his chosen profession. The company of engineers was ordered to Mexico and left for the front during the month of September.

The diary that follows begins with the departure from West Point and continues the narrative of McClellan’s experiences through the battle of Cerro Gordo in April, 1847. It ends at this point, except for a line or two jotted down later on in moments of impatience or ennui.

To the student of McClellan’s life this diary presents certain striking contrasts in character between the youthful soldier, not yet twenty years of age, and the general or politician of fifteen or twenty years later. At this time McClellan was by nature happy-go-lucky, joyous, carefree, and almost irresponsible. In after years he became extremely serious, deeply and sincerely religious, sometimes oppressed by a[3] sense of duty. And yet at this early age we can plainly discern many of the traits that stand out so prominently in his mature life. He was in a way one of the worst subordinates and best superiors that ever lived. As a subordinate he was restless, critical, often ill at ease. He seemed to have the proverbial “chip” always on his shoulder and knew that his commanding officers would go out of their way to knock it off; or else he imagined it, which amounted to the same thing. As a commanding officer he always was thoughtful, considerate and deeply sympathetic with his men, and they knew this and loved him for it.

These same traits perhaps will explain much of the friction during the early years of the Civil War between McClellan and Lincoln and also the devotion that reached almost to adoration which the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac showed for their beloved commander. And McClellan had many intimate friends, friends of high character, who stood by him through thick and thin until the very day of his death. This relationship could not have continued strong to the last had he not in some measure deserved it. His integrity, his inherent truthfulness and sense of honor, stood out predominant.

McClellan could write. In fact his pen was too ready and in later years it often led him into[4] difficulties. He had a keen sense of humor, though it was tempered by too much self-confidence and at times was tinged with conceit. He was proud, ambitious and deeply sensitive. All this appears in the diary, and it will be seen that this little book offers a key to the explanation of much that followed.

McClellan took a prominent and brilliant part, for so young a man, in the later events of Scott’s campaign which ended in the capture of the City of Mexico. He showed himself to be able, brave and extremely skilful. He was promoted to the rank of brevet first lieutenant, August 20, “for gallant and meritorious conduct in the battles of Contreras and Cherubusco,” and brevet captain on September 13 for his services at Chapultepec. He was brevetted in addition for Molino del Rey on September 8, and the nomination was confirmed by Congress, but he declined the honor on the ground that he had not taken part in that battle, while this brevet “would also cause him to rank above his commanding officer—Lieut. G. W. Smith—who was present at every action where he was and commanded him.” (Ms. letter from McClellan to General R. Jones, Adj. Gen. U. S. A., dated “Washington City, August 1848.” McClellan Papers, Library of Congress, Vol. I.)

[5]The diary gives a vivid picture of Mexico, the land and its people. Furthermore, there is a fine description of the life of the soldiers on the march, of the siege of Vera Cruz, and of the ill behavior and lack of discipline of the volunteer forces. The notes will show that General George Gordon Meade, later the Union commander at Gettysburg, also was a lieutenant in Taylor’s army, and his estimate of the volunteers agrees in every particular with that mentioned above.

McClellan’s career has been the subject of endless controversy, often pursued with such acrimony and gross unfairness that its memory rankles today in the minds of many. Furthermore, upon the outcome of this controversy have depended the reputations of many prominent men, for if McClellan should be proved to have been in the wrong the mantle of greatness still might rest upon the shoulders of certain politicians and generals hitherto adjudged to be “great.” On the other hand, if McClellan was in the right, and the present writer believes that in large part he was, then he was a victim of envy and downright falsehood. His name should now be cleared of all unjust accusations, and also history should reverse its judgment of many of his opponents.

Wm. Starr Myers.

[6]

PARTS OF TEXAS & MEXICO COVERING

THE SEAT OF THE WAR

IN MEXICO

[7]

We left West Point on the 24th of September 1846 for General Taylor’s army in Mexico—Company “A” Engineers[1] consisted of Captain [A. J.] Swift, Lieutenant G. W. Smith,[2] myself and 71 rank and file. On Saturday the 26th we sailed from the Narrows bound to Brazos de Santiago [Texas] where we were so fortunate as to arrive in 14 days. We had a very pleasant passage, on the whole. Felt very much the want[8] of ice, and claret. At one time could only eat raw tomatoes.

The result of my experience with respect to the transportation of troops by sea is,—

In the first place see that the part of the vessel destined to receive them is thoroughly policed, washed and well scraped out before the vessel sails; then let a strong police party be detailed every day, so that the part between decks may always be well washed out and smell well. Wind-sails are very necessary. The acting commissary of subsistence should see for himself exactly what is put on board for the use of the troops and should cause a written requisition to be made upon him for the quantity used from day to day or week to week. He should have a reliable and intelligent sergeant at his disposal. Care should be taken that good cooking arrangements are provided. Mush appeared to be a favorite and agreeable food for the men at sea. The muskets should be inspected every day, when the weather permits, as also the quarters. Men must be required to wear their worst clothes (working overalls, etc.) on board. Care should be taken that camp equipage and all articles necessary for immediate use of troops when landed are so stowed that they can be got at at once.

Brazos is probably the very worst port that[9] could be found on the whole American coast. We are encamped on an island which is nothing more than a sand bar, perfectly barren, utterly destitute of any sign of vegetation. It is about six miles long and one-half mile broad. We are placed about one hundred yards from the sea, a row of sand hills some twenty feet high intervening. Whenever a strong breeze blows the sand flies along in perfect clouds, filling your tent, eyes and everything else. To dry ink you have merely to dip your paper in the sand. The only good thing about the place is the bathing in the surf. The water which we drink is obtained by digging a hole large enough to contain a barrel. In this is placed a bottomless barrel in which the water collects. You must dig until you find water, then “work-in” the barrel until it is well down. This water is very bad. It is brackish and unhealthy. The island is often overflowed to the depth of one or two feet. To reach this interesting spot, one is taken from the vessel in a steamboat and taken over a bar on which the water is six feet deep, and where the surf breaks with the greatest violence. It is often impossible to communicate with the vessels outside for ten days or two weeks at a time.

We have been here since Monday afternoon and it is now Friday. We expect to march for[10] the mouth of the Rio Grande tomorrow morning at break of day—thence by steamboat to Matamoros where we will remain until our arrangements for the pontoon train are complete. We received when we arrived the news of the battle of Monterey. Three officers who were present dined with us today—Nichols of the 2nd Artillery, Captain Smith (brother of G. W. Smith) formerly Captain of Louisiana Volunteers now an amateur, Captain Crump of the Mississippi Volunteers—fine fellows all. Saw Bailie Peyton and some others pass our encampment this morning from Monterey. I am now writing in the guard tent (I go on guard every other day). Immediately in front are sand hills, same on the right, same in the rear, sandy plain on the left. To the left of the sand hills in front are a number of wagons parked, to the left of them a pound containing about 200 mules, to the left and in front of that about fifty sloops, schooners, brigs and steamboats; to the left of that and three miles from us may be seen Point Isabel.

Camp opposite Camargo,[3] November 15th,[11] 1846. We marched from Brazos to the mouth of the Rio Grande and on arriving there found ourselves without tents, provisions or working utensils, a cold Norther blowing all the time. We, however, procured what we needed from the Quarter Master and made the men comfortable until the arrival of Captain Swift with the wagons, who reached the mouth late in the afternoon, whilst we got there about 10 A. M. Thanks to Churchill’s kindness G. W. Smith and myself got along very well. We left in the Corvette the next morning (Sunday) for Matamoros, where we arrived at about 5 P. M. The Rio Grande is a very narrow, muddy stream. The channel is very uncertain, changing from day to day. The banks are covered with the mesquite trees, canes, cabbage trees, etc. The ranches are rather sparse, but some of them are very prettily situated. They all consist of miserable huts built of mesquite logs and canes placed upright—the interstices filled with mud. The roofs are thatched, either with canes or the leaves of the cabbage tree (a species of palmetto). Cotton appears to grow quite plentifully on the banks, but is not cultivated at all. The Mexicans appear to cultivate nothing whatever but a little Indian corn (maize). They are certainly the laziest people in existence—living in a rich and[12] fertile country (the banks of the river at least) they are content to roll in the mud, eat their horrible beef and tortillas and dance all night at their fandangos. This appears to be the character of the Mexicans as far as I have seen, but they will probably improve as we proceed further in the country.

Matamoros is situated about a quarter mile from the river. Some of the houses on the principal streets are of stone, there is one near the Plaza built in the American style with three stories and garrets. All the rest are regular Mexican. On the Plaza is an unfinished cathedral, commenced on a grand scale, but unfinished from a want of funds. The great majority of the houses are of log. The place is quite Americanized by our army and the usual train of sutlers, etc., etc.,—you can get almost everything you want there. We were encamped near the landing. I rode over to Resaca and Palo Alto, but as there is just now a prospect of our returning to Matamoros, before moving on Tampico, I shall write no description of the fields until I have visited them again. After being sick for nearly two weeks in Matamoros I left with the company for Camargo on the “Whiteville,” where we arrived two weeks ago tomorrow, and I have been in[13] Hospital Quarters ever since until day before yesterday.[4]

Now I am in camp, the wind blowing the dust in such perfect clouds that it is perfectly horrible—one can hardly live through it. My quarters in Camargo were the Palace of Don Jesus, the brother of the Alcalde [Mayor of the town]—he (the Don) having absquatatated [sic]. The main body of the Palace (!) is one storied. It consists of two rooms—the smaller one occupied by Dr. Turner, the other by “Legs” and myself (together with Jimmie Stuart for a part of the time). The floor is of hard earth, the walls white, and very fancifully decorated with paintings—the roof flat and painted green—an inscription on it showing that “Se acabó [This house was finished] esta casa entiaso [this word is not Spanish] Dio[s] &c. &c. 1829.” Altogether it was[14] quite a recherché establishment. Jimmie Stuart came down to take care of me when I first got there, and after doing so with his usual kindness was unfortunately taken with a fever, and had to stay there anyhow.[5]

We are to accompany General Patterson[6] to Tampico. I hope and suppose that we will have a fight there, then join General Taylor, then hey for San Luis [Potosi] and another fight.

[15]December 5th [1846]. Mouth of the Rio Grande. After getting up quite an excitement about a fight at Tampico etc., we were completely floored by the news that the navy had taken it without firing a single gun[7]—the place having been abandoned by the Mexican troops, who are doubtless being concentrated at San Luis Potosi in anticipation of a grand attack on the place—ah! if we only fool them by taking Vera Cruz and its castle, and then march on the capital—we would have them completely. After a great many orders and counter orders we have at length arrived thus far on our way to Tampico. We left Camargo on Sunday evening last (November 29th) in the corvette, with Generals Patterson and Pillow[8] and a number of other officers (among them Captain Hunter 2nd Dragoons, Major Abercrombie, Captain Winship, Seth[16] Williams,[9] and about a thousand volunteers). We had decidedly a bad passage—running on sand bars very often—being blown up against a bank by the wind—breaking the rudder twice, etc., etc. We left General P[atterson], Captain Swift and many others at Matamoros. The General started with the intention of going to Tampico by sea—all the troops (except the Tennessee cavalry) were to go by sea, but at Reinosa an express overtook us ordering the General to proceed by land with all the troops except this company, which is to go by sea (!). Captain Swift remained at Matamoros on account of his health.

I was perfectly disgusted coming down the river. I found that every confounded Voluntario in the “Continental Army” ranked me—to be ranked and put aside for a soldier of yesterday, a miserable thing with buttons on it, that knows nothing whatever, is indeed too hard a case. I have pretty much made up my mind that if I cannot increase my rank in this war, I shall resign shortly after the close of it. I cannot stand the idea of being a Second Lieutenant all my life. I have learned some valuable lessons in this war.[17] I am (I hope and believe) pretty well cured of castle building. I came down here with high hopes, with pleasing anticipations of distinction, of being in hard fought battles and acquiring a name and reputation as a stepping stone to a still greater eminence in some future and greater war. I felt that if I could have a chance I could do something; but what has been the result—the real state of the case? The first thing that greeted my ears upon arriving off Brazos was the news of the battle of Monterey[10]—the place of all others where this Company and its officers would have had an ample field for distinction. There was a grand miss, but, thank heaven, it could not possibly have been avoided by us. Well, since then we have been dodging about—waiting a week here—two weeks there for the pontoon train—a month in the dirt somewhere else—doing nothing—half the company sick—have been sick myself for more than a month and a half—and here we are going to Tampico. What will be the next thing it is impossible to guess at. We may go to San Luis—we may go to Vera Cruz—we may go home from Tampico, we may see a fight, or a dozen of them—or we may not see a shot fired. I have made up my mind to act the[18] philosopher—to take things as they come and not worry my head about the future—to try to get perfectly well—and above all things to see as much fun as I can “scare up” in the country.

I have seen more suffering since I came out here than I could have imagined to exist. It is really awful. I allude to the sufferings of the Volunteers. They literally die like dogs. Were it all known in the States, there would be no more hue and cry against the Army, all would be willing to have so large a regular army that we could dispense entirely with the volunteer system. The suffering among the Regulars is comparatively trifling, for their officers know their duty and take good care of the men.[11]

[19]I have also come to the conclusion that the Quartermaster’s Department is most wofully conducted—never trust anything to that Department which you can do for yourself. If you need horses for your trains, etc., carry them with you. As to provisions (for private use) get as much[20] as possible from the Commissaries—you get things from them at one-half the price you pay sutlers. Smith has ridden over to Brazos de Santiago to endeavor to make arrangements for our immediate transportation to Tampico. Captain Hunter went with him on my mare. They return in the morning. Whilst at Camargo, Smith had a discussion with General Patterson about his (General Patterson’s) right to order us when en route to join General Taylor, under[21] orders from Head Quarters at Washington. The General was obliged to succumb and admit the truth of the principle “That an officer of Engineers is not subject to the orders of every superior officer, but only to those of his immediate chief, and that General (or other high officer) to whom he may be ordered to report for duty.”

There goes Gerber with his tattoo—so I must stop for the present.

December 6th [1846]. Go it Weathercocks! Received an order from Major McCall[12] this morning to go back to Matamoros, as we are to march to Tampico, via Victoria, with the column under General Patterson.[13] Smith is away at[22] Brazos and if the order had been one day and a half later we would have been off to Tampico by sea. Have fine sea bathing here. It is blowing very hard from the south east, so much so as to raise the sand too much for comfort entirely. Bee and Ward at the Brazos—coming over this morning—will at least have an opportunity of giving Georgie that letter of Madame Scott’s! I feel pleased at the idea of going by land—we will have a march to talk about, and may very probably have a fight on the way. I firmly believe that we will have a brush before reaching Tampico. Unfortunately the whole column is Voluntario.

[23]January 2nd, 1847. Rancho Padillo, on Soto la Marina river. I “firmly believed” we would have a brush!—the devil I did!—and a pretty fool I was to think I’d have such good luck as that. I’ve given it up entirely. But I was right in the other—the whole column is Voluntario—and a pretty column it is too. To go on with our affairs.—We reached Matamoros on the 8th [December] and encamped on the river bank just below the Mexican batteries. Smith went down to the mouth [of the river] again to select tools for the march, leaving me in command. After various orders and counter orders we were finally (December 21st) directed to appear upon the Plaza as early as possible in order to march to El Moquete, where General Pillow was encamped with the 3rd and 4th Illinois Volunteers. “Mind, Mr. Smith” said the old Mustang[14] the night before, “mind and appear as early as possible, so that you may not delay us”—all this with that air of dignity and importance so peculiarly[24] characteristic of Mustangs; well we got up at daybreak and reached the Plaza a little after seven, immediately reported ourselves ready to start and were informed that we should wait for the guide who was momentarily expected. We were to march in advance, then the wagon train, then Gibson with his artillery (a twelve pounder field piece and twenty-four pounder howitzer) was to bring up the rear.

I waited and waited in the hot sun on the Plaza, watched the men gorging themselves with oranges, sausages etc., them took to swearing by way of consolation. When I had succeeded in working myself into a happy frame of mind (about one o’clock) old Abercrombie[15] ordered Gibson to start in advance and our company to bring up the rear. I wont attempt to describe the beauties of forming a rear guard of a wagon train. Suffice it to say that the men straggled a great deal, some got rather drunk, all very tired. We reached the banks of El Arroyo Tigre about 8 o’clock (two hours after dark) and then encamped as we best could.

I rode on in advance of the company to see El Tigre and found Gibson amusing himself by endeavoring to curse a team (a caisson) across the river, which (the caisson, not the river—well,[25] both were, after all) had got mired in the middle. I rode back and met the company about one mile from the camp ground, struggling along—tired to death and straining their eyes to see water through the darkness. I consoled them somewhat by telling them that it was not more than a mile to the water, but they soon found that a mile on foot was a great deal longer than a mile on horseback. However, we got there at last, pitched our camp, and soon forgot all our troubles in sound sleep.

I rode in advance next morning through the long wagon train to find a new ford. We crossed and encamped with General Pillow’s Brigade. Went down to Major Harris’ (4th Illinois) tent, where I had a fine drink of brandy and the unspeakable satisfaction of seeing a democratic Volunteer Captain (in his shirt sleeves) sit, with the greatest unconcern, on a tent peg for at least an hour. Gibson and I then went to Winship’s tent where we found G. W. [Smith] and an invitation to dine with General Pillow.

During dinner it began to rain like bricks. We adjourned to Winship’s tent, and the sight we presented would have amused an hermit. The water [was] about an inch deep in the tent, and we four sitting on the bed passing around a tumbler continually replenished from that old keg[26] of commissary whiskey—oh lord! how it did fly ’round! and we were as happy a set of soldiers as ever lived “in spite of wind and weather.” “Whoa Winship,” says Gibson, “that’s too strong” so he drank it all to keep us from being injured. Well, we amused ourselves in this way until dark—then we waded back to our respective domiciles (is a tent a domicile?) having previously seen old Patt make his grand entrée in the midst of a hard rain—he in Dr. Wright’s[16] covered wagon (looking for all the world like an old Quaker farmer going to market), his escort and staff dripping with the rain. We wondered why they looked so dismal and thought that it had not been such a horrid bad day after all!

This evening G. W. [Smith] and myself had a grand cursing match over an order from the “stable” requiring a detail from our camp to pitch and unpitch the General’s tents etc. However, we sent them just about the meanest detail that they ever saw. At this place our large army was divided into two columns. We moved at the head of the first column. General Pillow came on one day after us.

We started about 7.30—a bright sunny morning. Nothing of interest this day—the men improved in their marching. We encamped about[27] three o’clock at Guijano, where there were two ponds of very good water. We had a beautiful spot for our encampment, and a most delightful moonlight evening. There is one house—hut rather—at this place. From Matamoros to this place the road is excellent requiring no repairs—chaparral generally thick on roadside—one or two small prairies—road would be boggy in wet weather. From Matamoros to Moquete [is] about ten miles, from El Moquete to El Guijano about ten miles.

On the next day (December 24th) we marched to Santa Teresa, a distance of 27 miles. It was on this march that we (i. e. Songo[17]) made the “raise” on General Patterson’s birds. He sent us four for supper. We ate as many as we could and had five left for breakfast—fully equal to the loaves and fishes this. We stopped for nearly an hour at Salina—a pond of rather bad water about half way to Santa Teresa—what a rush the Voluntarios made for the water! When we arrived we found the mustang crowd taking their lunch.[18] As Songo had just then made one of[28] his periodical disappearances we were left without anything to eat for some time, but at last we descried him caracoling across the prairie on his graceful charger. The mustangs did not have the politeness to ask us to partake of their lunch, but when Songo did come our brandy was better than theirs anyhow. At Santa Teresa the water was very bad—being obtained from a tancho. I bluffed off a volunteer regiment some 100 yards from our camp. As the Lieutenant Colonel of this same regiment (3rd Illinois) was marching them along by the flank he gave the command[29] “by file left march!”—to bring it on the color line. The leading file turned at about an angle of 30 degrees. “Holloa there” says the Colonel “you man there, you dont know how to file.” “The h—l I dont” yells the man “d—n you, I’ve been marching all day, and I guess I’m tired.”

Road good—passes principally through prairie—at Salina wood scarce in immediate vicinity of the water, plenty about three quarters of a mile from it. Wood not very plenty at Santa Teresa—enough however.

December 25th. We started at sunrise, and it was a sunrise well worthy of the day. A cloud obscured the sun at first, but it seemed a cloud of the brightest, purest gold, and the whole east was tinged with a hue which would defy the art of man to imitate. It was one of those scenes which occur but once in many years, and which elevate us for a moment above the common range of our thoughts. In an instant I thought of my whole life, of the happy Christmas days of my childhood, of my mother, of the very few others I love—how happy Arthur and Mary[19] must have been at that moment with their Christmas gifts! When I was a child—as they are now—I little thought that I should ever spend a Christmas day upon the march, in Mexico. The time[30] may come hereafter when I shall spend Christmas in a way little anticipated by me on this Christmas day. God grant that my troubles may be as few and my thoughts as pleasant as they were then!

I rode off into the prairie—followed by Songo—and in the excitement of chasing some rabbits managed to lose the column. I at length found my way back, and was told that I had created quite an excitement. When I was first seen in the distance they did not know whether I was a Mexican or a white man. Patt, finally concluded that I must be a straggling “Tennessee horse,” gave the Colonel a blowing up for allowing his men to leave the column, and directed him to send out a guard to apprehend the “vagrom man.” Just about that time Smith found out what was going on, discovered who it was and rectified the mistake.

Passed Chiltipine about 11 A. M.—sent Songo to buy eggs and milk. After we had passed about a mile beyond the Ranche [Rancho, a hut], I heard a peculiar neigh—which I recognized as Jim’s—and loud laughing from the volunteers. I turned around and saw Jim “streaking it against time” for the mare—head up, eyes starting and neighing at every jump, minus Songo. I rode back to see what had become of the “faithful[31] Jumbo,” Jim following like a little puppy dog. It appeared that Jim had thrown his “fidus Achates.” When we stopped at Chiltipine Dr. Wright gave us a drink of first rate brandy.

At Chiltipine (or very near there) we left the road and took a prairie path to the left. The grass was so high that we found ourselves at about 1 P. M. out of sight of the train and artillery. Pat became very much agitated and ordered a halt, glasses were put in requisition (brandy and spy) but no train could be discovered. Pat became highly excited and imagined all kinds of accidents. At last some artillery was discovered. Pat’s excitement reached its highest pitch, for he took it into his head that they were Mexicans. “Good G—d, Mr. Smith! Take your glass—take your glass—those are our artillery or something worse! I fear they have been cut off.” However, it turned out to be Gibson, and Pat’s countenance changed suddenly from a “Bluntish,” blueish, ghastly white to a silly grin.

At last we reached our camp at a dirty, muddy lake—ornamented by a dead jackass. Pat ensconced himself in the best place with Tennessee horse as a guard, put Gibson “in battery” on the road, with us on his left flank—a large interval between us and the Tennessee horse—a similar[32] one between Gibson and the Illinois foot. Gibson had orders to defend the road. How he was to be informed of the approach of the enemy “this deponent knoweth not,” such a thing as a picket was not thought of. I suppose Pat thought the guns old enough to speak for themselves.

For our Christmas dinner we had a beefsteak and some fried mush. Not quite so good as turkey and mince pies, but we enjoyed it as much as the cits at home did their crack dinners. We finished a bottle of the Captain’s best sherry in a marvellous short time. Songo looked as if he thought we ought to be fuddled, but we were too old soldiers for that. After dinner we started off “to see Seth Williams,” but saw the mustangs at their feed and “huevosed” the ranche. By the bye, we thought that ordinary politeness would have induced old Pat to have given us an invitation to dine, but we spent our time more pleasantly than we would have done there. We went from Pat’s to Colonel Thomas’s, and returned thence to Gibson, whom we found in a very good humor, and whose Volunteer Sub-Lieutenant (W——) was most gloriously and unroariously [sic] corned. He yelled like a true Mohawk, and swore that “little Jane” somebody had the prettiest foot and hand in all Tennessee. He[33] set the men a most splendid example of good conduct and quietness, but what can you expect from a Volunteer? One of his ideas was first rate—“Just imagine old Patt being attacked by the Mexicans, and running over here in his shirt tail—breaking thro’ the pond with old Abercrombie after him. The d—d old fox put us here where he thought the enemy would get us. Suppose they should come in on the other side? D—n him we’d see him streaking over here, with old McCall and Abercrombie after, their shirt tails flying, by G—d.”

December 26th. Marched 20 miles to San Fernando where we arrived a little after sunset. Road level until we arrived within about 5 miles of San Fernando, when it became rocky and hilly but always practicable. About 4 miles from San Fernando we reached the summit of a hill from which we beheld a basin of hills extending for miles and miles—not unlike the hills between the Hudson and Connecticut opposite West Point. About two miles from San Fernando are some wells of pretty good water—the men were very thirsty—Gerber offered a volunteer half a dollar for a canteen full of water. My little mare drank until I thought she would kill herself. The Alcalde and his escort met General Patterson at this place. He was all bows, smiles and politeness.[34] Murphy of whom more anon had the honor of taking San Fernando by storm. He was the first to enter it, mounted on his gallant steed. We first saw San Fernando as we arrived at the summit of a high hill, the last rays of the sun shining on its white houses, and the dome of the “Cathedral” gave it a beautiful appearance. It was a jewel in the midst of these uninhabited and desert hills. We encamped in a hollow below the town—had a small eggnog and dreamed of a hard piece of work we had to commence on the morrow. Mañana [tomorrow morning] por la mañana.

December 27th. We had our horses saddled at reveillé and before sunrise were upon the banks of El Rio de San Fernando—a clear, cold and rapid mountain stream, about 40 yards wide and two and a half feet deep—bottom of hard gravel. We crossed the stream and found ourselves the first American soldiers who had been on the further bank. The approaches to the stream from the town required some repairs, nothing very bad—it was horrible on the other side. As we again crossed the stream we halted to enjoy the beautiful view—the first rays of the sun gave an air of beauty and freshness to the scene that neither pen nor pencil can describe.

With a detail of 200 men and our own[35] company we finished our work before dinner. Walked up into the town in the afternoon. On this day General Pillow overtook us. He had a difficulty with a volunteer officer who mutinied, drew a revolver on the General, etc., etc. The General put him in charge of the guard—his regiment remonstrated, mutinied, etc., and the matter was finally settled by the officer making an apology.

December 28th. Crossed the stream before sunrise under orders to move on with the Tennessee horse one day in advance of the column in order to repair a very bad ford at the next watering place—Las Chomeras. Very tiresome and fatiguing march of about 22 miles. Road pretty good, requiring a few repairs here and there. Water rather brackish. Very pretty encampment. Stream about 20 yards wide and 18 inches deep. No bread and hardly any meat for supper.

December 29th. Finished the necessary repairs about 12 noon. We partook of some kid and claret with Colonel Thomas. While there General Patterson arrived and crossed the stream, encamping on the other side. Waded over the stream to see the Generals—were ordered to move on in advance next morning with two companies of horse and 100 infantry.

[36]December 30th. Started soon after daybreak minus the infantry who were not ready. Joined advanced guard, where Selby raised a grand scare about some Indians who were lying in ambush at a ravine called “los tres palos” in order to attack us. When we reached the ravine the guard halted and I rode on to examine it and look for the Indians—I found a bad ravine but no Indians.

On this same day the Major commanding the rear guard (Waterhouse, of the Tennessee Cavalry) was told by a wagonmaster that the advanced guard was in action with the Mexicans. The men, in the rear guard, immediately imagined that they could distinguish the sound of cannon and musketry. The cavalry threw off their saddle bags and set off at a gallop—the infantry jerked off their knapsacks and put out—Major and all deserted their posts on the bare report of a wagonmaster that the advance was engaged. A beautiful commentary this on the “citizen soldiery.” Had we really been attacked by 500 resolute men we must inevitably have been defeated, although our column consisted of 1700—for the road was narrow—some men would have rushed one way, some another—all would have been confusion—and all, from the General down to the dirtiest rascal of the filthy crew,[37] would have been scared out of their wits (if they ever had any).

Our 100 infantry dodged off before we had done much work, and our own men did everything. We reached Encinal about 4 P. M. after a march of about 17 miles, and almost incessant labor at repairs. It was on this day that General Patterson sent back Brigadier General Pillow to tell Second Lieutenant Smith to cut down a tree around which it was impossible to go!!

December 31st. We left Encinal at daybreak and arrived at about 2 P. M. at Santander, o’ Jimenez. Road good for about ten miles when we found ourselves on the brow of a hill, some 350 feet above the vast plain, in the midst of which was the little town of Santander. No other indication of life was to be seen than its white houses. The descent was very steep, the road bad from the foot of the hill to Santander. We had a slight stampede here, some one imagined that he saw an armed troop approaching (which turned out to be the Alcalde and his suite). We passed the town, crossed the river and encamped. Songo got 19 eggs and we had a “bust.” Colonel Thomas turned out some whiskey to Gibson for an eggnog—before he arrived the eggnog was gone. I have some indistinct ideas of my last sensible moments being spent in kneeling on my[38] bed, and making an extra eggnog on the old mess chest. I dont recollect whether I drank it or not, but as the pitcher was empty the next morning, I rather fancy that I must have done so.

January 1st, 1847. Woke up and found the ridge pole off at one end. I rather suspect that G. W. [Smith] must have done it by endeavoring to see the old year out—perhaps the new one came in via our tent, and did the damage in its passage. We began the new year by starting on the wrong road. After invading about two miles of the enemies’ country we were overtaken by an officer at full gallop, who informed us that the column had taken another road and that we must make our way to the front as we best could. Smith had been informed the preceding day by Winship (General Pillow’s Adjutant General) that the road we took was the right one to Victoria. We quickly discovered the magnitude of our mistake, for we got amongst the Volunteers, and the lord deliver us from ever getting into such a scrape again. Falstaff’s company were regulars in comparison with these fellows—most of them without coats; some would have looked much better without any pants than with the parts of pants they wore; all had torn and dirty shirts—uncombed heads—unwashed faces—they were dirt and filth from top to toe. Such marching![39] They were marching by the flank, yet the road was not wide enough to hold them and it was with the greatest difficulty that you could get by—all hollowing, cursing, yelling like so many incarnate fiends—no attention or respect paid to the commands of their officers, whom they would curse as quickly as they would look at them. They literally straggled along for miles.

In making a short cut through the chaparral we came upon a detachment of mounted Volunteers, amongst whom the famous Murphy, captor of two cities, stood out predominant. He was mounted on the “crittur” he had “drawn,” i. e. stolen in the bushes. The beast was frisky and full of life at first, but by dint of loading him down with knapsacks and muskets he had tamed him pretty well. Imagine an Irishman some six feet, two inches high, seated on the “hindmost slope of the rump” of a jackass about the size of an ordinary Newfoundland dog, his legs extended along its sides, and the front part of the beast loaded down with knapsacks etc. Murphy steered the animal with his legs, every once and a while administering a friendly kick on the head, by way of reminding him that he was thar.

When we crossed the San Fernando I saw a Mexican endeavoring to make two little jackasses cross. He was unable to do so and finally sold[40] them to a Volunteer for fifty cents; the Volunteer got them over safely. After regaling ourselves with a view of Murphy we considered ourselves fully repaid for the extra distance we had marched. At last we gained our place at the head of the column and arrived at Marquesoto about 12 noon, without further incident—except that General Pillow appropriated one of our big buckets to the purpose of obtaining water from the well. We had a very pretty ground for our encampment and had a fine eggnog that night, with Winship to help us drink it. From Santander to Marquesoto about ten miles.

January 2nd. Started before daylight, Captain Snead’s Company in advance. Road very rough, covered with loose stones—could not improve it with the means at our command. Pat thought we might have done it—but hang Pat’s opinion. Saw for the first time the beautiful flower of the Spanish bayonet—a pyramid, about two and a half or three feet high, composed of hundreds of white blossoms. Pat immediately began to talk about “δενδρον” this and “δενδρον” that—and the “δενδρα” in his conservatory. San Antonio is the place where Iturbide[20] was taken—as Arista’s map says.... It is a large yellow house—looking quite modern in the wilderness.

Facsimile reproduction of McClellan’s manuscript.

First Page of the Mexican War Diary.

[41]The crossing at the stream was very bad, and required a great deal of work. Major McCall thought it would take two days—in two days we were at Victoria. The stream is a branch of the Soto la Marina and is called San Antonio. It is a clear cold stream—the banks lined with cypress trees—the first I ever saw. Pat (after ringing in to the owner of the ranch for a dinner) ensconced himself in the roots of a large cypress and with a countenance expressing mingled emotions of fear, anxiety, impatience and disgust watched the progress of the work—yelled at everyone who rode into the water etc., etc.

January 3rd. We started before daylight and succeeded in getting clear of the volunteer camp[42] by dint of great exertions. After marching about five miles through a fertile river bottom we reached the main branch of the Soto la Marina, a most beautiful stream of the clearest, coldest, most rapid water I ever saw—about sixty yards wide and three feet deep. Songo had some trouble in crossing without being washed off “Jim.”

Padilla is situated on the banks of this stream—an old town rapidly going to ruin—with a quaint old Cathedral built probably 200 years ago, if not more. After marching about twelve miles more we reached the stream of La Corona, another branch of La Marina, similar in its character to the others. After working for about an hour on the banks we encamped on the further side. The Tennessee horse gave our men a “lift” over both the last streams—some of the Sappers[21] had evidently never been mounted before.

January 4th. Very early we started for Victoria—and had to work our way through the camp of the Illinois regiments which was placed along the road. At last we cleared them and found ourselves marching by moonlight through a beautiful grove of pecan trees. I know nothing more pleasant than this moonlight marching, everything is so beautiful and quiet. Every few[43] moments a breath of warm air would strike our faces—reminding us that we were almost beneath the Tropic. After we had marched for about four hours we heard a little more yelling than usual among the Volunteers. Smith turned his horse to go and have it stopped when who should we see but the General and his staff in the midst of the yelling. We concluded that they must be yelling too, so we let them alone. This is but one instance of the many that occurred when these Mustang Generals were actually afraid to exert their authority upon the Volunteers.—Their popularity would be endangered. I have seen enough on this march to convince me that Volunteers and Volunteer Generals wont do. I have repeatedly seen a Second Lieutenant of the regular army exercise more authority over the Volunteers—officers and privates—than a Mustang General.

The road this day was very good and after a march of about seventeen miles we reached Victoria. The Volunteers had out their flags, etc.—those that had uniforms put them on, especially the commandant of the advanced guard. Picks and shovels were put up—Generals halted and collected their staffs, and in they went in grand procession—evidently endeavoring to create the impression that they had marched in this way all[44] the way—the few regular officers along laughing enough to kill themselves.

General [John A.] Quitman came out to meet General Patterson—but old Zach [Taylor], who arrived with his regulars about an hour before we did, stayed at home like a sensible man.[22] We made fools of ourselves (not we either, for I was laughing like a wise man all the time) by riding through the streets to General Quitman’s quarters where we had wine and fruit. Then we rode down to the camp ground—a miserable stony field—we in one corner of it, the “Continental Army” all over the rest of it. We at last got settled. About dark started over to General Taylor’s camp. Before I had gone 200 yards I met the very person I was going to see—need[45] not say how glad I was to meet him after a two months absence.

This reminds me that when at Matamoros—a day or two before we started on the march—we received the news of poor Norton’s death. I had written a letter to him the day before which was in my portfolio when I heard of his death. The noble fellow met his death on board the Atlantic, which was lost in Long Island Sound near New London on the 27th November 1846. Captain Cullum and Lieutenant C. S. Stewart were both on board, and both escaped. Norton exerted himself to the last to save the helpless women and children around him—but in accordance with the strange presentiment that had been hanging over him for some time, he lost his own life. He was buried at West Point—which will seem to me a different place without him.

One night when at Victoria I was returning from General Taylor’s camp and was halted about 150 yards from our Company by a Volunteer sentinel. As I had not the countersign I told him who I was. He said I should not go by him. I told him “Confound you I wont stay out here all night.” Said he “You had no business to go out of camp.” Said I “Stop talking, you scoundrel, and call the Corporal of the Guard.”—“I ain’t got no orders to call for the[46] Corporal and wont do it—you may, though, if you want.” “What’s the number of your post?” “Dont know.” “Where’s the Guard tent?” “Dont know.”—As I was debating whether to make a rush for it, or to seek some softer hearted specimen of patriotism, another sentinel called out to me “Come this way, Sir!”—It appeared that the first fellow’s post extended to one side of the road, and the last one’s met it there.—“Come this way, Sir” said he, “Just pass around this bush and go in.” “Hurrah for you” said I, “you’re a trump, and that other fellow is a good for nothing blaguard.”

Left Victoria January 13th and arrived at Tampico on the 23rd. Wednesday January 13th. From Victoria to Santa Rosa four leagues. Road not very hilly, but had to be cut through thick brush; two very bad wet arroyos [gulches] were bridged. Santa Rosa a miserable ranche—could only get a half dozen eggs and a little pig in the whole concern—good water in the stream.

[January] 14th. Started before daylight and before going 200 yards we landed in a lake—the road, or path, passed directly through it, and during the rest of the day it was necessary to cut the road through thick brush—no cart had ever been there before. Bridged two wet arroyos and encamped about sunset by a little stream.[47] Just as enough water had been procured the stream was turned off—probably by the Mexicans. We had a stampede this day. Rode on about six miles with the guide. Country a perfect wilderness—not a ranche between Santa Rosa and Fordleone.

[January] 15th. Started early, road cut through a mesquit[e] forest, many gullies, two bad arroyos before reaching El Pastor. Here General Twiggs[23] caught us, about 11 A. M., army encamped, but we went on. I worked the road for about five miles, and started back at 4[48] [o’clock]. Smith and Guy de L....[24] rode on about ten miles. Road better but very stony. “Couldn’t come the cactus” over Guy de L.... this day. He (G. de L.) shot five partridges at a shot which made us a fine supper.

[January] 16th. Reveillé at 3—started at 4—arrived at end of preceding day’s work just at daybreak. Road very stony in many places—swore like a trooper all day—arrived at Arroyo Albaquila about 11 [A. M.]. Twiggs came up and helped us wonderfully by his swearing—got over in good time—cussed our way over another mile and a half—then encamped by the same stream—water very good.

[January] 17th. Started before daybreak—road quite good—prairie land—arrived at Fordleone or Ferlón at about half after ten. Fine large stream of excellent water—good ford—gravelly bottom—gentle banks. 11 miles.

[January] 18th. Reveillé at 3. Started long before daybreak—eyes almost whipped out of my head in the dark by the branches. Crossed the Rio Persas again at a quarter before seven—road[49] rather stony in some places, but generally good. Great many palmetto trees—beautiful level country, covered with palmettos and cattle. “Struck” a bottle of aguardiente, or sugar cane rum. Made a fine lunch out of cold chicken and rum toddy—had another toddy when we arrived at our journey’s end. Water from a stream, but bad.... Rode on about three miles and found the road pretty good.

[January] 19th. On comparing notes at reveillé found that the rum and polonay had made us all sick.[25] Started at 5, road pretty good. Much open land, fine pasture—great deal of cattle. Reached Alamitos at about 9 A. M.—fine hacienda [farm]—good water, in a stream. Had a bottle of champagne for lunch—thanks to General Smith. From this place to Tampico, the principal labor consisted in making a practicable wagon road across the numerous arroyos—most of them dry at the time we passed: the banks[50] very steep. Altamira is a pretty little town, one march from Tampico. The road between them passes through a very magnificent forest of live oaks. We encamped three miles from Tampico for about four days, and then moved into quarters in the town—the quarters so well known as “The Bullhead Tavarn.”

Tampico is a delightful place[26]—we passed a very pleasant time there, and left it with regret. We found the Artillery regiments encamped around the city. Many of the officers came out to meet us near Altamira. Champagne suppers were the order of the day (night I should say) for a long time. From Victoria to Tampico we were detached with Guy Henry’s company of the 3rd—and Gantt’s of the 7th—Henry messed with us. When within about four days march of Tampico we saw in front of us Mount Bernal, which is shaped like a splendid dome.

[51]We left Tampico[27] at daylight on the 24th February [1847] on board a little schooner called the Orator—a fast sailer, but with very inferior accommodations. I really felt sorry to leave the old “Bullhead Tavarn” where I had passed so many pleasant moments. The view of the fine city of Tampico as we sailed down the river was beautiful. Its delightful rides, its beautiful rivers, its lagoons and pleasant Café will ever be present to my mind. Some of the happiest hours of my life were passed in this same city—Santa Anna de Tamaulipas.

On arriving at Lobos[28] we found that we had[52] arrived a day in advance of the “Army of the Rhine,” which had started a day before us. Lobos is a small island formed by a coral reef—about 18 or 20 miles from the shore, forming under its lee a safe but not very pleasant anchorage. I went on shore but found nothing remarkable. Some 60 vessels were there when we started. At last the order was given to sail for Point Anton Lizardo. We sailed next but one after the generals and arrived before any of them except Twiggs. We ran on the reef under the lee of Salmadina Island, were immediately taken off by the navy boats which put us on shore where we were very kindly received by the Rocketeers. It was a great relief to get rid of that confounded red and white flag—“send a boat with an officer”—and the disagreeable duty of reporting to the ‘Generál en Géfe’ every morning. A French sailor of the Orator undertook to pilot us and carried us on a reef of what he called Sacrificios[29] but what turned out to be Anton Lizardo.

[53]On the morning of the 9th of March we were removed from the Orator to the steamer Edith, and after three or four hours spent in transferring the troops to the vessels of war and steamers, we got under weigh and sailed for Sacrificios. At half past one we were in full view of the town [Vera Cruz] and castle, with which we soon were to be very intimately acquainted.

Shortly after anchoring the preparations for landing commenced, and the 1st (Worth’s)[30] Brigade was formed in tow of the “Princeton” in two long lines of surf boats—bayonets fixed and colors flying. At last all was ready, but just before the order was given to cast off a shot whistled over our heads. “Here it comes” thought everybody, “now we will catch it.” When the order was given the boats cast off and forming in three parallel lines pulled for the shore, not[54] a word was said—everyone expected to hear and feel their batteries open every instant. Still we pulled on and on—until at last when the first boats struck the shore those behind, in the fleet, raised that same cheer which has echoed on all our battlefields—we took it up and such cheering I never expect to hear again—except on the field of battle.

Without waiting for the boats to strike the men jumped in up to their middles in the water and the battalions formed on their colors in an instant—our company was the right of the reserve under [Lieut.-] Colonel Belton. Our company and the 3rd Artillery ascended the sand hills and saw—nothing. We slept in the sand—wet to the middle. In the middle of the night we were awakened by musketry—a skirmish between some pickets. The next morning we were sent to unload and reload the “red iron boat”—after which we resumed our position and took our place in the line of investment. Before we commenced the investment, the whole army was drawn up on the beach. We took up our position on a line of sand hills about two miles from the town. The Mexicans amused themselves by firing shot and shells at us—all of which (with one exception) fell short.

The sun was most intensely hot, and there was[55] not a particle of vegetation on the sand hills which we occupied. Captain Swift found himself unable to stand it, and at about half past twelve gave up the command to G. W. Smith and went on board the “Massachusetts” that same afternoon. He did not resume the command, but returned to the United States. He died in New Orleans on the 24th of April.

About one we were ordered to open a road to Malibran (a ruined monastery at the head of the lagoon). The Mohawks had been skirmishing around there, but, as I was afterward informed by some of their officers, that they fired more on each other than on the Mexicans. After cutting the road to Malibran we continued it as far as the railroad—a party of Volunteers doing the work and some 25 of our men acting as a guard. When we arrived at the railroad, we found it and the chaparral occupied by the Mexicans. Our men had a skirmish with them—charged the chaparral and drove them out of it.

We returned to Malibran and bivouacked on the wet grass without fires—hardly anything to eat—wet and cold. Got up in the morning and resumed our work on the road—from the railroad to the “high bare sand hill”—occupied by the Pennsylvanians the night before. The work was very tedious, tiresome and difficult—the hill very[56] high and steep—and the work not at all facilitated by the shells and shot that continually fell all around us. At last we cut our way to the summit—tired to death. A M—— rifleman was killed this morning by a 24 pound shot—on top of the hill. Lieutenant Colonel Dickenson and some few Volunteers were wounded by escopette[31] balls.

I was sent up in the morning to find the best path for our road and just as I got up to the top of the hill the bullets commenced whistling like hail around me. Some Lancers[32] were firing at the Volunteers—who were very much confused and did not behave well. Taylor’s Battery and the rest of Twiggs’s Division moved over the hill towards their position on the left of the line. Worth’s Division (or Brigade as it was then called) occupied the right of the investment, the Mohawks under Patterson the centre, and Twiggs the left. After resting our men at Malibran, we moved back to our old position with the 3rd Artillery, where we bivouacked.

[57]I had observed on the preceding day the position of the aqueduct supplying the city with water. I told Lieutenant Beauregard[33] next morning what I had seen. He reported it to Colonel [Joseph G.] Totten [Chief of Engineers] and Smith and myself were ordered to cut off the water, Foster remaining at home. We took a party, cut off the water, Smith exploded a humbug of Gid Pillow’s and we started on a reconnoitring expedition of our own. I stopped to kill a “slow deer” and Smith went on. I then followed him with three men and overtook him a little this side of the cemetery. We went on to within 900 yards of the city and at least a mile and a half in advance of the line of investment—ascertained the general formation of the ground and where to reconnoitre. We returned after dark, Foster much troubled as to what had become of us. It was upon reporting to Colonel Totten on this night (12th) that he said that I[58] and G. W. [Smith] were the only officers who had as yet given him any information of value—that we had done more than all the rest, etc., etc. All forgotten with the words as they left his mouth—vide his official report of the siege. G. W. and myself will never forget how we passed this blessed night—(new fashioned dance).

On the next day Foster was sent after our baggage and camp equipage. I was ordered to move the company and pitch the tents on a spot on the extreme right. Smith went out with Major [John L.] Smith to where we had been the night before, but went no further toward the city than we had been.

[March 14th]. The next day Foster was detailed to assist Major Smith and Beauregard in measuring a base line etc. on the sand hills. G. W. and myself went to the lime kiln in the morning, where we saw Captain [John R.] Vinton, Van Vliet, Laing, Rodgers and Wilcox (Cadmus)—took a good look at the town and its defences—and determined to go along the ridge by the cemetery that night and to go nearer the city. While at the lime kiln an order was received from General Worth informing Captain Vinton that the enemy’s picquets would be driven in that day and that he (Captain Vinton) must not attempt to support them—as there were strong reserves.

[59]We returned to camp, got our dinner and started again—being a little fearful that our picquets would be so far advanced as to interfere with our operations. But we found them about 150 yards in advance of the line of investment, stooping, whispering, and acting as if they expected to be fired upon every moment—whilst we had been a mile and a half in advance of their position with a dozen men. They were at first disposed to dissuade us from going on—as being too dangerous etc. We went on though, accompanied by Captain Walker of the 6th. The Captain left us before we got to the cemetery. I took one man (Sergeant Starr) and went down to reconnoitre it—in order to ascertain whether it was occupied by the enemy, whilst G. W. [Smith] went on to examine a hill which covered the valley from Santiago and the Castle to some extent. I went down to the cemetery (finding a good road) went around it and got in it—satisfying myself that it was not occupied. I rejoined G. W. and together we went on very near the town. We returned late, being the only officers of any corps who had gone as far as, much less beyond the cemetery.

[March] 15th. The next day we were ordered to cut an infantry road as far as the cemetery. We found that one had been cut before we got[60] out by Captain Johnson as far as the old grave yard. We cut one completely concealed from view from there to the hollow immediately opposite the cemetery. Captain Walker’s company was behind the cemetery. Whilst there one of his sentinels reported the approach of some Lancers. They stopped at a house about 30 yards from the other side of the cemetery—and came no farther. On the strength of the approach of these 15 or 20 Lancers a report got back to camp that the advanced picquets had been attacked by a strong force of Mexicans—so on our return we met nearly the whole division marching out to drive them back—litters for the “to be wounded” and all. It was a glorious stampede—well worthy of Bold Billy Jenkins.

[March] 16th. The next day we went out [and] met Major Scott who went with G. W. to [the] position afterward occupied by the six gun battery—whilst I had a hole made through the cemetery wall and broke into the chapel—hoping to be able to reach the dome, and ascertain from that place the direction of the streets. I could not—we rather—get up to the dome, so we left the cemetery, determining to push on toward the town. G. W. found a very fine position for a battery about 450 yards from Santiago and enfilading the principal street. We met Colonel[61] Totten and Captain [R. E.] Lee[34]—showed them the place—they were very much pleased with it.

We came out with the Company (Captain Lee, Smith, Foster and myself) that evening, arrived at the place after dark, and Captain Lee, Smith and Foster went in to lay out a battery—leaving me, in command of the Company, in the road. When on our return we were passing by the old grave yard a sharp fire of musketry commenced—one of our pickets had been fired upon.

The next day (17th) we cut a path to the position of this battery (in perspective). As we returned they discovered us and opened a fire of 24 pound shot upon us which enfiladed our path beautifully. They fired too high and hit no one. We reached at length a sheltered position where we remained until the firing ceased—the balls striking one side of the hill—we being snugly ensconced on the other.

On the next day (18th) the position of the batteries was definitely fixed. In the afternoon I was ordered by Colonel Totten to arrange at the Engineers’ Depot (on the beach) tools for[62] a working party of 200 men—and be ready to conduct it as soon as it was dark to the proper position. The working party (3rd Artillery, Marines, and 5th Infantry—all under Colonel Belton) did not arrive until long after dark—and it was quite late when we arrived at the position for the batteries. I was placed in charge of Mortar Battery No. 1—G. W. in charge of No. 2—a parallel was also made across the little valley. Each of these batteries was for three mortars. No. 1 was formed by cutting away the side of a hill, so that we had merely to form the epaulments[35] and bring the terreplein[36] down to the proper level—the hill sheltering us from the direct fire of the Castle and Santiago. So also with No. 2—which was made in the gorge where the road to the cemetery crossed the ridge on left of valley.

The tools for [the] working party were arranged on the beach in parallel rows of tools for 20 men each and about four feet apart, so that they might take up the least possible space. Each man was provided with a shovel and either a pick,[63] axe, or hatchets (about 140 picks and mattocks). The party was conducted in one rank, by the right flank. The men were well covered by daylight.

[March] 19th. Mason, Foster, and I think [I. I.] Stevens, relieved Captain Lee, Beauregard, Smith and myself at 3 A. M. During the day they continued the excavation of the two batteries and the short parallel across the valley. The enemy kept up a hot fire during the forenoon but injured no one. During the evening of this day Smith laid out and commenced the parallel leading from No. 1 to the position afterward occupied by the 24 pounder battery. The work was difficult on account of the denseness of the chaparral and the small number of workmen. The parapet was made shot proof (or sufficiently so to answer the purpose of covering the morning relief) by daybreak. The enemy fired grape etc. for a short time, but not sufficiently well aimed or long enough kept up to impede the progress of the work. The battery known as the Naval Battery was commenced on this same night. The enemy were kept in entire ignorance of the construction of this battery until the very night before it opened, and then they only discovered that something was being done there—they did not know what. The Mexican[64] Chief Engineer told Colonel Totten of this fact after the capitulation.

[March] 20th. The construction of the parallel and of the mortar batteries Nos. 1 and 2 was carried on during this day. By 3 P. M., when Mason and myself went out there—the parallel was finished—the excavation of the two batteries completed—the sandbag traverses in No. 2 finished—those in No. 1 very nearly so. We were to lay out and excavate the positions for the two magazines of each battery, to commence Mortar Battery No. 3 (for four mortars), lay the platforms and place the magazine frames—which were to be brought out at night fall. By the direction of Mason, I had the positions of the magazines prepared and laid out before dark. Colonel Totten came out and directed me to lay out No. 3. I also laid out the boyau[37] leading from 1 to 2. Mason took charge of the magazines 1 and 2 and directed me to take charge of No. 3. I employed four sets of men on the battery at the same time—one set throwing the earth from the rear of the parallel upon the berm[38]—a[65] second on the berm disposing of this earth thrown on the berm—a third set working at the rear of the battery, excavating toward the front, these threw the earth so as to form slight epaulments, and in rear. A fourth set were employed in making the excavations for the magazines. A very violent Norther arose which obliged me to employ the first and second sets in front of the battery—they excavating a ditch.

At daylight the parapet was shot proof and the battery required about one hour’s digging to finish it. Owing to some mistake the platforms and magazine frames did not arrive until very late and but little progress was made as far as they were concerned. Had they arrived in time all three batteries could have opened on the afternoon of the 21st. The construction of the battery on the left of the railroad [was] still progressing. They fired rockets etc. at us during the early part of the night.

[March] 21st. During this day not very much was done—some progress was made with the six gun battery—magazines, platforms, etc.

[March] 22nd. Not being aware of a change in the detail I went out at 3 A. M. Found the magazines of No. 2 finished, the small magazines of No. 1 the same. Took charge of large magazine of No. 1—whilst Mason was engaged with[66] those of No. 3. About 8 [o’clock] was informed of change of detail, went to camp and was requested by Colonel Totten to go out to the trenches “extra” and give all the assistance in my power, since the General wished to send in a summons to the town at 2 P. M. and open upon them if they refused to surrender. I went out and was chiefly occupied during the day in covering the magazine of No. 1 with earth. This was done under fire of Santiago and adjacent bastion, which batteries having a clear view of my working party made some pretty shots at us—striking the earth on the magazine once in a while, but injuring no one. At 2 P. M. we were ready to open with three mortars in No. 1—three in No. 2—one in No. 3.—seven in all.

The flag was carried in by Captain Johnston, the enemy ceased firing when they saw it. Colonel Bankhead[39] informed the Commandants of Batteries 1 and 3 that the discharge of a mortar from No. 2 would be the signal to open from all the mortars. The flag had hardly commenced its return from the town when a few spiteful shots from Santiago at my party on the magazine told us plainly enough what the reply had been. Probably half an hour elapsed before a[67] report from No. 2 gave us the first official intimation that General Morales[40] had bid defiance to us, and invited us to do our worst.

The command “Fire!” had scarcely been given when a perfect storm of iron burst upon us—every gun and mortar in Vera Cruz and San Juan, that could be brought to bear, hurled its contents around us—the air swarmed with them—and it seemed a miracle that not one of the hundreds they fired fell into the crowded mass that filled the trenches. The recruits looked rather blue in the gills when the splinters of shells fell around them, but the veterans cracked their jokes and talked about Palo Alto and Monterey. When it was nearly dark I went to the left with Mason and passed on toward the town where we could observe our shells—the effect was superb. The enemy’s fire began to slacken toward night, until at last it ceased altogether—ours, though, kept steadily on, never ceasing—never tiring.

Immediately after dark I took a working party and repaired all the damage done to the parapets by the enemy’s fire, besides increasing the thickness of the earth on the magazines of No. 1.[68] Captain Vinton was killed a short time before dark near Battery No. 3 by a spent shell—two men were wounded by fragments of shells near No. 1. Shortly after dark, three more mortars were put in Battery No. 3—making 10 mortars in all. Captain [John] Saunders was employed upon the 6 gun battery (24 pounders). He revetted[41] it with one thickness of sand bags, all of which fell down next morning. I brought out from the Engineer Depot the platforms for this battery during the night—the magazine frame was brought out next day. The battery on the left of the railroad [was] still progressing, under the charge of Captain [R. E.] Lee, [Lieut. Z. B.] Tower and [G. W.] Smith—who relieved each other.

[March] 23rd. Firing continued from our mortars steadily—fire of enemy by no means so warm as when we opened on the day before. Our mortar platforms were much injured by the firing already. The 24 pounder battery had to be re-revetted entirely—terreplein levelled. During this day and night the magazine was excavated, and the frame put up. Two traverses made—the positions of platforms and embrasures determined. Two platforms laid and the guns run in—the[69] embrasures for them being partly cut. One other gun was run to the rear of the battery.

[March] 24th. On duty with Captain Saunders again—could get no directions so I had the two partly cut embrasures marked with sand bags and dirt, and set a party at work to cover the magazine with earth as soon as it was finished. During this day the traverses[42] were finished, the platforms laid, the magazine entirely finished, and a large number of sand bags filled for the revetments of the embrasures. The “Naval Battery” opened today, their fire was fine music for us, but they did not keep it up very long. The crash of the eight-inch shells as they broke their way through the houses and burst in them was very pretty. The “Greasers” had had it all in their own way—but we were gradually opening on them now. Remained out all night to take charge of two embrasures. The Alabama Volunteers, who formed the working party, did not come until it was rather late—we set them at work to cut down and level the top of parapet—thickening it opposite the third and fourth guns. Then laid out the embrasures and put seven men in each. Foster had charge of two, Coppée of two,[70] and I of two. Mine were the only ones finished at daylight—the Volunteers gave out and could hardly be induced to work at all.

[March] 25th. Mason and Stevens relieved Beauregard and Foster—but I remained. I had the raw hides put on—and with a large party of Volunteers opened the other embrasures. This was done in broad daylight, in full view of the town—yet they had not fired more than three or four shots when I finished and took in the men. The battery then opened. We then gave it to Mexicans about as hotly as they wished. We had ten mortars—three 68s, three 32s, four 24s, and two eight-inch howitzers playing upon them as fast as they could load and fire. Captain Anderson, 3rd Artillery, fired on this morning thirty shells in thirty minutes from his battery of three mortars (No. 1).

As I went to our camp I stopped at Colonel Totten’s tent to inform him of the state of affairs—he directed me to step in and report to General Scott. I found him writing a despatch. He seemed to be very much delighted and showed me the last words he had written which were “indefatigable Engineers.” Then we were needed and remembered—the instant the pressing necessity passed away we were forgotten. The echo of the last hostile gun at Vera Cruz had not died[71] away before it was forgotten by the Commander in Chief that such a thing existed as an Engineer Company.[43]

Facsimile reproduction of a pencil sketch by McClellan.

Church at Camargo, seen from the Palace.

The superiority of our fire was now very apparent. I went out again at 3 P. M.—met Mason carrying a large goblet he had found in a deserted ranch. Found Captain Lee engaged in the construction of a new mortar battery for four mortars, immediately to the left of No. 1—in the parallel. There was a complete cessation of firing—a flag having passed in relation to the consuls, I think. The platforms of this battery were laid, but not spiked down. A traverse was made[72] in boyau between Nos. 1 and 2, just in front of the entrance of the large magazine of No. 1, it being intended to run a boyau from behind this traverse to the left of the new battery. I laid out a boyau connecting Stevens’s communications with the short “parallel” of No. 2, then Captain Lee explained his wishes in relation to the new battery and left me in charge of it. I thickened the parapet from a ditch in front—inclined the superior slope upward, left the berm, made the traverses, had the platforms spiked, etc. The mortars were brought up and placed in the battery that night. Captain Saunders sent me to repair the embrasures of the 24 pounder battery—doing nothing himself. He then sent me to excavate the boyau I had laid out.

About 11.30 the discharge of a few rockets by our rocketeers caused a stampede amongst the Mexicans—they fired escopettes and muskets from all parts of their walls. Our mortars reopened about 1.30 with the greatest vigor—sometimes there were six shells in the air at the same time. A violent Norther commenced about 1 o’clock making the trenches very disagreeable. About three quarters of an hour, or an hour after we reopened we heard a bugle sound in town. At first we thought it a bravado—then reveillé, then a parley—so we stopped firing to await the result.[73] Nothing more was heard, so in about half an hour we reopened with great warmth. At length another chi-wang-a-wang was heard which turned out to be a parley. During the day the terms of surrender of the town of Vera Cruz[44] and castle of San Juan de Ulua were agreed upon, and on 29th of March, 1847 the garrison marched out with drums beating, colors flying and laid down their arms on the plain between the lagoon and the city ... muskets were stacked and a number of escopettes ... pieces of artillery were found in the town and ... in the castle.

After the surrender of Vera Cruz we moved our encampment—first to the beach, then to a position on the plain between our batteries and the city. Foster was detached on duty with the other Engineers to survey the town and castle. Smith and myself were to superintend the landing of the pontoon and engineers trains, and to collect them at the Engineer Depot. Between the Quartermasters and Naval Officers this was hardly done when we left. I dismantled the batteries, magazines etc.—then amused myself until we left, with the chills and fever.