The Project Gutenberg eBook of A handbook of library appliances, by James D. Brown

Title: A handbook of library appliances

The technical equipment of libraries: fittings, furniture, charging systems, forms, recipes, etc.

Author: James D. Brown

Editors: J. Y. W. MacAlister

Thomas Mason

Release Date: May 19, 2022 [eBook #68130]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Library Association of the United Kingdom.

This Association was founded on 5th October, 1877, at the conclusion of the International Conference of Librarians held at the London Institution, under the presidency of the late Mr. J. Winter Jones, then principal librarian of the British Museum.

Its objects are: (a) to encourage and aid by every means in its power the establishment of new libraries; (b) to endeavour to secure better legislation for rate-supported libraries; (c) to unite all persons engaged or interested in library work, for the purpose of promoting the best possible administration of libraries; and (d) to encourage bibliographical research.

The Association has, by the invitation of the Local Authorities, held its Annual Meetings in the following towns: Oxford, Manchester, Edinburgh, London, Cambridge, Liverpool, Dublin, Plymouth, Birmingham, Glasgow, Reading, Nottingham, and Paris.

The Annual Subscription is One Guinea, payable in advance, on 1st January. The Life Subscription is Fifteen Guineas. Any person actually engaged in library administration may become a member, without election, on payment of the Subscription to the Treasurer. Any person not so engaged may be elected at the Monthly or Annual Meetings. Library Assistants, approved by the Council, are admitted on payment of a Subscription of Half-a-Guinea.

The official organ of the Association is The Library, which is issued monthly and sent free to members. Other publications of the Association are the Transactions and Proceedings of the various Annual Meetings, The Library Chronicle, 1884-1888, 5 vols., and The Library Association Year-Book (price one shilling), in which will be found full particulars of the work accomplished by the Association in various departments.

A small Museum of Library Appliances has been opened in the Clerkenwell Public Library, Skinner Street, London, E.C., and will be shown to any one interested in library administration. It contains Specimens of Apparatus, Catalogues, Forms, &c., and is the nucleus of a larger collection contemplated by the Association.

All communications connected with the Association should be addressed to Mr. J. Y. W. MacAlister, 20 Hanover Square, London, W. Subscriptions should be paid to Mr. H. R. Tedder, Hon. Treasurer, Athenæum Club, Pall Mall, London, W.

COTGREAVE’S LIBRARY INDICATOR.

This Invention is now in use in some 200 Public Libraries (30 in London and Suburbs), and has everywhere given great satisfaction. The following is a brief summary of its more useful features:

1. Show at a glance both to borrower and Librarian the books or magazines in or out. Also the titles can be shown to the borrower if desired. 2. Who has any book that is out, and how long it has been out. 3. The names of every borrower that has had any book since it was added to the Library. 4. The dates of accession, binding, or replacement of any book. 5. The title, author, number of volumes, and date of publication. 6. The book any individual has out, and every book he has had out since joining the library. 7. If a borrower’s ticket has been misplaced in the indicator, it will instantly denote, if referred to, the exact number where such ticket will be found. 8. It will show at a glance by a colour arrangement the number of books issued each day or week, and consequently which are overdue. 9. Stocktaking can be carried out in one quarter of the time usually required, and without calling the books in. 10. Wherever it has been adopted the cost of labour and losses of books have been very greatly reduced, so much so that in a very short time it has recouped the cost of purchase. Thus all book-keeping or other record may be entirely dispensed with.

Sole Agent and Manufacturer:

W. MORGAN, 21 CANNON STREET, BIRMINGHAM.

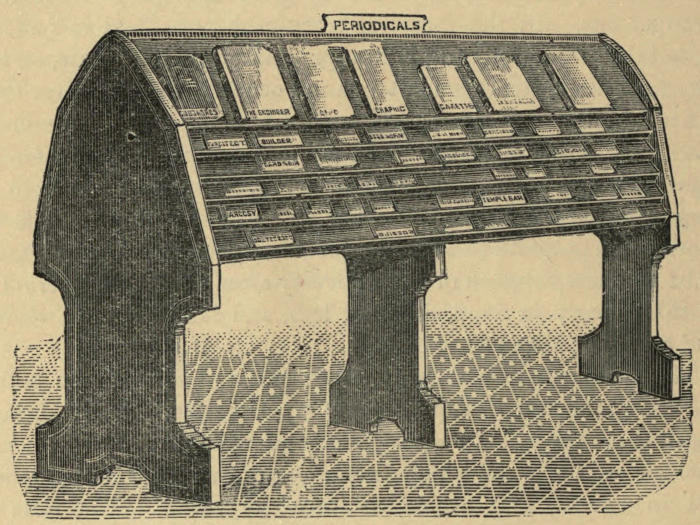

Cotgreave’s Rack for Periodicals and Magazines.

This design is now used in a large number of Libraries and Reading Rooms with great advantage. Periodicals of any size can be kept alphabetically arranged either in covers or without. There are no clips, springs, or other mechanical fittings, but everything is as simple as can be.

Manufacturer:

WAKE & DEAN, 111 LONDON ROAD, LONDON, S.E.

Cotgreave’s Solid Leather Covers for Periodicals.

These covers are made of solid leather and will last longer than a dozen of any other material. Several Libraries have had them in use for a dozen years or more, without any appearance of wear.

Manufacturer:

W. MORGAN, 21 CANNON STREET, BIRMINGHAM.

N.B. Any special information required may be obtained from the inventor, A. COTGREAVE, Public Libraries, West Ham, London, E.

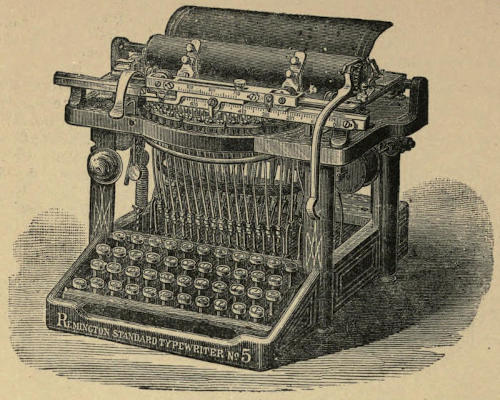

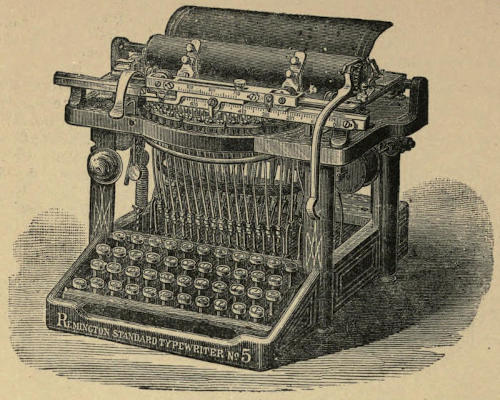

Remington Standard Typewriter.

Used and endorsed as the best everywhere. The following is one of the strongest testimonials which could possibly be received:—

AMERICAN NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS’ ASSOCIATION.

Officers:

Executive Committee:

Address all communications to the Secretary, care NEW YORK OFFICE, 206 POTTER BUILDING.

To the Members of the American Newspaper Publishers’ Association.

NEW YORK, MAY 11, 1892.

Gentlemen,

The undersigned, a committee appointed by the President to investigate into the merits of the various typewriting machines with a view to the adoption of some machine for the use of members of this association, respectfully report that in their judgment, all things having been considered, the “Remington” is the machine which they would recommend for adoption, believing that in its superiority of design and excellence of workmanship, its great simplicity, durability and easy manipulation, it is more desirable for use in newspaper offices than any other. In addition, the fact that it is understood and operated by a great many thousands of young men and women, that the use of it is being taught not only in the public schools, but in commercial schools and colleges throughout the land, and, its being generally referred to as the standard: the large number of offices which the company have scattered throughout the country, making it easy to have repairs made at the least expense, have all had some effect in basing their judgment.

L. L. MORGAN, J. S. SEYMOUR, W. C. BRYANT.

Write for Further Information:

WYCKOFF, SEAMANS and BENEDICT,

100 Gracechurch St., London, E.C.

Library Association Series

EDITED BY THE HON. SECRETARIES OF THE ASSOCIATION

No. 1.

LIBRARY APPLIANCES

BY

JAMES D. BROWN

THE ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS.

The Library Association Series

EDITED BY J. Y. W. MacALISTER AND THOMAS MASON

HON. SECRETARIES OF THE ASSOCIATION

No. 1.

THE

TECHNICAL EQUIPMENT OF LIBRARIES:

FITTINGS, FURNITURE, CHARGING SYSTEMS, FORMS, RECIPES

&c.

BY

JAMES D. BROWN

CLERKENWELL PUBLIC LIBRARY, LONDON

PUBLISHED FOR THE ASSOCIATION BY DAVID STOTT

370 OXFORD STREET, W.

LONDON

1892

PRICE ONE SHILLING NET

The Council of the Library Association have arranged for the issue of a series of Handbooks on the various departments of Library work and management. Each Handbook has been entrusted to an acknowledged expert in the subject with which he will deal—and will contain the fullest and latest information that can be obtained.

Every branch of library work and method will be dealt with in detail, and the series will include a digest of Public Library Law and an account of the origin and growth of the Public Library Movement in the United Kingdom.

The comprehensive thoroughness of the one now issued is, the Editors feel, an earnest of the quality of the whole series. To mere amateurs, it may appear that it deals at needless length with matters that are perfectly familiar; but it is just this kind of thing that is really wanted by the people for whom Mr. Brown’s Handbook is intended. It seems a simple matter to order a gross of chairs for a library; but only experience teaches those little points about their construction which make so much difference as regards economy and comfort.

With this Handbook in their possession, a new committee, the members of which may never have seen the inside of a public library, may furnish and equip the institution under their charge as effectively as if an experienced library manager had lent his aid.

The second issue of the series will be on “Staff,” by Mr. Peter Cowell, Chief Librarian of the Liverpool Free Public Libraries.

The Editors.

London, August, 1892.

By James D. Brown, Librarian, Clerkenwell Public Library, London.

This Handbook bears some analogy to the division “miscellaneous” usually found in most library classifications. It is in some respects, perhaps, more exposed to the action of heterogeneity than even that refuge of doubt “polygraphy,” as “miscellaneous” is sometimes seen disguised; but the fact of its limits being so ill-defined gives ample scope for comprehensiveness, while affording not a little security to the compiler, should it be necessary to deprecate blame on the score of omissions or other faults. There is, unfortunately, no single comprehensive word or phrase which can be used to distinguish the special sort of library apparatus here described—“appliances” being at once too restricted or too wide, according to the standpoint adopted. Indeed there are certain bibliothecal sophists who maintain that anything is a library appliance, especially the librarian himself; while others will have it that, when the paste-pot and scissors are included, the appliances of a library have been named. To neither extreme will this tend, but attention will be strictly confined to the machinery and implements wherewith libraries, public and other, are successfully conducted. It would be utterly impossible, were it desirable, to describe, or even mention, every variety of fitting or appliance which ingenuity and the craving for change have introduced, and the endeavour shall be accordingly to notice the more generally established apparatus, and their more important modifications. It is almost needless to point out that very many of the different methods of accomplishing the same thing, hereinafter described, result from similar causes to those which led in former times to[2] such serious political complications in the kingdom of Liliput. There are several ways of getting into an egg, and many ways of achieving one end in library affairs, and the very diversity of these methods shows that thought is active and improvement possible. As Butler has it—

Hence it happens that all library appliances are subject to the happy influences of disagreement, which, in course of time, leads to entire changes of method and a general broadening of view. Many of these differences arise from local conditions, or have their existence in experiment and the modification of older ideas, so that actual homogeneity in any series of the appliances described in this Handbook must not be expected. It will be sufficient if the young librarian finds enough of suggestion and information to enable him to devise a system of library management in its minor details which shall be consistent and useful.

To some extent the arrangement of fittings and furniture will be dealt with in the Handbook on Buildings, so that it will only be necessary here to consider their construction, variety, and uses.

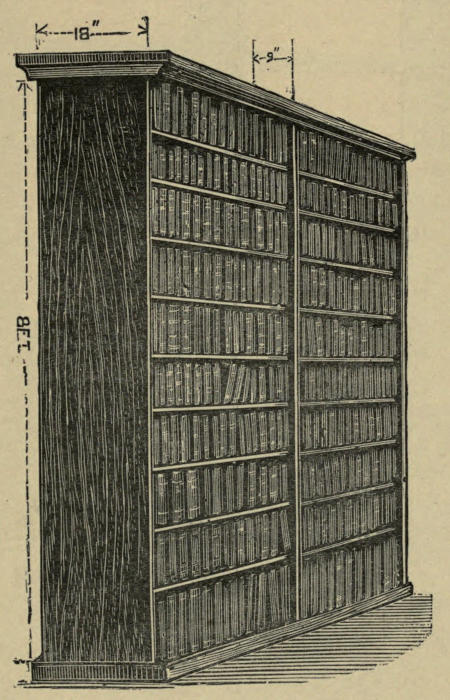

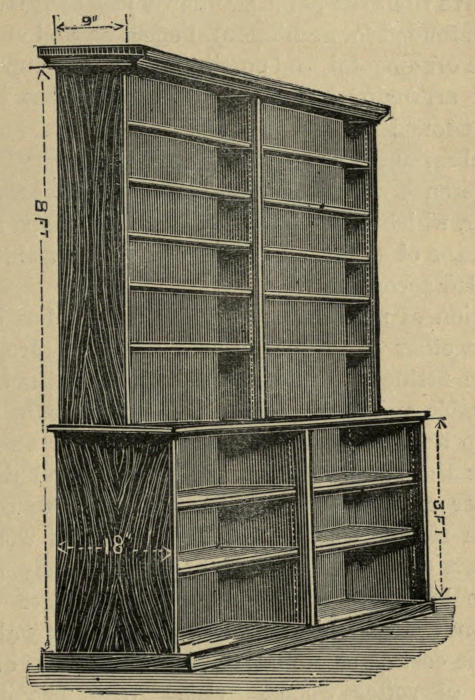

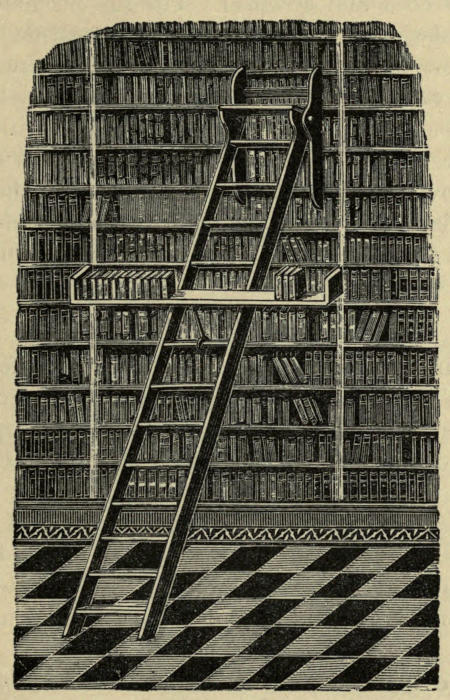

Standard cases or presses, designed for what is called the “stack” system of arrangement, are constructed with shelves on both sides, and are intended to stand by themselves on the floor. They are without doors or glass fronts, and their dimensions must be decided entirely by the requirements of each library and the class of books they are to contain. For ordinary lending libraries a very convenient double case with ten shelves of books to the tier can be made about 9 feet 6 inches wide × 8 feet 6 inches high, including cornice and plinth × 18 inches deep—the depth of the shelves being about 9 inches, their length 3 feet, and their thickness, as finished, not less than ¾″ nor more than 1 inch. Such a case will hold about 1800[3] volumes in 8vo and 12mo sizes, and the top shelf can be reached by a middle-sized person from a step or stool 12 inches high. Lower cases should be provided if rapidity of service is particularly required and there is plenty of floor space to carry the stock. The top shelf of a case 7 feet high, including cornice and plinth, can be reached from the floor by any one of ordinary height, small boys and girls of course excluded. These cases are made with middle partitions between the backs of the shelves, though some librarians prefer a simple framework of uprights, cornice, and plinth. For the sake of security and the necessary rigidity a central partition ought to be included, and if this is formed of thin ¼″ boarding, double and crossing diagonally, with a strong iron strap between screwed tight into the outer uprights, all tendency to bulging will be obviated, and the cases will be firm and workmanlike. The skeleton or framework cases have to be[4] stayed in all directions by iron rods and squares fixed in the floor, and, when empty, look very unsightly and rickety; besides, books get pushed or tumble over on to the adjoining shelf, and the plea of ventilation, which is practically the only recommendation for this plan of construction, loses much of its weight in a lending library where most of the books are in circulation.

Fig. 1.[1]—Standard Book-case.

Fig. 2.[2]—Standard Book-case without Partition.

The shelves should have rounded edges, and ought not to exceed 3′ or 3′ 6″ in length. If longer ones are used they must be thin, in order to be easily moved, and so these become bent in course of time, especially if heavy books are placed on them. The[5] objection to long shelves which are very thick is simply that they are unhandy and difficult to move and waste valuable space. All shelves should be movable, and if possible interchangeable. No paint or varnish should be applied to any surface with which the books come in contact, but there is nothing to be said against polishing. Indeed, to reduce as far as possible the constant friction to which books are exposed in passing to and from their resting-places, it ought to be remembered that smooth surfaces are advantageous. Few libraries can afford leather-covered shelves like those of the British Museum, but all can have smoothness and rounded edges.

Fig. 3.—Ledged Wall Book-Case.

Reference library cases are constructed similarly to those above described; but as folio and quarto books require storage in this department, it is necessary to make provision for them. This is usually done by making the cases with projecting bases, rising at least 3′ high, and in the enlarged space so obtained fair-sized[6] folios and quartos can be placed. Very large volumes of plates or maps should be laid flat on shelves made to slide over hard wood runners like trays, as they frequently suffer much damage from standing upright. A special, many-shelved press should be constructed for books of this generally valuable class, and each volume should be allowed a tray for itself. If the tray is covered with leather, felt, or baize, so much the better. Wall cases, and cases arranged in bays or alcoves, are generally much more expensive than the plain standards just described, because, as they are intended for architectural effect as well as for storage, they must be ornamental, and possibly made from superior woods. The plan of arranging books round the walls has been almost entirely abandoned in modern lending libraries, but there are still many librarians and architects who prefer the bay arrangement for reference departments. The matter of arrangement is one, however, which depends largely upon the shape and lighting of rooms, means of access, and requirements of each library, and must be settled accordingly.

The question of material is very important, but of course it depends altogether upon the amount which is proposed to be spent on the fittings. It is very desirable that the cases should be made durable and handsome, as it is not pleasant to have bad workmanship and ugly fittings in a centre of “sweetness and light”. For the standards previously mentioned there can be nothing better or cheaper than sound American or Baltic yellow pine, with, in reference cases, oak ledges. This wood is easily worked, wears very well, and can be effectively stained and varnished to look like richer and more expensive woods. Of course if money is no object, oak, mahogany, or walnut can be used; but the cost of such materials usually works out to nearly double that of softer woods. Cases with heavily moulded cornices should be boarded over the top, and not left with huge empty receptacles for dust and cobwebs. This caution is tendered, because joiners very often leave the space made by the cornice vacant and exposed.

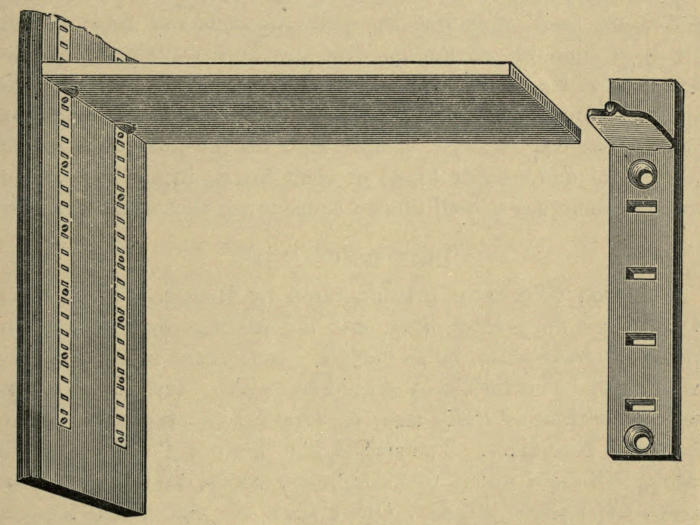

Fig. 4.—Metal Shelf Fitting.

Shelf fittings for wooden book-presses are required in all modern

libraries where movable shelves are almost universally used.

Cases with fixed shelves are much cheaper than those fitted with[7]

one of the button or other spacing arrangements now in the

market, but the serious disadvantage of having to size the

books to fit the shelves disposes of any argument that can

be urged on behalf of fixtures. There are many varieties

of shelf fitting designed to assist in the necessary differential

spacing of shelves, from the old-fashioned, and by no means

cheap, wooden ratchet and bar arrangement to the comparatively

recent metal stud. The fitting which is most often

adopted in new libraries is that of Messrs. E. Tonks, of

Birmingham. It consists of metal strips, perforated at 1-inch

intervals, let into the uprights of the cases and small gun-metal

studs for supporting the shelves. As is shown in the

illustration, the studs fit into the perforations and support the

shelves on little points which sink into the wood, and prevent

tilting or sliding. The strips should not go either to the top or

bottom of the uprights, and at least two feet can be saved in

every division by stopping 6 inches from both ends. Though

rather more expensive than pegs, or the studs mentioned below,

it is very desirable to have Tonks’ fittings, because of their

superiority to all others in the matters of convenience and ease in[8]

adjusting. Another form of stud often used is the one shaped

like this ![]() which fits into holes drilled in the uprights

and supports the shelf on the lower rectangular part. These are

most effective in operation when let into grooves as broad as the

studs, otherwise the shelves must be cut shorter than the width of

the divisions; and in that case end spaces are caused and security

is considerably sacrificed. The peg part of this stud is very apt

in course of time, to enlarge the wooden holes, and when any

series of shelves have to be frequently moved, the result of such

enlargement is to make the studs drop out. If perforated metal

strips are used, of course the price immediately goes up, and

there is then no advantage over the Tonks’ fitting. Another

form of peg for use in the same kind of round hole is that similar

in shape to the pegs used for violins, and, like them, demanding

much judicious thumbing before they can be properly adjusted.

There are many other kinds of shelf fitting in the market, but

none of them are so well known or useful as those just described.

which fits into holes drilled in the uprights

and supports the shelf on the lower rectangular part. These are

most effective in operation when let into grooves as broad as the

studs, otherwise the shelves must be cut shorter than the width of

the divisions; and in that case end spaces are caused and security

is considerably sacrificed. The peg part of this stud is very apt

in course of time, to enlarge the wooden holes, and when any

series of shelves have to be frequently moved, the result of such

enlargement is to make the studs drop out. If perforated metal

strips are used, of course the price immediately goes up, and

there is then no advantage over the Tonks’ fitting. Another

form of peg for use in the same kind of round hole is that similar

in shape to the pegs used for violins, and, like them, demanding

much judicious thumbing before they can be properly adjusted.

There are many other kinds of shelf fitting in the market, but

none of them are so well known or useful as those just described.

The iron book-cases manufactured by Messrs. Lucy & Co. of Oxford are very convenient, and in buildings designed as fire-proof, in basements, or in certain cases where much weight is wanted to be carried, they should be useful. They can be fitted up as continuous wall-cases, or supplied as standards holding books on both sides. The size B, 7′ 6″ high × 4′ 1″ wide × 1′ 3″ deep, will hold about 640 demy 8vo books, and the ironwork costs £4, shelves £1 4s. Other sizes are made, and the continuous wall-shelving is charged per yard run—7 feet high, £3 3s.; shelves of wood, 12 inches deep, 5s. each; if iron, felt covered, 4s. 6d. each. The durability of these cases is beyond question, and the expense is not great when their security, strength, and neatness are considered. The arrangement for spacing the shelves is convenient and effective. The sliding iron book-cases swung in the galleries of the British Museum, and their prototype[3] at Bethnal Green Free Library, London, have been so often and so fully described elsewhere[4] that it is needless to do more here than[9] to briefly refer to them. The British Museum pattern, the invention of Mr. Jenner of the Printed Books Department, consists of a double case suspended from strong runners, which can be pushed against the permanent cases when not in use, or pulled out when books are required. Only libraries with very wide passages between the cases could use them, and only then by greatly strengthening the ordinary wooden presses in existence.[5] The revolving wooden book-cases now so extensively used for office purposes, and in clubs or private libraries, can be bought for £3 and upwards. They should not be placed for public use in ordinary libraries to which all persons have access, though there is no reason why subscription libraries and kindred institutions should not have them for the benefit of their members.

Other fittings connected with book-cases are press and shelf numbers, contents or classification frames, blinds, and shelf-edging. The press marks used in the fixed location are sometimes painted or written in gold over the cases, but white enamelled copper tablets, with the numbers or letters painted in black or blue, are much more clear and effective. They cost only a few pence each. The numbering of shelves for the movable location, or their lettering for the fixed location, is usually done by means of printed labels. These are sold in sheets, gummed and perforated, and can be supplied in various sizes in consecutive series at prices ranging from 2s. 6d. per 1000 for numbers, and 1d. or 2d. each for alphabets. Shelf numbers can also be stamped on in gold or written with paint, and brass numbers are also made for the purpose, but the cost is very great. The little frames used for indicating the contents of a particular case or division are usually made of brass, and have their edges folded over to hold the cards. Some are made like the sliding carte-de-visite frames, but the object in all is the same, namely—to carry descriptive cards referring to the contents or classification of book-cases. They are most often used in reference libraries where readers are allowed direct access to the shelves, and are commonly screwed to the uprights. A convenient form is that used with numbered presses, and the card bears such particulars as these—

| Shelf. | Case 594. |

|---|---|

| A | Buffon’s Nat. Hist. |

| B | Geological Rec. |

| C | Sach’s Bot.; Bot. Mag. |

| D | &c. |

| E | &c. |

| F | &c. |

Others bear the book numbers, while some simply refer to the shelf contents as part of a particular scheme of classification, viz.:—

941·1 Northern Scotland.

To keep these contents-cards clean it is usual to cover them with little squares of glass.

Glazed book-cases are not recommended, wire-work being much better in cases where it is necessary to have locked doors. The mesh of the wire-work should be as fine as possible, because valuable bindings are sometimes nail-marked and scratched by inquisitive persons poking through at the books. It is only in very special circumstances that locked presses are required, such as when they are placed in a public reading-room or in a passage, and though glazed book-cases are a tradition among house furnishers, no librarian will have them if it can possibly be avoided. Their preservative value is very questionable, and books do very well in the open, while there can be no two opinions as to their being a source of considerable trouble. Blinds concealed in the cornices of book-cases are sometimes used, their object being to protect the books from dust during the night, but they do not seem to be wanted in public libraries. In regard to the various shelf-edgings seen in libraries, leather is only ornamental, certainly not durable; while scalloped cloth, though much more effective, may also be dispensed with.

To the practical librarian a good counter is a source of perennial joy. It is not only the theatre of war, and the centre to which every piece of work undertaken by the library converges, but it is a barrier over which are passed most[11] of the suggestions and criticisms which lead to good work, and from which can be gleaned the best idea of the business accomplished. For these reasons alone a first-class counter is very desirable. As in every other branch of library management, local circumstances must govern the size and shape of the counter to be provided. Lending libraries using indicators require a different kind of counter than those which use ledgers or card-charging systems, and reference libraries must have them according to the plan of arrangement followed for the books. A lending library counter where no indicator is used need not be a very formidable affair, but it ought to afford accommodation for at least six persons standing abreast, and have space for a screened desk and a flap giving access to the public side. On the staff side should be plenty of shelves, cupboards, and drawers, and it may be found desirable to place in it a locked till also for the safe-keeping of money received for fines, catalogues, &c. All counter-tops should project several inches beyond the front to keep back the damage-working toes of the public, and on the staff side a space of at least 3 inches should be left under the pot-board. A height of 3 feet and a width of 2 feet will be found convenient dimensions for reference and non-indicator lending library counters. Where indicators are used a width of 18 inches and a height of 30 of 32 inches will be found best. If the counter is made too high and wide neither readers nor assistants can conveniently see or reach the top numbers. As regards length, everything will depend on the indicator used and the size of the library. An idea of the comparative size of some indicators may be got from the following table:—

| Counter space | required for | 12,000 numbers | Cotgreave 15 feet. |

| ” | ” | ” | Elliot (small) 16 feet. |

| ” | ” | ” | Duplex (small) 22 feet. |

| ” | ” | ” | ” (full) 32 feet. |

| ” | ” | ” | Elliot (full) 36 feet. |

Allowing 12 feet of counter space for service of readers, 2 feet for desk space, and 2 feet for flap, a Cotgreave indicator for 12,000 numbers would mean a counter 31 feet long, a small Elliot 32 feet, a small Duplex 38 feet, a full Duplex 48 feet, and a full Elliot 52 feet. For double the quantity of numbers the smallest indicator would require a counter 46 feet long, and the largest one 88 feet.[12] These are important points to bear in mind when planning the counter; though it must be said generally that, in nearly every instance where a Library Committee has proceeded with the fitting of a new building before appointing a librarian, they are over-looked, because the architect invariably provides a counter about 6 feet long, 3 feet wide, and 3 feet high, with a carved front of surpassing excellence! What has been already said respecting materials applies with equal force to this class of fitting; but it should be added that a good hard-wood counter will likely last for ever. Some librarians who use card catalogues prefer to keep them in drawers opening to the public side of the reference library counter. This point is worth remembering in connection with the fitting of the reference department.

In addition to the store cupboards provided behind the counters there should be plenty of wall or other presses fixed in convenient places for holding stationery, supplies of forms, &c. Locked store presses are also useful; and every large library should have a key-press, in which should be hung every public key belonging to the building, properly numbered and labelled to correspond with a list pasted inside the press itself. These useful little cabinets are infinitely superior to the caretaker’s pocket, and much inconvenience is avoided by their use. Desks for the staff use should be made with a beading all round the top and at bottom of slope to prevent papers, pens, and ink from falling or being pushed over. Superintendents’ desks should be made large, and to stand on a double pedestal of drawers, so that they may be high enough for useful oversight and capacious enough for stationery or other supplies. There is an admirable specimen of a superintendent’s desk in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow.

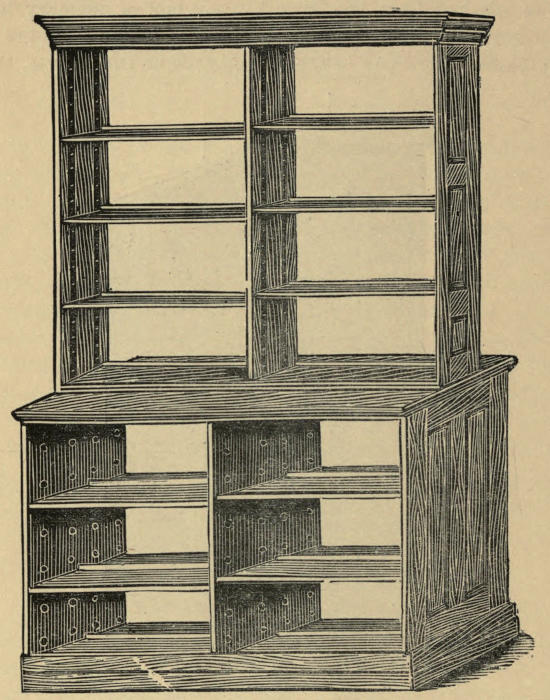

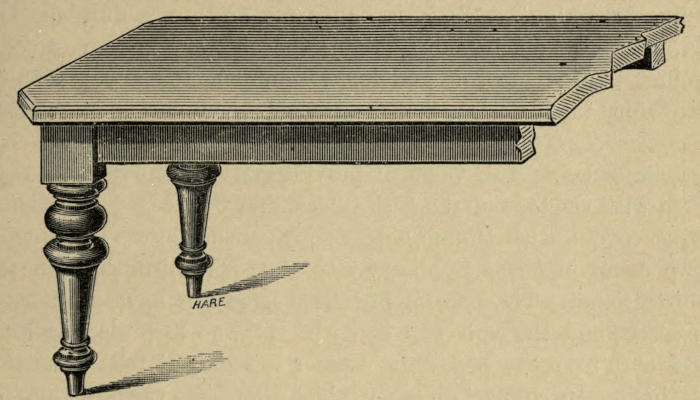

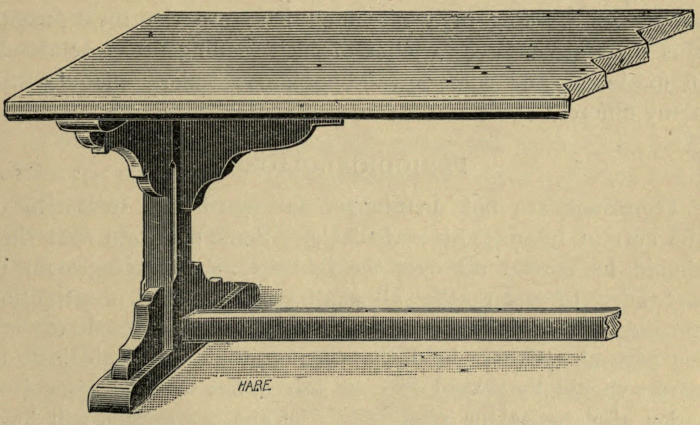

Fig. 5.[6]

Fig. 6.

Tables for reading or writing at are best made in the

form of a double desk,  which gives readers the most

convenience, and affords an effective but unobtrusive means of

mutual oversight. The framing and rails should be as shallow as

possible, so as not to interfere with the comfort of readers, and

elaborately turned or carved legs should be avoided, because certain[13]

to harbour dust, and likely to form resting-places for feet. Tables

with flat tops resting on central pedestals, and without side rails,

are very useful in general reading-rooms, the free leg space being

a decided advantage. Long tables are not recommended, nor are

narrow ones which accommodate readers on one side only. The

former are obstructive, and the latter are neither economical as

regards the seating of readers, nor of much use for the necessary

mutual oversight which ought to be promoted among the public.

Very good dimensions for reading-room tables are 8 to 10 feet

long by 3 to 3 feet 6 inches wide by 2 feet 6 inches high.[14]

But the librarian who wishes to consult the varying requirements

of his readers will have his tables made different heights—some

29, some 30, and some 32 inches high. Whatever

materials may be used for the framing and legs of tables, let

the tops be hard-wood, like American or English oak, mahogany,

or walnut. Teak is handsome and very durable, but

its cost is much more than the better known woods.

Yellow pine is too soft and looks common, and should not be

used for tops unless the most rigid economy is absolutely

necessary. Heavy tables, like those used in clubs, are not

recommended. Ink wells, if provided at all, should be let in

flush with the tops of the desk tables, and ought to have sliding

brass covers, with thumb-notches for moving instead of knobs.

Two common forms of library tables are shown in the annexed

illustrations. The one on pedestals need not have such large

brackets, and the ends can easily be allowed to project at least

18 inches from the pedestals in order to admit of readers sitting

at them. In connection with tables there are various kinds of

reading slopes made for large books, of which those with movable

supporters working in a ratcheted base are the most useful.

But there are endless varieties of such reading desks or stands

in existence, and some invalid-appliance makers manufacture

many different kinds.

which gives readers the most

convenience, and affords an effective but unobtrusive means of

mutual oversight. The framing and rails should be as shallow as

possible, so as not to interfere with the comfort of readers, and

elaborately turned or carved legs should be avoided, because certain[13]

to harbour dust, and likely to form resting-places for feet. Tables

with flat tops resting on central pedestals, and without side rails,

are very useful in general reading-rooms, the free leg space being

a decided advantage. Long tables are not recommended, nor are

narrow ones which accommodate readers on one side only. The

former are obstructive, and the latter are neither economical as

regards the seating of readers, nor of much use for the necessary

mutual oversight which ought to be promoted among the public.

Very good dimensions for reading-room tables are 8 to 10 feet

long by 3 to 3 feet 6 inches wide by 2 feet 6 inches high.[14]

But the librarian who wishes to consult the varying requirements

of his readers will have his tables made different heights—some

29, some 30, and some 32 inches high. Whatever

materials may be used for the framing and legs of tables, let

the tops be hard-wood, like American or English oak, mahogany,

or walnut. Teak is handsome and very durable, but

its cost is much more than the better known woods.

Yellow pine is too soft and looks common, and should not be

used for tops unless the most rigid economy is absolutely

necessary. Heavy tables, like those used in clubs, are not

recommended. Ink wells, if provided at all, should be let in

flush with the tops of the desk tables, and ought to have sliding

brass covers, with thumb-notches for moving instead of knobs.

Two common forms of library tables are shown in the annexed

illustrations. The one on pedestals need not have such large

brackets, and the ends can easily be allowed to project at least

18 inches from the pedestals in order to admit of readers sitting

at them. In connection with tables there are various kinds of

reading slopes made for large books, of which those with movable

supporters working in a ratcheted base are the most useful.

But there are endless varieties of such reading desks or stands

in existence, and some invalid-appliance makers manufacture

many different kinds.

Librarians are not unanimous as regards the treatment of the current numbers of periodicals. Some maintain that they should be spread all over the tables of the reading-room in any order, to ensure that all shall receive plenty of attention at the hands of readers, whether they are wanted or not for perusal. Others hold the opinion that the periodicals in covers should be spread over the tables, but in some recognised order, alphabetical or otherwise. Yet another section will have it that this spreading should be accompanied by fixing, and that each cover should be fastened in its place on the table. Finally, many think that the magazines, &c., should be kept off the tables entirely, and be arranged in racks where they will be accessible without littering the room, and at the same time serve as a sort of indicator to periodicals which are in or out of use. For the unfixed alphabetical arrangement several appliances[15] have been introduced. At Manchester the periodicals are arranged on raised desks along the middle of the tables. In the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, each table is surmounted by a platform raised on brackets which carries the magazine covers, without altogether obstructing the reader’s view of the room and his neighbours. Each periodical is given a certain place on the elevated carriers, and this is indicated to the reader by a label fixed on the rail behind the cover. On the cover itself is stamped the name of the periodical and its table number. Each table has a list of the periodicals belonging to it shown in a glazed tablet at the outer end of the platform support. Wolverhampton and St. Martin’s, London, furnish very good examples of the fixed arrangement. In the former library each periodical is fastened to its table by a rod, and has appropriated to it a chair, so that removal and disarrangement cannot occur. In the latter those located in the newsroom are fastened on stands where chairs cannot be used, and the arrangement is more economical as regards space than at Wolverhampton. The periodicals in the magazine room are fixed by cords to the centre of the table and signboards indicate the location of each periodical. This seems to be the best solution of the difficulty after all. Every periodical in this library is fixed, more or less, and it is therefore easy to find out if a periodical is in use.

The rack system has many advocates, and can be seen both in libraries and clubs in quite a variety of styles. At the London Institution there is an arrangement of rails and narrow beaded shelves on the wall, which holds a large number of periodicals not in covers, and seems to work very well. The rails are fastened horizontally about two inches from the walls at a distance above the small shelf sufficient to hold and keep upright the periodicals proposed to be placed on it, and a small label bearing a title being fixed on the rail, the corresponding periodical is simply dropped behind it on to the shelf, and so remains located. A similar style of rail-rack has been introduced for time-tables, &c., in several libraries, and has been found very useful. Another style of periodical-rack is that invented by Mr. Alfred Cotgreave, whereby periodicals are displayed on two sides of a large board, and secured in their places by means of clips. The same inventor has also an arrangement similar to that described as in the London Institution for magazines in[16] covers. The ordinary clip-rack used largely by newsvendors has been often introduced in libraries where floor space was not available, and is very convenient for keeping in order the shoals of presented periodicals, which live and die like mushrooms, and scarcely ever justify the expense of a cover. An improvement on the usual perpendicular wall-rack just mentioned is that used in the National Liberal Club, London, which revolves on a stand, and can be made to hold two or three dozen periodicals or newspapers, according to dimensions.

Fig. 7.—Periodical Rack.

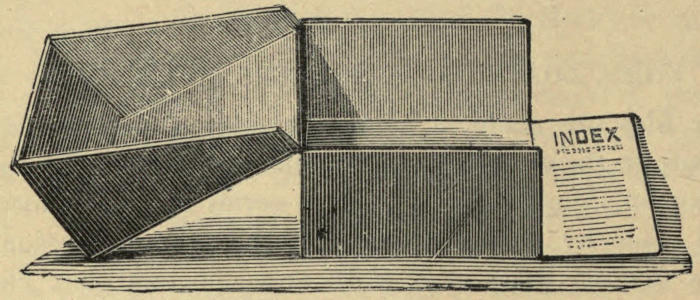

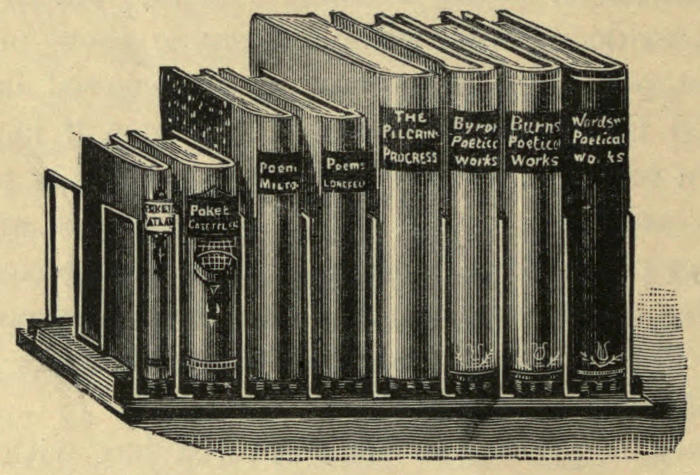

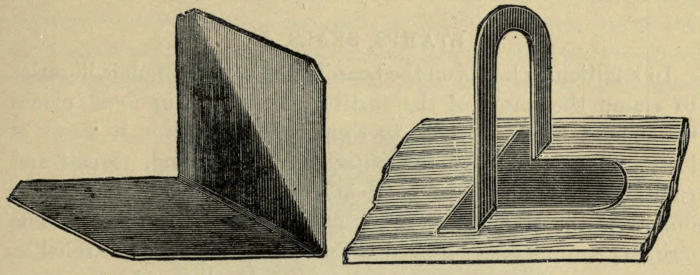

The racks just mentioned are all designed to hold periodicals without covers, but there are several kinds in existence for holding them in their covers. Among such are the table supports, in metal and wood, on the same principle as shelf book-holders, in which the magazines lie in their cases on their fore-edges, and are distinguished by having the titles lettered along the back or otherwise. Probably the best of all the racks devised for periodicals in their cases is that on the system of overlapping sloping shelves, shown in the illustration. The idea of this rack is simply that the covers should lie on the shelves with only the title exposed. They are retained in place by a beading just deep enough to afford a catch for one cover, and so avoid the chance[17] of their being hidden by another periodical laid above. These racks can also be made single to stand against the wall if floor space is not available. Oak, walnut, and mahogany are the best woods to use, but pitch or ordinary yellow pine may also be used.

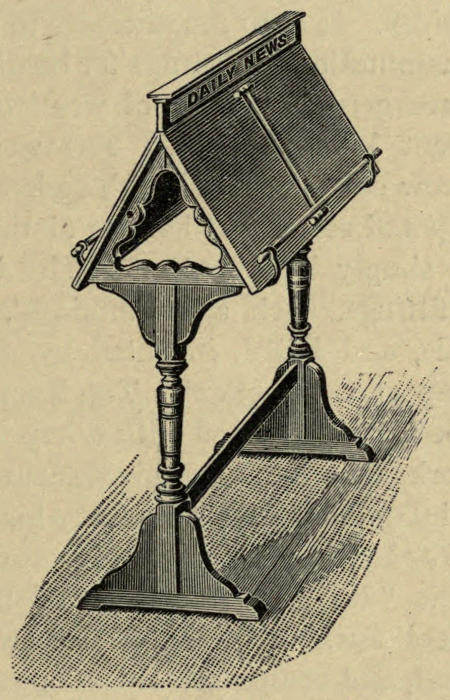

Fig. 8.—Newspaper Stand.

The day has not yet come when octavo-sized newspapers will obviate the necessity for expensive and obstructive stands on which the day’s news is spread in the manner least conducive to the comfort of readers. The man who runs and reads has no necessity for much study, while he who stands and reads does so with the consciousness that at any moment he may be elbowed from his studies by impatient news-seekers, and be subjected to the added discomfort of being made a leaning pillar for half-a-dozen persons to embrace. Meanwhile it is necessary to provide convenient reading desks for the broadsheets which are issued. It is cheaper to have double stands, holding four spread papers, than single ones, holding only two, though there is certainly less comfort to readers with the larger size. The illustration shows a single[18] stand, but it should be remembered that the design can be made much heavier and richer. The dimensions should be for double stands 7′ 6″ long, 2′ 6″ high for slope, and about 3′ from floor to bottom of slope. Single ones should be 4′ long, with the other measurements as before. Half-stands for going against the wall have only the slope to the front, and are generally made in long lengths to cover the whole side of a room. The slope should not in any case be made either too steep or too great—the former always causing the papers to droop, and the latter placing the upper parts beyond the sight of short persons. Before adopting any type of stand, it is advisable to visit a few other libraries and examine their fittings. It is so much easier to judge what is liked best by actual examination. Fittings for holding the newspapers in their places are generally made of wood or brass, and there are many different kinds in use. The wooden ones usually consist of a narrow oak bar, fitted with spikes to keep the paper up, hinged at top and secured at bottom of the slope by a staple and padlock, or simply by a button. The brass ones include some patented fittings, such as Cummings’, made by Messrs. Denison of Leeds, and Hills’, invented by the library superintendent of Bridgeport, Connecticut. The former is a rod working on an eccentric bed, and is turned with a key to tighten or loosen it; the latter works on a revolving pivot secured in the middle of the desk, and is intended more particularly for illustrated periodicals, like the Graphic, &c., which require turning about to suit the pictures. The “Burgoyne” spring rod made by the North of England School Furnishing Co., Darlington and London, is very effective, neat, and comparatively inexpensive. It is secured by a catch, which requires a key to open it, but it is simply snapped down over the paper when changes are made. Other varieties of brass holders are those secured by ordinary locks or strong thumb-screws. In cases where the rods have no spikes (which are not recommended) or buttons, or which do not lie in grooves, it is advisable to have on them two stout rubber rings, which will keep the papers firmly pressed in their places, and so prevent slipping. A half-inch beading along the bottom of the slope is sometimes useful in preventing doubling down and slipping. The names of the papers may be either gilded or painted on the title-board, or they may be done in black or blue letters on white enamelled title-pieces and screwed to the head board. These[19] latter are very cheap, durable, and clear. Some librarians prefer movable titles; and in this case grooved holders or brass frames must be provided to hold the names, which can be printed on stiff cards, or painted on wood or bone tablets. The brass rail at the foot of the slope, shown in the illustration, is meant to prevent readers from leaning on the papers with their arms. By some librarians it is thought quite unnecessary, by others it is considered essential; but it is really a matter for the decision of every individual librarian.

The chairs made in Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire are

the best and cheapest in the market, and more satisfaction will

result from orders placed direct with the makers than from

purchasing at an ordinary furniture dealer’s. It is better to

have small chairs made with the back and back legs all in

one piece, thus, ![]() rather than with legs and back rails all

separately glued into the seat like this,

rather than with legs and back rails all

separately glued into the seat like this, ![]() . The reason is

of course that by the former plan of construction greater strength

is obtained, and future trouble in the way of repairs will be

largely obviated. Avoid showy chairs, and everything that smacks

of the cheap furniture market. It will strengthen the chairs

to have hat rails as well as ordinary side rails, and be a convenience

to readers as well. They should cross from the bottom

side rail, thus,

. The reason is

of course that by the former plan of construction greater strength

is obtained, and future trouble in the way of repairs will be

largely obviated. Avoid showy chairs, and everything that smacks

of the cheap furniture market. It will strengthen the chairs

to have hat rails as well as ordinary side rails, and be a convenience

to readers as well. They should cross from the bottom

side rail, thus,  . Arm-chairs should be provided at

discretion. In magazine rooms where there is a rack, tables can

be largely dispensed with if arm-chairs are used. If neither

wood-block flooring nor linoleum is used, the chairs may with

great advantage be shod with round pieces of sole leather

screwed through a slightly sunk hole to the ends of the legs.

These deaden the noise of moving greatly, and are more durable

than india-rubber. Two or three dozen of chairs more than are

actually required should be ordered. Umbrella stands are best

patronised when attached to the tables, like ordinary pew ones.[20]

An umbrella stand close to the door is such an obvious temptation

to the thief that careful readers never use them on any consideration.

Of rails for fixing to the tables there are many

kinds, but probably the hinged pew variety, plain rail, or

rubber wheel, all with water-pans, will serve most purposes.

Many libraries make no provision at all either of hat rails or

umbrella stands, for the simple reason that 50% of the readers

do not enter to stay, while 99% never remove their hats. In

proprietary libraries everything is different, and an approach

to comforts of the sort indicated must be made. The standard

hat rack and umbrella stand combined, like that used in

clubs, schools, the House of Commons, &c., is the best for such

institutions.

. Arm-chairs should be provided at

discretion. In magazine rooms where there is a rack, tables can

be largely dispensed with if arm-chairs are used. If neither

wood-block flooring nor linoleum is used, the chairs may with

great advantage be shod with round pieces of sole leather

screwed through a slightly sunk hole to the ends of the legs.

These deaden the noise of moving greatly, and are more durable

than india-rubber. Two or three dozen of chairs more than are

actually required should be ordered. Umbrella stands are best

patronised when attached to the tables, like ordinary pew ones.[20]

An umbrella stand close to the door is such an obvious temptation

to the thief that careful readers never use them on any consideration.

Of rails for fixing to the tables there are many

kinds, but probably the hinged pew variety, plain rail, or

rubber wheel, all with water-pans, will serve most purposes.

Many libraries make no provision at all either of hat rails or

umbrella stands, for the simple reason that 50% of the readers

do not enter to stay, while 99% never remove their hats. In

proprietary libraries everything is different, and an approach

to comforts of the sort indicated must be made. The standard

hat rack and umbrella stand combined, like that used in

clubs, schools, the House of Commons, &c., is the best for such

institutions.

Show-cases ought to be well made by one of the special firms who make this class of fitting. Glass sides and sliding trays, with hinged and locked backs, are essential. For museum purposes all sorts of special cases are required, and the only way to find out what is best is to visit one or two good museums for the purpose.

Charging Systems and Indicators.—The charging of books includes every operation connected with the means taken to record issues and returns, whether in lending or reference libraries. Although the word “charging” refers mainly to the actual entry or booking of an issue to the account of a borrower, it has been understood in recent years to mean the whole process of counter work in circulating libraries. It is necessary to make this explanation at the outset, as many young librarians understand the meaning of the word differently. For example, one bright young man on being asked what was the system of “charging” pursued in his library responded: “Oh! just a penny for the ticket!” And another equally intelligent assistant replied to the same question: “We don’t charge anything unless you keep books more than the proscribed time!” Before proceeding to describe some of the existing systems it may be wise to impress on assistants in libraries the advisability of trying to think for themselves in this matter. There is nothing more discouraging than to find young librarians slavishly following the methods bequeathed by their predecessors, because in no sphere[21] of public work is there a larger field for substantial improvement, or less reason to suppose that readers are as easily satisfied as they were thirty years ago. The truth is that every library method is more or less imperfect in matters of detail, and there are numerous directions in which little improvements tending to greater homogeneity and accuracy can be effected. It is all very well, and likewise easy, to sit at the feet of some bibliothecal Gameliel, treasuring his dicta as incontrovertible, and at the same time assuming that the public is utterly indifferent to efficiency and simplicity of system. But it ought to be seriously considered that everything changes, and that the public knowledge of all that relates to their welfare increases every day; so that the believer in a dolce far niente policy must be prepared for much adverse criticism, and possibly for improvements being effected in his despite, which is very unpleasant. In libraries conducted for profit, everything likely to lead to extension of business, or to the increased convenience of the public, is at once adopted, and it is this sort of generous flexibility which ought to be more largely imported into public library management. A suitable reverence for the good work accomplished in the past should be no obstacle to improvement and enlargement of ideas in the future.

The present state of the question of charging turns largely on the respective merits of indicator and non-indicator systems, or, in other words, whether the burden of ascertaining if books are in or out should be placed on readers or the staff. There is much to be said on both sides, and reason to suppose that the final solution lies with neither. The non-indicator systems come first as a matter of seniority. The advantages of all ledger and card-charging systems are claimed to be that readers are admitted directly to the benefit of intercourse with the staff; that they are saved the trouble of discovering if the numbers they want are in; that they are in very many cases better served, because more accustomed to explain their wants; that less counter space is required; that the initial expense of an indicator is saved; and, finally, that with a good staff borrowers can be more quickly attended to. Some of these statements may be called in question, but they represent the views of librarians[22] who have tried both systems. From the readers’ point of view there can hardly be a doubt but that the least troublesome system is the most acceptable; and it is only fair to the non-indicator systems to assert that they are the least troublesome to borrowers. The original method of charging, still used in many libraries, consisted in making entries of all issues in a day-book ruled to show the following particulars:—

| Date of Issue. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Progressive No. | Title of Book. | Class Letter. | No. | Vols. | Date of Return. | Name of Borrower. | No. of Card. | Fines. |

| 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||

But after a time certain economies were introduced, columns 2, 7, and 9 being omitted, and day-books in this later form, perhaps with the arrangement slightly altered, are in common use now. Of course it is plain that a book on issue was entered in the first vacant line of the day-book, and the progressive number, borrower’s number, and date were carried on to its label. On return, the particulars on the label pointed out the day and issue number, and the book was duly marked off. It will at once be seen that this form of ledger only shows what books are out, but cannot readily show the whereabouts of any particular volume without some trouble. As to what book any reader has is another question which cannot be answered without much waste of time. A third disadvantage is that as borrowers retain their tickets there is very little to prevent unscrupulous persons from having more books out at one time than they should. A fourth weakness of this ledger is that time is consumed in marking off, and books are not available for re-issue until they are marked off. For various reasons some librarians prefer a system of charging direct to each borrower instead of journalising the day’s operations as above described. These records were at one time kept in ledgers, each borrower being apportioned a page or[23] so, headed with full particulars of his name, address, guarantor, date of the expiry of his borrowing right, &c. These ledgers were ruled to show date of issue, number of book, and date of return, and an index had to be consulted at every entry. Now-a-days this style of ledger is kept on cards arranged alphabetically or numerically, and is much easier to work. Subscription and commercial circulating libraries use the system extensively. The main difficulty with this system was to find out who had a particular book; and “overdues” were hard to discover, and much time was consumed in the process. To some extent both these defects could be remedied by keeping the borrowers’ cards and arranging them in dated trays, so that as books were returned and the cards gradually weeded out from the different days of issue, a deposit of overdue borrowers’ cards pointing to their books would result. Another form of ledger is just the reverse of the last, the reader being charged to the book instead of the book to the reader. This is a specimen:—

| K 5942. Wood—East Lynne. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of Issue. | Borrowers’ No. | Date of Return. | Date of Issue. | Borrowers’ No. | Date of Return. |

| 4 May | 395 | 18 May | |||

| 6 June | 3421 | ||||

Every book has a page or more, according to popularity, and there can hardly be a doubt of its superiority to the personal ledger, because the question of a book’s whereabouts is more often raised than what book a given reader has. Dates of issue and return are stamped, and all books are available for issue on return. The borrowers’ cards, if kept in dated trays as above, show at once “overdues” and who have books out. But the “overdues” can be ascertained also by periodical examination of the ledger. In this system book ledgers are as handy as cards. In both of the ledger systems above described classified day sheets for statistical purposes are used. They are generally ruled thus:—

| Date. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

and the issues are recorded by means of strokes or other figures. At one time it was considered an ingenious arrangement to have a series of boxes lettered according to classes, with locked doors and apertures at the top, in which a pea could be dropped for every issue in any class; but this seems to have been now completely abandoned. Certainly neither the sheet-stroking nor pea-dropping method of getting at the number of daily issues can be recommended, because in both cases the account is at the mercy of assistants, who may either neglect to make such charges, or register some dozen issues at a time to account for intervals spent in idling. An application slip is the best solution of the difficulty. This can either be filled up by the assistants or the borrowers. In certain libraries these slips are of some permanence, being made of stout paper in long narrow strips, on which borrowers enter their ticket-numbers and the numbers and classes of the books they would like. The assistant stamps the current date against the book had out, and the slips, after the statistics are compiled from them, are sorted in order of borrowers’ numbers and placed in dated trays. Of course when the borrower returns the book, his list is looked out, and the name of the returned book heavily cancelled and another work procured as before. There are various kinds of ticket-books issued for this purpose, some with counterfoils and detachable cheques, and others with similar perforated slips and ruled columns for lists of books wanted to read. Messrs. Lupton & Co. of Birmingham, Mr. Ridal of Rotherham Free Library, and Messrs. Waterston & Sons, stationers, Edinburgh, all issue different varieties of call-books, or lists of wants. Some libraries provide slips of paper, on which the assistant jots down the book-number after the borrower hands it in with his ticket-number written in thus:—

| Ticket. | Book. |

|---|---|

| 5963 | C 431 |

These are simply filed at the moment of service, and become the basis of the statistical entry for each day’s operations. Such slips save the loss of time which often arises when careful entries have to be made on day-sheets or books, and there can be no question as to their greater accuracy. These are the main points in connection with the most-used class of day-books and ledgers.

Somewhat akin to the ledger systems are the various card- and pocket-charging methods which work without the intervention of an indicator. There are several of such systems in existence both in Britain and the United States, most of them having features in common, but all distinguished by differences on points of detail. At Bradford a pocket system has long been in use. It is worked as follows: Every book has attached to one of the inner sides of its boards a linen pocket, with a table of months for dating, and an abstract of the lending rules. Within this pocket is a card on which are the number and class of the book, its title and author. To each reader is issued on joining a cloth-covered card and a pocket made of linen, having on one side the borrower’s number, name, address, &c., and on the other side a calendar. The pockets are kept in numerical order at the library, and the readers retain their cards. When a borrower wishes a book, he hands in a list of numbers and his card to the assistant, who procures the first book he finds in. He next selects from the numerical series of pockets the one bearing the reader’s number. The title card is then removed from the book and placed in the reader’s numbered pocket, and the date is written in the date column of the book pocket. This completes the process at the time of service. At night the day’s issues are classified and arranged in the order of the book numbers, after the statistics are made up and noted in the sheet ruled for the purpose, and are then placed in a box bearing the date of issue.[26] When a book is returned the assistant turns up its date of issue, proceeds to the box of that date, and removes the title card, which he replaces in the book. The borrower’s pocket is then restored to its place among its fellows. The advantages of this plan are greater rapidity of service as compared with the ledger systems, and a mechanical weeding out of overdues somewhat similar to what is obtained by the “Duplex” indicator system described further on. Its disadvantages are the absence of permanent record, and the danger which exists of title cards getting into the wrong pockets.

A system on somewhat similar lines is worked at Liverpool and Chelsea, the difference being that in these libraries a record is made of the issues of books. It has the additional merit of being something in the nature of a compromise between a ledger and an indicator system, so that to many it will recommend itself on these grounds alone. The Cotgreave indicator is in this system used for fiction and juvenile books only, and as the records of issues are made on cards, the indicator is simply used to show books out and in. Mr. George Parr, of the London Institution, is the inventor of an admirable card-ledger, and though it has been in use for a number of years its merits do not seem to be either recognised or widely known. The main feature of this system, which was described at the Manchester meeting of the L.A.U.K. in 1879, is a fixed alphabetical series of borrowers’ names on cards, behind which other cards descriptive of books issued are placed. The system is worked as follows: Every book has a pocket inside the board somewhat similar to that used at Bradford and Chelsea, in which is a card bearing the title and number of the book. When the book is issued the card is simply withdrawn and placed, with a coloured card to show the date, behind the borrower’s card in the register. When it is returned the title card is simply withdrawn from behind the borrower’s card, replaced in the book, and the transaction is complete. This is the brief explanation of its working, but Mr. Parr has introduced many refinements and devices whereby almost any question that can be raised as regards who has a book, when it was issued, and what book a given person has, can be answered with very little labour. This is accomplished by means of an ingenious system of projecting guides on the cards, together with different colours for each 1000[27] members, and with these aids a ready means is afforded of accurately finding the location in the card-ledger of any given book or borrower. As regards its application to a popular public library, the absence of a permanent record would in most cases be deemed objectionable, but there seems no reason why, with certain modifications, it could not be adapted to the smaller libraries, where neither pocket systems nor indicators are in use. This very ingenious and admirable system suggests what seems in theory a workable plan for any library up to 10,000 volumes. Instead of making a fixed alphabet of borrowers, as in Mr. Parr’s model, a series of cards might be prepared, one for each book in the library, in numerical order, distributed in hundreds and tens, shown by projections to facilitate finding. A label would be placed in each book, ruled to take the borrower’s number and date of issue, and a borrower’s card like that used for Mr. Elliot’s indicator, ruled to take the book numbers only. When a book is asked for, all that the assistant has to do is to write its number in the borrower’s card, the number of the borrower’s card and the date on the book label, and then to issue the book, having left the borrower’s card in the register. The period of issue could be indicated by differently coloured cards to meet the overdue question, and a simple day-sheet ruled for class letters and numbers of books issued would serve for statistical purposes. The register of book-numbers could be used as an indicator by the staff in many cases, and such a plan would be as easily worked, as economical, and as accurate as most of the charging systems in use in small libraries.

There are many other card-charging systems in use, but most of them are worked only in the United States. A large number of British libraries, especially those established under the “Public Libraries Acts,” use one or other of the various indicators which have been introduced since 1870, and it now becomes necessary to describe some of these.

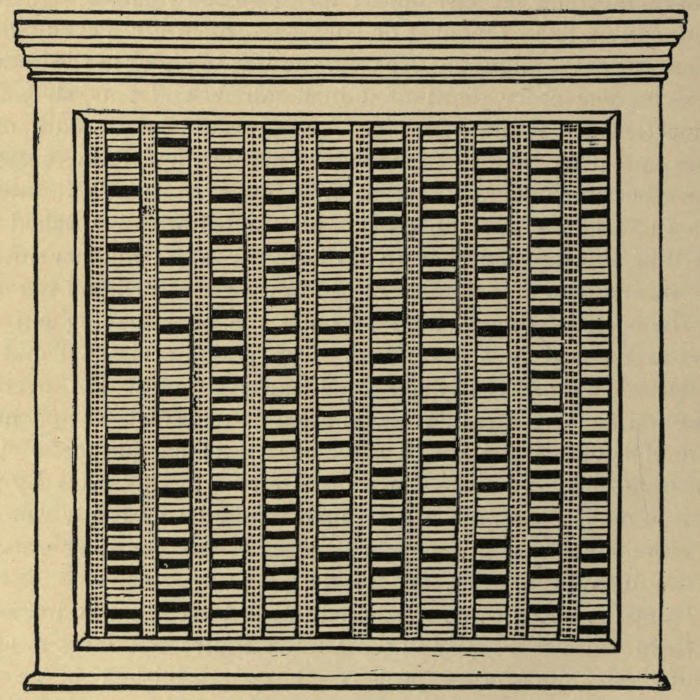

Fig. 9.[7]—Elliot’s Indicator.

The first indicator of any practical use was that invented by Mr. John Elliot, of Wolverhampton, in 1870. Previous to that date various make-shift contrivances had been used to aid the staff in finding what books were in or out without[28] the trouble of actually going to the shelves, chief among which was a board drilled with numbered holes to receive pegs when the books represented by the numbers were out. Elliot’s indicator is a large framework of wood, divided, as shown in the engraving, into ten divisions by wooden uprights, on which are fastened printed columns of numbers 1 to 100, 101 to 200, &c., representing volumes in the library. Between each number, in the spaces between the uprights, are fastened small tin slides, forming a complete series of tiny shelves for the reception of borrowers’ tickets, which are placed against the numbers of the books taken out. The numbers are placed on both sides of the indicator, which is put on the counter, with one side glazed to face the borrowers. Its working is simple: Every borrower receives on joining a ticket in the shape of a book, having spaces[29] ruled to show the numbers of books and dates of issue, with the ends coloured red and green. On looking at the indicator the borrower sees so many vacant spaces opposite numbers, and so many occupied by cards, and if the number he wishes is shown blank he knows it is in and may be applied for. He accordingly does so, and the assistant procures the book, writes in the borrower’s card the number and date of issue, and on the issue-label of the book the reader’s ticket-number and date. When the book is returned the assistant simply removes the borrower’s card from the space and returns it, and the transaction is complete. A day-sheet is commonly used for noting the number of issues; but, of course, application forms can also be used. The coloured ends of the borrowers’ tickets are used to show overdue books, red being turned outwards one fortnight, or whatever the time allowed may be, and green the next. Towards the end of the second period the indicator is searched for the first colour, and the “overdues” noted. The main defect of the Elliot indicator lies in the danger which exists of readers’ tickets being placed in the wrong spaces, when they are practically lost.

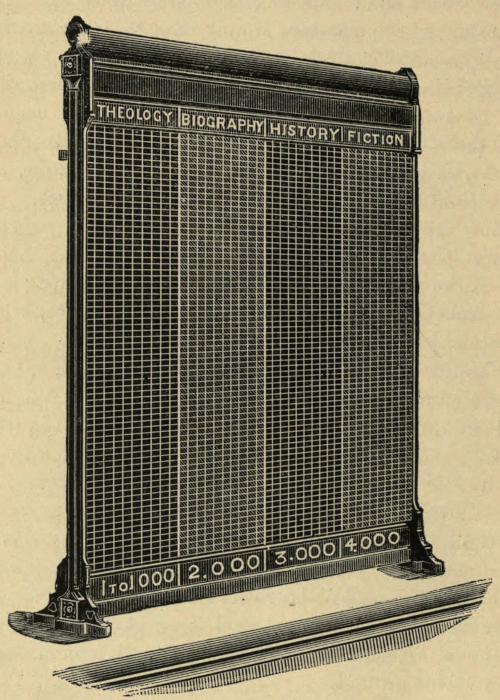

The “Cotgreave” indicator, invented by Mr. Alfred Cotgreave,

now librarian of West Ham, London, differs from the Elliot in

principle and appearance, and is more economical in the space

required. It consists of an iron frame, divided into columns

of 100 by means of wooden uprights and tin slides; but has

numbered blank books in every space, instead of an alternation

of numbered uprights and spaces. Into each space is fitted a

movable metal case, cloth-covered, containing a miniature ledger

ruled to carry a record of borrowers’ numbers and dates of issue.

These cases are turned up at each end, thus ![]() , and the

book-number appears at one end on a red ground and at the

other on a blue ground.

, and the

book-number appears at one end on a red ground and at the

other on a blue ground.

Fig. 10.[8]—Cotgreave’s Indicator

The blue end is shown to the public to indicate books in, and the red end to indicate books out. The ordinary method of working it is as follows: The borrower, having found the number of the book wanted indicated in (blue), asks for it by number at the counter, and hands over his ticket. The assistant, having procured the book, next withdraws the indicator-book and enters in the first blank space the reader’s ticket-number and the date, reverses the little ledger to show the number out, and leaves in it[30] the borrower’s card; stamps or writes the date on the issue-label of the book, and gives it to the reader. On return the indicator number is simply turned round, and the borrower receives back his card. “Overdues” can be shown by means of coloured clips, or by having the borrowers’ cards shaped or coloured, and issues are recorded on day-sheets, or by means of application forms. There are, however, endless ways of working both the Elliot and Cotgreave indicators, though there is only space to describe the most elementary forms. Like every other department of library work, the working of an indicator-charging system will bear careful thought, and leave room for original developments. The “Duplex” indicator, invented by Mr. A. W. Robertson, librarian of[31] Aberdeen, has several novel features which call for attention. A full-sized Duplex indicator occupies 5 ft. 4 in. of counter space for every 2000 numbers, while a smaller pattern for a similar number occupies 3 ft. 8 in. of counter space, both being 4 ft. high, and is a frame fitted with slides in the manner of the Cotgreave and Elliot indicators. It is also a catalogue, and the numbers and titles of books are given on the blocks which fit into numbered spaces. Each block has a removable and reversible sheet for carrying a record consisting of borrower’s number, number in ticket-register, and date of issue. The borrowers’ cards are made of wood, and also bear a removable slip for noting the numbers of books read. When a book is asked for the assistant proceeds first to the indicator and removes the block, which bears on its surface the location marks and accession number of the book, and on one end the number and title of the book; the other being coloured red to indicate out, but also bearing the number. He then carries the reader’s number on to the block, and having got and issued the book, leaves the block and card on a tray. This is all that is done at the moment of issue, and it is simple enough, all the registration being postponed till another time. The assistant who does this takes a tray of blocks and cards and sits down in front of the ticket-register, which is a frame divided into compartments, consecutively numbered up to five hundred or more, and bearing the date of issue. He then selects a card and block, carries the book-number on to the borrower’s card, and the number of the first vacant ticket-register compartment, with the date, on to the book block, and leaves the borrower’s card in the register. Probably the statistical returns will also be made up at this time. The blocks are then placed reversed in the indicator, and so are shown out to the public. When a book is returned, the assistant proceeds to the indicator to turn the block, and while doing so notes the date and register number, and then removes and returns the borrower’s card. By this process the ticket-register is gradually weeded, till on the expiry of the period during which books can be kept without fine, all tickets remaining are removed to the overdue register, which bears the same date, and are placed in its compartments according to the order of the ticket-register. A slip bearing those numbers is pinned down the side of the overdue register so that defaulters can easily be found.

These are the principal points in the three best indicators yet[32] invented, and it only remains to note their differences. The Elliot indicator system makes the charge to the borrower, and preserves no permanent record of book issues apart from the label in the book itself. The Cotgreave system charges the borrower to the book, and does keep a permanent record of the issues. The “Duplex” system shows who has had a certain book, what books a certain reader has had, in addition to a record on the book itself similar to that kept with the Elliot and Cotgreave systems, but only in a temporary manner. So far as permanency of record is concerned the Cotgreave is the only indicator which keeps this in itself. The reading done by borrowers is not shown in a satisfactory manner by any of the three systems, as worked in their elementary stages, and the Elliot and Duplex records are only available when the readers’ tickets are in the library and their places known. Much difference of opinion exists among librarians as regards the necessity for a double entry charging system, many experienced men holding that a simple record of the issues of a book is all that is required. Others are equally positive that a separate record of a borrower’s reading is only a logical outcome of the spirit of public library work, which aims at preserving, as well as compiling, full information touching public use and requirements. In this view the writer agrees, and strongly recommends every young librarian to avoid the slipshod, and go in heart and soul for thoroughness. A simple double record of borrowers’ reading and books read, which will give as little trouble to the public as possible, is much required, and will repay the attention bestowed on it by the young librarian. Where application slips are used, which give book- and borrower-numbers, it is a simple matter compiling a daily record of the reading done by each borrower. At several libraries where Cotgreave’s indicator is used, it is done by the process of pencilling the number of the book taken out on to a card bearing the reader’s number. These cards form a numerical register of borrowers, and are posted up from the application forms.

Before leaving the subject of charging systems let it again be strongly urged that no system of charging should be adopted without a careful thinking-out of the whole question; giving due consideration of the matters before raised, at counters (p. 10) and above, touching space and public convenience in the use of[33] indicators. Though it is claimed for the indicator that it reduces friction between assistant and public, facilitates service, and secures impartiality, it should be remembered that it is expensive; occupies much space; abolishes most of the helpful relations between readers and staff; quickens service only to the staff; and after all is not infallible in its working, especially when used without any kind of cross-check such as is afforded by application forms and separate records of issues to borrowers.

Reference library charging is usually accomplished by placing the reader’s application in the place vacated by the book asked for, and removing and signing it on return. In some libraries these slips are kept for statistical purposes; in others they are returned to the reader as a sort of receipt; and in others, again, the form has a detachable portion which is used for the same purpose. In some libraries two different colours of slips are used to facilitate the examination of the shelves on the morning after the issues.