*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 67834 ***

THE ADAM CHASER

By B. M. Bower

Author of “Black Thunder,” “The Meadowlark Name,” Etc.

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in

the September 7, 1925 issue of The Popular Magazine.

Treasures of the storied past, records of prehistoric settlements

of the American Indian, lure a young archaeologist, Professor Abington,

to the Sonora caves of Arizona where fate plays him a grim trick,

and makes him arbiter of the destinies of living men.

CHAPTER I

A BAD HOMBRE

Halfway up a long cañon that cut a six-mile gash through rugged

mountains thinly pock-marked with prospect holes, the radiator cap

of John Abington’s car blew off with a pop like amateur home-brew.

For a matter of a minute, perhaps, that particular brand of

automobile developed a lively hot-water geyser. Followed a brief

period of steaming, and after that it stalled definitely and set

square in the trail which ran through deep sandy gravel and rock

rubble—a hot car and a sulky one, if you know what I mean.

Abington harried the starter with vicious jabs of his heel, then

crawled reluctantly out into the blistering wind which felt as if it

were driving down the sunlight with sharp needle points of heat that

stung and smarted the skin where they struck.

The canteens were buried deep under much camp paraphernalia, a

circumstance which gave occasion for a few minutes of eloquent

monologue. Curiously, the driver’s vituperation was directed neither

at the car nor the wind nor the heat, but at an absent individual

whom he called “Shorty”—and at another named Pete.

Considerable luggage was shifted before the canteens were finally

excavated from the floor of the tonneau; both canteens, because the

first one was so completely empty that it made no sound when

Abington impatiently shook it.

He was standing beside the car, mechanically sloshing a pint or so

of water in the second grimy, flat-bottomed canteen, when a

dust-covered roadster came coasting down the four-per-cent grade of

the cañon half a mile or so away. He glanced at the approaching car,

set the canteen in the sand and helped himself to a cigarette from a

silver-trimmed leather case. Abington was leaning against the rear

fender in the narrow bit of shade when the roadster came down upon

him, slowed with a squealing of dry brakes and stopped perforce. In

the rocks and deep sand that bordered the road a caterpillar truck

could scarcely have driven around the stalled car.

“In trouble?” A perspiring tanned face leaned out, squinting ahead

into the sun through desert-wrinkled eyelids.

“None whatever,” Abington calmly replied, smiling to make the words

cheerful. “I’m waiting here for the car to cool off a bit. I hope

you’re not in a hurry?”

The driver of the roadster slanted a quick glance at his companion,

who slumped sidewise in the seat with his hat pulled low over his

eyes.

“Kinda. Got plenty of water?” This in a hopeful tone, which his next

sentence explained. “I’m kinda short, myself, but I’ll hit Mina

before long, so I ain’t worrying. How much you going to need? Half a

canteen do you any good?”

The stalled driver walked forward with a loose, negligent stride

which nevertheless covered the ground with amazing ease. From under

straight, black brows his eyes looked forth with apparent

negligence, though they saw a great deal with a flicking glance or

two.

“It might take me back to where I can fill my canteens, sheriff. I

don’t suppose there’s a quart of water in the radiator, and

everything’s empty. My fault. I discharged a couple of men I had

with me, and I should have been on my guard against some such trick

as this. As it was, I failed to stand over them while they unloaded

their plunder from the car. At any rate, here I am for the present.”

“Tough luck. I’ll let you have what water I’ve got, but it ain’t

much. She kept heating on me, climbing the summit. How far you

going?”

“Back to Mina. I want to find those two fellows I let off there.”

Abington’s questing black eyes rested on the roadster’s other

occupant, shifted to the driver’s hard yet not unkindly face, and he

waved the cigarette significantly.

“Better give this fellow a drink, before I empty the canteen.” He

nodded toward the slack figure. “And if you’ll pardon the

suggestion, sheriff, I’d turn him loose for a bit. Pretty rough

riding, even when you’ve got all your hands and feet to hang on by.”

The other gave a short, apologetic laugh.

“Say, this feller’s plumb mean—that’s why I got him shackled that

way. Car broke down, the other side of Tonopah, and I’m taking him

through alone. He’s a slippery cuss. Had us chasin’ him off and on

for two years. I can’t take any chances.”

“You’re not.” If the tone was ironic the eyes were friendly enough.

“But the man looks sick. A drink of water and a smoke won’t make him

any more dangerous, I imagine.”

“Yeah, I know he acts sick, and he looks sick. But it might be a

stall, at that,” The officer turned and eyed his prisoner

doubtfully. “I don’t want to be hard on anybody—and I don’t want to

be bashed over the bean and throwed out on the desert to die,

neither! She’s a lonely road—I’ll tell anybody.”

For all that, he got out, unlocked the tool box on the running

board, took out a smaller box of screws, bolts, nuts and cotter

pins, fumbled within it with thumb and finger and finally produced a

small flat key.

“Never pays to be in a hurry to git a pair of handcuffs open,” he

muttered to Abington. “This way’s safe as I can make it. He’s a bad

hombre.”

Abington nodded understanding and stood back while the deputy

sheriff walked around the car and freed his passenger from the

handcuffs which were fastened behind his back.

For an appreciable space the fellow drooped indifferently where he

was, not even taking the trouble to rub his chafed wrists, though

they must have pained him considerably, swollen and discolored as

they were with the snug steel bands and the awkward position forced

upon him.

“Have a drink of water,” Abington suggested, not too kindly. More as

if he were speaking to a man who was free to go where he pleased.

The fellow looked up at him, nodded and lifted a hand shaking from

cramp. Abington unscrewed the cap and steadied the canteen to the

man’s mouth. He drank thirstily, pushed the canteen away with the

back of his hand, lifted his hat and drew a palm across his flushed

forehead where the veins stood out like heavy cords drawn just under

the skin.

“Thanks!” He gave Abington another glance, a gleam in his eyes as of

throttled speech.

“Have a smoke. Here, keep the case while we’re getting the car

started.” Abington glanced at the officer. “You’ve no objection, I

suppose?”

“Hell, no! What do you take me for? Just because I use some

precautions against being brained while I’m busy driving don’t mean

I’m hard boiled.” He sent a measuring glance toward either side of

the straight-walled cañon. Within half a mile there was no cover for

a man, and the cliffs rose sheer. “You can get out if you want to,

Bill,” he said to the prisoner. “Guess you won’t go far with them

leg irons.”

“Thanks.” The prisoner’s voice was perfunctory, and he seemed in no

great hurry to avail himself of the privilege. While the others

walked to the stalled car—the deputy watching over his

shoulder—the prisoner sat where he was, smoking a cigarette from

Abington’s leather-and-silver case.

The stalled car refused to start. That mechanical condition, which

is called freezing, held the cylinders locked fast until such time

as the expansion subsided, and in the fierce heat of that cañon the

motor cooled very slowly. Abington suggested coasting backward to

the first place where a turnout had been provided.

“There’s a turnout, back here a couple of hundred yards or such a

matter. If you can give me a push over this little hump, I think the

car will roll down the road easily enough,” he explained. “I’ll have

to keep it in the road, sheriff, or I could manage alone.”

The deputy rather liked being called sheriff, and he was anxious to

reach Carson City that evening with his prisoner. Until Abington’s

car moved out of the way, he himself was stalled, since he could not

move forward more than the hundred feet which separated the two

cars. There was no other road down that cañon.

“If Bill Jonathan wasn’t feeling so tough, I’d take off the hobbles

and make him get out and help,” he grumbled, looking back at the

roadster. “But I guess he’s sick, all right. He ain’t left the car

yet. Well, you get in and hold ’er in the ruts, Mister”

“My name is Abington. I’m an archaeologist—”

“That right? My name’s Park. I’m sure glad to meet you, Doctor

Abington. Heard a lot about you and them petrified animals and

things you’ve been digging up. Got the brake off? All right—”

But the best he could do, just at first, was to rock the car a few

inches each way. Between shoves he looked over his shoulder. The

prisoner apparently preferred the shade of the car to the heat of

the sun, and Park soon ceased to worry about him. Midway between

Tonopah and Mina would be a poor spot to choose for a walk away,

even if the man were free to walk, he reflected.

However desperate he might be, Bill Jonathan was no fool. He knew

well enough that Park would shoot at the first hint of trouble. The

deputy grunted and turned his attention to the work at hand.

Abington got out and helped claw the hot loose sand away from behind

the rear wheels, got in again and steered while Park braced himself

and heaved against the front fender. The car moved backward nearly a

foot, and the two grinned triumphantly at one another.

“Next time—I’ll get her—Doctor Abington!” the deputy puffed,

glancing over his shoulder as he mopped trickles of sweat from face

and neck. A thin wreath of cigarette smoke waved out from the

prisoner’s side of the roadster, and Park grinned at Abington behind

the wheel.

“Hope you’re well fixed for cigarettes!” He chuckled good-humoredly.

“Bill’s trying to smoke enough to last till he gets outa the pen,

looks like.”

“He’s welcome,” Abington returned, a smile hidden under his pointed

black beard. “I’ve plenty more.”

“Just as you say. All right, let’s give her another shove. Gosh,

it’s hot!”

Grunting and straining, Park moved the car three feet backward to

where a nest of small stones halted it again. Encouraged by the

small progress, the two knelt again behind the rear wheels and began

to paw a clear path in the gravel. The “hump,” one of those small

ridges which characterized desert roads, would be passed within the

next six feet.

At the precise moment when Park was kneeling with his back half

turned from his own car, he heard his starter whir with an instant

roar of the motor just under a full feed of gas.

The roadster shot backward up the trail, guided evidently by guess

and a helpful divinity, since Bill Jonathan’s head never once

appeared outside the car to watch the trail behind him. Park jumped

up, pulled his old-fashioned range-model Colt and fixed six shots in

rapid succession, evidently realizing that he must get them all in

before the car was out of range. With the sixth shot the glass was

seen to fly from a headlight, then the hammer clicked futilely

against an empty shell.

Park swore as he started running up the trail after the car, the

driver’s head now plainly in sight as he leaned out and watched the

road. A good fifteen miles an hour he was making in reverse; and

unless a car came down the cañon and stopped him as Park had been

halted, for the simple reason that he could not turn out, Bill

Jonathan seemed in a fair way of making his escape.

“The damn fool! He can’t get far with them leg irons on!” Park

grunted, coming to a stop where the roadster had stood. “That’s what

I get for being so damn soft hearted! I told you he was a

bad hombre, Doctor Abington!”

CHAPTER II

SYMBOLS OF MYSTERY

Abington walked forward a few steps, stooped and picked up his

cigarette case from the hot sand of the trail.

“Spencer founded his whole philosophy on the premise that there is a

soul of goodness even in things evil,” he observed with the little

hidden smile tucked into the corners of his black-bearded lips.

“Your man has made off with your car, but he very thoughtfully

returned my cigarette case—not altogether empty, either. Not

knowing I have a full carton in the car, he has left us a cigarette

apiece; which proves the soul of goodness within the evil. Will you

have a smoke, sheriff?”

“Might as well, I guess,” Park grumbled, his eyes on the departing

car. “This is a hell of a note! Doctor Abington, what we’ve got to

do is make it in to Mina and get word out to the different towns

before Bill can make Tonopah or Goldfield.

“Thunder! Who’d ever think he’d try to pull off a stunt like that? I

was going to take the irons off his legs, but I kinda had a hunch

not to. Never dreamed he’d pull out with the car while his legs was

shackled; did you?”

“I’m afraid my mind was quite taken up with my own problem.”

Abington confessed in a slightly apologetic tone. “I’m not

accustomed to chasing live men, you know. It’s the dead ones I’m

interested in, and the longer they’ve been dead the better.

“Nevertheless, sheriff, I realize your predicament. If there’s a

long-distance telephone in Mina you can intercept the fellow at

Tonopah, I should think.” He was thoughtfully turning the cigarette

case over in his fingers as if his habit was to admire its glossy

brown leather and the silver filigree. Now he slipped it into his

pocket and turned to retrace his steps.

“I suppose we ought to get the old boat headed down the trail,

sheriff. Your prisoner went off with your canteen, you know, so

we’ll have to pet my motor along as best we can. But she’ll roll

down the cañon in neutral, and then we’ll drive it as far as we

can—which may not be far.

“At the turnout, down the road here, I’ll get the car headed in the

other direction, and it wouldn’t surprise me if we beat your man in,

after all. Will he have gas enough to take him to Tonopah?”

“Lord, yes! I filled the tank plumb full, and it’s one of them old

thirty-gallon tanks. But somebody’ll maybe run across him trying to

fill the radiator or something, and see the leg irons and take him

in. Tires ain’t none too good—maybe he’ll have tire trouble. I sure

hope so,” he added unnecessarily.

Abington, leaning to push at the side of the car while he kept one

hand on the steering wheel, did not answer. Park added his weight at

the front fender, straining until his gloomy countenance went

purple. The car rolled over the hump, and Abington hopped nimbly to

the running board, watched his chance and straddled in behind the

wheel.

Some time was lost in negotiating the turn. After that, coasting

down the road with a dead engine cooled the cylinders considerably.

By skillful management Abington was able to start the motor and use

what power was needed to drive the car up over certain small knolls

near the foot of the cañon.

At the edge of the long valley, a hill gave them momentum sufficient

to carry them well down toward a white, leprous expanse, called Soda

Lake, with a tiny settlement a few miles beyond. Here, in the chuck

holes of the soda-incrusted lake bed, the car refused to go any

farther without power, and power in that grilling heat required a

full radiator.

Even so, the two made fair time walking, and at the settlement

Abington was able to hire a man to haul water out to the car. Also,

Park was successful in getting wires through to the sheriff’s office

at Tonopah, and also at Goldfield, the only points he believed Bill

Jonathan would attempt to reach.

“If you like, sheriff, we can follow up your man at once,”

Abington suggested when Park came out of the telegraph office

looking less worried. “I’m willing to postpone the pleasure of

chastising Shorty and Pete, and drive you straight through to

Tonopah. Water is the only thing I needed for the trip, and the man

is waiting out here with a full supply, ready to drive us back to my

car. At the most we will be only three hours behind the fugitive

and, as you say, he can’t do much with leg irons on.

“He’ll need to have a remarkable run of luck if he reaches there

ahead of us. For instance, your motor had been heating, and you had

only half a canteen of water. As I remember the road, there’s a

long, hard climb for several miles beyond that cañon. He’ll be

compelled to fill up with water at that spring just over the summit;

one stop, at least, where he will have enough awkward walking to

hold him there twice as long as a man with his legs free. So—”

“Say, Doctor Abington, you sure can figure things out!” Park grinned

while he bit the end off a forlorn-looking cigar he had just bought

at the little store. “You ought to be a detective.”

“I am. I’ve been trying to detect the origin of the human race, for

years now,” Abington smiled. “It’s the same kind of figuring brought

down to modern conditions. If you’re ready, sheriff, we’ll get

underway.”

So back they went, roaring up the long rough trail to the cañon and

on to Tonopah. They did not meet a soul on the way, nor did they

overtake Bill Jonathan and the roadster. Neither did they glimpse

anywhere a sign of his turning aside from the main highway, though

Park’s eyes watered from watching intently the trail.

Abington proved to be a scientifically reckless driver and a silent

one withal. Within an incredibly short time he landed a grateful

deputy at the sheriff’s office in Tonopah, bade him an unperturbed

adieu, drove his car into a garage and established himself

comfortably in the best hotel the town afforded—all with the brisk,

purposeful air of one who is clearing away small matters so that he

may take up the business which really engrosses his mind.

In his room at the hotel John Abington dragged the most comfortable

chair directly under the two-globe chandelier, lighted a cigarette

from the pasteboard box which he took from his pocket, and pulled

out the leather cigarette case as if this was what he had been all

along preparing to do.

“Got a tack from the upholstery, no doubt, for a stylus,” he

mused. “Old car—binding probably loose on the door pocket—that’s

where it gives first. H’m! That’s what he waited for. Knew he meant

to escape, of course—saw it in his eyes. H’m! Let’s see, now.”

Abington blew a cloud of smoke and thoughtfully examined the case as

he turned it over slowly in his hand, just as he had done when he

picked it up in the cañon road.

As he studied it his lips moved in that silent musing speech which

was his habit —the black beard offering perfect concealment for his

soundless whisperings.

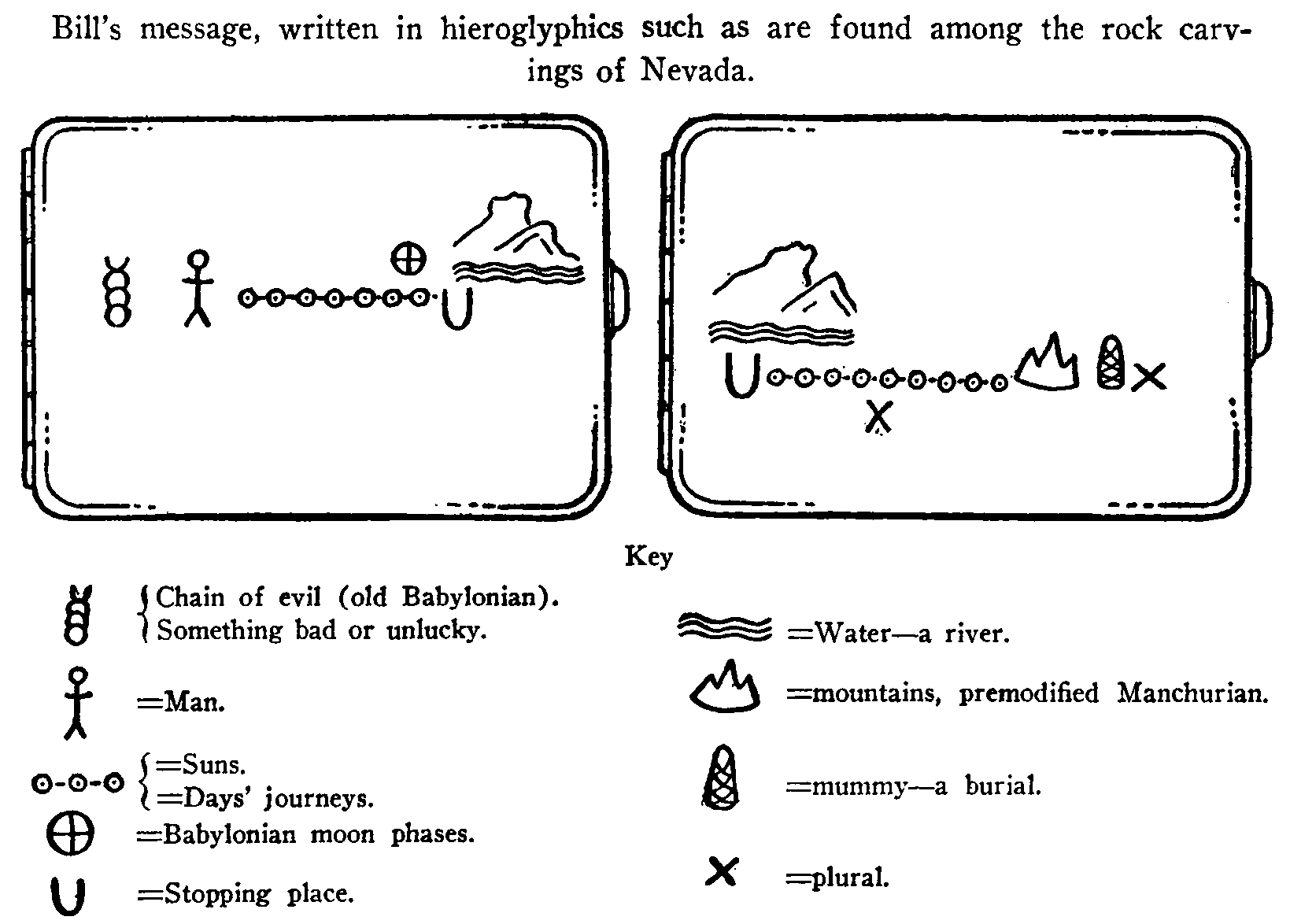

“H’m! Clever of him—hieroglyphics adapted to code work. Let’s see.

The old Babylonian ‘chain of evil’—three links, meaning ‘not so

bad.’ Following that, a man. Humph! That’s Bill himself, no doubt.

“Nest—h’m!—that’s Egyptian; the old Egyptian symbol denoting the

number of days in a journey, but with the Babylonian and Manchurian

moon month at the end. Probably meant a month’s journey, and didn’t

know the sign for it. Bill, my lad, you show intelligence above the

average layman, at least.

“Now, what’s all this? Water sign, mountains, stopping place— Bill

descended to picture writing there, I see! That’s the mountain

across from my camp where I took Bill in and fed him—gave him my

best hiking boots, too, by Jove! My camp by the river— Bill, you

are ingenious!

“Without a doubt you wish me to understand that within a month you

will be at my old camp by the river—counting on more food and more

boots, perhaps! H’m! I don’t just know about that.

“Don’t see how you are going to make it. Handicap too heavy. Doubt

whether I myself could overcome the obstacles—leg irons, officers

on the watch, posses on the trail, three hundred miles to go— Bill,

old fellow, if you make it you’ll prove yourself a man worth

helping! You won’t get half the distance—but if you do, you may

have my next-best boots and welcome!”

Abington turned the case over, held it closer to the light, frowned

and gave a faint whistle at what he saw. He had supposed that the

message had been repeated here as a precaution against his failure

to notice the barely discernible markings in the leather on the

other side.

But as he peered sharply at the fine indentations his eyes

brightened with interest. For although the river and the

stopping-place symbols were repeated, and the string of tiny circles

which signified the number of days’ journeying, the plural sign was

there just below them. At the end of the journey, mountains—but

they were indicated by the conventional, premodified Manchurian

symbol and, close by, the sign of a mummy.

“What the deuce!” breathed Abington, pulling black eyebrows

together. “He’s blundered there—maybe means he’ll leave my camp

only in custody. No, by Jove! That can’t be it, either.”

For a long time he sat motionless except when he turned the

cigarette case for a renewed scrutiny of the other side. The message

that had seemed so simple presented an unexpected little twist of

mystery.

Bill Jonathan, pursued by the chain of evil, meant to journey for

perhaps a month and arrive at John Abington’s camp in the mountains

that bordered the river. That much seemed fairly plain, and one

would logically expect no further information at present.

But there was more to it, apparently. Bill had not sat in that

roadster idly scratching hieroglyphics on the cigarette case of an

archaeologist just to pass the time away. Meaning to escape in the

car, uncertain too of the number of minutes at his disposal, he must

have grudged every second of delay while he worked out his message.

Abington permitted his cigarette to go out while he brooded over

those crude lines. His thoughts harked back to the time, four months

before, when Bill Jonathan had come limping into camp, crippled with

stone bruises from traveling the rough granite hills in thin-soled

shoes worn to tattered leather. He had been hungry, too, by the

manner in which he wolfed his first meal whenever he thought

Abington was not looking his way.

He had not told his name, and Abington had taken the hint and asked

no questions. Bill had called himself a prospector, said he had an

outfit back in the hills and had come down to Abington’s camp to see

if he could rustle a pair of boots and a little tobacco. A likable

fellow, Abington had found him; one of those rare individuals who

can display an intelligent interest in the other fellow’s subject.

Abington at that time had been searching out and recording with a

camera all the ancient rock carvings along the river. While Bill’s

feet were healing he had wanted to know all about the various

symbols and their meanings. He had told Abington of two or three

cañons where writings could be found, and he had discussed with

Abington the possibility of finding petrified human remains—

“By Jove!” Abington ejaculated, straightening suddenly in his chair.

“I wonder if that is not what he means! That we’ll both journey to a

spot in the mountains where I can find my fossilized man!”

The idea once implanted in his mind, Abington could not seem to get

rid of it. Without a doubt, that was the meaning Bill had meant to

convey; that he had found the fossil man which would mean more to

Abington than a gold mine—for such is the peculiar point of view

held by scientists of a certain school.

“Told him that mummy symbol indicated a burial—remember we

discussed it. He recognized the sign from having seen one on a rock.

I told him it undoubtedly meant that some one had been buried there.

H’m! Nothing else he could mean. Wasn’t sitting in that car

drawing marks for fun. Couldn’t write a message. Afraid Park might

pick up the case, no doubt. Too bad—handicapped too heavily. Never

will make it.”

Nevertheless Abington loitered for four days in Tonopah, though he

had no business to hold him there. He heard nothing of an escaped

convict being captured in that part of the country, so finally went

his way.

He had meant to hire more men and carry his explorations over into

Utah, but the sporting instinct for once prevailed over scientific

zeal. He still believed that Bill would never make it—that the

“chain of evil” was too strong. But being an archaeologist, he had

learned the sublime lesson of a patient, plodding persistence that

simply ignores failure. Abington returned alone to a field already

pretty thoroughly covered, and rëestablished his old camp by the

river. There he sat himself down to wait, with a brooding patience

not unlike the eternal hills that hemmed him in.

CHAPTER III

ON THE JUMP

Into the firelight Bill Jonathan came walking one evening, barely

within the month he had given himself in the symbolic message. Face

drawn and sallow, eyes staring out from under his hat brim with a

glassy dullness born of hunger, fever and fatigue mingled, perhaps,

with that never-sleeping fear which dogs the soul of the hunted. But

none of this showed in his manner, nor in his greeting which gave

the arrival a casual note.

“Hello, professor! Got my message, I see. Well, I had one merry heck

of a trip, but here I am.” He dropped down where he could lean

against Abington’s favorite camp boulder—lean there at ease or

crawl swiftly out of sight behind the broken ledge, Abington

observed with that negligent, flicking glance of his. Another glance

dropped briefly to Bill’s ankles, and Bill laughed wryly.

“Didn’t think I meant to wear them things permanent, did you,

professor? Hell, I ain’t no Aztec princess, going around with

anklets on that’d sink a whale. No, I was up at the old Honey Boy

Mine, in the blacksmith shop, setting on a bench with one foot in a

vise, filing faster than a buzz saw when I heard you folks go past,

down in the gulch. At least, I s’pose it was you folks, because it

was a cinch nobody would pass you in the cañon, and I had it doped

out you’d roll down to where you could get water, and come chasing

me up. Hauled my nursemaid on into Tonopah, I’ll bet!”

“I did that.” Abington smiled, tossing Bill his cigarette case

before opening a can of baked beans while the coffee heated. “I

really didn’t think you’d make it, though. Handicap too heavy.”

Bill accepted the cigarette case, pausing to eye with prideful

interest the markings. He lighted a cigarette and relishfully

inhaled three gratified mouthfuls before he spoke.

“If you mean them irons, I didn’t wear ’em long. Just till I could

get the bus up to the old Honey Boy. Wonder you didn’t spot the

place where I turned off—maybe you did. It was on your side the

road.” He saw Abington nod, and grinned appreciatively. “Well, it

rained some that night, and that helped dim the tracks. Nobody came

near the mine; not while I was there, anyhow.

“Friend Park had a fair lot of grub in the back of the car, and I

rustled a little more at the mine. Waited till dark and beat it back

down the cañon and over to Bishop. Made Randsburg, drove the car

over a cliff into a brushy cañon just before I got there, walked in

with an old bed roll I’d fixed up at the Honey Boy, as good a

blanket stiff as the next one! Worked there a week and blew out

again, first pay day—hit it just right, as it happened.

“Hoboed to San Berdoo, doubled back to Needles—hanging tight to my

blanket roll and my time check to show I’d worked not so long ago.

And I’ve been hoofing it up the river since then.”

Abington nodded again and pulled the coffeepot off the coals, using

a crooked stick for the purpose. It may have occurred to him that

crooked sticks are sometimes more useful than straight ones, for he

gave Bill Jonathan an unhurried measuring look as he extended a cup

of black coffee.

“That mummy sign, Bill. Did you mean by that you had discovered more

ancient writings, or did you by any chance refer to skeletal

remains?”

Bill took a great swallow of coffee and set down the cup. His tired

eyes brightened in the fire glow. “Maybe you’d call ’em skeletons,

professor—I’d say they’re rock. All you want. Thought you’d like to

take a look at ’em. So when we met up with you on the way to Carson

I made up my mind I wouldn’t wait till I was turned loose. You might

be to hell an’ gone by that time, or some nosey Adam chaser might

run acrost ’em. I seen last spring how you’ve got your heart set on

finding the granddaddy of all men, or some such thing, and I’d kinda

hate to see anybody beat you to it. So I made my git-away in order

to show you where they’re at.”

Having thus explained the matter to his own satisfaction, Bill

forthwith began to empty the can of beans in a manner best pleasing

to himself.

John Abington poked absently at the fire, gently rapping upon a

burning juniper branch until it broke under the blows, spurting

sparks as it fell into the coals.

“Adam chasers, as you call it, are not so numerous in this country,”

he said softly. “Not nearly so numerous as—er—deputy sheriffs.”

Bill Jonathan leaned sidewise, reached the coffeepot and refilled

his cup. “Yeah, I get you,” he said finally. “But this is wild

country we’re going into. I ain’t taking such an awful chance, now I

got this far. I was duckin’ sheriffs when I found these stone men.

I’ve got to go on duckin’ sheriffs anyway—that, or else let ’em

ketch me and put me in for five or ten years. It’s six one way and a

half dozen the other.

“This is how I’ve got it doped out, professor. You and me throw in

together. I’ll show you Adam—or his wife’s folks, anyway—and you

furnish me with grub and tobacco so I don’t have to show up where I

can be nabbed. I’ll draw on you for supplies and keep along close

without trailing right with you. So you won’t get in bad if it’s

found out I’m in the hills.” He looked across the fire at Abington.

“How’s it strike you, professor?”

Over and over Abington had considered this very point during his

month of waiting. It all depended on Bill himself, he had decided.

Some men are so constituted that preying upon society is second

nature to them. Others fall afoul of the law through no real

criminal intent. There is a vast difference between the two types,

Abington knew. It all depended on Bill.

“I never did function as guardian angel to escaped convicts,”

Abington said with brutal directness. “Laws are better kept than

broken, as you will probably agree, and it ill becomes a loyal

citizen to help any man dodge the penalty for his misdeeds. On the

other hand, even lawbreakers may contribute something to the general

welfare of the world. Discovering the skeletal relics of a man of

the Cretaceous period may not materially help to liquidate the

national debt, but it would be a priceless contribution to the

scientific knowledge of the human race.”

“Yeah, and I can go on and finish that argument, myself. I can’t do

no more damage to society while I’m herdin’ with the coyotes, and if

I can help you find what you’re lookin’ for, that’s better than

loafin’ around doing time in Carson. So you won’t be doing nothing

worse than taking a boarder off the hands of the State. That’s about

the way you doped it out, ain’t it, professor?”

“Essentially the same, yes,” Abington admitted. “I’m glad you have

so thorough an understanding of the matter. I think if your offense

was not too great I could perhaps get you paroled and placed in my

charge, but that would take time and— They’ve just discovered the

skull of an ape man in Rhodesia, Bill! I’d give a good deal to be

able to show them a Cretaceous man found in America.”

Bill leaned back with a sigh of repletion and lighted his second

cigarette. “Well, I dunno how Cretaceous they are, professor, but

they’re fossils all right enough. Stone, anyway, way back in a

cave—you have to crawl on your belly quite a ways, where I went in.

I guess maybe there’s another opening somewhere. I didn’t look for

it. I had pinon knots for torches, and I lit a fresh one soon as I

come into this chamber—or cave. And when the blaze showed them

stone skeletons— Say, professor, I backed right out the same way

I’d went in!”

“How do you know they were fossilized? They may have been modern—no

more than a hundred years old! They may even have been frontiersmen

trapped in there while trying to escape from hostile Indians.”

Abington’s tone was crisp.

“I went back,” Bill declared calmly. “Got over my scare and wanted

to see for sure whether them skeletons was twelve feet high like

they looked to be, or just plain man size. So I looked good, next

time in. There was four, and the biggest wasn’t over eight feet. And

they was solid stone, far as I could tell.”

“I don’t suppose you could describe the geologic conditions—I shall

have to determine that, of course, when I arrive at the spot.”

During five minutes Bill smoked and silently eyed the archaeologist,

who sat meditatively tapping another burned stick into coals.

“One thing I better tell you, professor,” he ventured at last,

vaguely stirred by the rapt look in Abington’s dark eyes. “There’s a

lot more to it than just arriving ‘at the spot,’ as you say. When I

went into that cave, I was scared in. There’s something up in there

that got my goat. I beat it outa there—that’s how I got nabbed by

the law.

“I can’t tell you what it is, professor. Some kinda animal. Makes

tracks like a mountain sheep—but it ain’t a sheep; or if it is— All

I can say is that us Adam chasers will have to keep our eyes

peeled.”

CHAPTER IV

THE FOOTPRINT CLEW

Abington stood absolutely motionless with his head drooped forward,

his narrowed eyes surveying with brief, darting glances his

devastated camp. The small brown tent, lying in a tattered heap with

slits crisscrossing one another in the balloon silk which was so

light to carry—and so costly—received a second scrutiny. The camp

supplies, which had been neatly piled just where he had unloaded

them from the two burros that carried his own outfit, were strewn

about in indescribable disorder, as if a drove of hogs had held

carnival there for an hour or so.

Because of the view it gave of the fantastic, red-sandstone crags

across the valley, Abington had pitched his camp on a smooth hard

ledge a few feet above the level with a cliff at his back and a

spring of good water hidden away in a tiny cleft in the cañon at his

right. It was a cool, sightly spot, free from bothersome ant hills

or weedy growth that might harbor rattlesnakes or other venomous

creatures.

True to his word, Bill Jonathan camped apart from Abington. In this

particular location he had chosen a cave half a mile up the

cañon—and he had immediately set about walling up the entrance so

that he must squeeze in between two rocks which he could move across

the aperture at night.

“Getting close to the range of that gosh-awful thing, professor,” he

had explained. “Better hunt a hole yourself and crawl into

it—’specially at night. And you want to keep your eyes peeled, and

don’t go prowlin’ around without your gun or a knife or something.”

Abington liked his little brown-silk tent, however, and he was not

particularly impressed by the gosh-awfulness of the thing which Bill

Jonathan could not even describe—he having failed to catch so much

as a glimpse of it, as he had been forced to admit under Abington’s

repeated questioning.

Here was the ruin left by some animal, however, and Abington found

himself completely at a loss as he circled the camp, going slowly

and studying the wreckage foot by foot. On the ledge itself he did

not expect to see any tracks. He walked therefore to the edge of the

hard-pan and examined the softer gravel at the foot of the two-foot

slope.

There, cleanly outlined in a finer streak of red gravelly sand, he

discovered the imprint of a pointed, cloven foot; a gigantic sheep,

by the track, or possibly an elk, though elk were not known in that

country.

For some minutes he stood there looking for other tracks. When he

found one, he whistled under his breath. From the length of the

stride indicated by that second hoofprint he judged that this

particular animal must be considerably larger than a caribou.

“Gosh-awful” it certainly must be!

Abington stared down the wash, for a moment tempted to follow the

tracks. But with night coming on and an empty stomach clamoring to

be filled, he hesitated. There was the wrecked camp to set to rights

and such supplies as had not been destroyed must be gathered

together and placed where this malicious-minded animal could not

reach them again.

Moreover, the tracks might not be fresh, for the damage could have

been done at any time during the afternoon while he and Bill were

exploring a complex assortment of crooked ravines, tangled at the

head of the larger one where Bill had prepared to hole up in gloomy

security.

Abington was thoughtfully regarding a sack of flour that had been

slashed lengthwise and dragged in wanton destructiveness half across

the ledge, when Bill Jonathan’s voice sounded behind him, swearing a

dismayed oath.

“Looks like it’s been here a’ready!” Bill gasped, when Abington

turned and glanced at him.

“Looks as though something has been here,” Abington agreed. “Very

unusual incident, in some of the details. Certain incongruities can

scarcely be accounted for until I have further investigated the

matter. I have had a herd of wild elephants stampede through camp,

and I know the work of every marauding animal from jungle tigers to

the wolverines of Canada. But I have never seen anything quite like

this.

“For instance,” he went on, “the slits in that tent plainly started

from the peak and extended downward, with an upward thrust near the

bottom, leaving a triangular rent. Any horned animal that could rip

a tent like that invariably lowers the head and gores with an upward

toss. So does a hog. Certain indications would seem to point to a

wild hog—or a drove of them!—but I believe the longest slits in

the tent were accomplished while it was still standing.

“You will observe,” he continued, “that the rents are spaced with a

regularity impossible to attain while the material lay bundled in a

heap on the ground. The cloth has not been chewed, therefore it

could not be the work of wild cattle. Moreover, that sack of salt

was not touched. Wouldn’t you suppose, Bill, that any herbivorous

animal would smell the salt and go after it first?”

“Yeah, but it don’t ever touch salt, professor. Not as far as I

know. Did it leave any tracks?”

“Down here in the sand are some enormous hoofprints resembling sheep

or elk tracks, Bill. From its stride the beast must be as large as a

camel.”

“Yeah, and I’ve known it to leave mule tracks behind it!” Bill

declared glumly. “Now, maybe you’ll want to crawl into my cave,

professor!”

“I may decide to let you store what supplies are left, but I myself

don’t fancy caves except for research work. By the way, did you

notice any eoliths in that cave of yours, Bill?”

“I dunno. Killed a scorpion about four inches long and his tail

curled up. You ain’t afraid of bugs, are you, professor?”

Abington gave him a sharp glance, but Bill was innocent and looked

it.

“It doesn’t matter now,” Abington said, “since I shall probably

spend a week or more exploring these ravines. There should be a good

many artifacts left in the caves hereabouts. The carvings indicate

that the ancient people lived here and I have an idea that their

occupancy of this section of the country extended over considerable

period of time. This old Cretaceous sandstone gives every—”

“Yeah, and it’ll give ’em just the same to-morrow, don’t you think,

professor? I’m going to take what’s left of the flour and cache it

away in my cave, and that can of coffee. Looks to me like the thing

was scared off before it finished the job. All the times I’ve saw it

get in its work before now, it sure was thorough! You must ’ave

scared it—”

“In that case I may be able to catch it.”

Abington turned and strode again to where the tracks lay printed

deep in the packed sand. He stepped down off the ledge and followed

the hoofprints, scanning each one sharply as he came to it.

“Hey! You can’t trail that thing, professor!” Bill called anxiously.

“I tried that—once when it was a sheep and another time when it was

a mule. Tracks take to the hills and quit.

“Aw, gwan and find out for yourself, then!” he grumbled, when

Abington merely flung up his hand to show he heard and continued

along the wash. “Won’t be satisfied to take my word—never seen such

a bullheaded cuss. But it won’t be long, old boy, till you’ll be

tickled to death if you’re able to dodge it!”

Dusk deepened. Bill hurriedly salvaged what supplies were not

utterly destroyed, looking frequently over his shoulder when his

work would not permit him to keep his back toward the cliff. It

seemed a long while before Abington returned.

Bill’s uneasiness had reached the point where he threw back his head

to send a loud halloo booming out into the darkness; but at that

very moment Abington came stumbling up to the ledge, leaning heavily

on a dead mescal stalk while one foot dragged. Bill leaped forward

and pulled him up the slope.

“Rock rolled down the hill and started a slide,” Abington explained

in a flat, tired tone. “Dodged most of the rubble, but one fragment

struck against my ankle. Temporarily paralyzed my foot. Be all right

in a short time, Bill.” He sat down, breathing rather heavily.

“Who done it?” Bill knelt and tentatively felt the injured foot.

“No one, so far as I know. I am not sure, of course, but my

impression is that the slide was purely accidental.”

“See anything of your sheep?”

“Too dark to detect any signs after it took to the rocks. Heard

something—up the hill. Couldn’t exactly locate the sound. Any

coffee, Bill?”

Bill had been itching to get back to his cave and make coffee there,

but now he looked at Abington and hesitated. Neither Abington nor

any other man could laugh at Bill and call him a coward. There had

been a small pile of firewood; it was scattered around somewhere

among the débris. The coffeepot, he knew, had been flattened as if

an elephant had stepped on it; but he could find a can that would

serve.

He groped for the wood, found it and got a fire started. A cheerful

light pushed back the shadows, making them eerier than when all was

gloom. He set about supper of a sort, keeping his back to the ledge

with a persistence that might have amused Abington if he had not

been wholly occupied with the mystery that had impinged upon an

otherwise uneventful trip.

“I can’t fathom it,” he said at last, speaking half to himself. “It

is not a mountain sheep, I’m certain of that. Those slits in the

tent and the salt sack ignored—those two details alone place the

depredations apart from the work of any such animal.”

“Yeah, there ain’t no such animal!” Bill looked up to remark. “Now

you know why I wanted a gun, professor. You thought it was for

killing sheriffs, maybe, but you was wrong there. I told you there

was something up here we’d have to look out for. I asked you to get

me a gun, because I ain’t got much hopes of killin’ this thing by

throwin’ rocks at it. That’s why.”

“I’m sorry, Bill, but I really couldn’t buy you a gun,” Abington

told him gravely. “And I don’t think you will need one. The beast

keeps himself out of sight, it seems. It isn’t likely to attack

either of us.”

“Well, I’d about as soon be attacked as scared to death,” Bill

demurred. “That’s just it, professor. I wouldn’t give a cuss if I

could look the thing over, once. What I hate is coming in and

finding camp demolished and the grub all throwed out and nothing you

can fight back at. Well, here’s your coffee. It’s about all I could

find to cook, in the dark.”

They drank the coffee in silence, even the self-contained Abington

pausing every minute or so to stare into the darkness, listening. It

was a nerve-trying pastime which netted them nothing in the way of

enlightenment.

What it cost Bill to shoulder a load of more-or-less damaged

supplies and go off alone up the cañon, his way lighted only by the

stars, Abington could only guess. In justice to the peace officers

of the county he could not give the man a gun, and he sensed that

Bill was really afraid of the unknown marauder, and with good

reason, Abington was forced to admit.

Bill had been hunted from camp to camp by the thing which he had

never seen. He had been robbed and his food supplies destroyed until

at last he had fled the place only to fall into the hands of the

watchful sheriff. Abington couldn’t blame Bill for his fears. All

the same, Abington did not want to place a gun in the hands of an

escaped prisoner. That, it seemed to him, would be going rather

strong, even in the interests of science.

He was sitting with his back against the cliff with the dying fire

before him, rubbing his numbed ankle to which sensation was

returning with sharp stabs of pain, when Bill came up out of the

cañon mouth with his bundle still on his shoulders and his eyes

staring.

“It’s been to the cave,” he announced in a suppressed tone. “Clawed

out the rocks I walled the opening up with and raised hell with my

stuff. Professor, how bad do you want them stone Adamses?”

CHAPTER V

GALLOPING BURROS

Across the valley the moon peered over a jagged pinnacle, looking as

if broken teeth had bitten deep into its lower rim. That effect was

soon brushed away as the pale disk swung higher, and the blood-red

sandstone peaks stood fantastically revealed in the swimming

radiance. The valley straightway became enchanted ground wherein

fairy folk might dance on the smooth sand strips or play laughing

games of hide and seek among the strange pillars and jutting crags.

Beside the dying fire Bill Jonathan dozed, head bent with now and

then an involuntary drop forward, whereupon he would rouse and

glance sharply to left and right—the habit of a man who knows

himself hunted, a man whose safety lies in unsleeping vigilance.

“Lie down on the tent, Bill,” Abington advised him, after his third

startled awakening. “Lie down and make yourself comfortable.

To-morrow you can watch while I sleep.”

“Aw, I can keep awake, professor. All that climbing around to-day

made me kinda tired, is all. If I know you’re asleep, I’ll keep my

eyes open wide enough.”

“But I don’t want to sleep, Bill. This little mystery must be solved

before we go any farther with our chief business. Couldn’t sleep if

I wanted to.”

“You’ll stay awake a darn long while, professor, if you wait to put

salt on the tail of the thing that haunts this valley,” Bill opined.

Abington calmly knocked the dottle from his pipe and began to refill

it, ready for another long, meditative smoke. “For every problem in

the universe there is a correct answer,” he said quietly. “It is

only our ignorance that makes mysteries of things simple enough in

themselves. A peculiar arrangement of details has given this

‘gosh-awful’ animal of yours an air of mystery, but the explanation

is simple enough, I’ll guarantee.”

“Yeah, but how are you going to find this explanation—that you

think is so darned simple?” Bill stifled a yawn.

“Just as I find the meaning of the hieroglyphics; by studying the

symbols already familiar to me, and from them arriving at the

natural relation of the unknown characters. This thing left tracks,

and it managed to accomplish a certain amount of destruction in a

given time. To-morrow morning I’ll take a look at your cave, and the

answer to the puzzle will not be so hard to find as you imagine.”

Bill mumbled a half-finished sentence and lay down on the torn tent,

and presently the rhythmic sound of snoring hushed the strident

chorus of stone crickets on the ledge.

Until the moon had swum its purple sea and reached shore on the

western rim of the valley, Abington lounged beside the cliff, so

quiet that any observer might have thought him asleep. For a time

his pipe sent up a thin column of aromatic smoke, then went cold;

and after that only the moonlight shining on his wide-open eyes

betrayed the fact that Abington was very much awake.

An owl hooted monotonously in the cañon at his right, probably near

the spring. A coyote yammered on the steep hillside across the cañon

mouth, and a little later Abington heard the frightened, squealing

cry of a rabbit caught unawares by that coyote or another.

On a cliff just over his head, shadowed now as the moon slipped

behind the hill, the ancient people he was tracing had carved

intricate tribal records. These had endured far beyond the last

vague legend of those whose valor had thus been blazoned before

their little world, a world that had seemed so vast and

imperishable, no doubt, to heroes and historians alike.

It seemed to him that here was a land well fitted to hold the full

story of these forgotten lives. Could he but find it, and read it

aright, might not his own name be blazoned before his own people—to

be forgotten perchance in ages to come, as these were forgotten now?

The cave that held fast the bones of these ancients lay somewhere in

the bewildering maze of cañons across the valley. Bill Jonathan

would recognize the spot, so he had declared whenever Abington

questioned him. A certain rock on the cañon’s northern rim, shaped

like the head of a huge rhinoceros with two tusks on his snout—Bill

was positive he could not miss it, once he got inside the cañon. The

opening to the cave was directly under the first tusklike rock

spire. A matter of ten miles perhaps, Bill had guessed as he stood

on the ledge and gazed across.

Here on this side were caves and even with the hope of finding the

fossil skeletons Bill had described, Abington had wanted to explore

these before going on. He still wanted to do so, if he and Bill

could manage to hunt down the unknown pillager of camps, or at least

guard their supplies against further depredations. If the raid on

Bill’s cave had been as complete as on his own camp, he would be

compelled to postpone all research work while he plodded with the

burros to the nearest town for fresh supplies. Bill could not go,

that was certain.

At daybreak Abington was planning drowsily to send Bill up the cañon

after the burros, load on what was left of the outfit and cross

immediately to the other side of the valley, where they would

endeavor to find the skeletons first of all and be sure of them

before he went out for supplies. He would then be able to take out

specimens to send on to his museum, thus saving a bothersome trip

later on.

His hand reached out to shake Bill’s leg and rouse him to the day’s

work, when a great clattering sounded in the cañon mouth near by.

Bill needed no shaking to bring him to his feet. As the two

automatically faced toward the noise, there came the three burros in

a panicky gallop out of the cañon and into the open.

In one great leap Bill left the ledge and ran yelling and flailing

his arms to head them off before they stampeded down the valley. The

leading burro, a staid, mouse-colored little beast, swerved from

him, wheeled toward the hills opposite, stumbled and fell in a heap.

The second kept straight on down the valley, the third burro at its

heels. Bill let them go while he ran to the fallen leader.

Though it took but a minute to cover the short distance, the burro’s

eyes were already glazing when Bill arrived. As he stopped and bent

over it a shuddering convulsion seized its legs and immediately it

stiffened. It was dead.

Bill stood dumfounded, eying it stupidly for a moment before he

turned to call Abington. But the shout died in his throat, for his

glance had fallen upon a fresh disaster. The two other burros were

down and kicking convulsively, just as the first had done. They were

dead before he could reach them.

Abington was not in sight when Bill, walking heavily under the

burden of this new tragedy, returned to the ledge; but presently he

came limping out of the cañon and into camp.

“I thought I could discover what had stampeded the burros,” Abington

said, coming up with an indefinable air of surprise that Bill should

be standing there passive with that blank look on his face. “Too

late, again. If it was the gosh-awful, he’d disappeared before I

could get up there. Did you head off the burros? I want to move camp

this morning.”

“Yeah—but you’ll have to git along without ’em this morning. The

damn things is dead.”

Abington looked at him, looked past him to where Bill pointed an

unsteady finger. He got off the ledge and limped over to the nearest

carcass, looked it over carefully, walked to the others and examined

them, and returned thoughtfully to camp.

Bill had kindled a fire and was starting off to the spring with an

empty bucket when Abington stopped him.

“Hey, come back here! Don’t use any water from that spring.”

“Yeah? Where will I use water from, then?”

“From a canteen. I filled two yesterday. The burros were at the

spring this morning and stampeded from there. I can’t be certain

yet, of course, but I think the water is poisoned.”

Bill stared, his jaw sagging. Abington was looking out across the

valley, his eyes narrowed and blacker than Bill had ever seen them.

“I may be wrong, Bill, but we can’t afford to take a chance. One

burro might suddenly pass out with heart failure, but when three of

them turn up their toes in the same way and at the same moment, the

coincidence will bear investigation, I think!”

“How could that sheep thing poison a spring?” Bill’s tone implied

violent incredulity.

“I don’t know. I’m merely stating what appears to be a fact. Three

burros drank at that spring and afterward stampeded out of the cañon

and dropped dead in the open. I’m assuming that the water in the

spring, or at least in the little pool below it, was poisoned. They

must have been scared away, else they would have died right there

near the spring. Yes, I think it will bear investigation!”

“Yeah, but in the meantime we’ve got to have water,” Bill said

gloomily, shaking a canteen gently before he poured a little into

his makeshift coffeepot. “I don’t aim to stick around till my tongue

swells up, doing fancy thinkin’ about a poisoned spring. Suit

yourself, professor, but I’m going to hunt water, soon as we go

through the motions of eating.”

“I suppose in time the spring will clear itself and run pure,”

Abington reassured him with a twitching of his bearded lips. “If we

were to stay here, we could divert the trickle from the rocks and

soon have another pool. But we could never be sure that it was not

poisoned again. No, Bill, we’ll have to get our belongings together

and move across the valley.”

“A darn hard job,” muttered Bill, “packing everything on our backs.”

And he added: “That sheep thing can travel, too; don’t overlook that

fact, professor.”

CHAPTER VI

READY FOR A BLOW

The eastern rim of the valley stood crimson where the westering sun

struck it full, bringing into bold relief each cañon and crag, the

smallest fold and the smoothest boulder; as if a contour map had

been painstakingly modeled on a gigantic scale in red sealing wax,

or as if a world aflame had been paralyzed into utter silence.

Toward that garish pile of shattered hills, Abington and Bill

Jonathan plodded with the low sun at their backs, which were

burdened heavily with as much of their camp supplies as they had

been able to retrieve and could carry.

The start that morning had been delayed until nearly noon while they

searched vainly for some clew to the mystery that had in a few hours

held an orgy of wanton destructiveness in two camps and had poisoned

their water supply and killed three burros. Human malevolence had

been displayed in that last attack, Abington was convinced.

Yet in spite of all his skill, all the careful attention to details

which his scientific training had made second nature, he had failed

to discover the slightest evidence of a human agency at work against

them. Not a sign, not a track, save those enormous sheep tracks

leaving the vicinity of the spring and going off up a narrow ravine

in great strides which made it hopeless to think of overtaking it;

for without water he did not dare attempt any prolonged search. Now,

with a half mile of red sand to plow through before they reached the

first bold hillside, their eyes clung perforce to the seamed, broken

rampart they were nearing.

A dazzling light that flashed and was gone, then came again and

stood motionless for a space while one might count fifteen, showed

high up on a ridge as evenly serrated as a rooster’s comb, and quite

as red. Abington came to a full stop which he made a rest period by

slipping the heavy pack from his shoulders. Nothing loath, Bill did

likewise. The two sat down on the sand beside their bundles, mopping

perspiration from faces and necks.

“Bill, when I get up and stand in front of you, look past me at the

sharp peak just south of the mountain—the first one on the ridge

straight before us. Tell me if you see anything that might be a

reflection of the sun—from a telescope, we’ll say, or more likely a

pair of field glasses. No, don’t look yet. Remember that with good

glasses a man could read the expression on your face, read your

lips, too, if he’s had any training.”

At the first sentence Bill’s face had hardened. “You don’t have to

preach caution to a man that’s been on the dodge long as I have,” he

muttered bitterly, under cover of lighting a cigarette. “Shoot. What

d’you think—that it’s an officer, maybe?”

“I’m not thinking past the field glasses that I believe are focused

on us,” Abington parried, rising and standing so that his back was

to the ridge while he held up his watch before Bill’s face. “He may

think I’m trying to hypnotize you, but it’s an excuse. Look right

past this watch, to a point between the second and third little

pinnacles on the ridge. See anything?”

“Something moved, in the notch just below that pinnacle. I got it

against the sky for a minute. There ain’t any shine, though. Might

have been a sheep.”

Abington put away his watch, stooped and shouldered his pack.

Bill slipped his arms through the rope loops and wriggled his own

burden into place on his back as he got up. “Wouldn’t think they’d

be lookin’ for me away down here,” he said uneasily, after a few

rods of silent plodding. “Not unless you—” He sent an involuntary

glance toward his companion.

“Unless I informed on you when I went after supplies, and arranged

for your capture after I had benefited by your information,”

Abington answered the look. “You don’t really think that, Bill.”

“I don’t know why I wouldn’t think it, if somebody’s planted up

there watching for us with glasses,” Bill retorted, not more than

half in earnest but yielding to the ugly mood born of nerve strain

and muscle weariness.

“Of course, you can think any idiotic thing you choose,” Abington

returned, in that tolerant tone which he could summon when he wished

to bite into a man’s self-esteem. “Any other brilliant ideas on the

subject, explaining why, if I were contemplating treachery, I should

call your attention to that light on the ridge up there?”

“Yeah, I might have one or two,” Bill growled. “I was a fool to

start across here in broad daylight. Now, if they come after me, I

ain’t even got a gun!”

Abington sent a quick, sidelong glance toward Bill’s face. That gun

question was becoming a touchy subject between them. “No, you

haven’t a gun. So you are not quite so liable to a few extra

years—or a chair in the gas house—if you are caught!”

“Well, I ain’t caught yet!” Bill’s upper lip lifted away from his

teeth. “Not by a damn sight!”

Abington gave him another sidelong glance. The snarl was not lost

upon him, though he made no reply. Like many another man who is

agreeable enough in ordinary circumstances, Bill Jonathan’s good

nature did not always stand up under hardship.

That blustery impatience at the physical discomforts of a long

grilling walk was beginning to crop out in Bill, mostly in the form

of a surly ill temper and a grumbling against conditions which

neither could help. Abington had reached the point of gauging the

exact degree of surliness and to set up mental defenses against his

moods.

Bill had taken the initiative in this quest and he was surely

receiving full value for his efforts. From a sporting admiration for

Bill’s daring, and a certain liking for his whimsical shrewdness,

Abington was consciously beginning to chafe at the man’s crabbed

temper; he felt a growing distrust, too, which was yet formless and

only vaguely realized.

He caught himself wishing now that he had asked Park what crime

stood against Bill Jonathan. No use asking Bill; he would say what

he pleased and the other could believe it or not.

“If you’ve got any wild idea of finding out from me where them stone

skeletons is, and then turning me over to the sheriff, you better

revise the notion, professor,” Bill said abruptly, having brooded

over it for five minutes. “I’m nobody’s fool.”

“Then why talk like one?” Exhaustion was beginning to draw a white

line beside Abington’s nostrils and his bruised ankle ached cruelly.

He began to feel that he’d had enough of Bill’s grousing. “You’ve

nothing to kick about, so shut up. I’m doing packer’s work rather

than have men along who might go out and betray you.”

“Yeah. You knew mighty well I wouldn’t stir a foot if you brought in

a bunch of mouthy roughnecks,” Bill growled back. “How do I know

what you framed in town?”

Abington slipped his pack off his shoulders and swung toward Bill

with a menacing glitter in his eyes. “That’s going a bit strong,

even for you,” he said sharply. “If you’ve any reason for

saying that, out with it! If not, I’ll thank you to keep such

thoughts behind your teeth. You’re getting quite as much as you are

giving, Bill Jonathan—and by that I mean to include loyalty and

fair play.

“For all I know,” Abington went on, “you invented the story of

fossilized human remains as a temptation that would insure my

protection and the food you’d need in case you made your escape from

Park. Do you suppose I was so blind I did not see that possibility

from the start? A fossilized man, as you knew, was bait I’d be

pretty sure to swallow. Well, I did swallow it—but not with my eyes

shut, I assure you. Please give me credit for that much

intelligence.

“I took you at your word,” he continued, “and I have played the game

straight. I shall continue to play it square, until I find that you

have lied to me.”

He waited, balanced, ready for the blow he expected. Instead, he saw

the expression in Bill’s eyes change to a grudging mollification, as

if the very abusiveness of the attack reassured him.

“I never said anything to put you on your ear,” Bill hedged

morosely, after an uncomfortable pause. “What are you razzing me

for? I said I wouldn’t be caught and I won’t be. That goes,

professor.”

“Very well, let’s have no more talk about it.” Abington lifted his

pack to his galled shoulders and started on, leaving Bill to his own

devices; wherefore Bill presently overtook him and walked alongside.

The truce held while the clouds flamed with the sunset, a barbaric

pageant that could not rival the sanguine magnificence of that wild

ensemble of towering hills slashed with deep gorges whose openings

were frequently hidden away behind bold, jutting pinnacles.

“Looks like the devil was practicing on these hills, trying to make

a world of his own with nothing but fire for building material,”

Bill observed at last, wanting to appear friendly and awed in spite

of himself before the spectacle. “When God came along and told him

to knock off, looks like the devil just kicked it all to thunder and

dragged his feet through the mess a few times and walked off and

left it like that. Don’t you think so, professor?”

“I’ve heard theories advanced that were not half so plausible,”

Abington replied, his voice once more calm and slightly ironic, as

if he still doubted Bill’s sincerity. “A man could spend a lifetime

in this country without exhausting its archaeological

possibilities.”

“Yeah—or without getting caught,” Bill added, speaking as had the

other of the thing nearest his own heart.

CHAPTER VII

INTO THE BLACKNESS

Bill and Abington came to and entered a narrow, straight-walled

gorge. It had a loose, sandy bottom and every indication that ages

before it had been a watercourse with the floods of glacial rainfall

sluicing down to the valley. Presently Bill, plowing laboriously

ahead to a certain spring he remembered in a cave up this ravine,

gave a grunt and stopped short.

In the peculiar, amethystine veil of the afterglow which lay upon

the hills like a cunning stage effect of, colored lights, he pointed

a finger stiffly to a certain mark in the sand. Abington limped

forward and joined him.

“I see the gosh-awful is here ahead of us,” he said listlessly.

“Well, it will be obliged to wreck us personally this time, Bill,

since all our worldly goods are literally on our backs. We may get a

sight of it at last.”

“That all you care?” Bill stared at him. “Maybe I’d feel that way

about it, too, if I had a gun to defend myself with. You’re making a

big mistake, professor. You’ll see it before you’re through.”

“Possibly.” Abington’s tone was skeptical. “How far is it to the

spring?”

Bill did not reply. He was still staring at the strange tracks that

were too large for any sheep one could imagine, yet not shaped like

cattle tracks, nor much resembling the elk they had discussed last

night. Blurred though they were in the fine sand, they were yet

easily distinguishable to being the same hoof prints they had seen

across the valley.

The tracks did not look very fresh, and after a brief study of them

Abington took the lead, perhaps because he was armed and Bill was

not.

Presently Abington stopped and pointed to a cleft in the rocks.

“Whatever it is, it turned out of the gorge and went up there,” he

said. “Pretty good climbing, even for a sheep.”

“I’ll go ahead and show you the spring,” Bill volunteered and

Abington chuckled to himself.

Bill looked back at him with sullen eyes. “All right for you,

professor—with two guns handy,” he said resentfully. “Put you in

here with just your bare hands and maybe you wouldn’t be so damn

nervy, yourself.”

“I’d probably wait until I saw some danger before I became alarmed.”

Bill muttered something under his breath, and stepped out more

briskly. Both were thirsty, but since they had left the western side

of the valley with one canteen nearly full, the need of water had

not yet become acute. It was the tramp across the valley with packs

too heavy for them that had told on the tempers of the two men—with

Abington’s bruised foot and Bill’s nervous dread of pursuit for good

measure.

The spring proved to be well protected, in a water-worn cave that

seemed to offer excellent shelter. A tangle of nondescript oak

bushes grew near the entrance and drew moisture from the overflow

which, though slight, was yet sufficient for the scant vegetation.

The cave itself was not large, with a fine sandy floor and a lofty

arched roof of irregular blocks of the red sandstone which was the

regular formation of these hills. A lime dyke broke through here and

there in sharp peaks and ridges in a fairly continuous outcropping

roughly pointing toward the river.

Abington slipped off his pack, drank from the spring and sat down

against the wall of the cave to unlace his boot from his lame foot.

Bill began gathering dry twigs and branches and set about making

coffee and frying a little bacon. “We oughta git a sheep or

something,” he grumbled, breaking a long moody silence. “This time

of year there’s generally sheep running in through here.”

“I’ll take a hunt, when my foot has had a rest. We can manage for a

day or two,” Abington replied without looking up.

“Say, you’d be in a hell of a fix if you broke your leg,” Bill

sneered. “You’d starve to death before you’d trust me with a gun,

wouldn’t you?”

“There’s meat for to-night. To-morrow will take care of itself.”

“Yeah, maybe it will—and it’ll leave us to do the same,” Bill

retorted. “What the heck are you scared of, professor?”

“Nothing at all. Not even your gosh-awful. Will you fill that corn

can with water for me, Bill? I’ll try a cold compress on the foot.”

Bill did as he was requested and a sight of the discolored foot

stirred him to sympathy. Abington, he suddenly saw, must have

suffered cruelly all day, though he hadn’t said anything about it.

Bill remembered too that Abington had remained awake all last night

while he himself had slept. But it was not Bill’s way to apologize.

“That’s a hell of a looking foot!” he growled. “Hot water beats

cold. After supper I’ll heat a can of water—”

“After supper I’m going to sleep,” Abington rebuffed him. “Cold

water will do.”

“Have it your way—it’s your foot,” snapped Bill, and relapsed into

his morose silence.

It was not an agreeable supper, and neither spoke while they drank

coffee and ate bacon and fried corn from the same frying pan.

Bill was tired and full of uneasy fears and he bitterly resented

Abington’s action in regard to the guns. He was accustomed to the

feel of a gun’s weight against his hip and the thought of facing

trouble without a weapon gave him an uncomfortable feeling of

helplessness. Add mystery to the hazard, and Bill reacted with a

dread not far removed from panic.

Abington ate and drank his share, then forced himself to explore the

cave with a lamp. He chose for himself a niche in one side of the

wall near the entrance, where he would hear any intruder and would

still be fairly well concealed.

At least, that was his idea when he settled himself in the recess.

As a matter of fact not even his aching foot could keep him awake.

He dropped almost at once into the deep dreamless sleep of

exhaustion. When he opened his eyes it was to see the sunlight

slanting into the cave—a circumstance which at first convinced him

that it must be nearly noon, since the cave opening faced the south

and the cañon walls were high.

After a brief space of mental fogginess, however, his mind snapped

into alertness. He remembered that he had stooped to enter the

cavern; the sunlight bathed the high-arched roof just over his head

and brought into relief certain symbols—left there by the ancients,

he had no doubt.

For a time he lay looking up at the roof, deciphering each crude

character, his eyes tracing the lines which even in that sheltered

place showed the erosion of many centuries. Some of the lines were

dimmed; none retained the sharp outlines left by the engravers.

Now he knew that the cave had a high opening through which the sun

was shining; a common occurrence in that old formation that had

suffered the buffetings of wind and water for millions of years, and

moreover had been rocked and twisted by many a primeval earthquake.

He thought no more of the opening, but insensibly slipped under the

spell of those ancient records, his imagination thrilling to each

new sign as it caught his eye.

The story of a journey was depicted there, a journey of death, he

judged from certain priestly emblems and the sign of burial. Perhaps

they had attempted to depict the journey of the soul, though he

could only guess at that, his speculations revolving around a figure

of a dog or wolf, very similar to the jackal which in the belief of

ancient Egypt was supposed to carry souls across the desert to

paradise. He wondered, searching farther along the roof for further

inscriptions.

Like an old rangeman riding up to a herd of strange cattle,

unconsciously reading the brands and mentally identifying the

owners, Abington could not seem to pull his mind away from that

roof. Beyond the sunlit patch the carvings extended into obscurity

so deep that, stare as he would, he could not distinguish the lines.

A sense of bafflement nagged at him. Just as the cattleman will

follow a range animal for half a mile, seeking the vague

satisfaction of seeing what brand had been burned into its hide,

Abington sat up and put on his boots, and picked up the can of

carbide and miner’s lamp which he used in preference to candles when

exploring dark caverns. He started climbing up a tilted shelf of

rock that offered a precarious footing for a man tall enough to

bridge certain places where the shelf had dropped completely away

and left gaps in what may once have been a steep narrow trail.

From the floor of the cave it looked impossible for anything save a

fly or a lizard to climb to the roof. When he started, Abington had

not expected to do more than reach a point from where he could view

the shadowed writing at closer range. He kept going, however, while

the lame foot protested with twinges of pain that gradually ceased

as the muscles limbered. Presently he stood on a low irregular

balcony, the writings just over his head.

This was something he had not suspected even while lying on his back

studying the roof. He made his way along the ledge, forced to stoop