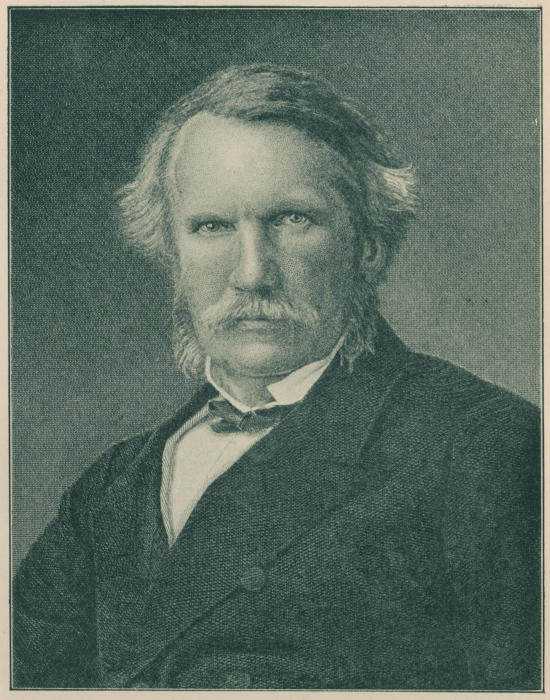

FIELD-MARSHAL EARL ROBERTS, V.C., G.C.B.

From an engraving of the portrait by W. W. Ouless, R.A., by permission of Henry Graves & Co., Ltd.

THE TALE OF

THE GREAT MUTINY

FIELD-MARSHAL EARL ROBERTS, V.C., G.C.B.

From an engraving of the portrait by W. W. Ouless, R.A., by permission of Henry Graves & Co., Ltd.

THE TALE OF

THE GREAT MUTINY

BY

W. H. FITCHETT, B.A., LL.D.

AUTHOR OF “DEEDS THAT WON THE EMPIRE,” “FIGHTS FOR

THE FLAG,” “HOW ENGLAND SAVED EUROPE,”

“WELLINGTON’S MEN,” ETC.

WITH PORTRAITS AND MAPS

THIRD IMPRESSION

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1903

[All rights reserved]

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | MUNGUL PANDY | 1 |

| II. | DELHI | 34 |

| III. | STAMPING OUT MUTINY | 65 |

| IV. | CAWNPORE: THE SIEGE | 84 |

| V. | CAWNPORE: THE MURDER GHAUT | 111 |

| VI. | LUCKNOW AND SIR HENRY LAWRENCE | 148 |

| VII. | LUCKNOW AND HAVELOCK | 185 |

| VIII. | LUCKNOW AND SIR COLIN CAMPBELL | 209 |

| IX. | THE SEPOY IN THE OPEN | 237 |

| X. | DELHI: HOW THE RIDGE WAS HELD | 263 |

| XI. | DELHI: THE LEAP ON THE CITY | 305 |

| XII. | DELHI: RETRIBUTION | 331 |

| XIII. | THE STORMING OF LUCKNOW | 345 |

| INDEX | 373 |

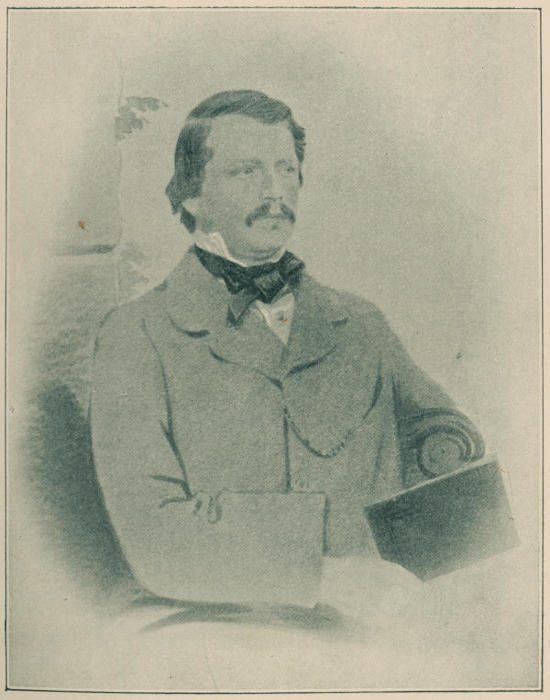

| FIELD-MARSHAL EARL ROBERTS, V.C., G.C.B. | Frontispiece | |

| LIEUTENANT GEORGE WILLOUGHBY | To face page | 40 |

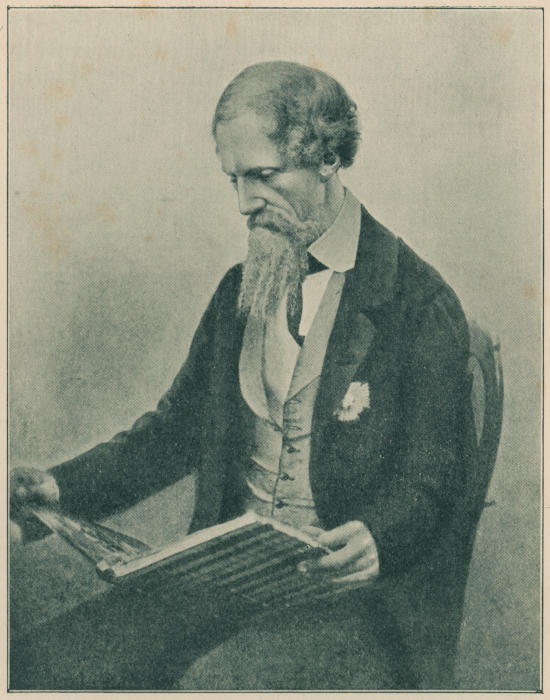

| SIR HENRY LAWRENCE | ” | 148 |

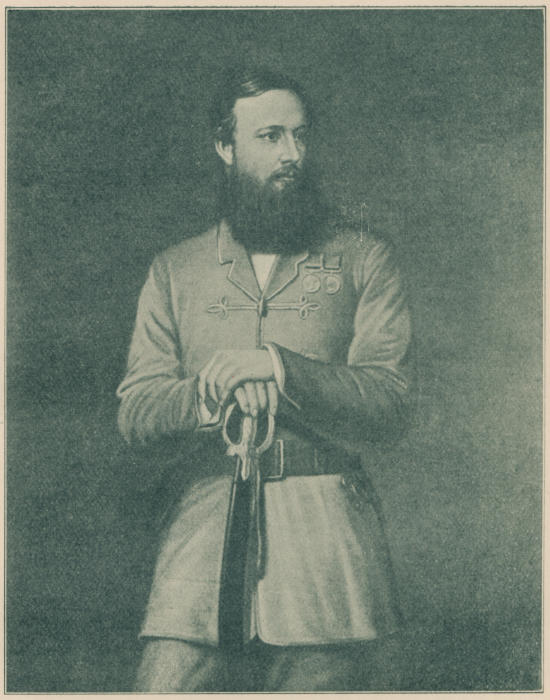

| MAJOR-GENERAL SIR HENRY HAVELOCK, K.C.B. | ” | 184 |

| LORD LAWRENCE | ” | 264 |

| MAJOR-GENERAL SIR HERBERT EDWARDES, K.C.B. | ” | 270 |

| BRIGADIER-GENERAL JOHN NICHOLSON | ” | 298 |

| LIEUTENANT-GENERAL SIR JAMES OUTRAM, BART. | ” | 350 |

| PAGE | ||

| CAWNPORE, JUNE 1857 | 87 | |

| CAWNPORE, GENERAL WHEELER’S ENTRENCHMENTS | 87 | |

| LUCKNOW, 1857 | 186 | |

| DELHI, 1857 | 275 | |

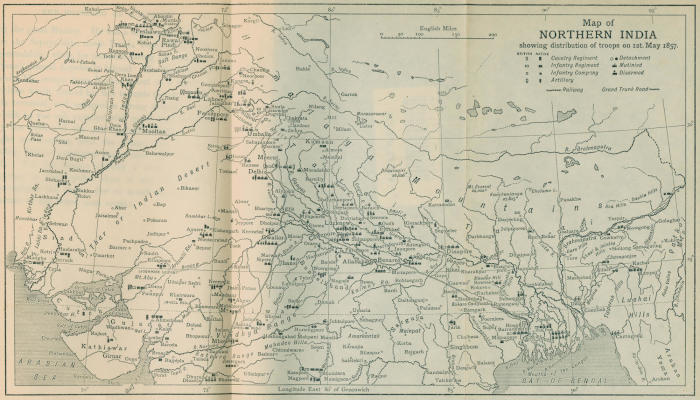

| MAP SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF TROOPS, MAY 1, 1857 | To face page | 370 |

The scene is Barrackpore, the date March 29, 1857. It is Sunday afternoon; but on the dusty floor of the parade-ground a drama is being enacted which is suggestive of anything but Sabbath peace. The quarter-guard of the 34th Native Infantry—tall men, erect and soldierly, and nearly all high-caste Brahmins—is drawn up in regular order. Behind it chatters and sways and eddies a confused mass of Sepoys, in all stages of dress and undress; some armed, some unarmed; but all fermenting with excitement. Some thirty yards in front of the line of the 34th swaggers to and fro a Sepoy named Mungul Pandy. He is half-drunk with bhang, and wholly drunk with religious fanaticism. Chin in air, loaded musket in hand, he struts backwards and forwards, at a sort of half-dance, shouting in shrill and nasal monotone, “Come[2] out, you blackguards! Turn out, all of you! The English are upon us. Through biting these cartridges we shall all be made infidels!”

The man, in fact, is in that condition of mingled bhang and “nerves” which makes a Malay run amok; and every shout from his lips runs like a wave of sudden flame through the brains and along the nerves of the listening crowd of fellow-Sepoys. And as the Sepoys off duty come running up from every side, the crowd grows ever bigger, the excitement more intense, the tumult of chattering voices more passionate. A human powder magazine, in a word, is about to explode.

Suddenly there appears upon the scene the English adjutant, Lieutenant Baugh. A runner has brought the news to him as he lies in the sultry quiet of the Sunday afternoon in his quarters. The English officer is a man of decision. A saddled horse stands ready in the stable; he thrusts loaded pistols into the holsters, buckles on his sword, and gallops to the scene of trouble. The sound of galloping hoofs turns all Sepoy eyes up the road; and as that red-coated figure, the symbol of military authority, draws near, excitement through the Sepoy crowd goes up uncounted degrees. They are about to witness a duel between revolt and discipline, between a mutineer and an adjutant!

Mungul Pandy has at least one quality of a good soldier. He can face peril coolly. He steadies himself,[3] and grows suddenly silent. He stands in the track of the galloping horse, musket at shoulder, the man himself moveless as a bronze image. And steadily the Englishman rides down upon him! The Sepoy’s musket suddenly flashes; the galloping horse swerves and stumbles; horse and man roll in the white dust of the road. But the horse only has been hit, and the adjutant struggles, dusty and bruised, from under the fallen beast, plucks a loaded pistol from the holster, and runs straight at the mutineer. Within ten paces of him he lifts his pistol and fires. There is a flash of red pistol-flame, a puff of white smoke, a gleam of whirling sword-blade. But a man who has just scrambled up, half-stunned, from a fallen horse, can scarcely be expected to shine as a marksman. Baugh has missed his man, and in another moment is himself cut down by Mungul Pandy’s tulwar. At this sight a Mohammedan Sepoy—Mungul Pandy was a Brahmin—runs out and catches the uplifted wrist of the victorious Mungul. Here is one Sepoy, at least, who cannot look on and see his English officer slain—least of all by a cow-worshipping Hindu!

Again the sound of running feet is heard on the road. It is the English sergeant-major, who has followed his officer, and he, too—red of face, scant of breath, but plucky of spirit—charges straight at the mutinous Pandy. But a sergeant-major, stout and middle-aged, who has run in uniform three-quarters[4] of a mile on an Indian road and under an Indian sun, is scarcely in good condition for engaging in a single combat with a bhang-maddened Sepoy, and he, in turn, goes down under the mutineer’s tulwar.

How the white teeth gleam, and the black eyes flash, through the crowd of excited Sepoys! The clamour of voices takes a new shrillness. Two sahibs are down before their eyes, under the victorious arm of one of their comrades! The men who form the quarter-guard of the 34th, at the orders of their native officer, run forward a few paces at the double, but they do not attempt to seize the mutineer. Their sympathies are with him. They halt; they sway to and fro. The nearest smite with the butt-end of their muskets at the two wounded Englishmen.

A cluster of British officers by this time is on the scene; the colonel of the 34th himself has come up, and naturally takes command. He orders the men of the quarter-guard to seize the mutineers, and is told by the native officer in charge that the men “will not go on.” The colonel is, unhappily, not of the stuff of which heroes are made. He looks through his spectacles at Mungul Pandy. A six-foot Sepoy in open revolt, loaded musket in hand—himself loaded more dangerously by fanaticism strongly flavoured with bhang—while a thousand excited Sepoys look on trembling with angry sympathy,[5] does not make a cheerful spectacle. “I felt it useless,” says the bewildered colonel, in his official report after the incident, “going on any further in the matter.... It would have been a useless sacrifice of life to order a European officer of the guard to seize him.... I left the guard and reported the matter to the brigadier.” Unhappy colonel! He may have had his red-tape virtues, but he was clearly not the man to suppress a mutiny. The mutiny, in a word, suppressed him! And let it be imagined how the spectacle of that hesitating colonel added a new element of wondering delight to the huge crowd of swaying Sepoys.

At this moment General Hearsey, the brigadier in charge, rides on to the parade-ground: a red-faced, wrathful, hard-fighting, iron-nerved veteran, with two sons, of blood as warlike as their father’s, riding behind him as aides. Hearsey, with quick military glance, takes in the whole scene—the mob of excited Sepoys, the sullen quarter-guard, the two red-coats lying in the road, and the victorious Mungul Pandy, musket in hand. As he rode up somebody called out, “Have a care; his musket is loaded.” To which the General replied, with military brevity, “Damn his musket!” “An oath,” says Trevelyan, “concerning which every true Englishman will make the customary invocation to the recording angel.”

Mungul Pandy covered the General with his musket. Hearsey found time to say to his son, “If[6] I fall, John, rush in and put him to death somehow.” Then, pulling up his horse on the flank of the quarter-guard, he plucked a pistol from his holster, levelled it straight at the head of the native officer, and curtly ordered the men to advance and seize the mutineer. The level pistol, no doubt, had its own logic; but more effective than even the steady and tiny tube was the face that looked from behind it, with command and iron courage in every line. That masterful British will instantly asserted itself. The loose line of the quarter-guard stiffened with instinctive obedience; the men stepped forward; and Mungul Pandy, with one unsteady glance at Hearsey’s stern visage, turned with a quick movement the muzzle of his gun to his own breast, thrust his naked toe into the trigger, and fell, self-shot. He survived to be hanged, with due official ceremonies, seven days afterwards.

It was a true instinct which, after this, taught the British soldier to call every mutinous Sepoy a “Pandy.” That incident at Barrackpore is really the history of the Indian Mutiny in little. All its elements are there: the bhang-stimulated fanaticism of the Sepoy, with its quick contagion, running through all Sepoy ranks; the hasty rush of the solitary officer, gallant, but ill-fated, a single man trying to suppress a regiment. Here, too, is the colonel of the 34th, who, with a cluster of regiments on the point of mutiny, decides that it is “useless”[7] to face a dangerously excited Sepoy armed with a musket, and retires to “report” the business to his brigadier. He is the type of that failure of official nerve—fortunately very rare—which gave the Mutiny its early successes. General Hearsey, again, with his grim “D⸺ his musket!” supplies the example of that courage, swift, fierce, and iron-nerved, that in the end crushed the Mutiny and restored the British Empire in India.

The Great Mutiny, as yet, has found neither its final historian, nor its sufficient poet. What other nation can show in its record such a cycle of heroism as that which lies in the history of the British in India between May 10, 1857—the date of the Meerut outbreak, and the true beginning of the Mutiny—and November 1, 1858, when the Queen’s proclamation officially marked its close? But the heroes in that great episode—the men of Lucknow, and Delhi, and Arrah, the men who marched and fought under Havelock, who held the Ridge at Delhi under Wilson, who stormed the Alumbagh under Clyde—though they could make history, could not write it. There are a hundred “Memoirs,” and “Journals,” and “Histories” of the great revolt, but the Mutiny still waits for its Thucydides and its Napier. Trevelyan’s “Cawnpore,” it is true, will hold its readers breathless with its fire, and movement, and graphic force; but it deals with only one picturesque and dreadful episode of the Great Mutiny. The “History of the Mutiny,” by[8] Kaye and Malleson, is laborious, honest, accurate; but no one can pretend that it is very readable. It has Kinglake’s diffuseness without Kinglake’s literary charm. The work, too, is a sort of literary duet of a very controversial sort. Colonel Malleson, from the notes, continually contradicts Sir John Kaye in the text, and he does it with a bluntness, and a diligence, which have quite a humorous effect.

Not only is the Mutiny without an historian, but it remains without any finally convincing analysis of its causes. Justin McCarthy’s summary of the causes of the Mutiny, as given in his “History of Our Own Times,” is a typical example of wrong-headed judgment. Mr. McCarthy contemplates the Mutiny through the lens of his own politics, and almost regards it with complacency as a mere struggle for Home Rule! It was not a Mutiny, he says, like that at the Nore; it was a revolution, like that in France at the end of the eighteenth century. It was “a national and religious war,” a rising of the many races of India against the too oppressive Saxon. The native princes were in it as well as the native soldiers.

The plain facts of the case are fatal to that theory. The struggle was confined to one Presidency out of three. Only two dynastic princes—Nana Sahib and the Ranee of Jhansi—joined in the outbreak. The people in the country districts were passive; the British revenue, except over the actual field of strife, was regularly paid. If their own trained native[9] soldiery turned against the British, other natives thronged in thousands to their flag. A hundred examples might be given where native loyalty and valour saved the situation for the English.

There were Sepoys on both sides of the entrenchment at Lucknow. Counting camp followers, native servants, &c., there were two black faces to every white face under the British flag which fluttered so proudly over the historic Ridge at Delhi. The “protected” Sikh chiefs, by their fidelity, kept British authority from temporary collapse betwixt the Jumna and the Sutlej. They formed what Sir Richard Temple calls “a political breakwater,” on which the fury of rebellious Hindustan broke in vain. The Chief of Pattalia employed 5000 troops in guarding the trunk road betwixt the Punjaub and Delhi, along which reinforcements and warlike supplies were flowing to the British force on the Ridge. This enabled the whole strength of the British to be concentrated on the siege. The Chief of Jhind was the first native ruler who appeared in the field with an armed force on the British side, and his troops took part in the final assault on Delhi. Golab Singh sent from his principality, stretching along the foot of the Himalayas, strong reinforcements to the British troops besieging Delhi. “The sight of these troops moving against the mutineers in the darkest hour of British fortunes produced,” says Sir Richard Temple, “a profound moral effect on the Punjaub.”

If John Lawrence had to disband or suppress 36,000 mutinous Sepoys in the Punjaub, he was able to enlist from Ghoorkas and Sikhs and the wild tribes on the Afghan borders more than another 36,000 to take their places. He fed the scanty and gallant force which kept the British flag flying before Delhi with an ever-flowing stream of native soldiers of sufficient fidelity. At the time of the Mutiny there were 38,000 British soldiers in a population of 180,000,000. If the Mutiny had been indeed a “national” uprising, what chances of survival would the handful of British have had?

It is quite true that the Mutiny, in its later stages, drew to itself political forces, and took a political aspect. The Hindu Sepoy, says Herbert Edwardes, “having mutinied about a cartridge, had nothing to propose for an Empire, and fell in, of necessity, with the only policy which was feasible at the moment, a Mohammedan king of Delhi. And so, with a revived Mogul dynasty at its head, the Mutiny took the form of a struggle between the Moslem and the Christian for empire, and this agitated every village in which there was a mosque or a mollah.” But the emergence of the Mogul dynasty in the struggle was an afterthought, not to say, an accident. The old king at Delhi, discrowned and almost forgotten, was caught up by the mutineers as a weapon or a flag.

The outbreak was thus, at the beginning, a purely military mutiny; but its complexion and character[11] later on were affected by local circumstances. In Oude, for example, the Mutiny was welcomed, as it seemed to offer those dispossessed by the recent annexation, a chance of revenge. At Delhi it found a centre in the old king’s palace, an inspiration in Mohammedan fanaticism, and a nominal leader in the representative of the old Mogul dynasty. So the Mutiny grew into a new struggle for empire on the part of some of the Mohammedan princes.

Many of the contributing causes of the Mutiny are clear enough. Discipline had grown perilously lax throughout Bengal; and the Bengal troops were, of all who marched under the Company’s flag, the most dangerous when once they got out of hand. They consisted mainly of high-caste Brahmins and Rajpoots. They burned with caste pride. They were of incredible arrogance. The regiments, too, were made up largely of members of the same clan, and each regiment had its own complete staff of native officers. Conspiracy was easy in such a body. Secrets were safe. Interests and passions were common. When the British officers had all been slaughtered out, the regiment, as a fighting machine, was yet perfect. Each regiment was practically a unit, knit together by ties of common blood, and speech, and faith, ruled by common superstitions, and swayed by common passions.

The men had the petulance and the ignorance of children. They believed that the entire population of England consisted of 100,000 souls. When the[12] first regiment of Highlanders landed, the whisper ran across the whole Presidency, that there were no more men in England, and that, in default of men, the women had been sent out! Later on, says Trevelyan, the native mind evolved another theory to explain the Highlanders’ kilts. They wore petticoats, it was whispered, as a public and visible symbol that their mission was to take vengeance for the murder of English ladies.

Many causes combined to enervate military discipline. There had been petty mutinies again and again, unavenged, or only half avenged. Mutineers had been petted, instead of being shot or hanged. Lord Dalhousie had weakened the despotic authority of the commanding officers, and had taught the Sepoy to appeal to the Government against his officers.

Now the Sepoy has one Celtic quality: his loyalty must have a personal object. He will endure, or even love, a despot, but it must be a despot he can see and hear. He can be ruled; but it must be by a person, not by a “system.” When the commander of a regiment of Sepoys ceased to be a despot, the symbol and centre of all authority, and became only a knot in a line of official red tape, he lost the respect of his Sepoys, and the power to control them. Said Rajah Maun Singh, in a remarkable letter to the Talookdars of his province: “There used to be twenty to twenty-five British officers to every 1000 men, and these[13] officers were subordinate to one single man. But nowadays there are 1000 officers and 1000 kings among 1000 men: the men are officers and kings themselves, and when such is the case there are no soldiers to fight.”

Upon this mass of armed men, who had lost the first of soldierly habits, obedience, and who were fermenting with pride, fanaticism, and ignorance, there blew what the Hindus themselves called a “Devil’s wind,” charged with a thousand deadly influences. The wildest rumours ran from barracks to barracks. One of those mysterious and authorless predictions which run before, and sometimes cause, great events was current. Plassey was fought in 1757; the English raj, the prediction ran, would last exactly a century; so 1857 must see its fall. Whether the prophecy was Hindu or Mohammedan cannot be decided; but it had been current for a quarter of a century, and both Hindu and Mohammedan quoted it and believed it. As a matter of fact, the great Company did actually expire in 1857!

Good authorities hold that the greased cartridges were something more than the occasion of the Mutiny; they were its supreme producing cause. The history of the greased cartridges may be told almost in a sentence. “Brown Bess” had grown obsolete; the new rifle, with its grooved barrel, needed a lubricated cartridge, and it was whispered that the cartridge was greased with a compound of cow’s fat[14] and swine’s fat, charged with villainous theological properties. It would destroy at once the caste of the Hindu, and the ceremonial purity of the Mohammedan! Sir John Lawrence declares that “the proximate cause of the Mutiny was the cartridge affair, and nothing else.” Mr. Lecky says that “recent researches have fully proved that the real, as well as the ostensible, cause of the Mutiny was the greased cartridges.” He adds, this is “a shameful and terrible fact.” The Sepoys, he apparently holds, were right in their belief that in the grease that smeared the cartridges was hidden a conspiracy against their religion! “If mutiny,” Mr. Lecky adds, “was ever justifiable, no stronger justification could be given than that of the Sepoy troops.”

But is this accusation valid? That the military authorities really designed to inflict a religious wrong on the Sepoys in the matter of the cartridges no one, of course, believes. But there was, undoubtedly, much of heavy-handed clumsiness in the official management of the business. As a matter of fact, however, no greased cartridges were actually issued to any Sepoys. Some had been sent out from England, for the purpose of testing them under the Indian climate; large numbers had been actually manufactured in India; but the Sepoys took the alarm early, and none of the guilty cartridges were actually issued to the men. “From first to last,” says Kaye, “no such cartridges were ever issued to[15] the Sepoys, save, perhaps, to a Ghoorka regiment, at their own request.”

When once, however, the suspicions of the Sepoys were, rightly or wrongly, aroused, it was impossible to soothe them. The men were told that they might grease the cartridges themselves; but the paper in which the new cartridges were wrapped had now, to alarmed Sepoy eyes, a suspiciously greasy look, and the men refused to handle it.

The Sepoy conscience was, in truth, of very eccentric sensitiveness. Native hands made up the accused cartridges without concern; the Sepoys themselves used them freely—when they could get them—against the British after the Mutiny broke out. But a fanatical belief on the part of the Sepoys, that these particular cartridges concealed in their greasy folds a dark design against their religion, was undoubtedly the immediate occasion of the Great Mutiny. Yet it would be absurd to regard this as its single producing cause. In order to assert this, we must forget all the other evil forces at work to produce the cataclysm: the annexation of Oude; the denial of the sacred right of “adoption” to the native princes; the decay of discipline in the Sepoy ranks; the loss of reverence for their officers by the men, &c.

The Sepoys, it is clear, were, on many grounds, discontented with the conditions of their service. The keen, brooding, and somewhat melancholy[16] genius of Henry Lawrence foresaw the coming trouble, and fastened on this as one of its causes. In an article written in March 1856, he says that the conditions of the Indian Army denied a career to any native soldier of genius, and this must put the best brains of the Sepoys in quarrel with the British rule. Ninety out of every hundred Sepoys, he said in substance, are satisfied; but the remaining ten are discontented, some of them to a dangerous degree; and the discontented ten were the best soldiers of the hundred! But, as it happened, the Mutiny threw up no native soldier of genius, except, perhaps, Tantia Topee, who was not a Sepoy!

“The salt water” was undoubtedly amongst the minor causes which provoked the Mutiny. The Sepoys dreaded the sea; they believed they could not cross it without a fatal loss of caste, and the new form of military oath, which made the Sepoy liable for over-sea service, was believed, by the veterans, to extend to them, even though they had not taken it: and so the Sepoy imagination was disquieted.

Lord Dalhousie’s over-Anglicised policy, it may be added, was at once too liberal, and too impatient, for the Eastern mind, with its obstinacy of habit, its hatred of change, its easily-roused suspiciousness. As Kaye puts it, Lord Dalhousie poured his new wine into old bottles, with too rash a hand. “The wine was good wine, strong wine, wine to gladden the[17] heart of man;” but poured into such ancient and shrunken bottles too rashly, it was fatal. It was because we were “too English,” adds Kaye, that the great crisis arose; and “it was only because we were English that, when it arose, it did not overwhelm us.” We trod, in a word, with heavy-footed British clumsiness on the historic superstitions, the ancient habitudes of the Sepoys, and so provoked them to revolt. But the dour British character, which is at the root of British clumsiness, in the end, overbore the revolt.

The very virtues of the British rule, thus proved its peril. Its cool justice, its steadfast enforcement of order, its tireless warfare against crime, made it hated of all the lawless and predatory classes. Every native who lived by vice, chafed under a justice which might be slow and passionless, but which could not be bribed, and in the long-run could not be escaped.

Some, at least, of the dispossessed princes, diligently fanned these wild dreams and wilder suspicions which haunted the Sepoy mind, till it kindled into a flame. The Sepoys were told they had conquered India for the English; why should they not now conquer it for themselves? The chupatties—mysterious signals, coming whence no man knew, and meaning, no man could tell exactly what—passed from village to village. Usually with the chupatti ran a message—“Sub lal hojaega” (“everything will become red”)—a Sibylline announcement, which might be accepted as a warning against the too[18] rapid spread of the English raj, or a grim prediction of universal bloodshed. Whence the chupatties came, or what they exactly meant, is even yet a matter of speculation. The one thing certain is, they were a storm signal, not very intelligible, perhaps, but highly effective.

That there was a conspiracy throughout Bengal for the simultaneous revolt of all Sepoys on May 31, cannot be doubted, and, on the whole, it was well for the English raj that the impatient troopers broke out at Meerut before the date agreed upon.

Sir Richard Temple, whose task it was to examine the ex-king of Delhi’s papers after the capture of the city, found amongst them an immense number of letters and reports from leading Mohammedans—priests and others. These letters glowed with fanatical fire. Temple declared they convinced him that “Mohammedan fanaticism is a volcanic agency, which will probably burst forth in eruptions from time to time.” But were Christian missions any source of political peril to British rule in India? On this point John Lawrence’s opinion ought to be final. He drafted a special despatch on the subject, and Sir Richard Temple, who was then his secretary, declares he “conned over and over again every paragraph as it was drafted.” It represented his final judgment on the subject. He held that “Christian things done in a Christian way could never be politically dangerous in India.” While scrupulously abstaining[19] from interference in the religions of the people, the Government, he held, “should be more explicit than before”—not less explicit—“in avowing its Christian character.”

The explanation offered by the aged king of Delhi, is terse, and has probably as much of truth as more lengthy and philosophical theories. Colonel Vibart relates how, after the capture of Delhi, he went to see the king, and found him sitting cross-legged on a native bedstead, rocking himself to and fro. He was “a small and attenuated old man, apparently between eighty and ninety years of age, with a long white beard, and almost totally blind.” Some one asked the old king what was the real cause of the outbreak at Delhi. “I don’t know,” was the reply; “I suppose my people gave themselves up to the devil!”

The distribution of the British forces in Bengal, in 1857, it may be noted, made mutiny easy and safe. We have learned the lesson of the Mutiny to-day, and there are now 74,000 British troops, with 88 batteries of British artillery, in India, while the Sepoy regiments number only 150,000, with 13 batteries of artillery. But in 1857, the British garrison had sunk to 38,000, while the Sepoys numbered 200,000. Most of the artillery was in native hands. In Bengal itself, it might almost be said, there were no British troops, the bulk of them being garrisoned on the Afghan or Pegu frontiers. A map showing the distribution of troops on May 1, 1857—Sepoys in[20] black dots, and British in red—is a thing to meditate over. Such a map is pustuled with black dots, an inky way stretching from Cabul to Calcutta; while the red points gleam faintly, and at far-stretched intervals.

All the principal cities were without European troops. There were none at Delhi, none at Benares, none at Allahabad. In the whole province of Oude there was only one British battery of artillery. The treasuries, the arsenals, the roads of the North-West Provinces, might almost be said to be wholly in the hands of Sepoys. Betwixt Meerut and Dinapore, a stretch of 1200 miles, there were to be found only two weak British regiments. Never was a prize so rich held with a hand so slack and careless! It was the evil fate of England, too, that when the storm broke, some of the most important posts were in the hands of men paralysed by mere routine, or in whom soldierly fire had been quenched by the chills of old age.

Of the deeper sources of the Mutiny, John Lawrence held, that the great numerical preponderance of the Sepoys in the military forces holding India, was the chief. “Was it to be expected,” he asked, “that the native soldiery, who had charge of our fortresses, arsenals, magazines, and treasuries, without adequate European control, should fail to gather extravagant ideas of their own importance?” It was the sense of power that induced them to rebel. The[21] balance of numbers, and of visible strength, seemed to be overwhelmingly with them.

Taken geographically, the story of the Mutiny has three centres, and may be covered by the tragedy of Cawnpore, the assault on Delhi, and the heroic defence and relief of Lucknow. Taken in order of time, it has three stages. The first stretches from the outbreak at Meerut in May to the end of September. This is the heroic stage of the Mutiny. No reinforcements had arrived from England during these months. It was the period of the massacres, and of the tragedy of Cawnpore. Yet during those months Delhi was stormed, Cawnpore avenged, and Havelock made his amazing march, punctuated with daily battles, for the relief of Lucknow. The second stage extends from October 1857, to March 1858, when British troops were poured upon the scene of action, and Colin Campbell recaptured Lucknow, and broke the strength of the revolt. The third stage extends to the close of 1858, and marks the final suppression of the Mutiny.

The story, with its swift changes, its tragical sufferings, its alternation of disaster and triumph, is a warlike epic, and might rather be sung in dithyrambic strains, than told in cold and halting prose. If some genius could do for the Indian Mutiny what Napier has done for the Peninsular War, it would be the most kindling bit of literature in the English language. What a demonstration the whole story[22] is, of the Imperial genius of the British race! “A nation,” to quote Hodson—himself one of the most brilliant actors in the great drama—“which could conquer a country like the Punjaub, with a Hindoostanee army, then turn the energies of the conquered Sikhs to subdue the very army by which they were tamed; which could fight out a position like Peshawur for years, in the very teeth of the Afghan tribes; and then, when suddenly deprived of the regiments which effected this, could unhesitatingly employ those very tribes to disarm and quell those regiments when in mutiny—a nation which could do this, is destined indeed to rule the world!”

These sketches do not pretend to be a reasoned and adequate “history” of the Mutiny. They are, as their title puts it, the “Tale” of the Mutiny—a simple chain of picturesque incidents, and, for the sake of dramatic completeness, the sketches are grouped round the three heroic names of the Mutiny—Cawnpore, Lucknow, and Delhi. Only the chief episodes in the great drama can be dealt with in a space so brief, and they will be told in simple fashion as tales, which illustrate the soldierly daring of the men, and the heroic fortitude of the women, of our race.

On the evening of May 10, 1857, the church bells were sounding their call to prayer across the parade-ground, and over the roofs of the cantonment at[23] Meerut. It had been a day of fierce heat; the air had scorched like a white flame; all day long fiery winds had blown, hot as from the throat of a seven times heated furnace. The tiny English colony at Meerut—languid women, white-faced children, and officers in loosest undress—panted that long Sunday in their houses, behind the close blinds, and under the lazily swinging punkahs. But the cool night had come, the church bells were ringing, and in the dusk of evening, officers and their wives were strolling or driving towards the church. They little dreamed that the call of the church bells, as it rose and sank over the roofs of the native barracks, was, for many of them, the signal of doom. It summoned the native troops of Meerut to revolt; it marked the beginning of the Great Mutiny.

Yet the very last place, at which an explosion might have been expected, was Meerut. It was the one post in the north-west where the British forces were strongest. The Rifles were there, 1000 strong; the 6th Dragoons (Carabineers), 600 strong; together with a fine troop of horse artillery, and details of various other regiments. Not less, in a word, than 2200 British troops, in fair, if not in first-class, fighting condition, were at the station, while the native regiments at Meerut, horse and foot, did not reach 3000. It did not need a Lawrence or a Havelock at Meerut to make revolt impossible, or to stamp it instantly and fiercely out if it were attempted. A[24] stroke of very ordinary soldiership might have accomplished this; and in that event, the Great Mutiny itself might have been averted.

The general in command at Meerut, however, had neither energy nor resolution. He had drowsed and nodded through some fifty years of routine service, rising by mere seniority. He was now old, obese, indolent, and notoriously incapable. He had agreeable manners, and a soothing habit of ignoring disagreeable facts. Lord Melbourne’s favourite question, “Why can’t you leave it alone?” represented General Hewitt’s intellect. These are qualities dear to the official mind, and explain General Hewitt’s rise to high rank, but they are not quite the gifts needed to suppress a mutiny. In General Hewitt’s case, the familiar fable of an army of lions commanded by an ass, was translated into history once more.

On the evening of May 5 cartridges were being served out for the next morning’s parade, and eighty-five men of the 3rd Native Cavalry refused to receive or handle them, though they were the old familiar greased cartridges, not the new, in whose curve, as we have seen, a conspiracy to rob the Hindu of his caste, and the Mohammedan of his ceremonial purity, was vehemently suspected to exist. The men were tried by a court-martial of fifteen native officers—six of them being Mohammedans and nine Hindus—and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment.

At daybreak on the 9th, the whole military force[25] of the station was assembled to witness the military degradation of the men. The British, with muskets and cannon loaded, formed three sides of a hollow square; on the fourth were drawn up the native regiments, sullen, agitated, yet overawed by the sabres of the Dragoons, the grim lines of the steady Rifles, and the threatening muzzles of the loaded cannon. The eighty-five mutineers stood in the centre of the square.

One by one the men were stripped of their uniform—adorned in many instances with badges and medals, the symbols of proved courage and of ancient fidelity. One by one, with steady clang of hammer, the fetters were riveted on the limbs of the mutineers, while white faces and dark faces alike looked on. For a space of time, to be reckoned almost by hours, the monotonous beat of the hammer rang over the lines, steady as though frozen into stone, of the stern British, and over the sea of dark Sepoy faces that formed the fourth side of the square. In the eyes of these men, at least, the eighty-five manacled felons were martyrs.

The parade ended; the dishonoured eighty-five marched off with clank of chained feet to the local gaol. But that night, in the huts and round the camp fires of all the Sepoy regiments, the whispered talk was of mutiny and revenge. The very prostitutes in the native bazaars with angry scorn urged them to revolt. The men took fire. To wait for the[26] 31st, the day fixed for simultaneous mutiny throughout Bengal, was too sore a trial for their patience. The next day was Sunday; the Sahibs would all be present at evening service in the church; they would be unarmed. So the church bells that called the British officers to prayer, should call their Sepoys to mutiny.

In the dusk of that historic Sabbath evening, as the church bells awoke, and sent their pulses of clangorous sound over the cantonment, the men of the 3rd Native Cavalry broke from their quarters, and in wild tumult, with brandished sabres and cries of “Deen! Deen!” galloped to the gaol, burst open the doors, and brought back in triumph the eighty-five “martyrs.” The Sepoy infantry regiments, the 11th and 20th, ran to their lines, and fell into rank under their native officers. A British sergeant, running with breathless speed, brought the news to Colonel Finnis of the 11th. “For God’s sake, sir,” he said, “fly! The men have mutinied.”

Finnis, a cool and gallant veteran, was the last of men to “fly.” He instantly rode down to the lines. The other British officers gathered round him, and for a brief space, with orders, gesticulations, and appeals, they held the swaying regiments steady, hoping every moment to hear the sound of the British dragoons and artillery sweeping to the scene of action. On the other side of the road stood the 20th Sepoys. The British officers there also, with[27] entreaties and remonstrances and gestures, were trying to keep the men in line. For an hour, while the evening deepened, that strange scene, of twenty or thirty Englishmen keeping 2000 mutineers steady, lasted: and still there was no sound of rumbling guns, or beat of trampling hoofs, to tell of British artillery and sabres appearing on the scene. The general was asleep, or indifferent, or frightened, or helpless through sheer want of purpose or of brains!

Finnis, who saw that the 20th were on the point of breaking loose, left his own regiment, and rode over to help its officers. The dusk by this time had deepened almost into darkness. A square, soldierly figure, only dimly seen, Finnis drew bridle in front of the sullen line of the 20th, and leaned over his horse’s neck to address the men. At that moment a fiercer wave of excitement ran across the regiment. The men began to call out in the rear ranks. Suddenly the muskets of the front line fell to the present, a dancing splutter of flame swept irregularly along the front, and Finnis fell, riddled with bullets. The Great Mutiny had begun!

The 11th took fire at the sound of the crackling muskets of the 20th. They refused, indeed, to shoot their own officers, but hustled them roughly off the ground. The 20th, however, by this time were shooting at every white face in sight. The 3rd Cavalry galloped on errands of arson and murder to the officers’ houses. Flames broke out on every side. A[28] score of bungalows were burning. The rabble in the bazaar added themselves to the mutineers, and shouts from the mob, the long-drawn-out splutter of venomous musketry, the shrieks of flying victims, broke the quiet of the Sabbath evening.

Such of the Europeans in Meerut that night as could make their escape to the British lines were safe; but for the rest, every person of European blood who fell into the hands of the mutineers or of the bazaar rabble was slain, irrespective of age or sex. Brave men were hunted like rats through the burning streets, or died, fighting for their wives and little ones. English women were outraged and mutilated. Little children were impaled on Sepoy bayonets, or hewn to bits with tulwars. And all this within rifle-shot of lines where might have been gathered, with a single bugle-blast, some 2200 British troops!

General Hewitt did, indeed, very late in the evening march his troops on to the general parade-ground, and deployed them into line. But the Sepoys had vanished; some on errands of murder and rapine, the great body clattering off in disconnected groups along the thirty odd miles of dusty road, barred by two rivers, which led to Delhi.

One trivial miscalculation robbed the outbreak of what might well have been its most disastrous feature. The Sepoys calculated on finding the Rifles, armed only with their side-arms, in the church. But on that very evening, by some happy chance, the[29] church parade was fixed for half-an-hour later than the previous Sunday. So the Native Cavalry galloped down to the lines of the Rifles half-an-hour too soon, and found their intended victims actually under arms! They wheeled off promptly towards the gaol; but the narrow margin of that half-hour saved the Rifles from surprise and slaughter.

Hewitt had, as we have seen, in addition to the Rifles, a strong troop of horse artillery and 600 British sabres in hand. He could have pursued the mutineers and cut them down ruthlessly in detail. The gallant officers of the Carabineers pleaded for an order to pursue, but in vain. Hewitt did not even send news to Delhi of the revolt! With a regiment of British rifles, 1000 strong, standing in line, he did not so much as shoot down, with one fierce and wholesome volley, the budmashes, who were busy in murder and outrage among the bungalows. When day broke Meerut showed streets of ruins blackened with fire, and splashed red with the blood of murdered Englishmen and Englishwomen. According to the official report, “groups of savages were actually seen gloating over the mangled and mutilated remains of their victims.” Yet Hewitt thought he satisfied all the obligations of a British soldier by peacefully and methodically collecting the bodies of slaughtered Englishmen and Englishwomen. He did not shoot or hang a single murderer!

It is idle, indeed, to ask what the English at Meerut[30] did on the night of the 10th; it is simpler to say what they did not do. Hewitt did nothing that night; did nothing with equal diligence the next day—while the Sepoys that had fled from Meerut were slaying at will in the streets of Delhi. He allowed his brigade, in a helpless fashion, to bivouac on the parade-ground; then, in default of any ideas of his own, took somebody else’s equally helpless advice, and led his troops back to their cantonments to protect them!

General Hewitt explained afterwards that while he was responsible for the district, his brigadier, Archdale Wilson, was in command of the station. Wilson replied that “by the regulations, Section XVII.,” he was under the directions of General Hewitt, and, if he did nothing, it was because that inert warrior ordered nothing to be done. Wilson, it seems, advised Hewitt not to attempt any pursuit, as it was uncertain which way the mutineers had gone. That any attempt might be made to dispel that uncertainty did not occur, apparently, to either of the two surprising officers in command at Meerut! A battery of galloper guns outside the gates of Delhi might have saved that city. It might, indeed, have arrested the Great Mutiny.

But all India waited, listening in vain for the sound of Hewitt’s cannon. The divisional commander was reposing in his arm-chair at Meerut; his brigadier was contemplating “the regulations,[31] Section XVII.,” and finding there reasons for doing nothing, while mutiny went unwhipped at Meerut, and was allowed at Delhi to find a home, a fortress, and a crowned head! It was rumoured, indeed, and believed for a moment, over half India, that the British in Meerut had perished to a man. How else could it be explained that, at a crisis so terrible, they had vanished so completely from human sight and hearing? Not till May 24—a fortnight after the outbreak—did a party of Dragoons move out from Meerut to suppress some local plunderers in the neighbourhood.

One flash of wrathful valour, it is true, lights up the ignominy of this story. A native butcher was boasting in the bazaar at Meerut how he had killed the wife of the adjutant of the 11th. One of the officers of that regiment heard the story. He suddenly made his appearance in the bazaar, seized the murderer, and brought him away a captive, holding a loaded pistol to his head. A drum-head court-martial was improvised, and the murderer was promptly hanged. But this represents well-nigh the only attempt made at Meerut during the first hours after the outbreak to punish the mutiny and vindicate law.

Colonel Mackenzie, indeed, relates one other incident of a kind to supply a grim satisfaction to the humane imagination even at this distance of time. Mackenzie was a subaltern in one of the revolting[32] regiments—the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry. When the mutiny broke out he rode straight to the lines, did his best to hold the men steady, and finally had to ride for his life with two brother officers, Lieutenant Craigie and Lieutenant Clarke. Here is Colonel Mackenzie’s story. The group, it must be remembered, were riding at a gallop.

The telegraph lines were cut, and a slack wire, which I did not see, as it swung across the road, caught me full on the chest, and bowled me over into the dust. Over my prostrate body poured the whole column of our followers, and I well remember my feelings as I looked up at the shining hoofs. Fortunately I was not hurt, and regaining my horse, I remounted, and soon nearly overtook Craigie and Clarke, when I was horror-struck to see a palanquin-gharry—a sort of box-shaped venetian-sided carriage—being dragged slowly onwards by its driverless horse, while beside it rode a trooper of the 3rd Cavalry, plunging his sword repeatedly through the open window into the body of its already dead occupant—an unfortunate European woman. But Nemesis was upon the murderer. In a moment Craigie had dealt him a swinging cut across the back of the neck, and Clarke had run him through the body. The wretch fell dead, the first Sepoy victim at Meerut to the sword of the avenger of blood.

For the next few weeks Hewitt was, probably, the best execrated man in all India. We have only to imagine what would have happened if a Lawrence, instead of a Hewitt, had commanded at Meerut that night, to realise for how much one fool counts in[33] human history. That Hewitt did not stamp out mutiny or avenge murder in Meerut was bad; his most fatal blunder was, that he neither pursued the mutineers in their flight to Delhi, nor marched hard on their tracks to the help of the little British colony there.

Lord Roberts, indeed, holds that pursuit would have been “futile,” and that no action by the British commanders at Meerut could have saved Delhi; and this is the judgment, recorded in cold blood nearly forty years afterwards, by one of the greatest of British soldiers. Had the Lord Roberts of Candahar, however, been in command himself at Meerut, it may be shrewdly suspected the mutineers would not have gone unpursued, nor Delhi unwarned! Amateur judgments are not, of course, to be trusted in military affairs; but to the impatient civilian judgment, it seems as if the massacres in Delhi, the long and bitter siege, the whole tragical tale of the Mutiny, might have been avoided if Hewitt had possessed one thrill of the fierce energy of Nicholson, or one breath of the proud courage of Havelock.

Delhi lies thirty-eight miles to the south-west of Meerut, a city seven miles in circumference, ancient, stately, beautiful. The sacred Jumna runs by it. Its grey, wide-curving girdle of crenellated walls, is pierced with seven gates. It is a city of mosques and palaces and gardens, and crowded native bazaars. Delhi in 1857 was of great political importance, if only because the last representative of the Grand Mogul, still bearing the title of the King of Delhi, resided there in semi-royal state. The Imperial Palace, with its crowd of nearly 12,000 inmates, formed a sort of tiny royal city within Delhi itself, and here, if anywhere, mutiny might find a centre and a head.

Moreover, the huge magazines, stored with munitions of war, made the city of the utmost military value to the British. Yet, by special treaty, no British troops were lodged in Delhi itself; there were none encamped even on the historic Ridge outside it.

The 3rd Cavalry, heading the long flight of[35] mutineers, reached Delhi in the early morning of the 11th of May. They spurred across the bridge, slew the few casual Englishmen they met as they swept through the streets, galloped to the king’s palace, and with loud shouts announced that they had “slain all the English at Meerut, and had come to fight for the faith.”

The king, old and nervous, hesitated. He had no reason for revolt. Ambition was dead in him. His estates had thriven under British administration. His revenues had risen from a little over £40,000 to £140,000. He enjoyed all that he asked of the universe, a lazy, sensual, opium-soaked life. Why should he exchange a musky and golden sloth, to the Indian imagination so desirable, for the dreadful perils of revolt and war? But the palace at Delhi was a moral plague-spot, a nest of poisonous insects, a vast household in which fermented every bestial passion to which human nature can sink. And discontent gave edge and fire to every other evil force. A spark falling into such a magazine might well produce an explosion. And the shouts of the revolted troopers from Meerut at its gates supplied the necessary spark.

While the old king doubted, and hesitated, and scolded, the palace guards opened the gates to the men of the 3rd Cavalry, who instantly swept in and slaughtered the English officials and English ladies found in it. Elsewhere mutiny found many victims.[36] The Delhi Bank was attacked and plundered, and the clerks and the manager with his family were slain. The office of the Delhi Gazette shared the same fate, the unfortunate compositors being killed in the very act of setting up the “copy” which told of the tragedy at Meerut. All Europeans found that day in the streets of Delhi, down to the very babies, were killed without pity.

There were, as we have said, no white troops in Delhi. The city was held by a Sepoy garrison, the 38th, 54th, and 74th Sepoy regiments, with a battery of Sepoy artillery. The British officers of these regiments, when news of the Meerut outbreak reached them, made no doubt but that Hewitt’s artillery and cavalry from Meerut would follow fierce and fast on the heels of the mutineers. The Sepoys were exhorted briefly to be true to their salt, and the men stepped cheerfully off to close and hold the city gates against the mutineers.

The chief scene of interest for the next few hours was the main-guard of the Cashmere Gate. This was a small fortified enclosure in the rear of the great gate itself, always held by a guard of fifty Sepoys under a European officer. A low verandah ran around the inner wall of the main-guard, inside which, were the quarters of the Sepoys; a ramp or sloping stone causeway led to the summit of the gate itself, on which stood a small two-roomed house, serving as quarters for the British officer on duty.[37] From the main-guard, two gates opened into the city itself.

The guard on that day consisted of a detachment of the 38th Native Infantry. They had broken into mutiny, and assisted with cheers and laughter at the spectacle of Colonel Ripley, of the 54th N.I., with other officers of that regiment, being hunted and sabred by some of the mutinous light cavalry who had arrived from Meerut. Two companies of the 54th were sent hurriedly to the gate, and met the body of their colonel being carried out literally hacked to pieces.

Colonel Vibart, one of the officers of the 54th, has given in his work, “The Sepoy Mutiny,” a vivid account of the scene in the main-guard, as he entered it. In one corner lay the dead bodies of five British officers who had just been shot. The main-guard itself was crowded with Sepoys in a mood of sullen disloyalty. Through the gate which opened on the city could be seen the revolted cavalry troopers, in their French-grey uniforms, their swords wet with the blood of the British officers they had just slain. A cluster of terrified English ladies—some of them widows already, though they knew it not—had sought refuge here, and their white faces added a note of terror to the picture.

Major Abbott, with 150 men of the 74th N.I., presently marched into the main-guard; but the hold of the officers on the men was of the slightest, and[38] when mutiny, in the mass of Sepoys crowded into the main-guard, would break out into murder, nobody could guess.

Major Abbott collected the dead bodies of the fallen officers, put them in an open bullock-cart, covered them with the skirts of some ladies’ dresses, and despatched the cart, with its tragic freight, to the cantonments on the Ridge. The cart found its way to the Flagstaff Tower on the Ridge, and was abandoned there; and when, a month afterwards, the force under Sir Henry Barnard marched on to the crest the cart still stood there, with the dead bodies of the unfortunate officers—by this time turned to skeletons—in it.

Matters quickly came to a crisis at the Cashmere Gate. About four o’clock in the afternoon there came in quick succession the sound of guns from the magazine. This was followed by a deep, sullen, and prolonged blast that shook the very walls of the main-guard itself, while up into the blue sky slowly climbed a mighty cloud of smoke. Willoughby had blown up the great powder-magazine; and the sound shook both the nerves and the loyalty of the Sepoys who crowded the main-guard. There was kindled amongst them the maddest agitation, not lessened by the sudden appearance of Willoughby and Forrest, scorched and blackened by the explosion from which they had in some marvellous fashion escaped.

Brigadier Graves, from the Ridge, now summoned[39] Abbott and the men of the 74th back to that post. After some delay they commenced their march, two guns being sent in advance. But the first sound of their marching feet acted as a match to the human powder-magazine. The leading files of Abbott’s men had passed through the Cashmere Gate when the Sepoys of the 38th suddenly rushed at it and closed it, and commenced to fire on their officers. In a moment the main-guard was a scene of terror and massacre. It was filled with eddying smoke, with shouts, with the sound of crackling muskets, of swearing men and shrieking women. Here is Colonel Vibart’s description of the scene:—

The horrible truth now flashed on me—we were being massacred right and left, without any means of escape! Scarcely knowing what I was doing, I made for the ramp which leads from the courtyard to the bastion above. Every one appeared to be doing the same. Twice I was knocked over as we all frantically rushed up the slope, the bullets whistling past us like hail, and flattening themselves against the parapet with a frightful hiss. To this day it is a perfect marvel to me how any one of us escaped being hit. Poor Smith and Reveley, both of the 74th, were killed close beside me. The latter was carrying a loaded gun, and, raising himself with a dying effort, he discharged both barrels into a knot of Sepoys, and the next moment expired.

The struggling crowd of British officers and ladies reached the bastion and crowded into its embrasures,[40] while the Sepoys from the main-guard below took deliberate pot-shots at them. Presently a light gun was brought to bear on the unhappy fugitives crouching on the summit of the bastion. The ditch was twenty-five feet below, but there was no choice. One by one the officers jumped down. Some buckled their sword-belts together and lowered the ladies. One very stout old lady, Colonel Vibart records, “would neither jump down nor be lowered down; would do nothing but scream. Just then another shot from the gun crashed into the parapet; somebody gave the poor woman a push, and she tumbled headlong into the ditch beneath.” Officers and ladies scrambled up the almost perpendicular bank which forms the farther wall of the ditch, and escaped into the jungle beyond, and began their peril-haunted flight to Meerut.

Abbott, of the 74th, had a less sensational escape. His men told him they had protected him as long as they could; he must now fly for his life. Abbott resisted long, but at last said, “Very well. I’m off to Meerut; but,” he added, with a soldier’s instinct, “give me the colours.” And, carrying the colours of his regiment, he set off with one other officer on his melancholy walk to Meerut.

LIEUTENANT GEORGE WILLOUGHBY, Bengal Artillery

Reproduced, by kind permission of his niece, Miss Wallace, from a photograph of an unfinished water-colour drawing, taken about 1857

The most heroic incident in Delhi that day was the defence and explosion of the great magazine. This was a huge building, standing some 600 yards from the Cashmere Gate, packed with munitions of[41] war—cannon, ammunition, and rifles—sufficient to have armed half a nation, and only a handful of Englishmen to defend it. It was in charge of Lieutenant Willoughby, who had under him two other officers (Forrest and Raynor), four conductors (Buckley, Shaw, Scully, and Crowe), and two sergeants (Edwards and Stewart); a little garrison of nine brave men, whose names deserve to be immortalised.

Willoughby was a soldier of the quiet and coolly courageous order; his men were British soldiers of the ordinary stuff of which the rank and file of the British Army is made. Yet no ancient story or classic fable tells of any deed of daring and self-sacrifice nobler than that which this cluster of commonplace Englishmen was about to perform. The Three Hundred who kept the pass at Thermopylae against the Persian swarms, the Three, who, according to the familiar legend, held the bridge across the Tiber against Lars Porsena, were not of nobler fibre than the Nine who blew up the great magazine at Delhi rather than surrender it to the mutineers.

Willoughby closed and barricaded the gates, and put opposite each two six-pounders, doubly loaded with grape; he placed a 24-pound howitzer so as to command both gates, and covered other vulnerable points with the fire of other guns. In all he had ten pieces of artillery in position—with only nine men to work them. He had, indeed, a score of native officials, and he thrust arms into their reluctant[42] hands, but knew that at the first hostile shot they would run.

But the Nine could not hope to hold the magazine finally against a city in revolt. A fuse was accordingly run into the magazine itself, some barrels of powder were broken open, and their contents heaped on the end of the fuse. The fuse was carried into the open, and one of the party (Scully) stationed beside it, lighted port-fire in hand. Willoughby’s plan was to hold the magazine as long as he could work the guns. But when, as was inevitable, the wave of mutinous Sepoys swept over the walls, Willoughby was to give the signal by a wave of his hat, Scully would instantly light the fuse, and the magazine—with its stores of warlike material, its handful of brave defenders, and its swarm of eager assailants—would vanish in one huge thunderclap!

Presently there came a formal summons in the name of the King of Delhi to surrender the magazine. The summons met with a grim and curt refusal. Now the Sepoys came in solid columns down the narrow streets, swung round the magazine, and girdled it with shouts and a tempest of bullets. The native defenders, at the first shot, clambered down the walls and vanished, and the forlorn but gallant Nine were left alone. Hammers were beating fiercely on the gates. A score of improvised scaling-ladders were placed against the walls, and in a moment the Sepoys were swarming up. A gate was burst open,[43] but, as the assailants tried to rush in, a blast of grape swept through them. Willoughby’s nine guns, each worked by a single gunner, poured their thunder of sound, and storm of shot, swiftly and steadily, on the swaying mass of Sepoys that blocked the gate.

Lieutenant Forrest, who survived the perils of that fierce hour, has told, in cool and soldierly language, its story:—

Buckley, assisted only by myself, loaded and fired in rapid succession the several guns above detailed, firing at least four rounds from each gun, and with the same steadiness as if standing on parade, although the enemy were then some hundreds in number, and kept up a hot fire of musketry on us within forty or fifty yards. After firing the last round, Buckley received a musket ball in his arm above the elbow; I, at the same time, was struck in the left hand by two musket balls.

When, before or since, has there been a contest so heroic or so hopeless? But what can Nine do against twice as many hundreds? From the summit of the walls a deadly fire is concentrated on the handful of gallant British. One after another drops. In another moment will come the rush of the bayonets. Willoughby looks round and sees Scully stooping with lighted port-fire over the fuse, and watching for the agreed signal. He lifts his hand. Coolly and swiftly Scully touches the fuse with his port-fire. The red spark runs along its centre; there is[44] an earth-shaking crash, as of thunder, a sky-piercing leap of flame. The walls of the magazine are torn asunder; bodies of men and fragments of splintered arms fly aloft. The whole city seems to shake with the concussion, and a great pillar of smoke, mushroom-topped and huge, rises slowly in the sky. It is the signal to heaven and earth of how the Nine British, who kept the great magazine, had fulfilled their trust.

Of those gallant Nine, Scully, who fired the train, and four others vanished, along with hundreds of the mutineers, in one red rain. But, somehow, they themselves scarcely knew how, Willoughby, with his two officers, and Conductor Buckley found themselves, smoke-blackened and dazed, outside the magazine, and they escaped death, for the moment at least.

The fugitives who escaped from the Cashmere Gate had some very tragical experiences. Sinking from fatigue and hunger, scorched by the flame-like heat of the sun, wading rivers, toiling through jungles, hunted by villagers, they struggled on, seeking some place of refuge. Some reached Meerut, others Umballa, but many died. Of that much-enduring company of fugitives, it is recorded that the women often showed the highest degree of fortitude and patience. Yet more than one mother had to lay her child, killed by mere exposure or heat, in a nameless jungle grave; more than one wife[45] had to see her husband die, of bullet or sword-stroke, at her feet.

But the fate of these wanderers was happier than that of the Europeans left in the city. Some twenty-seven—eleven of them being children and eight women—took refuge in a house near the great mosque. They held the house for three days, but, having no water, suffered all the agonies of thirst. The Sepoys set vessels of water in front of the house, and bade the poor besieged give up their arms and they should drink. They yielded, gave up the two miserable guns with which they had defended themselves, and were led out. No water was given them. Death alone was to cool those fever-blackened lips. They were set in a row, the eleven children and sixteen men and women, and shot. Let tender-hearted mothers picture that scene, transacted under the white glare of the Indian sun!

Some fifty Europeans and Eurasians barricaded themselves in a strong house in the English quarter of the city. The house was stormed, the unhappy captives were dragged to the King of Delhi’s palace, and thrust into an underground cellar, with no windows and only one door. For five days they sweltered and sickened in that black hole. Then they were brought out, with one huge rope girdling them—men, women, and children, a pale-faced, haggard, half-naked crowd, crouching under one of the great trees in the palace garden. About them[46] gathered a brutal mob of Sepoys and Budmashes, amongst whom was Abool Bukr, the heir-apparent to the King of Delhi. The whole of the victims were murdered, with every accompaniment of cruelty, and it is said that the heir-apparent himself devised horrible refinements of suffering.

Less than six months afterwards Hodson, of Hodson’s Horse, shot that princely murderer, with a cluster of his kinsfolk, under the walls of Delhi, and in the presence of some 6000 shuddering natives, first explaining, that they were the murderers of women and children. Their bodies were brought in a cart through the most public street of the city, laid side by side, under the tree and on the very spot where they had tortured and murdered our women.

Mutiny grows swiftly. On Sunday night was fired, from the ranks of the 20th Sepoys, the volley that slew Colonel Finnis, and was, so to speak, the opening note in the long miserere of the Mutiny. At four o’clock on Monday afternoon the thunder of the great magazine, as it exploded, shook the walls of Delhi. Before the grey light of Tuesday morning broke over the royal city every member of the British race in it was either slain or a captive.

When a powder-magazine is fired, the interval of time between the flash of the first ignited grain and the full-throated blast of the explosion is scarcely measurable. And if the cluster of keen and plotting[47] brains behind the Great Mutiny had carried out their plans as they intended, the Mutiny would have had exactly this bewildering suddenness of arrival. There is what seems ample evidence to prove that Sunday, May 31, was fixed for the simultaneous rising of all the Sepoy regiments in Bengal. A small committee of conspirators was at work in each regiment, elaborating the details of the Mutiny. Parties were to be told off in each cantonment, to murder the British officers and their families while in church, to seize the treasury, release the prisoners, and capture the guns. The Sepoy regiments in Delhi were to take possession of that great city, with its arsenal.

The outbreak at Meerut not merely altered the date, it changed the character of the revolt. The powder-magazine exploded, so to speak, in separate patches, and at intervals spread over weeks. It was this circumstance—added to the fact that the Sepoys had rejected the greased cartridges, and with them the Enfield rifle, against which Brown Bess was at a fatal disadvantage—that, speaking humanly, robbed the Mutiny of half its terror, and helped to save the British Empire in India.

But, even allowing for all this, a powder-magazine—although it explodes only by instalments—is a highly uncomfortable residence while the explosion is going on; and seldom before or since, in the long stretch of human history, have human courage and fortitude been put to such a test, as in the case of the[48] handful of British soldiers and civilians who held the North-West Provinces for England during the last days of May 1857.

Sir George Campbell, who was in Simla at the time, has told the story of how he stood one day, early in June, beside the telegraph operator in Umballa, and listened while the wire, to use his own words, “seemed to repeat the experience of Job.” “First we heard that the whole Jullunder brigade had mutinied, and were in full march in our direction, on the way to Delhi. While that message was still being spoken, came another message, to tell us that the troops in Rajpootana had mutinied, and that Rohilcund was lost; following which, I heard that the Moradabad regiment had gone, and that my brother and his young wife had been obliged to fly.”

Let it be remembered that the revolted districts equal in area France, Austria, and Prussia put together; in population they exceeded them. And over this great area, and through this huge population, the process described by the telegrams, to whose rueful syllables Sir George Campbell listened, was being swiftly and incessantly repeated. The British troops did not number 22,000 men, and they were scattered over a hundred military stations, and submerged in a population of 94,000,000. Let the reader imagine fifteen or sixteen British regiments sprinkled in microscopic fragments over an area so vast, and amongst populations so huge!

The Sepoy army in Bengal numbered 150,000 men, and within six weeks of the shot which killed Colonel Finnis at Meerut, of its 120 regiments of horse and foot, only twenty-five remained under the British flag, and not five of these could be depended upon! A whole army, in a word, magnificently drilled, perfectly officered, strong in cavalry, and yet more formidable in guns, was in open and murderous revolt. Some idea of the scale and completeness of the Mutiny can be gathered from the single fact that every regiment of regular cavalry, ten regiments of irregular cavalry out of eighteen, and sixty-three out of seventy-four regiments of infantry, then on the strength of the Bengal army, disappeared finally and completely from its roster!

In each cantonment during the days preceding the revolt, the British officers on the spot were—to return to our figure—like men shut up in a powder-magazine with the train fired. There might be a dozen or twenty British officers with their families at a station held by a battery of native artillery, a couple of squadrons of native horse, and a regiment of native infantry—all plotting revolt and murder! Honour forbade the British to fly. To show a sign of mistrust or take a single visible precaution would be to precipitate the outbreak. Many of the old Bengal officers relied on their Sepoys, with a fond credulity that nothing could alarm, and that made them blind and deaf to the facts about them. “It was not,” says[50] Trevelyan, “till he saw his own house in flames, and not till he looked down the barrels of Sepoy muskets, and heard Sepoy bullets whizzing round his ears, that an old Bengal officer could begin to believe that his men were not as staunch as they ought to be.”

But all officers were not so blind as this. They knew their peril. They saw the tragedy coming. They walked day after day in front of the line of their men’s muskets on parade, not knowing when these iron tubes would break into red flame and flying bullets. They lay down night after night, knowing that the Sepoys in every hut were discussing the exact manner and time of their murder. Yet each man kept an untroubled brow, and went patiently the round of his duty, thanking God when he had no wife and child at the station to fall under the tender mercies of the mutineers. Farquhar, of the 7th Light Cavalry, writing to his mother at the time, said, “I slept every night dressed, with my revolver under my pillow, a drawn sword on my bed, and a loaded double-barrelled gun just under my bed. We remained in this jolly state,” he explained, “a fortnight.”

When the outbreak came, and the bungalows were in flames, and the men were shouting and firing on the parade-ground, it was a point of honour among the officers to hurry to the scene and make one last appeal to them, dying too often under the bullets of their own soldiers. The survivors then had to fly,[51] with their women and children, and hide in the hot jungle or wander over the scorching plains, on which the white heat burns like a flame, suffering all the torments of thirst and weariness, of undressed wounds, and of wearing fever. If some great writer, with full knowledge and a pen of fire, could write the story of what was dared and suffered by Englishmen and Englishwomen at a hundred scattered posts throughout the North-West Provinces, in the early stages of the Mutiny, it would be one of the most moving and heroic tales in human records.

Sir Joseph Fayrer tells how, early in 1857, he was a member of a tiger-shooting expedition into the Terai. It was a merry party, and included some famous shots and great civil officials. They had killed their eleventh tiger when the first news of the rising reached the party. “All my companions,” says Fayrer, “except Gubbins, were victims of the Mutiny during the year. Thomason was murdered at Shah Jehanpore; Gonne in the Mullahpore district; Colonel Fischer was killed by the men of his own regiment; Thornhill was murdered at Seetapore; Lester was shot through the neck during the siege of Lucknow; Graydon was killed after the first relief of Lucknow.” Swift-following deaths of this sort have to be multiplied over the whole area of the Mutiny, before we can realise what it cost in life.

Fayrer, as a single example of the sort of tragedies which took place on every side, tells how his brother,[52] who was an officer in a regiment of irregular cavalry, was killed. He was second in command of a detachment supposed to be of loyalty beyond suspicion. It had been sent by Lawrence from Lucknow to maintain order in the unsettled districts. There was no sign that the men intended to rise. The morning bugle had gone, the troop was ready to start, and young Fayrer, who had gone out, walked to a well with his charger’s bridle over his arm, and was drinking water from a cup. Suddenly one of his own troopers came up behind him and cut him down through the back of the neck with his tulwar. “The poor lad—only twenty-three—fell dead on the spot, gasping out the word ‘mother’ as he fell.” The troopers instantly rode at the three other British officers of the detachment. One of these slew three Sepoys before he was killed himself; the second, ill mounted, was overtaken and slain; the third, a splendid rider, made a reckless leap over a nullah, where his pursuers dared not follow, and so escaped.

Before describing the great drama at Cawnpore, or Lucknow, or Delhi, it is worth while to give, if only as hasty vignettes, some pictures of what happened at many of the stations scattered through Oude and the Punjaub. They are the opening episodes of a stupendous tragedy.

According to Sir Herbert Edwardes, it was the act of an English boy that saved the Punjaub. A very youthful operator—a mere lad—named Brendish, was[53] by some accident alone in the Delhi Telegraph Office. When the Mutiny broke out he had to flee like the rest; but, before leaving, he wired a somewhat incoherent message to Umballa. “We must leave office,” it ran; “all the bungalows are on fire, burning down by the Sepoys of Meerut. They came in this morning.... Nine Europeans are killed.” That message reached Umballa, was sent on to Lahore, and was read there as a danger-signal so expressive, that the authorities at once decided to disarm the native troops at that station. The cryptic message was then flashed on to Peshawur, and was there read in the same sense, and acted upon with the same promptitude. Brendish was one of the few who afterwards escaped from Delhi.

At some of the stations, where cool heads and steadfast courage prevailed, the Sepoys were disarmed with swiftness and decision. This was especially the case in the Punjaub, where the cause of England was upheld by the kingly brain of John Lawrence, the swift decision of Herbert Edwardes, and the iron courage of Neville Chamberlain and of John Nicholson.

Lord Roberts has told how, on May 12, he was present as scribe at a council of war held in Peshawur. Round the table sat a cluster of gallant soldiers, such as might well take charge of the fortunes of a nation in the hour of its deadliest peril. Herbert Edwardes was there, and Neville Chamberlain,[54] and Nicholson. They had to consider how to hold the Punjaub quiet while all Bengal was in a flame of mutiny. The Punjaub was a newly conquered province; its warlike population might well be expected to seize the first opportunity of rising against its conquerors. It was held by an army of over 80,000 troops, and of these only 15,000 were British—the rest, some 65,000, were almost sure to join the Mutiny. For every British soldier in the Punjaub, that is, there were four probable mutineers, while behind these was a warlike population, just subdued by the sword, and ready to rise again.

But the cool heads that met in that council were equal to their task. It was resolved to disarm all doubtful regiments, and raise new forces in their stead in the Punjaub itself, and from its wild frontier clans. A movable column, light-footed, hard-hitting, was to be formed under Neville Chamberlain’s command, with which to smite at revolt whenever it lifted its head. So the famous Movable Column came into being, commanded in turn by Chamberlain and by Nicholson. That column itself had to be purged heroically again and again to cleanse it from mutinous elements, till it practically came to consist of one field-battery, one troop of horse-artillery, and one infantry regiment, all British. Then it played a great part in the wild scenes of the Mutiny.

Before new levies could be raised in the Punjaub,[55] however, the English had to give some striking proof of decision and strength. No Indian race will fight for masters who do not show some faculty for command. The crisis came at Peshawur itself, towards the end of May. The Sepoys had fixed May 22 for rising against their officers. On the 21st the 64th Native Infantry was to march into Peshawur, and on the following morning the revolt was to take place. Herbert Edwardes and Nicholson, however, were the last men in the world to be caught off their guard. At 7 A.M. on the morning of the 21st, parade was held, and, as the result of some clever manœuvres, the five native regiments found themselves confronted by a line of British muskets, and ordered to “pile arms.” The intending mutineers were reduced, almost with a gesture, to the condition of an unarmed mob, and that lightning-stroke of decision saved the Punjaub. Levies poured in; new regiments rose like magic; a loyal army became possible.