Title: Norse mythology; or The religion of our forefathers, containing all the myths of the Eddas, systematized and interpreted

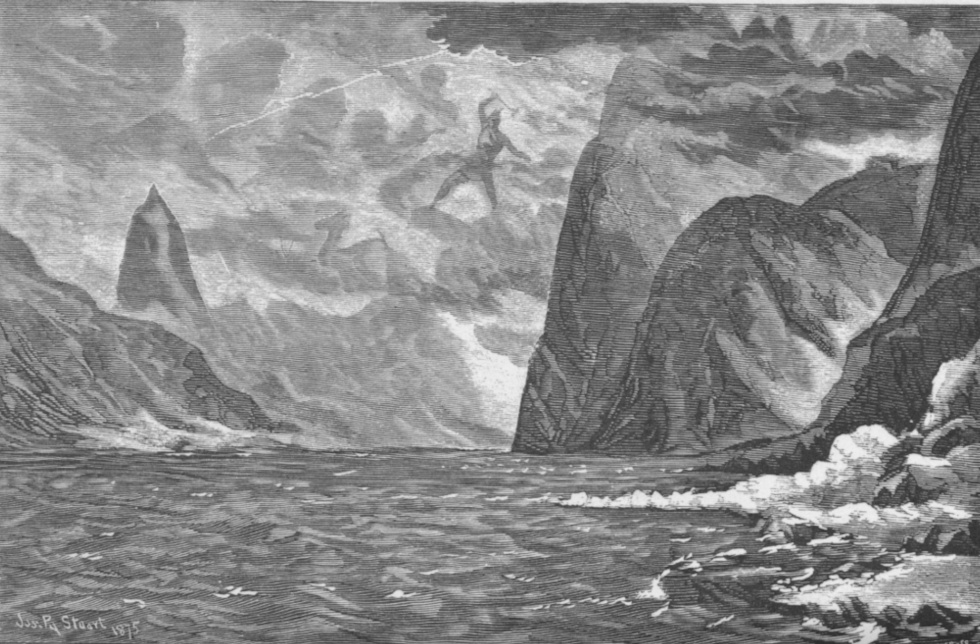

Thor Fighting The Giants.

2Copyright 1875.

By S. C. GRIGGS AND COMPANY.

ELECTROTYPED BY ZEESE & CO.

5I think Scandinavian Paganism, to us here, is more interesting than any other. It is, for one thing, the latest; it continued in these regions of Europe till the eleventh century: eight hundred years ago the Norwegians were still worshipers of Odin. It is interesting also as the creed of our fathers; the men whose blood still runs in our veins, whom doubtless we still resemble in so many ways. Strange: they did believe that, while we believe so differently. Let us look a little at this poor Norse creed, for many reasons. We have tolerable means to do it; for there is another point of interest in these Scandinavian mythologies: that they have been preserved so well.

Neither is there no use in knowing something about this old Paganism of our fathers. Unconsciously, and combined with higher things, it is in us yet, that old faith withal. To know it consciously brings us into closer and clearer relations with the past,—with our own possessions in the past. For the whole past, as I keep repeating, is the possession of the present. The past had always something true, and is a precious possession. In a different time, in a different place, it is always some other side of our common human nature that has been developing itself.

—Thomas Carlyle.

America Not Discovered by Columbus having been so favorably received by the press generally, as well as by many distinguished scholars, who have expressed themselves in very flattering terms of our recent début in English, we venture to appear again; and, although the subject is somewhat different, it still (as did the first) has its fountain head in the literature of the North.

We come, this time, encouraged by all your kind words, with higher aspirations, and perhaps, too, with less timidity and modesty. We come to ask your opinion of Norse mythology. We come to ask whether Norse mythology is not equally as worthy of your attention as the Greek. Nay, we come to ask whether you will not give the Norse the preference. We propose to call your attention earnestly, in this volume, to the merits of our common Gothic or Teutonic inheritance, and to chat a few hours with you about the imaginative, poetic and prophetic period of our Gothic history.

We are well aware that we are here giving you a book full of imperfections so far as style, originality, arrangement and external adornment of the 8subject is concerned, and we shall not take it much to heart, even if we are severely criticised in these respects; we shall rather take it as an earnest admonition to study and improve in language and composition for the future.

But, if the spirit of the book, that is, the cause which we have undertaken to plead therein,—if that be frowned down, or rejected, or laughed at, we shall be the recipient of a most bitter disappointment, and yet we shall not wholly despair. The time must come, when our common Gothic inheritance will be loved and respected. There will come men—ay, there are already men in our midst who will advocate and defend its rights on American soil with sharper steel than ours. And, though we may find but few roses and many thorns on our pathway, we shall not suffer our ardor in our chosen field of labor to be diminished. We are determined not to be discouraged.

What we claim for this work is, that it is the first complete and systematic presentation of the Norse mythology in the English language; and this we think is a sufficient reason for our asking a humble place upon your book-shelves. And, while we make this claim, we fully appreciate the value of the many excellent treatises and translations that have appeared on this subject in England. We do not undervalue the labors of Dasent, Thorpe, Pigott, Carlyle, etc., but none of these give a comprehensive 9account of all the deities and the myths in full. There is, indeed, no work outside of Scandinavia that covers the whole ground. So far as America is concerned, the only work on Norse mythology that has hitherto been published in this country is Barclay Pennock’s translation of the Norse Professor Rudolph Keyser’s Religion of the Northmen. This is indeed an excellent and scholarly work, and a valuable contribution to knowledge; but, instead of presenting the mythology of the Norsemen, it interprets it; and Professor Keyser is yet one of the most eminent authorities in the exposition of the Asa doctrine. Pennock’s translation of Keyser is a book of three hundred and forty-six pages, and of these only sixteen are devoted to a synopsis of the mythology; and it is, as the reader may judge, nothing but a very brief synopsis. The remaining three hundred and thirty pages contain a history of Old Norse literature, an interpretation of the Odinic religion, and an exhibition of the manner of worship among the heathen Norsemen. In a word, Pennock’s book presupposes a knowledge of the subject; and for one who has this, we would recommend Pennock’s Keyser as the best work extant in English. We are indebted to it for many valuable paragraphs in this volume.

This subject has, then, been investigated by many able writers; and, in preparing this volume, we have borrowed from their works all the light they could 10shed upon our pathway. The authors we have chiefly consulted are named in the accompanying list. While we have used their very phrase whenever it was convenient, we have not followed them in a slavish manner. We have made such changes as in our judgment seemed necessary to give our work harmony and symmetry throughout. We at first felt disposed to give the reader a mere translation either of N. M. Petersen, or of Grundtvig, or of P. A. Munch; but upon further reflection we came to the conclusion that we could treat the subject more satisfactorily to ourselves, and fully as acceptably to our readers, by sketching out a plan of our own, and making free use of all the best writers upon this subject. And as we now review our pages, we find that N. M. Petersen has served us the most. Much of his work has been appropriated in an almost unchanged form.

Although many of the ideas set forth in this work may seem new to American readers, yet they are by no means wholly original. Many of them have for many years been successfully advocated in Scandinavian countries, and to some extent, also, in Germany and England. Our aim has not at present been so much to make original investigations, as—that which is far more needed and to the purpose—to give the fruits of the labors performed in the North, and call the attention of the American public earnestly to the wealth stored up in the Eddas and Sagas of Iceland. No one can doubt the correctness 11of our position in this matter, when he reflects that we now drawing near the close of the nineteenth century, and have not yet had a complete Norse mythology in the English language, while the number of Greek and Roman mythologies is legion. Bayard Taylor said to us, recently, that the Scandinavian languages, in view of their rich literature, in view of the light which this literature throws upon early English history, and in view of the importance of Icelandic in a successful study of English and Anglo-Saxon, ought to be taught in every college in Vinland; and that is the very pith of what we have to say in this preface.

We have had excellent aid from Dr. S. H. Carpenter, who combines broad general culture with a thorough knowledge of Old English and Anglo-Saxon. He has read every page of this work, and we hereby thank him for the generous sympathy and advice which he has invariably given us. To President John Bascom we are under obligations for kind words and valuable suggestions. We hereby extend heartfelt thanks to Professor Willard Fiske, of Cornell University, for aid and encouragement; to Mrs. Ole Bull, for free use of her excellent library; and to the poet, H. W. Longfellow, for permitting us to make extracts from his works, and to inscribe this volume to him as the Nestor among American writers on Scandinavian themes. May the persons here named find that this our work, in spite of its faults, advances, 12somewhat, the interest in the studies of Northern literature in this country.

While Mallet’s Northern Antiquities is a very valuable work, we cannot but make known our regrets that Blackwell’s edition of it ever was published. Mr. Blackwell has in many ways injured the cause which he evidently intended to promote. While we, therefore, urge caution in the use of Mallet’s Northern Antiquities by Blackwell, we can with all our heart recommend such writers upon the North as Dasent, Laing, Thorpe, Gosse, Pennock, Boyesen, Marsh, Fiske, the Howitts, Pigott, Lord Dufferin, Maurer, Möbius, Morris, Magnússon, Vigfusson, Hjaltalin, and several others.

It is sincerely hoped that by this our effort we may, at least for the present, fill a gap in English literature, and accomplish something in awakening among students some interest in Norse mythology, history, literature and institutions. Let it be remembered, that Carlyle, and many others of our best scholars, claim that it is from the Norsemen we have derived our vital energy, our freedom of thought, and, in a measure that we do not yet suspect, our strength of speech.

We are conscious that our work contains many imperfections, and that others might have performed the task better; and thus we commend this volume to the kind indulgence of the critic and the reader.

R. B. ANDERSON.

University of Wisconsin, May 15, 1875.

The following authors have been consulted in preparing this work, and to them the reader is referred, if he wishes to make special study of the subject of Norse mythology.

Of the Elder Edda we have used Benjamin Thorpe’s translation and Sophus Bugge’s edition of the original. It has been found necessary to make a few alterations in Thorpe’s translation. Of the Younger Edda we have used Dasent’s translation and Sveinbjorn Egilsson’s edition of the original. Of modern Scandinavian writers we have confined ourselves mainly to N. M. Petersen, N. F. S. Grundtvig, P. A. Munch, Rudolph Keyser, Finn Magnússon, and Christian Winther. Other authors borrowed from more or less are: H. W. Longfellow, H. G. Möller, R. Nyerup, E. G. Geier, M. Hammerich, F. J. Mone, Jacob Grimm, Thomas Keightly, Thomas Carlyle, Max Müller, and Geo. W. Cox.

The recent excellent work of Alexander Murray has been referred to on the subject of Greek mythology. It claims on its title-page to give an account of Norse mythology; but we were surprised to find 14that the author dismisses the subject with fifteen pages and a few wood-cuts of questionable value.

The philological notes are chiefly based upon the Icelandic Dictionary recently published by Macmillan & Co., and edited by Gudbrand Vigfusson, of Oxford University, England. We object to the price of it, which is thirty-two dollars, but it is indeed a scholarly work, and marks a new epoch in the study of the Icelandic language.

For the engraving opposite the title-page we are indebted to Mr. James R. Stuart, who has devoted many years in America and Europe to the study of his art. The painting, from which the engraving is made, is wholly original, and was made expressly for this work. We hereby extend our thanks to Mr. Stuart, and hope some day to see more of Norse mythology treated by his brush.

WHAT IS MYTHOLOGY, AND WHAT IS NORSE MYTHOLOGY?

The myth the oldest form of truth—The Unknown God—Ingemund the Old—Thorkel Maane—Harald Fairfax—Every cause in nature a divinity—Thor the thunder-storm—Prominent faculties impersonated—These gods worthy of reverence—Church ceremonies—Different religions—Hints to preachers—The mythology of our ancestors—In its oldest form it is Teutonic—What Dasent says—Thomas Carlyle, 23

WHY CALL THIS MYTHOLOGY NORSE? OUGHT IT NOT RATHER TO BE CALLED GOTHIC OR TEUTONIC?

Introduction of Christianity—The Catholic priests—The Eddas—Mythology in its Germanic form—Thor not the same in Norway and Denmark—Norse mythology—Max Müller, 41

NORSE MYTHOLOGY COMPARED WITH GREEK.

Norse and Greek mythology differ—Balder and Adonis—Greek gods free from decay—The Deluge—Not the same but a similar tradition—The hand stone weeps tears—The separate groups exquisite—Greek mythology an epic poem—Theoktony—The 16Norse yields the prize to the Greek—Depth of Norse and Christian thought—Naastrand—Outward nature influences the mythology—Visit Norseland—Norse scenery—Simple and martial religion—Sincerity and grace—Norse and Greek mythology, 51

ROMAN MYTHOLOGY.

Oxford and Cambridge—The Romans were robbers—We must not throw Latin wholly overboard—We must study English and Anglo-Saxon—English more terse than Latin—Greek preferable to Hebrew or Latin—Shakespeare—He who is not a son of Thor, 71

INTERPRETATION OF NORSE MYTHOLOGY.

Aberration from the true religion—Historical interpretation—Ethical interpretation—Physical interpretation—Odin, Thor, Argos, Io—Our ancestors not prosaic—The Romans again—Physical interpretation insufficient—Natural science—Historical prophecy—A complete mythology, 80

THE NORSE MYTHOLOGY FURNISHES ABUNDANT AND EXCELLENT MATERIAL FOR THE USE OF POETS, SCULPTORS AND PAINTERS.

How to educate the child—Ole Bull—Men frequently act like ants—Oelenschlæger—Thor’s fishing—The dwarfs—Ten stanzas in Danish—The brush and the chisel—Nude art—The germ of the faith—We Goths are a chaste race—Dr. John Bascom—We are growing too prosaic and ungodly, 94

THE SOURCES OF NORSE MYTHOLOGY AND INFLUENCE OF THE ASA-FAITH.

The Elder Edda—Icelandic poetry—Beowulf’s Drapa and Niebelungen-Lied—Influence of the Norse mythology—Influence of the Asa-faith—Samuel Laing—Odinic rules of life—Hávamál—The lay of Sigdrifa—Rudolph Keyser—The days of the week, 116

17PART I.

THE CREATION AND PRESERVATION OF THE WORLD.

THE CREATION.

Section i. The original condition of the world—Ginungagap. Section ii. The origin of the giants—Ymer. Section iii. The origin of the crow Audhumbla and the birth of the gods—Odin, Vile and Ve. Section iv. The Norse deluge and the origin of heaven and earth. Section v. The heavenly bodies, time, the wind, the rainbow—The sun and moon—Hrimfaxe and Skinfaxe—The seasons—The Elder Edda—Bil and Hjuke. Section vi. The Golden Age—The origin of the dwarfs—The creation of the first man and woman—The Elder Edda. Section vii. The gods and their abodes. Section viii. The divisions of the world, 171

THE PRESERVATION.

The ash Ygdrasil—Mimer’s fountain—Urd’s fountain—The norns or fates—Mimer and the Urdar-fountain—The norns, 188

EXEGETICAL REMARKS UPON THE CREATION AND PRESERVATION OF THE WORLD.

Pondus iners—The supreme god—The cow Audhumbla—Trinity—The Golden Age—Creation of man—The giants—The gods kill or marry the giants—Elves and hulders—Trolls—Nisses and necks—Merman and mermaid—Ygdrasil—Mimer’s fountain—The norns, 192

18PART II.

THE LIFE AND EXPLOITS OF THE GODS.

ODIN.

Section i. Odin. Section ii. Odin’s names. Section iii. Odin’s outward appearance. Section iv. Odin’s attributes. Section v. Odin’s journeys. Section vi. Odin and Mimer. Section vii. Hlidskjalf. Section viii. The historical Odin. Section ix. Odin’s wives. Section x. Frigg’s maid-servants. Section xi. Gefjun—Eir. Section xii. Rind. Section xiii. Gunlad—The origin of poetry. Section xiv. Saga. Section xv. Odin as the inventor of runes. Section xvi. Valhal. Section xvii. The valkyries, 215

HERMOD, TYR, HEIMDAL, BRAGE AND IDUN.

Section i. Hermod. Section ii. Tyr. Section iii. Heimdal. Section iv. Brage and Idun. Section v. Idun and her apples, 270

BALDER AND NANNA, HODER, VALE AND FORSETE.

Section i. Balder. Section ii. The death of Balder the Good. Section iii. Forsete, 279

THOR, HIS WIFE SIF AND SON ULLER.

Section i. General synopsis—Thor, Sit and Uller. Section ii. Thor and Hrungner. Section iii. Thor and Geirrod. Section iv. Thor and Skrymer. Section v. Thor and the Midgard-serpent (Thor and Hymer). Section vi. Thor and Thrym, 298

VIDAR, 337

THE VANS.

Section i. Njord and Skade. Section ii. Æger and Ran. Section iii. Frey. Section iv. Frey and Gerd. Section v. Worship of Frey. Section vi. Freyja. Section vii. A brief review, 341

THE DEVELOPMENT OF EVIL, LOKE AND HIS OFFSPRING.

Section i. Loke. Section ii. Loke’s children—The Fenriswolf. Section iii. Jormungander or the Midgard-serpent. Section iv. Hel. Section v. The Norsemen’s idea of death. Section vi. Loke’s punishment. Section vii. The iron post. Section viii. A brief review, 371

RAGNAROK AND REGENERATION.

RAGNAROK, 413

REGENERATION, 428

Vocabulary, 439

Index, 462

The word mythology (μυθολογόα, from μῦθος, word, tale, fable, and λόγοc, speech, discourse,) is of Greek origin, and our vernacular tongue has become so adulterated with Latin and Greek words; we have studied Latin and Greek in place of English, Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Gothic so long that we are always in a quandary (qu’en dirai-je?), always tongue-tied when we attempt to speak of something outside or above the daily returning cares of life. Our own good old English words have been crowded out by foreign ones; this is our besetting sin. But, as the venerable Professor George Stephens remarks in his elaborate work on Runic Monuments, we have watered our mother tongue long enough with bastard Latin; let us now brace and steel it with the life-water of our own sweet and soft and rich and shining and clear-ringing and manly and world-ranging, ever-dearest English.

Mythology is a system of myths; a collection of popular legends, fables, tales, or stories, relating to the gods, heroes, demons or other beings whose names have been preserved in popular belief. Such tales are not found in the traditions of the ancient Greeks, Hindoos 24and Egyptians, only, but every nation has had its system of mythology; and that of the ancient Norsemen is more simple, earnest, miraculous, stupendous and divine than any other mythological system of which we have record.

The myth is the oldest form of truth; and mythology is the knowledge which the ancients had of the Divine. The object of mythology is to find God and come to him. Without a written revelation this may be done in two ways: either by studying the intellectual, moral and physical nature of man, for evidence of the existence of God may be found in the proper study of man; or by studying nature in the outward world in its general structure, adaptations and dependencies; and truthfully it may be said that God manifests himself in nature.

Our Norse forefathers (for it is their religion we are to present in this volume) had no clearly-defined knowledge of any god outside of themselves and nature. Like the ancient Greeks, they had only a somewhat vague idea about a supreme God, whom the rhapsodist or skald in the Elder Edda (Hyndluljóð 43, 44) dare not name, and whom few, it is said, ever look far enough to see. In the language of the Elder Edda:

Odin goes to meet the Fenriswolf in Ragnarok (the twilight of the gods; that is, the final conflict between all good and evil powers); but now let the reader compare the above passage from the Elder Edda with the following passage from the seventeenth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles:

Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars’ Hill and said: Ye men of Athens, I perceive that in all things ye are too superstitious; for as I passed by and beheld your devotions, I found an altar with this inscription: TO THE UNKNOWN GOD. Whom therefore ye ignorantly worship, him declare I unto you.

It was of this same unknown God that one of the ancient Greek poets had said, that in him we live and move and have our being. Thus did the Greeks find Jehovah in the labyrinth of their heathen deities; and when we claim that the Norse mythology is more divine than any other system of mythology known, we mean by this assertion, that the supreme God is mentioned and referred to oftener, and stands out in bolder relief in the Norseman’s heathen belief, than in any other.

It is a noticeable fact that long before Christianity was introduced or had even been heard of in Iceland, it is recorded that Ingemund the Old, a heathen Norseman, bleeding and dying, prayed God to forgive Rolleif, his murderer.

Another man of the heathen times, Thorkel Maane, a supreme judge of Iceland, a man of unblemished life and distinguished among the wisest magistrates of that 26island during the time of the republic, avowed that he would worship no other God but him who had created the sun; and in his dying hour he prayed the Father of Light to illuminate his soul in the darkness of death. Arngrim Jonsson tells us that when Thorkel Maane had arrived at the age of maturity and reflection, he disdained a blind obedience to traditionary custom, and employed much of his time in weighing the established tenets of his countrymen by the standard of reason. He divested his mind of all prejudice; he pondered on the sublimity of nature, and guided himself by maxims founded on truth and reason. By these means he soon discovered not only the fallacy of that faith which governed his countrymen, but became a convert to the existence of a supreme power more mighty than Thor or Odin. In his maker he acknowledged his God, and to him alone directed his homage from a conviction that none other was worthy to be honored and worshiped. On perceiving the approach of death, this pious and sensible man requested to be conveyed into the open air, in order that, as he said, he might in his last moments contemplate the glories of Almighty God, who has created the heavens and the earth and all that in them is.

Harald Fairfax (Haarfager), the first sovereign of Norway, the king that united Norway under his scepter in the year 872, is another remarkable example in this respect. He was accustomed to assist at the public offerings made by his people in honor of their gods. As no better or more pure religion was known in those days, he acted with prudence in not betraying either contempt or disregard for the prevailing worship of the country, lest his subjects, stimulated by such example, might become indifferent, not only to their sacred, but 27also to their political, duties. Yet he rejected from his heart these profane ceremonies, and believed in the existence of a more powerful god, whom he secretly adored. I swear, he once said, never to make my offerings to an idol, but to that God alone whose omnipotence has formed the world and stamped man with his own image. It would be an act of folly in me to expect help from him whose power and empire arises from the accidental hollow of a tree or the peculiar form of a stone.

Such examples illustrate how near the educated and reflecting Norse heathen was in sympathy with Christianity, and also go far toward proving that the object of mythology is to find God and come to him.

Still we must admit that of this supreme God our forefathers had only a somewhat vague conception; and to many of them he was almost wholly unknown. Their god was a natural human god, a person. There can be no genuine poetry without impersonation, and a perfect system of mythology is a finished poem. Mythology is, in fact, religious truth expressed in poetical language. It ascribes all events and phenomena in the outward world to a personal cause. Each cause is some divinity or other—some god or demon. In this manner, when the ancients heard the echo from the woods or mountains, they did not think, as we now do, that the waves of sound were reflected, but that there stood a dwarf, a personal being, who repeated the words spoken by themselves. This dwarf had to have a history, a biography, and this gave rise to a myth. To our poetic ancestors the forces of nature were not veiled under scientific names. As Carlyle truthfully remarks, they had not yet learned to reduce to their fundamental elements and lecture learnedly about this beautiful, 28green, rock-built, flowery earth, with its trees, mountains and many-sounding waters; about the great deep sea of azure that swims over our heads, and about the various winds that sweep through it. When they saw the black clouds gathering and shutting out the king of day, and witnessed them pouring out rain and ice and fire, and heard the thunder roll, they did not think, as we now do, of accumulated electricity discharged from the clouds to the earth, and show in the lecture room how something like these powerful shafts of lightning could be ground out of glass or silk, but they ascribed the phenomenon to a mighty divinity—Thor—who in his thunder-chariot rides through the clouds and strikes with his huge hammer, Mjolner. The theory of our forefathers furnishes food for the imagination, for our poetical nature, while the reflection of the waves of sound and the discharge of electricity is merely dry reasoning—mathematics and physics. To our ancestors Nature presented herself in her naked, beautiful and awful majesty; while to us in this age of Newtons, Millers, Oersteds, Berzeliuses and Tyndalls, she is enwrapped in a multitude of profound scientific phrases. These phrases make us flatter ourselves that we have fathomed her mysteries and revealed her secret workings, while in point of fact we are as far from the real bottom as our ancestors were. But we have robbed ourselves to a sad extent of the poetry of nature. Well might Barry Cornwall complain:

The old Norsemen said: The mischief-maker Loke cuts for mere sport the hair of the goddess Sif, but 29the gods compel him to furnish her new hair, Loke gets dwarfs to forge for her golden hair, which grows almost spontaneously. We, their prosaic descendants, say: The heat (Loke) scorches the grass (Sif’s hair), but the same physical agent (heat) sets the forces of nature to work again, and new grass with golden (that is to say bright) color springs up again.

Thus our ancestors spoke of all the workings of nature as though they were caused by personal agents; and instead of saying, as we now do, that winter follows summer, and explaining how the annual revolutions of the earth produce the changes that are called seasons of the year, they took a more poetical view of the phenomenon, and said that the blind god Hoder (winter) was instigated by Loke (heat) to slay Balder (the summer god).

This idea of personifying the visible workings of nature was so completely developed that prominent faculties or attributes of the gods also were subject to impersonation. Odin, it was said, had two ravens, Hugin and Munin; that is, reflection and memory. They sit upon his shoulders, and whisper into his ears. Thor’s strength was redoubled whenever he girded himself with Megingjarder, his belt of strength; his steel gloves, with which he wielded his hammer, produced the same effect. Nay, strength was so eminent a characteristic with Thor that it even stands out apart from him as an independent person, and is represented by his son Magne (strength), who accompanies him on his journeys against the frost-giants.

In this manner a series of myths were formed and combined into a system which we now call mythology; a system which gave to our fathers gods whom they worshiped, and in whom they trusted, and which gives 30to us a mirror in which is reflected the popular life, the intellectual and moral characteristics of our ancestors. And these gods were indeed worthy of reverence; they were the embodiments of the noblest thoughts and purest feelings, but these thoughts and feelings could not be awakened without a personified image. As soon as the divine idea was born, it assumed a bodily form, and, in order to give the mind a more definite comprehension of it, it was frequently drawn down from heaven and sculptured in wood or stone. The object was by images to make manifest unto the senses the attributes of the gods, and thus the more easily secure the devotion of the people. The heathen had to see the image of God, the image of the infinite thought embodied in the god, or he would not kneel down and worship. This idea of wanting something concrete, something within the reach of the senses, we find deeply rooted in human nature. Man does not want an abstract god, but a personal, visible god, at least a visible sign of his presence. And we who live in the broad daylight of revealed religion and science ought not to be so prone to blame our forefathers for paying divine honors to images, statues and other representations or symbols of their gods, for the images were, as the words imply, not the gods themselves to whom the heathen addressed his prayers and supplications, but merely the symbols of these gods; and every religion, Christianity included, is mythical in its development. The tendency is to draw the divine down to earth, in order to rise with it again to heaven. When God suffers with us, it becomes easier for us to suffer; when he redeems us, our salvation becomes certain. God is in all systems of religion seen, as it were, through a glass—never face to face. No one can see Jehovah and live.

31Even as in our present condition our immortal soul cannot do without the visible body, and cannot without this reveal itself to its fellow-beings, so our faith requires a visible church, our religion must assume some form in which it can be apprehended by the senses. Our faith is made stronger by the visible church in the same manner as the mind gains knowledge of the things about us by means of the bodily organs. The outward rite or external form and ceremonial ornament, which are so conspicuous in the Roman and Greek Catholic churches, for instance, serve to awaken, edify and strengthen the soul and assist the memory in recalling the religious truths and the events in the life of Christ and of the saints more vividly and forcibly to the mind; besides, pictures and images are to the unlettered what books are to those educated in the art of reading. Did not Christ himself combine things supersensual with things within the reach of the senses? The purification and sanctification of the soul he combined with the idea of cleansing the body in the sacrament of baptism. The remembrance of him and of his love, how he gave his body and blood for the redemption of fallen man, he combined with the eating of bread and drinking of wine in the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. He gave his religion an outward, visible form; and, just as the soul is mirrored in the eyes, in the expression of the countenance, in the gestures and manners of the body, so our faith is reflected in the church. This is what is meant by mythical development; and when we discover this tendency to cling to visible signs and ceremonies manifesting itself so extensively even in the Christian church of our own time, it should teach us to be less severe in judging and blaming the heathen for their idol-worship.

32As long as the nations have inhabited the earth, there have been different religions among men; and how could this be otherwise? The countries which they have inhabited; the skies which they have looked upon; their laws, customs and social institutions; their habits, language and knowledge; have differed so widely that it would be absurd to look for uniformity in the manner in which they have found, comprehended and worshiped God. Nay, this is not all. Even among Christians, and, if we give the subject a careful examination, even among those who confess one and the same faith and are members of one and the same church, we find that the religion of one man is never perfectly like that of another. They may use the same prayers, learn and subscribe to the same confession, hear the same preacher and take part in the same ceremonies, but still the prayer, faith and worship of the one will differ from the prayer, faith and worship of the other. Two persons are never precisely alike, and every one will interpret the words which he hears and the ceremonies in which he takes part according to the depth and breadth of his mind and heart—according to the extent and kind of his knowledge and experience, and according to other personal peculiarities and characteristics. Even this is not all. Every person changes his religious views as he grows older, as his knowledge and experience increase, so that the faith of the youth is not that of the child, nor does the man with silvery locks approach the altar with precisely the same faith as when he knelt there a youth. For it is not the words and ceremonies, but the thoughts and feelings, that we combine with these symbols, that constitute our religion; it is not the confession which we learned at school, but the ideas that are suggested by it in our 33minds, and the emotions awakened by it in our hearts, that constitute our faith.

If the preachers of the Christian religion realized these truths more than they generally seem to do, they would perhaps speak with more charity and less scorn and contempt of people who differ from them in their religious views. They would recognize in the faith of others the same connecting link between God and man for them, as their own faith is for themselves. They would not hate the Jew because he, in accordance with the Mosaic commandment, offers his prayers in the synagogue to the God of his fathers; nor despise the heathen because he, in want of better knowledge, in childlike simplicity lifts his hands in prayer to an image of wood or stone; for, although this be perishable dust, he still addresses the prayer of his inmost soul to the supreme God, even as the child, that kisses the picture of his absent mother, actually thinks of her.

The old mythological stories of the Norsemen abound in poetry of the truest and most touching character. These stories tell us in sublime and wonderful speech of the workings of external nature, and may make us cheerful or sad, happy or mournful, gay or grave, just as we night feel, if from the pinnacle of Gausta Fjeld we were to watch the passing glories of morning and evening tide. There is nothing in these stories that can tend to make us less upright and simple, while they contain many thoughts and suggestions that we may be the better and happier for knowing. All the so-called disagreeable features of mythology are nothing but distortions, brought out either by ill-will or by a superficial knowledge of the subject; and, when these distortions are removed, we shall find only things beautiful, lovely and of good report. We shall find the 34simple thoughts of our childlike, imaginative, poetic and prophetic forefathers upon the wonderful works of their maker, and nothing that we may laugh at, or despise, or pity. These words of our fathers, if read in the right spirit, will make us feel as we ought to feel when we contemplate the glory and beauty of the heavens and the earth, and observe how wonderfully all things are adapted to each other and to the wants of man, that the thoughts of him who stands at the helm of this ship of the universe (Skidbladner) must be very deep, and that we are sensible to the same joys and sufferings, are actuated by the same fears and hopes and passions, that were felt by the men and women who lived in the dawn of our Gothic history. We will begin to realize how the great and wise Creator has led our race on—slowly, perhaps, but nevertheless surely—to the consciousness that he is a loving and righteous Father, and that he has made the sun and moon and stars, the earth, and all that in them is, in their season.

The Norse mythology reflects, then, the religious, moral, intellectual and social development of our ancestors in the earliest period of their existence. We say our ancestors, for we must bear in mind that in its most original form this mythology was common to all the Teutonic nations, to the ancestors of the Americans and the English, as well as to those of the Norsemen, Swedes and Danes. Geographically it extended not only over the whole of Scandinavia, including Iceland, but also over England and a considerable portion of France and Germany. But it is only in Iceland, that weird island of the icy sea, with the snow-clad volcano Mt. Hecla for its hearth, encircled by a wall of glaciers, and with the roaring North Sea for its grave,—it is 35only in Iceland that anything like a complete record of this ancient Teutonic mythology was put in writing and preserved; and this fact alone ought to be quite sufficient to lead us to cultivate a better acquaintance with the literature of Scandinavia. To use the words of that excellent Icelandic scholar, the Englishman George Webbe Dasent: It is well known, says he, that the Icelandic language, which has been preserved almost incorrupt in that remarkable island, has remained for many centuries the depository of literary treasures, the common property of all the Scandinavian and Teutonic races, which would otherwise have perished, as they have perished in Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Germany and England. There was a time when all these countries had a common mythology, when the royal race each of them traced its descent in varying genealogies up to Odin and the gods of Asgard. Of that mythology, which may hold its own against any other that the world has seen, all memory, as a systematic whole, has vanished from the mediæval literature of Teutonic Europe. With the introduction of Christianity, the ancient gods had been deposed and their places assigned to devils and witches. Here and there a tradition, a popular tale or a superstition bore testimony to what had been lost; and, though in this century the skill and wisdom of the Grimms and their school have shown the world what power of restoration and reconstruction abides in intelligent scholarship and laborious research, even the genius of the great master of that school of criticism would have lost nine-tenths of its power had not faithful Iceland preserved through the dark ages the two Eddas, which present to us, in features that cannot be mistaken, and in words which cannot die, the very form 36and fashion of that wondrous edifice of mythology which our forefathers in the dawn of time imagined to themselves as the temple at once of their gods and of the worship due to them from all mankind on this middle earth. For man, according to their system of belief, could have no existence but for those gods and stalwart divinities, who, from their abode in Asgard, were ever watchful to protect him and crush the common foes of both, the earthly race of giants, or, in other words, the chaotic natural powers. Any one, therefore, that desires to see what manner of men his forefathers were in their relation to the gods, how they conceived their theogony, how they imagined and constructed their cosmogony, must betake himself to the Eddas, as illustrated by the Sagas, and he will there find ample details on all these points; while the Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic literatures only throw out vague hints and allusions. As we read Beowulf and the Traveler’s Song, for instance, we meet at every step references to mythological stories and mythical events, which would be utterly unintelligible were it not for the full light thrown upon them by the Icelandic literature. Thus far Dasent’s opinion.

The Norse mythology, we say, then, shows what the religion of our ancestors was; and their religion is the main fact that we care to know about them. Knowing this well, we can easily account for the rest. Their religion is the soul of their history. Their religion tells us what they felt; their feelings produced their thoughts, and their thoughts were the parents of their acts. When we study their religion, we discover the unseen and spiritual fountain from which all their outward acts welled forth, and by which the character of these was determined.

The mythology is neither the history nor the poetry 37nor the natural philosophy of our ancestors; but it is the germ and nucleus of them all. It is history, for it treats of events; but it is not history in the ordinary acceptance of that word, for the persons figuring therein have never existed. It is natural philosophy, for it investigates the origin of nature; but it is not natural philosophy according to modern ideas, for it personifies and deifies nature. It is metaphysics, for it studies the science and the laws of being; but it is not metaphysics in our sense of the word, for it rapidly overleaps all categories. It is poetry in its very essence; but its pictures are streams that flow together. Thus the Norse mythology is history, but limited to neither time nor place; poetry, but independent of arses or theses; philosophy, but without abstractions or syllogisms.

We close this chapter with the following extract from Thomas Carlyle’s essays on Heroes and Hero-worship; an extract that undoubtedly will be read with interest and pleasure:

In that strange island—Iceland—burst up, the geologists say, by fire, from the bottom of the sea; a wild land of barrenness and lava; swallowed, many months of the year, in black tempests, yet with a wild, gleaming beauty in summer-time; towering up there, stern and grim, in the North Ocean; with its snow-jökuls, roaring geysers, sulphur pools and horrid volcanic chasms, like the waste, chaotic battle-field of frost and fire—where of all places we least looked for literature or written memorials; the record of these things was written down. On the seaboard of this wild land is a rim of grassy country, where cattle can subsist, and men, by means of them and of what the sea yields; and it seems they were poetic men, these—men who had deep thoughts in them, and uttered musically their thoughts. Much would be lost had Iceland not been burst up from the sea—not been discovered by the Northmen! The old Norse poets were many of them natives of Iceland.

Sæmund, one of the early Christian priests there, who perhaps had a lingering fondness for paganism, collected certain of 38their old pagan song, just about becoming obsolete then—poems or chants, of a mythic, prophetic, mostly all of a religious, character: this is what Norse critics call the Elder or Poetic Edda. Edda, a word of uncertain etymology, is thought to signify Ancestress. Snorre Sturleson, an Iceland gentleman, an extremely notable personage, educated by this Sæmund’s grandson, took in hand next, near a century afterwards, to put together, among several other books he wrote, a kind of prose synopsis of the whole mythology, elucidated by new fragments of traditionary verse; a work constructed really with great ingenuity, native talent, what one might call unconscious art; altogether a perspicuous, clear work—pleasant reading still. This is the Younger or Prose Edda. By these and the numerous other Sagas, mostly Icelandic, with the commentaries, Icelandic or not, which go on zealously in the North to this day, it is possible to gain some direct insight even yet, and see that old system of belief, as it were, face to face. Let as forget that it is erroneous religion: let us look at it as old thought, and try if we cannot sympathize with it somewhat.

The primary characteristic of this old Northland mythology I find to be impersonation of the visible workings of nature—earnest, simple recognition of the workings of physical nature, as a thing wholly miraculous, stupendous and divine. What we now lecture of as science, they wondered at, and fell down in awe before, as religion. The dark, hostile powers of nature they figured to themselves as Jötuns (giants), huge, shaggy beings, of a demoniac character. Frost, Fire, Sea, Tempest, these are Jötuns. The friendly powers, again, as Summer-heat, the Sun, are gods. The Empire of this Universe is divided between these two; they dwell apart in perennial internecine feud. The gods dwell above in Asgard, the Garden of the Asas, or Divinities; Jötunheim, a distant, dark, chaotic land, is the home of the Jötuns.

Curious, all this; and not idle or inane if we will look at the foundation of it. The power of Fire or Flame, for instance, which we designate by some trivial chemical name, thereby hiding from ourselves the essential character of wonder that dwells in it, as in all things, is, with these old Northmen, Loge, a most swift, subtle demon, of the brood of the Jötuns. The savages of the Ladrones Islands, too (say some Spanish voyagers), thought Fire, which they had never seen before, was a devil, or god, 39that bit you sharply when you touched it, and lived there upon dry wood. From us, too, no chemistry, if it had not stupidity to help it, would hide that flame is a wonder. What is flame? Frost the old Norse seer discerns to be a monstrous, hoary Jötun, the giant Thrym, Hrym, or Rime, the old word, now nearly obsolete here, but still used is Scotland to signify hoar-frost. Rime was not then, as now, a dead chemical thing, but a living Jötun, or Devil; the monstrous Jötun Rime drove home his horses at night, sat combing their manes;—which horses were Hail-clouds, or fleet Frost-winds. His cows—no, not his, but a kinsman’s, the giant Hymer’s cows—are Icebergs. This Hymer looks at the rocks with his devil-eye, and they split in the glance of it.

Thunder was then not mere electricity, vitreous or resinous; it was the god Donner (Thunder), or Thor,—god, also, of the beneficent Summer-heat. The thunder was his wrath; the gathering of the black clouds is the drawing down of Thor’s angry brows; the fire-bolt bursting out of heaven is the all-rending hammer flung from the hand of Thor. He urges his loud chariot over the mountain tops—that is the peal; wrathful he blows in his red beard—that is the rustling storm-blast before the thunder begins. Balder, again, the White God, the beautiful, the just and benignant, (whom the early Christian missionaries found to resemble Christ,) is the sun—beautifulest of visible things: wondrous, too, and divine still, after all our astronomies and almanacs! But perhaps the notablest god we hear tell of is one of whom Grimm, the German etymologist, finds trace: the god Wünsch, or Wish. The god Wish, who could give us all that we wished! Is not this the sincerest and yet the rudest voice of the spirit of man? The rudest ideal that man ever formed, which still shows itself in the latest forms of our spiritual culture. Higher considerations have to teach us that the god Wish is not the true God.

Of the other gods or Jötuns, I will mention, only for etymology’s sake, that Sea-tempest is the Jötun Ægir, a very dangerous Jötun; and now to this day, on our river Trent, as I learn, the Nottingham bargemen, when the river is in a certain flooded state (a kind of back-water or eddying swirl it has, very dangerous to them), call it Eager. They cry out, Have a care! there is the Eager coming! Curious, that word surviving, like the peak of a submerged world! The oldest Nottingham barge-men 40had believed in the god Ægir. Indeed, our English blood, too, in good part, is Danish, Norse,—or rather, at the bottom, Danish and Norse and Saxon have no distinction except a superficial one—as of Heathen and Christian, or the like. But all over our island we are mingled largely with Danes proper—from the incessant invasions there were; and this, of course, in a greater proportion along the east coast; and greatest of all, as I find, in the north country. From the Humber upward, all over Scotland, the speech of the common people is still in singular degree Icelandic; its Germanism has still a peculiar Norse tinge. They, too, are Normans, Northmen—if that be any great beauty!

Of the chief god, Odin, we shall speak by-and-by. Mark, at present, so much: what the essence of Scandinavian, and, indeed, of all paganism, is: a recognition of the forces of nature as godlike, stupendous, personal agencies—as gods and demons. Not inconceivable to us. It is the infant thought of man opening itself with awe and wonder on this ever stupendous universe. It is strange, after our beautiful Apollo statues and clear smiling mythuses, to come down upon the Norse gods brewing ale to hold their feast with Aegir, the Sea-Jötun; sending out Thor to get the caldron for them in the Jötun country; Thor, after many adventures, clapping the pot on his head, like a huge hat, and walking off with it—quite lost in it, the ear of the pot reaching down to his heels! A kind of vacant hugeness, large, awkward gianthood, characterizes that Norse system; enormous force, as yet altogether untutored, stalking helpless, with large, uncertain strides. Consider only their primary mythus of the Creation. The gods having got the giant Ymer slain—a giant made by warm winds and much confused work out of the conflict of Frost and Fire—determined on constructing a world with him. His blood made the sea; his flesh was the Land; the Rocks, his bones; of his eyebrows they formed Asgard, their gods’ dwelling; his skull was the great blue vault of Immensity, and the brains of it became the Clouds. What a Hyper-Brobdignagian business! Untamed thought; great, giantlike, enormous; to be tamed, in due time, into the compact greatness, not giantlike, but godlike, and stronger than gianthood of the Shakespeares, the Goethes! Spiritually, as well as bodily, these men are our progenitors.

In its original form, the mythology, which is to be presented in this volume, was common to all the Teutonic nations; and it spread itself geographically over England, the most of France and Germany, as well as over Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland. But when the Teutonic nations parted, took possession of their respective countries, and began to differ one nation from the other, in language, customs and social and political institutions, and were influenced by the peculiar features of the countries which they respectively inhabited, then the germ of mythology which each nation brought with it into its changed conditions of life, would also be subject to changes and developments in harmony and keeping with the various conditions of climate, language, customs, social and political institutions, and other influences that nourished it, while the fundamental myths remained common to all the Teutonic nations. Hence we might in one sense speak of a Teutonic mythology. That would then be the mythology of the Teutonic peoples, as it was known to them while they all lived together, some four or five hundred years before the birth of Christ, in the south-eastern part of Russia, without any of the peculiar features that have been added later by any of the several 42branches of that race. But from this time we have no Teutonic literature. In another sense, we must recognize a distinct German mythology, a distinct English mythology, and even make distinction between the mythologies of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.

That it is only of the Norse mythology we have anything like a complete record, was alluded to in the first chapter; but we will now make a more thorough examination of this fact.

The different branches of the Teutonic mythology died out and disappeared as Christianity gradually became introduced, first in France, about five hundred years after the birth of Christ; then in England, one or two hundred years later; still later, in Germany, where the Saxons, Christianized by Charlemagne about A.D. 800, were the last heathen people.

But in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Iceland, the original Gothic heathenism lived longer and more independently than elsewhere, and had more favorable opportunities to grow and mature. The ancient mythological or pagan religion flourished here until about the middle of the eleventh century; or, to speak more accurately, Christianity was not completely introduced in Iceland before the beginning of the eleventh century; in Denmark and Norway, some twenty to thirty years later; while in Sweden, paganism was not wholly eradicated before 1150.

Yet neither Norway, Sweden nor Denmark give us any mythological literature. This is furnished us only by the Norsemen, who had settled in Iceland. Shortly after the introduction of Christianity, which gave the Norsemen the so-called Roman alphabetical system instead of their famous Runic futhorc, there was put in writing in Iceland a colossal mythological and historical 43literature, which is the full-blown flower of Gothic paganism. In the other countries inhabited by Gothic (Scandinavian, Low Dutch and English) and Germanic (High German) races, scarcely any mythological literature was produced. The German Niebelungen-Lied and the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf’s Drapa are at best only semi-mythological. The overthrow of heathendom was too abrupt and violent. Its eradication was so complete that the heathen religion was almost wholly obliterated from the memory of the people. Occasionally there are found authors who refer to it, but their allusions are very vague and defective, besides giving unmistakable evidence of being written with prejudice and contempt. Nor do we find among the early Germans that spirit of veneration for the memories of the past, and desire to perpetuate them in a vernacular literature; or if they did exist, they were smothered by the Catholic priesthood. When the Catholic priests gained the ascendancy, they adopted the Latin language and used that exclusively for recording events, and they pronounced it a sin even to mention by name the old pagan gods oftener than necessity compelled them to do so.

Among the Norsemen, on the other hand, and to a considerable extent among the English, too, the old religion flourished longer; the people cherished their traditions; they loved to recite the songs and Sagas, in which were recorded the religious faith and brave deeds of their ancestors, and cultivated their native speech in spite of the priests. In Iceland at least, the priests did not succeed in rooting out paganism, if you please, before it had developed sufficiently to produce those beautiful blossoms, the Elder and Younger Eddas. The chief reason of this was, that the people continued to use their mother-tongue, in writing as well as in speaking, 44so that Latin, the language of the church, never got a foothold. It was useless for the monks to try to tell Sagas in Latin, for they found but few readers in that tongue. An important result of this was, that the Saga became the property of the people, and not of the favored few. In the next place, our Norse Icelandic ancestors took a profound delight in poetry and song. The skald sung in the mother-speech, and taking the most of the material for his songs and poems from the old mythological tales, it was necessary to study and become familiar with these, in order that he might be able, on the one hand, to understand the productions of others, and, on the other, to compose songs himself. Among the numerous examples which illustrate how tenaciously the Norsemen clung to their ancient divinities, we may mention the skald Hallfred, who, when he was baptized by the king Olaf Tryggvesson, declared bravely to the king, that he would neither speak ill of the old gods, nor refrain from mentioning them in his songs.

The reason, then, why we cannot present a complete and thoroughly systematic Teutonic or German or English or Danish or Swedish Mythology, is not that these did not at some time exist, but because their records are so defective. Outside of Norway and Iceland, Christianity, together with disregard of past memories, has swept most of the resources, with which to construct them, away from the surface, and there remain only deeply buried ruins, which it is difficult to dig up and still more difficult to polish and adjust into their original symmetrical and comprehensive form after they have been brought to the surface. It is difficult to gather all the scattered and partially decayed bones of the mythological system, and with the breath of human 45intellect reproduce a living vocal organism. Few have attempted to do this with greater success than the brothers Grimm.

For the elucidation of our mythology in its Germanic form, for instance, the materials, although they are not wholly wanting, are yet difficult to make use of, since they are widely scattered, and must be sought partly in quite corrupted popular legends, partly in writings of the middle ages, where they are sometimes found interpolated, and where we often least should expect to find them. But in its Norse form we have ample material for studying the Asa-mythology. Here we have as our guide not only a large number of skaldic lays, composed while the mythology still flourished, but even a complete religious system, written down, it is true, after Christianity had been introduced in Iceland, still, according to all evidence, without the Christian ideas having had any special influence upon its delineation, or having materially corrupted it. These lays, manuscripts, etc., which form the source of Norse mythology, will be more fully discussed in another chapter of this Introduction.

We may add further, that if we had, in a complete system, the mythology of the Germans, the English, etc., we should find, in comparing them with the Norse, the same correspondence and identity as see find existing between the different branches of the Teutonic family of languages. We should find in its essence the same mythology in all the Teutonic countries, we should find this again dividing itself into two groups, the Germanic and the Gothic, and the latter group, that is, the Gothic, would include the ancient religion of the Scandinavians, English, and Low Dutch. If we had sufficient means for making a comparison, we should find that 46any single myth may have become more prominent, may have become more perfectly developed by one branch of the race than by another; one branch of the great Teutonic family may have become more attached to a certain myth than another, while the myth itself would remain identical everywhere. Local myths, that is, myths produced by the contemplation of the visible workings of external nature, are colored by the atmosphere of the people and country where they are fostered. The god Frey received especial attention by the Asa-worshipers in Sweden, but the Norse and Danish Frey are still in reality the same god. Thunder produces not the same effect upon the people among the towering and precipitous mountains of Norway and the level plains of Denmark, but the Thor of Norway and of Denmark are still the same god; although in Norway he is tall a mountain, his beard is briers, and he rushes upon his heroic deeds with the strength and frenzy of a berserk, while in Denmark he wanders along the sea-shore, a youth, with golden looks and downy beard.

It is the Asa-mythology, as it was conceived and cherished by the Norsemen of Norway and Iceland, which the Old Norse literature properly presents to us, and hence the myths will in this volume be presented in their Norse dress, and hence its name, Norse Mythology. From what has already been said, there is no reason to doubt that the Swedes and Danes professed in the main the same faith, followed the same religious customs, and had the same religious institutions; and upon this supposition other English writers upon this subject, as for instance Benjamin Thorpe, have entitled their books Scandinavian Mythology. But we do not know the details of the religious faith, customs and 47institutions of Sweden and Denmark, for all reliable inland sources of information are wanting, and all the highest authorities on this subject of investigation, such as Rudolph Keyser, P. A. Munch, Ernst Sars, N. M. Petersen and others, unanimously declare, that although the ancient Norse-Icelandic writings not unfrequently treat of heathen religious affairs in Sweden and Denmark, yet, when they do, it is always in such a manner that the conception is clearly Norse, and the delineation is throughout adapted to institutions as they existed in Norway. We are aware that there are those who will feel inclined to criticise us for not calling this mythology Scandinavian or Northern (a more elastic term), but we would earnestly recommend them to examine carefully the writings of the above named writers before waxing too zealous on the subject.

As we closed the previous chapter, with an extract from Thomas Carlyle, so we will close this chapter with a brief quotation frown an equally eminent scholar, the author of Chips from a German Workshop. In the second volume of that work Max Müller says:[1]

There is, after Anglo-Saxon, no language, no literature, no mythology so full of interest for the elucidation of the earliest history of the race which now inhabits these British isles as the Icelandic. Nay, in one respect Icelandic beats every other dialect of the great Teutonic family of speech, not excepting Anglo-Saxon and Old High German and Gothic. It is in Icelandic alone that we find complete remains of genuine Teutonic heathendom. Gothic as a language, is more ancient than Icelandic; but the only literary work which we we possess in Gothic is a translation of the Bible. The Anglo-Saxon literature, with the exception of the Beowulf, is Christian. The old heroes of the Niebelunge, such as we find them represented in the Suabian epic, have been converted into church-going knights; whereas, in the ballads of 48the Elder Edda, Sigurd and Brynhild appear before us in their full pagan grandeur, holding nothing sacred but their love, and defying all laws, human and divine, in the name of that one almighty passion. The Icelandic contains the key to many a riddle in the English language and to many a mystery in the English character. Though the Old Norse is but a dialect of the same language which the Angles and Saxons brought to Britain, though the Norman blood is the same blood that floods and ebbs in every German heart, yet there is an accent of defiance in that rugged northern speech, and a spring of daring madness in that throbbing northern heart, which marks the Northman wherever he appears, whether in Iceland or in Sicily, whether on the Seine or on the Thames. At the beginning of the ninth century, when the great northern exodus began, Europe, as Dr. Dasent remarks, was in danger of becoming too comfortable. The two nations destined to run neck-and-neck in the great race of civilization, Frank and Anglo-Saxon, had a tendency to become dull and lazy, and neither could arrive at perfection till it had been chastised by the Norsemen, and finally forced to admit an infusion of northern blood into its sluggish veins. The vigor of the various branches of the Teutonic stock may be measured by the proportion of Norman blood which they received; and the national character of England owes more to the descendants of Hrolf Ganger[2] than to the followers of Hengist and Horsa.

But what is known of the early history of the Norsemen? Theirs was the life of reckless freebooters, and they had no time to dream and ponder on the past, which they had left behind in Norway. Where they settled as colonists or as rulers, their own traditions, their very language, were soon forgotten. Their language has nowhere struck root on foreign ground, even where, as in Normandy, they became earls of Rouen, or, as in these isles, kings of England. There is but one exception—Iceland. Iceland was discovered, peopled and civilized by Norsemen in the ninth century; and in the nineteenth century the language spoken there is still the dialect of Harald Fairhair, and the stories told there are still the stories of the Edda, or the Venerable Grandmother. Dr. Dasent gives us a rapid sketch of the first landings of the Norse refugees on the fells and forths of Iceland. He describes how love of freedom drove the subjects 49of Harald Fairhair forth from their home; how the Teutonic tribes, though they loved their kings, the sons of Odin, and sovereigns by the grace of God, detested the dictatorship of Harald. He was a mighty warrior, so says the ancient Saga, and laid Norway under him, and put out of the way some of those who held districts, and some of them he drove out of the land; and besides, many men escaped out of Norway because of the overbearing of Harald Fairhair, for they would not stay to be subjects to him. These early emigrants were pagans, and it was not till the end of the tenth century that Christianity reached the Ultima Thule of Europe. The missionaries, however, who converted the freemen of Iceland, were freemen themselves. They did not come with the pomp and the pretensions of the church of Rome. They preached Christ rather than the Pope; they taught religion rather than theology. Nor were they afraid of the old heathen gods, or angry with every custom that was not of Christian growth. Sometimes this tolerance may have been carried too far, for we read of kings, like Helge, who mixed in their faith, who trusted in Christ, but at the same time invoked Thor’s aid whenever they went to sea or got into any difficulty. But on the whole, the kindly feeling of the Icelandic priesthood toward the national traditions and customs and prejudices of their converts must have been beneficial. Sons and daughters were not forced to call the gods whom their fathers and mothers had worshiped, devils; and they were allowed to use the name of Allfadir, whom they had invoked in the prayers of their childhood, when praying to Him who is our Father in Heaven.

The Icelandic missionaries had peculiar advantages in their relation to the system of paganism which they came to combat. Nowhere else, perhaps, in the whole history of Christianity, has the missionary been brought face to face with a race of gods who were believed by their own worshipers to be doomed to death. The missionaries had only to proclaim that Balder was dead, that the mighty Odin and Thor were dead. The people knew that these gods were to die, and the message of the One Everliving God must have touched their ears and their hearts with comfort and joy. Thus, while in Germany the priests were occupied for a long time in destroying every trace of heathenism, in condemning every ancient lay as the work of the 50devil, in felling sacred trees and abolishing national customs, the missionaries of Iceland were able to take a more charitable view of the past, and they became the keepers of those very poems and laws and proverbs and Runic inscriptions which on the continent had to be put down with inquisitorial cruelty. The men to whom the collection of the ancient pagan poetry of Iceland is commonly ascribed were men of Christian learning: the one,[3] the founder of a public school; the other,[4] famous as the author of a history of the North, the Heimskringla (the Home-Circle—the World). It is owing to their labors that we know anything of the ancient religion, the traditions, the maxims, the habits of the Norsemen. Dr. Dasent dwells most fully on the religious system of Iceland, which is the same, at least in its general outline, as that believed in by all the members of the Teutonic family, and may truly be called one of the various dialects of the primitive religious and mythological language of the Aryan race. There is nothing more interesting than religion in the whole history of man. By its side, poetry and art, science and law, sink into comparative insignificance.

Dr. Dasent says the Norse mythology may hold its own against any other in the world. The fact that it is the religion of our forefathers ought to be enough to commend it to our attention; but it may be pardonable in us to harbor even a sense of pride, if we find, for instance, that the mythology of our Gothic ancestors suffers nothing, but rather is the gainer in many respects by a comparison with that world-famed paganism of the ancient Greeks. We would therefore invite the attention of the reader to a brief comparison between the Norse and Greek systems of mythology.

A comparison between the two systems is both interesting and important. They are the two grandest systems of cosmogony and theogony of which we have record, but the reader will generously pardon the writer if he ventures the statement already at the outset, that of the two the Norse system is the grander. These two, the Greek and the Norse, have, to a greater extent than all other systems of mythology combined, influenced the civilization, determined the destinies, socially and politically, of the European nations, and shaped their polite literature. In literature it might indeed seem that the Greek mythology has played a more important part. We admit that it has acted a more conspicuous part, but we imagine that there exists a wonderful blindness, 52among many writers, to the transcendent influence of the blood and spirit of ancient Norseland on North European, including English and American, character, which character has in turn stamped itself upon our literature (as, for instance, in the case of Shakespeare, the Thor among all Teutonic writers); and, furthermore, we rejoice in the absolute certainty to which we have arrived by studying the signs of the times, that the comparative ignorance, which has prevailed in this country and in England, of the history, literature, ancient religion and institutions of a people so closely allied to us by race, national characteristics, and tone of mind as the Norsemen, will sooner or later be removed; that a school of Norse philology and antiquities will ere long flourish on the soil of the Vinland of our ancestors, and that there is a grand future, not far hence, when Norse mythology will be copiously reflected in our elegant literature, and in our fine arts, painting, sculpturing and music.

The Norse mythology differs widely from the Greek. They are the same in essence; that is to say, both are a recognition of the forces and phenomena of nature as gods and demons; but all mythologies are the same in this respect, and the differences, between the various mythological systems, consist in the different ways in which nature has impressed different peoples, and in the different manner in which they have comprehended the universe, and personified or deified the various forces and phenomena of nature. In other words, it is in the ethical clothing and elaboration of the myths, that the different systems of mythology differ one from the other. In the Vedic and Homeric poets the germs of mythology are the same as in the Eddas of Norseland, but this common stock of materials, that is, the forces and phenomena of nature, has been moulded into an infinite 53variety of shapes by the story-tellers of the Hindoos, Greeks and Norsemen.

Memory among the Greeks is Mnemosyne, the mother of the muses, while among the Norsemen it is represented by Munin, one of the ravens perched upon Odin’s shoulders. The masculine Heimdal, god of the rainbow among the Norsemen, we find in Greece as the feminine Iris, who charged the clouds with water from the lakes and rivers, in order that it might fall again upon the earth in gentle fertilizing showers. She was daughter of Thaumas and Elektra, granddaughter of Okeanos, and the swift-footed gold-winged messenger of the gods. The Norse Balder is the Greek Adonis. Frigg, the mother of Balder, mourns the death of her son, while Aphrodite sorrows for her special favorite, the young rosy shepherd, Adonis. Her grief at his death, which was caused by a wild boar, was so great that she would not allow the lifeless body to be taken from her arms until the gods consoled her by decreeing that her lover might continue to live half the year, during the spring and summer, on the earth, while she might spend the other half with him in the lower world. Thus Balder and Adonis are both summer gods, and Frigg and Aphrodite are goddesses of gardens and flowers. The Norse god of Thunder, Thor (Thursday), who, among the Norsemen, is only the protector of heaven and earth, is the Greek Zeus, the father of gods and men. The gods of the Greeks are essentially free from decay and death. They live forever on Olympos, eating ambrosial food and drinking the nectar of immortality, while in their veins flows not immortal blood, but the imperishable ichor. In the Norse mythology, on the other hand, Odin himself dies, and is swallowed by the Fenriswolf; Thor conquers the Midgard-serpent, but retreats only nine paces 54and falls poisoned by the serpent’s breath; and the body of the good and beautiful Balder is consumed in the flames of his funeral pile. The Greek dwelt in bright and sunny lands, where the change from summer to winter brought with it no feelings of overpowering gloom. The outward nature exercised a cheering influence upon him, making him happy, and this happiness he exhibited in his mythology. The Greek cared less to commune with the silent mountains, moaning winds, and heaving sea; he spent his life to a great extent in the cities, where his mind would become more interested in human affairs, and where he could share his joys and sorrows with his kinsmen. While the Greek thus was brought up to the artificial society of the town, the hardy Norseman was inured to the rugged independence of the country. While the life and the nature surrounding it, in the South, would naturally have a tendency to make the Greek more human, or rather to deify that which is human, the popular life and nature in the North would have a tendency to form in the minds of the Norsemen a sublimer and profounder conception of the universe. The Greek clings with tenacity to the beautiful earth; the earth is his mother. Zeus, surrounded by his gods and goddesses, sits on his golden throne, on Olympos, on the top of the mountain, in the cloud. But that is not lofty enough for the spirit of the Norsemen. Odin’s Valhal is in heaven; nay, Odin himself is not the highest god; Muspelheim is situated above Asaheim, and in Muspelheim is Gimle, where reigns a god, who is mightier than Odin, the god whom Hyndla ventures not to name.

In Heroes and Hero Worship, Thomas Carlyle makes the following striking comparison between Norse and Greek mythology: To me, he says, there is in the 55Norse system something very genuine, very great and manlike. A broad simplicity, rusticity, so very different from the light gracefulness of the old Greek paganism, distinguishes this Norse system. It is thought, the genuine thought of deep, rude, earnest minds, fairly opened to the things about them, a face-to-face and heart-to-heart inspection of things—the first characteristic of all good thought in all times. Not graceful lightness, half sport, as in the Greek paganism; a certain homely truthfulness and rustic strength, a great rude sincerity, discloses itself here. Thus Carlyle.

As the visible workings of nature are in the great and main features the same everywhere; in all climes we find the vaulted sky with its sun, moon, myriad stars and flitting clouds; the sea with its surging billows; the land with its manifold species of plants and animals, its elevations and depressions; we find cold, heat, rain, winds, etc., although all these may vary widely in color, brilliancy, depth, height, degree, and other qualities; and as the minds and hearts of men cherish hope, fear, anxiety, passion, etc., although they may be influenced and actuated by them in various ways and to various extents; and as mythology is the impersonation of nature’s forces and phenomena as contemplated by the human mind and heart, so all mythologies, no matter in what clime they originated and were fostered, must of necessity have their stock of materials, their ground-work or foundation and frame in common, while they may differ widely from each other in respect to peculiar characteristics, both in the ethical elaboration of the myth and in the architectural effect of the tout ensemble. Thus we have a tradition about a deluge, for instance, in nearly every country on the globe, but no two nations tell it alike. In Genesis we read of Noah and his ark, 56and how the waters increased greatly upon the earth, destroying all flesh that moved upon the earth excepting those who were with him in the ark. In Greece, Deukalion and his wife Pyrrha become the founders of a new race of men. According to the Greek story, a great flood had swept away the whole human race, except one pair, Deukalion and Pyrrha, who, as the flood abated, landed on Mt. Parnassos, and thence descending, picked up stones and cast them round about, as Zeus had commanded. From these stones sprung a new race—men from those cast by Deukalion, and women from those cast by his wife. In Norseland, Odin and his two brothers, Vile and Ve, slew the giant Ymer, and when he fell, so much blood flowed from his wounds, that the whole race of frost-giants was drowned, except a single giant, who saved himself with his household in a skiff (ark), and from him descended a new race of frost-giants. Now this is not a tradition carried from one place to the other; it is a natural expression of the same thought; it is a similar effort to account for the origin of the land and the race of man. A people develops its mythology in the same manner as it develops its language. The Norse mythology is related to the Greek mythology to the same extent that the Norse language is related to the Greek language, and no more; and comparative mythology, when the scholar wields the pen, is as interesting as comparative philology.

The Greeks have their chaos, the all-embracing space, the Norsemen have Ginungagap, the yawning abyss between Niflheim (the nebulous world) and Muspelheim (the world of fire). The Greeks have their titans, corresponding in many respects to the Norse giants. The Greeks tell of the Melian nymphs; the Norsemen of the elves, etc.; but these comparisons are chiefly interesting 57for the purpose of studying the differences between the Norse and Greek mind, which reflects itself in the expression of the thought.

The hard stone weeps tears, both in Greece and in Norseland; but let us notice how differently it is expressed. In Greece, Niobe, robbed of her children, was transformed into a rugged rock, down which tears trickled silently. She becomes a stone and still continues her weeping—

as the poet somewhere has it. In Norseland all nature laments the sad death of Balder, even the stones weep for him (gráta Baldr).

Let us take another idea, and notice how differently the words symbolize the same truth or thought in the Bible, in Greece, and in Norseland. In the Bible:

And Jesus sat over against the treasury, and beheld how people cast money into the treasury: and many that were rich cast in much. And there came a certain poor widow, and she threw in two mites, which make a farthing. And he called unto him his disciples and said unto them, Verily I say unto you, that this poor widow hath cast more in, than all they which have cast into the treasury: for all they did cast in of their abundance; but she of her want did cast in all that she had, even all her living.

In Greece:

A rich Thessalian offered to the temple at Delphi one hundred oxen with golden horns. A poor citizen from Hermion took as much meal from his sack as he could hold between two fingers, and he threw it into the fire that burned on the altar. Pythia said, that the gift of the poor man was more pleasing to the gods than that of the rich Thessalian.

In Norseland the Elder Edda has it: