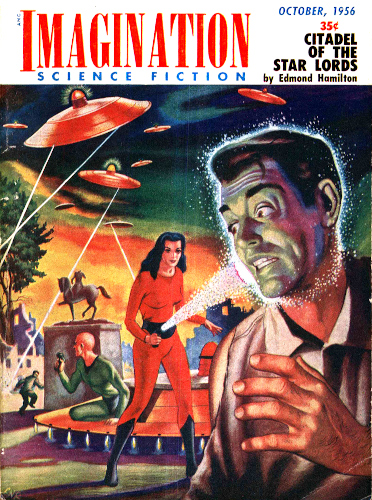

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Citadel of the Star Lords, by Edmond Hamilton

Title: Citadel of the Star Lords

Author: Edmond Hamilton

Release Date: July 9, 2021 [eBook #65813]

Language: English

Produced by: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Out of the dark vastness of the void came a

conquering horde, incredible and invincible,

with Earth's only weapon—a man from the past!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

October 1956

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

As he gunned his plane northward through the night, Price thought of the roller-coaster when he'd been a kid, of how you went faster and faster until you hit the big plunge.

Well, he was on the big plunge now. And what would end this roller-coaster ride—prison, or escape, or a crash? It had to be one of those.

He was to remember that, later. He was to think later that it was well he didn't dream the fantastic fate he was really racing toward....

He looked down, and there was only blackness. The deserts of California and Nevada are dark and wide, and he was keeping well away from the airways beacons and the main highways.

He kept the Beechcraft as high as he could. He was flying without lights, but with what they already had against him, that minor infraction wasn't important. He kept looking back, expecting every minute to see the red-and-green winglights of Border Patrol planes coming up on his tail.

If he was lucky, if he slipped them long enough, if he crossed north without being sighted by the passenger planes that shuttled between Las Vegas and Los Angeles, he might just make it to Bill Willerman's and get the Beechcraft under cover. If—if—if—

There was another if, Price thought bitterly. If he'd had any brains, he wouldn't be in this spot at all.

He turned on the radio. He flipped the dial around, getting loud music from a Vegas hotel, then a political speech, then more music—and then a news broadcast. As he'd expected, he was at the top of the news.

"—so that even while Arnolfo Ruiz, firebrand revolutionary exile, is under arrest by Mexican police, United States authorities are conducting an intensive air-dragnet search for the American pilot who smuggled Ruiz across the border. That unknown pilot is known to have returned across the border an hour ago, and police of three states have been alerted.

"The AEC announces that its next test will be that of an experimental small new H-bomb whose effects will be studied for—"

Price savagely cut the radio. He damned the announcer, and Ruiz, and himself. Most of all, himself.

He'd acted like a halfwit. Because a smooth talker had given him a phony story about a secret business trip, he had smuggled the most dangerous trouble-maker in the hemisphere down into a friendly republic. Who would believe he hadn't known? He had done it, and pressure from Washington would make sure that he got full pay for his folly.

He might as well look the truth in the face. If it hadn't been this, it would have been something else. He'd been playing the fool for years, ever since Korea. Other fliers had come home from there and taken up their jobs again, but a job had been too dull for him; he'd drifted along with the fast-buck fly-boys out for fun and excitement, hauling hunting and fishing parties, spending the profits in bordertown bars, going broke and starting over again—and now finally this. His roller-coaster ride was about over.

It would be over for good if he didn't reach Willerman's ranch before daylight. Bill would hide the plane for him. He'd saved Bill's neck a couple of times in the old days, and he could depend on him. But he had to reach him, first.

He saw the glow in the sky that came from the lights of Las Vegas, and he kept warily wide of it. He looked back again. No Patrol planes yet. As he rushed on, Price began to feel that he was going to make it.

Then, suddenly and disastrously, everything happened at once.

He saw lights on the ground ahead—an oddly scattered pattern of lights too thin to be a town, too wide-spread to be a ranch.

At the same moment, two fast jets screamed down from the upper darkness and nearly tore his wings off. They curved around for another pass at him.

"Air Force planes!" thought Price. "Hell, that tears it—"

It seemed crazy that the government was that hot to catch him. But the jets were making another lightning pass to him, trying to scare him, to force him down.

He had less than a chance in a million to lose them, and he knew it. But he was going to be a long time in jail, and he might as well give them a run for it. Just possibly, the slower Beechcraft could get away in the dark the next time they overshot him.

He gunned the plane wide open, rushing high over the scattered lights. And then, incredibly, he was free of his pursuers. He looked over his shoulder and saw them drawing back.

It didn't make sense. Why would they suddenly draw back? Anyway, with those jets off his tail, he still had a chance.

Price looked down. Among the lights down there he saw lights on a queer steel tower. He'd seen pictures of a tower like that somewhere. It wasn't an oil-rig, but something he couldn't remember.

And then, suddenly, he remembered, and a terrible coldness choked him and his flesh flinched as he saw a door into nightmare opening.

That tower, and the announcement of a new H-bomb test, and the distance he was from Vegas, and the way those frantic jets had drawn back....

"Oh, no," said Price. "Oh, no, oh no, oh no—"

He was still saying it when the bomb went off and the universe cracked wide open under his racing plane.

CHAPTER II

The cataclysm that hit Price was without light or sound. That, when he thought of it later, was the most awful feature of it.

He felt a shock, but not the shock of ultimate annihilation he expected. This was a shuddering impact as of the plane, himself, hitting some barrier and forcing through, a rending, tearing, dizzying thing that was like no sensation he had ever experienced.

He yelled, naked terror forcing the air from his lungs. His weight flung against the straps, and he knew from that that the plane was in a spin. Mechanically, his hands reached to the controls. He levelled off....

But he wasn't dead. He was alive, undestroyed, and how could that be if the raving energies of a hydrogen bomb had been unloosed beneath him?

Price's mind was a mad turmoil. What had happened?

He had blundered right over the bomb test-area, right over the bomb-tower. And the jets guarding the area had tried to stop him. Probably, if his radio hadn't been off, he would have heard them screaming frantic warnings to him.

But had the bomb really gone off? If it had, he would surely have been instantly annihilated.

He hadn't been. He was alive. The plane was ticking along through the night. The instruments functioned.

But something terrific had happened. That ghastly, wrenching shock that had seemed to outrage the very atoms of his body—his flesh still crawled with the memory of it. Something had happened. But what?

Price couldn't think. The mind just could not grapple with a thing like this. He sat, mechanically touching the controls, and the Beechcraft roared on and on.

Gradually, his mind came alive. He shakily swung the plane around. He was going back to Las Vegas. Right now, arrest and prison looked good to him compared to what had happened, or nearly happened.

If he hadn't been so tensely trying to escape, he thought, he would have remembered about the bomb-tests coming up. There had been newspaper stories. Guarded stories about a radical physical effect detected during explosions of the new-type H-bombs, and mention of elaborate preparations being made to study these unusual effects.

Price's thoughts leaped suddenly. He recalled a scientist's statement that the center of explosion of the new-type bomb might be like the eye of a hurricane, a focus of inconceivable forces but affected in a radically different way by those forces.

Had the bomb gone off under him, then? Had his plane and himself, at the "eye" of the tremendous explosion, been hurled somehow through spatial barriers into safety before the light and sound and destruction could even reach him?

It seemed an insane speculation. Yet everything about this was insane. He would be himself, if he didn't get down to Earth soon.

He could not see the glow of Las Vegas anywhere in the night. He cut his radio in and spoke hoarsely into it.

"Beechcraft 4556 calling Las Vegas Airport! Come in, Las Vegas!"

There was no answer. The radio seemed operative—but when he turned the receiver dials, not a sound came out.

"Knocked out," Price muttered. "And no wonder, if—"

He couldn't finish the thought, it was too soul-shaking a thing to speculate on, the thing that might have happened to him.

He curved the plane around, looking for highway lights, for an airways beacon, anything.

Nothing. Nothing but the darkness and the stars.

A little frantically, he swung the plane around and started eastward again. He must have missed Las Vegas. But if he kept going east, he'd surely cut the main highways. There were always lots of cars on them at night, in the summer.

He flew on and on. And the darkness continued. No lights at all, not even the glimmer from a lonely ranch.

Nothing.

He would have landed, gladly now, but he did not know where he was or what was under him. The Beechcraft was equipped with extra fuel tanks for long flights away from any source of supply, and they had been full when he started. He could fly a long time yet.

He flew.

After a while he began to think that there was only one explanation. He was dead, and flying in limbo.

And limbo, it seemed, went on forever.

Finally, after many hours there began to be a light in the blackness ahead of him, and his heart leaped up, thinking that at last he had raised the glow of a big town. But it was only the dawn. He watched it creep cold and gray across the world, and now he understood that he was alive. But he was not cheered. Now he could see what was underneath him.

Forest. Rolling like a dark green sea from north to south, from east to west. He had left the desert far behind. He figured that he was over Missouri now, and there should have been towns, villages, farms, cultivated fields.

There was forest.

The light turned rosy, then golden. The sun sprang up and it was day. Far ahead the Mississippi gleamed. Price sent the Beechcraft at full throttle, toward St. Louis. He could not see any smoke from the great complex of city and industry that sprawled there over both banks of the river, and he could not see any bridges. But St. Louis had to be there.

It was. But it had changed since he saw it last. The high buildings were brought low, and the low buildings were mounds, shells covered with brush and fox-grape, and trees grew in the public streets and through the broken windows. The river, vast and placid, was empty except for a floating log. Obstructions along the shores might once have been docks, but were so no longer. And there was a great stillness.

For one wild moment Price thought, The bomb did it last night, the new-type bomb with energies they didn't even dream about. Then he realized that that was hardly possible. You can destroy a city with an H-bomb in a matter of seconds, but you can't grow an oak tree sixty feet high in the rubble of the City Hall in much under a century.

Time had passed since last night.

This was too much to take in all at once. Price didn't even try. He looked for a place to land, but there wasn't any, so he kept on flying, eastward across the river.

Time had passed, and he had passed with it. Slowly it began to come to Price, the dreadful and incredible truth of what had happened. The wrenching, tearing shock he had felt in the eye of the blast was not physical but temporal. The uncomprehended powers of the bomb had been mightier than anyone had guessed. They warped the ordered fabric of the space-time continuum itself, and acting on the matter of himself and his plane at the "eye" of the explosion, had warped them too—into the future.

The Beechcraft went droning through the empty sky. Price looked down on desolation, green and peaceful and as unproductive as it had been before men ever came with axe and plow to tame it.

How far in the future?

He did not know.

Were there still men, surviving somewhere in this wilderness? Or had humanity destroyed itself in a final act of atomic madness? Were all the cities dead and dust?

He did not know that either.

He only knew that he was too numb and exhausted to go much farther. He had to have water and food and sleep. He had to have a place to land.

He found it well beyond the river, a natural prairie in the midst of trees. He tried to gauge the way the wind was blowing by the ripple of the grass, and then he circled in a long curve to the north to head it. As he did so he thought he saw an iron glinting to the northeast, something very vast and strange as of the sun reflecting from a face of metal mountain-high and wide. Then he dropped low over the tree-tops, and whatever the glinting was he could not see it any more.

The Beechcraft bumped and bounded to a stop. Price sat for a moment watching his hands shake on the controls, and then some last measure of caution made him taxi the plane back, to the extreme edge of the prairie and nose it into the wind, ready to take off again with no delay.

He had a sporting rifle and revolver in the plane. He buckled on the revolver, stuffed his pockets full of cartridges for the rifle, and climbed down to the ground. He stood for several minutes in the shelter of the plane's wing, looking around, but he could not see any signs of life except a pair of crows flapping over his head with rusty cawing. It was late summer, and the wind was dry and hot. He began to walk toward the woods.

He looked a little dazedly, as he walked, toward the northeast. What was it, the incredible iron vastness he had glimpsed far away there?

About thirty yards from the plane Price stopped suddenly, his heart pounding and a sudden sweat breaking on his skin. The grass was trampled here in an irregular circle, with scars of bare earth ripped in the ground. There was a large quantity of blood, scarcely dry. A wide flattened track led to the woods. Something had been killed here, something big, like a horse or a cow, and the carcass dragged in among the trees.

Men. Hunters. An animal would have devoured its kill where it lay.

But what kind of men?

Price stood half crouched over the bloody ground, his rifle ready, looking this way and that and seeing nothing. The hot wind went running over the prairie and the encircling trees bowed to it and tossed their branches, but there was no other motion, no other sound. Even the crows had gone.

Price shouted. "Hello! Hello! Is anybody there? I'm lost. I need help. Hello!"

His voice was shocking in the stillness, loud and impolite.

There was no answer.

He went on down the flattened track toward the trees. He was afraid, and desperately tired.

"Hello?" he said, and now his voice was pleading. "Please. Where are you? Help me—"

Help me, you men of an unknown future, you hunters in impossibility, you lurkers in nightmare. Help me, or I die.

The shadows were heavy under the trees. The prairie grass did not grow here, but there were briars and other things to show a crushed trail. It was not a long one. He saw the carcass lying in a little glade. It was a black-and-white cow, already partially butchered. He moved toward it, and then from the branches overhead and the underbrush on either side short ropes of braided leather came flying, weighted at their ends with stones. Price fell down helpless and floundering, painfully bruised, his arms and legs wrapped in the tough bolo-like ropes, and one around his neck cutting off his breath so he could not even cry out.

In a swift and furious rush six men sprang from among the trees and stood about him. One snatched his rifle, another his revolver. They wore sketchy garments of tanned leather, and they were as dark and wild as the Shawnees and Wyandots who had hunted these woodland prairies long ago, except that some of them had light hair and all of them were bearded.

One of them, a tall lean wide-shouldered man with a shock of sun-bleached brown hair and eyes more blue, more blazing and filled with hate than any Price could remember seeing in his life, crouched beside him and tore the strangling rope ungently from his neck. Price tried to speak, but before he could do more than gasp for breath the brown-haired man whipped out a knife and drove the point of it straight for Price's throat.

"Now," he said, "you star-spawn—we'll see if your blood is any redder than the kind we breed on Earth!"

The steel bit hard. Price screamed.

CHAPTER III

The brown-haired man withdrew the knife with a nice dexterity, its tip reddened for perhaps a quarter of an inch. Price looked at it and at him in dumb horror. The six wolfish faces collected in a close circle above him and peered down, smiling.

"It's the same color, Burr. Who'd have thought it?"

"Just blood. Hah! And I always thought they'd bleed hard and shiny, like quicksilver."

"Stick him again, Burr."

"I wish we had time," said Burr, and licked his lips with a red tongue. "But they know where we are." He sighed and raised the knife again. "We got to get out of here. Fast."

Price found his voice. "For God's sake," he cried. "For God's sake, what are you doing? I ask you for help, and you—" He struggled furiously against the ropes. "You haven't any right to kill me. I haven't done you any harm."

"Star-spawn," said Burr softly, using that word for the second time. He prodded Price above the belt with the knife-point. "If I had time I'd do this slowly, very slowly. Be glad we don't have time."

"But why?" Price shouted. "What for?" He glared up at the circle of hairy faces. "I only got here today. I couldn't have done anything to you. I came from—"

From yesterday? A hundred years ago? Through time? Tell them, and ask them to believe it. Maybe they will. I don't.

"—from the West," he said. "From Nevada. I haven't anything to do with stars."

Burr laughed. He raised the knife. But another man, with a shrewd dark eye and gray hairs in his beard, caught his wrist.

"Wait a minute. Look at his hair. It's as dark as mine."

"Dyed," said Burr. "Look at his clothes. Look at the flier he came in, at his weapons. Look where he is—in the Forbidden Belt. If he isn't from the Citadel—don't be a foolish man, Twist. Let go."

"Why would he dye his hair to look like a human and then come to us in a flier? Is that reasonable? Now hold on, Burr. You hear me? There's a way to tell."

Burr grumbled, but he relaxed, and Twist let him go. He caught Price by the collar and dragged him into the glade by the butchered cow, where the sunlight fell in strong shafts. Then he rolled Price's head back and forth, studying it with intense interest. The others looked over his shoulder.

"His eyes are dark too," said Twist. "You can't dye eyeballs. And look here. See that, Burr? Feel it. He's got the sproutings of a beard. Now we all know the Starlords don't grow hair on their lovely faces."

"Hey," said the others. "That's right. Twist is right."

"Of course he's right," said Price. "I'm human." He knew that much. The rest of the talk was a mystery, but that didn't matter. Not right now. "I come from the West. I'm a friend."

Burr looked sullen. "Humans don't fly. Only Starlords do that."

"Maybe he's a collaborator?" said a yellow-haired boy, all bright and eager, and Burr smiled again.

"Maybe. Anyway, he's none of us. Stand by, Twist."

But Twist did not stand by. He faced the others in fatherly anger at their stupidity.

"You're almighty anxious for a killing Burr. Now what's the Chief going to say when we come back and tell him that a human man came in an airplane, and asked us for help, and we stuck him like a pig and left the plane for the Star Lords?"

For some reason the word "plane" sobered them down and made them thoughtful. Twist pressed his advantage.

"You've all seen the old pictures. You know this flier isn't from the Citadel. It ain't the same shape and it don't make the same noise. It's a plane. Maybe the last one on Earth, and this man knows how to fly it. And you want to cut his throat?"

There was a short silence, during which Price thought he could hear the drops of sweat trickling down his forehead. Then Burr said, without rancor,

"I guess you're right. We'd better take him to the Chief."

"All right," said Twist. He crouched down and began unwrapping the bolo ropes. Price said, "Thanks." It seemed a very small word, and inadequate. Twist grunted.

"If you prove out to be a collaborator," he said, "you'll wish I'd let you die an easy death."

"I'm not," said Price. His brain had been working with abnormal speed. "This is an—an old plane. The papers are still in it. It's been kept hidden, except—" He groped desperately for explanations. "It's a tradition in my family to fly. We're taught, father to son."

That was true enough. Price's father had taken to the air in World War I, and for years afterward had run a flying service. The rest of it he had to play by ear, and God help him if he guessed wrong.

Twist helped him to his feet. "Now," he said to the others, "I want to know what about that plane."

"Get it under cover," Burr said. "Hide it."

"We might do that," Twist said. "And the first flying-eye that happened along would find it. They do more than see, you know. They smell, too. They smell metal, if it's much bigger than a knife." He held out the stone-weighted ropes and shook them. "That's why we use these when we hunt in the Belt. Remember?"

"Now, there's no call to be jeering, Twist," said Burr. "If you got a better idea, we'll listen to it."

"Fly it out," said Twist sharply. "How else are we going to get it to the Chief? On our backs? Cut up and packed on the horses? No." He turned to the man who had taken Price's pistol. "Give me that, Larkin. And you, Harper, hand that rifle to Burr. Larkin, you're in charge of the party. Get the beef back to the camp, and as soon as you've smoked it load up and head home. Keep an eye out for trouble—this is liable to poke up the Citadel like you'd poke a beehive."

Larkin, a short powerful man with a curly poll like a certain type of bull Price had once seen, asked in a mild high voice, "Where are you and Burr going?"

Twist pointed a thumb sky-ward. "Up there," he said, and his eyes shone with excitement. He looked at Burr and grinned.

Burr was scared. It showed in his eyes, in the way his mouth tightened. But he wouldn't say so. Instead he reached out and grabbed Price by the shirt and shook him fiercely.

"There'll be a gun at your head every minute, and don't you forget. You do anything wrong, and you're dead."

Price forebore to explain what would happen to Burr and Twist if they shot him in mid-air. He only nodded and said,

"Don't worry. I'm as anxious to get to your Chief as you are." He took a deep breath and plunged. "That's what I came for."

Burr said, "You're a long way out of your way."

"This is new country to me. I got lost."

You don't know how lost. You don't know how alone.

"Come on," said Twist. "There's been too much yattering already."

He led the way back to the edge of the trees. Price and Burr followed him. The others were already working on the carcass. Presently they were hidden from sight. At the verge of the prairies the three men stopped and examined the visible world before they left cover. Price looked around and did not see anything and was ready to go on. Burr and Twist not only looked at earth and sky, they sniffed the wind and seemed to feel the quality of the air, like animals.

Twist gave a kind of shrug and said, "Well, we're in it now, whole hog." He began to run through the long grass toward the plane. Burr went fleetly after him. Price, oppressed with many things of which physical exhaustion was the least, ran heavily behind them.

When they were within perhaps fifteen feet of the plane a glittering thing came over the tops of the trees and hesitated, making a couple of short spirals in the air. Then it centered over the plane and hung there, high above. It was a disc-shaped object maybe three feet across, with a big lens on its underside.

Twist and Burr had stopped. Price came panting up to them. They were looking up at the disc, and Price saw in their faces a wild mingling of rage and hate and the despairing fear of men faced with an enemy that no amount of bravery or physical strength can prevail against.

"What is it?" he asked, and Twist said hoarsely,

"You must be from a long way west if you've never seen a flying-eye." His hands dropped to his sides. "Well. That's finished."

Burr began to curse at the thing. He looked as if he wanted to cry.

"What will it do?" asked Price.

"It'll hang there, right where it is, to guide the fliers from the Citadel. They can see us here where we stand, right now, in the Citadel." Burr's face was getting whiter by the second, like a man who has been stung by some venomous thing and realizes that in this present moment, between strides as it were, he must die. "They'll be starting. It's forbidden to come into the Belt. They'd kill us for that alone. But with the plane—God knows what they'll do."

"We can try and dodge them in the woods," said Twist, without hope. "Come on."

He started away, but Price said, "Can't we outfly it?"

"The flying-eye? It'll follow us like a hungry hound."

Some kind of television-scanner, Price thought, with a metal-detection unit and a signal relay to alert the main control in the Citadel. And what was the Citadel, and who or what within it was now watching him as he stood, and preparing for his death?

He said, catching the sudden terror from the others, "Shoot it down."

"Shoot it?"

"Smash the lens. Then it can't see us. Here, give me the rifle."

Burr said, "You crazy? No gun will carry that far."

"What kind of guns have you got?" said Price. "Damn it, give me the rifle."

Twist said, "Let him have it."

Price was a good shot. Not brilliant, just good. But today he was phenomenal. He blasted the lens and whatever insides there were behind it as fast as he could pump the cartridges into the chamber and fire them. He didn't miss once. And the disc flopped and slipped and crashed down sideways in the woods.

Price leaped for the plane. "Come on," he said.

The others were staring at him, with their jaws hanging open. "Did you see that? Did you see that gun?"

"Come on," Price yelled, "or I'm going without you!"

They tumbled in. Price started the motor, gunned it savagely, and took off as though the devil was on his tail. One of the men, he didn't know which, yelled out in sheer fright, once. Then they were clear of the tree-tops and climbing fast.

Price looked over his shoulder, and once again he thought he saw that dark metallic gleaming in the northeast.

"Which way?"

"Back across the river. And then," said Twist slowly, "I don't know. They've seen the plane. They'll come looking for it, and the first place they'll look is the Capitol, and after that the villages. They'll find it if it's anywhere near, and you can figure what they'll do to the people. They let us have our guns and our hunting knives, so we can kill game and even each other if we feel like it, but artillery, no. Explosives, no. And planes, no, no, no. Especially not planes. I don't suppose there's been one in the air for almost a century."

Twist shivered, his eyes shining, his hands gripping the seat.

"I'm glad I got to do this before I die. It's—" He fumbled for a word and gave up. "I can't say. But it makes you think what we were once, what we could have been today if it hadn't been for them." And he jerked his head back to indicate the direction of the Citadel. "The star-spawn. The damned Star Lords."

Burr looked out the cabin window. "It's an awful long way down." Then he asked Price, "Why'd you say you came to find the Chief?"

A suspicious man, Price thought, and so is Twist. Careful, careful. But how can you be careful when you don't know what's going on in the world, and you don't dare ask?

Price said, "I came to give him the plane. I'm the last of my family. I wanted to join up with somebody, and—there aren't many in the desert." This, he thought, was a safe assumption. "Life's too hard. I wanted to come where there are trees and water."

It was a good story. He didn't know whether they believed it.

The Beechcraft left a fleeting shadow on the river and passed on. Twist peered anxiously into the sky behind.

"Can you go any faster?"

"I'm wide open now."

"Not fast enough. They come like lightning. Whoom!" Jets, thought Price, and began to look for a hole in the forest. Twist said, "And if they don't find us the first time, they'll send the flying-eyes."

"And they can smell metal," Price said. "So we've got to find a place away from any town and not only out of sight from above but also screened from a magnetic detector. Say in a cave, under a rock ledge, or close to some heavy concentration of metal they're already used to. Can you think of any place?"

There was a total silence, and he realized that they were looking at him with cold and bitter eyes.

"How do you know so much?" asked Burr.

"Isn't it obvious?" said Price impatiently.

"Not to us. What's all this about magnetic detectors and screens—and where did you learn it if you're not working for the Citadel?"

Twist laid the muzzle of the revolver casually against his neck.

"I wouldn't shoot me now," said Price, and explained why, very quickly. "Besides, that's a hell of a way to act. Just because I happen to know a little elementary science—how else do you suppose the flying-eyes find metal? By some supernatural method?"

"Hm," said Twist, and withdrew the revolver. "Maybe he's right, Burr. After all, we're hunters. We never studied much into those things." Burr grunted derisively, but he sat still, apparently convinced that there was nothing to be done about Price now. Twist thought hard for a minute. Then he said, "I know a place. There's a kind of a secret cave there, and room enough for you to land, I guess, figuring by what you took before."

He squinted out the window, confused by the differentness of how things looked from above. But finally he picked out a direction and told Price, "There."

After some low-level circling and searching Price found the place, a fairly flat stretch of bottomland in a little valley, beside an overhanging wall of granite. Twist's estimate of the room was hardly generous, but he made it, and taxied over bumpy sod as close as he could to the cave-mouth Twist pointed out. Then he sent the others to clear away some rocks and dangling creepers, and with a final heave and roar he managed to lurch into the cave itself. He cut the motor. He had about four hours' flying time left in the tanks.

He got out of the Beechcraft and dragged stones under the wheels to chock it. Then he helped Burr and Twist rearrange the hanging vines over the entrance.

A high shrill screaming in the sky gave them less than ten seconds' warning. They ducked back under the overhanging ledge and peered motionless from under it. And Price saw close above him, skimming the rolling land like an eager hawk, an ovoid craft that was not like any jet he had ever seen, wingless, leaving no trail, but tearing with a mighty shriek of power through the sky.

CHAPTER IV

Trapped in a strange dream, Price looked down from the forested ridge into a shallow green valley. Burr pointed and said,

"There it is. The Capitol of the Missouris."

He said it with pride. He and Twist had talked of this place, in the two days since they had hidden the plane and headed north. And they had talked of it proudly. Their home, the city of their people, the focus of a shadowy government that ruled the forest-lands which once had been two great states.

Price looked at it, and he felt pity. Pity, and a wrenching regret for what the world had once been, and what it had become during the lost years.

In the valley, straddling a clear little river, lay a half-dozen streets of wooden houses and workshops and smithies. The buildings were neat enough, of massive squared timbers. But the streets were unpaved and dusty, and their only traffic was loaded wagons from the surrounding tilled lands, and pack-horse trains from the forest trails, and men, women, children in drab leather and wool. A faint sound of creaking axles drifted up through the drowsy afternoon air.

"The Capitol of the Missouris," Price thought. "And oh God, why did it have to happen to our world?"

He had listened, on the way here, to everything Burr and Twist said. Bit by bit, the jigsaw fragments of information had fallen into place, and a few casual questions had completed the apocalyptic picture.

It had happened long ago in the lost years, the years that Price had been hurled through. As near as he could make out the date had been 1979, sixty years ago.

That had been the year of doom. That had been the year when they had first come from outer space.

The Star Lords. The Vurna, as they called themselves. The accursed star-spawn, as men called them. Their tremendous cruisers had come out of the blue, had poised above the Earth, and then had struck.

Every city, every big town, every atomic power-plant, every arsenal, every important bridge, viaduct, dam and factory. In one week of holocaust, they had been smashed by the remorseless cruisers that went round and round the planet. Millions died, that week. And the Star Lords' cruisers went away.

Quickly, they had returned. This time, not to destroy but to seize. What had been the fat, smiling lands of Illinois and Indiana, they had made their domain. In it, they built their Citadel.

The Citadel was a fortress, a city, above all, a base. The Star Lords contemptuously refrained from attacking the dazed Earth peoples who had been thrown back to near-primitive conditions. To the lords of the Citadel, Earth was only the site of an important base. Or so they said.

Was it any wonder, Price thought, that these men of the Missouris would kill anyone, anything, from the Citadel? Just hearing of it all had kindled his own rage. These men's fathers had lived it, and they were still living it.

He looked down at the wooden town, as he and Burr and Twist went down a trail, and he thought,

"Careful, though! They still think I may be from the Citadel—Watch every word!"

Two hours later, Price sat in a wooden-walled room in the biggest of the houses, facing the Chief of the Missouris.

His name was Sawyer, and he was old. But he looked formidable as an old panther in his buckskins. His leathery face held deep pride, intelligence, and a brutal ruthlessness. Behind him stood the Chiefs of the Indianas and of the Illinois, those scattered peoples on whose lands the Citadel now stood.

Sawyer listened without a word to Price's story, and all the time Price told it he thought how thin and far-fetched it sounded. But, looking at these faces, he knew he could never convince them of the truth.

"Two days ago," said Sawyer finally, "the Vurna were here. They were almighty hot and bothered. They were looking for a plane. I never saw a plane in my life, and I said so."

He paused, his swarthy, wrinkled face brooding, and no one, least of all Price, dared speak.

He went on. "Since then, the sky's been lousy with their flying-eyes, hunting and hunting. You must have seen them."

Burr took that as an opening. "We did. We kept ducking them, all the way."

Sawyer looked out the doorway at the dusty, sunlit street and then back again to Price and he said with sudden blazing fierceness,

"You tell me you heard of us Missouris way out in your mountains, that you wanted to bring your plane to us—why?"

Price floundered. "Why, I wanted to help you—"

"To help us do what?" A garnet light was in the old man's eyes now. "What did you hear we were doing that you wanted to help on?"

Price sensed from the other's fierceness that he was in imminent danger, that something he had said had deepened suspicion.

He almost welcomed the interruption that saved him from answering now, though it was a sound that raised the short hairs on his neck.

The sound of shrieking power across the sky, the sound of the sky-hunters from the Citadel....

"That's the damned star-spawn coming down here again!" said one of the men behind Sawyer.

The old man got to his feet with amazing alacrity. He rapped an order to Twist and Burr, pointing to Price.

"Take him upstairs. If he makes a peep, cut his throat—but do it quiet."

Little more than a minute later, Price was in a hot, dusty little room. It had gun-slots in its heavy wooden shutters, and they let level bars of golden light into the room.

He heard the whine of the flier, coming down fast. He went to the gun-slot.

"No," said Burr.

Price turned and looked at him. He kept his voice low. "The hell with you," he said. "You can stand behind me with your knife. I'm not going to yell. But I'm going to see."

He heard Burr and Twist come up close behind him, as he peered out the wide slot.

Out in the green square, a white craft marked with a curious insigne was making a vertical landing. He thought it was a type of aerodyne. He had never seen one in flight, back in that strangely far-off and quickly-fading time from which he had come, but he had seen sketches and a working model. This seemed to be a refinement of the same principle, faster than a jet and maneuverable as a toy balloon. His hands itched to fly it.

He saw the insigne on its side—a golden sunburst with what looked like a many-colored, many-faceted globe at its heart. He did not know what it signified but he knew what it was. The mark of the Star Lords, of the Vurna. And even as he looked, four of them came out of the craft.

They came along the street to where Sawyer and the other Chiefs and a little crowd of leather-clad men silently waited. No one had a gun, no one made a motion. Yet that dusty street was electric with a hatred so deep and strong and quivering that it made Price shiver.

Yet the four Vurna came straight on. The Star Lords, they from unguessable spaces who had smashed Earth like a child's toy, to make it their footstool. Price pressed closer to the gun-slot. He wanted to see them very clearly indeed.

Especially one of them.

The star lords were tall and well-formed, and they looked much like Earthmen except that they wore tight-fitting garments of various colors, but all cut to the same pattern. Price guessed that they were uniforms, with the colors indicating rank or branch. The other chief difference was the coloring of the Star Lords themselves. They were bronzed as though by radiations fiercer than any known on Earth, and their hair was silver. Not white, and not pallid, but a rich silver. The men—three of the four were men—wore their hair short.

The woman wore hers long, rippling onto her shoulders. It caught the sunset light and gleamed like hot metal. Her uniform was a deep crimson, duskier than flame, molding her long thighs and her high, just-full-enough breasts.

Sawyer was speaking to them now, his voice rolling out harshly in the silence. "If you're still hunting for that plane, my answer's the same. I've never seen one."

One of the Vurna men, who seemed to have the authority, stepped a pace in front of the other two men and the woman.

The woman had raised her head and was looking restlessly at the blank or shuttered windows of the timber houses. Price felt uneasily that she knew he was there and was looking at him through the gun-slot. But that, of course, was ridiculous.

"Sawyer, listen to me," said the man of the Vurna. He spoke clear but stilted English, with strong tones of some alien tongue in its unaccustomed rhythms. He wore a black uniform with a small gold sunburst at the collar. It was impossible to guess his age. And while he kept his voice quiet and his manner calm, there was anger in him.

There was anger in Price too, a deep rage growing in him as he looked at the men and the woman who stood here like conquerors on the planet they had ruined, indifferent to the hatred they faced.

"Here is no time and no place for stubborn obstructions," the Vurna man was saying. "Things move quickly now. We have an enemy before us so vast and powerful that we dare not have one also at our backs, no matter how weak. I ask you to believe that, Sawyer. I ask you to understand that if we Vurna fall, you perish—" he made a sudden chopping gesture of the hand "—utterly."

"I ask you," said Sawyer, "to look at my white hairs, and not insult them by talking to me like I was a child." His voice was strong, and anything but servile. "You can forget that old tale of the 'enemy'. I laughed at it when I was in my cradle. There's been only one enemy seen on this Earth, and that was you."

The crowd muttered, Yes.

"Your starships," Sawyer said, "smashed our cities and broke our nation and our world down to where it is. My own father saw it happen. One day a free world, the next—nothing. So fast there was hardly even a blow struck back. You did it."

The crowd muttered louder. Price felt Burr and Twist move beside him, breathing in the dark. Breathing hate.

"Don't come to me, an old man," Sawyer said, "and ask me to believe foolishness. As for the plane you say you saw, I tell you again I haven't got it. And if I did have I wouldn't give it up to you, nor the man either. And you know it, Arrin."

The woman spoke briefly in her own language to Arrin, her tone and gesture seeming to say that they were wasting their time. Her voice was low and clear, as beautiful as the rest of her, but there was an impatient contempt in it that made Price bristle. The same thing was in her eyes when she looked at the old Chief of the Missouris.

Arrin shook his head. "Sawyer, I tell you once more, as you have been told for two generations, it was not the Vurna who destroyed your world, but the Ei. And I tell you that the Ei may even attack the Citadel, and that the fate of Earth would be decided in that battle, just as much as ours."

His voice rose suddenly in very human anger. "There is a war, you stubborn old man! A war vast—huge—" His arm swung in a wide circle that seemed to include the whole sunset sky. "Beyond your comprehension. Earth is nothing in it. A forward base, an observation post, that is all. But if we lose it, the Ei will sweep this part of the galaxy and you will regret it more than we. We can withdraw. You cannot. You think you are cruelly treated now. You will weep to have us back!"

Sawyer remained unbending and unimpressed. Arrin sighed. His voice was quiet when he spoke again, but it had a ring of iron in it.

"I feel pity for your barbarism, until I remember that it continues because of your own proud stupidity. If ever you people of Earth had been willing to work with us—but let it be. And now I warn you, Sawyer."

He seemed to grow tall, grim, alien, the spokesman of inhuman forces. Price felt the skin grow cold along his back, and his belly knotted tight with the pricking of fear.

Arrin said, "If you are planning an attack upon the Citadel, forget it. We will slaughter you without mercy—not because we wish to, but because we must—"

Price caught the sharp intake of breath from the men beside him, and suddenly he understood many things he had not understood before.

Arrin was still speaking. "I will give you three days in which to deliver to me the plane and the man who flew it. If this is not done, we will be forced to use harsher measures. You understand?"

Sawyer said, in a tone as cold as Arrin's, "Is that all?"

"One more thing. Keep your hunters out of the Belt. It is a military zone, not a game preserve. Any more incursions will be regarded as a possible invasion—"

Again Twist made a sharp, harsh sound in the darkness.

"—and we will make of it a blasted barren where not even a mouse or a beetle can survive. Consider that, Sawyer."

Arrin turned and walked away, the two men and the woman falling in behind him. Price watched the dark-crimson figure with the bright hair until he could see it no longer, and it dawned on him, as though the two things had a connection, that he was alive and living in this crazy world of Sawyers and Citadels and invaders from the stars, that these were his realities now and he had better wake up and grapple with them, or he would die—and the death would be for real, and not any portion of a dream.

The aerodyne took off with a scream and a whistle. The crowd in the square began to break up. Sawyer turned and came into the house, the chiefs and the sub-chiefs following him.

Burr opened the shutters, and a welcome breath of air came into the stifling room, with a last gleam of dying sunlight. Price looked at his companions. They were watching him, their eyes sharp and hostile.

"So that's why you were so frantic for the plane," he said. "You're planning an attack."

Burr said fiercely, "You should've let me kill him when I wanted to, Twist. And we should've left the plane where it was. Then they wouldn't have got suspicious."

"Maybe so," said Twist, and nodded. "Maybe so. On the other hand, if he is telling the truth, it might make all the difference."

There was a clattering on the loft stair, a man running up the steps. He came in and nodded to Burr and Twist.

"Sawyer says, bring the prisoner down—and hurry!"

CHAPTER V

Sawyer was standing in the middle of the room, talking rapidly to the chiefs of the Indianas and the Illinois. The Indiana chief was old and fat and lazy, but the Chief of the Illinois was young, heavy-jowled and hard-eyed, the type that is born suspicious and never gets over it.

Sawyer turned to look at Price. He was intent and wire-drawn, a man poised on the brink of great happenings, at that crucial point from which he may still choose whether to advance or retreat. Price bore his gaze steadily, and it was not easy to do, because the eyes of this tough old man seemed to be laying bare everything within him.

"But you can't take him there," said the Illinois Chief violently, looking also at Price. "The biggest secret on Earth, and if he's a spy—"

"If he's a spy," Sawyer interrupted harshly, "he'll never live to tell what he sees there."

He spoke to Price. "We're going on a journey. You're going too. And you two—" to Burr and Twist "—will guard him."

Burr and Twist nodded silently, and got their guns. The rifle and revolver had been handed over to Sawyer for safe hiding, and these guns were the clumsy, short-range bolt-action rifles of their own handcrafting.

Price said, "This is a hell of a way to treat a man who comes to you as a friend. I hate the Vurna as much as you do, for what they've done to Earth, and—"

Sawyer stopped him, saying ominously, "Save your words, you'll need them later. We've got a hard ride before morning. Let's go."

They all went out through a back door, except the old chief of the Indianas who was not going. In the twilight outside, there were horses ready.

Sawyer and Oakes of the Illinois led off, and Price followed with Burr ahead of him and Twist behind him. One man rode ahead of the whole party with a lantern made to shine down but not up. The flying-eyes watched of night, too.

The six horses went all night at a steady pace, single file along a narrow track that dipped and wound through the forest. Price felt sure, from what he had overheard, that they were riding toward some great secret council. He guessed that his fate would be decided there, and probably the fate of the rest of mankind too.

There was nothing he could do about it till he got there. Meanwhile he thought about a long-thighed girl in crimson, with her bright hair swinging on her shoulders as she walked. He wished he could have had a closer look at her face. It had seemed beautiful, a clear forehead and a fine chin, but it was the eyes that told you what a person was, and he had not been able to study them. Could she be as heartless as all the Vurna were supposed to be?

He thought she must be. His hate of the conquering Star Lords was rapidly growing. Before they had come, this dark, wild forest he was riding through had been rich farmland and pleasant towns. And when they had smashed all that, and built the Citadel to hold the ruined Earth, they had tried to make men willing captives by telling them that story of the Ei. It was the old Big Lie technique, but this lie had been too big for anyone to believe.

The woman might not be cruel. Arrin might be only a decent officer in a hard position. But all the same, they were aliens, despoilers of Earth, and he was an Earthman. These were his people—Sawyer, Burr, Twist, even the hateful and suspicious Oakes. These were the ones he would fight for, and with.

If they let him.

But they had to let him. He was the man with the plane. And as he rode wearily through the dark, he thought he knew the argument to use.

Just before dawn, when the world was at its blackest and most silent, there was a challenge in the woods ahead, and the man with the lantern answered. Here and there among the trees other shielded lanterns flickered, widely scattered, and the woods were full of quiet sounds, the creak of leather and jingle of bridle-chains, the soft thump of hoofs, the somnolent blowing of picketed horses. What men there were spoke in low voices.

Price's party dismounted and walked quietly among the picket lines. In a few minutes they reached the edge of the sheltering woods. The man with the lantern gave a low whistle, and another man materialized out of the blank dark ahead.

"This way," he said. "And watch your foot."

Now the man with the lantern followed him, the others coming after in Indian file. And Price began to see that the darkness was not as blank as he had thought. There were pale areas that gathered the faint starlight to themselves on flat, broken surfaces. He realized presently that these were walls, or had been once, and that he was walking on the shattered fragments of a city street. The feel of gritty concrete was unmistakable.

They went for quite a long way, apparently on some known path through the ruined city, and the sky began to pale before they reached their destination. Price could now make out the ghostly looming of building-fronts on both sides, high fronts with nothing behind them, so that the window-holes looked like a kind of elaborate pierced-work. It was deathly still, so still that their own breathing and the stealthy padding of their feet woke furtive echoes from the stone.

Their guide stopped beside a small black hole no different from all the other small black holes that lurked under fallen masonry and flattened girders. "Down there," he said, and left them.

They climbed down a wide steel stairway, bent and twisted, but mostly intact. A great wave of warmth from close-packed and steaming humanity rolled up the stair to meet them, mingled with the smells of candle-grease, smoke, leather, sweat and the lingering overtones of horse.

Beyond the bottom of the stair there was a comparative blaze of light. Price knew they were in the basement of what had been a public building or department store, a space foreshortened by a mass of rubble and hanging steel where part of it had caved in. It was crammed with men, and their voices growled in that low enclosed space like the growling of a great animal too long caged.

There was a small group of men sitting somewhat apart, and Sawyer joined them, with Oakes. Chiefs, thought Price, and realized that this was a very big council indeed, and planned for long ahead. Burr and Twist stood close on either side of him, but he forgot them for the moment, looking around in fascination at these his countrymen.

Forest-runners and hunters, like Burr and Twist, in greasy buckskins. Men from the lower river, from the swamp and bayou country, soft-spoken, hard-handed, dressed in coarse cotton dyed in bright Indian colors, yellow and red and green. Gaunt hill-farmers in hickory homespun, with their rifles between their hands. Boatmen down from the northern lakes, with a faint smell of fish about them, and long lean riders up from the southwest, leather-skinned and dangerous as rattlesnakes. Men from the black cornlands of Iowa, following their chief to talk of war. America, Price thought, basically unchanged, basically recognizable, but with all the fat sweated off it and all the luxuries stripped away, fined down to the ruggedness and strength of an earlier day, when men like this made a nation out of a wilderness.

He had a feeling they could do it again, in spite of the overwhelming power of the Star Lords. And if they couldn't, they would go down fighting like wildcats to the last.

The Chiefs were talking among themselves. Twist knew some of them, leaders of the Iowas, the Michigans, the Arkansas, the Mississippis. Others they could guess at, Nebraska, Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana. The two Missouri hunters were as excited as hounds before a hunt. Twist said there had never been a council this big in his memory. It would go on until the issue was decided, the men staying under cover in the ruins, the horses hidden in the surrounding woods.

Price realized suddenly that the assembled chiefs were all looking at him with an intense and largely hostile interest. Sawyer's news seemed to have upset them badly. The Chief of the Michigans, a huge black-bearded man with an enormous voice, bellowed suddenly for silence. In seconds the place was absolutely quiet, except for the shuffle of men closing in to see and hear a little better.

"Sawyer of the Missouris has something to tell you," shouted Michigan. "You listen hard. Because what he's got to say will make the difference whether we fight or hold our peace."

An astounded and angry roar broke out. Michigan jumped up on a makeshift stand and cursed them till they fell quiet.

"Do your howling afterward," he said. "This isn't just a whim on Sawyer's part. Something's happened. Shut up and listen."

Now they were alarmed and uneasy. They watched Sawyer climb the stand, their faces dark-bronze in the smoky light, their eyes glistening.

Sawyer said, "Twist—come up here."

Twist pushed his way to the stand and got on it. Burr moved closer to Price, his hand curled lightly around the haft of the knife in his belt.

Sawyer said, "Tell them."

Perfectly at ease, aware of his importance but not impressed by it, Twist told the story of the landing of Price's plane in the Forbidden Belt, and what had been done with both of them afterward. He told only the simple facts, scrupulously avoiding any attempt to incite his listeners for or against Price.

The simple facts were enough. They heard them, the men of the Great Lakes and the southern bayous, the plains riders and the hillmen and hunters and farmers, and their reactions were various and wonderful after the first shock of incredulous amazement. Twist had to stop to let the tumult die down, and when he could make himself heard again he said,

"Yes, it was just what I said, a plane, and I flew in it. Not one of those whistling fliers, but a plane—so." He made a graphic pantomime with his hands and a remarkably accurate motor sound. "Now I guess that's all," he said, and stepped back.

Sawyer said, his words carrying clearly to the farthest man, "The Vurna have turned our lands upside down to find the plane. They haven't found it. Last night Arrin—" A furious snarl greeted that name, so apparently it was well known, "—Arrin gave me three days to surrender the plane and the man who flew it. I've brought him here, instead."

He held up his hands, to quell the rising voices. "Listen! I'm not finished yet. Arrin had some other things to say. He said, if you are planning an attack on the Citadel, forget it. He said, We will slaughter you without mercy."

"Now," said Sawyer, "here is what we have to decide. Two things. Is this man Price a friend offering us a weapon, or a spy of the Vurna offering us death? And shall we fight, or let it go until another year? They're big questions, the biggest you'll ever have to answer in your lives. Don't come at them like hasty boys, all feeling and no sense. Come at them man-like, slow and careful."

Michigan rumbled, "Those are good words. Heed them. And now let's have the man up here."

Burr gave Price a shove. "That's you."

Price shouldered forward through the pack and climbed the stand. As he did so Twist whispered in his ear, "You'd better make this good, boy. You won't get another chance."

His voice sounded friendly. Price was glad of it.

He stood on the platform and faced the chiefs and the representatives of the people.

Michigan said, "You tell your side of it. And speak up so everyone can hear."

Price spoke up, loud. But he said, "What's the good of that? I've told my side of it a dozen times already, and nobody believes me." He glared around the close-packed circle of men. "If I'd known you'd treat me like this, I'd have smashed the plane and left it for the coyotes."

"Just the same," said Michigan, "tell it again."

Price told it. "I didn't know you were up to anything in particular: it just seemed obvious that a plane might be useful to you sometime, now or later, and it wasn't doing any good where it was." He had coached himself so carefully in the story that it was beginning to seem like truth to him, gathering little embellishments and embroideries. "I brought guns, too, better than anything you have. And does anybody say, Thank you? The hell they do. They accuse me of being a spy for the Vurna."

A low animal grunt from the listeners. Their faces were as hard as flint.

Price shouted, "Would the Vurna be so anxious to get me back if they'd just sent me out as a spy? You heard Sawyer."

The Chief of the Louisianas said, "It would be a very smart trick for them to say so, for just that reason."

"And how is it," cried the Chief of the Arkansas, "that right away the minute you turn up, Arrin says that about attacking the Citadel? Doesn't that show they know something, and want to know more?"

"I should think that was obvious," said Price. "There hasn't been a plane in the air for two generations. All of a sudden there is one. Wouldn't the Vurna want to know where you got it, and whether you're building more like it? And do you suppose they'd figure that with a weapon like that you wouldn't be planning an attack of some kind on them?"

That was good sense, and they thought it over, muttering among themselves. Price began to feel he was getting somewhere, and marshalled his words for the final argument. Then the Chief of the Oklahomas spoke up and said,

"My word would be to kill this man and hand his body, and the plane, to Arrin. That way we comply, but not to his advantage. Arrin knows no more than when he started, but we look innocent. We look as though we have no use for a plane. And when their backs are turned, we go ahead as we planned all along."

And that sounded better yet, even to Price. Especially since he knew better than any of them the relative usefulness of one Beechcraft as a weapon against the kind of forces the Star Lords had.

But he knew if they began to think of that he was finished. So he said, "Listen, you need that plane. It can reconnoiter, it can carry bombs—"

"Shut up," said someone fiercely. "Shut up, all of you. I hear something."

They quieted, and listened. Price could not hear anything but the tense mass breathing of the men. Then on the far side of the room first one man and then several began to dig like dogs after a rabbit into the heaped-up rubble.

"Here it is! Here it is—look!"

"What is it? Let's see."

"Ain't nothing but a little bitty box—"

"No! It's one of their contraptions! Let me through!"

A man in a linen shirt of green and yellow came bursting through the crowd, carrying something high over his head in one hand. He put it down on the stand, where it lay buzzing gently.

"Is that Vurna, or ain't it?"

Everyone drew back and away from it, as though fearing it might explode. It was a little metal box no bigger than a cigarette case, but Price knew what it was. He stepped forward and smashed it underfoot.

"You'd better clear out of here," he said. "Fast. That was a radio transmitter, broadcasting a steady guide signal to bring the Vurna right here."

There was one stunned moment of absolute silence, and then the place erupted into sound and movement. In the midst of it, in the heart of it, the Chief of the Michigans and the man in the linen shirt were possessed of the same idea. Crying "Spy!", they flung themselves at Price with their knives drawn.

Remembering a trick or two the Army had taught him, Price stepped inside the chief's rush, caught his wrist, and flung him into the other, who had been slowed by the necessity of climbing onto the stand. And Price yelled at them furiously,

"Are you crazy? I wasn't near that side of the room. I didn't bring it and plant it here."

Twist stepped between him and the two men, drawing his own knife. "He wasn't, and that's a fact. Besides—"

"Get out of my way!" roared Michigan.

Unexpectedly, Burr leaped up and pulled him back. "I was close to him as his own skin, every minute," he said. "He didn't move, and he didn't have that thing on him to drop if he'd wanted to."

"We searched him," said Twist, "days ago. Personal."

"Then you're traitors too," said Michigan, clinging to his single idea. He started to charge again, and now there were others swarming up onto the stand after him, screaming for Price's blood.

Sawyer moved like a big cat. Michigan stopped in mid-stride, with the point of Sawyer's knife touching his heart-ribs.

"These are my men," said Sawyer mildly. "I don't like having their loyalty called in question any more than they do."

Price leaned over and grabbed a rifle out of somebody's hands. He clubbed it and began to swing, scattering men like ten-pins off the edge of the stand.

"Get out of here, you fools!" he howled at them. "Can't you get it through your thick skulls? The Vurna are coming. Get out!"

Numbers of them were already streaming up the stairs. Now more and more took up the cry, seeming to understand suddenly that someone's treachery had made this place a trap. Sawyer said to the Chief of the Michigans,

"Go on, take that hot head back to the lake and cool it. Hurry up, before they get you."

Michigan snorted like an angry bull, but he turned and jumped down into the crowd. The man with the linen shirt was gone. Price was about to follow when he saw the muzzle of a rifle, upflung, glinting darkly in the lamplight. He shouted to Burr and Twist to look out, and then flung himself upon Sawyer. The shot was stunning in that closed space. He heard the slug go whistling overhead and then ricochet from the low concrete roof. Someone on the far side of the room cried out in rage and pain. "I thank you," said Sawyer, "and now let's get off this damned target."

They got off, the four of them sticking close together. Price did not see Oakes, nor the man who had carried their lantern. Most of the lights were going out, knocked over and trampled. The dark surge of running men carried them to the stair and up and out into full, blinding day.

Somebody pointed to the sky and yelled, "There they come—the Vurna!"

CHAPTER VI

They were still a long way off but coming fast, whistling down the sky. Price could make out about a dozen bright dots flashing against the blue. Sawyer said,

"We'd better run for it!"

They fled, along the twisting path through the ruins. All around them, ahead and behind, other men were running, bolting away like wild creatures into the shadows of the broken walls.

And this was once their city, Price thought. A place of streets and homes and schools and churches, a good place, built with long hope and striving. What right did the Vurna have to break it?

He looked up at the fliers. They were larger now, moving swiftly above ragged crenellations that showed stark white in the hot summer sun. He looked down, and there was desolation. He ran in it, leaping and stumbling over the bones of a city, driven like the rest.

Sawyer swept a lean arm out in a commanding gesture. "Take cover!"

They dodged into the crevices of an unidentifiable mass half grown with creepers and rank grass. The old bricks tottered and threatened to fall as they pressed past them. They lay panting and listened to the Vurna fliers go over.

"They've broken formation," Price said. He had listened to hostile craft before. "Spread out. They'll sweep back and forth—"

A section of wall collapsed, close by them, with a rumble and a great puff of white dust. They leaped back, and Sawyer said, "That makes a beacon for them. Well, come on."

They ran out, crouching low, scurrying along the ravaged streets where their grandfathers had walked in peace. Price could see the green woods in the distance, but the air was full of the power-scream of the searching aerodynes, and he did not think that they would make it. He was right.

One of the ships shot down to hover three feet off the ground ahead of them, and another dropped behind. Sawyer turned to the right. A third ship came down. He turned to the left. A fourth one blocked him. He stopped where he was, too proud to look farther for escape where he knew there was none. Burr and Twist stood with him. All three lifted their rifles and prepared to die.

Price had nothing in his hands. The bright hovering ships mocked him, their noise deafened him, the wind of their air-blasts tore at him with vicious force. He hated them. He had never hated anything so much in his life, not even the enemy he had fought in Korea. He groped among the rubbish around his feet, half-blinded by dust and a red haze that was of his own making.

A very loud metallic voice spoke to them from one of the ships. "Put down your weapons and stand together with your hands high. You will not be harmed." Sawyer laughed. He hunched the rifle to his shoulder and fired. The slug went splat! on the skin of the aerodyne, and dropped.

"Put down your weapons and stand together. We will count six. At that time we will fire. Six. Five. Four."

Sawyer laid his rifle into the dust at his feet and straightened, folding his arms. Twist and Burr did the same. Tears stood in Burr's eyes, tears of outraged anger.

And this was their city, Price thought. My city. Ours.

Men began now to jump out of the hovering aerodynes, Vurna with cropped silvery hair. They wore uniforms of dark green. This was not their city, it was not their world. Price's fingers closed over the end of an iron bar in the rubbish.

He sprang forward, holding the iron bar.

A beam of cold light, hardly visible in the sunshine, flashed out from the nearest ship. Price was running, and then he was not running, he was face down on the ground with the white dust in his hair. The bar spun out of his hand and fell with a faint clatter.

The Vurna closed in. They escorted Sawyer and Burr and Twist each into one of the ships. Two of the green-clad soldiers bent and picked up Price and carried him to the fourth. They clambered in, and the aerodynes rose whistling into the air.

Over the place from which the Earthmen had fled, roughly in the center of the city, several of the ships were gathered. They circled slowly, but nothing moved in the streets. At length all but one of them rose up, and that one made brief lightnings flicker from its underbelly. Down below a volcano erupted, thundered, burned, and died, sinking into ash and dust. That gathering-place would not be used again, and any store of arms or powder concealed in it would not be used either.

The ships of the Vurna raced away toward the east. Behind them the forest was full of men and horses, moving out.

After a while a remote and disoriented consciousness returned to Price. He opened his eyes and saw a blur of red and silver and flesh tones. A little later he opened them again, and the blur had become a woman with silver hair and a uniform of dark crimson.

The woman.

She said, "You will be normal again in an hour or so. The shock-ray does no permanent damage."

He looked at her, not caring very much about how he would feel an hour from now. He felt pleasantly languid, forgetful of his cares. Her eyes were a curious color, not like Earth eyes at all. They were like little bits of sky and moonglow and the far-off fires of stars, cool and strange and lovely. He said,

"They're not cruel, after all."

"What are you talking about?"

"Your eyes. They're beautiful. Like you."

A faint flush touched her cheeks. But she only said, "How are you called?"

He told her, and she wrote it down. He saw now that she held a kind of clipboard on her knee. Just beyond her was a cabin window. Streamers of torn cloud whirled by it so fast that he was startled. Then other things began to impinge on his senses, air-scream, a smooth rush of speed. He sat up.

The man beside the pilot turned abruptly, his hand reaching for a weapon at his belt. The woman spoke to him in her own tongue, and then said to Price,

"We do not wish to stun you again. You will not make it necessary."

"No," said Price. He leaned forward, staring in fascination at the controls of the aerodyne, watching the pilot's movements.

"You are interested? As a pilot?"

"Yes." The controls seemed surprisingly simple. These controlled the force of the air-flow, those the angle of the blast—"It's so much more maneuverable than a jet, and so much more powerful than any 'copter. I—"

He shut his mouth, abruptly conscious that he had made a bad slip. But the woman did not seem to have noticed it. He asked her hastily, changing the subject, "What's your name?"

"Linna," she said. "Of Vrain Four. That's the planet of a star you never heard of, in the Hercules Cluster. I have some other identifying words, a patronym much like yours and a set of code-numbers such as have been used on this world also."

"You seem to know a lot about us, for a girl from—uh—Vrain Four."

"That's my business. I'm a specialist in Earth cultures. Section 7-Y, Social Technics. Where is your home?"

She was friendly, almost too much so. Price was wary now, his mind shaking off the lethargy of the shock.

"Nevada."

She wrote on the clipboard, some kind of shorthand. "I have not been that far west. What is Nevada like?"

He told her, leaving out any mention of cities. The aerodyne raced forward, and he watched the controls avidly. So simple. So beautifully, functionally simple. His fingers twitched with eagerness.

"You have flown a great deal?"

"My father taught me." Careful, Price thought. These people are probably no brighter or shrewder than my own, but they're better able to investigate and check on things. "Tell me, what's it like on Vrain Four?"

"We eat and sleep, make love and die," she said, "very much like you. The sky is very beautiful at night. The stars are close and burning, not cold and far-away like yours." She paused.

"Where did your father learn to fly?"

"From his father. It's a family tradition."

"And the plane had belonged to your family since the Ei destroyed the atomic cultures of your Earth-year 1979?"

"Since the Vurna destroyed it—yes."

She did not argue the point. "How old was the plane then?"

Sneaky little question, quietly asked. What was she driving at? Price began to feel that he was in a trap, but he could not quite see the shape of it. Then, before he was forced into an answer that might very well be the wrong one, he saw something that gave him the perfect excuse to ignore it.

The thing he saw was a starship.

He had never seen a starship before in his life, but he knew this could not be anything else. He judged that they must be back across the river now and well within the Forbidden Belt. The ship stood like a tower of white metal, enormous, slim, delicate, a thing of slumbering power that caught the throat with awe and wonder. There were no trees anywhere near it, and the earth underneath was fused and hardened to a substance more durable than iron or concrete.

Linna said, "That is one reason we do not want men in the Belt. There is danger of being caught in a take-off or a landing."

The aerodyne flashed past, and Price looked back as long as he could at the dwindling shape, splendid but curiously lonely in the middle of nowhere.

"I would have thought you'd have a port, close in. By the Citadel, I mean."

Linna shook her head. "Dispersal is much safer. That is why the Belt is so wide. We have a number of ships."

The man beside the pilot spoke, and Linna touched Price's shoulder, pointing ahead. "In a minute you will see the Citadel."

What he saw first was that iron blinking in the low air that he had seen from the plane. It grew with fantastic speed, taking shape, acquiring height and substance. Price had been prepared for something tremendous. In spite of that, he was wide-eyed and astonished as any tribesman.

The Citadel rose from a level barren, swept clear of every living thing. It was round, a vast flat-topped tower stunning in its stark hugeness. It did not fit on Earth at all. This monstrous, man-made metal mountain belonged to another world.

Around it as far as he could see were launching-pads for a species of missile that looked more deadly than any of the ICBM'S they had been dreaming up in his own day. Atop the Citadel, on the vast plain of metal that was its roof, there were installations that looked like radar, and others he could only guess at—something in the radio-telescope line, perhaps, with elaborate grids. Set around the perimeter of the roof, and looking ominously out across the Belt, were hooded emplacements that made Price think of Arrin's warning: We will make of the Belt a blasted barren, where not even a beetle can survive....

"You see how helpless," Linna said, quietly echoing his own thoughts. "Men with knives and little guns—they would be throwing their lives away."

The old anger came back to Price, and he said sullenly, "The Siegfried Line was supposed to be impregnable, too."

But he knew she was right, and he looked down with a sinking heart as the aerodyne swept in for a landing on the roof. How could Earthmen ever hope to throw this mighty power from their backs?

He stepped down to the iron deck, still a little slow and shaky when he moved. Other aerodynes were dropping down one by one. He looked around for Sawyer and Burr and Twist, but he did not see them. Vurna guards fell in on either side and Linna said,

"I think your friends have already landed, and are with Arrin below. Come on."

The invitation was pure rhetoric. He had no choice. The guard took him toward a circle painted bright red for the guidance of pilots, and about eight feet across. He asked, "Is Arrin the big boss?"

"The Supreme Commander of this base. You see how important you are to us—you and your plane?"

They stood on the red circle, and it dropped with them smoothly down a gleaming metal shaft. It did not drop too far. They stepped from it into a corridor, brightly lighted by tubes sunk into the low ceiling. There were many doors on either side, and Vurna in uniforms of various colors passed back and forth.

The office of the Supreme Commander was as austere and functional as everything else Price had seen. Narrow windows with flush shutters of steel looked out across the sunlit Belt. One wall was a maze of screens and dials, communicator devices, and another had rows of tube-mouths with vari-colored tabs. Arrin stood facing Sawyer, with Burr and Twist behind their chief. There were several guards. As Price came in with Linna, Sawyer was saying,

"I told you I wouldn't give the man up, nor the plane. As for the meeting, your paid traitor can tell you all about it. And now you can go ahead and kill me."

Arrin said impatiently, "It isn't your life I want from you, but only a little cooperation." He looked up at Price, his eyes narrowing. "This is the man?"

Linna spoke to him in the Vurna tongue. A look of surprise showed for an instant on Arrin's face. He questioned Linna. Sawyer, meantime, said to Price,

"We thought they'd killed you."

Price shook his head. He was worried about what Linna was saying to the Commander. Once more he had the feeling of a trap he could not see.

Arrin nodded curtly, and gave some order to Price's guards. Linna said in English, "You are to come with me."

Price said, "I'd rather stay with my friends."

"Perhaps later."

There was no use arguing. Price went where he was told. On another and much lower level, which might have been underground for all he knew, he was ushered into a small, neat, impersonal cubicle with no window and with a lock on the outside of the door. Obviously, a cell.

Linna said, "I would like your shirt, please."

He stared at her. "What?"

"Give me your shirt."

Again there was no use arguing with her. He took it off and handed it to her.

"Food and drink will be provided," she said. "You will be quite comfortable."

She went away, with the guards. Securely locked in the cubicle, Price sat and brooded. Food and water came, packaged, through a slot device in the wall. He ate and drank, and brooded again.

Finally, Linna came back. She handed him his shirt and watched him soberly while he put it on. And then she dropped her bomb.

"You have been lying to me," she said quietly. "I know now where you came from."