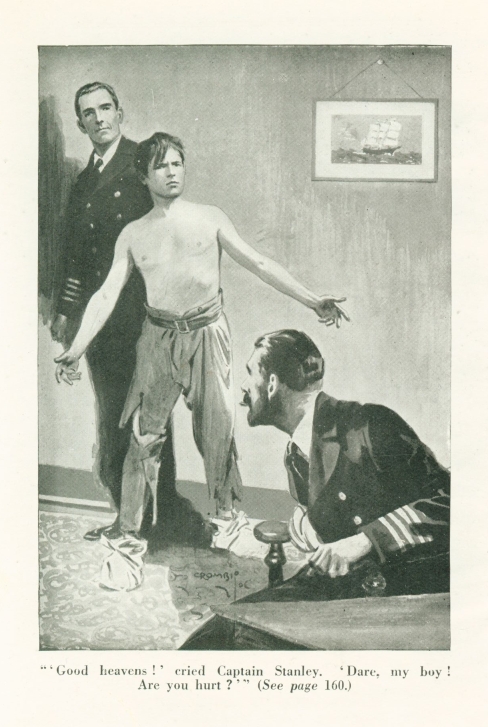

"'Good heavens!' cried Captain Stanley. 'Dare, my boy! Are you hurt?'" (See page 160.)

A Tale of Modern Smugglers

By

E. R. Spencer

Author of "A Young Sea Rover," etc.

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, Toronto, Melbourne and Sydney

First published 1926

Printed in Great Britain

TO

SPENCER LAKE

AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES

OF

FORTUNE, NEWFOUNDLAND

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

2. First Blood to the Smugglers

5. On the Trail

6. Dare's Story

7. In the Night

9. Checkmate!

10. The Escape

CONTRABAND

A TALE OF MODERN SMUGGLERS

The mail packet S.S. Glenbow, ploughing her way up the south-west coast of Newfoundland in a beam sea and half a gale of wind, rolled rail in rail out as she neared St. Lawrence.

Dare Stanley, who had been lying down in his berth, felt the necessity of fresh air, and slipping on an oilskin coat he made his way on deck. The air was fresh enough there in all conscience! He found all but the bridge deserted; the heavy sea made a stay on deck undesirable. Yet he did not wish to return to his cabin, having a desire for company of some sort, so, watching his chance, he fought his way aft to where the smoke-room was situated.

Short as was the trip, he was drenched and had the breath half knocked out of him before he could gain sanctuary. Once he reached the smoke-room he had to exert all his strength to open the door, which was pressed to as with a vice by the weight of the wind. He managed to get it open enough to slip inside, when the door closed precipitately behind him and knocked him half-way across the room.

He was helped to his feet by the chief engineer, who was seated at a card-table with the captain and two passengers. Three other passengers completed the company.

"Hello, young Stanley!" shouted the captain, who was a friend of Dare's father. "Bit rough outside, is it?"

Dare showed his teeth in a grin for answer, and stripped himself of his oilskins, while the company returned to consideration of the game his entry had interrupted. It was soon finished. The captain, who was partnered with one of the passengers, showed great good humour as he drew in his share of the winnings. Not so the chief, who had lost.

"There ye are," said that disgruntled individual as he paid out. "Man, dear, did ye ever see sich cards in all your born days! If my luck keeps bad I'll have to follow the lead of the fo'c'sle crew and play for tobacco."

This humorous sally was greeted by an appreciative guffaw.

"Speaking of tobacco," said one of the passengers during the conversational lull which followed, "I'm a living witness that the only way you can get rid of it on this coast is to give it away."

"That's so," agreed his companion. They were both, it seemed, representatives of tobacco firms. "And of all the places on the coast Saltern Bay is the worst."

"It's a crying shame!"

This topic in lieu of a better was seized upon as likely to yield something of interest.

"How's that, Mr. Parsons?" said the captain insinuatingly.

"Smuggling," answered Mr. Parsons tersely, and all the company, including Dare, pricked up their ears. For although this was a perennial subject of discussion, it never failed to rouse interest, for the simple reason that it touched nearly everyone's feelings or pockets, or both, in one way or another.

"Smuggling, sir," repeated Mr. Parsons. "Saltern Bay is a hotbed of smugglers. Mind you, I don't mind a man bringing in a little brandy or tobacco on the quiet free of duty, but when you get a gang of men organizing a regular supply of the stuff and thus undermining the legitimate trade of the country, then I say it's time to stop it."

"You're right," asserted his colleague. "If I had my way I'd blow St. Pierre Colony sky-high out of water. Why we were ever fools enough to give it back to the French when once we'd won it, I don't know. It's been nothing but a thorn in the side of the tobacco business ever since."

"Oh come, Mr. Bayley," protested the captain good-humouredly; "you wouldn't go so far as that surely. St. Pierre is all right. A jolly little town in its way."

"And as for giving it back to the French," put in the chief, "man, there were reasons for that, diplomatic reasons which take no account of individual likes or dislikes. The English had to smooth down the French a little at the time, and the cheapest way of doing it was to cede them St. Pierre and the rights of fishing on the so-called French coast, an injustice to the islanders if there ever was one."

"I'm with you there," put in a passenger who had hitherto remained silent, a merchant from Bay de Verde.

"Well, I'm not worrying about the fishing rights," said Mr. Parsons egoistically; "it's the tobacco rights I'm interested in."

"Of course," said the captain dryly.

"It's come to the time when the Government has got to take action or be for ever disgraced in the eyes of its electors," declared Mr. Parson's colleague somewhat grandiosely.

"Bad as that, is it?" said the captain, intent on drawing both men out.

"Worse," interpolated Mr. Parsons pessimistically. "Do you know the extent of my order for the district between Point Day and Barmitage Bay, captain? A measly five hundred dollars, on a route that ought to yield a three thousand dollar order every month."

"Umph!" The sympathetic articulation came from the chief, who had a just appreciation of figures as such. "Man, dear, the smugglers must be doing a roaring trade," he added, "for there's not a man on the coast that doesna' smoke or chew the weed."

"A true word," said Mr. Parsons sadly. "But what would you? Five out of ten of them do their own smuggling, and the rest are supplied by the smuggling gang. It's impossible to compete with their cutthroat prices."

"A gang, is there?" inquired the captain, who had been up and down the coast for twenty years and probably knew more about Mr. Parsons' subject of grievance than that worthy himself did.

"Of course there's a gang, captain. There must be. There's a regular underground trade."

"What are the Revenue people doing?" put in the merchant from Bay de Verde.

"Bah!" Mr. Parsons expectorated in disgust, then attacked the Service in earnest.

"What do they ever do," he declared, "but send a dinky little gunboat up and down the coast?—a boat that every smuggler recognizes twenty miles away and avoids accordingly. What they need to do is to place men on land, not ten miles off it. Saltern Bay is honeycombed with coves and beaches where the smugglers can land and no one the wiser. Have a few men spying up and down the land. Let them keep their eyes open and find out the smugglers' cache—then make a raid. A few raids and smuggling wouldn't be so brisk, for smugglers can no more afford to lose their goods than other people."

Mr. Parsons' colleague nodded in agreement.

"I seem to remember hearing that the Customs at Saltern attempted something of that kind," hazarded the captain.

"Bah!" said Mr. Parsons. "Old man Johnson, sixty if he's a day, made a daylight trip to 'Madam's Notch' and found half a case of brandy and a few pounds of tobacco. There's those who believe the smugglers placed it there on purpose. I'm one of them. There's others who say that Johnson will never be a poor man if he lives to be a hundred and that the smugglers have made his inactivity worth while. He ought to be kicked out."

"He has been." Dare could not resist the opportunity of being the conveyor of new and interesting information.

Mr. Parsons and his colleague turned surprised looks on their informant.

"What's that!" ejaculated Mr. Parsons incredulously.

"Didn't you know?" said the captain easily, saving Dare the trouble of repeating his statement. "Johnson resigned about three weeks ago. Captain Stanley, this young man's father, has been appointed in his place."

"News to me," confessed Mr. Parsons.

"We've been on the Northern route this past month," informed Mr. Bay ley in explanation.

"Seems to me," said Mr. Parsons after an appropriate silence and a hard scrutiny of Dare's countenance that caused the latter to change colour, "seems to me that I've heard of Captain Stanley before."

"Well, you ought to have done," the chief declared, "for there's not a man on the island has done more to rid the Revenue service of graft and sheer inefficiency."

"Oh, that's the man, is it? There was a question asked in the House about him, I remember. Well, good luck to him if he's bound on cleaning up Saltern Bay. All I can say is that he's got his work cut out, for there's not a cleverer or rougher lot ever swindled the Government out of revenue."

This point seemed to be mutually recognized as bringing an end to the conversation. The subject for the time being was dropped. Soon after, the captain withdrew to visit the bridge, and the chief, grumbling about cheap engines, went to see how those that were serving the Glenbow so well were progressing.

Dare was left with the four other passengers, who were soon drawn irresistibly to the card table. But he paid little attention to his fellow-voyagers. His mind had been stimulated by the recent conversation and was busy formulating guesses as to the real situation in Saltern, and the likelihood of there being some excitement to relieve the monotony he must otherwise endure in a small village where he knew no one.

As the captain of the Glenbow had stated, Captain Stanley was Dare's father, and, more than that, he was something in the nature of a hero to his son. Bred to the merchant service, Captain Stanley had, after twenty-five years of the Western Ocean trade, retired from the sea and accepted from the Government a position as a special inspector in the Revenue Service.

That was five years ago, and they had been busy years, full of incident and sometimes yielding adventure. In the past year or two Dare had been taken a little into his father's confidence, and on one occasion had proved very useful in the solving of a particularly stiff problem centring upon illicit trading. When, therefore, his father had been appointed temporary Customs Officer at Saltern, the real reason for the appointment being the elimination of the smuggling rife in the Saltern Bay district, he naturally hoped to be allowed to take a hand in the affair.

Captain Stanley had gone to Saltern two days after his appointment, but Dare and the captain's old retainer, Ben Saleby, had been left behind, Dare to finish his term at Bishop Field's College, and Ben to attend to the details involved in closing the captain's town house.

Now, however, both were on their way to join the captain.

Dare was an average youth, quick, intelligent, well set up. He had fair hair which lay close to his head and had a tendency to curl. His eyes were blue, the colour of those of most adventurers, and he wore for the most part a winning smile. That smile hovered about his lips as he sat in the smoke-room thinking of Saltern and the work ahead. Things promised well.

The blowing of the siren and the sudden realization that the ship was in smooth water roused him from his pleasant meditations. The ship was making harbour. A glimpse through the port-hole showed him a low point of land. He quickly donned his oilskin coat and went on deck. The ship was now in calm water sheltered by the land. He went forward and watched the town slowly come into view. While he was eyeing it someone nudged his elbow. He turned round to face Ben.

"Hello, Ben!" he shouted, pleased. "Well, we're getting there."

"And about time too," Ben grumbled. "I've seen a windjammer work the coast quicker'n this one."

"What place is this? St. Lawrence?"

"Aye. Weren't you sure? But I fergot; you ain't been this way before."

"That's so. I say, Ben, there was a chap in the smoke-room spouting a lot of stuff about the smugglers in Saltern Bay. He said they were a tough lot. Looks as if there's warm work ahead."

"Reckon the cap'n kin be tough, too," said Ben with an odd touch of pride.

"You ought to know," laughed Dare.

Ben had sailed with Captain Stanley for years and had left the sea at the same time, though it must be admitted it had been with reluctance. Only his loyalty to the captain enabled him to make the break, for the change from bos'n of a ship to major-domo of a town house did not appeal to his deep-water tastes. The monotony of town life was relieved now and then, however, by the captain's Revenue Service activities, for when there was work of a more than usually difficult character ahead, Ben's services were always impressed, to his great content.

"It's only an eight-hour run from here," said Dare.

"Ten on a day like this," declared Ben.

"I hope we'll be able to land," said Dare anxiously. "It's pretty rough."

"We'll lose this sea when we rounds into the Bay," Ben told him. "There's smooth water off Saltern. Never fear, we'll land all right."

"I hope so!" ejaculated Dare.

"I say, Ben," he added, a little later, "do you suppose it's true what that chap was saying about those Saltern fellows being the hardest lot going?"

"I don't disbelieve it," said the old sailor. He put his hand in his pocket and drew out a black-bowled clay pipe of incredible age, and began to fill it dotingly. Dare remained silent while the rite was being performed, gazing the while on the grizzled veteran.

Ben was also "sixty if he was a day," but hard as nails yet. His face, tanned the colour of a barked sail, was battered and ugly, but good nature lit it and made it human and friendly. His short stature, long arms, bowed legs, and slightly leaning-forward posture gave him the appearance of a gorilla; but there the resemblance ended, for under his hardened exterior he had the tender heart of a child.

"There's one of 'em in the steerage," he said when his pipe was drawing well.

"One of what?" asked Dare.

"One of them fellers from Saltern Bay."

"A smuggler?" exclaimed Dare, excited at the possibility.

"That's as may be. He hails from Tarnish. He told me a lot about the smugglin' game."

"Ah!"

"Aye, he knows a thing or two, he do. Know what he said?"

"No."

"He laughed when I asked if there warn't no way of stoppin' the smugglin', and said, 'Not while there's a oven in Saltern Bay,' said he.

"'And what eggsactly do you mean by that?" I asked him.

"'Oh,' he said, 'that's a riddle.'

"'But what might ovens which is meant for cookin' have to do with it, anyhow?' I asks again.

"He laughed a great laugh and he said, 'That's fer you to find out.'"

"Well?" demanded Dare eagerly, as Ben stopped. "What then?"

"Nothing," replied Ben. "That's all."

"It sounds meaningless to me," said Dare. "Do you suppose he was pulling your leg?"

"He might have been and yet he might not."

"You didn't tell him the business we're on?"

"Trust me," assured Ben dryly.

"Well, we can do little but guess about things yet. I expect father will have a few things to tell us when we see him."

"Not a doubt of it."

"Let's see. What time ought we to get there? Eight hours' run. It's two o'clock now. Allow an hour for delay here. We ought to do it by eleven o'clock."

"Aye, around midnight," said Ben.

At half an hour after midnight, the Glenbow rounded Saltern Head and drawing in close to the land dropped her anchor about ten minutes' row from Saltern Quay. The wind had dropped, and the sea under the shelter of the land was quite calm. The town was hidden from sight in the darkness, which was more than ordinarily intense owing to the clouded sky and the lack of a moon. Ashore, the light on the quay blinked its warning, and two or three other late lights showed where the town lay asleep.

A raucous blast of the ship's siren woke echoes between the surrounding hills, but did not seemingly awake the people who lay sleeping between them. Dare, leaning eagerly over the rail with his gaze fixed shorewards, thought ruefully that such a sleepy town was not likely to yield much in the shape of adventure. He had not much time to dwell on that, however. Soon Ben, who had been collecting the luggage and seeing it safely stowed in the boat, which had just been lowered, came up, and they both went to the ship's ladder. A few minutes later they were being rowed ashore.

As the boat shot between the quays jutting out from the harbour, Dare searched the blackness in vain for the gleam of a friendly light.

"Doesn't look as if father has come to meet us," he said to Ben. That worthy merely grunted.

The boat was rowed towards some steps at the foot of the quay on the town side, and they disembarked without further speech. Their luggage was taken out of the boat and placed on the quay by the boat's crew, which then went swinging off into the darkness, leaving Ben and Dare to make their way through the town as best they could.

"Here's a to-do," then grumbled Ben. "No one to meet us and it pitch dark and we not knowin' the road or the house."

"The best thing we can do is to follow the boat's crew," suggested Dare. "It's likely the post office is not far from the Customs."

They were, in fact, housed in the same building. Ben agreed, and picking their way as well as they could, they set off to follow the crew, with only the sound of the others' heavy tread to guide them.

They managed well enough until they came to a turning, and by that time the crew were so far ahead that neither Ben nor Dare could determine which way they had taken. In this somewhat absurd predicament they hesitated, Ben making use of the occasion as an opportunity to air his vocabulary. They were about to go straight ahead, when they saw a light approaching from the turning, and decided to accost whoever carried it. As the bearer of the light approached, they saw that it was a woman. Ben, taking the initiative, went to speak to her.

"Beggin' your pardon, ma'am——" he began.

"I'm sure it's the first time you ever done it, Ben Saleby," came the tart interpolation.

"Why, it's Martha!" exclaimed Dare joyfully. Ben grunted.

Martha, the family servant for twenty years, and housekeeper since the death of Mrs. Stanley ten years before, had in the course of her duties married Ben, to that individual's never-ending surprise and astonishment. They got along very well together, however, having both the same interests—that is, the welfare of the Stanleys, and although Martha, by virtue of her superior position and her longer length of service, was inclined to be tart with Ben now and then, Ben did not seem to mind it. He had been well disciplined on the quarterdeck, and it is to be supposed that he found something reminiscent of his sailing days in Martha's summary treatment of him at times.

"Yes, it's me, Mr. Derek," answered Martha. Dare's real name was Derek, but a tendency during early childhood to dare his acquaintances to dare him to attempt incredible exploits had earned him his nickname, which had in time ousted his real name from use by all except Martha, who was exceedingly rigid as regards the impropriety of misnaming those she served.

"And what might you be doing, Ben Saleby, talking to a female like this?"

"I was goin' to ask the way. We've lost our bearings," explained Ben. Martha sniffed.

"And how might you be, Martha?" Ben asked appeasingly.

"Well enough," said Martha shortly.

Ben nudged Dare's arm and said sotto voce, "In a temper."

"What's that?" demanded Martha, who was sharp of hearing.

"I was saying I hoped the cap'n was well and hearty," stated Ben mendaciously.

"Well, you can keep on hoping," returned Martha. "Your father is kept to the house, Mr. Derek," she explained. "He hurt his leg the other day, and can't use it very well yet. That's why he's not come to meet you."

Dare was concerned to hear this and said so.

"It's nothing serious," Martha hastened to assure him, and turned on Ben.

"Now then, Ben Saleby, pick up the baggage and don't keep us waiting here all night. This way, Mr. Derek," she directed, and the trio took the turning leading to the Customs House, where Captain Stanley was lodged.

They spoke little on the way. Martha was moody and out of sorts, and at that hour none of them had much relish for gossip. As they halted before a high-roofed building with lights showing below and above, Martha spoke, however.

"I might as well tell you both," she said brusquely, "that the captain got his bad leg from the smugglers."

Ben and Dare took this surprising information in different ways. Dare was speechless, but Ben, ever ready to fill such a breach, voiced several full-blooded oaths. Martha turned on him like a virago.

"Less of that, Ben Saleby, or I'll lay this lantern about your head. Yes, Mr. Derek, it's so. They set upon him two days ago when he was gallivanting goodness knows where. He's got a arm broke, too," she admitted.

Dare found speech at this. He knew Martha would make light of the affair, and he felt certain that his father was much worse than she had revealed. He turned on her impatiently, demanding to be admitted to the house and shown to his father's room; and Martha, lifting the lantern high, straightway led him up the stairs to the captain's apartments.

Captain Stanley was in bed, but awake, to receive them. To Dare's relief there was little sign of serious illness to be seen in his father's face.

"What's this about being beaten up by the smugglers?" Dare demanded affectionately when the first few embarrassed moments of their greeting were over.

As he lay in bed, all that could be seen of the captain was his head, but that was clear enough evidence of his character and former profession. The head was round, and the hair on it close cut; the face full and red, the eyes blue and twinkling, the mouth firm but able to relax in mellow moments, the chin square and dogged. A man whom you would like and trust on sight, one in whom you would readily confide, and to whom you would not hesitate to give responsibility.

He smiled at Dare as the latter lightly asked his question so as to hide his real feelings.

"So Martha told you," said the captain. "Yes, Dare, first blood to the smugglers, my boy."

"Hurt much?" asked Dare shyly. He had never witnessed his father helpless before.

"No, no," the captain was quick to say. "My arm's broken below the elbow, and my ankle's sprained a bit, but I'll be as well as ever in two weeks. In fact, I'm going to get up to-morrow, but I won't be able to move about, confound it. But sit down, sit down. And you there, Ben—come in."

Ben had been hanging about outside the door, and at the order he came rolling into the bedroom. He stopped at the foot of the bed and raised his hand in salute.

"Howdy-do, cap'n? Bad news, cap'n. In dock for repairs, I hears."

The captain nodded, still retaining his smile.

"Leakin' bad, cap'n?" queried Ben.

"Oh no," said the captain, and repeated the information he had given Dare concerning the extent of his injuries.

"It might be worse," said Ben, and added truculently, "I'd like to have a go at them fellers."

"And I too!" put in Dare, indignant at the treatment to which his father had been subjected. "How did it happen?"

"That's a long story," said the captain, "but I know you won't go to bed till you hear it, so make yourselves comfortable. Ben, sit down and take it easy while Martha makes you both something hot."

They obeyed, and Captain Stanley wrinkled his forehead in the effort of concentration as he prepared to accede to their wishes.

"In the first place, this is a much more difficult business than I expected," he began.

"Ah!" said Ben, leaning forward with eager interest.

"Yes. These chaps here are a crafty lot, and hard—hard as nails. It's my belief they won't stop at anything short of murder to prevent anyone spoiling their trade. And close! I've never met such closeness. I've been here nearly three weeks now, and I haven't found out a fact that's of real importance, though I've discovered a few things that bear upon the case and reveal the extent of the difficulty we're up against.

"But I'd better begin at the beginning. The day after I landed I took over the office here. The tide-waiter was helpful but not very enthusiastic about my coming. In fact, the majority of the people seem to resent it. The merchants are the only men who are downright glad to see me. There's some resentment naturally at Johnson's being fired. He's lived here a long time and has his home here still. The truth of it is, of course, the majority of the people benefit by the smuggling, for it's not only liquor and tobacco that's smuggled, but commodities like sugar, luxuries (though in a smaller way) such as perfume, and much more extensive than that, the smuggling of gear. But the tobacco and liquor trade is the heaviest.

"This attitude of the townspeople—the place, by the way, is little more than a village—made things difficult for me from the start. Naturally I'd expected to extract a good deal of information from the people, but they won't talk. As for my predecessor in office, I couldn't very well, in the nature of things, expect to learn much from him. He turned over the office to me and left me to work out my own salvation.

"The news of my coming travelled fast, of course, and no doubt the smugglers knew it before anyone else. I received a letter hinting at bribery before I'd been here a week, and when I didn't answer it I received another, threatening me and advising me to go back to St. John's, as Saltern wasn't a healthy place for busybodies. I didn't take any notice, of course. I've been threatened before. I kept on with my work.

"I hired a boat and sailed up and down the coast by day and night. I took long walks on the cliff-head when there was a chance of being unobserved. And last of all, I kept my ears well open, but for all I saw or discovered I might have saved myself the trouble. Nevertheless, I knew that all I had to do was to keep at it. Something was bound to turn up. Someone was sure to talk. Or the smugglers were sure to make a slip or to relax their vigilance some time or other.

"The smugglers and the villagers probably realized this as much as I did, and in the first ten days I was here I became the most unpopular man in the district. They'd all found out by that time that I wasn't to be bribed or frightened off by threatening letters. So they changed their tactics and commenced an offensive. I found myself being deliberately hindered in my work. My boat's gear was stolen and when afterwards I kept the new gear locked up, they sunk the boat at her moorings. The windows of the house here were broken late one night—pure hooliganism, that—and the man who was helping me work the boat gave up the job. And I found I couldn't get another, though I offered big money. Those who would have liked to take the money were afraid. The gang here really dominates the district. They're not outlaws, but they're very nearly becoming so. Of course, there's no police force. A sleepy fat old constable keeps the peace, but he's practically useless except to settle domestic quarrels and to fine people for keeping dogs without a licence.

"I had to deal with the hooliganism alone, but all I could do was to lodge a complaint and guard against similar trouble in future. For a while I was successful. Then I was caught, not off my guard, but in a defenceless position, without a weapon except a heavy walking-stick, for I don't believe in carrying a revolver."

A knock at the door interrupted the narrative at this point, and Martha came in bearing three steaming bowls of chocolate and a plate of sandwiches. She refused to leave the room until the chocolate had been drunk and the sandwiches eaten.

When Martha, satisfied, finally left the room the captain took up the thread of his story.

"By one thing and another I had my attention turned from the coast to what is known as the Spaleen road. This is a cross-country road linking Saltern to Spaleen, and running beyond Saltern to Shagtown, Tarnish, etc., farther round the Bay. It seemed to me there was a great deal of traffic on this road between Spaleen and Saltern. I knew, of course, that the people used it a great deal for the purpose of farming small patches of land in the district, and to cart fire-wood from the hills. But that did not seem to me to account for the large amount of traffic.

"I made up my mind I'd keep a closer watch on it. One day I took up a stand on a small hill overlooking the road three miles from the town, and with the aid of a pair of binoculars spied on all who passed. And I had a piece of luck; for I'd not been there an hour when I saw two horse-drawn carts meet and stop. The men driving them engaged in conversation, and I actually saw a bottle which I dare say contained whiskey change hands, and also a package which looked suspiciously like a box of tobacco.

"Of course, that was a very slight exchange, and I might easily have been mistaken in the articles passed, but I didn't think so then, and later something occurred which proved, or at least made me feel certain, that I was right.

"I began to puzzle out where the traffic had its head. Spaleen, I thought, was too far away to be considered practicable, seeing that the smugglers could have their cache so much nearer Saltern and the centre of Saltern Bay. I decided to examine a road map before I made any further investigations, and returned to town.

"That same day I located a road map in the office and discovered what I might have expected, that the Spaleen road was a devious one, and at two points it approached to within a few miles of the coast between Spaleen and Saltern.

"One of the points was near Spaleen, the other in the neighbourhood of Saltern. I fixed upon the latter as being relative to my suspicions. I suspected the smugglers of having a cache somewhere on the coast near Saltern and that the back-door of this cache gave upon the Spaleen road, which could be made to serve admirably the needs of distribution, as there was a great deal of traffic on it daily and movement of any kind would not be liable to excite the curiosity and suspicion of those who, either by nature of their profession or their sympathies, were antipathetic to the trade.

"The thing I had to do was to prove my suspicion well founded. But the trouble was, how? It's harder to escape observation on a country road than in a city street. I couldn't very well go in the daytime without my every movement being watched. And it was little use looking for a track to the coast on a dark night—and the nights have been particularly dark lately. The only thing to do was to compromise, and set out at dawn, when there were few people stirring. And that's what I did.

"Well, to cut a long story short, I was about four miles from the town and passing a wood when a gang sprang up from nowhere, and jumping on me from behind had me at their mercy before I could strike a blow or even turn upon them.

"They didn't trouble to tie me up but hit out with their boots, and one of them lay about him with a heavy stick. I thought they were going to finish me, but just before I lost my senses I heard one of them shout: 'Don't kill him; Payter said only make him wish he was dead!'"

Both Dare and Ben broke out into indignant speech at healing this, then allowed the captain to finish.

"They dumped me in a bush a gunshot from the road. That's where I was when I came to. I would have been pretty badly situated, for I couldn't walk, if a passing countryman hadn't heard my shouts for help and taken me to Saltern in his cart.

"I sent for the doctor, feeling pretty bad. Apart from my arm, and a twisted ankle, a great number of bruises and two cuts on the head, I was in excellent condition, he told me ironically, and sent me to bed. And here I am."

Dare and Ben, who had hitherto restrained their feelings, now broke into excited comment.

"Of all the dirty, underhand, mean ways of fighting!" exclaimed Dare.

"Did you know any of them, cap'n?" asked Ben, who had for a few minutes relapsed into the language of the fo'c'sle without rebuke.

"No," replied the captain, "I didn't recognize their voices and I didn't see their faces. As I've said, they came on me from behind. And when I did glimpse their faces I was too dazed and stunned to see them clearly. All I discovered was that Payter didn't want me killed, though who Payter is I don't know. I've never heard the name mentioned here."

"He might be the leader of the gang," suggested Dare.

"I've thought so myself," said his father.

"There was no doubtin' but that 'twas the smugglers who bate you, cap'n?" asked Ben.

"Who else would it be?" returned the captain.

"Aye, who?" agreed Ben.

Further discussion that night, or rather that morning, was then resolutely forbidden by Captain Stanley.

"It's time you both turned in," he declared. "We'll talk again later in the day. Now, away with you!"

Obeying orders, they both left the room and retired for a much-needed rest.

"What are you going to do about it, father?"

It was ten o'clock the same day. The captain had carried out his threat to get up and was reclining in an easy chair with his lame leg resting on a footstool. Dare was squatting on the floor beside him, and Ben, whom Martha had driven out of the kitchen, was hanging about in the background in the manner of a faithful watchdog. At Dare's question he pricked up his ears and waited for the captain's answer.

"I suppose you mean, what am I going to do about this assault?" the captain counter-questioned.

Dare nodded.

"Well," said his father, "as a matter of fact I'm not going to do anything—not at present. I could call in reserves, but I'm not going to. I'm going to work this thing out myself. And, mind you, although I'm not a boasting man, I'm going to make someone pay heavily for that licking I got."

"That's the talk," approved Dare. "And as to reserves, why, you've got Ben and myself."

"And very good reserves too," said the captain, his eyes twinkling, "but I don't think I can use them at present."

"You'll be givin' us a rayson, cap'n, no doubt," said Ben, while Dare checked his disappointment as it was about to find expression.

"Yes, Ben, I will," said the captain affably. "To be frank, at present there's absolutely nothing we can do in Saltern. Those chaps are too much on their guard. We've got to play a waiting game. We must wait, as I said before, until somebody talks or the smugglers make a slip. Meanwhile, about all we can do at the moment is to prevent stuff coming in openly, as I'm assured it did in Johnson's time."

"But why can't Ben and I go on with the work where you dropped it?" protested Dare. "I'm a good wood scout if I do say it myself, and Ben can smell a whiskey bottle a mile away, as you know."

"Agreed," said the captain. "But I'm not going to have you two get a dose of the medicine they gave me. And that's all that would happen if you attempted to play my game at present. It's useless, as I've said. You wouldn't be a mile along the Spaleen road before every smuggler in the district would know you were coming. I could, as I've said, call up enough reserves to search the woods and the cliff-head adequately. But I don't want to do that. The time for reserves is when we've discovered the cache ourselves, and can plan a coup that will catch the beggars red-handed.

"No, the thing to do is to play at patience. I've got two weeks or more of enforced leisure in which to think out a plan, and I promise you that at the end of that time things will begin to happen."

"Two weeks!" exclaimed Dare ruefully.

"It may seem a long time to wait for action, but it will soon pass," consoled the captain.

"Cap'n," said Ben, who had been making heavy work at thinking, "there's more than one place to find out things."

"What exactly do you mean, Ben?"

"Well, now, ain't it a fact that all the liquor and things comes from St. Pierre?"

"Certainly."

"Well, cap'n, if you was to ask me I'd say the St. Pierre end was a good place to pick up a little smuggling news on the quiet."

Captain Stanley considered the idea.

"Ben," he said at last, "you're right. There's something in that."

"Aye," said Ben, greatly gratified. "Men will talk, cap'n, especially when havin' taken drink, and where would they be as free in their ways and speech as in a place that's outside the laws of the country they're robbin'?"

Dare, who knew when to listen, did so now.

"Certainly something might come of that," said Captain Stanley, now frankly interested in the action Ben had suggested. "Of course, I shall have to send someone not known to the Saltern people or the smugglers. Now who is there I can give the job to?"

"There's me, cap'n," said Ben modestly.

"There's no one I'd rather send, Ben, but all Saltern will know who you are as soon as you put your head out of doors."

"And what if I don't put it out?" asked Ben.

The captain did not answer.

"Did you meet anyone when you came ashore last night?" he asked instead.

"Nary a one," declared Ben, "except Martha."

"And I've said nothing to anyone about your coming. There's no one in my confidence here. Who came ashore with you?"

"No one but the boat's crew with the mail-bags."

"They may have talked."

"Who to, cap'n?"

"Well, the postmistress."

"Send Martha to find out, cap'n. If there's news of that kind ready to the post-mistress's tongue she's not likely to hide it."

"I'll do it. Ask Martha to come here."

Ben left the room and a few moments later returned, preceded by the housekeeper. The captain explained clearly what he wanted her to do.

"Go down for my letters, Martha, and engage the postmistress in gossip. Find out if she knows anything about Ben and Dare having arrived last night. Don't put a leading question. But there, you'll know well enough how to set about it. You haven't spoken to anyone yourself about their coming here, have you, Martha?"

"Not me, sir. There's no one here I'd want to talk to about your affairs—or my own."

"Good woman. Well, we want to keep their presence here a secret if it's not already known."

Martha left on her errand, and Ben, enthused at the prospect of action, paced up and down the room as though he were on watch at sea once again.

"If there's no one the wiser for my being here, you'll send me, cap'n?"

"Certainly, Ben."

"And what about me, father?" demanded Dare excitedly, breaking into speech at last.

"It's not a job I care for you to go on, Dare."

"Oh come, now, is that fair? I don't want to blow my own horn, but didn't I come in handy on that last job?"

"Yes, you did."

"Well, sir, why not give me the benefit of the doubt in this case?"

"I'm not suggesting you wouldn't be useful, my boy, but I'm afraid of your running too many risks. St. Pierre can be a rough spot at times."

"But Ben would be there."

"Ben would be there, certainly, but you know yourself that you're not likely to be restrained much by Ben's presence."

"That's not saying much for my discretion," said Dare ruefully.

"Well, to be frank, Dare, you are inclined to be over-impulsive, you know. It's a good fault—on the right side. But it might lead to serious consequences on a spying-out-the-land job like this."

Dare jumped to his feet.

"Look here, sir," he said, "I swear if you'll only let me go that I'll take my orders from Ben like I would from you. I won't do a thing that he forbids me to do. Word of honour, sir."

"Well, you seem very keen, Dare, and I'm sure you mean what you say, but even so I can't promise."

"But it's not dangerous work, sir!"

"Not if the men sent know their business. I can trust Ben to be in character—he's never anything else. No one would ever suspect him of being an amateur detective. But if you went with him, you with your soft hands, your educated speech, how would you explain your relation to him? Ben has to pretend he's a fisherman. But that will make your presence seem an incongruity, for you don't look like a fisherman and I don't think you ever will."

"Beggin' your pardon, cap'n, but I think that's easier nor what you make out," said Ben, who was obviously on Dare's side.

"He could go as my nevvy, the only child of my niece who married a clerk in St. John's, who give the boy a good eddication afore he died, and who, leavin' him without a penny, his mother bein' already dead, he was forced to come to me to earn his living, he bein' without friends or pull of any kind, and me bein' glad to have him."

The captain's face twisted amusedly at the construction and the content of Ben's unusually long speech.

"I didn't know you had so much imagination, Ben. It's sound enough, of course, what you say, and as I've said already, there's very little danger in the job if you go about it rightly, as I've no doubt you will."

"Then you'll let me go, father?" demanded Dare eagerly.

"Perhaps. We'll see what Martha says first."

Martha came back with the information that so far as she could discover no one in Saltern excepting themselves knew of Dare and Ben's presence.

"Then that settles it," declared the captain. "You'll continue to keep under cover, Ben, and you also, Dare. If you give me your word not to rush your fences, as the hunting men say, you can go with Ben."

"I'll promise that quick enough," said Dare, overjoyed. "It's awfully good of you, father."

"Well, that's arranged then. I'm not sure you'll accomplish much, but certainly nothing can be lost by trying. Now, as to plans——

"There's one thing certain; you can't start from here. People would be too curious. Besides, you've got to keep out of their sight. You must go to Shagtown—stay here to-day and to-night, and early to-morrow morning slip out of the house before people are stirring. It's a four-mile jaunt to Shagtown, but you won't mind that, especially as you're travelling light.

"At Shagtown, which is somewhat larger than Saltern, you'll not attract much notice. You can tell them you're baymen come to buy a boat. And that, in fact, will be the truth, for that's the first thing you must do. I advise you to buy a stout, decked boat. Ben knows the type I mean. They're much used by the fishermen here. Commission her and leave Shagtown the next day. I don't want you to make the trip to St. Pierre at night, though it is only a matter of twenty-five miles. Ben can find his way there easily enough. We've harboured often at St. Pierre in the old days.

"Don't run up too many expenses, even though the Government is footing the bill. And you're to telegraph me every four or five days 'O.K.,' so that I'll know you're all right. Don't sign it. I give you two weeks. At the end of that time I'll expect you to return whether you've been successful or not."

Dare and Ben listened closely to every word that fell from the captain's lips, nodding repeatedly in agreement and understanding.

"Have Martha pack two of Ben's old dunnage bags, one for each of you. And you, Dare, get out your very oldest and roughest clothes, roughen up your hands a bit and don't wash your face too often. By the time you get to St. Pierre you'll be more in character, though as Ben's 'eddicated' nephew there's not much for you to assume in that way.

"When you get to St. Pierre, Ben, you can talk a bit about your own smuggling propensities. But there, I leave that part of your programme to you. No doubt it will be dictated by what you find happening on the spot."

The rest of that day and the early night was given up to considering ways and means. Both Ben and Dare entered into the adventure in optimistic spirit. The captain, while not so sanguine of their success, was inclined to be enthusiastic about the project. Martha was the only one to disapprove of it. But Captain Stanley won her over with a few phrases, repeatedly assuring her that there was no danger and that the outing could be looked upon in the nature of a holiday.

At three o'clock the next morning, Dare and Ben slipped unnoticed out of the house, the captain's guarded "Good luck!" sounding in their ears.

They took to the Shagtown road with a will, striking into a walk that would bring them to the town in an hour or so. They reached it without having met a single person, and made at once for the quay. They had in a knapsack a plentiful supply of food, and on reaching the quay they chose a snug corner and prepared to eat while waiting for the town to awake.

There was a good deal of shipping in the harbour, from imposing three-masted ships to fishermen's boats such as they themselves intended to acquire. One of the latter lay by the quay near them, and, at the sight of smoke issuing from the small fo'c'sle, Ben suggested asking the owner for something hot to drink, as the morning was a raw and chilly one.

Dare agreeing, they gave the boat a hail, and in response a shutter was pulled back and a bearded, good-natured face appeared.

"Good mornin' to you," said Ben.

"And to you," said the man, eyeing them in a friendly manner.

"We was wonderin' if you was boilin' the kettle and if we could get a drap of tay. We've the money to pay."

"As to your money," said the man, "I want none of it. But you're welcome to take a drap of tay. Come aboard."

They proceeded quickly to accept the invitation, and leaving their bags on deck were soon sitting down in the cramped but otherwise comfortable fo'c'sle. In return for the tea they shared their food, which Martha had put up with a liberal hand. When all three had partaken freely, the two older men exchanged tobacco pouches and prepared to gossip, while Dare, to whom the unusual environment was keenly stimulating, stretched himself out and prepared to listen.

"You're up early on the go," said the boat's master.

"Aye," said Ben. "To tell the truth we got to the town too late, or too early you might say, to take a bed, and was waitin' for sun-up."

"No sun to-day," said the fisherman with a glance up through the companion-way at the grey sky, across which swift clouds were moving. "The wind's from the east."

"So 'tis," agreed Ben, who was very pleased with his surroundings.

"You'll not be Saltern men, I reckon," said the fisherman.

"No," replied Ben warily, "we comes from beyant Spaleen. Name of Wheeler. This here boy is me nevvy. We come to Shagtown to buy a boat."

"And wouldn't you be finding one in Saltern, then?"

"The Saltern boats is not to our likin'. We heard tell that Shagtown is a good place fer boats Barmitage Bay built."

"So 'tis," admitted their host. "This boat of mine is one of 'em."

"I knowed as much from her lines," said Ben. "A good boat, I reckon."

"Aye, good enough," returned the other, then added with some pride: "She can do eight knots in a breeze and you don't have to take in sail until it's too bad weather for any Christian to be out. But she's a little small for my needs."

"Say you so? 'Tis one like her we're lookin' for. She's not too big an' she's got the speed. If you can put us next to one we'd be obleeged."

"Ah, that's easier said nor done," declared the fisherman. He eyed Ben with more interest than hitherto. "You was goin' to pay cash, I doubt?" he said.

"We was," stated Ben; and, his attention caught by something calculating in the other's look, he added: "It'd be the great luck to find a one like this. You wouldn't be sellin' her for a penny, I bet."

"No," replied the man, "but I'm not sure I wouldn't be sellin' her for the right price."

"Ah!"

"She's worth seventy-five dollars the way she stands now."

"A nice price," said Ben. "We was goin' to give sixty, weren't we, nevvy?"

"Sixty," agreed Dare solemnly.

The fisherman seemed to lose all interest in the conversation. He was silent for some minutes, then as though it were no matter of great concern, he said:

"You'd want her fer fishin', I s'pose?"

"Well, in a way," admitted Ben. Then, as though revealing something of importance, he added: "We was thinkin' of runnin' to St. Pierre now and then."

The fisherman nodded sagely in a manner that showed he understood.

"Was you, now? Tobaccy is a big price, 'tis true."

"And so is sugar and whiskey and gear," said Ben.

Quite satisfied now of the character of his guests, the other said: "But they're cheaper in St. Pierre."

Ben nodded. "That's so."

"Eighty dollars, was it, I said I'd take for her?"

"Seventy-five. But we mentioned we was going to give sixty for one if we found her."

"Ah, was it so? 'Tis a pity, but no doubt you'll find one to suit you."

"Aye, no doubt. There's a man I knows here who is well knowledged in boats."

"I'm not sayin' I wouldn't take seventy, mind you," said the fisherman.

"Would you, now? Sixty-five is our limit, ain't it, nevvy?"

"We wouldn't go above sixty-five," agreed Dare.

"Cash, I think you said?" put in the fisherman.

"Cash," repeated Ben and Dare in chorus.

"Then if you're agreeable, we'll make a bargain."

Delighted more than he could say by this opportune offer, Ben stated his willingness and the two immediately put their heads together.

"You can take her over right now," said the fisherman, "if you likes to pay a extry five dollars fer the cookin' gear and stove. The dory, of course, goes with her."

Ben was agreeable. By taking over the boat practically ready for sea, they would save time and money. He suggested that they should go ashore when the bank opened, and sign the necessary papers in the presence of witnesses. And this they did, leaving Dare in charge.

By ten o'clock Ben was the owner of the boat and was in possession. And by noon they had provisioned her and made her ready for sea. Before taking leave of them the fisherman wished them good luck, and advised them when they went to St. Pierre to trade at Giraud's. "You can't do better," he told them.

At this time the wind was blowing a good steady breeze from the east, which meant a fair wind for St. Pierre, and Ben, who had examined the sky closely, was inclined to put to sea immediately.

"We've done the business of buyin' a boat much quicker'n the cap'n expected," he said to Dare. "If we can work out of the harbour, and I think we can, though the wind's blowin' in a bit, we could make the run to St. Pierre in three hours. The weather's clear and there's no sign of worse to come. What do you say, Mr. Dare?"

"The quicker the better," replied Dare; "to-morrow the weather may not be so good."

"Then get ready, and put on your oilskins, for it'll be wet outside."

Dare obeyed and in half an hour the boat, named the Nancy, cast off.

They had difficulty in working the boat out of the harbour, but under reduced sail and Ben's expert handling they eventually managed it.

Once they were far enough off the land to clear Shagtown Cape they had straight sailing, and shaking out the reef in the big foresail they settled down to the short voyage. They passed Saltern a mile from the land, which was skirted by the white foam of breaking seas.

The boat gave an admirable exhibition of her qualities and proved her late owner's boast correct, for with a fair wind and a following sea she did her eight knots in grand style.

Dare and Ben had an opportunity to observe the Saltern coast, and found it wild and rugged. Cliffs ranging from two hundred to four hundred feet in height rose uncompromisingly upright from the sea, but were broken at points by intersecting small sandy beaches which gave upon less precipitous backgrounds.

Except for a solitary merchantman beating her way towards Shagtown, they had the sea to themselves, for the weather was too rough for the local fishermen to go to their trawls and nets.

Ben gave Dare the tiller of the Nancy and turned a pair of binoculars on the Saltern cliffs, subjecting them to a long, close scrutiny. Except for a few sheep and goats, and a fisherman's cottage or so in lonely, desolate-looking spots, there was no sign of life or human habitation. A rugged, solitary coast it certainly Was.

Further from Saltern, however, the coast became more pleasing to the eye, and sloped down more gradually to the sea. Ben, at this point, took the tiller again and changed the course a little. Miquelon, the companion island of St. Pierre, could be plainly seen, as could Green Island, and setting his course by the latter Ben turned the boat's head definitely from the land. This necessitated taking in some sheet and subjected the boat to a rough beam sea. She was, fortunately, in good ballast, and had little to fear from the press of wind bearing her down heavily as she sank into the hollows. Dare, who was with Ben in the cockpit, the deck at a level with their waists, welcomed the rough water. The sting of the spray, the roar of the wind, stimulated him to a high degree, and enjoyment swallowed up any concern there might have been as to their safety.

Ben, chewing with gusto a plug of tobacco, was in his natural element. He had not enjoyed himself so much for years. Now and then he gave a grunt of approval as the boat rose gallantly from under a breaking sea, but for the most part he was stoically inexpressive, his gaze fixed ever ahead, his capable hand hard set on the tiller.

At four o'clock they brought open the roadstead of St. Pierre harbour, and half an hour later, in half a gale of wind and a blinding rainstorm, they made the inner harbour.

Considerably elated at their successful run, they headed the boat towards the public quay next Treloar's wharf, and in calm water tied her up and made her shipshape for the night.

"Four hours an' a half from one quay to t'other," said Ben in high good humour. "Now we'll go below and put the kettle on and have a cup o' tea."

It was snug and cosy in the little fo'c'sle and Dare, stripped of his oilskins, listened with growing pleasure in his environment to the wail of the wind, the beat of the rain, and the uneasy chafing of the boat and the shipping in her vicinity as the wind streamed through their rigging.

Now and then there sounded a long warning note from a siren, a dog would bark, and a solitary cart rattle by on the cobble-stoned quay.

A stormy night, Ben prophesied, but as they were snug in harbour they could ignore the weather. Ben, like the seasoned campaigner he was, went about the business of boiling the kettle, and in a short time he had fashioned a delectable meal consisting of a roasted piece of cod fish, cold ham, pickles, bread, butter, jam, and tea, all tasting a little of smoke and the tang of salt water.

Dare, as he consumed prodigious quantities of this fare, felt he had never supped better in his life. After the meal was finished he made himself useful and washed up. Ben filled his pipe and took his pleasure of it. His work done, Dare stretched out on a blanket. For awhile both he and Ben maintained a strict silence, listening to the steady drip of the rain on deck.

"We won't telegraph the cap'n till to-morrer," Ben said at last. "He won't be expectin' us to get here before then. As it's a dirty night and'll be dark early, we won't go ashore now but take our comfort here."

Dare, lying on his back, his head supported by his clasped hands, nodded contentedly. St. Pierre was lying waiting for him. He could afford to be patient. There would be all the joy of discovery in watching the town awake next morning.

"Ah, these is good times, Mr. Dare," said Ben after another silence. "It does my heart good to be lyin' here like this. Many's the time I've laid me down to sleep to the sound of wind and water, and woke to hear the cry of the watch, and the sound of the waves striking like a steel hammer on the deck overhead. And other nights there was when I took me blankets on deck and laid me down under the stars, with the sea that smooth you could frame it like a picture with the horizon, and the air that warm an' soft you would be thinkin' you was in the tropics, instead of in the Western Ocean not two days sail from the Azores."

Dare nodded dreamily, Ben's voice like distant music in his ears. What boy has not had his imagination sent rioting by thinking of such things? A fine life, a clean life, a brave life, that of the sailor, with strange ports always lying ahead, and the sea, the vast sea always about one, bringing calm and storm, monotony and drama and adventure.

He slept that night the sleep of eager youth and dreamed rosy dreams of the things he should do some fine day when he came into his kingdom—that delectable world which lies before youth when it attains the age of manhood and emancipation, that bright, that chivalrous age of twenty-one.

Early the next morning he was roused by Ben's shout of "show a leg!" He tumbled out eagerly. Ben had already kindled a fire. He shoved his head above deck and saw the town wrapt in a morning mist, and on the waters of the harbour the dimly seen hulls of the ships.

There was a nip in the air that drove sleep and dreams from him and made him keen to launch forth into action and adventure. He went on deck, and drawing up a bucket of water plunged his head deep into it. His toilet was soon made. He grinned as he remembered that for the first time in his life he had an adequate excuse for not scrubbing his face. When he had finished he went to the fo'c'sle head and called down to Ben.

"Brekfus is not ready yet," Ben told him. "As you're up there you might as well wash down the deck and take a turn at the pump."

While he was doing this the mist rolled away and the sun appeared as if by magic, gilding the town and the shipping with early morning beauty.

The boat was too far below the quay for him to see anything but the upper stories of the buildings facing the harbour, so he had to content himself with gazing upon the latter and the variegated shipping that filled it. Steam trawlers, coal tramps, American deep-water fishermen, Newfoundland Bank fishermen, cargo boats, sailing and steam yachts, steam tugs and a host of smaller craft filled the basin.

He gazed on this scene as he had so often gazed on St. John's harbour as seen from the college windows, admiring the beautiful lines of some of the vessels, the ugliness of others, indeed their endless variety.

He was torn from this pleasant exercise by the call to breakfast. After the meal was over they loosened the sails and shook them out to dry, then prepared to go ashore. By this time the town was well awake. At a neighbouring quay one vessel was discharging coal and another produce, both of which commodities were being loaded on to antiquated ox-carts drawn by even more antiquated oxen. Numerous dogs were barking and pretending to be fiercely excited by pieces of stick floating in the water, and one after another were diving off the quay, encouraged by errant bakers' boys and other seemingly unattached youths.

The sound of strange speech struck the ear, a French that Dare could hardly believe was the same language he was taught at school.

In time they prepared to enter this strange world. Ben locked up the fo'c'sle, asked the crew of a nearby boat to keep an eye on the Nancy, then, followed by Dare, climbed up the side of the quay and stood erect on dry land.

The town of St. Pierre has been formed by the needs of the visiting sailors and fishermen of France, America, and Newfoundland. Old as age goes in the Americas, the remains of the English fortifications can still be seen, but now by the Treaty of Utrecht, no garrisoning or fortification of the island is permitted. Its architecture is such as one finds in the seaports of Brittany and sea towns such as Marseilles. There has been a rich trade done there in its day, but its importance has declined with the importance of St. Pierre et Miquelon as a colony, the only French colony in the Atlantic, and little more in reality than a station for her Bank fishermen.

But enough remains of the colony's importance to ensure a brisk trade in the summer months when the population is greatly augmented by the visiting fleets.

The principal street is known as the waterfront. It runs parallel to the quays and is flanked by numerous cafés, shops, and marine stores.

Breaking it about half-way is a large square with a decrepit fountain and an uneven, cobble-stoned pavement. It was into this square that Ben and Dare stepped on their first visit ashore.

Ben, faced by several routes, stopped to consider his movements.

"We can't do better than walk a little way along the waterfront, and drop in on Madame Roquierre," he said. "It's a little early for the cafés, but madame is always on hand night and day."

Dare, to whom even the name of Madame Roquierre was unfamiliar, nodded agreement, and they sauntered on their way. The waterfront presented a very animated scene. Scores of sailors strolled up and down, proprietors of magasins and cafés stood outside their premises exchanging salutations with the passers-by and not omitting to call attention to the exclusive benefits patronage of themselves would bring, teams of oxen plodded slowly by, and gendarmes strolled on their rounds, keeping a vigilant eye on one and all.

Ben had little eyes for so familiar a scene, but to Dare every detail was foreign to anything in his previous experience and therefore worthy of interest and attention.

They eventually reached Madame Roquierre's café, a large square box of a building with a prevailing atmosphere of sour wine inside and out. The bar was empty except for an old manservant busy raising a cloud of dust. In response to Ben's inquiries after madame, he answered, "Elle est sortie."

Dare recognized the phrase and translated it for Ben's benefit.

"Out, is she?" said Ben. "Well, it's no matter; we can come back again." They returned to the waterfront.

"The madame," explained Ben, "is a wise old bird. She knows everyone and everything in St. Pierre. She's kept that there grogshop of hers for forty years and more. Although it's ten years since I've been here, I'm willin' to bet she can remember me. Aye, that's so. You might think I wouldn't want to be remembered as a bos'n of the cap'n's. But you'd be wrong. Madame ain't the one to blab, and when I tells her that I'm named Wheeler an' that I wants everybody who knows me to forget they've seen me before, she'll catch on as quick as anything. Nothin' can't surprise her. She's seen too much in her time. I'm countin' to hear a bit from her about this end of the smuggling game. And maybe she'll be able to give us a few names. We'll go to her fer our dinner and supper—she keeps a good kitchen, as I knows of old. It ain't convenient to eat aboard all the time."

Dare welcomed this plan and said so, it being likely to offer them diversion as well as benefit their mission.

They spent the morning sauntering from quay to quay in the manner of others of their kind. Now and then they were drawn into conversation, and on such occasions responded genially and with that seeming openness most likely to inspire confidences. At noon they went to the telegraph office and cabled the captain. They then returned to the quay and had a look at the boat. Then they wended their way once more towards Madame Roquierre's.

All was changed now. The bar was fairly crowded, and through the swing door leading to the kitchen came a delectable odour, and a burst of sound comparable to that attendant upon the feeding of a battalion.

Ben pushed through the crowd at the bar, Dare in his wake, and went into the kitchen. There, presiding over the distribution of an enormous tureen of soup, was Madame Roquierre. She was stout, possessed a heavy moustache, and very white teeth which were often revealed in an excess of geniality. She found time, amidst her other duties, to greet everyone who entered, and Dare and Ben were no exceptions. Ben called out a "bonjoor, madame," while Dare silently gave an imitation of a bow.

They took seats at a long table already well filled, and as soon as they were seated immense bowls of soup were placed before them. The soup seemed to Dare to contain nearly every known vegetable, but decidedly it was good. Ben attacked it with gusto, and before long Dare was following his example.

"Never anything else here in the kitchen but soup," said Ben. "If you want other things they're special. But after a bowl or two of this you don't want much. I come here because it would look funny our askin' fer a private room. We're not of that sort now. But later I'll have a talk with madame and we can have what we like here in the kitchen."

After the soup they ordered coffee, and sat so long over it that the room was practically empty when they rose to go. Before they could reach the door, madame confronted them.

"Bon jour, messieurs," she said genially. "Ah, I have seen you before, my fren'," she said to Ben, and wrinkled her forehead in an effort to remember. "So! It was with the capitaine——"

"No names, madame, if you please," interrupted Ben. "I'd take it as a favour if you'd fergit you've seen me before."

"Hein? Ah, so, I see! Eh bien, it is as you say. You stay long?"

"Two weeks, perhaps. Perhaps less."

"So! It is well. You shall come to see me again, is it not?"

"We was thinkin' of takin' dinner and supper here, madame."

"Good," declared madame. "But stay, you will drink a brandy?"

Ben, who looked upon the offer of hospitality as most favourable to his intentions, accepted.

"And you, m'sieu?" said madame, turning to Dare.

"Nothing, thank you," replied Dare.

"But a sirop," insisted madame, "a bon sirop." And Dare perforce could do no other than accept.

They seated themselves again at a table and madame, who was inclined to gossip, joined them.

"It is long, I think, since you came last," she said to Ben.

"Aye, madame, ten years."

"Ma foi! How the time it goes! And you sail no more with the capitaine who shall not be named?"

"That's so. I got a boat of me own, madame. Me and me nevvy here, we intends to run between St. Pierre and the mainland. Tobaccy is dear on the mainland. Savvy?"

Madame smiled wisely.

"There is light," she answered. "So, you also, hein? Well, and why not? The poor should not have to pay taxes."

"You said it, madame."

"Tobacco, you have said. And wine, yes?"

"Liquor, madame, is like tobaccy. If you got to have it, get it cheap."

"So you are wise. Now I—— Well, my fren', I have a large cellar. Vous comprenez? And you shall do as well by me as at that ol' thief Giraud's, who boasts he has all the trade of such as yourself."

"I've heard of Giraud," said Ben cautiously.

"A thief, my fren'. I have said it. And it is not true that he has all the trade, for, mark you, I, Roquierre, say it—Pierre has taken from me no less than one mille of the three-cross brandy since two years."

"And who might Pierre be, madame?" Ben made the mistake of inquiring.

Madame's expression changed the slightest bit. A curtain of reserve slowly descended.

"You know not Pierre?" she asked, a little surprised.

"Never heard of him," admitted Ben. "A smuggler, is he?"

Madame rose to her feet, smiling enigmatically.

"A smuggler?" she said. "But what is that? Here we name not such things. If one wishes to take a bottle or two quietly, ma foi, is he then to be called a smuggler?"

"What else, madame?"

"It makes nothing," madame quietly answered. "We talk of other things, n'est-ce pas?"

"But this Pierre feller?" insisted Ben stupidly.

Madame eyed him for a moment, then leaned forward impressively.

"Understand, m'sieu, one does not talk lightly of Pierre to those who know him not. So, enough. I have already said too much. Au'voir, messieurs. You are welcome always, and forget not what I have said of Giraud."

She gave them a guarded smile and left the room. Ben watched her go without a word, then, beckoning to Dare to follow, made for the street.

"Well, we didn't get much forrarder there," he exclaimed ruefully, as he stood in the street outside.

"You went about it in the wrong way," said Dare impatiently. "If you hadn't asked her who Pierre was, she would have been telling you all about him in a few minutes."

"Aye, I reckon that's so," agreed Ben, abashed. "What a dunderhead I be! Why didn't you stop me, Mr. Dare?"

"I didn't have a chance. Madame, as you've said, is a wise old lady," he added. "She thought it was queer your not knowing Pierre if you were a smuggler. Pierre, who took no less than a thousand cases of brandy from her in two years!"

"Aye, I reckon it seemed funny," said Ben humbly. "But anyhow, we got somethin' to go by, we can keep a look-out for that feller Pierre."

"That's so, of course. He must be a smuggler in a pretty big way, don't you think?"

"There's no tellin', but it seems so. A thousand of brandy from one cellar in two years is not bad work, not to mention what he might have had from Giraud."

"Of course, he may be running cargoes down the coast, and not in Saltern Bay at all."

"That's what we've got to find out. One of the first things we got to do is see Giraud."

"We might go up there later in the afternoon."

"Aye. And to-night I'll try and get on the right side of madame again. I don't believe she thinks I'm not what I give myself out to be."

"No," agreed Dare. "But you'll have to go carefully there. It's my belief it's no use trying to pump her now. She'll be on her guard. Still, it won't hurt to quieten down her suspicions if she has any."

"You said it."

In a few minutes they had reached the quay. The Nancy was lying almost level with it on a flood tide.

"What shall we do now?" asked Dare.

"I was thinkin' of takin' a nap," confessed Ben. "There's no use tryin' to see that feller Giraud till three o'clock."

"All right," said Dare. "As for me, I'm going across the square to that barber's shop you see there, to get a hair-cut. Then I'll take a stroll around and be back here for you at three sharp."

They parted on that understanding.

Ben overslept. That is to put it mildly. He woke with a start to discover that it was five o'clock. After magnifying his conduct in appropriate language he hurried on deck to look for Dare. But there was no sign of Dare either on board or ashore on the quay.

Ben, frankly, did not quite know what to do then. He thought it queer that Dare should not have roused him at the hour they had arranged to meet. Perhaps Dare had not come back at all. Or could it be that he had returned and, finding him, Ben, asleep, had gone ashore again? Ben was more inclined to think the former. And from thinking thus he began to wonder why Dare had not returned. Had he been prevented? Was he hurt? Ben turned cold at the thought of harm coming to the "cap'n's boy" while the latter was, in a way, under his care.

Well, there was no use in sitting still, he decided, and set out to make inquiries. The men hanging about the quay helped him little. They could not remember seeing anyone of Dare's description in their vicinity during the last hour or so. Ben, shaking off their negatives impatiently, plunged across the square in the direction of the barber's shop. It was possible the barber might have noted which direction Dare had taken when he left the premises.

The barber, an exquisite to his finger-tips, scented, hair curled, beard drawn silkily to a point, smiled professionally as Ben entered, but lost some of his interest when he discovered that Ben was there merely to ask questions. He could, as it happened, speak English, and he began to do so with those flourishes most Latins find necessary in their attempts at self-expression.

A youth? English? But no. But yes! It is to say, a young man, blond, sans barbe, with the air pleasing, and muscular, oh yes, muscular, most decidedly. The young man had come to his shop at two of the clock, but what he had come for it was not to be known, for to the most astonishment this young man after a reading of the journal short and inadequate, considering that it was the most admirable "Journal of the Débats," that young man had thrown down the journal with force and had run, yes decidedly, run from the shop with a manner excitable, l'air excité.

Ben listened with impatience, following the long rambling sentence with difficulty, due to the accent of the speaker.

"But what way did he go?" he demanded of the barber.

Oh, as to that, it was to be regretted, but it was not known. Tiens, no! The young man had gone so quickly.

Ben, seeing there was no more to be learned there, thanked his informant gruffly, and like an annoyed bear set off once again on his search, grumbling audibly at himself and the inadequacy of the information he had received.

Now what could have caused Mr. Dare to run from the shop like that? Something interesting, belike. Or it may have been no more than a dog fight or a fight between street boys, which was much the same thing, seen from the shop window. In any event the fight, or whatever it was that had had him out of the place so quickly, was long over now. That was no explanation of his failure to turn up at three o'clock. But had he failed to turn up? How did he, Ben, know? He didn't know and he had to admit it.

He crossed the square in a humour which was a mixture of chagrin and anxiety, though as yet he could not very well see in what there was cause for the latter. It was broad daylight, and St. Pierre wasn't Port Said by any means; and a boy ought to be as safe on its streets as in St. John's. Still, there was no denying that there were more facilities for trouble in the French town for a venturesome lad, and Mr. Dare was all of that.

He returned to the quay and took a look at the Nancy in case Dare had returned, but the boy was still missing. Ben bethought him then of their intention to visit Giraud. What more likely than that Dare, not finding him waiting on the quay, had gone on to Giraud's alone? The boy might be there even now, still waiting for him.

At this thought Ben's mood lightened and he set out for Giraud's in the hope of reaching it before the store closed.

It was a comparatively easy matter to find one's way to Giraud's. Giraud had seen to that. From the harbour one could see the towering sign on his store, and once on shore, there was always to be seen round some corner or other, the one word, Giraud's.

The premises were next the dry dock on the opposite side of the waterfront. Dark, dingy, huge, lacking paint and adequate windows, the place was impressive only because of the vast quantities of merchandise it stored.

Huge butts of rum and brandy, seven feet in diameter, nearly all on tap, lay in the darkest regions. Piles of rope, mountains of paint tins, great anchors, barrels of tar, ochre, bales of oakum, etc., filled another section, and still another part of the premises was given up to lighter articles such as soap, tobacco, ship's biscuit, cheese, and margarine. All these commodities, each with a distinctive odour, gave the place an atmosphere indescribable. It was too strong to be attractive to most people, yet to some it was very pleasing, none the less.

Ben, who was not over delicate in such matters, wrinkled his nose in appreciation as he entered the store.

The entrance gave upon a small space which had the semblance of an office, with various merchandise as its walls. A cash register, a few account books, and a desk of polished wood on high rickety legs, together with an old clerk, deaf and shortsighted, completed the paraphernalia of the place.

Ben entered this space, gave "good day" to the deaf old clerk, and then looked about him for someone in authority—Giraud, if possible.

Down long lanes of merchandise he caught sight of several clerks and a number of customers. He hesitated which way to take, then was saved the necessity of choice by the appearance of the proprietor.

Ben recognized him from descriptions heard on the waterfront, and from a glimpse he had had of him in the old days. It was not a figure to be forgotten, once seen. Giraud was a man of commanding presence. His bulk alone inspired respect. He was enormously tall for a Frenchman, over six feet, and his immense girth, his great rounding shoulders, gave a suggestion of bull strength. On top of this great mass of flesh was set a head which, in proportion with the trunk, looked ridiculously small. The face was clean shaven, and under a low forehead were set two crafty-looking eyes which hid their cunning, under heavy half-lowered lids.

Ben was no more a match in duplicity for such a person than a new-born babe. He had the intelligence to realize this and decided that he would make the interview as short as possible.

Giraud's eyelids flicked once indifferently, and he felt that he knew all about Ben, his antecedents, his occupation, his very innermost thoughts.

"Mr. Giraud, I think," said Ben in his bluff, simple manner.

"Yes," admitted Giraud non-committally.

"I heerd of you from Sam Stooding," said Ben expansively. "I bought that there boat of his, the Nancy. A good boat, too, in her way. Sam finds out one way and another that I'm likely to make a trip to St. Pierre now and then, so he says to me, you take my word fer it, Ben—Ben Wheeler, that's me name—you take my word fer it, Ben, says Sam, you can't do better than trade at Giraud's if you ever think of bringin' in a little brandy or tobaccy. I got a good respect fer Sam; Sam knows what's what. So here I be and right glad to meet you, mister."

Giraud's face remained expressionless during this garrulous introduction, but he acknowledged Ben's cordiality with a slight nod not to be mistaken for the courtesy of a bow. He did not remember ever having heard Stooding's name before. But then, there were scores of his customers whom he never saw, much less knew by name, and it was not the first time that the indirect recommendation of such had had good results.