Title: Pecan Diseases and Pests and Their Control

MP-313

NOVEMBER 1958

TEXAS AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION ...

TEXAS AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE

College Station, Texas

| DISEASES OF THE LEAVES | |||

| Olive spots on underside | page 5 | Scab | |

| Downy, buff, or greenish-yellow lesions | page 7 | Downy Spot | |

| Small, reddish-brown to gray spots on underside | page 6 | Brown Leaf Spot | |

| Dark brown to black lesions on veins and stems | page 6 | Vein Spot | |

| Tiny white tufts of fungal growth on underside | page 9 | Articularia Leaf Mold | |

| Small olive green velvety spots. By midsummer, black pimple-like dots appear in the spots | page 7 | Leaf Blotch | |

| Leaflets yellowish, mottled, narrowed and crinkled with reddish-brown spots, may be perforated | page 8 | Rosette | |

| Broomy type of twig growth, bunching of leaves | page 8 | Bunch Disease | |

| DISEASES OF THE NUTS | |||

| Small black sunken or raised spots which may fuse to cover entire surface of shuck | page 5 | Scab | |

| Pink spore masses on shuck surface | page 9 | Pink Mold | |

| DISEASES OF THE ROOTS | |||

| Galls of various sizes on larger roots | page 7 | Crown Gall | |

| Splitting and deterioration of bark of infected roots, strands of buff-colored fungal growth may be present | page 10 | Cotton Root Rot | |

| NONPARASITIC PLANTS ON THE LIMBS AND BARK | |||

| Whitish-gray mosslike masses on the bark | page 9 | Lichens | |

| Accumulations of grayish strands hanging from limbs and twigs or ball-like growth on limbs and branches | page 9 | Spanish Moss, Ball Moss | |

| INSECTS ATTACKING THE NUTS | ||||

| Olive-green caterpillars up to ½ inch long feeding in the nuts, or later in the season, in the shucks | page 10 | Pecan Nut Casebearer | ||

| White caterpillars up to ⅜ inch long tunneling in the shucks | page 11 | Hickory Shuckworm | ||

| White legless grubs feeding in the nuts in late summer | page 12 | Pecan Weevil | ||

| Green or brown bugs sucking the sap from the nuts | page 12 | Stink Bugs and Plant Bugs | ||

| INSECTS ATTACKING THE FOLIAGE | ||||

| Soft-bodied yellow insects producing honeydew or small black insects causing yellow blotches on the foliage | page 13 | Aphids | ||

| Tiny green arthropods in webs near the midrib, leaves appear scorched | page 13 | Mites | ||

| Caterpillars feeding in gray cases about ½ inch long in the spring; small winding blotches produced in the leaves in the summer | page 14 | Pecan Leaf Casebearer | ||

| Olive-green caterpillars tunneling in the shoots in the early spring | page 10 | Pecan Nut Casebearer | ||

| Tiny caterpillars in light brown cigar-shaped cases about ¼ inch long | page 15 | Pecan Cigar Casebearer | ||

| Galls on the leaves, twigs and nuts | page 14 | Pecan Phylloxera | ||

| Leaves eaten in the early spring by a light green caterpillar which leaves the midribs and veins intact | page 14 | Sawfly | ||

| Beetles feeding on the foliage at night | page 15 | May Beetles | ||

| Caterpillars in large white webs encasing entire branches | page 15 | Fall Webworm | ||

| Caterpillars with long soft hairs feeding in colonies on the foliage without producing webs | page 16 | Walnut Caterpillar | ||

| Dark gray, active caterpillars up to 3 inches long feeding on the foliage in early spring | page 16 | Pecan Catocala | ||

| Masses of frothy white foam enclosing tiny, light green insects in the spring | page 16 | Pecan Spittlebug | ||

| Tiny greenish caterpillars feeding in the terminals and axils of the buds on young pecan trees | page 16 | Pecan Bud Moth | ||

| INSECTS ATTACKING THE LIMBS, TRUNK AND TWIGS | ||||

| Beetle girdling twigs and limbs in late summer and fall | page 17 | Pecan Twig Girdler | ||

| Holes about ⅛ inch in diameter in dying limbs | page 17 | Red-shouldered Shot-hole Borer | ||

| White borers with an enlargement behind the head tunneling underneath the bark of trunk and limbs | page 17 | Flatheaded Borers | ||

| Limbs encrusted with scales, which closely resemble the color of the bark | page 18 | Obscure Scale | ||

| Name of spray and time of application | Insect or disease to be controlled | Spray materials, per 100 gallon | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepollination spray, when first leaves are one-third grown | Scab, downy spot, vein spot | Zineb,[A] 2 pounds | If phylloxera is a problem, see page 14. | |

| First cover spray, when tips of small nuts have turned brown and nut casebearer eggs are observed | Scab, downy spot, vein spot, leaf blotch, brown leaf spot | Zineb, 2 pounds | ||

| Pecan nut casebearer, pecan leaf casebearer | 3 pounds 50 percent wettable DDT, or 1 pound 25 percent wettable parathion, or 1 pint nicotine sulfate plus 2 quarts summer oil, or 5 pounds 40 percent wettable toxaphene, or 3 pounds 25 percent wettable malathion | |||

| Rosette | Zinc sulfate, 2 pounds | If rosette is a problem, include zinc sulfate in spray. | ||

| Second cover spray, 3 to 4 weeks after first cover spray | Scab, downy spot, vein spot, leaf blotch, brown leaf spot | Zineb, 2 pounds Zinc sulfate, 2 pounds | ||

| Rosette | ||||

| Third cover spray, 3 to 4 weeks after second cover spray | Scab, brown leaf spot, liver spot, aphids, mites | Zineb, 2 pounds | If aphid or mite infestations are severe, use insecticides recommended on page 13. | |

| Walnut caterpillar, fall webworm | If walnut caterpillars or fall webworms are a problem, use insecticides recommended on pages 15 and 16. | |||

| Rosette | Zinc sulfate, 2 pounds | |||

| Fourth cover spray | Pecan weevil | 6 pounds 50 percent wettable DDT | For control of weevils, apply spray when as many as three weevils can be jarred from a tree. If scab is present add 2 pounds zineb to DDT spray. |

David W. Rosberg and D. R. King

Respectively, associate professor, Department of Plant Physiology and Pathology, and associate professor, Department of Entomology.

The pecan tree must be protected from attack by the many destructive diseases and insects that affect it to produce a bountiful nut crop.

The diseases that affect the pecan, especially those caused by fungi, are rapidly spread throughout the trees in an orchard in the early spring. During this season of frequent rains, the spores of the disease fungi germinate and invade the young tender tissues of the shoots, leaves and nuts. Under conditions of prolonged damp weather, when the humidity remains high, the disease organisms reproduce at a rapid rate and cause severe shedding of leaves and nuts.

Pecans are attacked by more than 20 species of insects that cause damage to leaves, nuts, twigs, buds, branches and even the bark. The development of commercial pecan acreages has provided ideal conditions for the increase in severity of both disease and insect damage because of the abundant food supply in a concentrated planting of pecans. In its natural habitat the pecan is less subject to the devastations of diseases and insects.

The many destructive insects and diseases must be controlled for successful pecan production. The pecan grower must also understand the nature and habits of the various disease and insect pests that threaten his crop and use certain cultural practices which help to reduce damage from diseases and insects.

The diseases which affect the pecan are of four different types: namely fungus, bacterial, virus and physiological. The fungus diseases, the most numerous and widespread, are caused by small microscopic molds. Approximately 12 different fungus organisms cause harmful diseases of the pecan.

The bacterial disease organisms, unlike the disease producing fungi, are single celled and can be seen only under a microscope. Bacterial diseases are fewer and of less economic importance than fungus diseases.

Virus diseases are caused by extremely small agents which can be seen only under special ultra-microscopes such as the electron microscope. Plant viruses are protein substances, but their exact nature is unknown.

Physiological disorders (sometimes called physiological diseases) are caused by a variety of environmental conditions. A physiological disorder in a pecan tree may result from infertile soil, excessive moisture, or the absence or degree of available nutritional mineral elements to the growing tree. These various environmental factors have special adverse effects, manifested by specific symptoms caused by insufficient levels of a given nutritional mineral element or elements, which are easily corrected by supplying the tree the necessary mineral elements either through soil application or foliage sprays.

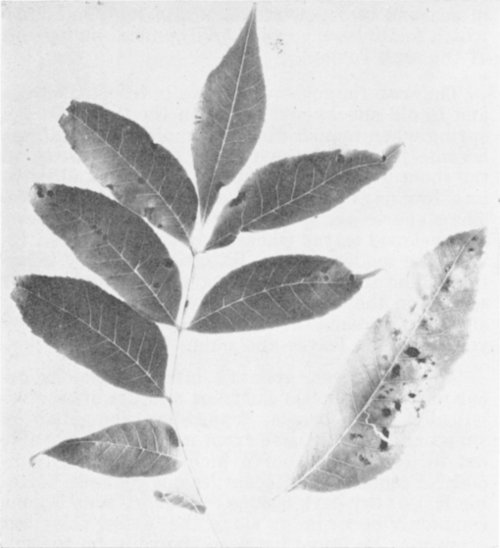

Pecan scab, caused by the fungus Cladosporium effusum (Wint.) Demaree, is the most destructive disease of pecans in Texas. The fungus invades the young rapidly growing shoots and leaves and later the developing nuts. Severely infected nuts on highly scab-susceptible varieties fall or fail to develop, resulting in a total nut crop loss. Early season defoliation often occurs in seasons of frequent rains and high humidity which facilitate the rapid development and spread of the scab fungus.

The scab fungus overwinters in infected shoots and in old shucks and leaves in the trees. In the spring when temperature and moisture conditions become favorable, the fungus begins to grow in the shoot lesions, old leaves and shucks, and within a few days produces great numbers of spores. These spores are spread by wind and rain to newly developed leaves where they germinate and invade the tender tissues, initiating primary infection. The fungus produces a great abundance of spores on the surface of these primary infection sites and spreads throughout the tree and infects young shoots, leaves and nuts.

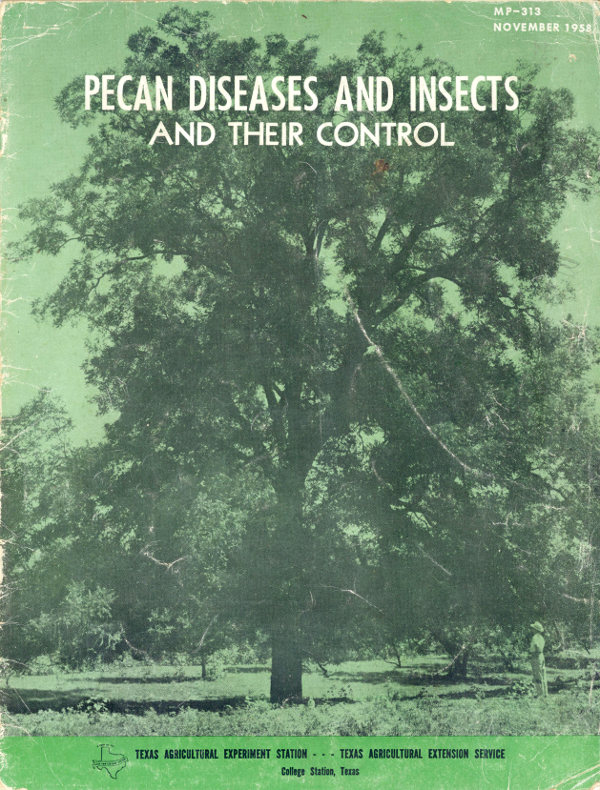

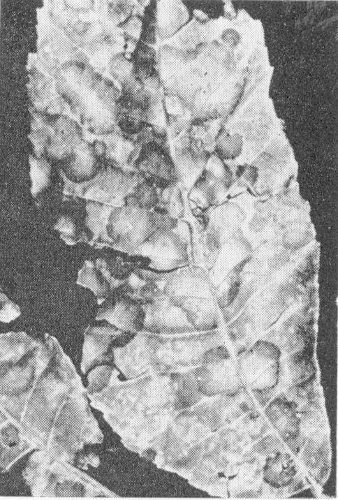

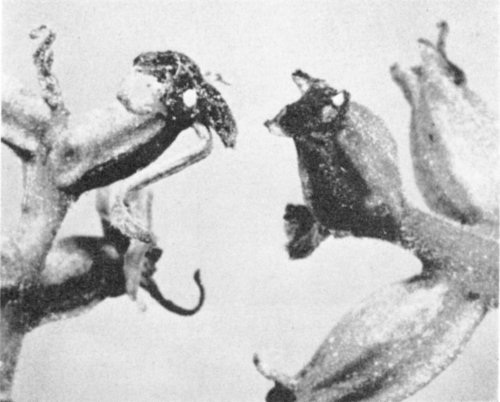

On the leaves, primary infection lesions occur on the lower leaf surfaces and are characteristically olive brown, somewhat elongated in shape and vary in size from a barely discernible dot to lesions one-fourth inch or more in diameter. Frequently, adjacent lesions coalesce, forming large very dark lesions. Primary scab lesions commonly occur on or along the leaflet veins but often may be found between the veins on the underleaf surface. On the nuts, scab lesions appear as small black dots, which are elevated or sunken 6 in older infections. Adjacent lesions on the nuts may coalesce forming large sunken black lesions, Figure 1. When infection is severe, the entire nut surface is black in appearance, development is arrested and the nuts drop prematurely.

Figure 1. Scab lesions on leaves and nuts of Delmas variety. Note concave lesions and overall scabby appearance of severely infected nuts.

Pecan varieties vary in their susceptibility to scab disease. Among the highly susceptible varieties are: Burkett, Delmas, Schley, Moore, Halbert and most western varieties. Moneymaker, Success and Curtis are moderately resistant. Mahan, Stuart and Desirable varieties are highly resistant to the scab fungus. However, this character of resistance varies, depending on the area of the state, local environmental conditions and the particular strain of the scab fungus present.

Scab disease development is favored by rainy periods and cloudy days when the humidity remains high and leaf surfaces are wet. Under these conditions, spores of the fungus in contact with the wet leaf surface of a pecan leaflet or nut germinate rapidly, invade the tender tissues and initiate infection within 6 hours. Lesions resulting from these infection sites, become visible to the naked eye within 7 to 14 days, depending on environmental conditions. A period of warm dry weather after infection occurs may retard lesion development.

Control.—The control of pecan scab disease depends primarily on the protection of tender leaf, nut and shoot surfaces with proper application of an effective fungicide. A protective film of fungicide chemical prevents scab fungus infections by killing the spores immediately after their germination, thereby preventing invasion of susceptible tissues. Unfortunately, once the fungus has invaded the tissues it becomes protected from chemical attack and produces spores in great abundance. Therefore, thorough coverage of leaf, nut and shoot surfaces with a fungicide chemical must be maintained to prevent secondary infections, ([6], [10], [11]).

Sanitation measures, such as removal of old attached shucks and leaf stems in trees and plowing or disk harrowing under fallen leaves and shucks help reduce primary infections. See spray schedule, page 4, for scab disease control.

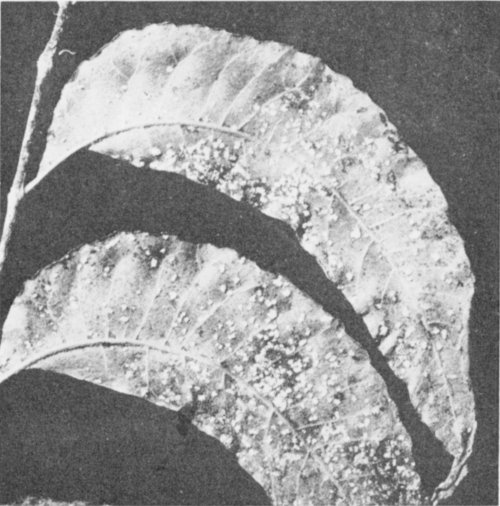

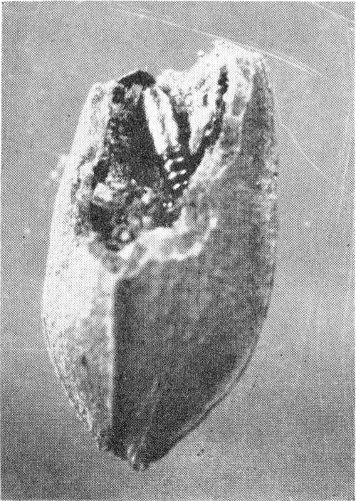

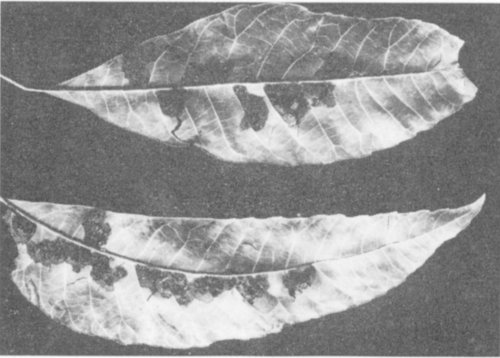

The brown leaf spot disease fungus Cercospora fusca (Heald and Walf) Rand affects only mature leaves and usually does not appear until the latter part of May or mid-June. Primary lesions develop on the lower leaf surfaces as small dots, which gradually enlarge and become reddish brown with a grayish cast. The shape of the lesions may be circular or irregular, especially where two or more lesions develop adjacent to one another, Figure 2. In seasons favorable for brown leaf spot development pecan trees may be completely defoliated within 3 to 4 months if the disease is not controlled. Most pecan varieties which are maintained in a vigorous state of growth are resistant to brown spot disease.

Control.—See spray schedule, page 4.

Vein spot disease is caused by the fungus Gnomonia nerviseda. The symptoms of the disease are similar to the leaf lesion symptoms of scab disease, but vein spot disease, unlike scab 7 disease, affects only the leaves. Lesions of vein spot disease develop on the veins or stems of leaflets and leaves, are usually less than one-fourth inch in diameter and are characteristically dark brown to black. Leaflets and leaf stems which are severely affected drop, resulting in premature defoliation.

The fungus lives in fallen leaves over the winter. The following spring when temperature and moisture conditions are favorable, spores formed in special structures called perithecia are forcibly discharged into the air and carried by wind currents to the newly formed spring foliage, initiating primary infections.

Control.—See spray schedule, page 4.

Leaf blotch disease is caused by the fungus Mycosphaerella dendroides (Cke.) Demaree and Cole. The disease occurs mainly in trees of poor vigor, which may be due to neglect, infertile soil, rosette or overcrowding. Nursery trees are particularly susceptible to the disease.

The fungus overwinters in fallen leaves. In the early spring, large numbers of spores produced in the old leaves on the ground are carried by wind currents to the young leaves in the tree, where they germinate and rapidly invade the tender leaf tissue.

The disease symptoms first appear on the undersurface of mature leaves in early summer, as small olive-green velvety spots. By midsummer black pimplelike dots become especially noticeable in the leaf spots after the surface spore masses have been removed by wind and rain, giving the diseased areas of the leaves a black, shiny appearance. When the disease is severe, infected leaflets are killed, which causes defoliation of the trees in late summer or early fall and results in reduced tree vigor and increased susceptibility to disease and insect attack.

Control.—Leaf blotch disease can be controlled effectively in the early spring by disking under old fallen leaves that harbor the fungus pathogen.

In areas where a spray program for the control of scab disease is carried out, leaf blotch usually is not a damaging disease. In localities where leaf blotch disease occurs in the absence of other pecan diseases, two applications of fungicide will control the disease effectively. The first spray should be applied after pollination when the tips of the nutlets have turned brown and the second spray application should be made 3 to 4 weeks later. See spray schedule, page 4.

Crown gall disease, caused by the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens (E. F. and Town.) Conn., often is damaging to pecan trees. Nursery trees as well as trees in bearing pecan orchards are susceptible to the disease.

Figure 2. Brown leaf spot diseased pecan leaflet showing typical symptoms. Lesions are circular to irregular in shape.

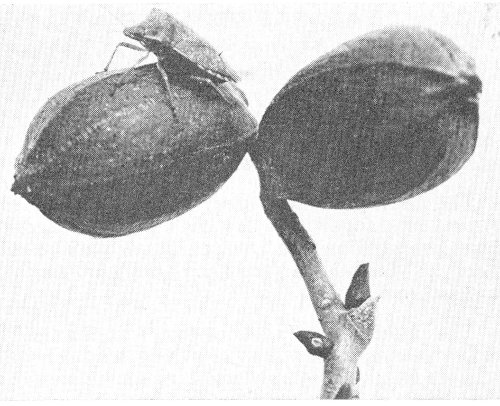

The development of galls is confined primarily to larger roots near the base of the tree trunk, although small roots may become infected and galls develop on them. The smaller galls are under the soil surface and cannot be detected unless the soil is carefully removed from around the roots, Figure 3. Large galls, often 10 to 18 inches in diameter, develop on larger roots and may protrude well above the surface of the soil.

Figure 3. Crown gall disease symptoms on young infected pecan tree.

Galls on nursery trees develop at or below the soil surface on the taproot and larger secondary roots.

Control.—All infected nursery trees should be dug and immediately burned. Crown gall-diseased orchard trees sometimes can be saved by digging the soil from around large roots and removing the exposed galls. Where galls were removed, the damaged root surfaces should be painted with a creosote-coal tar mixture (one part creosote to three parts coal tar) to prevent spread of the disease[9]. Cultivation of the soil around the trunk base of infected trees should be avoided to prevent root wounds and spreading of the crown gall pathogen.

Downy spot disease, caused by the fungus Mycosphaerella caryigena (Ell. and Ev.) Damaree and Cole, attacks all pecan varieties. Only 8 leaves are susceptible to the disease. Primary infection of new leaves in the spring occurs from spores produced in specialized fruiting bodies in old overwintered leaves. The downy spots appear usually during the summer months on the lower surfaces of leaflets. The downy character of the lesions is due to the production by the fungus of thousands of minute spores on the surface of each spot. The spores are spread by wind and rain to adjacent leaves and to neighboring trees. After spore dissemination is complete, the lesions visible from both leaf surfaces are one-eighth to one-fourth inch in diameter and greenish yellow. Later in the season the lesions turn brown due to the death of the leaf cells in the diseased area.

Moneymaker and Stuart varieties are most susceptible to downy spot disease although all pecan varieties are moderately to slightly susceptible.

Control.—Disk under old fallen leaves in the early spring before the leafbuds begin to swell. This practice covers the leaves with soil and prevents the discharge of spores into the air, thereby controlling primary infection of new leaves. In seasons when heavy rains make early spring disking impossible, downy spot disease can be controlled by spraying the trees as indicated in the spray schedule on page 4.

Although the cause of bunch disease is not known, evidence indicates it is an infectious disease, which suggests that the causal agent may be a virus.

Trees affected with bunch disease show the bunching symptom, which is due to excessive growth of slender succulent twigs from lateral buds that normally remain dormant. In moderately affected trees one or several branches will show the “bunch” growth symptom. Bunching in severely affected trees may involve all main branches which produce thick masses of sucker-like growth and few, if any, nuts.

Observations indicate that the Stuart variety is the most resistant to bunch disease.

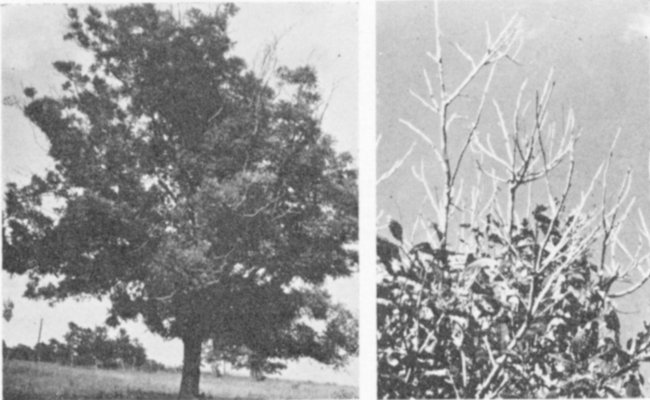

Figure 4. Rosette die-back symptoms of pecan tree showing severe zinc deficiency.

Control.—There is no known effective control for bunch disease. Early detection of the first symptom of bunch and pruning out of the affected branch may prevent spread of the disease throughout the tree. When the tree is severely affected, and limbs are involved, the tree should be destroyed to protect nearby healthy trees from infection.

For propagation purposes, all bud or scion wood should be taken only from bunch disease-free trees.

Rosette is a nutritional deficiency disease caused by certain soil conditions which make zinc unavailable to the pecan tree. All pecan trees require zinc for growth.

Trees showing the first symptom of zinc deficiency have yellowed tops. The individual leaflets when examined are yellowish and mottled. The next season the foliage may be yellowish and the leaflets narrowed and crinkled. More severely affected trees produce foliage which is a yellowish to reddish-brown overall color, and the leaflets are very narrow with reddish-brown spots and may be perforated. Shoots are much shortened and the leaves are produced in compact bunches of dense foliage.

Trees affected by rosette for several seasons have many dead shoots and small branches from the dying-back of each season’s growth, Figure 4. Such trees are greatly stunted, of poor vigor and produce few, if any, nuts.

Control.—Rosette is controlled readily by applying zinc sulfate to the tree either as a foliage spray or in the dry form as a soil application. Where a disease and insect spray control program is being carried out, zinc sulfate may be added to the spray mixture.

Foliage spray. Two pounds zinc sulfate (36 percent) per 100 gallons of water.

First application: after pollination when tips of nutlets turn brown.

Second application: 3 to 4 weeks later.

Third application: 3 to 4 weeks later.

Soil application. Application of zinc sulfate to the soil, particularly in a large orchard is a more expensive operation, but it provides longer protection against rosette.

In highly alkaline soils, or soils that readily fix zinc and make it unavailable to the tree, foliage spray applications of zinc sulfate are more economical because of the excessive rates required to supply available zinc through the soil.

Rate of application of zinc sulfate: Mildly rosetted trees—apply 5 pounds zinc sulfate (36 percent) annually for 2 to 3 years. Severely rosetted trees—apply 5 to 10 pounds zinc sulfate (36 percent) annually until rosette symptoms disappear.

Time and method of application: Apply zinc sulfate to the soil around trees in late February or early March. Broadcast zinc sulfate under the tree from the trunk to several feet beyond the limb canopy. Disking, harrowing, or any operation that mixes the zinc sulfate with the soil, is desirable to prevent washing away and surface soil fixing of zinc.

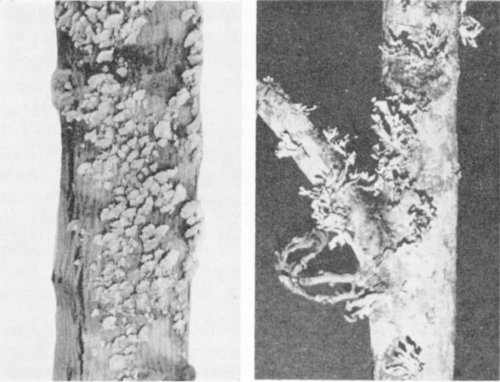

Lichens commonly are found growing on the branches and trunks of pecan trees, especially in humid areas and river bottom orchards having poor air drainage.

Lichens are nonparasitic to the pecan tree, but merely attach themselves to the bark surfaces. Lichens grow equally well on rocks, fence posts, bricks and other objects. There are several types of lichens that occur on pecan trees, none of which are damaging except perhaps in appearance to the trees in cases of extremely heavy infestations, Figure 5.

Figure 5. Lichens commonly found on the bark of pecan trees. Left, a fan-shaped type. Right, an erect-branched type.

Control.—The occurrence of lichens in trees regularly sprayed with copper-containing fungicides is rare.

Articularia leaf mold caused by the fungus Articularia quercina (PK) Hoehn is a disease of minor occurrence and importance. The disease occurs most commonly following rainy periods and in areas of high relative humidity in the leaves of trees of poor vigor.

The fungus produces on the lower surfaces of the leaves a conspicuous growth of white tufts which contain masses of spores, Figure 6.

Figure 6. Articularia leaf mold fungus, showing white tufts on lower leaf surfaces of pecan leaflets.

Control.—Articularia leaf mold does not occur in trees or in orchards which have been sprayed for disease control.

A single application of fungicide such as zineb at 2 pounds per 100 gallons of water when the disease is first detected is usually sufficient to control Articularia leaf mold disease.

Pink mold, Cephalothecium roseum Corda, usually occurs on nuts infected with the scab fungus. The pink mold fungus apparently enters the nuts through scab lesions on the shucks and continues to produce masses of pink spores on shuck surfaces until late fall. The fungus sometimes invades the kernel of thin-shelled pecan varieties causing “pink rot” which is characterized by an oily appearance of the nut shell and a rancid odor.

Control.—Pink mold rarely occurs on the shucks of nuts in the absence of scab disease. In areas where scab disease control is regularly practiced pink mold is not a problem.

Spanish moss, Tillandsia usneoides, and Ball moss, Tillandsia recurvata L., are not parasitic to the pecan tree and are similar to lichens in that they both derive their food from the air, rain or atmospheric moisture.

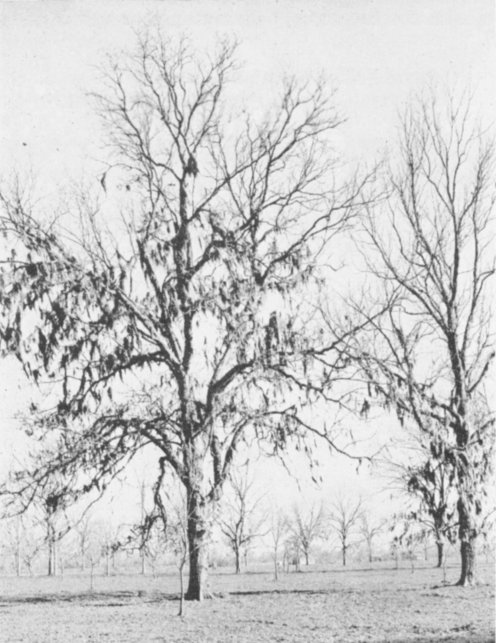

Neglected orchards in areas of high humidity or poor air drainage are most troubled with Spanish moss and Ball moss. When large and excessive growths of Spanish moss develop in pecan trees, the shading effect to the leaves is detrimental to tree vigor, bearing and growth, Figure 7.

Control.—The Spanish moss plant like the pecan tree requires sunlight for vigorous growth. 10 A pecan tree kept in a vigorous state of growth produces dense foliage that effectively shades accumulations of Spanish moss and retards its growth.

Spanish moss is not a problem in pecan trees in orchards which are sprayed with fungicide for disease control. Both Spanish moss and Ball moss can be controlled by spraying pecan trees with 6 pounds of lead arsenate per 100 gallons of water[3]. Do not allow livestock to graze in orchards sprayed with lead arsenate.

Cotton root rot disease is caused by the fungus Phymatotrichum omnivorum (Shear) Dvgg., a soil-inhabiting pathogen that attacks a wide range of host plants including the pecan.

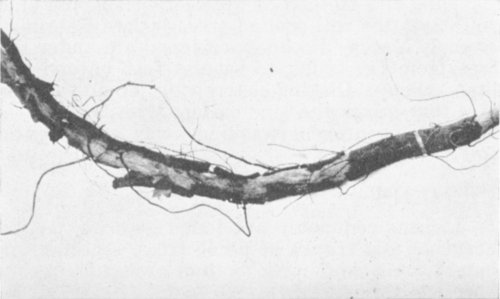

The roots of the pecan tree are invaded during the summer when growth of the fungus in the soil is most active. The infected roots are killed, disrupting the transportation of water to the leaves, Figure 8. Trees diseased by cotton root rot produce yellow foliage, and shedding of leaflets occurs during dry periods. Diseased trees usually die 1 to 3 years after becoming infected.

Figure 7. Spanish moss accumulation in pecan trees reduces vigor from excessive shading.

Figure 8. Cotton root infected with cotton root rot fungus. Note the splitting and general deterioration of the root.

Control.—An effective control for cotton root rot disease has not been developed.

New orchards should not be planted in soil having a history of cotton root rot disease.

The pecan nut casebearer, Acrobasis caryae Grote, is the major pest of pecans in Texas. Early in the spring, the overwintered generation feeds first in the buds and then in the developing shoots, causing them to wilt and die. Succeeding generations feed on the nuts during the late spring and summer, Figure 9. Severe infestations may destroy the entire crop of pecans.

The adult is a light gray moth which is about one third inch in length. The wings are gray, and the forewings have a ridge of dark scales across them about one-third the distance from the base. The moths fly at night and spend the day in concealment.

The young larvae are white to pink, but later become olive gray to green and attain a length of about one-half inch.

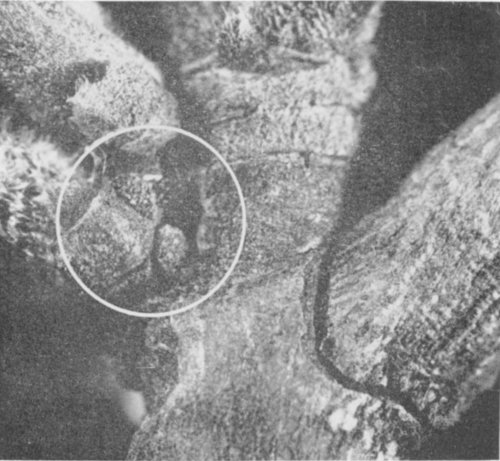

This insect passes the winter as a partially grown larva in a tiny silken cocoon called a hibernaculum, which is usually attached to a bud, Figure 10. In the spring, the larvae feed for a short time on the buds, after which they tunnel in the developing shoots until they reach maturity, Figure 11. Pupation usually occurs in these burrows, and the moths emerge in late April and May.

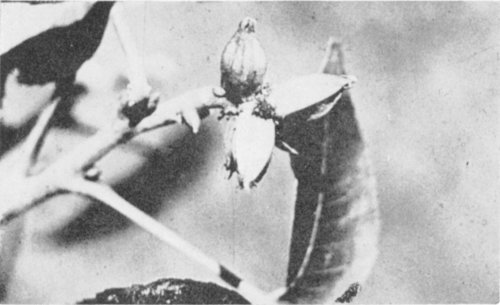

Two or 3 days after the adults emerge, they deposit eggs on the tips of the nuts, Figure 12. Each female may deposit from 50 to 150 eggs. The eggs, which are just visible to the naked eye, are greenish white when they are deposited but assume a reddish appearance a few days later. The first-generation larvae hatch from the eggs in 4 or 5 days and migrate to the buds below the nuts to feed. After a day or two, they enter the nuts, usually at the base, and feed in them, each larva frequently destroying an entire cluster. Bits of frass and webbing may be observed projecting from the injured nuts. Upon reaching maturity, the larvae pupate in the nuts and emerge as adults in June and early July.

Figure 9. Injury to nuts caused by first generation larvae of the pecan nut casebearer.

The adults deposit eggs in grooves on the tips or bases of the nuts. Second-generation larvae which hatch from these eggs also feed in the nuts. Less injury is produced by this generation because the nuts are larger and each larva requires only one or two nuts to complete its development. Pupation takes place in the hollowed out nuts, Figure 13, and the moths emerge from late July to early September.

A third generation usually follows, but the shells of the nuts have become hard, and only a few of them are penetrated by the larvae. Instead, they feed in the shucks. A number of third-generation larvae construct hibernacula, while the remainder pupate and appear as adults, emerging from late August to October. These adults deposit eggs, which hatch into fourth-generation larvae. If nuts are available, their shucks constitute the principal food of the larvae of this generation. In the absence of nuts, the larvae feed on buds and leaf stems. Overwintering hibernacula are constructed by the partially grown larvae by the middle of November[2].

Control.—The necessity for control of this pest may be determined by examination of the trees when the shoots appear in the spring. If a number of them are wilted, the following control measures probably will be required.

A spray application should be made when eggs of the first generation appear on the tips of the young nuts in late April or May. The period of egg deposition usually coincides with the completion of pollination, at which time the tips of the nuts turn brown. Satisfactory control may be obtained by using any of several insecticides. See spray schedule, page 4.

Ordinarily, only one application of spray is required to control the nut casebearer. However, if trees surrounding the treated area are not sprayed, moths may enter the sprayed area and a serious infestation of second-generation larvae may develop. Under these circumstances, a second spray may be required in June or early July when second-generation eggs are deposited[6], [11].

The hickory shuckworm, Laspeyresia caryana (Fitch), frequently causes severe injury to pecans. In the late summer and fall the shucks are tunneled out. As a result, the nuts are slower to mature and the kernels do not develop properly. The shucks stick to the nuts and fail to open, thus increasing the difficulty of harvest.

The adult shuckworm is a dark, grayish-black moth with a wing span of a little over one-half inch. The larva is white with a light brown head. It attains a length of three-eighths inch at maturity.

The winter is passed by the larvae in fallen pecan or hickory shucks. They pupate in late winter and emerge as adults during the spring. The adults deposit eggs principally on hickory trees on the leaves and young nuts, and the larvae feed in developing nuts in early summer.

Succeeding generations develop in pecan shucks. Before pupating, the larvae cut a hole to the outside, and then spin a cocoon. When the moth emerges, the empty pupal skin is left projecting from the hole and can be seen afterward on the shuck. As many as five generations may be completed each year before the last generation larvae go into hibernation.

Control.—No economical chemical control for the shuckworm has been developed. Cultural measures will aid in reducing populations. Plowing during July and August to turn under the infested shucks is relatively effective. The larvae are unable to mature in the decaying shucks, and the adults cannot emerge from the soil. Care should be taken to completely cover the fallen shucks, but the depth of plowing should be regulated or damage to the roots will result.

Figure 10. Location of overwintering cocoons, or hibernacula, of the pecan nut casebearer.

The pecan weevil, Curculio caryae (Horn), is a late-season pest of pecans in Texas. In years when severe infestations occur, this insect may destroy a large portion of the pecan crop. The kernels are eaten out by the larvae.

The adult is a brownish weevil which is about three-eighths inch long. The female has a snout which is as long as the body; the male’s is somewhat shorter.

The weevil appears in late August and early September. After the nut kernels have hardened, the female chews a hole in the shell and deposits her eggs in little pockets in the nuts. Creamy white grubs hatch from the eggs and feed inside the nuts during the fall, attaining a length of about three-fifths inch. When they reach maturity, the grubs chew a hole about one-eighth inch in diameter in the shell, emerge from the nut and drop to the ground in late fall and early winter. They burrow in the soil to a depth of 4 to 12 inches and construct a cell. Some individuals remain in the larval stage until the following fall when pupation occurs. Other larvae do not transform to pupae until the succeeding year. The adults appear during the summer, following pupation. The entire life cycle requires from 2 to 3 years, most of this time being spent in the soil.

Figure 11. Overwintered larva of the pecan nut casebearer and characteristic injury to the developing shoots.

Control.—Frequently, certain trees in the orchard are more heavily infested than others, since the adults usually do not go far from the tree upon which they developed. The time at which insecticide applications should be made to control this insect can be determined by jarring the trees. Begin checking the first week in August. A large sheet should be placed under a tree and the limbs jarred with a padded pole. The weevils drop to the ground and remain motionless for a short period, at which time they may be counted. When three or more weevils are jarred from each tree, an application of spray containing 6 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder per 100 gallons of water should be made[8].

Figure 12. Eggs of the first generation pecan nut casebearer deposited on the tips of the young nuts.

The adults of several species of stink bugs and plant bugs suck the sap from young pecan nuts causing an injury known as black pit, in which the interior of the nuts turns black. The injured nuts fall from the trees before the shells harden.

Feeding by the insects after shell hardening, Figure 14, produces brown or black spots on the kernels. Areas affected taste bitter, but the remainder of the kernel is unaffected.

Stink bugs are familiar to everyone. Plant bugs resemble them and are usually shades of brown, smaller and narrower in body outline.

Plant bugs and stink bugs overwinter in the adult stage in debris on the ground. In the spring, the adults are attracted to growing vegetation such as cover crops or weeds, where they deposit their eggs. The immature bugs develop on low-growing vegetation. When they reach maturity, their wings are fully developed and they fly to pecan trees. A few eggs may be deposited on pecan trees, but the young bugs apparently are unable to develop on them. Only the adults are present in sufficient number to inflict economic injury. There may be as many as four generations each year.

Control.—Although certain insecticides will control these pests, the number and frequency of spray applications necessary for control would not be economical.

Care should be taken to keep weeds down in the orchard during the growing season. Winter cover crops should be plowed down early in the spring so they will not be attractive to the adults coming out of hibernation. If this operation is delayed, the bugs will leave the cover crop when it is removed and migrate to the trees in large numbers.

These soft-bodied insects appear during the summer and fall. They suck the sap from the leaves, causing them to turn yellow or brown and fall to the ground. Heavy infestations may cause defoliation in the late summer reducing the nut crop in the current and succeeding year.

The black pecan aphid, Melanocallis caryaefoliae (Davis), is about one-sixteenth inch long when full grown, robust and greenish black. Its back is decorated with tubercles.

Bright yellow blotches up to one-fourth inch in diameter appear around the punctures produced by the feeding of this insect.

The yellow aphids, Monellia spp., which attack pecans inflict injury similar to that caused by the black pecan aphid. However, the large yellow blotches on the leaves do not result from their feeding. A sticky substance called “honeydew” is secreted by these insects creating an ideal medium for sooty mold fungus to develop[5].

Both black and yellow aphids overwinter in the egg stage in crevices in the bark. In the spring the eggs hatch, and the aphids begin feeding on the leaves. Many generations are completed each year. Only females, which may be wingless or winged, are produced during the growing season. The winged individuals fly to different parts of the tree or to other trees. In the fall, males and females appear and eggs are deposited under the bark.

Figure 13. Pupa of the second generation of the pecan nut casebearer in a hollowed out nut.

Usually, these insects are not present in sufficient numbers to cause serious injury until mid or late summer. Infestations earlier in the season rarely assume damaging proportions. As is the case with mites, aphid populations may increase, following the application of certain insecticides applied for the control of the pecan nut casebearer or following treatment with bordeaux mixture for pecan scab disease control.

Figure 14. Southern green stink bug on developing nuts.

Control.—When damaging infestations appear, the trees should be sprayed with either 1 pound of 12 percent gamma BHC wettable powder; or 1 pint of 40 percent nicotine sulfate plus 3 pounds of soap; or 1 pound of 25 percent parathion wettable powder[9].

These tiny pests attack the leaves usually on the underside causing irregular brown areas to appear. Trees which are heavily infested appear scorched and may lose their leaves in late summer or fall.

Mites usually are light green and are just large enough to be seen without the aid of a hand lens. They are wingless and feed principally on the underside of the leaves along the midrib. Colonies of them produce webs in which molted skins and eggs may be found. The life cycle of mites is very short and several generations occur each year. Large populations may develop during the late summer and fall.

The use of certain insecticides for the control of the pecan nut casebearer or bordeaux mixture for scab control frequently contributes to increases in mite populations later in the season.

Control.—Mites may be controlled in three ways when damaging infestations develop. An application of 2 pounds of wettable sulfur per 100 gallons of water may be made; 6 pounds of wettable sulfur per 100 gallons of water may be added to the spray applied for the control of the nut casebearer; and repeated applications of zineb included in a regular spray schedule for pecan scab control will effectively control mites. However, a single application of zineb is not effective[7].

On occasion, this insect, Acrobasis juglandis (LeB.), develops to damaging numbers and causes economic injury. Early in the spring the larva feeds on unfolding leaves and buds. It may prevent leaf development for weeks, resulting in a greatly decreased yield of nuts.

The adult is a dark gray moth marked with brown. Its forewings, which have a spread of about two-thirds inch, are gray with black blotches. There is a reddish mark near the base of the forewings.

The immature larva is brown, but changes to dark green as it develops to a length of one-half inch. It has a shiny, brownish black head and is enclosed in a gray case which completely covers the body and is borne in a position nearly perpendicular to the leaf on which the larva is feeding.

The pecan leaf casebearer overwinters as an immature larva in a hibernaculum around a bud. It emerges in late March or early April as the buds open. The larvae mature in April, May and June and transform into pupae within their gray cases, Figure 15. The moths are present from May until early August. Eggs are deposited during this period on the underside of the leaves. The larvae which hatch from these eggs develop slowly, and do not attain a length of more than one-sixteenth inch during that season. They construct little winding cases in which they live. Their feeding produces irregular blotches on the leaf surface, Figure 16. Before the leaves drop in the fall, the larvae migrate to the buds, and construct their overwintering hibernacula. Only one generation is completed each year.

Control.—Control of this insect is accomplished by spraying for the pecan nut casebearer. See spray schedule, page 4. The insecticides recommended for nut casebearer control also reduce infestations of the leaf casebearer.

Figure 15. Overwintered larvae of pecan leaf casebearer in their cases.

Figure 16. Summer injury to the leaves by the pecan leaf casebearer.

The pecan phylloxera, Phylloxera devastatris Perg., and the pecan leaf phylloxera, P. notabilis Perg., produce galls on the new growth of pecans. Leaves, twigs and nuts may be affected.

The galls are conspicuous swellings, Figure 17, which attain a size of from one-tenth to 1 inch in diameter. They are caused by a soft-bodied insect which is closely related to aphids.

The winter is passed in the egg stage in crevices in the bark. In the spring, the egg hatches and the tiny nymph feeds on the tender, young growth, apparently secreting a substance which stimulates the plant tissues to develop into galls.

After the nymph reaches maturity, a number of eggs are deposited inside the gall. The young nymphs of the succeeding generation develop within the gall, which splits open in 1 to 3 weeks, liberating them. Several generations follow during the summer and fall, as long as there is fresh young growth on the tree. From 4 to 5 weeks are required for each generation[4].

Control.—The dormant oil spray recommended for obscure scale control will prevent the development of phylloxera. If dormant oil is not applied, use 2 pints of nicotine sulfate plus 6 pounds of soap; 3 pounds of 25 percent malathion wettable powder; or two and a half pounds of 10 percent gamma isomer BHC wettable powder per 100 gallons of water when the leaves are one-third grown.

Sawfly larvae, Periclista sp. and others, feed on the foliage of pecans during April and early May. The larvae, which are light green, chew holes in the leaves. Usually the midrib and veins are left intact, giving the leaflets a lacy appearance, Figure 18.

The adults closely resemble wasps, except that they are not “wasp-waisted.”

Fig. 17. Developing galls of the pecan phylloxera. Note the open gall on the lower leaf.

Control.—The larvae may be controlled with an application of 2 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder or 1 pound of 25 percent parathion wettable powder per 100 gallons of water.

Figure 18. Sawfly injury to pecan foliage.

Many species of May beetles may damage pecans early in the spring. The beetles appear only at night and spend the day concealed beneath the surface of the soil. They feed on the young leaves and prevent the foliage from developing.

Beetles of the most common species are one-half to three-fourths inch long and shiny dark brown. They are attracted to lights and are observed commonly on porches or screen doors at night. The larvae are the grubworms, or white grubs, which feed in the soil on the roots of many plants.

The female beetle deposits eggs in the soil, where the larva develops. Most species require two summers for the larva to mature. Pupation is accomplished in a cell which is constructed in the ground in the fall of the second year. The beetles emerge the following spring. Both larvae and adults may be found in the soil during the winter.

Control.—May beetles are usually a problem in orchards which are not cultivated because the larvae feed on the roots of the sod cover. Cultivation of the orchard periodically will reduce the food supply of the grubs, and smaller infestations of adults will appear the following year. Where cultivation is not feasible, sprays will control the adults. Apply 2 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder; 4 pounds of lead arsenate; or 1 pound of 25 percent parathion wettable powder per 100 gallons of water when damage by this insect is severe[9].

The pecan cigar casebearer, Coleophora caryaefoliella (Clem), may be damaging in some years. The larva feeds on the leaves, producing tiny holes. It constructs a light brown, cigar-shaped case about one-fourth inch in length which encases it throughout development.

Control.—The spray applied for control of the nut casebearer will usually prevent significant injury by the cigar casebearer. See spray schedule, page 4.

The webs produced by the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Drury), are familiar to everyone. Leaves are eaten by the larvae which live in loosely woven, dirty white webs, Figure 19.

The adult is a white moth which may have black or brown spots on the forewing. Its wings have a span of about 1 inch.

The larvae are pale yellow spotted with black. They attain a length of 1 inch when full grown and are covered with long black and white hairs.

The insect overwinters as a pupa in lightly woven cocoons in debris on the soil or under the bark. In the spring the adults emerge and lay masses of greenish white eggs on the leaves. The caterpillars which hatch from the eggs feed on the leaves in colonies under webs which they construct. After feeding for a month to 6 weeks, the larvae crawl down the tree and pupate in loose cocoons in debris, under bark, or in loose soil. Adults appear during the summer and deposit eggs for the second generation. The larvae of this generation feed extensively until fall, crawl down the tree and pupate for the winter.

Control.—Light infestations on a few trees can be eliminated by pruning out the affected branches and burning them. If this method of control is not practicable, the trees should be 16 sprayed with 2 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder; 1 pound of 25 percent parathion wettable powder; or 3 pounds of lead arsenate per 100 gallons of water[9].

Figure 19. Web of the fall webworm on a pecan limb.

During the spring and summer, the walnut caterpillars, Datana integerrima G. & R. and others, may strip the leaves from branches or entire small trees. The adult is a moth with a wingspan of 1½ to 2 inches. The forewings are light brown with darker wavy lines. The hindwings are lighter in color without lines.

The immature larva is reddish brown with narrow yellowish lines that extend the length of the body. The full-grown larva is almost black with two grayish lines on the back and two on the sides. Many long, soft gray hairs are distributed over the body.

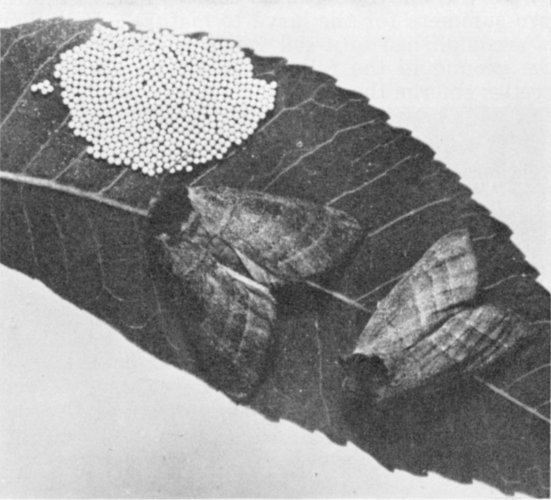

This insect overwinters in the pupal stage in the soil. The adult emerges in the spring and deposits eggs in masses on the underside of the leaves, Figure 20. The larvae feed in colonies on the leaves for about 3 weeks. At periodic intervals, the groups of larvae move to the trunk to molt and, after shedding their skins, they return to the leaves to feed until the next molt. They do not encase themselves in webs. There are two generations each year, the first appearing in late spring and early summer, the second in later summer and fall. Larvae of the second generation complete development and crawl down to pupate in the soil.

Control.—When these insects become abundant enough to defoliate portions of the tree, they may be controlled by applying a spray containing 2 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder; 3 pounds of lead arsenate; or 1 pound of 25 percent parathion wettable powder per 100 gallons of water.

Figure 20. Walnut caterpillar adults and egg mass on a pecan leaflet.

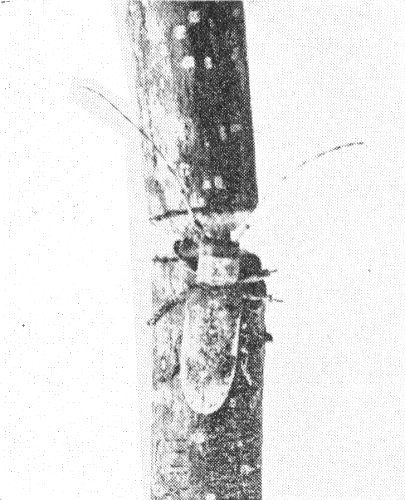

Several species of catocalas, Figure 21, among them Catocala maestosa Hlst., may strip the leaves of pecans in the spring leaving only the midribs. The caterpillars are very dark gray and attain a length of about 3 inches when full grown. They are very active when disturbed and move with a looping motion. Both the caterpillars and the moths are well camouflaged. When they rest on the trees during the day, their color so harmonizes with the color of the bark that they are frequently indistinguishable.

Control.—One application of 2 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder per 100 gallons of water controls this pest. Although the majority of catocala larvae reach maturity before the time to spray for the nut casebearer, a number of them will be killed when the recommended spray is applied for the latter insect.

In the spring and early summer a number of buds and small nuts may be covered with foamy white masses. Inside these masses are several small insects called spittlebugs, Clastoptera obtusa (Say). The white froth is produced probably to maintain an artificial high humidity, which is required for development. The adults resemble leafhoppers and fly actively during the summer.

This insect has not been known to cause any significant injury on pecans in Texas.

The pecan bud moth, Gretchena bolliana (Sling.), damages nursery stock and freshly top-worked pecans. The greenish larvae feed in the axils of the newly set buds and in the terminals 17 of young trees, causing extensive branching. There are several generations each year.

Figure 21. Moth of the pecan catocala.

Control.—This insect may be controlled by applying a spray containing 2 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder per 100 gallons of water.

The adult twig girdler, Oncideres cingulata (Say) (O. texana of some authors), girdles twigs and branches, weakening them so that they fall off or die on the tree, Figure 22. This insect is active during the late summer and early fall. Many twigs may be found on the ground under a severely infested tree. Secondary branching may occur and the number of bearing twigs is reduced.

The twig borer is a grayish brown beetle one-half to five-eighths inch in length with a broad gray band over the middle of the wing covers. Its head is reddish brown and bears a pair of long antennae, which extend beyond the abdomen on the male.

The larva is a white legless grub about three-fourths inch long when it reaches maturity.

This insect overwinters as a partially grown larva in a twig on the tree or ground. It develops rapidly in the spring feeding in the twig. Following pupation, the adult emerges in late August or early September. The female systematically girdles twigs and deposits eggs in the severed portion since the larva is unable to develop in healthy sapwood. The eggs hatch in a few weeks into larvae which remain small until the following spring when they complete development, pupate and emerge as adults in the late summer and fall. There is one generation annually, although some individuals require 2 years to mature[1].

Control.—Infestations may be reduced by removing girdled branches from the trees and the ground and burning them.

Chemical control is also effective. The trees should be sprayed with 4 pounds of 50 percent DDT wettable powder per 100 gallons of water when the first injured branches are observed in late August or early September. Two or three applications at 2-week intervals may be required for most effective control[9].

The red-shouldered shot-hole borer, Xylobiops basilare (Say), and other shot-hole borers also injure trees in a devitalized condition. The larvae feed in wood, pupate and emerge as adults through round holes about one-eighth inch in diameter in the bark. Many of these holes may be observed in close proximity to each other.

Control.—Since this insect feeds on dying or dead wood, prunings and dead limbs should be removed from the orchard and burned.

Adequate fertilizer and water will keep trees in a healthy condition and prevent injury by this pest.

The flatheaded apple tree borer, Chrysobothris femorata (Oliv.), and other species of flatheaded borers attack unhealthy or recently transplanted pecan trees by burrowing in the bark and sapwood of the large branches and trunk. Their presence is indicated by the appearance of darkened, depressed areas in the bark from which traces of frass may protrude. When these portions of the bark are removed, shallow winding burrows packed with sawdust may be observed. The burrows usually are on the sunny side of the trunk or branch, but may extend completely around and penetrate the wood to a depth of 2 inches. Young trees may be girdled by this insect.

The adult beetle is about one-half inch long, broad and blunt at the head end and tapering to a point posteriorly. Its wing covers, which have a metallic sheen, are dark colored and corrugated.

The larva, or borer, which is legless and yellowish white, attains a length of 1¼ inches when full grown. Immediately behind the head is a broad, flattened expanded area from which the insect takes its name.

The winter is passed by larvae in varying stages of development within the tree. In the spring, they change to pupae in their burrows, emerging as adults during the spring and summer. The female beetles deposit their eggs in cracks or bruises in the bark. The larvae which hatch from these eggs feed during the remainder of the season and pass the winter. There is only one generation each year.

Figure 22. Adult twig girdler and characteristic injury to twig.

Control.—The beetles are attracted to trees or areas of trees in a devitalized condition, induced by transplanting, drouth, sunscald, bruises or poor growing conditions. The trees must be kept in a healthy, vigorous condition by proper fertilization and watering. On young or transplanted trees, wrapping the trunks in early spring before the adults appear is the only effective control known for these insects. Injury can be prevented by thoroughly wrapping the entire trunk from ground level to the branches with heavy paper or other wrapping material. The wrapping should be tied securely with twine and should be maintained on the tree for 2 years. Regular observations should be made to see that the twine does not girdle the tree.

In older trees, the borers can be removed with a sharp knife. Care should be taken to injure as little of the healthy wood as possible. If the wound is extensive, it should be trimmed and then painted with a commercial tree paint or with a mixture of one part creosote and three parts coal tar. Dead and dying limbs and trees should be removed from the orchard each year and burned before the following spring. If they are not burned, the borers in them may mature and re-infest surrounding trees. Commercial tree borer preparations are of little value in controlling this insect.

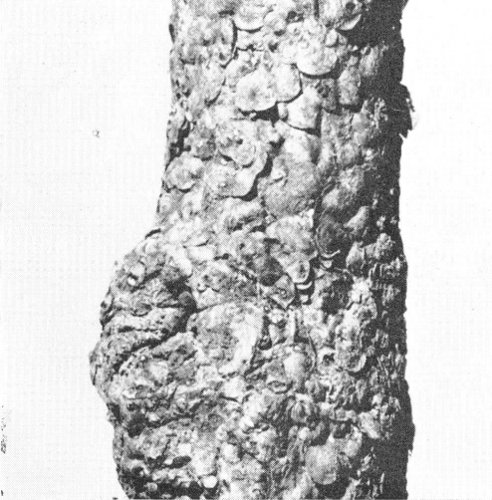

The obscure scale, Chrysomphalus obscurus (Comst.), is a pest of considerable importance, particularly in the more arid portions of the State. The tiny insect under its scale covering sucks the sap from the limbs and branches, causing them to lose their leaves and die back from the tips. The tree is so devitalized by the feeding of this insect that it is made vulnerable to attack by wood borers.

The scale covering over a full-grown female is about one-eighth inch long and is usually dark gray, and closely resembles the bark of the tree. Infested limbs appear to have had wood ashes sprinkled over them, Figure 23. Numerous pits appear in the bark where the insects feed, producing a roughened appearance.

Figure 23. Severe infestation of obscure scale on a pecan twig.

The winter is passed by the female scales under their coverings on the bark. Eggs laid in the spring hatch into tiny, salmon-colored crawlers which move about for a short time, then settle down and insert their beaks. While they are feeding, a scale covering develops which is made up of secreted wax and cast skins.

The females never move again from the spot they have selected, but the adult males develop wings and emerge from their scale coverings to mate with the females. Only one generation is produced each year.

Control.—When damaging populations develop, a spray application of 3½ gallons of 97 percent miscible dormant oil per 100 gallons of water during the dormant season will keep this pest under control.

When possible, fungicides for disease control and insecticides for insect control should be combined in the spray tank and applied to the trees in one operation. The spray materials should be applied evenly and thoroughly to all the leaf and nut surfaces to provide a chemical barrier to disease organisms and insects. Do not neglect the tops of the trees. Diseases and insects can harbor and multiply in all unsprayed areas of the tree.

Thorough coverage with spray materials is essential for effective control. As a guideline, apply approximately 1 gallon of spray mixture for each foot of tree height. Apply 20 gallons to a 20-foot tree and 40 gallons to a 40-foot tree, etc.

Various types of spray machines for application of fungicides and insecticides to pecan trees are available. The spray machines employ 19 either a high pressure hydraulic pump, high pressure centrifugal pump or low pressure high air velocity systems. All the machines are portable and are equipped with a gasoline engine or operate from a truck or tractor power takeoff shaft.

For pecan spraying, a tank having a minimum capacity of 300 gallons is desirable. The pump should deliver 20 to 30 gallons per minute and maintain a pressure of 400 to 600 pounds per square inch while operating. A spray gun which is adjustable to produce a mist spray for spraying small trees or the lower canopy of large trees and a narrow stream that will reach the tops of tall trees is essential.

For safety and durability high pressure rubber hose having an inside diameter of three-fourths inch should be used with all high pressure spray machines.

can furnish you the latest information on farming, ranching and homemaking. They represent both The Texas A. & M. College System and the United States Department of Agriculture in your county.

Most county extension agents have their offices in the county courthouse or agriculture building. They welcome your visits, calls or letters for assistance.

This publication is one of many prepared by the Texas Agricultural Extension Service to present up-to-date, authoritative information, based on results of research. Extension publications are available from your local agents or from the Agricultural Information Office, College Station, Texas.

Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics. The Texas A. & M. College System and United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress of May 8, 1914, as amended, and June 30, 1914.

10M-3-59. Reprint.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.