AUTHOR OF "THE HUMAN SIDE OF PLANTS"

WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR BY

ROBERT SHEPARD McCOURT

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1916, by

Frederick A. Stokes Company

All rights reserved

TO

ANNE RHODES

FAITHFUL FRIEND, GOOD FELLOW, AND RARE SOUL

NOTE

The author is especially indebted to Mr. Read

Hersey for valuable suggestions and criticism in

the preparation of this book.

It was a beautiful evening in the forest, and under the moonlight there was a great gathering of friends. Mr. and Mrs. Elephant, and the Kangaroos, the Foxes, and the handsome Leopards, even sprightly little Miss Lynx, and a number of the aristocratic jungle Deer were seated, all in a great circle, around the pleasant pool which shone in the moonlight, and displayed the loveliest of lilies afloat upon its surface.

"Then, it is decided," said the venerable Mr. Tapir. "We are, my friends, going to contest for a dancing prize. It is felt that such an entertainment will relieve the rather tedious monotony of our evenings in this lovely spot.

"One week from to-night there will be the finest party we have ever given. No expense is to be spared. Music will be supplied by the celebrated company of Baboons and Macaws; and the ladies will adjourn, forthwith, as a committee on refreshments."

Mr. Tapir went on at great length, for all the animals loved to hear him talk, and he loved to hear himself. He had been to London. He knew how things ought to be done. So he said it all over several times, but he always ended with, "and the ladies will adjourn forthwith," which beautiful words struck the animals as the finest they had ever heard.

"What oratory! Such a flow of London speech!" they whispered. And the lovely Miss Giraffe broke down and cried. Such is the power of eloquence.

Great jealousies ensued, however, for Mrs. Kangaroo let it be known straightway that the prize was hers for sure. No one could dance as she could. She had only to straighten her waist, lift her chin, and give a leap. It was her specialty.

"When it comes to grace and speed," Mrs. Leopard remarked, "there is something in my motion which is utterly lacking to the rest of you."

Now, Mrs. Elephant kept quiet. She knew what they thought of her. She was always referred to as "that good, solid, easy-going person" unless her friends were spiteful, when they did not hesitate to call her "that ungainly old cow of an elephant." She knew their ways and spite.

"But I shall get that prize," she grunted, as she trudged to her handsome, roomy home under the chocolate trees. Nor did she feel less determined in the cool bright morning, when, as a rule, the resolutions of the night before grow pale. Immediately she put her housekeeping into the hands of her sister-in-law, who was young and willing.

"I have much to do," she said.

Then she set out to find her friends, the bull-frogs. They would pipe their tunes all day in the shade, and she would practise her steps.

It was hard at first, but soon she devised a wonderful dance. Up and down and around she went all day, and most all night. But she kept her doings a secret; and it was well she did, for all the animals would only have laughed at her had they seen her flopping around on the edge of the bull-frogs' pond.

The night of the dance came. The elegance of the costumes and the abundance of the refreshments were a delight.

It was a little game of sly Mrs. Fox's to urge everybody to eat as much as possible, and this she would do with the sweetest smile.

"Oh, do eat another bunch of bananas," she would say to Mrs. Elephant; for she wanted everybody to overeat except herself. Then they could not dance, she knew, and she would get the prize if she showed only her wonderful walking steps.

But the animals guessed her scheme. They only thanked her, and stroked their dresses or went off into corners to try their steps.

It was a brave show, and after a few had risen to the floor and danced their steps, favor was plainly directed to the lithe and lovely Mrs. Leopard.

"Just wait for Mrs. Kangaroo," was whispered from one to another. "She's wonderful, you know."

Then Mrs. Kangaroo came forth. Yes, it was marvelous what she could accomplish. First she strutted high and proud, then she bounded up and down, and finally made a great leap; but it was a leap before she looked, for what did she do but jump right into the lily pond, ker-splash!

Great embarrassment seized the company, and the less polite, such as the monkeys, simply yelled in derision.

"Mrs. Elephant! Mrs. Elephant!" was now the cry.

"Yes, yes, Mrs. Elephant!" came from all sides; for the animals, already amused by Mrs. Kangaroo's unfortunate conclusion, were ready to be boisterous. They could roar at Mrs. Elephant if they wanted to; she was so thick-skinned, as they thought, that you could never hurt her feelings anyway.

But Mrs. Elephant was very modest, and a trifle grand. Besides, she was all polished and trimmed in a manner most affecting. All that afternoon her sister-in-law had stood in the water with her, smoothing down her dress and rubbing her head; and two simple palm leaves behind her ears, with a little rope of moon-flowers garlanded over her placid forehead gave her a regal aspect which the animals were surprised and delighted to note.

"How thin she's grown! How do you suppose she did it?" they gasped.

Then Mrs. Elephant danced.

At her special request, Mr. Frog played for her, not too fast, on his elegant flute. But scarcely had she taken her first two steps when the orchestra struck up that grand old march, Tigers Bold and Monkeys Gay, which, as you know, would set anybody a-marching even if they had nowhere to go.

Waving her splendid arms to the sky, and making the most wonderful bows, flapping her ears and curling and pointing her trunk, all to the tune of the music, she was, as the eloquent Mrs. Tapir was moved to say, "as majestic as the night."

At her signal, when she knew she had captivated the audience, the music changed, and she came tripping toward them with open arms and the pinkest, biggest smile the world has ever seen. She begged them all to strike up the chorus; and suddenly, without knowing what they were about (for such is the way with an audience, once the hard-worked artist has enraptured his fellow-beings), they were all shouting the stirring words:

Of course she took the prize. And all she would say, or all, indeed, that can be got out of her to this day, about it is:

"Practise, my dears, practise. No, I have never done it since, nor would I think of trying. I only wished to feel in my old age that I had accomplished something. The race, as wise men have said, is not to the swift. Determination and careful, unremitting practise: that's what is wanted."

Sister Alligator and Miss Mud-Turtle had always been exceedingly good friends, and always helped each other out of trouble. One day Miss Mud-Turtle flopped over to Sister Alligator in great excitement.

"Look here, my friend, I'm going to have a picnic over on the other side of your big pond, and I want you to help me!" she said.

"Well, I'm right here to do what I can for you. Just tell me of what service I may be," replied Sister Alligator, as she lazily opened her sleepy eyes.

"You are a wonderfully good neighbor," declared Miss Mud-Turtle, "and I was just wondering if you would mind carrying all my young friends, the swamp turtles, across the pond on your big back? It would take you only a minute to swim us across, and if we tried to go around the pond, I am afraid Old Lady Wildcat might catch us on the way. You know she is always trying to get the best of us mud-turtles."

Sister Alligator's sleepy eyes opened wider.

"I have the very idea!" she exclaimed. "Just send Old Lady Wildcat an invitation to come to the picnic. Then I'll swim out into the pond and dive under and drown her, for all of you mud-turtles can swim."

Miss Mud-Turtle laughed so hard she had to wipe the tears from her eyes.

"Sister Alligator, your sleepy old head is not on your body for nothing! You surely have some brains! That is the very idea for disposing of Old Lady Wildcat! I'll make a carpet out of her soft hide for my young friends to play on before the sun goes down."

So Miss Mud-Turtle sent an invitation to Old Lady Wildcat, all written on a grape leaf in grand style. It told of the big dinner they were to have, and where it was to be, and that Sister Alligator would carry them all across the pond on her back.

When Old Lady Wildcat got the invitation she mewed to Mr. 'Possum, who had brought it, that she would be there all right, but that they must be very careful when they carried her over the pond, as her rheumatism was bad.

Then, when Mr. 'Possum went to take her message to Miss Mud-Turtle, Old Lady Wildcat laughed so loudly she had to hide her face with her paws for fear Miss Mud-Turtle would hear her. She was just planning how to get the best of Miss Mud-Turtle.

"Whenever I dine with low-down mud-turtles and alligators it is time for me to lose this fine coat of mine. I suppose they forget who I am! Ha! What would all my grandchildren think of their grandmother dining with mud-turtles!"

Then she began laughing again, and her grandchildren, who were sleeping away up in the branches of a big pine-tree, came down to see what had tickled her so.

Old Lady Wildcat was holding her sides and dancing about in glee.

"Oh, children," she laughed, "we're going to have some fun! Old Miss Mud-Turtle is trying to get your grandmother to dine with her across the pond. Get yourselves ready for the big feast, and I'll start over on Sister Alligator's back, while you all go on ahead and eat up the dinner."

"Hooray!" cried the young wildcats. "We'll slip along behind to see how you get started, and then we'll run around the pond and get the dinner before Miss Mud-Turtle and Sister Alligator can come."

So Old Lady Wildcat loped down to the pond, and there were Miss Mud-Turtle and Sister Alligator. All the little mud-turtles climbed on the alligator raft.

"Be very careful, Mrs. Wildcat," Sister Alligator cautioned, "not to wet your feet. You might take cold."

Old Lady Wildcat smiled pleasantly and jumped; and then away swam Sister Alligator.

It was fine riding till they got to about the middle of the pond. Then Sister Alligator stopped.

"I'm very sorry," she said politely, "but I have the cramps, ooh! ooh! I must drop to the bottom of the pond."

And down she dived.

But Old Lady Wildcat was too quick for her. She sprang up into the air and caught a grapevine, climbed up on it, and finally got to land. Then she ran through the woods to where her grandchildren were, and there they had the greatest feast you ever saw.

Finally, just as Sister Alligator and Miss Mud-Turtle with all the children came in sight, Old Lady Wildcat climbed up into a tree and laughed and mewed at them.

And this is what she said:

"Never try to fool folks, Sister Alligator and Miss Mud-Turtle, by plotting against them, for you'll find that you are only fooling yourselves!"

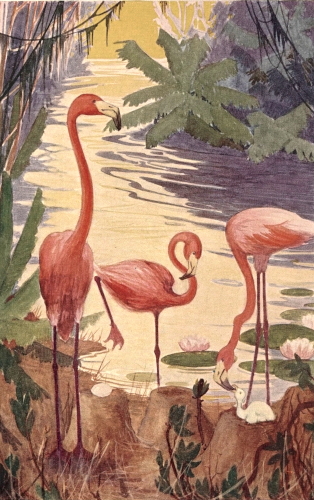

"Also, it is said that ages and ages ago Mrs. Frog and her family dwelt at the bottom of the sea."

"In the ocean?" queried surprised little Kingfisher, who was listening to all that Professor Crane could tell him.

"Yes, in the great salt water," replied Professor Crane, as he shifted his position and stood on the other leg. "Far deeper it was, too, than this pond."

For the learned Crane and little Kingfisher were spending a quiet hour under the shade of the wild orange trees, on the shores of a narrow lagoon. It was a hot, still day, and they were each of them resting after a morning's exertion. Professor Crane was always a talker after dinner, for he knew much and was sociable. He could discourse by the hour if any one would listen; and if nobody was disposed to heed him, he would meditate by himself. But just now he had an alert and inquisitive companion, for if Kingfisher loved two things in the world, one was to hear all the scandal, and the other was to pick feathers out of the back of a crow as he flew.

But apparently Professor Crane had decided to tell no more, for he rested his long bill on his breast, and let his eyes close to a narrow slit. This made him look infinitely wiser than he really was; but like a good many talkative persons he knew the value of waiting to be asked.

Kingfisher eyed his friend earnestly and opened his mouth several times to speak, but shut it again. Finally, however, thinking that Professor Crane had forgotten what he was saying, he piped out:

"How strange!"

And that stirred the venerable scholar to resume his narrative.

"Yes, strange indeed; yet nothing so wonderful after all. Nothing is past belief if you have studied long enough, and I have had signal advantages. It was, you may be pleased to know, a relative of mine, a Doctor Stork, who had perched all his life on the chimney of a great university in Belgium, who told me the truth about the frog. Of course, that is nothing to you, as you are not versed in the universities. But that's not your fault. At any rate, as I was saying, Mrs. Frog lived in the sea and had a palace of coral and pearl. She was very much larger than she is now, and was of a totally different color. She was red as the reddest coral, and her legs were as yellow as gold. Very striking, she was; and her voice was a deep contralto. But she was never content with her home, and couldn't decide whether she wanted to be in or out of the water. That's the way with all inferior characters. Men, you observe, are given to such traits of indecision, never being content where they are.

"Mrs. Frog, for all the pleasures of her coral hall, found it pleasant to sit on the rocks and stare at the land. And the more she stared, the more she wished to go ashore. But she was built for swimming, you know, and, for the life of her, she couldn't get over the sands."

"How on earth did she learn?" put in Kingfisher.

"Necessity and, as I might say, emergency," Professor Crane replied. "One day she let the waves carry her high and dry on the beach, trusting to another wave to take her back. But the other wave never came. She had come on the very last roller of the high tide. By and by she saw two eyes glaring at her from under the grass. It was probably a snake that was after her. Then, because she had to, she got back to the water. That's the way, you know. What folks have to do they generally accomplish, but until they're frightened into it they generally stand still."

"True, true," Kingfisher agreed. "I was afraid to fly when I was a baby. The last to leave the nest was myself, and finally my father pushed me out. I flew, of course, and never knew how I learned."

"Same with Mrs. Frog," added Professor Crane. "She got there. But the knowledge that she could hop if she wanted to was her undoing. She was never at home when she was wanted, and if Mr. Bullfrog had not watched the eggs in her place, there would have been no more frogs to talk about. At last he grew as neglectful as she was, however, and all the frogs caught the madness. That's when they took to tying their eggs up in packages and leaving them to care for themselves."

"How careless!" Kingfisher thought, as he recalled the hours that his wife spent sitting on hers, and what enemies would get them if he did not perch on guard.

"But the frogs got all the dry land they wanted. The sea turned itself into one great wave and spilled all over the mountains, you know. Yes, that was the time the moon changed from a golden dish to a silver platter. Some say it was from a pumpkin to a green cheese. But the weight of authority, the preponderance of learning is on the side of the silver platter."

"The preponderance of what?" interrupted Kingfisher. For although he knew what Professor Crane meant, he felt it was a compliment to him to ask for a repetition of these handsome words.

But Professor Crane went right on, which is the proper thing to do.

"And when the water went back where it belonged, it went farther than ever before. Half of the earth was high and dry that formerly had been under water. And Mrs. Frog was on that half."

"How terrible!" his listener exclaimed. "And how uncomfortable she must have been!"

"I should say she was!" Professor Crane agreed. "It was hotter, too, than fire. In fact she was destined to spend a long time regretting her previous state, while she sweltered, high and dry.

"The desert, you know, is the home of competition."

Professor Crane waited for this observation to sink in, for he felt that it was one of the best he had ever made.

"I mean that it is the worst place to live because everybody else wants you to die. That's what competition is, my friend Kingfisher. And on the sandy desert it is that way.

"There wasn't drinking water enough to go around, and the plants and trees, because they could burrow down and find a few drops, had the best of it. They stored it up, too, inside of themselves, and then, to keep people from breaking in for a drink, they threw out every kind of needle and thorn you can think of.

"But they grew beautiful flowers, and Mrs. Frog said that these reminded her of corals. The cactus flowers were indeed her only consolation, and she would sit under them all day. She didn't dare to hop out on the sands, for the birds were sure to see her and eat her, and so she took to running her tongue out and catching what she could in that way."

"Very convenient, I'm sure," Kingfisher observed. "I wish I could do it myself. It would save me much gadding about."

"Yes, my young friend, it would; but you'd never be patient enough. And Mrs. Frog is just so much patience on a lily pad. It's her whole life.

"She learned patience, you may be sure, on that desert, and her enemies were so many that she feared for her life every time she ventured out from under the cactus blossom. So she only went out at night and was, even then, careful about getting into the moonshine.

"Poor thing; she nearly starved to death, and grew thinner and thinner until her beautiful figure was gone. Then her skin shriveled into creases, and she finally got the leathery look that she has to-day."

"And how did she change her color?" Kingfisher begged to know.

"I don't think I care to tell you," said Professor Crane, with a sudden change in his voice.

This produced great surprise in little Mr. Kingfisher, for he never knew the Professor to withhold anything. Usually he was only too eager to load you with facts. So the small bird kept silence very respectfully, not knowing just what to say.

"You are yourself very saucy, and full of your foolishness," the wise Crane finally observed, "and you are not likely to believe what I tell you. But you can make what you choose of it, and it may do you good to know."

Professor Crane cleared his throat, and wagged his long bill up and down several times, much as a truly bearded professor strokes his chin in delivering the hardest part of his lecture. Then he coughed, for that is effective, too, and changed from his left foot to his right.

"Well," he resumed, "she prayed to the Man in the Moon, as that was the only thing that she knew to do, and begged him to give her a bog.

"'Just a bog, or a piece of a swamp, Mr. Moon,' she kept saying, 'even a few inches of water will do,' and after she had done this to every full moon for a year, and nothing had come of it, she changed her tune."

Kingfisher looked startled. He had personally the greatest respect for the Moon. He had heard much evil about it, however, and was not a little cautious of expressing his views on the subject.

"What did she beg of the Moon after that?" was all he could say.

"She had concluded that the Man in the Moon was unable to give her a bog, even if he wanted to, so she decided to start out and find one. That was the beginning of the end of her troubles. She begged Mr. Moon to show her how to get there, when she came to the point of starting, and she only added, 'Give me a green dress, Mr. Moon, Mr. Moon!' And that's exactly what the Man in the Moon did for her. The frogs made their journey in a body, on the darkest night of the year. But there was just one Moonbeam and it was on duty for this one thing, to show the frogs how to go."

"Wonderful!" exclaimed Kingfisher. "Wonderful! But which night of the year was it?" Mr. Kingfisher thought of several things he might do, if he knew which night was the blackest.

"The darkest night of all, my dear friend, is the one when you change the color of your life."

This silenced Mr. Kingfisher; and Professor Crane, perceiving that the words had taken effect, concluded his story.

"That single Moonbeam Angel was very beautiful and powerful. For, just as the frogs came at last to the valleys and found a deep swamp where they could forever be happy, with water or land as they wanted, Moonbeam touched them farewell, and their dresses turned to russet and green."

There were no remarks to be made, for Professor Crane clapped his bill together exactly as though he brought the book of history together with a bang; and he ruffled his wings as if he were about to fly off.

So little Kingfisher, not knowing just how to thank the great bird, said something about going home to supper.

"Just so, just so," clacked Professor Crane.

And the two birds flew up and away, Kingfisher to his nest in the tree-top, and the learned Professor to his books and studies.

A very little squirrel, who was but a month old, was looking out across an orchard from the top of a high tree. It was early morning and the sun had just risen, so that everything was sparkling with dew, and the air was cool and sweet to breathe.

He rubbed his fat cheeks with his paws and sat very straight on his haunches, looking his best and trying to sing, for he wanted very much to say something by way of letting the world know what he thought of it. Feeling as he did, so exceedingly happy, he wished to join the lovely sounds around him, for birds were singing everywhere, and even the river at the foot of the orchard had a song.

So the little squirrel made all the noise he could, which is just what the children do when they have all day to play and the sky is blue and clear above the fields.

But just as he paused for breath he heard his words repeated from another tree. Somebody was mocking him, word for word, and making a very ridiculous thing of his happy little song. His tail bristled with anger, and he ran higher in the tree to get a better view of his neighbor. He would teach another squirrel to mock him! No living creature could he see, but he heard a bluebird call, and then, as if to insult him, came again his own exultant chirp, chirp-chee, chee, chee, chee, and after it a perfect flood of laughter, just like the silly notes of the little owl who sits up all night to laugh at the moon.

Indeed, the squirrel was more puzzled than angry now, and he rushed home to his mother in the highest branches of the walnut-tree, and as fast as he could chatter he told her all about it. She was a very busy woman, Mrs. Squirrel, and she was too much engaged in her sweeping and making of beds to stop and talk with her little son. Moreover, she did not know exactly what to say; so she told him to find the wise old woodchuck under the hill, who was lazy and good-natured and fond of company, and to inquire of him just why the mocking-bird should repeat everything that was said or sung.

So off to the foot of the orchard and the old rail-fence the little squirrel scampered, and, as he expected, the good old woodchuck was lounging by his door-step, blinking at the sunlight and munching clover.

"There's nothing here for you," the woodchuck muttered with his mouth full. "You've come to the wrong house for breakfast."

"No, no," the squirrel hastened to say. "You do not know my errand. I've come to ask you why the mocking-bird is so fond of mocking. Has he no song of his own? And why should he laugh at me?"

Poor little squirrel was so full of anger, as he spoke his mind, that he puffed and bristled mightily, and the fat woodchuck burst out laughing.

"So he jeered at you, did he? Why, that's his business; but you mustn't mind the things he says. He's really a very fine fellow, Mr. Mocking-bird, and everybody loves him."

Then the woodchuck brushed the clover aside and came out a little farther into the sun to warm his back, for he was very wise, and he knew that the sun on the back was good for the shoulder-blades.

"Mr. Mocking-bird," he began, "is a great artist. That's why he can say what he thinks and do what he wants to do. And once, in the long ago, he taught all the songs in the world to the birds. You see it was this way:

"The thrush and the robin and the catbird fell to disputing about their songs. And all the noisy blackbirds and the little wrens, even the crows with their ugly notes, entered the discussion, with results which I can't describe. Oh, it lasted years and years, and every bird thought he was the best singer in the world and tried to sing everything he ever heard, whether it was his own song or not; and at last the confusion was so terrible that if the robin flew North, everybody thought he was a finch, and when he came back, he made a noise like a wild goose."

"Impossible!" exclaimed the squirrel.

"Not at all. That's the way with singers the world over, until they are sharply taught where they belong. Few people are content with their own talents. My own family is the only modest and unassuming one that I know of. We are content to dig and eat and sit in the sun. We have never trained our voices or gone in for dancing. Very different from your family, young Mr. Squirrel, which is frivolous and noisy. But you must pardon that—it was a mere observation. As I was saying, the only way to decide the business and restore order was to hold a meeting of all the birds, with a few good judges of music on hand to decide the question once for all.

"The adder, being deaf, was the chairman. Deafness, they say, is the prime requirement in a critic, for it allows him time to think. And the buzzard, also, was there to award the prizes. A peculiar choice, you might say, but he has a horrid way of putting things and he wears a cut-away coat.

"So the day came. The woods and the orchards were full of birds, singing and calling and screaming and whistling. Everybody was too much excited to think of eating, and every bush held a crowd of contestants. It was orderly enough, however, when the contest began.

"The wood dove began the concert. Very soft and sweet. It always makes me think of my giddy youth and my first wife to hear the wood dove. She's really a little bit too sad.

"Then they came on, each one in turn. It was a fine cherry-tree where they sang, and it was so full of blossoms that you could hardly see the performers. Poor little Miss Wren was scared to death. She tried to sing, but all she could say was, Tie me up, tie me up, and she fell off the branch with fright. One redbird, and the tanager, and that whole gay family of buntings—what a brilliant, showy lot! But they were very clear and high and full of little scraps of tune in their singing. More suited to the hedgerow, however, than the concert room.

"The best, to my thinking, was the thrush. You can hear him any evening down there in the alder bushes. He's very retiring and elegant. They say he sings of India and the lotus flowers. It's something sad and far away that he just remembers. I'm not much of a hand at poetry myself, and I personally have a great fondness for the crows. Good, sharp, business men, the crows, and although they are not strictly musical, they appeal to me. You see, we have a great deal in common, the crows and myself, by way of looking after the young corn. We meet, as you might say, in a business way.

"Well, the contest was long and lively. The bluebird and rice-birds, and even the orioles performed in wonderful fashion; and at last, when it was all over, the prize was never given at all. For right out of the clear sky came the mocking-bird, who had kept himself out of the contest until the end, and after he lighted on a branch of that cherry-tree and began his song, there was simply nothing to be said. It dawned on the whole lot of them that they had sung their notes wrong! Yes, young Mr. Squirrel, fine and noisy as it all had been, not one of these birds had sung the tune his father had taught him! Just by trying to outsing each other all those years, their own sweet notes were injured. And only the mocking-bird could remember every lovely song as it should be done. Even the thrush had to admit as much. The adder crawled off in disgust, and the buzzard grew positively insulting in his remarks. He said he had been detained for nothing.

"'Listen, listen, listen,' said the mocking-bird, and straightway he sang like the nonpareil, and then you would have thought him the oriole. It was enough to break your heart, for it was just the lovely old songs that the birds used to sing.

"And what do you suppose came of it all?" added the worthy woodchuck after he had wiped a tear from his eyes, for thoughts of the old days made him sad.

"What do you suppose the other birds agreed upon? They decided never to raise the burning question again, and they begged the mocking-bird to teach them their songs once more. That's why the robins fly South in the fall of the year, along with the other songsters. They want their children to hear the mocking-bird. Yes, Mr. Squirrel, I have that on authority. There's nothing so fine for the singer as a good start and a good teacher. And even the robin, who is full of conceit, has admitted to me that he feels at times the need of a little correction. He hates to go North without a few lessons from that wonderful teacher, the mocking-bird."

With all this, little Mr. Squirrel was greatly entertained and was at a loss how to thank Mr. Woodchuck; but he was spared the necessity of it, for the good warm sun and the sound of his own voice had induced Mr. Woodchuck into a pleasant sleep, and he was already snoring on his door-step. Little Squirrel tiptoed away and ran home in glee. He felt that he had learned all that there was to learn in the wide world.

Anyway, he had learned what he wanted to know, and that is the best of learning.

It was the loveliest of moonlight nights in the early autumn when word was carried from house to house that Mrs. Raccoon would give an oyster supper.

There was Mrs. Coon herself, the present Mr. Coon, and four little Coons. At the upper farm lived several branches of the family—uncles and aunts and their respective children. For the Coons, as a lot, lived mainly on the farmsteads, or near to them; for, as Mrs. Ringtail Coon, the oldest of them, always declared: "It is altogether wiser to keep in touch with civilization." By which she meant it was wise to live as near as possible to the orchards and the corn-fields, and the good things which farmers keep planting every year, apparently for the especial benefit of just such persons as Mr. Coon and Mr. Crow.

"And it is wonderful what a variety of good things you can find to eat if you can run and climb trees and dig in the ground," Mr. Coon would add, "especially if you live where they are very generous in the gathering, and you can have the best of apples and pears and the sweet corn to add to your table."

So it was altogether best to stick as close to the haunts of mankind as possible, if you could do so without foregoing the pleasures of the river and the woodland.

The great river, be it said, which was sluggish and muddy, contained a thousand things which the Coons declared in rather snobbish fashion were not to their taste. They wouldn't go fishing if they could. But the fat mussels which lived in the mud-banks were exactly to Mr. and Mrs. Coon's liking. And to open them is not difficult for a Coon who has once learned the trick.

"That's what your wonderful, black fingernails are for," Mr. Coon always told the children when he taught them to open oysters. "You need only give the joint of the thing a sharp bite, and pull out that tough bit of meat at the end, and then with your nails you can pry the shell right open."

The ability to do this was a matter of pride to the Coons, for they knew of no one else who could open oysters. Like many people who may excel in a particular art, they fancied that they were the only adepts in the world.

"But there's where they are mistaken," Mr. Fox would laugh, whenever he heard of the Coons and their oyster suppers. For he knew of some one else who could get the juicy meat out of those shells, although it was not himself.

"I really pity their ignorance," he would say. "If they ever went abroad in the daytime they'd see a thing or two, and maybe they'd learn that there are wiser folks in the world than themselves."

This was an unfair thrust at the Coons, for their habit of sleeping most of the day should not be laid against them. The world is wisely divided into day workers and night workers anyway, and Mr. Coon, for his part, always put down such criticism by asking what on earth would happen if everybody rushed to his meals at the same identical moment.

And in this Mr. Coon revealed the gentility of his nature, for he was a person of manners, and believed not only in a six o'clock dinner, but kept his clothes in the neatest fashion and was constantly washing his face between his two fore legs, brushing his hair and attending to his ears after the accepted fashion of the cat. And the cat, as all the world knows, is the cleanest of beasts.

"Your Fox is a shaggy creature," he would say. "Almost as unkempt as the farm Dog, whom I despise."

So it is not to be wondered that Mrs. Coon, if she were going to have an oyster supper, would have an elegant one.

Elegance in the matter of suppers is simply a question of due preparation, and of this Mrs. Coon was thoroughly aware. Nothing would please her husband more, she knew, than to have the party go off without a hitch.

"We'll spend to-night getting ready," she planned. "I can't bear to see people digging in the mud and eating at the same time. It is not nice. Perhaps it is well enough on a merely family picnic to let everybody shift for himself, and I know the children rather enjoy getting dirty. I did when I was a little girl. But my ideal of the thing, done as it should be, is to have a great lot of oysters already dug, and arranged in an appetizing pile. It saves time, too, and makes the guests feel better. I never liked these parties where you go digging for your own victuals."

How could an elegant gentleman have a wife more in accord with his desires than that? Immediately Mr. Coon embraced Mrs. Coon in a loving clasp, for he felt that she was responding to his best and most refined impulses.

For two nights, then, while the October moon rode serenely overhead, Ringtail Coon and Mother Coon, with little Grayfur and Brownie, and the two boys, Broadhead and Fuzzy Muzzle, went from their home in the sweet-gum tree, through the wood to the farm road, under the fence to the orchard, back of the orchard to the corn-field, and then downhill to the steep clay banks of the river. At that point they let themselves tumble over the edge, for there were only bushes to fall into, and Mr. Coon did not approve of sliding down mud-banks.

"It's hard on the seat of your trousers," he said; "and Mother has all the washing she can do."

And then they lost no time digging, but scampered here and there, nosing out the great black shells, which they scratched and worried out of the wet soil, sometimes venturing into the water to get a particularly fat and enticing one.

"We'll store them here in a hole under this cornel bush," Ringtail decided; "and if we cover them well, putting back all this driftwood and rubbish on top, no one will guess what's been done."

And no one, indeed, but sly old Mr. Fox would ever have known what had happened. The tempting collection of oysters, pecks of them, was not, however, to remain unmolested. But as the Coons increased their provisions, and worked mightily until the moon went down, they foresaw no accident, and only entertained themselves with happy visions of the remarks and exclamations which their cousins would be sure to make when they beheld such stunning abundance.

"Dear me, Ringtail, there's only one thing that troubles me. I feel that we ought to invite the 'Possums. You know how generous they were in that matter of the persimmons. No one would ever have guessed that there was such a tree in the whole State; and it was, after all, an invitation that they gave us, even if you did threaten Mr. 'Possum in a business way."

"I guess I did," laughed Ringtail as he put another handful of oysters into the hole and stamped them down; "I told Wooly 'Possum not to be hiding his assets that way or I'd bite his tail off. But go ahead and invite them, if you want to. It'll show that we're not snobbish anyway. And the 'Possums are as likely to appreciate all this as anybody. You'll have to open their oysters for them, you know."

"Surely, my dear. I will do so gladly. A hostess never gets any of her own party anyway. I don't expect to do anything but watch other people eat. That's the way of receptions and such."

For Mrs. Coon had arrived at that stage of excitement in which a hostess feels herself elevated and ennobled above humanity in general by virtue of the toiling she has gone through in order to make the rest of the world happy.

By this time they had to stop and take a bite themselves, for day was beginning to break, and the children, at least, must have something to eat. Then, having arranged the top of their secret store with the greatest care, and very loath to leave it, they scrambled up the bank and set out for home. Tired they were and a little cross, so that the youngsters quarreled a good deal, and Mr. Coon, slightly worried, was not so pleasant as when he set out.

"Oh, nothing," he replied to his wife's inquiry as to why he was so glum. "Only I'm a bit anxious about those oysters. It's just possible that somebody may find them."

"Oh, pshaw!" was all she would say. "Nobody's going near that spot. And if anybody did and went and sat right down on top of them, he'd never guess what was under all those sticks."

But somebody did exactly this. For the Coons were all fast asleep in the sweet-gum tree, not even dreaming of their party, when Mr. Fox edged along the river shore, greatly elated at discovering so many little foot-prints in the mud. It was plain who had been there. And as the dainty tracks centered under the cornel bush, it took no wits at all, and only a little brisk pawing, to discover the secret.

Mr. Fox laughed as though he would give up. For that is a trait of all foxy natures to go into fits of laughter when the possibility of turning a mean trick presents itself.

"Well, of all things!" he finally gasped, as he held his sides. "How mighty kind of them!" Then, licking his chops, and fairly choking with humor, he set off just as fast as he could go. Up the shore and through the woods he ran; and at a certain tree where a great sentinel crow sat eying the farmers in a distant field, he barked out one short, sharp message.

He had to say nothing more. Before he could get back to the spot where the delicious supper was stored, the crows were coming, one and two at a time, then three and four, and finally a small flock of them.

Mr. Fox got very little for his pains, for the crows were as quick as lightning in their motions. Up in the air they flew with an oyster in their beaks, and over the rocks and bowlders which jutted from the shore they would pause but a second to drop their burden. Down it would come, breaking to pieces as it fell on the rock, and then the crow would come down almost as fast as the oyster, to tear out the meat and swallow it. Mr. Fox played around the edges, as it were; for too many crows had come, and they fought him off when he tried to snap up his share.

"Oh, well, I don't care much for oysters anyway," he muttered, trying to console himself. But he was in reality bitterly tantalized, and he was truly in tears of disgust when the great black crowd of noisy birds flew at him in a body and drove him off. They benefited by his confidence, but they were utterly selfish, and he suddenly felt wickedly put upon.

What he had done to the Coons never occurred to him.

Mr. Coon never recovered from the mortification of that evening. The guests had assembled in a body; all of his brother's family and their dependents, and the little 'Possums, who were so set up at the invitation that they fairly beamed. Such toilets had been performed and such preparation of pleasant remarks had gone on, that everybody was in the finest of party feeling.

The walk through the corn-field, the ease and happy expectancy! Getting down the mud-bank was not altogether a formal ceremony, for some slid, and some just plunged headlong; but at the bottom everybody brushed his clothes, and the little Coons and the little 'Possums danced in glee.

Then, lo and behold, there was no supper at all! The work that the crows had done was apparent enough. But how they ever knew where to find the banquet was an unsolved mystery to Mr. Coon.

Never again did Ringtail or his wife try to be fashionable. "Dig and swallow," became the rule at all the oyster suppers; and even at this one, after the disaster had bestowed its first stunning blow, the guests and the company as a whole fell to digging as hard as they could, and ate with might and main.

Mrs. Coon, having urged the 'Possums to come, had to open oysters until her thumbs were sore; but she did it with a good grace, and after everybody got to going, there was all the laughter and happiness the heart could wish.

"Yes, it was a merry party, after all," Mr. Coon admitted several hours later. He was curling up in his sweet-gum tree bedroom, ready for another day's sleep. "But it was a free for all, a regular guzzling. What's the use of trying to be nice when all the world's made up of crows?"

But in this query, Mr. Ringtail Coon was only a bit petulant. The best of it is that he does not know the ignorance of the world. For scarcely anybody appreciates or even guesses the true elegance and the dainty ways of Mr. and Mrs. Raccoon.

It was a beautiful morning, very early, with the dew on the grass and the mists lifting from the sea, when Mrs. Goose with her seven little goslings walked through the farm gate, down the path to the road, and then waddled under the fence into the pasture.

"You are well along now, my children," she was saying, "and your travels should begin."

"And what are our travels?" the little geese piped as they stepped along beside their stately parent.

"Your travels, my dears, are those excursions away from the cramping and monotonous surroundings of the farmyard. That's what your travels are. None of your family are given to staying always and forever at home."

"Oh, no," the goslings all quacked in chorus. "We don't want to stay around that farmyard all our days. That's what the chickens do, and the guinea-hens. But where are we going now, Mother?"

For the beautiful Mrs. Goose was heading straight for the swamp at the foot of the great pasture, and already she was taking them through the tufted grass and the low bushes, through which they could not easily descry her stately form. They were quite out of breath, and bore along behind her, being very careful to keep exactly in her foot-prints.

"We are going to the great salt river, and the marshes," she called back to them. "That is where your cousins live and we shall spend a lovely day with them. But we must hurry through these bushes. I never feel safe until I am well out of them."

She explained no more than this, for she was a bird well versed in the bringing up of children, and she did not wish to frighten them. But, truth to tell, this bushy part of the path to her favorite haunts was always full of its terrors for her.

"It looks so very much like the spot where my first husband was attacked by a fox," she confided to one of her friends. "He was never seen again, of course, and although I was not long a widow, still I have never been consoled for his taking off."

Naturally, then, she had for the rest of her days a distrust of bushy paths, and it was with a great quack of relief that she emerged with all her little ones on the banks of the deep, narrow stream which was a part of the great marsh.

Off she swam on the water, paddling with a majestic ease, and down they hopped and splashed and paddled beside her, the seven of them, highly excited over the prospect of a day's adventure.

The stream was narrow and deep, much unlike the shallow duck-pond in the farmyard, and it gave the goslings an exhilarating sensation to be thus abroad on a real stream.

"How good it is," Mrs. Goose quacked, "to feel the clear, cool water, and to know that you are not paddling across a mere mud-puddle!

"And there are no tin cans and other rubbish here," she went on. "Very different, all this, from the rather common surroundings of the duck-pond. You must realize that your family is a superior one, and that while the ducks on the farm do very well for neighbors, they are not the aristocrats that we are. And I am taking you purposely, my children, to visit my most exclusive friends."

The old goose was indeed a haughty personage, as any one could tell by the way she held her head. For she swam as a soldier marches, with eyes to the front and a splendid air.

Soon they came to where the narrow inlet of the marsh widened into a broad expanse of water banked by low, wide areas of reeds and rushes. Many channels and enticing little bays made off into the depths of shady and inviting spots where there were cedars and alders and dense, tangled vines. There were delicious odors in the air, and this made the goslings suddenly very hungry. They begged their mother to let them run through the grasses to pluck the tender and inviting things which their eyes caught sight of. But she shook her downy head and kept them paddling along beside her, cautioning them very wisely:

"Never go browsing by yourself until you know the ways of the country. Where there are others feeding it is safe for goslings. But to go into those tall grasses, tempting as they are, is to walk right into danger. You have never met Mr. Blacksnake, and I hope you never will until you are too big to tempt him!"

Immediately, of course, they clamored for the details about this dreadful creature, but their mother spared them any unhappy visions of the sort.

"You must not dwell on such uncomfortable things," she would say. "All you need think of when you are out with me are the bright sky and the good green world. But here we are, almost at Mrs. Bittern's gate. And there is Grandpa Bittern waiting for us at the door."

As she spoke, the goslings all craned their necks; but they were not big enough to see over the top of things as their mother could, and they were totally in doubt as to who the Bitterns were, or where they lived.

Suddenly there was a great quacking and flapping of wings on the part of their mother, and they found themselves touching bottom in a beautiful shallow where the black earth and the mosses grew over the very water. Here all was shaded and hidden by the overhanging bushes, and great tree-trunks rose close at hand, with clinging vines and innumerable strands of leaf and tendril swaying in the clear air.

Never had they dreamed of such a beautiful spot. But they were not to realize how lovely it was all at once, for they were to get acquainted with it only after the greetings of the visit were over.

Their cousin, Mrs. Bittern, who was so slim and brown, with black trimmings to her wings, and a bit of gray lace at her bosom, and the stately gentleman who stood guard by her nest, were quite enough to overpower the little goslings. They couldn't remember their own names and they stammered with embarrassment; and in the nest was a solitary youngster, with a very long bill, and big, frightened eyes, whom they were cautious in approaching. His only greeting was a vicious poking at them with his little head, and they noted that his neck was very strong.

"Billy isn't used to children yet," Mrs. Bittern hastened to apologize. "But he'll soon get used to them. Just hand him a bit of fish, Father, and a few of those small crabs. Oh, a very small one, Father. You nearly choked him to death with that big one you gave him at breakfast."

True enough, little Billy Bittern was in a better humor when something more had gone down his throat; and while the two mothers fell into an immediate discussion of the stupidity of fathers and uncles, the baby Bittern and the little goslings were quacking and playing around the nest in the noisiest fashion.

"So this, my dears, is a true country home," their mother said as she turned to them. "This is the kind of thing that your father and I have always wanted; a little place of our own in the swamp!"

"Oh, Mother dear, wouldn't it be lovely!" they all burst out, really transported with joy at the thought of living forever where it was all like this, so free and open and sweet.

"Ha! ha!" laughed the tall owner of the charming retreat. "That is what you farm people always say when you get here. But you know very well you'll be glad to get back to what you call the conveniences and elegance of life."

By this he meant the cracked corn, and the snug quarters, and the rest of the good things in the farmer's yard.

But Mrs. Goose pretended not to understand him at all, and was helping Mrs. Bittern to put the nest to rights as they all prepared to go out for a walk. For that is always the first thing to do when you visit your country cousins.

Such precautions as the Bitterns took when they left the house! It was cover the nest here and put a stick there, and finally, to effect a complete disguise, they raked a lot of straw over the top. Why, you never would have guessed it was a house at all!

Then through the grasses and the deep, black mud, and over innumerable tufts of green, where there were great wild cabbages and tempting bunches of mallow and flag, they went in happy procession. The goslings nibbled and tasted and feasted, wherever their mother was sure it was wise, and little Billy with his sharp beak poked incessantly in the mud for the things he liked best in the way of tadpoles and beetles.

Almost all day they picnicked in this delightful place, and only stopped in their leisurely stroll when they came to a grassy knoll where the mother birds thought it well to let the children rest.

All the gossip of the year was gone over by their elders. Mrs. Bittern told of her winter sojourn far to the South.

"We stayed much of the time with the Herons and the Spoonbills. Theirs is such an attractive rookery, you know, and I delight in Southern society. We came North with your first cousin, Mrs. Hudson Goose. A noble family, your great Northern relatives, my dear Fluffy. But they fly a little too fast for us Bitterns. We parted after a few days. Longbill, you know, likes to take it easy when he travels."

But the children observed that Mrs. Bittern was moved to tears when their mother alluded to her late half-brother and another relative, uniting these names with a reference to Christmas dinner. But they did not understand the connection, and it puzzled them when Cousin Bittern answered:

"Never mind, dear Fluffy Goose, there's little danger for you. You know you're getting tough. Let's see, you're twenty now, are you not?"

And they were still more surprised when their mother bridled at this and said that surely Mrs. Bittern was mistaken. No, she was only eighteen, and if her neck was spared it was not at all because she was tough. It was because she possessed the ability to lay the most and largest eggs, and to rear the finest families.

Mrs. Bittern was only too eager to agree with her companion. Not for the world would she have her words taken amiss; so the little family quarrel was passed over, and Mr. Bittern merely observed that the ladies were getting a little tired, and he thought that they had all better go home.

But if he had been very quiet, this dignified Mr. Bittern, he was, like a good many modest people, none the less able to distinguish himself, for after they reached the welcome door-yard, and Mrs. Goose and her family were about to depart for home, he supplied the treat of the whole day.

"Surely, Cousin Longbill," Mrs. Goose had remarked, "you are going to boom for us before we go. I wouldn't have the babies miss it for anything."

Whereat, to their dismay, Mr. Bittern began making the most frightful sound they had ever heard. It was his great feat, that for which his family was renowned, and it was not like anything ever known on sea or land. To do it he filled himself so full of air that he was like to burst. And he was very red in the face when he got through, like a good many famous singers.

"Isn't it wonderful!" said his wife. "I never knew one to sing the national anthem better."

For, to her simple soul, her husband's song was of course the one and only song. It must consequently be very important.

Scarcely could Mrs. Goose praise her cousin enough, and the goslings all begged him to do it again. But once was enough, he reminded them, and they discreetly forbore from disagreeing with him.

By this time they must hurry to get home, and their farewells were hasty. Like many return journeys, the way back was the shortest; and before they knew it, the goslings were trailing through the bushes at the foot of their own pasture. And somehow the little hill and the pair of bars and the bit of road, even the farmyard strewn with straw and pleasingly disordered, suddenly looked better to them than the lonely home of the Bitterns far out in the great swamp.

"Ah, my dears," their mother said, as they waddled up to their home under the burdocks and the currant bushes, "that's what a day away from home does for you. It makes you glad for what you have."

And indeed they were happy to nestle under her ample wings, as the stars came out and the house dog bayed at the moon. And they were very happy to have heard their Cousin Bittern do his booming, and hoped, as many people hope after a great performance, that they would never have to hear it again!

Once upon a time, long, long ago, Mrs. Rabbit lived down by the sea on a great sand-hill. She was a very kind neighbor and disturbed no one. She was poor, but she owned a great gray goose who laid wonderful big eggs.

The goose had come to her in the strangest way, years and years ago. For it happened one day that just as Mrs. Rabbit was locking up her house to go and visit her cousins, she heard a sad voice in the bushes cry, "Oh, Mrs. Rabbit, Mrs. Rabbit, please do help me in. I have broken my wing and fallen here, and all the other geese that were flying with me are gone. They left me where I fell."

At that Mrs. Rabbit gave up her intended visit, and took poor Downy Goose into the house, sent for Dr. 'Possum, and did her best to comfort her.

When Dr. 'Possum came, he took one look at the afflicted goose, shook his head, and declared he could do nothing for her. Mrs. Rabbit thereupon told the unfortunate wayfarer that she must live there always.

"You must make your home with me," she said, "and we will make the best of things. Even with your poor broken wing you can manage to get along, for there is a fine swamp below the ridge of this hill and near it is the best of green grass and shady bushes."

Poor Downy Goose was overcome with happiness. She could only dry her streaming eyes with a plantain leaf, while she kept saying:

"You are so kind, so very kind, dear Mrs. Rabbit! I shall do my best to lay an egg every day for you—omitting Sundays, of course, and the Fourth of July."

At this Mrs. Rabbit threw her arms around poor Downy's neck and they wept with joy. And from that day to this they have been the closest friends.

Nor did the good gray goose fail in her promise. Indeed, she did her best; and always by noon, while Mrs. Rabbit would be dusting and sweeping, or getting the boiled grass ready for dinner, the lady goose would sit in the door-yard mending socks or reading poetry, when suddenly she would lay an egg, and then, calling to her dear friend to bring the basket, they would put the egg away on the pantry shelf. Then they would betake themselves for the rest of the day to the field and the edge of the swamp where Mrs. Rabbit would nibble the tender grass, and Downy Goose would wade in the soft, cool mud.

Now, it was soon known among all the neighbors that Mrs. Rabbit and the strange goose were living together. Also it was soon told abroad that the goose was paying her board in eggs—big eggs—that she paid it every day, and that Mr. and Mrs. Rabbit were faring on the finest food. They had scrambled eggs, and omelettes and pound cake at every meal—and all this for merely taking in the poor, afflicted goose!

You would think that all who heard it would have been glad to know how happy the rabbits were, and they ought to have pitied the poor goose who could never fly again; but that is not the way of the world. Instead of saying nice things, they said ugly ones, and behind Mrs. Rabbit's back, the neighbors, Mrs. Fox in particular, expressed the bitterest jealousy.

Mrs. Fox, indeed, grew so envious of these big goose eggs that at last she could stand it no longer, and resolved upon a plan for stealing them. She put all her wits to work, for, to get such big eggs and carry them without breaking them open was a thing which only the cleverest thief in the world could do. Nevertheless, every day for five days, an egg disappeared from Mrs. Rabbit's pantry.

Mrs. Rabbit was greatly disturbed, but she never dreamed who was stealing the eggs. Finally she decided to watch the nest all the time; and to her surprise found that the thieves were her neighbors—Mr. and Mrs. Fox.

How cleverly they managed! Mr. Fox lay on his back and held the big egg while Mrs. Fox pulled him over the hill by means of a rope tied to his tail. In this way they got the egg home.

But Mrs. Rabbit laughed as she thought of how poor Mr. Fox's back would be skinned, and how she would get revenge.

Nor was it long before a way was opened for her to recover the lost eggs, and to put Mrs. Fox to confusion. For who should come walking in one morning but Mr. Bear, to say that invitations were out for a wonderful feast of goose eggs at Mrs. Fox's home on the following Saturday night. And he asked Mrs. Rabbit if she were going.

That was enough! Mrs. Rabbit determined to get back the eggs. But she would have to be very clever to fool Mrs. Fox.

Mrs. Rabbit knew that Mrs. Fox would come for the last goose egg soon. So she bored a hole in this egg at each end, and blew in at one end till the contents all flew out at the other and the shell was empty. Then she slipped inside, and Mr. Rabbit pasted small pieces of white paper over the openings.

And here Mrs. Rabbit waited for the thieves to come, while Mr. Rabbit hid behind a tree near by.

Soon they came, and after much effort the big egg was carried into Mrs. Fox's home. Mrs. Rabbit chuckled to herself as she saw the other five big eggs through a tiny peephole in the paper.

While the gay old foxes were in the next room, entertaining their guests, Mrs. Rabbit broke the paper at one end and slipped out. Then she called softly to her husband to bring the wheel-barrow; and they piled in all the eggs and carried them away.

Nor were they more pleased to recover their lost property than was the obliging goose when she learned of all that had been going on.

"To think," she exclaimed, "that I have been laying eggs for those dreadful foxes!"

And Mr. and Mrs. Fox wonder to this day who stole the goose eggs.

Long, long ago Mrs. Frog lived on the hillsides. She was a goddess worshiped by all the fairies because she ruled the sunshine and the rain, and she was a friend to them all, being generous and dutiful.

With her seventy daughters, she spent the days in spinning the most beautiful cloth of gold for the fairies to wear, and the flax which she spun was as yellow as the biggest and ripest pumpkin you ever saw.

All the years that she served the fairies by her industry, and was dutiful in calling down the rains to refresh the earth, she was in great favor with the world, and no one was so much beloved by all the animals as Mrs. Frog.

But the seventy daughters who were so handsome, and who spun such miles of yellow thread, grew restless, and kept begging their mother for a holiday. She, too, owned to being a little weary, and would often remark with a yawn that it wasn't the spinning, nor yet the weaving, which tired her, but the lack of diversion.

"And think, dear Mother," they would say, "think of our lazy brothers, who do nothing but admire their shapely legs all day, and spend the whole night dancing and singing and eating suppers. It isn't fair!"

On speaking thus the daughters were very artful. For if there was one thing which angered Mrs. Frog, it was the laziness of her sons. Years and years ago she had given up trying to get them to do a single useful thing. And it was no consolation to observe that they got along in the world somehow, whether they did anything or not.

"Look at their awful stomachs," she would exclaim. "The lazy creatures, always eating and singing. What a life!"

It was thus that the seventy daughters played upon her feelings of disgust, urging her to adopt a change and give up spinning. Each one spoke to her alone, seven times a week, when she would reply:

"Yes, my daughter, I am listening, and I don't know but what you are quite right."

And then, when all the whole seventy spoke together, as they made a point of doing when they knew she was tired out and had the headache, she could only clasp her hands to her ears and flee to her bedroom.

At last the daughters won and Mrs. Frog began her holiday. She meant to take but a single evening and a day, hoping to get back to work there-after, rested and refreshed. But alas! once she began her career of dancing, and feasting, and staying up till morning to sing and laugh and watch the sun come up, the day never came that she was willing to spin the yellow flax.

Forty of the lovely daughters danced themselves to death within a week, but Mrs. Frog was so busy waltzing and marching and singing that in each instance, as the sad news came to her that another daughter was dead, she was too gay to care or even to ask, "Which one?"

Terrible disaster began to come upon the land. All the birds and plants were dying for water. Clouds passed by, but Mrs. Frog was too lazy to make the rain fall. If she wasn't dancing, she was sleeping, and so no time remained for her duties.

One day the animals from the forest came to call on Mrs. Frog, to plead for rain. The mother rabbits came from long distances to tell Mrs. Frog how their babies were perishing for water and for tender bits of green grass.

But Mrs. Frog had become hardened and told them to leave her alone.

"Please give us rain! Please give us rain!" the birds all pleaded; but Mrs. Frog only frowned at having been awakened.

Then came all the bees and the butterflies from the hillsides, tired, hot, and dusty.

"We are your neighbors and friends," they cried. "Do give us rain! The flowers are all dead and we have no honey to eat!"

"Go away!" croaked Mrs. Frog. "I must sleep during the day, and I have no time to worry with you! If you don't like the way I manage this hillside, go to the swamp lands!"

Next came the fairies for their yellow dresses, which Mrs. Frog was to have spun from the yellow flax. Mrs. Frog was fast asleep, but when they called and called her she awoke. She rubbed her sleepy eyes and awakened all the family to help her spin the flax; but the sun shone down on the hot, dry earth so burningly that all her spinning-wheels caught on fire and everything in her house was burned up.

"Oh, for a drop of water!" the birds and the animals were calling. "Help us, Mrs. Frog! Do help us!"

But it was too late. Even Mrs. Frog's wand, with which she called forth the rain from the clouds, was burned up. And Mrs. Frog was so terribly hot and thirsty that she didn't know what to do.

As a last resort she started for the swamp lands, thirty of her exhausted daughters trailing after her. They were all so tired they could no longer walk, and finally, being faint and bent over to the ground, they took to hopping.

Down, down, down, through the hills they hopped until at last they reached the dark, damp swamp. The daughters had become as lazy as the sons; and Mrs. Frog herself desired nothing in the world but a cool, muddy bed at night, and a good log or a lily pad to sit on throughout the livelong day.

But in her muddy bed she doesn't sleep; for all night long one may hear her calling: "More rain! More rain! More rain!"

While Mr. Frog croaks: "Knee deep! Knee deep! Knee deep!"

And all the little frogs: "Wade in! Wade in! Wade in!"

There was a time when the world was mostly forest. There were plains, to be sure, and rich valleys, but the trees were everywhere, so that even the towns and farms were hidden by them; and there were no great cities at all.

It was then that the animals lived in peace, and they were not driven to hide themselves, nor to be always moving farther and farther away to find new shelters.

But the days came when the forests were cut away. A little at a time, and always along the edges of the woods, men began to hack and to chop and to saw, until one by one the great trees came down. With them as they crashed to the earth came the birds' nests; and where the trees had stood, the mosses and the grass dried up and died, for the hot sun poured in where once it had been shady and cool.

In the days when this began it distressed the animals; so that the poor creatures at last resorted to a wonderful plan. To them the woods were very dear, and never were they frightened at what they saw or heard; although the depths of the forest were so full of terrors to foolish men.

News was spread through the glens and across the mountains that something was going to be done to save the woods. The birds and the swift, scampering little weasels, and the soft-footed wildcat, who can cover many miles and never be seen or heard, took the messages far and away. Time was allowed; for the beaver and the mud-turtle were necessary to the plan, and even at her best Mrs. Beaver is slow in her motions. It was none other than crafty old Major Wolf who had conceived the plan by which they would teach the wood-cutters a lesson.

"Such simple and foolish creatures they are!" he remarked. "We've only to frighten them out of their wits, by some device or other, and if we scare them enough they'll keep away from these woods forever!"

With that he snapped his terrible jaws and turned his great yellow eyes on the company. Before him and around him were all the animals of the forest. The deer, who could think of nothing to do but to run, the fox, who knew every possible way of deceiving his enemies, the bear and the panther and many of the small creatures, down to the sleek little mole, were all talking at once.

The bear and the wildcat were very impatient. They were all for fighting outright.

"You hug and I'll scratch," said the lynx to the bear.

"We can do up an army of choppers if we get the chance," added the panther; but he was lost in the debate, for the wisest of all, the great gray wolf, reminded them that if the men with their axes so much as caught sight of the animals, they would go away only to come back with their guns and to fill the forest with every conceivable trap.

Then he pointed to a great, dead tree which stood alone and on the brow of the hill. The animals looked and tried to get his meaning. Some of them yawned, such as the hedgehog, whose wits are slow; but the quick Mrs. Fox jumped and cried, "That's it, that's it! We'll make that tree into a giant to guard the path to our woods."

Then Major Wolf exclaimed that the sagacious fox had guessed his plan.

The wind and the frost had bent and broken the tree until it was like nothing in the world so much as a giant. Its arms were there and its shoulders; and its terrible body, as high as the church steeple, was bent forward as if to fall on any one so rash as to come near it. But it needed a great deal of what the heron called "touching up"; for the heron is an artist, and goes every year, they say, to study the sculptures of Egypt.

"It needs a mouth and two eyes, as any one can see for himself," the lynx remarked; and the mole and the hedgehog suggested that the feet might be improved. Here was the task for the beavers; for carving and cabinet work is their specialty. And to chisel great holes for the eyes and the mouth was exactly what the woodpeckers and the squirrels could do.

The work was so briskly done, that it was indeed completed before the admiring circle could gasp out its astonishment. While the chips and the saw-dust were flying, Major Wolf was moved to observe in the most pious tones:

"How marvelous that these poor little cousins of ours, these smaller, gnawing creatures (if I may call them such without hurting their feelings) should alone be able to serve the purposes of us more noble beasts."

And he waved his paw to include the bear and the panther in the nobility.

But the gentle Mrs. Deer knew what a terrible hypocrite Major Wolf was. And she moved with her children to the other side of the meeting; for she had watched his mouth water even as he spoke such wonderful sentiments.

The squirrel was boring away at the great giant's limbs, carving and cutting; and even the slow old turtle, with his powerful nippers, was pruning the tangle of vines from the feet.

But the morning was close at hand. The wood creatures had barely enough time to complete their work and scamper off. They crouched in the bushes to await the effect of their scheme. And even though they knew the giant was no giant at all, but just a great, dead tree, they were awestruck at the result of their work.

As if to add to the strength of their purpose, the sun was rising in a terrible glory of red, with the blackest of clouds all round.

It was terrible. The red light of the morning, through the gaping mouth and awful eyes, the waving arms and the immensity of the giant were frightful.

The wood-cutters came. But only one of them got as far as the tree. With a howl of fear, he turned and fled, dropping his ax as he ran. He told of the awful giant with eyes and mouth of fire, and the others refused to come near.

The animals were greatly elated; but the wisest of them knew that some day the foolish wood-cutters would find out the truth. And such was the case; although it was a long, long time, and the great giant which the animals made warded off their enemies for many a year.

Once upon a time the animals who live away up North, in the cold Arctic regions, came together for a feast in celebration of their blessings. The bears, the wolves, the minks, the sables, even the big, spluttery seals that swim in the icy water, were all on hand to make a great noise, singing and shouting and devouring the things that they all loved to eat.

All were there except Mrs. Fox, and why she was not invited no one knew. Maybe Mr. Penguin, who wrote the invitations, was responsible for the omission, but at any rate it is a fact that the fox family was left out in the cold.

Of course, Mrs. Fox felt herself sorely slighted. She and her six children came near enough, however, to learn that after the celebration and the dance, which was to be held on the ice floor of the Bear palace, there was to be a great supper in Mrs. Bear's kitchen. It was to be a feast of the eggs of the eider-duck. A supper, needless to say, that any bear or fox would travel night and day to enjoy.

On the night of the feast Mrs. Fox crept quietly up to the bears' house.

Mrs. Bear and all the ladies were in the bedroom, brushing down their rich winter suits, and prinking away to look their best before going down to meet the other guests. And, of all things, they were gossiping about Mrs. Fox! Just because she wasn't there (as they thought), they were speaking of her in the most slighting terms. It seemed as if they were all talking at once; but Mrs. Fox, whose ear was close to the chimney, could hear Mrs. Wolf's deep voice distinctly.

"That old coat of Mrs. Fox's is the shabbiest I have ever seen," she was saying in her severest tone. "One would think that a woman of her build, slinky and queer as it is, would put on white every winter. I would wear white myself if I didn't think this handsome gray of mine an elegant thing the year round."

They all agreed that Mrs. Wolf was indeed very elegant, and that Mrs. Fox was very shabby. Little Miss Ermine, who, as all the world knows, has the finest white coat in the world, piped up shrill and cross:

"Right you are, Mrs. Wolf. White's the thing in winter, but only for those adapted to it. It scarcely becomes every one."

At this she made a great showing of her own dainty figure, cutting several merry dance figures before the mirror.

Mrs. Fox had heard enough. She waited for the ladies to go downstairs to the great room where all the gentlemen sat about. She knew what they would do. There would be wonderful speeches by the biggest and oldest bears, about the midnight sun and other blessings; the walrus would make a long speech, too, mostly about seaweed and fish; and then, after a dance or two, they would all come trooping out to the kitchen. Old Uncle Penguin would make a very long prayer, and everybody would eat until he could eat no more.

Mrs. Fox was very angry. She resolved that there should be no supper for her mean, back-biting friends.

Cautiously she felt her way down the sides of the cliff which was the outside of Mrs. Bear's great house. As she expected, the eider-duck eggs were in a basket suspended from the pantry window. Quick as a flash she ran back for her children, and in another minute they were all beside her on the roof of Mrs. Bear's kitchen.

"Old Mrs. Sloth, who cooks for Mrs. Bear, is sound asleep by the fire. Don't wake her up. And do just what I tell you to," whispered Mother Fox.

The little foxes held their breath.

"Stand in a line! Now each one of you take hold of the next one's tail. Each of you except little Fuzzypaw. He's the quickest and the lightest and he is going to run up and down the ladder which the rest of you will make, and bring me those eggs, one by one. Just grip each other's tails as tight as you can, and don't make a sound!"

It was no sooner said than done. One after another the eggs were brought up to the edge of the roof by the little fox, who ran up and down the ladder as nimbly as a weasel. Mrs. Fox stowed the eggs away carefully in a brand-new basket she had brought with her, and in a few minutes the basket by Mrs. Bear's pantry window was quite empty.

Then off through the big woods the little foxes trotted gaily behind their mother.

What happened when the supper party found that it had no supper, Mrs. Fox never knew. For while Mrs. Bear and her guests were reduced to confusion and disappointment, the foxes were at home roasting eggs by the fire, and sitting up to all hours in the jolliest fashion.

The next year Mrs. Fox was invited. Old Mr. Wolf, who knew a thing or two, thought it would be the wisest thing to ask her. So all the other animals agreed; and Mrs. Fox never found society in the Arctic Circle more cordial than after the season it ignored her and she stole the eggs of the eider-duck from Mrs. Bear.

Very much out of the beaten track—in fact, only to be approached by an old road that had long fallen into disuse—stood a neglected cabin, a poor weather-beaten thing with sunken roof and decaying timbers.

Its door-yard had already begun to grow the young pine trees which come up in great plumes of long, green needles; and the little garden plot, which used to boast its vegetables, had become a mass of brambles and nettles.

"How sad this all is," the poor little cabin used to sigh. "Although I suppose it is better to be harboring rabbits and squirrels, and to have my beams plastered up with nests, than to have no living thing enjoy my shelter. Still, I wish spring when it comes would bring people to unlock my door and children to fill these poor little rooms with their laughter."

For the cabin could remember many children that had lived there, and sometimes it seemed to him that he heard them again, playing in the nearby woods, or running and calling down the road.

Sometimes he did hear such voices, for people often passed the cabin on the way to a distant plantation, and children were as likely to be among them as not.

But the squirrels and the rabbits had it pretty much their own way with the deserted cabin, running in and out beneath the underpinning; and the only noise around the place was that of Mrs. Yellowhammer when she came pounding at the roof for what the decayed old shingles might conceal.

"I declare, you poor old house!" the energetic bird would say. "It's terrible how the worms are eating at your timbers and shingles." Whereat she would fall to and nearly pound the life out of the poor old cabin, in her determination to get all there was.

But Mrs. Yellowhammer and the rabbits that danced in the moonlight were not the only visitors, for often in the summer time came the humming-birds to visit the trumpet-vine which covered nearly all of one end of the structure.

"I am the saving grace, the chief beauty of this establishment," the Lady Trumpet would say. "And I know it."

"Of course you are," Mrs. Yellowhammer would reply. "And it was a great mistake that you were ever planted here. A lady of your elegance, among such weeds and common things, and at the very edge of nowhere!"