The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Lost Dryad, by Frank R. Stockton

Title: The Lost Dryad

Author: Frank R. Stockton

Release Date: July 14, 2021 [eBook #65841]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell, Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE LOST DRYAD

ONE THOUSAND COPIES OF THIS BOOK HAVE BEEN PRINTED AT HILLACRE FOR THE UNITED WORKERS OF GREENWICH—EASTERN BRANCH, INCORPORATED.

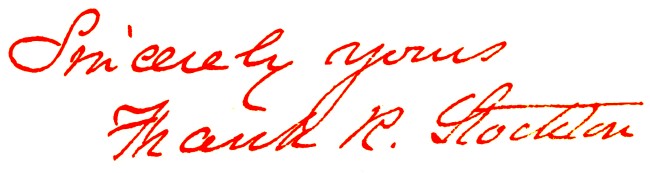

Sincerely yours

Frank R. Stockton

BY

PRINTED AT HILLACRE

FOR THE EASTERN BRANCH OF

THE UNITED WORKERS OF GREENWICH

RIVERSIDE, CONN.

1912

Copyright, 1911, by The Curtis Publishing Co.

Copyright, 1912, by The United Workers of Greenwich.

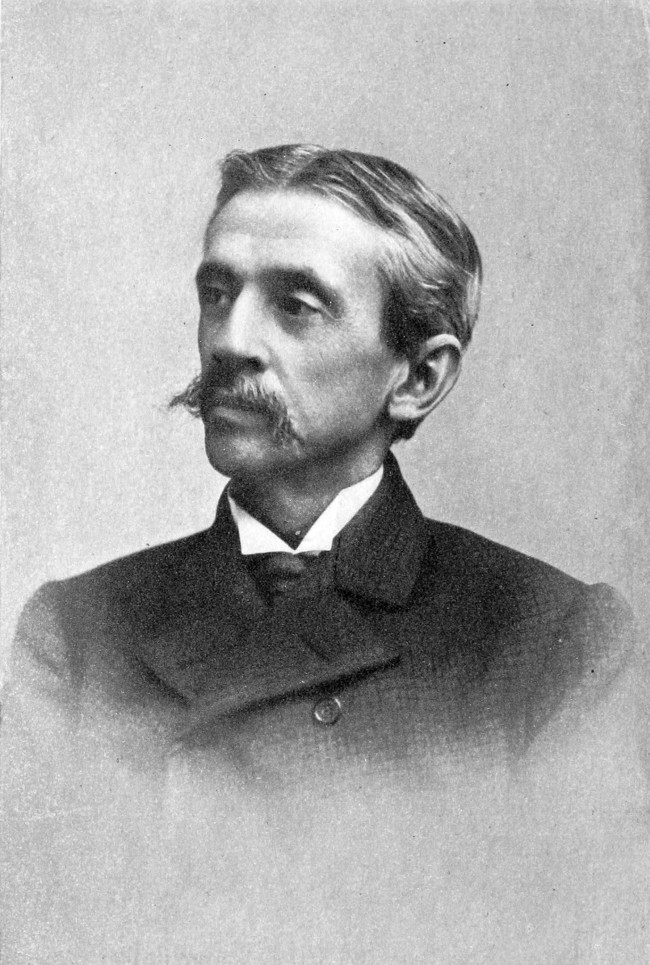

A dozen years ago, when every one was still reading Rudder Grange and The Merry Chanter, Frank R. Stockton asked Mrs. Frederick Gotthold which of his stories she liked best. Her choice of the fairy tale, Old Pipes and The Dryad, pleased him. The fanciful stories he wrote for children were very near to his own heart.

Some time after this, when the publishers were preparing a new edition of Stockton, Mrs. Gotthold persuaded them to have printed for her a copy of[6] Old Pipes, each page on a leaf of vellum. This she illuminated and decorated, bound it in leather and sent it to Mr. Stockton.

One day Mrs. Gotthold’s mail contained a parcel. Being opened, this proved to be a small leather-bound book of neatest manuscript, bearing on the inside cover this inscription:

To Mrs. Florence W. Gotthold, this little story—which was written for her, and of which there is no other copy—is gratefully presented by

FRANK R. STOCKTON

Claymont, Nov. 3, 1901.

Transcribed by E. W. Tuttle.

A title-page, also in Mr. Stockton’s handwriting, read:

The | Lost Dryad | By | Frank R. Stockton | Only Copy. | Claymont | Charles Town, W. Va. | 1901

The book consisted of twenty pages written by Mr. Stockton’s sister-in-law from his dictation.

Ten years have passed. Mr. Stockton died in April, 1902. None[7] of his immediate family remain. The friend for whom he dictated this quaint little tale has regretted that her pleasure in it was not being shared by others. Her interest in the Eastern Branch of The United Workers of Greenwich, Connecticut, has prompted her now to give the story to them for publication. The magazine rights were sold to the Curtis Publishing Company. The money thus obtained has been expended in producing this edition of one thousand copies—the first edition of one of the last tales of America’s well-loved story-teller.

The proceeds from the sale of this book will go into the construction of a children’s club-house and playground in a very poor little village, where some of the little ones wander through childhood almost as forlornly as the Lost Dryad bereft of her oak-tree. To prolong the youth and bring joy to the lives of these children is the purpose of[8] this publication of the troubles and adventures of The Lost Dryad.

COS COB, CONNECTICUT,

Thanksgiving day, 1911.

There was once a dryad who was truly lost. The summer was drawing to a close; the nights were becoming cool, she had no home, and she did not know where she was.

Not long before, while she was still in her oak tree, there had been a terrible storm; the tree had been dashed to the ground and splintered to pieces, while the poor dryad had been blown away, and away, and away, she did not know where. Now she was looking for another oak tree to live in, but she[10] was lost, absolutely lost. One tree she found, which she thought might shelter her, but when she examined it she found that it was getting old and its trunk was badly cracked. After her terrible experience she was afraid to go into a cracked tree, and so she kept on her way.

At a little distance, she saw a village, shaded by trees, and the thought came to her that she might possibly find a home in a big oak there. That would be fine, truly. She had never lived in a village, it would be a new experience.

So she kept on, but when she reached the place she found that few of the trees were oaks, and these were not very well grown and too small for her. It was nearly supper-time in the village and, therefore, there were not many people in the street, but presently she met a big man with a cross face.

“Oho! Oho!” he cried, “who[11] are you? You cannot go about the street like that!”

The poor dryad was terribly frightened. “Like what?” she asked.

“You must go home and dress,” he said.

“I am dressed,” said she; “these are all the clothes I ever wear.”

“Do you call these clothes?” he said. “Come along with me! I am a constable. I will take you to the lock-up. You must be crazy! But they will take care of you there and, at any rate, will dress you properly.”

The poor dryad trembled from head to foot. She did not know what a lock-up was, but she knew it must be a terrible place, and she had never seen anyone look so cruel as this man. He had already seized her by the arm, and if his grasp should become tighter, she believed her arm would break in two. Poor, weak, beautiful dryad! What could she do?

She[12] thought of something. It was her only hope! It must be remembered that there is a peculiar property pertaining to the kiss of a dryad. Whenever a dryad kisses a human being, that person becomes ten years younger. So all good mothers are very careful to keep their children away from large oak trees. If a girl, of a dozen years, were to sit in the shade of one of these trees, she might attract the attention of an affectionate tree dweller; and then, if this dryad should kiss her, the little toddler of two years might go home—if perchance, she remembered where she lived—and astound her parents. But if a child who was not yet ten should be kissed, it would disappear utterly.

The dryad remembered her rare gift, as she looked up tearfully into the stern face of the constable.

“Please, sir,” she said, “don’t take[13] me away; I shall be frightened to death if you do. I have something to tell you, but only you must hear it. Please let me whisper it to you.”

The constable looked at her. He was fond of hearing secrets, and it was quite proper that people should confide in him. So he bent down his head to hear what the dryad had to say. In a moment she kissed him twice, and, before he had time to notice the change, he was a man of thirty years of age, vigorous and handsome. He released his grasp upon her arm and stood up, straight and tall.

“Oho!” he cried, “and who are you?”

“Put down your head,” said the dryad, “and let me tell you.” Then she gave him two more kisses.

Now there stood before her a boy of ten, very much troubled.

“I don’t know what is the matter with my clothes,” said he, “my breeches[14] are all down about my feet. They are like an old man’s trousers. And my shoes and stockings! Where did I get such big shoes and stockings? And this great jerkin, it is too big for me. I am going to throw it off.”

“That is right, little boy,” said the dryad, “throw it off, and pull off those shoes and stockings; you can walk a great deal better in your bare feet. You must have been asleep and in a dream you put on your father’s clothes.”

“I expect that was it,” said he, “it must have been that.”

“Now run along home, little boy,” said the dryad, “and carry carefully your father’s jerkin and his shoes and stockings. Perhaps if you put them where you found them, he may never know. Now run along!”

And the little boy ran along.

The dryad was now alone, but she was still frightened. She was sure there were no trees here which would suit[15] her and she was afraid of meeting some other cruel person, so she slipped into a side street, and there she saw a light coming through a glass door. This was the only light in the street and she went up to it and looked in.

Inside was a small room, not very well furnished, and by a table, with a light on it, there sat a girl, trimming a hat. The dryad smiled with pleasure; she was not afraid of a girl, especially one who was so pretty, and looked so gentle. Perhaps she might tell her where there was a good oak tree; so she opened the door, without making any noise, and stepped in.

At first the girl was startled and dropped the hat she was trimming, but when the dryad quickly told her who[16] she was and what a sad plight she was in, she was reassured. She had heard of dryads and was glad to see one.

“But you must remember this,” she exclaimed, “on no account must you kiss me. I am engaged to be married and I would not have you kiss me, for the world.”

“Oh, no! no! no!” said the dryad, “no matter how good you are to me, I shall be very careful. And can you tell me where there is a large oak tree?”

“I do not remember any,” said the girl, “but I expect you sorely need one for you must feel cold in the evening.”

“Oh, no!” said the dryad, “I am not cold. But what a beautiful hat you are making! Such lovely silk and lace you are putting on it!”

“Yes,” said the girl, holding up the hat before the lamp, “I am trying to make it pretty, but this silk is tarnished; it has lost a good deal of its color. My step-mother thinks it is good enough for[17] me and so I must do the best I can with it.”

“Poor girl!” said the dryad, “she ought to give you the nicest stuffs there are in the village, you are so pretty.” And, moved by pity and affection, she was about to give the girl a kiss of sympathy, but remembering just in time that that would never do, she kissed the hat. Instantly the silk and the lace were as bright and new as if they had just come out of the shop. The dryad exclaimed with delight.

“Look! look!” she cried, “did you ever see more charming colors?”

The girl had never seen more charming colors, but her countenance fell.

“They are very pretty,” she said, “but what an old-fashioned hat! It looks like one of those hats people used to wear ten years ago.”

Now the poor dryad was greatly troubled. “Have I spoiled it?” she said. “Oh! I shall be too sorry if I have done that.”

The girl turned the hat around and looked at it on every side.

“Of course, I could not wear it as it is,” she said, “but I am sure I can alter it. Yes, I can change the shape and then, with these new trimmings, it will be perfectly lovely. I thank you ever so much. But please do not come any nearer; you might forget yourself.”

“And you are going to be married?” asked the dryad.

“Yes, truly, if I can,” said the girl, “but my step-mother does not wish it; she wants me to stay here and work for her. But I shall be patient and, in the meantime, I am so glad that he will see me in my new hat.”

“And is your step-mother so very cross?” asked the dryad.

“Oh, very! If she were at home I could not let you stay here, and as I expect her to come back shortly, I am afraid—”

The poor dryad clasped her hands.[19] “You do not mean,” she said, “that I must go away? I hoped that I might stay here until the people of the village were all in bed.”

“I am very sorry,” said the girl, “but really, if my step-mother should come back and see you here I don’t know what would happen; but I will tell you what I will do: I will lend you one of my frocks and a cape, and you can put on my sun-bonnet; then you can go out and look for a tree and people will not be apt to notice you, and if you will come back after a while, when my step-mother has gone to bed, I will go out with you and help you to find a tree if you have not found one. Oh, now please don’t! People can be very grateful without kissing, you know, and I will bring you the clothes in a minute.”

When[20] the dryad had put on the frock and the little cape and the sun-bonnet, she looked very much like an ordinary person, and when she went out on the street nobody noticed her, for there were girls in that village who were so poor that they were obliged to go barefooted.

This lost dryad had no very good idea of time and, after she had walked about the streets, and even a little way into the country, looking for a tree and finding none, she thought that the cruel step-mother must surely have gone to bed, and so she went back to the house of her friend the girl, and opening the door she slipped in. There she saw the cruel step-mother scolding the girl. As she entered, the step-mother stopped short in her scolding, and the poor girl looked as if she was about to faint.

“Heigho!” cried the woman, “and[21] who is this? How dare you come in without knocking? What! Where did you get that sun-bonnet? You wretched creature!” she cried, addressing her step-daughter, “what does this mean? And your cape and your frock?” And without waiting for an answer she stepped up to the dryad.

“Take that off this minute, whoever you are!” she cried, and as she said this she grasped the sun-bonnet and pulled it from the dryad’s head.

The girl almost fainted and sank into a chair, while the poor dryad, nearly scared out of her wits, had barely sense enough left to throw her arms around the step-mother’s neck and give her four kisses, as quick as lightning.

The next day was the step-mother’s birthday, and she intended to celebrate the occasion by inviting some of her old cronies to sup with her; but now there was a little girl standing on the floor, beginning to cry. The dryad clapped[22] her hands with delight.

“So many clothes,” she exclaimed, “and such a dear little body in the middle of them all!”

The girl with the hat cried out, “Oh, what have you done!” But, in spite of her consternation, she could not help laughing.

“She does look funny,” said she. There was such a difference between the little child and the cross step-mother, that it was impossible for any one to be really sorry.

“How queer it is!” said the dryad. “She knows nothing at all of the life she has lived.”

“Of course not,” said the girl, “she could not look back on her future, you know.”

“I want to go to bed,” said the little one, rubbing her eyes, “and please take these things off.”

“That is what we must do,” cried the dryad, “we must undress her and[23] put her to bed.”

“No, let me do it alone, you might forget,” said the girl.

So the little child was put to bed in the back room and, in a moment, was asleep.

“Now I need not go away,” cried the dryad.

“No, indeed,” said the girl, “I should be afraid to be left alone with that little thing who was my step-mother.”

The dryad threw aside the uncomfortable gown and cape, and her face sparkled with delight; she was so glad that she need not go away and was so happy at what she had done.

“Now,” said she to the girl, “you can be married, and you two can take care of the little girl.”

“Yes, I can be married,” said the other, “but not immediately, and in the meantime I must support this little child and myself. I have no money and how am I going to do that?”

“Oh, I wish I could help you,” cried the dryad. “Could not I live here until you are married? I really ought to do something for you, and I will never kiss you or the child.”

“But how could you help me?” said the girl, smiling.

“I don’t know,” said the dryad, reflecting, “perhaps there are some people in the village who would like to be younger.”

“Yes,” said the girl, “that might do. We could live here together and setup a kisserie. It will be very pleasant for me to have everything my own way and not to be scolded, and I shall take the best possible care of the child. I know there are people who would like to be kissed, but you will have to be very,[25] very careful not to make mistakes.”

“Oh, I will do that!” cried the dryad. “I promise you, that, from this moment, I will never kiss anybody, old or young, unless you tell me to.”

At this moment, there was a sound of hurrying feet outside. The door was thrown open and an excited group of men and women rushed into the room.

“A dreadful thing has happened,” cried one of the women; “the constable, Johann Milder, has disappeared. He left his clothes behind him. Stranger yet, there is a little boy at his house who says he lives there, and who he is and where he came from nobody knows. We have come to see your step-mother; she is a wise woman and perhaps she may help us. Where is she? Call her[26] quickly!”

“She is here,” said the girl, and stepping to the bed, she turned down the covering.

Then all the people pushed into the back room and when they saw the sleeping child, two women fainted, just where they stood. The others were so much astounded that not one of them could speak a word. Then the dryad, who, so far, had not been noticed, laughed out merrily. It was all so funny that she could not help it.

At this the people turned and stared at her. There were some among them who had seen dryads and they set up a great shout.

“A dryad!” they cried, “a wicked spirit, a tree witch! She has done this! She has been about with her sinful kisses.”

With one accord the villagers dashed at the dryad as if they would pound her into pieces and trample them[27] upon the floor.

But the dryad was in the door way, between the two rooms, and she moved so quickly that they could not touch her. Had she felt free to do as she pleased, she might have rushed in among them and, in a very few minutes, have made a kindergarten of the whole company, but she had promised her dear friend, the girl, that, without her permission, she would never kiss anybody, and she could not break her word. So she fled through the open door and away, and away, and away, until she was far from the village.

It was not long before the dryad came to the great oak which was old and whose trunk was cracked.

“Ah!” she cried, “here is this tree which I would not enter, but I shall not despise it again. It will shelter me, for a time, and I must no longer remain out in this cruel world.”

So she slipped into the oak, and[28] was so glad to feel herself safe that she kissed the inside of the tree, over and over again, telling it how thankful she was to have its protection, and to feel again as if she was at home.

It was not long before the aged oak was a hundred years younger; strong, vigorous, clad in the brightest green and able to withstand the fiercest storm.

Now, when the villagers knew what had happened, they thought it quite right that the girl should marry and take care of the child who had been her step-mother, and when the boy who had been the constable grew up, he married this child, and there was a great deal more happiness in that village than there would have been, if the lost dryad had not come to it, looking for a tree.

Transcriber’s Notes:

Punctuation and spelling inaccuracies were silently corrected.

Archaic and variable spelling has been preserved.

Variations in hyphenation and compound words have been preserved.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.