The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Seven who were Hanged, by Leonid Andreyev This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Seven who were Hanged Author: Leonid Andreyev Release Date: June 1, 2009 [EBook #6722] Last Updated: September 15, 2019 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SEVEN WHO WERE HANGED *** Produced by Eric Eldred, and David Widger

| FOREWORD | |

| INTRODUCTION | |

| THE SEVEN WHO WERE HANGED | |

| CHAPTER I | AT ONE O’CLOCK, YOUR EXCELLENCY! |

| CHAPTER II | CONDEMNED TO BE HANGED |

| CHAPTER III | WHY SHOULD I BE HANGED? |

| CHAPTER IV | WE COME FROM ORYOL |

| CHAPTER V | KISS—AND SAY NOTHING |

| CHAPTER VI | THE HOURS ARE RUSHING |

| CHAPTER VII | THERE IS NO DEATH |

| CHAPTER VIII | THERE IS DEATH AS WELL AS LIFE |

| CHAPTER IX | DREADFUL SOLITUDE |

| CHAPTER X | THE WALLS ARE FALLING |

| CHAPTER XI | ON THE WAY TO THE SCAFFOLD |

| CHAPTER XII | THEY ARE HANGED |

DEDICATION

To Count Leo N. Tolstoy

This Book is Dedicated

by Leonid Andreyev

The Translation of this Story

Is Also Respectfully Inscribed to

Count Leo N. Tolstoy

by Herman Bernstein

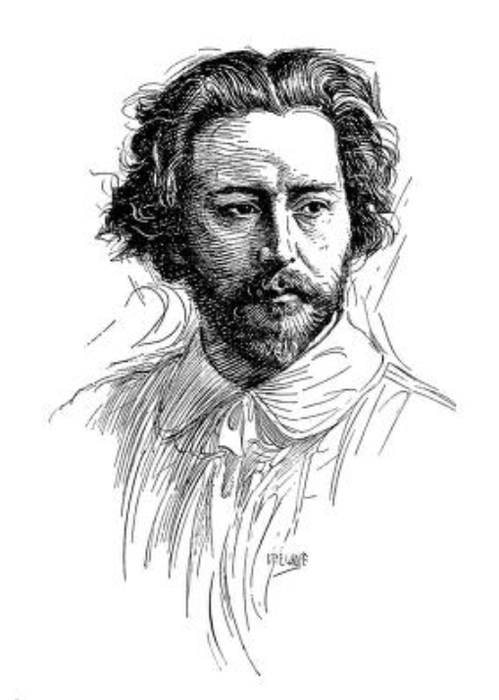

Leonid Andreyev, who was born in Oryol, in 1871, is the most popular, and next to Tolstoy, the most gifted writer in Russia to-day. Andreyev has written many important stories and dramas, the best known among which are “Red Laughter,” “Life of Man,” “To the Stars,” “The Life of Vasily Fiveisky,” “Eliazar,” “Black Masks,” and “The Story of the Seven Who Were Hanged.”

In “Red Laughter” he depicted the horrors of war as few men had ever before done it. He dipped his pen into the blood of Russia and wrote the tragedy of the Manchurian war.

In his “Life of Man” Andreyev produced a great, imaginative “morality” play which has been ranked by European critics with some of the greatest dramatic masterpieces.

The story of “The Seven Who Were Hanged” is thus far his most important achievement. The keen psychological insight and the masterly simplicity with which Andreyev has penetrated and depicted each of the tragedies of the seven who were hanged place him in the same class as an artist with Russia’s greatest masters of fiction, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev and Tolstoy.

I consider myself fortunate to be able to present to the English-reading public this remarkable work, which has already produced a profound impression in Europe and which, I believe, is destined for a long time to come to play an important part in opening the eyes of the world to the horrors perpetrated in Russia and to the violence and iniquity of the destruction of human life, whatever the error or the crime.

New York.

HERMAN BERNSTEIN.

I am very glad that “The Story of the Seven Who Were Hanged” will be read in English. The misfortune of us all is that we know so little, even nothing, about one another—neither about the soul, nor the life, the sufferings, the habits, the inclinations, the aspirations of one another. Literature, which I have the honor to serve, is dear to me just because the noblest task it sets before itself is that of wiping out boundaries and distances.

As in a hard shell, every human being is enclosed in a cover of body, dress, and life. Who is man? We may only conjecture. What constitutes his joy or his sorrow? We may guess only by his acts, which are oft-times enigmatic; by his laughter and by his tears, which are often entirely incomprehensible to us. And if we, Russians, who live so closely together in constant misery, understand one another so poorly that we mercilessly put to death those who should be pitied or even rewarded, and reward those who should be punished by contempt and anger—how much more difficult is it for you Americans, to understand distant Russia? But then, it is just as difficult for us Russians to understand distant America, of which we dream in our youth and over which we ponder so deeply in our years of maturity.

The Jewish massacres and famine; a Parliament and executions; pillage and the greatest heroism; “The Black Hundred,” and Leo Tolstoy—what a mixture of figures and conceptions, what a fruitful source for all kinds of misunderstandings! The truth of life stands aghast in silence, and its brazen falsehood is loudly shouting, uttering pressing, painful questions: “With whom shall I sympathize? Whom shall I trust? Whom shall I love?”

In the story of “The Seven Who Were Hanged” I attempted to give a sincere and unprejudiced answer to some of these questions.

That I have treated ruling and slaughtering Russia with restraint and mildness may best be gathered from the fact that the Russian censor has permitted my book to circulate. This is sufficient evidence when we recall how many books, brochures and newspapers have found eternal rest in the peaceful shade of the police stations, where they have risen to the patient sky in the smoke and flame of bonfires.

But I did not attempt to condemn the Government, the fame of whose wisdom and virtues has already spread far beyond the boundaries of our unfortunate fatherland. Modest and bashful far beyond all measure of her virtues, Russia would sincerely wish to forego this honor, but unfortunately the free press of America and Europe has not spared her modesty, and has given a sufficiently clear picture of her glorious activities. Perhaps I am wrong in this: it is possible that many honest people in America believe in the purity of the Russian Government’s intentions—but this question is of such importance that it requires a special treatment, for which it is necessary to have both time and calm of soul. But there is no calm soul in Russia.

My task was to point out the horror and the iniquity of capital punishment under any circumstances. The horror of capital punishment is great when it falls to the lot of courageous and honest people whose only guilt is their excess of love and the sense of righteousness—in such instances, conscience revolts. But the rope is still more horrible when it forms the noose around the necks of weak and ignorant people. And however strange it may appear, I look with a lesser grief and suffering upon the execution of the revolutionists, such as Werner and Musya, than upon the strangling of ignorant murderers, miserable in mind and heart, like Yanson and Tsiganok. Even the last mad horror of inevitably approaching execution Werner can offset by his enlightened mind and his iron will, and Musya, by her purity and her innocence. ***

But how are the weak and the sinful to face it if not in madness, with the most violent shock to the very foundation of their souls? And these people, now that the Government has steadied its hands through its experience with the revolutionists, are being hanged throughout Russia—in some places one at a time, in others, ten at once. Children at play come upon badly buried bodies, and the crowds which gather look with horror upon the peasants’ boots that are sticking out of the ground; prosecutors who have witnessed these executions are becoming insane and are taken away to hospitals—while the people are being hanged—being hanged.

I am deeply grateful to you for the task you have undertaken in translating this sad story. Knowing the sensitiveness of the American people, who at one time sent across the ocean, steamers full of bread for famine-stricken Russia, I am convinced that in this case our people in their misery and bitterness will also find understanding and sympathy. And if my truthful story about seven of the thousands who were hanged will help toward destroying at least one of the barriers which separate one nation from another, one human being from another, one soul from another soul, I shall consider myself happy.

Respectfully yours,

LEONID ANDREYEV.

As the Minister was a very stout man, inclined to apoplexy, they feared to arouse in him any dangerous excitement, and it was with every possible precaution that they informed him that a very serious attempt upon his life had been planned. When they saw that he received the news calmly, even with a smile, they gave him, also, the details. The attempt was to be made on the following day at the time that he was to start out with his official report; several men, terrorists, whose plans had already been betrayed by a provocateur, and who were now under the vigilant surveillance of detectives, were to meet at one o’clock in the afternoon in front of his house, and, armed with bombs and revolvers, were to wait till he came out. There the terrorists were to be trapped.

“Wait!” muttered the Minister, perplexed. “How did they know that I was to leave the house at one o’clock in the afternoon with my report, when I myself learned of it only the day before yesterday?”

The Chief of the Guards stretched out his arms with a shrug.

“Exactly at one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency,” he said.

Half surprised, half commending the work of the police, who had managed everything skilfully, the Minister shook his head, a morose smile upon his thick, dark lips, and still smiling obediently, and not desiring to interfere with the plans of the police, he hastily made ready, and went out to pass the night in some one else’s hospitable palace. His wife and his two children were also removed from the dangerous house, before which the bomb-throwers were to gather upon the following day.

While the lights were burning in the palace, and courteous, familiar faces were bowing to him, smiling and expressing their concern, the dignitary experienced a sensation of pleasant excitement—he felt as if he had already received, or was soon to receive, some great and unexpected reward. But the people went away, the lights were extinguished, and through the mirrors, the lace-like and fantastic reflection of the electric lamps on the street, quivered across the ceiling and over the walls. A stranger in the house, with its paintings, its statues and its silence, the light—itself silent and indefinite—awakened painful thoughts in him as to the vanity of bolts and guards and walls. And then, in the dead of night, in the silence and solitude of a strange bedroom, a sensation of unbearable fear swept over the dignitary.

He had some kidney trouble, and whenever he grew strongly agitated, his face, his hands and his feet became swollen. Now, rising like a mountain of bloated flesh above the taut springs of the bed, he felt, with the anguish of a sick man, his swollen face, which seemed to him to belong to some one else. Unceasingly he kept thinking of the cruel fate which people were preparing for him. He recalled, one after another, all the recent horrible instances of bombs that had been thrown at men of even greater eminence than himself; he recalled how the bombs had torn bodies to pieces, had spattered brains over dirty brick walls, had knocked teeth from their roots. And influenced by these meditations, it seemed to him that his own stout, sickly body, outspread on the bed, was already experiencing the fiery shock of the explosion. He seemed to be able to feel his arms being severed from the shoulders, his teeth knocked out, his brains scattered into particles, his feet growing numb, lying quietly, their toes upward, like those of a dead man. He stirred with an effort, breathed loudly and coughed in order not to seem to himself to resemble a corpse in any way. He encouraged himself with the live noise of the grating springs, of the rustling blanket; and to assure himself that he was actually alive and not dead, he uttered in a bass voice, loudly and abruptly, in the silence and solitude of the bedroom:

“Molodtsi! Molodtsi! Molodtsi! (Good boys)!”

He was praising the detectives, the police, and the soldiers—all those who guarded his life, and who so opportunely and so cleverly had averted the assassination. But even though he stirred, even though he praised his protectors, even though he forced an unnatural smile, in order to express his contempt for the foolish, unsuccessful terrorists, he nevertheless did not believe in his safety, he was not sure that his life would not leave him suddenly, at once. Death, which people had devised for him, and which was only in their minds, in their intention, seemed to him to be already standing there in the room. It seemed to him that Death would remain standing there, and would not go away until those people had been captured, until the bombs had been taken from them, until they had been placed in a strong prison. There Death was standing in the corner, and would not go away—it could not go away, even as an obedient sentinel stationed on guard by a superior’s will and order.

“At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!” this phrase kept ringing, changing its tone continually: now it was cheerfully mocking, now angry, now dull and obstinate. It sounded as if a hundred wound-up gramophones had been placed in his room, and all of them, one after another, were shouting with idiotic repetition the words they had been made to shout:

“At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!”

And suddenly, this one o’clock in the afternoon to-morrow, which but a short while ago was not in any way different from other hours, which was only a quiet movement of the hand along the dial of his gold watch, assumed an ominous finality, sprang out of the dial, began to live separately, stretched itself into an enormously huge black pole which cut all life in two. It seemed as if no other hours had existed before it and no other hours would exist after it—as if this hour alone, insolent and presumptuous, had a right to a certain peculiar existence.

“Well, what do you want?” asked the Minister angrily, muttering between his teeth.

The gramophone shouted:

“At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!” and the black pole smiled and bowed. Gnashing his teeth, the Minister rose in his bed to a sitting posture, leaning his face on the palms of his hands—he positively could not sleep on that dreadful night.

Clasping his face in his swollen, perfumed palms, he pictured to himself with horrifying clearness how on the following morning, not knowing anything of the plot against his life, he would have risen, would have drunk his coffee, not knowing anything, and then would have put on his coat in the hallway. And neither he, nor the doorkeeper who would have handed him his fur coat, nor the lackey who would have brought him the coffee, would have known that it was utterly useless to drink coffee, and to put on the coat, since a few instants later, everything—the fur coat and his body and the coffee within it—would be destroyed by an explosion, would be seized by death. The doorkeeper would have opened the glass door.... He, the amiable, kind, gentle doorkeeper, with the blue, typical eyes of a soldier, and with medals across his breast—he himself with his own hands would have opened the terrible door, opened it because he knew nothing. Everybody would have smiled because they did not know anything.

“Oho!” he suddenly said aloud, and slowly removed his hands from his face. Peering into the darkness, far ahead of him, with a fixed, strained look, he outstretched his hand just as slowly, felt the button on the wall and pressed it. Then he arose, and without putting on his slippers, walked in his bare feet over the rug in the strange, unfamiliar bedroom, found the button of another lamp upon the wall and pressed it. It became light and pleasant, and only the disarranged bed with the blanket, which had slipped off to the floor, spoke of the horror, not altogether past.

In his night-clothes, with his beard disheveled by his restless movements, with his angry eyes, the dignitary resembled any other angry old man who suffered with insomnia and shortness of breath. It was as if the death which people were preparing for him, had made him bare, had torn away from him the magnificence and splendor which had surrounded him—and it was hard to believe that it was he who had so much power, that his body was but an ordinary plain human body that must have perished terribly in the flame and roar of a monstrous explosion. Without dressing himself and not feeling the cold, he sat down in the first armchair he found, stroking his disheveled beard, and fixed his eyes in deep, calm thoughtfulness upon the unfamiliar plaster figures of the ceiling.

So that was the trouble! That was why he had trembled in fear and had become so agitated! That was why Death seemed to stand in the corner and would not go away, could not go away!

“Fools!” he said emphatically, with contempt.

“Fools!” he repeated more loudly, and turned his head slightly toward the door that those to whom he was referring might hear it. He was referring to those whom he had praised but a moment before, who in the excess of their zeal had told him of the plot against his life.

“Of course,” he thought deeply, an easy, convincing idea arising in his mind. “Now that they have told me, I know, and feel terrified, but if I had not been told, I would not have known anything and would have drunk my coffee calmly. After that Death would have come—but then, am I so afraid of Death? Here have I been suffering with kidney trouble, and I must surely die from it some day, and yet I am not afraid—because I do not know anything. And those fools told me: ‘At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!’ and they thought I would be glad. But instead of that Death stationed itself in the corner and would not go away. It would not go away because it was my thought. It is not death that is terrible, but the knowledge of it: it would be utterly impossible to live if a man could know exactly and definitely the day and hour of his death. And the fools cautioned me: ‘At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!’”

He began to feel light-hearted and cheerful, as if some one had told him that he was immortal, that he would never die. And, feeling himself again strong and wise amidst the herd of fools who had so stupidly and impudently broken into the mystery of the future, he began to think of the bliss of ignorance, and his thoughts were the painful thoughts of an old, sick man who had gone through endless experience. It was not given to any living being—man or beast—to know the day and hour of death. Here had he been ill not long ago and the physicians told him that he must expect the end, that he should make his final arrangements—but he had not believed them and he remained alive. In his youth he had become entangled in an affair and had resolved to end his life; he had even loaded the revolver, had written his letters, and had fixed upon the hour for suicide—but before the very end he had suddenly changed his mind. It would always be thus—at the very last moment something would change, an unexpected accident would befall—no one could tell when he would die.

“At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!” those kind asses had said to him, and although they had told him of it only that death might be averted, the mere knowledge of its possibility at a certain hour again filled him with horror. It was probable that some day he should be assassinated, but it would not happen to-morrow—it would not happen to-morrow—and he could sleep undisturbed, as if he were really immortal. Fools—they did not know what a great law they had dislodged, what an abyss they had opened, when they said in their idiotic kindness: “At one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency!”

“No, not at one o’clock in the afternoon, your Excellency, but no one knows when. No one knows when! What?”

“Nothing,” answered Silence, “nothing.”

“But you did say something.”

“Nothing, nonsense. I say: to-morrow, at one o’clock in the afternoon!”

There was a sudden, acute pain in his heart—and he understood that he would have neither sleep, nor peace, nor joy until that accursed black hour standing out of the dial should have passed. Only the shadow of the knowledge of something which no living being could know stood there in the corner, and that was enough to darken the world and envelop him with the impenetrable gloom of horror. The once disturbed fear of death diffused through his body, penetrated into his bones.

He no longer feared the murderers of the next day—they had vanished, they had been forgotten, they had mingled with the crowd of hostile faces and incidents which surrounded his life. He now feared something sudden and inevitable—an apoplectic stroke, heart failure, some foolish thin little vessel which might suddenly fail to withstand the pressure of the blood and might burst like a tight glove upon swollen fingers.

His short, thick neck seemed terrible to him. It became unbearable for him to look upon his short, swollen fingers—to feel how short they were and how they were filled with the moisture of death. And if before, when it was dark, he had had to stir in order not to resemble a corpse, now in the bright, cold, inimical, dreadful light he was so filled with horror that he could not move in order to get a cigarette or to ring for some one. His nerves were giving way. Each one of them seemed as if it were a bent wire, at the top of which there was a small head with mad, wide-open frightened eyes and a convulsively gaping, speechless mouth. He could not draw his breath.

Suddenly in the darkness, amidst the dust and cobwebs somewhere upon the ceiling, an electric bell came to life. The small, metallic tongue, agitatedly, in terror, kept striking the edge of the ringing cap, became silent—and again quivered in an unceasing, frightened din. His Excellency was ringing his bell in his own room.

People began to run. Here and there, in the shadows upon the walls, lamps flared up—there were not enough of them to give light, but there were enough to cast shadows. The shadows appeared everywhere; they rose in the corners, they stretched across the ceiling; tremulously clinging to each and every elevation, they covered the walls. And it was hard to understand where all these innumerable, deformed silent shadows—voiceless souls of voiceless objects—had been before.

A deep, trembling voice said something loudly. Then the doctor was hastily summoned by telephone; the dignitary was collapsing. The wife of his Excellency was also called.

Everything befell as the police had foretold. Four terrorists, three men and a woman, armed with bombs, infernal machines and revolvers, were seized at the very entrance of the house, and another woman was later found and arrested in the house where the conspiracy had been hatched. She was its mistress. At the same time a great deal of dynamite and half finished bomb explosives were seized. All those arrested were very young; the eldest of the men was twenty-eight years old, the younger of the women was only nineteen. They were tried in the same fortress in which they were imprisoned after the arrest; they were tried swiftly and secretly, as was done during that unmerciful time.

At the trial all of them were calm, but very serious and thoughtful. Their contempt for the judges was so intense that none of them wished to emphasize his daring by even a superfluous smile or by a feigned expression of cheerfulness. Each was simply as calm as was necessary to hedge in his soul, from curious, evil and inimical eyes, the great gloom that precedes death.

Sometimes they refused to answer questions; sometimes they answered, briefly, simply and precisely, as though they were answering not the judge, but statisticians, for the purpose of supplying information for particular special tables. Three of them, one woman and two men, gave their real names, while two others refused and thus remained unknown to the judges.

They manifested for all that was going on at the trial a certain curiosity, softened, as though through a haze, such as is peculiar to persons who are very ill or are carried away by some great, all-absorbing idea. They glanced up occasionally, caught some word in the air more interesting than the others, and then resumed the thought from which their attention had been distracted.

The man who was nearest to the judges called himself Sergey Golovin, the son of a retired colonel, himself an ex-officer. He was still a very young, light-haired, broad-shouldered man, so strong that neither the prison nor the expectation of inevitable death could remove the color from his cheeks and the expression of youthful, happy frankness from his blue eyes. He kept energetically tugging at his bushy, small beard, to which he had not become accustomed, and continually blinking, kept looking out of the window.

It was toward the end of winter, when amidst the snowstorms and the gloomy, frosty days, the approaching spring sent as a forerunner a clear, warm, sunny day, or but an hour, yet so full of spring, so eagerly young and beaming that sparrows on the streets lost their wits for joy, and people seemed almost as intoxicated. And now the strange and beautiful sky could be seen through an upper window which was dust-covered and unwashed since the last summer. At first sight the sky seemed to be milky-gray—smoke-colored—but when you looked longer the dark blue color began to penetrate through the shade, grew into an ever deeper blue—ever brighter, ever more intense. And the fact that it did not reveal itself all at once, but hid itself chastely in the smoke of transparent clouds, made it as charming as the girl you love. And Sergey Golovin looked at the sky, tugged at his beard, blinked now one eye, now the other, with its long, curved lashes, earnestly pondering over something. Once he began to move his fingers rapidly and thoughtlessly, knitted his brow in some joy, but then he glanced about and his joy died out like a spark which is stepped upon. Almost instantly an earthen, deathly blue, without first changing into pallor, showed through the color of his cheeks. He clutched his downy hair, tore their roots painfully with his fingers, whose tips had turned white. But the joy of life and spring was stronger, and a few minutes later his frank young face was again yearning toward the spring sky.

The young, pale girl, known only by the name of Musya, was also looking in the same direction, at the sky. She was younger than Golovin, but she seemed older in her gravity and in the darkness of her open, proud eyes. Only her very thin, slender neck, and her delicate girlish hands spoke of her youth; but in addition there was that ineffable something, which is youth itself, and which sounded so distinctly in her clear, melodious voice, tuned irreproachably like a precious instrument, every simple word, every exclamation giving evidence of its musical timbre. She was very pale, but it was not a deathly pallor, but that peculiar warm whiteness of a person within whom, as it were, a great, strong fire is burning, whose body glows transparently like fine Sèvres porcelain. She sat almost motionless, and only at times she touched with an imperceptible movement of her fingers the circular mark on the middle finger of her right hand, the mark of a ring which had been recently removed.

She gazed at the sky without caressing kindness or joyous recollections—she looked at it simply because in all the filthy, official hall the blue bit of sky was the most beautiful, the purest, the most truthful object, and the only one that did not try to search hidden depths in her eyes.

The judges pitied Sergey Golovin; her they despised.

Her neighbor, known only by the name of Werner, sat also motionless, in a somewhat affected pose, his hands folded between his knees. If a face may be said to look like a false door, this unknown man closed his face like an iron door and bolted it with an iron lock. He stared motionlessly at the dirty wooden floor, and it was impossible to tell whether he was calm or whether he was intensely agitated, whether he was thinking of something, or whether he was listening to the testimony of the detectives as presented to the court. He was not tall in stature. His features were refined and delicate. Tender and handsome, so that he reminded you of a moonlit night in the South near the seashore, where the cypress trees throw their dark shadows, he at the same time gave the impression of tremendous, calm power, of invincible firmness, of cold and audacious courage. The very politeness with which he gave brief and precise answers seemed dangerous, on his lips, in his half bow. And if the prison garb looked upon the others like the ridiculous costume of a buffoon, upon him it was not noticeable, so foreign was it to his personality. And although the other terrorists had been seized with bombs and infernal machines upon them, and Werner had had but a black revolver, the judges for some reason regarded him as the leader of the others and treated him with a certain deference, although succinctly and in a business-like manner.

The next man, Vasily Kashirin, was torn between a terrible, dominating fear of death and a desperate desire to restrain the fear and not betray it to the judges. From early morning, from the time they had been led into court, he had been suffocating from an intolerable palpitation of his heart. Perspiration came out in drops all along his forehead; his hands were also perspiring and cold, and his cold, sweat-covered shirt clung to his body, interfering with the freedom of his movements. With a supernatural effort of will-power he forced his fingers not to tremble, his voice to be firm and distinct, his eyes to be calm. He saw nothing about him; the voices came to him as through a mist, and it was to this mist that he made his desperate efforts to answer firmly, to answer loudly. But having answered, he immediately forgot question as well as answer, and was again struggling with himself silently and terribly. Death was disclosed in him so clearly that the judges avoided looking at him. It was hard to define his age, as is the case with a corpse which has begun to decompose. According to his passport, he was only twenty-three years old. Once or twice Werner quietly touched his knee with his hand, and each time Kashirin spoke shortly:

“Never mind!”

The most terrible sensation was when he was suddenly seized with an insufferable desire to cry out, without words, the desperate cry of a beast. He touched Werner quickly, and Werner, without lifting his eyes, said softly:

“Never mind, Vasya. It will soon be over.”

And embracing them all with a motherly, anxious look, the fifth terrorist, Tanya Kovalchuk, was faint with alarm. She had never had any children; she was still young and red-cheeked, just as Sergey Golovin, but she seemed as a mother to all of them: so full of anxiety, of boundless love were her looks, her smiles, her sighs. She paid not the slightest attention to the trial, regarding it as though it were something entirely irrelevant, and she listened only to the manner in which the others were answering the questions, to hear whether the voice was trembling, whether there was fear, whether it was necessary to give water to any one.

She could not look at Vasya in her anguish and only wrung her fingers silently. At Musya and Werner she gazed proudly and respectfully, and she assumed a serious and concentrated expression, and then tried to transfer her smile to Sergey Golovin.

“The dear boy is looking at the sky. Look, look, my darling!” she thought about Golovin.

“And Vasya! What is it? My God, my God! What am I to do with him? If I should speak to him I might make it still worse. He might suddenly start to cry.”

So like a calm pond at dawn, reflecting every hastening, passing cloud, she reflected upon her full, gentle, kind face every swift sensation, every thought of the other four. She did not give a single thought to the fact that she, too, was upon trial, that she, too, would be hanged; she was entirely indifferent to it. It was in her house that the bombs and the dynamite had been discovered, and, strange though it may seem, it was she who had met the police with pistol-shots and had wounded one of the detectives in the head.

The trial ended at about eight o’clock, when it had become dark. Before Musya’s and Golovin’s eyes the sky, which had been turning ever bluer, was gradually losing its tint, but it did not turn rosy, did not smile softly as in summer evenings, but became muddy, gray, and suddenly grew cold, wintry. Golovin heaved a sigh, stretched himself, glanced again twice at the window, but the cold darkness of the night alone was there; then continuing to tug at his short beard, he began to examine with childish curiosity the judges, the soldiers with their muskets, and he smiled at Tanya Kovalchuk. When the sky had darkened Musya calmly, without lowering her eyes to the ground, turned them to the corner where a small cobweb was quivering from the imperceptible radiations of the steam heat, and thus she remained until the sentence was pronounced.

After the verdict, having bidden good-by to their frock-coated lawyers, and evading each other’s helplessly confused, pitying and guilty eyes, the convicted terrorists crowded in the doorway for a moment and exchanged brief words.

“Never mind, Vasya. Everything will be over soon,” said Werner.

“I am all right, brother,” Kashirin replied loudly, calmly and even somewhat cheerfully. And indeed, his face had turned slightly rosy, and no longer looked like that of a decomposing corpse.

“The devil take them; they’ve hanged us,” Golovin cursed quaintly.

“That was to be expected,” replied Werner calmly.

“To-morrow the sentence will be pronounced in its final form and we shall all be placed together,” said Tanya Kovalchuk consolingly. “Until the execution we shall all be together.”

Musya was silent. Then she resolutely moved forward.

Two weeks before the terrorists had been tried the same military district court, with a different set of judges, had tried and condemned to death by hanging Ivan Yanson, a peasant.

Ivan Yanson was a workman for a well-to-do farmer, in no way different from other workmen. He was an Esthonian by birth, from Vezenberg, and in the course of several years, passing from one farm to another, he had come close to the capital. He spoke Russian very poorly, and as his master was a Russian, by name Lazarev, and as there were no Esthonians in the neighborhood, Yanson had practically remained silent for almost two years. In general, he was apparently not inclined to talk, and was silent not only with human beings, but even with animals. He would water the horse in silence, harness it in silence, moving about it, slowly and lazily, with short, irresolute steps, and when the horse, annoyed by his manner, would begin to frolic, to become capricious, he would beat it in silence with a heavy whip. He would beat it cruelly, with stolid, angry persistency, and when this happened at a time when he was suffering from the aftereffects of a carouse, he would work himself into a frenzy. At such times the crack of the whip could be heard in the house, with the frightened, painful pounding of the horse’s hoofs upon the board floor of the barn. For beating the horse his master would beat Yanson, but then, finding that he could not be reformed, paid no more attention to him.

Once or twice a month Yanson became intoxicated, usually on those days when he took his master to the large railroad station, where there was a refreshment bar. After leaving his master at the station, he would drive off about half a verst away, and there, stalling the sled and the horse in the snow on the side of the road, he would wait until the train had gone. The sled would stand sideways, almost overturned, the horse standing with widely spread legs up to his belly in a snow-bank, from time to time lowering his head to lick the soft, downy snow, while Yanson would recline in an awkward position in the sled as if dozing away. The unfastened ear-lappets of his worn fur cap would hang down like the ears of a setter, and the moist sweat would stand under his little reddish nose.

Soon he would return to the station, and would quickly become intoxicated.

On his way back to the farm, the whole ten versts, he would drive at a fast gallop. The little horse, driven to madness by the whip, would rear, as if possessed by a demon; the sled would sway, almost overturn, striking against poles, and Yanson, letting the reins go, would half sing, half exclaim abrupt, meaningless phrases in Esthonian. But more often he would not sing, but with his teeth gritted together in an onrush of unspeakable rage, suffering and delight, he would drive silently on as though blind. He would not notice those who passed him, he would not call to them to look out, he would not slacken his mad pace, either at the turns of the road or on the long slopes of the mountain roads. How it happened at such times that he crushed no one, how he himself was never dashed to death in one of these mad rides, was inexplicable.

He would have been driven from this place, as he had been driven from other places, but he was cheap and other workmen were not better, and thus he remained there two years. His life was uneventful. One day he received a letter, written in Esthonian, but as he himself was illiterate, and as the others did not understand Esthonian, the letter remained unread; and as if not understanding that the letter might bring him tidings from his native home, he flung it into the manure with a certain savage, grim indifference. At one time Yanson tried to make love to the cook, but he was not successful, and was rudely rejected and ridiculed. He was short in stature, his face was freckled, and his small, sleepy eyes were somewhat of an indefinite color. Yanson took his failure indifferently, and never again bothered the cook.

But while Yanson spoke but little, he was listening to something all the time. He heard the sounds of the dismal, snow-covered fields, with their heaps of frozen manure resembling rows of small, snow-covered graves, the sounds of the blue, tender distance, of the buzzing telegraph wires, and the conversation of other people. What the fields and telegraph wires spoke to him he alone knew, and the conversation of the people were disquieting, full of rumors about murders and robberies and arson. And one night he heard in the neighboring village the little church bell ringing faintly and helplessly, and the crackling of the flames of a fire. Some vagabonds had plundered a rich farm, had killed the master and his wife, and had set fire to the house.

And on their farm, too, they lived in fear; the dogs were loose, not only at night, but also during the day, and the master slept with a gun by his side. He wished to give such a gun to Yanson, only it was an old one with one barrel. But Yanson turned the gun about in his hand, shook his head and declined it. His master did not understand the reason and scolded him, but the reason was that Yanson had more faith in the power of his Finnish knife than in the rusty gun.

“It would kill me,” he said, looking at his master sleepily with his glassy eyes, and the master waved his hand in despair.

“You fool! Think of having to live with such workmen!”

And this same Ivan Yanson, who distrusted a gun, one winter evening, when the other workmen had been sent away to the station, committed a very complicated attempt at robbery, murder and rape. He did it in a surprisingly simple manner. He locked the cook in the kitchen, lazily, with the air of a man who is longing to sleep, walked over to his master from behind and swiftly stabbed him several times in the back with his knife. The master fell unconscious, and the mistress began to run about, screaming, while Yanson, showing his teeth and brandishing his knife, began to ransack the trunks and the chests of drawers. He found the money he sought, and then, as if noticing the mistress for the first time, and as though unexpectedly even to himself, he rushed upon her in order to violate her. But as he had let his knife drop to the floor, the mistress proved stronger than he, and not only did not allow him to harm her, but almost choked him into unconsciousness. Then the master on the floor turned, the cook thundered upon the door with the oven-fork, breaking it open, and Yanson ran away into the fields. He was caught an hour later, kneeling down behind the corner of the barn, striking one match after another, which would not ignite, in an attempt to set the place on fire.

A few days later the master died of blood poisoning, and Yanson, when his turn among other robbers and murderers came, was tried and condemned to death. In court he was the same as always; a little man, freckled, with sleepy, glassy eyes. It seemed as if he did not understand in the least the meaning of what was going on about him; he appeared to be entirely indifferent. He blinked his white eyelashes, stupidly, without curiosity; examined the sombre, unfamiliar courtroom, and picked his nose with his hard, shriveled, unbending finger. Only those who had seen him on Sundays at church would have known that he had made an attempt to adorn himself. He wore on his neck a knitted, muddy-red shawl, and in places had dampened the hair of his head. Where the hair was wet it lay dark and smooth, while on the other side it stuck up in light and sparse tufts, like straws upon a hail-beaten, wasted meadow.

When the sentence was pronounced—death by hanging—Yanson suddenly became agitated. He reddened deeply and began to tie and untie the shawl about his neck as though it were choking him. Then he waved his arms stupidly and said, turning to the judge who had not read the sentence, and pointing with his finger at the judge who read it:

“He said that I should be hanged.”

“Who do you mean?” asked the presiding judge, who had pronounced the sentence in a deep, bass voice. Every one smiled; some tried to hide their smiles behind their mustaches and their papers. Yanson pointed his index finger at the presiding judge and answered angrily, looking at him askance:

“You!”

“Well?”

Yanson again turned his eyes to the judge who had been silent, restraining a smile, whom he felt to be a friend, a man who had nothing to do with the sentence, and repeated:

“He said I should be hanged. Why must I be hanged?”

“Take the prisoner away.”

But Yanson succeeded in repeating once more, convincingly and weightily:

“Why must I be hanged?”

He looked so absurd, with his small, angry face, with his outstretched finger, that even the soldier of the convoy, breaking the rule, said to him in an undertone as he led him away from the courtroom:

“You are a fool, young man!”

“Why must I be hanged?” repeated Yanson stubbornly.

“They’ll swing you up so quickly that you’ll have no time to kick.”

“Keep still!” cried the other convoy angrily. But he himself could not refrain from adding:

“A robber, too! Why did you take a human life, you fool? You must hang for that!”

“They might pardon him,” said the first soldier, who began to feel sorry for Yanson.

“Oh, yes! They’ll pardon people like him, will they? Well, we’ve talked enough.”

But Yanson had become silent again.

He was again placed in the cell in which he had already sat for a month and to which he had grown accustomed, just as he had become accustomed to everything: to blows, to vodka, to the dismal, snow-covered fields, with their snow-heaps resembling graves. And now he even began to feel cheerful when he saw his bed, the familiar window with the grating, and when he was given something to eat—he had not eaten anything since morning. He had an unpleasant recollection of what had taken place in the court, but of that he could not think—he was unable to recall it. And death by hanging he could not picture to himself at all.

Although Yanson had been condemned to death, there were many others similarly sentenced, and he was not regarded as an important criminal. They spoke to him accordingly, with neither fear nor respect, just as they would speak to prisoners who were not to be executed. The warden, on learning of the verdict, said to him:

“Well, my friend, they’ve hanged you!”

“When are they going to hang me?” asked Yanson distrustfully. The warden meditated a moment.

“Well, you’ll have to wait—until they can get together a whole party. It isn’t worth bothering for one man, especially for a man like you. It is necessary to work up the right spirit.”

“And when will that be?” persisted Yanson. He was not at all offended that it was not worth while to hang him alone. He did not believe it, but considered it as an excuse for postponing the execution, preparatory to revoking it altogether. And he was seized with joy; the confused, terrible moment, of which it was so painful to think, retreated far into the distance, becoming fictitious and improbable, as death always seems.

“When? When?” cried the warden, a dull, morose old man, growing angry. “It isn’t like hanging a dog, which you take behind the barn—and it is done in no time. I suppose you would like to be hanged like that, you fool!”

“I don’t want to be hanged,” and suddenly Yanson frowned strangely. “He said that I should be hanged, but I don’t want it.”

And perhaps for the first time in his life he laughed, a hoarse, absurd, yet gay and joyous laughter. It sounded like the cackling of a goose, Ga-ga-ga! The warden looked at him in astonishment, then knit his brow sternly. This strange gayety of a man who was to be executed was an offence to the prison, as well as to the very executioner; it made them appear absurd. And suddenly, for the briefest instant, it appeared to the old warden, who had passed all his life in the prison, and who looked upon its laws as the laws of nature, that the prison and all the life within it was something like an insane asylum, in which he, the warden, was the chief lunatic.

“Pshaw! The devil take you!” and he spat aside. “Why are you giggling here? This is no dramshop!”

“And I don’t want to be hanged—ga-ga-ga!” laughed Yanson.

“Satan!” muttered the inspector, feeling the need of making the sign of the cross.

This little man, with his small, wizened face—he resembled least of all the devil—but there was that in his silly giggling which destroyed the sanctity and the strength of the prison. If he laughed longer, it seemed to the warden as if the walls might fall asunder, the grating melt and drop out, as if the warden himself might lead the prisoners to the gates, bowing and saying: “Take a walk in the city, gentlemen; or perhaps some of you would like to go to the village?”

“Satan!”

But Yanson had stopped laughing, and was now winking cunningly.

“You had better look out!” said the warden, with an indefinite threat, and he walked away, glancing back of him.

Yanson was calm and cheerful throughout the evening. He repeated to himself, “I shall not be hanged,” and it seemed to him so convincing, so wise, so irrefutable, that it was unnecessary to feel uneasy. He had long forgotten about his crime, only sometimes he regretted that he had not been successful in attacking his master’s wife. But he soon forgot that, too.

Every morning Yanson asked when he was to be hanged, and every morning the warden answered him angrily:

“Take your time, you devil! Wait!” and he would walk off quickly before Yanson could begin to laugh.

And from these monotonously repeated words, and from the fact that each day came, passed and ended as every ordinary day had passed, Yanson became convinced that there would be no execution. He began to lose all memory of the trial, and would roll about all day long on his cot, vaguely and happily dreaming about the white melancholy fields, with their snow-mounds, about the refreshment bar at the railroad station, and about other things still more vague and bright. He was well fed in the prison, and somehow he began to grow stout rapidly and to assume airs.

“Now she would have liked me,” he thought of his master’s wife. “Now I am stout—not worse-looking than the master.”

But he longed for a drink of vodka, to drink and to take a ride on horseback, to ride fast, madly.

When the terrorists were arrested the news of it reached the prison. And in answer to Yanson’s usual question, the warden said eagerly and unexpectedly:

“It won’t be long now!”

He looked at Yanson calmly with an air of importance and repeated:

“It won’t be long now. I suppose in about a week.”

Yanson turned pale, and as though falling asleep, so turbid was the look in his glassy eyes, asked:

“Are you joking?”

“First you could not wait, and now you think I am joking. We are not allowed to joke here. You like to joke, but we are not allowed to,” said the warden with dignity as he went away.

Toward evening of that day Yanson had already grown thinner. His skin, which had stretched out and had become smooth for a time, was suddenly covered with a multitude of small wrinkles, and in places it seemed even to hang down. His eyes became sleepy, and all his motions were now so slow and languid as though each turn of the head, each move of the fingers, each step of the foot were a complicated and cumbersome undertaking which required very careful deliberation. At night he lay on his cot, but did not close his eyes, and thus, heavy with sleep, they remained open until morning.

“Aha!” said the warden with satisfaction, seeing him on the following day. “This is no dramshop for you, my dear!”

With a feeling of pleasant gratification, like a scientist whose experiment had proved successful again, he examined the condemned man closely and carefully from head to foot. Now everything would go along as necessary. Satan was disgraced, the sacredness of the prison and the execution was re-established, and the old man inquired condescendingly, even with a feeling of sincere pity:

“Do you want to meet somebody or not?”

“What for?”

“Well, to say good-by! Have you no mother, for instance, or a brother?”

“I must not be hanged,” said Yanson softly, and looked askance at the warden. “I don’t want to be hanged.”

The warden looked at him and waved his hand in silence.

Toward evening Yanson grew somewhat calmer.

The day had been so ordinary, the cloudy winter sky looked so ordinary, the footsteps of people and their conversation on matters of business sounded so ordinary, the smell of the sour soup of cabbage was so ordinary, customary and natural that he again ceased believing in the execution. But the night became terrible to him. Before this Yanson had felt the night simply as darkness, as an especially dark time, when it was necessary to go to sleep, but now he began to be aware of its mysterious and uncanny nature. In order not to believe in death, it was necessary to hear and see and feel ordinary things about him, footsteps, voices, light, the soup of sour cabbage. But in the dark everything was unnatural; the silence and the darkness were in themselves something like death.

And the longer the night dragged the more dreadful it became. With the ignorant innocence of a child or a savage, who believe everything possible, Yanson felt like crying to the sun: “Shine!” He begged, he implored that the sun should shine, but the night drew its long, dark hours remorselessly over the earth, and there was no power that could hasten its course. And this impossibility, arising for the first time before the weak consciousness of Yanson, filled him with terror. Still not daring to realize it clearly, he already felt the inevitability of approaching death, and felt himself making the first step upon the gallows, with benumbed feet.

Day quieted him, but night again filled him with fear, and so it was until one night when he realized fully that death was inevitable, that it would come in three days at dawn with the sunrise.

He had never thought of what death was, and it had no image to him—but now he realized clearly, he saw, he felt that it had entered his cell and was looking for him, groping about with its hands. And to save himself, he began to run wildly about the room.

But the cell was so small that it seemed that its corners were not sharp but dull, and that all of them were pushing him into the center of the room. And there was nothing behind which to hide. And the door was locked. And it was dark. Several times he struck his body against the walls, making no sound, and once he struck against the door—it gave forth a dull, empty sound. He stumbled over something and fell upon his face, and then he felt that IT was going to seize him. Lying on his stomach, holding to the floor, hiding his face in the dark, dirty asphalt, Yanson howled in terror. He lay; and cried at the top of his voice until some one came. And when he was lifted from the floor and seated upon the cot, and cold water was poured over his head, he still did not dare open his tightly closed eyes. He opened one eye, and noticing some one’s boot in one of the corners of the room, he commenced crying again.

But the cold water began to produce its effect in bringing him to his senses. To help the effect, the warden on duty, the same old man, administered medicine to Yanson in the form of several blows upon the head. And this sensation of life returning to him really drove the fear of death away. Yanson opened his eyes, and then, his mind utterly confused, he slept soundly for the remainder of the night. He lay on his back, with mouth open, and snored loudly, and between his lashes, which were not tightly closed, his flat, dead eyes, which were upturned so that the pupil did not show, could be seen.

Later, everything in the world—day and night, footsteps, voices, the soup of sour cabbage, produced in him a continuous terror, plunging him into a state of savage uncomprehending astonishment. His weak mind was unable to combine these two things which so monstrously contradicted each other—the bright day, the odor and taste of cabbage—and the fact that two days later he must die. He did not think of anything. He did not even count the hours, but simply stood in mute stupefaction before this contradiction which tore his brain in two. And he became evenly pale, neither white nor redder in parts, and appeared to be calm. Only he ate nothing and ceased sleeping altogether. He sat all night long on a stool, his legs crossed under him, in fright. Or he walked about in his cell, quietly, stealthily, and sleepily looking about him on all sides. His mouth was half-open all the time, as though from incessant astonishment, and before taking the most ordinary thing into his hands, he would examine it stupidly for a long time, and would take it distrustfully.

When he became thus, the wardens as well as the sentinel who watched him through the little window, ceased paying further attention to him. This was the customary condition of prisoners, and reminded the wardens of cattle being led to slaughter after a staggering blow.

“Now he is stunned, now he will feel nothing until his very death,” said the warden, looking at him with experienced eyes. “Ivan! Do you hear? Ivan!”

“I must not be hanged,” answered Yanson, in a dull voice, and his lower jaw again drooped.

“You should not have committed murder. You would not be hanged then,” answered the chief warden, a young but very important-looking man with medals on his chest. “You committed murder, yet you do not want to be hanged?”

“He wants to kill human beings without paying for it. Fool! fool!” said another.

“I don’t want to be hanged,” said Yanson.

“Well, my friend, you may want it or not, that’s your affair,” replied the chief warden indifferently. “Instead of talking nonsense, you had better arrange your affairs. You still have something.”

“He has nothing. One shirt and a suit of clothes. And a fur cap! A sport!”

Thus time passed until Thursday. And on Thursday, at midnight a number of people entered Yanson’s cell, and one man, with shoulder-straps, said:

“Well, get ready. We must go.”

Yanson, moving slowly and drowsily as before, put on everything he had and tied his muddy-red muffler about his neck. The man with shoulder-straps, smoking a cigarette, said to some one while watching Yanson dress:

“What a warm day this will be. Real spring.”

Yanson’s small eyes were closing; he seemed to be falling asleep, and he moved so slowly and stiffly that the warden cried to him:

“Hey, there! Quicker! Have you fallen asleep?”

Suddenly Yanson stopped.

“I don’t want to be hanged,” said he.

He was taken by the arms and led away, and began to stride obediently, raising his shoulders. Outside he found himself in the moist, spring air, and beads of sweat stood under his little nose. Notwithstanding that it was night, it was thawing very strongly and drops of water were dripping upon the stones. And waiting while the soldiers, clanking their sabres and bending their heads, were stepping into the unlighted black carriage, Yanson lazily moved his finger under his moist nose and adjusted the badly tied muffler about his neck.

The same council-chamber of the military district court which had condemned Yanson had also condemned to death a peasant of the Government of Oryol, of the District of Yeletzk, Mikhail Golubets, nicknamed Tsiganok, also Tatarin. His latest crime, proven beyond question, had been the murder of three people and armed robbery. Behind that, his dark past disappeared in a depth of mystery. There were vague rumors that he had participated in a series of other murders and robberies, and in his path there was felt to be a dark trail of blood, fire, and drunken debauchery. He called himself murderer with utter frankness and sincerity, and scornfully regarded those who, according to the latest fashion, styled themselves “expropriators.” Of his last crime, since it was useless for him to deny anything, he spoke freely and in detail, but in answer to questions about his past, he merely gritted his teeth, whistled, and said:

“Search for the wind of the fields!”

When he was annoyed in cross-examination, Tsiganok assumed a serious and dignified air:

“All of us from Oryol are thoroughbreds,” he would say gravely and deliberately. “Oryol and Kroma are the homes of first-class thieves. Karachev and Livna are the breeding-places of thieves. And Yeletz—is the parent of all thieves. Now—what else is there to say?”

He was nicknamed Tsiganok (gypsy) because of his appearance and his thievish manner. He was black-haired, lean, with yellow spots on his prominent, “Tartar-like cheek-bones. His glance was swift, brief, but fearfully direct and searching, and the thing upon which he looked for a moment seemed to lose something, seemed to deliver up to him a part of itself, and to become something else. It was just as unpleasant and repugnant to take a cigarette at which he looked, as though it had already been in his mouth. There was a certain constant restlessness in him, now twisting him like a rag, now throwing him about like a body of coiling live wires. And he drank water almost by the bucket.

To all questions during the trial he answered shortly, firmly, jumping up quickly, and at times he seemed to answer even with pleasure.

“Correct!” he would say.

Sometimes he emphasized it.

“Cor-r-rect!”

At one time, suddenly, when they were speaking of something that would hardly have seemed to suggest it, he jumped to his feet and asked the presiding judge:

“Will you allow me to whistle?”

“What for?” asked the judge, surprised.

“They said that I gave the signal to my comrades. I would like to show you how. It is very interesting.”

The judge consented, somewhat wonderingly. Tsiganok quickly placed four fingers in his mouth, two fingers of each hand, rolled his eyes fiercely—and then the dead air of the courtroom was suddenly rent by a real, wild, murderer’s whistle—at which frightened horses leap and rear on their hind legs and human faces involuntarily blanch. The mortal anguish of him who is to be assassinated, the wild joy of the murderer, the dreadful warning, the call, the gloom and loneliness of a stormy autumn night—all this rang in his piercing shriek, which was neither human nor beastly.

The presiding officer shouted—then waved his arm at Tsiganok, and Tsiganok obediently became silent. And, like an artist who had triumphantly performed a difficult aria, he sat down, wiped his wet fingers upon his coat, and surveyed those present with an air of satisfaction.

“What a robber!” said one of the judges, rubbing his ear.

Another one, however, with a wild Russian beard, but with the eyes of a Tartar, like those of Tsiganok, gazed pensively above Tsiganok’s head, then smiled and remarked:

“It is indeed interesting.”

With light hearts, without mercy, without the slightest pangs of conscience, the judges brought out against Tsiganok a verdict of death.

“Correct!” said Tsiganok, when the verdict was pronounced. “In the open field and on a cross-beam! Correct!”

And turning to the convoy, he hurled with bravado:

“Well, are we not going? Come on, you sour-coat. And hold your gun—I might take it away from you!”

The soldier looked at him sternly, with fear, exchanged glances with his comrade, and felt the lock of his gun. The other did the same. And all the way to the prison the soldiers felt that they were not walking but flying through the air—as if hypnotized by the prisoner, they felt neither the ground beneath their feet, nor the passage of time, nor themselves.

Mishka Tsiganok, like Yanson, had had to spend seventeen days in prison before his execution. And all seventeen days passed as though they were one day—they were bound up in one inextinguishable thought of escape, of freedom, of life. The restlessness of Tsiganok, which was now repressed by the walls and the bars and the dead window through which nothing could be seen, turned all its fury upon himself and burned his soul like coals scattered upon boards. As though he were in a drunken vapor, bright but incomplete images swarmed upon him, failing and then becoming confused, and then again rushing through his mind in an unrestrainable blinding whirlwind—and all were bent toward escape, toward liberty, toward life. With his nostrils expanded, like those of a horse, Tsiganok smelt the air for hours long—it seemed to him that he could smell the odor of hemp, of the smoke of fire—the colorless and biting smell of burning. Now he whirled about in the room like a top, touching the walls, tapping them nervously with his fingers from time to time, taking aim, boring the ceiling with his gaze, filing the prison bars. By his restlessness, he had tired out the soldiers who watched him through the little window, and who, several times, in despair, had threatened to shoot. Tsiganok would retort, coarsely and derisively, and the quarrel would end peacefully because the dispute would soon turn into boorish, unoffending abuse, after which shooting would have seemed absurd and impossible.

Tsiganok slept during the nights soundly, without stirring, in unchanging yet live motionlessness, like a wire spring in temporary inactivity. But as soon as he arose, he immediately commenced to walk, to plan, to grope about. His hands were always dry and hot, but his heart at times would suddenly grow cold, as if a cake of unmelting ice had been placed upon his chest, sending a slight, dry shiver through his whole body. At such times, Tsiganok, always dark in complexion, would turn black, assuming the shade of bluish cast-iron. And he acquired a curious habit; as though he had eaten too much of something sickeningly sweet, he kept licking his lips, smacking them, and would spit on the floor, hissingly, through his teeth. When he spoke, he did not finish his words, so rapidly did his thoughts run that his tongue was unable to compass them.

One day the chief warden, accompanied by a soldier, entered his cell. He looked askance at the floor and said gruffly:

“Look! How dirty he has made it!”

Tsiganok retorted quickly:

“You’ve made the whole world dirty, you fat-face, and yet I haven’t said anything to you. What brings you here?”

The warden, speaking as gruffly as before, asked him whether he would act as executioner. Tsiganok burst out laughing, showing his teeth.

“You can’t find any one else? That’s good! Go ahead, hang! Ha! ha! ha! The necks are there, the rope is there, but there is nobody to string it up. By God! that’s good!”

“You’ll save your neck if you do it.”

“Of course—I couldn’t hang them if I were dead. Well said, you fool!”

“Well, what do you say? Is it all the same to you?”

“And how do you hang them here? I suppose they’re choked on the sly.”

“No, with music,” snarled the warden.

“Well, what a fool! Of course it can be done with music. This way!” and he began to sing, with a bold and daring swing.

“You have lost your wits, my friend,” said the warden. “What do you say? Speak sensibly.”

Tsiganok grinned.

“How eager you are! Come another time and I’ll tell you.”

After that, into that chaos of bright, yet incomplete images which oppressed Tsiganok by their impetuosity, a new image came—how good it would be to become a hangman in a red shirt. He pictured to himself vividly a square crowded with people, a high scaffold, and he, Tsiganok, in a red shirt walking about upon the scaffold with an ax. The sun shone overhead, gaily flashing from the ax, and everything was so gay and bright that even the man whose head was soon to be chopped off was smiling. And behind the crowd, wagons and the heads of horses could be seen—the peasants had come from the village; and beyond them, further, he could see the village itself.

“Ts-akh!”

Tsiganok smacked his lips, licking them, and spat. And suddenly he felt as though a fur cap had been pushed over his head to his very mouth—it became black and stifling, and his heart again became like a cake of unmelting ice, sending a slight, dry shiver through his whole body.

The warden came in twice again, and Tsiganok, showing his teeth, said:

“How eager you are! Come in again!”

Finally one day the warden shouted through the casement window as he passed rapidly:

“You’ve let your chance slip by, you fool! We’ve found somebody else.”

“The devil take you! Hang yourself!” snarled Tsiganok, and he stopped dreaming of the execution.

But toward the end, the nearer he approached the time, the weight of the fragments of his broken images became unbearable. Tsiganok now felt like standing still, like spreading his legs and standing—but a whirling current of thoughts carried him away and there was nothing at which he could clutch—everything about him swam. And his sleep also became uneasy. Dreams even more violent than his thoughts appeared—new dreams, solid, heavy, like wooden painted blocks. And it was no longer like a current, but like an endless fall to an endless depth, a whirling flight through the whole visible world of colors.

When Tsiganok was free he had worn only a pair of dashing mustaches, but in the prison a short, black, bristly beard grew on his face and it made him look fearsome, insane. At times Tsiganok really lost his senses and whirled absurdly about in the cell, still tapping upon the rough, plastered walls nervously. And he drank water like a horse.

At times toward evening when they lit the lamp, Tsiganok would stand on all fours in the middle of his cell and would howl the quivering howl of a wolf. He was peculiarly serious while doing it, and would howl as though he were performing an important and indispensable act. He would fill his chest with air and then exhale it, slowly in a prolonged tremulous howl, and, cocking his eyes, would listen intently as the sound issued forth. And the very quiver in his voice seemed in a manner intentional. He did not scream wildly, but drew out each note carefully in that mournful wail full of untold sorrow and terror.

Then he would suddenly break off howling and for several minutes would remain silent, still standing on all fours. Then suddenly he would mutter softly, staring at the ground:

“My darlings, my sweethearts!... My darlings, my sweethearts! have pity.... My darlings!... My sweethearts!”

And it seemed again as if he were listening intently to his own voice. As he said each word he would listen.

Then he would jump up and for a whole hour would curse continually.

He cursed picturesquely, shouting and rolling his blood-shot eyes.

“If you hang me—hang me!” and he would burst out cursing again.

And the sentinel, in the meantime white as chalk, weeping with pain and fright, would knock at the door with the butt-end of the gun and cry helplessly:

“I’ll fire! I’ll kill you as sure as I live! Do you hear?”

But he dared not shoot. If there was no actual rebellion they never fired at those who had been condemned to death. And Tsiganok would gnash his teeth, would curse and spit. His brain thus racked on a monstrously sharp blade between life and death was falling to pieces like a lump of dry clay.

When they entered the cell at midnight to lead Tsiganok to the execution he began to bustle about and seemed to have recovered his spirits. Again he had that sweet taste in his mouth, and his saliva collected abundantly, but his cheeks turned rosy and in his eyes began to glisten his former somewhat savage slyness. Dressing himself he asked the official:

“Who is going to do the hanging? A new man? I suppose he hasn’t learned his job yet.”

“You needn’t worry about it,” answered the official dryly.

“I can’t help worrying, your Honor. I am going to be hanged, not you. At least don’t be stingy with the government’s soap on the noose.”

“All right, all right! Keep quiet!”

“This man here has eaten all your soap,” said Tsiganok, pointing to the warden. “See how his face shines.”

“Silence!”

“Don’t be stingy!”

And Tsiganok burst out laughing. But he began to feel that it was getting ever sweeter in his mouth, and suddenly his legs began to feel strangely numb. Still, on coming out into the yard, he managed to exclaim:

“The carriage of the Count of Bengal!”

The verdict concerning the five terrorists was pronounced finally and confirmed upon the same day. The condemned were not told when the execution would take place, but they knew from the usual procedure that they would be hanged the same night, or, at the very latest, upon the following night. And when it was proposed to them that they meet their relatives upon the following Thursday they understood that the execution would take place on Friday at dawn.

Tanya Kovalchuk had no near relatives, and those whom she had were somewhere in the wilderness in Little Russia, and it was not likely that they even knew of the trial or of the coming execution. Musya and Werner, as unidentified people, were not supposed to have relatives, and only two, Sergey Golovin and Vasily Kashirin, were to meet their parents. Both of them looked upon that meeting with terror and anguish, yet they dared not refuse the old people the last word, the last kiss.

Sergey Golovin was particularly tortured by the thought of the coming meeting. He dearly loved his father and mother; he had seen them but a short while before, and now he was in a state of terror as to what would happen when they came to see him. The execution itself, in all its monstrous horror, in its brain-stunning madness, he could imagine more easily, and it seemed less terrible than these other few moments of meeting, brief and unsatisfactory, which seemed to reach beyond time, beyond life itself. How to look, what to think, what to say, his mind could not determine. The most simple and ordinary act, to take his father by the hand, to kiss him, and to say, “How do you do, father?” seemed to him unspeakably horrible in its monstrous, inhuman, absurd deceitfulness.

After the sentence the condemned were not placed together in one cell, as Tanya Kovalchuk had supposed they would be, but each was put in solitary confinement, and all the morning, until eleven o’clock, when his parents came, Sergey Golovin paced his cell furiously, tugged at his beard, frowned pitiably and muttered inaudibly. Sometimes he would stop abruptly, would breathe deeply and then exhale like a man who has been too long under water. But he was so healthy, his young life was so strong within him, that even in the moments of most painful suffering his blood played under his skin, reddening his cheeks, and his blue eyes shone brightly and frankly.

But everything was far different from what he had anticipated.

Nikolay Sergeyevich Golovin, Sergey’s father, a retired colonel, was the first to enter the room where the meeting took place. He was all white—his face, his beard, his hair, and his hands—as if he were a snow statue attired in man’s clothes. He had on the same old but well-cleaned coat, smelling of benzine, with new shoulder-straps crosswise, that he had always worn, and he entered firmly, with an air of stateliness, with strong and steady steps. He stretched out his white, thin hand and said loudly:

“How do you do, Sergey?”

Behind him Sergey’s mother entered with short steps, smiling strangely. But she also pressed his hands and repeated loudly:

“How do you do, Seryozhenka?”

She kissed him on the lips and sat down silently. She did not rush over to him; she did not burst into tears; she did not break into a sob; she did not do any of the terrible things which Sergey had feared. She just kissed him and silently sat down. And with her trembling hands she even adjusted her black silk dress.

Sergey did not know that the colonel, having locked himself all the previous night in his little study, had deliberated upon this ritual with all his power. “We must not aggravate, but ease the last moments of our son,” resolved the colonel firmly, and he carefully weighed every possible phase of the conversation, every act and movement that might take place on the following day. But somehow he became confused, forgetting what he had prepared, and he wept bitterly in the corner of the oilcloth-covered couch. In the morning he explained to his wife how she should behave at the meeting.

“The main thing is, kiss—and say nothing!” he taught her. “Later you may speak—after a while—but when you kiss him, be silent. Don’t speak right after the kiss, do you understand? Or you will say what you should not say.”

“I understand, Nikolay Sergeyevich,” answered the mother, weeping.

“And you must not weep. For God’s sake, do not weep! You will kill him if you weep, old woman!”

“Why do you weep?”

“With women one cannot help weeping. But you must not weep, do you hear?”

“Very well, Nikolay Sergeyevich.”

Riding in the drozhky, he had intended to school her in the instructions again, but he forgot. And so they rode in silence, bent, both gray and old, and they were lost in thought, while the city was gay and noisy. It was Shrovetide, and the streets were crowded.

They sat down. Then the colonel stood up, assumed a studied pose, placing his right hand upon the border of his coat. Sergey sat for an instant, looked closely upon the wrinkled face of his mother and then jumped up.

“Be seated, Seryozhenka,” begged the mother.

“Sit down, Sergey,” repeated the father.

They became silent. The mother smiled.

“How we have petitioned for you, Seryozhenka! Father—”

“You should not have done that, mother——”

The colonel spoke firmly:

“We had to do it, Sergey, so that you should not think your parents had forsaken you.”

They became silent again. It was terrible for them to utter even a word, as though each word in the language had lost its individual meaning and meant but one thing—Death. Sergey looked at his father’s coat, which smelt of benzine, and thought: “They have no servant now, consequently he must have cleaned it himself. How is it that I never before noticed when he cleaned his coat? I suppose he does it in the morning.” Suddenly he asked:

“And how is sister? Is she well?”

“Ninochka does not know anything,” the mother answered hastily.

The colonel interrupted her sternly: “Why should you tell a falsehood? The child read it in the newspapers. Let Sergey know that everybody—that those who are dearest to him—were thinking of him—at this time—and—”

He could not say any more and stopped. Suddenly the mother’s face contracted, then it spread out, became agitated, wet and wild-looking. Her discolored eyes stared blindly, and her breathing became more frequent, and briefer, louder.

“Se—Se—Se—Ser—” she repeated without moving her lips. “Ser—”

“Dear mother!”

The colonel strode forward, and all quivering in every fold of his coat, in every wrinkle of his face, not understanding how terrible he himself looked in his death-like whiteness, in his heroic, desperate firmness. He said to his wife:

“Be silent! Don’t torture him! Don’t torture him! He has to die! Don’t torture him!”

Frightened, she had already become silent, but he still shook his clenched fists before him and repeated:

“Don’t torture him!”

Then he stepped back, placed his trembling hands behind his back, and loudly, with an expression of forced calm, asked with pale lips:

“When?”

“To-morrow morning,” answered Sergey, his lips also pale.

The mother looked at the ground, chewing her lips, as if she did not hear anything. And continuing to chew, she uttered these simple words, strangely, as though they dropped like lead:

“Ninochka told me to kiss you, Seryozhenka.”

“Kiss her for me,” said Sergey.

“Very well. The Khvostovs send you their regards.”

“Which Khvostovs? Oh, yes!”

The colonel interrupted:

“Well, we must go. Get up, mother; we must go.” The two men lifted the weakened old woman.

“Bid him good-by!” ordered the colonel. “Make the sign of the cross.”

She did everything as she was told. But as she made the sign of the cross, and kissed her son a brief kiss, she shook her head and murmured weakly:

“No, it isn’t the right way! It is not the right way! What will I say? How will I say it? No, it is not the right way!”

“Good-by, Sergey!” said the father. They shook hands, and kissed each other quickly but heartily.

“You—” began Sergey.

“Well?” asked the father abruptly.

“No, no! It is not the right way! How shall I say it?” repeated the mother weakly, nodding her head. She had sat down again and was rocking herself back and forth.