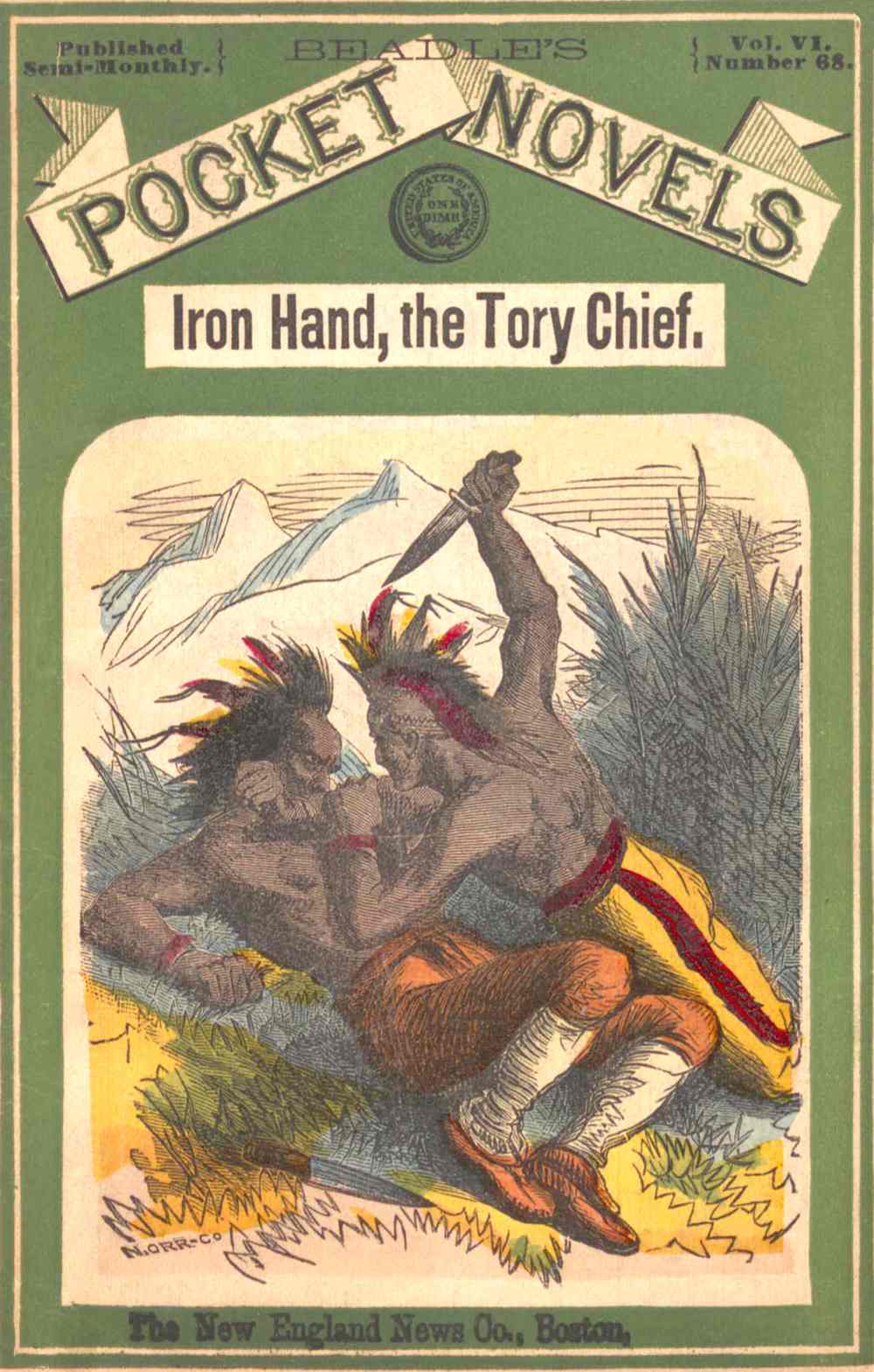

Vol. VI.] FEBRUARY 3, 1877. [No. 68.

BY FREDERICK FOREST.

NEW YORK.

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871, by

FRANK STARR & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | THE QUARREL. | 9 |

| II. | THE MURDERED MAN. | 16 |

| III. | THE STRANGE FACE. | 21 |

| IV. | THE NIGHT RIDE. | 29 |

| V. | THE RED WITNESS. | 32 |

| VI. | THE HOT TRAIL. | 43 |

| VII. | THE SECRET MISSION. | 52 |

| VIII. | THE HUNTED LIFE. | 67 |

| IX. | A SAVAGE FRIEND. | 75 |

| X. | THE MASK REMOVED. | 82 |

| XI. | THE UNNATURAL BROTHER. | 87 |

| XII. | THE END OF THE TRANSGRESSOR IS HARD. | 89 |

| XIII. | SMILES THROUGH TEARS. | 93 |

[Pg 9]

IRON HAND,

CHIEF OF THE TORY LEAGUE:

OR,

THE DOUBLE FACE.

When the colonists had acquired a mastery over the savages of the wilderness, and assisted in breaking the French power on their frontier, they began to feel their manhood stirring within them, and they tacitly agreed no longer to submit to the narrow and oppressive policy of Great Britain. Their industry and commerce were too expansive to be confined within the narrow limits of those restrictions which the Board of Trade, from time to time, had imposed, and they determined to cast off these chains. Moreover, the principles of civil and religious liberty urged them on; and, at last, the trumpet of the Revolution was sounded, as the violent result of their dissatisfactions.

It was during the fourth year of this Revolution, in the year of our Lord 1778, that our tale opens in the vicinity of Lake George, near Fort Ann.

In a pretty, white cottage a short distance from the fort sat two men over their wine, discussing the politics of the day.

One, who is destined to be our hero, was about five and twenty years of age; he was tall and commanding; his features nicely molded and in perfect harmony; the eyes were gray, although, at a distance, one might mistake them for black, and his hair was dark-brown and curled close to his head.

[10]

Edgar Sherwood, for such was his name, was of English birth. Another brother and he were the last of an aristocratic family. These two had, however, some few years previous, separated on account of a misunderstanding in regard to their paternal acres. After the death of their father, our hero inherited the greater part of the estate. This his brother declared to be unjust, and had sworn he would have satisfaction. Thus they parted.

Edgar had been treated perhaps a little unfairly by his native country in some affairs, and becoming enraged against her he had come to America to espouse the cause of the struggling colonists.

The man with whom Edgar Sherwood was conversing was the father of his betrothed; his name was Thomas Lear. He was a native of England, and a thorough Tory.

“Can it be possible, young man, that you are so rash as to think of joining the Continental army?” said Thomas Lear, gazing at Edgar Sherwood with a look of astonishment, and his face flushing to a deep crimson.

“It is, sir.”

“And have you no respect for your king, or love for your family and friends?”

“For the former, none whatever, but for the latter a great deal of love and respect.”

“Well, then, how can you go to work deliberately and bring this disgrace upon them? Why, Sherwood, it is absurd to think of doing such a thing!” and Lear began to grow angry.

“If it is absurd to lend one’s aid to a righteous cause, then I am willing to be called absurd or rash, but I am determined to do this.”

“But, do you have faith in this war? Do you believe these colonists will ever overcome King George?”

“Most assuredly they will!” replied Edgar Sherwood. “Why, sir, they fight like tigers, and they never will remain conquered. What arouses these men to arms is the love of liberty, their firesides, their wives and children.”

“Very well; perhaps they are good at fighting, but, where is the money coming from to maintain this war any longer? Congress has none.”

[11]

“They will fight without pay; and, moreover, each soldier will contribute his mite.”

“Nevertheless, they are but a handful at best, and can not hold out much longer.”

“Ah, my good sir!” and Edgar Sherwood’s eyes sparkled with enthusiasm, “do not be deceived in this. The colonists, though few in number, have been compelled from the beginning to be self-reliant, and have been made strong by their mother’s neglect. Heretofore they have built fortifications, raised armies, and fought battles for England’s glory and their own preservation, without England’s aid and without her sympathy; and, think you now they can not do this again, with twofold zeal, for themselves?”

Thomas Lear was beginning to chafe under the young man’s patriotic words, and perceiving that he could not persuade him to abandon his purpose, he became very angry.

“I ask you once more, Sherwood,” said he, “to pause and consider the consequences; think—I entreat you—of my daughter, Imogene, before you take this rash step.”

“I have considered it all, sir, but my mind remains the same.”

Lear grew deathly pale with rage at these last words. Thomas Lear was a rich man, and he had long counted upon having Edgar Sherwood for a son-in-law, but this could not be under these circumstances. He dashed his wine-glass savagely upon the table, and sprung to his feet.

“You are mad! stark mad!” he cried. “Henceforth our connection is severed; never dare to cross my threshold again, for you are a traitor to your king, sir—begone!”

Having uttered these words, the old man sunk back in his chair perfectly exhausted.

At this moment, the door was suddenly thrown open, and Imogene Lear—Edgar Sherwood’s betrothed—appeared upon the scene.

“Oh, father!” she cried, casting herself at the feet of her parent, “I implore you to have mercy! Recall your words—forgive!”

“Never!” cried Lear.

“Be it so!” said Edgar Sherwood, scornfully, and was gone.

[12]

One month has passed away since the events last related, and during this time Edgar Sherwood had become a captain in the American army, and was stationed with his regiment at Fort Ann.

It was a bright, clear morning in the month of September, and a gentle breeze caused the flag of freedom to rise and fall in graceful folds over the garrison, inspiring the heart of every loyal man with patriotic fervor as he looked up to it.

Within the fort, every thing seemed in commotion, but without, all was quiet, and an observer would never have surmised that any thing particular was going on. The soldiers were hurrying back and forth; and some were collected in groups busily talking.

During the past night, the commander had received information from one of his spies that the notorious band, called the Tory League, led by their villainous chief, Iron Hand, was preparing to attack the house of a prominent Whig, and that it would be necessary to send a company or two of men to secure the patriot’s safety.

The colonel had chosen Captain Sherwood to go on this little expedition with his company, and the men were now preparing for that purpose.

The Tory League was composed of Tories and Indians, whom King George, foreseeing at the beginning of the war would be valuable allies to him if but secured, sent over agents to enlist in his cause. Among these agents came the man who had made himself so notorious throughout the country under the title of Iron Hand, which name the Indians gave him. The villainous deeds of this band and their white chief were countless, and they had become a terror to all stanch Whigs.

A large reward had been offered for the capture of Iron Hand, dead or alive, but to no profit; he was too artful for his enemy. In fact, no one, as yet, in the Continental army had been able even to obtain a sight of him. Search had been made for the rendezvous of the band but without success.

The attacks of the Tory League were always made with so much privacy as to exclude the sufferers, not only from succor, but frequently, through a dread of future depredations, from the commiseration of their neighbors also.

[13]

The soldiers received the orders to prepare for action with delight; excitement of any kind had been scarce for the last few months around the fort, and time dragged heavily on with them. Captain Sherwood felt some pleasure also on being chosen for this occasion, as he had had but little opportunity to show his valor since his enlistment. Yet, all day long his face wore a troubled look, and his whole manner seemed changed from usual gayety to sadness. The few who had observed this attributed it to fear, and yet could not believe that such a man should even know the meaning of the word.

When evening came, and a few hours before he was to start out upon his mission, he sat down, and, writing a short note, dispatched it to the little white cottage on the hill.

Imogene Lear, on receiving her lover’s note, cast a shawl about her delicate form, and hastened to the place appointed for their meeting. It was in a thick grove of cedars a short distance from the cottage.

Captain Sherwood, dressed in his long military cloak, with his sword girded to his side, was pacing to and fro in a thoughtful mood under the shadow of the stalwart trees.

“Edgar,” whispered Imogene, approaching with noiseless steps behind him, and placing her little white hand upon his shoulder.

“Imogene? It is you!” said he, turning quickly and throwing his arm around her waist. “I was afraid you would be unable to come, my darling.”

“Father was asleep and I stole out unobserved, but I must not remain long away, or he may awake and miss me.”

“Is he as savage against me as ever?” asked Edgar.

“Yes; but, do not let this trouble you, dear Edgar, I am the same—as—ever.”

“I know you are, my darling,” and he imprinted a kiss upon her cheek.

Imogene Lear was eighteen years of age. She was tall in stature, and most exquisitely formed. Her skin was white, even waxen white; and now and then a tinge of the rose visited her cheek; her lips were of that ruby red which goes with perfect health; perfectly arched brows, and long, dark lashes, shading eyes of wonderful brilliancy and depth of expression, made up this face suitable for an angel.

[14]

“Let us sit down,” said Edgar, leading the way to a fallen tree. “How are we to overcome this prejudice of your father, Imogene?”

“I know not,” said she; “he is very angry with you, but time may change him.”

“Do you think he is right and I am wrong in this matter?”

Imogene colored and did not reply. Edgar saw this, and dropping his head, said, sorrowfully:

“Then you think I am in the wrong?”

“Oh, no! but you know—he—is my father.”

“Yes, yes, I know,” said Edgar, impatiently.

“There, dear Edgar, do not let us quarrel about this; of course you are in the right.”

Then the couple remained silent for some time.

“We were to be married next month. Need this rupture between your father and me make any difference?”

“You would not urge me to marry against his will?”

“Oh, no,” said Edgar, coldly.

“We can wait awhile and he may relent.”

“And pray how long will you wait for me?”

“All my lifetime, if need be!” and Imogene looked him full in the face with her beautiful eyes.

“And will you never forget, whatever may happen?”

“Never.”

“My beautiful one, I believe you. Forgive me for asking you to do wrong.”

“You said in your note, Edgar, that you were going away to-night.”

The same troubled look that had haunted him all day now again was plainly visible on Edgar Sherwood’s face.

“Yes,” said he, “but we return to-morrow morning.”

“Are you going to battle?” asked Imogene, quickly, perceiving this look. “Is there any thing serious about to happen?”

“No; why do you ask?”

“Because you seem troubled about something.”

“I am a little—shall I tell you why?”

“Certainly, dear Edgar, are we to have any secrets between us?”

“But you will laugh at me if I tell you?”

“Try me.”

[15]

“Are you superstitious, Imogene?”

“No, not very.”

“Well, it is all about a strange dream that I had last night, and you will say that I am superstitious if I tell it to you.”

“Come, now, do not delay any longer, but tell it to me at once; my curiosity is excited.”

“It appeared to me as follows:

“I seemed to be walking by the side of a lake, when, suddenly, a shriek, which fairly chilled my blood, filled the air, and then I thought I saw you rush past me, dressed in white, and crying, help! help! help!

“Approaching the water you sprung into a canoe and pushed far away from the shore. I could neither move nor speak to you, and my agony was killing me. The canoe began to float, I thought, bearing you with it. Then I was trying to swim to you, when, in a moment, the boat mysteriously disappeared. I was paralyzed, and looking down into the clear water, I thought I saw you lying upon the bottom.

“At this moment some one behind me laughed—laughed as only a fiend could laugh. Turning around, I thought I saw my own image, and I started back a step. The apparition approached, and pointing down at you, said: ‘Look, look, this shall be your grave also! Beware of your shadow!’ and then it vanished.

“I awoke. Cold perspiration stood in great beads upon my forehead. You will tell me that I ought not to let this trouble me, as it was only a dream; nevertheless, I can not help it; it has taken a strong hold upon me, and I can not shake it off.”

“It was strange,” mused Imogene. “I hope nothing will happen to you, Edgar, for if I could hear that you were—well, never mind what—I should die with grief.”

The couple now observed that there was a light in the cottage.

“I must go now,” said Imogene, starting up, half-affrighted lest her father should miss her.

“I will go part way with you,” and they moved away.

As they arrived near the house, they stopped a moment before parting, and Edgar happened to cast a glance back to the woods.

[16]

There, standing by a huge tree, where the moonlight fell upon him, was the form of a man—a perfect copy in every respect of Edgar Sherwood.

“Do you see it?” whispered Imogene, trembling and turning ashy pale.

“Yes.”

It was near midnight when Captain Sherwood and his men arrived in the vicinity of the Whig’s house. They had miscalculated the distance from the fort, and were later than was designed.

The Whig’s residence was one of the old-fashion farmhouses common in those days, and on all sides of it was a thick growth of foliage which, at a short distance, completely hid it from view.

The soldiers marched in single file cautiously up the road that led to the front of the house and halted. All was quiet and dark around the place. Captain Sherwood advanced a few steps and listened—the low, melancholy howl of a dog broke the stillness. Then he approached the front door to knock, but finding it open, entered.

The lower rooms of the house were dark and deserted; the furniture was scattered about in great disorder. Again the captain heard the howl of a dog which seemed to come from over his head, and hastening up the stairs he entered one of the upper rooms, where a horrid spectacle met his sight. There, on the floor, lay an old man weltering in his blood—dead. His body was horribly mangled and the scalp torn from his head. A faithful Newfoundland dog was standing with his forepaws upon the dead man’s breast, mourning over him.

Captain Sherwood turned away sick at heart, and darted down the stairs back to his men.

“The villains have been here,” said he, “and sacked the house. The old man lies dead upon the floor; the rest of the family were probably taken prisoners. Let War-Cloud hunt out their trail, for we must shoot every man of this gang.”

[17]

The soldiers were furious at this new outrage, and manifested their willingness to follow the Tory League to the end of the earth, for vengeance. In a few moments War-Cloud—the scout—gave the signal that he had found the trail, and the company started off in pursuit. Every foot of the ground was familiar to the scout, and he had no difficulty in leading the way.

All night long they hurried on in pursuit, over hills and valleys, through woods, and across plains. The trees, clad in their autumnal garb, looked like iron warriors in the moonlight, and every now and then, as a slight wind whirled the leaves to the ground, the troops would stop and listen for their enemy.

The night wore on until the moon having completed her course, left the land in darkness—but darkness not long to last, for soon the orient heralded the approach of dawning day.

As the eastern horizon began to show these signs, the soldiers, being fatigued, halted upon the summit of a high hill. Their tramp had been a long one, but still there were no signs of the Tory League save their trail, which they seemed to have taken no pains to conceal. The League had undoubtedly got a good start and were improving their advantage.

Captain Sherwood and War-Cloud withdrew a short distance from the troops, to a cliff that jutted out from the general line of the mountain. Here they could command a view of an entire valley to the distance of many miles. It was quite level and presented a beautiful scene. The surface was covered with a carpet of bright green, enameled by flowers that gleamed like many-colored gems, and here and there the willow mingled its foliage in soft shady groves, forming inviting retreats. A stream, like a silver serpent, bisected the valley—not running in a straight course, but in luxuriant windings, as though it loved to tarry in the midst of the bright scene.

War-Cloud, after scanning the whole plain before him for some time, turned to the captain with delight.

“Look, chief!” said he, pointing to that part of the valley almost below them. “See! white and red devils right there.”

Yes, there was the Tory League sure enough, quietly seated[18] upon the ground, enjoying their morning meal in full sight of the captain.

It was a motley crowd, indeed. There were white men dressed in British uniforms and others merely in loose hunting-shirts and breeches, together with the dusky savages who were in full war-costume—that is, naked to the waist, and painted over the breast and face so as to render them as frightful as possible. Their heads were closely shaven over the temples and behind the ears—a patch upon the top was cropped short, but in the center of the crown, one long lock of hair remained uncut, which was intermingled with plumes and plaited so as to hang down the back.

“Surely,” said the captain, “this is but a small part of the Tory League, for there are hardly more than seventy-five men here, and the band is said to number two or three hundred.”

“We’ll make the snakes these many less!” said the scout.

“Yes, we’ll give the villains their deserts in a short space of time; but where are the prisoners?” exclaimed the captain, glancing searchingly over the band.

“There!” said War-Cloud, his practiced eye observing them at once, seated beneath the shade of a willow tree. “Three women.”

“To their rescue at once!” cried the captain, dashing away to his company. “Up, up, every man of you, and follow me!”

The path that led from the cliff to the valley was nearly half a mile in length before it reached the level below, winding through a growth of young trees which completely hid the soldiers from view.

Down, down the mountain’s side they hurried faster and faster, until at length they burst forth upon the open plain within a few hundred yards of the enemy.

“Now, my brave fellows!” shouted Captain Sherwood, wielding his sword above his head, “teach these British villains and red rascals decency!” and away the whole troop rushed wildly upon the foe.

This was a surprise to the Tories and Indians, and a general panic seized upon them. Unmindful of every thing but their own safety, they took to flight, leaving their prisoners.[19] But, after fleeing a short distance, and finding themselves hard pressed by their foe, they turned about like hunted game at bay to give battle.

But a moment elapsed, and full two hundred men were engaged in deadly conflict.

Crack—crack—crack, went the rifles, and a sulphury smoke spread a cloud upon the air. As the vapory mass cleared away, some were seen dashing at each other with their empty guns, some twanging their bows from a distance, and others grappling in hand-to-hand combat.

Neither bugle nor drum sent forth its inspiring notes; no cannon rolled its thunder; no rocket blazed; but every now and then the wild war-whoop rung out upon the air, making the blood of the listener run cold. And then came the fierce charging cheer of the troops, and the cries of triumph and vengeance.

While the fight was raging, War-Cloud, observing two Indians making for their prisoners, lashed under the willow tree, uttered the war-cry and started after them at full speed. The savages looked behind them, and seeing but one adversary, gave fight. War-Cloud whirled his tomahawk at the foremost one’s head, but the savage with a quick movement evaded the weapon and sprung forward with his knife. Then there was a desperate struggle of life and death. The bodies of the combatants seemed twined around each other; then one of them fell heavily to the ground. War-Cloud’s antagonist had fallen. But before the scout could whirl about, the other Indian—an active warrior—rushed upon him and bore him down. His knee was pressed on War-Cloud’s breast, and his arm raised on high to drive the deadly blade into his heart! but at this instant Captain Sherwood’s trusty rifle sounded on the air—the savage dropped dead, and the scout was saved.

At length, after an hour of hard fighting, the Tories were completely routed; and but few ever lived to tell the tale of their disaster. After the excitement was over, and while the soldiers were looking after their dead and wounded, the white captives, who had been silent observers of the fray, were released from their fetters. Their joy was great at being restored to liberty again, but their grief was greater for their[20] murdered father. The story of the captives was to this effect:

At an early hour in the evening, and while the old man and his three daughters were gathered round their fireside chatting, their Newfoundland dog sprung to his feet and rushed toward the door, growling fiercely.

His growl shortly increased to a bark—so earnest, that it was evident some one was outside. The door was shut and barred; but the old man, thinking perhaps it might be the soldiers whom he expected, pulled out the bar, and opened the door without inquiring.

He had scarcely shown himself, when the wild whoops of Indians rung on their ears, and a blow from a heavy club prostrated him upon the threshold. In spite of the terrible onset of the brave dog, the savages, white and red, rushed into the house yelling fearfully, and brandishing their weapons. In less than five minutes the house was plundered of every valuable article. The old man, partly recovering, had seized his gun and mounted the stairs, where he was met and butchered outright. When the marauders had finished plundering, they seized their prisoners and made off in haste.

Such was the tale of the three females.

The soldiers were soon collected into ranks, and were ready for marching orders. They had been triumphant, and were in good spirits. Nearly every man of their foe lay dead or dying upon the field, while they had lost but three men and only five wounded. However, in the midst of their exultations, a murmur ran through the crowd, and every man looked at his companion inquiringly. “What had become of their brave leader, Captain Sherwood?” each asked, in a whisper. He had disappeared from their midst.

An hour was spent in search for him; the valley and surrounding woods were scoured in vain, for he was not found. The troops were obliged to turn their steps homeward without him. It was nearly evening when they arrived at the fort, where they were hailed with loud shouts from their comrades when the news of victory was proclaimed. But, afterward, when it was found that the captain was missing, a shade of sadness seemed to fall on all. Immediately scouts were sent in all directions to search for him.

[21]

The ladies of the garrison for some time had been suffering ennui, and after holding a consultation, they resolved to petition for some change to break the monotonous life. Accordingly, when all their feminine forces were brought to bear upon the officers, they forthwith yielded, and it was determined that the following night—the night after the soldiers’ return—should be a gala occasion; a night devoted to Terpsichore.

The ladies set to work with an ardent zeal, decorating the hall where the ball was to be held. It was a long barracks used for the officers’ mess-room. The regimental flags were placed here and there about the room, and foliage, brought from the woods, ornamented the walls, so that in a short time the place had assumed quite a festive appearance.

During the afternoon of this day, and while everybody in the fort seemed to be talking about him, Captain Sherwood made his appearance. He was pale, and looked fatigued; his uniform showed marks of hard usage, being badly torn and bespattered with blood.

An eager crowd was soon collected around him to listen to his exploits. All were greatly surprised upon learning that he had not been taken prisoner as was supposed. His story was as follows:

During the battle he had come in hand-to-hand combat with an Indian who appeared to be the leader of the Tory party, as Iron Hand himself was not with them. He finally managed, after a hard contest, to wound the arm of his antagonist, whereupon the savage turned about and took to flight. The captain hotly pursued, and in a few moments, both were separated from the main body of the combatants in a secluded portion of the woods; however, the officer was fast gaining ground on the Indian, and in a few moments would have had him in his power, when suddenly he received[22] a shot from some unseen foe. Staggering forward he fell, and this was the last he remembered.

He had fainted, and when he recovered, he found himself prone in a hole in the earth about four or five feet deep, with a heap of hemlock boughs covering the top. The dirt had been just thrown out, and whoever had dug the hole had undoubtedly intended it for his grave. But they probably had been frightened away, and consequently left their work only half accomplished.

When the captain had thoroughly revived, and became aware of his situation, he managed to crawl out of the horrid place and drag himself to a stream near by, where he quaffed a draught which started his blood on the regular course again and restored vitality.

After bathing a wound in his leg—which was not serious, as the ball had merely cut the flesh—and bandaging it up with his handkerchief, he started for the garrison, where he had arrived, weak and exhausted from loss of blood and want of food.

Every attention was now paid to him, for Captain Sherwood had become a great favorite with all since his first entering the fort. The surgeon was summoned immediately to dress his wound, and the cooks of the garrison vied with each other in serving up their best dish for the gallant officer in the quickest possible time. The ladies offered their services also, but the captain declared that he would not have any thing more done for him. He was as well as any of them, he said, having partaken of a good dinner, and to prove this, he marched to the mess-room and spent the remainder of the afternoon in assisting the fair ones arranging the hall for the evening entertainment.

And now, dear reader, while our hero is there amusing himself, let us transport ourselves from the fort to a pretty, white cottage, which stands half-way down the side of a large hill three miles in the distance.

It was near sunset. A sunset more brilliant than common. The western sky was filled with masses of colored clouds, on which gold and purple and blue mingled together in gorgeous magnificence; and in which the eye of the beholder could not fail to note the outlines of strange forms, and fancy them[23] bright and glorious beings of another world. It was a picture to gladden the eye, to give joy to the heart that was sad, and make happier the happy.

All this beauty was not unobserved. Eyes were dwelling upon it—beautiful eyes—and yet there was a sadness in their look, that ill-accorded with the picture on which they were gazing. Though apparently regarding the sunset, the thoughts which gave them expression were drawn from a far different source. The heart within was dwelling upon another object.

The owner of those eyes was a beautiful girl, or rather a fully-developed woman. She was tall and majestic, of soft graces and waving outlines. The lady was Imogene Lear. She was walking backward and forward in a little garden at the back of the house, as if waiting for the arrival of some one.

Every now and then her eyes sought the grove of cedars at the foot of the inclosure, through whose slender trunks gleamed the silvery surface of a stream. Upon this spot they rested from time to time, with an expression of strange interest. No wonder that to those eyes that was an interesting spot—it was there where love’s first vows had been uttered and two young hearts plighted forever.

Often as she gazed at this place a look of sadness would steal over her face as if some thought were flying through her brain that was unpleasant, and it brought with it clouds upon her brow, and imparted an air of uneasiness. What was that thought?

Ah! a stern father caused it. No longer could she meet that lover, who had rendered this grove sacred, openly as in former times, but was obliged to resort to deceit and have their interviews in secret.

Sometimes she had been half tempted to forsake her home and go with Edgar Sherwood. But no, she could not do that; sober thought always brought her back to reason, and she would determine again to stay by him and tend him in his old age, for she was his only child and comfort, and then before this trouble he had ever been very kind to her and undoubtedly, ere long, he would relent and give his consent to her marriage with Edgar.

Such were the thoughts she consoled herself with.

Imogene Lear was naturally open and frank, and the deceit[24] which she now practiced on her father was something altogether new and foreign to her noble nature, and it troubled her exceedingly, but then her love for Edgar Sherwood was strong, and love prevailed over conscience.

While continuing her walk up and down the garden path she stopped short, as if having taken some sudden resolution.

“I will go—I ought to gratify him!” she muttered to herself. Sitting down upon a bench near by, and opening a folded slip of paper, she read:

“Dear Imogene—I have just returned from the war-path safe, and wish to see you very much. We are to have a ball at the garrison to-night. You must come—do not refuse, dearest one. If you do I shall be miserable all the evening. As soon as your father has retired for the night, hasten to our old place of meeting with your brave steed, where I shall be in waiting. Adieu, my dearest, for a few hours.

E.”

When she had finished reading the note, she pressed it to her lips and kissed it fervently.

“No, Edgar, I will not refuse: I will go!” she murmured, and thrusting the letter into her bosom, she glided softly into the house.

A few hours after sunset, and when it was dark, Imogene again stole forth into the garden. This time she was closely muffled in an ample cloak and her head was donned with a riding-hat.

After proceeding a short distance she stopped and listened. Perfect stillness reigned around the cottage. Then there came a low whistle from the lower end of the garden, and she tripped along over the sanded walk to the place, on reaching which she called:

“Jeff?”

“Here, lady,” answered a man, stepping a little more into the light. He was her trusty servant.

“All saddled?”

“Yes, Miss Imogene.”

“Is he here?”

“Out there on the road waiting.”

The man assisted his mistress to mount, and the next moment, giving her steed a tap with her whip, she dashed away to meet her lover.

[25]

As Edgar and Imogene met, their eyes sparkled with the thought of love, but neither gave utterance to their thoughts until their horses had borne them away from the cottage. Edgar was the first to speak.

“Were you intending to ride over to the garrison to-night, Imogene?” he said.

“No, not until I received your note.”

“My note?” and Edgar looked puzzled.

“Yes.”

“Why, Imogene, I sent you no note.”

“I have got it in my pocket.”

“Let me see it.”

She handed the note to him which she had received, and he ran his eye over the contents.

He looked astonished.

“By Heavens!” he exclaimed, “somebody is plotting against us; but, thank God, I was in time to frustrate their plan!”

“Then you really did not write it?” and Imogene appeared frightened.

“I never saw this note before—I did not even know you were going to the fort until I met your servant on the edge of the grove, who said you would be ready in a few moments, and then hastened away before I could speak to him.”

“Who could have done this? Oh, Edgar, I fear there is some dreadful mystery about this!”

“No, no, Imogene! there is nothing of the kind,” he said, observing her alarm; “do not let this frighten you. Undoubtedly some one of your servants did this with no good design, but he will not dare try the same trick again.”

Here a new thought seemed to enter Imogene’s brain and she asked, quickly:

“Your dream, Edgar? has any thing come from it?”

“No,” replied he, forcing a laugh; “how foolish I was to let a silly dream trouble me!”

“I am very glad; it annoyed me much.”

“Let it be forgotten, dearest, for it was nothing more than a common dream, although at the time I was quite certain it was a vision—a presentiment.”

They were now entering a straggling patch of woods, which stood at either side of the road but a short distance from[26] fort. Imogene was about to speak again, when her quick ears caught a sound that appeared odd to her. It was but a slight rustling among the autumnal leaves that were lying in heaps along the roadside, and might have been caused by the wind had there been any, but not a breath was stirring. Something else had caused it. What could it be?

Edgar and Imogene turned their heads simultaneously and looked behind. At the same moment each caught a glance of the face and form they had seen a few nights previous in the grove near the cottage—the face that Edgar had declared he had seen in his dream! There it stood in the middle of the road, wrapped in a white, shaggy cloak, which gave the mysterious form a frightful appearance, and the face, pale and motionless, gazing after them.

In a moment it had disappeared, and Edgar and Imogene each drew a long breath. Captain Edgar Sherwood was no coward—was a brave man, and had often stood face to face with death; but this was an apparition, something mysterious which he could not understand. His lips grew white, and the perspiration leaped into drops upon his forehead. He was about to turn his horse’s head and ride back to where the specter had stood, but Imogene was very much agitated, and urged him forward to the fort.

Around the entrance of the garrison a large crowd of soldiers were collected, to observe the guests as they arrived, and when Edgar and Imogene passed through the men gave them a loud and hearty cheer. This seemed to awaken the couple from the lethargy into which they had fallen after beholding the apparition.

Dismounting, they hurried to the ball-room, where they found a gay assembly. The hall was brilliantly lighted and handsomely decorated. The music, which consisted of the regimental band, was playing a waltz, while a throng of dancers whirled round the room.

There was a large number of persons present, composed of the officers and their ladies, and the patriots dwelling in the neighborhood. It was a merry company, and one that seemed to dispel all troubles from the minds of our hero and heroine.

Imogene had hardly entered the room before she became[27] the center of attraction. The captain led her to the upper end of the room, where they joined Colonel Hall, the commander of the garrison, and his lady.

Now it was that the wound in his leg annoyed the captain, for it kept him from engaging in the dance with Imogene. In order to keep the knowledge of this from her, he was obliged to find a partner for her among the lieutenants. A lucky accident for them, and the fortunate one appreciated it, too.

While the dance was going on, and when the company seemed in the hight of enjoyment, a man dressed in the garb of a hunter, entered the hall, and forced his way to the colonel. It was a noted American spy, Hank Putney by name, who had been dispatched the day previous to search for Captain Sherwood. He whispered a few words to the commander, and both retired from the room together, but so quietly that no one perceived them.

Upon leaving the hall, they directed their steps to the colonel’s head-quarters, where the following conversation took place between them:

“You say that you have news of importance, Putney?” said the colonel, handing the scout a seat.

“Indeed, very important, colonel,” answered Putney, taking a folded paper from his pocket and laying it upon the table. “If ye’ll just run yer eye over that, perhaps ye’ll understand what it is.”

Colonel Hall took up the paper, and with some difficulty managed to read the poorly-written and badly-spelled document. It was a description of the notorious Iron Hand.

“Well, really, this is good news, Putney. How did you succeed in obtaining a sight of him?”

“Oh, easy enough! The band forgot to cover their trail this time, and I tracked ’em. But look ye again at th’ paper. Do ye not know him? You’ve seen him a hundred times.”

The colonel read the description over again carefully, then paused for a moment in thought.

“There is a man in the garrison,” said he, “who answers to this description, but then of course we should be mad to think it meant Captain Edgar Sherwood!”

“I thought ye’d know him!” said Putney, and his eye twinkled with satisfaction. “No madness about it, colonel.[28] He’s the man—this villain Iron Hand and our cap’n are one!”

“Why, man, it is impossible!” cried the colonel, starting to his feet, with astonishment. “What! Sherwood a British spy! No, no, no!”

“Sartin, sir, sartin! Bill Hawkins and I saw him in their camp yesterday, and he war their leader. I took down his description, and we’ll sw’ar to it.”

Colonel Hall paced up and down the floor in great agitation. Every little circumstance which had taken place during the past few days again appeared to him, but in a changed form. After a few moments’ thought, he was obliged to admit that some things had transpired which looked suspicious. Sherwood’s story about being nearly buried, might be only a fabulous invention gotten up to cloak his real actions, and the wound, perchance, he may have received in the fray.

It also occurred to him now, that Sherwood, during the past month, had been frequently absent from the fort, sometimes for a day and night together. Then, again, the father of his betrothed, Thomas Lear, was known to be a stanch Tory, and although it was reported that Sherwood and he had quarreled when the former entered the American army, yet this might have been done for the purpose of carrying out their deception.

“I suspect that’s why the cap’n was late with th’ soldiers th’ night th’ Tories attacked the Whig’s house, ’cause he war waitin’ for ’em to finish th’ job,” said Putney, adding additional fuel to the fire.

“Great heavens!” exclaimed the colonel, stopping short in his walk. “Have we all been blinded by this villain? Can it really be that Sherwood is a traitor?”

“He’s Iron Hand, I’m sure o’ that!” again added Putney.

“Well, man,” Colonel Hall turned about so as to face the scout, “I shall have him arrested at once, but if it turns out that the charge is false, you shall be punished in his stead. Now I ask you once more, are you sure he is the man?”

Putney turned very pale, but answered:

“I am.”

The colonel then dispatched him for an officer. In a short[29] time, guards began to appear at the different places of ingress and exit to the ball-room. The assembly noticed this and the dance stopped suddenly. A sergeant entered the room, and informed Captain Sherwood that the colonel requested his presence. The company stood still with astonishment. What had happened—were the British approaching?

In a moment the news spread like wild-fire in the assembly, that Captain Edgar Sherwood was arrested, and imprisoned on a charge of being the Tory chieftain, Iron Hand, and a British spy! At this announcement, a loud shriek burst forth from the upper end of the room, and Imogene Lear sunk fainting to the floor.

The night had turned out dark and drear, and the lowering clouds denoted the approach of a storm. The last echo of the booming gun had scarcely died away, warning the inmates of the fort that it was time for all unnecessary lights to be extinguished, and for all nightly revels to cease.

The shrill cry of the sentinel’s “All’s well” had passed from mouth to mouth, denoting the security of the hour, and the non-apprehension of an attack. The lights in the different quarters were gradually extinguished, showing a reluctance of the occupants to abandon their evening amusements.

As the last glimmer died away, the battlements of the fort were wrapped in an almost impenetrable gloom. Nothing broke the deathlike stillness, save the measured tread of the guard as he walked his lonely post, or the hooting of the owl, as it rung upon the silence of the night from the depth of the neighboring forest.

Suddenly one of the postern gates opposite the residence of the commandant was thrown open, from which issued a flood of light, making the surrounding darkness more intense, and revealing a small group of officers and ladies, on the countenances of whom were depicted gloom and sadness,[30] caused by the extraordinary and unlooked-for proceedings of the earlier part of the evening. They had just emerged from their dwelling to witness the departure of Miss Lear, after having made ineffectual efforts to induce her to postpone her journey till morning.

Imogene, wrapped in a heavy military cloak, and leaning upon the arm of the garrison commander, followed by the rest of the company, moved toward her steed, which, in charge of one of the soldiers, stood outside of the gate, champing his bit and pawing the ground impatiently.

Refusing all proffered assistance, she leaped gayly into the saddle, and tried, by assuming a more genial appearance which ill-bespoke the agony that wrung her heart, to banish the thoughts that clouded the brows and dampened the feelings of all present.

Her horse, a noble animal of coal-black color, long, flowing tail and mane, with limbs of most delicate proportions, and whose general symmetry of form defied the criticism of the most observant, and denoted a capability of excessive endurance, feeling again his accustomed burden, seemed to partake of the happier moments of his mistress, and commenced to curvet and gambol about to the extreme annoyance of his attendant.

After portraying to Imogene the numerous dangers that might befall her on the road, Colonel Hall made an urgent but fruitless appeal to her to remain at the fort during the night, or else to accept of an escort to her father’s house. With an ill-affected smile, Imogene tried to allay the apprehensions of her friends by making light of them, then waving a parting farewell to the assembled company, in a few moments afterward she was buried in the gloom.

The assemblage waited until the rattling of her horse’s hoofs had died away in the distance, then slowly returned to the apartment which they had left a few minutes previous. Each member of the assembly seemed deeply engaged with his own respective thoughts, the uppermost of which was, no doubt, the surprising scenes that had transpired during the evening.

The silence was finally broken by Colonel Hall, who had been for several moments seemingly absorbed in a deep,[31] meditative mood, turning abruptly toward a young officer, who, in a fit of abstraction, was standing with one arm leaning on the mantel, whom he addressed as follows:

“Lieutenant Mansfield, I have resolved to dispatch a body of horse to follow the direction taken by Miss Lear, in case she should be molested, as I have apprehensions of the safety of the route which she must traverse, for you are aware that it is only a few days ago that those three Tory spies, now immured in the bastion, were captured in the vicinity of her father’s residence. Should it be agreeable, I will give the command of the troops to you; but remember, the matter is optional.”

“Colonel, I am at your service, and nothing would be more pleasing to me than to be the protector of virtue, and if possible, in the performance of my duty, to rid the country of some of those bloodthirsty desperadoes that are such a scourge to society.”

“Those are soldierly sentiments, lieutenant,” answered Colonel Hall.

“The sentiments of the entire garrison,” responded the lieutenant.

“I am pleased to learn that such chivalrous feelings pervade the breasts of the men under my command,” said the colonel; “however, lieutenant, as the time passes rapidly by, and several minutes have already elapsed since the departure of Miss Lear, it would be well to make preparations as speedily as possible.”

The lieutenant making a low bow, retired to perform the wishes of his commander. In a moment afterward, the troopers, armed to the teeth, and mounted on their caparisoned chargers, looking like so many grim specters, dashed through the open gate and were soon lost to view. The gate creaked on its rusty hinges as it swung back into its customary place, and silence again reigned supreme.

[32]

Imogene, after her departure from the fort, sped rapidly onward, heedless of the extended branches and immense brambles that threatened every moment to drag her from her saddle. Collecting her confused thoughts, which were exceedingly harassed by her multiplied troubles, she checked the impetuosity of her steed, and compelling him to assume a more moderate gait, fell into a revery.

“Can it be possible,” she murmured, “that Colonel Hall could have had any intimation of impending danger? he seemed to persist so strongly that I should remain in the fort till daylight!” Immediately recovering herself, she exclaimed:

“A truce to such thoughts! It is only the wandering of my disordered imagination, that turns every harmless tree into a robber, and every neighboring bush into the lurking-place of some concealed assassin. However, I must confess that when I first entered the forest, an indescribable feeling of dread seemed to chill my very blood; but I must scout such ideas, which if I do not, they will entirely unnerve me, and render me unfit to enter the presence of my father, who must not receive from me even the slightest suspicion of Edgar’s misfortune.”

In vain did she endeavor to shake off the gloomy feeling that possessed her. The moon, which had been concealed during the earlier part of the evening behind the immense banks of clouds that had obscured the heavens, now became occasionally visible, and its fitful beams served only to render the intense darkness of the woods more apparent, and lend a more spectral appearance to surrounding objects.

Imogene, having relapsed into her former mood, rode slowly along the well-beaten path, unmindful of the cold, keen wind that swept through the surging forest, causing the stanch old oaks to gently bend their hoary tops to the blast.

[33]

The deep baying of her father’s hounds awakened her, at length, from her musings. Congratulating herself upon having reached the terminus of her journey in safety, she tried to smile at the absurd fears of her friends, when her steed, with a snort of terror, made a sudden pause, throwing himself back on his haunches, almost unseating his mistress.

Imogene peered into the darkness beyond, but in consequence of the intensity of the gloom, was unable to ascertain the cause of her horse’s fear, and vainly endeavored to urge her trembling animal forward, at first, by gentle applications of the whip, and finally by kind words and caresses, but with like success. It was with the utmost difficulty that she succeeded in calming his excitement, and preventing him from dashing headlong into the surrounding woods.

At that moment, the moon, which had been hidden for a short time by a passing cloud, again burst forth, lighting up the surrounding darkness, and by the aid of the few faint beams that struggled through the dense foliage overhead, Imogene perceived a man at a few yards distant, standing on the side of the road, partly concealed behind a tree.

Seeing that he was discovered, he stepped into the middle of the path, as if he desired to speak. He appeared to be advanced in years, with long, flowing, silvery locks, and with little or no beard. His frame was still strong and sinewy, though somewhat bent, apparently both by age and toil. His countenance, however, bore but few traces of either age or suffering, and had quite a prepossessing look, were it not for the expression of his eyes, which were cold and repelling, but with a glance sharp and piercing that seemed to read the inmost secrets of any object on which it was cast.

These organs were nearly concealed by a pair of black, shaggy brows, that ill-accorded with the excessive whiteness of their owner’s hair. The stranger, noticing the anxious and half-affrighted look of Imogene, broke the silence by saying:

“Young lady, be not afraid; I am but a poor, harmless old man who has been traveling nearly the entire day over hill and dale, and am only seeking some fit habitation where I may rest my weary limbs.”

[34]

Imogene gazed upon the singular being before her, for some moments in silence, unable to utter a word, so sudden was the shock of his unexpected appearance. Recovering herself at length, she replied:

“For what reason, my good sir, are you, at such an hour in a place so isolated. Do you not fear any danger?”

“I entered these woods to seek shelter from the impending storm which threatened to take place during the earlier part of the evening,” he answered. “As for danger, why should I fear? Who would think of injuring a harmless old man like me? No, no, these freebooters of the road look for higher game than I, in my poverty, could offer!”

These last words were uttered in such a sarcastic tone that Imogene, who had been adjusting her horse’s bridle, looked up with astonishment and bent her penetrating gaze upon the speaker, but seeing his harmless and abject appearance, her features relaxed and softened into a look of pity.

Desiring to terminate the conversation, she said:

“My friend, these woods are not a suitable spot for either of us, and as you remarked that you were seeking for a place of shelter and safety, I will direct you where your wishes will be gratified. Follow this path, without deviating either to the right or left, and you will reach the habitation of my father, where you will find a place to rest yourself. Lead on, I will follow.”

Up to this moment, the stranger had not moved from the position he had first assumed; but seeing the intention of Imogene to proceed, he drew back a step and raised his hand, motioning her to stop. She did as he requested.

“Before I accept your kind invitation,” continued the old man, “I would wish to know, good lady, to whose generosity I am indebted; whether it be friend or foe.”

“That matters not,” replied Imogene; “it is sufficient that you are homeless and in want. I consider not whether the recipient of my charity be friend or enemy, neither do I care. You seek assistance, and that assistance I offer you—what more is necessary? I am not your enemy, nor do I bear hostile feeling to anybody. Let this answer suffice.”

The energy with which Imogene uttered these words caused the rich blood to suffuse her countenance, which lent[35] an additional charm to her excessive beauty. The stranger sent an admiring look upon the beautiful young girl, but it passed like a flash as he resumed the conversation.

“Young lady, pray forgive my hesitancy; but, as you are aware, in these troublesome times a man is at a loss to know whom to trust, and I am afraid that should I fall into the hands of some, I might receive a reception disagreeable to my nature,” at this he turned an inquisitive look upon his companion, as if he sought to elicit a reply to his somewhat equivocal answer.

“You doubt, then, the honesty of my hospitable offers,” returned Imogene, with some animation.

“No, no, young lady; you misconstrue my meaning. I doubt not your upright intentions; but, as I said before, you know a person can not be too scrupulous in these matters.”

“In order not to deprive you of the comforts which you seem to need, I will endeavor to dispel your ungrounded fears by giving you the requisite information. The house to which I have directed you is the residence of Thomas Lear, and—”

At the last-mentioned name, the stranger started back with a look of surprise.

“Then you are Imogene, the daughter of old Lear, the Tory?” he exclaimed.

These words were uttered in a much different key. A strong, manly voice had taken the place of the weak, wheezing tone of the old man. The hot blood mantled the brow of Imogene, as she quickly retorted to this seemingly insulting language:

“Though Thomas Lear should be a supporter of the king’s cause, his daughter, at least, should be free from insult. He is my father, and I wish not to hear his name spoken of in so wanton and disrespectful a manner. I have directed you to a harbor of safety, where you may find a place of rest, and provide for your wants. If you wish to avail yourself of my offer you may do so, but you must use your own discretion in the matter. I have already tarried too long—I must depart.”

“A word with you, Miss Lear, for such you have acknowledged yourself to be, before you go,” replied the stranger; and drawing nearer to Imogene, he whispered, in a subdued[36] undertone, a few words which seemed to make her recoil with an expression of horror.

“Away, vile wretch! Is it thus you would repay my kindness? Begone!” She cast upon him such a look of disgust and contempt that he seemed to writhe under her stinging rebuff.

“You reject, then, my offer?” he replied.

“I refuse to parley with such a despicable creature. Make way; I must leave this spot.”

“Not quite so fast, young lady. I wish to allow you a moment to reconsider your decision,” returned the old man without moving from his position in the center of the path.

“You have heard my answer.”

“You persist in your refusal?

“I do.”

The stranger gave a low, short whistle, and immediately disappeared in the brushwood. Before Imogene could recover from her surprise at this sudden disappearance, her horse’s bridle was seized by an armed ruffian, while two others confronted her with drawn weapons. Imogene was immediately alive to the danger that threatened her.

“What means this outrage—this detention?” she exclaimed in an excited manner.

“It means,” returned one of the party, who appeared to be the leader, in a gruff voice, “that you’re our prisoner.”

At this juncture one of the men raised his hand as a signal for all to remain silent. In an instant every one assumed a listening attitude, intent on catching the slightest sound. At first nothing could be heard, save the sighing of the wind through the trees, but the practiced ears of the desperadoes quickly distinguished the clatter of approaching hoofs.

“What’s that?” exclaimed the man who had given the signal of alarm, casting an inquiring look at his leader.

“It’s a party o’ those cursed rebels from the fort, and we must go into the woods until they pass, or they’ll be on our backs in no time.”

As he said this, he turned toward Imogene, and, drawing a pistol from his belt, ordered her to dismount.

“Dismount, I tell ye,” cried the ruffian, in a voice husky with rage, seeing that Imogene utterly disregarded his command,[37] “or by th’ light o’ Heaven, I’ll put this piece o’ lead through yer brain; for I’ve promised to deliver yer body, dead or alive, and I’ll do so, should it cost me my life.”

Imogene looked at the villain, and saw by the fierce expression of his countenance and the malignant fire that sparkled in his eye, that he was capable of any enormity possible to humanity, and would not hesitate an instant to put his threat into execution.

There was no one to succor her; she beheld only the other villains, his accomplices in crime. Oh, how she wished that her noble Edgar was by her side, were it but for a moment.

“Make haste,” exclaimed the ruffian, impatiently.

“I refuse,” replied Imogene, with vehemence.

In an instant, before she could divine their intention, a large mantle was suddenly cast over her head to prevent her from making any outcry, and she was forcibly dragged from her saddle and borne into the woods. In a moment afterward the man who had held the rein of Imogene’s steed, uttering a cry of pain, dashed after them.

“What’s all this noise about?” sharply asked the ruffian leader, casting a savage look upon his comrade.

“The horse! the horse!” was all he could ejaculate, and holding up his hand which was sadly cut and mangled, “see there,” he cried, with an oath, “that infernal brute almost wrenched my arm out of its socket with his teeth,” and holding tightly on the wounded member, he groaned aloud with the excruciating pain.

“Ye’d better stop that howlin’ o’ yours, afore ye bring th’ whole rebel pack down upon us,” was the consoling remark. The wounded man, with a look of pain and hatred, obeyed.

The heavy tramp of horses denoted the rapid advance of the troopers, and the bushes had hardly closed on the form of the last of the retreating rascals, when they rode swiftly by the hiding-place of their foe, looking like so many ghostly images, as the moonbeams faintly reflected on their clanking sabers, and the garnished trappings of their steeds.

When the last sound of the retreating horsemen had died away in the distance, the leader of the party noiselessly emerged from his place of concealment, and took a short, quick survey of the surroundings.

[38]

Upon observing their freedom from all immediate danger, he ordered his companions to mount with all possible expedition. Carefully placing the swooning and almost inanimate form of Imogene on the back of his own horse, he exclaimed:

“Now, then, put yer horses to the test, for we must place many miles betwixt us and this spot afore daylight; for that bloody red-skin, War-Cloud, is at th’ fort, and if he gets on our trail, only a miracle ’ll save us from goin’ under. Should th’ rebel dogs overtake us, they’ll show us no quarters.”

In obedience to the command of their captain, one of the party rode some distance in advance, in order to keep a sharp look-out for any signs of danger; the leader with his helpless burden occupied the center; while the wounded man, who was engaged in binding up his lacerated hand, guarded the rear.

In this manner they proceeded for several miles in silence, not a sound breaking the deep and deathlike stillness of the forest, except the dull echoes of the horses’ tread.

They had almost reached the verge of the woods through which they were traveling, and were about to enter upon the highway, in order to pursue their way more rapidly, trusting to the darkness as a safeguard against their being observed, and the proximity of the woods into which they could plunge in case of the approach of any suspicious party, when the man in front gave a low whistle as a signal to halt.

Riding back to his companions, he pointed out to them through the trees, a faint, glimmering light that appeared to issue from a large house near the roadside, but so nearly hidden in an angle of the woods, that they almost came upon it unawares. This was no other than the residence of the old Whig who had been so cruelly murdered during the visit of Iron Hand’s band the evening previous.

After debating among themselves for several moments the one who had first given the alarm agreed to go and reconnoiter the place. Dismounting, he hastened across the road, and disappeared in the shadows of the trees that nearly surrounded the habitation.

His friends, in their place of concealment, anxious to hear the result. After an elapse of about half an hour he returned,[39] and informed his comrades that the house was apparently empty, and that the inmates had either fled or been taken captives, as he had minutely examined several of the apartments, and there was not a single sound to denote the presence of any living being about the premises.

At this piece of intelligence, the three ruffians concluded that instead of proceeding further on their journey, as both themselves and their horses were greatly fatigued by their rapid traveling, to take up their abode for the remainder of the night in their newly-discovered place of shelter.

The trio advanced cautiously until they reached the house, where they dismounted and securely fastened their animals. The horses, together with the still insensible person of Imogene, were left in charge of the wounded member of the party, while the other two entered the building.

All was silence within. At the end of a large hall into which they had ushered themselves, was a wide stair-case leading to the room where the light was first discovered. Looking into several smaller apartments without seeing any suspicious sign, the two worthies concluded that the place was still unoccupied, and immediately prepared to proceed to the room above, in order to ascertain the cause of the light which they had seen.

As they ascended, the stairs creaked and groaned, sending forth at every step a hollow, dismal sound, whose echoes broke the monotonous stillness, and lent additional horror to the deep gloom that pervaded the entire place.

Entering the chamber, a scene of terrible confusion was spread before their eyes. Broken and disarranged furniture was scattered in every direction, while on the end of the mantel near one of the windows, stood a light with the flame just flickering in the socket. This it was that first attracted the attention of the abducting party.

It was obvious by the great disorder everywhere visible, that the inmates had decamped in haste, as not a single piece of furniture had been removed, and that the house had been recently abandoned, either in consequence of a real or expected attack.

It was also apparent that the place had not been deserted more than an hour or two. Evidently the last resident[40] entertained little apprehension of an unwelcome visit, as the light in the apartment was so placed that its rays could be easily distinguished by the least observant passing that way.

Could it be that the inmates had heard their approach and had secreted themselves until they had fairly entrapped their victims? As this thought suggested itself to the minds of the two ruffians, a cold perspiration bathed their brows, and they were on the point of beating a hasty retreat; but being reassured by the prevailing quietude, they endeavored, with an air of assumed bravado, to rally their drooping courage.

In a noiseless, but faltering manner, they commenced an examination of the apartment. One of them gave a sudden bound, accidentally knocking over a chair in his fright, as he trod on some small, hard object lying on the floor.

“Curse on ye!” exclaimed his companion, in a tone of mingled alarm and anger, “ye’ll bring th’ whole neighborhood about our ears.”

Assuring themselves, however, that the noise had not aroused anybody, they continued their search. As the ruffian who had been startled so suddenly, stooped down to ascertain the cause of his alarm, the dim rays of the candle reflected on a richly-mounted dagger.

He picked it up, and was about to place it in his girdle, when his comrade, the leader of the party, who was watching his movements, caught sight of the glittering blade.

“What’s that?” he asked, as he rudely grasped the arm of the other.

“Only a knife.”

“By heavens, I’ve seen that knife afore!” he soliloquized, as they both minutely examined the instrument by the aid of the candle’s faint and flickering flame.

The handle of the weapon was tastefully ornamented with mother-of-pearl and several beautiful and sparkling brilliants, denoting that the owner was of no ordinary rank. They held it closer to the light in order to inspect what appeared to be spots of rust on the keen but peculiar-shaped blade.

“Blood! as I’m a livin’ man.”

“And fresh blood at that,” replied the other, as he scrutinized it more closely.

[41]

“See!” was the excited exclamation.

“What?”

“Those letters,” answered the leader, as he pointed to the initials “I. H.” handsomely engraved on the hilt of the weapon.

“Wal, what of ’em?”

“Don’t yer know?”

After slowly repeating the letters over several times in his endeavors to unravel the enigma, the other quickly exclaimed:

“I have it—the knife’s our chief’s.”

“Sartinly.”

“Wonder how it came here?”

“Th’ chief hisself or some of th’ league have been around and at work.”

They then proceeded without delay to look about them for some traces of a melée . The walls were besmeared in several places with clots of blood, giving unmistakable signs of an encounter, while in the center of the floor was a small pool of human gore not yet dry, denoting that the victim, whether dead or wounded, had been but recently removed.

The expiring flame of the candle threw a sickly glare over the apartment, wrapping every thing in a ghostly gloom. The ruffians, though steeled to scenes of blood and murder, could not drive away the indescribable feeling of awe that crept over them as they stood there alone.

The bloody weapon of their chieftain, the not-to-be-mistaken marks of a recent combat, the light, the deserted house with its entire contents intact—all these, to the minds of the ruffians, were an unbroken chain of circumstances which to them was an inexplicable mystery.

Murder and rapine in their direst forms they could look upon unflinchingly, but to be there alone, with nothing but the dumb and sanguinary witnesses of the slaughtered victim around them, was more than their treacherous souls could withstand.

Filled with superstitious fears, they hastened precipitately down the stairs, casting occasional furtive glances behind them, and ceased not their hasty retreat until they had reached their horses, which quickly mounting, they drove their rowels[42] into their flanks and in a moment were dashing down the road in hurried flight.

Not a word was uttered until they were satisfied that they had placed themselves beyond the reach of all danger, real or imaginary, when they checked their steeds, and related to their wondering and almost bewildered comrade what they had seen.

After a short and silent ride, the party finally reached a small, but pretty and tasteful, dwelling, surrounded by neat and beautiful grounds. It presented no appearance of wanton injury and desolation, and was quite a pleasing contrast to the numerous forsaken and half-burned houses that everywhere abounded in that part of the country.

This pleasant retreat was evidently abandoned by its former occupants, as the three ruffians approached it unhesitatingly, without using their customary precautions. The place was, no doubt, one of the many resorts belonging to the band of which these men were members, and had been spared from the general waste to be reserved for this purpose.

Having made secure the apartment in which Imogene was placed, so as to prevent escape, the trio, before a large, crackling wood fire which they had enkindled on the hearth, prepared to make themselves as comfortable as circumstances would permit.

After discussing the creature comforts with appetites rendered extremely sharp by their weary ride, two of the party, while the other mounted guard for the night, rolled themselves in their blankets and were soon buried in slumber.

[43]

After leaving the fort, the dragoons followed the well-worn but solitary path leading to the residence of Mr. Lear, which they were certain Imogene had taken.

Onward they swiftly rode, hoping at every moment to overtake their intended charge. Though they frequently listened to catch the slightest sound, however, nothing was audible save the monotonous rattling of their sabers.

The deep baying of hounds, the same that had awakened Imogene from her reverie, told them they were near their journey’s end. In a few moments afterward the dragoons drew up their panting steeds before the residence of Thomas Lear.

All was still. The lieutenant dismounted and rapped loudly on the door with the hilt of his saber. Finding that the summons was unanswered, he repeated his rap with redoubled vehemence. The echo had hardly died away when the door was partly opened, and a negro domestic peering cautiously out inquired the reason of their visit at such an unseemly hour.

Hearing, in reply to her question, the deep, heavy tones of a man’s voice, and seeing the person himself garbed in the habiliments of a continental soldier, she was about to quickly close the door in her fright; but the assurance that she was to be in no wise molested filled her with more confidence, and after some hesitancy she admitted the strange visitors.

Upon making inquiries, the lieutenant was astounded to find that Imogene had not yet returned, and was on the point of dispatching some of his men to scour the woods in the vicinity, when her steed, riderless and with saddle and girth nearly torn from his back, came dashing up the lawn.

Mr. Lear, on hearing the loud tones of the conversation carried on below, hurried down-stairs. Seeing a party of soldiers congregated before his house, his mind was filled with forebodings of some impending calamity.

[44]

“What is the meaning of this unseasonable visit?” he eagerly inquired, turning to the lieutenant of the dragoons.

“We have come in obedience to the command of Colonel Hall, to ascertain whether Miss Lear has yet arrived from the fort, which she persisted in leaving this evening unattended.”

“Imogene at the fort! What mean you—how came she there?”

“She was at the ball, sir.”

“At the ball! You mystify me—explain yourself;” but just at that moment, catching sight of the riderless steed, he started back with an agonizing groan. “I understand,” he murmured, “something has happened to Imogene.”

“Indeed, sir, I fear there has been foul play.”

“No, no, there must be some dreadful mistake here!” exclaimed the old man, nervously grasping the arm of the officer. “Who could be so base as to harm my child?”

“In truth, the affair is enveloped in profound mystery. We have examined the horse and find no traces of blood, and I greatly fear that your daughter has been—”

“What?” cried Mr. Lear, seeing the soldier hesitate.

“Abducted.”

“Oh! my God! what new villainy is this!” and the sorrow-stricken parent staggered at the fearful intelligence. Clutching the lieutenant with feverish suddenness, he frantically exclaimed:

“Oh! save my daughter, my darling girl! Reclaim her from the hands of those merciless fiends, and my property, my life, my all is yours! Oh! my child! my child! my child!” and with a heartrending cry, the poor afflicted father reeled, then sunk to the floor.

Leaving the grief-stricken old man in the care of his weeping servants, with the assurance that nothing would be left undone to recover Miss Lear from the hands of her abductors, the lieutenant vaulted into his saddle, and in company with his men hurried back to the fort to impart to the commandant the unwelcome news.

“Lieutenant,” said Colonel Hall, after the officer had related to him what had taken place, “you will hold yourself and command in readiness to start at break of day, in pursuit of these villains.”

[45]

The dragoon was about departing, when the colonel stopped him.

“The Indian, War-Cloud, is still in the garrison, is he not?” he asked.

“He is, sir.”

“Send him to me, then, without delay.”

The officer bowed and retired. The Indian quickly obeyed the summons.

War-Cloud was a chief of the Oneidas. Although a great part of his tribe went over to the British with the Five Nations, of which it was a member, he always remained a stanch friend of the Americans, and an inveterate foe of the Mohawks.

He was one of the most trustworthy scouts attached to the Continental army, and in that capacity had performed invaluable service in the cause of liberty.

To Captain Sherwood he was especially attached, and would have been ready at any moment to sacrifice his life in his behalf. A large, crackling wood-fire shed its rays about the room which he entered.

As the Indian stood there, calmly awaiting the pleasure of his commander, with his arms quietly folded on his breast, with the beautiful war-plumes that decorated his head drooping over his countenance so as to give a more somber shade to his finely-molded features, he looked like some brazen colossus and the beau-ideal of a true warrior.

Colonel Hall was pacing up and down the apartment, deeply absorbed in meditation. He stopped a moment and looked up.

“Ah!” he exclaimed, as he beheld his visitor, “you have come!”

Placing a chair near the table for the scout, he seated himself opposite.

“I suppose you are aware of the reason that has caused me to send for you?” continued the colonel.

The Indian bowed in response.

“You have already heard of the abduction of Miss Lear?”

“War-Cloud knows all,” answered the scout.

“Then you will hold yourself ready to accompany the troopers on the trail of the abductors in the morning.” After[46] giving the Indian his instructions, the commander dismissed him.

The remainder of the night was spent by a greater part of the inmates of the fort, in a state of feverish excitement. It was deemed prudent to withhold the knowledge of Imogene’s abduction from Captain Sherwood, until more particulars of her fate were obtained.

The next morning, just as the bright sun commenced to tint the neighboring hill-tops and light up the eastern horizon, witnessed the departure of the dragoons from the fort.

They immediately took the path of the previous evening, which they slowly followed, scrutinizing every foot of the ground minutely, until they reached the spot where Imogene had been stopped by her abductors. This they knew by the trampled state of the earth.

Dismounting, War-Cloud made a careful examination of the numerous footprints, while the remainder of the company patiently awaited the result of his investigation.

Quickly beckoning the commander to his side, the scout pointed to several deep prints in the soft soil.

“Well, what’s peculiar about them?” asked the officer, inspecting them closely.

“White man’s tracks.”

“White men’s! How know you that?”

“See!” exclaimed the scout, as he directed the officer’s attention to several nearly erased marks, “Indian no wear boots—Indian wear moccasin.”

Sure enough, there, in the loose earth, were imprinted the faint outlines of boot-traces. Penetrating the trampled bushes on either side of the path, War-Cloud at length came upon the spot where the inanimate form of Imogene had been placed during the passage of the dragoons.

These signs not only satisfied the party that they had struck upon the right trail, but also gave convincing proof that the abductors were white men, not Indians, as at first supposed.

Without stopping to waste any more time in words, the dragoons started on the trail, with War-Cloud a short distance in advance. The traces of the fugitives were so broad and plain, and so little care had been taken to conceal them, that they could be followed with but little difficulty.

[47]

However, as the troopers entered deeper into the heart of the forest, their progress became slower and more difficult, and the trail less distinct.

At length, however, they reached the deserted house where the abducting party had stopped the previous evening. They surrounded the building, but this precaution was unnecessary, as a hasty examination showed that their intended victims had departed several hours before.

The old trail was again resumed, which led them to the dwelling in which we left Imogene and her abductors in the previous chapter.

It was now dark, and the obscurity and quietude in which the house was buried seemed to foreshadow another disappointment. The lieutenant knocked loudly at the door; no answer. He knocked again; still no answer. He was about to effect an entrance by force, when the shadow of a man was observed to flit across the lawn.

The dragoons started in hurried pursuit. Through the dim twilight the fugitive was hardly distinguishable. He had almost reached the woods—in another moment he would be safe, when the sharp, whip-like report of War-Cloud’s rifle was heard, and the fleeing man fell to the dust.

The next instant he was surrounded by his pursuers, who made a litter for him with their rifles, and carried him to the house. The injured man was bleeding copiously, and appeared to be seriously, if not mortally wounded.

“Who are you, and what were you doing here?” inquired the lieutenant, after seeing that the sufferer’s position had been made as comfortable as possible.

“What’s thet to ye?” was the surly reply.