The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Pillars of Hercules; vol. 1, by David Urquhart

Title: The Pillars of Hercules; vol. 1

A Narrative of Travels in Spain and Morocco in 1848

Author: David Urquhart

Release Date: April 22, 2022 [eBook #67903]

Language: English

Produced by: Sonya Schermann and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

MEMOIRS OF PRINCE RUPERT AND THE CAVALIERS. By Eliot Warburton. Numerous Fine Portraits. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s.

THE CONQUEST OF CANADA. By the Author of “Hochelaga.” 2 vols., 8vo., 28s.

CORRESPONDENCE OF SCHILLER WITH KÖRNER. From the German. By Leonard Simpson. 3 vols., 31s. 6d.

THE FAIRFAX CORRESPONDENCE: Memoirs of Charles the First. Part II.—The Great Civil War. By Robert Bell. 4 vols., 8vo., 60s.

⁂ Either Part may be had separately.

A HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY. By Sir Harris Nicolas, G.C.M.G. 2 vols., 8vo., 28s.

A HISTORY OF THE JESUITS, from the Foundation of their Society. By Andrew Steinmetz. 3 vols., 8vo., 45s.

LOUIS XIV., and the Court of France in the Seventeenth Century. By Miss Julia Pardoe. Third Edition. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s.

THE HISTORY OF THE REIGN OF FERDINAND AND ISABELLA, THE CATHOLICS OF SPAIN. By W. H. Prescott. Second Edition. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s.

HISTORY OF THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO, with the Life of the Conqueror, Hernandez Cortes. By W. H. Prescott. Fourth Edition. 2 vols., 8vo., 32s.

THE CONQUEST OF PERU. By W. H. Prescott. 2 vols., 8vo., 32s.

BIOGRAPHICAL AND LITERARY ESSAYS. By W. H. Prescott. 8vo., 14s.

MEMOIRS OF THE REIGNS OF EDWARD VI. AND MARY. By Patrick Fraser Tytler. 2 vols., 8vo., 24s.

NAVAL HISTORY OF GREAT BRITAIN, with a Continuation of the History to the Present Time. By W. James. Numerous Portraits, &c. 6 vols., 8vo., 54s.

MEMOIRS OF THE REIGN OF GEORGE III. By Horatio Lord Orford. Edited, with Notes, by Sir Denis Le Marchant, Bart. 4 vols., 8vo., 56s.

BENTLEY’S COLLECTIVE EDITION OF THE LETTERS OF HORACE WALPOLE. 6 vols., 63s.

LETTERS TO SIR HORACE MANN. By Horace Walpole. (Second Series). 4 vols., 8vo., 56s.

CHARACTERISTIC SKETCHES OF ENGLISH SOCIETY, POLITICS, AND LITERATURE, comprised in a Series of Letters to the Countess of Ossory. By Horace Walpole. Edited by the Right Hon. R. Vernon Smith, M.P. 2 vols., 8vo., 30s.

MEMOIRS OF THE COURT OF ENGLAND DURING THE REIGN OF THE STUARTS. By J. Heneage Jesse. 4 vols., 8vo., 56s.

MEMOIRS OF THE COURT OF ENGLAND UNDER THE HOUSES OF NASSAU AND HANOVER. By J. Heneage Jesse. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s.

MEMOIRS OF THE CHEVALIER AND PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD, or the Pretenders and their Adherents. By J. Heneage Jesse. 2 vols. 8vo., 28s.

RICHARD BENTLEY, New Burlington Street.

GEORGE SELWYN AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES; with Memoirs and Notes. By J. Heneage Jesse. 4 vols., 8vo, 56s.

MEMOIRS OF EXTRAORDINARY POPULAR DELUSIONS. By Charles Mackay, LL.D. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s.

MEMOIRS OF KING HENRY V. By J. Endell Tyler, B.D. 2 vols., 8vo., 21s.

A HISTORY OF HIS OWN TIME; Comprising Memoirs of the Courts of Elizabeth and James I. By Dr. Goodman, Bishop of Gloucester. Edited by J. S. Brewer, M.A. 2 vols., 8vo., 18s.

MARSH’S ROMANTIC HISTORY OF THE HUGUENOTS; or, the Protestant Reformation in France. 2 vols., 8vo., 30s.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF ENGLISH HISTORY, IN A NEW SERIES OF ORIGINAL LETTERS; now first published from the original MSS. in the British Museum, State Paper Office, &c. By Sir Henry Ellis. 4 vols., post 8vo., 24s.

MEMOIRS OF THE TWO REBELLIONS IN SCOTLAND IN 1715 AND 1745; or, the Adherents of the Stuarts. By Mrs. Thomson. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s.

AN ACCOUNT OF THE KINGDOM OF CAUBUL AND ITS DEPENDENCIES IN PERSIA, TARTARY, AND INDIA. By the Right Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone. 2 vols., 8vo., 28s.

A CENTURY OF CARICATURES; or, England under the House of Hanover. By Thomas Wright. 2 vols., 8vo., 30s.

SOCIAL LIFE IN ENGLAND AND FRANCE. By Miss Berry. 2 vols., small 8vo., 21s.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF MAGIC, PRODIGIES, AND APPARENT MIRACLES. From the French. Edited and illustrated with Notes by A. T. Thomson, M.D. 2 vols., 8vo., 28s.

AN ANTIQUARIAN RAMBLE IN THE STREETS OF LONDON, with anecdotes of their most celebrated Residents. By John Thomas Smith. Second Edition. 2 vols., 8vo., 28s.

DIARIES AND CORRESPONDENCE OF JAMES HARRIS, FIRST EARL OF MALMESBURY. Edited by his grandson, the third Earl. 4 vols., 8vo., 60s.

MEMOIRS OF THE EMPEROR NAPOLEON; to which are now first added a history of the Hundred Days, of the Battle of Waterloo, and of Napoleon’s Exile and Death at St. Helena. By M. Bourrienne. Numerous Portraits. 4 vols., 8vo., 30s.

MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE AND TIMES OF SIR CHRISTOPHER HATTON, K.G, By Sir Harris Nicolas, G.C.M.G. 8vo., 15s.

HOWITT’S HOMES AND HAUNTS OF THE BRITISH POETS. Numerous Fine Engravings. 2 vols., 8vo., 21s.

THE PROSE WRITERS OF AMERICA, with a Survey of the History, Condition, and Prospects of American Literature. By R. W. Griswold. 1 vol., 8vo., 18s.

THE LIFE AND REMAINS OF THEODORE HOOK. By the Rev. R. D. Barham. Second Edition. 2 vols., post 8vo., 21s.

ROLLO AND HIS RACE; or, Footsteps of the Normans. By Acton Warburton. Second Edition. 2 vols., 21s.

RICHARD BENTLEY, New Burlington Street.

OR

A NARRATIVE OF TRAVELS

IN

SPAIN AND MOROCCO

IN 1848.

BY

DAVID URQUHART, ESQ., MP.,

AUTHOR OF

“TURKEY AND ITS RESOURCES,” “THE SPIRIT OF THE EAST,” ETC.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY,

Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty.

1850.

LONDON:

Printed by S. & J. Bentley and Henry Fley,

Bangor House, Shoe Lane.

[Pg iii]

I did not visit Morocco or Spain on any settled plan. I was on my way to Italy by sea, and passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, was so fascinated by the beauty and mysteries of the adjoining lands, that I relinquished my proposed excursion for the explorations which are here recorded.

Barbary, to the attraction of the unknown and the original, which it shares in common with China and Japan, adds that of association with the country which, of all others, has a claim on our affections—Canaan. With Barbary also is interwoven the history of various races, great, ancient, and mysterious: the Canaanite, the Hebrew, the Highland Celt, and the Saracen. It has become the last refuge of the Philistine. The Jews, in other countries, by adopting the habits of strangers, have lost their type, which is to be seen alone in Barbary, where Judæa, effaced in Asia, doubly survives. Here must we seek the living interpretation of the Scriptures; here may we find insight into early things.

The connexion of the Scotch clans with Barbary depends on no ethnographic affinity, but their passage through, and sojourn in, this land, reveal the history of their wanderings, and explain the peculiarities of their race. Here are to be found to-day the people[Pg iv] who made Spain a garden, taught it at once the arts of war and peace; and thence spread that knowledge to the rest of Europe. That stream which then overflowed, has retired to its fountain, where it lies deep, but not changed.

Spain and Morocco present treasures unknown, in those regions which have been subject to repeoplings and fundamental changes. “The life of nations,” says Erchhoff, “manifests itself in their language, which is the faithful representative of their vicissitudes. Where chronology stops, and the thread of tradition is broken, the antique genealogy of words that have survived the ruin of empires comes in to shed light on the very cradle of humanity, and to consecrate the memory of generations long since engulfed in the quicksands of time.” The unchanged tongue here gives additional force to that genealogy—here history is nearly mute. The same monumental character, however, belongs to manners, costume, and tradition. I have not, therefore, hesitated to devote considerable space to these inquiries, as, indeed, they constituted the chief attraction of the excursions, which seemed to be less through new countries than remote ages.

I have to bespeak the reader’s indulgence for inviting him often to accompany me with his attention through homely paths. I have brought him in presence of the most trivial practices. I have not described, as a stranger would, a different manner of life; but endeavoured, as a native, to explain matters[Pg v] from which we might derive benefits in health, comfort, happiness, or taste, from their old experience. Wherever I have drawn comparisons, it has been for our advantage, not for theirs. It has, therefore, been their merits, not ours, that I have placed in evidence.

I have no expectation that my suggestions will modify the lappet of a coat, or the leavening of a loaf; but there is one subject in which I am not without hope of having placed a profitable habit more within the chance of adoption than it has hitherto been—I mean the bath.

Cleanliness, like inebriety or intemperance, may be at once a fashion and a passion. Appearing amongst us under both shapes, it has also assumed that of charity. As soon as it was felt that it was shameful to be dirty, it became a work of charity to wash the filthy, no less than to feed the hungry. These dispositions offer an opportunity of reviving the bath in all its classic grace, and investing it with all its Eastern attractions; but the occasion may be lost—that is, we may rest satisfied with what we have done, and the new wash-houses may pass current as achievements of economy and models of cleanliness. The occasion can be put to profit only by the knowledge of the bath in its bearings on the individual and on society; and I have made the attempt to describe it, so that it shall be understood in its uses, enjoyments, and construction.

We have recently been imitating barbarous times in church architecture. These times offer to our[Pg vi] admiration usages as well as forms. Shall we have eyes for a Gothic spire, and none for a Roman bath? Nations may have refinement, and yet be destitute of common sense; they may be possessed of sense, and yet be without refinement. A people without the bath can lay claim to neither.

Morocco calls attention to the past; Spain directs it to the future. We pass from dreams to delusions, from poetry to politics. Belgium has been termed the battle-field of Europe—Spain is its bone of contention. The Italian Peninsula is the field of the rivalries of France and Austria, which England balances and adjusts. In the East, England and France are united by the advance of Russia; in the Spanish Peninsula they are alone in presence of each other: the aim of each is to gain ascendancy, and thence a constant source of irritation.

The political experiment which is at present being made in Spain, consists in applying European terms to a country where there are no European ideas, and European institutions to a state of things wholly unlike Europe. The following fragment of a conversation with a leading statesman conveys that contrast in the fewest words.

Spaniard.—I am sorry that you see Spain in such a distracted condition.

Author.—I am rejoiced to find her in one so flourishing.

Sp.—I wish it were so. Surely you are not in earnest?

[Pg vii]

A.—I wish my country were in the same condition as yours.

Sp.—But your country is rich, powerful, united. We are poor, weak, and distracted.

A.—I am thinking of the contrast between your people and ours.

Sp.—In what does that contrast consist?

A.—In a larger share of comforts, and fewer political evils.

Sp.—As to the former, I think you are right. I do not think that the people of France have so much of the enjoyments of life as ours; but as for our being freer from political evils than England, I cannot agree with you.

A.—If you will permit me to take them separately, I think we shall find no difficulty in agreeing.

Sp.—Certainly.

A.—The chief source of our animosities springs from differences in religion.

Sp.—We are not troubled with these in Spain.

A.—The next is difference of race.

Sp.—We are free from this too.

A.—Have you two great organized interests, commercial and agricultural?

Sp.—From these too we are free.

A.—Have you two powerful opinions, monarchical and republican, as those which divide France?

Sp.—We have not.

A.—Have you been brought to within an hour of revolution and bankruptcy by an “ideal standard?”

[Pg viii]

Sp.—Spain has no financial difficulties of an abstract kind.

A.—Do you suffer from the despotic power of a sovereign?

Sp.—No.

A.—Have you to fear the turbulence of a mob?

Sp.—No; the people of Spain are docile, when left alone.

A.—Are there oppressive privileges belonging to the aristocracy?

Sp.—No.

A.—Is the power of the Church excessive, and misapplied, or its wealth inordinate?

Sp.—No, we have none of these evils in Spain.

A.—Have you pauperism?

Sp.—No;—nevertheless we are distracted.

A.—It is, therefore, my turn now to ask, why?

Sp.—I should like to hear your reasons.

A.—They are contained in the fact, that it is I who ask these questions, and you who reply.

Sp.—Our distractions would not subside, if I thought as well of Spain as you do.

A.—My meaning is, that the imitation of Europe is the source of the troubles of Spain.

Since this conversation occurred, Spain has justified these conclusions, by remaining unmoved amidst the storm of opinion which has swept over Europe.

London, October, 1849.

[Pg ix]

| BOOK I. | |

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE STRAITS OF GIBRALTAR | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE CURRENTS OF THE STRAITS | 21 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| GIBRALTAR OF THE MOORS | 32 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| EXCURSION ROUND THE STRAITS | 51 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| ALGECIRAS—TARIFA | 60 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| CEUTA | 85 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| CEUTA—BOMBARDMENT OF TANGIER | 114 |

| [Pg x] CHAPTER VIII. | |

| CADIZ | 126 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| EXCURSION ROUND THE STRAITS | 145 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| EXCURSION IN THE STRAITS—CADIZ POLITENESS | 172 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| CARTEIA—TYRE AND HER WARES—GLASS | 188 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE STONE OF HERCULES | 204 |

| BOOK II. | |

| THE COUNTRY OF THE ROVERS. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| OFF SALEE | 254 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| RABAT | 277 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE JEWS AND JEWRY IN RABAT | 299 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE BAÏRAM | 317 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE SULTAN: HIS COMMERCIAL SYSTEM | 332 |

| [Pg xi] CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN RABAT | 339 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| CONNEXION BETWEEN MAURITANIA AND AMERICA | 353 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE MOORS | 364 |

| BOOK III. | |

| THE ARAB TENT. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| HUNTING EXPEDITION TO SHAVOYA | 377 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| KUSCOUSSOO | 398 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE HAÏK | 416 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| A BOAR-HUNT | 440 |

[Pg 1]

“Nullus amor populi nec fœdera sunto:

Exoriare aliquis nostris ex ossibus ultor,

Qui face Dardanios ferroque sequare colonos;

Nunc, olim, quocunque dabunt se tempore vires.

Littora littoribus contraria, fluctibus undas

Imprecor, arma armis, pugnent ipsique nepotes.”

To thread one’s way through a narrow gap from the outer Ocean into a basin spread between Asia, Africa, and Europe, is an occasion which even books of geography cannot render wholly uninteresting and common-place.

This sea has, at each extremity, a narrow entrance; through both the water rushes in: each forms the point of junction of two quarters of the globe,—Europe[Pg 2] there meeting Asia—here, Africa. The first is acknowledged to be the most important position of the globe. The land and sea there reciprocally command each other. A capital, an emporium, and a fortress, combined in one, are placed at the meeting of two continents and two seas, “like a diamond,” to use the words of a Turkish annalist, “between two emeralds and two sapphires, the master-stone in the ring of empire.”

Had the western entrance received the slightest pressure at its formation, had one of the hills since slipped down into its channel, the Gut of Gibraltar would not be the Ring on the finger, but the rod of Empire in the hand of whoever possessed it. Happily, however, no guns can cross, and no batteries command, the passage through which flows the commerce of the world, and, at times, the food of nations.

Both banks of the Bosphorus are under the same dominion, and inhabited by the same people. The channel bisects an Empire and traverses a Capital. Two people, so dissimilar, occupy here the opposite shores, that they might belong to different planets. No fishing-boat ventures across, and if so driven, they take care if they can to anchor beyond musket-shot. As to neighbourhood, the whole Atlantic might as well roll between them. As to intercourse, they might as well belong to distinct orders of creation. They hold each other like to those unsightly and malignant monsters to which ancient mythology[Pg 3] consigned the western portions of the world. If intercourse is rendered necessary, there is a preliminary parley and a flag of truce, and even the ceremonial of a friendly meeting records the accomplishment of Dido’s prophecy and curse.

Yet this is no forbidding land. There are neither sands nor precipices. There are neither rudeness and asperity, nor barrenness and waste. There are lowly vales and verdant plains, as well as gigantic mountains. This great, this beautiful country—this corner of a mighty continent—almost touches Europe. One-half of our whole trade passes along it; yet it is sealed against us more effectually than China or Japan.

European enterprize, by lust of conquest, love of gain, or spirit of proselytism, has made the wide world its vineyard; and, combining its various engines, has, far and near, shattered thrones, and subjugated or extinguished races. How is it that Morocco stands unmoved and unassailed?

All the nations which formed part of the Roman Empire, and have become Mussulmans, have fallen under the sway of Constantinople, Morocco alone excepted. All the barbarous States, which have attracted the cupidity of Europeans, have fallen under their sway, Morocco alone excepted. But the breakers of her shores, the sands of her deserts, the valour of her sons, the wildness of her tribes, have not alone done this. Threatened now by a new enemy and a new danger, the past is worth sifting, in order to anticipate whether or not she will hold her own;[Pg 4] or if she fall, whether she will rot away, or sink brightly and bravely, preserving

Genio y figura

Hasta la sepultura.

It is an old story, and we have forgotten it, that on Morocco our first and greatest essays of conquest were made. England expended upon the fortification of Tangier more than all she ever advanced for the conquest of India. Portugal and Spain, who had found it necessary to separate, by half the globe, their other enterprizes, here combined, and expended more lives, ships, and treasure in their fruitless attempts than in the subjugation of the East Indies and the West. Neighbourhood, political hatred, religious animosity, combined with the prospects of dominion, and the hope of obtaining supplies of the precious metals, to urge them to make and continue these attempts. Elsewhere, by their wonderful successes, unknown adventurers—a Cortez, a Pizzaro, and an Albukerque—were converted into heroes. Here Princes of the State and Church, Kings and Emperors, were the leaders—to experience only failure and disgrace. Elsewhere handfuls of men conquered myriads. Here mighty armaments have been annihilated by despised foes. Elsewhere a native power had to do with but one European assailant. Morocco numbered amongst her assailants every European power. She holds the bones of English peers, of Turkish beys, of Portuguese princes, Andalusian kings. She has foiled[Pg 5] an Emperor of Austria, and discomfited in succession the warlike operations, or the political plans of Cardinal Ximenes, of Philip II., Don Sebastian, and Barbarossa. Spain has some fortified points upon the coast, but they are blockaded; and this smothered warfare is a living record of our aggressions, and her delivery.

That event is one of the most remarkable of revolutions.[1] The Spaniards were in possession of all the north country. The Portuguese had extended themselves along the whole of the seaboard of the west, down as far as Suz. The native troops in their pay at one time exceeded 100,000. The four kingdoms of which Morocco is now constituted, were then distinct, and the various courts rivalled each other in pusillanimity and corruption, exhibiting every[Pg 6] symptom of dissolution, from the disorders within and the power that threatened from abroad. It was then that a family of mendicants and fanatics issued like lions from the desert, upset the ruling dynasties, re-kindled the flame of patriotism, rallied the sinking people, drove forth the invaders, constructed a common Empire out of these divided States, and placed their Dynasty upon the throne, which it occupies to this day.

From that time only have Europe and Africa become strangers to each other; and so Morocco has maintained the independence so strangely won.

What renders this non-intercourse surprising is neighbourhood; yet that is its explanation. Here Europeans could not be taken for Children of the Sun, nor supposed to be quiet traders seeking only commerce: the watchfulness of this people was not, as in India, overreached, nor their affections, as in America, surprised.

The men who, in times of difficulty, have made themselves immortal names, have done nothing more than endeavour to arouse their countrymen from false security, or to guard them against mistaken confidence. The Moor is deficient in polite literature and is ignorant of Greek; but he already was in himself what the wisest words of Demosthenes might have taught him to be, and was prepared to do what the loftiest strains of Tyrtæus might have inspired. From the beginning the African has been preyed upon by the other quarters of the globe. His wrongs have been stored up in his[Pg 7] retentive breast.[2] Thence that hate which is his life; by it he has anticipated the lessons of wisdom, and by it he is a match for science and power.[3]

Morocco has consequently been in this distinguished from the other countries that surround the Mediterranean—she has not till now furnished to France and England fuel or field for rivalry and contention. Now she is brought again within the vortex of European politics, and identified in interest with Spain by having the same neighbour, and that neighbour the rival of England. We may again see rehearsed on the same arena, the drama of Rome and Carthage.

As I floated down this river, of which the Atlantic is[Pg 8] the fountain, and the Mediterranean the sea, remembering the Dardanelles, I felt with Cicero, that he indeed was happy who could visit, on the one hand, the Straits of Pontus, and on the other, those

“Europam Lybiamque rapax ubi dividit unda.”

And that Atlas, sustaining the heavens on his shoulders,[4] no less than Prometheus fixed upon the Caucasus, might convey in fables early and divine truths.

This is a spot which has influenced the destinies and formed the character, not of one but of many people: it is the home of the fleeing Canaanite, the bourne of the wandering Arab; it was the limit of the ancient world. That world of mystery and of poetry, was not like ours. It was not crammed into a Gazetteer, nor were its laws a school-boy lesson learned by rote. These Straits,[5] then the peculiar domain of mythology, were approached with natural wonder and religious awe. The doubtful inquirer came hither to see if the sky met and rested upon the earth—if Atlas did indeed bear a starry burden—to discover what the[Pg 9] world was—whether an interminable plain, or a ball launched in space or floating on the water—whether the ocean was a portion of it or supported it—whether beyond the “Pillars”[6] was the origin of present things, or the receptacle of departed ones—whether the road lay to Chaos or to Hades.

And something, too, of these feelings crept over me, even although I came hither merely to ruminate on the past deeds of men, the shadows of which I looked for on the face of that watery mirror, which was the centre of their solid globe—the resolver, the adjuster of all their contests. The Mediterranean has made the world such as it is. Ancient history has been balanced on its bosom; and without the passage connecting it with the ocean, none of the events of recent history could have happened.

To the dwellers on the skirt of Palestine she was a handmaid for a thousand years, affording a liquid way for the wares which they scattered over half the globe: From her bosom rose on all sides those sea-kings of the south, the Pelasgi. She bore the Etruscans to their Ausonian homes. She furnished to the African daughter of Tyre the elements of the power by which she was enabled to compete for the dominion of the world.[Pg 10] Transferred by the struggle of a few hours, and by the sinking of a few craft—she carried with her that dominion to Rome, and fixed it there for centuries.

When the course of that Empire was run, and barbarism had spread over the land, she fitted up new and beautiful things upon her shores; nurtured Amalphi and Venice and Pisa, and built up Genoa and Barcelona. Then opened a new order. Seamanship, by magnetic touch endowed with wings, dared to lose sight of earth: issuing from these portals, it gave to the princes of the Peninsula the knowledge of a new world, and the title of lords of the eastern and western hemispheres.

Maritime power, now no longer pent up within the land, was successively competed for and attained by Holland and by England: it conferred upon the one independence at home—upon the other, dominion in the remotest regions of the earth. Here are connected the first enterprizes of man and his last struggles. Hence was the path sought to Britain. Here now floats Britain’s standard. The ruins of the Temple of Hercules saw Trafalgar’s fight. Here the hero of the Phœnix, prince, navigator, trader, conqueror of monsters, fertilizer of lands, found again the tides of his early home in the Indian ocean,[7] and[Pg 11] set up his Pillars. His mighty shade has its resting place on the spot which is honoured with his name.

The next stage of discovery brings us to Columbus and Gama: this was the goal of the enterprise of the Phœnician—it was the starting-post of the Ligurian. In the unexplored waste a second Thule succeeded, and a new Peru supplied the exhausted one of old. “The stone of Hercules” and the “cup of Apollo”[8] showed the way to the regions towards which the one had travelled and where the other set. But the modern adventurers had the problem solved for them, not in the reasonings only, but in the poetry of the ancients.[9] They had divided the earth, by degrees—fixed their number and measure—they knew the length of the day—they knew how many hours the sun spent over the regions they were acquainted with. Fifteen twenty-fourths of his time they could account for. Nine hours remained unexplored to complete the circle.[10]

[Pg 12]

But whilst Don Henry was daily gazing over the unmeasured expanse to the west, the use of the globes and the rationale of geography were being taught in Italy in verse. The sun must be expected, Pulci sings, there whither he hastens; where he sets, it cannot be night: space is not useless because to us unknown, nor that ocean without shores beyond which washes ours. Then there are continents bordering the deep, and islands studding its bosom; nor are these barren of herbs, nor are herbs and fruits given in vain: there, too, there must be men, who have gods like us, the work of their hands, and sorrows the fruit of their will. Read his vaticination.

“Passato il fiume Bagrade ch’io dico,

Presso a lo stretto son di Gibilterra,

Dove pose i suoi segni il Greco antico

Abila e Calpe, a dimostrar ch’egli erra

Non per iscogli o per vento nimico,

Ma perchè il globo cala de la terra

Chi va più oltre, e non trova poi fondo,

[Pg 13]Tanto che cade giu nel basso mondo.

“Rinaldo allor riconosciuto il loco,

Perche altra volta I’aveva veduto,

Dicea con Astarotte: dimmi un poco.

A quel che questo segno ha proveduto?

Disse Astarotte: un error lungo e fioco

Per molti secol non ben conosciuto,

Fa che si dice d’Ercol le colonne,

E che più là molti periti sonne.

“Sappi che questa opinione è vana;

Perchè più oltre navicar si puote

Però che l’acqua in ogni parte è piana,

Benchè la terra abbi forma di ruote:

Era più grossa allor la gente umana:

Tal che potrebbe arrossirne le gote

Ercole ancor d’aver posti que segni,

Perchè più oltre passerano i legni.

“E puossi andar qui ne l’altro emisperio,

Però che al centro ogni cosa reprime;

Si che la terra per divin misterio

Sospesa sta fra le stelle sublime,

E là giù son città, castella e imperio,

Ma nol cognobbon quelle genti prime:

Vedi che il sol di camminar s’affretta,

Dove io ti dico che là giù s’aspetta.

“E come un segno surge in oriente,

Un altro cade con mirabil’ arte,

Come si vede qua ne l’occidente,

Però che il ciel giustamente comparte;

Antipodi appellata è quella gente;

Adora il sole e Juppiterra e Marte

E piante e animal come voi hanno,

E spesso insieme gran battaglie fanno.”[11]

This remarkable passage has been esteemed a prognostication[Pg 14] of the discovery of America; it should rather be called directions to find it out.[12]

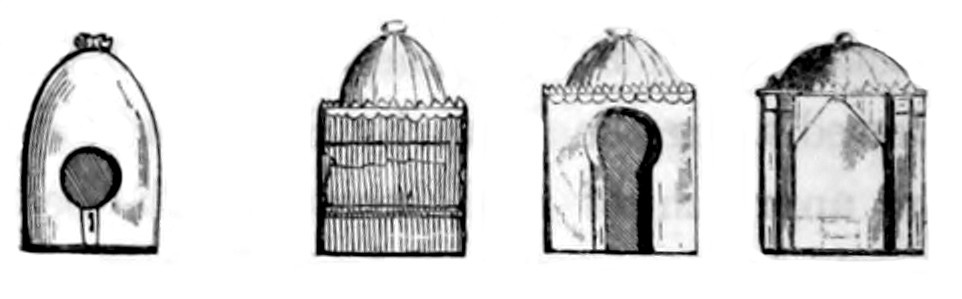

But what were the Pillars of Hercules, and where are we to look for them? Are they really the rocks which frown or smile across the Straits, such as it has pleased the imagination of poets to picture them? If so, then might the fable be deemed an extravagance. As Jacob set up his stone at Bethel, and called it the house of God;[13] as Joshua set up in Jordan pillars for the tribes of Israel, so did Hercules set up his altars, when he had reached the ocean. Over them in subsequent times the temple which bore his name was raised, but there was no image;[14] none of the child-sacrifices of Baal; none of the lasciviousness[15] of Bætica, and of the worship of Astaraoth. They worshipped, indeed, deities unknown, or consecrated thoughts, and services contemned elsewhere. Three altars were there to Art, Old Age, and Poverty. From a Greek tourist, who, thaumaturgist as he was, comprehended very little of what he saw, I quote the following:—

“In this temple, two Herculeses are worshipped[Pg 15] without having statues erected to them. The Egyptian Hercules has two brazen altars without inscriptions, the Theban but one. Here we saw engraved in stone the Hydra, and Diomedes’ mares, and the twelve labours of Hercules, together with the golden olive of Pygmalion, wrought with exquisite skill, and placed here no less on account of the beauty of its branches, than on that of its fruit, of emeralds, which appeared as if real. Besides the above, the golden belt of the Telamonian Teucer was shown to us.... The Pillars in the temple were composed of gold and silver; and so nicely blended were the metals as to form but one colour. They were more than a cubit high, of a quadrangular form, like anvils, whose capitals were inscribed with characters neither Egyptian, nor Indian, nor such as could be deciphered. These Pillars are the chains which bind together the earth and sea. The inscriptions on them were executed by Hercules in the house of the Parcæ, to prevent discord arising among the elements, and that friendship being interrupted which they have for each other.”[16]

There was no Hercules, but the Tyrian worshipped here. The temple was Tyrian, the rites were Tyrian, and the Tyrians did not borrow from the Greeks. What I say is but the repetition of what Appian, Arrian[17] and others have said. In fact, there was but[Pg 16] one Hercules. The writing could only be Phœnician. By the testimony of Greek travellers, the pillars were square stones; and the tradition of their being the links which bind together the earth and the sea, again connects these with the occasion upon which they were erected: they were both in Europe.[18]

To call Calpe and Abyla “The Pillars of Hercules” was a license, and might be a poetic one; but to assume these mountains to be so geographically, was to withdraw the license by destroying the poetry. This solecism modern philosophy has adopted![19]

Out of this error arose the dull plagiarism of the Bœotian Charles, who gave to the presumptuous arms, in which those of the Peninsula were quartered with those of the Empire, two Pillars as supporters, which are to stand for the traditional altars and the figurative hills. The motto was “plus ultra,” taken from “ne plus ultra,” both equally meaningless after the discovery of America. The dropping of the particle[Pg 17] ne announced the unlimited ambition of his nature, and the narrow limits of his mind and scholarship.[20]

The Two Columns are still often heard of throughout the Mediterranean, and sometimes seen in the shape of the dollar of Charles V., which is superior in value to those of his successors, and is known by the name of Colonato. Strange vicissitude! The Phœnician Melcarth’s votive offering become a money-changer’s tale! The story is now ended, and the circle complete. Bright-eyed poetry—strong-handed enterprise, have descended to ambition and solecism, vulgarity and gain, and having begun with virtue idolized, we end with gold become the idol.

I have been speculating on the influence exercised by this passage on human events: the physical condition of the globe offers a parallel field.

Let us suppose, that the gap had been just wide enough to supply the water lost by evaporation, for which the thousandth part of the present passage would suffice:—the Mediterranean would have been a salt-pan.

The yearly deposit would have been an inch, the yearly produce 80 millions of cart loads, or 50,000 times the quantity of earth displaced in constructing the London and Birmingham Railway. Supposing then this evaporation to have gone on since the deluge, the result would be, a field of 750,000 square miles of[Pg 18] salt, fifty fathoms thick—that is, the Mediterranean would be a tank of brine, and perhaps we should have a fresh-water ocean outside in lieu of a salt one.[21] This has been prevented by the straits being wide and deep enough to allow an admixture of the waters.

In all other geological facts, there are presented subordinate effects only. You may reason from the completeness of the whole, and the adaptation of the parts to a supreme creating Will. But this adjustment of the forms of nature to the use of man, appears less a geological incident than a specimen of animal organization.

Going a step further, let us suppose the ocean shut out altogether.[22] What sights should we then have seen? Since the Deluge the evaporation, at the present rate, would have reduced by this time the level 8,000 or 10,000 feet; but in proportion as it sunk, and the shallow borders became dry land, the temperature[Pg 19] would rise, and the moisture of the atmosphere diminish. The evaporation would be more and more rapid, and the surface of the Mediterranean might have sunk as far beneath its present level as Mont Blanc soars above it.[23]

It is singular that the Tartarus of Virgil and Dante is cast in this very region; but it would then have been no fabled terrors: natural objects would have outstripped their fancies. The breath of this furnace would not have been pent up in its caverns, but have spread its blight over the finest regions of Africa, Europe, and Asia, blasting in their bud the glories of the Capitol, the eloquence of the Bema, the sculptures of the Parthenon, the trophies of the Memnonium, the enterprise of Tyre, and the wealth of Carthage; and these fair and fertile shores would have been a wilderness, overhanging an abyss of death. The Chinese, the Hindoo, or, perchance, the Seminole philosopher, would have been journeying here to visit the bowels of the earth laid open to the sun.

What observations and experiments to make on the converse phenomena to ours—on the increase of intensity of heat and pressure on the powers of men or animals! What speculations on the old orders of the animal and vegetable kingdoms under new conditions! What new ones called into existence! What magnetic and electric phenomena to reward the Empedocles[Pg 20] who ventured into this crater of 4,000 miles circumference! Imagine Lebanon or Etna rising 30,000 or 60,000 feet, and Cyprus, a plateau, suspended a mile and a half above the plain of burning salt or boiling brine! What treasures for the historian—the exuviæ of animals and men—the refuse of centuries washed down by the streams—the dead of extinguished races buoyed up and floating through each other in the brine, or caught and cured in the salt as the mammoth in the ice! The geologist would then have enjoyed the sight of strata unmodified by a retiring deluge, and feasted his eyes on the reality of chaos, and an earth fitted for salamanders, megalosauri, cheirotheria, and mastodons. The Simoon would have extended its empire from the Zahara to the plains of Languedoc, and, cherished by his breath, the locust would have asserted her sway up to the English sea. Such, horrid and inane, must have been the “sweet south,” had not this channel been dug, and this purple sea poured in—reflecting the heavens above,—dispensing around moisture to the fields, health to the people,—yielding its body to their keels, its breezes to their sails. For this were these portals opened, which man so long has deemed a mystery denying his scrutiny, and a barrier defying his adventure.

[1] Ferdinand of Castile, after the death of Isabella, and the conclusion of the Neapolitan war, joined the Portuguese in the conquest of Morocco, on which they were then engaged, and settled the distribution of future conquests. The Spaniards were to have all eastward of Tetuan, the Portuguese all westward of Ceuta. Ferdinand himself led a great expedition of a hundred thousand men; and a second, equally powerful, sailed under Cardinal Ximenes. Millella, Penon de Velez, Oran, Tremcen, Fidelitz, Mostagan, Algiers, Bugia, Tunis, and finally Tripoli, were captured, or occupied on the flight of the inhabitants; so that the Kings of Spain were in possession of the whole coast of Africa, from Egypt to the Straits of Gibraltar; while the distracted Moorish State was vigorously attacked by the Portuguese on the other side, where they had obtained either permanent or temporary possession of Ceuta, Tangier, Arzilla, Larache, Salee, Azymore, Mogadore; and their conquests extended beyond the Ha Ha spur of the Atlas into Suz.

[2] “Extraordinary Occurrence in Africa.—A letter from Gerli (Gerba), regency of Tunis, recounts a strange scene of recent occurrence. There exists at Gerli a sort of pyramid, constructed of the heads of decapitated Christians, principally Maltese, Sicilians, and Spaniards, who fell or were taken prisoners at the battle of the 29th of July, 1560. At the request of Sir T. Reade, the British Consul, and the Vicar Apostolic of Terrara, the Bey sent orders to the Governor for the demolition of this lugubrious monument. Saturday, the 7th of August, was the day fixed for the ceremony. All the authorities were assembled. No sooner, however, had the masons commenced operations, than some Zouavian soldiers and other armed individuals rushed into the arena, and with yells of rage shouted that the time was come for substituting the skulls of the Christians present on the spot for those of which the pyramid was constructed. The Governor attempted in vain to appease these fanatics. He was so ill-treated as to be compelled to retire. It is hoped that Sir T. Reade will be called upon to obtain satisfaction for this outrage.”—Paris paper.

[3] “Africa, in its interior, is the least known quarter of the globe, and perhaps fortunately for its inhabitants will long remain so.”—Heeren, Carthag. c. iv.

Ἐπεί με χ’ ἁἱ κασιγνήτου τύχοι

Τείρουσ’ Ἄτλαντος, ὁς πρὸς ἑσπέρους τύπους

ἔστηκε, κίον’ ούρανοῦ τε καὶ χθονὸς

ὤμοιν ἐρείδων, ἄχθος οὺκ εὐάγκαλον.

Esch. Prom.

[5] The Straits were the pivot of Cicero’s cosmography. In the Tusculan Disputations, commemorating the wonders of nature, he speaks of “the globe of the Earth standing forth out of the Sea, fixed in the middle space of the universal World, habitable and cultivated in two distant regions; that which we inhabit being placed under the axis towards the seven stars; the other region, the Australian, unknown to us; the remainder uncultivated, stiffened with cold, or burnt up with heat.”

Ὑμεἴς δ’, ὥ μοῦσαι, σκολίας ἐνέποιτε κελεύθους

Ἀρξάμεναι στοιχηδὸν ἀφ’ ἑσπέρου Ὠκεανοῖο.

Ἔνθά τε καὶ στῆλαι περὶ τέρμασιν Ἡρακλῆος

Ἑστῦσιν, μέγα θαῦμα παρ’ ἐσχατόεντα Γἀδειρα,

Μακρὸν ὑπὸ πρηῶνα πολυσπέρεων Ἀτλάντων,

Ἡχί τε καὶ χάλκειος ἐς οὐρανὸν ἔδραμε κίων,

Ἡλίβατος, πυκινοῖσι καλυπτόμενος νεφέεσσι.

Dionysius Africanus.

[7] Philostratus, in the life of Apollonius, mentions that he himself had seen the ebb and flow, which he ascribes to the true cause. “All the phases of the moon during the increase, fulness and wane, are to be observed in the sea. Hence it comes to pass that the ocean follows the changes of the moon by increasing and decreasing with it.”

[8] By the rediscovery of the mariner’s compass, the voyage along the Western coast of Africa became practicable, and to this is owing the passage by the Cape to India, as well as the discovery of America. Without Columbus that discovery would have been made. The Portuguese, in their second expedition to India, fell on the Brazils just as the Chinese junk on its way to England was forced to America.

Ὠκεανός τε πέριξ ἐν ὔδασι γαῖαν

Ἑἱλἰσσων.

Song of Orpheus.

Ὁς περικυμαίνει γαίης περιτέρμονα κύκλον. Id.

[10] Eratosthenes of Cyrene measured the terrestrial meridian by the problem worked out from the well of Syene. To predict eclipses the mechanism of the heavens must be known. They were predicted by the ancients, e.g. Thales in the seventh century before Christ, Eparcus of Mycea, in the second; Hellico of Cyzycus, and Eudemus. Anaxagoras of Clasomene narrowly escaped death for explaining their cause. Among the Romans, Sulpicius Gallus predicted an eclipse during the war against Perseus; and Drusus, by doing so, quelled an insurrection (Tacit. Annals. I. 28). Pythagoras taught publicly that the earth was a sphere, and the centre of the universe; but he communicated to the initiated its double motion round its axis and the sun. Cicero was the friend of the man who calculated the exact distance of the moon, and approached to that of the sun.

[11] “Morgante Maggiore,” Canto xxv. stanza 205-9.

[12] The proposition of Columbus was, “Buscar el levante por el ponente.” To find the east by the west. This was precisely the mistake made by the Greeks, who had gained the idea of the spherical form of the east without the knowledge of its dimensions. It was, in fact, the repetition of the words of Aristotle—

—Συνάπτειν τὰν, περὶ τὰς Ἡρακλείους στήλας, τόπον περὶ τῷ τὴν Ἰνδικήν.

[13] In the Highlands the church is still called clachan, or the stones.

[14] “Sed nulla effigies simulacrave nota deorum.”—Sil. Ital.

[15] “Castumque cubile.”—Id.

[16] Phil. in Apoll. v. 5.

[17] Καὶ τῷ φοινίκων νόμῳ ὄτι νεὼς πεποίηται τῷ Ἡρακλεῖ τῷ ἔκει καὶ θυσίαι θύοντο.—L. 2.

[18] Ἀπὸ Ἡρακλεἴων στηλὼν τὼν εν τῇ Εὐρὡπη ἑμπόρια πολλὰ, κ.τ.λ.—Scylax.

Cadiz has still retained them as her arms:—

“The Tyrian islanders,

On whose proud ensigns floating to the wind,

Alcides’ Pillars towered.”—The Lusiad, b. iv.

[19] There is a dispute between Mannert and Gosselin about Hanno’s measurements, because they will not take his point of departure, viz. “the pillars of Hercules,” but will take mounts Abyla and Calpe. Heeren, as usual, interferes, and settles the matter thus: “The pillars of Hercules did not so much mean Abyla and Calpe as the whole Straits!”

[20] Bacon has adorned his first edition of his “Novum Organum” with a frontispiece, where a vessel is seen sailing forth between the two columns.

[21] I am here venturing to anticipate a future conclusion of science, viz. that the sea is salt only to a certain depth.

[22] “How different would have been the present state of temperature, of vegetation, of agriculture, and even of human society, if the major axes of the old and new continents had been given the same direction; if the chain of the Andes, instead of following a meridian, had been directed from east to west; if no heat-radiating mass of tropical land extended to the south of Europe; or if the Mediterranean, which was once in connection both with the Caspian and Red Sea, and which has so powerfully favoured the social establishment of nations, were not in existence; that is to say, if its bed had been raised to the level of the plains of Lombardy and of the ancient Cyrene.”—Cosmos, vol. i. p. 205.

[23] “The levels of the Sea of Tiberias and the Dead Sea are respectively 666 and 1,311 English feet below the level of the Mediterranean.”—Cosmos, vol. i. p. 288.

[Pg 21]

The Mediterranean is like a bag with two necks filling at both ends. The current through the Dardanelles presents exciting varieties, but no perplexing mysteries. It is the discharge of the surplus of the Black Sea, and the current is subject to the influences of the northerly and southerly winds; being reversed when the latter long prevails. At Gibraltar all is disorder—the stream incessant—the level on both sides the same. The tide rises and falls, yet the current always runs out of the ocean and into the Mediterranean. So determined is this rush, that the gales of the Equinox neither quicken nor retard it, and the phases of the moon have no power over it. It bursts through all obstacles and transgresses all laws, and seems to move by a will of its own—too strong to be disturbed, too deep to be discovered. During my excursions I was engaged in examining these phenomena, and I will commence with stating the results of several months’ cogitation and inquiries.

I first applied myself to test the old explanation of an under-current, by endeavouring to float substances[Pg 22] at various levels, and after great trouble in procuring lines, and having machines of various kinds made, I found that without a frigate’s tackle and crew no results could be obtained. I was thus reduced to mere scrutiny of the alleged facts, and of the alleged theory. The facts amount to this: a vessel, in 1754,[24] was fired into from the battery, it sank in face of the rock, and was afterwards cast up in the bay of Tangier.

A vessel, when it sinks, goes to the bottom, and if fragments of it are detached and are cast ashore, it is only because they float, that is, they rise to the surface. This story will not, therefore, serve the theory, even if authentic. There is nothing to prevent a ship or timber from floating out; for close in shore, on both sides, the tides of the ocean rise within the Straits to the height of four feet: of these, boats take advantage to get through against both wind and current. Sometimes, indeed, though it very rarely happens, the whole current is reversed; and vessels working during the night, and reckoning on being carried fifty miles to the eastward, have found themselves in the morning ninety miles to the westward of the point where they expected to be, that is to say, carried forty miles over the ground to the westward during the night.[25]

Having thus disposed of the only, but incessantly quoted fact, I proceed to the theory. Reasoning,[Pg 23] however, there is none, for it amounts to nothing more than this: “What becomes of all this water? It cannot go to the Black Sea, from which the Mediterranean receives water; it cannot escape by a subterranean passage into the Red Sea, for the level of the Red Sea is higher by thirty feet. Then there is an under-current discharging the water back again into the ocean.”

Water moves by its weight. Unless there is difference of level, there is no motion. The resistance is from the bottom according to its roughness, and the vis inertiæ is felt at the top—thus the greatest speed is at about two-thirds of the depth; here there is no difference of level, nor is the water acted on superficially by any propelling power. There is no prevalence of winds to account for a current at the surface. So great is the momentum of the stream, that, unlike the currents of the Dardanelles, it is neither accelerated by favourable winds, nor even retarded by adverse storms. The idea of an over-current running against an under-current is so opposed to all experience, that to be admissible, proofs would be required, and it could never be received as an hypothesis to account for an unexplained phenomenon.

Thus, the theoretical explanations utterly fail; yet there is action without agent, momentum without motor, currents without winds or declivity, and a vessel constantly filling without escape or overflow. A mighty river rushes over its bed; but this river[Pg 24] is not moved by its weight; it runs on a dead level[26] to the sea it reaches from the fountain whence it springs.—That fountain is the ocean itself! No wonder that this should be the first of ancient mysteries, and the last to be explained.

Before I had discarded the idea of an under-current, or had discovered the insufficiency of the evaporation to account for the indraught, I was sitting on Partridge Island, (a small rock within the Straits,) and gazing with astonishment at the enormous mass of water running by me, when the question occurred to me, what becomes of the salt? If the water evaporate, the salt remains; here then is the sluice of a mighty salt-pan—where is the produce? This has been going on for thousands of years; is there a deposit of salt at the bottom? If so, why have the abysses of the Mediterranean not been filled up? But salt is not deposited; how then is the Mediterranean not become brine? Then I saw that the evaporation would not account for the indraught, and before I descended from that rock, I had solved the problem. That solution is—an under-current produced by a difference of specific gravity between the water of the Mediterranean and the ocean.

If you take two vessels, and fill one with fresh water, and the other with salt, or the one with sea-water[Pg 25] at its ordinary charge of 1030, and the other with sea-water of higher specific gravity, such as would result from evaporating a portion of it, say 1100, and colour differently the water in the two vessels, and then raise a sluice between them, you will instantly have two currents established in opposite directions. In fact, you produce currents of water, like currents of wind, by the converse of rarefaction.

“Recent discoveries,” says Humboldt, “have shown that the ocean has its currents exactly as the air. Living, as we do, upon the surface, they have been beyond our reach; but now, having obtained soundings to the depth of four miles, we have ascertained that there is a rush of icy water from the Pole to the Equator, just as there is a draft of air close to the earth into the centre of Africa. The Mediterranean offers an apparent anomaly of a higher temperature at great depths. This Arago explains by the fact, ‘That the surface of the water flows in as a Westerly current, whilst a counter current prevails beneath, and prevents the influx from the ocean of the cold current from the Pole.’[27] If there was nothing to determine the currents at the entrance of the Mediterranean, save the relative degrees of cold at great depths between it and the ocean, the cold water would run in at the lowest depths, and the warm water would run out on the surface, which is precisely the reverse of what it does.

Here is a body of water 740,000 square miles in[Pg 26] extent, subject hourly to the increase of its specific gravity. Upon the surface, a crust of salt is left in the course of every year, sufficient to give a double charge to the depth of six fathoms. To adjust the difference thus created with the ocean, there is but a narrow inlet,—a mere crack upon the side of the vessel, an interval of six miles left in a circumference of four thousand. By this, in its deepest part, the heavier water will have to find its way out, and thus occasion an indraught of water above, besides the demand created by evaporation. It remains to be ascertained by experiment, that the specific gravity of the water in the Straits varies at different levels, and at what level it commences to move outwards. These experiments will present great practical difficulties from the tides at the sides, which will mingle the streams; and, from the shallowness towards the ocean, they must be made in the middle and at the Mediterranean side. The evaporation, and the differences of specific gravity, will give the means of calculating the amount of water passing through in both directions, and the depth and velocity of the two currents. But it may be inferred that the currents will have the greatest speed at the top and the bottom,—that their velocity will diminish towards the centre, and that a neutral space of dead water will remain, not only in consequence of the counter-impetus of the currents, but because of the nearer approach of specific gravity, and the mingling of the two waters, which would destroy the moving power.

[Pg 27]

With this solution we can at once understand the powerlessness of tides and storms, currents without difference of level, or prevalence of winds: the volume of the stream is accounted for, the mass of salt disposed of, and the apparent rebellion against the laws of Nature put down.

By tables kept for several years at Malta, it appears that the Mediterranean, at that point, varies in level between winter and summer no less than three feet. In winter, when there is no evaporation, and when the quantity of water falling in the immediate vicinity of the Mediterranean is greatest, the level is lowest. The cause, I should take to be the pressure of wintry wind. In like manner, those erratic movements in the Straits may result from difference of atmospheric pressure without and within.

These currents, by the testimony of the ancients, have not held from the beginning—they have been the results of successive modifications of the channel. This is singularly borne out by the traditions of the neighbouring people and the geological features of the coast.

Eldressi narrates, as an old and popular story of his day, that “the Sea of Cham (Mediterranean) was in ancient times a lake surrounded on all sides, like the Sea of Tabaristan (Caspian), the waters of which have no communication with any other seas. So that the inhabitants of the extreme west invaded the people of Andalusia, doing them much injury, which they, in like manner, did to the others, living[Pg 28] always in war, until the time of Alexander,[28] who consulted his wise men and artificers about cutting that arid isthmus and opening a canal. Thereupon they measured the earth, and the depth of the two seas, and saw that the Sea of Cham was not much lower than the Sea Muhit, (Ocean); so they raised the towns that were on the coast of the Sea of Cham, changing them to the high ground. Then he ordered the earth to be dug out; and they dug it away to the bottom of the mountains on both sides; and he built there two terraces with stones and lime the whole length between the two seas, which was twelve miles; one on the side of Tankhe (Tangier), and one on the side of Andeluz. When this was done, he caused the[Pg 29] mound to be broken, and the water rushed in from the great sea with violence, raising the waters of the Sea of Cham, so that many cities perished, and their inhabitants were drowned, and the waters rose above the dykes, and carried them away, and did not rest until they had reached the mountains on both sides.”

The Moors have also a Myth. “The sea,” they say, “was created fresh, but exalting itself against its Maker, gnats were sent to drink it up. It then humbled itself in the stomach of the gnats, and prayed to be relieved, so the gnats were ordered to vomit it forth again, but the salt remained from the stomach of the gnats an eternal sign of its disobedience.”

Before suggesting the interpretation of these Myths, I will point out the change which the coasts and channel have undergone.

The description of the Straits by Greek and Roman writers is so unlike their present appearance, that, but for the impossibility of doubting the identity of the objects, we must have supposed their words to apply to some undiscovered region. Who could recognize the deep sea and the iron-bound coasts of these narrows, in a plain of sand furrowed by rivers running in from the ocean, which it was difficult to reach, not from the strength of the stream, but the intricacies of the passage—who would imagine the necessity of constructing flat-bottomed boats to get across from Gibraltar to Ceuta, where now there is above one thousand fathoms, or of transferring the ferry to the Atlantic side of the Straits, where at present the depth[Pg 30] is not one-sixth of what it is in the other, in order to get more water? Yet there is no doubt that these details apply to these spots, nor can we question the known accuracy of the writers, or escape from the concurrence of their testimony. We are reduced, then, to the necessity of admitting some great revolution in the features of the country, and a total change in the nature of the current.

The explanation is easy: the bank of sand, left by the retiring waters of the Deluge, which covers the western border of Africa, reached to the coast of Andalusia, and the remnants of it still lie on the eastern side of Gibraltar, and fill the caverns exposed to that side; on the depression of the Mediterranean by evaporation, the water of the ocean would filter in, the sand would be gradually removed. The amount of sand on the Mediterranean side of the “Rock,” shows that a plain nearly one thousand feet above the level of the sea, once stretched across to Africa, where now the channel is one thousand fathoms deep. This has been worked out by the overfall, while on the Atlantic side the water shoals to one hundred and eighty fathoms, presenting the character of an estuary with a bar from the rush outward of the under waters, since the Gut was sufficiently deepened to admit of the currents in opposite directions. The centre part of the channel is worn down to the rock or to gravel, every particle of sand has been removed from the bottom. Two inferences may be drawn: 1st. That the process of removal was likely to be accompanied by sudden[Pg 31] inbursts, which would submerge the borders. 2nd. That the Mediterranean, in early ages, was fresh, and afterwards became, as it evaporated, very salt, until the channel was deepened to allow of its mixing with the ocean. What else is implied by the Myth of the midges and the fable of Alexander?

[24] See James’s History of Gibraltar.

[25] This happened to the Phantome.

[26] The excellent geodesic operations of Corabœuf and Deleros have shown, that at the two extremities of the Pyrenæan chain, as well as at Marseilles and the northern coast of Holland, there is no sensible difference between the level of the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.—Cosmos, vol. i. p. 297.

[27] Cosmos, vol. i. p. 296.

[28] In eastern tradition there are two Alexanders: the first is Dualkernein, whom the Bretons claim as their leader from the Holy Land, and the opponent of Joshua. According to the authorities cited in Price’s Arabia (p. 54), the first Alexander was also a Macedonian, and built a city in Egypt, on the site of the city afterwards raised by the Macedonian. The ramparts of brass at the Caspian gate were attributed to both Alexanders—they are by the Koran given to the first. (Sale’s Koran, ch. xvii. p. 120; Merkhond’s Early Kings of Persia, p. 368). Al Makkari says, the same Alexander built towns of brass in the Canary Islands. Macarius, patriarch of Antioch, speaks of the Dardanelles being opened by Alexander, and that he placed his own statue on the top of one of the hills (Travels, vol. i. p. 33-40). Thus confounding together the deluge of Ogyges—the cutting the canal of Athos—the opening the Straits of Gibraltar. Alexander seems to have adopted the title of the two former to favour the analogy (see Merkhnd, 334; Price, 49; Temple of Jerusalem, p. 119). Alexander Dualkernein, is still a hero of the Spanish nurseries.

[Pg 32]

There is no place of which it is more difficult to form an idea without seeing it, than Gibraltar. One naturally expects to find a fortress closing the Mediterranean with its celebrated galleries and enormous guns facing the Straits. It is nothing of the kind.

The Straits are, at the narrowest part, seven miles and a quarter wide; but that part is fifteen miles from Gibraltar. It is only after you have passed the Narrows that you see the “Rock” away to the left. Ceuta, in like manner, recedes to the right; the width being here twelve miles. The current runs in the centre, sweeping vessels along, and instead of being exposed to inconvenience from either fortress, they would generally find it difficult to get under their guns. The batteries and galleries face Spain, and look landward, not seaward. Whatever its value in other respects, it is quite a mistake to suppose that it commands the Straits, or has ever had a gun mounted for that purpose.

Gibraltar is a tongue three miles long and one broad, running out into the sea, pointing to Africa,[Pg 33] and joined to Spain at the northern extremity by a low isthmus of sand: it presents an almost perpendicular face to the Spanish coast. Seen from the “Queen of Spain’s Chair,” it resembles a lion couching on the point, its head towards Spain, its tail towards Africa, as if it had cleared the Straits at a spring. Geologically speaking, it belongs to the African hills, which are limestone, and not to those of the opposite Spanish coast, which are crystalline. Mount Abyla is called by the Moors after Muza, who planned the expedition, and Calpe is now named after Tarif, the leader who conducted it. Seen from the mountains above Algesiras, the rock resembles a man lying on his back with his head on one side. The resemblance of Mount Athos to a man I have made out in a similar manner.

The side towards the Mediterranean is now made inaccessible by scarping, but it was nearly so before. Towards the point at the south, the rock lowers and breaks down till, on the Bay side, it shelves into the sea; thence along the Bay, which in its natural state was an open beach of sand, gently sloping up until shouldered by the steep sides or precipices of the Rock. This level ground affords the site for the present town. The southern and larger portion has been converted into the beautiful pleasure-ground called the Almeida, or is occupied by barracks and private residences. Half of this bristling tongue was formed unapproachable,—man has fenced in the other. This sea-wall from end to end is the work of the[Pg 34] Moors. Antiquarians have endeavoured to find here Roman and Phœnician remains. I should just as soon expect to find a Roman fortress at John O’Groat’s, or a Phœnician emporium on Salisbury Plain. It was reserved for a shrewder people than Carthaginians, Romans, Greeks, or Goths, to discover Gibraltar’s worth.

There are three elevations on the ridge, one in the centre, and one at each extremity. That in the centre is the highest; and here is the signal station, from which works are carried straight down to the beach at the ragged staff. The upper part of the Rock is like a roof, and down it, like forked lightning, runs a zig-zag wall. Below this stony thatching there is a story or two of precipices; the line of defence drops over them and on the works, which shut in the town on the south, and which consist of a curtain-bastion and ditch. In the rear of this wall (the zig-zag) there are the remains of a still more ancient one. A great amount of labour has been expended upon this almost inaccessible height. These zig-zag, or flanking lines, are naturally assumed to be modern, and the wall goes by the name of Charles V., who restored the fortification below; but the loop-holes are for cross-bows. The diagonal steps at the landing-places, the materials and the coating, as well as the whole aspect, show them to be Moorish. Heterodox as this opinion was held when I first broached it, it was not impugned after two inspections by the officers best qualified to pronounce on such a matter.

[Pg 35]

On the north, too, all our defences are restorations of the Moorish works: even in the galleries they have been our forerunners. Their open works were in advance of ours, and a staircase is cut out through the Rock down to the beach. In fact, save in what is requisite for the application of gunpowder, or what is superfluous for defence, the Moors had rendered Gibraltar what it is to-day. They have even left us structures of the greatest service, as resisting the effects of gunpowder, and such as we are able neither to rival nor to imitate. On the great lines, in consequence of the many changes which have taken place, the original work has been displaced, or covered up, and especially so along the sea-wall; but, ascend to the signal-post,—crawl out on the face of the Rock to the north,—examine even yet Europa Point—Rozier Bay, and everywhere you find the Moor.

It is impossible to move about at Gibraltar, without having the old tower in sight, and it is difficult to take one’s eyes off it when it is so. No aspiring lines, no graceful sweeps, no columned terraces exert their fascination, nor is it ruin and dilapidation that speak to the heart. The building is plain in its aspect, mathematical in its forms, clean in its outlines, with a sturdy and stubborn middle-aged air, without a shade of fancy or of wildness. Nevertheless, the eye is drawn to it, and then your thoughts are fixed on it—and they are so, precisely because you cannot tell why.

It constitutes the apex of a triangular fort, and[Pg 36] massy and lofty itself, it thus assumes a station of dignity and command. The annals of time are traced on it—here by the arrow-head still sticking,[29] there by the hollow of the shot and shell. It has borne the brunt of a score of sieges, and stands to-day without a single repair. On its summit, seventy feet from the ground, guns are planted. The terrace on the roof is cracked, but the surface is otherwise as smooth as if just finished. The pottery-pipes fitted in to carry away the water, are precisely such as might have been shipped from London. A semicircular arch supports a gallery on the inner side. A window opening in this gallery, now blocked up, is like a church window with the Gothic arch chamfered. The exterior was plastered in fine lime, and there are traces of its having been divided off into figures. It has now, by the barbarians in possession, been rubbed over with dirty brown to make it look ancient. The turrets on the walls below have been furbished up to look like cruet-stands, and the staring face of a clock[30] is stuck in a Saracen tower.

The upper story only is explored and open; the flooring is perfectly smooth, and the roof stuccoed. There is a bath-room, and a mosque; the former has a figured aperture slanting through ten or twelve feet of wall to admit the light, as in the domes of Eastern baths. The other parts of the building are as much[Pg 37] unknown as those of the unopened Pyramids. If these ruins had been in the hands of the tribe that live on the rock above, there would have been exhibited at least as much taste, and certainly more curiosity.

The standing walls adjoining the towers exhibit faces of arches that covered in halls and surrounded courts. The second portion of the fort is at present used as a prison. The lower enclosure is of greater extent, and in the line of the wall is a remarkable Egyptian-looking building, square with buttresses at the angles and a pyramidal roof—roof and walls one mass of Moorish concrete (Tapia). It is as perfect as it was a thousand years ago, and may be equally so a thousand years hence. It is at present used as a powder-magazine, and is divided into two stories. The flooring of the upper hall is supported in the middle by a block of masonry some fifty feet square. This apartment is curiously ventilated.

This Moorish fort is, as a whole, a building of great interest. An architect of the last century speaks of it as one of the most remarkable on the soil of Europe. It was no embellishment of, or defence for a capital; it was raised in time of trouble on a remote promontory as a protection for insurgents. It was antecedent to art in Europe,—the people who raised it did not imitate Rome; they must have brought this art with them. It stands a match for man and time, defying at once the inventions of the one and the ravages of the other.

[Pg 38]

Here is an original in design and substance, a work surpassing those of the Romans in strength, and equalling those of the Egyptians in durability.

As the zig-zag lines have been attributed to the Spaniards, so on high authority is a much more recent date[31] than that which I here assign to them given to the Moorish fort and tower; but supposing them to be of no earlier date than the fourteenth century, they would still illustrate a style of architecture which the Moors introduced, and which, like language, is lost in the mists of antiquity.

They are now busy in demolishing the works that connected the Moorish fort with the harbour. Whilst tracing the old wall from the former to the latter, I came upon a large arch, and satisfied myself that this had been an entrance to an inner harbour. On subsequent reference to James’s History of Gibraltar, I find that this was well known in his time.

During these researches, in which I spent a month, I had not the aid that is generally obtained from the observations of others. I often attempted to look[Pg 39] into books, but was always constrained to throw them aside, and return to the writings on the wall. What manner of men were these Moors?—the ruins suggested the question, and books furnished no answer.

On the sea-side, Gibraltar is open to the fire of vessels, and would have been captured on one occasion, but for the dissensions between the combined forces. We have retained it only by a new invention, red-hot shot.

The land-entrance is defended as follows: first, the isthmus round the north face of the Rock is dug out and filled with water, and between this basin, called the Inundation, and the Bay, a causeway only is left, which can be swept away at once by the enormous guns from the overhanging caverns. Behind the Inundation, is the glacis, elaborately mined; and behind the ditch there is a curtain, mounting eighteen or twenty guns, which fills up the gap between the Rock and the works on the port. As you advance along the narrow causeway between the Inundation and the Bay, you have this curtain in front. To the right stretches out into the water, a long low mole called the “Devil’s Tongue,” and between it and the curtain, there is tier upon tier of embrasures over the Port and the Port entrance. To the left of the curtain, the sharp engineering lines scale the rocks, and link the chain of defence to the Moorish Tower. Thence the cliffs sweep away round to the left, parallel to the causeway, along which you are advancing. The Rock[Pg 40] is shaved into lines for musketry, or pierced with port-holes, which stretch away in rows far and high. On the crest of the first precipice, batteries and guns are scattered. You see them again on the loftiest summit of the Rock, so that as you approach, you pass over ground swept with metal, and through successive centres of converging fire. This is by the Spaniards called “Bocca del Fuego.” At each step, from all around, above, below, from Merlon, rock, and cavern, mouths of iron—some of them caverns themselves—open upon you.

This is the only portion of the contour of the place that an assailant could approach or batter. With a sufficient garrison, and superiority at sea, so as to throw in provisions, the place is clearly impregnable. The breaching batteries would have to be advanced beyond the guns on the northern portion of the rock, and the advanced works would be looked into, and down upon. In no sieges had either breach been attempted, or third parallel drawn. The batteries on the crest of the Rock, termed Willis’s, were the effectual defence, by their plunging fire into the Spanish works. The siege, properly speaking, was an attempt to starve, by cutting off supplies at sea, and to break down by sheer superiority of fire and shelling. The operations from the sea would have been successful but for the red-hot shot. The vaunted galleries have been constructed since the siege, and are mere matters of ostentation.

Gibraltar has neither dock nor harbour. The Bay[Pg 41] and anchorage are commanded by the Spanish forts, St. Barbara and St. Philip. These are levelled at present; but they will arise on the only occasion that we can require protection—that is to say, a war with Spain. They, therefore, must be restored in the mind’s eye, if you would form any estimate of the value of this fortress in case of war. They were dismantled during the late war by the Spanish government, lest the French should occupy them, and destroy the English shipping. The Spanish government, however, formally reserved its right to rebuild them. The question has been lately raised by our sinking one of their men-of-war in their own waters, while pursuing a smuggler.

The guns of St. Barbara command the anchorage and batter the harbour; the shells from it and St. Philip pass clean over the Rock, lengthways, and can be dropped into every creek where a shoulder of rock might shelter a vessel from the direct fire. During the siege by France and Spain, the post was of no use. Unless when superior at sea, we had to sink our vessels to save them.

In Gibraltar, there is little trade except contraband; the natural commerce having been systematically discouraged, that the martial departments might not be troubled, and with the view of reducing it to a mere military establishment. The fiscal regulations of Spain, which sustain this traffic, would long since have fallen but for its retention by England. We, therefore, lose the legitimate trade of all Spain for[Pg 42] the smuggling profits (which go to the Spaniards) at this port.

Gibraltar does not command the Straits. It does not present means of repairs for the navy. It does not afford shelter for shipping in case of war. It does not advantage, but seriously incommodes our trade. It does not afford the means of invading or of overawing, or even in any way annoying Spain, however much it may irritate her; for no fertile country, populous region, or wealthy city is exposed to it, and there is no highway by land or sea which it can command.

William III., when he conspired for the partition of the Spanish monarchy, on the demise of Charles the Second, stipulated for Gibraltar, the ports of Mahon, and Oran, and a portion of Spain’s transatlantic dominions. On the death of the last of the line of Philip Le Bel, Louis XIV. was bought off by the offer of the crown for his grandson. The English and the Dutch then set up Charles the Third, and sent a squadron in his name to summon Gibraltar to surrender. The garrison consisted only of one hundred and ninety men; but it held out. The Dutch and English battered, and took it. The flag of Charles the Third was hoisted, but suddenly hauled down and replaced by the English, to the surprise and indignation of our Dutch allies. Thus was revealed the secret condition of the compact.

Gibraltar was all that England did get out of that war, and as this robbery went a great way to ensure[Pg 43] her discomfiture, and to establish Philip the Fifth upon the throne, we may consider Gibraltar as the cause of the first of those ruinous wars which, made without due authority, and carried on by anticipations of Revenue, have introduced among us those social diseases which have counterbalanced and perverted the mechanical advancement of modern times.

Gibraltar was confirmed to us at the Treaty of Utrecht, but without any jurisdiction attached to it, and upon the condition that no smuggling should be carried on thence into Spain. These conditions we daily violate. We exercise jurisdiction by cannon shot in the Spanish waters (for the Bay is all Spanish). Under our batteries, the smuggler runs for protection; he ships his bales at our quays; he is either the agent of our merchants, or is insured by them; and the flag-post at the top of the Rock is used to signal to him the movements of the Spanish cruisers.[32]

We take it for granted that Gibraltar has been honourably, some will even say chivalrously, won in fair fight; that it has been secured by treaty and is retained on duly observed conditions; or, perhaps, we never trouble ourselves about such matters, and imagine, therefore, that other nations are equally indifferent; but if any one of us would take the trouble to imagine the fortress of Dover in the possession of[Pg 44] France, or Austria, or Russia, he would then comprehend why Napoleon said that “Gibraltar was a pledge which England had given to France by securing to herself the undying hatred of Spain.”[33]

Now let us see the cost. The first item in the account is the Spanish War of Succession. From the consequences of that war and the retention of Gibraltar, the family compact of the Bourbons arose. The subsequent European wars are thus partly the cost-price of Gibraltar.