| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.82592 |

BY

NEW YORK

THOMAS SELTZER

1923

COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY

THOMAS SELTZER, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO

ALL AMERICANS

BETWEEN ALASKA AND ANGORA

This book contains my own observations and my own deductions from them. The responsibility for them is mine alone. I have never engaged in commercial, educational or missionary work. My interest in the Near and Middle East began with a newspaper assignment, and has continued with curiosity as its motive. This book is the result.

My thanks are due to the proprietors of Current History, New York, and Fortnightly Review, London, for their courteous permission to re-print herein parts of certain articles which have previously appeared in their pages.

Clair Price.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| MUSTAPHA KEMAL PASHA, THE MAN | 1 |

| His personal appearance—The Eastern tradition of government under which he was born—The Western tradition which he has sought to transplant to his country—The diversion of the Turks from a military to an economic life, which he is beginning—“Do you think you will succeed?” | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE OLD OTTOMAN EMPIRE | 11 |

| Kemal’s birth at Salonica—How he became a Young Turk—What the old Ottoman Empire was like—The division of its population into religious communities—The Western challenge of its Rûm (Greek) community—Its duty to Islam. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE YOUNG TURKISH PROGRAM | 22 |

| Kemal’s arrest and his exile to Damascus—His eventual return to Salonica—What the Young Turks wanted—The religious conservatism which confronted them—The role of American missionaries and educators—Christendom vs. Islam. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE RUSSIAN MENACE | 38 |

| How Russia and Great Britain fought across the old Ottoman Empire—How Russia entered Trans-Caucasia and came into contact with the Armenians—How it approached the back of British India through Central Asia—How Great Britain finally surrendered in the Anglo-Russian Treaty of 1907. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE YOUNG TURKISH REVOLUTION | 48 |

| “On the morning of July 23, 1908”—The Old Turkish counter-revolution and its defeat—How Islam and the Christian communities nullified the Young Turkish program—Kemal’s break with Enver and his retirement from politics—The Balkan wars and nationalism. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| GERMANY AND THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE | 56 |

| British policy at Constantinople—The Bagdad railway concessions—Russia’s veto and the change of route—The Achilles’ Heel of Aleppo—Germany and Islam—The British Indian frontier in Serbia—The Great War. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| CHRISTENDOM AND THE WAR | 65 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE WAR AND ISLAM | 68 |

| Kemal hurries back to Constantinople and Rauf Bey asks the British Embassy to finance neutrality—Enver enters the war and Persia attempts to follow him—The hard position of Islam in India. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE ARMENIAN DEPORTATIONS OF 1915 | 76 |

| Enver and the Armenian Patriarch—Where the Armenians lived—American missionaries and the Armenians—Russia and the Armenians—Great Britain joins Russia in the 1907 Treaty—Enver’s demand for British administrators in the Eastern provinces—The War and the Armenian deportations. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE 1907 TREATY AND THE CALIPHATE | 89 |

| Great Britain promises Constantinople to Russia—Arab nationalism and the Holy Places of Islam—The Hejaz becomes independent of Constantinople—The British capture Jerusalem—The Caliphate agitation in India. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| THE COLLAPSE OF CZARIST RUSSIA | 98 |

| The Czar abdicates—The French depose Constantine at Athens—Kemal urges Enver to withdraw from the War—Mr. Lloyd George’s new war aims in Turkey—The Anglo-Russian Treaty of 1907 abrogated—Pan-Turanianism leaps into life on the heels of the Russian rout—The Mudros Armistice opens the British road to the chaos in Russia. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| THE ANGLO-RUSSIAN WAR OF 1918-’20 | 108 |

| How Mr. Lloyd George tried to impose alone upon Islam that fate which Great Britain and Russia had agreed to impose together in 1907—The Anglo-Persian Agreement—The “Central Asian Federation”—The American Mandate in Trans-Caucasia—The return of Soviet Russia. | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| THE GRECO-TURKISH WAR BEGINS | 120 |

| Constantinople and the growth of Greek Nationalism—Surrounded by British forces, the Turks go back to peace—Application of the secret treaties which the Allies had drawn up during the War—The Oecumenical Patriarchate breaks off its relations with the Ottoman government. | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| SMYRNA, 1919 | 127 |

| Kemal returns to Constantinople—Turkish confusion in the capital—The Turks ask for an American mandate—How Kemal and Rauf Bey left for Samsun and Smyrna, respectively—The Greek Pontus program—The Greek occupation of Smyrna—The Turks go back to war. | |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| THE ORTHODOX SCHISM IN ANATOLIA | 142 |

| Kemal falls to the status of a “bandit”—Turkish Nationalism begins to re-mobilize and re-equip its forces—The Erzerum Program and the Nationalist victory in the Ottoman elections—How Papa Eftim Effendi broke with the Oecumenical Patriarchate—The Turkish Orthodox Church—Papa Eftim himself. | |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| THE TREATY OF SEVRES | 154 |

| Rauf Bey takes the Nationalist Deputies from Angora to Constantinople—India compels Mr. Lloyd George to leave Constantinople to the Turk and General Milne breaks up the Parliament, deporting Rauf and many of his colleagues to Malta—The Sevres Treaty and how Damad Ferid Pasha secured authority to sign it. | |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| ANGORA | 160 |

| Fevzi, Rafet and Kiazim Karabekr Pashas and their military dictatorship under Kemal Pasha—The “Pontus” deportations—Mosul, the Kurds and the split in Islam—The Franco-Armenian Front in Cilicia, the Greek Front before Smyrna, and the Allied Front before Constantinople—How the broken parliament was reconstructed at Angora—Ferid’s counter-revolution at Konia. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| TURKISH NATIONALISM | 177 |

| The Western tradition of government to which the Grand National Assembly was built—How Nationalism was created—Greek defeat at the Sakaria River—Peace with the French in Cilicia—How a civilian administration was begun at Angora while Fevzi Pasha was re-mobilizing and re-equipping the Turkish Armies. | |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| SMYRNA, 1922 | 199 |

| Allied efforts to hitch the Sevres Treaty to Turkish Nationalism—Greeks transfer troops from Smyrna to Eastern Thrace for a move on Constantinople and when Fethy Bey is refused a hearing in London, Fevzi Pasha launches his attack—The Turkish recovery of Smyrna—Mr. Lloyd George resigns and the Ottoman Sultan flees—Lausanne. | |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| THE REAL PROBLEM OF TURKISH NATIONALISM | 219 |

| Economic beginnings in the new Turkish State—Mustapha Kemal Pasha opens the Smyrna Congress—The Chester Concession a step from imperialism to law. | |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| THE REBIRTH OF TURKEY | 229 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |

|---|---|

| FIELD MARSHAL MUSTAPHA KEMAL PASHA | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

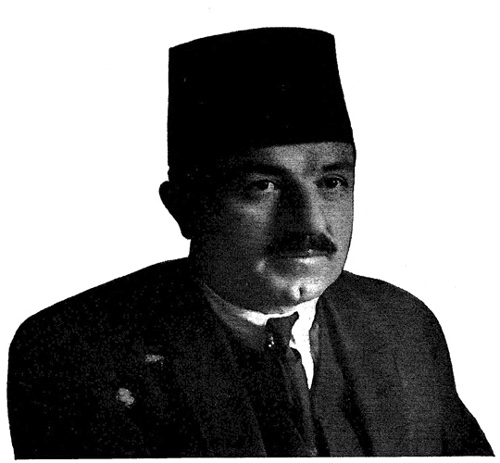

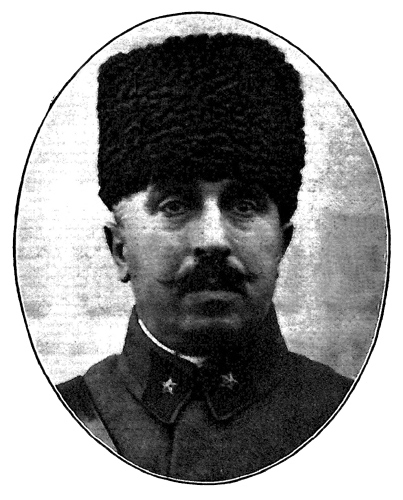

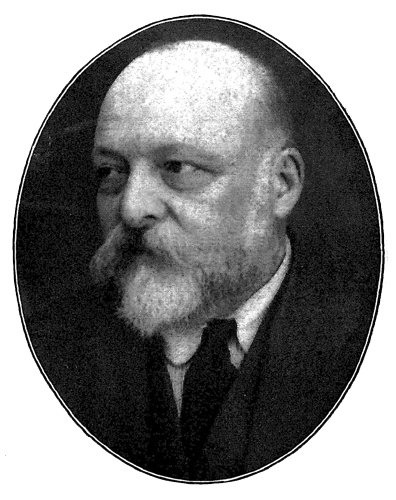

| HUSSEIN RAUF BEY GENERAL RAFET PASHA |

16 |

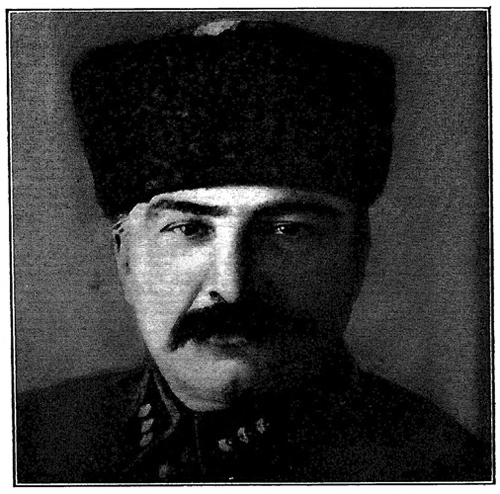

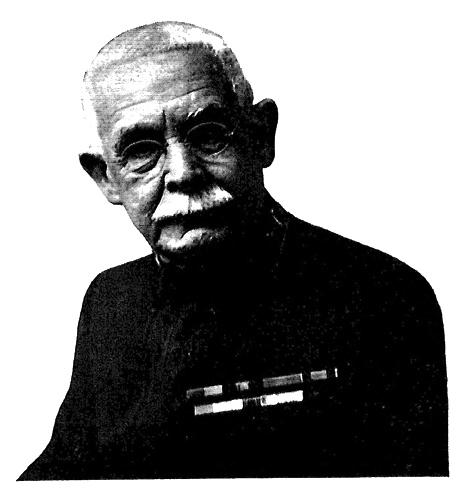

| FIELD MARSHAL FEVZI PASHA ALI FETHY BEY |

48 |

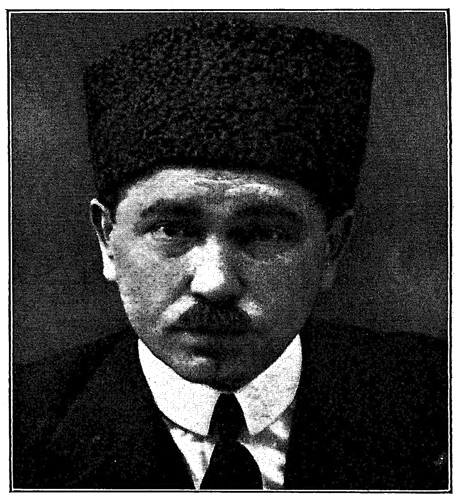

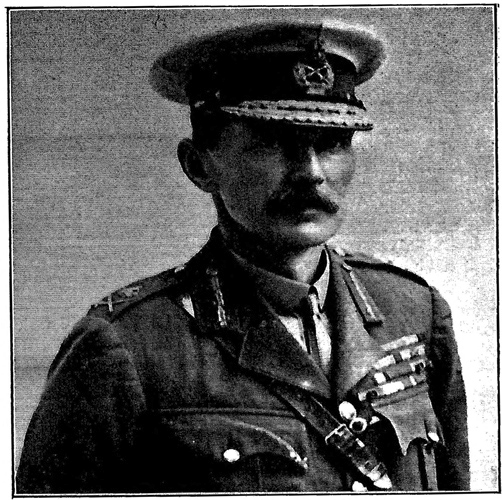

| LIEUT.-GEN. SIR CHARLES A. HARINGTON, G. B. E., K. C. B., D. S. O. GENERAL ISMET PASHA |

80 |

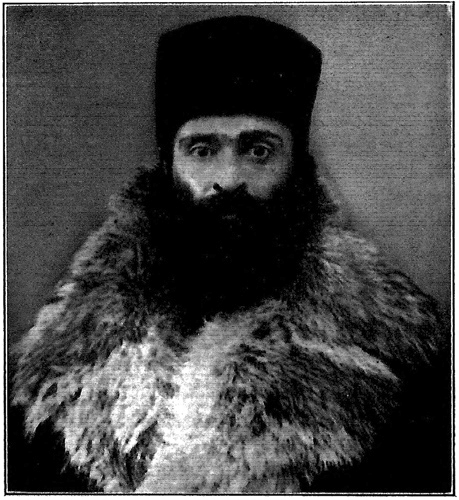

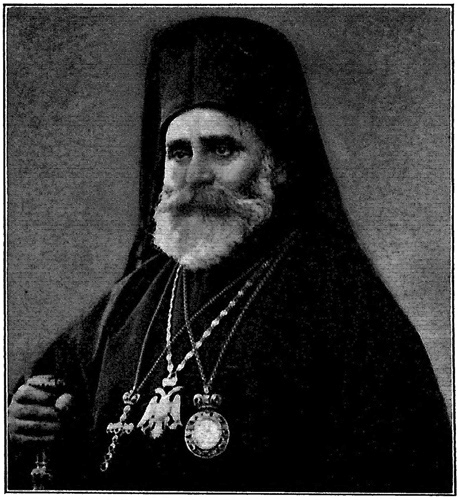

| PAPA EFTIM EFFENDI MELETIOS IV |

112 |

| ASSEMBLY BUILDING AT ANGORA | 144 |

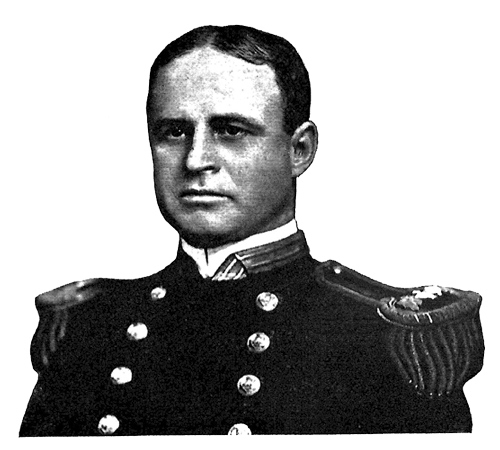

| REAR-ADMIRAL COLBY M. CHESTER REAR-ADMIRAL MARK L. BRISTOL, U. S. N. |

176 |

| GENERAL MOUHEDDIN PASHA MEHMED EMIN BEY |

208 |

HIS PERSONAL APPEARANCE—THE EASTERN TRADITION OF GOVERNMENT UNDER WHICH HE WAS BORN—THE WESTERN TRADITION WHICH HE HAS SOUGHT TO TRANSPLANT TO HIS COUNTRY—THE DIVERSION OF THE TURKS FROM A MILITARY TO AN ECONOMIC LIFE, WHICH HE IS BEGINNING—“DO YOU THINK YOU WILL SUCCEED?”

Having applied at the Foreign Office in Angora for an appointment with Mustapha Kemal Pasha, a message finally reached me about 2 o’clock in the afternoon that a half-hour had been arranged for me at the close of the day’s session of the Grand National Assembly. The gray granite building which houses the Assembly, stands at the foot of Angora, with the red and white Crescent and Star flying above it by night as well as by day. “The Pasha’s” car stood at the curb. He lives in a villa presented to him by the town of Angora, at Tchan-Kaya, a suburb three miles away, and the sight of his car, a long gray machine of German make, is one of the few means of tracing him. He is the easiest of all men to meet, but the most difficult of all men to find.

Within the building, one of Kemal’s aides led me to a large room off the corridor, within which to await the end of the session. It was the room in which I had first met him, a large room with a flat-top desk in the center of one side, with a row of chairs around the four walls, and a sheet-iron stove with a pile of cut wood beside it, in the middle of the carpet. I waited possibly a half-hour, listening to the noise from the Assembly’s chamber and making guesses as to what the trouble was. I had hoped to secure an hour or two with Kemal and had been listing, during the month I spent at Angora, a number of subjects on which I was anxious to secure his opinions. But he is not only difficult to find but difficult to hold for long. I had applied to the Foreign Office a week before and I believe they were not only willing but anxious to secure the appointment I wanted. My application, however, happened to coincide with a crisis in the Assembly and I had to make the best of a half-hour.

The session had no sooner broken up and the clamor of the deputies begun to overflow from the chamber into the corridor, than the aide summoned me. We crossed the corridor into a small room with a flat-top desk and, in the corner behind the desk, the limp folds of a tall green banner inscribed with Turkish letters of gold. From his chair at the desk, the military figure of Kemal himself in civilian clothes rose to greet me—a man with a face of iron beneath a great iron-gray kalpak. He spoke in French and the flash of much gold in his lower teeth gave sparkle to the military incisiveness of his manner, a manner which conveyed an instant reminder of cavalry.

His face is one of severely simple lines. The lower line of the kalpak comes down close to the straight eyebrows, and there is no waste space between the eyebrows and the eyes themselves. “The Pasha” is reputed to have occasional fits of temper which reveal themselves in a noticeable squint in the pupils of his eyes, but during all the time I talked with him that afternoon, those eyes of pale blue fixed themselves on me and never left me.

There is a story of some famous German general who is reputed to have smiled only twice in his life, once when his mother-in-law died and once when he heard that the Swedish General Staff had referred to certain military works outside Stockholm as a fortress. Applied to Kemal, the story would hardly hold true for he has the gift of making himself genuinely pleasant when he cares to exercise it. I can speak of it only in connection with the handful of Westerners who have lived in Angora during the last four years. Turkey has been not only Turkish but desperately Turkish during these last years, yet no public celebration of its victories has occurred in Angora without the handful of Westerners in the town attending and without Kemal himself making an opportunity to receive them upon its conclusion. On these occasions, they have been received with a sensitive cordiality hardly understandable by those Westerners at home to whom it has never occurred that nations are born, not in debating societies, but in the mud and blood of suffering.

Kemal is, however, a professional soldier, dismissed from the old Ottoman Army by the Damad Ferid Ministry in Constantinople and now occupying a politico-military position at the head of the new Turkish Government. He has brought to Angora the blunt directness of the soldier rather than the statesman, and his remarkable personal prestige has colored his entire Government. Yet it is not sufficient to define him as a soldier. The head of the new Turkish State happens to be a soldier because the dominant tradition of the old Ottoman Empire was the Turkish military tradition. In any country with a great military tradition, the best brains of the country tend to flow into the Army and the best brains of the Army tend to flow into the General Staff. Kemal reached the General Staff of the old Ottoman Army at a time when the best brains in the country were attempting to carry it from those Eastern traditions of government in which it had had a long and rich experience, to the newer Western traditions at which it is still serving its apprenticeship.

If it is possible to press down the difference between these two traditions of government into the limits of a single sentence, it might be said that the Eastern tradition is that of action and the Western tradition is that of argument. Under the Eastern tradition, government is centralized in a single ruler whose power is as nearly absolute as his own personal abilities enable him to make it. Under the Western tradition, the functions of government are decentralized and authority is carried down to a popular electorate, represented by deputies in a parliament to which the Government of the day is immediately responsible. Under the Eastern tradition, all things are possible to an individual ruler as long as he disposes of sufficient force to impose them. Under the Western tradition, all things are possible to an electorate as long as it abstains from force in imposing them. London is the home of the modern Western tradition but to find the home of the Eastern tradition today it is necessary to go farther east than Turkey, to a country like Afghanistan. One episode which illustrates the contrast between the two traditions, is that of an Afghan notable who happened to be in London at a time when the Government fell, and who lost no time in sending an aide into the West End to purchase arms with which to defend himself. For further illustration, I might draw on my own experience. I called on the Afghan Ambassador at Angora in the course of my stay there and discovered, I thought, an astonishing ignorance of our Western ways. His was a charming tea, served by a charming gentleman who kept a charming revolver on his desk throughout the period of our talk and two charmingly brawny Secretaries of Embassy close at hand in case, I suppose, of emergency. It happened, however, that no emergency developed and our talk of an hour’s duration ended as happily as it began.

But if we Westerners have slowly built up our own peculiar traditions of government at home, we have not always carried them with us into the East. In our contacts with Eastern peoples in their own lands, we have tended to adopt the Eastern tradition. We have met force with force and it is possibly difficult to blame the more provincial of Eastern peoples if they conclude from their contacts with us along their own frontiers, that our traditions of government are the same as theirs. We cherish at home the reign of law, but our imperialisms in the East have not always exemplified our love of law. Probably their relatively lawless nature has been justified by necessity, for the complicated machinery of Western trade demands conditions of security if it is to work smoothly. Doubtless imperialism which is the simplest method of affording it a degree of security, will continue as long as it is able to command superior force, although naturally it is a daily humiliation to the strongest of Eastern peoples. Necessity will tend to justify its continuance until Easterners demonstrate that they can adapt our tradition of law to their own needs and that they are themselves able to afford legitimate Western trade (not of the get-rich-quick sort) that security which it has a right to expect. It is this task of adapting the Western tradition of law to Eastern needs, of substituting in the East a new and Eastern regime of law for the lawlessness of imperialism, while disturbing as little as possible the inter-flow of sound and legitimate trade—it is this task which constitutes the Turkish problem today.

Kemal is a Westerner who was born under the Eastern absolutism of Abdul Hamid. He has known the East, the West and that curious offspring of both of them, imperialism. He is the son of a country which has belonged in the past to any man who proved strong enough to take it and which has rewarded its strong men with prestige or a cup of poison or both. He has been a consistent Young Turk, although his beliefs once flung him out of his country in disgrace and later tossed him the dying remnant of his country to do what he could with it. In his unaffected bearing, he embodies the old Ottoman officer type at its best, and at its best that type was a very fine type indeed. He is a great Turk and as a man among men he towers head and shoulders above the type of man which our Western democracies have sometimes projected into political life. A century from now, the historian of the future will see him in a larger and more adequate perspective than we are able to look upon him as he moves among us today.

He resumed his chair behind the desk, with the green and gold banner hanging limply in the corner behind him, and took from his pocket a string of amber beads with a brown tassel. His cheek bones are rather high, his nose is straight and strong, his mouth is straight and thin-lipped. I think a cartoonist would find him easy to do—a towering iron-gray kalpak, and beneath it the straight strong lines of the eyebrows, the mouth and the chin. He wore an English shooting suit of tweed, a gray soft collar with a gray tie, and high-laced tan boots with the short vamp which is native to the Near East. Physically, he gives a lean, wiry impression.

He speaks either Turkish or French (he knows no English) in the mildest of tones, hardly above a whisper and with a blunt frankness which manages to remain free from any suggestion of truculence. I formed the impression that he does not find talk congenial; he says what needs to be said but he prefers to listen. Certainly he is quite devoid of that love of talk which sometimes afflicts Western statesmen and which is one of the less beautiful aspects of our Western tradition of popular government. Like any other good soldier, there is not the faintest trace of pose in him. He does not employ to Westerners the, to us, exaggerated courtesies of the East; when he does talk to us, he talks as we ourselves endeavor to talk to each other, with simplicity and directness. At one time in our talk, I asked him for photographs of himself since they were not then obtainable elsewhere in Angora and weeks afterward I happened to mention the matter to a Western friend in Constantinople. “What did he tell you?” “That he would have them sent me the next day.” “And did he?” “Yes.” My friend thought it over; he has lived in Constantinople for some thirty years. “If you can really get any Turk to give you a definite word on any subject under the sun without making you wait a month for it,” he said finally, “its fairly certain there’s been a revolution in the country.”

I had a feeling from the first that I was talking to an iron image, that his brain was miles away busying itself with a thousand and one affairs. He had a manner of dismissing question with question as though he were very busy but desired not to be discourteous, and the heaped-up pile of papers on his very neat and orderly desk made it probable that this was precisely the case. I changed my tactics finally and began firing questions at him abruptly, determined to get his undivided attention. He reached up suddenly with a gesture which might have savored slightly of impatience, and flung aside his kalpak, revealing a tall sloping forehead, fringed at the top with very thin brown hair, a forehead totally out of keeping with the severely simple lines of his face. If his face is the iron face of the cavalry officer, his forehead is the forehead of the statesman.

I kept on firing questions at him until I felt that his brain had paused at its distance to listen. I continued to fire questions at him until I felt that his brain had turned, had rushed down from its distance and was sitting intently behind those fixed blue eyes, staring out at its questioner:

“Suppose Turkey’s Western population leaves the country en masse when it becomes certain that the Capitulations are ended?”

“The West can help us or hinder us greatly,” he said, “but it ought to be remembered that we Turks have our own problem to work out in Turkey.”

“Just what do you mean by your own problem?”

“You have seen the country, you know the condition in which Turkey is. Our villages, our towns, our communications, all need to be built anew from the ground up. We have had a good Army in times past. I don’t believe there has been a better Army in Europe. But we hope soon to be able to demobilize and then our real work will begin. We shall have a potentially rich country on our hands and we shall have the right which we have not had recently, to do what we can with it. We want to make it a country worthy of its name, we want to give it not only the best its own civilization offers it but the best we can take from other civilizations. To that end, we shall welcome the help of others but in the very nature of our task, any help we secure from others must be subordinated to our own efforts. If we can not succeed, nobody else can.”

“Do you think you will succeed?”

“If you will come back two years after the peace, you will see what sort of beginning we have made.”

When my time was up, I left him and walked back in silence to my rooms. I dispatched the aged Armenian maid after tea, took off my shoes and donned my slippers. I felt somewhat as a man does when he has seen a great cavalry charge and has returned to his billet and taken his boots off. I became aware finally of the squeak of ox-carts beneath my windows. A long string of them was passing on its 300-mile trek up from the coast to the Army bases in the interior. The air was filled with their slow screaming squeak, a squeak which with infinite deliberation removed the skin from every note in the chromatic scale, the squeak of wooden axles daubed with tar to tickle the musical palates of a team of oxen. Each cart, a mere wooden platform mounted on wooden wheels, bore a tall mound of hay for the oxen and beneath the hay the rope-handled ends of two or four or six new wooden boxes protruded, the number of boxes depending on the calibre of the shells within. Most of the drivers were Turkish peasant women, jacketed and pantalooned, their feet shod in rope-bound woollens, their faces and hands reddened by exposure. Dead men’s fathers and sons and brothers in the Army, widows and dead men’s daughters behind the Army—but still the rope-handled boxes squeaked up from the sea….

It is out of the dumb stubborn strength of this peasantry that the Turkish military tradition has been fashioned in centuries past. But can the Turks direct this strength from their native military tradition into a new and Western economic tradition? This is the question mark which hangs over the Turkish problem today and Kemal knows it.

“Do you think you will succeed?” I had asked him.

“If you will come back two years after the peace, you will see what sort of beginning we have made.”

KEMAL’S BIRTH AT SALONICA—HOW HE BECAME A YOUNG TURK—WHAT THE OLD OTTOMAN EMPIRE WAS LIKE—THE DIVISION OF ITS POPULATION INTO RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES—THE WESTERN CHALLENGE OF ITS Rûm (GREEK) COMMUNITY—ITS DUTY TO ISLAM.

Forty-two years ago, when Abdul Hamid II ruled in Constantinople and the Ottoman Crescent and Star still floated over Salonica, an underling in the Salonica customs office died, leaving his widow with a small daughter and an infant son on her hands. The daughter in time grew up and married, as is the way of Turkish daughters. The son was intended by his mother for the mosque school and the career of a hoja, as is the way of Turkish mothers, but he became fascinated by the uniforms of the Ottoman Army officers whom he saw about the streets, as is the way of Turkish sons. In time he succeeded in passing the examinations for the military preparatory school at Salonica, where his mathematics teacher became so fond of him that he left off calling him by his given name of Mustapha and dubbed him Kemal, a Turkish name meaning rightness.

The military preparatory school at Salonica, the officers’ school at Monastir and the War Academy at Constantinople finally graduated him, a headstrong youth of 22, into the Army in 1902 with the rank of lieutenant. He had hardly reached the War Academy from Monastir before his adolescent mind became tainted by the political ferment with which the school was secretly permeated. A copy of the forbidden play Watan (The Fatherland) fell into his hands. Abdul Hamid had caused every known copy of it to be confiscated and burned; he had forced its author, despite his very high place in modern Turkish literature, to flee into exile; he had driven out of the capital every Ottoman subject whom his spies suspected of having read it. But Watan gave the young Kemal his first taste of Western ideas and made him secretly a Young Turk and a bitter opponent of Abdul Hamid, which at the time was a rather ridiculous thing to be.

Abdul Hamid was an able Easterner who maintained his grip on his country by such a system of espionage that the life and liberty of no Ottoman subject was safe who was remotely suspected of having heard of the French Revolution, a system of espionage which could not keep Western ideas out of the capital but which could, and did, keep them underground. The military tradition of the country continued to attract its best brains into the Army but the network of espionage which radiated from Yildiz Kiosk had the effect of giving the Army a sort of dual existence. On the surface, it continued to be a military organism, the trustee of an Eastern military tradition, but beneath the surface it became a ferment of forbidden Western ideas and the example of Nihilism in Russia which did much to spread the secret society craze, found no more fertile element to work upon than the yeasty mentality of the War Academy and the Military College of Medicine in Constantinople. So a secret political society which called itself the Society of Liberty was formed among the students at the War Academy and a similar society, the Society of Progress, was launched across the Bosphorus at the Military College of Medicine. But both were mere seeds sprouting underground in the rich and rotting soil of the capital. The country itself, outside the capital, was still a primitive Eastern land ruled by any man who proved himself strong enough to take it.

There were some 600,000 square miles in the old Ottoman Empire when Abdul Hamid came to the Throne. It was a compact area, lying at the junction of three continents. On the west, it ran deeply into the Balkans in Europe; on the east, it extended into Trans-Caucasia and down the frontier of Old Persia in Asia; on the south, it followed the Arabian coast of the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean and crossed to the African coast to include a waning sovereignty over Egypt. In the Balkans and Asia Minor, it consisted of a mountainous massif tilting up to the high plateau of Trans-Caucasia, its slopes dotted with isolated villages quite out of effective touch with any Government which might exist in Constantinople. Only the larger villages had a gendarmerie post, fewer still had a telegraph key to connect them with the provincial capital and throughout most of the country such Western contrivances as railroads were wholly unknown. With the country’s administration rigidly centralized in Constantinople, only the high prestige of the Padishah linked these scattered villages in their loosely organized provinces.

South of Asia Minor, the mountains dipped into a great desert arched by the Tigris-Euphrates basin on the east and by the green Syrian corridor on the west. Here, except in the Syrian corridor, the inaccessibility of the country from Constantinople and the nomadic nature of its sparse population gave the provincial administrations a degree of semi-independence which increased to complete independence down in the Arabian peninsula. The case of the Syrian corridor was exceptional, however. Compared with the distant Tigris-Euphrates basin, it was easily accessible from Constantinople; it was the home of a settled population with a very high culture of its own; and it was on the only line of land communication with the most venerable holy places of Islam, the Haram-esh-Sherif at Jerusalem, the Prophet’s Tomb at Medina and the sacred Kaaba at Mecca. The first of these lay at the southern end of the corridor and the other two amid the arid mountains which parallel the Arabian coast of the Red Sea.

Over these 600,000 square miles of country, the Sultan at Constantinople maintained the loosest sort of government, permitting his subjects to conduct their own affairs largely in their own ways and confining his administration to the task of keeping the trade routes open and the taxes collected, for under the Eastern tradition this was the whole duty of government. There were about 25,000,000 of his subjects, the overwhelming majority of them Moslems. The great Moslem reformation had swept the entire area centuries ago, but in accordance with the tolerance prescribed by the Prophet, Christians and Jews, while set aside in their own community organizations as dissenters, had been allowed to worship in their own ways. This was quite in accord with the loose Eastern idea of government which permitted every man to go his own way as long he paid his taxes regularly and refrained from disturbing the peace of the country. Even foreigners were likewise set apart under the Capitulations and were permitted to govern themselves under their own laws and customs.

On the surface, the Sultan’s administration of his country from Constantinople was very much like the King’s administration of his realm from London. Both the Ottoman Sultan and the British King were the heads of the dominant faiths in their respective countries. The Sultans had become Caliphs of Islam in 1517, although not all Moslems recognize them as such, just as the British Kings had become Defenders of the Faith in 1521, although not all Christians recognize them as such. The Sultan administered the spiritual affairs of his country through the Sheikh-ul-Islam and its temporal affairs through the Grand Vizier, just as the King in London administers the spiritual affairs of his realm through the Archbishop of Canterbury and its temporal affairs through the Prime Minister. The surface of both countries is feudal and mediaeval, and springs from the same source, but their resemblance in the reign of Abdul Hamid II stopped at the surface. Beneath the surface, England during the latter half of the nineteenth century, was in a state of transition from feudalism to the modern Western idea of democracy. A growing industrial plant was giving rise to trade unions and trade unions, exerting a growing influence on ideas of government, were drawing authority down to a popular electorate. Government was tightening its hold on the lowliest peasant and a civil service was being formed as a permanent body to which the increasing duties of government were entrusted. The country was becoming a powerful industrial unit, able to mobilize the vast new energies which machinery was opening up to it. It was embarking on manufacture and trade on such a scale as had never been dreamed of before. It was becoming the ganglion of a financial nervous system whose sensitive fibres covered the world. The old religious aspect of government was dwindling and in its place we saw a drilled and disciplined industrialism taking form beneath the feudal trappings which still constitute the surface of British government.

HUSSEIN RAUF BEY

Head of the Ottoman Delegation which signed the Mudros Armistice, October, 1918; Nationalist Party Leader in the Ottoman Chamber, January and February, 1920; arrested and deported to Malta, March 16, 1920; Minister of Public Works and Prime Minister of the First Grand National Assembly after his return from Malta in November, 1921.

GENERAL RAFET PASHA

Minister of War and Interior of the First Grand National Assembly until November, 1921; Minister of War until January, 1922; Governor of Eastern Thrace since November, 1922.

But when Abdul Hamid II ascended the Ottoman Throne at Constantinople, religion was still the dominant factor in his primitive and loosely organized country. From its surface to its core, the Ottoman Empire was still Eastern. The Moslem community was still the governing community, a community with a profound self-respect and a knowledge of its own duties as well as of the deference which was due to it. The dissenting communities were exempt by Moslem law from the duty of preserving the peace and hence were able frequently to attain a degree of prosperity which many Moslems never knew. Since the bulk of the Sultan’s revenue was obtained from taxation provided for in Moslem law, foreigners, most of whom were Christians, were naturally exempt from the payment of any but secular taxes such as land tax and customs duties. We Westerners think of it today as a hopelessly mediaeval method of governing a country, but we sometimes forget that it permitted every man in the country a generous liberty which we in the West have lost. It exemplified the Eastern tradition at its best and if we in the West have won for ourselves the blessings of modern industrialism, we have paid for them with a considerable share of the liberties we once enjoyed. What larger liberties our new industrial democracies may yet confer upon us in exchange for the liberties they have taken from us, remain to be seen. We are still evolving our Western tradition of government, but at present it has taken from us feudalism and the open fields and given us in exchange democracy and the machine-shop.

Even before Abdul Hamid II came to the Throne, the Western tradition had begun to make itself felt in the old Empire, for it was obvious that Western industrialism would succeed eventually in generating such power that no non-industrial country could stand against it. The disturbing lure of the Western tradition was heightened by the religious element, for both Islam and Christendom, while divided within themselves, tend to draw together when menaced from without. The Islamic world found its political leadership in Constantinople, its scholastic leadership in Cairo and its juridical leadership in Mecca, and it was natural that it should resent any menace to the old Ottoman Empire within whose frontiers these three centers of leadership lay. At the same time, the memory of the great Moslem reformation had not yet passed from Christendom and it was natural that it should resent the fact of Moslem rule over Palestine and the inferior position necessarily accorded to Christian communities in a Moslem country. There were a number of these Christian communities in the Ottoman Empire, but we shall confine ourselves here to the mention of the two of them which most vitally concern us—the Rûm community which included all members of the powerful Orthodox Church who recognized the Oecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople, and the Ermeni community or the Gregorian Church, a small but historic sect whose membership was limited to Armenians. Both these communities were exempt from the operation of Moslem law and subject instead to their own Christian laws. Both were officially established and represented in the Sultan’s Government, the Oecumenical Patriarch himself representing the Rûm community and the Ermeni community, since the seat of its Catholicos is in Trans-Caucasia, being represented by a Patriarch appointed for the purpose in Constantinople. These communities included most of the Christians who had survived the great Moslem reformation and on the whole they lived quite peaceably under Moslem rule. While their Moslem neighbors formed the governing class, they formed the trading class and in any feudal country trading is the occupation of the lower class. Still, their ablest men were frequently utilized by the Sultan in the government of the country and when they were so utilized, they were called upon quite without reference to their position as religious dissenters, just as Nonconformists, Catholics and Jews are utilized in the British Government without reference to their attitude toward the Church of England.

It was through the Greeks, as the Rûm community is called in the West, that the Western tradition of government was first introduced into the Ottoman Empire. They introduced it in its crudest form, a form in which the basis of the State was shifted from religion to race. The Greeks of Old Greece revolted successfully in the 1820’s and were immediately recognized by the West as an independent State. But a curious feature of their State was that it contained none of the provisions for reasonably secure dissent which had marked the Empire. Although the modern Greeks were without experience in the government of dissenters, the West gave them immediate and full control over their entire population without community organizations for dissenters or Capitulations for foreigners. We Christians appear to be characterized by this inability to tolerate dissent. Once we were burning dissenters at the stake and today, although we have won religious liberty for ourselves in the West, we have not even yet succeeded in looking upon all religions and all races with the broad tolerance which distinguishes Islam.

The revolt of the Old Greeks disturbed the peaceful relations which had existed between the Sultan and his Rûm community, but not as violently as might have been expected. In time it disturbed Moslem minds, for if this Western emphasis upon race were to gain any headway in the Empire, there was literally no end to the amount of disruption it could effect. As a country inhabited by 18,000,000 Moslems, 5,000,000 Christians and a scattering of lesser faiths, the internal life of the Empire had been generally peaceful and not ignoble, but if its population were to be changed over into a matter of 9,000,000 Turks, 8,000,000 Arabs, 2,000,000 Greeks, 2,000,000 Kurds, 1,500,000 Armenians, etc., all of them inter-tangling into each other, the prospect of trouble was limitless, not only for the Turks themselves but for every race in the country.

To the Greeks of Old Greece, the new Westernism offered the prospect of a reversal of the subordinate position they had occupied ever since the Moslem reformation had all but swept Christianity out of existence in the very land of its origin, and this prospect was heightened by the increasing territorial losses which the Ottoman Empire had suffered for two centuries. The same prospect made itself quickly felt throughout the West, a fact which may afford evidence that the unity of Christendom is greater than it appears to be on the surface, for surely there can be no greater contrast within the limits of a single faith than the contrast between the rich and decadent ritual of Orthodoxy on one hand and the Spartan simplicity of British Non-conformism and American Protestantism on the other.

But the challenge which the Greeks had found it comparatively easy to fling down, was far from easy for the governing Moslems of the Empire to pick up. In the first place, they had built the Empire to the specifications of their own Moslem law and in the second place, quite irrespective of any wishes they might have had in the matter, they bore a heavy responsibility to the rest of Islam for their faithful stewardship of that law. It had come to a time when the Empire was one of the very few Moslem States which were able to interpret Moslem law independently of external pressure, and Islam looked as it had never looked before to its political leadership in Constantinople and its juridical leadership in Mecca. The Sultan was the trustee of that venerable Eastern civilization which was Islam’s own. The Caliphate which Selim the Grim had lightly taken at Cairo in 1517, when Islam was powerful, was now in the days of Islam’s political decline, becoming an actual and heavy responsibility. The position was not a hopeless one, for Indian Moslems who comprise some of the best brains in Islam, had shown in their accommodation to the fact of British India, that Moslem law is not inflexible. But for Moslems both within and without the Empire, the challenge which the Old Greeks had flung down, produced a position about as serious as can be imagined.

The Ottoman Empire was becoming the cockpit of an enormous arena whose slopes extended from the back hills of Java to the country towns of the United States. With the eyes of this worldwide audience upon them, a handful of Young Turks in Constantinople were beginning secretly to grope about after a way out of the apparent impasse in which they found themselves, after some formula which should adapt the Empire, not to the hothouse Westernism of the Old Greeks, but to the maturer and healthier Westernism of England. Luckily, the fact of India’s 70,000,000 Moslems had thrown the Caliph of Islam in Constantinople and the Emperor of India in London into intimate contact.

KEMAL’S ARREST AND HIS EXILE TO DAMASCUS—HIS EVENTUAL RETURN TO SALONICA—WHAT THE YOUNG TURKS WANTED—THE RELIGIOUS CONSERVATISM WHICH CONFRONTED THEM—THE ROLE OF AMERICAN MISSIONARIES AND EDUCATORS—CHRISTENDOM VS. ISLAM.

The young Kemal had no sooner been graduated from the General Staff classes at the War Academy in Constantinople, than he engaged a small apartment in Stamboul to serve as the headquarters of the secret Society of Liberty. But an acquaintance whom he trusted and whom he permitted to sleep in the apartment at night on the plea that he was penniless, proved to be one of Abdul Hamid’s spies and Kemal was arrested. Having been questioned at Yildiz Kiosk, he was held for three months in a police cell and then exiled late in 1902 to a cavalry regiment in Damascus. Fresh from the War Academy, fired with the spirit of revolution and schooled in its technique, he lost no time at Damascus in getting into touch with other exiles from the War Academy and the Military College of Medicine in the capital. His colonel, Lutfi Bey, introduced him to the keeper of a small stationery shop in the Damascus bazaars who had been exiled from the College of Medicine, and the two of them secretly organized a branch of the Society of Liberty among the officers of the garrison. Under the supposed necessity of his military duties, Kemal was soon dispatched to Jaffa and Jerusalem where similar branches were organised, the Jaffa branch attaining considerable strength. He soon became convinced, however, that work in Syria was a mistake, that if the challenge of Westernism which Old Greece had flung down was ever to be picked up, it would have to be picked up where it had been flung down.

The political life of the Empire centered in Constantinople, but the espionage system which radiated from Yildiz had the capital so completely in its grip that revolutionary work there was subject to the greatest dangers. Outside of the capital, the life of the Empire was divided into two categories, that of the coast towns and that of the interior. The life of the former was in a sort of touch with the outside world, but the provincial capitals of the interior were quite self-sufficient. Smyrna, the greatest of all the coast towns, was in touch with all the outside world, but it was confronted in the interior by Konia whose historic dervish tekkes were a well of Islam undefiled. It was the tchelebi of the Mevlevi dervishes at Konia who girded each new Caliph with the Prophet’s sword forty days after his accession to the Throne, and when proud Konia spoke, its voice was weighted with all the venerable conservatism of Islam.

But in Europe the coast town of Salonica was faced by no such conservatism in its hinterland. The raw turbulent races of the Balkans were already in a ferment of Westernism and in their grim way were preparing to disentangle themselves in the wake of the retreating Empire. Salonica, Uskub and Monastir were already seething with forbidden political ideas and if the Empire were ever to halt its retreat, it was here it would have to make its peace with Westernism. It was here that Old Greece had flung down its challenge and it was here that challenge would have to be picked up. Furthermore, if any force were to be mobilized to thrust Westernism upon Abdul Hamid in Constantinople, it was from Salonica that it would inevitably be launched.

Kemal accordingly abandoned his work in Syria and induced Lutfi Bey to give him leave under an assumed name to Smyrna, intending to make his way from there to Salonica. Fearing, however, that Constantinople would detect his presence in Smyrna, he went to Egypt instead and sailed from Alexandria to the Piraeus, whence he reached Salonica. Constantinople was coming more and more completely into the grip of Abdul Hamid. The General Staff was being periodically broken up and scattered to the four corners of the Empire, and the Military College of Medicine was finally locked up and abandoned. Hamid was beginning in similar fashion to tighten his grip on Salonica and, although Kemal remained there in strictest hiding, his presence was discovered after four months and he fled precipitately to Jaffa, where a convenient outbreak of “trouble” at Akaba on the Red Sea gave him an alibi which served to soothe the ruffled feelings of the capital. From Akaba he went back to Damascus and waited there until a change of War Ministers in Constantinople made it possible for him to request, and secure, a transfer to the Staff of the Third Army at Salonica. Back in Salonica again, he threw himself into the work of the secret Young Turkish organization.

A little group of Ottoman exiles in Paris of whom Ahmed Riza Bey was the leader, had discovered the formula which was to achieve that internal unity which the Empire had long enjoyed and without which no Empire could endure. It was the formula of Ottomanization. “A new Ottoman Empire one and indivisible” was their dream, an expression which they had borrowed from the French Revolution. “Oh, non-Moslem Ottomans—Oh, Moslem Ottomans” was their program. All the races of the Empire were to be drawn together into “a new nation,” “a new Ottoman Empire,” whose military strength would enable it to halt its long retreat and put an end to interference in its internal affairs from without. To Riza Bey, Moslems and Christians alike were sufferers under Abdul Hamid’s Easternism. The restoration of the still-born Constitution of thirty years before, was his objective; with the Constitution restored, Moslems and Christians would enjoy alike the rights and the duties of Ottoman citizenship. Moslems would no longer suffer in silence. Christians would no longer lift their complaints throughout Europe and the United States. “We shall no longer be slaves, but a new Ottoman nation of freemen.”

This was the ideal which Riza Bey lifted up in the little revolutionary periodical Mechveret which was smuggled into every garrison in the Empire from his little flat in the Place Monge, near the Montmarte section of Paris. This was the ideal which young Turks like Enver and Niazi and Kemal were propagating, as they built up the secret organization which was to compel Abdul Hamid to restore the Constitution. Throughout the Empire, they had their agents in every garrison, converting both the officers and the enlisted personnel of Abdul Hamid’s Army, and assassinating hostile officers and men known to be spies. Small organizing committees had been planted in all the larger garrisons and directing committees were functioning in Constantinople, Salonica, Smyrna, Adrianople, Uskub and Monastir. Under the Eastern tradition of government, it was the Army which immediately mattered. Deprived of his Army, Abdul Hamid for the moment would be caught defenseless.

But in reality the Army was only the instrument of Abdul Hamid’s power. The substance of his power lay in Moslem law and in the unswerving devotion to it of the Old Turks. Strong simple men, these Old Turks were, men who knew nothing of the arts of debate, broadly tolerant of the usages of others and rigidly conservative of their own usages, men who took their starkly simple faith very seriously, in whose lives religion was still the dominating factor. They were found in the mosque schools rather than in the War Academy, in Konia rather than in Salonica, and in winning over the Army, the Young Turks were not touching the vast and silent body of conservative Old Turkish opinion which formed Abdul Hamid’s real strength. Here was a dead weight of usage which knew no necessity for change and which would have resisted to the end if it had. True, there was a section of Old Turkish opinion in the capital and the larger provincial centers, which disliked Abdul Hamid the Sultan, but Abdul Hamid the Caliph was quite another matter. Under the Caliph, Moslem and non-Moslem were not equal. Non-Moslems had been given far more tolerant treatment under the Caliph than religious dissenters had sometimes been given under Christian rule in the West, but the tolerance which the Caliph guaranteed them did not make them the equals of Moslems.

Whether Moslem law was really thus inflexible was obviously a matter for Moslems themselves to determine, but the record of India’s Moslems in accommodating themselves to British rule would have seemed to indicate otherwise. India’s Moslems, however, were in touch with the Western world as the Old Turks were not. The very fact of British rule, not to mention their long contact with Hindus, had given India’s Moslems a breadth of vision which Old Turkish opinion lacked. Old Turkish leadership embodied Islam at its best, but in the range of its experience it embodied Islam at its narrowest.

Meanwhile, the Rûm community whose relations with the Sultan-Caliph were still generally peaceful, had a very large source of strength outside the Empire. Had the Young Turks eventually proved successful in equalizing Moslem and non-Moslem in an Ottoman citizenry, the Rûm community might or might not have accepted the change and undertaken to work the newly Ottomanized Empire. But if the Young Turks failed, there were sources of outside strength available to the Oecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople which would have broken the Old Turks by force and substituted a new regime which might be described as Old Greek. The old Byzantine Empire had been snuffed out as an independent political entity in 1453, but it still lived as an ecclesiastical, commercial and political force in the Oecumenical Patriarchate in the Phanar suburb of Stamboul. Its clergy still perpetuated its memory in the black cylindrical hats and the black robes of Orthodoxy, but for the time being their communicants wore the red fez which marked the Ottoman subject.

The King at Athens whence the challenge of Westernism had first been flung down to the Empire, had adopted the title of King of the Greeks and Orthodoxy dominated Old Greece with a degree of intolerance which had never marked Islam in the Empire. Orthodoxy had established its hold on Russia and Orthodox Russia had become the most powerful enemy Islam had ever known. Russia had acquired the protectorship of the Rûm community in the Empire and the great yellow-brown mosque of Ayiah Sophia in Stamboul had become the most sacred irredentum of the Orthodox. Russia sent thousands of pilgrims annually from Odessa to Palestine, and built a hospice on the Mount of Olives which commands Jerusalem in a military sense, with a tower which could not have been better adapted for the uses of a signal tower if it had been built for the purpose. Between Orthodoxy and Islam, there had arisen that state of bitter truce which was typified in the juxtaposition of a Russian church and a Turkish serai.

France which had divorced Church and State at home, still held the protectorship of the Katolik community in the Ottoman Empire. Italy whose relations with the Vatican at home had not always been friendly clung tenaciously to the rights of Italian Catholic orders in Palestine. Germany whose Lutherans had no specified rights in the Christian holy places and whose Kaiser had proclaimed himself the friend of Islam, had planted stronger colonies in Palestine and more buildings in Jerusalem than any other Western Power, and had built a hospice on the Mount of Olives “strengthened” by a wall which could hardly have been better adapted for the uses of military defense if it had been built for the purpose. So we had a city sacred to Moslems, Christians and Jews, dominated by Russian and German hospices on the Mount of Olives, strong fortress-like structures erected ad gloriam maiorem Dei. Meanwhile the Caliph of Islam continued to administer the city with fairness to the communicants of all three faiths, keeping his garrison down at Jaffa on the coast except on the occasions of such religious festivals as required its temporary presence in Jerusalem.

One expects from American Protestantism and British Nonconformism an attitude of aloofness from this sort of thing, for both have revolted against the use of the Church by the State. Both have revolted against that ritualism which marks the older forms of Christianity and have set up for themselves a form of service severely simple and aggressively evangelical. In accordance with the finest of its evangelical traditions, American Protestantism has carried on a long and vigorous missionary endeavor in the old Ottoman Empire, but actual contact with Islam in its own country has done much to make plain to the missionaries themselves the reasons for the great Moslem reformation which all but swept Christianity out of existence in the land of its origin. Whatever may have been thought in the United States as to the work in which American missionaries have been engaged in the Empire, that work has been directed towards the reformation of the decadent survivals of Christian worship. The missionaries themselves, as distinct from their supporters in the United States, have rightly observed that Christianity will not command the respect of Islam until Moslems have been shown a different type of Christian from that type to which they have been accustomed. The missionaries accordingly, beginning on one of the outermost fringes of Christendom, have devoted themselves to work largely among the Armenians and have drawn away from their Gregorian Church a new community which the Caliph in Constantinople recognized as the Prodesdan community.

But an important circumstance exists which is inevitably present in any missionary endeavor in an alien land and of which we sometimes need to remind ourselves. In actual practice, Islam is not only a religion but a form of civilization as well and, in the life of any devout Moslem, it would be very difficult to say where the one ends and the other begins. Precisely the same is true of American Protestantism. It might be simple enough to state the theology of American Protestantism, but that theology would fall far short of defining the actual missionary. For the missionary is not only a Protestant but an American as well, and in any alien country he embodies the American Protestant form of civilization. However rigidly he may seek to confine his work within the limits of religious teaching (and I am thoroughly convinced that the overwhelming majority of missionaries have so sought to confine their work in the Ottoman Empire), it is impossible for him not to be an American and a center of American ideas. In actual practice, it proved impossible for him not to stand as a center of Westernism in an Eastern country to which the application of Western ideas necessitated the utmost caution. The Armenians among whom most of the missionaries worked, were the farthest East of all the Ottoman peoples and among the non-Moslem communities they were the last to respond to the Western lure. For centuries they have lived generally in peace under the Caliph’s rule. Themselves an Eastern people, they had lived under their Eastern masters in the enjoyment of the autonomy of their community institutions. The terms under which the Ermeni community conducted its own affairs in its own way, were the only terms under which they could have enjoyed the degree of autonomy which they did enjoy, for they had a majority in no province[1] and the Western idea presupposes a majority as the first requisite of independence.

If Christian worship as it was practiced in the Ottoman Empire was ever to command the respect of Moslems, in theory it was all to the good that the missionaries should draw their new Protestant community out of the old Gregorian Church. But that the Armenians should be exposed incautiously to Western ideas of nationalism was quite another matter. Events might have worked out differently had the missionaries been able to lay aside their Americanism, had they became Ottoman subjects themselves and confined their work to the propagation of Protestantism under Ottoman rule. But this sort of thing is not done. Without the steadying influence of responsibility to the Ottoman Government, they permitted their work to take them into the most intimate and delicate parts of the Ottoman structure. Their attitude toward the Ottoman Government was that of the Capitulations, their only responsibility was to their American supporters at home to whom the Ottoman Government was as far away as the moon.

Nobody has ever expected American missionaries in the Ottoman Empire to become Ottoman subjects. Indeed, nothing could have made such a proceeding more ridiculous than the mere mention of it, and I am inclined to believe that in the very ridicule which its mention would have provoked, there is food for very sober reflection. Among imperialists, one can thoroughly understand such an attitude, for imperialism is based on force and prestige is the very necessary legend of the invincibility of Western force. But do we Christians also build on force?

Yet the history of Old Greece is by no means an isolated instance of intolerance in modern Christendom. We Christians have built a world in which only Christian nations are admitted to equality (the recent example of Japan to the contrary notwithstanding). Old Greece and Old Russia we have recognized as complete equals with us and if the Armenians had gained their independence, presumably we would have recognized Armenia also as an equal, although every American missionary who knows the Armenians in their own country knows what their abilities are. But forgetting that the true worth of a nation lies in character, we have never recognized Moslem nations as equals with us. We found in the Turks a people of integrity and tolerance, but because they refused to turn Christian, we have concurred in the modern Capitulations and have visited the butcher-legend upon them while exalting Greeks and Armenians upon an equally artificial martyr-legend. Among imperialists, one can understand the necessity of an inflexible attitude of superiority, but among Christians it corresponds neither to reality nor to the teachings of the First Christian.

“And he spake also this parable unto certain who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and set all others at nought: Two men went up into the temple to pray; the one a Pharisee, and the other a publican. The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, God, I thank thee, that I am not as the rest of men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican. I fast twice in the week; I give tithes of all that I get. But the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto heaven, but smote his breast, saying, God, be Thou merciful to me a sinner. I say unto you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other: for every one that exalteth himself shall be humbled; but he that humbleth himself shall be exalted…”

The missionaries remained Americans as well as Protestants. They administered Westernism as well as Protestantism to the Armenians, and the result of the administration of Westernism was bloodshed. The example of Nihilism in Russia lured the Armenians on into the secret society craze. Armenian revolutionary societies answered bloodshed with more bloodshed, and the tragedy began whose ghastly fruition we have seen.

Some of the missionaries recoiled from further missionary effort and opened schools and hospitals instead which they threw open impartially to all the races of the Empire. These schools were instituted solely for educational purposes and the largest of them offered as good a schooling as most American colleges in the United States offered. Their effort was to offer the best that Americans at home had and even in such incidentals as the architecture of their buildings, they made themselves as completely American as possible. Two of the largest of them were built high on the wooded shores of the Bosphorus and nobody can glance at them today without knowing at once that they are American. High above the suburbs of the old capital, they look as if they had been transported bodily from Chicago.

One can share our pride in our own devices and our own customs, one can sympathize in our desire to see other countries adapt themselves to American methods, but it was not the effort of these schools to strike a balance between American and Ottoman cultures. What these schools offered was out-and-out Americanism and their attitude toward the Ottoman Government was the sharply aloof attitude of the Capitulations. This was obviously a quite unusual proceeding in any supposedly independent foreign country and the only defense of it which can be made is that it was the customary thing among all Westerners in the Ottoman Empire. Behind the Capitulations, Western schools, Western missionaries, Western traders and a number of less creditable Westerners, alike found freedom to carry on their own affairs in their own way. The Capitulations provided Western imperialists with an opportunity which they were not likely to overlook and as long as imperialism flourished at Constantinople, American schools and American missionaries enjoyed a security which was well-nigh complete, however humiliating this state of things might have been to the Ottoman Government. Even today there are American educators and American missionaries in Constantinople to whom the word “imperialism” means nothing, who say in the dazed manner of men who have suddenly seen the very ground drop out from under their feet, “Imperialism has never bothered us….”

While Christendom stood thus gazing into the Ottoman cockpit, the Old Turks were not idle. Abdul Hamid had lifted up the imperilled Caliphate in Constantinople so that all of Islam could see it. As far back as 1889, Pan-Islamism had sought to bring the Shiah Moslems of Persia under the suzerainty of the Sunni Caliph and this scheme involved considerations so far-reaching in their scope that it finally brought about a project for a conference of all Islam at Mecca in 1902. But Abdul Hamid had his own imperialism to consider, made necessary though it was by the Eastern institution of the Caliphate, and his fear that his Arab populations would use the conference to air their secessionist program led him to quash the project. Pan-Islamism gave way to the new Pan-Turanian program under which Turkish and Tartar Moslems were to shelve the Arabs who had given Islam to the world, the Turkish tongue was to supplant Arabic as the sacred tongue of Islam, and all Arabic words were to be rooted out of the Turkish language. This proved too large a morsel for conservative Islam to swallow, and Pan-Turanianism prospered no more than Pan-Islamism. It did live, however, as a political project for welding the Tartar peoples against Orthodox Russia, for the Turkish ancestry runs deeply into Central Asia.

Much of this Islamic maneuvring was the work of sophisticated Islamic capitals. Old Turkish opinion itself continued to place its simple reliance in the institution of the Caliphate which had now become the repository of the most venerable of Moslem usages. To the more thoughtful of the Old Turks, it was a matter of profound re-assurance that the British Empire contained 100,000,000 Moslems to 80,000,000 Christians, and that the Emperor of India in London was in friendly contact with the Caliph. Those were the days when the Sheikh-ul-Islam in Constantinople was one of the last independent interpreters of Moslem law, and when the British Empire proudly called itself the greatest Moslem Power in the world.

But King Edward’s first visit to Austria in 1903 disquieted Moslem opinion both in the Ottoman Empire and in India. The Emperor of India was growing impatient. His further visits in 1905 and 1907 resulted in a program of reforms in gendarmerie, finances, judiciary, public works and the Army, which were to be imposed from without upon the rigidly conservative Empire. To the Young Turks who had been working feverishly ever since the first visit to Austria in 1903, preparing to attempt the imposition of their really fundamental reforms from within, his program was only a step toward the final break-up of the Empire. Already, instead of securely bridging the gap between East and West the Empire creaked and cracked as though presently it would tumble into the widening chasm.

Late in 1907, the Emperor of India’s patience ran out. In the spring of 1908, Edward VII touched a match to the carefully laid gun-powder of Young Turkish revolution which lit the Empire with the flare-up of 1908. Ten years later, the blackened ruin of a once noble structure disappeared from history and the gap between East and West yawned wide and empty.

[1] My authority for this statement is “Reconstruction in Turkey,” a book published for private distribution in 1918 by the American Committee of Armenian and Syrian Relief, the predecessor of the Near East Relief. “The estimate of their (the Armenians’) number in the empire before the war,” says Dr. Harvey Porter of Beirut College on page 15, “ranges from 1,500,000 to 2,000,000, but they were not in a majority in any vilayet.”

HOW RUSSIA AND GREAT BRITAIN FOUGHT ACROSS THE OLD OTTOMAN EMPIRE—HOW RUSSIA ENTERED TRANS-CAUCASIA AND CAME INTO CONTACT WITH THE ARMENIANS—HOW IT APPROACHED THE BACK OF BRITISH INDIA THROUGH CENTRAL ASIA—HOW GREAT BRITAIN FINALLY SURRENDERED IN THE ANGLO-RUSSIAN TREATY OF 1907.

Old Russia was a great Eastern absolutism which had looked upon the modern West and faithfully copied the methods of its imperialism. These it utilized in its search for a secure outlet to the sea. It had reached the sea at Archangel on the Arctic, but Archangel is blocked by ice for nine months of the year. It had reached the sea along the Baltic shores, but its Baltic ports were as landlocked as the Lake ports in the United States. The Baltic was commanded by Germany and Germany in turn was commanded by Great Britain. It had touched salt water along the Black Sea, but its Black Sea ports were commanded by the Ottoman Empire astride the Bosphorus and Dardanelles.

It was unable to rectify its position in the Baltic without precipitating a European war and European wars are not only expensive but to Eastern Powers like Russia are sometimes disastrous. It spent the better part of a century in trying to solve its Black Sea problem by hewing back the Ottoman Empire and attempting to fasten its control over the Ottoman Sultan at Constantinople. But the Straits had already become the most vulnerable spot in the armor of the British Indian sea lines and the Ottoman Sultan was accordingly backed by all the influence which the great British Embassy in Constantinople could exert.

Thus when Russia compelled the Sultan to pay its price for stopping Mohammed Ali’s drive up the Syrian corridor from Egypt in 1832, Great Britain did not hesitate to quash Russia’s treaty with the Sultan. And when the issues which the quashing of that treaty had left unsettled, were revived twenty years later, Great Britain did not hesitate to enter the Crimean War to hold Russia back from any further approach to the Straits. And when twenty years still later, the Mother Slav State, following the lead of the South Slavs of Serbia, declared war on the Sultan and smashed its way into San Stefano in the very suburbs of Constantinople, the British Navy did not hesitate to steam boldly up the Straits and anchor off the Ottoman capital. For if the Russian Army had been permitted to occupy it, the British sea lines from India might easily have been thrown back to the long Cape route and another Trafalgar necessitated in order to settle again the question of the command of the Mediterranean, a question which the British Navy did not propose to re-open.

So we reach that titanic struggle between two outside imperialisms which kept the Ottoman Empire tied hand and foot but still alive. Against Russia, Great Britain made common cause with the Ottoman Empire. The Emperor of India and the Caliph of Islam stood together. It is our misfortune that the Church of England was not able to avail itself of the position which its Defender then occupied, to discover what common ground existed on which the two great monotheistic faiths of Christianity and Islam might co-operate. Success in such a task would have placed all of us, Christians and Moslems alike, heavily in its debt. But Englishmen to this day have never discovered the full breadth and depth of the meaning of British India.

Despite the Russian naval base of Sebastopol, Great Britain not only kept the Sultan in command of the Straits but even kept the Black Sea neutral. East of the Black Sea, however, the British writ did not run. Here between the Black Sea and the Caspian is the ancient barrier of the Caucasus Range, below which the Trans-Caucasian plateau forms a bridge both to the back of the Ottoman Empire and to Persia. Below the blue peaks of the Caucasus Range lay Tiflis, the capital of the Georgian Kingdom midway between the Black Sea and the Caspian, with the Turkish village of Batum on the Black Sea shores and the Tartar village of Baku on the Caspian. Turks and Tartars were both Moslem, but the old Georgian Kingdom was Orthodox and, extending in a broad belt down through the Ottoman provinces in eastern Asia Minor were most of the Armenians.

Expanding Russia was not long in bursting the barrier of the Caucasus Range. More than a century ago, it swallowed the Georgian Kingdom, snuffed out the eight little Tartar chieftains around Baku and found itself in contact with the Armenian Catholicos and the eastern fringes of the Ermeni community in the Ottoman Empire. In further accord with its policy of undermining that Empire, it availed itself of the presence of the Armenians in the usual imperialist manner and, in its war of 1876 against the Sultan, it drove its way deeply into his eastern provinces, transferring the Armenians from Ottoman to Russian sovereignty as it went. Its objective was the great bay of Alexandretta on the Mediterranean which was to free it of its Black Sea jail, a scheme which Great Britain recognized by secretly taking over the “administration” of Cyprus from the Sultan. The treaty of San Stefano stopped the Russian advance hundreds of miles short of Alexandretta and in front of the new Ottoman frontier, Russia developed Kars into a great fortress as a base for its further advance toward Alexandretta when opportunity offered.

Having seized Batum from the Sultan, Russia continued the consolidation of Trans-Caucasia under its own provincial governors and stamped the entire region with the unmistakable imprint of a Russian economic regime. It pierced the barrier of the Caucasus Range with a military highroad to Tiflis, which it prolonged as a railroad to Kars and the Armenian center of Erivan. It drove its railways past the east end of the Caucasus Range to make a Russian railhead and a Russian Caspian port of Baku, around which lay one of the greatest oil-fields in the world. It developed the village of Batum into a fortified Russian port on the Black Sea and with its Trans-Caucasian railroads from Batum via Tiflis to Baku, it made Batum the gate to the Caspian for all the Western world. Long before, it had driven the Persians from the Caspian, making a Russian lake of that inland sea, and Russian steamship lines from Baku to Enzeli, the port of Teheran, now made Batum the world’s gate to the Persian capital.

From the Trans-Caucasian bridge, the Russian march toward the sea forked into two directions. The direction in which the Russian Armies of 1876 turned, was toward Alexandretta on the Mediterranean. The other direction was indicated later when a railroad was carried from Kars to the Persian frontier, whence it was to be continued when requisite to Tabriz and Teheran. This might have exposed the Persian Gulf to Russia, but the Government of India had already made the Gulf more British than the Mediterranean. The Gulf had become a land-locked British lake whose narrow door-way into the Indian Ocean was dominated by the potential British naval base of Bunder Abbas. If Russia had succeeded in reaching the Gulf through Persia, a Russian port on its shores would have been imprisoned by Bunder Abbas, as the Russian Black Sea ports were already imprisoned by Constantinople and the Russian Baltic ports by the Sound. For the time being, the Russian Trans-Caucasian railhead on the north-west frontier of Persia awaited events.

East of the Caspian, however, a century of Russian advances down across the Moslem populations of Central Asia had brought the Russian frontiers all the way down to Persia and Afghanistan. Russian rule throughout this vast area had been as thoroughly consolidated under Russian provincial governments as had the Trans-Caucasian bridge. In time, a line of railway was driven from St. Petersburg via Moscow and Orenburg to Tashkent at the back of Afghanistan, whence it linked with the Trans-Caspian Railway from Krasnovodsk, opposite Baku on the Caspian. Direct communication was thus afforded from St. Petersburg and from the Trans-Caucasian country to Persia and Afghanistan. With a Russian resident ruling in the ancient Moslem capital of Bokhara, a spur had been dropped from the Trans-Caspian line at Bokhara City to Termez on the northern frontier of Afghanistan whence a caravan road threads its way up into the passes of the Hindu Kush and down again to Kabul and the Khyber Pass. From the Merv oasis, also on the Trans-Caspian line, another spur had been dropped to Kushklinsky Post on the Afghan frontier whence the traditional Herat-Kandahar-Kabul road leads to the Khyber Pass and the fat plains of India.

This long loop of line from St. Petersburg and the Caspian to the back of Afghanistan traversed territory securely held by Russian arms and the British had no contact with it, except the frontal contact of their railheads on the southern frontier of Afghanistan, i. e., within India itself. Except for diplomatic exchanges between London and St. Petersburg, the Government of India had no means of making itself felt at Bokhara City and the Merv oasis. Indeed, Russia had made even the Afghan capital of Kabul an intermittent nightmare in India. Long ago, Russian intrigue in the Afghan capital had compelled the East India Company in 1839 to dispatch an expeditionary force to occupy Kabul and unseat its Amir, an expeditionary force which found Afghanistan so hostile that it was wiped out of existence in such a disaster as British India has never known before or since. Again in 1879, Russian resentment over the Congress of Berlin led to the dispatch of a Russian mission to Kabul and when a British mission was turned back at the frontier, the Government of India sent a second expeditionary force to set up a new Amir at Kabul. Intrigue at Kabul became Russia’s favorite reply to any strain in Anglo-Russian relations, but it was not in Afghanistan that the real weight of Russian expansion finally made itself felt. Its construction of the Trans-Caspian railway had given it a base at Askabad on Persia’s north-east frontier, for an advance down across Persia to the Indian Ocean outside Bunder Abbas. Here was a project which at one stroke would not only free Russia of its inner Black Sea jail and its outer Mediterranean jail, but would enable it to create a second Vladivostok on the Indian Ocean which would take the British Indian sea lines in the flank and cut the Indian peninsula bodily out of the British Empire.

Russia now projected a railway from Askabad to the Persian provincial capital of Meshed and thence south past the Seistan, reaching the Indian Ocean presumably at Chahbar or Gwatter Bay. Having filled the Persian capital of Teheran with Russian intrigue and having thoroughly Russianized Meshed, Russia now began to close the Seistan gateway through which the great British Indian fortress of Quetta flanked the route of its projected railway. Belgian customs officials in the employ of the Russianized Persian Government, Russian “scientific” missions and a strange “plague cordon” began mysteriously to break up the caravans which were moving into and out of the Seistan.

In the meantime, the Government of India had drawn the western frontier of its Baluchistan province to include Gwatter Bay and had made a British railhead of Chahbar. Further than this, it was difficult to go effectively. There was no subject population in the south of Persia to subvert from its rulers in the north, as was the case with the Arabs in the adjacent Ottoman Empire. Nor could the great British Legation at Teheran bolster up the weak Persian Government as a buffer against Russia, for the Persian capital lay far away to the north in the very shadow of Russia. Ever since that day a century ago when Russia burst the barrier of the Caucasus Range, a day whose dire meaning for India was only beginning to be realized, Teheran had been exposed to Russia. It lay now only 200 miles from Enzeli on the Russianized Caspian and some 1,600 miles from Quetta inside the Seistan, a caravan route so arduous as to be out of the question. The Government of India’s only road to Teheran was the 800-mile highroad via Bagdad from Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf.