Motion pictures are still changing so much, in their development from year to year, that any survey of this vast, chaotic new industry is in danger of being out-of-date long before its time. With this in mind, I have attempted to stress those phases of movie-making, and of the story-telling that underlies each photoplay, that do not change. A generation hence, the fundamental problems confronting the makers—how to show real people, doing interesting things in interesting places—will be the same.

Grateful acknowledgment is due Walter P. McGuire, of “The American Boy,” where much of the material embodied in this book first appeared in article form, for his assistance in planning the original articles, as well as in editorial supervision of the work as it progressed. If there is good entertainment, as6 well as instructive value, in these pages, and interest for old minds as well as young ones, much of the credit is due to him.

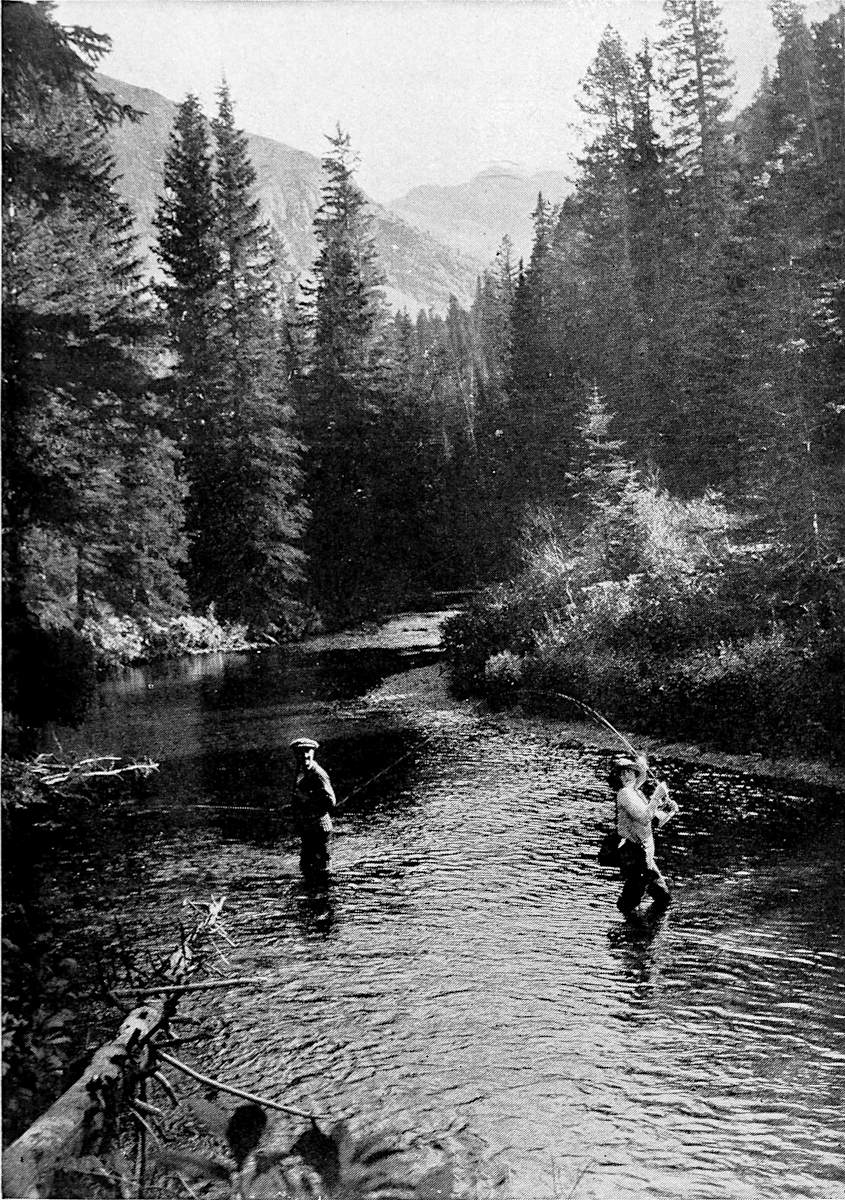

Grover Cleveland was a great fisherman. Once, after he was famous and President, some one asked him what he did, all those hours he spent, waiting so patiently for the fish to bite.

“Oh,” he is reported to have answered, “sometimes I sit and think, and other times I just sit.”

That’s the way most of us watch motion pictures—with the accent on the sit.

We don’t use our brains enough, where the movies are concerned, either in the selection of pictures to go to see, or in analyzing—and appreciating or criticizing—what we see.

How often do you watch motion pictures?

Do you know anything about how they’re made? And who makes the best ones? And14 how they do it? And why they are better? And how you can tell them? And what it means in your life to see good ones—or bad ones?

More than twenty years ago, at a Yale-Harvard football game in New Haven, Harvard got the ball somewhere near midfield, in the second half, and hammered away towards the Yale goal. It was a cold, rainy day, with gray skies overhead and mud underfoot. Harvard weighed more, and was better trained, and had better men. From the very first they had the better of it; early in the game they plowed through to two touchdowns, while lumps came into the throats of the draggled Yale thousands, looking helplessly down from the great packed bleachers.

Then came that march down the field in the second half, with the rain falling again, and the players caked with mud until you couldn’t tell Red from Blue, and the last hopes of the Yale rooters sinking lower and lower.

But as Harvard pounded and plowed and splashed past midfield—half a yard, three yards, two yards, half a yard again—(five yards to a first down in those heartbreaking15 days) the cheering for that beaten, broken, plucky, fighting eleven swelled into a solid roar of encouragement and sympathy. It rose past the cheer leaders—ignored them; old grads and undergrads, and boys who wouldn’t reach Yale for years to come. Yale—Yale—Yale—over and over again, and then the famous Brek-ek-ek-ek! Co-ex! Co-ex!—rolling back again into the Nine Long Yales. All the way from midfield they kept it up, without a break or waver—there in the rain and the face of defeat—all the way down to the goal—and across it. Loyalty!

Another game. Yale-Princeton this time, with Yale ahead, all the way. And at the very end of the game, with the score twenty or more to nothing against them, those Princeton men gritted their teeth and dug in, holding Yale for downs with just half a yard to go! And on the stands the Princeton cohorts, standing up with their hats off, singing that wonderful chant of defeat:

16

Great!

But what of it? And what has it to do with motion pictures?

Just this. Each person, of all the thousands watching those games, was impressed.

Could not help but be. Few will ever forget all of what they saw, or all of what they felt. Something of the loyalty of the Yale stands, the fighting spirit of that dauntless Princeton eleven, became a part of each spectator.

Do you get it?

It’s the things that we see, the things that we hear, the things that we read, the things that we feel and do, that taken together make us, in large measure, what we are. Yes, the movies among the rest.

Every time we go to a loosely played baseball game, and see perhaps some center-fielder, standing flat-footed because he thinks he’s been cheated of a better position, muff an unimportant fly—we’re that much worse off. We don’t realize it, and of course taken all alone one impression doesn’t necessarily mean much of anything, but when it comes to our turn at the17 middle garden, it’ll be just that much simpler to slack down—and take things easy. And every time we see c. f. on a snappy nine, playing right on his toes, turn and race after a liner that looks like a home run, and lunge into the air for it as it streaks over his shoulder, and stab it with one hand and the luck that seems to stick around waiting for a good try, and hold it, and perhaps save the game with a sensational catch—why, we’re that much better ball-players ourselves, for the rest of our lives.

It’s a fact. An amazing, appalling, commonplace fact. But still a fact, and so one of the things you can’t get away from. The things we hear, the things we do, the things we see, make us what we are.

Take stories. The fellow who reads a raft of wishy-washy stories, until he gets so that he doesn’t care about any other kind particularly, becomes a wishy-washy sort of chap himself. On the other hand, too much of the “dime-novel” stuff is just as bad, with its distorted ideas and ideals. Twenty-five years ago, the Frank Merriwell stories, a nickel a week, were all the thing, and sometimes it seemed to many18 a boy unfair foolishness that Father and Mother were so against reading them. But Father and Mother knew best, as those same boys will admit to-day. Too much of that sort of thing is as bad for a fellow as a diet of all meat and no vegetables. Wishy-washy, sentimental books can be compared to meals that are all custard and blanc mange.

To watch first-class motion pictures (when you can find them) is like reading worth-while stories. They tell us, show us, as often as not, places that are interesting, and different from the parts of the world we live in. They bring all people, and all times, before us on the screen. But the poor pictures that we see twist out of shape our ideas of people and life; they show things that are not and could not be true, they gloss over defects of character that a fellow should—that a regular fellow will—face squarely. A clothing-store-dummy “hero” does things that no decent scout would do—and we’re just as much hurt by watching him on the screen as we would be by watching that flat-footed center fielder on the losing baseball team.

19

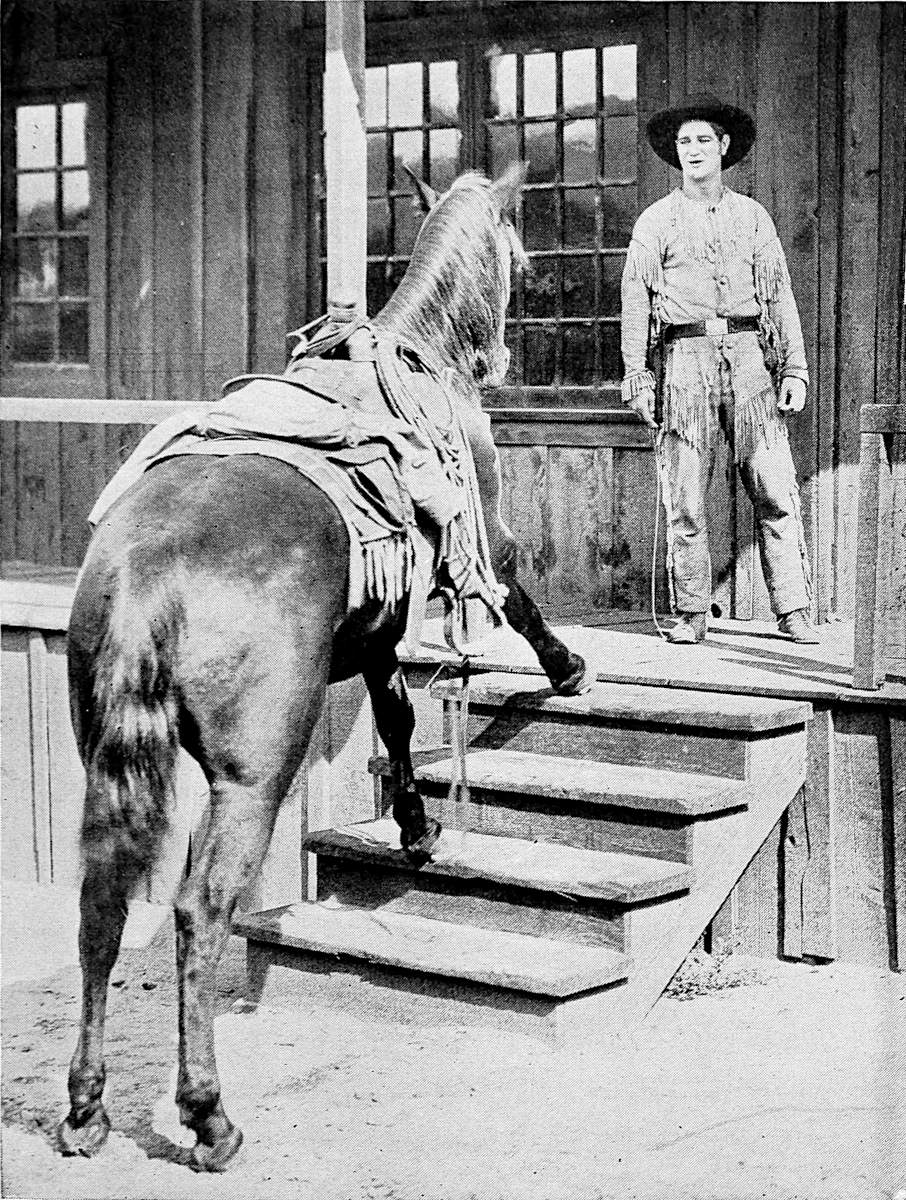

Why are the Bill Hart pictures about the best of the so-called “Westerns” of the last seven or eight years? Isn’t it because on the whole Bill Hart has played the sort of chap that is most worth while—with courage, kindness, and loyalty, and ability to control his temper and do the right thing?

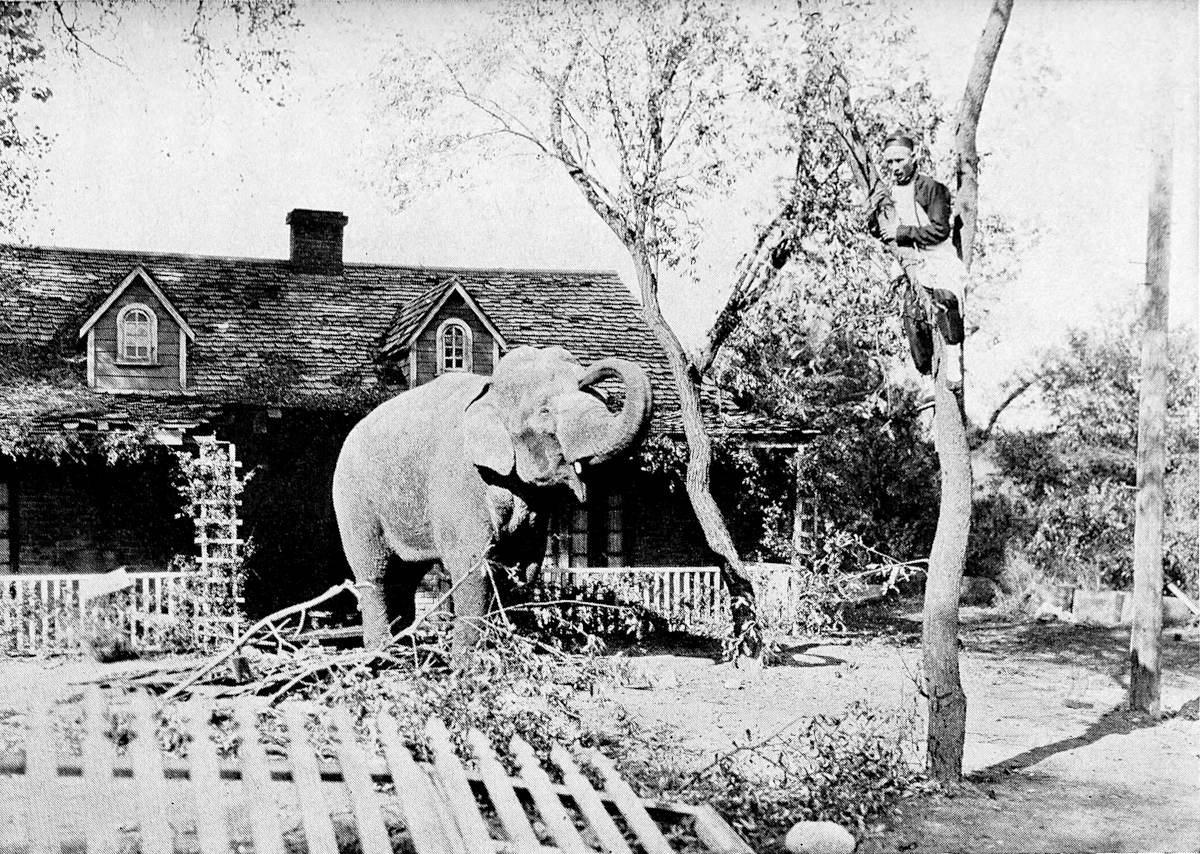

Only, did you ever stop to wonder how it happened that so often Bill Hart’s “hero” was a bandit or train-robber or outlaw? If the fellow Hart played had really been as good as he made out, would he have been robbing or killing so many times? At least, it’s worth thinking about. And in one of Hart’s Westerns the hero had to ride a horse over a twenty-foot bank—almost a cliff—to get away from his pursuers. It made you wonder how they could “pull a stunt” like that without too much risk. It looked as though both horse and rider were hurt.—As a matter of fact, the horse actually broke a leg, and had to be shot. Nobody seemed to think there was anything out of the way about that—merely killing one horse to get a good picture. But how does it strike you?

Of course, that horse incident is an unusual20 one, but there are hundreds of interesting problems that come up in the making of motion pictures nowadays. Pictures are one of the things that week by week are making us the fellows we are—oughtn’t we to know something about them?

In one year, according to the government tax paid on box-office admissions, nearly $800,000,000 worth of photoplay tickets were bought. That means more than $2,000,000 a day paid to see motion pictures. If the admissions averaged about twenty cents apiece, that means some 10,000,000 people a day watching the movies—getting their amusement and instruction, good or bad, and their impressions, good or bad, that go to determine what sort of people they will be, and what sort of a nation, twenty years from now, the United States will be.

What about it? Isn’t it a pretty important thing for us to know something about the best movies, and the worst, and why they are the best, or the worst? And how they might be better?—So that we can encourage the right films, and censure the ones that ought to be21 censured, and do it intelligently, playing our part in improving one of the biggest influences that this country or any other has ever seen? For surely we all know that if we can avoid the photoplays that aren’t worth while, they will be just that much less profitable for the men who make them, and the pictures that we do see, that are worth while (if we can tell which ones they are, and recommend them to our friends after we’ve seen them), will have just that much more chance to live and show a profit and drive out the poorer specimens and get more worth while pictures made.

One of Marshall Neilan’s pictures was called “Dinty.” It told the story of a little newsboy in San Francisco. It contained a lot of cleverness and a lot of laughs; for instance, Dinty had a string tied to his alarm clock, that wound around the alarm as it went off, and tipped a flatiron off the stove, and the weight of the flatiron yanked a rope that pulled the covers off Dinty.—Then, on the other hand, there was a lot of stuff in it that was not so good.

Now, when you saw that picture, if you did, could you tell what was good and what was not22 so good, and why the poorer part was poor? If you could tell that, you’re in a position to profit most from such pictures as you see, and get the least possible harm. Also, you can help the whole game along by intelligent comment and criticism, and enthusiasm for the right thing.

Of course, you can get some fun out of watching a picture as a two-year-old watches a spinning top, but you can get a lot more if you use your brains. Try it.

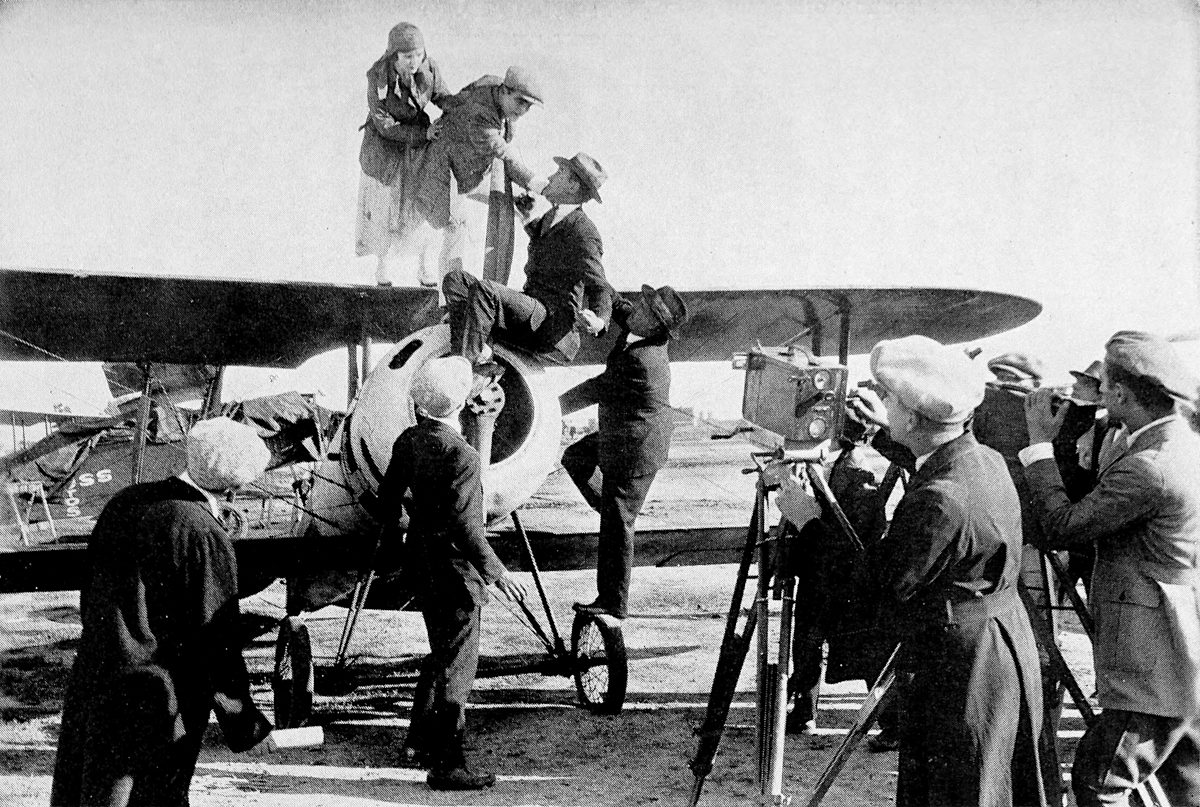

Motion pictures are not only important; they are fascinating. There’s a glamor that surrounds the whole industry. Think of starting out at daybreak—three big autos full of people, and a whole cavalcade on horseback as well—to stage a “real sham battle” between cowboys and Indians!—Think of all the interesting results that can be secured, with the use of a little ingenuity and knowledge of the amazing things that a camera will do!

Haven’t you ever wondered, when watching moving pictures, why this or that was so, how that or this was done? Whether or not a real person had to make that dive off the cliff—or perhaps why, in some color pictures, there are sudden unaccountable blotches of color, yellow or red, perhaps green?

24

For instance, you have noticed, probably, in news reels and so on, how fast marching men always walk? A regiment comes past at the quickstep—almost at a run. Yet obviously, when the picture was taken, the men were marching along steadily enough, at a swinging stride that would set your pulse throbbing.

There are two reasons for that: one is a fairly normal convention that has become firmly established in motion-picture theaters, and that has nothing whatever—or at least practically nothing—to do with the taking of the picture. The other concerns the camera man or director in charge, and is a plain matter of judgment, good or bad.

You have probably seen strips of the celluloid ribbon, with little holes along the sides, that they call motion-picture “film.” It’s about an inch wide, and the little pictures run crosswise, sixteen of them to the foot of film. When the camera man turns the little crank of his motion-picture camera twice around, it carries a foot of film past the lens of the camera. Sixteen exposures. Ordinarily, the speed of this cranking is one second for the two turns—one foot of25 film, or sixteen exposures, per second; sixty feet a minute.

When the film is developed and a print made for exhibition, it is run through the projecting machine of a theater: if it were run at the rate of a foot a second, sixty feet a minute, the figures on the screen would move just as fast as they did in real life when the picture was taken—no faster and no slower.

But the custom has grown up of running film through the projecting machines faster than the film was run through the camera. Instead of being run sixty feet a minute, it is usually clicked along at the rate of seventy feet or more a minute. Seventy-two feet or more a minute is called “normal speed” for projection. So that on the screen everything happens about one-fifth faster than it did in real life, and frequently even faster than that—much faster, since more and more there is a tendency to “speed up” still further, until the feet of marching men in the news reels almost dance along the street, and their knees snap back and forth like mad.

Of course, you see more in a minute, watching26 in a theater where film is run through the projection machine so fast—but what you see is distorted, instead of being quite so much of the real thing, as would be the case if it were run more slowly. Probably on the whole it would be better if the convention of “speeding up” the projection machines were done away with, and all film ordinarily run at only the actual speed of real life—except where there happened to be some special reason for hurrying it along.

Then—the other way of making things happen on the screen faster than they do in real life. For instance, when one automobile is chasing another, and turns a corner so fast it almost makes you jump out of your seat—the hind wheels slewing around so dizzily it seems as though the whole thing would surely go in the ditch.

That’s done by what is called “Slow Cranking.” The director, we will say, wants to show an automobile crossing in front of the Lightning Express, with only half a second to spare. If he were really to send the auto with its driver and passengers across the track just in27 time to escape the flying cowcatcher, it would be too terrible a risk. So they “slow down” the action. Instead of crashing along at sixty or seventy miles an hour the train is held down to a mere crawl—say ten miles an hour, so that it could be stopped short, if necessity arose, in time to avoid an accident. The auto would cross the tracks at a correspondingly slow gait. And the camera man, instead of cranking his film at normal speed, two turns to a second, would slow down to a single turn in three seconds, or thereabouts. That would mean it would take six seconds for one foot of film to pass the lens of the camera, instead of the usual second. So that when the picture appears on the screen, projected at normal speed, we should see in one second what actually occurred in six seconds; the train traveling at ten miles an hour would hurry past, on the screen, at sixty; the automobile bumping cautiously over the tracks in low speed or intermediate, at six or seven miles an hour, would flash past the approaching cowcatcher at somewhere around forty.

In comedies, this trick of “slow cranking”28 has been used until it has grown rather tiresome, unless done with some new effect or with real cleverness. Autos have zigzagged around corners, or skidded in impossible circles, men have climbed like lightning to the tops of telegraph poles, and nursemaids have run baby-carriages along sidewalks at racetrack speed until we are a little inclined to yawn when we see one of the old stunts coming off again.

But there are always legitimate uses of slow cranking—as in the case of the train and the automobile.

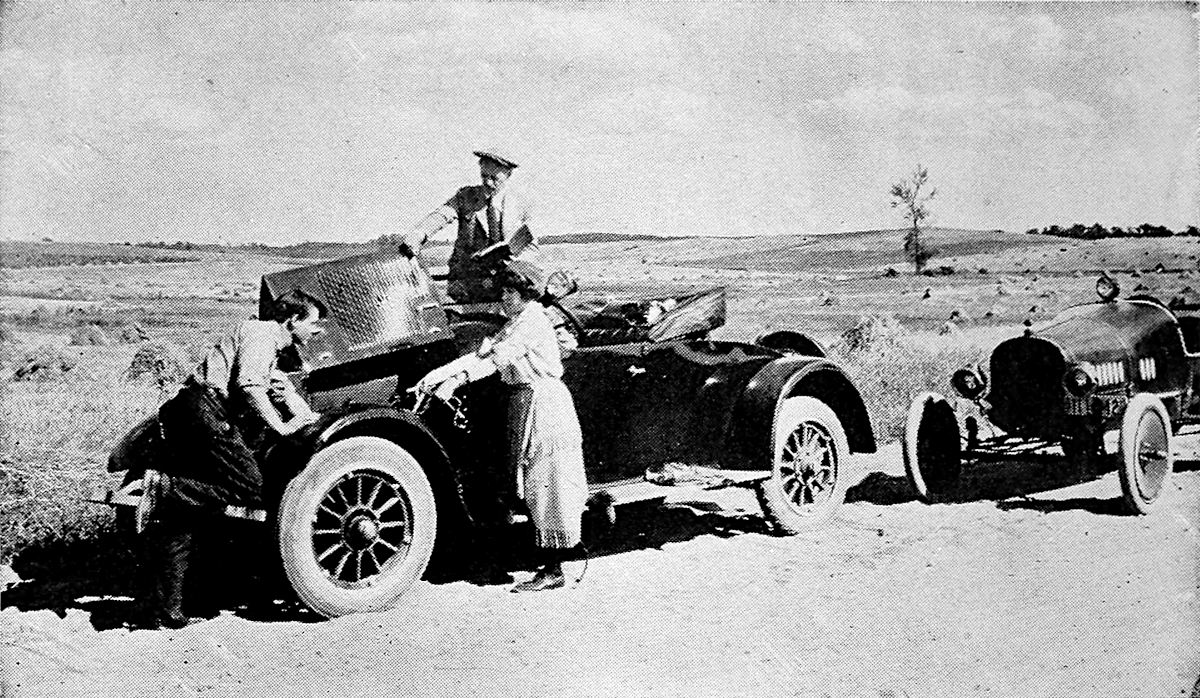

At one time a company was filming an episode that occurs in the story of a cross-country automobile tour. In the story, the girl, who is driving to the Pacific Coast with her father, stops the machine and gives a lift to a tramp. This tramp proves to be a bad man, and decides to hold up the defenseless girl and her invalid father. He is standing on the running-board, beside the wheel, and threatens to turn the car over the steep embankment at the side of road if the girl doesn’t do just as he says. This keeps her from slowing down, or giving any signal for help to machines that pass in the 29opposite direction. The tramp evidently means what he says, and would be able to jump safely off as he sent the car smashing to destruction. It would look like a mere accident, and with the girl and her father killed nothing could very well be proved.

But at the last moment, along comes The Boy, who is following the girl in a smart little roadster, and sees what is happening. He takes a chance and drives alongside the larger car, makes a lasso of his tow-rope and yanks the bad man off the running-board, spilling him in the road.

Fair enough. But how are you going to make a picture of that, with close-ups and everything?

By slow cranking.

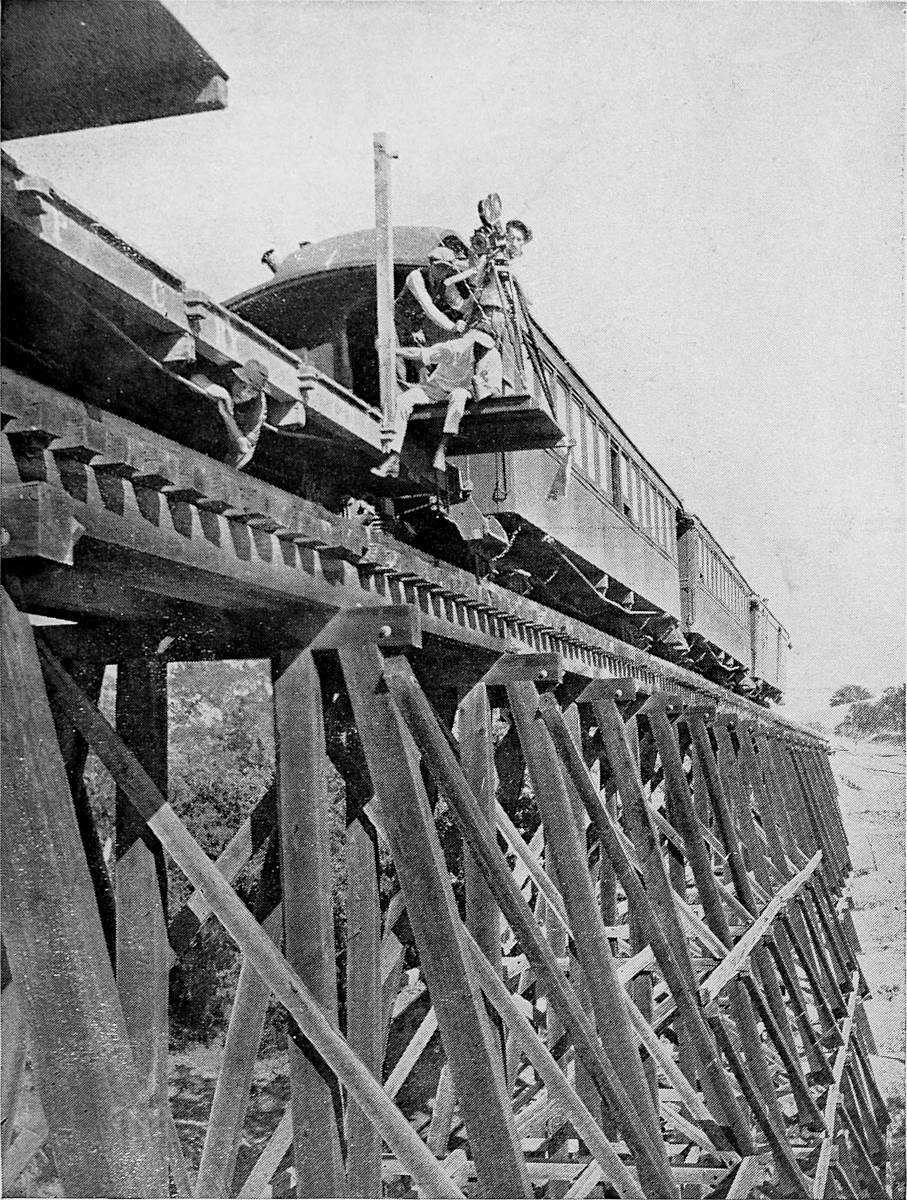

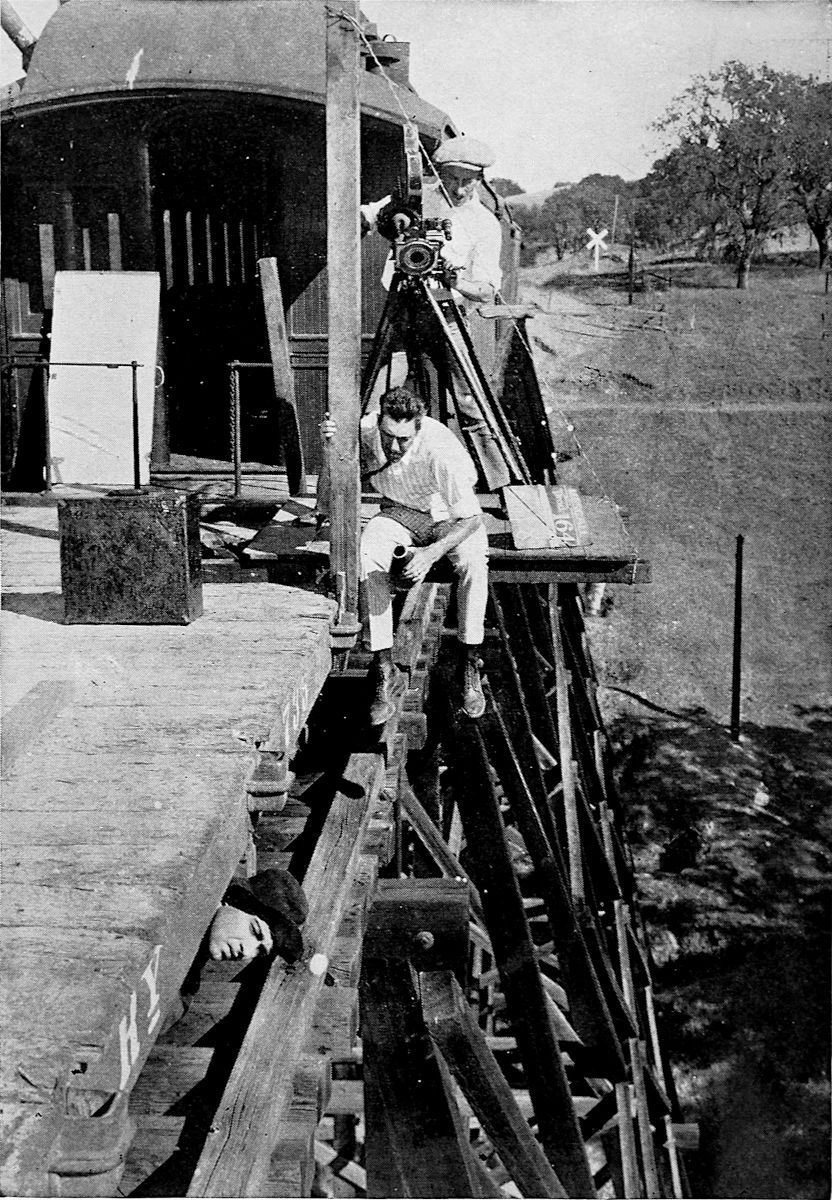

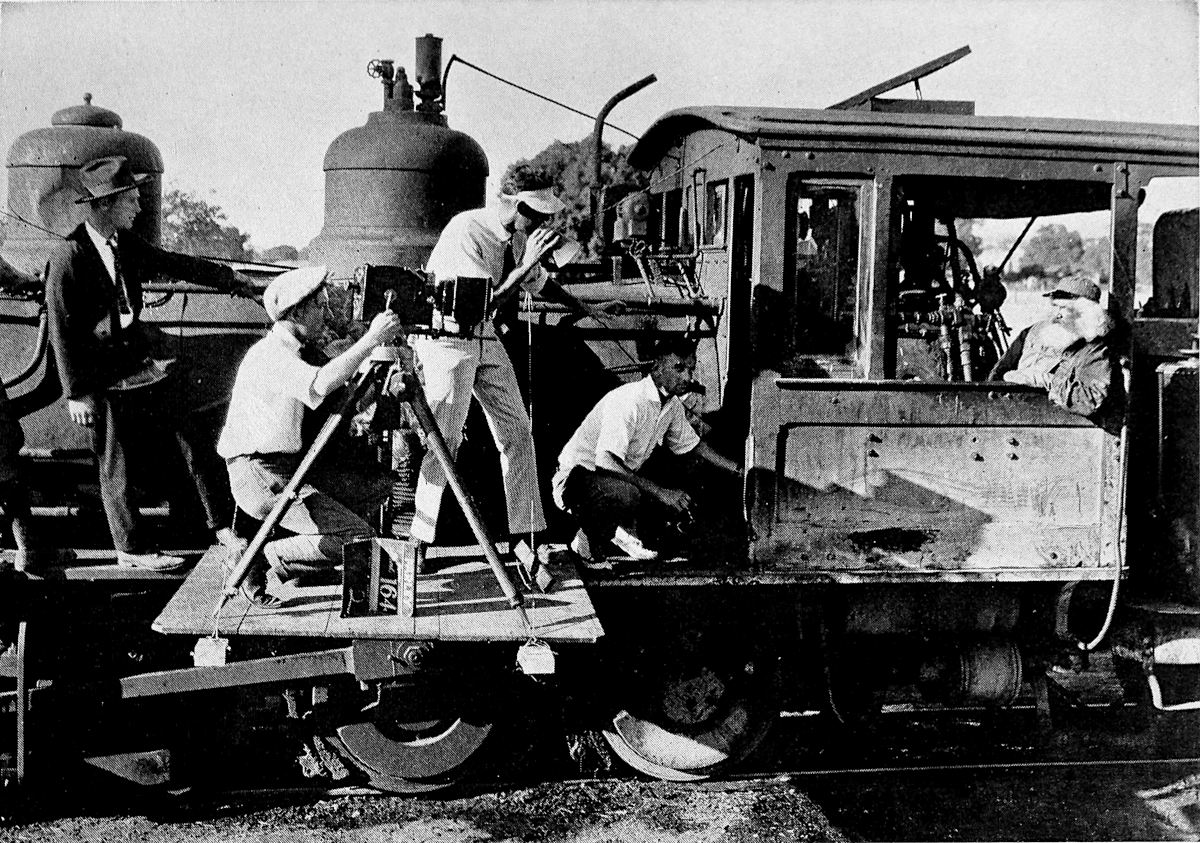

The camera is put on a platform projecting in front of a third automobile. This car follows after the other two, “shooting” the action from the rear, as the hero yanks the tramp from the running board of the girl’s car. For close-up shots of the faces, to bring out the emotions and drama of the action, the camera is put on one machine or the other as needed,30 taking pictures that show only the tramp, or the girl and her father, or all three—or, on the little roadster, the boy hero.

You can see how important the slow cranking is, when you take the point of view of the tramp—who of course is really no tramp at all, but a very daring and probably well-paid actor. Imagine yourself acting the part; standing on the running-board of a moving machine, you are yanked backwards by some one on another machine traveling alongside. You have to fall into the road between the two machines, using whatever strength and resourcefulness you may possess to keep out from under the rear wheels of either car. Then, to make things better still, along comes the camera car immediately behind, so that you have to roll out of the way to avoid being run over by that.

If the whole action were taken at the speed supposed in the story, with both machines traveling at twenty or thirty miles an hour, it would be too dangerous. Couldn’t be done, without the risk of death. But by slowing the cars down, and having all the actors make31 every movement as slowly as possible, and slow-cranking the camera, the incident can be pictured with little danger of more than a scratched face or wrenched shoulder, and will provide a great thrill for audiences who see it on the screen.

Another bit of action in the same story, where a man who has stolen an automobile is racing to escape his pursuers, and drives by accident over the edge of a cliff, to die beneath the wreckage of the stolen car:

On turns, along the dangerous road, the stolen car is “shot” from behind, as described above. These scenes are varied with “long shots,” taken from the distance, that show the road along the precipice, with both pursued and pursuers racing along. Then we have a fairly close “shot” of the wheels of the stolen car, as they come close enough to the edge of the cliff to make you shudder; this “close-up” is taken from behind, with slow cranking. Then, perhaps, we have a view of the road ahead, the camera being placed (supposedly) on the stolen car. We see the road apparently32 running towards us, the edge of the cliff at one side so close that it seems as though we’d surely go over.

Next, say, a close-up of the thief, showing his expression of terror as he loses control of the car and realizes that it is about to plunge over the cliff into space.

Then, the real “trick action” of the incident.

The car is rolled by hand to the very edge of the precipice, and blocked there with little stones that do not show—the tires of the front wheels actually projecting over the cliff. The actor taking the part of the thief holds his hands above his head, looking as terrified as he can, and brings them very slowly down in front of him, at the same time releasing the clutch of the car, with the gears in reverse and the motor running. The camera, placed quite close at one side, is slow-cranked backward. So that when the print from the film is projected at normal speed, we see the car dash to the very edge of the cliff, while the thief lets go of the wheel and throws his hands above his head just as the machine makes the plunge.

For the next shot, of course, we have a distant33 view of the scene, a “long shot,” showing the car plunging down to destruction, with the thief still behind the wheel. This is done with a dummy figure. But on the screen, when the picture is completed, we jump from the close scene of the thief throwing up his hands as the car reaches the edge of the cliff to the long shot of the car falling with the dummy, and the illusion is perfect.

Before the car is pushed over the edge for the real fall, the engine is taken out, and everything else of value that can be salvaged is detached. In the final scene of this tragic death these accessories may be scattered around the wreck of the car, adding to the total effect of utter destruction. The body of the thief, half covered by one of the crumpled fenders—the real actor, of course, this time, shamming unconsciousness or death, properly smeared with tomato-catsup-and-glycerine blood, adds the finishing ghastly touch.

Do you believe that any one could see that picture,—well done, the chase along the mountainside, the rush to the edge of the cliff, the drop through space, and the wrecked car on the34 ground—without a thrill? It would be quite convincing, and few indeed could tell which scenes were actual “straight” photographs and which were “tricked.”

In fact, it is really that classification that makes the difference: How well is the thing done? Does it give an impression that is true to life? The fact that a trick is used is nothing against the film; indeed, it may be decidedly in favor of it, providing a novel and realistic effect is secured.

For example, when the scenes described above were first assembled in the finished film, the effect was not as good as had been anticipated. The camera man had not cranked quite slowly enough. Consequently, in some of the scenes the automobiles did not move fast enough on the screen; they rounded dangerous curves with such caution that when one car finally went over the cliff, it looked like a fake. The illusion of the story, that made it true to life, was destroyed, because of giving first an impression of cautious driving, and then of an accident that would only have occurred as a result of terror or recklessness.

35

So still another trick was resorted to: a purely mechanical one. Every other “frame” or individual exposure in the slow scenes was cut out, and the remaining frames of the film patched together again. Action that had been filmed in one second, with sixteen exposures, was reduced to eight frames, or half a second. It was a careful cutting and “patching” as the re-cementing of the film is called—but the second trick remedied the defects of the first.

By adding an additional “fake” to the first, the picture was made more nearly true to life!

Then a final touch was added to the whole business.

Immediately after the car plunged over the cliff, in the finished film, there comes a scene of the ground, far below, flying up at you. It is as though you were sitting in the car with the doomed thief, and get the effect of falling with him through the air.

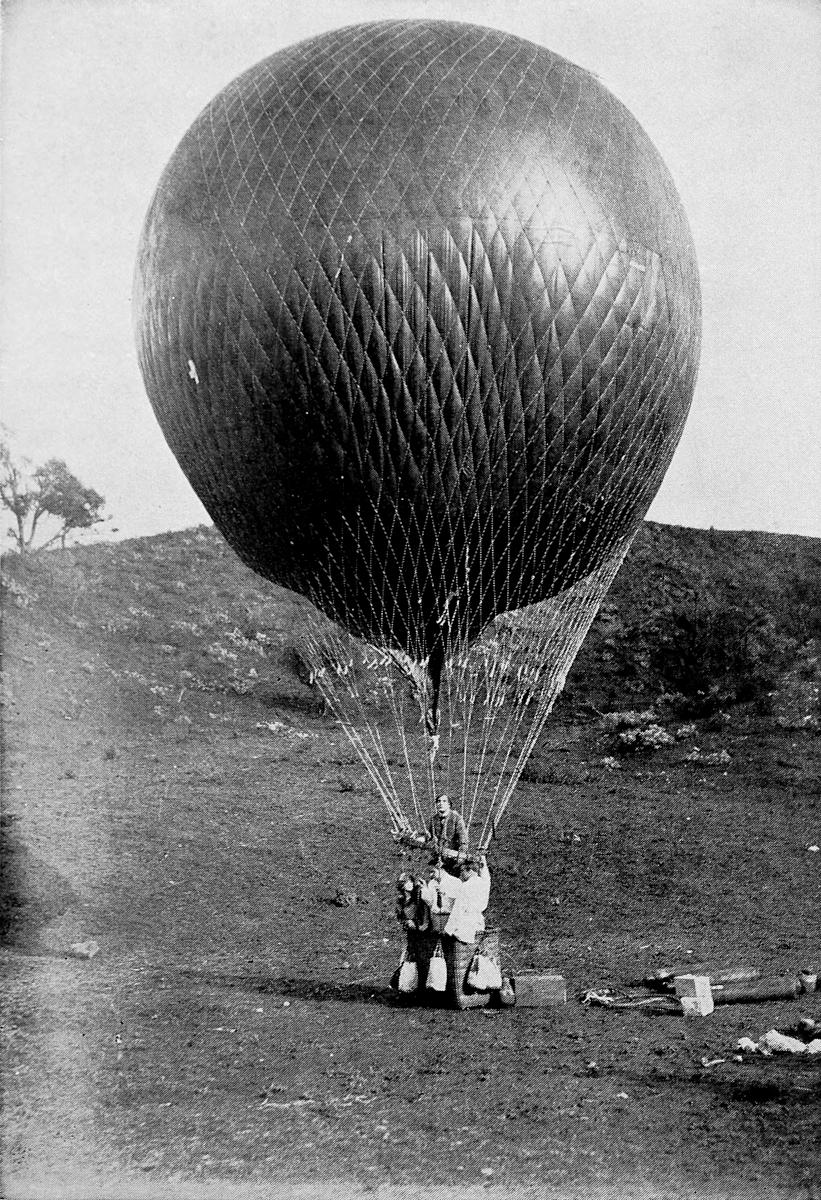

To get the shot, it had been planned to lower a camera man over the precipice with ropes, allowing him to crank very slowly as he was lowered. But the natural difficulties were too great. The distance that the camera man36 would have to be lowered, to secure the necessary effect, proved to be enormous. There was too much danger. The director was willing to go ahead, but the camera man balked. He said the director could go over the cliff and crank the camera himself if he wanted to—he’d be willing to risk his camera. But the director didn’t want to. All he was willing to risk was his camera man.

Looking at the picture after it was nearly ready for release, the producers decided that the thrill of the accident would be much greater with that ground-jumping-up-at-you shot, that everybody had been afraid to make, included. And the art director came to their assistance. He said he’d make the scene for them in the studio without danger, for fifteen dollars. They opened their mouths, in astonishment, and when they could get their breath, told him to go ahead.

He took a piece of bristol-board and in a few minutes sketched on it a rough, blurred view of open country, such as you might imagine you’d see looking down from a high cliff. Then he photographed it at normal speed, moving it 37rapidly toward the lens and turning it a little as the camera was cranked. Result, secured in connection with the other scenes already made: the thrill of falling in an automobile through the air, and seeing the ground fly up at you.

In one of D. W. Griffith’s shorter photoplays a number of girls leave a party with a fellow in a Ford; a storm is coming up. We see the car leaving the lighted house and starting down the dark street, we see the gathering storm, see the car jouncing along in the blinding rain as the storm breaks, see it cross a little bridge, with lightning flashes illuminating the scene, and finally we see it arrive safely at the home of the heroine, who gets out and runs to the back door in the dark like a half-drowned kitten.

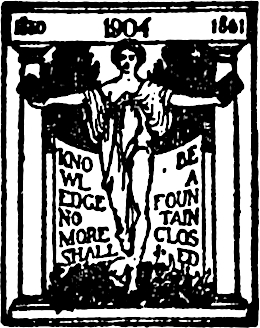

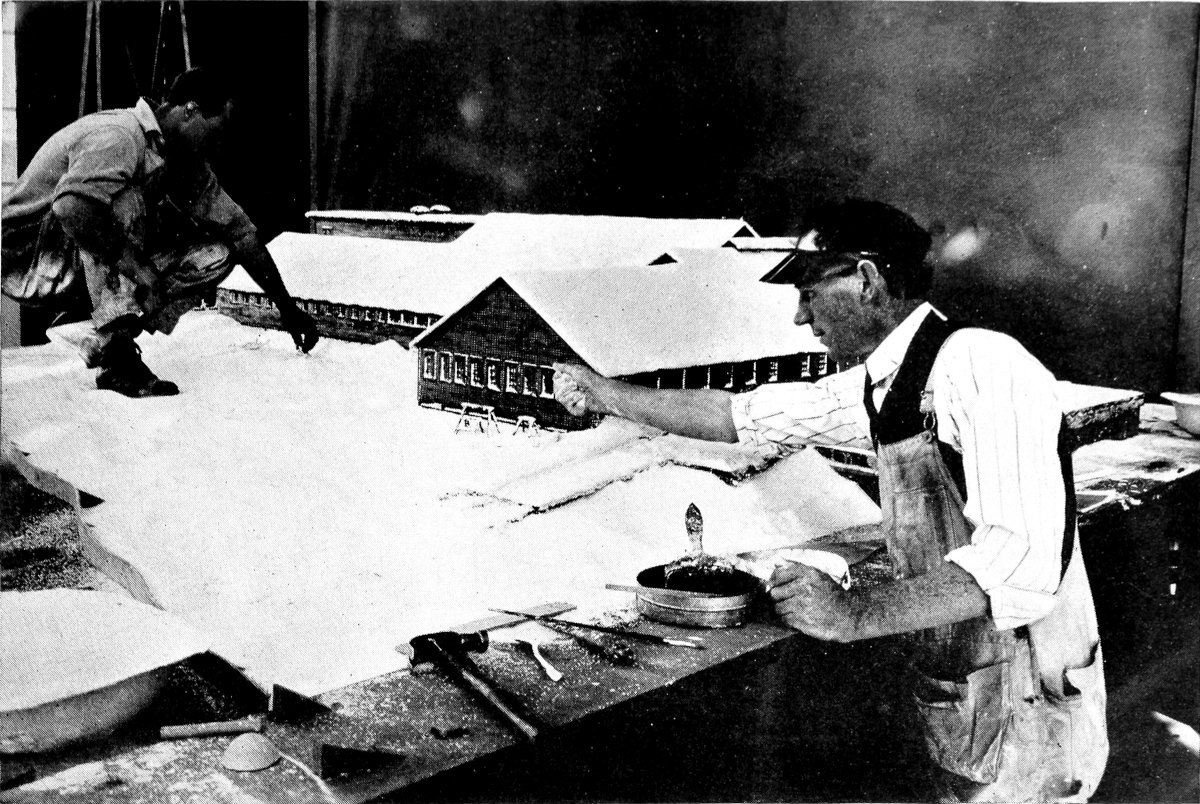

The street scene was taken with lights illuminating the house windows, and enough of the street to show dimly the outlines of trees and so on in the supposed night. The short scene of the gathering storm (merely a picture of masses of moving clouds, taken of course some bright day when there happened to be a good cloud-effect) gives us the impression of38 an impending deluge. The scene of the car in the driving rain was taken in the studio, with a black curtain hung behind the car, a man lying concealed on the farther running board jouncing up and down to give the impression that the machine was bumping rapidly along over a rough road, and a hose squirting rain upon the scene in front of the car, being driven upon it and past it by the blast of air from a huge aeroplane propeller whirling just out of the camera’s sight. The scene of the auto crossing the little bridge was done in miniature; that is, a toy auto, mechanically propelled, equipped with tiny electric searchlights, was wound up and sent across a little eight-inch bridge, over a road that wound between trees made of twigs ten or twelve inches high, stuck in damp sand—with little fences, houses, everything, perfect—and the lightning made by switching a big sputtering arc-light behind the camera on and off. Then, the final scene, of the girl leaving the auto, was taken in fading daylight, with a hose again supplying the drenching “rain,” and the print tinted dark blue to indicate night.

39

On the screen, the illusion of the whole was perfect. As I said, it is not whether or not a trick is used that counts—but how perfectly the thing is done, how complete the illusion that is carried, and how faithfully and sincerely that illusion or impression conveys a really worth-while idea, or a story that is convincingly true to life.

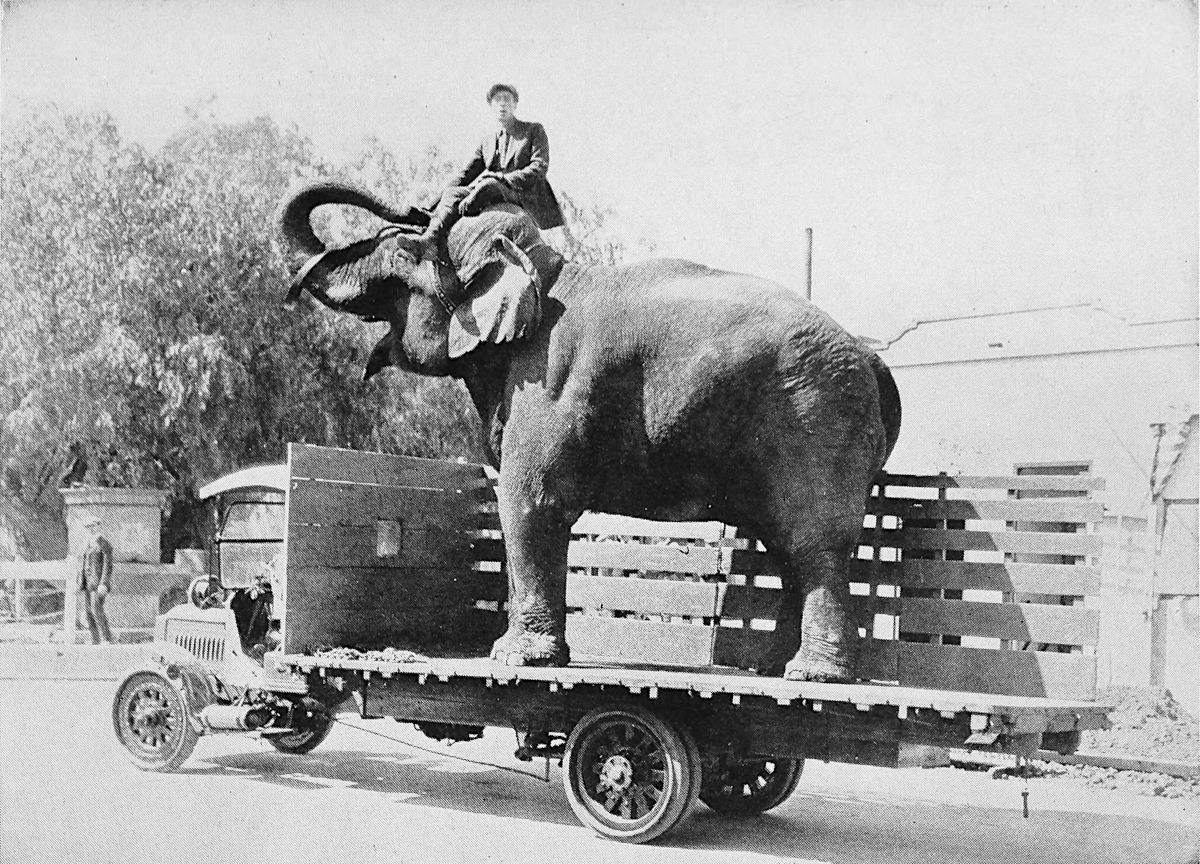

You mustn’t think, though, that all the big effects on the screen are secured by tricks. For indeed they are not. Sets are constructed that cost thousands and thousands of dollars, locomotives are run head on into each other, whole companies travel into out-of-the-way and dangerous places to film unusual scenes,—shipwreck, tropical adventures, Arctic rescues. A camera man told me of how, in a shelter on top of a rock above a water-hole in Central Africa, he watched for days to photograph wild elephants, and saw a fight between an elephant and a big bull rhinoceros, and in the end almost lost his life.

All over the world the moving-picture camera is now finding its way, blazing new trails, bringing back information of how this gold40 field really looks, or how in the next range logging is carried on at ten thousand feet. Sooner or later you and I will see it on the screen, and it is for us to know something about the business—for the film is taking the place of many and many a printed page, and the picture, in part at least, is the speech of to-morrow.

There are two kinds of motion pictures.

One sort is the regular “feature,”—usually a six or seven reel photoplay, the bulk of the evening’s entertainment—and the other kind is illustrated by the “news reels.”

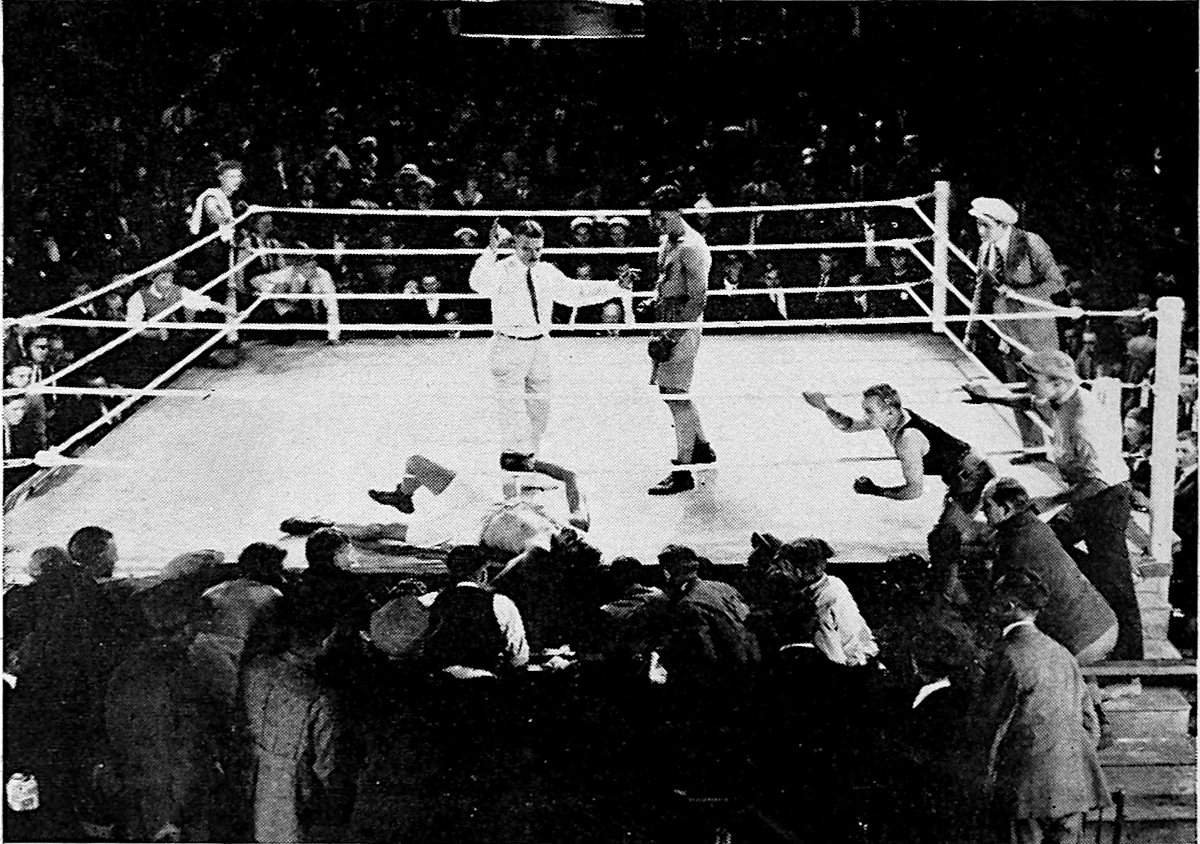

One kind tells stories. The other shows facts. “Robin Hood,” for instance, tells a story. But the wonderful picture that showed the great horse-race between Man-o’-War and Sir Barton was merely a series of remarkable photographs of what actually happened.

There are of course many intermediate pictures and combinations, part way between the two, as we shall see; but when you stop to think of it all pictures fall under one or another of the two main classifications. Either they are entertainment pure and simple, possibly with a background of truth or philosophy42 or fact, or else they are reality, presented as entertainment.

And here is an interesting thing: while the story side of motion-picture making, that has developed to a great extent from stage drama, has already reached very great heights, the other side of picture-making, that we see illustrated in the news reels, is still relatively in its babyhood. Scenics and news reels and an occasional so-called “scientific” or instructive reel are about all we have so far on this side of picture making, that will probably within our own lifetime come to be far greater than the other.

The “reality” films have developed from straight photography. They take the place of kodak snapshots, and stereopticon slides, and illustrations in magazines, newspapers, and books.

Between the two, cameras have come already to circle the whole world.

Not long ago in a New York skyscraper given over mostly to motion-picture offices and enterprises, three camera men met.

“Say, I’m glad to be back!” exclaimed one;43 “I’ve been down in the Solomons for nearly a year. Australia before that, and all through the South Seas. Got some wonderful pictures of head-hunters. They nearly got me, once, when I struck an island where they were all stirred up because some white man had killed a couple of them.”

“I’m just back from India, myself,” remarked the second, “Upper Ganges, and all through there. Got a lot of great religious stuff.”

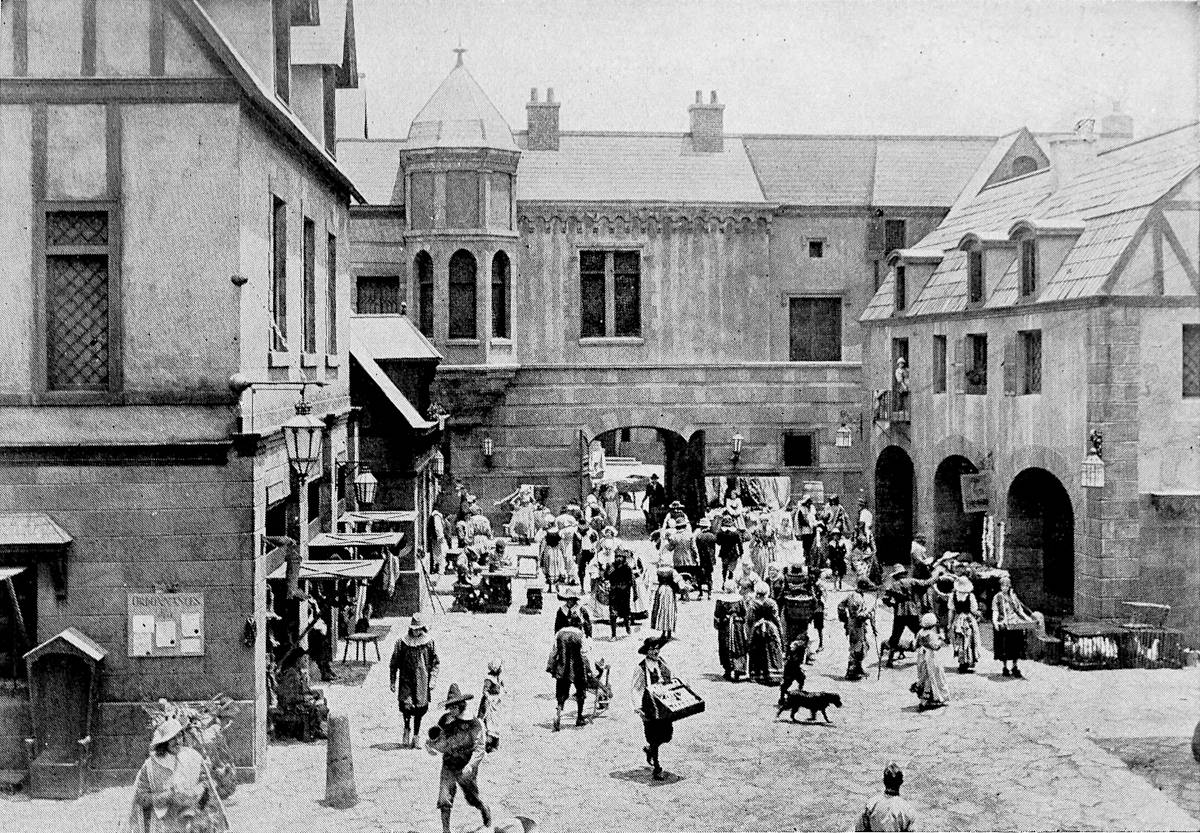

“You fellows have been seeing a lot of the world,” sighed the third, “while I’ve been stuck right here solid for the last eighteen months. Last eight months on a big French Revolution picture.”

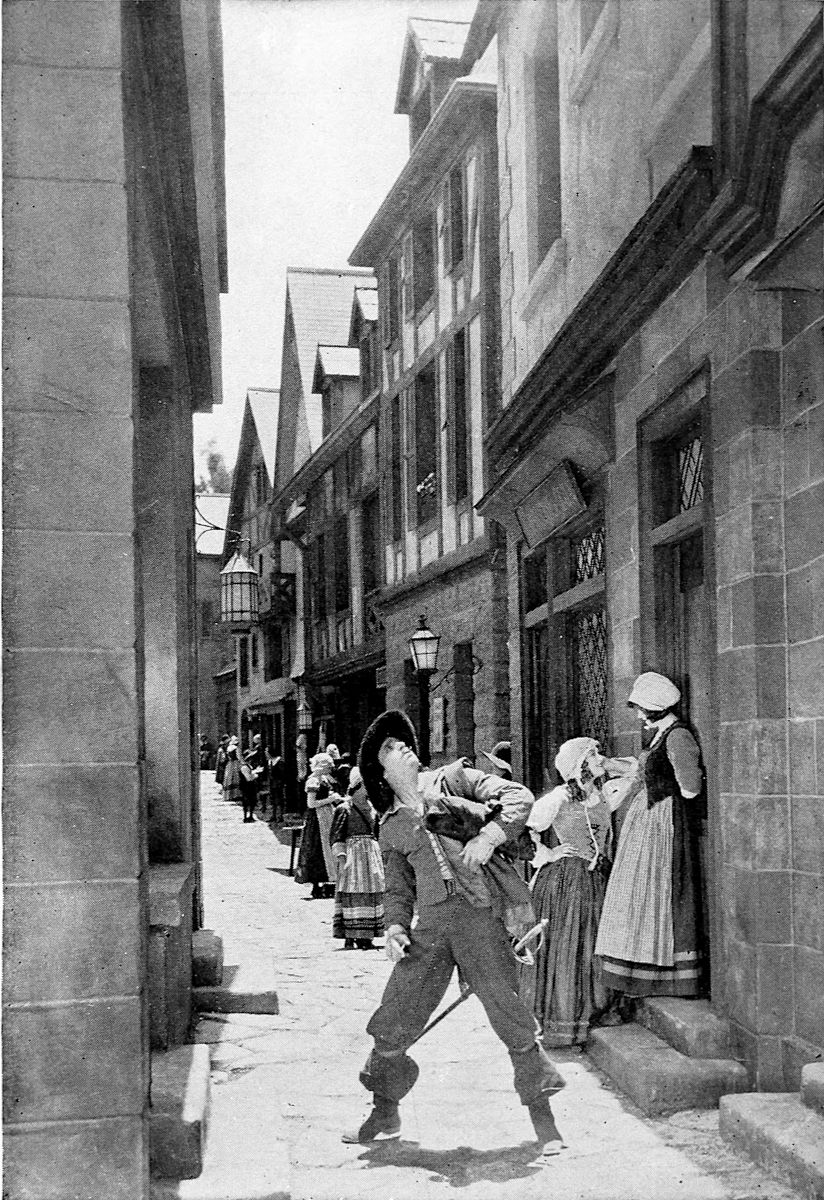

Two of the men were globe-trotting “travelogue” photographers; the third was a regular “studio” camera man; while the two had been searching the world, to secure motion pictures of actual scenes, the third had been taking pictures of carefully prepared “sets” that faithfully reproduced—just outside New York City—streets and houses of Paris as they were in the year 1794.

44

Let us take up first the kind of movies that we usually see to-day—the photoplays made in Hollywood or New York or Paris or wherever the studio may happen to be, that tell a story or show a dramatic representation of life somewhere else.

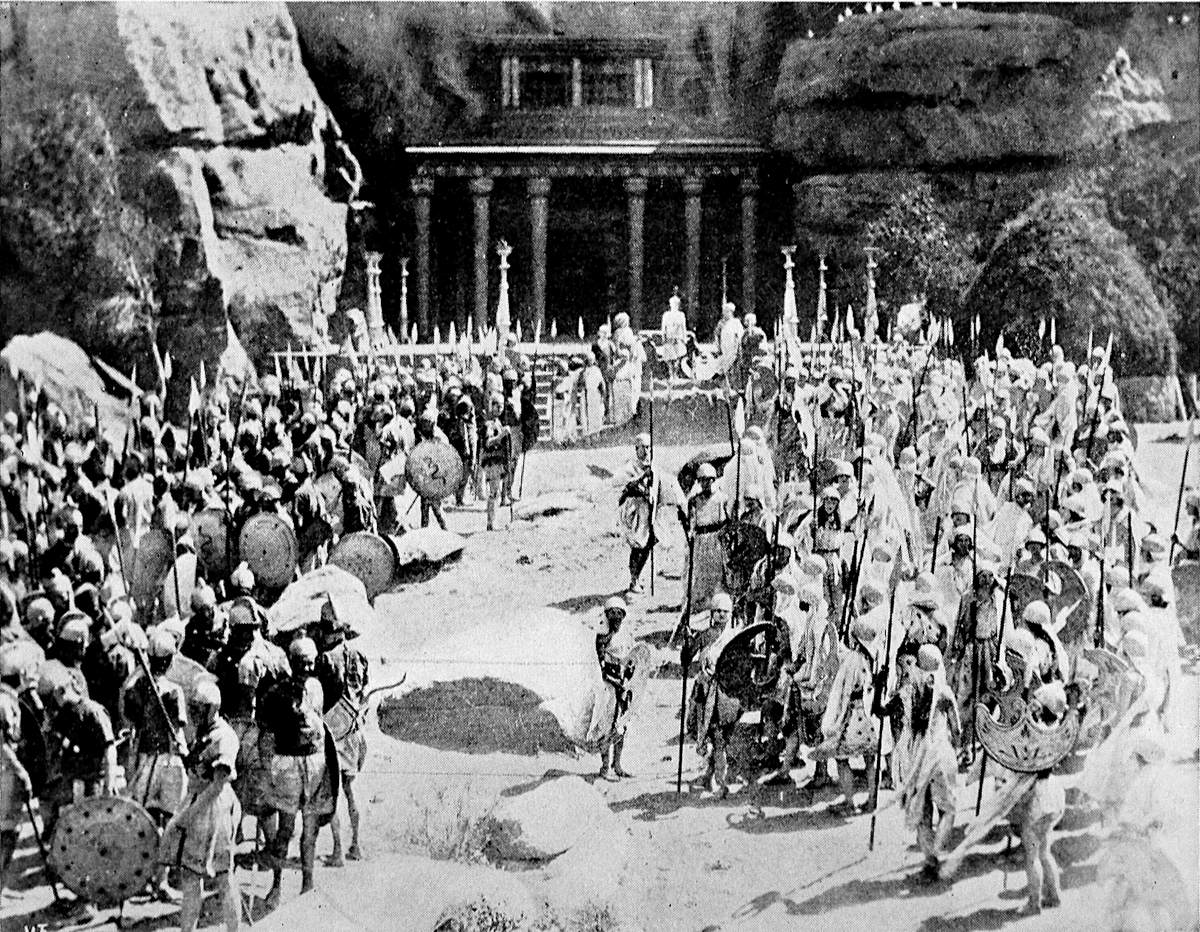

Suppose a story of the Sahara Desert is to be filmed at Culver City, California, where several different big studios are located.

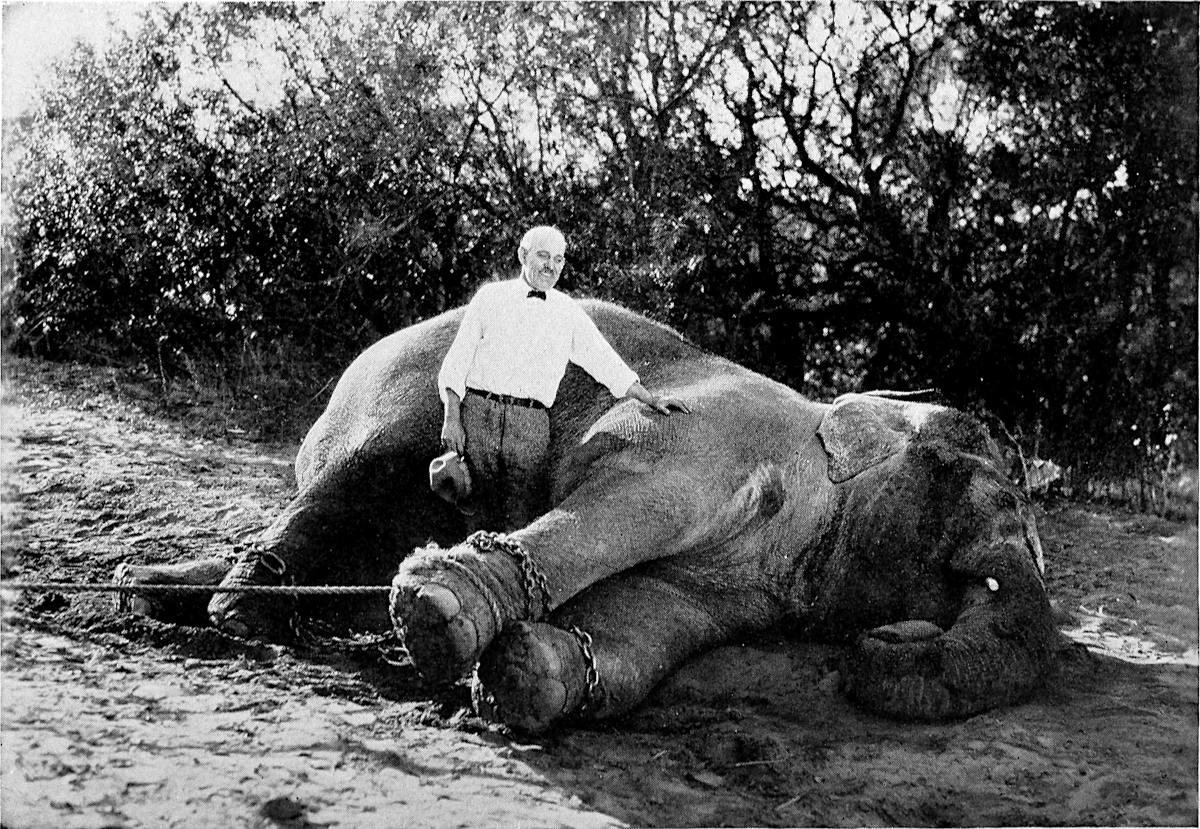

Costumes are designed or hired, and actors and actresses are made up and togged out to represent desert chieftains and wild desert beauties and languid harem maidens and uncouth tribesmen. Horses are fitted out with all the trappings of Arab steeds. Half a dozen rebellious camels are hired from one of the big menageries that makes a specialty of renting wild animals to film companies.

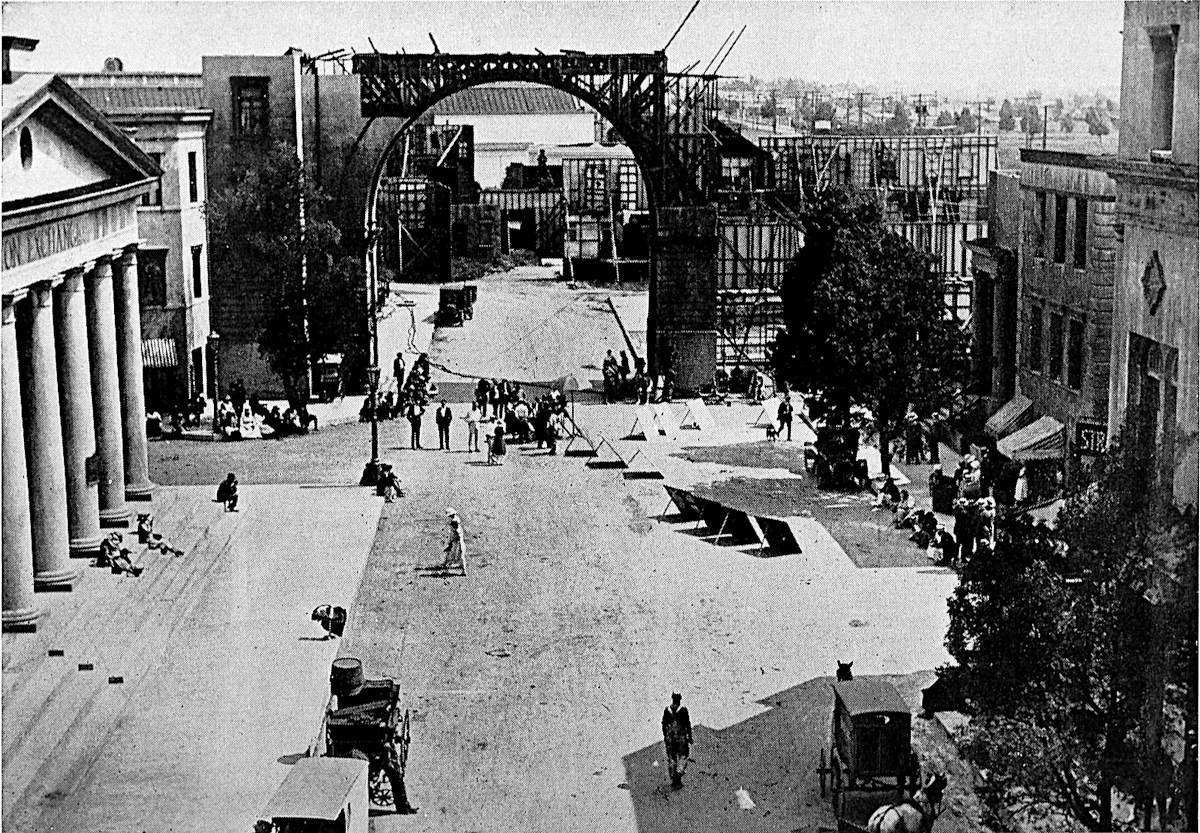

Then, sets are constructed to represent the interiors of buildings in Tunis or Algiers, or some of the little cities of the desert. Possibly a whole street is constructed—and it is only necessary to build the fronts of the houses, of course, propped up from behind by braces and scaffolding that do not show in45 the picture—to reproduce an alley of some town near the North African Coast.

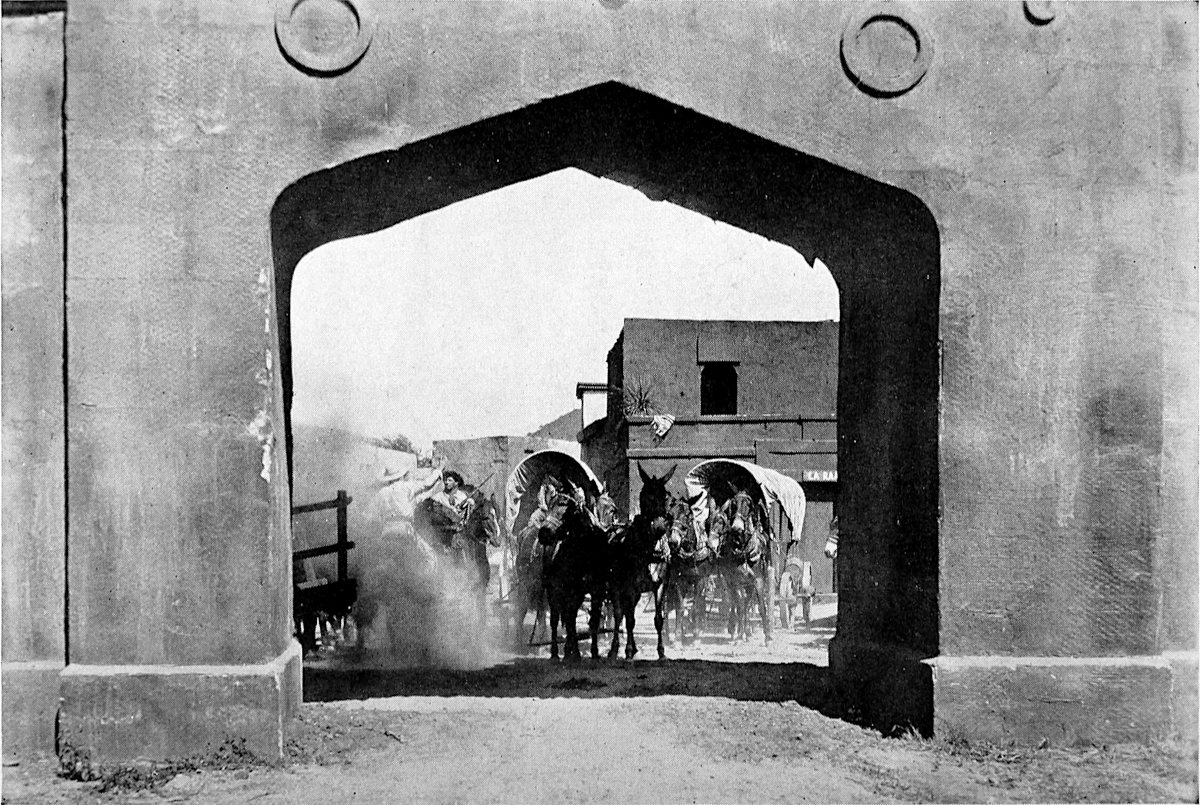

Finally, as the scenes of the story or “continuity” are filmed, one after another, the company goes out “on location” to get the balance of the exterior scenes. Perhaps the sand dunes of Manhattan Beach, one of the small resorts near Los Angeles, not far from Culver City, are used to represent the hummocks of the Sahara Desert. Perhaps a part of the desolate bed of the San Gabriel River, where it leaves the mountains twenty miles east of Los Angeles, is used to show a supposed Sahara gulley. Or the company may travel to the Mohave Desert, or all the way into Arizona, or some desolate portion of Old Mexico near the border town of Tia Juana below San Diego, to get just a bit of the real “Sahara” that they want. Maybe a desert tent is set up beneath the palm-trees of a supposed oasis, that, by careful photographing, looks like the real thing and gives no hint of the Los Angeles suburban traffic officer at a busy crossing less than fifty yards away.

The result? Possibly a very good picture of46 the Sahara Desert, with Americans playing the parts of Mohammedan tribesmen and pieces of America representing Africa. But naturally there are many chances for mistakes. The costumes may be wrong. The actors may not look the parts, or act as the types they are supposed to represent really do. The dunes behind Manhattan Beach, or the “Wash,” of the San Gabriel, may not really look like the Sahara at all.

Recently a widely traveled oil man was telling me of an afternoon he spent at a trading town on the East African coast, a thousand miles or so north of the Cape.

“I was killing the day with an old trader,” he said. “We were to set out into the interior the next morning, and had nothing to do but amuse ourselves until we were ready to start. We saw the posters of a movie that was being shown, that told a story of the very town where we were. And say! When we went in, we certainly were amused, all right!

“It was an American film, made by one of the Hollywood companies. The heroine was washed ashore from the wreck, and regained consciousness just in time to see a tiger ready47 to spring at her from under the palm-trees at the edge of the beach. But the hero was Johnny-on-the-spot. He was tiger-hunting himself, and dropped the beast with a single shot. He was wearing riding-breeches, and puttees, and a pith helmet,—sort of a cross between a motion-picture director and a polo player.”

“What was the matter with it?” I asked, “Everything?”

“Pretty much. First place, the beach along those parts isn’t anything like what was shown in the picture. There aren’t any palm-trees within a thousand miles. Tigers don’t grow in that part of the world, either. Lions, yes. But tigers, no. You have to go clear to India to get tigers.

“But that hero’s outfit was the best. In the heat, there, he’d have died in six hours, in that outfit. My friend the old trader and I were wearing about all that anybody ever wears in those parts—ragged old shirts, and “shorts”—like running pants, or B. V. D.’s—and keeping out of the sun. If you do have to go around, in the heat of the day, the one important thing is48 to wear some kind of a hat or cloth that protects the back of your neck and saves you from sunstroke. But the movie hero was sprinting around in the middle of the day with leather legs and a cartridge belt that would weigh at least ten pounds. Say, we had a great laugh!”

Not long ago I was asked to look at a film, made in Austria, that told a story of love and intrigue among the American millionaires. The hero’s father was supposed to be a railroad king who lived in New York City, and the girl’s mother, who also lived in New York, was a “railroad queen” at the head of a rival organization. Each morning the lovers, the hero and the heroine, slipped away from their homes—that looked more like the New York Public Library or the Pennsylvania Station than anything else except an Austrian palace—and ran down to the railroad yards. The boy stole a regular German engine from his father’s round-house, and the girl got its twin sister from her mother’s shop on the other side of the city, and they each climbed aboard and ran them outside the city until they met, on the same track, head on. Then the lovers got down 49and kissed each other on both cheeks in true American fashion (Austrian interpretation) somewhere near Hoboken, I suppose.

On the other hand, in contrast to these hurriedly made, inaccurate pictures, made to make money for ignorant people by entertaining still more ignorant people, are the really worth while historical films and others made with painstaking care. Some of the great American directors maintain entire departments for research work, that check up on the accuracy of each detail before it goes into production, costumes are verified, past or present, details of architecture are reproduced from actual photographs, and even incidents of history and the appearance of historic individuals are treated with scrupulous accuracy.

Valuable impressions of life in ancient Babylon could be gathered from Griffith’s great picture “Intolerance.” While not necessarily accurate in every detail, the wonderful Douglas Fairbanks films “Robin Hood” and “The Three Musketeers” instruct as well as entertain. In a magnificent series of historic spectacle films such as “Peter The Great,”50 “Passion,” and “Deception,” the Germans have set a high-water mark of film production that combines dramatic entertainment with semi-historical setting.

It seems a pity after watching one of the really well-made historical photoplays, to have to see a picture of the American Revolution so carelessly made, in spite of its cost of nearly $200,000, that you feel sorry for the poor British redcoats at the battle of Concord, when the American minute men, outnumbering them about ten to one, fire on them at close range from behind every stone wall and tree or hummock big enough to conceal a rabbit. Why, according to that particular director’s conception of the British retreat from Lexington, the patriots might just as well have stepped out from behind their protecting tree-trunks and put the entire English army out of its misery by clubbing it to death in three minutes.

Leaving dramatic photoplays, then, let us turn to the other kind of movie that shows what actually happens.

The news reels are the simplest form of this kind of movie. They correspond to the headlines51 in the daily newspapers, or newspaper illustrations. Indeed, a good many newspaper illustrations, nowadays, are merely enlargements made from single exposures, or “clippings,” from the news reels. You may yourself have noticed pictures in the rotogravure sections of Sunday newspapers that show the same scenes you have already seen in motion in the news reels during the week.

To get the news reel material camera men are stationed, like newspaper correspondents, at various places all over the globe. Or, when some important event is to occur at some far-away place, they are sent out from the headquarters of the company, just as special correspondents or reporters would be sent out by a big city newspaper, or newspaper syndicate. Sometimes a camera man and reporter work together; usually, however, each works separately, for newspapers and movies are still a long way apart. If a new president is elected in China, a news-reel camera man—Fox, or Pathé, or International, or some other, or maybe a whole group of them—will be on hand to photograph the ceremonies. If a new eruption52 is reported at Mount Etna, some donkey is liable to get sore feet packing a heavy motion-picture camera and tripod up the mountain while the ground is still hot, so that a news-reel camera man—possibly risking his life to do it—may get views of the crater, still belching fire and smoke and hot ashes and lava, for you to see on the screen.

The news camera men, like city news reporters, have to work pretty hard, not infrequently face many dangers, and get no very great pay. The tremendous salaries and movie profits that you sometimes hear about usually go to the studio companies, and not to these traveling employees.

Recently I talked with a “free lance” camera man, who had just completed a full circuit of the earth—England, Continental Europe, Turkey, and Asia Minor, through the Suez Canal and down into India, then Australia, New Zealand, Samoan Islands, and back to New York by way of San Francisco. He had paid his way largely with contributions to news reels, sold at a dollar or a dollar and a53 half a foot. The last part of the way home he had worked his passage on a steamer. He had borrowed enough money from a friend in San Francisco to get him back to New York. He had about ten thousand feet—ten reels—of “travel” pictures, for which he hoped to find a purchaser and make his fortune. But he owed the laboratory that had developed his film for him a bill of some three hundred dollars that he couldn’t pay, and was offering to sell the results of his whole year’s work for fifteen hundred dollars. And at that he couldn’t find a purchaser.

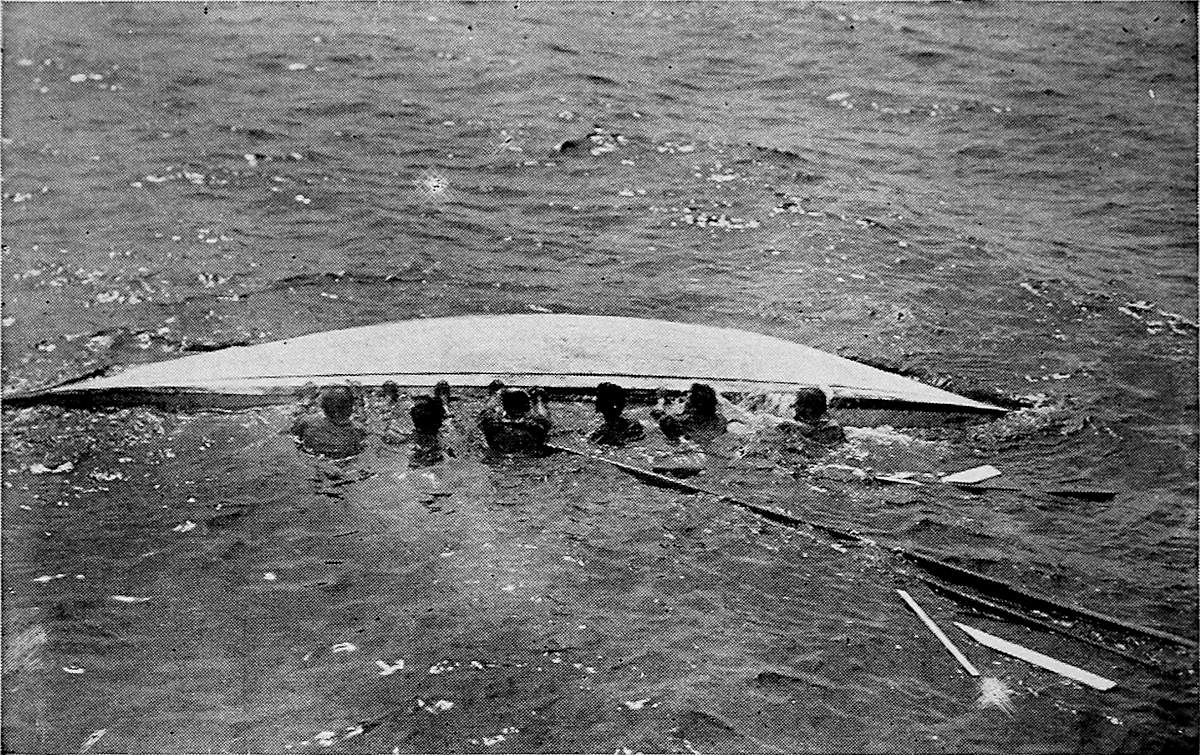

News reels and travel pictures, and beautiful “scenics” too, are only the forerunners of much more ambitious efforts to come, that before many more years have passed will be bringing the whole world before us through the camera’s eye. Did you happen to see the marvelous record of sinking ships made by a German camera man on one of the U-boats during the ruthless submarine campaign of the Great War? Or the equally remarkable series taken of the marine victims of the German54 cruiser Emden? They show what the camera can do, when the movie subject is a sufficiently striking one.

More than two years ago a camera man named Flaherty secured the backing of a fur-exporting firm to make a trip with his camera to the Far North. After laborious months of Arctic travel he returned to the Canadian city whence he had started with some thousands of feet of splendid negative. While it was being examined—so the story goes—a dropped cigarette ash set it on fire. Celluloid burns almost like gunpowder. The entire negative was destroyed in a few moments.

But Flaherty started out again, and returned once more with thousands of feet of film depicting the Eskimos’ struggle for life against the mighty forces of Nature in the frozen North. From this negative a “Feature Film” was edited, called “Nanook of the North.” It showed how the Eskimos build their snow huts or igloos, how an Eskimo waits to spear a seal, and how he has to fight to get him even after the successful thrust.

At first the big distributing companies that55 handle most of the films that are rented by theater owners in this country didn’t want to handle the picture because it was so different from the ordinary movie that they didn’t think audiences would like it. But finally, after it had been “tried out” successfully at one or two suburban theaters, the Pathé Company decided to release it. Likely you’ve heard of it. It has been a big success. It is now being shown all over the world. It will probably bring in more than $300,000. Flaherty, as camera man, director, and story-teller rolled into one, has been engaged by one of the big photoplay producing companies at a princely salary to “do it again.” This time, he has gone down into the South Seas, to bring back a story of real life among the South Sea Islanders.

Quite a number of years back a man named Martin Johnson went across Africa and secured some very remarkable pictures of wild animals. These jungle reels were released by Universal, and proved such capital entertainment that they brought in a fortune. Others followed Johnson’s example, but for years no56 one was able to equal his success. As Flaherty has done more recently, Johnson next went to the South Seas and made another “Feature Film” of life upon the myriad islands that dot the Southern Pacific Ocean. The film was fairly successful, but did not begin to make the hit that had been scored by the animal reels.

“Hunting Big Game in Africa,” the next big “reality” film to make a hit with American audiences—aside from short reel pictures and an occasional story-scenic—“broke” on the New York market in 1923. It was made by an expedition under H. A. Snow, from Oakland, California, and represented some two years of work and travel, with a big expenditure of money.

Snow’s experience in getting his picture before the public was not unlike that of Flaherty. The motion-picture distributors and exhibitors were so used to thinking in terms of the other kind of pictures, the regular movies or photoplays that you can see nearly every night in the week, that they were afraid people wouldn’t be interested in “just animal stuff.” In spite of the success made by “Nanook of the North,”57 and the Martin Johnson pictures before that, they were afraid to try out pictures that were different from the usual run.

“Hunting Big Game in Africa” was more than ten reels long—two hours of solid “animal stuff.” The Snow company finally decided to hire a theater themselves and see what would happen when the picture was presented to a New York audience.

You can imagine what the audience did. They “ate it up.” The picture started off with views of the ship that was carrying the expedition to South Africa. Then there were shots of porpoises and whales. And thousands and thousands and thousands—they seemed like millions—of “jackass penguins” on desolate islands near the South African coast. Funny, stuffy little birds with black wings and white waistcoats, that sat straight up on end like dumb-bells in dinner jackets—armies and armies of them, a thousand times more interesting (for a change at least) than seeing the lovely heroine rescued from the villain in the nick of time, in the same old way that she was rescued last week and the week before. And58 for that matter, two or ten years ago—or ever since movie heroes were invented to rescue movie heroines from movie villains when the movies first began.

From the penguins on, “Hunting Big Game in Africa” was certainly “sold” to each audience that saw it. There were scenes that showed a Ford car on the African desert, chasing real honest-to-goodness wild giraffes, and knocking down a tired wart hog after he had been run ragged. Only at the very end of the picture was there any particularly false note, when a small herd of wild elephants, that appeared very obviously to be running away from the camera, were labeled “charging” and “dangerous.” Possibly they really were dangerous, but the effort to make them seem still more terrible than they actually were fell flat. When you’re telling the truth with the camera, you have to be mighty careful how you slip in lies, or call out, “Let’s pretend!”

Then there came another Martin Johnson picture of animals in Africa, possibly even better than the Snow film, and quite as successful. As usual, Martin Johnson took his wife59 along, and the spectacle of seeing a young woman calmly grinding away with the camera, or holding her own with a rifle only a few yards away from charging elephants or rhinoceri was thrill enough for any picture. At many of the scenes audiences applauded enthusiastically—a sure sign of unqualified approval.

An interesting discovery that has come with the success of these “photographic” pictures, that show what actually happens as pure entertainment, so interesting that you don’t think of its being instructive, is that ordinary dramatic movies can be made vastly more interesting and worth while if a good “reality” element is introduced.

The Germans were on the trail of this when they had wit enough to plan their historical pictures based on fact and actual historical personages, that would appeal to people of almost any civilized nation on the globe. So good was their example, that we have followed suit, here in America, with “Orphans of the Storm,” and the big Douglas Fairbanks pictures, and a whole lot more.

But now, we have gone a step farther, a step60 that adds to the danger and difficulty in picture making, but that shows more and more the wonderful possibilities of the screen.

Take “Down to the Sea in Ships.”

A writer named Pell who lived up near New Bedford, Massachusetts, where the old whaling industry used to center, in the days before steam whalers carried the business—or what there is left of it—to the Pacific coast—had an idea. He wrote a story about a hero who turned sailor-man and went to sea on a whaler, and harpooned a real whale.

They make some wonderful motion pictures in Hollywood, but they don’t harpoon many whales there. When you’re a motion-picture actor, harpooning a real whale is a good trick—if you can do it.

Pell took his story to Mr. D. W. Griffith, famous ever since “The Birth of a Nation.” But Mr. Griffith didn’t have time to play with it, so he turned it over to a director named Elmer Clifton, who decided that a picture of a real whale would make a “real whale” of a picture. He got a company together and went to work.

61

They decided the first thing to do would be to get the whale. If that part worked all right, they’d go ahead and make the rest of the picture, if it didn’t—well, they could start over again and make some other picture, of a cat or a dog or a trick horse that wouldn’t be so hard to play with.

They held a convention of old sea-captains, who decided that Sand Bay or some such place, in the West Indies, would be a likely spot for whales. They fitted up an old vessel, the last of the real old whalers, and sailed away.

Luck was with them. They struck a whole school of whales almost as soon as they had dropped anchor at the point that had been selected.

Green hands at whaling, they started off with every whale-boat they had, and cameras cranking. They tried to harpoon the first whale they came to, I’m told,—and missed it. But luck was with them again, decidedly. Missing the big whale, which happened to be a female, the harpoon passed on and struck a calf on the far side of her, that the amateur whalemen hadn’t even seen.

62

Ordinarily, they say, a school of whales will “sound” or dive and scatter for themselves when one of their number is harpooned, but in this case it was a calf that was struck, and its mother stuck by it, and the rest of the school stuck by her, while the movie-whalers herded them about almost like cattle. They got some wonderful pictures.

Later, they captured a big bull whale, and had an exciting time of it. More pictures, and a smashed rowboat.

Then they returned to New Bedford and completed the photoplay.

As a “Feature Film” the final picture, “Down to the Sea in Ships” is nothing to boast about, except for the whales. Without the whaling incidents, it is a more or less ordinary melodrama, beautifully photographed, of the whaling days in old New Bedford. But the real whales make the picture worth going a long way to see.

A Scandinavian film, released in this country by the Fox organization under the name of “The Blizzard,” does the same thing as “Down to the Sea in Ships.” Only, it has a reel that63 shows reindeer incidents, instead of whales. But it is just as remarkable. You see a whole gigantic herd of reindeer—hundreds and hundreds of them, the real thing—follow their leader across frozen hillsides and rivers and lakes, through sunshine and storm. Finally, in a blizzard, the men holding the leader that guides the herd get into trouble. One of them falls through the ice, while the other is dragged by the leader of the herd over hill and dale, snowbank and precipice until at last the rope breaks. The herd bolts and is lost.

It’s a wonderful picture. Because of the reindeer incidents. But it couldn’t have been made in Hollywood. It combines fiction with fascinating touches of actual fact.

About the time the reindeer picture was released in this country, a five-reel film that was made in Switzerland was shown at the big Capitol Theater in New York. It was made up of scenes of skiing, ski-jumps, and ski-races, in the Alps. Nothing else. But it furnished many thrills and real entertainment.

Here we come back again to the crux of the whole matter, entertainment. A picture has to64 entertain us, whether we want to be instructed, or only amused. But between the two kinds of pictures that I have outlined in this chapter—the movies that merely tell a story and the pictures that show facts—there is this difference: Photoplays that are designed to be merely entertaining, to be good, have to seem real.

But photoplays that actually are real have to be genuinely entertaining.

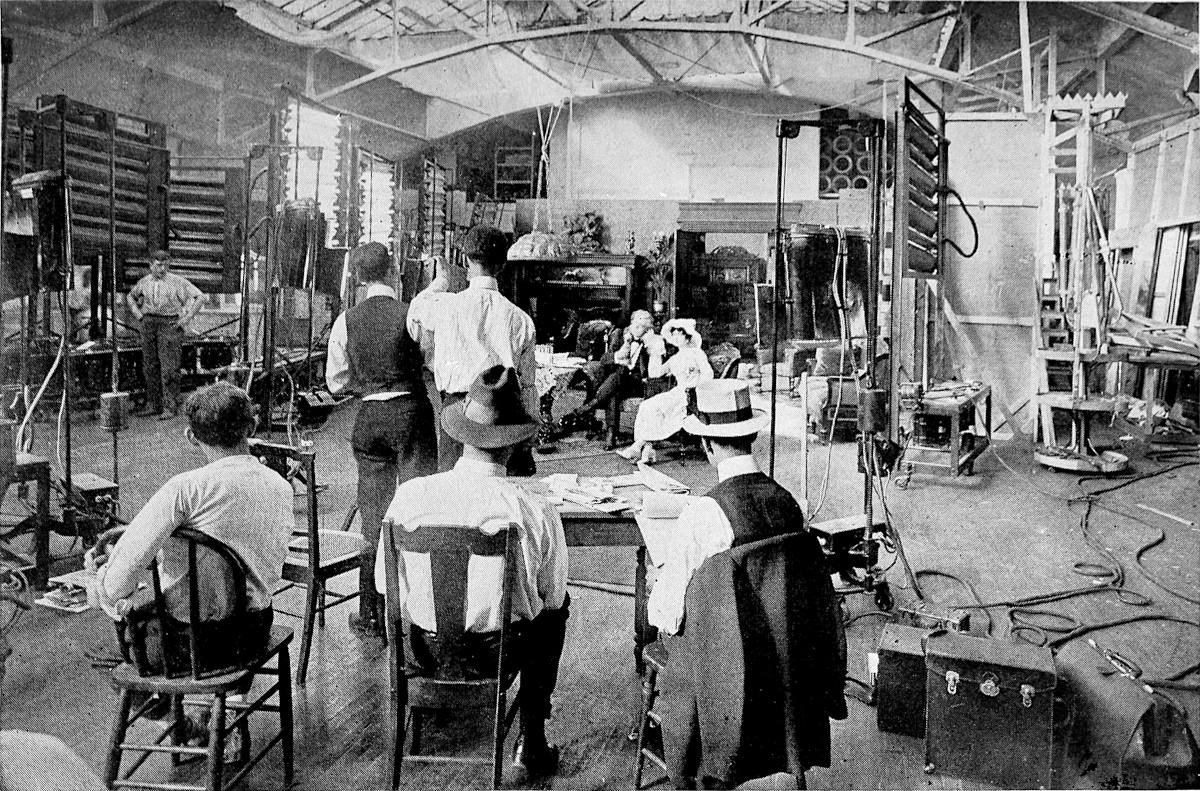

If you have never been inside a motion-picture studio, an interesting experience lies ahead of you. For what soon becomes an old story to any one working “on the lot,” is fascinating enough to any one who sees it for the first time.

At Universal City, California, just across a range of hills outside Hollywood, lies a motion-picture plant that covers acres and acres. Administration and executive offices, big “light” and “daylight” stages, property rooms, costume department, garage, restaurant, power plant, carpenter shop, laboratory, great menagerie even, are all grouped along the base of rolling California hills that furnish countless easy “locations” for stories of the Kansas prairies or Western ranchos, or even the hills of old New England.

In the heart of New York City, close beside66 the roaring trains of the Second Avenue “L” and within hooting distance of the tug-boats on the Harlem River, stands the old Harlem Casino—for years a well-known East-side dance-hall. In this building, now converted into a compact motion picture studio, the first big Cosmopolitan productions came into existence—“Humoresque,” “The Inside of the Cup,” and all the rest.

Both the great “lot” at Universal City, under the blazing California sun, and the old Harlem Casino, with dirty February snow piled outside under the tracks of the elevated,—each absolutely different from the other—are typical motion-picture studios.

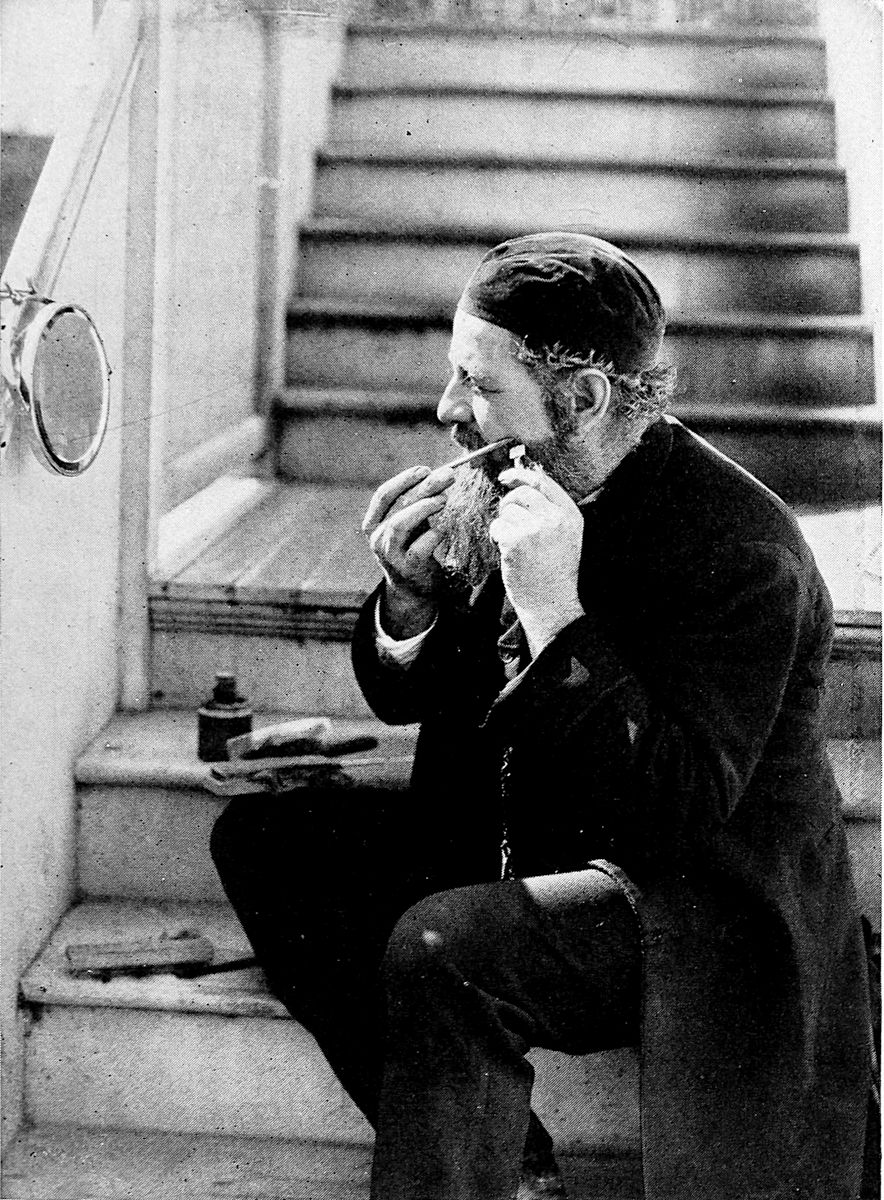

In each you can find the same blazing white or greenish-blue lights, with their tangled cables like snakes underfoot, the same kind of complicated “sets” on various stages, the same nonchalant camera men chewing gum and cranking unconcernedly away while the director implores the leading lady with tears in his voice—and perhaps even a megaphone at his mouth—to: “Now see him! On the floor at your feet! Stare at him! Now down—kneel67 down! Now touch him! Touch him again, as if you were afraid of him! Now quicker—feel of him! Feel of him! He’s DEAD!”

Suppose we step inside the door of a typical motion-picture studio. We find ourselves in a little ante-room, separated by a railing from larger offices beyond. The place seems like a sort of cross between an employment office and the outer office of some big business enterprise. At one point there is a little barred cashier’s window like that at a bank. There is usually an attendant at a desk or window marked “Information,” with one or two office boys, like “bell-hops” in a hotel, to run errands.

Coming and going, or waiting on benches along the walls, are a varied assortment of people: a young woman with a good deal of rouge on her cheeks and a wonderful coiffure of blonde hair, an old man with a wrinkled face and long whiskers, a couple of energetic-looking young advertising men, and a chap with big hoot-owl spectacles and a flowing tie who wants to get a position as scenario writer. In the most comfortable chair a fat man, with eyeglasses astride a thick curved nose, is waiting68 to see the general manager, and fretting at being detained so long.

A very pretty girl comes into the office with a big collie dog on a leash, as a motor purrs away from the door outside. One of the boys like bell-hops jumps to open the inner door for her, and she sails on through without even a glance around. She is one of the minor stars, with a salary of about six hundred dollars a week. The collie is an actor, too: he is on the pay-roll at $75 a week—and worth every dollar of it to the pictures.

At one side is the office of the “casting director,” who passes on the various “types,” hires the “extras,” and decides whether or not this or that actor or actress is a real “trouper” who can fill the bill. Into this office the army of “extra people” who make a precarious living picking up a day’s work here and there around the studios as “atmosphere” gradually find their way; here the innumerable applicants for screen honors come to be looked over, and given a try, or turned away with a shake of the head, and perhaps a single comment 69such as “eyes won’t photograph well—too blue”; here the many experienced actors, temporarily out of work, come to be greeted by: “Hello, Harry! You’re just the bird I wanted to see! Got a great little part for you in an English story; older brother—sort of half-heavy”; or: “Sorry, Mame—not a thing to-day. Try us next week. We’ll probably begin casting for ‘Wheels of Fate’ about Friday.”

But let us pass on beyond the outer offices, and see where the girl with the collie went.

Through a hallway we come suddenly into a vast, dark, cavernous interior, high and wide and shadowy. From somewhere off at our left comes a sound of hammering, where a new “set” is being erected. Off at the right is more hammering and pounding with the squeaking of nails being drawn as another set, in which the “shooting” has been finished, is being “struck,” or taken down. From a far corner of the great cavern there is a radiance of bluish-green light, where one of the companies is “working.”

Curiously enough, this huge dark place is called the “light” stage. It gets its name from70 the fact that scenes can be photographed on it only with artificial light.

All about is a labyrinth of still standing sets—here a corner of a business office, and just beyond the interior of a drawing room in a rich home, with a beautiful curved stairway mounting ten feet or so into nothing at the right. Next comes the corner of a large restaurant. Under the guidance of an assistant director, in the glare of a single bluish-green Cooper-Hewitt “bank” turned on as a work light, property men are “dressing” it. They are putting yellow table-cloths on the tables (in the finished picture they will look white; in reality they are yellow instead of white in order not to be too glaring, before the picture can be exposed long enough to bring out the contours and details that are more important in the darker places); and hanging a row of horse-race pictures along the wall.

This is a big studio, supposed to be making a dozen or more pictures at once. We are surprised that on this whole great dark “light” stage only one company is working; we learn that two others are “shooting” elsewhere on71 the lot; one in back of the carpenter shop, where a clever director has found an ideal “location” for his purpose right under his nose, and another on one of the big “daylight” stages that we shall see presently. Several other companies are out on location miles from the studio—one perhaps in another State on a trip that will last a couple of weeks. Still others are not at the “shooting” stage of their picture at all; one or two are still “casting,” one that follows the methods used by Griffith is “in rehearsal,” and still others are merely waiting while scenario writer and director work out the final details of the scenario or “continuity,” or while the director “sits in” with the cutter or “screen editor” and title writer to put the finishing touches on the completed product.

We go over to the corner where the one company on the big stage is “shooting.” A dozen people are sitting around on chairs or stools, just outside the lights. About in the middle of them, with a whole phalanx of lights at right and left, two cameras are set up. Beside them, in a comfortable folding camp-chair with a72 back rest, sits the director. He is wearing what a humorous writer has called the “director’s national costume” of soft shirt, knickerbockers, and puttees. On the floor beside his chair is a megaphone.

If you hold your hands together with the palms flat, making a narrow angle about a third of a right angle, you can get an idea of what a camera “sees.” This angle is called the “camera angle.” Only what happens within that narrow angle will be recorded on the film. Sometimes white chalk-lines are drawn on the floor to mark the camera angle; what is within the lines will be photographed, while what is outside will not show.

Along the sides of this open space that the camera will photograph are ranged the bright white carbon lights and the bluish-green vacuum lights that illumine the scene. Overhead, suspended by heavy chains from tracks that traverse the ceiling of the great stage, are more lights; white carbon “dome” lights, and additional bluish-green Cooper-Hewitt “overhead banks.”

73

Thin bluish smoke, like vapor, curls outward and upward from most of the white carbon lights. They give off a good deal of heat. A couple of spot-lights like those used in theaters are situated on scaffolding higher than a man’s head, behind the cameras to left and to right, with an attendant in charge of each.

In the bright glare the faces of all who are not “made up” with grease paint and powder look greenish yellow. All color values are distorted. Tan-colored shoes look green.

A scene has just been taken. The assistant director turns to an electrician. “Kill ’em!” he says. The electrician goes to the different lights, pulling switches to “cut ’em off.” In a moment only one of the bluish-green “double banks” is left to serve as a working light. This is to save electricity, of which the array of lights takes an enormous amount.

The scene that has been taken is, we will say, of an old-fashioned New England sitting room. In the center is a marble-topped table. In a far corner is a “what-not,” with marble shelves. There is a bookcase against one of74 the walls, and old prints and lithographs are hung here and there. In one place is a needlework “sampler,” with a design and motto.

The director is talking with the two actresses who were in the scene. They are in costumes of the Civil War period, with flounces and hoopskirts. They are supposed to be sisters.

Suddenly the director decides to take the scene over again. He has thought of a bit of more effective action that will get the point he is trying to make in the story over more effectively. “We’ll shoot it again,” he says. “Let’s run through it once more first.”

The two actresses, already thoroughly familiar with the scene, rehearse it again, adding the new bit of detail as the director instructs them. He is not quite satisfied, and takes one of the parts himself, showing the actress how he wants her to put her hand up to her face. Finally she does it to suit him, and he is satisfied. “All right,” he says, “we’ll shoot it.—Lights!”

The lights are switched on once more, and in the bright, sputtering glare the sisters walk into the scene. Just before they cross the line75 into the camera angle both camera men start grinding.

After about fifteen seconds of action the director nods, well pleased. “Cut!” he says shortly, and both camera men stop.

Half an hour’s preparation and rehearsal for fifteen seconds of action!

Again the lights are switched off. The man in charge of the script, sitting on a stool with a sheet of paper snapped on a board on his lap, puts down the number of the scene and adds details of costume—what each sister is wearing, the flowers that one is carrying in her hand, and so on—to have a complete record in case of “retake,” or other scenes that match with this before or after.

“Now we’ll move up on ’em,” says the director. The cameras are moved closer, and the action of the preceding scenes is repeated. This time the cameras are so close that the faces of the actresses will appear large on the screen, with every detail of expression showing. Before the close-ups are begun, the lights are moved up, too, and one of the spot lights switched around more to one side to give an76 attractive “back lighting” effect on the hair of the sisters, that appears almost like a halo, later, when it is seen on the screen.

Before each scene is taken an assistant holds a slate with the director’s name, the head camera man’s name, and the number of the scene, written on it, in front of the cameras, and the camera men grind a few turns. In this way, the “take” is made.

When the different “takes” are finally matched together in the finished picture these numbers will be cut off, but they are necessary to facilitate the work of identifying the hundreds or even thousands of different shots of which the final picture is composed.

Leaving the great dark “light stage” we pass on into the lot beyond. In front of us is another great stage, but this time open to the sky. Instead of artificial lights, there are great white cloth “reflectors,” to deflect the sunlight on to the scene and intensify the light where under the sun’s direct rays alone there would be shadows.

Sets, actors, camera men and action are all as they were on the other stage, except that77 instead of a profusion of sets we find here only one or two, as not nearly so many scenes are taken here as on the other stage.

Formerly nearly all scenes were taken in sunlight, and studios were built that had no provision for lighting except the sun. But while the film industry was still in its infancy the development of artificial lighting made possible results that could not be secured with sunlight alone, and since that time artificial lighting is used on most motion-picture scenes that represent “interiors.”

About us on the “lot” are other stages, covered with glass, that lets in the sunlight but keeps out the rain, so that work may go on uninterruptedly. On most of these a combination of natural and artificial light is used—electric lights as in the “light stage,” supplemented by daylight.

We pass on to the property houses—great buildings like warehouses ranged one behind the other. In one place we find a room where modeling is going on; skilled artists are making statues that will be used in a picture depicting the life of a sculptor. In another place78 special furniture is being made. One great warehouse-like building is devoted to “flats” and “drops,” of which the differing sets can in part, at least, be built. Then there are the costume rooms, and the “junk” rooms, with knick-knacks of all descriptions.

You’d be amazed to know how many properties are needed in the making of even the simplest motion pictures. Take, for instance, the set that we have already described—an old New England sitting-room. The furniture, the marble-topped table and the what-not with its marble shelves and the chairs and possibly a hair-cloth sofa, were of course obvious. The old prints and lithographs and even the sampler, hardly less so; but in addition to these, think of the ornaments that would have to appear on the what-not shelves and the kind of lamp that would be on the table and what books there would have to be in the bookcase. Without these details, the room would not look natural.

Take a look around the room where you are reading this page. Notice how many little things there are that you would never think of 79arranging, if you were to have carpenters and property men reconstruct it for you as a set for a picture. Newspapers—all the hundred and one little things, left here and there, that go to make a home what it is—even to the scratches on the walls, or the corner knocked off one arm of a chair.

The property man of a famous director once told me: “I’ve got the greatest collection of junk in the whole business. Just odds and ends. No one thing in the whole outfit worth anything in itself, but the King (he was referring to the director) would be crazy if he sold it for ten thousand dollars—yes, or twenty-five thousand, either. I tell you, sometimes junk is the most important thing in a picture.”

After a set has been built, it is usually “dressed” by hiring first the furniture from one of the concerns that have grown up for just this purpose—renting furniture, old or new, to motion-picture companies that want to use it for a few weeks. If, in addition to what has been rented, the producing company is able to supply bits of “junk” from its own80 property room and make the set look more natural, so much the better.

The story is told of one enterprising concern in Los Angeles that started in collecting beer-bottles just after prohibition went into effect. Since the bottles were no longer returnable, they were able to buy them here and there for almost nothing, until they had on hand a tremendous supply. The word went around that such and such a concern was in the market for bottles, and every boy in Los Angeles gathered up what he could find and took them around while the market was still good. People thought they were crazy, and had a good laugh at the movie industry that didn’t know any more than to buy up hundreds and hundreds of old beer-bottles that nobody would ever be able to use again.

Then one of the producing companies wanted a batch of bottles for some bar-room scene and found that they didn’t happen to have any on the lot. They went to the big property concern that they usually traded with, only to find that they, too, didn’t happen to have any beer-bottles. So they went to the concern that81 had been buying them all up at junk prices.

Certainly they could have some bottles—all they wanted! They would be thirty cents a week each, and a dollar apiece for any that were broken or not returned. Take it or leave it!

The corner on old beer-bottles had suddenly become profitable. The producing company tried to get bottles elsewhere and beat the monopoly—but time was pressing. When the overhead of a single company is running at hundreds of dollars a day, a property man will not be forgiven if he holds up the whole production while he scours the city to save money on beer-bottles. The price was paid.

But let us get on with our tour of the studio. We have not yet come to one of the most important places of all—the laboratory where the film is developed.

The laboratory work of many producing companies is not done on the lot at all, but is sent away to one of the big commercial laboratories that does work for many different companies. But several of the larger producers have their own laboratory plants.

82

In the laboratory we visit first the developing-room, feeling our way cautiously into the dark around many corners that cut off every possible ray of light from outside. Walking on wet slats we reach at last the chamber in the middle of what seems to be an almost impenetrable labyrinth, and in the dim red light can barely make out the vats where the strips of celluloid, wound back and forth on wooden hand-racks, are being dipped into the developer.

Nowadays many of the laboratories are equipped with complicated developing machines, that combine all the processes of developing, washing, “fixing,” and drying in one. Where prints, made from the original negative, are being developed, tinting is added. The undeveloped film, tightly wound in small rolls, is threaded through one end of the developing machine in the dark-room; it travels over little cog-wheels that mesh into the holes at the edges of the film, and goes down into a long upright tube filled with developer. Coming back out of this, still on the cogs, it travels next down into a tube of clear water83 for washing. Then down into another tube containing “hypo,” and up again for another tube and second washing. Then, still winding along on the little cogs it travels through a partition and out into a light room, where it passes through an airshaft for drying, across an open space for inspection, and is finally wound into as tight a roll as it started from in its undeveloped state.

In the printing-room, still in the dim red light, we see half a dozen printing-machines at work, with raw film and negative feeding together past the aperture where the single flash of white light makes the exposure that leaves the negative image upon the print.

Next, in daylight once more, we see the great revolving racks of the drying-room used for film developed by the hand process—with hundreds of feet of the celluloid ribbon wrapped around and around great wooden drums.

In the assembling-room we find girls at work winding up strips of film and cementing or patching the ends of the film together to make a continuous reel.

Another room is more interesting still. This84 room is dark once more, with a row of high-speed projection machines along one side and a blank wall on the other. Here the finished film, colored and patched, receives its final inspection. Against the white wall four or five pictures are flickering simultaneously. Since the projection machines are only a few feet away from the white surface that acts as a screen, each picture measures only two or three feet long and two-thirds as much in height. In one picture we may see a jungle scene; alongside it a reel of titles is being flashed through, one after another; next to this again is the “rush stuff” for a news reel with the president shaking hands so fast it looks as if he had St. Vitus dance; next comes a beautifully colored scenic, and at the end of the row the dramatic climax of a “society film,” rushing along at nearly double its normal theater speed.

Leaving the laboratory, we pass down a street, bordered on one side by a row of little boxlike offices that are used by the directors of the different companies; opposite, in a similar row of offices, the scenario writers are housed.85 The end of the street brings us back once more to the building that houses the administrative offices through which we came when we entered.

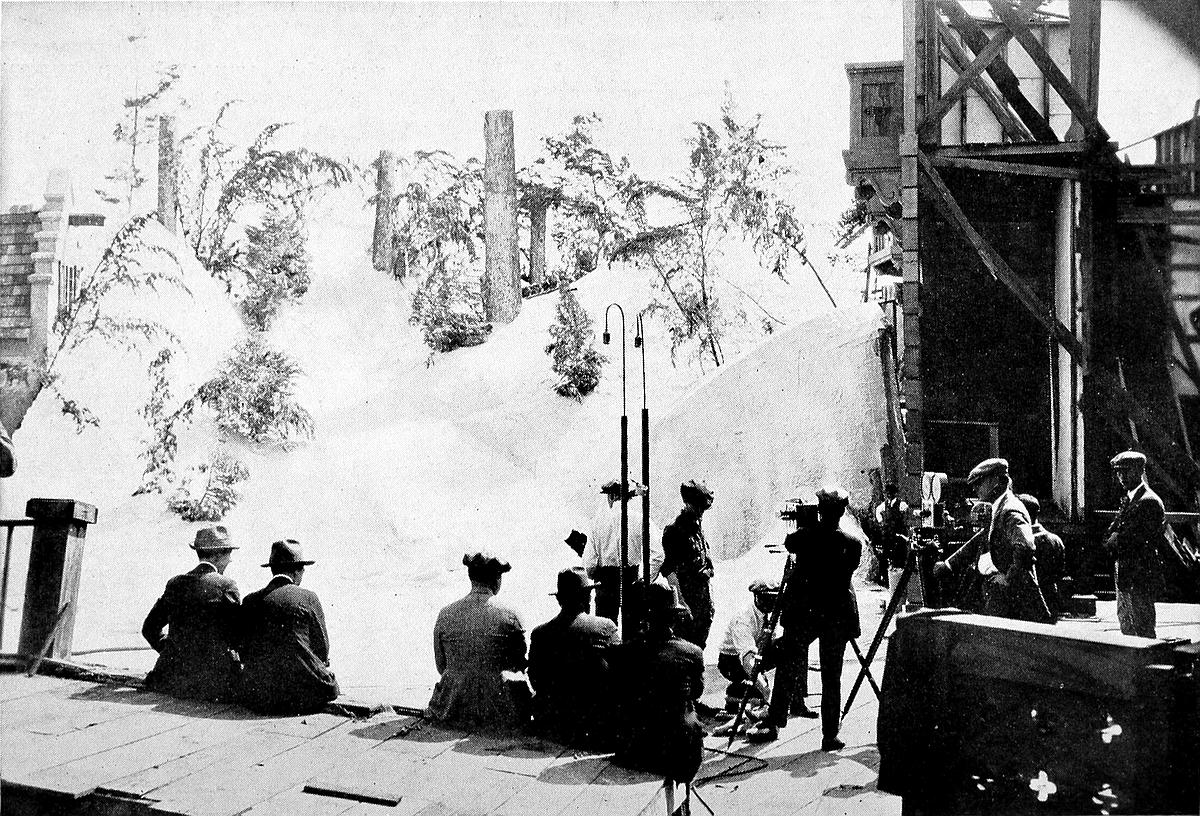

If we had time we could visit the menagerie that lies at the rear of the studio proper, and that makes even the line-up of a circus tent look tame. Or, we could spend a day watching the company shooting the storm scene at the back edge of the lot, where the customary old airplane propeller has been mounted on a solid block with a motor attached and backed up alongside the scenes to furnish a gale of wind.

But we have already seen enough for an introduction.

To make a six-reel picture takes from three or four weeks to twice as many months and costs all the way from ten or fifteen thousand dollars to half a million, and sometimes even a million. You can imagine the investment required where a producing organization is running ten or a dozen companies at once, each turning out pictures at top speed.

Only the other day one of the Hollywood86 studios changed hands at the sale price of three-quarters of a million dollars. Some are worth twice that amount.

But it is not the size of the investment that counts. It is the quality of the finished product. That is the thing we want to look farther into.

Once I was turned loose in New York City with thirty-odd thousand dollars and a novel by a popular author, and told to make a movie out of them.

Suppose that should happen to you. How would you begin?

Of course you would want to make a better picture than so many of these other fellows seem able to turn out. But how would you start? Just by hiring some actors and a camera man and telling them to get busy?

It is not so easy as that.

The first thing for me, to be sure, was getting together the men who would help make the photoplay. Re-writing the story into a scene-by-scene continuity, hiring a studio and attending to all the business details, selecting a cast, picking out the “locations” for scenes, designing88 the “sets” and supervising the construction of them, and “directing” the scenes, is more than any one person can do. The Swiss Family Robinson itself couldn’t do it alone.

So I selected and hired a director, and a camera man, and a continuity writer, and an art director to design the sets. That took quite a while.

Then the trouble began.

The director decided he wanted an assistant director; the camera man decided he wanted an assistant camera man; the art director decided that I didn’t know what I was doing, and the “owners” decided that everything done so far was all wrong.

That brought out two very interesting things about motion pictures that apply to lots of other businesses as well. And sports, too, if you like, and almost everything else.

The first is the matter of coöperation.

When the rowers in a boat pull only when they feel like it, the boat goes wabbling all over the place, instead of straight ahead, and everybody gets his knuckles barked. Everybody89 has to pull together. Imagine a football team without any teamwork!

Movies are so complicated, in the making, that dozens of people, hundreds often, have to pull together when they are being made.

That very thing is one of the big reasons why moving pictures to-day aren’t any better than they are. Mostly movie people haven’t yet learned to pull well together, or how exceedingly important it is in the making of pictures.

If you can’t work with other fellows without bucking and kicking,—don’t ever try motion-picture work.

The other trouble was with the owners. There were too many bosses on the job, which always makes a mess.

That quaint, humorous philosopher, “Josh Billings,” once said, “It ain’t ignorance that makes so much trouble; it’s so many people knowing too many things that ain’t so.”

With movies, that’s an ever-present danger.

Mostly, we’re all of us so sure of things, that we saw or heard or thought or remember, that we just know we’re right, about this or90 that, and can’t be wrong. If we know a little bit about surveying, we feel we can tell surveyors how to survey, and so on. And the less we know about a thing (as long as we do know something about it) and the more indefinite that thing and the knowledge about it are, the more we think we know about it.