[Pg 233]

The Penn Publishing Company Philadelphia

[Pg 234]

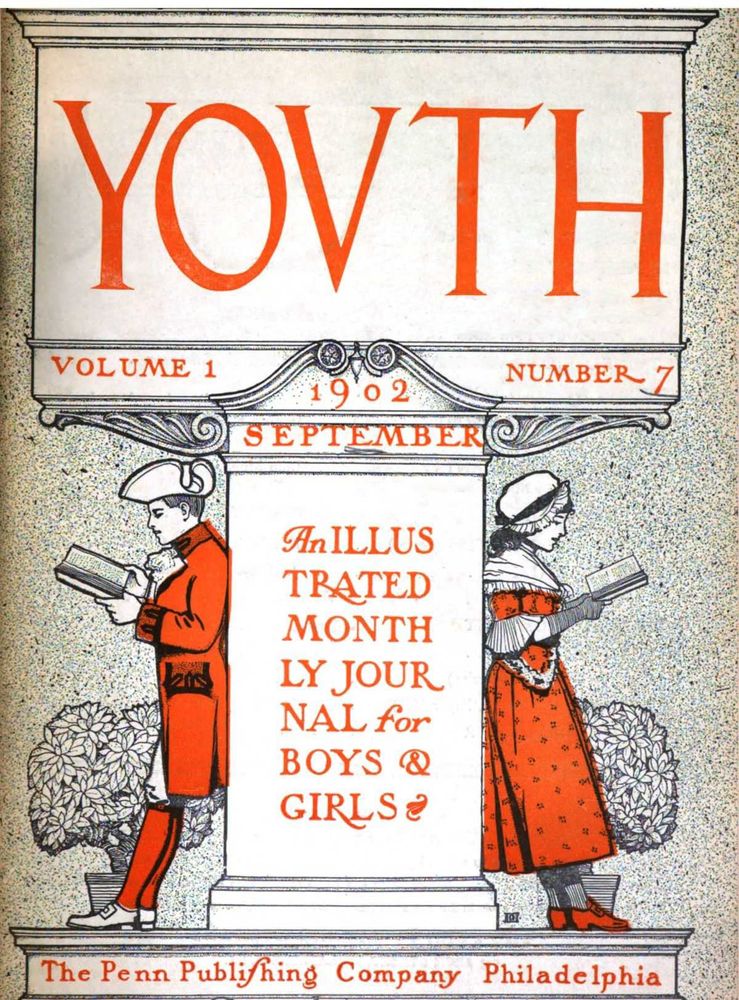

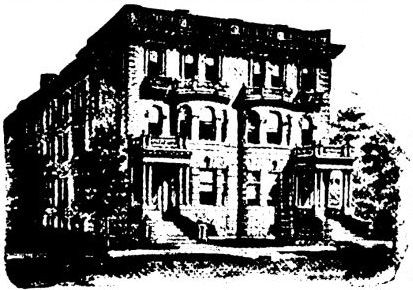

| FRONTISPIECE (The Penn Cottage) | PAGE | |

| THE PENN COTTAGE | Allen Biddle | 237 |

| WITH WASHINGTON AT VALLEY FORGE (Serial) | W. Bert Foster | 239 |

| Illustrated by F. A. Carter | ||

| IN THE FLORIDA EVERGLADES | William A. Stimpson | 246 |

| AUDUBON AT BIRD ROCK | 249 | |

| A DAUGHTER OF THE FOREST (Serial) | Evelyn Raymond | 250 |

| Illustrated by Ida Waugh | ||

| THE FLOWERLESS PLANTS | Julia McNair Wright | 257 |

| Illustrated by Nina G. Barlow | ||

| WHIP-POOR-WILL | Geo. E. Winkler | 259 |

| LITTLE POLLY PRENTISS (Serial) | Elizabeth Lincoln Gould | 260 |

| WOOD-FOLK TALK | J. Allison Atwood | 268 |

| WITH THE EDITOR | 270 | |

| EVENT AND COMMENT | 271 | |

| OUT OF DOORS | 272 | |

| THE OLD TRUNK (Puzzles) | 273 | |

| IN-DOORS (Parlor Magic, Paper VII) | Ellis Stanyon | 274 |

| WITH THE PUBLISHER | 275 | |

| ADVERTISEMENTS | 276 |

An Illustrated

Monthly Journal for Boys and Girls

SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION $1.00

Sent postpaid to any address Subscriptions

can begin at any time and must be paid in advance

Remittances may be made in the way most convenient to the sender,

and should be sent to

The Penn Publishing Company

923 ARCH STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA.

Copyright 1902 by The Penn Publishing Company

[Pg 235]

[Pg 236]

THE PENN COTTAGE.

[Pg 237]

VOL. I SEPTEMBER 1902 No. 7

BY ALLEN BIDDLE

“Pitch upon the very middle of the plat where the town or line of houses is to be laid or run, facing the harbor of the great river, for the situation of my house; ... the distance of each house from the creek or harbor should be, in my judgment, a measured quarter of a mile; or, at least, two hundred paces, because of building hereafter streets down to the harbor.” Such were the instructions which William Penn, founder of Philadelphia, gave to his commissioners, William Crispin, John Bezar, and Nathaniel Allen, for the building of what is now known as Penn’s Cottage.

It was in 1681 that the great Quaker completed the negotiations for the grant of Pennsylvania, and in the next year the first work of the building of the Proprietary House was begun. The plat chosen for its site was the one bounded by Front, Chestnut, Letitia, and High streets, the last now being named Market. In the place of the little cottage and its surrounding yard there is, to-day, one of the most thickly-built portions of Philadelphia. But the true centre of the city, at one time radiating from this point, has now, owing to the growth of two hundred years, moved a mile to the westward.

According to one tradition, the Penn or Letitia House was the first brick building erected in Philadelphia; to another, it was the first house to have a cellar. The name, “Letitia,” was given to it by Penn himself, as the house was intended eventually to be the portion of his daughter, Letitia. It is from this source, too, that Letitia Street gets its name.

One of the most interesting stories of this little structure is that the bricks and most of the finer building materials used in its construction were brought over from England. More recently doubt has been thrown upon this statement by the discovery that even at that time quite as excellent a quality of brick was being made in Philadelphia.

Despite its diminutive size, the cottage required what, to-day, would be an unusual time in its building, and it was well into the year 1683 before it was ready for the house-warming. Quaint, angular, and comfortable in appearance, it faithfully reflects the spirit of Philadelphia’s early people. True to the founder’s ideal in the laying-out of the city, the house, too, is characterized by economy of space and absence of mere ornament. Doors, windows, sills, and sashes—everything, in fact, except the gabled roof, is plain and rectangular.

[Pg 238]

From the front door, we enter its largest room, serving, perhaps, at one time as dining hall, sitting-room, kitchen, and library. On its plain, bare walls we now see collections of old wood cuts, illustrating events which occurred in the time of the founder, including reproductions of Benjamin West’s painting of that famous treaty with the Indians which “was not signed and never broken.” Above the door hangs an old print of the wampum belt which was presented to Penn by the Indians upon that occasion. Near by are facsimiles of the charter of the Province of Pennsylvania, granted by Charles II, and also the first charter of the city of Philadelphia, granted in 1691. In the further corner to the left is an ample fireplace before whose glow we can readily recall to our imagination the serene features of the great founder surrounded by his family.

From this room, extending to the rear of the building, is a short hallway, on either side of which is a room so small that we wonder what could have been their function in the Penn household. Quaint and cozy as is the little mansion, we can scarce believe it to have been the home of one who owned our whole great State of Pennsylvania.

In the year 1684, after a stay of twenty-one months, Penn was forced to return to England to protect his proprietary interests, as they were at that time threatened by the plans of Lord Baltimore. In his absence, the proprietorship fell upon his cousin, Markham, the Lieutenant-Governor, who then took up his abode in the Letitia House. Later, according to the wish of Penn, who desired that his house be devoted to public service, it became the State House. It is hard to imagine such a dignified body as was undoubtedly the provincial council meeting in the tiny brick cottage. What a contrast it makes with Independence Hall, or the great capitol now at Harrisburg!

In after years, when other houses had grown up on all sides, the little cottage fell into obscurity. At one time, even, it was thrown open as a public inn, and the little room which at one time held the Penn family circle now became the haunt of the wayfarer and the chronic idler. But, recently, folks of the great State have come to think more of the little house and to recognize gratefully the part which it played in their history. They have lifted it from its late dingy surroundings and, as if to put before it the city’s best, have placed it on the west bank of the Schuylkill, overlooking Fairmount Park. Here, far away from the city’s centre, with its face toward the broad, green valley of the river, the little mansion rests patiently, as if waiting until the city shall again closely encircle it in its westward growth.

As would have been the wish of the great Quaker, the door is still left hospitably open, and citizen and stranger alike may freely enter the house of him who founded their State. Here, daily, come many pilgrims. The Schuylkill, too, winding placidly down from its hills, loiters gently in its course through the picturesque valley, as if to catch a momentary glimpse of the quaint old house.

[Pg 239]

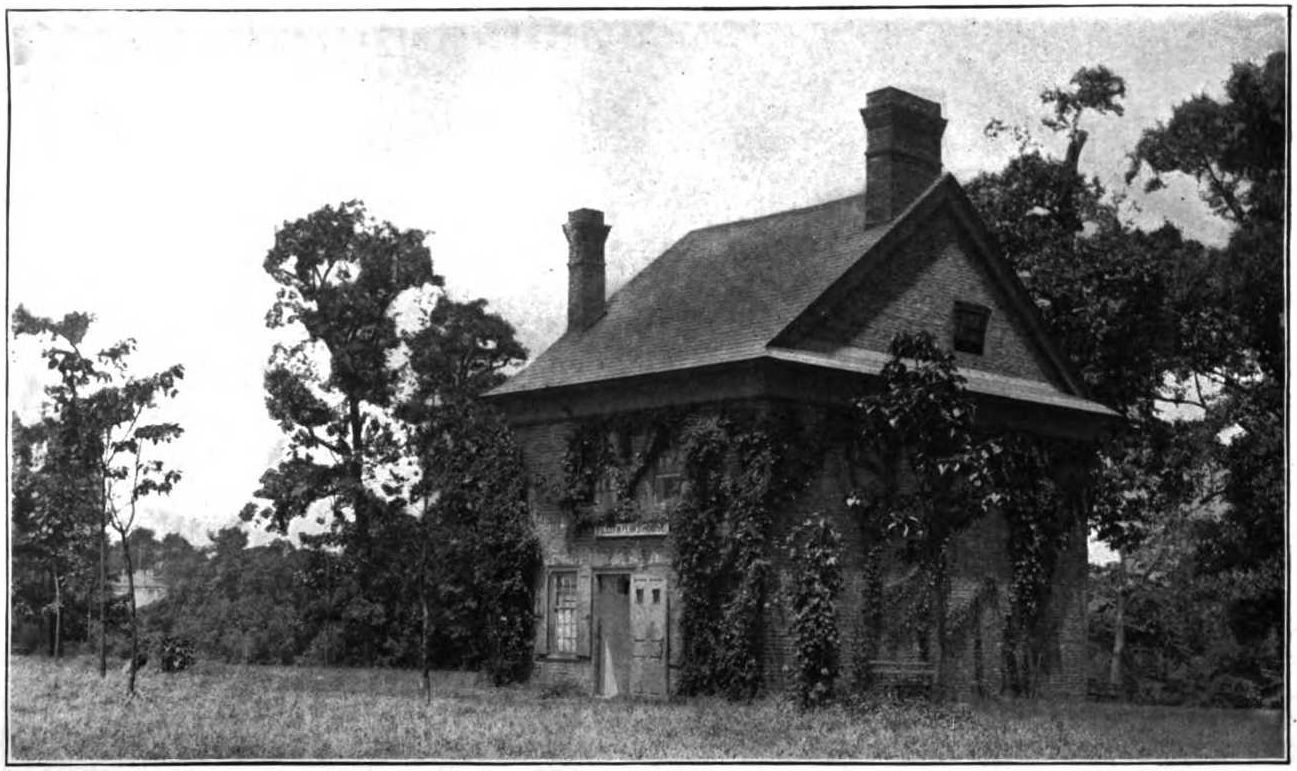

By W. Bert Foster

The story opens in the year 1777, during one of the most critical periods of the Revolution. Hadley Morris, our hero, is in the employ of Jonas Benson, the host of the Three Oaks, a well-known inn on the road between Philadelphia and New York. Like most of his neighbors, Hadley is an ardent sympathizer with the American cause. When, therefore, he is intrusted with a message to be forwarded to the American headquarters, the boy gives up, for the time, his duties at the Three Oaks and sets out for the army. Here he remains until after the fateful Battle of Brandywine. On the return journey he discovers a party of Tories who have concealed themselves in a woods in the neighborhood of his home. By approaching cautiously to the group around the fire, Hadley overhears their plan to attack his uncle for the sake of the gold which he is supposed to have concealed in his house. With the assistance of Colonel Knowles, who, although a British officer, seems to have taken a liking to Hadley, our hero successfully thwarts the Tory raid. No sooner is the uncle rescued, however, than he ungratefully shuts the door upon his nephew. Thereupon Hadley immediately returns to the American army and joins the forces under that dashing officer, “Mad Anthony” Wayne. In the disastrous night engagement at Paoli our hero is left upon the battlefield wounded. In this condition he is found by his old friend, Lafe Holdness, the American scout, who treats the wound so skillfully that our hero is enabled to return home. But not for long. No sooner is he strong enough to ride than he again sets out for the army, which is just then preparing for that terrible winter at Valley Forge.

Hadley slept that night at a friendly farmer’s, some miles to the north of Germantown. A large force of British were quartered about where Washington’s army lay the first day the boy had crossed the river and made his way to the Commander-in-Chief’s headquarters with the dispatches so nearly lost by the wounded courier. As far as he could learn, the Americans still rested at Skippack Creek, to which locality they had retired after the enemy entered Philadelphia.

He made a long detour the next morning to avoid the Germantown outposts, but fell in with a foraging party of Continentals before noon, and was near to losing his horse. But he was not so afraid of these marauders now as he had been the night he was halted on the Germantown road and his dispatches seized. So, after an argument with these fellows and the mention of Colonel Cadwalader’s name, he got away, with directions regarding the shortest path to headquarters. He was halted a good many times before he found the Pennsylvania troops; but the pickets saw that he was a recruit and let him through without trouble.

He found John Cadwalader with General Wayne, and was able to obtain speech with him without dismounting from his horse, as the officers were about starting on a tour of inspection through the camp. “And you want to see more fighting, do you, my lad—and your wound not healed yet?” said the colonel. “What good d’ye think a wounded man will be to us?”

“But I’m all right on horseback, and I’ve brought my horse,” Hadley declared.

“I wish we had more such fellows—and as eager to fight, Colonel,” said General Wayne. “He’s but a boy, too!”

“And how about the promise to your mother, Master Morris?” queried the other officer.

“My uncle has cast me off for carrying dispatches, and for being in the Paoli fight, where I got wounded,” the boy said, sadly. [Pg 240] “I can do nothing for him now. So I have come to do what I can.”

“Well, well. I will speak to His Excellency about you. There is a certain long-legged Yankee hereabout who, if I mistake not, has been inquiring for you through the camp.”

“Lafe Holdness!” exclaimed Hadley.

“The same. He said he knew you had got away from Philadelphia; but where you had gone was another matter, and one of which he was not cognizant. Now, Master Morris, you will find your friend, Captain Prentice, somewhere to the west of here. Keep near him and then you will be near me. When the propitious moment comes to present you to the Commander-in-Chief, I shall want you in a hurry.”

The officers rode on, and Hadley sought out Captain Prentice. “My faith, Hadley!” was the captain’s exclamation, “but we’re a pretty pair of winged birds.” His own arm was still in a sling, but he had taken active command of his company again.

“You can scarcely call me winged,” said Hadley, “for the ball went through my leg.” He climbed down from Molly and allowed a soldier to take her away. He could scarcely walk, having been so many hours in the saddle; but Captain Prentice made him welcome and saw to it that he had a bed for a few hours, where he slept away much of his weariness.

At this time Washington’s forces lay about twenty miles from Philadelphia and fourteen from Germantown. For some days the Continentals had been resting after the arduous campaign which had followed the landing of the British troops. The officers were planning some important move; but the army was kept in ignorance of its nature until the night of the 3d of October. Then the columns were put into motion quickly and took the road to Germantown. It was to be a night march to surprise the enemy, and never did Hadley Morris forget it. He and his friend, Captain Prentice, were both mounted—the latter on a sorry nag which his orderly had picked up somewhere—and there might have been some ill-feeling expressed among the other officers of the infantry over Prentice’s riding had he not been wounded. But those fourteen miles were hard enough for both the captain and Hadley, despite the fact that they were not obliged to tramp through the heavy roads.

Before the head of the column was half way to Germantown, the night fog began to gather, and before daylight it was so thick that it was almost impossible to clearly distinguish figures moving a rod ahead. Just at daybreak, however, despite the fog which had enveloped the whole territory, sharp firing broke out ahead. The troops were rushed forward, and the British, who at first had supposed the firing to be but a skirmish between outposts, were quickly being driven back by a solid phalanx of Americans.

After the first surprise the enemy formed and stood their ground; but the attack of the Americans was so desperate that they would surely have been overwhelmed in a short time had it not been for two things. Howe, hearing early of the battle, rushed forward reinforcements and came in person to encourage his soldiery. And the other thing which stayed the Americans, beside the smother of fog, was the imposing mansion belonging to Master Chew, which, occupied by the British, was a veritable fort, and withstood every effort of the attacking force.

It was a stone building, and with its doors and lower windows barricaded, and a strong force of the enemy using the upper casements to fire from, it soon became the pivotal point on the battlefield. The British kept up a destructive fire upon the American lines from the house, and, in spite of the fog, the casualties were considerable. Attempts again and again were made to capture it. The American lines could not go past, and it guarded the way to the British front.

And, with the long delay occasioned by the obstinate defence of the Chew house, the elements themselves seemed to be arrayed against the Americans. The fog became so dense that the men could not see each other a few paces apart, and only the spurts of red flame ahead betrayed the whereabouts [Pg 241] of the enemy. The Continental troops grew bewildered; aids were unable to find the officers to whom they were sent with messages from the commanders. There were shoutings and reiterated commands in the fog, but the files did not know where their officers stood and became bewildered and unmanageable.

General Washington’s plans were disarranged. The Americans had fought bravely and, without doubt, were on the eve of a decisive victory. But an alarm was created—the tramp of a regiment of American troops brought up from the rear was thought to be the approach of a flanking force—and the men who had fought so tenaciously during the day retreated in disorderly confusion.

Added to the general depression caused by this defeat was the fact that half the Maryland militia was reported to have deserted before the battle. It was the beginning of that awful winter when naught but the extraordinary virtues of George Washington himself kept the semblance of an army together. The American forces were rapidly becoming a disorganized mob, and the fault lay with Congress, which numbered in its group few of the really great and unselfish men who had once met in Philadelphia to approve of and sign the second greatest document in our history.

The period had now arrived when men of the second rank had come to the front in charge of the uncertain affairs of the struggling Colonies. Dr. Franklin was in Paris and John Adams joined him during the winter, for the purpose of watching Silas Deane, who was a bitter foe of Washington, and had sent over the infamous Conway to hamper and embitter the great man’s very existence. Jay, Rutledge, Livingston, Patrick Henry, and Thomas Jefferson were employed at home, and Hancock had resigned [Pg 242] from the governing house. Samuel Adams was at home in New England for most of that winter; and men much the inferior of these had taken their places—men who lacked foresight and that loftiness of purpose and love of country which had, earlier in the war, kept private jealousies and quarrels in check.

Without an organized quartermaster’s department, the soldiers could not be properly clothed or fed, and the warnings of Washington were utterly disregarded by Congress. The troops began to need clothing soon after Brandywine, and by November they were still in unsheltered camps without sufficient clothing, blankets, or tents. Hadley Morris, suffering with the rank and file, saw them lying out o’ nights at Whitemarsh, half clad and without protection from either the frozen ground or the desperate chill of the night air. Forts Mercer and Mifflin had fallen, and there was little cheer brought to these poor fellows by the news that Burgoyne had actually surrendered to General Gates and that the British army of invasion which had started so confidently from Canada was utterly crushed.

December came, and snow followed frost. The British were snug and warm in the “rebel capital.” Well fed, well clothed, spending the time in idleness and amusement, the invaders were secure of any attack from the starving, half-clothed men who, with Washington at their head, crawled slowly over the Chester hills toward the little hollow on the bank of the Schuylkill. There was gold in plenty at the command of General Howe, and for this gold the farmers about Philadelphia were glad to sell their grain. And who can blame them for preferring the good English gold to the badly-printed, worthless currency issued by the American Congress?

The ten redoubts from Fairmount to Cohocksink were stout and well manned. There was little danger of the Continentals attacking them, for the hills were already whitening with the coverlet of winter. The river was open, supplies and reinforcements were on the way from across the ocean, and the British had nothing to fear. So they gave themselves up to ease and merriment. And fortunate for the cause, then trembling in the balance, that they did so, for had they then conducted the campaign against Washington’s starving troops with vigor, the “rebellion” would never have risen in history to the dignity of a “revolution”!

To-day, after the passing of a century and a quarter, the Chester hills are much as they were on that chill winter’s day when the straggling lines of ragged, almost barefooted men marched along the old Gulph road. It is a farming country still, and although the forest has been cut away, in places the woodland is now as thickly grown as then. Here and there along the route the admiring descendants of those faithful patriots have erected monuments to their name; yonder can still faintly be defined the outlines of the Star Redoubt; there stands the house which was the headquarters of General Varnum, who commanded the Rhode Island troops; to the left of the road as one travels toward Valley Forge, is the line of breastworks running through the timber, which has been felled and grown up thrice since the axes of the Continentals rang from hill to hill.

One night they rested on the toilsome march near the old Gulph Mills, where the road passed through the deep cut between wooded heights: then on again, the various brigades separating and following different roads to the places assigned them. But the roads were, many of them, ill-defined, the timber was thick, the fields rugged. Little wonder that Baron de Kalb described the site chosen for the winter quarters of the American army as a wilderness.

Nevertheless, the situation selected for the encampment was a good one. In some of the towns, perhaps—Trenton, Lancaster, Reading, or Wilmington—there would have been shelter for the troops; but there were many objections to each place named. Had clothing and supplies been abundant, the little army might have harassed the British [Pg 243] all winter long, and even shut them up completely in Philadelphia when the spring opened. If the officers quarreled with the commander for his obstinacy in choosing this position, the men set to in some cheerfulness to build shelters. They were not afraid of hard work, and they had suffered enough already from the cold and storms to appreciate the log cabins which went up as if by magic on hillside and in hollow.

On the bank of Valley Creek, near its junction with the Schuylkill, stood a stone cottage (as it stands to-day) of two small, low-ceiled rooms on each of its two floors. Behind it was a “lean-to” kitchen, in the floor of which was a trap which was the entrance to a secret passage which, when the house had been erected, led to the river, being a means of escape should the stone house be attacked by Indians. When Washington selected this house for his headquarters at Valley Forge the secret passage had long since been walled up and the entrance chamber was simply a prosaic potato cellar. The house itself was meagrely furnished—not at all the sort of a headquarters that Lord Howe enjoyed in Philadelphia.

Some distance up the creek, beyond the forge which lent its name to the valley, were the headquarters of big Major-General Henry Knox, of the artillery, and near him was the young French Marquis, Lafayette, but then recovering from the wound received at the battle of the Brandywine—also a Major-General, and trusted and loved by the Commander-in-Chief to a degree only equaled by the latter’s feeling for Colonel Pickering. General Woodford, of Virginia, who commanded the right of the line, was quartered at a house in the neighborhood of Knox and Lafayette.

Up on the Gulph road, the southern troops, lying nearest to Washington’s headquarters, were commanded by that Southern-Scotsman, Lachlin McIntosh, and strung along within sight of the road were Huntingdon’s Connecticut militia, Conway’s Pennsylvania troops, Varnum’s Rhode Islanders, and Muhlenberg, Weeden, Patterson, Learned, Glover, Poor, Wayne, and Scott on the extreme front of the embattled camp. Hadley Morris, still with Wayne’s division, messed with Captain Prentice, but found himself often attached to “Mad Anthony’s” personal staff in the capacity of messenger, for the Quaker general occupied a house in a most exposed quarter, some distance beyond the line of defences, and was in constant communication with the Commander-in-Chief.

Hadley, indeed, scarce knew whom he served. At first his wound had incapacitated him from participating in much of the work which fell to the lot of the rank and file, and, as he rode one of the fleetest horses in the American camp, he came to be looked upon as a sort of volunteer aide, for he had never been regularly mustered into the service. He often saw Lafe Holdness in the camp, and was not surprised, therefore, one day, when he had been sent post-haste to General Washington with some papers from Wayne, to find the Yankee in the front room of the Potts’ cottage in close conversation with His Excellency.

Hadley never entered the presence of the great man without, in a measure, feeling that sense of Washington’s superiority which he had experienced when first he saw him, and he stood at one side now, ill at ease, waiting for a chance to deliver his packet. The Commander had a way of seeing and recognizing those who entered the room without appearing to do so—if he were busily engaged at the time—and suddenly wheeling in his chair and pointing to the boy, said in a tone that made Hadley start:

“Is this the young man you want, Master Holdness?”

“I reckon he’ll do, Gin’ral—if he can be spared,” Lafe replied, with the usual queer twist to his thin lips. “He’s gettin’ more important around here than a major-gin’ral, I hear; but ef things wont go quite ter rack an’ ruin without him for a few days, I guess I’ll take him with me on this little ja’nt.”

Hadley blushed redly, but knew better than to grow angry over Lafe’s mild sarcasm. [Pg 244] His Excellency seemed to understand both the scout and his youthful friend pretty well. “I have a high opinion of Master Morris,” he said, kindly. “Take care of him, Holdness. It is upon such young men as he that we most earnestly depend. Some of us older ones may not live to see the end of this war, and the younger generation must live to carry it on.”

Hadley did not think him austere now; his eyes were sad and his face worn and deeply lined. Not alone did the rank and file of the American army suffer physically during that awful winter; many of the officers went hungry, too, and it was whispered that often Washington’s own dinner was divided among the hollow-eyed men who guarded his person and sentineled the road leading to the little stone cottage.

Lafe nodded to the boy and they withdrew. On the road outside the scout placed his hand upon Hadley’s shoulder. “Had, that’s a great man in yonder,” said he, in his homely way. “You ’n’ I don’t know how great he is; but there’ll come folks arter us that will. He’s movin’ heaven an’ airth ter git rations for this army an’ they aint one of us suffers that he don’t feel it.”

“HADLEY UNTIED HIS HORSE.”

Hadley untied his horse and they went on in silence until they came to the sheds behind an old country inn not far from headquarters. Here Holdness had left his great covered wagon and team of sturdy draught horses. Despite the condition of affairs in the territory about Philadelphia, the scout retained his character of teamster and continued to go in and come out of the city as he pleased. How he allayed the suspicions of the British was known only to himself; but, evidently, General Washington trusted him implicitly.

Hadley, as they drove slowly through the camp, gave Black Molly over into Captain Prentice’s care. Not until they were beyond the picket lines of the Americans entirely did Holdness offer any explanation of the work before them. “We’re goin’ ter stop at a place an’ take a load of grain into Philadelphy,” he began. “I ’greed ter do this last week. I aint sayin’ but I’d like ter turn about an’ cart it inter aout lines; but that can’t be. The man ’at owns it is a Tory an’ he’s shippin’ his grain inter town so as to save it from the ’Mericans. He’s got his convictions, same’s we’ve got ourn; ’taint so bad for him to sell ter them Britishers as it is for some o’ these folks ’t claim ter have the good of the cause at heart, an’ yet won’t take scrip fer their goods.”

When they came to the farmer’s in question the great wagon was heavily loaded with sacks of grain. Hadley, who had so plainly seen the need of such commodity in the American camp, suggested that they take a roundabout way and deliver the sacks of grain to their friends instead of to the British, without the Tory being any the wiser. “And spile my game?” cried Lafe, with a chuckle. “I guess not. Reckon His Excellency wouldn’t thank us for that. I’m wuth more to him takin’ the stuff into Philadelphy than the grain would be. We’re goin’ in there to git some information. Hadley, my son—this ain’t no pleasure ja’nt.”

“But what can I do?” queried the boy.

“What you’re told—and I reckon you’ve l’arned that already with Gin’ral Wayne. A boy like yeou can git ’round ’mongst folks without being suspicioned better’n me. It’s whispered, Hadley, that them Britishers contemplate making a sortie on aour camp. You know the state we’re in—God help us!—an’ if the British mean to attack we must know it and be ready for them. Every crumb of information you can pick up must be treasured. I’ll take ye to Jothan Pye an’ you can be an apprentice of his. He kin git you access to the very houses in which some o’ them big bugs is quartered. If plans are really laid for an attack, you’ll hear whispers of it. Them whispers yeou’ll give to me, sonny. D’ye understand?”

Hadley nodded. He understood what was expected of him; also he understood that the mission would be perilous. But he had been in danger before, and he did not lack some measure of confidence in himself now.

The huge wagon rumbled on toward the British lines. When they were halted, Lafe [Pg 245] managed to give such a good account of himself that he was allowed to pass through with little questioning, for the grain was assigned to the quartermaster’s department. Hadley was simply considered a country bumpkin who had come into town to see the sights. Soon the old scout and the boy separated, Hadley making his way swiftly to the Quaker’s habitation near the Indian Queen, where good Mistress Pye welcomed him warmly.

Friend Pye was a merchant and dealt in such foreign commodities—particularly in West India goods—as were in demand among the British officers. As previously noted, the Quaker had lived so circumspectly in the city throughout the war that his loyalty to the king was considered unshaken by his Tory neighbors, and yet he was so retiring and so worthy a man that the Whigs had not considered him a dangerous enemy.

If anybody noted, during these cold days of middle winter, that Friend Pye had a new ’prentice boy, it was not particularly remarked. The gossip of the camp and, indeed, all conversation was tinged with military life and happenings. Friend Pye’s young man carried goods to the Norris house where My Lord Rawdon—that swarthy, haughty nobleman, both hated and feared by all who came in contact with him—was quartered, and even to Peter Reeves’ house on Second Street, where Lord Cornwallis held a miniature court. Hadley was, in his new duties, quick and obliging. The British officers often remarked that, for a country bumpkin, Pye’s apprentice was marvelously polite and possessed some grace and gentleness. But all the time Hadley Morris was keeping both his eyes and ears open, and when Holdness came to the Quaker’s house under cover of the night, he told him all he had heard and seen, even to details which seemed to him quite worthless.

“Ye never know how important little things may be,” Holdness had told him. “It’s the little things that sometimes turn aout ter be of th’ greatest value. Stick to it, Had.”

But, one day, Hadley experienced something of a shock—indeed, two of them. He was walking through Spruce Street, carrying a bundle with which his employer had entrusted him to deliver at an officer’s residence, when a carriage came slowly toward him. It was a very fine coach—much finer than any he had observed in Philadelphia thus far—and it was drawn by a pair of magnificent horses. The horses were bay, and before many moments the boy, with a start, recognized them. His eyes flew from the handsome team to the coachman, perched on the high seat.

The bays were the same he had seen so often while Colonel Creston Knowles was a guest at the Three Oaks Inn, and the driver was William, the silent Cockney. The coach window was wide open and Hadley could see within. There, on the silken cushions, was seated Mistress Lillian herself! The boy stared, stopping on the edge of the walk in his surprise. Of course, he might have expected to find the British officer and his daughter here, yet he was amazed, nevertheless.

But he was evidently not the only person astonished. Lillian saw him. She leaned from the carriage window and, for an instant, he thought she was about to call to him. Then she glanced up at the driver’s seat and said something to William. At once the bays began to trot and the carriage rolled swiftly past. But Hadley had looked up at the driver, too, and for the first time saw and recognized the person sitting beside William on the high perch.

William was gorgeous in a maroon livery: the person beside him was in livery, also, and evidently acted as footman. But, despite his gay apparel, Hadley recognized this footman instantly. It was Alonzo Alwood, and as he gazed after the retreating carriage, the American youth was conscious that Lon had twisted around in his seat and was staring at him with scowling visage.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

[Pg 246]

By William A. Stimpson

“Good-by, fellows; don’t expect me back before supper time.” Waving his hand to his friends, Alfred Whyte pushed the bateau into the water, took his seat in the centre, and with a few strong, even strokes of the paddle sent the frail craft out of sight around a bend in the stream.

It was on the edge of the Florida Everglades, those low, marshy tracts of swamp land that cover the whole of the lower end of the peninsula. Two New York boys, Willard King and Marvin Stebbins, had homesteaded a claim in the heart of the morass and were engaged in growing tomatoes for the northern markets. Alfred, a former schoolmate, was spending a few weeks with them in their southern home.

The piece of land upon which the two northerners had settled was about fifty acres in extent. It rose, island-like, from out the midst of the network of little creeks and streams that crisscrossed in every direction and made a veritable land-and-water spider’s web of that part of the State.

The tomato plants were set out in February and now, the first of April, the tomatoes had begun to turn red and were large enough to be picked. They had to be handled very carefully, wrapped in tissue paper, and packed in light wooden crates, so as to permit the process of ripening to be completed on the trip north. Picking and packing them was tedious and took considerable time. Both the young truck farmers had their hands full, and when a flock of wild ducks flew overhead on their way to the feeding grounds half a mile further inland, they merely directed a passing glance upward and then, stifling their sportsmen’s instinct, turned to their work again.

All the morning the wild fowl could be heard thrashing about in the tall grass at the lagoon, and both King and Stebbins were sorely tempted several times to slip up stream in the hope of bagging a couple. But the steamer on which they intended shipping their produce sailed from Lincoln, fifteen miles east, the next afternoon, and by working persistently until dark they could hardly get their crop ready for an early start on the following morning for the river town.

“If neither of you fellows can spare the time to go duck shooting, why can’t I paddle up there and try a shot or two?” asked Alfred, late in the afternoon.

“All the reason in the world, Al,” replied King. “No one except a native, or a person who has lived here as long as we have, can traverse this swamp in safety. Why, before you reach the lake where the ducks are you will pass eight or ten little streams, any one of which you are just as likely to enter as to keep on up the main channel. We’re afraid you’ll get lost, Al. Don’t you think so?” he asked, turning to Stebbins.

“But I’ve been all around there with you fellows,” explained Alfred, trying in vain to conceal his disappointment. “I’ve been up to the lake, too, and I know the main stream perfectly well. I’m going to try it, for I must have some roast duck.”

Both the boys tried to dissuade him from the undertaking, but he was insistent, and finally they gave a reluctant consent. Realizing fully his lack of acquaintance with the swamp, Whyte paid particular attention to his surroundings as he paddled on, fearing that he might turn into one of those little side streams of which King had warned him.

Suddenly, ahead of him, he saw the ducks. Paddling noiselessly, scarcely rippling the water as he passed through, he [Pg 247] got within range of the flock without alarming them. Bang! bang! went both barrels of his twelve-bore, and at the reports the ducks rose from the water with a loud whirr. One bird was wounded and lagged behind the others. It fluttered along a hundred yards or so, then sank in a clump of marsh grass, took wing again, but went less than ten yards, when it turned a somersault in the air and dropped.

A few strokes of the paddle carried the bateau close to where the bird had fallen, but when he reached the spot Whyte found that a stretch of marsh lay between the edge of the water and his prize. He tried to reach the duck with the paddle but could not do so. It was a fine, fat bird, as he could plainly see, but it lay beyond his reach.

“Just my luck,” he muttered, after several unsuccessful attempts to reach the bird. “I wonder if those hummocks will hold me,” noticing the tufts of thick, coarse grass that dotted the morass in every direction.

The hummocks looked firm enough to bear his weight, so pushing the prow of the boat as far into the edge of the bank as he could, he stepped out and tried the first one. It was solid and unyielding. Certain, then, that his plan was a feasible one, he sprang to the next hummock and on until he had the bird in his hand. In returning, he rested too much weight upon one of the tufts of thick grass. The treacherous mud gave way, his foot slipped, and down he went into the black ooze up to his thighs.

With an exclamation of impatience, he endeavored to withdraw his feet and legs. They stuck fast. He tried a second time, but the mud held him as in a vise. Putting forth all his strength and seizing several blades of the long, coarse grass within his reach, he tried his best to extricate himself, but to his dismay he found the sticky mud to be as unyielding as quicksand. What was worse, when he ceased his efforts he discovered that he had sunk deeper in the mire and was now embedded nearly up to his breast.

Thoroughly frightened, he remained perfectly passive and began to think. He realized that he was in a serious predicament, held a prisoner, as he was, in the black, slimy mud of the swamp, and it was cold there, too. His gun lay within reach, and, resting the arm lengthwise, he made another attempt to release himself, but his efforts were unavailing. The gun sank in the ooze, and in extracting it he found that his exertions had caused him to sink several inches deeper. The top of the mud now reached to his armpits.

He glanced at the sun, and, seeing it low in the west, was comforted. King and Stebbins, becoming alarmed at his non-appearance, would soon be setting out to look for him, he thought, if they were not already doing so. His eyes wandered towards the opposite bank, and he was struck with its unfamiliar appearance. Instead of the low, flat marsh that lined that side of the stream, as he well knew, he was looking upon a patch of higher land similar to the one upon which King and Stebbins had their home. It dawned upon him then for the first time that he had left the main channel.

As the realization of his true position came home to him, hope died. Thinking that he was somewhere along the stream, he had felt sure of rescue, but his discovery altered the situation completely. How far out of his true course he was he had no way of knowing, and the thought of the awful days and nights that would pass while he stood there dying, if the mud did not eventually bury him and make his death even a more horrible one, was far from pleasant.

Frantically he struggled to free himself, but he was held fast as though he had been shackled in irons, and his struggles only left him exhausted. Great beads of perspiration stood out on his brow. His mouth was dry and parched and his head began to swim. He felt that he was losing his reason, but he pulled himself together with a herculean effort. His legs and feet were cold and numb, and the keen night wind nipped his ears and nose cruelly. The mud under his arms had begun to freeze, and unless he kept breaking it continually [Pg 248] with his hands, a stiff crust would form at the top.

He racked his brain to devise some plan of escape from his terrible position, but could think of nothing except to shout. That, he supposed, would only be a waste of energy, but he must do something. Gathering himself together, he essayed to call, but his mouth was so parched that his voice did not penetrate further than ten yards. He tried again, and this time found himself shouting louder. Again and again he shouted until his voice echoed and re-echoed through the everglades.

As the sounds died away his ear caught a faint call that seemed like an answer to his own. Flushed with hope, he shouted again and then strained his ears to listen. But silence, broken only by the twittering of the night birds, reigned about him.

Once more he shouted, and again he thought he heard a reply, or was it an echo of his own voice? The ordeal was too much for him, and with a groan his head drooped and he lost consciousness.

With King and Stebbins the time passed until sundown before they realized how late it was, and then they dropped their work and looked along the stream in the direction taken by their guest.

“It is nearly seven o’clock, Marvin,” remarked King, consulting his watch. “Al said he would be back by supper time, and here it is an hour after. I believe he’s lost.”

“If that’s the case, we must find him before dark, or he’ll have to stay in the swamp all night,” said Stebbins.

Both young men were hurrying towards the boat landing as they spoke. “Maybe he’ll row around there a week before he finds his way out,” declared King.

Stepping into the remaining boat, they both seized a paddle and sent the light skiff whirling along towards the lake, keeping a sharp lookout for any signs of the missing boat. “He promised not to go further than the lake,” said Stebbins, as they reached a point where the stream began to widen. “Let’s course over some of those creeks back there,” indicating a part of the swamp in the rear of their island home.

The boat’s prow was accordingly turned in that direction, and they had proceeded but a few yards when King’s ear detected a faint call somewhere in the distance. It was so low and indistinct that he was unable to tell from what direction it came, but shouted loudly in answer.

“Did you hear anything?” asked Stebbins, whose hearing was not so keen.

“I thought I did,” answered King, “and shouted in the hope that it might be Alfred. He’s certainly out of the channel and is calling us. Halloo! halloo! we’re coming! Where are you?” he shouted.

The boys rested a moment or two and listened for a reply. None came. “We don’t know which way to go,” said King. “Let’s go south on a venture.”

“Call again,” said Stebbins, after they had been paddling for a few minutes. King did so, and in answer came a faint shout that both boys heard. “We’re right, keep on straight ahead,” said King, excitedly. “Where are you?” he called, but they did not receive any further answer.

They paddled an eighth of a mile along this course, calling constantly without seeing anything of the person for whom they were looking. “Strange he doesn’t answer us,” remarked Stebbins, thoughtfully. “I’m afraid something’s happened to him.”

King said nothing, but kept peering ahead into the gathering gloom. Darkness had fallen by this time and objects were hardly distinguishable. Rounding a bend in the stream, they suddenly saw a boat—the one in which Alfred had rowed away—drawn up on the bank. With a shout the boys pushed ahead with rapid strokes. “Alfred, where are you?” they called. As there was no response, they backed water, and bringing their bateau to a stop, looked with blanched faces into the empty boat.

“Where can he be?” muttered Stebbins.

“Look there! look there!” exclaimed King, rising in the skiff and nearly upsetting it.

Stebbins followed the direction indicated, and saw what appeared to be a man’s head upright on the ground.

[Pg 249]

“It’s Alfred, and he’s fast in the mud,” exclaimed Stebbins, grasping the situation. “He’s dead!” he groaned.

Without further words, the boat was driven to the bank, and, stepping on the very hummocks that had supported Whyte, they reached his side. “Quick, Stebbins, get your paddle under his left arm; I will do the same on my side,” said King, and, working together, they succeeded in raising the apparently lifeless form from its position. In another moment they had placed the unfortunate youth in the boat beside them, and while one sent the skiff skimming towards home, the other rubbed and chafed the cold hands and feet. At last they were rewarded by seeing the eyes open and feeling the heart beat faintly.

By the time the party reached the house, Whyte was himself again, but so weak and sick that he had to be carried from the landing and put to bed. A doctor was brought from Lincoln the next day and left some medicine and a few directions, but Alfred’s robust health and good constitution did more for him than all the pills and powders, and in a few days he had recovered from all traces of his terrible experience, except the memory of it. That will stay with him always.

An interesting account, showing the numbers in which birds often live together, is the following, written by Audubon. The great ornithologist was, at the time of writing, visiting Bird Rock, a little granite island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, so named from its only inhabitants, birds, mostly of a species called Gannet.

“About ten, a speck rose on the horizon, which I was told was the Rock. We sailed well, the breeze increased fast, and we neared the object apace. At eleven, I could distinguish its top plainly from the deck, and thought it covered with snow to the depth of several feet. This appearance existed on every portion of the flat, projecting shelves. Godwin (the guide) said, with the coolness of a man who had visited this rock for successive seasons, that what we saw was not snow, but Gannets. I rubbed my eyes, took my spy-glass, and in an instant the strangest picture stood before me. They were birds we saw—a mass of birds of such size as I never before cast my eyes on. The whole of my party stood astounded and amazed, and all came to the conclusion that such a sight was of itself sufficient to invite anyone to come across the gulf to view it at this season. The nearer we approached, the greater our surprise at the enormous number of these birds, all calmly seated on their eggs or newly-hatched brood, their heads all turned to the windward and toward us. The air above for a hundred yards, and for the same distance around the Rock, was filled with Gannets on the wing, which, from our position, made it appear as if a heavy fall of snow was directly above us. The whole surface (of the island) is perfectly covered with nests, placed about two feet apart, in such regular order that you may look through the lines as you would look through those of a planted patch of sweet potatoes or cabbages. When one reaches the top, the birds, alarmed, rise with a noise like thunder, and fly off in such a hurried, fearful confusion as to throw each other down, often falling on each other until there is a bank of them many feet high.”

This was in 1833. If Audubon could visit the island now, how he would find the “snows” melted. There is to-day not a single Gannet nesting on the top of the rock. On the ledges and in the crannies about its sides, the birds still dwell in great numbers, even in thousands, but not in the countless myriads of the past.

[Pg 250]

By Evelyn Raymond

Brought up in the forests of northern Maine, and seeing few persons excepting her uncle and Angelique, the Indian housekeeper, Margot Romeyn knows little of life beyond the deep hemlocks. Naturally observant, she is encouraged in her out-of-door studies by her uncle, at one time a college professor. Through her woodland instincts, she and her uncle are enabled to save the life of Adrian Wadislaw, a youth who, lost and almost overcome with hunger, has been wandering in the neighboring forest. To Margot the new friend is a welcome addition to her small circle of acquaintances, and after his rapid recovery she takes great delight in showing him the many wonders of the forest about her home. But finally, after many weeks, the uncle decides, because of reasons which will be known later, that it would be better for Margot if Adrian left them. Accordingly, he puts the matter before the young man, who, although reluctant to leave his new friends, volunteers to go. Under the guidance of Pierre Ricord, a young Indian, the lad sets out for the nearest settlement. After many adventures, including a narrow escape from the dangerous rapids, in which the travelers lost the canoe and nearly all their possessions, the two reach Donovan’s, their destination. Here they separate, Adrian going straight to New York and the home which he left seemingly so long ago. We leave him on the threshold of his father’s city mansion, wondering what welcome there will be for the prodigal. Pierre returns to Peace Island, where, with Margot and her uncle, we again take up the story.

“No sign yet?”

“No sign.” Margot’s tone was almost hopeless. Day after day, many times each day, she had climbed the pine-tree flagstaff and peered into the distance. Not once had anything been visible, save that wide stretch of forest and the shining lake.

“Suppose you cross again, to Old Joe’s. He might be back by this time. I’ll fix you a bite of dinner, and you better, maybe—”

The girl shook her head and clasped her arms about old Angelique’s neck. Then the long repressed grief burst forth in dry sobs that shook them both, and pierced the housekeeper’s faithful heart with a pain beyond endurance.

“Pst! pouf! Hush, sweetheart, hush! ’Tis nought. A few days more, and the master will be well. A few days more, and Pierre will come. Ah! but I had my hands about his ears this minute. That would teach him—yes—to turn his back on duty—him. The ingrate! Well, what the Lord sends the body must bear, and if the broken glass—”

Margot lifted her head, shook back her hair, and smiled wanly. The veriest ghost of her old smile it was, yet, even such, a delight to the other’s eyes.

“Good. That’s right. Rouse up. There’s a wing of a fowl in the cupboard, left from the master’s broth—”

“Angel, he didn’t touch it, to-day. Not even touch it.”

“’Tis naught. When the fever is on the appetite is gone. Will be all right once that is over.”

“But, will it be over? Day after day, just the same. Always that tossing to and fro, the queer, jumbled talk, the growing thinner—all of the dreadful signs of how he suffers. Angelique, if I could bear it for him. I am so young and strong and worth nothing to this world, while he’s so wise and good. Everybody who ever knew him must be the better for Uncle Hughie, Angelique.”

“’Tis truth. For that, the good God will spare him to us. Of that be sure.”

[Pg 251]

“But I pray and pray and pray, and there comes no answer. He is never any better. You know that. You can’t deny it. Always before, when I have prayed, the answer has come swift and sure; but now—”

“Take care, Margot. ’Tis not for us to judge the Lord’s strange ways. Else were not you and me and the master shut up alone on this island, with no doctor near, and only our two selves to keep the dumb things in comfort. Though, as for dumbness, hark yonder beast!”

“Reynard! Oh! I forgot. I shut him up because he would hang around the house and watch your poor chickens. If he’d stay in his own forest, now, I would be so glad. Yet I love him—”

“Aye, and he loves you. Be thankful. Even a beastie’s love is of God’s sending. Go feed him. Here—the wing you’ll not eat yourself.”

They were dark days now on the once sunny Island of Peace.

That day when Mr. Dutton had said, “Your father is still alive,” seemed now to Margot, looking back, as one of such experiences as change a whole life. Up till that morning she had been a thoughtless, unreflecting child, but the utterance of those fateful words altered everything.

Amazement, unbelief of what her ears told her, indignation that she had been so long deceived, as she put it, were swiftly followed by a dreadful fear. Even while he spoke, the woodlander’s figure swayed and trembled, the hoe-handle on which he rested wavered and fell, and he, too, would have fallen had not the girl’s arms caught and eased his sudden sinking in the furrow he had worked. Her shrill cry of alarm had reached Angelique, always alert for trouble and then more than ever, and had brought her swiftly to the field. Between them they had carried the now unconscious man within and laid him on his bed. He had never risen from it since; nor, in her heart, did Angelique believe he ever would, though she so stoutly asserted to the contrary before Margot.

“We have changed places, Angelique, dear,” the child often said. “It used to be you who was always croaking and looking for trouble. Now you see only brightness.”

“Well, good sooth. ’Tis a long lane has no turnin’, and better late nor never. Sometimes ’tis well to say, ‘Stay, good trouble, lest worser comes,’ eh? But things’ll mend. They must. Now, run and climb the tree. It might be this ver’ minute that wretch, Pierre, was on his way across the lake. Pouf! but he’ll stir his lazy bones, once he touches this shore! Yes, yes, indeed. Run and hail him, maybe.”

So Margot had gone, again and again, and had returned to sit beside her uncle’s bed, anxious and watchful.

Often, also, she had paddled across the narrows and made her way swiftly to a little clearing on her uncle’s land, where, [Pg 252] among giant trees, old Joseph Wills, the Indian guide, and faithful friend of all on Peace Island, made one of his homes. Once Mr. Dutton had nursed this red man through a dangerous illness, and had kept him in his old home for many weeks thereafter. He would have been the very nurse they now needed, in their turn, could he have been found. But his cabin was closed, and on its doorway, under the family sign-picture of a turtle on a rock, he had printed, in dialect, what signified his departure for a long hunting trip.

Now, as Angelique advised, she resolved to try once more; and, hurrying to the shore, pushed her canoe into the water and paddled swiftly away. She had taken the neglected Reynard with her, and Tom had invited himself to be a party of the trip; and in the odd but sympathetic companionship Margot’s spirits rose again.

“It must be as Angelique says. The long lane will turn. Why have I been so easily discouraged? I never saw my precious uncle ill before, and that is why I have been so frightened. I suppose anybody gets thin and says things when there is fever. But he’s troubled about something. He wants to do something that neither of us understand. Unless—oh! I believe I do understand. My head is clearer out here on the water, and I know, I know! It is just about the time of year when he goes away on those long trips of his. And we’ve been so anxious we never remembered. That’s it. Surely it is. Then, of course, Joe will be back now or soon. He always stays on the island when uncle goes, and he’ll remember. Oh! I’m brighter already, and I guess, I believe, it is as Angelique claims—God won’t take away so good a man as uncle and leave me alone. Though I am not alone. I have a father! I have a father somewhere, if I only knew—all in good time—and I’m growing gladder and gladder every minute.”

She could even sing to the stroke of her paddle, and she skimmed the water with increasing speed. Whatever the reason for her growing cheerfulness, whether the reaction of youth or a prescience of happiness to come, the result was the same; she reached the further shore flushed and eager-eyed, more like the old Margot than she had been for many days.

“Oh! he’s there. He is at home. There is smoke coming out of the chimney. Joseph! Oh, Joseph! Joseph!”

She did not even stop to take care of her canoe, but left it to drift whither it would. Nothing mattered, Joseph was at home. He had canoes galore, and he was help indeed.

She was quite right. The old man came to his doorway and waited her arrival with apparent indifference, though surely no human heart could have been unmoved by such unfeigned delight. Catching his unresponsive hands in hers, she cried:

“Come at once, Joseph! At once.”

“Does not the master trust his friend? It is the time to come. Therefore, I am here.”

“Of course. I just thought about that. But, Joseph, the master is ill. He knows nothing any more. If he ever needed you, he needs you doubly now. Come, come at once.”

Then, indeed, though there was little outward expression of it, was old Joseph moved. He stopped for nothing, but leaving his fire burning on the hearth and his supper cooking before it, went out and closed the door. Even Margot’s nimble feet had ado to keep pace with his long strides, and she had to spring before him to prevent his pushing off without her.

“No, no. I’m going with you. Here—I’ll tow my own boat, with Tom and Reynard—don’t you squabble, pets—but I’ll paddle no more while you’re here to do it for me.”

Joseph did not answer, but he allowed her to seat herself where she pleased, and with one strong movement sent his big birch a long distance over the water.

Margot had never made the passage so swiftly, but the motion suited her exactly; and she leaped ashore almost before it was reached, to speed up the hill and call out to Angelique wherever she might be:

“All is well! All will now be well—Joseph has come.”

[Pg 253]

The Indian reached the house but just behind her and acknowledged Angelique’s greeting with a sort of grunt; yet he paused not at all to ask the way or if he might enter the master’s room, passing directly into it as if by right.

Margot followed him, cautioning, with finger on lip, anxious lest her patient should be shocked and harmed by the too-sudden appearance of the visitor.

Then, and only then, when her beloved child was safely out of sight, did Angelique throw her apron over her head and give her own despairing tears free vent. She was spent and very weary; but help had come; and in the revulsion of that relief nature gave way. Her tears ceased, her breath came heavily, and the poor woman slept, the first refreshing slumber of an unmeasured time.

When she waked, at length, Joseph was crossing the room. The fire had died out, twilight was falling, she was conscious of duties left undone. Yet there was light enough left for her to scan the Indian’s impassive face with keen intensity; and though he turned neither to the right nor left, but went out with no word or gesture to satisfy her craving, she felt that she had had her answer.

“Unless a miracle is wrought, my master is doomed. Oh, the broken glass—the broken glass!”

From the moment of his entrance to the sick room, old Joe assumed all charge of it, and with scant courtesy banished from it both Angelique and Margot.

“But he is mine, my own precious uncle. Joe has no right to keep me out!” protested Margot, vehemently.

Angelique was wiser. “In his own way, among his own folks, that Indian good doctor. Leave him be. Yes. If my master can be save’, Joe Wills’ll save him. That’s as God plans; but if I hadn’t broke—”

“Angelique! Don’t you ever, ever let me hear that dreadful talk again. I can’t bear it. I don’t believe it. I won’t hear it. I will not. Do you suppose that our dear Lord is—will—”

She could not finish her sentence and Angelique was frightened by the intensity of the girl’s excitement. Was she, too, growing feverish and ill? But Margot’s outburst had worked off some of her own uncomprehended terror, and she grew calm again. Though it had not been put into so many words, she knew both from Angelique’s and Joseph’s manner that they anticipated but one end to her guardian’s illness. She had never seen death, except among the birds and beasts of the forest, and even then it had been horrible to her; and that this should come into her own happy home was unbearable.

Then she reflected. Hugh Dutton’s example had been her instruction, and she had never seen him idle. At times when he seemed most so, sitting among his books, or gazing silently into the fire, his brain had been active over some problem that perplexed or interested him. “Never hasting, never wasting” time, nor thought, nor any energy of life. That was his rule, and she would make it hers.

“I can, at least, make things more comfortable out-of-doors. Angelique has let even Snowfoot suffer, sometimes, for want of the grooming and care she’s always had. The poultry, too, and the poor garden. I’m glad I’m strong enough to rake and hoe, even if I couldn’t lift Uncle as Joe does.”

Her industry brought its own reward. Things outside the house took on a more natural aspect. The weeds were cleared away, and both vegetables and flowers lifted their heads more cheerfully. Snowfoot showed the benefit of the attention she received, and the forgotten family in the Hollow chattered and gamboled in delight at the reappearance among them of their indulgent mistress. Margot herself grew lighter of heart and more positive that, after all, things would end well.

“You see, Angelique dismal, we might as well take that broken glass sign to mean [Pg 254] good things as evil; that uncle will soon be up and around again, Pierre be at home; and the ‘specimen’ from the old cave prove copper or something just as rich, and—everybody be as happy as a king.”

Angelique grunted her disbelief, but was thankful for the other’s lighter mood.

“Well, then, if you’ve so much time and strength to spare, go yonder and redde up the room that Adrian left so untidy. Where he never should have been, had I my own way, but one never has that in this world; hey, no. Indeed, no. Ever’thin’ goes contrary, else I’d have cleared away all trace long sin’. Yes, indeed, yes.”

“Well, he is gone. There’s no need to abuse him, even if he did not have the decency to say good-by. Though, I suppose it was my uncle put a stop to that. What Uncle has to do he does at once. There’s never any hesitation about Uncle. But I wish—I wish—Angelique Ricord, do you know something? Do you know all the history of this family?”

“Why should I not, eh?” demanded the woman, indignantly. “Is it not my own family, yes? What is Pierre but one son? I love him, oh, yes! But—”

“WHERE IS MY FATHER?”

“You adore him, bad and trying as he is. But there is something you must tell me, if you know it. Maybe you do not. I did not, till that awful morning when he was taken ill. But that very minute he told me what I had never dreamed. I was angry; for a moment I almost hated him because he had deceived me, though afterward I knew that he had done it for the best and would tell me why when he could. So I’ve tried to trust him just the same and be patient. But—he may never be able—and I must know. Angelique, where is my father?”

The housekeeper was so startled that she dropped the plate she was wiping and broke it. Yet even at that fresh omen of disaster she could not remove her gaze from the girl’s face nor banish the dismay of her own.

“He told—you—that—that—”

“That my father is still alive. He would, I think, have told me more; all that there may be yet to tell, if he had not so suddenly been stricken. Where is my father?”

“Oh, child, child! Don’t ask me. It is not for me—”

“If Uncle cannot and you can, and there is no other person, Angelique—you must!”

“This much, then. It is in a far, far away city, or town, or place, he lives. I know not, I. This much I know: he is good, a ver’ good man. And he have enemies. Yes. They have done him much harm. Some day, in many years, maybe, when you have grown a woman, old like me, he will come to Peace Island and forget. That is why we wait. That is why the master goes, once each summer, on the long, long trip. When Joseph comes, and the bad Pierre to stay. I, too, wait to see him, though I never have. And when he comes, we must be ver’ tender, me and you, for people who have been done wrong to, they—they—pouf! ’Twas anger I was that the master could put the evil-come into that room, yes.”

“Angelique! Is that my father’s room? Is it? Is that why there are the very best things in it? And that wonderful picture? And the fresh suits and clothing? Is it?”

Angelique slowly nodded. She had been amazed to find that Margot knew thus much of a long-withheld history, and saw no harm in adding these few facts. The real secret, the heart of the matter—that was not yet. Meanwhile, let the child accustom herself to the new ideas, and so be prepared for what she must certainly and further learn, should the master’s illness be a fatal one.

“Oh, then, hear me. That room shall always now be mine to care for. I haven’t liked the housewifery, not at all. But if I have a father and I can do things for him—that alters everything. Oh! you can’t mean that it will be so long before he comes. You must have been jesting. If he knew Uncle was ill he would come at once, wouldn’t he? He would, I know.”

Poor Angelique turned her face away to hide its curious expression, but in her new interest concerning the “friend’s room,” as it had always been called, Margot did not notice this. She was all eagerness and loving excitement.

“To think that I have a father who may [Pg 255] come, at any minute, for he might, Angelique, you know that, and not be ready for him. Your best and newest broom, please, and the softest dusters. That room shall, indeed, be ‘redded’—though uncle says nobody but a few people like you ever use that word, nowadays—better than anybody else could do it. Just hurry, please, I must begin. I must begin right away.”

She trembled so that she could hardly braid and pin up her long hair out of the way, and her face had regained more than its old-time color. She was content to let all that was still a mystery remain for the present. She had enough to think about and enjoy.

Angelique brought the things that would be needed and, for once, forebore advice. Let love teach the child—she had nought to say. In any case, she could not have seen the dust, herself, for her dark eyes were misty with tears, and her thoughts on matters wholly foreign to household cares.

Margot opened the windows and began to dust the various articles which could be set out in the wide passage, and did not come round to the heavy dresser for some moments. As she did so finally, her glance flew instantly to a bulky parcel, wrapped in sheets of white birch bark, and bearing her own name, in Adrian’s handwriting.

“Why, he did remember me, then!” she cried, delightedly, tearing the package open. “Pictures! the very ones I liked the best. Xanthippé and Socrates, and oh! that’s Reynard. Reynard, ready to speak. The splendid, beautiful creature; and the splendid, generous boy, to have given it. He called it his ‘masterpiece,’ and, indeed, it was by far the best he ever did here. Harmony Hollow—but that’s not so fine. However, he meant to make it like, and—why, here’s a note! Why didn’t I come in here before? Why didn’t I think he would do something like this? Forgive me, Adrian, wherever you are, for misjudging you so. I’m sorry Uncle didn’t like you, and sorry—for lots of things. But I’m glad—glad you weren’t so rude and mean as I believed. If I ever see you, I’ll tell you so. Now, I’ll put these in my own room and then get to work again. This room you left so messed shall be as spotless as a snowflake before I’ve done with it.”

For hours she labored there—brushing, renovating, polishing; and when all was finished she called Angelique to see and criticise—if she could. But she could not; and she, too, had something now of vital importance to impart.

“It is beautiful’ done, yes, yes. I couldn’t do it more clean myself, I, Angelique, no. But, ma p’tite I hear, hear, and be calm! The master is himself! The master has awoke, yes, and is askin’ for his child. True, true. Old Joe, he says, ‘Come! quick, soft, no cry, no laugh, just listen.’ Yes. Oh, now all will be well!”

Margot almost hushed her very breathing. Her uncle awake, sane, asking for her. Her face was radiant, flushed, eager, a face to brighten the gloom of any sick room, however dark.

But this one was not dark. Joe knew his patient’s fancies. He had forgotten none. One of them was the sunshine and fresh air; and though in his heart he believed that these two things did a world of harm, and that the ill-ventilated and ill-lighted cabins of his own people were more conducive to recovery, he opposed nothing which the master desired. He had experimented, at first, but finding a close room aggravated Mr. Dutton’s fever, reasoned that it was too late to break up the foolish habits of a man’s lifetime; and as the woodlander had lived in the sunlight, so he would better die in it, and easier.

If she had been a trained nurse, Margot could not have entered her uncle’s presence more quietly, though it seemed to her that he must hear the happy beating of her heart and how her breath came fast and short. He was almost too weak to speak at all, but there was all the old love, and more, in his whispered greeting.

“My precious child!”

“Yes, Uncle. And such a happy child because you are better.”

She caught his hand and covered it with kisses, but softly, oh! so softly, and he smiled the rare, sweet smile that she had [Pg 256] feared she’d never see again. Then he looked past her to Angelique, in the doorway, and his eyes roved toward his desk in the corner. A little fanciful desk that held only his most sacred belongings and had been Margot’s mother’s. It was to be hers, some day, but not till he had done with it, and she had never cared to own it, since doing so meant that he could no longer use it. Now she watched him and Angelique wonderingly.

For the woman knew exactly what was required. Without question or hesitation, she answered the command of his eyes by crossing to the desk and opening it with a key she took from her own pocket. Then she lifted a letter from an inner drawer and gave it into his thin fingers.

“Well done, good Angelique. Margot—the letter—is yours.”

“Mine? I am to read it? Now? Here?”

“No, no. No, no, indeed! Would you tire the master with the rustlin’ of paper? Take it, else. Not here, where ever’thin’ must be still as still.”

Mr. Dutton’s eyes closed. Angelique knew that she had spoken for him, and that the disclosure which that letter would make should be faced in solitude.

“Is she right, Uncle, dearest? Shall I take it away to read?”

His eyes assented, and the tender, reassuring pressure of his hand.

“Then I’m going to your own mountain top with it. To think of having a letter from you, right here, at home! Why, I can hardly wait! I’m so thankful to you for it, and so thankful to God that you are getting well. That you will be soon; and then—why, then—we’ll go a-fishing!”

A spasm of pain crossed the sick man’s wasted features, and poor Angelique fled the place, forgetful of her own caution to “be still as still,” and with her own dark face convulsed with grief for the grief which the letter would bring to her idolized Margot.

But the girl had already gone away up the slope, faster and faster. Surely, a letter from nobody but her uncle, and at such a solemn time, must concern but one subject—her father. Now she would know all, and her happiness should have no limit.

But it was nightfall when she, at last, came down from the mountain, and though there were no signs of tears upon her face, neither was there any happiness in it.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

The following are the “State flowers,” as adopted by the several States. In Maine, Michigan, and Oklahoma Territory the decision was made by the Legislature, in the other cases by the votes of the scholars in the public schools.

Alabama, goldenrod; Arkansas, aster; California, California poppy; Colorado, columbine; Delaware, peach blossom; Idaho, syringa; Iowa, wild rose; Maine, pine cone and tassel; Michigan, apple blossom; Minnesota, moccasin flower; Missouri, goldenrod; Montana, bitterroot; Nebraska, goldenrod; New Jersey (State tree, maple); New York, rose (State tree, maple); North Dakota, goldenrod; Oklahoma Territory, mistletoe; Oregon, Oregon grape; Rhode Island, violet; Vermont, red clover; Washington, rhododendron. In Kansas, the sunflower is usually known as the State flower.

The largest bell in the world is the great bell at Moscow, at the foot of the Kremlin. Its circumference is nearly 68 feet, and its height more than 21 feet. It is 23 inches thick in its stoutest part, and weighs 433,722 pounds. It has never been hung.

[Pg 257]

By JULIA McNAIR WRIGHT

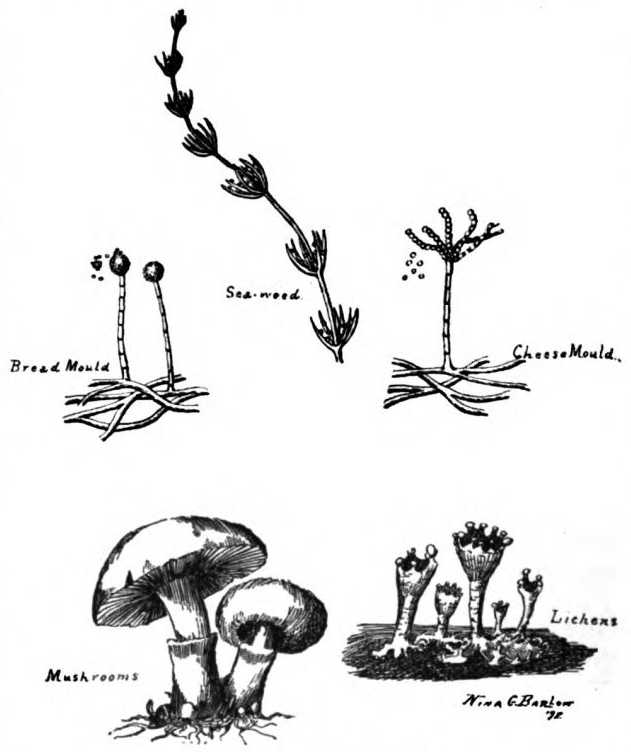

The year around and the world around, journey the plant pilgrims. Among those perennials which are found in all latitudes and seasons are the lichens and fungi. In September, while we wait for fruits and seeds to finish ripening, let us make small studies in these related groups in the vegetable sub-kingdom called the thallogens.

This sub-kingdom, one of the chief divisions of the vegetable kingdom, is known as the class thallophytes. It contains the simplest forms of vegetable life. Its chief groups are the fungi and algæ, the lichens being related to both, as if algæ and fungi had united in one plant, dividing and somewhat changing the characteristic of each.

At any period of the year you can find lichens in abundance. They cover ragged rocks, dress up old roofs, walls, fence rails and dead stumps, especially delighting in the north side of trees. If we examine them through a magnifying glass, we shall see that they are made up of cells, laid side by side like little chains of beads, or of cells expanded into short tubes or threads lying like heaps of tiny fagots. Instead of seeds, lichens have a fine dust, called spores, from which they develop.

Lichens are exceedingly long-lived and excessively slow of growth. The lily attains its lovely maturity in a few months; the oaks, elms, pines, become great trees in twenty or thirty years; the humble lichen often lives forty or fifty years before it is old enough to complete its growth by producing spores. Botanists say that the life of a lichen is fitful and strange, and is practically indefinite as to duration. Lichens simply live on and on.

Some lichens have been known to live nearly fifty years without seeming to grow; they appear to dry up, and nearly vanish; then, suddenly, from some cause there is a revival of growth—they expand again. Small and insignificant as these lichens are, they often outlive those longest-lived of trees, the cedar of Lebanon and the California redwood.

The condition of lichen existence is water, for from moisture alone, in dew or rain, they secure their food. The carbon, oxygen, ammonia, hydrogen, in air and rain, afford them their nourishment. The lichen generally refuses to grow in foul air laden with noxious gases. In the impure air of cities few appear, but they abound in the open country. They absorb by all the surface, except the base by which they are fastened to their place of dwelling. They have no roots, and simply adhere to bare rocks, sapless wood, even to naked glass, from which they can receive no nutriment whatever.

In comparison with what is known of plants in general, our knowledge of lichens is yet very limited. They seem to be made chiefly of a kind of gelatin which exists in lichens only. Humble as they appear, they have always been of large importance in arts and manufactures. They produce exquisite dyes—a rich, costly purple, a valuable scarlet, many shades of brown, and particularly splendid hues of blue and yellow are obtained from these common little growths, which in themselves display chiefly shades of black, gray green, varied with pink, red, and orange cups, balls, and edges.

While not so abundant as lichens, the fungi are well known everywhere. We cannot claim, as for the lichens, that they are harmless, for many are a virulent poison: others have a disgusting odor, and [Pg 258] nearly all are dangerous in their decay. On the other hand, many of them are a useful, delicious food, and nearly all are beautiful when first developed. Their variety, also, is very fascinating.

THE FLOWERLESS PLANTS

In a walk of less than two miles in a wet summer, may be found twenty different kinds of fungi—some no larger than a pea, some eight inches in diameter. They may be round, oval, flat, cup-shaped, horn-shaped, cushion-shaped, saucer-shaped; they are snow-white, gray, tan, yellow, lavender, orange, dark brown, pink, crimson, purple, and variously mottled, scaly or smooth as with varnish. Placed on a large platter among dark green mosses, they will be, for one day, a magnificent collection.

One large, egg-shaped variety, growing in pairs, is of a purple shade, very solid, and when broken open seems filled with glittering matter like iron or steel filings. Another tan-colored, plum-shaped fungus, firm and smooth, is of a nearly royal purple within.

September is a good month for the study of fungi, especially after the early fall rains, when the woods and pastures will be found well-filled, not only with brilliant, useless, or poisonous varieties, but with delicious edible kinds. Popularly, people call the edible specimens “mushrooms,” and the rest “toadstools,” the number of poisonous or of edible instances so named depending rather upon the amount of knowledge of the collector than upon the real qualities of the fungi, for many denominate as “toadstools” what others know to be an excellent food.

Many varieties not usually eaten are wholesome, and many which human beings reject, other animals thrive upon. One large, brown “toadstool” of the woods is, at this season of the year, the chief food of that epicure, the wood-tortoise.

In general a fungus may be defined as a thallophyte without any chlorophyl or leaf-green in its composition. Among the brilliant colors displayed by fungi no green or blue can be found.

The most popular and most useful fungus is the table mushroom. This rarely ever grows in the woods, in shade, on wet lands, or on decaying stumps. It prefers the open, breezy, well-sunned pastures, where the grass is kept short by the grazing of sheep or cattle. Early in the morning or shortly before sunset, the dainty white or cream-colored buttons, borne on snow-white stalks, push up through the soil and gradually expand until the discs are flat or slightly convex. From two to six inches is the diameter, seldom more than three.

Varieties of the pasture mushroom are few and can readily be learned. The mushroom is composed of stem and cap; the stem is finger-shaped, with the roundish end in the earth. About half way up is usually a [Pg 259] ring of the covering skin, where, in the button shape, the veil of the mushroom was attached.