BY

AUTHOR OF “THE SECRET PLAY,” “THE LUCKY SEVENTH,” ETC.

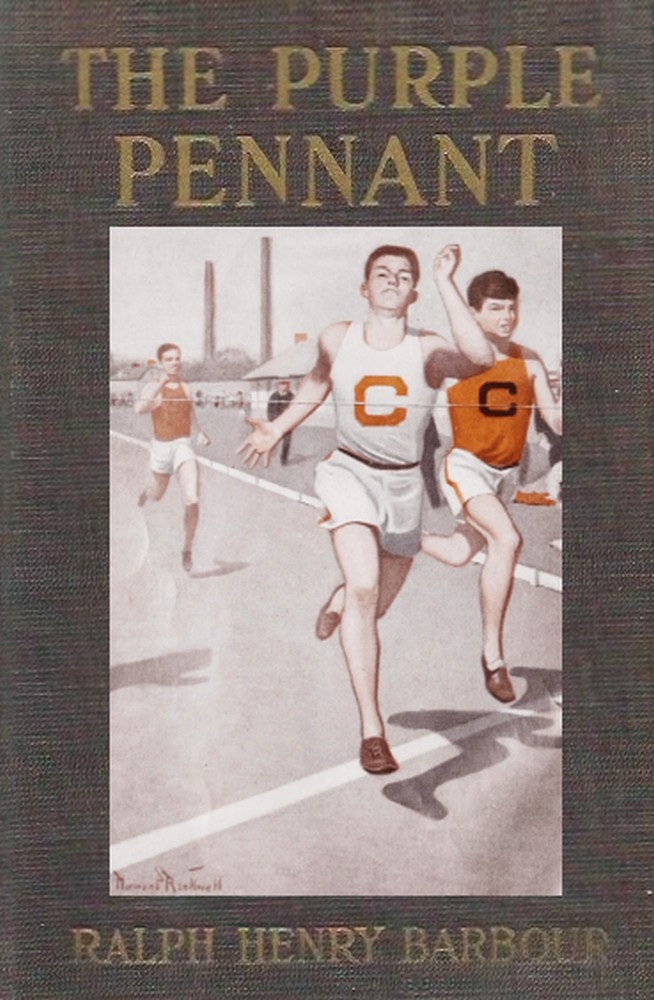

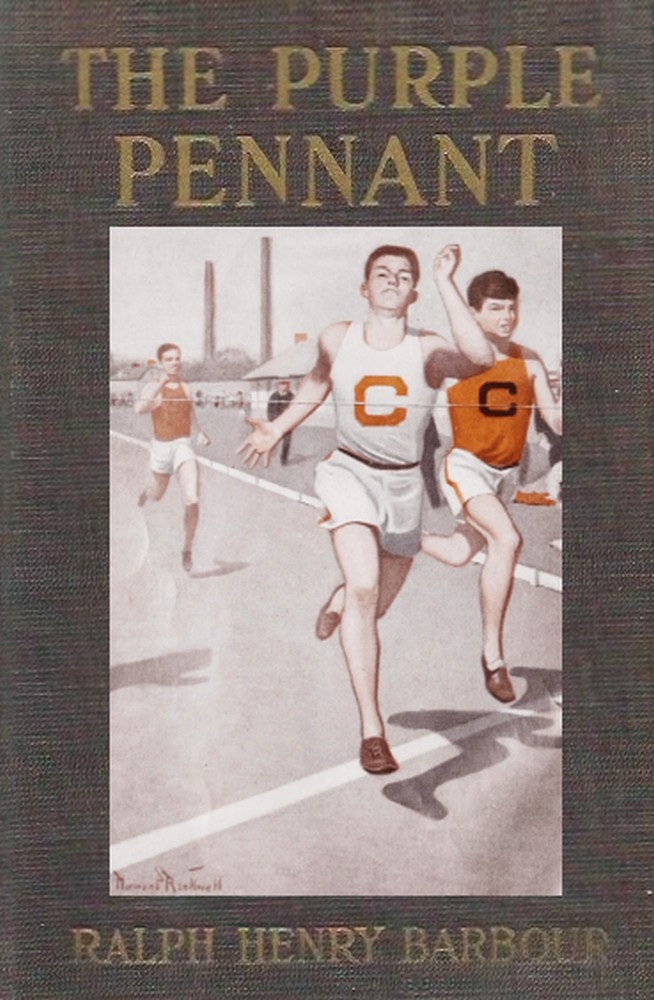

ILLUSTRATED BY

NORMAN P. ROCKWELL

Copyright, 1916, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Fudge Is Interrupted | 1 |

| II. | The Try-out | 11 |

| III. | The Shadow on the Curtain | 23 |

| IV. | The Ode to Spring | 38 |

| V. | Perry Remembers | 50 |

| VI. | The False Mustache | 61 |

| VII. | Fudge Revolts | 74 |

| VIII. | Lanny Studies Steam Engineering | 89 |

| IX. | The New Sign | 99 |

| X. | The Borrowed Roller | 110 |

| XI. | Gordon Deserts His Post | 120 |

| XII. | On Dick’s Porch | 130 |

| XIII. | Foiled! | 142 |

| XIV. | The Game with Norrisville | 152 |

| XV. | The White Scar | 166 |

| XVI. | Sears Makes a Suggestion | 179 |

| XVII. | The Squad at Work | 190 |

| XVIII. | The Officer at the Door | 202 |

| XIX. | The Train-robber Is Warned | 213 |

| XX. | Mr. Addicks Explains | 226 |

| XXI. | On the Track | 240 |

| XXII. | The New Coach | 258 |

| XXIII. | Out at the Plate! | 273 |

| XXIV. | Clearfield Concedes the Meet | 290 |

| XXV. | Springdale Leads | 300 |

| XXVI. | The Purple Pennant | 311 |

| Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “‘On your mark!... Set!... Go!’” | 18 |

| “‘What’s that?’ asked Perry, startled” | 220 |

| “Lanny, dropping to his knees on the plate, got it a foot from the ground” | 286 |

“‘Keys,’” murmured Fudge Shaw dreamily, “‘please’—‘knees’—‘breeze’—I’ve used that—‘pease’—‘sneeze’—Oh, piffle!” His inspired gaze returned to the tablet before him and he read aloud the lines inscribed thereon:

“‘The Sun to shine——,’” he muttered raptly, “‘The Sun to shine’; ‘squeeze’—‘tease’—‘fleas’—— Gee, I wish I hadn’t tried to rhyme all the lines. Now, let’s see: ‘You make the birds——’”

“O Fudge! Fudge Shaw!”

Fudge raised his head and peered through the young leaves of the apple-tree in which he was perched, along the side yard to where, leaning over the fence, was a lad of about Fudge’s age. The visitor alternately directed his gaze toward the tree and the house, for it was Sunday afternoon and Perry Hull was doubtful of the propriety of hailing his friend in week-day manner.

“Hello, Perry, come on in!” called Fudge. And thereupon he detached the “Ode to Spring” from the tablet, hastily folded it and put it in his pocket. When Perry climbed the ladder which led to the platform some eight feet above the ground Fudge was in the act of closing a Latin book with a tired air.

“What are you doing?” asked Perry. He was a nice-looking chap of fifteen, with steady dark-brown eyes, hair a shade or two lighter and a capable and alert countenance. He swung himself lithely over the rail instead of crawling under, as was Fudge’s custom, and seated himself on the narrow bench beyond the books.

“Sort of studying,” answered Fudge, ostentatiously shoving the books further away and scowling distastefully at them. “Where have you been?”

“Just moseying around. Peach of a day, isn’t it?”

It was. It had rained until nearly dinner time, and grass and leaves were still beaded with moisture which an ardent April sun was doing its best to burn away. It was the first spring-like day in over a week of typical April weather during which Clearfield had remained under gray skies. Fudge assented to Perry’s observation, but it was to be seen that his thoughts were elsewhere. His lips moved soundlessly. Perry viewed him with surprise and curiosity, but before he could demand an explanation of his host’s abstraction Fudge burst forth triumphantly.

“‘B-b-bees!’” exclaimed Fudge. (Excitement always caused him to stammer, a fact which his friends were aware of and frequently made use of for their entertainment.) Perry involuntarily ducked his head and looked around.

“Where?” he asked apprehensively.

“Nowhere.” Fudge chuckled. “I was just thinking of something.”

“Huh!” Perry settled back again. “You’re crazy, I guess. Better come for a walk and you’ll feel better.”

“Can’t.” Fudge looked gloomily at the books. “Got to study.”

“Then I’ll beat it.”

“Hold on, can’t you? You don’t have to go yet.[4] I—there isn’t such an awful hurry.” The truth was that Fudge was not an enthusiastic pedestrian, a fact due partly to his physical formation and partly to a disposition contemplative rather than active. Nature had endowed Fudge—his real name, by the way, was William—with a rotund body and capable but rather short legs. Walking for the mere sake of locomotion didn’t appeal to him. He would have denied indignantly that he was lazy, and, to do him justice, he wasn’t. With Fudge it was less a matter of laziness than discrimination. Give him something to do that interested him—such as playing baseball or football—and Fudge would willingly, enthusiastically work his short legs for all that was in them, but this thing of deliberately tiring oneself out with no sensible end in view—well, Fudge couldn’t see it! He had a round face from which two big blue eyes viewed the world with a constant expression of surprise. His hair was sandy-red, and he was fifteen, almost sixteen, years old.

“It’s too nice a day to sit around and do nothing,” objected Perry. “Why don’t you get your studying done earlier?”

“I meant to, but I had some writing to do.” Fudge looked important. Perry smiled slightly. “I finished that story I told you about.”

“Did you?” Perry strove to make his question[5] sound interested. “Are you going to have it printed?”

“Maybe,” replied the other carelessly. “It’s a pippin, all right, Perry! It’s nearly fourteen thousand words long! What do you know about that, son? Maybe I’ll send it to the Reporter and let them publish it. Or maybe I’ll send it to one of the big New York magazines. I haven’t decided yet. Dick says I ought to have it typewritten; that the editors won’t read it unless it is. But it costs like anything. Morris Brent has a typewriter and he said I could borrow it, but I never wrote on one of the things and I suppose it would take me a month to do it, eh? Seems to me if the editors want good stories they can’t afford to be so plaguey particular. Besides, my writing’s pretty easy reading just as soon as you get used to it.”

“You might typewrite the first two or three sheets,” suggested Perry, with a chuckle, “and then perhaps the editor would be so anxious to know how it ended he’d keep right on. What are you going to call it, Fudge?”

Fudge shook his head. “I’ve got two or three good titles. ‘The Middleton Mystery’ is one of them. Then there’s ‘Young Sleuth’s Greatest Case.’ I guess that’s too long, eh?”

“I like the first one better.”

“Yes. Then I thought of ‘Tracked by Anarchists.’ How’s that sound to you?”

“‘The Meredith Mystery’ is the best,” replied Perry judicially.

“‘Middleton,’” corrected Fudge. “Yep, I guess it’ll be that. I told that fellow Potter about it and he said if I’d let him take it he’d see about getting it published in the Reporter. He’s a sort of an editor, you know. But I guess the Reporter isn’t much of a paper, and a writer who’s just starting out has to be careful not to cheapen himself, you see.”

“Will he pay you for it?” asked Perry.

“He didn’t say. I don’t suppose so. Lots of folks don’t get paid for their first things, though. Look at—look at Scott; and—and Thackeray, and—lots of ’em! You don’t suppose they got paid at first, do you?”

“Didn’t they?” asked Perry in some surprise.

“Oh, maybe Thackeray got a few dollars,” hedged Fudge, “but what was that? Look what he used to get for his novels afterwards!”

Perry obligingly appeared deeply impressed, although he secretly wondered what Thackeray did get afterwards. However, he forebore to ask, which was just as well, I fancy. Instead, tiring of Fudge’s literary affairs, he observed: “Well, I hope they print it for you, anyway. And maybe[7] they’ll take another one and pay for that. Say, aren’t you going out for baseball, Fudge?”

“Oh, I’m going out, I guess, but it won’t do any good. I don’t intend to sit around on the bench half the spring and then get fired. The only place I’d stand any chance of is the outfield, and I suppose I don’t hit well enough to make it. You going to try?”

Perry shook his head. “No, I don’t think so. I can’t play much. Warner Jones told me the other day that if I’d come out he’d give me a good chance. I suppose he thinks I can play baseball because I was on the Eleven.”

“Well, gee, if you could get to first you’d steal all the other bases, I’ll bet,” said Fudge admiringly. “You sure can run, Perry!”

“Y-yes, and that makes me think that maybe I could do something on the Track Team. What do you think, Fudge?”

“Bully scheme! Go out for the sprints! Ever try the hundred?”

“No, I’ve never run on the track at all. How fast ought I to run the hundred yards, Fudge, to have a show?”

“Oh, anything under eleven seconds would do, I suppose. Maybe ten and four-fifths. Know what you can do it in?”

“No, I never ran it. I’d like to try, though.”

“Why don’t you? Say, I’ve got a stop-watch in the house. You wait here and I’ll get it and we’ll go over to the track and——”

“Pshaw, I couldn’t run in these clothes!”

“Well, you can take your coat and vest off, can’t you? And put on a pair of sneakers? Of course, you can’t run as fast, but you can show what you can do. Perry, I’ll just bet you anything you’ve got the making of a fine little sprinter! You wait here; I won’t be a minute.”

“But it’s Sunday, Fudge, and the field will be locked, and—and you’ve got your lessons——”

“They can wait,” replied Fudge, dropping to the ground and making off toward the side door. “We’ll try the two-twenty, too, Perry!”

He disappeared and a door slammed. Perry frowned in the direction of the house. “Silly chump!” he muttered. Then he smiled. After all, why not? He did want to know if he could run, and, if they could get into the field, which wasn’t likely, since it was Sunday and the gates would be locked, it would be rather fun to try it! He wondered just how fast ten and four-fifths seconds was. He wished he hadn’t done so much walking since dinner, for he was conscious that his legs were a bit tired. At that moment in his reflections there came[9] a subdued whistle from the house and Fudge waved to him.

“Come on,” he called in a cautious whisper. “I’ve got it. And the sneakers, too.” He glanced a trifle apprehensively over his shoulder while he awaited Perry’s arrival and when the latter had joined him he led the way along the side path in a quiet and unostentatious manner suggesting a desire to depart unobserved. Once out of sight of the house, however, his former enthusiasm returned. “We’ll climb over the fence,” he announced. “I know a place where it isn’t hard. Of course, we ought to have a pistol to start with, but I guess it will do if I just say ‘Go!’” He stopped indecisively. “Gordon has a revolver,” he said thoughtfully. “We might borrow it. Only, maybe he isn’t home. I haven’t seen him all day.”

“Never mind, we don’t need it,” said Perry, pulling him along. “He’d probably want to go along with us, Fudge, and I don’t want any audience. I dare say I won’t be able to run fast at all.”

“Well, you mustn’t expect too much the first time,” warned the other. “A chap’s got to be in condition, you know. You’ll have to train and—and all that. Ever do any hurdling?”

“No, and I don’t think I could.”

“It isn’t hard once you’ve caught the knack of it.[10] I was only thinking that if you had plenty of steam you might try sprints and hurdles both. All we’d have to do would be to set the hurdles up. I know where they’re kept. Then——”

“Now, look here,” laughed Perry, “I’m willing to make a fool of myself trying the hundred-yard dash, Fudge, but I’m not going to keep you entertained all the rest of the afternoon.”

“All right, we’ll just try the hundred and the two-twenty.”

“No, we won’t either. We’ll just try the hundred. Will those shoes fit me? And oughtn’t they to have spikes?”

“Sure, they ought, but they haven’t. We’ll have to make allowance for that, I guess. And they’ll have to fit you because they’re all we’ve got. I guess you wear about the same size that I do. Here we are! Now we’ll go around to the Louise Street side; there’s a place there we can climb easily.”

The High School Athletic Field—it was officially known as Brent Field—occupied two whole blocks in the newer part of town. The school had used it for a number of years, but only last summer, through the generosity of Mr. Jonathan Brent, Clearfield’s richest and most prominent citizen, had it come into actual possession of the field. The gift had been as welcome as unexpected and had saved the school from the difficult task of finding a new location for its athletic activities. But, unfortunately, the possession of a large tract of ground in the best residential part of the town was proving to have its drawbacks. The taxes were fairly large, repairs to stands and fences required a constant outlay, the field itself, while level enough, was far from smooth, and the cinder track, a make-shift affair at the beginning, stood badly in need of reconstruction. Add to these expenses the minor ones of water rent, insurance on buildings and care-taking and you will[12] see that the Athletic Association had something to think about.

The town folks always spoke of it as “the town,” although it was, as a matter of fact, a city and boasted of over seventeen thousand inhabitants—supported the High School athletic events, notably football and baseball, generously enough, but it was already evident to those in charge that the receipts from gridiron and diamond attractions would barely keep the field as it was and would not provide money for improvements. There had been some talk of an endowment fund from Mr. Brent, but whether that gentleman had ever said anything to warrant the rumor or whether it had been started by someone more hopeful than veracious was a matter for speculation. At any rate, no endowment fund had so far materialized and the Athletic Committee’s finances were at a low ebb. Two sections of grandstand had been replaced in the fall, and that improvement promised to be the last for some time, unless, as seemed improbable, the Committee evolved some plan whereby to replenish its treasury. Various schemes had been suggested, such as a public canvass of the town and school. To this, however, Mr. Grayson, the Principal, had objected. It was not, he declared, right to ask the citizens to contribute funds for such a purpose. Nor would he allow a[13] petition to the Board of Education. In fact, Mr. Grayson as good as said that now that the school had been generously presented with an athletic field it was up to the school to look after it. Raising money amongst the students he had no objection to, but the amount obtainable in that manner was too small to make it worth while. The plan of raising the price of admission to baseball and football from twenty-five cents to fifty was favored by some, while others feared that it would keep so many away from the contests that there would be no profit in it. In short, the Committee was facing a difficult problem and with no solution in sight. And the field, from its patched, rickety, high board fence to grandstands and dressing-rooms, loudly demanded succor. Fudge voiced the general complaint when, having without difficulty mounted the fence and dropped to the soggy turf inside, followed more lithely by Perry Hull, he viewed the cinder track with disfavor. The recent rain had flooded it from side to side, and, since it was lower than the ground about it and had been put down with little or no provision for drainage, inch-deep puddles still lingered in the numerous depressions.

“We can’t practice here,” said Perry.

“Wouldn’t that agonize you?” demanded Fudge. “Gee, what’s the good of having an athletic field[14] if you can’t keep it up? This thing is g-g-going to be a regular w-w-white elephant!”

“It looks pretty soppy, doesn’t it?” asked Perry. “I guess we’d better wait until it’s drier. I don’t mind running, but I wasn’t counting on having to swim!”

“Maybe it’s better on the straightaway,” responded Fudge more cheerfully. “We’ll go over and see.”

As luck had it, it was drier on the far side of the field, and Fudge advanced the plea that by keeping close to the outer board Perry could get along without splashing much. Perry, however, ruefully considered his Sunday trousers and made objections.

“But it isn’t mud,” urged Fudge. “It’s just a little water. That won’t hurt your trousers a bit. And you can reef them up some, too. Be a sport, Perry! Gee, I’d do it in a minute if I could!”

“Guess that’s about what I’ll do it in,” said the other. “Well, all right. Here goes. Give me the sneakers.”

“Here they are. Guess we’d better go down to the seats and change them, though. It’s too damp to sit down here.”

So they walked to the grandstand at the turn and Perry pulled off his boots and tried the sneakers on. They were a little too large, but he thought they[15] would do. Fudge suggested stuffing some paper in the toes, but as there was no paper handy that plan was abandoned. Perry’s hat, coat and vest were laid beside his boots and he turned up the bottoms of his trousers. Then they walked along the track, skirting puddles or jumping over them. Fortunately, they had the field to themselves, thanks to locked gates, something Perry was thankful for when Fudge, discouraging his desire to have the event over with at once, insisted that he should prance up and down the track and warm up.

“You can’t run decently until you’ve got your legs warm and your muscles limber,” declared Fudge wisely. “And you’d better try a few starts, too.”

So, protestingly, Perry danced around where he could find a dry stretch, lifting his knees high in the manner illustrated by Fudge, and then allowed the latter to show him how to crouch for the start.

“Put your right foot up to the line,” instructed Fudge. “Here, I’ll scratch a line across for you. There. Now put your foot up to that—your right foot, silly! That’s your left! Now put your left knee alongside it and your hands down. That’s it, only you want to dig a bit of a hole back there for your left foot, so you’ll get away quick. Just scrape[16] out the cinders a little. All right. Now when I say ‘Set,’ you come up and lean forward until the weight comes on your front foot and hands; most on your foot; your hands are just to steady yourself with. That’s the trick. Now then; ‘On your mark!’ Wait! I didn’t say ‘Set!’”

“Oh, well, cut out the trimmings,” grumbled Perry. “I can’t stay like this forever. Besides, I’d rather start on the other foot, anyway.”

“All right; some fellows do,” replied Fudge, untroubled, neglecting to explain that he had made a mistake. Perry made the change and expressed his satisfaction.

“That’s more like it. Say, how do you happen to know so much about it, Fudge?”

“Observation, son. Now, all right? Ready to try it? Set!... Go!”

Perry went, but he stumbled for the first three or four steps and lost his stride completely.

“You had your weight on your hands instead of your feet,” commented the instructor. “Try it again.”

He tried it many times, at last becoming quite interested in the problem of getting away quickly and steadily, and finally Fudge declared himself satisfied. “Now I’ll stand back here a ways where I can start you and at the same time see when you cross the line[17] down there. Of course, we ought to have another fellow here to help, but I guess I can manage all right.” He set his stop-watch, composed his features into a stern frown and retired some twenty yards back from the track and half that distance nearer the finish line. “On your mark!” called Fudge. “Set!... Go!”

Perry sped from the mark only to hear Fudge’s arresting voice. “Sorry, Perry, but I forgot to start the watch that time. Try it again.”

“That’s a fine trick! I had a bully getaway,” complained the sprinter. “Make it good this time, Fudge; I’m getting dog-tired!”

“I will. Now, then! On your mark!... Set!... Go!”

Off leaped Perry again, not quite so nicely this time, and down the wet path he sped, splashing through the puddles, head back, legs twinkling. And, as though trying to make pace for him, Fudge raced along on the turf in a valiant endeavor to judge the finish. Perry’s Sunday trousers made a gray streak across the line, Fudge pressed convulsively on the stem of the watch and the trial was over!

“Wh-what was it?” inquired Perry breathlessly as he walked back. Fudge was staring puzzledly at the dial.

“I made it twelve seconds,” he responded dubiously.

“Twelve! And you said I’d ought to do it under eleven!” Perry viewed him discouragedly.

“Well, maybe I didn’t snap it just when I should have,” said the timer. “It’s hard to see unless you’re right at the line.”

“You must have! I’ll bet anything I did it better than twelve. Don’t you think I did?”

“Well, it looked to me as if you were going pretty fast,” answered Fudge cautiously. “But those trousers, and not having any spikes, and the track being so wet—Gee, but you did get splashed, didn’t you?”

“I should say so,” replied Perry, observing his trousers disgustedly. “The water even went into my face! Say, let’s try it again, Fudge, and you stand here at the finish.”

“All right, but how’ll I start you?”

“Wave a handkerchief or something?”

“I’ve got it. I’ll clap a couple of sticks together.” So Fudge set out to find his sticks while Perry, rather winded, seated himself on the stand. Fudge finally came back with the required articles and Perry declared himself rested and ready for another trial. “I’ll clap the sticks together first for you to get set and then for the start. Like this.” Fudge illustrated. “Suppose you can hear it?”

“Sure.” Perry proceeded back to the beginning of the straightaway and Fudge stationed himself at the finish, scuffling a line across the track for his better guidance. Then, while the sprinter was getting his crouch, he experimented with slapping the sticks and snapping the watch at the same instant, a rather difficult proceeding.

“All ready!” shouted Perry, poised on finger-tips and knee.

“All right!” called Fudge in response. He examined his watch, fixed a finger over the stem, took a deep breath and clapped the sticks. Perry set. Another clap and a simultaneous jab at the watch, and Perry was racing down the track. Fudge’s eyes took one fleeting look at the runner and then fixed themselves strainedly on the line he had drawn across the cinders. Nearer and nearer came the scrunch of the flying sneakers, there was a sudden blur of gray in Fudge’s vision and he snapped the watch. Perry turned and trotted anxiously back.

“Well?” he asked.

“Better,” replied Fudge. “Of course, the track’s awfully slow——”

“How much? Let’s see?”

Fudge yielded the watch and Perry examined it. “Eleven and two-fifths!” he shouted protestingly.[20] “Say, this thing’s crazy! I know mighty well I didn’t run nearly so fast as I did the first time!”

“I didn’t snap it soon enough the other time,” explained Fudge. “Honest, Perry, eleven and two-fifths isn’t half bad. Why, look at the slow track and your long trousers——”

“Yes, and they weigh a ton, they’re so wet,” grumbled Perry. “And so do these shoes. I’m going to try it some time when the track’s dry and I’ve got regular running things on. I suppose eleven and two-fifths isn’t terribly bad, considering!”

“Bad! It’s mighty good,” said Fudge warmly. “Why, look here, Perry, if you can do it in that time to-day you can do it nearly a second faster on a dry track and—and all! You see if you can’t. I’ll bet you you’ll be a regular sprinter by the time we meet Springdale!”

“Honest, Fudge?”

“Honest to goodness! To-morrow you put your name down for the Track Team and get yourself some running things. I’ll go along with you if you like. I know just what you ought to have.”

“I don’t suppose I’ll really have any show for the team,” said Perry modestly. “But it’ll be pretty good fun. Say, Fudge, I didn’t know I could run as fast as I did that first time. It seemed to me I[21] was going like the very dickens! It—it’s mighty interesting, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” replied Fudge, as Perry donned his things. “You don’t want to try the two-twenty or the hurdles, do you?”

“I should say not! I’m tuckered out. I’m going to try the two-twenty some day, though. I don’t think I’d care about hurdling.”

“You can’t tell,” murmured Fudge thoughtfully.

Later, when they had once more surmounted the fence and were heading toward B Street, Fudge, who had said little for many minutes, observed: “I wonder, Perry, if a fellow wouldn’t have more fun with the Track Team than with the Nine. I’ve a good mind to go in for it.”

“Why don’t you?” asked Perry, encouragingly eager. “What would you try? Running or—or what?” His gaze unconsciously strayed over his friend’s rotund figure.

“N-no,” replied Fudge hesitantly. “I don’t think so. I might go in for the mile, maybe. I don’t know yet. I’m just thinking of it. I’d have to study a bit. Perhaps the weights would be my line. Ever put the shot?” Perry shook his head. “Neither have I, but I’ll bet I could. All it takes is practice. Say, wouldn’t it be funny if you and I both made the team?”

“It would be dandy,” declared Perry. “Do you suppose there’d be any chance of it?”

“Why not?” asked Fudge cheerfully.

The two boys parted at Main and B Streets, Fudge to loiter thoughtfully southward under the budding maples and Perry to continue briskly on along the wider thoroughfare to where, almost at the corner of G Street, a small yellow house stood in a diminutive yard behind a decaying picket fence. Over the gate, which had stood open ever since Perry had grown too old to enjoy swinging on it, was a square lantern supported on an iron arch. At night a dim light burned in it, calling the passer’s attention to the lettering on the front:

No. 7—Dr. Hull—Office.

Beside the front door a second sign proclaimed the house to be the abode of Matthew P. Hull, M. D.

Nearby was an old-fashioned bell-pull and, just below it, a more modern button. Above the latter were the words “Night Bell.” The house looked[24] homelike and scrupulously clean, but evidences of disrepair were abundant. The bases of the four round pillars supporting the roof of the porch which ran across the front were rotting, the steps creaked ominously under Perry’s feet and the faded yellow paint was blistered and cracked.

Dr. Hull only rented the house, and the owner, since the retail business district had almost surrounded it and he expected to soon sell, was extremely chary of repairs. Perry’s father had lived there so long that he hated the thought of moving. He had grown very fond of the place, a fondness shared to a lesser extent by Mrs. Hull and scarcely at all by Perry. But Dr. Hull’s motives in remaining there were not wholly sentimental. He had slowly and arduously accumulated a fair practice and, now that the town was over-supplied with physicians, he feared that a change of location would lose him his clients. Dr. Hull was not an old man, but he was forty-odd and rather of the old-style, and shook his head over the pushing methods of the newcomers. Perry assured him that it would be a good thing if he did lose some of his present practice, since half of it brought him little or no money, and that in a better location he could secure a better class of patients. But Perry wasn’t very certain of this, while his mother, who sighed secretly for[25] a home where the plaster didn’t crumble nor the floors creak, had even less faith in the Doctor’s ability to begin over again.

Perry glanced through the open door of the tiny waiting room on the left as he hung up his cap and, finding it empty and the further door ajar, knew that his father was out. He went on up the stairs, which complained at almost every footfall, and stole noiselessly down the narrow hall to his own room. His mother’s door was closed and this was the hour when, on Sundays, she enjoyed what she termed “forty winks.” Perry’s room was small and lighted by three narrow windows set close together. While they admitted light they afforded but little view, for beyond the shallow back-yard loomed the side wall of a five-storied brick building which fronted on G Street. Directly on a level with Perry’s windows was Curry’s Glove factory, occupying the second floor of the building. Below was a bakery. Above were offices; a dentist’s, a lawyer’s, and several that were empty or changed tenants so frequently that Perry couldn’t keep track of them. In winter the light that came through the three windows was faint and brief, but at other seasons the sunlight managed somehow to find its way there. This afternoon a golden ray still lingered on the table, falling athwart the strapped pile of[26] school books and spilling over to the stained green felt.

Perry seated himself at the table, put an elbow beside the pile of books and, cupping chin in hand, gazed thoughtfully down into the yard. There was a lean and struggling lilac bush against one high fence and its green leaves were already unfolding. That, reflected the boy, meant that spring was really here again at last. It was already nearly the middle of April. Then came May and June, and then the end of school. He sighed contentedly at the thought. Not that he didn’t get as much pleasure out of school as most fellows, but there comes a time, when buds are swelling and robins are hopping and breezes blow warmly, when the idea of spending six hours of the finest part of the day indoors becomes extremely distasteful. And that time had arrived.

Perry turned to glance with sudden hostility at the piled-up books. What good did it do a fellow, anyway, to learn a lot of Latin and algebra and physics and—and all the rest of the stuff? If he only knew what he was going to be when he grew up it might save a lot of useless trouble! Until a year ago he had intended to follow in his father’s footsteps, but of late the profession of medicine had failed to hold his enthusiasm. It seemed to him that doctors had to work very hard and long for[27] terribly scant returns in the way of either money or fame. No, he wouldn’t be a doctor. Lawyers had a far better time of it; so did bankers and—and almost everyone. Sometimes he thought that engineering was the profession for him. He would go to Boston or New York and enter a technical school and learn civil or mining engineering. Mining engineers especially had a fine, adventurous life of it. And he wouldn’t have to spend all the rest of his life in Clearfield then.

Clearfield was all right, of course; Perry had been born in it and was loyal to it; but there was a whole big lot of the world that he’d like to see! He got up and pulled an atlas from the lower shelf of his book-case and spread it open. Colorado! Arizona! Nevada! Those were names for you! And look at all the territory out there that didn’t have a mark on it! Prairies and deserts and plateaus! Miles and miles and miles of them without a town or a railroad or anything! Gee, it would be great to live in that part of the world, he told himself. Adventures would be thick as blueberries out there. Back here nothing ever happened to a fellow. He wondered if it would be possible to persuade his father to move West, to some one of those fascinating towns with the highly romantic names; like Manzanola or Cotopaxi or Painted Rock. His thoughts[28] were far afield now and, while his gaze was fixed on the lilac bush below, his eyes saw wonderful scenes that were very, very foreign to Clearfield. The sunlight stole away from the windows and the shadows gathered in the little yard. The room grew dark.

Just how long Perry would have sat there and dreamed of far-spread prairies and dawn-flushed deserts and awesome cañons had not an interruption occurred, there’s no saying. Probably, though, until his mother summoned him to the Sunday night supper. And that, since it was a frugal repast of cold dishes and awaited the Doctor’s presence, might not have been announced until seven o’clock. What did rouse him from his dreaming was the sudden appearance of a light in one of the third floor windows of the brick building. It shone for a moment only, for a hand almost immediately pulled down a shade, but its rays were bright enough to interrupt the boy’s visions and bring his thoughts confusedly back.

When you’ve been picturing yourself a cowboy on the Western plains, a cowboy with a picturesque broad-brimmed sombrero, leather chaps, a flannel shirt and a handkerchief knotted about your neck, it is naturally a bit surprising to suddenly see just such a vision before your eyes. And that’s what happened to Perry. No sooner was the shade drawn[29] at the opposite window than upon it appeared the silhouette of as cowboyish a cowboy as ever rode through sage-brush! Evidently the light was in the center of the room and the occupant was standing between light and window, standing so that for a brief moment his figure was thrown in sharp relief against the shade, and Perry, staring unbelievingly, saw the black shadow of a broad felt hat whose crown was dented to a pyramid shape, a face with clean-cut features and a generous mustache and, behind the neck, the knot of a handkerchief! Doubtless the flannel shirt was there, too, and, perhaps, the leather cuffs properly decorated with porcupine quills, but Perry couldn’t be sure of this, for before he had time to look below the knotted bandana the silhouette wavered, lengthened oddly and faded from sight, leaving Perry for an instant doubtful of his vision!

“Now what do you know about that?” he murmured. “A regular cowboy, by ginger! What’s he doing over there, I wonder. And here I was thinking about him! Anyway, about cowboys! Gee, that’s certainly funny! I wish I could have seen if he wore a revolver on his hip! Maybe he’ll come back.”

But he didn’t show himself again, although Perry sat on in the darkness of his little room for the[30] better part of a half-hour, staring eagerly and fascinatedly at the lighted window across the twilight. The shade still made a yellowish oblong in the surrounding gloom of the otherwise blank wall when his mother’s voice came to him from below summoning him to supper and he left his vigil unwillingly and went downstairs.

Dr. Hull had returned and supper was waiting on the red cloth that always adorned the table on Sunday nights. Perry was so full of his strange coincidence that he hardly waited for the Doctor to finish saying grace before he told about the vision. Rather to his disappointment, neither his father nor mother showed much interest, but perhaps that was because he neglected to tell them that he had been thinking of cowboys at the time. There was no special reason why he should have told them other than that he suspected his mother of a lack of sympathy on the subject of cowboys and the Wild West.

“I guess,” said the Doctor, helping to the cold roast lamb and having quite an exciting chase along the back of the platter in pursuit of a runaway sprig of parsley, “I guess your cowboy would have looked like most anyone else if you’d had a look at him. Shadows play queer tricks, Perry.”

Dr. Hull was tall and thin, and he stooped quite[31] perceptibly. Perhaps the stoop came from carrying his black bag about day after day, for the Doctor had never attained to the dignity of a carriage. When he had to have one he hired it from Stewart, the liveryman. He had a kindly face, but he usually looked tired and had a disconcerting habit of dropping off to sleep in the middle of a conversation or, not infrequently, half-way through a meal. Perry was not unlike his father as to features. He had the same rather short and very straight nose and the same nice mouth, but he had obtained his brown eyes from his mother. Dr. Hull’s eyes were pale blue-gray and he had a fashion of keeping them only a little more than half open, which added to his appearance of weariness. He always dressed in a suit of dark clothes which looked black without actually being black. For years he had had his suits made for him by the same unstylish little tailor who dwelt, like a spider in a hole, under the Union Restaurant on Common Street. Whether the suits, one of which was made every spring, all came off the same bolt of cloth, I can’t say, but it’s a fact that Mrs. Hull had to study long to make out which was this year’s suit and which last’s. On Sunday evenings, however, the Doctor donned a faded and dearly-loved house-jacket of black velveteen with frayed silk frogs, for on Sunday evenings he kept[32] no consultation hours and made no calls if he could possibly help it.

In spite of Perry’s efforts, the cowboy was soon abandoned as a subject for conversation. The Doctor was satisfied that Perry had imagined the likeness and Mrs. Hull couldn’t see why a cowboy hadn’t as much right in the neighboring building as anyone. Perry’s explanations failed to convince her of the incongruity of a cowboy in Clearfield, for she replied mildly that she quite distinctly remembered having seen at least a half-dozen cowboys going along Main Street a year or two before, the time the circus was in town!

“Maybe,” chuckled the Doctor, “this cowboy got left behind then!”

Perry refused to accept the explanation, and as soon as supper was over he hurried upstairs again. But the light across the back-yard was out and he returned disappointedly to the sitting-room, convinced that the mystery would never be explained. His father had settled himself in the green rep easy chair, with his feet on a foot-rest, and was smoking his big meerschaum pipe that had a bowl shaped like a skull. The Doctor had had that pipe since his student days, and Perry suspected that, next to his mother and himself, it was the most prized of the Doctor’s possessions. The Sunday papers lay spread[33] across his knees, but he wasn’t reading, and Perry seized on the opportunity presented to broach the matter of going in for the Track Team. There had been some difficulty in the fall in persuading his parents to consent to his participation in football, and he wasn’t sure that they would look any more kindly on other athletic endeavors. His mother was still busy in the kitchen, for he could hear the dishes rattling, and he was glad of it; it was his mother who looked with most disfavor on such things.

“Dad, I’m going to join the Track Team and try sprinting,” announced Perry carelessly.

The Doctor brought his thoughts back with a visible effort.

“Eh?” he asked. “Join what?”

“The Track Team, sir. At school. I think I can sprint a little and I’d like to try it. Maybe I won’t be good enough, but Fudge Shaw says I am, and——”

“Sprinting, eh?” The Doctor removed his pipe and rubbed the bowl carefully with the purple silk handkerchief that reposed in an inner pocket of his house-jacket. “Think you’re strong enough for that, do you?”

“Why, yes, sir! I tried it to-day and didn’t have any trouble. And the track was awfully wet, too.”

“To-day?” The Doctor’s brows went up. “Sunday?”

Perry hastened to explain and was cheered by a slight smile which hovered under his father’s drooping mustache when he pictured Fudge trying to be at both ends of the hundred-yards at once. “You see, dad, I can’t play baseball well enough, and I’d like to do something. I ought to anyway, just to keep in training for football next autumn. I wouldn’t wonder if I got to be regular quarter-back next season.”

“Sprinting,” observed the Doctor, tucking his handkerchief out of sight again, “makes big demands on the heart muscles, Perry. I’ve no reason for supposing that your heart isn’t as strong as the average, but I recall in my college days a case where a boy over-worked himself in a race, the quarter-mile, I think it was, and never was good for much afterwards. He was in my class, and his name was—dear, dear, now what was it? Well, it doesn’t matter. Anyway, that’s what you’ll have to guard against, Perry.”

“But if I began mighty easy, the way you do, and worked up to it, sir——”

“Oh, I dare say it won’t hurt you. Exercise in moderation is always beneficial. It’s putting sudden demands on yourself that does the damage. With[35] proper training, going at it slowly, day by day, you know—well, we’ll see what your mother says.”

Perry frowned and moved impatiently on the couch. “Yes, sir, but you know mother always finds objections to my doing things like that. You’d think I was a regular invalid! Other fellows run and jump and play football and their folks don’t think anything of it. But mother——”

“Come, come, Perry! That’ll do, son. Your mother is naturally anxious about you. You see, there’s only one of you, and we—well, we don’t want any harm to come to you.”

“Yes, sir,” said Perry, more meekly. “Only I thought if you’d say it was all right, before she comes in——”

The Doctor chuckled. “Oh, that’s your little game, is it? No, no, we’ll talk it over with your mother. She’s sensible, Perry, and I dare say she won’t make any objections; that is, if you promise to be careful.”

“Yes, sir. Why, there’s a regular trainer, you know, and the fellows have to do just as he tells them to.”

“Who is the trainer?”

“‘Skeet’ Presser, sir. He’s——”

“Skeet?”

“That’s what they call him. He’s small and[36] skinny, sort of like a mosquito. I guess that’s why. I don’t know what his real name is. He used to be a runner; a jim-dandy, too, they say. He’s trainer at the Y. M. C. A. I guess he’s considered pretty good. And very careful, sir.” Perry added that as a happy afterthought.

The Doctor smiled. “I guess we ought to make a diplomat out of you, son, instead of a doctor.”

“I don’t think I’ll be a doctor, dad.”

“You don’t? I thought you did.”

“I used to, but I—I’ve sort of changed my mind.”

“Diplomats do that, too, I believe. Well, I dare say you’re right about it. It doesn’t look as if I’d have much of a practice to hand over to you, anyway. It’s getting so nowadays about every second case is a charity case. About all you get is gratitude, and not always that. Here’s your mother now. Mother, this boy wants to go in for athletics, he tells me. Wants to run races and capture silver mugs. Or maybe they’re pewter. What do you say to it?”

“Gracious, what for?” ejaculated Mrs. Hull.

Perry stated his case again while his mother took the green tobacco jar from the mantel and placed it within the Doctor’s reach, plumped up a pillow on the couch, picked a thread from the worn red carpet and finally, with a little sigh, seated herself in the small walnut rocker that was her especial[37] property. When Perry had finished, his mother looked across at the Doctor.

“What does your father think?” she asked.

“Oh, I think it won’t do him any harm,” was the reply from the Doctor. “Might be good for him, in fact. I tell him he must be careful not to attempt too much at first, that’s all. Running is good exercise if it isn’t overdone.”

“Well, it seems to me,” observed Mrs. Hull, “that if he can play football and not get maimed for life, a little running can’t hurt him. How far would it be, Perry?”

“Oh, only about from here to the corner and back.”

“Well, I don’t see much sense in it, but if you want to do it I haven’t any objection. It doesn’t seem as if much could happen to you just running to G Street and back!”

The Doctor chuckled. “It might be good practice when it comes to running errands, mother. Maybe he’ll be able to get to the grocery and back the same afternoon!”

“Well,” laughed Perry, “you see, dad, when you’re running on the track you don’t meet fellows who want you to stop and play marbles with them!”

With the advent of that first warm spring-like weather the High School athletic activities began in earnest. During March the baseball candidates had practiced to some extent indoors and occasionally on the field, but not a great deal had been accomplished. The “cage” in the basement of the school building was neither large nor light, while cold weather, with rain and wet ground, had made outdoor work far from satisfactory. Of the Baseball Team, Clearfield had high hopes this spring. There was a wealth of material left from the successful Nine of the previous spring, including two first-class pitchers, while the captain, Warner Jones, was a good leader as well as a brainy player. Then too, and in the judgment of the school this promised undoubted success, the coaching had been placed in the hands of Dick Lovering. Dick had proven his ability as a baseball coach the summer before and had subsequently piloted the football[39] team to victory in the fall, thus winning an admiration and gratitude almost embarrassing to him.

Dick, who had to swing about on crutches where other fellows went on two good legs, came out of school Monday afternoon in company with Lansing White and crossed over to Linden Street where a small blue runabout car stood at the curb. Dick was tall, with dark hair and eyes. Without being especially handsome, his rather lean face was attractive and he had a smile that won friends on the instant. Dick was seventeen and a senior. Lansing, or Lanny, White was a year younger, and a good deal of a contrast to his companion. Lanny fairly radiated health and strength and high spirits. You’re not to conclude that Dick suggested ill-health or that he was low-spirited, for that would be far from the mark. There was possibly no more cheerful boy in Clearfield than Richard Lovering, in spite of his infirmity. But Lanny, with his flaxen hair and dark eyes—a combination as odd as it was attractive—and his sun-browned skin and his slimly muscular figure, looked the athlete he was, every inch of him. Lanny was a “three-letter man” at the High School; had captained the football team, caught on the nine and was a sprinter of ability. And, which was no small attainment, he possessed more friends than any other fellow in school. Lanny couldn’t help[40] making friends; he appeared to do it without conscious effort; there had never been on his part any seeking for popularity.

Lanny cranked the car and seated himself beside Dick. Fully half the students were journeying toward the field, either to take part in practice or to watch it, and the two boys in the runabout answered many hails until they had distanced the pedestrians.

“This,” said Lanny, as they circumspectly crossed the car-tracks and turned into Main Street, “is just the sort of weather the doctor ordered. If it keeps up we’ll really get started.”

“This is April, though,” replied Dick, “and everyone knows April!”

“Oh, we’ll have more showers, but once the field gets dried out decently they don’t matter. I suppose it’ll be pretty squishy out there to-day. What we ought to do, Dick, is have the whole field rolled right now while it’s still soft. It’s awfully rough in right field, and even the infield isn’t what you’d call a billiard table.”

“Wish we could, Lanny. But I guess if we get the base paths fixed up we’ll get all that’s coming to us this spring. Too bad we haven’t a little money on hand.”

“Oh, I know we can’t look to the Athletic Association for much. I was only wondering if we[41] couldn’t get it done somehow ourselves. If we knew someone who had a steam roller we might borrow it!”

“The town has a couple,” laughed Dick, “but I’m afraid they wouldn’t loan them.”

“Why not? Say, that’s an idea, Dick! Who do you borrow town property from, anyway? The Mayor?”

“Street Department, I guess. Tell Way to go and see them, why don’t you?”

“Way” was Curtis Wayland, manager of the baseball team. Lanny smiled. “Joking aside,” he said, “they might do it, mightn’t they? Don’t they ever loan things?”

“Maybe, but you’d have to have the engineer or chauffeur or whatever they call him to run it for you, and that would be a difficulty.”

“Pshaw, anyone could run a steam roller! You could, anyway.”

“Can’t you see me?” chuckled Dick. “Suppose, though, I got nabbed for exceeding the speed limit? I guess, Lanny, if that field gets rolled this spring it will be done by old-fashioned man-power. We might borrow a roller somewhere and get a lot of the fellows out and have them take turns pushing it.”

“It would take a week of Sundays,” replied[42] Lanny discouragingly. “You wait. I’m not finished with that other scheme yet.”

“Borrowing a roller from the town, you mean? Well, I’ve no objection, but don’t ask me to run it. I’d be sure to put it through the fence or something; and goodness knows we need all the fence we’ve got!”

“Yes, it’ll be a miracle if it doesn’t fall down if anyone hits a ball against it!”

“If it happens in the Springdale game you’ll hear no complaint from me,” said Dick, adding hurriedly, “That is, if it’s one of our team who does it!”

“Ever think of putting a sign on the fence in center field?” asked Lanny. “‘Hit This Sign and Get Ten Dollars,’ or something of that sort, you know. It might increase the team’s average a lot, Dick.”

“You’re full of schemes to-day, aren’t you? Does that fence look to you as if it would stand being hit very often?” They had turned into A Street and the block-long expanse of sagging ten-foot fence stretched beside them. “I’ve about concluded that being presented with an athletic field is like getting a white elephant in your stocking at Christmas!”

“Gee, this field is two white elephants and a pink hippopotamus,” replied Lanny as he jumped out in[43] front of the players’ gate. Dick turned off the engine and thoughtfully removed the plug from the dash coil, thus foiling youngsters with experimental desires. His crutches were beside him on the running-board, and, lifting them from the wire clips that held them there, he deftly swung himself from the car and passed through the gate. They were the first ones to arrive, but before they had returned to the dressing-room under the nearer grandstand after a pessimistic examination of the playing field, others had begun to dribble in and a handful of youths were arranging themselves comfortably on the seats behind first base. But if the audience expected anything of a spectacular nature this afternoon they were disappointed, for the practice was of the most elementary character.

There was a half-hour at the net with Tom Nostrand and Tom Haley pitching straight balls to the batters and then another half-hour of fielding, Bert Cable, last year’s captain and now a sort of self-appointed assistant coach, hitting fungoes to outfielders, and Curtis Wayland, manager of the team, batting to the infield. The forty or fifty onlookers in the stands soon lost interest when it was evident that Coach Lovering had no intention of staging any sort of a contest, and by ones and twos they took their departure. Even had they all gone, however,[44] the field would have been far from empty, for there were nearly as many team candidates as spectators to-day. More than forty ambitious youths had responded to the call and it required all the ingenuity of Dick Lovering and Captain Warner Jones to give each one a chance. The problem was finally solved by sending a bunch of tyros into extreme left field, under charge of Manager Wayland, where they fielded slow grounders and pop-flies and tested their throwing arms.

It was while chasing a ball that had got by him that Way noticed a fluttering sheet of paper near the cinder track. It had been creased and folded, but now lay flat open, challenging curiosity. Way picked it up and glanced at it as he returned to his place. It held all sorts of scrawls and scribbles, but the words “William Butler Shaw,” and the letters “W. B. S.,” variously arranged and entwined, were frequently repeated. Occupying the upper part of the sheet were six or seven lines of what, since the last words rhymed with each other, Way concluded to be poetry. Since many of the words had been scored out and superseded by others, and since the writing was none too legible in any case, Way had to postpone the reading of the complete poem. He stuffed it in his pocket, with a chuckle, and went back to amusing his awkward squad.

Fudge Shaw sat on the bench between Felker and Grover and awaited his turn in the outfield. Fudge had played in center some, but he was not quite Varsity material, so to speak, and his hopes of making even the second team, which would be formed presently, from what coach and captain rejected, were not strong. Still, Fudge “liked to stick around where things were doing,” as he expressed it, and he accepted his impending fate with philosophy. Besides, he had more than half made up his mind to cast his lot with the Track Team this spring. He was discussing the gentle art of putting the twelve-pound shot with Guy Felker when Dick summoned the outfield trio in and sent Fudge and two others to take their places. Fudge trotted out to center and set about his task of pulling down Bert Cable’s flies. Perhaps his mind was too full of shot-putting to allow him to give the needed attention to the work at hand. At all events, he managed to judge his first ball so badly that it went six feet over his head and was fielded in by one of Way’s squad. Way was laughing when Fudge turned toward him after throwing the ball to the batter.

“A fellow needs a pair of smoked glasses out here,” called Fudge extenuatingly. This, in view of the fact that the sun was behind Fudge’s right shoulder, was a lamentably poor excuse. Possibly[46] he realized it, for he added: “My eyes have been awfully weak lately.”

Way, meeting the ball gently with his bat and causing a wild commotion amongst his fielders, nodded soberly. “And for many other reasons,” he called across.

“Eh?” asked Fudge puzzled. But there was no time for more just then as Bert Cable, observing his inattention, meanly shot a long low fly into left field, and Fudge, starting late, had to run half-way to the fence in order to attempt the catch. Of course he missed it and then, when he had chased it down, made matters worse by throwing at least twelve feet to the left of Cable on the return. The ex-captain glared contemptuously and shouted some scathing remark that Fudge didn’t hear. After that, he got along fairly well, sustaining a bruised finger, however, as a memento of the day’s activities. When practice was over he trudged back to the dressing-room and got into his street clothes. Fortunately, most of the new fellows had dressed at home and so it was possible to find room in which to squirm out of things without collisions. While Fudge was lacing his shoes he observed that Way and his particular crony, Will Scott, who played third base, were unusually hilarious in a far corner of the room.

But Fudge was unsuspicious, and presently he found himself walking home with the pair.

“Say, this is certainly peachy weather, isn’t it?” inquired Will as they turned into B Street. “Aren’t you crazy about spring, Way?”

“Am I? Well, rather! O beauteous spring!”

“So am I. You know it makes the birds sing in the trees.”

“Sure. And it makes the April breeze to blow.”

“What’s wrong with you chaps?” asked Fudge perplexedly. The strange words struck him as dimly familiar but he didn’t yet connect them with their source.

“Fudge,” replied Way sadly, “I fear you have no poetry in your soul. Doesn’t the spring awaken—er—awaken feelings in your breast? Don’t you feel the—the appeal of the sunshine and the singing birds and all that?”

“You’re batty,” said Fudge disgustedly.

“Now for my part,” said Will Scott, “spring art, I ween, the best of all the seasons.”

“Now you’re saying something,” declared Way enthusiastically. “It clothes the earth with green——”

“And for numerous other reasons,” added Will gravely.

A great light broke on Fudge and his rotund[48] cheeks took on a vivid tinge. “W-w-what you s-s-silly chumps think you’re up to?” he demanded. “W-w-where did you g-g-g-get that st-t-t-tuff?”

“Stuff!” exclaimed Way protestingly. “That’s poetry, Fudge. Gen-oo-ine poetry. Want to hear it all?”

“No, I don’t!”

But Will had already started declaiming and Way chimed in:

“I hope you ch-ch-choke!” groaned Fudge. “W-w-where’d you get it? Who t-t-told you——”

“Fudge,” replied Way, laughingly, “you shouldn’t leave your poetic effusions around the landscape if you don’t want them read.” He pulled the sheet of paper from his pocket and flaunted it temptingly just out of reach. “‘You make the birds sing in the trees——’”

“‘The April breeze to blow,’” continued Will.

“‘The sun to shine——’ What’s the rest of it, Fudge? Say, it’s corking! It’s got a swing to it that’s simply immense!”

“And then the sentiment, the poetic feeling!” elaborated Will. “How do you do it, Fudge?”

“Aw, q-q-quit it, fellows, and g-g-g-give me that!” begged Fudge shame-facedly. “I just did it for f-f-fun. It d-d-dropped out of my p-p-p——”

But “pocket” was too much for Fudge in his present state of mind, and he gave up the effort and tried to get the sheet of paper away. He succeeded finally, by the time they had reached Lafayette Street, where their ways parted, and tore it to small bits and dropped it into someone’s hedge. Way and Will departed joyfully, and until they were out of earshot Fudge could hear them declaiming the “Ode to Spring.” He went home a prey to a deep depression. He feared that he had by no means heard the last of the unfortunate poetical effort. And, as the future proved, his fears were far from groundless.

Fudge had an engagement to go to the moving pictures that evening with Perry Hull. They put on the new reels on Mondays and Fudge was a devoted “first-nighter.” Very shortly after supper was over he picked up a book and carelessly strolled toward the hall.

“Where are you going, William?” asked his mother.

“Over to the library,” replied Fudge, making a strong display of the book in his hand.

“Well, don’t stay late. Haven’t you any studying to do to-night?”

“No’m, not much. I’ll do it when I come back.”

“Seems to me,” said Mrs. Shaw doubtfully, “it would be better to do your studying first.”

“I don’t feel like studying so soon after supper,” returned Fudge plaintively. “I won’t be gone very long—I guess.”

“Very well, dear. Close the door after you. It’s downright chilly again to-night.”

“Yes’m.” Fudge slipped his cap to the back of his round head and opened the side door. There he hesitated. Of course, he was going to the library, although he didn’t especially want to, for it was many blocks out of his way, but he meant to make his visit to that place as short as possible in order to call for Perry and reach the theater early enough not to miss a single feature of the evening’s program. And he was practically telling a lie. Fudge didn’t like that. He felt decidedly uneasy as he stood with the door knob in hand. The trouble was that his mother didn’t look kindly on moving pictures. She didn’t consider them harmful, but she did think them a waste of time, and was firmly convinced that once a month was quite often enough for Fudge to indulge his passion for that form of entertainment. Fudge had a severe struggle out there in the hallway, and I like to think that he would have eventually decided to make known his principal destination had not Mrs. Shaw unfortunately interrupted his cogitations.

“William, have you gone?”

“No’m.”

“Well, don’t hold the door open, please. I feel a draft on my feet.”

“Yes’m.” Fudge slowly closed the door, with himself on the outside. The die was cast. He tried to comfort himself with the assurance that if his mother hadn’t spoken just when she did he would have asked permission to go to the “movies.” It wasn’t his fault. He passed out of the yard whistling blithely enough, but before he had reached the corner the whistle had died away. He wished he had told the whole truth. He was more than half inclined to go back, but it was getting later every minute and he had to walk eight blocks to the library and five back to the theater, and it would take him several minutes to exchange his book, and Perry might not be ready——

Fudge was so intent on all this that he passed the front of the Merrick house, on the corner, without, as usual, announcing his transit with a certain peculiar whistle common to him and his friends. He walked hurriedly, determinedly, trying to keep his thoughts on the pleasure in store, hoping they’d have a rattling good melodrama on the bill to-night and would present less of the “sentimental rot” than was their custom. But Conscience stalked at Fudge’s side, and the further he got from home the more uncomfortable he felt in his mind; and his thoughts refused to stay placed on the “movies.” But while he paused in crossing G Street to let one of the big[53] yellow cars trundle past him a splendid idea came to him. He would telephone! There was a booth in the library, and if he had a nickel—quick examination of his change showed that he was possessed of eleven cents beyond the sum required to purchase admission to the theater. With a load off his mind, he hurried on faster than ever, ran across the library grounds with no heed to the “Keep off the Grass” signs and simply hurtled through the swinging green doors.

It was the work of only a minute or two to seize a book from the rack on the counter—it happened to be a treatise on the Early Italian Painters, but Fudge didn’t care—and make the exchange. The assistant librarian looked somewhat surprised at Fudge’s choice, but secretly hoped that it indicated a departure from the sensational fiction usually selected by the boy, and passed the volume across to him at last with an approving smile. Fudge was too impatient to see the smile, however. The book once in his possession, he hurried to the telephone booth in the outer hall and demanded his number. Then a perfectly good five-cent piece dropped forever out of his possession and he heard his mother’s voice at the other end of the line.

“This is Fudge. Say, Ma, I thought—I’m at the library, Ma, and I got the book I wanted, and I[54] thought, seeing it’s so early—say, Ma, may I go to the movies for a little while?”

“You intended to go all the time, didn’t you, William?” came his mother’s voice.

“Yes’m, but——”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

That was something of a poser. “Well, I meant to, but—but you said not to keep the door open and—and——” Fudge’s voice dwindled into silence.

“Why do you tell me now?”

Gee, but she certainly could ask a lot of hard questions, he reflected. “I thought maybe—oh, I don’t know, Ma. May I? Just for a little while? I’m going with Perry—if you say I can.”

“I’d rather you told me in the first place, William, but telling me now shows that you know you did wrong. You mustn’t tell lies, William, and when you said you were going to the library——”

“Yes’m, I know!” Fudge was shifting impatiently from one foot to the other, his eyes fixed on the library clock, seen through an oval pane in one of the green baize doors. “I—I’m sorry. Honest, I am. That’s why I telephoned, Ma.”

“If I let you go to-night you won’t ask to go again next week?”

“No’m,” replied Fudge dejectedly.

“Very well, then you may go. And you needn’t[55] leave before it’s over, William, because if you don’t go next week you might as well see all you can this time.”

“Yes’m! Thanks! Good-by!”

Fudge knew a short cut from Ivy Street to G Street, and that saved nearly a minute even though it necessitated climbing a high fence and trespassing on someone’s premises. He reached Perry’s and, to his vast relief, found that youth awaiting him at the gate. Perry was slightly surprised to be hailed from the direction opposite to that in which he was looking, but joined Fudge at the corner and, in response to the latter’s earnest and somewhat breathless appeal to “Get a move on,” accompanied him rapidly along the next block. Just as they came into sight of the brilliantly illumined front of the moving picture house, eight o’clock began to sound on the City Hall bell and Fudge broke into a run.

“Come on!” he panted. “We’ll be late!”

They weren’t, though. The orchestra was still dolefully tuning up as they found seats. The orchestra consisted principally of a pianist, although four other musicians were arranged lonesomely on either side. The two boys were obliged to sit well over toward the left of the house and when the orchestra began the overture Fudge’s gaze, attracted to the performers, stopped interestedly at the pianist.[56] “Say, Perry,” he said, “they’ve got a new guy at the piano. See?”

Perry looked and nodded. Then he took a second look and frowned puzzledly. “Who is he?” he asked.

“I don’t know. But the other fellow was short and fat. Say, I hope they have a good melodrama, don’t you?”

“Yes, one of those Western plays, eh?” Perry’s gaze went back to the man at the piano. There was something about him that awakened recollection. He was a tall, broad-shouldered man of twenty-six or -seven, with clear-cut and very good-looking features, and a luxuriant mustache, as Perry could see when he turned to smile at one of the violinists. He played the piano as though he thoroughly enjoyed it, swaying a little from the hips and sometimes emphasizing with a sudden swift bend of his head.

“He can play all around the other guy,” said Fudge in low and admiring whispers. “Wish I could play a piano like that. I’ll bet he can ‘rag’ like anything!”

At that moment the house darkened and the program commenced with the customary weekly review. Fudge sat through some ten minutes of that patiently, and was only slightly bored when a rustic comedy was unrolled before him, but when the next[57] film developed into what he disdainfully called “one of those mushy things,” gloom began to settle over his spirits. He squirmed impatiently in his seat and muttered protestingly. A sharp-faced, elderly lady next to him audibly requested him to “sit still, for Mercy’s sake!” Fudge did the best he could and virtue was rewarded after a while. “Royston of the Rangers,” announced the film. Fudge sat up, devoured the cast that followed and, while the orchestra burst into a jovial two-step, nudged Perry ecstatically.

“Here’s your Western play,” he whispered.

Perry nodded. Then the first scene swept on the screen and Fudge was happy. It was a quickly-moving, breath-taking drama, and the hero, a Texas Ranger, bore a charmed life if anyone ever did. He simply had to. If he hadn’t he’d have been dead before the film had unrolled a hundred feet! Perry enjoyed that play even more than Fudge, perhaps, for he was still enthralled by yesterday’s dreams. There were rangers and cowboys and Mexicans and a sheriff’s posse and many other picturesque persons, and “battle, murder and sudden death” was the order of the day. During a running fight between galloping rangers and a band of Mexican desperados Fudge almost squirmed off his chair to the floor. After that there was a really funny[58] “comic” and that, in turn, was followed by another melodrama which, if not as hair-raising as the first, brought much satisfaction to Fudge. On the whole, it was a pretty good show. Fudge acknowledged it as he and Perry wormed their way out through the loitering audience at the end of the performance.

They discussed it as they made their way along to Castle’s Drug Store where Perry was to treat to sodas. For Fudge at least half the fun was found in talking the show over afterwards. He was a severe critic, and if the manager of the theater could have heard his remarks about the “mushy” film he might have been moved to exclude such features thereafter. When they had had their sodas and had turned back toward Perry’s house, Perry suddenly stood stock-still on the sidewalk and ejaculated: “Gee, I know where I saw him!”

“Saw who?” demanded Fudge. “Come on, you chump.”

“Why, the fellow who played the piano. I’ll bet you anything he’s the cowboy!”

“You try cold water,” said Fudge soothingly. “Just wet a towel and put it around your head——”

“No, listen, will you, Fudge? I want to tell you.” So Perry recounted the odd coincidence of the preceding evening, ending with: “And I’ll bet you anything you like that’s the same fellow who was[59] playing the piano there to-night. I recognized him, I tell you, only I couldn’t think at first.”

“Well, he didn’t look like a cowboy to-night,” replied Fudge dubiously. “Besides, what would he be doing here? This isn’t any place for cowboys. I guess you kind of imagined that part of it. Maybe he had on a felt hat; I don’t say he didn’t; but I guess you imagined the rest of it. It—it’s psychological, Perry. You were thinking about cowboys and such things and then this fellow appeared at the window and you thought he was dressed like one.”

“No, I didn’t. I tell you I could see the handkerchief around his neck and—and everything! I don’t say he really is a cowboy, but I know mighty well he was dressed like one. And I know he’s the fellow we saw playing the piano.”

“Oh, shucks, cowboys don’t play pianos, Perry. Besides, what does it matter anyway?”

“Nothing, I suppose, only—only it’s sort of funny. I’d like to know why he was got up like a cowboy.”

“Why don’t you ask him? Tell you what we’ll do, Perry, we’ll go up there to-morrow after the show’s over and lay in wait for him.”

“Up to his room? I wonder if he has an office. Maybe he gives lessons, Fudge.”

“What sort of lessons?”

“Piano lessons. Why would he have an office?”

“Search me. But we’ll find out. We’ll put ‘Young Sleuth’ on his trail. Maybe there’s a mystery about him. I’ll drop around after practice to-morrow and we’ll trail him down. Say, what about the Track Team? Thought you were going to join.”

“I was. Only—oh, I got to thinking maybe I couldn’t run very fast, after all.”

“Piffle! We’ll have another trial, then. I’ll get Gordon to hold the watch at the start and I’ll time you at the finish. What do you say? Want to try it to-morrow?”

“No, I’d feel like a fool,” muttered Perry. “Maybe I’ll register to-morrow, anyway. I dare say it won’t do any harm even if I find I can’t sprint much. What about you and putting the shot?”

“I’m going to try for it, I guess. Baseball’s no good for me. They won’t even give me a place on the Second, I suppose. Guess I’ll talk to Felker about it to-morrow. You’re silly if you don’t have a try at it, Perry. You’ve got the making of a dandy sprinter; you mark my words!”

“If you’ll register for the team, I will,” said Perry.

“All right! It’s a bargain!”

“Well?” asked Lanny.

Curtis Wayland shook his head and smiled. “He thought I was fooling at first. Then he thought I was crazy. After that he just pitied me for not having any sense.”

“I’ve pitied you all my life for that,” laughed Lanny. “But what did he say?”

“Said in order for him to let us have the use of town property he’d have to introduce a bill or something in the Council and have it passed and signed by the Mayor and sworn to by the Attorney and sealed by the Sealer and—and——”

“And stamped by the stamper?” suggested Dick Lovering helpfully.

“Cut out the comedy stuff,” said Lanny. “He just won’t do it, eh?”

“That’s what I gathered,” Way assented dryly. “And if, in my official capacity of——”

“Or incapacity,” interpolated Lanny sweetly.

Way scowled fearsomely. “If in my capacity of manager of this team,” he resumed with dignity, “I’m required to go on any more idiotic errands like that I’m going to resign. I may be crazy and foolish, but I hate to have folks mention it.”

“We’re all touchy on our weak points,” said Lanny kindly. “Well, I suppose you did the best you could, Way, but I’m blessed if I see how it would hurt them to let us use their old road roller.”

“He also dropped some careless remark about the expense of running it,” observed Way, “from which I gathered that, even if he did let us take it, he meant to sock us about fifteen dollars a day!”

“Who is he?” Dick asked.

“He’s Chairman or something of the Street Department.”

“Superintendent of Streets,” corrected Way. “I saw it on the door.”

“I mean,” explained Dick, “what’s his name?”

“Oh, Burns. He’s Ned Burns’ father.”

“Uncle,” corrected Way.

“Could Burns have done anything with him, do you suppose?” Dick asked thoughtfully.

“I don’t believe so. The man is deficient in public spirit and lacking in—in charitable impulse, or something.” Lanny frowned intently at Way until the latter said:

“Out with it! What’s on your mind?”

“Nothing much. Only—well, that field certainly needs a good rolling.”

“It certainly does,” assented Way. “But if you’re hinting for me to go back and talk to that man again——”

“I’m not. The time for asking has passed. We gave them a chance to be nice about it and they wouldn’t. Now it’s up to us.”

“Right-o, old son! What are we going to do about it?”

Lanny smiled mysteriously. “You just hold your horses and see,” he replied. “I guess the crowd’s here, Dick. Shall we start things up?”

“Yes, let’s get at it. Hello, Fudge!”

“Hello, fellers! Say, Dick, I’m quitting.”

“Quitting? Oh, baseball, you mean. What’s the trouble?”

“Oh, I’m not good enough and there’s no use my hanging around, I guess. I’m going out for the Track Team to-morrow. I thought I’d let you know.”

“Thanks. Well, I’m sorry, Fudge, but you’re right about it. You aren’t quite ready for the team yet. Maybe next year——”

“That’s what I thought. Lanny’ll be gone then and maybe I’ll catch for you.”

“That’s nice of you,” laughed Lanny. “I was worried about what was going to happen after I’d left. Meanwhile, though, Fudge, what particular stunt are you going to do on the Track Team?”

“Weights, I guess. Perry Hull’s going out for the team and he dared me to. Think I could put the shot, Dick?”

“I really don’t know, Fudge. It wouldn’t take you long to find out, though. You’re pretty strong, aren’t you?”

“I guess so,” replied Fudge quite modestly. “Anyway, Felker’s yelling for fellows to join and I thought there wouldn’t be any harm in trying.”

“‘And for many other reasons,’” murmured Way. The others smiled, and Fudge, with an embarrassed and reproachful glance, hurried away to where Perry was awaiting him in the stand.

“Fellows who read other fellows’ things that aren’t meant for them to read are pretty low-down, I think,” he ruminated. “And I’ll tell him so, too, if he doesn’t let up.”

“Don’t you love spring?” asked Perry as Fudge joined him. “It makes——”

Fudge turned upon him belligerently. “Here, don’t you start that too!” he exclaimed warmly.

“Start what?” gasped Perry. “I only said——”

“I heard what you said! Cut it out!”

“What’s the matter with you?” asked Perry. “Can’t I say that I like spring if I want to?”

“And what else were you going to say?” demanded Fudge sternly.

“That it makes you feel nice and lazy,” replied the other in hurt tones.

“Oh! Nothing about—about the birds singing or the April breeze?”

Perry viewed his friend in genuine alarm. “Honest, Fudge, I don’t know what you’re talking about. Aren’t you well?”

“Then you haven’t heard it.” Fudge sighed. “Sorry I bit your head off.”

“Heard what?” asked Perry in pardonable curiosity.

Fudge hesitated and tried to retreat, but Perry insisted on being informed, and finally Fudge told about the “Ode to Spring” and the fun the fellows were having with him. “I get it on all sides,” he said mournfully. “Tappen passed me a note in Latin class this morning; wanted to know what the other reasons were. Half the fellows in school are on to it and I don’t hear anything else. I’m sick of it!”

Perry’s eyes twinkled, but he expressed proper sympathy, and Fudge finally consented to forget his grievance and lend a critical eye to the doings[66] of the baseball candidates. They didn’t remain until practice was over, however, for, in his capacity of “Young Sleuth,” Fudge was determined to unravel the mystery of the cowboy-pianist, as he called the subject for investigation. The afternoon performance at the moving picture theater was over about half-past four or quarter to five, and a few minutes after four the two boys left the field and went back to town. Fudge explained the method of operation on the way.

“We’ll wait outside the theater,” he said. “I’ll be looking in a window and you can be on the other side of the street. He mustn’t see us, you know.”

“Why?” asked Perry.

“Because he might suspect.”

“Suspect what?”

“Why, that we were on his track,” explained Fudge a trifle impatiently. “You don’t suppose detectives let the folks they are shadowing know it, do you?”

“I don’t see what harm it would do if he saw us. There isn’t anything for him to get excited about, is there?”

“You can’t tell. I’ve been thinking a lot about this chap, Perry, and the more I—the more I study the case the less I like it.” Fudge frowned intensely. “There’s something mighty suspicious about him,[67] I think. I wouldn’t be surprised if he’d done something.”

“What do you mean, done something?”

“Why, committed some crime. Maybe he’s sort of hiding out here. No one would think of looking for him in a movie theater, would they?”

“Maybe not, but if they went to the theater they’d be pretty certain to see him, wouldn’t they?”

“Huh! He’s probably disguised. I’ll bet that mustache of his is a fake one.”

“It didn’t look so,” Perry objected. “What sort of—of crime do you suppose he committed, Fudge?”

“Well, he’s pretty slick-looking. I wouldn’t be surprised if he turned out to be a safe-breaker. Maybe he’s looking for a chance to crack a safe here in Clearfield; sort of studying the lay of the land, you know, and seeing where there’s a good chance to get a lot of money. We might go over to the police station, Perry, and see if there’s a description of him there. I’ll bet you he’s wanted somewhere for something all right!”

“Oh, get out, Fudge! The fellow’s a dandy-looking chap. And even if he had done something and I knew it, I wouldn’t go and tell on him.”

“Well, I didn’t say I would, did I? B-b-but there’s no harm in finding out, is there?”