R. F. Taylor

Col. 33d N.Y.S. Vols

R. F. Taylor

Col. 33d N.Y.S. Vols

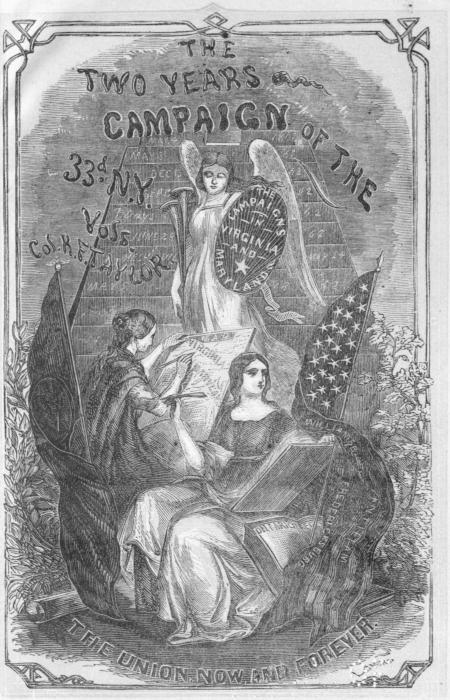

THE TWO YEARS CAMPAIGN OF THE 33d. N.Y. Vols.

Col. R. F. Taylor.

THE UNION NOW AND FOREVER.

BY DAVID W. JUDD,

(Correspondent of the New York Times.)

Illustrations from Drawings by Lieut. L. C. Mix.

ROCHESTER:

BENTON & ANDREWS, 29 BUFFALO STREET.

1864.

This volume does not propose to review the causes, rise and progress of the unhappy civil strife, which for more than two years has rent our land; neither is it designed to describe all the operations which have marked the war in the single department of Virginia and Maryland.

It aims merely, as the title page indicates, at giving a narrative of one of the many Regiments which the Empire State has sent into the field, together with a description of the various campaigns in which it participated.

Nor should it be inferred, from the embodying of their experience in book form, that the soldiers of the 33d esteem their services more worthy of notice than those of numerous other Regiments. The work has its origin in the general desire expressed on the part of the members and friends of the command to have the scenes and incidents connected with its two years’ history collected and preserved in readable shape—valuable for future reference—interesting as a souvenir of the times.

The plan, as will readily be seen, comprises separate sketches of each company until merged into the Regiment; the regimental history from the period of its organization at Elmira, in May, 1861, until its return from the war, May, 1863; brief biographies of the various officers, and muster rolls of the men.

Such facts as did not come under the personal observation of the writer, have been derived from the statements and reports of Division and Brigade Generals, and other sources. Owing to the confusion consequent upon the death, disease and desertion attending a two years’ campaign of nearly one thousand men, some of the members may find themselves incorrectly “accounted for.”

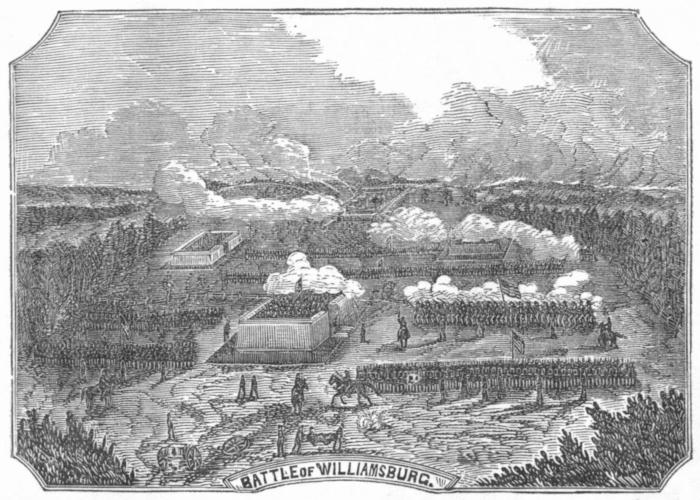

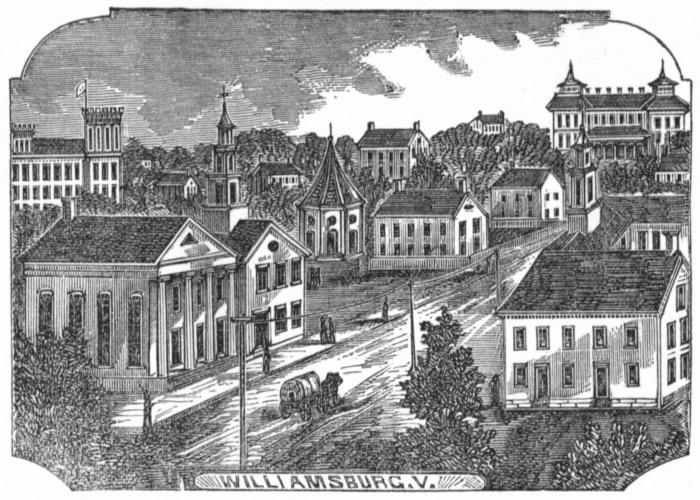

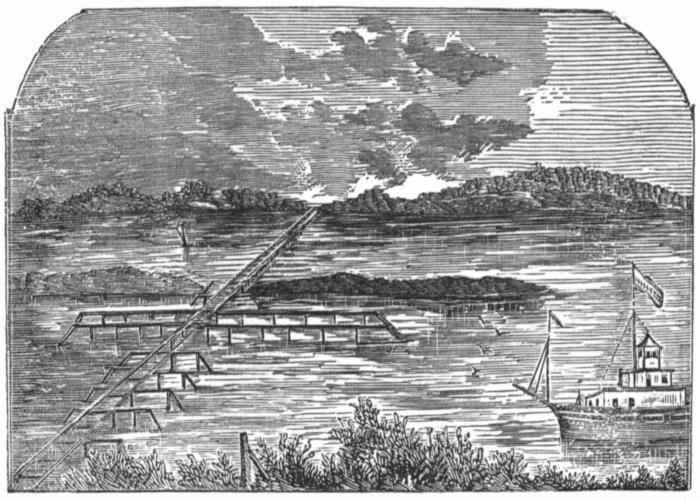

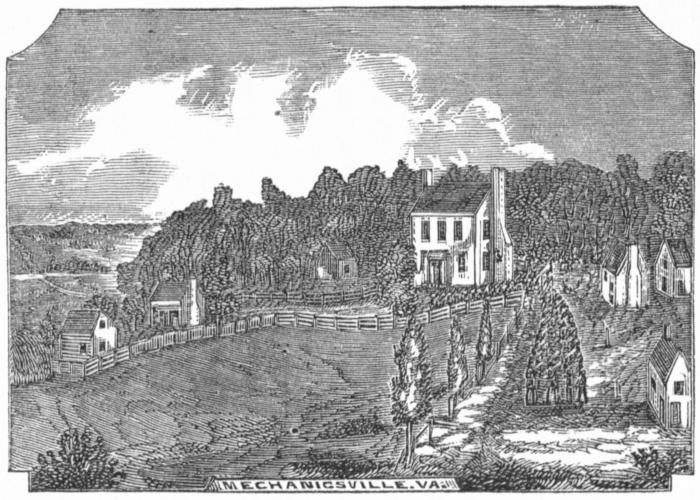

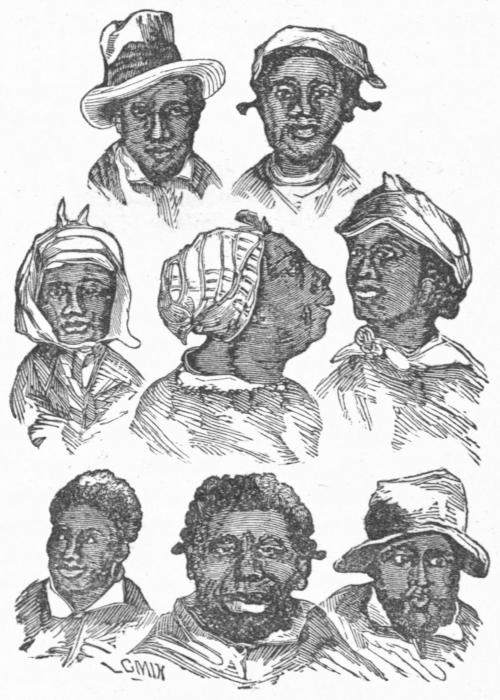

A double interest attaches to the numerous engravings which embellish the volume, from the fact that instead of being gotten up to order, they were “drawn on the spot” by a skilful artist—an officer of the Regiment—who participated in all the scenes through which it passed. They constitute in themselves a pictorial history of the first two years of the Eastern campaigns.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Patriotism of Central New York.—Determination of the People to put down the Rebellion.—Raising of Troops.—Organization of the various Companies of the 33d New York Regiment, | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Elmira a Place of Rendezvous.—Arrival of Troops.—Organization of the Thirty-third.—A Beef Incident.—Presentation of a Flag.—Mustering into the United States Service, | 30 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Departure for Washington.—Patriotism of the Williamsport Ladies.—Arrival at the Capital.—Camp Granger.—Destroying a Liquor Establishment.—“Cleaning-out” a Clam Peddler.—Review by Governor Morgan.—First Death in the Regiment.—First Battle of Bull Run.—Changes among the Officers, | 39 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Removal to Vicinity of Chain Bridge.—Upsetting of Ambulances.—The Regiment Brigaded.—Frequent Alarms and Reconnoissances.—Reviewed by General McClellan.—Crossing of the Potomac.—Forts Marcy and Ethan Allen.—Formation of Divisions.—Colonel Stevens.—First Skirmish with the Enemy at Lewinsville Camp.—General Brooks.—General Davidson.—The Seventy-seventh New York added to the Brigade.—A Novel Wedding in Camp.—Circulating a Temperance Pledge.—Battle of Drainesville, | 45[2] |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Grand Review of the Army, at Bailey’s Cross-Roads.—Pleasant Acquaintances formed.—Changes and Deaths at Camp Griffin.—Dissatisfaction at the General Inactivity.—President’s War Orders.—Gen. McClellan’s Plans and Correspondence with the President, | 60 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Advance of the Army of the Potomac.—The Thirty-third taking up the line of march.—Flint Hill.—General McClellan decides to move on Richmond by way of the Peninsula.—Embarkation of the Thirty-third at Alexandria.—Embarkation Scene.—Mount Vernon.—The Monitor.—Arrival at Fortress Monroe.—Agreeable change of the climate.—Hampton.—Reconnoissance to Watt’s Creek.—Rebel Epistolary Literature.—Bathers shelled by the rebel gunboat Teaser.—Building a Redoubt, | 56 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Continued Arrival of Troops.—Advance of the Army of the Peninsula.—Arrival of the Regiment at Young’s Mills.—An Aged Contraband.—Lee’s Mills.—The Various Companies of the Thirty-third ordered to the Front.—Caisson struck by a rebel Ball.—Continued Firing of the Enemy.—Falling back of the National Forces.—Heavy Rain Storm.—The Beef Brigade.—Enemy’s Fortifications.—Troublesome Insects.—Night Skirmishing.—Celerity of the Paymaster’s Movements.—Evacuation of Yorktown.—Early information of the fact brought to Col. Corning by Contrabands.—The Rebel Works taken possession of, | 76 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Battle of Williamsburg, | 82 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Williamsburg.—Condition of the Roads.—Pamunkey River.—Contrabands.—Arrival of General Franklin, | 94 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Battle of Mechanicsville, | 103[3] |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| “Gaines’ Farm.”—Liberty Hall.—Battle of Seven Pines.—Fair Oaks.—Rapid rise of the Chickahominy.—The Gaines Estate.—An aged Negro.—Golden’s Farm.—Camp Lincoln.—Letter from an Officer, | 109 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Proximity to the Rebels.—Colonel Taylor fired at by a Sharpshooter.—Picket Skirmishing.—Building a Bridge.—Position of Affairs.—General McClellan Reconnoitring.—He writes to the President.—Lee’s Plans.—Second Battle of Mechanicsville.—Shelling the Thirty-third’s Camp.—Battle of Gaines’ Farm.—A Retreat to the James decided upon, | 118 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Battle of Golden’s Farm, | 127 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Retreat Commenced.—The Thirty-third one of the last Regiments to Leave.—Savage’s Station.—Destruction of Property.—General Davidson Sun-struck, | 134 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| A Tedious Night March.—White Oak Swamp.—Sudden Attack by the Enemy.—Narrow Escape of General Smith.—A Cowardly Colonel, | 142 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

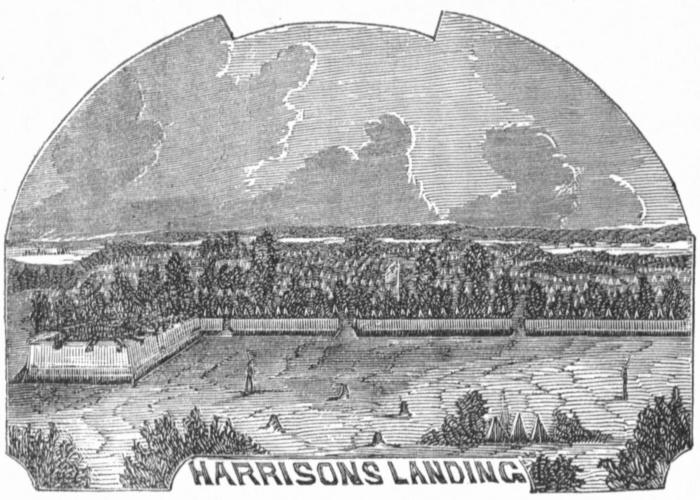

| The Enemy Out-generaled.—Arrival at Malvern Hills.—The Thirty-third assigned to Picket Duty.—Battle of Malvern.—Arrival at Harrison’s Landing.—General McClellan’s Address.—Building a Fort.—Slashing Timber, | 148[4] |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Arrival of Reinforcements.—Visit of President Lincoln.—Attack by the Enemy.—Reconnoissance to Malvern Hills.—A Deserter drummed out of Camp.—A change of base decided upon.—Return March to Fortress Monroe.—Scenes by the way, | 159 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Abandonment of the Peninsula.—Arrival at Acquia Creek.—Disembarkation at Alexandria.—Pope’s Operations.—Death of Generals Stevens and Kearney.—Retreat to the Fortifications.—Responsibility for the Disaster.—Fitz-John Porter, | 165 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| General McClellan Restored to Command.—Re-organization of the Army.—Advance of the Enemy into Maryland.—March from Washington.—Battle of Crampton’s Pass.—Harper’s Ferry Surrendered, | 176 |

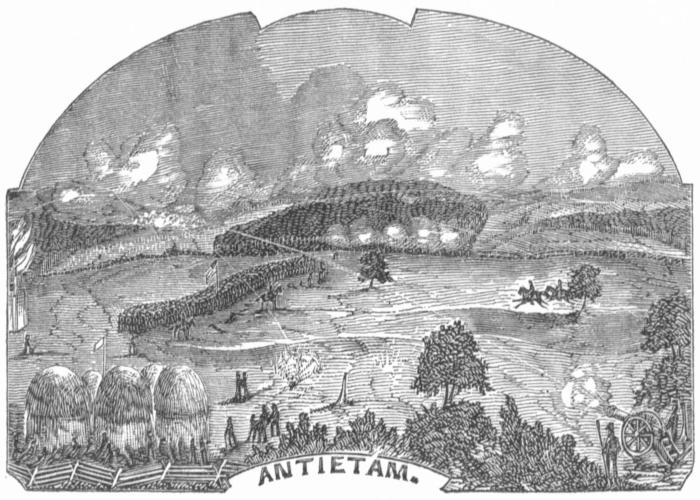

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Battle of Antietam, | 184 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Appearance of the Field after the strife.—Union Losses and Captures.—Bravery of the Raw Levies.—The Thirty-third complimented by the Brigade Commander, | 196 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Pennsylvania Militia.—Visit of the President.—Beautiful Scenery along the Potomac.—Harper’s Ferry.—“Jefferson’s Rock.”, | 202 |

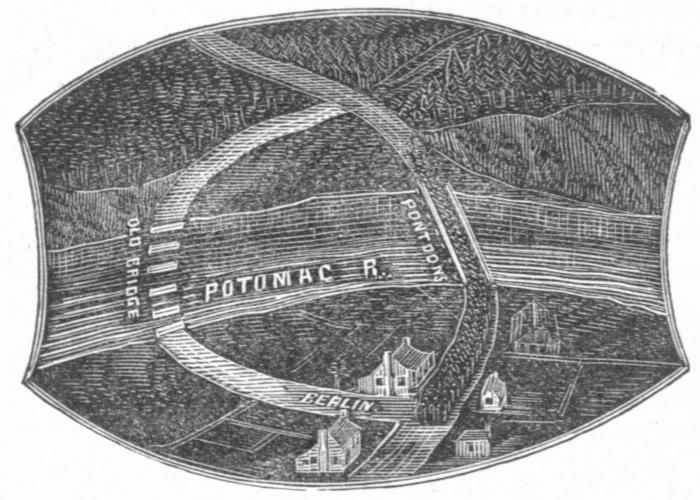

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Hagerstown.—Martinsburg.—A New Campaign.—Return of Colonel Taylor.—Crossing the river at Berlin.—Appearance of the Country.—Loyal Quakers.—Removal of General McClellan.—His Farewell Address.—Causes of his Popularity, | 207[5] |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Gen. McClellan’s Departure.—Gen. Burnside’s Address.—March to Fredericksburg.—Reasons for choosing this Route.—Randolph Estate.—Failure of the Pontoons to Arrive.—Stafford Court House.—The Thirty-third preparing Winter Quarters.—Scouting Parties.—The Ashby Family, | 218 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Completion of the Potomac Creek Bridge.—An interesting relic of Virginia Aristocracy.—General Burnside determines to cross the river.—March of the Sixth Corps.—White-Oak Church, | 228 |

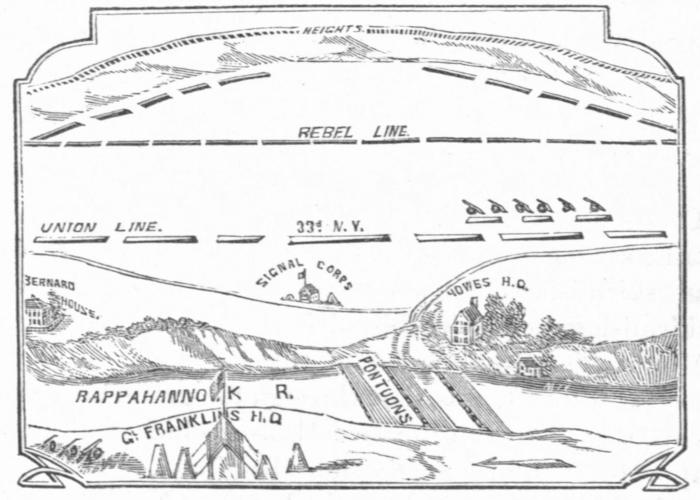

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

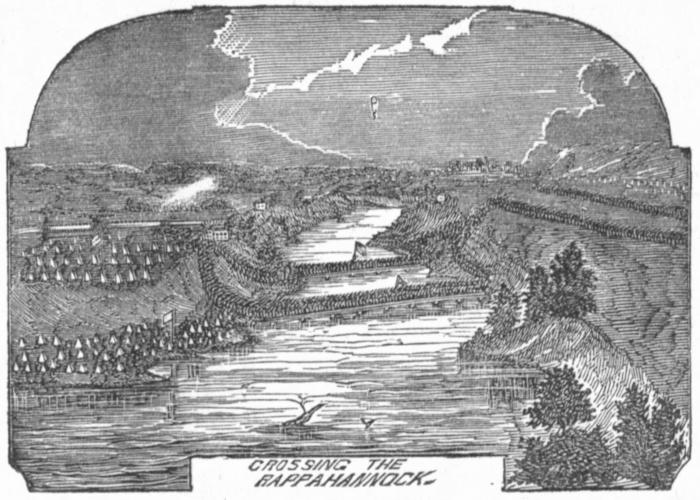

| Laying of the Bridges.—A solemn scene.—Bombardment of Fredericksburg.—Gallantry of the Seventh Michigan and other Regiments.—Crossing of the left Grand Division, | 236 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Battle of Fredericksburg, | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Events succeeding the Battle.—A North Carolina Deserter.—The Bernard Estate.—Re-crossing the River.—The Thirty-third in its Old Camp.—Families on the Picket Line.—A Courageous Female.—Changes in the Regiment, | 251 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Another Advance.—The Army stalled in mud.—Removal of General Burnside.—General Hooker succeeds him.—Character of the two men.—General Franklin relieved, and General Smith transferred to the 9th Army Corps.—His Parting Address.—Colonel Taylor assigned to a Brigade.—A Contraband Prayer Meeting.—Sanitary Condition of the Army, | 261[6] |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

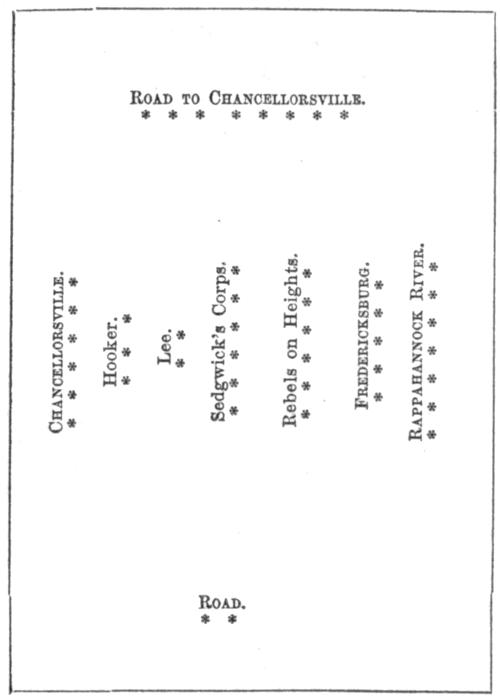

| Splendid Condition of the Army.—Gen. Hooker’s Programme.—A Forward Movement.—Battles of Chancellorsville and Vicinity.—Jackson turns Hooker’s Right Wing.—Operations below Fredericksburg.—Strategy.—Address from the Commanding General.—The Washington Estate.—Crossing the Rappahannock, | 276 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

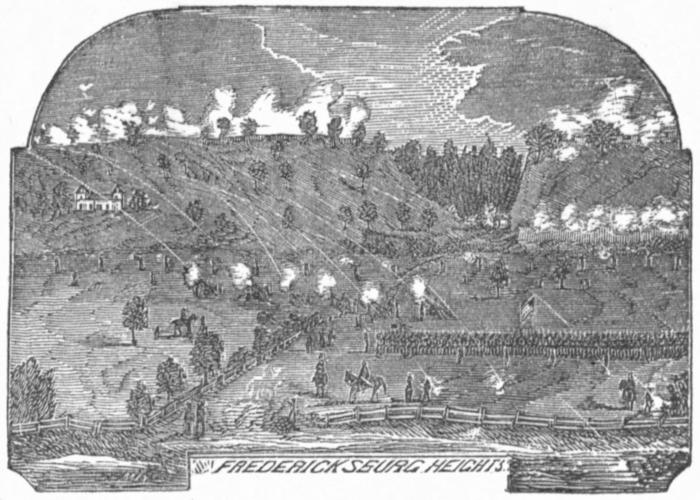

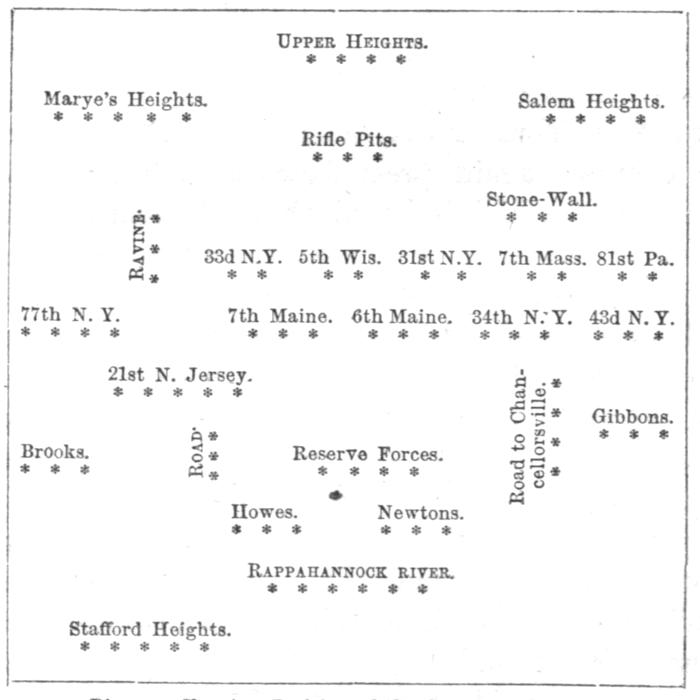

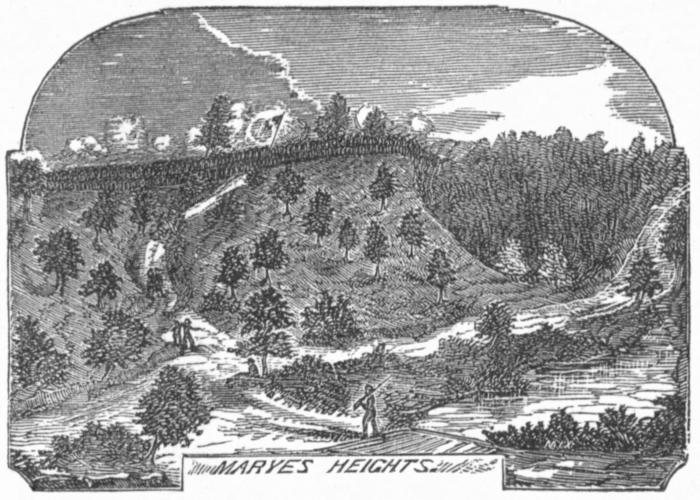

| The Storming of Fredericksburg Heights, | 290 |

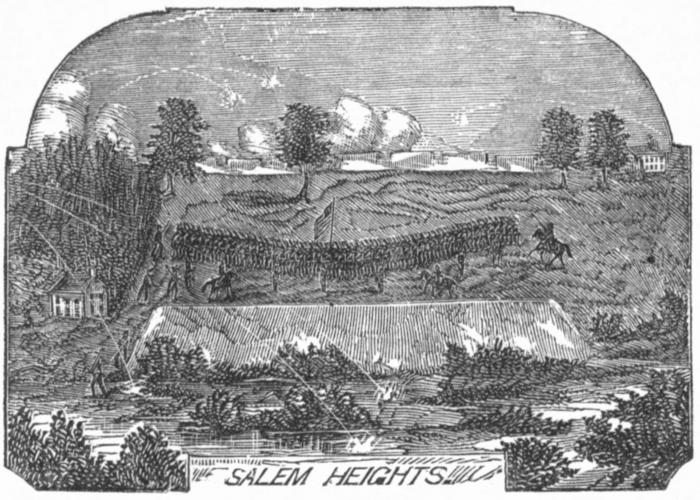

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Battles of Salem Heights, | 302 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Gen. Stoneman’s Expedition Successful.—Reasons for the Campaign proving a Failure.—Death of Jackson.—His Character.—Gen. Neill’s Report, | 315 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Departure for Home.—Ovations at Geneva and Canandaigua, | 322 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Splendid Ovation at Canandaigua.—Speeches and Addresses by E. G. Lapham, J. P. Faurot, and the Colonel, Lieutenant-Colonel, and Chaplain of the Regiment.—Return of the Regimental Banner to the Ladies of Canandaigua.—Parting Exercises.—The Thirty-third passes into History, | 334 |

The period through which we are now passing, may properly be said to comprise one of the three great epochs which, according to Voltaire, mark the history of every nation. Nay more. Have not the providential developments of the rebellion revealed a new goal in our national progress? Instead of being a dire calamity, may we not rather consider the present civil war as a means, in the hand of Divine Providence, for the solution of a great moral problem—the overthrow of slavery? So completely had the South become wedded to her peculiar institution, that no other instrumentality save the sword was adequate to effect their separation. The shock of battle would alone loosen the bonds of the captive. If this were the design of Providence in inflicting this war upon us, no one can deny that events are slowly though surely working for its accomplishment. Every acre of territory gained possession of by our soldiers is an acre gained for freedom, and already entire States have been wrested from the grasp of the usurper. Such a design precluded the possibility of success on the part of the[8] rebels; for, as the death of one of the Siamese twins necessarily terminates the existence of the other, so will the destruction of slavery ensure the downfall of the Southern Oligarchy.

Alexander Stephens has styled it “The Corner-stone of the New Confederacy.” The corner-stone demolished, how can the superstructure remain? If, then, the blood which has flowed on so many battle-fields, will wash out the foul stain from our national escutcheon, will it have been shed in vain?

Yet this war, though it may result, under Providence, in the destruction of slavery, is waged, on our part, for a different object, for our national existence; and who so unjust as to deny to the nation the same right which is freely accorded to the individual—that of self-preservation? The motives which prompted the instigators of this revolution allow of no misconstruction. Envious of the growing North; imbittered through disappointed ambition; forgetful of our memories as a people, and recreant to the sacred trust handed down by our fathers, they deliberately plotted the common ruin of our country. Nor is it owing to any lack of exertion on their part that the government is not now overthrown; our capitol and national archives in their possession; Toombs calling the roll of his slaves on Bunker Hill, and grass-growing in the streets of New York and Philadelphia. It was against men prompted by such motives and their infatuated followers that the sword was unsheathed, and is now wielded.

Admitting, however, which was not the case, that they aimed simply at a peaceful withdrawal from the Union, we could not have consented to this, without ensuring the ultimate, if not speedy, downfall of our own government.[9] The right of secession once admitted, or, what is the same thing, Mr. Buchanan’s theory, that secession, though unconstitutional, resistance to it on the part of the executive is equally so, acquiesced in—is there a state which would not eventually discover grievances justifying a withdrawal from the Federal compact? One “wayward sister” allowed to depart in peace, the whole family of States would eventually become separated. It is, therefore, a duty which we owe to ourselves, and the world, whose hopes and progress are identified with this last and noblest experiment of a free government, to manfully and successfully resist the breaking away of a single thread from the woof of our national fabric, the erasure of a single star from our national constellation.

War is the legitimate result of man’s evil nature, and in falling upon these evil times, we are merely experiencing the misfortune common to all lands and all ages. Grim visaged Mars has presided at the birth, and brooded over the career of nearly every nation. “What,” asks Dr. Fuller, “is the history of nations, but an account of a succession of mighty hunters and their adherents, each of whom, in his day, caused terror in the land of the living? The earth has been a kind of theatre, in which one part of mankind, being trained and furnished with weapons, have been employed to destroy another; and this, in a great measure, for the gratification of the spectators.” America is not the first country which has been called upon to give up the flower of her youth. Yet our losses, though heavy, do not compare with those which have hitherto marked the annals of blood. The siege and reduction of Jerusalem resulted in the loss of 1,000,000 lives; 90,000 Persians were slain at the battle of Arbela, and 100,000 Carthaginians in the engagement[10] of Palermo; 12,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry perished on the fatal field of Issus. Spain lost 2,000,000 lives during her persecutions of the Arabians, and 800,000 more in expelling the Jews. Frederick the Great inflicted a loss of 40,000 on the Austrians in the conflicts of Leuthen and Leignitz. The battle of Jenna, and the lesser engagements immediately following, cost the Prussian army over 70,000 men. At the battle of Leipsic the French suffered casualties to the number of 60,000, and the Swedes and their allies 40,000 more; 50,000 French and Russian soldiers lay dead and dying on the field after the battle of Moskowa, and Napoleon again lost 47,000 at Waterloo, and the Duke of Wellington, 15,000.

War has its lights as well as shadows. A retrospect of the world’s history reveals the fact that the sword has been no mean instrumentality in the development of the human race. Though leaving a trackless waste behind, it has opened a way for the advance of civilization. From the earliest period down to the late Russian war, when the English army made known the true religion to the Turks, it has been the forerunner of Christianity. Whatever the impelling motives; the resort to arms is always attended with some good results. The enervation and effeminacy which a long peace begets, disappear before a chivalric ardor and a sublime energy. A generous and self-sacrificing spirit is developed where selfishness and venality before existed; the political atmosphere over-heated, foul, corrupt, is cooled, cleared, and purified by the shafts and thunderbolts of war.

We, that is the North, have experienced but few of the evils, and all the benefits, resulting from a condition of hostility. Indeed, were it not for the absence of so many familiar countenances, we should with difficulty realize[11] that the country is engaged in a bloody civil strife. On every side are to be seen unmistakable evidences of national prosperity. The industrial arts are pursued with more vigor and success than ever before. The various channels of commerce, instead of being drained, dried up, are crowded to their utmost capacity. At no former period have our ship-builders been so active in constructing vessels for our own and other governments as at the present time. New factories are being built, and new avenues of trade opened all over the Eastern States, while the inexhaustible resources of the great West are being developed in an unparalleled manner. The inhabitants of Ohio reduced their debts last year to the amount of twenty millions of dollars, and it is estimated that the wealth of the country is increasing at the rate of six hundred millions per annum. A national debt, it is true, is all the time accumulating, but as a recent writer on political economy has well said: “When a nation maintains a war upon the enemy’s soil, and so manages its affairs that the annual expenses fall below the real value of its industrial products, it is evident that it must be increasing in wealth. The merchant who makes more than he spends, increases in riches, and it is the same with a nation. An increase of national debt is no sign of increasing poverty in the people, for this debt may be a simple transfer of only a small portion of the surplus wealth of individuals to the general fund of the commonwealth—an investment in public instead of private stocks.” There is every reason for encouragement, and if we will prosecute the war in which we are now engaged steadily and unflinchingly, victory and a glorious, honorable, and permanent peace will crown our efforts.

Patriotism of Central New York.—Determination of the People to put down the Rebellion.—Raising of Troops.—Organization of the various Companies of the 33d New York Regiment.

No portion of the Loyal North was more deeply stirred by the events of April, ’61, than the people of Western New York. The firing of the rebel guns on Anderson and his little band reverberated among her hills and valleys, arousing man, woman and child to the highest pitch of excitement and patriotism. There was no locality, however remote, no hamlet, however obscure, to which this wild fervor did not penetrate. Every thought and action were for the time absorbed in the one great resolve of avenging the insult offered to our flag, and suppressing the rebellion. Neither was it the sudden, fitful resolution, which comes and goes with the flow and ebb of passion; but the calm, inflexible determination, which springs from a sense of wrongs inflicted, purity of purpose, and a lofty patriotism.

The enthusiasm of the people at once assumed[14] tangible shape in the raising of volunteers. The rebels had deliberately begun war, and war they should have to the bitter end.

Among the very first Regiments to be organized and hastened forward to the battle-ground, was the Thirty-third, consisting of the following companies:

| FIRST COMMANDER. |

LAST COMMANDER. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, | Capt. | Guion, | Capt. | Tyler, |

| B, | 〃 | Corning, | 〃 | Draime, |

| C, | 〃 | Aikens, | 〃 | Cole, |

| D, | 〃 | Cutler, | 〃 | Gifford, |

| E, | 〃 | Warford, | 〃 | Warford, |

| F, | 〃 | McNair, | 〃 | McNair, |

| H, | 〃 | Walker, | 〃 | Drake, |

| I, | 〃 | Letts, | 〃 | Root, |

| K, | 〃 | McGraw, | 〃 | McGraw. |

On the reception of the news that the rebels had deliberately begun hostilities in Charleston Harbor, the utmost excitement was occasioned in the quiet village of Seneca Falls. Meetings were held in the Public Hall, under the auspices of prominent citizens, and immediate steps taken for the raising of volunteers. An agent was at once dispatched to Albany, in order to secure the necessary authority for organizing a company. The inhabitants aided materially with their funds and influence in furthering the enterprise.

E. J. Tyler, Esq., established an enrolling office, and placards were posted up in prominent parts of the village, calling for recruits.

During the first two days between forty and fifty were secured, and in a week’s time the number was increased to eighty. As fast as recruited, the men were set to drilling, in an ample building secured for that purpose.

On the 9th of May the company held an election for officers, which resulted as follows:

Not long after, J. T. Miller, Esq., now Inspector General of the State, presented a beautiful flag to the Company, in behalf of the ladies of the place. Captain Guion responded in a brief speech, as he received the banner, promising in behalf of the members of his command, that it should ever be defended, and never suffered to trail in the dust. The presentation exercises, which were held in the Public Hall, were very largely attended, and passed off with great eclat and spirit.

On the 13th of May the Company departed for Elmira, amid the wildest enthusiasm of the citizens, where it soon after became Co. A, 33d N. Y.

This Company was raised in Palmyra, Wayne County. Monday, April 20th, Hon. Joseph W. Corning, Member of the Assembly, who had just returned from Albany, volunteered as a private, for the war, attaching his name to an enlistment roll, and was followed in turn by Josiah J. White and Henry J. Draime. The nucleus of an organization was thus formed, which by the 24th numbered thirty-eight members. Four days later seventy-seven men answered to their names on the roll, and the Company immediately proceeded to organize, by the election of the following officers:

With but few exceptions, the citizens of the place exhibited a lively interest in the formation of this their first Volunteer Company. Every man was supplied with towels, handkerchiefs, et cetera, and many of them furnished with board from the day of enlistment until their departure. A fund of seven thousand dollars was subscribed for the support of such of their families as might require assistance during their absence. A sword, sash and belt were presented to each of the officers. The ladies of the village exhibited their patriotism in the presentation of a beautiful silk flag to the Company.

The 16th of May was designated as the day for its departure. Relatives and friends of the Volunteers, from the surrounding country, began to make their appearance early in the day, and long before the hour of leaving, the streets were thronged with people. The Company, now increased to eighty-two strong, was escorted to the depot by the Palmyra Light Guards, headed by the Brass Band. Following next in order were the Clergy of the place, and citizens on foot and in carriages, constituting a long and imposing procession. Flags, handkerchiefs and bunting of every description were waved from the windows and house-tops, and banners and emblems, with appropriate mottoes, were displayed at the street corners, as the procession moved along. It was a scene which the spectators and participants will never forget. Arriving at the depot, James Peddie, Esq., delivered a farewell address, and the Company was soon en route for Elmira.

Reaching there late in the evening, the men remained in the village until the next day, when accommodations were provided for them at Southport, some two miles distant. They were quartered here until the organization became Co. B of the Thirty-third New York, when they were transferred to the barracks.

This Company was recruited at Waterloo, Seneca County. The people throughout the village and[18] township heartily co-operated in the various plans undertaken for raising volunteers. War meetings were held at different places, from time to time, and a large relief fund contributed for the benefit of all such as should enlist.

Among those most active in organizing this Company, were Hon. A. P. King, Hon. D. S. Kendig, Messrs. R. P. Kendig, Wm. Knox, Sterling G. Hadley, Henry C. Wells, E. H. Mackey, Joseph Wright, and Dr. Samuel Wells. These gentlemen contributed freely of their funds and influence to the cause.

Eighty-six volunteers came forward and attached their names to the Roll. The following were chosen officers:

On the 26th of April the Company was sworn into the State service by Major John Bean, of Geneva, and received the name of the “Waterloo Wright Guards,” in honor of Joseph Wright, Esq. The ladies of the village devoted several weeks to preparing outfits for the men, who were bountifully furnished with every thing conducive to a soldier’s comfort. They likewise presented to the Company, through S. G. Hadley, Esq., a finely wrought silk banner. Rev. Dr. Parkes, of the Episcopal Church, receiving it, assured them that though torn and tattered in the fierce encounters of battle, this banner would never, he was confident, be dishonored.[19] On the 30th of April the men departed for Elmira, where they were quartered in a barrel factory, and afterwards in the barracks.

The call for troops which followed the commencement of hostilities, received a hearty response from the inhabitants of Canandaigua—the loveliest of our western Villages. The Stars and Stripes were flung to the breeze from the Old Court House, and the building turned into a recruiting station. Charles Sanford was the first one to enroll his name. Ninety-three others were added in the course of a few days to the list. On the 28th of April the following officers were elected:

Gideon Granger, Esq., Henry G. Chesebro and other prominent citizens, interested themselves in the Company, and aided materially in completing its organization. The ladies of the place, likewise, contributed very much to the comfort and enjoyment of the men, by furnishing them with ample supplies of clothing, manufactured under the auspices of the Relief Society. The Company was encamped on the beautiful and spacious Fair Grounds, east of the village, where several hours were devoted daily to drilling. On the 10th of May it took its departure for Elmira, 99 strong, where it became Co. D of the Thirty-third.

Inspired with the common feeling of patriotism which everywhere suddenly manifested itself during the month of April, ’61, the inhabitants of Geneseo, Livingston County, immediately adopted measures for raising their quota of men for the war. A public meeting was called at the American Hotel, enrolling papers produced, and several recruits secured. A second meeting was soon after held in the Town-hall, and during the week a third convened at the same place. Hon. Wm. H. Kelsey, Messrs. E. R. Hammond, John Rorbach, H. V. Colt and Jas. T. Norton, Editor of the Geneseo Republican, were prominent movers in the matter.

A company consisting of thirty-four was immediately raised, and volunteered in response to the call for seventeen thousand troops from New York State. They were not accepted at first. The organization was, however, continued, and the men went into camp on the fair ground, tents being furnished them. The Agricultural Buildings were also placed at their disposal. When the order was issued at Albany requiring the maximum number of each company accepted to be seventy-four, the list of recruits was increased to that figure, and the company accepted. On the 4th of May it was mustered[21] into the State Volunteer service for two years, by Col. Maxwell. The election for officers had resulted as follows:

Large numbers of spectators were attracted to the Fair Grounds to witness the drill of the men in infantry tactics, to which several hours were devoted daily. On the ninth of May the mustering papers were received from Albany, accompanied with marching orders. The Company did not leave, however, until the 15th, nearly a week afterwards. Prior to its departure a splendid battle flag was received from Company A, Fifty-ninth Regiment, N. Y. S. Militia, Sidney Ward, Esq., making the presentation remarks, and Taylor Scott, Esq., replying in behalf of the Company. The citizens of the place also presented Captain Warford with an elegant silver-mounted revolver. Leaving in the morning, amidst much enthusiasm, the Company reached Elmira on the afternoon of the same day, and soon afterward became Co. E, Thirty-third N. Y.

On the afternoon of Friday, April 19th, 1861, a brief telegram was received at the village of Nunda, from Gen. Fullerton, inquiring if “Nunda could furnish a Company under the call of the President for 75,000 men.” A meeting was immediately convened that evening, F. Gibbs, Esq.,[22] presiding. After brief speeches from the Chairman and others, volunteers were called for from among the audience, mostly made up of young men. Twenty-eight immediately stepped forward and entered their names upon the enlistment roll. On the succeeding Monday, Wednesday and Saturday evenings, meetings were again held, and enough more recruits secured to form a Company. Messrs. Skinner, Dickinson and Grover were appointed a Committee to superintend its organization. The citizens generously received volunteers into their homes, and provided for them while perfecting themselves in drill.

The ladies were, in the meantime, employed in manufacturing various articles for their comfort during the career on which they were about to enter. A relief fund was also raised for the support of such families as would be left dependent. On the 6th of May the Company was mustered by Maj. Babbitt, and the following were elected officers.

Capt. McNair immediately proceeded to Albany, and procured the acceptance of the officers and men, the time of their service to date from May 13th. This intelligence was received at Nunda with all the enthusiasm which would now attend the reception of the news of a great victory.

The citizens turned out en masse to witness and participate in the exercises connected with the departure[23] of the Company for the place of rendezvous. After music, prayer and the delivery of an address to the little band by the Rev. Mr. Metcalf, a revolver was bestowed upon Lieut. King by the Society of B. B. J., also one on Sergeant Hills, by Leander Hills, Esq. Each member of the Company was likewise provided with a Testament by Rev. Mr. Metcalf and John E. McNair, Esq. Miss Mary Linkletter then stepped forward and presented, on behalf of the ladies of the village, a silk flag, which was received by Captain McNair. The brass band and fire companies headed the escorting procession to the depot. Reaching Elmira on the 18th of May, the men were quartered on Lake Street, and, on becoming Co. F, Thirty-third N. Y., at the barracks.

Known as the Buffalo Company, was raised in that city, immediately succeeding the fall of Sumter. Fired with the patriotic zeal which everywhere exhibited itself during that eventful period, the inhabitants of the city put forth every exertion to raise volunteers for the Republic. Of the many companies organized, none were composed of better material, or presented a more martial appearance, than this. T. B. Hamilton, Esq., who has since become Lieutenant Colonel of the Sixty-Second New York Regiment, superintended its organization. Volunteers flocked to the recruiting station, and in a few days after the books were opened, seventy-seven names were enrolled. The Company was[24] named the Richmond Guards, after Dean Richmond, Esq., of Batavia, and received many flattering attentions from the city. The requisite number of men being obtained, the election of officers was held, which resulted as follows:

A few days later it departed for Elmira, when it became Co. G of the Thirty-third.

Geneva was not behind her sister villages in that display of enthusiasm and patriotism which marked the memorable days of April, and through the hitherto quiet streets the fife and drum were heard summoning the young men to arms. Messrs. Calvin Walker and John S. Platner moved at once in the formation of a Volunteer Company. The law office of the first named gentleman was turned into a recruiting station, and his name, together with Mr. Platner’s, headed a recruiting roll. In a week’s time seventy-seven volunteers were secured, and an election held for officers, resulting as follows:

Proceeding to Albany the Captain procured the necessary organization papers, and by the 25th of the month the Company was mustered into the State service by Maj. Bean. The ladies, in the[25] meantime, had formed a Soldiers’ Relief Society, of which Mrs. Judge Folger was President, and Mrs. John M. Bradford, Secretary, and met daily to prepare garments for the men. All, or nearly all, of them were supplied with outfits consisting of shirts, stockings, blankets, &c., &c. Agreeable to orders they made arrangements to leave for Elmira on the 1st day of May, but owing to the unpleasant weather and other causes of delay, did not get away until the 3d. On the morning of that day the Company were drawn up before the Franklin House, when a tasteful silk flag was presented to it by the Rev. Mr. Curry, in behalf of the ladies of the place, Capt. Walker responding. Splendid swords were also donated to Lieutenants Platner and Drake, and Bibles and Testaments to both officers and men. In the afternoon the Company marched through the principal streets of the village, escorted by the Fire Department and a lengthy procession of citizens, and proceeded to the steamboat landing.

The wharves were crowded for a long distance with admiring spectators, while the perfect shower of bouquets which was rained down upon the men testified to the regard which was entertained for them. Amid the waving of handkerchiefs, display of flags, and deafening cheers of their fellow townsmen, they steamed away from the wharf, while the roar of artillery reverberated over the placid waters of Seneca Lake as they disappeared from view. Reaching Elmira on the following day, the men were quartered in the town-hall, where they[26] remained until becoming Co. H. of the Thirty-third N. Y., when they were transferred to the barracks. Captain Walker being chosen Lieut.-Colonel of the Thirty-third, Lieutenant Platner was promoted to Captain, Lieutenant Drake to 1st Lieutenant, and S. C. Niles to 2nd Lieutenant.

Immediately after the President’s proclamation calling for 75,000 volunteers reached Penn Yan, a meeting was called at Washington Hall. General A. F. Whitaker presided, and George R. Cornwell was Secretary. Several addresses were made, and the session continued till a late hour. A roll was presented, and thirty-four names obtained.

On Thursday evening, April 25th, a much larger gathering was held, bands of music parading the streets and playing patriotic airs. Resolutions were adopted to raise a company of volunteers, and recruits came forward freely. After the County Union assembly on Saturday, April 27th, the Finance Committee appointed at that meeting, Messrs. E. B. Jones, C. C. Sheppard, D. A. Ogden, and F. Holmes, circulated a subscription to raise funds to provide for the families of volunteers.

On the ninth day of May, 1861, the Company, which at this time was known as the “Kenka Rifles,” was inspected by Major John E. Bean, of Geneva, and mustered into the State service. On the same day an election was held for officers, resulting as follows:

The Company continued to drill under its officers until receiving orders to go into camp at Elmira, on the 18th of May. On that day the Company departed, being escorted to the Railroad Depot by the firemen and citizens. A large concourse was assembled, and the ladies of Penn Yan presented a beautiful flag to the Company, which was addressed by Hon. D. A. Ogden and Mr. E. B. Jones. Each member was also presented with a Testament. Up to this period every effort had been made by the citizens of Penn Yan and vicinity to assist in its organization and contribute to the success of the command. This patriotic zeal extended to all classes, but to none more than to the ladies, who rendered every assistance and attention to the men. On their arrival at Elmira they were quartered in Rev. T. K. Beecher’s church, and on the 24th May became Company I of the Thirty-third Regiment of New York State Volunteers. On the 3rd July, 1861, it was mustered into the United States service by Captain Sitgreaves, and from that time its history became identified with that of the Regiment.

Americans will ever remember with gratitude the patriotism displayed by our adopted fellow citizens, during the progress of the great uprising.[28] Teuton and Celt alike manifested their devotion for their adopted country, by rallying to the rescue. This was true to a remarkable degree of the Irish population of Seneca Falls. The call of the President for troops led to the immediate formation of an Irish Company. Patrick McGraw, who had served in Her Majesty’s service for upwards of fifteen years, superintended its organization, and was afterwards chosen Captain. He was materially aided by Brig. Gen. Miller, and Messrs. John McFarland and George Daniels. On Sunday afternoon, April 11th, the Sabbath quietude of the village was disturbed by the music of bands and tramp of citizens. Every one was on the alert, and every eye turned towards one point, the Catholic Church, for there the organization of the Company was to receive, after Vespers, the sanction and benediction of the Catholic Pastor. A procession was formed at the Village Armory, composed of the Volunteers, headed by Capt. McGraw, the Jackson Guards, under the command of Capt. O’Neil, bands of music, and vast crowds of citizens. At 4 P. M. the procession arrived at the Church, which was immediately filled to its utmost capacity. Union flags gracefully hung around the sanctuary, and the choir sang the “Star Spangled Banner” and the “Red, White and Blue.” Vespers ended, an address was delivered by the Pastor, who urged loyalty to the Union, the defence of a common country, and the perpetuation of the traditional bravery of the Irish race.

Tuesday afternoon, May 22d, 1861, the Company[29] prepared to leave for Elmira. It was a general holiday in the village and suburbs. The factories ceased work, stores were closed, bells rung out their liveliest peals, the “Big Gun” blazed away, and every one was on the qui vive. The men were supplied with a graceful fatigue dress, of home manufacture. Equipped in their rakish caps, knit woolen shirts and dark grey pantaloons, they marched through the streets, accompanied by the Jackson Guards, the Fire Companies, and many thousands of loyal citizens. On the Fair Grounds the Company was presented with a flag, the gracious offering of the citizens. The Captain received, on the same occasion, a beautiful sword, Rev. Edward McGowan making the presentation speech.

The “Jackson Guards” and “Continentals” accompanied the men to Geneva, and escorted them to the steamboat provided for conveying them to Elmira. At the landing, the crowds were immense, and cheer after cheer went up from the assemblage for the Irish Volunteers, as the boat steamed away from the dock.

On reaching Elmira, the men were provided with quarters, and soon after became attached to the Thirty-third, as Co. K.

Elmira a Place of Rendezvous.—Arrival of Troops.—Organization of the Thirty-third.—A Beef Incident.—Presentation of a Flag.—Mustering into the United States Service.

The reader will remember that Elmira had been designated as the point of rendezvous for volunteers from the central and western portions of the State. Battalions, Companies and squads flocked hither daily, and were consolidated into regiments. In this manner the 12th, 13th, 19th, 21st, 23rd, 26th and 27th, among other regiments, were formed. The plan and arrangements for consolidation were to a certain extent left with the various commands, each one being permitted to select and act upon its own regimental organization.

On the 17th of May the officers of eight of the previously described Companies met and decided upon forming themselves into a regiment, the two other Companies afterwards joining them. On the 21st the organization was rendered complete by the election and appointment of the following field and staff officers:

The regiment was designated as the Thirty-third New York State Volunteers, and assigned to barrack number five, at Southport, where it remained until the departure for Washington.

The entire change in the mode of life occasioned some uneasiness, at first, on the part of the men. They were not made up of the refuse material of our large cities, “the scum that rises uppermost when the nation boils,” but had come from homes supplied with every comfort. A few days, however, served to inure them to the change, and they learned to sleep soundly in the rude hammocks, and thrive on the plain bill of fare.

As a general thing they were supplied with wholesome and nutritious food; but an occasional oversight would occur, when, woe to the unlucky purveyor. On one occasion some meat was sent to[32] them, which, imparting a suspicious odor to their olfactories, the boys immediately collected, and bearing it away to a prepared receptacle, deposited the stuff with all the funeral pomp and ceremony which formerly attended the burial of Euclid at Yale College. The funeral oration abounded in not the most complimentary allusion to the Commissariat, who, improving on the wholesome advice administered, ever afterwards furnished the Regiment with beef that would pass muster.

The principal event connected with the sojourn of the Thirty-third here, was the reception of a splendid banner from the patriotic ladies of Canandaigua. The Regiment being formed into a hollow square, Mrs. Chesebro, of Canandaigua, stepped forward and presented the flag to Colonel Taylor, in the following felicitous remarks:

“Colonel Taylor, and Members of the Ontario Regiment: In behalf of the wives, mothers and daughters of Canandaigua, I ask your acceptance of this Regimental Banner. On the one side is the coat of arms of our noble Empire State; on the reverse, the Seal of old Ontario, adopted by your forefathers shortly after the Revolution, in 1790. And who—seeing the sudden transformation of her peaceful citizens into armed soldiers—can doubt the loyalty and patriotism of the men of Ontario? Soldiers! in assuming the name of a time-honored county as the bond of union for this Regiment, you assume to emulate the virtues which characterized the pioneers of civilization in Western New York,[33] and like them, let forbearance and moderation actuate your motives and temper your zeal. Let the thought that brave hearts at home, have, with more than Roman heroism, parted with those most dear to them, inspire each soul to acts of courage, and nerve each arm to deeds of daring. And though ‘the pomp and circumstance of war’ are, to woman’s timid nature, but other terms for death and desolation, this banner is the assurance of our sympathy with the cause of Liberty and our Country. Bear it forth with you in the heat of battle, where each soldier may fix his eye upon it, and if it comes back riddled with bullets and defaced with smoke, we shall know that a traitor has answered with his life for every stain upon it. Bear it forth, as you go, followed by our best wishes, and our earnest prayers; and may the God of Battles preserve and bless you, and crown your efforts and those of all our brave defenders of the stars and stripes with speedy and signal victory! Take it, and may God’s blessing go with you and it.”

Colonel Taylor responded:

“Mrs. Chesebro, and Members of the Committee from Canandaigua: I thank you most heartily for the beautiful gift which you have presented to the Thirty-third Regiment. It shall be most gratefully prized as a token of the kind interest and loyalty of the ladies of Canandaigua; and I promise that it shall never be dishonored or disgraced. But, unfortunately, I am not much given to talking; my business lies in another direction; and I am willing[34] to let the acts and doings of the Ontario Regiment speak for me. I have the pleasure of introducing to you the Chaplain of the Thirty-third, the Rev. Mr. Cheney, who will address you more fully.”

He then introduced Chaplain Cheney, who addressed Mrs. Chesebro and the delegation accompanying her, as follows:

“I think that I hardly need an introduction to those who hail from Canandaigua; and although I might well wish that the part I now undertake to discharge, had been conferred upon one better able to do justice to the occasion and the theme, yet, belonging as I do by birth and early associations to Ontario County, the task is to me one of pleasantness. And when I strive, as I now do, to return most heartfelt acknowledgments to the ladies of Canandaigua for this token of interest and confidence in our Regiment, I only strive to utter the sentiment which fills every soldier’s breast this moment.

“It is an old proverb, and one which has been more than once graven on the warrior’s shield “not words but deeds,” and I would be mindful of the spirit of the saying; and yet I hazard nothing in assuring the patriotic women of Canandaigua that they shall never see the day when they will regret the confidence which they have placed in the men of the Thirty-third. It may be, that in the fortunes of war no opportunity will be given them of great distinction, and I cannot promise for them that under these colors they shall win bloody fields and[35] achieve splendid victories. I cannot promise in their behalf, feats of arms which future poets shall sing, and future historians record; but I can, and I do here pledge them, never, in camp or in field, to bring disgrace on this banner, nor on the name ‘Ontario’ which its folds display. I cannot promise you a glorious and safe return of this Banner, but I think that I can, in behalf of every man in these ranks, declare that death shall be welcome sooner than its dishonor. Storms may disfigure it, shot may pierce and rend its silken folds, brave blood may wet and stain its blue and gold, but the men of the Ontario Regiment will guard it with their lives; and their arms shall be nerved, and their souls inspired, not only by the love of their imperilled country, but also by the remembrance of the confidence and expectation which the gift implies. They will guard it. They will fight for it, not only because it is entrusted to their keeping by loyal women, but also because it comes to them from that beautiful old town which never yet has been dishonored by a traitor-son, but which has been famous in all the land as the home of Spencer, and Howell, and Sibley, and Worden, and Granger, and others whose names are part of the history of our State and Country.

“Perhaps we do not appreciate the part that woman bears in every great struggle for national existence. We are too apt to consider all as achieved by the work and sacrifice of men. And yet, noble and heroic as they are who go forth to battle for the[36] right—not less noble and heroic are their loved ones, mothers, sisters, wives, who give them up in the hour of need, and who at home, without surrounding excitements to sustain them, without any prospect of renown to reward them, watch, labor and pray to the God of Hosts in behalf of that cause for which they have bravely but tearfully risked their heart’s dearest treasures. Who can estimate the influence of loyal women in our country’s present struggle? Not the less potent in that it is for the most part unobtrusive and beneath the surface; an influence manifested not in bloody smiting, but in humble labors to alleviate the necessities and miseries of war, in words and acts of inspiring encouragement.

“Bear, then, to the ladies of Canandaigua our heartfelt gratitude. Tell them that their trust shall not be dishonored. Tell them that their gift shall not be in vain, but that by its influence, cheering on our men to true and loyal heroism, it will be gratefully remembered and cherished as one of the powers and instrumentalities by which, we trust to God, that ere long from the rock-ribbed coast of Maine to the Keys of Florida,

The Elmira Cornet Band then discoursed a patriotic air, after which the Regiment returned to the barracks and partook of a sumptuous repast, provided by the citizens of Elmira.

This beautiful banner, which has ever been the[37] pride of the Regiment, was made of the finest blue silk, bearing upon one side the Coat-of-Arms of the State of New York, and on the reverse the Seal of the County of Ontario, adopted in 1790. Over this seal appeared in bold gilt letters, the words: “Ontario County Volunteers.” Surmounting the staff was a highly finished carved Eagle, with spread pinions—the whole forming one of the most elegant battle-flags ever wrought by fair hands.

Six hours were allotted each day to drilling, though, owing to the absence of arms, the men were confined, during the entire time of sojourn at Elmira, to the rudimentary principles of the manual. Books, newspapers, and other reading material, purchased and contributed by various benevolent associations, whiled away many hours which would otherwise have hung heavily.

Meanwhile our forces were being massed on the Potomac, and the men became anxious to depart for the seat of war. They had enlisted to fight the rebels at once, and, unexperienced as they were in military matters, could not understand the necessity of devoting so much time to preparation. Not that they chafed under discipline, but longed to be up and at the miscreants who had dared to fire on their country’s flag, and were then menacing its capital.

Friday, July 3d, the Regiment was drawn up in front of the barracks, and Captain Sitgreaves, a regular officer, proceeded to muster it by companies into the United States’ service for two years, dating[38] from May 22d, the time at which it was organized.

All those who desired to do so, were permitted to visit their homes on the 4th, with the understanding that they should return immediately. Arms and equipments were for the first time furnished on the 6th and 7th, and preparations made for an immediate departure to Washington, via Harrisburg. A long train of freight and cattle cars were drawn up to receive the men, but Col. Taylor declined to “embark” his command in any such vehicles, and passenger cars were furnished in their stead.

Departure for Washington.—Patriotism of the Williamsport Ladies.—Arrival at the Capital.—Camp Granger.—Destroying a Liquor Establishment.—“Cleaning-out” a Clam Peddler.—Review by Governor Morgan.—First Death in the Regiment.—First Battle of Bull Run.—Changes among the Officers.

About noon on Tuesday, the 8th, the Companies marched down to the depot, preceded by the Elmira Cornet Band, which had been attached to the Regiment. Two hours later they moved away, amidst tremendous cheering from the assembled multitude, waving of handkerchiefs, throwing of bouquets, &c.

On reaching Williamsport, Pa., the ladies of the place crowded around the cars, showering oranges, apples, cakes and other edibles upon the men, filling their canteens with coffee, and in other ways displaying their patriotism and hospitality. They will long be held in grateful remembrance by the Regiment. Passing through Harrisburg the train reached Baltimore about noon, the men marching through the streets with fixed bayonets to the Washington Depot.

When within about fifteen miles of Baltimore, some fifty of the officers and men, who had gone in search of water on the stoppage of the train, were[40] left, much to their own chagrin and the amusement of the Regiment. Arriving in Washington at three o’clock P.M., the Companies formed and proceeded down Pennsylvania Avenue to the various quarters assigned them. It rained fiercely that afternoon, and they were glad enough to get under shelter, without waiting to gratify their curiosity by an inspection of the Capitol buildings.

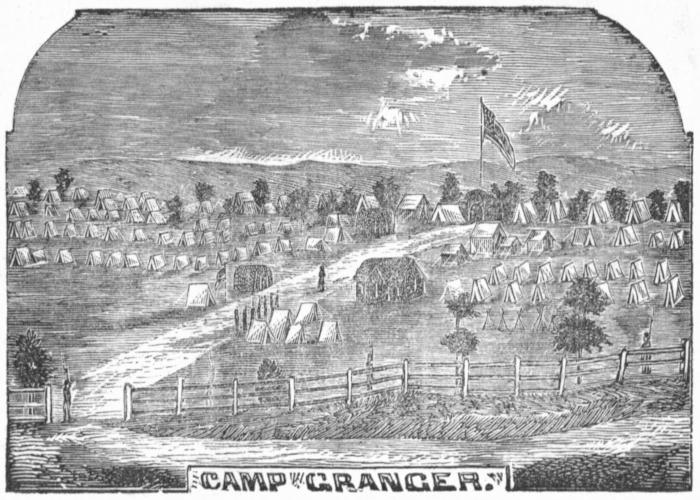

The next day, Wednesday, they were marched out on Seventh Street, two and one-half miles from the city, to the spot designated for their encampment, which was named “Camp Granger,” in honor of Gen. John A. Granger, Esq., of Canandaigua, who had interested himself much in behalf of the Regiment. This was the first experience of most of the men in the art of castramentation, and many were the droll incidents which occurred in connection with the pitching of the tents. After repeated trials, however, they were all satisfactorily adjusted.

The habitations completed, drilling was the next thing in order, which, together with target-shooting, scouting, and mock skirmishing, was kept up from day to day. The first lessons in “guard running” were learned here, many of the men managing to escape to the city, under cover of night, and return without detection before the sounding of the morning reveille. As a general thing they were temperate and abstemious in their habits, manifesting their disrelish for ardent spirits, by destroying on one occasion a liquor establishment which had been opened on the grounds. There were some, however,[43] who, thinking it necessary to partake of their “bitters,” would smuggle liquor into camp, bringing it in in their gun barrels, or by some other ingenious means.

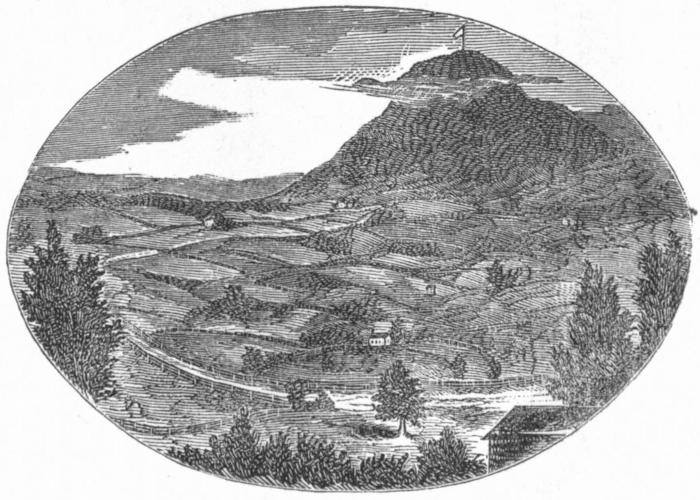

CAMP GRANGER.

One afternoon a clam peddler was so imprudent as to leave his wagon for a few moments within the camp enclosure. A mischievous member of Company—observing this, cautiously removed the end board, and, mounting the driver’s seat, started the horse off at a rapid pace, scattering the bivalves along the ground in front of the tents for several rods. All the boys were heartily regaled on clam soup that night, greatly to the discomfiture of the peddler, who ever afterwards steered clear of the Thirty-third. Many other incidents of a similar character served to relieve the monotony of camp life.

Governor Morgan inspected the Regiment on one occasion. Sickness, arising from change of climate and damp weather, had thinned out the ranks to some extent, but they made a fine appearance while passing in review before him, and the Governor expressed himself highly pleased with their morale and general condition. Frequent visits were received from members of the Sanitary Commission, who made contributions of various articles from time to time.

The first death in the Regiment occurred here. E. Backerstose, a member of Company H, was killed by the accidental discharge of his gun. The remains were forwarded, in charge of some of his comrades, to Geneva, where his parents resided.

It was while the Regiment was encamped at Camp Granger that the first battle of Bull Run was fought, July 21st. From sunrise until sunset, through the long hours of that memorable Sabbath day, the booming of cannon could be distinctly heard in the distance. Every rumor that reached the city was conveyed to and circulated through the camp, producing the most feverish excitement on the part of the men, and an eager desire to cross over the Potomac and participate in the conflict. Towards evening it appeared as if their wishes were to be gratified, the Thirty-third, together with several other regiments, receiving marching orders. All sprang with alacrity to their places, and moved off in the direction of Long Bridge. On reaching the Treasury Department, however, the orders were countermanded, and the men returned to camp, uncertain of the fortunes of the day, fearful of what the morrow would bring forth.

What followed the unhappy termination of the engagement at Manassas is familiar to every one. The Thirty-third shared in the universal gloom which for a time settled, down upon the nation. Instead, however, of occasioning despondency and despair, the Bull Run defeat furnished an additional incentive to action, and the soldiers impatiently bided their time. Captain Aikens, of Company C, resigned here, and was succeeded by First Lieutenant Chester H. Cole. Lieutenant Schott, Company C, was succeeded by L. C. Mix, Commissary Sergeant; John Connor, of Company E, and William Riker, died of disease.

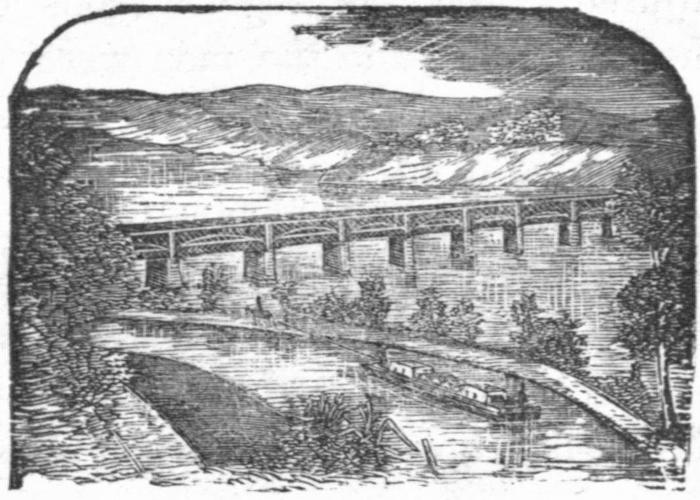

CHAIN BRIDGE.

Removal to Vicinity of Chain Bridge.—Upsetting of Ambulances.—The Regiment Brigaded.—Frequent Alarms and Reconnoissances.—Reviewed by General McClellan.—Crossing of the Potomac.—Forts Marcy and Ethan Allen.—Formation of Divisions.—Colonel Stevens.—First Skirmish with the Enemy at Lewinsville Camp.—General Brooks.—General Davidson.—The Seventy-seventh New York added to the Brigade.—A Novel Wedding in Camp.—Circulating a Temperance Pledge.—Battle of Drainesville.

Thursday, July 6th, the Regiment broke camp, and proceeding through Georgetown, along the River Road, took up a new position near the Reservoir, about one-half of a mile from Chain Bridge.

This spot had previously been designated as[46] Camp Lyon, after the lamented hero of Springfield, Mo. Two heavy four-horse ambulances, containing the sick, were accidentally precipitated down a steep embankment, while moving to the new camp. Fortunately no one was killed, though several were severely injured. The baggage wagons did not come up the first night, and the men were compelled to sleep in the open air, without blankets. A report being brought in that the rebels were advancing on the Maryland side of the river, a detachment of one hundred men, consisting of ten from each Company, started out on a reconnoissance about one o’clock in the morning. Discovering no signs of the enemy, however, the force returned at daylight.

The Thirty-third was here for the first time brigaded, being placed, together with the Third Vermont and 6th Maine, under the command of Colonel, since General, W. F. Smith. The Second Vermont was afterwards attached to the Brigade. The time was principally employed in drilling, constructing rifle-pits, and a redoubt mounting three guns. There were repeated alarms during the stay here.

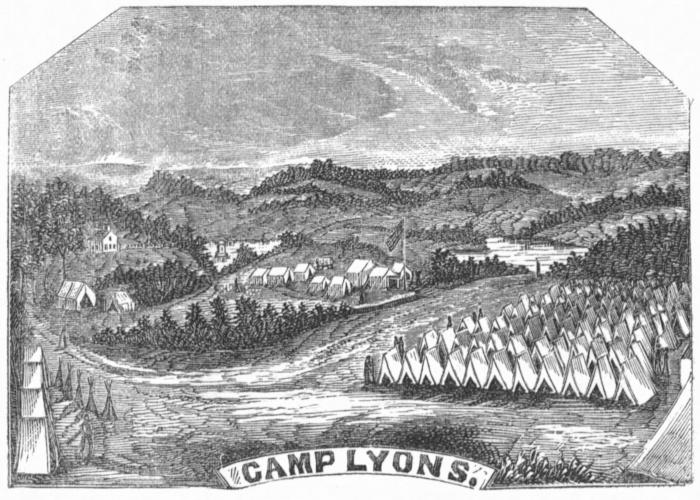

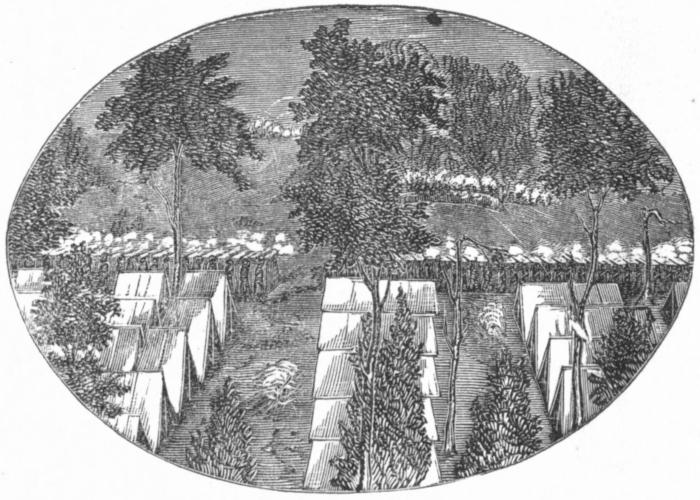

CAMP LYONS.

On one occasion word was received from General McClellan that the enemy had crossed the Potomac in large force, and were advancing upon the city. General Smith immediately ordered out his command, posting the Thirty-third behind a stone wall, where they remained until the returning cavalry scouts reported the alarm to be false. During the[49] latter part of the month one Company crossed the Long Bridge, on a reconnoissance, with a section of artillery and fifty cavalry, and proceeding on the Falls Church road, thence to Lewinsville, drove the rebel cavalry pickets to their camp at Vienna, arrested a prominent secessionist, and returned by way of Langley, reaching camp at sunset.

General McClellan, accompanied by President Lincoln, Secretaries Seward, Chase and Cameron, reviewed the Brigade on the 29th of August.

The following changes took place while here: Henry N. Alexander appointed Quarter-Master, vice H. S. Suydam, resigned.

Sylvanus Mulford, promoted to full Surgeon, vice T. R. Spencer, promoted to Brigade Surgeon.

Patrick Ryan, 2nd Lieutenant of Company K, resigned, succeeded by Edward Cary, who was immediately detailed to General Smith’s staff.

Peter Weissgreber, Co. G, died in camp.

On the 3rd of September a detachment of fifty-two men, from Companies C and D, crossed the river, and proceeding as far as Langley, threw out skirmishers to the right and left of the road. During the afternoon an alarm was created by the pickets coming upon General Porter’s, stationed further to the left, who were mistaken for rebels. They were all immediately withdrawn, with the exception of three members of Company D, who refused to leave, in their eagerness to get a shot at the supposed grey-backs. This mistake provoked considerable merriment, although it resulted very[50] unfortunately in the shooting of the most valuable spy in the employ of the government, who imprudently ventured beyond the line of skirmishers.

About eleven o’clock on the same evening the entire Brigade crossed over the Long Bridge. On reaching the Virginia shore the Thirty-third filed off in the fields at the left, Companies A, F and D being deployed in front, as skirmishers, for a mile or more. The remainder of the Regiment lay upon their arms all night, with the exception of a small party employed in cutting away timber which interfered with the artillery range.

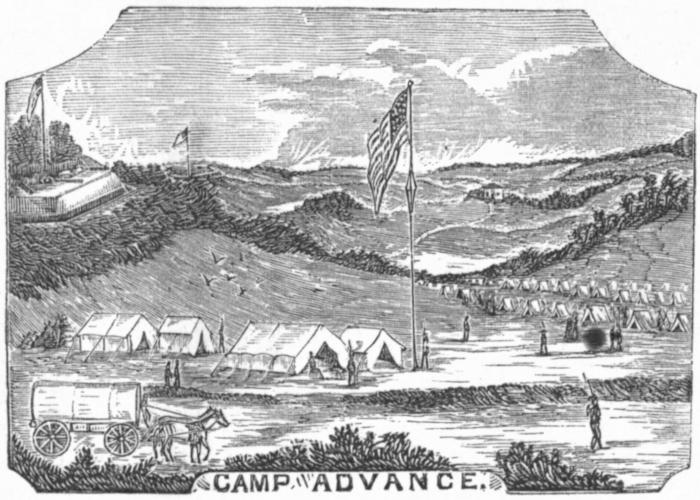

Other troops, to the number of ten thousand, likewise crossed over that night, and eighteen hundred axes were immediately set to work in felling the dense forest of half-grown pines, where forts Marcy and Ethan Allen now stand. This location was christened Camp Advance. Numerous fortifications were constructed, and in three days’ time heavy siege guns mounted. The troops always slept upon their arms, ready to repel an attack at a moment’s notice. One night a severe rain storm washed several of the knapsacks belonging to the Thirty-third into a gully running near by, filled the band instruments with water, and drenched through to the skin all who were not provided with shelter. The arrival of tents on the 15th occasioned much joy among the men.

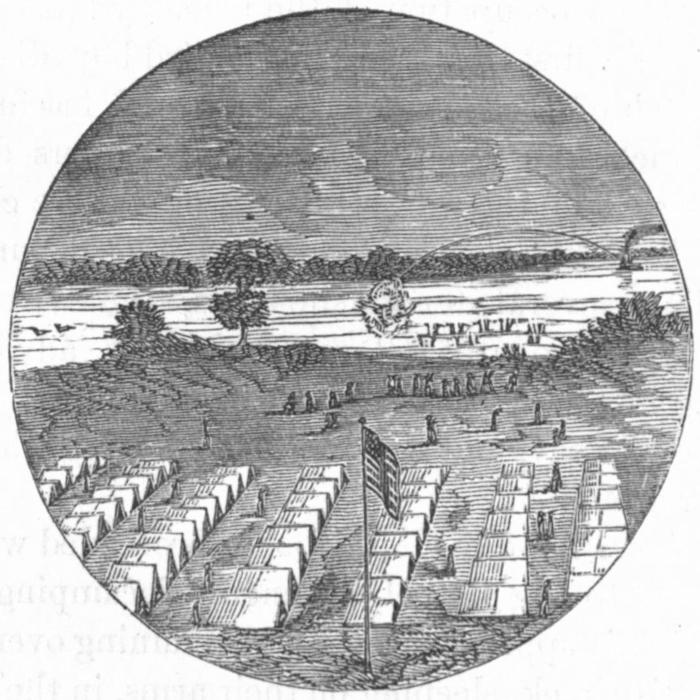

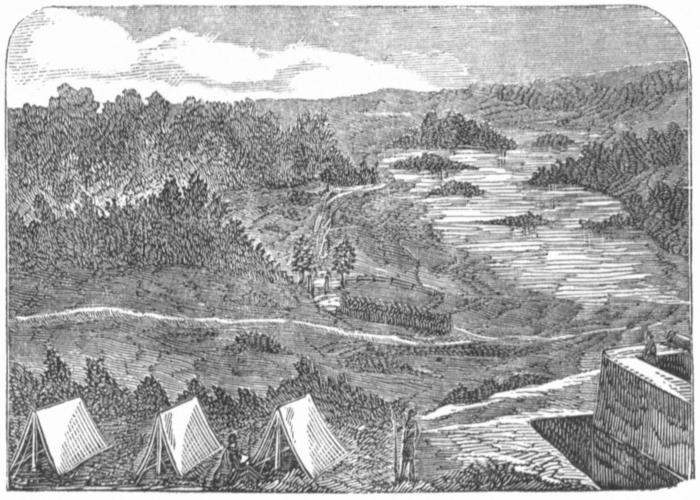

CAMP ADVANCE.

During the same day the æronauts reported the enemy as moving in large numbers, and the entire army slept on their arms. The “movement”[53] proved to be merely a raid for the purpose of destroying “Hall’s House,” and property belonging to other Unionists. Lieutenants Mix and Gifford were sent north from here on recruiting service, and D’Estaing Dickinson, of Watertown, was appointed Assistant Surgeon.

Hitherto the army had been organized into Brigades simply. Divisions were now formed, and the Thirty-third was attached to the Third Brigade, commanded by the lamented Colonel Stevens, and consisting of the Forty-ninth and Seventy-ninth N. Y. and Forty-seventh Pa. General Smith was appointed commander of the Division. This change consummated, Camp Advance was abandoned for Camp Ethan Allen, which was taken possession of September 24th. The men were employed in working on Fort Allen, slashing timber, performing picket duty, &c., &c. A visit from the Paymaster was made here, who distributed several months’ pay among the troops. Colonel Stevens, in a special order, prohibited profanity in his command.

It was while lying at Camp Ethan Allen that the Thirty-third engaged in its first skirmish with the enemy.

On the morning of September 29th, Smith’s entire Division moved up the Lewinsville Turnpike, to attack, as was generally supposed, the rebel force at Vienna. On arriving, however, at Makell’s Hill, between Langley and Lewinsville, the men were formed in line of battle, and Mott’s battery planted in front, supported by the Thirty-third. Other batteries[54] were also unlimbered, and placed in position. Co. B., together with twenty-five New Hampshire sharp shooters, were deployed in front as skirmishers. After firing a few shots—from Mott’s battery—at and dispersing a squad of rebel cavalry in the distance, the force moved forward to the edge of a dense pine forest. Taking seven men with him, Lieut. Draime proceeded through the thicket, to reconnoitre the country beyond, and was, not long after, followed by the entire Company, under Captain Corning. Several herd of cattle were captured, and a large amount of booty secured, at the residence of Captain Ball, the rebel cavalryman who was taken prisoner at Alexandria, and afterwards violated his parole. Great numbers of wagons were in the meantime sent out, in various directions, to secure forage. Very suddenly, however, the rebels opened a warm artillery fire along the whole line, which was responded to by our batteries. Many of the enemy’s missiles struck among the Thirty-third, but fortunately no one of the regiment was injured during the entire skirmish. Seeing Lieutenant Draime and his men at the Ball residence, they shelled them furiously, but did not prevent their carrying off a good supply of honey, which was highly relished by them and their comrades.

Having obtained a large amount of spoil, the whole force returned to camp. Lieut. Col. Walker resigned at Camp Ethan Allen, and Capt. Corning was appointed to his place. He was succeeded by Lieut. White, and he, in turn, by 2d Lieut. Draime.

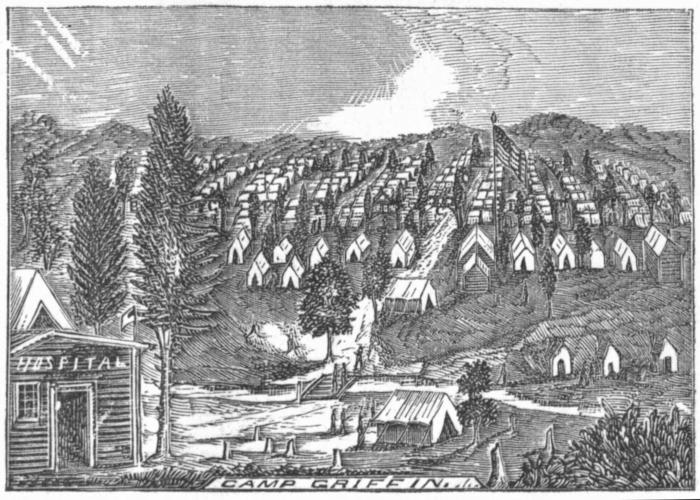

CAMP GRIFFIN.

On the 10th of October, the whole Division again moved out to Makell’s Hill, and formed in line of battle, skirmishers being thrown out in front. After remaining here several hours, the force fell back to Langley, and from there proceeded east on the Kirby road to “Big Chestnut.” In the afternoon of the next day they advanced half a mile further, and went into camp, at what has since been known as “Camp Griffin,” where the Thirty-third remained until the final advance was made.

On the second day after locating here, sixty men, under command of Capt. Platner, proceeded on a reconnoissance beyond the picket line, and falling in with some rebel cavalry, killed two of the number; Lieut. White shooting one of them dead. The fleeing enemy were pursued until they reached the cover of a dense thicket, when, being strongly reinforced, they turned upon the pursuing party, who escaped back in safety to camp by closely following the sinuous windings of the Virginia rail fences.

On the same afternoon Co. E. had a skirmish with the rebel cavalry, killing several of them in the woods where they were engaged. Some of the other Companies hastened to its support, but did not reach the ground in time to participate in the melée. This was the last of the picket firing before Washington. The men were employed here in drilling, “slashing,” reviews, sham-fights, and picket duty. Frequently they proceeded out on picket at two or three o’clock in the morning, when the mud was knee-deep, often remaining for thirty hours or more without being relieved.

During the month of October, Col. Stevens left for the south, taking the Seventy-ninth Highlanders with him. Col. Taylor assumed command of the Brigade, until Gen. Brennan was sent to take charge of it. Not long after he was likewise ordered south. The Forty-seventh Pennsylvania accompanied him, the Eighty-sixth New York taking its place. Gen. Brooks now commanded the Brigade for a few days, at the end of which time General Davidson, a loyal Virginian, from Fairfax County, was placed over it. Previous to the outbreak he had been a Major in the regular cavalry service, and was a brave and popular officer. He rode a spirited mustang, presented to him by Kit Carson, while serving on the western frontier. The Eighty-sixth New York was soon sent back to Casey’s Division, and the Seventy-seventh, raised in the vicinity of Saratoga, succeeded it. As an instance of the great cutting down of the impedimenta of our armies, this regiment then employed one hundred and five double wagons for transportation, where only five are now used for that purpose. The same can be said of most of the commands.

A novel wedding came off one night at the Chaplain’s quarters, the happy couple being a private and a laundress belonging to Company C. The affair was conducted with all the ceremony the circumstances of the case would permit of, and to the satisfaction of the guests, who were regaled with wedding cake, wine, and other refreshments, decidedly palatable after the long experience on “hard tack.”[59] While the after-festivities were happily progressing, the fortunate bridegroom suddenly brought them to a close by grasping the hand of his “fair one,” and disappearing in the direction of his domicile, with a general invitation to “call round.” The wife remained with her husband until the battle of Antietam, when, he being wounded, they both departed for the North.

About $400 were contributed by the various Companies for a chapel-tent and reading-room. A temperance pledge, circulated among the men, was signed by a large number, many of whom have kept it until this time. On the day of the battle of Drainesville, the long roll beat, and the Brigade proceeded out to “Freedom Hill,” where it was drawn up in line of battle to intercept the rebels, should they, in case of a defeat, attempt to escape in that direction. The enemy not appearing, the Regiments returned to camp at sunset.

At the time of the Ball’s Bluff affair they were furnished with three days’ rations preparatory to again moving, but were not called out.

Grand Review of the Army, at Bailey’s Cross Roads.—Pleasant Acquaintances formed.—Changes and Deaths at Camp Griffin.—Dissatisfaction at the General Inactivity.—President’s War Orders.—Gen. McClellan’s Plans and Correspondence with the President.

The grand review by Gen. McClellan took place while the Thirty-third was encamped at Camp Griffin; the troops, over seventy thousand, were assembled at Bailey’s Cross-Roads, early in the day, to await the arrival of their Chief. Towards noon Gen. McClellan appeared, accompanied by the President and other distinguished personages, and as the party rode along in front of the line, cheer after cheer rent the air. Having assumed a stationary position on an elevated spot, the various commands passed in review before them. The day was mild and beautiful, the roads in good condition, men in fine spirits, and the review presented a most imposing spectacle, surpassing anything of the kind ever before witnessed in America. Surgeon Dickerson was unfortunately thrown from his horse by a collision on this occasion, receiving a severe concussion. The Surgeon attending pronounced the case a fracture of the skull producing compression of the brain, when a Herald attaché, standing by, added: “died[61] in a few moments,” and a telegram was published to that effect in the Herald of the following day.

During their stay here, the officers and men made the acquaintance of several interesting families in the vicinity. Among them was the “Woodworths,” residing on the picket line. Mr. W., who originally moved from Oswego County, New York, had suffered much at the hands of the enemy. After the first battle of Bull Run, the rebels entered his house, robbing it of many valuables, and conducted him to Richmond, where he was imprisoned. Being released in the following October, he returned to find his once happy home nearly in ruins. The officers spent many pleasant hours in the society of his entertaining daughters, and in listening to the old man’s narrative of the wrongs inflicted upon him for his Union sentiments. All the members of the family apparently vied with each other in their efforts to render the sojourn of the Thirty-third in that locality as pleasant as possible.

The following changes occurred at Camp Griffin: Major Robert H. Mann resigned; succeeded by John S. Platner, Captain Co. H, who in turn was succeeded by First Lieutenant A. H. Drake. Chaplain George N. Cheney resigned; succeeded by Rev. A. H. Lung, Pastor of the First Baptist Church Canandaigua. John R. Cutler, Captain Co. D, succeeded by Henry J. Gifford, 1st Lieutenant, transferred from the Thirteenth New York. Samuel A. Barras, 2d Lieutenant Co. D, resigned, George T. Hamilton, 1st Lieutenant Co. F, resigned. Henry[62] G. King, promoted from 2d to 1st Lieutenant Co. F, vice G. T. Hamilton, resigned. Henry A. Hills, promoted to 2d Lieutenant, from 1st Sergeant, vice H. G. King, promoted. George W. Brown, promoted from ranks to 1st Lieutenant Co. D, vice H. J. Gifford, promoted. Jefferson Bigelow, promoted from 1st Sergeant to 2d Lieutenant Co. D, vice S. A. Barras, resigned. John W. Corning, appointed 2d Lieutenant Co. B, vice H. J. Draime, promoted.

Prior to his departure, the Chaplain was presented with an elegant gold watch, as a testimonial of the regard entertained for him.

The following deaths occurred from disease:

Company B, David Hart; Company C, Corporal George A. Langdon; Company C, Pierre Outry; Company E, Peter Zimmer; Company F, George E. Prentice; Company F, Gardner Bacon; Company F, Irwin Van Brunt; Company G, Patrick Conner; Company G, Wm. Cooper; Company H, James H. Gates; Company I, Archibald Coleman; Company K, Augustus Murdock.

William Humphrey, Company J, and Joseph Finnegan, Company K, were accidentally killed.

The long inactivity which prevailed in all our armies was as unsatisfactory as it was inexplicable to the country. Day after day, week after week, and month after month, brought the same story, “All quiet along the lines,” until the patience of the people became well nigh exhausted, and they began to clamor for the removal of this and that leader, declaring that they all

On the 19th of January, however, the President issued orders for a general movement of all the Federal forces; one result of which was the series of victories at the West, which so revived the drooping hopes of the nation. Twelve days afterwards, he issued a special order directed to the Army of the Potomac, which had not yet moved. It read as follows:

Executive Mansion, Washington, January 31st, 1861.

President’s Special War Order No. 1.

Ordered, that all the disposable force of the Army of the Potomac, after providing safely for the defence of Washington, be formed into an expedition for the immediate object of seizing and occupying a point upon the railroad south-westward of what is known as Manassas Junction; all details to be in the discretion of the General-in-Chief, and the expedition to move before or on the 22d day of February next.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

General McClellan replied, in writing, to this order, objecting to the plan which it proposed, as involving “the error of dividing our army by a very difficult obstacle (the Occoquan), and by a distance too great to enable the two portions to support each other, should either be attacked by the masses of the enemy.” In conclusion he expressed himself desirous[64] of moving against the enemy, either by the way of the Rappahannock or the Peninsula. This reply explains the reason of his having so long delayed operations. His aim was to mass together a large army, thoroughly equipped and drilled, and leaving a sufficient force to guard Washington, throw the remainder of his army suddenly in the enemy’s rear, or hurl them swiftly upon the rebel capital, before they could move to its support.

The President did not agree with his young General, as will be seen from the following communication, which he addressed him in reply:

“Executive Mansion, Washington, February 3d, 1862.

“My Dear Sir:—You and I have distinct and different plans for a movement of the Army of the Potomac; yours to be down the Chesapeake, up the Rappahannock to Urban, and across land to the terminus of the railroad on York river; mine to move directly to a point on the railroad south-west of Manassas. If you will give me satisfactory answers to the following questions, I shall gladly yield my plan to yours:

“1. Does not your plan involve a greatly larger expenditure of time and money than mine?

“2. Wherein is a victory more certain by your plan than mine?

“3. Wherein is a victory more valuable by your plan than mine?

“4. In fact, would it not be less valuable in this—that[65] it would break no great line of the enemy’s communication, which mine would?

“5. In case of disaster, would not a safe retreat be more difficult by your plan than by mine?

“Yours, truly,

“A. LINCOLN.”

He afterwards, however, yielded to General McClellan. Thus affairs stood, until the first week in March, when the enemy were discovered to be retreating from Manassas, and the grand advance commenced.

Advance of the Army of the Potomac.—The Thirty-third taking up the line of march.—Flint Hill.—General McClellan decides to move on Richmond by way of the Peninsula.—Embarkation of the Thirty-third at Alexandria.—Embarkation Scene.—Mount Vernon.—The Monitor.—Arrival at Fortress Monroe.—Agreeable change of the climate.—Hampton.—Reconnoisance to Watt’s Creek.—Rebel Epistolary Literature.—Bathers shelled by the rebel gunboat Teaser.—Building a Redoubt.

On the 10th of March the Army of the Potomac unfurled its banners, and began the forward march. Comprised of legions of brave men perfected in discipline through long months of drill; supplied with everything pertaining to the material of war, and headed by a General the very mention of whose name inspired to deeds of daring—in this grand army were centred the Nation’s hopes. The long delay was ended, the public pulse quickened, and with light heart and elastic step the volunteer moved away, confident that he moved to victory.

The Thirty-third took up their line of march at 3½ o’clock in the morning, while a severe rain-storm was prevailing, which continued during the day, rendering the roads almost impassable. Four and a half hours were consumed in marching the distance of two miles, and many of the wagons were stuck fast[67] in the mud before reaching Lewinsville. The brigade encamped the first night at Flint Hill, on an abandoned rebel site, having marched ten miles. The men, weary, hungry, foot sore, and wet to the skin, hailed with feelings such as they had never before experienced, the orders to “halt, stack arms, and encamp for the night.” The division remained in this locality four days, being again reviewed by their commander.

It was here that the men began to learn, for the first time, to their chagrin and mortification, that the enemy had retreated southward. After beleaguering the capital, blockading the river, and keeping our army at bay for more than six months, they had quietly absconded, taking everything with them.

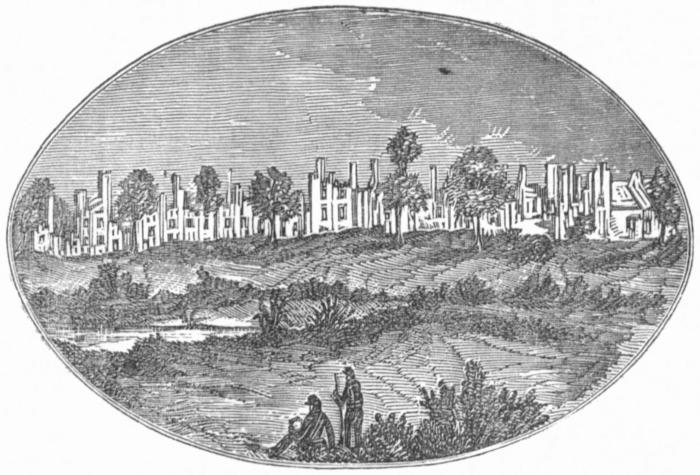

Fairfax Court House.

About this time, March 13th, General McClellan convened a council of his Corps Commanders at[68] Fairfax Court House, informing them that he had previously determined on moving forward towards Richmond by the way of the Rappahannock; but further deliberation had led him to abandon this route for the one via Fortress Monroe. Thereupon every preparation was made for transferring the scene of operations to the Peninsula. The larger portion of the army had proceeded no further in the direction of Manassas than the Court House. A small force, however, had advanced to the Rappahannock, ascertaining that the country was clear of rebels to that river.

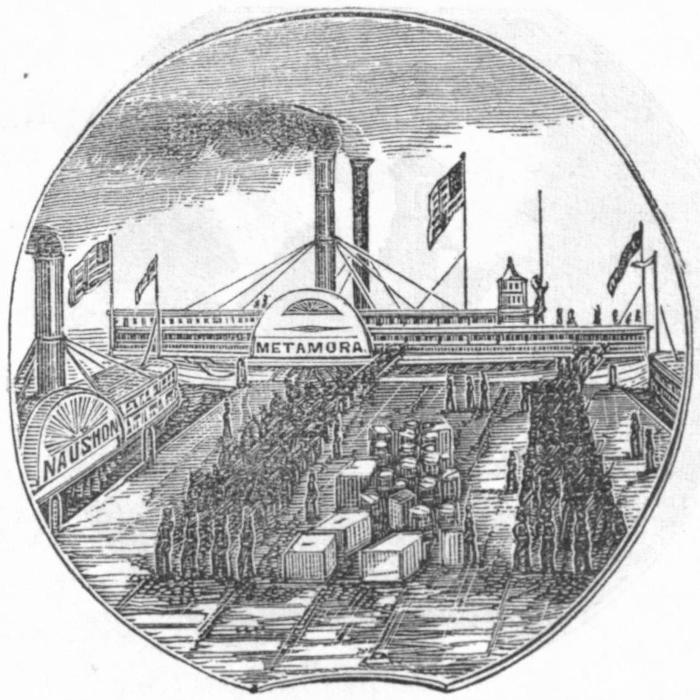

Embarkation at Alexandria.