The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

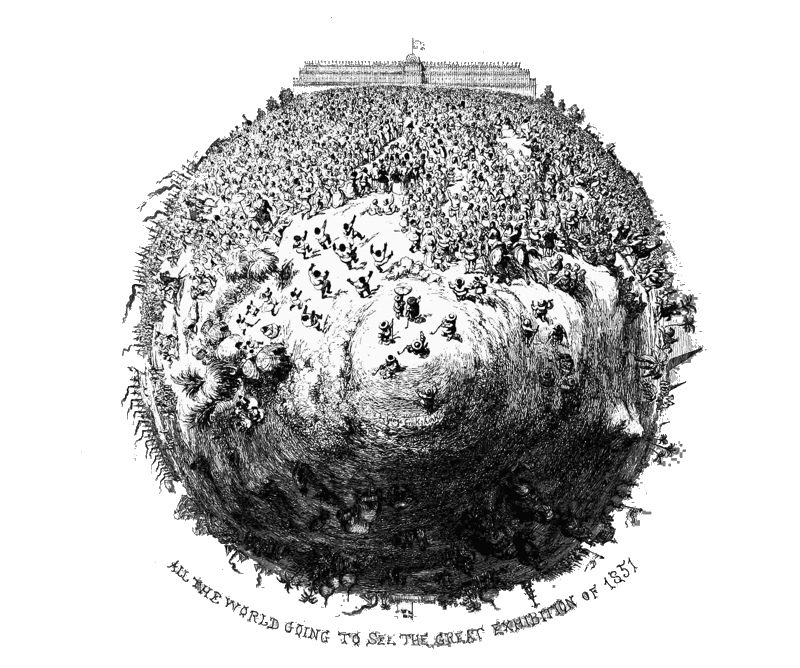

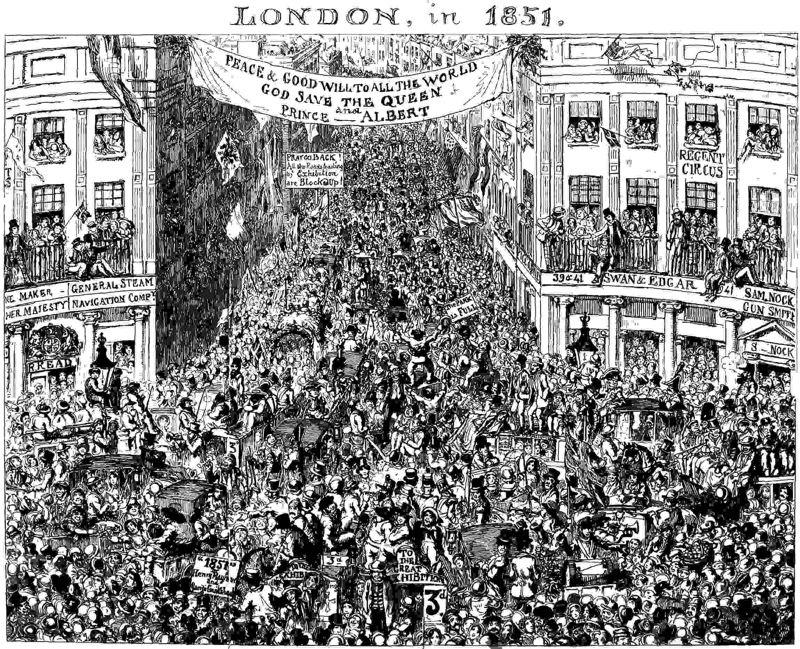

ALL THE WORLD GOING TO SEE THE GREAT EXHIBITION OF 1851.

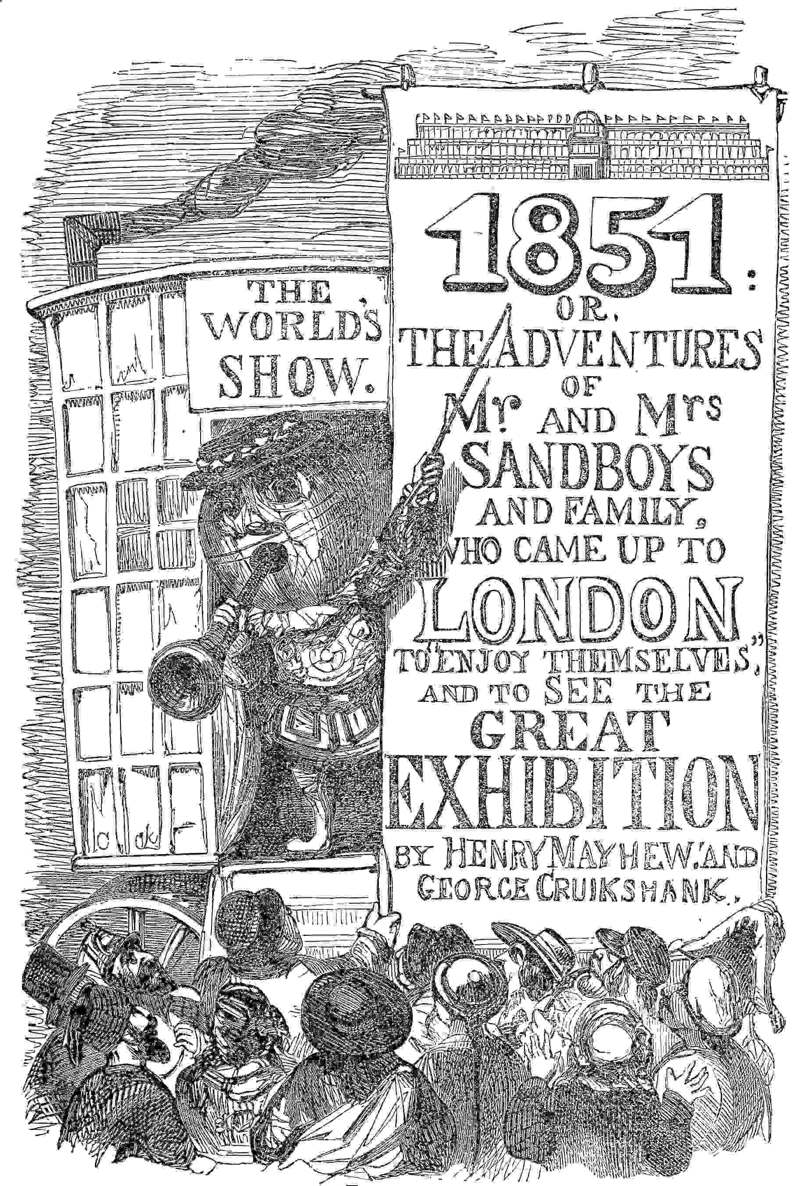

LONDON: GEORGE NEWBOLD, 303 & 304, STRAND, W.C.

| ALL THE WORLD GOING TO THE GREAT EXHIBITION | Frontispiece |

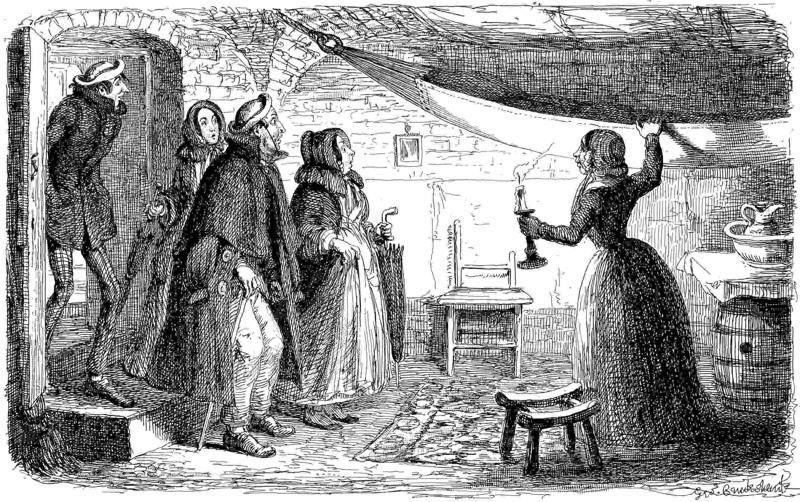

| LOOKING FOR LODGINGS | 54 |

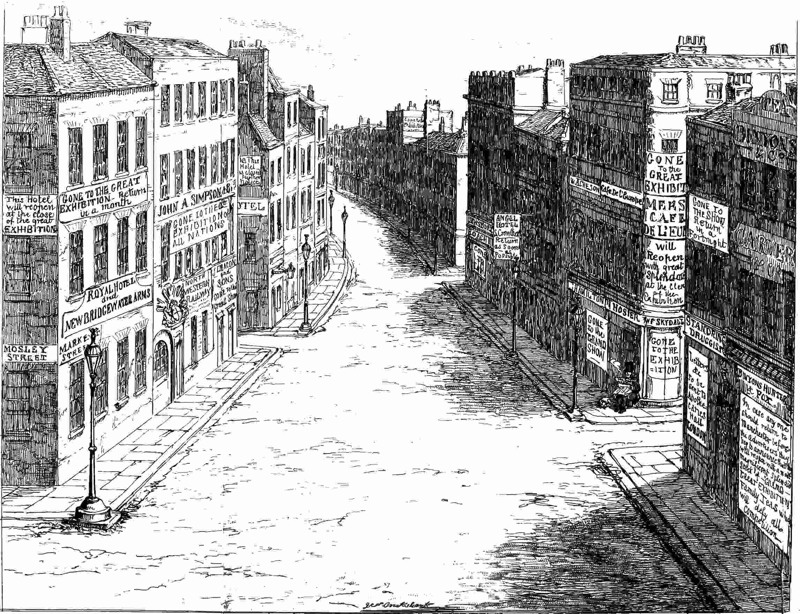

| LONDON CRAMMED AND MANCHESTER DESERTED—2 PLATES | 59 |

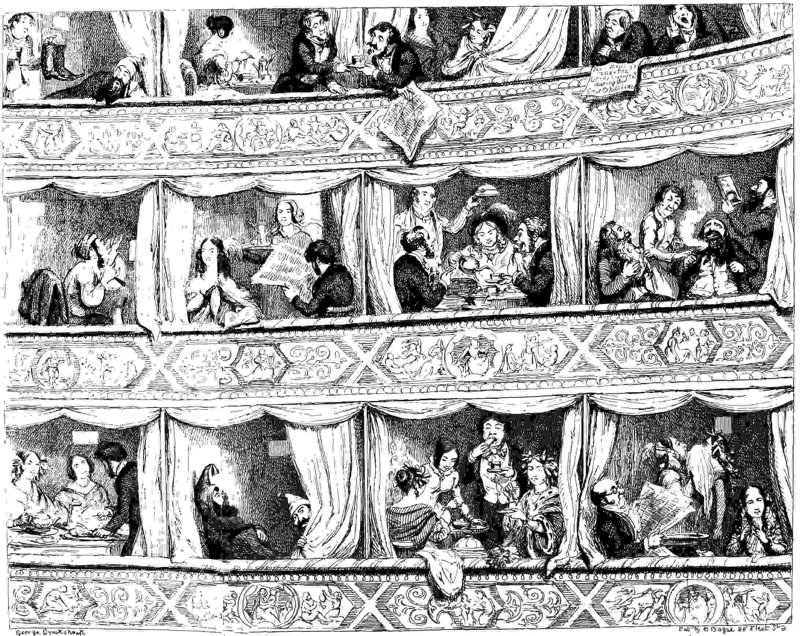

| THE OPERA BOXES DURING THE TIME OF THE GREAT EXHIBITION | 117 |

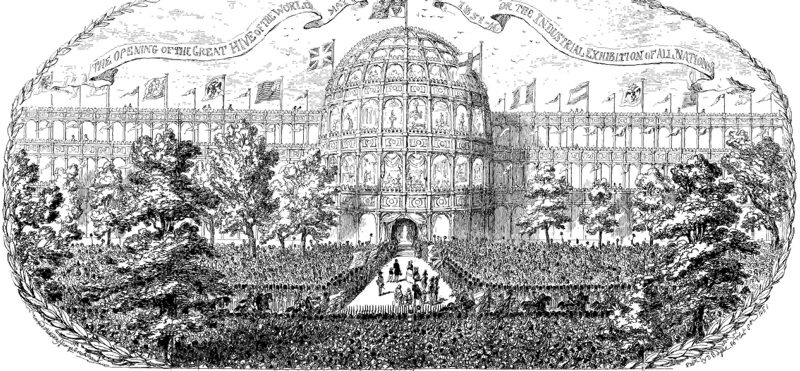

| THE OPENING OF THE GREAT BEE-HIVE | 136 |

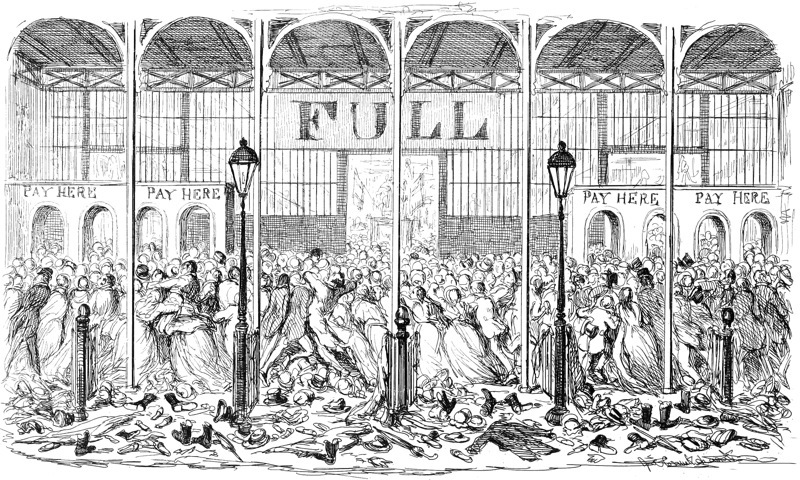

| THE FIRST SHILLING-DAY | 153 |

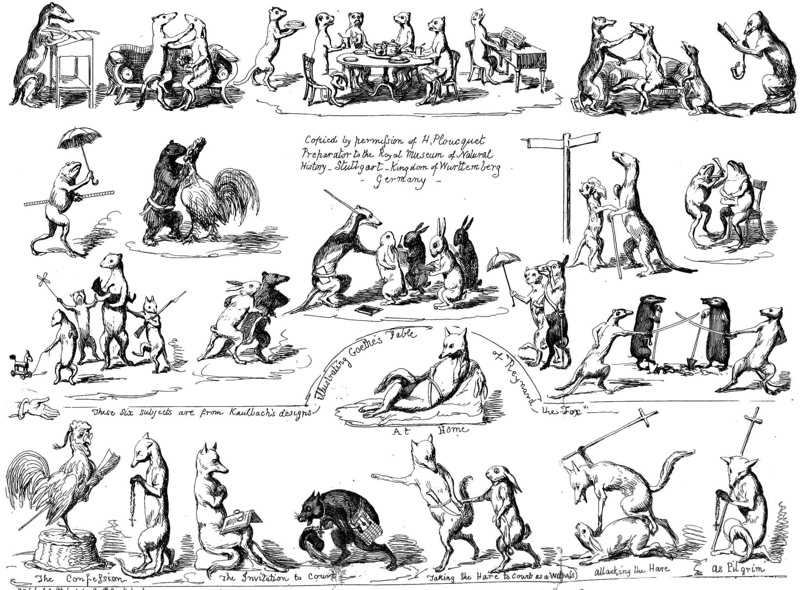

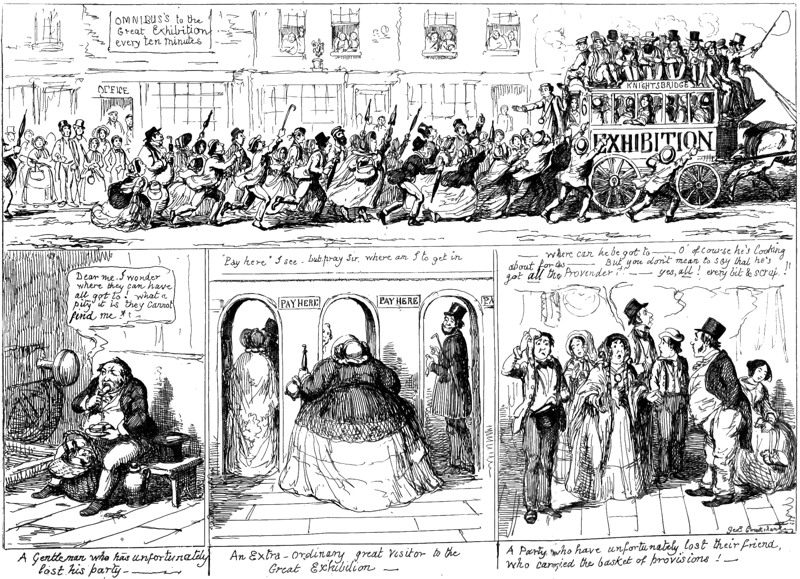

| SOME OF THE DROLLERIES OF THE GREAT EXHIBITION | 160 |

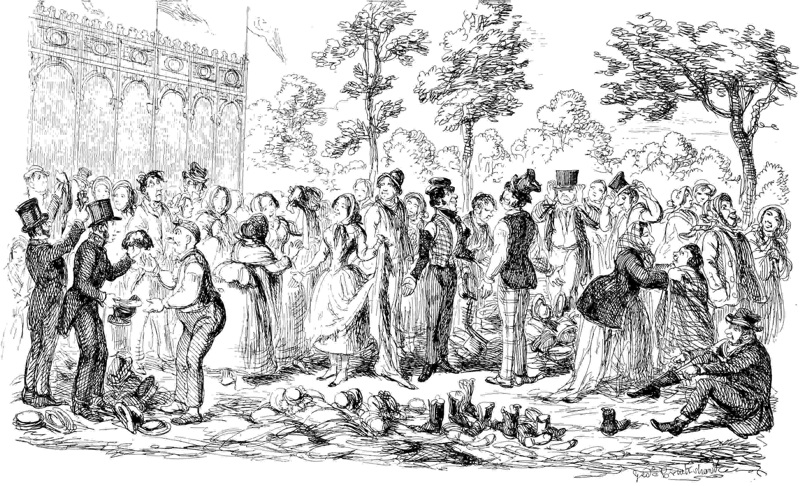

| ODDS AND ENDS, IN, OUT, AND ABOUT THE GREAT EXHIBITION | 162 |

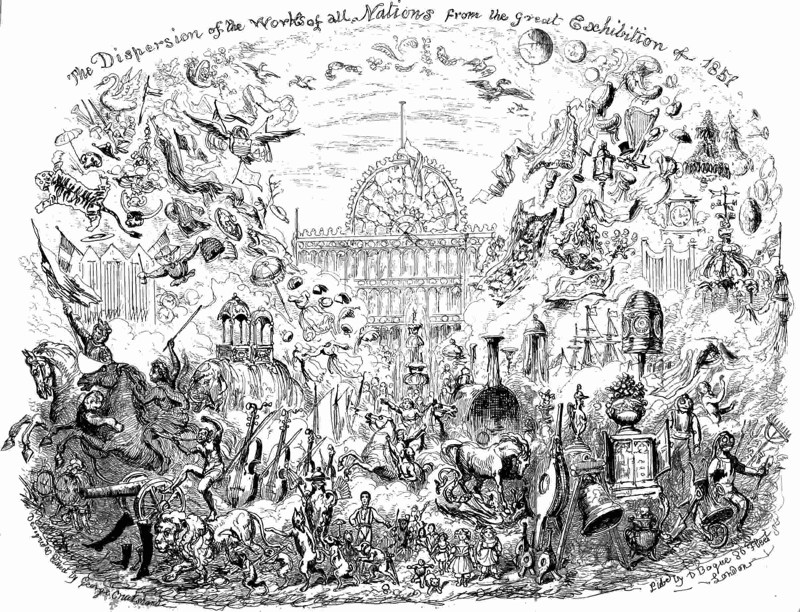

| DISPERSION OF THE WORKS OF ALL NATIONS | 238 |

India Proof impressions of the above Ten Plates may be had, all printed on paper of uniform size (23½ by 17½ inches), quite perfect, and free from folds, price 15s. per set.

THE GREAT EXHIBITION was about to attract sight-seers of all the world—the sight-seers, who make up nine-tenths of the human family. The African had mounted his ostrich. The Crisp of the Desert had announced an excursion caravan from Zoolu to Fez. The Yakutskian Shillibeer had already started the first reindeer omnibus to Novogorod. Penny cargoes were steaming down Old Nile, in Egyptian “Daylights;” and “Moonlights,” while floating from the Punjaub, and congregating down the Indus, Scindian “Bridesmaids” and “Bachelors” came racing up the Red Sea, with Burmese “Watermen, Nos. 9 and 12,” calling at the piers of Muscat and Aden, to pick up passengers for the Isthmus—at two-pence a-head.

The Esquimaux had just purchased his new “registered paletot” of seal-skin from the great “sweater” of the Arctic Regions. The Hottentot Venus had already added to the graceful ebullitions of nature, the charms of a Parisian crinoline. The Yemassee was busy blueing his cheeks with the rouge of the backwoods. The Truefit of New Zealand had dressed the full buzz wig, and cut and curled the horn of the chief of the Papuas. The Botocudo had ordered a new pair of wooden ear-rings. The Maripoosan had japanned his teeth with the best Brunswick Black Odonto. The Cingalese was hard at work with a Kalydor of Cocoa-Nut-Oil, polishing himself up like a boot; and the King of Dahomey—an ebony Adam—in nankeen gaiters and epaulets, was wending his way towards London to tender his congratulations to the Prince Consort.

Nor was the commotion confined alone to the extremes of the world—the metropolis of Great Britain was also in a prodigious excitement. Alexis Soyer was preparing to open a restaurant of all nations, where the universe might dine, from sixpence to a hundred guineas, off cartes ranging from pickled whelks to nightingale’s tongues—from the rats à la Tartare of the Chinese, to the “turkey and truffles” of the Parisian gourmand—from the “long sixes, au naturel,” of the Russian, to the “stewed Missionary of the Marquesas,” or the “cold roast Bishop” of New Zealand. Here, too, was to be a Park with Swiss cottages, wherein the sober Turk might quaff his Dublin stout; and Chinese Pagodas, from whose golden galleries the poor German student, dreaming of the undiscoverable noumena of Kant, might smoke his penny Pickwick, sip his Arabian chicory, and in a fit of absence, think of his father-land and pocket the sugar.

St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey (“in consequence of the increased demand”) were about to double their prices of admission, when M. Jullien, “ever ready to deserve the patronage of a discerning public,” made the two great English cathedrals so tempting an offer that they “did not think themselves justified in refusing it.” And there, on alternate nights, were shortly to be exhibited, to admiring millions, the crystal curtain, the stained glass windows illuminated with gas, and the statues lighted up with rose-coloured lamps; the “Black Band of his Majesty of Tsjaddi, with a hundred additional bones;” the monster Jew’s harp; the Euhurdy-gurdychon; the Musicians of Tongoose; the Singers of the Maldives; the Glee Minstrels of Paraguay; the Troubadours of far Vancouver; the Snow Ball Family from the Gold Coast; the Canary of the Samoiedes; the Theban Brothers; and, “expressly engaged for the occasion,” the celebrated Band of Robbers from the Desert.

Barnum, too, had “thrown up” Jenny Lind, and entered into an agreement with the Poor Law Commissioners to pay the Poor Rates of all England during one year for the sole possession of Somerset House, as a “Grand Hotel for all Nations,” under the highly explanatory title of the “Xenodokeion Pancosmopolitanicon;” where each guest was to be provided with a bed, boudoir, and banquet, together with one hour’s use per diem of a valet, and a private chaplain (according to the religious opinions of the individual); the privilege of free admission to all the theatres and green-rooms; the right of entrée to the Privy Council and the Palace; a knife and fork, and spittoon at pleasure, at the tables of the nobility; a seat with nightcap and pillow in the House of Commons, and a cigar on the Bench with the Judges; the free use of the columns of “The Times” newspaper, and the right of abusing therein their friends and hosts of the day before; the privilege of paying visits in the Lord Mayor’s state-carriage (with the freedom of the City of London), and of using the Goldsmiths’ state barge for aquatic excursions; and finally, the full right of presentation at the Drawing-room to her most gracious Majesty, and of investiture with the Order of the Garter at discretion, as well as the prerogative of sitting down, once a week, in rotation, at the dinner table of His Excellency General Tom-Thumb. These advantages Mr. Barnum, to use his own language, had “determined upon offering to a generous and enlightened American public at one shilling per head per day—numbers alone enabling him to complete his engagements.”

While these gigantic preparations for the gratification of foreign visitors were being made, the whole of the British Provinces likewise were preparing extensively to enjoy themselves. Every city was arranging some “monster train” to shoot the whole of its inhabitants, at a halfpenny per ton, into the lodging-houses of London. All the houses of York were on tiptoe, in the hope of shaking hands in Hyde Park with all the houses of Lancaster. Beds, Bucks, Notts, Wilts, Hants, Hunts, and Herts were respectively cramming their carpet-bags in anticipation of “a week in London.” Not a village, a hamlet, a borough, a township, or a wick, but had each its shilling club, for providing their inhabitants with a three days’ journey to London, a mattrass under the dry arches of the Adelphi, and tickets for soup ad libitum. John o’Groats was anxiously looking forward to the time when he was to clutch the Land’s End to his bosom,—the Isle of Man was panting to take the Isle of Dogs by the hand, and welcome Thanet, Sheppy, and Skye to the gaieties of a London life,—the North Foreland was preparing for a friendly stroll up Regent-street with Holy-Head on his arm—and the man at Eddystone Lighthouse could see the distant glimmer of a hope of shortly setting eyes upon the long-looked-for Buoy at the Nore.

Bradshaw’s Railway Guide had swelled into an encyclopædia, and Masters and Bachelors of Arts “who had taken distinguished degrees,” were daily advertising, to perfect persons in the understanding of the Time Tables, in six easy lessons, for one guinea. Omnibus conductors were undergoing a Polyglott course on the Hamiltonian system, to enable them to abuse all foreigners in their native tongues; the “Atlases” were being made extra strong, so that they might be able to bear the whole world on top of them; and the proprietors of the Camberwell and Camden Town ’Busses were eagerly watching for the time when English, French, Prussians, and Belgians should join their Wellingtons and Bluchers on the heights of “Waterloo!”

Such was the state of the world, the continent, the provinces, and the metropolis. Nor was the pulse that beat so throbbingly at Bermondsey, Bow, Bayswater, Brixton, Brompton, Brentford, and Blackheath, without a response on the banks of Crummock Water and the tranquil meadows of Buttermere.

He who has passed all his life amid the chaffering of Cheapside, or the ceaseless toil of Bethnal Green, or the luxurious ease of Belgravia,—who has seen no mountain higher than Saffron Hill,—has stood beside no waters purer than the Thames—whose eye has rested upon no spot more green than the enclosure of Leicester Square,—who knows no people more primitive than the quaker corn-factors of Mark Lane, and nothing more truthful than the “impartial inquiries” of the Morning Chronicle, or more kind-hearted than the writings of the Economist,—who has drunk of no philosophy deeper than that of the Penny Cyclopædia,—who has felt no quietude other than that of the City on a Sunday,—sighed for no home but that which he can reach for “threepence all the way,” and wished for no last resting-place but a dry vault and a stucco cenotaph in the theatrical Golgothas of Kensal and of Highgate;—such a man can form no image of the peace, the simplicity, the truth, and the beauty which aggregate into the perpetual Sabbath that hallows the seclusion about and around the Lake of Buttermere.

Here the knock of the dun never startles the hermit or the student—for (thrice blessed spot!) there are no knockers. Here are no bills, to make one dread the coming of the spring, or the summer, or the Christmas, or whatever other “festive” season they may fall due upon, for (oh earthly paradise!) there are no tradesmen, and—better still—no discounters, and—greater boon than all—no! not one attorney within nine statute miles of mountain, fell, and morass, to ruffle the serenity of the village inn. Here that sure-revolving tax-gatherer—as inevitable and cruel as the Fate in a Grecian tragedy—never comes, with long book and short inkhorn, to convince us it is Lady-day—nor “Paving,” nor “Lighting,” nor “Water,” “Sewers,” nor “Poors,” nor “Parochials,” nor “Church,” nor “County,” nor “Queen’s,” nor any other accursed accompaniment of our boasted civilization. Here are no dinner-parties for the publication of plate; no soirées for the exhibition of great acquaintances; no conversaziones for the display of your wisdom, with the full right of boring your friends with your pet theories; nor polkas, nor schottisches, nor Cellarii, for inflaming young heirs into matrimony. Here there are no newspapers at breakfast to stir up your early bile with a grievance, or to render the merchant’s morning meal indigestible with the list of bankrupts, or startle the fundholder with a sense that all security for property is at an end. Here there are no easy-chair philosophers,—not particularly illustrious themselves for a delight in hard labour,—to teach us to “sweep all who will not work into the dust-bin.” Here, too, there are no Harmonic Coalholes, or Cyder Cellars, nor Choreographic Casinos, or Cremornes, or other such night colleges for youth, where ethics are taught from professional chairs occupied by “rapid” publicans, or by superannuated melodists, with songs as old as themselves, and as dirty as their linen.

No! According to a statistical investigation recently instituted, to the great alarm of the inhabitants, there were, at the beginning of the ever-to-be-remembered year 1851, in the little village situate between the Lakes of Crummock and Buttermere, fifteen inhabited houses, one uninhabited, and one church about the size of a cottage; and within three miles of these, in any direction, there was no other habitation whatsoever. This little cluster of houses constituted the village called Buttermere, and consisted of four farm-houses, seven cottages, two Squires’ residences, and two inns.

The census of the nine families who resided in the fifteen houses of Buttermere—for many of these same families were the sons and nephews of the elders—was both curious and interesting. There were the Flemings, the Nelsons, the Cowmans, the Clarks, the Riggs, the Lancasters, the Branthwaites, the Lightfoots—and The Jopson, the warm-hearted Bachelor Squire of the place. The remaining Squire—also, be it said, a Bachelor—had left, when but a stripling, the cool shades of the peaceful vales for the wars of India. His name was but as a shadow on the memory of the inhabitants; once he had returned with—so the story ran—“an Arabian Horse;” but “his wanderings not being over,” as his old housekeeper worded it, with a grave shake of her deep-frilled cap, he had gone back “t’ hot country with Sir Henry Hardinge to fight t’ Sikhs,” promising to return again and end his days beside his native Lake of Buttermere.

Of the families above cited, two were related by marriage. The Clarks had wedded with the Riggs, and the Cowmans with the Lightfoots, so that, in reality, the nine were but seven; and, strange to say, only one of these—the Clarks—-were native to the place. It was curious to trace the causes that had brought the other settlers to so sequestered a spot. The greatest distance, however, that any of the immigrants had come from was thirty miles, and some had travelled but three; and yet, after five-and-twenty years’ residence, were spoken of by the aboriginal natives as “foreigners.”

Only one family—Buttermere born—had been known to emigrate, and they had been led off, like the farmers who had immigrated, by the lure of more fertile or more profitable tenancies. Three, however, had become extinct; but two in name only, having been absorbed by marriage of their heiresses, while the other one—the most celebrated of all—was utterly lost, except in tradition, to the place. This was the family of Mary Robinson, the innkeeper’s daughter, and the renowned Beauty of Buttermere, known as the lovely, simple-hearted peasant girl, trapped by the dashing forger into marriage, widowed by the hangman, amidst a nation’s tears, and yet—must we write it—not dying broken-hearted,—but—alas, for the romance and constancy of the sex!—remarried ere long to a comfortable farmer, and ending her days the stout well-to-do mother of seven bouncing boys and girls.

Mr. Thornton, the eminent populationist, has convinced every thinking mind, that, in order that the increase of the people may be duly regulated, every husband and wife throughout the country should have only one child and a quarter. In Buttermere, alas! (we almost weep as we announce the much-to-be-regretted fact) there are seventeen parents and twenty-nine children, which is at the frightful rate of one child and three-quarters and a fraction, to each husband and wife!

Within the last ten years, too, Buttermere has seen, unappalled, three marriages and nine births. The marriages were all with maids of the inn, where the memory of Mary Robinson still sheds a traditionary grace over each new chambermaid, and village swains, bewitched by the association, come annually to provide themselves with “Beauties.”

The deaths of Buttermere tell each their peculiar story. Of the seven who have passed away since the year 1840, one was an old man who had seen the snow for eighty winters lie upon Red Pike; another was little Mary Clarke, who for eight years only had frolicked in the sunshine of the happy valley. Two were brothers, working at the slate-quarries high up on Honister Craig: one had fallen from a ladder down the precipice side—the other, a tall and stalwart man, had, in the presence of his two boys, been carried up bodily into the air by a whirlwind, and dashed to death on the craigs below. Of the rest, one died of typhus fever, and another, stricken by the same disease, was brought, at his special request, from a distance of twenty-one miles, to end his days in his mountain home. The last, a young girl of twenty, perished by her own hand—the romance of village life! Mary Lightfoot, wooed by her young master, the farmer’s son, of Gatesgarth, sat till morning awaiting his return from Keswick, whither he had gone to court another. Through the long, lone night, the misgivings of her heart had grown by daylight into certainty. The false youth came back with other kisses on his lip, and angry words for her. Life lost its charms for Mary, and she could see no peace but in the grave.[1]

1. The custom of night courtship is peculiar to the county of Cumberland and some of the districts of South Wales. The following note, explanatory of the circumstance, is taken from the last edition of “The Cumberland Ballads of Robert Anderson,” a work to be found, well thumbed, in the pocket of every Cumbrian peasant-girl and mountain shepherd:—“A Cumbrian peasant pays his addresses to his sweetheart during the silence and solemnity of midnight. Anticipating her kindness, he will travel ten or twelve miles, over hills, bogs, moors, and morasses, undiscouraged by the length of the road, the darkness of the night, or the intemperance of the weather; on reaching her habitation, he gives a gentle tap at the window of her chamber, at which signal she immediately rises, dresses herself, and proceeds with all possible silence to the door, which she gently opens, lest a creaking hinge, or a barking dog should awaken the family. On his entrance into the kitchen, the luxuries of a Cumbrian cottage—cream and sugared curds—are placed before him; next the courtship commences, previously to which, the fire is darkened and extinguished, lest its light should guide to the window some idle or licentious eye; in this dark and uncomfortable situation (at least uncomfortable to all but lovers), they remain till the advance of day, depositing in each other’s bosoms the secrets of love, and making vows of unalterable affection.”

Nor are the other social facts of Buttermere less interesting.

According to a return obtained by two gentlemen, who represented themselves as members of the London Statistical Society, and who, after a week’s enthusiasm and hearty feeding at the Fish Inn, suddenly disappeared, leaving behind them the Occupation Abstract of the inhabitants and a geological hammer,—according to these gentlemen, we repeat, the seventy-two Buttermerians may be distributed as follows: two innkeepers, four farmers (including one statesman and one sinecure constable), nine labourers (one of them a miner, one a quarrier, and one the parish-clerk), twelve farm-servants, seventeen sons, nine daughters, fourteen wives, three widows, one ’squire, and one pauper of eighty-six years of age.

“But,” says the Pudding-lane reader, “if this be the entire community, how do the people live? where are the shops? where that glorious interchange of commodities, without which society cannot exist! Where do they get their bread—their meat—their tea—their sugar—their clothing—their shoes? If ill, what becomes of them? Their children, where are they taught? Their money, where is it deposited? Their letters?—for surely they cannot be cut off from all civilization by the utter absence of post-office and postman! Are they beyond the realms of justice, that no attorney is numbered amongst their population? They have a constable—where, then, the magistrate? They have a parish-clerk—then where the clergyman?”

Alas! reader, the picturesque is seldom associated with the conveniences or luxuries of life. Wash the peasant-girl’s face and bandoline her hair, she proves but a bad vignette for that most unpicturesque of books—the Book of Beauty. Whitewash the ruins and make them comfortable; what artist would waste his pencils upon them? So is it with Buttermere: there the traveller will find no butcher, no baker, no grocer, no draper, no bookseller, no pawnbroker, no street-musicians, no confectioners, and no criminals. Burst your pantaloons—oh, mountain tourist!—and it is five miles to the nearest tailor. Wear the sole of your shoe to the bone on the sharp craigs of Robinson or of the Goat-gills, and you must walk to Lowes Water for a shoemaker. Be mad with the toothache, caught from continued exposure to the mountain breeze, and, go which way you will—to Keswick or to Cockermouth—it is ten miles to the nearest chemist. Be seized with the pangs of death, and you must send twenty miles, there and back, for Dr. Johnson to ease your last moments. To apprise your friends by letter of your danger, a messenger must go six miles before the letter can be posted. If you desire to do your duty to those you may leave behind, you must send three leagues to Messrs. Brag and Steal to make your will, and they must travel the same distance before either can perform the office for you. You wish to avail yourself of the last consolations of the Church; the clergyman, who oscillates in his duties between Withorp and Buttermere (an interval of twelve miles), has, perhaps, just been sent for to visit the opposite parish, and is now going, at a hard gallop, in the contrary direction, to another parishioner. Die! and you must be taken five miles in a cart to be buried; for though Buttermere boasts a church, it stands upon a rock, from which no sexton has yet been found hardy enough to quarry out a grave!

But these are the mere dull, dry matters of fact of Buttermere—the prose of its poetry. The ciphers tell us nothing of the men or their mountains. We might as well be walking in the Valley of Dry Bones, with Maculloch, Porter, Macgregor, or the Editor of the Economist, for our guides. Such teachers strip all life of its emotions, and dress the earth in one quaker’s suit of drab. All they know of beauty is, that it does not belong to the utilities of life—feeling with them is merely the source of prejudice—and everything that refines or dignifies humanity, is by such men regarded as sentimentalism or rodomontade.

And yet, the man who could visit Buttermere without a sense of the sublimity and the beauty which encompass him on every side, must be indeed dead to the higher enjoyments of life. Here, the mountains heave like the billows of the land, telling of the storm that swept across the earth before man was on it. Here, deep in their huge bowl of hills, lie the grey-green waters of Crummock and of Buttermere, tinted with the hues of the sloping fells around them, as if the mountain dyes had trickled into their streams. Look which way you will, the view is blocked up by giant cliffs. Far at the end stands a mighty mound of rocks, umber with the shadows of the masses of cloud that seem to rest upon its jagged tops, while the haze of the distance hangs about it like a bloom. On the one side and in front of this rise the peaks of High Craig, High Stile, and Red Pike, far up into the air, breaking the clouds as they pass, and the white mists circling and wreathing round their warted tops, save where the blue sky peeps brightly between them and the sun behind streams between the peaks, gilding every craig. The rays go slanting down towards the lake, leaving the steep mountain sides bathed in a rich dark shadow—while the waters below, here dance in the light, sparkling and shimmering, like scales of a fish, and there, swept by the sudden gust, the spray of their tiny waves is borne along the surface in a powdery shower. Here the steep sloping sides are yellow-green with the stinted verdure, spotted red, like rust, with the withered fern, or tufted over with the dark green furze. High up, the bare, ash-grey rocks thrust themselves through the sides, like the bones of the meagre Earth. The brown slopes of the more barren craigs are scored and gashed across with black furrows, showing the course of dried up torrents; while in another place, the mountain stream comes leaping down from craig to craig, whitening the hill-side as with wreaths of snow, and telling of the “tarn” which lies silent and dark above it, deep buried in the bosom of the mountain. Beside this, climbs a Wood, feathering the mountain sides, and yet so lost in the immensity that every tree seems but a blade of fern. Then, as you turn round to gaze upon the hills behind you, and bend your head far back to catch the Moss’s highest craigs, you see blocks and blocks of stone tumbled one over the other, in a disorder that fills and confounds the mind, with trees jutting from their fissures, and twisting their bare roots under the huge stones, like cords to lash them to their places; while the mountain sheep, red with ruddle, stands perched on some overhanging craig, nipping the scanty herbage. And here, as you look over the tops of Hassness Wood, you see the blue smoke of the unseen cottage curling lightly up into the air, and blending itself with the bloom of the distant mountains. Then, as you journey on, you hear the mountain streams, now trickling softly down the sides, now hoarsely rushing down a rocky bed, and now, in gentle and harmonious hum, vying with the breeze as it comes sighing down the valley.

Central between the Waters, and nestling in its mountains, lies the little village of Buttermere, like a babe in its mother’s lap. Scarce half-a-dozen houses, huddled together like sheep for mutual shelter from the storm, make up the humble mountain home. On each side, in straggling order, perched up in the hill-side nooks, the other dwellings group themselves about it. In the centre stands the unpretending village inn. Behind it stretched the rich, smooth, and velvety meadows, spotted with red cattle, and looking doubly green and soft and level, from the rugged, brown, and barren mountains, that rise abrupt upon them. To stand in these fields, separating as they do the twin waters, is, as it were, to plant the foot upon the solid lake, and seem to float upon some verdant raft. High on the rock, fronting the humble inn, stands sideways the little church, smaller than the smallest cottage, with its two bells in tiny belfry crowning its gable end, and backed by the distant mountain that shows through the opening pass made by the hill on whose foot it rests. Round and about it circles the road, in its descent towards the homesteads that are grey with the stone, and their roofs green with the slate of their native hills, harmonious in every tint and shade with all around them. Beside the bridge spanning the angry nook which hurries brawling round the blocks of stone that intercept its course, stands the other and still more humble inn, half clad in ivy, and hiding the black arch through which the mountain “beck,” white with foam, comes dashing round the turn.

In the village road, for street there is none, not a creature is to be seen, save where a few brown or mottled “short-horns” straggle up from the meadows,—now stopping to stare vacantly about them, now capering purposeless with uplifted tails, or butting frolicsome at each other; then marching to the brook, and standing knee-deep in the scurrying waters, with their brown heads bent down to drink, and the rapid current curling white around their legs, while others go leaping through the stream, splashing the waters in transparent sheets about them. Not a fowl is to be seen scratching at the soil, nor duck waddling pompously toward the stream. Not even a stray dog crosses the roadway, unless it be on the Sunday, and then every peasant or farmer who ascends the road has his sharp-nosed, shaggy sheep-dog following at his heels, and vying with his master in the enjoyment of their mutual holiday. Here, too, ofttimes may be seen some aged dame, with large white cap, and bright red kerchief pinned across her bosom, stooping to dip her pail into the brook; while over the bridge, just showing above the coping-stone, appears the grey-coated farmer, with drab hat, and mounted on his shaggy brown pony, on his way to the neighbouring market. Here, too, the visitor may sometimes see the farmers’ wives grouped outside one of the homestead gates—watching their little lasses set forth on their five-mile pilgrimage to school, their baskets filled with their week’s provisions hanging on their arms, and the hoods of their blue-grey cloaks dancing as they skip playfully along, thoughtless of the six days’ absence, or mountain road before them. At other times, some good-wife or ruddy servant girl, sallies briskly from the neighbouring farm, and dodges across the road the truant pig that has dashed boldly from the midden. Anon, climbing the mountain side, saunters some low-built empty cart, with white horse, and grey-coated carter, now, as it winds up the road, hidden by the church, now disappearing in the circling of the path behind the slope, then seen high above the little belfry, and hanging, as it were, by the hill side, as the carter pauses to talk with the pedlar, who, half buried in his pack, descends the mountain on his way to the village. Then, again ascending, goes the cart, higher and higher, till it reach the highest platform, to vanish behind the mountain altogether from the sight.

Such, reader, is a faint pen-and-ink sketch of a few of the charms and rural graces of Buttermere. That many come to see, and but few to appreciate them, the visitors’ book of the principal inn may be cited as unquestionable evidence. Such a book in such a scene one would expect to find filled with sentiments approximating to refinement, at least, if not to poetry; but the mountains here seem more strongly to affect the appetite of Southerners than their imaginations, as witness the under-written, which are cited in all their bare and gross literality.

“Messrs. Bolton, Campbell, and Co., of Prince’s Park, Liverpool, visited this inn, and were pleased with the lamb-chops, but found the boats dear. June 28, 1850.”

“Thomas Buckram, sen., Ludley Park;

George Poins, sen., Ludley Bridge;

Came to Buttermere on the 26th, 12 mo, 1850; that day had a glorious walk over the mountains from Keswick; part of the way by Lake Derwent by boat. Stayed at Buttermere all night. Splendid eating!!!

“Rev. Joshua Russell and Son,

Blackheath.

The whisky is particularly fine at this house, and we made an excellent dinner.”

“Oct. 7th, 50.

The Fish a most comfortable inn. A capital dinner. Good whisky. The only good glass we have met with in the whole Lake district.”

“Mr. Edward King, Dalston, London, and 7, Fenchurch-street, London: walked from Whitehaven to Ennerdale Lake, calling at the Boat House on the margin of the Lake, where, having invigorated the inward man, I took the mountain path between Floutern Tarn and Grosdale, passed Scale Force, and arrived in the high mountain which overlooks Crummoch and Buttermere: here, indeed, each mountain scene is magnificently rude. I entered the beautiful vale of Buttermere; was fortunate enough to find the Fish Inn, where all were extremely civil; and from the landlady I received politeness and very excellent accommodation. Had a glorious feed for 1s. 3d.!! Chop, with sharp sauce, 6d.; potatoes. 1d.; cheese. 1d.; bread, 1d.; beer, 5d.; waitress (a charming, modest, and obliging young creature, who put me in mind of the story of the Maid of Buttermere, and learnt me the names of all the mountains), 1d.; total, 1s. 3d. Thursday, April 18, 1850.”[2]

2. The reader is requested to remember that these are not given as matters of invention, but as literal extracts, with real names and dates, copied from the books kept by Mrs. Clark, the excellent hostess of the Fish Inn, Buttermere.

Hard upon a mile from the village before described lived the hero, the heroine, and herolets of the present story, by names Mr. and Mrs. Sandboys, their son, Jobby, and their daughter, Elcy. Their home was one of the two squires’ houses before spoken of as lying at the extremes of the village. Mr. Christopher, or, as after the old Cumberland fashion he was called, “Cursty,” Sandboys, was native to the place, and since his college days of St. Bees, had never been further than Keswick or Cockermouth, the two great emporia and larders of Buttermere. He had not missed Keswick Cheese Fair for forty Martinmasses, and had been a regular attendant at Lanthwaite Green, every September, with his lean sheep for grazing. Nor did the Monday morning’s market at Cockermouth ever open without Mr. Christopher Sandboys, but on one day, and that was when the two bells of Lorton Church tried to tinkle a marriage peal in honour of his wedding with the heiress of Newlands. A “statesman” by birth, he possessed some hundred acres of land, with “pasturing” on the fell side for his sheep; in which he took such pride that the walls of his “keeping-room,” or, as we should call it, sitting-room, were covered on one side with printed bills telling how his “lamb-sucked ewes,” his “Herdwickes” and his “shearling tups” and “gimmers” had carried off the first and second best prices at Wastdale and at Deanscale shows. Indeed, it was his continual boast that he grew the coat he had on his back, and he delighted not only to clothe himself, but his son Jobby (much to the annoyance of the youth, who sighed for the gentler graces of kerseymere) in the undyed, or “self-coloured,” wool of his sheep, known to all the country round as the “Sandboys’ Grey”—in reality a peculiar tint of speckled brown. His winter mornings were passed in making nets, and in the summer his winter-woven nets were used to despoil the waters of Buttermere of their trout and char. He knew little of the world but through the newspapers that reached him, half-priced, stained with tea, butter, and eggs, from a coffee-shop in London—and nothing of society but through that ideal distortion given us in novels, which makes the whole human family appear as a small colony of penniless angels and wealthy demons. His long evenings were, however, generally devoted to the perusal of his newspaper, and, living in a district to which crime was unknown, he became gradually impressed by reading the long catalogues of robberies and murders that filled his London weekly and daily sheets, that all out of Cumberland was in a state of savage barbarism, and that the Metropolis was a very caldron of wickedness, of which the grosser scum was continually being taken off, through the medium of the police, to the colonies. In a word, the bugbear that haunted the innocent mind of poor Mr. Cursty Sandboys was the wickedness of all the world but Buttermere.

And yet to have looked at the man, one would never suppose that Sandboys could be nervous about anything. Taller than even the tallest of the villagers, among whom he had been bred and born, he looked a grand specimen of the human race in a country where it is by no means uncommon to see a labouring man with form and features as dignified, and manners as grave and self-possessed, as the highest bred nobleman in the land. His complexion still bore traces of the dark Celtic mountain tribe to which he belonged, but age had silvered his hair, which, with his white eyebrows and whiskers, contrasted strongly and almost beautifully with a small “cwoal-black een.” So commanding, indeed, was his whole appearance, though in his suit of homespun grey, that, on first acquaintance, the exceeding simplicity of his nature came upon those who were strangers to the man and the place with a pleasant surprise.

Suspicious as he was theoretically, and convinced of the utter evil of the ways of the world without Buttermere, still, practically, Cursty Sandboys was the easy dupe of many a tramp and Turnpike Sailor, that with long tales of intricate and accumulative distress, supported by apocryphal briefs and petitions, signed and attested by “phantasm” mayors and magistrates, sought out the fastnesses of Buttermere, to prey upon the innocence and hospitality of its people.[3]

3. To prove to the reader how systematic and professional is the vagrancy and trading beggary of this county, a gentleman, living in the neighbourhood of Buttermere, and to whom we are indebted for many other favours, has obliged us with the subjoined registry and analysis of the vagabonds who sought relief at his house, from April 1, 1848, to March 31, 1849:—

| Males (strangers) | 80 |

| Males (previously relieved) | 73 |

| Females (strangers) | 10 |

| Females (previously relieved) | 41 |

| ── | |

| Total | 204 |

This is at the rate of two beggars a week, for the colder six months in the year, and six a week in the warm weather, visiting as remote, secluded, and humble a village as any in the kingdom. It is curious to note in the above the great number of females “previously relieved” compared with the “strangers,” as showing that when women take to vagrancy they seldom abandon the trade. It were to be desired that gentlemen would perform similar services to the above in their several parts of the kingdom, so that, by a large collection of facts, the public might be at last convinced how pernicious to a community is promiscuous charity. Of all lessons there is none so dangerous as to teach people that they can live by other means than labour.

It was Mr. Sandboys’ special delight, of an evening, to read the newspaper aloud to his family, and endeavour to impress his wife and children with the same sense of the rascality of the outer world as reigned within his own bosom. But his denunciations, as is too often the case, served chiefly to draw attention and to excite curiosity touching subjects, which, without them, would probably have remained unheard of: so that his family, unknown to each other, were secretly sighing for that propitious turn of destiny which should impel them where fashion and amusement never failed, as their father said, to lure their victim from more serious pursuits.

The mind of Mrs. Sandboys was almost as circumscribed as that of the good Cursty himself. If Sandboys loved his country, and its mountains, she was lost in her kitchen, her beds, and her buckbasket. His soul was hemmed in by “the Hay-Stacks,” Red Pike, Melbrake, and Grassmoor; and hers, by the four walls of Hassness house. She prided herself on her puddings, and did not hesitate to take her stand upon her piecrust. She had often been heard to say, with extreme satisfaction, that her “Buttered sops” were the admiration of the country round—and it was her boast that she could turn the large thin oat-cake at a toss; while the only feud she had ever been known to have in all her life, was with Mrs. Gill, of Low-Houses, Newlands, who declared that in her opinion the cakes were better made with two “backbwords” than one; and though several attempts had been made towards reconciliation, she had ever since withstood all advances towards a renewal of the ancient friendship that had cemented the two families. It was her glory that certain receipts had been in her family—the heirlooms of the eldest daughter—for many generations; and, when roused on the subject, she had been heard to exclaim, that she would not part with her wild raspberry jelly but with her life; and, come what may, she had made up her mind, to carry her “sugared curds” down with her to her grave.

The peculiar feature of Mrs. Sandboys’ mind was to magnify the mildest trifles into violent catastrophes. If a China shepherdess, or porcelain Prince Albert, were broken, she took it almost as much to heart as if a baby had been killed. Washing, to her, was almost a sacred ceremony, the day being invariably accompanied with fasts. Her beds were white as the opposite waters of “Sour Milk Gill;” and the brightness of the brass hobs in the keeping-room at Hassness were brilliant tablets to record her domestic virtues. She was perpetually waging war with cobwebs, and, though naturally of a strong turn of mind, the only time she had been known to faint was, when the only flea ever seen in Hassness House made its appearance full in the front of Cursty Sandboys’ shirt, at his dinner, for the celebration of a Sheep-Shearing Prize. If her husband dreaded visiting London on account of its iniquities, she was deterred by the Cumberland legend of its bugs—for, to her rural mind, the people of the Great Metropolis seemed to be as much preyed upon by these vermin, as the natives of India by the white ants—and it was a conviction firmly implanted in her bosom, that if she once trusted herself in a London four-post, there would be nothing left of her in the morning but her nightcap.

The son and daughter of this hopeful pair were mere common-place creatures. The boy, Jobby, as Joseph is familiarly called in Cumberland, had just shot up into hobbledehoyhood, and was long and thin, as if Nature had drawn him, like a telescope, out of his boots. Though almost a man in stature, he was still a boy in tastes, and full of life and activity—ever, to his mother’s horror, tearing his clothes in climbing the craigs for starlings and magpies, or ransacking the hedges for “spinks” and “skopps;” or else he terrified her by remaining out on the lake long past dusk, in a boat, or delighting to go up into the fells after the sheep, when overblown by the winter’s snow. His mother declared, after the ancient maternal fashion, that it was impossible to keep that boy clean, and however he wore out his clothes and shoes was more than she could tell. The pockets of the youth—of which she occasionally insisted on seeing the contents—will best show his character to the discerning reader; these usually proved to comprise gentles, oat-cake, a leather sucker, percussion caps, a short pipe, (for, truth to say, the youth was studying this great art of modern manhood), a few remaining blaeberries, a Jew’s-harp, a lump of cobbler’s wax, a small coil of shining gut, with fish-hooks at the end, a charge or two of shot, the Cumberland Songster, a many-bladed knife with cork-screw, horsepicker, and saw at the back, together with a small mass of paste, swarming with thin red worms, tied up in one of his sister’s best cambric pocket-handkerchiefs.

Elcy, or Alice Sandboys, the sister of the last-named young gentleman, was some two or three years his elder; and, taking after her mother, had rather more of the Saxon complexion than her father or brother. At that age when the affections seek for something to rest themselves upon, and located where society afforded no fitting object for her sympathies, her girlish bosom found relief in expending its tenderness on pet doves, and squirrels, and magpies, and such gentler creatures as were denizens of her father’s woods. These, and all other animals, she spoke of in diminutive endearment; no matter what the size, all animals were little to her; for, in her own language, her domestic menagerie consisted of her dovey, her doggey, her dickey, her pussey, her scuggy, her piggey, and her cowey. In her extreme love for the animal creation, she would have taken the young trout from its play and liberty in the broad lake beside her, and kept it for ever circling round the crystal treadmill of a glass globe. But the course of her true love ran anything but smooth. Jobby was continually slitting the tongue of her magpie with a silver sixpence, to increase its powers of language, or angling for her gold fish with an elaborate apparatus of hooks, or carrying off her favourite spaniel to have his ears and tail cut in the last new fashion, at the farrier’s, or setting her cat on a board down the lake, or performing a hundred other such freaks as thoughtless youth alone can think of, to the annoyance of susceptible maidens. Herself unaware of the pleasures of which she deprived the animals she caged and globed, and on which her sole anxiety was to heap every kindness, she was continually remonstrating with her brother (we regret to say with little effect) as to the wickedness of fishing, or, indeed, of putting anything to pain.

Such was the character of the family located at Hassness House,—the only residence that animated the solitary banks of Buttermere—and such doubtless would the Sandboys have ever remained but for the advent of the year 1851. The news of the opening of the Great Exhibition had already penetrated the fastnesses of Buttermere, and the villagers, who perhaps, but for the notion that the whole world was about to treat itself to a trip to the metropolis, would have remained quiet in their mountain homes, had been, for months past, subscribing their pennies with the intention of having their share in the general holiday. Buttermere was one universal scene of excitement from Woodhouse to Gatesgarth. Mrs. Nelson was making a double allowance of her excellent oat-cakes; Mrs. Clark, of the Fish Inn, was packing up a jar of sugared butter, among other creature comforts for the occasion. John Cowman was brushing up his top-shirt; Dan Fleming was greasing his calkered boots; John Lancaster was wondering whether his hat were good enough for the great show; all the old dames were busy ironing their deep-frilled caps, and airing their hoods; all the young lasses were stitching at all their dresses, while some of the more nervous villagers, who had never yet trusted themselves to a railway, were secretly making their wills—preparatory to their grand starting for the metropolis.

Amidst this general bustle and excitement there was, however, one house where the master was not absorbed in a calculation as to the probable length and expenses of the journey; where the mistress was not busy preparing for the comfort of the outward and inward man of her lord and master; where the daughter was not in deep consultation as to the prevailing metropolitan fashions—and this house was Hassness. For Mr. Sandboys, with his long-cherished conviction of the wickedness of London, had expressed in unmeasured terms his positive determination that neither he himself, nor any that belonged to him, should ever be exposed to the moral pollution of the metropolis. This was a sentiment in which Mrs. Sandboys heartily concurred, though on very different grounds—the one objecting to the moral, the other to the physical, contamination of the crowded city. Mr. Sandboys had been thrice solicited to join the Buttermere Travelling Club, and thrice he had held out against the most persuasive appeals. But Squire Jopson, who acted as Treasurer to the Travelling Association for the Great Exhibition of 1851, not liking that his old friend Sandboys should be the only one in all Buttermere who absented himself from the general visit to the metropolis, waited upon him at Hassness, to offer him the last chance of availing himself of the advantages of that valuable institution as a means of conveying himself and family, at the smallest possible expense, to the great metropolis, and of allowing him and them a week’s stay, as well as the privilege of participating in all the amusements and gaieties of the capital at its gayest possible time.

It was a severe trial for Sandboys to withstand the united batteries of Jopson’s enthusiastic advocacy, his daughter’s entreaties, his son’s assurances of steadiness. But Sandboys, though naturally possessed of a heart of butter, delighted to assure himself that he carried about a flint in his bosom; so he told Jopson, with a shake of his head, that he might as well try to move Helvellyn or shake Skiddaw; and that, while he blushed for the weakness of his family, he thanked Heaven that he, at least, was adamant.

Jopson showed him by the list he brought with him that the whole of the villagers were going, and that Hassness would be left neighbourless for a circuit of seven miles at least; whereupon Sandboys observed with a chuckle, that the place could not be much more quiet than it was, and that with those fine fellows, Robinson and Davy Top, and Dod and Honister around him, he should never want company.

Jopson talked sagely of youths seeing the world and expanding their minds by travel; whereat the eyes of the younger Sandboys glistened; but the father rejoined, that travel was of use only for the natural beauties of the scenery it revealed, and the virtues of the people with whom it brought the traveller into association; “and where,” he asked, with evident pride of county, “could more natural beauty or greater native virtue be found, than amongst the mountains and the pastoral race of Buttermere?” Seizing the latest Times that had reached him the evening before, he pointed triumphantly to some paragraph, headed “Ingenious Fraud on a Yokel!” wherein a country gentleman had been cleverly duped of some hundreds of pounds paid to him that morning at Smithfield; and he asked with sarcasm, whether those were the scenes and those the people that Jopson thought he could improve his son Jobby by introducing him to?

In vain Jopson pulled from his pocket a counter newspaper, and showed him the plan of some Monster Lodging House which was to afford accommodation for one thousand persons from the country at one and the same time, “for one-and-three per night!”—how, for this small sum, each of the thousand was to be provided “with bedstead, good wool mattress, sheets, blankets, and coverlet; with soap, towels, and every accommodation for ablution;”—how the two thousand boots of the thousand lodgers were to be cleaned at one penny per pair, and their one thousand chins to be shaven by relays of barbers continually in attendance—how a surgeon was “to attend at nine o’clock every morning,” to examine the lodgers, and “instantly remove all cases of infectious disease”—how there was to be “a smoking-room, detached from the main-building, where a band of music was to play every evening, gratis”—how omnibuses to all the theatres and amusements and sights were to carry the thousand sight-seers at one penny per head—how “cold roast and boiled beef and mutton, and ditto ditto sausages and bacon, and pickles, salads, and fruit pies (when to be procured), were to be furnished, at fixed prices,” to the thousand country gentlemen with the thousand country appetites—how “all the dormitories were to be well lighted with gas to secure the complete privacy of the occupants”—how “they were to be watched over by efficient wardens and police constables”—how “an office was to be opened for the security of luggage”—and how “the proprietor pledged himself that every care should be taken to ensure the comfort, convenience, and strict discipline of so large a body.”

Sandboys, who had sat perfectly quiet while Jobson was detailing the several advantages of this Brobdignagian boarding-house, burst out at the completion of the narrative with a demand to be informed whether it was probable that he, who had passed his whole life in a village consisting of fifteen houses and but seven families, would, in his fifty-fifth year, consent to take up his abode with a thousand people under one roof, with a gas-light to secure the privacy of his bed-room, policemen to watch him all night, and a surgeon to examine him in the morning!

Having thus delivered himself, he turned round, with satisfaction, to appeal to his wife and children, when he found them, to his horror, with the newspaper in their hands, busily admiring the picture of the very building that he had so forcibly denounced.

Early the next morning, Mrs. Sandboys, with Jobby and Elcy, went down to the Fish Inn, to see the dozen carts and cars leave, with the united villagers of Buttermere, for the “Travellers’ Train” at Cockermouth. There was the stalwart Daniel Fleming, of the White Howe, mounted on his horse, with his wife, her baby in her arms, and the children, with the farm maid, in the cart,—his two men trudging by its side. There was John Clark, of Wilkinsyke, the farmer and statesman, with his black-haired sons, Isaac and Johnny, while Richard rode the piebald pony; and Joseph and his wife, with little Grace, and their rosy-cheeked maid, Susannah, from the Fish Inn, sat in the car, kept at other times for the accommodation of their visitors. After them came Isaac Cowman, of the Croft, the red-faced farmer-constable, with his fine tall, flaxen, Saxon family about him; and, following in his wake, his Roman-nosed nephew John, the host of “The Victoria,” with his brisk, bustling wife on his arm. Then came handsome old John Lancaster, seventy years of age, and as straight as the mountain larch, with his wife and his sons, Andrew and Robert, and their wives. And following these, John Branthwaite, of Bowtherbeck, the parish-clerk, with his wife and wife’s mother; and Edward Nelson, the sheep-breeder, of Gatesgarth, dressed in his well-known suit of grey, with his buxom gudewife, and her three boys and her two girls by her side; while the fresh-coloured bonnie lassie, her maid, Betty Gatesgarth, of Gatesgarth, in her bright green dress and pink ribbons, strutted along in their wake. Then came the Riggs’: James Rigg, the miner, of Scots Tuft, who had come over from his work at Cleator for the special holiday; and there were his wife and young boys, and Jane Rigg, the widow, and her daughter Mary Ann, the grey-eyed beauty of Buttermere, in her jaunty jacket-waisted dress; with her swarthy black-whiskered Celtic brother, and his pleasant-faced Saxon wife carrying their chubby-cheeked child; and behind them came Ann Rigg, the slater’s widow, from Craig House, with her boys and little girl; and, leaning on their shoulders, the eighty-years old, white-haired Braithwaite Rigg and his venerable dame; and close upon them was seen old Rowley Lightfoot, his wife, and son John. Squire Jobson’s man walked beside the car from the Fish Inn, talking to the tidy, clean old housekeeper of Woodhouse; while the Squire himself rode in the rear, proud and happy as he marshalled the merry little band along;—for, truth to say, it would have been difficult to find in any other part of England so much manliness and so much rustic beauty centred in so small a spot.

As they moved gently along the road, John Cowman, the host of the Victoria, struck up the following well-known song, which was welcomed with a shout from the whole “lating”—

Then the gust rushed down the valley, and the voices of the happy holiday throng were swept, for a moment, away; as it lulled again, the ear, familiar to the song, could catch the laugh and cheers that accompanied the next verse:—

Again the voices were lost in the turning of the road, and presently, as they shot out once more, they might be heard singing in full chorus—

At last, all was still—but scarcely more still than when the whole of the cottages were filled with their little families, for the village, though now utterly deserted, would have seemed to the stranger to have been as thickly populated and busy as ever.

The younger Sandboys took the departure of the villagers more to heart than did their mother; though, true to her woman’s nature, had the trip been anywhere but to London, she would have felt hurt at not making one of the pleasure party. On reaching home, she and Mr. Sandboys congratulated one another that they were not on their way to suffer the miseries of a week’s residence amidst either the dirt or the wickedness of the metropolis; but Elcy and Jobby began, for the first time, to feel that the retirement, which they heard so much vaunted every day, and which so many persons came from all parts of the country to look at and admire, cut them off from a considerable share of the pleasures which all the world else seemed so ready to enjoy, and which they began shrewdly to suspect were not quite so terrible as their father was in the habit of making out.

Thus matters continued at Hassness till the next Tuesday evening, when Mrs. Sandboys remarked that it was “very strange” that “Matthew Harker, t’ grocer, had not been to village” with his pony and cart that day; and what she s’ud do for t’ tea, and sugar, and soft bread, she didn’t know.

Now, seeing that the nearest grocer was ten miles distant, and that there was no borrowing this necessary article from any of their neighbours, as the whole village was then safely housed in London, such a failure in the visit of the peripatetic tea-man, upon whom the inhabitants of Buttermere and Crummock Water one and all depended for their souchong, and lump, and moist, and wheaten bread, was a matter of more serious importance than a townsman might imagine.

It was therefore arranged that Postlethwaite their man should take Paddy t’ pony over to Keswick the next day, to get the week’s supply of grocery, and learn what had happened to Harker, in whom the Sandboys took a greater interest from the fact of their having subscribed, with others of the gentry, when Harker lost his hand by blasting cobbles, to start him in the grocery business, and provide him with a horse and cart to carry his goods round the country.

Postlethwaite—a long, grave, saturnine-looking man, who was “a little” hard of hearing, was, after much shouting in the kitchen, made to comprehend the nature of his errand. But he had quitted Hassness only a short hour, when he returned with the sad intelligence—which he had picked up from Ellick Crackenthorpe, who was left in charge of Keskadale, while the family had gone to town,—that Harker, finding all the folk about Keswick had departed for the Great Exhibition, and hearing that Buttermere had done the same, had put his wife and his nine children inside his own van, and was at that time crawling up by easy stages to London.

Moreover, Postlethwaite brought in the dreary tidings that, in coming down from the top of the Hause, just by Bear’s fall, Paddy had cast a shoe, and that it was as much as he could do to get him down the Moss side. This calamity was a matter of as much delight to the youngsters as it was of annoyance to the elder Sandboys; for seeing that Bob Beck, the nearest blacksmith, lived six miles distant, and that it was impossible to send either to Cockermouth or Keswick for the necessaries of life, until the pony was armed against the rockiness of the road, it became a matter of considerable difficulty to settle what could be done.

After much serious deliberation, it was finally arranged that Postlethwaite should lead the pony on to the “smiddy,” at Loweswater, to be shod, and then ride him over to Dodgson’s, the grocer’s, at Cockermouth.

Postlethwaite, already tired, and, it must be confessed, not a little vexed at the refusal of Mr. Sandboys to permit him to accompany his fellow-villagers on this London trip—the greatest event of all their lives—started very sulky, and came back, long after dusk, with the pony lamed by a stone in his foot, and himself savage with hunger, and almost rebellious with fatigue; for, on getting to the “smiddy,” he found that Beck the blacksmith had ruddled on his door the inscription—

and, worse than all to Postlethwaite, he discovered, moreover, on seeking his usual ale at Kirkstile, that Harry Pearson, the landlord, had accompanied the Buttermere travellers’ train up to town; and that John Wilkinson, the other landlord, had followed him the day after; so that there was neither bite nor sup to be had in the place, and no entertainment either for man or beast.

In pity to Paddy, if not in remembrance of the farmer’s good cheer, Postlethwaite, on his way back, turned down to Joe Watson’s, at Lanthwaite, and there found it impossible to make anybody hear him, for the farmer and his six noble-looking sons—known for miles round as the flower of the country—had also joined the sight-seers on their way to the train at Cockermouth.

This was sad news to the little household. It was the first incident that gave Mrs. Sandboys an insight into the possible difficulties that their remaining behind, alone, at Hassness, might entail upon the family. She, and Mr. Sandboys, had hitherto only thought of the inconveniences attending a visit to London, and little dreamt that their absence from it, at such a time, might force them to undergo even greater troubles. She could perhaps have cheerfully tolerated the abdication of the Cockermouth milliner—she might have heard, without a sigh, that Mr. Bailey had put up the shutters of his circulating library, and stopped the supply of “Henrietta Temples,” “Emilia Wyndhams,” and “The Two Old Men;” she might not even have complained had Thompson Martin, the draper, cut short her ribbons and laces, by shutting up his shop altogether—but to have taken away her tea and sugar, was more than a lady in the vale of years, and the valley of Buttermere, could be expected to endure, without some outrage to philosophy!

The partiality of the sex in general for their morning and evening cup of souchong and “best refined,” is now ranked by physiologists among those inscrutable instincts of sentient nature, which are beyond the reach of scientific explanation. What oil is to the Esquimaux, what the juice of the cocoa-nut is to the monkey, what water is to the fish, what dew is to the flower, and what milk is to the cat—so is tea to woman! No person yet, in our own country, has propounded any sufficient theory to account for the English washerwomen’s all-absorbing love of the Chinese infusion—nor for the fact of every maid-servant, when stipulating the terms of her engagement, always making it an express condition of the hiring, that she should be provided with “tea and sugar,” and of every mistress continually declaring that she “would rather at any time go without her dinner than her tea.”

What sage has yet taught us why womankind is as gregarious over tea as mankind over wine? Sheridan has called the Bottle the sun of the table; but surely the Teapot, with its attendant cups, may be considered as a heavenly system, towards which all the more beautiful bodies concentre, where the piano may be said to represent the music of the spheres, and in which the gentlemen, heated with wine, and darting in eccentric course from the dining-room, may be regarded as fiery comets. We would ask any lady whether Paradise could have been a garden of bliss without the tea-plant; and whether the ever-to-be-regretted error of our first mother was not the more unpardonable from the fact of her having preferred to pilfer an apple rather than pluck the “fullest flavoured Pekoe.” And may not psychology here trace some faint transcendental reason for the descendants of Adam still loving to linger over their apples after dinner, shunning the tea-table and those connected with it. Yet, perhaps, even the eating of apples has not been more dangerous to the human family than the sipping of tea. If sin came in with pippins, surely scandal was brought into the world with Bohea! Adam fell a victim to his wife’s longing for a Ribston, and how many Eves have since fallen martyrs to the sex’s love of the slanderous Souchong.

Mrs. Sandboys was not prepared for so great a sacrifice as her tea, and when she first heard from Postlethwaite the certainty of Harker’s departure, and saw, by the result of this second journey, that there was no hope of obtaining a supply from Cockermouth, there was a moment when she allowed her bosom to whisper to her, that even the terror of a bed in London would be preferable to a tea-less life at Hassness.

Mr. Sandboys, however, no sooner saw that there was no tea or sugar to be had, than he determined to sweeten his cup with philosophy; so, bursting out with a snatch of the “Cumberland Lang Seyne,” he exclaimed, as cheerily as he could under the circumstances—

and immediately after this, decided upon the whole family’s reverting to the habits of their ancestors, and drinking “yale” for breakfast. This was by no means pleasant, but as it was clear she could do nothing else, Mrs. Sandboys, like a sensible woman, turned her attention to the contents of the ale-cask, and then discovered that some evil-disposed person, whom she strongly suspected to be Master Jobby—for that young gentleman began to display an increasing enjoyment in each succeeding catastrophe—had left the tap running, and that the cellar floor was covered three inches deep with the liquid intended to take off the dryness and somewhat sawdusty character of the oat-cake, which, in the absence of any wheaten bread, now formed the staple of their morning meal.

Now it so happened, that it wanted a fortnight of the return of Jennings’ man, the brewer, whose periodical circumgyrations with the beer, round about Buttermere, gave, like the sun, life and heat to the system of its inhabitants. In this dire emergency, Postlethwaite, whose deafness was found to increase exactly in proportion to the inconvenience of the journeys required of him, was had out, and shaken well, and bawled at, preparatory to a walk over to Lorton Vale, where the brewery was situated—only six miles distant.

But his trip on this occasion was about as successful as the last, for on reaching the spot, he found that the brewer, like the grocer, the farrier, and the publicans, had disappeared for London on the same pleasurable mission.

The family at Hassness was thus left without tea, beer, or bread, and, consequently, reduced to the pure mountain stream for their beverage, and oaten cakes and bacon for their principal diet. Their stock of fresh meat was usually procured from Frank Hutchison, the butcher of Cockermouth, but to go or send thither, under their present circumstances, appeared to be impossible. So that Mrs. Sandboys began to have serious alarms about two or three pimples that made their appearance on Cursty’s face, lest a continued course of salt meat and oat-cake should end in the whole family being afflicted with the scurvy. She would immediately have insisted on putting them, one and all, under a severe course of treacle and brimstone, with a dash of cream of tartar in it, to “sweeten their blood;” only, luckily, there was neither treacle nor brimstone, nor cream of tartar, to be had for twenty miles, nor anybody to go for it, and then, probably, nobody at Mr. Bowerbank’s to serve it.

Sandboys, seeing that he had no longer any hope in Postlethwaite, was now awakened to the necessity of making a personal exertion. His wife, overpowered by this addition of the loss of dinner to the loss of tea, did not hesitate to suggest to him, that perhaps it might be as well, if they consented to do like the rest of the world, and betake themselves for a few days to London. For her own part, she was ready to make any sacrifice, even to face the London dirt. But Sandboys would listen to no compromise, declared that greatness showed itself alone in overcoming circumstances,—and talked grandly of his forefathers, who had held out so long in these self-same mountain fastnesses. Mrs. Sandboys had no objection to make to the heroism, but she said that really Elcy’s complexion required fresh meat; and that although she herself was prepared to give up a great deal, yet her Sunday’s dinner was more than she was inclined to part with, and as for sacrifices, she had already sacrificed enough in the loss of her tea. Mr. Sandboys upon this bethought him of John Banks, the pig-butcher at Lorton, and having a young porker just ready for the knife, fancied he could not do better than despatch Postlethwaite with the animal to Lorton to be slaughtered. This, however, was sooner decided upon than effected; for Postlethwaite, on being summoned, made his appearance in slippers, and declared he had worn out, in his several foraging excursions about the country, the only pair of shoes he had left. Whereupon his master, though it was with some difficulty he admitted the excuse,—and this not until Postlethwaite, with a piteous gravity, had brought out a pair of calkered boots in the very worst possible condition,—began to foresee that there was even more necessity for Postlethwaite to be shod than Paddy, for that unless he could be got over to Cockermouth, they might be fairly starved out. Accordingly, he gave his son Jobby instructions to make the best of his way to the two shoemakers who resided within five miles of Hassness, for he made sure that one of the cobblers at least could be prevailed upon to put Postlethwaite in immediate travelling order.

It was long after nightfall, and Mrs. Sandboys had grown very uneasy as to the fate of her dear boy, when Postlethwaite was heard condoling over the miserable plight of Master Jobby. His mother rushed out to see what had happened, and found the bedraggled youth standing with one shoe in the hall, the other having been left behind in a bog, which he had met with in his attempt to make a short cut home on the other side of the lake by Melbrake.

Nor was the news he brought of a more cheerful nature. John Jackson the shoemaker was nowhere to be found. He had not been heard of since the departure of the train; and John Coss, the other shoemaker, had turned post-boy again, and refused to do any cobbling whatsoever. Coss had told him he got a job to take some gentlefolks in a car over to Carlisle, to meet the train for London, and he was just about to start; and if Jobby liked, he would give him a lift thus far on t’ road to Girt ’Shibition.

This was a sad damper for Sandboys, for with John Jackson the shoemaker seemed to vanish his last hope. Postlethwaite had worn out his boots, Jobby had lost his shoes, and John Jackson and John Coss, the only men, within ten miles, who could refit them, were both too fully taken up with the Great Exhibition to trouble their heads about the destitution of Hassness.

Postlethwaite almost smiled when he heard the result of Jobby’s twelve-mile walk, and drily remarked to the servant-maid, who already showed strong symptoms of discontent—having herself a sweetheart exposed, without her care, to the temptations and wickedness of London—that the whole family would be soon barefoot, and going about the countryside trying to get one another shod.

Sandboys consulted with his wife as to what was to be done, but she administered but little consolation; for the loss of her tea, and the prospect of no Sunday’s dinner, had ruffled her usual equanimity. The sight of her darling boy, too, barefoot and footsore, aroused every passion of her mother’s heart. Jobby had no other shoes to his feet, she told her husband, for the rate at which that boy wore his things out was quite terrible to a mother’s feelings; but Mr. Sandboys had no right to send the lad to such a distance, after such weather as they had just had. He might have known that Jobby was always taking short cuts, and always getting up to his knees in some mess or other; and he must naturally have expected that Jobby would have left both his shoes behind him instead of one—and those the only shoes he had. She should not wonder if Mr. Sandboys had done it for the purpose. Who was to go the errands now, she should like to know? Mr. Sandboys, perhaps, liked living there, in that out of the way hole, like a giant or a hermit. Did he expect that she or Elcy were going to drive that pig to Lorton?—And thus she continued, going over and over again every one of the troubles that their absence from London had brought upon them, until Sandboys was worried into excitement, and plumply demanded of her whether she actually wished to go herself to the Exhibition? Mrs. Sandboys was at no loss for a reply, and retorted, that what she wanted was her usual meals, and shoes for her children; and if she could not get them there, why, she did not care if she had to go to Hyde Park for them.

Sandboys was little prepared for this confession of hostilities on the part of his beloved Aggy. He had never known her address him in such a tone since the day she swore at Lorton to honour and obey him. He jumped from his chair and began to pace the room—now wondering what had come to his family and servants, now lamenting the want of tea, now sympathizing with the absence of ale, now biting his thumb as he contemplated the approximating dilemma of a dinnerless Sunday, and now inwardly cursing the Great Exhibition, which had not only taken all his neighbours from him, and deprived him of almost all the necessaries of life, but seemed destined to estrange his wife and children!

For a moment the idea passed across his mind, that perhaps it might be better to give way; but he cast the thought from him immediately, and as he trod the room with redoubled quickness and firmness of step, he buttoned his grey coat energetically across his breast, swelling with a resolution to make a desperate effort. He would drive the pig himself over to John Banks, the pig-butcher’s, at Lorton! But, as in the case of Postlethwaite, Mr. Cursty Sandboys soon found that resolving to drive a pig was a far different thing from doing it. Even in a level country the pig-driving art is none of the most facile acquirements,—but where the way to be traversed consists at every other yard of either a fell, a craig, a gill, a morass, a comb, a pike, a knot, a rigg, a skar, a beck, a howe, a force, a syke, or a tarn, or some other variety of those comfortable quarters into which a pig, with his peculiar perversity, would take especial delight in introducing his compagnon de voyage—the accomplishment of pig-driving in Cumberland partakes of the character of what aesthetic critics love to term “High Art.”

Nor did Mr. Sandboys’ pig—in spite of the benevolence and “sops” administered during his education by the gentle Elcy, who shed tears at his departure—at all detract from the glories of his race. Contrary to the earnest advice of Postlethwaite, founded on the experience of ages, who exhorted his master to keep the string loose in his hand—Sandboys, who had a theory of his own about pig-driving, and who was afraid that if the animal once got away from him in the hills, he would carry with him the family’s only chance of fresh meat for weeks to come—made up his mind to keep a safe hold of him, and so, twisted the string which he had attached to the porker’s leg two or three turns round his own wrist.

Scarcely had Elcy petitioned her brother for the gentle treatment of her pet “piggy,” than, crack! Jobby, who held the whip at the gate, while his father adjusted the reins, sent a flanker on the animal’s hind-quarters. Away went “piggy,” and we regret to say, away went the innocent Sandboys, not after, but with him—and precisely in the opposite direction to what he had intended. “Cwoley,” the dog, who had been dancing round the pig at the gate, no sooner saw the animal start off at score, than entering into the spirit of the scene, he gave full chase, yelping, and jumping, and snapping at him, so that the terrified porker fetched sharp round upon Sandboys, and bolted straight up the mountain side.

Now, to the stranger it should be made known, that climbing the fells of Cumberland is no slight task—even when the traveller is allowed to pick his steps; but, with a pig to lead, no choice but to follow, and a dog behind to urge the porker on, the operation becomes one of considerable hardship, if not peril. Moreover, the mountain over which Mr. Sandboys’ pig had chosen to make his course, was called “the Moss,” or “Morass,” from its peculiar swampy character. Up went the pig, through bracken, and furze, and holly-bush, and up by the stunted oaks, and short-cut stumps, and straight on, up through the larches, over the rugged clump above Hassness; and up went Mr. Sandboys, over and through every one of the same obstacles, making a fresh rent in his trousers at every “whin-bush”—scratched, torn, panting, slipping, and—if we must confess it—swearing; now tumbling, now up again, but still holding on to the pig, or the pig holding on to him, for grim death.

But if it were difficult to ascend a Cumberland fell with a pig in front, how much more trying the descent! No sooner had “Cwoley” turned the pig at the top, than Sandboys, as he looked down the precipitous mountain up which his porker had dragged him, “saw his work before him.” It required but a slight momentum to start him; then, away they all three went together—in racing technology “you might have covered them with a sheet”—-the dog barking, and the pig squeaking, and dragging Mr. Sandboys down the hill at a rate that promised to bring him to the bottom with more celerity than safety. Unfortunately, too, the pig took his course towards the beck formed by the torrent at the “Goat’s Gills;” and no sooner did it reach the ravine, than, worried by the dog, it precipitated itself and Mr. Sandboys right down into the foaming, but luckily not very deep, waters.

But, if it were not deep, the bottom of the beck was at least stony; and there, on his back, without breath to cry out, lay the wretched Sandboys, a victim to his theory, his coat skirtless, his pantaloons torn to shreds, and the waters curling white about him, with the driving string in his hand, cut by the sharp craigs in his fall—while the legs, the loin, the griskin, and the chine—that were to have consoled the family for weeks, were running off upon the pettitoes which he had privately set aside for his own supper on some quiet evening.

Elcy, who, throughout the whole chase, had been bewailing the poor “piggy’s” troubles, and exclaiming to her father not to hurt it, screamed with terror, as, from the gate, she saw the plunge and splash; while the wicked Jobby, who had been rendered powerless by laughter, and the want of shoes, and Postlethwaite, who also had been inwardly enjoying the scene, now rushed forward to the rescue, in company with the whole household, and dragged out from the beck the bruised, tattered, bedraggled, bespattered, bedrenched, and wretched Sandboys—the more annoyed, because the first inquiry addressed to him by Mrs. Sandboys, in a voice of mingled terror and tenderness, was, “Whatever has become of the pig?”

That was a mystery which took some hour or two to solve; for it was not until Elcy and Jobby, in Postlethwaite’s old shoes, had explored both Robinson and the Moss, that they caught sight of “Cwoley” on the slope beside the foot of Buttermere Lake, dancing, in wild delight, round the shaft of a deserted mine, known as “Muddock,” where, as became evident from the string twisted round the bushes, the pig, like Curtius, had plunged suicidally into the gulf, and was then lying, unbaked, unroasted, and unboiled, in twelve foot water!

Sandboys, when the news was brought him, was, both metaphorically and literally, in hot water. He sat with his two feet in a steaming pail, and wrapped in a blanket, with a basin of smoking oatmeal gruel in his hand, Mrs. Sandboys by his side, airing a clean shirt at the fire, and vowing all the while, that she would not wonder if his obstinacy in stopping down there, starving all the family, and denying them even the necessaries of life, to gratify his own perversity, were not the death of herself and the dear children. If he caught his death, he would only have himself to blame; for there was not a Dover’s Powder within twenty miles to be had for love or money; and as for tallowing his nose, it was more than she could afford to do, for the candles were running so short, and there was not a tallow-chandler remaining in the neighbourhood, so that in a few days she knew that, all through his fine management, they would be left not only tealess, beerless, meatless, and, she would add, her dear boy shoeless, but also in positive darkness.