Transcriber’s Note:

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

A list of spelling and accent corrections appears at the end of this eBook.

THE LANGHAM SERIES

AN ILLUSTRATED COLLECTION

OF ART MONOGRAPHS

EDITED BY SELWYN BRINTON, M.A.

THE LANGHAM SERIES OF

ART MONOGRAPHS

EDITED BY SELWYN BRINTON, M.A.

Vol. I.—Bartolozzi and his Pupils in England. By Selwyn Brinton, M.A.

Vol. II.—Colour-Prints of Japan. By Edward F. Strange.

Vol. III.—The Illustrators of Montmartre. By Frank L. Emanuel.

Vol. IV.—Auguste Rodin. By Rudolph Dircks, Author of “Verisimilitudes” and “The Libretto.”

Vol. V.—Venice as an Art City. By Albert Zacher. [Nearly ready

Vol. VI.—London as an Art City. By Mrs. Steuart Erskine, Author of “Lady Diana Beauclerc,” &c. [In the Press

These volumes will be artistically presented and profusely illustrated, both with colour plates and photogravures, and neatly bound in art canvas. 1s. 6d. net, or in leather, 2s. 6d. net.

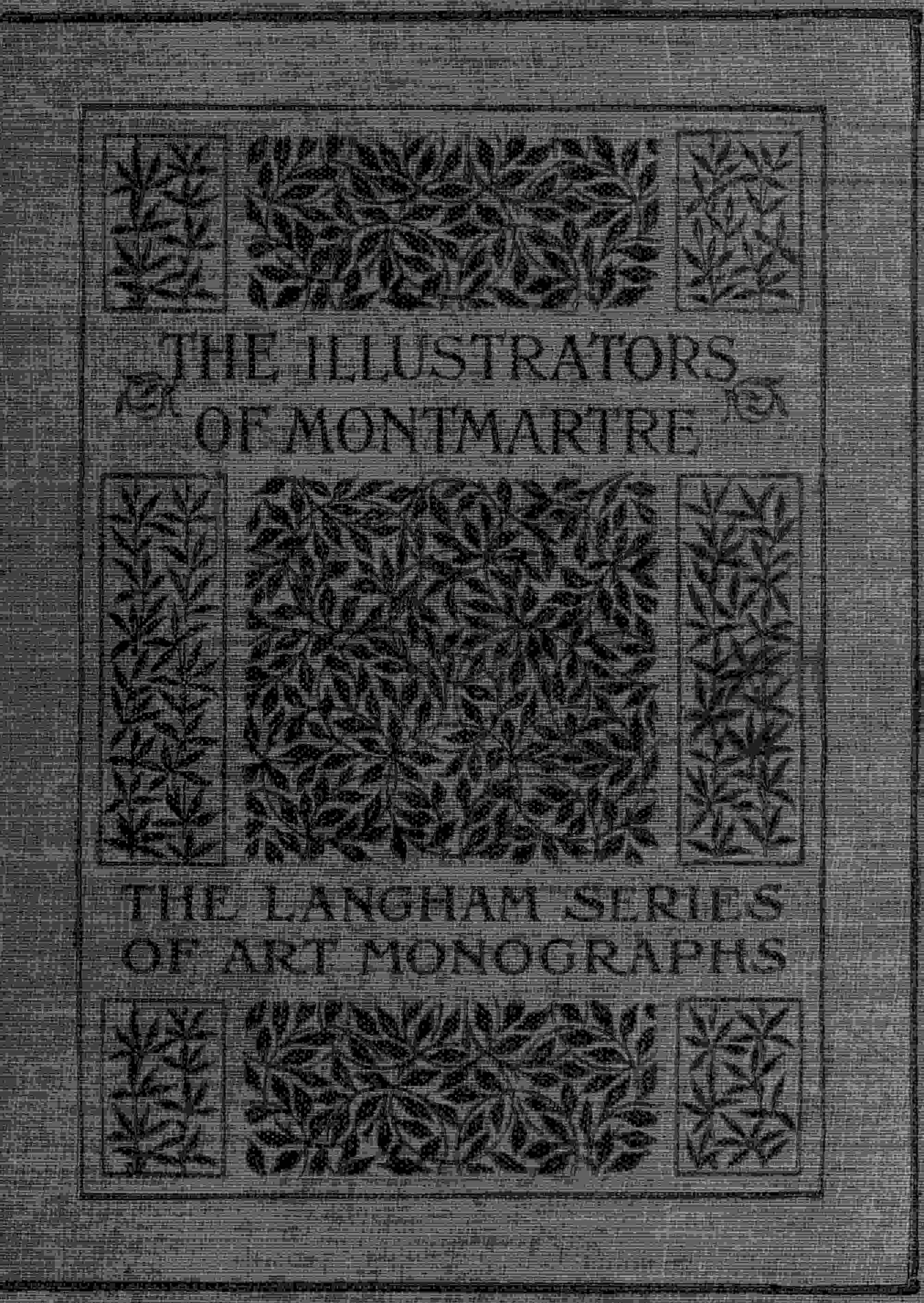

STEINLEN

TROTTIN

(Dressmaker’s Apprentice)

BY

FRANK L. EMANUEL

A. SIEGLE

2 LANGHAM PLACE, LONDON, W.

1904

All rights reserved

TO MY BROTHERS

CHARLES

WALTER

ALFRED

| 1. | Dressmaker’s Apprentice (By Steinlen) | Frontispiece |

| Facing page |

||

| 2. | A “Montmartre Tapestry” Design (By Steinlen) | 2 |

| 3. | On an Exterior Boulevard (By Steinlen) | 6 |

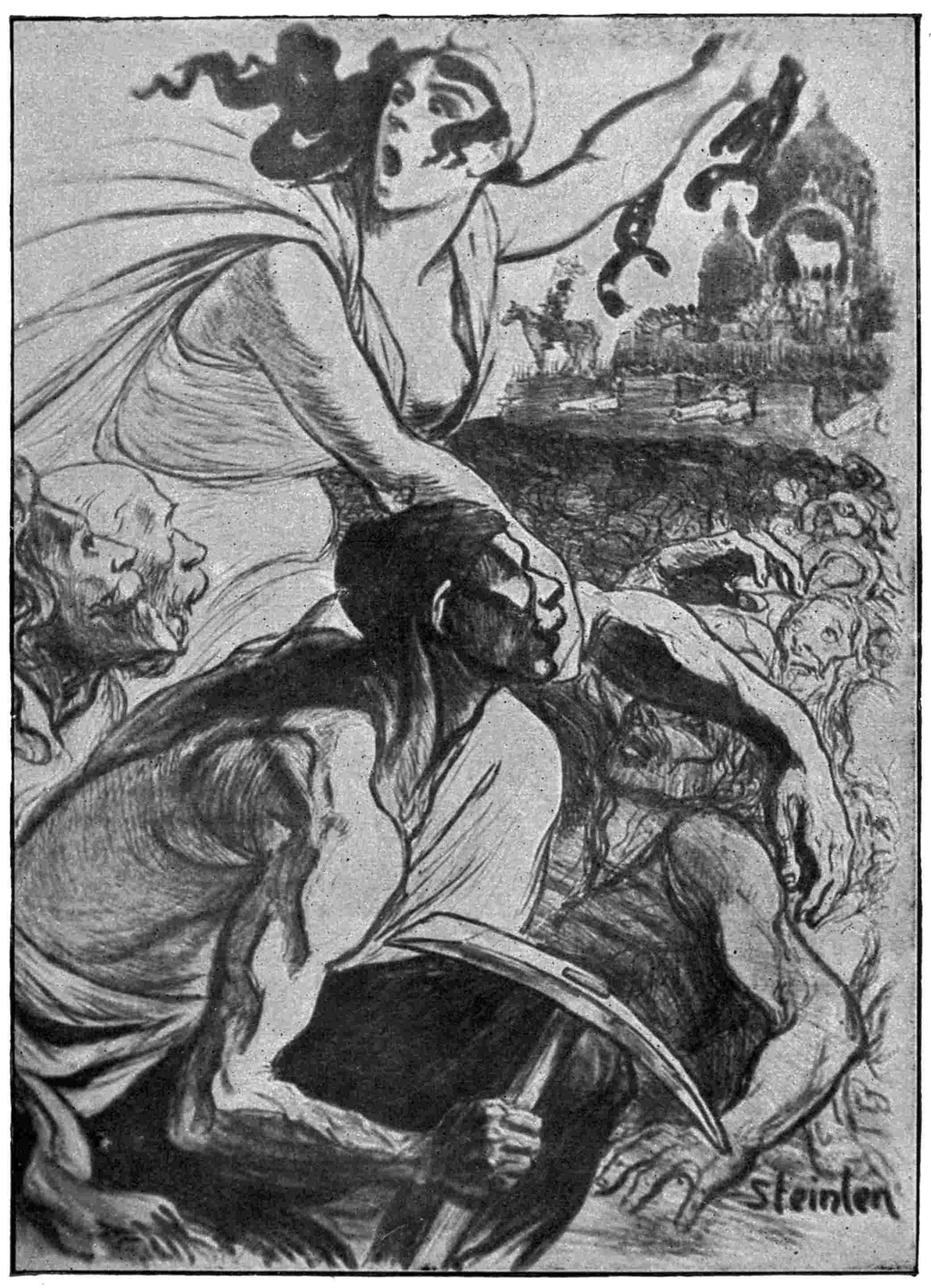

| 4. | Révolution (By Steinlen) | 10 |

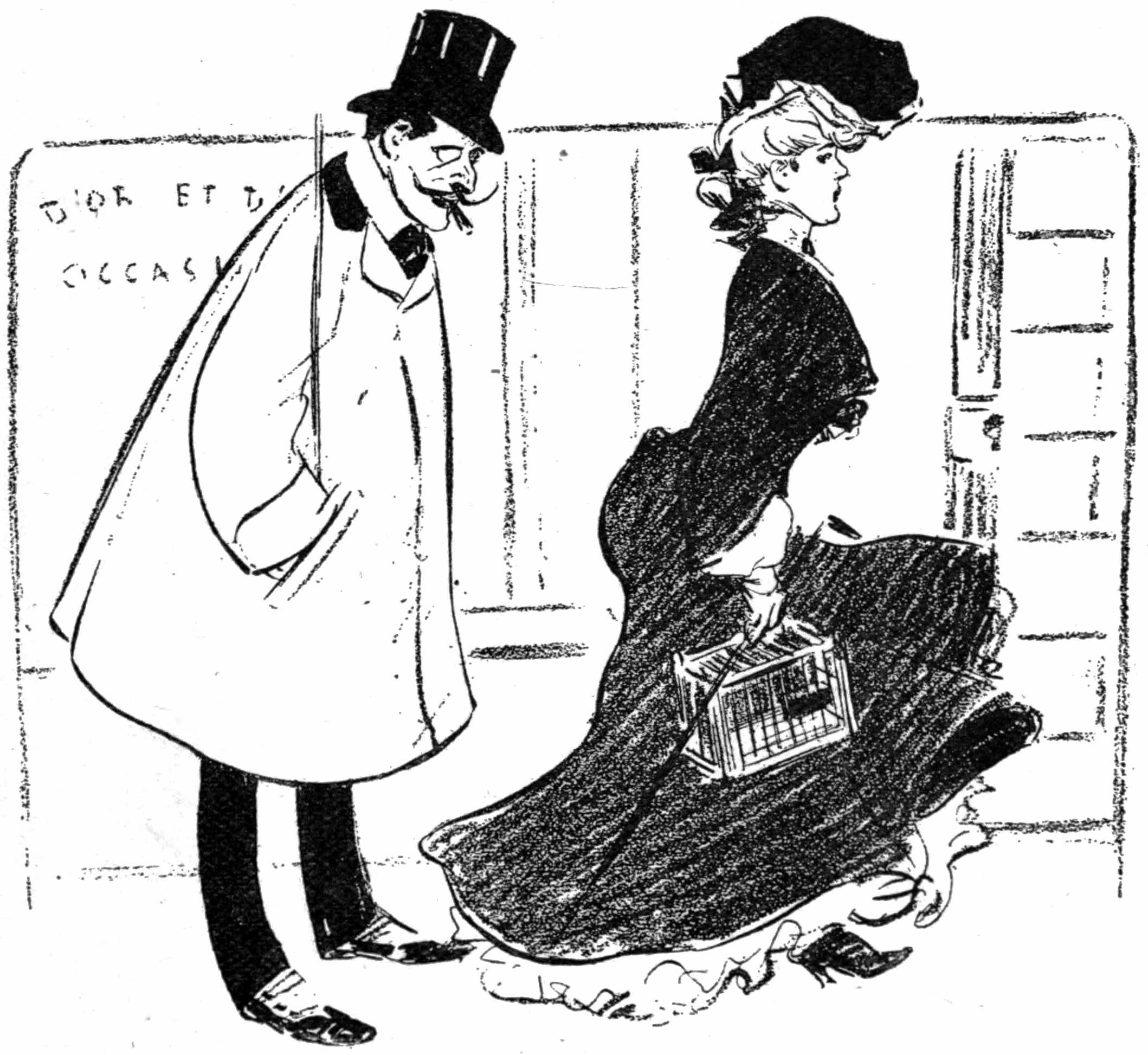

| 5. | En Promenade (By Steinlen) | 14 |

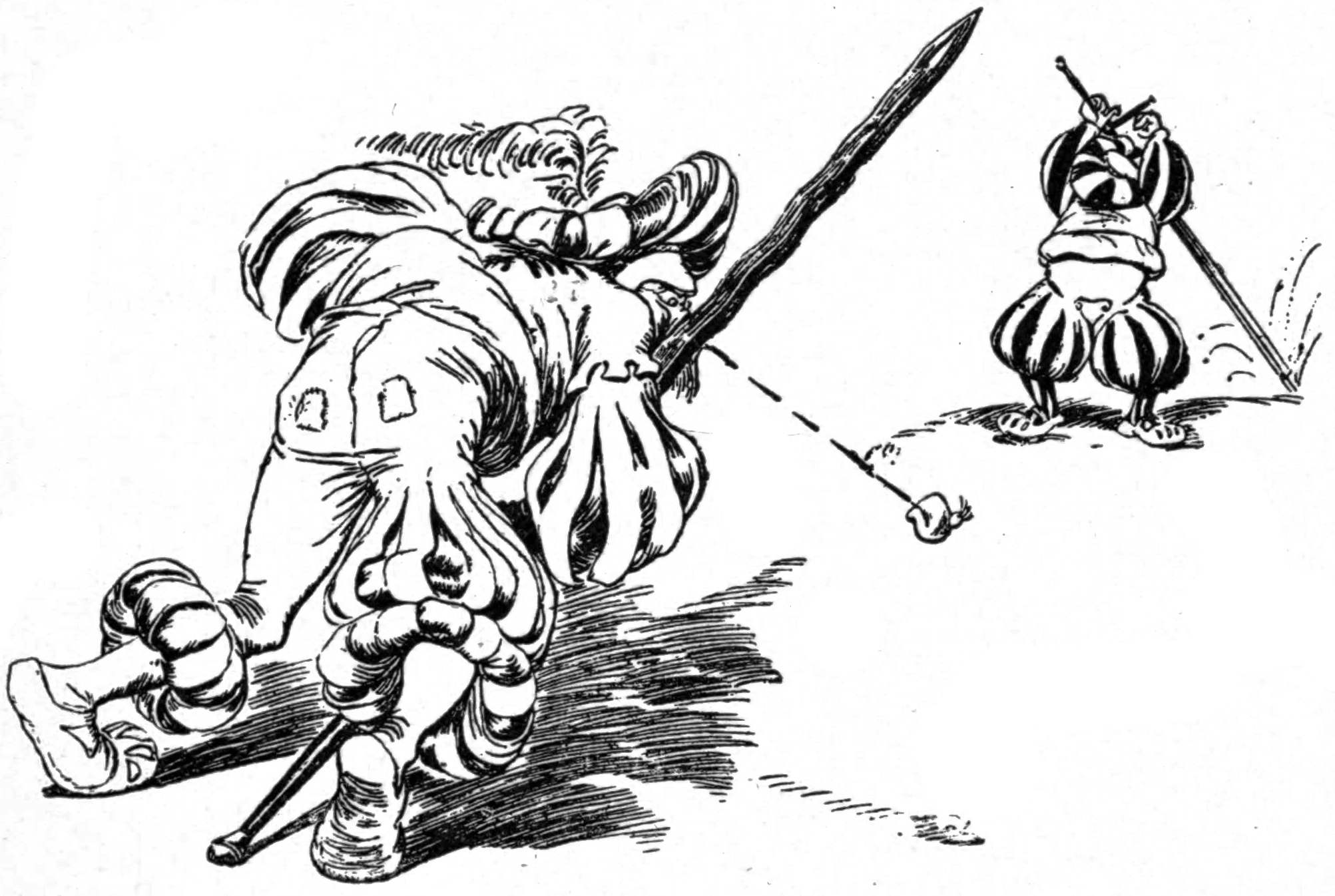

| 6. | The Combat (By Caran d’Ache) | 19 |

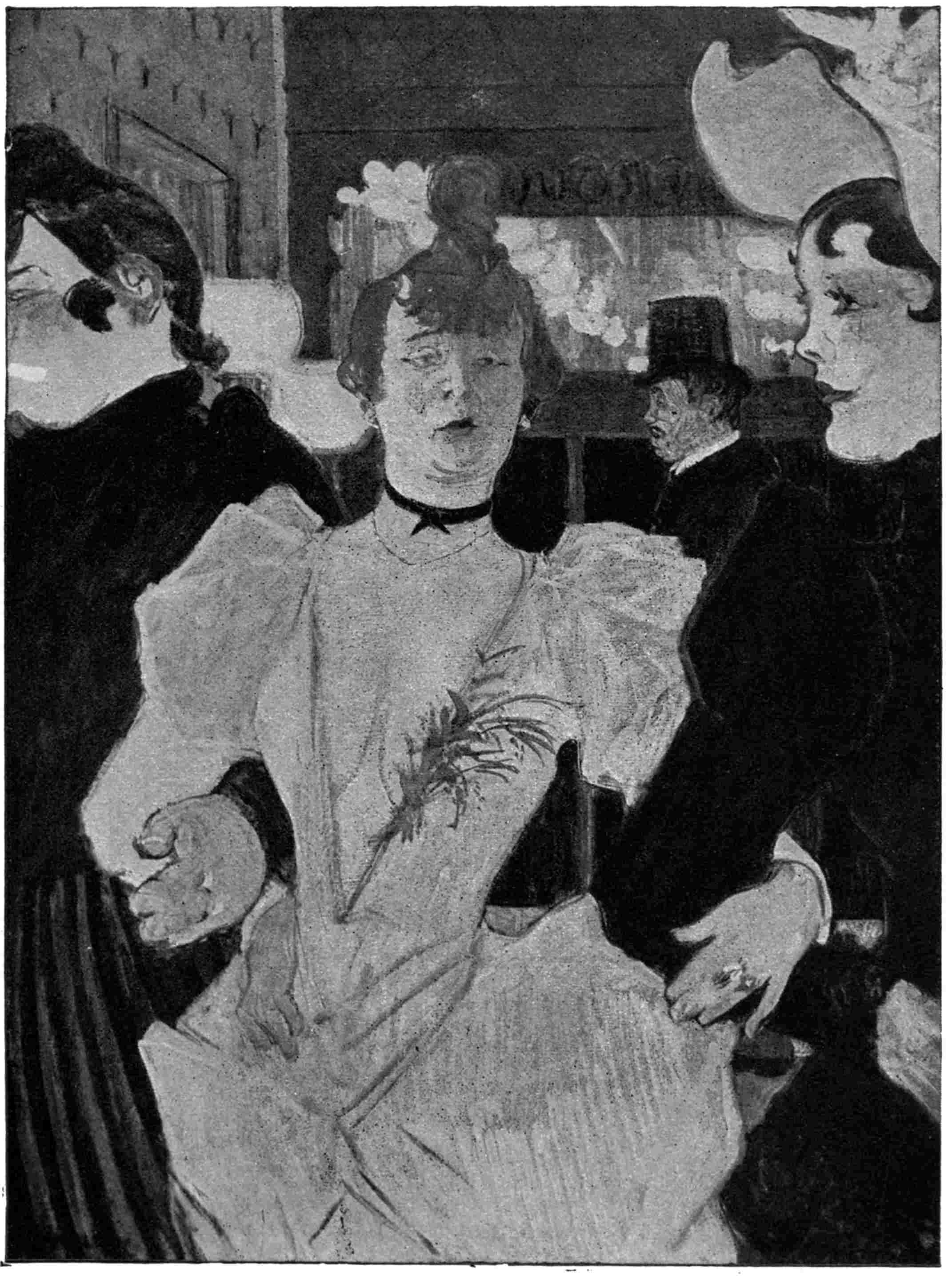

| 7. | At the Moulin Rouge (By De Toulouse Lautrec) | 24 |

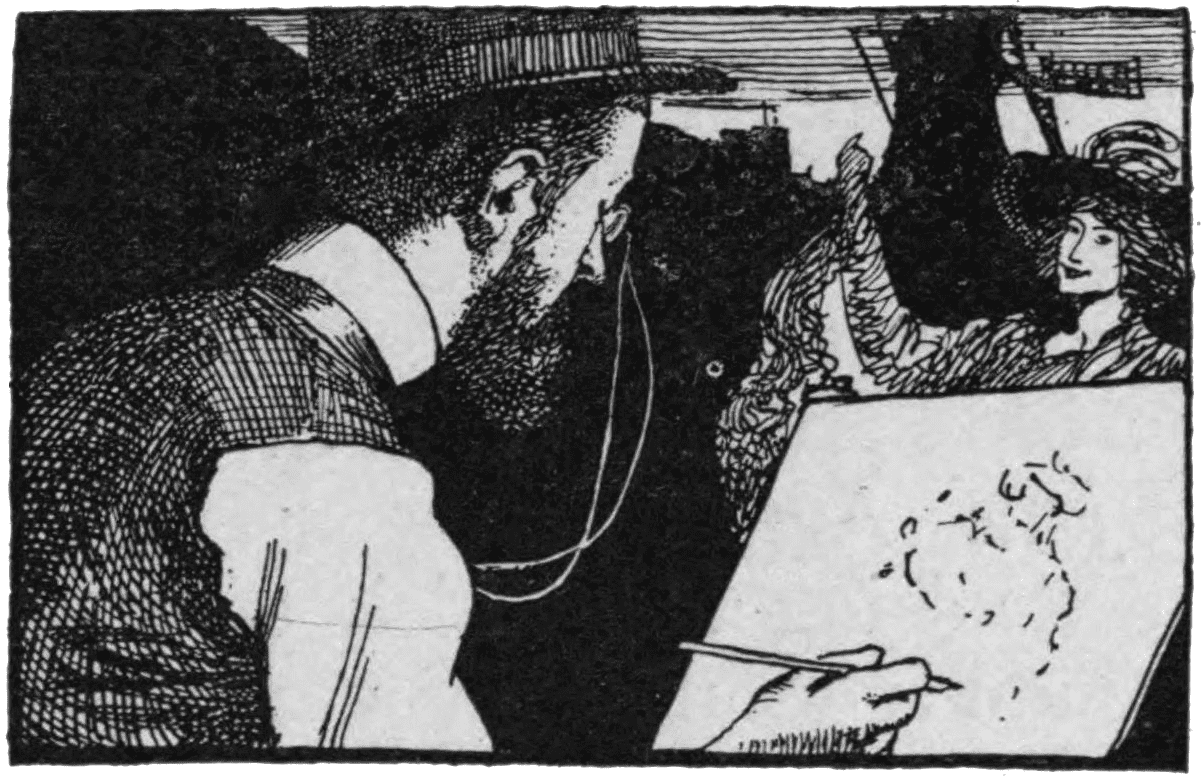

| 8. | Portrait of De Toulouse Lautrec (F. L. Emanuel) | 25 |

| 9. | Yvette Guilbert (By De Toulouse Lautrec) | 28 |

| 10. | “Mimi Pinson, tu iras en Paradis” (By Willette) | 33 |

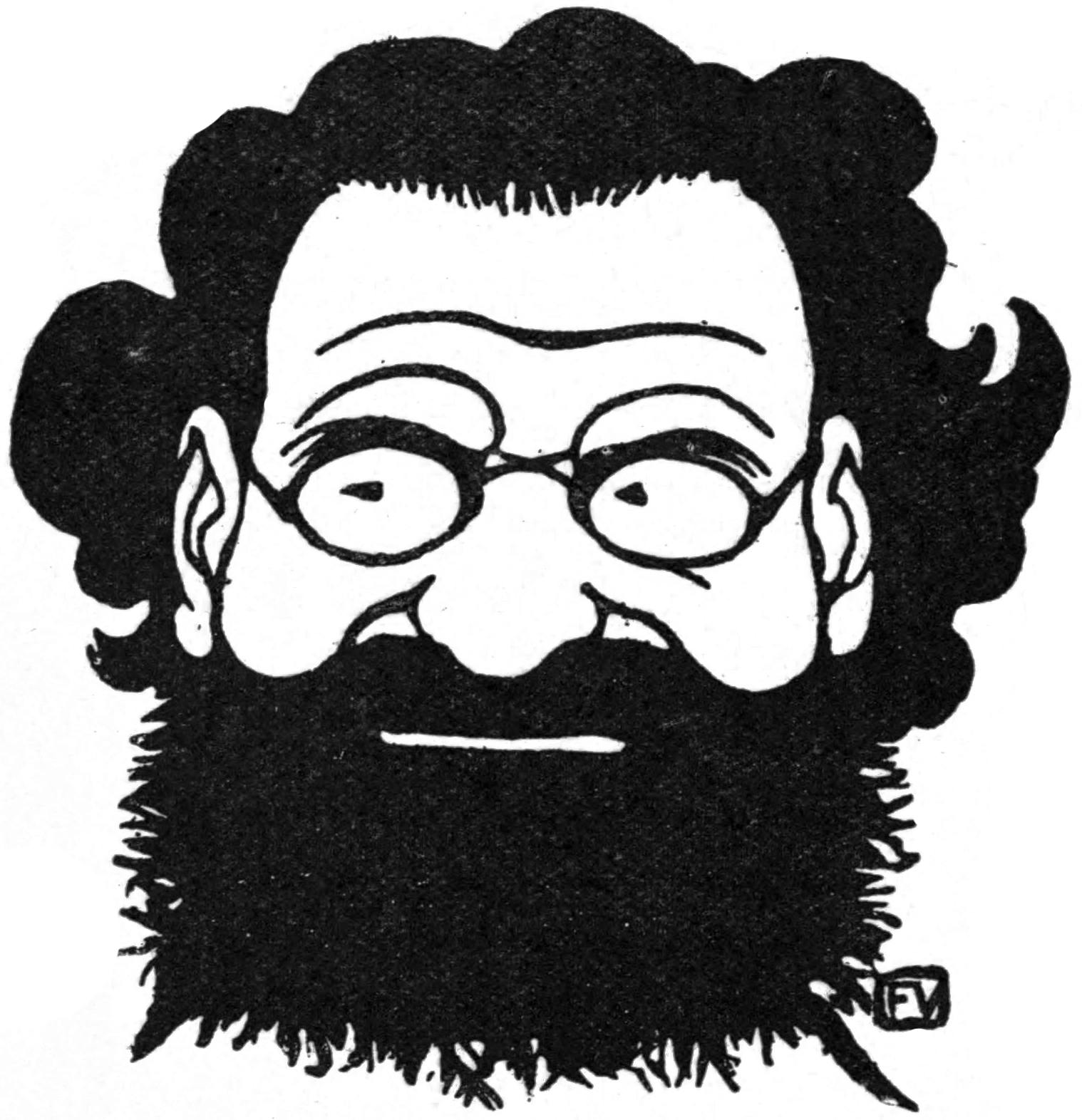

| 11. | Portrait of Drumont (By Vallotton) | 38 |

| 12. | Portrait of Louis Morin (By Morin) | 41 |

| 13. | Knife Grinders (By Huard) | 49 |

| 14. | Psychologue (By Malteste) | 62 |

| 15. | A Moulin Rouge Poster (By De Toulouse Lautrec) | 66 |

| 16. | Rudolph Salis (By Léandre) | 73 |

| 17. | Les Chanteurs de Montmartre (By Léandre) | 78 |

| 18. | Léandre (By Léandre) | 80 |

| 19. | Deux Amis (By Léandre) | 82 |

| 20. | Pierrot, Artiste-Peintre (By Willette) | 86 |

vii

| CHAPTER I | |

| A. STEINLEN | |

| A painter’s painter—His field of operations—The “Chat Noir”—His sympathies and work | Pp. 1–14 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| CARAN D’ACHE | |

| The quality of his humour—His life and military training—His “œuvre” | Pp. 15–21 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| H. DE TOULOUSE LAUTREC | |

| A pathetic life-story—Student days—Comet-like career and sad end | Pp. 22–28 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| P. BALLURIAU | |

| The modern Boucher | Pp. 29–32 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| F. VALLOTTON | |

| His vigorous technique—The “Enfantillistes” and the strong men—His woodcuts | Pp. 34–39viii |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| L. MORIN | |

| A Watteau of our day—His spirituality, and distinction as a writer—The “Chat Noir” shadow plays | Pp. 40–47 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| C. HUARD | |

| The portrayer of provincials—His insight into character | Pp. 48–56 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

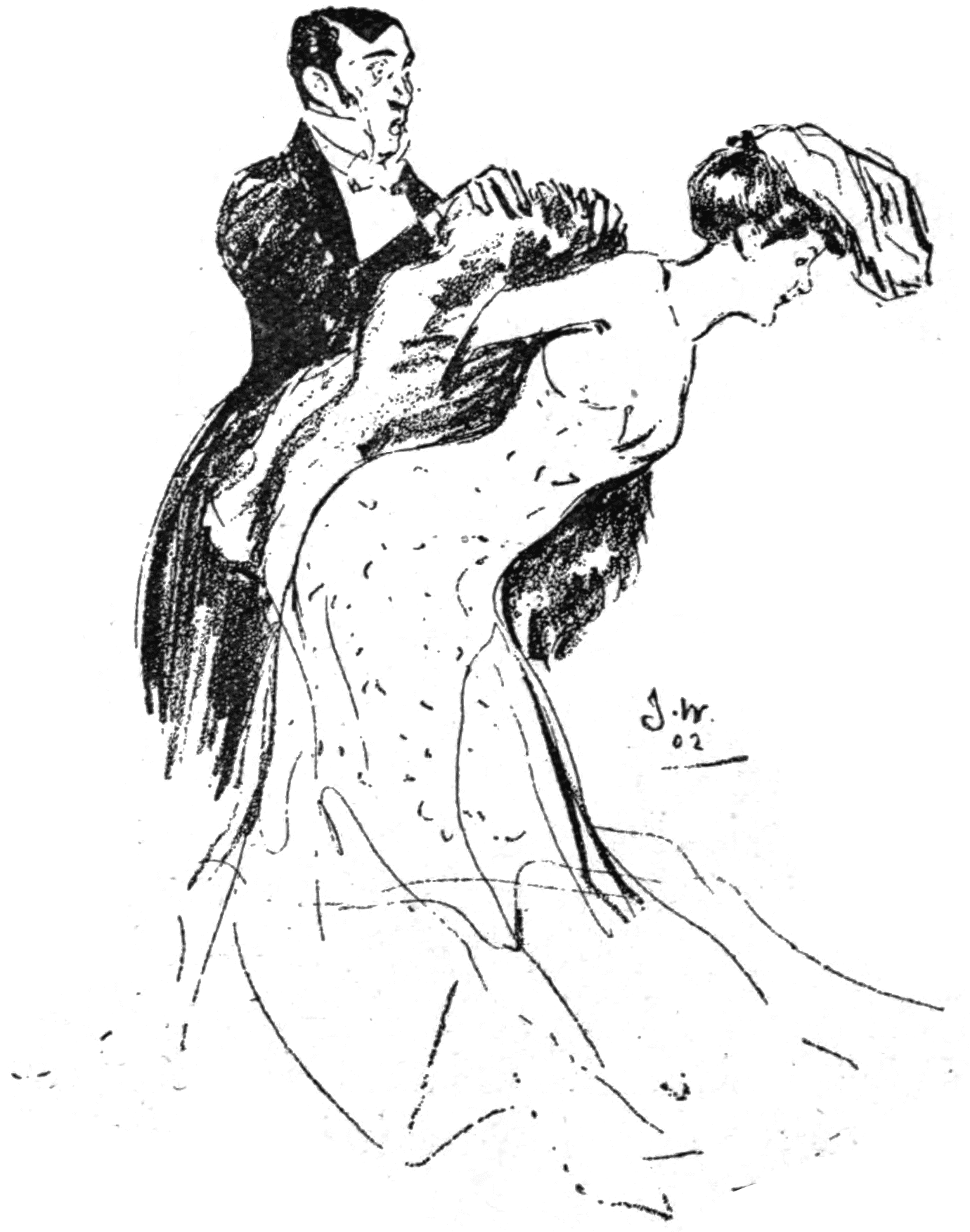

| J. WÉLY | |

| His grace and “esprit”—The modern choice of medium for drawing for reproduction | Pp. 57–61 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| L. MALTESTE | |

| Drawing under difficulties—Strong and serious work | Pp. 62–66 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| J. L. FORAIN | |

| Subtlety of technique and forceful caustic wit | Pp. 67–71 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| C. LÉANDRE | |

| An irresistible caricaturist—The influence of Renouard—His theatre of work | Pp. 72–80 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| CONCLUSION | |

| Temperament of Montmartre and her Free Lances—Plea for a National Gallery of Black and White Art | Pp. 81–83 |

1

There is no modern illustrator whose work has more completely won the admiration of his fellows of the brush, whatever their predilection in art, than Steinlen. Be the studio in Paris, in London, in Munich, be it even in Timbuctoo, from some discreet corner will be drawn a treasured copy or two of Gil Blas Illustré illustrated by Steinlen—forthwith to be discussed, and as surely lauded without stint.

This is not to imply that Steinlen is what is termed “a painter’s painter” and nothing more; for the artist we are now considering is one of the few who are sufficiently great to have captured the warmest appreciation from the public at large, as well as from the critical ranks of his fellow workers.

The “painters’ painter” is, as a rule, if nothing else, a master of technique, one whose work shows2 on the face of it the sheer joy evinced in the skilful manipulation of the medium employed—the exceptions to this rule being the men whose work reflects some subtle or involved workings of the brain, and whose great thoughts are felt to outweigh the shortcomings of faulty technique. They are of course styled “painters’ painters” because their work appeals to artists and other highly trained critics; and it is useless to expect any but the most3 sensitive among the public to appreciate them. In smoothness and “softness” consists the acme of technical perfection in the eyes of the untrained, who, as regards figure subjects, prefer something which appears to the artist to be inane and common-place, and as regards landscape subjects, insipid prettiness is always preferred to greatness or originality of view. In either case an excess of detail is a “sine quâ non,” and such plébiscites as have been taken in England have almost invariably proved that the inferior painters are the most popular.

Yet, occasionally a great artist arises who will upset these canons, and compel the admiration of connoisseur and public alike; such an one is Steinlen.

Just as it may be presumed that J. F. Millet’s popularity extends to all classes, so is it certain that the “Millet of the streets” will be equally widely and lastingly appreciated.

The pioneer work that Millet did in interpreting the toilsome life of the French peasantry has been extended by Steinlen to the denizens—reputable and disreputable—of the nearer suburbs of Paris.

Born in Lausanne, he was trained for the church; and we may feel sure that had he joined that profession he would have been a forcible advocate of the poor and the ill-favoured, and that his blunt honesty of diction would have dealt his congregation some rude shocks indeed.

This was not to be, however, for the art in the4 man would out. In 1882 he journeyed to Paris; there to undergo much privation and many hardships before getting a foothold in the form of a drawing accepted by the paper Le Chat Noir, which was to prove the first rung on his ladder to fame.

Rudolph Salis’ artistic cabaret of the “Black Cat” was the editorial office of this paper, and at the same time a centre of all that was Bohemian and daring and go-ahead, a forcing ground of impatient talent. These first notable studies by Steinlen were of cats and of children. It was here that our artist met the authors whose work he was later to illustrate; more particularly he struck up a friendship with that fierce poet cabaretier, Aristide Bruant, whose powerful and terror-striking poems dealt with the very world that interested Steinlen to the quick, and provided him with the stimulus for many of his finest drawings. They both show us the, to us, shabby joys of the faubouriens, and their terrible struggles with one another and with Dame Fortune.

Steinlen’s field of labour has been in the so-called5 eccentric quarters of Paris—that is to say, on that soiled fringe of nondescript outlying districts of the Ville Lumière, which is separated from the city proper by the circlet of shabby-genteel exterior boulevards. Many of these suburbs were at one time peaceful, outlying villages; but they have now been swallowed, and more or less thoroughly digested, by the metropolis. Thus it comes that many of them consist of a queer mixture of humble rustic abodes jostling against towering blocks of tenement buildings, or busy factories for ever being pressed outwards by the expanding city.

No less incongruous than these streets are their inhabitants,—chiefly composed of armies upon armies of toiling workers, while there is nevertheless an effervescing sediment or substratum of those who live by violence and crime. The less successful of those who trade on the weaknesses and follies of a vicious city are forced by circumstances to live in these cheaper suburbs, just as are the poorest of the honest classes; and this is so despite the fact that throughout Paris the upper stories of all flats are occupied by the lower, or at any rate the poorer, classes.

Curiosity, and a search for novel experiences wherewith to whet their jaded appetites, brought numbers of roysterers of a higher social grade to the places of amusement affected by this poverty-stricken and criminal population. These same humble places of amusement, more particularly round and about6 Montmartre rapidly flourished out of all recognition of their former selves, and until the recent waning of the craze others were frequently being added to the list. This influx added to the complex character of such neighbourhoods. Artists, authors, and other persons of more or less Bohemian tastes, many of them men of great renown and genius, have ever found their home on the commanding heights of the Montmartre cliff.

Among them Steinlen has settled, perched high7 over the myriad glittering roofs and towers and domes of Paris, which lies seething far below. The roar and clatter of the great city reach his window but fitfully, as the sounds are hurried hither and thither on the wings of wayward breezes, the while great stretches of urban landscape are plunged into purple shadow or bathed in golden sunlight as the fleeting clouds chase one another across the great dome of sky.

Most of the artists to be referred to in this little volume are intimately connected with this same breezy, turbulent suburb, and also with the before-mentioned “Chat Noir”. This cabaret, founded and carried on by Salis, himself an artist, for years attracted le tout Paris by means of its réunions of the most up-to-date artists, authors, and actors, and its unique theatre. Along with its sprightly, risky weekly paper it would form matter for a weighty volume of itself. The students from the Quartier Latin, moreover, came to share their joyous, reckless hours of leisure between their own beloved neighbourhood of the Boul’ Mich’, and the far-away Mount of the Windmills—Montmartre.

Peasants, workgirls, the starving, the insane, the destitute, those who are fighting misery and those who are making it, garrotters, thieves, murderers, and a large assortment of parasitical ruffians as well, have all found a sympathetic student and recorder in Steinlen. He understands them, he has a big8 heart, and he pities them all, and what is more he makes us, willy-nilly, pity them also. He delights in showing us that one little touch of remaining nature that makes the whole world akin, and will out in his most abandoned wretch. He makes us feel that his criminals are what nature and cruel circumstances have led them to be. Never does he descend to the narrow-minded, short-sighted, spiteful views of current events, discernible in the work of so many of his talented confrères. The firm tenderness of his nature reveals itself in the very lines of his drawings, which, as if to counterbalance the brilliant vivacity of the work of so many French illustrators, display a sturdy thoroughness and sanity.

A notable feature about his work is that—although he depicts the most depraved and immoral, as well as the most poverty-stricken of his fellow citizens—it cannot be said to be low or vulgar.

His drawings of simple peasant life have all the air of having been undertaken as a relaxation from the contemplation of more lurid subjects. He sallies forth among his chance models, sketch-book in hand, ready to put down notes of salient features and expressive poses, later to be incorporated in the wonderfully complete drawings which are shown to the public.

Steinlen is a prolific worker. First in importance among the many publications whose pages he has enriched comes the Gil Blas Illustré. It was9 Steinlen who initiated the idea of this Paris daily paper issuing a halfpenny supplement on Sundays containing feuilletons and poetry, illustrated with drawings to be reproduced in two or more colours. Since the year 1891, and until recently, the front and frequently other pages of this paper have consisted of splendid drawings by him, as a rule depicting some terrible or pathetic episode in the lives of the faubouriens or faubouriennes to whom we have already alluded. In every case a background, equally masterly and full of local character, has been introduced. This series of essentially modern subjects was occasionally varied by the appearance of a drawing such as the Chevalier à la Fée or Les Digitales, inspired by some mediæval incident or legend. These Steinlen would treat in an entirely different but equally successful manner—the style employed somewhat resembling that of another masterly designer, namely, Eugène Grasset. Of his more usual style to pick out such splendid drawings as his suicide in À l’eau, the terrible street fight in the Voix du Sang or Le Vagabond, L’Immolation, Pour les Amoureux et pour les Oiseaux, Marchand de Marrons or 14 Juillet, is but to recall hundreds of others equally worthy of special attention.

In 1895 the Gil Blas employed more colours in its reproductions, and Steinlen rose to the occasion with some daring colour schemes exemplified in La Terre Chante au Crépuscule, Le Poil de Carotte10 and many another drawing. Towards 1896 the range of his subjects noticeably widened.

Among other publications to which he has contributed one recalls Le Chambard, in which appeared splendid lithographs from his own hand, La Feuille, L’Assiette au Beurre, La Vie en Rose, Le Canard Sauvage, etc. In the following music albums will be found some further superb lithographs by Steinlen, namely, Chanson de Montmartre, Chansons du Quartier Latin, and Chanson de Femmes. Among the books he has illustrated are: Les Gaitès Bourgeois, Prison fin de Siècle, Dans la Rue, and Dans la Vie—the latter in colour.

Description of a few of his notable drawings, culled here and there, may help us to a better understanding of their quality.

First, then, he shows us the gallery of some dark, putrid Assembly Hall; the air is thick with garlic, and oaths, and gas, whose garish light illuminates a disreputable mob of frenzied anarchists, who are applauding with delirious gusto the sentiments of “Down with everything,” “Death to every one.”

STEINLEN

REVOLUTION

(Lithographed Poster)

Next we are taken to some dull, superstitious Breton hamlet; a blind and crippled tramp has arrived, hobbling through on crutches. We feel that his infirmities have hardly saved him from a career of violence. We can almost hear his raucous appeal for alms, as it falls on the ears of a group of simple village children, pitying, yet more than half-fearing, the uncanny stranger—just as they did the chained bear that passed through a week before.

Less gruesome is a great healthy farmer’s lass, surrounded by cocks and hens and clattering her wooden shoon across the cobbled farmyard; or the two fresh little laundry girls, swinging along laden with three great baskets of clean linen. “Look out! there’s another of those beastly bicycles,” says one of them; “and on Sunday too,” comments the other.

Then again there are idyllic scenes on the sordid Paris fortifications, or yet further afield. Trompe la Mort shows us a crowd of humble folk scandal-mongering in hushed tones, their tittle-tattle provoked to its utmost by the climax indicated in the background by a sombre hearse. Another drawing transports us to the midst of a crowd in quite a different frame of mind. A hue and cry has been raised, and an infuriated mob is tearing down the street at the heels of its hapless prey. Next we see one of the many drawings dealing with a side of life which in less safe hands might be offensive. An unctuous old harpy waylays two fresh little workgirls, and insidiously lays the seeds which, to her profit, shall lead to their downfall. Steinlen occasionally, if rarely, makes drawings of which humour is the motive power. Among these I recall a café-concert study of his. Yvette Guilbert, at that time as thin as a lath, holds the stage, and among the audience is a great, porpoise-like woman who says,12 threateningly to her poor, inoffensive little wisp of a husband—“Perhaps that’s your style.... Satyr.”

One of his most charming drawings reproduced in colour in Le Rire is called “le bon Gîte.” The hapless Krüger, all war stained, is seated in some peaceful Dutch cottage, where Queen Wilhelmina, as an awe-struck peasant lassie, fills for him the pipe of peace, the while her martial German husband eagerly engages the old man in fighting his battles over again.

Nor can we forget the splendid double-page drawing that appeared in L’Assiette au Beurre for May 23, 1901. Here we see a big boy’s seminary, representing the French army of the future, the hope of the country, going out for its daily walk in charge of a number of priests—every one of them a monument of craftiness, superstition or bigoted intolerance, thus representing the power that poisoned a great nation’s sense of justice during the hateful period of the Dreyfus trials.

Then again in the same paper for June 27, 1901, appears among others one of his most notable drawing, a veritable tour de force, representing the harrowing scene of the identification of corpses after the dynamite explosion at Issy.

It is interesting to compare such powerful work as this with one of his earliest successes, namely the illustrations to Les Gaitès Bourgeoises, a set of chic and delicate little pen-drawings instinct with humour and gaiety.

13

Steinlen is a giant in the artistic poster movement. Some of his productions were lithographs in colour of enormous size, each printed from as many as thirty different lithographic stones. Here and there a poster would give him the opportunity to introduce some of the marvellous drawings of cats for which he is so justly renowned; and in this connection we cannot forbear mentioning two splendid drawings of cocks which appeared in the earlier numbers of Cocorico, as well as some wonderfully spirited comic drawings of frogs in a volume entitled “Entrée de Clowns.”

Those who keep an eye on the picture galleries of the Paris streets can never forget, so splendid was their design and colouring, Steinlen’s great posters for La Rue, or the equally long and fresco-like groups of realistic Parisian types advertising the “Affiches Charles Verneau.” Then, who does not love the “Lait Pur Sterilisé” poster with its golden-haired little girl in scarlet drinking out of a saucer, while three inimitable cats beg at her knee. His poster for Zola’s “Paris” was a poem in itself; and in the “Tournée du Chat Noir” the noble beast concerned is treated to a glory of decoration. Then there are his daring “La Feuille” poster, his “Yvette Guilbert,” and many another, not to mention programme covers and such smaller game.

Finally, Steinlen has produced charming etchings, both in colour and in black and white, and such splendid oil paintings as Les Blanchisseuses.

14

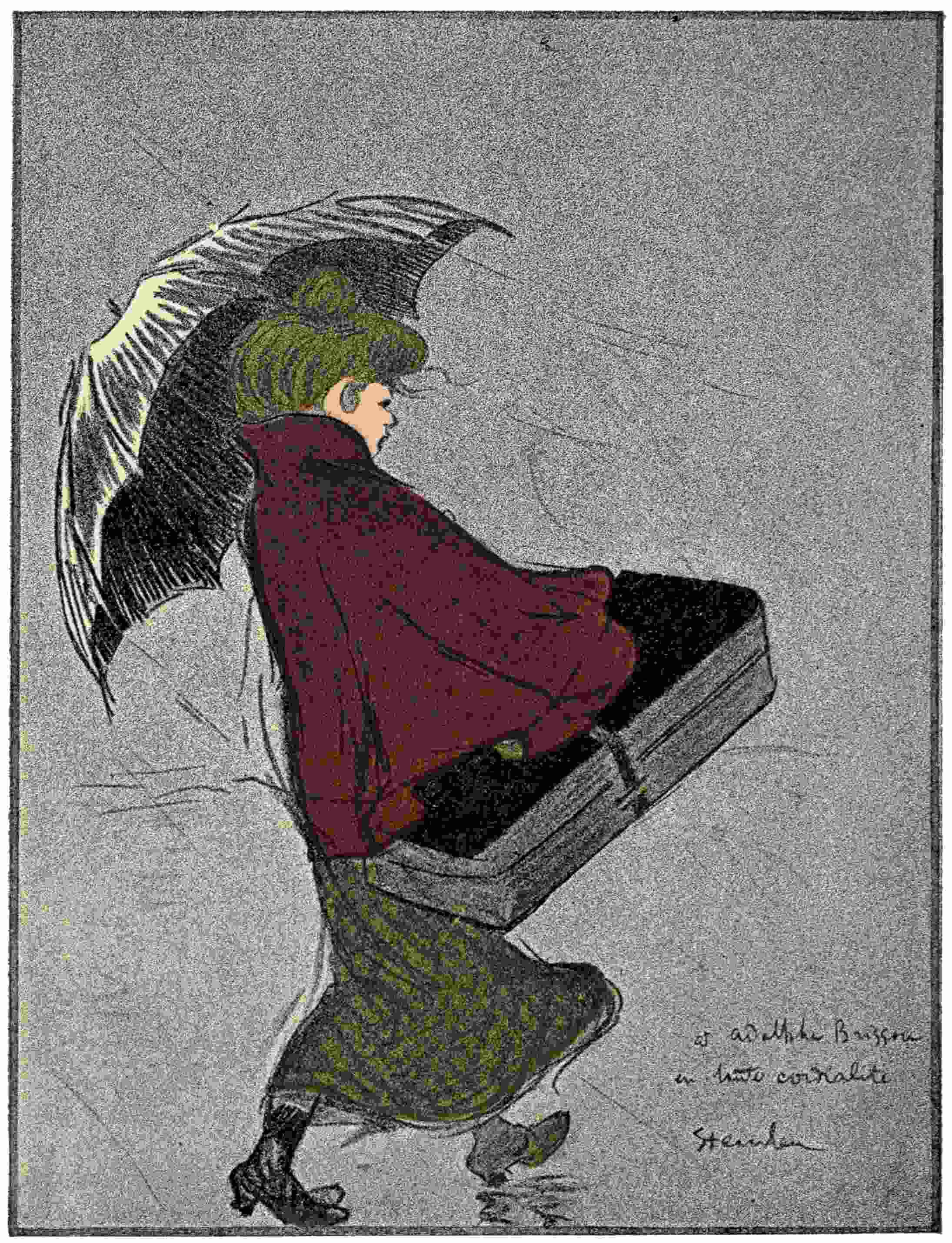

STEINLEN

Gil Blas Illustré

EN PROMENADE

(Pen drawing)

15

Emmanuel Poiré, better known by his Russian pseudonym of Caran d’Ache (pencil), is a public benefactor, in that he has considerably added to the gaiety of nations; and if it be true that one laughs and grows fat, then he must also be responsible for much of the extra weight that those nations carry with them.

The man upon whom one may count to make one merry is sure to be popular. Caran d’Ache, as we have already hinted, has made whole nations merry, and he is a popular favourite. It is true that sometimes his own infectious laughter is cynical, or spiteful, or cruel to a minority, but he always has the majority to laugh with him, and follow him in his pictured tirades—be they well-considered or ill-considered. But, after all, that is perhaps a matter of politics, or nationality, or religion, or what not; and the fact remains that16 his drawings are irresistibly humorous, and are always excellent works of art.

Caran d’Ache was born in Moscow, of French parents, but when twenty years of age he came to Paris, where his innate talent soon evinced itself.

While undergoing his military service in the early eighties his unquenchable passion for drawing was put by the authorities to their practical use, in making studies of past and current military uniforms for the War Office. The costumes of the glorious Napoleonic era and of Germany were made a speciality, and the knowledge thus acquired was carefully retained by the young artist, and served him in good stead in his later years.

Caran d’Ache, like every thorough-going Frenchman, preserves his love for the army, incidents in whose life he is never tired of depicting with that spirited brilliance we have come to know so well. And the military officer’s smartness of bearing has stuck to him, for he is recognised as an “ultra chic”,—a very dandy among the illustrators, and an eccentric one at that. Yet at the same time he refuses to associate himself with the smart set in Paris; he has too much of the artist temperament for that.

He was early attracted to the “Chat Noir” on the Butte of Montmartre, and Rudolph Salis—that keen exploiter or genial art patron, which you will—was not long in appreciating the talent of his client. Soon we hear of him achieving an artistic17 triumph with his astoundingly perfect shadow pantomime, L’Epopée, at the little “Chat Noir” Theatre. Caran d’Ache had spared no trouble to make his silhouettes and the effects in which they were set as perfect as possible. No greater pains could have been taken preliminary to the painting of a series of Salon pictures; and he reaped fame as his reward.

“L’Epopée” dealt with Napoleon’s succession of military triumphs. Opportunity was thus early given to M. Poiré to display his astonishing knowledge of the horse in all its varied attitudes.

The horse he delights and excels in is a magnificent, proud, high-mettled beast, whom he puts at some breakneck charge, or causes to career about in high-strung excitement. Caran d’Ache’s army horses are not surpassed even by those of such acknowledged masters as Meissonier and Détaille. The Studio published some splendid equine studies of his a year or so ago, which must have been a revelation to those who had previously looked on Caran d’Ache as a comic artist and nothing more.

His drawings have been produced in innumerable papers, magazines, and books, and are for ever being re-reproduced abroad. Collections of his caricatures have been published as “L’Album Caran-d’-Ache,” “Bric-a-Brac,” “Le Carnet de Cheques,” “La Comédie du Jour,” “Les Courses dans l’Antiquité,” “Fantaisies,” “Galérie Comique,” “Les Peintres chez-eux,” apart from his illustrations to “C’est à18 prendre ou à laisser,” “Prince Kozakokoff,” “Malbrough,” &c. More recently “L’Album” published a selection of his works, including some drawings done in a bolder style than that which he generally produces for reproduction,—such are the Battery of Dreadnoughts, bold and grim, and the splendid Charge. In the drawing of himself there is a good specimen of those caricature portraits for which he is so renowned.

His work appeared in the pages of Tout Paris, La Vie Moderne, La Revue Illustrée, and Le Chat Noir, &c.; superb military sketches came out in La Caricature; and every week he carries on a running fire of pencilled commentary in Le Journal, and Le Figaro, contributing at the same time to Le Canard Sauvage, and Le Rire. A special number of the latter paper entitled Tactique et Stratégie consisted of a short series of vigorous military cartoons, representing various epochs, drawn on a large scale, and some of them reproduced in colours.

However, it is by his stories without words that Caran d’Ache has attracted most attention, and, it must be confessed, they are simply captivating. Comic stories have been told by the same means in Germany for half a century or more, but Caran d’Ache is credited with having introduced the progressive drawing into France.

Caran d’Ache’s little tales need not a syllable of explanation. All is told by the subtlest of alterations19 in the expressions on the faces of his figures, in the movements of their bodies, or of other animated or inanimate bodies; there is never any mistaking the gist of a Caran d’Ache story. His attention to detail is marvellous, yet everything takes its right place, and the venue is never confused.

Nothing could better than—say—the set of thirty-eight drawings entitled M. Toutbeau catches the 5.17 a.m. Express. We trace the dear, fat old fellow through all his agony. He is asleep. He wakes in a perspiration of fright—ten to five—on with them—that accursed tight boot—almost forgot to wash—tie—good gracious, seven to—hallo, there20 goes a button—Palsembleu!—5 o’clock—hair done—now for my coat—I shall never do it! And so on, through all the terrors of hasty packing, ringings for the servant, getting, discussing and paying the hotel bill—umbrella left behind and recovered at the last moment—the dash into a crawling cab—and then Mr. Toutbeau is seen beaming in his first-class railway carriage.

Who does not know the Great Expectations set, wherein the expectant nephew, to his joy, is telegraphed for by his dying uncle; and how the latter miraculously gets stronger and plumper day by day, just as the erstwhile buoyant and vigorous nephew’s growing disappointment drags him visibly nearer and nearer to an untimely grave.

Then there is the little set of three Shooting Impressions of my Friend Marius, who presumably hails from the Midi. First he is in the North of France with his gun and his dog—nothing in sight, no game at all! Next he is in the Midlands, both man and dog are happier, There’s just a little, and a bird has been bagged. Lastly, he’s in his beloved and romantic Midi and there’s too much; there’s no room to walk for the game; they press round and caress the bloodthirsty Marius, a hare is making up to the dog, and one confiding game bird has brought its nest of young and actually settled with them on the gun barrel!

Another splendid set is that of The Finest Conquest of Man, wherein is traced the marvellous horsemanship21 of a swell, who, with the greatest of ease and suavity, completely subdues a very demon of a horse.

But we could proceed thus ad infinitum and yet never give an idea of the wonderful spirit of the drawings, which must be seen to be loved.

Most of them are executed with a thin, very precise and sensitive line. How successfully he can manage bold masses when necessary we can judge by his excellent Cossack poster for the “Exposition Russe,” or in those used to advertise the exhibition of his own works at the Fine Art Society, London, in 1898.

22

Lautrec is one of those artists whose work is so uneven and out of the ordinary, that opinions as to its merits or demerits will ever remain as strongly divided now that he is gone, as ever they were during his lifetime. His short life work consists of a mixed series of talented absurdities, and of veritable tours de force. His genius, alas! was of the species that borders on insanity. Occasionally the border was overstepped.

In more ways than one Aubrey Beardsley’s short life may be compared to that of Lautrec. His genius was of a similar order, and as one examines his work, so will one be inclined first to call him an unwholesome incompetent, and next feel convinced that he is a pioneer artist of the first rank.

Lautrec’s life story is a very pathetic one. With him in 1901 was extinguished the last remnant of an ancient line of nobles. His father was an amateur23 sculptor and painter, who was extremely fond of sport. The family came to live in Paris in 1883. The artist son was a dwarf, and after fighting hard against his handicap, and cheerfully entering the ring to tilt successfully for fame, his mind gave way, and he died at an early age in his father’s castle at Albi, after having been confined in a private asylum.

Lautrec’s student days were passed in Paris at Cormon’s atelier. His work done from the life in the studio did not hold out any great promise of later achievement; but, as is often the case, the untrammelled work he did outside was recognised at once as being out of the ordinary, and frequently of great merit. He would bring to the studio to show his comrades very clever sketches of types he had encountered during his rambles along the Boulevards. Indeed, Lautrec occasionally asserted with some bitterness in after days that it was these studies that had inspired Steinlen to make the character-drawings through which he had become famous—Steinlen having previously made cats and children his chief study.

However this may be, one has not much patience with such claims. Real plagiarism is a detestable thing, but surely there is room for more than one artist in the field of the life of the poor, or of the amusements of a huge city like Paris, without being suspected of that offence. In any case Steinlen has treated his subject as no one else has done, or probably could do.

24

Lautrec was deservedly popular with his fellow students; his excellent wit, delivered in a strident voice, and punctuated with the gesticulations of a pair of extraordinarily short arms, always proved entertaining to those in the midst of whose company he happened to be.

His best work is probably to be found amongst his posters and portraits. His illustrations, except in his earliest work, as seen in Paris Illustré, more frequently show those crude vagaries of form and colour, which would point to an unevenly balanced judgment.

That Anquetin’s drawings strongly influenced Lautrec’s work is evident, while Raffaëlli, Degas and Renoir were his particular gods in art. Whether Ibels influenced him, or vice versâ, it is difficult to judge; but in any case there is a remarkable similarity in the aims and peculiarities of their art.

DE TOULOUSE LAUTREC

Paris—Collection Bernheim

AT THE MOULIN ROUGE

(Oil-Painting)

There is a magnificent poster of the poet-saloon-keeper, Aristide Bruant, by Lautrec, which alone would have been sufficient to place him high among modern artists. Bruant in a large soft hat and wrapped in a cloak of a gorgeous subdued blue, moves with vivid energy across the sheet. His strong face, printed in grey, is wonderfully rendered with a few telling strokes. Little less attractive is his Bruant at the Ambassadeurs Music Hall. These are but two of many fine posters, done since his first essay in 1888, to advertise the stars of that peculiar firmament of the Cafés Chantants, to which Lautrec was drawn as a moth to the flame.

He lithographed posters of Cissy Loftus, of the beautiful Anna Held, La Goulue the dancer of the Moulin Rouge, and May Belfort; and being particularly attracted by the picturesque possibilities of Yvette Guilbert, with her then lithe figure and inevitable long black gloves, he introduces her into many of his works. Then there is a remarkable poster advertising Babylone d’Allemagne, and a yet more striking one for La Vache Enragée, where we see a mad cow charging an old coloured dandy down a street. There is also the startling advertisement for “L’artisan moderne,” and the truly terrible “At the Foot of the Scaffold.” Apart from these there are his posters “in little,” and programme-covers, such as those for Le Missionaire and L’Argent.

The very peculiarities and incomprehensibilities inherent in Lautrec’s work were sure to arrest attention, and demand that scrutiny which is of the very essence of the successful poster. In every one of Lautrec’s poster designs there is something26 strikingly unusual. Very rarely is a figure drawn in its entirety; the margin cuts off part of it, otherwise the design would have been too conventional for him.

The artiste Caudieux zig-zags across a stage seen in violent perspective, while down in a corner is a worried member of the orchestra studying the coming bars. Caudieux’s head is full of life and pent-up strength, and the whole movement of this quaintly placed figure is striking in the extreme.

Jane Avril’s poster shows an anæmic-looking artiste doing a high kick on the stage. The foreground is occupied by a monster hand holding the head of a ’cello in the orchestra.

The poster for the Divan Japonais, on the other hand, shows us a lady and gentleman in the audience listening to a singer on the stage, behind an orchestra. Of the singer we see monster black gloves, and everything but the head; of the orchestra we are shown two ’cello heads, and, of the conductor, the arms alone. The lady in the foreground—who looks as though she always turned night into day—is wonderfully depicted, as is her companion, the dissipated, bearded swell. Perhaps his most graceful work in the poster line is that advertising Elles.

Finally in the poster for La Gitane, an unsavoury actress, arms akimbo, who comes right out of the design in the left hand foreground, smiles over her shoulder at the bold bad brigand who strides, in27 shadow, out of the poster at the top right hand corner. In all these and his other posters the lettering is bold and legible.

Lautrec’s studies in the music halls are uncompromising in their garishness; he apparently does not attempt to seek beauty where it exists in such small quantities, or has been so carefully hidden. He delights in the flare and glare, the powder and paint, the discords and the inconsistencies of the thing. He prefers the raucous screech of the bold-faced jig, whose reputation as a songstress rests on her fine limbs, to the exquisite song of the highly-trained opera singer. He would reject gold in favour of tinsel. Yet this same man in another mood would paint a splendid and refined portrait.

Then there is Lona Barrison, jauntily leading her white horse out of the ring, followed by her manager with the pale chrome hair and beard; and then the hideous negro—“Chocolat dancing in a bar.” All of these figures, despite their faulty drawing and their element of caricature, carry conviction with them.

Lautrec’s travels in Spain, in England, Holland, and Belgium seem to have left little impression on his work. It is probable that the unhealthy surroundings and late hours imposed by his studies in café-concerts, in green-rooms, in libertine ballrooms and worse, hastened the end of that frail, feverish life—a life like that of a gaudily coloured rocket, brilliant and soon spent.

28

In his later years he had evinced a great attraction towards the repulsive and the gruesome, and took a pleasure in seeing medical operations performed. Curiously enough, his studio window overlooked a cemetery.

By De Toulouse Lautrec

YVETTE GUILBERT

29

Balluriau is best known as the artist who has supplemented Steinlen’s realism in the pages of the Gil Blas Illustré with drawings full of fancy and imagination. Just as we shall call Morin the Watteau, so he may be styled the Boucher of the modern French press.

His work, however, has not been confined to the pages of Gil Blas, for his gay and irresponsible (we had almost said reckless and unfettered) sketches have been noticeable in many another journal of far less steady gait. Nor has he restricted himself entirely to allegorical or eighteenth-century pastoral subjects. Occasionally he bursts forth as a strong modern realist, walking sturdily in Steinlen’s steps.

Balluriau has that thorough knowledge of the human figure which enables him to draw it with freedom and certainty, and makes him a painter of classical allegories par excellence. Further, he has a30 broad, open style, and a very charming and delicate sense of colour. His favourite medium is apparently the chalk point, which he handles vigorously; occasionally, however, he varies his method by using pen and ink.

For ten years past his brilliant work has graced the pages of Gil Blas Illustré. He is essentially the artist of lovers; and no better choice of an illustrator for that paper’s series, “Les Poètes de l’Amour,” than that of Paul Balluriau could have been made.

To judge by these illustrations Cupid has handed over all the resultant knowledge of his long experience to Balluriau; for there is very little about the outward signs of love and passion which he has not carefully noted, thereafter to render in his drawings. From the first shy gesture to the tender murmur of adoration, and thence, through the whole gamut, to the frenzied passion of uncontrollable love—we find the recording crayon of Balluriau to be ever present.

The settings in which he places his graceful lovers, his Bacchanalian dances, his fauns and his nymphs, are suitably idyllic and beautiful.

Innumerable are the backgrounds of fair lawns shaded by great trees, of lovely bowers, and of secluded nooks in some great park in Dreamland.

Perhaps there is some serio-comic difficulty to be settled, and we see two charming little ladies, in high powdered coiffures and bared to the waist, fighting a duel with swords under the trees. Or perhaps it is31 twilight, and some deep and placid stream murmuring beneath the darkling trees carries on its bosom a fairy bark and its cargo of love.

Then it is the mysterious hour of moonrise, and in the shadow of the garden wall, which climbs serpent-like up hill and down dale, we shall find our lovers serenely happy, but hushed by the beauty of the waking night.

Frequently Balluriau will carry us back to a century of delicate silks and satins; and in the broad sunlight will show a band of amorous beaux and belles, full of the joie de vivre, and about to start a game of blind man’s buff. His figures live within their old-time costumes; he draws handsome men and beautiful women, for the ugly or the grotesque rarely attract him. But he has proved in such charming works as his “Printemps,” and many others, that he also finds in the lovers of to-day sufficient beauty to include them in his répertoire. The embrace of the sentimental young student in the felt hat and caped overcoat, who has just met the darling of his heart in the Bois de Boulogne, is every whit as tender and graceful as is that of the perruqued galant of the eighteenth century, arrayed in pink satins, who, behind a sculptured satyr, has stolen a kiss from his coy and dainty partner in the last minuet on the sward. Look, in his illustration to “Badinage Sentimental,” how natural is the whole scene, how easy the pose, and how charming the face of the little Parisienne, who32 listens, half fearing the ardent words of the young exquisite who is stealing a conversation with her.

Balluriau also knows how to deal with subjects requiring more vigour of treatment—such as he displays in his Breton figure subjects. His drawing Partance is a case in point. The scene is laid in a sailors’ cabaret, on the tiled floor are rough tables, at and on which sit peaceful groups of Breton peasants; and sailor-men and buxom bonnes are bidding each other their last adieux—for the sailors are about to embark in one of the ships we see through the wide-open window.

And in the rare drawings where he touches on poverty and serious tragedy he proves himself impressive and capable of deep feeling. His drawings La Toussaint Héroïque, the terrible beer-house brawl, L’Été, and Un Mendiant Rousse, are worthy of Steinlen.

But it is in his illustrations of classical and allegorical subjects that he stands alone, and shows his greatest individuality.

Such subjects as his Bacchantes, his weird Vers le Sabbat, his Chloé, or his La Mort des Lys, to mention but a few in the Gil Blas alone, could have come from no other hand; for excellency of draughtsmanship combined with trained composition and an exquisitely refined sense of colour, they are hard to beat.

33

A. WILLETTE

Courrier Français

“MIMI PINSON, TU IRAS EN PARADIS!”

34

Vallotton’s work has probably appeared less frequently in the French press than that of many of his confrères to whom we are directing our attention.

His drawings are marked by a singular boldness of execution; and his skilful manipulation of masses of pure black gives his work distinction, and makes them attractive on any page.

Good draughtsmanship, and this clever use of unbroken black masses—wherewith to indicate and model both his shadows and his half-tones—is wherein Vallotton struck out a new line for himself, and established his individuality. This he did, too, at a time when there was a lamentable aberration evident among the ranks of the French illustrators. It became the fashion for the comic draughtsmen to draw as though they could not draw—a proceeding which provided a grand opportunity for those who could not draw if they would to join their ranks35 on even terms, and to pass as geniuses of a very spirituel order.

The irritating group to whom I refer, in its frantic efforts to be original, hit on the idea of drawing with the naïveté of the untutored child; and this rôle was for several years acted so thoroughly that some of the papers looked as if their illustrations had been copied from a collection of babies’ slates. Terrible examples of this evident incapability passing muster as genius may be seen in the ludicrous discords by “Bob,” and, in a less degree, in the many works by Dépaquit, Delaw, Rabier and others.

Midway between this group of soi-disant or actual incompetents, and the valiant band of thorough unflinching draughtsmen of realism—in whose ranks we find Renouard, Steinlen, Léandre, Huard, Malteste, Wély, and others—came an intervening group. Their work was, and is, extremely interesting. They adopted much of the naïveté of the enfantillistes, but wedded to it much knowledge and artistic feeling. In this class one may mention Lautrec, who wavered between one group and the other, Ibels, who did much the same, Jossot, who, amongst a large number of weird drawings, has produced some really fine, strong work in black and white and in colour, Metivet, who has similarly produced both classes of work, Hermann Paul, an undeniably great draughtsman, and the subject of this chapter, Frédéric Vallotton.

36

The curious thing about Vallotton’s drawings is that we do not miss the half-tones; the unbroken blacks are so skilfully managed that we do not feel the want of Nature’s intervening tones between pure black and pure white. His convention in no wise shocks one, but gives keen artistic pleasure.

This question of the accepting of conventions must strike one as a very remarkable matter. The human face, in reality covered with a smooth, soft skin, delicately gradated in tone and colour, is quite completely and satisfactorily conveyed to us by Vallotton, in a cunning arrangement of black splotches; while Huard will model the delicate roundness of a cheek with two or three bold black lines in curves. In both cases we at once realise the truth to Nature, and can even from such suggestions conjure up the particular colouring and flesh texture of the person represented.

Vallotton adds a keen sense of humour to his great ability as a draughtsman. Look at his coloured drawing Don’t Move, in Le Rire, where we see a petty official and his family, tidied up for the occasion, being photographed on a national fête day. A typical photographer, engrossed in his work, counts one! two! three! preparatory to removing the cap from his camera. So engrossed in his counting is he that he does not notice that his carefully composed group is becoming rapidly discomposed. In the foreground is fat nou-nou, beaming down at the youngest hopeful in her37 arms; yet more bulgy maman swerves over to tickle her youngest, while the next eldest clutches her mother’s skirts in terror of the great ugly man with the camera.

In the background is the father of the family, looking over his wife’s shoulder at the baby; while he places one hand on the shoulder of his eldest boy, who is rapidly outgrowing his knickerbockers, but is nevertheless determined to “come out well” in the group. The party is completed by the grown-up sister, who toys coyly with a straw flower lent her for that exact purpose.

A couple of drawings record with equal force and truth the effect on the public of the cry “Stop Thief.” First we see the excited rabble in full chase; and then the victim (absolutely innocent) being hurried off to the police station by victorious gendarmes, followed by a gesticulating crowd of knowing ones, who declare the prisoner is a murderer who has killed a woman and six children. On another page are two street wrestlers, drawn to the life. One of them is shouting himself hoarse in his endeavours to collect a crowd to witness the marvellous accomplishments of his colleague, a mountain of flesh who is about to lift a stupendous pair of dumb-bells.

Yet another coloured drawing in Le Rire, called Le Coup de Main is very remarkable in its composition and handling, and like most of Vallotton’s work shows an appreciation of Japanese38 methods. It depicts a team drawing a huge block of stone which has come to a standstill, while a group of labouring men are all lending a helping hand to get the huge white mass on the move.

Among the papers which Vallotton has helped to illustrate may be mentioned Le Cri de Paris, Le Sifflet, and Le Canard Sauvage.

The hoardings of Paris have been enlivened from time to time by vigorous posters by Vallotton, a class of work to which his art is eminently adaptable. A most notable example was the bold and telling39 one he cut on the wood, for the publisher Sagot. But it is Vallotton’s portraits of contemporary celebrities that entitle him most to lasting fame. Some of these have appeared in the French journals, as a magnificent set of powerful woodcuts, done in a large style and on a large scale.

A fine example of this work was published in The Studio in 1899, in a portrait of Puvis de Chavannes, which Vallotton drew and cut on the wood specially for that journal.

A very subtle and delicately coloured reproduction of Vallotton’s work in colour appeared also in The Studio a few years back; and an excellently rendered landscape woodcut by him appeared in the volume that so fully indicated the claims of modern wood engraving, namely, “L’Image.”

40

Morin is the Watteau of the modern illustrated press. He is, so to speak, an eighteenth-century maître galant of the twentieth century. He inherits Watteau’s gaiety and light-hearted joy in the fêtes and intrigues of the butterfly life of a time now gone by—a life half imaginary and half real. His figures tip-toe airily through an atmosphere scented with roses, ever ready for ardent love-making, for a stately minuet on the sward, or for a reckless break-neck dance over the cobble stones. Anon his figures laze in swan-like gondolas, gliding along the moonlit canals of Venice to the throbbing music of the mandoline. Moreover, all his delightful personages are instinct with life; they flirt and romp, and their boisterous gaiety is infectious; we must laugh with them for sheer joy—aye, and weep with them, now and then, for sheer sorrow.

Morin wields magic pens and pencils. His lines41 are full of nerve and verve; they are impelled by the passionate excitement of the moment, and can be no mere outcome of patient plodding. If ever an artist’s fingertips were the ready, unquestioning servants of a lively brain, those fingertips are Morin’s; in its effervescent spirit and gaiety, the quality of his brain is essentially Gallic.

LOUIS MORIN

(By himself)

Morin was born in Paris in 1855, and was educated (education being much against his youthful will) first at Versailles, and then at one of the Paris Lycées. He was trained as an architect, but left that profession in favour of sculpture, producing excellent portrait busts and such exquisite work as his “Moineau42 de Lesbie,” &c. As an author Louis Morin has gained great distinction. His “Cabaret du Puits sans Vin,” written in 1884, was crowned by the Académie Française, and further was awarded a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition.

In 1883 he had produced “Jeannik,” a book resulting from a stay in his beloved Brittany, and illustrated with eighty-seven drawings of eighteenth century Brittany. Later he travelled in Italy, and found inspiration for his book, “Les Amours de Gilles,” which he adorned with 178 spirited sketches of the beaux and belles of Old Venice, their manners and their customs. In 1886 he wrote and illustrated “La Légende de Robert le Diable,” to charm the little ones. He has also illustrated for his juvenile admirers, “Pikebikecornegramme,” and “Dansons la Capucine”; later he wrote and illustrated with ninety sketches his delightful “L’Enfant Prodigue.” Then there are his works on “French Illustrators,” and on “Quelques Artistes de ce Temps,” as well as “Dimanches Parisiens,” with twenty-five etchings by the greatest wood engraver of modern times—A. Lepère.

He has also illustrated the following books: “Vieille Idylle” with twelve drypoints, “Le petit Chien de la Marquise,” “Les Cerisettes,” “Le dernier Chapître de mon Roman,” “Vingt Masques,” “Carnavals Parisiens” (with 178 drawings), and “Les Confidences d’une Aïeule.”

43

In the early eighties Morin started drawing for La Caricature and Le Chat Noir, and later on for the Revue Illustrée, the Revue des Lettres et des Arts, Figaro Illustré, St. Nicolas, Le Canard Sauvage, La Vie en Rose, &c.

Morin was one of the leading spirits of the “Chat Noir” shadow pantomimes, and produced there in 1890 his enchanting “Carnaval de Venise,” in 1892 “Pierrot Pornographe,” in 1894 “Le Roi débarque,” and in 1896 “L’honnête Gendarme.” In 1891 he produced his pantomime “Au Dahomey” at the Musée Grévin.

A fair sized room having been acquired as an annexe to the artistic cabaret of the “Chat Noir,” a white sheet was fixed at one end of it over a miniature stage, and surrounded by a quaint and elaborate gold frame. From the wings at the rear were thrown on to the sheet the shadows of marvellous little figures cut out by such artists as Morin, the great Henri Rivière, Caran-d’-Ache, Henri Somm and others, who thereby achieved great fame. All kinds of ingenious little pieces of machinery and clever combinations were invented and employed to build up the great success, which proved attractive enough to draw “all Paris” to Montmartre for some years, and to fill the pockets of proprietor Rudolph Salis, the “King of Montjoie-Montmartre,” so full that towards 1897 he was enabled to purchase and retire to a noble estate in the country. From this estate, however, he was shortly44 to be recalled by the magnetic attraction of his beloved Montmartre.

A glance at the pages of the Revue des Quat’ Saisons, which consists of four dainty parts written and illustrated by Morin, serves to give us a very good idea of his later work. Each of the quarterly parts is contained in a paper cover embellished with a different design in colour by the artist-author, which gives one a foretaste of the treat of spices contained within; for within, interspersed amongst the larger plates of a refined colouration, are numberless little masterpieces of pen draughtsmanship, incredibly gay and graceful and supple. Morin herein shows himself a superb draughtsman, his excited little figures career about the pages, their shapely forms palpitating and quivering with the joie de vivre. The artist’s quick eye has detected the slightest inflection in the body’s outline, caused by some momentary and wayward impulse, and crystallises the beautiful thing for his own joy and for ours.

The intoxication of the carnival pervades the greater part of this book, whose literary contents consist of a series of chapters on such interesting45 matters as the “Courrier Français Ball,” “The Ball of the Medical Students,” and the final two Quat’z’arts Balls—at which latter the Paris art students and their models used, until the heavy hand of the law fell upon them, to vie with one another in producing the most artistic and audacious groups of revellers in (and without) fancy dress ever seen. Another chapter is devoted to a “Night Fête at Venice” in the olden time, with its scenes of love and revelry. Yet another, illustrated with silhouettes such as helped to make the success of the Chat Noir Theatre, deals with the influence of that institution on latter-day Art and Poetry. Then follows an article on “Spanish and Eastern dances,” illustrated with gracefully whirling votaries of the terpsichorean art; next comes a chapter on “Modern Sculpture,” decorated with irresistibly comic drawings of models posing in excruciating attitudes to satisfy the modern sculptor’s supposed craving for originality.

The amount of ingenuity, facility, and anatomical sureness shown in this little set astounds one.

Most of the drawings have evidently been done with a very flexible pen, capable alike of giving a line that with but slight pressure passes from great delicacy to corresponding strength.

By Louis Morin

The Vie en Rose contained many contributions from Morin; occasionally he essayed a drawing executed with the bold thick line then in vogue, but anything approaching brutality in method or subject46 could not but come amiss to him, and it is in such delightful fancies in this journal as the Façon de voir la vie en Rose—Le Dessinateur—that we see him at his best. A draughtsman of elegant appearance, surrounded with bric-a-brac, is here seen in his censer-perfumed studio, reclining on an enormous rose-coloured cushion; his cigarette is in one hand, and the crayon which is limning a female form in the other. Two adoring little models watch and guard him; while a procession of respectful art47 patrons stream in humbly to offer their thousand-franc notes for the sketches he is tossing off.

Other less discreet studio incidents, treated with even more delicacy of colour and draughtsmanship, are contained in the journal.

Morin stands alone in his particular style of workmanship: those who have come nearest him are the joyful and boisterous Robida, and the more reserved Henri Pille.

From all the above it is easy to gather that Louis Morin is little short of a genius; a charming and wonderful personality, endowed with one of the keenest and most versatile brains of our day.

48

Huard has done for the denizens of the godly, deadly dull French villages and provincial towns of France what Steinlen has done for Paris—and he has done it exceedingly well. It is difficult to conceive how these worthy people, so fully convinced of their own importance, so proud of their deviltries and or their little wickednesses, and so full of tittle-tattle about their neighbours could have been better introduced to us.

Huard’s collection of one hundred sketches, published in book form, and entitled “Province,” should prove a valuable document to future writers on the manners and customs of a section of French provincials at the commencement of the twentieth century. He interests himself mainly with the local official and petit commerçant (or tradesman) classes, deviating occasionally to draw within his net a few stray soldiers, or some dignified member of the old nobility of France.

49

A man of healthy mien and fine physique, Huard is excessively reserved and retiring, seeking the companionship of very few, and entirely engrossed in his work. Moreover, he is most modest, and has in no wise been spoilt by the lasting success and renown his work has earned for him, at an age when others are but commencing to hammer at the door of Fame.

Huard was born in Paris, but brought up in a provincial town. His schooldays, we are told, were marked by indomitable diligence in the successful finding of means of evading the tedium of one school after another. It is a ludicrous fact that although none of his humorous sketches are50 actual portraits, his own townspeople have taken such dire offence at what appeared to them as hits at themselves, that they have so far boycotted the satirist that he willingly banishes himself from the town in which he passed his youth. It is even reported that one old lady said, quite seriously, that if he ever dared to draw her she would disfigure him for life with vitriol. Possibly this is the marvellous person, in a good temper, whose physiognomy appears on the cover of the Huard number of “L’Album.”

Of course it is not to be denied that Huard has “made game” of the provincials; and, knowing the inherent pettiness of the classes he has held up to ridicule, it is small wonder that they resent fun poked at their expense by one who to them can appear to be no less than a traitor. Huard, however, is never spiteful or malicious; he sees better and further than his neighbours, and he knows how to tell the truth about what he has seen, without being warped by local influences.

A perusal of “Province,” and other works to be mentioned, will, I am sure, prove the truth of these remarks.

His figures are as a rule set in fitting urban landscapes, every whit as truthful as the personages they frame. Look at the drawing among those classed Les Officiels, entitled Midday Mass is far the most aristocratic—wherein a procession of regular church-goers debouches out of a picturesque, half-hearted,51 somnolent High Street into the blazing sunlight of the “Grande Place.” The local member and his wife, the lawyer, and all the other pious scandalmongers of the town are going to make their daily penitence. We can see these good folk, we can feel the sunshine, and we can even hear the clangour of the bells in the church tower. Then look in another sketch at the two editors of The Revenge. Were ever such chauvinistes, such firebrands? Getting on in years—true; but as dangerous as not yet extinct volcanoes, they reek of pistols for two and coffee for one.

A drawing labelled The Express conveying the President will pass at five o’clock, is most amusing. There, on the little railway platform, is gathered all the official rank and society of Tilliere-Sur-Ruron. Inflated, yet nervous, they fidget about, awaiting impatiently the proudest moment of their lives. We know them all; the mayor with his address is there, surrounded by his satellites of the Municipal Council, all arrayed in heirloom dress suits, members of the Gymnastic Society are there—some lithe, some burly—then there are ces braves pompiers, and the stern gendarmes; and behind them, dressed in their best, but shut out from view and from seeing, are the townspeople in their thousands. No matter, they are about to receive a main topic of conversation for many a weary year to come.

Then there are the poor, dear, terrible old ladies, to whom Huard introduces us under the heading52 “Les Vieilles Dames,”—thin-lipped, moustachioed, bigoted, deadly-dull personages are they, most of them; but they do not think so. They are contented, and are even conceited, as to the figure they cut, despite their shocking clothes; for is not each of them so much more Parisian in appearance and manners than “Madame Chose”—round the corner, and just out of hearing.

Here and there, however, we are presented to some real dignity, the dignity which pertains to old parchment. For example there are the portraits of the Mlles. Petanville de Grandcourt, in whom will expire the most purple blood of the country.

Under Soirs de Province we are shown with quaint humour the nocturnal dissipations of a provincial town. Two troopers, one as drunk as the other, are zig-zagging an erratic coursee home to barracks. One says to the other: “Vidalène—you hurt me to the quick ... you won’t wait for me because you think I’m drunk ... you are ashamed of me!” Again, the musical genius of the place has brought his violin to an at-home, and says: “What I prefer in music is imitations. Listen, I’ll give you first ‘Mother-in-Law in hysterics,’ and then ‘The Nightingale.’”

Then amongst the group of drawings headed Rentiers et Retraités look at the two retired tradesmen, chatting in the middle of a deserted square. In bated breath one of these busybodies relates to the other—“You know the whole town is agog53 with it. Mrs. Lepinçon visited the new dentist three times in the same day!”

A splendid set of drawings is included in the group Au café. We can see that they are so many resumés of the hurried sketches, for ever being made in the sketch-books which are Huard’s never-failing companions. The handling, whether in pen and ink or in chalk, is always frank and bold, and occasionally is like that of Raffaëlli. Among the Raisonneurs et Sentimentaux are two old gossips seated on their favourite bench on the fringe of the town; it is evident that neither of them, even in his palmiest days, could have set the local brook on fire. Yet one of them explains that “there have only been two men who have understood the proper course for France to pursue—M. Thiers and I. M. Thiers is dead, and they will not listen to me!” A joyful break in the monotony of life in the provincial town is most admirably rendered in Market day at Pavigny-le-Gras. Everyone and everything is fat, and hot, and smiling. Joy and plenty are the key notes of the harmony; exuberant good nature exudes from every pore. Even the houses around the Place de la Cathédrale seem to beam and bulge in purring contentment.

A review of Huard’s work leads one to regret that he does not render his survey of provincial types more complete, by occasionally including studies of that manly and womanly beauty which54 exists in even the most forsaken community, to leaven the predominant ugliness. However, it may be that such forms of rustic beauty do not attract Huard, and we must rest grateful for his view of such types as do interest him deeply.

M. Huard—equally with several others of the illustrators mentioned in this little volume—has been honoured by having an entire number of “L’Album” devoted to his work. Therein we learn that to the few Huard is known as a most able oil and pastel painter of seafaring folk; and the etchings and chalk drawings reproduced convince us that it is a well-earned reputation. The double-page centre drawing of the number consists of a masterly Return from Mass, in which we see the good souls repairing homewards in the moonlight, soothed and contented in mind and in spirit. A few pages further on we come to two piou-pious, or “tommies,” enjoying their Plaisir du Dimanche: they are seated, and one of them smokes a cheap cigar. The comment runs, “You wanted to come here so as to show yourself off smoking a cigar; but we could have had much more fun at the station watching the trains go through.”

Le Rire has published a quantity of Huard’s work, the strength and vigour of which never seems to fail. The subjects are frequently drawn from the quays of Paris, or from cafés and restaurants patronised by visitors from the provinces to the gay city. The humour of a drawing called Plages, in55 which a rather vulgar Paris tripper to the seaside, paddling with her friends, exclaims in astonished appreciation—“By Jove, sand like at Charenton” (shall we translate Putney?), is apparent to all. In these, as in all his sketches, whether drawn from a low Paris “pub,” or from an innocent village café, indoors or out, the entire truth to nature of the type chosen, the very cut and hang of every garment is absolutely convincing, and unerringly put in with a few bold touches of the pen.

A pathetic drawing is that of the poor workwoman, who has tramped out to the sordid wastes of the fortifs, or fortifications of Paris; and, in her enjoyment of the faint echo of the real country, there to be found, exclaims—“If I were rich I’d come here every day!”

Huard has drawn for L’Assiette au Beurre, L’Image, Le Rire, and Cocorico some remarkable military subjects, in which he has depicted the French soldier to the life. Here, we have him disclosing to a comrade on the quay his modest dreams of fortune—there, he is discussing rations with his colonel, and in another splendid double-page drawing we see him at night, shouting some rude refrain, and painting the town scarlet generally; but the finest of all is perhaps a vivid drawing in colour of a squad on a drill ground,—red caps, white suits, and a yellow background,—the whole making a most striking page. Huard is very successful with these coloured illustrations, many of which56 appear in Le Rire, and charm us with their quaint breadth and simplicity of treatment. Nothing in this way could be better than the old concièrge and his dumpy wife, who are painting a cast of the “Venus of Milo” with canary yellow, and decide that it is much prettier like that, and much less indecent.

For the exhibition of La Demi Douzaine, the little group of artists among whom he exhibits his marine work, Huard has done an excellent poster.

57

Wély is one of the more recent stars in the firmament of Parisian illustrators; nevertheless he shines with a peculiar brilliance of his own.

His drawing of the female form divine, more or less disclosed in dainty décolleté, is well nigh unsurpassed. The excellence of the draughtsmanship, which is so generally attained in the Paris Schools of Art, is very frequently not traceable in work produced later in the artist’s career. This, however, is not the case with Wély; the sureness of drawing required in the schools remains, plus a large quantity of vim and esprit. The adjective which best labels his work is charming; and here it may be well to state that the more emancipated any one is the greater the number of Wély’s drawings he is able to admit to his collection, to charm again and again. For Wély is the artist of adventures—the adventures of the bedroom. He is a humorist, and not a58 caricaturist. He has too much love of human beauty to caricature the human face and figure, and it is possible that for the same reason he never produces a coarse drawing; however risky the situation he depicts, that which attracts and interests one is the beauty of his drawing, and the technical dexterity of his handling.

It is possible that admiration for the work of Jules Chéret, the master poster-maker, has had something to do with the formation of his style. His work, like that of most of the later illustrators, is done with chalk or charcoal, very little pen-work being produced. The perfection to which the photo-reproduction of drawings now attains has been chiefly responsible for this, together with the praiseworthy attempt of the modern men to vie with the magnificent series of drawings on stone, done half a century ago, by Gavarni, Daumier, De Beaumont, Cham, and other splendid draughtsmen. The revival of their method of treating drawings with a broad point seems for the time to have more than half submerged the exquisite pen-and-ink work, such as was contributed to the illustrated papers some twenty years ago by Lunel, Courboin, Jeanniot, Vogel, José Roy, Vierge, Luigi Loir, Moulignié, Gorguet, Robida, G. Stein, Galice, Myrbach, G. Scott, F. Fau and others. But the situation is saved by the fact that Guillaume, Caran-d’Ache, Job, Morin, and a few other leading illustrators are still faithful to pen and ink. In any case it is certain that of those who59 use crayon, charcoal, or lithographic chalk, none produce work which is so subtle and yet so facile and so sure as Wély. He is a light-hearted Steinlen of my lady’s dressing-room; or an emboldened Helleu.

The relations between artist and artist’s model frequently attract Wély’s pencil, while other outside subjects seem to tempt him much less frequently. The hard-working, penniless, happy-go-lucky artist rapins he draws are a delightful crew, most excellently put upon paper.

A specimen of his humour is indicated in the words accompanying one of his rare pen and ink drawings, which appeared in Cocorico. A chic little lady is seated in a shop, while a female attendant unrolls pile after pile of material in the hope of supplying her wants. The lady says: “Why certainly, show me some more: I’m not a bit tired.”

A beautiful little drawing, of two dainty Parisiennes gossiping on a pier, discloses the method he has employed to produce a telling piece of work. The outline has been rapidly sketched in with a few bold, subtly curving lines from a pen, while modelling and colour have been given to the whole with deft crayon touches. We feel the joy the artist must have evinced in regulating the pressure he put on the crayon, so as to give each line its exact breadth, and depth of tone. The pleasure he takes in manipulating his medium is always manifest in his work. The complete modelling of a dainty neck60 and shoulders, or of a shapely ankle, is frequently accomplished by the merest touch of the chalk—but a touch in exactly the right place, and of exactly the right size.

Wély has contributed to the pages of the Frou Frou; and very frequently to La Vie en Rose. His small illustrations to “Aristophane à Paris,” and to “La Maîtresse du Prince Jean,” which first appeared in the latter journal, are full of ability, humour and vivacity. A drawing entitled Quelques Predictions pour 1902, shows us a delightful little coquette in déshabillé, who is consulting the cards with an old woman fortune-teller, the while a tiny kitten plays with a ball of worsted. They are so life-like and so subtly depicted that we almost expect to see them move on the paper. Passe temps du jeune Age, is one of the most astoundingly able and beautiful studies of the nude that one can recall by any artist, and also appears in La Vie en Rose.

The type of man usually introduced into our artist’s drawings is not conspicuous for its beauty; it generally depicts a bit of a scamp, a bon viveur, who is used artistically as a foil to some fresh and dainty young person of the opposite sex.

Several pages in colour, which appeared in the Vie en Rose, evinced a charmingly refined sense in that direction; while some illustrated covers for Le Rabelais, each most successfully dealing with61 an entirely different and difficult colour problem were among the most striking examples of that branch of art yet produced.

By J. Wély

62

By Malteste

PSYCHOLOGUE

63

Among the workers on the French illustrated papers none produces a steadier flow of thoroughly conscientious, sound work than Louis Malteste.

His are no chance effects, no tours de force of mere eccentricity or charlatanism, but are the outcome of knowledge, hard work and assurance.

He is a splendid draughtsman, unerring and direct, a seeker and finder of individual character, who does not attempt to electrify the world with his audacity, or his at-any-cost originality; for he is content to delineate for us, in masterly fashion, specimens of humanity as they appear to the man of keen discernment.

At the time of the loathsome trials of Dreyfus, Malteste was one of several artists who specially distinguished themselves by splendid sketches of the actors concerned therein. In the writer’s possession is a collection of these spirited and life-like drawings.64 They are doubly admirable when one considers under what disadvantages they were produced. The task of the artist, told off to a sweltering, over-crowded court-house, surcharged with violent excitement, and commissioned to make portrait groups of interested persons, who are incessantly changing their positions, is none too easy. Yet these drawings show no hesitation; in each case some fleeting gesture or attitude is caught in a vigorous drawing, and fixed for ever.

No wonder then that publishers such as Hachette, and the weekly illustrated papers Le Monde Illustré, L’Illustration, &c., should have availed themselves of his talent; or that when he turned his crayon to more fanciful subjects he should have found a ready outlet in the pages of such papers as La Vie en Rose, Le Rire, L’Assiette au Beurre, and many others, wherein to let fly that gauloiserie which flows in the veins of even the most serious Frenchman.

Most of the drawings in La Vie en Rose are excellent works in chalk of actions governed by sudden impulse; and, in technique, strongly recall the admirable drawings of the English draughtsman, Gunning King, whose work Malteste has probably never seen. It is most likely, however, that the style of both artists has largely resulted from profound and well-placed admiration of the work of the veteran Renouard.

There is in La Vie en Rose an amusing series of drawings by Malteste of coachmen of all grades—each65 a strong piece of work, full of character, and well placed on the page. Another series in colour consists of fancy portraits of potentates; here again Malteste has distinguished himself, as witness the Léopold, Roi des Belges, a harmony in white, yellow, and brown. Malteste shows himself as a tender colourist in the excellent drawing of a milking scene, entitled La Traité des Blanches; another farm scene, Le Fléau, is as excellent an example of black and white work, and only surpassed by the chalk drawing Psychologue, a superb delineation of two ragged, storm-beaten rag pickers toiling homewards with their baskets.

His little studies of queer bits of gnarled humanity are splendid; witness his Femmes Fidèles, La Femme qui prise, his droll lady who declares There is nothing like a good swig, his Woman with a Dog, his Woman with the Cats, or the group called Types of Electors in the Ville Lumière. We recognise all those electors at first sight; there is the heavy, obstinate man, who gets his way by force of sheer dead-weight, there the suave complaisant “good-sort,” there the pugnacious, quixotic fellow, who adores a riotous meeting, there the pensive philosopher, and so on. There is no mistaking the true character of any one of them; to a companion page of Femmes Infidèles the same remarks apply.

A noteworthy quality in Malteste’s work is the invariably excellent drawing of the hands. To any but the surest draughtsmen hands are66 a veritable bête noire, to be avoided whenever possible.

Besides his reputation as an illustrator, Malteste has made his mark as a painter of note, and in collaboration with Gélis-Didot has executed a charming poster for L’Absinthe Parisienne; while his poster for the Théâtre Antoine is one of the finest things of its kind yet produced.

67

The collection of two hundred and fifty sketches, published in book form under the title “La Comédie Parisienne,” at once established Forain as a firm favourite both with the public and with artists.

It could not well have been otherwise. For these tender, graceful, little sketches touching on the private life and foibles of dancers, bankers, lawyers and others, appealed to the risible faculties and the sympathies of all Parisians; while artists admired the delicacy of touch and apparent facility with which the little scenes were “flicked in.” The expression “apparent facility” is purposely employed; for despite the appearance of careless ease of execution conveyed by the slightness of these sketches, those who have seen the artist at work know that for each sketch presented to the public three or four have been rejected by their author as unsatisfactory.

68

A very large proportion of the drawings in “La Comédie Parisienne,” treat of matters to which it is quite customary to refer in French publications, but which in England are discreetly relegated to the confidential whisper of intimates; so that it is rather difficult here to give specimens of the delicate wit displayed therein,—lest it should be classed as indelicate wit. The standard of delicacy topples over at such very different angles in England and on the Continent.

Whatever the subject treated, however, one is struck by the keen observation these drawings display, the requisite movement or attitude being perfectly rendered with the minimum number of lines. They are snap-shots of propitious moments; but taken by an artist’s eye in place of a photographic lens, and an artist’s science to display what is necessary and to discard what is unnecessary for the illustration of the point at issue.

The drawings here and there reflect the touch of melancholy in the author’s nature, as well as his caustic wit.

A charming and sympathetic drawing is that of the working man playing with his crooning babe, while the mother, who is getting supper ready, says to her husband “Ah! wouldn’t you be stunning, if you’d only give up drinking.” In another drawing a poor woman says to her drunken husband “Aren’t you ashamed to be in this state on a Tuesday?” How telling too the sketch of the rascally picture69 dealer who bursts in on the famishing artist and his starving wife and baby, and says—“I must have three Corots and a Diaz within six days—Madame, make him work!”

Then there is another delightful artist subject. The landlord breaks in on poor hard-working Pinceau. “Sir, you’ve made me call twenty times—you owe me seven quarters’ rent, I tell you I’ve had enough of it!” “Gracious—is that all you’ve got to think about then,” is the cool reply.

How beautiful in its simplicity and how exquisitely the curt legend “—— Rothschild,” fits that drawing of the little ballet dancer who whispers the portentous name into the ear of her sister coryphée, the while the moneyed man behind the scenes passes them.

Once more, look at the husband stupefied at the bill which accompanies the host of packages in the midst of which he and his wife are standing. “What, what! two thousand seven hundred and fifty-three francs, forty five centimes! and all that so as to go away to the seaside for three weeks!”—“Well, yes, you are right, my dear, I will send back one of the umbrellas!”

These drawings are almost all executed with a thin, pin-point pen line, of even thickness throughout, and with flat tones of shading added by means of mechanically engraved dots. Forain, Vogel, and Willette, although their methods differ, are among the few70 who now illustrate with such faint lines and aim at such fragile effects.

A collection in book form of his political and topical illustrations, which had appeared in Le Figaro were republished under the title “Doux Pays.”