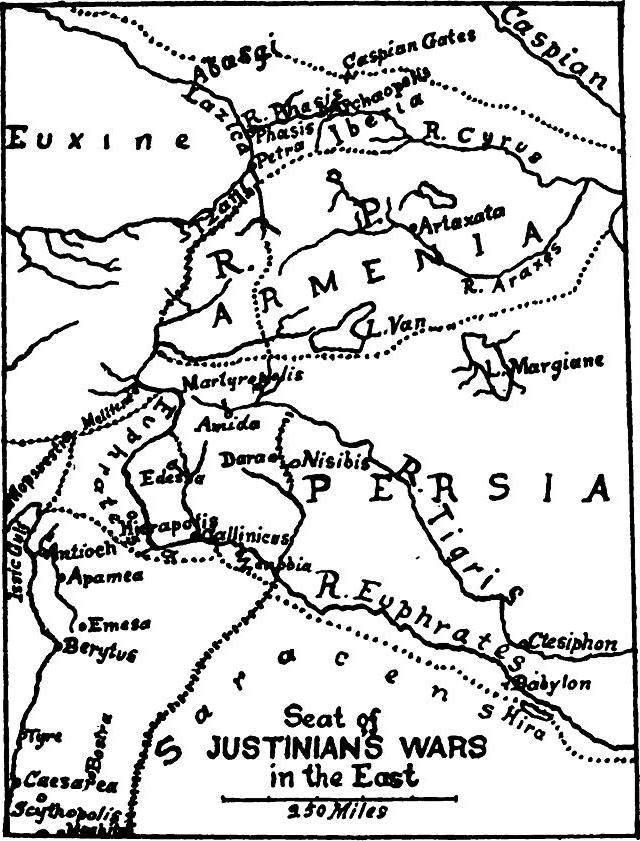

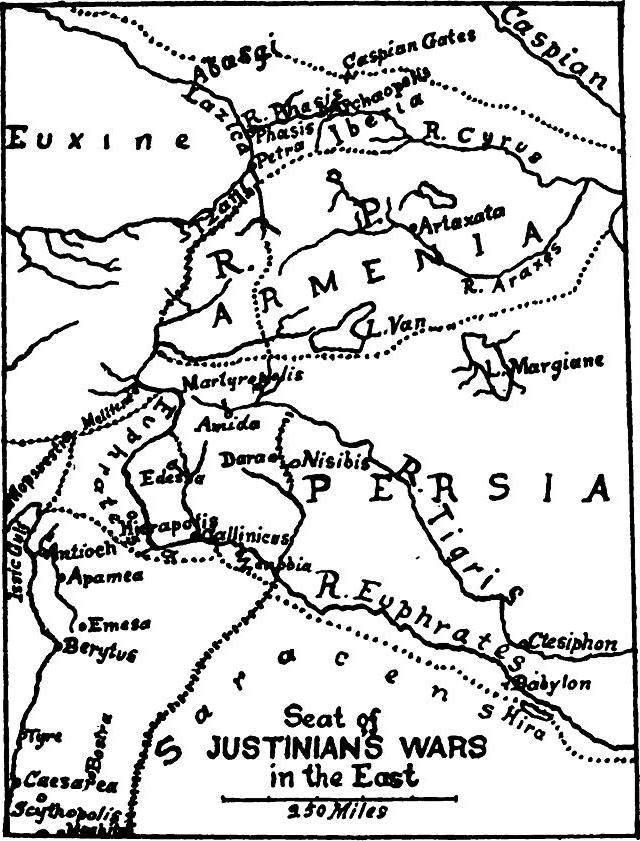

Seat of JUSTINIAN'S WARS in the East

Obvious printer errors have been corrected. Hyphenation has been rationalised.

The Corrigenda at the end include references to Volume I as well as to this volume.

BY

WILLIAM GORDON HOLMES

VOL. II

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

G. BELL AND SONS, LTD.

1912

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

| Chap. | PAGE | |

| V. | The Persians and Justinian's First War with them | 365 |

| VI. | The Schools of Philosophy at Athens and their Abolition by Justinian | 420 |

| VII. | The Internal Administration of the Empire: Insurrection of the Circus Factions in the Capital | 440 |

| VIII. | Carthage under the Romans: Recovery of Africa from the Vandals | 489 |

| IX. | The Building of St. Sophia: The Architectural Work of Justinian | 529 |

| X. | Rome in the Sixth Century: War with the Goths in Italy | 544 |

| XI. | The Second Persian War: Fall of Antioch: Military Operations in Lazica | 584 |

| XII. | Private Life in the Imperial Circle and its Dependencies | 605 |

| XIII. | The Final Conquest of Italy and its Annexation to the Empire | 624 |

| XIV. | Religion in the Sixth Century: Justinian as a Theologian | 668 |

| XV. | Peculiarities of Roman Law: The Legislation of Justinian | 706 |

| XVI. | The Last Days of Justinian: Literature and Art in the Sixth Century: Summary and Review of the Reign | 726 |

| Index | 761 | |

| MAPS | ||

| Seat of Justinian's Wars in the East | 396 | |

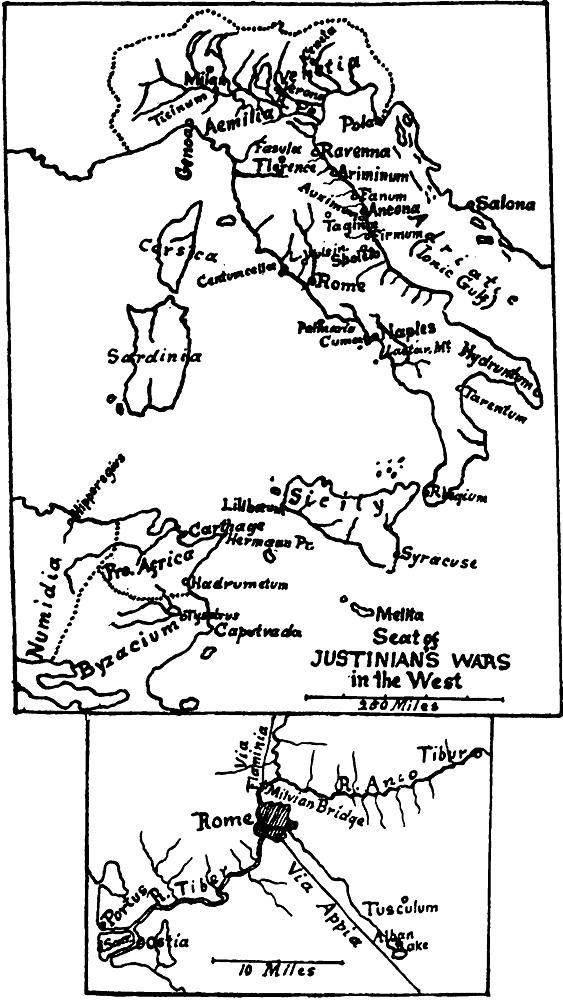

| Seat of Justinian's Wars in the West | 572 | |

ON the death of Justin the absolute control of the Empire became centred in the hands of Justinian. Nine years of virtual sovereignty during the lifetime of his uncle had familiarized him with Imperial procedure, and nullified the influence of a bureaucracy which might aspire to govern vicariously by taking advantage of his ignorance of affairs. His tutors in the art of autocracy were dead or superannuated, and his present subordinates owed their elevation to his favour and judgment. The new Emperor was a man of middle stature, spare rather than stout, and on the verge of becoming bald and gray. His features were sufficiently regular, his face was round, his complexion florid, and he wore neither beard nor moustache.[1] Those {366} whom he impressed unfavourably were fond of pointing out that he bore a striking resemblance to Domitian.[2] He affected a pleasant demeanour, appeared always with a set smile,[3] and was so studious of personal popularity that even the meanest of his subjects might hope for an audience of his sovereign. With an unbounded belief in his own capacity for discrimination, he was always ready to listen, but never to be convinced. His assurance communicated itself to those with whom he came in contact, and his associates rarely ventured to dispute his opinions.[4] His mode of life {367} tended strongly towards asceticism, and he yielded no indulgence to his natural appetites. In his diet he restricted himself to the barest necessaries, he seemed to exist almost without sleep, and there is no evidence that he was ever attracted sexually by any woman except Theodora. Without commanding abilities, his mental activity was incessant, and he was perpetually busy in every department of the state.[5] He plunged into politics, law, and theology, with the conviction that he could master every detail and deal effectively with all questions which might arise for decision. Yet he was credulous and lent a willing ear to those who brought in doubtful reports, which he was generally prone to act upon without due inquiry as to their authenticity.[6]

The Empress Theodora,[7] after her elevation, still presented in most aspects of her life and character a marked contrast to Justinian. She was devoted to the care of her person, and a great part of each day was given over to the mysteries of her toilet.[8] She trusted especially to sleep for the preservation of her beauty, and passed an excessive number of hours, both day and night, upon her couch. Gratification of the senses absorbed most of her time, and {368} she indulged herself in the luxury of a table always spread with the rarest delicacies. The air of the city was uncongenial to her, and she resided during the greater part of the year at the Heraion,[9] a palace over against the capital on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus, where a second centre of Imperial state was maintained for her benefit with lavish magnificence. But she was ever vigilant in preserving the closest relationship with the machinery of government, and in her retirement she meditated persistently on the exigencies of the autocracy. Her numerous emissaries were to be observed continually passing and repassing the strait which separated the Heraion from Constantinople, regardless of tempestuous weather, and even of a ferocious whale which had long infested the vicinity and made a practice of attacking the small craft sailing in those waters, often with fatal result to the occupants.[10] The personal relations of the royal partners during the whole course of their joint reign, continued to be of the most intimate description. Justinian not only deferred habitually to the judgment of his consort, but took every opportunity of making a public profession of his indebtedness to her co-operation. In Imperial acts and edicts she appeared constantly as the "revered wife whom God had granted to him as the participator of his counsels."[11] {369} It may, indeed, be assumed as certain that the resolution and verve to be found in the character of Theodora supplied some real deficiencies in the imperturbable and less acute nature of her husband;[12] and Justinian was well inclined to justify his extraordinary marriage by insisting that exceptional advantages accrued to the state from his choice of so able a consort. Although the spectacle of a Roman empress electing to lead the life of a prostitute was almost a familiar one in previous history,[13] that an actual courtesan should be raised to the throne, was a unique event in the annals of the empire. Nor was Theodora at all exercised to veil her ascendancy in the affairs of government; on the contrary, she scarcely refrained from proclaiming publicly that her will was predominant in the work of the administration.[14] Her pretensions were generally allowed, and those who sought preferment through Court influence regularly crowded her ante-chamber, with the assurance that success depended on winning her favourable regard. Unlike Justinian, Theodora made herself difficult of access, and an assiduous attendance for many days was an indispensable preliminary to obtaining an audience of the Empress.[15] Doubtless but a small portion of each day could be spared from the seclusion she imposed on herself for the nurture and elaboration of her person. As both Emperor and Empress by an un-hoped for chance had leaped to the Imperial seat from the obscurity of plebeian life, they were {370} proportionately jealous of their authority in the lofty position to which they had attained without the qualifications of rank or lineage. Hence they exacted the most servile respect from all who approached them, and emphasized more than at any former time humility of speech and abject prostration in the presence of the sovereign. Any subject, without the exception of patricians or even of foreign ambassadors, on arriving at the foot of the throne was compelled to extend himself on the ground with his face to the floor and then to kiss both feet of the monarch before he was privileged to deliver his message or to make a request.[16] On such occasions the titles of "emperor" and "empress," as expressing a merely official hegemony, were considered to be insufficient, and it was expected that, by substituting the terms "master" and "mistress," the subject should confess himself to be the actual slave of his sovereign.[17] In previous reigns the forms of adoration had been reserved for the Emperor, but Theodora ignored such precedents and claimed for herself all the homage due to an independent potentate. In one respect only did the conjugal harmony of the Imperial couple appear to be seriously disturbed; while Justinian was strictly orthodox in religion, Theodora gave an uncompromising support to the Monophysites. The public, however, refused to believe in the reality of this dissension, and attributed the seeming discord to an astute policy which obliged the conflicting sects to give their united support to the throne.[18]

The war with Persia, which had developed in a desultory fashion under Justin, began to be waged with determination at the outset of Justinian's reign. A thousand years before {371} this date the Persian Empire, founded by Cyrus the Achaemenian, had reached from the frontiers of India to the shores of the Mediterranean, and had even held Egypt precariously as an integral province. Diverse nationalities marched under her standard, and immense hosts of Asiatics were habitually mustered for the achievement of foreign conquest. But this monarchy proved to be short-lived, and was destroyed in less than two centuries, after the invasion of Greece by Darius and Xerxes had disclosed the fact that a few thousands of patriotic Hellenes were of more martial worth than the vast and heterogeneous armies led by the Persian king. Less than ten years of actual warfare sufficed to bring the Achaemenian Empire and its dependencies under the rule of Alexander; and the indigenous races were kept in subjection by the Graeco-Macedonian invaders for a longer period than the kindred dynasty established by Cyrus had endured. The Persian Empire, in its widest extent, as it existed under the Achaemenidae, was never restored; nor did any subsequent conqueror issue from the west to repeat the exploits of Alexander. The Asiatic successors of that monarch, the Seleucidae,[19] were gradually ousted from their dominions by a wild race which attacked them from the north, and became known historically as the Parthians. Under their native rulers, the Arsacidae, they might have restored the empire of Cyrus, but the simultaneous growth of the Latin power in Asia Minor and Syria for ever confined the Parthians to the eastern bank of the Euphrates. The policy of Rome, as defined by Augustus, forbade the extension of the empire beyond the limits assigned to it after the battle of Actium; but at least one emperor, the indomitable Trajan, was ambitious of emulating the prowess of Alexander {372} and designed to advance on India. Although not uniformly victorious, he transformed the kingdom of Armenia into a Roman province, and almost reduced Parthia to the condition of a vassal state.[20] Death, or the more pressing claims of home affairs, imposed a term to his activity in the field, and his great schemes of conquest were never again entertained; but several later emperors, notably Severus, Carus, and Galerius, often demonstrated the superiority of the Roman forces under competent generalship over their Oriental antagonists.[21] But after the Graeco-Roman supremacy had declined to the stagnant mediocrity of Byzantinism this ascendancy could no longer be maintained; and as often as East and West came into collision the honours of war almost invariably rested with the Asiatic power.

For more than five centuries after the overthrow of Darius by the armies of Macedon the remnants of the Persian race languished in the Province of Persis, a small state lying east of the Persian Gulf, to which was allowed a semi-independence by the supreme government. Here was the original home of Cyrus, and here he matured his plans {373} for the conquest of Media. From thence was derived the name of Persia, which was applied by the western nations to the whole land of Iran, the native appellation of the extensive plateau ranging from the Hindu Kush to the river Tigris. In Persis was situated Persepolis, the traditional capital of the Persians, where the sacred fires of the Zoroastrians was kept perpetually alight in a temple by the Magi. In a drunken freak, or perhaps as a signal to all Asia that he had succeeded to the sovreignty of Iran, the ancient city had been committed to the flames by Alexander;[22] but eventually a capital was reinstated on the old site, and in later centuries became known as Istakhr.[23] About 200 A.D. a reawakening of Persian aspirations became apparent, and a new Cyrus arose at Istakhr to lead his nation to the reconquest of their former empire. Ardeshír was the grandson of Sásán, who by a fortunate marriage had united the pre-eminence of the priestly caste with that of the princely house of Persis. Having gained possession of the local throne by his superior energy, he began to exercise himself in active warfare by attacking the neighbouring states, whose princes, like himself, were the vassals of the Parthian king. At first his operations were disregarded, and not until he had made himself the lord of a considerable territory was he summoned by his suzerain to explain his encroachments. His reply was a defiance and a challenge to battle. In the war which ensued Artabanus was overthrown by Ardeshír, and the Parthian dynasty of the Arsacidae was replaced by that of the Sassanidae (c. 227). {374} The Persian now assumed the title of Shahinshah, that is "King of Kings," which had usually been affected by the potentates of all Iran, and established himself at the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon on the Tigris, a position more suitable for the seat of government than the remote Persepolis. The empire thus regenerated by the Sassanians, held its own among the surrounding powers for four hundred years, until the general irruption over Asia of the fanatical hosts of Islam.[24]

The dominions of Ardeshír and his successors covered an area almost equal to that of the Eastern Empire, but were probably much less populous. The table-land of Iran is far from being so well adapted for the sustentation of animal and vegetable life as the countries amalgamated into a single state by the Roman arms. More than a fourth of the surface is occupied by desert and salt swamps;[25] while the greater portion of the remainder is broken up by immense mountain ranges, some of which rise to a height of 18,000 feet. The prevailing population of this region within the historic period has always been a division of the Aryan race, of the great Indo-Germanic family of mankind, who at some early epoch spread themselves across two continents, from the frontiers of Burmah to the Atlantic seaboard {375} of Europe. Originally the possessors of a common language, the elements of their speech are to be found in the Sanskrit, once colloquial throughout the valley of the Ganges, and in the Erse of the Irish peasant, who inhabits the wilds of Connemara. Although the face of the country has been scarred by the march of numerous invaders, and even by religious revolution, the sociological condition of these Eastern lands has scarcely changed at all during the millenniums of recorded history; and the Persian citizen or rustic of to-day is almost a counterpart of those who looked out on the progresses of Darius and Xerxes.[26] The primitive Iranians were an agricultural people, and as such showed an attachment to the cattle which composed their farm stock almost amounting to veneration. But the tiller of the soil in Iran was often exposed to harsh conditions in the effort to draw his livelihood from the ground. The land was not uniformly fertile, climatic severity not seldom hampered the labourer, and predatory bands of nomads, who raided the country from the north, were a frequent cause of disaster.[27] Life was a series of vicissitudes, circumstances of time and place were in general sharply contrasted, and the normal activities of nature seemed to the peaceful native to be the outcome of perpetual strife between spirits of good and evil. In Bactria, the north-eastern tract of {376} Iran, all these conditions were most typically presented. About 1000 B.C. that region was ruled by King Vistaspa,[28] under whom flourished the prophet Zarathushtra, the original redactor of the religion and ethical system accepted by the Persians. He gave a distinct expression to the philosophical tendencies of his age, and refined the loose polytheistic conceptions at first held by the Aryans to the complete dualism in which Ahura-Mazda, the Lord of Wisdom, and Angra-Mainyu, the Devisor of Evil, became the essential factors of a definite theological faith.[29] On this foundation an Avesta or Bible of Mazdeism was elaborated, which laid down the law for the whole conduct of human life.[30] Among the primitive deities most reverence had been {377} paid to Mithra, the sun-god, to Spenta Aramaiti, the earth spirit, and to Anahita, the goddess of the waters.[31] As subordinates of Ahura-Mazda, these divinities still held an established place, and were made the immediate objects of the rites and ceremonies imposed on the pious Iranian. Hence the sanctity of fire, earth, and water became an article of faith, and it was believed to be a heinous crime to contaminate them with any impurity. Whatever was evil was esteemed to be impure, and, therefore, the work of Angra-Mainyu. The Druj Nasu, a female demon, personifying the lie, was regarded as his universal agent, and as being present imminently under all adverse circumstances. Such were the principles of Mazdeism, the rigid application of which, and they were rigidly applied by the Magi, was productive of many curious sociological phenomena strangely at variance with the customs of other nations.[32] Death was {378} considered to be the greatest of calamities, and hence a corpse became possessed of the Druj, and the most active of all sources of contamination. That so foul an object should be placed in intimate contact with the holy elements of fire, earth, or water, was sacrilege in the highest degree. Cremation and burial were, therefore, held in abhorrence, and a deceased person had to be borne to some isolated spot, far from fire and water, there to be exposed on an elevated bier with the intention that the flesh should be devoured by wild dogs, birds, etc.[33] Disease was, of course, a grade of demoniacal obsession, so that sympathy for the sick was almost alienated by superstition. If an ordinary soldier were taken ill on the march he was abandoned by the wayside, some provisions being left with him, and also a stick, with which to beat off any carnivorous animals. Should he recover, on his reappearance all fled from him as from an apparition risen out of the infernal regions; nor could he resume intercourse with his relations until he had undergone a rigorous purification by the Magi.[34] Owing to the holiness of water great reverence was felt for rivers, which were protected by law from all defilement; and no good Zoroastrian would travel by ship lest he should pollute the sea with his normal excrement.[35] For purposes of cleansing {379} water was used very charily, and it was sinful to take a bath.[36] The vegetable productions of the earth were viewed with profound admiration, wherefore the cultivation of gardens and parks was among the greatest delights of the Persians.[37] The estimation in which cattle were held was the cause of some singular legislation and ritual enactments. Thus the urine of the cow was habitually collected and made use of daily for the purification of the body by washing.[38] The sheep-dog was an object of extreme solicitude, so much so that the penalty exacted for manslaughter was only half as onerous as that inflicted for the crime of giving bad food to such a precious animal,[39] but even the latter was a mild offence compared with the infamy of killing a water-dog, the name by which the otter was identified, as the wretch convicted was sentenced to be beaten to death.[40] On the other hand, noxious animals were regarded as the creation of Angra-Mainyu, and the Magi made it a religious duty to kill them with their own hands, especially ants, serpents, {380} reptiles in general, and certain birds.[41] In some cases it was permitted to the subject to take the law into his own hands and to slay the guilty person on the spot. Such culprits were the highwayman, the sodomite, the prostitute, and anyone caught in the act of burning a corpse.[42] On the whole, however, capital punishment was infrequent, and almost any trespass, even murder, could be atoned for by making a money payment to the Magi.[43]

In the sociology of Mazdeism the strangest phenomenon that developed itself was the tenet that affinity by blood was the highest requisite in a marriage contract. This principle was inculcated by the priests to an extreme degree, so that the closer the relationship the more acceptable was the union affirmed to be in the eyes of the Deity. Not only could brother and sister marry under religious sanction, but {381} even father and daughter;[44] and, most repugnant of all to the common inclinations of humanity, the nuptials of mother and son were expressly enjoined as a righteous act by the Avesta. This anomalous association of the sexes was justified partly by the false analogy of certain physiological facts supplied by the animal kingdom, and partly by an appeal to precedents to be found in the Iranian mythology. Hybrids were notoriously infertile, and the congress of horses with asses engendered mules who were impotent to propagate their kind. Hence the mingling of family blood was indicated as essential to preserving the integrity of the race. Further, it was pointed out that the primaeval man, Gaya Maretan, impregnated Spenta Aramaiti; that is, his mother earth, the result of this conjunction being a son and a daughter. By this union the brother and sister became the progenitors of the whole human race. At least one Parthian, and probably several of the Achaemenian and Sassanian kings, may be noted as having chosen their own mother for their consort on the throne.[45] Such marriages were not merely ceremonial, although in some instances the chief inducement may have been to insure the support of the Magi for a disputed succession.[46] Incestuous offspring were {382} not unknown, and the case of Sisimithres, a provincial potentate subdued by Alexander, is specially mentioned as {383} that of one whose mother-wife had borne him two sons.[47] Rich Persians indulged themselves with several wives, besides maintaining numerous concubines, but, as monogamy only was contemplated by the Avesta, the senior wife was the undisputed mistress of the household.[48]

The Parthians found it politic to assimilate their supremacy to that of the Greeks whom they had displaced; and thus to attract to themselves the influence which had so recently been predominant throughout Iran. They, therefore, distinguished themselves by the epithet of "Philhellen," and continued to impress their coins in Greek characters with that affix, even after the Romans had become most potent in the East. By degrees, however, the memory of the Greek dominion faded, and before the middle of the second Christian century orientalism was completely re-established. Legends in the Pahlavi, or Parthian language, were adopted for the superscription of the currency, upon which the Hellenized Serapis now yielded his place to Mithras or the Mazdean fire-altar.[49] As a scion of the house of Sásán, Ardeshír was naturally much swayed by priestly influence, and relied on the support of the Magi as the chief element of his power. By his edicts and inscriptions he proclaimed himself to be a Mazdayasn, or devout servant of Ahura-Mazda, and the dynasty he founded was always noted {384} for its firm adherence to the national religion.[50] On his accession Ardeshír undertook the restoration of the Avesta, a great part of which had been neglected or altogether lost, and under the supervision of the Magi he caused a purification or reformation of the faith of Zarathushtra to be begun.[51] This work was continued by his successors, but, as no canon of scripture had been formed, there were many conflicting sects, and not until the reign of Sapor II[52] (c. 330) was the text of the sacred book fixed beyond dispute. Then Adarbâd, a holy man, produced his recension of the Avesta among the assembled Magi, and offered to submit himself to the ordeal of fire in proof of its strict orthodoxy. Molten brass was poured upon his breast, he passed the test unscathed, and his reading of the tenets of Mazdeism was never afterwards contested.[53] {385}

Ardeshír did not, however, base his message of fortune solely on an appeal to the mystical emotions of his nation; but he also sought to attach them to himself by stimulating their patriotism. He professed that he would avenge the murder of Darius on the inheritors of Alexander, and asserted himself to be the rightful ruler of all western Asia, which had been unlawfully wrested from his ancestors. Thus the Persian empire, as restored by the Sassanians, was inspired with sentiments which urged it to maintain an inveterate conflict with Rome.[54]

Although there is evidence of constant religious commotion in Persia under the Sassanidae, it does not appear that any considerable number of the historical adherents of Zarathushtra ever swerved from their faith. The numerous priestly tribe of the Magi not only surrounded the throne, but were fully disseminated throughout the provinces as the guardians of Mazdeism. The valley of the Euphrates and Tigris, however, the most densely populated district of the empire, was the site of a very heterogeneous ethnology, with archaeological records which extend backwards for some thousands of years prior to the descent of the Arians into Iran. There had existed the kingdoms of Sumer and Akkad, having an ancient mythology of their own, which was liable to be diversified by the infiltration of Semitic elements from {386} the south-west.[55] In this region Mani flourished and was enabled to spread his doctrines, but as soon as he threatened to pervert the loyal Zoroastrians his downfall was brought about by the resentment of the Magi.[56] Here also Christianity essayed to penetrate into Persia, but with the same result, and we possess some details of the cruel persecution to which Christians were subjected whenever they came into collision with the established religion of the state.[57] In some instances, however, Roman heretics, such as the Nestorians who fled before the face of an orthodox Emperor, were accorded an asylum in Persia by a politic Shah.[58]

Towards the end of the fifth century a serious ferment in the ranks of the Zoroastrians themselves was occasioned by the preaching of a fanatical demagogue named Mazdak. This reformer aimed at nothing less than a subversion of the existing sociological status by the induction of a communistic partage of women and property. All practical class distinctions were thus to be swept away, so that a level affluence should prevail throughout the land. It appears that {387} in the early years of his reign Cavades found himself greatly hampered by the arrogant pretensions of his nobles, wherefore he lent a favourable ear to the new propaganda, and gave public encouragement to Mazdak. But the power of the throne was unequal for the achievement of such a revolution; the Magi and the nobles met in council, deposed Cavades, and, with some hesitation conceding to him his life, caused him to be imprisoned in a stronghold called the Castle of Oblivion. From this durance he was shortly released through the devotion of a handsome sister-wife, who seduced the fidelity of the gaoler by the promise of her person. Being allowed to sleep for one night in her brother's apartment, she had him carried out next morning enrolled in her bed-furniture, for the exemption of which from inspection she invented a plausible excuse.[59] Cavades now made good his escape to Bactria, where he spent a couple of years as a guest of the King of the Hephthalites. Ultimately he obtained the loan of an army from that monarch,[60] {388} with which he drove his brother Jamâsp, who had been created king in the meantime, from the throne. As for Mazdak, it seems that for the next quarter of a century he was allowed a free hand to propagate his opinions, an attitude of neutrality being adopted by the Shah and the Magi. His gospel was accepted by an increasing number of the Iranians, whom he persuaded that his communism was the only mode of life which accorded with the precepts of Zarathushtra. At length the growing transformation of the social system began to be viewed with alarm; a generation of children had sprung up who were ignorant of their parentage, and in all directions the ownership of property was falling into abeyance.[61] It was resolved, therefore, by the Shah and priests in council that the Mazdakites should be extirpated by the sweeping Oriental device of a general massacre. In order to achieve this object an assemblage of all the members of the sect was convened by Chosroes, the designated heir to the crown, who had ingratiated himself with Mazdak and his disciples under the pretence of being a convert to their doctrines. It was represented that Cavades on a certain day would abdicate in favour of his son, who would at once reinstate the throne on the principle that for the future the Mazdakites should be its chief supporters. The ruse succeeded; Cavades received the leaders in state surrounded by the Magi, asserted his imminent retirement, and desired them to muster their whole following in a place apart. {389} There Chosroes would join them and institute the new régime with due formality. They obeyed, and were immediately surrounded by a division of the army, who cut them to pieces. The remnants of the sect throughout the provinces were afterwards hunted down, and got rid of by burning at the stake.[62]

The moment we turn our attention to the Persian court, and begin to observe the material and ceremonial attributes of the monarch, we discover the prototype of almost the whole fabric of Byzantine state as displayed at Constantinople. In the East was found the model of those accretions which gradually transformed the unassuming Roman Emperor of the Tiber into the haughty autocrat who overawed his subjects with pageantry on the Bosphorus; but the native sobriety of Europe always stopped short of the pronounced extravagance and hyperbole of Orientalism. The throne of the Sassanians stood between four pillars which upheld a ciborium.[63] On sitting down, the Shahinshah inserted his head into the crown, a mass of precious metal and jewels suspended by a chain, too ponderous to be worn without extraneous support.[64] No epithet was too lofty for {390} the Persian monarch to assume in his epistles; he was brother of the sun and moon, a god among men, and in merely mundane affairs the King of kings, the lord of all nations, as well as everything else expressive of unlimited power and success.[65] When he made a progress out of doors the streets were cleansed and decorated in the manner already described as customary during the passage of the Eastern Emperor.[66] Personal reverence was, of course, carried to the extreme point, and even officials of the highest rank kissed the ground before venturing to address the Shah.[67] The succession to the throne was strictly hereditary and, although several revolutions occurred during the four {391} centuries of the Sassanian rule, in every instance the crown devolved to a prince of the blood of Ardeshír.[68]

A Persian army of this date was very similar to a Roman one, but there were some essential differences. With the exception of the Royal guards, which, like those of the Achaemenians, included a body of ten thousand, called "the Immortals,"[69] and necessary garrisons, a standing army was not maintained.[70] On each occasion, therefore, the fighting force had to be levied afresh whenever a campaign was in prospect, but, as a traditional part of Persian education was that every youth should be taught to ride and to become an efficient archer,[71] the new recruits were not necessarily deficient in military training. During a battle, in fact, they relied chiefly on their missiles, and a Persian horseman was provided with two bows and thirty arrows.[72] Less importance was attached to the infantry, but they also consisted of bands of archers. The cavalry were generally almost as numerous, and in addition a troop of elephants was often a prominent feature in a Persian army.[73]

The revenue of Persia previous to the sixth century was {392} mainly derived from agricultural industry; and every inhabitant who cultivated the ground handed over to the state collectors a tithe of whatever economical growth his land produced. Cavades, however, from personal observation became impressed with the disadvantages of this system, which often seriously hampered his subjects in providing for their daily wants, and deprived them of the full benefit of the newly ripened crops.[74] Thus the rustic population feared to be accused of falsification if they ventured to supply their present needs before the arrival of an official whose duty it was to inspect the produce of the soil and of the fruit-bearing trees while still in position, and to deliver to them their note of assessment. Cavades, therefore, decided on the abolition of tithes in favour of a land-tax, a sweeping reform, beset with many difficulties, which engaged his attention for many years, and was only fully established by his successor.[75] With the inhabitants of towns and villages, who did not {393} subsist by agriculture, the Persians adopted the usual expedient, in this age, of imposing a poll-tax.[76]

The Sassanian Empire did not distinguish itself in the realm of art; and the scanty remains which have been discovered indicate that their architectural productions owed much to Byzantine co-operation.[77] As temple worship was a minor feature of the Zoroastrian religion, which consisted almost wholly in forms of private devotion,[78] no ruins pertaining to buildings of that class have been found;[79] but in several places portions of dilapidated palaces exist, which enable us to estimate accurately the artistic proficiency of the Sassanians.[80] The residence of the Shahinshah was a quadrangular edifice built around a central court. Externally the walls were diversified by two or three superimposed rows of slender columns, those rising from the ground being much taller than the upper ranges. The distinctive part of the architectural design was an arched entrance, wide and lofty, {394} which led into a great domical hall, from whence small doors gave access to the various chambers of the palace. All the apartments, at least those of any size, were covered with a domed roof. To the rather tasteless exterior decoration of these palaces the remains of an unfinished one discovered at Mashita, on the edge of the Syrian desert,[81] offers a striking exception. For several feet from the foundations the walls are covered with an intricate tracing of carving, in which lions, tigers, and doves, appear entangled amid the leaves and contorted branches of some luxuriant vegetation.[82] A considerable number of bas-reliefs have come to light among the ruins of Sassanian palaces, some of them illustrating the achievements of the dynasty during its wars with Rome and various powers, others representing hunting scenes in which are shown the methods of the chase and the magnificence of the monarch on such occasions amid his attendant throng of courtiers and guards. The execution of these works cannot be spoken of as art in the Hellenic sense, but in chiselling the forms of animal life some approach to excellence may sometimes be noted, especially in the case of elephants.[83] As for literature, it appears that the Sassanians produced little or nothing national, with the exception of priestly elaboration of the Mazdean scriptures, but in the last days of the empire, a crude history under the title of Shahnameh, that is, a Book of Kings, was compiled.[84]

{395} The first important commission entrusted to Belisarius by Justinian, after his accession to undivided power, was the construction of a fort at Mindo, a village on the Roman frontier between Dara and Nisibis.[85] As soon as the news of this bold measure was announced to Cavades he determined to prevent the execution of the work by every means in his power. He had already despatched a considerable army under two of his sons through Persarmenia in order to make an incursion into Lazica. This force he now diverted from its original purpose, and directed them to march with all speed to the scene of the offensive operations.[86] Information of the impending attack was immediately transmitted to the Emperor. He promptly resolved to frustrate it by a counter-move of a similar kind. The troops posted in the province of Libanus under the brothers Cutzes and Butzes, two young Thracians, were therefore ordered to hasten northwards to strengthen the hands of Belisarius. Their arrival was well-timed, and the Persians found themselves intercepted before they could make an onslaught against the works. The Orientals halted and proceeded to encamp themselves {396} methodically over against the Romans. They then took the precaution to cover their line secretly with a series of pits, at the bottom of which they fixed stakes, and afterwards restored the surface so as to give the appearance of unbroken ground.[87] The young Thracians, rash and inexperienced, neglected to observe the precise movements of the enemy, nor did they delay to take counsel with Belisarius, but pushed forwards impetuously to join battle with their opponents as soon as they were able to dispose their forces in order for an attack. The Persians calmly awaited the assault until the Byzantines had entered on the treacherous ground, and became disorganized by falling into the numerous traps which had been prepared for them. An indiscriminate slaughter then ensued, most of the officers being killed, but some of them were taken prisoners, among the latter being Cutzes. No effort could now avail to save the fort, which was at once abandoned by Belisarius, who, with the wreck of the army, made good his retreat to Dara.

Seat of JUSTINIAN'S WARS in the East

After this disaster Justinian promoted Belisarius to the rank of Master of the Forces in the East, and authorized him to levy an army of the greatest possible strength. In this task he joined with him Hermogenes, Master of the Offices, whom, with Rufinus, a patrician, he despatched to the theatre of war. The latter was well known as a legate at the Persian court, and he was directed to take advantage of the customary suspension of hostilities during the winter, which was now at hand, to make overtures to Cavades for the conclusion of a peace. An interchange of propositions on the subject was kept up for some months, during which the Shah maintained an equivocal attitude, {397} until, on the approach of spring, scouts brought in the intelligence that the Persians were advancing with a great army, evidently counting on the capture of Dara. In a short time a taunting message was brought to Belisarius from Perozes, who was in chief command, charging him to prepare a bath in the town against his arrival on the following evening.[88] This Perozes was one of the elder sons of Cavades,[89] and his insolent confidence was inspired by the success of the recent action, in which he had borne the principal part. His notice was taken as a serious warning, and the Roman generals at once set about disposing their forces in order of battle, anticipating a decisive engagement on the following day. Their army consisted of about 25,000 men, most of whom were mounted, and they were drawn up within a stone's throw of the wall of Dara. Belisarius and Hermogenes, surrounded by their personal guards, posted themselves in the rear, next to the town. Immediately in front of them was ranged the main body of their troops, in a long line, made up of alternating squads of horse and foot. A little in advance of these, at each end, was stationed a battalion of six hundred Huns.[90] Such was the centre to which, but at some distance forward, wings were supplied, each one composed of about three thousand cavalry. A trench, interrupted at intervals for passage and dipping in to meet the centre, covered the whole of this formation in front, but excluding the two bodies of Hunnish horse standing at each reentrant angle.[91] Lastly, advantage {398} was taken of a small hill lying on the extreme left to form an ambush of three hundred Herules under their native leader, Pharas.

As soon as the Persian host had established itself on the field, they were perceived to be much more numerous than the Romans, amounting to quite forty thousand men. The Mirrhanes, such was the military title borne by Perozes, drew up his forces in two lines with the design that when those in front were exhausted they should be replaced by fresh troops from behind, the movement to become alternating, if necessary, with intervening periods of rest for each line. The wings were composed of cavalry, the famous band of Immortals being stationed on the left, whilst Perozes himself led the van, supported by the heaviest mass of combatants. On the first day that the armies stood facing each other the Persians' left wing suddenly improvised a skirmish with those opposed to them, but retired after a brief collision with the loss of seven of their number. Later on a Persian youth of great prowess rode into the interspace and defied any Roman to meet him in single combat. No soldier seemed inclined to respond, but at length one Andrew, the tent-keeper of Buzes, lately a trainer of athletes at Constantinople, took up the challenge. The adversaries charged each other with poised lances, the Persian was unhorsed, and Andrew, quickly dismounting, cut his throat with a knife. The Romans shouted with delight, whilst the Persians, chagrined, determined to retrieve the mischance, and soon presented another champion. A horseman, middle-aged, but of great weight, advanced cracking his whip and calling out for some confident opponent. {399} Still no response from the military on the Roman side. At last Andrew, despite the express prohibition of Hermogenes, advanced again and braced himself for the encounter. The pair charged, their lances glanced aside, but the horses crashed against each other breast to breast, and both animals rolled over on the turf. The riders essayed to rise, but the athlete anticipated his heavy opponent and despatched him before he could regain his feet. It was now almost nightfall, and both armies withdrew from their positions, the Persians to their encampment, the Romans within the walls of Dara.

Next day the troops were drawn out on both sides in the same order, but the Roman generals, relying on the peace proposals, which they considered to be still in progress, deemed it possible that a conflict might be avoided. They addressed a letter, therefore, to the Mirrhanes, representing the uselessness of further bloodshed at a time when their respective sovereigns were bent on the resumption of amicable relations. In his answer Perozes accused his adversaries of ill faith, and declared his disbelief in the genuineness of their overtures on behalf of peace. To this Belisarius replied that Rufinus would shortly be at hand with letters which would convict the Persians of a wanton rupture of their engagements, and that they should be fixed to the top of his standard at the outset of the battle. The rejoinder of the Mirrhanes closed the parley; he expressed unbounded confidence, and reiterated his mocking request that a bath and a suitable repast should be prepared for him forthwith within the city. His assurance was, in fact, increased at the moment, for, that very morning, a reinforcement of ten thousand men had joined him from Nisibis.[92] {400}

As a prelude to the battle the opposing leaders mutually harangued their men. "The recent encounter," said the Byzantine generals, "has taught you that the Persians are not invincible. You are better soldiers than they, and it is easy to see that on former occasions you suffered because you disobeyed your officers. The enemy knew it, and came on here trusting to profit by your want of discipline, but since their arrival they have been awed by your firm array. You see before you an immense host, but the infantry are contemptible, wretched rustics, and mere camp-followers, fit only to dig beneath the walls or to strip the slain. They carry no arms to assault you with, and merely cover themselves with great shields to avoid our darts. Bear yourselves bravely, and the Persians will never again dare to invade our country." On the other side, Perozes bade his troops to take no heed of the skilful tactics now first observable among the Romans. "You think," said he, "that your adversaries have become more warlike because of this imposing formation. On the contrary, the ditch they have covered their positions with proves their increased timidity; nor have they, though thus protected, ventured to attack us. But never doubt that they will fall into their accustomed confusion the moment we assault them; and remember that your conduct will hereafter be judged of by the Shahinshah."

Shortly after midday[93] the action was begun by the Persian archers, and, until the quivers were exhausted, showers of arrows were discharged from each side so thick as to darken the sky. The rain of missiles from the Orientals was heaviest, {401} but an adverse wind rendered it less effective, so that the Byzantines suffered no more than they inflicted. On its cessation several thousands of the Persians bore down on the left wing of the Romans and threw it into disorder. Already the flight had commenced, when the six hundred Huns held in reserve on that side charged the left flank of the enemy; and simultaneously the three hundred Herules, rushing down the slope of the hill from their ambush, fell upon them behind. Terrified by these unforseen attacks the Persians turned and fled indiscriminately, whereupon the Romans joined in a triple band to take the offensive, and inflicted on them a loss of fully three thousand before they could reach their own lines. Considering it unwise, however, to proceed too far, the Romans soon desisted from the pursuit, and retired to their original positions.

A moment later the Persian left wing, including the whole regiment of Immortals, made a fierce descent on those opposite them, and succeeded in beating them back to the wall of Dara. At the sight of this defeat, however, the Byzantine generals ordered the Hunnish reserve just returned from pursuit to join their fellows of the right wing, and launched the whole twelve hundred, together with their personal guards, against the enemy's flank. As a result that wing of the Persians was cut in two, the after portion being arrested in its charge, and among these happened to be the standard-bearer, who was slain on the spot. Alarmed at the collapse of the ensign, those who were fighting in advance, being the majority, now turned to attack the mass of troops who had gained possession of the ground in their rear. The discomfited right wing of the Byzantines, thus freed from danger, immediately rallied and dashed forward after their lately victorious adversaries. Simultaneously the {402} general of the Persian wing in action fell before the lance of one of the leaders of the Roman reserves and disappeared from his saddle. A panic then seized on the Orientals, and they thought of nothing but escape by flight. From all sides the Romans rushed to make an onslaught on them, they became hemmed in by a circle of steel, and were slaughtered without resistance to the number of five thousand. A general rout of the Persian army ensued; the infantry, on seeing the destruction of the cavalry, threw away their shields and fled, but they were quickly overtaken, so that a great majority of them perished. Belisarius and his colleague, however, fearing lest the reaction of despair in so great a host might lead to some disaster, recalled their forces as soon as they judged the defeat of the enemy to be complete. Such was the victory of Dara, the achievement of which appears to have been due mainly to the military talents of Belisarius, whose age at this date (530) was probably under thirty.[94] For the rest of this war the Persians always avoided fighting a pitched battle with the Romans.[95]

During the succeeding summer desultory hostilities were carried on in Armenia, where, as a rule, the Byzantines had the advantage; and two fortified posts of some importance, Bolum and Pharangium,[96] in the Persian division of that {403} country, fell into their hands. At the same time three Persarmenians, who held commands in the Persian service, deserted and fled to Constantinople. There they were received and provided for by a fellow-countryman of their own, the eunuch Narses, who at the moment filled the office of Count of the Privy Purse, the same who afterwards attained to great military celebrity.[97] This part of the war was conducted by Sittas, who had become the husband of Comito, the sister of Theodora.[98] He also had been promoted to the rank of a Master of Soldiers.

In the meantime Justinian was still desirous of concluding a peace, and towards the close of 530 his ambassador, Rufinus, succeeded in gaining an audience of Cavades. In reply to a general appeal the Persian monarch complained bitterly that the whole responsibility of guarding the Caspian Gates had been thrown on his shoulders, and that the fortress of Dara was maintained as a constant threat against his frontier. He also adverted to the fact that Persia was a poor country, and accused the Romans of penuriousness in money matters. "Either," said he, "let Dara be dismantled, or pay an equitable sum towards the upkeep of the Caspian Gates."[99] He showed no inclination, however, to agree to {404} any specific terms, and dismissed the Roman emissaries in the evident expectation that some decisive success would enable him to dictate the articles of a treaty. He was encouraged by the fact that he was entertaining at the time several thousand refugees of the Samaritan sect, who had been driven from their homes in Palestine by religious persecution. Such internal disorders must lessen the offensive powers of his rival, whilst the expatriated sectarians were even anxious to bear arms against their late oppressor.[100]

In the beginning of spring (531) it became manifest that the Persians had been maturing a plan of campaign based on a strategical diversion, by which they hoped to surprise the enemy and possess themselves of a rich booty before their operations could be arrested. The originator of the scheme was Alamundar, his Saracenic ally, who pointed out to Cavades that if a descent were made on Euphratesia, the overlying province of Syria, they might advance to the walls of Antioch through a populous district teeming with wealthy towns but slightly guarded, and totally unapprehensive of their security being threatened. "Antioch itself," said he, "the richest city of the East, is always given over to public festivities and theatrical rivalries, and is divested of a garrison. Well might we capture it and make good our retreat to Persia without meeting with a hostile force. In Mesopotamia, to which the war has been confined hitherto, the enemy is prepared for us, and we can inflict no damage on them without engaging in a perpetual series of battles." His advice was acted upon, and a Persian general, Azarathes, {405} invaded Euphratesia with fifteen thousand horse, supported by a numerous body of Saracenic auxiliaries. The news of their entry on Roman territory was speedily conveyed to Belisarius at Dara, and he resolved to proceed at once by forced marches to meet the raiders. His army consisted of about twenty thousand men, including cavalry and infantry, and he moved with such rapidity that he succeeded in bringing the enemy to a stand at Gabbulae, before they had had time to commit any serious depredations.[101] Azarathes and Alamundar were taken aback at this encounter, which falsified all their calculations. They were devoid of confidence in their power to resist a Roman force, especially when led by a general who had so lately proved his superiority; and they, therefore, decided to abandon the expedition and to retrace their steps with all haste to their own country. Belisarius, on his side, was well satisfied when he perceived that his adversaries were anxious only to beat a retreat, and he determined to leave them unmolested, but to follow their movements until he saw them safely over the border of the province. The two armies were separated from each other by about a day's march, and they proceeded for several days in an easterly direction along the bank of the Euphrates, which lay to the left of their route. Each evening the Byzantines spread their tents on the same camping ground which had been occupied by the Orientals during the previous night. They began to cross the northern extremity of the Syrian desert.[102] In the meantime, however, {406} the Roman troops had become inflamed with the desire to attack an enemy whom they saw constantly flying before them; and at length they broke into open murmurs against their general who, from sloth and timidity, they exclaimed, was restraining them from a glorious success. Belisarius strove to repress their ardour by urging that no fruitful victory was possible under the conditions present, whereas the enemy, if driven to desperation, might inflict a defeat which would restore to them their liberty of action, and be attended with disastrous consequences to the surrounding country. He also represented to his men that their strength was sapped by incessant marching, and especially by the fasts imposed on them by the season of Lent, through which they were passing; finally, that a portion of the army had not yet arrived. At last he was overborne by their clamours, in which many of his officers joined, and even expressed his confidence that a general could not fail to conquer when in command of troops so eager to be led into action.[103] {407}

On Easter Eve the Romans overtook the Persians, and the two armies encamped in sight of each other at a short distance from the town of Callinicus on the Euphrates. The day was observed as a strict fast, but nevertheless on the Sunday morning Belisarius drew out his forces and disposed them in order of battle. His infantry he placed on the left, so that their flank should be protected by the river. The centre was composed of cavalry, among whom he took up his own station, whilst the right wing was allocated to a body of Saracens under Arethas, a sheikh who had been induced to become an ally of the Empire as a counterpoise to the power of Alamundar. On the other side two divisions only were made, the Persians occupying the right and the Saracens the left. As usual the engagement was begun by the archers, who consumed nearly two-thirds of the day in emptying their quivers. The Persians, however, shot out weakly with relaxed strings, and their darts were to be seen continually leaping backwards after impinging on cuirasses, helmets, or shields. But the Byzantine bowmen, though much fewer in number, were more robust, and almost always succeeded in transfixing those whom they struck with their arrows. A determined charge on the Romans by the best troops of the enemy ensued, upon which the tribesmen led by Arethas, cowed by the superior prestige of Alamundar, fled almost without striking a blow. As a consequence Belisarius, with his cavalry, was surrounded on three sides, and subjected to a fierce attack which it was impossible to resist. A band of two thousand Isaurians, who had been among those most eager for a conflict, scarcely dared to use their weapons, and nearly all of them were slain on the spot. A large number of the centre, however, exhausted though they were with fasting, defended themselves strenuously, and inflicted {408} great loss on their opponents. When at length Belisarius saw that there was no hope for the residue of his cavalry but annihilation, he drew them off rapidly to the left, and joined those of the infantry who still held their ground on the river's bank. There, with great presence of mind, he improvised a phalanx, dismounting himself and ordering all his horsemen to follow his example. With serried shields and projecting lances they formed an impenetrable mass which every effort of the enemy failed to break. Again and again the whole body of the Persian horse rode down upon the bristling phalanx; but the Romans drove them back with lance thrusts, and so terrified the animals by clashing their shields, that they shook their riders off. The conflict was only terminated by nightfall, when the Persians returned to their camp, and Belisarius, having obtained possession of a ferry-boat, transferred the remnant of the army to a safe retreat on an adjacent island of the river. Next day he summoned a batch of transports from Callinicus, and in a short time all were securely lodged within the town.[104]

Soon after the battle on the Euphrates Justinian recalled Belisarius to Constantinople and entrusted him with the organization of an expedition which he contemplated against the Vandals in the west. The chief command in the east then devolved on Sittas.[105] As for the Persian generals who {409} had been opposed to Belisarius in the two leading engagements of the war, they incurred almost equal odium in the eyes of their royal master. The Mirrhanes was deprived of the rich insignia of an order of nobility which conferred a dignity second only to that of the throne; whilst Azarathes, who claimed the honours of a victorious general on his reappearance at court, could produce no evidence of his success and, after a muster of the troops, was upbraided by Cavades for having lost the half of his army.[106]

At this juncture Justinian seems almost to have despaired of obtaining a peace on any equitable terms from Persia, although he kept his legates, Rufinus and Hermogenes, on the confines of both empires in continual readiness to institute negotiations. He began, therefore, to devise some means of neutralizing the injurious effect of being in perpetual conflict with his impracticable neighbour. To provoke a hostile incursion against his antagonist from some remote frontier might force him to suspend his assaults on the Empire; whilst the serious interference with Byzantine commerce due to the import of silk across his enemy's dominions being in abeyance would disappear if the trade in that indispensable commodity could be diverted to some friendly route. The geographical and political situation of Aethiopia or Axum and the amicable relations of that kingdom with the Empire seemed to satisfy all the conditions essential to the success of this project. The civilization of Axum and part of its population had originally been derived from the Arabian province of Yemen, on the opposite side of the Red Sea. In the course of time the offspring prospered and turned {410} upon its parent; and by the middle of the fourth century the Negus[107] of Axum had become the overlord of his less powerful neighbour, the king of the Homerites or Himyarites, as the inhabitants of that district of Arabia were called in this age. Christian missions began to penetrate these regions shortly after the reign of Constantine, and at the present time the Axumites were enthusiastic votaries of that religion and of Rome. Himyar, however, was full of Jews who had fled before Hadrian and his predecessors after the subjection of Palestine and the destruction of Jerusalem, and, therefore, of religious dissension; and the championship of the Cross more than once furnished an occasion for the Aethiopian despot to carry his arms into the Arabian kingdom for the maintenance of his rather precarious suzerainty. Only recently, in the reign of Justin (c. 524), the Negus of the day, Elesbaas,[108] had crossed the gulf, expelled a Jewish ruler, and established Esimphaeus, a Christian, in his stead.[109]

To Elesbaas, therefore, Justinian determined to apply, and forthwith detached an ambassador named Julian to enlist his aid against Persia. The embassy, provided with a letter and suitable presents, took ship for Alexandria, navigated the Nile to Coptos, crossed the desert to Berenice, and from thence sailed down the Red Sea to Adule.[110] The Negus was transported {411} with joy as soon as he heard that a party of Roman delegates was approaching Axum, and advanced from his capital to meet them sustained by all the excess of barbaric state. He was standing on a lofty car adorned with plates of gold, which was drawn by four elephants. His guards crowded around him, each one armed with a pair of gilded spears and a small gilt shield, and a company of musicians blew with exultant strains on their shrill pipes. The dusky potentate himself was almost devoid of clothing proper, but was decked from head to foot with a profusion of precious ornaments. On his head he wore a white turban interwoven with gold thread and four golden chains hung from it on each side. A linen mantle weighted with pearls and golden nails, open in front, flowed from his shoulders; and a kilt seamed with precious metal was dependent from his girdle. A necklace and bracelets of gold, with arms similar to those borne by his guards, completed his equipment.[111]

Julian knelt and presented his letter, but was immediately bidden to rise, whilst the Negus kissed the seal of the missive, and listened to its contents as read by an interpreter. He at once promised compliance with all Justinian's requests; an army of his vassal Saracens should march against the Sassanian realm, and the cargoes of silk from Malabar should be diverted from the Persian Gulf to be discharged {412} at Adule.[112] After the lapse of a year another envoy was despatched from Constantinople, and Nonnosus, one of a family of legates, familiarized with these regions by constant visits, traversed not only Axum, but Yemen, in order to stimulate the execution of these important schemes.[113] In the end, however, the project failed of achievement; the tribes of Himyar shrunk from entering on a long and arduous journey over the sandy wastes to attack an enemy whom they believed to be more bellicose than themselves, while the shipmasters could not be induced to avoid the Persian ports, where they found eager buyers for all the silk they could procure.[114] The death of Elesbaas occurred shortly afterwards, but not before an interior revolt had freed Himyar for a time from the Aethiopian supremacy.[115]

In the next phase of the war, martial activity centred around Martyropolis, a fortified town of Roman Armenia, situated on the river Nymphius. A considerable Persian army, under several veteran generals, beset the stronghold with all the engines proper to a determined siege in the warfare of the period. At the same time Cavades, octogenarian though he was, resolute in his purpose to do all the damage possible to his adversaries, provoked an artificial irruption of the Huns into Roman territory, and opened the Caspian Gates to a great host of those barbarians. At his instigation they carried their depredations rapidly to the south, and in the autumn of 531 effected a junction with the Persian forces {413} around Martyropolis. Buzes and Bessas commanded the garrison of the town, but without confidence in their powers of resistance to the assault; for not only were the walls easily surmountable in many places, but the beleaguered were ill supplied with sustenance, and with warlike machines to repel the assaults of the enemy.[116] Nor had the Byzantines any troops in the field with whom they could hope to raise the siege; and Sittas, though posted at only one day's march from the scene of hostilities, feared to approach nearer with the slender army at his disposal.[117] From time to time successful sallies were made by the besieged, and Bessas, who was a bold cavalry leader, now, as on former occasions, found opportunities of inflicting considerable loss on the foe; but nevertheless it was felt that a crisis disastrous to the Romans could not long be delayed.[118] In this impass a stratagem was concerted and carried out effectively, which blunted the ardour of the siege and eventually saved the town. As in all ages, it was the practice to maintain spies in an enemy's camp; and between both nations there was a habitual interchange of renegades who were anxious to betray the secrets of their country, attracted by the substantial rewards which generally accrued to such treason. A man of this class was now at hand, one whose reliability had been tested by the Emperor himself, and he {414} was instructed to reveal to the Persian generals with professed good faith his pretended discovery that the Huns, corrupted by Byzantine gold, only awaited an opportune moment to change sides in their warfare. The spy executed his commission faithfully, and his communication was listened to with consternation by the military council.[119] The Orientals, distrustful of their uncongenial allies, relaxed their energies, and the siege was protracted until the severity of the weather compelled a cessation of arms for the season. The Persians gladly agreed to a truce and retired into winter quarters, but the Huns, now freed from control, began to work their way towards the south with Antioch as their goal, plundering every assailable habitation which lay in their track. They were pursued unremittingly by Bessas, who cut up marauding bands, captured their spoils, and finally succeeded in chasing the survivors out of the country.[120]

In the meantime an event had occurred which produced an immediate change in the relations of the two empires, and virtually ended the war before the advent of spring called for a resumption of hostilities. Early in September Cavades was suddenly prostrated by illness, whereupon he summoned Chosroes, and caused him to be crowned hastily at his bedside. A few days afterwards he expired, at the age of eighty-two in the forty-fourth year of his reign.[121] As usual {415} in Oriental successions the new Shah was unable to seat himself firmly on the throne without making away with several of his near relatives who formed a nucleus around whom malcontents might cluster.[122] Preoccupied, therefore, with his domestic affairs, he was anxious to be relieved from the onus of a foreign war, and signified shortly to the Roman legates his willingness to negotiate a treaty.[123] Rufinus was credited with being a peculiarly grateful personage to Chosroes owing to his having consistently advised Cavades, during his long intimacy with him, to elevate his third son to the throne. It was also reported that the Persian queen-mother was in secret sympathy with Christianity and, therefore, used her influence over her son to promote peaceful relations with the Byzantines.[124] But the lessons of the war {416} had not been lost on Chosroes, and he felt strong enough to impose conditions so exacting that the Roman plenipotentiaries were unable to accept them on their own responsibility. Invasion of the empire in force had been the distinctive feature of every campaign and, while Persian territory had been subjected only to some desultory raids, the brunt of the war had been borne by the Byzantines on their own ground. Under an obligation to perform the double journey in seventy days, Rufinus posted to Constantinople to hold a special conference with Justinian. He returned with a virtual consent to all the effective demands of Chosroes, and in less than a year after the death of Cavades a treaty was ratified under the reassuring title of "the Perpetual Peace." By this convention the substantial captures made by each party were to be exchanged; the fugitive Iberians were to be allowed the option of residing peacefully in their own country or of remaining under the protection of Justinian; Dara was not to be demolished, but the military Duke of Mesopotamia was to remove his headquarters from thence to an unimportant town at some distance from the frontier;[125] and the Caspian Gates were to be left in the sole charge of Persia. The two last articles were concessions on the part of the Shahinshah, to counterbalance which the Romans agreed to pay an indemnity of one hundred and ten centenaries of gold (£440,000).[126] Rufinus deposited the amount in specie at Nisibis, and the war was thus terminated with some military glory to the Byzantines, but with no {417} inconsiderable loss of their material possessions, which accrued for the most part to the advantage of the Orientals.

During the whole of this period the barbarians to the north of the Danube and Euxine were kept in a state of active commotion by various influences; and, if at any moment the countless wild hordes, who peopled that immense region, could have been moved by a unanimous impulse to hurl their combined force against the Empire, it seems impossible but that the Byzantine administration must have succumbed at once and finally to the irresistible shock. But there were always three forces in being which co-operated to avert such a catastrophe, and saved the Empire for many centuries from sudden annihilation. Its lengthened preservation in this connection was due to the diverse powers of arms, of wealth, and of religion. Conversion to Christianity was continually inspiring a proportion of these semi-savage races with a desire to enter into amicable relations with the Roman Emperor, in whom they saw the prime source of the mystical lore which they had just been taught to regard with awe. Rich presents were despatched to the most accessible of the barbarian rulers, who were thus induced to pledge their allegiance to the Byzantine state.[127] {418} These various influences not only protected the Empire from many impending assaults, but, by animating the barbarians with invidious feelings against each other, often caused dissentient tribes to engage in the work of mutual self-destruction. Lastly, the residue who actually crossed the frontier with hostile intent were met by the Masters of Soldiers, and with varying success checked in their advance, or cut to pieces.

The influence of religion, at the same time conjunctive and disruptive, has already been exemplified in connection with Lazica and Iberia; and a couple of nearly similar instances, occurring shortly after the accession of Justinian, will be noticed explicitly in a future chapter.[128] An illustration of the advantage derived by the Emperor from the judicious bestowal of treasure on barbarian potentates is also brought before us during this war with Persia.[129] Two Hunnish kings, subsidized by Cavades, were on the march to join the Persian army with an auxiliary force amounting to twenty thousand men. But a queen of the Sabirian Huns, named Boarex, who had been the recipient of Justinian's liberality, was able to put a hundred thousand of her nation under arms. This martial female did not hesitate to attack her kindred; but, falling on them before they could reach their destination, destroyed the expeditionary force, slew one of the leaders, and sent the other to Constantinople, where he was impaled on the shore at Sycae, by order of the Emperor.[130] On the Illyrian frontier the Masters of the Forces in that region were in almost perpetual conflict with barbarian {419} raiders. Previous to 529 the command on the Danube had been entrusted to Ascum, a Christian Hun, but, being captured by a marauding band of his own race during a skirmish, he was carried off and permanently retained by them in their native abodes. He was succeeded by Mundus, a Gepœd of royal race, who had formerly been in the service of Italy. After the death of Theodoric, however, he placed his sword at the disposal of Justinian, to whom he proved a faithful servant not only in the defence of Illyricum, but shortly afterwards at a critical period of his reign in the capital.[131]

[1] The minute description of Justinian's personal appearance is due to Procopius (Anecd., 8), and Malala (xviii, p. 425), whose descriptions seem to correspond fairly. There are several representations of Justinian, but it is doubtful whether any of them rise to actual portraiture. Those found on a large gold medal formerly in a museum at Paris (stolen 1835) were probably the best (reproduced by Isambert, op. cit.; Diehl, op. cit., p. 23). He appears in the great mosaics at Ravenna (see p. 91), and also in a half-length figure in St. Apollinare of the same town. Further there is a MS. sketch at CP. (Mordtmann, op. cit., p. 65). In addition there is the current coinage, especially the copper, on which his image is impressed. Generally the face is pronouncedly round, but, one and all, these likenesses are too crude to convey any physiognomical information. See also p. 308.

[2] Procopius, Anecd., 8. He relates that after the butchery of Domitian all his statues were broken to pieces, but his wife afterwards fitted the fragments of his body together and caused a new figure to be sculptured from them. There is an almost perfect statue of Domitian in the Vatican, which may be the one he alludes to, if there is any truth in his story.

[3] Jn. Malala, xviii, p. 425; Chron. Paschal, an. 566. "You would have taken him for a man with the mind of a sheep," says Procopius, Anecd., 13.

[4] His character and manners can be collected from Procopius (Anecd., 6, 8, 10, 13, 15, 22, etc.) and Zonaras, xiv, 8. His personal influence is well illustrated by the incident already related (p. 303) of his rescuing a patrician from the mob although at the time he was only a Candidate; and by his deliberate mésalliance with Theodora being permitted without a murmur from Church or State. His stolid conviction may be compared to that of Robespierre, of whom, when he first began to speak on public affairs, Mirabeau remarked, "That young man will go far; he believes every word he says."

[5] Procopius, Anecd., 8; 13. In many of his enactments he emphasizes his unremitting assiduity in the interest of his subjects, e.g.: "We shun no difficulties, continually watching, fasting, and labouring for our subjects, even beyond what can be borne by the human frame"; Nov. xxx, 11; cf. viii, pf.; lxxx, pf., etc.

[6] Procopius, Anecd., 22. "He was excessively senseless and like a dull ass that follows whoever holds the bridle," ibid., 8. "As to his opinions he was lighter than dust, and at the mercy of those who wished to urge him to one side or the other," ibid., 13.

[7] There is but one representation of Theodora, that in the companion mosaic to the one above-mentioned at Ravenna, but the face is too unfinished and expressionless to give any idea of her features or character.

[8] Procopius, Anecd., 12.

[9] Procopius, Anecd., 15.

[10] Procopius, Anecd., 15. This Porphyrio, such was the popular name bestowed on the monster, must have been a cachalot or sperm whale, which inhabits tropical and sub-tropical seas. It grows to a length of 50 or 60 feet. The males fight viciously among themselves. Small ships have been damaged by the animal when provoked by an attack.

[11] Nov. viii, 1. Officials, on taking office, had to swear to Justinian and Theodora conjointly; ibid., jusjur.; cf. Nov. xxviii, 5; xxix, 4; xxx, 6, 11. Zonaras remarks, "In the time of Justinian there was not a monarchy, but a dual reign. His partner for life was not less potent, perhaps even more so than himself," xiv, 6; cf. Paul Silent., i, 62. The reign has been compared to that of Louis XIV; but the character of that monarch was more evident in Theodora than in her husband.

[12] "In fact she was much abler than he was and highly ingenious in finding new and varied expedients." Zonaras, loc. cit.

[13] As Messalina, the elder Faustina, Soaemias, etc.; see chap. iv.

[14] Procopius, Anecd., 2.

[15] Ibid., 15.

[16] Procopius, Anecd., 30.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., 10; Evagrius, iv, 10; Victor Ton.

[19] See Bevan's House of Seleucus, Lond., 1902.

[20] The campaigns of Trajan are very imperfectly recorded in the only extant account, that of Dion Cassius as preserved in the careless epitome of Xiphilinus; Zonaras, xi, 21. It is certain that he took the twin capitals of Parthia, Seleucia and Ctesiphon, which faced each other from opposite sides of the Euphrates, and advanced to the Persian Gulf. He marched into Arabia, but the evidence that he penetrated to the Indian Ocean, as Tillemont thinks, is insufficient.

[21] The capture of Seleucia by Avidius Cassius (165), and his brutal massacre of 300,000 of its inhabitants, mostly Greeks, is often alluded to as an irreparable blow to Western civilization in the East; Dion Cas., lxxi, 2, etc. Severus took Ctesiphon in 199; Herodian; Hist. August. In 283 Carus also took Ctesiphon; Hist. August.; Aurelius Vict. Under Diocletian, Galerius extended the Empire beyond the Tigris; Aurel. Vict.; Eutropius, ix.

[22] See Plutarch's account of the affair and his general remarks on it; Vit. Alex.

[23] In the vicinity of Shiraz; described by modern travellers as a garden of fertility.

[24] Most information as to the rise, etc., of Ardeshír (Artakhshathr on coins, that is, Artaxerxes as adapted to their language by the Greeks), will be found in Tabari with Nöldeke's commentary; op. cit.; cf. Zotenberg, op. cit., ii, 40. The great value of Nöldeke's book consists not so much in the flimsy text as in his notes and excursuses which bring together all collateral information to be found in other writers of the period. Zotenberg's version is, of course, from the Persian, the translation of a translation.

[25] The Great Salt Desert in the interior of Persia is somewhat triangular, each of the sides measuring about 400 miles.

[26] Modern Orientalists are of opinion that the pictures of Persian life given by James Morier (Hajji Baba of Ispahan, 1824, etc.) may be applied without much loss of truth even to the age of the Achaemenians. When we reflect that till 1888 Persia had no railway, and now only eight miles, the verisimilitude of the statement will be apparent.

[27] See the first Fargard of the Vendidâd where the "Kine's soul," representing mankind, bewails her hard lot before the supreme being. Generally the primitive conditions of life in Iran are well set forth by Max Duncker, Hist. of Antiquity, Lond. 1881, vol. v.

[28] His actual date is unknown, and his existence at any time not certain, but Duncker surmises this period.

[29] The Iranian mythology is summarized at length by Duncker, but the person of Zoroaster is altogether shadowy, and his date can only be fixed by conjecture. He is, of course, done away with altogether by some Orientalists, e.g. Darmsteter. In later times, as among the modern Persians (Parsees), the names of the opposing gods were abbreviated to Ormuzd and Ahriman.