The Bird Boys’ Aeroplane Wonder

Judge of Their Astonishment and Wild Delight When They Saw the Aeroplane Leave the Earth.

Judge of Their Astonishment and Wild Delight When They Saw the Aeroplane Leave the Earth.

“Was there ever such great luck, fellows?”

“Whew! for one, I feel like giving a vote of thanks to the striking masons, who loafed pretty much all summer, and held the repair work on the Bloomsbury High building up till now.”

“Them’s my sentiments, Elephant!”

“And they say now the work can’t be finished and school taken up till December! What d’ye think of that, Frank, and you, Larry?”

“Glory to goodness! two extra months’ vacation, and right through October too, when the chestnuts are ripe, and walnuts are dropping! What bully days we’ve got ahead of us, boys!”

“And November, too, mind you,” went on the little “runt” who had been called “Elephant” in a joke by his chums and could not shake off the name, “the month when the frisky cottontail is also ripe. Say, Frank, won’t you have a ge-lorious time trying out that new Marlin pump-gun you got for your last birthday?”

The third member of the group sitting under the beech tree had as yet not spoken, since his two companions started to give expression to their extravagant delight over the wonderful news brought by Fenimore Cooper Small, the aforesaid “Elephant,” whose father happened to be the head Selectman of the town, and could fetch the decision of the Board of School Trustees home before the rest of the worthy citizens had been put wise to the facts.

“Well,” said Frank Bird, with one of his rare smiles that always made him friends wherever he went, “I had a pretty good idea it would end that way, when I heard how the trustees failed to find any building in town that would answer to house the high school pupils. Yes, I’m glad for some things, and sorry for others. But it’ll give the Bird boys a chance to do a little more flying before winter sets in and stops all that fun.”

Frank and his cousin Andy had become quite famous throughout the region around Bloomsbury, a town in Central New York, on account of the wonderful success they had made of aviation.

Indeed, some of the doings of the Bird Boys, as they were called, had even found their way into the columns of the big metropolitan papers, and among professional birdmen they were looked upon as most promising “comers.”

Back of Frank’s house—where he lived with his father, Professor Bird, once a noted balloonist and scientist, together with an old gentleman who had served as guardian to Frank when his father was believed to have perished on one of his long flights while exploring parts of the Panama Isthmus—in a field some distance in the rear of his house there had been built a fine workshop, where the two boys spent most of their time when not in the air.

Already they had invented quite a few ingenious contrivances which gave promise that some day their names would figure along with those that have made aviation in heavier-than-air machines what it is today—those of the Wright brothers.

Close to this workshop was the great “hangar” in which they kept their aeroplane when it was not in use; and since enemies had frequently tried to injure their property these buildings were not only securely locked but as a rule watched of nights.

To tell even a small portion of the doings of these bold cousins when navigating the air would consume too much space and time; and the reader who has been unfortunate enough not to have enjoyed their perusal is referred back to the previous volumes in this Series, where they will be found recorded at length, and the story told in an entertaining manner.

The third member of the little group taking it easy under the wide spreading beech tree, with its thick branches, was one Larry Geohegan, a firm friend of the Bird boys; whose only fault was the envy he often felt because he could never accompany either of his flying chums aloft, being afflicted with a weakness that made him dizzy whenever he looked down from any height.

Elephant had met the other two quite by accident on the road, and stopped to communicate the grand news, which he had heard his father tell at the breakfast table.

Apparently the other two lads were going fishing, for they had poles and bait cans lying on the ground. There was a beautiful lake named Sunrise, upon which the town lay; and a mile away a stream ran into this which could always be depended upon to furnish a splendid string of bass, chubs, sunfish and horned pouts or catfish, when the wind was favorable, as happened on this lovely morning. “What were you waiting here for under this tree; did you expect Andy to show up?” asked Elephant after he had declared his intention of joining the fishing party, and cutting a pole when he got on the grounds.

“Just what we did,” replied Frank. “He spent last night out at Spencer’s, because as you all know, the old gentleman is especially fond of Andy, and every once in so often begs him to come out and cheer him up.”

“Yes, and they do say he means to leave all he’s got to Andy, in trust of his father, Doctor Bird,” declared Larry, that little streak of envy again making itself evident in his voice; for it did seem to him that things were always coming to his chums and passing him by.

“Oh! that’s silly talk,” laughed Frank, “I wouldn’t pay any attention to it, if I were you, Larry. I’m sure Andy never gives such a thing a thought. He’s only too glad to oblige the poor old man who’s so crippled with rheumatism that he can hardly hobble around. And you know that years and years ago he used to be a noted traveler, and a lecturer as well. Why, fellows, there hasn’t hardly been a country on the face of the earth that Mr. Spencer hasn’t visited, and explored. I could sit for hours and just hear him tell about what he’s seen and gone through with. I try to go out with Andy every chance I get; but last night I was too busy with a knotty problem I had to solve.”

“I just bet you it was about some new contraption you’re making up to surprise the flying people. Already you’ve done a heap along that line, Frank; and they do say that the time is sure to come when you’ll give the Wrights, and all that bunch, a rude jolt, by inventing something that they’ve all been trying hard to discover, but nixey, nothing doing up to date; because the time ain’t ripe, and the Bird boys haven’t had a fair chance to show what they can do.”

Frank only laughed when Elephant applied this thick coat of flattery. He was accustomed to hearing this sort of talk from that quarter; because the Small boy had always been one of his greatest admirers from the time when he and Andy were struggling with their first rude pattern of an aeroplane, in which they had installed some sort of cranky engine, and actually taken short flights, without getting their necks or legs broken.

“But you must have agreed to meet Andy here then, didn’t you?” Elephant went on to remark, stretching his neck to glance along the road as he spoke.

“That was the agreement when he went off on his wheel yesterday afternoon,” replied Frank Bird. “If the morning looked fishy, Larry and myself were to wait here under the old beech at eight o’clock until he came along. You see, I’ve got a pole for him; and we dug lots of worms. Larry even went out last night with a lantern, and picked up a can of big fat night-walkers that look like young snakes. I dropped in at Andy’s house on the way here, and told them he wouldn’t be back till evening, if the fish took good, and the bathing turned out fine. We’ve also got plenty of grub along; yes, enough for you, too, Elephant.”

“Hoop-la! you make me feel happy when you say that, Frank; because I was born with an appetite, you must know; and when I can’t get my grub at least three times per diem I’m apt to complain,” and the Small boy grinned good-naturedly as he made this remark.

“I say, Frank, have you and Andy invested that reward money the bank insisted on you accepting when you captured the two hobo yeggmen who broke into their safe; and also stole Percy Carberry’s biplane to make their get-away in?” asked Larry, who, it might as well be confessed right here, had a pretty average streak of curiosity in his make-up, and was forever wanting to know this, that, and the other thing.

“Oh!” answered the other carelessly, “we’ve still got that in bank, and may put it into another machine later on; or else invest in some parts we want to work with, Andy having a new idea this time that looks worth while experimenting with.”

“You sure are the luckiest pair I ever ran up against, and that’s a fact!” declared Larry.

“We think so ourselves,” Frank admitted. “There’s one thing certain, and that is we don’t deserve all the great times we’ve been having this year and more.”

“Don’t you believe it!” exclaimed Elephant. “It ain’t luck so much as being everlastingly at it, and minding how you do things. You deserve all you’ve got, Frank; and lots of people say so besides me.”

“Here comes Andy,” remarked Larry, anxious to turn the conversation just then, for he was really somewhat ashamed of his weakness, “I saw him flash past that open place up the road, and spinning along like fun.”

“Yes, you’re right there, Larry,” added Frank, “and here he is.” A boy mounted on a fine bicycle came whirling along the road, and speedily drew up at the beech with the dense foliage, which later on would yield a harvest of the small but sweet nuts boys love so well when it is a “fat” season.

Andy Bird was not quite as tall as his cousin, though well built and rather stocky at that. There was more or less resemblance between them, although their temperaments differed in many ways, Andy being more inclined to impulsiveness than the cooler and far-seeing Frank. But they were exceedingly fond of each other, and had been inseparable for years.

Andy threw himself from his saddle, and lowering his wheel to the ground after the usual boyish way, dropped down beside the others.

“Whew! I hit it up at a lively clip all the way down!” he remarked. “You see, it’s awful hard to break away from Mr. Spencer, and he kept me up to the last minute. I knew you said eight o’clock, Frank, and I didn’t want to keep you waiting. Glad you turned up, Elephant; we tried to get you on the phone yesterday afternoon; but they said you’d gone off, and nobody knew where. Going with us, ain’t you?”

“Make your mind easy on that, Andy,” replied the diminutive Elephant, glibly. “I never could hold out when there was any fishing going on. I just revel in pulling out the gamey bass, the festive catfish, and the acrobatic eel; while as for perch and pickerel and sunfish, why, I delight to see them wriggling on the hook, ready to take their places in the pan. See you’ve got a fryingpan along, Larry; and that means we’ll have fish for dinner today—after we grab ’em out of the water.”

“But Andy, think of the bully good news Elephant’s gone and brought with him,” Larry went on to say, jubilantly, “the trustees have finally decided that, as the big repairs on the high school building have been started, and can’t possibly be done till early winter, why, because there’s no place in town that could be used just now, vacation has got to be lengthened until about the first of December.”

Andy Bird looked delighted, as what boy would not. Immediately his eyes traveled in the direction of his cousin, and there was exchanged between them a significant series of nods and winks, that possibly meant their thoughts were along the same lines; and that now they would have the time to go with certain work that had been taking their attention of late. “By the way,” said Frank, “I stopped at your house on the way out, Andy, to tell your father that you would go fishing with us, and not to expect you till night. And he gave me a letter for you that he said had come in the early morning mail. From the postmark I see it’s from your uncle Jethro, away down on that Arizona ranch you were telling me about. Here it is, and a fine fat one too.”

Andy hastily opened the letter, and was heard to give vent to a low cry that seemed to spell both astonishment and delight.

“What’s this mean?” exclaimed Frank, stooping to pick up a paper that had fallen to the ground, “why, as sure as you live, it’s a check made out to you, Andy, and signed by the old bachelor uncle, your mother’s brother. Hold your breath, fellows, while I whisper what the amount is he takes pleasure in sending to his beloved nephew—four figures in it, as sure as you live—a clean thousand dollars!”

Larry gave a groan and threw up his hands while his eyes rolled.

“Of all the lucky fellows, you Bird boys do certain sure take the cake!” he cried.

“Ain’t you going to read it out, Andy?” asked Elephant, anxiously.

“Wait till he gets through, can’t you?” asked Larry, although he was fairly trembling with eagerness to hear what the sending of that glorious check could mean; when he looked at the small bit of paper Frank was holding he almost held his breath with awe, for to tell the truth Larry had never seen a check a quarter as large as that in all his life.

Andy could not say a word when he finished reading. He seemed to be fairly overpowered with emotion, and holding the letter out to Frank, motioned that he should accommodate the other two.

And so Frank started in. The letter was written in a cramped hand, as if uncle Jethro Witherspoon had rather lost the knack of using a pen; but then Frank could wade through it, even if he did hesitate here and there.

It started in after this fashion:

“My Dear Nephew, Andrew Bird:—I’ve been hearing a whole lot about the way you and your cousin Frank are coming along with that airship business, and your mother has got me worked up to pretty nigh fever pitch about your precious doing. Now here I am, an old and cranky bachelor, with a big and successful cattle ranch on my hands, and no chick or child to cheer me up. I want you two boys to pay me a long visit, and bring that wonder of an aeroplane along with you. I sounded your mother some time back, without her letting you know, and she was agreeable, if only it could be arranged without interfering with your school duties. And here today your good dad, the doctor, has wired me that he believes there is going to be an extension of the vacation period for another two months.

“Seems like things might be working to please a lonely old man out this way. Now here’s a little check to cover expenses. If you need any more draw on me to any amount. What’s money for anyway but to give pleasure to somebody? Pack up that flying machine of yours, and either tuck it under your arm or else ship it by the fastest express you can get to receive it, regardless of cost.

“I’m not going to take no for an answer. I want you and that smart cousin Frank down here to show some of my cow-punchers what’s doing in the line of this flying business. But most of all I want to see you. I’ve got your pictures before me as I write, and I’m counting the days until you arrive, bag and baggage. Wire me on receipt of this all about your plans and when you can start. If you say you can’t come, I’m going up after you. I’m used to having my own way, the boys down here will tell you. With lots of love, believe me,

“Your affectionate uncle,“Jethro Witherspoon.”

When Frank finished reading this remarkable letter, Larry gasped for breath; while little Elephant stood on his hands and cracked his heels together.

“That sure takes the cake, Andy, Frank!” he declared, when he had once more resumed his customary position, with his head higher than his heels. “And my stars! what a ge-lorious time you two will have of it, away down in that desert corner of Arizona! Cowboys—bucking bronchos—whirling ropes—branding cattle—the merry round-up—the camp-outs on the plains, and all them stunts. Oh! what wouldn’t I give to be going along with you, fellers?”

“It’s always better to be born lucky than rich; I’ve said that before, and I’m ready to stick by it!” stoutly asserted Larry. “Frank, can we go, do you think?” asked Andy, almost in a whisper, as though he had hardly as yet recovered his breath, taken away at the wonderful news contained in that letter which his cousin had brought him.

“We’ll think it over and see,” replied the other, always avoiding the rush tactics that Andy frequently displayed, and which made him a valued member of the Bloomsbury High football eleven. “But I rather guess it could be arranged, if my father is willing.”

“Huh! no danger of him saying no,” grunted Larry. “He ought to know that you two boys can take care of yourselves anywhere on the face of the earth. After you went down to Colombia in South America, and figured out where he must have drifted to, when he lost control of his balloon; afterwards rescuing him from that queer old valley surrounded by the high cliffs, that made him a prisoner, the Professor’d say yes if you wanted to try a trip to the moon. And some of us’d believe you, if you said you’d been that far in your airship, and shook hands with the Old Man up there.”

“But he wants us to take our aeroplane along, Frank; could we pack that up and send it by express, do you think? Will they take anything as big and cumbersome as that, in boxes or crates, by express?” Andy went on, eagerly, as though in his mind the fact of their going was already assured.

“I guess they’ll take anything short of a house!” declared Elephant. “Even if it needs a special car to carry it along. If you sent the thing by freight, chances are it’d be a whole month getting there.”

“And time counts with Uncle Jethro more than money does with most men,” remarked Larry. “You see he wants to get you there with your flier regardless of expense. Why, I’d wire him tonight, Andy, and pack up in a couple of days. Elephant ’nd me’ll help out all we can.”

“Well, I should say we’d thank you for the chance,” spoke up the Small boy.

“It’s hard to believe we’ve got such a great chance to see something of that country down there among the mountains and deserts and plains of Arizona,” Andy went on to say, as though he wanted some one to stick him with a pin, so as to find out whether he were really awake, or only dreaming.

“And I never dreamed we’d have such a great opening to visit that country,” the other Bird boy went on to say, while his face beamed with delight which refused to be repressed. “That uncle of yours must be a fine old chap, Andy. His letter is a peach, and I’m as sure as anything we’ll like him from the word go. Think of his throwing you a check for a thousand just like it might be thirty cents; and telling you to draw on him to any amount. He must think we’ll be wanting to charter a special train to take us and the aeroplane along.”

“Chances are he’d stand for it,” ventured Larry. “Say, why didn’t some rich old uncle of mine think of me, and send a little piece of paper this way? I’ve got half a dozen wealthy ones, but they don’t know I’m on the face of the earth.”

“Well,” said Elephant, “get busy then, and make the name of Geohegan famous, and then they’ll all break their necks trying to get you to let ’em adopt you. The trouble is, Larry, you hide your light under a bushel too much. Fly high, like the Bird boys do, and everybody ’ll see what you are.”

The other gave a dismal groan.

“That’s just what ails me,” he complained, “I can’t fly at all. Why, I get dizzy in a swing; and even when I go out on the lake, if she’s the least bit rough, you’ll find me hangin’ over the side right away, tryin’ to see how deep it is, and wonderin’ if drowning’d stop my troubles easy like. I reckon I’ll just have to make up my mind that if ever I set this old world afire, it’s got to be by doin’ some stupendous intellectual stunt. That seems to be my long hold, just as eatin’s yours, Elephant.”

“Rats,” jeered the other, contemptuously, “as if you couldn’t stow away twice as much as me any day you felt like it. I talk a heap about the grub racket; but you can work them jaws of yours to beat the band, Larry Geohegan.”

“Well, do we start off now, or fuss around and chatter like a lot of monkeys?” demanded the party thus referred to by Elephant.

“What about your wheel, Andy; you don’t want to lug that along through the timber by that snaky trail?” asked Frank.

“I had fixed all that in my mind as I pedalled,” was the reply. “You know we have to pass the Fletcher place just above here, before we strike off the road, and I can leave the bike there till we come out this afternoon.”

“Sure thing!” commented Elephant, nodding his head sagely; just as though when he approved of a suggestion it had the hall mark of wisdom stamped on it.

“I’ve done that more’n once when I had my wheel along,” declared Larry, bent on showing his chums that he could have an original idea once in a while, even though fame had not picked him out for a favorite.

“Did you bring a pole along for me, Frank?” asked Andy.

“Yes, and plenty of hooks, and lines, and sinkers, and what-not,” replied the one addressed. “Elephant, here, says he’ll cut a pole after we get on the ground; and the chances are he’ll be the luckiest fisherman of the lot. Nearly always turns out that way, I notice; for the fellow who just takes things as they come along gets the biggest fish and the greatest number. Now, you see, I’ve got a rod along, a real jointed split bamboo rod that was given to me last Christmas by my guardian, old Colonel Whympers. I’m going to be the toney angler, and try all sorts of stunts while the rest of you are pulling in the fish. But to me a pound bass caught on light tackle is better than one that weighs three times as heavy, if I have to just yank him in with a pole, and a cord tied to the end—no reel, no fine leader, only a hook in a bunch of wiggling worms, and a float above the sinker.”

“Huh! you’re getting big notions, Frank,” grunted Larry. “Time was when you seemed just as well pleased with one of these long cane poles. I’m mighty much afraid you’re getting spoiled, my boy.”

“Well, if somebody made you a present of a beautiful jointed rod like that, now, Larry——” began Andy.

“Ain’t no chance for that to happen; nobody ever thinks to remember my birthday, ’cept you fellers; when you pound me nearly to death, and then treat to the ice cream to make up for it,” Larry lamented, dolefully.

“But supposing they did,” persisted Andy, who never liked to give up anything on which he had started; “now, wouldn’t you want to get acquainted with it; and if you caught a good fish that way, and felt how he pulled, and saw the slender rod bend nearly double, wouldn’t you want to try it again and again, honest Injun, Larry tell me?”

“Oh! I guess so, Andy,” answered the other, making a grimace, “but there ain’t no such luck for me. I must a been born under an evil star, my mom says, because I’m always bustin’ things at home. She says it’s because I’m so clumsy; but I know better. Why, seems like some things just fall over and smash, when I happen to look at ’em.”

“Then for goodness sake quit looking at me like that, Larry!” exclaimed Elephant. “I ain’t got no hoops around me right now, and I tell you I don’t want to bust any—not till after we’ve had that bully old camp dinner today, anyhow. Just turn your eyes the other way, thank you.”

Andy had meanwhile carefully placed the wonderful check inside the envelope once more, and with a pin fastened the latter in his coat pocket. It was Frank’s suggestion that he do this; for the latter knew from experience that Andy could be a bit careless at times. And the thought of losing that windfall, when so delightful a future beckoned to them through its means, would be enough to give any boy the heart-ache.

“All ready, boys?” asked Frank, presently, as he stooped and carefully picked up the little covered case in which his fine rod lay, each joint reposing in the groove that was made to hold it.

“Yep. Let me carry the poles, Larry. You’re always getting things caught in the bushes and trees as we go along. Why, only the last time we came fishin’ didn’t you hook me in the ear, and make me howl like anything? You take care of that fryingpan, and the bundle of grub. And walk ahead, so’s we c’n kinder keep an eye on you, please, Larry.”

“Huh! think you’re smart to say that, don’t you, Elephant?” grunted the other, but in spite of the fact that these two were usually in some sort of a “spat,” they were really great friends, and ready to do almost anything, one for the other.

So the four boys left the shelter of the fine old beech that stood alongside the road, while its mates grew over on the other fence; for strangely enough, Frank had noticed that beech trees like company, and are rarely if ever, found alone.

They walked briskly along the road, with their backs turned in the direction of the not far distant town. A little ways off they would climb the fence, pass through a field, enter the woods, and by a short-cut reach the fishing grounds much more easily than if they had skirted the lake, and coming to the little river, followed up its sinuous course.

Just as they came to the bend a short ways above, Larry, who was ahead, happening to turn around in order to say something was seen to stare, and then exclaim:

“Well, now, if that don’t beat anything going!”

Of course his strange words, together with the look on his face, aroused the curiosity of the other three boys. They, too, turned their heads, thinking in this fashion to discover what had given Larry so great a shock; but so far as they could see, there was nothing at all in sight.

“What was it?” demanded Andy.

“Did you see somebody?” demanded Elephant, getting his poles in every sort of trouble, in his eagerness to learn what it was all about back there.

“Yes, and what do you think, fellows, he just dropped down out of the branches of that big birch tree, and hurried into the bushes like fun. Take my word for it, he must a-been up there all the time we was sittin’ talking; and if that’s so, he learned about Andy here getting that letter and check from Uncle Jethro, ’way down in the cow-puncher country.”

“But who in the mischief was it, Larry, did you know him?” persisted Elephant.

“I should say yes; and who but that sneak of a Sandy Hollingshead, the shadow that hangs around after Percy Carberry, and does most of his mean work for him. And chances are, he’s makin’ for town right now, to tell all he’s learned. Say, won’t your old rival, Percy, be mad, though, when he hears of the luck that has come to the Bird boys?”

Andy looked somewhat serious when Larry said this; but Frank on his part only laughed.

“Well, what does it matter?” he remarked. “The thing will be town talk in a little while, and those fellows would hear it that way. Let Sandy run with his great news and give his chum a pain. You don’t think for a minute that because we’ve got a chance to go off there to the cattle country, that Percy Carberry would make up his mind to hike that way, with some sort of machine he’s got coming, to take the place of that new biplane the bank thieves wrecked for him in Lake Ontario?”

“But you know how bitter he’s always been against us, Frank?” expostulated Andy.

“Many’s the time he’s tried to do us a bad turn; and even up in the air he used to take the greatest delight in swooping past us, just as close as he dared, and give us a scare; though he quit that when you threatened to lick him.”

“But didn’t you do Perc a great favor that time he had his machine knocked to flinders on the table rock up yonder?” demanded Elephant, turning to point his rods upwards to where quite a mountain reared its head toward the clouds, and which was locally known as Old Thunder-Top, though in the atlas it had another name.

Nobody had ever been able to climb to the summit of that precipitous height, and when the Bird boys landed there once from their aeroplane and planted a flag above the nest of the white-headed eagles they achieved a great triumph. The incident to which Elephant alluded had been brought about during a sudden thunder storm that had caught the rival aeroplanes while making a flight to the top of the mountain; and at that time the Bird boys were indeed placed in a position to save the lives of Percy Carberry and his comrade Sandy; but since gratitude was a foreign element in the make-up of the jealous rival, he had never shown that he meant to change his tactics toward Frank and Andy.

“Oh! never mind about what we did,” remarked Frank. “Forget it, just as Percy has done. Tomorrow, we’ll get as busy as beavers, packing the machine in the cases; and how lucky we didn’t break them up as you wanted to do, Andy, just to get rid of the stuff, you said. I guess we ought to be able to ship on the next day, and then learn just how long it’ll be on the way, so we can time our own going.”

“Huh! seems to me you ain’t botherin’ much about whether your dad’ll give his consent, eh, Frank?” remarked Larry, grinning.

“Oh! I’m taking that for granted; because you all seemed so sure he wouldn’t refuse me that favor,” chuckled Frank. “But come along, boys; what do we care if Sandy did get the news first hand, by climbing that tree when he saw us coming along the road, and keeping those big ears of his wide open. So far as I’m concerned I’d just as soon tell them myself all about our plans; because if we’re away down in Arizona, and they stay here in old Bloomsbury, I don’t think Percy’s got a long enough arm to reach that far, and do us any harm.”

“He sure would if he could, and don’t you forget it,” muttered Elephant; and at that Andy looked more or less troubled.

As our story concerns the doings of the Bird boys in other fields than that of their old stamping grounds around the home town, we need not accompany them further on their visit to the fishing hole. Enough to state that the finny tribes bit eagerly at times, and that besides having a fish dinner at noon, they all carried home respectable strings to exhibit as evidence of their prowess with hook and line.

Frank doubtless felt satisfied with his sport, even though he did not take the largest bass, nor the greatest number for that matter; and the whole of them came home by sundown, tired, yet satisfied with the day’s sport.

During the many hours spent alongside the deep hole where the fish loved to lie in these late summer days, there was plenty of time in which to discuss the coming departure of Frank and Andy for the Far West. And it can be set down as certain that the subject was threshed as dry as a bone before the quartette separated for the night.

Early the next day Elephant and Larry showed up at Frank’s house, to find him already busily at work out there at the hangar, taking off bolts, and dismembering the wonderful aeroplane with the confidence of one who was familiar with every minute detail of its construction; which was only the truth, for with his cousin he had partly built at least three “fliers” up to now, and was continually thinking up some new arrangement that would make the task of piloting aeroplanes through the upper air currents much easier, or possibly add to their safety when rocked by furious gusts of wind among the clouds. Andy soon showed up, and almost quivering with eagerness to get busy. There did not seem to be the slightest thing in sight to disturb the two who were planning such great things.

And that was indeed a busy morning for the four friends.

Elephant and Larry were only too anxious to do all that lay in their power, in order to assist. True, their knowledge of the mechanism connected with these amazing air travelers was rather limited; but then both were willing to do odd jobs of carrying, and nailing up cases; so that altogether they made themselves very useful indeed.

Larry managed to bottle up his envy on this occasion, and even seemed quite gay. As a rule he was a good companion, cheerful, willing, and generous to a degree. And Elephant could hardly have been any happier even though given the opportunity to accompany the pair of adventurous voyagers on their long trip.

Then came the afternoon session, and they went at it with renewed vim. It is astonishing what an amount of solid work four husky boys can put in during a whole day with the tools, especially when two of them are as expert in handling monkey wrenches and the like as Frank and Andy were.

By four o’clock the aeroplane had been completely and securely packed, and they were waiting for the big truck which Frank had engaged at the livery stable, to show up, in order to carry the same to the freight station of the railroad.

The man presently came along, and with the help of the four boys the various boxes and crates were loaded. Then they started off, headed for the railroad; and as their route lay directly through town it was not long before quite a following of youngsters trailed along, chattering about the mysterious way in which Frank Bird was about to ship his aeroplane, and inventing all sorts of miraculous stories about certain races in which the two cousins were slated to take part; until one boy more daring than his mates, managed to climb up on the truck, and read the address which had been plainly printed on every piece of freight.

So it was known that the aeroplane was being shipped far away to Arizona; and it may be set down as certain that this fact only served to whet the curiosity of that crowd of half-grown lads more than ever.

Frank had learned on the preceding evening how it would have to be sent out. The express people would handle it after a certain fashion, shipping by what they called fast freight. The agent calculated that in this way it would take about ten or twelve days for the aeroplane to reach the border town where Andy’s uncle was to meet them upon their arrival.

Of course that meant a long delay, and much fretting; but it was the best that could be arranged, and Andy had to abide by it. But between them he and Elephant and Larry had decided that they would not let the precious freight go unguarded for a minute, until it was placed in a car on the following morning, and had left Bloomsbury on the freight that would rush it to the nearest city, where it could be attached to the fast train that left daily for Western points.

Frank was inclined to make fun of his cousin for his suspicions, and declared that according to his mind they had nothing to fear, except the possibilities of a fire sweeping down upon the ramshackle freight house, which was the best Bloomsbury could boast until the new stone one was completed.

“Do just whatever you want to, boys,” he had remarked, after they had received the receipt for the freight, and paid the charges all the way through, with some of the cash that wonderful check had been exchanged for after Andy had written his full name across the back; “but I rather think you’ll have all your trouble for your pains. As for me, I’ve got a few important things to work at tonight, and so, if you don’t mind, I’ll spend the time in the shop. Good luck to you all! Let me know the first thing in the morning if everything’s O.K.” With that Frank swung around on his heel and strode away.

“How about that, Andy,” demanded Larry, when they saw Frank vanish beyond the open door of the freight shed; “is he really giving us the hook because we think it best to watch the blooming freight tonight, for fear that tricky Perc Carberry and his man Friday, I mean Sandy, swoop down upon it, and do something to make your fine airship good only for the scrap-heap?”

Andy laughed as he replied:

“You just don’t know Frank as well as I do,” he observed. “Chances are that if we hadn’t set up that howl about being afraid something was going to happen here, my cousin would have quietly sneaked along this way after dark, and stood on guard the whole blessed night.”

“What’s that you say, Andy, and he just laughed at us too? I didn’t think Frank had it in him to play a joke like that,” exclaimed Elephant, looking hurt.

“Well,” went on Andy Bird, “you see he knew we were bent on keeping guard here, and Frank does hate to see anybody disappointed; so he just let us have our own way about it. And then when he said he had something important to do at our shop, he spoke the truth; because he’s right now on the heels of a discovery that may mean a whole lot to us.”

“All right,” remarked Larry. “We’re only too glad to let Frank off, and run the whole shooting match ourselves, for once. Now, how shall we fix it so every fellow can get home to supper, and yet keep tab on what’s going on here all the while?”

This was very easily adjusted, however. They left Larry on guard, because he said his folks had supper later than the rest; and both Elephant and Andy promised to hurry back as soon as they could get enough to eat; and let their folks know just why they did not expect to occupy their beds that night.

This plan worked all right.

When the two boys turned up together, one having called for the other, of course the first thing they asked Larry was whether anything had happened; perhaps their sharp eyes detected the fact that he looked somewhat excited, and they judged that this could hardly be unless he had seen something suspicious.

“Well,” remarked Larry, with his favorite drawl, “I kept myself hid just as nice as you please, and I was glad I’d been so smart; because who should walk in here talking to the agent but Perc himself. Seemed to be asking if any freight had come along for him, and made out to be pretty huffy over the delay of the railroad to deliver stuff. Got the agent to hustle around, looking to see whether it could a-been overlooked, and hidden out of sight behind other things. But say, when he was sure the other’s back was turned, what did Perc do but step up to your stuff, Andy, and take a quick look at the directions you marked on each package. Then I heard him chuckle, step back, and measure distances with his eye; just like a feller might do that expected to come back here in the dark and prowl around and wanted to get his bearings well in his head!”

“Wow! now what d’ye think of that?” exclaimed Elephant, showing his white teeth aggressively, and doubling up his diminutive fist; for, although unusually small in stature, he was a spirited lad; just as the little bantam rooster seems ready to fight a big Plymouth Rock, or a Shanghai, for that matter, if the opportunity offers, and he feels that his dignity has been affronted.

Andy nodded his head, and looked rather pleased.

“Let’em come,” he said, “it won’t be the first time I’ve lain in wait, expecting a sneaking night visit from Percy Carberry and some of his crowd. And history has a way of repeating itself; so in that case he’s going to be in for a mighty unpleasant experience, or my name isn’t Andy Bird.”

The boys had thought fit to approach the agent, and tell him that since there was no way of locking up the heavy freight that lay around under that shed; and they had reason to fear that an attempt would be made to injure the crated aeroplane, they meant to watch throughout the night. Of course, he had not the slightest objection to offer. The company would be liable to damages should any occur, but that would prove but sorry compensation to the Bird boys for the loss of their aeroplane; since such a catastrophe was apt to prevent them from accepting the warm invitation of Uncle Jethro in far-away Arizona. And after night set in the three sentries arranged matters to suit the plans of Andy, who had figured out a little scheme which he believed would cover the ground, and not only warn them when intruders started to lay hostile hands on the freight, but play havoc with their mean plans.

The time passed slowly, and it must have been very near midnight when they heard the first indication that prowlers were about. The hanging door at the end of the old freight shed squeaked somewhat when moved; and this sound came plainly to the ears of Andy and his two chums.

They touched each other, as if to give warning, and to make sure that no one of the guardians of the boxed aeroplanes could by any possibility be asleep. Then they got themselves ready to meet the intruders with a little surprise that was calculated to give them more or less of a shock.

And as the three friends crouched there behind the boxes which they had moved in position for this very same purpose, they heard low faint whispering sounds that seemed to be gradually drawing closer and closer, as though those who groped their way in the dark might be comparing notes, and thus deciding whether they were moving along the right track.

It looked as though the crisis might be very near; and that in perhaps another minute they would be compelled to throw off the mask and give the skulkers the surprise of their lives.

“H’st! flash that light a little!”

These low words were plainly heard by the two concealed boys. They came immediately after there had been some sort of head-on collision between a couple of the prowlers, which had resulted in grunts, and a plain unmistakable groan.

Immediately a little shaft of bright light began moving this way and that. Some one carried a very small edition of an electric flash-light. It gave only an apology for a glow, and yet by moving this to the right and to the left, it would be possible to discover obstructions, and thus avoid any further collisions.

Besides this, the eager searching eyes of the intruders would be apt to discover the boxed aeroplane, for undoubtedly Percy was one of the lot, and he must have marked the whereabouts of the freight pretty accurately in his mind, at the time he wandered around with the agent, pretending to search for his own stuff.

“I see it!” some one said, in a satisfied tone.

“Then for goodness sake show us,” grumbled another fellow, who was possibly rubbing an injured head or arm as he spoke.

“This way, everybody; and get ready to do what I say!”

That must surely be Percy Carberry talking, though neither Andy nor Elephant, nor yet Larry, could recognize the voice, which seemed strangely muffled. But the closer they examined the three approaching figures, slouching along in a half hearted way, as though conscious of the danger that hung over their heads while thus entering upon the property of the railroad, the more convinced Andy and his chums became that they had some sort of muffler fastened across the lower part of their faces, which interfered with their voices.

Perhaps this had been done in the hope and expectation that, if by chance they were discovered while attempting to injure the aeroplane, they might pass for a lot of hobos attempting to pilfer something from the railroad yards that could be sold for enough money to buy liquor.

Andy gave each of his companions a nudge, for Elephant was ranged on one side, while Larry crouched on the other. This was understood to be a signal. It just as much as said, “get ready now, to let go when you hear me start in!” And both of the others immediately drew in the greatest breath they were capable of containing, according to the capacity of their lungs.

That odd little glow kept wavering around in a queer manner. If Percy were holding the electric torch in his hand he must be trying to show his companions just how things lay, so that they could see how to get to work.

In that moment of intense excitement none of the watchers thought of trying to guess what sort of mischief the prowlers had in view. It was quite enough for them to know that the precious aeroplane was the object of their malicious scheming.

“Are you all on?” demanded a hoarse whisper.

“Yes,” came from two other quarters, for the three intruders seemed to have ranged along side the heap of freight in as many different quarters, as though it might be their prearranged plan to attack it from various points.

“Then get busy with you, fellows!”

That was of course the last straw on the camel’s back. When Andy heard these words, and realized that the attack on the boxed flying machine was about to start in, he could hold back no longer.

“Soak ’em, tigers!” The words were shouted at the top of his voice; and both Larry and the Small boy joined in the refrain, making all the noise they could possibly bring to bear, according to the amount of wind they had pent up in their lungs.

No doubt the outburst of sound must have struck terror to the hearts of the trio of guilty skulkers, already very nervous on account of their knowledge that they were doing a mean and criminal act. In that minute they probably received one of the greatest shocks of their lives. Detected in wrong-doing their consciences must have stabbed them like sharp-pointed knives; and the possible shameful results of being caught in the act, and held up as awful examples before the rest of the town, gave them a wrench.

But that was not all.

Andy and his companions had made preparations for bombarding the enemy with a shower of stones that were of no mean size. While the scantiness of the illumination might make such a thing as taking aim a difficult task, still, at such close quarters there were sure to be frequent collisions between the rapidly flying missiles and some parts of the bodies of the fleeing boys. Above the cries of the assailants could be heard the shouts which the retreating skulkers gave vent to, as they fell over unseen packages of freight, banged headlong against walls that seemed strangely out of place, and doubtless accumulated a fine collection of bumps and bruises that would remind them of the adventure for a long time to come.

Of course, as soon as the flight was fully on, Andy and his chums ceased bombarding the panic-stricken enemy, thinking that they had enough troubles of their own in trying to make the partly open door of the shed.

When he went home to supper Andy had secured a little hand torch of his own, and one that possessed considerable more power than that Percy had fetched along. This he now brought into play; and by shooting the shaft of light ahead he was able to discover the three fleeing figures nearing the exit, and sprawling every-which-way, as they met up with obstacles of all sorts.

“Come on, let’s capture ’em!” shouted Andy, and with his companions he started as if in hot pursuit, though of course this was meant only as a little additional spur, to add to the alarm of the runners.

When Andy and the other two boys broke out of the end of the freight shed they could still hear the frightened fellows banging up against things, for the yard was not kept as neatly as it might have been. One flying figure that they gave chase to fell into an open culvert, and though they looked for him, he had evidently crawled far underneath, in his great alarm, for they could not find a trace of the poor wretch, who must have remained there, wet and shivering, for hours, before he mustered up enough courage to crawl out and sneak home.

Another made a headlong plunge over a pile of scrap iron; and though he managed to scramble excitedly to his feet, when he went off it was hopping on one leg a good deal of the way, and with a series of grunts that told how it hurt.

“I guess that’s enough, fellows,” wheezed Andy, for he was himself so out of breath that he could hardly talk.

The first thing they all did was to bend over, and laugh until their sides really ached. It doubtless looked mighty humorous to the three who had done all the chasing; but those other fellows would have a different story to tell, if asked. But then the old fable is always true, and what is “fun for the boys is death to the frogs;” no fellow ever plays a practical joke that amuses him highly, but what some one has to pay the bill and do the crying.

So Andy led his army back once more to the interior of the freight shed.

“Let’s look to see if they managed to do the first bit of damage,” suggested the leader, and quickly adding, “why, looky here what they’ve gone and left behind ’em—a hatchet, an augur, a chisel, a screw driver—enough tools to stock a carpenter shop. Now, if we knew who owned these, we’d have it on him pretty strong.”

But when, in the morning, Andy started an investigation, thinking that the tools might serve to identify the three boys who had entered the railroad freight shed bent on damaging the crated aeroplane, he found that Percy Carberry with his customary shrewdness had looked out for this and covered his tracks deftly.

The tools upon being exhibited were soon claimed by Mr. Mallet, the carpenter, who said that when he reached his shop that morning he found a window had been forced, and quite a quantity of his property carried away. And so it was rendered impossible to identify the rascals by the abandoned tools.

Of course, had Andy wished to carry the thing further he might have drawn attention to the fact that Percy Carberry, Sandy Hollingshead, and another boy often seen in their company were absent from their customary haunts that morning; and if interviewed at home would be found to have sundry patches of court plaster adorning their noses and foreheads which would indicate that there must have been an epidemic of falling out of bed on the preceding night. But of course Andy did not mean to pursue the matter any further, believing that “all was well that ended well,” and that the boys had already been sufficiently punished.

What he did do immediately after leaving the shed was to call up Frank on the phone at the drug store. Frank did not often oversleep, but being up late on the night before, seemed to cause him to lie abed a little later on this morning. He happened to be eating his breakfast at the time the bell rang; and as the phone was in the diningroom of course he answered it.

“Hello! this you, Frank?” came in a voice he recognized as belonging to Andy.

“Yes, what’s all this row about?” answered Frank, humorously.

“Coming down here soon; I’m at the drugstore close to the station, you know?” the other went on to say.

“What’s the matter—anything happen?” demanded the boy at the other end of the wire as if realizing from Andy’s manner that there had something occurred that must be out of the common.

“Sure. We had company, and the greatest old time you ever heard of, Frank. Tell you about it when you get here. We’re going to breakfast now, and will meet you at the freight shed later to see the stuff packed in the car.”

“Hold on. Was there any damage done to our machine?” demanded the other.

“Never a scratch; but it was a close shave. So-long, Frank; see you later!” and having accomplished his object, which was to excite his cousin’s curiosity to fever pitch, for it was seldom he had the chance to do such a thing as this, Andy abruptly severed connections and hurried home to get something to eat.

Frank was there all right when Andy got back to the station; and doubtless he had managed to pick up some sort of an account of what had happened; for he seemed to be cross-questioning one of the freight handlers, even while examining the boxed and crated aeroplane. Of course Andy gave him the whole story; and as both Elephant and Larry had by this time shown up, the four of them laughed again and again, while each of the several witnesses of the panic related their version of the affair, adding such humorous touches as might occur to them.

The boys agreed to let the matter drop, since Percy and his cronies must have been sufficiently punished. Besides, being boys, they were not inclined to be hard on other fellows; even though they felt more or less indignation at the mean way in which Percy Carberry always tried to even his scores.

One thing sure, they meant to hang around that station until the precious aeroplane was not only securely placed in a car, but the train pulled out that was to start it on its long western journey to the far-away Arizona cattle ranch where Uncle Jethro waited to receive them with open arms.

And there they did remain until the train pulled out and they had the last glimpse of the precious air wonder, safely stowed in its car and headed toward the Land of Promise.

After that the boys were content to walk home, where Frank and Andy soon got busy again in their shop; for they had many things in process of building, on which they could always spend a spare hour; while Larry and Elephant hung around, ready and willing to assist if only told how to do things.

Of course much of the conversation concerned the new and strange sights that were likely to be the portion of the Bird boys while spending the coming weeks upon a real Southwestern cattle ranch. They brushed up their knowledge of things supposed to be associated with cowboy life; but which of course had been for the most part gleaned from books and the newspapers.

“Ten days, and perhaps our aeroplane will be there,” Andy was saying that evening, as he and Frank locked up, preparatory to going home; and he had been yawning for the last hour, on account of having had so little sleep on the preceding night. “That ought to mean we must start from here by another week, don’t you think, Frank?”

“Yes, a week from tomorrow morning would be about the right time,” replied the other, as he turned the key in the lock and tried the door.

Andy chuckled.

“Mighty careful about that door, I see, Frank; don’t mean to take any chances of somebody getting in our shop, like they did once before when we had that old lock on it. But I know just three fellows who are not thinking of trying any caper like that tonight. If you mentioned it to them, like as not they’d shiver all over and look sick. Because they got the scare of their lives last night. I just reckon they won’t feel like creeping in any old dark place for a long time after this.”

The two cousins walked along until they came to Frank’s house when Andy prepared to stalk off alone.

“Goodnight, Frank,” he said, “and here’s hoping that we get as good a start as we gave the airship today. A week from tomorrow, you say? Well, in the morning—” another big yawn—“we’ll have to get busy, and send Uncle Jethro a long message, telling him when he can look for us, and to have the agent out there keep a watch for our freight. Wow! but I’m that sleepy I can hardly see straight. No, can’t stop over with you, because I was away last night, you know, and mom might be worried. So-long, Frank! See you again after breakfast, when we’ll get busy with that new drag brake you’re working on, and which ought to work like a charm.”

“Call me up on the wire when you get home, Andy,” said Frank, after him.

“Hey! d’ye think somebody’s going to try and kidnap me on the road?” demanded the other.

“No; but I’m afraid you may go to sleep on the way, and keep on walking everlastingly,” called out Frank, laughingly, and then closed the door.

“We’re almost there, Frank!”

“Yes, the next station is Witherspoon, the brakesman said. Got all your traps ready, Andy?”

“Oh! I’ve had them gathered up this half hour and more. Whee! ain’t it hot down here, though; and won’t I be glad to get out of this stuffy sleeper?”

The two cousins had made the long journey at a pretty rapid pace, and at the time these words passed between them, were nearing the end. They had for some time skirted deserts and mountains that looked very strange to their Northern eyes. And when occasionally they caught fugitive glimpses of distant herds of cattle grazing on some miles of grass lands bordering the course of a hidden stream, naturally their thoughts went out to what they expected to see when they had arrived at the cattle ranch of Andy’s uncle.

“Uncle Jethro must be a man of some importance down this way,” Andy went on to say, “when they go so far as to even name the station after him.” At that Frank chuckled.

“Well,” he remarked, drily, “if it looks like some we’ve seen, that isn’t paying your relative a very great honor; because they were the most terrible tumbledown places I ever did set eyes on. But let’s hope Witherspoon will turn out to be something different.”

“Frank, I do believe the train’s beginning to slacken up right now!” cried Andy, all of a tremble with eagerness.

“You’re right it is and here comes our friend the brakesman to help us off with all our truck,” observed the other Bird boy, who did not show his excitement as much, although no doubt he too was quivering with the anticipation of the coming introduction to Western ways.

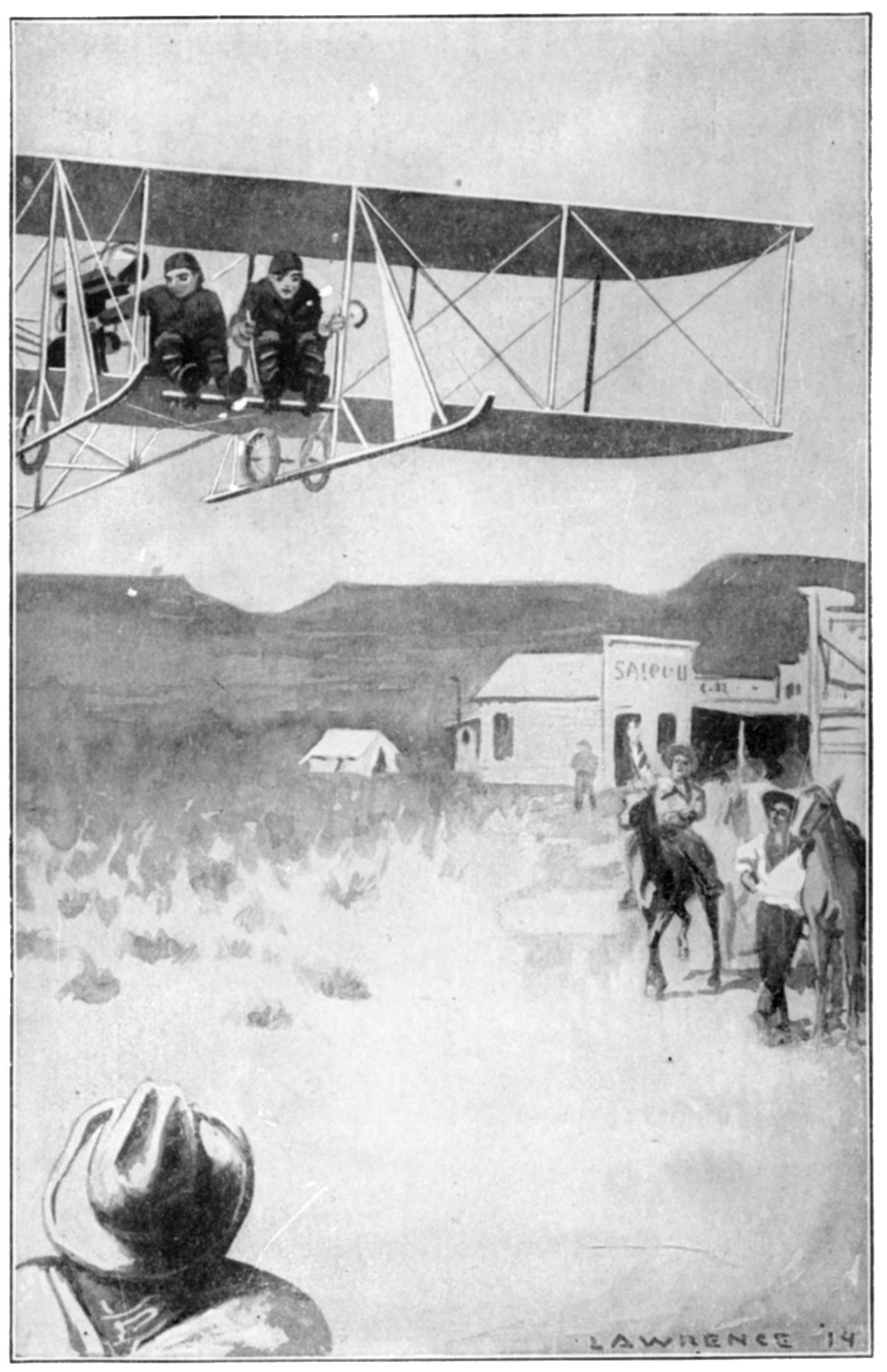

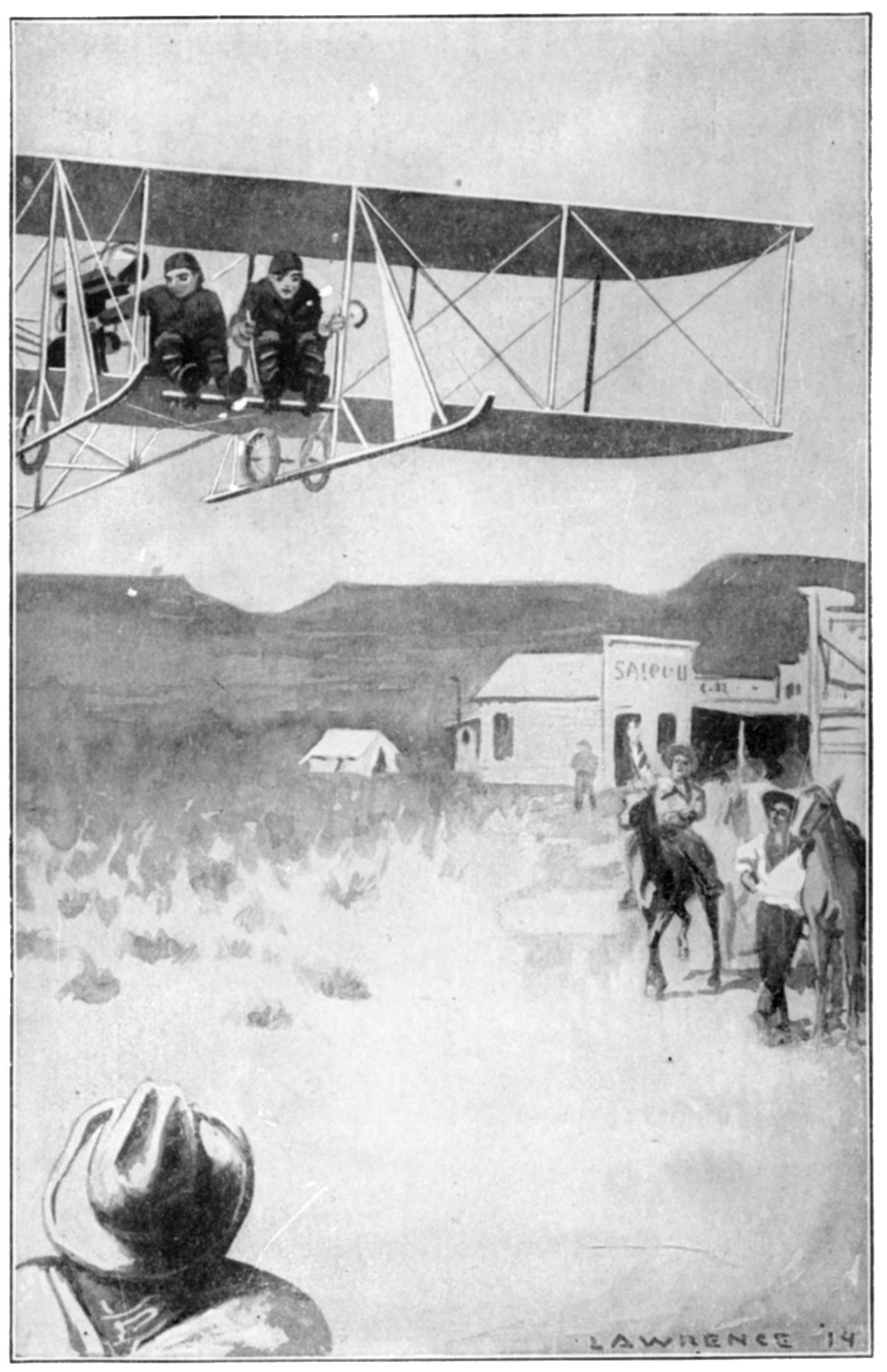

Presently the train came to a stop, and the boys having reached the platform of the sleeper stepped off.

As they did so there was a loud whoop from a dozen lusty throats. Looking in the direction from whence these vociferous sounds proceeded they saw a collection of rough and ready picturesque cowboys, just like those who had appeared in the moving picture plays which Frank and Andy had enjoyed from time to time in the little playhouse in Bloomsbury.

They were on foot, but their horses could be seen hitched along a rail close by, and exhibiting more or less of spirit because of the hissing engine, to which they were evidently not accustomed.

Frank had just shaken hands with the accommodating brakesman, and tipped the colored porter of the sleeper, when he discovered Andy caught in the arms of a tall man, whose snow-white mustache and goatee gave him a distinguished appearance.

Of course this could be no other than Uncle Jethro. Frank knew he would like the ranchman from the start, and that nearly everybody must. While his word was law in that section, at the same time the owner of the ranch was a genial gentleman, whom most of his cowboy hands thought so much of, that they would be willing to go through fire and flood at any time to serve him.

Frank at first sight thought Uncle Jethro looked like a Kentucky Colonel; and that impression never left him.

“So, this is Frank Bird, is it?” exclaimed the cattleman, hurrying over with extended hand which closed on that of the boy with a vim that made him wince. “Well, it does my heart good to see you both. We’re going to try and give you the time of your lives down here. Yes, your freight is in the house yonder, and we’re prepared to haul it to the ranch right away. I must say I’m pleased to find you both such a hearty looking lot. And a spell out in this free air will do you a world of good. But won’t you come over and shake hands with my boys; they’re just wild to meet you. For ten days, now, all the talk around here has been of flying machines. Most of us have never seen such a thing; and you’d laugh yourselves sick to hear the guesses that have been made about what they look like. Most of the boys are of the opinion it’s only a big gas balloon. Here you are, and now let me do the honors.”

The train had already pulled out, so that they had the little Arizona station to themselves. One by one the cow punchers stepped up, and were properly introduced to each of the Bird boys in turn; generally with some little side remarks that might apply to their appearance or the name they went by.

In this way the newcomers felt that they already knew considerable about their new friends, even before they had met them five minutes. Cowboys as a rule are not a hard lot to get acquainted with; they are blunt and open and full of questions.

It could be seen that the two boys from the Far East were objects of intense curiosity to every one of the bunch. They watched them closely, just as though some were secretly of the opinion that Frank and Andy might at any moment suddenly develop a pair of wings that they had up to then kept hidden about their persons, call out a hasty goodbye, and bob up in the air as easy as the ordinary cowpuncher would hurl himself on his pony.

“Now, let’s see about getting your freight started, boys,” called out Uncle Jethro, after this ceremony had been completed, and the newcomers had been duly welcomed with hearty handshakes by the grinning punchers. “You see, we fetched a big wagon along, with four horses; and likely enough that will get the stuff out home by night. If it looks hard, I’ll send back another lot of horses to help pull. And your trunk can go along with you on the back of the carryall. The boys wanted to fetch mounts for you both, but I reckoned that you might not be wholly as much at home on the back of a pony as in your flying machine, so I drove in myself.”

Frank thought that was very kind and considerate of Uncle Jethro; who must have known that the wild spirits among the cowboys would be apt to make it a bit unpleasant for greenhorns who were unused to their harum-scarum ways when in the saddle. Wait until they had been there a week, and he believed that he and Andy might be able to hold their own fairly well; for both of them had done more or less horseback riding, such as is practiced on Eastern roads, and which must be pretty tame compared with the dash of these reckless riders of the range.

The whole lot trooped after them when they accompanied the cattleman to the little freight house. Here their precious aeroplane was found, and so far as they were able to tell from a quick survey of the outside, not the slightest injury had been done during its long journey. This was doubtless due at least to the care the boys had shown in crating and boxing the various parts; and which experience had taught them just how to go about.

Amid more or less excitement and shouting the big wagon was backed up to the door of the freight shed; and then, under the directions of Frank, the loading began. No lack of willing hands, when every one of those sturdy fellows seemed just wild for a chance to just touch the wonderful flying machine, of which they had heard so many stories, most of which they did not believe, of course; for it seemed like a yarn from the Arabian Nights or Baron Munchausen, this idea of mere boys going up in the air thousands of feet, in a shell of a machine, with a little buzzing motor attached to it; or flying hundreds of miles over the wild forests away down in South America, where they were said to have found the long-lost father of Frank.

All the same, they handled the crates with more or less tenderness. Although no doubt most of them had already decided that it was pretty much of a fake, and that they would be a sold lot by another day, still they were as eager as a parcel of eight year old lads to see what was coming. Talk about the excitement that strikes an Eastern country town when the circus arrives, it could not bear any comparison with the feverish spirit that possessed those jostling cow punchers as they heaved and tugged and loaded up the wagon just as Frank wanted.

When the last crate had been placed on top, the heavier engine being away under all the rest, Frank saw to it that stout ropes secured the whole. And watching just how the boy directed these things, Uncle Jethro nodded his head toward his foreman, Waldo Kline, and winked one eye, just as if to say, “He’ll do!”

Finally all seemed ready, and the horses were apparently anxious to start on the return journey; for quite a number of miles lay between the station where cattle were shipped, and the ranch buildings proper.

Uncle Jethro last of all cautioned the driver to take his time, no matter how long the trip seemed. Not for worlds would he have any upset occur, or a runaway take place. If any injury were done the precious flying machine at this stage of its long journey he would never forgive the one responsible for the trouble. They had waited so long to see the wonderful contraption really sail through the air that he would not answer for what the rest of the boys would do, should they find themselves disappointed.

After that it might be set down for granted that the driver would exercise more than ordinary care in transporting the freight. If an accident should happen the chances were he would feel like mounting a horse immediately and putting for the railroad, to board a train, fearful for his life.

Having strapped the trunk on behind the carryall in which Frank and Andy were already seated, the joyous bunch of punchers made a rush for their horses. The two Easterners watched eagerly to see whether the pictures did them full justice in mounting; and on the whole they were not in the least disappointed; for every fellow seemed to have his own odd way of flinging himself into the saddle; and the instant the pony felt his weight there would be an upheaval and some tall jumping about, until the rider found his seat, and thrust his toes into the stirrups, and from that instant he seemed to become a part of the animal itself.

“Great, isn’t it, Frank? I’ve pictured that lots of times, but never thought I’d see it with my own eyes. And they seem to be a bully bunch of fellows, warm-hearted as the day is long; and I guess we’re going to like it down here, all right!”

Frank thought just the same as Andy seemed to, even though he had not as yet expressed himself that way. Among the dozen cow punchers they would doubtless find a number who would become fast friends; others they might not happen to fancy as well, perhaps on account of some peculiarities, or it might be a retiring disposition on the part of the nomads. But first impressions count for a lot; and it must be confessed that both of the Bird boys were mighty well pleased with their hearty reception by the outfit connected with the Double X Ranch. “All ready?” called out Mr. Witherspoon; and as no one said anything to the contrary he waved his hand to the circling boys.

Immediately a series of shrill “yip-yips” broke out, as the riders went tearing off at a furious pace, to wheel presently and come charging headlong down toward the carryall, waving their hats, and carrying on as though possessed.

“Don’t mind ’em, boys,” remarked Uncle Jethro, complacently. “They’ve just got to work off some of the surplus energy that this free life seems to stow up in a man. You’ll be doing the same before you’re here a week, mark my words. But I have got as fine a bunch of boys as ever threw leg over a bucking broncho; and you’ll say as much when you get to know the most of them. Not that they haven’t got their faults, but we overlook small things out in this big country, you know, where the sky seems to bend down and touch the earth all around you. Now, step lively along there, Dexter and Silas, you ornery mules, hit up a pace!”

The Bird Boys would not soon forget that invigorating ride. On all sides they saw a thousand things that excited their wonder; and which they did not hesitate to ask about. And Uncle Jethro was only too willing to explain; he wanted these bright-faced boys who had come to visit him, to learn all about the things with which they would come in daily contact, and the sooner the better.

From this time on there would be a complete change in the air around Frank and Andy. The talk of the cowboys was along the line of ranch life; and by degrees many of the phrases that went to describe such things entering into the daily life of these wild plains riders, would become familiar to the “tenderfeet.”

They saw the cactus that grew along the border of the desert; the tufts of what Uncle Jethro called “buffalo grass,” possibly because the bison that formerly covered these same plains in countless tens of thousands used to feed upon it; watched the queer antics of a village of prairie dogs they passed on the way to the ranch; and heard the boys speak of a muddy hole as a “buffalo wallow,” though the chances were it had been half a century since such an animal had lain down to rid himself of the flies, by wallowing in the mud and water that came from a rainfall.

Here were a few stray cattle which the rancher termed “Mavericks;” and called to the foreman to mark down, so they could be rounded-up and branded on the morrow; there they overtook an Indian family on the move, with a calico horse harnessed to a couple of long drag-poles, upon which were piled all their worldly possessions, including the squaw herself and a dusky papoose; and once in the distance they saw a line of white-topped wagons that gave the boys a thrill, thinking of those old days when emigrants were in the habit of crossing the plains in such vehicles; until Uncle Jethro kindly explained that this was a freighter’s caravan, the prairie schooners being loaded with supplies for the mines that were located away up in the mountains, where it was difficult to get such material, the smelting being done on the ground, and only the pure copper shipped out to the market.

It was altogether too short a ride, Andy loudly declared, when his uncle announced that the ranch buildings were in sight ahead. He had seen so many new and interesting sights that he thought he could never drink in enough of this air, heated though it might be.

All the same, both lads looked eagerly ahead, anxious to know what the Double X Ranch would turn out to be like.

They saw a cluster of white buildings, none of them over one story in height; and partly surrounded by green trees, that had doubtless influenced the owner to make his headquarters in this particular spot, where good water was to be had in abundance.

Already the boys had started on a gallop for the house, whooping as usual. A genuine happy-go-lucky cow puncher is probably about the noisiest creature on the face of the earth; he never seems to be fully satisfied unless he is making some sort of a racket, either chasing cattle, cavorting on his pony amidst his comrades, or shooting up a border town when on one of his “pay-day” outings.

Before they reached the buildings they had drawn close enough to the passing freight caravan for the boys to even hear the vicious crack of the teamster’s long blacksnake whips, and to hear a choice collection of words when some little accident happened to delay the creaking wagons a brief time. Uncle Jethro was an old bachelor. He had a very efficient housekeeper in a Mrs. Ogden, a middle-aged widow, whose husband had been some sort of cousin to the owner of the ranch, and connected with him slightly in the business, at the time he died.

A beaming Celestial cook, who sailed under the name of Charley Woo, looked after the kitchen, and seemed to satisfy the demands of the vigorous punchers. When he was out with the boys in charge of the “grub wagon,” during their round-ups, those left at home were well taken care of by the housekeeper herself.

Everything was so fine that both Andy and Frank knew they were going to have the time of their lives; and would begrudge the days that slipped past. They meant to soak in all the information possible, as well as show these dashing riders that if they were greenhorns in all that was connected with cattle punching, at least they occupied a high standard when it came to bold exploits away up in the clouds.

During the remainder of the day they went here and there, making fresh discoveries at every turn, and fairly saturating themselves with the multitude of things that were associated with this new life.

One of the cowboys in particular had attracted the attention of Andy; and Frank also admitted having taken an immediate liking for the same fellow. He was a lively boy, full of vim and go, and yet with something winning about his ways. They called him “Buckskin,” and it was quite a long time before either of the newcomers learned that he had another name, Oliver Cromwell Jones.

He seemed more eager to hear about the exploits of the young aviators than any of the rest; though for that matter they were every one of them hanging around every minute they could spare from their duties, showing the newcomers their bunkhouse, the big stables, the enclosure where the saddle band of horses was usually kept when not in use, and everything else they could think of, until both Andy and Frank felt that they were growing confused under so much attention.

And what pleased Frank most of all was a rude building or shed which Uncle Jethro had had built to serve as a hangar for the biplane. Where he got his ideas from they did not know; but it must have been some magazine article; because the affair seemed to answer all requirements; though of course it was a mere shed, and not intended to be locked up.

But such a thing as injury coming to the precious aeroplane in this isolated place never once occurred to the boys. Surely there was no malicious Percy Carberry, and his shadow Sandy Hollingshead, away down here to want to render the biplane worthless for use; and every one of the punchers acted as though he believed the greatest treat of his whole life would arrive when he actually saw with his own eyes those daring young aviators mount upward toward the sky, until they seemed like a mere speck in the blue vault.

There was one occupant of the ranch building whom the boys were pleased indeed to meet. This was a little fairy of five, named Becky, a blue-eyed child, daughter of a niece of Mr. Witherspoon, who had departed this life. She was a winsome little thing, and the cow punchers seemed to fairly worship her.

Frank guessed that there was a little mystery attached to her, but he did not mean to seem curious, and ask any questions. In due time they learned from Buckskin that this niece had run away with a dashing Mexican named Jose Sandero; and after being cruelly treated by him, had fled once more across the border, arriving with her tiny baby at the Double X Ranch so worn out with fatigue that she had soon passed away. Her child had been left to Uncle Jethro; but not wanting to risk any chances, he had taken legal means to make himself the guardian of little Becky. And ever since she had been the sunlight of the whole ranch. The boys would stop in the midst of any wordy war, or wild singing, just to listen to the music of her sweet childish voice, that seemed capable of arousing all the best emotions in their natures.

Nothing had ever been seen of the father, and it was taken for granted that he must either be dead, or never wanted to attempt to claim his child. And, Buckskin declared that if ever he did show up round that region, he stood the finest possible chance of pulling hemp that any man ever knew.

That supper was one never to be forgotten. With the smiling Chinaman waiting on the noisy crowd, and appeasing every demand, Andy thought he had never enjoyed anything half so much in all his life. He had often camped out, and eaten the fare that is so greatly relished by every healthy lad with red blood in his veins, but there were so many things connected with this meal at the long table, where some ten ranch riders sat, and exchanged comments characteristic of their occupation, with everything so strange to the tenderfoot, that it made a deep impression on both the newcomers, never to be eradicated.

Then the punchers trooped off to their bunkhouse, to leave the travelers alone, for they felt that they needed considerable of a rest to make up for the fatigues of their long journey.

The man who drove the double team connected with the wagon must have coaxed considerable speed out of them after all without meeting with any accident on the road, for the freight had shown up an hour before sunset, and ere the call came for supper it had all been safely stowed away in the rude hangar, where Frank and his cousin could work at it on the morrow.

It was rather early when the boys sought their comfortable little room, where the white sheets invited them to sound slumber; and the soft night breeze fanned their cheeks, coming through the many windows that were always open.

They sat at the window some time, talking in low tones about many of the strange things they had already seen, and speculating on how this dry air of the desert border would affect them, when they made their first ascension.

Far away the mysterious lowing of herds came faintly to their ears; they could also catch the whinnying of horses in the stockade; and now and then the sound of music in the shape of a deftly manipulated accordion; or it might be the soft twanging of a Mexican mandolin, while one of the boys warbled softly about some black-eyed senorita he had left behind him in the country of the dons.

After a while the cousins decided that they ought to be in bed, and getting rested for the labors that awaited them in the morning. And once they threw themselves down, they were lost to the world in a few minutes.

Of course they dreamed as every boy does pretty much all the time. And it was only natural that Andy’s mind should go back while he slept to other days, when he and Frank were engaged in the hottest of races with their rival, Percy Carberry, who was just as deeply interested in all matters connected with aviation as they had been.

Many a time had they found themselves compelled to sit up and guard their property when they had by some successful exploit aroused the worse elements in the jealous nature of this rival. And even now, though removed from the home town and Percy by several thousand miles, Andy had to dream that once again a dark cloud was hovering over their fortunes, and all caused by the hatred of this boy who for more than two years had been the one thorn in their flesh.

So vivid had been his dream that Andy actually suddenly awoke with a low cry, and sat up in bed, trembling all over.

“What’s the matter?” demanded Frank, also springing up.

Before Andy could frame any sort of answer, owing to the confusion of ideas that seemed to be tumbling pell mell through his brain, both of them were thrilled to hear a voice from somewhere outside shouting:

“Wake up! help! help! fire! Whoop! get busy there, fellows!”

As though governed by a couple of springs the cousins leaped from their comfortable bed, and rushing over to one of the windows that looked toward where the new shed covering the precious aeroplane stood, they saw a sight that thrilled as well as alarmed them.

“Oh! it’s our hangar on fire!” gasped Andy.

“Quick, get into something then, and out we go!” cried Frank, always the prompt one to act in an emergency.

Andy hardly knew how he ever did manage to drag on a pair of trousers, and his shoes. His hands were shaking so he could hardly do what he aimed to accomplish; and all the while the shouts were increasing in violence, as well as that terrible light growing brighter.

By the time he had managed to get the second shoe on, Frank was already outside; and having seen how easily the other jumped through the window to the ground, Andy hastened to follow his example.