The Project Gutenberg eBook of Early Woodcut Initials, by Oscar Jennings

Title: Early Woodcut Initials

Containing over Thirteen Hundred Reproductions of Ornamental Letters of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

Author: Oscar Jennings

Release Date: July 15, 2021 [eBook #65847]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

Many of the initials in this text are displayed reduced in size. Full size images may be opened by clicking on the images (this option may not be available in all formats).

EARLY

WOODCUT INITIALS

CONTAINING OVER THIRTEEN

HUNDRED REPRODUCTIONS OF

ORNAMENTAL LETTERS OF THE

FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH

CENTURIES, SELECTED AND

ANNOTATED BY

OSCAR JENNINGS, M.D.

MEMBER OF THE

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

METHUEN AND CO.

36 ESSEX STREET

LONDON

First published in 1908

I DEDICATE THESE PAGES TO

MY WIFE

AS A SLIGHT RECOGNITION OF

HER CONSTANT PATIENCE

AND DEVOTION

[vii]

From the number of works that have been published within the last few decades on early printing and the decoration of early books, it is evident that an increasing interest is taken in these subjects, not only by those whose studies have specially fitted them to appreciate such researches, but also by the general educated public.

There is, however, one variety of engraving that has hitherto attracted but little attention, and the importance of which, both from artistic and documentary points of view, is still unrecognised, and it may even be said unsuspected by the great majority of students. Whilst every engraving that may technically be termed a cut or an illustration is catalogued and recorded in the different monographs on special printers, those which take the form of initial letters, often of equal, if not superior merit, are represented much more sparsely, and as having a secondary importance only.

In a monograph on fifteenth-century printing in a certain German town, for instance, the writer, a professional bibliographer, gives about ten or twelve initial letters, whereas the extent of the material upon which he might have drawn may be judged from the fact that a more recent authority, in his history of one printer only of this town, has been able to reproduce more than fifty specimens, many of which are quite equal in interest to illustrations proper, some of them having been recently pointed out by a London expert as constituting the chief attraction of a volume[1] with both initials and illustrations which came under his hammer.

[1] The initials in the Leben der Heiligen Drei Könige of Knoblochtzer.

[viii]

The above lines, written ten years ago, when I first began to collect material for this volume, are perhaps no longer as true absolutely as when first penned. Besides the works of Butsch, Reiber, and Heitz which were already in existence, Ongania’s book on Venice bibliography contains a great many initials; Heitz has devoted a volume to those of Holbein and other artists of the school of Basle, and others to certain initials of Strasburg and Hagenau; and Redgrave, Haebler, Claudin, Schorbach, Spirgatis, and Kristeller give a certain prominence to initials in their respective monographs.

I still think, however, that a special work on the subject is needed to do justice to the richness of artistic material available in this special matter.

The woodcuts in early books are often merely illustrative, that is to say explanatory of the text, and were not designed as ornaments; but the initials were intended to be decorative, and one can see in them a real artistic effort and sentiment.

Quaritch, indeed, has recently called attention to this fact, of the superiority in some early books of the initials over the woodcuts, and it is beginning to be recognised also by several great booksellers, whose catalogues contain increasing numbers of reproductions of ornamental letters in preference to other specimens of early engraving.

Unfortunately, circumstances have prevented my completing my first programme, and what I offer here can only be considered as a general introduction to the subject. But such as they are, these fragmentary notes will not, I hope, be found entirely devoid of interest.

In conclusion, I have to express my thanks to Mr. A. W. Pollard, the amiable and indefatigable secretary of the Bibliographical Society, for help in seeing this volume through the press, and for many valuable suggestions and criticisms.

OSCAR JENNINGS.

[ix]

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preface, | vii | ||

| Introduction, | 1 | ||

| CHAP. | |||

| I. | Block-Books: The Invention of Printing: The Psalter of Mayence, | 6 | |

| II. | Augsburg, | 14 | |

| III. | Ulm and Nuremberg, | 22 | |

| IV. | Basle and Zurich, | 29 | |

| V. | Lübeck and Bamberg, | 39 | |

| VI. | Strasburg and Reutlingen, | 43 | |

| VII. | Cologne and Geneva, | 51 | |

| VIII. | Venice, | 55 | |

| IX. | Other Italian Towns, | 64 | |

| X. | Lyons, | 73 | |

| XI. | Paris, | 82 | |

| XII. | French Provincial Towns, | 90 | |

| XIII. | Spanish Towns,[x] | 96 | |

| XIV. | Early Dutch Initials, | 101 | |

| XV. | Later German Initials: Hagenau, Magdeburg, Metz, Oppenheim, Ingoldstadt, etc. etc., | 103 | |

| XVI. | English Initials, | 108 | a |

| Reproductions of Initials, | 111 | ||

| Index, | 281 | ||

[1]

The ornamentation of books dates probably from the time of their invention, that is to say, it goes back to a very remote antiquity. From Greece, where the book-trade was flourishing at an early period, it passed into Italy, extending thence to the provinces of the Empire, to Gaul and Spain, where book-lovers became more and more numerous, and as civilisation became more refined, increasingly particular about bindings and ornamentation.

The verse of Tibullus,

shows the extent of the embellishments to which bibliophiles had then become accustomed, requiring the titles of their favourite authors to be engrossed in coloured or illuminated letters.[2]

[2] Numerous passages might be quoted from Latin writers to show how great an interest they took in books, and how valuable rare, and what might be called original, editions had even then become. It would seem, too, that they even knew the pleasures of book-hunting, for Aulus Gellius relates how, having a few hours to spare after landing at Brindisi, he spent his time looking through the contents of an old book-stall, and was lucky enough to discover a very old work on occult science.

Besides the title, the headings of chapters and the initial letters were also distinguished in the same way from the rest of the work, a custom which passed from the Roman copyists to those of the Lower Empire, and in course of time became generally adopted in the preparation of manuscripts. But this was not all. It is now recognised that book illustration[2] was known to the Romans, and that the miniatures of the mediæval manuscripts only followed the fashion of the rich and sumptuous volumes transcribed by the copyists of Athens and Rome. The fourth-century Virgil, for instance, one of the treasures of the Vatican, which has been so well described by M. Pierre de Nolhac, is an example of this, containing as it does a large number of figures. Like all manuscripts of the time, it was written exclusively in majuscules, very similar to those used in Roman inscriptions.[3]

[3] Pliny speaks of a marvellous, almost divine, invention by which pictures were added to the book of Imagines of Varro—no doubt printed by stamping.

The taste for luxury spreading from the third century, Byzantium became the centre of the most extravagant and costly elegance in all its manifestations, and books of that origin have come down to us written on purple parchment in letters of gold. It was not until several centuries later that a reaction took place, when Leo the Isaurian, in 741, considering such refinement as sinful, put an end to it by burning the public library, together with its staff of bibliothecarii and copyists, the survivors finding a refuge for their art in the western cloisters and monasteries.

The intelligent protection and encouragement and hospitality afforded to men of letters by Charlemagne was a great contrast to the bigotry of Leo the Byzantine. Interesting himself warmly in all questions relating to instruction, he took a special interest in the copying and transcription of manuscripts, inviting to his kingdom the Irish and Anglo-Saxon monks, who from the sixth century had made a special study of calligraphy, and were celebrated all over Europe for their miniatures and historiation.

In consequence of the patronage of Charlemagne and of Charles the Bald, son of Louis the Débonnaire, artists of all nationalities, but more particularly Germans and Italians, who had come from Oriental schools, received a warm welcome. At first in the sixth century the initial letter was of the same size as the others, only distinguished by the difference of colour, being in minium or cinnabar. A hundred years later, under the Byzantine influence, the letter grows[3] larger, until it occupies the whole page, at the same time being painted with the most vivid colours according to the fancy and caprice of the artist. Little by little the Byzantine style first introduced became modified, and assumed by degrees a national character. The decoration of the initials took the form of interlaced chequer-work or of historiated arabesques, resembling the mosaics of enamelled specimens of Gallo-Frank jewellery.

Then come figures of animals, in which the imagination of the artist runs riot, as in the alphabet of which Montfaucon has given a specimen in his Origins of the French Monarchy.

To quote the opinion of a contemporary writer, there was nothing under heaven or earth that had not served as a model for designers of ornamental letters.

Towards the fourteenth century this exuberance of decoration quiets down. Fancy is by no means excluded, but it becomes more regulated and more sure, to the advantage of art itself, which speaks through the skill of the painters, whose names, however, with but few exceptions, unfortunately remain unknown to us.

Paris was renowned at an early period for the excellence of its manuscripts, and the talents of its copyists and illuminators. Richard de Bury, Bishop of Durham and Chancellor of England, speaks in his Philobiblion of the five libraries he had seen in that town, and the magnificent books that he had been able to buy.

In England, illumination had flourished from before the twelfth to the fourteenth century, but by the middle of the fifteenth art was dead, and when handsome miniatures or other decorations were required for books, it was to French artists that it was necessary to apply.

In Italy, the influence, as regards book ornamentation, of French art may be judged from the passage of Dante, who, speaking to a miniaturist of his profession, is obliged to use a periphrase to design it:

[4]

The dawn of printing was at hand. Manuscripts, whether handsomely embellished or copied simply without ornament, were expensive luxuries which only the rich could purchase. With the revival of learning, for students in general, for the poorer classes, for school children, cheap books costing as little as possible, but serving the same end as the manuscript, were necessary, and the xylograph came at its hour.[4]

[4] It should be mentioned that block-books are now considered by some authorities to have come later than the invention of printing with movable type, i.e. about 1460.

From the earliest times copyists had used stamps[5] and copper stencillings in order to apply initials that recurred frequently, a practice which contains in it the first germ of printing. Playing-cards were printed by the same process and afterwards illuminated.

[5] Passavant.

Picture-books came next, with text and illustrations cut on the same block, the leaves being printed on one side only, and afterwards gummed back to back.

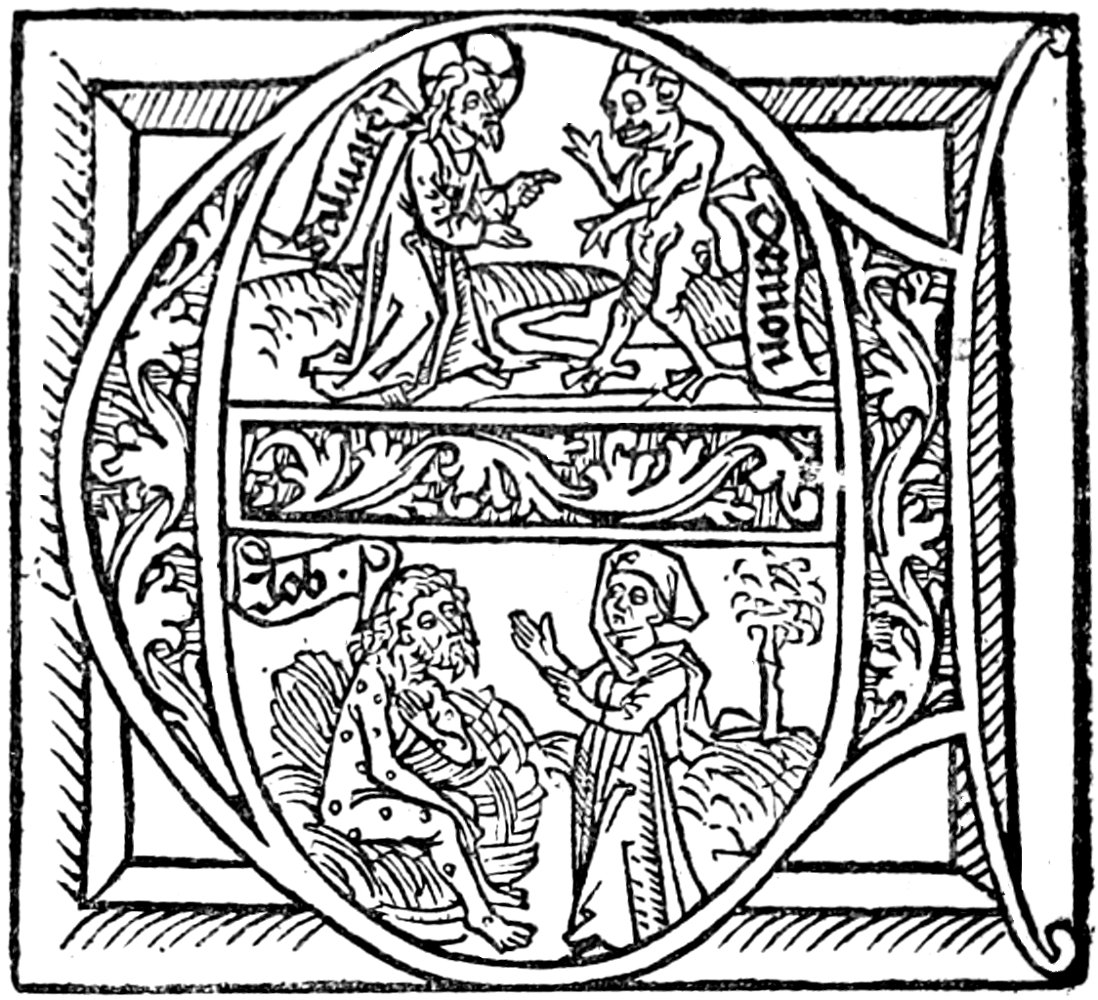

Such was the book known as the Biblia Pauperum, ‘Figurae typicae veteris atque antitypicae novi testamenti,’ a short pictorial history in forty leaves of the Old and New Testament. Another of these block-books is devoted to the history of St. John the Evangelist and his apocalyptic dreams, of which there are six different editions, with texts in Flemish, Saxon, and German. The Ars Moriendi, or temptations of the dying, with terrifying pictures, shows a moribund man assailed by devils,[6] but, as in all similar productions, the terrible is relieved by a touch of the grotesque. The Speculum humanae salvationis is remarkable for being printed partly from blocks and partly with movable characters. This shows the transition from xylography to printing proper. The printer of this work, in order to economise the composition of twenty-seven leaves, used the blocks he possessed, and printed them together with twenty-seven others composed with movable type. The example is not unique.

[6] See, under ‘Paris,’ the representation of one of these death-scenes in an initial of Chevallon’s.

A last variety of xylographic impressions is known under the generic name of ‘Donatus.’ This is a little primer of[5] Latin grammar first compiled by the grammarian Aelius Donatus, by whose name it was afterwards known.

We have mentioned the xylographic publications, because in a certain number of them ornamental initials are to be met with. These, as would naturally be supposed, are of the same style as those found in manuscripts of the same period. It may be observed here, that whilst books of price were embellished with expensive work, the less valuable manuscripts were left either without initials at all, or with ornamental letters of a few stereotyped patterns, that experience had shown to be most harmonious to the written text. Of these patterns the most popular is the Maiblümchen, or lily of the valley design, constantly seen in manuscript books, and adopted by many of the early printers. This design will be seen in many of the first initials of the Augsburg printers, and especially of Rihel of Basle.

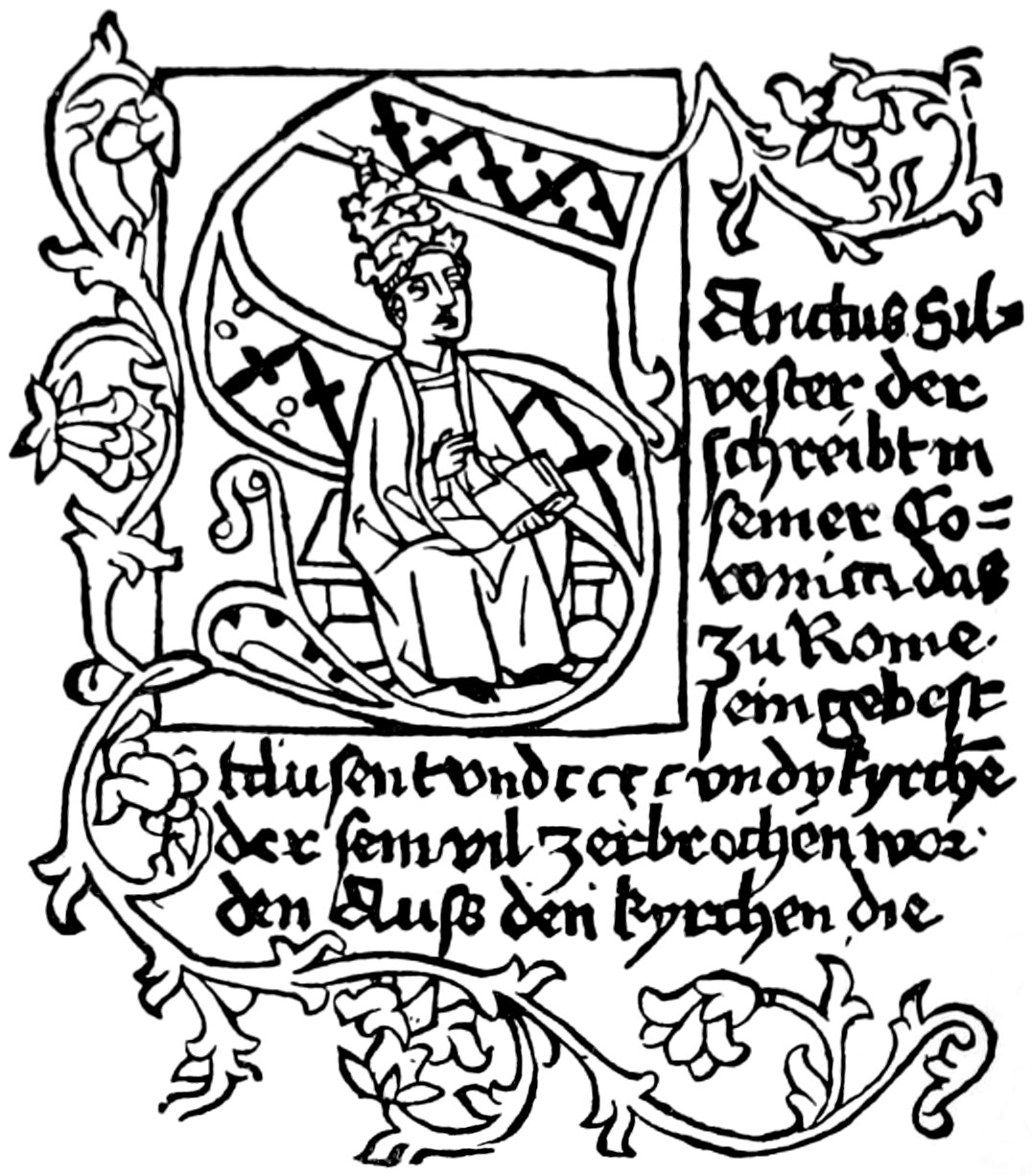

Historiated initials are less frequent in the block-books, the only one we have found being the S of an Ars Memorandi, of which a reproduction is given.

We have noted briefly the successive changes in the manuscript book, the different phases of its evolution towards its final formula and expression as an impression from movable type.

This brings us to the invention of printing, but it must be noted that printing, which revolutionised in so many ways the world, did not immediately put an end to the professions of the rubricator and illuminator. Some printed works of the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth centuries are embellished with miniatures of the very highest merit and illuminated letters of the greatest beauty.

[6]

Printing, with the discovery or invention of which the name of Gutenberg is intimately associated, goes back to the year 1454, or, if we accept the recent discovery of an almanac which can only refer to 1448, some six years earlier.

This is not the place to relate its general history, which is to be found in all the special works on the question. We shall set down here only the facts which concern our subject more particularly, and show the evolution of ornamental letters in books of the first period after the discovery of the new art.

It is known that Gutenberg, after the expensive experiments that had crippled his resources, had borrowed money from his fellow-citizen Fust, for the purpose of developing his new discovery.

His methods were, however, incomplete, and, according to one of many conjectures, it was not until two or three years later that Peter Scheffer, presumably a workman in Gutenberg’s office, perfected it by the invention of punches and matrices, so discovering a means of founding the type for which he devised a more suitable alloy instead of engraving each letter. This brought Scheffer into favour with Fust, who gave him his daughter in marriage. A quarrel with the original inventor ensued, and Gutenberg, nearly ruined, was[7] forced to retire, leaving the two others in possession of the field.

The object of the first printers was no doubt to imitate the manuscript book as closely as possible. Gutenberg in his Bible had only attempted to copy the letterpress proper. The two partners gave in 1457 as their diploma piece an edition of the Psalter with two hundred and eighty-eight capitals in two colours, besides the great initial B, the whole forming a perfect imitation by the press of a highly decorated manuscript.

At the present time an expert could see at a glance that this book is printed, instead of being written. But in 1457, and until the invention of printing had become generally known, no one could have guessed that it was anything but what it appeared, a beautifully finished manuscript.

Of the letters, which are mostly in red and blue, the handsomest is the initial B at the beginning of the first psalm, which is surrounded by arabesques, continued along the margin. Besides these ornaments, figures of a dog and bird are stencilled, as it were, in white on the red ground of the letter.

Writers are by no means agreed as to the way in which these initials were executed, but until recently the explanation most generally accepted was that of emboîtement, each part of the letter being inked separately and afterwards joined. According to Mr. Gordon Duff, it is impossible to determine exactly how they were produced, but in one edition, that of 1515, the exterior ornament has been printed, while the letter itself and the interior ornament have not. This shows that the letter and ornament were not on one block, and that the exterior and interior ornaments were on different blocks. Mr. Blades thought that the design was not printed but impressed in blank, and afterwards filled in with colour by the illuminator. The last opinion, that of Mr. Weale, is that the letters were not set up and printed with the rest of the book, but subsequently to the typography, not by a pull of the press but by a blow of the mallet on the superimposed block.

[8]

It is not, perhaps, without interest to note that the white ornaments which have been already mentioned are reproduced on one of the initials of the Bamberg missal. Whether or not this lends additional likelihood to the Bamberg printer having been a workman of Gutenberg, the reader must judge for himself.

We have said that the object of the first printers was to produce an imitation manuscript. It has even been suggested that Scheffer tried to palm off some of the copies of the Bible as, and at the price of, the manuscripts.

Gabriel Naudé, in his addition to the history of King Louis XI., is responsible for this accusation, which has been reproduced without investigation by several historians. The passage is too long to quote here, but he states positively that Scheffer sold the first copies pour manuscrites at seventy-five écus a copy, selling others afterwards at from twenty to thirty. Those who had paid the higher price brought an action against him for survente, and he had to fly from Paris to Mayence, where not being in safety he took refuge at Strasburg, living for a time with Messire Philippe de Commines.

The story is charmingly circumstantial but hardly convincing. At any rate, it is certain that no sharp practice could have been attempted after 1457, as the colophon of the Psalter states the volume ‘Venustate capitalium decoratus rubricationibusque sufficienter distinctus adinventione artificiosa imprimendi et characterizandi; absque calami ulla exaratione sic effigiatus.’

It has also been said that Scheffer was not the first to use the Psalter initials, which formed part of the stock which Gutenberg was compelled to relinquish in payment of the money he had borrowed of Fust.

Fischer at the beginning of the last century published the description of a Donatus of 1451 with some of these initials, of which he gave a facsimile, and which he attributes to Gutenberg, but this book is no longer to be found, and it is supposed that he was the victim of a hoax.[7] The only[9] copy now known with these initials has come down to us in the shape of a fragment which is preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale. The catalogue gives the date as 1468, but Hessels and many other good judges place it at 1456. It is printed in the type of the forty-two line Bible, with thirty-five lines to the page. In the colophon Scheffer makes use of the expression ‘cum suis capitalibus,’ which Hessels translates ‘with his capital letters,’ a rendering, says Mr. Gordon Duff, which is surely impossible.

[7] According to M. de Laborde, ‘Bodman archiviste de Mayence, tourmenté par Oberlin, Fischer et tous les bibliographes du temps pour leur trouver quelques nouveaux renseignements sur Gutenberg, n’imagina rien de mieux que d’en fabriquer.’ Fischer in his Essai sur les monuments Typographiques de Jean Gutenberg declares that he found two leaves of a Donatus, which was printed by Gutenberg with the same initials as were afterwards used by Scheffer. These leaves were in the cover of an account-book dated 1451, which was discovered in the Archives of Mayence by Bodman. These leaves have since disappeared.

Two other questions remain to be considered: Why Scheffer should have used the initials frequently until 1462, and then (with the exception of successive editions of the Psalter) have given up their use entirely? Who was their author?

For the first there was a combination of several reasons. The opposition of the Formschneiders may have had something to do with it. On the other hand, Scheffer may have got tired of always using the same initials which had been cut for him by an exceptionally clever engraver, of whom he had afterwards lost sight. In the third place, the sack of Mayence in 1462, which led to the dispersion of his workmen, may have been partly the reason, but that he did not lose his material is proved by the initials appearing in the antiquarian reprints of the Psalter.

In our opinion the second reason is most probable, and it is supported by the testimony of Papillon as to the identity of the artist, which seems to have escaped recent bibliographers.

According to Heineken, a certain Meydenbach is mentioned in Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia, and also by an anonymous author in Serarius, as being one of Gutenberg’s assistants. Heineken on these grounds considers that he accompanied Gutenberg from Strasburg to Mayence, also[10] that he was probably an engraver or illuminator, and Von Murr thinks he was the artist who engraved the large initials.

Fischer is convinced that they were engraved by Gutenberg himself, ‘a person experienced in such work, as we are taught by his residence in Strasburg,’ which Jackson declares teaches no such thing.

Papillon’s history is too long to be related here verbatim, but in substance it is as follows: A German who was making the tour de France applied to him for work. He stated that his name was Cocksperger, and that he was descended from Peter Cocksperger who had engraved the initials of the Psalter of Mayence. Papillon only saw him three times in 1737, when he showed him some of his work, which, although somewhat coarse, was well cut, of a pretty taste, and not common. His ancestors had lived in Mayence, Cologne, and Nuremberg. One of them, Peter, had worked with Fust and Scheffer at their first impressions, and it was a tradition in the family that he was a scribe and miniaturist, and also engraved neatly on wood. He had been engaged by Scheffer, who lodged him in his house, to design and engrave on wood large initials embellished with ornaments like those he was in the habit of drawing and painting. Also that one of his brothers, Jacques, together with a friend named Thomas Forkanach who also engraved on wood, had helped him to engrave the initials for Scheffer’s Psalter. He showed Papillon a book of ‘figures of the mass,’ a xylographic tract printed au frotton. Not being able to get acceptable work, he left Paris. ‘This man,’ says Papillon, was ‘franc et de très bon caractère,’ he had means to live quietly at home, had not l’envie de voyager made him leave Germany.[8]

[8] Papillon, Histoire de la gravure sur bois.

We have not seen any references to Cocksperger in modern works, but Dibdin in one of his books quotes Papillon’s account of him. It would be curious to know whether there was really a family of this name in Mayence at the date Papillon gives, and whether there is any trace there of such a tradition.

[11]

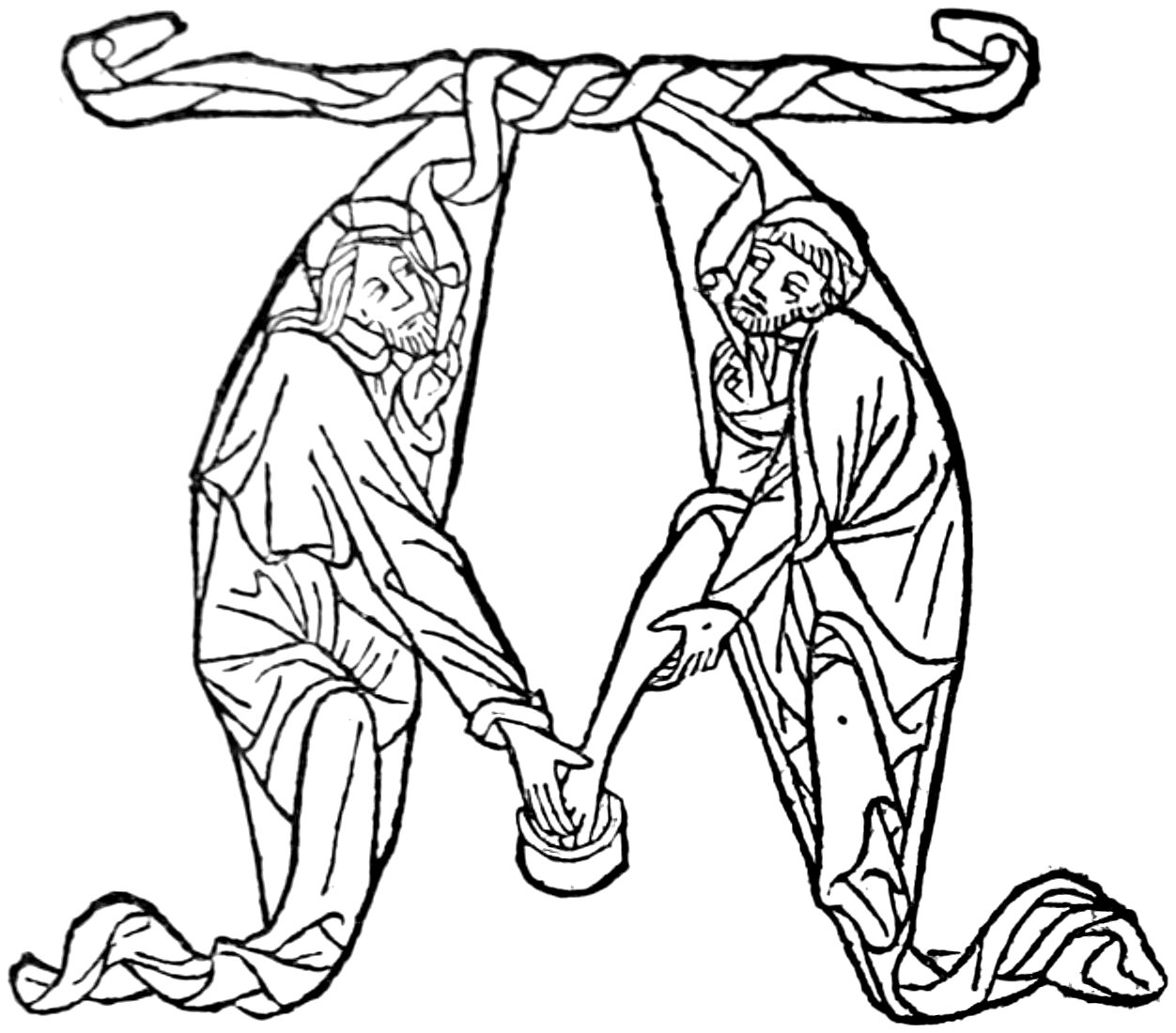

Besides the initials used in the different editions of the Psalter, and in some other publications such as the Rationale Durandi, which has the same subscription as the Psalter, but with the date changed to 1459, Scheffer had a splendid bichrome T for the Canon of the Mass, considered by many as quite equal to the B of the Psalter.

Later in the century polychrome initials, as these letters in two colours are somewhat incorrectly termed, are said to have been used in early Dutch impressions. Humphreys in his History of Printing gives the reproduction of a Q in two colours from the Dyalogus Creaturarum, printed at Gouda in 1480 by Gerard Leeu, which he supposes to be printed, and which he considers, as we think erroneously, to be quite equal to Scheffer’s B.

Initials printed in one colour are not uncommon. They are to be found, for instance, in the Etymologicum Magnum of Callierges, and sometimes in missals, such as the Missale Olumucense of Bamberg and the Rouen Missal, ‘ad usum insignis ecclesie Atrebatensis.’

It has been said that the Psalter letters ceased to be used in 1462. Whatever may have been the reason for this, and it is possible after all that it was simply from motives of economy, Scheffer’s example, as regards the suppression of ornament, was followed by the other printers, and with the exception of Pfister, whose impressions from movable characters have every appearance of xylographic productions, for some years no books were issued with typographical embellishments.

It is probable that, for the two years during which he flourished, Pfister’s illustrated publications were tolerated because they were generally supposed to be block-books, and that he was compelled to stop operations by the Guilds, as soon as they found out that he was in reality one of the hated printers. For it was not only as craftsmen that the Formschneiders were hostile to the members of the new trade. The engravers had become the printers of the xylographic books, then a new and profitable industry, and they were afraid of the sale of their own productions being interfered with by the illustrated works of the type-printers.

[12]

From the point of view of ornamental initials there is little to say about the xylographic impressions.

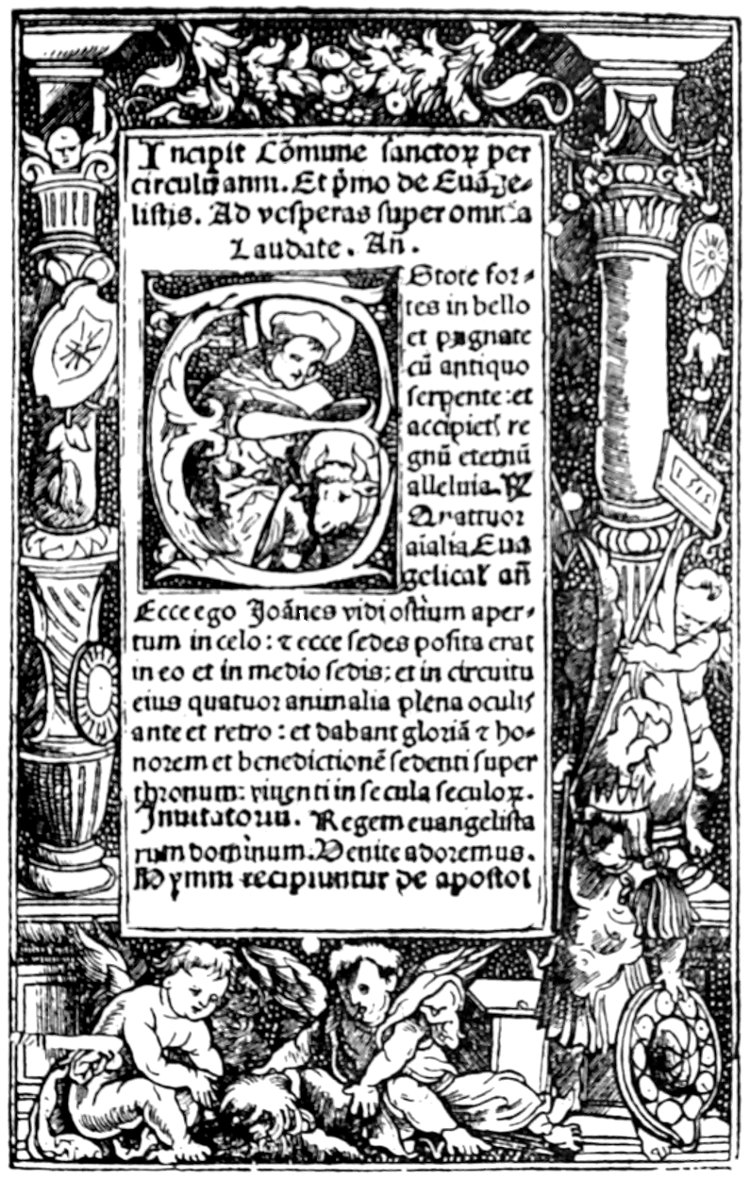

Before the invention of printing, the copies of block-books were obtained, as has been already mentioned, by what is known as the frotton process, the paper being placed over the engraved block and rubbed with a special pad. The ink in the originals is of a brownish yellow. After the invention of the press, certain popular treatises continued to be struck off from xylographic cuts, but by impression, like ordinary books. One of these, the Mirabilia Romae, a guide-book to Rome at the end of the fifteenth century, has a large historiated S at the beginning. It is remarkable from the fact that the letterpress, of which a specimen is given with the initial, is not cut in imitation of type, but, as can be seen in our reproduction, of ordinary hand-writing.

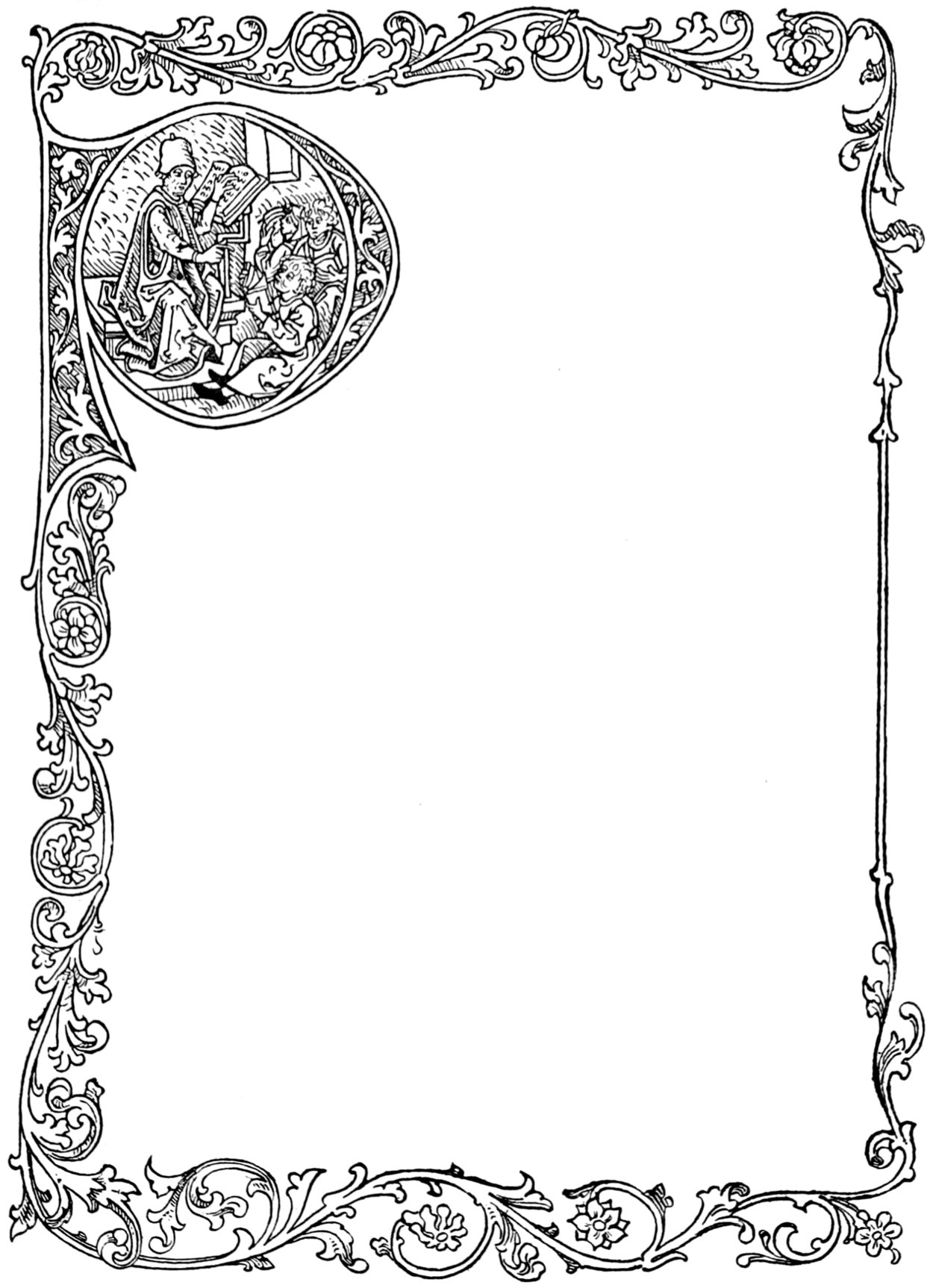

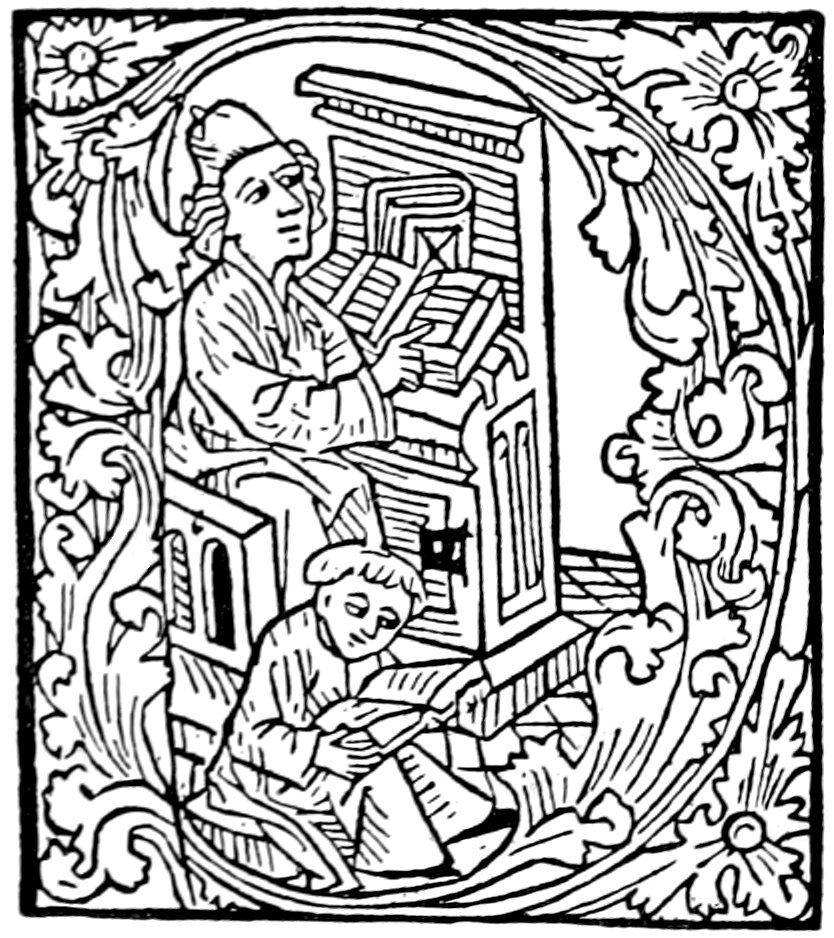

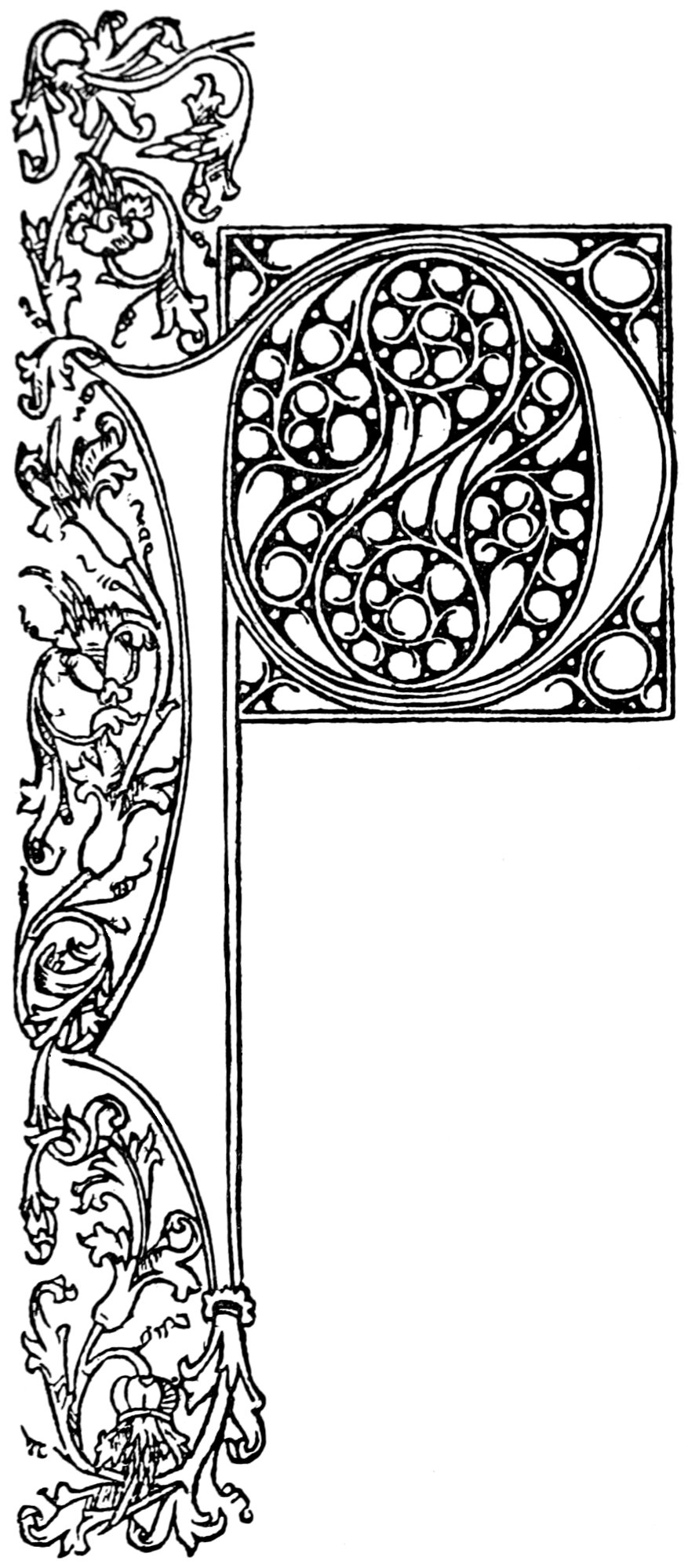

Another specimen of this kind of printing is the P, which we reproduce with a border, from a Donatus, the first and eighth leaves of which were preserved for centuries in an old binding.

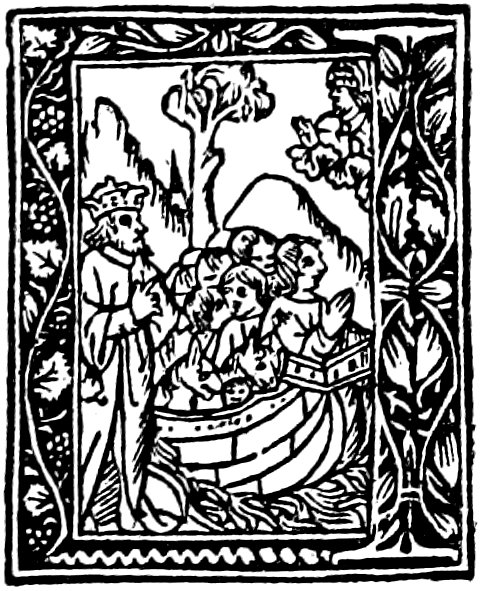

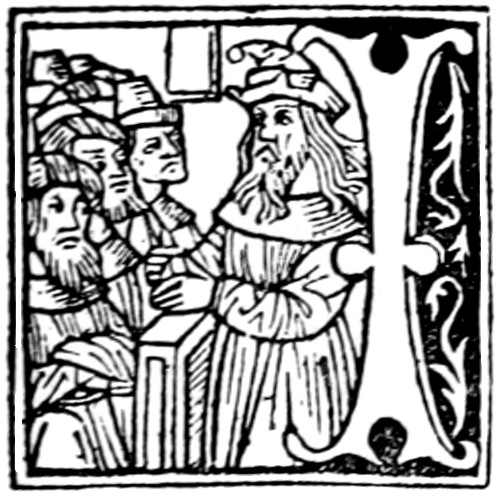

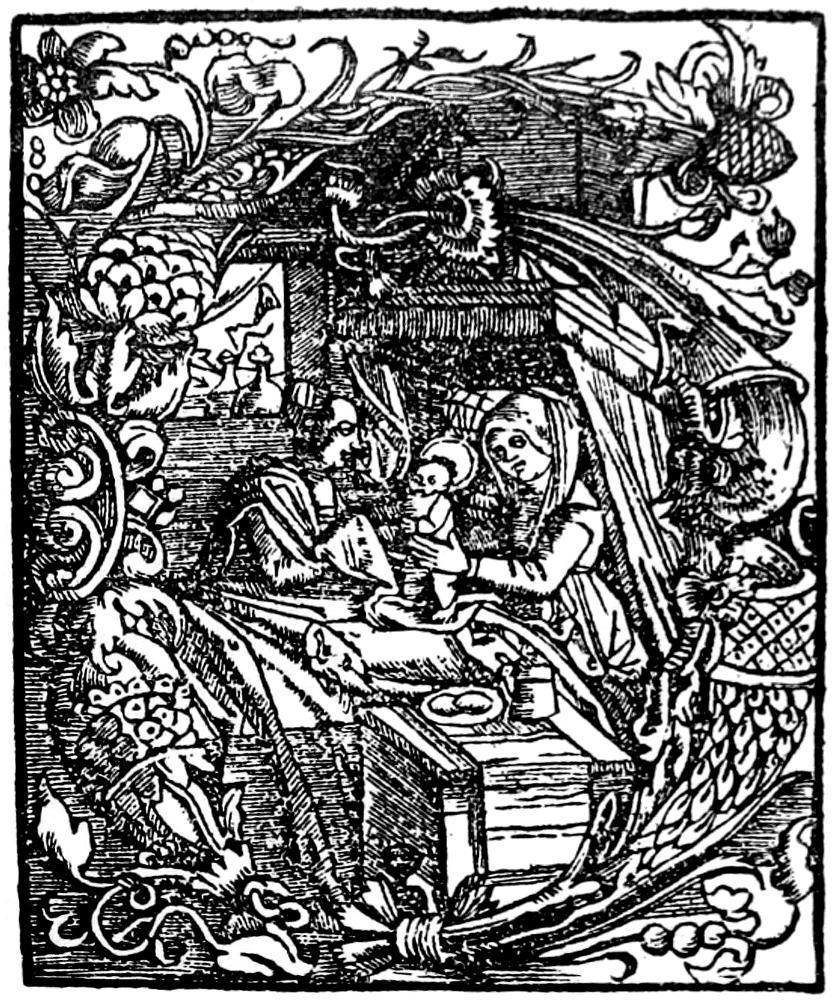

This Donatus, of which the only leaves remaining belong to the Leipsic Museum, was printed by Dinckmut. There is another xylographic fragment with a colophon bearing the same name in the Bodleian Library. The initial itself represents a schoolmaster surrounded by his pupils, a subject frequently met with as a frontispiece to books of this class, and it is prolonged into a border which frames the page.

When the initial of a Donatus does not represent a pedagogue and his class, the subject is often the Virgin and Holy Family. J. Rosenthal has an extremely valuable edition with the Virgin, the Child, and St. Catherine. Amongst our specimens of Cologne is a Donatus without name of printer or date, but no doubt printed by Quentell towards 1500, in which, besides the Virgin and Child, there are grotesque profiles in the two left corners which look as if copied from the same source as one of the Bämler initials, and the initial with grotesques in the Bâle Psalters.[9]

[9] The Donatus, always being in demand, was generally one of the first books printed at a new press. It was the first work issued by Pannartz and Sweynheim when they started at Subiaco.

[13]

During the remainder of the fifteenth century there was very little in the way of initial ornamentation in books published at Mayence, where Scheffer, who was always the chief printer, seems to have exhausted his possibilities in this direction with his first experiment.

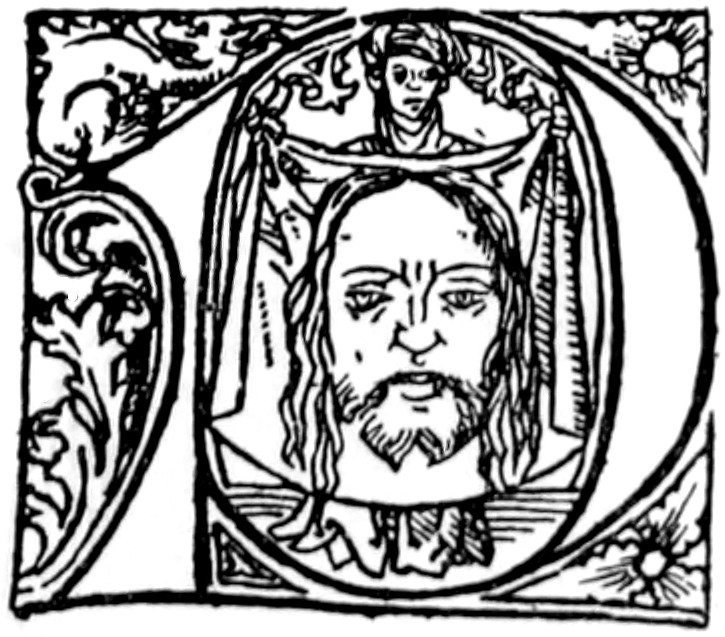

There is, however, a fine large historiated D in a German translation of Æsop—Das Buch und Leben des Fabeldichters Æsop—without printer’s name or date, but attributed to Scheffer, towards 1480. This initial has already been reproduced in Muther’s Bücher-Illustration, and more recently in a bibliography of incunabula and books printed before 1501, by Ludwig Rosenthal. The only other interesting ornamental letter we are acquainted with of Mayence origin before 1500 is the G at the commencement of Erhardt Reuwich’s Breidenbach.

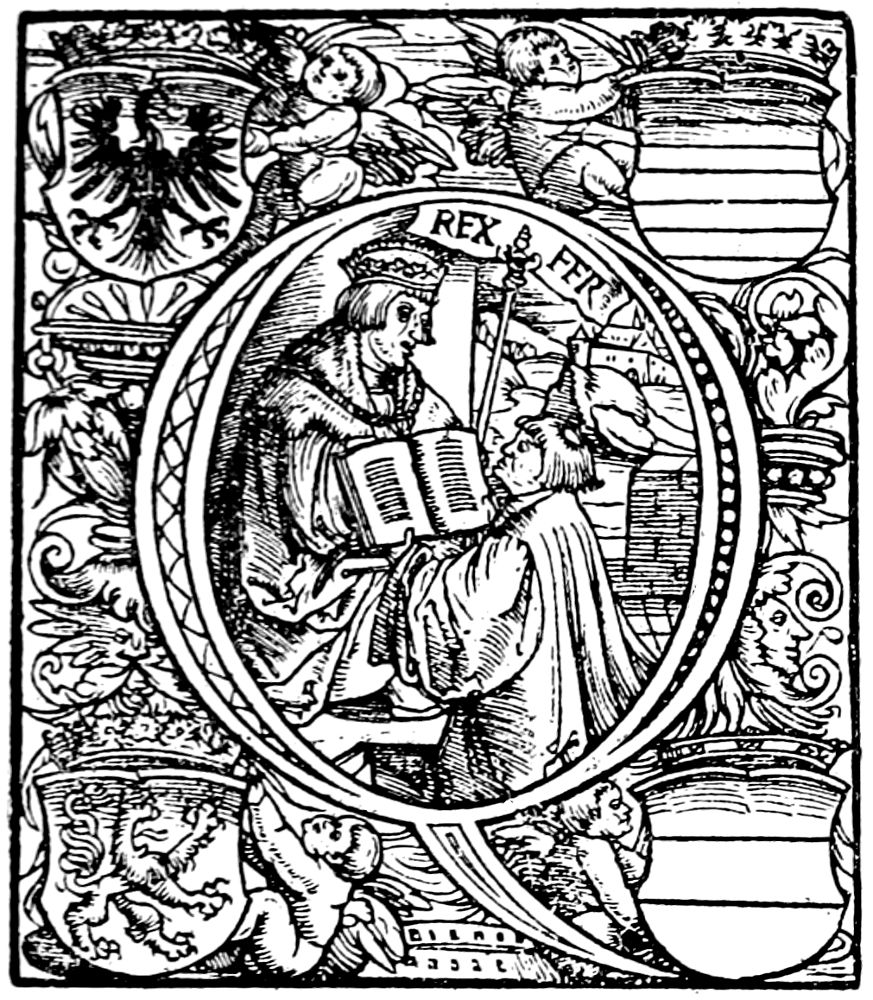

During the first two decades of the sixteenth century there is the same dearth of anything like ornament in Mayence books, but towards 1520 John, the grandson of the first Peter Scheffer, has several alphabets, one of very large letters with arabesques of flowers, foliage, and birds, used first in his Livy of 1518, published under the patronage of Brandeburg, Archbishop of Magdeburg and Mayence. There is also a smaller one with the most varied subjects, besides a few letters with children on a black ground, and one or two linear initials also with children, copied from Venetian models.

[14]

From what has been already said, it seems evident that the aim of the first printers was to produce by the new art as perfect as possible an imitation of the manuscript.

Scheffer printed books with ornamental letters in the manuscript style. The other printers left them to be added by hand, which produced the same effect. It was not until the beginning of the seventies that the printed book assumed its definite form, and that it was recognised that new methods and new processes were necessary. The printed book was henceforth to be a printed book, and not an imitation manuscript. It was no longer to pass, for accessory embellishment, through a number of successive hands, but to be finished at a single impression.

It would not be exact to say that it was Günther Zainer who relinquished the fiction of a printed manuscript, and who recognised that, in virtue of the economic principle of which the press itself is a manifestation, text and ornamental embellishments should be produced as simply as possible.

The alteration was brought about by the Augsburg printers generally, rather than by any one in particular, and was a matter of evolution rather than of sudden change.

It was hindered, too, to a great extent by the opposition of the Guild of Engravers, who saw in the innovation a menace to their privileges, and who brought an action against[15] Zainer and Schussler in 1471 to prevent them using wood-engraving in their books, and even opposed their admission as burgesses. It was only at the intervention of Melchior Stanheim, Abbot of St. Ulrich, that the matter was arranged, on the understanding that they should insert in their books neither woodcut pictures nor letters, a prohibition that was only withdrawn after a new arrangement which bound the printers to employ only recognised members of the Formschneider Guild.

As an example of the jealousy with which these privileges of corporations were maintained, it may be mentioned that Albert Dürer was compelled to pay four florins to the Society of Painters of Venice for working at his profession during his stay in that city.

Günther Zainer’s first woodcut initials, if they can be called ‘woodcuts,’ are merely outline letters without any kind of ornament. They were intended simply as a guide to the rubricator.

In the next stage we have a framed initial with an ornamental groundwork, but the composition is less effective in black and white than when the letter itself is picked out in red. A good example of this is in the alphabet of the Zainer German Bible, afterwards used in the Summa Confessorum of J. Friburgensis. In these initials, what a contemporary authority on lettering calls a ‘friskiness’ of the design leads to a difficulty of distinguishing between the ornamental prolongation of the different parts of the letter, and the very similar decorative groundwork,—so much so, that even the rubricator was sometimes mistaken, the colour being left unapplied where needed, and vice versâ.

Finally we come to initials, of which the specimens that have come down to us are coloured as often as not. These are more effective when not so treated, and were probably intended to be left as printed. The reader can judge from the specimens reproduced.

Butsch (Bücher-Ornamentik) mentions the Gulden Bibel of Rampigollis, the Belial of 1472, and the Glossae of Salemo, as the earliest works of G. Zainer with woodcut initials.[16] The Belial, he says, has a large ornamental initial of arabesque design.

Our first selections are from the Summa Confessorum; the large P is from the Margarita Davitica of 1475.

The new plan was soon adopted by the other Augsburg printers, and spread thence to other towns and countries.

As far as Augsburg is concerned, it should be noted that the same letters were often used by different printers, and they are therefore as much illustrative of the town and period, as of any one particular press. Ludwig Hohenwang, for instance, uses the same initials in his Gulden Bibel of 1477, as does J. Pflantzmann in his Glossa of Salemo of the same year. The two specimens given of these printers might have been taken from either volume.

Our other examples are taken from works published by Sorg, Keller, Bämler, and Schönsperger.

The Bämler selection is exceedingly curious as presenting probably the first example, if our date is correct, of what was afterwards so common—the grotesque profile.

Unfortunately we are unable to give their exact origin, as they form part of a collection of initials, cut from early books, but if the attribution ‘Bämler, 1475,’ is correct, they are of the same date as the Rihel Bible of 1475, in which there are two initials with profiles, but neither of them grotesque.[10]

[10] There are two pictorial letters in the fifth German Bible (see the reproductions of both at pp. 118, 119), in which the border is formed partly of a grotesque profile.

The five specimens given are selected from the thirteen letters comprised in the collection, and need no description. The others consist of a D, which is in reality the same as our C but reversed; a G, two L’s, an R, a T, and a V. One of the L’s has a sun with full face, and the T, besides being of an unusual pattern, has also a grotesque profile. Unfortunately it has been daubed over by a rubricator too badly for reproduction. The S with the two human figures occurs several times in Rihel’s Latin Bible, and was given by us in a former essay[11] as a specimen of Basle woodcuts. We now class it provisionally with Augsburg.

[11] ‘On Some Old Initial Letters.’ The Library, January 1901.

[17]

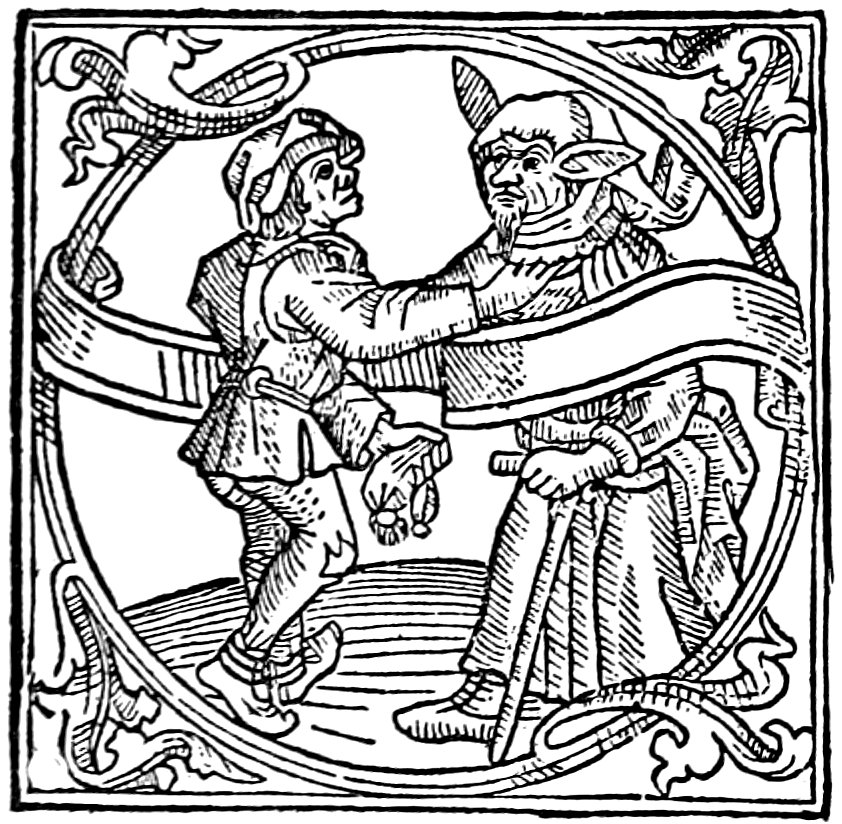

Of Sorg, our earliest specimens are of the pure Maiblümchen pattern, the S without any trace of historiation being from a copy of St. Ambrosius on St. Luke of 1476. Other letters of this type are to be found in his Breidenbach and other works, but later on they become almost identical with those of Keller. Compare the A and the H from the Valerius Maximus of Sorg of 1480, with the E and V from the Keller edition of Aristotle’s Opera Nonnulla of 1479. The S with a grotesque profile at each end and the letters G I A dates from 1480, and is the first initial we have met with in which the fool, so popular in the imagery of the period, here complete with cap, ass’s ears, bells and cockscomb, is represented.

Schönsperger’s initials, of which four reproductions are given, are a little later, 1489.

We come now to pictorial initials, and in this respect the printers of Augsburg had been anticipated by those of Ulm and Nuremberg.

It was in 1473 that the fourth German Bible was published at Nuremberg. It was probably the success of this edition that induced Günther Zainer to bring out the magnificent folio classed as fifth, which may truly, from its size and solidity, be considered as a typographical monument.

Zainer’s first edition (the fifth German Bible) was undated, but was published either in 1474 or 1475. It succeeded so well that another edition, this time dated and in two volumes, was published in 1477, with small ornamental initials at the beginnings of the chapters, as well as the large pictorial letters previously used at the commencement of each book.

The difference between the Augsburg and Nuremberg initials can be seen in our reproductions, the former being taller and surrounded with accessory ornaments. In the Nuremberg Bible, Corinthians 1 and 2, Ephesians, Philippians, Thessalonians 1 and 2, Timothy 1 and 2, Titus and Philemon, all have the same initial. Hebrews has no initial at all, nor has Galatians. In the Augsburg edition the letters are all different; Galatians has its initial, and Hebrews begins with a pictorial Z.

[18]

In Sorg’s Bible of 1477, the only large historiated letter is the B at the beginning of the dedicatory epistle, with bishop and cardinal in a cell which, as can be seen in the corresponding Nuremberg initial, looks like a third-class railway compartment. There is a smaller D, not worth reproducing. The different books of the Bible are mostly preceded by small engravings.

But Sorg’s best historiated initials, in fact the only ones with which we are acquainted (for the B in his Bible is a copy of Zainer’s), are to be found in a work by Henricus Suso, ‘dictus Amandus,’ published in 1482: Das Buch das heisset Der Seusse, a translation of his Horologium aeternae Sapientiae.

This book contains a number of engravings on Biblical subjects, which are most often painted over beyond the possibility of reproduction. Such is the case with the copies both in the British Museum and in the Paris National Library.

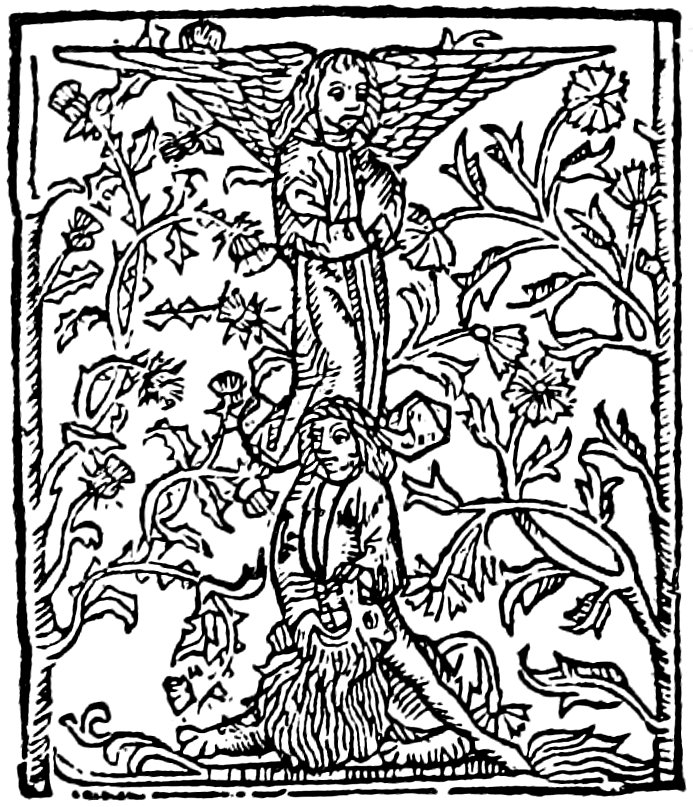

Besides these illustrations there are three large pictorial initials, C, R, and S, of which the C alone occurs twice, representing, the C an angel appearing to a woman, the R a saint with a crozier, and the S an eagle, the background being filled up with Maiblümchen.

Towards the end of the century Ratdolt, who had returned from Venice, was the chief printer at Augsburg.

Amongst his other productions, Ratdolt printed a number of liturgical works, the most beautiful that we have seen being the folio Breviary of 1493. The type is admirable, and those pages which begin with the large letters, such as the C with the Pope, or the H (All Saints), printed as they are with the brilliant black ink of the period, are particularly effective. The B at the beginning of the Psalter is used again in the smaller Psalter of 1499, as are several of the smaller initials. The pars aestivalis begins with the U. The C with St. Urban is at the commencement of the section De Sanctis.

Two of the smaller initials occur in the larger Psalter, which are not in the smaller one. A D representing a kind of Indian with a club and feathers is the fool referred to in the opening words of the Psalm Dixit insipiens. Another D[19] has Jesus kneeling to His father (Dixit Deus Domino meo). On the other hand, the crucifixion initials of the Psalter of 1499 are not in this edition.

The Psalter of 1499, Psalterium cum apparatu vulgari familiariter impresso—Lateinisch Psalter mit dem teutschen nutzlichen dabey gedruckt, has not the imposing appearance of the earlier folio volume, but like all Ratdolt’s work is well printed. This would appear to have been taken as a model for Psalters in the Vulgate. There are several editions of different towns with the text framed, as it were, by a translation in the vernacular in smaller type. The Psalter of Furter has the same disposition, the initial letters, although different in treatment, corresponding almost exactly with those of Ratdolt’s Psalter. Knoblouch has a similar Psalter, but with non-historiated initials. In the Metz Psalter of Hochffeder, otherwise on the same plan, the only initial is on the title-page.

In the Missal of Frisingen of 1492 there are no historiated letters, and the ornamental initials in the Venetian style are unfortunately most outrageously coloured in the only copy we have seen. Amongst other letters there is in it an extremely curiously designed S which is difficult to describe, but which we would recommend to students of lettering. In the D, which is in the shape of a Gothic German Q reversed, and the P, there is a branch-work pattern starting tangentially from a central circle and ending in trifoliated ornaments altogether graceful and harmonious. Ratdolt’s mark is on the last page, and above it:

Ratdolt continued to print liturgical works for some part of the sixteenth century, but the only other volume of the kind that we have had at our disposal is the Pars Aestivalis of the Breviarium Constantiense. Ratdolt, Aug Vindel, 1516. In this book there are four pages with borders, one of which is reproduced, and on the opposite sides are full-page engravings. There are eight initials, which we reproduce, and[20] which are also, we believe, to be found in his Ratisbon Breviary.

Hitherto, with the exception of the last-mentioned work, we have had to do with what may be called the first style of engraving, in which designs and pictures drawn by the artist were executed by the wood-cutter in linear reproduction only.

With Albert Dürer, however, came a new epoch, and it became the custom for artists not only to design but also to engrave their own work. This practice, which was commenced by Dürer, who served a long apprenticeship to the celebrated Wohlgemuth, was continued by most of his pupils, and new technical methods were naturally the consequence. Henceforth the more liberal use of shading, and the invention of cross-hatching, enabled effects to be produced which had been before impossible.

The results may be seen to this day in the magnificent engravings by the great artists of the beginning of the sixteenth century, which, notwithstanding the difficulties under which they laboured, have never been excelled.[12] Their productions, even when it comes to initials, are real compositions with a personal character.

[12] At this time the wood employed for engraving was pear, and the surface of the block was parallel to the fibre. This made cross-hatching most difficult of execution, and in consequence of the extreme care and attention necessary, it is said that the work took eight or nine times as long as at present. It is only since the days of Bewick that boxwood has been used, and the blocks cut with the fibre of the wood perpendicular to the surface.

To mention those only who designed initial letters, and of whose works we shall give specimens, there were Albert Dürer, Hans Burgkmair, Hans Holbein, Hans Schauffelein, Anton von Worms, Lucas Cranach, Hans Baldung Grün.

We have here to speak of the initials generally attributed to Hans Burgkmair, but which, according to Dr. H. Röttinger, ought to be assigned to Hans Weiditz, one of his pupils.

These initials are to be met with for the most part in the publications of Heinrich Steyner in 1531 and the following ten or eleven years, and come mostly from German translations of classical authors. The influence of Albert Dürer, of whom Burgkmair was himself the pupil, is clearly seen.[21] Different treatises and different editions of Cicero were published in 1531, 1535, 1540; of Herodianus in 1531; Justinus, 1531; Boccaccio, 1532; Cassiodorus, 1533; Plutarch, 1534; Petrarch, 1542, in all of which we meet with specimens of these letters.

The Z with a fox trying to get at the poultry in the market-woman’s basket is from the German Cicero. The C (bagpiper) and the N (caricature with big head and small legs) and the P with a peacock are from the Magni Aurelii Cassiodori variarum libri xii. The E with the monk and nun, and the C and H in a different style, are from the German Petrarch. The other initials are from one or other of the volumes mentioned.

[22]

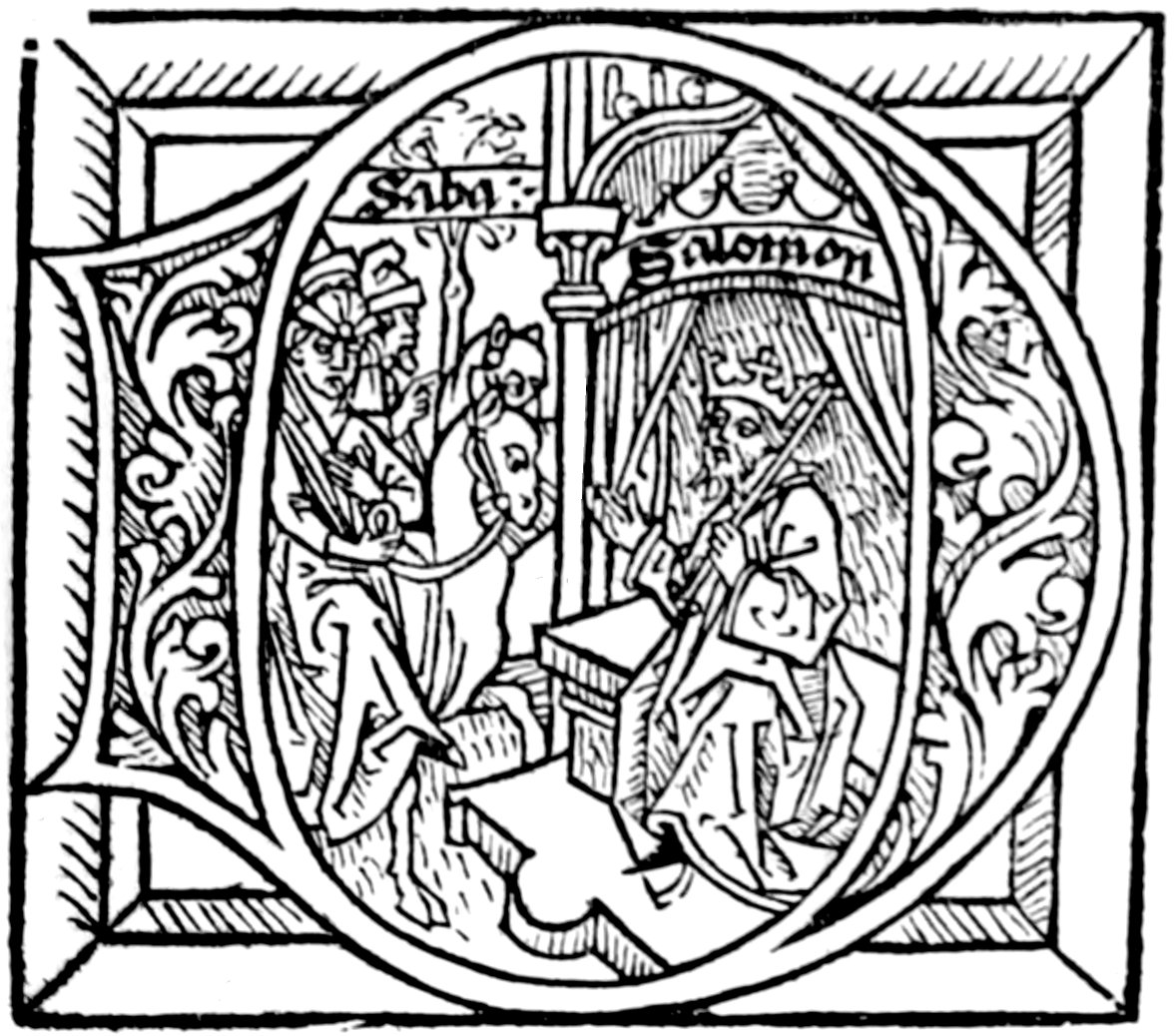

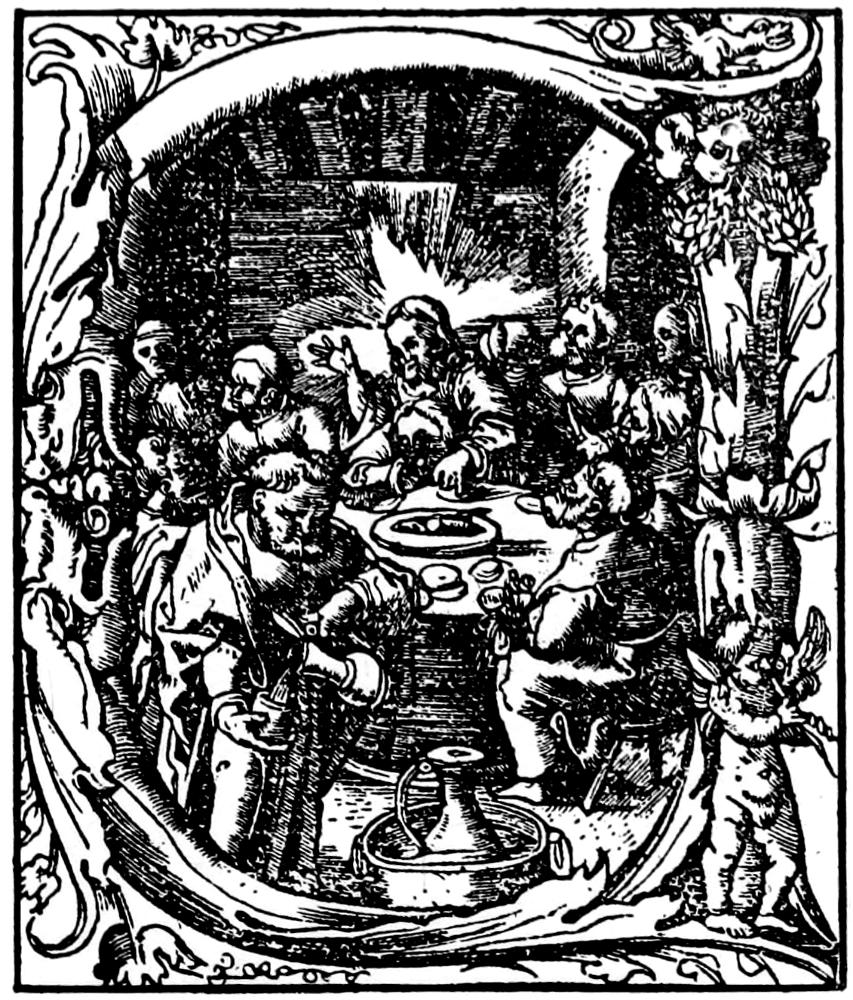

Most writers on early bibliography, amongst others Bodemann and Muther, who both give reproductions of the initial border at the beginning of the Latin Boccaccio, quote J. Zainer as the first printer in Ulm to use woodcut initials. The date of the Boccaccio is 1473. In addition to the initial border it contains a complete alphabet,[13] of which we give several specimens. From a decorative point of view this alphabet is not very remarkable, the letters being of small size, but the book is interesting on account of the very large historiated initial at the beginning, which is prolonged along the side and upper margins into a floro-foliated border in imitation of the more elaborate decoration of the old manuscripts. The subject represents that very unfortunate incident in the history of the first woman which was the cause of all the subsequent unhappiness of mankind. Eve, who is the heroine of the first chapter of this book on celebrated women, is represented in the act of receiving the apple from the arch deceiver, who is ensconced in the branches of the fatal tree with his tail twisted into the letter S. Above, in the branches of the tree, are small personages emblematic of the seven deadly sins. In a German edition of the same book of the same year, the initial becomes a D, and contains[23] the arms of the noble to whom the work is dedicated, with winged angels at the corners, being prolonged into borders along the two adjacent margins. In these two instances the initial letter forms part of the general composition.

[13] Copied from a manuscript of the fifteenth century, the ‘Evangeliare of St. Udalrich.’

In another style of border the initial is merely placed in juxtaposition, and the same design is thus able to serve for any book with any letter.

There is a remarkably vigorous folio-floral border with the head and shoulders of a fool with his cap, bells, and other insignia, at the angle of the two margins in the Liber Biblie Moralis, 1474. The same composition is used in the Alvarus Pelagius the year before.[14]

[14] In church architecture, and in early book ornamentation, which reflects so well the ideas and customs of the time, the fool did not make his appearance before the middle of the fifteenth century. Wright, in his History of Caricature, mentions as early instances some sculptures of this date in churches of Cornwall, and it was about the same time that this personage is first seen in manuscript decoration.

The idea, however, was much older, springing from that taste for the grotesque which characterised the Middle Ages, and the relics of which are seen in so many artistic remains of the period. From the tenth century and even earlier, companies of fools existed in all large towns, and on certain occasions Mother Folly and the Lord of Misrule reigned supreme. The cult of the ass, whose ears were to become later part of the fool’s insignia, was another outcome of this love of the burlesque.

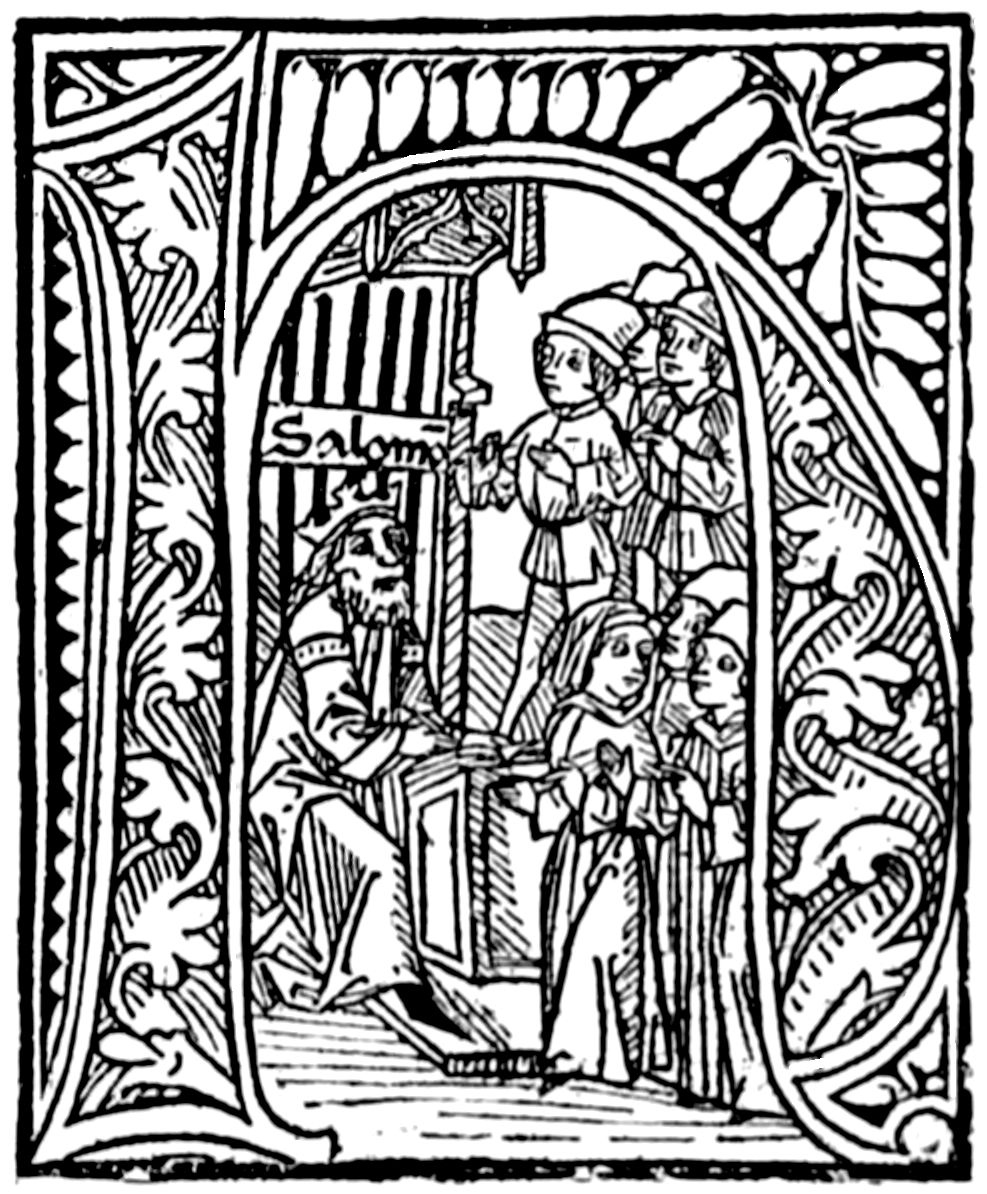

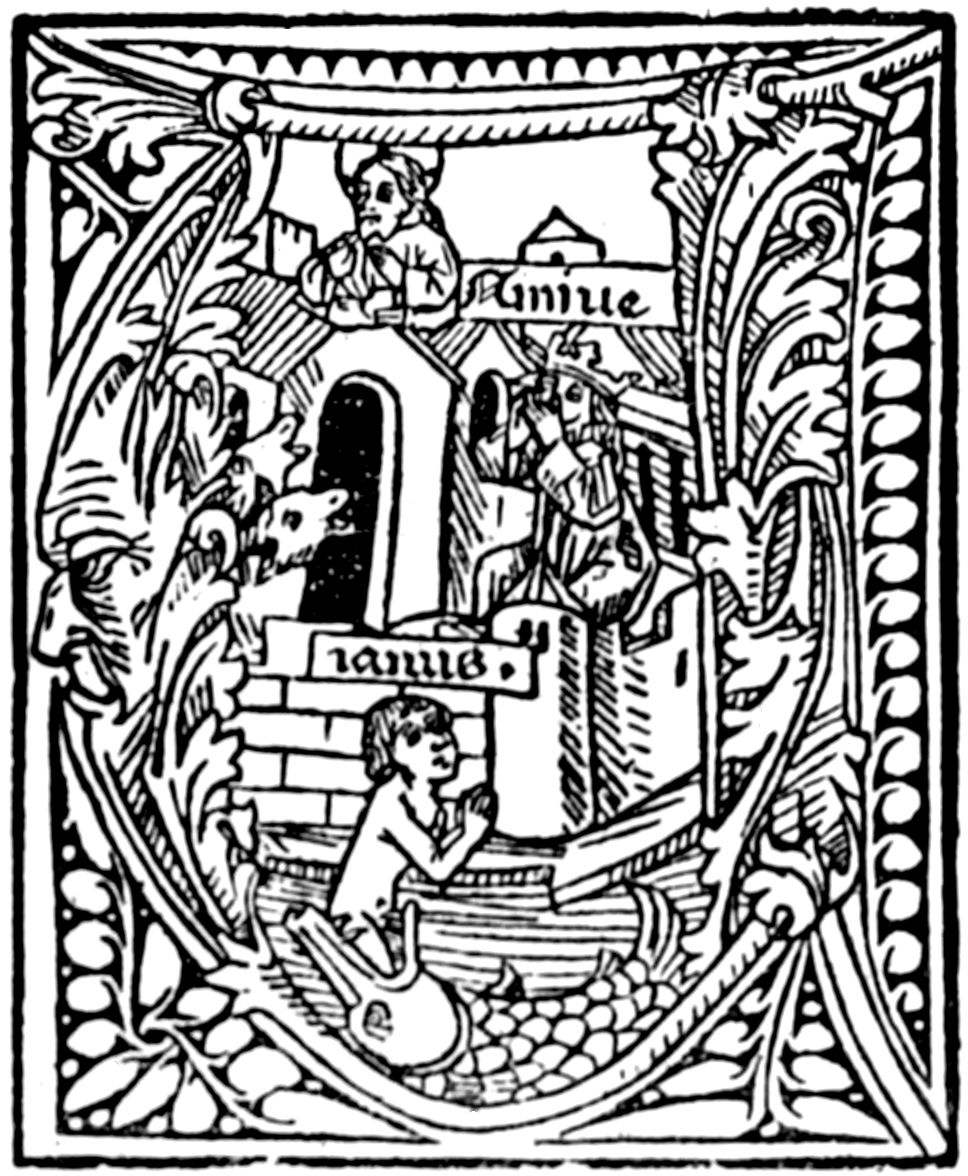

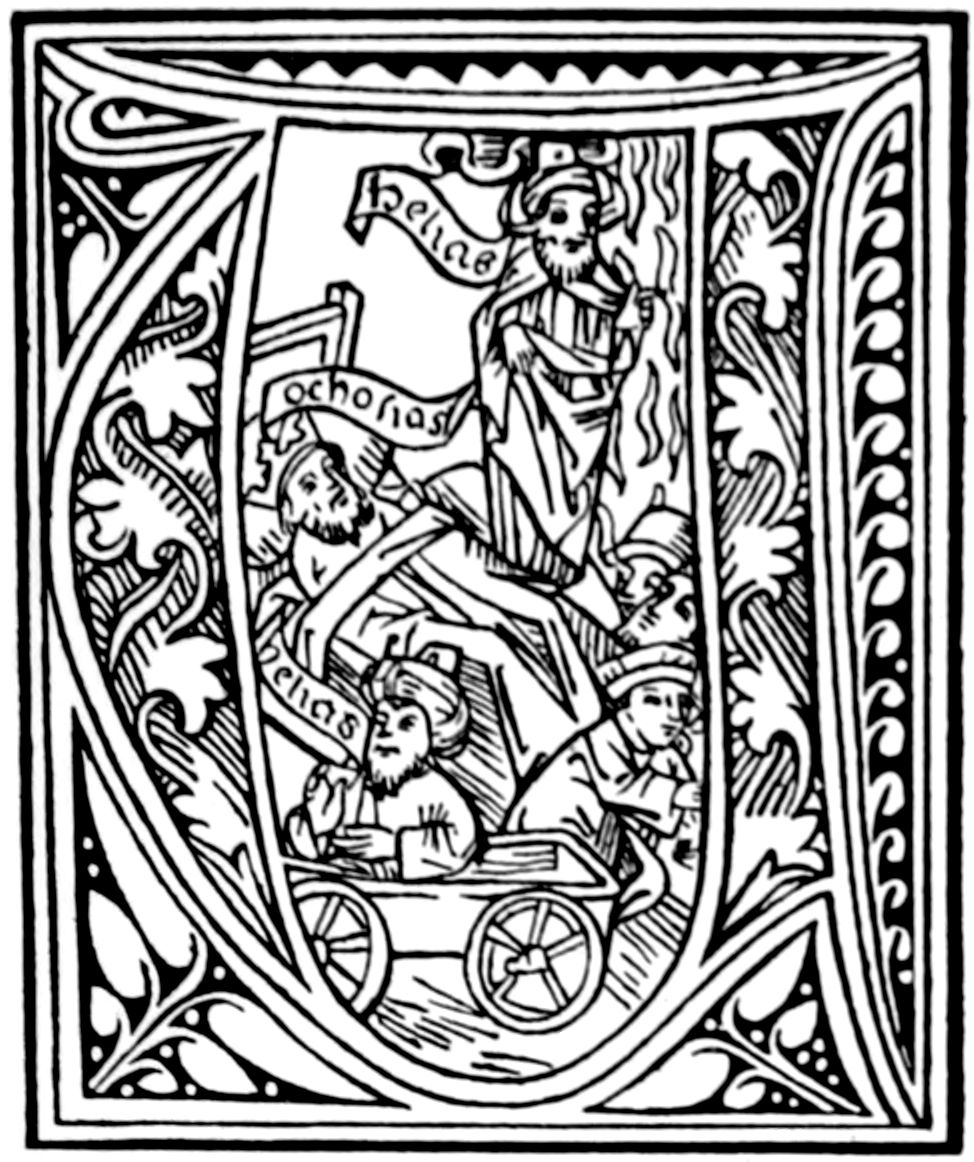

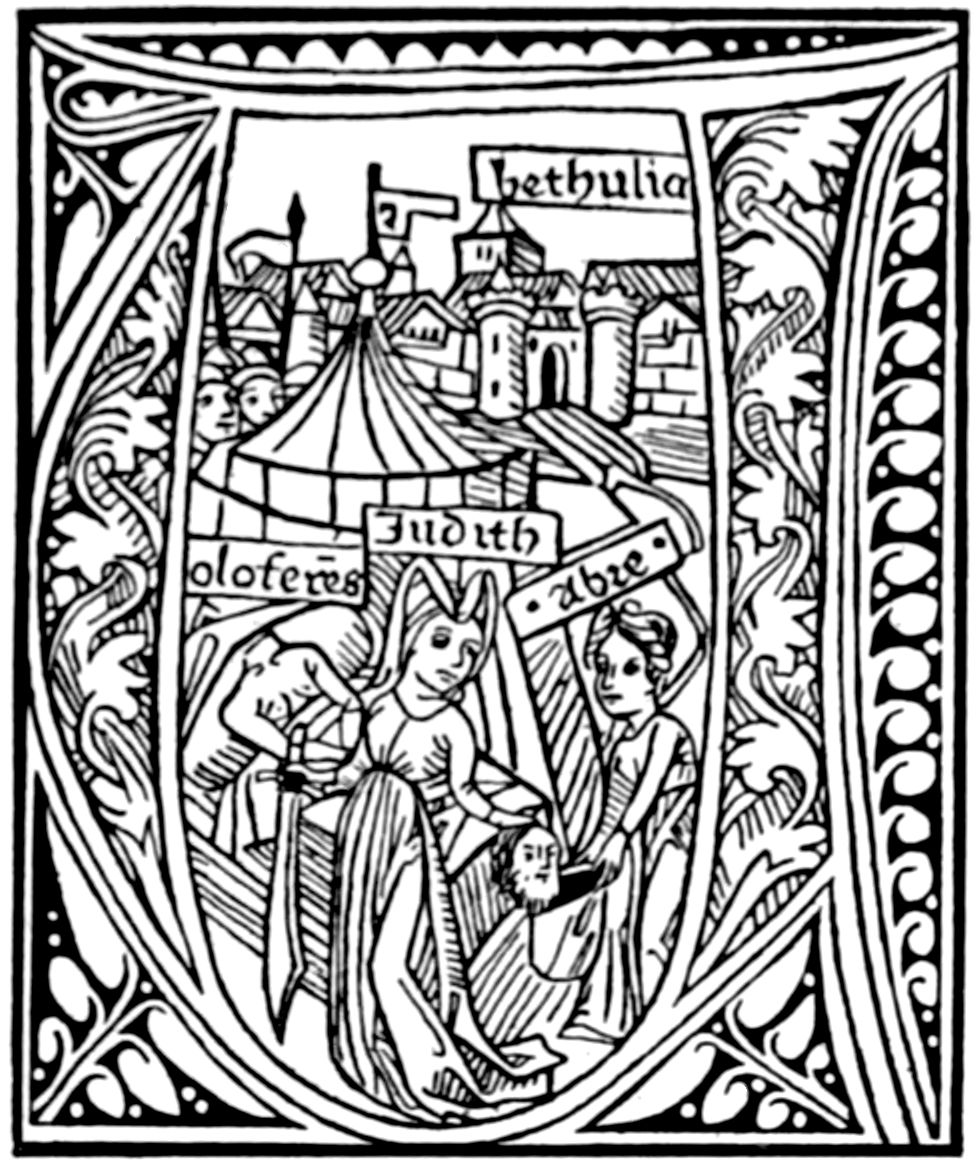

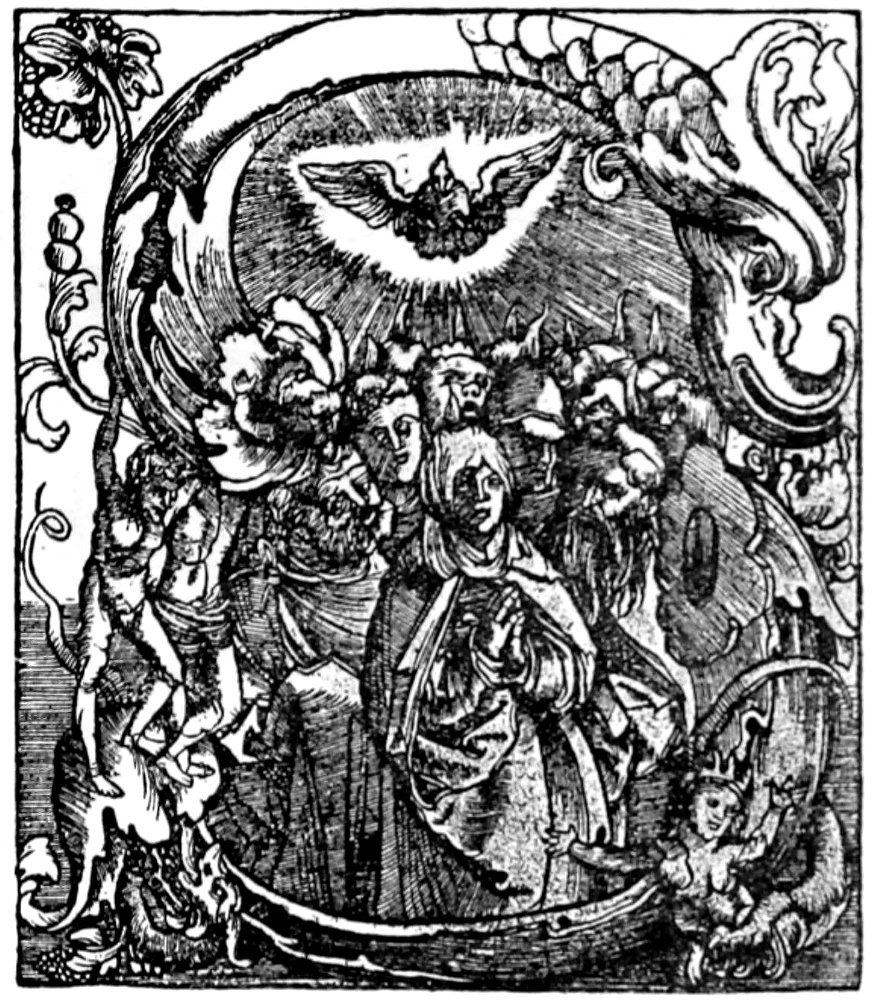

In printed books, the first engraving we are acquainted with of a fool is in the border to the Liber Biblie Moralis of 1475. In initial letters, as far as we have been able to ascertain, this subject was not used before 1480, when it is to be found in specimens both of Augsburg and of Strasburg. A remarkable portrait of a fool is contained in an O in Schott’s Plenarium, printed, as is stated in the colophon, at ‘Strospurg,’ in 1481. Knoblochtzer’s large S, for the Dyalogus Solomonis et Marcolfi, gives a fool with another personage at full length, and at last the typical fool, with a marotte and all other accoutrements, is met with in initials of different Psalters, being well seen in that of Fürter of Basle.

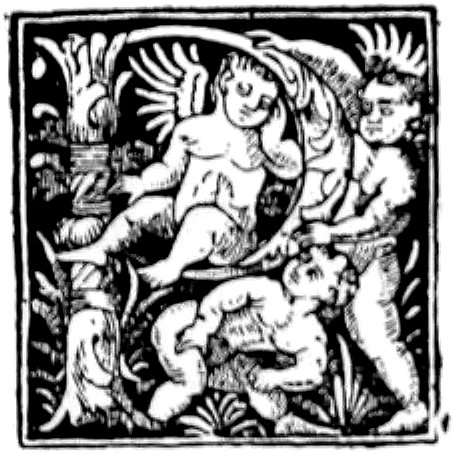

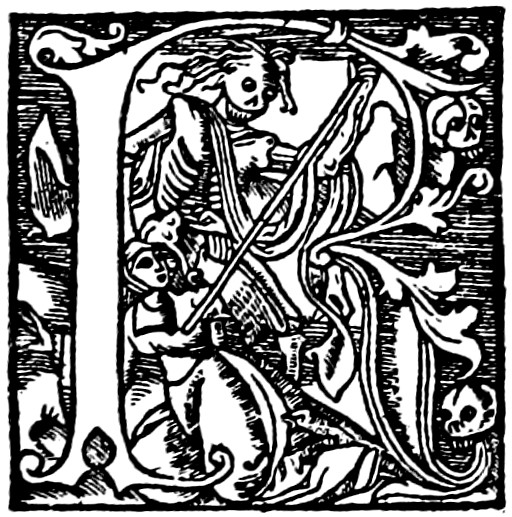

Henceforth, with a face characterised by leering cunning, the type is to remain unchanged, and Brandt, Erasmus, and Holbein only add to its popularity, without modifying the general conception. There is a little pictorial initial by Quentell, in which the usual expression is replaced by one of extreme finesse, but coarser cunning is the rule, and it is under this aspect that the fool is depicted by Holbein in the R of the alphabet of Death.

In the Quadragesimale of Gritsch there is a similar border, but the fool is replaced by a personage with a doctor’s bonnet. The letters accompanying these borders belong to the alphabet, of which we give several reproductions, and which is the most frequently used in J. Zainer’s works.[15]

[15] Reiber in his Art pour Tous gives a similar alphabet of the Augsburg Zainer, which, he says, is copied from a manuscript of the tenth century.

[24]

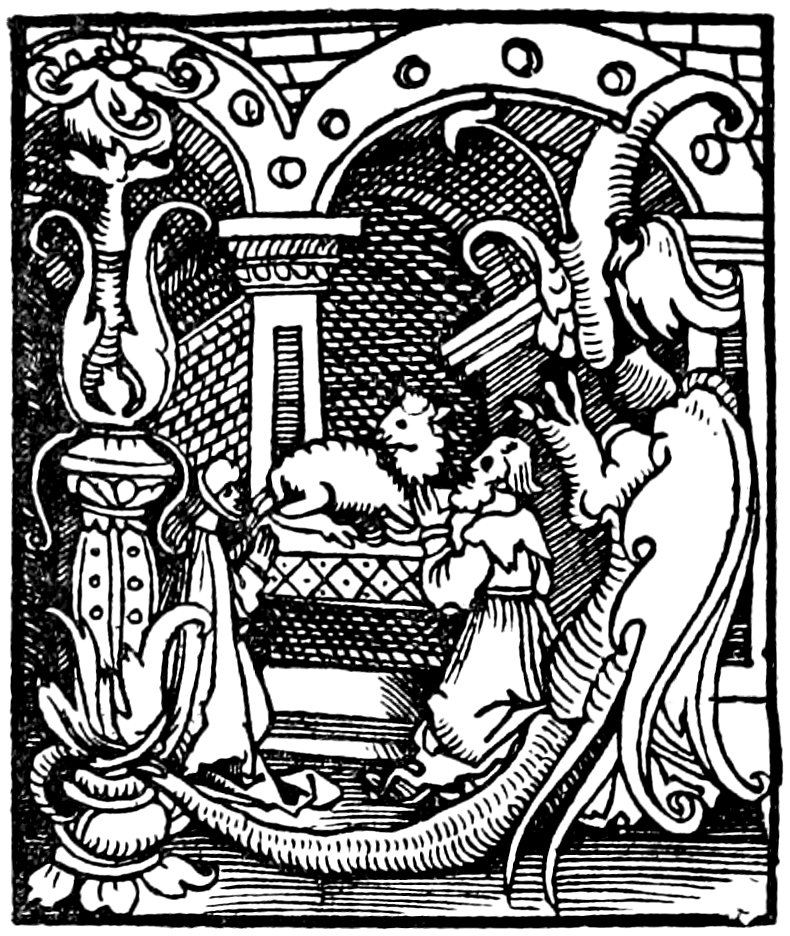

Another great work from the Ulm press is the Cosmographia of Ptolemy, printed by Leonard Holl, in which there is an alphabet of initials not unlike those of Schönsperger already given. Those of L. Holl ought to have been preferred as illustrations, inasmuch as they are earlier than the others, 1482, but they are almost invariably painted and unfit for zincotype reproduction. The chief interest, moreover, in the book is in its two large historiated initials on the first two pages, the first showing the printer offering his book to the Pope, the second representing probably Ptolemy himself.

Our last specimen of J. Zainer’s engraving is the F which begins the dedicatory epistle of the Latin Bible of 1480, and which is a curious example of the peregrinations of woodcuts through different workshops, and of the incongruous uses to which they were put.

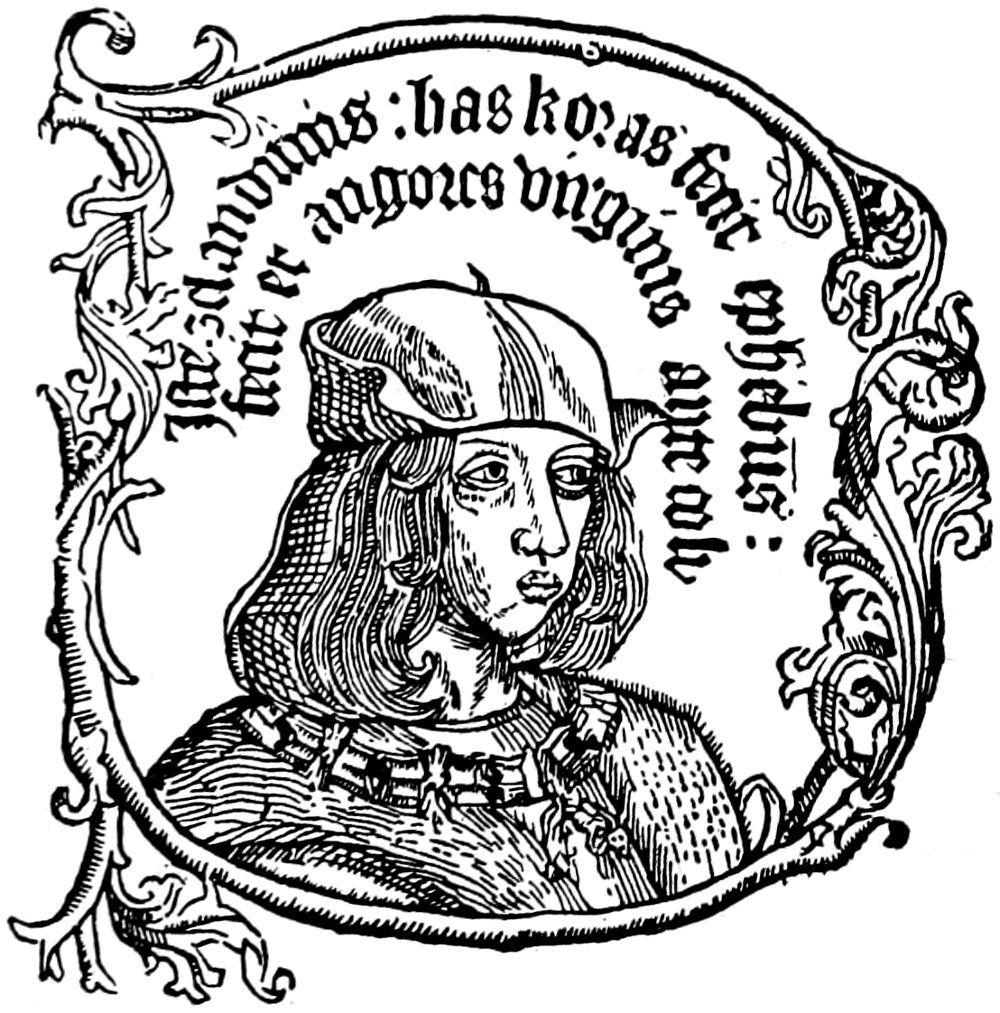

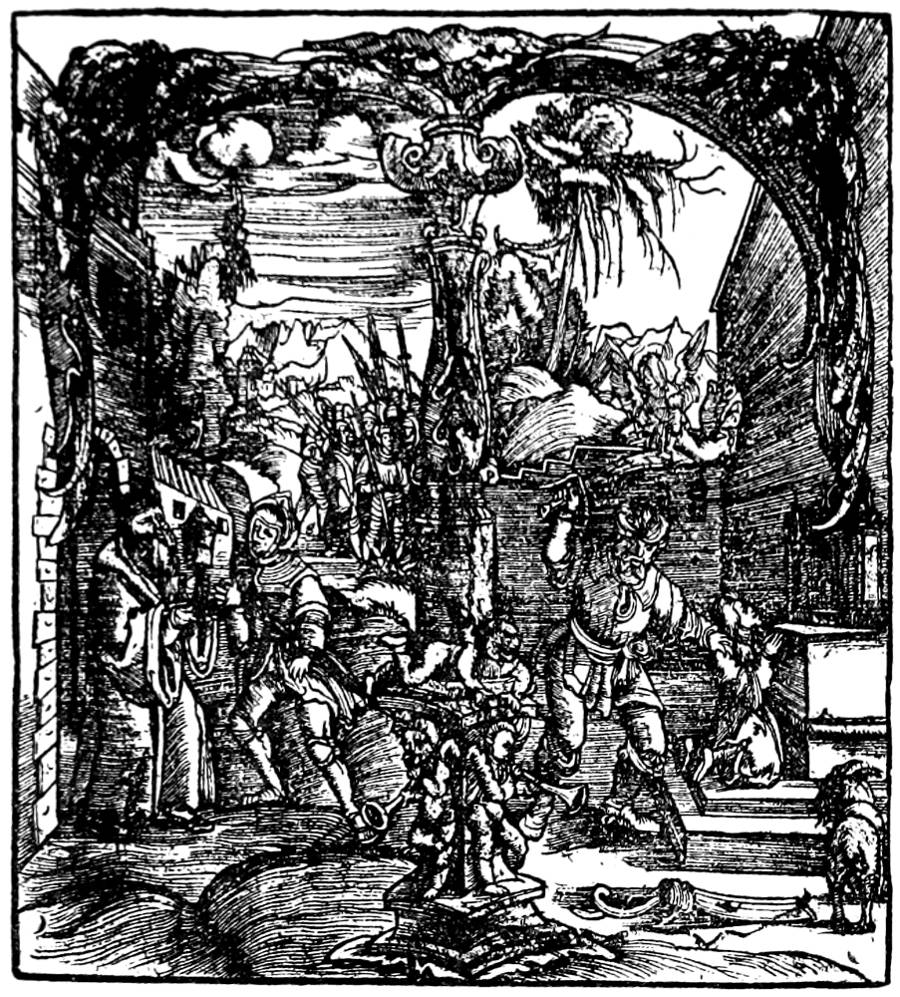

In the Ulm Bible the letter is much fresher and the border-line very little broken, but our reproduction is from an impression made when it was much the worse for wear, and had passed into the hands of Hupfuff of Strasburg. It has been used by him without any kind of apropos, not as an initial but as a frontispiece to a tract published in 1507 with the following title: Canon Sacratissime Misse una cū; Expositione ejusdem ubi in primis praemittitur pulchra contemplatio ante missam habenda de Cristi pulchritudine.[16]

[16] On the title-page of a little pamphlet entitled ‘Deploration sur le Trepas de tres noble Princesse Madame Magdalain de France Royne Descoce,’ of which only one copy is known, the frontispiece is a B showing the Queen holding up a dagger, and with the motto ‘Memento mori.’

Every student of bibliography has met with instances of the use of illustrations having no reference to the text, simply to fill up a space and because nothing more suitable was at hand. Cuts, for instance, from Brandt’s illustrations to Grüninger’s Virgil are to be found in some volumes of Geyler’s Sermons. The same indifference to the reader’s opinion was often displayed in connection with ornamental letters. When the letter is simply ornamental it does not much matter: a C turned over becomes a D, and vice versâ.[25] An M at a pinch serves reversed as a W, an N on its side does for a Z. But when, as is sometimes the case, the letter taken liberties with is pictorial or historiated, the resulting effect is far from artistic.

Here there is, of course, no absolute incompatibility between text and illustration, which was probably considered a very satisfactory makeshift for the cut which often adorns the recto or verso of contemporary title-pages, representing the author presenting his book to a patron.

In 1496 J. Reger published books with initials, of which we have selected the M, the C, and the S. They come from the Obsidionis Rhodie Urbis descriptio of Caoursin, a work very much sought after on account of its full-page woodcuts, some of which represent incidents in the siege, others the entertainment of an ambassador by the Grand Master. The M and the C are the only letters with animated subjects; the others, R, H, N, and G are simply foliated, and the proofs are too inferior for reproduction.

The same printer has another book of the same date about Rhodes, the Stabilimenta Rhodiorum militum, with three interesting initials, an F, a boy with a dog, an O, a naked winged babe, and an X, a bird with foliage.

—If Zainer at Augsburg was the first to introduce woodcut letters printed in black ink, the practice was adopted very soon after at Nuremberg, if indeed, setting aside the outline initials already mentioned, Nuremberg has not the priority as regards genuine ornamental woodcutting. For whereas the Belial of 1472 is the first work mentioned by Butsch with woodcut letters at Augsburg, at Nuremberg, where J. Müller of Königsberg (Regiomontanus), as is stated by Panzer, settled in 1471, his first publication, the Theoricae Novae Planetarum of Georgius Purbachius, is embellished with eight initials. These are interesting as affording another example of the fact that the earlier designs were generally taken from manuscripts, for Olschki, in his Monumenta Typographica, gives the reproduction of a manuscript initial which is of the same size and of the same pattern as the S[26] we have given from the Theoricae Novae, and which contains besides eight smaller initials, D, L, M, O, P, Q, S, V, measuring 2·4 centimetres.

There is a Q of the same style and size in the Astronomicon of M. Manilius, published by Müller in 1473.

Müller, or Regiomontanus, as he styles himself in his colophons, was not only a printer, but one of the most learned mathematicians of the day. In 1471 he printed a Calendarium of his own with many astronomical figures and woodcut initials.

In 1476 Ratdolt and his partners printed an edition of this with a charming border and initials at Venice, and in 1496 it was published by J. Hamman de Landoia.

In 1473 appeared the first German Bible with large pictorial initials, the Nuremberg Bible of Frisner and Sensenschmidt, known as the fourth German Bible. In our opinion the work on these initials is amongst the best of the time, and often much superior to what is to be found in ordinary illustrative cuts of the same date. The subjects are the same as in the Augsburg Bible, but the initials differ in being wider than tall in the Nuremberg edition, and in the absence of the Maiblümchen decorative border which is a feature of the others.

After the German Bible, we know of no initials of very great interest in Nuremberg books for some years. Koberger, who reigned supreme in this town, did not favour their use.[17]

[17] In a recent catalogue of thirty-seven works published by him, no woodcut initials occur in any.

In 1489 a book was published, generally attributed to G. Stuchs, which is interesting in many ways.[18] The title, which is xylographic, runs as follows:

‘Versehung leib sel er unnd gut,’

anglicé: ‘The way to preserve body, soul, honour, and means,’ and on the verso is a remarkable engraving of a sick person in bed surrounded by attendants, which evidently suggested the cut representing the sick fool in Brandt’s celebrated Navis Fatuorum. At the end of the volume is a great[27] typographical curiosity, which constitutes, when completed by hand, an ex-libris. This is a woodcut engraving occupying nearly the whole of the page, with a shield in blank and two scrolls. On one of these are engraved the words, Das Puch und der Schild ist, the corresponding one being intended for the owner’s name, and the shield for his coat of arms.

[18] Proctor ascribes this work to either Conrad Zeninger or Peter Wagner.

In our copy this book-plate remains in its original condition, but we have seen another that was filled up at the time, and which has been the means of rescuing the name of a worthy monk from oblivion. In it, the first part of the sentence is completed by the addition of the words, des Closters zum Parfusen hat Eundres Gewder gemacht, the whole forming an ex-libris of the Monastery of Barefooted Brothers of St. Francis, and testifying to the skill of the ‘bibliothecarius,’ Andrew Gewder, who engrossed and illuminated it.

There are two specimens of this page also in the Franks collection of book-plates at the British Museum. In one of these the space is blank, in the other it is filled up with the name of a nun, Barbara.

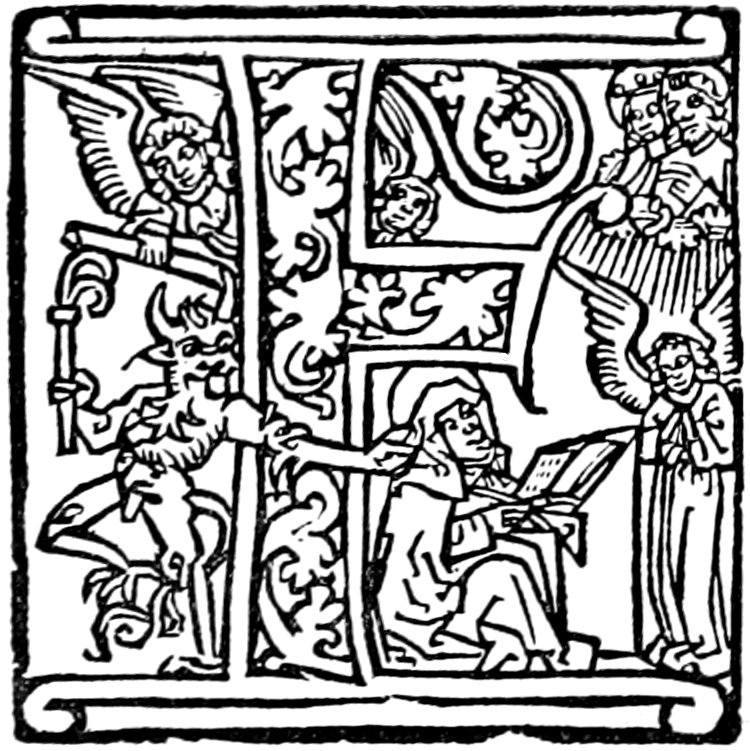

The chief interest of this volume, however, resides in its initial letters, after the designs which are preserved at the Pinacothek at Munich, of Israel von Mecken. Many of them are repeated a great many times, there being altogether between seventy and eighty impressions; but these represent only eight different letters of the alphabet, A, D, E, H, I, M, P, S. Of these the E, which we give, is the only letter which is both engraved and printed perfectly, the A being the next best. Nearly all the others are flat, often wanting in depth and relief, besides being badly printed.

Altogether this book is one of the most interesting relics of early typography, and is especially noticeable as being the first volume illustrated by a known artist.

In the early sixteenth century, works published at Nuremberg were not as a rule well supplied with ornamental initials, the complicated calligraphic letters that became so common in German books, and that were little used elsewhere, taking[28] their place. Butsch in his reproductions of alphabets of this period does not give any specimens. This is all the more remarkable in that Nuremberg was the home of Albert Dürer and the great centre of the wood-engraver’s art. The few examples, moreover, that we have seen, are very primitive both in design and in execution, as the reader can see from the reproductions taken from the Missale Pataviense, printed by Jodocus Gutnecht, 1514.

[29]

Printing was introduced into Basle before 1468, having been preceded, as in most other towns of the upper Rhine, by xylographic publications. No Basle book bears a printed date earlier than 1473, but the absence of such printed date does not prove that the introduction of printing into Basle did not take place earlier, and a note of the purchase in 1468 of a copy of St. Gregory’s Moralia in Job, printed by Berthold Rodt or Ruppel of Hanau, shows that he must have been at work at that time.

From the point of view of initial letters we will pass over Berthold Rodt and Michael Wenssler, to come to the publications of Bernard Richel, the most interesting of which are his Sachsenspiegel of 1474 and the Latin Bible, which had several editions, these appearing in 1471-75-77. In describing this work, Panzer in his Annales Typographici remarks that the woodcut initials do not occur in all the copies. In some of them their place is left blank. This is another evidence of the early printer’s reluctance to adopt printed ornaments as the definite formula, and if any further proof is necessary it will be found in the fact that even where woodcut letters are used, they are often more or less enlivened with colours.

We have already alluded to these initials in describing those of Bämler, and we have touched upon the point as to[30] who was the first to make use of the historiated S which has a certain analogy with the xylographic letter mentioned in a former chapter, from the Ars Memorandi.

There are in this Bible four different sets of letters, but of none of these is there a complete alphabet, although but few letters are wanting of the largest. The next nearly complete is the second in size.

Of the four different sets, the second in size is of a special design, different to anything we have met with. The others are pure specimens of Maiblümchen ornamentation, and amongst the best of the kind.

The three different-sized initials with human faces are the only letters in the volume with any trace of historiation.

Several Psalters were published either at the end of the fifteenth or at the beginning of the sixteenth century, of exactly the same size and general disposition, two of them with initial letters that correspond in subject although very different in treatment. These are the Psalters of Basle and Augsburg.

The latter has been dealt with in a previous chapter. The Basle Psalter was published by Furter in 1501, and the initials of the two volumes can be contrasted and compared with those that have just been dealt with.

In these letters, the fool who saith in his heart there is no God (Dixit insipiens), is represented in the D which begins the Psalm as a jester, which is not quite appropriate. In the Mallermi Bible, where there is instead of an historiated letter a little cut, the rendering is more correct. The fool is there, a man with dishevelled hair, and having every appearance of having lost his reason. The C with Absalom hanging by his hair is reproduced as an example of Basle woodcutting in Muther’s Bücherillustration.

There is amongst these initials a nondescript kind of letter which is an example of the carelessness that sometimes occurred in the workshop. It was intended for an E, but the draughtsman forgot that the drawing would be reversed in the printing, and the printer has arranged matters in the text by turning the letter upside down.

[31]

In a former essay (The Library, 1901) we gave three specimens—S, T, and V—from a book entitled Liber Decretorum sive panormia, etc. etc., as examples of Furter’s ornamentation. Letters of this alphabet occur also in an extremely rare book unknown to Hain, without date or name of printer, but undoubtedly printed at Basle, the Decreta Consilii Basiliensis. It is, however, certain that they were used in a work printed at Besançon some ten years before the Liber Decretorum, and although the fifth volume of Claudin’s Histoire de l’Imprimerie en France in which this work was to be described has not yet appeared, we have reason to believe that they are to be attributed to this town, and were to be given in the chapter in which it is mentioned.

We shall have to refer later to the frequency of the repetition in some volumes of the same initial. In the German Bibles, for instance, the different books most often begin by the word ‘Der,’ and consequently by an initial D. In a book of sermons by that extraordinarily fertile writer, Geyler von Kaisersperg, not only does every section commence with the letter D, but with the same identical initial. In this volume, the Christianliche Bilgerschaft, printed by Adam Petri in 1512, the preface begins by a floral letter of no consequence. After that the D, with a pilgrim and a cross on his shoulder, is repeated at the commencement of every chapter, possibly thirty times. The title-page has an illustration by Urs Graf with the same subject.

The last years of the fifteenth century had passed away, but the German printers, including even Ratdolt, who had returned to Augsburg from Venice, still resisted the influence of Renaissance art. In the Narrenschiff of Brandt of 1493 we can see the science of the draughtsmen excellently interpreted, but the Gothic facture still holds good against the encroachment of more modern artistic tendencies, and it is not until towards 1512 or 1513 that the new ideas begin to be more generally accepted.

But as a modern writer has said: ‘Dès que la Renaissance lumineuse a paru, traînant derrière elle l’admirable cortège de ses maîtres délicats, fils de la Grèce antique qui moulaient la[32] feuille divine de l’acanthe sur le sein d’une vierge endormie, le vieux monde s’écroula et l’ornement gothique fit place à la triomphante et poétique arabesque devenue l’aurore nouvelle.’

It is in the Ritter von Thurn, published by Furter in 1515, that we see first this influence in the form of a title by Urs Graf, copied from the Venetian original, and ornamented with dolphins and acanthus. Besides a great many titles, Urs Graf also engraved a certain number of alphabets, inspired to a great extent by those of Tacuinus de Tridino, but wanting in originality, and generally inferior to the originals. The reader can compare the two kinds of initials.

But it was the arrival of a young artist of genius that completed the revolution at Basle in the ornamentation of books. This is not the place to discuss the merit of Holbein as a painter, nor to study the long series of title-pages, borders, friezes, and printers’ marks which he composed for different printers of Basle and elsewhere.

We are concerned here only with his alphabets; and of those which bear more particularly the mark of his genius, the alphabet of Death occupies the first place.

This as a composition is a chef d’œuvre, and it was engraved on wood by an artist of the very highest merit, Hans Lützelberger.

These initials, notwithstanding their small dimensions, about twenty-four millimetres square, can well bear comparison with the larger engravings in Les Simulachres et Historiées Faces de la Mort which was to appear several years later at Lyons, in 1538, chez les frères Trechsel Soubz l’escu de Coloigne. The alphabet is composed of twenty-four letters, and several of the original proof-sheets are to be found in different Continental museums. Basle and Dresden each possess one.

The letters of this alphabet may be met with in different works published by Bebelius, such as the New Testament in Greek of 1525, that of 1531, the Galen of 1538, and particularly in the two folio volumes of Aristotle which appeared in 1532. In the five first, A to E, the body of the letter is in[33] white. In the others there is a double outline which softens their appearance and reduces their size. Each of the letters merits a separate description, but the reproductions given, as far as they go, obviate all commentary, permitting the reader to judge for himself, and to appreciate the justice of the praise that has been lavished upon them by art critics.

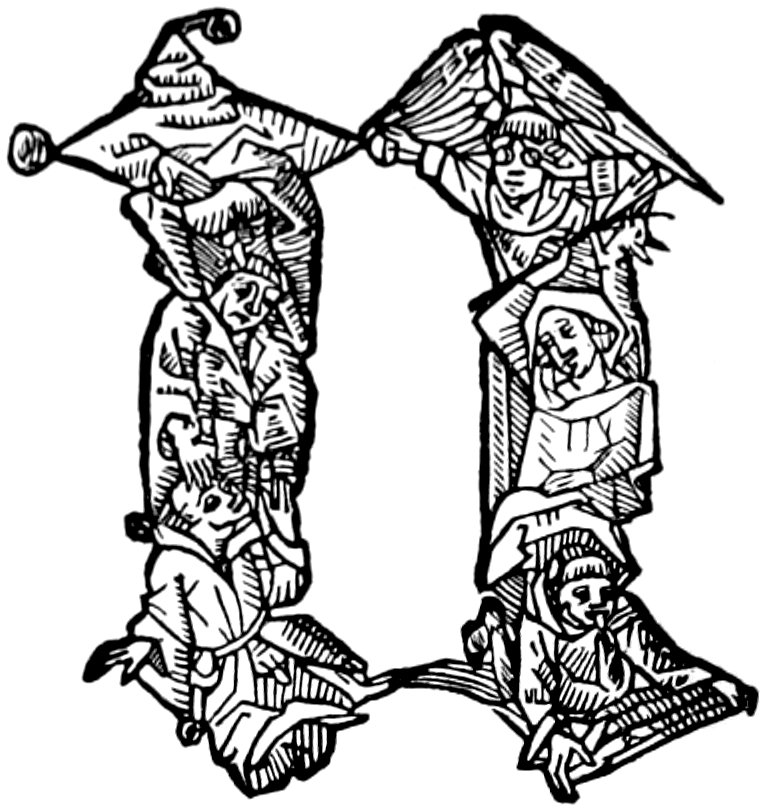

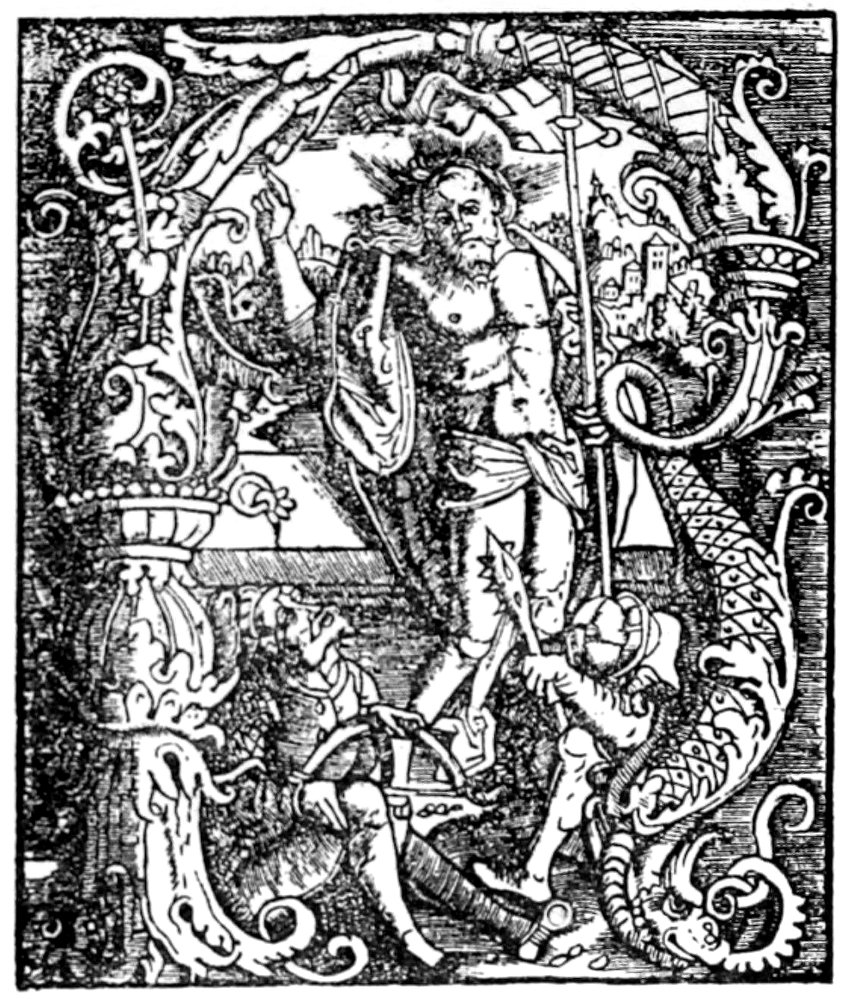

The subjects in the alphabet of Death are the same as in the celebrated Basle frescoes. In each of these scenes, men and women of all sorts and conditions are invited to accompany him by Death, who will take no refusal nor hear of any previous engagement; from B and C the Pope and Emperor, to V the merchant, from the Hermit full of years W, to the child in its cradle V, the Last Judgment Z, finishing the series.

The Latin alphabet (for there are some Greek initials) contains two subjects not to be found either in the frescoes or in the larger illustrations for the well-known satire, V the horseman with Death sitting behind like black care, and S the courtesan. In the Greek alphabet of inferior execution, certainly not the work of Lützelberger, of which we give three specimens, there are also two other subjects, the Σ and the Ω, a peasant and a smith.

Curiously enough, an enlarged copy of this alphabet, but of much inferior merit, was used more than ten years before by Cephaleus of Strasburg, who also had a smaller series in the same coarse engraving. Some of the letters are given for comparison.

A very curious alphabet, which although not equalling Lützelberger’s is of more than average execution, can be but little known to bibliographers, for as far as we have ascertained it only occurs in a few books published at Stella, in Spain. The scenes are selected from the Simulachres, and each letter is a complete little picture.

Besides these alphabets a certain number of Dance of Death letters are to be found in other books of Basle, of which the V, with Death on horseback with an hour-glass, will serve as an example. They are also to be met with in books of Cologne.

The Dance of Death, although intimately associated with[34] the name of Holbein, was not his creation, the subject having always been a favourite one in the Middle Ages, and having been treated also by Albert Dürer. It was the general rule to represent Death, who although a skeleton was endowed with motion, with withered muscles. In an extremely precious book, printed by Meydenbach at Mayence, Der Doten Tantz mit Figuren Clage unt Antwort schon von Allen Staten der Welt, which is illustrated with forty-one curious cuts with the same subjects as Holbein’s alphabet, Death is thus represented, and the same thing is seen in other German editions of this work of the fifteenth century, and in the numerous French editions of the Danse Macabre which appeared about the same time. Holbein, however, preferred to suppress these, and in so doing exhibited his ignorance of the anatomy of the human frame. Not only are the shoulder-blades and pelvis wrongly drawn, but the arm and thigh are represented each with two bones, whilst the fore-arm has only one.

These mistakes have frequently been pointed out before, but the fact that they furnish an argument in the controversy about Holbein’s possible sojourn in Italy seems to have been less noticed. There is no positive evidence on this point, but arguing from a change in Holbein’s style after a certain period, in which the influence of Mantegna and Leonardo da Vinci is manifest, it is said by some of his biographers that he must have studied under these masters. It must be remembered, however, that in Italy at this time there were regular schools of painting, and it is difficult to suppose the masters above-named to have been as ignorant of anatomy as must have been the case had Holbein been their pupil. If his knowledge was derived, on the contrary, from contemporary German books, his mistakes become more comprehensible.

The peasants’ alphabet, also composed of twenty-four letters but of a different character, is another of his best compositions. The museums of Basle and Dresden possess proofs of this alphabet.

The letters are to be found in the publications of Froben,[35] Cratander, and Bebelius, and Voltmann in his Bibliography of Holbein has given some specimens of them. Butsch reproduces the whole alphabet, as indeed he does several others, including that of the Dance of Death. The realistic scenes depicted in some of the letters, taken from life, are not always edifying, but this is the fault of the models rather than that of the artist.

In A, we have musicians playing on their instruments, B to K show some couples dancing, L is a love-scene, M a fight with swords, O a boy holding a girl, while another boy is cooling his ardour by throwing water over him. In P the water is being offered to a girl from a pail, V shows a bowling ground, with a game of nine-pins, W the ride home.

Our three specimens are taken not from this alphabet but from letters with similar subjects in the Galen.

Of the same size as the peasants’ is the children’s alphabet, which is treated with the same happiness and talent of observation. Holbein must have been especially fond of children, for they figure in a great many of his compositions, titles, borders, and printers’ marks, and he paints them with a grace that Lützelberger, for it is probable that he engraved them, has caught most happily. The different incidents of juvenile life, chiefly games, are rendered with great realism. Sixteen letters of this alphabet can be found in the Lactantius of Cratander and Bebelius of 1532, others in various Basle works. In a larger alphabet, children are engaged in all sorts of trades—forging, cooking, baking, building, carpentering, fishing, playing at coopering, at being bath-keepers and tanners. The W, which is rarely met with, represents a boy taking off a doctor with spectacles on his nose, whilst another is reading a book, and the third preparing some physic.

This playing at adult occupations has been taken as a subject for alphabets by other artists, the best being that of J. van Calcar, to be mentioned presently.

Holbein composed two sets of initials for Valentin Curio, whose name appears on publications which are often on philological questions.

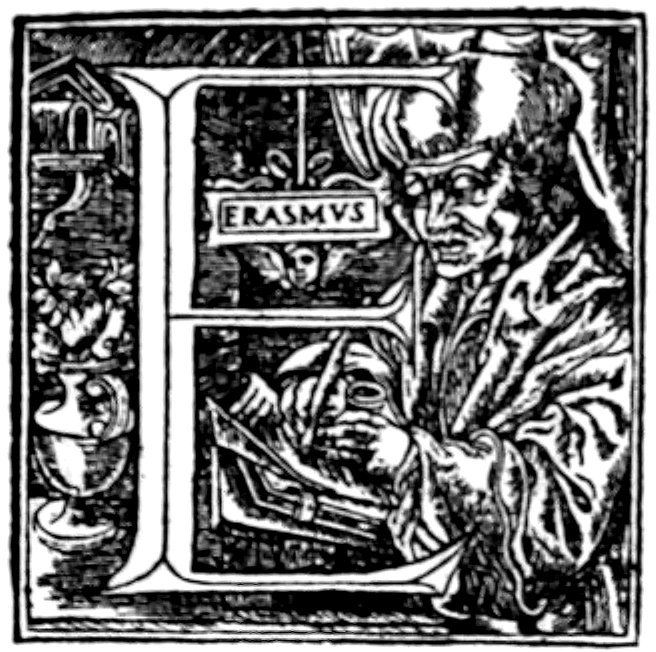

These letters, also with children, are to be found in volumes[36] often ornamented with pictorial borders by the same hand, our reproductions, C, D, O, Q, being taken from the Strabo of Walder, and others being met with in the Enchiridion of Erasmus. From a smaller set by the same printer we select A, I, N, Q, V, X, Y, Z. The A, C, D, D, H, I, O, P, Q, V, with animals and personages, are also from the same press.

Of the many other initials we will mention the Greek capitals of the Lexicon Graeco-Latinum of René Gelli, published by Froben in 1532, found also in the Lexicon Graecum of J. Walder, 1539, in which the Δ represents a young woman struggling as she is carried off by Death. This letter is of singular beauty. This leads us to speak of the four large Greek initials which we give from the Galen of 1538, of Bebelius and Cratander, remarkable from every point of view. The Δ represents Silenus on a pig, the Θ Samson with the jaw-bone of the ass, the Π the prodigal son eating at the same trough as the swine, the Ω a child sailing on a shell.

Besides these four beautiful letters, of which there are only five proofs in the work, one at the beginning of each of the five folio volumes, the Θ occurring twice, there are numerous initials from other alphabets scattered through its pages, such as the series of which we give a Π with a child and a ram, and some specimens of the alphabet engraved on metal, of which we reproduce the F representing the Deluge, Noah’s Ark being dimly perceived through the rain, the M Jacob’s ladder, and the Q Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. These initials, although generally in very bad impressions, are to be met with in volumes of Bebelius and others, and were even copied abroad. They are to be found, for instance, in the Commentaires sur l’Histoire des Plantes printed by Jacques Gazeau in 1549.

An alphabet, of which we give the B, I, and M, is found in the Cyprianus of Froben of 1521, and in many of his later impressions. The I with the three children, the front one with the basket on his back, is generally by itself, that is to say, not with initials of the same size and character.

The O, also with three children, belongs to one of the[37] alphabets in the same style, which are no doubt imitated from Venetian models. We must mention the alphabet of the Master I F on a black ground in publications by Froben after 1518, the first letters of which represent the labours of Hercules, the following ones different scriptural and classical subjects. The B with a child in its cradle, and the E (a winged child on a sea-horse), are samples of the initials from Basle books of the time, which are possibly by Ambrose rather than Hans Holbein, as are the K and Z with children and grotesques, on a black ground with stars.

But, however interesting the work of Holbein, however varied and supple his genius, we cannot do more than give specimens of the whole. The reader who is desirous of fuller documentation can refer to Woltmann’s Holbein und seine Zeit, Leipsic, 1872; to the Bücher-Ornamentik of Butsch, or to the more complete collection of Holbein’s Initials, recently published by Heitz.

Holbein’s alphabets and initials were soon adopted by all the printers of Basle, and with few exceptions until 1545 there is nothing to note of any other artist. It was in this year, the date of Holbein’s death, that the Basle edition of Vesalius’s De Corporis humani fabrica was printed, a work that may be considered as one of the most remarkable products of the German Renaissance.

This book had been previously published at Venice, and its success was so great that it was shortly after pirated at Cologne. Vesalius, in his preface to the Basle edition, alludes to the want of international copyright, to the dishonesty, and particularly to the vandalism, of publishers who substituted detestable copies for the wonderful originals of his anatomical plates, which he would have preferred to lend them. Besides these plates, which have never been surpassed in beauty, there is the admirable frontispiece by J. van Calcar representing a lesson on anatomy, and two series of initial letters depicting children, who, with inimitable seriousness, are acting as medical consultants. In a later edition Van Calcar’s initials are replaced by a much inferior set by another hand.

[38]

—There are several interesting alphabets in the books published by Froschouer of Zurich, the most important of which is illustrated with scenes from the Bible. The two A’s, the D, the reversed D that serves as a C, and the F, are said to be by N. Manuel, the S with Jesus overturning the money-changers’ tables in the Temple by Ambrose Holbein.

[39]

Lübeck is represented here by two printers, Lucas Brandis and Bartholomew Ghotan. In one of his recent catalogues J. Rosenthal has given the reproduction of an alphabet from a Herbal, but the letters are of very little interest, being about the same size as those of the Ulm Boccaccio and with the same kind of ornamentation. As the first letters used in the town of Ulm, and one of the first sets used by any printer, and so showing the evolution of typographical ornamentation, the Ulm initials have a certain interest, but they would not have been worth reproducing from a book dated almost twenty years later.

Lucas Brandis published two immense folios, the Rudimenta Novitiorum, the Latin original of the Mer des Hystoires, the other the History of the Jews by Josephus. The first, which appeared in 1477, is a kind of History of the World, and, like the Nuremberg Chronicle, is full of cuts representing towns, kings, philosophers, and other subjects. These, however, are much less interesting than the initials, which are the first examples of what are called passe-partouts, the central picture being removable at will and adaptable to any frame. Some of them are special to one or other volume, but most of them are to be found in both.