RACE DISTINCTIONS IN AMERICAN LAW

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

America has to-day no problem more perplexing and disquieting than that of the proper and permanent relations between the white and the colored races. Although it concerns most vitally the twenty millions of Caucasians and the eight millions of Negroes in eleven States of the South, still it is a national problem, because whatever affects one part of our national organism concerns the whole of it. Although this question has been considered from almost every conceivable standpoint, few have turned to the laws of the States and of the Nation to see how they bear upon it. It was with the hope of gaining new light on the subject from this source that I undertook the present investigation.

I have examined the Constitutions, statutes, and judicial decisions of the United States and of the States and Territories between 1865 and the present to find the laws that have made any distinctions between persons on the basis of race. Reference has been made to some extent to laws in force before 1865, but only as the background of later legislation and decision. In order to make this study comparative as well as special, the writer has abandoned his original plan of confining it to the Southern States and laws applicable only to Negroes, and has extended viiiit to include the whole United States and all the races.

Immediately after the Negro became a free man in 1865, the Federal Government undertook, by a series of constitutional amendments and statutory enactments, to secure to him all the rights and privileges of an American citizen. My effort has been to ascertain how far this attempt has been successful. The inquiry has been: After forty-five years of freedom from physical bondage, how much does the Negro lack of being, in truth, a full-fledged American citizen? What limitations upon him are allowed or imposed by law because he is a Negro?

This is not meant, however, to be a legal treatise. Although the sources are, in the main, constitutions, statutes, and court reports, an effort has been made to state the principles in an untechnical manner. Knowing that copious citations are usually irksome to those who read for general information, I have relegated all notes to the ends of the chapters for the benefit of the more curious reader who often finds them the most profitable part of a book. There he will find citations of authorities for practically every important statement made.

All the chapters, except the last two, were published serially in The American Law Review/cite> during the year 1909. The substance of the chapter on “Separation of Races in Public Conveyances” was published also in The American Political Science Review for May, 1909.

I wish that I could make public acknowledgment of my indebtedness to all who have helped me in the preparation of this volume. Hundreds of public officials in the South—mayors of cities, clerks of courts, attorneys-general, ixsuperintendents of public instruction, etc.—have responded generously to my requests for information. I am thankful to Mr. John H. Arnold, Librarian of the Harvard Law School, for access to the stacks of that library, without which privilege my work would have been greatly delayed, and to his assistants for their uniform courtesy while I was making such constant demands upon them. I am under especial obligation to Professor Albert Bushnell Hart, of Harvard University, for his direction and assistance in my examination of the sources and his valuable advice while I have been preparing the material for publication in this form; also to Mr. Charles E. Grinnell, former Editor of The American Law Review, for his encouragement and suggestions during the preparation of the articles for his magazine. Lastly, I would express my gratitude to Mr. Charles Vernon Imlay, of the New York Bar, the value of whose painstaking help in the revision of the manuscript of this book is truly inestimable.

| CHAPTER I | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PAGE | |||

| Introductory | 1–11 | ||

| What is a Race Distinction in Law | 1 | ||

| Distinctions and Discriminations Contrasted | 2 | ||

| Legal and Actual Distinctions | 5 | ||

| All Race Elements Included | 6 | ||

| Period Covered from 1865 to Present | 7 | ||

| CHAPTER II | |||

| What is a Negro? | 12–25 | ||

| Legal Definition of Negro | 12 | ||

| Proper Name for Black Men in America | 20 | ||

| CHAPTER III | |||

| Defamation to Call a White Person a Negro | 26–34 | ||

| CHAPTER IV | |||

| The “Black Laws” of 1865–68 | 35–66 | ||

| “Black Laws” of Free States | 36 | ||

| Restrictions upon Movement of Negroes | 40 | ||

| Limitations upon Negroes in Respect to Occupations | 41 | ||

| Sale of Firearms and Liquor to Negroes | 43 | ||

| Labor Contracts of Negroes | 46 | ||

| Apprentice Laws | 53 | ||

| Vagrancy Laws | 58 | ||

| xii | Pauper Laws | 60 | |

| CHAPTER V | |||

| Reconstruction of Marital Relations | 67–77 | ||

| Remarriages | 68 | ||

| Certificates of Marriage | 70 | ||

| Slave Marriages Declared Legal by Statute | 73 | ||

| Marriages Between Slaves and Free Negroes | 74 | ||

| Federal Legislation | 75 | ||

| CHAPTER VI | |||

| Intermarriage and Miscegenation | 78–101 | ||

| Intermarriage During Reconstruction | 78 | ||

| Present State of the Law Against Intermarriage | 81 | ||

| To Whom the Laws Apply | 81 | ||

| Effect of Attempted Intermarriage | 83 | ||

| Punishment for Intermarriage | 84 | ||

| Punishment for Issuing Licenses | 86 | ||

| Punishment for Performing the Ceremony | 87 | ||

| Cohabitation Without Intermarriage | 88 | ||

| States Repealing Laws Against Intermarriage | 89 | ||

| Marriages Between the Negro and Non-Caucasian Races | 90 | ||

| Effect Given to Marriages in Other States | 92 | ||

| Intermarriage and the Federal Constitution | 95 | ||

| Intermarriages in Boston | 98 | ||

| CHAPTER VII | |||

| Civil Rights of Negroes | 102–153 | ||

| Federal Civil Rights Legislation | 103 | ||

| State Legislation Between 1865 and 1883 | 111 | ||

| In States Outside of South | 112 | ||

| In South | 115 | ||

| State Legislation After 1883 | 120 | ||

| In South | 120 | ||

| In States Outside of South | 120 | ||

| Hotels | 124 | ||

| Restaurants | 127 | ||

| Barber-shops | 129 | ||

| xiii | Bootblack Stands | 130 | |

| Billiard-rooms | 131 | ||

| Saloons | 132 | ||

| Soda Fountains | 133 | ||

| Theatres | 134 | ||

| Skating-Rinks | 136 | ||

| Cemeteries | 136 | ||

| Race Discrimination by Insurance Companies | 138 | ||

| Race Discriminations by Labor Unions | 140 | ||

| Churches | 141 | ||

| Negroes in the Militia | 144 | ||

| Separation of State Dependents | 146 | ||

| CHAPTER VIII | |||

| Separation of Races in Schools | 154–206 | ||

| Berea College Affair | 154 | ||

| Exclusion of Japanese from Public Schools of San Francisco | 159 | ||

| Dr. Charles W. Eliot on Separation of Races in Schools | 163 | ||

| Separation Before 1865 | 165 | ||

| Present Extent of Separation in Public Schools | 170 | ||

| In South | 170 | ||

| In States Outside of South | 177 | ||

| Separation in Private Schools | 190 | ||

| Equality of Accommodations | 192 | ||

| Division of Public School Fund | 194 | ||

| CHAPTER IX | |||

| Separation of Races in Public Conveyances | 207–236 | ||

| Origin of “Jim Crow” | 208 | ||

| Development of Legislation Prior to 1875 | 208 | ||

| Legislation Between 1865 and 1881 | 211 | ||

| Separation of Passengers on Steamboats | 214 | ||

| Separation of Passengers in Railroad Cars | 216 | ||

| Interstate and Intrastate Travel | 217 | ||

| Sleeping Cars | 219 | ||

| Waiting-Rooms | 220 | ||

| Trains to which Laws do not Apply | 221 | ||

| xiv | Passengers to whom Law does not Apply | 222 | |

| Nature of Accommodations | 223 | ||

| Means of Separation | 224 | ||

| Designation of Separation | 225 | ||

| Punishment for Violating Law | 225 | ||

| Separation of Postal Clerks | 227 | ||

| Separation of Passengers in Street Cars | 227 | ||

| Present Extent of Separation | 228 | ||

| Method of Separation | 229 | ||

| Enforcement of Laws | 231 | ||

| Exemptions | 232 | ||

| CHAPTER X | |||

| Negro in Court Room | 237–280 | ||

| As Spectator | 237 | ||

| As Judge | 238 | ||

| As Lawyer | 239 | ||

| As Witness | 241 | ||

| As Juror | 247 | ||

| Actual Jury Service by Negroes in South | 253 | ||

| Separate Courts | 272 | ||

| Different Punishments | 273 | ||

| CHAPTER XI | |||

| Suffrage | 281–347 | ||

| Negro Suffrage Before 1865 | 282 | ||

| Suffrage Between 1865 and 1870 | 285 | ||

| Suffrage Between 1870 and 1890 | 288 | ||

| Southern Suffrage Amendments Since 1890 | 294 | ||

| Citizenship | 296 | ||

| Age | 297 | ||

| Sex | 298 | ||

| Residence | 298 | ||

| Payment of Taxes | 299 | ||

| Ownership of Property | 300 | ||

| Educational Test | 301 | ||

| “Grandfather Clauses” | 305 | ||

| “Understanding and Character Clauses” | 308 | ||

| Persons Excluded from Suffrage | 310 | ||

| xv | Suffrage in Insular Possessions of United States | 312 | |

| Constitutionality of Suffrage Amendments | 313 | ||

| Maryland and Fifteenth Amendment | 317 | ||

| Extent of Actual Disfranchisement | 320 | ||

| Qualifications for Voting in the United States | 322 | ||

| CHAPTER XII | |||

| Race Distinctions versus Race Discriminations | 348–362 | ||

| Race Distinctions not Confined to One Section | 348 | ||

| Race Distinctions not Confined to One Race | 350 | ||

| Race Distinctions not Decreasing | 351 | ||

| Distinctions not Based on Race Superiority | 353 | ||

| Solution of Race Problem Hindered by Multiplicity of Proposed Remedies | 354 | ||

| Search for a Common Platform | 355 | ||

| Proper Place of Race Distinctions | 356 | ||

| Obliteration of Race Discriminations | 358 | ||

| Table of Cases Cited | 363 | ||

| Index | 369 | ||

A race distinction in the law is a requirement imposed by statute, constitutional enactment, or judicial decision, prescribing for a person of one race a rule of conduct different from that prescribed for a person of another race. If, for instance, a Negro is required to attend one public school, a Mongolian another, and a Caucasian a still different one, a race distinction is created, because the person must regulate his action accordingly as he belongs to one or another race. Or, if a person, upon entering a street car, is required by ordinance or statute to take a seat in the front part of the car if he is a Caucasian, but in the rear if he is a Negro, this rule is a race distinction recognized by law. Again, a race distinction is made by the law when intermarriage between Negroes and Caucasians is prohibited.

Distinctions in law have been made on grounds other than race. Thus, in those States in which men may vote by satisfying the prescribed requirements, but in which women may not vote under any circumstances, the law 2creates a distinction on the basis of sex. Laws forbidding persons under seven years of age from testifying in court and laws exempting from a poll tax persons under twenty-one years of age give rise to age distinctions. Other instances might be cited, but only race distinctions have a place here.

It is important, at the outset, to distinguish clearly between race distinctions and race discriminations; more so, because these words are often used synonymously, especially when the Negro is discussed. A distinction between the Caucasian and the Negro, when recognized and enforced by the law, has been interpreted as a discrimination against the latter. Negroes have recognized that they are the weaker of the two races numerically, except in the Black Belt of the South, and intellectually the less developed. Knowing that the various race distinctions have emanated almost entirely from white constitution-makers, legislators, and judges, they regard these distinctions as expressions of the aversion on the part of the Caucasian to association with the Negro. Naturally, therefore, they have resented race distinctions upon the belief and, in many instances, upon the experience that they are equivalent to race discriminations.

In fact, there is an essential difference between race distinctions and race discriminations. North Carolina, for example, has a law that white and Negro children shall not attend the same schools, but that separate schools shall be maintained. If the terms for all the public schools 3in the State are equal in length, if the teaching force is equal in numbers and ability, if the school buildings are equal in convenience, accommodations, and appointments, a race distinction exists but not a discrimination. Identity of accommodation is not essential to avoid the charge of discrimination. If there are in a particular school district twice as many white children as there are Negro children, the school building for the former should be twice as large as that for the latter. The course of study need not be the same. If scientific investigation and experience show that in the education of the Negro child emphasis should be placed on one course of study, and in the education of the white child, on another; it is not a discrimination to emphasize industrial training in the Negro school, if that is better suited to the needs of the Negro pupil, and classics in the white school if the latter course is more profitable to the white child. There is no discrimination so long as there is equality of opportunity, and this equality may often be attained only by a difference in methods.

On the other hand, if the term of the Negro school is four months, and that of the white, eight; if the teachers in the Negro schools are underpaid and inadequately or wrongly trained, and the teachers of the white schools are well paid and well trained; if Negro children are housed in dilapidated, uncomfortable, and unsanitary buildings, and white children have new, comfortable, and sanitary buildings; if courses of study for Negro children are selected in a haphazard fashion without any regard to their peculiar needs, and a curriculum is carefully adapted to the needs of white children; if such conditions 4exist under the law, race distinctions exist which are at the same time discriminations against Negroes. Where the tables are turned and Negro children are accorded better educational advantages than white, the discriminations are against Caucasians.

A law of Virginia requires white and Negro passengers to occupy separate coaches on railroad trains. If the coaches for both races are equally clean, equally comfortable, and equally well appointed; if both races are accorded equally courteous service by the employees of the railroad; if, in short, all the facilities for travel are equal for both races, race distinctions exist but not race discriminations. The extent of accommodations need not be identical. The railroad company, for instance, need furnish only the space requisite for the accommodation of each race. If, however, the white passengers are admitted to clean, well-lighted, well-ventilated coaches and Negroes, to foul, unclean, uncomfortable coaches; if white coaches are well-policed, while Negro passengers are subjected to the insults of disorderly persons; if, in other words, the Negro passenger does not receive as good service for his fare as the white, a discrimination against the Negro is made under the guise of a legal distinction.

In like manner, one might consider each of the race distinctions recognized in the law and show how it may be applied so as not to work a discrimination against either race and, as easily, how it may be used to work an injustice to the weaker race. A race distinction connotes a difference and nothing more. A discrimination necessarily implies partiality and favoritism.

There is a difference between actual race distinctions—those practiced every day without the sanction of law—and legal race distinctions—those either sanctioned or required by statutes or ordinances. Law is crystallized custom. Race distinctions now recognized by law were habitually practiced long before they crystallized into statutes. Thus, actual separation of races on railroad coaches—if not in separate coaches, certainly in separate seats or portions of the coach—obtained long before the “Jim Crow” laws came into existence. Moreover, miscegenation was punished before the legislature made it a crime. Some race distinctions practiced to-day will probably be sanctioned by statute in the future; others will persist as customs. In some Southern cities, for instance, there are steam laundries which will not accept Negro patronage. Everywhere in the South and in many places in other sections, there are separate churches for the races. It is practically a universal custom among the white people in the South never to address a Negro as “Mister” or “Mistress.” This custom obtains to some extent elsewhere. Thus, in a recent case before a justice of the peace in Delaware in which the parties were Negroes, one of them insisted upon speaking of another Negro as “Mister.” The justice forbade him so to do, and, upon his persisting, fined him for contempt. Yet, these distinctions and many others that might be cited are not required by law, and some of them, if expressed in statutes, would be unconstitutional.

Most race distinctions, however, are still uncrystallized. 6But these will be mentioned merely for illustration, since the purpose here is to discuss only those distinctions which have been expressed in constitutions, statutes, and judicial decisions. Mr. Ray Stannard Baker in his “Following the Colour Line,”[1] has admirably depicted actual race relations in the United States. He has gone in person out upon the cotton plantations of the Lower South; into the Negro districts of cities in the South, East, and North; into schools, churches, and court rooms; and has described how the Negro lives, what he does, what he thinks about himself and about the white man, and what the white man thinks about him. By studying the race distinctions he describes from the other standpoint suggested—that is, by tracing their gradual crystallization into statutes and judicial decisions, a better understanding may be had of race distinctions in general.

Attention will be directed not only to the Negro but to other races in the United States—the Mongolian in the Far West and the Indian in the Southwest. Of course, by far the largest race element after the Caucasian is the Negro with its 8,833,994 people of whom eighty-four and seven-tenths per cent. are in the thirteen States of the South. But it will be found that in those sections where the Indians have existed or still exist in appreciable numbers and come into association with the Caucasian—that is, where they do not still maintain their tribal relations—race distinctions have separated these two races. This is equally true of the Japanese and Chinese in the Pacific 7States. Most of the discussion will necessarily be of the distinctions between Caucasians and Negroes, but as distinctions applicable to Mongolians and Indians arise, they will be mentioned to show that race consciousness is not confined to any one section or race.

Race distinctions have existed and have been recognized in the law from the beginning of the settlement of the New World, long before the thirteen colonies became free and independent States, or before the Federal Constitution was adopted. The first cargo of Negroes was landed in Virginia in 1619, only twelve years after the founding of Jamestown. In 1630, eleven years later, the Virginia Assembly passed the following resolution:[2] “Hugh Davis to be soundly whipped before an assembly of Negroes and others, for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and the shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a Negro.” Many of the Colonies—later States—prohibited intermarriage between Caucasians and Negroes whether the latter were slave or free. The Colonies and States prohibited or limited the movements of free Negroes from one colony or State to another, prescribed special punishment for adultery between white persons and Negroes, forbade persons of color to carry firearms, and in divers other ways restricted the actions of Negroes.

It is not so profitable, however, at this day to study these early distinctions, for the distinctions based on race were then inseparably interwoven with those based on the 8state of slavery. Thus, it is impossible to say whether a law was passed to regulate a person’s actions because he was a slave or because he was of the Negro race. Moreover, the laws relating to race and slave distinctions prior to 1858 were compiled by John Codman Hurd in his two-volume work entitled “The Law of Freedom and Bondage in the United States,” published in 1858. Any attempt at a further treatment of the period covered by that work would result only in a digest of a multitude of statutes, most of which have been obsolete for many years. But a greater reason for the futility of a discussion of race distinctions before 1865 is that prior to that date, as it has been so often expressed, the Negro was considered to have no rights which the white man was bound to respect. The Dred Scott decision[3] in 1857 virtually held that a slave was not a citizen or capable of becoming one, and this dictum, unnecessary to the decision of the case, did much, says James Bryce,[4] “to precipitate the Civil War.” If the Negro could enjoy only licenses, claiming nothing as of right, it is not very valuable to study the distinctions which the master imposed upon him.

The year 1865 marked the beginning of the present era in race relations. It was in that year that the Negro became a free man, and that the Federal Government undertook by successive legislative enactments to secure and guarantee to him all the rights and privileges which the Caucasian race had so long enjoyed as its inalienable heritage.

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, issued as a military expedient, declared that, unless the seceding States were back in the Union by January 1, 1863, all 9slaves in those States should be emancipated. This did not apply to the Union States, as Delaware, which still had slaves. But immediately upon the cessation of hostilities, Congress set to work to make emancipation general throughout the Union and to give the Negro all the rights of a citizen. The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified December 18, 1865, abolished slavery and involuntary servitude except as a punishment for crime. The following April, the first Civil Rights Bill[5] was passed, which declared that “all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime ... shall have the same right, in every State and Territory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, ... and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings in the security of persons and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishments and penalties, and to none other....”

These rights were enlarged by the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, which provides that: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny to any person within 10its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Though the word “Negro” is not mentioned in this Amendment nor in any of the subsequent Federal enactments, it is not open to dispute that the legislators had in mind primarily the protection of the Negro.

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 was reënacted[6] in 1870, with the addition that it extended to all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States, and that it provided that all persons should be subject to like taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind.

The same year, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, which declared that the right of citizens of the United States to vote should not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any States on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

The Civil Rights Bill[7] of 1875, the most sweeping of all such legislation by Congress, declared that all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States should be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theatres, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude. It also provided that jurors should not be excluded on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

An enumeration of these Federal statutes and constitutional amendments has been made in order to show the efforts of Congress to secure to the Negro every civil 11and political right of a full-fledged citizen of the United States. Later they will be discussed in detail. By the Civil Rights Bill of 1875, Congress apparently intended to secure not only equal but identical accommodations in all public places for Negroes and Caucasians. If one looks only upon the surface of these several legislative enactments, it would seem impossible to have a race distinction recognized by law which did not violate some Federal statute or the Federal Constitution. But the succeeding pages will show that, under the shadow of the statutes and the Constitution, the legislatures and courts of the States have built up a mass of race distinctions which the Federal courts and Congress, even if so inclined, are impotent to attack.

1. Doubleday, Page & Co., 1908.

2. 1 Hen. 146, quoted in Hurd’s “Law of Freedom and Bondage,” I, p. 229.

3. 19 How. 393 (1857).

4. “American Commonwealth,” I, p. 257.

5. 14 Stat. L., 27, chap. 31.

6. 16 Stat. L., 144, chap. 114.

7. 18 Stat. L., 335, chap. 114.

“I had not been long engaged in the study of the race problem when I found myself face to face with a curious and seemingly absurd question: ‘What is a Negro?’” said Mr. Baker.[8]

Absurd as the question apparently is, it is one of the most perplexing and, at times, most embarrassing that has faced the legislators and judges.

If race distinctions are to be recognized in the law, it is essential that the races be clearly distinguished from one another. If a statute provides that Negroes shall ride in separate coaches and attend separate schools, it is necessary to decide first who are included under the term “Negroes.” It would seem that physical indicia would be sufficient, and, in most instances, this is true. It is never difficult to distinguish the full-blooded Negro, Indian, or Mongolian one from the other or from the Caucasian. But the difficulty arises in the blurring of the color line by amalgamation. The amount of miscegenation between the Mongolian and other races represented in the United States is negligible; but the extent of intermixture between the Caucasian and the Negro, the 13Negro and the Indian, and the Caucasian and the Indian is appreciable, and problems arising from it are serious.

It is absolutely impossible to ascertain the number of mulattoes—that is, persons having both Caucasian and Negro blood in their veins—in the United States. Mr. Baker[9] says: “I saw plenty of men and women who were unquestionably Negroes, Negroes in every physical characteristic, black of countenance with thick lips and kinky hair, but I also met men and women as white as I am, whose assertions that they were really Negroes I accepted in defiance of the evidence of my own senses. I have seen blue-eyed Negroes and golden-haired Negroes; one Negro girl I met had an abundance of soft, straight, red hair. I have seen Negroes I could not easily distinguish from the Jewish or French types; I once talked with a man I took at first to be a Chinaman but who told me he was a Negro. And I have met several people, passing everywhere for white, who, I knew, had Negro blood.”

A separate enumeration of mulattoes has been made four times—in 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1890 respectively. The census authorities themselves said that the figures were of little value, and any attempt to distinguish Negroes from mulattoes was abandoned in the census of 1900. If a person is apparently white, the census enumerator will feel a delicacy in asking him if he has Negro blood in his veins. If the enumerator does ask the question and if the other is honest in his answer, it is often that the latter does not know his own ancestry. Dr. Booker T. Washington, for instance, has said that he does not know who his father was.[10] Marital relations among Negroes during slavery were so irregular, and illicit intercourse between 14white men and slave women was so common that the line of ancestry of many mulattoes is hopelessly lost. But Mr. Baker makes the rough estimate, which doubtless is substantially correct, that 3,000,000 of the 10,000,000 (circa) Negroes are visibly mulattoes. This one third of the total Negro population represents every degree of blood, of color, and of physical demarcation from the fair complexion, light hair, blue eyes, thin lips, and sharp nose of the octoroon, who betrays scarcely a trace of his Negro blood, to the coal-black skin, kinky hair, brown eyes, thick lips, and flat nose of the man who has scarcely a trace of Caucasian blood. It is this gradual sloping off from one race into another which has made it necessary for the law to set artificial lines.

The difficulty arising from the intermixture of the races was realized while the Negro was still a slave. Throughout the statutes prior to 1860, one finds references to “persons of color,” a generic phrase including all who were not wholly Caucasian or Indian. This antebellum nomenclature has been brought over into modern statutes. It is surprising to find how seldom the word “Negro” is used in the statutes and judicial decisions.

Some States have fixed arbitrary definitions of “persons of color,” “Negroes,” and “mulattoes”; others, having enacted race distinctions, have then defined whom they intended to include in each race. This has been done particularly in the laws prohibiting intermarriage. The Constitution of Oklahoma[11] provides that “wherever in this Constitution and laws of this State, the word or words, ‘colored,’ or ‘colored race,’ or ‘Negro,’ or ‘Negro race,’ are used, the same shall be construed to mean, or 15apply to all persons of African descent. The term ‘white’ shall include all other persons.”

Taking up these definitions in the various States—many of them included within broader statutes—one finds that Alabama,[12] Kentucky,[13] Maryland,[14] Mississippi,[15] North Carolina,[16] Tennessee,[17] and Texas[18] define as a person of color one who is descended from a Negro to the third generation inclusive, though one ancestor in each generation may have been white. The Code Committee of Alabama of 1903 substituted “fifth” for “third,” so that at present in that State one is a person of color who has had any Negro blood in his ancestry in five generations.[19] The laws of Florida,[20] Georgia,[21] Indiana,[22] Missouri,[23] and South Carolina[24] declare that one is a person of color who has as much as one-eighth Negro blood: the laws of Nebraska[25] and Oregon[26] say that one must have as much as one-fourth Negro blood in order to be classed with that race. Virginia[27] and Michigan apparently draw the line in a similar way. In Virginia, a marriage between a white man and a woman who is of less than one-fourth Negro blood, “if it be but one drop less,” is legal. A woman whose father was white, and whose mother’s father was white, and whose great-grandmother was of a brown complexion, is not a Negro in the sense of the statute.[28] In 1866, the court of Michigan, under a law limiting the suffrage to “white male citizens,” held that all persons should be considered white who had less than one-fourth of African blood.[29] That State gave the right to vote also to male inhabitants of Indian descent, but its court held that a person having one-eighth Indian blood, one-fourth or three-eighths African, and the rest white was not included 16in that class.[30] Ohio limited the suffrage to white male citizens and made it the duty of judges of election to challenge any one with a “distinct and visible admixture of African blood,” but the latter requirement was held unconstitutional in 1867,[31] the court saying that, where the white blood in a person predominated, he was to be considered white. This definition is interesting because it is the only instance found of a court’s saying that a person with more than half white blood and the rest Negro should be considered white. In contrast with this is the following sweeping definition laid down in the Tennessee statute: “All Negroes, Mulattoes, Mestizoes,[32] and their descendants, having any African blood in their veins, shall be known in this State as ‘Persons of Color.’”[33] Arkansas also, in its statute separating the races in trains, includes among persons of color all who have “a visible and distinct admixture of African blood.”[34]

In everyday language, a mulatto is any person having both Caucasian and Negro blood. But several States have defined “mulatto” specifically. The Supreme Court of Alabama[35] held, in 1850, that a mulatto is the offspring of a Negro and a white person, that the offspring of a white person and a mulatto is not a mulatto; but this definition was enlarged in 1867[36] to include anyone descended from Negro ancestors to the third generation inclusive, though one ancestor in each generation be white. It has been seen already that this was recently extended to the fifth generation. The law of Missouri[37] defines a mulatto thus: “Every person other than a Negro, any one of whose grandfathers or grandmothers is or shall have been a Negro, although his or her other progenitors, except 17those descending from the Negro, may have been white persons, shall be deemed a mulatto, and every such person who shall have one-fourth or more Negro blood shall in like manner be deemed a mulatto.”

Some States have allowed facts other than physical characteristics to be presumptive of race. Thus, it has been held in North Carolina[38] that, if one was a slave in 1865, it is to be presumed that he was a Negro. The fact that one usually associates with Negroes has been held in the same State proper evidence to go to the jury tending to show that he is a Negro.[39] If a woman’s first husband was a white man, that fact, in Texas,[40] is admissible evidence tending to show that she is a white woman.

One may ascertain how some of the States define the other races from their laws against miscegenation. Thus, Mississippi, in prohibiting intermarriage between Caucasians and Mongolians, includes one having as much as one-eighth Mongolian blood. Oregon makes its similar law applicable to those having one-fourth or more Chinese or Kanakan[41] blood, or more than one-half Indian blood. Thus, three-eighths of Indian blood would not be sufficient to bar a man from intermarriage with a Caucasian, but one-fourth Negro, Chinese, or Kanakan blood would.

The above are the laws which define the races. The interpretation of them is a different question. Some statutes say that one is a person of color—in effect, a Negro—if he is descended from a Negro to the third generation inclusive, though one ancestor in each generation may have been white; others define as a person of color a man who has as much as one-eighth Negro blood; and 18still others, one who has as much as one-fourth Negro blood.

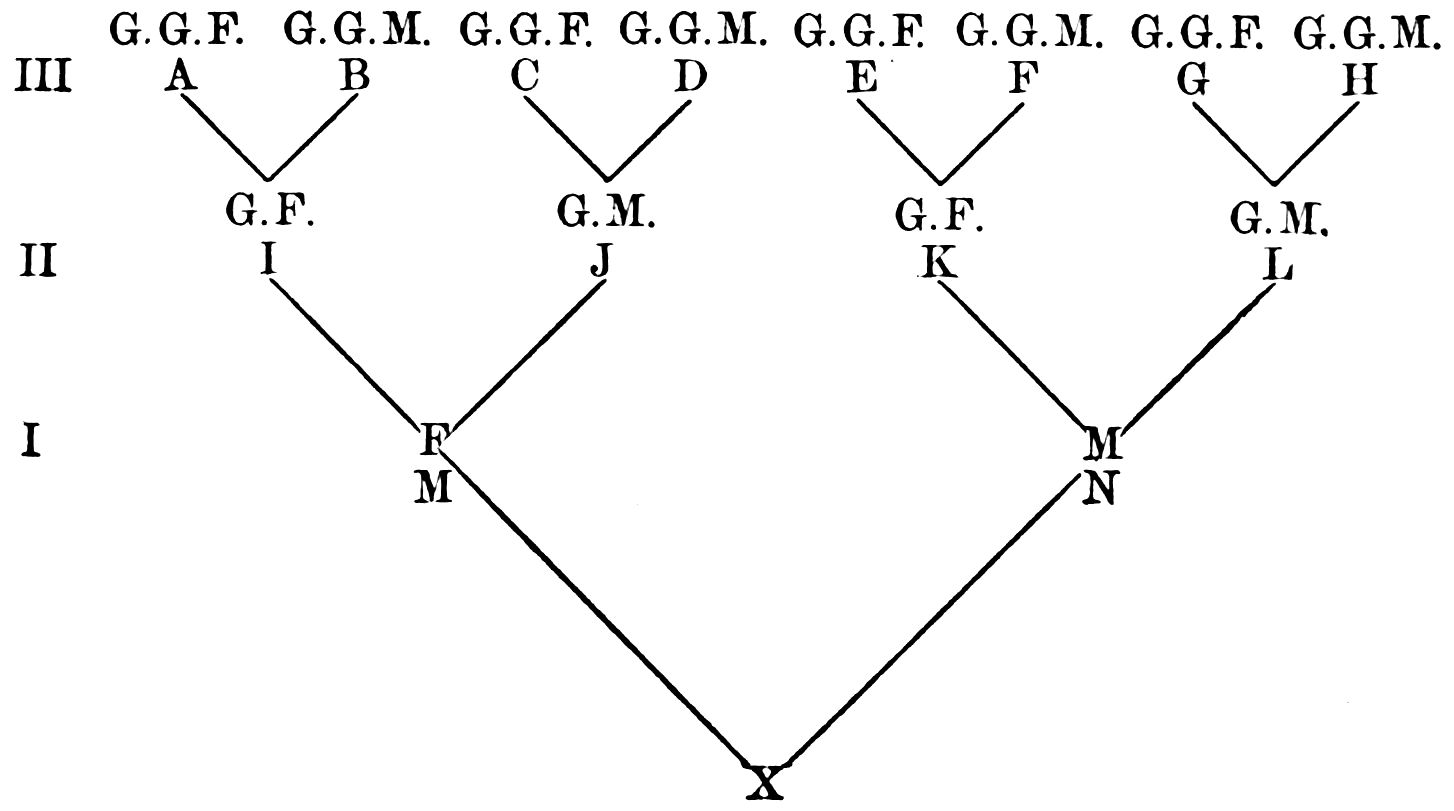

The following diagram will probably clarify these definitions:

Suppose it is desired to ascertain whether the son X is a white person or a Negro. The first generation above him is that of his parents, M and N. If either of them is white and the other a Negro, X has one-half Negro blood and would be considered a Negro everywhere. The second generation is that of his grandparents, I, J, K, and L. If any one of them is a Negro and the other three white, X has one-fourth Negro blood, and would be considered a Negro in every State except possibly Ohio. The third generation is that of his great-grandparents, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. If any one of these eight great-grandparents is a Negro, X has one-eighth Negro blood and would be considered a Negro in every State which defines 19a person of color as one who has one-eighth Negro blood or is descended from a Negro to the third generation inclusive. Suppose, for instance, the great-grandfather A was a Negro and all the rest of the great-grandparents were white. The grandfather I would be half Negro; the father M would be one-fourth Negro; and X would be one-eighth Negro. Thus, though of the fourteen progenitors of X only three had Negro blood, X would nevertheless be considered a Negro.

In the above illustrations only one of the progenitors has been a Negro and his blood has been the only Negro blood introduced into the line. Suppose, however, that there is Negro blood in both branches of the family, as where a mulatto marries a mulatto or a mulatto marries a Negro. One with a mathematical turn of mind may take these three generations and work out the various other combinations which would give X one-half, one-fourth, one-eighth, or any other fraction of Negro blood.

It is safe to say that in practice one is a Negro or is classed with that race if he has the least visible trace of Negro blood in his veins, or even if it is known that there was Negro blood in any one of his progenitors. Miscegenation has never been a bridge upon which one might cross from the Negro race to the Caucasian, though it has been a thoroughfare from the Caucasian to the Negro. Judges and legislators have gone the length of saying that one drop of Negro blood makes a man a Negro, but to be a Caucasian one must be all Caucasian. This shows very clearly that they have not considered Negro blood on a par with Caucasian; else, race affiliation would be determined by predominance of blood. By the latter test, if 20one had more Negro blood than white, he would be considered a Negro; if more white than Negro, a Caucasian. Therefore, at the very threshold of this subject, even in the definitions of terms, one discovers a race distinction. Whether it is a discrimination depends upon what one considers the relative desirability of Caucasian and Negro ancestry.

Having considered how the law defines that heterogeneous group of people called Negroes, one is brought face to face with the question: What, in actual practice, is the proper name for the black man in America? Is it “Negro?” Is it “colored person?” Is it “Afro-American?” If not one of these, what is it? Among the members of that group, the matter of nomenclature is of more than academic interest. Thus, Rev. J. W. E. Bowen, Professor of Historical Theology at Gamman Seminary, Atlanta, and editor of The Voice of the Negro, in 1906, published an article in that paper with the pertinent title, “Who are We?”

The ways of speaking of members of the Negro race are various. In the laws, as has been shown, they are called “Negroes,” “Persons of Color,” “Colored Persons,” “Africans,” and “Persons of African Descent”—more often “Persons of Color.” By those who would speak dispassionately and scientifically they are called Negroes and Afro-Americans. Those who are anxious not to wound the feelings of that race speak of them as “Colored People” or “Darkies”; while those who would speak contemptuously of them say “Nigger” or “Coon.” “Nigger” 21is confined largely to the South; “Coon,” to the rest of the country. Again, one occasionally finds “Blacks” and “Black Men” in contradistinction to “Whites” and “White Men.”

The question of the proper name for persons of African descent was brought into prominence in 1906. In that year a bill was laid before Congress relative to the schools of the City of Washington, which provided that the Board of Education should consist of nine persons, three of whom should be “of the colored race.” Representative Thetus W. Sims, of Tennessee, objected to the phrase on the ground that it would include “Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Malays, Sandwich Islanders, or any persons of the colored race,” and insisted that “Negroes” or “persons of the Negro race” should be substituted in its place. He wrote to Dr. Booker T. Washington, as one of the leaders of the Negro race, asking his views as to the proper word. The following is part of his reply: “... It has been my custom to write and speak of the members of my race as Negroes, and when using the term ‘Negro’ as a race designation to employ the capital ‘N.’ To the majority of the people among whom we live I believe this is customary and what is termed in the rhetorics ‘good usage.’... Rightly or wrongly, all classes have called us Negroes. We cannot escape that if we would. To cast it off would be to separate us, to a certain extent, from our history, and deprive us of much of the inspiration we now have to struggle on and upward. It is to our credit, not to our shame, that we have risen so rapidly, more rapidly than most other peoples, from savage ancestors through slavery to civilization. For my 22part, I believe the memory of these facts should be preserved in our name and traditions as it is preserved in the color of our faces. I do not think my people should be ashamed of their history, nor of any name that people choose in good faith to give them.”[42]

Representative Sims’s objection to the phrase “of the colored race” precipitated a discussion throughout the country. The New York Tribune[43] made a canvass of a great many prominent Negroes and white persons to ascertain what they thought the Negro should be called. The result of its inquiry is this: An average of eleven Negroes out of twenty desired to be spoken of as Negroes. The other nine spurned the word as “insulting,” “contemptuous,” “degrading,” “vulgar.” Two argued for “Afro-American,” two for “Negro-American,” one for “black man,” and one was indifferent so long as he was not called “Nigger.” Of the white men interviewed, ten out of thirteen, on an average, preferred the word “Negro.” The Negroes made a specially strong plea for capitalizing the word “Negro,” saying that it was not fair to accord that distinction to their dwarfish cousins, the Negritos in the Philippines, and to the many savage tribes in Africa and deny it to the black man in America. They were also strongly opposed to the word “Negress” as applied to the women of their race. This, they asserted, is objectionable because of its historical significance. For in times of slavery, “Negress” was the term applied to a woman slave at an auction, in contradistinction to “buck,” which referred to a male slave.

E. A. Johnson, Professor of Law in Shaw University, North Carolina, said: “The term ‘Afro-American’ is 23suggestive of an attempt to disclaim as far as possible our Negro descent, and casts a slur upon it. It fosters the idea of the inferiority of the race, which is an incorrect notion to instill into the Negro youth, whom we are trying to imbue with self-esteem and self-respect.”

Rev. J. W. E. Bowen, to whom reference has already been made, said: “Let the Negroes, instead of bemourning their lot and fretting because they are Negroes and trying to escape themselves, rise up and wipe away the stain from this word by glorious and resplendent achievements. Good names are not given; they are made.”

Rev. H. H. Proctor, pastor of the First Congregational Church, Atlanta, said: “What is needed is not to change the name of the people, but the people of the name. Make the term so honorable that men will consider it an honor to be called a Negro.”

Rev. Walter H. Brooks, pastor of the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church, Washington, wrote: “The black people of America have but to augment their efforts in lives of self-elevation and culture, and men will cease to reproach us by any name whatever.”

Finally, Charles W. Anderson, Collector of Internal Revenue, New York, said: “I am, therefore, inclined to favor the use of ‘Negro,’ partly because to drop it would expose me to the charge of being ashamed of my race (and I hate any man who is ashamed of the race from which he sprung), and partly because I know that no name or term can confer or withhold relative rank in this life. All races and men must win equality of rating and status for themselves.”

One is safe in concluding that the word “Negro” 24(with the capital “N”) will eventually be applied to the black man in America. White people are distinctly in favor of it: what Negroes now object to it do so because of its corrupt form, “Nigger.” As the Negro shows his ability to develop into a respectable and useful citizen, contemptuous epithets will be dropped by all save the thoughtless and vicious, and “Negro” will be recognized as the race name.

8. “Following the Colour Line,” p. 151.

9. Ibid., p. 151.

10. “Up From Slavery,” p. 2.

11. Art. XIII, sec. 11.

12. Code, 1867, p. 94; Code, 1876, p. 187, sec. 2; Code, 1886, I, p. 56, sec. 2; Code, 1896, I, p. 112, sec. 2.

13. Laws of Ky., 1865–66, p. 37.

14. Pub. Gen. Laws of Md., I, art. 27, sec. 305, p. 878.

15. Laws of Miss., 1865, p. 82.

16. Pell’s Revisal of 1908, II, sec. 3369.

17. Code, 1884, sec. 3291.

18. Laws of Tex., special session, 1884, p. 40.

19. Code, 1907, I, p. 218, sec. 2.

20. Laws of Fla., 1865, p. 30; Code, 1892, pp. 111 and 681; Gen. Stat., 1906, p. 165, sec. 1.

21. Laws of Ga., 1865–66, p. 239.

22. Annotated Stat., 1908, III, sec. 8360.

23. Annotated Stat, 1906, II, sec. 2174.

24. Laws of S. C, 1864–65, p. 271.

25. Compiled Stat., 1895, sec. 3644.

26. Bellinger and Cotton’s Code and Stat., II, sec. 5217.

27. Laws of Va., 1865–66, p. 84.

28. 25McPherson’s Case, 1877, 28 Grat. 939.

29. People v. Dean, 1866, 14 Mich. 406.

30. Walker v. Brockway, 1869, I Mich. N. P. (Brown) 57.

31. Monroe v. Collins, 1867, 17 O. S. 665.

32. A mestizo is a person of mixed blood, specially a person of mixed Spanish and American Indian parentage.—Century Dictionary, V, p. 3728.

33. Laws of Tenn., 1865–66, p. 63.

34. Kirby’s Digest, 1904, sec. 6632, p. 1378.

35. Thurman v. State, 1850, 18 Ala. 276.

36. Code, 1867, p. 94.

37. Laws of Mo., 1864, p. 67.

38. McMillan v. School Com., 1890, 12 S. E. 330; 107 N. C. 609.

39. Hopkins v. Bowers, 1892, 16 S. E. 1; 111 N. C. 175.

40. Bell v. State, 1894, 33 Tex. Cr. R. 163.

41. A Kanakan is a Hawaiian or Sandwich Islander.—Century Dictionary, IV, p. 3264.

42. The Norfolk, Va., Landmark, June 13, 1906.

43. The New York Daily Tribune, June 10, 1906, part IV, p. 2.

There are certain words which are so universally considered injurious to a person in his social or business relations if spoken of him that the courts have held that the speaker of such words is liable to an action for slander, and damages are recoverable even though the one of whom the words were spoken does not prove that he suffered any special damage from the words having been spoken of him. The speaking of such words is said to be actionable per se. In short, all the world knows that it is injurious to a man to speak such words of him, and the court does not require proof of facts which all the world knows. Such words are (1) those imputing an infamous crime; (2) those disparaging to a person in his trade, business, office, or profession; and (3) those imputing a loathsome disease. Thus, to say that a man is a murderer is to impute to him an infamous crime, and if he brings a suit for slander, it is not necessary for him to prove that he has been damaged by the statement. The result is the same if one says that a person will not pay his debts, because that injures him in his profession or business; or that a man has the leprosy, because that is imputing to him a loathsome disease.

From early times, it has been held to be slander, actionable 27per se, to say of a white man that he is a Negro or akin to a Negro. The courts have placed this under the second class—that is, words disparaging to a person in his trade, business, or profession. The first case in point arose in South Carolina[44] in 1791, when the courts held that, if the words were true, the party (the white person) would be deprived of all civil rights, and moreover, would be liable to be tried in all cases, under the “Negro Act,” without the privilege of a trial by jury, and that “any words, therefore, which tended to subject a citizen to such disabilities, were actionable.” In 1818, it was held actionable by a court of the same State to call a white man’s wife a mulatto.[45] But an Ohio[46] court, the same year, held that it was not slander, actionable per se, to charge a white man with being akin to a Negro inasmuch as it did not charge any crime or exclude one from society. The only explanation, apparently, of this conflict between the decisions of South Carolina and Ohio is that in the latter State it was not considered as much an insult to impute Negro blood to a white man as in the former. In North Carolina,[47] in 1860, there was the surprising decision that it was not actionable per se to call a white man a free Negro, even though the white man was a minister of the gospel.

The Supreme Court of Louisiana,[48] in 1888, said: “Under the social habits, customs, and prejudices prevailing in Louisiana, it cannot be disputed that charging a white man with being a Negro is calculated to inflict injury and damage.... No one could make such a charge, knowing it to be false, without understanding that its effect would be injurious and without intending to injure.”

In 1900, a Reverend Mr. Upton delivered a temperance 28address near New Orleans. The reporters, desiring to be complimentary, referred to him as a “cultured gentleman.” In the transmission of the dispatch by wire to the New Orleans paper, the phrase was, by mistake, changed to “colored gentleman.” The Times-Democrat of that city, unwilling to refer to a member of the Negro race as a “colored gentleman,” changed it to “Negro,” and that was the word finally printed in the report. As soon as he learned of the mistake, the editor of the paper duly retracted and apologized. But Mr. Upton, not appeased, brought a suit for libel and recovered fifty dollars damages.[49]

The News and Courier, of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1905, in reporting a suit by A. M. Flood against a street car company, referred to Mr. Flood as “colored.” The latter brought suit against the newspaper and recovered damages. In the course of its opinion, the court said: “When we think of the radical distinction subsisting between the white man and the black man, it must be apparent that to impute the condition of the Negro to a white man would affect his [the white man’s] social status, and, in case anyone publish a white man to be a Negro, it would not only be galling to his pride, but would tend to interfere seriously with the social relation of the white man with his fellow white men; and, to protect the white man from such a publication, it is necessary to bring such charge to an issue quickly.”[50] The court adds that its decision does not violate the Amendments to the Federal Constitution, for these do not refer to the social condition of the two races, but serve rather to give the two races equal civil and political rights. Finally, the court says, 29quoting People v. Gallagher: “... if one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane.”[51]

Where laws separating the races in railroad trains and street cars are in force, and the duty devolves upon the conductors to assign passengers of the two races to their respective coaches or compartments, it is surprising that they do not more often make the mistakes of assigning bright mulattoes to the white coach and dark-skinned white persons to the colored. There are several instances where the latter mistake has been made. One would not expect a mulatto to resent being assigned to the white coach and nothing would come of it, unless some white passenger recognized him as being a Negro and objected; but one would expect a white person to resent being assigned to the “Jim Crow” compartment.

In Atlanta, in 1904, a certain Mr. Wolfe and his sister boarded a street car and took seats in the part of the car reserved for white passengers. The conductor asked them to move back, and when they asked the reason, he answered that the rear of the car was for colored passengers. The lady asked if he thought they were colored, to which he replied: “Haven’t I seen you in colored company?” Mr. Wolfe demanded an apology, and later brought suit against the company. The court held that the street car company was liable, and that the good faith of the conductor in honestly thinking that they were Negroes would serve only in mitigation of damages. Two judges were of opinion that the company would not be liable if the conductor used “extreme care and caution” to ascertain the race of the passengers. The court held 30that it would take judicial notice of the social status of the two races and of their respective superiority and inferiority, saying: “The question has never heretofore been directly raised in this State as to whether it is an insult to seriously call a white man a Negro or to intimate that a person apparently white is of African descent. We have no hesitation, however, after the most mature consideration of every phase of the question, in declaring our deliberate judgment to be that the wilful assertion or intimation embodied in the declaration now before us constitutes an actionable wrong. We cannot shut our eyes to the facts of which courts are bound to take judicial notice. Certainly every court is presumed to know the habits of the people among which it is held, and their characteristics, as well as to know leading historical events and the law of the land. To recognize inequality as to the civil or political rights belonging to any citizen or class of citizens, or to attempt to fix the social status of any citizen either by legislation or judicial decision, is repugnant to every principle underlying our republican form of government. Nothing is further from our purpose. Under our institutions ‘every man is the architect of his own fortune.’ Every citizen, white and black, may gain, in every field of endeavor, the recognition his associates may award. That is his right, and his own concern. But the courts can take notice of the architecture without intermeddling with the building of the structure. It is a matter of common knowledge that, viewed from a social standpoint, the Negro race is in mind and morals inferior to the Caucasian. The record of each from the dawn of historic times denies equality. The fact was recognized 31by two of the leaders on opposite sides of the question of slavery, Abraham Lincoln and A. H. Stephens.”[52]

The following is a recent case arising in Kentucky, in which it was held that it is not slander per se to call a white person a Negro: A white woman entered a coach set apart for white people. The passengers therein complained that she was a Negro, and the brakeman, on hearing their remarks, asked her to go into the next coach. When, upon reaching the other coach, she found that it was set apart for Negroes, she left the train, which had not yet started from the station. She met the conductor, who, upon hearing her explanation, permitted her to go her journey in the white coach. Later, she brought suit against the railroad company and recovered a judgment for four thousand dollars. Upon appeal, the judgment of the lower court was reversed, the higher court saying: “What race a person belongs to cannot always be determined infallibly from appearances, and mistake must inevitably be made. When a mistake is made, the carrier is not liable in damages simply because a white person was taken for a Negro, or vice versa. It is not a legal injury for a white person to be taken for a Negro. It was not contemplated by the statute that the carrier should be an insurer as to the race of its passengers. The carrier is bound to exercise ordinary care in the matter, but if it exercises ordinary care, and is not insulting to the passenger, it is not liable for damages.”[53]

Probably the most recent case on the subject is one which arose about two years ago in Virginia. A certain Mrs. Stone boarded a train at Myrtle, Virginia. In spite of her protests, the conductor compelled her to go into 32the “Jim Crow” coach, thinking that she was a Negro. After she had entered the car, a Negro passenger recognized her and said, “Lor’, Miss Rosa, this ain’t no place for you; you b’long in the cars back yonder.” Mrs. Stone rode on to Suffolk, the next station, and left the train. She sued the railroad company for one thousand dollars damages. It appeared that Mrs. Stone was much tanned: this probably caused the conductor to mistake her for a Negro.

It will have been noticed that all the courts which have held it actionable per se to call a white person a Negro have been in the Southern States. It is doubtful whether the courts in other sections would take the same view, and even Kentucky, a Southern State, has refused so to do. The attitude of the court depends upon whether it is the consensus of opinion among the people of the community that it is injurious to a white man in his business and social relations to be called a Negro.

The above is clearly another race distinction. Although there are many decisions to the effect that it is actionable per se to call a white person a Negro, not one can be found deciding whether it would be so to call a Negro a white person. One event looks, in a measure, in this direction. The city of Asheville, North Carolina, in 1906, contracted with a printer to have a new city directory issued. The time-honored custom of the place was to distinguish white and Negro citizens by means of an asterisk placed before the names of all Negroes. After the directory had been distributed, it was found that asterisks had been placed before the names of two highly respected white citizens, thus indicating that they were 33of Negro lineage. From what has been seen, there is no doubt that this would found an action for libel. The newspaper report says: “On the heels of this suit brought by Mr. Lancaster [one of the white persons], it is said that Henry Pearson is seriously considering bringing suit against the same people because an asterisk was not[54] placed before his name. Henry is a Negro. In fact he is one of the best-known Negroes in Asheville. He is at present proprietor of the Royal Victoria, a Negro hotel, and complains that he has been the object of many unpleasant jests since the publication of the directory, and likewise inquiries as to just ‘when he turned white.’ Pearson fears that if the report goes abroad that he is a white man it will damage his hotel, and that the Negroes who make his place headquarters and who pay into Henry’s hands many shekels will cease to patronize his hotel, and that his losses will be grievous.”[55] This case is unique; whether it has been brought to court is as yet unknown. It is probable that to sustain his action it would be necessary for the Negro to prove special damage to his business; whereas Mr. Lancaster would not have to allege or prove any damage at all. But, save in such a case as the above, it would be hard to imagine a circumstance in which a court would hold that it is injurious to a Negro in his trade, business, office, profession, or in his social relations to be called a white man.

44. Eden v. Legare, 1791, 1 Bays (S. C.) 171.

45. Wood v. King, 1818, 1 Nott & McC. (S. C.) 184.

46. 34Barrett v. Jarvis, 1823, 1 O. (1 Hammond) 84, note.

47. McDowell v. Bowles, 1860, 8 Jones (N. C.) 184.

48. Spotarno v. Fourichon, 1888, 40 La. Ann. 423.

49. Upton v. Times-Democrat Pub. Co., 1900, 28 So. 970.

50. Flood v. News and Courier Co., 1905, 50 S. E. 63.

51. 93 N. Y. 438 (1883).

52. Wolfe v. Ry. Co., 1907, 58 S. E. 899.

53. So. Ry. Co. v. Thurman, 1906, 90 S. W. 240; 28 Ky. L. Rep. 699; 2 L. R. A. (N. S.) 1108.

54. Italics the writer’s.

55. Raleigh, N. C, News and Observer, July 25, 1906.

One set of race distinctions deserves to be treated by itself. They have long since become obsolete and were, during their existence, in a sense, anomalous; yet they are, perhaps, the most illuminating from a historical point of view of all the race distinctions in the law. They were the result of the statutes that were enacted by the legislatures of the Southern States between 1865 and 1868 for the definition and establishment of the status of the Negro. The War closed in 1865; the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution was ratified July 28, 1868; and the Reconstruction régime in the South was not under way till 1868 or later. Therefore, during the interval between the close of the War and the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment or the beginning of active Reconstruction, the Southern States were free to adopt such measures as they saw fit to establish the relation between the races.

The legislatures faced a new problem, or rather an old problem increased many fold in perplexity. They had to establish the industrial, legal, and political status of 4,000,000 people who had recently been slaves and were now freemen. It must be remembered that when the Southern legislatures convened in 1865 their actions with regard to 36the Negro were not beset by the limitations subsequently fixed by the Federal Government. The first Civil Rights Bill, that of 1866, had not been passed. The Southern States were at liberty to enact such statutes as they thought proper and to draw upon their own experience and that of the free States with regard to free Negroes.

These statutes of 1865–68 are here called the “Black Laws.” This term was first applied to the laws of the border and Northern States passed before and up to the Civil War to fix the position of free persons of color. It is well to make a cursory examination of these laws of the free States, because they are prototypes of many of the statutes enacted by the Southern States while unhampered by Federal legislation. All the States, North as well as South, had previously faced the problem of the free Negro and made laws concerning him. Naturally, therefore, the South, now that all its Negroes were declared free, turned for precedents to the other States which had already had experience with the free Negro.

The following are some of the statutes that had been enacted with regard to free Negroes by States lying outside of what was later the Confederacy:

Maryland,[56] in 1846, denied Negroes, slave or free, the right to testify in cases in which any white person was concerned, though it permitted the testimony of slaves against free Negroes. The Constitution[57] of 1851 forbade the legislature to pass any law abolishing the relation of master and servant.

37Delaware,[58] in 1851, prohibited the immigration of free Negroes from any State except Maryland: moreover, it forbade them to attend camp meetings, except for religious worship under the control of white people, or political gatherings. A law of 1852 provided that no free Negroes should have the right to vote or “to enjoy any other rights of a freeman other than to hold property, or to obtain redress in law and in equity for any injury to his or her person or property.”

Missouri,[59] in 1847, forbade the immigration into the State of any free Negro; enacted that no person should keep a school for the instruction of Negroes in reading and writing; forbade any religious meetings of Negroes unless a justice of the peace, constable, or other officer was present; and declared that schools and religious meetings for free Negroes were “unlawful assemblages.”

Ohio, which probably had the most notorious “Black Laws” of any free State, “required colored people to give bonds for good behavior as a condition of residence, excluded them from the schools, denied them the rights of testifying in courts of justice when a white man was party on either side, and subjected them to other unjust and degrading disabilities.”[60]

Indiana,[61] in 1851, prohibited free Negroes and mulattoes from coming into the State, and fined all persons who employed or encouraged them to remain in the State between ten and five hundred dollars for each offense.[62] The fines were to be devoted to a fund for the colonization of Negroes.[63] A law, which was submitted to a special vote and passed by a majority of ninety thousand, prohibited intermarriage between the races, provided for colonization 38of Negroes, and made incompetent the testimony of persons having one-eighth or more Negro blood.[64]

Illinois,[65] in 1853, made it a misdemeanor for a Negro to come into the State with the intention of residing there, and provided that persons violating this law should be prosecuted and fined or sold for a time to pay the fine.[66]

Iowa,[67] in 1851, forbade the immigration of free Negroes,[68] and provided that free colored persons should not give testimony in cases in which a white man was a party.

Oregon,[69] in 1849, forbade the entrance of Negroes as settlers or inhabitants, the reason being that it would be dangerous to have them associate with the Indians and incite the latter to hostility against white people.

This sketch of the “Black Laws” of some of the free States, incomplete as it is, is sufficient to show how those States regarded free Negroes. First, they tried to keep Negroes out; and, secondly, they subjected those that remained to various disabilities. When the first Civil Rights Bill was before Congress, the strongest opposition to its passage was on the ground that it would compel the free States to repeal these “Black Laws” and allow Negroes to intermarry with whites, attend the same schools, sit on juries, vote, bear firearms,[70] etc. The free Negro constituted a distinct class between the slave and the master, his condition being more nearly that of a slave.

The Southern States had been afraid of the free Negro. He was a sort of irresponsible being, neither bond nor free, who was likely to spread and foster discontent among the slaves. When a slave was emancipated, it was desired that he leave the State forthwith. Thus, the Virginia Constitution[71] of 1850 provided that emancipated 39slaves who remained in the Commonwealth more than twelve months after they became actually free, should forfeit their freedom and be reduced to slavery under such regulations as the law might prescribe. The free Negro was truly between the devil and the deep sea. If he stayed in the State, he would be reënslaved; if he went to a free State, he would be liable to prosecution there for violating the laws against the immigration of free persons of color.

As one turns to the first laws passed by the Southern States after Emancipation, he should keep in mind that these States were only grappling with the old problem of the free Negro, now on a much larger scale, which problem the free States had disposed of already in the manner just seen. As yet, the Southern States had no conception of the Negro as a citizen with inalienable rights to be recognized and protected. For instance, the Constitution of Mississippi[72] of 1832, as amended August 1, 1865, abolished slavery and empowered the legislature to make laws for the protection and security of the persons and property of freedmen, and to guard “them and the State against any evils that may arise from their sudden emancipation.” And the laws of South Carolina,[73] of the same year, provided that, “although such persons [Negroes] are not entitled to social or political equality with white persons,” they might hold property, make contracts, etc. except as hereinafter modified.

After 1865 there was comparatively little legislation as to the movement of Negroes from one State to another. It would have been utterly impossible to control the migration of the 4,000,000 Negroes then in the United States. In States where the free Negroes were numbered by only hundreds or even thousands, the entrance or exit of one was a noticeable event. Where, however, Negroes were in the majority, a hundred might have come or gone at once without being noticed. The Constitution of Georgia[74] of 1865 empowered the general assembly to make laws for the regulation or prohibition of the immigration of free persons of color into that State from other places; but the legislature seems not to have used this power.

Two years earlier, in 1863, the legislature of Kentucky[75] had declared that it was unlawful for any Negro or mulatto claiming to be free under the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, or under any other proclamation by the Government of the United States, to migrate to or remain in the State. Any Negro violating this law was treated as a runaway slave.

A law of South Carolina,[76] of 1865, provided that no person of color should migrate to or reside in the State unless, within twenty days after his arrival, he entered into a bond with two freeholders as sureties in a penalty of one thousand dollars, conditioned on his good behavior and for his support if he should become unable to support himself. If he should fail to execute the required bond, he had to leave the State within ten days, or be liable to corporal punishment. If, after being so punished, he 41should still remain in the State fifteen days longer, he was to be transported beyond the limits of the State for life “or kept at hard labor, with occasional solitary confinement, for a period not exceeding five years.” The same punishment of banishment for life, or confinement and hard labor for a term was prescribed for any person of color coming or being brought into South Carolina after having been convicted of an infamous crime in another State.

That the Southern States believed that the day of the Negro as a laborer was over was evidenced, not only by their efforts to keep Negroes out of the State, but also by the fact that so many of them, during the first years after the War, passed statutes encouraging and offering inducements to foreign immigrants. The movement to bring foreigners into the South is still going on, but it has never met with much success.

Although to-day many places, both in the North and in the South, do not permit Negroes to reside within their borders or even to stay over night, the above are apparently the last instances where attempts to limit the movement of Negroes[77] have been made by State legislatures. Most of the States have concluded to allow Negroes to come and go at will, but to fix their status while in the State.

From some occupations Negroes were wholly excluded; others, they were permitted to engage in, only after obtaining licenses. The Alabama Code[78] of 1867 provided that no free Negro should be licensed to keep a tavern or to 42sell vinous or spirituous liquors. There had been a statute of the same State which declared that a free Negro should not be employed to sell or to assist in the sale of drugs or medicine, under a penalty of one hundred dollars, but this had been repealed in 1866.[79]

In South Carolina,[80] it was unlawful for a Negro either to own a distillery of spirituous liquors or any establishment where they were sold. The violation of this law was a misdemeanor punishable by fine, corporal punishment or hard labor. The law of this State[81] went still further by enacting that no person of color should pursue or practice the art, trade, or business of an artisan, mechanic, or shopkeeper, “or any other trade, employment, or business (besides that of husbandry, or that of a servant under contract for service or labor) on his own account and for his own benefit, or in partnership with a white person, or as agent or servant of any person” until he should have obtained a license. This license was good for one year only. Before granting the license the judge had to be satisfied of the skill, fitness, and good moral character of the applicant. If the latter wished to be a shopkeeper or peddler, the annual license fee was one hundred dollars; if a mechanic, artisan, or a member of any other trade, ten dollars. The judge might revoke the license upon a complaint made to him. Negroes could not practice any mechanical art or trade without showing either that they had served their term of apprenticeship or were then practicing the art or trade. For violation of this rule, the Negro had to pay a fine of double the amount of the license, one-half to go to the informer.

In some States, there was a limitation upon the right 43of Negroes to hold land as tenants. A statute of Mississippi[82] in 1865 gave them the right to sue and be sued, to hold property, etc., but declared that the provisions of the statute should not be construed to allow any freeman, free Negro, or mulatto to rent or lease any lands, except in incorporated towns or cities in which places the corporate authorities should control the same. The same statute required every freeman, free Negro, or mulatto to have on January 1, 1866, and annually thereafter, a lawful home and employment with written evidence thereof. If living in an incorporated town, he must have a license from the mayor, authorizing him to do irregular job work—that is, if he was not under some written contract for service; if living outside such a town, he must have a similar license from a member of the board of police of his precinct.

Tennessee,[83] on the other hand, went to the length of expressly throwing open all trades to Negroes who complied with the license laws which were applicable to whites and blacks alike.

A fruitful subject of legislation was that relative to the sale of firearms to Negroes. On January 15, 1866, the legislature of Florida[84] enacted a law declaring that it was unlawful for a Negro to own, use, or keep in his possession or control “any bowie-knife, dirk, sword, firearms or ammunition of any kind” unless he had obtained a license from the probate judge of the county. To get the license, he had to present the certificate of two respectable citizens of the county as to the peaceful and 44orderly character of the applicant. The violation of this statute was a misdemeanor punishable by the forfeiture to the use of the informer of such firearms and ammunition and by standing in a pillory one hour or by being whipped not over thirty-nine stripes.

In Mississippi[85] the law was that any freedman, free Negro, or mulatto, not in the military service of the United States nor having a specified license, who should keep or carry firearms of any kind or any ammunition, dirk, or bowie-knife should be punished by a fine of not over ten dollars, and all such arms, etc., should be forfeited to the informer. The law further provided that, if any white person lent or gave a freedman, free Negro, or mulatto any firearms, ammunition, dirk, or bowie-knife, such white person should be fined not over fifty dollars, or imprisoned not over thirty days. South Carolina[86] did allow a Negro who was the owner of a farm, to keep a “shot-gun or rifle, such as is ordinarily used in hunting, but not a pistol, musket, or other firearm or weapon appropriate for purposes of war.”

It has been seen that some States forbade Negroes to make or sell intoxicating liquor. Others went a step further and made it unlawful to sell liquor to Negroes. It is worth noting that one of the early acts of the legislature of Alabama[87] was to repeal such a law. But Kentucky[88] forbade a coffee-house keeper to sell liquor to free Negroes under penalty of a bond of five hundred dollars. Mississippi[89] made it an offence, punishable by a fine of not over fifty dollars or imprisonment for not more than thirty days, for a white man to sell, give, or lend a Negro any intoxicating liquors, except that a master, mistress, or employer 45might give him spirituous liquors, but not in quantities sufficient to produce intoxication.