Title: Strength and How to Obtain It

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected.

The contents list was prepared by the transcriber.

BY

EUGEN SANDOW,

WITH

ANATOMICAL CHART,

ILLUSTRATING

EXERCISES FOR PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT.

REVISED EDITION.

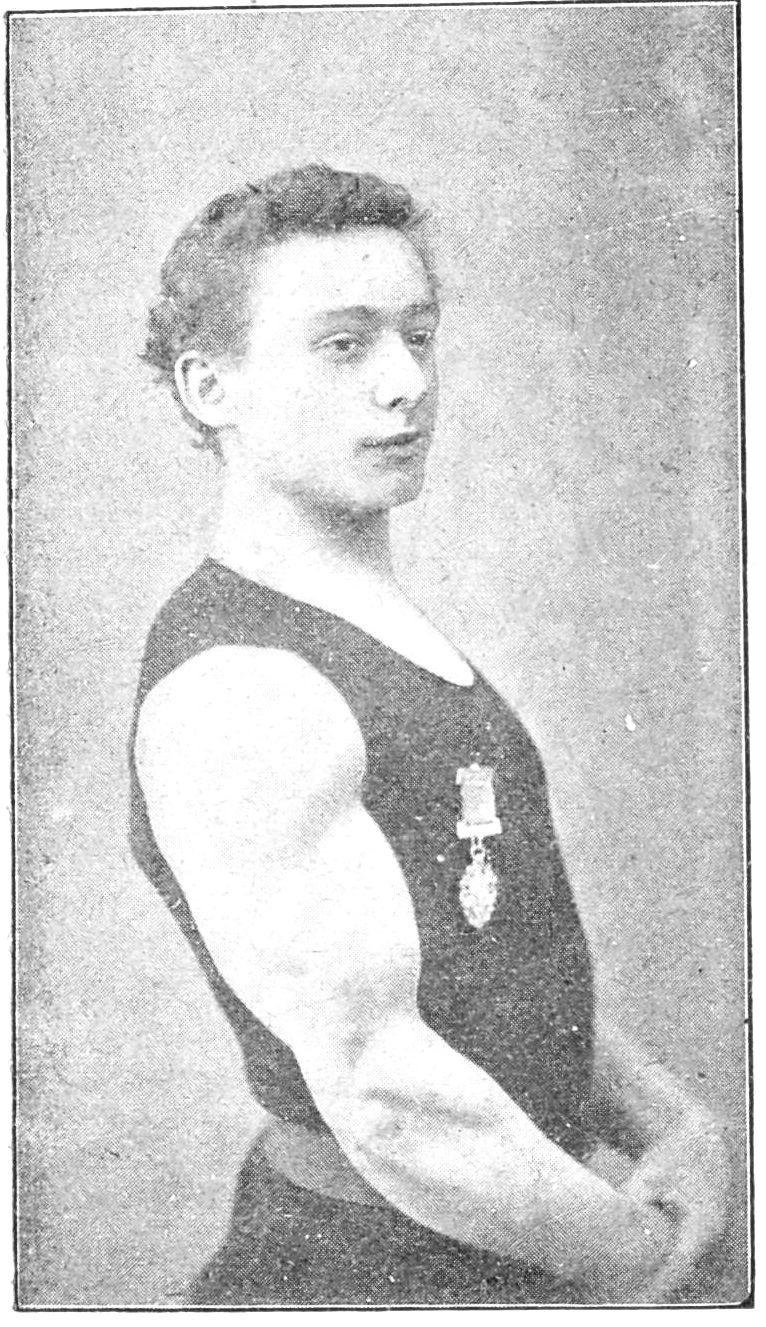

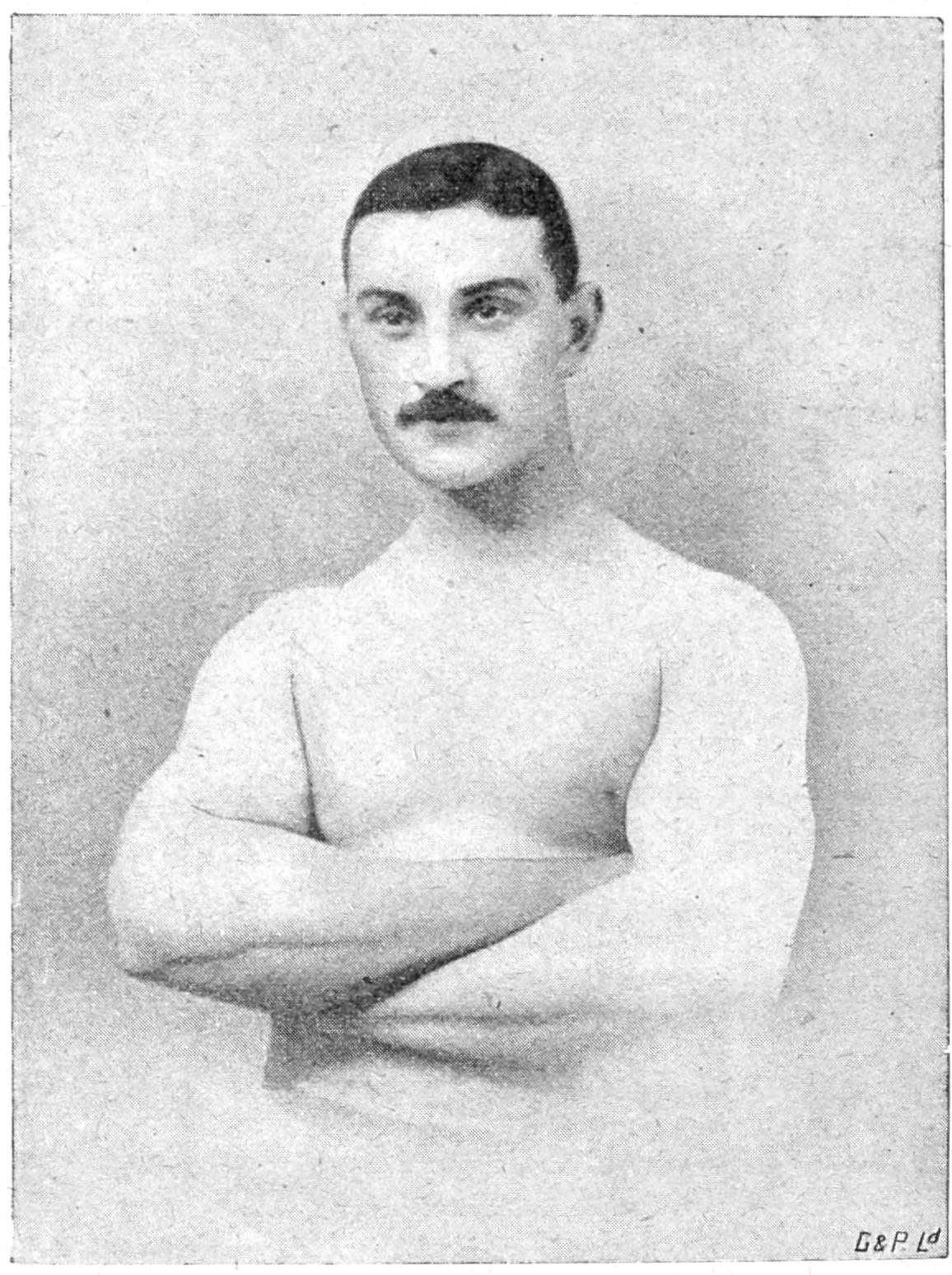

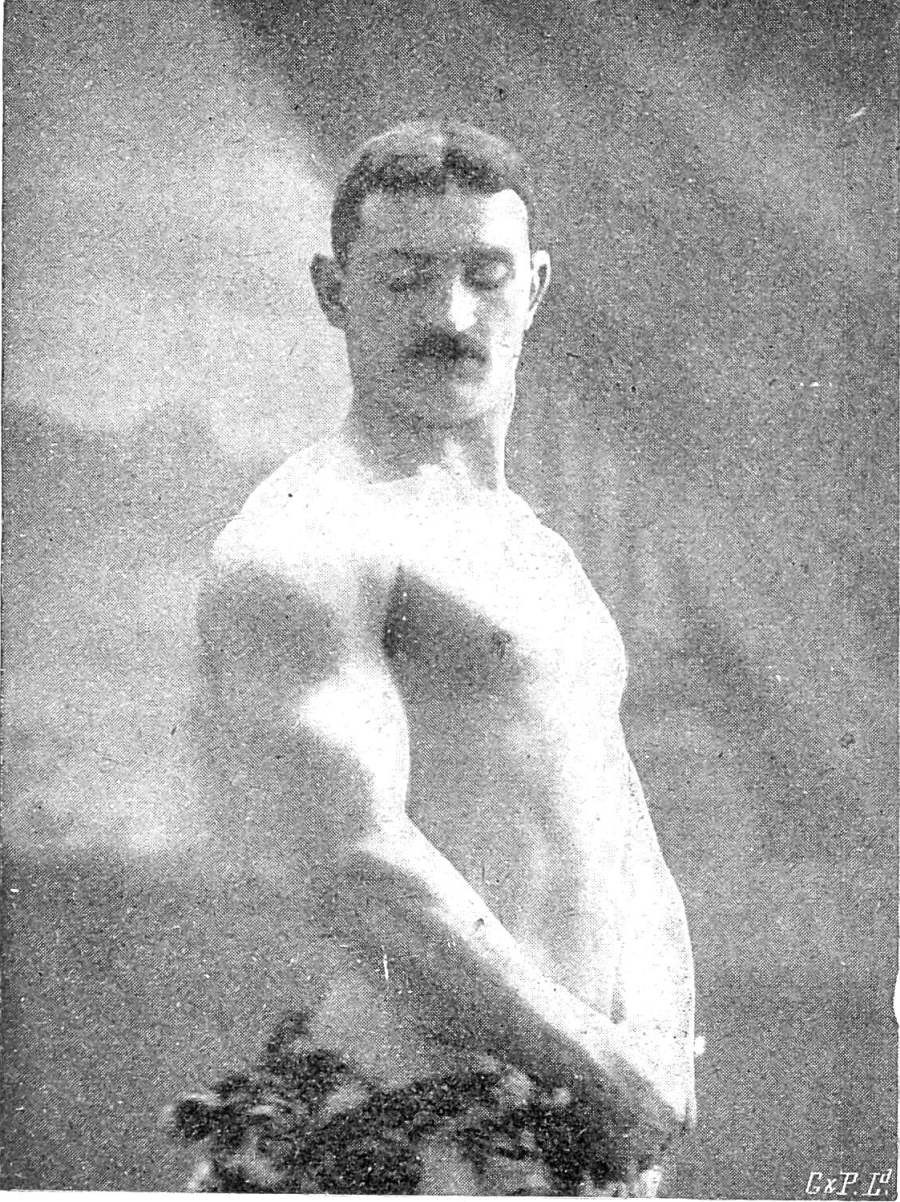

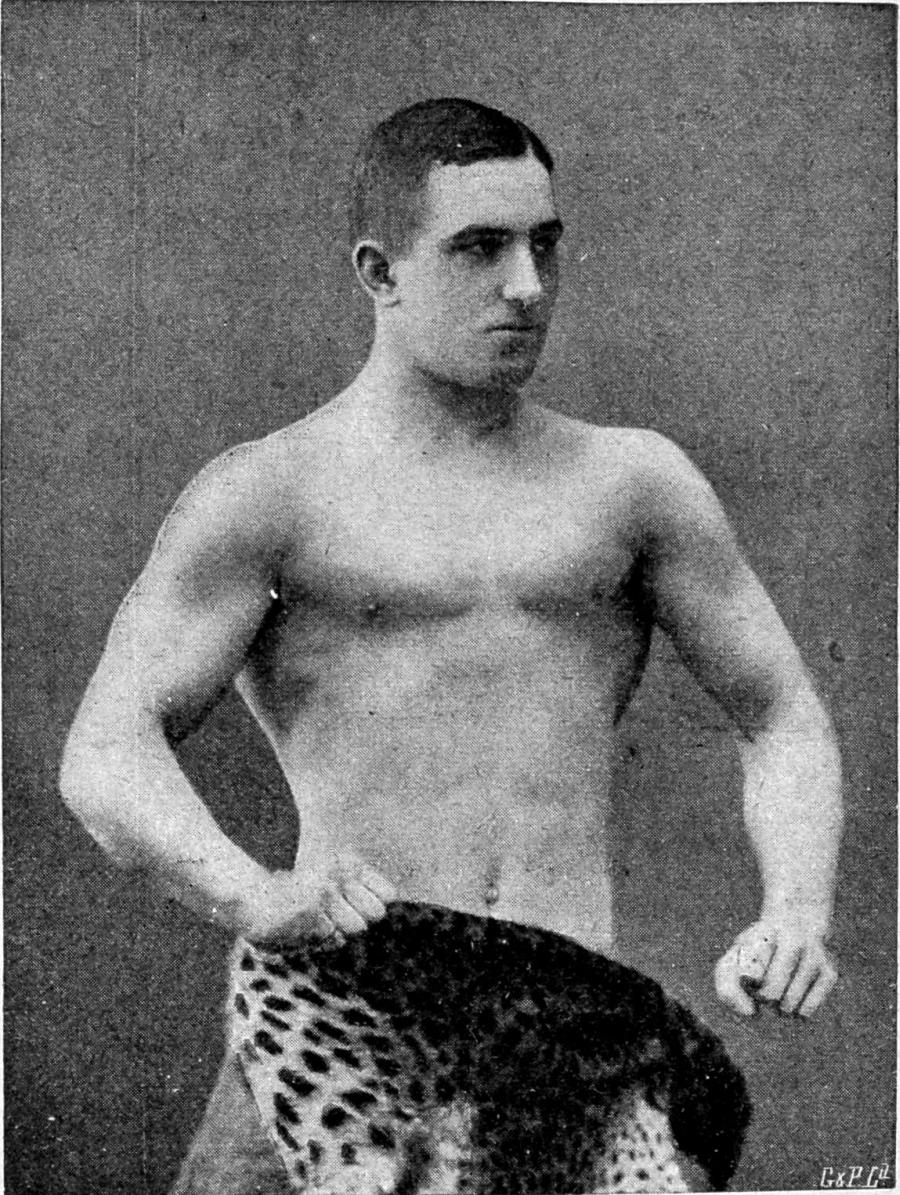

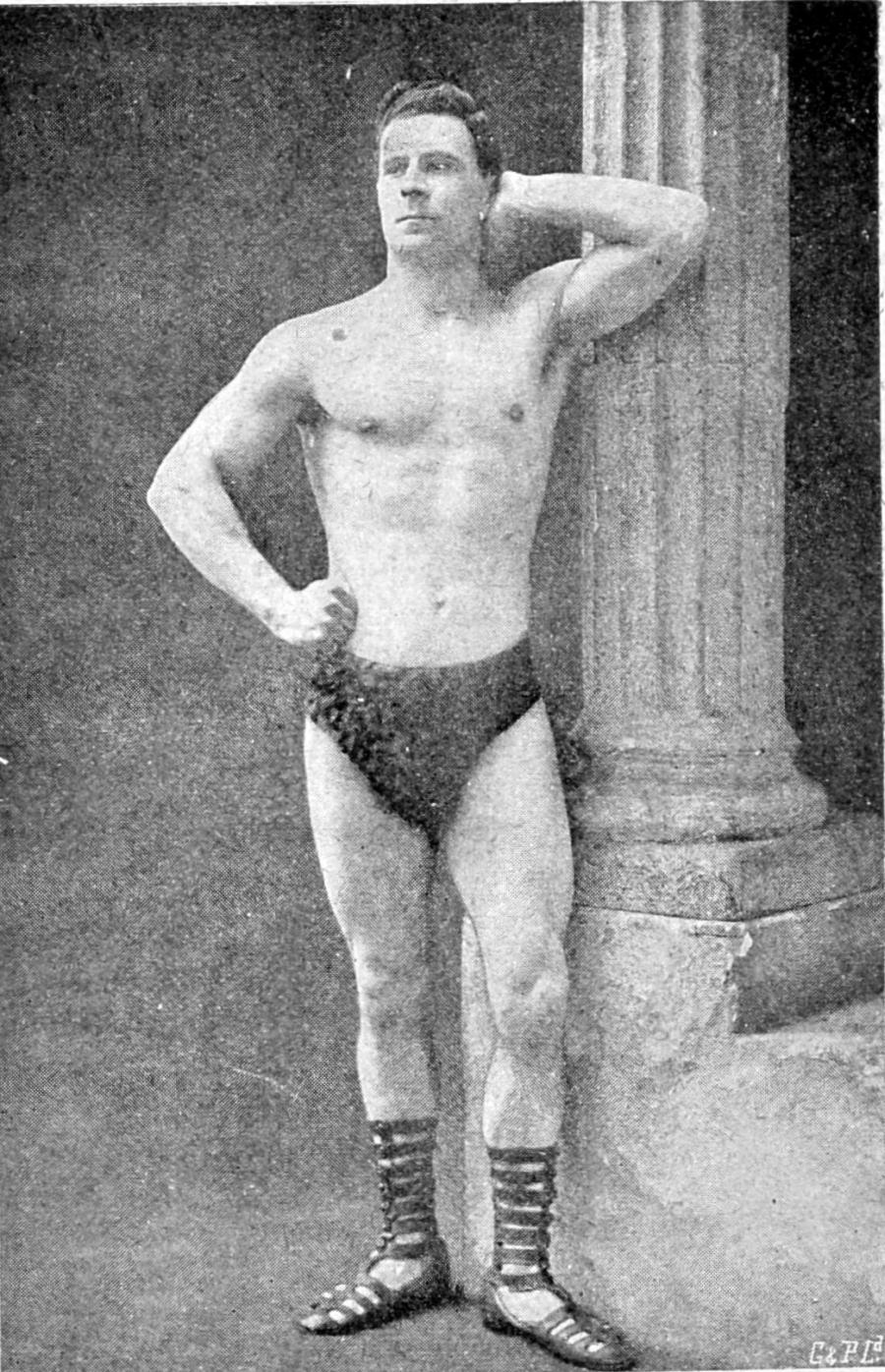

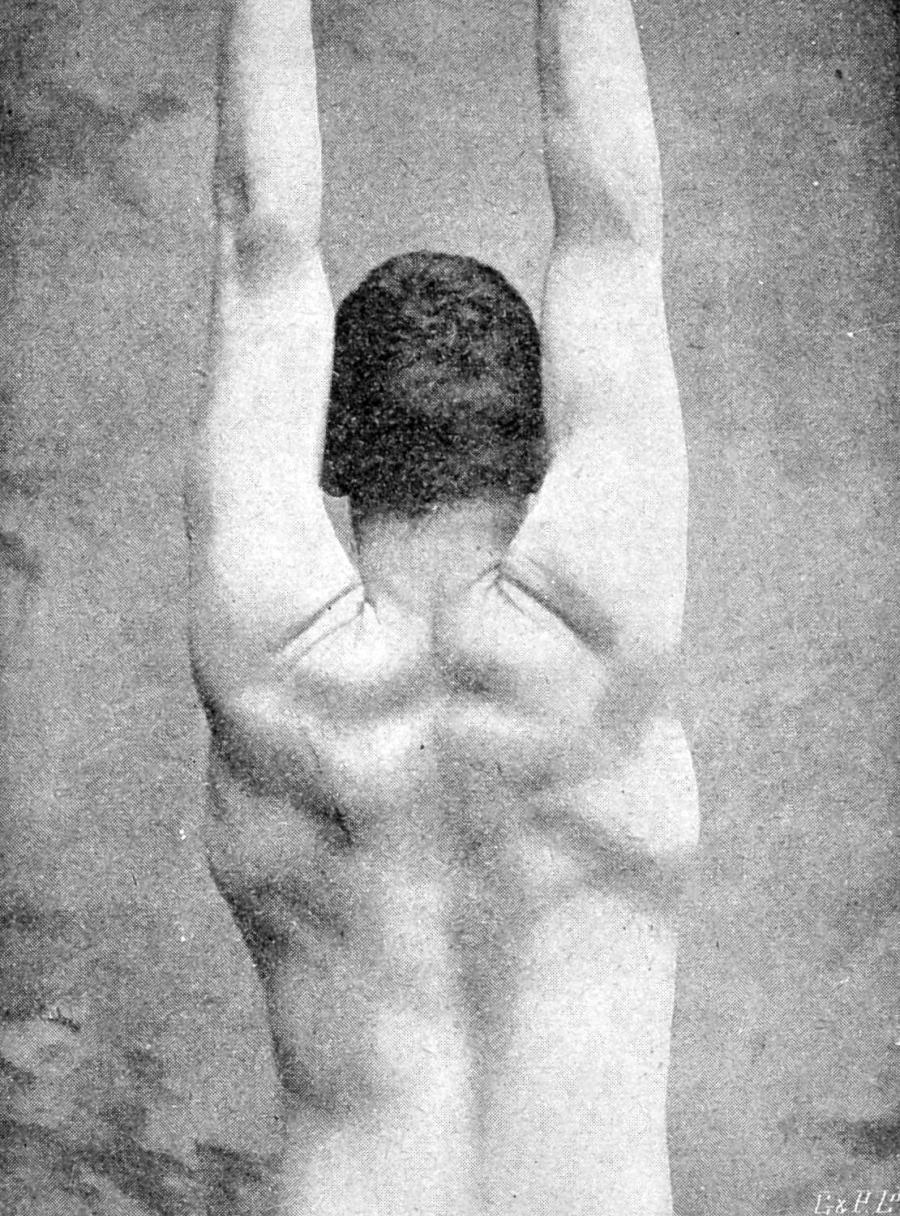

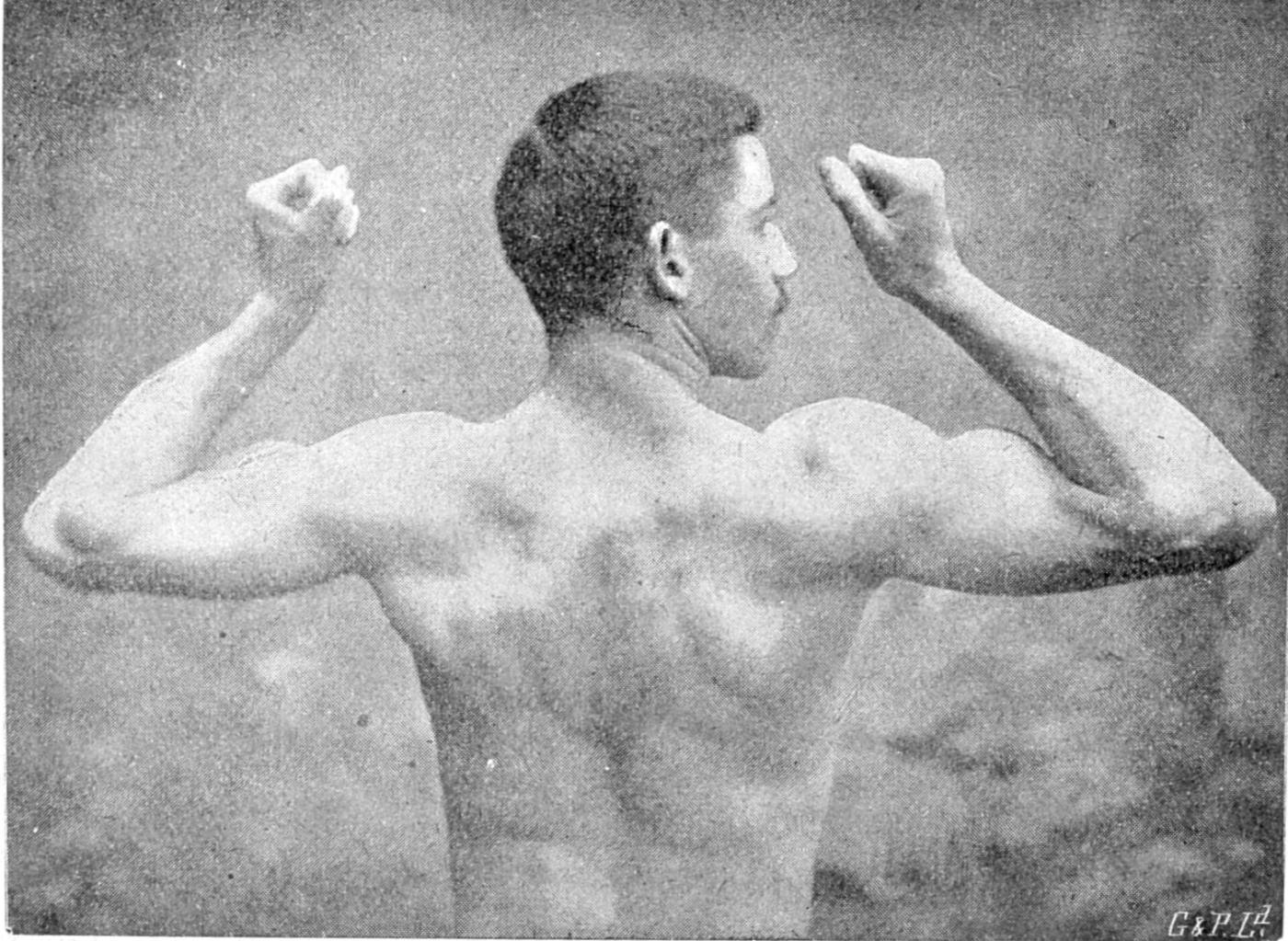

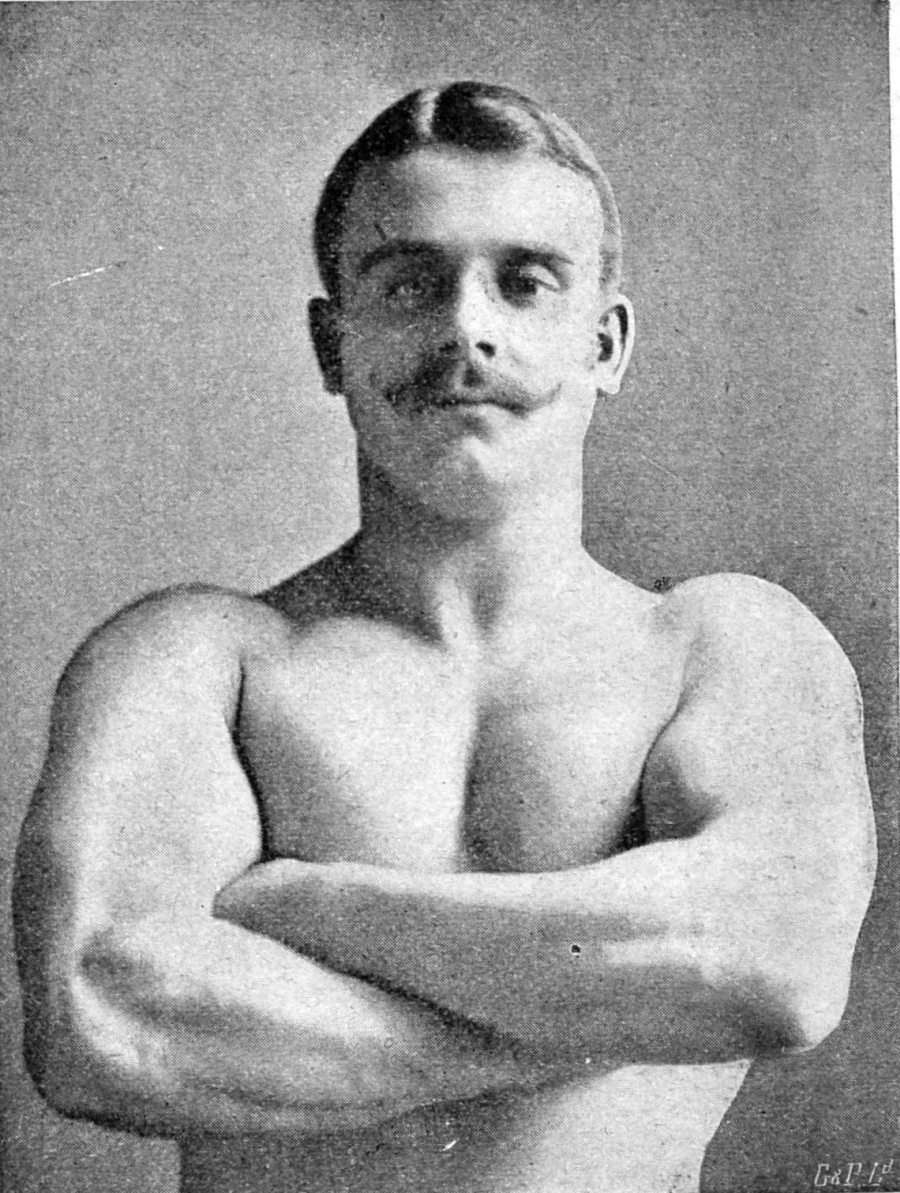

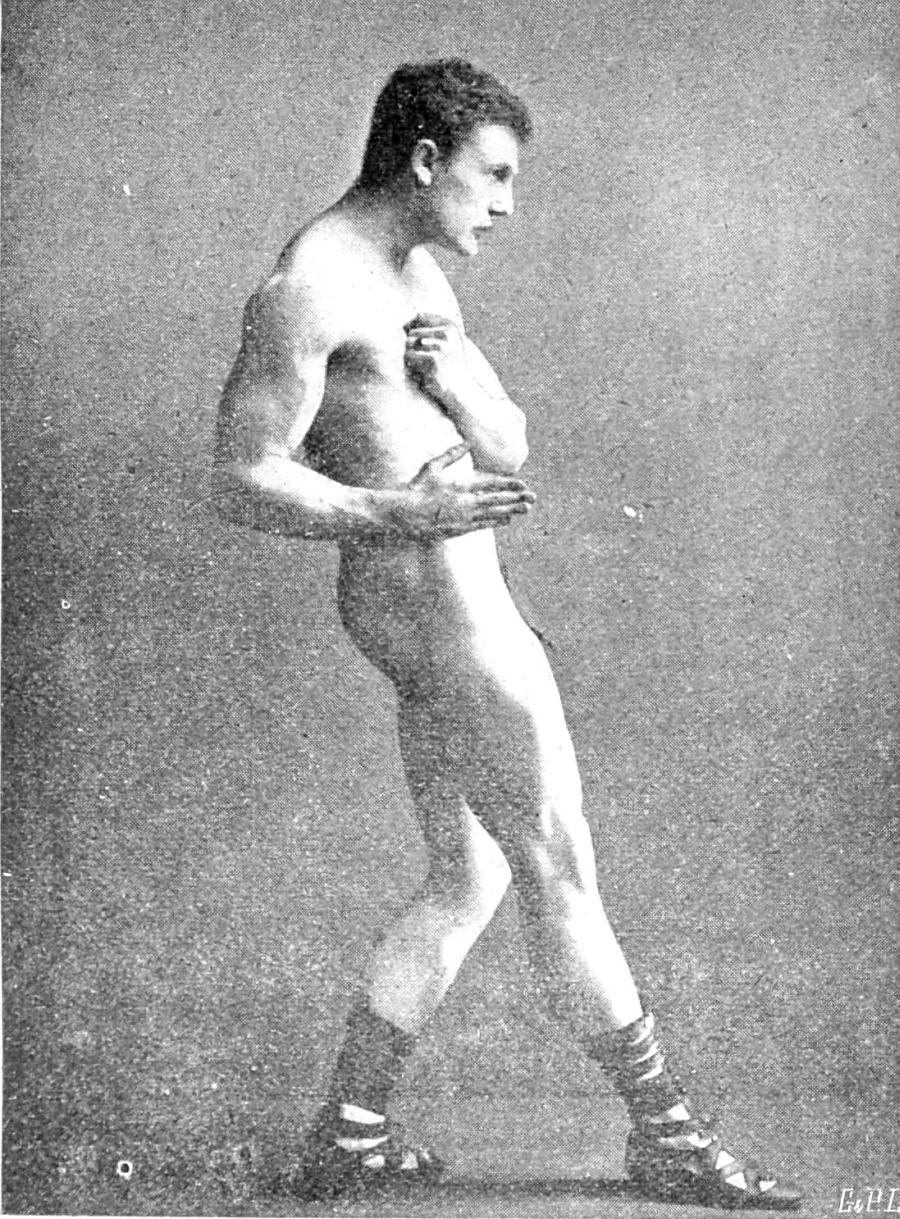

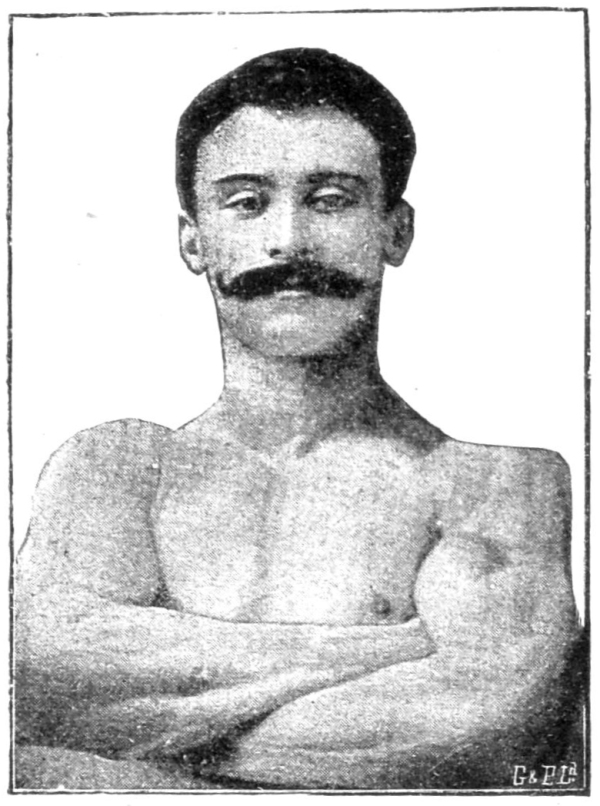

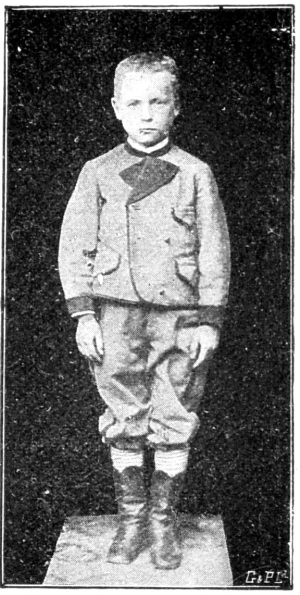

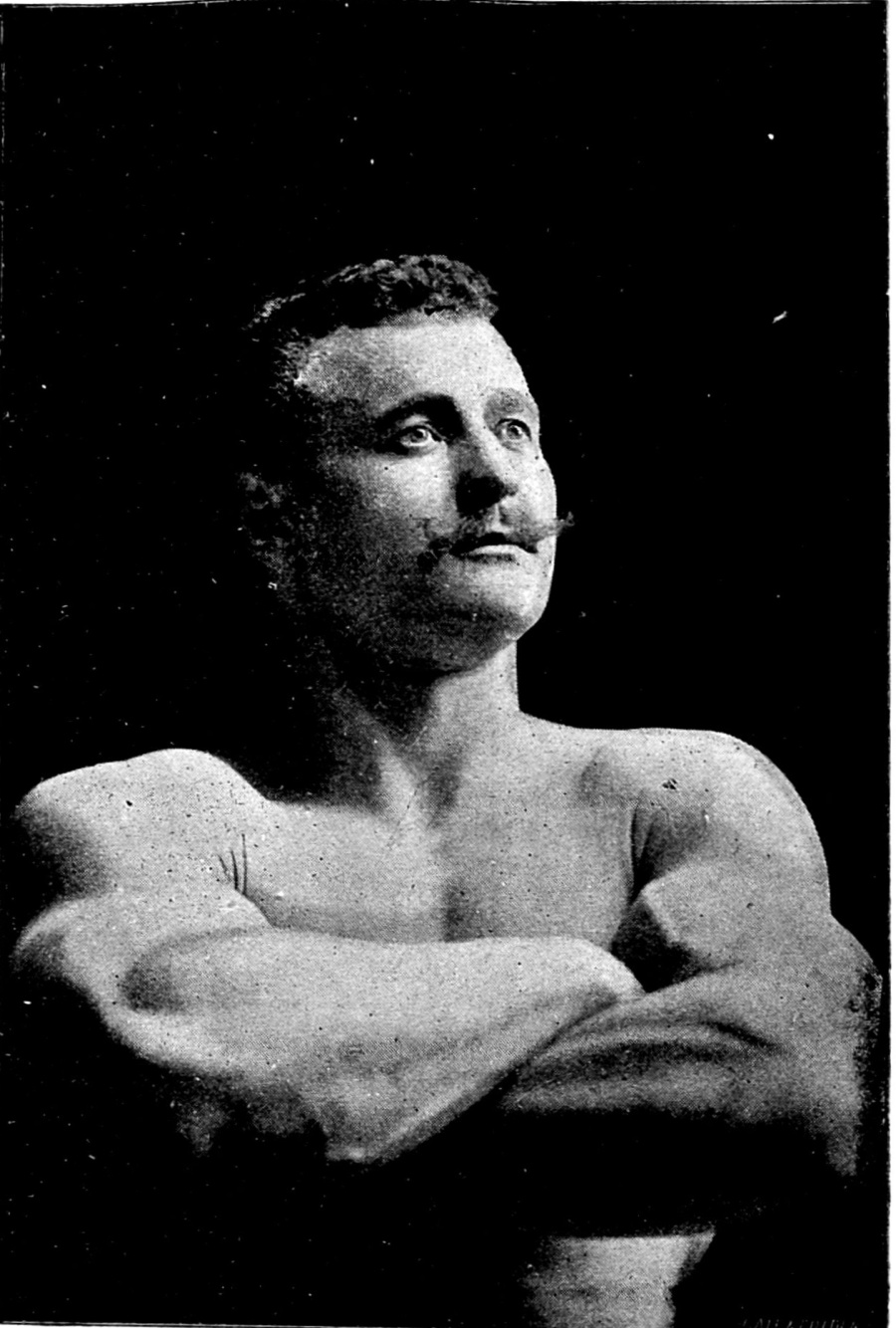

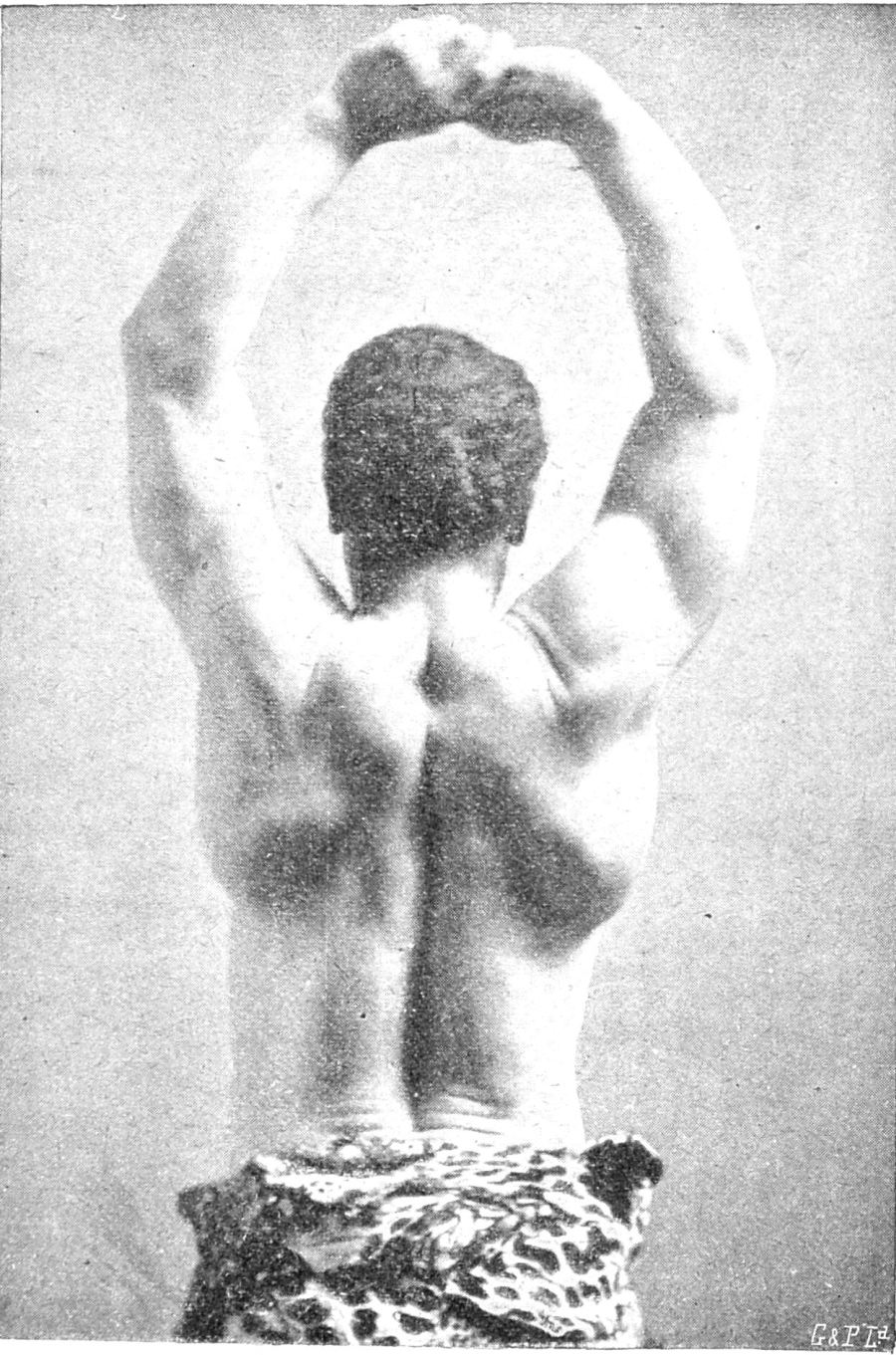

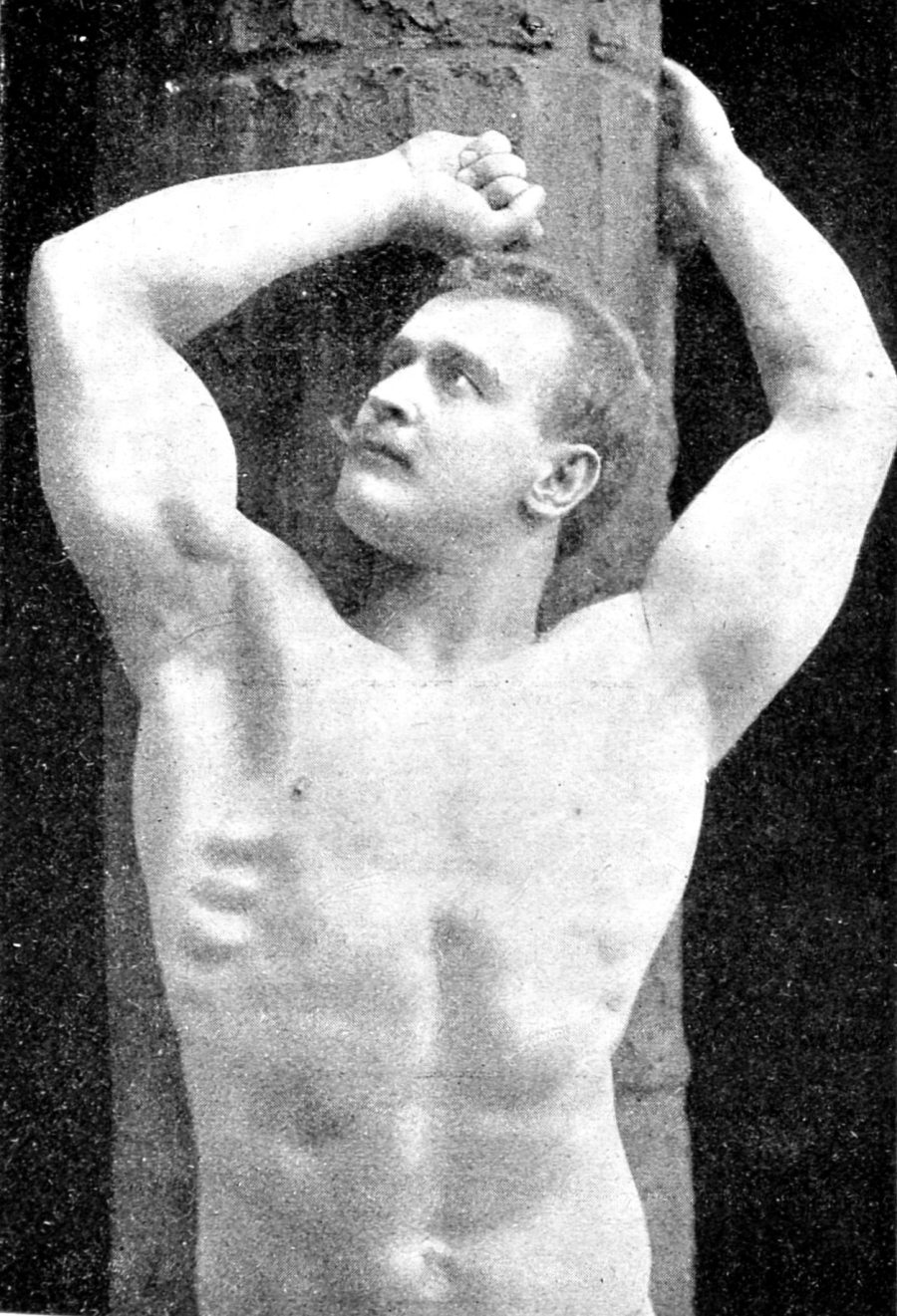

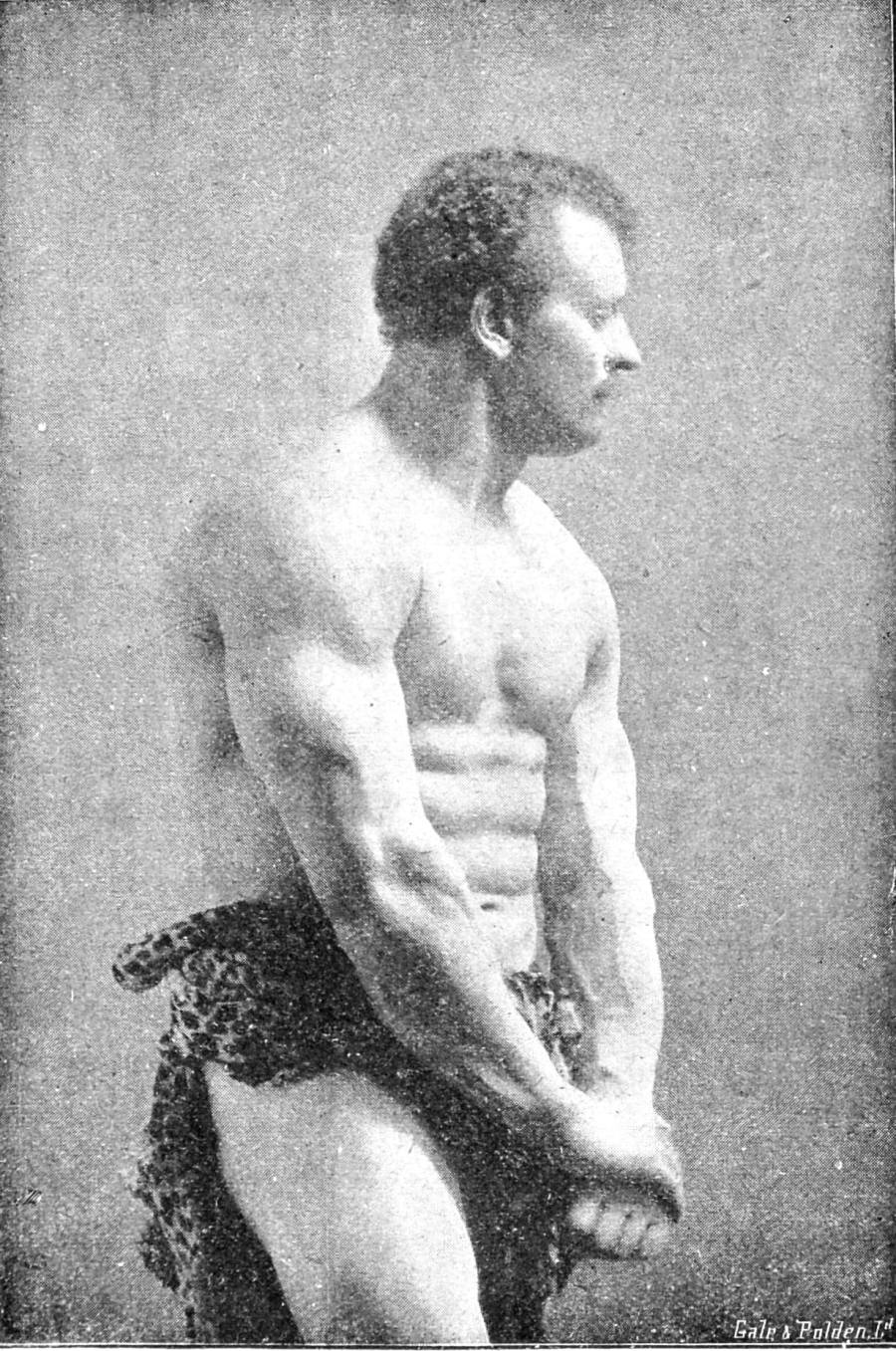

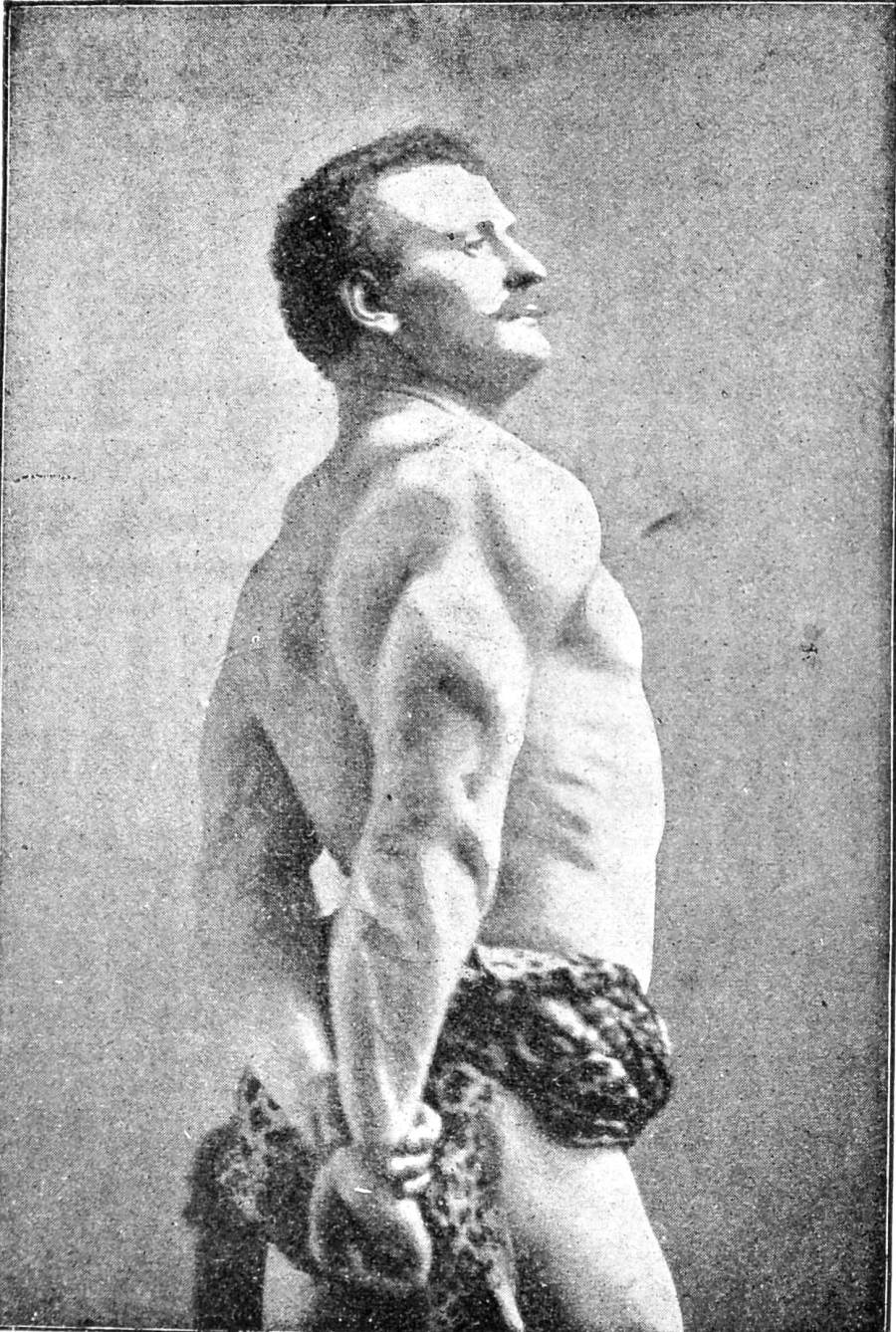

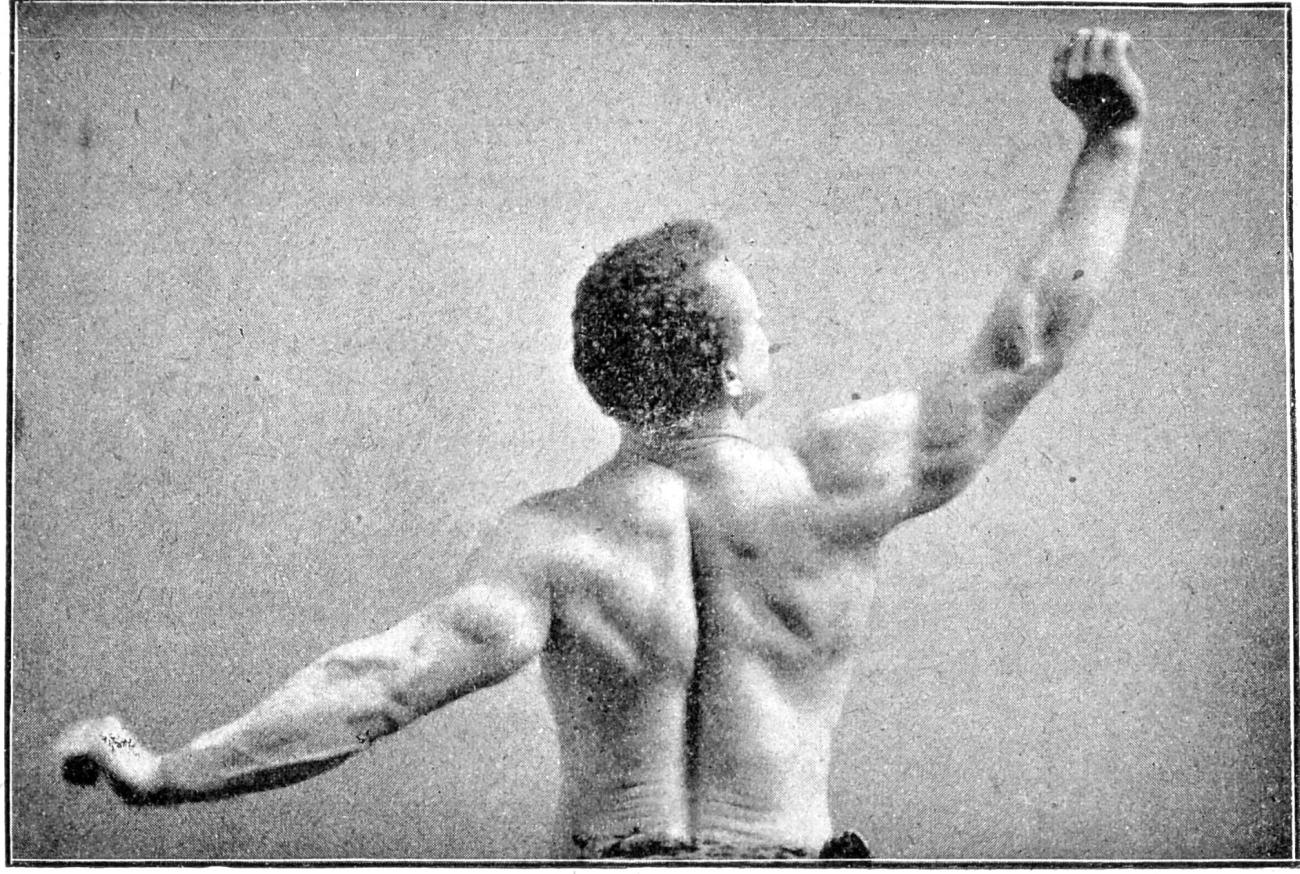

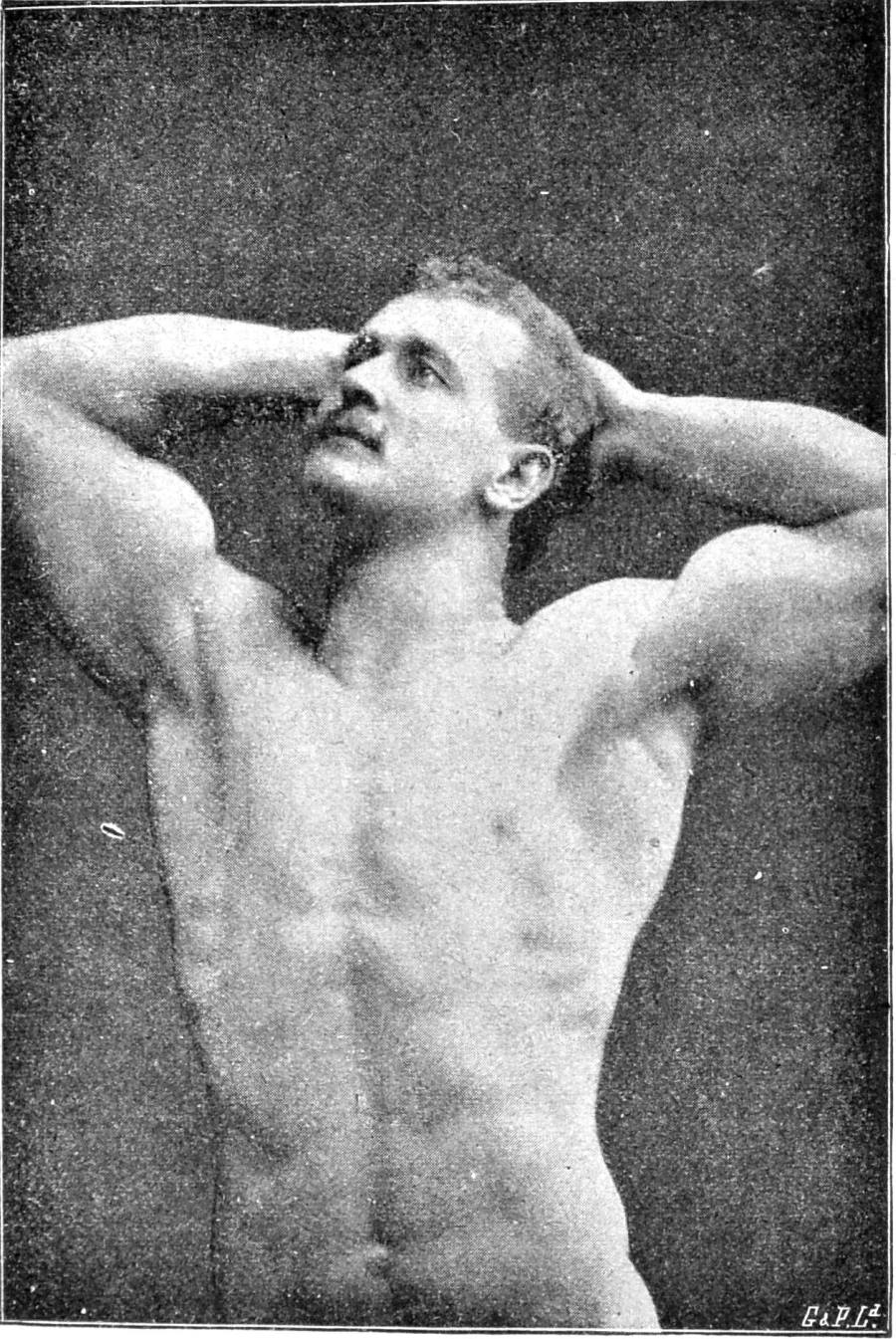

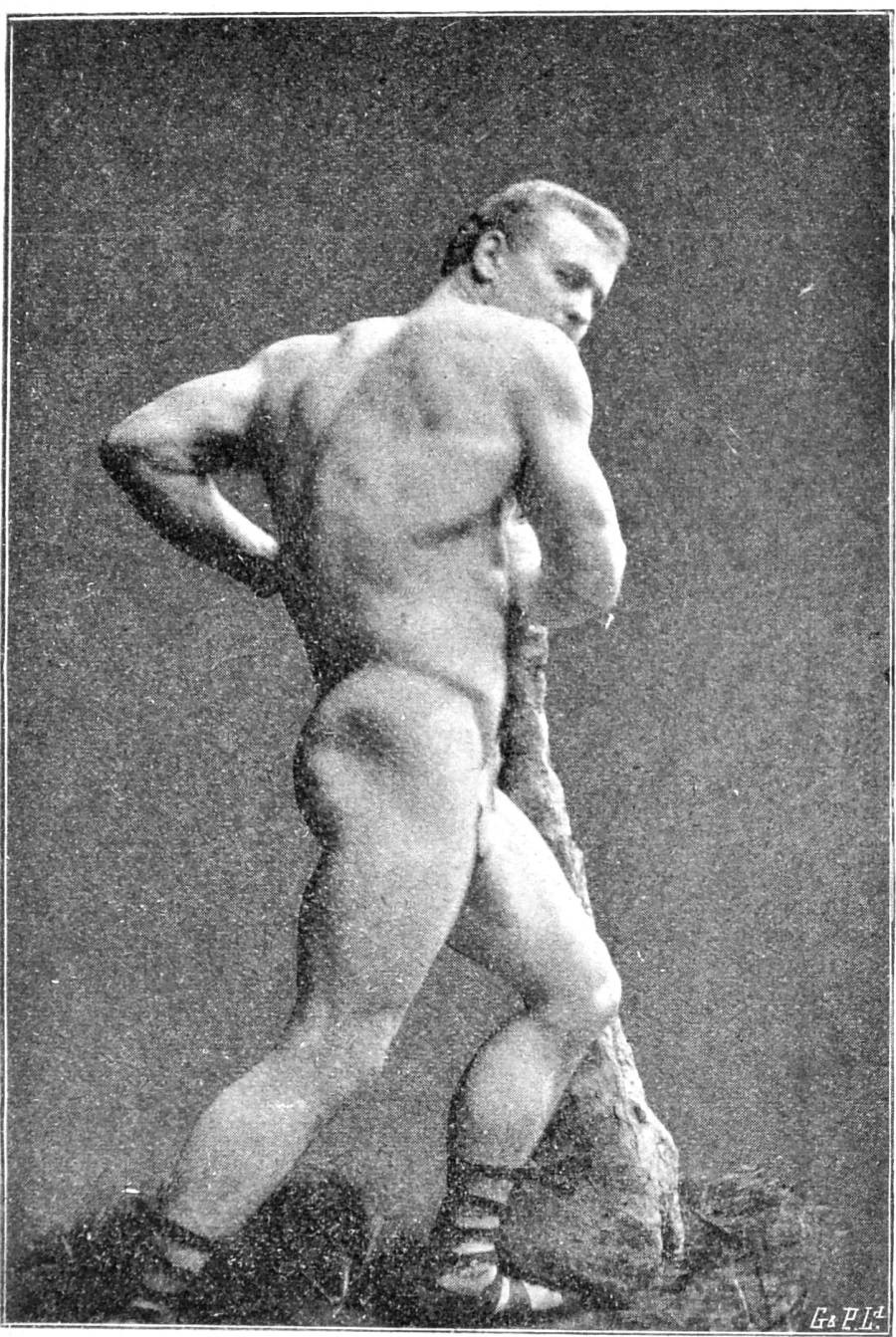

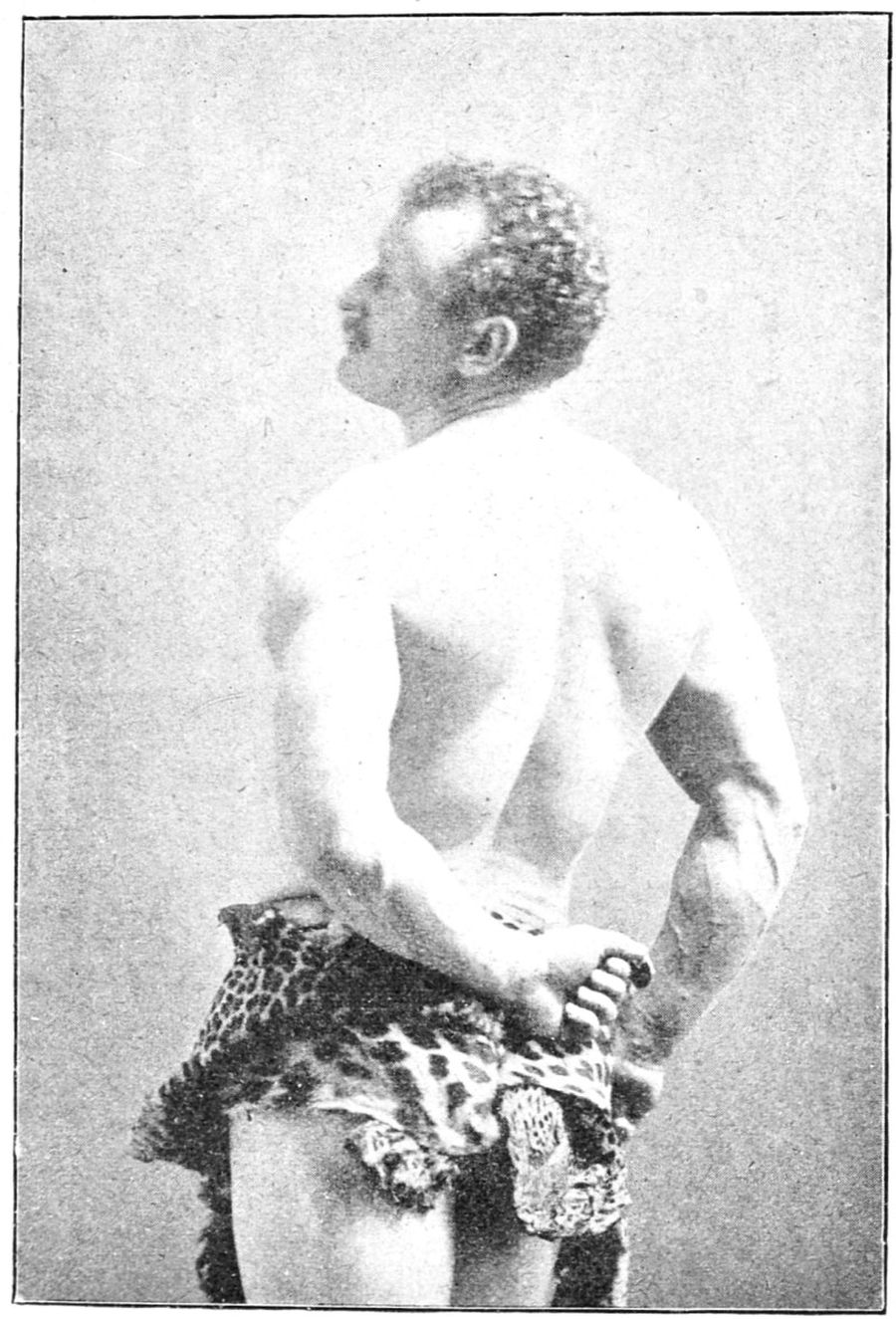

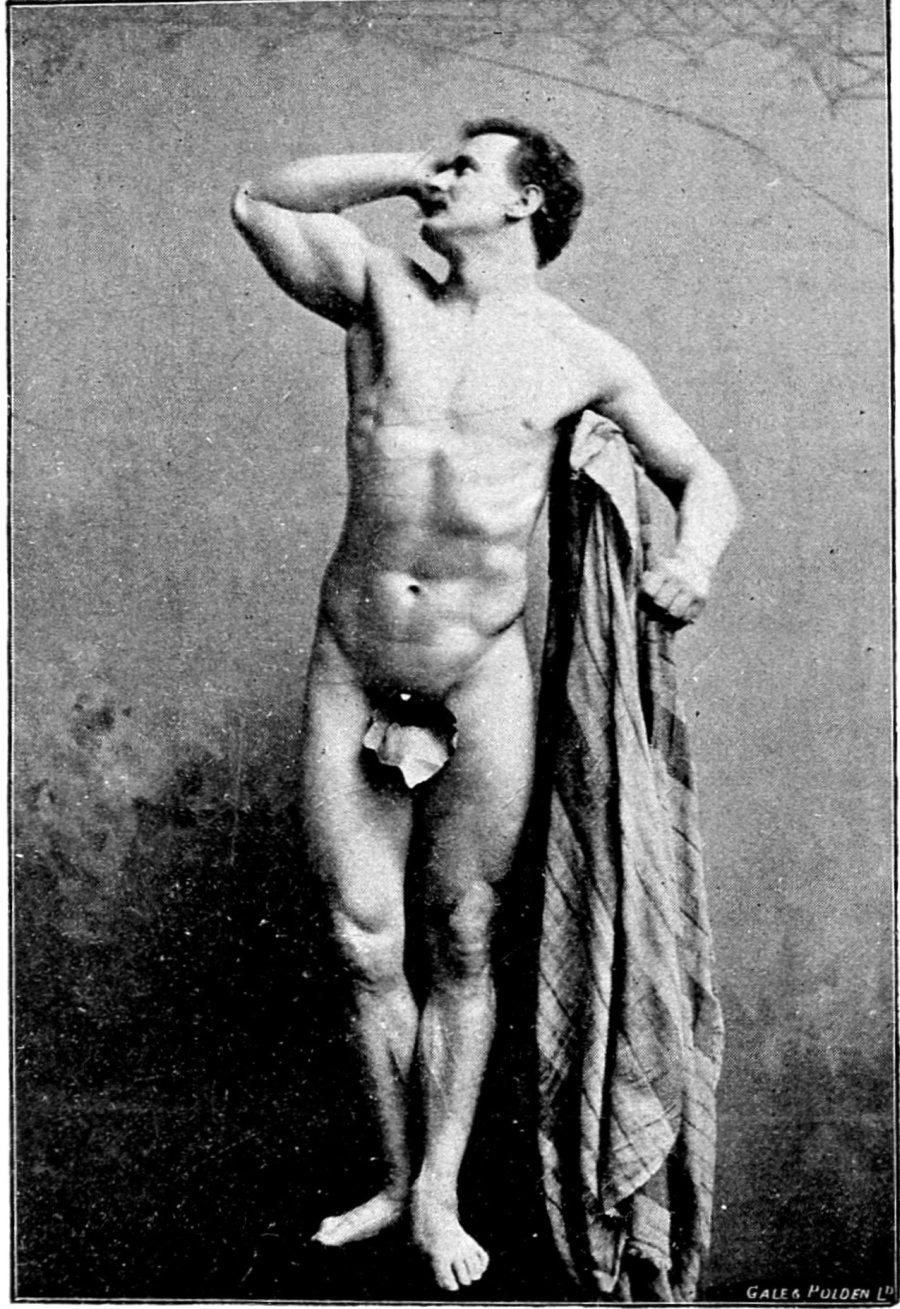

ILLUSTRATED WITH FULL PAGE PORTRAITS OF THE AUTHOR

AND SOME OF HIS PUPILS.

Reproduced from Photographs by Falk of New York, and

Warwick Brookes of Manchester.

London:

GALE & POLDEN, Ltd.,

2, AMEN CORNER, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C., AND WELLINGTON WORKS,

ALDERSHOT.

TWO-AND-SIX NETT.

Printed by Gale & Polden, Ltd.,

Wellington Works,

Aldershot.

Copyright—Gale & Polden, Ltd.

In writing this book I have taken it as a commonplace that everyone—man, woman, and child—wants to be strong. Without strength—and by strength I mean health, vitality, and a general sense of physical well-being—life is but a gloomy business. Wealth, talent, ambition, the love and affection of friends, the pleasure derived from doing good to those about one, all these things may afford some consolation for being deprived of life’s chief blessing, but they can never make up for it. “But,” I am constantly being asked, “it is all very well for you to say this, and everyone of sense agrees with you; the point is, can we obtain this much-prized blessing?” In the vast majority of cases I can say unhesitatingly “Yes.” You can all be strong, all enjoy the heritage which was intended for you. Not all to the same extent, perhaps. Those who are afflicted with some hereditary disease, who may have unsound organs handed down to them, cannot reasonably expect to get such results as their more fortunate brethren. Still, even they need not despair; even if their condition be such as to put out of the question any such thing as athletics, they can, at all events, attain to such a condition as will permit of their enjoying life, and render them fit to carry on their work without difficulty. And after all, those who wish to be strong for this reason are innumerable. It is only the young and vigorous who desire to excel in athletic pastimes, but the middle-aged and elderly, the delicate women and young children, who yearn for health are countless. I claim that by carefully following out my system, as set out in the following pages, and fully illustrated in the Anatomical Chart at the end of the volume, these results may be attained.

It is nearly two years since the first edition of “Strength and How to Obtain it” was published, and its success has been very gratifying to me. It plainly demonstrates that the people of my adopted country are gradually beginning to understand and appreciate what is meant by “physical culture,” and that my ideas are steadily taking root in productive ground. I am, therefore, encouraged to bring out a new edition of the book, which, I trust, will be an improvement upon its predecessor. Several chapters have been added and a few inaccuracies and ambiguities remedied, and I trust the book in its new form will find favour with my readers. I wish to draw particular attention to chapters V. and VIII., in which I refer to “My ‘Grip’ Dumb-bell” and to “Physical Culture for Women.” There are various other additions to which I need not refer here. Sufficient to say that during the past eighteen months I have learned much, and that so far as lies in my power I have endeavoured to give the benefit of such knowledge as I have acquired to all who believe with me that the cultivation of the body is a sacred and imperative duty.

EUGEN SANDOW.

STRENGTH

AND

HOW TO OBTAIN IT.

It is curious to me to look back a year or two and to reflect upon the change in public opinion upon this subject which has taken place in so short a time. When I first began to preach the “gospel of health and strength” the general tendency was to make fun of me. Some people called me a fool; others, a charlatan. Very few indeed took the trouble to see whether there was anything in my theories, and to test for themselves their truth or falsity. That was, so to speak, only yesterday; what an alteration, and an alteration for the better, is to be observed to-day. I shall not be accused of undue egotism if I say that my ideas have “caught on.” All over the country, among the young, “physical culture” is now the rage, and that it is no mere passing fancy is proved by the fact that those who are no longer in their first youth are its equally devoted, though possibly less feverish, disciples.

“And what is physical culture?” is naturally the question which arises to the lips of those to whom the subject is still unfamiliar. Let me begin by saying what it is not. To begin with, to suppose, as many people do suppose, that athletics and physical culture are the same thing is quite a mistaken notion. Then is physical culture opposed to athletics? Certainly not. Cricket and football and rowing and swimming, and,[Pg 4] indeed, all forms of manly sport and exercise, are admirable things in their way, but they are not physical culture. A part of it, if you like; but physical culture is something far wider in its scope, infinitely loftier in its ideals.

What was the ideal of the Greeks? They were ardent athletes, but their pastimes were only regarded as a means to an end. The Greeks regarded the culture of the body as a sacred duty; their aim was to bring it to the highest possible state of power and beauty, and we know how they succeeded. Surely what they succeeded in doing cannot be impossible for us.

Does the reader now begin to get a clearer idea of what is meant by physical culture? As I have previously said, it is to the body what culture, in the accepted sense of the word, is to the mind. To constantly and persistently cultivate the whole of the body so that at last it shall be capable of anything that sound organs and perfectly developed muscles can accomplish—that is physical culture. The production, in short, of an absolutely perfect body—that is physical culture. To undo the evil for which civilization, and all the drawbacks it has brought in its train, have been responsible in making man regard his body lightly—that is the aim of physical culture. I think I am justified in saying that while it embraces every variety of athletics it goes very much further.

Possibly there are people who will refuse to admit that this aim is in itself a desirable one. They may say that the sound body is only valuable in so far as it enables the sound mind to perform its work. This I regard as nonsensical cant. I absolutely and strenuously refuse to allow for an instant that the cultivation of the body is, per se, a comparatively valueless thing. On the contrary, I maintain that he who neglects his body—and not to cultivate it is to neglect it—is guilty of the worst sin; for he sins against Nature. I take my stand upon this then—that the care of the body is in itself an absolutely good thing, and its neglect is no more to be excused than is the neglect of the opportunities of mental[Pg 5] advancement which have been placed in a man’s way. I am quite aware that it takes a very long time to thoroughly free ourselves from the trammels of old-established prejudice. I am quite prepared to hear of some worthy folk gravely shaking their heads and deprecating any great amount of attention being paid to the body as likely to engender undue vanity and self-esteem. I do not think that is likely to be so, but even if it should be the case I do not hold it to be such a grievous matter. If a man has striven his utmost to make the best of himself a certain amount of pride in the fact may well be forgiven him. Or, at all events, we can look upon his failing with the eye of charity.

I do not think I can conclude this chapter better than by reprinting some remarks on the subject which I wrote in the first number of “Physical Culture,” my monthly magazine. The article was carefully thought out, and I do not think there is any need for me to add to it. “For after all, why should not a man feel some pride in a healthy and well-cared-for body? Though I contend that it in itself is emphatically a good thing, that is not to say the effects of physical culture are confined to the body. In bringing the body to its highest pitch of perfection, various moral qualities, the value of which it would be difficult to over-estimate, must necessarily be brought into play. The first essential to success is the power of concentrating the will upon the work. Muscles are not developed by muscular action alone. Physical exertion, however arduous and long continued, will not make a man strong, or the day labourer and the blacksmith would be the strongest of men. Mechanical and desultory exertion will never materially increase a man’s strength. He must first learn the great secret, which ought to be no secret at all. He must use his mind. He may not be able to add a cubit to his stature, but by taking thought a man can most assuredly increase the size of his muscles, strengthen all his organs, and add to his general vitality. But he must put his mind, as well as his muscles, into the work. And by exercise and practice the will-power is greatly increased,[Pg 6] until, in course of time, the whole organism is so absolutely under its control that the muscles can be kept in perfect condition even without what, in ordinary language, is called “exercise.” That is to say, that without violent exertion, but merely by the exertion of the will, the muscles can be exercised almost to any extent. Can it for a moment be supposed that this cultivation of the will-power is not of great value to an individual, no matter what sort of task or work he may be engaged in? Is it not largely by the exercise of will-power that most things are achieved? Take two men of equal talents; give them equal opportunities; but let one’s will-power and power of concentration be relatively much greater than his fellow’s. Then set them to perform the same task. Which will succeed best? No person endowed with ordinary intelligence can be in doubt for a moment. Will-power is a mighty factor—perhaps the mightiest—in all that goes to make up the sum of human success or failure. But the strengthening of will—though perhaps the chief—is not by a long way the only benefit which physical culture confers. The man who means to make his body as nearly perfect as possible must perforce cultivate habits of self-control and of temperance. Not the temperance which consists of rigidly abstaining from all the ‘pleasant vices,’ but the real temperance which teaches a man to say ‘No,’ which teaches him to indulge in all that is conducive to happiness without being in danger of that overstepping of the boundary line which leads to misery. The man who has cultivated his body has also cultivated self-respect. He has learned the virtue and the happiness of rigid personal cleanliness; his views of life are sane and wholesome. Respecting himself he learns to respect others. He is gentle, and only uses his powers against his fellowmen when called upon to do so in the defence of the oppressed and helpless. It is your weakling who is generally a bully and a tyrant. To take a few men who are exceptionally endowed by Nature, to make them extraordinarily strong, and to then train them to perform particular feats, is not a thing very difficult of[Pg 7] accomplishment. But that is not the aim of physical culture. Its ultimate object is to raise the average standard of the race as a whole. That is, no doubt, a stupendous task, and one which it may take many lifetimes to accomplish. But everything must have its beginning, and unless we set about improving the physique of the present generation, we cannot hope to benefit those who come after us. Healthier and more perfect men and women will beget children with better constitutions and more free from hereditary taint. They in their turn, if the principles and the duty of physical culture are early instilled into them, will grow up more perfect types of men and women than were their mothers and fathers. So the happy progression will go on, until, who knows, if in the days to come there will not be a race of mortals walking this earth of ours even surpassing those who, according to the old myth, were the offspring of the union of the sons of the gods with the daughters of men! That is, perhaps, an almost impossible ideal, but it is well to set one’s ideals high. Surely what has been done for the horse and the dog cannot be impossible of accomplishment in the case of man. At all events, it is worth trying.”

To wind up this chapter with a word of encouragement to those who come quite fresh to the subject; to those who in taking up Physical Culture are venturing into what is to them unexplored territory—“Read, think, and work. Do not be disheartened because your progress at first seems slow; nothing worth having is to be won without labour. I can only tell you what to do, only point out to you the right road. The rest lies with yourself. I should be the sorriest humbug if I endeavoured to make you believe otherwise, and you would be the simplest of fools if you did believe me. There is no royal road to success, and a very bad thing would it be if there were. For your reward lies not so much in the accomplishment as in the effort and struggle, and all the good qualities which they bring out.”

[Pg 8]

I have already remarked upon the satisfactory progress which the system has made during the last few years. It is probably well-known that my system has practically been adopted in the Army; although the method adopted in the Army gymnasia is not absolutely identical with that which I advocate, it is obviously based upon the same principles. People may be interested to hear that since I opened my first school, some eighteen months ago, amongst my pupils have been a great number of gentlemen, who, desirous of adopting the Army as a career, have been unable to do so through not coming up to the physical standpoint required. In many cases they have actually been rejected on this account; in others they have been fearful that such might be their fate, and have come to me in order to avoid it. Some have not been heavy enough for their height; others lacking in chest measurement, and so on. Now let my system be judged by the results. In not a single instance have I failed to do what is necessary. That may stand by itself without any further comment from me. However, as a further proof of the efficacy of the system, I may say that I have put an inch on the height of a young fellow in three weeks! This may sound incredible, but it is an absolute fact. The majority of these gentlemen, whom I have helped to pass the Army “medical,” have written me appreciative letters, and though for obvious reasons I cannot publish them, I shall be happy to show them to any reader who may care to call at the St. James’-street[Pg 9] school. That the value of the system is fully recognised in the Army is demonstrated by the letter from Colonel Fox, late inspector of the Army Gymnasia, which appears in this book. Amongst the civilian public the system is spreading rapidly; private individuals are taking it up and working steadily in their own homes, whilst in a great number of gymnasia throughout the country, classes are being formed to carry it out. In connection with this, it is highly diverting to notice that various individuals who are never tired of denouncing me and all my works, have set up as “professors” of physical culture, and are actually teaching my system! Of course they would be loth to admit this, and would assert that it is a system of their own. All I can say is that by a strange coincidence nearly every one of these systems which I have examined is based upon the same principles as my own. Now that I have made mention of those who try to gain notoriety by attacking my system, I cannot refrain from commenting upon certain statements which, having been widely circulated, may tend to do the system injury. The subject is, I think, worthy of a short chapter to itself.

[Pg 10]

The statement to which I refer is this—that though by my system a man may increase the size of his muscles, add to his bodily strength, and improve his physique, he does so at the expense of his vital organs. This statement has been freely bandied about by those who ought to be above such petty and stupid malice; men, who, professing to teach physical culture, are mostly quite ignorant of the very rudiments of the subject. Their reasons for such utterances are not far to seek; they are envious of the success which has attended the years of hard work and endeavour I have gone through, and regard me as a rival to damage whom everything is justifiable. One or two have even gone so far as to say that I myself am anything but sound, that my heart is in a very bad condition, and that there is every probability of my “going over to the majority” at a very early age.

Let me nail these outrageous lies to the counter once and for all. Some who repeat them doubtless do so in good faith; let them listen and amend their ways. For those who circulated them, well knowing them to be false, I have no words in which to express my contempt. Fair and square opposition I can face; but a lie, however groundless, once sent on its journey is difficult to overtake.

Now for my refutation. First, amongst my pupils have been many who, prior to coming to me, had been rejected as unsound by Life Insurance Companies; well, they have got their policies safely locked up now. Some[Pg 11] had weak hearts, some poor lungs, others were generally unfit. They came to me, generally, for two or three months, applied again, and were accepted. Those who doubt my word can, as in the case of the Army lads, see the proofs for themselves. Is that good enough, or does “our friend, the enemy,” require any further demonstration that, far from injuring the vital organs, in many cases my system is enormously beneficial to those who are delicate. If so, here it is. They say I am unsound; very well, here is an answer for them.

Some months ago I was insured for a large sum in the Norwich Union Life Insurance Company; I was accepted in the highest class, and the doctor who saw me expressed great surprise at the soundness of my heart, the strength of my lungs, and in fact at the fine condition of all my organs. Surely these envious people show little ingenuity in inventing falsehoods which can be so easily disproved.

[Pg 12]

In commencing the system of exercises described and illustrated by the anatomical chart, there are certain questions which every student naturally asks himself.

Probably the very first of these questions is, “What part of the day ought I to devote to these exercises?”

The answer to this question must depend on the pupil himself—on his leisure and on his inclination. Some persons find the early morning the best and most convenient time; others prefer the afternoon; and a third class, again, find that they feel best, and have the most leisure, at night. I do not, therefore, lay down a hard and fast rule of time. The golden rule is to select such part of the day as suits you best, always avoiding exercise immediately after meals. If possible, let two hours elapse between a meal and exercise. Moreover, do not exercise just before going to bed if you find it has a tendency to keep you awake. Many of my pupils find that they sleep much better after exercise; but there are some upon whom it has a reverse effect.

If possible, the pupil should always exercise stripped to the waist; if he wear a singlet it should be cut well away round the arms, so as to allow of free play for the muscles around the shoulder. It is also desirable to exercise before a looking-glass, for then the movements of the various muscles can be followed, and to see the muscles at work, and to mark their steady development, is itself a help and a pleasure.

In performing the exercises the pupil should bend the knees slightly and keep the muscles of the thighs tense; the legs will thus share in the benefit of all the movements.

[Pg 13]

What I wish to impress on delicate pupils is the desirability of progress by degrees. Many men before beginning my system of physical training have been so weak that doctors have thought little of the prospect of saving their lives, yet to-day they are amongst the strongest. They have progressed gradually, always being careful not to undertake too much, and thus to adapt the exercises to their own individual requirements. It may be mentioned also that the old, as well as the young, may derive great benefits from my system, though all who are over the age of fifty should moderate the exercises on the lines suggested in the table of ages for pupils between fifteen and seventeen. My exercises will also be found of considerable benefit to persons who suffer from obesity.

Pupils must not be discouraged because, after the first few days’ training, they may feel stiff. It sometimes happens that a young man or woman, or perhaps a middle-aged one, sets out on the course of training with the greatest enthusiasm. After the first two or three days the enthusiasm, perhaps, wears off. Then comes a period of stiffness, and the pupil is inclined to think that he cannot be bothered to proceed with the course. To such pupils, I would say, in all earnestness, “Don’t be overcome by apparent difficulties; if you wish to succeed, go forward; never draw back.” This stiffness, moreover, becomes a very pleasant feeling. You soon grow to like it; personally, indeed, it may be said that it is one of the most agreeable sensations I have ever had.

Frequently pupils ask me how long it should take them to get strong. The answer again depends on themselves, not only on their physical constitution, but also on the amount of will power they put into their exercises. As I have said already, it is the brain that developers the muscles. Brain will do as much as dumb-bells, even more. For example, when you are sitting down reading, practise contracting your muscles. Do this every time you are sitting down leisurely, and by contracting them harder and harder each time, you will[Pg 14] find that it will have the same effect as the use of dumb-bells or any more vigorous form of exercise.

It is very advisable for all pupils to get into the habit of constantly practising this muscle-contraction. In itself it is an admirable exercise, but it is perhaps even more valuable owing to the fact that it improves the will power and helps to establish that connection between the brain and the muscles which is the basis of strength and “condition.”

It will be noticed that throughout my exercises I make a point of alternate movements. By this means one arm, or, as the case may be, one set of muscles, is given a momentary rest whilst the other is in motion, and thus freer circulation is gained than by performing the movements simultaneously and the strain upon the heart and lungs relieved.

Another question which pupils are constantly asking me is whether it is right for them to perspire after the exercises. The answer to this question is that it depends on the constitution of the pupil. If you perspire, it does you good; if you do not it shows that your condition is sound already. Of course it will be understood that I am answering in this, as in other questions, for general cases. There are always exceptions.

Again, “What,” it is asked, “are the general benefits of the Sandow system of physical training?”

The benefits are not, of course, confined to the visible muscular development. The inner organs of the body also share them. The liver and kidneys are kept in good order, the heart and nerves are strengthened, the brain and energy are braced up. The body, in fact, like a child, wants to be educated, and only through a series of exercises can this education be given. By its aid the whole body is developed and, as will be seen, pupils who have conscientiously worked at my system testify freely to the good results obtained, not only in the direction of vastly increasing their muscular strength, but of raising the standard of their vitality and general health.

[Pg 15]

For the beginner the most difficult part of my system is so fully to concentrate his mind on his muscles as to get them absolutely under control. It will be found, however, that this control comes by degrees. The brain sends a message to the muscles; the nerves receive it, and pass it on to them. With regard to the will power that is exerted it should be remembered that whilst the effect of weight lifting is to contract the muscles, the same effect is produced by merely contracting the muscles without lifting the weight.

This question of “will power” has, I am aware, troubled a good many of my pupils. The majority find it difficult to “put all they know” into movements with small dumb-bells, and consequently are apt to be disappointed at the results of their work. Not infrequently I have received a letter stating that the writer is doing the exercises an immense number of times, occupying several hours a day—three or four or even more!—and yet does not find that there is very much improvement. The reason is obvious; he is simply “going through” the motions and not really working at them. On the other hand, here and there, I come across a man possessing an amount of will power out of all proportion to his strength. The consequence is that he soon gets exhausted, and either cannot get through his exercises or only does so at the cost of becoming thoroughly done up and jaded. The great rule that progress in the direction of the exertion of will power should be gradual and ever continuing, is one that many people confess they are unable to carry out.

Now I have for long been perplexed to find a means of remedying this, and at last I think I have discovered a method whereby the amount of will-power exerted by the pupil can be regulated. In the next chapter particulars are given of my new “Grip” Dumb-bell, which I think ought to prove a veritable godsend to all, and especially to those to whom reference has just been made.

[Pg 16]

This appliance is very simple and may be described in a few words. It consists of a dumb-bell made in two halves separated about an inch and a half from one another, the intervening space being occupied by a small steel spring. When exercising, the spring is compressed by gripping the bells and bringing the two halves close together, in which position they are kept until the exercise is over. The springs can be of any strength, and consequently the power necessary to keep the two halves together can be varied to any extent.

The advantages of this arrangement are obvious. Whether he will or no, the pupil must grip the bells hard, and as the strength of the springs are known he can regulate his progress to a nicety as he grows stronger. There is also another point in connection with the new device to which I want to draw particular attention. It will often happen that a pupil who is exercising will feel “a bit off-colour” one day, and consequently less inclined to exercise, or he may be worried and perplexed by his business affairs to a degree which lenders it almost impossible for him to concentrate his mind solely upon the work. The natural consequence of either of these two conditions is that unless he possess very uncommon will power, if he is exercising with ordinary bells, he only does so in a desultory and half-hearted manner, and benefits little thereby. Now this is impossible with the “grip” bell—however preoccupied and worried the pupil may be he has a definite point upon which to concentrate his mind; he must[Pg 17] exert a certain amount of force in gripping the bells to keep the two halves together, and consequently must put out a certain amount of will-power.

Of course there is no reason why in using the “grip” dumb-bells, only the grip necessary to keep the two halves together should be exerted. On the contrary, as with ordinary bells, a man may, and should put “all he knows” into the work; the special point and the great merit about the former is that with them the amount of power exerted can never fall below a known and easily regulated minimum.

The pupil who possesses these bells will find that instead of having to be continually buying heavier dumb-bells, one pair will suffice him for all time. All that it will be necessary for him to do will be to purchase, at a small expense, new springs from time to time. All pupils are advised to use the dumb-bell, upon the merits of which I need not further enlarge. As will have been seen, this is not a mechanical device which will render unnecessary the employment of will-power; that would be opposed to all my theories and teaching. On the contrary it will aid in developing will-power, as it will stimulate the pupil to put it forth, and guide him how to use it in the proper direction.

[Pg 18]

I am sometimes accused of being a bit of a faddist about the use of the cold bath, and possibly the heading of this chapter may give strength to that opinion. But its exhilarating and health-giving effects really justify the use of the adjective. The longer I live, and the greater my experience, the more am I convinced of its virtues. Let me advise every pupil after exercising, while the body is still hot, to take a cold bath. It does not matter how much he may be perspiring; the cold bath will prove exceedingly beneficial. He must be careful, however, not to take his bath if he is out of breath. The exercises will, no doubt, quicken the heart’s action; but in from three to five minutes after the series is completed, the heart should be beating normally again. For persons who suffer from weak heart I should not advise a cold bath. As a general rule there is no need to ask the question, “Is my heart weak?” For if it is weak you should know it beyond a doubt. After every little exertion, though the assertion may appear paradoxical, you will feel it beating in your head.

In advising cold baths, I speak, of course, for persons in the enjoyment of ordinary health. The bath should be begun in the summer and continued every morning throughout the year. In the winter, if the room is cold, light the gas and close the window. If your hair is not injuriously affected by cold water—and in many cases, I believe, cold water will be found to strengthen it—begin, as you stand over the bath, by splashing the[Pg 19] water five and twenty times over your head. In any case, if you are averse to wetting the hair, be careful to begin by sponging the temples and nape of the neck. Next, whilst still standing over the bath, splash the water fifteen times against the chest and ten times against the heart. Then jump into the bath, going right down under the water. In the summer you may remain in the water from ten to fifteen seconds, but in the winter let it be just a jump in and out again.

The subsequent rub down with towels is popularly supposed to produce half the benefits that result from a cold bath. I have no hesitation in saying that this is a great mistake. Let me explain the reason: As you get out of the bath you rub down first one part of the body and then the other, and thus, whilst the one part is being warmed by the friction, the other is getting cold. Many people who take cold baths in this way complain of touches of rheumatism, and the whole trouble arises, I believe, from different parts of the body being alternately warmed and chilled.

In order to overcome the risk of this ill-effect my advice is this: Do not spend any time over rubbing yourself down. If you do not like the idea of getting into your clothes wet, just take the water off the body as quickly as you possibly can with a dry towel, jump into your clothes, and let Nature restore your circulation in her own way. You will get quite as warm by this method as by vigorously rubbing down, with the added advantage that the heat of the body will be more evenly distributed. If, owing to poor health or other exceptional causes, the circulation is not fully and promptly restored, walk briskly up and down the room. If you should still feel cold in any part of the body probably the bath is not suited to your constitution, and in that case it is not advised. In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, however, the cold bath, taken as I have described, will have nothing but the most beneficial effects; and, if taken every morning throughout the year, it is the surest preventive that I know against catching cold. On the other hand, irregularity is liable[Pg 20] to produce cold. In short, having once begun the cold bath, make a rule, summer and winter, never to leave it off.

Personally, I find the very best form of the cold bath is to get into your clothes after it without drying the body at all. For the first moment or two the sensation may not be perfectly agreeable, but afterwards you feel better and warmer for adopting this method. The damp is carried away through the clothes and no particle of wet is left.

For pupils who have not the convenience of a bathroom a cold sponging down may be recommended as a substitute. In this case let two towels be taken and soaked with water. Rub the front of the body down with one, and the back with the other. This method prevents the towel from absorbing the heat from the body, and the cold sponging is thus distributed evenly over its surface. Afterwards dry the body quickly as before, letting no time be lost in getting into your clothes.

I have often been asked whether in the event of exercising at night it is advisable to take a cold bath afterwards. My reply is:—“certainly.” Always have a cold bath or sponge down after exercising. It will make you feel “as fresh as paint,” improve your appetite, and make the skin clean and firm, and be generally conducive to happiness and good health. Some people tell me that a cold bath immediately before retiring keeps them awake; if that be so, I should advise them to exercise earlier in the day. But the exercise and the cold bath ought to be regarded as inseparable.

[Pg 21]

It is scarcely necessary for me to say that the benefits to be obtained by conscientiously working upon my system are by no means confined to the young and vigorous. On the contrary, it is particularly suitable for the middle-aged, who are all too apt to suffer from the effects of the period of physical indolence which has succeeded their youthful activity. To such, the system should prove invaluable. It is quite a false notion to suppose that when once youth is passed exercise is no longer necessary. So long as life lasts, if an individual wants to keep healthy, exercise is just as necessary as food. It is through neglecting to recognise this that so many men become aged before their time. When a man begins to get into middle life he has a natural tendency to “take things easy.” He lives more luxuriously, devotes more time to the pleasures, of the table, and exerts himself as little as possible. Is it anything to wonder at that his health suffers, that he grows fat and flabby, and that his digestive apparatus quickly gets out of gear? If in his youth he has been an athlete the more will his changed mode of life tell upon him; it is indeed better never to have exercised at all than to exercise for a few years and then drop it entirely. It is for this reason we hear of the health of so many athletes failing them at a comparatively early age. And this failure is, as a rule, erroneously ascribed to the effects upon their constitution of their early efforts. Once and again errors in “training” may be responsible for poor health in middle-age, but in ninety-nine cases out of a[Pg 22] hundred the complete cessation from active bodily work, combined with the greater indulgence which naturally follows, is alone responsible.

Of course, while it is advisable that the middle-aged man should exercise regularly, I must warn him not to do too much. He must remember that what is perfectly safe and prudent at five-and-twenty may be rash and hazardous at fifty; in short, that he, while exercising consistently and steadily, must be careful not to over-tax his powers. If he bears this in mind he will find that the discomforts and ailments which he has perhaps got to regard as natural to his time of life are quickly banished, and that, in spite of his grey beard and thinning hair, it is still “good to be alive.”

[Pg 23]

I am exceedingly anxious to remove the impression, which has, I fear, gained ground, that my system is not a thing for women. Now-a-days, when women have practically freed themselves from the antiquated ideas of a generation or so ago, there ought to be small difficulty in convincing them that to make the best of themselves, in a physical sense, is just as imperative a duty for them as for their brothers. Women go in for all sorts of sports and pastimes to-day; they bicycle, row, play tennis and hockey, and not infrequently display no small degree of excellence in sports which have hitherto been regarded as “for men only.” This is a hopeful sign, but I am not at all sure that in many cases it is not more provocative of harm than good. Women are possessed of a great amount of nervous energy, and, unless their bodies and organs are gradually and systematically trained to bear exertion and fatigue, they are likely to attempt performances which are quite beyond their physical power, although, buoyed up as they are by a fund of nervous energy and mental exhilaration, they may observe no ill-effects at the time. This is one reason why it is so advisable for women to commence by working upon my system, which is so mild and gradual that they can pursue it without any risks, and, while daily growing stronger and healthier, be scarcely conscious that they are making any effort whatever.

I am quite aware that there is a very wide-spread notion that exercise tends to coarsen and render a woman unbeautiful, but that is absolutely false. Were[Pg 24] there any truth in it I should indeed despair of converting my fair readers to my way of thinking, for truly it is woman’s mission to look beautiful. But the idea is absurd; Nature, which intended woman to look lovely, also intended her to be healthy; indeed, the two are practically synonymous. Of course, improper, violent and one-sided exercise will naturally result in making a woman clumsy, heavy, and ungraceful, but proper exercise, having for its object symmetrical and perfect development, will have an exactly contrary effect. Curiously enough, the visible effect of proper exercise upon a woman’s muscles is not precisely the same as upon those of a man. Regular and gradually progressive exercise will not make a woman’s muscles prominent, but will cause them to grow firm and round and impart to the outline of the figure those graceful contours which are so universally admired. Without well-conditioned muscle the most beautifully proportioned woman in the world will look comparatively shapeless and flabby; her muscles are not required to show up as in the case of a man’s, but they must be there all the same as a solid foundation for the overlying flesh. Take a woman’s arm, for instance; if it has been duly exercised and developed, it is easy enough to see that its shapeliness and good modelling are due to the muscles; white and soft though the skin may be, you can tell at a glance that it is firm and elastic to the touch. On the other hand, the arm of the woman who has never exercised the muscles, betrays the fact unmistakably; it may be plump and round, but its lines are lacking in beauty, its movements in grace; and so with the figure generally.

The effects of my system are very rapidly noticeable. It reduces the size of the waist, makes the limbs round, the figure pliant, the walk and carriage graceful and easy. For those women who are doomed to a more or less sedentary life it works wonders, and those whose means and occupation permit of their indulging in a healthier outdoor life will find it a splendid preparation for their favourite pastimes.

[Pg 25]

Just a word with regard to complexion. A fine skin and a good healthy colour are the best proofs of the possession of good health. Indeed, without health a good skin and complexion are out of the question; and where is the woman who does not desire to possess both? She is indeed rare. Therefore, to those women who, while they do not set a high enough value upon health and strength for their own sakes, yet desire to be fair to look upon, I say the two things must inevitably go hand in hand. Whether your prime object be to obtain beauty or health does not matter; by working upon my system you will obtain both.

[Pg 26]

From the following tables pupils of all ages will be able to see at a glance how many times the movements of each exercise illustrated by the anatomical chart should be practised daily.

It should be clearly understood that the tables are only intended as a guide, and that they are not intended to arbitrarily fix the amount of work which the pupil should do. It is an absolute impossibility to lay down rules which will suit every individual case, and consequently pupils must, after taking the table as a basis, use their own discretion as to how they shall vary them. The great thing to bear in mind is to proceed very gradually; while exercising, put “all you know” into the work, but don’t attempt to do too much. Exercise until the muscles ache, but never go on to the point of feeling thoroughly “blown” and exhausted. A quarter of an hour’s conscientious work is better than an hour spent in “going through the motions” in a desultory fashion. Pupils who are in any difficulty and wish for special guidance are advised to go in for the 2s. 6d. course of instruction by post which is given in connection with “Physical Culture,” full particulars of which are given in this book. As I have already said, I should advise all pupils to use the “Grip” dumb-bell; then, instead of buying a heavier pair of dumb-bells after the exercises are being done a certain number of times, all that will be necessary will be to use a stronger spring. I do not advise pupils to keep on with the same weight bells or the same spring too long; when the exercises are done a very great number of times the work becomes monotonous and there is a natural tendency to do it in[Pg 27] a mechanical manner. Roughly speaking, when it takes much over half-an-hour to get through the whole series it is desirable to begin again with heavier bells or springs.

Parents who desire to see their little ones grow into well-developed men and women may be advised to buy their babies light wooden dumb-bells as playthings. The exercises themselves, of course, should not be attempted until the child has reached the age of six or seven. Parents especially would do well to remember, as has already been said, that the tables are only intended as a guide, and they should exercise their own discretion with regard to the weight of bells used by their children, and the number of times the exercises should be done. In some cases a girl or boy of ten years may be so delicate as to have no more strength than a more sturdy child two or three years younger; in such cases the table for the younger child should be adhered to. From that age onwards be guided in the amount of practice by the tables. In order that every reader may understand the exercises easily, the leading muscles only are mentioned in the chart.

Pupils should guard against over-exertion; and, above all things, should not exercise violently. It will be found convenient to let each arm (not both arms) move once in a second. Thus, for example, the time of ten movements with each arm of the first exercise would be twenty seconds. As a general rule, this time will be found to give just the exercise that is needed. Faster movements are not recommended for either young or old. Be careful also not to jerk the movements. Always exercise easily and gracefully, and when contracting the muscles take care not to hold the breath. Many pupils are inclined to do this unconsciously when bringing their minds to bear upon the muscles, but it is quite wrong, and the tendency must be striven against until it is overcome. In one or two exercises, as will be seen on the chart, there are special instructions with regard to the breath; in all the others the breathing should be perfectly natural.

[Pg 28]

Table 1.

For Children of Both Sexes

Between the Ages of Seven and Ten.

(Using one pound dumb-bells only.)

When the maximum has been reached, the child should continue to use the same weight bells and the same spring in the “Grip” dumb-bell until it arrives at the age at which it can follow Table No. 2, and so on with the other tables.

| No. of Exercise. (See Chart.) |

No. of Movements with each arm. |

Increase of Movements. (Not to exceed 30 for No. 1, and other Exercises in proportion.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 2 | 5 | ” |

| 3 | 5 | ” |

| 4 | 4 | One every five days. |

| 5 | 4 | ” |

| 6 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 7 | 6 | One every five days. |

| Exercises 8, 9, and 10 are not advised for young children. |

||

| 11 | 5 | One every five days. |

| 12 | 5 | ” |

| 13 | 1 | One every fortnight. |

| 14 | 5 | One every three days. |

| 15 | 3 | One every fortnight. |

| 16 (boys only) | 3 | ” |

| 17 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 18 | 10 | ” |

[Pg 29]

Table 2.

For Children of Both Sexes

Between the Ages of Ten and Twelve.

(Using two pound dumb-bells only.)

| No. of Exercise. |

No. of Movements |

Increase of Movements. (Not to exceed 40 for No. 1, and other Exercises in proportion.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 2 | 5 | ” |

| 3 | 5 | ” |

| 4 | 4 | One every five days. |

| 5 | 4 | ” |

| 6 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 7 | 6 | One every five days. |

| Exercises 8, 9, and 10 are not advised. | ||

| 11 | 5 | One every five days. |

| 12 | 5 | ” |

| 13 | 1 | One every fortnight. |

| 14 | 6 | One every three days. |

| 15 | 3 | One every fortnight. |

| Exercises 16 and 17 are not advised. | ||

| 16 (boys only) | 3 | One every fortnight. |

| 17 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 18 | 10 | ” |

[Pg 30]

Table 3.

For Children of Both Sexes

Between the Ages of Twelve and Fifteen.

(Using three pound dumb-bells only.)

| No. of Exercise. |

No. of Movements |

Increase of Movements. (Not to exceed 50 for No. 1, and other Exercises in proportion.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 2 | 5 | ” |

| 3 | 5 | ” |

| 4 | 4 | One every five days. |

| 5 | 4 | ” |

| 6 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 7 | 6 | One every five days. |

| Exercises 8, 9, and 10 are not advised. | ||

| 11 | 5 | One every five days. |

| 12 | 5 | ” |

| 13 | 1 | One every fortnight. |

| 14 | 6 | One every three days. |

| 15 | 3 | One every fortnight. |

| 16 (boys only) | 3 | ” |

| 17 | 15 | One every three days. |

| 18 | 10 | ” |

[Pg 31]

Table 4.

For Girls

Between the Ages of Fifteen and Seventeen.

(Using three pound dumb-bells only.)

| No. of Exercise. |

No. of Movements |

Increase of Movements. (Not to exceed 60 for No. 1, and other Exercises in proportion.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | One every three days. |

| 2 | 8 | ” |

| 3 | 6 | ” |

| 4 | 6 | One every five days. |

| 5 | 4 | ” |

| 6 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 7 | 8 | One every five days. |

| Exercises 8, 9, and 10 are not advised. | ||

| 11 | 5 | One every five days. |

| 12 | 5 | ” |

| 13 | 1 | One every fortnight. |

| 14 | 8 | One every three days. |

| 15 | 3 | One every fortnight. |

| Exercise 16 is not advised. | ||

| 17 | 15 | One every fortnight. |

| 18 | 15 | One every three days. |

[Pg 32]

Table 5.

For Boys

Between the Ages of Fifteen and Seventeen.

(Using at first three-pound dumb-bells.)

At this age boys, when they have increased the number of movements of the first exercise from 30 to 60, and all others in proportion, are recommended to go through the course again with five pound dumb-bells.

| No. of Exercise. |

No. of Movements |

Increase of Movements. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | One every other day. |

| 2 | 15 | One every three days. |

| 3 | 10 | ” |

| 4 | 8 | ” |

| 5 | 5 | One every three days. |

| 6 | 12 | One every three days. |

| 7 | 8 | One every three days. |

| Exercises 8, 9, and 10 are not advised. | ||

| 11 | 5 | One every two days. |

| 12 | 5 | ” |

| 13 | 2 | One a week. |

| 14 | 15 | One every other day. |

| 15 | 3 | One every three days. |

| 16 | 3 | One every fortnight. |

| 17 | 25 | One every three days. |

| 18 | 25 | ” |

[Pg 33]

Table 6.

For Girls.

Of Seventeen Years of Age and Upwards.

(Using three-pound dumb-bells only.)

| No. of Exercise. |

No. of Movements |

Increase of Movements. (Not to exceed 80 for No. 1, and other Exercises in proportion.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | One every other day. |

| 2 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 3 | 7 | ” |

| 4 | 7 | ” |

| 5 | 4 | One every three days. |

| 6 | 10 | One every two days. |

| 7 | 8 | One every three days. |

| 8, 9, and 10 until the pupil feels tired. | ||

| 11 | 5 | One every two days. |

| 12 | 5 | ” |

| 13 | 1 | One a week. |

| 14 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 15 | 3 | ” |

| Exercise 16 is not advised. | ||

| 17 | 20 | One every three days. |

| 18 | 20 | ” |

[Pg 34]

Table 7.

For Youths.

Of Seventeen Years of Age and Upwards.

(Using at first four-pound dumb-bells.)

When the pupil has increased the number of movements of No. 1 to 80, he should keep at the maximum with the same weight dumb-bells for six months; he may then increase 1lb., beginning the course over again, and so on every six months. The heaviest bells used, however, should not exceed 10lbs.

I am aware that in the former edition of the book I placed 20lbs. as the limit, but the experience gained in my schools has taught me that for the majority of men this is far too heavy. It is always better to use bells too light than too heavy; the latter are liable to cause strains and other injuries.

| No. of Exercise. |

No. of Movements |

Increase of Movements. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | Five every day. |

| 2 | 25 | Two every day. |

| 3 | 10 | One every day. |

| 4 | 10 | One every three days. |

| 5 | 5 | One every two days. |

| 6 | 15 | ” |

| 7 | 10 | ” |

| 8, 9, and 10 until the pupil feels tired.$1 | ||

| 11 | 10 | One every two days. |

| 12 | 10 | ” |

| 13 | 3 | One every three days. |

| 14 | 25 | Two every day. |

| 15 | 3 | One every two days. |

[Pg 35]

The reader of the second part of this book will see how my professional career was thrust upon me. It came through no seeking of my own, after my defeat of Samson. I accepted it partly because the offers seemed too good to be thrown away, and partly because they enabled me to gratify a wish to see something of the world. My ambition, however, was always to form and build up a system for the service of others, rather than exhibit merely the results of that system in my own person. That ambition, I hope, is to be realised, for I have founded several schools of training for men, women, and children of both sexes, and in the course of time, I intend to establish branches in every important town.

The schools are conducted entirely on my own system of physical culture. Instruction is given by specially qualified teachers, and every exercise is lucidly described and clearly demonstrated. The pupils have every opportunity of developing their bodies to the highest extent, and from time to time I personally examine them.

The instructors employed in the school have been specially trained for their work by me, so that the pupils have the benefit of my best information, and of thus learning the whole of my system exactly. In addition to the classes for men, women, and children, arrangements are made for giving private lessons when required.

My brother-in-law, Mr. Warwick Brookes, jun., is the best pupil I have ever had. For the past six years he has followed my system thoroughly, and the results have been remarkable. When I first met him he was exceedingly[Pg 36] delicate. He could only walk with the aid of crutches. Gradually, however, he began to improve, and under my personal supervision, by the help of my system, his strength has so increased that to-day he is like a new man.

By means of the schools I hope to do something to substantially aid the physical development of this and succeeding generations. Letters from past pupils testify to the great benefits which can be derived from careful training under my system, and if the training has the further advantage of individual instruction those benefits should be increased even more than by studying this book.

It is a pleasant ambition to hope by one’s efforts to leave the world just a little better here and there than one found it; and that has always been and is my ambition. My pupils can help me to realise it.

As I have said, I intend opening schools in every large town in the country; at present schools are open at the following addresses:—

[Pg 37]

None of my departments has shown a more gratifying development than has the correspondence department. Letters pour in from all parts of the world asking for advice and instruction in such numbers that I have been obliged to organise a special system and department for dealing with the enquiries of my many friends, who, owing to their living at a distance and to other reasons, cannot attend the schools personally.

Every week many letters reach me from the Colonies alone—from India, Canada, Australia, South Africa—even from distant Klondike—and from one and all I have received flattering testimonials as to the benefits they have derived from following my instructions. This is an example:—Mr. Dunbar, of Queensland, writes:—

“Dear Mr. Sandow,

“I cannot express my gratitude for the wonderful benefit I have derived from your three months’ course of instruction. Previous to practising your system I was a chronic dyspeptic, and owing to my sedentary occupation, for many years I had not known what it was to feel the natural exhilaration and energy of a healthy man. Now I honestly believe that there is not a healthier man in the whole Colony.”

One pleasing feature of this undertaking is the steady increase in the number of applications from ladies. This department has already become the most important part of my work, and anyone wishing to keep in touch with my system of Physical Culture can do so by forwarding to me their measurements, sex, age, and occupation. In the case of any physical peculiarity, or organic weakness, a doctor should be consulted, and the result of his examination stated in the letter of communication. A form is inserted at the end of this book as a guide to those wishing to apply. These forms are dealt with by myself and each case receives my individual consideration and instruction, and is signed by me.

[Pg 38]

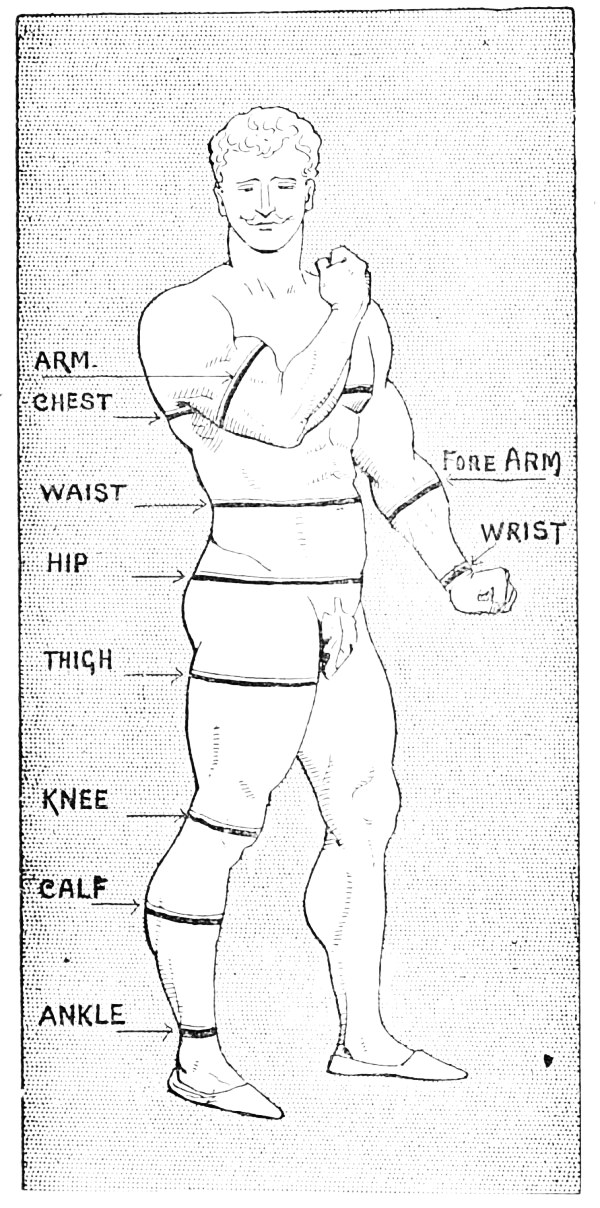

The figure will show pupils how to take their own measurements. They are advised to keep a careful record of these month by month, so they can see how they are progressing. The chest should be measured both with the lungs full of air and empty, as well as in its normal condition.

Date when training commenced. .....................................................

Date on completion of course. .....................................................

| Measurements then. | Measurements now. |

| Age | |

| Weight | |

| Height | |

| Neck | |

| Chest Contracted | |

| Chest Expanded | |

| Upper Right Arm | |

| Upper Left Arm | |

| Forearm, Right | |

| Forearm, Left | |

| Waist | |

| Thigh, Right | |

| Thigh, Left | |

| Calf, Right | |

| Calf, Left |

[Pg 39]

[Pg 40]

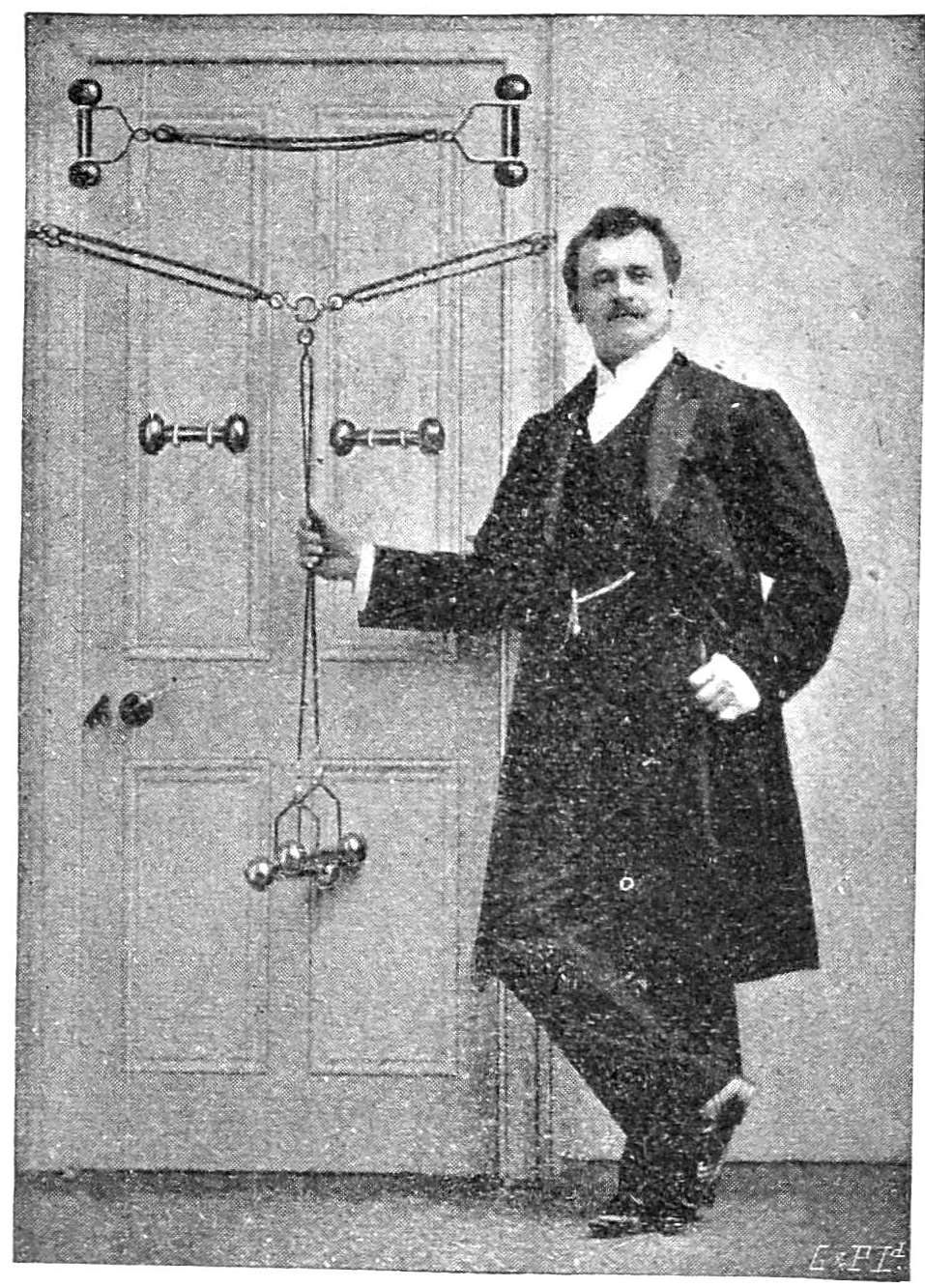

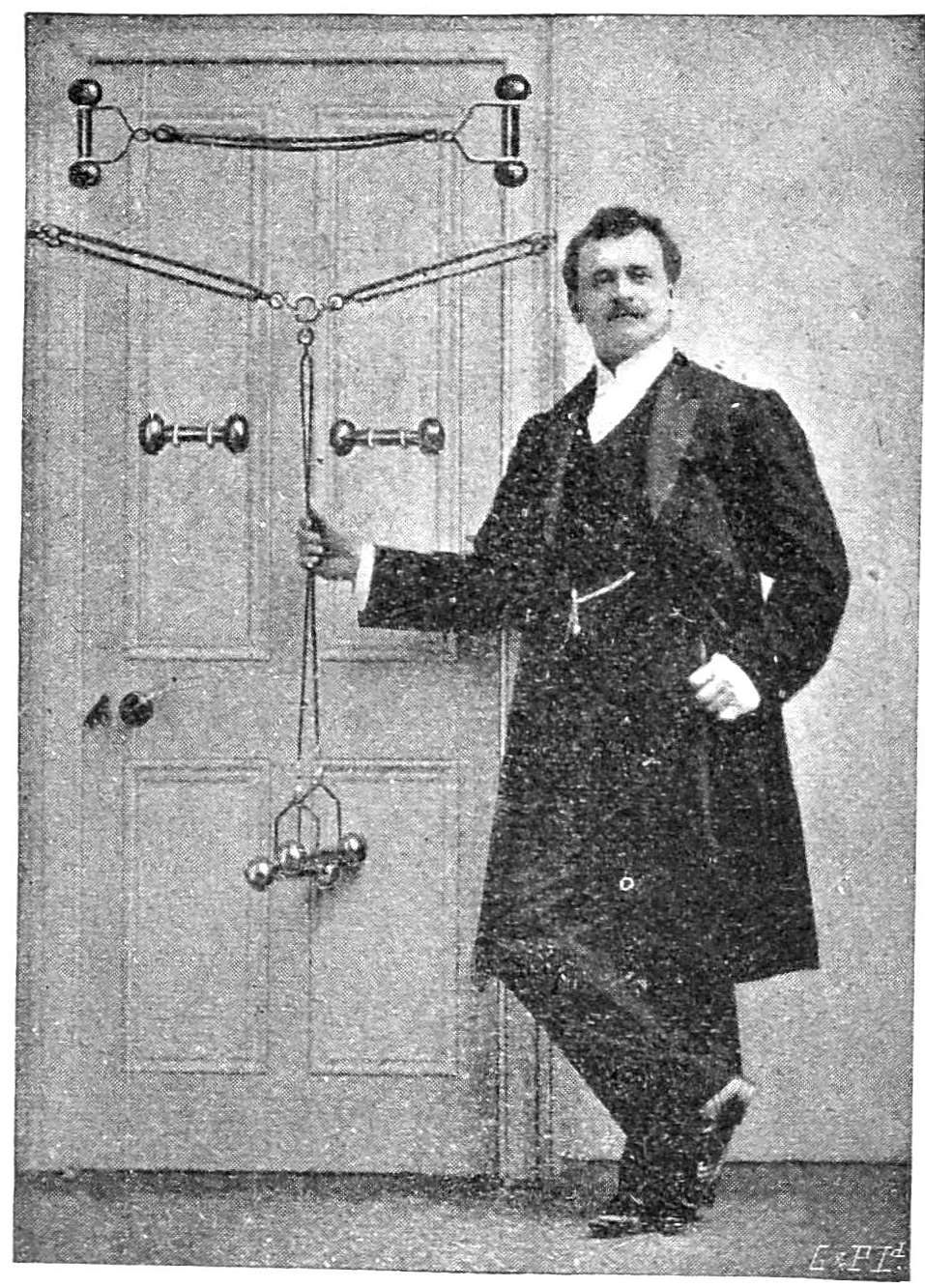

After considerable experience and exhaustive experiments with rubber machines, I have succeeded in inventing one which allows of a combination of dumb-bell and rubber exercises.

Exclusive rubber exercise has not the effect of producing hard, firm, and supple muscles, therefore I have patented the detachable dumb-bell handles, which are simplicity itself.

This developer can be so regulated as to prove equally beneficial to a weak man as to myself.

From an economic point of view it stands alone, as at a small outlay a Developer can be purchased, which is sufficient for a whole family, and constitutes an entire athletic outfit.

The detachable rubbers and handles allow of the machine to be fixed up to any tension, so that as one becomes stronger, one has ample scope for gradually increasing one’s strength. The fatal drawback to the ordinary rubber exerciser is that it only proves beneficial up to a certain point, and then it is not sufficient to carry one any further. Consequently one has to make another outlay in purchasing a heavier machine. My Developer has been designed to obviate this, as it can be regulated up to any strength.

The machine is simply made and easily fixed, causing no damage to the door or wall to which it is attached. There being no pulleys, no oiling is required, and there is no friction to wear out the covering of the cords. Thus the Developer is very durable.

Charts, illustrating Chest Expander, Dumb-bell and Developer exercises, together with a pair of nickel-plated dumb-bells, are given free with each machine. The dumb-bells being detachable can be used separately for the exercises as prescribed in this book. The exercises are specially arranged by myself, introducing several of the[Pg 41] movements in my system of development which cannot be properly executed on any other machine.

In the charts are included special exercises for strengthening the legs; many pupils have found this very beneficial.

The great value of the Developer lies in the fact that it serves to render the muscles pliable, and the whole body flexible and supple. Certain movements with it, too, are difficult to perform satisfactorily with dumb-bells alone. I recommend pupils to use the dumb-bells and complete Developer alternately; by this means I find the most satisfactory results are obtained. Exercise with the rubber Developer affords a welcome change from work with the dumb-bells.

[Pg 42]

It is not my purpose in this book to give anything beyond general directions for lifting heavy weights. You can become thoroughly strong and enjoy perfect health by means of the series of exercises already described. Heavy weight-lifting requires personal instruction; that instruction will be given to those who may desire it at my schools. Under qualified instructors it may be pursued without the risk of danger.

Generally, however, it may be observed that to lift heavy weights it is desirable first to see what weight can be used without undue strain. Slowly raise this weight from your shoulder over your head, or, if from the ground, raise it somewhat more quickly. See how many times you are able to raise the weight first selected, and when you can perform the exercise with comparative ease, raising it, say, ten times, up to 80 lbs., six times from 80 to 100, and afterwards three times, increase the weight for the next day’s exercise by five pounds. Continue this increase as you grow more capable, remembering always to bring the left hand into play as well as the right; at the same time, though it should not be neglected, avoid overtaxing the left side.

The great thing to remember is to go slowly. Avoid anything like spasmodic efforts, and endeavour before trying a lift to thoroughly think out the different movements. Weight-lifting should never be practised in a confined space or where the weight cannot be readily dropped. To attempt to hold on to a weight after the balance has been lost may result in serious strains and other injuries; the pupil should practice dropping a weight from any position safely and gracefully. If the[Pg 43] pupil bear these few hints in mind he will come to no harm, but, as I have said, weight-lifting is best left alone until it can be practised under the personal supervision of an experienced instructor.

A PLEASING TRIBUTE.

The following letter was written me by Colonel Fox, late Her Majesty’s Inspector of Army Gymnasia, a gentleman to whom I am very greatly indebted for the interest he has taken for years past in my work and for the zeal he has shown in getting the system introduced into the British Army:—

The Gymnasium. Aldershot.

29th July, 1893.

Dear Mr. Sandow,

I am in receipt of your letter from New York which reached me on the 23rd instant, and am very glad to hear of your success in America. The book you speak of as being about to be published should also be very successful, and ought to do much towards making your system of physical development widely known.[1] Since your last visit to us here my Staff Instructors and non-commissioned officers under training have been energetically practicing the light dumb-bell exercises you so kindly showed them.

I am convinced that your series of exercises are excellent and most carefully thought out, with a comprehensive view to the development of the body as a whole. Any man honestly following out your clear and simple instructions could not fail to enormously and rapidly improve his physique.

It is almost superfluous for me to add that you yourself, in propria persona, are the best possible advertisement of the merits of your system of training and developing of the human body.

[Pg 44]

Any individual gifted with a fair amount of determination, is absolutely certain to develop his physical powers at an extraordinarily rapid rate and with the most happy results to his general health and mental powers and activity, by following with intelligence your system. As you very rightly say, it is only by bringing the brain to bear upon our exercises that we can hope to produce the best results with the shortest possible expenditure of time.

The absence of expensive and cumbrous apparatus is no small recommendation of your system, and you are thoroughly in the right when you assert that lasting muscular development, and consequent strength, can be best produced by the constant and energetic use of light dumb-bells, employed in a sound and scientific manner.

Believe me, yours very truly,

(Signed) G. M. Fox, Lieut.-Colonel,

H.M. Inspector of Gymnasia in Great Britain.

Professor Eugen Sandow, New York, U.S.A.

[1] The book referred to is the large one which was published some years ago, and which is now out of print.

[Pg 45]

In the following pages will be found a selection from many thousands of letters which have been addressed to me by pupils who have already profited from my system of Physical Culture. Attention is specially directed to the measurements before and after training, showing the actual progress made in muscular development.

[Pg 46]

Vachwen,

Marlborough Road,

Watford,

March 11th, 1899.

Mr. Sandow.

Dear Sir,

I have just completed a course of lessons at your “School of Physical Culture,” from which I have derived untold benefit. Through the greater part of last year I was so ill that for some time it was feared I might go into consumption. I was medically treated, and at length permitted by my doctor to try what your exercises would do.

I entered your School with weak heart, weak lungs, digestion sadly impaired. After three lessons, with persistent home work, I began very slowly to gain strength and an appetite, and now, at the end of my course, I am quite a new creature—full of vitality and energy.

The upper part of the lung, which was the chief cause of my trouble, is quite healed and healthy. I never know now what it is to feel pain and tightness in the bronchial tubes, from which I constantly suffered in the past. My digestive organs too are quite well.

| I have gained in weight | 7 lbs. |

| I have gained round the neck | 1 in. |

| I have gained in the chest (contracted) | 3½ ins. |

| I have gained in the chest (expanded) | 4 ins. |

| I have gained in forearm | 2½ ins. |

| I have gained in upper arm | 2½ ins. |

| I have gained in lung capacity | 100 cbc. ins. |

[Pg 47]

I should be quite pleased to be of use to you at any time in recommending to weak ones, who may be timid to commence the work, the immense benefit to be derived from it, by my own personal experience. I should like also to mention the very kind and careful treatment I have received both from your Manager, Mr. Clease, and the Class Instructor. They give the weak ones their particular attention, so that in working one is never over-worked.

I remain,

Yours gratefully,

Mary E. S. Adams.

[Pg 48]

EBURY STREET SCHOOL.

Copy of Measurement Sheet.

Name:—Miss Adams.

Address:—Marlborough Road, Watford.

Result of Medical Examination:—“Very Bad.”

Nature of Illness:—“The doctors say consumption.”

Remarks:—“This is the weakest case I have ever had to treat.”

| Before Training. |

After 6 weeks. |

After 3 months. |

Increases. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | 11 | 11¾ | 12 | 1 |

| Chest Contracted | 28 | 30½ | 31½ | 3½ |

| Chest Expanded | 30 | 33 | 35 | 5 |

| Upper Arm, Right | 8½ | 10 | 11 | 2½ |

| Upper Arm, Left | 8 | 10 | 10½ | 2½ |

| Fore Arm, Right | 8¼ | 9½ | 10¾ | 2½ |

| Fore Arm, Left | 8¼ | 9½ | 10¼ | 2 |

| Waist | 22 | 23 | 23 | 1 |

| Thigh, Right | 16 | 17½ | 18½ | 2½ |

| Thigh, Left | 16 | 17½ | 18½ | 2½ |

| Calf, Right | 10¾ | 11¼ | 11¾ | 1 |

| Calf, Left | 10¾ | 11¼ | 11¾ | 1 |

| Height | 5ft. 6in. | 5ft. 6½in. | 5ft. 7in. | 1in. |

| Weight | 7st. 2lb. | 7st. 8lb. | 7st. 9lb. | 7lb. |

| Lung Capacity | 100 | 170 | 200 | 100 |

| Chest Expansion | 2 | 2½ | 3½ | 1½ |

[Pg 49]

57, Gloucester Terrace, W.,

March 12th, 1899.

Dear Sir,

I am glad to take this opportunity of saying how very much my health has benefited in every way from your system of Physical Culture. It always gives me great pleasure to recommend the same to my friends.

I am,

Yours faithfully,

Julia F. M. Johnston.

E. Sandow, Esq.[Pg 50]

EBURY STREET SCHOOL.

Copy of Measurement Sheet.

Name:—Miss J. F. M. Johnston.

Address:—57, Gloucester Terrace, W.

| Before Training. |

After 6 weeks. |

After 3 months. |

Increases. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | 12⅜ | 13 | 13¼ | ⅞ |

| Chest Contracted | 29½ | 31 | 31½ | 2 |

| Chest Expanded | 32 | 36½ | 37 | 5 |

| Upper Arm, Right | 10 | 12 | 12½ | 2½ |

| Upper Arm, Left | 10⅛ | 12 | 12½ | 2⅜ |

| Fore Arm, Right | 9½ | 10¼ | 10½ | 1 |

| Fore Arm, Left | 8¾ | 10¼ | 10½ | 1¾ |

| Waist | 24 | 24 | 24½ | ½ |

| Thigh, Right | 18½ | 19½ | 19¾ | 1¼ |

| Thigh, Left | 18½ | 19½ | 19¾ | 1¼ |

| Calf, Right | 12 | 13 | 13¼ | 1¼ |

| Calf, Left | 12 | 13 | 13¼ | 1¼ |

| Height | 5ft. 4⅜in. | 5ft. 4¾in. | — | ⅜ |

| Weight | 8st. 3lb. | 8st. 4lb. | 8st. 6lb. | 3lb. |

| Lung Capacity | 200 | 219 | 222 | 22 |

| Chest Expansion | 2½ | 5½ | 5½ | 3 |

[Pg 51]

[Pg 52]

23, Church Row,

Limehouse, E.,

December 3rd.

Mr. E. Sandow,

Dear Sir,

I write these few lines to convey to you my thanks and gratitude for the boon you have given me and the public at large. I refer to your excellent book on how to gain health, muscle, and strength.

I procured one about two years ago, and have studied and practised the drills incessantly since. The result is far beyond my expectations. I am nineteen years of age and small of stature, being only five feet in height and seven stone in weight, yet, without exaggeration, I can say that my strength and muscular development would do credit to a man six feet high.

I have gained this solely by your system and cannot praise it too highly.

Another great advantage over other systems is the small outlay required, as I have obtained for a few shillings all that is necessary to train with, whereas if I had trained under another system I should have had to have made a much larger outlay for apparatus.

I enclose a list stating what I have gained in strength and muscle since I started training.

It will always be a great pleasure to me to answer any questions concerning your system, likewise interview anyone who might be desirous of seeing me.

I remain,

Yours truly,

Thos. A. Fox.

[Pg 53]

Name:—T. A. Fox.

Address:—23, Church Row, Limehouse, E.

MEASUREMENTS.

| Before Training. | After Training. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest | 29 | inches | 32½ | inches |

| Chest (expanded) | 30 | ” | 34 | ” |

| Biceps | 10 | ” | 13 | ” |

| Forearm | 9½ | ” | 12 | ” |

| Thigh | 16½ | ” | 20 | ” |

| Calf | 11 | ” | 13 | ” |

| Waist | 26 | ” | 26 | ” |

HEAVY WEIGHT-LIFTING.

Before Training.

| From ground above head | Right hand | 56lb dumb-bell. | |

| Left hand | 46lb dumb-bell. | ||

| Both hands | 84lb bar. | ||

| Holding at arm’s length straight from shoulder | Right hand | 22lb weight. | |

| Left hand | 20lb weight. | ||

After two years’ training under your system.

| From ground above head | Right hand | 100lb dumb-bell. |

| Left hand | 80lb dumb-bell. | |

| Both hands | 130lb dumb-bell. | |

| Holding at arm’s length straight from shoulder | Right hand | 40lb weight. |

| Left hand | 30lb weight |

[Pg 54]

[Pg 55]

[Pg 56]

Mon Repos,

66a, Herne Hill,

London, S.E.,

March 6th.

Manager Clease,

Dear Sir,

It is just over three years since I started to improve my physical power by means of the Sandow system, and I take this opportunity of forwarding some photographs taken at different periods. In what measure I have succeeded can best be seen by comparison of my original efforts and my present attainments, of which I also forward a list. Although they are as yet nothing to boast about or sufficiently great to be handed down to posterity, they are the result of close application to the system Mr. Sandow originated, and by means of which, in a few years, I hope to attain the culmination of human strength, and, if possible, to rival that of Sandow himself, for I am a firm believer in starting with an almost unattainable ideal, then gradually coming within measurable distance of it, and eventually, perhaps, to reach it. To do this will require the exercise of many mental qualities, determination, perseverance, and endurance. I suppose there are many young men like myself in whom Mr. Sandow has awakened a latent ambition to muscular prowess, and in doing so I state without any hesitation that he alone has done as much good for the country as any man of the present century.

[Pg 57]

I can only conclude with expressing my deep gratitude to Mr. Sandow for the splendid facilities he has offered to those who wish to be classed as nature’s men (which is indeed the duty of man), and in doing so I am but echoing the sentiments of many of his pupils.

I have the honour to be,

Faithfully yours,

John D. Peters.

[Pg 58]

EBURY STREET SCHOOL.

Copy of Measurement Sheet.

Name:—John Peters.

Address:—66a, Herne Hill, S.E.

| Before Training. |

After Course. |

Increase. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | 16 | 18½ | 2½ |

| Chest, contracted | 38 | 40 | 2 |

| Chest, expanded | 44 | 47 | 3 |

| Upper Arm, Right | 15¾ | 17½ | 1¾ |

| Upper Arm, Left | 15 | 17 | 2 |

| Forearm, Right | 13 | 15 | 2 |

| Forearm, Left | 12¼ | 14½ | 2¼ |

| Waist | 30 | 30 | — |

| Thigh, Right | 23½ | 24½ | 1 |

| Thigh, Left | 23¾ | 24¼ | ½ |

| Calf, Right | 15½ | 16½ | 1 |

| Calf, Left | 15½ | 16 | ½ |

| Height | 5ft. 11in. | 6ft. ⅜in. | 1¼ |

| Weight | 13 st. | 13st. 6lb | 6 |

| Lung Capacity | 276 | 320 | 44 |

| Chest Expansion | 6 | 7 | 1 |

Mr. Peters is a fine weight-lifter, having accomplished the splendid feat of raising 210lb from the floor to arms’ length above the head, using one hand only. This is probably the amateur record. As he is only 23 years old there is yet plenty of time for him to far eclipse even this striking feat.

[Pg 59]

30, Guildford Street,

Russell Square,

W.C.,

13th March.

Dear Sir,

It affords me much pleasure in stating that since I commenced taking your course of instruction I have greatly increased in strength and physical development—my biceps having increased two inches, and my other muscles proportionately. I am convinced that a course of your instruction would prove beneficial to any one, whether naturally muscular or otherwise. Your system is one of such gradual progression that it cannot fail to strengthen the constitution of a person even in a delicate state of health. I shall have much pleasure in recommending your School of Physical Culture to my friends.

Yours sincerely,

Leslie Hood.

Eugen Sandow, Esq.

[Pg 60]

[Pg 61]

EBURY STREET SCHOOL.

Copy of Measurement Sheet.

Name:—L. Hood.[2]

Address:—30, Guildford St., W.C.

| Before Training. |

After 3 months. |

Increases. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | 15 | 16 | 1 |

| Chest Contracted | 35½ | 36 | ½ |

| Chest Expanded | 38⅝ | 42 | 3⅜ |

| Upper Arm, Right | 13⅞ | 15¼ | 1⅜ |

| Upper Arm, Left | 13⅞ | 14¾ | ⅞ |

| Fore Arm, Right | 12 | 13¼ | 1¼ |

| Fore Arm, Left | 11⅞ | 13 | 1⅛ |

| Waist | 28½ | 29½ | 1 |

| Thigh, Right | 22 | 22¾ | ¾ |

| Thigh, Left | 21¾ | 22½ | ¾ |

| Calf, Right | 14¾ | 15 | ⅜ |

| Calf, Left | 14⅛ | 14½ | ⅜ |

| Height | 5ft. 7¼in. | — | — |

| Weight | 10st. 8lbs. | 10st.9lbs. | 1 |

| Lung Capacity | 281 | — | — |

| Chest Expansion | 3⅛ | 6 | 2⅞ |

[2] This pupil had been working three months before joining this school, hence the increases are not so marked as in the case of a beginner.

[Pg 62]

[Pg 63]

34, Duke Street,

St. James’s, S.W.,

March 4th, 1899.

Dear Mr. Sandow,

Not often is it given to us in this life to sow our seed and gather in the full fruits of the same. Therefore it is with more than ordinary pleasure that I write this letter to say that with your system of Physical Culture this extremely satisfactory result is to be obtained.

When first I joined your school some four or five months ago I was a very fair average specimen of a young Englishman (and our national thews and sinews are by no means to be despised), but owing, in a great measure, I suppose, to my city life, I had run a little to seed, and more than once had required the aid of doctors and tonics. The advice of the former invariably ended with the same formula, “take more exercise.”

I was quite ready to agree with them, as during my holidays in the country, when I was exercising in one form or another nearly the whole day, I felt quite a different man and as fit as possible.

But work in the city is a little difficult to reconcile with plenty of exercise. Some time previously Mr. Sandow had opened his school for Physical Culture, and having often admired him and his feats from afar, I resolved to go to him.

I am a business man, and from a business point of view I never did a better stroke of business in my life.

[Pg 64]

I am a mortal being, and speaking from a human point of view I never in my life came to a happier conclusion than when I resolved to become a pupil of the School of Physical Culture. I have increased in girth and weight without scarcely a superfluous ounce of flesh.

My working capabilities and staying powers are all doubled, and what before was an effort has now become a pleasure. Indigestion, torpid lassitudes, rasped nerves, and jaded appetite, are to me now unknown quantities.

With splendid appetite, long peaceful nights, and wondrous powers of vigour and vitality, I can face the world and with a deep sense of gratitude say, this is what Mr. Sandow and his system of Physical Culture have done for me.

Yours sincerely,

Roland Hastings.

P.S.—I may add I am a pupil at the St. James’s Street School.

[Pg 65]

St. JAMES’S STREET SCHOOL.

Copy of Measurement Sheet.

Name:—Roland Hastings.

Address:—Southsea House, Threadneedle St., E.C.

| Before Training. |

After 3 months. |

Increases. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | 14½ | 16¾ | 2¼ | |

| Chest Contracted | 34½ | 36 | 1½ | |

| Chest Expanded | 36½ | 43¼ | 6¾ | |

| Upper Arm, Right | 11¾ | 15 | 3¼ | |

| Upper Arm, Left | 11⅝⅝ | 15 | 3⅜ | |

| Fore Arm, Right | 11⅞ | 14 | 2⅛ | |

| Fore Arm, Left | 11⅞ | 14 | 2⅛ | |

| Waist | 29¼ | 30¾ | 1½ | |

| Thigh, Right | 20½ | 22½ | 2 | |

| Thigh, | Left | 20½ | 22½ | 2 |

| Calf, Right | 13½ | 14¼ | ¾ | |

| Calf, | Left | 13⅝ | 14¼ | ⅝ |

| Height | 5ft. 7½in | 5ft. 7½in | — | |

| Weight | 10st. 4lbs | 11st. 4lbs | 1st. | |

| Lung Capacity | 255 | — | — | |

| Chest Expansion | 2 | 7¼ | 5¼ |

[Pg 66]

[Pg 67]

18, St. Stephen’s Road,

Bayswater, W.,

March 10th, 1899.

Dear Sir,

Your system has certainly done me a lot of good and freshened me up, although I can hardly claim to have tested it fairly, as I must plead guilty to having done none of the exercises out of the school during the three months’ course that I have just concluded there.

Attending the school obviates three defects in working by yourself:—

(i.) You learn—not merely the exercises—but the way to do them.

(ii.) You get an instructor who knows his work, and keeps you at yours.

(iii.) You are stimulated by seeing others working in the same room.