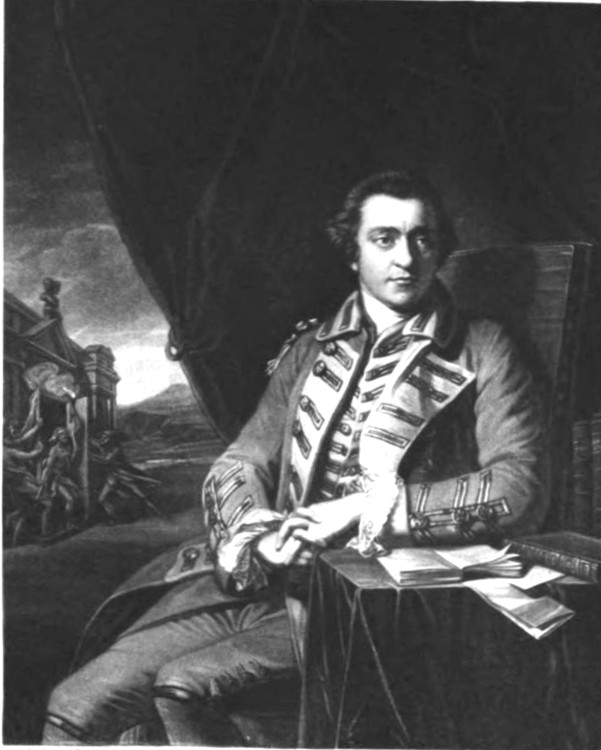

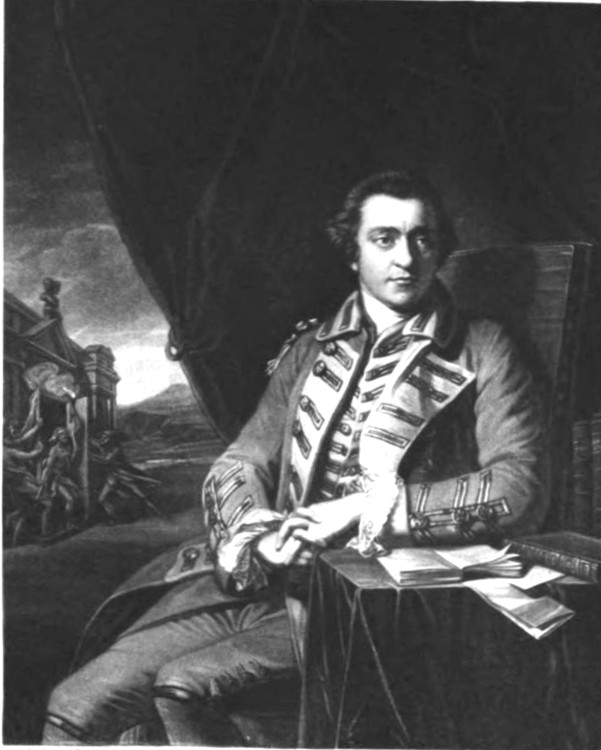

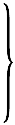

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Walker & Burstall Ph. Sc.

John Hale

First Colonel of the 17th Light Dragoons.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of A History of the 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own), by John Fortescue

Title: A History of the 17th Lancers (Duke of Cambridge's Own)

Author: John Fortescue

Release Date: June 9, 2022 [eBook #68270]

Language: English

Produced by: Brian Coe, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

A History of the 17th Lancers

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Walker & Burstall Ph. Sc.

John Hale

First Colonel of the 17th Light Dragoons.

BY

HON. J. W. FORTESCUE

London

MACMILLAN AND CO.

AND NEW YORK

1895

All rights reserved

To the Memory

OF

MAJOR-GENERAL JAMES WOLFE

WHO FELL GLORIOUSLY IN THE MOMENT OF VICTORY

ON THE PLAINS OF ABRAHAM BEFORE QUEBEC

13TH SEPTEMBER 1759

THIS HISTORY

OF THE REGIMENT RAISED IN HIS HONOUR

BY HIS COMRADE IN ARMS

JOHN HALE

IS PROUDLY AND REVERENTLY INSCRIBED

[ix]

This history has been compiled at the request of the Colonel and Officers of the Seventeenth Lancers.

The materials in possession of the Regiment are unfortunately very scanty, being in fact little more than the manuscript of the short, and not very accurate summary drawn up nearly sixty years ago for Cannon’s Historical Records of the British Army. The loss of the regimental papers by shipwreck in 1797 accounts for the absence of all documents previous to that year, as also, I take it, for the neglect to preserve any sufficient records during many subsequent decades. I have therefore been forced to seek information almost exclusively from external sources.

The material for the first three chapters has been gathered in part from original documents preserved in the Record Office,—Minutes of the Board of General Officers, Muster-Rolls, Paysheets, Inspection Returns, Marching Orders, and the like; in part from a mass of old drill-books, printed Standing Orders, and military treatises, French and English, in the British Museum. The most important[· is a smudge?] of these latter are Dalrymple’s Military Essay, Bland’s Military Discipline, and, above all, Hinde’s Discipline of the Light Horse (1778).

For the American War I have relied principally on the[x] original despatches and papers, numerous enough, in the Record Office, Tarleton’s Memoirs, and Stedman’s History of the American War,—the last named being especially valuable for the excellence of its maps and plans. I have also, setting aside minor works, derived much information from the two volumes of the Clinton-Cornwallis Controversy compiled by Mr. B. Stevenson; and from Clinton’s original pamphlets, with manuscript additions in his own hand, which are preserved in the library at Dropmore.

For the campaigns in the West Indies the original despatches in the Record Office have afforded most material, supplemented by a certain number of small pamphlets in the British Museum. The Maroon War is treated with great fulness by Dallas in his History of the Maroons; and there is matter also in Bridges’ Annals of Jamaica, and the works of Bryan Edwards. The original despatches are, however, indispensable to a right understanding of the war. Unfortunately the despatches that relate to St. Domingo are not to be found at the Record Office, so that I have been compelled to fall back on the few that are published in the London Gazette. Nor could I find any documents relating to the return of the Regiment from the West Indies, which has forced me unwillingly to accept the bald statement in Cannon’s records.

The raid on Ostend and the expedition to La Plata have been related mainly from the accounts in the original despatches, and from the reports of the courts-martial on General Whitelocke and Sir Home Popham. There is much interesting information as to South America,—original memoranda by Miranda, Popham, Sir Arthur Wellesley (the Duke of Wellington) and other documents—preserved among the manuscripts at Dropmore.

[xi]

The dearth of original documents both at the Record Office and the India Office has seriously hampered me in tracing the history of the Regiment during its first sojourn in India and through the Pindari War. I have, however, to thank the officials of the Record Department of the India Office for the ready courtesy with which they disinterred every paper, in print or manuscript, which could be of service to me.

Respecting the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny I have received (setting aside the standard histories) much help from former officers, notably Sir Robert White, Sir William Gordon, and Sir Drury Lowe, but especially from Sir Evelyn Wood, who kindly found time, amid all the pressure of his official duties, to give me many interesting particulars respecting the chase of Tantia Topee. Above all I have to thank Colonel John Brown for information and assistance on a hundred points. His long experience and his accurate memory, quickened but not clouded by his intense attachment to his old regiment, have been of the greatest value to me.

My thanks are also due to the officials of the Record Department of the War Office, and to Mr. S. M. Milne of Calverley House, Leeds, for help on divers minute but troublesome points, and to Captain Anstruther of the Seventeenth Lancers for constant information and advice. Lastly, and principally, let me express my deep obligations to Mr. Hubert Hall for his unwearied courtesy and invaluable guidance through the paper labyrinth of the Record Office, and to Mr. G. K. Fortescue, the Superintendent of the Reading-Room at the British Museum, for help rendered twice inestimable by the kindness wherewith it was bestowed.

[xii]

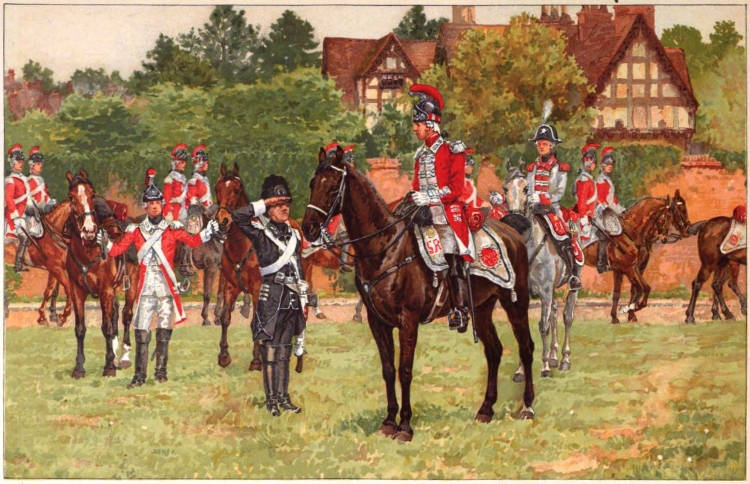

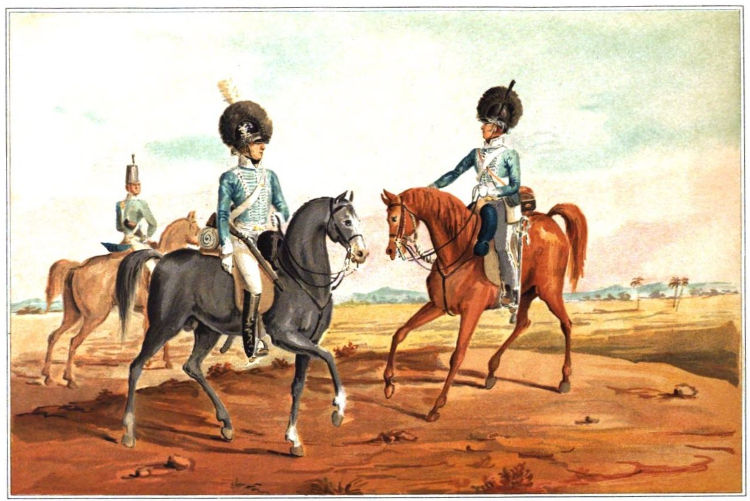

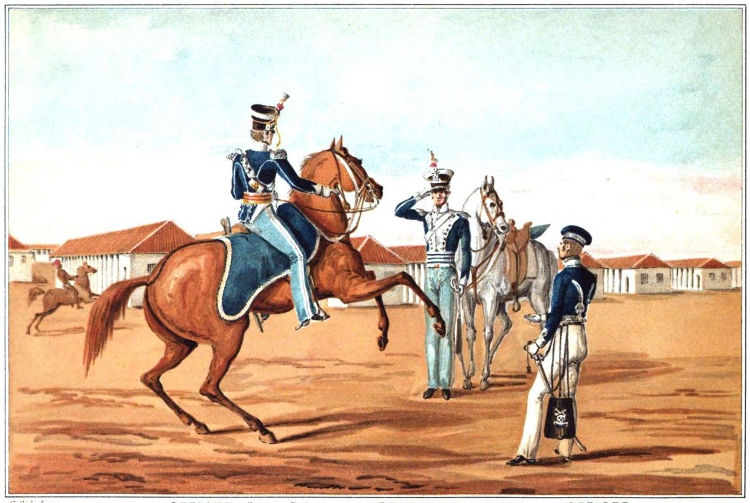

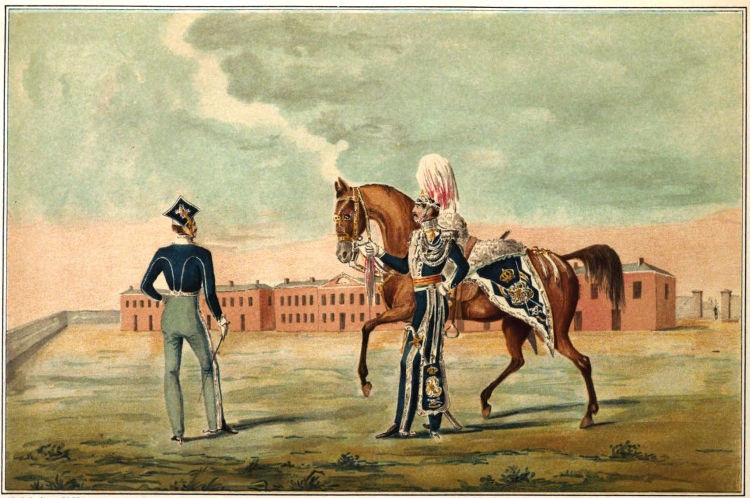

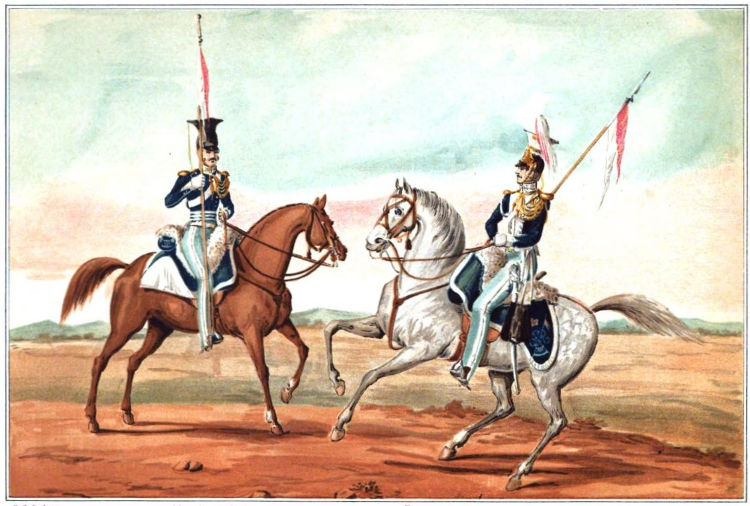

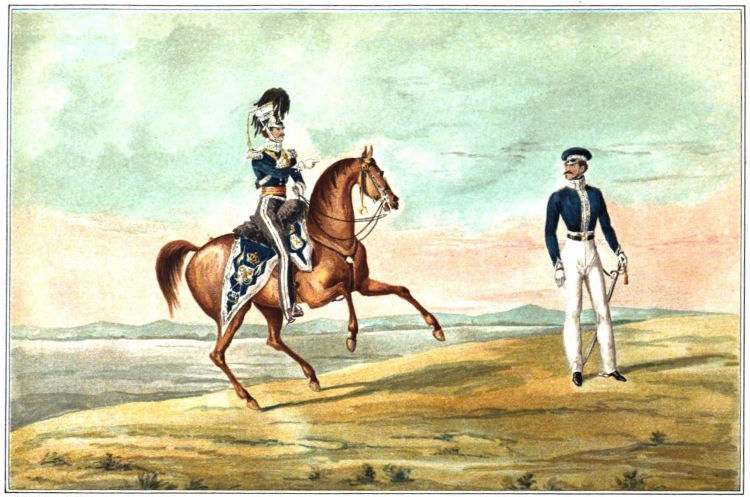

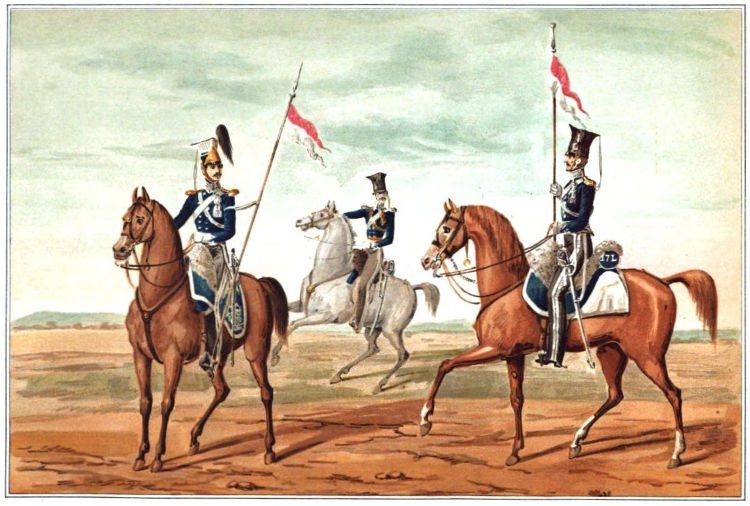

The first and two last of the coloured plates in this book have been taken from original drawings by Mr. J. P. Beadle. The remainder are from old drawings, by one G. Salisbury, in the possession of the regiment. They have been deliberately chosen as giving, on the whole, a more faithful presentment of the old and extinct British soldier than could easily be obtained at the present day, while their defects are of the obvious kind that disarm criticism. The portrait of Colonel John Hale is from an engraving after a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, the original of which is still in possession of his lineal descendant in America. That of Lord Bingham is after a portrait kindly placed at the disposal of the Regiment by his son, the present Earl of Lucan. Those of the Duke of Cambridge and of Sir Drury Lowe are from photographs.

May, 1895.

[xiii]

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The Rise of the 17th Light Dragoons, 1759 | 1 |

| 2. | The Making of the 17th Light Dragoons | 10 |

| 3. | Reforms after the Peace of Paris, 1763–1774 | 20 |

| 4. | The American War—1st Stage—The Northern Campaign, 1775–1780 | 31 |

| 5. | The American War—2nd Stage—The Southern Campaign, 1780–1782 | 49 |

| 6. | Return of the 17th from America, 1783—Ireland, 1793—Embarkation for the West Indies, 1795 | 65 |

| 7. | The Maroon War in Jamaica, 1795 | 73 |

| 8. | Grenada and St. Domingo, 1796 | 87 |

| 9. | Ostend—La Plata, 1797–1807 | 96 |

| 10. | First Sojourn of the 17th in India, 1808–1823—The Pindari War | 110 |

| 11. | Home Service, 1823–1854 | 121 |

| 12. | The Crimea, 1854–1856 | 128 |

| 13. | Central India, 1858–1859 | 144 |

| 14. | Peace Service in India and England, 1859–1879 | 166 |

| 15. | The Zulu War—Peace Service in India and at Home, 1879–1894 | 174[xiv] |

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| A. | A List of the Officers of the 17th Light Dragoons, Lancers | 181 |

| B. | Quarters and Movements of the 17th Lancers since their Foundation | 236 |

| C. | Pay of all Ranks of a Light Dragoon Regiment, 1764 | 241 |

| D. | Horse Furniture and Accoutrements of a Light Dragoon, 1759 | 243 |

| E. | Clothing, etc. of a Light Dragoon, 1764 | 244 |

| F. | Evolutions required at the Inspection of a Regiment, 1759 | 245 |

[xv]

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant-Colonel John Hale | Frontispiece | |

| H.R.H. The Duke of Cambridge, K.G., Colonel-in-Chief 17th Seventeenth Light Dragoons, 1764 | To face | 1 |

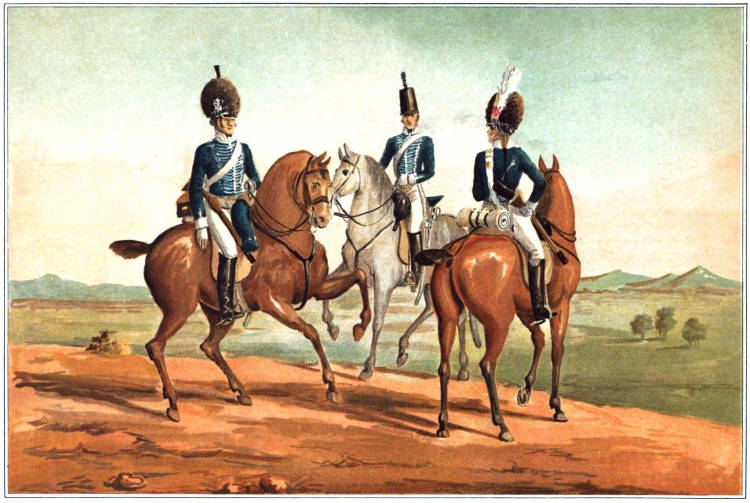

| Seventeenth Light Dragoons, 1764 | „ | 11 |

| Privates, 1784–1810 | „ | 31 |

| Officers, 1810–1813 | „ | 48 |

| Privates, 1810–1813 | „ | 48 |

| Officer, Corporal, and Privates, 1814 | „ | 65 |

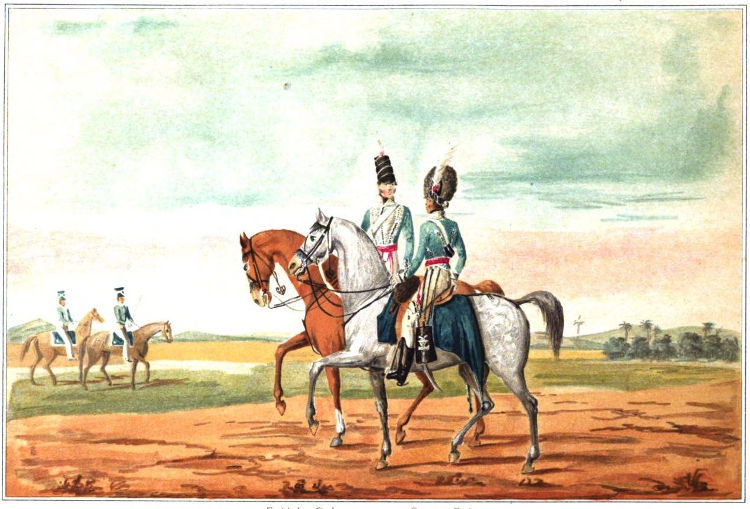

| Officers and Private, 1817–1823 | „ | 87 |

| Officers, 1824 | „ | 102 |

| Privates, 1824–1829 | „ | 117 |

| George, Lord Bingham | „ | 121 |

| Officers, 1829 | „ | 128 |

| Officer and Privates, 1829–1832 | „ | 143 |

| Officers, 1832–1841 | „ | 155 |

| Central India, 1858, 1859 | „ | 165 |

| Lieutenant-General Sir Drury Curzon Drury Lowe, K.C.B. | „ | 179 |

| Seventeenth Lancers, 1895 | „ | 227 |

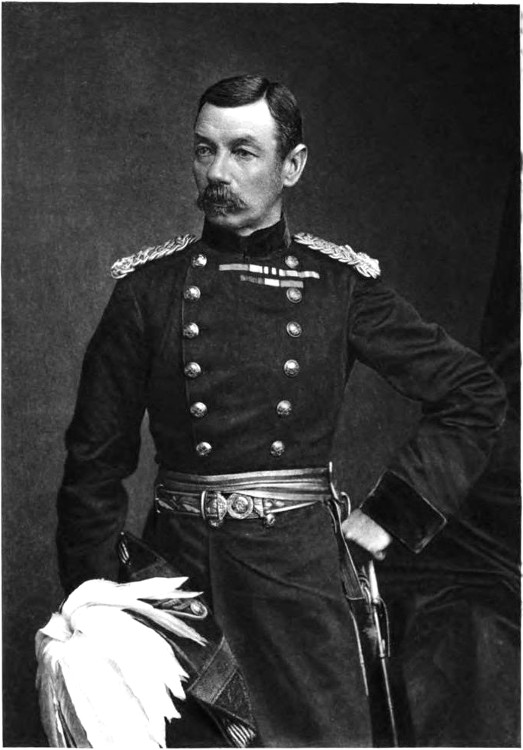

W. & D. Downey Photo.

Walker & Burstall Ph. Sc.

H.R.H. The Duke of Cambridge, K.G.

Colonel-in-chief 17th Lancers, 1876.

[1]

The British Cavalry Soldier and the British Cavalry Regiment, such as we now know them, may be said to date from 1645, that being the year in which the Parliamentary Army, then engaged in fighting against King Charles the First, was finally remodelled. At the outbreak of the war the Parliamentary cavalry was organised in seventy-five troops of horse and five of dragoons: the Captain of the 67th troop of horse was Oliver Cromwell. In the winter of 1642–43 Captain Cromwell was promoted to be Colonel, and entrusted with the task of raising a regiment of horse. This duty he fulfilled after a fashion peculiarly his own. Hitherto the Parliamentary horse had been little better than a lot of half-trained yeomen: Colonel Cromwell took the trouble to make his men into disciplined cavalry soldiers. Moreover, he raised not one regiment, but two, which soon made a mark by their superior discipline and efficiency, and finally at the battle of Marston Moor defeated the hitherto invincible cavalry of the Royalists. After that battle Prince Rupert, the Royalist cavalry leader, gave Colonel Cromwell the nickname of Ironside; the name was passed on to his regiments, which grew to be known no longer as Cromwell’s, but as Ironside’s.

In 1645, when the army was remodelled, these two famous regiments were taken as the pattern for the English cavalry; and having been blent into one, appear at the head of the list as Sir Thomas Fairfax’s Regiment of Horse. Fairfax was General-in-Chief, and his appointment to the colonelcy was of course a[2] compliment to the regiment. Besides Fairfax’s there were ten other regiments of horse, each consisting of six troops of 100 men apiece, including three corporals and two trumpeters. As the field-officers in those days had each a troop of his own, the full establishment of the regiments was 1 colonel, 1 major, 4 captains, 6 lieutenants, 6 cornets, 6 quartermasters. Such was the origin of the British Cavalry Regiment.

The troopers, like every other man in this remodelled army, wore scarlet coats faced with their Colonel’s colours—blue in the case of Fairfax. They were equipped with an iron cuirass and an iron helmet, armed with a brace of pistols and a long straight sword, and mounted on horses mostly under fifteen hands in height. For drill in the field they were formed in five ranks, with six feet (one horse’s length in those days), both of interval and distance, between ranks and files, so that the whole troop could take ground to flanks or rear by the simple words, “To your right (or left) turn;” “To your right (or left) about turn.” Thus, as a rule, every horse turned on his own ground, and the troop was rarely wheeled entire: if the latter course were necessary, ranks and files were closed up till the men stood knee to knee, and the horses nose to croup. This formation deservedly bore the name of “close order.” For increasing the front the order was, “To the right (or left) double your ranks,” which brought the men of the second and fourth ranks into the intervals of the first and third, leaving the fifth rank untouched. To diminish the front the order was: “To the right (or left) double your files,” which doubled the depth of the files from five to ten in the same way as infantry files are now doubled at the word, “Form fours.”

The principal weapons of the cavalry soldiers were his firearms, generally pistols, but sometimes a carbine. The lance, which had formerly been the favourite weapon, at Crecy for instance, was utterly out of fashion in Cromwell’s time, and never employed when any other arm was procurable. Firearms were the rage of the day, and governed the whole system of cavalry[3] attack. Thus in action the front rank fired its two pistols, and filed away to load again in the rear, while the second and third ranks came up and did likewise. If the word were given to charge, the men advanced to the charge pistol in hand, fired, threw it in the enemy’s face, and then fell in with the sword. But though there was a very elaborate exercise for carbine and pistol, there was no such thing as sword exercise.

Moreover, though the whole system of drill was difficult, and required perfection of training in horse and man, yet there was no such thing as a regular riding-school. If a troop horse was a kicker a bell was placed on his crupper to warn men to keep clear of his heels. If he were a jibber the following were the instructions given for his cure:—

“If your horse be resty so as he cannot be put forwards then let one take a cat tied by the tail to a long pole, and when he [the horse] goes backward, thrust the cat within his tail where she may claw him, and forget not to threaten your horse with a terrible noise. Or otherwise, take a hedgehog and tie him strait by one of his feet to the horse’s tail, so that he [the hedgehog] may squeal and prick him.”

For the rest, certain peculiarities should be noted which distinguish cavalry from infantry. In the first place, though every troop and every company had a standard of its own, such standard was called in the cavalry a Cornet, and in the infantry an Ensign, and gave in each case its name to the junior subaltern whose duty it was to carry it. In the second place there were no sergeants in old days except in the infantry, the non-commissioned officers of cavalry being corporals only. In the third place, the use of a wind instrument for making signals was confined to the cavalry, which used the trumpet; the infantry as yet had no bugle, but only the drum. There were originally but six trumpet-calls, all known by foreign names; of which names one (Butte sella or Boute selle) still survives in the corrupted form, “Boots and saddles.”

How then have these minor distinctions which formerly separated cavalry from infantry so utterly disappeared? Through[4] what channel did the two branches of the service contrive to meet? The answer is, through the dragoons. Dragoons were originally mounted infantry pure and simple. Those of the Army of 1645 were organised in ten companies, each 100 men strong. They were armed like infantry and drilled like infantry; they followed an ensign and not a cornet; they obeyed, not a trumpet, but a drum. True, they were mounted, but on inferior horses, and for the object of swifter mobility only; for they always fought on foot, dismounting nine men out of ten for action, and linking the horses by the rude process of throwing each animal’s bridle over the head of the horse standing next to it in the ranks. Such were the two branches of the mounted service in the first British Army.

A century passes, and we find Great Britain again torn by internal strife in the shape of the Scotch rebellion. Glancing at the list of the British cavalry regiments at this period we find them still divided into horse and dragoons; but the dragoons are in decided preponderance, and both branches unmistakably “heavy.” A patriotic Englishman, the Duke of Kingston, observing this latter failing, raised a regiment of Light Horse (the first ever seen in England) at his own expense, in imitation of the Hussars of foreign countries. Thus the Civil War of 1745 called into existence the only arm of the military service which had been left uncreate by the great rebellion of 1642–48. Before leaving this Scotch rebellion of 1745, let us remark that there took part in the suppression thereof a young ensign of the 47th Foot, named John Hale—a mere boy of seventeen, it is true, but a promising officer, of whom we shall hear more.

The Scotch rebellion over, the Duke of Kingston’s Light Horse were disbanded and re-established forthwith as the Duke of Cumberland’s own, a delicate compliment to their distinguished service. As such they fought in Flanders in 1747, but were finally disbanded in the following year. For seven years after the British Army possessed no Light Cavalry, until at the end of 1755 a single troop of Light Dragoons—3 officers and 65 men[5] strong—was added to each of the eleven cavalry regiments on the British establishment, viz., the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Dragoon Guards, and the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, 7th, 10th, and 11th Dragoons. These light dragoons were armed with carbine and bayonet and a single pistol, the second holster being filled (sufficiently filled, one must conclude) with an axe, a hedging-bill, and a spade. Their shoulder-belts were provided with a swivel to which the carbine could be sprung; for these light troops were expected to do a deal of firing from the saddle. Their main distinction of dress was that they wore not hats like the rest of the army, but helmets—helmets of strong black jacked leather with bars down the sides and a brass comb on the top. The front of the helmet was red, ornamented with the royal cypher and the regimental number in brass; and at the back of the comb was a tuft of horse-hair, half coloured red for the King, and half of the hue of the regimental facings for the regiment. The Light Dragoon-horse, we learn, was of the “nag or hunter kind,” standing from 14.3 to 15.1, for he was not expected to carry so heavy a man nor such cumbrous saddlery as the Heavy Dragoon-horse. Of this latter we can only say that he was a most ponderous animal, with a character of his own, known as the “true dragoon mould, short-backed, well-coupled, buttocked, quartered, forehanded, and limbed,”—all of which qualities had to be purchased for twenty guineas. At this time, and until 1764, all troop horses were docked so short that they can hardly be said to have kept any tail at all.

In the year 1758 nine of these eleven light troops took part in an expedition to the coast of France, England having two years before allied herself with Prussia against France for the great struggle known as the Seven Years’ War. 1759. So eminent was the service which they rendered, that in March 1759, King George II. decided to raise an entire regiment of Light Dragoons. On the 10th of March, accordingly, the first regiment was raised by General Elliott and numbered the 15th. The Major of this regiment, whom we shall meet again as Brigadier of cavalry in America, was William Erskine. On the 4th August another[6] regiment of Light Dragoons was raised by Colonel Burgoyne, and numbered the 16th. We shall see the 16th distinguished and Burgoyne disgraced before twenty years are past.

And while these two first Light Dragoon regiments are a-forming, let us glance across the water to Canada, where English troops are fighting the French, and seem likely to take the country from them. Among other regiments the 47th Foot is there, commanded (since March 1758) by Colonel John Hale, the man whom we saw fighting in Scotland as an ensign fourteen years ago. Within the past year he has served with credit under General Amherst at the capture of Cape Breton and Louisburg, and in these days of August, while Burgoyne is raising his regiment, he is before Quebec with General Wolfe. Three months more pass away, and on the 13th of October Colonel John Hale suddenly arrives in London. He is the bearer of despatches which are to set all England aflame with pride and sorrow; for on the 13th of September was fought the battle on the plains of Abraham which decided the capture of Quebec and the conquest of Canada. General Wolfe fell at the head of the 28th Regiment in the moment of victory; and Colonel Hale, who took a brilliant share in the action at the head of the 47th, has been selected to carry the great news to the King. Colonel Hale was well received; the better for that Wolfe’s last despatches, written but four days before the battle, had been marked by a tone of deep despondency; and, we cannot doubt, began to wonder what would be his reward. He did not wonder for long.

Very shortly after Hale’s arrival the King reviewed the 15th Light Dragoons, and was so well pleased with their appearance that he resolved to raise five more such regiments, to be numbered the 17th to the 21st.

The raising of the first of these regiments, that now known to us as the Seventeenth Lancers, was intrusted to Colonel John Hale, who received his commission for the purpose on the 7th[7] November. For the time, however, the regiment was known as the Eighteenth, for what reason it is a little difficult to understand; since the apology for a corps which received the number Seventeen was not raised until a full month later (December 19th). As we shall presently see, this matter of the number appears to have caused some heartburning, until Lord Aberdour’s corps, which had usurped the rank of Seventeenth, was finally disbanded, and thus yielded to Hale’s its proper precedence.

On the very day when Colonel Hale’s commission was signed, which we may call the birthday of the Seventeenth Lancers, the Board of General Officers was summoned to decide how the new regiment should be dressed. As to the colour of the coat there could be no doubt, scarlet being the rule for all regiments. For the facings white was the colour chosen, and for the lace white with a black edge, the black being a sign of mourning for the death of Wolfe. But the principal distinction of the new regiment was the badge, chosen by Colonel Hale and approved by the King, of the Death’s Head and the motto “Or Glory,”—the significance of which lies not so much in claptrap sentiment, as in the fact that it is, as it were, a perpetual commemoration of the death of Wolfe. It is difficult for us to realise, after the lapse of nearly a century and a half, how powerfully the story of that death seized at the time upon the minds of men.

Two days after the settlement of the dress, a warrant was issued for the arming of Colonel Hale’s Light Dragoons; and this, being the earliest document relating to the regiment that I have been able to discover, is here given entire:—

George R.

Whereas we have thought fit to order a Regiment of Light Dragoons to be raised and to be commanded by our trusty and well-beloved Lieutenant-Colonel John Hale, which Regiment is to consist of Four troops, of 3 sergeants, 3 corporals, 2 drummers, and 67 private men in each troop, besides commission officers, Our will and pleasure is, that out of the stores remaining within the Office of our Ordnance under your charge you cause 300 pairs of pistols, 292 carbines, 292 cartouche boxes, and 8 drums, to be issued and delivered to the said Lieutenant-Colonel John Hale, or to such[8] person as he shall appoint to receive the same, taking his indent as usual, and you are to insert the expense thereof in your next estimate to be laid before Parliament. And for so doing this shall be as well to you as to all other our officers and ministers herein concerned a sufficient Warrant.

Given at our Court at St. James’ the 9th day of November 1759, in the 33rd year of our reign.

To our trusty and well-beloved Cousin and Councillor John Viscount Ligonier, Master-General of our Ordnance.

These preliminaries of clothing and armament being settled, Colonel Hale’s next duty was to raise the men. Being a Hertfordshire man, the son of Sir Bernard Hale of Kings Walden, he naturally betook himself to his native county to raise recruits among his own people. The first troop was raised by Captain Franklin Kirby, Lieutenant, 5th Foot; the second by Captain Samuel Birch, Lieutenant, 11th Dragoons; the third by Captain Martin Basil, Lieutenant, 15th Light Dragoons; and the fourth by Captain Edward Lascelles, Cornet, Royal Horse Guards. If it be asked what stamp of man was preferred for the Light Dragoons, we are able to answer that the recruits were required to be “light and straight, and by no means gummy,” not under 5 feet 5½ inches, and not over 5 feet 9 inches in height. The bounty usually offered (but varied at the Colonel’s discretion) was three guineas, or as much less as a recruit could be persuaded to accept.

[9]

Whether from exceptional liberality on the part of Colonel Hale, or from an extraordinary abundance of light, straight, and by no means gummy men in Hertfordshire at that period, the regiment was recruited up to its establishment, we are told, within December. the space of seventeen days. Early in December it made rendezvous at Watford and Rickmansworth, whence it marched to Warwick and Stratford-on-Avon, and thence a fortnight later to Coventry. Meanwhile orders had already been given (10th December) that its establishment should be augmented by two more troops of the same strength as the original four; and little 1760. 28th Jan. more than a month later came a second order to increase each of the existing troops still further by the addition of a sergeant, a corporal, and 36 privates. Thus the regiment, increased almost as soon as raised from 300 to 450 men, and within a few weeks again strengthened by one-half, may be said to have begun life with an establishment of 678 rank and file. To them we must add a list of the original officers:—

Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant.—John Hale, 7th November 1759.

Major.—John Blaquiere, 7th November 1759.

Captains.

| Franklin Kirby | 4th | Nov. |

| Samuel Birch | 5th | „ |

| Martin Basil | 6th | „ |

| Edward Lascelles | 7th | „ |

| John Burton | 7th | „ |

| Samuel Townshend | 8th | „ |

Lieutenants.

| Thomas Lee | 4th | Nov. |

| William Green | 5th | „ |

| Joseph Hall | 6th | „ |

| Henry Wallop | 7th | „ |

| Henry Cope | 7th | „ |

| Yelverton Peyton | 8th | „ |

Cornets.

| Robert Archdall | 4th | Nov. |

| Henry Bishop | 5th | „ |

| Joseph Stopford | 6th | „ |

| Henry Crofton | 7th | „ |

| Joseph Moxham | 7th | „ |

| Daniel Brown | 8th | „ |

Adjutant.—Richard Westbury.

Surgeon.—John Francis.

[10]

Details of the regiment’s stay at Coventry are wanting, the only discoverable fact being that, in obedience to orders from headquarters, it was carefully moved out of the town for three days in August during the race-meeting. But as these first six months must have been devoted to the making of the raw recruits into soldiers, we may endeavour, with what scanty material we can command, to form some idea of the process. First, we must premise that with the last order for the augmentation of establishment was issued a warrant for the supply of the regiment with bayonets, which at that time formed an essential part of a dragoon’s equipment. Swords, it may be remarked, were provided, not by the Board of Ordnance, but by the Colonel. It is worth while to note in passing how strong the traditions of 1645 still remain in the dragoons. The junior subaltern is indeed no longer called an ensign, but a cornet; but the regiment is still ruled by the infantry drum instead of the cavalry trumpet.

Farrier. Officer. Trumpeter.

1763.

Let us therefore begin with the men; and as we have already seen what manner of men they were, physically considered, let us first note how they were dressed. Strictly speaking, it was not until 1764 that the Light Dragoon regiments received their distinct dress regulations; but the alterations then made were so slight that we may fairly take the dress of 1764 as the dress of 1760. To begin with, every man was supplied by the Colonel, by contract, with coat, waistcoat, breeches, and cloak. The coat, of [11]course, was of scarlet, full and long in the skirt, but whether lapelled or not before 1763 it is difficult to say. Lapels meant a good deal in those days; the coats of Horse being lapelled to the skirt, those of Dragoon Guards lapelled to the waist, while those of Dragoons were double-breasted and had no lapels at all. The Light Dragoons being a novelty, it is difficult to say how they were distinguished in this respect, but probably in 1760 (and certainly in 1763) their coats were lapelled to the waist with the colour of the regimental facing, the lapels being three inches broad, with plain white buttons disposed thereon in pairs.

The waistcoat was of the colour of the regimental facing—white, of course, for the Seventeenth; and the breeches likewise. The cloaks were scarlet, with capes of the colour of the facing. In fact, it may be said once for all that everything white in the uniform of the Seventeenth owes its hue to the colour of the regimental facing.

Over and above these articles the Light Dragoon received a pair of high knee-boots, a pair of boot-stockings, a pair of gloves, a comb, a watering or forage cap, a helmet, and a stable frock. Pleased as the recruit must have been to find himself in possession of smart clothes, it must have been a little discouraging for him to learn that his coat, waistcoat, and breeches were to last him for two, and his helmet, boots, and cloak for four years. But this was not all. He was required to supply out of an annual wage of £13: 14: 10 the following articles at his own expense:—

| 4 shirts at 6s. 10d. | £1 | 7 | 4 |

| 4 pairs stockings at 2s. 10d. | 0 | 11 | 4 |

| 2 pairs shoes at 6s. | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| A black stock | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Stock-buckle | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 1 pair leather breeches | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| 1 pair knee-buckles | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 2 pairs short black gaiters | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| 1 black ball (the old substitute for blacking) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 shoe-brushes | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| £4 | 7 | 1 |

[12]

Nor was even this all, for we find (though without mention of their price) that a pair of checked sleeves for every man, and a powder bag with two puffs for every two men had likewise to be supplied from the same slender pittance.

Turning next from the man himself to his horse, his arms, and accoutrements, we discover yet further charges against his purse, thus—

| Horse-picker and turnscrew | £0 | 0 | 2 |

| Worm and oil-bottle | 0 | 0 | 3½ |

| Goatskin holster tops | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Curry-comb and brush | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Mane comb and sponge | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Horse-cloth | 0 | 4 | 9 |

| Snaffle watering bridle | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| £0 | 11 | 7½ |

Also a pair of saddle-bags, a turn-key, and an awl.

All these various items were paid for, “according to King’s regulation and custom,” out of the soldier’s “arrears and grass money.” For his pay was made up of three items—

| “Subsistence” (5d. a day nominal) | £9 | 2 | 0 | per annum. |

| “Arrears” (2d. a day nominal) | 3 | 1 | 0 | „ |

| “Grass money” | 1 | 11 | 10 | „ |

| £13 | 14 | 10 | „ |

We must therefore infer that his “subsistence” could not be stopped for his “necessaries” (as the various items enumerated above are termed); but none the less twopence out of the daily stipend was stopped for his food, while His Majesty the King deducted for his royal use a shilling in the pound from the pay of every soul in the army. Small wonder that heavy bounty-money was needed to persuade men to enlist.

What manner of instruction the recruit received on his first appearance it is a little difficult to state positively, though it is still possible to form a dim conception thereof. The first thing[13] that he was taught, apparently, was the manual and firing exercise, of which we are fortunately able to speak with some confidence. As it contains some eighty-eight words of command, we may safely infer that by the time a recruit had mastered it he must have been pretty well disciplined. The minuteness of the exercise and the extraordinary number of the motions sufficiently show that it counted for a great deal. “The first motion of every word of command is to be performed immediately after it is given; but before you proceed to any of the other motions you must tell one, two, pretty slow, by making a stop between the words, and in pronouncing the word two, the motion is to be performed.” In those days the word “smart” was just coming into use, but “brisk” is the more common substitute. Let us picture the squad of recruits with their carbines, in their stable frocks, white breeches, and short black gaiters, and listen to the instructions which the corporal is giving them:—

“Now on the word Shut your pans, let fall the primer and take hold of the steel with your right hand, placing the thumb in the upper part, and the two forefingers on the lower. Tell one, two, and shut the pan; tell one, two, and seize the carbine behind the lock with the right hand; then tell one, two, and bring your carbine briskly to the recover. Wait for the word. Shut your—pans, one—two, one—two, one—two.”

There is no need to go further through the weary iteration of “Join your right hand to your carbine,” “Poise your carbine,” “Join your left hand to your carbine,” whereby the recruit learned the difference between his right hand and his left. Suffice it that the manual and firing exercise contain the only detailed instruction for the original Light Dragoon that is now discoverable. “Setting-up” drill there was apparently none, sword exercise there was none, riding-school, as we now understand it, there was none, though there was a riding-master. A “ride” appears to have comprised at most twelve men, who moved in a circle round the riding-master and received his teaching as best they could. But it must not be inferred on that account that the men could not[14] ride; on the contrary the Light Dragoons seem to have particularly excelled in horsemanship. Passaging, reining back, and other movements which call for careful training of man and horse, were far more extensively used for purposes of manœuvre than at present. Moreover, every man was taught to fire from on horseback, even at the gallop; and as the Light Dragoons received an extra allowance of ammunition for ball practice, it is reasonable to conclude that they spent a good deal of their time at the butts, both mounted and dismounted.

As to the ordinary routine life of the cavalry barrack, it is only possible to obtain a slight glimpse thereof from scattered notices. Each troop was divided into three squads with a corporal and a sergeant at the head of each. Each squad formed a mess; and it is laid down as the duty of the sergeants and corporals to see that the men “boil the pot every day and feed wholesome and clean.” The barrack-rooms and billets must have been pretty well filled, for every scrap of a man’s equipment, including his saddle and saddle-furniture, was hung up therein according to the position of his bed. As every bed contained at least two men, there must have been some tight packing. It is a relief to find that the men could obtain a clean pair of sheets every thirty days, provided that they returned the foul pair and paid three halfpence for the washing.

The fixed hours laid down in the standing orders of the Light Dragoons of 14th May 1760 are as follows:—

The drum beat for—

| Réveille from | Ladyday to | Michaelmas | 5.30 A.M. | Rest of year | 6.30 |

| Morning stables | „ | „ | 8 A.M. | „ | 9.0 |

| Evening stables | „ | „ | 4 P.M. | „ | 3.0 |

| “Rack up” | „ | „ | 8 P.M. | ||

| Tattoo[1] | „ | „ | 9 P.M. | „ | 8.0 |

If there was an order for a mounted parade the drum beat—

[15]

1st drum—“To horse.” The men turned out, under the eye of the quartermaster and fell in before the stable door in rank entire. Officers then inspected their troops; and each troop was told off in three divisions.

2nd drum—“Preparative.” By the Adjutant’s order.

3rd drum—“A flam.” The centre division stood fast; the right division advanced, and the left division reined back, each two horses’ lengths.

4th drum—“A flam.” The front and rear divisions passaged to right and left and covered off, thus forming the troop in three ranks.

5th drum—“A march.” The quartermasters led the troops to their proper position in squadron.

6th drum—“A flam.” Officers rode to their posts (troop-leaders on the flank of their troops), facing their troops.

7th drum—“A flam.” The officers halted, and turned about to their proper front.

Then the word was given—“Take care” (which meant “Attention”). “Draw your swords;” and the regiment was thus ready to receive the three squadron standards, which were escorted on to the ground and posted in the ranks, in the centre of the three squadrons.

Each squadron was then told off into half-squadrons, into three divisions, into half-ranks, into fours, and into files. As there are many people who do not know how to tell off a squadron by fours, it may be as well to mention how it was done. The men were not numbered off, but the officer went down each rank, beginning at the right-hand man, and said to the first, “You are the right-hand man of ranks by fours.” Then going on to the fourth he said, “You are the left-hand man of ranks by fours,” and so on. Telling off by files was a simpler affair. The officer rode down the ranks, pointing to each man, and saying alternately, “You move,” “You stand,” “You move,” “You stand.” Conceive what the confusion must have been if the men took it into their heads to be troublesome. “Beg your honour’s pardon, but you said I was to stand,” is the kind of speech that must have been heard pretty often in those days, when field movements went awry.

If the mounted parade went no further, the men marched back[16] to their quarters in fours, each of the three ranks separately; for in those days “fours” meant four men of one rank abreast. If field movements were practised, the system and execution thereof were left to the Colonel, unhampered by a drill-book. There was, however, a batch of “evolutions” which were prescribed by regulation, and required of every regiment when inspected by the King or a general officer. As these “evolutions” lasted, with some modification, till the end of the century, and (such is human nature) formed sometimes the only instruction, besides the manual exercise, that was imparted to the regiment, it may be as well to give a brief description thereof in this place. The efficiency of a regiment was judged mainly from its performance of the evolutions, which were supposed to be a searching test of horsemanship, drill, and discipline.

First then the squadron was drawn up in three ranks, at open order, that is to say, with a distance equal to half the front of the squadron between each rank. Then each rank was told off by half-rank, third of rank, and fours; which done, the word was given, “Officers take your posts of exercise,” which signified that the officers were to fall out to their front, and take post ten paces in rear of the commanding officer, facing towards the regiment. In other words, the regiment was required to go through the coming movements without troop or squadron leaders. Then the caution was given, “Take care to perform your evolutions,” and the evolutions began.

To avoid tedium an abridgment of the whole performance is given at some length in the Appendix, and it is sufficient to say here that the first two evolutions consisted in the doubling of the depth of the column. The left half-ranks reined back and passaged to the right until they covered the right half-ranks; and the original formation having been restored by more passaging, the right half-ranks did likewise. The next evolution was the conversion of three ranks into two, which was effected by the simple process of wheeling the rear rank into column of two ranks, and bringing it up to the flank of the front and centre[17] ranks. Then came further variations of wheeling, and wheeling about by half-ranks, thirds of ranks, and fours; each movement being executed of course to the halt on a fixed pivot, so that through all these intricate manœuvres the regiment practically never moved off its ground. No doubt when performed, as in smart regiments they were performed, like clockwork, these evolutions were very pretty—and of course, like all drill, they had a disciplinary as well as an æsthetic value; but it must be confessed that they left a blight upon the British cavalry for more than a century. It is only within the last twenty years that the influence of these evolutions, themselves a survival from the days of Alexander the Great, has been wholly purged from our cavalry drill-books.

Meanwhile at this time (and for full forty years after for that matter) an immense deal of time was given up to dismounted drill; for the dragoons had not yet lost their character of mounted infantry. To dismount a squadron, the even numbers (as we should now say) reined back and passaged to the right; and the horses were then linked with “linking reins” carried for the purpose, and left in charge of the two flank men, while the rest on receiving the word, “Squadrons have a care to march forward,” formed up in front, infantry wise, and were called for the time a battalion. This dismounted drill formed as important a feature of an inspection as the work done on horseback. Probably the survival of the march past the inspecting officer on foot may be traced to the traditions of those days.

If it be asked how time was found for so much dismounted work, the explanation is simple. From the 1st of May to the 1st October the troop horses were turned out to grass, and committed to the keeping of a “grass guard”—having, most probably, first gone through a course of bleeding at the hands of the farriers. It appears to have mattered but little how far distant the grass might be from the men’s quarters; for we find that if it lay six or eight miles away, the “grass guard” was to consist of a corporal and six men, while if it were within a mile or two, two[18] or three old soldiers were held to be amply sufficient. Men on “grass guard” were not allowed to take their cloaks with them, but were provided with special coats, whereof three or four were kept in each troop for the purpose. “Grass-time,” it may be added, was not the busy, but the slack time for cavalrymen in those days—the one season wherein furloughs were permitted.

The close of the “grass-time” must have been a curious period in the soldier’s year, with its renewal of the long-abandoned stable work and probable extra tightening of discipline. On the farriers above all it must have borne heavily, bringing with it, as we must conclude, the prospect of reshoeing every horse in the regiment. Moreover, the penalty paid by a farrier who lamed a horse was brutally simple: his liquor was stopped till the horse was sound. Nevertheless the farrier had his consolations, for he received a halfpenny a day for every horse under his charge, and must therefore have rejoiced to see his troop stable well filled. The men, probably, in a good regiment, required less smartening after grass-time than their horses. Light Dragoons thought a great deal of themselves, and were well looked after even on furlough. At the bottom of every furlough paper was a note requesting any officer who might read it to report to the regiment if the bearer were “unsoldierly in dress or manner.” We gather, from a stray order, “that soldiers shall wear their hair under their hats,” that even in those days men were bitten with the still prevailing fashion of making much of their hair; but we must hope that Hale’s regiment knew better than to yield to it.

Every man, of course, had a queue of leather or of his own hair, either hanging at full length, in which case it was a “queue,” or partly doubled back, when it became a “club.” Which fashion was favoured by Colonel Hale we are, alas! unable to say,[2] but we gain some knowledge of the coiffure of the Light Dragoons from the following standing orders:—

[19]

“The Light Dragoon is always to appear clean and dressed in a soldier-like manner in the streets; his skirts tucked back, a black stock and black gaiters, but no powder. On Sundays the men are to have white stocks, and be well powdered, but no grease on their hair.”

Here, therefore, we have a glimpse of the original trooper of the Seventeenth in his very best: his scarlet coat and white facings neat and spotless, the skirts tucked back to show the white lining, the glory of his white waistcoat, and the sheen of his white breeches. “Russia linen,” i.e. white duck, would be probably the material of these last—Russia linen, “which lasts as long as leather and costs but half-a-crown,” to quote one of our best authorities. Then below the white ducks, fitting close to the leg, came a neat pair of black cloth gaiters running down to dull black shoes, cleaned with “black ball” according to the regimental recipe. Round on his neck was a spotless white stock, helping, with the powder on his hair, to heighten the colour of his round, clean-shaven face. Very attractive he must have seemed to the girls of Coventry in the spring of 1760. What would we not give for his portrait by Hogarth as he appeared some fine Sunday in Coventry streets, with the lady of his choice on his arm, explaining to her that in the Light Dragoons they put no grease on their heads, and in proof thereof shaking a shower of powder from his hair on to her dainty white cap! Probably there were tender leave-takings when in September the regiment was ordered northward; possibly there are descendants of these men, not necessarily bearing their names, in Coventry to this day.

[20]

In September Hale’s Light Dragoons moved up to Berwick-on-Tweed, and thence into Scotland, where they were appointed to remain for the three ensuing years. Before it left Coventry the regiment, in common with all Light Dragoon regiments, had gathered fresh importance for itself from the magnificent behaviour of the 15th at Emsdorf on the 16th July; in which engagement Captain Martin Basil, who had returned to his own corps from Colonel Hale’s, was among the slain. The close of the year brings us to the earliest of the regimental muster-rolls, which is dated Haddington, 8th December 1760. One must speak of muster-rolls in the plural, for there is a separate muster-roll for each troop—regimental rolls being at this period unknown.

[21]

These first rolls are somewhat of a curiosity, for that every one of them describes Hale’s regiment as the 17th, the officers being evidently unwilling to yield seniority to the two paltry troops 1761. raised by Lord Aberdour. The next muster-rolls show considerable difference of opinion as to the regimental number, the head-quarter troop calling itself of the 18th, while the rest still claim 1762. to be of the 17th. In 1762 for the first time every troop 1763. acknowledges itself to be of the 18th, but in April 1763 the old conflict of opinion reappears; the head-quarter troop writes itself down as of the 18th, two other troops as of the 17th, while the remainder decline to commit themselves to any number at all. A gap in the rolls from 1763–1771 prevents us from following the controversy any further; but from this year 1763, the Seventeenth, 1763. as shall be shown, enjoys undisputed right to the number which it originally claimed.

Albeit raised for service in the Seven Years’ War, the regiment was never sent abroad, though it furnished a draft of fifty men and horses to the army under Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick. All efforts to discover anything about this draft have proved fruitless; though from the circumstance that Lieutenant Wallop is described in the muster-rolls as “prisoner of war to the French,” it is just possible that it served as an independent unit, and was actively engaged. But the war came to an end with the Treaty of Paris early in 1763; and with the peace came a variety of important changes for the Army, and particularly for the Light Dragoons.

The first change, of course, was a great reduction of the military establishment. Many regiments were disbanded—Lord Aberdour’s, the 20th and 21st Light Dragoons among them. Colonel Hale’s regiment was retained, and became the Seventeenth; and, as if to warrant it continued life, Hale himself was promoted to be full Colonel. We must not omit to mention here that, whether on account of his advancement, or from other simpler causes, Colonel Hale in this same year took to himself a wife, Miss Mary Chaloner of Guisbrough. History does not relate whether the occasion was duly celebrated by the regiment, either at the Colonel’s expense or at its own; but it is safe to assume that, in those hard-drinking days, such an opportunity for extra consumption of liquor was not neglected. If the fulness of the quiver be accepted as the measure of wedded happiness, then we may fearlessly assert that Colonel Hale was a happy man. Mrs. Hale bore him no fewer than twenty-one children, seventeen of whom survived him.

The actual command of the regiment upon Colonel Hale’s promotion devolved upon Lieut.-Colonel Blaquiere, whose duty it now became to carry out a number of new regulations laid down after the peace for the guidance of the Light Dragoons. 1764. By July 1764 these reforms were finally completed; and as they remained[22] in force for another twenty years, they must be given here at some length. The pith of them lies in the fact that the authorities had determined to emphasise in every possible way the distinction between Light and Heavy Cavalry. Let us begin with the least important, but most sentimental of all matters—the dress.

Privates

Coat.—(Alike for all ranks.) Scarlet, with 3-inch white lapels to the waist. White collar and cuffs, sleeves unslit. White lining. Braid on button-holes. Buttons, in pairs, white metal with regimental number.

Waistcoat.—White, unembroidered and unlaced. Cross pockets.

Breeches.—White, duck or leather.

Boots.—To the knee, “round toed and of a light sort.”

Helmet.—Black leather, with badge of white metal in front, and white turban round the base, plume and crest scarlet and white.

Forage Cap.—Red, turned up with white. Regimental number on little flap.

Shoulder Belts.—White, 2¾ inches broad. Sword belt over the right shoulder.

Waist Belt.—White, 1¾ inches broad.

Cloaks.—Red, white lining; loop of black and white lace on the top. White cape.

Epaulettes.—White cloth with white worsted fringe.

Corporals

Same as the men. Distinguished by narrow silver lace round the turn-up of the sleeves. Epaulettes bound with white silk tape, white silk fringe.

Sergeants

Same as the men. Epaulettes bound with narrow silver lace; silver fringe. Narrow silver lace round button-holes. Sash of spun silk, crimson with white stripe.

Quartermasters

Same as the men. Silver epaulettes. Sash of spun silk, crimson.

Officers

Same as the men; but with silver lace or embroidery at the Colonel’s[23] discretion. Silk sash, crimson. Silver epaulettes. Scarlet velvet stock and waist belts.

Trumpeters

White coats with scarlet lapels and lining; lace, white with black edge; red waistcoats and breeches. Hats, cocked, with white plume.

Farriers

Blue coats, waistcoats, and breeches. Linings and lapels blue; turn-up of sleeves white. Hat, small black bearskin, with a horse-shoe of silver-plated metal on a black ground. White apron rolled back on left side.

Horse Furniture.—White cloth holster caps and housings bordered with white, black-edged lace. XVII. L. D. embroidered on the housings on a scarlet ground, within a wreath of roses and thistles. King’s cypher, with crown over it and XVII. L. D. under it embroidered on the holster caps.

Officers had a silver tassel on the holster caps and at the corners of the housings.

Quartermasters had the same furniture as the officers, but with narrower lace, and without tassels to the holster caps.

Arms

Officers.—A pair of pistols with barrels 9 inches long. Sword (straight or curved according to regimental pattern), blade 36 inches long. A smaller sword, with 28-inch blade, worn in a waist belt, for foot duty.

Men.—Sword and pistols, as the officers. Carbine, 2 feet 5 inches long in the barrel. Bayonet, 12 inches long. Carbine and pistols of the same bore. Cartridge-box to hold twenty-four rounds.

So much for the outward adornment and armament of the men, to which we have only to add that trumpeters, to give them further distinction, were mounted on white horses, and carried a sword with a scimitar blade. Farriers, who were a peculiar people in those days, were made as dusky as the trumpeters were gorgeous. They carried two churns instead of holsters on their saddles, wherein to stow their shoeing tools, etc., and black bearskin furniture with crossed hammer and pincers on the housing. Their weapon was an axe, carried, like the men’s swords, in a belt[24] slung from the right shoulder. When the men drew swords, the farriers drew axes and carried them at the “advance.” The old traditions of the original farrier still survive in the blue tunics, black plumes, and axes of the farriers of the Life Guards, as well as in the blue stable jackets of their brethren of the Dragoons.

Passing now from man to horse, we must note that from 27th July 1764 it was ordained that the horses of Horse and Dragoons should in future wear their full tails, and that those of Light Dragoons only should be docked.[3] This was the first step towards the reduction of the weight to be carried by the Light Dragoon horse. The next was more practical. A saddle much lighter than the old pattern was invented, approved, and adopted, with excellent results. It was of rather peculiar construction: very high in the pommel and cantle, and very deep sunk in the seat, in order to give a man a steadier seat when firing from on horseback. Behind the saddle was a flat board or tray, on to which the kit was strapped in a rather bulky bundle. It was reckoned that this saddle, with blanket and kit complete, 30 lbs of hay and 5 pecks of oats, weighed just over 10 stone (141 lbs.); and that the Dragoon with three days’ rations, ammunition, etc., weighed 12 stone 7 lbs. more; and that thus the total weight of a Dragoon in heavy marching order with (roughly speaking) three days’ rations for man and horse, was 22 stone 8 lbs. In marching from quarter to quarter in England, the utmost weight on a horse’s back was reckoned not to exceed 16 stone.

A few odd points remain to be noticed before the question of saddlery is finally dismissed. In the first place, there was rather an uncouth mixture of colours in the leather, which, though designed to look well with the horse furniture, cannot have been beautiful without it. Thus the head collar for ordinary occasions was brown, but for reviews white; bridoons were black, bits of bright steel; the saddle was brown, and the carbine bucket black. These buckets were, of course, little more than leather caps five[25] or six inches long, fitting over the muzzle of the carbine, practically the same as were served out to Her Majesty’s Auxiliary Cavalry less than twenty years ago. Light Dragoons, however, had a swivel fitted to their shoulder-belt to which the carbine could be sprung, and the weapon thus made more readily available. The horse furniture of the men was not designed for ornament only; for, being made in one piece, it served to cover the men when encamped under canvas. As a last minute point, let it be noted that the stirrups of the officers were square, and of the men round at the top.

We must take notice next of a more significant reform, namely, the abolition of side drums and drummers in the Light Dragoons, and the substitution of trumpeters in their place. By this change the Light Dragoons gained an accession of dignity, and took equal rank with the horse of old days. The establishment of trumpeters was, of course, one to each troop, making six in all. When dismounted they formed a “band of music,” consisting of two French horns, two clarionets, and two bassoons, which, considering the difficulties and imperfections of those instruments as they existed a century and a quarter ago, must have produced some rather remarkable combinations of sound. None the less we have here the germ of the regimental band, which now enjoys so high a reputation.

Over and above the trumpeters, the regiment enjoyed the possession of a fife, to whose music the men used to march. At inspection the trumpets used to sound while the inspecting officer went down the line; and when the trumpeters could blow no longer, the fife took up the wondrous tale and filled up the interval with an ear-piercing solo. The old trumpet “marches” are still heard (unless I am mistaken) when the Household Cavalry relieve guard at Whitehall. But more important than these parade trumpet sounds is the increased use of the trumpet for signalling movements in the field. The original number of trumpet-calls in the earliest days of the British cavalry was, as has already been mentioned, but six. These six were apparently[26] still retained and made to serve for more purposes than one; but others also were added to them. And since, so far as we can gather, the variety of calls on one instrument that could be played and remembered was limited by human unskilfulness and human stupidity, this difficulty was overcome by the employment of other instruments. These last were the bugle horn and the French horn; the former the simple curved horn that is still portrayed on the appointments of Light Infantry, the latter the curved French hunting horn. The united efforts of trumpet, bugle horn, and French horn availed to produce the following sounds:—

| Stable call—Trumpet. | |

| (Butte Sella).[4] | Boot and saddle—Trumpet. |

| (Monte Cavallo).[4] | Horse and away—Trumpet. But sometimes bugle horn; used also for evening stables. |

| (? Tucquet).[4] | March—Trumpet. |

| Water—Trumpet. | |

| (Auquet).[4] | Setting watch or tattoo—Trumpet. Used also for morning stables. |

| (? Tucquet).[4] | The call—Trumpet. Used for parade or assembly. |

| Repair to alarm post—Bugle horn. | |

| (Alla Standarda).[4] | Standard call—Trumpet. Used for fetching and lodging standards; and also for drawing and returning swords. |

| Preparative for firing—Trumpet. | |

| Cease firing—Trumpet. | |

| Form squadrons, form the line—Bugle horn. | |

| Advance—Trumpet. | |

| (Carga).[4] | Charge or attack—Trumpet. |

| Retreat—French horns. | |

| Trot, gallop, front form—Trumpet. | |

| Rally—Bugle horn. | |

| Non-commissioned officers’ call—Trumpet. | |

| The quick march on foot—The fife. | |

| The slow march on foot—The band of music. |

All attempts to discover the notation of these calls have, I regret to say, proved fruitless, so that I am unable to state[27] positively whether any of them continue in use at the present day. The earliest musical notation of the trumpet sounds that I have been able to discover dates from the beginning of this century,[5] and is practically the same as that in the cavalry drill-book of 1894; so that it is not unreasonable to infer that the sounds have been little altered since their first introduction. Indeed, it seems to me highly probable that the old “Alla Standarda,” which is easily traceable back to the first quarter of the seventeenth century, still survives in the flourish now played after the general salute to an inspecting officer. As to the actual employment of the three signalling instruments in the field, we shall be able to judge better while treating of the next reform of 1763–1764, viz. that of the drill.

The first great change wrought by the experience of the Seven Years’ War on the English Light Dragoon drill was the final abolition of the formation in three ranks. Henceforward we shall never find the Seventeenth ranked more than two deep. Further, we find a general tendency to less stiffness and greater flexibility of movement, and to greater rapidity of manœuvre. The very evolutions sacrifice some of their prettiness and precision in order to gain swifter change of formation. Thus, when the left half rank is doubled in rear of the right, the right, instead of standing fast, advances and inclines to the left, while the latter reins back and passages to the right, thus accomplishing the desired result in half the time. Field manœuvres are carried out chiefly by means of small flexible columns, differing from the present in one principal feature only, viz. that the rear rank in 1763 does not inseparably follow the front rank, but that each rank wheels from line into column of half-ranks or quarter-ranks independently. Moreover, we find one great principle pervading all field movements: that Light Dragoons, for the dignity of their name, must move with uncommon rapidity and smartness. The very word “smart,” as applied to the action of a soldier, appears, so far as I know, for the first time in a drill-book made for Light[28] Dragoons at this period. In illustration, let us briefly describe a parade attack movement, which is particularly characteristic.

The regiment having been formed by previous manœuvres in echelon of wings (three troops to a wing) from the left, the word is given, “Advance and gain the flank of the enemy.”

First Trumpet.—The right files (of troops?) of each wing gallop to the front, and form rank entire; unswivel their carbines, and keep up a rapid irregular fire from the saddle.

Under cover of this fire the echelon advances.

Second Trumpet.—The right wing forms the “half-wedge” (single echelon), passes the left or leading wing at an increased pace, and gains the flank of the imaginary enemy by the “head to haunch” (an extremely oblique form of incline), and forms line on the flank.

Third Trumpet—“Charge.”—The skirmishers gallop back through the intervals to the rear of their own troops, and remain there till the charge is over.

French Horns—“Retreat.”—The skirmishers gallop forward once more, and keep up their fire till the line is reformed.

The whole scheme of this attack is perhaps a shade theatrical, and, indeed, may possibly have been designed to astonish the weak mind of some gouty old infantry general; but a regiment that could execute it smartly could hardly have been in a very inefficient state.

In 1765 the Seventeenth was moved to Ireland, though to what part of Ireland the gap in the muster-rolls disenables us to say. Almost certainly it was split up into detachments, where we have reason to believe that the troop officers took pains to teach their men the new drill. We must conceive of the regiment’s life as best we may during this period, for we have no information to help us. Colonel Blaquiere, we have no doubt, paid visits to the outlying troops from time to time, and probably was able now and again to get them together for work in the field, particularly when an inspecting officer’s visit was at hand. We know, from the inspection returns, that the Seventeenth advanced and gained the flank of the enemy every year, in a fashion which commanded[29] the admiration of all beholders. And let us note that in this very year the British Parliament passed an Act for the imposition of stamp duties on the American Colonies—preparing, though unconsciously, future work on active service for the Seventeenth.

For the three ensuing years we find little that is worth the chronicling, except that in 1766 the regiment suffered, for a brief period, a further change in its nomenclature, the 15th, 16th, and 17th being renumbered the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Light Dragoons. In this same year we discover, quite by chance, that two troops of the Seventeenth were quartered in the Isle of Man, for how long we know not. In 1767 a small matter crops up which throws a curious light on the grievances of the soldier in those days. Bread was so dear that Government was compelled to help the men to pay for it, and to ordain that on payment of fivepence every man should receive a six-pound loaf—which loaf was to last him for four days. Let us note also, as a matter of interest to Colonel Blaquiere, a rise in the value of another article, namely, the troop horse, whereof the outside price was in this year raised from twenty to twenty-two guineas.

In 1770 we find Colonel Hale promoted to be Governor of Limerick, and therewith severed from the regiment which he had raised. As his new post must presumably have brought him over to Ireland, we may guess that the regiment may have had an opportunity of giving him a farewell dinner, and, as was the fashion in those days, of getting more than ordinarily drunk. From this time forward we lose sight of Colonel Hale, though he is still a young and vigorous man, and has thirty-three years of life before him. His very name perishes from the regiment, for if ever he had an idea of placing a son therein, that hope must have been killed long before the arrival of his twenty-first child. His successor in the colonelcy was Colonel George Preston of the Scots Greys, a distinguished officer who had served at Dettingen, Fontenoy, and other actions of the war of 1743–47, as well as in the principal battles of the Seven Years’ War.

Meanwhile, through all these years, the plot of the American[30] 1770. dispute was thickening fast. From 1773 onwards the news of trouble and discontent across the Atlantic became more frequent; and at last in 1774 seven infantry regiments were despatched to Boston. Then probably the Seventeenth pricked up its ears and discussed, with the lightest of hearts, the prospect of fighting the 1775. rebels over the water. The year 1775 had hardly come in when the order arrived for the regiment to complete its establishment with drafts from the 12th and 18th, and hold itself in readiness to embark at Cork for the port of Boston. It was the first cavalry regiment selected for the service—a pretty good proof of its reputation for efficiency.[6]

Marching Order. Field-day Order. Review Order.

PRIVATES, 1784–1810.

[31]

It would be beside the purpose to enter upon a relation of the causes which led to the rupture between England and the thirteen North American Colonies, and to the war of American Independence. The immediate ground of dispute was, however, one in which the Army was specially interested, namely, the question of Imperial defence. Fifteen years before the outbreak of the American War England had, by the conquest of Canada, relieved the Colonies from the presence of a dangerous neighbour on their northern frontier, and for this good service she felt justified in asking from them some return. Unfortunately, however, the British Government, instead of leaving it to the Colonies to determine in what manner their contribution to the cost of Imperial defence should be raised, took the settlement of the question into its own hands, as a matter wherein its authority was paramount. Ultimately by a series of lamentable blunders the British ministers contrived to create such irritation in America that the Colonies broke into open revolt.

It was in the year 1774 that American discontent reached its acutest stage; and the centre of that discontent was the city of Boston. In July General Gage, at that time in command of the forces in America, and later on to be Colonel-in-Chief of the 17th Light Dragoons, feeling that the security of Boston was now seriously threatened by the rebellious attitude of the citizens, moved down with some troops and occupied the neck of the[32] 1774. isthmus on which the city stands. This step increased the irritation of the people so far that in a month or two he judged it prudent to entrench his position and remove all military stores from outlying stations into Boston. By November the temper of the Colonists had become so unmistakably insubordinate that Gage issued a proclamation warning them against the consequences of revolt. This manifesto was taken in effect as a final signal for general and open insurrection. Rhode Island and New Hampshire broke out at once; and the Americans began their military preparations by seizing British guns, stores, and ammunition 1775. wherever they could get hold of them. By the opening of 1775 the seizure, purchase, and collection of arms became so general that Gage took alarm for the safety of a large magazine at Concord, some twenty miles from Boston, and detached a force to secure it. This expedition it was that led to the first shedding of blood. The British troops succeeded in reaching Concord and destroying the stores; but they had to fight their way back to Boston through the whole population of the district, and finally arrived, worn out with fatigue, having lost 240 men, killed, 19th April. wounded, and missing, out of 1800. The Americans then suddenly assembled a force of 20,000 men and closely invested Boston.

It was just about this time that there arrived in Boston Captain Oliver Delancey, of the 17th Light Dragoons, with despatches announcing that reinforcements would shortly arrive from England under the command of Generals Howe and Clinton. Captain Delancey was charged with the duty of preparing for the reception of his regiment, and in particular of purchasing horses whereon to mount it. Two days after his arrival, therefore, he started for New York to buy horses, only to find at his journey’s end that New York also had risen in insurrection, and that there was nothing for it but to return to Boston.

And while Delancey was making his arrangements, the Seventeenth was on its way to join him. The 12th and 18th Regiments had furnished the drafts required of them, and the Seventeenth,[33] 1775. thus raised to some semblance of war strength, embarked for its first turn on active service. Here is a digest of their final muster, dated, Passage, 10th April 1775, and 10th April. endorsed “Embarkation”—

Lieutenant-Colonel.—Samuel Birch.

Major.—Henry Bishop.

Adjutant.—John St. Clair, Cornet.

Surgeon.—Christopher Johnston.

Surgeon’s mate.—Alexander Acheson.

Deputy-Chaplain.—W. Oliver.

Major Bishopp’s Troop.

Robert Archdale, Captain. Frederick Metzer, Cornet.

1 Quartermaster, 2 sergeants, 2 corporals, 1 trumpeter, 29 dragoons, 31 horses.

Captain Straubenzee’s Troop.

Henry Nettles, Lieutenant. Sam. Baggot, Cornet.

5 Non-commissioned officers, 1 trumpeter, 26 dragoons, 31 horses.

Captain Moxham’s Troop.

Ben. Bunbury, Lieutenant. Thomas Cooke, Cornet.

5 Non-commissioned officers, 1 trumpeter, 26 dragoons, 31 horses.

Captain Delancey’s Troop.

Hamlet Obins, Lieutenant. James Hussey, Cornet.

5 Non-commissioned officers, 1 trumpeter, 1 hautboy, 27 dragoons,

31 horses.

Captain Needham’s Troop.

Mark Kerr, Lieutenant. Will. Loftus, Cornet.

5 Non-commissioned officers, 1 trumpeter, 26 dragoons, 31 horses.

Captain Crewe’s Troop.

Matthew Patteshall, Lieutenant. John St. Clair (Adjutant), Cornet.

5 Non-commissioned officers, 1 trumpeter, 1 hautboy, 26 dragoons, 31 horses.

[34]

What manner of scenes there may have been at the embarkation that day at Cork it is impossible to conjecture. We can only bear in mind that there were a great many Irishmen in the ranks, and that probably all their relations came to see them off, and draw what mental picture we may. Meanwhile it is worth while to compare two embarkations of the regiment on active service, at roughly speaking, a century’s interval. In 1879 the Seventeenth with its horses sailed to the Cape in two hired transports—the England and the France. In 1776 it filled no fewer than seven ships, the Glen, Satisfaction, John and Jane, Charming Polly, John and Rebecca, Love and Charity, Henry and Edward—whereof the very names suffice to show that they were decidedly small craft.

The voyage across the Atlantic occupied two whole months, but, like all things, it came to an end; and the regiment June 15–19. disembarked at Boston just in time to volunteer its services for the first serious action of the war. That action was brought about in this way. Over against Boston, and divided from it by a river of about the breadth of the Thames at London Bridge, is a peninsula called Charlestown. It occurred, rather late in the day, to General Gage that an eminence thereupon called Bunker’s Hill was a position that ought to be occupied, inasmuch as it lay within cannon-shot of Boston and commanded the whole of the town. Unfortunately, precisely the same idea had occurred to the Americans, who on the 16th June seized the hill, unobserved by Gage, and proceeded to entrench it. By hard work and the aid of professional engineers they soon made Bunker’s Hill into a formidable position; so that Gage, on the following day, found that his task was not that of marching to an unoccupied height, but of attacking an enemy 6000 strong in a well-fortified post. None the less he attacked the 6000 Americans with 2000 English, and drove them out at the bayonet’s point after the bloodiest engagement thitherto fought by the British army. Of the 2000 men 1054, including 89 officers, went down that day; and the British occupied the Charlestown peninsula.

[35]

The acquisition was welcome, for the army was sadly crowded in Boston and needed more space; but the enemy soon erected new works which penned it up as closely as ever. Moreover the Americans refused to supply the British with fresh provisions, so that the latter—what with salt food, confinement, and the heat of the climate—soon became sickly. The Seventeenth were driven to their wit’s end to obtain forage for their horses. It was but a poor exchange alike for animals and men to forsake the ships for a besieged city. The summer passed away and the winter came on. The Americans pressed the British garrison more hardly than ever through the winter months, and finally, on the 1776.2nd March 1776, opened a bombardment which fairly drove the English out. On the 17th March Boston was evacuated, and the army, 9000 strong, withdrawn by sea to Halifax.

However mortifying it might be to British sentiment, this evacuation was decidedly a wise and prudent step; indeed, but for the determination of King George III. to punish the recalcitrant Boston, it is probable that it would have taken place long before, for it was recommended both by Gage, who resigned his command in August 1775, and by his successor, General Howe. They both saw clearly enough that, as England held command of the sea, her true policy was to occupy the line of the Hudson River from New York in the south to Lake Champlain in the north. Thereby she could isolate from the rest the seven provinces of Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, and reduce them at her leisure; which process would be the easier, inasmuch as these provinces depended almost entirely on the States west of the Hudson for their supplies. The Americans, being equally well aware of this, and having already possession of New York, took the bold line of attempting to capture Canada while the English were frittering their strength away at Boston. And they were within an ace of success. As early as May 1775 they captured Ticonderoga and the only King’s ship in Lake Champlain, and in November they obtained possession of[36] Chambly, St. John’s, and Montreal. Fortunately Quebec still held out, though reduced to great straits, and saved Canada to England. On the 31st December the little garrison gallantly repelled an American assault, and shortly after it was relieved by the arrival of a British squadron which made its way through the ice with reinforcements of 3500 men under General Burgoyne. This decided the fate of Canada, from which the Americans were finally driven out in June 1776.

One other small incident requires notice before we pass to the operations of Howe’s army (whereof the Seventeenth formed part) in the campaign of 1776. Very early in the day Governor Martin of North Carolina had recommended the despatch of a flying column or small force to the Carolinas, there to rally around it the loyalists, who were said to be many, and create a powerful diversion in England’s favour. Accordingly in December 1775, five infantry regiments under Lord Cornwallis were despatched from England to Cape Fear, whither General Clinton was sent by Howe to meet them and take command. An attack on Charleston by this expedition proved to be a total failure; and on the 21st June 1776, Clinton withdrew the force to New York. This episode deserves mention, because it shows how early the British Government was bitten with this plan of a Carolina campaign, which was destined to cost us the possession of the American Colonies. Three times in the course of this history shall we see English statesmen make the fatal mistake of sending a weak force to a hostile country in reliance on the support of a section of disaffected inhabitants, and each time (as fate ordained it) we shall find the Seventeenth among the regiments that paid the inevitable penalty. From this brief digression let us now return to the army under General Howe.

While the bulk of this force was quartered at Halifax, the Seventeenth lay, for convenience of obtaining forage, at Windsor, some miles away. In June the 16th light Dragoons arrived at Halifax from England with remounts for the regiment; but it is questionable whether they had any horses to spare, for[37] we find that out of 950 horses 412 perished on the voyage. About the same time arrived orders for the increase of the Seventeenth by 1 cornet, 1 sergeant, 2 corporals, and 30 privates per troop; but the necessary recruits had not been received by the time when the campaign opened. On the 11th June the regiment, with the rest of Howe’s army, was once more embarked at Halifax and reached Sandy Hook on the 29th. Howe then landed his force on Staten Island, and awaited the arrival of his brother, Admiral Lord Howe, who duly appeared with a squadron and reinforcements on the 1st July. Clinton with his troops from Charleston arrived on the 1st August, and further reinforcements from England on the 12th. Howe had now 30,000 men, 12,000 of them Hessians, under his command in America, two-thirds of whom were actually on the spot around New York.