This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A Jayhawker in Europe

Author: W. Y. (William Yoast) Morgan

Release Date: July 2, 2021 [eBook #65744]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A JAYHAWKER IN EUROPE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/jayhawkerineurop00morg |

Changes made are noted at the end of the book.

A

Jayhawker in Europe

BY

W. Y. MORGAN

Author of “A Journey of a Jayhawker”

MONOTYPED AND PRINTED BY

CRANE & COMPANY

TOPEKA

1911

Copyright 1911,

By Crane & Company

These letters were printed in the Hutchinson Daily News during the summer of 1911. There was no ulterior motive, no lofty purpose, just the reporter’s idea of telling what he saw.

They are now put in book form without revision or editing, because the writer would probably make them worse if he tried to make them better.

W. Y. MORGAN.

Hutchinson, Kansas, November 1, 1911.

To the Jayhawkers

who stay at home and take their European trips

in their minds and in the books, this

volume is respectfully dedicated

by one of the

gadders

| Page | |

| New York in the Hot Time, | 1 |

| Breaking Away, | 7 |

| On the Potsdam, | 12 |

| The Lions of the Ship, | 18 |

| Ocean Currents, | 25 |

| The Dutch Folks, | 30 |

| In Old Dordrecht, | 37 |

| The Dutchesses, | 44 |

| The Pilgrims’ Start, | 50 |

| Amsterdam, and Others, | 56 |

| Cheeses and Bulbses, | 63 |

| Historic Leyden, | 72 |

| The Dutch Capital, | 80 |

| “The Dutch Company,” | 88 |

| The Great River, | 96 |

| Along the Rhine, | 104 |

| In German Towns, | 112 |

| Arriving in Paris, | 120 |

| The French Character, | 127 |

| The Latin Quarter, | 135 |

| The Boulevards of Paris, | 144 |

| Some French Ways, | 154 |

| In Dover Town, | 162 |

| Old Canterbury Today, | 169 |

| The English Strike, | 178 |

| Englishman the Great, | 187 |

| The North of Ireland, | 198 |

| Scotland and the Scotch, | 211 |

| The Land of Burns, | 220 |

| The Journey’s End. | 228 |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The scrubbing-brush the national emblem of Holland | 41 |

| No place for a man from Kansas | 74 |

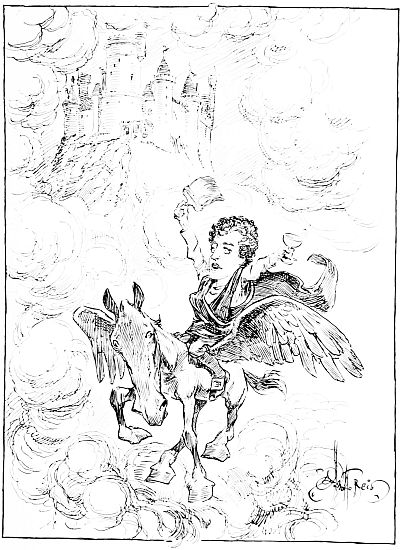

| The poet Byron building castles | 100 |

| The handsome knight she met in Elmdale Park | 111 |

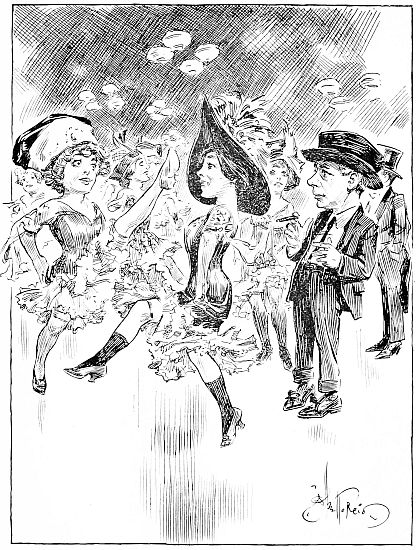

| The plain Quadrille at the Moulin Rouge | 148 |

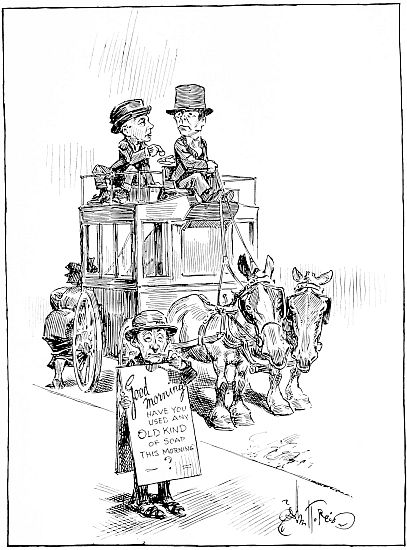

| Seeing London from the old English bus | 188 |

| Introducing a joke to our British cousins | 234 |

New York, July 10, 1911.

The last day on American soil before starting on a trip to other lands should be marked with a proper spirit of seriousness, and I would certainly live up to the propriety of the occasion if it were not for two things,—the baggage and the weather. But how can a man heave a sigh of regret at departing from home, when he is chasing over Jersey City and Hoboken after a stray trunk, and the thermometer is breaking records for highness and the barometer for humidity? I have known some tolerably warm zephyrs from the south which were excitedly called “hot winds,” but they were balmy and pleasant to the touch in comparison with the New York hot wave which wilts collar, shirt and backbone into one mass. The prospect of tomorrow being [2]out on the big water with a sea breeze and a northeast course does not seem bad, even if you are leaving the Stars and Stripes and home and friends. There is nothing like hot, humid weather to destroy patriotism, love, affection, and common civility. I speak in mild terms, but I have returned from Hoboken, the station just the other side of the place whose existence is denied by the Universalists. This is the place the ship starts from, and not from New York, as it is advertised to do.

Speaking of weather reminds me that the West is far ahead of New York in the emancipation of men. The custom here is for men to wear coats regardless of the temperature, whereas in the more intelligent West a man is considered dressed up in the evening if he takes off his gallusses along with his coat. Last night we went to a “roof garden” and expected that it would be a jolly Bohemian affair, but every man sat with his coat on and perspired until he couldn’t tell whether the young ladies of the stage were kicking high or not, and worse than that, he did not care.

I have been again impressed with the fact that there are no flies in New York City. There are no screens on the windows, not even of the dining-rooms, and yet I have not seen a fly. I wish Dr. Crumbine would tell us why it is that flies swarm out in Kansas and leave without a friendly visit such a rich pasture-ground as they would find on the millions of humans on Manhattan island. If I were a fly I would leave the swatters and the hostile board of health of Kansas, and take the limited train for New York and one perpetual picnic for myself and family.

This afternoon I went to the ball game, of course. Some people would have gone to the art exhibit or the beautiful public library. But New York and Chicago were to play and Matthewson was to pitch, and the call of duty prevailed over the artistic yearnings which would have taken me elsewhere. Coming home from the game I had an idea—which is a dangerous thing to do in hot weather. There has been a good deal of talk in the newspapers about the Republicans not agreeing on a candidate, and the question as to whether Taft [4]can be reëlected or not is being vigorously debated. Put ’em all out and nominate Christy Matthewson. This would insure the electoral vote of New York, for if the Republicans put “Matty” on the ticket the election returns would be so many millions for Matthewson and perhaps a few scattering.

There were about as many errors and boneheads in the game between Chicago and New York as there would be in a Kansas State League game, and more than would come to pass in the match between the barbers and the laundrymen of Hutchinson. The players did not indulge in that brilliant repartee with the umpire which is a feature of the Kansas circuit, and the audience, while expressing its opinion of the judgments, had no such wealth of phrases as pours over the boxes from the grandstand at home. The language used could have come from the ministerial alliance, and sometimes the game seemed more like a moving-picture show than a real live game of baseball. Chicago won, 3 to 2 in ten innings, and I feel that my European trip is a decided success so far.

This morning I took a little walk down Wall street and saw the place in which the Great Red Dragon lives. These New York bankers and brokers are not so dangerous as I have been led to believe by reading some of the speeches in Congress. There was no blood around the Standard Oil building, and the office of J. Pierpont was filled with men who looked as uncomfortable and unhappy as I felt with the heat. Sometimes I think the men of Wall street, New York, are just like the men at home,—getting all they can under the rules of the game and only missing the bases when the umpire looks the other way. The few with whom I talked were really concerned about the crops and the welfare of the people of Kansas, perhaps because they have some of their money invested in our State, and I got the idea that Wall street and all it represents is interested in the prosperity of the country and knows that hard times anywhere mean corresponding trouble for some of them in New York.

New York is a growing city. In many respects it is like Hutchinson. The street pav[6]ing is full of holes and new buildings are going up in every direction. Every few months “the highest skyscraper” is erected, and now one is being constructed that will have fifty or sixty stories—it doesn’t matter which. The buildings are faced with brick or stone, but really built of iron. I saw one today on which the bricklaying had been begun at the seventh story and was proceeding in both directions. That was the interesting feature of the building to me. That and the absence of flies and the baseball game are the general results of my efforts today to see something of the greatest city in America.

We sail tomorrow morning. Then it will be ten days on the ship for us. One thing about an ocean voyage is reasonably sure: If you don’t like it you can’t get off and walk. A really attractive feature is that there is no dust and you don’t watch the clouds and wish it would rain so you will not have to water the lawn.

Steamship Potsdam, July 11.

The sailing of an ocean steamer is always a scene of delightful confusion and excitement. Thousands of people throng the pier and the ship, saying goodbyes to the hundreds who are about to leave. The journey across the ocean, though no longer a matter of danger or hardship, is yet enough of an event to start the emotions and make the emoters forget everything but the watery way and the long absence.

The crowd is anxious, expectant, sad, and unrestrained. Men who rarely show personal feeling look with glistening eyes on the friends to be left behind. Women, who are always seeing disaster to their loved ones, strive with pats, caresses and fond phrases to say the consoling words or to express the terror in their hearts. The timid girl, off for a year’s study, wishes she had not been so venturesome. The father rubs his eyes and talks loudly about the baggage. The mother clings [8]to her son’s arm and whispers to him how she will pray for him every night, and hopes he will change his underclothes when the days are cool. Young folks hold hands and tell each other of the constant remembrance that they will have. Big bouquets of flowers are brought on by stewards, the trunks go sliding up the plank and into the ship, the officers strut up and down, conscious of the admiring glances of the curious, orders are shouted, sailors go about tying and untying ropes, the rich family parades on with servants and boxes, the whistle blows for the visitors to leave, and the final goodbyes and “write me” and “lock the back door” and “tell Aunt Mary” and such phrases fill the air while handkerchiefs alternately wipe and wave.

Slowly the big boat backs into the stream amid a fog of cheers and sobs, then goes ahead down the harbor, past the pier still alive with fluttering handkerchiefs, the voices no longer to be heard, and the passengers feel that sinking of the heart that comes from the knowledge of the separation by time and distance coming to them for weeks and months, perhaps forever. Sorrowfully they strain for [9]a last look at the crowd, now too far away to distinguish the wanted face, and then they turn around, look at their watches, and wonder how long it will be before lunch. Of course the Dutch band played the Star-Spangled Banner as the boat trembled and started; of course the last passenger arrived just a minute late and was prevented from making an effort to jump the twenty feet of water which then separated the ship from the pier. Of course the boys sold American flags and souvenir post cards. Of course the tourists wondered if they would be seasick and their friends rather hoped they would be, though they did not say so. The steamboats whistled salutes, and the band changed its tune to a Dutch version of “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” and with flags flying the Potsdam moved past the big skyscrapers, past the Battery, alongside the Statue of Liberty, and out toward the Atlantic like a swan in Riverside Park. The voyage has begun. The traveler has to look after his baggage, which is miraculously on board, find his deck chairs and his dining-room seats, and between times rush out occasionally to get one more glimpse [10]of the New Jersey coast, which is never very pretty except when you are homeward bound, when even Oklahoma would look good.

This boat, the Potsdam, of the Holland-American line, is not one of the big and magnificent floating hotels which take travelers across the Atlantic so rapidly that they do not get acquainted with each other and in such style that they think they are at a summer resort. But it is a good-sized, easy-sailing, slow-going ship that will take about ten days across and has every comfort which the Dutch can think of, and they are long on having things comfortable. It has a reputation for steadiness and good meals which makes it popular with people who have traveled the Atlantic and who enjoy the ocean voyage as the best part of a trip abroad. It lands at Rotterdam, one of the best ports of Europe and right in the center of the most interesting part of the Old World.

The pilot left us at Sandy Hook, and now the Potsdam is sailing right out into the big [11]water. A cool breeze has taken the place of the hot air of New York. The ocean is smooth; there is neither roll nor heave to the ship. Everybody is congratulating himself that this is to be a smooth voyage. A substantial luncheon is still staying where it belongs, and we are looking over the other passengers and being looked over by them. There is no chance to get off and go back if we wanted to do so. And we don’t want to—not yet.

Steamship Potsdam, July 14.

The daily life on shipboard might be considered monotonous if one were being paid for it, but under the present circumstances and surroundings the time goes rapidly. Everybody has noticed that the things he is obliged to do are dull and uninteresting. Any ordinary American would demand about $10 a day for fastening himself in a boat and remaining there for ten days. He would get tired of the society, sick of the meals and sore on his job. But call it “fun” and he pays $10 a day for the pleasure of the ride. The Potsdam is 560 feet long, sixty-two feet wide, and seven stories high,—four above the water-line and three below. On this trip its first-class accommodations are filled, about 260 people; but the second class is not crowded, and less than a hundred steerage passengers occupy that part of the ship which often carries 2,100 people. The steerage is crowded on the trip to America, filled with men and women who [13]are leaving home and fatherland in order to do better for themselves and their children. They go back in later years, for a visit, but they do not travel in the steerage. They carry little American flags and scatter thoughts of freedom and free men in the older lands.

This is a Dutch ship and the language of the officers and crew is Dutch. While a few of them speak some English and most of them know a little, the general effect is that of getting into an entirely foreign environment. The Dutch language is a peculiar blend. It seems to be partly derived from the German, partly from the English, and partly from the Choctaw. The pronunciation is difficult because it is unlike the German, the English or the Latin tongues. An ordinary word spelled out looks like a freight train of box cars with several cabooses. As one of my Dutch fellow-passengers said when he was instructing me how to pronounce the name of the capital of Holland, “Don’t try to say it; sneeze it.” A great deal of interest is added to the smallest bits of conversation by the doubt as to whether the Dutch speaker is telling you [14]that it is dinner-time or whether he has swallowed his store teeth.

Which reminds me of a little story Ben Nusbaum told me of the Dutchman who came into the Oxford café, sat up to the counter and in proper Dutch etiquette greeted the waiter with the salutation, “Wie gehts?” Turning toward the kitchen the waiter sang out, “wheat cakes!” “Nein! nein!” shouted the Dutchman. “Nine,” said the waiter, scornfully; “you’ll be dam lucky if you get three!”

The principal occupation on board a Dutch ship is eating, and the next most important is drinking. The eats begin with a hearty breakfast from 8 to 10 o’clock. At 11 o’clock, beef soup, sandwiches and crackers. At 12:30, an elaborate luncheon. At 4 o’clock, afternoon tea, with sandwiches and fancy cakes. At 7 o’clock, a great dinner. At 9 o’clock, coffee, sandwiches, etc. Any time between these meals you can get something to eat, anything from beef to buns, and the table in the smoking-room is always loaded with cheese, sausage, ham, cakes and all the little knick-knacks [15]that tempt you to take one as you go by. And yet there is surprise that some people are seasick.

You can get anything you want to drink except water, which is scarce, and apparently only used for scrubbing and bathing. Of course the steward will find you a little water, if you are from Kansas, but he thinks you are sick, wants to add a hot-water bag, and suggests that the ship doctor might help you some.

I have spoken before of the Dutch band. It is a good one, and loves to play. The first concert is at 10 in the morning. There is orchestra music during luncheon and dinner, and band concerts afternoon and evening. I like a German band, or a Dutch band, so long as it sticks to its proper répertoire. But there never was a German band that could play “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Swanee River,” and every German band persists in doing so in honor of the Americans. I suppose this desire to do something you can’t do is not confined to Dutch musicians. I know a man who can whistle like a bird, but he in[16]sists that he is a violinist, and plays second fiddle. I know a singer with a really great voice who persists in the theory that he can recite, which he can’t. Therefore he is a great bore, and nobody thinks he can even sing. Nearly all of us are afflicted some along this line, and the Dutch band on the Potsdam is merely accenting the characteristic in brass.

Today I saw a whale. Every time I am on the ocean I see a whale. At first nobody else could see it, but soon a large number could. There was a good deal of excitement, and the passengers divided into two factions, those who saw the whale and those who didn’t and who evidently thought we didn’t. The argument lasted nearly all the morning, and would be going on yet if a ship had not appeared in the distance, and our passengers divided promptly as to whether it was a Cunarder, a French liner, or a Norwegian tramp freighter. This discussion will take our valuable time all the afternoon. Friends will become enemies, and some of those who rallied around the whale story are almost glaring at each other over the nationality of that distant vessel. I am [17]trying to keep out of this debate, as I am something of a Hero because I saw the whale. I have already told of my nautical experience on Cow creek, so while I feel I would be considered an authority, it is better to let some of the other ambitious travelers get a reputation.

Steamship Potsdam, July 19.

There are always "lions" on a ship, not the kind that roar and shake their manes, but those the other passengers point at and afterward recall with pride. I often speak carelessly of the time I crossed with Willie Vandergould, although he never left his room during the voyage and was probably sleeping off the effects of a long spree. Once I was a fellow-passenger with Julia Marlowe, a fact Julia never seemed to recognize. There are always a few counts and capitalists on an ocean steamer, and a ship without a lion is unfortunate. Our largest and finest specimen is Booth Tarkington, the head of the Indiana school of fiction, an author whose books have brought him fame and money, and a playwright whose dramatizations have won success. He is the tamest lion I ever crossed with. He is delightfully democratic, not a bit chesty, but rather modest, and as friendly to a traveling Jayhawker as he is to the distinguished [19]members of the company. In fact, he understands and speaks the Kansas language like a native. His ideal of life is to have a home on an island in the track of the ocean steamers so he can sit on the porch and watch the ships come and go. Not for me. It is too much like living in a Kansas town where No. 3 and No. 4 do not stop, and every day the locomotives snort and go by without even hesitating.

Tarkington is an honest man, so he says, and he tells good sea stories. His favorite true story is of Toboga Bill, a big shark which followed ships up and down the South-American coast, foraging off the scraps the cooks threw overboard. Tarkington’s friend, Captain Harvey, got to noticing that on every trip his boat was escorted by Toboga Bill, whose bald spot on top and a wart on the nose made him easily recognizable. Harvey got to feeding him regularly with the spoiled meat and vegetables, and Toboga Bill would come to the surface, flop his fin at the captain and thank him as plainly as a shark could do. After several years of this mutual acquaintance the [20]captain happened to be in a small-boat going out to his ship at a Central-American port. The boat upset, and the captain and sailors were immediately surrounded by a herd of man-eating sharks. The shore was a mile away and the captain swam that distance, the only one who escaped; and all the way he could see Toboga Bill with his fin standing up straight, keeping the other sharks from his old friend. Occasionally Toboga would give the captain a gentle shove, and finally pushed him onto the beach.

This story Tarkington admitted sounded like a fish story, but he has a motor-boat named Toboga Bill, which verifies the tale.

That reminded me of a Kansas fish story which I introduced to the audience. Everybody in Kansas knows of the herd of hornless catfish which has been bred near the Bowersock dam at Lawrence. Some years ago Mr. Bowersock, who owns the dam that furnishes power for the mill and other factories, conceived the idea that big Kaw river catfish going through the mill-race and onto the water-wheel added much to the power generated. [21]Then he read that fish are very sensitive to music. So he hired a man with an accordion to stand over the mill-race and play. The catfish came from up and down stream to hear the music, and almost inevitably drifted through the race, onto the wheel, and increased the power. The fishes’ horns used to get entangled in the wheel and injure the fish; so Mr. Bowersock, who is a kind-hearted man and very persistent, had a lot of the fish caught and dehorned, and in a year or two he had a large herd of hornless catfish. These fish not only turn out to hear the music, but they have learned to enjoy the trip through the mill-race and over the wheel, so that every Sunday or oftener whole families of catfish—and they have large families—come to Bowersock’s dam to shoot the chutes something as people go out to ride on the scenic railway. Whenever the water in the river gets low Mr. Bowersock has the band play: the catfish gather and go round and round over the wheel, furnishing power for the Bowersock mill when every other wheel on the river is idle from lack of water.

There were some skeptical folks who heard [22]my simple story and affected to disbelieve. But I assured them that it could be easily proven, and if they would go to Lawrence I would show them the Bowersock dam and the catfish. It is always a good idea to have the proofs for a fish story.

The next “lion” on board is Gov. Fook, returning from the Dutch West Indies, where he has been governing the islands and Dutch Guiana. The governor is a well-informed gentleman, and a splendid player of pinochle. The Dutch have the thrifty habit of making their colonies pay. They are not a “world power” and do not have to be experimenting with efforts to lift the white man’s burden. Their idea is that the West-Indian and the East-Indian who live under the Dutch flag shall work. The American idea is to educate and convert the heathen and pension them from labor. Our theory sounds all right, but it results in unhappy Filipinos and increased expense for Americans. The Dutch colonials pay their way whether they get an education or not.

One unfamiliar with modern steamship travel would think that the captain and his first and second officers were the important officials on board. They are not. The officers rank about as follows: 1st, the cook; 2nd, the engineer; 3rd, the barber, and after that the rest. The cook on an ocean steamer gets more pay than the captain, and is now ranked as an officer. The managing director of a big German company was accustomed on visiting any ship of their line, to first shake hands with the cook and then with the captain. When one of the officers suggested that he was not following etiquette he answered that there was no trouble getting captains and lieutenants but it was a darned hard job to find a cook. The cook has to buy, plan meals, supervise the kitchen and run it economically for the company and satisfactorily for the passengers, for over 2,000 people.

The barber is the man on the ship who knows everything for sure. Ask the captain when we will get to Rotterdam and he will qualify and trim his answer by referring to possible winds and tides, and he won’t say exactly. Ask the barber and he will tell you [24]we will get there at 10 o’clock on Friday night. He knows everything going on in the boat, from the kind of freight carried in the hold to the meaning of the colors painted on the smokestack. During this voyage I have had more numerous and interesting facts than anybody, because I have not fooled with talking to the captain or the purser or the steward, but gotten my information straight from the fountain of knowledge, the barber shop. However, this is not peculiar to ships. The same principle applies at Hutchinson and every other town.

Steamship Potsdam, July 21.

This is the eleventh day of the voyage from New York, and if the Potsdam does not have a puncture or bust a singletree she will arrive at Rotterdam late tonight. The Potsdam is a most comfortable boat, but it is in no hurry. It keeps below the Hutchinson speed limit of fifteen miles an hour. But a steamship never stops for water or oil, or to sidetrack or to wait for connections. This steady pounding of fourteen miles an hour makes an easy speed for the passenger, and the verdict of this ship’s company is that the Potsdam is a bully ship and the captain and the cook are all right.

Nearly all the way across the Atlantic we have been in the Gulf stream. I have read of this phenomenal current which originates in the Gulf of Mexico and comes up the eastern coast of the United States so warm that it affects the climate wherever it touches. [26]Then nearly opposite New England it turns and crosses the Atlantic, a river of warm water many miles wide, flowing through the ocean, which is comparatively cold. This stream is a help to the boats going in its direction, although it has the bad feature of frequent fogs caused by the condensation which comes when the warm and cold air currents meet. The Gulf stream is believed to be responsible for the green of Ireland and for the winter resorts of southern England. It goes all the way across the Atlantic and into the English Channel, with a branch off to Ireland. What causes the Gulf stream? I forget the scientific terms, but this is the way it is, according to my friend Mr. Vischer, formerly of the German navy. The water in the Gulf of Mexico is naturally warm. The motion of the earth, from west to east, and other currents coming into the gulf, crowd the warm water out and send the big wide stream into the Atlantic with a whirl which starts it in a northerly and easterly direction. The same Providence that makes the grass grow makes the course of the current, and it flows for thousands of miles, [27]gradually dissipating at the edges, but still a warm-water river until it breaks on the coast of the British Isles and into the North Sea. Perhaps Mr. Vischer would not recognize this explanation, but I have translated it into a vernacular which I can understand.

The Gulf stream reminds me of the Mediterranean. Not having much else to worry about, I have gone to worrying over the Mediterranean Sea. The ocean always flows into the sea. The current through the strait of Gibraltar is always inward. Many great rivers contribute to the blue waters of the great sea. There is no known outlet. Why does not the Mediterranean run over and fill the Sahara desert, which is considerably below the sea-level? Scientists have tried to figure this out, and the only tangible theory is that the bottom of the Mediterranean leaks badly in some places, and that the water finds its way by subterranean channels back to the ocean. What would happen if an eruption of Vesuvius should stop up the drain-pipe? Now worry.

Tonight we saw another phenomenon, the aurora borealis. It looked to me like a beautiful sunset in the north. We are sailing in the North Sea along the coast of Belgium, and the water reaches northward to the pole. The aurora borealis is another phenomenon not easily explained, but Mr. Vischer says it is probably the reflection of the sun from the ice mirror of the Arctic. And it does make you feel peculiar to see what is apparently the light of the sunset flare up toward the “Dipper” and the North Star.

Some of our passengers disembarked today at Boulogne. This was the first time the Potsdam had paused since she left New York a week ago last Tuesday. This was the stop for the passengers who go direct to Paris. The Dutch who are homeward bound and those of us who think it best to fool around a little before encountering the dangers of Paris, continue to Rotterdam. We should be spending the evening with maps and guide books preparing ourselves for the art galleries, cathedrals, canals and windmills. As a matter of fact, we are wondering what is going[29] on at home. There is a balance-wheel in the human heart that makes the ordinary citizen who is far afield or afloat turn to the thoughts of the home which he left, seeking a change.

A smoking-room story: An American in a European art gallery was heading an aggregation of family and friends for a study of art. His assurance was more pronounced than his knowledge. “See this beautiful Titian,” he said. [30]“What glorious color, and mark the beauty of the small lines. Isn’t it a jim dandy? And next to it is a Rubens by the same artist!”

Rotterdam, Holland, July 23.

It seemed to me unnecessary, but I had to explain to some friends why I was going especially to Holland. It is the biggest little country in the world. In art it rivals Italy, in business it competes with England, historically it has had more thrills to the mile than France, and in appearance it is the oddest, queerest, and most different from our own country, of all the nations of central Europe. Holland gives you more for your money and your time than any other, and that’s why I am back here to renew the hurried acquaintance with the Dutch made a few years ago.

Landing in Rotterdam was an experiment. The guide books and the tourist authorities pass Rotterdam over with brief mention. Baedeker, the tripper’s friend, suggests that you can see Rotterdam in a half-day. That is because Rotterdam is short on picture galleries and cathedrals. It is a great, busy[31] city of a half-million people, and one of the most active commercially in the world. It is the port where the boats from the Rhine meet the ships of the sea. It is the greatest freight shipping and receiving port of northern Europe. It is the coming city of the north, because of its natural advantages in cheap freight rates. After looking it over hurriedly it seems to me to be one of the most interesting of cities. I am not going to run away from cathedrals and galleries. I am not intending to dodge when I see a beautiful landscape coming. But I have done my duty in the past and have seen the great cathedrals and the exhibitions of art. No one can come to Europe and not see these things once, for if he did he would not be able to lift up his head in the presence of other travelers. But he does not have to do them a second time. If I want to see pictures of Dutch ladies labeled “Madonna,” I will see them. If I don’t want to, I do not have to. In other words, if I go to the “tourist delights” it will be my own fault.

I would rather see the people themselves than the pictures of them. I want to observe[32] how they work, what they work for, what their prospects are, and wherein they differ from the great Americans.

Man made most of Holland. Nearly all of the country is below the level of the sea, much of it many feet below. All that keeps the tide of the North Sea from flooding the country with from ten to a hundred feet of water every day are the dikes which man has built. Behind these huge embankments lies a country as flat as the flattest prairie in Kansas. A few sandhills and an occasional little rise of ground might stick out of the water if the dikes broke, but I doubt it. This “made” land has been fertilized and built up by the silt of the rivers, added to by the labor and science of man, until it is a vast market garden. The water of the rivers is diverted in every direction into canals. There is no current to the rivers; the surface is too flat, and the fresh water is backed up twice a day by the ocean tides at the mouths. There are practically no locks and the movement of the water is hardly perceptible, except near the coast, where it responds to the[33] advance and retreat of the sea. These canals are an absolute necessity for drainage, otherwise the country would be a swamp. Then they are used as roads, and practically all the freight is carried to market cheaply in canal-boats. The canals also serve as fences. The drainage water is pumped by windmills, which are then used to furnish power for every imaginable manufacturing purpose, from sawing lumber to grinding wheat. The cheap wind-power enabled the people to clear the land of water. So you see why there are dikes, canals and windmills in Holland: because they were the only available instruments in the hand of man to beat back the sea and build a productive soil. They were not inserted in the Holland landscape for beauty or for art’s sake, but because they were necessities; and yet great artists come to Holland to paint pictures of these practical things, and when they want to add more beauty they insert Dutch cattle and wooden shoes. All of which shows that the plain everyday things around us are really picturesque; and they are, whether you look at[34] the sandhills along the Arkansas or the dunes along the North Sea.

In this little country, containing 12,500 square miles of land and water, smaller than the seventh congressional district of Kansas, live almost 6,000,000 of the busiest people on earth. Their character may be drawn from their history. They first beat the ocean out of the arena and then made the soil. They met and overcame more obstacles than any other people in getting their land. And then for several centuries they had to fight all the rest of Europe to keep from being absorbed by one or the other of the great powers. They drove out the Spaniards at a time when Spain was considered invincible. They licked England on the sea, and the Dutch Admiral Tromp sailed up and down the Channel with a broom at the mast of his ship. They drove Napoleon’s soldiers and his king out of the country. They never willingly knuckled down to anybody, and they never stayed down long when they were hit.

The Dutch have for centuries been considered the best traders in Europe. They[35] have the ports for commerce and they have the money. They own 706,000 square miles of colonies, with a population six times as large as their own. From the beginning they have been ruled by merchants and business men, rather than by kings and princes, by men who knew how to buy and sell and fight. They have been saving and thrifty, and can dig up more cash than any other bunch of inhabitants on the globe. They have sunk some money in American railroads, but they have made it back, and they always take interest. Market-gardening and manufacturing and trade have been their resources, and nothing can beat that three of a kind for piling up profits and providing a way to keep the money working.

Of course these characteristics and this environment have made the Dutch peculiar in some ways, and they are generally counted a little close or “near.” They habitually use their small coin, the value of two-fifths of an American cent, and they want and give all that is coming. They have good horses, fat stomachs, and lots of children. They are pleasant but not effusive, and they are as[36] proud of their country as are the inhabitants of any place on earth. They believe in everybody working, including the women and the dogs. Their struggle with the sea never ends, and they follow the same persistent course in every line of development. They are so clean it is a wonder they are comfortable, and they believe in eating and drinking and having a good time, just so it doesn’t cost too much. They are a great people, and here’s looking at them.

Dordrecht, July 23.

This is the oldest town in Holland, and once upon a time was the great commercial city. It is about fifteen miles from Rotterdam, and remember that fifteen miles is a long distance in this country. It is built upon an island; two rivers and any number of canals run around it and through it whenever the tide ebbs or flows. Good-sized ocean steamers come to its wharves, and until other cities developed deeper harbors Dordrecht was the Hutchinson of southwest Holland. And now let me explain that the people of this country do not call it Holland, but The Netherland. Originally Holland was the western part of the present Netherland. Dordrecht is in old South Holland. About nine hundred years ago the Count of Holland, who then ruled in this precinct, decided to levy a tax or a tariff on all goods shipped on this route, the main traveled road from England to the Orient. The other counts and kings and bishops[38] kicked, but after a fight the right of the Count of Holland was vindicated, and he built the city of Dordrecht as a sort of customs house. This was in 1008. For several hundred years Dordrecht prospered and was known as a great commercial city. Then Antwerp, Rotterdam and Amsterdam came forward with better harbors, and Dordrecht took a back seat. But it has always been one of the important places in The Netherland. When William of Orange took hold of the revolution against Spain, the first conference of the representatives of the Dutch states was held in Dordrecht, and it was always loyal to the cause of Dutch freedom. The best hotel and restaurant in the city today is The Orange, named for the royal house which has so long been at the head of the Dutch government. My idea of a really important statesman is one for whom hotels and cigars are named centuries after he has passed away.

This is Sunday, and I am forced to believe that the Dutch are not good churchgoers. We went to the evening service in the great cathedral. In fact, we went to the cathedral and[39] suddenly the service began without our having time to retire gracefully. So we decided to stay, and in a prominent place was a list of the prices of seats. Some cost ten cents, some five cents, and some were marked free. I handed ten cents to the lady in charge, and we took two seats in the rear, which I afterward discovered were free. The women seem to run the church much as they do at home. The Dutch hymns were not so bad, but the Dutch sermon was not interesting to me. During the closing song, we thought we would slip out quietly, but when we reached the door we found it locked. The custom is to lock the door and allow no one to enter or leave during the service, but as a special favor to Americans, who evidently did not know what they were doing, the guardian of the door unlocked it, and out we went amid general interest of the congregation.

We came from Rotterdam on a little steam-boat, which scooted along the rivers and canals like a street car. Very often the canal was built higher than the adjoining land, and it gave the peculiar feeling of boating in the air.[40] There is no waste ground. Every foot of it not occupied by a house or a chicken-yard, is pasture or under cultivation. Every farmer has a herd of those black-and-white cattle. Some of the herds are as many as six or seven cows. But every cow acted as if she were doing her full duty toward making Holland the wealthiest of nations.

The streets of Dordrecht are generally narrow, like those of all old towns. Many of the buildings are very old, and a favorite style of architecture is to have the front project several feet forward over the street. The tops of opposite buildings often almost meet. I don’t see why they do not meet and come down kerwhack, but they don’t. Imagine these quaint streets with old Dutch houses, white and blue, with red tiled roofs, and green and yellow thrown in to give them color, with angles and dormers and curious corners, the tops projecting toward one another, and you can see how interesting a Dutch street can be if it tries, as it does in Dordrecht. Of course in the outer and newer parts of the town are larger streets and more modern houses, with [41]beautiful gardens and flower beds that would baffle a painter for color, but old Dordrecht is the most interesting. Add to the street picture a canal down the middle, and you get a frequent variation. Put odd Dutch boats in the water, fill them with freight and children, and you have another. If this were not picturesque it would be grotesque to American eyes, but it is the actual development of Dutch civilization, and it is the thing you pay money for when some artist catches the inspiration which he can get here if anywhere.

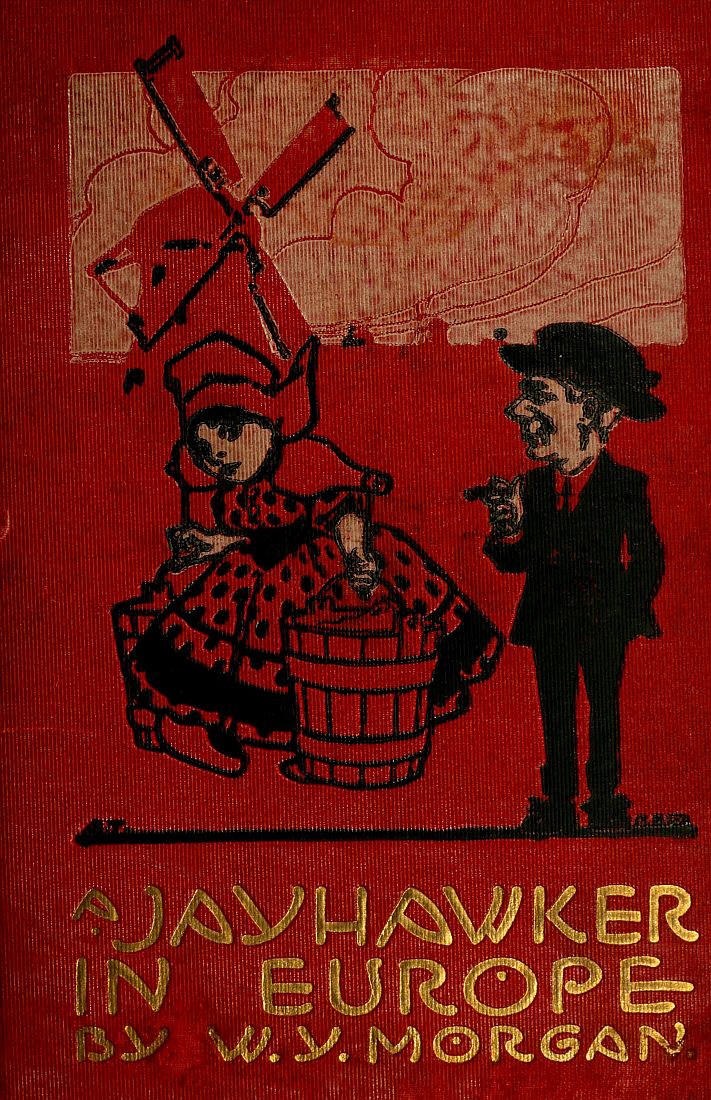

THE SCRUBBING-BRUSH THE NATIONAL EMBLEM OF HOLLAND

Of course the streets are paved, and they are as clean as the floor of an ordinary American dwelling. Everyone knows that the Dutch are clean and that their national emblem ought to be a scrubbing-brush. They are so clean that it almost hurts. Very often there are no sidewalks, and when there are they are not level, and are generally fenced in. They belong to the abutting property, and are not to be walked on by the public. The people walk in the street, and that custom is a little hard to get used to. Before the front window of nearly every house is a mirror, so[42] fastened that those within the house can see up and down the street, observe who is coming and who is going, and where. This custom, if introduced at home, would save a good deal of neck-stretching. But at first one is overly conscious of the many eyes which are observing his walk and the many minds which are undoubtedly trying to guess just where and why and who. But this mirror custom does not bother the Dutch young folks, not much. It is also the custom for the young man and his sweetheart to parade along the street hand in hand, arm in arm, or catch-as-catch-can, if they want to,—and they want to a great deal. At first this looked like a rude demonstration of affection, but after you have observed it some, say for an hour or so, it doesn’t seem half bad,—if you were only Dutch.

Dordrecht has about 40,000 people, and all of them are on the street or at the window on Sunday. The saloons are open, but nothing is sold stronger than gin. The Dutch in a quiet, gentlemanly and ladylike way, are evidently trying to consume all the beer that can[43] be made in Holland or imported. Of course they can’t succeed, but, as the story goes, they can probably make the breweries work nights. There is really a need for a temperance organization in this country, and I should say it would have work enough to last it several thousand years.

Rotterdam, July 24.

The secret of the success of the Dutch is no secret at all. Everybody works, not excepting father, grandfather and grandmother. I suppose this habit began with the unceasing fight against the sea, the building of the dikes, the pumping out of the water, and the construction of a soil. It has continued until there is no other people more persistently industrious. They rise early and get busy. The women cook and scrub and work on the canal-boats, in the shops and in the fields. The children go to school eleven months in the year. The men are stout, quick, and work from early to late. Even the dogs work in Holland. At first it seemed rather hard to see the dogs hitched to the little carts and pulling heavy loads, sometimes a man riding on the cart. This is a serious country for the canine, and must be the place where the phrase “worked like a dog” got its start. In most places the dog is the companion and pet[45] of man, but in Holland he has to do his part in making a living, and he soon learns to draw the load, pulling hard and conscientiously on the traces. He has little time to fight and frolic, but he has the great pleasure of the rest that comes from hard labor. However, if I were a dog and were picking out a country for a location, I would stay far away from Holland. It is no uncommon sight to see a woman with a strap over her shoulders dragging a canal-boat or pulling a little wagon. In fact, the women of The Netherland have rights which they are not even asking in the United States, and no one disputes their prerogative of hard work. There are no “Suffragettes” in Holland, but a woman can do nearly anything she wants to unless it is vote, which she apparently does not care for. There are many rich Hollanders; in fact, there are few that are poor. But they do not constitute a leisure class. The wealthy Dutch gent merely works the harder and the wealthy Dutch “vrouw” scrubs and manages the household or runs the store just as she did in the earlier years of struggle.

Speaking of the Dutch women, I think they are good-looking. They are almost invariably strong and well in appearance, with good complexions, clever eyes and capable expression. They may weigh a little strong for some, but that is a matter of taste. The old Dutch peasant costumes are still worn in places, but as a rule their clothes come from the same models as those for the American women. The Dutchess has been reared to work, to manage, and to advise with her man. She is intelligent in appearance and quick in action. She is educated and companionable. What if her waist line disappears? What if she has no ankles, only feet and legs? Perhaps it will be thought that I am going too far in my investigation, but the Dutch ladies ride bicycles so generally that even a man from America can see a few things, no matter how hard he tries to look the other way and comes near getting run over.

The Queen of Holland is a woman. This is not a startling statement, for so far as I know a man has never been a queen in any country. But there is no king. Queen Wilhelmina’s[47] husband, Prince Henry, is not a king. If there is any ruling to do in Holland it is done by Wilhelmina. Henry can’t even appoint a notary public. No one pays any attention to him, and I understand Wilhelmina has given it out that what Henry says does not go with her. I am trying to investigate the status of affairs in the royal family, because I had entertained the idea that Wilhelmina was an unfortunate young queen with a bad husband. That may have been so a few years ago, but now I understand she bats poor Henry around scandalously, pays no heed to his wishes, and pointedly calls his attention about three times a day to the fact that he is nothing but a one-horse prince while she is the boss of the family and the kingdom. This pleases the Dutch immensely, for Henry is a German and the Dutch don’t like the Germans. They think the Germans are conceited and arrogant, and that Emperor William is planning to eventually annex The Netherland to Germany. So every time Wilhelmina turns down the German prince all the Dutch people think it is fine, and her popularity is immense. Henry gets a good salary, but his job would be a hard[48] one for a self-respecting American. I understand he is much dissatisfied, but he was not raised to a trade, and if Wilhelmina should stop his pay he would go hungry and thirsty, two conditions which would make life intolerable for a German prince.

Wilhelmina has a daughter, two years old, named Juliana. I suppose Henry is related to Juliana, but he gets no credit for it. Everywhere you go you see pictures of Wilhelmina and Juliana, but not of Henry. A princess is really what the Dutch want, for their monarch has actually no power, and the government is entirely managed by the representatives of the people. But a prince would likely be wild, and might want to mix into public affairs. A princess makes a better figurehead of the state. She will be satisfied with a new dress and a hand-decorated crown, and not be wanting an army and battleships as a prince might do. Wilhelmina represents to the Dutch people the ruling family of Orange, which brought them through many crises, and Juliana is another Orange. Henry is only a lemon which the Germans handed to them.

The royal family are off on a visit to Brussels, and I have not met any of them. This information I have gleaned from the hotel porters, the boat captains, the chambermaids, and the clerks who speak English. I imagine I have come nearer getting the facts than if I had sent in my card at the royal palace.

Delftshaven, July 25.

This is the town from which the Pilgrims sailed on the trip which was to make Plymouth Rock famous. Nearly a hundred of the congregation of Rev. John Robinson at Leyden came to this little suburb of Rotterdam, and embarked on the Speedwell. The night before the start was spent by the congregation in exhortation and prayer in a little church which still stands, and has the fact recorded on a big tablet. The Pilgrims went to Southampton, discovered the Speedwell was not seaworthy, and transferred to the Mayflower.

Those English Puritans who had emigrated from their own country to Holland were considered “religious cranks” even in those days when fighting and killing for religion was regarded the proper occupation of a Christian. The Puritans in England were strong in numbers, and while Queen Elizabeth had frowned[51] upon them as dissenters from the church of which she was the head, she was politician enough to restrain the persecution of them, for they were useful citizens and loved to die fighting Spaniards. But a few extremists who persisted in preaching in public places were sentenced to jail, and some of these skipped to Holland. Queen Elizabeth died and James became the King of England, and he was a pinhead. He hated non-conformists as much as Catholics. So, more of the Puritans who could not pretend to conform went to Holland, and in Leyden and Amsterdam they founded little settlements. Holland was a land of liberty, and the Puritans wanted the right to disagree, non-conform, argue and debate over disputed questions. There were several congregations of them, and they did not agree on important doctrines, such as whether John the Baptist’s hair was parted on the side or in the middle. Public debates were held and great enjoyment therefrom resulted, although there is no record of anyone having his opinion changed by the arguments, and the side whose story you are reading always overcame the other.

The Puritans did not mix much with the Dutch, and naturally grew lonesome in their exile. They conceived the plan of emigrating to the New World and there establishing the right to worship God in accord with their own conscience. Influential Puritans in England who had not been so cranky as to leave home, helped with the king, and finally they secured permission from James to settle in America and to own the land they should develop. James remarked at the time he would prefer that they go to Hell, where they belonged, but he was needing a loan from the English Puritans, so he gave the permit. The Puritans in old England also provided a good part of the money with which to fit out the expedition. At the time there was a general movement among the Puritans in England for a big migration to the New World. This was to be a sort of experiment station. At the time, James was king, and Charles, a dissolute prince, was to follow. The Puritans were sick at heart and ready to leave their native land. But soon after the Pilgrims had made their settlement in New England, the Puritans at home developed leaders who put them into[53] the fight for Old England. Then along came Cromwell, and for many years English Puritans were running the government, and the necessity for a safe place across the sea and an asylum for religious liberty disappeared so far as they were concerned, though their interest in the Colonists was maintained. The sons of these Puritans who crossed the ocean rather than go to the established church, refused to pay a tax on tea, about 150 years later, and formed a new country with a new flag. That was part of the result of the sailing of the little company from Rev. Mr. Robinson’s flock after a night spent in prayer in this town of Delftshaven, just about this time of the year in 1620.

The stay of the Puritans in Holland had no effect on the Dutch. They let the Puritans shoot their mouths any way they pleased, and the Puritan only prospers and proselytes on opposition. But the Dutch of the present day are getting good returns for that investment of long ago. There are a dozen places in Holland, here and at Amsterdam and Leyden, visited by Americans every year because they are historic spots in connection with the[54] Pilgrims. At each and every place the contribution-box is in sight, and the Dutch church or town which owns the property gets a handsome revenue. New England churches give liberally to the fixing up of the Dutch churches which can show a record of having been just once the place where some Puritan preached.

Wooden shoes have not gone out of style in Holland. They are still worn generally in the country, and by the poorer children and men in the cities. They are cheap, which is a big recommendation to the Dutch. They are warm, said to be much warmer than leather. It does not hurt them to be wet, a very desirable feature in this water-soaked country. These are all good reasons, and as soon as you get used to the clatter and the apparent awkwardness you appreciate the fact that the “klompen,” as the Dutch call them, are a reasonable style for Holland. They are not worn in the house but dropped in the entryway, and house shoes or stocking feet go within. The Dutch farmer is proud of his clogs, paints them, carves them, and scrubs them. A man with idle time, like a fisherman, will often spend months decorating a pair of[55] wooden shoes. They are considered a proper present from a young husband to his bride, and she will use them when scrubbing, which is a good part of the time. The shoes are generally made of poplar, and to the size of the foot. When the foot grows you can hollow out a little more shoe. Wooden shoes are as common here as overalls in America, and they will not grow less popular unless Holland goes dry—of which I see no indication.

The farm-houses are usually built in connection with the barns, the family living in front and the stock and feed occupying the rear. This is rather customary in cold climates, and you must remember that Holland is farther north than Quebec. The winters get very cold and the canals and rivers freeze over. Skating is the great national sport. There does not seem to be much summer sport except scrubbing. All through the summer the people dig and weed and fertilize and prepare for market. The dikes and canals must be maintained and the best made of a short season. In the winter they can live with the pretty black-and-white cattle, the sheep and the horses, and have a good time.

Amsterdam, July 27

This is the largest and most important city of Holland. It has about as much commerce as Rotterdam, and is longer on history, manufactures, art, and society. It was the first large city built up on a canal system, and its 600,000 population is a proof that something can be built out of nothing. Along about 1300 and 1400 it was a small town in a swamp. When the war for independence from Spain began, in 1656, Amsterdam profited by its location on the Zuyder Zee. The Spaniards ruined most of the rival towns and put an end to the commerce of Antwerp for a while, and Amsterdam received the mechanics and merchants fleeing from the soldiers of Alva. The name means a “dam,” or dike, on the Amstel river. The swamp was reclaimed from the water by dikes and drainage canals, but even now every house in the city must have its foundation on piles. The word dam, or its inclusion in a name, means just about what[57] it does in English, provided you refer to the proper dam, not the improper damn. As nearly all of the Dutch towns are built on dam sites a great many of them are some-kind-of-a-dam. Amsterdam is built below the level of the sea, which is just beside it, and the water in the canals is pumped out by big engines and forced over the dike into the sea. If this were not done the water would come over the town site and Amsterdam would go back to swamp and not be worth a dam site.

Amsterdam is the chief money market of Holland, and one of the financial capitals of the world. It is the place an American promoter makes for when he is out after the stuff with which to make the female horse travel. A large part of its business men are Jews, and their ability and wealth have maintained the credit of Dutch interests in all parts of the globe. At a time when the Jews were being persecuted nearly everywhere they were given liberty in Holland, and much of the country’s progress is due to that fact and to the religious toleration of all kinds of sects.

The canals run along nearly all the streets,[58] and are filled with freight-boats from the country and from other cities. Thousands of these canal boats lie in the canals of Amsterdam and are the homes of the boatmen, who are the commerce carriers of Holland. Under our window is tied up a canal-boat which could carry as much freight as a dozen American box cars. The power is a sail or a pole or a man or a woman, whichever is most convenient. The boatman and his wife and ten or fifteen children, with a dog and a cat, live comfortably in one end, and we can watch them at their work and play. A dozen more such boats are lying in this block, some with steam engines and some with gasoline engines. The Standard Oil Company does a great business in Holland, and as usual is a great help to the people. It is introducing cheap power for canal-boats by means of proper engines, and in a short time will probably free the boatman and his wife from the pull-and-push system received from the good old days.

The canals are lined with big buildings, business and residence, mostly from four to six stories high, with the narrow, peaked and picturesque architecture made familiar to us[59] by the pictures. All kinds of color are used and ornamented fronts are common. Imagine a street such as I describe and you have this one that is under our hotel window and which is the universal street scene of Amsterdam. Some one called this the Venice of the North, but to my mind it is prettier than Venice, although it lacks some of the oriental architecture and smell.

Last night we went to the Rembrandt theatre to see “The Mikado,” in Dutch. Of course we could follow the music of the old-time friend, and the language made the play funnier than ever. The Dutch are not near so strong on music as are their German or French neighbors. They utilize compositions of other nations, and American airs are very common. The window of a large fine music store is playing up “Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?” A few Americans were at the big garden Krasnapolsky, listening to a really fine orchestra with an Austrian leader. We sent up a request for the American national air and it came promptly: “Whistling Rufus.” The Europeans think the cake-walk is something[60] like a national dance in our country, and whenever they try to please us they turn loose one of our rag-time melodies. They do not mind chucking the “Georgia Campmeeting” or “Rings on My Fingers and Bells on My Toes,” into a program of Wagner and Tschudi and other composers whom we are taught at home to consider sacred.

The most entertaining feature of the Amsterdam landscape that I have seen is a Dutch lady in a hobble skirt. The fashion is here all right, and it would make an American hobble appear tame and common. In the first place, the Dutch lady is not of the proper architecture, and in the second place, she still wears a lot more underskirts, or whatever they are, than are considered necessary in Paris or Hutchinson. But she does not expand the hobble. The shopping street of Amsterdam is filled with fashionably dressed Dutch ladies who look like tops, and who are worth coming a long ways to see. Far be it from me to criticize the freaks of female fashion. I never know what they are until after they are past due. But if the Dutch[61] hobble ever reaches the American side of the Atlantic it will be time for the mere men to organize.

The greatest art gallery in Europe is here, The Rijks Museum. I went to see it—once. I do not get the proper thrills from seeing a thousand pictures in thirty minutes. They make me tired. But Rembrandt’s Night Watch, or nearly anything a good Dutch artist has painted, is a real pleasure. The Dutch are recognizing their own modern art, and in that way they are going to distance the Italians. The Dutch artists are good at portraying people and common things, such as cats and dogs and ships. They are not strong in allegory or imaginative work, and you do not have to be educated up to enjoy them. And they run a little fun into their work occasionally, which would shock a Dago artist out of his temperament.

Wages are higher in Holland than elsewhere in Europe. A street car conductor gets a dollar a day. Ordinary labor is paid sixty to eighty cents a day. Farm laborer about $15[62] per month, but boards himself. A good all-around hired girl is a dollar a week. Mechanics receive from one dollar to two dollars a day. The necessaries of life are not so high as with us. Vegetables are cheaper. Tobacco is much less. Meats are about as high. Clothing is cheaper, but our people wouldn’t wear it. Beer is two cents a glass and lemonade is five cents. The ordinary workingman lives on soup, vegetables, and very little meat; gets a new suit of clothes about once in five years, and takes his family to a garden for amusement, where they get all they want for ten cents. The Dutch citizen on foot is plain, honest, a little rude, but of good heart and very accommodating. I have not met the citizens in carriages and on horseback, who make up a very small part of the procession in Holland.

Alkmaar, July 28.

Of course Holland is the greatest cheese country on earth, and Alkmaar is the biggest cheese market in Holland. Every Friday the cheesemakers of the district bring their product to the public market, and buyers, local and foreign, bargain for and purchase the cheeses. That is why we came to Alkmaar on Friday. The cheese market is certainly an interesting and novel sight. All over the big public square are piled little mounds of cheeses, shaped like large grape-fruit and colored in various shades of red and yellow. Each wholesaler has his carriers in uniform of white, and a straw hat and ribbons colored as a livery. When a sale is made, two carriers take a barrow which they carry suspended from their shoulders and with a sort of two-step and many cries to get out of the way they bring their load to the public weigh-house, where it is officially weighed. Then off the cheeses go to the store-rooms or to[64] the canal-boats which line one side of the square, waiting to take their freight to the cities or to the sea. The farmers look over each other’s cheeses as they do hogs at the Kansas State Fair, with comments of praise or criticism. There is much chaffing and chaffering between them and the buyers. In about two hours the cheeses are gone, the square is empty and the beer-houses are full. The women-folks do not take an active part in the market, but they are present and looking things over, and I suspect they had been permitted to milk the cows and make the cheese.

About $3,000,000 worth of cheese is sold annually in the Alkmaar market. The country round about, North Holland, is all small farms, with gardens and pastures and little herds of the black-and-white cattle. The cheese wholesales at about 60 cents a cheese, and in America we pay about twice that much for the same, or for the Edam, which is like it. The farmers look prosperous, drive good horses and very substantial gaily painted wagons.

Alkmaar has 18,000 population, and is therefore about the size of Hutchinson. But it is a good deal older. Back in 1573 it successfully defended itself against the Spaniards. The name means “all sea,” because the country was originally covered with water. The land is kept above the water now by pumping and pouring into canals which are higher than the farms through which they flow. This is done very systematically and by windmills. A district thus maintained is called a “polder,” something like our irrigation district, and on one of them near Alkmaar, about the size of a Kansas township, six miles square, there are 51 windmills working all the time, pumping the water. These are not little windmills like those in a Kansas pasture, but great fellows with big arms fifty feet long, and they stand out over the polder like so many giants. The picture of these mills in a most fertile garden-spot, with canal streaks here and there and boats on the canals looming up above the land, is certainly a striking one. And it shows clearly what energy can do when properly applied.

The soil is as sandy as in South Hutchinson. But dirt and fertilizer are brought from the back country and the soil is kept constantly renewed. It seems to me that with comparatively little work the sandy soil of the Arkansas valley can be made into a market garden, producing many times its present value, whenever our people take it into their heads to manufacture their own soil and apply water when needed and not just when it rains. That time will come, but probably not until a dense population forces a great increase in production.

I have another idea. Along the coast of Holland are the “sand dunes,” which are exactly like our sand hills. What we should do is to change the name from sand hills to “dunes,” brag about them and charge people for visiting them. The city of Amsterdam gets its supply of drinking-water from the dunes. This was important news to me, for it confirmed my theory as to the similarity of the dunes and the sand hills, and also suggested that somebody in Amsterdam[67] used water for drinking purposes, a fact I had not noticed while there.

We spent part of a day in Haarlem, where the tulips come from. The soil conditions are like those at Alkmaar, but the country is a mass of nurseries, flower gardens, and beautiful growing plants. We are out of season for tulips, but this is the time when the bulbs are being collected and dried to be shipped in all directions. Not only tulips but crocuses, hyacinths, lilies, anemones, etc., are raised for the market,—cut flowers to the cities, bulbs to all parts of the world. Just now the gardens are filled with phlox, dahlias, larkspurs, nasturtiums,—by the acre. The flowers are about the same as at home. Out of this thin, scraggly, sandy soil the gardeners of North Holland are taking money for flowers and bulbs faster than miners in gold-fields. With flowers and cheeses these Dutch catch about all kinds of people.

Haarlem is the capital of the province of North Holland, and is full of quaint houses[68] of ancient architecture. It was one of the hot towns for independence when the war with Spain began. The Spaniards besieged it, and after a seven months gallant defense, in which even the women fought as soldiers, the town surrendered under promise of clemency. The Spaniards broke their promise and put to death the entire garrison and nearly all the townspeople. This outrage so incensed the Dutch in other places that the war was fought more bitterly than before, and the crime—for such it was—really aided in the final expulsion of the Spaniards.

Along in the seventeenth century was the big boom in Haarlem. The tulip mania developed and bulbs sold for thousands of dollars. Capitalists engaged in the speculation and the trade went into big figures. Millions of dollars were spent for the bulbs, and so long as the demand and the market continued every tulip-raiser was rich. Finally the reaction came, as it always does to a boom, and everybody went broke. A bulb which sold for $5,000 one year was not worth 50 cents the next. The government added to the con[69]fusion by decreeing that all contracts for future deliveries were illegal. The usual phenomenon of a panic followed, everybody losing and nobody gaining. A hundred years later there was about the same kind of a boom in hyacinths, and the same result. It will be observed that the Dutch are not so much unlike Americans when it comes to booms, only it takes longer for them to forget and calls for more experience.

Frans Hals, a great Dutch painter, almost next to Rembrandt, was born in Haarlem, and a number of his pictures are in the city building. It was customary in those days for the mayor and city council to have a group picture painted and hung in the town hall. This was the way most of the Dutch artists got their start, for the officials were always wealthy citizens who were willing to pay more for their own pictures than for studies of nature or allegory. I wonder if the officials paid their own money or did they voucher it through the city treasury and charge it to sprinkling or street work?

Both Alkmaar and Haarlem are interesting because they are intensely Dutch. Their principal occupations, cheesemaking and flower-raising, have been their principal occupations for centuries. They had nothing to start with and had to fight for that. Now they are loaning money to the world. If the people of Kansas worked as hard as do the Dutch and were as economical and saving, in one generation they would have all the money in the world. But they wouldn’t have much fun.

The American way of economizing may be illustrated by a story. Once upon a time in a certain town—which I want to say was not in Kansas, for I have no desire to be summoned before the attorney-general to tell all about it—a man and his wife were in the habit of sending out every night and getting a quart of beer for 10 cents. They drank this before retiring, and were reasonably comfortable. Prosperity came to them, and the man bought a keg of beer. That night he drew off a quart, and as he sat in his stocking-feet he philosophized to his wife and said: “See how we are saving money. By buying a keg of[71] beer at a time this quart we are drinking costs only 6 cents. So we are saving 4 cents.” She looked at him with admiration, and replied: [72]“How fine! Let’s have another quart and save 4 cents more.”

Leyden, July 31.

We came to Leyden to spend the night, and have stayed three days. This was partly because it is necessary to sometimes rest your neck and feet, and partly because the Hotel Levedag is one of those delightful places where the beds are soft, the eats good and the help around the hotel does its best to make you comfortable. Leyden itself is worth while, but ordinarily it would be disposed of in two walks and a carriage-ride. It is a college town, and this is vacation; so everybody in the place has had the time to wait on wandering Americans and make the process of extracting their money as sweet and as long drawn out as possible.

Leyden is a good deal like Lawrence, Kansas. It is full of historic spots, and is very quiet in the summer-time. In Leyden they refer to the siege by the Spaniards in 1573 just as the Lawrence people speak of the[73] Quantrill raid. The Dutch were in their war for independence, and the Duke of Alva’s army besieged Leyden. They began in October, and as the town was well fortified it resisted bravely. Early in the year the neighboring town of Haarlem had surrendered and the Spaniards had tied the citizens back to back and chucked them into the river. The Leydenites preferred to die fighting rather than surrender and die. They had just about come to starvation in March of the next year, when they decided to break down the dikes and let the sea take the country. The sea brought in a relief fleet sent by William the Silent, Prince of Orange, and the Spaniards retreated before the water. Then the wind changed, drove back the waves, and William fixed the dikes. This siege of Leyden was really one of the great events in history, and the story goes that out of gratitude to the people of the town William offered to exempt them from taxes for a term of years or to establish a University in their city. Leyden took the University, which is hard to believe of the Dutch, unless they were farseeing enough to know that the students would be[74] a never-ending source of income and that the taxes would come back. The university thus established by William of Orange in 1575 has been one of the best of the educational institutions in Europe, and has produced many great scholars. It now has 1700 students and a strong faculty. Some of the boys must be making up flunks by attending summer school, for last night at an hour when all good Dutchmen should be in bed, the sweet strains came through the odor of the canal, same old tune but Dutch words: “I don’t care what becomes of me, while I am singing this sweet melody, yip de yaddy aye yea, aye yea, yip-de yaddy, aye yea.”

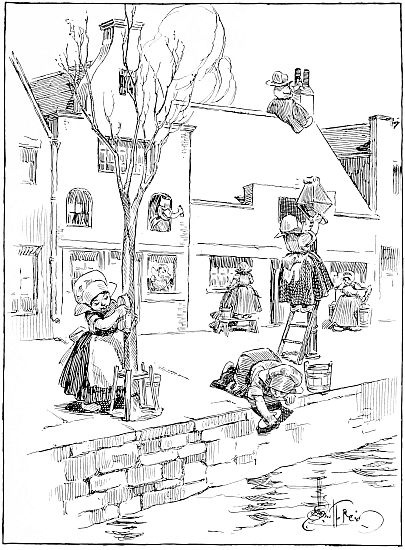

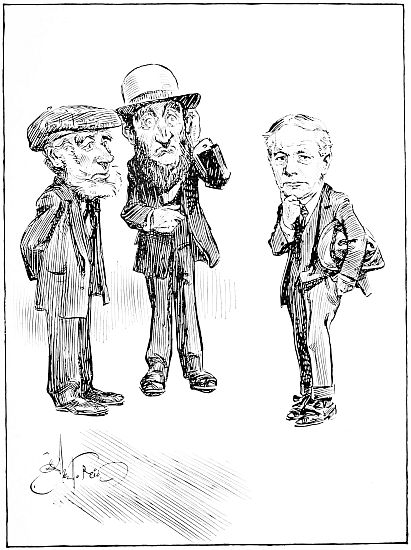

NO PLACE FOR A MAN FROM KANSAS

The river Rhine filters through Leyden and to the sea. It never would get there, for Leyden is several feet below the sea-level, but by the use of big locks the Dutch raise the river to the proper height and pour it in. These are the dikes the Dutch opened to drive out the Spaniards. It is so easy I wonder they did not do it earlier. At any rate, the Spaniards never got much of a hold in this part of Holland again. The sand[75]hills along the beach make an ideal bathing-place. I took a canal-boat and in three hours time covered the six miles from Leyden to Katryk. The Dutch ladies and gentlemen were playing in the water and on the sand, and it was no place for a man from Kansas. I have no criticism of these big bathing-beaches and we have some in our own fair land where the scenery is just as startling. But the Dutch ladies consider a skirt which does not touch the ground the same as immodest. And no Dutch gentleman will appear in public without his vest as well as his coat. On the beach the reaction is great, so great that I don’t blame the Spaniards for running away.

It was in Leyden that the congregation of Puritans resided which sent the delegation of Pilgrim Fathers across the Atlantic in 1620. In St. Peter’s church John Robinson, the pastor, lies buried, and there he is said to have preached. A tablet tells of the house across the way which occupies the site of the little church in which Robinson held forth for years. The present house was not built un[76]til 1683, but that is close enough to make it interesting. The Puritans had several congregations in Leyden, but the Robinson church is the only one that made history. When the civil war broke out in England and Cromwell was leading the cause of liberty, all of the Puritans in Leyden who had not gone to America and who could raise the fare, returned to England and disappeared from the Dutch records. They were fine people in many ways, but the Dutch did not try to get them to stay. They dearly loved to argue, and when it was necessary to promote religious freedom by punching the heads of those who did not believe as they did, the Puritans were there with the punch.

Rembrandt, the great Dutch painter, was born in Leyden, in 1606. A stable now marks the spot where he first saw the light. It is a little difficult to get up a thrill in a livery stable, but we did our best. Rembrandt’s father was a miller, and operated one of these big Dutch windmills. When Rembrandt was about 25 years old he married and moved to Amsterdam, but he did not settle down.[77] While he became popular and made a good deal of money, he was no manager and he spent like a true sport. When his wife died he went broke, and lived the last years of his life in a modest way. About 550 paintings are now known and attributed to him, together with about 250 etchings and more than a thousand drawings. His portrayals of expression and of lights and shadows are the great points of excellence in his work, but he was a master of every detail of the art. His pictures command more money than those of any other artist, and to my notion he is the greatest of all the great painters. Most of the other old fellows have left but few masterpieces, while Rembrandt never did anything but great work. The Dutch worship God, Rembrandt and William of Orange, and I never can tell which comes first with them.

There is a hill in Leyden, eighty feet high and several hundred yards around the base. It is well covered with trees, and was topped with a fort in the good old days. Unfortunately, the buildings around it—for it is in the middle of town—keep it from being seen[78] at a distance. People come from far and near to see the hill. It is as much of a novelty in this part of Holland as a Niagara would be in Kansas.