Neju did not hate the God-men, but he did

hate the metal demons they used to destroy his

people. So he prayed to the Old Gods for aid....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

December 1952

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"I hate to leave."

"... But the time has come."

"I suppose so ... but momma?"

"Yes?"

"May we leave them a present?"

"What, my child, what could they want for?"

"... I don't know: surely there's something. One of my toys or something. I'd like to leave them something."

"That's very thoughtful, but...."

"Please, momma."

"Perhaps we could."

"They might find use for a toy, someday."

"Might they, child? Well.... Who knows? Perhaps they might."

The night, starry, cold, clear, was around them, unfriendly. The natives huddled at the edge of the clearing and stared out at the stockade. There was movement there—two sentries, abreast, threading their way in and out of shadows. The moonlight was pale and uncertain, blending away harshness, distorting, enlarging. The night was still. One of the natives let himself down until he lay flat upon the ground. A twig crackled sharply, and the other four held their breath, but the sound did not carry to the sentries. Another and another and another lay down near the first, and then all of them began to inch their way slowly through the tall swift growing grasses toward the stockade.

Their progress was slow; every few minutes they paused until their breathing returned to normal. The light, sunset shower had not softened the ground, for it was in the middle of the dry season when the rain fell sparingly. After tedious, hard gained feet, sweat stood glistening on their nearly naked bodies and grass shoots, saw edged, itched and stung their skins. Rough top roots and sharp, brutal rocks reddened them in welts and bruises.

Still they went forward, slowly, doggedly. The moon fell away toward the horizon, and the shadows unhuddled from trees and the stockade wall and stretched out on the grasses.

With clock-like precision the sentries passed along the narrow walk atop the wall. The wall was made of conje trunks, sheered of limbs, driven upright into the ground, pressed so closely together that between logs there was scarcely a chink. For the people inside the stockade, aided by a howling demon of steel that uprooted and stripped trees effortlessly, it had been scarcely the work of a day; for the natives outside, depending for power upon their own muscles it would represent the year's work of a village.

Each time the sentries passed the spot nearest the natives, they pressed hard to the ground and held their breath for fear some tiny, artificial movement would reveal them.

The moon hovered on the far tree tops and then vanished from sight, leaving a curtain of night, faintly star-dotted.

The five natives were at the edge of the grasses. Beyond them, to the stockade wall, there was no protection. As one they straightened and ran fleetly to the conje trunks. Under their feet, a few pebbles crunched and rattled. They pressed in against the wall, merging with the darker shadow of it, waiting for the sentries to pass. The heavy booted footfalls became louder and louder, until they came from directly overhead. The natives hugged the wall, praying silently to their alien Gods, and the footfalls slowly emptied into silence.

One of the five sent exploring hands over the wooden surface. It was rough enough for his purpose, and awkwardly, hesitantly, he began to work his way upward. Once bark peeled from under his foot and fell away, but it was caught and silenced by one of those below. He drew himself over the top of the wall with a swift, sure movement, and dropped the two feet to the walk on the other side. He crouched there, fumbling with the coil of rope at his waist.

It was a slender, moist rope, and, as he cast the end over the wall, it slithered through his hand like a line of liquid. He could hear the muffled approach of feet, and his heart beat faster. Hurriedly he expanded the slip loop in the end of the rope. He placed the loop over one of the trunks and forced it down between those on each side. It was a tight fit, and he had to jerk it savagely once. That done, he pulled it tight and slipped over the wall, looping the rope in his hand to support himself. Almost immediately the sentries were overhead.

The rope began to slip down the pole; it slipped an inch and jerked; two inches. His muscles stood out, bulging the skin. He closed his eyes.

There were voices above. The rope slipped again, and then the knot began to peel. In another moment, the rope would give way and the native would crash loudly to the ground. The footsteps began again, but only one pair now. Somewhere above in the silence a sentry was waiting. The sentry, unconcerned, lit his pipe and the match flare made those below catch their breaths. The rope slipped again.

In desperation, the native threw one arm over the wall. He glanced down fearfully. Then cautiously he drew himself up. In the pale star shine he could see that the sentry was not facing him. He dropped to the inside walk. The sentry half-turned.

Reluctantly, the native leaped the few intervening feet and hit him. There was a brittle snap and the native lowered the sentry gently to the walk. Then he turned, relooped the rope, pulled it more securely around the trunk. Up came the four who had been waiting below.

In a whispery hiss, he explained what had happened. The leader of the group shook his head in the darkness. "If we go inside, now," he said, "the other will discover this one and then warn the demon before we can destroy it. We must silence the other one too."

They nodded.

One of the group bent and removed the fallen sentry's weapon. He turned it over and over in his hands, curiously.

"Hey! Hey!" the other sentry called, suddenly, from out of the darkness along the wall. "Hey, Ed!" Receiving no answer, he fumbled his weapon into his hand. "Hey! Ed! Answer me!"

"Too late," the leader of the natives hissed. "He will wake the demon. Run!"

They vaulted the wall, striking the ground and scattered toward the tall grasses and the forest beyond. One dragged a broken leg painfully.

The body of Ed, the limp sentry, teetered for a moment on the walk and then slipped awkwardly over the side. It struck a wall buttress and bent over it like a horseshoe.

The other sentry rushed to the corner. One glance was enough to tell him what had happened. He grabbed the huge spotlamp at the juncture of the two walls and tripped the button. Inside the stockade a generator whined and the arc of the lamp flared its sunbright blue.

The beam was temporarily blinding, and the sentry cursed. Then his field of vision came clear, and all the details of the grassy stretch were etched sharply. He saw two running figures, each at the outer edge of the beam. He swiveled the light until it focused upon the nearest one.

It was the leader—the one with the broken leg—and he froze in the light. He did not even attempt to fall to the ground.

The sentry stared for a fraction of a second before he could bring his gun to eye level and fire it.

The leader of the natives waited, blinking his faceted orange eyes in the cruel blinding glare. The eyes glistened brightly. The four arms hung motionless, relaxed at his side.

The sentry shuddered involuntarily as the leader came within his sights. He squeezed the trigger and a burst of hissing flame came from the muzzle. The flame died in the air and the gun jumped in recoil.

The projectile struck and the leader screamed in pain. He twitched but he did not fall. One hand shot out to support himself, but still his eyes blinked into the light and still he remained upright, a perfect target.

The sentry fired twice more, one projectile kicking up a tiny shower of rocks and moaning away, almost spent; the other, scoring in the target.

The native in the field whined. But still he did not fall.

Shuddering, the sentry fired time after time at him, and finally, very slowly, the native crumpled to the ground. Once or twice the tip of the tail twitched and then the body was absolutely motionless.

The sentry swung the light again. The other natives were gone. He shuddered again and spat out toward the body.

Lights in the stockade began to come on, sucking at the tiny generator. They were dim lights.

Looking down, the sentry saw his companion lying across the buttress.

The sentry began to curse nervously. Then, with fumbling fingers, he shut off the arc lamp and the lights inside the stockade brightened.

The sentry glanced out at the vast alien darkness beyond the wall. He whimpered in sudden, childish fear.

Within the forest, beyond the terrifying brilliance of the stockade light, the natives stopped running. After the light went off, they called to each other with piping, night bird whistles. Slowly they came together, forming a silent lonely group.

"We must leave him there," one said, in the shrill, chattering native language.

Reluctantly they turned their backs on the stockade. Leaves crackled under their feet. Branches whipped at their faces, bringing sharp tears. They hurried, and dry things rustled and startled animals fled. From time to time they grunted at each other, more for encouragement, more as protest against the tangle of vines than for communication. Neju carried the stolen stockade weapon pressed tightly to his chest.

On they went, and finally the sun came up, penetrating the forest here and there, sending sharp rays of new light mottling the ground. Once they stopped to rest, but only for a short time.

After two hours of sun they came to the natural clearing and the tribal village.

The village was a crude thing by stockade standards. It was a cluster of mud and stick houses around the central more pretentious Chieftain's lodge. Before the lodge there was the large fireplace where the community roasted the hunters' kills on three huge spits. The ground around the fireplace was smooth and covered with white sand taken from the bottom of the fast running creek that at the far left of the clearing threaded its way off into the tangle of trees. Bones and other refuse were carried in reed baskets to a pit well back in the forest away from the clearing. The whole of the village was clean and orderly, and, in back of the lodge, there was a patch of flower-like plants most of which were dead with autumn and frost.

Several meat animals were staked out near the stream and two tiny domesticated arboreal animals called corlieu sat before their owners' huts, in the sunshine.

When the four natives stepped into the clearing, all other activity ceased. Children broke off their cries, and adults turned from their labors. A great silence fell upon the village. Natives appeared at doors.

Slowly the four walked toward the lodge; one limped slightly from a thorn in his naked foot. All eyes turned to mark their progress.

The Chieftain sat at the door of his lodge. Upon their funeral-like approach, he rose. He stared at each one in turn as if trying to believe one of them were someone else. Then he shifted his eyes over their heads to the spot in the forest where they had emerged.

Neju shook his head slowly and the Chieftain seemed to retreat as if from an invisible blow; then he stood erect, gestured that they should enter, and followed them in.

Slowly, outside, movement began again. There was a floating whisper of soft words and the children moved gravely about. Even the corlieus seemed to sense the change and did not try to attract attention. Overhead, a great bird flapped by.

Inside the lodge the four arranged themselves differentially at their Chieftain's feet.

The Chieftain was old. His arms were loose shells of skin over bone and his face was pinched with wrinkles; even the eyes were misty and bluish with age. And his voice, when he broke the silence, was thin and querulous.

"You have returned," he said.

The four remained quiet, sitting with their legs coiled under them as pillows. After a while, Neju answered, "Yes, we have returned."

The ritual question and answer gave the old Chieftain time to get his emotions under control; his eyes were clouded with grief, and his head bobbed loosely on his skinny neck. And then: he was unsure as to why there were tears in his eyes.

"He will not join us," Neju said quietly.

The old one sighed and rubbed a wrinkled hand over his face.

Outside, the mourners began their chant, slow, terrifying. A distant drum picked up the beat and throbbed out the heart-rhythm.

"We took one of the weapons," Neju said. "But we were prevented from entering their village."

The old one nodded. He closed his eyes and turned his face toward the ceiling of the lodge. He was tired; it was odd, how suddenly tired. Yesterday there had been ... no, that was not yesterday. His son coming up from the stream with his first catch. The air had been bright (it was no longer bright any more) and he had laughed, saying.... But now there was something about a demon somewhere, wasn't there? A fearsome thing. It was hard to believe in demons; yes, and in Gods, too. That summer when his father pointed to the moon being eaten by shadow, he had believed in Gods, then. He must tell his grandson about that. It was very strange. And there was an old ritual one should make when the drought came....

"Here, their weapon...."

The old one opened his eyes once more. His young friend, Neju, was handing him a strange thing. He marveled at it, thinking that perhaps the Gods had left it when they went away.

"It is dangerous."

The old one was trying to think. There was something about the new Gods who had come down from the sky; but they brought demons with them, so perhaps they were not Gods at all and it was quite confusing, being old. He must remember to ask his grandson to tell him all about it. They placed the weapon before him and rose, making their bows, and left him in peace.

He stared at the weapon for many minutes. His grandson, Zoon—no, Zoon had been his son—his grandson's name was—was—ah—Zoee, yes. A little child.

An odd thing, what weapon, and perhaps.... No, it was not for spring planting. And winters used to be longer: we plant earlier—a moon earlier, now, at least. And Zoee was a grown man, and Zoon was dead. Or was it the other way around?

He blinked his eyes, and strangely, it seemed that they were both dead. They were playing the funeral dirge out there in the sunshine.

The old one stirred uneasily.

Neju sat on the white sand before the fire place. Two of his hands plucked nervously at the sliver of wood. A group of hunters formed a semicircle around him.

"The old Father is ill with sorrow," he said, after a while. "And with time."

The others nodded, and again the hunters' council fell silent. The rest of the village was muted, and the women went about gathering funeral offerings for their Chieftain.

Neju studied the splinter, trying to focus his thoughts on it. Finally he said, "We did not destroy the demon."

"We must try again," one of the hunters said, and like a tired sigh, agreement ran from mouth to mouth.

Neju flipped the splinter into the ashes and sat with eyes downcast.

"The demon must be destroyed," the hunter repeated. "Or it will kill again and again."

Neju stared across the fireplace at the forest beyond. His eyes clouded.

On his right, a young hunter who had been with him the previous night at the wall cleared his throat nervously. "They come from the sky, but they are not Gods." He wrinkled his brow as if this were difficult to understand. "It is strange," he said. "They come like Gods, but they are not. Gods are kind." He looked appealing at Neju.

Neju smiled wearily and touched the young hunter on the shoulder. "They are not Gods."

"They are servants of the demon," another hunter insisted. "I was there," he said monotonously. "After they came."

The others stirred uneasily.

"We watched the demon," the hunter said, his voice still flat, as if (although he knew them to be true) he could not quite believe the words himself. "I was with Mela. We watched the demon go to the forest and rip out a standing tree by the roots. Then trembling, Mela stepped out to greet it with a friendship offering. And the demon turned on her and roared down on her and mashed her body lifeless under it, and the god-man who was astride the demon became so terrified that he seemed to laugh. I fled."

There was silence for a moment.

"The Old Gods," one hunter began, but he did not finish the sentence.

The hunters shuffled.

"I saw the demon kill Mela," the hunter said with finality. "We must kill the demon."

The young hunter cleared his throat again. "They are not Gods, but still I should not have harmed the god-man, last night, at the wall. We do not mean them any harm." He paused. "Only the demon."

The hunters nodded.

"They will thank us for destroying the demon."

"The god-men, themselves, have killed four of us," Neju said suddenly.

"They cannot help themselves," the young hunter insisted. "They must do the demon's will." He paused again. "They cannot be gods, to obey the demon, but we should not harm them."

Suddenly the funeral drum ceased in mid-note.

The village began to stir uncertainly, and a native burst, running, upon the clearing. He was crying something in an excited voice. A wail went up from those nearest him, and each ran off toward his house. A young lad sped toward the seated hunters.

When he arrived, he was panting. "A demon comes! It is in the air like a bird!"

The hunters glanced at Neju for leadership. Then, from a great distance, they heard a whirring like the beat of giant wings.

"Run!" Neju cried, and they scrambled to their feet.

"Separate and run!" Neju cried.

The other villagers were scattering toward the forest in all directions. Neju glanced around him. He saw a female stop, rush back, scoop up a child who had been playing with a polished bone. Then, almost as if by magic, the village was empty. The staked animals began to whine, and one of the corlieu at the far edge of the clearing gave a gigantic leap and disappeared into the tightly woven branches.

Then Neju turned to run and the sound of the air demon was nearer. But he had taken only two or three steps before he stopped, frozen, for a single instant. Then he turned and sped toward the Chieftain's lodge.

No one had warned the old Father.

At the moment he reached the door of the lodge, the helicopter burst upon the clearing. Neju darted it one frightened glance and then ducked through the doorway.

The old one still sat as Neju had left him, motionless, staring at the strange weapon before him. He did not even look up when Neju entered.

"Come, Father," Neju said very gently.

"Eh?"

Neju glanced over his shoulder. The sky demon was heading straight for the lodge.

Very tenderly, Neju drew the old one to his feet. He wrapped two arms around his body, protectively. "We must hurry, Father."

The old one blinked, but he moved as Neju urged, and the two of them stepped from the back entrance of the lodge. The helicopter was flying low, and it seemed almost on top of them.

It was then that the Chieftain saw it. There was fear and wonder in his eyes.

"We must run!" Neju said.

Together they trampled across the dying garden, their feet moving rapidly, and the old one's breath came in sharp rasps.

Then the very edge of the helicopter's shadow touched them.

And there was a blinding light and a great wave of air that threw them to the ground like a giant hand, and there was a roar greater than the northern cataracts. And the sound and light was gone, but still their ears rang with the thunder of it and their eyes pained.

Ahead of them there was another roar. And a group of huts seemed to come apart from quick flashes inside of them. Bits of the lodge plopped down on their backs, and one huge piece of timber embedded in the earth only a foot from Neju's body.

Neju threw himself over the old Chieftain to protect him; he felt dirt and sticks and dust shower over him and the air smelled sharp and bitter and stifling.

Wham! Wham! Wham!

The earth jarred with explosions, one after another, measured, methodical. Neju gritted his teeth and closed his eyes tightly.

And the world was light and noise and flying debris.

Then it was over. Neju was holding his breath. For several minutes, he did not dare lift his head; his ears rang and his head was weighted. He brushed at it, and his hand came away wet with blood.

He looked up, and the air demon was gone.

The lodge was no more—only a smoking crater, and, except for two huts, miraculously intact, all of the village was mashed flat as though a giant hammer had worked it over carefully.

Neju bent to the Chieftain. The old one moaned.

They constructed a crude shelter for the Chieftain back of the clearing, fast in the forest, where the old one could not see the scene of destruction. All that night, almost fearfully, the villagers crouched near him. When the moon first dropped its rays across his face they all tensed, hushed, waiting, and when his breathing continued they sighed in relief (for he would live another day: a Chieftain's spirit always goes up the first moon path to the stars, or else it will not leave until the moon path comes again).

The night was long and cold, and toward dawn, they drew in upon each other and the fire for warmth.

When the sun was an hour high and the hasty meal was over, the young hunters surrounded Neju, looking to him for leadership since the last of the royal line lay in a coma.

"You will be our leader until our Chieftain Father is well again," they told Neju, one after another.

Neju sat for a long time in thought and silence. At last he said, almost sadly, "I will serve until the old Father is well again."

There was a relieved sigh from the listeners.

Again there was a long silence.

Neju toyed with a new grass shoot, rubbing it between his fingers. He rumbled deep in his chest to break the silence. "We must move further into the forest. Wait for the god-men and the demons to go away. We cannot fight."

"Perhaps they will not go away."

Neju thought about this. "The Old Gods came from the sky," he said. "The Old Gods went away." He looked around him at the circle of taut, angry faces. "I do not like to give up our home ground," he said slowly. He shrugged helplessly. "With two demons, one to watch while the other sleeps, how can we steal near enough to destroy them?" He looked at the mashed grass shoot. "The earth is kind. We can live and be happy in some new place."

A hunter slipped out of the brush near Neju, scarcely rustling it. Neju turned his head and the hunter bent and whispered in his ear. Neju looked suddenly concerned and frightened. He stood up, motioning for the others to keep their seats. He turned and followed the hunter into the forest.

They threaded their way toward what was left of their village. Near the edge of the natural clearing, the hunter hissed and began to advance cautiously.

When they both stood looking out from behind a clump of clato, Neju saw a group of the god-men in the middle of the wrecked village; the god-men were poking around idly, kicking rubble, fingering this and that. They talked. Their voices were, to Neju, slow, low pitched, lazy. Neju held his breath, watching.

Finally one of the god-men, seemingly the leader, started toward the very spot where they were standing.

Neju and his companions drew back hastily, and their movements rustled a dew heavy bush, causing it to shower a spray of water on the dead leaves of the ground.

Almost immediately, there was the deadly hiss of the leader's weapon, and a projectile thudded into a tree, just to the left of Neju.

"I saw two of them! Over here!" the leader called, running heavily toward the forest. The other god-men galvanized into action.

"Let's hide," Neju's companion whimpered, terrified.

"No! They'd find us. Follow me." Neju started off, skirting the clearing, going away from the direction of the villagers' temporary camp.

The god-men fired four times in the direction of their flight. The shots came at short, measured intervals, and they struck in a fan-like arc. The nearest one snapped by Neju's ear with a loud popping noise.

"This way!" the god-man cried excitedly crashing after his prey. He was joined by the others, all running heavily, and the air was filled with their coarse explosive curses.

Neju and the hunter ran for what seemed a long time, the noise of pursuit still loud behind them. Then the noise ceased.

Neju stopped, puzzled, breathing heavily. On the other side of a small clump of viny scarbj, there was the sound of god-men's voices.

"They might be leading us into a trap," the one said.

There was assent.

"They must be near. I don't hear 'em runnin' any more. Over that way. Let's spray that whole damn section!"

Their weapons began to hiss.

Neju instinctively dropped flat to the ground. In following his lead, the hunter coughed once, a projectile catching him in the chest even as he was dropping. Blood gurgled in his throat.

"That's one, by God!" one of the god-men cried in elation, and after another barrage of increased violence, they began to withdraw, nervously, darting glances at the quiet trees around them.

Neju remained motionless. Then, leaving his dead comrade, he set off at a lope in the direction of the makeshift camp.

When he arrived the villagers were still huddled fearfully together.

Neju walked to the circle of young hunters. "They killed Whenj just now," he said without preamble.

He sat down.

"Come here!" he said. "I want you all to come here!"

Slowly the natives gathered around him.

"Sit down."

They sat down, and Neju waited until they quieted. There was fear and uncertainty in the air; mothers darted anxious glances in the direction of their sons.

Neju began to speak. He spoke slowly. "I have just seen the god-men chase and kill. They are controlled by demons that cannot be appeased. One has only to hear them—the hate in their voices—to know." He swallowed and looked around at the green brilliant foliage and listened to the life movements in the trees. "I said that we should move away into the forest.... But now.... I cannot think like a demon, but I somehow see that ... unlike the Old Gods ... the demons will not leave us to the world in peace. They are creatures of hate, who will hunt us out, little by little, and destroy us all...." He looked around at the frightened faces. "They will build more and bigger villages for their servants, the god-men. They will strip away our forests and burn our grasses. They will kill our food and destroy our homes wherever they find them. They will trample our gardens. They will force us back and ever further back until we have no place left to go.... And only after they have killed us all, only then, will the demons be satisfied and leave our world.... That is what I see."

The rest, terrified, waited.

"I am your Chieftain while the Father is ill. Yet, I cannot command you in this. What shall we do? Shall we flee to live in fear, or...?"

There was a sad little moan from the women.

"One demon," Neju said, "we might have killed. But I do not know how many demons there are."

The men moved nervously.

Finally one said, very softly, "If there are a hundred, we must not flee."

Assent muttered among them.

"Very well," Neju said. He stood up. "I will go see the Father. He must guide me in my actions now. Perhaps he can recall a weapon to fight demons with. Perhaps the destruction of the village will help him to think."

From the distance there was the great beat of demon wings on the air.

Neju went to the old one. He frowned at the woman who had been assigned to care for him. She stood, bowed, and withdrew.

Neju sat down beside the Father.

"Father," he said softly. "Father, can you hear me?"

The Chieftain moved his head wearily; his lips opened slowly. "Yes," he whispered.

"We must destroy great demons. We must have the help of the Old Gods. What must we do, Father? You could not remember when Zoee asked you. Can you remember now?"

The Chieftain lay silent for a long time. A tiny insect crawled unnoticed over one wrinkled arm. He had heard the question but somehow the sense had gone out of the words. The Old Gods—did he believe in Old Gods? Was that the question?

He tried to remember: Old Gods had come from the sky—but that had been long ago. His father had seen them—no, no—grandfather, wasn't it? Or even further back than that? The Chieftain imagined the stars, which were bright souls in the sky, and had the Old Gods really come down from the sky at all? Maybe no one had ever seen them: maybe it was a dream, there were so many dreams. Here he was dreaming that he was old, and only yesterday his mother had whipped him for going too near the yeama Zaptl had staked out over at the base of the hill. Or was it yesterday?

"We must have the Old Gods' help," Neju repeated quietly.

The Old Gods' help? He tried to remember. There had been something—a dance—a ritual—a chant, hadn't there?

"For the killing of demons."

The Chieftain was tired. It seemed that there was something important to remember. Hadn't.... What was it?

"Please, Father."

The old one wished the voice would go away because he was sleepy. Wasn't that the moonlight on his face?

"Pray," he said, dying.

After a time, Neju stood up. The Chieftain was very quiet.

He left the side of the dead and turned to the female waiting a short distance away. "After the moon has taken his soul tonight, prepare him for the funeral. His soul is very quiet as it waits. And there is no need to disturb him."

Pray, the old one had said. The moon came down full, splintering beams on a tangle of branches overhead. The old Chieftain was covered with the ceremonial cloak of fur and by his side the formal mourner buried her head in her hands, rocked back and forth intoning musically, "Ah, ahhhhha, ah, ah."

"Old Gods," Neju said, standing in the middle of the villagers, "... Old Gods, I do not know how to talk to you the way I should." His voice was small and embarrassed. "I hope you do not mind too much. I'm trying to get it right. Old Gods, legends tell how you controlled mighty demons when you came to our world. Now there have come to our world some demons who control god-men." He wrinkled his brow, trying to state the case as dearly as possible.

"These demons are very bad. They kill our people." He paused a moment. "We want you to help us kill these demons so the god-men will be free and we can live without fear."

Neju waited. The ground did not tremble. The moon did not darken. The Old Gods did not answer.

"Maybe we haven't any right to ask, for ourselves," Neju said. "But for the god-men, who are your brothers from the sky. Help us to free them, Old Gods. They want to be free, like all things want to be free."

Still the Old Gods did not answer.

Slowly, from mouth to mouth, a moan passed among the villagers.

"Answer us, Old Gods," Neju pleaded.

The moan grew louder and louder.

"Answer us, Old Gods," Neju repeated. "Please answer us."

And still no answer; only a vagrant breeze in the leaves; no sound, no voice, no sign that the Old Gods had heard.

And the moan died helplessly.

Neju stood, head bowed until silence came.

"I cannot talk to the Gods," he said. "I am no Chieftain. I am not worthy to talk to Gods."

"We prayed too," a female said. "We all prayed with you. And still they did not answer."

Neju smiled twistedly. "We do not know how to pray. Or the Gods do not know how to listen."

The female said, "They came long ago. Perhaps they have forgotten us."

Silence fell.

Neju looked toward the dead Chieftain. "How can I lead you, unless They make a sign?"

Morning. A corlieu dropped into the clearing to beg for food. A fire sputtered wetly. The mourners came back from the Chieftain's grave (only they knew its location, and the autumn leaves hid the spot).

The hunters slowly came to Neju. They stood awkwardly in a circle around him. Finally one spoke.

"We talked among ourselves, last night, after you went away."

"Yes?" Neju said.

The native shifted on his feet. "You say we must destroy the demons. As you say, we cannot run, only to run again and again."

"The Old Gods did not make a sign to me," Neju said wearily.

"The Father said only to pray. He did not say that They would answer."

Neju considered this gravely.

"We must give the god-men heart," the native continued. "They must take courage from us. Together with the god-men, we can defeat the demons. If the Old Gods do not help us, the god-men must."

Neju still listened; only his arms moved, restlessly.

"First we must show the god-men that we are not afraid of demons."

Neju waited.

"All of us, children, females, the old, all, must go toward their village, beating drums, crying encouragement. We must show no fear. The god-men will take heart."

Neju stirred.

"They will see that we are not afraid, and they will lose their fear. Together we will turn on the evil demons and destroy them. And you must lead us."

"Leave me," Neju said. "I must think about it."

Neju stood for the hour preceding the heat. The sun moved to a position directly overhead. Then he arose stiffly.

"People!" he called.

The villagers stopped their work. They turned to face him.

"Come to me!" he called.

They came.

"You have heard the plan of the hunters?" he asked when they were quiet.

One by one they nodded their heads.

"And you are not afraid?"

They were silent. Finally, one said, "We are afraid. But we will do what must be done."

"... Very well," Neju said. "If it is what you wish, I will lead you."

"We only do what we must," one said.

Neju looked them over carefully. "We will eat, and then we will leave. We will travel to the village of the god-men. Each of you will bring an instrument upon which to make noise to frighten the demons and hearten the god-men."

They nodded, silently, and began to drift away.

Neju named three hunters to remain with him.

"Before we do this," he told them when the others had gone, "we must try once more to slip beyond the wall and slay the demons."

"They will guard each other," a hunter protested. "We cannot overcome them without the help of the god-men."

"We must try," Neju said.

The three hunters looked at each other.

"We will leave the party at the edge of the clearing when the moon is high and try as we did before. And if we fail then they must follow us crying encouragement to the god-men. But we must try first."

The hunters, one by one, said, "We will obey you."

They gathered, all of them. And they began to move: a slow, twisting line, hesitating now and again to help the older members. A baby cried and its mother shushed it. The forest was alive with movement and chattering. There was fear and resolve on the natives' faces.

Neju and the three hunters led them. They scouted the territory ahead.

The column rested frequently and the aged clucked to themselves, confused, uncertain. And the others tried to reassure them and make them comfortable. The children ranged, but not far. The tame corlieu followed them in the tree tops, chattering down, from time to time, bewildered.

On they moved and the sun fell and the first forest shadows came out to welcome the night. The sunset shower came, unusually heavy, silencing the forest sounds by its patter on the leaves. The air smelled new and crisp.

A group of birds huddled together, chirping sleepily, in a century old conje tree.

"We must hurry," Neju said.

And the column moved faster, its sounds of movement being hushed by the damp foliage. Vines and branches parted before it and folded into place after it, swishing softly. The children huddled in, and the column hurried.

When twilight was full upon the forest, and the first bright hero souls were in the sky, Neju slipped back from the advance of the column to whisper, "We are almost there. Be very still."

Neju gestured that they should spread out, and when their positions suited him, he motioned for them to advance.

And finally they came to the edge of the forest.

There lay the stockade, asparkle with electric lights. The females drew in sharp breaths at the sight of such a magnificent structure—Ah, what the demons build for their servants! they seemed to say. And the helicopter, coming in from a long flight of exploration settled inside the stockade, its blades sparkling in the new moon.

The natives shuddered in superstitious awe; they clutched their noise makers closer to their bodies as if for protection.

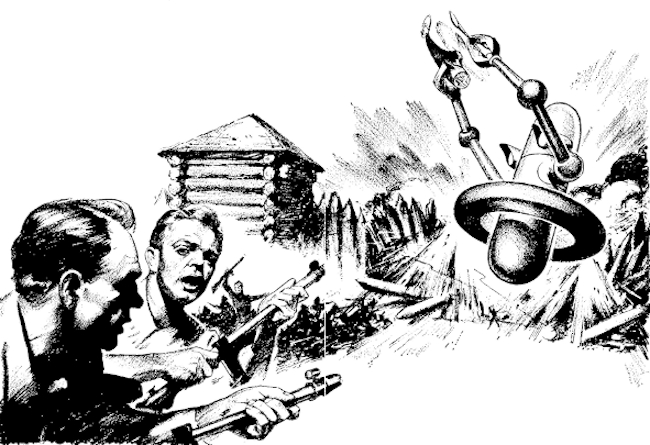

Neju and the three hunters were at the edge of the grasses; the stockade was silent except for the pound of sentry boots.

Neju motioned for the three to remain. He hunched his body and ran to the base of the wall, breaking the almost invisible wire without noticing.

On the wall a red light blinked three times. But Neju did not notice it. Frantically his hands sought holds in the trunks of the wall.

"Here's one of them!" someone cried above. "Over here!"

"They didn't catch us asleep this time!" another voice said.

"I toldja they'd be back!"

There was swearing, and Neju froze, terrified.

Above him, the pounding of many boots.

"What's wrong with this light?... Ah, there!"

And the light came on.

It cut a path across the grasses.

A weapon hissed in the direction of a shadow.

"They're out there somewhere!"

"I don't see 'em!"

A weapon hissed again.

"See something?"

"Nah. Thought I did's all."

Neju pressed in against the wall. The light put him in full view but still they did not look down. Neju glanced toward his comrades. As yet those on the wall had not seen them.

"Hey! Look!" a god-man screamed. "There's one!"

Neju looked up.

"Right there!"

And Neju tensed, waiting.

"Well, I'll be damned!"

Neju was looking into two of their faces; the faces were demon controlled, contorted with fear and hate. He saw one of the god-men bring up a weapon. He stared unbelieving into it.

It spurted flame.

In his left side he felt a hot searing arrow of fire. His hands relaxed and he was falling. He fell a long time, through sickness and unreality. Then he was not falling.

In the distance he heard the drum beats and cries from his people. He wanted to tell them something. He twitched in pain trying to cry out.

"Look!" the god-men cried.

The natives burst from the forest crying encouragement to the god-men. "Take heart! Turn on the demons! We will free you! Join us!"

"Like sitting ducks!" someone on the wall screamed in elation. "Look at 'em come! Crazy! Chatterin' like monkeys!"

The natives were nearer, shaking their noise makers, screaming.

Someone on the wall smiled and fired and one of the natives stumbled and fell.

"Like sitting ducks!" he screamed.

The other god-men began swiveling their most powerful weapons, focusing the natives in their sights.

And still the natives came, crying that the god-men take heart.

And then the ground trembled!

The forest behind the natives began to crackle; trees came apart in all directions flying like matchwood.

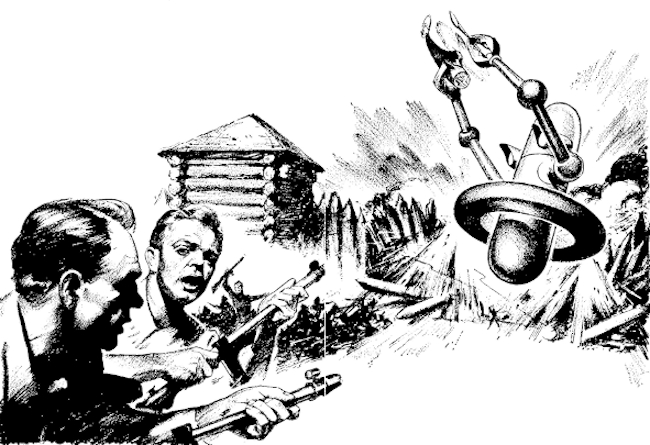

A giant being trampled aside all obstructions with invincible power.

Then the metal monster was clear of the forest. It hovered carefully over, around, between the natives.

The stockade light swung, halted.

And a concerted gasp went up from the wall; then curses of terror.

There it stood. A shining colossus. Huge. And serene beyond imagining. It was facing the stockade.

It had traveled far: from the deep, sheltered cave in the far north—where it had rested in silence until, upon its vastly complex and sensitive electronic brain it had received the commands of its owners. After many, many years, as the little child master had thought, they had need of it.

It moved again.

Stockade weapons swiveled; all the hellish energy that they were capable of spewed in its direction.

In its way, it smiled.

Then, very methodically, it began to take the stockade apart, cracking the conje trunks like toothpicks.

It noticed one of its masters, Neju, lying wounded by the base of the stockade. It bent and carefully scooped him up. It placed him tenderly in the shoulder pocket, out of harm's way, observing the seriousness of his wound and automatically remembering the proper treatment.

The helicopter took off and headed east.

Absently the toy of a child of the Old Gods swatted the helicopter out of the air, knocking it nearly a quarter of a mile before it crashed into the conje trunks of the forest....